User login

Elevated disease activity, cytokine levels linked to diabetes risk in RA

Key clinical point: Higher disease activity and elevated levels of cytokines/chemokines are associated with a greater risk of diabetes mellitus (DM) in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

Major finding: High Disease activity Score (DAS28)-C reactive protein (CRP) was associated with an increased risk of DM (test for trend: P less than .001). Several cytokines/chemokines analyzed showed independent association with DM risk including interleukin (IL)-1, IL-6, and select macrophage-derived cytokines/chemokines (hazard ratio per standard deviation range, 1.11-1.26). These associations were independent of the DAS28-CRP.

Study details: This longitudinal analysis included 1,866 patients with RA without prevalent DM from Veteran’s Affairs Rheumatoid Arthritis Registry. Thirty cytokines and chemokines were measured in banked serum obtained at the time of enrolment.

Disclosures: No study sponsor was identified. The presenting author has received consulting fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb and Gilead.

Source: Baker JF. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021 Jan 4. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-219140

Key clinical point: Higher disease activity and elevated levels of cytokines/chemokines are associated with a greater risk of diabetes mellitus (DM) in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

Major finding: High Disease activity Score (DAS28)-C reactive protein (CRP) was associated with an increased risk of DM (test for trend: P less than .001). Several cytokines/chemokines analyzed showed independent association with DM risk including interleukin (IL)-1, IL-6, and select macrophage-derived cytokines/chemokines (hazard ratio per standard deviation range, 1.11-1.26). These associations were independent of the DAS28-CRP.

Study details: This longitudinal analysis included 1,866 patients with RA without prevalent DM from Veteran’s Affairs Rheumatoid Arthritis Registry. Thirty cytokines and chemokines were measured in banked serum obtained at the time of enrolment.

Disclosures: No study sponsor was identified. The presenting author has received consulting fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb and Gilead.

Source: Baker JF. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021 Jan 4. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-219140

Key clinical point: Higher disease activity and elevated levels of cytokines/chemokines are associated with a greater risk of diabetes mellitus (DM) in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

Major finding: High Disease activity Score (DAS28)-C reactive protein (CRP) was associated with an increased risk of DM (test for trend: P less than .001). Several cytokines/chemokines analyzed showed independent association with DM risk including interleukin (IL)-1, IL-6, and select macrophage-derived cytokines/chemokines (hazard ratio per standard deviation range, 1.11-1.26). These associations were independent of the DAS28-CRP.

Study details: This longitudinal analysis included 1,866 patients with RA without prevalent DM from Veteran’s Affairs Rheumatoid Arthritis Registry. Thirty cytokines and chemokines were measured in banked serum obtained at the time of enrolment.

Disclosures: No study sponsor was identified. The presenting author has received consulting fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb and Gilead.

Source: Baker JF. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021 Jan 4. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-219140

Hydroxychloroquine use not linked to heart failure risk in patients with RA

Key clinical point: Use of hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) is not associated with increased risk of developing heart failure (HF) in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

Major finding: HCQ cumulative dose was not associated with HF (odds ratio [OR], 0.96 [95% confidence interval (CI), 0.90-1.03] per 100 g). No statistically significant association was found for patients with a cumulative dose of 300 g or more (OR, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.41-2.08). Duration of HCQ use prior to index was not associated with HF (OR, 0.98; 95% CI, 0.91-1.05).

Study details: The data come from a nested case-control study of 143 RA cases diagnosed with HF and 143 non-HF RA controls.

Disclosures: The study was funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Sorour AA et al. J Rheumatol. 2021 Jan 15. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.201180

Key clinical point: Use of hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) is not associated with increased risk of developing heart failure (HF) in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

Major finding: HCQ cumulative dose was not associated with HF (odds ratio [OR], 0.96 [95% confidence interval (CI), 0.90-1.03] per 100 g). No statistically significant association was found for patients with a cumulative dose of 300 g or more (OR, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.41-2.08). Duration of HCQ use prior to index was not associated with HF (OR, 0.98; 95% CI, 0.91-1.05).

Study details: The data come from a nested case-control study of 143 RA cases diagnosed with HF and 143 non-HF RA controls.

Disclosures: The study was funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Sorour AA et al. J Rheumatol. 2021 Jan 15. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.201180

Key clinical point: Use of hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) is not associated with increased risk of developing heart failure (HF) in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

Major finding: HCQ cumulative dose was not associated with HF (odds ratio [OR], 0.96 [95% confidence interval (CI), 0.90-1.03] per 100 g). No statistically significant association was found for patients with a cumulative dose of 300 g or more (OR, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.41-2.08). Duration of HCQ use prior to index was not associated with HF (OR, 0.98; 95% CI, 0.91-1.05).

Study details: The data come from a nested case-control study of 143 RA cases diagnosed with HF and 143 non-HF RA controls.

Disclosures: The study was funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Sorour AA et al. J Rheumatol. 2021 Jan 15. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.201180

Gestational diabetes carries CVD risk years later

Women who’ve had gestational diabetes are 40% more likely to develop coronary artery calcification later in life than are women haven’t, and attaining normal glycemic levels doesn’t diminish their midlife risk for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.

“The new finding from this study is that women with gestational diabetes had twice the risk of coronary artery calcium, compared to women who never had gestational diabetes, even though both groups attained normal blood sugar levels many years after pregnancy,” lead author Erica P. Gunderson, PhD, MS, MPH, said in an interview about a community-based prospective cohort study of young adults followed for up to 25 years, which was published in Circulation (2021 Feb 1. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.047320).

Previous studies have reported a higher risk of heart disease in women who had gestational diabetes (GD) and later developed type 2 diabetes, but they didn’t elucidate whether that risk carried over in GD patients whose glycemic levels were normal after pregnancy. In 2018, the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Cholesterol Clinical Practice Guidelines specified that a history of GD increases women’s risk for coronary artery calcification (CAC).

This study analyzed data of 1,133 women ages 18-30 enrolled in the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study who had no diabetes in the baseline years of 1985-1986 and had given birth at least once in the ensuing 25 years. They had glucose tolerance testing at baseline and up to five times through the study period, along with evaluation for GD status and coronary artery calcification CAC measurements at least once at years 15, 20 and 25 (2001-2011).

CARDIA enrolled 5,155 young Black and White men and women ages 18-30 from four distinct geographic areas: Birmingham, Ala.; Chicago; Minneapolis; and Oakland, Calif. About 52% of the study population was Black.

Of the women who’d given birth, 139 (12%) had GD. Their average age at follow-up was 47.6 years, and 25% of the GD patients (34) had CAC, compared with 15% (149/994) in the non-GD group.

Dr. Gunderson noted that the same relative risk for CAC applied to women who had GD and went on to develop prediabetes or were diagnosed with type 2 diabetes during follow-up.

Risks persist even in normoglycemia

In the GD group, the adjusted hazard ratio for having CAC with normoglycemia was 2.3 (95% confidence interval, 1.34-4.09). The researchers also calculated HRs for prediabetes and incident diabetes: 1.5 (95% CI, 1.06-2.24) in no-GD and 2.1 (95% CI, 1.09-4.17) for GD for prediabetes; and 2.2 (95% CI, 1.3-3.62) and 2.02 (95% CI, 0.98-4.19), respectively, for incident diabetes (P = .003).

“This means the risk of heart disease may be increased substantially in women with a history of gestational diabetes and may not diminish even if their blood-sugar levels remain normal for years later,” said Dr. Gunderson, an epidemiologist and senior research scientist at the Kaiser Permanente Northern California Division of Research in Oakland.

“The clinical implications of our findings are that women with previous GD may benefit from enhanced traditional CVD [cardiovascular disease] risk factor testing – i.e., for hypertension, dyslipidemia, and hyperinsulinemia,” Dr. Gunderson said. “Our findings also suggest that it could be beneficial to incorporate history of GD into risk calculators to improve CVD risk stratification and prevention.”

Strong findings argue for more frequent CVD screening

These study results may be the strongest data to date on the long-term effects of GD, said Prakash Deedwania, MD, professor of cardiology at the University of California, San Francisco. “It’s the strongest in the sense in that it’s sponsored, involved four different communities in different parts of the United States, enrolled individuals when they were young and followed them, and saw very few patients drop out for such a long-term study.” The study reported follow-up data on 72% of patients at 25 years, a rate Dr. Deedwania noted was “excellent.”

“Patients who have had GD should be screened aggressively – for not only diabetes, but other cardiovascular risk factors – early on to minimize the subsequent risk of cardiovascular disease is a very important point of this study,” he added. In the absence of a clinical guideline, Dr. Deedwania suggested women with GD might have screening for CV risk factors every 5-7 years depending on their risk profile, but emphasized that parameter isn’t settled.

Future research should focus on the link between GD and CVD risk, Dr. Gunderson said. “Research is needed to better characterize the severity of GD in relation to CVD outcomes, and to identify critical pregnancy-related periods to modify cardiometabolic risk.” The latter would include life-course studies across the full pregnancy continuum from preconception to lactation. “Interventions for primary prevention of CVD and the importance of modifiable lifestyle behaviors with the highest relevance to reduce both diabetes and CVD risks during the first year post partum merit increased research investigation,” she added.

Future studies might also explore the role of inflammation in the GD-CVD relationship, Dr. Deedwania said. “My hypothesis is, and it’s purely a hypothesis, that perhaps the presence of coronary artery calcification scores score in these individuals who were described as having normal glucose but who could be at risk could very well be related to the beginning of inflammation.”

Dr. Gunderson and Dr. Deedwania have no financial relationships to disclose. The study was funded by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

Women who’ve had gestational diabetes are 40% more likely to develop coronary artery calcification later in life than are women haven’t, and attaining normal glycemic levels doesn’t diminish their midlife risk for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.

“The new finding from this study is that women with gestational diabetes had twice the risk of coronary artery calcium, compared to women who never had gestational diabetes, even though both groups attained normal blood sugar levels many years after pregnancy,” lead author Erica P. Gunderson, PhD, MS, MPH, said in an interview about a community-based prospective cohort study of young adults followed for up to 25 years, which was published in Circulation (2021 Feb 1. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.047320).

Previous studies have reported a higher risk of heart disease in women who had gestational diabetes (GD) and later developed type 2 diabetes, but they didn’t elucidate whether that risk carried over in GD patients whose glycemic levels were normal after pregnancy. In 2018, the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Cholesterol Clinical Practice Guidelines specified that a history of GD increases women’s risk for coronary artery calcification (CAC).

This study analyzed data of 1,133 women ages 18-30 enrolled in the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study who had no diabetes in the baseline years of 1985-1986 and had given birth at least once in the ensuing 25 years. They had glucose tolerance testing at baseline and up to five times through the study period, along with evaluation for GD status and coronary artery calcification CAC measurements at least once at years 15, 20 and 25 (2001-2011).

CARDIA enrolled 5,155 young Black and White men and women ages 18-30 from four distinct geographic areas: Birmingham, Ala.; Chicago; Minneapolis; and Oakland, Calif. About 52% of the study population was Black.

Of the women who’d given birth, 139 (12%) had GD. Their average age at follow-up was 47.6 years, and 25% of the GD patients (34) had CAC, compared with 15% (149/994) in the non-GD group.

Dr. Gunderson noted that the same relative risk for CAC applied to women who had GD and went on to develop prediabetes or were diagnosed with type 2 diabetes during follow-up.

Risks persist even in normoglycemia

In the GD group, the adjusted hazard ratio for having CAC with normoglycemia was 2.3 (95% confidence interval, 1.34-4.09). The researchers also calculated HRs for prediabetes and incident diabetes: 1.5 (95% CI, 1.06-2.24) in no-GD and 2.1 (95% CI, 1.09-4.17) for GD for prediabetes; and 2.2 (95% CI, 1.3-3.62) and 2.02 (95% CI, 0.98-4.19), respectively, for incident diabetes (P = .003).

“This means the risk of heart disease may be increased substantially in women with a history of gestational diabetes and may not diminish even if their blood-sugar levels remain normal for years later,” said Dr. Gunderson, an epidemiologist and senior research scientist at the Kaiser Permanente Northern California Division of Research in Oakland.

“The clinical implications of our findings are that women with previous GD may benefit from enhanced traditional CVD [cardiovascular disease] risk factor testing – i.e., for hypertension, dyslipidemia, and hyperinsulinemia,” Dr. Gunderson said. “Our findings also suggest that it could be beneficial to incorporate history of GD into risk calculators to improve CVD risk stratification and prevention.”

Strong findings argue for more frequent CVD screening

These study results may be the strongest data to date on the long-term effects of GD, said Prakash Deedwania, MD, professor of cardiology at the University of California, San Francisco. “It’s the strongest in the sense in that it’s sponsored, involved four different communities in different parts of the United States, enrolled individuals when they were young and followed them, and saw very few patients drop out for such a long-term study.” The study reported follow-up data on 72% of patients at 25 years, a rate Dr. Deedwania noted was “excellent.”

“Patients who have had GD should be screened aggressively – for not only diabetes, but other cardiovascular risk factors – early on to minimize the subsequent risk of cardiovascular disease is a very important point of this study,” he added. In the absence of a clinical guideline, Dr. Deedwania suggested women with GD might have screening for CV risk factors every 5-7 years depending on their risk profile, but emphasized that parameter isn’t settled.

Future research should focus on the link between GD and CVD risk, Dr. Gunderson said. “Research is needed to better characterize the severity of GD in relation to CVD outcomes, and to identify critical pregnancy-related periods to modify cardiometabolic risk.” The latter would include life-course studies across the full pregnancy continuum from preconception to lactation. “Interventions for primary prevention of CVD and the importance of modifiable lifestyle behaviors with the highest relevance to reduce both diabetes and CVD risks during the first year post partum merit increased research investigation,” she added.

Future studies might also explore the role of inflammation in the GD-CVD relationship, Dr. Deedwania said. “My hypothesis is, and it’s purely a hypothesis, that perhaps the presence of coronary artery calcification scores score in these individuals who were described as having normal glucose but who could be at risk could very well be related to the beginning of inflammation.”

Dr. Gunderson and Dr. Deedwania have no financial relationships to disclose. The study was funded by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

Women who’ve had gestational diabetes are 40% more likely to develop coronary artery calcification later in life than are women haven’t, and attaining normal glycemic levels doesn’t diminish their midlife risk for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.

“The new finding from this study is that women with gestational diabetes had twice the risk of coronary artery calcium, compared to women who never had gestational diabetes, even though both groups attained normal blood sugar levels many years after pregnancy,” lead author Erica P. Gunderson, PhD, MS, MPH, said in an interview about a community-based prospective cohort study of young adults followed for up to 25 years, which was published in Circulation (2021 Feb 1. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.047320).

Previous studies have reported a higher risk of heart disease in women who had gestational diabetes (GD) and later developed type 2 diabetes, but they didn’t elucidate whether that risk carried over in GD patients whose glycemic levels were normal after pregnancy. In 2018, the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Cholesterol Clinical Practice Guidelines specified that a history of GD increases women’s risk for coronary artery calcification (CAC).

This study analyzed data of 1,133 women ages 18-30 enrolled in the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study who had no diabetes in the baseline years of 1985-1986 and had given birth at least once in the ensuing 25 years. They had glucose tolerance testing at baseline and up to five times through the study period, along with evaluation for GD status and coronary artery calcification CAC measurements at least once at years 15, 20 and 25 (2001-2011).

CARDIA enrolled 5,155 young Black and White men and women ages 18-30 from four distinct geographic areas: Birmingham, Ala.; Chicago; Minneapolis; and Oakland, Calif. About 52% of the study population was Black.

Of the women who’d given birth, 139 (12%) had GD. Their average age at follow-up was 47.6 years, and 25% of the GD patients (34) had CAC, compared with 15% (149/994) in the non-GD group.

Dr. Gunderson noted that the same relative risk for CAC applied to women who had GD and went on to develop prediabetes or were diagnosed with type 2 diabetes during follow-up.

Risks persist even in normoglycemia

In the GD group, the adjusted hazard ratio for having CAC with normoglycemia was 2.3 (95% confidence interval, 1.34-4.09). The researchers also calculated HRs for prediabetes and incident diabetes: 1.5 (95% CI, 1.06-2.24) in no-GD and 2.1 (95% CI, 1.09-4.17) for GD for prediabetes; and 2.2 (95% CI, 1.3-3.62) and 2.02 (95% CI, 0.98-4.19), respectively, for incident diabetes (P = .003).

“This means the risk of heart disease may be increased substantially in women with a history of gestational diabetes and may not diminish even if their blood-sugar levels remain normal for years later,” said Dr. Gunderson, an epidemiologist and senior research scientist at the Kaiser Permanente Northern California Division of Research in Oakland.

“The clinical implications of our findings are that women with previous GD may benefit from enhanced traditional CVD [cardiovascular disease] risk factor testing – i.e., for hypertension, dyslipidemia, and hyperinsulinemia,” Dr. Gunderson said. “Our findings also suggest that it could be beneficial to incorporate history of GD into risk calculators to improve CVD risk stratification and prevention.”

Strong findings argue for more frequent CVD screening

These study results may be the strongest data to date on the long-term effects of GD, said Prakash Deedwania, MD, professor of cardiology at the University of California, San Francisco. “It’s the strongest in the sense in that it’s sponsored, involved four different communities in different parts of the United States, enrolled individuals when they were young and followed them, and saw very few patients drop out for such a long-term study.” The study reported follow-up data on 72% of patients at 25 years, a rate Dr. Deedwania noted was “excellent.”

“Patients who have had GD should be screened aggressively – for not only diabetes, but other cardiovascular risk factors – early on to minimize the subsequent risk of cardiovascular disease is a very important point of this study,” he added. In the absence of a clinical guideline, Dr. Deedwania suggested women with GD might have screening for CV risk factors every 5-7 years depending on their risk profile, but emphasized that parameter isn’t settled.

Future research should focus on the link between GD and CVD risk, Dr. Gunderson said. “Research is needed to better characterize the severity of GD in relation to CVD outcomes, and to identify critical pregnancy-related periods to modify cardiometabolic risk.” The latter would include life-course studies across the full pregnancy continuum from preconception to lactation. “Interventions for primary prevention of CVD and the importance of modifiable lifestyle behaviors with the highest relevance to reduce both diabetes and CVD risks during the first year post partum merit increased research investigation,” she added.

Future studies might also explore the role of inflammation in the GD-CVD relationship, Dr. Deedwania said. “My hypothesis is, and it’s purely a hypothesis, that perhaps the presence of coronary artery calcification scores score in these individuals who were described as having normal glucose but who could be at risk could very well be related to the beginning of inflammation.”

Dr. Gunderson and Dr. Deedwania have no financial relationships to disclose. The study was funded by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

FROM CIRCULATION

Long-acting injectable antipsychotics during COVID-19

Long-acting injectable antipsychotics (LAIs) are an essential tool in the treatment of patients with psychotic disorders, allowing for periods of stable drug plasma concentration and confirmed adherence.1 The current coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic presents unique challenges for administering LAIs and requires a thoughtful and prospective approach in order to ensure continuity of psychiatric care while minimizing the risk of infection with COVID-19. Ideally, patients should be seen in person as infrequently as clinically prudent during this public health emergency; however, LAI administration necessitates direct physical contact between patient and clinician.

Patients with serious mental illness (SMI), who comprise the majority of individuals who receive LAIs, are at heightened risk for cardiovascular and pulmonary comorbidities. These factors are the primary reason the life expectancy of a patient with SMI is nearly 30 years shorter than that of the general population.2-5 The risk of health care workers becoming infected or inadvertently spreading COVID-19 is heightened when working with patients in group living environments (ie, a shelter or group home), who have both increased exposure and increased risk of further transmission.6 Additional patient populations, including older adults, immunocompromised individuals, and those with preexisting conditions, are at heightened risk for serious complications if they were to contract COVID-19.7,8

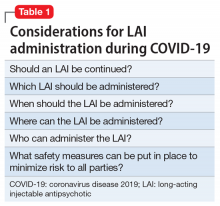

Thus, the questions of whether LAIs should be administered, and how to do so safely (both during the ongoing, acute phase of the pandemic as well as during the subsequent recovery period until the pandemic abates) need to be carefully considered. In this article, we provide concrete advice for clinicians and clinics on these topics, with the goal of maintaining patients’ psychiatric stability while protecting patients, health care workers, and the broader society from COVID-19 infection. Table 1 summarizes the questions regarding LAIs that clinicians need to address during this crisis. While we focus on outpatient care, inpatient teams should keep these considerations in mind if they are starting and discharging a patient on an LAI. More than ever, close collaboration and communication between inpatient and outpatient teams is critical.

Should an LAI be continued?

An important first step to approaching this challenge is to create a spreadsheet for all patients receiving LAIs. Focusing on a population-based approach is helpful to be systematic and ensure that no patients fall through the cracks during this public health emergency.9 Once all patients have been identified, the treatment team should review each patient to determine if continuing to administer the antipsychotic as an LAI formulation is essential, taking into account the patient’s current psychiatric status, historical medication adherence, potential severity and dangerousness of decompensation if nonadherent, and structures to support stability. For example, can a patient move in with family who can monitor medication adherence during the pandemic? Is it possible for the group home to assume medication administration? Additional consideration should be given to the living environment and health-vulnerability of the patient and the individuals living with them.

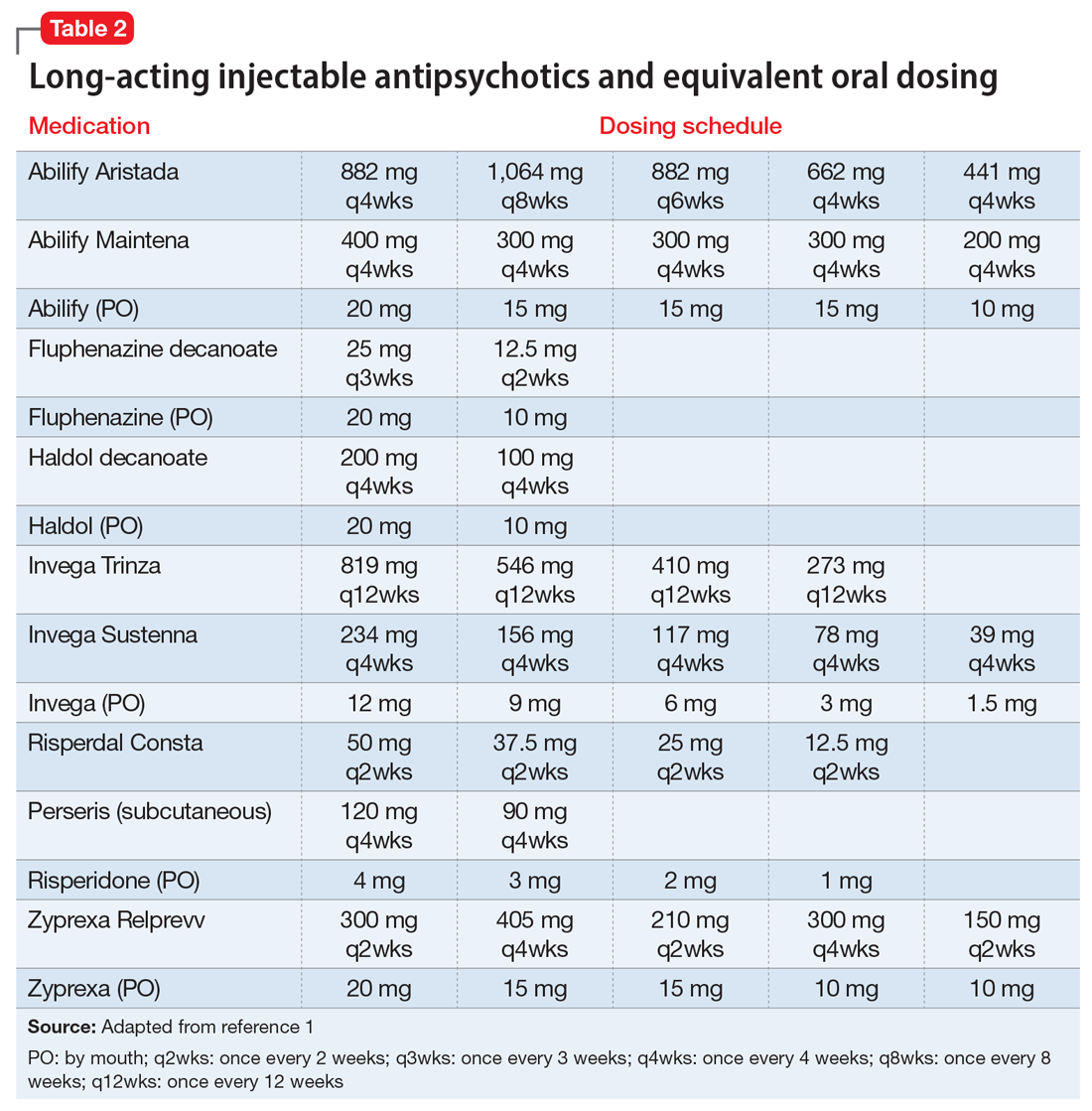

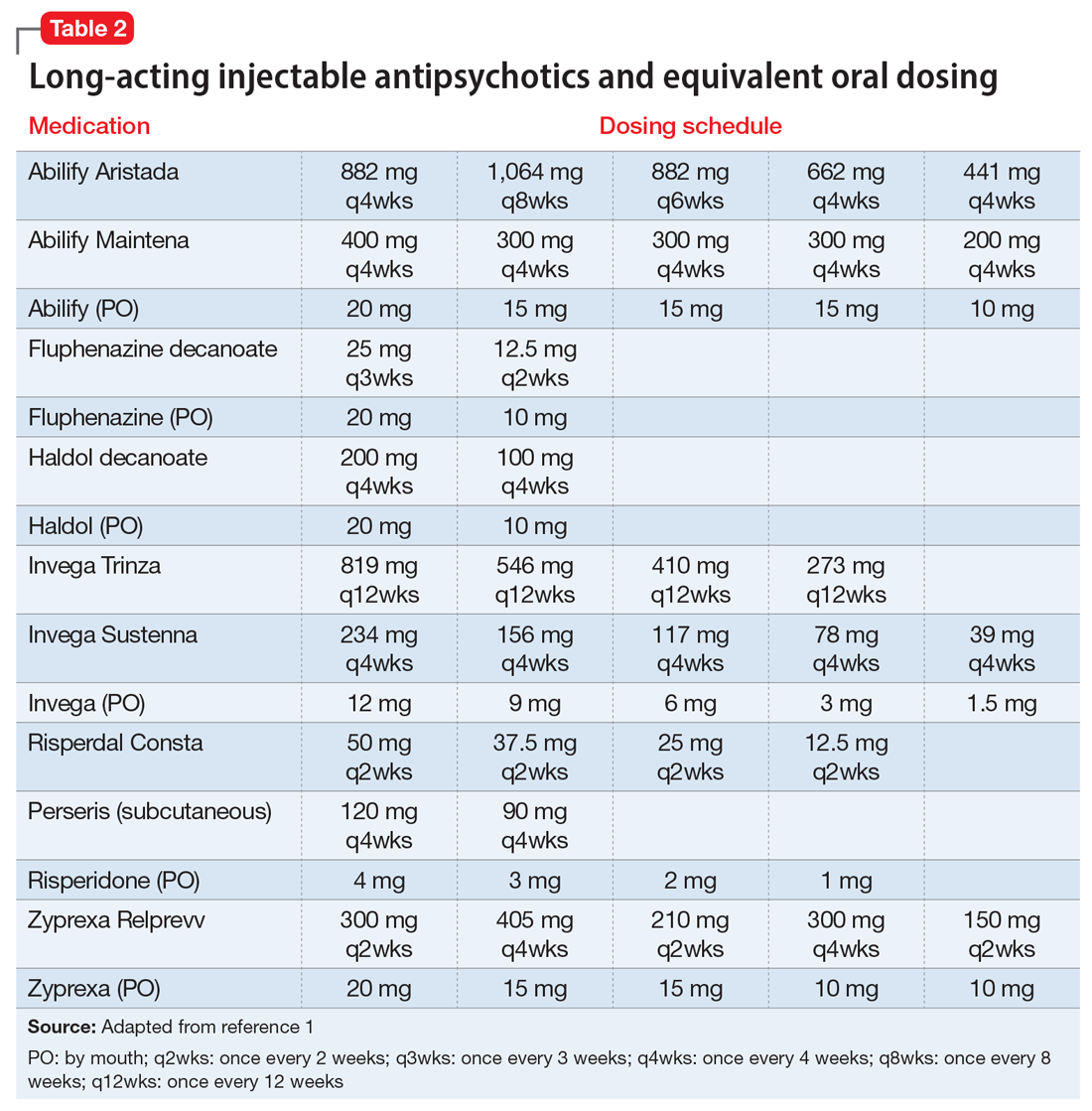

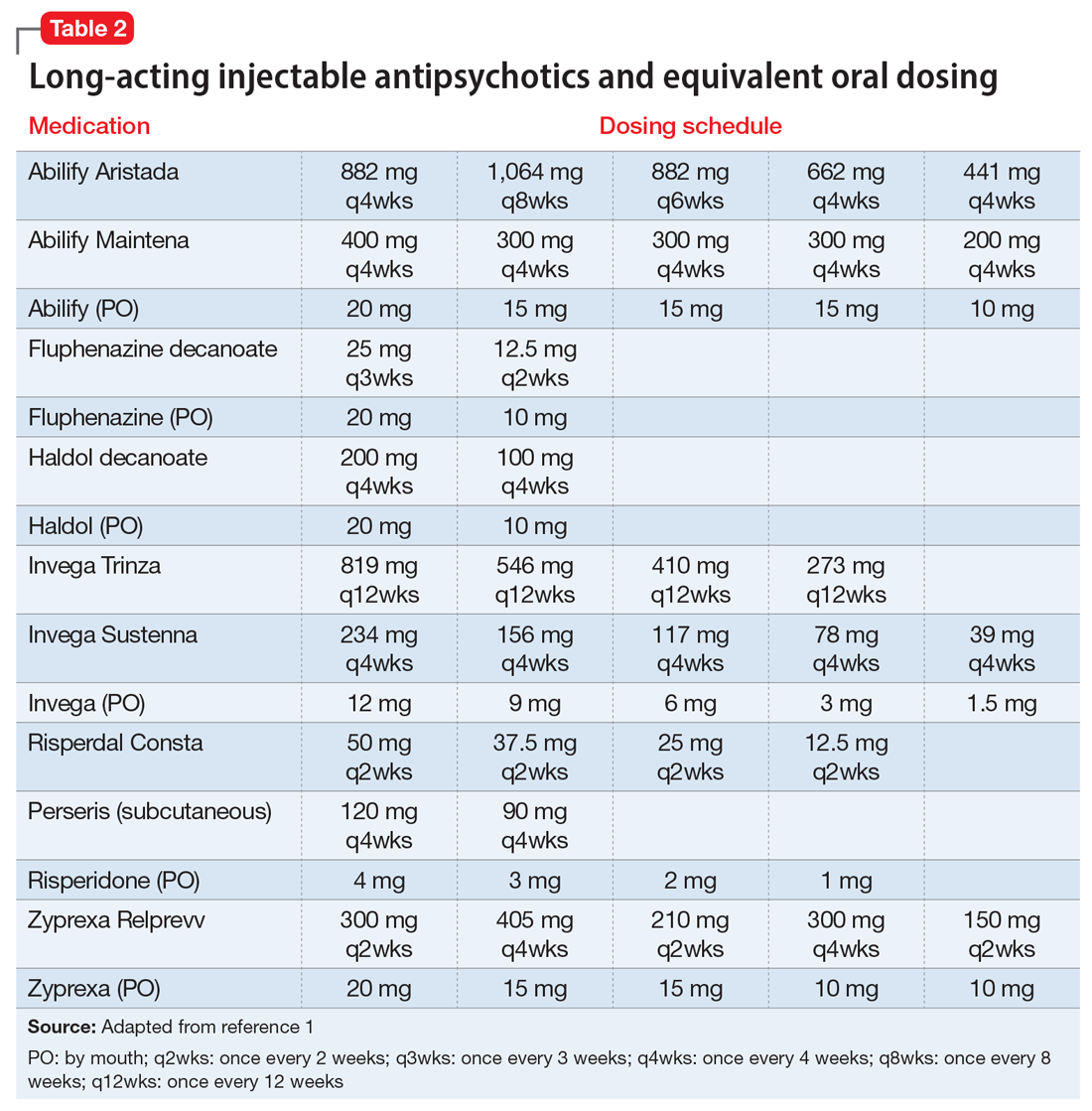

If the risk calculation does not point strongly towards a need for continuing the LAI, it may be prudent to temporarily transition the patient to the corresponding oral antipsychotic preparation. Table 2 lists all LAIs available in the United States and their approximate equivalent oral dosing. It is important to note that such transitions are not without clinical risk, to emphasize to the patient that the transition is intended as a temporary measure, and to discuss a proposed timeline for re-initiating the LAI. Also, emphasize to the patient and family that this transition does not diminish the previous reasoning for needing an LAI, but is a temporary measure taken in light of weighing the risks and benefits during a pandemic.

Which LAI should be administered?

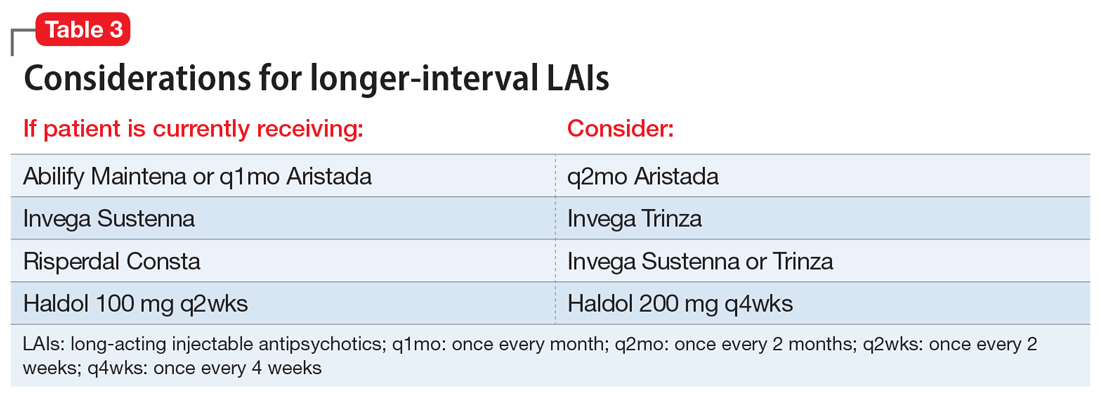

If continuing the LAI is determined to be clinically necessary, consider switching the patient to a longer-acting preparation to maximize intervals between administrations and minimize the potential for infection. From a public health perspective, the longest clinically prudent interval between injections may be the most important consideration, provided the patient can receive a dose necessary to retain stability, and the LAI should be chosen accordingly. Deltoid injections may be able to be administered with reduced contact, or on a “drive-up” basis.10 Consider transitioning a patient who is receiving olanzapine pamoate to an alternate LAI or oral formulation, because the 3-hour observation period that is required after olanzapine pamoate administration is particularly problematic. While it may not be ideal to make medication changes during a pandemic, it is worth carefully weighing the patient’s stability and historical experience with other LAIs to determine if a safer/longer-spaced option is worth trying.11

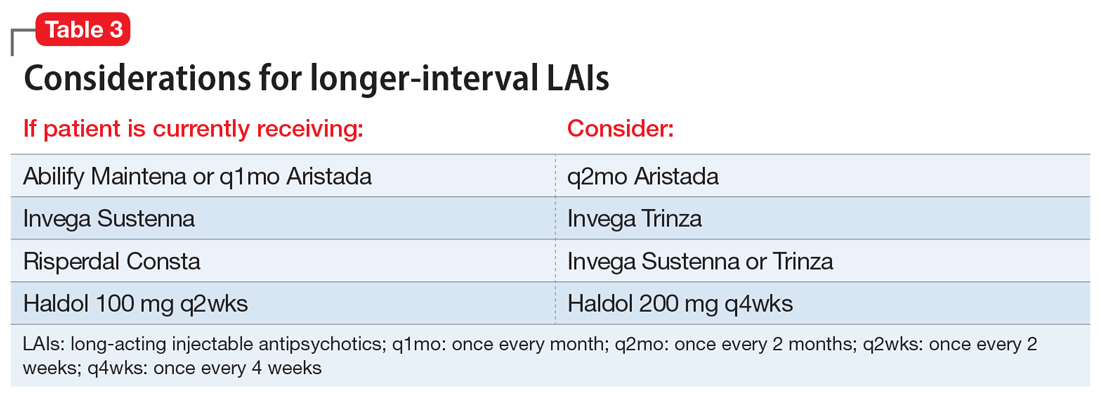

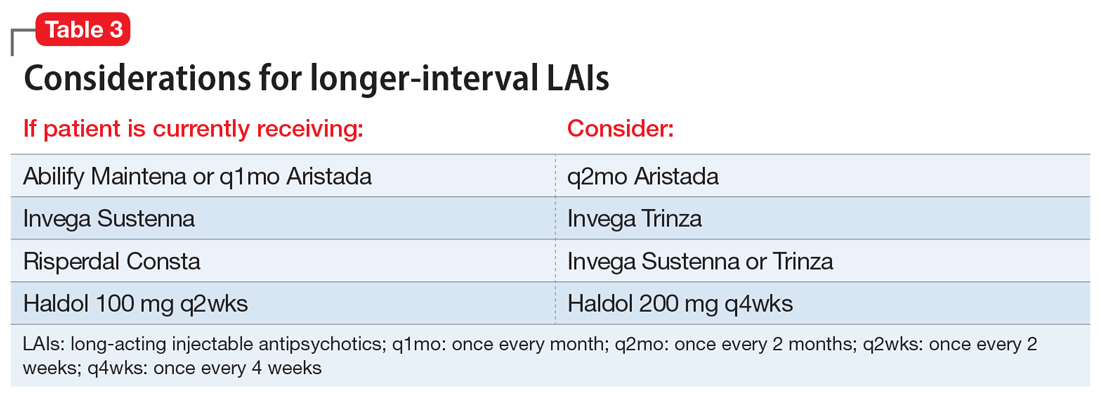

We recommend only switching among similar antipsychotics (ie, risperidone to paliperidone), or between different preparations of the same drug (ie, Abilify Maintena to Aristada), if possible, as these are the lowest risk transitions with regards to relapse. Table 3 provides examples.

Continue to: When should the LAI be administered?

When should the LAI be administered?

The pharmacokinetics of LAIs allow for some flexibility in terms of when an LAI needs to be administered. The package inserts of all second-generation LAIs include missed-dose guidelines. These guidelines provide information on how long one can wait before the next injection is due, and what additional measures must be taken when beyond that date. Delaying an injection may be prudent, and the missed dose guidelines will indicate when one must consider supplementing with oral medications. For patients who are in quarantine, it may be better to delay an injection until the patient ends their quarantine than to deliver the dose during quarantine. Administering an injection earlier also is usually safe; off-cycle visits may help minimize patient contact (ie, if the patient happens to be coming into the vicinity of the clinic, or requires phlebotomy for therapeutic drug monitoring), and assist in planning for possible resurgences. When appropriate, and after considering the risk of worsening adverse effects, administering a higher dose than the usual maintenance dose would provide a buffer if the next injection was to be delayed. Therapeutic drug monitoring can help to optimize dosing and avoid low plasma drug levels, which may be not be sufficient, particularly during this time of stress.12 To provide optimal protection against relapse, consider administering a dose that puts patients at the higher range of plasma drug levels.

Where can the LAI be administered, and who can give it?

For patients who usually travel to a clinic, consider arranging for a more local injection (ie, at the patient’s primary care clinic in their hometown, or at a local mental health center), and explore if the patient may be able to receive their injection in their home through a visiting nurse association (VNA). In many states (approximately 30 currently), clinicians at pharmacies are also able to administer patient injections. Clinics would do well to at least plan for alternate staffing models in the event of staff illness. A pool of individuals should be available to give injections; consider training additional staff members (including MDs who may have never previously administered an LAI but could be quickly instructed to do so) to administer LAIs. Theoretically, during a public health emergency, family members, particularly those who have a background in health care, could be trained to give an injection and provided education on LAI storage and post-injection monitoring. This approach would not be consistent with FDA labeling, however, and should only be considered as a last resort.

What safety measures can be put in place?

Face-to-face time for injection administration should be kept as brief as possible. Before the encounter, obtain the patient’s clinical information, ideally through telehealth or from an acceptable distance. Medication should be drawn ahead of time, and not in an enclosed space with the patient present. Strongly consider abandoning the traditional enclosed room for the injection, and instead use larger spaces, doorways, or outside, if feasible. As previously noted, some clinics and clinicians have used a drive-up approach for LAI administration, particularly for deltoid injections.10 Individuals who administer the injections should wear personal protective equipment, and the clinic should obtain an adequate supply of this equipment well in advance.

Lessons learned at our clinic

In our community mental health center clinic, planning around these questions has allowed us to provide safe and continuous psychiatric care with LAIs during this public health emergency while reducing the risk of infection. We have worked to transfer LAI administration to VNAs and transition patients to longer-lasting formulations or oral medications where appropriate, which has resulted in an approximately 50% decrease in in-person visits. Reducing the number of in-person visits does not need to result in less frequent clinical follow-up. Telepsychiatry visits can make up for lost in-person visits and have generally been well accepted.

As we are preparing for the next phase, routine medical health monitoring (eg, metabolic monitoring, monitoring for tardive dyskinesia) that has not been at the forefront of concerns should be carefully reintroduced. Challenges encountered have included difficulty in having VNA accept patients for short-term LAI visits, changes to where on the body the injection is delivered, and patients with SMI and their families being reluctant to depart from previous routines and administration schedules.

Continue to: There is great value...

There is great value in the collective lessons learned during this public health emergency (eg, the need for a flexible, population health-based approach; acceptability of combination telehealth and in-person visits) that can lead to more person-centered and accessible care for patients with SMI.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank North Suffolk Mental Health Association, the Freedom Trail Clinic, and their patients.

Bottom Line

When caring for a patient with a psychotic illness during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, evaluate whether it is necessary to continue a longacting injectable antipsychotic (LAI). If yes, reconsider which LAI should be administered, when and where it should be given, and by whom. Implement safety measures to minimize the risk of COVID-19 exposure and transmission.

Related Resources

- American Association of Community Psychiatrists. Clinical Tip Series. Long acting antipsychotic medications. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1unigjmjFJkqZMbaZ_ftdj8oqog49awZs/view?usp=sharing

- SMI Adviser. What are clinical considerations for giving LAIs during the COVID-19 public health emergency? https://smiadviser.org/knowledge_post/what-are-clinical-considerations-for-giving-lais-during-the-covid-19-public-health-emergency

- CDC. Infection control basics. https://www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/basics/index.html

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Aripiprazole for extended- release injectable suspension • Abilify Maintena

Aripiprazole lauroxil • Aristada

Haloperidol • Haldol

Haloperidol injection • Haldol decanoate

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Olanzapine for extended-release injectable suspension • Zyprexa Relprevv

Paliperidone • Invega

Paliperidone palmitate extended-release injectable suspension • Invega Sustenna

Paliperidone palmitate extended-release injectable suspension • Invega Trinza

Risperidone • Risperdal

Risperidone for extended- release injectable suspension • Perseris

Risperidone injection • Risperdal Consta

1. Freudenreich O. Long-acting injectable antipsychotics. In: Freudenreich O. Psychotic disorders: a practical guide. Springer; 2020:249-261.

2. Olfson M, Gerhard T, Huang C, et al. Premature mortality among adults with schizophrenia in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(12):1172-1181.

3. Reilly S, Olier I, Planner C, et al. Inequalities in physical comorbidity: a longitudinal comparative cohort study of people with severe mental illness in the UK. BMJ Open. 2015;5(12):e009010.

4. Brown S, Inskip H, Barraclough B. Causes of the excess mortality of schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;177:212-217.

5. Goff DC, Cather C, Evins AE, et al. Medical morbidity and mortality in schizophrenia: guidelines for psychiatrists. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(2):183-194.

6. Baggett TP, Keyes H, Sporn N, et al. Prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in residents of a large homeless shelter in Boston. JAMA. 2020;323(21):2191-2192.

7. CDC COVID-19 Response Team. Severe outcomes among patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)—United States, February 12–March 16, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(12):343-346.

8. Docherty AB, Harrison EM, Green CA, et al. Features of 20 133 UK patients in hospital with covid-19 using the ISARIC WHO Clinical Characterisation Protocol: prospective observational cohort study. BMJ. 2020;369:m1985. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1985

9. Etches V, Frank J, Di Ruggiero E, et al. Measuring population health: a review of indicators. Annu Rev Public Health. 2006;27:29-55.

10. Chepke C. Drive-up pharmacotherapy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(5):29-30.

11. Sajatovic M, Ross R, Legacy SN, et al. Initiating/maintaining long-acting injectable antipsychotics in schizophrenia/schizoaffective or bipolar disorder - expert consensus survey part 2. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2018;14:1475-1492.

12. Schoretsanitis G, Kane JM, Correll CU, et al; American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology, Pharmakopsychiatrie TTDMTFOTAFNU. Blood levels to optimize antipsychotic treatment in clinical practice: a joint consensus statement of the American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology and the Therapeutic Drug Monitoring Task Force of the Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Neuropsychopharmakologie und Pharmakopsychiatrie. J Clin Psychiatry. 2020;81(3):19cs13169. doi: 10.4088/JCP.19cs13169

Long-acting injectable antipsychotics (LAIs) are an essential tool in the treatment of patients with psychotic disorders, allowing for periods of stable drug plasma concentration and confirmed adherence.1 The current coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic presents unique challenges for administering LAIs and requires a thoughtful and prospective approach in order to ensure continuity of psychiatric care while minimizing the risk of infection with COVID-19. Ideally, patients should be seen in person as infrequently as clinically prudent during this public health emergency; however, LAI administration necessitates direct physical contact between patient and clinician.

Patients with serious mental illness (SMI), who comprise the majority of individuals who receive LAIs, are at heightened risk for cardiovascular and pulmonary comorbidities. These factors are the primary reason the life expectancy of a patient with SMI is nearly 30 years shorter than that of the general population.2-5 The risk of health care workers becoming infected or inadvertently spreading COVID-19 is heightened when working with patients in group living environments (ie, a shelter or group home), who have both increased exposure and increased risk of further transmission.6 Additional patient populations, including older adults, immunocompromised individuals, and those with preexisting conditions, are at heightened risk for serious complications if they were to contract COVID-19.7,8

Thus, the questions of whether LAIs should be administered, and how to do so safely (both during the ongoing, acute phase of the pandemic as well as during the subsequent recovery period until the pandemic abates) need to be carefully considered. In this article, we provide concrete advice for clinicians and clinics on these topics, with the goal of maintaining patients’ psychiatric stability while protecting patients, health care workers, and the broader society from COVID-19 infection. Table 1 summarizes the questions regarding LAIs that clinicians need to address during this crisis. While we focus on outpatient care, inpatient teams should keep these considerations in mind if they are starting and discharging a patient on an LAI. More than ever, close collaboration and communication between inpatient and outpatient teams is critical.

Should an LAI be continued?

An important first step to approaching this challenge is to create a spreadsheet for all patients receiving LAIs. Focusing on a population-based approach is helpful to be systematic and ensure that no patients fall through the cracks during this public health emergency.9 Once all patients have been identified, the treatment team should review each patient to determine if continuing to administer the antipsychotic as an LAI formulation is essential, taking into account the patient’s current psychiatric status, historical medication adherence, potential severity and dangerousness of decompensation if nonadherent, and structures to support stability. For example, can a patient move in with family who can monitor medication adherence during the pandemic? Is it possible for the group home to assume medication administration? Additional consideration should be given to the living environment and health-vulnerability of the patient and the individuals living with them.

If the risk calculation does not point strongly towards a need for continuing the LAI, it may be prudent to temporarily transition the patient to the corresponding oral antipsychotic preparation. Table 2 lists all LAIs available in the United States and their approximate equivalent oral dosing. It is important to note that such transitions are not without clinical risk, to emphasize to the patient that the transition is intended as a temporary measure, and to discuss a proposed timeline for re-initiating the LAI. Also, emphasize to the patient and family that this transition does not diminish the previous reasoning for needing an LAI, but is a temporary measure taken in light of weighing the risks and benefits during a pandemic.

Which LAI should be administered?

If continuing the LAI is determined to be clinically necessary, consider switching the patient to a longer-acting preparation to maximize intervals between administrations and minimize the potential for infection. From a public health perspective, the longest clinically prudent interval between injections may be the most important consideration, provided the patient can receive a dose necessary to retain stability, and the LAI should be chosen accordingly. Deltoid injections may be able to be administered with reduced contact, or on a “drive-up” basis.10 Consider transitioning a patient who is receiving olanzapine pamoate to an alternate LAI or oral formulation, because the 3-hour observation period that is required after olanzapine pamoate administration is particularly problematic. While it may not be ideal to make medication changes during a pandemic, it is worth carefully weighing the patient’s stability and historical experience with other LAIs to determine if a safer/longer-spaced option is worth trying.11

We recommend only switching among similar antipsychotics (ie, risperidone to paliperidone), or between different preparations of the same drug (ie, Abilify Maintena to Aristada), if possible, as these are the lowest risk transitions with regards to relapse. Table 3 provides examples.

Continue to: When should the LAI be administered?

When should the LAI be administered?

The pharmacokinetics of LAIs allow for some flexibility in terms of when an LAI needs to be administered. The package inserts of all second-generation LAIs include missed-dose guidelines. These guidelines provide information on how long one can wait before the next injection is due, and what additional measures must be taken when beyond that date. Delaying an injection may be prudent, and the missed dose guidelines will indicate when one must consider supplementing with oral medications. For patients who are in quarantine, it may be better to delay an injection until the patient ends their quarantine than to deliver the dose during quarantine. Administering an injection earlier also is usually safe; off-cycle visits may help minimize patient contact (ie, if the patient happens to be coming into the vicinity of the clinic, or requires phlebotomy for therapeutic drug monitoring), and assist in planning for possible resurgences. When appropriate, and after considering the risk of worsening adverse effects, administering a higher dose than the usual maintenance dose would provide a buffer if the next injection was to be delayed. Therapeutic drug monitoring can help to optimize dosing and avoid low plasma drug levels, which may be not be sufficient, particularly during this time of stress.12 To provide optimal protection against relapse, consider administering a dose that puts patients at the higher range of plasma drug levels.

Where can the LAI be administered, and who can give it?

For patients who usually travel to a clinic, consider arranging for a more local injection (ie, at the patient’s primary care clinic in their hometown, or at a local mental health center), and explore if the patient may be able to receive their injection in their home through a visiting nurse association (VNA). In many states (approximately 30 currently), clinicians at pharmacies are also able to administer patient injections. Clinics would do well to at least plan for alternate staffing models in the event of staff illness. A pool of individuals should be available to give injections; consider training additional staff members (including MDs who may have never previously administered an LAI but could be quickly instructed to do so) to administer LAIs. Theoretically, during a public health emergency, family members, particularly those who have a background in health care, could be trained to give an injection and provided education on LAI storage and post-injection monitoring. This approach would not be consistent with FDA labeling, however, and should only be considered as a last resort.

What safety measures can be put in place?

Face-to-face time for injection administration should be kept as brief as possible. Before the encounter, obtain the patient’s clinical information, ideally through telehealth or from an acceptable distance. Medication should be drawn ahead of time, and not in an enclosed space with the patient present. Strongly consider abandoning the traditional enclosed room for the injection, and instead use larger spaces, doorways, or outside, if feasible. As previously noted, some clinics and clinicians have used a drive-up approach for LAI administration, particularly for deltoid injections.10 Individuals who administer the injections should wear personal protective equipment, and the clinic should obtain an adequate supply of this equipment well in advance.

Lessons learned at our clinic

In our community mental health center clinic, planning around these questions has allowed us to provide safe and continuous psychiatric care with LAIs during this public health emergency while reducing the risk of infection. We have worked to transfer LAI administration to VNAs and transition patients to longer-lasting formulations or oral medications where appropriate, which has resulted in an approximately 50% decrease in in-person visits. Reducing the number of in-person visits does not need to result in less frequent clinical follow-up. Telepsychiatry visits can make up for lost in-person visits and have generally been well accepted.

As we are preparing for the next phase, routine medical health monitoring (eg, metabolic monitoring, monitoring for tardive dyskinesia) that has not been at the forefront of concerns should be carefully reintroduced. Challenges encountered have included difficulty in having VNA accept patients for short-term LAI visits, changes to where on the body the injection is delivered, and patients with SMI and their families being reluctant to depart from previous routines and administration schedules.

Continue to: There is great value...

There is great value in the collective lessons learned during this public health emergency (eg, the need for a flexible, population health-based approach; acceptability of combination telehealth and in-person visits) that can lead to more person-centered and accessible care for patients with SMI.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank North Suffolk Mental Health Association, the Freedom Trail Clinic, and their patients.

Bottom Line

When caring for a patient with a psychotic illness during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, evaluate whether it is necessary to continue a longacting injectable antipsychotic (LAI). If yes, reconsider which LAI should be administered, when and where it should be given, and by whom. Implement safety measures to minimize the risk of COVID-19 exposure and transmission.

Related Resources

- American Association of Community Psychiatrists. Clinical Tip Series. Long acting antipsychotic medications. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1unigjmjFJkqZMbaZ_ftdj8oqog49awZs/view?usp=sharing

- SMI Adviser. What are clinical considerations for giving LAIs during the COVID-19 public health emergency? https://smiadviser.org/knowledge_post/what-are-clinical-considerations-for-giving-lais-during-the-covid-19-public-health-emergency

- CDC. Infection control basics. https://www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/basics/index.html

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Aripiprazole for extended- release injectable suspension • Abilify Maintena

Aripiprazole lauroxil • Aristada

Haloperidol • Haldol

Haloperidol injection • Haldol decanoate

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Olanzapine for extended-release injectable suspension • Zyprexa Relprevv

Paliperidone • Invega

Paliperidone palmitate extended-release injectable suspension • Invega Sustenna

Paliperidone palmitate extended-release injectable suspension • Invega Trinza

Risperidone • Risperdal

Risperidone for extended- release injectable suspension • Perseris

Risperidone injection • Risperdal Consta

Long-acting injectable antipsychotics (LAIs) are an essential tool in the treatment of patients with psychotic disorders, allowing for periods of stable drug plasma concentration and confirmed adherence.1 The current coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic presents unique challenges for administering LAIs and requires a thoughtful and prospective approach in order to ensure continuity of psychiatric care while minimizing the risk of infection with COVID-19. Ideally, patients should be seen in person as infrequently as clinically prudent during this public health emergency; however, LAI administration necessitates direct physical contact between patient and clinician.

Patients with serious mental illness (SMI), who comprise the majority of individuals who receive LAIs, are at heightened risk for cardiovascular and pulmonary comorbidities. These factors are the primary reason the life expectancy of a patient with SMI is nearly 30 years shorter than that of the general population.2-5 The risk of health care workers becoming infected or inadvertently spreading COVID-19 is heightened when working with patients in group living environments (ie, a shelter or group home), who have both increased exposure and increased risk of further transmission.6 Additional patient populations, including older adults, immunocompromised individuals, and those with preexisting conditions, are at heightened risk for serious complications if they were to contract COVID-19.7,8

Thus, the questions of whether LAIs should be administered, and how to do so safely (both during the ongoing, acute phase of the pandemic as well as during the subsequent recovery period until the pandemic abates) need to be carefully considered. In this article, we provide concrete advice for clinicians and clinics on these topics, with the goal of maintaining patients’ psychiatric stability while protecting patients, health care workers, and the broader society from COVID-19 infection. Table 1 summarizes the questions regarding LAIs that clinicians need to address during this crisis. While we focus on outpatient care, inpatient teams should keep these considerations in mind if they are starting and discharging a patient on an LAI. More than ever, close collaboration and communication between inpatient and outpatient teams is critical.

Should an LAI be continued?

An important first step to approaching this challenge is to create a spreadsheet for all patients receiving LAIs. Focusing on a population-based approach is helpful to be systematic and ensure that no patients fall through the cracks during this public health emergency.9 Once all patients have been identified, the treatment team should review each patient to determine if continuing to administer the antipsychotic as an LAI formulation is essential, taking into account the patient’s current psychiatric status, historical medication adherence, potential severity and dangerousness of decompensation if nonadherent, and structures to support stability. For example, can a patient move in with family who can monitor medication adherence during the pandemic? Is it possible for the group home to assume medication administration? Additional consideration should be given to the living environment and health-vulnerability of the patient and the individuals living with them.

If the risk calculation does not point strongly towards a need for continuing the LAI, it may be prudent to temporarily transition the patient to the corresponding oral antipsychotic preparation. Table 2 lists all LAIs available in the United States and their approximate equivalent oral dosing. It is important to note that such transitions are not without clinical risk, to emphasize to the patient that the transition is intended as a temporary measure, and to discuss a proposed timeline for re-initiating the LAI. Also, emphasize to the patient and family that this transition does not diminish the previous reasoning for needing an LAI, but is a temporary measure taken in light of weighing the risks and benefits during a pandemic.

Which LAI should be administered?

If continuing the LAI is determined to be clinically necessary, consider switching the patient to a longer-acting preparation to maximize intervals between administrations and minimize the potential for infection. From a public health perspective, the longest clinically prudent interval between injections may be the most important consideration, provided the patient can receive a dose necessary to retain stability, and the LAI should be chosen accordingly. Deltoid injections may be able to be administered with reduced contact, or on a “drive-up” basis.10 Consider transitioning a patient who is receiving olanzapine pamoate to an alternate LAI or oral formulation, because the 3-hour observation period that is required after olanzapine pamoate administration is particularly problematic. While it may not be ideal to make medication changes during a pandemic, it is worth carefully weighing the patient’s stability and historical experience with other LAIs to determine if a safer/longer-spaced option is worth trying.11

We recommend only switching among similar antipsychotics (ie, risperidone to paliperidone), or between different preparations of the same drug (ie, Abilify Maintena to Aristada), if possible, as these are the lowest risk transitions with regards to relapse. Table 3 provides examples.

Continue to: When should the LAI be administered?

When should the LAI be administered?

The pharmacokinetics of LAIs allow for some flexibility in terms of when an LAI needs to be administered. The package inserts of all second-generation LAIs include missed-dose guidelines. These guidelines provide information on how long one can wait before the next injection is due, and what additional measures must be taken when beyond that date. Delaying an injection may be prudent, and the missed dose guidelines will indicate when one must consider supplementing with oral medications. For patients who are in quarantine, it may be better to delay an injection until the patient ends their quarantine than to deliver the dose during quarantine. Administering an injection earlier also is usually safe; off-cycle visits may help minimize patient contact (ie, if the patient happens to be coming into the vicinity of the clinic, or requires phlebotomy for therapeutic drug monitoring), and assist in planning for possible resurgences. When appropriate, and after considering the risk of worsening adverse effects, administering a higher dose than the usual maintenance dose would provide a buffer if the next injection was to be delayed. Therapeutic drug monitoring can help to optimize dosing and avoid low plasma drug levels, which may be not be sufficient, particularly during this time of stress.12 To provide optimal protection against relapse, consider administering a dose that puts patients at the higher range of plasma drug levels.

Where can the LAI be administered, and who can give it?

For patients who usually travel to a clinic, consider arranging for a more local injection (ie, at the patient’s primary care clinic in their hometown, or at a local mental health center), and explore if the patient may be able to receive their injection in their home through a visiting nurse association (VNA). In many states (approximately 30 currently), clinicians at pharmacies are also able to administer patient injections. Clinics would do well to at least plan for alternate staffing models in the event of staff illness. A pool of individuals should be available to give injections; consider training additional staff members (including MDs who may have never previously administered an LAI but could be quickly instructed to do so) to administer LAIs. Theoretically, during a public health emergency, family members, particularly those who have a background in health care, could be trained to give an injection and provided education on LAI storage and post-injection monitoring. This approach would not be consistent with FDA labeling, however, and should only be considered as a last resort.

What safety measures can be put in place?

Face-to-face time for injection administration should be kept as brief as possible. Before the encounter, obtain the patient’s clinical information, ideally through telehealth or from an acceptable distance. Medication should be drawn ahead of time, and not in an enclosed space with the patient present. Strongly consider abandoning the traditional enclosed room for the injection, and instead use larger spaces, doorways, or outside, if feasible. As previously noted, some clinics and clinicians have used a drive-up approach for LAI administration, particularly for deltoid injections.10 Individuals who administer the injections should wear personal protective equipment, and the clinic should obtain an adequate supply of this equipment well in advance.

Lessons learned at our clinic

In our community mental health center clinic, planning around these questions has allowed us to provide safe and continuous psychiatric care with LAIs during this public health emergency while reducing the risk of infection. We have worked to transfer LAI administration to VNAs and transition patients to longer-lasting formulations or oral medications where appropriate, which has resulted in an approximately 50% decrease in in-person visits. Reducing the number of in-person visits does not need to result in less frequent clinical follow-up. Telepsychiatry visits can make up for lost in-person visits and have generally been well accepted.

As we are preparing for the next phase, routine medical health monitoring (eg, metabolic monitoring, monitoring for tardive dyskinesia) that has not been at the forefront of concerns should be carefully reintroduced. Challenges encountered have included difficulty in having VNA accept patients for short-term LAI visits, changes to where on the body the injection is delivered, and patients with SMI and their families being reluctant to depart from previous routines and administration schedules.

Continue to: There is great value...

There is great value in the collective lessons learned during this public health emergency (eg, the need for a flexible, population health-based approach; acceptability of combination telehealth and in-person visits) that can lead to more person-centered and accessible care for patients with SMI.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank North Suffolk Mental Health Association, the Freedom Trail Clinic, and their patients.

Bottom Line

When caring for a patient with a psychotic illness during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, evaluate whether it is necessary to continue a longacting injectable antipsychotic (LAI). If yes, reconsider which LAI should be administered, when and where it should be given, and by whom. Implement safety measures to minimize the risk of COVID-19 exposure and transmission.

Related Resources

- American Association of Community Psychiatrists. Clinical Tip Series. Long acting antipsychotic medications. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1unigjmjFJkqZMbaZ_ftdj8oqog49awZs/view?usp=sharing

- SMI Adviser. What are clinical considerations for giving LAIs during the COVID-19 public health emergency? https://smiadviser.org/knowledge_post/what-are-clinical-considerations-for-giving-lais-during-the-covid-19-public-health-emergency

- CDC. Infection control basics. https://www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/basics/index.html

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Aripiprazole for extended- release injectable suspension • Abilify Maintena

Aripiprazole lauroxil • Aristada

Haloperidol • Haldol

Haloperidol injection • Haldol decanoate

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Olanzapine for extended-release injectable suspension • Zyprexa Relprevv

Paliperidone • Invega

Paliperidone palmitate extended-release injectable suspension • Invega Sustenna

Paliperidone palmitate extended-release injectable suspension • Invega Trinza

Risperidone • Risperdal

Risperidone for extended- release injectable suspension • Perseris

Risperidone injection • Risperdal Consta

1. Freudenreich O. Long-acting injectable antipsychotics. In: Freudenreich O. Psychotic disorders: a practical guide. Springer; 2020:249-261.

2. Olfson M, Gerhard T, Huang C, et al. Premature mortality among adults with schizophrenia in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(12):1172-1181.

3. Reilly S, Olier I, Planner C, et al. Inequalities in physical comorbidity: a longitudinal comparative cohort study of people with severe mental illness in the UK. BMJ Open. 2015;5(12):e009010.

4. Brown S, Inskip H, Barraclough B. Causes of the excess mortality of schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;177:212-217.

5. Goff DC, Cather C, Evins AE, et al. Medical morbidity and mortality in schizophrenia: guidelines for psychiatrists. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(2):183-194.

6. Baggett TP, Keyes H, Sporn N, et al. Prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in residents of a large homeless shelter in Boston. JAMA. 2020;323(21):2191-2192.

7. CDC COVID-19 Response Team. Severe outcomes among patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)—United States, February 12–March 16, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(12):343-346.

8. Docherty AB, Harrison EM, Green CA, et al. Features of 20 133 UK patients in hospital with covid-19 using the ISARIC WHO Clinical Characterisation Protocol: prospective observational cohort study. BMJ. 2020;369:m1985. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1985

9. Etches V, Frank J, Di Ruggiero E, et al. Measuring population health: a review of indicators. Annu Rev Public Health. 2006;27:29-55.

10. Chepke C. Drive-up pharmacotherapy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(5):29-30.

11. Sajatovic M, Ross R, Legacy SN, et al. Initiating/maintaining long-acting injectable antipsychotics in schizophrenia/schizoaffective or bipolar disorder - expert consensus survey part 2. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2018;14:1475-1492.

12. Schoretsanitis G, Kane JM, Correll CU, et al; American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology, Pharmakopsychiatrie TTDMTFOTAFNU. Blood levels to optimize antipsychotic treatment in clinical practice: a joint consensus statement of the American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology and the Therapeutic Drug Monitoring Task Force of the Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Neuropsychopharmakologie und Pharmakopsychiatrie. J Clin Psychiatry. 2020;81(3):19cs13169. doi: 10.4088/JCP.19cs13169

1. Freudenreich O. Long-acting injectable antipsychotics. In: Freudenreich O. Psychotic disorders: a practical guide. Springer; 2020:249-261.

2. Olfson M, Gerhard T, Huang C, et al. Premature mortality among adults with schizophrenia in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(12):1172-1181.

3. Reilly S, Olier I, Planner C, et al. Inequalities in physical comorbidity: a longitudinal comparative cohort study of people with severe mental illness in the UK. BMJ Open. 2015;5(12):e009010.

4. Brown S, Inskip H, Barraclough B. Causes of the excess mortality of schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;177:212-217.

5. Goff DC, Cather C, Evins AE, et al. Medical morbidity and mortality in schizophrenia: guidelines for psychiatrists. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(2):183-194.

6. Baggett TP, Keyes H, Sporn N, et al. Prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in residents of a large homeless shelter in Boston. JAMA. 2020;323(21):2191-2192.

7. CDC COVID-19 Response Team. Severe outcomes among patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)—United States, February 12–March 16, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(12):343-346.

8. Docherty AB, Harrison EM, Green CA, et al. Features of 20 133 UK patients in hospital with covid-19 using the ISARIC WHO Clinical Characterisation Protocol: prospective observational cohort study. BMJ. 2020;369:m1985. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1985

9. Etches V, Frank J, Di Ruggiero E, et al. Measuring population health: a review of indicators. Annu Rev Public Health. 2006;27:29-55.

10. Chepke C. Drive-up pharmacotherapy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(5):29-30.

11. Sajatovic M, Ross R, Legacy SN, et al. Initiating/maintaining long-acting injectable antipsychotics in schizophrenia/schizoaffective or bipolar disorder - expert consensus survey part 2. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2018;14:1475-1492.

12. Schoretsanitis G, Kane JM, Correll CU, et al; American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology, Pharmakopsychiatrie TTDMTFOTAFNU. Blood levels to optimize antipsychotic treatment in clinical practice: a joint consensus statement of the American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology and the Therapeutic Drug Monitoring Task Force of the Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Neuropsychopharmakologie und Pharmakopsychiatrie. J Clin Psychiatry. 2020;81(3):19cs13169. doi: 10.4088/JCP.19cs13169

COVID-19 and the risk of homicide-suicide among older adults

On March 25, 2020, in Cambridge, United Kingdom, a 71-year-old man stabbed his 71-year-old wife before suffocating himself to death. The couple was reportedly anxious about the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic lockdown measures and were on the verge of running out of food and medicine.1

One week later, in Chicago, Illinois, a 54-year-old man shot and killed his female partner, age 54, before killing himself. The couple was tested for COVID-19 2 days earlier and the man believed they had contracted the virus; however, the test results for both of them had come back negative.2

Intimate partner homicide-suicide is the most dramatic domestic abuse outcome.3 Homicide-suicide is defined as “homicide committed by a person who subsequently commits suicide within one week of the homicide. In most cases the subsequent suicide occurs within a 24-hour period.”4 Approximately one-quarter of all homicide-suicides are committed by persons age ≥55 years.5,6 We believe that during the COVID-19 pandemic, the risk of homicide-suicide among older adults may be increased due to several factors, including:

- physical distancing and quarantine measures. Protocols established to slow the spread of the virus may be associated with increased rates of depression and anxiety7 and an increased risk of suicide among older adults8

- increased intimate partner violence9

- increased firearm ownership rates in the United States.10

In this article, we review studies that identified risk factors for homicide-suicide among older adults, discuss the impact the COVID-19 pandemic has had on these risks, and describe steps clinicians can take to intervene.

A review of the literature

To better characterize the perpetrators of older adult homicide-suicide, we conducted a literature search of relevant terms. We identified 9 original research publications that examined homicide-suicide in older adults.

Bourget et al11 (2010) reviewed coroners’ charts of individuals killed by an older (age ≥65) spouse or family member from 1992 through 2007 in Quebec, Canada. They identified 19 cases of homicide-suicide, 17 (90%) of which were perpetrated by men. Perpetrators and victims were married (63%), in common-law relationships (16%), or separated/divorced (16%). A history of domestic violence was documented in 4 (21%) cases. The authors found that 13 of 15 perpetrators (87%) had “major depression” and 2 perpetrators had a psychotic disorder. Substance use at the time of the event was confirmed in 6 (32%) cases. Firearms and strangulation were the top methods used to carry out the homicide-suicide.11

Cheung et al12 (2016) conducted a review of coroners’ records of homicide-suicide cases among individuals age ≥65 in New Zealand from 2007 through 2012. In all 4 cases, the perpetrators were men, and their victims were predominantly female, live-in family members. Two cases involved men with a history of domestic violence who were undergoing significant changes in their home and social lives. Both men had a history suggestive of depression and used a firearm to carry out the homicide-suicide.12

Continue to: Cohen et al

Cohen et al13 (1998) conducted a review of coroners’ records from 1988 through 1994 in 2 regions in Florida. They found 48 intimate partner homicide-suicide cases among “old couples” (age ≥55). All were perpetrated by men. The authors identified sociocultural differences in risk factors between the 2 regions. In west-central Florida, perpetrators and victims were predominantly white and in a spousal relationship. Domestic violence was documented in <4% of cases. Approximately 55% of the couples were reported to be ill, and a substantial proportion were documented to be declining in health. One-quarter of the perpetrators and one-third of the victims had “pain and suffering.” More than one-third of perpetrators were reported to have “depression,” 15% were reported to have talked about suicide, and 4% had a history of a suicide attempt. Only 11% of perpetrators were described as abusing substances.

The authors noted several differences in cases in southeastern Florida. Approximately two-thirds of the couples were Hispanic, and 14% had a history of domestic violence. A minority of the couples were in a live-in relationship. Less than 15% of the perpetrators and victims were described as having a decline in health. Additionally, only 19% of perpetrators were reported to have “depression,” and none of the perpetrators had a documented history of attempted suicide or substance abuse. No information was provided regarding the methods used to carry out the homicide-suicide in the southeastern region.13 Financial stress was not a factor in either region.

Malphurs et al14 (2001) used the same database described in the Cohen et al13 study to compare 27 perpetrators of homicide-suicide to 36 age-matched suicide decedents in west central Florida. They found that homicide-suicide perpetrators were significantly less likely to have health problems and were 3 times more likely to be caregivers to their spouses. Approximately 52% of perpetrators had at least 1 documented psychiatric symptom (“depression” and/or substance abuse or other), but only 5% were seeking mental health services at the time of death.14

De Koning and Piette15 (2014) conducted a retrospective medicolegal chart review from 1935 to 2010 to identify homicide-suicide cases in West and East Flanders, Belgium. They found 19 cases of intimate partner homicide-suicide committed by offenders age ≥55 years. Ninety-five percent of the perpetrators were men who killed their female partners. In one-quarter of the cases, either the perpetrator or the victim had a health issue; 21% of the perpetrators were documented as having depression and 27% had alcohol intoxication at the time of death. A motive was documented in 14 out of 19 cases; “mercy killing” was determined as the motive in 6 (43%) cases and “amorous jealousy” in 5 cases (36%).15 Starting in the 1970s, firearms were the most prevalent method used to kill a partner.

Logan et al16 (2019) used data from the National Violent Death Reporting System between 2003 and 2015 to identify characteristics that differentiated male suicide decedents from male perpetrators of intimate partner homicide-suicide. They found that men age 50 to 64 years were 3 times more likely than men age 18 to 34 years to commit intimate partner homicide-suicide, and that men age ≥65 years were approximately 5 times more likely than men age 18 to 34 years to commit intimate partner homicide-suicide. The authors found that approximately 22% of all perpetrators had a documented history of physical domestic violence, and close to 17% had a prior interaction with the criminal justice system. Furthermore, one-third of perpetrators had relationship difficulties and were in the process of a breakup. Health issues were prevalent in 34% of the victims and 26% of the perpetrators. Perpetrator-caregiver burden was reported as a contributing factor for homicide-suicide in 16% of cases. In 27% of cases, multiple health-related contributing factors were mentioned.16

Continue to: Malphurs and Cohen

Malphurs and Cohen5 (2002) reviewed American newspapers from 1997 through 1999 and identified 673 homicide-suicide events, of which 152 (27%) were committed by individuals age ≥55 years. The victims and perpetrators (95% of which were men) were intimate partners in three-quarters of cases. In nearly one-third of cases, caregiving was a contributing factor for the homicide-suicide. A history of or a pending divorce was reported in nearly 14% of cases. Substance use history was rarely recorded. Firearms were used in 88% of the homicide-suicide cases.5

Malphurs and Cohen17 (2005) reviewed coroner records between 1998 and 1999 in Florida and compared 20 cases of intimate partner homicide-suicide involving perpetrators age ≥55 years with matched suicide decedents. They found that 60% of homicide-suicide perpetrators had documented health issues. The authors reported that a “recent change in health status” was more prevalent among perpetrators compared with decedents. Perpetrators were also more likely to be caregivers to their spouses. The authors found that 65% of perpetrators were reported to have a “depressed mood” and 15% of perpetrators had reportedly threatened suicide prior to the incident. However, none of the perpetrators tested positive for antidepressants as documented on post-mortem toxicology reports. Firearms were used in 100% of homicide-suicide cases.17

Salari3 (2007) reviewed multiple American media sources and published police reports between 1999 and 2005 to retrieve data about intimate partner homicide-suicide events in the United States. There were 225 events identified where the perpetrator and/or the victim were age ≥60 years. Ninety-six percent of the perpetrators were men and most homicide-suicide events were committed at the home. A history of domestic violence was reported in 14% of homicide-suicide cases. Thirteen percent of couples were separated or divorced. The perpetrator and/or victim had health issues in 124 (55%) events. Dementia was reported in 7.5% of cases, but overwhelmingly among the victims. Substance abuse was rarely mentioned as a contributing factor. In three-quarters of cases where a motive was described, the perpetrator was “suicidal”; however, a “suicide pact” was mentioned in only 4% of cases. Firearms were used in 87% of cases.3

Focus on common risk factors

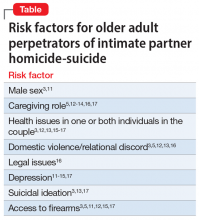

The scarcity and heterogeneity of research regarding older adult homicide-suicide were major limitations to our review. Because most of the studies we identified had a small sample size and limited information regarding the mental health of victims and perpetrators, it would be an overreach to claim to have identified a typical profile of an older perpetrator of homicide-suicide. However, the literature has repeatedly identified several common characteristics of such perpetrators. They are significantly more likely to be men who use firearms to murder their intimate partners and then die by suicide in their home (Table3,5,11-17). Health issues afflicting 1 or both individuals in the couple appear to be a contributing factor, particularly when the perpetrator is in a caregiving role. Relational discord, with or without a history of domestic violence, increases the risk of homicide-suicide. Finally, older perpetrators are highly likely to be depressed and have suicidal ideations.

How COVID-19 affects these risks

Although it is too early to determine if there is a causal relationship between the COVID-19 pandemic and an increase in homicide-suicide, the pandemic is likely to promote risk factors for these events, especially among older adults. Confinement measures put into place during the pandemic context have already been shown to increase rates of domestic violence18 and depression and anxiety among older individuals.7 Furthermore,

Continue to: Late-life psychiatric disorders

Late-life psychiatric disorders