User login

2021 Update on bone health

Recently, the National Osteoporosis Foundation (NOF) changed its name to the Bone Health and Osteoporosis Foundation (BHOF). Several years ago, in 2016 at my urging, this column was renamed from “Update on osteoporosis” to “Update on bone health.” I believe we were on the leading edge of this movement. As expressed in last year’s Update, our patients’ bone health must be emphasized more than it has been in the past.1

Consider that localized breast cancer carries a 5-year survival rate of 99%.2 Most of my patients are keenly aware that periodic competent breast imaging is the key to the earliest possible diagnosis. By contrast, in this country a hip fracture carries a mortality in the first year of 21%!3 Furthermore, approximately one-third of women who fracture their hip do not have osteoporosis.4 While the risk of hip fracture is greatest in women with osteoporosis, it is not absent in those without the condition. Finally, the role of muscle mass, strength, and performance in bone health is a rapidly emerging topic and one that constitutes the core of this year’s Update.

Muscle mass and strength play key role in bone health

de Villiers TJ, Goldstein SR. Update on bone health: the International Menopause Society white paper 2021. Climacteric. 2021;24:498-504. doi:10.1080/13697137.2021.1950967.

Recently, de Villiers and Goldstein offered an overview of osteoporosis.5 What is worthy of reporting here is the role of muscle in bone health.

The bone-muscle relationship

Most clinicians know that osteoporosis and osteopenia are well-defined conditions with known risks associated with fracture. According to a review of PubMed, the first article with the keyword “osteoporosis” was published in 1894; through May 2020, 93,335 articles used that keyword. “Osteoporosis” is derived from the Greek osteon (bone) and poros (little hole). Thus, osteoporosis means “porous bone.”

Sarcopenia is characterized by progressive and generalized loss of skeletal muscle mass, strength, and function, and the condition is associated with a risk of adverse outcomes that include physical disabilities, poor quality of life, and death.6,7 “Sarcopenia” has its roots in the Greek words sarx (flesh) and penia (loss), and the term was coined in 1989.8 A PubMed review that included “sarcopenia” as the keyword revealed that the first article was published in 1993, with 12,068 articles published through May 2020.

Notably, muscle accounts for about 60% of the body’s protein. Muscle mass decreases with age, but younger patients with malnutrition, cachexia, or inflammatory diseases are also prone to decreased muscle mass. While osteoporosis has a well-accepted definition based on dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) measurements, sarcopenia has no universally accepted definition, consensus diagnostic criteria, or treatment guidelines. In 2016, however, the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (CD-10-CM) finally recognized sarcopenia as a disease entity.

Currently, the most widely accepted definition comes from the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People, which labeled presarcopenia as low muscle mass without impact on muscle strength or performance; sarcopenia as low muscle mass with either low muscle strength or low physical performance; and severe sarcopenia has all 3 criteria being present.9

When osteosarcopenia (osteoporosis or osteopenia combined with sarcopenia) exists, it can result in a threefold increase in risk of falls and a fourfold increase in fracture risk compared with women who have osteopenia or osteoporosis alone.10

The morbidity and mortality from fragility fractures are well known. Initially, diagnosis of risk seemed to be mainly T-scores on bone mineral density (BMD) testing (normal, osteopenic, osteoporosis). The FRAX fracture risk assessment tool, which includes a number of variables, further refined risk assessment. Increasingly, there is evidence of crosstalk between muscle and bone. Sarcopenia, the loss of skeletal muscle mass, strength, and performance, appears to play an important role as well for fracture risk. Simple tools to evaluate a patient’s muscle status exist. At the very least, resistance and balance exercises should be part of all clinicians’ patient counseling for bone health.

Continue to: Denosumab decreased falls risk, improved sarcopenia measures vs comparator antiresorptives...

Denosumab decreased falls risk, improved sarcopenia measures vs comparator antiresorptives

El Miedany Y, El Gaafary M, Toth M, et al; Egyptian Academy of Bone Health, Metabolic Bone Diseases. Is there a potential dual effect of denosumab for treatment of osteoporosis and sarcopenia? Clin Rheumatol. 2021;40:4225-4232. doi: 10.1007/s10067-021 -05757-w.

Osteosarcopenia, the combination of osteoporosis or osteopenia with sarcopenia, has been shown to increase the overall rate of falls and fracture when compared with fall and fracture rates in women with osteopenia or osteoporosis alone.10 A study by El Miedany and colleagues examined whether denosumab treatment had a possible dual therapeutic effect on osteoporosis and sarcopenia.11

Study details

The investigators looked at 135 patients diagnosed with postmenopausal osteoporosis and who were prescribed denosumab and compared them with a control group of 272 patients stratified into 2 subgroups: 136 were prescribed alendronate and 136 were prescribed zoledronate.

Assessments were performed for all participants for BMD (DXA), fall risk (falls risk assessment score [FRAS]), fracture risk (FRAX assessment tool), and sarcopenia measures. Reassessments were conducted after 5 years of denosumab or alendronate therapy, 3 years of zoledronate therapy, and 1 year after stopping the osteoporosis therapy.

The FRAS uses the clinical variables of history of falls in the last 12 months, impaired sight, weak hand grip, history of loss of balance in the last 12 months, and slowing of the walking speed/change in gait to yield a percent chance of sustaining a fall.12 Sarcopenic measures include grip strength, timed up and go (TUG) mobility test, and gait speed. There were no significant demographic differences between the 3 groups.

Denosumab reduced risk of falls and positively affected muscle strength

On completion of the 5-year denosumab therapy, falls risk was significantly decreased (P = .001) and significant improvements were seen in all sarcopenia measures (P = .01). One year after denosumab was discontinued, a significant worsening of both falls risk and sarcopenia measures (P = .01) occurred. This was in contrast to results in both control groups (alendronate and zoledronate), in which there was an improvement, although less robust in gait speed and the TUG test (P = .05) but no improvement in risk of falls. Thus, the results of this study showed that denosumab not only improved bone mass but also reduced falls risk.

Compared with bisphosphonates, denosumab showed the highest significant positive effect on both physical performance and skeletal muscle strength. This is evidenced by improvement of the gait speed, TUG test, and 4-m walk test (P<.001) in the denosumab group versus in the alendronate and zoledronate group (P<.05).

These results agree with the outcomes of the FREEDOM (Fracture Reduction Evaluation of Denosumab in Osteoporosis 6 months) trial, which revealed that not only did denosumab treatment reduce the risk of vertebral, nonvertebral, and hip fracture over 36 months, but also that the denosumab-treated group had fewer falls (4.5%) compared with the other groups (5.7%) (P = .02).13

These data highlight that osteoporosis and sarcopenia may share similar underlying risk factors and that muscle-bone interactions are important to minimize the risk of falls, fractures, and hospitalizations. While all 3 antiresorptives (denosumab, alendronate, zoledronate) improved measures of BMD and sarcopenia, only denosumab resulted in a reduction in the FRAS risk of falls score.

Continue to: Estrogen’s role in bone health and its therapeutic potential in osteosarcopenia...

Estrogen’s role in bone health and its therapeutic potential in osteosarcopenia

Mandelli A, Tacconi E, Levinger I, et al. The role of estrogens in osteosarcopenia: from biology to potential dual therapeutic effects. Climacteric. 2021;1-7. doi: 10.1080/13697137.2021.1965118.

Osteosarcopenia is a particular term used to describe the coexistence of 2 pathologies, osteopenia/ osteoporosis and sarcopenia.14 Sarcopenia is characterized by a loss of muscle mass, strength, and performance. Numerous studies indicate that higher lean body mass is related to increased BMD and reduced fracture risk, especially in postmenopausal women.15

Menopause, muscle, and estrogen’s physiologic effects

Estrogens play a critical role in maintaining bone and muscle mass in women. Women experience a decline in musculoskeletal quantity and quality at the onset of menopause.16 Muscle mass and strength decrease rapidly after menopause, which suggests that degradation of muscle protein begins to exert a more significant effect due to a decrease in protein synthesis. Indeed, a reduced response to anabolic stimuli has been shown in postmenopausal women.17 Normalization of the protein synthesis response after restoring estrogen levels with estrogen therapy supports this hypothesis.18

In a meta-analysis to identify the role of estrogen therapy on muscle strength, the authors concluded that estrogens benefit muscle strength not by increasing the skeletal mass but by improving muscle quality and its ability to generate force.19 In addition, however, it has been demonstrated that exercise prevents and delays the onset of osteosarcopenia.20

Estrogens play a crucial role in maintaining bone and skeletal muscle health in women. Estrogen therapy is an accepted treatment for osteoporosis, whereas its effects on sarcopenia, although promising, indicate that additional studies are required before it can be recommended solely for that purpose. Given the well-described benefits of exercise on muscle and bone health, postmenopausal women should be encouraged to engage in regular physical exercise as a preventive or disease-modifying treatment for osteosarcopenia.

When should bone mass be measured in premenopausal women?

Conradie M, de Villiers T. Premenopausal osteoporosis. Climacteric. 2021:1-14. doi: 10.1080/13697137 .2021.1926974.

Most women’s clinicians are somewhat well acquainted with the increasing importance of preventing, diagnosing, and treating postmenopausal osteoporosis, which predisposes to fragility fracture and the morbidity and even mortality that brings. Increasingly, some younger women are asking for and receiving both bone mass measurements that may be inappropriately ordered and/or wrongly interpreted. Conradie and de Villiers provided an overview of premenopausal osteoporosis, containing important facts that all clinicians who care for women should be aware of.21

Indications for testing

BMD testing is only indicated in younger women in settings in which the result may influence management decisions, such as:

- a history of fragility fracture

- diseases associated with low bone mass, such as anorexia nervosa, hypogonadism, hyperparathyroidism, hyperthyroidism, celiac disease, irritable bowel disease, rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, renal disease, Marfan syndrome

- medications, such as glucocorticoids, aromatase inhibitors, premenopausal tamoxifen, excess thyroid hormone replacement, progesterone contraception

- excessive alcohol consumption, heavy smoking, vitamin D deficiency, calcium deficiency, occasionally veganism or vegetarianism.

BMD interpretation in premenopausal women does not use the T-scores developed for postmenopausal women in which standard deviations (SD) from the mean for a young reference population are employed. In that population, the normal range is up to -1.0 SD; osteopenia > -1.0 < -2.5 SD; and osteoporosis > -2.5 SD. Instead, in premenopausal patients, Z-scores, which compare the measured bone mass to an age- and gender-matched cohort, are employed. Z-scores > 2 SD below the matched population should be used rather than the T-scores that are already familiar to most clinicians.

Up to 90% of these premenopausal women with such skeletal fragility will display the secondary causes described above. ●

Very specific indications are required to consider bone mass measurements in premenopausal women. When measurements are indicated, the values are evaluated by Z-scores that compare them to those of matched-aged women and not by T-scores meant for postmenopausal women. When fragility or low-trauma fractures or Z-scores more than 2 SD below their peers are present, secondary causes of premenopausal osteoporosis include a variety of disease states, medications, and lifestyle situations. When such factors are present, many general women’s health clinicians may want to refer patients for consultation to a metabolic bone specialist for workup and management.

- Goldstein SR. Update on bone health. OBG Manag. 2020;32:16-20, 22-23.

- American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2020. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2020. https://www .cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts -and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2020/cancer -facts-and-figures-2020.pdf. Accessed November 11, 2021.

- Downey C, Kelly M, Quinlan JF. Changing trends in the mortality rate at 1-year post hip fracture—a systematic review. World J Orthop. 2019;10:166-175.

- Schuit SC, van der Klift M, Weel AE, et al. Fracture incidence and association with bone mineral density in elderly men and women: the Rotterdam Study. Bone. 2004;34:195-202.

- de Villiers, TJ, Goldstein SR. Update on bone health: the International Menopause Society white paper 2021. Climacteric. 2021;24:498-504.

- Goodpaster BH, Park SW, Harris TB, et al. The loss of skeletal muscle strength, mass, and quality in older adults: the health, aging and body composition study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006;61:1059-1064.

- Santilli V, Bernetti A, Mangone M, et al. Clinical definition of sarcopenia. Clin Cases Miner Bone Metab. 2014;11:177-180.

- Rosenberg I. Epidemiological and methodological problems in determining nutritional status of older persons. Proceedings of a conference. Albuquerque, New Mexico, October 19-21, 1989. Am J Clin Nutr. 1989;50:1231-1233.

- Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Baeyens JP, Bauer JM, et al; European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People. Sarcopenia: European consensus on definition and diagnosis—report of the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People. Age Ageing. 2010;39:412-423.

- Sepúlveda-Loyola W, Phu S, Bani Hassan E, et al. The joint occurrence of osteoporosis and sarcopenia (osteosarcopenia): definitions and characteristics. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21:220-225.

- El Miedany Y, El Gaafary M, Toth M, et al; Egyptian Academy of Bone Health, Metabolic Bone Diseases. Is there a potential dual effect of denosumab for treatment of osteoporosis and sarcopenia? Clin Rheumatol. 2021;40:4225-4232.

- El Miedany Y, El Gaafary M, Toth M, et al. Falls risk assessment score (FRAS): time to rethink. J Clin Gerontol Geriatr. 2011;21-26.

- Cummings SR, Martin JS, McClung MR, et al; FREEDOM Trial. Denosumab for prevention of fractures in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 2009;361: 756-765.

- Inoue T, Maeda K, Nagano A, et al. Related factors and clinical outcomes of osteosarcopenia: a narrative review. Nutrients. 2021;13:291.

- Kaji H. Linkage between muscle and bone: common catabolic signals resulting in osteoporosis and sarcopenia. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2013;16:272-277.

- Sipilä S, Törmäkangas T, Sillanpää E, et al. Muscle and bone mass in middle‐aged women: role of menopausal status and physical activity. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2020;11: 698-709.

- Bamman MM, Hill VJ, Adams GR, et al. Gender differences in resistance-training-induced myofiber hypertrophy among older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2003;58:108-116.

- Hansen M, Skovgaard D, Reitelseder S, et al. Effects of estrogen replacement and lower androgen status on skeletal muscle collagen and myofibrillar protein synthesis in postmenopausal women. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2012;67:1005-1013.

- Greising SM, Baltgalvis KA, Lowe DA, et al. Hormone therapy and skeletal muscle strength: a meta-analysis. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;64:1071-1081.

- Cariati I, Bonanni R, Onorato F, et al. Role of physical activity in bone-muscle crosstalk: biological aspects and clinical implications. J Funct Morphol Kinesiol. 2021;6:55.

- Conradie M, de Villiers T. Premenopausal osteoporosis. Climacteric. 2021:1-14.

Recently, the National Osteoporosis Foundation (NOF) changed its name to the Bone Health and Osteoporosis Foundation (BHOF). Several years ago, in 2016 at my urging, this column was renamed from “Update on osteoporosis” to “Update on bone health.” I believe we were on the leading edge of this movement. As expressed in last year’s Update, our patients’ bone health must be emphasized more than it has been in the past.1

Consider that localized breast cancer carries a 5-year survival rate of 99%.2 Most of my patients are keenly aware that periodic competent breast imaging is the key to the earliest possible diagnosis. By contrast, in this country a hip fracture carries a mortality in the first year of 21%!3 Furthermore, approximately one-third of women who fracture their hip do not have osteoporosis.4 While the risk of hip fracture is greatest in women with osteoporosis, it is not absent in those without the condition. Finally, the role of muscle mass, strength, and performance in bone health is a rapidly emerging topic and one that constitutes the core of this year’s Update.

Muscle mass and strength play key role in bone health

de Villiers TJ, Goldstein SR. Update on bone health: the International Menopause Society white paper 2021. Climacteric. 2021;24:498-504. doi:10.1080/13697137.2021.1950967.

Recently, de Villiers and Goldstein offered an overview of osteoporosis.5 What is worthy of reporting here is the role of muscle in bone health.

The bone-muscle relationship

Most clinicians know that osteoporosis and osteopenia are well-defined conditions with known risks associated with fracture. According to a review of PubMed, the first article with the keyword “osteoporosis” was published in 1894; through May 2020, 93,335 articles used that keyword. “Osteoporosis” is derived from the Greek osteon (bone) and poros (little hole). Thus, osteoporosis means “porous bone.”

Sarcopenia is characterized by progressive and generalized loss of skeletal muscle mass, strength, and function, and the condition is associated with a risk of adverse outcomes that include physical disabilities, poor quality of life, and death.6,7 “Sarcopenia” has its roots in the Greek words sarx (flesh) and penia (loss), and the term was coined in 1989.8 A PubMed review that included “sarcopenia” as the keyword revealed that the first article was published in 1993, with 12,068 articles published through May 2020.

Notably, muscle accounts for about 60% of the body’s protein. Muscle mass decreases with age, but younger patients with malnutrition, cachexia, or inflammatory diseases are also prone to decreased muscle mass. While osteoporosis has a well-accepted definition based on dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) measurements, sarcopenia has no universally accepted definition, consensus diagnostic criteria, or treatment guidelines. In 2016, however, the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (CD-10-CM) finally recognized sarcopenia as a disease entity.

Currently, the most widely accepted definition comes from the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People, which labeled presarcopenia as low muscle mass without impact on muscle strength or performance; sarcopenia as low muscle mass with either low muscle strength or low physical performance; and severe sarcopenia has all 3 criteria being present.9

When osteosarcopenia (osteoporosis or osteopenia combined with sarcopenia) exists, it can result in a threefold increase in risk of falls and a fourfold increase in fracture risk compared with women who have osteopenia or osteoporosis alone.10

The morbidity and mortality from fragility fractures are well known. Initially, diagnosis of risk seemed to be mainly T-scores on bone mineral density (BMD) testing (normal, osteopenic, osteoporosis). The FRAX fracture risk assessment tool, which includes a number of variables, further refined risk assessment. Increasingly, there is evidence of crosstalk between muscle and bone. Sarcopenia, the loss of skeletal muscle mass, strength, and performance, appears to play an important role as well for fracture risk. Simple tools to evaluate a patient’s muscle status exist. At the very least, resistance and balance exercises should be part of all clinicians’ patient counseling for bone health.

Continue to: Denosumab decreased falls risk, improved sarcopenia measures vs comparator antiresorptives...

Denosumab decreased falls risk, improved sarcopenia measures vs comparator antiresorptives

El Miedany Y, El Gaafary M, Toth M, et al; Egyptian Academy of Bone Health, Metabolic Bone Diseases. Is there a potential dual effect of denosumab for treatment of osteoporosis and sarcopenia? Clin Rheumatol. 2021;40:4225-4232. doi: 10.1007/s10067-021 -05757-w.

Osteosarcopenia, the combination of osteoporosis or osteopenia with sarcopenia, has been shown to increase the overall rate of falls and fracture when compared with fall and fracture rates in women with osteopenia or osteoporosis alone.10 A study by El Miedany and colleagues examined whether denosumab treatment had a possible dual therapeutic effect on osteoporosis and sarcopenia.11

Study details

The investigators looked at 135 patients diagnosed with postmenopausal osteoporosis and who were prescribed denosumab and compared them with a control group of 272 patients stratified into 2 subgroups: 136 were prescribed alendronate and 136 were prescribed zoledronate.

Assessments were performed for all participants for BMD (DXA), fall risk (falls risk assessment score [FRAS]), fracture risk (FRAX assessment tool), and sarcopenia measures. Reassessments were conducted after 5 years of denosumab or alendronate therapy, 3 years of zoledronate therapy, and 1 year after stopping the osteoporosis therapy.

The FRAS uses the clinical variables of history of falls in the last 12 months, impaired sight, weak hand grip, history of loss of balance in the last 12 months, and slowing of the walking speed/change in gait to yield a percent chance of sustaining a fall.12 Sarcopenic measures include grip strength, timed up and go (TUG) mobility test, and gait speed. There were no significant demographic differences between the 3 groups.

Denosumab reduced risk of falls and positively affected muscle strength

On completion of the 5-year denosumab therapy, falls risk was significantly decreased (P = .001) and significant improvements were seen in all sarcopenia measures (P = .01). One year after denosumab was discontinued, a significant worsening of both falls risk and sarcopenia measures (P = .01) occurred. This was in contrast to results in both control groups (alendronate and zoledronate), in which there was an improvement, although less robust in gait speed and the TUG test (P = .05) but no improvement in risk of falls. Thus, the results of this study showed that denosumab not only improved bone mass but also reduced falls risk.

Compared with bisphosphonates, denosumab showed the highest significant positive effect on both physical performance and skeletal muscle strength. This is evidenced by improvement of the gait speed, TUG test, and 4-m walk test (P<.001) in the denosumab group versus in the alendronate and zoledronate group (P<.05).

These results agree with the outcomes of the FREEDOM (Fracture Reduction Evaluation of Denosumab in Osteoporosis 6 months) trial, which revealed that not only did denosumab treatment reduce the risk of vertebral, nonvertebral, and hip fracture over 36 months, but also that the denosumab-treated group had fewer falls (4.5%) compared with the other groups (5.7%) (P = .02).13

These data highlight that osteoporosis and sarcopenia may share similar underlying risk factors and that muscle-bone interactions are important to minimize the risk of falls, fractures, and hospitalizations. While all 3 antiresorptives (denosumab, alendronate, zoledronate) improved measures of BMD and sarcopenia, only denosumab resulted in a reduction in the FRAS risk of falls score.

Continue to: Estrogen’s role in bone health and its therapeutic potential in osteosarcopenia...

Estrogen’s role in bone health and its therapeutic potential in osteosarcopenia

Mandelli A, Tacconi E, Levinger I, et al. The role of estrogens in osteosarcopenia: from biology to potential dual therapeutic effects. Climacteric. 2021;1-7. doi: 10.1080/13697137.2021.1965118.

Osteosarcopenia is a particular term used to describe the coexistence of 2 pathologies, osteopenia/ osteoporosis and sarcopenia.14 Sarcopenia is characterized by a loss of muscle mass, strength, and performance. Numerous studies indicate that higher lean body mass is related to increased BMD and reduced fracture risk, especially in postmenopausal women.15

Menopause, muscle, and estrogen’s physiologic effects

Estrogens play a critical role in maintaining bone and muscle mass in women. Women experience a decline in musculoskeletal quantity and quality at the onset of menopause.16 Muscle mass and strength decrease rapidly after menopause, which suggests that degradation of muscle protein begins to exert a more significant effect due to a decrease in protein synthesis. Indeed, a reduced response to anabolic stimuli has been shown in postmenopausal women.17 Normalization of the protein synthesis response after restoring estrogen levels with estrogen therapy supports this hypothesis.18

In a meta-analysis to identify the role of estrogen therapy on muscle strength, the authors concluded that estrogens benefit muscle strength not by increasing the skeletal mass but by improving muscle quality and its ability to generate force.19 In addition, however, it has been demonstrated that exercise prevents and delays the onset of osteosarcopenia.20

Estrogens play a crucial role in maintaining bone and skeletal muscle health in women. Estrogen therapy is an accepted treatment for osteoporosis, whereas its effects on sarcopenia, although promising, indicate that additional studies are required before it can be recommended solely for that purpose. Given the well-described benefits of exercise on muscle and bone health, postmenopausal women should be encouraged to engage in regular physical exercise as a preventive or disease-modifying treatment for osteosarcopenia.

When should bone mass be measured in premenopausal women?

Conradie M, de Villiers T. Premenopausal osteoporosis. Climacteric. 2021:1-14. doi: 10.1080/13697137 .2021.1926974.

Most women’s clinicians are somewhat well acquainted with the increasing importance of preventing, diagnosing, and treating postmenopausal osteoporosis, which predisposes to fragility fracture and the morbidity and even mortality that brings. Increasingly, some younger women are asking for and receiving both bone mass measurements that may be inappropriately ordered and/or wrongly interpreted. Conradie and de Villiers provided an overview of premenopausal osteoporosis, containing important facts that all clinicians who care for women should be aware of.21

Indications for testing

BMD testing is only indicated in younger women in settings in which the result may influence management decisions, such as:

- a history of fragility fracture

- diseases associated with low bone mass, such as anorexia nervosa, hypogonadism, hyperparathyroidism, hyperthyroidism, celiac disease, irritable bowel disease, rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, renal disease, Marfan syndrome

- medications, such as glucocorticoids, aromatase inhibitors, premenopausal tamoxifen, excess thyroid hormone replacement, progesterone contraception

- excessive alcohol consumption, heavy smoking, vitamin D deficiency, calcium deficiency, occasionally veganism or vegetarianism.

BMD interpretation in premenopausal women does not use the T-scores developed for postmenopausal women in which standard deviations (SD) from the mean for a young reference population are employed. In that population, the normal range is up to -1.0 SD; osteopenia > -1.0 < -2.5 SD; and osteoporosis > -2.5 SD. Instead, in premenopausal patients, Z-scores, which compare the measured bone mass to an age- and gender-matched cohort, are employed. Z-scores > 2 SD below the matched population should be used rather than the T-scores that are already familiar to most clinicians.

Up to 90% of these premenopausal women with such skeletal fragility will display the secondary causes described above. ●

Very specific indications are required to consider bone mass measurements in premenopausal women. When measurements are indicated, the values are evaluated by Z-scores that compare them to those of matched-aged women and not by T-scores meant for postmenopausal women. When fragility or low-trauma fractures or Z-scores more than 2 SD below their peers are present, secondary causes of premenopausal osteoporosis include a variety of disease states, medications, and lifestyle situations. When such factors are present, many general women’s health clinicians may want to refer patients for consultation to a metabolic bone specialist for workup and management.

Recently, the National Osteoporosis Foundation (NOF) changed its name to the Bone Health and Osteoporosis Foundation (BHOF). Several years ago, in 2016 at my urging, this column was renamed from “Update on osteoporosis” to “Update on bone health.” I believe we were on the leading edge of this movement. As expressed in last year’s Update, our patients’ bone health must be emphasized more than it has been in the past.1

Consider that localized breast cancer carries a 5-year survival rate of 99%.2 Most of my patients are keenly aware that periodic competent breast imaging is the key to the earliest possible diagnosis. By contrast, in this country a hip fracture carries a mortality in the first year of 21%!3 Furthermore, approximately one-third of women who fracture their hip do not have osteoporosis.4 While the risk of hip fracture is greatest in women with osteoporosis, it is not absent in those without the condition. Finally, the role of muscle mass, strength, and performance in bone health is a rapidly emerging topic and one that constitutes the core of this year’s Update.

Muscle mass and strength play key role in bone health

de Villiers TJ, Goldstein SR. Update on bone health: the International Menopause Society white paper 2021. Climacteric. 2021;24:498-504. doi:10.1080/13697137.2021.1950967.

Recently, de Villiers and Goldstein offered an overview of osteoporosis.5 What is worthy of reporting here is the role of muscle in bone health.

The bone-muscle relationship

Most clinicians know that osteoporosis and osteopenia are well-defined conditions with known risks associated with fracture. According to a review of PubMed, the first article with the keyword “osteoporosis” was published in 1894; through May 2020, 93,335 articles used that keyword. “Osteoporosis” is derived from the Greek osteon (bone) and poros (little hole). Thus, osteoporosis means “porous bone.”

Sarcopenia is characterized by progressive and generalized loss of skeletal muscle mass, strength, and function, and the condition is associated with a risk of adverse outcomes that include physical disabilities, poor quality of life, and death.6,7 “Sarcopenia” has its roots in the Greek words sarx (flesh) and penia (loss), and the term was coined in 1989.8 A PubMed review that included “sarcopenia” as the keyword revealed that the first article was published in 1993, with 12,068 articles published through May 2020.

Notably, muscle accounts for about 60% of the body’s protein. Muscle mass decreases with age, but younger patients with malnutrition, cachexia, or inflammatory diseases are also prone to decreased muscle mass. While osteoporosis has a well-accepted definition based on dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) measurements, sarcopenia has no universally accepted definition, consensus diagnostic criteria, or treatment guidelines. In 2016, however, the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (CD-10-CM) finally recognized sarcopenia as a disease entity.

Currently, the most widely accepted definition comes from the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People, which labeled presarcopenia as low muscle mass without impact on muscle strength or performance; sarcopenia as low muscle mass with either low muscle strength or low physical performance; and severe sarcopenia has all 3 criteria being present.9

When osteosarcopenia (osteoporosis or osteopenia combined with sarcopenia) exists, it can result in a threefold increase in risk of falls and a fourfold increase in fracture risk compared with women who have osteopenia or osteoporosis alone.10

The morbidity and mortality from fragility fractures are well known. Initially, diagnosis of risk seemed to be mainly T-scores on bone mineral density (BMD) testing (normal, osteopenic, osteoporosis). The FRAX fracture risk assessment tool, which includes a number of variables, further refined risk assessment. Increasingly, there is evidence of crosstalk between muscle and bone. Sarcopenia, the loss of skeletal muscle mass, strength, and performance, appears to play an important role as well for fracture risk. Simple tools to evaluate a patient’s muscle status exist. At the very least, resistance and balance exercises should be part of all clinicians’ patient counseling for bone health.

Continue to: Denosumab decreased falls risk, improved sarcopenia measures vs comparator antiresorptives...

Denosumab decreased falls risk, improved sarcopenia measures vs comparator antiresorptives

El Miedany Y, El Gaafary M, Toth M, et al; Egyptian Academy of Bone Health, Metabolic Bone Diseases. Is there a potential dual effect of denosumab for treatment of osteoporosis and sarcopenia? Clin Rheumatol. 2021;40:4225-4232. doi: 10.1007/s10067-021 -05757-w.

Osteosarcopenia, the combination of osteoporosis or osteopenia with sarcopenia, has been shown to increase the overall rate of falls and fracture when compared with fall and fracture rates in women with osteopenia or osteoporosis alone.10 A study by El Miedany and colleagues examined whether denosumab treatment had a possible dual therapeutic effect on osteoporosis and sarcopenia.11

Study details

The investigators looked at 135 patients diagnosed with postmenopausal osteoporosis and who were prescribed denosumab and compared them with a control group of 272 patients stratified into 2 subgroups: 136 were prescribed alendronate and 136 were prescribed zoledronate.

Assessments were performed for all participants for BMD (DXA), fall risk (falls risk assessment score [FRAS]), fracture risk (FRAX assessment tool), and sarcopenia measures. Reassessments were conducted after 5 years of denosumab or alendronate therapy, 3 years of zoledronate therapy, and 1 year after stopping the osteoporosis therapy.

The FRAS uses the clinical variables of history of falls in the last 12 months, impaired sight, weak hand grip, history of loss of balance in the last 12 months, and slowing of the walking speed/change in gait to yield a percent chance of sustaining a fall.12 Sarcopenic measures include grip strength, timed up and go (TUG) mobility test, and gait speed. There were no significant demographic differences between the 3 groups.

Denosumab reduced risk of falls and positively affected muscle strength

On completion of the 5-year denosumab therapy, falls risk was significantly decreased (P = .001) and significant improvements were seen in all sarcopenia measures (P = .01). One year after denosumab was discontinued, a significant worsening of both falls risk and sarcopenia measures (P = .01) occurred. This was in contrast to results in both control groups (alendronate and zoledronate), in which there was an improvement, although less robust in gait speed and the TUG test (P = .05) but no improvement in risk of falls. Thus, the results of this study showed that denosumab not only improved bone mass but also reduced falls risk.

Compared with bisphosphonates, denosumab showed the highest significant positive effect on both physical performance and skeletal muscle strength. This is evidenced by improvement of the gait speed, TUG test, and 4-m walk test (P<.001) in the denosumab group versus in the alendronate and zoledronate group (P<.05).

These results agree with the outcomes of the FREEDOM (Fracture Reduction Evaluation of Denosumab in Osteoporosis 6 months) trial, which revealed that not only did denosumab treatment reduce the risk of vertebral, nonvertebral, and hip fracture over 36 months, but also that the denosumab-treated group had fewer falls (4.5%) compared with the other groups (5.7%) (P = .02).13

These data highlight that osteoporosis and sarcopenia may share similar underlying risk factors and that muscle-bone interactions are important to minimize the risk of falls, fractures, and hospitalizations. While all 3 antiresorptives (denosumab, alendronate, zoledronate) improved measures of BMD and sarcopenia, only denosumab resulted in a reduction in the FRAS risk of falls score.

Continue to: Estrogen’s role in bone health and its therapeutic potential in osteosarcopenia...

Estrogen’s role in bone health and its therapeutic potential in osteosarcopenia

Mandelli A, Tacconi E, Levinger I, et al. The role of estrogens in osteosarcopenia: from biology to potential dual therapeutic effects. Climacteric. 2021;1-7. doi: 10.1080/13697137.2021.1965118.

Osteosarcopenia is a particular term used to describe the coexistence of 2 pathologies, osteopenia/ osteoporosis and sarcopenia.14 Sarcopenia is characterized by a loss of muscle mass, strength, and performance. Numerous studies indicate that higher lean body mass is related to increased BMD and reduced fracture risk, especially in postmenopausal women.15

Menopause, muscle, and estrogen’s physiologic effects

Estrogens play a critical role in maintaining bone and muscle mass in women. Women experience a decline in musculoskeletal quantity and quality at the onset of menopause.16 Muscle mass and strength decrease rapidly after menopause, which suggests that degradation of muscle protein begins to exert a more significant effect due to a decrease in protein synthesis. Indeed, a reduced response to anabolic stimuli has been shown in postmenopausal women.17 Normalization of the protein synthesis response after restoring estrogen levels with estrogen therapy supports this hypothesis.18

In a meta-analysis to identify the role of estrogen therapy on muscle strength, the authors concluded that estrogens benefit muscle strength not by increasing the skeletal mass but by improving muscle quality and its ability to generate force.19 In addition, however, it has been demonstrated that exercise prevents and delays the onset of osteosarcopenia.20

Estrogens play a crucial role in maintaining bone and skeletal muscle health in women. Estrogen therapy is an accepted treatment for osteoporosis, whereas its effects on sarcopenia, although promising, indicate that additional studies are required before it can be recommended solely for that purpose. Given the well-described benefits of exercise on muscle and bone health, postmenopausal women should be encouraged to engage in regular physical exercise as a preventive or disease-modifying treatment for osteosarcopenia.

When should bone mass be measured in premenopausal women?

Conradie M, de Villiers T. Premenopausal osteoporosis. Climacteric. 2021:1-14. doi: 10.1080/13697137 .2021.1926974.

Most women’s clinicians are somewhat well acquainted with the increasing importance of preventing, diagnosing, and treating postmenopausal osteoporosis, which predisposes to fragility fracture and the morbidity and even mortality that brings. Increasingly, some younger women are asking for and receiving both bone mass measurements that may be inappropriately ordered and/or wrongly interpreted. Conradie and de Villiers provided an overview of premenopausal osteoporosis, containing important facts that all clinicians who care for women should be aware of.21

Indications for testing

BMD testing is only indicated in younger women in settings in which the result may influence management decisions, such as:

- a history of fragility fracture

- diseases associated with low bone mass, such as anorexia nervosa, hypogonadism, hyperparathyroidism, hyperthyroidism, celiac disease, irritable bowel disease, rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, renal disease, Marfan syndrome

- medications, such as glucocorticoids, aromatase inhibitors, premenopausal tamoxifen, excess thyroid hormone replacement, progesterone contraception

- excessive alcohol consumption, heavy smoking, vitamin D deficiency, calcium deficiency, occasionally veganism or vegetarianism.

BMD interpretation in premenopausal women does not use the T-scores developed for postmenopausal women in which standard deviations (SD) from the mean for a young reference population are employed. In that population, the normal range is up to -1.0 SD; osteopenia > -1.0 < -2.5 SD; and osteoporosis > -2.5 SD. Instead, in premenopausal patients, Z-scores, which compare the measured bone mass to an age- and gender-matched cohort, are employed. Z-scores > 2 SD below the matched population should be used rather than the T-scores that are already familiar to most clinicians.

Up to 90% of these premenopausal women with such skeletal fragility will display the secondary causes described above. ●

Very specific indications are required to consider bone mass measurements in premenopausal women. When measurements are indicated, the values are evaluated by Z-scores that compare them to those of matched-aged women and not by T-scores meant for postmenopausal women. When fragility or low-trauma fractures or Z-scores more than 2 SD below their peers are present, secondary causes of premenopausal osteoporosis include a variety of disease states, medications, and lifestyle situations. When such factors are present, many general women’s health clinicians may want to refer patients for consultation to a metabolic bone specialist for workup and management.

- Goldstein SR. Update on bone health. OBG Manag. 2020;32:16-20, 22-23.

- American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2020. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2020. https://www .cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts -and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2020/cancer -facts-and-figures-2020.pdf. Accessed November 11, 2021.

- Downey C, Kelly M, Quinlan JF. Changing trends in the mortality rate at 1-year post hip fracture—a systematic review. World J Orthop. 2019;10:166-175.

- Schuit SC, van der Klift M, Weel AE, et al. Fracture incidence and association with bone mineral density in elderly men and women: the Rotterdam Study. Bone. 2004;34:195-202.

- de Villiers, TJ, Goldstein SR. Update on bone health: the International Menopause Society white paper 2021. Climacteric. 2021;24:498-504.

- Goodpaster BH, Park SW, Harris TB, et al. The loss of skeletal muscle strength, mass, and quality in older adults: the health, aging and body composition study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006;61:1059-1064.

- Santilli V, Bernetti A, Mangone M, et al. Clinical definition of sarcopenia. Clin Cases Miner Bone Metab. 2014;11:177-180.

- Rosenberg I. Epidemiological and methodological problems in determining nutritional status of older persons. Proceedings of a conference. Albuquerque, New Mexico, October 19-21, 1989. Am J Clin Nutr. 1989;50:1231-1233.

- Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Baeyens JP, Bauer JM, et al; European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People. Sarcopenia: European consensus on definition and diagnosis—report of the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People. Age Ageing. 2010;39:412-423.

- Sepúlveda-Loyola W, Phu S, Bani Hassan E, et al. The joint occurrence of osteoporosis and sarcopenia (osteosarcopenia): definitions and characteristics. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21:220-225.

- El Miedany Y, El Gaafary M, Toth M, et al; Egyptian Academy of Bone Health, Metabolic Bone Diseases. Is there a potential dual effect of denosumab for treatment of osteoporosis and sarcopenia? Clin Rheumatol. 2021;40:4225-4232.

- El Miedany Y, El Gaafary M, Toth M, et al. Falls risk assessment score (FRAS): time to rethink. J Clin Gerontol Geriatr. 2011;21-26.

- Cummings SR, Martin JS, McClung MR, et al; FREEDOM Trial. Denosumab for prevention of fractures in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 2009;361: 756-765.

- Inoue T, Maeda K, Nagano A, et al. Related factors and clinical outcomes of osteosarcopenia: a narrative review. Nutrients. 2021;13:291.

- Kaji H. Linkage between muscle and bone: common catabolic signals resulting in osteoporosis and sarcopenia. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2013;16:272-277.

- Sipilä S, Törmäkangas T, Sillanpää E, et al. Muscle and bone mass in middle‐aged women: role of menopausal status and physical activity. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2020;11: 698-709.

- Bamman MM, Hill VJ, Adams GR, et al. Gender differences in resistance-training-induced myofiber hypertrophy among older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2003;58:108-116.

- Hansen M, Skovgaard D, Reitelseder S, et al. Effects of estrogen replacement and lower androgen status on skeletal muscle collagen and myofibrillar protein synthesis in postmenopausal women. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2012;67:1005-1013.

- Greising SM, Baltgalvis KA, Lowe DA, et al. Hormone therapy and skeletal muscle strength: a meta-analysis. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;64:1071-1081.

- Cariati I, Bonanni R, Onorato F, et al. Role of physical activity in bone-muscle crosstalk: biological aspects and clinical implications. J Funct Morphol Kinesiol. 2021;6:55.

- Conradie M, de Villiers T. Premenopausal osteoporosis. Climacteric. 2021:1-14.

- Goldstein SR. Update on bone health. OBG Manag. 2020;32:16-20, 22-23.

- American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2020. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2020. https://www .cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts -and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2020/cancer -facts-and-figures-2020.pdf. Accessed November 11, 2021.

- Downey C, Kelly M, Quinlan JF. Changing trends in the mortality rate at 1-year post hip fracture—a systematic review. World J Orthop. 2019;10:166-175.

- Schuit SC, van der Klift M, Weel AE, et al. Fracture incidence and association with bone mineral density in elderly men and women: the Rotterdam Study. Bone. 2004;34:195-202.

- de Villiers, TJ, Goldstein SR. Update on bone health: the International Menopause Society white paper 2021. Climacteric. 2021;24:498-504.

- Goodpaster BH, Park SW, Harris TB, et al. The loss of skeletal muscle strength, mass, and quality in older adults: the health, aging and body composition study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006;61:1059-1064.

- Santilli V, Bernetti A, Mangone M, et al. Clinical definition of sarcopenia. Clin Cases Miner Bone Metab. 2014;11:177-180.

- Rosenberg I. Epidemiological and methodological problems in determining nutritional status of older persons. Proceedings of a conference. Albuquerque, New Mexico, October 19-21, 1989. Am J Clin Nutr. 1989;50:1231-1233.

- Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Baeyens JP, Bauer JM, et al; European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People. Sarcopenia: European consensus on definition and diagnosis—report of the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People. Age Ageing. 2010;39:412-423.

- Sepúlveda-Loyola W, Phu S, Bani Hassan E, et al. The joint occurrence of osteoporosis and sarcopenia (osteosarcopenia): definitions and characteristics. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21:220-225.

- El Miedany Y, El Gaafary M, Toth M, et al; Egyptian Academy of Bone Health, Metabolic Bone Diseases. Is there a potential dual effect of denosumab for treatment of osteoporosis and sarcopenia? Clin Rheumatol. 2021;40:4225-4232.

- El Miedany Y, El Gaafary M, Toth M, et al. Falls risk assessment score (FRAS): time to rethink. J Clin Gerontol Geriatr. 2011;21-26.

- Cummings SR, Martin JS, McClung MR, et al; FREEDOM Trial. Denosumab for prevention of fractures in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 2009;361: 756-765.

- Inoue T, Maeda K, Nagano A, et al. Related factors and clinical outcomes of osteosarcopenia: a narrative review. Nutrients. 2021;13:291.

- Kaji H. Linkage between muscle and bone: common catabolic signals resulting in osteoporosis and sarcopenia. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2013;16:272-277.

- Sipilä S, Törmäkangas T, Sillanpää E, et al. Muscle and bone mass in middle‐aged women: role of menopausal status and physical activity. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2020;11: 698-709.

- Bamman MM, Hill VJ, Adams GR, et al. Gender differences in resistance-training-induced myofiber hypertrophy among older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2003;58:108-116.

- Hansen M, Skovgaard D, Reitelseder S, et al. Effects of estrogen replacement and lower androgen status on skeletal muscle collagen and myofibrillar protein synthesis in postmenopausal women. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2012;67:1005-1013.

- Greising SM, Baltgalvis KA, Lowe DA, et al. Hormone therapy and skeletal muscle strength: a meta-analysis. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;64:1071-1081.

- Cariati I, Bonanni R, Onorato F, et al. Role of physical activity in bone-muscle crosstalk: biological aspects and clinical implications. J Funct Morphol Kinesiol. 2021;6:55.

- Conradie M, de Villiers T. Premenopausal osteoporosis. Climacteric. 2021:1-14.

Cancer risk-reducing strategies: Focus on chemoprevention

In her presentation at The North American Menopause Society (NAMS) 2021 annual meeting (September 22–25, 2021, in Washington, DC), Dr. Holly J. Pederson offered her expert perspectives on breast cancer prevention in at-risk women in “Chemoprevention for risk reduction: Women’s health clinicians have a role.”

Which patients would benefit from chemoprevention?

Holly J. Pederson, MD: Obviously, women with significant family history are at risk. And approximately 10% of biopsies that are done for other reasons incidentally show atypical hyperplasia (AH) or lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS)—which are not precancers or cancers but are markers for the development of the disease—and they markedly increase risk. Atypical hyperplasia confers a 30% risk for developing breast cancer over the next 25 years, and LCIS is associated with up to a 2% per year risk. In this setting, preventive medication has been shown to cut risk by 56% to 86%; this is a targeted population that is often overlooked.

Mathematical risk models can be used to assess risk by assessing women’s risk factors. The United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) has set forth a threshold at which they believe the benefits outweigh the risks of preventive medications. That threshold is 3% or greater over the next 5 years using the Gail breast cancer risk assessment tool.1 The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) uses the Tyrer-Cuzick breast cancer risk evaluation model with a threshold of 5% over the next 10 years.2 In general, those are the situations in which chemoprevention is a no-brainer.

Certain genetic mutations also predispose to estrogen-sensitive breast cancer. While preventive medications specifically have not been studied in large groups of gene carriers, chemoprevention makes sense because these medications prevent estrogen-sensitive breast cancers that those patients are prone to. Examples would be patients with ATM and CHEK2 gene mutations, which are very common, and patients with BRCA2 and even BRCA1 variants in the postmenopausal years. Those are the big targets.

Risk assessment models

Dr. Pederson: Yes, I almost exclusively use the Tyrer-Cuzick risk model, version 8, which incorporates breast density. This model is intimidating to some practitioners initially, but once you get used to it, you can complete it very quickly.

The Gail model is very limited. It assesses only first-degree relatives, so you don’t get the paternal information at all, and you don’t use age at diagnosis, family structure, genetic testing, results of breast density, or body mass index (BMI). There are many limitations of the Gail model, but most people use it because it is so easy and they are familiar with it.

Possibly the best model is the CanRisk tool, which incorporates the Breast and Ovarian Analysis of Disease Incidence and Carrier Estimation Algorithm (BOADICEA), but it takes too much time to use in clinic; it’s too complicated. The Tyrer-Cuzick model is easy to use once you get used to it.

Dr. Pederson: Risk doesn’t always need to be formally calculated, which can be time-consuming. It’s one of those situations where most practitioners know it when they see it. Benign atypical biopsies, a strong family history, or, obviously, the presence of a genetic mutation are huge red flags.

If a practitioner has a nearby high-risk center where they can refer patients, that can be so useful, even for a one-time consultation to guide management. For example, with the virtual world now, I do a lot of consultations for patients and outline a plan, and then the referring practitioner can carry out the plan with confidence and then send the patient back periodically. There are so many more options now that previously did not exist for the busy ObGyn or primary care provider to rely on.

Continue to: Chemoprevention uptake in at-risk women...

Chemoprevention uptake in at-risk women

Dr. Pederson: We really never practice medicine using numbers. We use clinical judgment, and we use relationships with patients in terms of developing confidence and trust. I think that the uptake that we exhibit in our center probably is more based on the patients’ perception that we are confident in our recommendations. I think that many practitioners simply are not comfortable with explaining medications, explaining and managing adverse effects, and using alternative medications. While the modeling helps, I think the personal expertise really makes the difference.

Going forward, the addition of the polygenic risk score to the mathematical risk models is going to make a big difference. Right now, the mathematical risk model is simply that: it takes the traditional risk factors that a patient has and spits out a number. But adding the patient’s genomic data—that is, a weighted summation of SNPs, or single nucleotide polymorphisms, now numbering over 300 for breast cancer—can explain more about their personalized risk, which is going to be more powerful in influencing a woman to take medication or not to take medication, in my opinion. Knowing their actual genomic risk will be a big step forward in individualized risk stratification and increased medication uptake as well as vigilance with high risk screening and attention to diet, exercise, and drinking alcohol in moderation.

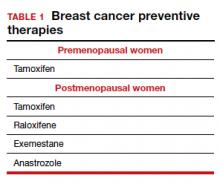

Dr. Pederson: The only drug that can be used in the premenopausal setting is tamoxifen (TABLE 1). Women can’t take it if they are pregnant, planning to become pregnant, or if they don’t use a reliable form of birth control because it is teratogenic. Women also cannot take tamoxifen if they have had a history of blood clots, stroke, or transient ischemic attack; if they are on warfarin or estrogen preparations; or if they have had atypical endometrial biopsies or endometrial cancer. Those are the absolute contraindications for tamoxifen use.

Tamoxifen is generally very well tolerated in most women; some women experience hot flashes and night sweats that often will subside (or become tolerable) over the first 90 days. In addition, some women experience vaginal discharge rather than dryness, but it is not as bothersome to patients as dryness can be.

Tamoxifen can be used in the pre- or postmenopausal setting. In healthy premenopausal women, there’s no increased risk of the serious adverse effects that are seen with tamoxifen use in postmenopausal women, such as the 1% risk of blood clots and the 1% risk of endometrial cancer.

In postmenopausal women who still have their uterus, I’ll preferentially use raloxifene over tamoxifen. If they don’t have their uterus, tamoxifen is slightly more effective than the raloxifene, and I’ll use that.

Tamoxifen and raloxifene are both selective estrogen receptor modulators, or SERMs, which means that they stimulate receptors in some tissues, like bone, keeping bones strong, and block the receptors in other tissues, like the breast, reducing risk. And so you get kind of a two-for-one in terms of breast cancer risk reduction and osteoporosis prevention.

Another class of preventive drugs is the aromatase inhibitors (AIs). They block the enzyme aromatase, which converts androgens to estrogens peripherally; that is, the androgens that are produced primarily in the adrenal gland, but in part in postmenopausal ovaries.

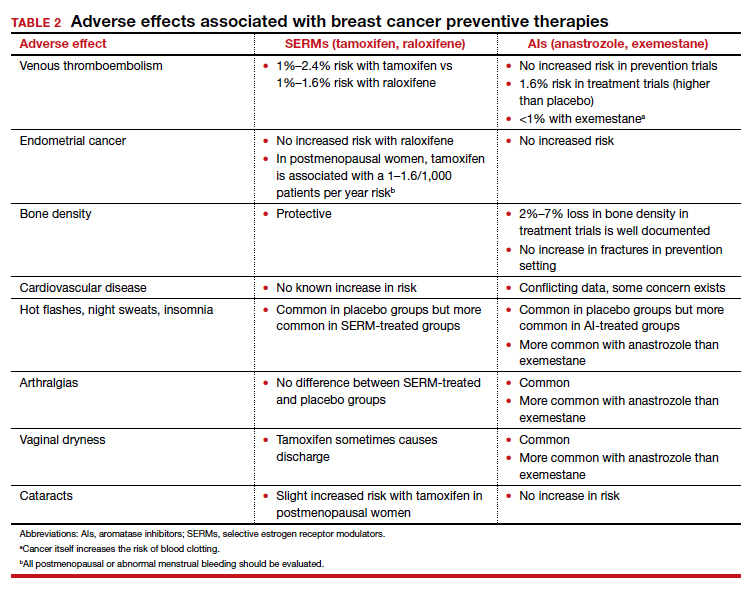

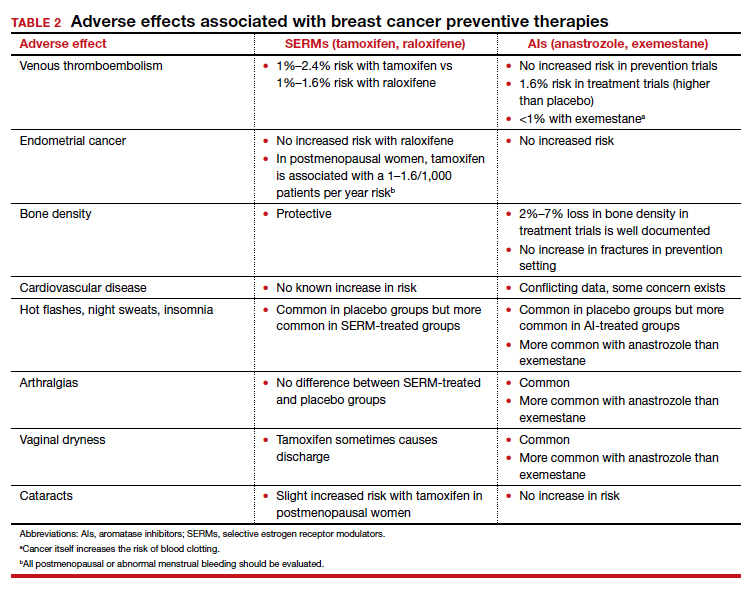

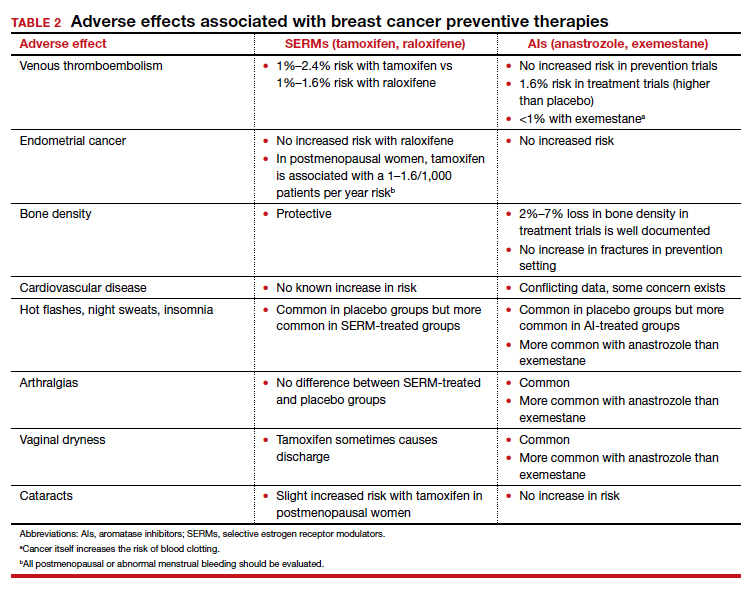

In general, AIs are less well tolerated. There are generally more hot flashes and night sweats, and more vaginal dryness than with the SERMs. Anastrozole use is associated with arthralgias; and with exemestane use, there can be some hair loss (TABLE 2). Relative contraindications to SERMs become more important in the postmenopausal setting because of the increased frequency of both blood clots and uterine cancer in the postmenopausal years. I won’t give it to smokers. I won’t give tamoxifen to smokers in the premenopausal period either. With obese women, care must be taken because of the risk of blood clots with the SERMS, so then I’ll resort to the AIs. In the postmenopausal setting, you have to think a lot harder about the choices you use for preventive medication. Preferentially, I’ll use the SERMS if possible as they have fewer adverse effects.

Dr. Pederson: All of them are recommended to be given for 5 years, but the MAP.3 trial, which studied exemestane compared with placebo, showed a 65% risk reduction with 3 years of therapy.3 So occasionally, we’ll use 3 years of therapy. Why the treatment recommendation is universally 5 years is unclear, given that the trial with that particular drug was done in 3 years. And with low-dose tamoxifen, the recommended duration is 3 years. That study was done in Italy with 5 mg daily for 3 years.4 In the United States we use 10 mg every other day for 3 years because the 5-mg tablet is not available here.

Continue to: Counseling points...

Counseling points

Dr. Pederson: Patients’ fears about adverse effects are often worse than the adverse effects themselves. Women will fester over, Should I take it? Should I take it possibly for years? And then they take the medication and they tell me, “I don’t even notice that I’m taking it, and I know I’m being proactive.” The majority of patients who take these medications don’t have a lot of significant adverse effects.

Severe hot flashes can be managed in a number of ways, primarily and most effectively with certain antidepressants. Oxybutynin use is another good way to manage vasomotor symptoms. Sometimes we use local vaginal estrogen if a patient has vaginal dryness. In general, however, I would say at least 80% of my patients who take preventive medications do not require management of adverse side effects, that they are tolerable.

I counsel women this way, “Don’t think of this as a 5-year course of medication. Think of it as a 90-day trial, and let’s see how you do. If you hate it, then we don’t do it.” They often are pleasantly surprised that the medication is much easier to tolerate than they thought it would be.

Dr. Pederson: It would be neat if a trial would directly compare lifestyle interventions with medications, because probably lifestyle change is as effective as medication is—but we don’t know that and probably will never have that data. We do know that alcohol consumption, every drink per day, increases risk by 10%. We know that obesity is responsible for 30% of breast cancers in this country, and that hormone replacement probably is overrated as a significant risk factor. Updated data from the Women’s Health Initiative study suggest that hormone replacement may actually reduce both breast cancer and cardiovascular risk in women in their 50s, but that’s in average-risk women and not in high-risk women, so we can’t generalize. We do recommend lifestyle measures including weight loss, exercise, and limiting alcohol consumption for all of our patients and certainly for our high-risk patients.

The only 2 things a woman can do to reduce the risk of triple negative breast cancer are to achieve and maintain ideal body weight and to breastfeed. The medications that I have mentioned don’t reduce the risk of triple negative breast cancer. Staying thin and breastfeeding do. It’s a problem in this country because at least 35% of all women and 58% of Black women are obese in America, and Black women tend to be prone to triple-negative breast cancer. That’s a real public health issue that we need to address. If we were going to focus on one thing, it would be focusing on obesity in terms of risk reduction.

Final thoughts

Dr. Pederson: I would like to direct attention to the American Heart Association scientific statement published at the end of 2020 that reported that hormone replacement in average-risk women reduced both cardiovascular events and overall mortality in women in their 50s by 30%.5 While that’s not directly related to what we are talking about, we need to weigh the pros and cons of estrogen versus estrogen blockade in women in terms of breast cancer risk management discussions. Part of shared decision making now needs to include cardiovascular risk factors and how estrogen is going to play into that.

In women with atypical hyperplasia or LCIS, they may benefit from the preventive medications we discussed. But in women with family history or in women with genetic mutations who have not had benign atypical biopsies, they may choose to consider estrogen during their 50s and perhaps take tamoxifen either beforehand or raloxifene afterward.

We need to look at patients holistically and consider all their risk factors together. We can’t look at one dimension alone.

- US Preventive Services Task Force. Medication use to reduce risk of breast cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2019;322:857-867.

- Visvanathan K, Fabian CJ, Bantug E, et al. Use of endocrine therapy for breast cancer risk reduction: ASCO clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37:3152-3165.

- Goss PE, Ingle JN, Alex-Martinez JE, et al. Exemestane for breast-cancer prevention in postmenopausal women. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2381-2391.

- DeCensi A, Puntoni M, Guerrieri-Gonzaga A, et al. Randomized placebo controlled trial of low-dose tamoxifen to prevent local and contralateral recurrence in breast intraepithelial neoplasia. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37:1629-1637.

- El Khoudary SR, Aggarwal B, Beckie TM, et al; American Heart Association Prevention Science Committee of the Council on Epidemiology and Prevention, and Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing. Menopause transition and cardiovascular disease risk: implications for timing of early prevention: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020;142:e506-e532.

In her presentation at The North American Menopause Society (NAMS) 2021 annual meeting (September 22–25, 2021, in Washington, DC), Dr. Holly J. Pederson offered her expert perspectives on breast cancer prevention in at-risk women in “Chemoprevention for risk reduction: Women’s health clinicians have a role.”

Which patients would benefit from chemoprevention?

Holly J. Pederson, MD: Obviously, women with significant family history are at risk. And approximately 10% of biopsies that are done for other reasons incidentally show atypical hyperplasia (AH) or lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS)—which are not precancers or cancers but are markers for the development of the disease—and they markedly increase risk. Atypical hyperplasia confers a 30% risk for developing breast cancer over the next 25 years, and LCIS is associated with up to a 2% per year risk. In this setting, preventive medication has been shown to cut risk by 56% to 86%; this is a targeted population that is often overlooked.

Mathematical risk models can be used to assess risk by assessing women’s risk factors. The United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) has set forth a threshold at which they believe the benefits outweigh the risks of preventive medications. That threshold is 3% or greater over the next 5 years using the Gail breast cancer risk assessment tool.1 The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) uses the Tyrer-Cuzick breast cancer risk evaluation model with a threshold of 5% over the next 10 years.2 In general, those are the situations in which chemoprevention is a no-brainer.

Certain genetic mutations also predispose to estrogen-sensitive breast cancer. While preventive medications specifically have not been studied in large groups of gene carriers, chemoprevention makes sense because these medications prevent estrogen-sensitive breast cancers that those patients are prone to. Examples would be patients with ATM and CHEK2 gene mutations, which are very common, and patients with BRCA2 and even BRCA1 variants in the postmenopausal years. Those are the big targets.

Risk assessment models

Dr. Pederson: Yes, I almost exclusively use the Tyrer-Cuzick risk model, version 8, which incorporates breast density. This model is intimidating to some practitioners initially, but once you get used to it, you can complete it very quickly.

The Gail model is very limited. It assesses only first-degree relatives, so you don’t get the paternal information at all, and you don’t use age at diagnosis, family structure, genetic testing, results of breast density, or body mass index (BMI). There are many limitations of the Gail model, but most people use it because it is so easy and they are familiar with it.

Possibly the best model is the CanRisk tool, which incorporates the Breast and Ovarian Analysis of Disease Incidence and Carrier Estimation Algorithm (BOADICEA), but it takes too much time to use in clinic; it’s too complicated. The Tyrer-Cuzick model is easy to use once you get used to it.

Dr. Pederson: Risk doesn’t always need to be formally calculated, which can be time-consuming. It’s one of those situations where most practitioners know it when they see it. Benign atypical biopsies, a strong family history, or, obviously, the presence of a genetic mutation are huge red flags.

If a practitioner has a nearby high-risk center where they can refer patients, that can be so useful, even for a one-time consultation to guide management. For example, with the virtual world now, I do a lot of consultations for patients and outline a plan, and then the referring practitioner can carry out the plan with confidence and then send the patient back periodically. There are so many more options now that previously did not exist for the busy ObGyn or primary care provider to rely on.

Continue to: Chemoprevention uptake in at-risk women...

Chemoprevention uptake in at-risk women

Dr. Pederson: We really never practice medicine using numbers. We use clinical judgment, and we use relationships with patients in terms of developing confidence and trust. I think that the uptake that we exhibit in our center probably is more based on the patients’ perception that we are confident in our recommendations. I think that many practitioners simply are not comfortable with explaining medications, explaining and managing adverse effects, and using alternative medications. While the modeling helps, I think the personal expertise really makes the difference.

Going forward, the addition of the polygenic risk score to the mathematical risk models is going to make a big difference. Right now, the mathematical risk model is simply that: it takes the traditional risk factors that a patient has and spits out a number. But adding the patient’s genomic data—that is, a weighted summation of SNPs, or single nucleotide polymorphisms, now numbering over 300 for breast cancer—can explain more about their personalized risk, which is going to be more powerful in influencing a woman to take medication or not to take medication, in my opinion. Knowing their actual genomic risk will be a big step forward in individualized risk stratification and increased medication uptake as well as vigilance with high risk screening and attention to diet, exercise, and drinking alcohol in moderation.

Dr. Pederson: The only drug that can be used in the premenopausal setting is tamoxifen (TABLE 1). Women can’t take it if they are pregnant, planning to become pregnant, or if they don’t use a reliable form of birth control because it is teratogenic. Women also cannot take tamoxifen if they have had a history of blood clots, stroke, or transient ischemic attack; if they are on warfarin or estrogen preparations; or if they have had atypical endometrial biopsies or endometrial cancer. Those are the absolute contraindications for tamoxifen use.

Tamoxifen is generally very well tolerated in most women; some women experience hot flashes and night sweats that often will subside (or become tolerable) over the first 90 days. In addition, some women experience vaginal discharge rather than dryness, but it is not as bothersome to patients as dryness can be.

Tamoxifen can be used in the pre- or postmenopausal setting. In healthy premenopausal women, there’s no increased risk of the serious adverse effects that are seen with tamoxifen use in postmenopausal women, such as the 1% risk of blood clots and the 1% risk of endometrial cancer.

In postmenopausal women who still have their uterus, I’ll preferentially use raloxifene over tamoxifen. If they don’t have their uterus, tamoxifen is slightly more effective than the raloxifene, and I’ll use that.

Tamoxifen and raloxifene are both selective estrogen receptor modulators, or SERMs, which means that they stimulate receptors in some tissues, like bone, keeping bones strong, and block the receptors in other tissues, like the breast, reducing risk. And so you get kind of a two-for-one in terms of breast cancer risk reduction and osteoporosis prevention.

Another class of preventive drugs is the aromatase inhibitors (AIs). They block the enzyme aromatase, which converts androgens to estrogens peripherally; that is, the androgens that are produced primarily in the adrenal gland, but in part in postmenopausal ovaries.

In general, AIs are less well tolerated. There are generally more hot flashes and night sweats, and more vaginal dryness than with the SERMs. Anastrozole use is associated with arthralgias; and with exemestane use, there can be some hair loss (TABLE 2). Relative contraindications to SERMs become more important in the postmenopausal setting because of the increased frequency of both blood clots and uterine cancer in the postmenopausal years. I won’t give it to smokers. I won’t give tamoxifen to smokers in the premenopausal period either. With obese women, care must be taken because of the risk of blood clots with the SERMS, so then I’ll resort to the AIs. In the postmenopausal setting, you have to think a lot harder about the choices you use for preventive medication. Preferentially, I’ll use the SERMS if possible as they have fewer adverse effects.

Dr. Pederson: All of them are recommended to be given for 5 years, but the MAP.3 trial, which studied exemestane compared with placebo, showed a 65% risk reduction with 3 years of therapy.3 So occasionally, we’ll use 3 years of therapy. Why the treatment recommendation is universally 5 years is unclear, given that the trial with that particular drug was done in 3 years. And with low-dose tamoxifen, the recommended duration is 3 years. That study was done in Italy with 5 mg daily for 3 years.4 In the United States we use 10 mg every other day for 3 years because the 5-mg tablet is not available here.

Continue to: Counseling points...

Counseling points

Dr. Pederson: Patients’ fears about adverse effects are often worse than the adverse effects themselves. Women will fester over, Should I take it? Should I take it possibly for years? And then they take the medication and they tell me, “I don’t even notice that I’m taking it, and I know I’m being proactive.” The majority of patients who take these medications don’t have a lot of significant adverse effects.

Severe hot flashes can be managed in a number of ways, primarily and most effectively with certain antidepressants. Oxybutynin use is another good way to manage vasomotor symptoms. Sometimes we use local vaginal estrogen if a patient has vaginal dryness. In general, however, I would say at least 80% of my patients who take preventive medications do not require management of adverse side effects, that they are tolerable.

I counsel women this way, “Don’t think of this as a 5-year course of medication. Think of it as a 90-day trial, and let’s see how you do. If you hate it, then we don’t do it.” They often are pleasantly surprised that the medication is much easier to tolerate than they thought it would be.

Dr. Pederson: It would be neat if a trial would directly compare lifestyle interventions with medications, because probably lifestyle change is as effective as medication is—but we don’t know that and probably will never have that data. We do know that alcohol consumption, every drink per day, increases risk by 10%. We know that obesity is responsible for 30% of breast cancers in this country, and that hormone replacement probably is overrated as a significant risk factor. Updated data from the Women’s Health Initiative study suggest that hormone replacement may actually reduce both breast cancer and cardiovascular risk in women in their 50s, but that’s in average-risk women and not in high-risk women, so we can’t generalize. We do recommend lifestyle measures including weight loss, exercise, and limiting alcohol consumption for all of our patients and certainly for our high-risk patients.

The only 2 things a woman can do to reduce the risk of triple negative breast cancer are to achieve and maintain ideal body weight and to breastfeed. The medications that I have mentioned don’t reduce the risk of triple negative breast cancer. Staying thin and breastfeeding do. It’s a problem in this country because at least 35% of all women and 58% of Black women are obese in America, and Black women tend to be prone to triple-negative breast cancer. That’s a real public health issue that we need to address. If we were going to focus on one thing, it would be focusing on obesity in terms of risk reduction.

Final thoughts

Dr. Pederson: I would like to direct attention to the American Heart Association scientific statement published at the end of 2020 that reported that hormone replacement in average-risk women reduced both cardiovascular events and overall mortality in women in their 50s by 30%.5 While that’s not directly related to what we are talking about, we need to weigh the pros and cons of estrogen versus estrogen blockade in women in terms of breast cancer risk management discussions. Part of shared decision making now needs to include cardiovascular risk factors and how estrogen is going to play into that.

In women with atypical hyperplasia or LCIS, they may benefit from the preventive medications we discussed. But in women with family history or in women with genetic mutations who have not had benign atypical biopsies, they may choose to consider estrogen during their 50s and perhaps take tamoxifen either beforehand or raloxifene afterward.

We need to look at patients holistically and consider all their risk factors together. We can’t look at one dimension alone.

In her presentation at The North American Menopause Society (NAMS) 2021 annual meeting (September 22–25, 2021, in Washington, DC), Dr. Holly J. Pederson offered her expert perspectives on breast cancer prevention in at-risk women in “Chemoprevention for risk reduction: Women’s health clinicians have a role.”

Which patients would benefit from chemoprevention?

Holly J. Pederson, MD: Obviously, women with significant family history are at risk. And approximately 10% of biopsies that are done for other reasons incidentally show atypical hyperplasia (AH) or lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS)—which are not precancers or cancers but are markers for the development of the disease—and they markedly increase risk. Atypical hyperplasia confers a 30% risk for developing breast cancer over the next 25 years, and LCIS is associated with up to a 2% per year risk. In this setting, preventive medication has been shown to cut risk by 56% to 86%; this is a targeted population that is often overlooked.

Mathematical risk models can be used to assess risk by assessing women’s risk factors. The United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) has set forth a threshold at which they believe the benefits outweigh the risks of preventive medications. That threshold is 3% or greater over the next 5 years using the Gail breast cancer risk assessment tool.1 The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) uses the Tyrer-Cuzick breast cancer risk evaluation model with a threshold of 5% over the next 10 years.2 In general, those are the situations in which chemoprevention is a no-brainer.