User login

COVID-19 cases in children continue to set records

As far as the pandemic is concerned, it seems like a pretty small thing. A difference of just 0.3%. Children now represent 11.8% of all COVID-19 cases that have occurred since the beginning of the pandemic, compared with 11.5% 1 week ago, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

Hiding behind that 0.3%, however, is a much larger number: 144,145. That is the number of new child cases that occurred during the week that ended Nov. 19, and it’s the highest weekly figure yet, eclipsing the previous high of 111,946 from the week of Nov. 12, the AAP and the CHA said in their latest COVID-19 report. For the week ending Nov. 19, children represented 14.1% of all new cases, up from 14.0% the week before.

In the United States, more than 1.18 million children have been infected by the coronavirus since the beginning of the pandemic, with the total among all ages topping 10 million in 49 states (New York is not providing age distribution), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam, the AAP/CHA data show. That works out to 11.8% of all cases.

The overall rate of child COVID-19 cases is now up to 1,573 per 100,000 children nationally, with considerable variation seen among the states. The lowest rates can be found in Vermont (344 per 100,000), Maine (452), and Hawaii (675), and the highest in North Dakota (5,589), South Dakota (3,993), and Wisconsin (3,727), the AAP and CHA said in the report.

Comparisons between states are somewhat problematic, though, because “each state makes different decisions about how to report the age distribution of COVID-19 cases, and as a result the age range for reported cases varies by state. … It is not possible to standardize more detailed age ranges for children based on what is publicly available from the states at this time,” the two organizations noted.

Five more COVID-19–related deaths in children were reported during the week of Nov. 19, bringing the count to 138 and holding at just 0.06% of the total for all ages, based on data from 43 states and New York City. Children’s share of hospitalizations increased slightly in the last week, rising from 1.7% to 1.8% in the 24 states (and NYC) that are reporting such data. The total number of child hospitalizations in those jurisdictions is just over 6,700, the AAP and CHA said.

As far as the pandemic is concerned, it seems like a pretty small thing. A difference of just 0.3%. Children now represent 11.8% of all COVID-19 cases that have occurred since the beginning of the pandemic, compared with 11.5% 1 week ago, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

Hiding behind that 0.3%, however, is a much larger number: 144,145. That is the number of new child cases that occurred during the week that ended Nov. 19, and it’s the highest weekly figure yet, eclipsing the previous high of 111,946 from the week of Nov. 12, the AAP and the CHA said in their latest COVID-19 report. For the week ending Nov. 19, children represented 14.1% of all new cases, up from 14.0% the week before.

In the United States, more than 1.18 million children have been infected by the coronavirus since the beginning of the pandemic, with the total among all ages topping 10 million in 49 states (New York is not providing age distribution), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam, the AAP/CHA data show. That works out to 11.8% of all cases.

The overall rate of child COVID-19 cases is now up to 1,573 per 100,000 children nationally, with considerable variation seen among the states. The lowest rates can be found in Vermont (344 per 100,000), Maine (452), and Hawaii (675), and the highest in North Dakota (5,589), South Dakota (3,993), and Wisconsin (3,727), the AAP and CHA said in the report.

Comparisons between states are somewhat problematic, though, because “each state makes different decisions about how to report the age distribution of COVID-19 cases, and as a result the age range for reported cases varies by state. … It is not possible to standardize more detailed age ranges for children based on what is publicly available from the states at this time,” the two organizations noted.

Five more COVID-19–related deaths in children were reported during the week of Nov. 19, bringing the count to 138 and holding at just 0.06% of the total for all ages, based on data from 43 states and New York City. Children’s share of hospitalizations increased slightly in the last week, rising from 1.7% to 1.8% in the 24 states (and NYC) that are reporting such data. The total number of child hospitalizations in those jurisdictions is just over 6,700, the AAP and CHA said.

As far as the pandemic is concerned, it seems like a pretty small thing. A difference of just 0.3%. Children now represent 11.8% of all COVID-19 cases that have occurred since the beginning of the pandemic, compared with 11.5% 1 week ago, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

Hiding behind that 0.3%, however, is a much larger number: 144,145. That is the number of new child cases that occurred during the week that ended Nov. 19, and it’s the highest weekly figure yet, eclipsing the previous high of 111,946 from the week of Nov. 12, the AAP and the CHA said in their latest COVID-19 report. For the week ending Nov. 19, children represented 14.1% of all new cases, up from 14.0% the week before.

In the United States, more than 1.18 million children have been infected by the coronavirus since the beginning of the pandemic, with the total among all ages topping 10 million in 49 states (New York is not providing age distribution), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam, the AAP/CHA data show. That works out to 11.8% of all cases.

The overall rate of child COVID-19 cases is now up to 1,573 per 100,000 children nationally, with considerable variation seen among the states. The lowest rates can be found in Vermont (344 per 100,000), Maine (452), and Hawaii (675), and the highest in North Dakota (5,589), South Dakota (3,993), and Wisconsin (3,727), the AAP and CHA said in the report.

Comparisons between states are somewhat problematic, though, because “each state makes different decisions about how to report the age distribution of COVID-19 cases, and as a result the age range for reported cases varies by state. … It is not possible to standardize more detailed age ranges for children based on what is publicly available from the states at this time,” the two organizations noted.

Five more COVID-19–related deaths in children were reported during the week of Nov. 19, bringing the count to 138 and holding at just 0.06% of the total for all ages, based on data from 43 states and New York City. Children’s share of hospitalizations increased slightly in the last week, rising from 1.7% to 1.8% in the 24 states (and NYC) that are reporting such data. The total number of child hospitalizations in those jurisdictions is just over 6,700, the AAP and CHA said.

Concussion linked to risk for dementia, Parkinson’s disease, and ADHD

new research suggests. Results from a retrospective, population-based cohort study showed that controlling for socioeconomic status and overall health did not significantly affect this association.

The link between concussion and risk for ADHD and for mood and anxiety disorder was stronger in the women than in the men. In addition, having a history of multiple concussions strengthened the association between concussion and subsequent mood and anxiety disorder, dementia, and Parkinson’s disease compared with experiencing just one concussion.

The findings are similar to those of previous studies, noted lead author Marc P. Morissette, PhD, research assistant at the Pan Am Clinic Foundation in Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada. “The main methodological differences separating our study from previous studies in this area is a focus on concussion-specific injuries identified from medical records and the potential for study participants to have up to 25 years of follow-up data,” said Dr. Morissette.

The findings were published online July 27 in Family Medicine and Community Health, a BMJ journal.

Almost 190,000 participants

Several studies have shown associations between head injury and increased risk for ADHD, depression, anxiety, Alzheimer’s disease, and Parkinson’s disease. However, many of these studies relied on self-reported medical history, included all forms of traumatic brain injury, and failed to adjust for preexisting health conditions.

An improved understanding of concussion and the risks associated with it could help physicians manage their patients’ long-term needs, the investigators noted.

In the current study, the researchers examined anonymized administrative health data collected between the periods of 1990–1991 and 2014–2015 in the Manitoba Population Research Data Repository at the Manitoba Center for Health Policy.

Eligible patients had been diagnosed with concussion in accordance with standard criteria. Participants were excluded if they had been diagnosed with dementia or Parkinson’s disease before the incident concussion during the study period. The investigators matched three control participants to each included patient on the basis of age, sex, and location.

Study outcome was time from index date (date of first concussion) to diagnosis of ADHD, mood and anxiety disorder, dementia, or Parkinson’s disease. The researchers controlled for socioeconomic status using the Socioeconomic Factor Index, version 2 (SEFI2), and for preexisting medical conditions using the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI).

The study included 28,021 men (mean age, 25 years) and 19,462 women (mean age, 30 years) in the concussion group and 81,871 men (mean age, 25 years) and 57,159 women (mean age, 30 years) in the control group. Mean SEFI2 score was approximately −0.05, and mean CCI score was approximately 0.2.

Dose effect?

Results showed that concussion was associated with an increased risk for ADHD (hazard ratio [HR], 1.39), mood and anxiety disorder (HR, 1.72), dementia (HR, 1.72), and Parkinson’s disease (HR, 1.57).

After a concussion, the risk of developing ADHD was 28% higher and the risk of developing mood and anxiety disorder was 7% higher among women than among men. Gender was not associated with risk for dementia or Parkinson’s disease after concussion.

Sustaining a second concussion increased the strength of the association with risk for dementia compared with sustaining a single concussion (HR, 1.62). Similarly, sustaining more than three concussions increased the strength of the association with the risk for mood and anxiety disorders (HR for more than three vs one concussion, 1.22) and Parkinson›s disease (HR, 3.27).

A sensitivity analysis found similar associations between concussion and risk for mood and anxiety disorder among all age groups. Younger participants were at greater risk for ADHD, however, and older participants were at greater risk for dementia and Parkinson’s disease.

Increased awareness of concussion and the outcomes of interest, along with improved diagnostic tools, may have influenced the study’s findings, Dr. Morissette noted. “The sex-based differences may be due to either pathophysiological differences in response to concussive injuries or potentially a difference in willingness to seek medical care or share symptoms, concussion-related or otherwise, with a medical professional,” he said.

“We are hopeful that our findings will encourage practitioners to be cognizant of various conditions that may present in individuals who have previously experienced a concussion,” Dr. Morissette added. “If physicians are aware of the various associations identified following a concussion, it may lead to more thorough clinical examination at initial presentation, along with more dedicated care throughout the patient’s life.”

Association versus causation

Commenting on the research, Steven Erickson, MD, sports medicine specialist at Banner–University Medicine Neuroscience Institute, Phoenix, Ariz., noted that although the study showed an association between concussion and subsequent diagnosis of ADHD, anxiety, and Parkinson’s disease, “this association should not be misconstrued as causation.” He added that the study’s conclusions “are just as likely to be due to labeling theory” or a self-fulfilling prophecy.

“Patients diagnosed with ADHD, anxiety, or Parkinson’s disease may recall concussion and associate the two diagnoses; but patients who have not previously been diagnosed with a concussion cannot draw that conclusion,” said Dr. Erickson, who was not involved with the research.

Citing the apparent gender difference in the strength of the association between concussion and the outcomes of interest, Dr. Erickson noted that women are more likely to report symptoms in general “and therefore are more likely to be diagnosed with ADHD and anxiety disorders” because of differences in reporting rather than incidence of disease.

“Further research needs to be done to definitively determine a causal relationship between concussion and any psychiatric or neurologic diagnosis,” Dr. Erickson concluded.

The study was funded by the Pan Am Clinic Foundation. Dr. Morissette and Dr. Erickson have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

new research suggests. Results from a retrospective, population-based cohort study showed that controlling for socioeconomic status and overall health did not significantly affect this association.

The link between concussion and risk for ADHD and for mood and anxiety disorder was stronger in the women than in the men. In addition, having a history of multiple concussions strengthened the association between concussion and subsequent mood and anxiety disorder, dementia, and Parkinson’s disease compared with experiencing just one concussion.

The findings are similar to those of previous studies, noted lead author Marc P. Morissette, PhD, research assistant at the Pan Am Clinic Foundation in Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada. “The main methodological differences separating our study from previous studies in this area is a focus on concussion-specific injuries identified from medical records and the potential for study participants to have up to 25 years of follow-up data,” said Dr. Morissette.

The findings were published online July 27 in Family Medicine and Community Health, a BMJ journal.

Almost 190,000 participants

Several studies have shown associations between head injury and increased risk for ADHD, depression, anxiety, Alzheimer’s disease, and Parkinson’s disease. However, many of these studies relied on self-reported medical history, included all forms of traumatic brain injury, and failed to adjust for preexisting health conditions.

An improved understanding of concussion and the risks associated with it could help physicians manage their patients’ long-term needs, the investigators noted.

In the current study, the researchers examined anonymized administrative health data collected between the periods of 1990–1991 and 2014–2015 in the Manitoba Population Research Data Repository at the Manitoba Center for Health Policy.

Eligible patients had been diagnosed with concussion in accordance with standard criteria. Participants were excluded if they had been diagnosed with dementia or Parkinson’s disease before the incident concussion during the study period. The investigators matched three control participants to each included patient on the basis of age, sex, and location.

Study outcome was time from index date (date of first concussion) to diagnosis of ADHD, mood and anxiety disorder, dementia, or Parkinson’s disease. The researchers controlled for socioeconomic status using the Socioeconomic Factor Index, version 2 (SEFI2), and for preexisting medical conditions using the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI).

The study included 28,021 men (mean age, 25 years) and 19,462 women (mean age, 30 years) in the concussion group and 81,871 men (mean age, 25 years) and 57,159 women (mean age, 30 years) in the control group. Mean SEFI2 score was approximately −0.05, and mean CCI score was approximately 0.2.

Dose effect?

Results showed that concussion was associated with an increased risk for ADHD (hazard ratio [HR], 1.39), mood and anxiety disorder (HR, 1.72), dementia (HR, 1.72), and Parkinson’s disease (HR, 1.57).

After a concussion, the risk of developing ADHD was 28% higher and the risk of developing mood and anxiety disorder was 7% higher among women than among men. Gender was not associated with risk for dementia or Parkinson’s disease after concussion.

Sustaining a second concussion increased the strength of the association with risk for dementia compared with sustaining a single concussion (HR, 1.62). Similarly, sustaining more than three concussions increased the strength of the association with the risk for mood and anxiety disorders (HR for more than three vs one concussion, 1.22) and Parkinson›s disease (HR, 3.27).

A sensitivity analysis found similar associations between concussion and risk for mood and anxiety disorder among all age groups. Younger participants were at greater risk for ADHD, however, and older participants were at greater risk for dementia and Parkinson’s disease.

Increased awareness of concussion and the outcomes of interest, along with improved diagnostic tools, may have influenced the study’s findings, Dr. Morissette noted. “The sex-based differences may be due to either pathophysiological differences in response to concussive injuries or potentially a difference in willingness to seek medical care or share symptoms, concussion-related or otherwise, with a medical professional,” he said.

“We are hopeful that our findings will encourage practitioners to be cognizant of various conditions that may present in individuals who have previously experienced a concussion,” Dr. Morissette added. “If physicians are aware of the various associations identified following a concussion, it may lead to more thorough clinical examination at initial presentation, along with more dedicated care throughout the patient’s life.”

Association versus causation

Commenting on the research, Steven Erickson, MD, sports medicine specialist at Banner–University Medicine Neuroscience Institute, Phoenix, Ariz., noted that although the study showed an association between concussion and subsequent diagnosis of ADHD, anxiety, and Parkinson’s disease, “this association should not be misconstrued as causation.” He added that the study’s conclusions “are just as likely to be due to labeling theory” or a self-fulfilling prophecy.

“Patients diagnosed with ADHD, anxiety, or Parkinson’s disease may recall concussion and associate the two diagnoses; but patients who have not previously been diagnosed with a concussion cannot draw that conclusion,” said Dr. Erickson, who was not involved with the research.

Citing the apparent gender difference in the strength of the association between concussion and the outcomes of interest, Dr. Erickson noted that women are more likely to report symptoms in general “and therefore are more likely to be diagnosed with ADHD and anxiety disorders” because of differences in reporting rather than incidence of disease.

“Further research needs to be done to definitively determine a causal relationship between concussion and any psychiatric or neurologic diagnosis,” Dr. Erickson concluded.

The study was funded by the Pan Am Clinic Foundation. Dr. Morissette and Dr. Erickson have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

new research suggests. Results from a retrospective, population-based cohort study showed that controlling for socioeconomic status and overall health did not significantly affect this association.

The link between concussion and risk for ADHD and for mood and anxiety disorder was stronger in the women than in the men. In addition, having a history of multiple concussions strengthened the association between concussion and subsequent mood and anxiety disorder, dementia, and Parkinson’s disease compared with experiencing just one concussion.

The findings are similar to those of previous studies, noted lead author Marc P. Morissette, PhD, research assistant at the Pan Am Clinic Foundation in Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada. “The main methodological differences separating our study from previous studies in this area is a focus on concussion-specific injuries identified from medical records and the potential for study participants to have up to 25 years of follow-up data,” said Dr. Morissette.

The findings were published online July 27 in Family Medicine and Community Health, a BMJ journal.

Almost 190,000 participants

Several studies have shown associations between head injury and increased risk for ADHD, depression, anxiety, Alzheimer’s disease, and Parkinson’s disease. However, many of these studies relied on self-reported medical history, included all forms of traumatic brain injury, and failed to adjust for preexisting health conditions.

An improved understanding of concussion and the risks associated with it could help physicians manage their patients’ long-term needs, the investigators noted.

In the current study, the researchers examined anonymized administrative health data collected between the periods of 1990–1991 and 2014–2015 in the Manitoba Population Research Data Repository at the Manitoba Center for Health Policy.

Eligible patients had been diagnosed with concussion in accordance with standard criteria. Participants were excluded if they had been diagnosed with dementia or Parkinson’s disease before the incident concussion during the study period. The investigators matched three control participants to each included patient on the basis of age, sex, and location.

Study outcome was time from index date (date of first concussion) to diagnosis of ADHD, mood and anxiety disorder, dementia, or Parkinson’s disease. The researchers controlled for socioeconomic status using the Socioeconomic Factor Index, version 2 (SEFI2), and for preexisting medical conditions using the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI).

The study included 28,021 men (mean age, 25 years) and 19,462 women (mean age, 30 years) in the concussion group and 81,871 men (mean age, 25 years) and 57,159 women (mean age, 30 years) in the control group. Mean SEFI2 score was approximately −0.05, and mean CCI score was approximately 0.2.

Dose effect?

Results showed that concussion was associated with an increased risk for ADHD (hazard ratio [HR], 1.39), mood and anxiety disorder (HR, 1.72), dementia (HR, 1.72), and Parkinson’s disease (HR, 1.57).

After a concussion, the risk of developing ADHD was 28% higher and the risk of developing mood and anxiety disorder was 7% higher among women than among men. Gender was not associated with risk for dementia or Parkinson’s disease after concussion.

Sustaining a second concussion increased the strength of the association with risk for dementia compared with sustaining a single concussion (HR, 1.62). Similarly, sustaining more than three concussions increased the strength of the association with the risk for mood and anxiety disorders (HR for more than three vs one concussion, 1.22) and Parkinson›s disease (HR, 3.27).

A sensitivity analysis found similar associations between concussion and risk for mood and anxiety disorder among all age groups. Younger participants were at greater risk for ADHD, however, and older participants were at greater risk for dementia and Parkinson’s disease.

Increased awareness of concussion and the outcomes of interest, along with improved diagnostic tools, may have influenced the study’s findings, Dr. Morissette noted. “The sex-based differences may be due to either pathophysiological differences in response to concussive injuries or potentially a difference in willingness to seek medical care or share symptoms, concussion-related or otherwise, with a medical professional,” he said.

“We are hopeful that our findings will encourage practitioners to be cognizant of various conditions that may present in individuals who have previously experienced a concussion,” Dr. Morissette added. “If physicians are aware of the various associations identified following a concussion, it may lead to more thorough clinical examination at initial presentation, along with more dedicated care throughout the patient’s life.”

Association versus causation

Commenting on the research, Steven Erickson, MD, sports medicine specialist at Banner–University Medicine Neuroscience Institute, Phoenix, Ariz., noted that although the study showed an association between concussion and subsequent diagnosis of ADHD, anxiety, and Parkinson’s disease, “this association should not be misconstrued as causation.” He added that the study’s conclusions “are just as likely to be due to labeling theory” or a self-fulfilling prophecy.

“Patients diagnosed with ADHD, anxiety, or Parkinson’s disease may recall concussion and associate the two diagnoses; but patients who have not previously been diagnosed with a concussion cannot draw that conclusion,” said Dr. Erickson, who was not involved with the research.

Citing the apparent gender difference in the strength of the association between concussion and the outcomes of interest, Dr. Erickson noted that women are more likely to report symptoms in general “and therefore are more likely to be diagnosed with ADHD and anxiety disorders” because of differences in reporting rather than incidence of disease.

“Further research needs to be done to definitively determine a causal relationship between concussion and any psychiatric or neurologic diagnosis,” Dr. Erickson concluded.

The study was funded by the Pan Am Clinic Foundation. Dr. Morissette and Dr. Erickson have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

From Family Medicine and Community Health

Foreign-Body Reaction to Orthopedic Hardware a Decade After Implantation

To the Editor:

Cutaneous reactions to implantable devices, such as dental implants, intracoronary stents, prosthetic valves, endovascular prostheses, gynecologic devices, and spinal cord stimulator devices, occur with varying frequency and include infectious, hypersensitivity, allergic, and foreign-body reactions. Manifestations have included contact dermatitis; urticarial, vasculitic, and bullous eruptions; extrusion; and granuloma formation.1,2 Immune complex reactions around implants causing pain, inflammation, and loosening of hardwarealso have been reported.3,4 Most reported cutaneous reactions typically occur within the first weeks or months after implantation; a reaction rarely presents several years after implantation. We report a cutaneous reaction to an orthopedic appliance almost 10 years after implantation.

A 67-year-old man presented with 2 painful nodules on the right clavicle that were present for several months. The patient denied fever, chills, weight loss, enlarged lymph nodes, or night sweats. Approximately 10 years prior to the appearance of the nodules, the patient fractured the right clavicle and underwent placement of a metal plate. His medical history included resection of the right tonsil and soft-palate carcinoma with radical neck dissection and postoperative radiation, which was completed approximately 4 years prior to placement of the metal plate. The patient recently completed 4 to 6 weeks of fluorouracil for shave biopsy–proven actinic keratosis overlying the entire irradiated area.

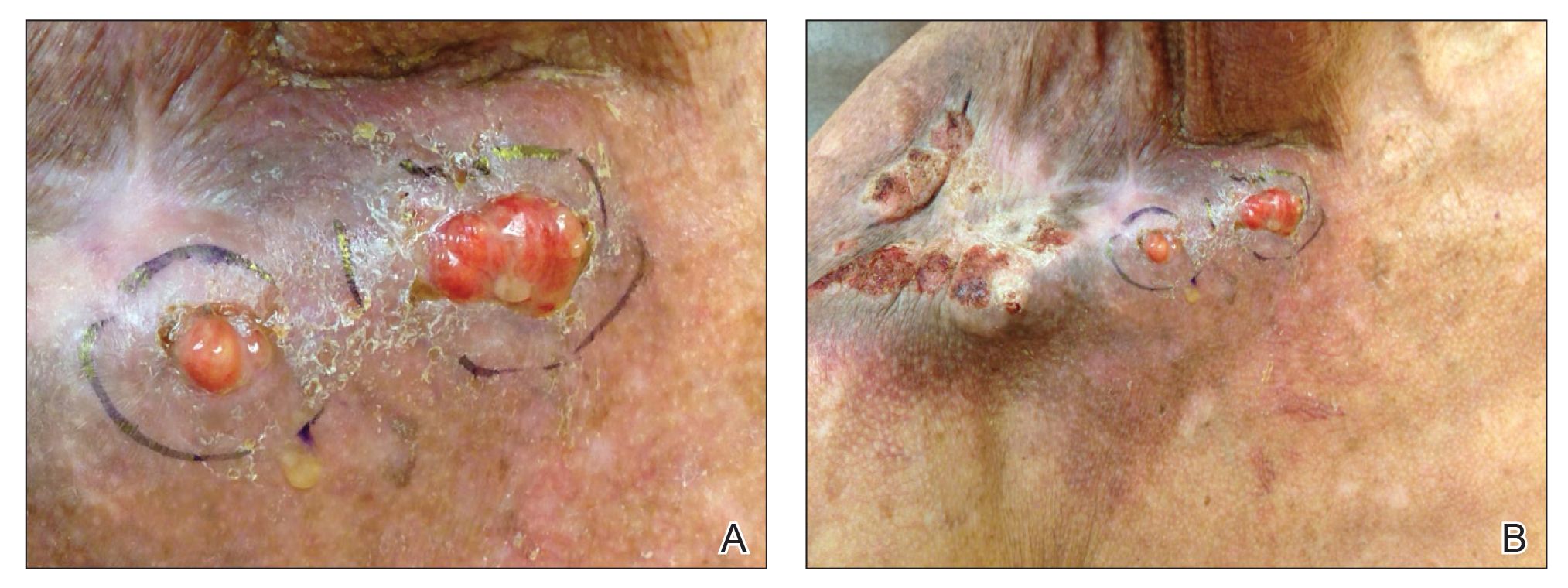

Physical examination revealed 2 pink friable nodules measuring 1.5 to 2.5 cm in diameter and leaking serous fluid within the irradiated area (Figure 1). The differential diagnosis included pyogenic granuloma, cutaneous recurrent metastasis, and atypical basal cell carcinoma. A skin biopsy specimen showed hemorrhagic ulcerated skin with acute and chronic inflammation and abscess.

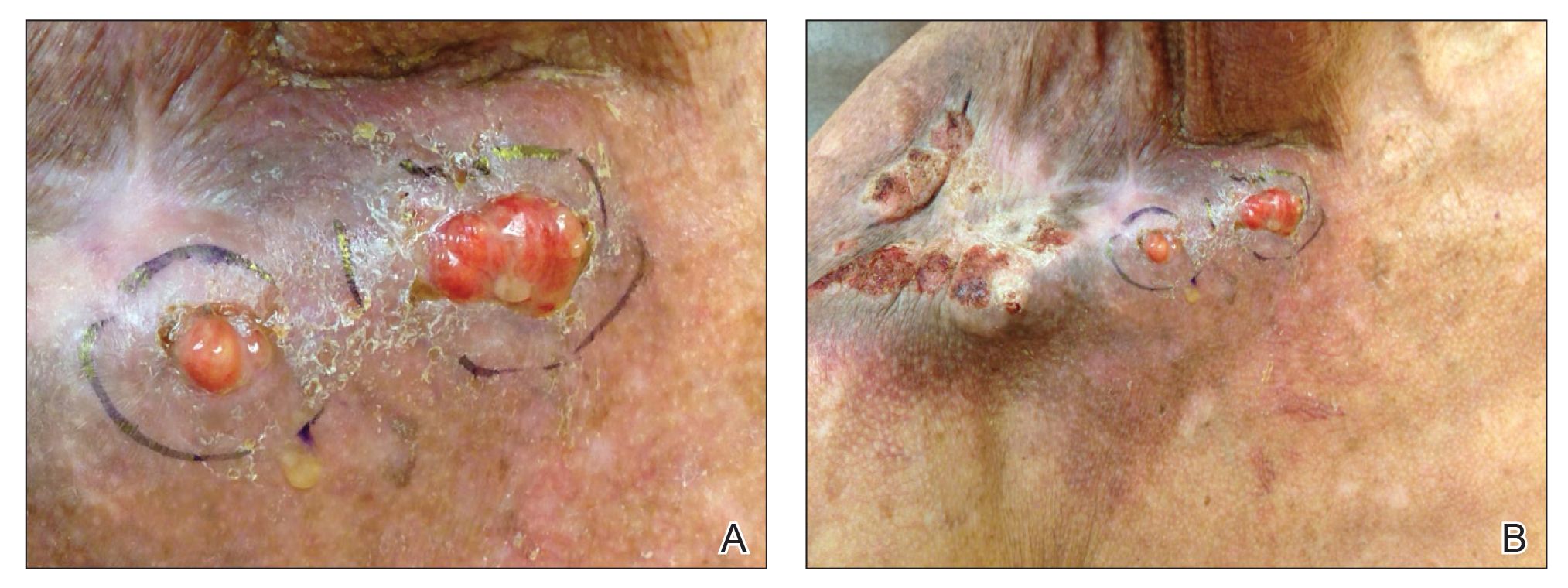

The patient presented for excisional biopsy of these areas on the right medial clavicle 1 week later. Physical examination revealed the 2 nodules had decreased in diameter; now, however, the patient had 4 discrete lesions measuring 4 to 7 mm in diameter, which were similar in appearance to the earlier nodules (Figure 2). He reported a low-grade fever, erythema, and increased tenderness of the area.

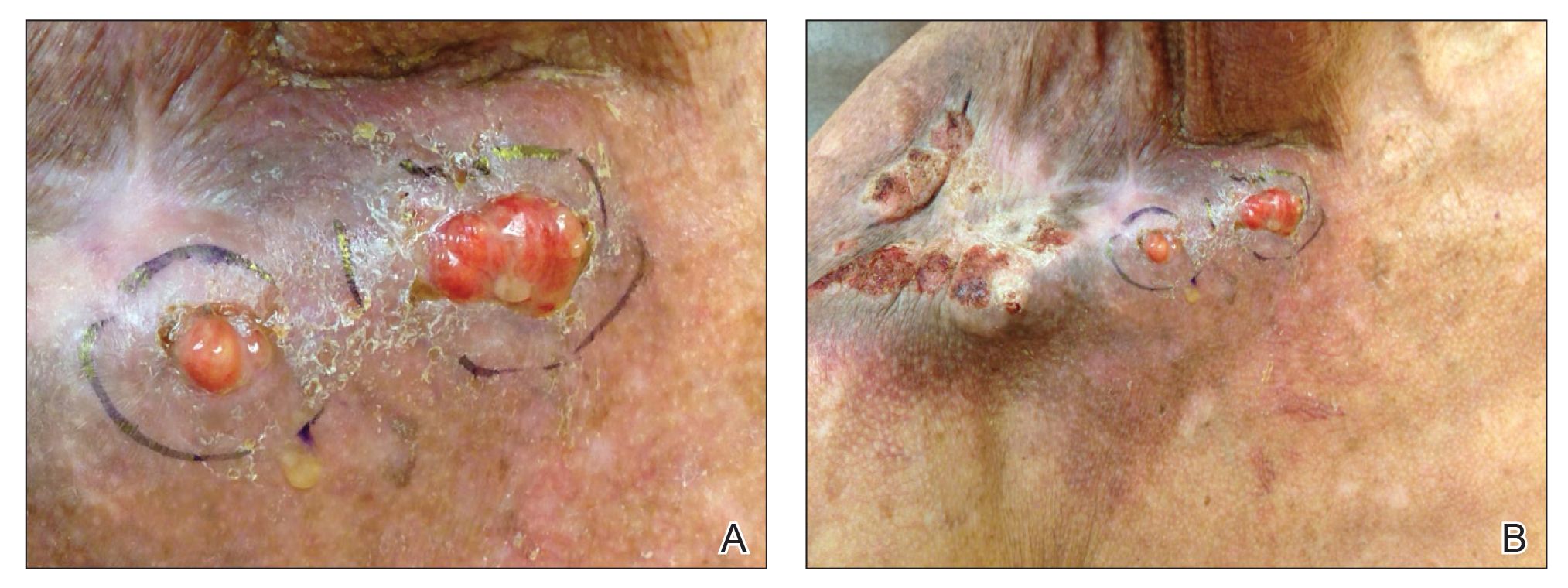

Underlying loosened orthopedic hardware screws were revealed upon punch biopsies of the involved areas (Figure 3). Wound cultures showed abundant Staphylococcus aureus and moderate group B Streptococcus; cultures for Mycobacterium were negative. The C-reactive protein level was elevated (5.47 mg/dL [reference range, ≤0.7 mg/dL]), and the erythrocyte sedimentation rate was increased (68 mm/h [reference range, 0–15 mm/h]). A complete blood cell count was within reference range, except for a mildly elevated eosinophil count (6.7% [reference range, 0%–5%]). The patient was admitted to the hospital, and antibiotics were started. Two days later, the orthopedic surgery service removed the hardware. At 3-week follow-up, physical examination revealed near closure of the wounds.

Cutaneous reactions to orthopedic implants include dermatitis, as well as urticarial, vasculitic, and bullous eruptions. Immune complex reactions can develop around implants, causing pain, inflammation, and loosening of hardware.1,3 Most inflammatory reactions take place within several months after implantation.3 Our patient’s reaction to hardware 10 years after implantation highlights the importance of taking a detailedand thorough history that includes queries about distant surgery.

- Basko-Plluska JL, Thyssen JP, Schalock PC. Cutaneous and systemic hypersensitivity reactions to metallic implants. Dermatitis. 2011;22:65-79.

- Chaudhry ZA, Najib U, Bajwa ZH, et al. Detailed analysis of allergic cutaneous reactions to spinal cord stimulator devices. J Pain Res. 2013;6:617-623.

- Huber M, Reinisch G, Trettenhahn G, et al. Presence of corrosion products and hypersensitivity-associated reactions in periprosthetic tissue after aseptic loosening of total hip replacements with metal bearing surfaces. Acta Biomater. 2009;5:172-180.

- Poncet-Wallet C, Ormezzano Y, Ernst E, et al. Study of a case of cochlear implant with recurrent cutaneous extrusion. Ann Otolaryngol Chir Cervicofac. 2009;126:264-268.

To the Editor:

Cutaneous reactions to implantable devices, such as dental implants, intracoronary stents, prosthetic valves, endovascular prostheses, gynecologic devices, and spinal cord stimulator devices, occur with varying frequency and include infectious, hypersensitivity, allergic, and foreign-body reactions. Manifestations have included contact dermatitis; urticarial, vasculitic, and bullous eruptions; extrusion; and granuloma formation.1,2 Immune complex reactions around implants causing pain, inflammation, and loosening of hardwarealso have been reported.3,4 Most reported cutaneous reactions typically occur within the first weeks or months after implantation; a reaction rarely presents several years after implantation. We report a cutaneous reaction to an orthopedic appliance almost 10 years after implantation.

A 67-year-old man presented with 2 painful nodules on the right clavicle that were present for several months. The patient denied fever, chills, weight loss, enlarged lymph nodes, or night sweats. Approximately 10 years prior to the appearance of the nodules, the patient fractured the right clavicle and underwent placement of a metal plate. His medical history included resection of the right tonsil and soft-palate carcinoma with radical neck dissection and postoperative radiation, which was completed approximately 4 years prior to placement of the metal plate. The patient recently completed 4 to 6 weeks of fluorouracil for shave biopsy–proven actinic keratosis overlying the entire irradiated area.

Physical examination revealed 2 pink friable nodules measuring 1.5 to 2.5 cm in diameter and leaking serous fluid within the irradiated area (Figure 1). The differential diagnosis included pyogenic granuloma, cutaneous recurrent metastasis, and atypical basal cell carcinoma. A skin biopsy specimen showed hemorrhagic ulcerated skin with acute and chronic inflammation and abscess.

The patient presented for excisional biopsy of these areas on the right medial clavicle 1 week later. Physical examination revealed the 2 nodules had decreased in diameter; now, however, the patient had 4 discrete lesions measuring 4 to 7 mm in diameter, which were similar in appearance to the earlier nodules (Figure 2). He reported a low-grade fever, erythema, and increased tenderness of the area.

Underlying loosened orthopedic hardware screws were revealed upon punch biopsies of the involved areas (Figure 3). Wound cultures showed abundant Staphylococcus aureus and moderate group B Streptococcus; cultures for Mycobacterium were negative. The C-reactive protein level was elevated (5.47 mg/dL [reference range, ≤0.7 mg/dL]), and the erythrocyte sedimentation rate was increased (68 mm/h [reference range, 0–15 mm/h]). A complete blood cell count was within reference range, except for a mildly elevated eosinophil count (6.7% [reference range, 0%–5%]). The patient was admitted to the hospital, and antibiotics were started. Two days later, the orthopedic surgery service removed the hardware. At 3-week follow-up, physical examination revealed near closure of the wounds.

Cutaneous reactions to orthopedic implants include dermatitis, as well as urticarial, vasculitic, and bullous eruptions. Immune complex reactions can develop around implants, causing pain, inflammation, and loosening of hardware.1,3 Most inflammatory reactions take place within several months after implantation.3 Our patient’s reaction to hardware 10 years after implantation highlights the importance of taking a detailedand thorough history that includes queries about distant surgery.

To the Editor:

Cutaneous reactions to implantable devices, such as dental implants, intracoronary stents, prosthetic valves, endovascular prostheses, gynecologic devices, and spinal cord stimulator devices, occur with varying frequency and include infectious, hypersensitivity, allergic, and foreign-body reactions. Manifestations have included contact dermatitis; urticarial, vasculitic, and bullous eruptions; extrusion; and granuloma formation.1,2 Immune complex reactions around implants causing pain, inflammation, and loosening of hardwarealso have been reported.3,4 Most reported cutaneous reactions typically occur within the first weeks or months after implantation; a reaction rarely presents several years after implantation. We report a cutaneous reaction to an orthopedic appliance almost 10 years after implantation.

A 67-year-old man presented with 2 painful nodules on the right clavicle that were present for several months. The patient denied fever, chills, weight loss, enlarged lymph nodes, or night sweats. Approximately 10 years prior to the appearance of the nodules, the patient fractured the right clavicle and underwent placement of a metal plate. His medical history included resection of the right tonsil and soft-palate carcinoma with radical neck dissection and postoperative radiation, which was completed approximately 4 years prior to placement of the metal plate. The patient recently completed 4 to 6 weeks of fluorouracil for shave biopsy–proven actinic keratosis overlying the entire irradiated area.

Physical examination revealed 2 pink friable nodules measuring 1.5 to 2.5 cm in diameter and leaking serous fluid within the irradiated area (Figure 1). The differential diagnosis included pyogenic granuloma, cutaneous recurrent metastasis, and atypical basal cell carcinoma. A skin biopsy specimen showed hemorrhagic ulcerated skin with acute and chronic inflammation and abscess.

The patient presented for excisional biopsy of these areas on the right medial clavicle 1 week later. Physical examination revealed the 2 nodules had decreased in diameter; now, however, the patient had 4 discrete lesions measuring 4 to 7 mm in diameter, which were similar in appearance to the earlier nodules (Figure 2). He reported a low-grade fever, erythema, and increased tenderness of the area.

Underlying loosened orthopedic hardware screws were revealed upon punch biopsies of the involved areas (Figure 3). Wound cultures showed abundant Staphylococcus aureus and moderate group B Streptococcus; cultures for Mycobacterium were negative. The C-reactive protein level was elevated (5.47 mg/dL [reference range, ≤0.7 mg/dL]), and the erythrocyte sedimentation rate was increased (68 mm/h [reference range, 0–15 mm/h]). A complete blood cell count was within reference range, except for a mildly elevated eosinophil count (6.7% [reference range, 0%–5%]). The patient was admitted to the hospital, and antibiotics were started. Two days later, the orthopedic surgery service removed the hardware. At 3-week follow-up, physical examination revealed near closure of the wounds.

Cutaneous reactions to orthopedic implants include dermatitis, as well as urticarial, vasculitic, and bullous eruptions. Immune complex reactions can develop around implants, causing pain, inflammation, and loosening of hardware.1,3 Most inflammatory reactions take place within several months after implantation.3 Our patient’s reaction to hardware 10 years after implantation highlights the importance of taking a detailedand thorough history that includes queries about distant surgery.

- Basko-Plluska JL, Thyssen JP, Schalock PC. Cutaneous and systemic hypersensitivity reactions to metallic implants. Dermatitis. 2011;22:65-79.

- Chaudhry ZA, Najib U, Bajwa ZH, et al. Detailed analysis of allergic cutaneous reactions to spinal cord stimulator devices. J Pain Res. 2013;6:617-623.

- Huber M, Reinisch G, Trettenhahn G, et al. Presence of corrosion products and hypersensitivity-associated reactions in periprosthetic tissue after aseptic loosening of total hip replacements with metal bearing surfaces. Acta Biomater. 2009;5:172-180.

- Poncet-Wallet C, Ormezzano Y, Ernst E, et al. Study of a case of cochlear implant with recurrent cutaneous extrusion. Ann Otolaryngol Chir Cervicofac. 2009;126:264-268.

- Basko-Plluska JL, Thyssen JP, Schalock PC. Cutaneous and systemic hypersensitivity reactions to metallic implants. Dermatitis. 2011;22:65-79.

- Chaudhry ZA, Najib U, Bajwa ZH, et al. Detailed analysis of allergic cutaneous reactions to spinal cord stimulator devices. J Pain Res. 2013;6:617-623.

- Huber M, Reinisch G, Trettenhahn G, et al. Presence of corrosion products and hypersensitivity-associated reactions in periprosthetic tissue after aseptic loosening of total hip replacements with metal bearing surfaces. Acta Biomater. 2009;5:172-180.

- Poncet-Wallet C, Ormezzano Y, Ernst E, et al. Study of a case of cochlear implant with recurrent cutaneous extrusion. Ann Otolaryngol Chir Cervicofac. 2009;126:264-268.

Practice Points

- Cutaneous reactions to implantable devices occur with varying frequency and include infectious, hypersensitivity, allergic, and foreign-body reactions.

- Most reactions typically occur within the first weeks or months after implantation; however, a reaction rarely may present several years after implantation.

Excited delirium: Is it time to change the status quo?

Prior to George Floyd’s death, Officer Thomas Lane reportedly said, “I am worried about excited delirium or whatever” to his colleague, Officer Derek Chauvin.1 For those of us who frequently work with law enforcement and in correctional facilities, “excited delirium” is a common refrain. It would be too facile to dismiss the concept as an attempt by police officers to inappropriately use medically sounding jargon to justify violence. “Excited delirium” is a reminder of the complex situations faced by police officers and the need for better medical training, as well as the attention of research on this commonly used label.

Many law enforcement facilities, in particular jails that receive inmates directly from the community, will have large posters educating staff on the “signs of excited delirium.” The concept is not covered in residency training programs, or many of the leading textbooks of psychiatry. Yet, it has become common parlance in law enforcement. Officers in training receive education programs on excited delirium, although those are rarely conducted by clinicians.

In our practice and experience, “excited delirium” has been used by law enforcement officers to describe mood lability from the stress of arrest, acute agitation from stimulant or phencyclidine intoxication, actual delirium from a medical comorbidity, sociopathic aggression for the purpose of violence, and incoherence from psychosis, along with simply describing a person not following direction from a police officer.

Our differential diagnosis when informed that someone was described by a nonclinician as having so-called excited delirium is wider than the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM). In addition, the term comes at a cost. Its use has been implicated in police-related deaths and brutality.2 There is also concern of its disproportionate application to Black people.3,4

Nonetheless, the term “excited delirium” can sometimes accurately describe critical medical situations. We particularly remember a case of altered mental status from serotonin syndrome, a case of delirium tremens from alcohol withdrawal, and a case of life-threatening dehydration in the context of stimulant intoxication. Each of those cases was appropriately recognized as problematic by perceptive and caring police officers. It is important for police officers to recognize these life-threatening conditions, and they need the language to do so. Having a common label that can be used across professional fields and law enforcement departments to express medical concern in the context of aggressive behavior has value. The question is: can psychiatry help law enforcement describe situations more accurately?

As physicians, it would be overly simple to point out the limited understanding of medical information by police and correctional officers. Naming many behaviors poses significant challenges for psychiatrists and nonclinicians. Examples include the use of the word “agitation” to describe mild restlessness, “delusional” for uncooperative, and “irritable” for opinionated. We must also be cognizant of the infinite demands placed on police officers and that labels must be available to them to express complex situations without being forced to use medical diagnosis and terminology for which they do not have the license or expertise. It is possible that “excited delirium” serves an important role; the problem may not be as much “excited delirium,” the term itself, as the diversion of its use to justify poor policing.

It must be acknowledged that debates, concerns, poor nomenclature, confusing labels, and different interpretations of diagnoses and symptoms are not unusual things in psychiatry, even among professionals. In the 1970s, the famous American and British study of diagnostic criteria, showed that psychiatrists used the diagnosis of schizophrenia to describe vastly different patients.5 The findings of the study were a significant cause of the paradigm shift of the DSM in its 3rd edition. More recently, the DSM-5 field trials suggested that the field of psychiatry continues to struggle with this problem.6 Nonetheless, each edition of the DSM presents a new opportunity to discuss, refine, and improve our ability to communicate while emphasizing the importance of improving our common language.

Emergency physicians face delirious patients brought to them from the community on a regular basis. As such, it makes sense that they have been at the forefront of this issue and the American College of Emergency Physicians has recognized excited delirium as a condition since 2009.7 The emergency physician literature points out that death from excited delirium also happens in hospitals and is not a unique consequence of law enforcement. There is no accepted definition. Reported symptoms include agitation, bizarre behavior, tirelessness, unusual strength, pain tolerance, noncompliance, attraction to reflective surfaces, stupor, fear, panic, hyperthermia, inappropriate clothing, tachycardia, tachypnea, diaphoresis, seizure, and mydriasis. Etiology is suspected to be from catecholaminergic endogenous stress-related catecholamines and exogenous catecholaminergic drugs. In particular is the importance of dopamine through the use of stimulants, specifically cocaine. The literature makes some reference to management, including recommendations aimed at keeping patients on one of their sides, using de-escalation techniques, and performing evaluation in quiet rooms.

We certainly condone and commend efforts to understand and define this condition in the medical literature. The indiscriminate use of “excited delirium” to represent all sorts of behaviors by nonmedical personnel warrants intelligent, relevant, and researched commentary by physicians. There are several potentially appropriate ways forward. First, psychiatry may decide that excited delirium is not a useful diagnosis in the clinical setting and does not belong in the DSM. That distinction in itself would be potentially useful to law enforcement officers, who might welcome the opportunity to create their own nomenclature and classification. Second, psychiatry may decide that excited delirium is not a useful diagnosis in the clinical setting but warrants a definition nonetheless, akin to the ways homelessness and extreme poverty are defined in the DSM; this definition could take into account the wide use of the term by nonclinicians. Third, psychiatry may decide that excited delirium warrants a clinical diagnosis that warrants a distinction and clarification from the current delirium diagnosis with the hyperactive specifier.

At this time, the status quo doesn’t protect or help clinicians in their respective fields of work. “Excited delirium” is routinely used by law enforcement officers without clear meaning. Experts have difficulty pointing out the poor or ill-intended use of the term without a precise or accepted definition to rely on. Some of the proposed criteria, such as “unusual strength,” have unclear scientific legitimacy. Some, such as agitation or bizarre behavior, often have different meanings to nonphysicians. Some, such as poor clothing, may facilitate discrimination. The current state allows some professionals to hide their limited attempts at de-escalation by describing the person of interest as having excited delirium. On the other hand, the current state also prevents well-intended officers from using proper terminology that is understood by others as describing a concerning behavior reliably.

We wonder whether excited delirium is an important facet of the current dilemma of reconsidering the role of law enforcement in society. Frequent use of “excited delirium” by police officers is itself a testament to their desire to have assistance or delegation of certain duties to other social services, such as health care. In some ways, police officers face a difficult position: Admission that a behavior may be attributable to excited delirium should warrant a medical evaluation and, thus, render the person of interest a patient rather than a suspect. As such, this person interacting with police officers should be treated as someone in need of medical care, which makes many interventions – including neck compression – seemingly inappropriate. The frequent use of “excited delirium” suggests that law enforcement is ill-equipped in handling many situations and that an attempt to diversify the composition and funding of emergency response might be warranted. Psychiatry should be at the forefront of this research and effort.

References

1. State of Minnesota v. Derek Michael Chauvin (4th Judicial District, 2020 May 29).

2. J Forensic Leg Med. 2008 May 15(4):227-30.

3. “Excited delirium: Rare and deadly syndrome or a condition to excuse deaths by police?” Florida Today. 2020 Jan 20.

4. J Forensic Sci. 1997 Jan;42(1):25-31.

5. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1971;25(2):123-30.

6. Am J Psychiatry. 2013 Jan;170(1):59-70.

7. White Paper Report on Excited Delirium Syndrome. ACEP Excited Delirium Task Force. 2009 Sep 10.

Dr. Amendolara is a first-year psychiatry resident at University of California, San Diego. He spent years advocating for survivors of rape and domestic violence at the Crime Victims Treatment Center in New York and conducted public health research at Lourdes Center for Public Health in Camden, N.J. Dr. Amendolara has no disclosures. Dr. Malik is a first-year psychiatry resident at the University of California, San Diego. She has a background in policy and grassroots organizing through her time working at the National Coalition for the Homeless and the Women’s Law Project. Dr. Malik has no disclosures. Dr. Abrams is a forensic psychiatrist and attorney in San Diego. He is an expert in addictionology, behavioral toxicology, psychopharmacology, and correctional mental health. He holds teaching positions at the University of California, San Diego. Among his writings are chapters about competency in national textbooks. Dr. Abrams has no disclosures. Dr. Badre is a forensic psychiatrist in San Diego and an expert in correctional mental health. He holds teaching positions at the University of California, San Diego, and the University of San Diego. He teaches medical education, psychopharmacology, ethics in psychiatry, and correctional care. Among his writings is chapter 7 in the book “Critical Psychiatry: Controversies and Clinical Implications” (Cham, Switzerland: Springer, 2019). He has no disclosures.

Prior to George Floyd’s death, Officer Thomas Lane reportedly said, “I am worried about excited delirium or whatever” to his colleague, Officer Derek Chauvin.1 For those of us who frequently work with law enforcement and in correctional facilities, “excited delirium” is a common refrain. It would be too facile to dismiss the concept as an attempt by police officers to inappropriately use medically sounding jargon to justify violence. “Excited delirium” is a reminder of the complex situations faced by police officers and the need for better medical training, as well as the attention of research on this commonly used label.

Many law enforcement facilities, in particular jails that receive inmates directly from the community, will have large posters educating staff on the “signs of excited delirium.” The concept is not covered in residency training programs, or many of the leading textbooks of psychiatry. Yet, it has become common parlance in law enforcement. Officers in training receive education programs on excited delirium, although those are rarely conducted by clinicians.

In our practice and experience, “excited delirium” has been used by law enforcement officers to describe mood lability from the stress of arrest, acute agitation from stimulant or phencyclidine intoxication, actual delirium from a medical comorbidity, sociopathic aggression for the purpose of violence, and incoherence from psychosis, along with simply describing a person not following direction from a police officer.

Our differential diagnosis when informed that someone was described by a nonclinician as having so-called excited delirium is wider than the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM). In addition, the term comes at a cost. Its use has been implicated in police-related deaths and brutality.2 There is also concern of its disproportionate application to Black people.3,4

Nonetheless, the term “excited delirium” can sometimes accurately describe critical medical situations. We particularly remember a case of altered mental status from serotonin syndrome, a case of delirium tremens from alcohol withdrawal, and a case of life-threatening dehydration in the context of stimulant intoxication. Each of those cases was appropriately recognized as problematic by perceptive and caring police officers. It is important for police officers to recognize these life-threatening conditions, and they need the language to do so. Having a common label that can be used across professional fields and law enforcement departments to express medical concern in the context of aggressive behavior has value. The question is: can psychiatry help law enforcement describe situations more accurately?

As physicians, it would be overly simple to point out the limited understanding of medical information by police and correctional officers. Naming many behaviors poses significant challenges for psychiatrists and nonclinicians. Examples include the use of the word “agitation” to describe mild restlessness, “delusional” for uncooperative, and “irritable” for opinionated. We must also be cognizant of the infinite demands placed on police officers and that labels must be available to them to express complex situations without being forced to use medical diagnosis and terminology for which they do not have the license or expertise. It is possible that “excited delirium” serves an important role; the problem may not be as much “excited delirium,” the term itself, as the diversion of its use to justify poor policing.

It must be acknowledged that debates, concerns, poor nomenclature, confusing labels, and different interpretations of diagnoses and symptoms are not unusual things in psychiatry, even among professionals. In the 1970s, the famous American and British study of diagnostic criteria, showed that psychiatrists used the diagnosis of schizophrenia to describe vastly different patients.5 The findings of the study were a significant cause of the paradigm shift of the DSM in its 3rd edition. More recently, the DSM-5 field trials suggested that the field of psychiatry continues to struggle with this problem.6 Nonetheless, each edition of the DSM presents a new opportunity to discuss, refine, and improve our ability to communicate while emphasizing the importance of improving our common language.

Emergency physicians face delirious patients brought to them from the community on a regular basis. As such, it makes sense that they have been at the forefront of this issue and the American College of Emergency Physicians has recognized excited delirium as a condition since 2009.7 The emergency physician literature points out that death from excited delirium also happens in hospitals and is not a unique consequence of law enforcement. There is no accepted definition. Reported symptoms include agitation, bizarre behavior, tirelessness, unusual strength, pain tolerance, noncompliance, attraction to reflective surfaces, stupor, fear, panic, hyperthermia, inappropriate clothing, tachycardia, tachypnea, diaphoresis, seizure, and mydriasis. Etiology is suspected to be from catecholaminergic endogenous stress-related catecholamines and exogenous catecholaminergic drugs. In particular is the importance of dopamine through the use of stimulants, specifically cocaine. The literature makes some reference to management, including recommendations aimed at keeping patients on one of their sides, using de-escalation techniques, and performing evaluation in quiet rooms.

We certainly condone and commend efforts to understand and define this condition in the medical literature. The indiscriminate use of “excited delirium” to represent all sorts of behaviors by nonmedical personnel warrants intelligent, relevant, and researched commentary by physicians. There are several potentially appropriate ways forward. First, psychiatry may decide that excited delirium is not a useful diagnosis in the clinical setting and does not belong in the DSM. That distinction in itself would be potentially useful to law enforcement officers, who might welcome the opportunity to create their own nomenclature and classification. Second, psychiatry may decide that excited delirium is not a useful diagnosis in the clinical setting but warrants a definition nonetheless, akin to the ways homelessness and extreme poverty are defined in the DSM; this definition could take into account the wide use of the term by nonclinicians. Third, psychiatry may decide that excited delirium warrants a clinical diagnosis that warrants a distinction and clarification from the current delirium diagnosis with the hyperactive specifier.

At this time, the status quo doesn’t protect or help clinicians in their respective fields of work. “Excited delirium” is routinely used by law enforcement officers without clear meaning. Experts have difficulty pointing out the poor or ill-intended use of the term without a precise or accepted definition to rely on. Some of the proposed criteria, such as “unusual strength,” have unclear scientific legitimacy. Some, such as agitation or bizarre behavior, often have different meanings to nonphysicians. Some, such as poor clothing, may facilitate discrimination. The current state allows some professionals to hide their limited attempts at de-escalation by describing the person of interest as having excited delirium. On the other hand, the current state also prevents well-intended officers from using proper terminology that is understood by others as describing a concerning behavior reliably.

We wonder whether excited delirium is an important facet of the current dilemma of reconsidering the role of law enforcement in society. Frequent use of “excited delirium” by police officers is itself a testament to their desire to have assistance or delegation of certain duties to other social services, such as health care. In some ways, police officers face a difficult position: Admission that a behavior may be attributable to excited delirium should warrant a medical evaluation and, thus, render the person of interest a patient rather than a suspect. As such, this person interacting with police officers should be treated as someone in need of medical care, which makes many interventions – including neck compression – seemingly inappropriate. The frequent use of “excited delirium” suggests that law enforcement is ill-equipped in handling many situations and that an attempt to diversify the composition and funding of emergency response might be warranted. Psychiatry should be at the forefront of this research and effort.

References

1. State of Minnesota v. Derek Michael Chauvin (4th Judicial District, 2020 May 29).

2. J Forensic Leg Med. 2008 May 15(4):227-30.

3. “Excited delirium: Rare and deadly syndrome or a condition to excuse deaths by police?” Florida Today. 2020 Jan 20.

4. J Forensic Sci. 1997 Jan;42(1):25-31.

5. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1971;25(2):123-30.

6. Am J Psychiatry. 2013 Jan;170(1):59-70.

7. White Paper Report on Excited Delirium Syndrome. ACEP Excited Delirium Task Force. 2009 Sep 10.

Dr. Amendolara is a first-year psychiatry resident at University of California, San Diego. He spent years advocating for survivors of rape and domestic violence at the Crime Victims Treatment Center in New York and conducted public health research at Lourdes Center for Public Health in Camden, N.J. Dr. Amendolara has no disclosures. Dr. Malik is a first-year psychiatry resident at the University of California, San Diego. She has a background in policy and grassroots organizing through her time working at the National Coalition for the Homeless and the Women’s Law Project. Dr. Malik has no disclosures. Dr. Abrams is a forensic psychiatrist and attorney in San Diego. He is an expert in addictionology, behavioral toxicology, psychopharmacology, and correctional mental health. He holds teaching positions at the University of California, San Diego. Among his writings are chapters about competency in national textbooks. Dr. Abrams has no disclosures. Dr. Badre is a forensic psychiatrist in San Diego and an expert in correctional mental health. He holds teaching positions at the University of California, San Diego, and the University of San Diego. He teaches medical education, psychopharmacology, ethics in psychiatry, and correctional care. Among his writings is chapter 7 in the book “Critical Psychiatry: Controversies and Clinical Implications” (Cham, Switzerland: Springer, 2019). He has no disclosures.

Prior to George Floyd’s death, Officer Thomas Lane reportedly said, “I am worried about excited delirium or whatever” to his colleague, Officer Derek Chauvin.1 For those of us who frequently work with law enforcement and in correctional facilities, “excited delirium” is a common refrain. It would be too facile to dismiss the concept as an attempt by police officers to inappropriately use medically sounding jargon to justify violence. “Excited delirium” is a reminder of the complex situations faced by police officers and the need for better medical training, as well as the attention of research on this commonly used label.

Many law enforcement facilities, in particular jails that receive inmates directly from the community, will have large posters educating staff on the “signs of excited delirium.” The concept is not covered in residency training programs, or many of the leading textbooks of psychiatry. Yet, it has become common parlance in law enforcement. Officers in training receive education programs on excited delirium, although those are rarely conducted by clinicians.

In our practice and experience, “excited delirium” has been used by law enforcement officers to describe mood lability from the stress of arrest, acute agitation from stimulant or phencyclidine intoxication, actual delirium from a medical comorbidity, sociopathic aggression for the purpose of violence, and incoherence from psychosis, along with simply describing a person not following direction from a police officer.

Our differential diagnosis when informed that someone was described by a nonclinician as having so-called excited delirium is wider than the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM). In addition, the term comes at a cost. Its use has been implicated in police-related deaths and brutality.2 There is also concern of its disproportionate application to Black people.3,4

Nonetheless, the term “excited delirium” can sometimes accurately describe critical medical situations. We particularly remember a case of altered mental status from serotonin syndrome, a case of delirium tremens from alcohol withdrawal, and a case of life-threatening dehydration in the context of stimulant intoxication. Each of those cases was appropriately recognized as problematic by perceptive and caring police officers. It is important for police officers to recognize these life-threatening conditions, and they need the language to do so. Having a common label that can be used across professional fields and law enforcement departments to express medical concern in the context of aggressive behavior has value. The question is: can psychiatry help law enforcement describe situations more accurately?

As physicians, it would be overly simple to point out the limited understanding of medical information by police and correctional officers. Naming many behaviors poses significant challenges for psychiatrists and nonclinicians. Examples include the use of the word “agitation” to describe mild restlessness, “delusional” for uncooperative, and “irritable” for opinionated. We must also be cognizant of the infinite demands placed on police officers and that labels must be available to them to express complex situations without being forced to use medical diagnosis and terminology for which they do not have the license or expertise. It is possible that “excited delirium” serves an important role; the problem may not be as much “excited delirium,” the term itself, as the diversion of its use to justify poor policing.

It must be acknowledged that debates, concerns, poor nomenclature, confusing labels, and different interpretations of diagnoses and symptoms are not unusual things in psychiatry, even among professionals. In the 1970s, the famous American and British study of diagnostic criteria, showed that psychiatrists used the diagnosis of schizophrenia to describe vastly different patients.5 The findings of the study were a significant cause of the paradigm shift of the DSM in its 3rd edition. More recently, the DSM-5 field trials suggested that the field of psychiatry continues to struggle with this problem.6 Nonetheless, each edition of the DSM presents a new opportunity to discuss, refine, and improve our ability to communicate while emphasizing the importance of improving our common language.

Emergency physicians face delirious patients brought to them from the community on a regular basis. As such, it makes sense that they have been at the forefront of this issue and the American College of Emergency Physicians has recognized excited delirium as a condition since 2009.7 The emergency physician literature points out that death from excited delirium also happens in hospitals and is not a unique consequence of law enforcement. There is no accepted definition. Reported symptoms include agitation, bizarre behavior, tirelessness, unusual strength, pain tolerance, noncompliance, attraction to reflective surfaces, stupor, fear, panic, hyperthermia, inappropriate clothing, tachycardia, tachypnea, diaphoresis, seizure, and mydriasis. Etiology is suspected to be from catecholaminergic endogenous stress-related catecholamines and exogenous catecholaminergic drugs. In particular is the importance of dopamine through the use of stimulants, specifically cocaine. The literature makes some reference to management, including recommendations aimed at keeping patients on one of their sides, using de-escalation techniques, and performing evaluation in quiet rooms.

We certainly condone and commend efforts to understand and define this condition in the medical literature. The indiscriminate use of “excited delirium” to represent all sorts of behaviors by nonmedical personnel warrants intelligent, relevant, and researched commentary by physicians. There are several potentially appropriate ways forward. First, psychiatry may decide that excited delirium is not a useful diagnosis in the clinical setting and does not belong in the DSM. That distinction in itself would be potentially useful to law enforcement officers, who might welcome the opportunity to create their own nomenclature and classification. Second, psychiatry may decide that excited delirium is not a useful diagnosis in the clinical setting but warrants a definition nonetheless, akin to the ways homelessness and extreme poverty are defined in the DSM; this definition could take into account the wide use of the term by nonclinicians. Third, psychiatry may decide that excited delirium warrants a clinical diagnosis that warrants a distinction and clarification from the current delirium diagnosis with the hyperactive specifier.

At this time, the status quo doesn’t protect or help clinicians in their respective fields of work. “Excited delirium” is routinely used by law enforcement officers without clear meaning. Experts have difficulty pointing out the poor or ill-intended use of the term without a precise or accepted definition to rely on. Some of the proposed criteria, such as “unusual strength,” have unclear scientific legitimacy. Some, such as agitation or bizarre behavior, often have different meanings to nonphysicians. Some, such as poor clothing, may facilitate discrimination. The current state allows some professionals to hide their limited attempts at de-escalation by describing the person of interest as having excited delirium. On the other hand, the current state also prevents well-intended officers from using proper terminology that is understood by others as describing a concerning behavior reliably.

We wonder whether excited delirium is an important facet of the current dilemma of reconsidering the role of law enforcement in society. Frequent use of “excited delirium” by police officers is itself a testament to their desire to have assistance or delegation of certain duties to other social services, such as health care. In some ways, police officers face a difficult position: Admission that a behavior may be attributable to excited delirium should warrant a medical evaluation and, thus, render the person of interest a patient rather than a suspect. As such, this person interacting with police officers should be treated as someone in need of medical care, which makes many interventions – including neck compression – seemingly inappropriate. The frequent use of “excited delirium” suggests that law enforcement is ill-equipped in handling many situations and that an attempt to diversify the composition and funding of emergency response might be warranted. Psychiatry should be at the forefront of this research and effort.

References

1. State of Minnesota v. Derek Michael Chauvin (4th Judicial District, 2020 May 29).

2. J Forensic Leg Med. 2008 May 15(4):227-30.

3. “Excited delirium: Rare and deadly syndrome or a condition to excuse deaths by police?” Florida Today. 2020 Jan 20.

4. J Forensic Sci. 1997 Jan;42(1):25-31.

5. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1971;25(2):123-30.

6. Am J Psychiatry. 2013 Jan;170(1):59-70.

7. White Paper Report on Excited Delirium Syndrome. ACEP Excited Delirium Task Force. 2009 Sep 10.

Dr. Amendolara is a first-year psychiatry resident at University of California, San Diego. He spent years advocating for survivors of rape and domestic violence at the Crime Victims Treatment Center in New York and conducted public health research at Lourdes Center for Public Health in Camden, N.J. Dr. Amendolara has no disclosures. Dr. Malik is a first-year psychiatry resident at the University of California, San Diego. She has a background in policy and grassroots organizing through her time working at the National Coalition for the Homeless and the Women’s Law Project. Dr. Malik has no disclosures. Dr. Abrams is a forensic psychiatrist and attorney in San Diego. He is an expert in addictionology, behavioral toxicology, psychopharmacology, and correctional mental health. He holds teaching positions at the University of California, San Diego. Among his writings are chapters about competency in national textbooks. Dr. Abrams has no disclosures. Dr. Badre is a forensic psychiatrist in San Diego and an expert in correctional mental health. He holds teaching positions at the University of California, San Diego, and the University of San Diego. He teaches medical education, psychopharmacology, ethics in psychiatry, and correctional care. Among his writings is chapter 7 in the book “Critical Psychiatry: Controversies and Clinical Implications” (Cham, Switzerland: Springer, 2019). He has no disclosures.

Implementing Change in the Heat of the Moment

Early in the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic, the World Health Organization issued guidance for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) management.1 Based on a high intubation rate among 12 subjects with Middle Eastern respiratory syndrome, noninvasive ventilation (NIV) was discouraged.2 While high-flow nasal oxygen (HFNO) was recognized as a reasonable strategy to avoid endotracheal intubation,1 uncertainty regarding the potential of both therapies to aerosolize SARS-CoV-2 and reports of rapid, unexpected respiratory decompensations were deterrents to use.3 As hospitals prepared for a surge of patients, reports of SARS-CoV-2 transmission to healthcare personnel also emerged. Together, these issues led many institutions to recommend lower than usual thresholds for intubation. This well-intentioned guidance was based on limited historical data, a rapidly evolving literature that frequently appeared on preprint servers before peer review, or as anecdotes on social media.

As COVID-19 caseloads increased, clinicians were immediately faced with patients who rapidly reached the planned intubation threshold, but also looked very comfortable with minimal to no use of accessory muscles of respiration. In addition, the pace of respiratory decompensation among those who ultimately required intubation was slower than expected. Moreover, intensive care unit (ICU) capacity was stretched thin, raising concern for an imminent need for ventilator rationing. Lastly, the risk of SARS-CoV-2 transmission to healthcare workers appeared well-controlled with the use of personal protective equipment.4

In light of this accumulating experience, sites worldwide evolved quickly from their initial management strategies for COVID-19 respiratory failure. However, the deliberate process described by Soares et al in this issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine is notable.5 Their transition towards the beginning of the pandemic from a conservative early intubation approach to a new strategy that encouraged use of NIV, HFNO, and self-proning is described. They were motivated by reports of good outcomes using these interventions, high mortality in intubated patients, and reassurance that aerosolization of respiratory secretions during NIV and HFNO was comparable to regular nasal cannula or face mask oxygen.3 The new protocol was defined and rapidly deployed over 4 days using multipronged communication from project and institutional leaders via in person and electronic means (email, Whatsapp, GoogleDrive). To facilitate implementation, COVID-19 patients requiring respiratory support were placed in dedicated units with bedside flowsheets for guidance. An immediate impact was demonstrated over the next 2 weeks by a significant decrease in use of mechanical ventilation in COVID-19 patients from 25.2% to 10.7%. In-hospital mortality, the primary outcome, did not change, ICU admissions decreased, as did hospital length of stay (10 vs 8.4 days, though not statistically significant), all providing supportive evidence for relative safety of the new protocol.

Soares et al exemplify a nimble system that recognized planned strategies to be problematic, and then achieved rapid implementation of a new protocol across a four-hospital system. Changes in medical practice are typically much slower, with some studies suggesting this process may take a decade or more. Implementation science focuses on translating research evidence into clinical practice using strategies tailored to particular contexts. The current study harnessed important implementation principles to quickly translate evidence into practice using effective engagement and education of key stakeholders across specialties (eg, emergency medicine, hospitalists, critical care, and respiratory therapy), the identification of pathways that mitigated barriers, frequent re-evaluation of a rapidly evolving literature, and an open-mindedness to the value of change.6 As the pandemic continues, traditional research and implementation science are critical not only to define optimal treatments and management strategies, but also to learn how best to implement successful interventions in an accelerated manner.7

Disclosures

The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Funding

Dr Hochberg is supported by a National Institutes of Health training grant (T32HL007534).

1. World Health Organization. Clinical management of severe acute respiratory infection when novel coronavirus (1019-nCoV) infection is suspected: interim guidance, 28 January 2020. Accessed October 25, 2020. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/330893

2. Arabi YM, Arifi AA, Balkhy HH, et al. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160:389-397. https://doi.org/ 10.7326/M13-2486

3. Westafer LM, Elia T, Medarametla V, Lagu T. A transdisciplinary COVID-19 early respiratory intervention protocol: an implementation story. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:372-374. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3456

4. Self WH, Tenforde MW, Stubblefield WB, et al. Seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 among frontline health care personnel in a multistate hospital network - 13 academic medical centers, April-June 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1221-1226. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6935e2

5. Soares WE III, Schoenfeld EM, Visintainer P, et al. Safety assessment of a noninvasive respiratory protocol. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:734-738. https://doi.org/ 10.12788/jhm.3548

6. Pronovost PJ, Berenholtz SM, Needham DM. Translating evidence into practice: a model for large scale knowledge translation. BMJ. 2008;337:a1714. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.a1714

7. Taylor SP, Kowalkowski MA, Beidas RS. Where is the implementation science? An opportunity to apply principles during the COVID19 pandemic. Online ahead of print. Clin Infect Dis. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa622

Early in the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic, the World Health Organization issued guidance for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) management.1 Based on a high intubation rate among 12 subjects with Middle Eastern respiratory syndrome, noninvasive ventilation (NIV) was discouraged.2 While high-flow nasal oxygen (HFNO) was recognized as a reasonable strategy to avoid endotracheal intubation,1 uncertainty regarding the potential of both therapies to aerosolize SARS-CoV-2 and reports of rapid, unexpected respiratory decompensations were deterrents to use.3 As hospitals prepared for a surge of patients, reports of SARS-CoV-2 transmission to healthcare personnel also emerged. Together, these issues led many institutions to recommend lower than usual thresholds for intubation. This well-intentioned guidance was based on limited historical data, a rapidly evolving literature that frequently appeared on preprint servers before peer review, or as anecdotes on social media.

As COVID-19 caseloads increased, clinicians were immediately faced with patients who rapidly reached the planned intubation threshold, but also looked very comfortable with minimal to no use of accessory muscles of respiration. In addition, the pace of respiratory decompensation among those who ultimately required intubation was slower than expected. Moreover, intensive care unit (ICU) capacity was stretched thin, raising concern for an imminent need for ventilator rationing. Lastly, the risk of SARS-CoV-2 transmission to healthcare workers appeared well-controlled with the use of personal protective equipment.4