User login

Hospitalist movers and shakers – November 2020

Erin Shaughnessy, MD, assumed the role of director of pediatric hospital medicine at the University of Alabama at Birmingham and Children’s of Alabama, also in Birmingham, on Sept. 1. Dr. Shaughnessy has done research in improving outcomes in hospitalized children, as well as improving communication between physicians and pediatric patients’ families during care transitions.

Prior to joining UAB and Children’s of Alabama, Dr. Shaughnessy was division chief of hospital medicine at Phoenix (Ariz.) Children’s Hospital while also serving as an associate professor at the University of Arizona, Phoenix.

Chandra Lingisetty, MD, MBA, MHCM, was recently named chief administrative officer for Baptist Health Physician Partners, Arkansas. BHPP is Baptist Health’s clinically integrated network (CIN) with more than 1,600 providers across the state.

Baptist Health Arkansas is the state’s largest not for profit health system with 12 hospitals, hundreds of provider clinics, a nursing school, and a graduate medical education residency program. Prior to his promotion, he worked in Baptist Health System as a hospitalist for 10 years, served on the board of managers at BHPP, and strategized COVID-19 care management protocols and medical staff preparedness as part of surge planning and capacity expansion. In his new role, he is focused on leading the clinically integrated network toward value-based care. He is also the cofounder and inaugural president of the Arkansas state chapter of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Grace Farris, MD, recently accepted a position with the division of hospital medicine at the Dell Medical School in Austin where she will be an assistant professor of internal medicine, as well as a working hospitalist.

Dr. Farris worked as chief of hospital medicine at Mount Sinai West Hospital in Manhattan from January 2017 until accepting her new position with Dell. In addition, she publishes a monthly comics column in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

Her visual storytelling through comics has appeared in several media outlets, and she has penned literal columns as well, including one recently in the New York Times about living apart from her children while treating COVID-19 patients in the emergency room.

Dell Medical School has also named a new division chief of hospital medicine. Read Pierce, MD, made the move to Texas from the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora. Dr. Pierce will also serve as associate chair of faculty development of internal medicine at Dell. He is eager to build on his experience and passion for developing people, creating outstanding culture, and changing complex systems in innovative, sustainable ways.

Dr. Pierce worked at University of Colorado for the past 8 years, serving as the associate director of the school’s Institute for Healthcare Quality, Safety and Efficiency (IHQSE), a program he co-founded. Prior to that, Dr. Pierce was chief resident at the University of San Francisco medical school and later founded the hospital medicine center at the San Francisco VA Medical Center.

Gurinder Kaur, MD, was recently named medical director of the Health Hospitalist Program at St. Joseph’s Health Rome (N.Y.) Memorial Hospital. Dr. Kaur’s focus will be on improving infrastructure to allow for the highest quality of care possible. She will oversee the facility’s crew of eight hospitalists, who rotate to be available 24 hours per day.

Dr. Kaur comes to Rome from St. Joseph’s Health in Syracuse, N.Y., where she was chief resident and a member of the hospitalist team.

Colin McMahon, MD, was recently appointed chief of hospital medicine at Eastern Niagara Hospital in Lockport, N.Y., where he will oversee the hospitalist program. He comes to ENH after serving as medical director of hospital operations at Buffalo (N.Y.) General Medical Center.

Dr. McMahon has worked in medicine for a quarter of a century. He also is the president and founder of Dimensions of Internal Medicine and Pediatric Care, PC (DMP). Associates from DMP Medicine make up the hospitalist team at ENH.

Sam Antonios, MD, has been promoted to chief clinical officer of Ascension Kansas, the parent group of Ascension Via Christi Hospital in Wichita, where Dr. Antonios has served as chief medical officer for the past 4 years. Dr. Antonios has emerged as a leader within Ascension Kansas during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Prior to his appointment at Via Christi, he worked at that facility as a hospitalist and as medical director of information systems. Dr. Antonios is a board-certified internist.

Bret J. Rudy, MD, was named a Top 25 Healthcare Innovator by Modern Healthcare magazine. Dr. Rudy is chief of hospital operations and senior vice president at NYU Langone Hospital-Brooklyn in New York, and the magazine cited his efforts in elevating the quality, safety, and accountability of the facility, which merged with NYU Langone Health in 2016.

Dr. Rudy has established a 24-hour hospitalist service, added full-time emergency faculty, and reduced hospital wait times, among other patient-experience benchmarks, since his appointment at Langone-Brooklyn.

Dr. Rudy is a board-certified pediatrician who has served on the National Institutes of Health’s HIV research networks, including a spot on the White House Advisory Committee on Adolescents for the Office of National AIDS Policy.

Nasim Afsar, MD, MBA, SFHM, a past president of SHM, was recently named chief operating officer at UCI Health in Orange, Calif. Dr. Afsar served previously as chief ambulatory officer and chief medical officer for accountable care organizations at UCI Health.

Anthony J. Macchiavelli, MD, FHM, was recognized by Continental Who’s Who as a “Top Distinguished Hospitalist” with AtlantiCare Regional Medical Center, in Atlantic City, N.J. He has been with AtlantiCare for the past ten years, and currently serves as medical director for the PACE program, as well as medical director for the Anticoagulation Clinic.

Dr. Macchiavelli has been involved in the development of 3 different hospital medicine programs throughout his career and was the founder of the Associates in Hospital Medicine program at Methodist Division of Thomas Jefferson University Hospitals. He serves as a mentor for SHM’s VTE-FAST Program, and has served on the Standards Review Panel for the Joint Commission developing the National Patient Safety Goal for anticoagulation therapy.

Erin Shaughnessy, MD, assumed the role of director of pediatric hospital medicine at the University of Alabama at Birmingham and Children’s of Alabama, also in Birmingham, on Sept. 1. Dr. Shaughnessy has done research in improving outcomes in hospitalized children, as well as improving communication between physicians and pediatric patients’ families during care transitions.

Prior to joining UAB and Children’s of Alabama, Dr. Shaughnessy was division chief of hospital medicine at Phoenix (Ariz.) Children’s Hospital while also serving as an associate professor at the University of Arizona, Phoenix.

Chandra Lingisetty, MD, MBA, MHCM, was recently named chief administrative officer for Baptist Health Physician Partners, Arkansas. BHPP is Baptist Health’s clinically integrated network (CIN) with more than 1,600 providers across the state.

Baptist Health Arkansas is the state’s largest not for profit health system with 12 hospitals, hundreds of provider clinics, a nursing school, and a graduate medical education residency program. Prior to his promotion, he worked in Baptist Health System as a hospitalist for 10 years, served on the board of managers at BHPP, and strategized COVID-19 care management protocols and medical staff preparedness as part of surge planning and capacity expansion. In his new role, he is focused on leading the clinically integrated network toward value-based care. He is also the cofounder and inaugural president of the Arkansas state chapter of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Grace Farris, MD, recently accepted a position with the division of hospital medicine at the Dell Medical School in Austin where she will be an assistant professor of internal medicine, as well as a working hospitalist.

Dr. Farris worked as chief of hospital medicine at Mount Sinai West Hospital in Manhattan from January 2017 until accepting her new position with Dell. In addition, she publishes a monthly comics column in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

Her visual storytelling through comics has appeared in several media outlets, and she has penned literal columns as well, including one recently in the New York Times about living apart from her children while treating COVID-19 patients in the emergency room.

Dell Medical School has also named a new division chief of hospital medicine. Read Pierce, MD, made the move to Texas from the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora. Dr. Pierce will also serve as associate chair of faculty development of internal medicine at Dell. He is eager to build on his experience and passion for developing people, creating outstanding culture, and changing complex systems in innovative, sustainable ways.

Dr. Pierce worked at University of Colorado for the past 8 years, serving as the associate director of the school’s Institute for Healthcare Quality, Safety and Efficiency (IHQSE), a program he co-founded. Prior to that, Dr. Pierce was chief resident at the University of San Francisco medical school and later founded the hospital medicine center at the San Francisco VA Medical Center.

Gurinder Kaur, MD, was recently named medical director of the Health Hospitalist Program at St. Joseph’s Health Rome (N.Y.) Memorial Hospital. Dr. Kaur’s focus will be on improving infrastructure to allow for the highest quality of care possible. She will oversee the facility’s crew of eight hospitalists, who rotate to be available 24 hours per day.

Dr. Kaur comes to Rome from St. Joseph’s Health in Syracuse, N.Y., where she was chief resident and a member of the hospitalist team.

Colin McMahon, MD, was recently appointed chief of hospital medicine at Eastern Niagara Hospital in Lockport, N.Y., where he will oversee the hospitalist program. He comes to ENH after serving as medical director of hospital operations at Buffalo (N.Y.) General Medical Center.

Dr. McMahon has worked in medicine for a quarter of a century. He also is the president and founder of Dimensions of Internal Medicine and Pediatric Care, PC (DMP). Associates from DMP Medicine make up the hospitalist team at ENH.

Sam Antonios, MD, has been promoted to chief clinical officer of Ascension Kansas, the parent group of Ascension Via Christi Hospital in Wichita, where Dr. Antonios has served as chief medical officer for the past 4 years. Dr. Antonios has emerged as a leader within Ascension Kansas during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Prior to his appointment at Via Christi, he worked at that facility as a hospitalist and as medical director of information systems. Dr. Antonios is a board-certified internist.

Bret J. Rudy, MD, was named a Top 25 Healthcare Innovator by Modern Healthcare magazine. Dr. Rudy is chief of hospital operations and senior vice president at NYU Langone Hospital-Brooklyn in New York, and the magazine cited his efforts in elevating the quality, safety, and accountability of the facility, which merged with NYU Langone Health in 2016.

Dr. Rudy has established a 24-hour hospitalist service, added full-time emergency faculty, and reduced hospital wait times, among other patient-experience benchmarks, since his appointment at Langone-Brooklyn.

Dr. Rudy is a board-certified pediatrician who has served on the National Institutes of Health’s HIV research networks, including a spot on the White House Advisory Committee on Adolescents for the Office of National AIDS Policy.

Nasim Afsar, MD, MBA, SFHM, a past president of SHM, was recently named chief operating officer at UCI Health in Orange, Calif. Dr. Afsar served previously as chief ambulatory officer and chief medical officer for accountable care organizations at UCI Health.

Anthony J. Macchiavelli, MD, FHM, was recognized by Continental Who’s Who as a “Top Distinguished Hospitalist” with AtlantiCare Regional Medical Center, in Atlantic City, N.J. He has been with AtlantiCare for the past ten years, and currently serves as medical director for the PACE program, as well as medical director for the Anticoagulation Clinic.

Dr. Macchiavelli has been involved in the development of 3 different hospital medicine programs throughout his career and was the founder of the Associates in Hospital Medicine program at Methodist Division of Thomas Jefferson University Hospitals. He serves as a mentor for SHM’s VTE-FAST Program, and has served on the Standards Review Panel for the Joint Commission developing the National Patient Safety Goal for anticoagulation therapy.

Erin Shaughnessy, MD, assumed the role of director of pediatric hospital medicine at the University of Alabama at Birmingham and Children’s of Alabama, also in Birmingham, on Sept. 1. Dr. Shaughnessy has done research in improving outcomes in hospitalized children, as well as improving communication between physicians and pediatric patients’ families during care transitions.

Prior to joining UAB and Children’s of Alabama, Dr. Shaughnessy was division chief of hospital medicine at Phoenix (Ariz.) Children’s Hospital while also serving as an associate professor at the University of Arizona, Phoenix.

Chandra Lingisetty, MD, MBA, MHCM, was recently named chief administrative officer for Baptist Health Physician Partners, Arkansas. BHPP is Baptist Health’s clinically integrated network (CIN) with more than 1,600 providers across the state.

Baptist Health Arkansas is the state’s largest not for profit health system with 12 hospitals, hundreds of provider clinics, a nursing school, and a graduate medical education residency program. Prior to his promotion, he worked in Baptist Health System as a hospitalist for 10 years, served on the board of managers at BHPP, and strategized COVID-19 care management protocols and medical staff preparedness as part of surge planning and capacity expansion. In his new role, he is focused on leading the clinically integrated network toward value-based care. He is also the cofounder and inaugural president of the Arkansas state chapter of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Grace Farris, MD, recently accepted a position with the division of hospital medicine at the Dell Medical School in Austin where she will be an assistant professor of internal medicine, as well as a working hospitalist.

Dr. Farris worked as chief of hospital medicine at Mount Sinai West Hospital in Manhattan from January 2017 until accepting her new position with Dell. In addition, she publishes a monthly comics column in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

Her visual storytelling through comics has appeared in several media outlets, and she has penned literal columns as well, including one recently in the New York Times about living apart from her children while treating COVID-19 patients in the emergency room.

Dell Medical School has also named a new division chief of hospital medicine. Read Pierce, MD, made the move to Texas from the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora. Dr. Pierce will also serve as associate chair of faculty development of internal medicine at Dell. He is eager to build on his experience and passion for developing people, creating outstanding culture, and changing complex systems in innovative, sustainable ways.

Dr. Pierce worked at University of Colorado for the past 8 years, serving as the associate director of the school’s Institute for Healthcare Quality, Safety and Efficiency (IHQSE), a program he co-founded. Prior to that, Dr. Pierce was chief resident at the University of San Francisco medical school and later founded the hospital medicine center at the San Francisco VA Medical Center.

Gurinder Kaur, MD, was recently named medical director of the Health Hospitalist Program at St. Joseph’s Health Rome (N.Y.) Memorial Hospital. Dr. Kaur’s focus will be on improving infrastructure to allow for the highest quality of care possible. She will oversee the facility’s crew of eight hospitalists, who rotate to be available 24 hours per day.

Dr. Kaur comes to Rome from St. Joseph’s Health in Syracuse, N.Y., where she was chief resident and a member of the hospitalist team.

Colin McMahon, MD, was recently appointed chief of hospital medicine at Eastern Niagara Hospital in Lockport, N.Y., where he will oversee the hospitalist program. He comes to ENH after serving as medical director of hospital operations at Buffalo (N.Y.) General Medical Center.

Dr. McMahon has worked in medicine for a quarter of a century. He also is the president and founder of Dimensions of Internal Medicine and Pediatric Care, PC (DMP). Associates from DMP Medicine make up the hospitalist team at ENH.

Sam Antonios, MD, has been promoted to chief clinical officer of Ascension Kansas, the parent group of Ascension Via Christi Hospital in Wichita, where Dr. Antonios has served as chief medical officer for the past 4 years. Dr. Antonios has emerged as a leader within Ascension Kansas during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Prior to his appointment at Via Christi, he worked at that facility as a hospitalist and as medical director of information systems. Dr. Antonios is a board-certified internist.

Bret J. Rudy, MD, was named a Top 25 Healthcare Innovator by Modern Healthcare magazine. Dr. Rudy is chief of hospital operations and senior vice president at NYU Langone Hospital-Brooklyn in New York, and the magazine cited his efforts in elevating the quality, safety, and accountability of the facility, which merged with NYU Langone Health in 2016.

Dr. Rudy has established a 24-hour hospitalist service, added full-time emergency faculty, and reduced hospital wait times, among other patient-experience benchmarks, since his appointment at Langone-Brooklyn.

Dr. Rudy is a board-certified pediatrician who has served on the National Institutes of Health’s HIV research networks, including a spot on the White House Advisory Committee on Adolescents for the Office of National AIDS Policy.

Nasim Afsar, MD, MBA, SFHM, a past president of SHM, was recently named chief operating officer at UCI Health in Orange, Calif. Dr. Afsar served previously as chief ambulatory officer and chief medical officer for accountable care organizations at UCI Health.

Anthony J. Macchiavelli, MD, FHM, was recognized by Continental Who’s Who as a “Top Distinguished Hospitalist” with AtlantiCare Regional Medical Center, in Atlantic City, N.J. He has been with AtlantiCare for the past ten years, and currently serves as medical director for the PACE program, as well as medical director for the Anticoagulation Clinic.

Dr. Macchiavelli has been involved in the development of 3 different hospital medicine programs throughout his career and was the founder of the Associates in Hospital Medicine program at Methodist Division of Thomas Jefferson University Hospitals. He serves as a mentor for SHM’s VTE-FAST Program, and has served on the Standards Review Panel for the Joint Commission developing the National Patient Safety Goal for anticoagulation therapy.

TNF inhibitor–induced psoriasis treatment algorithm maintains TNF inhibitor if possible

In a single-center retrospective analysis of 102 patients with psoriasis induced by tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors, most cases improved or resolved with use of topical medications or with discontinuation of the inciting TNF inhibitor, with or without other interventions. All patients were treated and diagnosed by dermatologists.

While TNF inhibitors have revolutionized management of numerous debilitating chronic inflammatory diseases, they are associated with mild and potentially serious adverse reactions, including de novo psoriasiform eruptions, noted Sean E. Mazloom, MD, and colleagues, at the Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio, in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. Despite the fact that it has been more than 15 years since the first reports of TNF inhibitor-induced psoriasis, optimal treatment strategies still remain poorly understood.

IBD and RA most common

Dr. Mazloom and colleagues identified 102 patients (median onset, 41 years; 72.5% female) with TNF inhibitor-induced psoriasis seen at a single tertiary care institution (the Cleveland Clinic) over a 10-year period. The authors proposed a treatment algorithm based on their findings.

Inciting TNF inhibitors were prescribed most commonly for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) (52%) and rheumatoid arthritis (RA) (24.5%). The most common inciting TNF inhibitor was infliximab (52%). TNF inhibitor-induced psoriasis improved or resolved with topical medications alone in 63.5% of patients, and cyclosporine and methotrexate (10 mg weekly) were often effective (cyclosporine in five of five patients; methotrexate in 7 of 13) if topicals failed.

Noting that the success with topicals in this cohort exceeded that of earlier reports, the authors suggested that more accurate diagnoses and optimal strategies attributable to the involvement of dermatologists may be explanatory.

In 67% of refractory cases, discontinuation of the inciting TNF inhibitor with or without other interventions improved or resolved TNF inhibitor-induced psoriasis. With switching of TNF inhibitors, persistence or worsening of TNF inhibitor-induced psoriasis was reported in 16 of 25 patients (64%).

Algorithm aims at balancing control

The treatment algorithm proposed by Dr. Mazloom and colleagues aims at balancing control of the primary disease with minimization of skin symptom discomfort and continuation of the inciting TNF inhibitor if possible. Only with cyclosporine or methotrexate failure amid severe symptoms and less-than-optimal primary disease control should TNF inhibitors be discontinued and biologics and/or small-molecule inhibitors with alternative mechanisms of action be introduced. Transitioning to other TNF inhibitors may be tried before alternative strategies when the underlying disease is well-controlled but TNF inhibitor-induced psoriasis remains severe.

“Most dermatologists who see TNF-induced psoriasis often are likely already using strategies like the one proposed in the algorithm,” commented senior author Anthony Fernandez, MD, PhD, of the Cleveland (Ohio) Clinic, in an interview. “The concern is over those who may not see TNF inhibitor-induced psoriasis very often, and who may, as a knee-jerk response to TNF-induced psoriasis, stop the inciting medication. When strong side effects occur in IBD and RA, it’s critical to know how well the TNF inhibitor is controlling the underlying disease because lack of control can lead to permanent damage.”

Risk to benefit ratio favors retaining TNF inhibitors

The dermatologist’s goal, if the TNF inhibitor is working well, should be to exhaust all reasonable options to control the psoriasiform eruption and keep the patient on the TNF inhibitor rather than turn to potentially less effective alternatives, Dr. Fernandez added. “The risk:benefit ratio still usually favors adding more immune therapies to treat these reactions in order to enable patients to stay” on their TNF inhibitors.

Study authors disclosed no direct funding for the study. Dr Fernandez, the senior author, receives research funding from Pfizer, Mallinckrodt, and Novartis, consults for AbbVie and Celgene, and is a speaker for AbbVie and Mallinckrodt.

SOURCE: Mazloom SE et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Dec;83(6):1590-8.

In a single-center retrospective analysis of 102 patients with psoriasis induced by tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors, most cases improved or resolved with use of topical medications or with discontinuation of the inciting TNF inhibitor, with or without other interventions. All patients were treated and diagnosed by dermatologists.

While TNF inhibitors have revolutionized management of numerous debilitating chronic inflammatory diseases, they are associated with mild and potentially serious adverse reactions, including de novo psoriasiform eruptions, noted Sean E. Mazloom, MD, and colleagues, at the Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio, in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. Despite the fact that it has been more than 15 years since the first reports of TNF inhibitor-induced psoriasis, optimal treatment strategies still remain poorly understood.

IBD and RA most common

Dr. Mazloom and colleagues identified 102 patients (median onset, 41 years; 72.5% female) with TNF inhibitor-induced psoriasis seen at a single tertiary care institution (the Cleveland Clinic) over a 10-year period. The authors proposed a treatment algorithm based on their findings.

Inciting TNF inhibitors were prescribed most commonly for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) (52%) and rheumatoid arthritis (RA) (24.5%). The most common inciting TNF inhibitor was infliximab (52%). TNF inhibitor-induced psoriasis improved or resolved with topical medications alone in 63.5% of patients, and cyclosporine and methotrexate (10 mg weekly) were often effective (cyclosporine in five of five patients; methotrexate in 7 of 13) if topicals failed.

Noting that the success with topicals in this cohort exceeded that of earlier reports, the authors suggested that more accurate diagnoses and optimal strategies attributable to the involvement of dermatologists may be explanatory.

In 67% of refractory cases, discontinuation of the inciting TNF inhibitor with or without other interventions improved or resolved TNF inhibitor-induced psoriasis. With switching of TNF inhibitors, persistence or worsening of TNF inhibitor-induced psoriasis was reported in 16 of 25 patients (64%).

Algorithm aims at balancing control

The treatment algorithm proposed by Dr. Mazloom and colleagues aims at balancing control of the primary disease with minimization of skin symptom discomfort and continuation of the inciting TNF inhibitor if possible. Only with cyclosporine or methotrexate failure amid severe symptoms and less-than-optimal primary disease control should TNF inhibitors be discontinued and biologics and/or small-molecule inhibitors with alternative mechanisms of action be introduced. Transitioning to other TNF inhibitors may be tried before alternative strategies when the underlying disease is well-controlled but TNF inhibitor-induced psoriasis remains severe.

“Most dermatologists who see TNF-induced psoriasis often are likely already using strategies like the one proposed in the algorithm,” commented senior author Anthony Fernandez, MD, PhD, of the Cleveland (Ohio) Clinic, in an interview. “The concern is over those who may not see TNF inhibitor-induced psoriasis very often, and who may, as a knee-jerk response to TNF-induced psoriasis, stop the inciting medication. When strong side effects occur in IBD and RA, it’s critical to know how well the TNF inhibitor is controlling the underlying disease because lack of control can lead to permanent damage.”

Risk to benefit ratio favors retaining TNF inhibitors

The dermatologist’s goal, if the TNF inhibitor is working well, should be to exhaust all reasonable options to control the psoriasiform eruption and keep the patient on the TNF inhibitor rather than turn to potentially less effective alternatives, Dr. Fernandez added. “The risk:benefit ratio still usually favors adding more immune therapies to treat these reactions in order to enable patients to stay” on their TNF inhibitors.

Study authors disclosed no direct funding for the study. Dr Fernandez, the senior author, receives research funding from Pfizer, Mallinckrodt, and Novartis, consults for AbbVie and Celgene, and is a speaker for AbbVie and Mallinckrodt.

SOURCE: Mazloom SE et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Dec;83(6):1590-8.

In a single-center retrospective analysis of 102 patients with psoriasis induced by tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors, most cases improved or resolved with use of topical medications or with discontinuation of the inciting TNF inhibitor, with or without other interventions. All patients were treated and diagnosed by dermatologists.

While TNF inhibitors have revolutionized management of numerous debilitating chronic inflammatory diseases, they are associated with mild and potentially serious adverse reactions, including de novo psoriasiform eruptions, noted Sean E. Mazloom, MD, and colleagues, at the Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio, in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. Despite the fact that it has been more than 15 years since the first reports of TNF inhibitor-induced psoriasis, optimal treatment strategies still remain poorly understood.

IBD and RA most common

Dr. Mazloom and colleagues identified 102 patients (median onset, 41 years; 72.5% female) with TNF inhibitor-induced psoriasis seen at a single tertiary care institution (the Cleveland Clinic) over a 10-year period. The authors proposed a treatment algorithm based on their findings.

Inciting TNF inhibitors were prescribed most commonly for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) (52%) and rheumatoid arthritis (RA) (24.5%). The most common inciting TNF inhibitor was infliximab (52%). TNF inhibitor-induced psoriasis improved or resolved with topical medications alone in 63.5% of patients, and cyclosporine and methotrexate (10 mg weekly) were often effective (cyclosporine in five of five patients; methotrexate in 7 of 13) if topicals failed.

Noting that the success with topicals in this cohort exceeded that of earlier reports, the authors suggested that more accurate diagnoses and optimal strategies attributable to the involvement of dermatologists may be explanatory.

In 67% of refractory cases, discontinuation of the inciting TNF inhibitor with or without other interventions improved or resolved TNF inhibitor-induced psoriasis. With switching of TNF inhibitors, persistence or worsening of TNF inhibitor-induced psoriasis was reported in 16 of 25 patients (64%).

Algorithm aims at balancing control

The treatment algorithm proposed by Dr. Mazloom and colleagues aims at balancing control of the primary disease with minimization of skin symptom discomfort and continuation of the inciting TNF inhibitor if possible. Only with cyclosporine or methotrexate failure amid severe symptoms and less-than-optimal primary disease control should TNF inhibitors be discontinued and biologics and/or small-molecule inhibitors with alternative mechanisms of action be introduced. Transitioning to other TNF inhibitors may be tried before alternative strategies when the underlying disease is well-controlled but TNF inhibitor-induced psoriasis remains severe.

“Most dermatologists who see TNF-induced psoriasis often are likely already using strategies like the one proposed in the algorithm,” commented senior author Anthony Fernandez, MD, PhD, of the Cleveland (Ohio) Clinic, in an interview. “The concern is over those who may not see TNF inhibitor-induced psoriasis very often, and who may, as a knee-jerk response to TNF-induced psoriasis, stop the inciting medication. When strong side effects occur in IBD and RA, it’s critical to know how well the TNF inhibitor is controlling the underlying disease because lack of control can lead to permanent damage.”

Risk to benefit ratio favors retaining TNF inhibitors

The dermatologist’s goal, if the TNF inhibitor is working well, should be to exhaust all reasonable options to control the psoriasiform eruption and keep the patient on the TNF inhibitor rather than turn to potentially less effective alternatives, Dr. Fernandez added. “The risk:benefit ratio still usually favors adding more immune therapies to treat these reactions in order to enable patients to stay” on their TNF inhibitors.

Study authors disclosed no direct funding for the study. Dr Fernandez, the senior author, receives research funding from Pfizer, Mallinckrodt, and Novartis, consults for AbbVie and Celgene, and is a speaker for AbbVie and Mallinckrodt.

SOURCE: Mazloom SE et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Dec;83(6):1590-8.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF DERMATOLOGY

Is a pelvic examination necessary 6 weeks after hysterectomy?

Doctors commonly perform pelvic examinations approximately 6 weeks following hysterectomy to assess the integrity of the vaginal cuff. But this practice may not be necessary if patients do not have symptoms, a study suggests.

“The 6-week posthysterectomy pelvic examination in asymptomatic women may not be necessary, as it neither detected cuff dehiscence nor negated future risk for dehiscence,” Ritchie Mae Delara, MD, said at the meeting sponsored by AAGL, held virtually this year.

Dr. Delara, of the Mayo Clinic in Phoenix, and colleagues conducted a retrospective cohort study of data from more than 2,000 patients to assess the utility of the 6-week posthysterectomy pelvic examination in detecting cuff dehiscence in asymptomatic women.

An unpredictable complication

Vaginal cuff dehiscence is a rare complication of hysterectomy that can occur days or decades after surgery, which makes “identifying an optimal time for cuff evaluation difficult,” Dr. Delara said. “Currently there is neither evidence demonstrating benefit of routine posthysterectomy examination in detecting vaginal cuff dehiscence, nor data demonstrating the best time to perform posthysterectomy examination.”

For their study, which was also published in the Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynecology, the researchers examined data from 2,051 women who underwent hysterectomy at a single institution during a 6-year period. Patients received at least one postoperative evaluation within 90 days of surgery. Examination of the vaginal cuff routinely was performed approximately 6 weeks after hysterectomy. Patients’ posthysterectomy symptoms and pelvic examination findings were recorded.

About 80% of patients were asymptomatic at the 6-week visit.

Asymptomatic patients were more likely to have normal pelvic examination findings, compared with patients with posthysterectomy symptoms (86.4% vs. 54.3%).

In all, 13 patients experienced complete cuff dehiscence. All of them had an intact vaginal cuff at their 6-week examination. Three had symptoms at that time, including vaginal bleeding in one patient and pelvic pain in two patients.

One patient experienced a complete cuff dehiscence that was provoked by intercourse prior to her examination. The patient subsequently developed two additional episodes of dehiscence provoked by intercourse.

Dehiscence may present differently after benign and oncologic hysterectomies, the study indicated.

Eight patients who experienced complete cuff dehiscence after benign hysterectomy had symptoms such as pelvic pain and vaginal bleeding at the time of presentation for dehiscence, which mainly occurred after intercourse.

Five patients who experienced dehiscence after oncologic hysterectomy were more likely to present without symptoms or provocation.

The median time to dehiscence after benign hysterectomy was about 19 weeks, whereas the median time to dehiscence after oncologic hysterectomy was about 81 weeks.

Surgeons should educate patients about symptoms of dehiscence and the potential for events such as coitus to provoke its occurrence, and patients should promptly seek evaluation if symptoms occur, Dr. Delara said.

Patients with risk factors such as malignancy may benefit from continued routine evaluation, she added.

Timely research

The findings may be especially relevant during the COVID-19 pandemic, when states have issued shelter-in-place orders and doctors have increased their use of telemedicine to reduce in-person visits, Dr. Delara noted.

In that sense, the study is “extremely timely” and may inform and support practice changes, commented Emad Mikhail, MD, in a discussion following the research presentation.

Whether the results generalize to other centers, including smaller centers that perform fewer surgeries, is unclear, said Dr. Mikhail, of the University of South Florida, Tampa.

“It takes vision and critical thinking to challenge these traditional practices,” he said. “I applaud Dr. Delara for challenging one of these.”

Dr. Delara and Dr. Mikhail had no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Delara RMM et al. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020 Nov 1. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2020.08.306.

Doctors commonly perform pelvic examinations approximately 6 weeks following hysterectomy to assess the integrity of the vaginal cuff. But this practice may not be necessary if patients do not have symptoms, a study suggests.

“The 6-week posthysterectomy pelvic examination in asymptomatic women may not be necessary, as it neither detected cuff dehiscence nor negated future risk for dehiscence,” Ritchie Mae Delara, MD, said at the meeting sponsored by AAGL, held virtually this year.

Dr. Delara, of the Mayo Clinic in Phoenix, and colleagues conducted a retrospective cohort study of data from more than 2,000 patients to assess the utility of the 6-week posthysterectomy pelvic examination in detecting cuff dehiscence in asymptomatic women.

An unpredictable complication

Vaginal cuff dehiscence is a rare complication of hysterectomy that can occur days or decades after surgery, which makes “identifying an optimal time for cuff evaluation difficult,” Dr. Delara said. “Currently there is neither evidence demonstrating benefit of routine posthysterectomy examination in detecting vaginal cuff dehiscence, nor data demonstrating the best time to perform posthysterectomy examination.”

For their study, which was also published in the Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynecology, the researchers examined data from 2,051 women who underwent hysterectomy at a single institution during a 6-year period. Patients received at least one postoperative evaluation within 90 days of surgery. Examination of the vaginal cuff routinely was performed approximately 6 weeks after hysterectomy. Patients’ posthysterectomy symptoms and pelvic examination findings were recorded.

About 80% of patients were asymptomatic at the 6-week visit.

Asymptomatic patients were more likely to have normal pelvic examination findings, compared with patients with posthysterectomy symptoms (86.4% vs. 54.3%).

In all, 13 patients experienced complete cuff dehiscence. All of them had an intact vaginal cuff at their 6-week examination. Three had symptoms at that time, including vaginal bleeding in one patient and pelvic pain in two patients.

One patient experienced a complete cuff dehiscence that was provoked by intercourse prior to her examination. The patient subsequently developed two additional episodes of dehiscence provoked by intercourse.

Dehiscence may present differently after benign and oncologic hysterectomies, the study indicated.

Eight patients who experienced complete cuff dehiscence after benign hysterectomy had symptoms such as pelvic pain and vaginal bleeding at the time of presentation for dehiscence, which mainly occurred after intercourse.

Five patients who experienced dehiscence after oncologic hysterectomy were more likely to present without symptoms or provocation.

The median time to dehiscence after benign hysterectomy was about 19 weeks, whereas the median time to dehiscence after oncologic hysterectomy was about 81 weeks.

Surgeons should educate patients about symptoms of dehiscence and the potential for events such as coitus to provoke its occurrence, and patients should promptly seek evaluation if symptoms occur, Dr. Delara said.

Patients with risk factors such as malignancy may benefit from continued routine evaluation, she added.

Timely research

The findings may be especially relevant during the COVID-19 pandemic, when states have issued shelter-in-place orders and doctors have increased their use of telemedicine to reduce in-person visits, Dr. Delara noted.

In that sense, the study is “extremely timely” and may inform and support practice changes, commented Emad Mikhail, MD, in a discussion following the research presentation.

Whether the results generalize to other centers, including smaller centers that perform fewer surgeries, is unclear, said Dr. Mikhail, of the University of South Florida, Tampa.

“It takes vision and critical thinking to challenge these traditional practices,” he said. “I applaud Dr. Delara for challenging one of these.”

Dr. Delara and Dr. Mikhail had no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Delara RMM et al. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020 Nov 1. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2020.08.306.

Doctors commonly perform pelvic examinations approximately 6 weeks following hysterectomy to assess the integrity of the vaginal cuff. But this practice may not be necessary if patients do not have symptoms, a study suggests.

“The 6-week posthysterectomy pelvic examination in asymptomatic women may not be necessary, as it neither detected cuff dehiscence nor negated future risk for dehiscence,” Ritchie Mae Delara, MD, said at the meeting sponsored by AAGL, held virtually this year.

Dr. Delara, of the Mayo Clinic in Phoenix, and colleagues conducted a retrospective cohort study of data from more than 2,000 patients to assess the utility of the 6-week posthysterectomy pelvic examination in detecting cuff dehiscence in asymptomatic women.

An unpredictable complication

Vaginal cuff dehiscence is a rare complication of hysterectomy that can occur days or decades after surgery, which makes “identifying an optimal time for cuff evaluation difficult,” Dr. Delara said. “Currently there is neither evidence demonstrating benefit of routine posthysterectomy examination in detecting vaginal cuff dehiscence, nor data demonstrating the best time to perform posthysterectomy examination.”

For their study, which was also published in the Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynecology, the researchers examined data from 2,051 women who underwent hysterectomy at a single institution during a 6-year period. Patients received at least one postoperative evaluation within 90 days of surgery. Examination of the vaginal cuff routinely was performed approximately 6 weeks after hysterectomy. Patients’ posthysterectomy symptoms and pelvic examination findings were recorded.

About 80% of patients were asymptomatic at the 6-week visit.

Asymptomatic patients were more likely to have normal pelvic examination findings, compared with patients with posthysterectomy symptoms (86.4% vs. 54.3%).

In all, 13 patients experienced complete cuff dehiscence. All of them had an intact vaginal cuff at their 6-week examination. Three had symptoms at that time, including vaginal bleeding in one patient and pelvic pain in two patients.

One patient experienced a complete cuff dehiscence that was provoked by intercourse prior to her examination. The patient subsequently developed two additional episodes of dehiscence provoked by intercourse.

Dehiscence may present differently after benign and oncologic hysterectomies, the study indicated.

Eight patients who experienced complete cuff dehiscence after benign hysterectomy had symptoms such as pelvic pain and vaginal bleeding at the time of presentation for dehiscence, which mainly occurred after intercourse.

Five patients who experienced dehiscence after oncologic hysterectomy were more likely to present without symptoms or provocation.

The median time to dehiscence after benign hysterectomy was about 19 weeks, whereas the median time to dehiscence after oncologic hysterectomy was about 81 weeks.

Surgeons should educate patients about symptoms of dehiscence and the potential for events such as coitus to provoke its occurrence, and patients should promptly seek evaluation if symptoms occur, Dr. Delara said.

Patients with risk factors such as malignancy may benefit from continued routine evaluation, she added.

Timely research

The findings may be especially relevant during the COVID-19 pandemic, when states have issued shelter-in-place orders and doctors have increased their use of telemedicine to reduce in-person visits, Dr. Delara noted.

In that sense, the study is “extremely timely” and may inform and support practice changes, commented Emad Mikhail, MD, in a discussion following the research presentation.

Whether the results generalize to other centers, including smaller centers that perform fewer surgeries, is unclear, said Dr. Mikhail, of the University of South Florida, Tampa.

“It takes vision and critical thinking to challenge these traditional practices,” he said. “I applaud Dr. Delara for challenging one of these.”

Dr. Delara and Dr. Mikhail had no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Delara RMM et al. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020 Nov 1. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2020.08.306.

FROM AAGL GLOBAL CONGRESS

Improving Primary Care Fall Risk Management: Adoption of Practice Changes After a Geriatric Mini-Fellowship

From the Senior Health Program, Providence Health & Services, Oregon, Portland, OR.

Abstract

Background: Approximately 51 million adults in the United States are 65 years of age or older, yet few geriatric-trained primary care providers (PCP) serve this population. The Age-Friendly Health System framework, consisting of evidence-based 4M care (Mobility, Medication, Mentation, and what Matters), encourages all PCPs to assess mobility in older adults.

Objective: To improve PCP knowledge, confidence, and clinical practice in assessing and managing fall risk.

Methods: A 1-week educational session focusing on mobility (part of a 4-week Geriatric Mini-Fellowship) for 6 selected PCPs from a large health care system was conducted to increase knowledge and ability to address fall risk in older adults. The week included learning and practicing a Fall Risk Management Plan (FRMP) algorithm, including planning for their own practice changes. Pre- and post-test surveys assessed changes in knowledge and confidence. Patient data were compared 12 months before and after training to evaluate PCP adoption of FRMP components.

Results: The training increased provider knowledge and confidence. The trained PCPs were 1.7 times more likely to screen for fall risk; 3.6 times more likely to discuss fall risk; and 5.8 times more likely to assess orthostatic blood pressure in their 65+ patients after the mini-fellowship. In high-risk patients, they were 4.1 times more likely to discuss fall risk and 6.3 times more likely to assess orthostatic blood pressure than their nontrained peers. Changes in physical therapy referral rates were not observed.

Conclusions: In-depth, skills-based geriatric educational sessions improved PCPs’ knowledge and confidence and also improved their fall risk management practices for their older patients.

Keywords: geriatrics; guidelines; Age-Friendly Health System; 4M; workforce training; practice change; fellowship.

The US population is aging rapidly. People aged 85 years and older are the largest-growing segment of the US population, and this segment is expected to increase by 123% by 2040.1 Caregiving needs increase with age as older adults develop more chronic conditions, such as hypertension, heart disease, arthritis, and dementia. However, even with increasing morbidity and dependence, a majority of older adults still live in the community rather than in institutional settings.2 These older adults seek medical care more frequently than younger people, with about 22% of patients 75 years and older having 10 or more health care visits in the previous 12 months. By 2040, nearly a quarter of the US population is expected to be 65 or older, with many of these older adults seeking regular primary care from providers who do not have formal training in the care of a population with multiple complex, chronic health conditions and increased caregiving needs.1

Despite this growing demand for health care professionals trained in the care of older adults, access to these types of clinicians is limited. In 2018, there were roughly 7000 certified geriatricians, with only 3600 of them practicing full-time.3,4 Similarly, of 290,000 certified nurse practitioners (NPs), about 9% of them have geriatric certification.5 Geriatricians, medical doctors trained in the care of older adults, and geriatric-trained NPs are part of a cadre of a geriatric-trained workforce that provides unique expertise in caring for older adults with chronic and advanced illness. They know how to manage multiple, complex geriatric syndromes like falls, dementia, and polypharmacy; understand and maximize team-based care; and focus on caring for an older person with a goal-centered versus a disease-centered approach.6

Broadly, geriatric care includes a spectrum of adults, from those who are aging healthfully to those who are the frailest. Research has suggested that approximately 30% of older adults need care by a geriatric-trained clinician, with the oldest and frailest patients needing more clinician time for assessment and treatment, care coordination, and coaching of caregivers.7 With this assumption in mind, it is projected that by 2025, there will be a national shortage of 26,980 geriatricians, with the western United States disproportionately affected by this shortage.4Rather than lamenting this shortage, Tinetti recommends a new path forward: “Our mission should not be to train enough geriatricians to provide direct care, but rather to ensure that every clinician caring for older adults is competent in geriatric principles and practices.”8 Sometimes called ”geriatricizing,” the idea is to use existing geriatric providers as a small elite training force to infuse geriatric principles and skills across their colleagues in primary care and other disciplines.8,9 Efforts of the American Geriatrics Society (AGS), with support from the John A. Hartford Foundation (JAHF), have been successful in developing geriatric training across multiple specialties, including surgery, orthopedics, and emergency medicine (www.americangeriatrics.org/programs/geriatrics-specialists-initiative).

The Age-Friendly Health System and 4M Model

To help augment this idea of equipping health care systems and their clinicians with more readily available geriatric knowledge, skills, and tools, the JAHF, along with the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI), created the Age-Friendly Health System (AFHS) paradigm in 2015.10 Using the 4M model, the AFHS initiative established a set of evidence-based geriatric priorities and interventions meant to improve the care of older adults, reduce harm and duplication, and provide a framework for engaging leadership, clinical teams, and operational systems across inpatient and ambulatory settings.11 Mobility, including fall risk screening and intervention, is 1 of the 4M foundational elements of the Age-Friendly model. In addition to Mobility, the 4M model also includes 3 other key geriatric domains: Mentation (dementia, depression, and delirium), Medication (high-risk medications, polypharmacy, and deprescribing), and What Matters (goals of care conversations and understanding quality of life for older patients).11 The 4M initiative encourages adoption of a geriatric lens that looks across chronic conditions and accounts for the interplay among geriatric syndromes, such as falls, cognitive impairment, and frailty, in order to provide care better tailored to what the patient needs and desires.12 IHI and JAHF have targeted the adoption of the 4M model by 20% of US health care systems by 2020.11

Mini-Fellowship and Mobility Week

To bolster geriatric skills among community-based primary care providers (PCPs), we initiated a Geriatric Mini-Fellowship, a 4-week condensed curriculum taught over 6 months. Each week focuses on 1 of the age-friendly 4Ms, with the goal of increasing the knowledge, self-efficacy, skills, and competencies of the participating PCPs (called “fellow” hereafter) and at the same time, equipping each to become a champion of geriatric practice. This article focuses on the Mobility week, the second week of the mini-fellowship, and the effect of the week on the fellows’ practice changes.

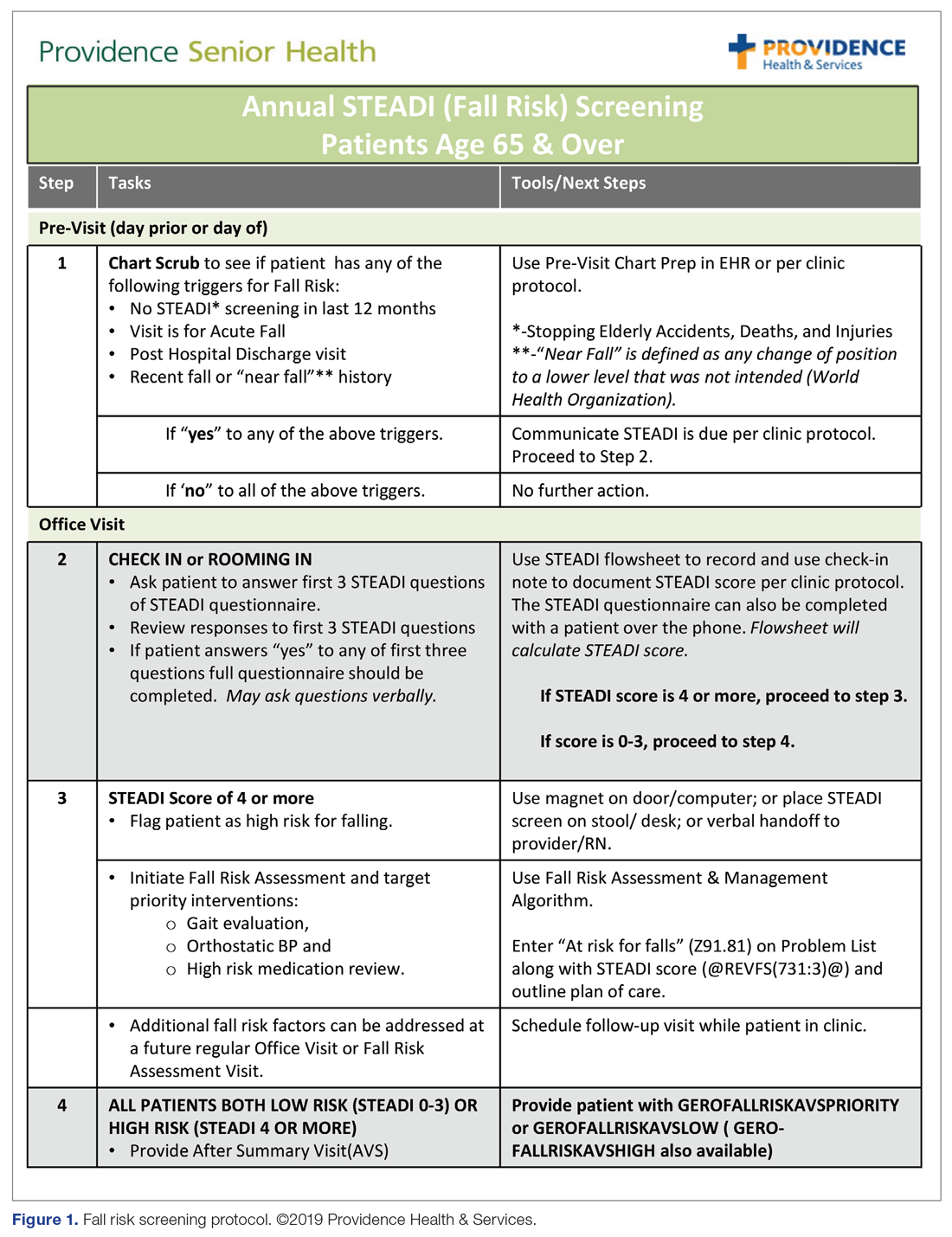

To construct the Mobility week’s curriculum with a focus on the ambulatory setting, we relied upon national evidence-based work in fall risk management. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has made fall risk screening and management in primary care a high priority. Using the clinical practice guidelines for managing fall risk developed by the American and British Geriatrics Societies (AGS/BGS), the CDC developed the Stopping Elderly Accidents, Deaths, and Injuries (STEADI) toolkit.13 Foundational to the toolkit is the validated 12-item Stay Independent falls screening questionnaire (STEADI questionnaire).14 Patients who score 4 or higher (out of a total score of 14) on the questionnaire are considered at increased risk of falling. The CDC has developed a clinical algorithm that guides clinical teams through screening and assessment to help identify appropriate interventions to target specific risk factors. Research has clearly established that a multifactorial approach to fall risk intervention can be successful in reducing fall risk by as much as 25%.15-17

The significant morbidity and mortality caused by falls make training nongeriatrician clinicians on how to better address fall risk imperative. More than 25% of older adults fall each year.18 These falls contribute to rising rates of fall-related deaths,19 emergency department (ED) visits,20 and hospital readmissions.21 Initiatives like the AFHS focus on mobility and the CDC’s development of supporting clinical materials22 aim to improve primary care adoption of fall risk screening and intervention practices.23,24 The epidemic of falls must compel all PCPs, not just those practicing geriatrics, to make discussing and addressing fall risk and falls a priority.

Methods

Setting

This project took place as part of a regional primary care effort in Oregon. Providence Health & Services-Oregon is part of a multi-state integrated health care system in the western United States whose PCPs serve more than 80,000 patients aged 65 years and older per year; these patients comprise 38% of the system’s office visits each year. Regionally, there are 47 family and internal medicine clinics employing roughly 290 providers (physicians, NPs, and physician assistants). The organization has only 4 PCPs trained in geriatrics and does not offer any geriatric clinical consultation services. Six PCPs from different clinics, representing both rural and urban settings, are chosen to participate in the geriatric mini-fellowship each year.

This project was conducted as a quality improvement initiative within the organization and did not constitute human subjects research. It was not conducted under the oversight of the Institutional Review Board.

Intervention

The mini-fellowship was taught in 4 1-week blocks between April and October 2018, with a curriculum designed to be interactive and practical. The faculty was intentionally interdisciplinary to teach and model team-based practice. Each week participants were excused from their clinical practice. Approximately 160 hours of continuing medical education credits were awarded for the full mini-fellowship. As part of each weekly session, a performance improvement project (PIP) focused on that week’s topic (1 of the 4Ms) was developed by the fellow and their team members to incorporate the mini-fellowship learnings into their clinic workflows. Fellows also had 2 hours per week of dedicated administration time for a year, outside the fellowship, to work on their PIP and 4M practice changes within their clinic.

Provider Education

The week for mobility training comprised 4 daylong sessions. The first 2 days were spent learning about the epidemiology of falls; risk factors for falling; how to conduct a thorough history and assessment of fall risk; and how to create a prioritized Fall Risk Management Plan (FRMP) to decrease a patient’s individual fall risk through tailored interventions. The FRMP was adapted from the CDC STEADI toolkit.13 Core faculty were 2 geriatric-trained providers (NP and physician) and a physical therapist (PT) specializing in fall prevention.

On the third day, fellows took part in a simulated fall risk clinic, in which older adults volunteered to be patient partners, providing an opportunity to apply learnings from days 1 and 2. The clinic included the fellow observing a PT complete a mobility assessment and a pharmacist conduct a high-risk medication review. The fellow synthesized the findings of the mobility assessment and medication review, as well as their own history and assessment, to create a summary of fall risk recommendations to discuss with their volunteer patient partner. The fellows were observed and evaluated in their skills by their patient partner, course faculty, and another fellow. The patient partners, and their assigned fellow, also participated in a 45-minute fall risk presentation, led by a nurse.

On the fourth day, the fellows were joined by select clinic partners, including nurses, pharmacists, and/or medical assistants. The session included discussions among each fellow’s clinical team regarding the current state of fall risk efforts at their clinic, an analysis of barriers, and identification of opportunities to improve workflows and screening rates. Each fellow took with them an action plan tailored to their clinic to improve fall risk management practices, starting with the fellow’s own practice.

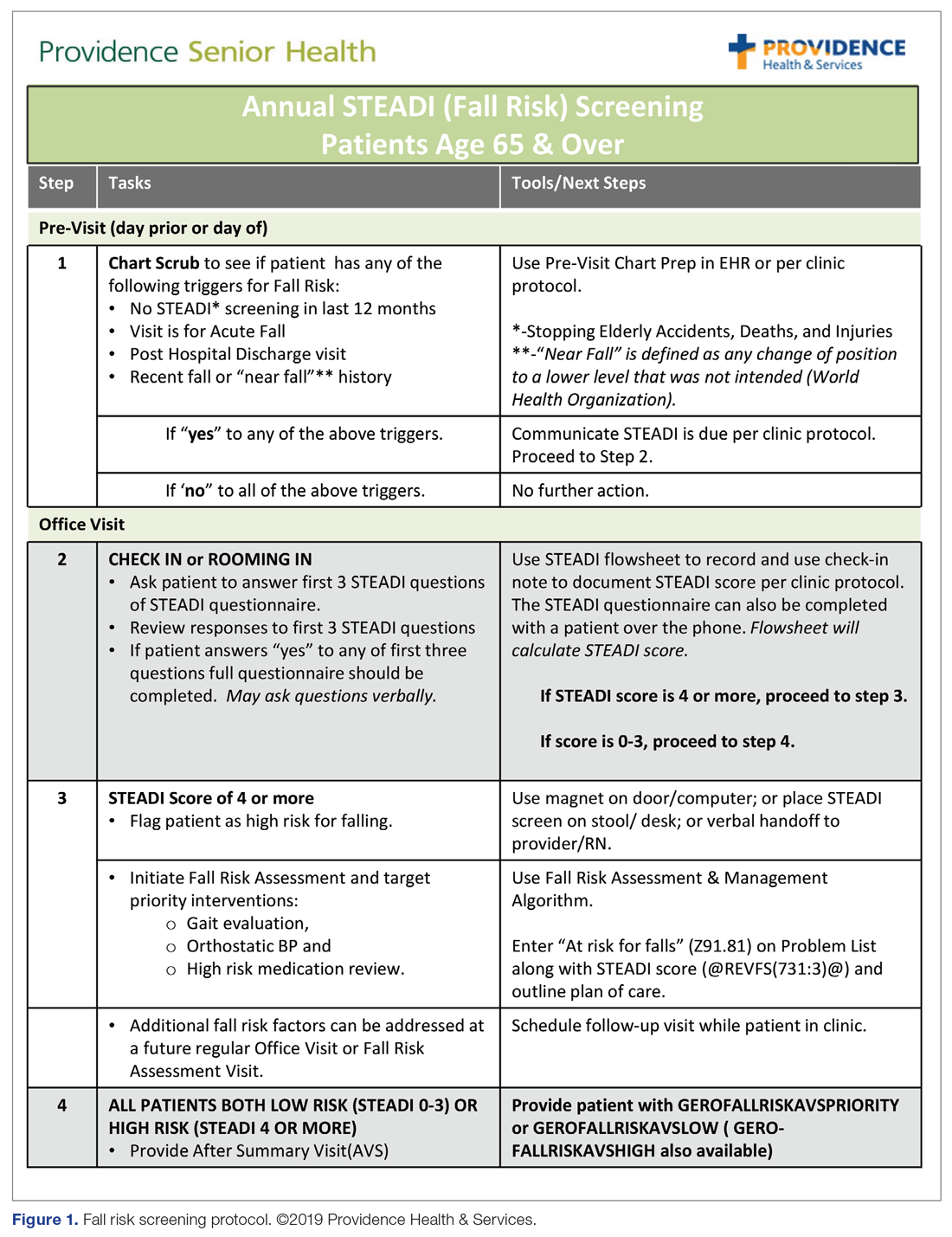

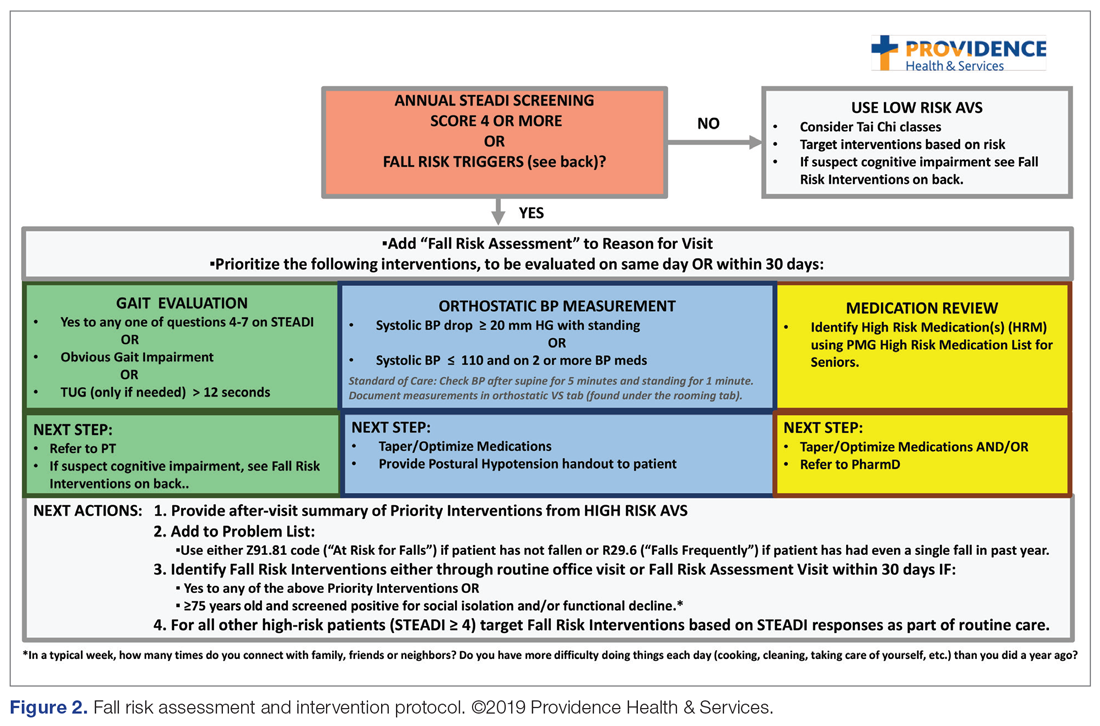

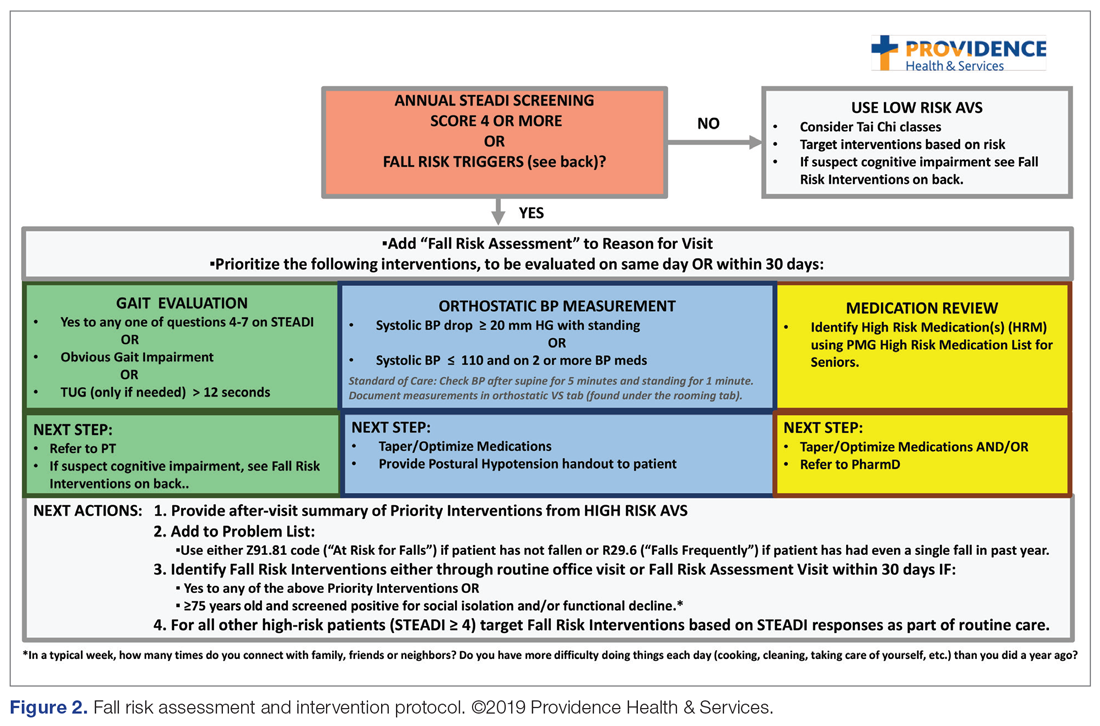

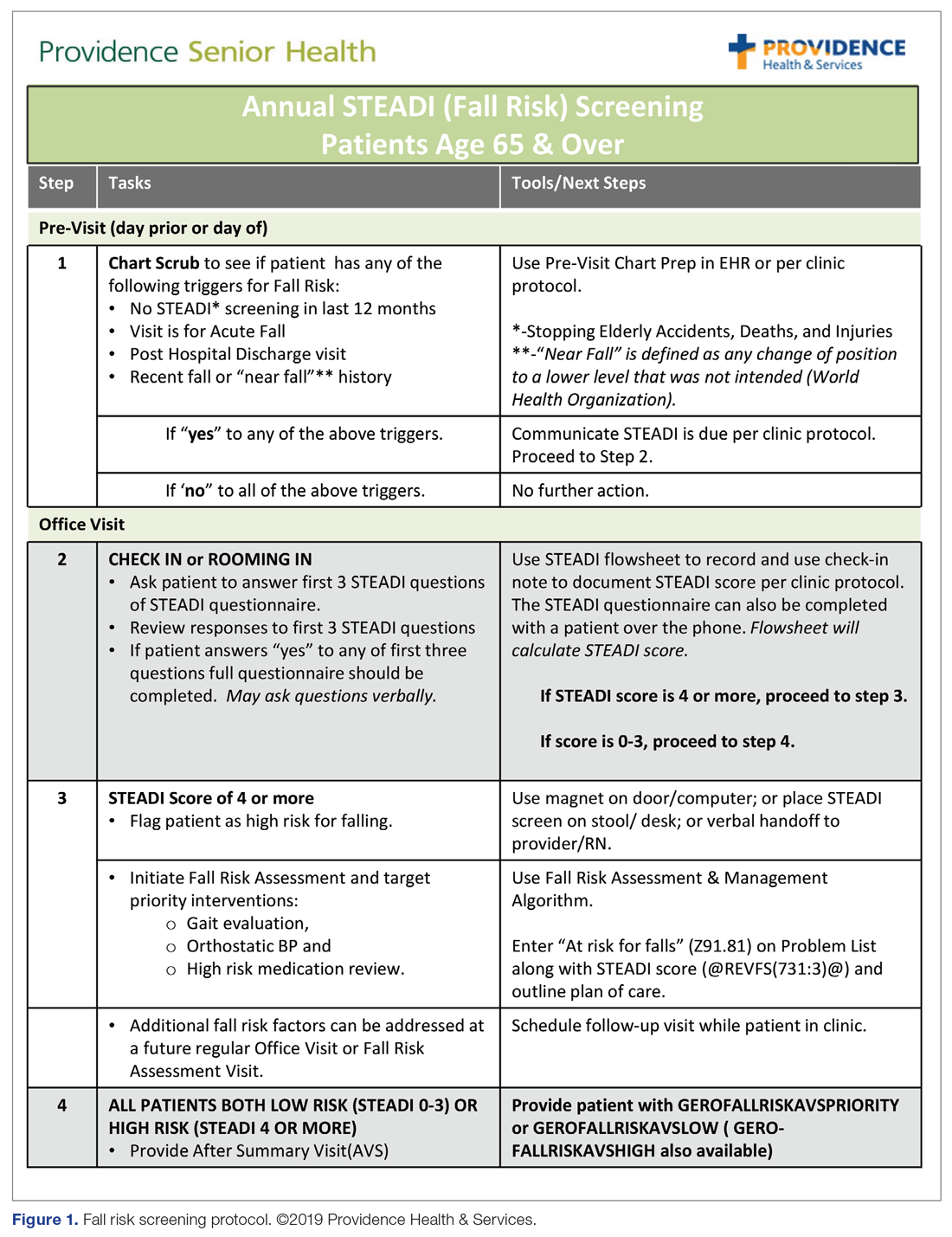

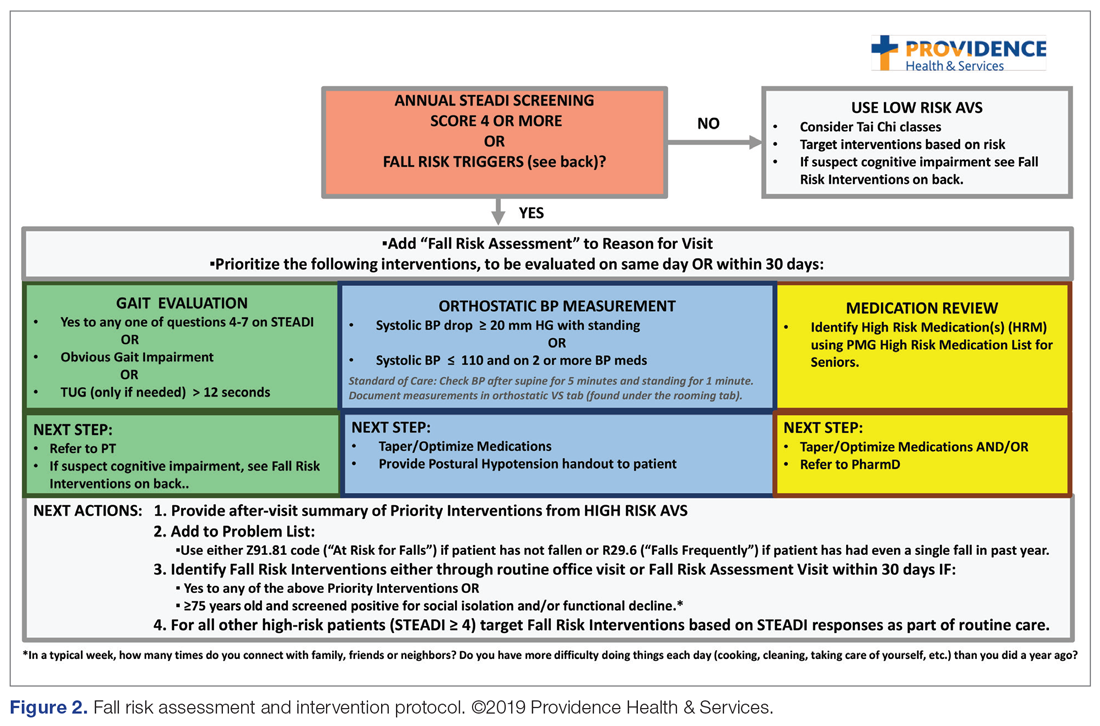

Fall Risk Management Plan

The educational sessions introduced the fellows to the FRMP. The FRMP, adapted from the STEADI toolkit, includes a process for fall risk screening (Figure 1) and stratifying a patient’s risk based on their STEADI score in order to promote 3 priority assessments (gait evaluation with PT referral if appropriate; orthostatic blood pressure; and high-risk medication review; Figure 2). Initial actions based on these priority assessments were followed over time, with additional fall risk interventions added as clinically indicated.25 The FRMP is intended to be used during routine office visits, Medicare annual wellness visits, or office visits focused on fall risk or related medical disorders (ie, fall risk visits.)

Providers and their teams were encouraged to spread out fall-related conversations with their patients over multiple visits, since many patients have multiple fall risk factors at play, in addition to other chronic medical issues, and since many interventions often require behavior changes on the part of the patient. Providers also had access to fall-related electronic health record (EHR) templates as well as a comprehensive, internal fall risk management website that included assessment tools, evidence-based resources, and patient handouts.

Assessment and Measurements

We assessed provider knowledge and comfort in their fall risk evaluation and management skills before and after the educational intervention using an 11-item multiple-choice questionnaire and a 4-item confidence questionnaire. The confidence questions used a 7-point Likert scale, with 0 indicating “no confidence” and 7 indicating ”lots of confidence.” The questions were administered via a paper survey. Qualitative comments were derived from evaluations completed at the end of the week.

The fellows’ practice of fall risk screening and management was studied from May 2018, at the completion of Mobility week, to May 2019 for the post-intervention period. A 1-year timeframe before May 2018 was used as the pre-intervention period. Eligible visit types, during which we assumed fall risk was discussed, were any office visits for patients 65+ completed by the patients’ PCPs that used fall risk as a reason for the visit or had a fall-related diagnosis code. Fall risk visits performed by other clinic providers were not counted.

Of those patients who had fall risk screenings completed and were determined to be high risk (STEADI score ≥ 4), data were analyzed to determine whether these patients had any fall-related follow-up visits to their PCP within 60 days of the STEADI screening. For these high-risk patients, data were studied to understand whether orthostatic blood pressure measurements were performed (as documented in a flowsheet) and whether a PT referral was placed. These data were compared with those from providers who practiced in clinics within the same system but who did not participate in the mini-fellowship. Data were obtained from the organization’s EHR. Additional data were measured to evaluate patterns of deprescribing of select high-risk medications, but these data are not included in this analysis.

Analysis

A paired-samples t test was used to measure changes in provider confidence levels. Data were aggregated across fellows, resulting in a mean. A chi-square test of independence was performed to examine the relationship between rates of FRMP adoption by select provider groups. Analysis included a pre- and post-intervention assessment of the fellows’ adoption of FRMP practices, as well as a comparison between the fellows’ practice patterns and those of a control group of PCPs in the organization’s other clinics who did not participate in the mini-fellowship (nontrained control group). Excluded from the control group were providers from the same clinic as the fellows; providers in clinics with a geriatric-trained provider on staff; and clinics outside of the Portland metro and Medford service areas. We used an alpha level of 0.05 for all statistical tests.

Data from 5 providers were included in the analysis of the FRMP adoption. The sixth provider changed practice settings from the clinic to the ED after completing the fellowship; her patient data were not included in the FRMP part of the analysis. EHR data included data on all visits of patients 65+, as well as data for just those 65+ patients who had been identified as being at high risk to fall based on a STEADI score of 4 or higher.

Results

Provider Questionnaire

All 6 providers responded to the pre-intervention and post-intervention tests. For the knowledge questions, fellows, as a composite, correctly answered 57% of the questions before the intervention and 79% after the intervention. Provider confidence level in delivering fall risk care was measured prior to the training (mean, 4.12 [SD, 0.62]) and at the end of the training (mean, 6.47 [SD, 0.45]), demonstrating a significant increase in confidence (t (5) = –10.46, P < 0.001).

Qualitative Comments

Providers also had the opportunity to provide comments on their experience during the Mobility week and at the end of 1 year. In general, the simulated interdisciplinary fall risk clinic was highly rated (“the highlight of the week”) as a practical strategy to embed learning principles. One fellow commented, “Putting the learning into practice helps solidify it in my brain.” Fellows also appreciated the opportunity to learn and meet with their clinic colleagues to begin work on a fall-risk focused PIP and to “have a framework for what to do for people who screen positive [for fall risk].”

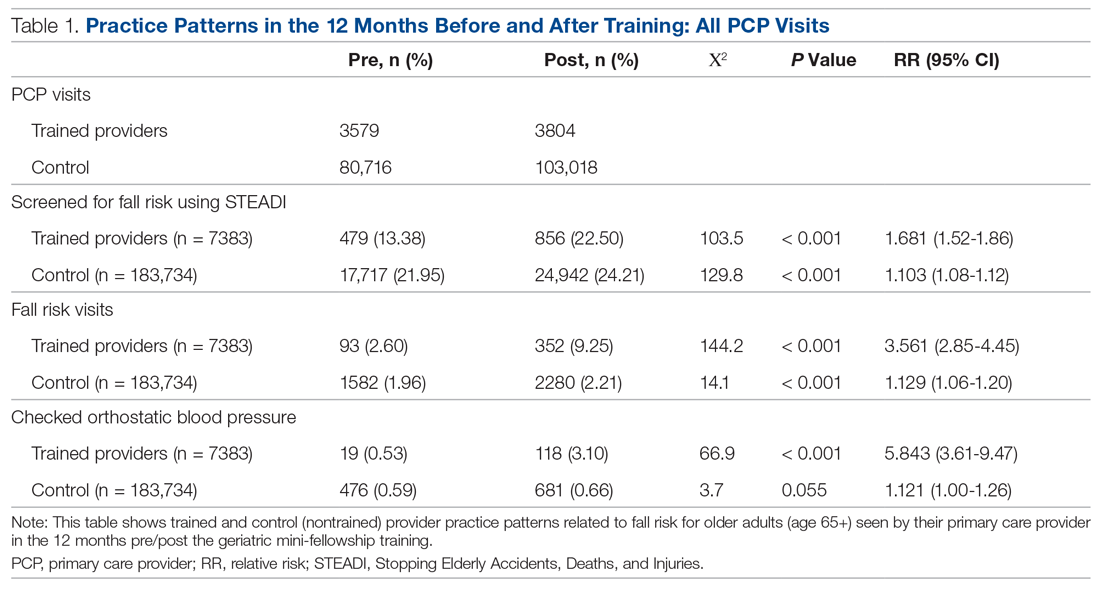

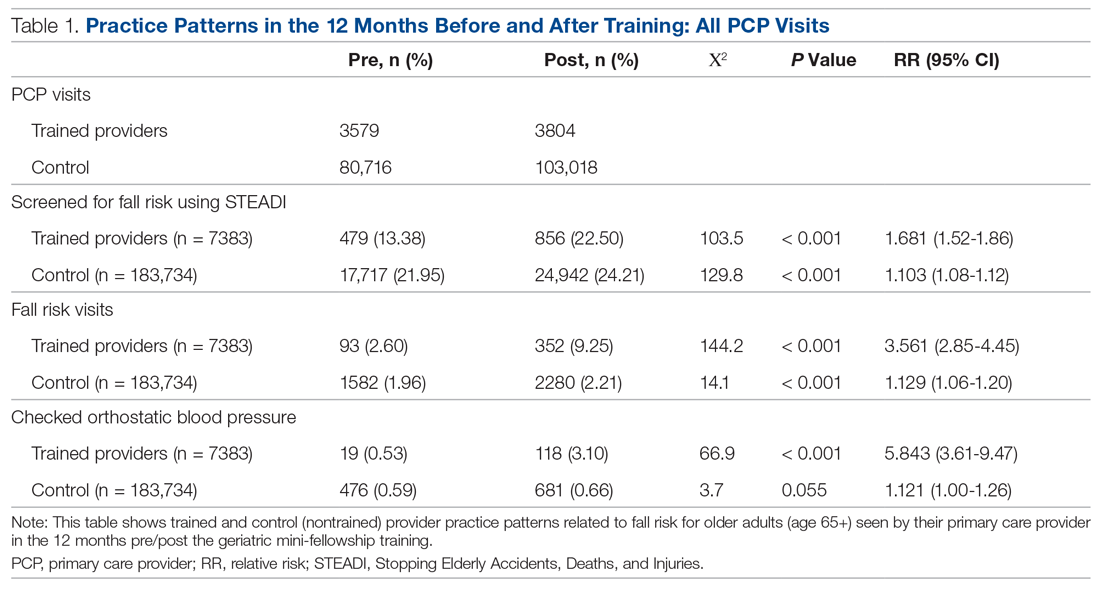

FRMP Adoption

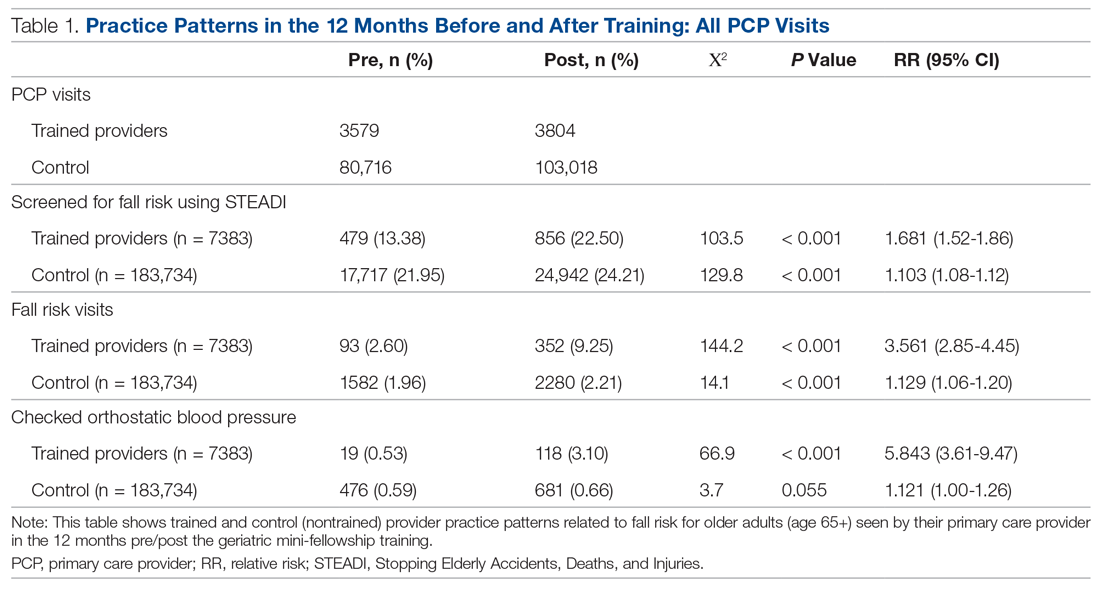

A comparison of the care the fellows provided to their patients 65+ in the 12 months pre- and post-training shows the fellows demonstrated significant changes in practice patterns. The fellows were 1.7 times more likely to screen for fall risk; 3.6 times more likely to discuss fall risk; and 5.8 times more likely to check orthostatic blood pressure than prior to the mini-fellowship (Table 1).

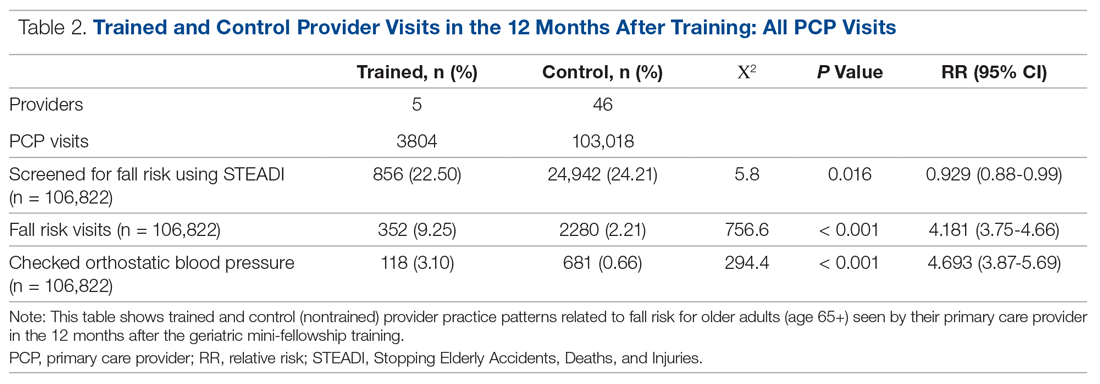

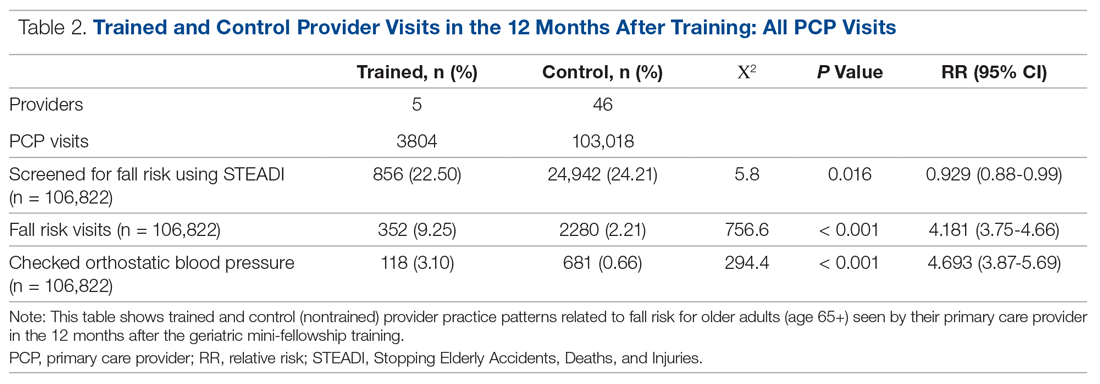

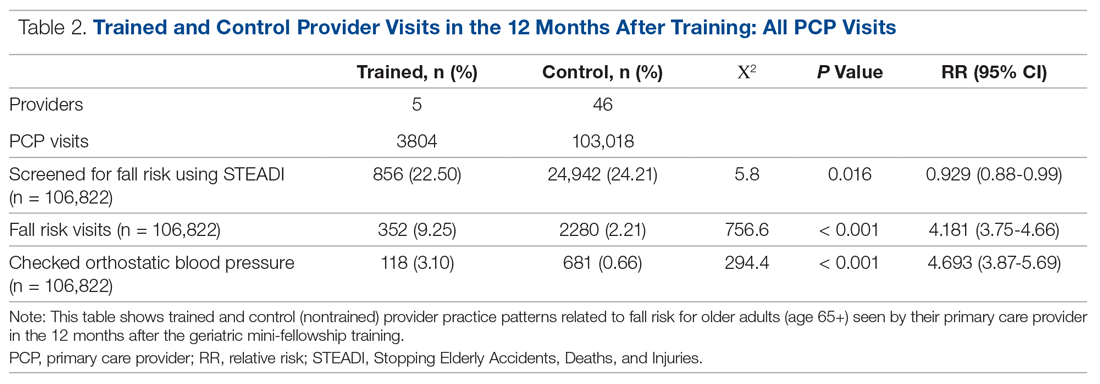

The control providers also demonstrated significant increases in fall risk screening and discussion of fall risk between the pre- and post-intervention periods; however, the relative risk (RR) was between 1.10 and 1.13 for this group. For the control group, checking orthostatic blood pressure did not significantly change. In the 12 months after training (Table 2), the fellows were 4.2 times more likely to discuss fall risk and almost 5 times more likely to check orthostatic blood pressure than their nontrained peers for all of their patients 65+, regardless of their risk to fall.

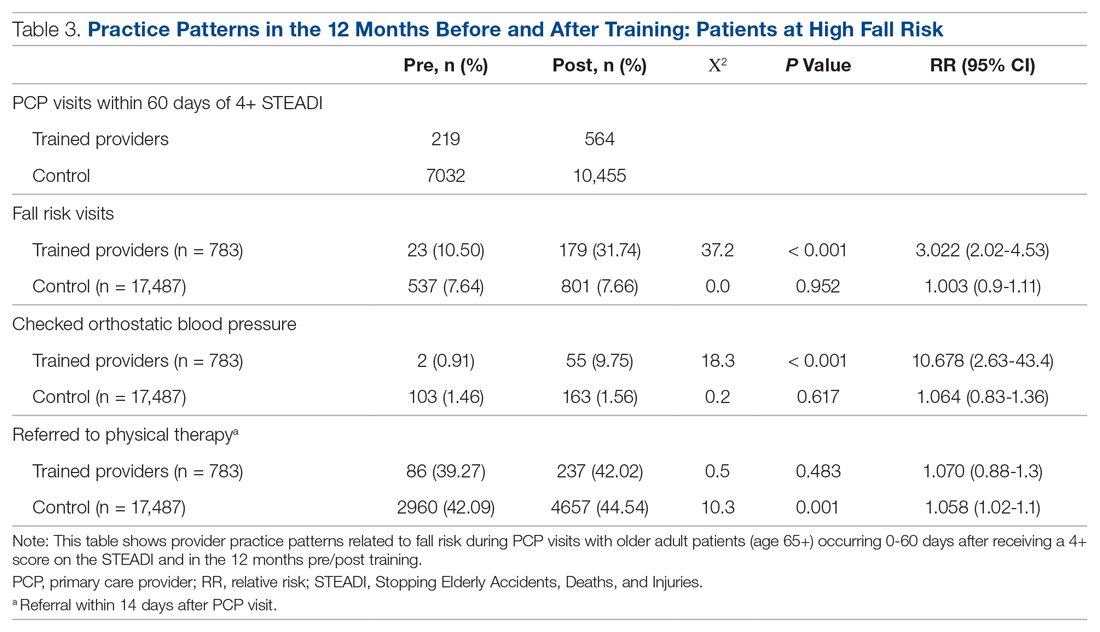

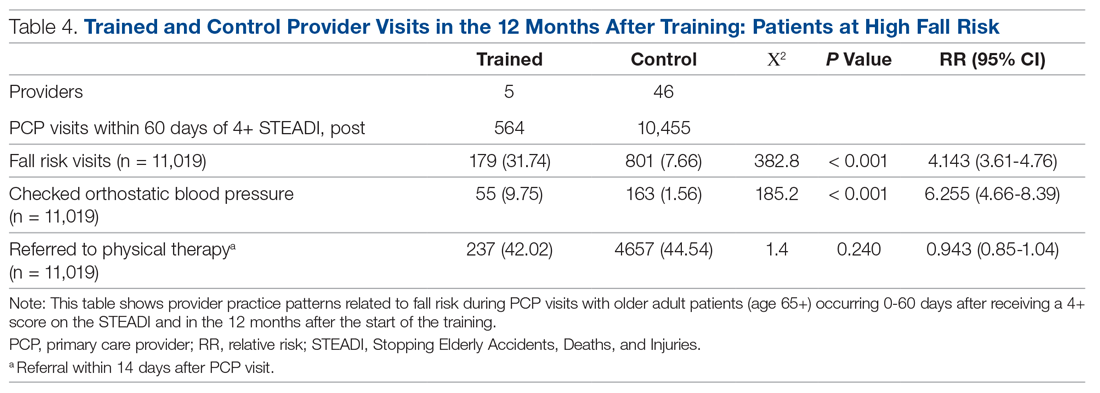

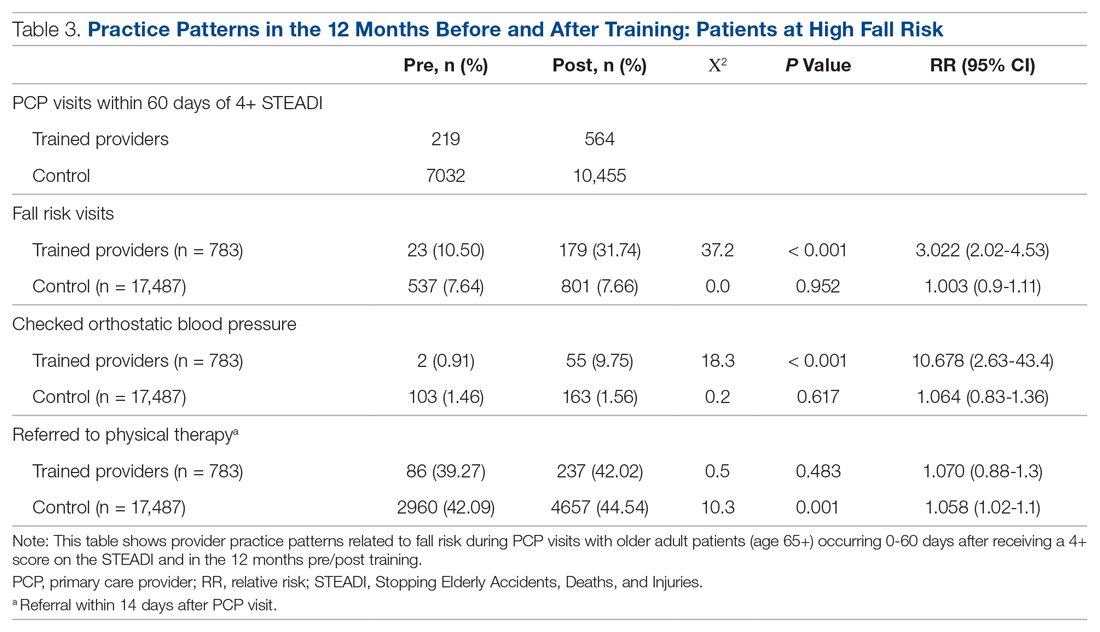

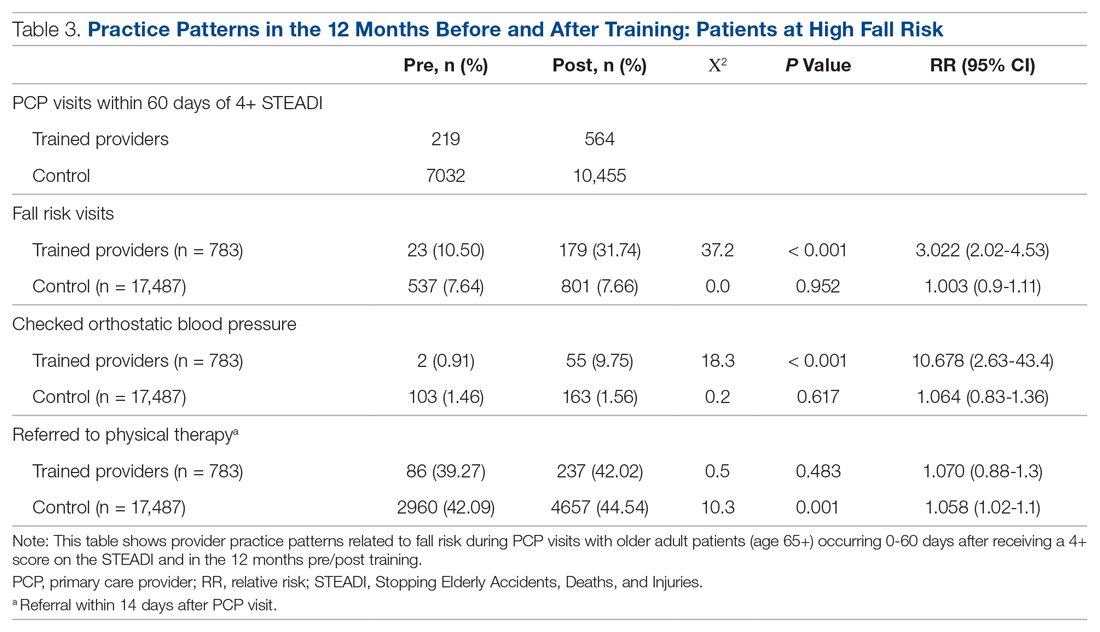

As shown in Table 3, for those patients determined to be at high risk of falling (STEADI score ≥ 4), fellows showed statistically significant increases in fall risk visits (RR, 3.02) and assessment of orthostatic blood pressure (RR, 10.68) before and after the mini-fellowship. The control providers did not show any changes in practice patterns between the pre- and post-period among patients at high risk to fall.

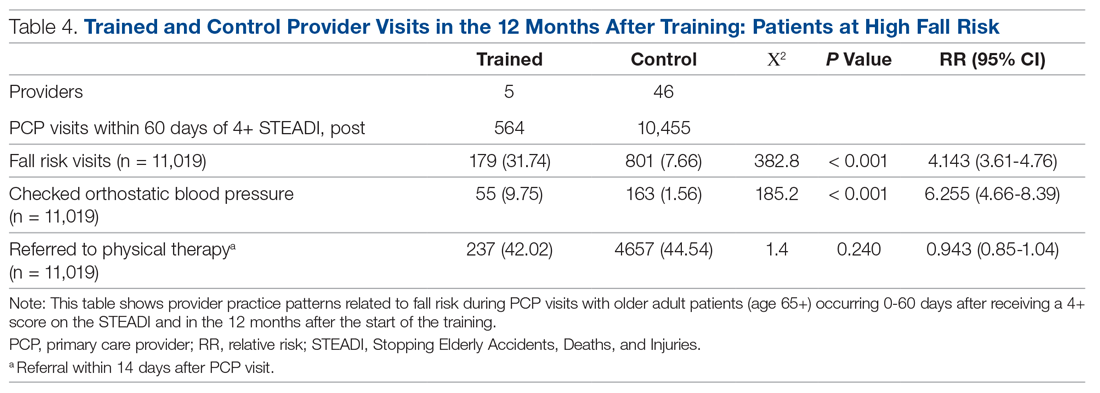

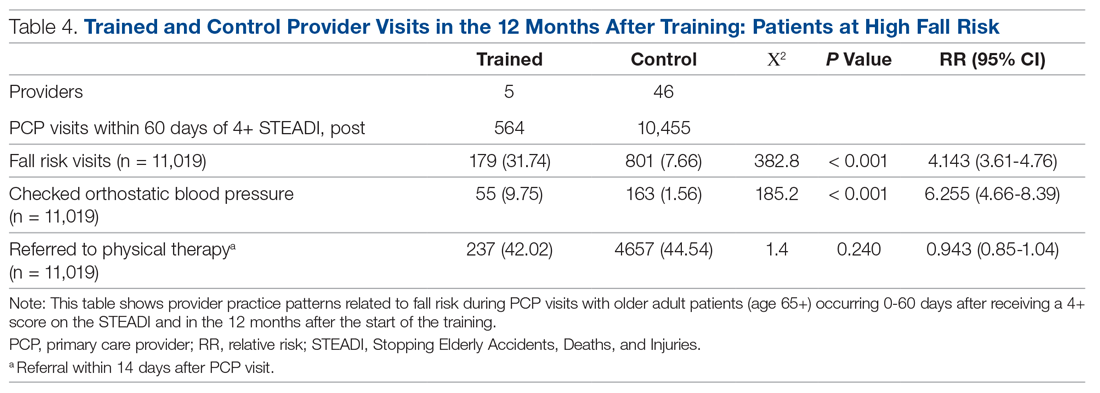

Neither the fellows nor the control group showed changes in patterns of referral to PT. In comparing the 2 groups in the 12 months after training (Table 4), for their patients at risk of falling, the fellows were 4 times more likely to complete fall risk visits and over 6 times more likely to assess orthostatic blood pressure than their nontrained peers. Subgroup analysis of the 75+ population revealed similar trends and significance, but these results are not included here.

Discussion

This study aimed to improve not only providers’ knowledge and confidence in caring for older adults at increased risk to fall, but also their clinical practice in assessing and managing fall risk. In addition to improved knowledge and confidence, we found that the fellows increased their discussion of fall risk (through fall risk visits) and their assessment of orthostatic blood pressure for all of their patients, not just for those identified at increased risk to fall. This improvement held true for the fellows themselves before and after the intervention, but also as compared to their nontrained peers. These practice improvements for all of their 65+ patients, not just those identified as being at high risk to fall, are especially important, since studies indicate that early screening and intervention can help identify people at risk and prevent future falls.15

We were surprised that there were no significant differences in PT referrals made by the trained fellows, but this finding may have been confounded by the fact that the data included all PT referrals, regardless of diagnosis, not just those referrals that were fall-related. Furthermore, our baseline PT referral rates, at 39% for the intervention group and 42% for the control group, are higher than national data when looking at rehabilitation use by older adults.26

In comparison to a study evaluating the occurrence of fall risk–related clinical practice in primary care before any fall-related educational intervention, orthostatics were checked less frequently in our study (10% versus 30%) and there were fewer PT referrals (42%–44% versus 53%).27 However, the Phelan study took place in patients who had actually had a fall, rather than just having a higher risk for a fall, and was based on detailed chart review. Other studies23,24 found higher rates of fall risk interventions, but did not break out PT referrals specifically.

In terms of the educational intervention itself, most studies of geriatric education interventions have measured changes in knowledge, confidence, or self-efficacy as they relate to geriatric competence,28-30 and do not measure practice change as an outcome outside of intent to change or self-reported practice change.31,32 In general, practice change or longer-term health care–related outcomes have not been studied. Additionally, a range of dosages of educational interventions has been studied, from 1-hour lunchtime presentations23,32 to half-day29 or several half-day workshops,28 up to 160 hours over 10 months30 or 5 weekends over 6 months.31 The duration of our entire intervention at 160 hours over 6 months would be considered on the upper end of dosing relative to these studies, with our Mobility week intervention comprising 32 hours during 1 week. In the Warshaw study, despite 107 1-hour sessions being taught to over 60 physicians in 16 practices over 4 years, only 2 practices ultimately initiated any practice change projects.32 We believe that only curricula that embed practice change skills and opportunities, at a significant enough dose, can actually impact practice change in a sustainable manner.

Knowledge and skill acquisition among individual providers does not take place to a sufficient degree in the current health care arena, which is focused on productivity and short visit times. Consistent with other studies, we included interdisciplinary members of the primary care team for part of the mini-fellowship, although other studies used models that train across disciplines for the entirety of the learning experience.28-30,33 Our educational model was strengthened by including other professionals to provide some of the education and model the ideal geriatric team, including PT, occupational therapy, and pharmacy, for the week on mobility.

Most studies exploring interventions through geriatric educational initiatives are conducted within academic institutions, with a primary focus on physician faculty and, by extension, their teaching of residents and others.34,35 We believe our integrated model, which is steeped in community-based primary care practices like Lam’s,31 offers the greatest outreach to large community-based care systems and their patients. Training providers to work with their teams to change their own practices first gives skills and expertise that help further establish them as geriatric champions within their practices, laying the groundwork for more widespread practice change at their clinics.

Limitations

In addition to the limitations described above relating to the capture of PT referrals, other limitations included the relatively short time period for follow-up data as well as the small size of the intervention group. However, we found value in the instructional depth that the small group size allowed.

While the nontrained providers did show some improvement during the same period, we believe the relative risk was not clinically significant. We suspect that the larger health system efforts to standardize screening of patients 65+ across all clinics as a core quality metric confounded these results. The data analysis also included only fall-related patient visits that occurred with a provider who was that patient’s PCP, which could have missed visits done by other PCP colleagues, RNs, or pharmacists in the same clinic, thus undercounting the true number of fall-related visits. Furthermore, counting of fall-related interventions relied upon providers documenting consistently in the EHR, which could also lead to under-represention of fall risk clinical efforts.

The data presented, while encouraging, do not reflect clinic-wide practice change patterns and are considered only proximate outcomes rather than more long-term or cost-related outcomes, as would be captured by fall-related utilization measures like emergency room visits and hospitalizations. We expect to evaluate the broader impact and these value-based outcomes in the future. All providers and teams were from the same health care system, which may not allow our results to transfer to other organizations or regions of clinical practice.

Summary

This study demonstrates that an intensive mini-fellowship model of geriatrics training improved both knowledge and confidence in the realm of fall risk assessment and intervention among PCPs who had not been formally trained in geriatrics. More importantly, the training improved the fall-related care of their patients at increased risk to fall, but also of all of their older patients, with improvements in care measured up to a year after the mini-fellowship. Although this article only describes the work done as part of the Mobility aim of the 4M AFHS model, we believe the entire mini-fellowship curriculum offers the opportunity to “geriatricize” clinicians and their teams in learning geriatric principles and skills that they can translate into their practice in a sustainable way, as Tinetti encourages.8 Future study to evaluate other process outcomes more precisely, such as PT, as well as cost- and value-based outcomes, and the influence of trained providers on their clinic partners, will further establish the value proposition of targeted, disseminated, intensive geriatrics training of primary care clinicians as a strategy of age-friendly health systems as they work to improve the care of their older adults.

Acknowledgment: We are grateful for the dedication and hard work of the 2018 Geriatric Mini-Fellowship fellows at Providence Health & Services-Oregon who made this article possible. Thanks to Drs. Stephanie Cha, Emily Puukka-Clark, Laurie Dutkiewicz, Cara Ellis, Deb Frost, Jordan Roth, and Subhechchha Shah for promoting the AFHS work within their Providence Medical Group clinics and to PMG leadership and the fellows’ clinical teams for supporting the fellows, the AFHS work, and their older patients.

Corresponding author: Colleen M. Casey, PhD, ANP-BC, Providence Health & Services, Senior Health Program, 4400 NE Halsey, 5th Floor, Portland, OR 97213; [email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

1. US Department of Health and Human Services. 2018 Profile of Older Americans. Administration on Aging. April 2018.

2. Roberts AW, Ogunwole SU, Blakeslee L, Rabe MA. The population 65 years and older in the United States: 2016. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; 2018.

3. American Board of Medicine Specialties. 2017-2018 ABMS Board Certification Report. https://www.abms.org/board-certification/abms-board-certification-report/. Accessed November 3, 2020.

4. US Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, National Center for Health Workforce Analysis. National and regional projections of supply and demand for geriatricians: 2013-2025. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2007.

5. American Association of Nurse Practitioners, NP Facts: The Voice of the Nurse Practitioner. 2020. https://storage.aanp.org/www/documents/NPFacts__080420.pdf.

6. Tinetti ME, Naik AD, Dodson JA, Moving from disease-centered to patient goals-directed care for patients with multiple chronic conditions: patient value-based care. JAMA Cardiol. 2016;1:9-10.

7. Fried LP, Hall WJ. Editorial: leading on behalf of an aging society. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:1791-1795.

8. Tinetti M. Mainstream or extinction: can defining who we are save geriatrics? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64:1400-1404.

9. Jafari P, Kostas T, Levine S, et al. ECHO-Chicago Geriatrics: using telementoring to “geriatricize” the primary care workforce. Gerontol Geriatr Educ. 2020;41:333-341.

10. Fulmer T, Mate KS, Berman A. The Age-Friendly Health System imperative. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66:22-24.

11. Mate KS, Berman A, Laderman M, et al. Creating Age-Friendly Health Systems - A vision for better care of older adults. Healthc (Amst). 2018;6:4-6.

12. Tinetti ME, et al. Patient priority-directed decision making and care for older adults with multiple chronic conditions. Clin Geriatr Med. 2016;32:261-275.

13. Stevens JA, Phelan EA. Development of STEADI: a fall prevention resource for health care providers. Health Promot Pract. 2013;14:706-714.

14. Rubenstein LZ, et al. Validating an evidence-based, self-rated fall risk questionnaire (FRQ) for older adults. J Safety Res. 2011;42:493-499.

15. Grossman DC, et al. Interventions to prevent falls in community-dwelling older adults: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2018;319: 1696-1704.

16. Tricco AC, Thomas SM, Veroniki AA, et al. Comparisons of interventions for preventing falls in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2017;318:1687-1699.

17. Gillespie LD, Robertson MC, Gillespie WJ, et al. Interventions for preventing falls in older people living in the community. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012(9):CD007146.

18. Bergen G, Stevens MR, Burns ER. Falls and fall injuries among adults aged ≥65 years - United States, 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:993-998.

19. Burns E, Kakara R. Deaths from falls among persons aged >=65 Years - United States, 2007-2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:509-514.

20. Shankar KN, Liu SW, Ganz DA. Trends and characteristics of emergency department visits for fall-related injuries in older adults, 2003-2010. West J Emerg Med. 2017;18:785-793.

21. Hoffman GJ, et al. Posthospital fall injuries and 30-day readmissions in adults 65 years and older. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2:e194276.

22. Eckstrom E, Parker EM, Shakya I, Lee R. Coordinated care plan to prevent older adult falls. 2018. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2018.

23. Eckstrom E, Parker EM, Lambert GH, et al. Implementing STEADI in academic primary care to address older adult fall risk. Innov Aging. 2017;1:igx028.

24. Johnston YA, Bergen G, Bauer M, et al. Implementation of the stopping elderly accidents, deaths, and injuries initiative in primary care: an outcome evaluation. Gerontologist. 2019;59:1182-1191.

25. Phelan EA, Mahoney JE, Voit JC, Stevens JA. Assessment and management of fall risk in primary care settings. Med Clin North Am. 2015;99:281-293.

26. Gell NM, Mroz TM, Patel KV. Rehabilitation services use and patient-reported outcomes among older adults in the United States. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2017;98:2221-2227.e3.

27. Phelan EA, Aerts S, Dowler D, et al. Adoption of evidence-based fall prevention practices in primary care for older adults with a history of falls. Front Public Health. 2016;4:190.

28. Solberg LB, Carter CS, Solberg LM. Geriatric care boot camp series: interprofessional education for a new training paradigm. Geriatr Nurs. 2019;40:579-583.

29. Solberg LB, Solberg LM, Carter CS. Geriatric care boot cAMP: an interprofessional education program for healthcare professionals. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63:997-1001.

30. Coogle CL, Hackett L, Owens MG, et al. Perceived self-efficacy gains following an interprofessional faculty development programme in geriatrics education. J Interprof Care. 2016;30:483-492.

31. Lam R, Lee L, Tazkarji B, et al. Five-weekend care of the elderly certificate course: continuing professional development activity for family physicians. Can Fam Physician. 2015;61:e135-141.

32. Warshaw GA, Modawal A, Kues J, et al. Community physician education in geriatrics: applying the assessing care of vulnerable elders model with a multisite primary care group. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58:1780-1785.