User login

Automated office BP measurement: The new standard in HTN screening

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 45-year-old woman with no chronic medical illness presents to your office for her annual physical examination. After a medical assistant (MA) applies an automatic BP cuff to the patient’s left arm, the BP reading is 155/92 mm Hg. The MA then rechecks the BP, and this time it reads 160/98 mm Hg. The MA performs a manual BP reading, which is 158/90 mm Hg (left arm) and 162/100 mm Hg (right arm). The patient denies any headache, visual changes, chest pain, or difficulty breathing and tells the MA that her BP is always high during a doctor visit. You are wondering if she has hypertension or if is this the white-coat effect.

Depending on the definition of hypertension, its prevalence among US adults 18 years or older varies from 46%, based on the American College of Cardiology guideline (≥ 130/80 mm Hg), to 29%, based on the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC-8) guideline (≥ 140/90 mm Hg for adults ages 18–59 years and ≥ 150/90 mm Hg for adults ≥ 60 years without diabetes and/or chronic kidney disease).2,3

According to JNC-8, the prevalence is similar among men (30.2%) and women (27.7%) and increases with age: 18 to 39 years, 7.5%; 40 to 59 years, 33.2%; and ≥ 60 years, 63.1%.3,4 When ranked by risk-attributable disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs), high systolic blood pressure (SBP) is the leading risk factor, accounting for 10.4 million deaths and 218 million DALYs globally in 2017.5 National medical costs associated with hypertension are estimated to account for about $131 billion in annual health care expenditures, averaged over 12 years from 2003 to 2014.6

When performed correctly, the auscultatory method using a mercury sphygmomanometer correlates well with simultaneous intra-arterial BP and was considered the gold standard for office-based measurements for many years.7,8 However, significant observer-related differences in auditory acuity and terminal digit rounding are sources of inaccurate measurement. White-coat hypertension cannot be detected with this method—another significant limitation. The inaccuracy of office-based BP readings leads to concerns about hypertension being inappropriately diagnosed in patients or delays in diagnosis occurring.9

A proposed solution to this problem is measurement using an oscillometric sphygmomanometer. This device uses a pressure transducer to assess the oscillations of pressure in a cuff during gradual deflation; it provides accurate BP measurements when fully automated and programmed to complete several BP measurements at appropriate intervals while the patient rests alone in a quiet room.10

The accuracy of this new method was tested in a 2009 cohort study of 309 patients referred to an ambulatory blood pressure (ABP) monitoring unit at an academic hospital for diagnosis or management of hypertension.11 The study compared mean awake

A 2019 meta-analysis that included 26 studies (N = 7116) comparing

Continue to: STUDY SUMMARY

STUDY SUMMARY

Automated office BP devices are just as accurate as more expensive ABP studies

This systematic review and meta-analysis (

The study also explored the protocol by which the best AOBP results could be obtained. For AOBP measurement, the included trials had no more than 2 minutes of elapsed time between individual AOBP measurements and had at least 3 AOBP readings to calculate the mean.

Compared with AOBP, in samples with an SBP of ≥ 130 mm Hg, SBP readings were significantly higher for both routine office visits (

Although there was statistical heterogeneity, the results were confirmed in the authors’ analysis of studies with high methodologic quality. In addition, researchers performed multiple

WHAT'S NEW

Study confirms unattended, automated office BP as preferred technique

This is the second recent comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis to directly compare AOBP with other common techniques of BP measurement in screening for and diagnosing hypertension in the clinical setting. 9

Continue to: This meta-analysis...

This meta-analysis emphasized the technique (see below) by which to obtain the best AOBP vs ABP results, whereas the other meta-analysis9 did not. Thus the study provides practice-based settings with the information they need to more closely replicate the results of the studies included in the meta-analysis.

Also, the equivalency comparison with the more expensive and intrusive ABP monitoring may save money, improve patient adherence, and increase patient satisfaction. Given these advantages, along with its demonstrated accuracy, AOBP should be adopted in routine clinical practice to screen patients for hypertension.

CAVEATS

Close adherence to measurementprocedures is a necessity

Effective use of AOBP in clinical practice requires close adherence to the AOBP study procedures described in this meta-analysis. These include taking multiple (at least 3) BP readings, 1 to 2 minutes apart, recorded with a fully automated oscillometric sphygmomanometer while the patient rests alone in a quiet place.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Adjusting workflows, addressing cost

Physicians may be reluctant to adopt this technique because they may not be convinced of its advantages compared with the traditional methods of recording BP and because of difficulties with implementing new rooming workflows.12 The cost of AOBP devices used in this study (Omron 907 and BpTRU; BpTRU ceased operations in 2017) were not disclosed, which may be a hindrance, as devices may cost $1000 or more.

An online search for “automated oscillometric BP monitor” by one of the PURL authors (RCM) found oscillometric AOBP devices ranging from $150 to > $1000, depending on whether the device was medical grade; a search for “Omron 907” found devices for ≤ $599 on multiple sites. However, none of the lower-cost devices indicated the ability to take multiple, unattended BP readings.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center for Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

1. Roerecke M, Kaczorowski J, Myers MG. Comparing automated office blood pressure readings with other methods of blood pressure measurement for identifying patients with possible hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179:351-362.

2. Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension. 2018;71:e13-e115. Published correction appears in Hypertension. 2018;71:e140-e144.

3. James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA. 2014;311:507-520. Published correction appears in JAMA. 2014;311:1809.

4. Fryar CD, Ostchega Y, Hales CM, et al. Hypertension prevalence and control among adults: United States, 2015-2016. NCHS Data Brief. 2017;(289):1-8.

5. GBD 2017 Risk Factor Collaborators. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 84 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2018;392:1923-1994.

6. Kirkland EB, Heincelman M, Bishu KG, et al. Trends in healthcare expenditures among US adults with hypertension: national estimates, 2003-2014. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7:e008731.

7. Pickering TG, Hall JE, Appel LJ, et al. Recommendations for blood pressure measurement in humans and experimental animals: part 1: blood pressure measurement in humans: a statement for professionals from the Subcommittee of Professional and Public Education of the American Heart Association Council on High Blood Pressure Research. Circulation. 2005;111:697-716.

8. Ogedegbe G, Pickering T. Principles and techniques of blood pressure measurement. Cardiol Clin. 2010;28:571-586.

9. Pappaccogli M, Di Monaco S, Perlo E, et al. Comparison of automated office blood pressure with office and out-of-office measurement techniques. Hypertension. 2019;73:481-490.

10. Reeves RA. The rational clinical examination. Does this patient have hypertension? How to measure blood pressure. JAMA. 1995;273:1211-1218.

11. Myers MG, Valdivieso M, Kiss A. Use of automated office blood pressure measurement to reduce the white coat response. J Hypertens. 2009;27:280-286.

12. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Decision memo for ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM) (CAG-00067R2). July 2, 2019. Accessed September 29, 2020. www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/details/nca-decision-memo.aspx?NCAId=294

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 45-year-old woman with no chronic medical illness presents to your office for her annual physical examination. After a medical assistant (MA) applies an automatic BP cuff to the patient’s left arm, the BP reading is 155/92 mm Hg. The MA then rechecks the BP, and this time it reads 160/98 mm Hg. The MA performs a manual BP reading, which is 158/90 mm Hg (left arm) and 162/100 mm Hg (right arm). The patient denies any headache, visual changes, chest pain, or difficulty breathing and tells the MA that her BP is always high during a doctor visit. You are wondering if she has hypertension or if is this the white-coat effect.

Depending on the definition of hypertension, its prevalence among US adults 18 years or older varies from 46%, based on the American College of Cardiology guideline (≥ 130/80 mm Hg), to 29%, based on the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC-8) guideline (≥ 140/90 mm Hg for adults ages 18–59 years and ≥ 150/90 mm Hg for adults ≥ 60 years without diabetes and/or chronic kidney disease).2,3

According to JNC-8, the prevalence is similar among men (30.2%) and women (27.7%) and increases with age: 18 to 39 years, 7.5%; 40 to 59 years, 33.2%; and ≥ 60 years, 63.1%.3,4 When ranked by risk-attributable disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs), high systolic blood pressure (SBP) is the leading risk factor, accounting for 10.4 million deaths and 218 million DALYs globally in 2017.5 National medical costs associated with hypertension are estimated to account for about $131 billion in annual health care expenditures, averaged over 12 years from 2003 to 2014.6

When performed correctly, the auscultatory method using a mercury sphygmomanometer correlates well with simultaneous intra-arterial BP and was considered the gold standard for office-based measurements for many years.7,8 However, significant observer-related differences in auditory acuity and terminal digit rounding are sources of inaccurate measurement. White-coat hypertension cannot be detected with this method—another significant limitation. The inaccuracy of office-based BP readings leads to concerns about hypertension being inappropriately diagnosed in patients or delays in diagnosis occurring.9

A proposed solution to this problem is measurement using an oscillometric sphygmomanometer. This device uses a pressure transducer to assess the oscillations of pressure in a cuff during gradual deflation; it provides accurate BP measurements when fully automated and programmed to complete several BP measurements at appropriate intervals while the patient rests alone in a quiet room.10

The accuracy of this new method was tested in a 2009 cohort study of 309 patients referred to an ambulatory blood pressure (ABP) monitoring unit at an academic hospital for diagnosis or management of hypertension.11 The study compared mean awake

A 2019 meta-analysis that included 26 studies (N = 7116) comparing

Continue to: STUDY SUMMARY

STUDY SUMMARY

Automated office BP devices are just as accurate as more expensive ABP studies

This systematic review and meta-analysis (

The study also explored the protocol by which the best AOBP results could be obtained. For AOBP measurement, the included trials had no more than 2 minutes of elapsed time between individual AOBP measurements and had at least 3 AOBP readings to calculate the mean.

Compared with AOBP, in samples with an SBP of ≥ 130 mm Hg, SBP readings were significantly higher for both routine office visits (

Although there was statistical heterogeneity, the results were confirmed in the authors’ analysis of studies with high methodologic quality. In addition, researchers performed multiple

WHAT'S NEW

Study confirms unattended, automated office BP as preferred technique

This is the second recent comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis to directly compare AOBP with other common techniques of BP measurement in screening for and diagnosing hypertension in the clinical setting. 9

Continue to: This meta-analysis...

This meta-analysis emphasized the technique (see below) by which to obtain the best AOBP vs ABP results, whereas the other meta-analysis9 did not. Thus the study provides practice-based settings with the information they need to more closely replicate the results of the studies included in the meta-analysis.

Also, the equivalency comparison with the more expensive and intrusive ABP monitoring may save money, improve patient adherence, and increase patient satisfaction. Given these advantages, along with its demonstrated accuracy, AOBP should be adopted in routine clinical practice to screen patients for hypertension.

CAVEATS

Close adherence to measurementprocedures is a necessity

Effective use of AOBP in clinical practice requires close adherence to the AOBP study procedures described in this meta-analysis. These include taking multiple (at least 3) BP readings, 1 to 2 minutes apart, recorded with a fully automated oscillometric sphygmomanometer while the patient rests alone in a quiet place.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Adjusting workflows, addressing cost

Physicians may be reluctant to adopt this technique because they may not be convinced of its advantages compared with the traditional methods of recording BP and because of difficulties with implementing new rooming workflows.12 The cost of AOBP devices used in this study (Omron 907 and BpTRU; BpTRU ceased operations in 2017) were not disclosed, which may be a hindrance, as devices may cost $1000 or more.

An online search for “automated oscillometric BP monitor” by one of the PURL authors (RCM) found oscillometric AOBP devices ranging from $150 to > $1000, depending on whether the device was medical grade; a search for “Omron 907” found devices for ≤ $599 on multiple sites. However, none of the lower-cost devices indicated the ability to take multiple, unattended BP readings.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center for Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 45-year-old woman with no chronic medical illness presents to your office for her annual physical examination. After a medical assistant (MA) applies an automatic BP cuff to the patient’s left arm, the BP reading is 155/92 mm Hg. The MA then rechecks the BP, and this time it reads 160/98 mm Hg. The MA performs a manual BP reading, which is 158/90 mm Hg (left arm) and 162/100 mm Hg (right arm). The patient denies any headache, visual changes, chest pain, or difficulty breathing and tells the MA that her BP is always high during a doctor visit. You are wondering if she has hypertension or if is this the white-coat effect.

Depending on the definition of hypertension, its prevalence among US adults 18 years or older varies from 46%, based on the American College of Cardiology guideline (≥ 130/80 mm Hg), to 29%, based on the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC-8) guideline (≥ 140/90 mm Hg for adults ages 18–59 years and ≥ 150/90 mm Hg for adults ≥ 60 years without diabetes and/or chronic kidney disease).2,3

According to JNC-8, the prevalence is similar among men (30.2%) and women (27.7%) and increases with age: 18 to 39 years, 7.5%; 40 to 59 years, 33.2%; and ≥ 60 years, 63.1%.3,4 When ranked by risk-attributable disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs), high systolic blood pressure (SBP) is the leading risk factor, accounting for 10.4 million deaths and 218 million DALYs globally in 2017.5 National medical costs associated with hypertension are estimated to account for about $131 billion in annual health care expenditures, averaged over 12 years from 2003 to 2014.6

When performed correctly, the auscultatory method using a mercury sphygmomanometer correlates well with simultaneous intra-arterial BP and was considered the gold standard for office-based measurements for many years.7,8 However, significant observer-related differences in auditory acuity and terminal digit rounding are sources of inaccurate measurement. White-coat hypertension cannot be detected with this method—another significant limitation. The inaccuracy of office-based BP readings leads to concerns about hypertension being inappropriately diagnosed in patients or delays in diagnosis occurring.9

A proposed solution to this problem is measurement using an oscillometric sphygmomanometer. This device uses a pressure transducer to assess the oscillations of pressure in a cuff during gradual deflation; it provides accurate BP measurements when fully automated and programmed to complete several BP measurements at appropriate intervals while the patient rests alone in a quiet room.10

The accuracy of this new method was tested in a 2009 cohort study of 309 patients referred to an ambulatory blood pressure (ABP) monitoring unit at an academic hospital for diagnosis or management of hypertension.11 The study compared mean awake

A 2019 meta-analysis that included 26 studies (N = 7116) comparing

Continue to: STUDY SUMMARY

STUDY SUMMARY

Automated office BP devices are just as accurate as more expensive ABP studies

This systematic review and meta-analysis (

The study also explored the protocol by which the best AOBP results could be obtained. For AOBP measurement, the included trials had no more than 2 minutes of elapsed time between individual AOBP measurements and had at least 3 AOBP readings to calculate the mean.

Compared with AOBP, in samples with an SBP of ≥ 130 mm Hg, SBP readings were significantly higher for both routine office visits (

Although there was statistical heterogeneity, the results were confirmed in the authors’ analysis of studies with high methodologic quality. In addition, researchers performed multiple

WHAT'S NEW

Study confirms unattended, automated office BP as preferred technique

This is the second recent comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis to directly compare AOBP with other common techniques of BP measurement in screening for and diagnosing hypertension in the clinical setting. 9

Continue to: This meta-analysis...

This meta-analysis emphasized the technique (see below) by which to obtain the best AOBP vs ABP results, whereas the other meta-analysis9 did not. Thus the study provides practice-based settings with the information they need to more closely replicate the results of the studies included in the meta-analysis.

Also, the equivalency comparison with the more expensive and intrusive ABP monitoring may save money, improve patient adherence, and increase patient satisfaction. Given these advantages, along with its demonstrated accuracy, AOBP should be adopted in routine clinical practice to screen patients for hypertension.

CAVEATS

Close adherence to measurementprocedures is a necessity

Effective use of AOBP in clinical practice requires close adherence to the AOBP study procedures described in this meta-analysis. These include taking multiple (at least 3) BP readings, 1 to 2 minutes apart, recorded with a fully automated oscillometric sphygmomanometer while the patient rests alone in a quiet place.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Adjusting workflows, addressing cost

Physicians may be reluctant to adopt this technique because they may not be convinced of its advantages compared with the traditional methods of recording BP and because of difficulties with implementing new rooming workflows.12 The cost of AOBP devices used in this study (Omron 907 and BpTRU; BpTRU ceased operations in 2017) were not disclosed, which may be a hindrance, as devices may cost $1000 or more.

An online search for “automated oscillometric BP monitor” by one of the PURL authors (RCM) found oscillometric AOBP devices ranging from $150 to > $1000, depending on whether the device was medical grade; a search for “Omron 907” found devices for ≤ $599 on multiple sites. However, none of the lower-cost devices indicated the ability to take multiple, unattended BP readings.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center for Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

1. Roerecke M, Kaczorowski J, Myers MG. Comparing automated office blood pressure readings with other methods of blood pressure measurement for identifying patients with possible hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179:351-362.

2. Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension. 2018;71:e13-e115. Published correction appears in Hypertension. 2018;71:e140-e144.

3. James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA. 2014;311:507-520. Published correction appears in JAMA. 2014;311:1809.

4. Fryar CD, Ostchega Y, Hales CM, et al. Hypertension prevalence and control among adults: United States, 2015-2016. NCHS Data Brief. 2017;(289):1-8.

5. GBD 2017 Risk Factor Collaborators. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 84 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2018;392:1923-1994.

6. Kirkland EB, Heincelman M, Bishu KG, et al. Trends in healthcare expenditures among US adults with hypertension: national estimates, 2003-2014. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7:e008731.

7. Pickering TG, Hall JE, Appel LJ, et al. Recommendations for blood pressure measurement in humans and experimental animals: part 1: blood pressure measurement in humans: a statement for professionals from the Subcommittee of Professional and Public Education of the American Heart Association Council on High Blood Pressure Research. Circulation. 2005;111:697-716.

8. Ogedegbe G, Pickering T. Principles and techniques of blood pressure measurement. Cardiol Clin. 2010;28:571-586.

9. Pappaccogli M, Di Monaco S, Perlo E, et al. Comparison of automated office blood pressure with office and out-of-office measurement techniques. Hypertension. 2019;73:481-490.

10. Reeves RA. The rational clinical examination. Does this patient have hypertension? How to measure blood pressure. JAMA. 1995;273:1211-1218.

11. Myers MG, Valdivieso M, Kiss A. Use of automated office blood pressure measurement to reduce the white coat response. J Hypertens. 2009;27:280-286.

12. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Decision memo for ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM) (CAG-00067R2). July 2, 2019. Accessed September 29, 2020. www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/details/nca-decision-memo.aspx?NCAId=294

1. Roerecke M, Kaczorowski J, Myers MG. Comparing automated office blood pressure readings with other methods of blood pressure measurement for identifying patients with possible hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179:351-362.

2. Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension. 2018;71:e13-e115. Published correction appears in Hypertension. 2018;71:e140-e144.

3. James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA. 2014;311:507-520. Published correction appears in JAMA. 2014;311:1809.

4. Fryar CD, Ostchega Y, Hales CM, et al. Hypertension prevalence and control among adults: United States, 2015-2016. NCHS Data Brief. 2017;(289):1-8.

5. GBD 2017 Risk Factor Collaborators. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 84 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2018;392:1923-1994.

6. Kirkland EB, Heincelman M, Bishu KG, et al. Trends in healthcare expenditures among US adults with hypertension: national estimates, 2003-2014. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7:e008731.

7. Pickering TG, Hall JE, Appel LJ, et al. Recommendations for blood pressure measurement in humans and experimental animals: part 1: blood pressure measurement in humans: a statement for professionals from the Subcommittee of Professional and Public Education of the American Heart Association Council on High Blood Pressure Research. Circulation. 2005;111:697-716.

8. Ogedegbe G, Pickering T. Principles and techniques of blood pressure measurement. Cardiol Clin. 2010;28:571-586.

9. Pappaccogli M, Di Monaco S, Perlo E, et al. Comparison of automated office blood pressure with office and out-of-office measurement techniques. Hypertension. 2019;73:481-490.

10. Reeves RA. The rational clinical examination. Does this patient have hypertension? How to measure blood pressure. JAMA. 1995;273:1211-1218.

11. Myers MG, Valdivieso M, Kiss A. Use of automated office blood pressure measurement to reduce the white coat response. J Hypertens. 2009;27:280-286.

12. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Decision memo for ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM) (CAG-00067R2). July 2, 2019. Accessed September 29, 2020. www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/details/nca-decision-memo.aspx?NCAId=294

PRACTICE CHANGER

Measure patients’ blood pressure (BP) using an oscillometric, fully automated office BP device, with the patient sitting alone in a quiet exam room, to accurately diagnose hypertension and eliminate the “white-coat” effect.

STRENGTH OF RECOMMENDATION

B: Based on a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials and cohort studies.1

Roerecke M, Kaczorowski J, Myers MG. Comparing automated office blood pressure readings with other methods of blood pressure measurement for identifying patients with possible hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179:351-362.

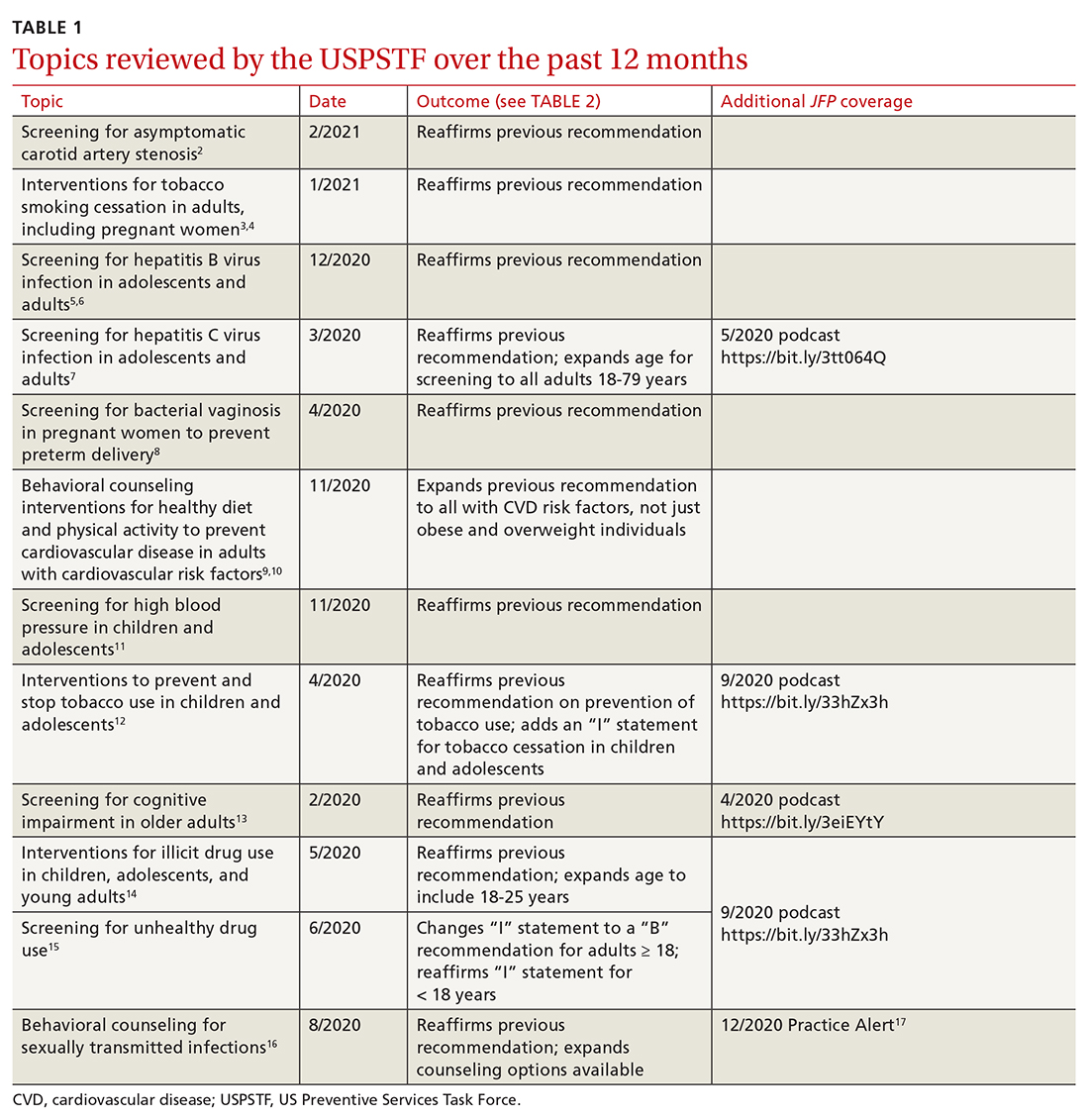

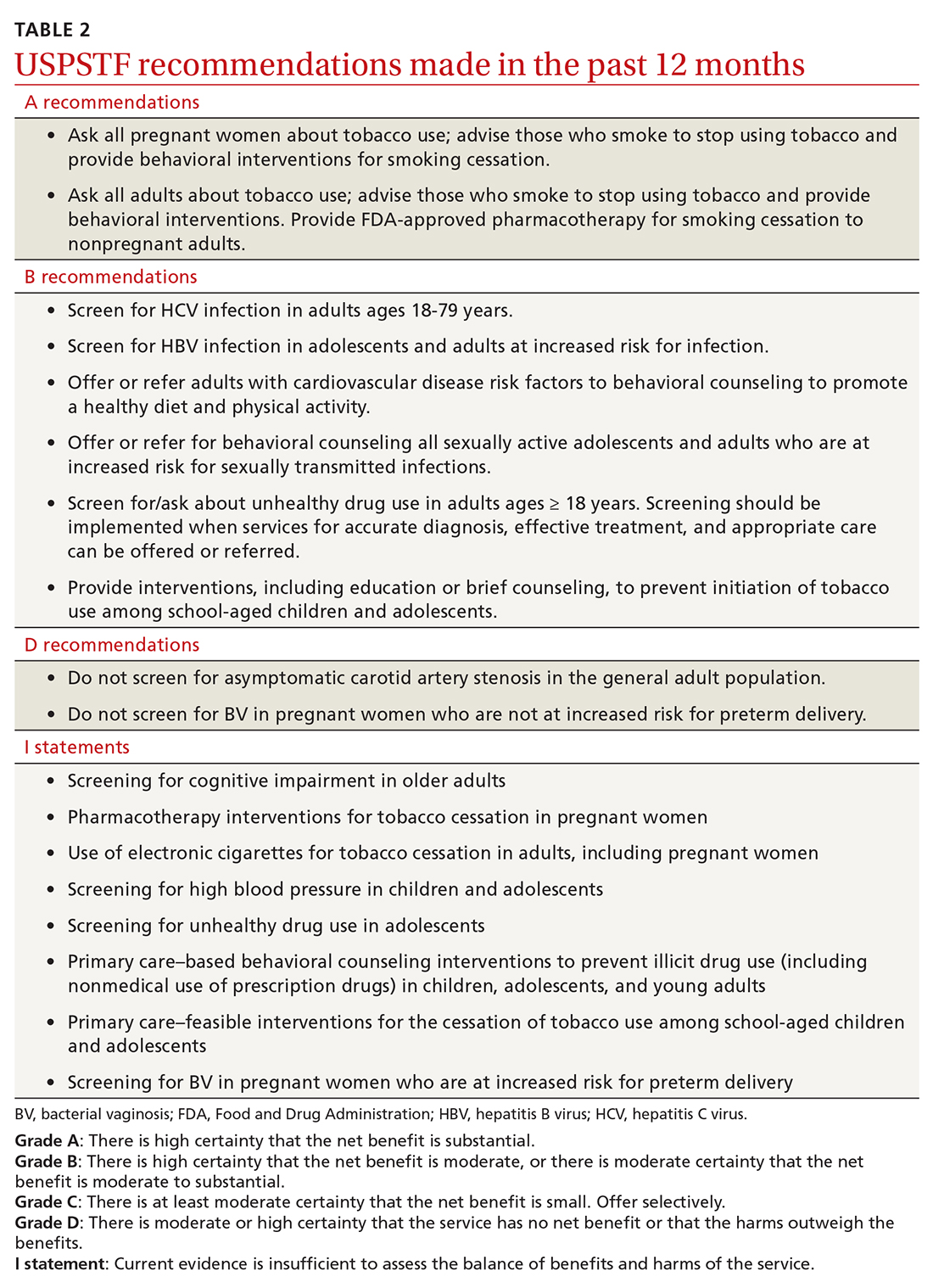

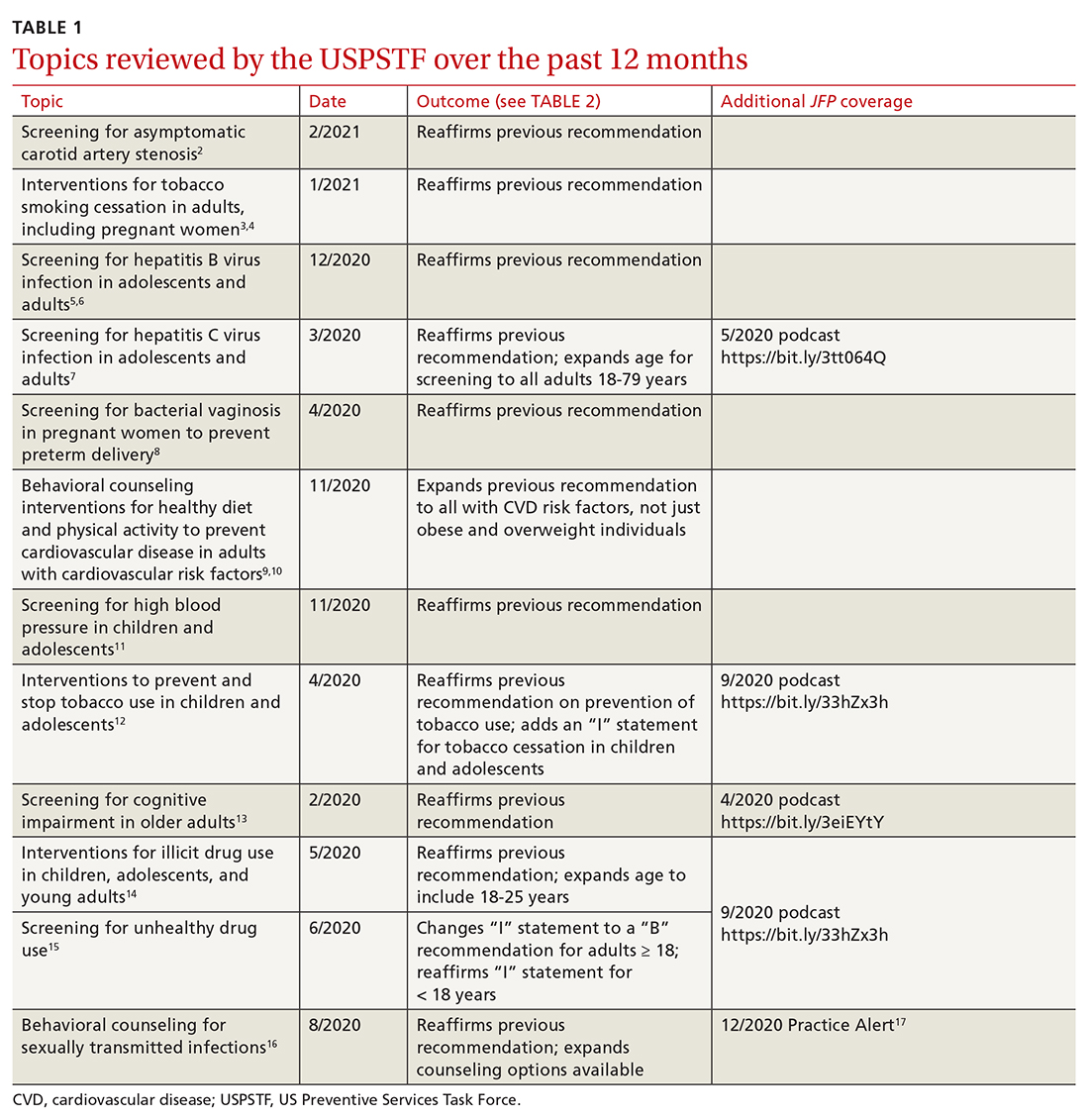

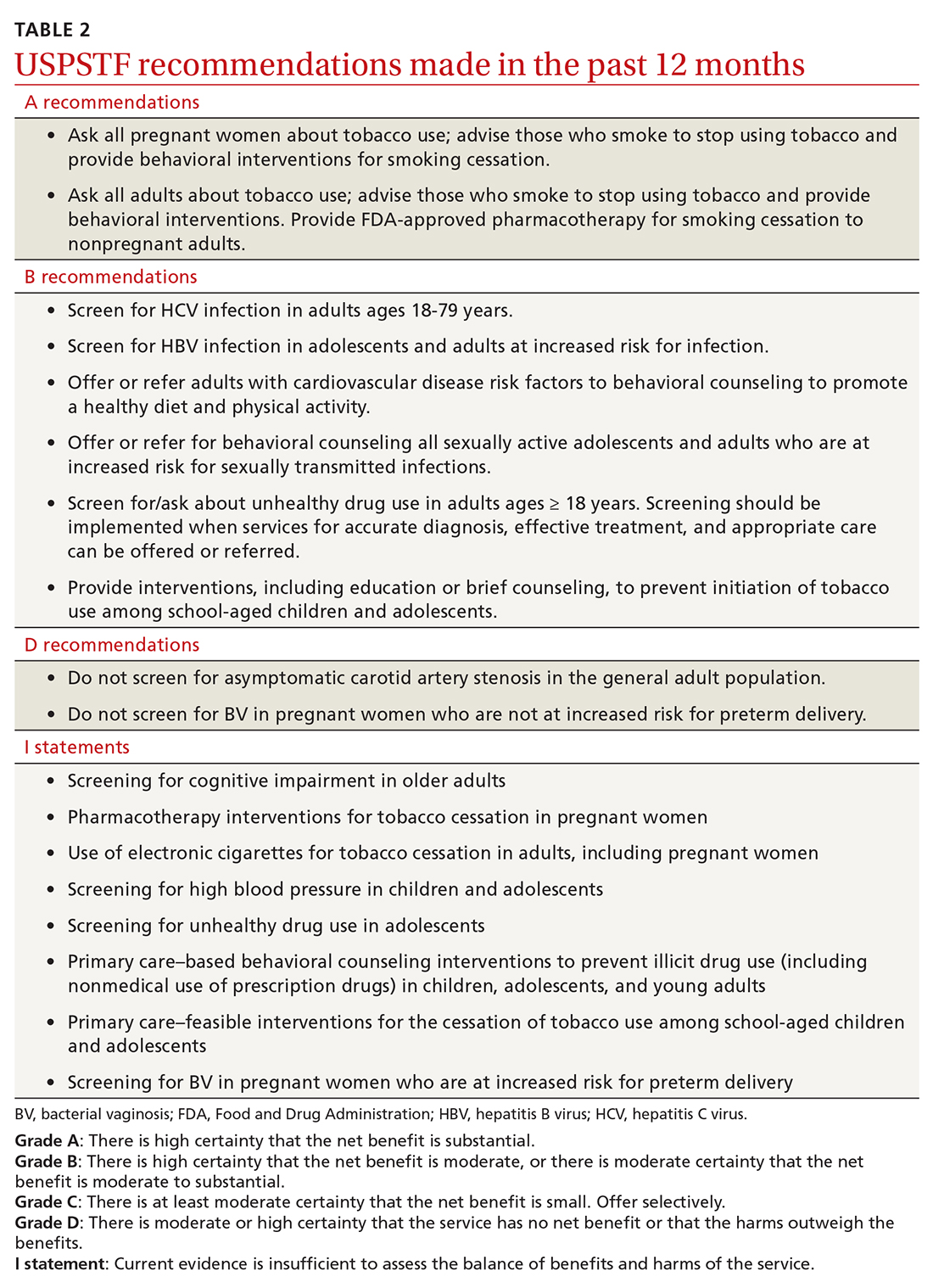

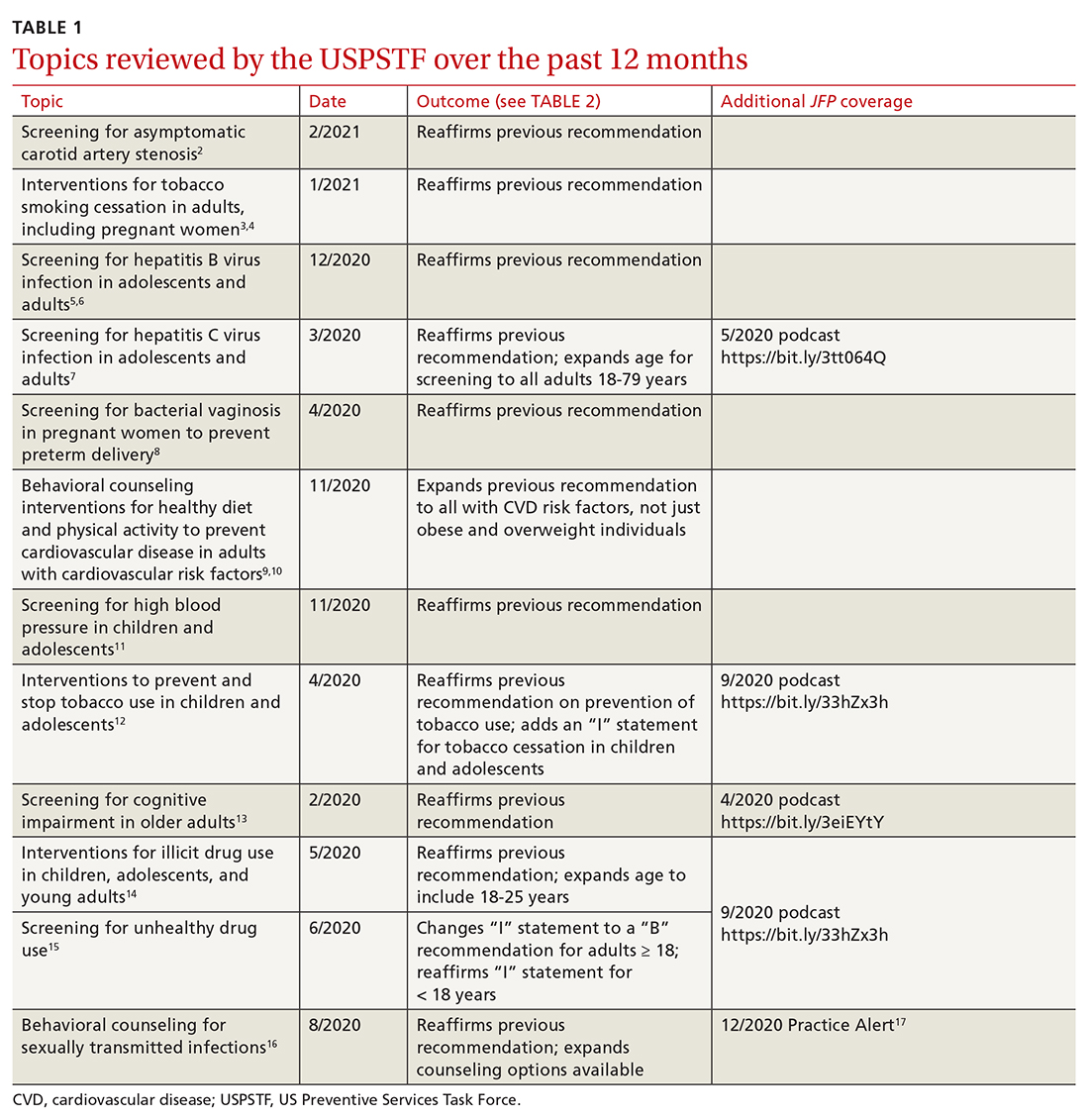

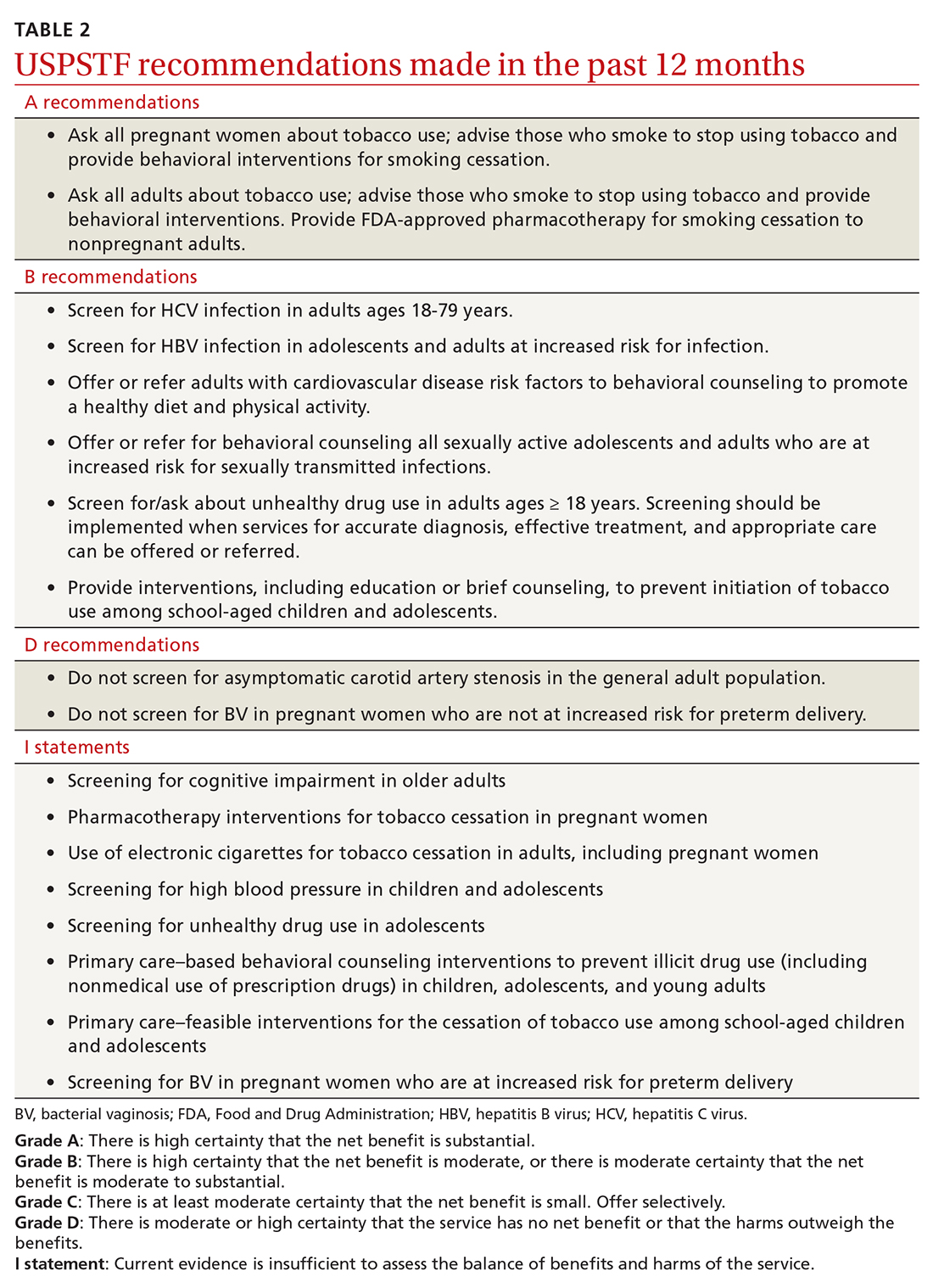

A review of the latest USPSTF recommendations

Since the last Practice Alert update on recommendations made by the US Preventive Services Task Force,1 the Task Force has completed work on 12 topics (TABLE 1).2-17 Five of these topics have been discussed in JFP audio recordings, and the links are provided in TABLE 1.

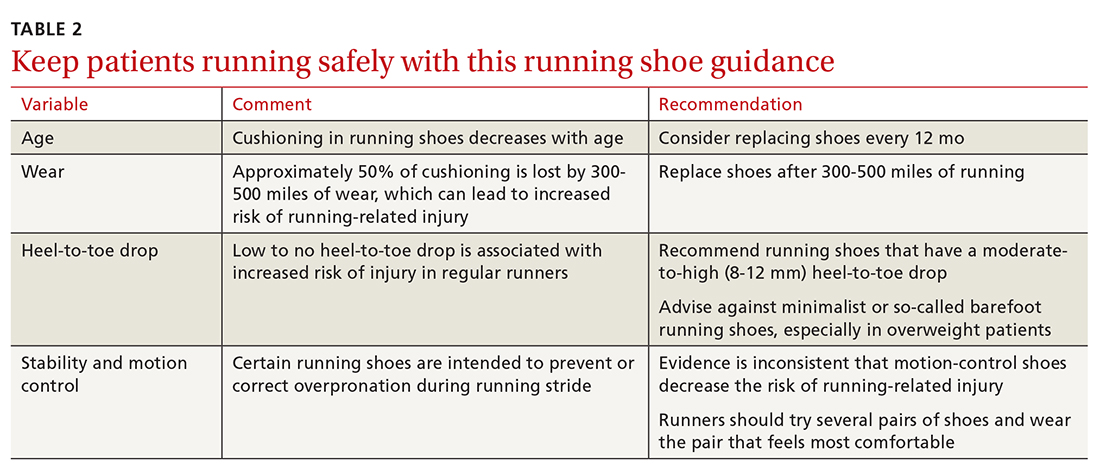

This latest Task Force endeavor resulted in 18 recommendations (TABLE 2), all of which reaffirm previous recommendations on these topics and expand the scope of 2. There were 2 “A” recommendations, 6 “B” recommendations, 2 “D” recommendations, and 8 “I” statements, indicating that there was insufficient evidence to assess effectiveness or harms. The willingness to make “I” statements when there is little or no evidence on the intervention being assessed distinguishes the USPSTF from other clinical guideline committees.

Screening for carotid artery stenosis

One of the “D” recommendations this past year reaffirms the prior recommendation against screening for carotid artery stenosis in asymptomatic adults—ie, those without a history of transient ischemic attack, stroke, or neurologic signs or symptoms that might be caused by carotid artery stenosis.2 The screening tests the Task Force researched included carotid duplex ultrasonography (DUS), magnetic resonance angiography, and computed tomography angiography. The Task Force did not look at the value of auscultation for carotid bruits because it has been proven to be inaccurate and they do not consider it to be a useful screening tool.

The Task Force based its “D” recommendation on a lack of evidence for any benefit in detecting asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis, and on evidence that screening can lead to harms through false-positive tests and potential complications from carotid endarterectomy and carotid artery angioplasty and stenting. In its clinical considerations, the Task Force emphasized the primary prevention of atherosclerotic disease by focusing on the following actions:

- screening for high blood pressure in adults

- encouraging tobacco smoking cessation in adults

- promoting a healthy diet and physical activity in adults with cardiovascular risk factors

- recommending aspirin use to prevent cardiovascular disease and colorectal cancer

- advising statin use for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in adults ages 45 to 75 years who have 1 or more risk factors (hyperlipidemia, diabetes, hypertension, smoking) and those with a 10-year risk of a cardiovascular event of 10% or greater.

This “D” recommendation differs from recommendations made by other professional organizations, some of which recommend testing with DUS for asymptomatic patients with a carotid bruit, and others that recommend DUS screening in patients with multiple risk factors for stroke and in those with known peripheral artery disease or other cardiovascular disease.18,19

Smoking cessation in adults

Smoking tobacco is the leading preventable cause of death in the United States, causing about 480,000 deaths annually.3 Smoking during pregnancy increases the risk of complications including miscarriage, congenital anomalies, stillbirth, fetal growth restriction, preterm birth, and placental abruption.

The Task Force published recommendations earlier this year advising all clinicians to ask all adult patients about tobacco use; and, for those who smoke, to provide (or refer them to) smoking cessation behavioral therapy. The Task Force also recommends prescribing pharmacotherapy approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for smoking cessation for nonpregnant adults. (There is a lack of information to assess the harms and benefits of smoking cessation pharmacotherapy during pregnancy.)

Continue to: FDA-approved medications...

FDA-approved medications for treating tobacco smoking dependence are nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), bupropion hydrochloride, and varenicline.3 NRT is available in transdermal patches, lozenges, gum, inhalers, and nasal sprays.

In addition, the Task Force indicates that there is insufficient evidence to assess the benefits and harms of e-cigarettes when used as a method of achieving smoking cessation: “Few randomized trials have evaluated the effectiveness of e-cigarettes to increase tobacco smoking cessation in nonpregnant adults, and no trials have evaluated e-cigarettes for tobacco smoking cessation in pregnant persons.”4

Hepatitis B infection screening

The Task Force reaffirmed a previous recommendation to screen for hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection only in adults who are at high risk,5 rather than universal screening that it recommends for hepatitis C virus infection (HCV).7 (See: https://bit.ly/3tt064Q). The Task Force has a separate recommendation to screen all pregnant women for hepatitis B at the first prenatal visit.6

Those at high risk for hepatitis B who should be screened include individuals born in countries or regions of the world with a hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) prevalence ≥ 2% and individuals born in the United States who have not received HBV vaccine and whose parents were born in regions with an HBsAg prevalence ≥ 8%.5 (A table listing countries with HBsAg ≥ 8%—as well as those in lower prevalence categories—is included with the recommendation.5)

HBV screening should also be offered to other high-risk groups that have a prevalence of positive HBsAg ≥ 2%: those who have injected drugs in the past or are currently injecting drugs; men who have sex with men; individuals with HIV; and sex partners, needle-sharing contacts, and household contacts of people known to be HBsAg positive.5

Continue to: It is estimated that...

It is estimated that > 860,000 people in the United States have chronic HBV infection and that close to two-thirds of them are unaware of their infection.5 The screening test for HBV is highly accurate; sensitivity and specificity are both > 98%.5 While there is no direct evidence that screening, detecting, and treating asymptomatic HBV infection reduces morbidity and mortality, the Task Force felt that the evidence for improvement in multiple outcomes in those with HBV when treated with antiviral regimens was sufficient to support the recommendation.

Screening for bacterial vaginosis in pregnancy

While bacterial vaginosis (BV) is associated with a two-fold risk of preterm delivery, treating BV during pregnancy does not seem to reduce this risk, indicating that some other variable is involved.8 In addition, studies that looked at screening for, and treatment of, asymptomatic BV in pregnant women at high risk for preterm delivery (defined primarily as those with a previous preterm delivery) have shown inconsistent results. There is the potential for harm in treating BV in pregnancy, chiefly involving gastrointestinal upset caused by metronidazole or clindamycin.

Given that there are no benefits—and some harms—resulting from treatment, the Task Force recommends against screening for BV in non-high-risk pregnant women. A lack of sufficient information to assess any potential benefits to screening in high-risk pregnancies led the Task Force to an “I” statement on this question.8

Behavioral counseling on healthy diet, exercise for adults with CV risks

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) remains the number one cause of death in the United States. The major risk factors for CVD, which can be modified, are high blood pressure, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, smoking, obesity or overweight, and lack of physical activity.

The Task Force has previously recommended intensive behavioral interventions to improve nutrition and physical activity in those who are overweight/obese and in those with abnormal blood glucose levels,9 and has addressed smoking prevention and cessation.4 This new recommendation applies to those with other CVD risks such as high blood pressure and/or hyperlipidemia and those with an estimated 10-year CVD risk of ≥ 7.5%.10

Continue to: Behavioral interventions...

Behavioral interventions included in the Task Force analysis employed a median of 12 contacts and an estimated 6 hours of contact time over 6 to 18 months.10 Most interventions involved motivational interviewing and instruction on behavioral change methods. These interventions can be provided by primary care clinicians, as well as a wide range of other trained professionals. The Affordable Care Act dictates that all “A” and “B” recommendations must be provided by commercial health plans at no out-of-pocket expense for the patient.

Nutritional advice should include reductions in saturated fats, salt, and sugars and increases in fruits, vegetables, and whole grains. The Mediterranean diet and the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet are often recommended.10 Physical activity counseling should advocate for 90 to 180 minutes per week of moderate to vigorous activity.

This new recommendation, along with the previous ones pertaining to behavioral interventions for lifestyle changes, make it clear that intensive interventions are needed to achieve meaningful change. Simple advice from a clinician will have little to no effect.

Task Force reviews evidence on HTN, smoking cessation in young people

In 2020 the Task Force completed reviews of evidence relevant to screening for high blood pressure11 and

The 2 “I” statements are in disagreement with recommendations of other professional organizations. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and the American Heart Association recommend routine screening for high blood pressure starting at age 3 years. And the AAP recommends screening teenagers for tobacco use and offering tobacco dependence treatment, referral, or both (including pharmacotherapy) when indicated. E-cigarettes are not recommended as a treatment for tobacco dependence.20

Continue to: The difference between...

The difference between the methods used by the Task Force and other guideline-producing organizations becomes apparent when it comes to recommendations pertaining to children and adolescents, for whom long-term outcome-oriented studies on prevention issues are rare. The Task Force is unwilling to make recommendations when evidence does not exist. The AAP often makes recommendations based on expert opinion consensus in such situations. One notable part of each Task Force recommendation statement is a discussion of what other organizations recommend on the same topic so that these differences can be openly described.

Better Task Force funding could expand topic coverage

It is worth revisiting 2 issues that were pointed out in last year’s USPSTF summary in this column.1 First, the Task Force methods are robust and evidence based, and recommendations therefore are rarely changed once they are made at an “A”, “B”, or “D” level. Second, Task Force resources are finite, and thus, the group is currently unable to update previous recommendations with greater frequency or to consider many new topics. In the past 2 years, the Task Force has developed recommendations on only 2 completely new topics. Hopefully, its budget can be expanded so that new topics can be added in the future.

1. Campos-Outcalt D. USPSTF roundup. J Fam Pract. 2020;69:201-204.

2. USPSTF. Screening for asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis. Accessed April 30, 2021. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/carotid-artery-stenosis-screening

3. USPSTF. Interventions for tobacco smoking cessation in adults, including pregnant persons. Accessed April 30, 2021. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/tobacco-use-in-adults-and-pregnant-women-counseling-and-interventions

4. USPSTF. Interventions for tobacco smoking cessation in adults, including pregnant persons. JAMA. 2021;325:265-279.

5. USPSTF. Screening for Hepatitis B virus infection in adolescents and adults. Accessed April 30, 2021. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/hepatitis-b-virus-infection-screening

6. USPSTF. Hepatitis B virus infection in pregnant women: screening. Accessed April 30, 2021. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/hepatitis-b-virus-infection-in-pregnant-women-screening

7. USPSTF. Hepatitis C virus infection in adolescents and adults: screening. Accessed April 30, 2021. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/hepatitis-c-screening

8. USPSTF; Owens DK, Davidson KW, Krisk AH, et al. Screening for bacterial vaginosis in pregnant persons to prevent preterm delivery: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2020;323:1286-1292.

9. Behavioral counseling to promote a healthful diet and physical activity for cardiovascular disease prevention in adults with cardiovascular risk factors: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161:587-593.

10. USPSTF. Behavioral counseling interventions to promote a healthy and physical activity for cardiovascular disease prevention in adults with cardiovascular risk factors: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2020;324:2069-2075.

11. USPSTF. High blood pressure in children and adolescents: screening. Accessed April 30, 2021. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/blood-pressure-in-children-and-adolescents-hypertension-screening

12. USPSTF. Prevention and cessation of tobacco use in children and adolescents: primary care interventions. Accessed April 30, 2021. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/tobacco-and-nicotine-use-prevention-in-children-and-adolescents-primary-care-interventions

13. USPSTF. Cognitive impairment in older adults: screening. Accessed March 26, 2021. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/cognitive-impairment-in-older-adults-screening

14. USPSTF. Illicit drug use in children, adolescents, and young adults: primary care-based interventions. Accessed April 30, 2021. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/drug-use-illicit-primary-care-interventions-for-children-and-adolescents

15. USPSTF. Unhealthy drug use: screening. Accessed April 30, 2021. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/drug-use-illicit-screening

16. USPSTF. Sexually transmitted infections: behavioral counseling. Accessed April 30, 2021. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/sexually-transmitted-infections-behavioral-counseling.

17. Campos-Outcalt D. USPSTF update on sexually transmitted infections. J Fam Pract. 2020;69:514-517.

18. Brott TG, Halperin JL, Abbara S, et al; ASA/ACCF/AHA/AANN/AANS/ACR/ASNR/CNS/SAIP/SCAI/SIR/SNIS/SVM/SVS guideline on the management of patients with extracranial carotid and vertebral artery disease. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2013;81:E76-E123.

19. Ricotta JJ, Aburahma A, Ascher E, et al; Society for Vascular Surgery. Updated Society for Vascular Surgery guidelines for management of extracranial carotid disease. J Vasc Surg. 2011;54:e1-e31.

20. Farber HJ, Walley SC, Groner JA, et al; Section on Tobacco Control. Clinical practice policy to protect children from tobacco, nicotine, and tobacco smoke. Pediatrics. 2015;136:1008-1017.

Since the last Practice Alert update on recommendations made by the US Preventive Services Task Force,1 the Task Force has completed work on 12 topics (TABLE 1).2-17 Five of these topics have been discussed in JFP audio recordings, and the links are provided in TABLE 1.

This latest Task Force endeavor resulted in 18 recommendations (TABLE 2), all of which reaffirm previous recommendations on these topics and expand the scope of 2. There were 2 “A” recommendations, 6 “B” recommendations, 2 “D” recommendations, and 8 “I” statements, indicating that there was insufficient evidence to assess effectiveness or harms. The willingness to make “I” statements when there is little or no evidence on the intervention being assessed distinguishes the USPSTF from other clinical guideline committees.

Screening for carotid artery stenosis

One of the “D” recommendations this past year reaffirms the prior recommendation against screening for carotid artery stenosis in asymptomatic adults—ie, those without a history of transient ischemic attack, stroke, or neurologic signs or symptoms that might be caused by carotid artery stenosis.2 The screening tests the Task Force researched included carotid duplex ultrasonography (DUS), magnetic resonance angiography, and computed tomography angiography. The Task Force did not look at the value of auscultation for carotid bruits because it has been proven to be inaccurate and they do not consider it to be a useful screening tool.

The Task Force based its “D” recommendation on a lack of evidence for any benefit in detecting asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis, and on evidence that screening can lead to harms through false-positive tests and potential complications from carotid endarterectomy and carotid artery angioplasty and stenting. In its clinical considerations, the Task Force emphasized the primary prevention of atherosclerotic disease by focusing on the following actions:

- screening for high blood pressure in adults

- encouraging tobacco smoking cessation in adults

- promoting a healthy diet and physical activity in adults with cardiovascular risk factors

- recommending aspirin use to prevent cardiovascular disease and colorectal cancer

- advising statin use for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in adults ages 45 to 75 years who have 1 or more risk factors (hyperlipidemia, diabetes, hypertension, smoking) and those with a 10-year risk of a cardiovascular event of 10% or greater.

This “D” recommendation differs from recommendations made by other professional organizations, some of which recommend testing with DUS for asymptomatic patients with a carotid bruit, and others that recommend DUS screening in patients with multiple risk factors for stroke and in those with known peripheral artery disease or other cardiovascular disease.18,19

Smoking cessation in adults

Smoking tobacco is the leading preventable cause of death in the United States, causing about 480,000 deaths annually.3 Smoking during pregnancy increases the risk of complications including miscarriage, congenital anomalies, stillbirth, fetal growth restriction, preterm birth, and placental abruption.

The Task Force published recommendations earlier this year advising all clinicians to ask all adult patients about tobacco use; and, for those who smoke, to provide (or refer them to) smoking cessation behavioral therapy. The Task Force also recommends prescribing pharmacotherapy approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for smoking cessation for nonpregnant adults. (There is a lack of information to assess the harms and benefits of smoking cessation pharmacotherapy during pregnancy.)

Continue to: FDA-approved medications...

FDA-approved medications for treating tobacco smoking dependence are nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), bupropion hydrochloride, and varenicline.3 NRT is available in transdermal patches, lozenges, gum, inhalers, and nasal sprays.

In addition, the Task Force indicates that there is insufficient evidence to assess the benefits and harms of e-cigarettes when used as a method of achieving smoking cessation: “Few randomized trials have evaluated the effectiveness of e-cigarettes to increase tobacco smoking cessation in nonpregnant adults, and no trials have evaluated e-cigarettes for tobacco smoking cessation in pregnant persons.”4

Hepatitis B infection screening

The Task Force reaffirmed a previous recommendation to screen for hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection only in adults who are at high risk,5 rather than universal screening that it recommends for hepatitis C virus infection (HCV).7 (See: https://bit.ly/3tt064Q). The Task Force has a separate recommendation to screen all pregnant women for hepatitis B at the first prenatal visit.6

Those at high risk for hepatitis B who should be screened include individuals born in countries or regions of the world with a hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) prevalence ≥ 2% and individuals born in the United States who have not received HBV vaccine and whose parents were born in regions with an HBsAg prevalence ≥ 8%.5 (A table listing countries with HBsAg ≥ 8%—as well as those in lower prevalence categories—is included with the recommendation.5)

HBV screening should also be offered to other high-risk groups that have a prevalence of positive HBsAg ≥ 2%: those who have injected drugs in the past or are currently injecting drugs; men who have sex with men; individuals with HIV; and sex partners, needle-sharing contacts, and household contacts of people known to be HBsAg positive.5

Continue to: It is estimated that...

It is estimated that > 860,000 people in the United States have chronic HBV infection and that close to two-thirds of them are unaware of their infection.5 The screening test for HBV is highly accurate; sensitivity and specificity are both > 98%.5 While there is no direct evidence that screening, detecting, and treating asymptomatic HBV infection reduces morbidity and mortality, the Task Force felt that the evidence for improvement in multiple outcomes in those with HBV when treated with antiviral regimens was sufficient to support the recommendation.

Screening for bacterial vaginosis in pregnancy

While bacterial vaginosis (BV) is associated with a two-fold risk of preterm delivery, treating BV during pregnancy does not seem to reduce this risk, indicating that some other variable is involved.8 In addition, studies that looked at screening for, and treatment of, asymptomatic BV in pregnant women at high risk for preterm delivery (defined primarily as those with a previous preterm delivery) have shown inconsistent results. There is the potential for harm in treating BV in pregnancy, chiefly involving gastrointestinal upset caused by metronidazole or clindamycin.

Given that there are no benefits—and some harms—resulting from treatment, the Task Force recommends against screening for BV in non-high-risk pregnant women. A lack of sufficient information to assess any potential benefits to screening in high-risk pregnancies led the Task Force to an “I” statement on this question.8

Behavioral counseling on healthy diet, exercise for adults with CV risks

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) remains the number one cause of death in the United States. The major risk factors for CVD, which can be modified, are high blood pressure, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, smoking, obesity or overweight, and lack of physical activity.

The Task Force has previously recommended intensive behavioral interventions to improve nutrition and physical activity in those who are overweight/obese and in those with abnormal blood glucose levels,9 and has addressed smoking prevention and cessation.4 This new recommendation applies to those with other CVD risks such as high blood pressure and/or hyperlipidemia and those with an estimated 10-year CVD risk of ≥ 7.5%.10

Continue to: Behavioral interventions...

Behavioral interventions included in the Task Force analysis employed a median of 12 contacts and an estimated 6 hours of contact time over 6 to 18 months.10 Most interventions involved motivational interviewing and instruction on behavioral change methods. These interventions can be provided by primary care clinicians, as well as a wide range of other trained professionals. The Affordable Care Act dictates that all “A” and “B” recommendations must be provided by commercial health plans at no out-of-pocket expense for the patient.

Nutritional advice should include reductions in saturated fats, salt, and sugars and increases in fruits, vegetables, and whole grains. The Mediterranean diet and the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet are often recommended.10 Physical activity counseling should advocate for 90 to 180 minutes per week of moderate to vigorous activity.

This new recommendation, along with the previous ones pertaining to behavioral interventions for lifestyle changes, make it clear that intensive interventions are needed to achieve meaningful change. Simple advice from a clinician will have little to no effect.

Task Force reviews evidence on HTN, smoking cessation in young people

In 2020 the Task Force completed reviews of evidence relevant to screening for high blood pressure11 and

The 2 “I” statements are in disagreement with recommendations of other professional organizations. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and the American Heart Association recommend routine screening for high blood pressure starting at age 3 years. And the AAP recommends screening teenagers for tobacco use and offering tobacco dependence treatment, referral, or both (including pharmacotherapy) when indicated. E-cigarettes are not recommended as a treatment for tobacco dependence.20

Continue to: The difference between...

The difference between the methods used by the Task Force and other guideline-producing organizations becomes apparent when it comes to recommendations pertaining to children and adolescents, for whom long-term outcome-oriented studies on prevention issues are rare. The Task Force is unwilling to make recommendations when evidence does not exist. The AAP often makes recommendations based on expert opinion consensus in such situations. One notable part of each Task Force recommendation statement is a discussion of what other organizations recommend on the same topic so that these differences can be openly described.

Better Task Force funding could expand topic coverage

It is worth revisiting 2 issues that were pointed out in last year’s USPSTF summary in this column.1 First, the Task Force methods are robust and evidence based, and recommendations therefore are rarely changed once they are made at an “A”, “B”, or “D” level. Second, Task Force resources are finite, and thus, the group is currently unable to update previous recommendations with greater frequency or to consider many new topics. In the past 2 years, the Task Force has developed recommendations on only 2 completely new topics. Hopefully, its budget can be expanded so that new topics can be added in the future.

Since the last Practice Alert update on recommendations made by the US Preventive Services Task Force,1 the Task Force has completed work on 12 topics (TABLE 1).2-17 Five of these topics have been discussed in JFP audio recordings, and the links are provided in TABLE 1.

This latest Task Force endeavor resulted in 18 recommendations (TABLE 2), all of which reaffirm previous recommendations on these topics and expand the scope of 2. There were 2 “A” recommendations, 6 “B” recommendations, 2 “D” recommendations, and 8 “I” statements, indicating that there was insufficient evidence to assess effectiveness or harms. The willingness to make “I” statements when there is little or no evidence on the intervention being assessed distinguishes the USPSTF from other clinical guideline committees.

Screening for carotid artery stenosis

One of the “D” recommendations this past year reaffirms the prior recommendation against screening for carotid artery stenosis in asymptomatic adults—ie, those without a history of transient ischemic attack, stroke, or neurologic signs or symptoms that might be caused by carotid artery stenosis.2 The screening tests the Task Force researched included carotid duplex ultrasonography (DUS), magnetic resonance angiography, and computed tomography angiography. The Task Force did not look at the value of auscultation for carotid bruits because it has been proven to be inaccurate and they do not consider it to be a useful screening tool.

The Task Force based its “D” recommendation on a lack of evidence for any benefit in detecting asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis, and on evidence that screening can lead to harms through false-positive tests and potential complications from carotid endarterectomy and carotid artery angioplasty and stenting. In its clinical considerations, the Task Force emphasized the primary prevention of atherosclerotic disease by focusing on the following actions:

- screening for high blood pressure in adults

- encouraging tobacco smoking cessation in adults

- promoting a healthy diet and physical activity in adults with cardiovascular risk factors

- recommending aspirin use to prevent cardiovascular disease and colorectal cancer

- advising statin use for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in adults ages 45 to 75 years who have 1 or more risk factors (hyperlipidemia, diabetes, hypertension, smoking) and those with a 10-year risk of a cardiovascular event of 10% or greater.

This “D” recommendation differs from recommendations made by other professional organizations, some of which recommend testing with DUS for asymptomatic patients with a carotid bruit, and others that recommend DUS screening in patients with multiple risk factors for stroke and in those with known peripheral artery disease or other cardiovascular disease.18,19

Smoking cessation in adults

Smoking tobacco is the leading preventable cause of death in the United States, causing about 480,000 deaths annually.3 Smoking during pregnancy increases the risk of complications including miscarriage, congenital anomalies, stillbirth, fetal growth restriction, preterm birth, and placental abruption.

The Task Force published recommendations earlier this year advising all clinicians to ask all adult patients about tobacco use; and, for those who smoke, to provide (or refer them to) smoking cessation behavioral therapy. The Task Force also recommends prescribing pharmacotherapy approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for smoking cessation for nonpregnant adults. (There is a lack of information to assess the harms and benefits of smoking cessation pharmacotherapy during pregnancy.)

Continue to: FDA-approved medications...

FDA-approved medications for treating tobacco smoking dependence are nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), bupropion hydrochloride, and varenicline.3 NRT is available in transdermal patches, lozenges, gum, inhalers, and nasal sprays.

In addition, the Task Force indicates that there is insufficient evidence to assess the benefits and harms of e-cigarettes when used as a method of achieving smoking cessation: “Few randomized trials have evaluated the effectiveness of e-cigarettes to increase tobacco smoking cessation in nonpregnant adults, and no trials have evaluated e-cigarettes for tobacco smoking cessation in pregnant persons.”4

Hepatitis B infection screening

The Task Force reaffirmed a previous recommendation to screen for hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection only in adults who are at high risk,5 rather than universal screening that it recommends for hepatitis C virus infection (HCV).7 (See: https://bit.ly/3tt064Q). The Task Force has a separate recommendation to screen all pregnant women for hepatitis B at the first prenatal visit.6

Those at high risk for hepatitis B who should be screened include individuals born in countries or regions of the world with a hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) prevalence ≥ 2% and individuals born in the United States who have not received HBV vaccine and whose parents were born in regions with an HBsAg prevalence ≥ 8%.5 (A table listing countries with HBsAg ≥ 8%—as well as those in lower prevalence categories—is included with the recommendation.5)

HBV screening should also be offered to other high-risk groups that have a prevalence of positive HBsAg ≥ 2%: those who have injected drugs in the past or are currently injecting drugs; men who have sex with men; individuals with HIV; and sex partners, needle-sharing contacts, and household contacts of people known to be HBsAg positive.5

Continue to: It is estimated that...

It is estimated that > 860,000 people in the United States have chronic HBV infection and that close to two-thirds of them are unaware of their infection.5 The screening test for HBV is highly accurate; sensitivity and specificity are both > 98%.5 While there is no direct evidence that screening, detecting, and treating asymptomatic HBV infection reduces morbidity and mortality, the Task Force felt that the evidence for improvement in multiple outcomes in those with HBV when treated with antiviral regimens was sufficient to support the recommendation.

Screening for bacterial vaginosis in pregnancy

While bacterial vaginosis (BV) is associated with a two-fold risk of preterm delivery, treating BV during pregnancy does not seem to reduce this risk, indicating that some other variable is involved.8 In addition, studies that looked at screening for, and treatment of, asymptomatic BV in pregnant women at high risk for preterm delivery (defined primarily as those with a previous preterm delivery) have shown inconsistent results. There is the potential for harm in treating BV in pregnancy, chiefly involving gastrointestinal upset caused by metronidazole or clindamycin.

Given that there are no benefits—and some harms—resulting from treatment, the Task Force recommends against screening for BV in non-high-risk pregnant women. A lack of sufficient information to assess any potential benefits to screening in high-risk pregnancies led the Task Force to an “I” statement on this question.8

Behavioral counseling on healthy diet, exercise for adults with CV risks

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) remains the number one cause of death in the United States. The major risk factors for CVD, which can be modified, are high blood pressure, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, smoking, obesity or overweight, and lack of physical activity.

The Task Force has previously recommended intensive behavioral interventions to improve nutrition and physical activity in those who are overweight/obese and in those with abnormal blood glucose levels,9 and has addressed smoking prevention and cessation.4 This new recommendation applies to those with other CVD risks such as high blood pressure and/or hyperlipidemia and those with an estimated 10-year CVD risk of ≥ 7.5%.10

Continue to: Behavioral interventions...

Behavioral interventions included in the Task Force analysis employed a median of 12 contacts and an estimated 6 hours of contact time over 6 to 18 months.10 Most interventions involved motivational interviewing and instruction on behavioral change methods. These interventions can be provided by primary care clinicians, as well as a wide range of other trained professionals. The Affordable Care Act dictates that all “A” and “B” recommendations must be provided by commercial health plans at no out-of-pocket expense for the patient.

Nutritional advice should include reductions in saturated fats, salt, and sugars and increases in fruits, vegetables, and whole grains. The Mediterranean diet and the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet are often recommended.10 Physical activity counseling should advocate for 90 to 180 minutes per week of moderate to vigorous activity.

This new recommendation, along with the previous ones pertaining to behavioral interventions for lifestyle changes, make it clear that intensive interventions are needed to achieve meaningful change. Simple advice from a clinician will have little to no effect.

Task Force reviews evidence on HTN, smoking cessation in young people

In 2020 the Task Force completed reviews of evidence relevant to screening for high blood pressure11 and

The 2 “I” statements are in disagreement with recommendations of other professional organizations. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and the American Heart Association recommend routine screening for high blood pressure starting at age 3 years. And the AAP recommends screening teenagers for tobacco use and offering tobacco dependence treatment, referral, or both (including pharmacotherapy) when indicated. E-cigarettes are not recommended as a treatment for tobacco dependence.20

Continue to: The difference between...

The difference between the methods used by the Task Force and other guideline-producing organizations becomes apparent when it comes to recommendations pertaining to children and adolescents, for whom long-term outcome-oriented studies on prevention issues are rare. The Task Force is unwilling to make recommendations when evidence does not exist. The AAP often makes recommendations based on expert opinion consensus in such situations. One notable part of each Task Force recommendation statement is a discussion of what other organizations recommend on the same topic so that these differences can be openly described.

Better Task Force funding could expand topic coverage

It is worth revisiting 2 issues that were pointed out in last year’s USPSTF summary in this column.1 First, the Task Force methods are robust and evidence based, and recommendations therefore are rarely changed once they are made at an “A”, “B”, or “D” level. Second, Task Force resources are finite, and thus, the group is currently unable to update previous recommendations with greater frequency or to consider many new topics. In the past 2 years, the Task Force has developed recommendations on only 2 completely new topics. Hopefully, its budget can be expanded so that new topics can be added in the future.

1. Campos-Outcalt D. USPSTF roundup. J Fam Pract. 2020;69:201-204.

2. USPSTF. Screening for asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis. Accessed April 30, 2021. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/carotid-artery-stenosis-screening

3. USPSTF. Interventions for tobacco smoking cessation in adults, including pregnant persons. Accessed April 30, 2021. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/tobacco-use-in-adults-and-pregnant-women-counseling-and-interventions

4. USPSTF. Interventions for tobacco smoking cessation in adults, including pregnant persons. JAMA. 2021;325:265-279.

5. USPSTF. Screening for Hepatitis B virus infection in adolescents and adults. Accessed April 30, 2021. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/hepatitis-b-virus-infection-screening

6. USPSTF. Hepatitis B virus infection in pregnant women: screening. Accessed April 30, 2021. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/hepatitis-b-virus-infection-in-pregnant-women-screening

7. USPSTF. Hepatitis C virus infection in adolescents and adults: screening. Accessed April 30, 2021. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/hepatitis-c-screening

8. USPSTF; Owens DK, Davidson KW, Krisk AH, et al. Screening for bacterial vaginosis in pregnant persons to prevent preterm delivery: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2020;323:1286-1292.

9. Behavioral counseling to promote a healthful diet and physical activity for cardiovascular disease prevention in adults with cardiovascular risk factors: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161:587-593.

10. USPSTF. Behavioral counseling interventions to promote a healthy and physical activity for cardiovascular disease prevention in adults with cardiovascular risk factors: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2020;324:2069-2075.

11. USPSTF. High blood pressure in children and adolescents: screening. Accessed April 30, 2021. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/blood-pressure-in-children-and-adolescents-hypertension-screening

12. USPSTF. Prevention and cessation of tobacco use in children and adolescents: primary care interventions. Accessed April 30, 2021. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/tobacco-and-nicotine-use-prevention-in-children-and-adolescents-primary-care-interventions

13. USPSTF. Cognitive impairment in older adults: screening. Accessed March 26, 2021. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/cognitive-impairment-in-older-adults-screening

14. USPSTF. Illicit drug use in children, adolescents, and young adults: primary care-based interventions. Accessed April 30, 2021. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/drug-use-illicit-primary-care-interventions-for-children-and-adolescents

15. USPSTF. Unhealthy drug use: screening. Accessed April 30, 2021. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/drug-use-illicit-screening

16. USPSTF. Sexually transmitted infections: behavioral counseling. Accessed April 30, 2021. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/sexually-transmitted-infections-behavioral-counseling.

17. Campos-Outcalt D. USPSTF update on sexually transmitted infections. J Fam Pract. 2020;69:514-517.

18. Brott TG, Halperin JL, Abbara S, et al; ASA/ACCF/AHA/AANN/AANS/ACR/ASNR/CNS/SAIP/SCAI/SIR/SNIS/SVM/SVS guideline on the management of patients with extracranial carotid and vertebral artery disease. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2013;81:E76-E123.

19. Ricotta JJ, Aburahma A, Ascher E, et al; Society for Vascular Surgery. Updated Society for Vascular Surgery guidelines for management of extracranial carotid disease. J Vasc Surg. 2011;54:e1-e31.

20. Farber HJ, Walley SC, Groner JA, et al; Section on Tobacco Control. Clinical practice policy to protect children from tobacco, nicotine, and tobacco smoke. Pediatrics. 2015;136:1008-1017.

1. Campos-Outcalt D. USPSTF roundup. J Fam Pract. 2020;69:201-204.

2. USPSTF. Screening for asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis. Accessed April 30, 2021. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/carotid-artery-stenosis-screening

3. USPSTF. Interventions for tobacco smoking cessation in adults, including pregnant persons. Accessed April 30, 2021. www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/tobacco-use-in-adults-and-pregnant-women-counseling-and-interventions

4. USPSTF. Interventions for tobacco smoking cessation in adults, including pregnant persons. JAMA. 2021;325:265-279.

5. USPSTF. Screening for Hepatitis B virus infection in adolescents and adults. Accessed April 30, 2021. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/hepatitis-b-virus-infection-screening

6. USPSTF. Hepatitis B virus infection in pregnant women: screening. Accessed April 30, 2021. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/hepatitis-b-virus-infection-in-pregnant-women-screening

7. USPSTF. Hepatitis C virus infection in adolescents and adults: screening. Accessed April 30, 2021. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/hepatitis-c-screening

8. USPSTF; Owens DK, Davidson KW, Krisk AH, et al. Screening for bacterial vaginosis in pregnant persons to prevent preterm delivery: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2020;323:1286-1292.

9. Behavioral counseling to promote a healthful diet and physical activity for cardiovascular disease prevention in adults with cardiovascular risk factors: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161:587-593.

10. USPSTF. Behavioral counseling interventions to promote a healthy and physical activity for cardiovascular disease prevention in adults with cardiovascular risk factors: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2020;324:2069-2075.

11. USPSTF. High blood pressure in children and adolescents: screening. Accessed April 30, 2021. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/blood-pressure-in-children-and-adolescents-hypertension-screening

12. USPSTF. Prevention and cessation of tobacco use in children and adolescents: primary care interventions. Accessed April 30, 2021. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/tobacco-and-nicotine-use-prevention-in-children-and-adolescents-primary-care-interventions

13. USPSTF. Cognitive impairment in older adults: screening. Accessed March 26, 2021. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/cognitive-impairment-in-older-adults-screening

14. USPSTF. Illicit drug use in children, adolescents, and young adults: primary care-based interventions. Accessed April 30, 2021. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/drug-use-illicit-primary-care-interventions-for-children-and-adolescents

15. USPSTF. Unhealthy drug use: screening. Accessed April 30, 2021. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/drug-use-illicit-screening

16. USPSTF. Sexually transmitted infections: behavioral counseling. Accessed April 30, 2021. https://uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/sexually-transmitted-infections-behavioral-counseling.

17. Campos-Outcalt D. USPSTF update on sexually transmitted infections. J Fam Pract. 2020;69:514-517.

18. Brott TG, Halperin JL, Abbara S, et al; ASA/ACCF/AHA/AANN/AANS/ACR/ASNR/CNS/SAIP/SCAI/SIR/SNIS/SVM/SVS guideline on the management of patients with extracranial carotid and vertebral artery disease. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2013;81:E76-E123.

19. Ricotta JJ, Aburahma A, Ascher E, et al; Society for Vascular Surgery. Updated Society for Vascular Surgery guidelines for management of extracranial carotid disease. J Vasc Surg. 2011;54:e1-e31.

20. Farber HJ, Walley SC, Groner JA, et al; Section on Tobacco Control. Clinical practice policy to protect children from tobacco, nicotine, and tobacco smoke. Pediatrics. 2015;136:1008-1017.

Systemic racism is a cause of health disparities

I applaud the joint statement by the editors of the family medicine journals to commit to the eradication of systemic racism in medicine ( J Fam Pract . 2021;70:3 -4). These are crucial times in our history, where proactive change is necessary. The leadership they have shown is important.

No one wants health disparities. So, to eliminate them, we need to know what they are and where they came from. In my presentations on health disparities to students, residents, and health care providers, I use 3 definitions of health disparities. My definitions are slightly different from those proposed in the seminal report, Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care, from the National Academy of Medicine (then Institute of Medicine).1 I like to think that my definitions elicit the information needed to guide change.

The first definition focuses on health statistics. When there are different outcomes for different demographic groups for the same disease, that is a disparity. This could be Black vs white, male vs female, or 1 zip code vs another.2 We owe ourselves an explanation for these differences if we are to be able to propose solutions.

Second, there are disparities in the provision of health care. If there are 2 individuals who present with the exact same symptoms, we need to ask ourselves why they would be treated differently. Even in systems where insurance status is the same, there are documented differences in care. A well-studied example of this is pain. In 1 such study, a meta-analysis showed that Blacks were less likely than whites to receive medication for acute pain in the emergency department (OR = 0.60 [95% CI, 0.43-0.83]).3 Other examples of differences by race include cardiac services,4 lung cancer screening,5 and stroke interventions.6

The third definition of health disparities involves differences in health-seeking behavior. This is not to blame the “victim,” but to understand the reason why the difference exists so that adequate interventions can be designed to improve outcomes. Traditionally, the concept of access referenced whether or not the patient had health insurance. But the provision of health insurance is insufficient to explain issues of access.7

Extrinsic and intrinsic factors at work. Factors related to insurance are an example of the extrinsic factors related to access. However, there are intrinsic factors related to access, most of which involve health literacy. We must ask ourselves: What are the best practices to educate patients to get the care they need? I will take this 1 step further; it is the duty of all health care professionals to improve health literacy 1 patient, 1 community at a time.

The next point that I make in my presentations on health disparities is that if you control for socioeconomic status, some of the health disparities go away. However, they rarely disappear. We measure socioeconomic status in a variety of ways: education, insurance status, income, and wealth. And as would be expected, these variables are usually correlated. We also know that these variables are not distributed equally by race. This is by design. This has been intentional. This has been, in many cases, our country’s policy. This is the result of systemic racism.

Continue to: It is necessary...

It is necessary for us to be willing to accept the toxicity of racism. This we can assess in 2 major ways. First, if we apply the Koch postulates or the Bradford Hill criteria for causation to racism, we can assess the degree to which racism is an explanation for health disparities. These principles offer methods for determining the relationship between risk and outcome.

Second, when we analyze the historical antecedents of health disparities, we find that racism is directly responsible not only for the current toxicity that Black people face today, but for the socioeconomic disparities that continue to exist. Let me give just a few examples.

- The Farm Security Administration was created in 1937 to avoid the collapse of the farming industry. As a compromise to southern legislators, a model was approved to allow local administration of support to farmers that essentially condoned the discrimination that had been occurring and would continue to occur—especially in the South.

- The National Housing Act of 1934 was created to provide stability to the banking industry at a time of national crisis. It subsidized a massive building program, and many of the units had restrictive covenants that prevented the sale to Blacks. It also codified redlining that prevented insured mortgages from being provided to Black communities.