User login

Moms using frozen embryos carry higher hypertensive risk

Women who become pregnant during in vitro fertilization (IVF) from previously frozen embryos have a significantly higher chance of developing hypertensive disorders such as preeclampsia than do women who become pregnant through natural conception, researchers have found.

The new findings come from a study presented at the 2022 annual meeting of the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology. In the study, which will soon be published in Hypertension, researchers analyzed more than 4.5 million pregnancies from Denmark, Norway, and Sweden.

“Our findings are significant because frozen embryo transfers are increasingly common all over the world, partly due to the elective freezing of all embryos,” said Sindre Hoff Petersen, PhD, a fellow in the department of public health and nursing at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, who led the study.

More than 320,000 IVF procedures were performed in the United States in 2020, according to preliminary data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Of those, more than 123,000 eggs or embryos were frozen for future use.

The use of assisted reproductive technology, which includes IVF, has more than doubled during the past decade, the CDC reports. Roughly 2% of all babies born in the United States each year are conceived through assisted reproductive technology.

Dr. Petersen and his colleagues compared maternal complications in sibling pregnancies. Women who became pregnant following the transfer of a frozen embryo were 74% more likely to develop a hypertensive disorder than women who became pregnant following natural conception (7.4% vs. 4.3%; adjusted odds ratio, 1.74; 95% confidence interval, P < .001). The difference was even higher with respect to sibling births: Women who became pregnant using frozen embryos were 102% more likely than women who became pregnant using natural conception to develop a hypertensive disorder (adjusted odds ratio 2.02; 95% CI, 1.72-2.39, P < .001).

The researchers found no difference in the risk of hypertensive disorders between women who used fresh embryos during IVF and women who used natural conception (5.9% vs. 4.3%, 95% CI, P = .382).

“When we find that the association between frozen embryo transfer and hypertensive disorders in pregnancy persists in sibling comparisons, we believe we have strong indications that treatment factors might in fact contribute to the higher risk,” Dr. Petersen told this news organization.

Women in the study who became pregnant after natural conception had a 4.3% chance of developing hypertensive disorders. That effect persisted after controlling for maternal body mass index, smoking, and time between deliveries, he said.

The findings can add to discussions between patients and doctors on the potential benefits and harms of freezing embryos on an elective basis if there is no clinical indication, Dr. Petersen said. The frozen method is most often used to transfer a single embryo in order to reduce the incidence of multiple pregnancies, such as twins and triplets, which in turn reduces pregnancy complications.

“The vast majority of IVF pregnancies, including frozen embryo transfer, are healthy and uncomplicated, and both short- and long-term outcomes for both the mother and the children are very reassuring,” Dr. Petersen said.

Women who become pregnant through use of frozen embryos should be more closely monitored for potential hypertensive disorders, although more work is needed to determine the reasons for the association, said Elizabeth S. Ginsburg, MD, at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology at Harvard Medical School, both in Boston.

“This is something general ob.gyns. need to be aware of, but it’s not clear which subpopulations of patients are going to be affected,” Dr. Ginsburg said. “More investigation is needed to determine if this is caused by the way the uterus is readied for the embryo transfer or if it’s patient population etiology.”

Some studies have suggested that the absence of a hormone-producing cyst, which forms on the ovary during each menstrual cycle, could explain the link between frozen embryo transfer and heightened preeclampsia risk.

Dr. Petersen and Dr. Ginsburg reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Women who become pregnant during in vitro fertilization (IVF) from previously frozen embryos have a significantly higher chance of developing hypertensive disorders such as preeclampsia than do women who become pregnant through natural conception, researchers have found.

The new findings come from a study presented at the 2022 annual meeting of the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology. In the study, which will soon be published in Hypertension, researchers analyzed more than 4.5 million pregnancies from Denmark, Norway, and Sweden.

“Our findings are significant because frozen embryo transfers are increasingly common all over the world, partly due to the elective freezing of all embryos,” said Sindre Hoff Petersen, PhD, a fellow in the department of public health and nursing at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, who led the study.

More than 320,000 IVF procedures were performed in the United States in 2020, according to preliminary data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Of those, more than 123,000 eggs or embryos were frozen for future use.

The use of assisted reproductive technology, which includes IVF, has more than doubled during the past decade, the CDC reports. Roughly 2% of all babies born in the United States each year are conceived through assisted reproductive technology.

Dr. Petersen and his colleagues compared maternal complications in sibling pregnancies. Women who became pregnant following the transfer of a frozen embryo were 74% more likely to develop a hypertensive disorder than women who became pregnant following natural conception (7.4% vs. 4.3%; adjusted odds ratio, 1.74; 95% confidence interval, P < .001). The difference was even higher with respect to sibling births: Women who became pregnant using frozen embryos were 102% more likely than women who became pregnant using natural conception to develop a hypertensive disorder (adjusted odds ratio 2.02; 95% CI, 1.72-2.39, P < .001).

The researchers found no difference in the risk of hypertensive disorders between women who used fresh embryos during IVF and women who used natural conception (5.9% vs. 4.3%, 95% CI, P = .382).

“When we find that the association between frozen embryo transfer and hypertensive disorders in pregnancy persists in sibling comparisons, we believe we have strong indications that treatment factors might in fact contribute to the higher risk,” Dr. Petersen told this news organization.

Women in the study who became pregnant after natural conception had a 4.3% chance of developing hypertensive disorders. That effect persisted after controlling for maternal body mass index, smoking, and time between deliveries, he said.

The findings can add to discussions between patients and doctors on the potential benefits and harms of freezing embryos on an elective basis if there is no clinical indication, Dr. Petersen said. The frozen method is most often used to transfer a single embryo in order to reduce the incidence of multiple pregnancies, such as twins and triplets, which in turn reduces pregnancy complications.

“The vast majority of IVF pregnancies, including frozen embryo transfer, are healthy and uncomplicated, and both short- and long-term outcomes for both the mother and the children are very reassuring,” Dr. Petersen said.

Women who become pregnant through use of frozen embryos should be more closely monitored for potential hypertensive disorders, although more work is needed to determine the reasons for the association, said Elizabeth S. Ginsburg, MD, at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology at Harvard Medical School, both in Boston.

“This is something general ob.gyns. need to be aware of, but it’s not clear which subpopulations of patients are going to be affected,” Dr. Ginsburg said. “More investigation is needed to determine if this is caused by the way the uterus is readied for the embryo transfer or if it’s patient population etiology.”

Some studies have suggested that the absence of a hormone-producing cyst, which forms on the ovary during each menstrual cycle, could explain the link between frozen embryo transfer and heightened preeclampsia risk.

Dr. Petersen and Dr. Ginsburg reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Women who become pregnant during in vitro fertilization (IVF) from previously frozen embryos have a significantly higher chance of developing hypertensive disorders such as preeclampsia than do women who become pregnant through natural conception, researchers have found.

The new findings come from a study presented at the 2022 annual meeting of the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology. In the study, which will soon be published in Hypertension, researchers analyzed more than 4.5 million pregnancies from Denmark, Norway, and Sweden.

“Our findings are significant because frozen embryo transfers are increasingly common all over the world, partly due to the elective freezing of all embryos,” said Sindre Hoff Petersen, PhD, a fellow in the department of public health and nursing at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, who led the study.

More than 320,000 IVF procedures were performed in the United States in 2020, according to preliminary data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Of those, more than 123,000 eggs or embryos were frozen for future use.

The use of assisted reproductive technology, which includes IVF, has more than doubled during the past decade, the CDC reports. Roughly 2% of all babies born in the United States each year are conceived through assisted reproductive technology.

Dr. Petersen and his colleagues compared maternal complications in sibling pregnancies. Women who became pregnant following the transfer of a frozen embryo were 74% more likely to develop a hypertensive disorder than women who became pregnant following natural conception (7.4% vs. 4.3%; adjusted odds ratio, 1.74; 95% confidence interval, P < .001). The difference was even higher with respect to sibling births: Women who became pregnant using frozen embryos were 102% more likely than women who became pregnant using natural conception to develop a hypertensive disorder (adjusted odds ratio 2.02; 95% CI, 1.72-2.39, P < .001).

The researchers found no difference in the risk of hypertensive disorders between women who used fresh embryos during IVF and women who used natural conception (5.9% vs. 4.3%, 95% CI, P = .382).

“When we find that the association between frozen embryo transfer and hypertensive disorders in pregnancy persists in sibling comparisons, we believe we have strong indications that treatment factors might in fact contribute to the higher risk,” Dr. Petersen told this news organization.

Women in the study who became pregnant after natural conception had a 4.3% chance of developing hypertensive disorders. That effect persisted after controlling for maternal body mass index, smoking, and time between deliveries, he said.

The findings can add to discussions between patients and doctors on the potential benefits and harms of freezing embryos on an elective basis if there is no clinical indication, Dr. Petersen said. The frozen method is most often used to transfer a single embryo in order to reduce the incidence of multiple pregnancies, such as twins and triplets, which in turn reduces pregnancy complications.

“The vast majority of IVF pregnancies, including frozen embryo transfer, are healthy and uncomplicated, and both short- and long-term outcomes for both the mother and the children are very reassuring,” Dr. Petersen said.

Women who become pregnant through use of frozen embryos should be more closely monitored for potential hypertensive disorders, although more work is needed to determine the reasons for the association, said Elizabeth S. Ginsburg, MD, at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology at Harvard Medical School, both in Boston.

“This is something general ob.gyns. need to be aware of, but it’s not clear which subpopulations of patients are going to be affected,” Dr. Ginsburg said. “More investigation is needed to determine if this is caused by the way the uterus is readied for the embryo transfer or if it’s patient population etiology.”

Some studies have suggested that the absence of a hormone-producing cyst, which forms on the ovary during each menstrual cycle, could explain the link between frozen embryo transfer and heightened preeclampsia risk.

Dr. Petersen and Dr. Ginsburg reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Hospital programs tackle mental health effects of long COVID

There’s little doubt that long COVID is real. Even as doctors and federal agencies struggle to define the syndrome, hospitals and health care systems are opening long COVID specialty treatment programs. As of July 25, there’s at least one long COVID center in almost every state – 48 out of 50, according to the patient advocacy group Survivor Corps.

Among the biggest challenges will be treating the mental health effects of long COVID.

Specialized centers will be tackling these problems even as the United States struggles to deal with mental health needs.

One study of COVID patients found more than one-third of them had symptoms of depression, anxiety, or PTSD 3-6 months after their initial infection. Another analysis of 30 previous studies of long COVID patients found roughly one in eight of them had severe depression – and that the risk was similar regardless of whether people were hospitalized for COVID-19.

“Many of these symptoms can emerge months into the course of long COVID illness,” said Jordan Anderson, DO, a neuropsychiatrist who sees patients at the Long COVID-19 Program at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland. Psychological symptoms are often made worse by physical setbacks like extreme fatigue and by challenges of working, caring for children, and keeping up with daily routines, he said.

“This impact is not only severe, but also chronic for many,” he said.

Like dozens of hospitals around the country, Oregon Health & Science opened its center for long COVID as it became clear that more patients would need help for ongoing physical and mental health symptoms. Today, there’s at least one long COVID center – sometimes called post-COVID care centers or clinics – in every state but Kansas and South Dakota, Survivor Corps said.

Many long COVID care centers aim to tackle both physical and mental health symptoms, said Tracy Vannorsdall, PhD, a neuropsychologist with the Johns Hopkins Post-Acute COVID-19 Team program. One goal at Hopkins is to identify patients with psychological issues that might otherwise get overlooked.

A sizable minority of patients at the Johns Hopkins center – up to about 35% – report mental health problems that they didn’t have until after they got COVID-19, Dr. Vannorsdall says. The most common mental health issues providers see are depression, anxiety, and trauma-related distress.

“Routine assessment is key,” Dr. Vannorsdall said. “If patients are not asked about their mental health symptoms, they may not spontaneously report them to their provider due to fear of stigma or simply not appreciating that there are effective treatments available for these issues.”

Fear that doctors won’t take symptoms seriously is common, says Heather Murray MD, a senior instructor in psychiatry at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora.

“Many patients worry their physicians, loved ones, and society will not believe them or will minimize their symptoms and suffering,” said Dr. Murray, who treats patients at the UCHealth Post-COVID Clinic.

Diagnostic tests in long COVID patients often don’t have conclusive results, which can lead doctors and patients themselves to question whether symptoms are truly “physical versus psychosomatic,” she said. “It is important that providers believe their patients and treat their symptoms, even when diagnostic tests are unrevealing.”

Growing mental health crisis

Patients often find their way to academic treatment centers after surviving severe COVID-19 infections. But a growing number of long COVID patients show up at these centers after milder cases. These patients were never hospitalized for COVID-19 but still have persistent symptoms like fatigue, thinking problems, and mood disorders.

Among the major challenges is a shortage of mental health care providers to meet the surging need for care since the start of the pandemic. Around the world, anxiety and depression surged 25% during the first year of the pandemic, according to the World Health Organization.

In the United States, 40% of adults report feelings of anxiety and depression, and one in three high school students have feelings of sadness and hopelessness, according to a March 2022 statement from the White House.

Despite this surging need for care, almost half of Americans live in areas with a severe shortage of mental health care providers, according to the Health Resources and Services Administration. As of 2019, the United States had a shortage of about 6,790 mental health providers. Since then, the shortage has worsened; it’s now about 7,500 providers.

“One of the biggest challenges for hospitals and clinics in treating mental health disorders in long COVID is the limited resources and long wait times to get in for evaluations and treatment,” said Nyaz Didehbani, PhD, a neuropsychologist who treats long COVID patients at the COVID Recover program at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas.

These delays can lead to worse outcomes, Dr. Didehbani said. “Additionally, patients do not feel that they are being heard, as many providers are not aware of the mental health impact and relationship with physical and cognitive symptoms.” .

Even when doctors recognize that psychological challenges are common with long COVID, they still have to think creatively to come up with treatments that meet the unique needs of these patients, said Thida Thant, MD, an assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of Colorado who treats patients at the UCHealth Post-COVID Clinic.

“There are at least two major factors that make treating psychological issues in long COVID more complex: The fact that the pandemic is still ongoing and still so divisive throughout society, and the fact that we don’t know a single best way to treat all symptoms of long COVID,” she said.

Some common treatments for anxiety and depression, like psychotherapy and medication, can be used for long COVID patients with these conditions. But another intervention that can work wonders for many people with mood disorders – exercise – doesn’t always work for long COVID patients. That’s because many of them struggle with physical challenges like chronic fatigue and what’s known as postexertional malaise, or a worsening of symptoms after even limited physical effort.

“While we normally encourage patients to be active, have a daily routine, and to engage in physical activity as part of their mental health treatment, some long COVID patients find that their symptoms worsen after increased activity,” Dr. Vannorsdall said.

Patients who are able to reach long COVID care centers are much more apt to get mental health problems diagnosed and treated, doctors at many programs around the country agree. But many patients hardest hit by the pandemic – the poor and racial and ethnic minorities – are also less likely to have ready access to hospitals that offer these programs, said Dr. Anderson.

“Affluent, predominantly White populations are showing up in these clinics, while we know that non-White populations have disproportionally high rates of acute infection, hospitalization, and death related to the virus,” he said.

Clinics are also concentrated in academic medical centers and in urban areas, limiting options for people in rural communities who may have to drive for hours to access care, Dr. Anderson said.

“Even before long COVID, we already knew that many people live in areas where there simply aren’t enough mental health services available,” said John Zulueta, MD, an assistant professor of clinical psychiatry at the University of Illinois at Chicago who provides mental health evaluations at the UI Health Post-COVID Clinic.

“As more patients develop mental health issues associated with long COVID, it’s going to put more stress on an already stressed system,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

There’s little doubt that long COVID is real. Even as doctors and federal agencies struggle to define the syndrome, hospitals and health care systems are opening long COVID specialty treatment programs. As of July 25, there’s at least one long COVID center in almost every state – 48 out of 50, according to the patient advocacy group Survivor Corps.

Among the biggest challenges will be treating the mental health effects of long COVID.

Specialized centers will be tackling these problems even as the United States struggles to deal with mental health needs.

One study of COVID patients found more than one-third of them had symptoms of depression, anxiety, or PTSD 3-6 months after their initial infection. Another analysis of 30 previous studies of long COVID patients found roughly one in eight of them had severe depression – and that the risk was similar regardless of whether people were hospitalized for COVID-19.

“Many of these symptoms can emerge months into the course of long COVID illness,” said Jordan Anderson, DO, a neuropsychiatrist who sees patients at the Long COVID-19 Program at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland. Psychological symptoms are often made worse by physical setbacks like extreme fatigue and by challenges of working, caring for children, and keeping up with daily routines, he said.

“This impact is not only severe, but also chronic for many,” he said.

Like dozens of hospitals around the country, Oregon Health & Science opened its center for long COVID as it became clear that more patients would need help for ongoing physical and mental health symptoms. Today, there’s at least one long COVID center – sometimes called post-COVID care centers or clinics – in every state but Kansas and South Dakota, Survivor Corps said.

Many long COVID care centers aim to tackle both physical and mental health symptoms, said Tracy Vannorsdall, PhD, a neuropsychologist with the Johns Hopkins Post-Acute COVID-19 Team program. One goal at Hopkins is to identify patients with psychological issues that might otherwise get overlooked.

A sizable minority of patients at the Johns Hopkins center – up to about 35% – report mental health problems that they didn’t have until after they got COVID-19, Dr. Vannorsdall says. The most common mental health issues providers see are depression, anxiety, and trauma-related distress.

“Routine assessment is key,” Dr. Vannorsdall said. “If patients are not asked about their mental health symptoms, they may not spontaneously report them to their provider due to fear of stigma or simply not appreciating that there are effective treatments available for these issues.”

Fear that doctors won’t take symptoms seriously is common, says Heather Murray MD, a senior instructor in psychiatry at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora.

“Many patients worry their physicians, loved ones, and society will not believe them or will minimize their symptoms and suffering,” said Dr. Murray, who treats patients at the UCHealth Post-COVID Clinic.

Diagnostic tests in long COVID patients often don’t have conclusive results, which can lead doctors and patients themselves to question whether symptoms are truly “physical versus psychosomatic,” she said. “It is important that providers believe their patients and treat their symptoms, even when diagnostic tests are unrevealing.”

Growing mental health crisis

Patients often find their way to academic treatment centers after surviving severe COVID-19 infections. But a growing number of long COVID patients show up at these centers after milder cases. These patients were never hospitalized for COVID-19 but still have persistent symptoms like fatigue, thinking problems, and mood disorders.

Among the major challenges is a shortage of mental health care providers to meet the surging need for care since the start of the pandemic. Around the world, anxiety and depression surged 25% during the first year of the pandemic, according to the World Health Organization.

In the United States, 40% of adults report feelings of anxiety and depression, and one in three high school students have feelings of sadness and hopelessness, according to a March 2022 statement from the White House.

Despite this surging need for care, almost half of Americans live in areas with a severe shortage of mental health care providers, according to the Health Resources and Services Administration. As of 2019, the United States had a shortage of about 6,790 mental health providers. Since then, the shortage has worsened; it’s now about 7,500 providers.

“One of the biggest challenges for hospitals and clinics in treating mental health disorders in long COVID is the limited resources and long wait times to get in for evaluations and treatment,” said Nyaz Didehbani, PhD, a neuropsychologist who treats long COVID patients at the COVID Recover program at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas.

These delays can lead to worse outcomes, Dr. Didehbani said. “Additionally, patients do not feel that they are being heard, as many providers are not aware of the mental health impact and relationship with physical and cognitive symptoms.” .

Even when doctors recognize that psychological challenges are common with long COVID, they still have to think creatively to come up with treatments that meet the unique needs of these patients, said Thida Thant, MD, an assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of Colorado who treats patients at the UCHealth Post-COVID Clinic.

“There are at least two major factors that make treating psychological issues in long COVID more complex: The fact that the pandemic is still ongoing and still so divisive throughout society, and the fact that we don’t know a single best way to treat all symptoms of long COVID,” she said.

Some common treatments for anxiety and depression, like psychotherapy and medication, can be used for long COVID patients with these conditions. But another intervention that can work wonders for many people with mood disorders – exercise – doesn’t always work for long COVID patients. That’s because many of them struggle with physical challenges like chronic fatigue and what’s known as postexertional malaise, or a worsening of symptoms after even limited physical effort.

“While we normally encourage patients to be active, have a daily routine, and to engage in physical activity as part of their mental health treatment, some long COVID patients find that their symptoms worsen after increased activity,” Dr. Vannorsdall said.

Patients who are able to reach long COVID care centers are much more apt to get mental health problems diagnosed and treated, doctors at many programs around the country agree. But many patients hardest hit by the pandemic – the poor and racial and ethnic minorities – are also less likely to have ready access to hospitals that offer these programs, said Dr. Anderson.

“Affluent, predominantly White populations are showing up in these clinics, while we know that non-White populations have disproportionally high rates of acute infection, hospitalization, and death related to the virus,” he said.

Clinics are also concentrated in academic medical centers and in urban areas, limiting options for people in rural communities who may have to drive for hours to access care, Dr. Anderson said.

“Even before long COVID, we already knew that many people live in areas where there simply aren’t enough mental health services available,” said John Zulueta, MD, an assistant professor of clinical psychiatry at the University of Illinois at Chicago who provides mental health evaluations at the UI Health Post-COVID Clinic.

“As more patients develop mental health issues associated with long COVID, it’s going to put more stress on an already stressed system,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

There’s little doubt that long COVID is real. Even as doctors and federal agencies struggle to define the syndrome, hospitals and health care systems are opening long COVID specialty treatment programs. As of July 25, there’s at least one long COVID center in almost every state – 48 out of 50, according to the patient advocacy group Survivor Corps.

Among the biggest challenges will be treating the mental health effects of long COVID.

Specialized centers will be tackling these problems even as the United States struggles to deal with mental health needs.

One study of COVID patients found more than one-third of them had symptoms of depression, anxiety, or PTSD 3-6 months after their initial infection. Another analysis of 30 previous studies of long COVID patients found roughly one in eight of them had severe depression – and that the risk was similar regardless of whether people were hospitalized for COVID-19.

“Many of these symptoms can emerge months into the course of long COVID illness,” said Jordan Anderson, DO, a neuropsychiatrist who sees patients at the Long COVID-19 Program at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland. Psychological symptoms are often made worse by physical setbacks like extreme fatigue and by challenges of working, caring for children, and keeping up with daily routines, he said.

“This impact is not only severe, but also chronic for many,” he said.

Like dozens of hospitals around the country, Oregon Health & Science opened its center for long COVID as it became clear that more patients would need help for ongoing physical and mental health symptoms. Today, there’s at least one long COVID center – sometimes called post-COVID care centers or clinics – in every state but Kansas and South Dakota, Survivor Corps said.

Many long COVID care centers aim to tackle both physical and mental health symptoms, said Tracy Vannorsdall, PhD, a neuropsychologist with the Johns Hopkins Post-Acute COVID-19 Team program. One goal at Hopkins is to identify patients with psychological issues that might otherwise get overlooked.

A sizable minority of patients at the Johns Hopkins center – up to about 35% – report mental health problems that they didn’t have until after they got COVID-19, Dr. Vannorsdall says. The most common mental health issues providers see are depression, anxiety, and trauma-related distress.

“Routine assessment is key,” Dr. Vannorsdall said. “If patients are not asked about their mental health symptoms, they may not spontaneously report them to their provider due to fear of stigma or simply not appreciating that there are effective treatments available for these issues.”

Fear that doctors won’t take symptoms seriously is common, says Heather Murray MD, a senior instructor in psychiatry at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora.

“Many patients worry their physicians, loved ones, and society will not believe them or will minimize their symptoms and suffering,” said Dr. Murray, who treats patients at the UCHealth Post-COVID Clinic.

Diagnostic tests in long COVID patients often don’t have conclusive results, which can lead doctors and patients themselves to question whether symptoms are truly “physical versus psychosomatic,” she said. “It is important that providers believe their patients and treat their symptoms, even when diagnostic tests are unrevealing.”

Growing mental health crisis

Patients often find their way to academic treatment centers after surviving severe COVID-19 infections. But a growing number of long COVID patients show up at these centers after milder cases. These patients were never hospitalized for COVID-19 but still have persistent symptoms like fatigue, thinking problems, and mood disorders.

Among the major challenges is a shortage of mental health care providers to meet the surging need for care since the start of the pandemic. Around the world, anxiety and depression surged 25% during the first year of the pandemic, according to the World Health Organization.

In the United States, 40% of adults report feelings of anxiety and depression, and one in three high school students have feelings of sadness and hopelessness, according to a March 2022 statement from the White House.

Despite this surging need for care, almost half of Americans live in areas with a severe shortage of mental health care providers, according to the Health Resources and Services Administration. As of 2019, the United States had a shortage of about 6,790 mental health providers. Since then, the shortage has worsened; it’s now about 7,500 providers.

“One of the biggest challenges for hospitals and clinics in treating mental health disorders in long COVID is the limited resources and long wait times to get in for evaluations and treatment,” said Nyaz Didehbani, PhD, a neuropsychologist who treats long COVID patients at the COVID Recover program at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas.

These delays can lead to worse outcomes, Dr. Didehbani said. “Additionally, patients do not feel that they are being heard, as many providers are not aware of the mental health impact and relationship with physical and cognitive symptoms.” .

Even when doctors recognize that psychological challenges are common with long COVID, they still have to think creatively to come up with treatments that meet the unique needs of these patients, said Thida Thant, MD, an assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of Colorado who treats patients at the UCHealth Post-COVID Clinic.

“There are at least two major factors that make treating psychological issues in long COVID more complex: The fact that the pandemic is still ongoing and still so divisive throughout society, and the fact that we don’t know a single best way to treat all symptoms of long COVID,” she said.

Some common treatments for anxiety and depression, like psychotherapy and medication, can be used for long COVID patients with these conditions. But another intervention that can work wonders for many people with mood disorders – exercise – doesn’t always work for long COVID patients. That’s because many of them struggle with physical challenges like chronic fatigue and what’s known as postexertional malaise, or a worsening of symptoms after even limited physical effort.

“While we normally encourage patients to be active, have a daily routine, and to engage in physical activity as part of their mental health treatment, some long COVID patients find that their symptoms worsen after increased activity,” Dr. Vannorsdall said.

Patients who are able to reach long COVID care centers are much more apt to get mental health problems diagnosed and treated, doctors at many programs around the country agree. But many patients hardest hit by the pandemic – the poor and racial and ethnic minorities – are also less likely to have ready access to hospitals that offer these programs, said Dr. Anderson.

“Affluent, predominantly White populations are showing up in these clinics, while we know that non-White populations have disproportionally high rates of acute infection, hospitalization, and death related to the virus,” he said.

Clinics are also concentrated in academic medical centers and in urban areas, limiting options for people in rural communities who may have to drive for hours to access care, Dr. Anderson said.

“Even before long COVID, we already knew that many people live in areas where there simply aren’t enough mental health services available,” said John Zulueta, MD, an assistant professor of clinical psychiatry at the University of Illinois at Chicago who provides mental health evaluations at the UI Health Post-COVID Clinic.

“As more patients develop mental health issues associated with long COVID, it’s going to put more stress on an already stressed system,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Nonphysician Clinicians in Dermatology Residencies: Cross-sectional Survey on Residency Education

To the Editor:

There is increasing demand for medical care in the United States due to expanded health care coverage; an aging population; and advancements in diagnostics, treatment, and technology.1 It is predicted that by 2050 the number of dermatologists will be 24.4% short of the expected estimate of demand.2

Accordingly, dermatologists are increasingly practicing in team-based care delivery models that incorporate nonphysician clinicians (NPCs), including nurse practitioners and physician assistants.1 Despite recognition that NPCs are taking a larger role in medical teams, there is, to our knowledge, limited training for dermatologists and dermatologists in-training to optimize this professional alliance.

The objectives of this study included (1) determining whether residency programs adequately prepare residents to work with or supervise NPCs and (2) understanding the relationship between NPCs and dermatology residents across residency programs in the United States.

An anonymous cross-sectional, Internet-based survey designed using Google Forms survey creation and administration software was distributed to 117 dermatology residency program directors through email, with a request for further dissemination to residents through self-maintained listserves. Four email reminders about completing and disseminating the survey were sent to program directors between August and November 2020. The study was approved by the Emory University institutional review board. All respondents consented to participate in this survey prior to completing it.

The survey included questions pertaining to demographic information, residents’ experiences working with NPCs, residency program training specific to working with NPCs, and residents’ and residency program directors’ opinions on NPCs’ impact on education and patient care. Program directors were asked to respond N/A to 6 questions on the survey because data from those questions represented residents’ opinions only. Questions relating to residents’ and residency program directors’ opinions were based on a 5-point scale of impact (1=strongly impact in a negative way; 5=strongly impact in a positive way) or importance (1=not at all important; 5=extremely important). The survey was not previously validated.

Descriptive analysis and a paired t test were conducted when appropriate. Missing data were excluded.

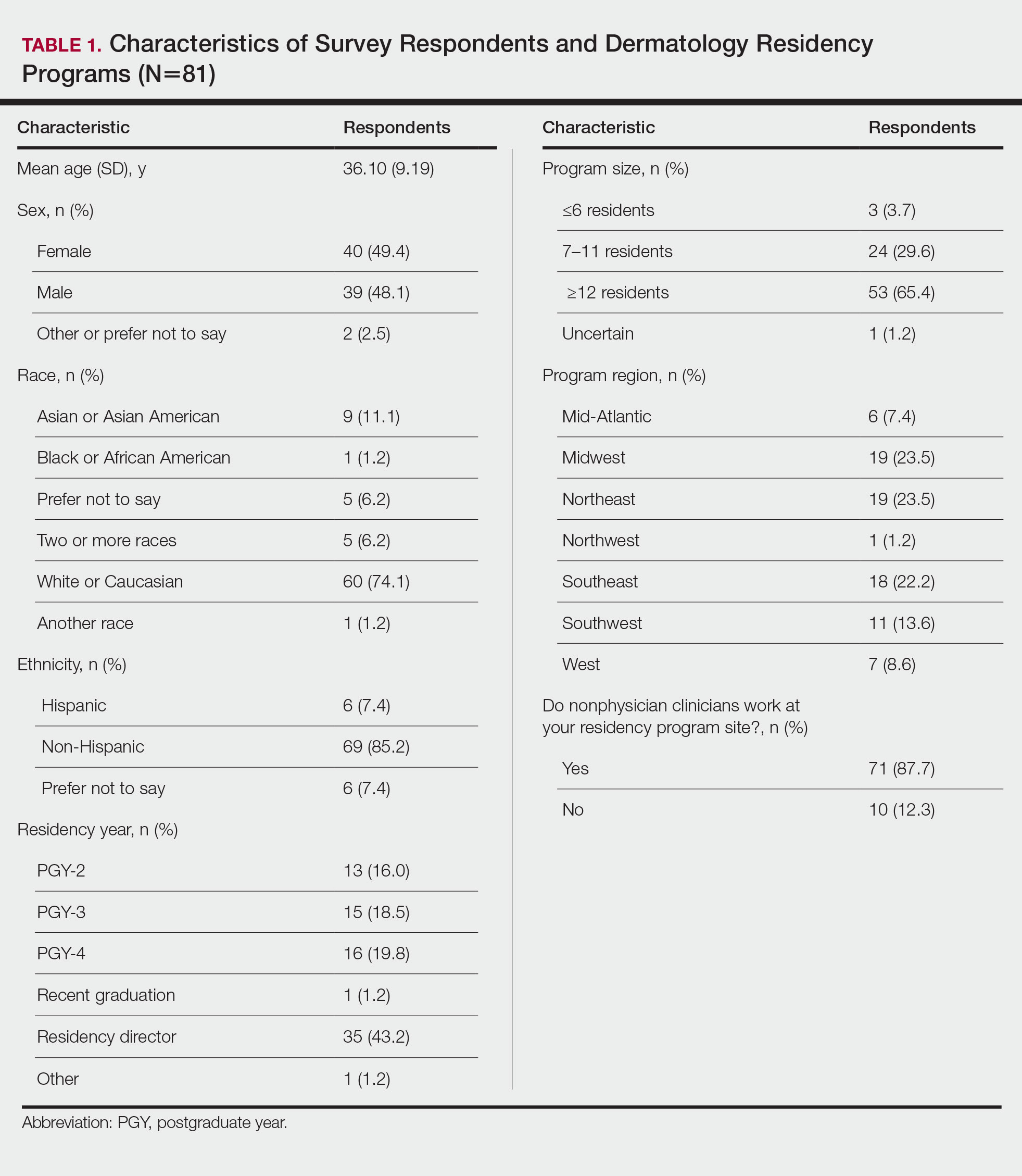

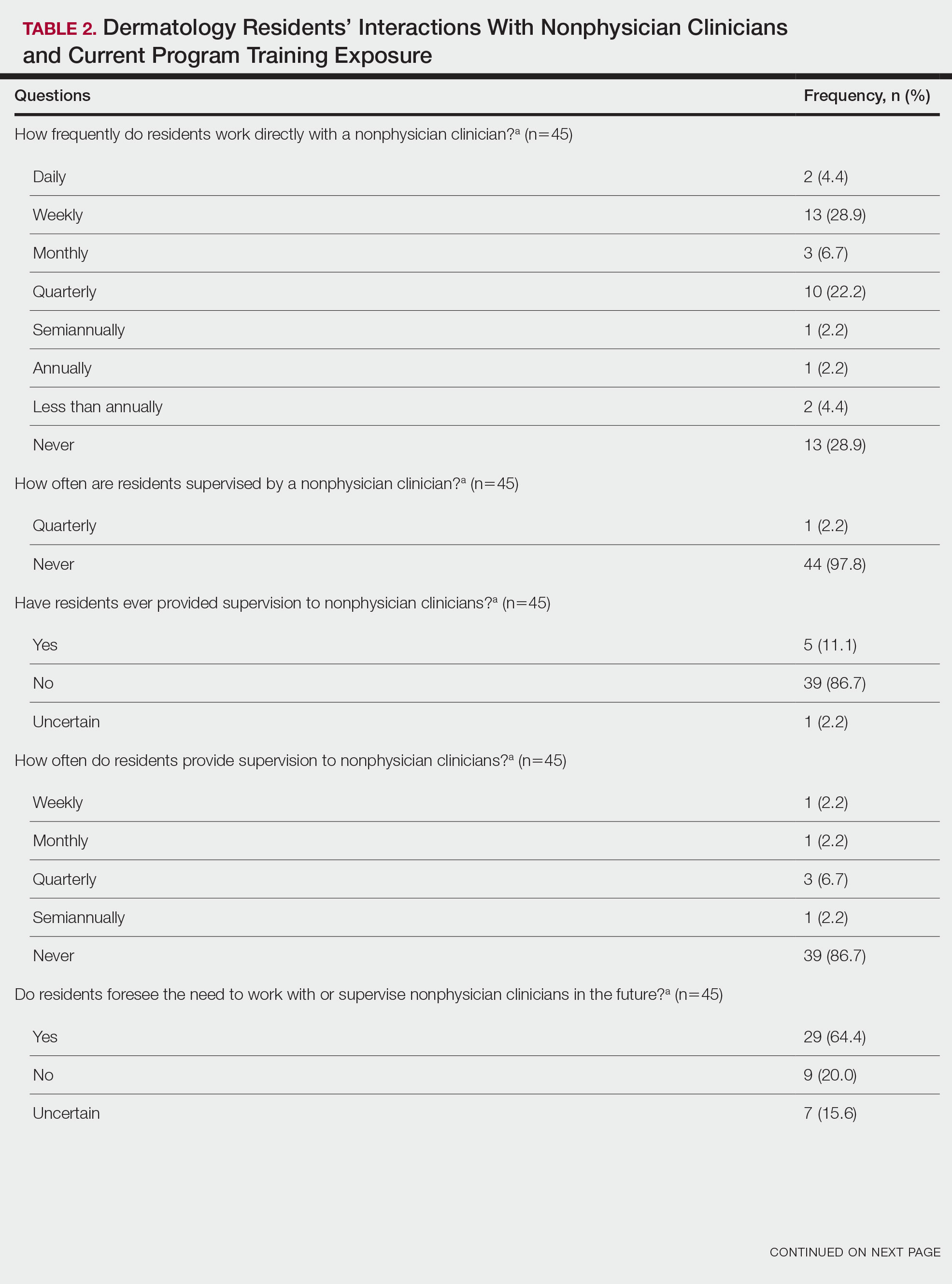

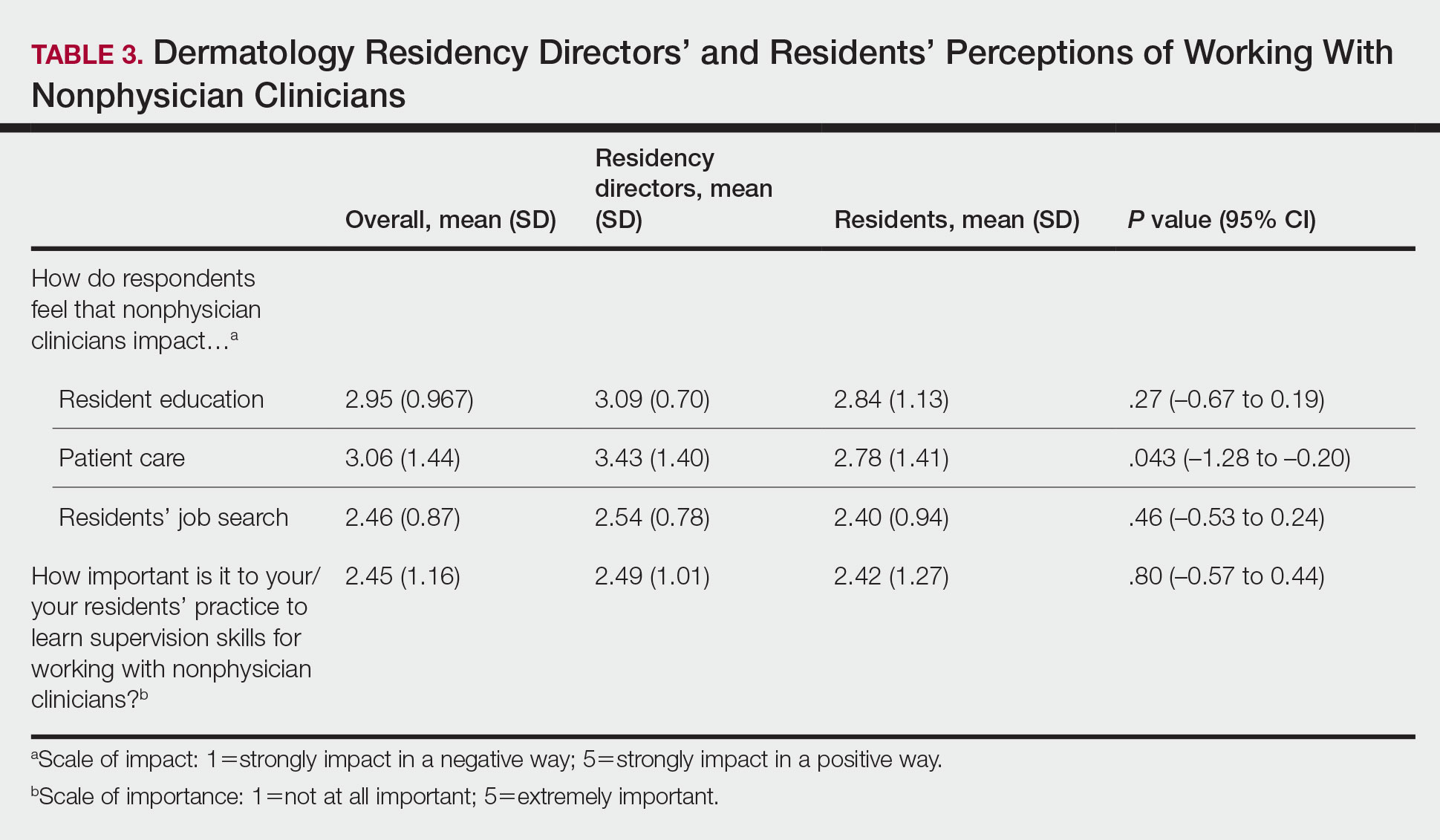

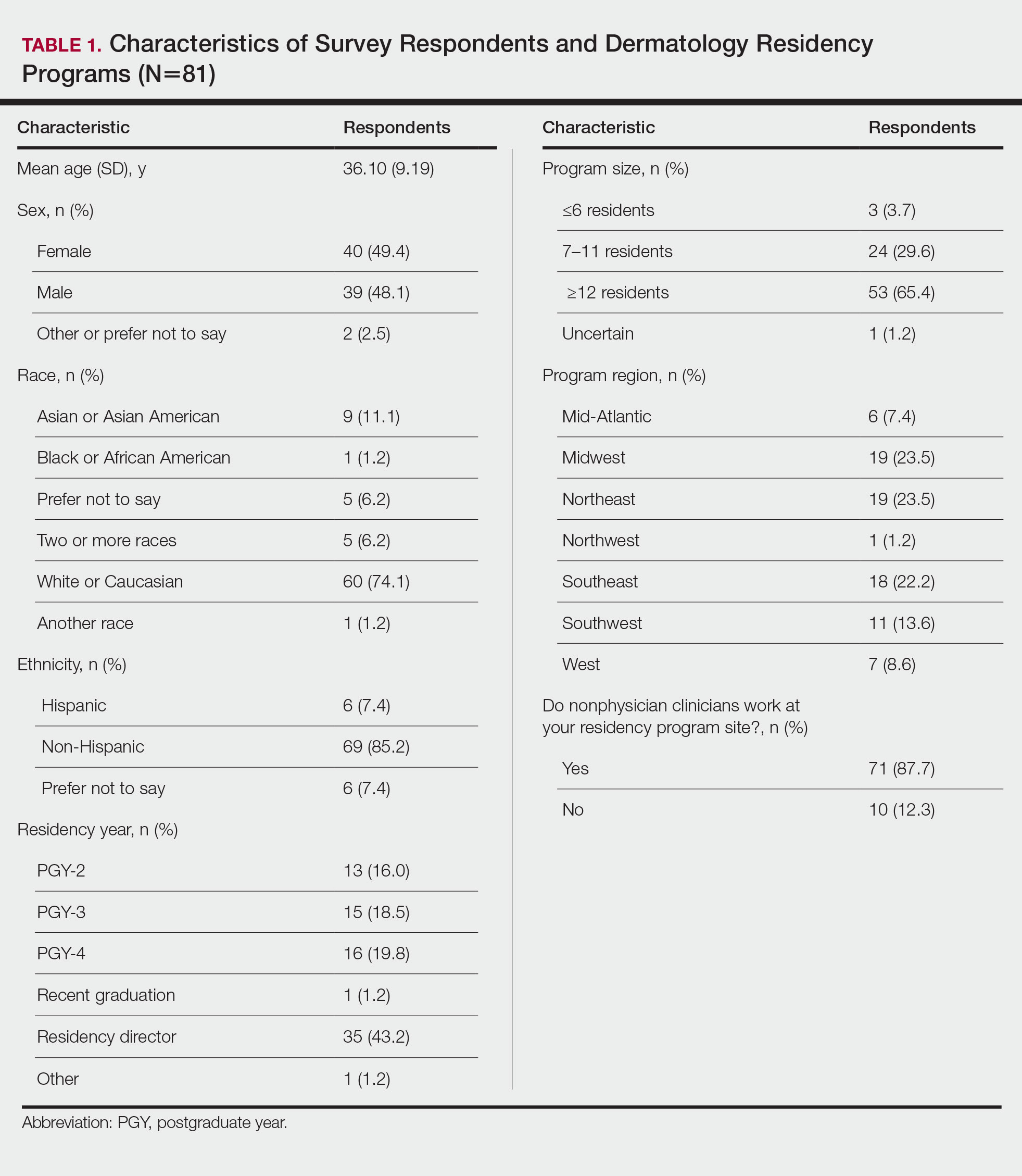

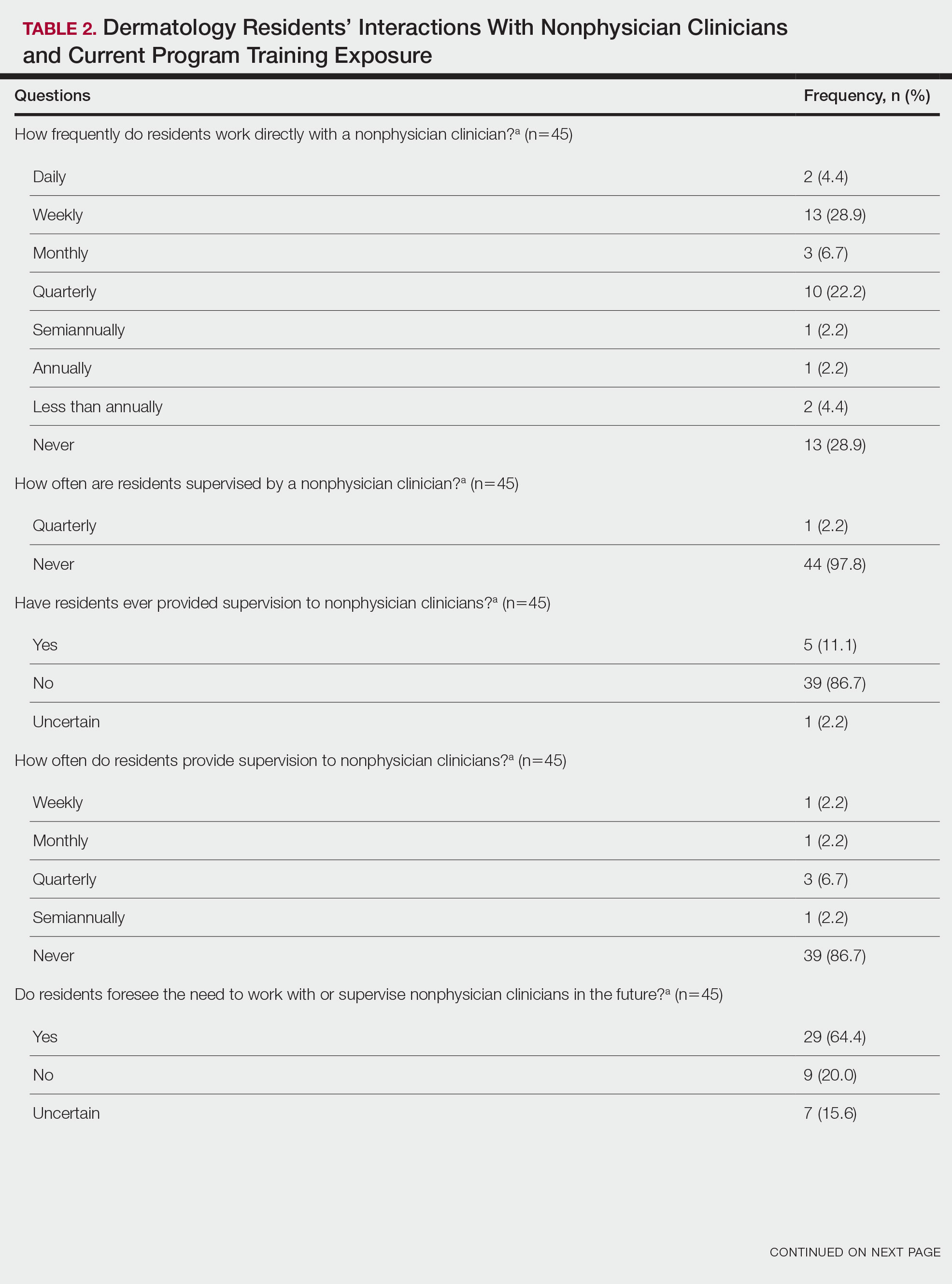

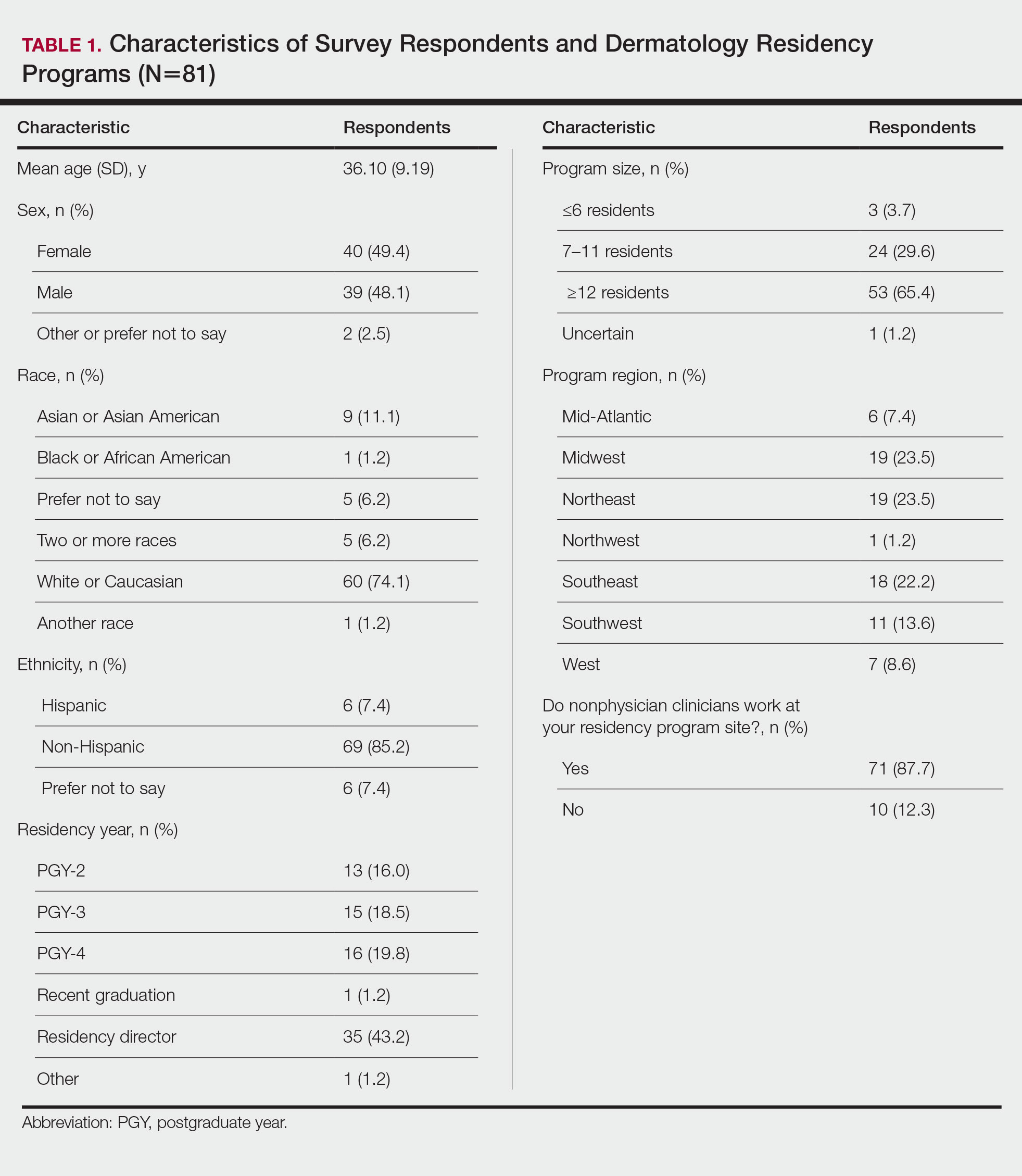

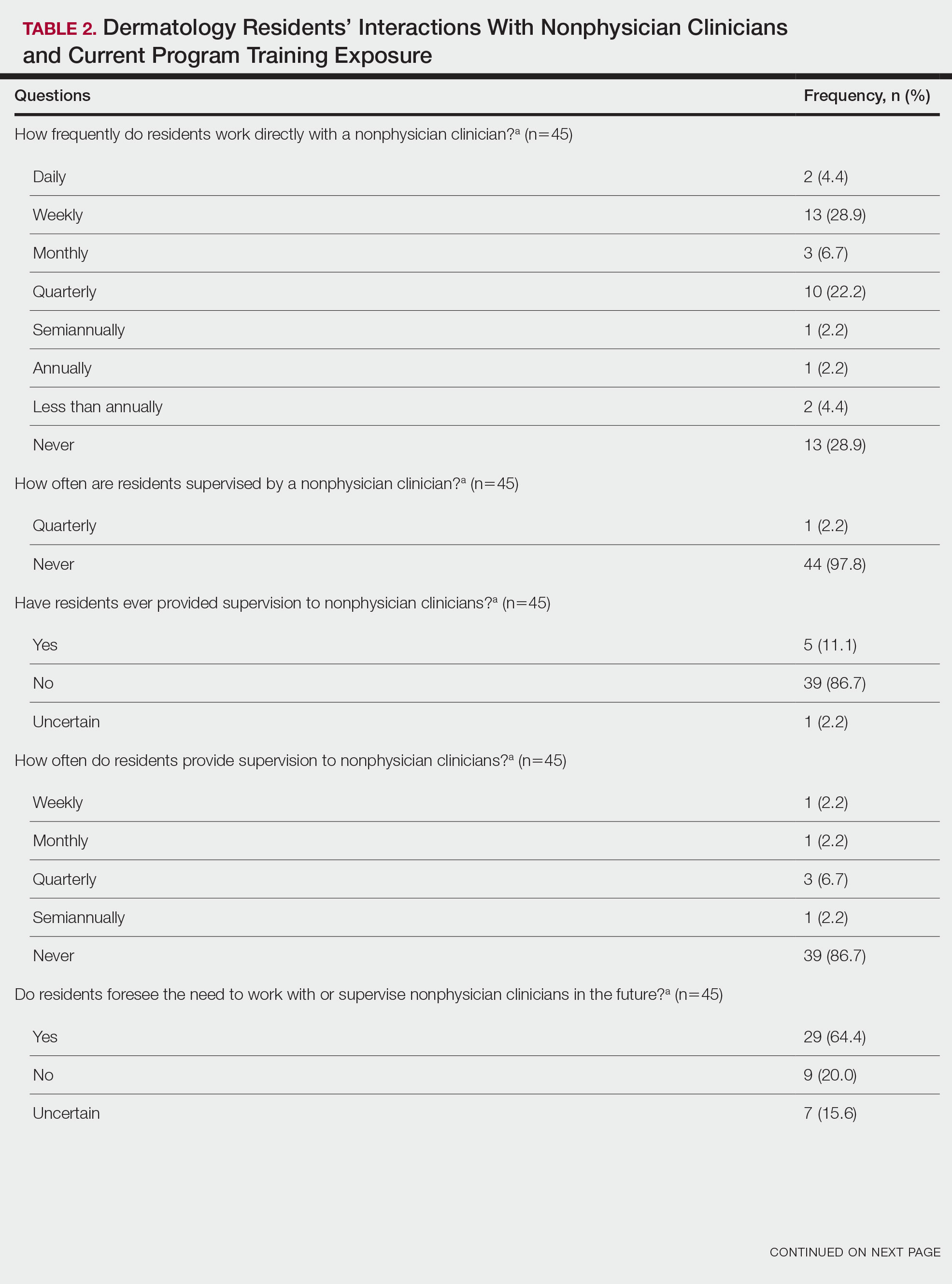

There were 81 respondents to the survey. Demographic information is shown Table 1. Thirty-five dermatology residency program directors (29.9% of 117 programs) responded. Of the 45 residents or recent graduates, 29 (64.4%) reported that they foresaw the need to work with or supervise NPCs in the future (Table 2). Currently, 29 (64.4%) residents also reported that (1) they do not feel adequately trained to provide supervision of or to work with NPCs or (2) were uncertain whether they could do so. Sixty-five (80.2%) respondents stated that there was no formalized training in their program for supervising or working with NPCs; 45 (55.6%) respondents noted that they do not think that their program provided adequate training in supervising NPCs.

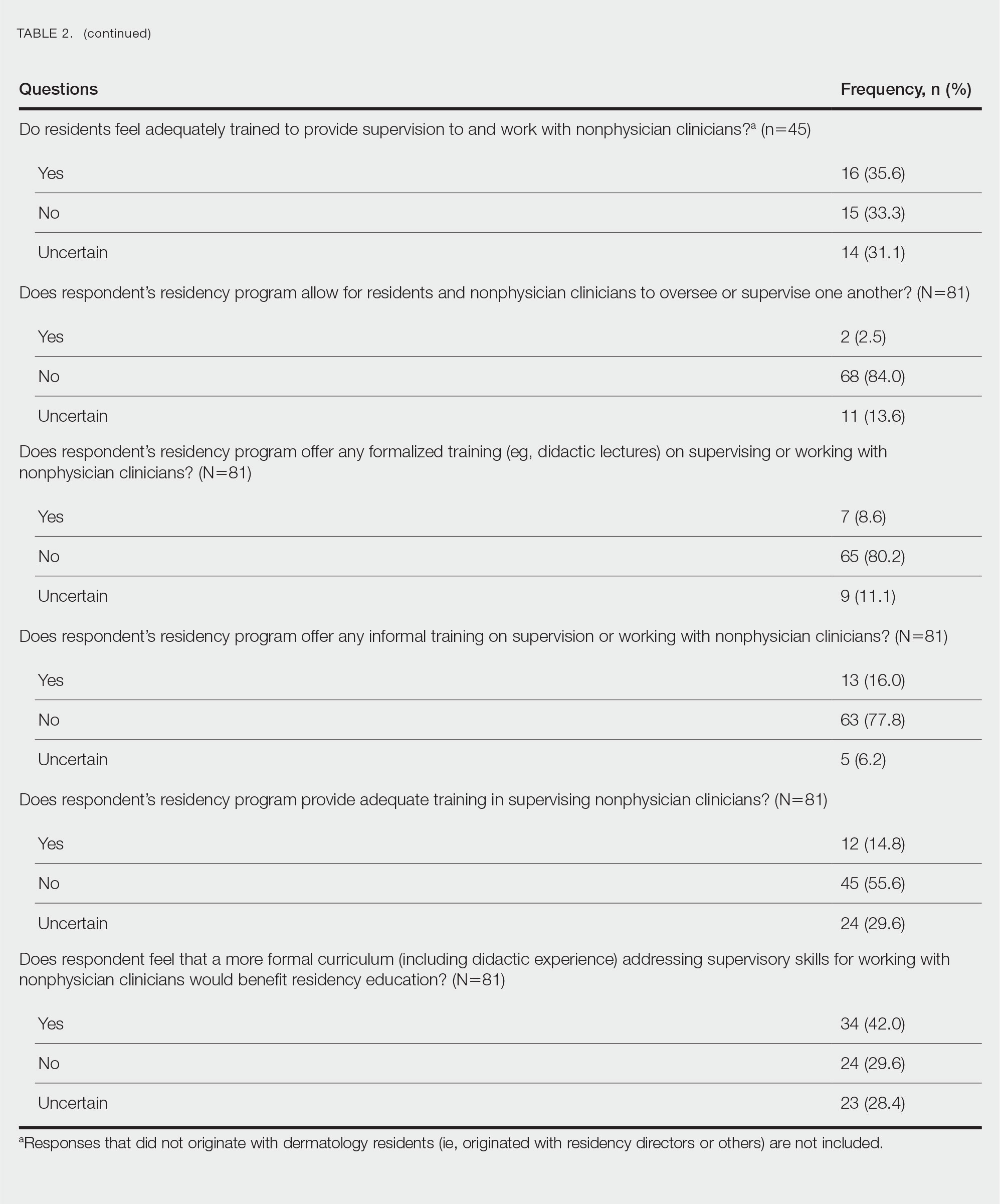

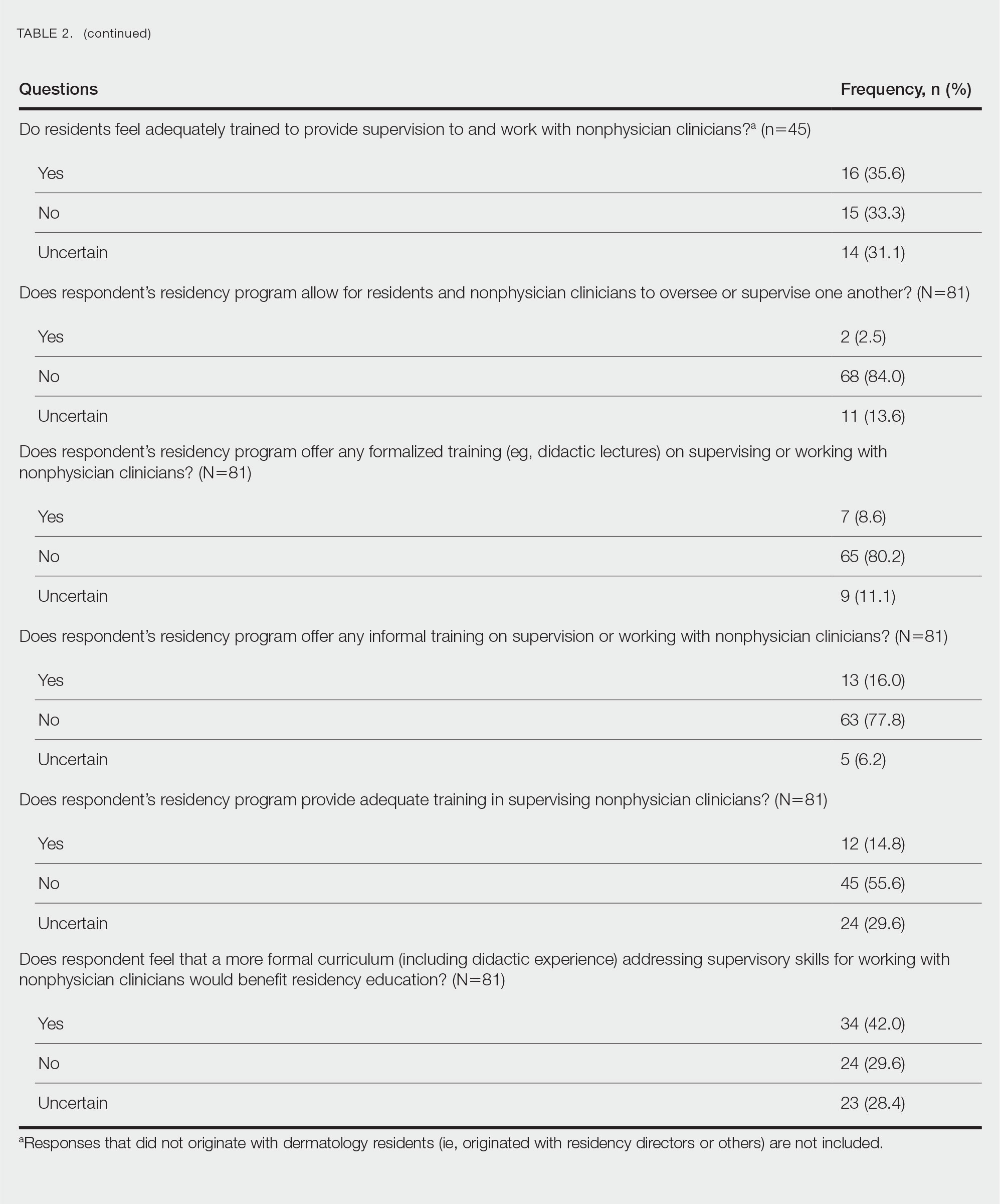

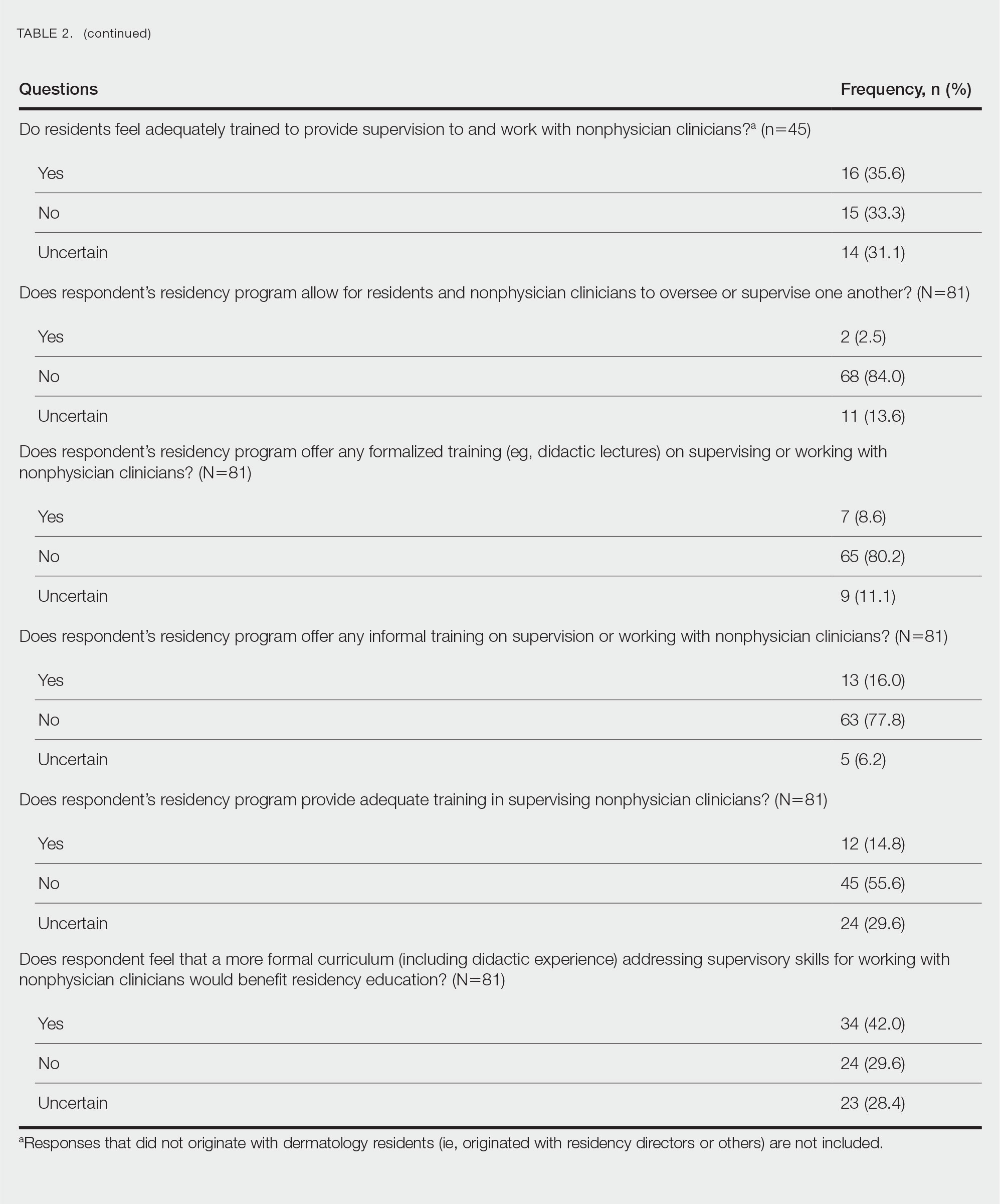

Regarding NPCs impact on care, residency program directors who completed the survey were more likely to rank NPCs as having a more significant positive impact on patient care than residents (mean score, 3.43 vs 2.78; P=.043; 95% CI, –1.28 to –0.20)(Table 3).

This study demonstrated a lack of dermatology training related to working with NPCs in a professional setting and highlighted residents’ perception that formal education in working with and supervising NPCs could be of benefit to their education. Furthermore, residency directors perceived NPCs as having a greater positive impact on patient care than residents did, underscoring the importance of the continued need to educate residents on working synergistically with NPCs to optimize patient care. Ultimately, these results suggest a potential area for further development of residency curricula.

There are approximately 360,000 NPCs serving as integral members of interdisciplinary medical teams across the United States.3,4 In a 2014 survey, 46% of 2001 dermatologists noted that they already employed 1 or more NPCs, a number that has increased over time and is likely to continue to do so.5 Although the number of NPCs in dermatology has increased, there remain limited formal training and certificate programs for these providers.1,6

Furthermore, the American Academy of Dermatology recommends that “[w]hen practicing in a dermatological setting, non-dermatologist physicians and non-physician clinicians . . . should be directly supervised by a board-certified dermatologist.”7 Therefore, the responsibility for a dermatology-specific education can fall on the dermatologist, necessitating adequate supervision and training of NPCs.

The findings of this study were limited by a small sample size; response bias because distribution of the survey relied on program directors disseminating the instrument to their residents, thereby limiting generalizability; and a lack of predissemination validation of the survey. Additional research in this area should focus on survey validation and distribution directly to dermatology residents, instead of relying on dermatology program directors to disseminate the survey.

- Sargen MR, Shi L, Hooker RS, et al. Future growth of physicians and non-physician providers within the U.S. Dermatology workforce. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23:13030/qt840223q6

- The current and projected dermatology workforce in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(suppl 1):AB122. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.02.478

- Nurse anesthetists, nurse midwives, and nurse practitioners.Occupational Outlook Handbook. Washington, DC: US Department of Labor. Updated April 18, 2022. Accessed July 14, 2022. https://www.bls.gov/ooh/health care/nurse-anesthetists-nurse-midwives-and-nurse-practitioners.htm

- Physician assistants. Occupational Outlook Handbook. Washington, DC: US Department of Labor. Updated April 18, 2022. Accessed July 14, 2022. https://www.bls.gov/ooh/healthcare/physician-assistants.htm

- Ehrlich A, Kostecki J, Olkaba H. Trends in dermatology practices and the implications for the workforce. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:746-752. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.06.030

- Anderson AM, Matsumoto M, Saul MI, et al. Accuracy of skin cancer diagnosis by physician assistants compared with dermatologists in a large health care system. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:569-573. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.0212s

- American Academy of Dermatology Association. Position statement on the practice of dermatology: protecting and preserving patient safety and quality care. Revised May 21, 2016. Accessed July 14, 2022. https://server.aad.org/Forms/Policies/Uploads/PS/PS-Practice of Dermatology-Protecting Preserving Patient Safety Quality Care.pdf?

To the Editor:

There is increasing demand for medical care in the United States due to expanded health care coverage; an aging population; and advancements in diagnostics, treatment, and technology.1 It is predicted that by 2050 the number of dermatologists will be 24.4% short of the expected estimate of demand.2

Accordingly, dermatologists are increasingly practicing in team-based care delivery models that incorporate nonphysician clinicians (NPCs), including nurse practitioners and physician assistants.1 Despite recognition that NPCs are taking a larger role in medical teams, there is, to our knowledge, limited training for dermatologists and dermatologists in-training to optimize this professional alliance.

The objectives of this study included (1) determining whether residency programs adequately prepare residents to work with or supervise NPCs and (2) understanding the relationship between NPCs and dermatology residents across residency programs in the United States.

An anonymous cross-sectional, Internet-based survey designed using Google Forms survey creation and administration software was distributed to 117 dermatology residency program directors through email, with a request for further dissemination to residents through self-maintained listserves. Four email reminders about completing and disseminating the survey were sent to program directors between August and November 2020. The study was approved by the Emory University institutional review board. All respondents consented to participate in this survey prior to completing it.

The survey included questions pertaining to demographic information, residents’ experiences working with NPCs, residency program training specific to working with NPCs, and residents’ and residency program directors’ opinions on NPCs’ impact on education and patient care. Program directors were asked to respond N/A to 6 questions on the survey because data from those questions represented residents’ opinions only. Questions relating to residents’ and residency program directors’ opinions were based on a 5-point scale of impact (1=strongly impact in a negative way; 5=strongly impact in a positive way) or importance (1=not at all important; 5=extremely important). The survey was not previously validated.

Descriptive analysis and a paired t test were conducted when appropriate. Missing data were excluded.

There were 81 respondents to the survey. Demographic information is shown Table 1. Thirty-five dermatology residency program directors (29.9% of 117 programs) responded. Of the 45 residents or recent graduates, 29 (64.4%) reported that they foresaw the need to work with or supervise NPCs in the future (Table 2). Currently, 29 (64.4%) residents also reported that (1) they do not feel adequately trained to provide supervision of or to work with NPCs or (2) were uncertain whether they could do so. Sixty-five (80.2%) respondents stated that there was no formalized training in their program for supervising or working with NPCs; 45 (55.6%) respondents noted that they do not think that their program provided adequate training in supervising NPCs.

Regarding NPCs impact on care, residency program directors who completed the survey were more likely to rank NPCs as having a more significant positive impact on patient care than residents (mean score, 3.43 vs 2.78; P=.043; 95% CI, –1.28 to –0.20)(Table 3).

This study demonstrated a lack of dermatology training related to working with NPCs in a professional setting and highlighted residents’ perception that formal education in working with and supervising NPCs could be of benefit to their education. Furthermore, residency directors perceived NPCs as having a greater positive impact on patient care than residents did, underscoring the importance of the continued need to educate residents on working synergistically with NPCs to optimize patient care. Ultimately, these results suggest a potential area for further development of residency curricula.

There are approximately 360,000 NPCs serving as integral members of interdisciplinary medical teams across the United States.3,4 In a 2014 survey, 46% of 2001 dermatologists noted that they already employed 1 or more NPCs, a number that has increased over time and is likely to continue to do so.5 Although the number of NPCs in dermatology has increased, there remain limited formal training and certificate programs for these providers.1,6

Furthermore, the American Academy of Dermatology recommends that “[w]hen practicing in a dermatological setting, non-dermatologist physicians and non-physician clinicians . . . should be directly supervised by a board-certified dermatologist.”7 Therefore, the responsibility for a dermatology-specific education can fall on the dermatologist, necessitating adequate supervision and training of NPCs.

The findings of this study were limited by a small sample size; response bias because distribution of the survey relied on program directors disseminating the instrument to their residents, thereby limiting generalizability; and a lack of predissemination validation of the survey. Additional research in this area should focus on survey validation and distribution directly to dermatology residents, instead of relying on dermatology program directors to disseminate the survey.

To the Editor:

There is increasing demand for medical care in the United States due to expanded health care coverage; an aging population; and advancements in diagnostics, treatment, and technology.1 It is predicted that by 2050 the number of dermatologists will be 24.4% short of the expected estimate of demand.2

Accordingly, dermatologists are increasingly practicing in team-based care delivery models that incorporate nonphysician clinicians (NPCs), including nurse practitioners and physician assistants.1 Despite recognition that NPCs are taking a larger role in medical teams, there is, to our knowledge, limited training for dermatologists and dermatologists in-training to optimize this professional alliance.

The objectives of this study included (1) determining whether residency programs adequately prepare residents to work with or supervise NPCs and (2) understanding the relationship between NPCs and dermatology residents across residency programs in the United States.

An anonymous cross-sectional, Internet-based survey designed using Google Forms survey creation and administration software was distributed to 117 dermatology residency program directors through email, with a request for further dissemination to residents through self-maintained listserves. Four email reminders about completing and disseminating the survey were sent to program directors between August and November 2020. The study was approved by the Emory University institutional review board. All respondents consented to participate in this survey prior to completing it.

The survey included questions pertaining to demographic information, residents’ experiences working with NPCs, residency program training specific to working with NPCs, and residents’ and residency program directors’ opinions on NPCs’ impact on education and patient care. Program directors were asked to respond N/A to 6 questions on the survey because data from those questions represented residents’ opinions only. Questions relating to residents’ and residency program directors’ opinions were based on a 5-point scale of impact (1=strongly impact in a negative way; 5=strongly impact in a positive way) or importance (1=not at all important; 5=extremely important). The survey was not previously validated.

Descriptive analysis and a paired t test were conducted when appropriate. Missing data were excluded.

There were 81 respondents to the survey. Demographic information is shown Table 1. Thirty-five dermatology residency program directors (29.9% of 117 programs) responded. Of the 45 residents or recent graduates, 29 (64.4%) reported that they foresaw the need to work with or supervise NPCs in the future (Table 2). Currently, 29 (64.4%) residents also reported that (1) they do not feel adequately trained to provide supervision of or to work with NPCs or (2) were uncertain whether they could do so. Sixty-five (80.2%) respondents stated that there was no formalized training in their program for supervising or working with NPCs; 45 (55.6%) respondents noted that they do not think that their program provided adequate training in supervising NPCs.

Regarding NPCs impact on care, residency program directors who completed the survey were more likely to rank NPCs as having a more significant positive impact on patient care than residents (mean score, 3.43 vs 2.78; P=.043; 95% CI, –1.28 to –0.20)(Table 3).

This study demonstrated a lack of dermatology training related to working with NPCs in a professional setting and highlighted residents’ perception that formal education in working with and supervising NPCs could be of benefit to their education. Furthermore, residency directors perceived NPCs as having a greater positive impact on patient care than residents did, underscoring the importance of the continued need to educate residents on working synergistically with NPCs to optimize patient care. Ultimately, these results suggest a potential area for further development of residency curricula.

There are approximately 360,000 NPCs serving as integral members of interdisciplinary medical teams across the United States.3,4 In a 2014 survey, 46% of 2001 dermatologists noted that they already employed 1 or more NPCs, a number that has increased over time and is likely to continue to do so.5 Although the number of NPCs in dermatology has increased, there remain limited formal training and certificate programs for these providers.1,6

Furthermore, the American Academy of Dermatology recommends that “[w]hen practicing in a dermatological setting, non-dermatologist physicians and non-physician clinicians . . . should be directly supervised by a board-certified dermatologist.”7 Therefore, the responsibility for a dermatology-specific education can fall on the dermatologist, necessitating adequate supervision and training of NPCs.

The findings of this study were limited by a small sample size; response bias because distribution of the survey relied on program directors disseminating the instrument to their residents, thereby limiting generalizability; and a lack of predissemination validation of the survey. Additional research in this area should focus on survey validation and distribution directly to dermatology residents, instead of relying on dermatology program directors to disseminate the survey.

- Sargen MR, Shi L, Hooker RS, et al. Future growth of physicians and non-physician providers within the U.S. Dermatology workforce. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23:13030/qt840223q6

- The current and projected dermatology workforce in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(suppl 1):AB122. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.02.478

- Nurse anesthetists, nurse midwives, and nurse practitioners.Occupational Outlook Handbook. Washington, DC: US Department of Labor. Updated April 18, 2022. Accessed July 14, 2022. https://www.bls.gov/ooh/health care/nurse-anesthetists-nurse-midwives-and-nurse-practitioners.htm

- Physician assistants. Occupational Outlook Handbook. Washington, DC: US Department of Labor. Updated April 18, 2022. Accessed July 14, 2022. https://www.bls.gov/ooh/healthcare/physician-assistants.htm

- Ehrlich A, Kostecki J, Olkaba H. Trends in dermatology practices and the implications for the workforce. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:746-752. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.06.030

- Anderson AM, Matsumoto M, Saul MI, et al. Accuracy of skin cancer diagnosis by physician assistants compared with dermatologists in a large health care system. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:569-573. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.0212s

- American Academy of Dermatology Association. Position statement on the practice of dermatology: protecting and preserving patient safety and quality care. Revised May 21, 2016. Accessed July 14, 2022. https://server.aad.org/Forms/Policies/Uploads/PS/PS-Practice of Dermatology-Protecting Preserving Patient Safety Quality Care.pdf?

- Sargen MR, Shi L, Hooker RS, et al. Future growth of physicians and non-physician providers within the U.S. Dermatology workforce. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23:13030/qt840223q6

- The current and projected dermatology workforce in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(suppl 1):AB122. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.02.478

- Nurse anesthetists, nurse midwives, and nurse practitioners.Occupational Outlook Handbook. Washington, DC: US Department of Labor. Updated April 18, 2022. Accessed July 14, 2022. https://www.bls.gov/ooh/health care/nurse-anesthetists-nurse-midwives-and-nurse-practitioners.htm

- Physician assistants. Occupational Outlook Handbook. Washington, DC: US Department of Labor. Updated April 18, 2022. Accessed July 14, 2022. https://www.bls.gov/ooh/healthcare/physician-assistants.htm

- Ehrlich A, Kostecki J, Olkaba H. Trends in dermatology practices and the implications for the workforce. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:746-752. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.06.030

- Anderson AM, Matsumoto M, Saul MI, et al. Accuracy of skin cancer diagnosis by physician assistants compared with dermatologists in a large health care system. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:569-573. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.0212s

- American Academy of Dermatology Association. Position statement on the practice of dermatology: protecting and preserving patient safety and quality care. Revised May 21, 2016. Accessed July 14, 2022. https://server.aad.org/Forms/Policies/Uploads/PS/PS-Practice of Dermatology-Protecting Preserving Patient Safety Quality Care.pdf?

Practice Points

- Most dermatology residency programs do not offer training on working with and supervising nonphysician clinicians.

- Dermatology residents think that formal training in supervising nonphysician clinicians would be a beneficial addition to the residency curriculum.

‘Reassuring’ safety data on PPI therapy

In a novel analysis accounting for protopathic bias, proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy was not associated with increased risk for death due to digestive disease, cancer, cardiovascular disease (CVD), or any cause, although the jury is out on renal disease.

“There have been several studies suggesting that PPIs can cause long-term health problems and may be associated with increased mortality,” Andrew T. Chan, MD, MPH, gastroenterologist and professor of medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, told this news organization.

“We conducted this study to examine this issue using data that were better able to account for potential biases in those prior studies. We found that PPIs were generally not associated with an increased risk of mortality,” Dr. Chan said.

The study was published online in Gastroenterology.

‘Reassuring’ data

The findings are based on data collected between 2004 and 2018 from 50,156 women enrolled in the Nurses’ Health Study and 21,731 men enrolled from the Health Professionals Follow-up Study.

During the study period, 10,998 women (21.9%) and 2,945 men (13.6%) initiated PPI therapy, and PPI use increased over the study period from 6.1% to 10.0% in women and from 2.5% to 7.0% in men.

The mean age at baseline was 68.9 years for women and 68.0 years for men. During a median follow-up of 13.8 years, a total of 22,125 participants died – 4,592 of cancer, 5,404 of CVD, and 12,129 of other causes.

Unlike other studies, the researchers used a modified lag-time approach to minimize reverse causation (protopathic bias).

“Using this approach, any increased PPI use during the excluded period, which could be due to comorbid conditions prior to death, will not be considered in the quantification of the exposure, and thus, protopathic bias would be avoided,” they explain.

In the initial analysis that did not take into account lag times, PPI users had significantly higher risks for all-cause mortality and mortality due to cancer, CVD, respiratory diseases, and digestive diseases, compared with nonusers.

However, when applying lag times of up to 6 years, the associations were largely attenuated and no longer statistically significant, which “highlights the importance of carefully controlling for the influence of protopathic bias,” the researchers write.

However, despite applying lag times, PPI users remained at a significantly increased risk for mortality due to renal diseases (hazard ratio, 2.45; 95% confidence interval, 1.59-3.78).

The researchers caution, however, that they did not have reliable data on renal diseases and therefore could not adjust for confounding in the models. They call for further studies examining the risk for mortality due to renal diseases in patients using PPI therapy.

The researchers also looked at duration of PPI use and all-cause and cause-specific mortality.

For all-cause mortality and mortality due to cancer, CVD, respiratory diseases, and digestive diseases, the greatest risks were seen mostly in those who reported PPI use for 1-2 years. Longer duration of PPI use did not confer higher risk for mortality for these endpoints.

In contrast, a potential trend toward greater risk with longer duration of PPI use was observed for mortality due to renal disease. The hazard ratio was 1.68 (95% CI, 1.19-2.38) for 1 to 2 years of use and gradually increased to 2.42 (95% CI, 1.23-4.77) for 7 or more years of use.

Notably, when mortality risks were compared among PPI users and histamine H2 receptor antagonist (H2RA) users without lag time, PPI users were at increased risk for all-cause mortality and mortality due to causes other than cancer and CVD, compared with H2RA users.

But again, the strength of the associations decreased after lag time was introduced.

“This confirmed our main findings and suggested PPIs might be preferred over H2RAs in sicker patients with comorbid conditions,” the researchers write.

‘Generally safe’ when needed

Summing up, Dr. Chan said, “We think our results should be reassuring to clinicians that recommending PPIs to patients with appropriate indications will not increase their risk of death. These are generally safe drugs that when used appropriately can be very beneficial.”

Offering perspective on the study, David Johnson, MD, professor of medicine and chief of gastroenterology at the Eastern Virginia School of Medicine, Norfolk, noted that a “major continuing criticism of the allegations of harm by PPIs has been that these most commonly come from retrospective analyses of databases that were not constructed to evaluate these endpoints of harm.”

“Accordingly, these reports have multiple potentials for stratification bias and typically have low odds ratios for supporting the purported causality,” Dr. Johnson told this news organization.

“This is a well-done study design with a prospective database analysis that uses a modified lag-time approach to minimize reverse causation, that is, protopathic bias, which can occur when a pharmaceutical agent is inadvertently prescribed for an early manifestation of a disease that has not yet been diagnostically detected,” Dr. Johnson explained.

Echoing Dr. Chan, Dr. Johnson said the finding that PPI use was not associated with higher risk for all-cause mortality and mortality due to major causes is “reassuring.”

“Recognizably, too many people are taking PPIs chronically when they are not needed. If needed and appropriate, these data on continued use are reassuring,” Dr. Johnson added.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health and the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation. Dr. Chan has consulted for OM1, Bayer Pharma AG, and Pfizer for topics unrelated to this study, as well as Boehringer Ingelheim for litigation related to ranitidine and cancer. Dr. Johnson reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In a novel analysis accounting for protopathic bias, proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy was not associated with increased risk for death due to digestive disease, cancer, cardiovascular disease (CVD), or any cause, although the jury is out on renal disease.

“There have been several studies suggesting that PPIs can cause long-term health problems and may be associated with increased mortality,” Andrew T. Chan, MD, MPH, gastroenterologist and professor of medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, told this news organization.

“We conducted this study to examine this issue using data that were better able to account for potential biases in those prior studies. We found that PPIs were generally not associated with an increased risk of mortality,” Dr. Chan said.

The study was published online in Gastroenterology.

‘Reassuring’ data

The findings are based on data collected between 2004 and 2018 from 50,156 women enrolled in the Nurses’ Health Study and 21,731 men enrolled from the Health Professionals Follow-up Study.

During the study period, 10,998 women (21.9%) and 2,945 men (13.6%) initiated PPI therapy, and PPI use increased over the study period from 6.1% to 10.0% in women and from 2.5% to 7.0% in men.

The mean age at baseline was 68.9 years for women and 68.0 years for men. During a median follow-up of 13.8 years, a total of 22,125 participants died – 4,592 of cancer, 5,404 of CVD, and 12,129 of other causes.

Unlike other studies, the researchers used a modified lag-time approach to minimize reverse causation (protopathic bias).

“Using this approach, any increased PPI use during the excluded period, which could be due to comorbid conditions prior to death, will not be considered in the quantification of the exposure, and thus, protopathic bias would be avoided,” they explain.

In the initial analysis that did not take into account lag times, PPI users had significantly higher risks for all-cause mortality and mortality due to cancer, CVD, respiratory diseases, and digestive diseases, compared with nonusers.

However, when applying lag times of up to 6 years, the associations were largely attenuated and no longer statistically significant, which “highlights the importance of carefully controlling for the influence of protopathic bias,” the researchers write.

However, despite applying lag times, PPI users remained at a significantly increased risk for mortality due to renal diseases (hazard ratio, 2.45; 95% confidence interval, 1.59-3.78).

The researchers caution, however, that they did not have reliable data on renal diseases and therefore could not adjust for confounding in the models. They call for further studies examining the risk for mortality due to renal diseases in patients using PPI therapy.

The researchers also looked at duration of PPI use and all-cause and cause-specific mortality.

For all-cause mortality and mortality due to cancer, CVD, respiratory diseases, and digestive diseases, the greatest risks were seen mostly in those who reported PPI use for 1-2 years. Longer duration of PPI use did not confer higher risk for mortality for these endpoints.

In contrast, a potential trend toward greater risk with longer duration of PPI use was observed for mortality due to renal disease. The hazard ratio was 1.68 (95% CI, 1.19-2.38) for 1 to 2 years of use and gradually increased to 2.42 (95% CI, 1.23-4.77) for 7 or more years of use.

Notably, when mortality risks were compared among PPI users and histamine H2 receptor antagonist (H2RA) users without lag time, PPI users were at increased risk for all-cause mortality and mortality due to causes other than cancer and CVD, compared with H2RA users.

But again, the strength of the associations decreased after lag time was introduced.

“This confirmed our main findings and suggested PPIs might be preferred over H2RAs in sicker patients with comorbid conditions,” the researchers write.

‘Generally safe’ when needed

Summing up, Dr. Chan said, “We think our results should be reassuring to clinicians that recommending PPIs to patients with appropriate indications will not increase their risk of death. These are generally safe drugs that when used appropriately can be very beneficial.”

Offering perspective on the study, David Johnson, MD, professor of medicine and chief of gastroenterology at the Eastern Virginia School of Medicine, Norfolk, noted that a “major continuing criticism of the allegations of harm by PPIs has been that these most commonly come from retrospective analyses of databases that were not constructed to evaluate these endpoints of harm.”

“Accordingly, these reports have multiple potentials for stratification bias and typically have low odds ratios for supporting the purported causality,” Dr. Johnson told this news organization.

“This is a well-done study design with a prospective database analysis that uses a modified lag-time approach to minimize reverse causation, that is, protopathic bias, which can occur when a pharmaceutical agent is inadvertently prescribed for an early manifestation of a disease that has not yet been diagnostically detected,” Dr. Johnson explained.

Echoing Dr. Chan, Dr. Johnson said the finding that PPI use was not associated with higher risk for all-cause mortality and mortality due to major causes is “reassuring.”

“Recognizably, too many people are taking PPIs chronically when they are not needed. If needed and appropriate, these data on continued use are reassuring,” Dr. Johnson added.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health and the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation. Dr. Chan has consulted for OM1, Bayer Pharma AG, and Pfizer for topics unrelated to this study, as well as Boehringer Ingelheim for litigation related to ranitidine and cancer. Dr. Johnson reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In a novel analysis accounting for protopathic bias, proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy was not associated with increased risk for death due to digestive disease, cancer, cardiovascular disease (CVD), or any cause, although the jury is out on renal disease.

“There have been several studies suggesting that PPIs can cause long-term health problems and may be associated with increased mortality,” Andrew T. Chan, MD, MPH, gastroenterologist and professor of medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, told this news organization.

“We conducted this study to examine this issue using data that were better able to account for potential biases in those prior studies. We found that PPIs were generally not associated with an increased risk of mortality,” Dr. Chan said.

The study was published online in Gastroenterology.

‘Reassuring’ data

The findings are based on data collected between 2004 and 2018 from 50,156 women enrolled in the Nurses’ Health Study and 21,731 men enrolled from the Health Professionals Follow-up Study.

During the study period, 10,998 women (21.9%) and 2,945 men (13.6%) initiated PPI therapy, and PPI use increased over the study period from 6.1% to 10.0% in women and from 2.5% to 7.0% in men.

The mean age at baseline was 68.9 years for women and 68.0 years for men. During a median follow-up of 13.8 years, a total of 22,125 participants died – 4,592 of cancer, 5,404 of CVD, and 12,129 of other causes.

Unlike other studies, the researchers used a modified lag-time approach to minimize reverse causation (protopathic bias).

“Using this approach, any increased PPI use during the excluded period, which could be due to comorbid conditions prior to death, will not be considered in the quantification of the exposure, and thus, protopathic bias would be avoided,” they explain.

In the initial analysis that did not take into account lag times, PPI users had significantly higher risks for all-cause mortality and mortality due to cancer, CVD, respiratory diseases, and digestive diseases, compared with nonusers.

However, when applying lag times of up to 6 years, the associations were largely attenuated and no longer statistically significant, which “highlights the importance of carefully controlling for the influence of protopathic bias,” the researchers write.

However, despite applying lag times, PPI users remained at a significantly increased risk for mortality due to renal diseases (hazard ratio, 2.45; 95% confidence interval, 1.59-3.78).

The researchers caution, however, that they did not have reliable data on renal diseases and therefore could not adjust for confounding in the models. They call for further studies examining the risk for mortality due to renal diseases in patients using PPI therapy.

The researchers also looked at duration of PPI use and all-cause and cause-specific mortality.

For all-cause mortality and mortality due to cancer, CVD, respiratory diseases, and digestive diseases, the greatest risks were seen mostly in those who reported PPI use for 1-2 years. Longer duration of PPI use did not confer higher risk for mortality for these endpoints.

In contrast, a potential trend toward greater risk with longer duration of PPI use was observed for mortality due to renal disease. The hazard ratio was 1.68 (95% CI, 1.19-2.38) for 1 to 2 years of use and gradually increased to 2.42 (95% CI, 1.23-4.77) for 7 or more years of use.

Notably, when mortality risks were compared among PPI users and histamine H2 receptor antagonist (H2RA) users without lag time, PPI users were at increased risk for all-cause mortality and mortality due to causes other than cancer and CVD, compared with H2RA users.

But again, the strength of the associations decreased after lag time was introduced.

“This confirmed our main findings and suggested PPIs might be preferred over H2RAs in sicker patients with comorbid conditions,” the researchers write.

‘Generally safe’ when needed

Summing up, Dr. Chan said, “We think our results should be reassuring to clinicians that recommending PPIs to patients with appropriate indications will not increase their risk of death. These are generally safe drugs that when used appropriately can be very beneficial.”

Offering perspective on the study, David Johnson, MD, professor of medicine and chief of gastroenterology at the Eastern Virginia School of Medicine, Norfolk, noted that a “major continuing criticism of the allegations of harm by PPIs has been that these most commonly come from retrospective analyses of databases that were not constructed to evaluate these endpoints of harm.”

“Accordingly, these reports have multiple potentials for stratification bias and typically have low odds ratios for supporting the purported causality,” Dr. Johnson told this news organization.

“This is a well-done study design with a prospective database analysis that uses a modified lag-time approach to minimize reverse causation, that is, protopathic bias, which can occur when a pharmaceutical agent is inadvertently prescribed for an early manifestation of a disease that has not yet been diagnostically detected,” Dr. Johnson explained.

Echoing Dr. Chan, Dr. Johnson said the finding that PPI use was not associated with higher risk for all-cause mortality and mortality due to major causes is “reassuring.”

“Recognizably, too many people are taking PPIs chronically when they are not needed. If needed and appropriate, these data on continued use are reassuring,” Dr. Johnson added.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health and the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation. Dr. Chan has consulted for OM1, Bayer Pharma AG, and Pfizer for topics unrelated to this study, as well as Boehringer Ingelheim for litigation related to ranitidine and cancer. Dr. Johnson reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

Biologics for IBD may come with added risks in Hispanic patients

Biologic agents may not be as safe or effective in Hispanic patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) as they are in non-Hispanic patients, suggest new data published online in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

To compare risk for hospitalization, surgery, and serious infections, Nghia H. Nguyen, MD, and his team at the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center at the University of California, San Diego, included a multicenter, electronic health record–based cohort of biologic-treated Hispanic and non-Hispanic patients with IBD and used 1:4 propensity score matching.

They compared 240 Hispanic patients (53% male; 45% with ulcerative colitis; 73% treated with tumor necrosis factor alpha [TNF-alpha] antagonist; 20% with prior biologic exposure) with 960 non-Hispanic patients (51% male; 44% with ulcerative colitis; 67% treated with TNF-alpha antagonist; 27% with prior biologic exposure). Patients were new users of biologics (TNF-alpha antagonist, ustekinumab, or vedolizumab).

Compared with non-Hispanic patients, Hispanic patients had a higher risk for all-cause hospitalization (31% vs. 23%) within 1 year of starting a biologic agent.

Hispanic patients also had almost twice the risk for IBD-related surgeries (7% vs. 4.6%, respectively) and trended toward a higher risk for serious infection (8.8% vs. 4.9%, respectively).

The findings are particularly important because incidence and prevalence of IBD in Hispanic adults are increasing rapidly, according to the authors.

“Currently, 1.2% of Hispanic adults in the United States report having IBD, and this number is expected to increase progressively over the next few years with global immigration patterns and changing demographics of the United States,” the authors write.

Potential drivers of disparities

Hispanic patients have been underrepresented in clinical trials of biologic agents in IBD, making up fewer than 5% of participants, the authors note. This has resulted in limited data and created challenges in discerning reasons for the disparity.

The authors note the potential role of genetics in the effectiveness of some biologic agents, although that has not been well studied in Hispanic patients.

Additionally, according to this study, Hispanic patients with IBD lived with more negative social determinants of health, particularly related to food insecurity (27%) and lack of adequate social support (83%), compared with non-Hispanic patients (unpublished data).

“In other studies on health care utilization, Hispanic patients were found to have limited access to appropriate specialist care and lack of insurance coverage,” the authors point out.