User login

Beta-adrenergic receptor blocker use improves overall survival in HCC

Key clinical point: Use of beta-adrenergic receptor blockers is associated with prolonged survival in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

Major finding: Beta-blocker use was associated with better overall survival (hazard ratio 0.69; P = .0031), with no significant heterogeneity across studies (I2 = 41%; P = .18).

Study details: The data come from a meta-analysis of 3 cohort studies involving 5148 patients with HCC that analyzed the association between the use of beta-blockers (including propranolol) and overall survival of the patients.

Disclosures: This study did not receive any funding. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Chang H and Lee SH. Beta-adrenergic receptor blockers and hepatocellular carcinoma survival: A systemic review and meta-analysis. Clin Exp Med. 2022 (Jun 23). Doi: 10.1007/s10238-022-00842-z

Key clinical point: Use of beta-adrenergic receptor blockers is associated with prolonged survival in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

Major finding: Beta-blocker use was associated with better overall survival (hazard ratio 0.69; P = .0031), with no significant heterogeneity across studies (I2 = 41%; P = .18).

Study details: The data come from a meta-analysis of 3 cohort studies involving 5148 patients with HCC that analyzed the association between the use of beta-blockers (including propranolol) and overall survival of the patients.

Disclosures: This study did not receive any funding. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Chang H and Lee SH. Beta-adrenergic receptor blockers and hepatocellular carcinoma survival: A systemic review and meta-analysis. Clin Exp Med. 2022 (Jun 23). Doi: 10.1007/s10238-022-00842-z

Key clinical point: Use of beta-adrenergic receptor blockers is associated with prolonged survival in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

Major finding: Beta-blocker use was associated with better overall survival (hazard ratio 0.69; P = .0031), with no significant heterogeneity across studies (I2 = 41%; P = .18).

Study details: The data come from a meta-analysis of 3 cohort studies involving 5148 patients with HCC that analyzed the association between the use of beta-blockers (including propranolol) and overall survival of the patients.

Disclosures: This study did not receive any funding. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Chang H and Lee SH. Beta-adrenergic receptor blockers and hepatocellular carcinoma survival: A systemic review and meta-analysis. Clin Exp Med. 2022 (Jun 23). Doi: 10.1007/s10238-022-00842-z

Lenvatinib plus IDADEB-TACE tops lenvatinib monotherapy in advanced HCC

Key clinical point: First-line lenvatinib plus idarubicin-loaded drug-eluting bead transarterial chemoembolization (IDADEB-TACE) is safe and offers a better safety profile than lenvatinib alone in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

Major finding: Patients receiving lenvatinib plus IDADEB-TACE vs lenvatinib alone had a significantly higher objective response rate (57.7% vs 25.7%; P < .001), longer median overall survival (15.7 vs 11.3 months; hazard ratio 0.50; P < .001), and comparable toxicity profile, with most adverse events being mild and manageable.

Study details: Findings are from a multicenter, retrospective cohort study that propensity-score matched patients with advanced HCC who received lenvatinib plus IDADEB-TACE (n = 78) with those who received lenvatinib alone (n = 78).

Disclosures: This study was sponsored by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, among others. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Source: Fan W et al. Idarubicin-loaded DEB-TACE plus lenvatinib versus lenvatinib for patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: A propensity score-matching analysis. Cancer Med. 2022 (Jun 13). Doi: 10.1002/cam4.4937

Key clinical point: First-line lenvatinib plus idarubicin-loaded drug-eluting bead transarterial chemoembolization (IDADEB-TACE) is safe and offers a better safety profile than lenvatinib alone in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

Major finding: Patients receiving lenvatinib plus IDADEB-TACE vs lenvatinib alone had a significantly higher objective response rate (57.7% vs 25.7%; P < .001), longer median overall survival (15.7 vs 11.3 months; hazard ratio 0.50; P < .001), and comparable toxicity profile, with most adverse events being mild and manageable.

Study details: Findings are from a multicenter, retrospective cohort study that propensity-score matched patients with advanced HCC who received lenvatinib plus IDADEB-TACE (n = 78) with those who received lenvatinib alone (n = 78).

Disclosures: This study was sponsored by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, among others. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Source: Fan W et al. Idarubicin-loaded DEB-TACE plus lenvatinib versus lenvatinib for patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: A propensity score-matching analysis. Cancer Med. 2022 (Jun 13). Doi: 10.1002/cam4.4937

Key clinical point: First-line lenvatinib plus idarubicin-loaded drug-eluting bead transarterial chemoembolization (IDADEB-TACE) is safe and offers a better safety profile than lenvatinib alone in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

Major finding: Patients receiving lenvatinib plus IDADEB-TACE vs lenvatinib alone had a significantly higher objective response rate (57.7% vs 25.7%; P < .001), longer median overall survival (15.7 vs 11.3 months; hazard ratio 0.50; P < .001), and comparable toxicity profile, with most adverse events being mild and manageable.

Study details: Findings are from a multicenter, retrospective cohort study that propensity-score matched patients with advanced HCC who received lenvatinib plus IDADEB-TACE (n = 78) with those who received lenvatinib alone (n = 78).

Disclosures: This study was sponsored by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, among others. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Source: Fan W et al. Idarubicin-loaded DEB-TACE plus lenvatinib versus lenvatinib for patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: A propensity score-matching analysis. Cancer Med. 2022 (Jun 13). Doi: 10.1002/cam4.4937

Meta-analysis supports the use of direct-acting antiviral therapy in HCV-related HCC

Key clinical point: Direct-acting antiviral (DAA) therapy prevents recurrence and improves overall survival (OS) in patients with hepatitis C virus (HCV)-related hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), especially in those with a sustained virologic response (SVR).

Major finding: Patients receiving DAA vs no therapy had a significantly reduced recurrence (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 0.55; P < .001) and improved OS (aHR 0.36; P = .017). After DAA therapy, patients with SVR vs nonresponders had significantly lower recurrence rates (hazard ratio [HR] 0.37; P = .017) and mortality (HR 0.17; P = .001).

Study details: This was a meta-analysis of 23 cohort studies that evaluated the effects of DAA therapy, interferon therapy, or no intervention on recurrence or OS in patients with HCV-related HCC.

Disclosures: This study was sponsored by the Taishan Scholars Program for Young Expert of Shandong Province, China, among others. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Liu H et al. Clinical benefits of direct-acting antivirals therapy in hepatitis C virus patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 (Jun 20). Doi: 10.1111/jgh.15915

Key clinical point: Direct-acting antiviral (DAA) therapy prevents recurrence and improves overall survival (OS) in patients with hepatitis C virus (HCV)-related hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), especially in those with a sustained virologic response (SVR).

Major finding: Patients receiving DAA vs no therapy had a significantly reduced recurrence (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 0.55; P < .001) and improved OS (aHR 0.36; P = .017). After DAA therapy, patients with SVR vs nonresponders had significantly lower recurrence rates (hazard ratio [HR] 0.37; P = .017) and mortality (HR 0.17; P = .001).

Study details: This was a meta-analysis of 23 cohort studies that evaluated the effects of DAA therapy, interferon therapy, or no intervention on recurrence or OS in patients with HCV-related HCC.

Disclosures: This study was sponsored by the Taishan Scholars Program for Young Expert of Shandong Province, China, among others. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Liu H et al. Clinical benefits of direct-acting antivirals therapy in hepatitis C virus patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 (Jun 20). Doi: 10.1111/jgh.15915

Key clinical point: Direct-acting antiviral (DAA) therapy prevents recurrence and improves overall survival (OS) in patients with hepatitis C virus (HCV)-related hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), especially in those with a sustained virologic response (SVR).

Major finding: Patients receiving DAA vs no therapy had a significantly reduced recurrence (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 0.55; P < .001) and improved OS (aHR 0.36; P = .017). After DAA therapy, patients with SVR vs nonresponders had significantly lower recurrence rates (hazard ratio [HR] 0.37; P = .017) and mortality (HR 0.17; P = .001).

Study details: This was a meta-analysis of 23 cohort studies that evaluated the effects of DAA therapy, interferon therapy, or no intervention on recurrence or OS in patients with HCV-related HCC.

Disclosures: This study was sponsored by the Taishan Scholars Program for Young Expert of Shandong Province, China, among others. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Liu H et al. Clinical benefits of direct-acting antivirals therapy in hepatitis C virus patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 (Jun 20). Doi: 10.1111/jgh.15915

Statin use ties with lower HCC risk in dialysis patients with HBV or HCV monoinfection

Key clinical point: Statin use is associated with a lower risk for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) incidence in dialysis patients with chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection.

Major finding: Statin users vs nonusers had a 41% reduced risk for HCC (subdistribution hazard ratio 0.59; P = .001) and a lower weighted HCC incidence rate (incidence rate difference −3.7; P < .001), with the incidence rate ratio being 0.56 (P < .001).

Study details: This retrospective observational study included 6165 patients aged ≥ 19 and < 85 years with HBV or HCV infection who were on maintenance dialysis and received ≥28 cumulative defined daily doses of statins (users; n = 2655) or did not receive statins (nonusers; n = 3510) in the first 3 months after dialysis commencement.

Disclosures: No financial support was reported. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Kim HW et al. Association of statin treatment with hepatocellular carcinoma risk in end-stage kidney disease patients with chronic viral hepatitis. Sci Rep. 2022;12:10807 (Jun 25. Doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-14713-w

Key clinical point: Statin use is associated with a lower risk for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) incidence in dialysis patients with chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection.

Major finding: Statin users vs nonusers had a 41% reduced risk for HCC (subdistribution hazard ratio 0.59; P = .001) and a lower weighted HCC incidence rate (incidence rate difference −3.7; P < .001), with the incidence rate ratio being 0.56 (P < .001).

Study details: This retrospective observational study included 6165 patients aged ≥ 19 and < 85 years with HBV or HCV infection who were on maintenance dialysis and received ≥28 cumulative defined daily doses of statins (users; n = 2655) or did not receive statins (nonusers; n = 3510) in the first 3 months after dialysis commencement.

Disclosures: No financial support was reported. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Kim HW et al. Association of statin treatment with hepatocellular carcinoma risk in end-stage kidney disease patients with chronic viral hepatitis. Sci Rep. 2022;12:10807 (Jun 25. Doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-14713-w

Key clinical point: Statin use is associated with a lower risk for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) incidence in dialysis patients with chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection.

Major finding: Statin users vs nonusers had a 41% reduced risk for HCC (subdistribution hazard ratio 0.59; P = .001) and a lower weighted HCC incidence rate (incidence rate difference −3.7; P < .001), with the incidence rate ratio being 0.56 (P < .001).

Study details: This retrospective observational study included 6165 patients aged ≥ 19 and < 85 years with HBV or HCV infection who were on maintenance dialysis and received ≥28 cumulative defined daily doses of statins (users; n = 2655) or did not receive statins (nonusers; n = 3510) in the first 3 months after dialysis commencement.

Disclosures: No financial support was reported. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Kim HW et al. Association of statin treatment with hepatocellular carcinoma risk in end-stage kidney disease patients with chronic viral hepatitis. Sci Rep. 2022;12:10807 (Jun 25. Doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-14713-w

Lenvatinib combination therapy vs monotherapy against HCC: Real-world results

Key clinical point: Lenvatinib-based combination therapies are associated with a significantly longer progression-free survival (PFS) and better objective response (OR) than lenvatinib monotherapy in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

Major finding: Lenvatinib combination therapy vs monotherapy was associated with a significantly longer PFS (Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumours [RECIST] v1.1: 7.77 vs 4.43 months; P = .045; modified RECIST [mRECIST]: 6.97 vs 5.27 months; P = .067) and a higher OR rate (RECIST v1.1: 37% vs 5%; P < .001; mRECIST: 53% vs 11%; P < .001) but no significant overall survival benefit (P = .71).

Study details: Findings are from a retrospective study that included 215 patients with HCC who received lenvatinib-based therapies.

Disclosures: This study was funded by the National Key R&D Program of China and National Natural Science Foundation of China. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Chen J et al. The combination treatment strategy of lenvatinib for hepatocellular carcinoma: a real-world study. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2022 (Jun 25). Doi: 10.1007/s00432-022-04082-2

Key clinical point: Lenvatinib-based combination therapies are associated with a significantly longer progression-free survival (PFS) and better objective response (OR) than lenvatinib monotherapy in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

Major finding: Lenvatinib combination therapy vs monotherapy was associated with a significantly longer PFS (Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumours [RECIST] v1.1: 7.77 vs 4.43 months; P = .045; modified RECIST [mRECIST]: 6.97 vs 5.27 months; P = .067) and a higher OR rate (RECIST v1.1: 37% vs 5%; P < .001; mRECIST: 53% vs 11%; P < .001) but no significant overall survival benefit (P = .71).

Study details: Findings are from a retrospective study that included 215 patients with HCC who received lenvatinib-based therapies.

Disclosures: This study was funded by the National Key R&D Program of China and National Natural Science Foundation of China. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Chen J et al. The combination treatment strategy of lenvatinib for hepatocellular carcinoma: a real-world study. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2022 (Jun 25). Doi: 10.1007/s00432-022-04082-2

Key clinical point: Lenvatinib-based combination therapies are associated with a significantly longer progression-free survival (PFS) and better objective response (OR) than lenvatinib monotherapy in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

Major finding: Lenvatinib combination therapy vs monotherapy was associated with a significantly longer PFS (Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumours [RECIST] v1.1: 7.77 vs 4.43 months; P = .045; modified RECIST [mRECIST]: 6.97 vs 5.27 months; P = .067) and a higher OR rate (RECIST v1.1: 37% vs 5%; P < .001; mRECIST: 53% vs 11%; P < .001) but no significant overall survival benefit (P = .71).

Study details: Findings are from a retrospective study that included 215 patients with HCC who received lenvatinib-based therapies.

Disclosures: This study was funded by the National Key R&D Program of China and National Natural Science Foundation of China. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Chen J et al. The combination treatment strategy of lenvatinib for hepatocellular carcinoma: a real-world study. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2022 (Jun 25). Doi: 10.1007/s00432-022-04082-2

A hypogastric nerve-focused approach to nerve-sparing endometriosis surgery

Radical resection of deep infiltrating endometriosis (DIE) or pelvic malignancies can lead to inadvertent damage to the pelvic autonomic nerve bundles, causing urinary dysfunction in up to 41% of cases, as well as anorectal and sexual dysfunction.1 Each of these sequelae can significantly affect the patient’s quality of life.

Nerve-sparing techniques have therefore been a trending topic in gynecologic surgery in the 21st century, starting with papers by Marc Possover, MD, of Switzerland, on the laparoscopic neuronavigation (LANN) technique. In an important 2005 publication, he described how the LANN technique can significantly reduce postoperative functional morbidity in laparoscopic radical pelvic surgery.2

The LANN method utilizes intraoperative neurostimulation to identify and dissect the intrapelvic nerve bundles away from surrounding tissue prior to dissection of the DIE or pelvic malignancies. The nerves are exposed and preserved under direct visualization in a fashion similar to that used to expose and preserve the ureters. Pelvic dissection using the LANN technique is extensive and occurs down to the level of the sacral nerve roots.

Dr. Possover’s 2005 paper and others like it spurred increased awareness of the intrapelvic part of the autonomic nervous system – in particular, the hypogastric nerves, the pelvic splanchnic nerves, and the inferior hypogastric plexus. Across additional published studies, nerve-sparing techniques were shown to be effective in preserving neurologic pelvic functions, with significantly less urinary retention and rectal/sexual dysfunction than seen with traditional laparoscopy techniques.

For example, in a single-center prospective clinical trial reported in 2012, 56 of 65 (86.2%) patients treated with a classical laparoscopic technique for excision of DIE reported neurologic pelvic dysfunctions, compared with 1 of 61 (1.6%) patients treated with a nerve-sparing approach.3

While research has confirmed the importance of nerve-sparing techniques, it also shone light on the reality that the LANN technique is extremely technically challenging and requires a high level of surgical expertise and advanced training. In my teaching of the technique, I also saw that few gynecologic surgeons were able to incorporate the advanced nerve-sparing technique into their practices.

A group consisting of myself and collaborators at the University of Bologna, Italy, and the University of Cambridge, England, recently developed an alternative to the LANN approach that uses the hypogastric nerves as landmarks. The technique requires less dissection and should be technically achievable when the pelvic neuroanatomy and anatomy of the presacral fascia are well understood. The hypogastric nerve is identified and used as a landmark to preserve the deeper autonomic nerve bundles in the pelvis without exposure and without more extensive dissection to the level of the sacral nerve roots.4,5

This hypogastric nerve-based technique will cover the vast majority of radical surgeries for DIE. When more advanced nerve sparing and more extensive dissection is needed for the very deepest levels of disease infiltration, patients can be referred to surgeons with advanced training, comfort, and experience with the LANN technique.

The pelvic neuroanatomy

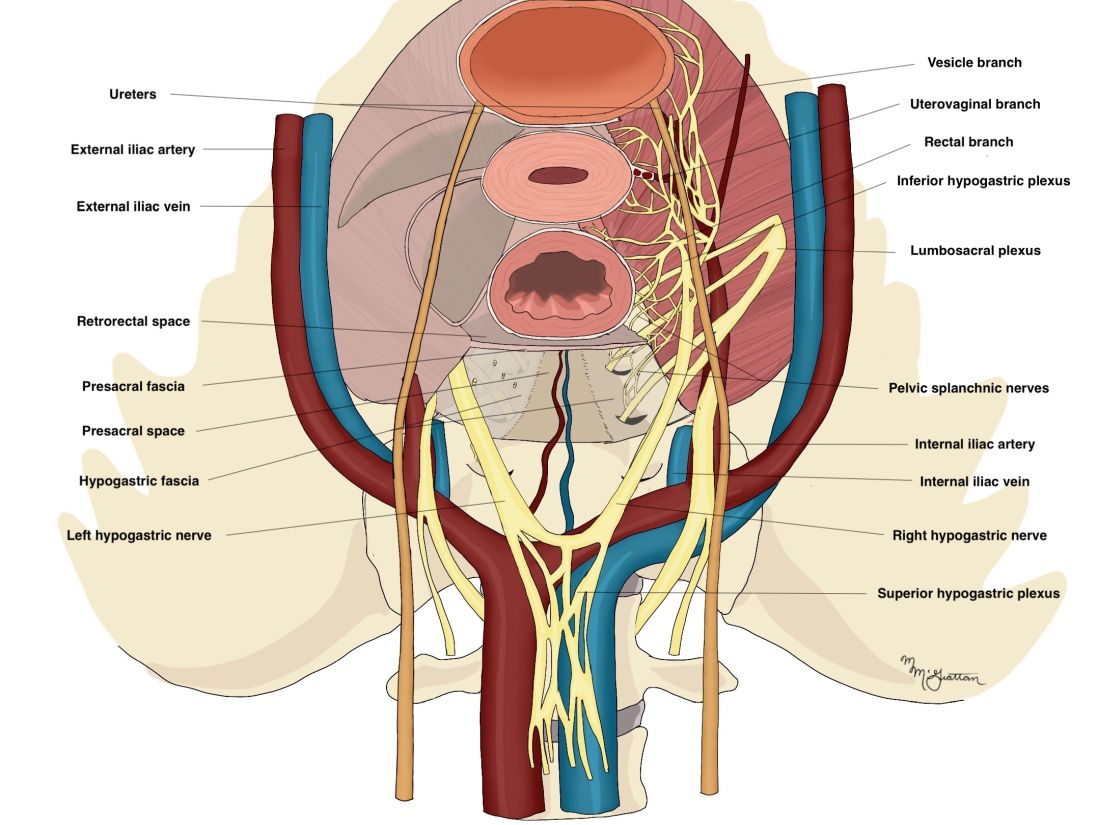

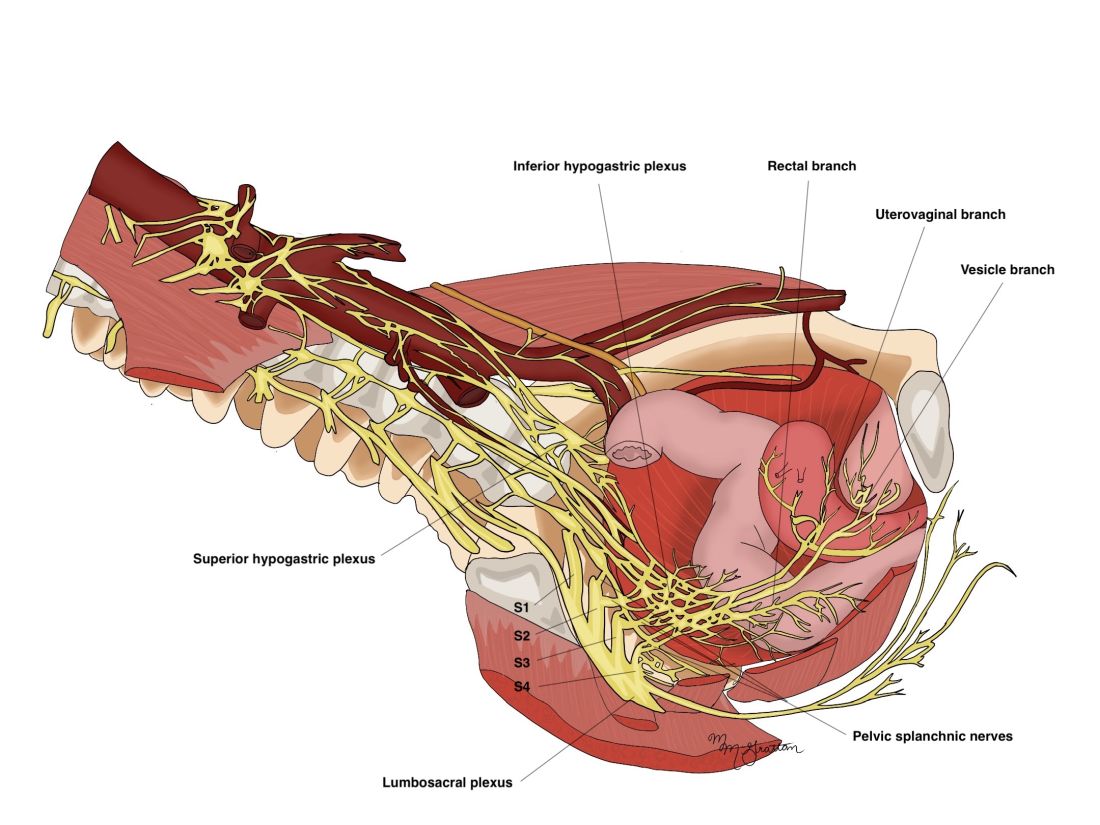

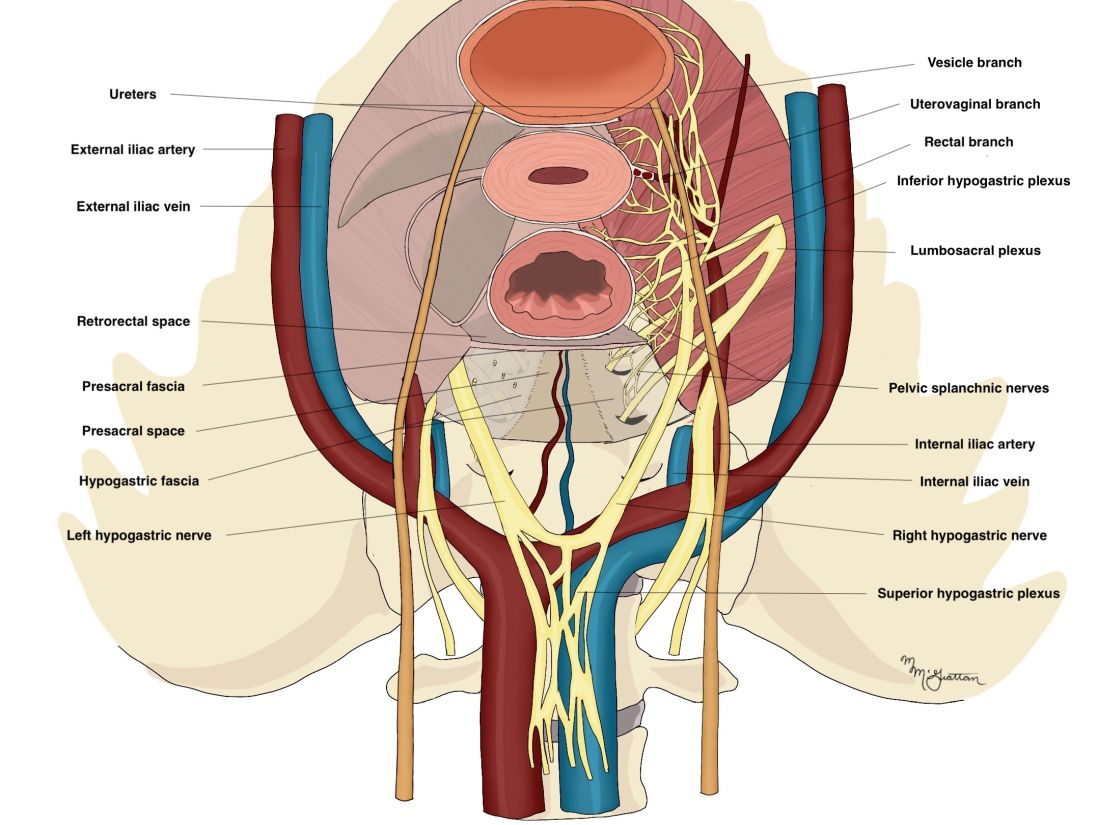

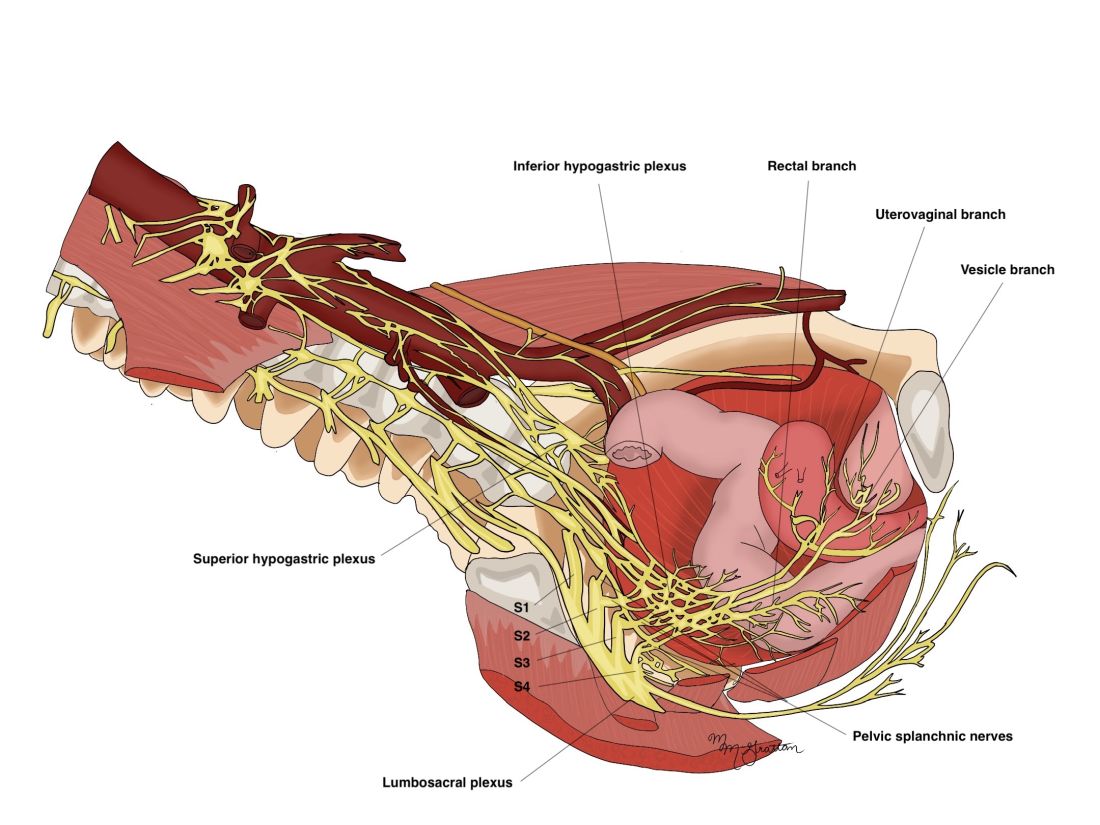

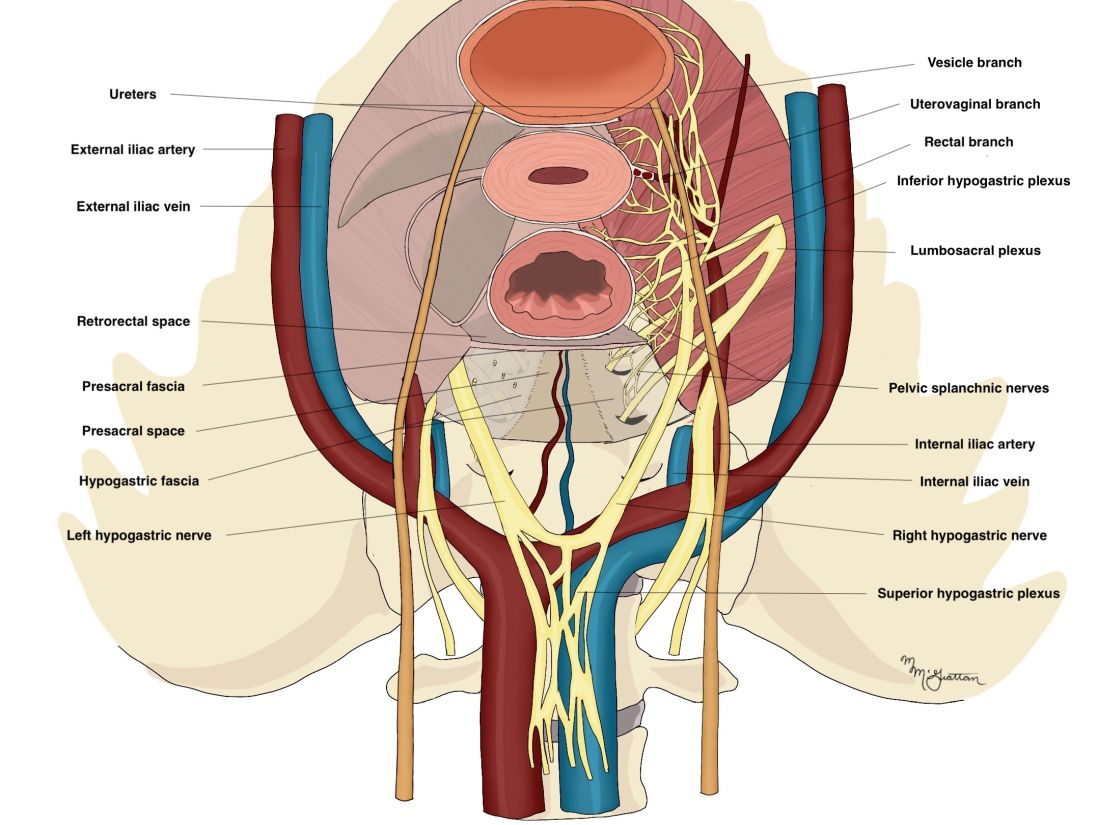

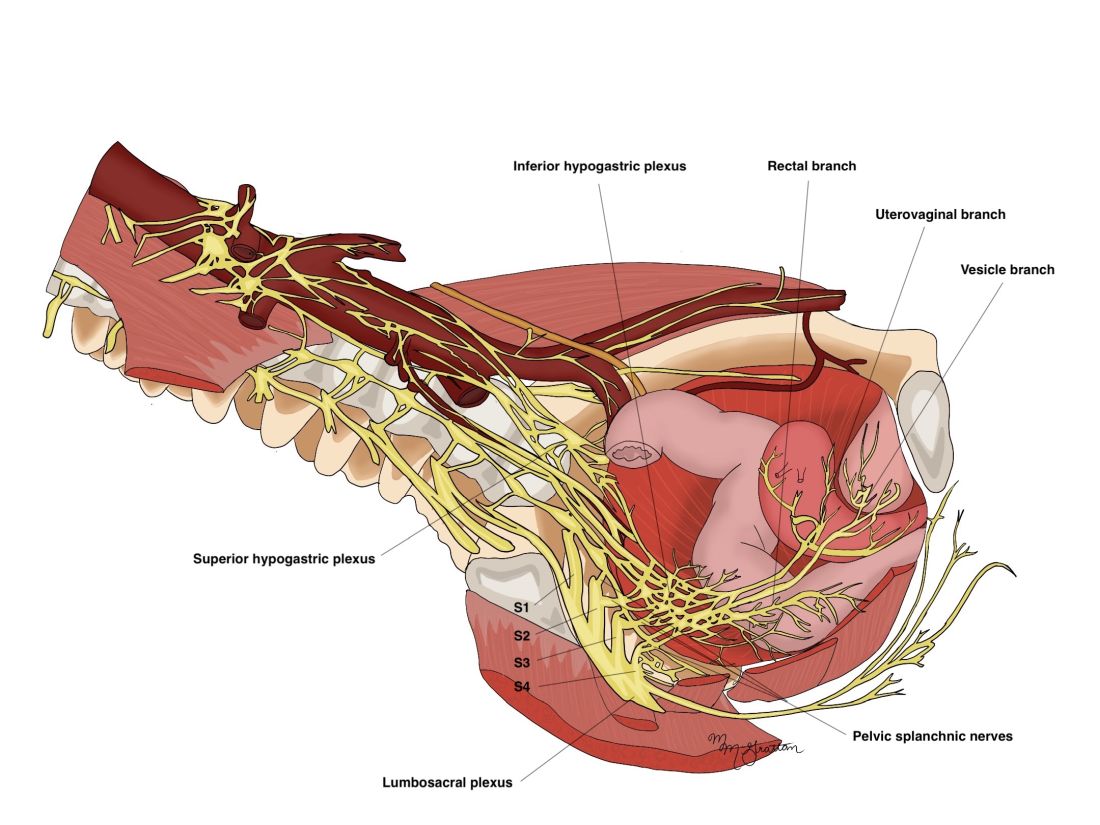

As described in our video articles published in 2015 in Fertility and Sterility6 and 2019 in the Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynecology,5 the left and right hypogastric nerves are the main sympathetic nerves of the autonomic nervous system in the pelvis. They originate from the superior hypogastric plexus and, at the level of the middle rectal vessels, they join the pelvic sacral splanchnic nerves to form the inferior hypogastric plexus. They are easily identifiable at their origin and are the most superficial and readily identifiable component of the inferior hypogastric plexus.

The sympathetic input from the hypogastric nerves causes the internal urethral and anal sphincters to contract, as well as detrusor relaxation and a reduction of peristalsis of the descending colon, sigmoid, and rectum; thus, hypogastric nerve input promotes continence.

The hypogastric nerves also carry afferent signals for pelvic visceral proprioception. Lesion to the hypogastric nerves will usually be subclinical and will put the patient at risk for unnoticeable bladder distension, which usually becomes symptomatic about 7 years after the procedure.7

The thin pelvic splanchnic nerves – which merge with the hypogastric nerves into the pararectal fossae to form the inferior hypogastric plexus – arise from nerve roots S2 and S4 and carry all parasympathetic signals to the bladder, rectum, and the sigmoid and left colons. Lesions to these bundles are the main cause of neurogenic urinary retention.

The inferior hypogastric plexi split into the vesical, uterine, and rectal branches, which carry the sympathetic, parasympathetic, and sensory fibers from both the splanchnic and hypogastric nerves. Damage to the inferior hypogastric plexi and/or its branches may induce severe dysfunction to the target organs of the injured fibers.

A focus on the hypogastric nerve

Our approach was developed after we studied the anatomic reliability of the hypogastric nerves through a prospective observational study consisting of measurements during five cadaveric dissections and 10 in-vivo laparoscopic surgeries for rectosigmoid endometriosis.4 We took an interfascial approach to dissection.

Our goal was to clarify the distances between the hypogastric nerves and the ureters, the midsagittal plane, the midcervical plane, and the uterosacral ligaments in each hemipelvis, and in doing so, enable identification of the hypogastric nerves and establish recognizable limits for dissection.

We found quite a bit of variance in the anatomic position and appearance of the hypogastric nerves, but the variances were not very broad. Most notably, the right hypogastric nerve was significantly farther toward the ureter (mean, 14.5 mm; range, 10-25 mm) than the left one (mean, 8.6 mm; range, 7-12 mm).

The ureters were a good landmark for identification of the hypogastric nerves because the nerves were consistently found medially and posteriorly to the ureter at a mean distance of 11.6 mm. Overall, we demonstrated reproducibility in the identification and dissection of the hypogastric nerves using recognizable interfascial planes and anatomic landmarks.4

With good anatomic understanding, a stepwise approach can be taken to identify and preserve the hypogastric nerve and the deeper inferior hypogastric plexus without the need for more extensive dissection.

As shown in our 2019 video, the right hypogastric nerves can be identified transperitoneally in most cases.5 For confirmation, a gentle anterior pulling on the hypogastric nerve causes a caudal movement of the peritoneum overlying the superior hypogastric plexus. (Intermittent pulling on the nerve can also be helpful in localizing the left hypogastric nerve.)

To dissect a hypogastric nerve, the retroperitoneum is opened at the level of the pelvic brim, just inferomedially to the external iliac vessels, and the incision is extended anteriorly, with gentle dissection of the underlying tissue until the ureter is identified.

Once the ureter is identified and lateralized, dissection along the peritoneum is carried deeper and medially into the pelvis until the hypogastric nerve is identified. Lateral to this area are the internal iliac artery, the branching uterine artery, and the obliterated umbilical ligament. In the left hemipelvis, the hypogastric nerve can reliably be found at a mean distance of 8.6 mm from the ureter, while the right one will be found on average 14.5 mm away.

The hypogastric nerves form the posteromedial limit for a safe and simple nerve-sparing dissection. Any dissection posteriorly and laterally to these landmarks should start with the identification of sacral nerve roots and hypogastric nerves.

Dr. Lemos reported that he has no relevant disclosures.

Dr. Lemos is associate professor in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Toronto.

References

1. Imboden S et al. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2021 Aug;28(8):1544-51. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2021.01.009.

2. Possover M et al. J Am Coll Surg. 2005;201(6):913-7. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2005.07.006.

3. Ceccaroni M et al. Surg Endosc. 2012;26(7):2029-45. doi: 10.1007/s00464-012-2153-3.

4. Seracchioli R et al. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2019;26(7):1340-5. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2019.01.010.

5. Zakhari A et al. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020;27(4):813-4. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2019.08.001

6. Lemos N et al. Fertil Steril. 2015 Nov;104(5):e11-2. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.07.1138.

7. Possover M. Fertil Steril. 2014 Mar;101(3):754-8. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.12.019.

Radical resection of deep infiltrating endometriosis (DIE) or pelvic malignancies can lead to inadvertent damage to the pelvic autonomic nerve bundles, causing urinary dysfunction in up to 41% of cases, as well as anorectal and sexual dysfunction.1 Each of these sequelae can significantly affect the patient’s quality of life.

Nerve-sparing techniques have therefore been a trending topic in gynecologic surgery in the 21st century, starting with papers by Marc Possover, MD, of Switzerland, on the laparoscopic neuronavigation (LANN) technique. In an important 2005 publication, he described how the LANN technique can significantly reduce postoperative functional morbidity in laparoscopic radical pelvic surgery.2

The LANN method utilizes intraoperative neurostimulation to identify and dissect the intrapelvic nerve bundles away from surrounding tissue prior to dissection of the DIE or pelvic malignancies. The nerves are exposed and preserved under direct visualization in a fashion similar to that used to expose and preserve the ureters. Pelvic dissection using the LANN technique is extensive and occurs down to the level of the sacral nerve roots.

Dr. Possover’s 2005 paper and others like it spurred increased awareness of the intrapelvic part of the autonomic nervous system – in particular, the hypogastric nerves, the pelvic splanchnic nerves, and the inferior hypogastric plexus. Across additional published studies, nerve-sparing techniques were shown to be effective in preserving neurologic pelvic functions, with significantly less urinary retention and rectal/sexual dysfunction than seen with traditional laparoscopy techniques.

For example, in a single-center prospective clinical trial reported in 2012, 56 of 65 (86.2%) patients treated with a classical laparoscopic technique for excision of DIE reported neurologic pelvic dysfunctions, compared with 1 of 61 (1.6%) patients treated with a nerve-sparing approach.3

While research has confirmed the importance of nerve-sparing techniques, it also shone light on the reality that the LANN technique is extremely technically challenging and requires a high level of surgical expertise and advanced training. In my teaching of the technique, I also saw that few gynecologic surgeons were able to incorporate the advanced nerve-sparing technique into their practices.

A group consisting of myself and collaborators at the University of Bologna, Italy, and the University of Cambridge, England, recently developed an alternative to the LANN approach that uses the hypogastric nerves as landmarks. The technique requires less dissection and should be technically achievable when the pelvic neuroanatomy and anatomy of the presacral fascia are well understood. The hypogastric nerve is identified and used as a landmark to preserve the deeper autonomic nerve bundles in the pelvis without exposure and without more extensive dissection to the level of the sacral nerve roots.4,5

This hypogastric nerve-based technique will cover the vast majority of radical surgeries for DIE. When more advanced nerve sparing and more extensive dissection is needed for the very deepest levels of disease infiltration, patients can be referred to surgeons with advanced training, comfort, and experience with the LANN technique.

The pelvic neuroanatomy

As described in our video articles published in 2015 in Fertility and Sterility6 and 2019 in the Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynecology,5 the left and right hypogastric nerves are the main sympathetic nerves of the autonomic nervous system in the pelvis. They originate from the superior hypogastric plexus and, at the level of the middle rectal vessels, they join the pelvic sacral splanchnic nerves to form the inferior hypogastric plexus. They are easily identifiable at their origin and are the most superficial and readily identifiable component of the inferior hypogastric plexus.

The sympathetic input from the hypogastric nerves causes the internal urethral and anal sphincters to contract, as well as detrusor relaxation and a reduction of peristalsis of the descending colon, sigmoid, and rectum; thus, hypogastric nerve input promotes continence.

The hypogastric nerves also carry afferent signals for pelvic visceral proprioception. Lesion to the hypogastric nerves will usually be subclinical and will put the patient at risk for unnoticeable bladder distension, which usually becomes symptomatic about 7 years after the procedure.7

The thin pelvic splanchnic nerves – which merge with the hypogastric nerves into the pararectal fossae to form the inferior hypogastric plexus – arise from nerve roots S2 and S4 and carry all parasympathetic signals to the bladder, rectum, and the sigmoid and left colons. Lesions to these bundles are the main cause of neurogenic urinary retention.

The inferior hypogastric plexi split into the vesical, uterine, and rectal branches, which carry the sympathetic, parasympathetic, and sensory fibers from both the splanchnic and hypogastric nerves. Damage to the inferior hypogastric plexi and/or its branches may induce severe dysfunction to the target organs of the injured fibers.

A focus on the hypogastric nerve

Our approach was developed after we studied the anatomic reliability of the hypogastric nerves through a prospective observational study consisting of measurements during five cadaveric dissections and 10 in-vivo laparoscopic surgeries for rectosigmoid endometriosis.4 We took an interfascial approach to dissection.

Our goal was to clarify the distances between the hypogastric nerves and the ureters, the midsagittal plane, the midcervical plane, and the uterosacral ligaments in each hemipelvis, and in doing so, enable identification of the hypogastric nerves and establish recognizable limits for dissection.

We found quite a bit of variance in the anatomic position and appearance of the hypogastric nerves, but the variances were not very broad. Most notably, the right hypogastric nerve was significantly farther toward the ureter (mean, 14.5 mm; range, 10-25 mm) than the left one (mean, 8.6 mm; range, 7-12 mm).

The ureters were a good landmark for identification of the hypogastric nerves because the nerves were consistently found medially and posteriorly to the ureter at a mean distance of 11.6 mm. Overall, we demonstrated reproducibility in the identification and dissection of the hypogastric nerves using recognizable interfascial planes and anatomic landmarks.4

With good anatomic understanding, a stepwise approach can be taken to identify and preserve the hypogastric nerve and the deeper inferior hypogastric plexus without the need for more extensive dissection.

As shown in our 2019 video, the right hypogastric nerves can be identified transperitoneally in most cases.5 For confirmation, a gentle anterior pulling on the hypogastric nerve causes a caudal movement of the peritoneum overlying the superior hypogastric plexus. (Intermittent pulling on the nerve can also be helpful in localizing the left hypogastric nerve.)

To dissect a hypogastric nerve, the retroperitoneum is opened at the level of the pelvic brim, just inferomedially to the external iliac vessels, and the incision is extended anteriorly, with gentle dissection of the underlying tissue until the ureter is identified.

Once the ureter is identified and lateralized, dissection along the peritoneum is carried deeper and medially into the pelvis until the hypogastric nerve is identified. Lateral to this area are the internal iliac artery, the branching uterine artery, and the obliterated umbilical ligament. In the left hemipelvis, the hypogastric nerve can reliably be found at a mean distance of 8.6 mm from the ureter, while the right one will be found on average 14.5 mm away.

The hypogastric nerves form the posteromedial limit for a safe and simple nerve-sparing dissection. Any dissection posteriorly and laterally to these landmarks should start with the identification of sacral nerve roots and hypogastric nerves.

Dr. Lemos reported that he has no relevant disclosures.

Dr. Lemos is associate professor in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Toronto.

References

1. Imboden S et al. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2021 Aug;28(8):1544-51. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2021.01.009.

2. Possover M et al. J Am Coll Surg. 2005;201(6):913-7. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2005.07.006.

3. Ceccaroni M et al. Surg Endosc. 2012;26(7):2029-45. doi: 10.1007/s00464-012-2153-3.

4. Seracchioli R et al. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2019;26(7):1340-5. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2019.01.010.

5. Zakhari A et al. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020;27(4):813-4. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2019.08.001

6. Lemos N et al. Fertil Steril. 2015 Nov;104(5):e11-2. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.07.1138.

7. Possover M. Fertil Steril. 2014 Mar;101(3):754-8. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.12.019.

Radical resection of deep infiltrating endometriosis (DIE) or pelvic malignancies can lead to inadvertent damage to the pelvic autonomic nerve bundles, causing urinary dysfunction in up to 41% of cases, as well as anorectal and sexual dysfunction.1 Each of these sequelae can significantly affect the patient’s quality of life.

Nerve-sparing techniques have therefore been a trending topic in gynecologic surgery in the 21st century, starting with papers by Marc Possover, MD, of Switzerland, on the laparoscopic neuronavigation (LANN) technique. In an important 2005 publication, he described how the LANN technique can significantly reduce postoperative functional morbidity in laparoscopic radical pelvic surgery.2

The LANN method utilizes intraoperative neurostimulation to identify and dissect the intrapelvic nerve bundles away from surrounding tissue prior to dissection of the DIE or pelvic malignancies. The nerves are exposed and preserved under direct visualization in a fashion similar to that used to expose and preserve the ureters. Pelvic dissection using the LANN technique is extensive and occurs down to the level of the sacral nerve roots.

Dr. Possover’s 2005 paper and others like it spurred increased awareness of the intrapelvic part of the autonomic nervous system – in particular, the hypogastric nerves, the pelvic splanchnic nerves, and the inferior hypogastric plexus. Across additional published studies, nerve-sparing techniques were shown to be effective in preserving neurologic pelvic functions, with significantly less urinary retention and rectal/sexual dysfunction than seen with traditional laparoscopy techniques.

For example, in a single-center prospective clinical trial reported in 2012, 56 of 65 (86.2%) patients treated with a classical laparoscopic technique for excision of DIE reported neurologic pelvic dysfunctions, compared with 1 of 61 (1.6%) patients treated with a nerve-sparing approach.3

While research has confirmed the importance of nerve-sparing techniques, it also shone light on the reality that the LANN technique is extremely technically challenging and requires a high level of surgical expertise and advanced training. In my teaching of the technique, I also saw that few gynecologic surgeons were able to incorporate the advanced nerve-sparing technique into their practices.

A group consisting of myself and collaborators at the University of Bologna, Italy, and the University of Cambridge, England, recently developed an alternative to the LANN approach that uses the hypogastric nerves as landmarks. The technique requires less dissection and should be technically achievable when the pelvic neuroanatomy and anatomy of the presacral fascia are well understood. The hypogastric nerve is identified and used as a landmark to preserve the deeper autonomic nerve bundles in the pelvis without exposure and without more extensive dissection to the level of the sacral nerve roots.4,5

This hypogastric nerve-based technique will cover the vast majority of radical surgeries for DIE. When more advanced nerve sparing and more extensive dissection is needed for the very deepest levels of disease infiltration, patients can be referred to surgeons with advanced training, comfort, and experience with the LANN technique.

The pelvic neuroanatomy

As described in our video articles published in 2015 in Fertility and Sterility6 and 2019 in the Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynecology,5 the left and right hypogastric nerves are the main sympathetic nerves of the autonomic nervous system in the pelvis. They originate from the superior hypogastric plexus and, at the level of the middle rectal vessels, they join the pelvic sacral splanchnic nerves to form the inferior hypogastric plexus. They are easily identifiable at their origin and are the most superficial and readily identifiable component of the inferior hypogastric plexus.

The sympathetic input from the hypogastric nerves causes the internal urethral and anal sphincters to contract, as well as detrusor relaxation and a reduction of peristalsis of the descending colon, sigmoid, and rectum; thus, hypogastric nerve input promotes continence.

The hypogastric nerves also carry afferent signals for pelvic visceral proprioception. Lesion to the hypogastric nerves will usually be subclinical and will put the patient at risk for unnoticeable bladder distension, which usually becomes symptomatic about 7 years after the procedure.7

The thin pelvic splanchnic nerves – which merge with the hypogastric nerves into the pararectal fossae to form the inferior hypogastric plexus – arise from nerve roots S2 and S4 and carry all parasympathetic signals to the bladder, rectum, and the sigmoid and left colons. Lesions to these bundles are the main cause of neurogenic urinary retention.

The inferior hypogastric plexi split into the vesical, uterine, and rectal branches, which carry the sympathetic, parasympathetic, and sensory fibers from both the splanchnic and hypogastric nerves. Damage to the inferior hypogastric plexi and/or its branches may induce severe dysfunction to the target organs of the injured fibers.

A focus on the hypogastric nerve

Our approach was developed after we studied the anatomic reliability of the hypogastric nerves through a prospective observational study consisting of measurements during five cadaveric dissections and 10 in-vivo laparoscopic surgeries for rectosigmoid endometriosis.4 We took an interfascial approach to dissection.

Our goal was to clarify the distances between the hypogastric nerves and the ureters, the midsagittal plane, the midcervical plane, and the uterosacral ligaments in each hemipelvis, and in doing so, enable identification of the hypogastric nerves and establish recognizable limits for dissection.

We found quite a bit of variance in the anatomic position and appearance of the hypogastric nerves, but the variances were not very broad. Most notably, the right hypogastric nerve was significantly farther toward the ureter (mean, 14.5 mm; range, 10-25 mm) than the left one (mean, 8.6 mm; range, 7-12 mm).

The ureters were a good landmark for identification of the hypogastric nerves because the nerves were consistently found medially and posteriorly to the ureter at a mean distance of 11.6 mm. Overall, we demonstrated reproducibility in the identification and dissection of the hypogastric nerves using recognizable interfascial planes and anatomic landmarks.4

With good anatomic understanding, a stepwise approach can be taken to identify and preserve the hypogastric nerve and the deeper inferior hypogastric plexus without the need for more extensive dissection.

As shown in our 2019 video, the right hypogastric nerves can be identified transperitoneally in most cases.5 For confirmation, a gentle anterior pulling on the hypogastric nerve causes a caudal movement of the peritoneum overlying the superior hypogastric plexus. (Intermittent pulling on the nerve can also be helpful in localizing the left hypogastric nerve.)

To dissect a hypogastric nerve, the retroperitoneum is opened at the level of the pelvic brim, just inferomedially to the external iliac vessels, and the incision is extended anteriorly, with gentle dissection of the underlying tissue until the ureter is identified.

Once the ureter is identified and lateralized, dissection along the peritoneum is carried deeper and medially into the pelvis until the hypogastric nerve is identified. Lateral to this area are the internal iliac artery, the branching uterine artery, and the obliterated umbilical ligament. In the left hemipelvis, the hypogastric nerve can reliably be found at a mean distance of 8.6 mm from the ureter, while the right one will be found on average 14.5 mm away.

The hypogastric nerves form the posteromedial limit for a safe and simple nerve-sparing dissection. Any dissection posteriorly and laterally to these landmarks should start with the identification of sacral nerve roots and hypogastric nerves.

Dr. Lemos reported that he has no relevant disclosures.

Dr. Lemos is associate professor in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Toronto.

References

1. Imboden S et al. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2021 Aug;28(8):1544-51. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2021.01.009.

2. Possover M et al. J Am Coll Surg. 2005;201(6):913-7. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2005.07.006.

3. Ceccaroni M et al. Surg Endosc. 2012;26(7):2029-45. doi: 10.1007/s00464-012-2153-3.

4. Seracchioli R et al. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2019;26(7):1340-5. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2019.01.010.

5. Zakhari A et al. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020;27(4):813-4. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2019.08.001

6. Lemos N et al. Fertil Steril. 2015 Nov;104(5):e11-2. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.07.1138.

7. Possover M. Fertil Steril. 2014 Mar;101(3):754-8. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.12.019.

Advanced HCC: Radiotherapy+anti-PD1 a better therapeutic regimen than TACE+sorafenib

Key clinical point: Radiotherapy (RT) plus monoclonal antibody against programmed cell death 1 (anti-PD1) has a better efficacy and safety profile than transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE) plus sorafenib for the treatment of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

Major finding: Patients receiving RT+anti-PD1 vs TACE+sorafenib showed significantly higher objective response (54.05% vs 12.20%; P < .001), disease control (70.27% vs 46.34%; P = .041), and 9-month overall survival (75.50% vs 60.60%; P < .001) rates. They also had a longer progression-free survival (hazard ratio 0.51; P = .017); and a lower grade ≥3 treatment-related adverse event rate (29.70% vs 75.60%; P < .001).

Study details: Findings are from a retrospective real-world study that included 78 adult patients with advanced HCC who received RT+anti-PD1 (n = 37) or TACE+sorafenib (n = 41).

Disclosures: This study was sponsored by the Development and Application Project for the Appropriate Technology of Health of Guangxi Province, China, among others. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Li JX et al. Efficacy and safety of radiotherapy plus anti-PD1 versus transcatheter arterial chemoembolization plus sorafenib for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a real-world study. Radiat Oncol. 2022;17:106 (Jun 11. Doi: 10.1186/s13014-022-02075-6

Key clinical point: Radiotherapy (RT) plus monoclonal antibody against programmed cell death 1 (anti-PD1) has a better efficacy and safety profile than transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE) plus sorafenib for the treatment of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

Major finding: Patients receiving RT+anti-PD1 vs TACE+sorafenib showed significantly higher objective response (54.05% vs 12.20%; P < .001), disease control (70.27% vs 46.34%; P = .041), and 9-month overall survival (75.50% vs 60.60%; P < .001) rates. They also had a longer progression-free survival (hazard ratio 0.51; P = .017); and a lower grade ≥3 treatment-related adverse event rate (29.70% vs 75.60%; P < .001).

Study details: Findings are from a retrospective real-world study that included 78 adult patients with advanced HCC who received RT+anti-PD1 (n = 37) or TACE+sorafenib (n = 41).

Disclosures: This study was sponsored by the Development and Application Project for the Appropriate Technology of Health of Guangxi Province, China, among others. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Li JX et al. Efficacy and safety of radiotherapy plus anti-PD1 versus transcatheter arterial chemoembolization plus sorafenib for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a real-world study. Radiat Oncol. 2022;17:106 (Jun 11. Doi: 10.1186/s13014-022-02075-6

Key clinical point: Radiotherapy (RT) plus monoclonal antibody against programmed cell death 1 (anti-PD1) has a better efficacy and safety profile than transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE) plus sorafenib for the treatment of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

Major finding: Patients receiving RT+anti-PD1 vs TACE+sorafenib showed significantly higher objective response (54.05% vs 12.20%; P < .001), disease control (70.27% vs 46.34%; P = .041), and 9-month overall survival (75.50% vs 60.60%; P < .001) rates. They also had a longer progression-free survival (hazard ratio 0.51; P = .017); and a lower grade ≥3 treatment-related adverse event rate (29.70% vs 75.60%; P < .001).

Study details: Findings are from a retrospective real-world study that included 78 adult patients with advanced HCC who received RT+anti-PD1 (n = 37) or TACE+sorafenib (n = 41).

Disclosures: This study was sponsored by the Development and Application Project for the Appropriate Technology of Health of Guangxi Province, China, among others. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Li JX et al. Efficacy and safety of radiotherapy plus anti-PD1 versus transcatheter arterial chemoembolization plus sorafenib for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a real-world study. Radiat Oncol. 2022;17:106 (Jun 11. Doi: 10.1186/s13014-022-02075-6

Sustained virologic response beneficial in patients with HCV-related HCC receiving nonsurgical management

Key clinical point: Sustained virologic response (SVR) decreases the risk for hepatic decompensation in patients with hepatitis C virus (HCV)-related hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) receiving nonsurgical treatment.

Major finding: Patients with SVR vs viremia had a significantly lower likelihood of hepatic decompensation (adjusted odds ratio 0.18; 95% CI 0.06-0.59).

Study details: Findings are from a multicenter, retrospective cohort study including adult patients with HCV cirrhosis and treatment-naive HCC who had active viremia (n = 431) or SVR before HCC diagnosis (n = 135).

Disclosures: This study was sponsored by the US National Institutes of Health. Some authors reported serving as consultants, advisory board members, speakers for, or receiving research funding or consulting fees from various sources.

Source: Parikh ND et al. Association between sustained virological response and clinical outcomes in patients with hepatitis C infection and hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer. 2022 (Jul 7). Doi: 10.1002/cncr.34378

Key clinical point: Sustained virologic response (SVR) decreases the risk for hepatic decompensation in patients with hepatitis C virus (HCV)-related hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) receiving nonsurgical treatment.

Major finding: Patients with SVR vs viremia had a significantly lower likelihood of hepatic decompensation (adjusted odds ratio 0.18; 95% CI 0.06-0.59).

Study details: Findings are from a multicenter, retrospective cohort study including adult patients with HCV cirrhosis and treatment-naive HCC who had active viremia (n = 431) or SVR before HCC diagnosis (n = 135).

Disclosures: This study was sponsored by the US National Institutes of Health. Some authors reported serving as consultants, advisory board members, speakers for, or receiving research funding or consulting fees from various sources.

Source: Parikh ND et al. Association between sustained virological response and clinical outcomes in patients with hepatitis C infection and hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer. 2022 (Jul 7). Doi: 10.1002/cncr.34378

Key clinical point: Sustained virologic response (SVR) decreases the risk for hepatic decompensation in patients with hepatitis C virus (HCV)-related hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) receiving nonsurgical treatment.

Major finding: Patients with SVR vs viremia had a significantly lower likelihood of hepatic decompensation (adjusted odds ratio 0.18; 95% CI 0.06-0.59).

Study details: Findings are from a multicenter, retrospective cohort study including adult patients with HCV cirrhosis and treatment-naive HCC who had active viremia (n = 431) or SVR before HCC diagnosis (n = 135).

Disclosures: This study was sponsored by the US National Institutes of Health. Some authors reported serving as consultants, advisory board members, speakers for, or receiving research funding or consulting fees from various sources.

Source: Parikh ND et al. Association between sustained virological response and clinical outcomes in patients with hepatitis C infection and hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer. 2022 (Jul 7). Doi: 10.1002/cncr.34378

RFA and TACE: Equally effective bridging treatments in HCC patients awaiting liver transplant

Key clinical point: Transplant waitlist mortality and dropout rates were not significantly different between patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) who received transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) and those who received radiofrequency ablation (RFA).

Major finding: TACE and RFA were associated with a comparable 5-year cumulative incidence of mortality or dropout in patients both within (13.4% and 12.9%, respectively; adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 0.91; 95% CI 0.79-1.03) and outside (19.2% and 19.0%, respectively; aHR 1.29; 95% CI 0.79-2.09) the Milan criteria.

Study details: This retrospective study analyzed the data of 11,824 patients with HCC (within and outside the Milan criteria) from the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients who underwent RFA (n = 2449) or TACE (n = 9375).

Disclosures: This study was funded by the US National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Kolarich AR et al. Radiofrequency ablation versus trans-arterial chemoembolization in patients with HCC awaiting liver transplant: An analysis of the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2022 Jun 28. Doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2022.06.016

Key clinical point: Transplant waitlist mortality and dropout rates were not significantly different between patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) who received transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) and those who received radiofrequency ablation (RFA).

Major finding: TACE and RFA were associated with a comparable 5-year cumulative incidence of mortality or dropout in patients both within (13.4% and 12.9%, respectively; adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 0.91; 95% CI 0.79-1.03) and outside (19.2% and 19.0%, respectively; aHR 1.29; 95% CI 0.79-2.09) the Milan criteria.

Study details: This retrospective study analyzed the data of 11,824 patients with HCC (within and outside the Milan criteria) from the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients who underwent RFA (n = 2449) or TACE (n = 9375).

Disclosures: This study was funded by the US National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Kolarich AR et al. Radiofrequency ablation versus trans-arterial chemoembolization in patients with HCC awaiting liver transplant: An analysis of the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2022 Jun 28. Doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2022.06.016

Key clinical point: Transplant waitlist mortality and dropout rates were not significantly different between patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) who received transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) and those who received radiofrequency ablation (RFA).

Major finding: TACE and RFA were associated with a comparable 5-year cumulative incidence of mortality or dropout in patients both within (13.4% and 12.9%, respectively; adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 0.91; 95% CI 0.79-1.03) and outside (19.2% and 19.0%, respectively; aHR 1.29; 95% CI 0.79-2.09) the Milan criteria.

Study details: This retrospective study analyzed the data of 11,824 patients with HCC (within and outside the Milan criteria) from the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients who underwent RFA (n = 2449) or TACE (n = 9375).

Disclosures: This study was funded by the US National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Kolarich AR et al. Radiofrequency ablation versus trans-arterial chemoembolization in patients with HCC awaiting liver transplant: An analysis of the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2022 Jun 28. Doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2022.06.016

First-line pembrolizumab: A promising therapeutic option in advanced HCC

Key clinical point: In systemic therapy-naive patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), pembrolizumab monotherapy demonstrates promising antitumor efficacy and survival outcomes, with a safety profile similar to that of second-line pembrolizumab in advanced HCC.

Major finding: After a 27-month median follow-up, the objective response rate was 16% (95% CI 7%-29%). The median progression-free and overall survival were 4 (95% CI 2-8) and 17 (95% CI 8-23) months, respectively. Treatment-related adverse events of grade ≥ 3 were observed in 16% of patients.

Study details: The data are derived from cohort 2 of the multicenter, phase 2 KEYNOTE-224 trial that included 51 systemic therapy-naive adult patients with advanced HCC who received 200 mg pembrolizumab every 3 weeks for ≤2 years.

Disclosures: This study was sponsored by Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp. (MSD), a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., NJ. Some authors declared receiving grants, personal fees, or other support from various sources, including MSD.

Source: Verset G et al. Pembrolizumab monotherapy for previously untreated advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: Data from the open-label, phase II KEYNOTE-224 trial. Clin Cancer Res. 2022;28(12):2547–2554 (Jun 13). Doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-21-3807

Key clinical point: In systemic therapy-naive patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), pembrolizumab monotherapy demonstrates promising antitumor efficacy and survival outcomes, with a safety profile similar to that of second-line pembrolizumab in advanced HCC.

Major finding: After a 27-month median follow-up, the objective response rate was 16% (95% CI 7%-29%). The median progression-free and overall survival were 4 (95% CI 2-8) and 17 (95% CI 8-23) months, respectively. Treatment-related adverse events of grade ≥ 3 were observed in 16% of patients.

Study details: The data are derived from cohort 2 of the multicenter, phase 2 KEYNOTE-224 trial that included 51 systemic therapy-naive adult patients with advanced HCC who received 200 mg pembrolizumab every 3 weeks for ≤2 years.

Disclosures: This study was sponsored by Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp. (MSD), a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., NJ. Some authors declared receiving grants, personal fees, or other support from various sources, including MSD.

Source: Verset G et al. Pembrolizumab monotherapy for previously untreated advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: Data from the open-label, phase II KEYNOTE-224 trial. Clin Cancer Res. 2022;28(12):2547–2554 (Jun 13). Doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-21-3807

Key clinical point: In systemic therapy-naive patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), pembrolizumab monotherapy demonstrates promising antitumor efficacy and survival outcomes, with a safety profile similar to that of second-line pembrolizumab in advanced HCC.

Major finding: After a 27-month median follow-up, the objective response rate was 16% (95% CI 7%-29%). The median progression-free and overall survival were 4 (95% CI 2-8) and 17 (95% CI 8-23) months, respectively. Treatment-related adverse events of grade ≥ 3 were observed in 16% of patients.

Study details: The data are derived from cohort 2 of the multicenter, phase 2 KEYNOTE-224 trial that included 51 systemic therapy-naive adult patients with advanced HCC who received 200 mg pembrolizumab every 3 weeks for ≤2 years.

Disclosures: This study was sponsored by Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp. (MSD), a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., NJ. Some authors declared receiving grants, personal fees, or other support from various sources, including MSD.

Source: Verset G et al. Pembrolizumab monotherapy for previously untreated advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: Data from the open-label, phase II KEYNOTE-224 trial. Clin Cancer Res. 2022;28(12):2547–2554 (Jun 13). Doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-21-3807