User login

Children and COVID: Many parents see vaccine as the greater risk

New COVID-19 cases rose for the second week in a row as cumulative cases among U.S. children passed the 14-million mark, but a recent survey shows that more than half of parents believe that the vaccine is a greater risk to children under age 5 years than the virus.

In a Kaiser Family Foundation survey conducted July 7-17, 53% of parents with children aged 6 months to 5 years said that the vaccine is “a bigger risk to their child’s health than getting infected with COVID-19, compared to 44% who say getting infected is the bigger risk,” KFF reported July 26.

More than 4 out of 10 of respondents (43%) said that they will “definitely not” get their eligible children vaccinated, while only 7% said that their children had already received it and 10% said their children would get it as soon as possible, according to the KFF survey, which had an overall sample size of 1,847 adults, including an oversample of 471 parents of children under age 5.

Vaccine initiation has been slow in the first month since it was approved for the youngest children. Just 2.8% of all eligible children under age 5 had received an initial dose as of July 19, compared with first-month uptake figures of more than 18% for the 5- to 11-year-olds and 27% for those aged 12-15, based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The current rates for vaccination in those aged 5 and older look like this: 70.2% of 12- to 17-year-olds have received at least one dose, versus 37.1% of those aged 5-11. Just over 60% of the older children were fully vaccinated as of July 19, as were 30.2% of the 5- to 11-year-olds, the CDC reported on its COVID Data Tracker.

Number of new cases hits 2-month high

Despite the vaccine, SARS-CoV-2 and its various mutations have continued with their summer travels. With 92,000 newly infected children added for the week of July 15-21, there have now been a total of 14,003,497 pediatric cases reported since the start of the pandemic, which works out to 18.6% of cases in all ages, the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association said in their weekly COVID-19 report.

The 92,000 new cases represent an increase of almost 22% over the previous week and mark the highest 1-week count since May, when the total passed 100,000 for 2 consecutive weeks. More recently the trend had seemed more stable as weekly cases dropped twice and rose twice as the total hovered around 70,000, based on the data collected by the AAP and CHA from state and territorial health departments.

A different scenario has played out for emergency department visits and hospital admissions, which have risen steadily since the beginning of April. The admission rate for children aged 0-17, which was just 0.13 new patients per 100,000 population on April 11, was up to 0.44 per 100,000 on July 21. By comparison, the highest rate reached last year during the Delta surge was 0.47 per 100,000, based on CDC data.

The 7-day average of emergency dept. visits among the youngest age group, 0-11 years, shows the same general increase as hospital admissions, but the older children have diverged form that path (see graph). For those aged 12-15 and 16-17, hospitalizations started dropping in late May and into mid-June before climbing again, although more slowly than for the youngest group, the CDC data show.

The ED visit rate with diagnosed COVID among those aged 0-11, measured at 6.1% of all visits on July 19, is, in fact, considerably higher than at any time during the Delta surge last year, when it never passed 4.0%, although much lower than peak Omicron (14.1%). That 6.1% was also higher than any other age group on that day, adults included, the CDC said.

New COVID-19 cases rose for the second week in a row as cumulative cases among U.S. children passed the 14-million mark, but a recent survey shows that more than half of parents believe that the vaccine is a greater risk to children under age 5 years than the virus.

In a Kaiser Family Foundation survey conducted July 7-17, 53% of parents with children aged 6 months to 5 years said that the vaccine is “a bigger risk to their child’s health than getting infected with COVID-19, compared to 44% who say getting infected is the bigger risk,” KFF reported July 26.

More than 4 out of 10 of respondents (43%) said that they will “definitely not” get their eligible children vaccinated, while only 7% said that their children had already received it and 10% said their children would get it as soon as possible, according to the KFF survey, which had an overall sample size of 1,847 adults, including an oversample of 471 parents of children under age 5.

Vaccine initiation has been slow in the first month since it was approved for the youngest children. Just 2.8% of all eligible children under age 5 had received an initial dose as of July 19, compared with first-month uptake figures of more than 18% for the 5- to 11-year-olds and 27% for those aged 12-15, based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The current rates for vaccination in those aged 5 and older look like this: 70.2% of 12- to 17-year-olds have received at least one dose, versus 37.1% of those aged 5-11. Just over 60% of the older children were fully vaccinated as of July 19, as were 30.2% of the 5- to 11-year-olds, the CDC reported on its COVID Data Tracker.

Number of new cases hits 2-month high

Despite the vaccine, SARS-CoV-2 and its various mutations have continued with their summer travels. With 92,000 newly infected children added for the week of July 15-21, there have now been a total of 14,003,497 pediatric cases reported since the start of the pandemic, which works out to 18.6% of cases in all ages, the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association said in their weekly COVID-19 report.

The 92,000 new cases represent an increase of almost 22% over the previous week and mark the highest 1-week count since May, when the total passed 100,000 for 2 consecutive weeks. More recently the trend had seemed more stable as weekly cases dropped twice and rose twice as the total hovered around 70,000, based on the data collected by the AAP and CHA from state and territorial health departments.

A different scenario has played out for emergency department visits and hospital admissions, which have risen steadily since the beginning of April. The admission rate for children aged 0-17, which was just 0.13 new patients per 100,000 population on April 11, was up to 0.44 per 100,000 on July 21. By comparison, the highest rate reached last year during the Delta surge was 0.47 per 100,000, based on CDC data.

The 7-day average of emergency dept. visits among the youngest age group, 0-11 years, shows the same general increase as hospital admissions, but the older children have diverged form that path (see graph). For those aged 12-15 and 16-17, hospitalizations started dropping in late May and into mid-June before climbing again, although more slowly than for the youngest group, the CDC data show.

The ED visit rate with diagnosed COVID among those aged 0-11, measured at 6.1% of all visits on July 19, is, in fact, considerably higher than at any time during the Delta surge last year, when it never passed 4.0%, although much lower than peak Omicron (14.1%). That 6.1% was also higher than any other age group on that day, adults included, the CDC said.

New COVID-19 cases rose for the second week in a row as cumulative cases among U.S. children passed the 14-million mark, but a recent survey shows that more than half of parents believe that the vaccine is a greater risk to children under age 5 years than the virus.

In a Kaiser Family Foundation survey conducted July 7-17, 53% of parents with children aged 6 months to 5 years said that the vaccine is “a bigger risk to their child’s health than getting infected with COVID-19, compared to 44% who say getting infected is the bigger risk,” KFF reported July 26.

More than 4 out of 10 of respondents (43%) said that they will “definitely not” get their eligible children vaccinated, while only 7% said that their children had already received it and 10% said their children would get it as soon as possible, according to the KFF survey, which had an overall sample size of 1,847 adults, including an oversample of 471 parents of children under age 5.

Vaccine initiation has been slow in the first month since it was approved for the youngest children. Just 2.8% of all eligible children under age 5 had received an initial dose as of July 19, compared with first-month uptake figures of more than 18% for the 5- to 11-year-olds and 27% for those aged 12-15, based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The current rates for vaccination in those aged 5 and older look like this: 70.2% of 12- to 17-year-olds have received at least one dose, versus 37.1% of those aged 5-11. Just over 60% of the older children were fully vaccinated as of July 19, as were 30.2% of the 5- to 11-year-olds, the CDC reported on its COVID Data Tracker.

Number of new cases hits 2-month high

Despite the vaccine, SARS-CoV-2 and its various mutations have continued with their summer travels. With 92,000 newly infected children added for the week of July 15-21, there have now been a total of 14,003,497 pediatric cases reported since the start of the pandemic, which works out to 18.6% of cases in all ages, the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association said in their weekly COVID-19 report.

The 92,000 new cases represent an increase of almost 22% over the previous week and mark the highest 1-week count since May, when the total passed 100,000 for 2 consecutive weeks. More recently the trend had seemed more stable as weekly cases dropped twice and rose twice as the total hovered around 70,000, based on the data collected by the AAP and CHA from state and territorial health departments.

A different scenario has played out for emergency department visits and hospital admissions, which have risen steadily since the beginning of April. The admission rate for children aged 0-17, which was just 0.13 new patients per 100,000 population on April 11, was up to 0.44 per 100,000 on July 21. By comparison, the highest rate reached last year during the Delta surge was 0.47 per 100,000, based on CDC data.

The 7-day average of emergency dept. visits among the youngest age group, 0-11 years, shows the same general increase as hospital admissions, but the older children have diverged form that path (see graph). For those aged 12-15 and 16-17, hospitalizations started dropping in late May and into mid-June before climbing again, although more slowly than for the youngest group, the CDC data show.

The ED visit rate with diagnosed COVID among those aged 0-11, measured at 6.1% of all visits on July 19, is, in fact, considerably higher than at any time during the Delta surge last year, when it never passed 4.0%, although much lower than peak Omicron (14.1%). That 6.1% was also higher than any other age group on that day, adults included, the CDC said.

Boosting hypertension screening, treatment would cut global mortality 7%

If 80% of individuals with hypertension were screened, 80% received treatment, and 80% then reached guideline-specified targets, up to 200 million cases of cardiovascular disease (CVD) and 130 million deaths could be averted by 2050, a modeling study suggests.

Achievement of the 80-80-80 target “could be one of the single most important global public health accomplishments of the coming decades,” according to the authors.

“We need to reprioritize hypertension care in our practices,” principal investigator David A. Watkins, MD, MPH, University of Washington, Seattle, told this news organization. “Only about one in five persons with hypertension around the world has their blood pressure well controlled. Oftentimes, clinicians are focused on addressing patients’ other health needs, many of which can be pressing in the short term, and we forget to talk about blood pressure, which has more than earned its reputation as ‘the silent killer.’ ”

The modeling study was published online in Nature Medicine, with lead author Sarah J. Pickersgill, MPH, also from the University of Washington.

Two interventions, three scenarios

Dr. Watkins and colleagues based their analysis on two approaches to blood pressure (BP) control shown to be beneficial: drug treatment to a systolic BP of either 130 mm Hg or 140 mm Hg or less, depending on local guidelines, and dietary sodium reduction, as recommended by the World Health Organization.

The team modeled the impacts of these interventions in 182 countries according to three scenarios:

- Business as usual (control): allowing hypertension to increase at historic rates of change and mean sodium intake to remain at current levels

- Progress: matching historically high-performing countries (for example, accelerating hypertension control by about 3% per year at intermediate levels of intervention coverage) while lowering mean sodium intake by 15% by 2030

- Aspirational: hypertension control achieved faster than historically high-performing countries (about 4% per year) and mean sodium intake decreased by 30% by 2027

The analysis suggests that in the progressive scenario, all countries could achieve 80-80-80 targets by 2050 and most countries by 2040; the aspirational scenario would have all countries meeting them by 2040. That would result in reductions in all-cause mortality of 4%-7% (76 million to 130 million deaths averted) with progressive and aspirational interventions, respectively, compared with the control scenario.

There would also be a slower rise in expected CVD from population growth and aging (110 million to 200 million cases averted). That is, the probability of dying from any CVD cause between the ages of 30 and 80 years would be reduced by 16% in the progressive scenario and 26% in the aspirational scenario.

Of note, about 83%-85% of the potential mortality reductions would result from scaling up hypertension treatment in the progressive and aspirational scenarios, respectively, with the remaining 15%-17% coming from sodium reduction, the researchers state.

Further, they propose, scaling up BP interventions could reduce CVD inequalities across countries, with low-income and lower-middle-income countries likely experiencing the largest reductions in disease rates and mortality.

Implementation barriers

“Health systems in many low- and middle-income countries have not traditionally been set up to succeed in chronic disease management in primary care,” Dr. Watkins noted. For interventions to be successful, he said, “several barriers need to be addressed, including: low population awareness of chronic diseases like hypertension and diabetes, which leads to low rates of screening and treatment; high out-of-pocket cost and low availability of medicines for chronic diseases; and need for adherence support and provider incentives for improving quality of chronic disease care in primary care settings.”

“Based on the analysis, achieving the 80-80-80 seems feasible, though actually getting there may be much more complicated. I wonder whether countries have the resources to implement the needed policies,” Rodrigo M. Carrillo-Larco, MD, researcher, department of epidemiology and biostatistics, School of Public Health, Imperial College London, told this news organization.

“It may be challenging, particularly after COVID-19, which revealed deficiencies in many health care systems, and care for hypertension may have been disturbed,” said Dr. Carrillo-Larco, who is not connected with the analysis.

That said, simplified BP screening approaches could help maximize the number of people screened overall, potentially identifying those with hypertension and raising awareness, he proposed. His team’s recent study showed that such approaches vary from country to country but are generally reliable and can be used effectively for population screening.

In addition, Dr. Carrillo-Larco said, any efforts by clinicians to improve adherence and help patients achieve BP control “would also have positive effects at the population level.”

The study was supported by a grant from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, with additional funding by a grant to Dr. Watkins from Resolve to Save Lives. No conflicts of interest were declared.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

If 80% of individuals with hypertension were screened, 80% received treatment, and 80% then reached guideline-specified targets, up to 200 million cases of cardiovascular disease (CVD) and 130 million deaths could be averted by 2050, a modeling study suggests.

Achievement of the 80-80-80 target “could be one of the single most important global public health accomplishments of the coming decades,” according to the authors.

“We need to reprioritize hypertension care in our practices,” principal investigator David A. Watkins, MD, MPH, University of Washington, Seattle, told this news organization. “Only about one in five persons with hypertension around the world has their blood pressure well controlled. Oftentimes, clinicians are focused on addressing patients’ other health needs, many of which can be pressing in the short term, and we forget to talk about blood pressure, which has more than earned its reputation as ‘the silent killer.’ ”

The modeling study was published online in Nature Medicine, with lead author Sarah J. Pickersgill, MPH, also from the University of Washington.

Two interventions, three scenarios

Dr. Watkins and colleagues based their analysis on two approaches to blood pressure (BP) control shown to be beneficial: drug treatment to a systolic BP of either 130 mm Hg or 140 mm Hg or less, depending on local guidelines, and dietary sodium reduction, as recommended by the World Health Organization.

The team modeled the impacts of these interventions in 182 countries according to three scenarios:

- Business as usual (control): allowing hypertension to increase at historic rates of change and mean sodium intake to remain at current levels

- Progress: matching historically high-performing countries (for example, accelerating hypertension control by about 3% per year at intermediate levels of intervention coverage) while lowering mean sodium intake by 15% by 2030

- Aspirational: hypertension control achieved faster than historically high-performing countries (about 4% per year) and mean sodium intake decreased by 30% by 2027

The analysis suggests that in the progressive scenario, all countries could achieve 80-80-80 targets by 2050 and most countries by 2040; the aspirational scenario would have all countries meeting them by 2040. That would result in reductions in all-cause mortality of 4%-7% (76 million to 130 million deaths averted) with progressive and aspirational interventions, respectively, compared with the control scenario.

There would also be a slower rise in expected CVD from population growth and aging (110 million to 200 million cases averted). That is, the probability of dying from any CVD cause between the ages of 30 and 80 years would be reduced by 16% in the progressive scenario and 26% in the aspirational scenario.

Of note, about 83%-85% of the potential mortality reductions would result from scaling up hypertension treatment in the progressive and aspirational scenarios, respectively, with the remaining 15%-17% coming from sodium reduction, the researchers state.

Further, they propose, scaling up BP interventions could reduce CVD inequalities across countries, with low-income and lower-middle-income countries likely experiencing the largest reductions in disease rates and mortality.

Implementation barriers

“Health systems in many low- and middle-income countries have not traditionally been set up to succeed in chronic disease management in primary care,” Dr. Watkins noted. For interventions to be successful, he said, “several barriers need to be addressed, including: low population awareness of chronic diseases like hypertension and diabetes, which leads to low rates of screening and treatment; high out-of-pocket cost and low availability of medicines for chronic diseases; and need for adherence support and provider incentives for improving quality of chronic disease care in primary care settings.”

“Based on the analysis, achieving the 80-80-80 seems feasible, though actually getting there may be much more complicated. I wonder whether countries have the resources to implement the needed policies,” Rodrigo M. Carrillo-Larco, MD, researcher, department of epidemiology and biostatistics, School of Public Health, Imperial College London, told this news organization.

“It may be challenging, particularly after COVID-19, which revealed deficiencies in many health care systems, and care for hypertension may have been disturbed,” said Dr. Carrillo-Larco, who is not connected with the analysis.

That said, simplified BP screening approaches could help maximize the number of people screened overall, potentially identifying those with hypertension and raising awareness, he proposed. His team’s recent study showed that such approaches vary from country to country but are generally reliable and can be used effectively for population screening.

In addition, Dr. Carrillo-Larco said, any efforts by clinicians to improve adherence and help patients achieve BP control “would also have positive effects at the population level.”

The study was supported by a grant from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, with additional funding by a grant to Dr. Watkins from Resolve to Save Lives. No conflicts of interest were declared.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

If 80% of individuals with hypertension were screened, 80% received treatment, and 80% then reached guideline-specified targets, up to 200 million cases of cardiovascular disease (CVD) and 130 million deaths could be averted by 2050, a modeling study suggests.

Achievement of the 80-80-80 target “could be one of the single most important global public health accomplishments of the coming decades,” according to the authors.

“We need to reprioritize hypertension care in our practices,” principal investigator David A. Watkins, MD, MPH, University of Washington, Seattle, told this news organization. “Only about one in five persons with hypertension around the world has their blood pressure well controlled. Oftentimes, clinicians are focused on addressing patients’ other health needs, many of which can be pressing in the short term, and we forget to talk about blood pressure, which has more than earned its reputation as ‘the silent killer.’ ”

The modeling study was published online in Nature Medicine, with lead author Sarah J. Pickersgill, MPH, also from the University of Washington.

Two interventions, three scenarios

Dr. Watkins and colleagues based their analysis on two approaches to blood pressure (BP) control shown to be beneficial: drug treatment to a systolic BP of either 130 mm Hg or 140 mm Hg or less, depending on local guidelines, and dietary sodium reduction, as recommended by the World Health Organization.

The team modeled the impacts of these interventions in 182 countries according to three scenarios:

- Business as usual (control): allowing hypertension to increase at historic rates of change and mean sodium intake to remain at current levels

- Progress: matching historically high-performing countries (for example, accelerating hypertension control by about 3% per year at intermediate levels of intervention coverage) while lowering mean sodium intake by 15% by 2030

- Aspirational: hypertension control achieved faster than historically high-performing countries (about 4% per year) and mean sodium intake decreased by 30% by 2027

The analysis suggests that in the progressive scenario, all countries could achieve 80-80-80 targets by 2050 and most countries by 2040; the aspirational scenario would have all countries meeting them by 2040. That would result in reductions in all-cause mortality of 4%-7% (76 million to 130 million deaths averted) with progressive and aspirational interventions, respectively, compared with the control scenario.

There would also be a slower rise in expected CVD from population growth and aging (110 million to 200 million cases averted). That is, the probability of dying from any CVD cause between the ages of 30 and 80 years would be reduced by 16% in the progressive scenario and 26% in the aspirational scenario.

Of note, about 83%-85% of the potential mortality reductions would result from scaling up hypertension treatment in the progressive and aspirational scenarios, respectively, with the remaining 15%-17% coming from sodium reduction, the researchers state.

Further, they propose, scaling up BP interventions could reduce CVD inequalities across countries, with low-income and lower-middle-income countries likely experiencing the largest reductions in disease rates and mortality.

Implementation barriers

“Health systems in many low- and middle-income countries have not traditionally been set up to succeed in chronic disease management in primary care,” Dr. Watkins noted. For interventions to be successful, he said, “several barriers need to be addressed, including: low population awareness of chronic diseases like hypertension and diabetes, which leads to low rates of screening and treatment; high out-of-pocket cost and low availability of medicines for chronic diseases; and need for adherence support and provider incentives for improving quality of chronic disease care in primary care settings.”

“Based on the analysis, achieving the 80-80-80 seems feasible, though actually getting there may be much more complicated. I wonder whether countries have the resources to implement the needed policies,” Rodrigo M. Carrillo-Larco, MD, researcher, department of epidemiology and biostatistics, School of Public Health, Imperial College London, told this news organization.

“It may be challenging, particularly after COVID-19, which revealed deficiencies in many health care systems, and care for hypertension may have been disturbed,” said Dr. Carrillo-Larco, who is not connected with the analysis.

That said, simplified BP screening approaches could help maximize the number of people screened overall, potentially identifying those with hypertension and raising awareness, he proposed. His team’s recent study showed that such approaches vary from country to country but are generally reliable and can be used effectively for population screening.

In addition, Dr. Carrillo-Larco said, any efforts by clinicians to improve adherence and help patients achieve BP control “would also have positive effects at the population level.”

The study was supported by a grant from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, with additional funding by a grant to Dr. Watkins from Resolve to Save Lives. No conflicts of interest were declared.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Native American Life Expectancy Dropped Dramatically During Pandemic

During the pandemic, Native Americans’ life expectancy dropped more than in any other racial or ethnic group. Essentially, they lost nearly 5 years. And they already had the lowest life expectancy of any racial or ethnic group.

Researchers from the University of Colorado-Boulder, the Urban Institute, and Virginia Commonwealth University compared life expectancy changes during 2019-2021 in the United States and 21 peer countries. The study is the first to estimate such changes in non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Native and Asian populations. The researchers were taken aback by their findings.

In those 2 years, Americans overall saw a net loss of 2.41 years: Life expectancy declined from 78.85 years in 2019 to 76.98 years in 2020 and 76.44 in 2021. Surprisingly, peer countries not only saw a much smaller loss (0.55 year), but actually had an increase of 0.26 year between 2020 and 2021. The US decline was 8.5 times greater than that of the average decline among 16 other high-income countries during the same period. “It’s like nothing we have seen since World War II,” said Dr. Steven Woolf, one of the coauthors of the study.

The decrease in life expectancy—or, put another way, mortality—was “highly racialized” in the United States, the researchers say. The largest drops in 2020 were among non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Native (4.48 years), Hispanic (3.72 years), non-Hispanic Black (3.20 years), and non-Hispanic Asian (1.83 years) populations. In 2021, the largest decreases were in the non-Hispanic White population. The reasons for the “surprising crossover” in outcomes are not entirely clear, the researchers say, and likely have multiple explanations.

However, the patterns, they note, “reflect a long history of systemic racism” and “inadequacies in how the pandemic was managed in the United States.” In a university news release, study coauthor Ryan Masters, PhD, said, “The US didn’t take COVID seriously to the extent that other countries did, and we paid a horrific price for it, with Black and brown people suffering the most.”

The researchers expected to see a decline among Native Americans, Masters said, because they often lack access to vaccines, quality health care, and transportation. But the magnitude of the drop in life expectancy was “shocking.” He added, “You just don’t see numbers like this in advanced countries in the modern day.”

Noting that the troubling downward trend in life expectancy had been on view even before the pandemic, Masters said, “This isn’t just a COVID problem. There are broader social and economic policies that placed the United States at a disadvantage long before this pandemic. The time to address them is long overdue.”

During the pandemic, Native Americans’ life expectancy dropped more than in any other racial or ethnic group. Essentially, they lost nearly 5 years. And they already had the lowest life expectancy of any racial or ethnic group.

Researchers from the University of Colorado-Boulder, the Urban Institute, and Virginia Commonwealth University compared life expectancy changes during 2019-2021 in the United States and 21 peer countries. The study is the first to estimate such changes in non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Native and Asian populations. The researchers were taken aback by their findings.

In those 2 years, Americans overall saw a net loss of 2.41 years: Life expectancy declined from 78.85 years in 2019 to 76.98 years in 2020 and 76.44 in 2021. Surprisingly, peer countries not only saw a much smaller loss (0.55 year), but actually had an increase of 0.26 year between 2020 and 2021. The US decline was 8.5 times greater than that of the average decline among 16 other high-income countries during the same period. “It’s like nothing we have seen since World War II,” said Dr. Steven Woolf, one of the coauthors of the study.

The decrease in life expectancy—or, put another way, mortality—was “highly racialized” in the United States, the researchers say. The largest drops in 2020 were among non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Native (4.48 years), Hispanic (3.72 years), non-Hispanic Black (3.20 years), and non-Hispanic Asian (1.83 years) populations. In 2021, the largest decreases were in the non-Hispanic White population. The reasons for the “surprising crossover” in outcomes are not entirely clear, the researchers say, and likely have multiple explanations.

However, the patterns, they note, “reflect a long history of systemic racism” and “inadequacies in how the pandemic was managed in the United States.” In a university news release, study coauthor Ryan Masters, PhD, said, “The US didn’t take COVID seriously to the extent that other countries did, and we paid a horrific price for it, with Black and brown people suffering the most.”

The researchers expected to see a decline among Native Americans, Masters said, because they often lack access to vaccines, quality health care, and transportation. But the magnitude of the drop in life expectancy was “shocking.” He added, “You just don’t see numbers like this in advanced countries in the modern day.”

Noting that the troubling downward trend in life expectancy had been on view even before the pandemic, Masters said, “This isn’t just a COVID problem. There are broader social and economic policies that placed the United States at a disadvantage long before this pandemic. The time to address them is long overdue.”

During the pandemic, Native Americans’ life expectancy dropped more than in any other racial or ethnic group. Essentially, they lost nearly 5 years. And they already had the lowest life expectancy of any racial or ethnic group.

Researchers from the University of Colorado-Boulder, the Urban Institute, and Virginia Commonwealth University compared life expectancy changes during 2019-2021 in the United States and 21 peer countries. The study is the first to estimate such changes in non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Native and Asian populations. The researchers were taken aback by their findings.

In those 2 years, Americans overall saw a net loss of 2.41 years: Life expectancy declined from 78.85 years in 2019 to 76.98 years in 2020 and 76.44 in 2021. Surprisingly, peer countries not only saw a much smaller loss (0.55 year), but actually had an increase of 0.26 year between 2020 and 2021. The US decline was 8.5 times greater than that of the average decline among 16 other high-income countries during the same period. “It’s like nothing we have seen since World War II,” said Dr. Steven Woolf, one of the coauthors of the study.

The decrease in life expectancy—or, put another way, mortality—was “highly racialized” in the United States, the researchers say. The largest drops in 2020 were among non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Native (4.48 years), Hispanic (3.72 years), non-Hispanic Black (3.20 years), and non-Hispanic Asian (1.83 years) populations. In 2021, the largest decreases were in the non-Hispanic White population. The reasons for the “surprising crossover” in outcomes are not entirely clear, the researchers say, and likely have multiple explanations.

However, the patterns, they note, “reflect a long history of systemic racism” and “inadequacies in how the pandemic was managed in the United States.” In a university news release, study coauthor Ryan Masters, PhD, said, “The US didn’t take COVID seriously to the extent that other countries did, and we paid a horrific price for it, with Black and brown people suffering the most.”

The researchers expected to see a decline among Native Americans, Masters said, because they often lack access to vaccines, quality health care, and transportation. But the magnitude of the drop in life expectancy was “shocking.” He added, “You just don’t see numbers like this in advanced countries in the modern day.”

Noting that the troubling downward trend in life expectancy had been on view even before the pandemic, Masters said, “This isn’t just a COVID problem. There are broader social and economic policies that placed the United States at a disadvantage long before this pandemic. The time to address them is long overdue.”

U.S. News issues top hospitals list, now with expanded health equity measures

For the seventh consecutive year, the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., took the top spot in the annual honor roll of best hospitals, published July 26 by U.S. News & World Report.

The 2022 rankings, which marks the 33rd edition, showcase several methodology changes, including new ratings for ovarian, prostate, and uterine cancer surgeries that “provide patients ... with previously unavailable information to assist them in making a critical health care decision,” a news release from the publication explains.

said the release. Finally, a new metric called “home time” determines how successfully each hospital helps patients return home.

Mayo Clinic remains No. 1

For the 2022-2023 rankings and ratings, U.S. News compared more than 4,500 medical centers across the country in 15 specialties and 20 procedures and conditions. Of these, 493 were recognized as Best Regional Hospitals as a result of their overall strong performance.

The list was then narrowed to the top 20 hospitals, outlined in the honor roll below, that deliver “exceptional treatment across multiple areas of care.”

Following Mayo Clinic in the annual ranking’s top spot, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles rises from No. 6 to No. 2, and New York University Langone Hospitals finish third, up from eighth in 2021.

Cleveland Clinic in Ohio holds the No. 4 spot, down two from 2021, while Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore and UCLA Medical Center in Los Angeles tie for fifth place. Rounding out the top 10, in order, are: New York–Presbyterian Hospital–Columbia and Cornell, New York; Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston; Northwestern Memorial Hospital, Chicago; Stanford (Calif.) Health Care–Stanford Hospital.

The following hospitals complete the top 20 in the United States:

- 11. Barnes-Jewish Hospital, St. Louis

- 12. UCSF Medical Center, San Francisco

- 13. Hospitals of the University of Pennsylvania–Penn Presbyterian, Philadelphia

- 14. Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston

- 15. Houston Methodist Hospital

- 16. Mount Sinai Hospital, New York

- 17. University of Michigan Health–Michigan Medicine, Ann Arbor

- 18. Mayo Clinic–Phoenix

- 19. Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn.

- 20. Rush University Medical Center, Chicago

For the specialty rankings, the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, remains No. 1 in cancer care, the Cleveland Clinic is No. 1 in cardiology and heart surgery, and the Hospital for Special Surgery in New York is No. 1 in orthopedics.

Top five for cancer

- 1. University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston

- 2. Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York

- 3. Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

- 4. Dana-Farber/Brigham and Women’s Cancer Center, Boston

- 5. UCLA Medical Center, Los Angeles

Top five for cardiology and heart surgery

- 1. Cleveland Clinic

- 2. Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

- 3. Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles

- 4. New York–Presbyterian Hospital–Columbia and Cornell, New York

- 5. New York University Langone Hospitals

Top five for orthopedics

- 1. Hospital for Special Surgery, New York

- 2. Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

- 3. Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles

- 4. New York University Langone Hospitals

- 5. (tie) Rush University Medical Center, Chicago

- 5. (tie) UCLA Medical Center, Los Angeles

According to the news release, the procedures and conditions ratings are based entirely on objective patient care measures like survival rates, patient experience, home time, and level of nursing care. The Best Hospitals rankings consider a variety of data provided by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, American Hospital Association, professional organizations, and medical specialists.

The full report is available online.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

For the seventh consecutive year, the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., took the top spot in the annual honor roll of best hospitals, published July 26 by U.S. News & World Report.

The 2022 rankings, which marks the 33rd edition, showcase several methodology changes, including new ratings for ovarian, prostate, and uterine cancer surgeries that “provide patients ... with previously unavailable information to assist them in making a critical health care decision,” a news release from the publication explains.

said the release. Finally, a new metric called “home time” determines how successfully each hospital helps patients return home.

Mayo Clinic remains No. 1

For the 2022-2023 rankings and ratings, U.S. News compared more than 4,500 medical centers across the country in 15 specialties and 20 procedures and conditions. Of these, 493 were recognized as Best Regional Hospitals as a result of their overall strong performance.

The list was then narrowed to the top 20 hospitals, outlined in the honor roll below, that deliver “exceptional treatment across multiple areas of care.”

Following Mayo Clinic in the annual ranking’s top spot, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles rises from No. 6 to No. 2, and New York University Langone Hospitals finish third, up from eighth in 2021.

Cleveland Clinic in Ohio holds the No. 4 spot, down two from 2021, while Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore and UCLA Medical Center in Los Angeles tie for fifth place. Rounding out the top 10, in order, are: New York–Presbyterian Hospital–Columbia and Cornell, New York; Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston; Northwestern Memorial Hospital, Chicago; Stanford (Calif.) Health Care–Stanford Hospital.

The following hospitals complete the top 20 in the United States:

- 11. Barnes-Jewish Hospital, St. Louis

- 12. UCSF Medical Center, San Francisco

- 13. Hospitals of the University of Pennsylvania–Penn Presbyterian, Philadelphia

- 14. Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston

- 15. Houston Methodist Hospital

- 16. Mount Sinai Hospital, New York

- 17. University of Michigan Health–Michigan Medicine, Ann Arbor

- 18. Mayo Clinic–Phoenix

- 19. Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn.

- 20. Rush University Medical Center, Chicago

For the specialty rankings, the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, remains No. 1 in cancer care, the Cleveland Clinic is No. 1 in cardiology and heart surgery, and the Hospital for Special Surgery in New York is No. 1 in orthopedics.

Top five for cancer

- 1. University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston

- 2. Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York

- 3. Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

- 4. Dana-Farber/Brigham and Women’s Cancer Center, Boston

- 5. UCLA Medical Center, Los Angeles

Top five for cardiology and heart surgery

- 1. Cleveland Clinic

- 2. Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

- 3. Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles

- 4. New York–Presbyterian Hospital–Columbia and Cornell, New York

- 5. New York University Langone Hospitals

Top five for orthopedics

- 1. Hospital for Special Surgery, New York

- 2. Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

- 3. Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles

- 4. New York University Langone Hospitals

- 5. (tie) Rush University Medical Center, Chicago

- 5. (tie) UCLA Medical Center, Los Angeles

According to the news release, the procedures and conditions ratings are based entirely on objective patient care measures like survival rates, patient experience, home time, and level of nursing care. The Best Hospitals rankings consider a variety of data provided by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, American Hospital Association, professional organizations, and medical specialists.

The full report is available online.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

For the seventh consecutive year, the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., took the top spot in the annual honor roll of best hospitals, published July 26 by U.S. News & World Report.

The 2022 rankings, which marks the 33rd edition, showcase several methodology changes, including new ratings for ovarian, prostate, and uterine cancer surgeries that “provide patients ... with previously unavailable information to assist them in making a critical health care decision,” a news release from the publication explains.

said the release. Finally, a new metric called “home time” determines how successfully each hospital helps patients return home.

Mayo Clinic remains No. 1

For the 2022-2023 rankings and ratings, U.S. News compared more than 4,500 medical centers across the country in 15 specialties and 20 procedures and conditions. Of these, 493 were recognized as Best Regional Hospitals as a result of their overall strong performance.

The list was then narrowed to the top 20 hospitals, outlined in the honor roll below, that deliver “exceptional treatment across multiple areas of care.”

Following Mayo Clinic in the annual ranking’s top spot, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles rises from No. 6 to No. 2, and New York University Langone Hospitals finish third, up from eighth in 2021.

Cleveland Clinic in Ohio holds the No. 4 spot, down two from 2021, while Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore and UCLA Medical Center in Los Angeles tie for fifth place. Rounding out the top 10, in order, are: New York–Presbyterian Hospital–Columbia and Cornell, New York; Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston; Northwestern Memorial Hospital, Chicago; Stanford (Calif.) Health Care–Stanford Hospital.

The following hospitals complete the top 20 in the United States:

- 11. Barnes-Jewish Hospital, St. Louis

- 12. UCSF Medical Center, San Francisco

- 13. Hospitals of the University of Pennsylvania–Penn Presbyterian, Philadelphia

- 14. Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston

- 15. Houston Methodist Hospital

- 16. Mount Sinai Hospital, New York

- 17. University of Michigan Health–Michigan Medicine, Ann Arbor

- 18. Mayo Clinic–Phoenix

- 19. Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn.

- 20. Rush University Medical Center, Chicago

For the specialty rankings, the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, remains No. 1 in cancer care, the Cleveland Clinic is No. 1 in cardiology and heart surgery, and the Hospital for Special Surgery in New York is No. 1 in orthopedics.

Top five for cancer

- 1. University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston

- 2. Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York

- 3. Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

- 4. Dana-Farber/Brigham and Women’s Cancer Center, Boston

- 5. UCLA Medical Center, Los Angeles

Top five for cardiology and heart surgery

- 1. Cleveland Clinic

- 2. Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

- 3. Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles

- 4. New York–Presbyterian Hospital–Columbia and Cornell, New York

- 5. New York University Langone Hospitals

Top five for orthopedics

- 1. Hospital for Special Surgery, New York

- 2. Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

- 3. Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles

- 4. New York University Langone Hospitals

- 5. (tie) Rush University Medical Center, Chicago

- 5. (tie) UCLA Medical Center, Los Angeles

According to the news release, the procedures and conditions ratings are based entirely on objective patient care measures like survival rates, patient experience, home time, and level of nursing care. The Best Hospitals rankings consider a variety of data provided by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, American Hospital Association, professional organizations, and medical specialists.

The full report is available online.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Multiple Fingerlike Projections on the Leg

The Diagnosis: Elephantiasis Nostras Verrucosa

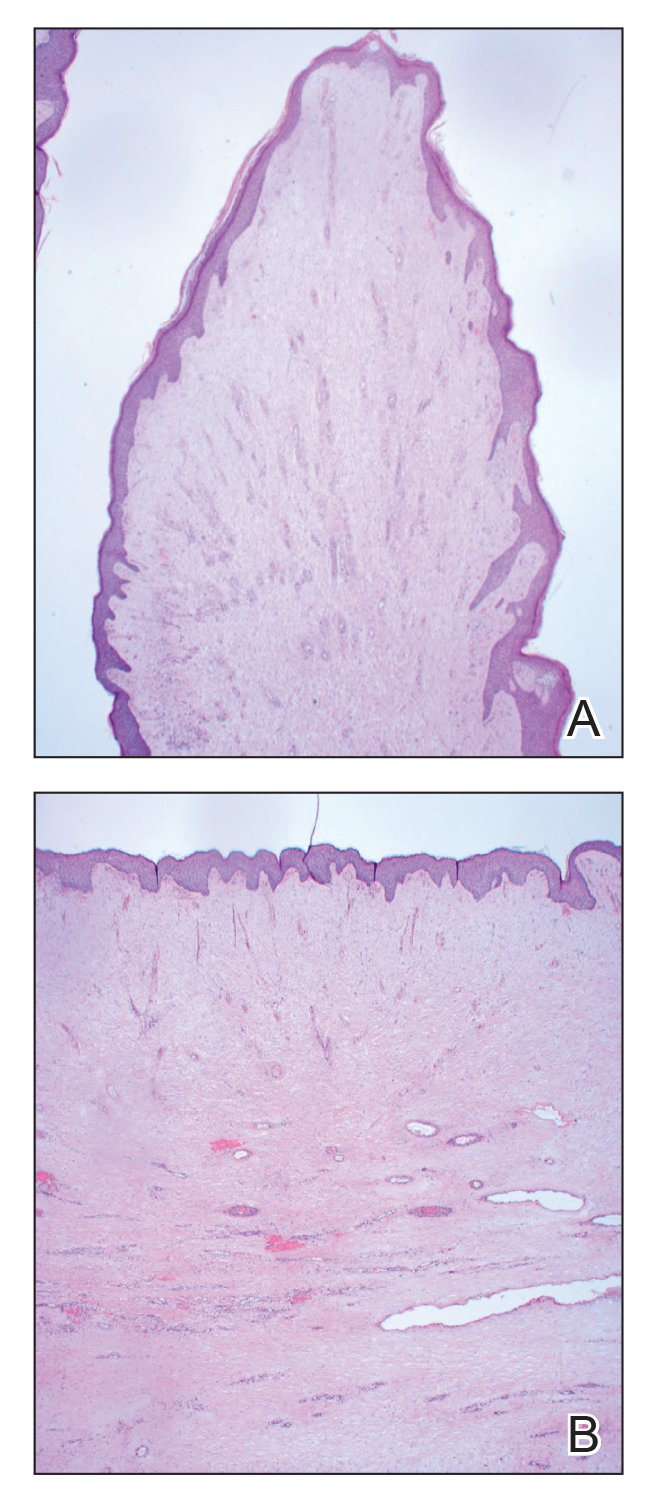

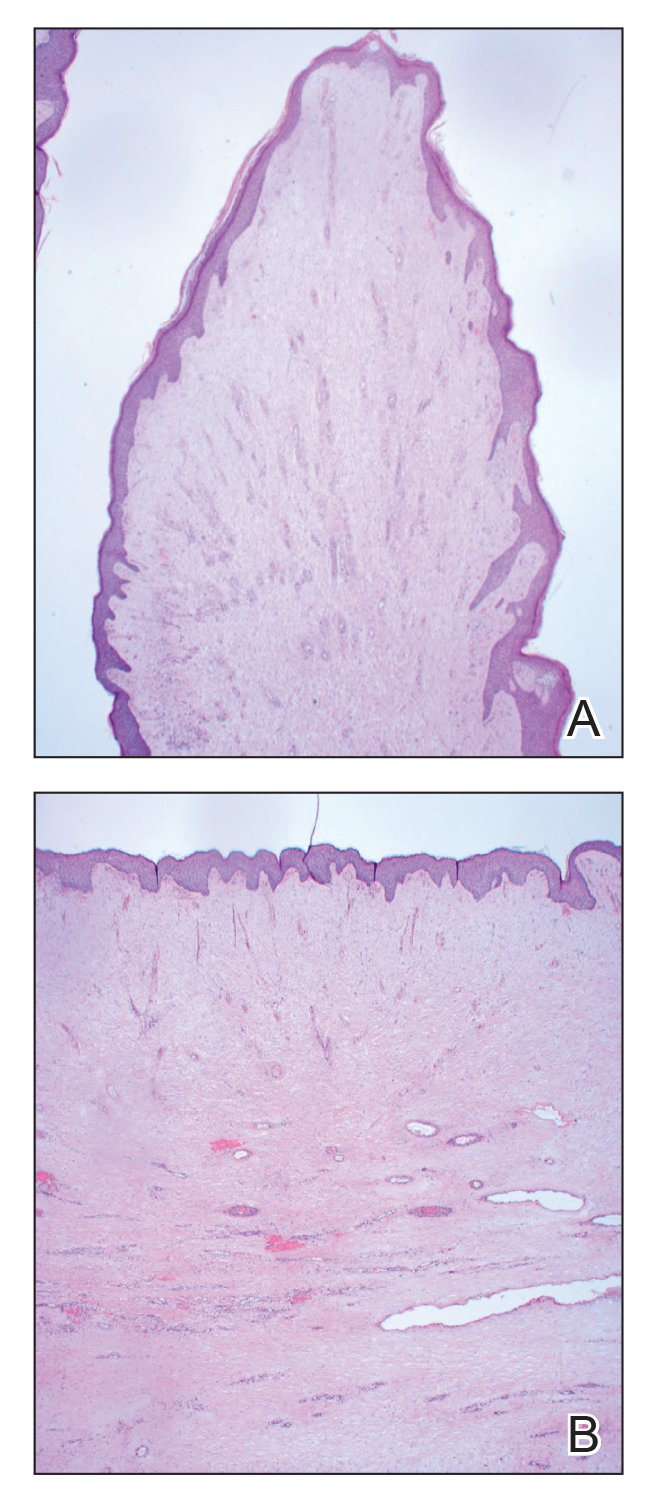

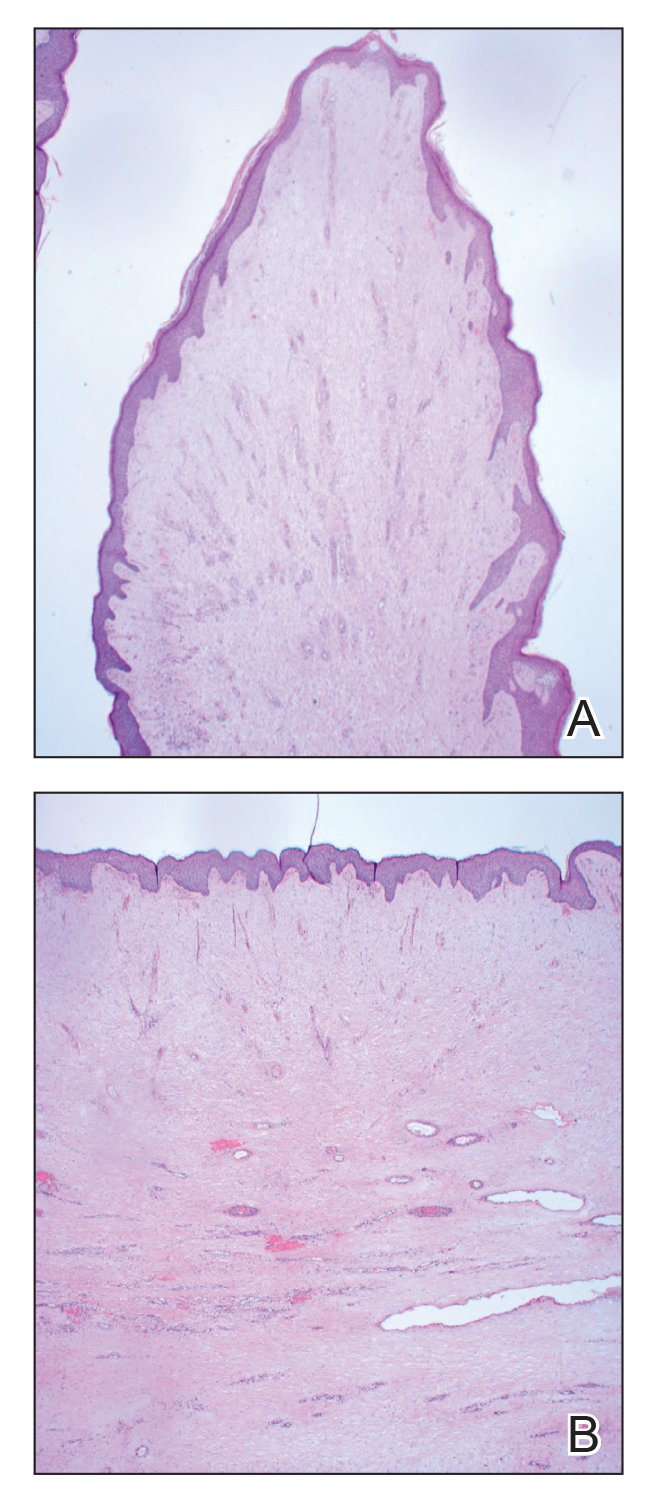

Histopathology revealed a benign fibroepithelial polyp demonstrating areas of hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, and focal papillomatosis (Figure, A). Increased superficial vessels with dilated lymphatics, stellate fibroblasts, edematous stroma, and plasmolymphocytosis also were noted (Figure, B). Clinical and histopathological findings led to a diagnosis of lymphedema papules in the setting of elephantiasis nostra verrucosa (ENV).

Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa is a complication of long-standing nonfilarial obstruction of lymphatic drainage leading to grotesque enlargement of the affected areas. Common cutaneous manifestations of ENV include nonpitting edema, dermal fibrosis, and extensive hyperkeratosis with verrucous and papillomatous lesions.1 In the beginning stages of ENV, the skin has a cobblestonelike appearance. As the disease progresses, the verrucous lesions continue to enlarge, giving the affected area a mossy appearance. Although less common, groupings of large papillomas similar to our patient’s presentation also can form.2 Ulcer formation is more likely to occur in advanced disease states, increasing the risk for bacterial and fungal colonization. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa classically affects the legs; however, this condition can develop in any area with chronic lymphedema. Cases of ENV involving the arms, abdomen, scrotum, and ear have been documented.3-5

The pathogenesis of ENV involves the proliferation of fibroblasts and fibrosis secondary to lymphostasis and inflammation.6 When interstitial fluid builds up in the affected region, the protein-rich fluid is believed to trigger fibrogenesis and increase macrophage, keratinocyte, and adipocyte activity.7 Because of this inflammatory process, dilation and fibrosis of the lymphatic channels develop. Lymphatic obstruction can have several etiologies, most notably infection and malignancy. Staphylococcal lymphangitis and erysipelas create fibrosis of the lymphatic system and are the main infectious causes of ENV.6 Large tumors or lymphomas are insidious causes of lymphatic obstruction and should be ruled out when investigating for ENV. Other risk factors include obesity, chronic venous insufficiency, surgery, trauma, radiation, and uncontrolled congestive heart failure.1,6,8

An ENV diagnosis is clinicopathologic, involving a comprehensive metabolic panel and complete blood cell count with differential. A biopsy is needed for pathologic confirmation and to rule out malignancy. Histologically, ENV is characterized by pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, dermal fibrosis, hyperkeratosis of the epidermis, and dilated lymphatic vessels.6,8 Additional studies for diagnosis include wound and lymph node culture, Wood lamp examination, and lymphoscintigraphy.

Given the chronic and progressive nature of the disease, ENV is difficult to treat. There currently is no standard of treatment, but the mainstay of management involves reducing peripheral edema. Lifestyle changes including weight loss, extremity elevation, and increased ambulation are helpful first-line therapies.3 Compression of the affected extremity using stockings or intermittent pneumatic compression devices has proven to be beneficial with long-term use.7 Patients should be followed for wound care to prevent the infection of ulcers.2 Pharmacologic treatments include systemic retinoids, which have been shown to reduce the appearance of hyperkeratosis, verrucous lesions, and papillomatous nodules.6 Prophylactic antibiotics are reserved for advanced stages of disease or in patients with recurrent infections.2,7 In severe cases of ENV that are unresponsive to medical management, surgical intervention such as lymphatic anastomosis and debulking may be considered.9,10

Other diagnoses to consider for ENV include pretibial myxedema, lymphatic filariasis, Stewart-Treves syndrome, and papillomatosis cutis carcinoides. Pretibial myxedema is an uncommon dermatologic manifestation of Graves disease. It is a local autoimmune reaction in the cutaneous tissue characterized by hyperpigmentation, nonpitting edema, and nodules on the anterior leg. Histopathology shows increased hyaluronic acid and chondroitin as well as compression of dermal lymphatics.11

Filariasis is a parasitic infection caused by Wuchereria bancrofti, Brugia malayi or Brugia timori, and Onchocerca volvulus.6 This condition presents with elephantiasis of the affected extremities but should be considered in areas endemic for filarial parasites such as tropical and subtropical countries.12 Eosinophilia and identification of microfilaria in a peripheral blood smear would indicate parasitic infection. Stewart-Treves syndrome is a rare angiosarcoma that arises in areas of chronic lymphedema. This condition classically is seen on the upper extremities following a mastectomy with lymphadenectomy, lymph node irradiation, or both.

Stewart-Treves syndrome presents with coalescing purpuric macules and nodules that eventually coalesce into cutaneous masses. Histopathology reveals proliferating vascular channels that split apart dermal collagen with hyperchromatism and pleomorphism in the tumor endothelial cells that line these channels.13

Papillomatosis cutis carcinoides is a low-grade squamous cell carcinoma that occurs secondary to human papillomavirus commonly affecting the mouth, anogenital area, and the plantar surfaces of the feet. It presents with exophytic growths and ulcerated tumors that are unilateral and asymmetrical. The presence of blunt-shaped tumor projections extending deep into the dermis to form sinuses and keratin-filled cysts is characteristic of papillomatosis cutis carcinoides.14

- Dean SM, Zirwas MJ, Horst AV. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa: an institutional analysis of 21 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64: 1104-1110. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2010.04.047

- Fife CE, Farrow W, Hebert AA, et al. Skin and wound care in lymphedema patients: a taxonomy, primer, and literature review. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2017;30:305-318. doi:10.1097/01.ASW.0000520501.23702.82

- Boyd J, Sloan S, Meffert J. Elephantiasis nostrum verrucosa of the abdomen: clinical results with tazarotene. J Drugs Dermatol. 2004; 3:446-448.

- Nakai K, Taoka R, Sugimoto M, et al. Genital elephantiasis possibly caused by chronic inguinal eczema with streptococcal infection. J Dermatol. 2019;46:E196-E198. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.14746

- Carlson JA, Mazza J, Kircher K, et al. Otophyma: a case report and review of the literature of lymphedema (elephantiasis) of the ear. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:67-72. doi:10.1097/DAD.0b013e31815cd937

- Sisto K, Khachemoune A. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa: a review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2008;9:141-146. doi:10.2165/00128071-200809030-00001

- Yoho RM, Budny AM, Pea AS. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2006;96:442-444. doi:10.7547/0960442

- Yosipovitch G, DeVore A, Dawn A. Obesity and the skin: skin physiology and skin manifestations of obesity. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:901-920. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2006.12.004

- Iwao F, Sato-Matsumura KC, Sawamura D, et al. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa successfully treated by surgical debridement. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:939-941. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2004.30267.x

- Tiwari A, Cheng KS, Button M, et al. Differential diagnosis, investigation, and current treatment of lower limb lymphedema. Arch Surg. 2003;138:152-161. doi:10.1001/archsurg.138.2.152

- Fatourechi V. Pretibial myxedema: pathophysiology and treatment options. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2005;6:295-309. doi:10.2165 /00128071-200506050-00003

- Addiss DG, Brady MA. Morbidity management in the Global Programme to Eliminate Lymphatic Filariasis: a review of the scientific literature. Filaria J. 2007;6:2. doi:10.1186/1475-2883-6-2

- Bernia E, Rios-Viñuela E, Requena C. Stewart-Treves syndrome. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:721. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.0341

- Schwartz RA. Verrucous carcinoma of the skin and mucosa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:1-24. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(95)90177-9

The Diagnosis: Elephantiasis Nostras Verrucosa

Histopathology revealed a benign fibroepithelial polyp demonstrating areas of hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, and focal papillomatosis (Figure, A). Increased superficial vessels with dilated lymphatics, stellate fibroblasts, edematous stroma, and plasmolymphocytosis also were noted (Figure, B). Clinical and histopathological findings led to a diagnosis of lymphedema papules in the setting of elephantiasis nostra verrucosa (ENV).

Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa is a complication of long-standing nonfilarial obstruction of lymphatic drainage leading to grotesque enlargement of the affected areas. Common cutaneous manifestations of ENV include nonpitting edema, dermal fibrosis, and extensive hyperkeratosis with verrucous and papillomatous lesions.1 In the beginning stages of ENV, the skin has a cobblestonelike appearance. As the disease progresses, the verrucous lesions continue to enlarge, giving the affected area a mossy appearance. Although less common, groupings of large papillomas similar to our patient’s presentation also can form.2 Ulcer formation is more likely to occur in advanced disease states, increasing the risk for bacterial and fungal colonization. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa classically affects the legs; however, this condition can develop in any area with chronic lymphedema. Cases of ENV involving the arms, abdomen, scrotum, and ear have been documented.3-5

The pathogenesis of ENV involves the proliferation of fibroblasts and fibrosis secondary to lymphostasis and inflammation.6 When interstitial fluid builds up in the affected region, the protein-rich fluid is believed to trigger fibrogenesis and increase macrophage, keratinocyte, and adipocyte activity.7 Because of this inflammatory process, dilation and fibrosis of the lymphatic channels develop. Lymphatic obstruction can have several etiologies, most notably infection and malignancy. Staphylococcal lymphangitis and erysipelas create fibrosis of the lymphatic system and are the main infectious causes of ENV.6 Large tumors or lymphomas are insidious causes of lymphatic obstruction and should be ruled out when investigating for ENV. Other risk factors include obesity, chronic venous insufficiency, surgery, trauma, radiation, and uncontrolled congestive heart failure.1,6,8

An ENV diagnosis is clinicopathologic, involving a comprehensive metabolic panel and complete blood cell count with differential. A biopsy is needed for pathologic confirmation and to rule out malignancy. Histologically, ENV is characterized by pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, dermal fibrosis, hyperkeratosis of the epidermis, and dilated lymphatic vessels.6,8 Additional studies for diagnosis include wound and lymph node culture, Wood lamp examination, and lymphoscintigraphy.

Given the chronic and progressive nature of the disease, ENV is difficult to treat. There currently is no standard of treatment, but the mainstay of management involves reducing peripheral edema. Lifestyle changes including weight loss, extremity elevation, and increased ambulation are helpful first-line therapies.3 Compression of the affected extremity using stockings or intermittent pneumatic compression devices has proven to be beneficial with long-term use.7 Patients should be followed for wound care to prevent the infection of ulcers.2 Pharmacologic treatments include systemic retinoids, which have been shown to reduce the appearance of hyperkeratosis, verrucous lesions, and papillomatous nodules.6 Prophylactic antibiotics are reserved for advanced stages of disease or in patients with recurrent infections.2,7 In severe cases of ENV that are unresponsive to medical management, surgical intervention such as lymphatic anastomosis and debulking may be considered.9,10

Other diagnoses to consider for ENV include pretibial myxedema, lymphatic filariasis, Stewart-Treves syndrome, and papillomatosis cutis carcinoides. Pretibial myxedema is an uncommon dermatologic manifestation of Graves disease. It is a local autoimmune reaction in the cutaneous tissue characterized by hyperpigmentation, nonpitting edema, and nodules on the anterior leg. Histopathology shows increased hyaluronic acid and chondroitin as well as compression of dermal lymphatics.11

Filariasis is a parasitic infection caused by Wuchereria bancrofti, Brugia malayi or Brugia timori, and Onchocerca volvulus.6 This condition presents with elephantiasis of the affected extremities but should be considered in areas endemic for filarial parasites such as tropical and subtropical countries.12 Eosinophilia and identification of microfilaria in a peripheral blood smear would indicate parasitic infection. Stewart-Treves syndrome is a rare angiosarcoma that arises in areas of chronic lymphedema. This condition classically is seen on the upper extremities following a mastectomy with lymphadenectomy, lymph node irradiation, or both.

Stewart-Treves syndrome presents with coalescing purpuric macules and nodules that eventually coalesce into cutaneous masses. Histopathology reveals proliferating vascular channels that split apart dermal collagen with hyperchromatism and pleomorphism in the tumor endothelial cells that line these channels.13

Papillomatosis cutis carcinoides is a low-grade squamous cell carcinoma that occurs secondary to human papillomavirus commonly affecting the mouth, anogenital area, and the plantar surfaces of the feet. It presents with exophytic growths and ulcerated tumors that are unilateral and asymmetrical. The presence of blunt-shaped tumor projections extending deep into the dermis to form sinuses and keratin-filled cysts is characteristic of papillomatosis cutis carcinoides.14

The Diagnosis: Elephantiasis Nostras Verrucosa

Histopathology revealed a benign fibroepithelial polyp demonstrating areas of hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, and focal papillomatosis (Figure, A). Increased superficial vessels with dilated lymphatics, stellate fibroblasts, edematous stroma, and plasmolymphocytosis also were noted (Figure, B). Clinical and histopathological findings led to a diagnosis of lymphedema papules in the setting of elephantiasis nostra verrucosa (ENV).

Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa is a complication of long-standing nonfilarial obstruction of lymphatic drainage leading to grotesque enlargement of the affected areas. Common cutaneous manifestations of ENV include nonpitting edema, dermal fibrosis, and extensive hyperkeratosis with verrucous and papillomatous lesions.1 In the beginning stages of ENV, the skin has a cobblestonelike appearance. As the disease progresses, the verrucous lesions continue to enlarge, giving the affected area a mossy appearance. Although less common, groupings of large papillomas similar to our patient’s presentation also can form.2 Ulcer formation is more likely to occur in advanced disease states, increasing the risk for bacterial and fungal colonization. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa classically affects the legs; however, this condition can develop in any area with chronic lymphedema. Cases of ENV involving the arms, abdomen, scrotum, and ear have been documented.3-5

The pathogenesis of ENV involves the proliferation of fibroblasts and fibrosis secondary to lymphostasis and inflammation.6 When interstitial fluid builds up in the affected region, the protein-rich fluid is believed to trigger fibrogenesis and increase macrophage, keratinocyte, and adipocyte activity.7 Because of this inflammatory process, dilation and fibrosis of the lymphatic channels develop. Lymphatic obstruction can have several etiologies, most notably infection and malignancy. Staphylococcal lymphangitis and erysipelas create fibrosis of the lymphatic system and are the main infectious causes of ENV.6 Large tumors or lymphomas are insidious causes of lymphatic obstruction and should be ruled out when investigating for ENV. Other risk factors include obesity, chronic venous insufficiency, surgery, trauma, radiation, and uncontrolled congestive heart failure.1,6,8

An ENV diagnosis is clinicopathologic, involving a comprehensive metabolic panel and complete blood cell count with differential. A biopsy is needed for pathologic confirmation and to rule out malignancy. Histologically, ENV is characterized by pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, dermal fibrosis, hyperkeratosis of the epidermis, and dilated lymphatic vessels.6,8 Additional studies for diagnosis include wound and lymph node culture, Wood lamp examination, and lymphoscintigraphy.

Given the chronic and progressive nature of the disease, ENV is difficult to treat. There currently is no standard of treatment, but the mainstay of management involves reducing peripheral edema. Lifestyle changes including weight loss, extremity elevation, and increased ambulation are helpful first-line therapies.3 Compression of the affected extremity using stockings or intermittent pneumatic compression devices has proven to be beneficial with long-term use.7 Patients should be followed for wound care to prevent the infection of ulcers.2 Pharmacologic treatments include systemic retinoids, which have been shown to reduce the appearance of hyperkeratosis, verrucous lesions, and papillomatous nodules.6 Prophylactic antibiotics are reserved for advanced stages of disease or in patients with recurrent infections.2,7 In severe cases of ENV that are unresponsive to medical management, surgical intervention such as lymphatic anastomosis and debulking may be considered.9,10

Other diagnoses to consider for ENV include pretibial myxedema, lymphatic filariasis, Stewart-Treves syndrome, and papillomatosis cutis carcinoides. Pretibial myxedema is an uncommon dermatologic manifestation of Graves disease. It is a local autoimmune reaction in the cutaneous tissue characterized by hyperpigmentation, nonpitting edema, and nodules on the anterior leg. Histopathology shows increased hyaluronic acid and chondroitin as well as compression of dermal lymphatics.11

Filariasis is a parasitic infection caused by Wuchereria bancrofti, Brugia malayi or Brugia timori, and Onchocerca volvulus.6 This condition presents with elephantiasis of the affected extremities but should be considered in areas endemic for filarial parasites such as tropical and subtropical countries.12 Eosinophilia and identification of microfilaria in a peripheral blood smear would indicate parasitic infection. Stewart-Treves syndrome is a rare angiosarcoma that arises in areas of chronic lymphedema. This condition classically is seen on the upper extremities following a mastectomy with lymphadenectomy, lymph node irradiation, or both.

Stewart-Treves syndrome presents with coalescing purpuric macules and nodules that eventually coalesce into cutaneous masses. Histopathology reveals proliferating vascular channels that split apart dermal collagen with hyperchromatism and pleomorphism in the tumor endothelial cells that line these channels.13

Papillomatosis cutis carcinoides is a low-grade squamous cell carcinoma that occurs secondary to human papillomavirus commonly affecting the mouth, anogenital area, and the plantar surfaces of the feet. It presents with exophytic growths and ulcerated tumors that are unilateral and asymmetrical. The presence of blunt-shaped tumor projections extending deep into the dermis to form sinuses and keratin-filled cysts is characteristic of papillomatosis cutis carcinoides.14

- Dean SM, Zirwas MJ, Horst AV. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa: an institutional analysis of 21 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64: 1104-1110. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2010.04.047

- Fife CE, Farrow W, Hebert AA, et al. Skin and wound care in lymphedema patients: a taxonomy, primer, and literature review. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2017;30:305-318. doi:10.1097/01.ASW.0000520501.23702.82

- Boyd J, Sloan S, Meffert J. Elephantiasis nostrum verrucosa of the abdomen: clinical results with tazarotene. J Drugs Dermatol. 2004; 3:446-448.

- Nakai K, Taoka R, Sugimoto M, et al. Genital elephantiasis possibly caused by chronic inguinal eczema with streptococcal infection. J Dermatol. 2019;46:E196-E198. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.14746

- Carlson JA, Mazza J, Kircher K, et al. Otophyma: a case report and review of the literature of lymphedema (elephantiasis) of the ear. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:67-72. doi:10.1097/DAD.0b013e31815cd937

- Sisto K, Khachemoune A. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa: a review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2008;9:141-146. doi:10.2165/00128071-200809030-00001

- Yoho RM, Budny AM, Pea AS. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2006;96:442-444. doi:10.7547/0960442

- Yosipovitch G, DeVore A, Dawn A. Obesity and the skin: skin physiology and skin manifestations of obesity. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:901-920. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2006.12.004

- Iwao F, Sato-Matsumura KC, Sawamura D, et al. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa successfully treated by surgical debridement. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:939-941. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2004.30267.x

- Tiwari A, Cheng KS, Button M, et al. Differential diagnosis, investigation, and current treatment of lower limb lymphedema. Arch Surg. 2003;138:152-161. doi:10.1001/archsurg.138.2.152

- Fatourechi V. Pretibial myxedema: pathophysiology and treatment options. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2005;6:295-309. doi:10.2165 /00128071-200506050-00003

- Addiss DG, Brady MA. Morbidity management in the Global Programme to Eliminate Lymphatic Filariasis: a review of the scientific literature. Filaria J. 2007;6:2. doi:10.1186/1475-2883-6-2

- Bernia E, Rios-Viñuela E, Requena C. Stewart-Treves syndrome. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:721. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.0341

- Schwartz RA. Verrucous carcinoma of the skin and mucosa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:1-24. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(95)90177-9

- Dean SM, Zirwas MJ, Horst AV. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa: an institutional analysis of 21 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64: 1104-1110. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2010.04.047

- Fife CE, Farrow W, Hebert AA, et al. Skin and wound care in lymphedema patients: a taxonomy, primer, and literature review. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2017;30:305-318. doi:10.1097/01.ASW.0000520501.23702.82

- Boyd J, Sloan S, Meffert J. Elephantiasis nostrum verrucosa of the abdomen: clinical results with tazarotene. J Drugs Dermatol. 2004; 3:446-448.

- Nakai K, Taoka R, Sugimoto M, et al. Genital elephantiasis possibly caused by chronic inguinal eczema with streptococcal infection. J Dermatol. 2019;46:E196-E198. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.14746

- Carlson JA, Mazza J, Kircher K, et al. Otophyma: a case report and review of the literature of lymphedema (elephantiasis) of the ear. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:67-72. doi:10.1097/DAD.0b013e31815cd937

- Sisto K, Khachemoune A. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa: a review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2008;9:141-146. doi:10.2165/00128071-200809030-00001

- Yoho RM, Budny AM, Pea AS. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2006;96:442-444. doi:10.7547/0960442

- Yosipovitch G, DeVore A, Dawn A. Obesity and the skin: skin physiology and skin manifestations of obesity. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:901-920. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2006.12.004

- Iwao F, Sato-Matsumura KC, Sawamura D, et al. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa successfully treated by surgical debridement. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:939-941. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2004.30267.x

- Tiwari A, Cheng KS, Button M, et al. Differential diagnosis, investigation, and current treatment of lower limb lymphedema. Arch Surg. 2003;138:152-161. doi:10.1001/archsurg.138.2.152

- Fatourechi V. Pretibial myxedema: pathophysiology and treatment options. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2005;6:295-309. doi:10.2165 /00128071-200506050-00003

- Addiss DG, Brady MA. Morbidity management in the Global Programme to Eliminate Lymphatic Filariasis: a review of the scientific literature. Filaria J. 2007;6:2. doi:10.1186/1475-2883-6-2

- Bernia E, Rios-Viñuela E, Requena C. Stewart-Treves syndrome. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:721. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.0341

- Schwartz RA. Verrucous carcinoma of the skin and mucosa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:1-24. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(95)90177-9

A 61-year-old man presented with painful skin growths on the right pretibial region of several months’ duration. The patient reported pain due to friction between the lesions and underlying skin, leading to erosions. His medical history was remarkable for morbid obesity (body mass index of 62), chronic venous stasis, and chronic lymphedema. The patient was followed for wound care of venous stasis ulcers. Dermatologic examination revealed multiple 5- to 30-mm, flesh-colored, fingerlike projections on the right tibial region. A biopsy was obtained and submitted for histopathologic analysis.

Students exit white coat ceremony over speaker’s abortion stance

A Twitter video of the walkout has gone viral. By press time, the video had garnered more than 9.5 million views.

The walkout comes days after more than 340 medical students at the school signed a petition opposing the selection of Michigan assistant professor Kristin Collier, MD, for the ceremony because of her anti-abortion views, according to The Michigan Daily.

In response to the incident, a medical school spokeswoman told this news organization that Dr. Collier was chosen to be speaker “based on nominations and voting by members of the UM Medical School Gold Humanism Honor Society, which is comprised of medical students, house officers, and faculty.”

The press statement continued, “The White Coat Ceremony is not a platform for discussion of controversial issues. Its focus will always be on welcoming students into the profession of medicine. Dr. Collier never planned to address a divisive topic as part of her remarks. However, the University of Michigan does not revoke an invitation to a speaker based on their personal beliefs.”

The university further stated that it remains committed to providing reproductive care for patients, including abortion care, which remains legal in Michigan following the recent U.S. Supreme Court ruling overturning abortion rights, according to the statement by Mary Masson, director of Michigan Medicine public relations.

The state has an abortion ban, but a recent court order temporarily blocked enforcement of it, according to the statement.

In her speech, Dr. Collier recognized the divisiveness of the issue. “I want to acknowledge the deep wounds our community has suffered over the past several weeks. We have a great deal of work to do for healing to occur. And I hope for today, for this time, we can focus on what matters the most, coming together with a goal to support our newly accepted students and their families.”

Following applause from the remaining audience, she continued to offer advice for the incoming students about how to thrive in their chosen profession.

Dr. Collier, a graduate of the med school and director of its Health, Spirituality, and Religion program, has 15.2K Twitter followers. She has been known to post anti-abortion sentiments, including those cited in the students’ petition.

“While we support the rights of freedom of speech and religion, an anti-choice speaker as a representative of the University of Michigan undermines the University’s position on abortion and supports the non-universal, theology-rooted platform to restrict abortion access, an essential part of medical care,” the petition reads, in part.

The petition states that the disagreement is not over personal opinions. “We demand that UM stands in solidarity with us and selects a speaker whose values align with institutional policies, students, and the broader medical community. This speaker should inspire the next generation of health care providers to be courageous advocates for patient autonomy and our communities.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A Twitter video of the walkout has gone viral. By press time, the video had garnered more than 9.5 million views.

The walkout comes days after more than 340 medical students at the school signed a petition opposing the selection of Michigan assistant professor Kristin Collier, MD, for the ceremony because of her anti-abortion views, according to The Michigan Daily.

In response to the incident, a medical school spokeswoman told this news organization that Dr. Collier was chosen to be speaker “based on nominations and voting by members of the UM Medical School Gold Humanism Honor Society, which is comprised of medical students, house officers, and faculty.”

The press statement continued, “The White Coat Ceremony is not a platform for discussion of controversial issues. Its focus will always be on welcoming students into the profession of medicine. Dr. Collier never planned to address a divisive topic as part of her remarks. However, the University of Michigan does not revoke an invitation to a speaker based on their personal beliefs.”

The university further stated that it remains committed to providing reproductive care for patients, including abortion care, which remains legal in Michigan following the recent U.S. Supreme Court ruling overturning abortion rights, according to the statement by Mary Masson, director of Michigan Medicine public relations.

The state has an abortion ban, but a recent court order temporarily blocked enforcement of it, according to the statement.

In her speech, Dr. Collier recognized the divisiveness of the issue. “I want to acknowledge the deep wounds our community has suffered over the past several weeks. We have a great deal of work to do for healing to occur. And I hope for today, for this time, we can focus on what matters the most, coming together with a goal to support our newly accepted students and their families.”

Following applause from the remaining audience, she continued to offer advice for the incoming students about how to thrive in their chosen profession.

Dr. Collier, a graduate of the med school and director of its Health, Spirituality, and Religion program, has 15.2K Twitter followers. She has been known to post anti-abortion sentiments, including those cited in the students’ petition.

“While we support the rights of freedom of speech and religion, an anti-choice speaker as a representative of the University of Michigan undermines the University’s position on abortion and supports the non-universal, theology-rooted platform to restrict abortion access, an essential part of medical care,” the petition reads, in part.

The petition states that the disagreement is not over personal opinions. “We demand that UM stands in solidarity with us and selects a speaker whose values align with institutional policies, students, and the broader medical community. This speaker should inspire the next generation of health care providers to be courageous advocates for patient autonomy and our communities.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A Twitter video of the walkout has gone viral. By press time, the video had garnered more than 9.5 million views.