User login

Indoor masking needed in almost 70% of U.S. counties: CDC data

In announcing new guidance on July 27, the CDC said vaccinated people should wear face masks in indoor public places with “high” or “substantial” community transmission rates of COVID-19.

Data from the CDC shows that designation covers 69.3% of all counties in the United States – 52.2% (1,680 counties) with high community transmission rates and 17.1% (551 counties) with substantial rates.

A county has “high transmission” if it reports 100 or more weekly cases per 100,000 residents or a 10% or higher test positivity rate in the last 7 days, the CDC said. “Substantial transmission” means a county reports 50-99 weekly cases per 100,000 residents or has a positivity rate between 8% and 9.9% in the last 7 days.

About 23% of U.S. counties had moderate rates of community transmission, and 7.67% had low rates.

To find out the transmission rate in your county, go to the CDC COVID data tracker.

Smithsonian requiring masks again

The Smithsonian now requires all visitors over age 2, regardless of vaccination status, to wear face masks indoors and in all museum spaces.

The Smithsonian said in a news release that fully vaccinated visitors won’t have to wear masks at the National Zoo or outdoor gardens for museums.

The new rule goes into effect Aug. 6. It reverses a rule that said fully vaccinated visitors didn’t have to wear masks indoors beginning June 28.

Indoor face masks will be required throughout the District of Columbia beginning July 31., D.C. Mayor Muriel Bowser.

House Republicans protest face mask policy

About 40 maskless Republican members of the U.S. House of Representatives filed onto the Senate floor on July 29 to protest a new rule requiring House members to wear face masks, the Hill reported.

Congress’s attending doctor said in a memo that the 435 members of the House, plus workers, must wear masks indoors, but not the 100 members of the Senate. The Senate is a smaller body and has had better mask compliance than the House.

Rep. Ronny Jackson (R-Tex.), told the Hill that Republicans wanted to show “what it was like on the floor of the Senate versus the floor of the House. Obviously, it’s vastly different.”

Among the group of Republicans who filed onto the Senate floor were Rep. Lauren Boebert of Colorado, Rep. Matt Gaetz and Rep. Byron Donalds of Florida, Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene of Georgia, Rep. Chip Roy and Rep. Louie Gohmert of Texas, Rep. Madison Cawthorn of North Carolina, Rep. Warren Davidson of Ohio, and Rep. Andy Biggs of Arizona.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

In announcing new guidance on July 27, the CDC said vaccinated people should wear face masks in indoor public places with “high” or “substantial” community transmission rates of COVID-19.

Data from the CDC shows that designation covers 69.3% of all counties in the United States – 52.2% (1,680 counties) with high community transmission rates and 17.1% (551 counties) with substantial rates.

A county has “high transmission” if it reports 100 or more weekly cases per 100,000 residents or a 10% or higher test positivity rate in the last 7 days, the CDC said. “Substantial transmission” means a county reports 50-99 weekly cases per 100,000 residents or has a positivity rate between 8% and 9.9% in the last 7 days.

About 23% of U.S. counties had moderate rates of community transmission, and 7.67% had low rates.

To find out the transmission rate in your county, go to the CDC COVID data tracker.

Smithsonian requiring masks again

The Smithsonian now requires all visitors over age 2, regardless of vaccination status, to wear face masks indoors and in all museum spaces.

The Smithsonian said in a news release that fully vaccinated visitors won’t have to wear masks at the National Zoo or outdoor gardens for museums.

The new rule goes into effect Aug. 6. It reverses a rule that said fully vaccinated visitors didn’t have to wear masks indoors beginning June 28.

Indoor face masks will be required throughout the District of Columbia beginning July 31., D.C. Mayor Muriel Bowser.

House Republicans protest face mask policy

About 40 maskless Republican members of the U.S. House of Representatives filed onto the Senate floor on July 29 to protest a new rule requiring House members to wear face masks, the Hill reported.

Congress’s attending doctor said in a memo that the 435 members of the House, plus workers, must wear masks indoors, but not the 100 members of the Senate. The Senate is a smaller body and has had better mask compliance than the House.

Rep. Ronny Jackson (R-Tex.), told the Hill that Republicans wanted to show “what it was like on the floor of the Senate versus the floor of the House. Obviously, it’s vastly different.”

Among the group of Republicans who filed onto the Senate floor were Rep. Lauren Boebert of Colorado, Rep. Matt Gaetz and Rep. Byron Donalds of Florida, Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene of Georgia, Rep. Chip Roy and Rep. Louie Gohmert of Texas, Rep. Madison Cawthorn of North Carolina, Rep. Warren Davidson of Ohio, and Rep. Andy Biggs of Arizona.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

In announcing new guidance on July 27, the CDC said vaccinated people should wear face masks in indoor public places with “high” or “substantial” community transmission rates of COVID-19.

Data from the CDC shows that designation covers 69.3% of all counties in the United States – 52.2% (1,680 counties) with high community transmission rates and 17.1% (551 counties) with substantial rates.

A county has “high transmission” if it reports 100 or more weekly cases per 100,000 residents or a 10% or higher test positivity rate in the last 7 days, the CDC said. “Substantial transmission” means a county reports 50-99 weekly cases per 100,000 residents or has a positivity rate between 8% and 9.9% in the last 7 days.

About 23% of U.S. counties had moderate rates of community transmission, and 7.67% had low rates.

To find out the transmission rate in your county, go to the CDC COVID data tracker.

Smithsonian requiring masks again

The Smithsonian now requires all visitors over age 2, regardless of vaccination status, to wear face masks indoors and in all museum spaces.

The Smithsonian said in a news release that fully vaccinated visitors won’t have to wear masks at the National Zoo or outdoor gardens for museums.

The new rule goes into effect Aug. 6. It reverses a rule that said fully vaccinated visitors didn’t have to wear masks indoors beginning June 28.

Indoor face masks will be required throughout the District of Columbia beginning July 31., D.C. Mayor Muriel Bowser.

House Republicans protest face mask policy

About 40 maskless Republican members of the U.S. House of Representatives filed onto the Senate floor on July 29 to protest a new rule requiring House members to wear face masks, the Hill reported.

Congress’s attending doctor said in a memo that the 435 members of the House, plus workers, must wear masks indoors, but not the 100 members of the Senate. The Senate is a smaller body and has had better mask compliance than the House.

Rep. Ronny Jackson (R-Tex.), told the Hill that Republicans wanted to show “what it was like on the floor of the Senate versus the floor of the House. Obviously, it’s vastly different.”

Among the group of Republicans who filed onto the Senate floor were Rep. Lauren Boebert of Colorado, Rep. Matt Gaetz and Rep. Byron Donalds of Florida, Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene of Georgia, Rep. Chip Roy and Rep. Louie Gohmert of Texas, Rep. Madison Cawthorn of North Carolina, Rep. Warren Davidson of Ohio, and Rep. Andy Biggs of Arizona.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

‘War has changed’: CDC says Delta as contagious as chicken pox

Internal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention documents support the high transmission rate of the Delta variant and put the risk in easier to understand terms.

In addition, the agency released a new study that shows that breakthrough infections in the vaccinated make people about as contagious as those who are unvaccinated. The new report, published July 30 in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR), also reveals that the Delta variant likely causes more severe COVID-19 illness.

Given these recent findings, the internal CDC slide show advises that the agency should “acknowledge the war has changed.”

A ‘pivotal discovery’

CDC Director Rochelle Walensky, MD, MPH, said in a statement that the MMWR report demonstrates “that [D]elta infection resulted in similarly high SARS-CoV-2 viral loads in vaccinated and unvaccinated people.

“High viral loads suggest an increased risk of transmission and raised concern that, unlike with other variants, vaccinated people infected with [D]elta can transmit the virus,” she added. “This finding is concerning and was a pivotal discovery leading to CDC’s updated mask recommendation.”

The investigators analyzed 469 COVID-19 cases reported in Massachusetts residents July 3 through 17, 2021. The infections were associated with an outbreak following multiple events and large gatherings in Provincetown in that state’s easternmost Barnstable County, also known as Cape Cod.

Notably, 346 infections, or 74%, of the cases occurred in fully vaccinated individuals. This group had a median age of 42, and 87% were male. Also, 79% of the breakthrough infections were symptomatic.

Researchers also identified the Delta variant in 90% of 133 specimens collected for analysis. Furthermore, viral loads were about the same between samples taken from people who were fully vaccinated and those who were not.

Four of the five people hospitalized were fully vaccinated. No deaths were reported.

The publication of these results was highly anticipated following the CDC’s updated mask recommendations on July 27.

Outside the scope of the MMWR report is the total number of cases associated with the outbreak, including visitors from outside Massachusetts, which now approach 900 infections, NBC Boston reported.

‘Very sobering’ data

“The new information from the CDC around the [D]elta variant is very sobering,” David Hirschwerk, MD, infectious disease specialist at Northwell Health in New Hyde Park, N.Y., said in an interview.

“The CDC is trying to convey and present this uncertain situation clearly to the public based on new, accumulated data,” he said. For example, given the evidence for higher contagiousness of the Delta variant, Dr. Hirschwerk added, “there will be situations where vaccinated people get infected, because the amount of the virus overwhelms the immune protection.

“What is new that is concerning is that people who are vaccinated still have the potential to transmit the virus to the same degree,” he said.

The MMWR study “helps us better understand the question related to whether or not a person who has completed a COVID-19 series can spread the infection,” agreed Michelle Barron, MD, a professor in the division of infectious disease at the University of Colorado, Aurora.

“The message is that, because the [D]elta variant is much more contagious than the original strain, unvaccinated persons need to get vaccinated because it is nearly impossible to avoid the virus indefinitely,” Michael Lin, MD, MPH, infectious diseases specialist and epidemiologist at Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, said when asked to comment.

The new data highlight “that vaccinated persons, if they become sick, should still seek COVID-19 testing and should still isolate, as they are likely contagious,” Dr. Lin added.

More contagious than other infections

The internal CDC slide presentation also puts the new transmission risk in simple terms. Saying that the Delta variant is about as contagious as chicken pox, for example, immediately brings back vivid memories for some of staying indoors and away from friends during childhood or teenage outbreaks.

“A lot of people will remember getting chicken pox and then having their siblings get it shortly thereafter,” Dr. Barron said. “The only key thing to note is that this does not mean that the COVID-19 [D]elta variant mechanism of spread is the same as chicken pox and Ebola. The primary means of spread of COVID-19, even the Delta variant, is via droplets.”

This also means each person infected with the Delta variant could infect an average of eight or nine others.

In contrast, the original strain of the SARS-CoV-2 virus was about as infectious as the common cold. In other words, someone was likely to infect about two other people on average.

In addition to the cold, the CDC notes that the Delta variant is now more contagious than Ebola, the seasonal flu, or small pox.

These Delta variant comparisons are one tangible way of explaining why the CDC on July 27 recommended a return to masking in schools and other indoor spaces for people – vaccinated and unvaccinated – in about 70% of the counties across the United States.

In comparing the Delta variant with other infections, “I think the CDC is trying to help people understand a little bit better the situation we now face since the information is so new. We are in a very different position now than just a few weeks ago, and it is hard for people to accept this,” Dr. Hirschwerk said.

The Delta variant is so different that the CDC considers it almost acting like a new virus altogether.

The CDC’s internal documents were first released by The Washington Post on July 29. The slides cite communication challenges for the agency to continue promoting vaccination while also acknowledging that breakthrough cases are occurring and therefore the fully vaccinated, in some instances, are likely infecting others.

Moving back to science talk, the CDC used the recent outbreak in Barnstable County as an example. The cycle threshold, or Ct values, a measure of viral load, were about the same between 80 vaccinated people linked to the outbreak who had a mean Ct value of 21.9, compared with 65 other unvaccinated people with a Ct of 21.5.

Many experts are quick to note that vaccination remains essential, in part because a vaccinated person also walks around with a much lower risk for severe outcomes, hospitalization, and death. In the internal slide show, the CDC points out that vaccination reduces the risk for infection threefold.

“Even with this high amount of virus, [the Delta variant] did not necessarily make the vaccinated individuals as sick,” Dr. Barron said.

In her statement, Dr. Walensky credited collaboration with the Commonwealth of Massachusetts Department of Public Health and the CDC for the new data. She also thanked the residents of Barnstable County for participating in interviews done by contact tracers and their willingness to get tested and adhere to safety protocols after learning of their exposure.

Next moves by CDC?

The agency notes that next steps include consideration of prevention measures such as vaccine mandates for healthcare professionals to protect vulnerable populations, universal masking for source control and prevention, and reconsidering other community mitigation strategies.

Asked if this potential policy is appropriate and feasible, Dr. Lin said, “Yes, I believe that every person working in health care should be vaccinated for COVID-19, and it is feasible.”

Dr. Barron agreed as well. “We as health care providers choose to work in health care, and we should be doing everything feasible to ensure that we are protecting our patients and keeping our coworkers safe.”

“Whether you are a health care professional or not, I would urge everyone to get the COVID-19 vaccine, especially as cases across the country continue to rise,” Dr. Hirschwerk said. “Unequivocally vaccines protect you from the virus.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Internal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention documents support the high transmission rate of the Delta variant and put the risk in easier to understand terms.

In addition, the agency released a new study that shows that breakthrough infections in the vaccinated make people about as contagious as those who are unvaccinated. The new report, published July 30 in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR), also reveals that the Delta variant likely causes more severe COVID-19 illness.

Given these recent findings, the internal CDC slide show advises that the agency should “acknowledge the war has changed.”

A ‘pivotal discovery’

CDC Director Rochelle Walensky, MD, MPH, said in a statement that the MMWR report demonstrates “that [D]elta infection resulted in similarly high SARS-CoV-2 viral loads in vaccinated and unvaccinated people.

“High viral loads suggest an increased risk of transmission and raised concern that, unlike with other variants, vaccinated people infected with [D]elta can transmit the virus,” she added. “This finding is concerning and was a pivotal discovery leading to CDC’s updated mask recommendation.”

The investigators analyzed 469 COVID-19 cases reported in Massachusetts residents July 3 through 17, 2021. The infections were associated with an outbreak following multiple events and large gatherings in Provincetown in that state’s easternmost Barnstable County, also known as Cape Cod.

Notably, 346 infections, or 74%, of the cases occurred in fully vaccinated individuals. This group had a median age of 42, and 87% were male. Also, 79% of the breakthrough infections were symptomatic.

Researchers also identified the Delta variant in 90% of 133 specimens collected for analysis. Furthermore, viral loads were about the same between samples taken from people who were fully vaccinated and those who were not.

Four of the five people hospitalized were fully vaccinated. No deaths were reported.

The publication of these results was highly anticipated following the CDC’s updated mask recommendations on July 27.

Outside the scope of the MMWR report is the total number of cases associated with the outbreak, including visitors from outside Massachusetts, which now approach 900 infections, NBC Boston reported.

‘Very sobering’ data

“The new information from the CDC around the [D]elta variant is very sobering,” David Hirschwerk, MD, infectious disease specialist at Northwell Health in New Hyde Park, N.Y., said in an interview.

“The CDC is trying to convey and present this uncertain situation clearly to the public based on new, accumulated data,” he said. For example, given the evidence for higher contagiousness of the Delta variant, Dr. Hirschwerk added, “there will be situations where vaccinated people get infected, because the amount of the virus overwhelms the immune protection.

“What is new that is concerning is that people who are vaccinated still have the potential to transmit the virus to the same degree,” he said.

The MMWR study “helps us better understand the question related to whether or not a person who has completed a COVID-19 series can spread the infection,” agreed Michelle Barron, MD, a professor in the division of infectious disease at the University of Colorado, Aurora.

“The message is that, because the [D]elta variant is much more contagious than the original strain, unvaccinated persons need to get vaccinated because it is nearly impossible to avoid the virus indefinitely,” Michael Lin, MD, MPH, infectious diseases specialist and epidemiologist at Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, said when asked to comment.

The new data highlight “that vaccinated persons, if they become sick, should still seek COVID-19 testing and should still isolate, as they are likely contagious,” Dr. Lin added.

More contagious than other infections

The internal CDC slide presentation also puts the new transmission risk in simple terms. Saying that the Delta variant is about as contagious as chicken pox, for example, immediately brings back vivid memories for some of staying indoors and away from friends during childhood or teenage outbreaks.

“A lot of people will remember getting chicken pox and then having their siblings get it shortly thereafter,” Dr. Barron said. “The only key thing to note is that this does not mean that the COVID-19 [D]elta variant mechanism of spread is the same as chicken pox and Ebola. The primary means of spread of COVID-19, even the Delta variant, is via droplets.”

This also means each person infected with the Delta variant could infect an average of eight or nine others.

In contrast, the original strain of the SARS-CoV-2 virus was about as infectious as the common cold. In other words, someone was likely to infect about two other people on average.

In addition to the cold, the CDC notes that the Delta variant is now more contagious than Ebola, the seasonal flu, or small pox.

These Delta variant comparisons are one tangible way of explaining why the CDC on July 27 recommended a return to masking in schools and other indoor spaces for people – vaccinated and unvaccinated – in about 70% of the counties across the United States.

In comparing the Delta variant with other infections, “I think the CDC is trying to help people understand a little bit better the situation we now face since the information is so new. We are in a very different position now than just a few weeks ago, and it is hard for people to accept this,” Dr. Hirschwerk said.

The Delta variant is so different that the CDC considers it almost acting like a new virus altogether.

The CDC’s internal documents were first released by The Washington Post on July 29. The slides cite communication challenges for the agency to continue promoting vaccination while also acknowledging that breakthrough cases are occurring and therefore the fully vaccinated, in some instances, are likely infecting others.

Moving back to science talk, the CDC used the recent outbreak in Barnstable County as an example. The cycle threshold, or Ct values, a measure of viral load, were about the same between 80 vaccinated people linked to the outbreak who had a mean Ct value of 21.9, compared with 65 other unvaccinated people with a Ct of 21.5.

Many experts are quick to note that vaccination remains essential, in part because a vaccinated person also walks around with a much lower risk for severe outcomes, hospitalization, and death. In the internal slide show, the CDC points out that vaccination reduces the risk for infection threefold.

“Even with this high amount of virus, [the Delta variant] did not necessarily make the vaccinated individuals as sick,” Dr. Barron said.

In her statement, Dr. Walensky credited collaboration with the Commonwealth of Massachusetts Department of Public Health and the CDC for the new data. She also thanked the residents of Barnstable County for participating in interviews done by contact tracers and their willingness to get tested and adhere to safety protocols after learning of their exposure.

Next moves by CDC?

The agency notes that next steps include consideration of prevention measures such as vaccine mandates for healthcare professionals to protect vulnerable populations, universal masking for source control and prevention, and reconsidering other community mitigation strategies.

Asked if this potential policy is appropriate and feasible, Dr. Lin said, “Yes, I believe that every person working in health care should be vaccinated for COVID-19, and it is feasible.”

Dr. Barron agreed as well. “We as health care providers choose to work in health care, and we should be doing everything feasible to ensure that we are protecting our patients and keeping our coworkers safe.”

“Whether you are a health care professional or not, I would urge everyone to get the COVID-19 vaccine, especially as cases across the country continue to rise,” Dr. Hirschwerk said. “Unequivocally vaccines protect you from the virus.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Internal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention documents support the high transmission rate of the Delta variant and put the risk in easier to understand terms.

In addition, the agency released a new study that shows that breakthrough infections in the vaccinated make people about as contagious as those who are unvaccinated. The new report, published July 30 in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR), also reveals that the Delta variant likely causes more severe COVID-19 illness.

Given these recent findings, the internal CDC slide show advises that the agency should “acknowledge the war has changed.”

A ‘pivotal discovery’

CDC Director Rochelle Walensky, MD, MPH, said in a statement that the MMWR report demonstrates “that [D]elta infection resulted in similarly high SARS-CoV-2 viral loads in vaccinated and unvaccinated people.

“High viral loads suggest an increased risk of transmission and raised concern that, unlike with other variants, vaccinated people infected with [D]elta can transmit the virus,” she added. “This finding is concerning and was a pivotal discovery leading to CDC’s updated mask recommendation.”

The investigators analyzed 469 COVID-19 cases reported in Massachusetts residents July 3 through 17, 2021. The infections were associated with an outbreak following multiple events and large gatherings in Provincetown in that state’s easternmost Barnstable County, also known as Cape Cod.

Notably, 346 infections, or 74%, of the cases occurred in fully vaccinated individuals. This group had a median age of 42, and 87% were male. Also, 79% of the breakthrough infections were symptomatic.

Researchers also identified the Delta variant in 90% of 133 specimens collected for analysis. Furthermore, viral loads were about the same between samples taken from people who were fully vaccinated and those who were not.

Four of the five people hospitalized were fully vaccinated. No deaths were reported.

The publication of these results was highly anticipated following the CDC’s updated mask recommendations on July 27.

Outside the scope of the MMWR report is the total number of cases associated with the outbreak, including visitors from outside Massachusetts, which now approach 900 infections, NBC Boston reported.

‘Very sobering’ data

“The new information from the CDC around the [D]elta variant is very sobering,” David Hirschwerk, MD, infectious disease specialist at Northwell Health in New Hyde Park, N.Y., said in an interview.

“The CDC is trying to convey and present this uncertain situation clearly to the public based on new, accumulated data,” he said. For example, given the evidence for higher contagiousness of the Delta variant, Dr. Hirschwerk added, “there will be situations where vaccinated people get infected, because the amount of the virus overwhelms the immune protection.

“What is new that is concerning is that people who are vaccinated still have the potential to transmit the virus to the same degree,” he said.

The MMWR study “helps us better understand the question related to whether or not a person who has completed a COVID-19 series can spread the infection,” agreed Michelle Barron, MD, a professor in the division of infectious disease at the University of Colorado, Aurora.

“The message is that, because the [D]elta variant is much more contagious than the original strain, unvaccinated persons need to get vaccinated because it is nearly impossible to avoid the virus indefinitely,” Michael Lin, MD, MPH, infectious diseases specialist and epidemiologist at Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, said when asked to comment.

The new data highlight “that vaccinated persons, if they become sick, should still seek COVID-19 testing and should still isolate, as they are likely contagious,” Dr. Lin added.

More contagious than other infections

The internal CDC slide presentation also puts the new transmission risk in simple terms. Saying that the Delta variant is about as contagious as chicken pox, for example, immediately brings back vivid memories for some of staying indoors and away from friends during childhood or teenage outbreaks.

“A lot of people will remember getting chicken pox and then having their siblings get it shortly thereafter,” Dr. Barron said. “The only key thing to note is that this does not mean that the COVID-19 [D]elta variant mechanism of spread is the same as chicken pox and Ebola. The primary means of spread of COVID-19, even the Delta variant, is via droplets.”

This also means each person infected with the Delta variant could infect an average of eight or nine others.

In contrast, the original strain of the SARS-CoV-2 virus was about as infectious as the common cold. In other words, someone was likely to infect about two other people on average.

In addition to the cold, the CDC notes that the Delta variant is now more contagious than Ebola, the seasonal flu, or small pox.

These Delta variant comparisons are one tangible way of explaining why the CDC on July 27 recommended a return to masking in schools and other indoor spaces for people – vaccinated and unvaccinated – in about 70% of the counties across the United States.

In comparing the Delta variant with other infections, “I think the CDC is trying to help people understand a little bit better the situation we now face since the information is so new. We are in a very different position now than just a few weeks ago, and it is hard for people to accept this,” Dr. Hirschwerk said.

The Delta variant is so different that the CDC considers it almost acting like a new virus altogether.

The CDC’s internal documents were first released by The Washington Post on July 29. The slides cite communication challenges for the agency to continue promoting vaccination while also acknowledging that breakthrough cases are occurring and therefore the fully vaccinated, in some instances, are likely infecting others.

Moving back to science talk, the CDC used the recent outbreak in Barnstable County as an example. The cycle threshold, or Ct values, a measure of viral load, were about the same between 80 vaccinated people linked to the outbreak who had a mean Ct value of 21.9, compared with 65 other unvaccinated people with a Ct of 21.5.

Many experts are quick to note that vaccination remains essential, in part because a vaccinated person also walks around with a much lower risk for severe outcomes, hospitalization, and death. In the internal slide show, the CDC points out that vaccination reduces the risk for infection threefold.

“Even with this high amount of virus, [the Delta variant] did not necessarily make the vaccinated individuals as sick,” Dr. Barron said.

In her statement, Dr. Walensky credited collaboration with the Commonwealth of Massachusetts Department of Public Health and the CDC for the new data. She also thanked the residents of Barnstable County for participating in interviews done by contact tracers and their willingness to get tested and adhere to safety protocols after learning of their exposure.

Next moves by CDC?

The agency notes that next steps include consideration of prevention measures such as vaccine mandates for healthcare professionals to protect vulnerable populations, universal masking for source control and prevention, and reconsidering other community mitigation strategies.

Asked if this potential policy is appropriate and feasible, Dr. Lin said, “Yes, I believe that every person working in health care should be vaccinated for COVID-19, and it is feasible.”

Dr. Barron agreed as well. “We as health care providers choose to work in health care, and we should be doing everything feasible to ensure that we are protecting our patients and keeping our coworkers safe.”

“Whether you are a health care professional or not, I would urge everyone to get the COVID-19 vaccine, especially as cases across the country continue to rise,” Dr. Hirschwerk said. “Unequivocally vaccines protect you from the virus.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

COVID brings evolutionary virologists out of the shadows, into the fight

It has been a strange, exhausting year for many evolutionary virologists.

“Scientists are not used to having attention and are not used to being in the press and are not used to being attacked on Twitter,” Martha Nelson, PhD, a staff scientist who studies viral evolution at the National Institutes of Health, said in an interview.

Over the past year and a half, the theory of evolution has been thrust into the spotlight – more now than ever, perhaps, as the world is stalked by the Delta variant and fears arise of a mutation that’s even worse.

The origins of SARS-CoV-2 and the rise of the Delta variant have been debated, and vaccine efficacy and the possible need for booster shots have been speculated upon. In all these instances, consciously or not, there is engagement with the field of evolutionary virology.

It has been central to deepening the understanding of the ongoing pandemic, even as SARS-CoV-2 has exposed gaps in what we understand about how viruses behave and evolve.

Evolutionary virology experts believe that, after the pandemic, their expertise and tools could be applied to and integrated with clinical medicine to improve outcomes and understanding of disease.

“From our perspective, evolutionary biology has been a side dish and something that hasn’t been integrated into the core practice of medicine,” said Dr. Nelson. “I’m really curious to see how that changes over time.”

Pandemic evolution

Novel pathogens, antibiotic-resistant bacteria, and cancer cells are all products of ongoing evolution. “Just like cellular organisms, viruses have genomes, and all genomes evolve,” Eugene Koonin, PhD, evolutionary genomics group leader at the NIH, said in an interview.

Compared with cellular organisms, viruses evolve quite fast, he said.

A study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences exemplifies evolutionary virology in action. In the study, Dr. Koonin and fellow researchers analyzed more than 300,000 genome sequences of SARS-CoV-2 variants that were publicly available as of January 2021 and mapped all the mutations in each sequence.

The researchers identified a small subset of mutations that arose independently more than once and that likely aided viral adaptation, said Nash Rochman, PhD, a research fellow at the NIH and coauthor of the PNAS study.

Many of these mutations were concentrated in two areas of the genome – the receptor binding domain of the spike protein, and a region of the nucleocapsid protein – and were often grouped together, possibly creating greater advantages for the virus than would have occurred individually, he said.

The researchers also found that, from the beginning of the pandemic, the SARS-CoV-2 genome has been evolving and diversifying in different regions around the world, allowing for the rise of new lineages and, possibly, even new species, Dr. Koonin said.

During the pandemic, researchers have used evolutionary virology tools to tackle many other questions. For example, Dr. Nelson tracked the spread of SARS-CoV-2 across Europe and North America. In a study that is currently undergoing peer review, the investigators found recently vaccinated individuals, who are only partially immune, are at the highest risk for incubating antibody-resistant variants.

C. Brandon Ogbunu, PhD, an evolutionary geneticist at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., whose work is focused on disease evolution, studied whether SARS-CoV-2 would evolve to become more transmissible, and if so, would it also become more or less virulent. His lab also investigated the transmission and spread of the virus.

“I think the last year, on one end, has been this opportunity to apply concepts and perspectives that we’ve been developing for the last several decades,” Dr. Ogbunu said in an interview. “At the same time, this pandemic has also been this wake-up call for many of us with regards to revealing the things we do not understand about the ways viruses infect, spread, and how evolution works within viruses.”

He emphasizes the need for evolutionary biology to partner with other fields – including information theory and biophysics – to help unlock viral mysteries: “We need to think very, very carefully about the way those fields intersect.”

Dr. Nelson also pointed to the need for better, more centralized data gathering in the United States.

The sheer volume of information scientists have collected about SARS-CoV-2 will aid in the study of virus evolution for years to come, said Dr. Koonin.

Evolution in medicine

Evolutionary virology and related research can be applied to medicine outside of the context of a global pandemic. “The principles and technical portions of evolutionary virology are very applicable to other diseases, including cancer,” Dr. Koonin said.

Viruses, bacteria, and cancer cells are all evolving systems. Viruses and bacteria are constantly evolving to thwart drugs and vaccines. How physicians and health care professionals practice medicine shapes the selection pressures driving how these pathogens evolve, Dr. Nelson said.

The rise of antibiotic-resistant bacteria is a particularly relevant example of how evolution affects the way physicians treat patients. Having an evolutionary perspective can help inform how to treat patients most effectively, both for individual patients as well as for broader public health, she said.

“For a long time, there’s been a lot of interest in pathogen evolution that hasn’t translated so much into clinical practice,” said Dr. Nelson. “There’s been kind of a gulf between the research side of evolutionary virology and pathogen emergence and actual practice of medicine.”

As genomic sequencing has become faster and cheaper, that gulf has started to narrow, she said. As this technology continues to prove itself by, for example, tracking the evolution of one virus in real time, Dr. Nelson hopes there will be a positive snowball effect, leading to more attention, investment, and improvements in genomic data and that its use in epidemiology and medicine will expand going forward.

Bringing viral evolution studies more into medicine will require a mindset shift, Dr. Ogbunu said. Clinical practice is, by design, very focused on the individual patient. Evolutionary biology, on the other hand, deals with populations and probabilities.

Being able to engage with evolutionary biology would help physicians better understand disease and explain it to their patients, he said.

To start, Dr. Nelson recommended requiring at least one course in evolutionary biology or evolutionary medicine in medical school and crafting continuing education in this area for physicians. (Presentations at conferences could be one way to do this.)

Dr. Nelson also recommended deeper engagement and collaboration between physicians who collect samples from patients and evolutionary biologists who analyze genetic data. This would improve the quality of the data, the analysis, and the eventual findings that could be relevant to patients and clinical practice.

Still, “my first and inevitable reaction is I would so much rather prefer to exist in relative obscurity,” said Dr. Koonin, noting that the tragedy of the pandemic outweighs the advancements in the field.

Although there’s no going back to prepandemic times, there is an enormous opportunity in the aftermath of COVID to increase dialogue between physicians and evolutionary virologists to improve medical practice as well as public health.

Dr. Nelson summed it up: “Everything we uncover about these pathogens may help us prevent something like this again.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

It has been a strange, exhausting year for many evolutionary virologists.

“Scientists are not used to having attention and are not used to being in the press and are not used to being attacked on Twitter,” Martha Nelson, PhD, a staff scientist who studies viral evolution at the National Institutes of Health, said in an interview.

Over the past year and a half, the theory of evolution has been thrust into the spotlight – more now than ever, perhaps, as the world is stalked by the Delta variant and fears arise of a mutation that’s even worse.

The origins of SARS-CoV-2 and the rise of the Delta variant have been debated, and vaccine efficacy and the possible need for booster shots have been speculated upon. In all these instances, consciously or not, there is engagement with the field of evolutionary virology.

It has been central to deepening the understanding of the ongoing pandemic, even as SARS-CoV-2 has exposed gaps in what we understand about how viruses behave and evolve.

Evolutionary virology experts believe that, after the pandemic, their expertise and tools could be applied to and integrated with clinical medicine to improve outcomes and understanding of disease.

“From our perspective, evolutionary biology has been a side dish and something that hasn’t been integrated into the core practice of medicine,” said Dr. Nelson. “I’m really curious to see how that changes over time.”

Pandemic evolution

Novel pathogens, antibiotic-resistant bacteria, and cancer cells are all products of ongoing evolution. “Just like cellular organisms, viruses have genomes, and all genomes evolve,” Eugene Koonin, PhD, evolutionary genomics group leader at the NIH, said in an interview.

Compared with cellular organisms, viruses evolve quite fast, he said.

A study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences exemplifies evolutionary virology in action. In the study, Dr. Koonin and fellow researchers analyzed more than 300,000 genome sequences of SARS-CoV-2 variants that were publicly available as of January 2021 and mapped all the mutations in each sequence.

The researchers identified a small subset of mutations that arose independently more than once and that likely aided viral adaptation, said Nash Rochman, PhD, a research fellow at the NIH and coauthor of the PNAS study.

Many of these mutations were concentrated in two areas of the genome – the receptor binding domain of the spike protein, and a region of the nucleocapsid protein – and were often grouped together, possibly creating greater advantages for the virus than would have occurred individually, he said.

The researchers also found that, from the beginning of the pandemic, the SARS-CoV-2 genome has been evolving and diversifying in different regions around the world, allowing for the rise of new lineages and, possibly, even new species, Dr. Koonin said.

During the pandemic, researchers have used evolutionary virology tools to tackle many other questions. For example, Dr. Nelson tracked the spread of SARS-CoV-2 across Europe and North America. In a study that is currently undergoing peer review, the investigators found recently vaccinated individuals, who are only partially immune, are at the highest risk for incubating antibody-resistant variants.

C. Brandon Ogbunu, PhD, an evolutionary geneticist at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., whose work is focused on disease evolution, studied whether SARS-CoV-2 would evolve to become more transmissible, and if so, would it also become more or less virulent. His lab also investigated the transmission and spread of the virus.

“I think the last year, on one end, has been this opportunity to apply concepts and perspectives that we’ve been developing for the last several decades,” Dr. Ogbunu said in an interview. “At the same time, this pandemic has also been this wake-up call for many of us with regards to revealing the things we do not understand about the ways viruses infect, spread, and how evolution works within viruses.”

He emphasizes the need for evolutionary biology to partner with other fields – including information theory and biophysics – to help unlock viral mysteries: “We need to think very, very carefully about the way those fields intersect.”

Dr. Nelson also pointed to the need for better, more centralized data gathering in the United States.

The sheer volume of information scientists have collected about SARS-CoV-2 will aid in the study of virus evolution for years to come, said Dr. Koonin.

Evolution in medicine

Evolutionary virology and related research can be applied to medicine outside of the context of a global pandemic. “The principles and technical portions of evolutionary virology are very applicable to other diseases, including cancer,” Dr. Koonin said.

Viruses, bacteria, and cancer cells are all evolving systems. Viruses and bacteria are constantly evolving to thwart drugs and vaccines. How physicians and health care professionals practice medicine shapes the selection pressures driving how these pathogens evolve, Dr. Nelson said.

The rise of antibiotic-resistant bacteria is a particularly relevant example of how evolution affects the way physicians treat patients. Having an evolutionary perspective can help inform how to treat patients most effectively, both for individual patients as well as for broader public health, she said.

“For a long time, there’s been a lot of interest in pathogen evolution that hasn’t translated so much into clinical practice,” said Dr. Nelson. “There’s been kind of a gulf between the research side of evolutionary virology and pathogen emergence and actual practice of medicine.”

As genomic sequencing has become faster and cheaper, that gulf has started to narrow, she said. As this technology continues to prove itself by, for example, tracking the evolution of one virus in real time, Dr. Nelson hopes there will be a positive snowball effect, leading to more attention, investment, and improvements in genomic data and that its use in epidemiology and medicine will expand going forward.

Bringing viral evolution studies more into medicine will require a mindset shift, Dr. Ogbunu said. Clinical practice is, by design, very focused on the individual patient. Evolutionary biology, on the other hand, deals with populations and probabilities.

Being able to engage with evolutionary biology would help physicians better understand disease and explain it to their patients, he said.

To start, Dr. Nelson recommended requiring at least one course in evolutionary biology or evolutionary medicine in medical school and crafting continuing education in this area for physicians. (Presentations at conferences could be one way to do this.)

Dr. Nelson also recommended deeper engagement and collaboration between physicians who collect samples from patients and evolutionary biologists who analyze genetic data. This would improve the quality of the data, the analysis, and the eventual findings that could be relevant to patients and clinical practice.

Still, “my first and inevitable reaction is I would so much rather prefer to exist in relative obscurity,” said Dr. Koonin, noting that the tragedy of the pandemic outweighs the advancements in the field.

Although there’s no going back to prepandemic times, there is an enormous opportunity in the aftermath of COVID to increase dialogue between physicians and evolutionary virologists to improve medical practice as well as public health.

Dr. Nelson summed it up: “Everything we uncover about these pathogens may help us prevent something like this again.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

It has been a strange, exhausting year for many evolutionary virologists.

“Scientists are not used to having attention and are not used to being in the press and are not used to being attacked on Twitter,” Martha Nelson, PhD, a staff scientist who studies viral evolution at the National Institutes of Health, said in an interview.

Over the past year and a half, the theory of evolution has been thrust into the spotlight – more now than ever, perhaps, as the world is stalked by the Delta variant and fears arise of a mutation that’s even worse.

The origins of SARS-CoV-2 and the rise of the Delta variant have been debated, and vaccine efficacy and the possible need for booster shots have been speculated upon. In all these instances, consciously or not, there is engagement with the field of evolutionary virology.

It has been central to deepening the understanding of the ongoing pandemic, even as SARS-CoV-2 has exposed gaps in what we understand about how viruses behave and evolve.

Evolutionary virology experts believe that, after the pandemic, their expertise and tools could be applied to and integrated with clinical medicine to improve outcomes and understanding of disease.

“From our perspective, evolutionary biology has been a side dish and something that hasn’t been integrated into the core practice of medicine,” said Dr. Nelson. “I’m really curious to see how that changes over time.”

Pandemic evolution

Novel pathogens, antibiotic-resistant bacteria, and cancer cells are all products of ongoing evolution. “Just like cellular organisms, viruses have genomes, and all genomes evolve,” Eugene Koonin, PhD, evolutionary genomics group leader at the NIH, said in an interview.

Compared with cellular organisms, viruses evolve quite fast, he said.

A study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences exemplifies evolutionary virology in action. In the study, Dr. Koonin and fellow researchers analyzed more than 300,000 genome sequences of SARS-CoV-2 variants that were publicly available as of January 2021 and mapped all the mutations in each sequence.

The researchers identified a small subset of mutations that arose independently more than once and that likely aided viral adaptation, said Nash Rochman, PhD, a research fellow at the NIH and coauthor of the PNAS study.

Many of these mutations were concentrated in two areas of the genome – the receptor binding domain of the spike protein, and a region of the nucleocapsid protein – and were often grouped together, possibly creating greater advantages for the virus than would have occurred individually, he said.

The researchers also found that, from the beginning of the pandemic, the SARS-CoV-2 genome has been evolving and diversifying in different regions around the world, allowing for the rise of new lineages and, possibly, even new species, Dr. Koonin said.

During the pandemic, researchers have used evolutionary virology tools to tackle many other questions. For example, Dr. Nelson tracked the spread of SARS-CoV-2 across Europe and North America. In a study that is currently undergoing peer review, the investigators found recently vaccinated individuals, who are only partially immune, are at the highest risk for incubating antibody-resistant variants.

C. Brandon Ogbunu, PhD, an evolutionary geneticist at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., whose work is focused on disease evolution, studied whether SARS-CoV-2 would evolve to become more transmissible, and if so, would it also become more or less virulent. His lab also investigated the transmission and spread of the virus.

“I think the last year, on one end, has been this opportunity to apply concepts and perspectives that we’ve been developing for the last several decades,” Dr. Ogbunu said in an interview. “At the same time, this pandemic has also been this wake-up call for many of us with regards to revealing the things we do not understand about the ways viruses infect, spread, and how evolution works within viruses.”

He emphasizes the need for evolutionary biology to partner with other fields – including information theory and biophysics – to help unlock viral mysteries: “We need to think very, very carefully about the way those fields intersect.”

Dr. Nelson also pointed to the need for better, more centralized data gathering in the United States.

The sheer volume of information scientists have collected about SARS-CoV-2 will aid in the study of virus evolution for years to come, said Dr. Koonin.

Evolution in medicine

Evolutionary virology and related research can be applied to medicine outside of the context of a global pandemic. “The principles and technical portions of evolutionary virology are very applicable to other diseases, including cancer,” Dr. Koonin said.

Viruses, bacteria, and cancer cells are all evolving systems. Viruses and bacteria are constantly evolving to thwart drugs and vaccines. How physicians and health care professionals practice medicine shapes the selection pressures driving how these pathogens evolve, Dr. Nelson said.

The rise of antibiotic-resistant bacteria is a particularly relevant example of how evolution affects the way physicians treat patients. Having an evolutionary perspective can help inform how to treat patients most effectively, both for individual patients as well as for broader public health, she said.

“For a long time, there’s been a lot of interest in pathogen evolution that hasn’t translated so much into clinical practice,” said Dr. Nelson. “There’s been kind of a gulf between the research side of evolutionary virology and pathogen emergence and actual practice of medicine.”

As genomic sequencing has become faster and cheaper, that gulf has started to narrow, she said. As this technology continues to prove itself by, for example, tracking the evolution of one virus in real time, Dr. Nelson hopes there will be a positive snowball effect, leading to more attention, investment, and improvements in genomic data and that its use in epidemiology and medicine will expand going forward.

Bringing viral evolution studies more into medicine will require a mindset shift, Dr. Ogbunu said. Clinical practice is, by design, very focused on the individual patient. Evolutionary biology, on the other hand, deals with populations and probabilities.

Being able to engage with evolutionary biology would help physicians better understand disease and explain it to their patients, he said.

To start, Dr. Nelson recommended requiring at least one course in evolutionary biology or evolutionary medicine in medical school and crafting continuing education in this area for physicians. (Presentations at conferences could be one way to do this.)

Dr. Nelson also recommended deeper engagement and collaboration between physicians who collect samples from patients and evolutionary biologists who analyze genetic data. This would improve the quality of the data, the analysis, and the eventual findings that could be relevant to patients and clinical practice.

Still, “my first and inevitable reaction is I would so much rather prefer to exist in relative obscurity,” said Dr. Koonin, noting that the tragedy of the pandemic outweighs the advancements in the field.

Although there’s no going back to prepandemic times, there is an enormous opportunity in the aftermath of COVID to increase dialogue between physicians and evolutionary virologists to improve medical practice as well as public health.

Dr. Nelson summed it up: “Everything we uncover about these pathogens may help us prevent something like this again.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Needed: More studies of CSF molecular biomarkers in psychiatric disorders

Psychiatry and neurology are the brain’s twin medical disciplines. Unlike neurologic brain disorders, where localizing the “lesion” is a primary objective, psychiatric brain disorders are much more subtle, with no “gross” lesions but numerous cellular and molecular pathologies within neural circuits.

Measuring the molecular components of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), the glorious “sewage system” of the brain, may help reveal granular clues to the neurobiology of psychiatric disorders.

Mental illnesses involve the disruption of brain structures and functions in a diffuse manner across the cortex. Abnormal neuroplasticity has been implicated in several major psychiatric disorders. Examples include hypoplasia of the hippocampus in major depressive disorder and cortical thinning/dysplasia in schizophrenia. Reductions of neurotropic factors such as nerve growth factor or brain-derived neurotropic factor have been reported in mood and psychotic disorders, and appear to correlate with neuroplasticity changes.

Recent advances in psychiatric neuroscience have provided many clues to the pathophysiology of psychopathological conditions, including neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, apoptosis, impaired energy metabolism, abnormal metabolomics and lipidomics, and hypo- and hyperfunction of various neurotransmitters systems (especially glutamate N-methyl-

Thus, psychiatric research should focus on exploring and detecting molecular signatures (ie, biomarkers) of psychiatric disorders, including biomarkers of axonal and synaptic damage, glial activation, and oxidative stress. This is especially critical given the extensive heterogeneity of schizophrenia and mood and anxiety disorders. The CSF is a vastly unexploited substrate for discovering molecular biomarkers that will pave the way to precision psychiatry, and possibly open the door for completely new therapeutic strategies to tackle the most challenging neuropsychiatric disorders.

A role for CSF analysis

It’s quite puzzling why acute psychiatric episodes of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, or panic attacks are not routinely assessed with a spinal tap, in conjunction with other brain measures such as neuroimaging (morphology, spectroscopy, cerebral blood flow, and diffusion tensor imaging) as well as a comprehensive neurocognitive examination and neurophysiological tests such as pre-pulse inhibition, mismatch negativity, and P-50, N-10, and P-300 evoked potentials. Combining CSF analysis with all those measures may help us stratify the spectra of psychosis, depression, and anxiety, as well as posttraumatic stress disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder, into unique biotypes with overlapping clinical phenotypes and specific treatment approaches.

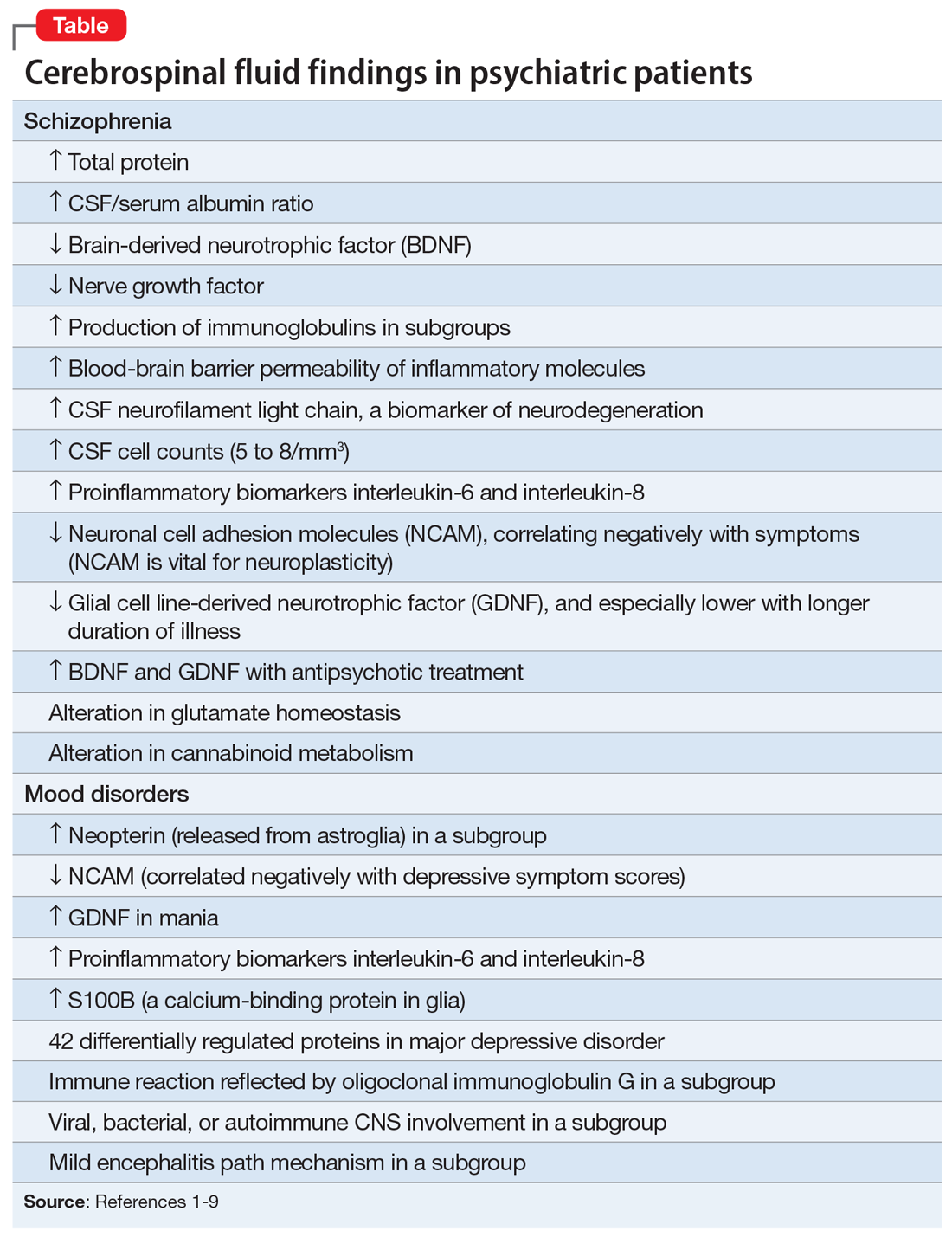

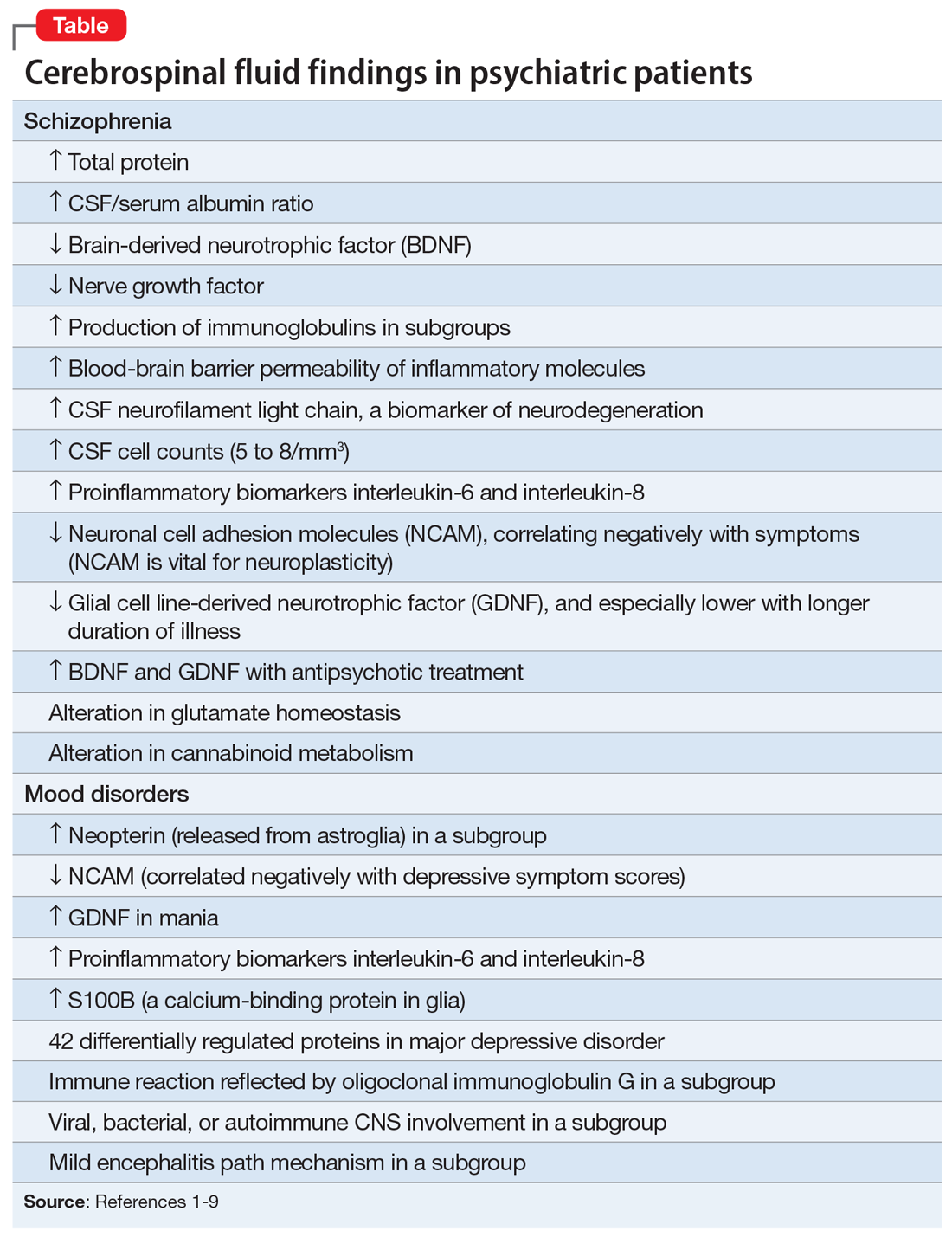

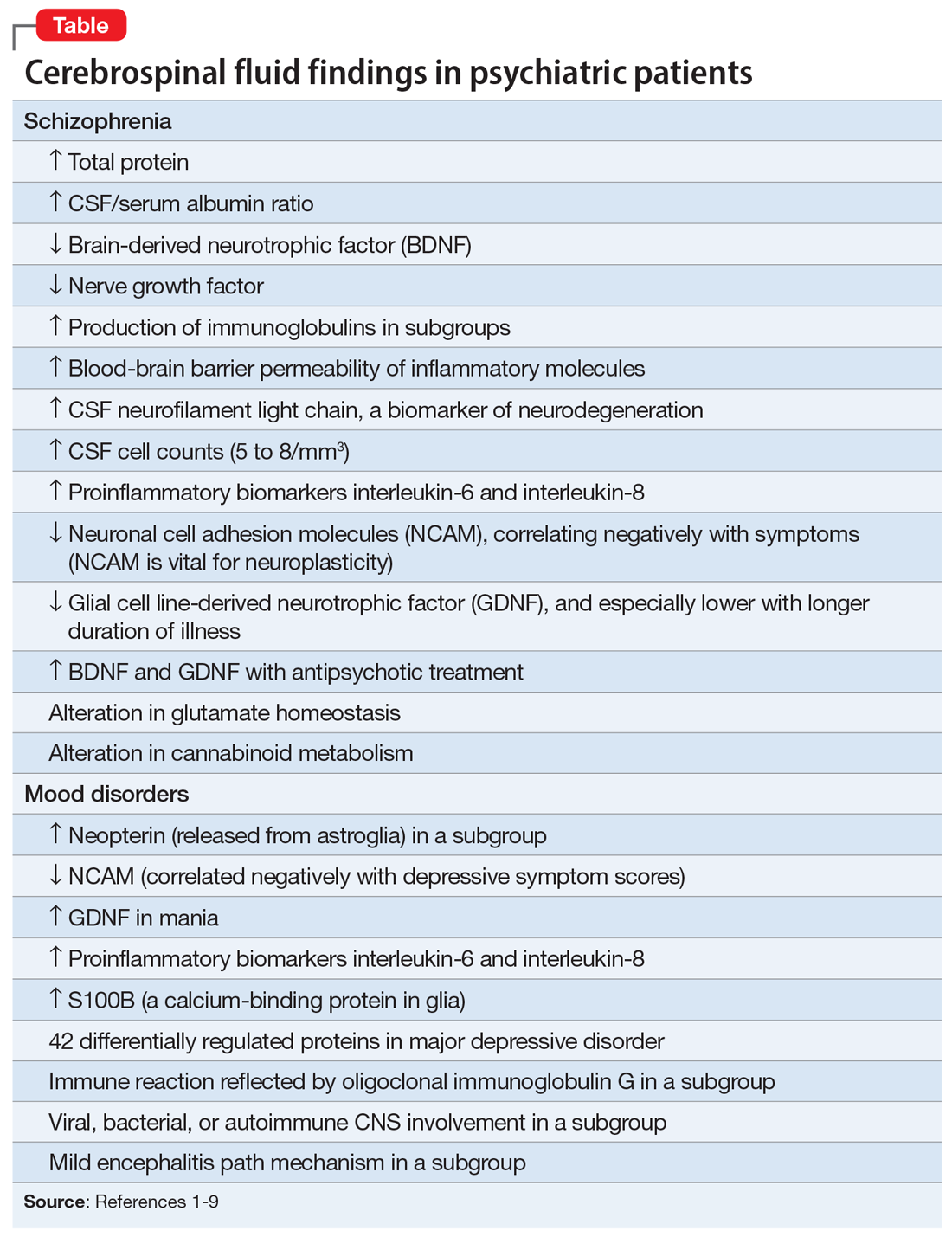

There are relatively few published CSF studies in psychiatric patients (mostly schizophrenia and bipolar and depressive disorders). The Table1-9 shows some of those findings. More than 365 biomarkers have been reported in schizophrenia, most of them in serum and tissue.10 However, none of them can be used for diagnostic purposes because schizophrenia is a syndrome comprised of several hundred different diseases (biotypes) that have similar clinical symptoms. Many of the serum and tissue biomarkers have not been studied in CSF, and they must if advances in the neurobiology and treatment of the psychotic and mood spectra are to be achieved. And adapting the CSF biomarkers described in neurologic disorders such as multiple sclerosis11 to schizophrenia and bipolar disorder (which also have well-established myelin pathologies) may yield a trove of neurobiologic findings.

If CSF studies eventually prove to be very useful for identifying subtypes for diagnosis and treatment, psychiatrists do not have to do the lumbar puncture themselves, but may refer patients to a “spinal tap” laboratory, just as they refer patients to a phlebotomy laboratory for routine blood tests. The adoption of CSF assessment in psychiatry will solidify its status as a clinical neuroscience, like its sister, neurology.

1. Vasic N, Connemann BJ, Wolf RC, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid biomarker candidates of schizophrenia: where do we stand? Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2012;262(5):375-391.

2. Pollak TA, Drndarski S, Stone JM, et al. The blood-brain barrier in psychosis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(1):79-92.

3. Katisko K, Cajanus A, Jääskeläinen O, et al. Serum neurofilament light chain is a discriminative biomarker between frontotemporal lobar degeneration and primary psychiatric disorders. J Neurol. 2020;267(1):162-167.

4. Bechter K, Reiber H, Herzog S, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid analysis in affective and schizophrenic spectrum disorders: identification of subgroups with immune responses and blood-CSF barrier dysfunction. J Psychiatr Res. 2010;44(5):321-330.

5. Hidese S, Hattori K, Sasayama D, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid neural cell adhesion molecule levels and their correlation with clinical variables in patients with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorder. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2017;76:12-18.

6. Tunca Z, Kıvırcık Akdede B, Özerdem A, et al. Diverse glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) support between mania and schizophrenia: a comparative study in four major psychiatric disorders. Eur Psychiatry. 2015;30(2):198-204.

7. Al Shweiki MR, Oeckl P, Steinacker P, et al. Major depressive disorder: insight into candidate cerebrospinal fluid protein biomarkers from proteomics studies. Expert Rev Proteomics. 2017;14(6):499-514.

8. Kroksmark H, Vinberg M. Does S100B have a potential role in affective disorders? A literature review. Nord J Psychiatry. 2018;72(7):462-470.

9. Orlovska-Waast S, Köhler-Forsberg O, Brix SW, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid markers of inflammation and infections in schizophrenia and affective disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mol Psychiatry. 2019;24(6):869-887.

10. Nasrallah HA. Lab tests for psychiatric disorders: few clinicians are aware of them. Current Psychiatry. 2013;12(2):5-7.

11. Porter L, Shoushtarizadeh A, Jelinek GA, et al. Metabolomic biomarkers of multiple sclerosis: a systematic review. Front Mol Biosci. 2020;7:574133. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2020.574133

Psychiatry and neurology are the brain’s twin medical disciplines. Unlike neurologic brain disorders, where localizing the “lesion” is a primary objective, psychiatric brain disorders are much more subtle, with no “gross” lesions but numerous cellular and molecular pathologies within neural circuits.

Measuring the molecular components of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), the glorious “sewage system” of the brain, may help reveal granular clues to the neurobiology of psychiatric disorders.

Mental illnesses involve the disruption of brain structures and functions in a diffuse manner across the cortex. Abnormal neuroplasticity has been implicated in several major psychiatric disorders. Examples include hypoplasia of the hippocampus in major depressive disorder and cortical thinning/dysplasia in schizophrenia. Reductions of neurotropic factors such as nerve growth factor or brain-derived neurotropic factor have been reported in mood and psychotic disorders, and appear to correlate with neuroplasticity changes.

Recent advances in psychiatric neuroscience have provided many clues to the pathophysiology of psychopathological conditions, including neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, apoptosis, impaired energy metabolism, abnormal metabolomics and lipidomics, and hypo- and hyperfunction of various neurotransmitters systems (especially glutamate N-methyl-

Thus, psychiatric research should focus on exploring and detecting molecular signatures (ie, biomarkers) of psychiatric disorders, including biomarkers of axonal and synaptic damage, glial activation, and oxidative stress. This is especially critical given the extensive heterogeneity of schizophrenia and mood and anxiety disorders. The CSF is a vastly unexploited substrate for discovering molecular biomarkers that will pave the way to precision psychiatry, and possibly open the door for completely new therapeutic strategies to tackle the most challenging neuropsychiatric disorders.

A role for CSF analysis

It’s quite puzzling why acute psychiatric episodes of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, or panic attacks are not routinely assessed with a spinal tap, in conjunction with other brain measures such as neuroimaging (morphology, spectroscopy, cerebral blood flow, and diffusion tensor imaging) as well as a comprehensive neurocognitive examination and neurophysiological tests such as pre-pulse inhibition, mismatch negativity, and P-50, N-10, and P-300 evoked potentials. Combining CSF analysis with all those measures may help us stratify the spectra of psychosis, depression, and anxiety, as well as posttraumatic stress disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder, into unique biotypes with overlapping clinical phenotypes and specific treatment approaches.

There are relatively few published CSF studies in psychiatric patients (mostly schizophrenia and bipolar and depressive disorders). The Table1-9 shows some of those findings. More than 365 biomarkers have been reported in schizophrenia, most of them in serum and tissue.10 However, none of them can be used for diagnostic purposes because schizophrenia is a syndrome comprised of several hundred different diseases (biotypes) that have similar clinical symptoms. Many of the serum and tissue biomarkers have not been studied in CSF, and they must if advances in the neurobiology and treatment of the psychotic and mood spectra are to be achieved. And adapting the CSF biomarkers described in neurologic disorders such as multiple sclerosis11 to schizophrenia and bipolar disorder (which also have well-established myelin pathologies) may yield a trove of neurobiologic findings.

If CSF studies eventually prove to be very useful for identifying subtypes for diagnosis and treatment, psychiatrists do not have to do the lumbar puncture themselves, but may refer patients to a “spinal tap” laboratory, just as they refer patients to a phlebotomy laboratory for routine blood tests. The adoption of CSF assessment in psychiatry will solidify its status as a clinical neuroscience, like its sister, neurology.

Psychiatry and neurology are the brain’s twin medical disciplines. Unlike neurologic brain disorders, where localizing the “lesion” is a primary objective, psychiatric brain disorders are much more subtle, with no “gross” lesions but numerous cellular and molecular pathologies within neural circuits.

Measuring the molecular components of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), the glorious “sewage system” of the brain, may help reveal granular clues to the neurobiology of psychiatric disorders.

Mental illnesses involve the disruption of brain structures and functions in a diffuse manner across the cortex. Abnormal neuroplasticity has been implicated in several major psychiatric disorders. Examples include hypoplasia of the hippocampus in major depressive disorder and cortical thinning/dysplasia in schizophrenia. Reductions of neurotropic factors such as nerve growth factor or brain-derived neurotropic factor have been reported in mood and psychotic disorders, and appear to correlate with neuroplasticity changes.

Recent advances in psychiatric neuroscience have provided many clues to the pathophysiology of psychopathological conditions, including neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, apoptosis, impaired energy metabolism, abnormal metabolomics and lipidomics, and hypo- and hyperfunction of various neurotransmitters systems (especially glutamate N-methyl-

Thus, psychiatric research should focus on exploring and detecting molecular signatures (ie, biomarkers) of psychiatric disorders, including biomarkers of axonal and synaptic damage, glial activation, and oxidative stress. This is especially critical given the extensive heterogeneity of schizophrenia and mood and anxiety disorders. The CSF is a vastly unexploited substrate for discovering molecular biomarkers that will pave the way to precision psychiatry, and possibly open the door for completely new therapeutic strategies to tackle the most challenging neuropsychiatric disorders.

A role for CSF analysis

It’s quite puzzling why acute psychiatric episodes of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, or panic attacks are not routinely assessed with a spinal tap, in conjunction with other brain measures such as neuroimaging (morphology, spectroscopy, cerebral blood flow, and diffusion tensor imaging) as well as a comprehensive neurocognitive examination and neurophysiological tests such as pre-pulse inhibition, mismatch negativity, and P-50, N-10, and P-300 evoked potentials. Combining CSF analysis with all those measures may help us stratify the spectra of psychosis, depression, and anxiety, as well as posttraumatic stress disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder, into unique biotypes with overlapping clinical phenotypes and specific treatment approaches.

There are relatively few published CSF studies in psychiatric patients (mostly schizophrenia and bipolar and depressive disorders). The Table1-9 shows some of those findings. More than 365 biomarkers have been reported in schizophrenia, most of them in serum and tissue.10 However, none of them can be used for diagnostic purposes because schizophrenia is a syndrome comprised of several hundred different diseases (biotypes) that have similar clinical symptoms. Many of the serum and tissue biomarkers have not been studied in CSF, and they must if advances in the neurobiology and treatment of the psychotic and mood spectra are to be achieved. And adapting the CSF biomarkers described in neurologic disorders such as multiple sclerosis11 to schizophrenia and bipolar disorder (which also have well-established myelin pathologies) may yield a trove of neurobiologic findings.

If CSF studies eventually prove to be very useful for identifying subtypes for diagnosis and treatment, psychiatrists do not have to do the lumbar puncture themselves, but may refer patients to a “spinal tap” laboratory, just as they refer patients to a phlebotomy laboratory for routine blood tests. The adoption of CSF assessment in psychiatry will solidify its status as a clinical neuroscience, like its sister, neurology.

1. Vasic N, Connemann BJ, Wolf RC, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid biomarker candidates of schizophrenia: where do we stand? Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2012;262(5):375-391.

2. Pollak TA, Drndarski S, Stone JM, et al. The blood-brain barrier in psychosis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(1):79-92.

3. Katisko K, Cajanus A, Jääskeläinen O, et al. Serum neurofilament light chain is a discriminative biomarker between frontotemporal lobar degeneration and primary psychiatric disorders. J Neurol. 2020;267(1):162-167.

4. Bechter K, Reiber H, Herzog S, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid analysis in affective and schizophrenic spectrum disorders: identification of subgroups with immune responses and blood-CSF barrier dysfunction. J Psychiatr Res. 2010;44(5):321-330.

5. Hidese S, Hattori K, Sasayama D, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid neural cell adhesion molecule levels and their correlation with clinical variables in patients with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorder. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2017;76:12-18.

6. Tunca Z, Kıvırcık Akdede B, Özerdem A, et al. Diverse glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) support between mania and schizophrenia: a comparative study in four major psychiatric disorders. Eur Psychiatry. 2015;30(2):198-204.

7. Al Shweiki MR, Oeckl P, Steinacker P, et al. Major depressive disorder: insight into candidate cerebrospinal fluid protein biomarkers from proteomics studies. Expert Rev Proteomics. 2017;14(6):499-514.

8. Kroksmark H, Vinberg M. Does S100B have a potential role in affective disorders? A literature review. Nord J Psychiatry. 2018;72(7):462-470.

9. Orlovska-Waast S, Köhler-Forsberg O, Brix SW, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid markers of inflammation and infections in schizophrenia and affective disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mol Psychiatry. 2019;24(6):869-887.

10. Nasrallah HA. Lab tests for psychiatric disorders: few clinicians are aware of them. Current Psychiatry. 2013;12(2):5-7.

11. Porter L, Shoushtarizadeh A, Jelinek GA, et al. Metabolomic biomarkers of multiple sclerosis: a systematic review. Front Mol Biosci. 2020;7:574133. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2020.574133

1. Vasic N, Connemann BJ, Wolf RC, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid biomarker candidates of schizophrenia: where do we stand? Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2012;262(5):375-391.

2. Pollak TA, Drndarski S, Stone JM, et al. The blood-brain barrier in psychosis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(1):79-92.

3. Katisko K, Cajanus A, Jääskeläinen O, et al. Serum neurofilament light chain is a discriminative biomarker between frontotemporal lobar degeneration and primary psychiatric disorders. J Neurol. 2020;267(1):162-167.

4. Bechter K, Reiber H, Herzog S, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid analysis in affective and schizophrenic spectrum disorders: identification of subgroups with immune responses and blood-CSF barrier dysfunction. J Psychiatr Res. 2010;44(5):321-330.

5. Hidese S, Hattori K, Sasayama D, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid neural cell adhesion molecule levels and their correlation with clinical variables in patients with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorder. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2017;76:12-18.

6. Tunca Z, Kıvırcık Akdede B, Özerdem A, et al. Diverse glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) support between mania and schizophrenia: a comparative study in four major psychiatric disorders. Eur Psychiatry. 2015;30(2):198-204.

7. Al Shweiki MR, Oeckl P, Steinacker P, et al. Major depressive disorder: insight into candidate cerebrospinal fluid protein biomarkers from proteomics studies. Expert Rev Proteomics. 2017;14(6):499-514.

8. Kroksmark H, Vinberg M. Does S100B have a potential role in affective disorders? A literature review. Nord J Psychiatry. 2018;72(7):462-470.

9. Orlovska-Waast S, Köhler-Forsberg O, Brix SW, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid markers of inflammation and infections in schizophrenia and affective disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mol Psychiatry. 2019;24(6):869-887.

10. Nasrallah HA. Lab tests for psychiatric disorders: few clinicians are aware of them. Current Psychiatry. 2013;12(2):5-7.

11. Porter L, Shoushtarizadeh A, Jelinek GA, et al. Metabolomic biomarkers of multiple sclerosis: a systematic review. Front Mol Biosci. 2020;7:574133. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2020.574133

Late-onset, treatment-resistant anxiety and depression

CASE Anxious and can’t sleep

Mr. A, age 41, presents to his primary care physician (PCP) with anxiety and insomnia. He describes having generalized anxiety with initial and middle insomnia, and says he is sleeping an average of 2 hours per night. He denies any other psychiatric symptoms. Mr. A has no significant psychiatric or medical history.

Mr. A is initiated on zolpidem tartrate, 12.5 mg every night at bedtime, and paroxetine, 20 mg every night at bedtime, for anxiety and insomnia, but these medications result in little to no improvement.

During a 4-month period, he is treated with trials of alprazolam, 0.5 mg every 8 hours as needed; diazepam 5 mg twice a day as needed; diphenhydramine, 50 mg at bedtime; and eszopiclone, 3 mg at bedtime. Despite these treatments, he experiences increased anxiety and insomnia, and develops depressive symptoms, including depressed mood, poor concentration, general malaise, extreme fatigue, a 15-pound unintentional weight loss, erectile dysfunction, and decreased libido. Mr. A denies having suicidal or homicidal ideations. Additionally, he typically goes to the gym approximately 3 times per week, and has noticed that the amount of weight he is able to lift has decreased, which is distressing. Previously, he had been able to lift 300 pounds, but now he can only lift 200 pounds.

[polldaddy:10891920]

The authors’ observations

Insomnia, anxiety, and depression are common chief complaints in medical settings. However, some psychiatric presentations may have an underlying medical etiology.

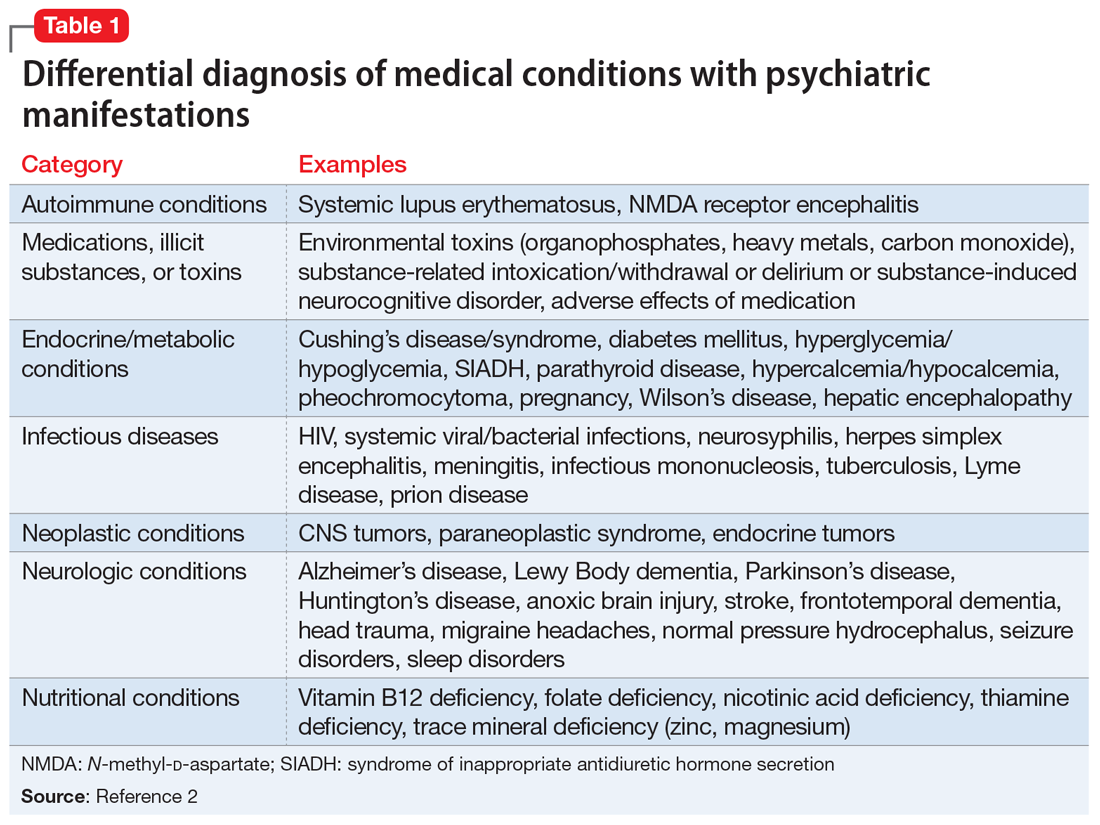

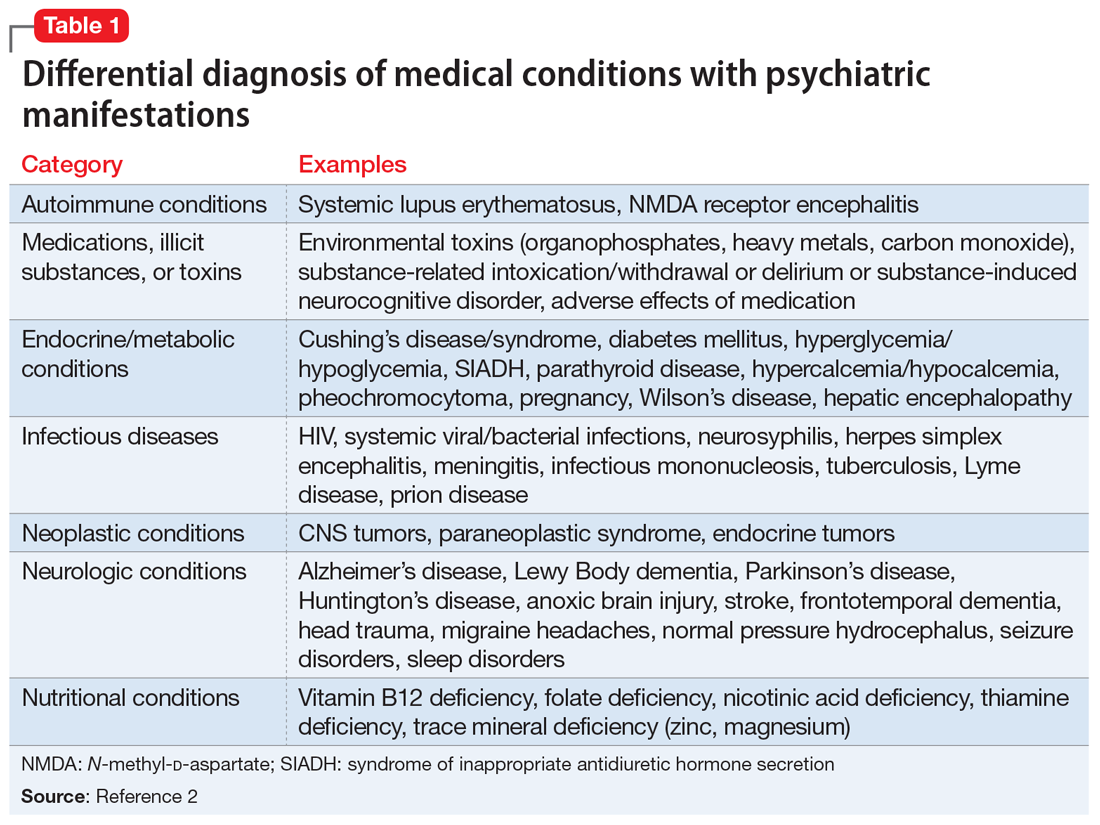

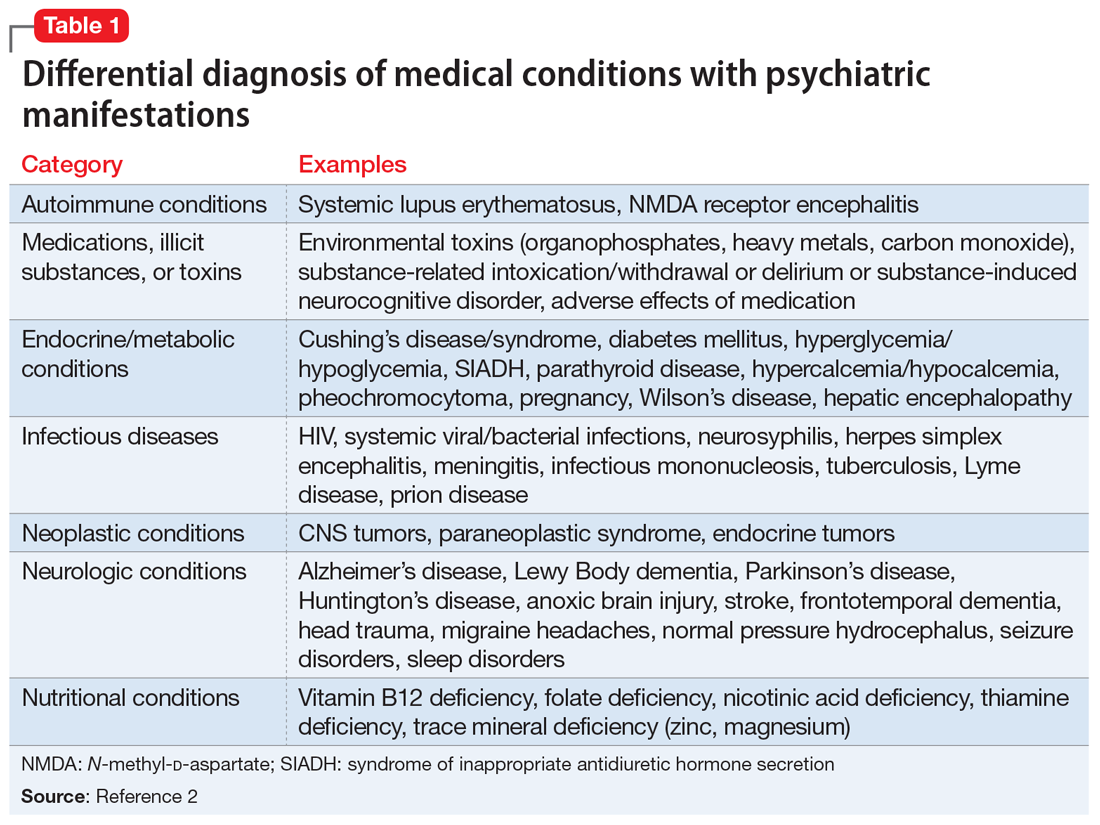

DSM-5 requires that medical conditions be ruled out in order for a patient to meet criteria for a psychiatric diagnosis.1 Medical differential diagnoses for patients with psychiatric symptoms can include autoimmune, drug/toxin, metabolic, infectious, neoplastic, neurologic, and nutritional etiologies (Table 12). To rule out the possibility of an underlying medical etiology, general screening guidelines include complete blood count, complete metabolic panel, urinalysis, and urine drug screen with alcohol. Human immunodeficiency virus testing and thyroid hormone testing are also commonly ordered.3 Further laboratory testing and imaging is typically not warranted in the absence of historical or physical findings because they are not advocated as cost-effective, so health care professionals must use their clinical judgment to determine appropriate further evaluation. The onset of anxiety most commonly occurs in late adolescence early and adulthood, but Mr. A experienced his first symptoms of anxiety at age 41.2 Mr. A’s age, lack of psychiatric or family history of mental illness, acute onset of symptoms, and failure of symptoms to abate with standard psychiatric treatments warrant a more extensive workup.

EVALUATION Imaging reveals an important finding

Because Mr. A’s symptoms do not improve with standard psychiatric treatments, his PCP orders standard laboratory bloodwork to investigate a possible medical etiology; however, his results are all within normal range.

After the PCP’s niece is coincidentally diagnosed with a pituitary macroadenoma, the PCP orders brain imaging for Mr. A. Results of an MRI show that Mr. A has a 1.6-cm macroadenoma of the pituitary. He is referred to an endocrinologist, who orders additional laboratory tests that show an elevated 24-hour free urine cortisol level of 73 μg/24 h (normal range: 3.5 to 45 μg/24 h), suggesting that Mr. A’s anxiety may be due to Cushing’s disease or that his anxiety caused falsely elevated urinary cortisol levels. Four weeks later, bloodwork is repeated and shows an abnormal dexamethasone suppression test, and 2 more elevated 24-hour free urine cortisol levels of 76 μg/24 h and 150 μg/24 h. A repeat MRI shows a 1.8-cm, mostly cystic sellar mass, indicating the need for surgical intervention. Although the tumor is large and shows optic nerve compression, Mr. A does not complain of headaches or changes in vision.

Continue to: Two months later...

Two months later, Mr. A undergoes a transsphenoidal tumor resection of the pituitary adenoma, and biopsy results confirm an adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH)-secreting pituitary macroadenoma, which is consistent with Cushing’s disease. Following surgery, steroid treatment with dexamethasone is discontinued due to a persistently elevated

[polldaddy:10891923]

The authors’ observations