User login

ACC, AHA issue new coronary revascularization guideline

Clinicians should approach decisions regarding coronary revascularization based on clinical indications without an eye toward sex, race, or ethnicity, advises a joint clinical practice guideline released Dec. 8 by the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology.

The new class 1 recommendation leads off the 109-page document and reflects evidence demonstrating that revascularization is equally beneficial for all patients. Still, studies show that women and non-White patients are less likely to receive reperfusion therapy or revascularization.

“This was extremely important to all the committee members because of all of the disparities that have been documented not only in diagnosis but [in] the care provided to underrepresented minorities, women, and other ethnic groups,” said Jennifer S. Lawton, MD, chief of cardiac surgery at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and guideline writing committee chair.

“We wanted to make it clear right at the beginning of the document that these guidelines apply to everyone, and we want it to be known that care should be the same for everyone,” she said in an interview.

The guideline was simultaneously published Dec. 9, 2021, in the journal Circulation and the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

It updates and consolidates the ACC/AHA 2011 coronary artery bypass surgery (CABG) guideline and the ACC/AHA/Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions 2011 and 2015 percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) guidelines.

The new document emphasizes in a class 1 recommendation the importance of the multidisciplinary heart team in patients with coronary artery disease (CAD) where the best treatment strategy is unclear. But it also stresses that treatment decisions should be patient centered – taking into account patient preferences and goals, cultural beliefs, health literacy, and social determinants of cardiovascular health – and made in collaboration with the patient’s support system.

“Oftentimes we recommend a strategy of revascularization that may not be what the patient wants or hasn’t taken into account the patient’s preferences and also the family members,” Dr. Lawson said. “So we felt that was very important.”

Patients should also be provided with available evidence for various treatment options, including risks and benefits of each option, for informed consent. The two new class 1 recommendations are highlighted in a figure illustrating the shared decision-making algorithm that, by design, features a female clinician and Black patient.

“We spent 2 years debating the best revascularization strategies and we’re considered experts in the field – but when we talk to our patients, they really don’t know the benefits and risks,” she said. “In order to translate it to the layperson in basic terms, it’s important to say, ‘If you choose this option, you will likely live longer’ rather than using the jargon.”

DAPT, staged PCI, stable IHD

Among the top 10 take-home messages highlighted by the authors is a 2a recommendation that 1-3 months of dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) after PCI with a transition to P2Y12 inhibitor monotherapy is “reasonable” in selected patients to reduce the risk of bleeding events. Previous recommendations called for 6 or 12 months of DAPT.

“We really respect all of the clinical trials that came out showing that a shorter duration of DAPT is not inferior in terms of ischemic events but less bleeding, yet I don’t know how many clinicians are actually just using 3 months of DAPT followed by P2Y12 monotherapy,” guideline committee vice chair Jacqueline Tamis-Holland, MD, professor of medicine, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, said in an interview. “So while it’s not a big, glaring giant recommendation, I think it will change a lot of practice.”

Similarly, she suggested that practice may shift as a result of a class 1 recommendation for staged PCI of a significantly stenosed nonculprit artery to reduce the risk for death or MI in selected hemodynamically stable patients presenting with ST-segment elevation MI and multivessel disease. “When you survey physicians, 75% of them do staged PCI but I think there will probably be more of an approach to staged PCI, as opposed to doing multivessel PCI at the time of primary PCI.”

Newer evidence from meta-analyses and the landmark ISCHEMIA trial showing no advantage of CABG over medical therapy in stable ischemic heart disease is reflected in a new class 2b recommendation – downgraded from class 1 in 2011 – that CABG “may be reasonable” to improve survival in stable patients with triple-vessel CAD.

The writing committee concluded that the ability of PCI to improve survival, compared with medical therapy in multivessel CAD “remains uncertain.”

Other recommendations likely to be of interest are that the radial artery is preferred, after the left internal mammary artery, as a surgical revascularization conduit over use of a saphenous vein conduit. Benefits include superior patency, fewer adverse cardiac events, and improved survival, the committee noted.

The radial artery is also recommended (class 1) in patients undergoing PCI who have acute coronary syndromes or stable ischemic heart disease to reduce bleeding and vascular complications compared with a femoral approach.

“Having both new radial recommendations sort of makes a bit of tension because the interventionalist is going to want to use the radial artery, but also the surgeon is too,” observed Dr. Tamis-Holland. “We see that in our own practice, so we try to have a collaborative approach to the patient to say: ‘Maybe do the cardiac cath in the dominant radial and then we can use the nondominant radial for a bypass conduit,’ but using both for each revascularization strategy will benefit the patient.

“So, we just have to remember that we’re going to talk together as a heart team and try to make the best decisions for each patient.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Clinicians should approach decisions regarding coronary revascularization based on clinical indications without an eye toward sex, race, or ethnicity, advises a joint clinical practice guideline released Dec. 8 by the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology.

The new class 1 recommendation leads off the 109-page document and reflects evidence demonstrating that revascularization is equally beneficial for all patients. Still, studies show that women and non-White patients are less likely to receive reperfusion therapy or revascularization.

“This was extremely important to all the committee members because of all of the disparities that have been documented not only in diagnosis but [in] the care provided to underrepresented minorities, women, and other ethnic groups,” said Jennifer S. Lawton, MD, chief of cardiac surgery at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and guideline writing committee chair.

“We wanted to make it clear right at the beginning of the document that these guidelines apply to everyone, and we want it to be known that care should be the same for everyone,” she said in an interview.

The guideline was simultaneously published Dec. 9, 2021, in the journal Circulation and the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

It updates and consolidates the ACC/AHA 2011 coronary artery bypass surgery (CABG) guideline and the ACC/AHA/Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions 2011 and 2015 percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) guidelines.

The new document emphasizes in a class 1 recommendation the importance of the multidisciplinary heart team in patients with coronary artery disease (CAD) where the best treatment strategy is unclear. But it also stresses that treatment decisions should be patient centered – taking into account patient preferences and goals, cultural beliefs, health literacy, and social determinants of cardiovascular health – and made in collaboration with the patient’s support system.

“Oftentimes we recommend a strategy of revascularization that may not be what the patient wants or hasn’t taken into account the patient’s preferences and also the family members,” Dr. Lawson said. “So we felt that was very important.”

Patients should also be provided with available evidence for various treatment options, including risks and benefits of each option, for informed consent. The two new class 1 recommendations are highlighted in a figure illustrating the shared decision-making algorithm that, by design, features a female clinician and Black patient.

“We spent 2 years debating the best revascularization strategies and we’re considered experts in the field – but when we talk to our patients, they really don’t know the benefits and risks,” she said. “In order to translate it to the layperson in basic terms, it’s important to say, ‘If you choose this option, you will likely live longer’ rather than using the jargon.”

DAPT, staged PCI, stable IHD

Among the top 10 take-home messages highlighted by the authors is a 2a recommendation that 1-3 months of dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) after PCI with a transition to P2Y12 inhibitor monotherapy is “reasonable” in selected patients to reduce the risk of bleeding events. Previous recommendations called for 6 or 12 months of DAPT.

“We really respect all of the clinical trials that came out showing that a shorter duration of DAPT is not inferior in terms of ischemic events but less bleeding, yet I don’t know how many clinicians are actually just using 3 months of DAPT followed by P2Y12 monotherapy,” guideline committee vice chair Jacqueline Tamis-Holland, MD, professor of medicine, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, said in an interview. “So while it’s not a big, glaring giant recommendation, I think it will change a lot of practice.”

Similarly, she suggested that practice may shift as a result of a class 1 recommendation for staged PCI of a significantly stenosed nonculprit artery to reduce the risk for death or MI in selected hemodynamically stable patients presenting with ST-segment elevation MI and multivessel disease. “When you survey physicians, 75% of them do staged PCI but I think there will probably be more of an approach to staged PCI, as opposed to doing multivessel PCI at the time of primary PCI.”

Newer evidence from meta-analyses and the landmark ISCHEMIA trial showing no advantage of CABG over medical therapy in stable ischemic heart disease is reflected in a new class 2b recommendation – downgraded from class 1 in 2011 – that CABG “may be reasonable” to improve survival in stable patients with triple-vessel CAD.

The writing committee concluded that the ability of PCI to improve survival, compared with medical therapy in multivessel CAD “remains uncertain.”

Other recommendations likely to be of interest are that the radial artery is preferred, after the left internal mammary artery, as a surgical revascularization conduit over use of a saphenous vein conduit. Benefits include superior patency, fewer adverse cardiac events, and improved survival, the committee noted.

The radial artery is also recommended (class 1) in patients undergoing PCI who have acute coronary syndromes or stable ischemic heart disease to reduce bleeding and vascular complications compared with a femoral approach.

“Having both new radial recommendations sort of makes a bit of tension because the interventionalist is going to want to use the radial artery, but also the surgeon is too,” observed Dr. Tamis-Holland. “We see that in our own practice, so we try to have a collaborative approach to the patient to say: ‘Maybe do the cardiac cath in the dominant radial and then we can use the nondominant radial for a bypass conduit,’ but using both for each revascularization strategy will benefit the patient.

“So, we just have to remember that we’re going to talk together as a heart team and try to make the best decisions for each patient.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Clinicians should approach decisions regarding coronary revascularization based on clinical indications without an eye toward sex, race, or ethnicity, advises a joint clinical practice guideline released Dec. 8 by the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology.

The new class 1 recommendation leads off the 109-page document and reflects evidence demonstrating that revascularization is equally beneficial for all patients. Still, studies show that women and non-White patients are less likely to receive reperfusion therapy or revascularization.

“This was extremely important to all the committee members because of all of the disparities that have been documented not only in diagnosis but [in] the care provided to underrepresented minorities, women, and other ethnic groups,” said Jennifer S. Lawton, MD, chief of cardiac surgery at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and guideline writing committee chair.

“We wanted to make it clear right at the beginning of the document that these guidelines apply to everyone, and we want it to be known that care should be the same for everyone,” she said in an interview.

The guideline was simultaneously published Dec. 9, 2021, in the journal Circulation and the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

It updates and consolidates the ACC/AHA 2011 coronary artery bypass surgery (CABG) guideline and the ACC/AHA/Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions 2011 and 2015 percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) guidelines.

The new document emphasizes in a class 1 recommendation the importance of the multidisciplinary heart team in patients with coronary artery disease (CAD) where the best treatment strategy is unclear. But it also stresses that treatment decisions should be patient centered – taking into account patient preferences and goals, cultural beliefs, health literacy, and social determinants of cardiovascular health – and made in collaboration with the patient’s support system.

“Oftentimes we recommend a strategy of revascularization that may not be what the patient wants or hasn’t taken into account the patient’s preferences and also the family members,” Dr. Lawson said. “So we felt that was very important.”

Patients should also be provided with available evidence for various treatment options, including risks and benefits of each option, for informed consent. The two new class 1 recommendations are highlighted in a figure illustrating the shared decision-making algorithm that, by design, features a female clinician and Black patient.

“We spent 2 years debating the best revascularization strategies and we’re considered experts in the field – but when we talk to our patients, they really don’t know the benefits and risks,” she said. “In order to translate it to the layperson in basic terms, it’s important to say, ‘If you choose this option, you will likely live longer’ rather than using the jargon.”

DAPT, staged PCI, stable IHD

Among the top 10 take-home messages highlighted by the authors is a 2a recommendation that 1-3 months of dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) after PCI with a transition to P2Y12 inhibitor monotherapy is “reasonable” in selected patients to reduce the risk of bleeding events. Previous recommendations called for 6 or 12 months of DAPT.

“We really respect all of the clinical trials that came out showing that a shorter duration of DAPT is not inferior in terms of ischemic events but less bleeding, yet I don’t know how many clinicians are actually just using 3 months of DAPT followed by P2Y12 monotherapy,” guideline committee vice chair Jacqueline Tamis-Holland, MD, professor of medicine, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, said in an interview. “So while it’s not a big, glaring giant recommendation, I think it will change a lot of practice.”

Similarly, she suggested that practice may shift as a result of a class 1 recommendation for staged PCI of a significantly stenosed nonculprit artery to reduce the risk for death or MI in selected hemodynamically stable patients presenting with ST-segment elevation MI and multivessel disease. “When you survey physicians, 75% of them do staged PCI but I think there will probably be more of an approach to staged PCI, as opposed to doing multivessel PCI at the time of primary PCI.”

Newer evidence from meta-analyses and the landmark ISCHEMIA trial showing no advantage of CABG over medical therapy in stable ischemic heart disease is reflected in a new class 2b recommendation – downgraded from class 1 in 2011 – that CABG “may be reasonable” to improve survival in stable patients with triple-vessel CAD.

The writing committee concluded that the ability of PCI to improve survival, compared with medical therapy in multivessel CAD “remains uncertain.”

Other recommendations likely to be of interest are that the radial artery is preferred, after the left internal mammary artery, as a surgical revascularization conduit over use of a saphenous vein conduit. Benefits include superior patency, fewer adverse cardiac events, and improved survival, the committee noted.

The radial artery is also recommended (class 1) in patients undergoing PCI who have acute coronary syndromes or stable ischemic heart disease to reduce bleeding and vascular complications compared with a femoral approach.

“Having both new radial recommendations sort of makes a bit of tension because the interventionalist is going to want to use the radial artery, but also the surgeon is too,” observed Dr. Tamis-Holland. “We see that in our own practice, so we try to have a collaborative approach to the patient to say: ‘Maybe do the cardiac cath in the dominant radial and then we can use the nondominant radial for a bypass conduit,’ but using both for each revascularization strategy will benefit the patient.

“So, we just have to remember that we’re going to talk together as a heart team and try to make the best decisions for each patient.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Genomic instability varies between breast cancer subtypes

More than 1,000 patients with TNBC, ER+ breast cancer, or ovarian cancer from five cohorts were examined for genomic instability scores (GIS) and the presence of BRCA deficiency, which showed that, while GIS was similar in BRCA-deficient TNBC and ovarian cancer, it was significantly different in ER+ breast cancer.

The analysis, presented at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium, showed that the genomic instability scores threshold, which could be used to dictate a patient’s treatment, should be lower for ER+ breast cancer than for TNBC.

“This indicates that different GIS thresholds are appropriate for breast cancer subtypes, and that the GIS threshold developed for ovarian caner is not appropriate for ER+ breast cancer,” said lead author Kirsten Timms, PhD, from Myriad Genetics.

This, she noted, is “consistent with the fact that ovarian cancer and TNBC are known to have similar molecular signatures.”

The researchers suggest that the “more inclusive” thresholds assessed in the study should be examined in further studies “to determine whether these cutoffs are associated with a benefit from treatment with DNA-targeting agents,” such as poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors.

Thomas P. Slavin, MD, chief medical officer at Myriad Genetics, said in an interview that there is “not a one size fits all” for GIS thresholds.

“When you look at ER+ breast cancer you see we need a different cutoff because it’s probably not as driven by homologous recombination deficiency [HRD], as least as a whole, compared to the other two,” he said. “There’s a little less genomic instability.”

He continued that their results suggest around half of TNBC patients have a GIS score that indicates the presence of significant HRD, which is “spot on for what we see with ovarian cancer” and “those people should respond pretty well to PARP-inhibitor therapies,” which is currently being investigated in clinical trials.

“But even in the ER+ group, when we look at the thresholds we used in this research, still about a third have what looks like a substantial amount of HRD, so that’s a huge biomarker,” Dr. Slavin said.

He explained that the importance of their score is that, rather than looking for the causes of HRD, they are looking for the consequences.

“We don’t know all the causes of why, all of a sudden, a tumor cell looks like it can’t replicate through homologous combination [but] what this test does is it says: ‘We don’t really care what the cause is ... we can just look at the genomic scarring and the consequences.’ ”

Elena Provenzano, MD, CRUK Therapeutic Discovery Laboratories, Cambridge (England) University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, who was not involved in the study, said in an interview it is “interesting work.”

“We have a personalized breast cancer program here in Cambridge and we’re running trials where we use PARP inhibitors and platinum-based therapy, and what we’re using to make these sorts of decisions is COSMIC mutational signatures associated with genetic instability. And I guess we also look at the total mutational burden,” Dr. Provenzano said.

She continued that the GIS is one of several ways of measuring HRD. “So the question is how it compares with the other measures that are being used to assess whether or not patients are suitable for PARP inhibitor and platinum-based therapy.”

Dr. Provenzano underlined that it has been known since the “early 2000s” that breast cancer is a group of different diseases. “Even within those categories there’s quite a lot of tumor types,” so it “makes sense you need to adjust the threshold slightly for it to become relevant to types of breast cancer.”

She added that the “holy grail in oncology is this concept of personalized medicine, so all these tests help us make sure that the right patient is getting the right treatment.

“At the moment TNBC is often getting treated in a similar way, although we know that there are different biological subtypes, so while there’s a significant group that falls into this BRCA-deficient group that are going to respond to PARPs there are other types that don’t.

“So these sorts of tests help us decide which subset are going to help us the most, and for the others ones we potentially need to identify other treatments as being optimal,” Dr. Provenzano said.

Previous studies have shown that HR-deficient tumors may benefit from treatment with DNA-damaging agents, and that tools such as the three-biomarker GIS can be used to identify HR deficiency.

The Food and Drug Administration has already approved a GIS threshold for identifying HR deficiency in ovarian cancer of 42, which was set as the 5th percentile for BRCA-deficient tumors. However, a recent published in Molecular Cancer Research, and a second published on MDPI Open Access Journals, indicated that a lower, first percentile, cutoff of at least 33 was associated with improved outcomes after platinum-based treatment.

As TNBC is known to have a similar molecular profile to ovarian cancer, the researchers investigated whether it has a different GIS threshold to that in ER+ breast cancer, gathering data on patients newly diagnosed with ovarian cancer, TNBC, or ER+ breast cancer from across five cohorts.

They included 127 ovarian cancer patients from Nature, 434 ovarian cancer, 44 TNBC, and 213 ER+ breast cancer patients from The Cancer Genome Atlas, 55 TNBC and 112 ER+ breast cancer patients from Breast Cancer Research, 19 TNBC and 25 ER+ breast cancer patients from TBCRC 008, and 56 ER+ breast cancer patients from OlympiAD.

GIS was defined as a combination of loss of heterozygosity, telomeric-allellic imbalance, and large-scale state transitions, identified through next-generation sequencing, and GIS distributions were compared between cancer types and subtypes.

The team also determined the presence of BRCA deficiency, finding that, among BRCA deficient tumors, the GIS distribution among patients with ER+ breast cancer was significantly different from that seen in both ovarian cancer (P = 9.6 x 10–5) and TNBC (P = 2.1 x 10–4).

The first percentile of a normal distribution of BRCA-deficient ER+ breast cancers indicated a GIS threshold of 24, with 45.1% of all ER+ tumors at or above this threshold found to be GIS positive. This translated into 98.7% of BRCA-deficient tumors and 32.7% that were BRCA intact.

The results also showed, however, that the GIS distribution for TNBC was not significantly different from that seen in ovarian cancer (P = .72), with the threshold of at least 33 Identifying 64.4% of TNBC tumors as GIS positive. This equated to 100% of BRCA-deficient tumors and 41.7% that were BRCA intact.

Dr. Timms and Dr. Slavin are employed by Myriad Genetics, who funded the study.

More than 1,000 patients with TNBC, ER+ breast cancer, or ovarian cancer from five cohorts were examined for genomic instability scores (GIS) and the presence of BRCA deficiency, which showed that, while GIS was similar in BRCA-deficient TNBC and ovarian cancer, it was significantly different in ER+ breast cancer.

The analysis, presented at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium, showed that the genomic instability scores threshold, which could be used to dictate a patient’s treatment, should be lower for ER+ breast cancer than for TNBC.

“This indicates that different GIS thresholds are appropriate for breast cancer subtypes, and that the GIS threshold developed for ovarian caner is not appropriate for ER+ breast cancer,” said lead author Kirsten Timms, PhD, from Myriad Genetics.

This, she noted, is “consistent with the fact that ovarian cancer and TNBC are known to have similar molecular signatures.”

The researchers suggest that the “more inclusive” thresholds assessed in the study should be examined in further studies “to determine whether these cutoffs are associated with a benefit from treatment with DNA-targeting agents,” such as poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors.

Thomas P. Slavin, MD, chief medical officer at Myriad Genetics, said in an interview that there is “not a one size fits all” for GIS thresholds.

“When you look at ER+ breast cancer you see we need a different cutoff because it’s probably not as driven by homologous recombination deficiency [HRD], as least as a whole, compared to the other two,” he said. “There’s a little less genomic instability.”

He continued that their results suggest around half of TNBC patients have a GIS score that indicates the presence of significant HRD, which is “spot on for what we see with ovarian cancer” and “those people should respond pretty well to PARP-inhibitor therapies,” which is currently being investigated in clinical trials.

“But even in the ER+ group, when we look at the thresholds we used in this research, still about a third have what looks like a substantial amount of HRD, so that’s a huge biomarker,” Dr. Slavin said.

He explained that the importance of their score is that, rather than looking for the causes of HRD, they are looking for the consequences.

“We don’t know all the causes of why, all of a sudden, a tumor cell looks like it can’t replicate through homologous combination [but] what this test does is it says: ‘We don’t really care what the cause is ... we can just look at the genomic scarring and the consequences.’ ”

Elena Provenzano, MD, CRUK Therapeutic Discovery Laboratories, Cambridge (England) University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, who was not involved in the study, said in an interview it is “interesting work.”

“We have a personalized breast cancer program here in Cambridge and we’re running trials where we use PARP inhibitors and platinum-based therapy, and what we’re using to make these sorts of decisions is COSMIC mutational signatures associated with genetic instability. And I guess we also look at the total mutational burden,” Dr. Provenzano said.

She continued that the GIS is one of several ways of measuring HRD. “So the question is how it compares with the other measures that are being used to assess whether or not patients are suitable for PARP inhibitor and platinum-based therapy.”

Dr. Provenzano underlined that it has been known since the “early 2000s” that breast cancer is a group of different diseases. “Even within those categories there’s quite a lot of tumor types,” so it “makes sense you need to adjust the threshold slightly for it to become relevant to types of breast cancer.”

She added that the “holy grail in oncology is this concept of personalized medicine, so all these tests help us make sure that the right patient is getting the right treatment.

“At the moment TNBC is often getting treated in a similar way, although we know that there are different biological subtypes, so while there’s a significant group that falls into this BRCA-deficient group that are going to respond to PARPs there are other types that don’t.

“So these sorts of tests help us decide which subset are going to help us the most, and for the others ones we potentially need to identify other treatments as being optimal,” Dr. Provenzano said.

Previous studies have shown that HR-deficient tumors may benefit from treatment with DNA-damaging agents, and that tools such as the three-biomarker GIS can be used to identify HR deficiency.

The Food and Drug Administration has already approved a GIS threshold for identifying HR deficiency in ovarian cancer of 42, which was set as the 5th percentile for BRCA-deficient tumors. However, a recent published in Molecular Cancer Research, and a second published on MDPI Open Access Journals, indicated that a lower, first percentile, cutoff of at least 33 was associated with improved outcomes after platinum-based treatment.

As TNBC is known to have a similar molecular profile to ovarian cancer, the researchers investigated whether it has a different GIS threshold to that in ER+ breast cancer, gathering data on patients newly diagnosed with ovarian cancer, TNBC, or ER+ breast cancer from across five cohorts.

They included 127 ovarian cancer patients from Nature, 434 ovarian cancer, 44 TNBC, and 213 ER+ breast cancer patients from The Cancer Genome Atlas, 55 TNBC and 112 ER+ breast cancer patients from Breast Cancer Research, 19 TNBC and 25 ER+ breast cancer patients from TBCRC 008, and 56 ER+ breast cancer patients from OlympiAD.

GIS was defined as a combination of loss of heterozygosity, telomeric-allellic imbalance, and large-scale state transitions, identified through next-generation sequencing, and GIS distributions were compared between cancer types and subtypes.

The team also determined the presence of BRCA deficiency, finding that, among BRCA deficient tumors, the GIS distribution among patients with ER+ breast cancer was significantly different from that seen in both ovarian cancer (P = 9.6 x 10–5) and TNBC (P = 2.1 x 10–4).

The first percentile of a normal distribution of BRCA-deficient ER+ breast cancers indicated a GIS threshold of 24, with 45.1% of all ER+ tumors at or above this threshold found to be GIS positive. This translated into 98.7% of BRCA-deficient tumors and 32.7% that were BRCA intact.

The results also showed, however, that the GIS distribution for TNBC was not significantly different from that seen in ovarian cancer (P = .72), with the threshold of at least 33 Identifying 64.4% of TNBC tumors as GIS positive. This equated to 100% of BRCA-deficient tumors and 41.7% that were BRCA intact.

Dr. Timms and Dr. Slavin are employed by Myriad Genetics, who funded the study.

More than 1,000 patients with TNBC, ER+ breast cancer, or ovarian cancer from five cohorts were examined for genomic instability scores (GIS) and the presence of BRCA deficiency, which showed that, while GIS was similar in BRCA-deficient TNBC and ovarian cancer, it was significantly different in ER+ breast cancer.

The analysis, presented at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium, showed that the genomic instability scores threshold, which could be used to dictate a patient’s treatment, should be lower for ER+ breast cancer than for TNBC.

“This indicates that different GIS thresholds are appropriate for breast cancer subtypes, and that the GIS threshold developed for ovarian caner is not appropriate for ER+ breast cancer,” said lead author Kirsten Timms, PhD, from Myriad Genetics.

This, she noted, is “consistent with the fact that ovarian cancer and TNBC are known to have similar molecular signatures.”

The researchers suggest that the “more inclusive” thresholds assessed in the study should be examined in further studies “to determine whether these cutoffs are associated with a benefit from treatment with DNA-targeting agents,” such as poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors.

Thomas P. Slavin, MD, chief medical officer at Myriad Genetics, said in an interview that there is “not a one size fits all” for GIS thresholds.

“When you look at ER+ breast cancer you see we need a different cutoff because it’s probably not as driven by homologous recombination deficiency [HRD], as least as a whole, compared to the other two,” he said. “There’s a little less genomic instability.”

He continued that their results suggest around half of TNBC patients have a GIS score that indicates the presence of significant HRD, which is “spot on for what we see with ovarian cancer” and “those people should respond pretty well to PARP-inhibitor therapies,” which is currently being investigated in clinical trials.

“But even in the ER+ group, when we look at the thresholds we used in this research, still about a third have what looks like a substantial amount of HRD, so that’s a huge biomarker,” Dr. Slavin said.

He explained that the importance of their score is that, rather than looking for the causes of HRD, they are looking for the consequences.

“We don’t know all the causes of why, all of a sudden, a tumor cell looks like it can’t replicate through homologous combination [but] what this test does is it says: ‘We don’t really care what the cause is ... we can just look at the genomic scarring and the consequences.’ ”

Elena Provenzano, MD, CRUK Therapeutic Discovery Laboratories, Cambridge (England) University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, who was not involved in the study, said in an interview it is “interesting work.”

“We have a personalized breast cancer program here in Cambridge and we’re running trials where we use PARP inhibitors and platinum-based therapy, and what we’re using to make these sorts of decisions is COSMIC mutational signatures associated with genetic instability. And I guess we also look at the total mutational burden,” Dr. Provenzano said.

She continued that the GIS is one of several ways of measuring HRD. “So the question is how it compares with the other measures that are being used to assess whether or not patients are suitable for PARP inhibitor and platinum-based therapy.”

Dr. Provenzano underlined that it has been known since the “early 2000s” that breast cancer is a group of different diseases. “Even within those categories there’s quite a lot of tumor types,” so it “makes sense you need to adjust the threshold slightly for it to become relevant to types of breast cancer.”

She added that the “holy grail in oncology is this concept of personalized medicine, so all these tests help us make sure that the right patient is getting the right treatment.

“At the moment TNBC is often getting treated in a similar way, although we know that there are different biological subtypes, so while there’s a significant group that falls into this BRCA-deficient group that are going to respond to PARPs there are other types that don’t.

“So these sorts of tests help us decide which subset are going to help us the most, and for the others ones we potentially need to identify other treatments as being optimal,” Dr. Provenzano said.

Previous studies have shown that HR-deficient tumors may benefit from treatment with DNA-damaging agents, and that tools such as the three-biomarker GIS can be used to identify HR deficiency.

The Food and Drug Administration has already approved a GIS threshold for identifying HR deficiency in ovarian cancer of 42, which was set as the 5th percentile for BRCA-deficient tumors. However, a recent published in Molecular Cancer Research, and a second published on MDPI Open Access Journals, indicated that a lower, first percentile, cutoff of at least 33 was associated with improved outcomes after platinum-based treatment.

As TNBC is known to have a similar molecular profile to ovarian cancer, the researchers investigated whether it has a different GIS threshold to that in ER+ breast cancer, gathering data on patients newly diagnosed with ovarian cancer, TNBC, or ER+ breast cancer from across five cohorts.

They included 127 ovarian cancer patients from Nature, 434 ovarian cancer, 44 TNBC, and 213 ER+ breast cancer patients from The Cancer Genome Atlas, 55 TNBC and 112 ER+ breast cancer patients from Breast Cancer Research, 19 TNBC and 25 ER+ breast cancer patients from TBCRC 008, and 56 ER+ breast cancer patients from OlympiAD.

GIS was defined as a combination of loss of heterozygosity, telomeric-allellic imbalance, and large-scale state transitions, identified through next-generation sequencing, and GIS distributions were compared between cancer types and subtypes.

The team also determined the presence of BRCA deficiency, finding that, among BRCA deficient tumors, the GIS distribution among patients with ER+ breast cancer was significantly different from that seen in both ovarian cancer (P = 9.6 x 10–5) and TNBC (P = 2.1 x 10–4).

The first percentile of a normal distribution of BRCA-deficient ER+ breast cancers indicated a GIS threshold of 24, with 45.1% of all ER+ tumors at or above this threshold found to be GIS positive. This translated into 98.7% of BRCA-deficient tumors and 32.7% that were BRCA intact.

The results also showed, however, that the GIS distribution for TNBC was not significantly different from that seen in ovarian cancer (P = .72), with the threshold of at least 33 Identifying 64.4% of TNBC tumors as GIS positive. This equated to 100% of BRCA-deficient tumors and 41.7% that were BRCA intact.

Dr. Timms and Dr. Slavin are employed by Myriad Genetics, who funded the study.

FROM SABCS 2021

What is the diagnosis?

As the lesion was growing, getting more violaceous and indurated, a biopsy was performed. The biopsy showed multiple discrete lobules of dermal capillaries with slight extension into the superficial subcutis. Capillary lobules demonstrate the “cannonball-like” architecture often associated with tufted angioma, and some lobules showed bulging into adjacent thin-walled vessels. Spindled endothelial cells lining slit-like vessels were present in the mid dermis, although this comprises a minority of the lesion. The majority of the subcutis was uninvolved. The findings are overall most consistent with a tufted angioma.

Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma (KHE) has been considered given the presence of occasional slit-like vascular spaces; however, the lesion is predominantly superficial and therefore the lesion is best classified as tufted angioma. GLUT–1 staining was negative.

At the time of biopsy, blood work was ordered, which showed a normal complete blood count with normal number of platelets, slightly elevated D-dimer, and slightly low fibrinogen. Several repeat blood counts and coagulation tests once a week for a few weeks revealed no changes.

The patient was started on aspirin at a dose of 5 mg/kg per day. After a week on the medication the lesion was starting to get smaller and less red.

Tufted angiomas are a rare type of vascular tumor within the spectrum of kaposiform hemangioendotheliomas. Most cases present within the first year of life; some occur at birth. They usually present as papules, plaques, or erythematous, violaceous indurated nodules on the face, neck, trunk, and extremities. The lesions can also be present with hyperhidrosis and hypertrichosis. Clinically, the lesions will have to be differentiated from other vascular tumors such as infantile hemangiomas, congenital hemangiomas, and Kaposi’s sarcoma, as well as subcutaneous fat necrosis of the newborn, cellulitis, and nonaccidental trauma.

Pathogenesis of tufted angiomas is poorly understood. A recent case report found a somatic mutation on GNA14.This protein regulates Ras activity and modulates endothelial cell permeability and migration in response to FGF2 and VEGFA. The p.205L mutation causes activation of GNA14, which upregulates pERK-MAPK pathway, suggesting MAPK inhibition as a potential target for therapy. Clinically, tufted angioma can present in three patterns: uncomplicated tufted angioma (most common type); tufted angioma without thrombocytopenia but with chronic coagulopathy, as it was seen in our patient; and tufted angioma associated with Kasabach-Merritt phenomenon (KMP). KMP is characterized by thrombocytopenia in association with microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, consumptive coagulopathy, and enlarging vascular tumor. Treatment of uncomplicated tufted angioma will depend on symptomatology, size, and location of the lesion. Smaller lesions in noncosmetically sensitive areas can be treated with surgical excision. Cases that are not amenable to excision can be treated with aspirin. There are also reports of response to topical modalities including tacrolimus and timolol. For complicated cases associated with KMP, sirolimus, systemic corticosteroids, ticlopidine, interferon, or vincristine are recommended. Some lesions may demonstrate spontaneous regression.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego.

References

Cohen S et al. Dermatol Online J. 2019 Sep 15;25(9):13030/qt6pv254mc.

Lim YH et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019 Nov;36(6):963-4.

Prasuna A, Rao PN. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6:266-8.

As the lesion was growing, getting more violaceous and indurated, a biopsy was performed. The biopsy showed multiple discrete lobules of dermal capillaries with slight extension into the superficial subcutis. Capillary lobules demonstrate the “cannonball-like” architecture often associated with tufted angioma, and some lobules showed bulging into adjacent thin-walled vessels. Spindled endothelial cells lining slit-like vessels were present in the mid dermis, although this comprises a minority of the lesion. The majority of the subcutis was uninvolved. The findings are overall most consistent with a tufted angioma.

Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma (KHE) has been considered given the presence of occasional slit-like vascular spaces; however, the lesion is predominantly superficial and therefore the lesion is best classified as tufted angioma. GLUT–1 staining was negative.

At the time of biopsy, blood work was ordered, which showed a normal complete blood count with normal number of platelets, slightly elevated D-dimer, and slightly low fibrinogen. Several repeat blood counts and coagulation tests once a week for a few weeks revealed no changes.

The patient was started on aspirin at a dose of 5 mg/kg per day. After a week on the medication the lesion was starting to get smaller and less red.

Tufted angiomas are a rare type of vascular tumor within the spectrum of kaposiform hemangioendotheliomas. Most cases present within the first year of life; some occur at birth. They usually present as papules, plaques, or erythematous, violaceous indurated nodules on the face, neck, trunk, and extremities. The lesions can also be present with hyperhidrosis and hypertrichosis. Clinically, the lesions will have to be differentiated from other vascular tumors such as infantile hemangiomas, congenital hemangiomas, and Kaposi’s sarcoma, as well as subcutaneous fat necrosis of the newborn, cellulitis, and nonaccidental trauma.

Pathogenesis of tufted angiomas is poorly understood. A recent case report found a somatic mutation on GNA14.This protein regulates Ras activity and modulates endothelial cell permeability and migration in response to FGF2 and VEGFA. The p.205L mutation causes activation of GNA14, which upregulates pERK-MAPK pathway, suggesting MAPK inhibition as a potential target for therapy. Clinically, tufted angioma can present in three patterns: uncomplicated tufted angioma (most common type); tufted angioma without thrombocytopenia but with chronic coagulopathy, as it was seen in our patient; and tufted angioma associated with Kasabach-Merritt phenomenon (KMP). KMP is characterized by thrombocytopenia in association with microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, consumptive coagulopathy, and enlarging vascular tumor. Treatment of uncomplicated tufted angioma will depend on symptomatology, size, and location of the lesion. Smaller lesions in noncosmetically sensitive areas can be treated with surgical excision. Cases that are not amenable to excision can be treated with aspirin. There are also reports of response to topical modalities including tacrolimus and timolol. For complicated cases associated with KMP, sirolimus, systemic corticosteroids, ticlopidine, interferon, or vincristine are recommended. Some lesions may demonstrate spontaneous regression.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego.

References

Cohen S et al. Dermatol Online J. 2019 Sep 15;25(9):13030/qt6pv254mc.

Lim YH et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019 Nov;36(6):963-4.

Prasuna A, Rao PN. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6:266-8.

As the lesion was growing, getting more violaceous and indurated, a biopsy was performed. The biopsy showed multiple discrete lobules of dermal capillaries with slight extension into the superficial subcutis. Capillary lobules demonstrate the “cannonball-like” architecture often associated with tufted angioma, and some lobules showed bulging into adjacent thin-walled vessels. Spindled endothelial cells lining slit-like vessels were present in the mid dermis, although this comprises a minority of the lesion. The majority of the subcutis was uninvolved. The findings are overall most consistent with a tufted angioma.

Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma (KHE) has been considered given the presence of occasional slit-like vascular spaces; however, the lesion is predominantly superficial and therefore the lesion is best classified as tufted angioma. GLUT–1 staining was negative.

At the time of biopsy, blood work was ordered, which showed a normal complete blood count with normal number of platelets, slightly elevated D-dimer, and slightly low fibrinogen. Several repeat blood counts and coagulation tests once a week for a few weeks revealed no changes.

The patient was started on aspirin at a dose of 5 mg/kg per day. After a week on the medication the lesion was starting to get smaller and less red.

Tufted angiomas are a rare type of vascular tumor within the spectrum of kaposiform hemangioendotheliomas. Most cases present within the first year of life; some occur at birth. They usually present as papules, plaques, or erythematous, violaceous indurated nodules on the face, neck, trunk, and extremities. The lesions can also be present with hyperhidrosis and hypertrichosis. Clinically, the lesions will have to be differentiated from other vascular tumors such as infantile hemangiomas, congenital hemangiomas, and Kaposi’s sarcoma, as well as subcutaneous fat necrosis of the newborn, cellulitis, and nonaccidental trauma.

Pathogenesis of tufted angiomas is poorly understood. A recent case report found a somatic mutation on GNA14.This protein regulates Ras activity and modulates endothelial cell permeability and migration in response to FGF2 and VEGFA. The p.205L mutation causes activation of GNA14, which upregulates pERK-MAPK pathway, suggesting MAPK inhibition as a potential target for therapy. Clinically, tufted angioma can present in three patterns: uncomplicated tufted angioma (most common type); tufted angioma without thrombocytopenia but with chronic coagulopathy, as it was seen in our patient; and tufted angioma associated with Kasabach-Merritt phenomenon (KMP). KMP is characterized by thrombocytopenia in association with microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, consumptive coagulopathy, and enlarging vascular tumor. Treatment of uncomplicated tufted angioma will depend on symptomatology, size, and location of the lesion. Smaller lesions in noncosmetically sensitive areas can be treated with surgical excision. Cases that are not amenable to excision can be treated with aspirin. There are also reports of response to topical modalities including tacrolimus and timolol. For complicated cases associated with KMP, sirolimus, systemic corticosteroids, ticlopidine, interferon, or vincristine are recommended. Some lesions may demonstrate spontaneous regression.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego.

References

Cohen S et al. Dermatol Online J. 2019 Sep 15;25(9):13030/qt6pv254mc.

Lim YH et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019 Nov;36(6):963-4.

Prasuna A, Rao PN. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6:266-8.

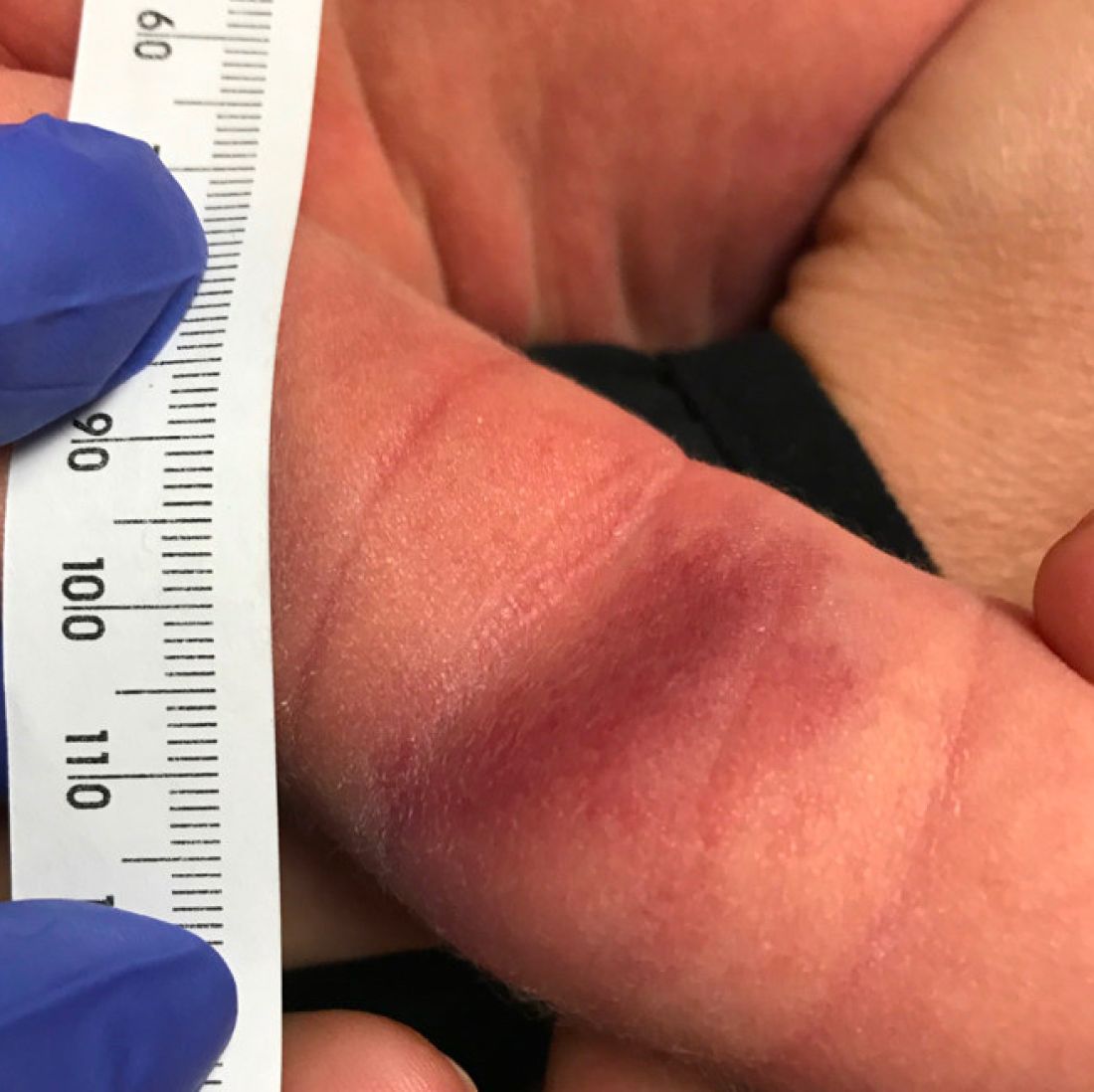

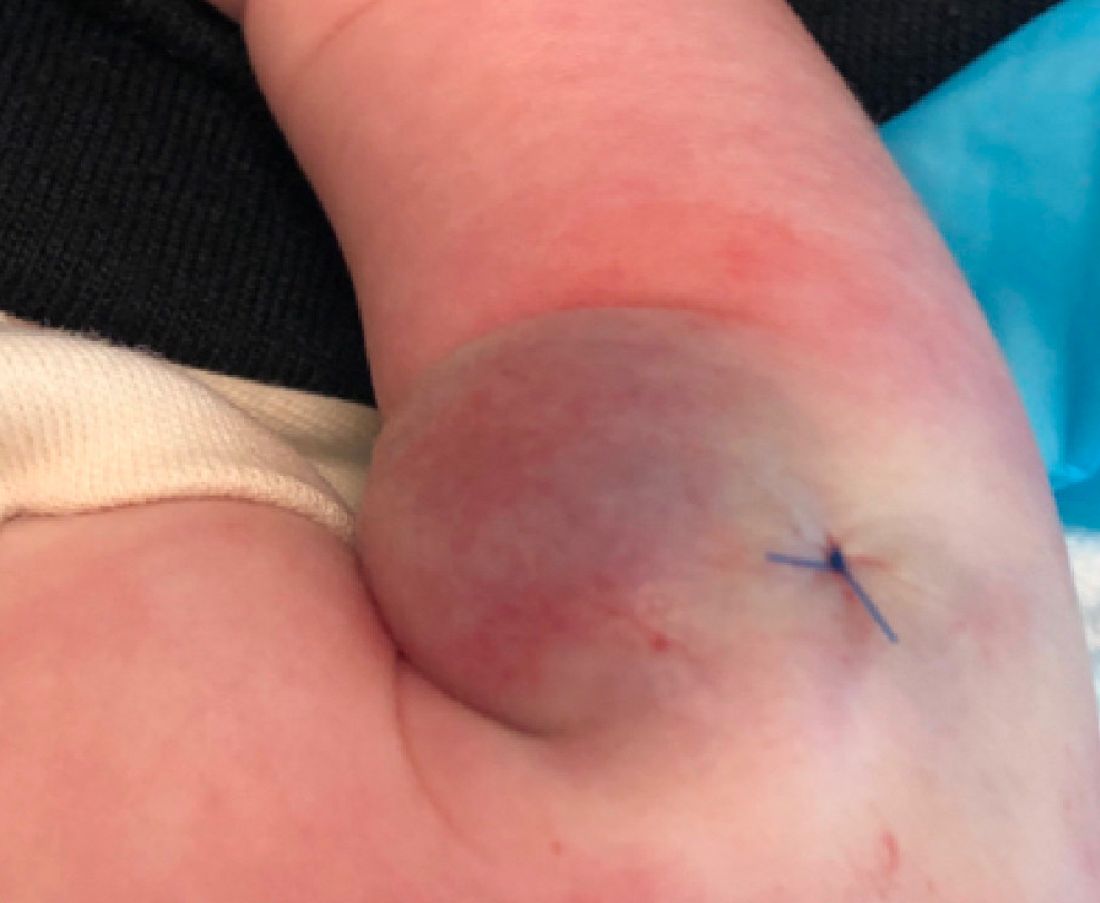

A 35-day-old female was referred to our pediatric dermatology clinic for evaluation of a red lesion on the right arm. The lesion presented at about 4 days of life as a red plaque (image 1 at 8 days of life).

On the following days, the lesion started growing but it didn't seem to be tender or bothersome to the patient (image 2, at 35 days of life).

At a 2-week follow up the lesion was getting fuller and more violaceous. There was no history of fever and the lesion didn't appear tender to the touch.

She was born via normal spontaneous vaginal delivery. There were no complications and the mother received prenatal care.

On exam she had a red to violaceous nodule on the right arm (image 3 at 45 days of life).

Ongoing HER2 breast cancer therapy may cost an additional $68,000 per patient

The current funding policy in British Columbia restricts patients to two lines of HER2-directed therapy for metastatic breast cancer, but accessing continued HER2 suppression has become more complex as novel agents have emerged, Emily Jackson, MD, and colleagues explained (in poster PD8-09) at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium.

Continuing HER2 suppression has improved progression free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS), but the financial implications of adapting funding policies to “reflect increasing lines of proven HER2 treatment” are unclear, they noted.

Drug funding is provided through the provincial government, but it can take months – and sometimes years – from when a drug is approved by Health Canada and when provincial protocols are approved and funding is made available, Dr. Jackson, co-chief resident (PGY5) at BC Cancer, Vancouver, said in an interview.

During that “lag time,” the province is negotiating drug prices with pharmaceutical companies and determining “which patients are eligible and under which circumstances,” she said.

To assess the potential costs, the investigators analyzed data from the BC Cancer outcomes unit, which collects clinical and outcome information on 85% of all patients diagnosed with breast cancer in the province. Information on therapy use was obtained from the BC Cancer pharmacy database.

Of 230 patients who received any HER2 treatment for metastatic breast cancer dispensed by BC Cancer between 2013 and 2018, 112 (49%) were eligible to continue beyond their second line of therapy.

“Of these, 86 patients accessed continued HER2-directed therapy, while 26 were eligible but unable to access continued HER2Rx,” they reported, noting that “the remaining 51% (n = 118) were not eligible for consideration of further HER2Rx due to either stable disease (n = 61) or deterioration precluding treatment (n = 57).”

At median follow-up of 42.2 months, the median number of lines of therapy in the entire study population was three. The median number of cycles in those who received HER2-directed therapy beyond second-line therapy was 33.

The median overall survival was 37.5 months for those who were eligible but did not continue HER2, compared with 57.9 months for those who did continue, they found.

The overall survival difference was not statistically significant (P = .13), but this was likely due to the small number of patients included in the initial analysis, Dr. Jackson said, noting that the finding is “hypothesis generating,” and should be further assessed.

Notably, most patients who continued HER2 therapy did so through pharmaceutical company compassionate access programs or clinical trials, she said.

The “conservative estimated cost per cycle of HER2Rx” was based on currently available trastuzumab biosimilars, and the potential financial implications were calculated based on the current cost of commonly used third-line therapies.

The findings demonstrate that most patients access continued treatment despite prohibitive funding policies, and suggest that significant increases in cost per patient can be expected if funding policies don’t evolve to meet treatment needs, they concluded, noting that “if these trends in survival continue we would expect an additional cost of $68,000 per patient over current costs.

“As the cost of novel therapies are likely to be higher than currently available biosimilars, there will be significant implications for both private payer and public payer healthcare systems,” they added.

A larger, more comprehensive analysis of the data is planned, said Dr. Jackson, who did not disclose any funding or other conflicts of interest associated with this study.

The current funding policy in British Columbia restricts patients to two lines of HER2-directed therapy for metastatic breast cancer, but accessing continued HER2 suppression has become more complex as novel agents have emerged, Emily Jackson, MD, and colleagues explained (in poster PD8-09) at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium.

Continuing HER2 suppression has improved progression free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS), but the financial implications of adapting funding policies to “reflect increasing lines of proven HER2 treatment” are unclear, they noted.

Drug funding is provided through the provincial government, but it can take months – and sometimes years – from when a drug is approved by Health Canada and when provincial protocols are approved and funding is made available, Dr. Jackson, co-chief resident (PGY5) at BC Cancer, Vancouver, said in an interview.

During that “lag time,” the province is negotiating drug prices with pharmaceutical companies and determining “which patients are eligible and under which circumstances,” she said.

To assess the potential costs, the investigators analyzed data from the BC Cancer outcomes unit, which collects clinical and outcome information on 85% of all patients diagnosed with breast cancer in the province. Information on therapy use was obtained from the BC Cancer pharmacy database.

Of 230 patients who received any HER2 treatment for metastatic breast cancer dispensed by BC Cancer between 2013 and 2018, 112 (49%) were eligible to continue beyond their second line of therapy.

“Of these, 86 patients accessed continued HER2-directed therapy, while 26 were eligible but unable to access continued HER2Rx,” they reported, noting that “the remaining 51% (n = 118) were not eligible for consideration of further HER2Rx due to either stable disease (n = 61) or deterioration precluding treatment (n = 57).”

At median follow-up of 42.2 months, the median number of lines of therapy in the entire study population was three. The median number of cycles in those who received HER2-directed therapy beyond second-line therapy was 33.

The median overall survival was 37.5 months for those who were eligible but did not continue HER2, compared with 57.9 months for those who did continue, they found.

The overall survival difference was not statistically significant (P = .13), but this was likely due to the small number of patients included in the initial analysis, Dr. Jackson said, noting that the finding is “hypothesis generating,” and should be further assessed.

Notably, most patients who continued HER2 therapy did so through pharmaceutical company compassionate access programs or clinical trials, she said.

The “conservative estimated cost per cycle of HER2Rx” was based on currently available trastuzumab biosimilars, and the potential financial implications were calculated based on the current cost of commonly used third-line therapies.

The findings demonstrate that most patients access continued treatment despite prohibitive funding policies, and suggest that significant increases in cost per patient can be expected if funding policies don’t evolve to meet treatment needs, they concluded, noting that “if these trends in survival continue we would expect an additional cost of $68,000 per patient over current costs.

“As the cost of novel therapies are likely to be higher than currently available biosimilars, there will be significant implications for both private payer and public payer healthcare systems,” they added.

A larger, more comprehensive analysis of the data is planned, said Dr. Jackson, who did not disclose any funding or other conflicts of interest associated with this study.

The current funding policy in British Columbia restricts patients to two lines of HER2-directed therapy for metastatic breast cancer, but accessing continued HER2 suppression has become more complex as novel agents have emerged, Emily Jackson, MD, and colleagues explained (in poster PD8-09) at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium.

Continuing HER2 suppression has improved progression free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS), but the financial implications of adapting funding policies to “reflect increasing lines of proven HER2 treatment” are unclear, they noted.

Drug funding is provided through the provincial government, but it can take months – and sometimes years – from when a drug is approved by Health Canada and when provincial protocols are approved and funding is made available, Dr. Jackson, co-chief resident (PGY5) at BC Cancer, Vancouver, said in an interview.

During that “lag time,” the province is negotiating drug prices with pharmaceutical companies and determining “which patients are eligible and under which circumstances,” she said.

To assess the potential costs, the investigators analyzed data from the BC Cancer outcomes unit, which collects clinical and outcome information on 85% of all patients diagnosed with breast cancer in the province. Information on therapy use was obtained from the BC Cancer pharmacy database.

Of 230 patients who received any HER2 treatment for metastatic breast cancer dispensed by BC Cancer between 2013 and 2018, 112 (49%) were eligible to continue beyond their second line of therapy.

“Of these, 86 patients accessed continued HER2-directed therapy, while 26 were eligible but unable to access continued HER2Rx,” they reported, noting that “the remaining 51% (n = 118) were not eligible for consideration of further HER2Rx due to either stable disease (n = 61) or deterioration precluding treatment (n = 57).”

At median follow-up of 42.2 months, the median number of lines of therapy in the entire study population was three. The median number of cycles in those who received HER2-directed therapy beyond second-line therapy was 33.

The median overall survival was 37.5 months for those who were eligible but did not continue HER2, compared with 57.9 months for those who did continue, they found.

The overall survival difference was not statistically significant (P = .13), but this was likely due to the small number of patients included in the initial analysis, Dr. Jackson said, noting that the finding is “hypothesis generating,” and should be further assessed.

Notably, most patients who continued HER2 therapy did so through pharmaceutical company compassionate access programs or clinical trials, she said.

The “conservative estimated cost per cycle of HER2Rx” was based on currently available trastuzumab biosimilars, and the potential financial implications were calculated based on the current cost of commonly used third-line therapies.

The findings demonstrate that most patients access continued treatment despite prohibitive funding policies, and suggest that significant increases in cost per patient can be expected if funding policies don’t evolve to meet treatment needs, they concluded, noting that “if these trends in survival continue we would expect an additional cost of $68,000 per patient over current costs.

“As the cost of novel therapies are likely to be higher than currently available biosimilars, there will be significant implications for both private payer and public payer healthcare systems,” they added.

A larger, more comprehensive analysis of the data is planned, said Dr. Jackson, who did not disclose any funding or other conflicts of interest associated with this study.

FROM SABCS 2021

Anticoagulant choice in antiphospholipid syndrome–associated thrombosis

Background: DOACs have largely replaced VKAs as first-line therapy for venous thromboembolism in patients with adequate renal function. However, there is concern in APS that DOACs may have higher rates of recurrent thrombosis than VKAs when treating thromboembolism.

Study design: Randomized noninferiority trial.

Setting: Six teaching hospitals in Spain.

Synopsis: Of adults with thrombotic APS, 190 were randomized to receive rivaroxaban or warfarin. Primary outcomes were thrombotic events and major bleeding. Follow-up after 3 years demonstrated new thromboses in 11 patients (11.6%) in the DOAC group and 6 patients (6.3%) in the VKA group (P = .29). Major bleeding occurred in six patients (6.3%) in the DOAC group and seven patients (7.4%) in the VKA group (P = .77). By contrast, stroke occurred in nine patients in the DOAC group while the VKA group had zero events, yielding a significant relative RR of 19.00 (95% CI, 1.12-321.90) for the DOAC group.

The DOAC arm was not proven to be noninferior with respect to the primary outcome of thrombotic events. The higher risk of stroke in this group suggests the need for caution in using DOACs in this population.

Bottom line: DOACs have a higher risk of stroke than VKAs in patients with APS without a significant difference in rate of a major bleed.

Citation: Ordi-Ros J et. al. Rivaroxaban versus vitamin K antagonist in antiphospholipid syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 2019;171(10):685-94. doi: 10.7326/M19-0291.

Dr. Portnoy is a hospitalist in the Division of Hospital Medicine, Mount Sinai Health System, New York.

Background: DOACs have largely replaced VKAs as first-line therapy for venous thromboembolism in patients with adequate renal function. However, there is concern in APS that DOACs may have higher rates of recurrent thrombosis than VKAs when treating thromboembolism.

Study design: Randomized noninferiority trial.

Setting: Six teaching hospitals in Spain.

Synopsis: Of adults with thrombotic APS, 190 were randomized to receive rivaroxaban or warfarin. Primary outcomes were thrombotic events and major bleeding. Follow-up after 3 years demonstrated new thromboses in 11 patients (11.6%) in the DOAC group and 6 patients (6.3%) in the VKA group (P = .29). Major bleeding occurred in six patients (6.3%) in the DOAC group and seven patients (7.4%) in the VKA group (P = .77). By contrast, stroke occurred in nine patients in the DOAC group while the VKA group had zero events, yielding a significant relative RR of 19.00 (95% CI, 1.12-321.90) for the DOAC group.

The DOAC arm was not proven to be noninferior with respect to the primary outcome of thrombotic events. The higher risk of stroke in this group suggests the need for caution in using DOACs in this population.

Bottom line: DOACs have a higher risk of stroke than VKAs in patients with APS without a significant difference in rate of a major bleed.

Citation: Ordi-Ros J et. al. Rivaroxaban versus vitamin K antagonist in antiphospholipid syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 2019;171(10):685-94. doi: 10.7326/M19-0291.

Dr. Portnoy is a hospitalist in the Division of Hospital Medicine, Mount Sinai Health System, New York.

Background: DOACs have largely replaced VKAs as first-line therapy for venous thromboembolism in patients with adequate renal function. However, there is concern in APS that DOACs may have higher rates of recurrent thrombosis than VKAs when treating thromboembolism.

Study design: Randomized noninferiority trial.

Setting: Six teaching hospitals in Spain.

Synopsis: Of adults with thrombotic APS, 190 were randomized to receive rivaroxaban or warfarin. Primary outcomes were thrombotic events and major bleeding. Follow-up after 3 years demonstrated new thromboses in 11 patients (11.6%) in the DOAC group and 6 patients (6.3%) in the VKA group (P = .29). Major bleeding occurred in six patients (6.3%) in the DOAC group and seven patients (7.4%) in the VKA group (P = .77). By contrast, stroke occurred in nine patients in the DOAC group while the VKA group had zero events, yielding a significant relative RR of 19.00 (95% CI, 1.12-321.90) for the DOAC group.

The DOAC arm was not proven to be noninferior with respect to the primary outcome of thrombotic events. The higher risk of stroke in this group suggests the need for caution in using DOACs in this population.

Bottom line: DOACs have a higher risk of stroke than VKAs in patients with APS without a significant difference in rate of a major bleed.

Citation: Ordi-Ros J et. al. Rivaroxaban versus vitamin K antagonist in antiphospholipid syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 2019;171(10):685-94. doi: 10.7326/M19-0291.

Dr. Portnoy is a hospitalist in the Division of Hospital Medicine, Mount Sinai Health System, New York.

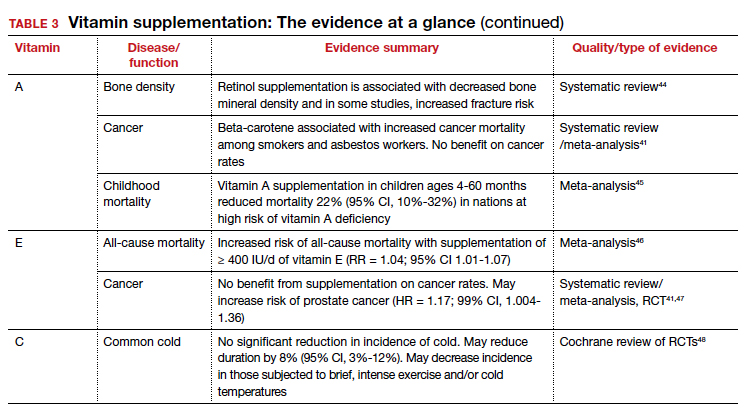

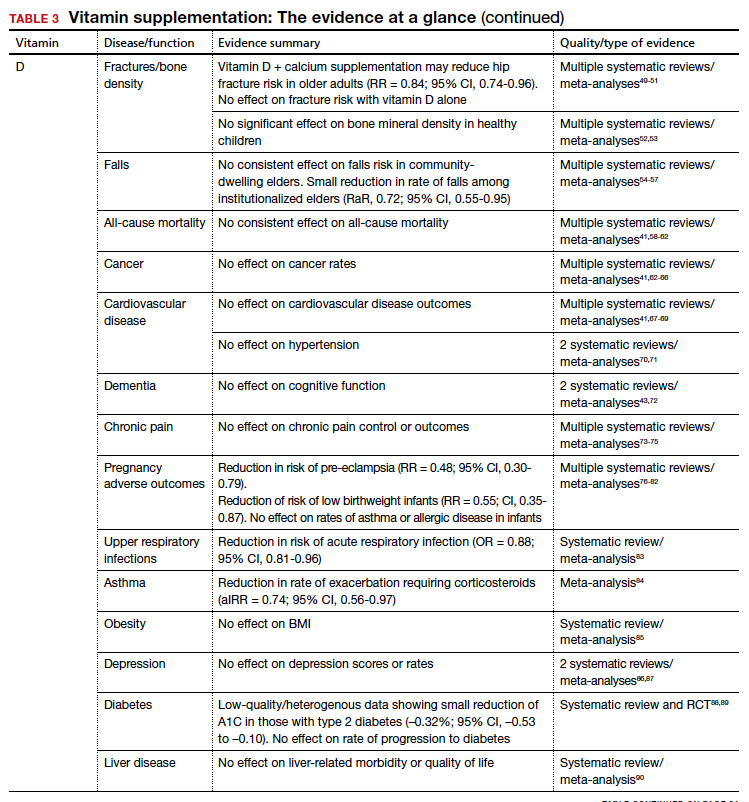

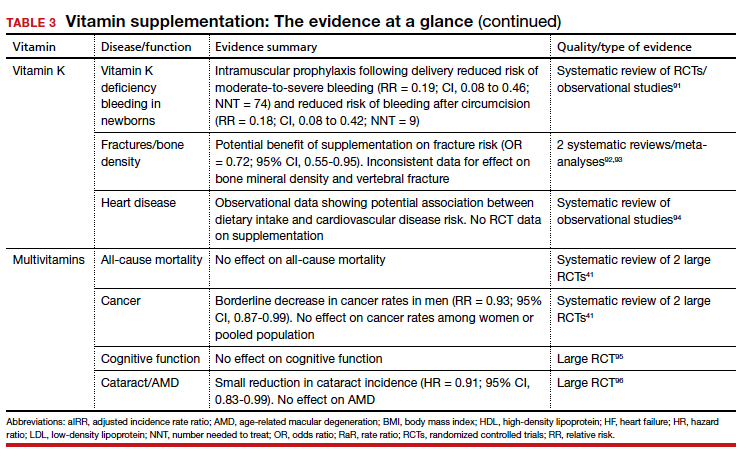

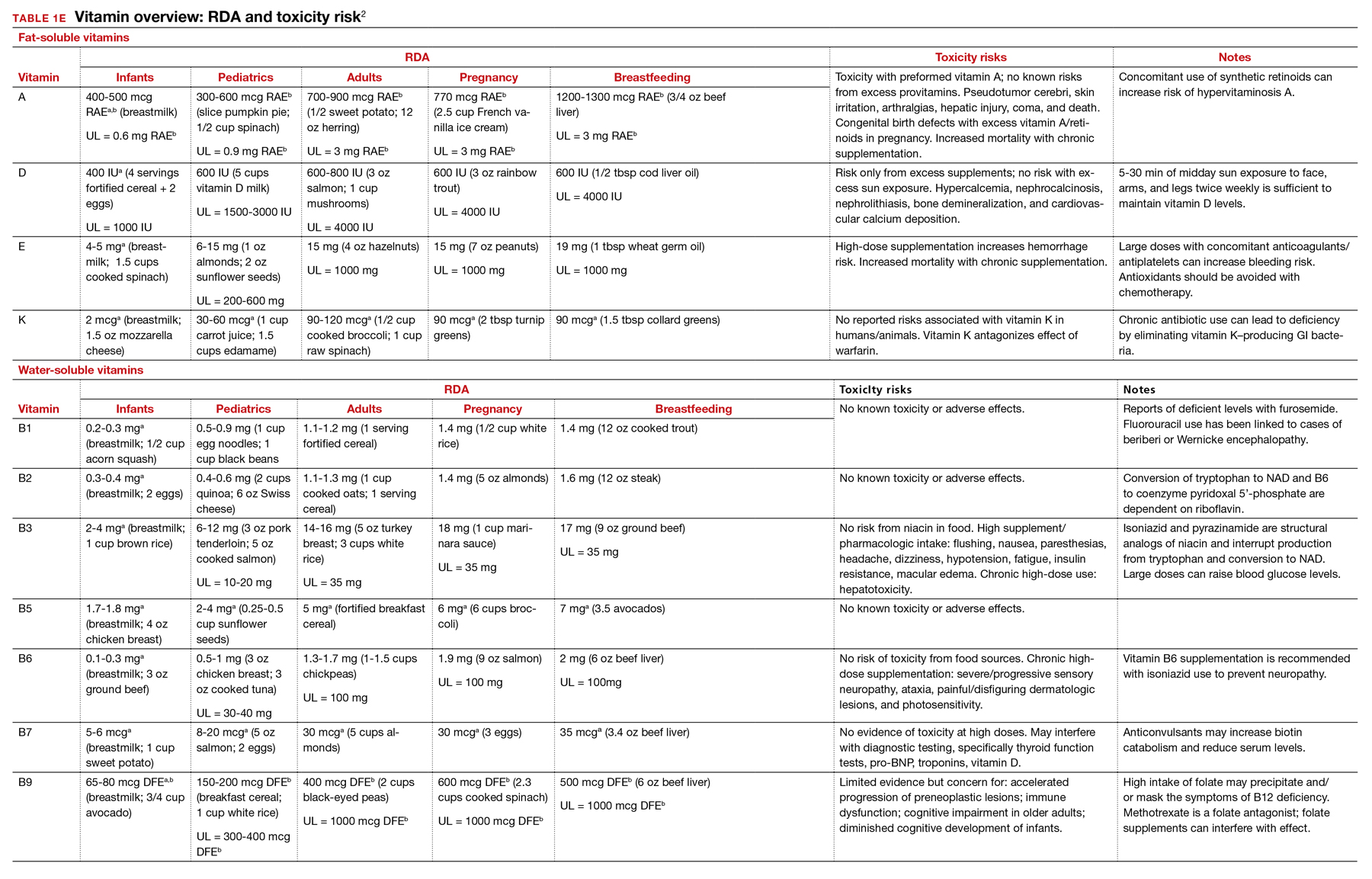

Vitamin supplementation in healthy patients: What does the evidence support?

Since their discovery in the early 1900s as the treatment for life-threatening deficiency syndromes, vitamins have been touted as panaceas for numerous ailments. While observational data have suggested potential correlations between vitamin status and every imaginable disease, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have generally failed to find benefits from supplementation. Despite this lack of proven efficacy, more than half of older adults reported taking vitamins regularly.1

While most clinicians consider vitamins to be, at worst, expensive placebos, the potential for harm and dangerous interactions exists. Unlike pharmaceuticals, vitamins are generally unregulated, and the true content of many dietary supplements is often difficult to elucidate. Understanding the physiologic role, foundational evidence, and specific indications for the various vitamins is key to providing the best recommendations to patients.

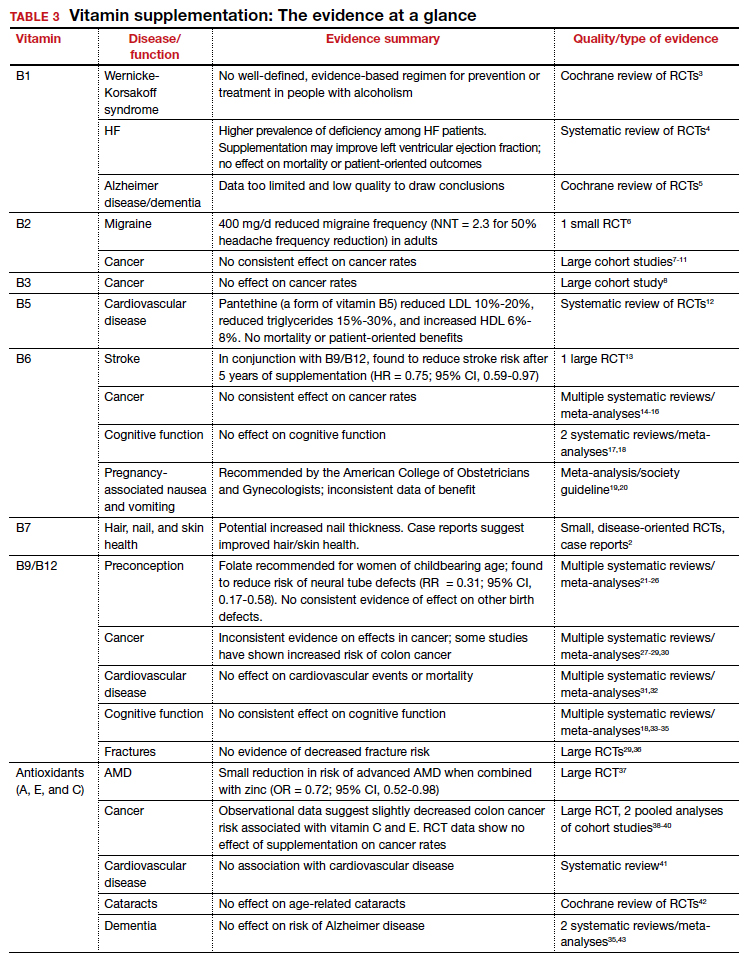

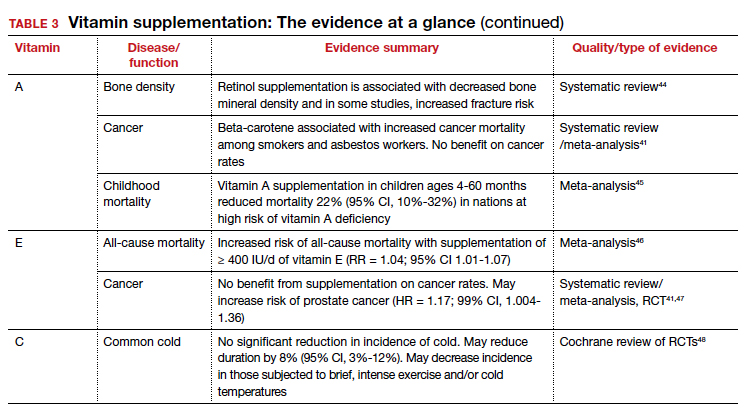

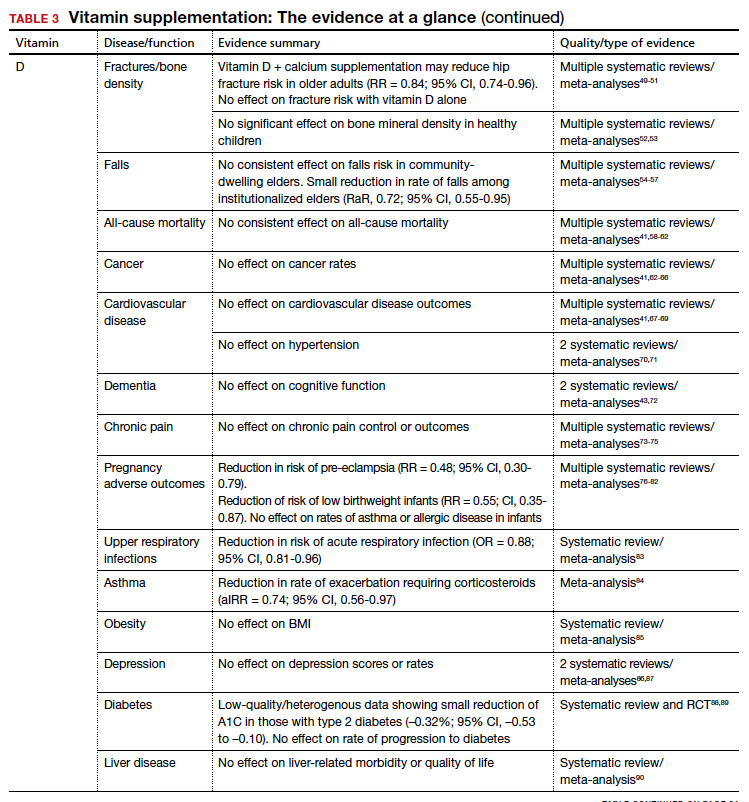

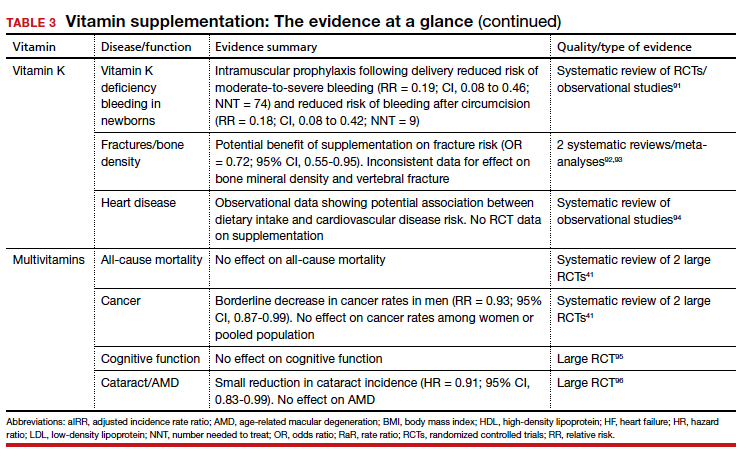

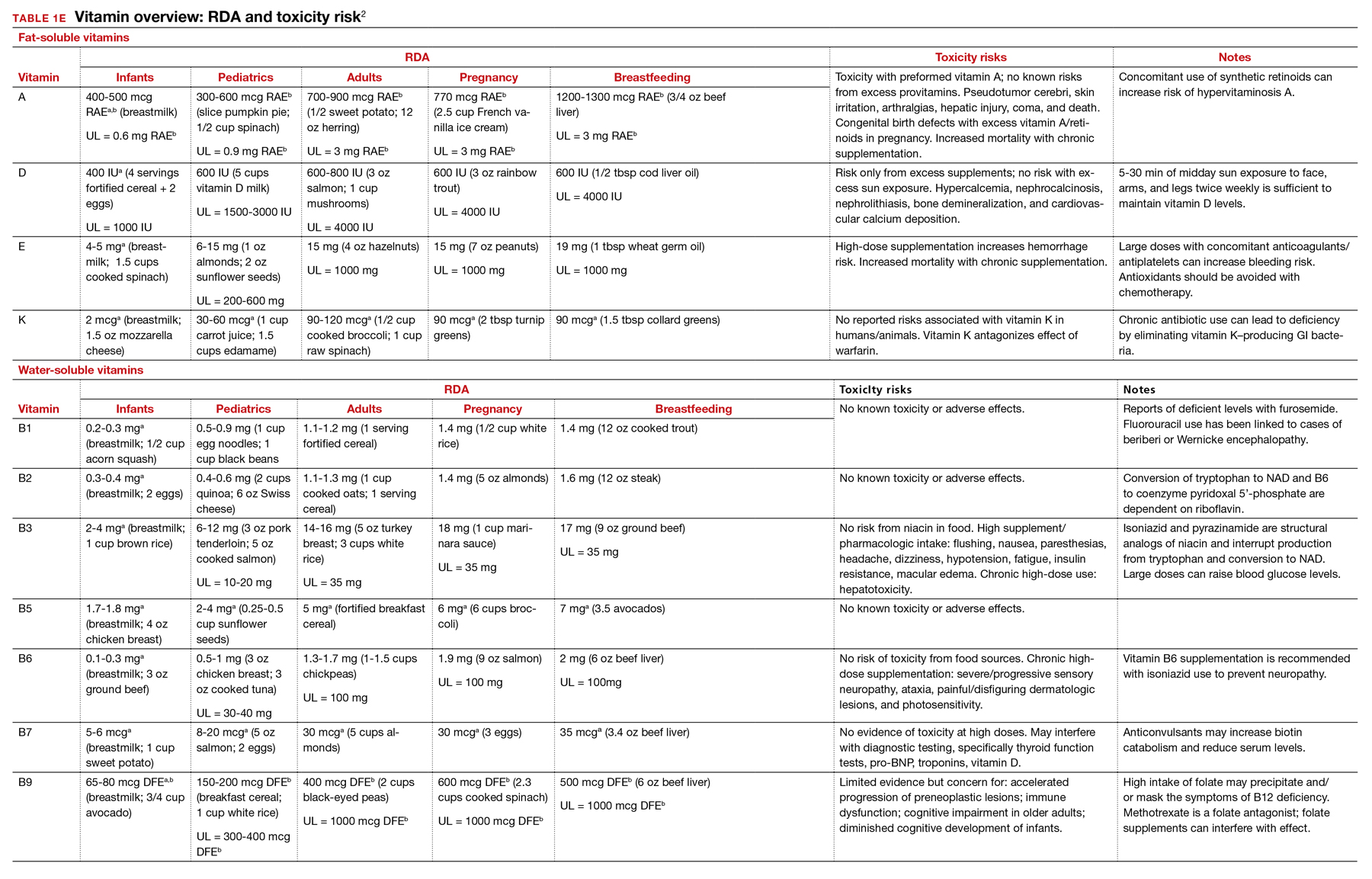

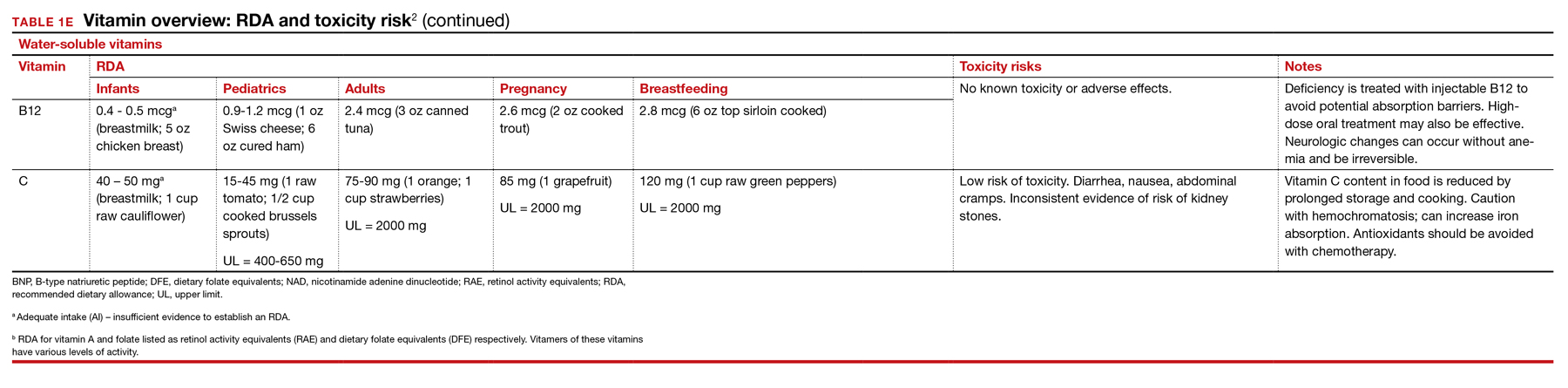

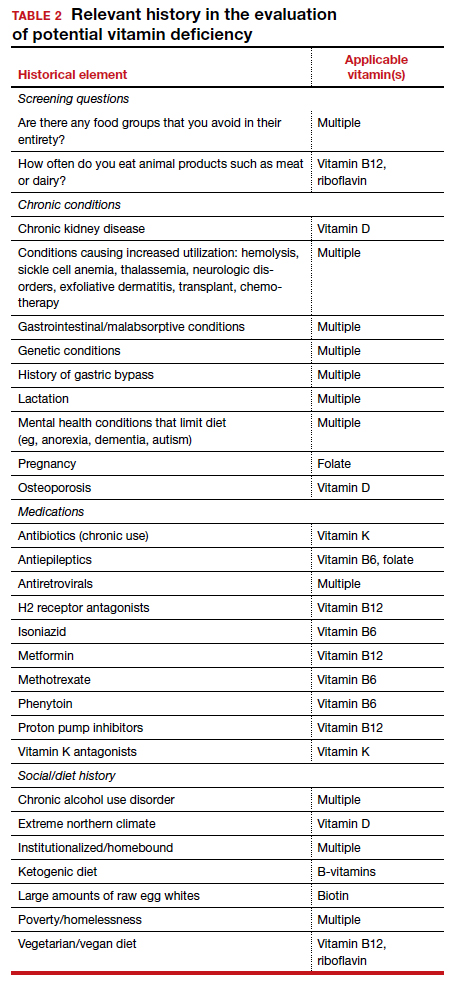

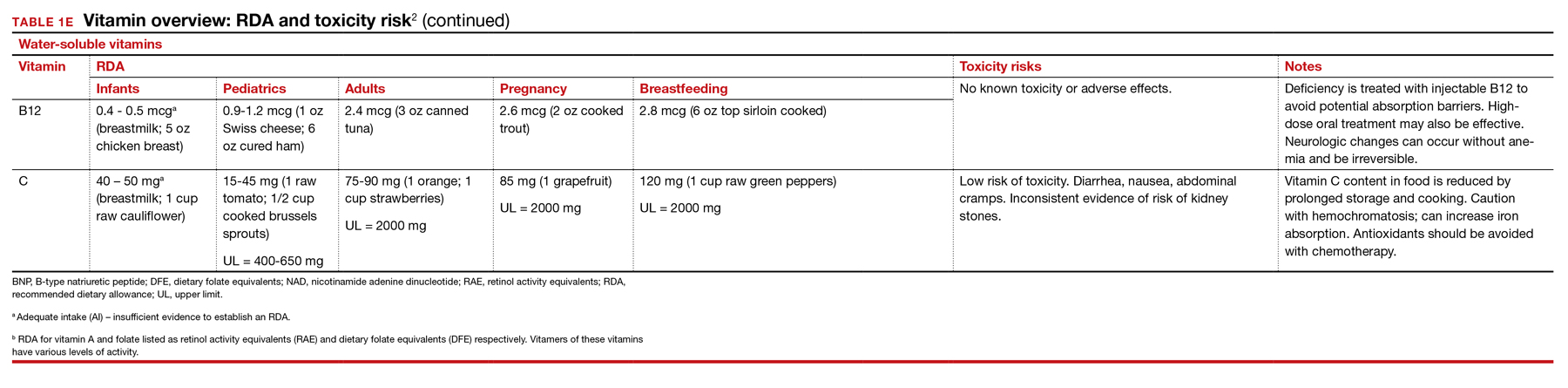

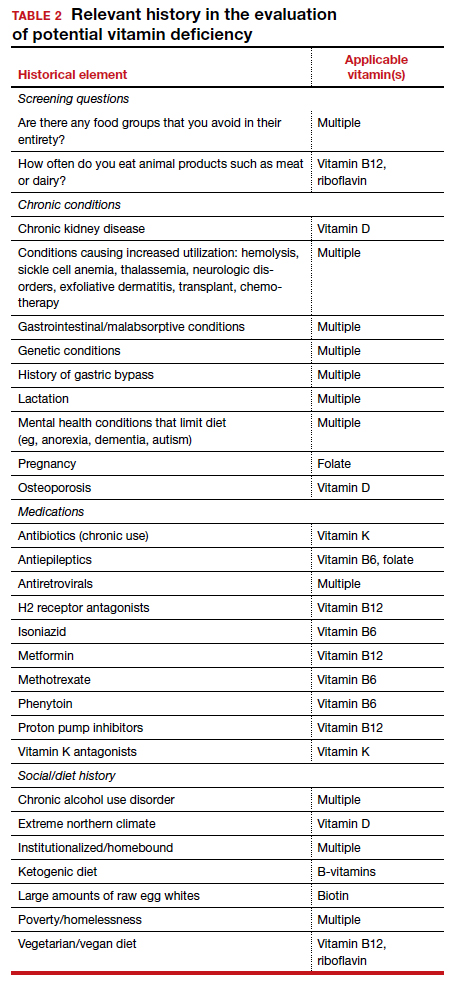

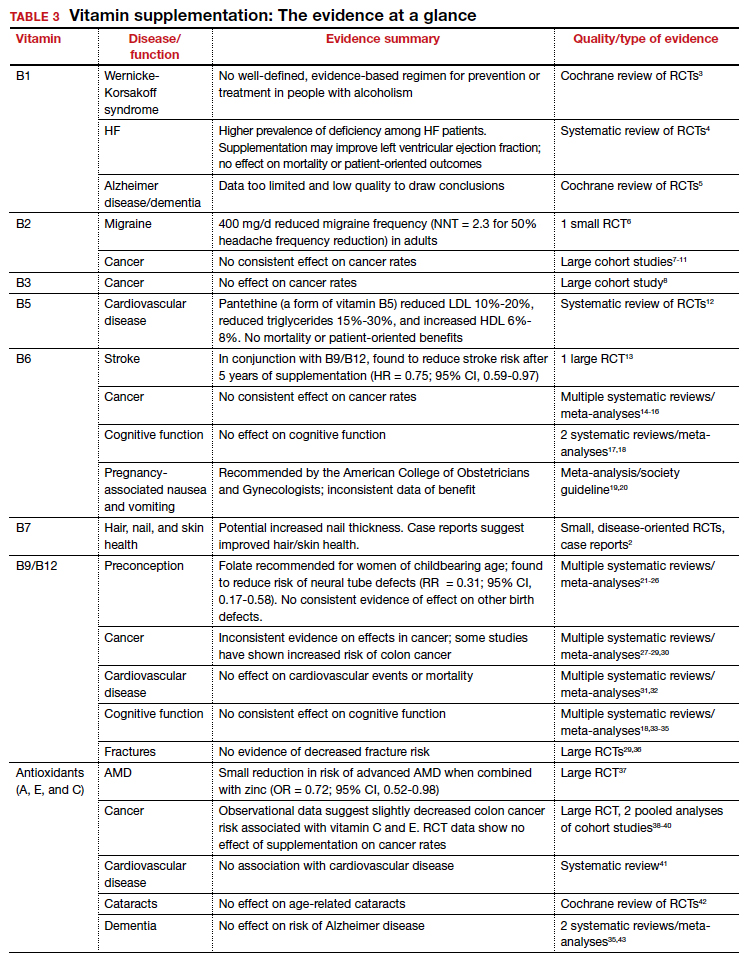

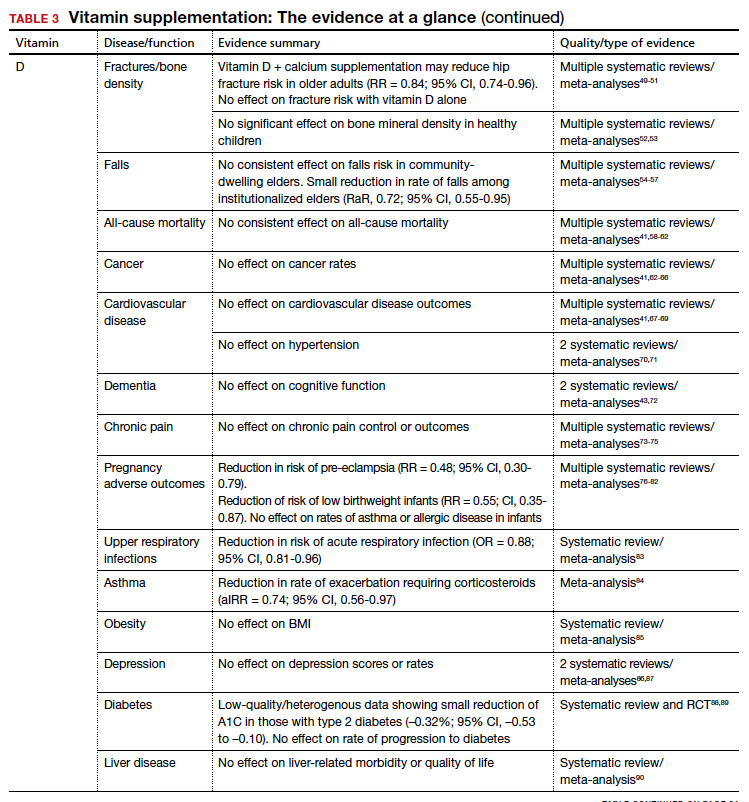

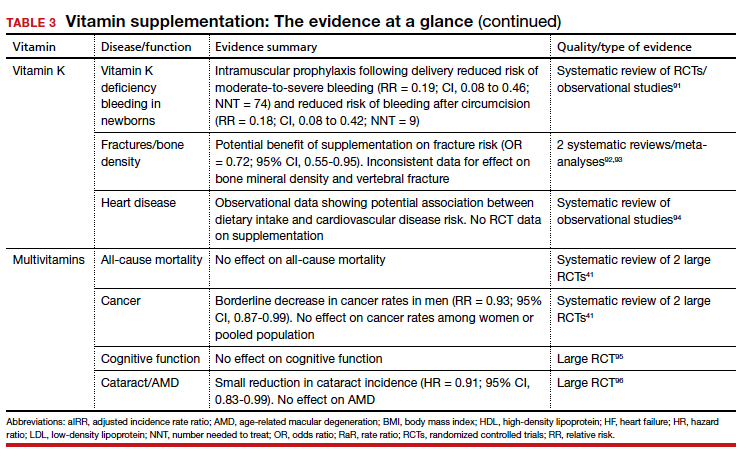

Vitamins are essential organic nutrients, required in small quantities for normal metabolism. Since they are not synthesized endogenously, they must be ingested via food intake. In the developed world, vitamin deficiency syndromes are rare, thanks to sufficiently balanced diets and availability of fortified foods. The focus of this article will be on vitamin supplementation in healthy patients with well-balanced diets. TABLE E12 lists the 13 recognized vitamins, their recommended dietary allowances, and any known toxicity risks. TABLE 22 outlines elements of the history to consider when evaluating for deficiency. A summary of the most clinically significant evidence for vitamin supplementation follows; a more comprehensive review can be found in TABLE 3.3-96

B Complex vitamins

Vitamin B1

Vitamers: Thiamine (thiamin)

Physiologic role: Critical in carbohydrate and amino-acid catabolism and energy metabolism

Dietary sources: Whole grains, meat, fish, fortified cereals, and breads

Thiamine serves as an essential cofactor in energy metabolism.2 Thiamine deficiency is responsible for beriberi syndrome (rare in the developed world) and Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome, the latter of which is a relatively common complication of chronic alcohol dependence. Although thiamine’s administration in these conditions can be curative, evidence is lacking to support its use preventively in patients with alcoholism.3 Thiamine has additionally been theorized to play a role in cardiac and cognitive function, but RCT data has not shown consistent patient-oriented benefits.4,5

The takeaway: Given the lack of evidence, supplementation in the general population is not recommended.

Continue to: Vitamin B2...

Vitamin B2

Vitamers: Riboflavin

Physiologic role: Essential component of cellular function and growth, energy production, and metabolism of fats and drugs

Dietary sources: Eggs, organ meats, lean meats, milk, green vegetables, fortified cereals and grains Riboflavin is essential to energy production, cellular growth, and metabolism.2

The takeaway: Its use as migraine prophylaxis has limited data,97 but there is otherwise no evidence to support health benefits of riboflavin supplementation.

Vitamin B3

Vitamers: Nicotinic acid (niacin); nicotinamide (niacinamide); nicotinamide riboside

Physiologic role: Converted to nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD), which is widely required in most cellular metabolic redox processes. Crucial to the synthesis and metabolism of carbohydrates, fatty acids, and proteins

Dietary sources: Poultry, beef, fish, nuts, legumes, grains. (Tryptophan can also be converted to NAD.)

Niacin is readily converted to NAD, an essential coenzyme for multiple catalytic processes in the body. While niacin at doses more than 100 times the recommended dietary allowance (RDA; 1-3 g/d) has been extensively studied for its role in dyslipidemias,2 pharmacologic dosing is beyond the scope of this article.

The takeaway: There is no evidence supporting a clinical benefit from niacin supplementation.

Vitamin B5

Vitamers: Pantothenic acid; pantethine

Physiologic role: Required for synthesis of coenzyme A (CoA) and acyl carrier protein, both essential in fatty acid and other anabolic/catabolic processes

Dietary sources: Almost all plant/animal-based foods. Richest sources include beef, chicken, organ meats, whole grains, and some vegetables

Pantothenic acid is essential to multiple metabolic processes and readily available in sufficient amounts in most foods.2 Although limited RCT data suggest pantethine may improve lipid measures,12,98,99 pantothenic acid itself does not seem to share this effect.

The takeaway: There is no data that supplementation of any form of vitamin B5 has any patient-oriented clinical benefits.

Continue to: Vitamin B6...

Vitamin B6

Vitamers: Pyridoxine; pyridoxamine; pyridoxal

Physiologic role: Widely involved coenzyme for cognitive development, neurotransmitter biosynthesis, homocysteine and glucose metabolism, immune function, and hemoglobin formation

Dietary sources: Fish, organ meats, potatoes/starchy vegetables, fruit (other than citrus), and fortified cereals

Pyridoxine is required for numerous enzymatic processes in the body, including biosynthesis of neurotransmitters and homeostasis of the amino acid homocysteine.2 While overt deficiency is rare, marginal insufficiency may become clinically apparent and has been associated with malabsorption, malignancies, pregnancy, heart disease, alcoholism, and use of drugs such as isoniazid, hydralazine, and levodopa/carbidopa.2 Vitamin B6 supplementation is known to decrease plasma homocysteine levels, a theorized intermediary for cardiovascular disease; however, studies have failed to consistently demonstrate patient-oriented benefits.100-102 While observational data has suggested a correlation between vitamin B6 status and cancer risk, RCTs have not supported benefit from supplementation.14-16 Potential effects of vitamin B6 supplementation on cognitive function have also been studied without observed benefit.17,18

The takeaway: Vitamin B6 is recommended as a potential treatment option for nausea in pregnancy.19 Otherwise, vitamin B6 is readily available in food, deficiency is rare, and no patient-oriented evidence supports supplementation in the general population.

Vitamin B7

Vitamers: Biotin

Physiologic role: Cofactor in the metabolism of fatty acids, glucose, and amino acids. Also plays key role in histone modifications, gene regulation, and cell signaling

Dietary sources: Widely available; most prevalent in organ meats, fish, meat, seeds, nuts, and vegetables (eg, sweet potatoes). Whole cooked eggs are a major source, but raw eggs contain avidin, which blocks absorption

Biotin serves a key role in metabolism, gene regulation, and cell signaling.2 Biotin is known to interfere with laboratory assays— including cardiac enzymes, thyroid studies, and hormone studies—at normal supplementation doses, resulting in both false-positive and false-negative results.103

The takeaway: No evidence supports the health benefits of biotin supplementation.

Vitamin B9

Vitamers: Folates; folic acid

Physiologic role: Functions as a coenzyme in the synthesis of DNA/RNA and metabolism of amino acids

Dietary sources: Highest content in spinach, liver, asparagus, and brussels sprouts. Generally found in green leafy vegetables, fruits, nuts, beans, peas, seafood, eggs, dairy, meat, poultry, grains, and fortified cereals.

Continue to: Vitamin B12...

Vitamin B12

Vitamers: Cyanocobalamin; hydroxocobalamin; methylcobalamin; adenosylcobalamin

Physiologic role: Required for red blood cell formation, neurologic function, and DNA synthesis

Dietary sources: Only in animal products: fish, poultry, meat, eggs, and milk/dairy products. Not present in plant foods. Fortified cereals, nutritional yeast are sources for vegans/vegetarians.

Given their linked physiologic roles, vitamins B9 and B12 are frequently studied together. Folate and cobalamins play key roles in nucleic acid synthesis and amino acid metabolism, with their most clinically significant role in hematopoiesis. Vitamin B12 is also essential to normal neurologic function.2

The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends preconceptual folate supplementation of 0.4-0.8 mg/d in women of childbearing age to decrease the risk of fetal neural tube defects (grade A).21 This is supported by high-quality RCT evidence demonstrating a protective effect of daily folate supplementation in preventing neural tube defects.22 Folate supplementation’s effect on other fetal birth defects has been investigated, but no benefit has been demonstrated. While observational studies have suggested an inverse relationship with folate status and fetal autism spectrum disorder,23-25 the RCT data is mixed.26

A potential role for folate in cancer prevention has been extensively investigated. An expert panel of the National Toxicology Program (NTP) concluded that folate supplementation does not reduce cancer risk in people with adequate baseline folate status based on high-quality meta-analysis data.27,104 Conversely, long-term follow-up from RCTs demonstrated an increased risk of colorectal adenomas and cancers,28,29 leading the NTP panel to conclude there is sufficient concern for adverse effects of folate on cancer growth to justify further research.104

While observational studies have found a correlation of increased risk for disease with lower antioxidant serum levels, RCTs have not demonstrated a reduction in disease risk with supplementation.

Given folate and vitamin B12’s homocysteine-reducing effects, it has been theorized that supplementation may protect from cardiovascular disease. However, despite extensive research, there remains no consistent patient-oriented outcomes data to support such a benefit.31,32,105

The evidence is mixed but generally has found no benefit of folate or vitamin B12 supplementation on cognitive function.18,33-35 Finally, RCT data has failed to demonstrate a reduction in fracture risk with supplementation.36,106

The takeaway: High-quality RCT evidence demonstrates a protective effect of preconceptual daily folate supplementation in preventing neural tube defects.22 The USPSTF recommends preconceptual folate supplementation of 0.4-0.8 mg/d in women of childbearing age to decrease the risk of fetal neural tube defects.

Antioxidants

In addition to their individual roles, vitamins A, E, and C are antioxidants, functioning to protect cells from oxidative damage by free radical species.2 Due to this shared role, these vitamins are commonly studied together. Antioxidants are hypothesized to protect from various diseases, including cancer, cardiovascular disease, dementia, autoimmune disorders, depression, cataracts, and age-related vision decline.2,37,107-112

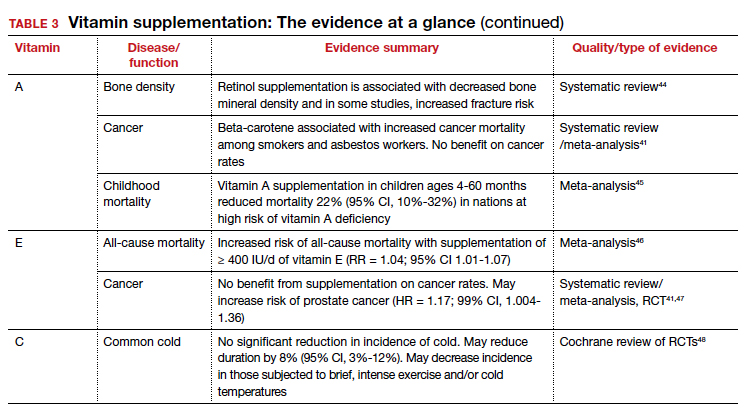

Though observational studies have found a correlation of increased risk for disease with lower antioxidant serum levels, RCTs have not demonstrated a reduction in disease risk with supplementation and, in some cases, have found an increased risk of mortality. While several studies have found potential benefit of antioxidant use in reducing colon and breast cancer risk,38,113-115 vitamins A and E have been associated with increased risk of lung and prostate cancer, respectively.47,110 Cardiovascular disease and antioxidant vitamin supplementation has similar inconsistent data, ranging from slight benefit to harm.2,116 After a large Cochrane review in 2012 found a significant increase in all-cause mortality associated with vitamin E and beta-carotene,117 the USPSTF made a specific recommendation against supplementation of these vitamins for the prevention of cardiovascular disease or cancer (grade D).118 Given its limited risk for harm, vitamin C was excluded from this recommendation.

Continue to: Vitamin A...

Vitamin A

Vitamers: Retinol; retinal; retinyl esters; provitamin A carotenoids (beta-carotene, alpha-carotene, beta-cryptoxanthin)

Physiologic role: Essential for vision and corneal development. Also involved in general cell differentiation and immune function