User login

Using the tools of positive psychiatry to improve clinical practice

FIRST OF 4 PARTS

What does wellness mean to you? A 2018 survey posed this question to more than 6,000 people living with depression and bipolar disorder. In addition to better treatment and greater understanding of their illnesses, other priorities emerged: a longing for better days, a sense of purpose, and a longing to function well and be happy.1 As one respondent explained, “Wellness means stability; well enough to hold a job, well enough to enjoy activities, well enough to feel joy and hope.” Traditional treatment that focuses on alleviating symptoms may not sufficiently address outcomes patients value. When the focus is primarily deficit-based, clinicians and patients may miss opportunities for optimization and transformation.

Positive psychiatry is the science and practice of psychiatry that seeks to enhance and promote well-being and health through the enhancement of positive psychosocial factors such as resilience, optimism, wisdom, and social support in people with illnesses or disabilities as well as those in the community at large.2 It is based on the principles that there is no health without mental health, and that mental health can improve through preventive, therapeutic, and rehabilitative interventions.3

Positive interventions are defined as “treatment methods or intentional activities that aim to cultivate positive feelings, behaviors, or cognitions.”4 They are evidence-based intentional exercises designed to increase well-being and enhance flourishing. Although positive interventions were originally studied as activities for nonclinical populations and for helping healthy people thrive, they are increasingly being valued for their therapeutic role in treating psychopathology.5 By adding positive interventions to their toolbox, psychiatrists can expand the range of treatment options, better engage patients during the treatment process, and bolster positive mental health.

In this article, we provide practical ways to integrate the tools and principles of positive psychiatry into everyday clinical practice. The goal is to broaden how clinicians think about mental health and therapeutic options and, above all, enhance our patients’ everyday well-being. Teaching patients to adopt a positive orientation, harness strengths, mobilize values, cultivate social connections, and optimize healthy habits are strategies clinicians can apply not only to provide a counterweight to the traditional emphasis on illness, but also to enhance the range and richness of their patients’ everyday experience.

Adopt a positive orientation

When a clinician first meets a patient, “What’s wrong?” is a typical conversation starter, and conversations tend to revolve around problems, failures, and negative experiences. Positive psychiatry posits that there is therapeutic benefit to emphasizing and exploring a patient’s positive emotions, experiences, and aspirations. Questions such as “What was your sense of well-being this week? What is your goal for today’s session? What is your goal for the coming week?” can reorient a session towards an individual’s potential and promote exploration of what’s possible.

To promote a positive orientation, clinicians may consider integrating the Savoring and Three Good Things exercises—2 well-studied interventions—into their repertoire to activate and enhance positive emotional states such as gratitude and joy.6 An example of a Savoring activity is taking a 20-minute daily walk while trying to notice as many positive elements as possible. Similarly, the Three Good Things exercise, in which patients are asked to notice and write down 3 positive events and reflect on why they happened, promotes positive reflection and gratitude. A 14-day daily diary study conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic found that higher levels of gratitude were associated with higher levels of positive affect, lower levels of perceived stress related to COVID-19, and better subjective health.7 In addition to coping with life’s negative events, deliberately enhancing the impact of good things is a positive emotion amplifier. As French writer François de La Rochefoucauld argued, “Happiness does not consist in things themselves but in the relish we have of them.”8

Continue to: Harness strengths

Harness strengths

A growing body of evidence suggests that in addition to focusing on a patient’s chief concern, identifying and cultivating an individual’s signature strengths can mitigate stress and enhance well-being. Signature strengths are positive personality qualities that reflect our core identity and are morally valued. The VIA Character Strengths Survey is the most used and validated psychometric instrument to measure and identify signature strengths such as curiosity, self-regulation, honesty, and teamwork.9

To incorporate this tool into clinical practice, ask patients to complete a strengths survey using a validated assessment tool such as the VIA survey (www.viacharacter.org). After a patient identifies their signature strengths, encourage them to explore and apply these strengths in everyday life and in new ways. In addition to becoming aware of and using their signature strengths, encourage patients to “strengths spot” in others. “What strengths did you notice your coworker, family, or friend using today?” is a potential question to explore with patients. A strengths-based approach may be particularly helpful in uncovering motivation and fully engaging patients in treatment. Moreover, integrating strengths into the typically negatively skewed narrative underscores to patients that therapy isn’t only about untwisting distorted thinking, but also about harnessing one’s strengths, talents, and abilities. Strengths expressed through pragmatic actions can boost coping skills as well as enhance well-being.

Mobilize values

Value affirmation exercises have been shown to generate lasting benefits in creating positive feelings and behaviors.10 Encouraging patients to think about what they genuinely value redirects their gaze towards possibility and diverts self-focus. For instance, ask a patient to identify 2 or 3 values and write about why they are important. By reflecting on their values in writing, they affirm their identity and self-worth, thus creating a virtuous cycle of confidence, effort, and achievement. People who put their values front and center are more attuned to the needs of others as well as their own needs, and they make better connections.11 Including a patient’s values in the treatment plan may increase problem-solving skills, boost motivation, and build better stress management skills.

The “life review” is another intervention that facilitates exploration of a patient’s values. This exercise involves asking patients to recount the story of their life and the experiences that were most meaningful to them. This process allows clinicians to gain a deeper understanding of the patient’s values, which can help guide treatment. Meta-analytic evidence has demonstrated these reminiscence-based interventions have significant effects on well-being.6 As Mahatma Gandhi famously said, “Happiness is when what you think, what you say, and what you do are in harmony.” Creating more overlap between a patient’s values and their everyday actions and behaviors bolsters resilience, buffers against stress, and can restore a healthier self-concept.

Cultivate social connections

Social connection is recognized as a core psychological need and essential for well-being. The opposite of connection—social isolation—has negative effects on overall health, including increases in inflammatory markers, depression rates, and even all-cause mortality.12 A 2015 meta-analytic review demonstrated that loneliness increased the likelihood of mortality by 26%—a similar increase as seen with smoking 15 cigarettes a day.13

Continue to: As with any vital sign...

As with any vital sign, exploring a patient’s number of social contacts, quantity of social visits per week, and quality of relationships is an important indicator of health. Giving patients tools to cultivate social connection and deepen their relationships can enhance therapeutic outcomes. Asking patients to perform acts of kindness is one example of a “social prescription.” Feeding a stranger’s parking meter, picking up litter, helping a friend with a chore, providing a meal to a person in need, and volunteering are potential ways for patients to engage in kind deeds. After each act, encourage the patient to write down what they did and how it made them feel.

“Prescribing” positive communication is another way to enhance a patient’s social connections. For instance, teaching them about active constructive responding (ACR)—responding with enthusiasm when another person shares information or good news—has been shown to strengthen bonds with friends and family.14 Making eye contact, giving the other person one’s full attention, inquiring about details, and responding with enthusiasm and interest are simple ways patients can apply ACR in their daily lives. Counseling a patient on increasing social connections, prescribing connections, and inquiring about quantity and quality of social interactions can help them not only add years to their life but also add health and well-being to those years.

Optimize healthy habits

Mounting research demonstrates that exercise, sleep, and nutrition are important for well-being. Evidence shows that therapeutic lifestyle changes can reduce depressive symptoms and boost positive feelings. Numerous meta-analyses have demonstrated the benefits of sleep and exercise interventions for reducing depressive symptoms in psychiatric patients.15,16 Longitudinal studies have provided evidence that healthy diets increase happiness, even after controlling for potential confounders such as socioeconomic factors.17 Other lifestyle factors—including financial stability, pet ownership, decreased social media use, and spending time in nature—have been shown to contribute to well-being.18

Despite the substantial evidence that lifestyle factors can improve health outcomes, few clinicians ask about, focus on, or promote positive habits.19 Positive psychiatry seeks to reorient clinicians towards lifestyle factors that enhance well-being. Clinicians can deploy a variety of strategies to support patients in making healthy and sustainable changes. Assessing readiness for change, motivational interviewing, setting SMART (specific, measurable, assignable, realistic, and time-related) goals, and referring patients to relevant community resources are ways to encourage and promote therapeutic lifestyle changes. Inquiring about a patient’s typical day—such as how they spend their free time, what they eat, when they go to bed, and how much time they spend outdoors—opens conversations about general well-being and shows the patient that therapy is about the whole person, and not only symptom management. Helping patients have better days can empower them to lead more satisfied lives.20

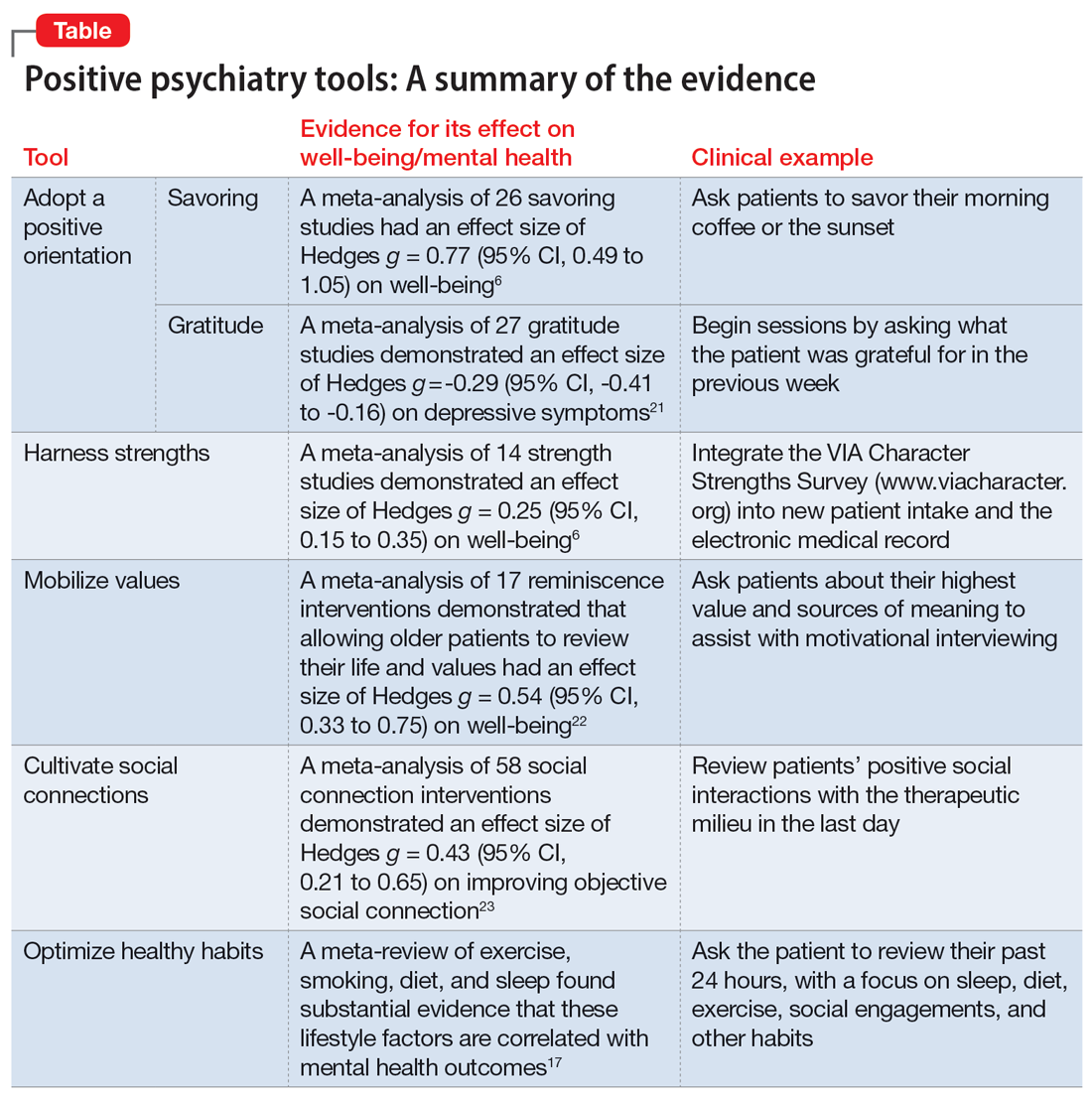

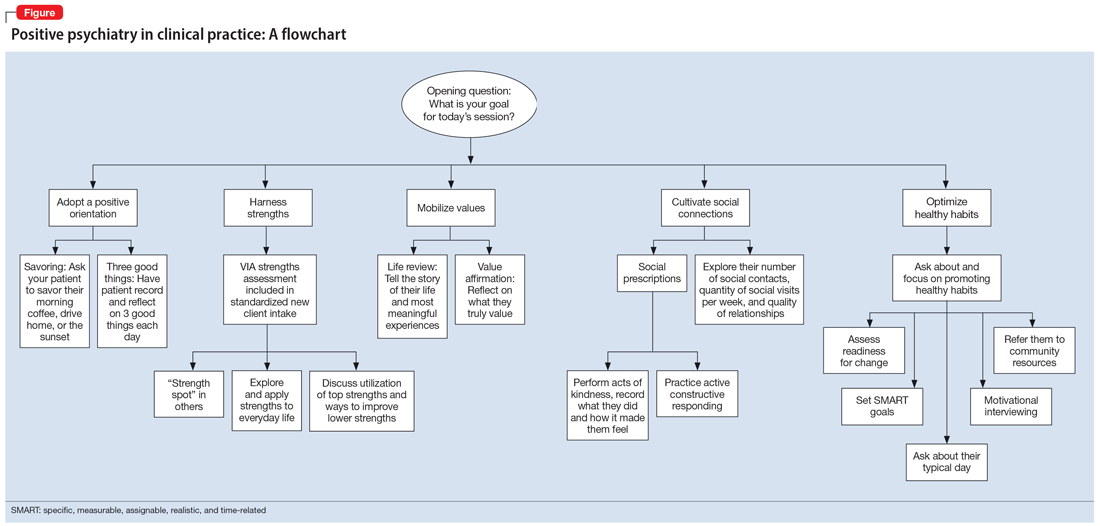

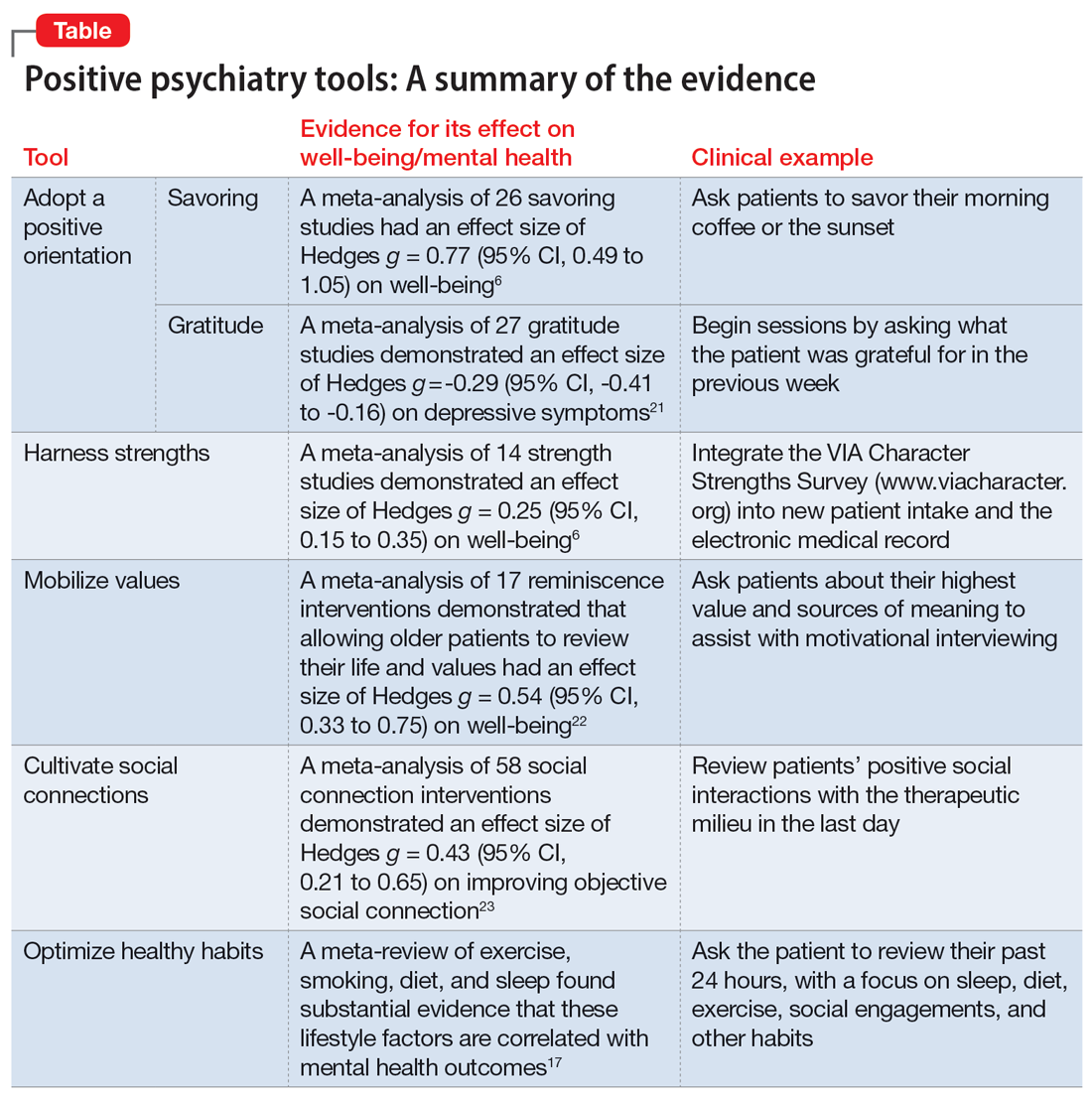

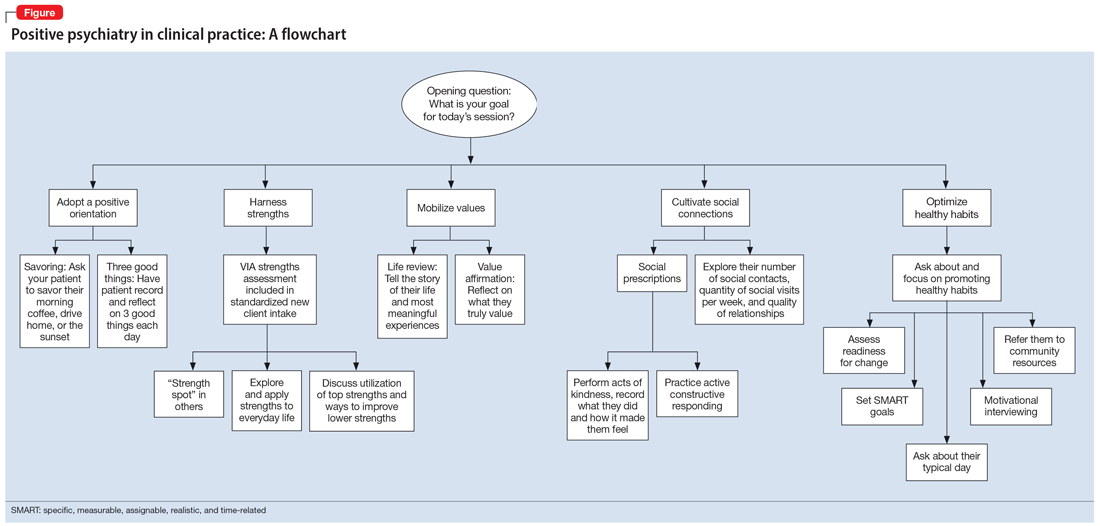

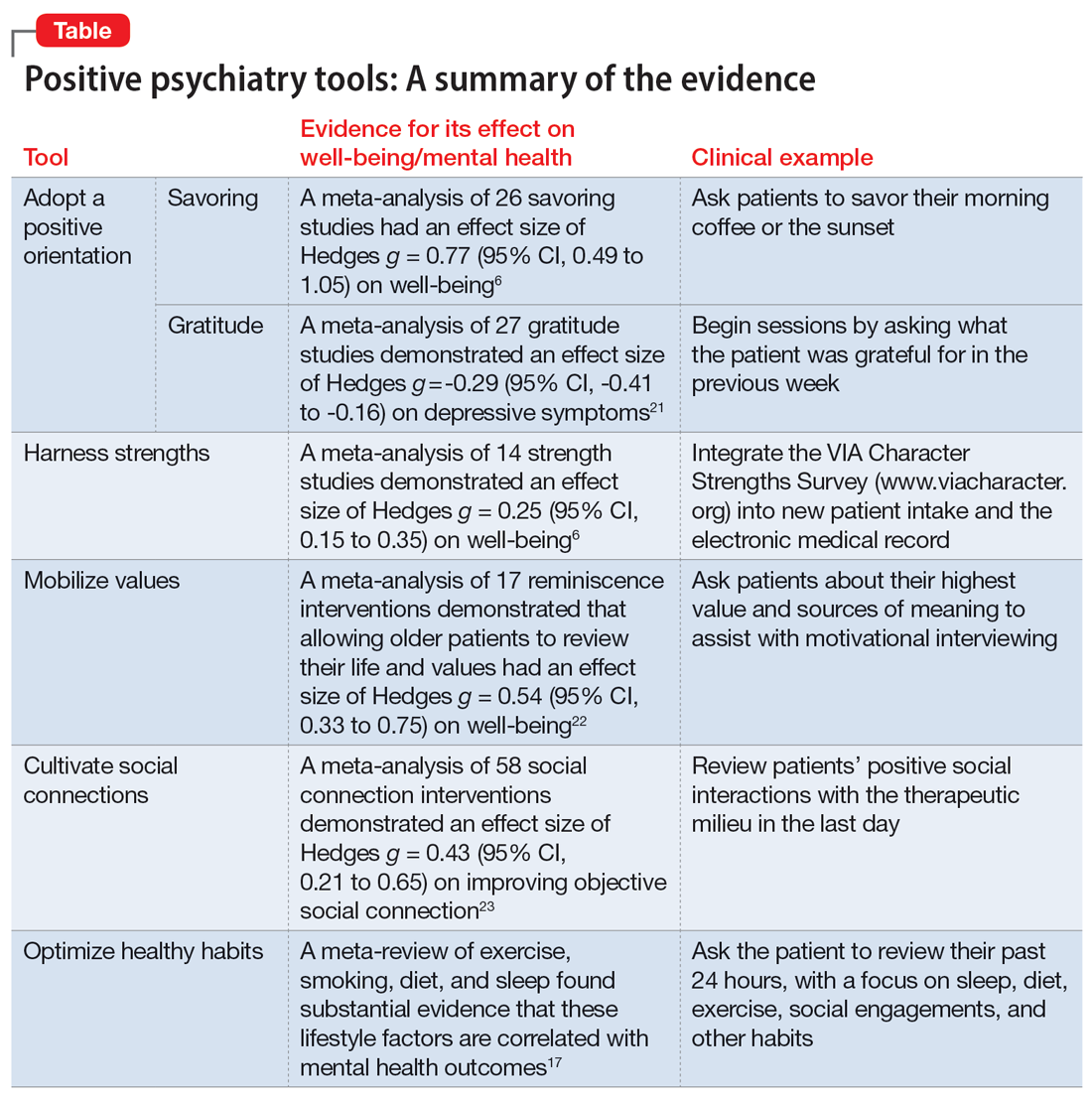

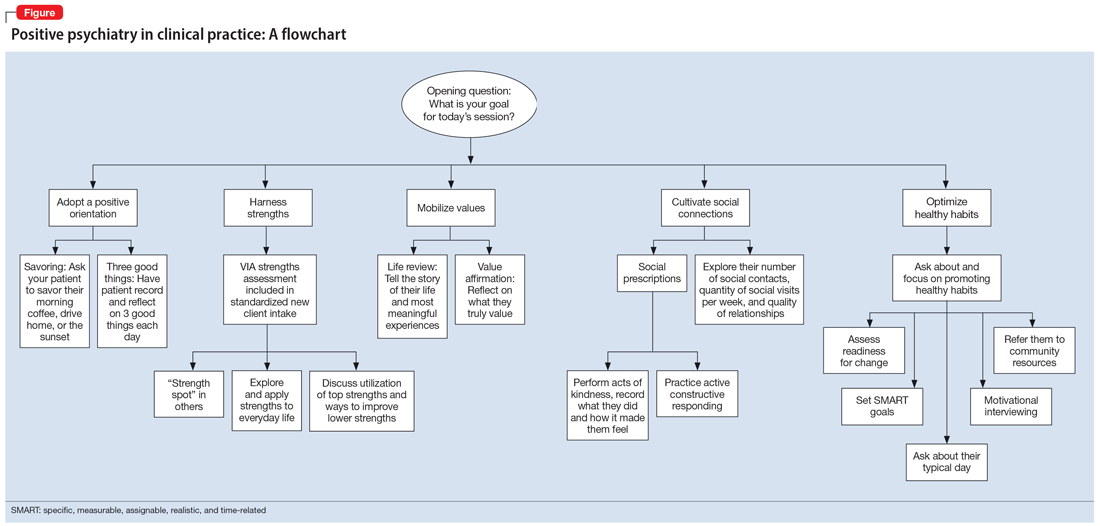

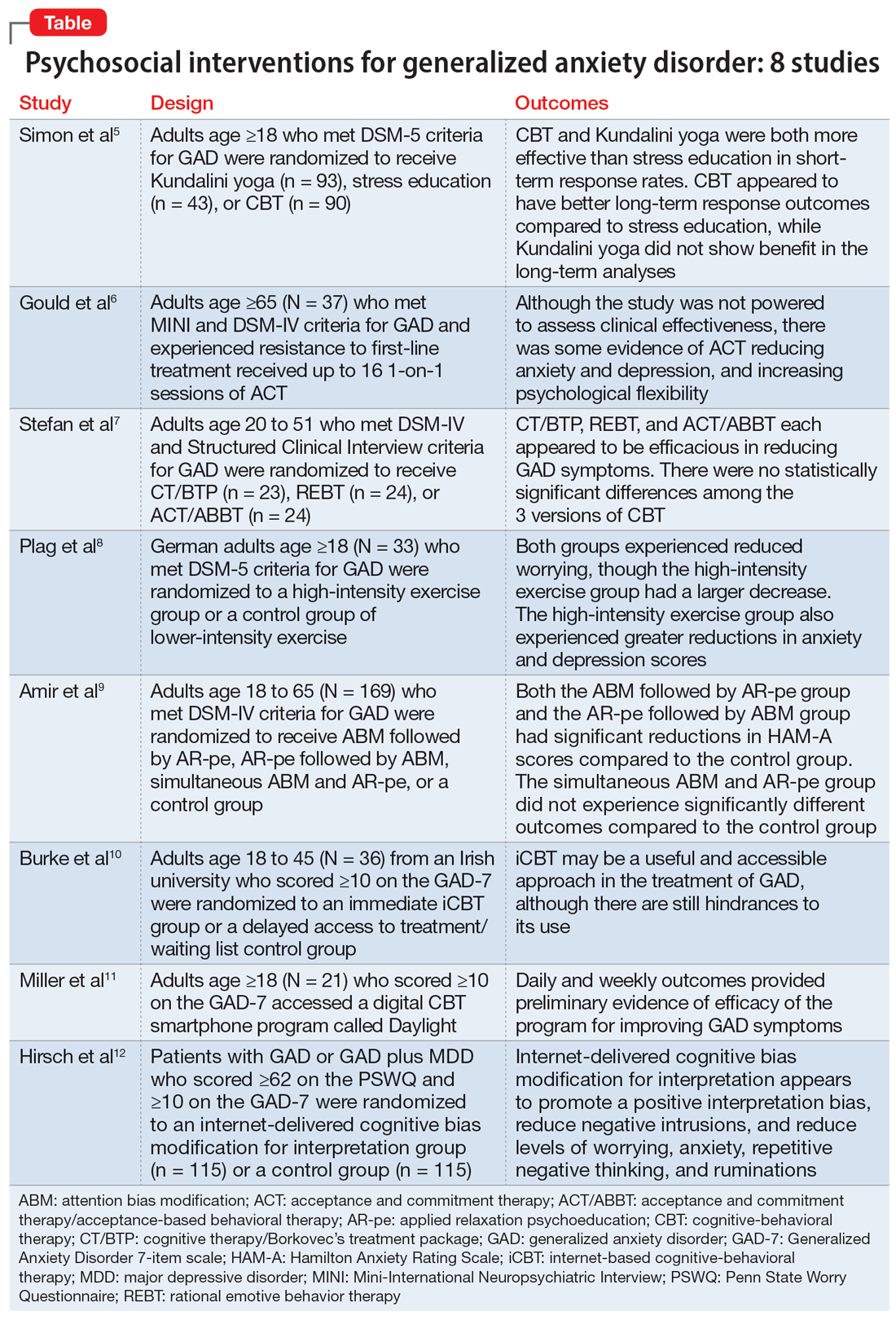

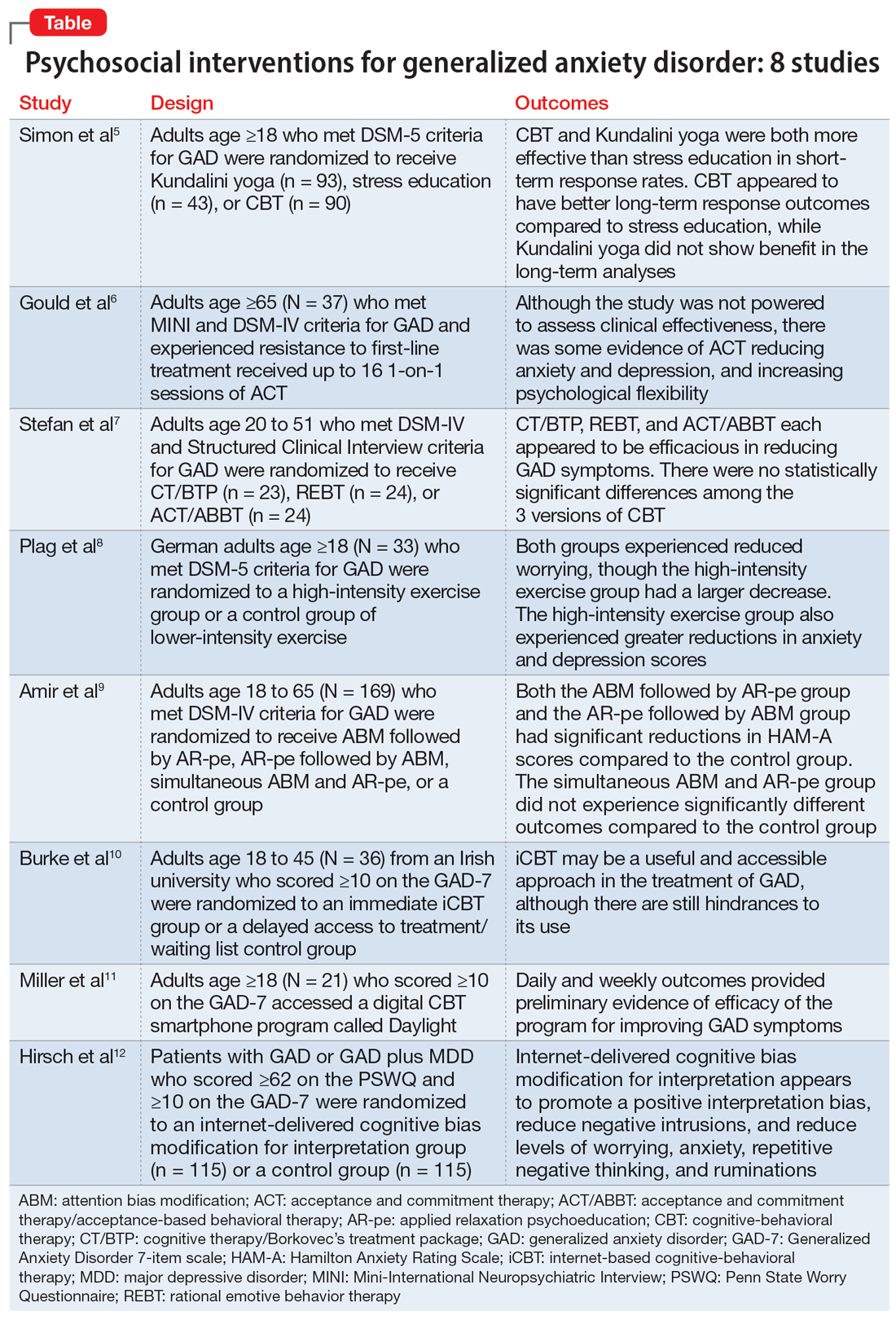

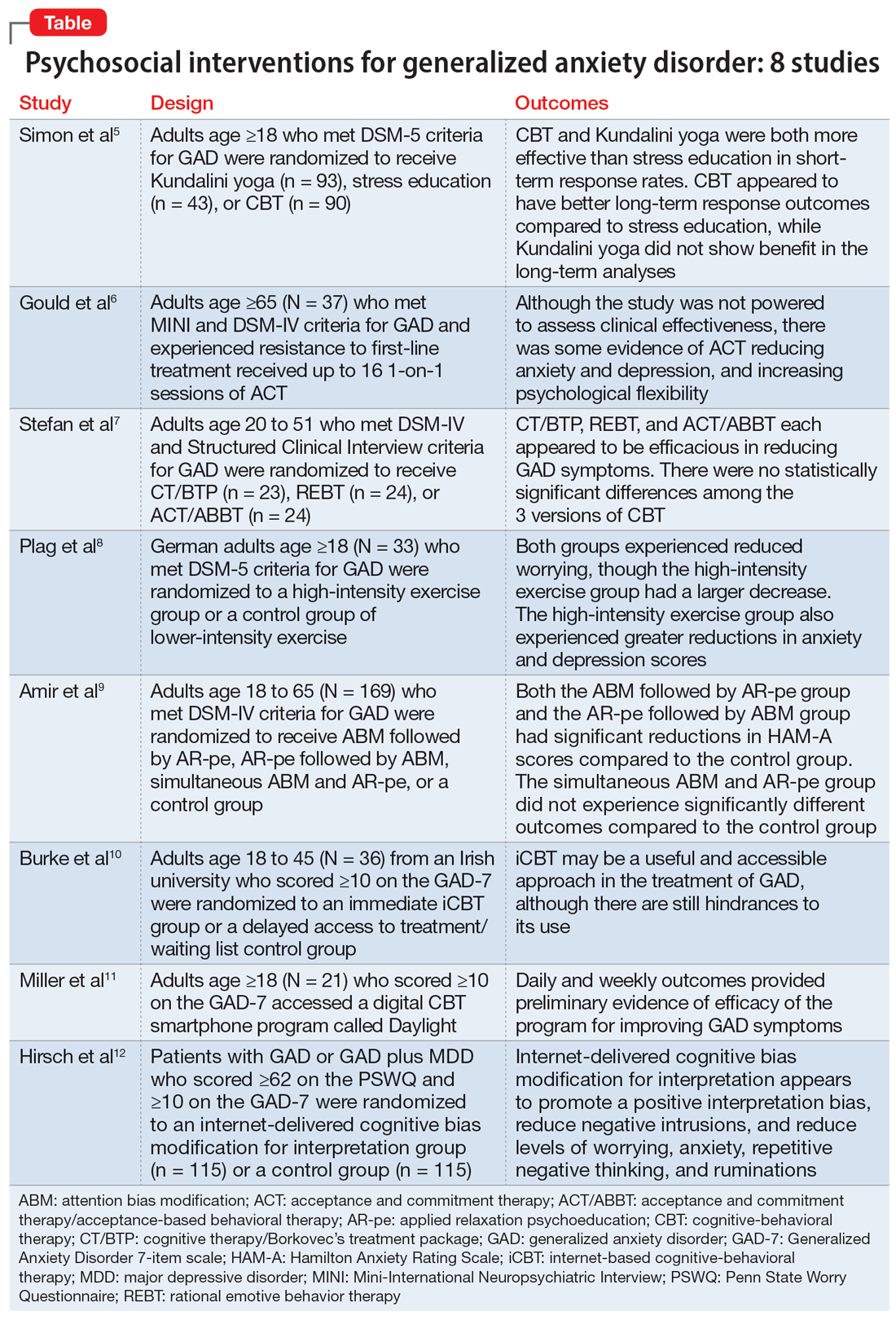

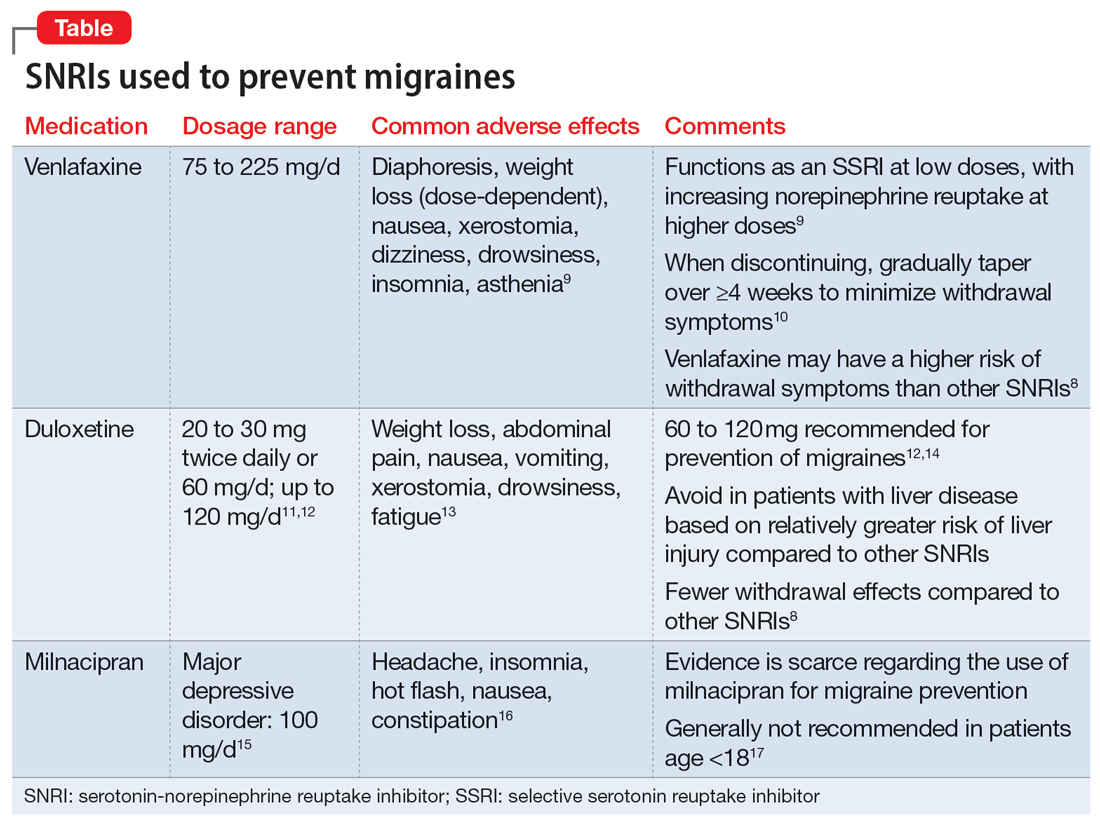

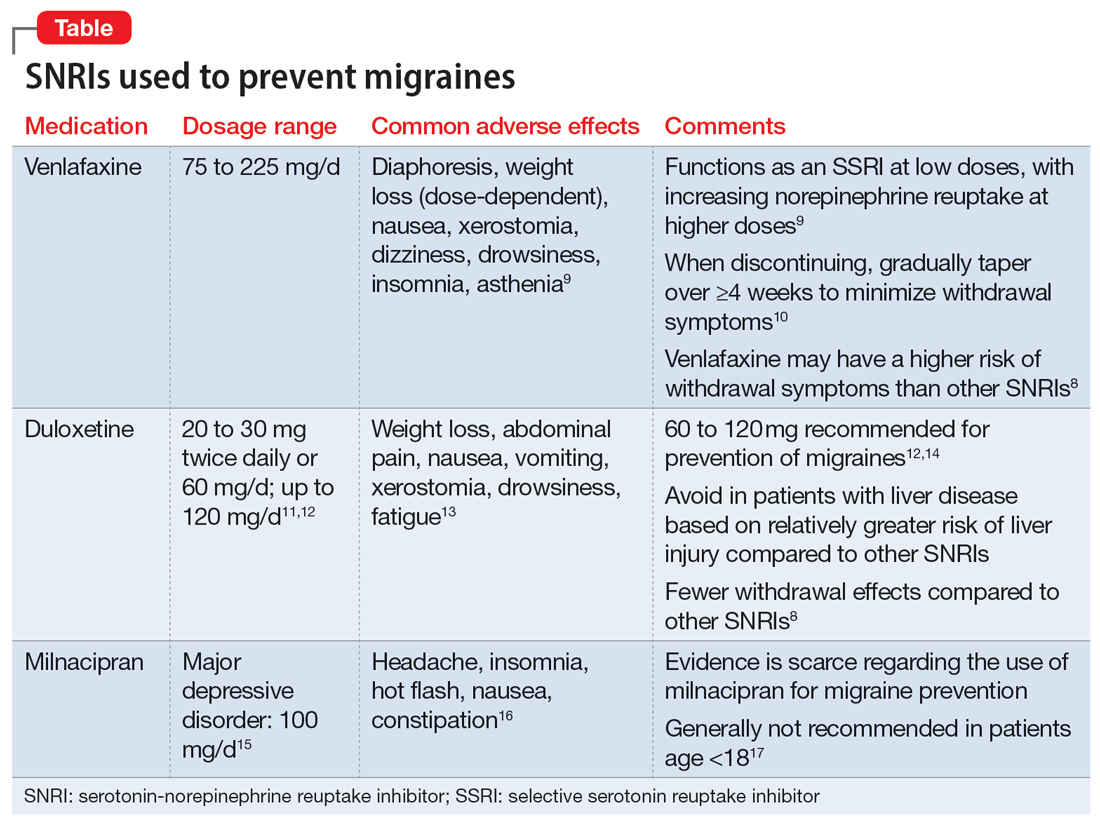

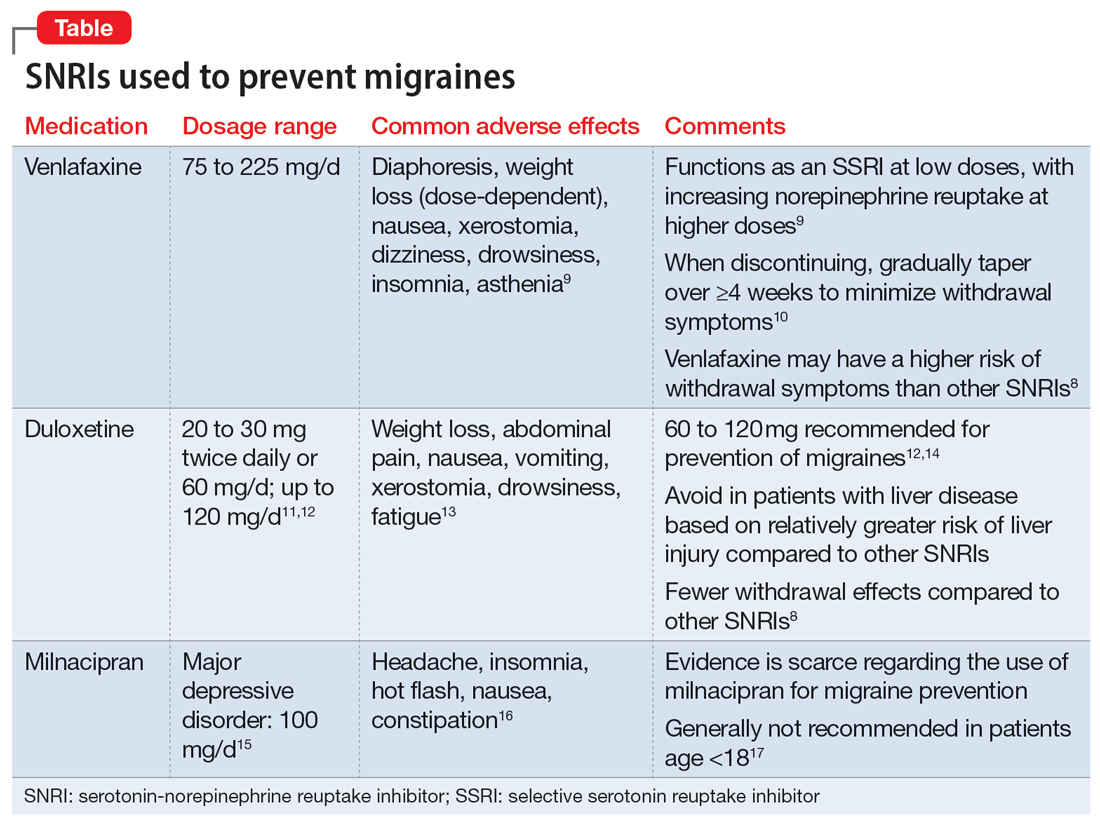

The Table6,17,21-23 summarizes the scientific evidence for the strategies described in this article. The Figure provides a flowchart for using these strategies in clinical practice.

Continue to: Balancing pathogenesis with salutogenesis

Balancing pathogenesis with salutogenesis

By exploring and emphasizing potential and possibility, positive psychiatry aims to create a balance between pathogenesis (the study and understanding of disease) with salutogenesis (the study and creation of health24). Clinicians are well positioned to manage symptoms and bolster positive states. Rather than an either/or approach to well-being, positive psychiatry strives for a both/and approach to well-being. By adding positive interventions to their toolbox, clinicians can expand the range of treatment options, better engage patients in the treatment process, and bolster mental health.

Bottom Line

Clinicians can integrate the tools and principles of positive psychiatry into clinical practice. Teaching patients to adopt a positive orientation, harness strengths, mobilize values, cultivate social connections, and optimize healthy habits can not only provide a counterweight to the traditional emphasis on illness, but also can enhance the range and richness of patients’ everyday experience.

Related Resources

- University of Pennsylvania. Authentic happiness. https://www.authentichappiness.sas.upenn.edu

- Jeste DV, Palmer BW (eds). Positive Psychiatry: A Clinical Handbook. American Psychiatric Publishing; 2015.

- Jeste DV, Palmer BW, Rettew DC, et al. Positive psychiatry: its time has come. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(6):675-683.

1. Morton E, Foxworth P, Dardess P, et al. “Supporting Wellness”: a depression and bipolar support alliance mixed-methods investigation of lived experience perspectives and priorities for mood disorder treatment. J Affect Disord. 2022;299:575-584.

2. Jeste DV, Palmer BW, Rettew DC, et al. Positive psychiatry: its time has come. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(6):675-683.

3. Jeste DV. Positive psychiatry comes of age. Int Psychogeriatr. 2018;30(12):1735-1738.

4. Sin NL, Lyubomirsky S. Enhancing well-being and alleviating depressive symptoms with positive psychology interventions: a practice-friendly meta-analysis. J Clin Psychol. 2009;65(5):467-487.

5. Seligman MEP, Rashid T, Parks AC. Positive psychotherapy. Am Psychol. 2006;61(8):774-788.

6. Carr A, Cullen K, Keeney C, et al. Effectiveness of positive psychology interventions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Posit Psychol. 2021;16(6):749-769.

7. Jiang D. Feeling gratitude is associated with better well-being across the life span: a daily diary study during the COVID-19 outbreak. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2022;77(4):e36-e45.

8. de La Rochefoucauld F. Maxims and moral reflections (1796). Gale ECCO: 2010.

9. Niemiec RM. VIA character strengths: Research and practice (The first 10 years). In: Knoop HH, Fave AD (eds). Well-being and Cultures. Springer;2013:11-29.

10. Cohen GL, Sherman DK. The psychology of change: self-affirmation and social psychological intervention. Annu Rev Psychol. 2014;65:333-371.

11. Thomaes S, Bushman BJ, de Castro BO, et al. Arousing “gentle passions” in young adolescents: sustained experimental effects of value affirmations on prosocial feelings and behaviors. Dev Psychol. 2012;48(1):103-110.

12. Cacioppo JT, Cacioppo S, Capitanio JP, et al. The neuroendocrinology of social isolation. Annu Rev Psychol. 2015;66:733-767.

13. Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Baker M, et al. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: a meta-analytic review. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2015;10(2):227-237.

14. Gable SL, Reis HT, Impett EA, et al. What do you do when things go right? The intrapersonal and interpersonal benefits of sharing positive events. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2004;87(2):228-245.

15. Gee B, Orchard F, Clarke E, et al. The effect of non-pharmacological sleep interventions on depression symptoms: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Sleep Med Rev. 2019;43:118-128.

16. Krogh J, Hjorthøj C, Speyer H, et al. Exercise for patients with major depression: a systematic review with meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis. BMJ Open. 2017;7(9):e014820. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014820

17. Firth J, Solmi M, Wootton RE, et al. A meta-review of “lifestyle psychiatry”: the role of exercise, smoking, diet and sleep in the prevention and treatment of mental disorders. World Psychiatry. 2020;19(3):360-380.

18. Piotrowski MC, Lunsford J, Gaynes BN. Lifestyle psychiatry for depression and anxiety: beyond diet and exercise. Lifestyle Med. 2021;2(1):e21. doi:10.1002/lim2.21

19. Janney CA, Brzoznowski KF, Richardson Cret al. Moving towards wellness: physical activity practices, perspectives, and preferences of users of outpatient mental health service. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2017;49:63-66.

20. Walsh R. Lifestyle and mental health. Am Psychol. 2011;66(7):579-592.

21. Cregg DR, Cheavens JS. Gratitude interventions: effective self-help? A meta-analysis of the impact on symptoms of depression and anxiety. J Happiness Stud. 2021;22(1):413-445.

22. Bohlmeijer E, Roemer M, Cuijpers P, et al. The effects of reminiscence on psychological well-being in older adults: a meta-analysis. Aging Ment Health. 2007;11(3):291-300.

23. Zagic D, Wuthrich VM, Rapee RM, et al. Interventions to improve social connections: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2022;57(5):885-906.

24. Mittelmark MB, Sagy S, Eriksson M, et al (eds). The Handbook of Salutogenesis [Internet]. Springer; 2017.

FIRST OF 4 PARTS

What does wellness mean to you? A 2018 survey posed this question to more than 6,000 people living with depression and bipolar disorder. In addition to better treatment and greater understanding of their illnesses, other priorities emerged: a longing for better days, a sense of purpose, and a longing to function well and be happy.1 As one respondent explained, “Wellness means stability; well enough to hold a job, well enough to enjoy activities, well enough to feel joy and hope.” Traditional treatment that focuses on alleviating symptoms may not sufficiently address outcomes patients value. When the focus is primarily deficit-based, clinicians and patients may miss opportunities for optimization and transformation.

Positive psychiatry is the science and practice of psychiatry that seeks to enhance and promote well-being and health through the enhancement of positive psychosocial factors such as resilience, optimism, wisdom, and social support in people with illnesses or disabilities as well as those in the community at large.2 It is based on the principles that there is no health without mental health, and that mental health can improve through preventive, therapeutic, and rehabilitative interventions.3

Positive interventions are defined as “treatment methods or intentional activities that aim to cultivate positive feelings, behaviors, or cognitions.”4 They are evidence-based intentional exercises designed to increase well-being and enhance flourishing. Although positive interventions were originally studied as activities for nonclinical populations and for helping healthy people thrive, they are increasingly being valued for their therapeutic role in treating psychopathology.5 By adding positive interventions to their toolbox, psychiatrists can expand the range of treatment options, better engage patients during the treatment process, and bolster positive mental health.

In this article, we provide practical ways to integrate the tools and principles of positive psychiatry into everyday clinical practice. The goal is to broaden how clinicians think about mental health and therapeutic options and, above all, enhance our patients’ everyday well-being. Teaching patients to adopt a positive orientation, harness strengths, mobilize values, cultivate social connections, and optimize healthy habits are strategies clinicians can apply not only to provide a counterweight to the traditional emphasis on illness, but also to enhance the range and richness of their patients’ everyday experience.

Adopt a positive orientation

When a clinician first meets a patient, “What’s wrong?” is a typical conversation starter, and conversations tend to revolve around problems, failures, and negative experiences. Positive psychiatry posits that there is therapeutic benefit to emphasizing and exploring a patient’s positive emotions, experiences, and aspirations. Questions such as “What was your sense of well-being this week? What is your goal for today’s session? What is your goal for the coming week?” can reorient a session towards an individual’s potential and promote exploration of what’s possible.

To promote a positive orientation, clinicians may consider integrating the Savoring and Three Good Things exercises—2 well-studied interventions—into their repertoire to activate and enhance positive emotional states such as gratitude and joy.6 An example of a Savoring activity is taking a 20-minute daily walk while trying to notice as many positive elements as possible. Similarly, the Three Good Things exercise, in which patients are asked to notice and write down 3 positive events and reflect on why they happened, promotes positive reflection and gratitude. A 14-day daily diary study conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic found that higher levels of gratitude were associated with higher levels of positive affect, lower levels of perceived stress related to COVID-19, and better subjective health.7 In addition to coping with life’s negative events, deliberately enhancing the impact of good things is a positive emotion amplifier. As French writer François de La Rochefoucauld argued, “Happiness does not consist in things themselves but in the relish we have of them.”8

Continue to: Harness strengths

Harness strengths

A growing body of evidence suggests that in addition to focusing on a patient’s chief concern, identifying and cultivating an individual’s signature strengths can mitigate stress and enhance well-being. Signature strengths are positive personality qualities that reflect our core identity and are morally valued. The VIA Character Strengths Survey is the most used and validated psychometric instrument to measure and identify signature strengths such as curiosity, self-regulation, honesty, and teamwork.9

To incorporate this tool into clinical practice, ask patients to complete a strengths survey using a validated assessment tool such as the VIA survey (www.viacharacter.org). After a patient identifies their signature strengths, encourage them to explore and apply these strengths in everyday life and in new ways. In addition to becoming aware of and using their signature strengths, encourage patients to “strengths spot” in others. “What strengths did you notice your coworker, family, or friend using today?” is a potential question to explore with patients. A strengths-based approach may be particularly helpful in uncovering motivation and fully engaging patients in treatment. Moreover, integrating strengths into the typically negatively skewed narrative underscores to patients that therapy isn’t only about untwisting distorted thinking, but also about harnessing one’s strengths, talents, and abilities. Strengths expressed through pragmatic actions can boost coping skills as well as enhance well-being.

Mobilize values

Value affirmation exercises have been shown to generate lasting benefits in creating positive feelings and behaviors.10 Encouraging patients to think about what they genuinely value redirects their gaze towards possibility and diverts self-focus. For instance, ask a patient to identify 2 or 3 values and write about why they are important. By reflecting on their values in writing, they affirm their identity and self-worth, thus creating a virtuous cycle of confidence, effort, and achievement. People who put their values front and center are more attuned to the needs of others as well as their own needs, and they make better connections.11 Including a patient’s values in the treatment plan may increase problem-solving skills, boost motivation, and build better stress management skills.

The “life review” is another intervention that facilitates exploration of a patient’s values. This exercise involves asking patients to recount the story of their life and the experiences that were most meaningful to them. This process allows clinicians to gain a deeper understanding of the patient’s values, which can help guide treatment. Meta-analytic evidence has demonstrated these reminiscence-based interventions have significant effects on well-being.6 As Mahatma Gandhi famously said, “Happiness is when what you think, what you say, and what you do are in harmony.” Creating more overlap between a patient’s values and their everyday actions and behaviors bolsters resilience, buffers against stress, and can restore a healthier self-concept.

Cultivate social connections

Social connection is recognized as a core psychological need and essential for well-being. The opposite of connection—social isolation—has negative effects on overall health, including increases in inflammatory markers, depression rates, and even all-cause mortality.12 A 2015 meta-analytic review demonstrated that loneliness increased the likelihood of mortality by 26%—a similar increase as seen with smoking 15 cigarettes a day.13

Continue to: As with any vital sign...

As with any vital sign, exploring a patient’s number of social contacts, quantity of social visits per week, and quality of relationships is an important indicator of health. Giving patients tools to cultivate social connection and deepen their relationships can enhance therapeutic outcomes. Asking patients to perform acts of kindness is one example of a “social prescription.” Feeding a stranger’s parking meter, picking up litter, helping a friend with a chore, providing a meal to a person in need, and volunteering are potential ways for patients to engage in kind deeds. After each act, encourage the patient to write down what they did and how it made them feel.

“Prescribing” positive communication is another way to enhance a patient’s social connections. For instance, teaching them about active constructive responding (ACR)—responding with enthusiasm when another person shares information or good news—has been shown to strengthen bonds with friends and family.14 Making eye contact, giving the other person one’s full attention, inquiring about details, and responding with enthusiasm and interest are simple ways patients can apply ACR in their daily lives. Counseling a patient on increasing social connections, prescribing connections, and inquiring about quantity and quality of social interactions can help them not only add years to their life but also add health and well-being to those years.

Optimize healthy habits

Mounting research demonstrates that exercise, sleep, and nutrition are important for well-being. Evidence shows that therapeutic lifestyle changes can reduce depressive symptoms and boost positive feelings. Numerous meta-analyses have demonstrated the benefits of sleep and exercise interventions for reducing depressive symptoms in psychiatric patients.15,16 Longitudinal studies have provided evidence that healthy diets increase happiness, even after controlling for potential confounders such as socioeconomic factors.17 Other lifestyle factors—including financial stability, pet ownership, decreased social media use, and spending time in nature—have been shown to contribute to well-being.18

Despite the substantial evidence that lifestyle factors can improve health outcomes, few clinicians ask about, focus on, or promote positive habits.19 Positive psychiatry seeks to reorient clinicians towards lifestyle factors that enhance well-being. Clinicians can deploy a variety of strategies to support patients in making healthy and sustainable changes. Assessing readiness for change, motivational interviewing, setting SMART (specific, measurable, assignable, realistic, and time-related) goals, and referring patients to relevant community resources are ways to encourage and promote therapeutic lifestyle changes. Inquiring about a patient’s typical day—such as how they spend their free time, what they eat, when they go to bed, and how much time they spend outdoors—opens conversations about general well-being and shows the patient that therapy is about the whole person, and not only symptom management. Helping patients have better days can empower them to lead more satisfied lives.20

The Table6,17,21-23 summarizes the scientific evidence for the strategies described in this article. The Figure provides a flowchart for using these strategies in clinical practice.

Continue to: Balancing pathogenesis with salutogenesis

Balancing pathogenesis with salutogenesis

By exploring and emphasizing potential and possibility, positive psychiatry aims to create a balance between pathogenesis (the study and understanding of disease) with salutogenesis (the study and creation of health24). Clinicians are well positioned to manage symptoms and bolster positive states. Rather than an either/or approach to well-being, positive psychiatry strives for a both/and approach to well-being. By adding positive interventions to their toolbox, clinicians can expand the range of treatment options, better engage patients in the treatment process, and bolster mental health.

Bottom Line

Clinicians can integrate the tools and principles of positive psychiatry into clinical practice. Teaching patients to adopt a positive orientation, harness strengths, mobilize values, cultivate social connections, and optimize healthy habits can not only provide a counterweight to the traditional emphasis on illness, but also can enhance the range and richness of patients’ everyday experience.

Related Resources

- University of Pennsylvania. Authentic happiness. https://www.authentichappiness.sas.upenn.edu

- Jeste DV, Palmer BW (eds). Positive Psychiatry: A Clinical Handbook. American Psychiatric Publishing; 2015.

- Jeste DV, Palmer BW, Rettew DC, et al. Positive psychiatry: its time has come. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(6):675-683.

FIRST OF 4 PARTS

What does wellness mean to you? A 2018 survey posed this question to more than 6,000 people living with depression and bipolar disorder. In addition to better treatment and greater understanding of their illnesses, other priorities emerged: a longing for better days, a sense of purpose, and a longing to function well and be happy.1 As one respondent explained, “Wellness means stability; well enough to hold a job, well enough to enjoy activities, well enough to feel joy and hope.” Traditional treatment that focuses on alleviating symptoms may not sufficiently address outcomes patients value. When the focus is primarily deficit-based, clinicians and patients may miss opportunities for optimization and transformation.

Positive psychiatry is the science and practice of psychiatry that seeks to enhance and promote well-being and health through the enhancement of positive psychosocial factors such as resilience, optimism, wisdom, and social support in people with illnesses or disabilities as well as those in the community at large.2 It is based on the principles that there is no health without mental health, and that mental health can improve through preventive, therapeutic, and rehabilitative interventions.3

Positive interventions are defined as “treatment methods or intentional activities that aim to cultivate positive feelings, behaviors, or cognitions.”4 They are evidence-based intentional exercises designed to increase well-being and enhance flourishing. Although positive interventions were originally studied as activities for nonclinical populations and for helping healthy people thrive, they are increasingly being valued for their therapeutic role in treating psychopathology.5 By adding positive interventions to their toolbox, psychiatrists can expand the range of treatment options, better engage patients during the treatment process, and bolster positive mental health.

In this article, we provide practical ways to integrate the tools and principles of positive psychiatry into everyday clinical practice. The goal is to broaden how clinicians think about mental health and therapeutic options and, above all, enhance our patients’ everyday well-being. Teaching patients to adopt a positive orientation, harness strengths, mobilize values, cultivate social connections, and optimize healthy habits are strategies clinicians can apply not only to provide a counterweight to the traditional emphasis on illness, but also to enhance the range and richness of their patients’ everyday experience.

Adopt a positive orientation

When a clinician first meets a patient, “What’s wrong?” is a typical conversation starter, and conversations tend to revolve around problems, failures, and negative experiences. Positive psychiatry posits that there is therapeutic benefit to emphasizing and exploring a patient’s positive emotions, experiences, and aspirations. Questions such as “What was your sense of well-being this week? What is your goal for today’s session? What is your goal for the coming week?” can reorient a session towards an individual’s potential and promote exploration of what’s possible.

To promote a positive orientation, clinicians may consider integrating the Savoring and Three Good Things exercises—2 well-studied interventions—into their repertoire to activate and enhance positive emotional states such as gratitude and joy.6 An example of a Savoring activity is taking a 20-minute daily walk while trying to notice as many positive elements as possible. Similarly, the Three Good Things exercise, in which patients are asked to notice and write down 3 positive events and reflect on why they happened, promotes positive reflection and gratitude. A 14-day daily diary study conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic found that higher levels of gratitude were associated with higher levels of positive affect, lower levels of perceived stress related to COVID-19, and better subjective health.7 In addition to coping with life’s negative events, deliberately enhancing the impact of good things is a positive emotion amplifier. As French writer François de La Rochefoucauld argued, “Happiness does not consist in things themselves but in the relish we have of them.”8

Continue to: Harness strengths

Harness strengths

A growing body of evidence suggests that in addition to focusing on a patient’s chief concern, identifying and cultivating an individual’s signature strengths can mitigate stress and enhance well-being. Signature strengths are positive personality qualities that reflect our core identity and are morally valued. The VIA Character Strengths Survey is the most used and validated psychometric instrument to measure and identify signature strengths such as curiosity, self-regulation, honesty, and teamwork.9

To incorporate this tool into clinical practice, ask patients to complete a strengths survey using a validated assessment tool such as the VIA survey (www.viacharacter.org). After a patient identifies their signature strengths, encourage them to explore and apply these strengths in everyday life and in new ways. In addition to becoming aware of and using their signature strengths, encourage patients to “strengths spot” in others. “What strengths did you notice your coworker, family, or friend using today?” is a potential question to explore with patients. A strengths-based approach may be particularly helpful in uncovering motivation and fully engaging patients in treatment. Moreover, integrating strengths into the typically negatively skewed narrative underscores to patients that therapy isn’t only about untwisting distorted thinking, but also about harnessing one’s strengths, talents, and abilities. Strengths expressed through pragmatic actions can boost coping skills as well as enhance well-being.

Mobilize values

Value affirmation exercises have been shown to generate lasting benefits in creating positive feelings and behaviors.10 Encouraging patients to think about what they genuinely value redirects their gaze towards possibility and diverts self-focus. For instance, ask a patient to identify 2 or 3 values and write about why they are important. By reflecting on their values in writing, they affirm their identity and self-worth, thus creating a virtuous cycle of confidence, effort, and achievement. People who put their values front and center are more attuned to the needs of others as well as their own needs, and they make better connections.11 Including a patient’s values in the treatment plan may increase problem-solving skills, boost motivation, and build better stress management skills.

The “life review” is another intervention that facilitates exploration of a patient’s values. This exercise involves asking patients to recount the story of their life and the experiences that were most meaningful to them. This process allows clinicians to gain a deeper understanding of the patient’s values, which can help guide treatment. Meta-analytic evidence has demonstrated these reminiscence-based interventions have significant effects on well-being.6 As Mahatma Gandhi famously said, “Happiness is when what you think, what you say, and what you do are in harmony.” Creating more overlap between a patient’s values and their everyday actions and behaviors bolsters resilience, buffers against stress, and can restore a healthier self-concept.

Cultivate social connections

Social connection is recognized as a core psychological need and essential for well-being. The opposite of connection—social isolation—has negative effects on overall health, including increases in inflammatory markers, depression rates, and even all-cause mortality.12 A 2015 meta-analytic review demonstrated that loneliness increased the likelihood of mortality by 26%—a similar increase as seen with smoking 15 cigarettes a day.13

Continue to: As with any vital sign...

As with any vital sign, exploring a patient’s number of social contacts, quantity of social visits per week, and quality of relationships is an important indicator of health. Giving patients tools to cultivate social connection and deepen their relationships can enhance therapeutic outcomes. Asking patients to perform acts of kindness is one example of a “social prescription.” Feeding a stranger’s parking meter, picking up litter, helping a friend with a chore, providing a meal to a person in need, and volunteering are potential ways for patients to engage in kind deeds. After each act, encourage the patient to write down what they did and how it made them feel.

“Prescribing” positive communication is another way to enhance a patient’s social connections. For instance, teaching them about active constructive responding (ACR)—responding with enthusiasm when another person shares information or good news—has been shown to strengthen bonds with friends and family.14 Making eye contact, giving the other person one’s full attention, inquiring about details, and responding with enthusiasm and interest are simple ways patients can apply ACR in their daily lives. Counseling a patient on increasing social connections, prescribing connections, and inquiring about quantity and quality of social interactions can help them not only add years to their life but also add health and well-being to those years.

Optimize healthy habits

Mounting research demonstrates that exercise, sleep, and nutrition are important for well-being. Evidence shows that therapeutic lifestyle changes can reduce depressive symptoms and boost positive feelings. Numerous meta-analyses have demonstrated the benefits of sleep and exercise interventions for reducing depressive symptoms in psychiatric patients.15,16 Longitudinal studies have provided evidence that healthy diets increase happiness, even after controlling for potential confounders such as socioeconomic factors.17 Other lifestyle factors—including financial stability, pet ownership, decreased social media use, and spending time in nature—have been shown to contribute to well-being.18

Despite the substantial evidence that lifestyle factors can improve health outcomes, few clinicians ask about, focus on, or promote positive habits.19 Positive psychiatry seeks to reorient clinicians towards lifestyle factors that enhance well-being. Clinicians can deploy a variety of strategies to support patients in making healthy and sustainable changes. Assessing readiness for change, motivational interviewing, setting SMART (specific, measurable, assignable, realistic, and time-related) goals, and referring patients to relevant community resources are ways to encourage and promote therapeutic lifestyle changes. Inquiring about a patient’s typical day—such as how they spend their free time, what they eat, when they go to bed, and how much time they spend outdoors—opens conversations about general well-being and shows the patient that therapy is about the whole person, and not only symptom management. Helping patients have better days can empower them to lead more satisfied lives.20

The Table6,17,21-23 summarizes the scientific evidence for the strategies described in this article. The Figure provides a flowchart for using these strategies in clinical practice.

Continue to: Balancing pathogenesis with salutogenesis

Balancing pathogenesis with salutogenesis

By exploring and emphasizing potential and possibility, positive psychiatry aims to create a balance between pathogenesis (the study and understanding of disease) with salutogenesis (the study and creation of health24). Clinicians are well positioned to manage symptoms and bolster positive states. Rather than an either/or approach to well-being, positive psychiatry strives for a both/and approach to well-being. By adding positive interventions to their toolbox, clinicians can expand the range of treatment options, better engage patients in the treatment process, and bolster mental health.

Bottom Line

Clinicians can integrate the tools and principles of positive psychiatry into clinical practice. Teaching patients to adopt a positive orientation, harness strengths, mobilize values, cultivate social connections, and optimize healthy habits can not only provide a counterweight to the traditional emphasis on illness, but also can enhance the range and richness of patients’ everyday experience.

Related Resources

- University of Pennsylvania. Authentic happiness. https://www.authentichappiness.sas.upenn.edu

- Jeste DV, Palmer BW (eds). Positive Psychiatry: A Clinical Handbook. American Psychiatric Publishing; 2015.

- Jeste DV, Palmer BW, Rettew DC, et al. Positive psychiatry: its time has come. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(6):675-683.

1. Morton E, Foxworth P, Dardess P, et al. “Supporting Wellness”: a depression and bipolar support alliance mixed-methods investigation of lived experience perspectives and priorities for mood disorder treatment. J Affect Disord. 2022;299:575-584.

2. Jeste DV, Palmer BW, Rettew DC, et al. Positive psychiatry: its time has come. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(6):675-683.

3. Jeste DV. Positive psychiatry comes of age. Int Psychogeriatr. 2018;30(12):1735-1738.

4. Sin NL, Lyubomirsky S. Enhancing well-being and alleviating depressive symptoms with positive psychology interventions: a practice-friendly meta-analysis. J Clin Psychol. 2009;65(5):467-487.

5. Seligman MEP, Rashid T, Parks AC. Positive psychotherapy. Am Psychol. 2006;61(8):774-788.

6. Carr A, Cullen K, Keeney C, et al. Effectiveness of positive psychology interventions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Posit Psychol. 2021;16(6):749-769.

7. Jiang D. Feeling gratitude is associated with better well-being across the life span: a daily diary study during the COVID-19 outbreak. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2022;77(4):e36-e45.

8. de La Rochefoucauld F. Maxims and moral reflections (1796). Gale ECCO: 2010.

9. Niemiec RM. VIA character strengths: Research and practice (The first 10 years). In: Knoop HH, Fave AD (eds). Well-being and Cultures. Springer;2013:11-29.

10. Cohen GL, Sherman DK. The psychology of change: self-affirmation and social psychological intervention. Annu Rev Psychol. 2014;65:333-371.

11. Thomaes S, Bushman BJ, de Castro BO, et al. Arousing “gentle passions” in young adolescents: sustained experimental effects of value affirmations on prosocial feelings and behaviors. Dev Psychol. 2012;48(1):103-110.

12. Cacioppo JT, Cacioppo S, Capitanio JP, et al. The neuroendocrinology of social isolation. Annu Rev Psychol. 2015;66:733-767.

13. Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Baker M, et al. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: a meta-analytic review. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2015;10(2):227-237.

14. Gable SL, Reis HT, Impett EA, et al. What do you do when things go right? The intrapersonal and interpersonal benefits of sharing positive events. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2004;87(2):228-245.

15. Gee B, Orchard F, Clarke E, et al. The effect of non-pharmacological sleep interventions on depression symptoms: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Sleep Med Rev. 2019;43:118-128.

16. Krogh J, Hjorthøj C, Speyer H, et al. Exercise for patients with major depression: a systematic review with meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis. BMJ Open. 2017;7(9):e014820. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014820

17. Firth J, Solmi M, Wootton RE, et al. A meta-review of “lifestyle psychiatry”: the role of exercise, smoking, diet and sleep in the prevention and treatment of mental disorders. World Psychiatry. 2020;19(3):360-380.

18. Piotrowski MC, Lunsford J, Gaynes BN. Lifestyle psychiatry for depression and anxiety: beyond diet and exercise. Lifestyle Med. 2021;2(1):e21. doi:10.1002/lim2.21

19. Janney CA, Brzoznowski KF, Richardson Cret al. Moving towards wellness: physical activity practices, perspectives, and preferences of users of outpatient mental health service. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2017;49:63-66.

20. Walsh R. Lifestyle and mental health. Am Psychol. 2011;66(7):579-592.

21. Cregg DR, Cheavens JS. Gratitude interventions: effective self-help? A meta-analysis of the impact on symptoms of depression and anxiety. J Happiness Stud. 2021;22(1):413-445.

22. Bohlmeijer E, Roemer M, Cuijpers P, et al. The effects of reminiscence on psychological well-being in older adults: a meta-analysis. Aging Ment Health. 2007;11(3):291-300.

23. Zagic D, Wuthrich VM, Rapee RM, et al. Interventions to improve social connections: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2022;57(5):885-906.

24. Mittelmark MB, Sagy S, Eriksson M, et al (eds). The Handbook of Salutogenesis [Internet]. Springer; 2017.

1. Morton E, Foxworth P, Dardess P, et al. “Supporting Wellness”: a depression and bipolar support alliance mixed-methods investigation of lived experience perspectives and priorities for mood disorder treatment. J Affect Disord. 2022;299:575-584.

2. Jeste DV, Palmer BW, Rettew DC, et al. Positive psychiatry: its time has come. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(6):675-683.

3. Jeste DV. Positive psychiatry comes of age. Int Psychogeriatr. 2018;30(12):1735-1738.

4. Sin NL, Lyubomirsky S. Enhancing well-being and alleviating depressive symptoms with positive psychology interventions: a practice-friendly meta-analysis. J Clin Psychol. 2009;65(5):467-487.

5. Seligman MEP, Rashid T, Parks AC. Positive psychotherapy. Am Psychol. 2006;61(8):774-788.

6. Carr A, Cullen K, Keeney C, et al. Effectiveness of positive psychology interventions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Posit Psychol. 2021;16(6):749-769.

7. Jiang D. Feeling gratitude is associated with better well-being across the life span: a daily diary study during the COVID-19 outbreak. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2022;77(4):e36-e45.

8. de La Rochefoucauld F. Maxims and moral reflections (1796). Gale ECCO: 2010.

9. Niemiec RM. VIA character strengths: Research and practice (The first 10 years). In: Knoop HH, Fave AD (eds). Well-being and Cultures. Springer;2013:11-29.

10. Cohen GL, Sherman DK. The psychology of change: self-affirmation and social psychological intervention. Annu Rev Psychol. 2014;65:333-371.

11. Thomaes S, Bushman BJ, de Castro BO, et al. Arousing “gentle passions” in young adolescents: sustained experimental effects of value affirmations on prosocial feelings and behaviors. Dev Psychol. 2012;48(1):103-110.

12. Cacioppo JT, Cacioppo S, Capitanio JP, et al. The neuroendocrinology of social isolation. Annu Rev Psychol. 2015;66:733-767.

13. Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Baker M, et al. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: a meta-analytic review. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2015;10(2):227-237.

14. Gable SL, Reis HT, Impett EA, et al. What do you do when things go right? The intrapersonal and interpersonal benefits of sharing positive events. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2004;87(2):228-245.

15. Gee B, Orchard F, Clarke E, et al. The effect of non-pharmacological sleep interventions on depression symptoms: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Sleep Med Rev. 2019;43:118-128.

16. Krogh J, Hjorthøj C, Speyer H, et al. Exercise for patients with major depression: a systematic review with meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis. BMJ Open. 2017;7(9):e014820. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014820

17. Firth J, Solmi M, Wootton RE, et al. A meta-review of “lifestyle psychiatry”: the role of exercise, smoking, diet and sleep in the prevention and treatment of mental disorders. World Psychiatry. 2020;19(3):360-380.

18. Piotrowski MC, Lunsford J, Gaynes BN. Lifestyle psychiatry for depression and anxiety: beyond diet and exercise. Lifestyle Med. 2021;2(1):e21. doi:10.1002/lim2.21

19. Janney CA, Brzoznowski KF, Richardson Cret al. Moving towards wellness: physical activity practices, perspectives, and preferences of users of outpatient mental health service. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2017;49:63-66.

20. Walsh R. Lifestyle and mental health. Am Psychol. 2011;66(7):579-592.

21. Cregg DR, Cheavens JS. Gratitude interventions: effective self-help? A meta-analysis of the impact on symptoms of depression and anxiety. J Happiness Stud. 2021;22(1):413-445.

22. Bohlmeijer E, Roemer M, Cuijpers P, et al. The effects of reminiscence on psychological well-being in older adults: a meta-analysis. Aging Ment Health. 2007;11(3):291-300.

23. Zagic D, Wuthrich VM, Rapee RM, et al. Interventions to improve social connections: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2022;57(5):885-906.

24. Mittelmark MB, Sagy S, Eriksson M, et al (eds). The Handbook of Salutogenesis [Internet]. Springer; 2017.

The accelerating societal entropy undermines mental health

According to the second law of thermodynamics, it is inevitable that entropy will continue to increase over time.1 Entropy is a measure of disorder, which can eventuate in chaos and lead to profound uncertainty, with serious psychological consequences.

The increase in entropy is usually gradual. It took hundreds of years for powerful empires and civilizations to collapse and disappear. Inanimate objects such as a house, a piece of furniture, or a piece of equipment eventually deteriorate and break down over time. Tidy offices will become messy, cluttered, and dirty unless attended to regularly. Living organisms, including humans, inevitably undergo an aging process with cellular senescence, atrophy, and loss of cerebral, muscle, and bone tissue, ending in death. Even human relationships will eventually fracture, wither, and end. The passage of time ruthlessly increases the entropy of everything in life. Even the 13-billion-year-old universe, which currently looks formidable and permanent to us, is inexorably expanding and hurtling towards a calamitous end a few billion years from now.

To slow down, halt, or reverse entropy, work and energy must be invested. A house requires regular maintenance for all its components to avoid deteriorating and becoming uninhabitable (very high entropy). Humans require massive amounts of work during fetal life, infancy, childhood, adolescence, adulthood, and throughout old age. This includes work by parents, teachers, friends, physicians, farmers, and manufacturers of food, clothing, and sundry supplies, all targeted to maintain an individual and slow the rate of entropy. But death is inevitable as the final stage of human entropy.

The brain is an entropic organ.2 Psychiatric disorders can be conceptualized as a neurobiologic consequence of a major rise in brain entropy. The chaos created by high brain entropy will lead to a disruption of basic mental functions such as thought, mood, affect, impulses, behavior, and cognition. Brain entropy increases can be due to genetics or the environment, but most often are due an interaction of both (G x E).

Societal entropy and our patients

Psychiatric patients are deeply influenced by the context in which they live (society). The entropy of contemporary society is rising at an alarming rate, which means that order is rapidly degenerating into disorder at an unprecedented pace. When the COVID-19 pandemic abruptly emerged in early 2020, it was a major public health shock that drastically changed the lives of all citizens and dramatically increased societal entropy. The pandemic led to lockdowns, fear of death, gut-wrenching uncertainty (especially for a whole year before vaccines were developed, but even after), loss of socialization and sexual intimacy, loss of employment, financial straits, and an inability to access routine medical or surgical procedures. Everyone in society developed anxiety and acute stress reaction, but those with pre-existing psychiatric disorders suffered the most with an intensification of their symptoms.

The unforeseen, sudden, and traumatically life-altering pandemic triggered various degrees of posttraumatic stress disorder across all age groups, and painful death in medically compromised individuals and older adults. Both physical and psychological entropy skyrocketed and the “order” of life as we knew it rapidly disintegrated into shambles and disorder. The abrupt traumatic jolt triggered various degrees of deleterious impacts on the brains of all who experienced it in real time. The rise in the psychobiological entropy was unprecedented across the structures of society, especially the population, its vulnerable human component.

But even as the worst of the pandemic is in our rearview mirror and life again has a semblance of normality, the rise of entropy continues to accelerate because we continue to be surrounded and engulfed by countless stressful events in contemporary society. Those nagging stresses continue to transmute order to chaos and metamorphose comforting predictability to entrenched uncertainty:

- Toxic political hyperpartisanship, with intense animus and visceral bidirectional hatred

- Racial tensions, with overt bias across groups

- Economic turmoil, with inflation and threats of recession

- Actual wars and threats of war

- Social media that spreads bad news and distorts facts

- An opioid crisis, with hundreds of thousands of deaths

- Skyrocketing crime, with a decline in policing and quick release of criminals without bail

- A ruthless and arbitrary “cancel culture” that doesn’t even spare the previously revered founders of the republic

- Cognitive dissonance of disparaging Abraham Lincoln despite his major achievement of eliminating slavery by waging a civil war

- The social and medical strife regarding access to abortion.

Continue to: I also would include...

(I also would include some “entropy pet peeves” of mine: Torn clothes as a fashion statement, transforming tattoos from an oddity to a fad, nose rings that disfigure pretty faces, and banishing neckties for men.)

Our role in this scenario

As psychiatrists, we must step up to intensify the work needed to slow down and even reverse the dangerously rising brain entropy in our patients. But that is not an easy task given the implosion of societal norms and traditional values, along with the radicalization of beliefs, with utter intolerance of others’ beliefs. We also face the challenge of maintaining a modicum of resilience and wellness in ourselves, which can be antidotes to entropy.

It’s impossible to stop the inevitability of rising entropy, both physical and psychological, but psychiatrists and other mental health professionals must invest their skills and talents now more than ever to at least slow down the pace of entropy among our patients. Otherwise, psychological chaos and disorder will be quite damaging to their lives, and worsen their outcomes.

1. Ben-Naim A. Entropy Demystified. World Scientific; 2007.

2. Carhart-Harris RL. The entropic brain - revisited. Neuropharmacology. 2018;142:167-178. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2018.03.010

According to the second law of thermodynamics, it is inevitable that entropy will continue to increase over time.1 Entropy is a measure of disorder, which can eventuate in chaos and lead to profound uncertainty, with serious psychological consequences.

The increase in entropy is usually gradual. It took hundreds of years for powerful empires and civilizations to collapse and disappear. Inanimate objects such as a house, a piece of furniture, or a piece of equipment eventually deteriorate and break down over time. Tidy offices will become messy, cluttered, and dirty unless attended to regularly. Living organisms, including humans, inevitably undergo an aging process with cellular senescence, atrophy, and loss of cerebral, muscle, and bone tissue, ending in death. Even human relationships will eventually fracture, wither, and end. The passage of time ruthlessly increases the entropy of everything in life. Even the 13-billion-year-old universe, which currently looks formidable and permanent to us, is inexorably expanding and hurtling towards a calamitous end a few billion years from now.

To slow down, halt, or reverse entropy, work and energy must be invested. A house requires regular maintenance for all its components to avoid deteriorating and becoming uninhabitable (very high entropy). Humans require massive amounts of work during fetal life, infancy, childhood, adolescence, adulthood, and throughout old age. This includes work by parents, teachers, friends, physicians, farmers, and manufacturers of food, clothing, and sundry supplies, all targeted to maintain an individual and slow the rate of entropy. But death is inevitable as the final stage of human entropy.

The brain is an entropic organ.2 Psychiatric disorders can be conceptualized as a neurobiologic consequence of a major rise in brain entropy. The chaos created by high brain entropy will lead to a disruption of basic mental functions such as thought, mood, affect, impulses, behavior, and cognition. Brain entropy increases can be due to genetics or the environment, but most often are due an interaction of both (G x E).

Societal entropy and our patients

Psychiatric patients are deeply influenced by the context in which they live (society). The entropy of contemporary society is rising at an alarming rate, which means that order is rapidly degenerating into disorder at an unprecedented pace. When the COVID-19 pandemic abruptly emerged in early 2020, it was a major public health shock that drastically changed the lives of all citizens and dramatically increased societal entropy. The pandemic led to lockdowns, fear of death, gut-wrenching uncertainty (especially for a whole year before vaccines were developed, but even after), loss of socialization and sexual intimacy, loss of employment, financial straits, and an inability to access routine medical or surgical procedures. Everyone in society developed anxiety and acute stress reaction, but those with pre-existing psychiatric disorders suffered the most with an intensification of their symptoms.

The unforeseen, sudden, and traumatically life-altering pandemic triggered various degrees of posttraumatic stress disorder across all age groups, and painful death in medically compromised individuals and older adults. Both physical and psychological entropy skyrocketed and the “order” of life as we knew it rapidly disintegrated into shambles and disorder. The abrupt traumatic jolt triggered various degrees of deleterious impacts on the brains of all who experienced it in real time. The rise in the psychobiological entropy was unprecedented across the structures of society, especially the population, its vulnerable human component.

But even as the worst of the pandemic is in our rearview mirror and life again has a semblance of normality, the rise of entropy continues to accelerate because we continue to be surrounded and engulfed by countless stressful events in contemporary society. Those nagging stresses continue to transmute order to chaos and metamorphose comforting predictability to entrenched uncertainty:

- Toxic political hyperpartisanship, with intense animus and visceral bidirectional hatred

- Racial tensions, with overt bias across groups

- Economic turmoil, with inflation and threats of recession

- Actual wars and threats of war

- Social media that spreads bad news and distorts facts

- An opioid crisis, with hundreds of thousands of deaths

- Skyrocketing crime, with a decline in policing and quick release of criminals without bail

- A ruthless and arbitrary “cancel culture” that doesn’t even spare the previously revered founders of the republic

- Cognitive dissonance of disparaging Abraham Lincoln despite his major achievement of eliminating slavery by waging a civil war

- The social and medical strife regarding access to abortion.

Continue to: I also would include...

(I also would include some “entropy pet peeves” of mine: Torn clothes as a fashion statement, transforming tattoos from an oddity to a fad, nose rings that disfigure pretty faces, and banishing neckties for men.)

Our role in this scenario

As psychiatrists, we must step up to intensify the work needed to slow down and even reverse the dangerously rising brain entropy in our patients. But that is not an easy task given the implosion of societal norms and traditional values, along with the radicalization of beliefs, with utter intolerance of others’ beliefs. We also face the challenge of maintaining a modicum of resilience and wellness in ourselves, which can be antidotes to entropy.

It’s impossible to stop the inevitability of rising entropy, both physical and psychological, but psychiatrists and other mental health professionals must invest their skills and talents now more than ever to at least slow down the pace of entropy among our patients. Otherwise, psychological chaos and disorder will be quite damaging to their lives, and worsen their outcomes.

According to the second law of thermodynamics, it is inevitable that entropy will continue to increase over time.1 Entropy is a measure of disorder, which can eventuate in chaos and lead to profound uncertainty, with serious psychological consequences.

The increase in entropy is usually gradual. It took hundreds of years for powerful empires and civilizations to collapse and disappear. Inanimate objects such as a house, a piece of furniture, or a piece of equipment eventually deteriorate and break down over time. Tidy offices will become messy, cluttered, and dirty unless attended to regularly. Living organisms, including humans, inevitably undergo an aging process with cellular senescence, atrophy, and loss of cerebral, muscle, and bone tissue, ending in death. Even human relationships will eventually fracture, wither, and end. The passage of time ruthlessly increases the entropy of everything in life. Even the 13-billion-year-old universe, which currently looks formidable and permanent to us, is inexorably expanding and hurtling towards a calamitous end a few billion years from now.

To slow down, halt, or reverse entropy, work and energy must be invested. A house requires regular maintenance for all its components to avoid deteriorating and becoming uninhabitable (very high entropy). Humans require massive amounts of work during fetal life, infancy, childhood, adolescence, adulthood, and throughout old age. This includes work by parents, teachers, friends, physicians, farmers, and manufacturers of food, clothing, and sundry supplies, all targeted to maintain an individual and slow the rate of entropy. But death is inevitable as the final stage of human entropy.

The brain is an entropic organ.2 Psychiatric disorders can be conceptualized as a neurobiologic consequence of a major rise in brain entropy. The chaos created by high brain entropy will lead to a disruption of basic mental functions such as thought, mood, affect, impulses, behavior, and cognition. Brain entropy increases can be due to genetics or the environment, but most often are due an interaction of both (G x E).

Societal entropy and our patients

Psychiatric patients are deeply influenced by the context in which they live (society). The entropy of contemporary society is rising at an alarming rate, which means that order is rapidly degenerating into disorder at an unprecedented pace. When the COVID-19 pandemic abruptly emerged in early 2020, it was a major public health shock that drastically changed the lives of all citizens and dramatically increased societal entropy. The pandemic led to lockdowns, fear of death, gut-wrenching uncertainty (especially for a whole year before vaccines were developed, but even after), loss of socialization and sexual intimacy, loss of employment, financial straits, and an inability to access routine medical or surgical procedures. Everyone in society developed anxiety and acute stress reaction, but those with pre-existing psychiatric disorders suffered the most with an intensification of their symptoms.

The unforeseen, sudden, and traumatically life-altering pandemic triggered various degrees of posttraumatic stress disorder across all age groups, and painful death in medically compromised individuals and older adults. Both physical and psychological entropy skyrocketed and the “order” of life as we knew it rapidly disintegrated into shambles and disorder. The abrupt traumatic jolt triggered various degrees of deleterious impacts on the brains of all who experienced it in real time. The rise in the psychobiological entropy was unprecedented across the structures of society, especially the population, its vulnerable human component.

But even as the worst of the pandemic is in our rearview mirror and life again has a semblance of normality, the rise of entropy continues to accelerate because we continue to be surrounded and engulfed by countless stressful events in contemporary society. Those nagging stresses continue to transmute order to chaos and metamorphose comforting predictability to entrenched uncertainty:

- Toxic political hyperpartisanship, with intense animus and visceral bidirectional hatred

- Racial tensions, with overt bias across groups

- Economic turmoil, with inflation and threats of recession

- Actual wars and threats of war

- Social media that spreads bad news and distorts facts

- An opioid crisis, with hundreds of thousands of deaths

- Skyrocketing crime, with a decline in policing and quick release of criminals without bail

- A ruthless and arbitrary “cancel culture” that doesn’t even spare the previously revered founders of the republic

- Cognitive dissonance of disparaging Abraham Lincoln despite his major achievement of eliminating slavery by waging a civil war

- The social and medical strife regarding access to abortion.

Continue to: I also would include...

(I also would include some “entropy pet peeves” of mine: Torn clothes as a fashion statement, transforming tattoos from an oddity to a fad, nose rings that disfigure pretty faces, and banishing neckties for men.)

Our role in this scenario

As psychiatrists, we must step up to intensify the work needed to slow down and even reverse the dangerously rising brain entropy in our patients. But that is not an easy task given the implosion of societal norms and traditional values, along with the radicalization of beliefs, with utter intolerance of others’ beliefs. We also face the challenge of maintaining a modicum of resilience and wellness in ourselves, which can be antidotes to entropy.

It’s impossible to stop the inevitability of rising entropy, both physical and psychological, but psychiatrists and other mental health professionals must invest their skills and talents now more than ever to at least slow down the pace of entropy among our patients. Otherwise, psychological chaos and disorder will be quite damaging to their lives, and worsen their outcomes.

1. Ben-Naim A. Entropy Demystified. World Scientific; 2007.

2. Carhart-Harris RL. The entropic brain - revisited. Neuropharmacology. 2018;142:167-178. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2018.03.010

1. Ben-Naim A. Entropy Demystified. World Scientific; 2007.

2. Carhart-Harris RL. The entropic brain - revisited. Neuropharmacology. 2018;142:167-178. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2018.03.010

More on varenicline

Murray et al have written a timely, thoughtful, and useful article (“Smoking cessation: Varenicline and the risk of neuropsychiatric adverse events,”

Just a few caveats regarding Murray et al’s excellent summary:

• The article did not address that nicotine is consumed in multiple ways, such as vaping, snuff, chewing tobacco, and hookah

• The safety of varenicline appears fair when psychiatric illness is well controlled but can be problematic (and even severely detrimental) when mental illness is not well controlled. This should not be glossed over, especially since it was the reason for the original black-box warning (for risks including behavioral impulsivity, suicidality, severe insomnia, and nightmares) that was removed in 2016

• Patients with severe mental illness may not fully understand the risks, benefits, and priorities of the treatment intervention. The importance of psychiatric and internal medicine in addition to pharmacy follow-up is critical and needs to be documented.

Varenicline has been contextualized in its current role as a first-line treatment for smoking cessation. By bypassing a sizeable population of patients who have unstable psychiatric illness (especially bipolar I disorder), the path has been opened for risky “off-label” varenicline prescribing to this population by internists, who should be very cautious and prudent about prescribing for such patients. This alone is probably a good reason to reinstate the black-box warning.

Interestingly, one review found that only 1 of 11 patients receiving varenicline stopped smoking.1 Not dramatically beneficial for a first-line treatment! Decreasing smoking occurs as well and is more robust with combinational use with bupropion, nicotine replacement therapy, and cognitive-behavioral therapy.

If we are focusing on patients with unstable mental illness—who are seen primarily by psychiatrists—adherence, urgency of intervention, and context regarding acute safety for this population must be seen as top priorities.

So-called “second-line” treatment options must also be considered. Sandiego et al3 make excellent points regarding the role of alpha-adrenergic agonists such as guanfacine, which have been shown to be helpful in smoking cessation. They work by decreasing cortical dopamine release and their calming effects on the noradrenergic system, which may decrease smoking precipitated by stress. For the particularly challenging subpopulation of unstable smokers, the combination of varenicline plus guanfacine ER may turn out to be a game-changer.

Varenicline has not proven itself to be useful in patients who are severely mentally ill, and due to its low success rate, expectations should remain tempered, pragmatically realistic, and safety-based.4,5 The bottom line is that in an unstable psychiatrically ill patient, interventions other than varenicline should be first-line.

1. Crawford P, Cieslak D. Varenicline for smoking cessation. Am Fam Physician. 2017;96(5).

2. Beard E, Jackson SE, Anthenelli RM, et al. Estimation of risk of neuropsychiatric adverse events from varenicline, bupropion and nicotine patch versus placebo: secondary analysis of results from the EAGLES trial using Bayes factors. Addiction. 2021;116(10):2816-2824.

3. Sandiego CM, Matuskey D, Lavery M, et al. The effect of treatment with guanfacine, an alpha2 adrenergic agonist, on dopaminergic tone in tobacco smokers: an [11C]FLB457 PET study. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2018;43(5):1052-1058.

4. Sharma R, Alla K, Pfeffer D, et al. An appraisal of practice guidelines for smoking cessation in people with severe mental illness. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2017;51(11):1106-1120.

5. Tofler IR. Varenicline for smoking cessation in the bipolar patient. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(5):625.

Murray et al have written a timely, thoughtful, and useful article (“Smoking cessation: Varenicline and the risk of neuropsychiatric adverse events,”

Just a few caveats regarding Murray et al’s excellent summary:

• The article did not address that nicotine is consumed in multiple ways, such as vaping, snuff, chewing tobacco, and hookah

• The safety of varenicline appears fair when psychiatric illness is well controlled but can be problematic (and even severely detrimental) when mental illness is not well controlled. This should not be glossed over, especially since it was the reason for the original black-box warning (for risks including behavioral impulsivity, suicidality, severe insomnia, and nightmares) that was removed in 2016

• Patients with severe mental illness may not fully understand the risks, benefits, and priorities of the treatment intervention. The importance of psychiatric and internal medicine in addition to pharmacy follow-up is critical and needs to be documented.

Varenicline has been contextualized in its current role as a first-line treatment for smoking cessation. By bypassing a sizeable population of patients who have unstable psychiatric illness (especially bipolar I disorder), the path has been opened for risky “off-label” varenicline prescribing to this population by internists, who should be very cautious and prudent about prescribing for such patients. This alone is probably a good reason to reinstate the black-box warning.

Interestingly, one review found that only 1 of 11 patients receiving varenicline stopped smoking.1 Not dramatically beneficial for a first-line treatment! Decreasing smoking occurs as well and is more robust with combinational use with bupropion, nicotine replacement therapy, and cognitive-behavioral therapy.

If we are focusing on patients with unstable mental illness—who are seen primarily by psychiatrists—adherence, urgency of intervention, and context regarding acute safety for this population must be seen as top priorities.

So-called “second-line” treatment options must also be considered. Sandiego et al3 make excellent points regarding the role of alpha-adrenergic agonists such as guanfacine, which have been shown to be helpful in smoking cessation. They work by decreasing cortical dopamine release and their calming effects on the noradrenergic system, which may decrease smoking precipitated by stress. For the particularly challenging subpopulation of unstable smokers, the combination of varenicline plus guanfacine ER may turn out to be a game-changer.

Varenicline has not proven itself to be useful in patients who are severely mentally ill, and due to its low success rate, expectations should remain tempered, pragmatically realistic, and safety-based.4,5 The bottom line is that in an unstable psychiatrically ill patient, interventions other than varenicline should be first-line.

Murray et al have written a timely, thoughtful, and useful article (“Smoking cessation: Varenicline and the risk of neuropsychiatric adverse events,”

Just a few caveats regarding Murray et al’s excellent summary:

• The article did not address that nicotine is consumed in multiple ways, such as vaping, snuff, chewing tobacco, and hookah

• The safety of varenicline appears fair when psychiatric illness is well controlled but can be problematic (and even severely detrimental) when mental illness is not well controlled. This should not be glossed over, especially since it was the reason for the original black-box warning (for risks including behavioral impulsivity, suicidality, severe insomnia, and nightmares) that was removed in 2016

• Patients with severe mental illness may not fully understand the risks, benefits, and priorities of the treatment intervention. The importance of psychiatric and internal medicine in addition to pharmacy follow-up is critical and needs to be documented.

Varenicline has been contextualized in its current role as a first-line treatment for smoking cessation. By bypassing a sizeable population of patients who have unstable psychiatric illness (especially bipolar I disorder), the path has been opened for risky “off-label” varenicline prescribing to this population by internists, who should be very cautious and prudent about prescribing for such patients. This alone is probably a good reason to reinstate the black-box warning.

Interestingly, one review found that only 1 of 11 patients receiving varenicline stopped smoking.1 Not dramatically beneficial for a first-line treatment! Decreasing smoking occurs as well and is more robust with combinational use with bupropion, nicotine replacement therapy, and cognitive-behavioral therapy.

If we are focusing on patients with unstable mental illness—who are seen primarily by psychiatrists—adherence, urgency of intervention, and context regarding acute safety for this population must be seen as top priorities.

So-called “second-line” treatment options must also be considered. Sandiego et al3 make excellent points regarding the role of alpha-adrenergic agonists such as guanfacine, which have been shown to be helpful in smoking cessation. They work by decreasing cortical dopamine release and their calming effects on the noradrenergic system, which may decrease smoking precipitated by stress. For the particularly challenging subpopulation of unstable smokers, the combination of varenicline plus guanfacine ER may turn out to be a game-changer.

Varenicline has not proven itself to be useful in patients who are severely mentally ill, and due to its low success rate, expectations should remain tempered, pragmatically realistic, and safety-based.4,5 The bottom line is that in an unstable psychiatrically ill patient, interventions other than varenicline should be first-line.

1. Crawford P, Cieslak D. Varenicline for smoking cessation. Am Fam Physician. 2017;96(5).

2. Beard E, Jackson SE, Anthenelli RM, et al. Estimation of risk of neuropsychiatric adverse events from varenicline, bupropion and nicotine patch versus placebo: secondary analysis of results from the EAGLES trial using Bayes factors. Addiction. 2021;116(10):2816-2824.