User login

What's the diagnosis?

Nipple eczema is a dermatitis of the nipple and areola with clinical features such as erythema, fissures, scaling, pruritus, and crusting.1,2 It is classically associated with atopic dermatitis (AD), though it may occur as an isolated condition less commonly. While it may affect female adolescents, nipple eczema has also been reported in boys and breastfeeding women.3,4 The overall risk of incidence of nipple dermatitis has also been shown to increase with age.5 Nipple eczema is considered a cutaneous finding of AD, and is listed as a minor diagnostic criteria for AD in the Hanifin-Rajka criteria.6 The patient had not related his history of AD, which was elicited after finding typical antecubital eczematous dermatitis, and he had not been actively treating it.

Diagnosis and differential

Nipple eczema may be a challenging diagnosis for various reasons. For example, a unilateral presentation and the changes in the eczematous lesions overlying the nipple and areola’s varying textures and colors can make it difficult for clinicians to identify.3 Many children and adolescents, including our patient, are initially diagnosed as having impetigo and treated with antibiotics. The diagnosis of nipple eczema is made clinically, and management straightforward (see below). However, additional testing may be appropriate including patch testing for allergic contact dermatitis or bacterial cultures if bacterial infection or superinfection is considered.7,8 The differential diagnosis for nipple eczema includes impetigo, gynecomastia, scabies, and allergic contact dermatitis.

Impetigo typically presents with honey-colored crusts or pustules caused by infection with Staphylococcus aureus or Streptococcus. Patients with AD have higher rates of colonization with S. aureus and impetiginized eczema in common. Impetigo of the nipple and areola is more common in breastfeeding women as skin cracking from lactation can lead to exposure to bacteria from the infant’s mouth.9 Treatments involve topical or oral antibiotics.

Gynecomastia is the development of male breast tissue with most cases hypothesized to be caused by an imbalance between androgens and estrogens.10 Some other causes include direct skin contact with topical estrogen sprays and recreational use of marijuana and heroin.11 It is usually a benign exam finding in adolescent boys. However, clinical findings such as overlying skin changes, rapidly enlarging masses, and constitutional symptoms are concerning in the setting of gynecomastia and warrant further evaluation.

Scabies, which is caused by the infestation of scabies mites, is a common infectious skin disease. The classic presentation includes a rash that is intensely itchy, especially at night. Crusted scabies of the nipples may be difficult to distinguish from nipple eczema. Areas of frequent involvement of scabies include palms, between fingers, armpits, groin, between toes, and feet. Treatments include treating all household members with permethrin cream and washing all clothes and bedding in contact with a scabies-infected patient in high heat, or oral ivermectin in certain circumstances.12

Allergic contact dermatitis is a common cause of breast and nipple dermatitis and should be considered within the differential diagnosis of nipple eczema with atopic dermatitis, or as an exacerbator.7,9 Patients in particular who present with bilateral involvement extending to the periareolar skin, or unusual bilateral focal patterns suggestive for contact allergy should be considered for allergic contact dermatitis evaluation with patch tests. A common causative agent for allergic contact dermatitis of the breast and nipple includes Cl+Me-isothiazolinone, commonly found in detergents and fabric softeners.7 Primary treatment includes avoidance of the offending agents.

Treatment

Topical corticosteroids are first-line treatment for treating nipple eczema. Low-potency topical steroids can be used for maintenance and mild eczema while more potent steroids are useful for more severe cases. In addition to topical medication therapy, frequent emollient use to protect the skin barrier and the elimination of any irritants are essential to a successful treatment course. Unilateral nipple eczema can also be secondary to inadequate treatment of AD, demonstrating the importance of addressing the underlying AD with therapy.3

Our patient was diagnosed with nipple eczema based on clinical presentation of an eczematous left nipple in the setting of active atopic dermatitis and minimal improvement on topical antibiotic. He was started on a 3-week course of fluocinonide 0.05% topical ointment (a potent topical corticosteroid) twice daily for 2 weeks with plans to transition to triamcinolone 0.1% topical ointment several times a week.

Ms. Park is a pediatric dermatology research associate in the division of pediatric and adolescent dermatology, University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital. Neither Ms. Park nor Dr. Eichenfield have any relevant financial disclosures.

References

1. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22(1):64-6.

2. Am J Dermatopathol. 2015;37(4):284-8.

3. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32(5):718-22.

4. J Cutan Med Surg. 2004;8(2):126-30.

5. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29(5):580-3.

6. Dermatologica. 1988;177(6):360-4.

7. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26(3):413-4.

8. BMJ Case Rep. 2020;13(8).

9. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80(6):1483-94.

10. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev. 2017;14(4):371-7.

11. JAMA. 2010;304(9):953.

12. JAMA. 2018;320(6):612.

Nipple eczema is a dermatitis of the nipple and areola with clinical features such as erythema, fissures, scaling, pruritus, and crusting.1,2 It is classically associated with atopic dermatitis (AD), though it may occur as an isolated condition less commonly. While it may affect female adolescents, nipple eczema has also been reported in boys and breastfeeding women.3,4 The overall risk of incidence of nipple dermatitis has also been shown to increase with age.5 Nipple eczema is considered a cutaneous finding of AD, and is listed as a minor diagnostic criteria for AD in the Hanifin-Rajka criteria.6 The patient had not related his history of AD, which was elicited after finding typical antecubital eczematous dermatitis, and he had not been actively treating it.

Diagnosis and differential

Nipple eczema may be a challenging diagnosis for various reasons. For example, a unilateral presentation and the changes in the eczematous lesions overlying the nipple and areola’s varying textures and colors can make it difficult for clinicians to identify.3 Many children and adolescents, including our patient, are initially diagnosed as having impetigo and treated with antibiotics. The diagnosis of nipple eczema is made clinically, and management straightforward (see below). However, additional testing may be appropriate including patch testing for allergic contact dermatitis or bacterial cultures if bacterial infection or superinfection is considered.7,8 The differential diagnosis for nipple eczema includes impetigo, gynecomastia, scabies, and allergic contact dermatitis.

Impetigo typically presents with honey-colored crusts or pustules caused by infection with Staphylococcus aureus or Streptococcus. Patients with AD have higher rates of colonization with S. aureus and impetiginized eczema in common. Impetigo of the nipple and areola is more common in breastfeeding women as skin cracking from lactation can lead to exposure to bacteria from the infant’s mouth.9 Treatments involve topical or oral antibiotics.

Gynecomastia is the development of male breast tissue with most cases hypothesized to be caused by an imbalance between androgens and estrogens.10 Some other causes include direct skin contact with topical estrogen sprays and recreational use of marijuana and heroin.11 It is usually a benign exam finding in adolescent boys. However, clinical findings such as overlying skin changes, rapidly enlarging masses, and constitutional symptoms are concerning in the setting of gynecomastia and warrant further evaluation.

Scabies, which is caused by the infestation of scabies mites, is a common infectious skin disease. The classic presentation includes a rash that is intensely itchy, especially at night. Crusted scabies of the nipples may be difficult to distinguish from nipple eczema. Areas of frequent involvement of scabies include palms, between fingers, armpits, groin, between toes, and feet. Treatments include treating all household members with permethrin cream and washing all clothes and bedding in contact with a scabies-infected patient in high heat, or oral ivermectin in certain circumstances.12

Allergic contact dermatitis is a common cause of breast and nipple dermatitis and should be considered within the differential diagnosis of nipple eczema with atopic dermatitis, or as an exacerbator.7,9 Patients in particular who present with bilateral involvement extending to the periareolar skin, or unusual bilateral focal patterns suggestive for contact allergy should be considered for allergic contact dermatitis evaluation with patch tests. A common causative agent for allergic contact dermatitis of the breast and nipple includes Cl+Me-isothiazolinone, commonly found in detergents and fabric softeners.7 Primary treatment includes avoidance of the offending agents.

Treatment

Topical corticosteroids are first-line treatment for treating nipple eczema. Low-potency topical steroids can be used for maintenance and mild eczema while more potent steroids are useful for more severe cases. In addition to topical medication therapy, frequent emollient use to protect the skin barrier and the elimination of any irritants are essential to a successful treatment course. Unilateral nipple eczema can also be secondary to inadequate treatment of AD, demonstrating the importance of addressing the underlying AD with therapy.3

Our patient was diagnosed with nipple eczema based on clinical presentation of an eczematous left nipple in the setting of active atopic dermatitis and minimal improvement on topical antibiotic. He was started on a 3-week course of fluocinonide 0.05% topical ointment (a potent topical corticosteroid) twice daily for 2 weeks with plans to transition to triamcinolone 0.1% topical ointment several times a week.

Ms. Park is a pediatric dermatology research associate in the division of pediatric and adolescent dermatology, University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital. Neither Ms. Park nor Dr. Eichenfield have any relevant financial disclosures.

References

1. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22(1):64-6.

2. Am J Dermatopathol. 2015;37(4):284-8.

3. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32(5):718-22.

4. J Cutan Med Surg. 2004;8(2):126-30.

5. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29(5):580-3.

6. Dermatologica. 1988;177(6):360-4.

7. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26(3):413-4.

8. BMJ Case Rep. 2020;13(8).

9. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80(6):1483-94.

10. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev. 2017;14(4):371-7.

11. JAMA. 2010;304(9):953.

12. JAMA. 2018;320(6):612.

Nipple eczema is a dermatitis of the nipple and areola with clinical features such as erythema, fissures, scaling, pruritus, and crusting.1,2 It is classically associated with atopic dermatitis (AD), though it may occur as an isolated condition less commonly. While it may affect female adolescents, nipple eczema has also been reported in boys and breastfeeding women.3,4 The overall risk of incidence of nipple dermatitis has also been shown to increase with age.5 Nipple eczema is considered a cutaneous finding of AD, and is listed as a minor diagnostic criteria for AD in the Hanifin-Rajka criteria.6 The patient had not related his history of AD, which was elicited after finding typical antecubital eczematous dermatitis, and he had not been actively treating it.

Diagnosis and differential

Nipple eczema may be a challenging diagnosis for various reasons. For example, a unilateral presentation and the changes in the eczematous lesions overlying the nipple and areola’s varying textures and colors can make it difficult for clinicians to identify.3 Many children and adolescents, including our patient, are initially diagnosed as having impetigo and treated with antibiotics. The diagnosis of nipple eczema is made clinically, and management straightforward (see below). However, additional testing may be appropriate including patch testing for allergic contact dermatitis or bacterial cultures if bacterial infection or superinfection is considered.7,8 The differential diagnosis for nipple eczema includes impetigo, gynecomastia, scabies, and allergic contact dermatitis.

Impetigo typically presents with honey-colored crusts or pustules caused by infection with Staphylococcus aureus or Streptococcus. Patients with AD have higher rates of colonization with S. aureus and impetiginized eczema in common. Impetigo of the nipple and areola is more common in breastfeeding women as skin cracking from lactation can lead to exposure to bacteria from the infant’s mouth.9 Treatments involve topical or oral antibiotics.

Gynecomastia is the development of male breast tissue with most cases hypothesized to be caused by an imbalance between androgens and estrogens.10 Some other causes include direct skin contact with topical estrogen sprays and recreational use of marijuana and heroin.11 It is usually a benign exam finding in adolescent boys. However, clinical findings such as overlying skin changes, rapidly enlarging masses, and constitutional symptoms are concerning in the setting of gynecomastia and warrant further evaluation.

Scabies, which is caused by the infestation of scabies mites, is a common infectious skin disease. The classic presentation includes a rash that is intensely itchy, especially at night. Crusted scabies of the nipples may be difficult to distinguish from nipple eczema. Areas of frequent involvement of scabies include palms, between fingers, armpits, groin, between toes, and feet. Treatments include treating all household members with permethrin cream and washing all clothes and bedding in contact with a scabies-infected patient in high heat, or oral ivermectin in certain circumstances.12

Allergic contact dermatitis is a common cause of breast and nipple dermatitis and should be considered within the differential diagnosis of nipple eczema with atopic dermatitis, or as an exacerbator.7,9 Patients in particular who present with bilateral involvement extending to the periareolar skin, or unusual bilateral focal patterns suggestive for contact allergy should be considered for allergic contact dermatitis evaluation with patch tests. A common causative agent for allergic contact dermatitis of the breast and nipple includes Cl+Me-isothiazolinone, commonly found in detergents and fabric softeners.7 Primary treatment includes avoidance of the offending agents.

Treatment

Topical corticosteroids are first-line treatment for treating nipple eczema. Low-potency topical steroids can be used for maintenance and mild eczema while more potent steroids are useful for more severe cases. In addition to topical medication therapy, frequent emollient use to protect the skin barrier and the elimination of any irritants are essential to a successful treatment course. Unilateral nipple eczema can also be secondary to inadequate treatment of AD, demonstrating the importance of addressing the underlying AD with therapy.3

Our patient was diagnosed with nipple eczema based on clinical presentation of an eczematous left nipple in the setting of active atopic dermatitis and minimal improvement on topical antibiotic. He was started on a 3-week course of fluocinonide 0.05% topical ointment (a potent topical corticosteroid) twice daily for 2 weeks with plans to transition to triamcinolone 0.1% topical ointment several times a week.

Ms. Park is a pediatric dermatology research associate in the division of pediatric and adolescent dermatology, University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital. Neither Ms. Park nor Dr. Eichenfield have any relevant financial disclosures.

References

1. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22(1):64-6.

2. Am J Dermatopathol. 2015;37(4):284-8.

3. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32(5):718-22.

4. J Cutan Med Surg. 2004;8(2):126-30.

5. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29(5):580-3.

6. Dermatologica. 1988;177(6):360-4.

7. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26(3):413-4.

8. BMJ Case Rep. 2020;13(8).

9. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80(6):1483-94.

10. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev. 2017;14(4):371-7.

11. JAMA. 2010;304(9):953.

12. JAMA. 2018;320(6):612.

A 12-year-old boy presents to the dermatology clinic with a 1-month history of crusting and watery sticky drainage from the left nipple. Given concern for a possible skin infection, the patient was initially treated with mupirocin ointment for several weeks but without improvement. The affected area is sometimes itchy but not painful. He reports no prior history of similar problems.

On physical exam, he is noted to have an eczematous left nipple with edema, xerosis, and scaling overlying the entire areola. There is no evidence of visible discharge, pustules, or honey-colored crusts in the area. The extensor surfaces of his arms bilaterally have skin-colored follicular papules, and his antecubital fossa display erythematous scaling plaques with mild lichenification and excoriations.

Pressure builds on CDC to prioritize both diabetes types for vaccine

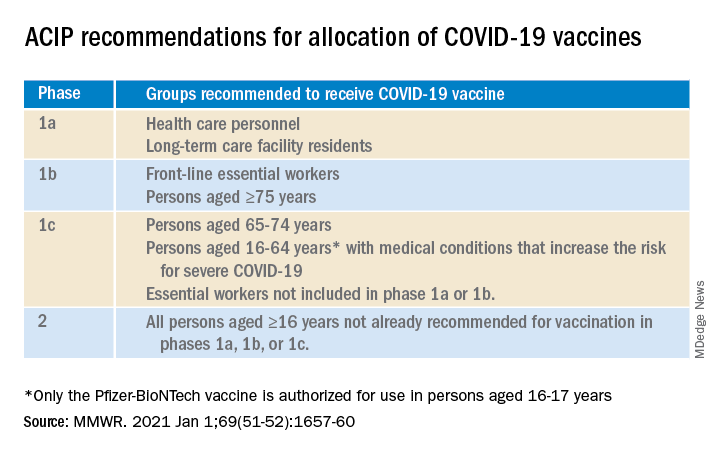

The American Diabetes Association, along with 18 other organizations, has sent a letter to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention urging them to rank people with type 1 diabetes as equally high risk for COVID-19 severity, and therefore vaccination, as those with type 2 diabetes.

On Jan. 12, the CDC recommended states vaccinate all Americans over age 65 and those with underlying health conditions that make them more vulnerable to COVID-19.

Currently, type 2 diabetes is listed among 12 conditions that place adults “at increased risk of severe illness from the virus that causes COVID-19,” with the latter defined as “hospitalization, admission to the intensive care unit, intubation or mechanical ventilation, or death.”

On the other hand, the autoimmune condition type 1 diabetes is among 11 conditions the CDC says “might be at increased risk” for COVID-19, but limited data were available at the time of the last update on Dec. 23, 2020.

“States are utilizing the CDC risk classification when designing their vaccine distribution plans. This raises an obvious concern as it could result in the approximately 1.6 million with type 1 diabetes receiving the vaccination later than others with the same risk,” states the ADA letter, sent to the CDC on Jan. 13.

Representatives from the Endocrine Society, American Association of Clinical Endocrinology, Pediatric Endocrine Society, Association of Diabetes Care & Education Specialists, and JDRF, among others, cosigned the letter.

Newer data show those with type 1 diabetes at equally high risk

While acknowledging that “early data did not provide as much clarity about the extent to which those with type 1 diabetes are at high risk,” the ADA says newer evidence has emerged, as previously reported by this news organization, that “convincingly demonstrates that COVID-19 severity is more than tripled in individuals with type 1 diabetes.”

The letter also cites another study showing that people with type 1 diabetes “have a 3.3-fold greater risk of severe illness, are 3.9 times more likely to be hospitalized with COVID-19, and have a 3-fold increase in mortality compared to those without type 1 diabetes.”

Those risks, they note, are comparable to the increased risk established for those with type 2 diabetes, as shown in a third study from Scotland, published last month.

Asked for comment, CDC representative Kirsten Nordlund said in an interview, “This list is a living document that will be periodically updated by CDC, and it could rapidly change as the science evolves.”

In addition, Ms. Nordlund said, “Decisions about transitioning to subsequent phases should depend on supply; demand; equitable vaccine distribution; and local, state, or territorial context.”

“Phased vaccine recommendations are meant to be fluid and not restrictive for jurisdictions. It is not necessary to vaccinate all individuals in one phase before initiating the next phase; phases may overlap,” she noted. More information is available here.

Tennessee gives type 1 and type 2 diabetes equal priority for vaccination

Meanwhile, at least one state, Tennessee, has updated its guidance to include both types of diabetes as being priority for COVID-19 vaccination.

Vanderbilt University pediatric endocrinologist Justin M. Gregory, MD, said in an interview: “I was thrilled when our state modified its guidance on December 30th to include both type 1 and type 2 diabetes in the ‘high-risk category.’ Other states have not modified that guidance though.”

It’s unclear how this might play out on the ground, noted Dr. Gregory, who led one of the three studies demonstrating increased COVID-19 risk for people with type 1 diabetes.

“To tell you the truth, I don’t really know how individual organizations dispensing the vaccination [will handle] people who come to their facility saying they have ‘diabetes.’ Individual states set the vaccine-dispensing guidance and individual county health departments and health care systems mirror that guidance,” he said.

Thus, he added, “Although it’s possible an individual nurse may take the ‘I’ll ask you no questions, and you’ll tell me no lies’ approach if someone with type 1 diabetes says they have ‘diabetes’, websites and health department–recorded telephone messages are going to tell people with type 1 diabetes they have to wait further back in line if that is what their state’s guidance directs.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

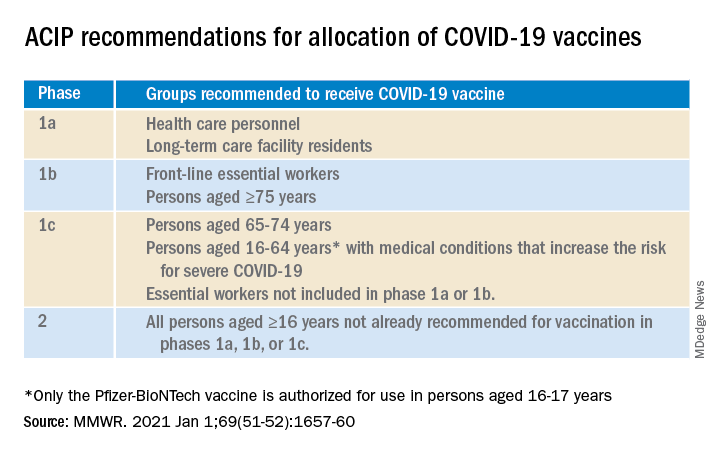

The American Diabetes Association, along with 18 other organizations, has sent a letter to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention urging them to rank people with type 1 diabetes as equally high risk for COVID-19 severity, and therefore vaccination, as those with type 2 diabetes.

On Jan. 12, the CDC recommended states vaccinate all Americans over age 65 and those with underlying health conditions that make them more vulnerable to COVID-19.

Currently, type 2 diabetes is listed among 12 conditions that place adults “at increased risk of severe illness from the virus that causes COVID-19,” with the latter defined as “hospitalization, admission to the intensive care unit, intubation or mechanical ventilation, or death.”

On the other hand, the autoimmune condition type 1 diabetes is among 11 conditions the CDC says “might be at increased risk” for COVID-19, but limited data were available at the time of the last update on Dec. 23, 2020.

“States are utilizing the CDC risk classification when designing their vaccine distribution plans. This raises an obvious concern as it could result in the approximately 1.6 million with type 1 diabetes receiving the vaccination later than others with the same risk,” states the ADA letter, sent to the CDC on Jan. 13.

Representatives from the Endocrine Society, American Association of Clinical Endocrinology, Pediatric Endocrine Society, Association of Diabetes Care & Education Specialists, and JDRF, among others, cosigned the letter.

Newer data show those with type 1 diabetes at equally high risk

While acknowledging that “early data did not provide as much clarity about the extent to which those with type 1 diabetes are at high risk,” the ADA says newer evidence has emerged, as previously reported by this news organization, that “convincingly demonstrates that COVID-19 severity is more than tripled in individuals with type 1 diabetes.”

The letter also cites another study showing that people with type 1 diabetes “have a 3.3-fold greater risk of severe illness, are 3.9 times more likely to be hospitalized with COVID-19, and have a 3-fold increase in mortality compared to those without type 1 diabetes.”

Those risks, they note, are comparable to the increased risk established for those with type 2 diabetes, as shown in a third study from Scotland, published last month.

Asked for comment, CDC representative Kirsten Nordlund said in an interview, “This list is a living document that will be periodically updated by CDC, and it could rapidly change as the science evolves.”

In addition, Ms. Nordlund said, “Decisions about transitioning to subsequent phases should depend on supply; demand; equitable vaccine distribution; and local, state, or territorial context.”

“Phased vaccine recommendations are meant to be fluid and not restrictive for jurisdictions. It is not necessary to vaccinate all individuals in one phase before initiating the next phase; phases may overlap,” she noted. More information is available here.

Tennessee gives type 1 and type 2 diabetes equal priority for vaccination

Meanwhile, at least one state, Tennessee, has updated its guidance to include both types of diabetes as being priority for COVID-19 vaccination.

Vanderbilt University pediatric endocrinologist Justin M. Gregory, MD, said in an interview: “I was thrilled when our state modified its guidance on December 30th to include both type 1 and type 2 diabetes in the ‘high-risk category.’ Other states have not modified that guidance though.”

It’s unclear how this might play out on the ground, noted Dr. Gregory, who led one of the three studies demonstrating increased COVID-19 risk for people with type 1 diabetes.

“To tell you the truth, I don’t really know how individual organizations dispensing the vaccination [will handle] people who come to their facility saying they have ‘diabetes.’ Individual states set the vaccine-dispensing guidance and individual county health departments and health care systems mirror that guidance,” he said.

Thus, he added, “Although it’s possible an individual nurse may take the ‘I’ll ask you no questions, and you’ll tell me no lies’ approach if someone with type 1 diabetes says they have ‘diabetes’, websites and health department–recorded telephone messages are going to tell people with type 1 diabetes they have to wait further back in line if that is what their state’s guidance directs.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

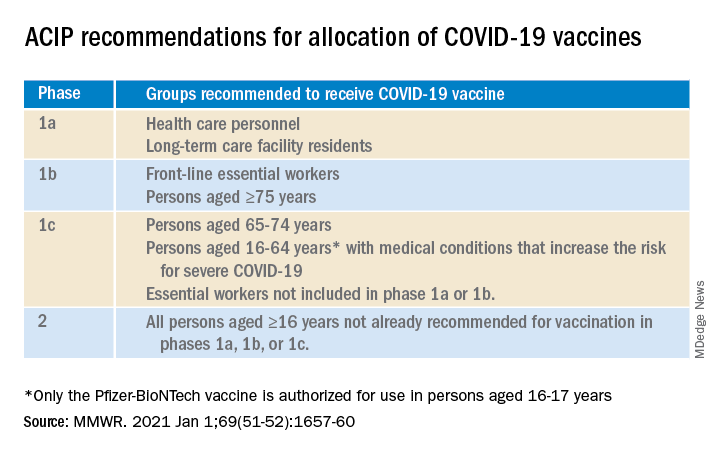

The American Diabetes Association, along with 18 other organizations, has sent a letter to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention urging them to rank people with type 1 diabetes as equally high risk for COVID-19 severity, and therefore vaccination, as those with type 2 diabetes.

On Jan. 12, the CDC recommended states vaccinate all Americans over age 65 and those with underlying health conditions that make them more vulnerable to COVID-19.

Currently, type 2 diabetes is listed among 12 conditions that place adults “at increased risk of severe illness from the virus that causes COVID-19,” with the latter defined as “hospitalization, admission to the intensive care unit, intubation or mechanical ventilation, or death.”

On the other hand, the autoimmune condition type 1 diabetes is among 11 conditions the CDC says “might be at increased risk” for COVID-19, but limited data were available at the time of the last update on Dec. 23, 2020.

“States are utilizing the CDC risk classification when designing their vaccine distribution plans. This raises an obvious concern as it could result in the approximately 1.6 million with type 1 diabetes receiving the vaccination later than others with the same risk,” states the ADA letter, sent to the CDC on Jan. 13.

Representatives from the Endocrine Society, American Association of Clinical Endocrinology, Pediatric Endocrine Society, Association of Diabetes Care & Education Specialists, and JDRF, among others, cosigned the letter.

Newer data show those with type 1 diabetes at equally high risk

While acknowledging that “early data did not provide as much clarity about the extent to which those with type 1 diabetes are at high risk,” the ADA says newer evidence has emerged, as previously reported by this news organization, that “convincingly demonstrates that COVID-19 severity is more than tripled in individuals with type 1 diabetes.”

The letter also cites another study showing that people with type 1 diabetes “have a 3.3-fold greater risk of severe illness, are 3.9 times more likely to be hospitalized with COVID-19, and have a 3-fold increase in mortality compared to those without type 1 diabetes.”

Those risks, they note, are comparable to the increased risk established for those with type 2 diabetes, as shown in a third study from Scotland, published last month.

Asked for comment, CDC representative Kirsten Nordlund said in an interview, “This list is a living document that will be periodically updated by CDC, and it could rapidly change as the science evolves.”

In addition, Ms. Nordlund said, “Decisions about transitioning to subsequent phases should depend on supply; demand; equitable vaccine distribution; and local, state, or territorial context.”

“Phased vaccine recommendations are meant to be fluid and not restrictive for jurisdictions. It is not necessary to vaccinate all individuals in one phase before initiating the next phase; phases may overlap,” she noted. More information is available here.

Tennessee gives type 1 and type 2 diabetes equal priority for vaccination

Meanwhile, at least one state, Tennessee, has updated its guidance to include both types of diabetes as being priority for COVID-19 vaccination.

Vanderbilt University pediatric endocrinologist Justin M. Gregory, MD, said in an interview: “I was thrilled when our state modified its guidance on December 30th to include both type 1 and type 2 diabetes in the ‘high-risk category.’ Other states have not modified that guidance though.”

It’s unclear how this might play out on the ground, noted Dr. Gregory, who led one of the three studies demonstrating increased COVID-19 risk for people with type 1 diabetes.

“To tell you the truth, I don’t really know how individual organizations dispensing the vaccination [will handle] people who come to their facility saying they have ‘diabetes.’ Individual states set the vaccine-dispensing guidance and individual county health departments and health care systems mirror that guidance,” he said.

Thus, he added, “Although it’s possible an individual nurse may take the ‘I’ll ask you no questions, and you’ll tell me no lies’ approach if someone with type 1 diabetes says they have ‘diabetes’, websites and health department–recorded telephone messages are going to tell people with type 1 diabetes they have to wait further back in line if that is what their state’s guidance directs.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Coping with vaccine refusal

Do you accept new families into your practice who have already chosen to not have their children immunized? What about families who have been in your practice for several months or years? In 2016 the American Academy of Pediatrics published a clinical report in which it stated that, under some circumstances, dismissing families who refuse to vaccinate is permissible. Have you felt sufficiently supported by that statement and dismissed any families after multiple attempts at education on your part?

In a Pediatrics Perspective article in the December issue of Pediatrics, two philosophers and a physician make the argument that, while in some situations dismissing a family who refuses vaccines may be “an ethically acceptable option” refusing to accept a family with the same philosophy is not. It is an interesting paper and worth reading regardless of whether or not you already accept and continue to tolerate vaccine deniers in your practice.

The Pediatrics Perspective is certainly not the last word on the ethics of caring for families who deny their children care that we believe is critical to their health and the welfare of the community at large. There has been a lot of discussion about the issue but little has been written about how we as the physicians on the front line are coping emotionally with what the authors of the paper call the “burdens associated with treating” families who refuse to follow our guidance.

It is hard not to feel angry when a family you have invested valuable office time in discussing the benefits and safety of vaccines continues to disregard what you see as the facts. The time you have spent with them is not just income-generating time for your practice, it is time stolen from other families who are more willing to follow your recommendations. In how many visits will you continue to raise the issue? Unless I saw a glimmer of hope I would usually stop after two wasted encounters. But, the issue would still linger as the elephant in the examination room for as long as I continued to see the patient.

How have you expressed your anger? Have you been argumentative or rude? You may have been able maintain your composure and remain civil and appear caring, but I suspect the anger is still gnawing at you. And, there is still the frustration and feeling of impotence. You may have questioned your ability as an educator. You should get over that notion quickly. There is ample evidence that most vaccine deniers are not going to be convinced by even the most carefully presented information. I suggest you leave it to others to try their hands at education. Let them invest their time while you tend to the needs of your other patients. You can try being a fear monger and, while fear can be effective, you have better ways to spend your office day than telling horror stories.

If vaccine denial makes you feel powerless, you should get over that pretty quickly as well and accept the fact that you are simply an advisor. If you believe that most of the families in your practice are following your recommendations as though you had presented them on stone tablets, it is time for a wakeup call.

Finally, there is the most troubling emotion associated with vaccine refusal and that is fear, the fear of being sued. Establishing a relationship with a family is one that requires mutual trust and certainly vaccine refusal will put that trust in question, particularly if you have done a less than adequate job of hiding your anger and frustration with their unfortunate decision.

For now, vaccine refusal is just another one of those crosses that those of us in primary care must bear together wearing the best face we can put forward. That doesn’t mean we can’t share those emotions with our peers. Misery does love company.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

Do you accept new families into your practice who have already chosen to not have their children immunized? What about families who have been in your practice for several months or years? In 2016 the American Academy of Pediatrics published a clinical report in which it stated that, under some circumstances, dismissing families who refuse to vaccinate is permissible. Have you felt sufficiently supported by that statement and dismissed any families after multiple attempts at education on your part?

In a Pediatrics Perspective article in the December issue of Pediatrics, two philosophers and a physician make the argument that, while in some situations dismissing a family who refuses vaccines may be “an ethically acceptable option” refusing to accept a family with the same philosophy is not. It is an interesting paper and worth reading regardless of whether or not you already accept and continue to tolerate vaccine deniers in your practice.

The Pediatrics Perspective is certainly not the last word on the ethics of caring for families who deny their children care that we believe is critical to their health and the welfare of the community at large. There has been a lot of discussion about the issue but little has been written about how we as the physicians on the front line are coping emotionally with what the authors of the paper call the “burdens associated with treating” families who refuse to follow our guidance.

It is hard not to feel angry when a family you have invested valuable office time in discussing the benefits and safety of vaccines continues to disregard what you see as the facts. The time you have spent with them is not just income-generating time for your practice, it is time stolen from other families who are more willing to follow your recommendations. In how many visits will you continue to raise the issue? Unless I saw a glimmer of hope I would usually stop after two wasted encounters. But, the issue would still linger as the elephant in the examination room for as long as I continued to see the patient.

How have you expressed your anger? Have you been argumentative or rude? You may have been able maintain your composure and remain civil and appear caring, but I suspect the anger is still gnawing at you. And, there is still the frustration and feeling of impotence. You may have questioned your ability as an educator. You should get over that notion quickly. There is ample evidence that most vaccine deniers are not going to be convinced by even the most carefully presented information. I suggest you leave it to others to try their hands at education. Let them invest their time while you tend to the needs of your other patients. You can try being a fear monger and, while fear can be effective, you have better ways to spend your office day than telling horror stories.

If vaccine denial makes you feel powerless, you should get over that pretty quickly as well and accept the fact that you are simply an advisor. If you believe that most of the families in your practice are following your recommendations as though you had presented them on stone tablets, it is time for a wakeup call.

Finally, there is the most troubling emotion associated with vaccine refusal and that is fear, the fear of being sued. Establishing a relationship with a family is one that requires mutual trust and certainly vaccine refusal will put that trust in question, particularly if you have done a less than adequate job of hiding your anger and frustration with their unfortunate decision.

For now, vaccine refusal is just another one of those crosses that those of us in primary care must bear together wearing the best face we can put forward. That doesn’t mean we can’t share those emotions with our peers. Misery does love company.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

Do you accept new families into your practice who have already chosen to not have their children immunized? What about families who have been in your practice for several months or years? In 2016 the American Academy of Pediatrics published a clinical report in which it stated that, under some circumstances, dismissing families who refuse to vaccinate is permissible. Have you felt sufficiently supported by that statement and dismissed any families after multiple attempts at education on your part?

In a Pediatrics Perspective article in the December issue of Pediatrics, two philosophers and a physician make the argument that, while in some situations dismissing a family who refuses vaccines may be “an ethically acceptable option” refusing to accept a family with the same philosophy is not. It is an interesting paper and worth reading regardless of whether or not you already accept and continue to tolerate vaccine deniers in your practice.

The Pediatrics Perspective is certainly not the last word on the ethics of caring for families who deny their children care that we believe is critical to their health and the welfare of the community at large. There has been a lot of discussion about the issue but little has been written about how we as the physicians on the front line are coping emotionally with what the authors of the paper call the “burdens associated with treating” families who refuse to follow our guidance.

It is hard not to feel angry when a family you have invested valuable office time in discussing the benefits and safety of vaccines continues to disregard what you see as the facts. The time you have spent with them is not just income-generating time for your practice, it is time stolen from other families who are more willing to follow your recommendations. In how many visits will you continue to raise the issue? Unless I saw a glimmer of hope I would usually stop after two wasted encounters. But, the issue would still linger as the elephant in the examination room for as long as I continued to see the patient.

How have you expressed your anger? Have you been argumentative or rude? You may have been able maintain your composure and remain civil and appear caring, but I suspect the anger is still gnawing at you. And, there is still the frustration and feeling of impotence. You may have questioned your ability as an educator. You should get over that notion quickly. There is ample evidence that most vaccine deniers are not going to be convinced by even the most carefully presented information. I suggest you leave it to others to try their hands at education. Let them invest their time while you tend to the needs of your other patients. You can try being a fear monger and, while fear can be effective, you have better ways to spend your office day than telling horror stories.

If vaccine denial makes you feel powerless, you should get over that pretty quickly as well and accept the fact that you are simply an advisor. If you believe that most of the families in your practice are following your recommendations as though you had presented them on stone tablets, it is time for a wakeup call.

Finally, there is the most troubling emotion associated with vaccine refusal and that is fear, the fear of being sued. Establishing a relationship with a family is one that requires mutual trust and certainly vaccine refusal will put that trust in question, particularly if you have done a less than adequate job of hiding your anger and frustration with their unfortunate decision.

For now, vaccine refusal is just another one of those crosses that those of us in primary care must bear together wearing the best face we can put forward. That doesn’t mean we can’t share those emotions with our peers. Misery does love company.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

Adjuvant nivolumab plus ipilimumab shows strong results in resected stage IV melanoma

Results of the

IMMUNED was a multicenter German double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial conducted by the Dermatologic Cooperative Oncology Group. It included 167 patients with resected stage IV melanoma and no evidence of disease who were randomized to adjuvant nivolumab (Opdivo) plus placebo, nivolumab plus ipilimumab (Yervoy), or double placebo, with relapse-free survival as the primary outcome, Merrick I. Ross, MD, explained at a forum on cutaneous malignancies jointly presented by Postgraduate Institute for Medicine and Global Academy for Medical Education.

“The patients who received adjuvant ipilimumab and nivolumab had amazing 24-month outcomes: a relapse-free survival of 70% versus 42% with nivolumab and 14% with placebo,” observed Dr. Ross, professor of surgical oncology and chief of the melanoma section at the University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, Houston.

“It’s not a long-term survival outcome, but we’ll see what happens long term. This could be a very interesting approach to move forward with,” he commented.

By way of background, the cancer surgeon noted that nivolumab has achieved standard-of-care status as adjuvant immunotherapy in patients with resected stage IIIB-C and stage IV melanoma, largely on the strength of the CheckMate-238 trial, which randomized 906 such patients at 130 academic centers in 25 countries to 1 year of adjuvant therapy with either intravenous nivolumab or ipilimumab. In the study, nivolumab emerged as the clear winner, with a 4-year recurrence-free survival of 51.7%, compared with 41.2% for ipilimumab, for a 29% relative risk reduction. Ipilimumab was associated with greater toxicity.

The between-group difference in relapse-free survival in the overall study population also held true in the subgroup comprised of 169 CheckMate 238 participants with resected stage IV melanoma and no evidence of disease at enrollment, Dr. Ross noted.

In the IMMUNED trial, the superior outcome achieved with adjuvant nivolumab plus ipilimumab came at the cost of significantly greater toxicity than with nivolumab alone. Treatment-related adverse events led to medication discontinuation in 62% of the dual-adjuvant therapy group, compared with 13% of those on adjuvant nivolumab.

IMMUNED was funded by Bristol-Myers Squibb.

Dr. Ross reported having no financial conflicts regarding his presentation.

Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same company.

Results of the

IMMUNED was a multicenter German double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial conducted by the Dermatologic Cooperative Oncology Group. It included 167 patients with resected stage IV melanoma and no evidence of disease who were randomized to adjuvant nivolumab (Opdivo) plus placebo, nivolumab plus ipilimumab (Yervoy), or double placebo, with relapse-free survival as the primary outcome, Merrick I. Ross, MD, explained at a forum on cutaneous malignancies jointly presented by Postgraduate Institute for Medicine and Global Academy for Medical Education.

“The patients who received adjuvant ipilimumab and nivolumab had amazing 24-month outcomes: a relapse-free survival of 70% versus 42% with nivolumab and 14% with placebo,” observed Dr. Ross, professor of surgical oncology and chief of the melanoma section at the University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, Houston.

“It’s not a long-term survival outcome, but we’ll see what happens long term. This could be a very interesting approach to move forward with,” he commented.

By way of background, the cancer surgeon noted that nivolumab has achieved standard-of-care status as adjuvant immunotherapy in patients with resected stage IIIB-C and stage IV melanoma, largely on the strength of the CheckMate-238 trial, which randomized 906 such patients at 130 academic centers in 25 countries to 1 year of adjuvant therapy with either intravenous nivolumab or ipilimumab. In the study, nivolumab emerged as the clear winner, with a 4-year recurrence-free survival of 51.7%, compared with 41.2% for ipilimumab, for a 29% relative risk reduction. Ipilimumab was associated with greater toxicity.

The between-group difference in relapse-free survival in the overall study population also held true in the subgroup comprised of 169 CheckMate 238 participants with resected stage IV melanoma and no evidence of disease at enrollment, Dr. Ross noted.

In the IMMUNED trial, the superior outcome achieved with adjuvant nivolumab plus ipilimumab came at the cost of significantly greater toxicity than with nivolumab alone. Treatment-related adverse events led to medication discontinuation in 62% of the dual-adjuvant therapy group, compared with 13% of those on adjuvant nivolumab.

IMMUNED was funded by Bristol-Myers Squibb.

Dr. Ross reported having no financial conflicts regarding his presentation.

Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same company.

Results of the

IMMUNED was a multicenter German double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial conducted by the Dermatologic Cooperative Oncology Group. It included 167 patients with resected stage IV melanoma and no evidence of disease who were randomized to adjuvant nivolumab (Opdivo) plus placebo, nivolumab plus ipilimumab (Yervoy), or double placebo, with relapse-free survival as the primary outcome, Merrick I. Ross, MD, explained at a forum on cutaneous malignancies jointly presented by Postgraduate Institute for Medicine and Global Academy for Medical Education.

“The patients who received adjuvant ipilimumab and nivolumab had amazing 24-month outcomes: a relapse-free survival of 70% versus 42% with nivolumab and 14% with placebo,” observed Dr. Ross, professor of surgical oncology and chief of the melanoma section at the University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, Houston.

“It’s not a long-term survival outcome, but we’ll see what happens long term. This could be a very interesting approach to move forward with,” he commented.

By way of background, the cancer surgeon noted that nivolumab has achieved standard-of-care status as adjuvant immunotherapy in patients with resected stage IIIB-C and stage IV melanoma, largely on the strength of the CheckMate-238 trial, which randomized 906 such patients at 130 academic centers in 25 countries to 1 year of adjuvant therapy with either intravenous nivolumab or ipilimumab. In the study, nivolumab emerged as the clear winner, with a 4-year recurrence-free survival of 51.7%, compared with 41.2% for ipilimumab, for a 29% relative risk reduction. Ipilimumab was associated with greater toxicity.

The between-group difference in relapse-free survival in the overall study population also held true in the subgroup comprised of 169 CheckMate 238 participants with resected stage IV melanoma and no evidence of disease at enrollment, Dr. Ross noted.

In the IMMUNED trial, the superior outcome achieved with adjuvant nivolumab plus ipilimumab came at the cost of significantly greater toxicity than with nivolumab alone. Treatment-related adverse events led to medication discontinuation in 62% of the dual-adjuvant therapy group, compared with 13% of those on adjuvant nivolumab.

IMMUNED was funded by Bristol-Myers Squibb.

Dr. Ross reported having no financial conflicts regarding his presentation.

Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same company.

Find and manage a kidney in crisis

“Kidney disease is the most common chronic disease in the United States and the world, and the incidence is on the rise,” said Kim Zuber, PA-C, executive director of the American Academy of Nephrology PAs and outreach chair for the National Kidney Foundation in St. Petersburg, Fla.

Kidney disease also is an expensive problem that accounts for approximately 20% of the Medicare budget in the United States, she said in a virtual presentation at the Metabolic & Endocrine Disease Summit by Global Academy for Medical Education.

“It’s important that we know how to identify it and how to slow the progression if possible, and what to do when we can no longer control the disease,” she said.

Notably, the rate of growth for kidney disease is highest among adults aged 20-45 years, said Ms. Zuber. “That is the group who will live for many years with kidney disease,” but should be in their peak years of working and earning. “That is the group we do not want to develop chronic diseases.”

“Look for kidney disease. It’s not always on the chart; it is often missed because people don’t think of it,” Ms. Zuber said. Anyone over 60 years has likely lost some kidney function. Other risk factors include minority/ethnicity, hypertension or cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and a family history of kidney disease.

Women are more likely to develop chronic kidney disease (CKD), but less likely to go on dialysis, said Ms. Zuber. “What I find fascinating is that a history of oophorectomy” increases risk. Other less obvious risk factors in a medical history that should prompt a kidney disease screening include mothers who drank during pregnancy, individuals with a history of acute kidney disease, lupus, sarcoid, amyloid, gout, or other autoimmune conditions, as well as a history of kidney stones of cancer. Kidney donors or transplant recipients are at increased risk, as are smokers, soda drinkers, and heavy salt users.

CKD is missed by many health care providers, Ms. Zuber said. For example, she cited data from more than 270,000 veterans treated at a Veterans Affairs hospital in Texas, which suggested that the likelihood of adding CKD to a patient’s diagnosis was 43.7% even if lab results confirmed CKD.

Find the patients

There are many formulas for defining kidney function, Ms. Zuber said. The estimation of creatinine clearance (eCrCl) and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) are among them. The most common definition is to calculate eGFR using the CKD-EPI formula. Cystatin C is more exact, but it is not standardized, so a lab in one state does not use the same formula as one in another state.

Overall, all these formulas are plus or minus 30%. “It is an estimate,” she said. Within the stages of CKD, “what we know is that, if you have a high GFR, that’s good, but patients who are losing albumin are at increased risk for CKD.” The albumin is more of a risk factor for CKD than GFR, so the GFR test used doesn’t make much difference, whereas, “if you have a lot of albumin in your urine, you are going downhill,” she said.

Normally, everyone loses kidney function with age, Ms. Zuber said. Starting at age 30, individuals lose about 1 mL/min per year in measures of GFR, however, this progression is more rapid among those with CKD, so “we need to find those people who are progressing more quickly than normal.”

The way to identify the high-risk patients is albumin, Ms. Zuber said. Health care providers need to test the urine and check albumin for high levels of albumin loss through urine, and many providers simply don’t routinely conduct urine tests for patients with other CKD risk factors such as diabetes or hypertension.

Albuminuria levels of 2,000 mg/g are the most concerning, and a urine-albumin-to-creatinine ratio (UACR) test is the most effective tool to monitor kidney function, Ms. Zuber said.

She recommends ordering a UACR test at least once a year to monitor kidney loss in all patients with hypertension, diabetes, lupus, and other risk factors including race and a history of acute kidney injury.

Keep them healthy

Managing patients with chronic kidney disease includes attention to several categories: hypertension, diabetes, obesity, and cardiovascular disease, and mental health, Ms. Zuber said.

“If hypertension doesn’t cause your CKD, your CKD will cause hypertension,” she said. The goal for patients with CKD is a target systolic blood pressure less than 120 mm Hg. “As kidney disease progresses, hypertension becomes harder to control,” she added. Lifestyle changes including exercise, low-fat diet, limited use of salt, weight loss if needed, and stress reduction strategies can help.

For patients with diabetes and CKD, work towards a target hemoglobin A1c of 7.0 for early CKD, and of 8% for stage 4/5 or for older patients with multiple comorbidities, Ms. Zuber said. All types of insulin are safe for CKD patients. “Kidney function declines at twice the normal rate for diabetes patients; however, SGLT2 inhibitors are very renoprotective. You may not see a drop in A1c, but you are protecting the kidney.”

For patients with obesity and CKD, data show that bariatric surgery (gastric bypass) lowers mortality in diabetes and also protects the heart and kidneys, said Ms. Zuber. Overall, central obesity increases CKD risk independent of any other risk factors, but losing weight, either by surgery or diet/lifestyle, helps save the kidneys.

Cardiovascular disease is the cause of death for more than 70% of kidney disease patients, Ms. Zuber said. CKD patients “are two to three times more likely to have atrial fibrillation, so take the time to listen with that stethoscope,” she added, also emphasizing the importance of statins for all CKD and diabetes patients, and decreasing smoking. In addition, “managing metabolic acidosis slows the loss of kidney function and protects the heart.”

Additional pearls for managing chronic kidney disease include paying attention to a patient’s mental health; depression occurs in roughly 25%-47% of CKD patients, and anxiety in approximately 27%, said Ms. Zuber. Depression “is believed to be the most common psychiatric disorder in patients with end stage renal disease,” and data suggest that managing depression can help improve survival in CKD patients.

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same parent company. Ms. Zuber had no financial conflicts to disclose.

“Kidney disease is the most common chronic disease in the United States and the world, and the incidence is on the rise,” said Kim Zuber, PA-C, executive director of the American Academy of Nephrology PAs and outreach chair for the National Kidney Foundation in St. Petersburg, Fla.

Kidney disease also is an expensive problem that accounts for approximately 20% of the Medicare budget in the United States, she said in a virtual presentation at the Metabolic & Endocrine Disease Summit by Global Academy for Medical Education.

“It’s important that we know how to identify it and how to slow the progression if possible, and what to do when we can no longer control the disease,” she said.

Notably, the rate of growth for kidney disease is highest among adults aged 20-45 years, said Ms. Zuber. “That is the group who will live for many years with kidney disease,” but should be in their peak years of working and earning. “That is the group we do not want to develop chronic diseases.”

“Look for kidney disease. It’s not always on the chart; it is often missed because people don’t think of it,” Ms. Zuber said. Anyone over 60 years has likely lost some kidney function. Other risk factors include minority/ethnicity, hypertension or cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and a family history of kidney disease.

Women are more likely to develop chronic kidney disease (CKD), but less likely to go on dialysis, said Ms. Zuber. “What I find fascinating is that a history of oophorectomy” increases risk. Other less obvious risk factors in a medical history that should prompt a kidney disease screening include mothers who drank during pregnancy, individuals with a history of acute kidney disease, lupus, sarcoid, amyloid, gout, or other autoimmune conditions, as well as a history of kidney stones of cancer. Kidney donors or transplant recipients are at increased risk, as are smokers, soda drinkers, and heavy salt users.

CKD is missed by many health care providers, Ms. Zuber said. For example, she cited data from more than 270,000 veterans treated at a Veterans Affairs hospital in Texas, which suggested that the likelihood of adding CKD to a patient’s diagnosis was 43.7% even if lab results confirmed CKD.

Find the patients

There are many formulas for defining kidney function, Ms. Zuber said. The estimation of creatinine clearance (eCrCl) and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) are among them. The most common definition is to calculate eGFR using the CKD-EPI formula. Cystatin C is more exact, but it is not standardized, so a lab in one state does not use the same formula as one in another state.

Overall, all these formulas are plus or minus 30%. “It is an estimate,” she said. Within the stages of CKD, “what we know is that, if you have a high GFR, that’s good, but patients who are losing albumin are at increased risk for CKD.” The albumin is more of a risk factor for CKD than GFR, so the GFR test used doesn’t make much difference, whereas, “if you have a lot of albumin in your urine, you are going downhill,” she said.

Normally, everyone loses kidney function with age, Ms. Zuber said. Starting at age 30, individuals lose about 1 mL/min per year in measures of GFR, however, this progression is more rapid among those with CKD, so “we need to find those people who are progressing more quickly than normal.”

The way to identify the high-risk patients is albumin, Ms. Zuber said. Health care providers need to test the urine and check albumin for high levels of albumin loss through urine, and many providers simply don’t routinely conduct urine tests for patients with other CKD risk factors such as diabetes or hypertension.

Albuminuria levels of 2,000 mg/g are the most concerning, and a urine-albumin-to-creatinine ratio (UACR) test is the most effective tool to monitor kidney function, Ms. Zuber said.

She recommends ordering a UACR test at least once a year to monitor kidney loss in all patients with hypertension, diabetes, lupus, and other risk factors including race and a history of acute kidney injury.

Keep them healthy

Managing patients with chronic kidney disease includes attention to several categories: hypertension, diabetes, obesity, and cardiovascular disease, and mental health, Ms. Zuber said.

“If hypertension doesn’t cause your CKD, your CKD will cause hypertension,” she said. The goal for patients with CKD is a target systolic blood pressure less than 120 mm Hg. “As kidney disease progresses, hypertension becomes harder to control,” she added. Lifestyle changes including exercise, low-fat diet, limited use of salt, weight loss if needed, and stress reduction strategies can help.

For patients with diabetes and CKD, work towards a target hemoglobin A1c of 7.0 for early CKD, and of 8% for stage 4/5 or for older patients with multiple comorbidities, Ms. Zuber said. All types of insulin are safe for CKD patients. “Kidney function declines at twice the normal rate for diabetes patients; however, SGLT2 inhibitors are very renoprotective. You may not see a drop in A1c, but you are protecting the kidney.”

For patients with obesity and CKD, data show that bariatric surgery (gastric bypass) lowers mortality in diabetes and also protects the heart and kidneys, said Ms. Zuber. Overall, central obesity increases CKD risk independent of any other risk factors, but losing weight, either by surgery or diet/lifestyle, helps save the kidneys.

Cardiovascular disease is the cause of death for more than 70% of kidney disease patients, Ms. Zuber said. CKD patients “are two to three times more likely to have atrial fibrillation, so take the time to listen with that stethoscope,” she added, also emphasizing the importance of statins for all CKD and diabetes patients, and decreasing smoking. In addition, “managing metabolic acidosis slows the loss of kidney function and protects the heart.”

Additional pearls for managing chronic kidney disease include paying attention to a patient’s mental health; depression occurs in roughly 25%-47% of CKD patients, and anxiety in approximately 27%, said Ms. Zuber. Depression “is believed to be the most common psychiatric disorder in patients with end stage renal disease,” and data suggest that managing depression can help improve survival in CKD patients.

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same parent company. Ms. Zuber had no financial conflicts to disclose.

“Kidney disease is the most common chronic disease in the United States and the world, and the incidence is on the rise,” said Kim Zuber, PA-C, executive director of the American Academy of Nephrology PAs and outreach chair for the National Kidney Foundation in St. Petersburg, Fla.

Kidney disease also is an expensive problem that accounts for approximately 20% of the Medicare budget in the United States, she said in a virtual presentation at the Metabolic & Endocrine Disease Summit by Global Academy for Medical Education.

“It’s important that we know how to identify it and how to slow the progression if possible, and what to do when we can no longer control the disease,” she said.

Notably, the rate of growth for kidney disease is highest among adults aged 20-45 years, said Ms. Zuber. “That is the group who will live for many years with kidney disease,” but should be in their peak years of working and earning. “That is the group we do not want to develop chronic diseases.”

“Look for kidney disease. It’s not always on the chart; it is often missed because people don’t think of it,” Ms. Zuber said. Anyone over 60 years has likely lost some kidney function. Other risk factors include minority/ethnicity, hypertension or cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and a family history of kidney disease.

Women are more likely to develop chronic kidney disease (CKD), but less likely to go on dialysis, said Ms. Zuber. “What I find fascinating is that a history of oophorectomy” increases risk. Other less obvious risk factors in a medical history that should prompt a kidney disease screening include mothers who drank during pregnancy, individuals with a history of acute kidney disease, lupus, sarcoid, amyloid, gout, or other autoimmune conditions, as well as a history of kidney stones of cancer. Kidney donors or transplant recipients are at increased risk, as are smokers, soda drinkers, and heavy salt users.

CKD is missed by many health care providers, Ms. Zuber said. For example, she cited data from more than 270,000 veterans treated at a Veterans Affairs hospital in Texas, which suggested that the likelihood of adding CKD to a patient’s diagnosis was 43.7% even if lab results confirmed CKD.

Find the patients

There are many formulas for defining kidney function, Ms. Zuber said. The estimation of creatinine clearance (eCrCl) and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) are among them. The most common definition is to calculate eGFR using the CKD-EPI formula. Cystatin C is more exact, but it is not standardized, so a lab in one state does not use the same formula as one in another state.

Overall, all these formulas are plus or minus 30%. “It is an estimate,” she said. Within the stages of CKD, “what we know is that, if you have a high GFR, that’s good, but patients who are losing albumin are at increased risk for CKD.” The albumin is more of a risk factor for CKD than GFR, so the GFR test used doesn’t make much difference, whereas, “if you have a lot of albumin in your urine, you are going downhill,” she said.

Normally, everyone loses kidney function with age, Ms. Zuber said. Starting at age 30, individuals lose about 1 mL/min per year in measures of GFR, however, this progression is more rapid among those with CKD, so “we need to find those people who are progressing more quickly than normal.”

The way to identify the high-risk patients is albumin, Ms. Zuber said. Health care providers need to test the urine and check albumin for high levels of albumin loss through urine, and many providers simply don’t routinely conduct urine tests for patients with other CKD risk factors such as diabetes or hypertension.

Albuminuria levels of 2,000 mg/g are the most concerning, and a urine-albumin-to-creatinine ratio (UACR) test is the most effective tool to monitor kidney function, Ms. Zuber said.

She recommends ordering a UACR test at least once a year to monitor kidney loss in all patients with hypertension, diabetes, lupus, and other risk factors including race and a history of acute kidney injury.

Keep them healthy

Managing patients with chronic kidney disease includes attention to several categories: hypertension, diabetes, obesity, and cardiovascular disease, and mental health, Ms. Zuber said.

“If hypertension doesn’t cause your CKD, your CKD will cause hypertension,” she said. The goal for patients with CKD is a target systolic blood pressure less than 120 mm Hg. “As kidney disease progresses, hypertension becomes harder to control,” she added. Lifestyle changes including exercise, low-fat diet, limited use of salt, weight loss if needed, and stress reduction strategies can help.

For patients with diabetes and CKD, work towards a target hemoglobin A1c of 7.0 for early CKD, and of 8% for stage 4/5 or for older patients with multiple comorbidities, Ms. Zuber said. All types of insulin are safe for CKD patients. “Kidney function declines at twice the normal rate for diabetes patients; however, SGLT2 inhibitors are very renoprotective. You may not see a drop in A1c, but you are protecting the kidney.”

For patients with obesity and CKD, data show that bariatric surgery (gastric bypass) lowers mortality in diabetes and also protects the heart and kidneys, said Ms. Zuber. Overall, central obesity increases CKD risk independent of any other risk factors, but losing weight, either by surgery or diet/lifestyle, helps save the kidneys.

Cardiovascular disease is the cause of death for more than 70% of kidney disease patients, Ms. Zuber said. CKD patients “are two to three times more likely to have atrial fibrillation, so take the time to listen with that stethoscope,” she added, also emphasizing the importance of statins for all CKD and diabetes patients, and decreasing smoking. In addition, “managing metabolic acidosis slows the loss of kidney function and protects the heart.”

Additional pearls for managing chronic kidney disease include paying attention to a patient’s mental health; depression occurs in roughly 25%-47% of CKD patients, and anxiety in approximately 27%, said Ms. Zuber. Depression “is believed to be the most common psychiatric disorder in patients with end stage renal disease,” and data suggest that managing depression can help improve survival in CKD patients.

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same parent company. Ms. Zuber had no financial conflicts to disclose.

FROM MEDS 2020

COVID-19 symptoms persist months after acute infection

, according to a follow-up study involving 1,733 patients.

“Patients with COVID-19 had symptoms of fatigue or muscle weakness, sleep difficulties, and anxiety or depression,” and those with “more severe illness during their hospital stay had increasingly impaired pulmonary diffusion capacities and abnormal chest imaging manifestations,” Chaolin Huang, MD, of Jin Yin-tan Hospital in Wuhan, China, and associates wrote in the Lancet.

Fatigue or muscle weakness, reported by 63% of patients, was the most common symptom, followed by sleep difficulties, hair loss, and smell disorder. Altogether, 76% of those examined 6 months after discharge from Jin Yin-tan hospital – the first designated for patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan – reported at least one symptom, they said.

Symptoms were more common in women than men: 81% vs. 73% had at least one symptom, and 66% vs. 59% had fatigue or muscle weakness. Women were also more likely than men to report anxiety or depression at follow-up: 28% vs. 18% (23% overall), the investigators said.

Patients with the most severe COVID-19 were 2.4 times as likely to report any symptom later, compared with those who had the least severe levels of infection. Among the 349 participants who completed a lung function test at follow-up, lung diffusion impairment was seen in 56% of those with the most severe illness and 22% of those with the lowest level, Dr. Huang and associates reported.

In a different subset of 94 patients from whom plasma samples were collected, the “seropositivity and median titres of the neutralising antibodies were significantly lower than at the acute phase,” raising concern for reinfection, they said.

The results of the study, the investigators noted, “support that those with severe disease need post-discharge care. Longer follow-up studies in a larger population are necessary to understand the full spectrum of health consequences from COVID-19.”

, according to a follow-up study involving 1,733 patients.

“Patients with COVID-19 had symptoms of fatigue or muscle weakness, sleep difficulties, and anxiety or depression,” and those with “more severe illness during their hospital stay had increasingly impaired pulmonary diffusion capacities and abnormal chest imaging manifestations,” Chaolin Huang, MD, of Jin Yin-tan Hospital in Wuhan, China, and associates wrote in the Lancet.

Fatigue or muscle weakness, reported by 63% of patients, was the most common symptom, followed by sleep difficulties, hair loss, and smell disorder. Altogether, 76% of those examined 6 months after discharge from Jin Yin-tan hospital – the first designated for patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan – reported at least one symptom, they said.

Symptoms were more common in women than men: 81% vs. 73% had at least one symptom, and 66% vs. 59% had fatigue or muscle weakness. Women were also more likely than men to report anxiety or depression at follow-up: 28% vs. 18% (23% overall), the investigators said.

Patients with the most severe COVID-19 were 2.4 times as likely to report any symptom later, compared with those who had the least severe levels of infection. Among the 349 participants who completed a lung function test at follow-up, lung diffusion impairment was seen in 56% of those with the most severe illness and 22% of those with the lowest level, Dr. Huang and associates reported.

In a different subset of 94 patients from whom plasma samples were collected, the “seropositivity and median titres of the neutralising antibodies were significantly lower than at the acute phase,” raising concern for reinfection, they said.

The results of the study, the investigators noted, “support that those with severe disease need post-discharge care. Longer follow-up studies in a larger population are necessary to understand the full spectrum of health consequences from COVID-19.”

, according to a follow-up study involving 1,733 patients.

“Patients with COVID-19 had symptoms of fatigue or muscle weakness, sleep difficulties, and anxiety or depression,” and those with “more severe illness during their hospital stay had increasingly impaired pulmonary diffusion capacities and abnormal chest imaging manifestations,” Chaolin Huang, MD, of Jin Yin-tan Hospital in Wuhan, China, and associates wrote in the Lancet.

Fatigue or muscle weakness, reported by 63% of patients, was the most common symptom, followed by sleep difficulties, hair loss, and smell disorder. Altogether, 76% of those examined 6 months after discharge from Jin Yin-tan hospital – the first designated for patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan – reported at least one symptom, they said.

Symptoms were more common in women than men: 81% vs. 73% had at least one symptom, and 66% vs. 59% had fatigue or muscle weakness. Women were also more likely than men to report anxiety or depression at follow-up: 28% vs. 18% (23% overall), the investigators said.

Patients with the most severe COVID-19 were 2.4 times as likely to report any symptom later, compared with those who had the least severe levels of infection. Among the 349 participants who completed a lung function test at follow-up, lung diffusion impairment was seen in 56% of those with the most severe illness and 22% of those with the lowest level, Dr. Huang and associates reported.

In a different subset of 94 patients from whom plasma samples were collected, the “seropositivity and median titres of the neutralising antibodies were significantly lower than at the acute phase,” raising concern for reinfection, they said.

The results of the study, the investigators noted, “support that those with severe disease need post-discharge care. Longer follow-up studies in a larger population are necessary to understand the full spectrum of health consequences from COVID-19.”

FROM THE LANCET

Invasive bacterial infections uncommon in afebrile infants with diagnosed AOM

Outpatient management of most afebrile infants with acute otitis media who haven’t been tested for invasive bacterial infection may be reasonable given the low occurrence of adverse events, said Son H. McLaren, MD, MS, of Columbia University, New York, and colleagues.

Dr. McLaren and associates conducted an international cross-sectional study at 33 emergency departments participating in the Pediatric Emergency Medicine Collaborative Research Committee of the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP): 29 in the United States, 2 in Canada and 2 in Spain.

The researchers sought first to assess prevalence of invasive bacterial infections and adverse events tied to acute otitis media (AOM) in infants 90 days and younger. Those who were clinically diagnosed with AOM and presented without fever between January 2007 and December 2017 were included in the study. The presence of fever, they explained, “is a primary driver for more expanded testing and/or empirical treatment of invasive bacterial infection (IBI). Secondarily, they sought to characterize patterns of diagnostic testing and the factors associated with it specifically in this patient population.

Of 5,270 patients screened, 1,637 met study criteria. Included patients were a median age of 68 days. A total of 1,459 (89.1%) met AAP diagnostic criteria for AOM. The remaining 178 patients were examined and found to have more than one of these criteria: 113 had opacification of tympanic membrane, 57 had dull tympanic membrane, 25 had decreased visualization of middle ear structures, 9 had middle ear effusion, 8 had visible tympanic membrane perforation and 5 had decreased tympanic membrane mobility with insufflation. None of the 278 infants with blood cultures had bacteremia, nor were they diagnosed with bacterial meningitis. Two of 645 (0.3%) infants experienced adverse events, as evidenced with 30-day follow-up or history of hospitalization.