User login

FDA expands Xofluza indication to include postexposure flu prophylaxis

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has expanded the indication for the antiviral baloxavir marboxil (Xofluza) to include postexposure prophylaxis of uncomplicated influenza in people aged 12 years and older.

“This expanded indication for Xofluza will provide an important option to help prevent influenza just in time for a flu season that is anticipated to be unlike any other because it will coincide with the coronavirus pandemic,” Debra Birnkrant, MD, director, Division of Antiviral Products, FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in a press release.

In addition, Xofluza, which was previously available only in tablet form, is also now available as granules for mixing in water, the FDA said.

The agency first approved baloxavir marboxil in 2018 for the treatment of acute uncomplicated influenza in people aged 12 years or older who have been symptomatic for no more than 48 hours.

A year later, the FDA expanded the indication to include people at high risk of developing influenza-related complications, such as those with asthma, chronic lung disease, diabetes, heart disease, or morbid obesity, as well as adults aged 65 years or older.

The safety and efficacy of Xofluza for influenza postexposure prophylaxis is supported by a randomized, double-blind, controlled trial involving 607 people aged 12 years and older. After exposure to a person with influenza in their household, they received a single dose of Xofluza or placebo.

The primary endpoint was the proportion of individuals who became infected with influenza and presented with fever and at least one respiratory symptom from day 1 to day 10.

Of the 303 people who received Xofluza, 1% of individuals met these criteria, compared with 13% of those who received placebo.

The most common adverse effects of Xofluza include diarrhea, bronchitis, nausea, sinusitis, and headache.

Hypersensitivity, including anaphylaxis, can occur in patients taking Xofluza. The antiviral is contraindicated in people with a known hypersensitivity reaction to Xofluza.

Xofluza should not be coadministered with dairy products, calcium-fortified beverages, laxatives, antacids, or oral supplements containing calcium, iron, magnesium, selenium, aluminium, or zinc.

Full prescribing information is available online.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has expanded the indication for the antiviral baloxavir marboxil (Xofluza) to include postexposure prophylaxis of uncomplicated influenza in people aged 12 years and older.

“This expanded indication for Xofluza will provide an important option to help prevent influenza just in time for a flu season that is anticipated to be unlike any other because it will coincide with the coronavirus pandemic,” Debra Birnkrant, MD, director, Division of Antiviral Products, FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in a press release.

In addition, Xofluza, which was previously available only in tablet form, is also now available as granules for mixing in water, the FDA said.

The agency first approved baloxavir marboxil in 2018 for the treatment of acute uncomplicated influenza in people aged 12 years or older who have been symptomatic for no more than 48 hours.

A year later, the FDA expanded the indication to include people at high risk of developing influenza-related complications, such as those with asthma, chronic lung disease, diabetes, heart disease, or morbid obesity, as well as adults aged 65 years or older.

The safety and efficacy of Xofluza for influenza postexposure prophylaxis is supported by a randomized, double-blind, controlled trial involving 607 people aged 12 years and older. After exposure to a person with influenza in their household, they received a single dose of Xofluza or placebo.

The primary endpoint was the proportion of individuals who became infected with influenza and presented with fever and at least one respiratory symptom from day 1 to day 10.

Of the 303 people who received Xofluza, 1% of individuals met these criteria, compared with 13% of those who received placebo.

The most common adverse effects of Xofluza include diarrhea, bronchitis, nausea, sinusitis, and headache.

Hypersensitivity, including anaphylaxis, can occur in patients taking Xofluza. The antiviral is contraindicated in people with a known hypersensitivity reaction to Xofluza.

Xofluza should not be coadministered with dairy products, calcium-fortified beverages, laxatives, antacids, or oral supplements containing calcium, iron, magnesium, selenium, aluminium, or zinc.

Full prescribing information is available online.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has expanded the indication for the antiviral baloxavir marboxil (Xofluza) to include postexposure prophylaxis of uncomplicated influenza in people aged 12 years and older.

“This expanded indication for Xofluza will provide an important option to help prevent influenza just in time for a flu season that is anticipated to be unlike any other because it will coincide with the coronavirus pandemic,” Debra Birnkrant, MD, director, Division of Antiviral Products, FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in a press release.

In addition, Xofluza, which was previously available only in tablet form, is also now available as granules for mixing in water, the FDA said.

The agency first approved baloxavir marboxil in 2018 for the treatment of acute uncomplicated influenza in people aged 12 years or older who have been symptomatic for no more than 48 hours.

A year later, the FDA expanded the indication to include people at high risk of developing influenza-related complications, such as those with asthma, chronic lung disease, diabetes, heart disease, or morbid obesity, as well as adults aged 65 years or older.

The safety and efficacy of Xofluza for influenza postexposure prophylaxis is supported by a randomized, double-blind, controlled trial involving 607 people aged 12 years and older. After exposure to a person with influenza in their household, they received a single dose of Xofluza or placebo.

The primary endpoint was the proportion of individuals who became infected with influenza and presented with fever and at least one respiratory symptom from day 1 to day 10.

Of the 303 people who received Xofluza, 1% of individuals met these criteria, compared with 13% of those who received placebo.

The most common adverse effects of Xofluza include diarrhea, bronchitis, nausea, sinusitis, and headache.

Hypersensitivity, including anaphylaxis, can occur in patients taking Xofluza. The antiviral is contraindicated in people with a known hypersensitivity reaction to Xofluza.

Xofluza should not be coadministered with dairy products, calcium-fortified beverages, laxatives, antacids, or oral supplements containing calcium, iron, magnesium, selenium, aluminium, or zinc.

Full prescribing information is available online.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A Review of ACR Convergence Abstracts on Psoriatic Arthritis

New study results from British researchers show that dactylitis may be a clinical indicator of an aggressive phenotype of psoriatic arthritis (PsA). That phenotype is marked by a significantly greater swollen joint count, tender joint count, C-reactive protein, erosive damage, and ultrasound synovitis in very early disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD)-naive PsA.

The dactylitis study is noted by Dr Saakshi Khattri, assistant professor of rheumatology and dermatology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, as one of the key findings on PsA presented at ACR Convergence 2020, the American College of Rheumatology's first all-virtual annual meeting. Researchers from Leeds, United Kingdom, concluded that dactylitis may help differentiate risk among patients in an early disease stage.

Another study from researchers in the UK also addresses very early DMARD-naive PsA patients. It found that clinically, swollen joints are linked to power Doppler‒detected synovitis, but tender, nonswollen joints are not.

Also in this ReCAP, Dr Khattri discusses a population-based study from the Mayo Clinic that shows that patients with a family history of psoriasis and severe psoriasis experience a delay in transitioning to PsA. She highlights an interim report about an emerging risk-prediction model that may improve early detection of PsA. Finally, Dr Khattri shares a quality-of-life survey from the National Psoriasis Foundation about the prevalence of unacceptable symptom states in PsA, which reinforces that PsA is far from adequately treated.

--

Saakshi Khattri, MBBS, MD, Assistant Professor, Department of Internal Medicine, Divisions of Rheumatology and Dermatology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai; Director, Center for Connective Tissue Diseases at Mount Sinai, New York, NY.

Saakshi Khattri, MBBS, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for: Novartis

Serve(d) as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for: Janssen

Received research grant from: Pfizer

Received income in an amount equal to or greater than $250 from: Pfizer; Novartis.

New study results from British researchers show that dactylitis may be a clinical indicator of an aggressive phenotype of psoriatic arthritis (PsA). That phenotype is marked by a significantly greater swollen joint count, tender joint count, C-reactive protein, erosive damage, and ultrasound synovitis in very early disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD)-naive PsA.

The dactylitis study is noted by Dr Saakshi Khattri, assistant professor of rheumatology and dermatology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, as one of the key findings on PsA presented at ACR Convergence 2020, the American College of Rheumatology's first all-virtual annual meeting. Researchers from Leeds, United Kingdom, concluded that dactylitis may help differentiate risk among patients in an early disease stage.

Another study from researchers in the UK also addresses very early DMARD-naive PsA patients. It found that clinically, swollen joints are linked to power Doppler‒detected synovitis, but tender, nonswollen joints are not.

Also in this ReCAP, Dr Khattri discusses a population-based study from the Mayo Clinic that shows that patients with a family history of psoriasis and severe psoriasis experience a delay in transitioning to PsA. She highlights an interim report about an emerging risk-prediction model that may improve early detection of PsA. Finally, Dr Khattri shares a quality-of-life survey from the National Psoriasis Foundation about the prevalence of unacceptable symptom states in PsA, which reinforces that PsA is far from adequately treated.

--

Saakshi Khattri, MBBS, MD, Assistant Professor, Department of Internal Medicine, Divisions of Rheumatology and Dermatology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai; Director, Center for Connective Tissue Diseases at Mount Sinai, New York, NY.

Saakshi Khattri, MBBS, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for: Novartis

Serve(d) as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for: Janssen

Received research grant from: Pfizer

Received income in an amount equal to or greater than $250 from: Pfizer; Novartis.

New study results from British researchers show that dactylitis may be a clinical indicator of an aggressive phenotype of psoriatic arthritis (PsA). That phenotype is marked by a significantly greater swollen joint count, tender joint count, C-reactive protein, erosive damage, and ultrasound synovitis in very early disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD)-naive PsA.

The dactylitis study is noted by Dr Saakshi Khattri, assistant professor of rheumatology and dermatology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, as one of the key findings on PsA presented at ACR Convergence 2020, the American College of Rheumatology's first all-virtual annual meeting. Researchers from Leeds, United Kingdom, concluded that dactylitis may help differentiate risk among patients in an early disease stage.

Another study from researchers in the UK also addresses very early DMARD-naive PsA patients. It found that clinically, swollen joints are linked to power Doppler‒detected synovitis, but tender, nonswollen joints are not.

Also in this ReCAP, Dr Khattri discusses a population-based study from the Mayo Clinic that shows that patients with a family history of psoriasis and severe psoriasis experience a delay in transitioning to PsA. She highlights an interim report about an emerging risk-prediction model that may improve early detection of PsA. Finally, Dr Khattri shares a quality-of-life survey from the National Psoriasis Foundation about the prevalence of unacceptable symptom states in PsA, which reinforces that PsA is far from adequately treated.

--

Saakshi Khattri, MBBS, MD, Assistant Professor, Department of Internal Medicine, Divisions of Rheumatology and Dermatology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai; Director, Center for Connective Tissue Diseases at Mount Sinai, New York, NY.

Saakshi Khattri, MBBS, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for: Novartis

Serve(d) as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for: Janssen

Received research grant from: Pfizer

Received income in an amount equal to or greater than $250 from: Pfizer; Novartis.

Microneedling: What’s the truth?

according to Catherine M. DiGiorgio, MD, MS.

During a virtual course on laser and aesthetic skin therapy, Dr. DiGiorgio, a laser and cosmetic dermatologist at the Boston Center for Facial Rejuvenation, provided a state-of-the-art update on microneedling, a procedure in which microneedles are rolled over the skin to create epidermal and dermal microwounds.

“The depths are adjustable and it’s purely mechanical: no energy is being delivered with these treatments,” she said. “The hypothesized mechanism of action is that microneedling creates microwounds which initiate wound healing to stimulate new collagen production. This breaks apart compact collagen in the superficial dermis while stimulating new collagen and elastin,” she explained, adding that it is also hypothesized that this “stimulates growth factors that directly impact collagen and elastin synthesis.”

Conditions that have been reported to be treatable with microneedling in the medical literature include scars – especially acne scars – as well as rhytides, skin laxity, striae, melasma, and enlarged pores. Microneedling can also be used for transdermal drug delivery, although it’s far inferior to microinjection of medications. Contraindications are similar to those with laser surgery, including active infection of the area, history of keloids, inflammatory acne, and immunosuppression; and it should not be performed on the same day as neuromodulator treatment, to avoid diffusion of the neuromodulator. Herpes simplex virus prophylaxis is also indicated prior to microneedling treatment.

Many devices are available for use, including fixed, manual needle rollers and electric-powered pens with single-use sterile cartridges. The devices vary by needle length, quantity, diameter, configuration, and material of which the microneedles are made of. The needle length is not reliable for penetration depth, especially when greater than 1 mm. Treatment guidelines vary based on the area being treated.

“You put tension on the skin and apply the device perpendicularly,” Dr. DiGiorgio said during the meeting, which was sponsored by Harvard Medical School, Massachusetts General Hospital, and the Wellman Center for Photomedicine. “It should be performed in quadrants, and I prefer to treat in cosmetic units. The endpoint is pinpoint bleeding versus deep purpura. Ice water–soaked sterile gauze can be applied after treatment and skin care can be resumed in 5-7 days.”

In an effort to compare the efficacy and safety of the 2940-nm Er:YAG laser and microneedling for the treatment of atrophic acne scars, researchers in Egypt performed a randomized, split-face study in 30 patients. Study participants were evaluated by two blinded physicians at baseline and at 3 months follow-up. Both modalities showed a significant improvement in acne scars, but those treated with the Er:YAG laser showed a statistically significant greater improvement (70% vs. 30%, respectively; P < .001). Histology revealed a significantly higher increase in the mean quantity of collagen fibers in the Er:YAG-treated patients, compared with those who underwent microneedling, but patients in the microneedling group experienced less erythema and edema. Pain scores were significantly higher in the microneedling group compared with the Er:YAG group.

In a more recent study, researchers performed a systematic review of 37 articles in the medical literature related to microneedling. They found that the procedure provides good results when used on its own, and is preferred by patients because of its minimal downtime and side effects. However, they concluded that, while microneedling is a safe and effective option, methodological shortcomings and further research is required to establish it as an evidence-based therapeutic option.

“There are a limited number of high-quality studies demonstrating the efficacy of microneedling,” Dr. DiGiorgio said. “It is a safe procedure, which could complement laser treatments, so you could perform it between expensive and high-downtime lasers. It is an option for patients who seek measurable results with little to no downtime, and it’s also an option for clinicians who do not use laser-resurfacing devices. Basically, further research is needed to establish microneedling as an evidence-based therapeutic option. Laser continues to remain the gold standard for treatment.”

Another treatment option is fractional microneedling with radiofrequency (RF). These are microneedles which deliver energy in the form of RF at the tip of the needle, which denatures collagen and creates thermal coagulative injury zones at temperatures greater than 65° C. The microneedles can be insulated or noninsulated. “Insulated tips are safer for darker skin types because the epidermis is protected from the heat damage,” Dr. DiGiorgio said.

These treatments are used for the improvement of rhytides and scars and for skin tightening. “The treatments are painful and require topical anesthesia,” she said. “Erythema can range from about 24 hours to 4 days depending on the device being used. Usually monthly treatments are recommended.”

A study by investigators in South Korea and China set out to analyze histometric changes of this approach in pigs. They treated the pigs with a fractional microneedle delivery system at various depths, conduction times, and energies, and performed punch biopsies immediately after treatment, 4 days post treatment, and at 2 weeks post treatment. They noted that depth and conduction time affected the height, width, and volume of the columns of coagulation, but that the energy only affected the level of tissue destruction. “They also noted that RF-induced coagulated columns had a mixed cellular infiltrate, neovascularization, granular tissue formation with fibroblasts, and neocollagenesis and elastogenesis in the dermis,” Dr. DiGiorgio said.

In another study, researchers in Thailand performed a study in two women who were going to undergo abdominoplasty. Participants received six treatments prior to abdominoplasty with biopsies at different time intervals following microneedling with radiofrequency. The researchers tested five energy levels and five test areas; no collagen denaturization was observed with microneedling alone.

“This supports the idea that heat is required to stimulate neocollagenesis, and needles alone do not denature collagen,” Dr. DiGiorgio said. “They also found that neocollagenesis and neoelastogenesis occurred at optimal heating levels.”

In a separate study, researchers from Denmark used a number of different imaging modalities to evaluate the impact of microneedle fractional RF-induced micropores. When they used reflectance confocal microscopy, they observed that the micropores showed a concentric shape. “They contained hyper-reflective granules, and the coagulated tissue was seen from the epidermis to the dermal-epidermal junction,” Dr. DiGiorgio said. “This was not seen in the low energy microneedle RF. On optical coherence tomography, they noted that high-energy needle RF showed deeper, more easily identifiable micropores versus low-energy microneedle RF.” On histology the researchers noted that tissue coagulation reached a depth of 1,500 mcm with high-energy microneedle RF, but low-energy microneedle RF only showed visible damage to the epidermis. “This also supports the idea that microneedles alone without energy do not reach the deeper layers of the dermis,” she said.

Dr. DiGiorgio concluded her presentation by discussing promising results from a split-face study of fractional microneedling RF for the treatment of rosacea. For the 12-week randomized study, researchers from South Korea performed two sessions 4 weeks apart, with no treatment to the control side. Erythema decreased 13.6% and results were maintained for about 2 months after treatment. The researchers also measured inflammatory markers and noticed decreased dermal inflammation and mast cell counts and decreased markers related to angiogenesis, inflammation, innate immunity, and neuronal cation channels. “This could be a promising treatment for inflammatory rosacea in the future,” Dr. DiGiorgio said.

She disclosed that she is a consultant for Allergan Aesthetics.

according to Catherine M. DiGiorgio, MD, MS.

During a virtual course on laser and aesthetic skin therapy, Dr. DiGiorgio, a laser and cosmetic dermatologist at the Boston Center for Facial Rejuvenation, provided a state-of-the-art update on microneedling, a procedure in which microneedles are rolled over the skin to create epidermal and dermal microwounds.

“The depths are adjustable and it’s purely mechanical: no energy is being delivered with these treatments,” she said. “The hypothesized mechanism of action is that microneedling creates microwounds which initiate wound healing to stimulate new collagen production. This breaks apart compact collagen in the superficial dermis while stimulating new collagen and elastin,” she explained, adding that it is also hypothesized that this “stimulates growth factors that directly impact collagen and elastin synthesis.”

Conditions that have been reported to be treatable with microneedling in the medical literature include scars – especially acne scars – as well as rhytides, skin laxity, striae, melasma, and enlarged pores. Microneedling can also be used for transdermal drug delivery, although it’s far inferior to microinjection of medications. Contraindications are similar to those with laser surgery, including active infection of the area, history of keloids, inflammatory acne, and immunosuppression; and it should not be performed on the same day as neuromodulator treatment, to avoid diffusion of the neuromodulator. Herpes simplex virus prophylaxis is also indicated prior to microneedling treatment.

Many devices are available for use, including fixed, manual needle rollers and electric-powered pens with single-use sterile cartridges. The devices vary by needle length, quantity, diameter, configuration, and material of which the microneedles are made of. The needle length is not reliable for penetration depth, especially when greater than 1 mm. Treatment guidelines vary based on the area being treated.

“You put tension on the skin and apply the device perpendicularly,” Dr. DiGiorgio said during the meeting, which was sponsored by Harvard Medical School, Massachusetts General Hospital, and the Wellman Center for Photomedicine. “It should be performed in quadrants, and I prefer to treat in cosmetic units. The endpoint is pinpoint bleeding versus deep purpura. Ice water–soaked sterile gauze can be applied after treatment and skin care can be resumed in 5-7 days.”

In an effort to compare the efficacy and safety of the 2940-nm Er:YAG laser and microneedling for the treatment of atrophic acne scars, researchers in Egypt performed a randomized, split-face study in 30 patients. Study participants were evaluated by two blinded physicians at baseline and at 3 months follow-up. Both modalities showed a significant improvement in acne scars, but those treated with the Er:YAG laser showed a statistically significant greater improvement (70% vs. 30%, respectively; P < .001). Histology revealed a significantly higher increase in the mean quantity of collagen fibers in the Er:YAG-treated patients, compared with those who underwent microneedling, but patients in the microneedling group experienced less erythema and edema. Pain scores were significantly higher in the microneedling group compared with the Er:YAG group.

In a more recent study, researchers performed a systematic review of 37 articles in the medical literature related to microneedling. They found that the procedure provides good results when used on its own, and is preferred by patients because of its minimal downtime and side effects. However, they concluded that, while microneedling is a safe and effective option, methodological shortcomings and further research is required to establish it as an evidence-based therapeutic option.

“There are a limited number of high-quality studies demonstrating the efficacy of microneedling,” Dr. DiGiorgio said. “It is a safe procedure, which could complement laser treatments, so you could perform it between expensive and high-downtime lasers. It is an option for patients who seek measurable results with little to no downtime, and it’s also an option for clinicians who do not use laser-resurfacing devices. Basically, further research is needed to establish microneedling as an evidence-based therapeutic option. Laser continues to remain the gold standard for treatment.”

Another treatment option is fractional microneedling with radiofrequency (RF). These are microneedles which deliver energy in the form of RF at the tip of the needle, which denatures collagen and creates thermal coagulative injury zones at temperatures greater than 65° C. The microneedles can be insulated or noninsulated. “Insulated tips are safer for darker skin types because the epidermis is protected from the heat damage,” Dr. DiGiorgio said.

These treatments are used for the improvement of rhytides and scars and for skin tightening. “The treatments are painful and require topical anesthesia,” she said. “Erythema can range from about 24 hours to 4 days depending on the device being used. Usually monthly treatments are recommended.”

A study by investigators in South Korea and China set out to analyze histometric changes of this approach in pigs. They treated the pigs with a fractional microneedle delivery system at various depths, conduction times, and energies, and performed punch biopsies immediately after treatment, 4 days post treatment, and at 2 weeks post treatment. They noted that depth and conduction time affected the height, width, and volume of the columns of coagulation, but that the energy only affected the level of tissue destruction. “They also noted that RF-induced coagulated columns had a mixed cellular infiltrate, neovascularization, granular tissue formation with fibroblasts, and neocollagenesis and elastogenesis in the dermis,” Dr. DiGiorgio said.

In another study, researchers in Thailand performed a study in two women who were going to undergo abdominoplasty. Participants received six treatments prior to abdominoplasty with biopsies at different time intervals following microneedling with radiofrequency. The researchers tested five energy levels and five test areas; no collagen denaturization was observed with microneedling alone.

“This supports the idea that heat is required to stimulate neocollagenesis, and needles alone do not denature collagen,” Dr. DiGiorgio said. “They also found that neocollagenesis and neoelastogenesis occurred at optimal heating levels.”

In a separate study, researchers from Denmark used a number of different imaging modalities to evaluate the impact of microneedle fractional RF-induced micropores. When they used reflectance confocal microscopy, they observed that the micropores showed a concentric shape. “They contained hyper-reflective granules, and the coagulated tissue was seen from the epidermis to the dermal-epidermal junction,” Dr. DiGiorgio said. “This was not seen in the low energy microneedle RF. On optical coherence tomography, they noted that high-energy needle RF showed deeper, more easily identifiable micropores versus low-energy microneedle RF.” On histology the researchers noted that tissue coagulation reached a depth of 1,500 mcm with high-energy microneedle RF, but low-energy microneedle RF only showed visible damage to the epidermis. “This also supports the idea that microneedles alone without energy do not reach the deeper layers of the dermis,” she said.

Dr. DiGiorgio concluded her presentation by discussing promising results from a split-face study of fractional microneedling RF for the treatment of rosacea. For the 12-week randomized study, researchers from South Korea performed two sessions 4 weeks apart, with no treatment to the control side. Erythema decreased 13.6% and results were maintained for about 2 months after treatment. The researchers also measured inflammatory markers and noticed decreased dermal inflammation and mast cell counts and decreased markers related to angiogenesis, inflammation, innate immunity, and neuronal cation channels. “This could be a promising treatment for inflammatory rosacea in the future,” Dr. DiGiorgio said.

She disclosed that she is a consultant for Allergan Aesthetics.

according to Catherine M. DiGiorgio, MD, MS.

During a virtual course on laser and aesthetic skin therapy, Dr. DiGiorgio, a laser and cosmetic dermatologist at the Boston Center for Facial Rejuvenation, provided a state-of-the-art update on microneedling, a procedure in which microneedles are rolled over the skin to create epidermal and dermal microwounds.

“The depths are adjustable and it’s purely mechanical: no energy is being delivered with these treatments,” she said. “The hypothesized mechanism of action is that microneedling creates microwounds which initiate wound healing to stimulate new collagen production. This breaks apart compact collagen in the superficial dermis while stimulating new collagen and elastin,” she explained, adding that it is also hypothesized that this “stimulates growth factors that directly impact collagen and elastin synthesis.”

Conditions that have been reported to be treatable with microneedling in the medical literature include scars – especially acne scars – as well as rhytides, skin laxity, striae, melasma, and enlarged pores. Microneedling can also be used for transdermal drug delivery, although it’s far inferior to microinjection of medications. Contraindications are similar to those with laser surgery, including active infection of the area, history of keloids, inflammatory acne, and immunosuppression; and it should not be performed on the same day as neuromodulator treatment, to avoid diffusion of the neuromodulator. Herpes simplex virus prophylaxis is also indicated prior to microneedling treatment.

Many devices are available for use, including fixed, manual needle rollers and electric-powered pens with single-use sterile cartridges. The devices vary by needle length, quantity, diameter, configuration, and material of which the microneedles are made of. The needle length is not reliable for penetration depth, especially when greater than 1 mm. Treatment guidelines vary based on the area being treated.

“You put tension on the skin and apply the device perpendicularly,” Dr. DiGiorgio said during the meeting, which was sponsored by Harvard Medical School, Massachusetts General Hospital, and the Wellman Center for Photomedicine. “It should be performed in quadrants, and I prefer to treat in cosmetic units. The endpoint is pinpoint bleeding versus deep purpura. Ice water–soaked sterile gauze can be applied after treatment and skin care can be resumed in 5-7 days.”

In an effort to compare the efficacy and safety of the 2940-nm Er:YAG laser and microneedling for the treatment of atrophic acne scars, researchers in Egypt performed a randomized, split-face study in 30 patients. Study participants were evaluated by two blinded physicians at baseline and at 3 months follow-up. Both modalities showed a significant improvement in acne scars, but those treated with the Er:YAG laser showed a statistically significant greater improvement (70% vs. 30%, respectively; P < .001). Histology revealed a significantly higher increase in the mean quantity of collagen fibers in the Er:YAG-treated patients, compared with those who underwent microneedling, but patients in the microneedling group experienced less erythema and edema. Pain scores were significantly higher in the microneedling group compared with the Er:YAG group.

In a more recent study, researchers performed a systematic review of 37 articles in the medical literature related to microneedling. They found that the procedure provides good results when used on its own, and is preferred by patients because of its minimal downtime and side effects. However, they concluded that, while microneedling is a safe and effective option, methodological shortcomings and further research is required to establish it as an evidence-based therapeutic option.

“There are a limited number of high-quality studies demonstrating the efficacy of microneedling,” Dr. DiGiorgio said. “It is a safe procedure, which could complement laser treatments, so you could perform it between expensive and high-downtime lasers. It is an option for patients who seek measurable results with little to no downtime, and it’s also an option for clinicians who do not use laser-resurfacing devices. Basically, further research is needed to establish microneedling as an evidence-based therapeutic option. Laser continues to remain the gold standard for treatment.”

Another treatment option is fractional microneedling with radiofrequency (RF). These are microneedles which deliver energy in the form of RF at the tip of the needle, which denatures collagen and creates thermal coagulative injury zones at temperatures greater than 65° C. The microneedles can be insulated or noninsulated. “Insulated tips are safer for darker skin types because the epidermis is protected from the heat damage,” Dr. DiGiorgio said.

These treatments are used for the improvement of rhytides and scars and for skin tightening. “The treatments are painful and require topical anesthesia,” she said. “Erythema can range from about 24 hours to 4 days depending on the device being used. Usually monthly treatments are recommended.”

A study by investigators in South Korea and China set out to analyze histometric changes of this approach in pigs. They treated the pigs with a fractional microneedle delivery system at various depths, conduction times, and energies, and performed punch biopsies immediately after treatment, 4 days post treatment, and at 2 weeks post treatment. They noted that depth and conduction time affected the height, width, and volume of the columns of coagulation, but that the energy only affected the level of tissue destruction. “They also noted that RF-induced coagulated columns had a mixed cellular infiltrate, neovascularization, granular tissue formation with fibroblasts, and neocollagenesis and elastogenesis in the dermis,” Dr. DiGiorgio said.

In another study, researchers in Thailand performed a study in two women who were going to undergo abdominoplasty. Participants received six treatments prior to abdominoplasty with biopsies at different time intervals following microneedling with radiofrequency. The researchers tested five energy levels and five test areas; no collagen denaturization was observed with microneedling alone.

“This supports the idea that heat is required to stimulate neocollagenesis, and needles alone do not denature collagen,” Dr. DiGiorgio said. “They also found that neocollagenesis and neoelastogenesis occurred at optimal heating levels.”

In a separate study, researchers from Denmark used a number of different imaging modalities to evaluate the impact of microneedle fractional RF-induced micropores. When they used reflectance confocal microscopy, they observed that the micropores showed a concentric shape. “They contained hyper-reflective granules, and the coagulated tissue was seen from the epidermis to the dermal-epidermal junction,” Dr. DiGiorgio said. “This was not seen in the low energy microneedle RF. On optical coherence tomography, they noted that high-energy needle RF showed deeper, more easily identifiable micropores versus low-energy microneedle RF.” On histology the researchers noted that tissue coagulation reached a depth of 1,500 mcm with high-energy microneedle RF, but low-energy microneedle RF only showed visible damage to the epidermis. “This also supports the idea that microneedles alone without energy do not reach the deeper layers of the dermis,” she said.

Dr. DiGiorgio concluded her presentation by discussing promising results from a split-face study of fractional microneedling RF for the treatment of rosacea. For the 12-week randomized study, researchers from South Korea performed two sessions 4 weeks apart, with no treatment to the control side. Erythema decreased 13.6% and results were maintained for about 2 months after treatment. The researchers also measured inflammatory markers and noticed decreased dermal inflammation and mast cell counts and decreased markers related to angiogenesis, inflammation, innate immunity, and neuronal cation channels. “This could be a promising treatment for inflammatory rosacea in the future,” Dr. DiGiorgio said.

She disclosed that she is a consultant for Allergan Aesthetics.

FROM A LASER & AESTHETIC SKIN THERAPY COURSE

A Review of ACR Convergence Abstracts on Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

The American College of Rheumatology hosted its first-ever all-virtual annual meeting this year. Convergence 2020 highlighted several important treatment abstracts related to systemic lupus erythematosus.

Dr Michelle Petri, of Johns Hopkins University, reports on the use of hydroxychloroquine, which was not found to be associated with QTc length in a large cohort of patients with lupus and rheumatoid arthritis. This is notable because hydroxychloroquine was implicated in ventricular arrhythmias in patients with COVID-19 who were also given azithromycin.

Dr Petri also looks at the results of two trials focusing on the effects of belimumab and obinutuzumab on renal outcomes.

In the belimumab trial, the primary outcome was a 700-mg reduction in the urine protein to creatinine ratio, and it met that outcome with a 10.8% delta that was statistically significant. It also met the complete renal response outcome of less than 500 mg with a 10% delta, which is statistically significant.

In the other study, obinutuzumab showed a marked improvement over rituximab as a B-cell depleter.

The completion of the phase 2 trial means that there are now 2 years of data showing a 19% delta between obinutuzumab and standard-of-care treatment.

Finally, Dr Petri highlights two studies focusing on nonrenal lupus and the use of both BIIB059 and iberdomide.

--

Michelle Petri, MD, MPH, Professor, Department of Medicine, Division of Rheumatology, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine; Director, Johns Hopkins Lupus Center, Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, Maryland.

Michelle Petri, MD, MPH, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Received research grant from: GlaxoSmithKline; Eli Lilly and Company; Thermo Fisher; Hexagen; AstraZeneca

Received income in an amount equal to or greater than $250 from: AbbVie; Amgen; AstraZeneca; Blackrock; Bristol-Myers Squibb; Hexagen; Glenmark; GlaxoSmithKline; IQVIA; Janssen; Eli Lilly and Company; Merck; EMD Serono; Novartis; Sanofi; Thermo Fisher; UCB

The American College of Rheumatology hosted its first-ever all-virtual annual meeting this year. Convergence 2020 highlighted several important treatment abstracts related to systemic lupus erythematosus.

Dr Michelle Petri, of Johns Hopkins University, reports on the use of hydroxychloroquine, which was not found to be associated with QTc length in a large cohort of patients with lupus and rheumatoid arthritis. This is notable because hydroxychloroquine was implicated in ventricular arrhythmias in patients with COVID-19 who were also given azithromycin.

Dr Petri also looks at the results of two trials focusing on the effects of belimumab and obinutuzumab on renal outcomes.

In the belimumab trial, the primary outcome was a 700-mg reduction in the urine protein to creatinine ratio, and it met that outcome with a 10.8% delta that was statistically significant. It also met the complete renal response outcome of less than 500 mg with a 10% delta, which is statistically significant.

In the other study, obinutuzumab showed a marked improvement over rituximab as a B-cell depleter.

The completion of the phase 2 trial means that there are now 2 years of data showing a 19% delta between obinutuzumab and standard-of-care treatment.

Finally, Dr Petri highlights two studies focusing on nonrenal lupus and the use of both BIIB059 and iberdomide.

--

Michelle Petri, MD, MPH, Professor, Department of Medicine, Division of Rheumatology, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine; Director, Johns Hopkins Lupus Center, Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, Maryland.

Michelle Petri, MD, MPH, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Received research grant from: GlaxoSmithKline; Eli Lilly and Company; Thermo Fisher; Hexagen; AstraZeneca

Received income in an amount equal to or greater than $250 from: AbbVie; Amgen; AstraZeneca; Blackrock; Bristol-Myers Squibb; Hexagen; Glenmark; GlaxoSmithKline; IQVIA; Janssen; Eli Lilly and Company; Merck; EMD Serono; Novartis; Sanofi; Thermo Fisher; UCB

The American College of Rheumatology hosted its first-ever all-virtual annual meeting this year. Convergence 2020 highlighted several important treatment abstracts related to systemic lupus erythematosus.

Dr Michelle Petri, of Johns Hopkins University, reports on the use of hydroxychloroquine, which was not found to be associated with QTc length in a large cohort of patients with lupus and rheumatoid arthritis. This is notable because hydroxychloroquine was implicated in ventricular arrhythmias in patients with COVID-19 who were also given azithromycin.

Dr Petri also looks at the results of two trials focusing on the effects of belimumab and obinutuzumab on renal outcomes.

In the belimumab trial, the primary outcome was a 700-mg reduction in the urine protein to creatinine ratio, and it met that outcome with a 10.8% delta that was statistically significant. It also met the complete renal response outcome of less than 500 mg with a 10% delta, which is statistically significant.

In the other study, obinutuzumab showed a marked improvement over rituximab as a B-cell depleter.

The completion of the phase 2 trial means that there are now 2 years of data showing a 19% delta between obinutuzumab and standard-of-care treatment.

Finally, Dr Petri highlights two studies focusing on nonrenal lupus and the use of both BIIB059 and iberdomide.

--

Michelle Petri, MD, MPH, Professor, Department of Medicine, Division of Rheumatology, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine; Director, Johns Hopkins Lupus Center, Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, Maryland.

Michelle Petri, MD, MPH, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Received research grant from: GlaxoSmithKline; Eli Lilly and Company; Thermo Fisher; Hexagen; AstraZeneca

Received income in an amount equal to or greater than $250 from: AbbVie; Amgen; AstraZeneca; Blackrock; Bristol-Myers Squibb; Hexagen; Glenmark; GlaxoSmithKline; IQVIA; Janssen; Eli Lilly and Company; Merck; EMD Serono; Novartis; Sanofi; Thermo Fisher; UCB

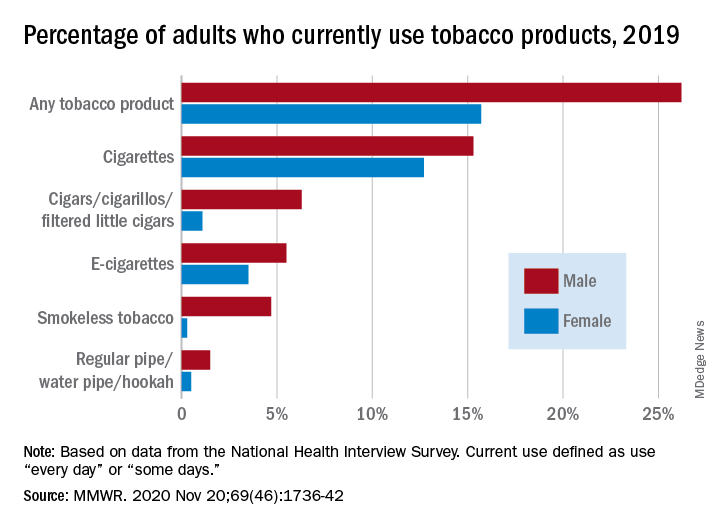

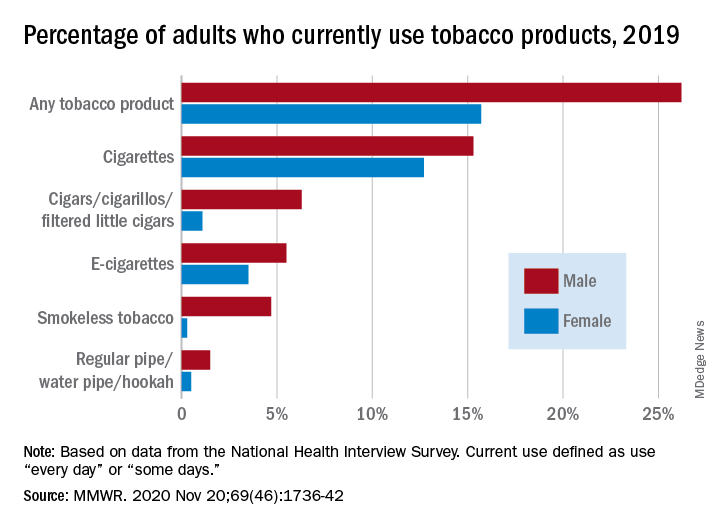

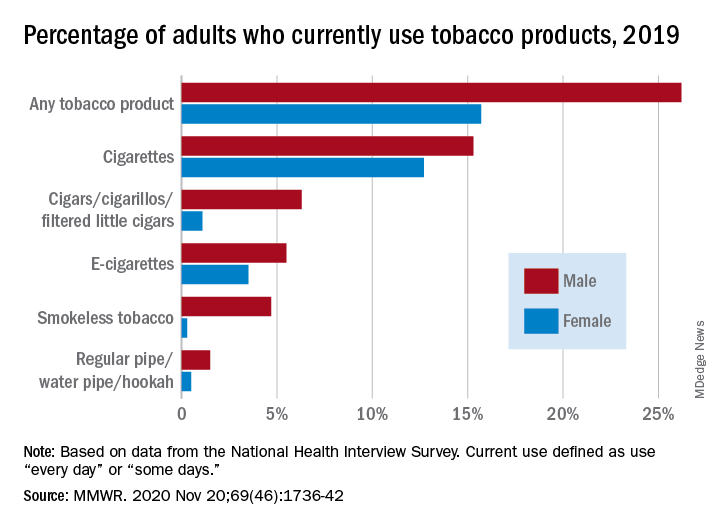

50.6 million tobacco users are not a homogeneous group

Cigarettes are still the product of choice among U.S. adults who use tobacco, but the youngest adults are more likely to use e-cigarettes than any other product, according to data from the 2019 National Health Interview Survey.

with cigarette use reported by the largest share of respondents (14.0%) and e-cigarettes next at 4.5%, Monica E. Cornelius, PhD, and associates said in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Among adults aged 18-24 years, however, e-cigarettes were used by 9.3% of respondents in 2019, compared with 8.0% who used cigarettes every day or some days. Current e-cigarette use was 6.4% in 25- to 44-year-olds and continued to diminish with increasing age, said Dr. Cornelius and associates at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion.

Men were more likely than women to use e-cigarettes (5.5% vs. 3.5%), and to use any tobacco product (26.2% vs. 15.7%). Use of other products, including cigarettes (15.3% for men vs. 12.7% for women), followed the same pattern to varying degrees, the national survey data show.

“Differences in prevalence of tobacco use also were also seen across population groups, with higher prevalence among those with a [high school equivalency degree], American Indian/Alaska Natives, uninsured adults and adults with Medicaid, and [lesbian, gay, or bisexual] adults,” the investigators said.

Among those groups, overall tobacco use and cigarette use were highest in those with an equivalency degree (43.8%, 37.1%), while lesbian/gay/bisexual individuals had the highest prevalence of e-cigarette use at 11.5%, they reported.

“As part of a comprehensive approach” to reduce tobacco-related disease and death, Dr. Cornelius and associates suggested, “targeted interventions are also warranted to reach subpopulations with the highest prevalence of use, which might vary by tobacco product type.”

SOURCE: Cornelius ME et al. MMWR. 2020 Nov 20;69(46);1736-42.

Cigarettes are still the product of choice among U.S. adults who use tobacco, but the youngest adults are more likely to use e-cigarettes than any other product, according to data from the 2019 National Health Interview Survey.

with cigarette use reported by the largest share of respondents (14.0%) and e-cigarettes next at 4.5%, Monica E. Cornelius, PhD, and associates said in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Among adults aged 18-24 years, however, e-cigarettes were used by 9.3% of respondents in 2019, compared with 8.0% who used cigarettes every day or some days. Current e-cigarette use was 6.4% in 25- to 44-year-olds and continued to diminish with increasing age, said Dr. Cornelius and associates at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion.

Men were more likely than women to use e-cigarettes (5.5% vs. 3.5%), and to use any tobacco product (26.2% vs. 15.7%). Use of other products, including cigarettes (15.3% for men vs. 12.7% for women), followed the same pattern to varying degrees, the national survey data show.

“Differences in prevalence of tobacco use also were also seen across population groups, with higher prevalence among those with a [high school equivalency degree], American Indian/Alaska Natives, uninsured adults and adults with Medicaid, and [lesbian, gay, or bisexual] adults,” the investigators said.

Among those groups, overall tobacco use and cigarette use were highest in those with an equivalency degree (43.8%, 37.1%), while lesbian/gay/bisexual individuals had the highest prevalence of e-cigarette use at 11.5%, they reported.

“As part of a comprehensive approach” to reduce tobacco-related disease and death, Dr. Cornelius and associates suggested, “targeted interventions are also warranted to reach subpopulations with the highest prevalence of use, which might vary by tobacco product type.”

SOURCE: Cornelius ME et al. MMWR. 2020 Nov 20;69(46);1736-42.

Cigarettes are still the product of choice among U.S. adults who use tobacco, but the youngest adults are more likely to use e-cigarettes than any other product, according to data from the 2019 National Health Interview Survey.

with cigarette use reported by the largest share of respondents (14.0%) and e-cigarettes next at 4.5%, Monica E. Cornelius, PhD, and associates said in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Among adults aged 18-24 years, however, e-cigarettes were used by 9.3% of respondents in 2019, compared with 8.0% who used cigarettes every day or some days. Current e-cigarette use was 6.4% in 25- to 44-year-olds and continued to diminish with increasing age, said Dr. Cornelius and associates at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion.

Men were more likely than women to use e-cigarettes (5.5% vs. 3.5%), and to use any tobacco product (26.2% vs. 15.7%). Use of other products, including cigarettes (15.3% for men vs. 12.7% for women), followed the same pattern to varying degrees, the national survey data show.

“Differences in prevalence of tobacco use also were also seen across population groups, with higher prevalence among those with a [high school equivalency degree], American Indian/Alaska Natives, uninsured adults and adults with Medicaid, and [lesbian, gay, or bisexual] adults,” the investigators said.

Among those groups, overall tobacco use and cigarette use were highest in those with an equivalency degree (43.8%, 37.1%), while lesbian/gay/bisexual individuals had the highest prevalence of e-cigarette use at 11.5%, they reported.

“As part of a comprehensive approach” to reduce tobacco-related disease and death, Dr. Cornelius and associates suggested, “targeted interventions are also warranted to reach subpopulations with the highest prevalence of use, which might vary by tobacco product type.”

SOURCE: Cornelius ME et al. MMWR. 2020 Nov 20;69(46);1736-42.

FROM MMWR

Metformin improves most outcomes for T2D during pregnancy

including reduced weight gain, reduced insulin doses, and fewer large-for-gestational-age babies, suggest the results of a randomized controlled trial.

However, the drug was associated with an increased risk of small-for-gestational-age babies, which poses the question as to risk versus benefit of metformin on the health of offspring.

“Better understanding of the short- and long-term implications of these effects on infants will be important to properly advise patients with type 2 diabetes contemplating use of metformin during pregnancy,” said lead author Denice S. Feig, MD, Mount Sinai Hospital, Toronto.

The research was presented at the Diabetes UK Professional Conference: Online Series on Nov. 17 and recently published in The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology.

Summing up, Dr. Feig said that, on balance, she would be inclined to give metformin to most pregnant women with type 2 diabetes, perhaps with the exception of those who may have risk factors for small-for-gestational-age babies; for example, women who’ve had intrauterine growth restriction, who are smokers, and have significant renal disease, or have a lower body mass index.

Increased prevalence of type 2 diabetes in pregnancy

Dr. Feig said that across the developed world there have been huge increases in the prevalence of type 2 diabetes in pregnancy in recent years.

Insulin is the standard treatment for the management of type 2 diabetes in pregnancy, but these women have marked insulin resistance that worsens in pregnancy, which means their insulin requirements increase, leading to weight gain, painful injections, high cost, and noncompliance.

So despite treatment with insulin, these women continue to face increased rates of adverse maternal and fetal outcomes.

And although metformin is increasingly being used in women with type 2 diabetes during pregnancy, there is a scarcity of data on the benefits and harms of metformin use on pregnancy outcomes in these women.

The MiTy trial was therefore undertaken to determine whether metformin could improve outcomes.

The team recruited 502 women from 29 sites in Canada and Australia who had type 2 diabetes prior to pregnancy or were diagnosed during pregnancy, before 20 weeks’ gestation. The women were randomized to metformin 1 g twice daily or placebo, in addition to their usual insulin regimen, at between 6 and 28 weeks’ gestation.

Type 2 diabetes was diagnosed prior to pregnancy in 83% of women in the metformin group and in 90% of those assigned to placebo. The mean hemoglobin A1c level at randomization was 47 mmol/mol (6.5%) in both groups.

The average maternal age at baseline was approximately 35 years and mean gestational age at randomization was 16 weeks. Mean prepregnancy BMI was approximately 34 kg/m2.

Of note, only 30% were of European ethnicity.

Less weight gain, lower A1c, less insulin needed with metformin

Dr. Feig reported that there was no significant difference between the treatment groups in terms of the proportion of women with the composite primary outcome of pregnancy loss, preterm birth, birth injury, respiratory distress, neonatal hypoglycemia, or admission to neonatal intensive care lasting more than 24 hours (P = 0.86).

However, women in the metformin group had significantly less overall weight gain during pregnancy than did those in the placebo group, at –1.8 kg (P < .0001).

They also had a significantly lower last A1c level in pregnancy, at 41 mmol/mol (5.9%) versus 43.2 mmol/mol (6.1%) in those given placebo (P = .015), and required fewer insulin doses, at 1.1 versus 1.5 units/kg/day (P < .0001), which translated to a reduction of almost 44 units/day.

Women given metformin were also less likely to require Cesarean section delivery, at 53.4% versus 62.7% in the placebo group (P = .03), although there was no difference between groups in terms of gestational hypertension or preeclampsia.

The most common adverse events were gastrointestinal complications, which occurred in 27.3% of women in the metformin group and 22.3% of those given placebo.

There were no significant differences between the metformin and placebo groups in rates of pregnancy loss (P = .81), preterm birth (P = .16), birth injury (P = .37), respiratory distress (P = .49), and congenital anomalies (P = .16).

Average birth weight lower with metformin

However, Dr. Feig showed that the average birth weight was lower for offspring of women given metformin than those assigned to placebo, at 3.2 kg (7.05 lb) versus 3.4 kg (7.4 lb) (P = .002).

Women given metformin were also less likely to have a baby with a birth weight of 4 kg (8.8 lb) or more, at 12.1% versus 19.2%, or a relative risk of 0.65 (P = .046), and a baby that was extremely large for gestational age, at 8.6% versus 14.8%, or a relative risk of 0.58 (P = .046).

But of concern, metformin was associated with an increased risk of small-for-gestational-age babies, at 12.9% versus 6.6% with placebo, or a relative risk of 1.96 (P = .03).

Dr. Feig suggested that this may be due to a direct effect of metformin “because as we know metformin inhibits the mTOR pathway,” which is a “primary nutrient sensor in the placenta” and could “attenuate nutrient flux and fetal growth.”

She said it is not clear whether the small-for-gestational-age babies were “healthy or unhealthy.”

To investigate further, the team has launched the MiTy Kids study, which will follow the offspring in the MiTy trial to determine whether metformin during pregnancy is associated with a reduction in adiposity and improvement in insulin resistance in the babies at 2 years of age.

Who should be given metformin?

During the discussion, Helen R. Murphy, MD, PhD, Norwich Medical School, University of East Anglia, England, asked whether Dr. Feig would recommend continuing metformin in pregnancy if it was started preconception for fertility issues rather than diabetes.

She replied: “If they don’t have diabetes and it’s simply for PCOS [polycystic ovary syndrome], then I have either stopped it as soon as they got pregnant or sometimes continued it through the first trimester, and then stopped.

“If the person has diabetes, however, I think given this work, for most people I would continue it,” she said.

The study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Lunenfeld-Tanenbaum Research Institute, and the University of Toronto. The authors have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

including reduced weight gain, reduced insulin doses, and fewer large-for-gestational-age babies, suggest the results of a randomized controlled trial.

However, the drug was associated with an increased risk of small-for-gestational-age babies, which poses the question as to risk versus benefit of metformin on the health of offspring.

“Better understanding of the short- and long-term implications of these effects on infants will be important to properly advise patients with type 2 diabetes contemplating use of metformin during pregnancy,” said lead author Denice S. Feig, MD, Mount Sinai Hospital, Toronto.

The research was presented at the Diabetes UK Professional Conference: Online Series on Nov. 17 and recently published in The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology.

Summing up, Dr. Feig said that, on balance, she would be inclined to give metformin to most pregnant women with type 2 diabetes, perhaps with the exception of those who may have risk factors for small-for-gestational-age babies; for example, women who’ve had intrauterine growth restriction, who are smokers, and have significant renal disease, or have a lower body mass index.

Increased prevalence of type 2 diabetes in pregnancy

Dr. Feig said that across the developed world there have been huge increases in the prevalence of type 2 diabetes in pregnancy in recent years.

Insulin is the standard treatment for the management of type 2 diabetes in pregnancy, but these women have marked insulin resistance that worsens in pregnancy, which means their insulin requirements increase, leading to weight gain, painful injections, high cost, and noncompliance.

So despite treatment with insulin, these women continue to face increased rates of adverse maternal and fetal outcomes.

And although metformin is increasingly being used in women with type 2 diabetes during pregnancy, there is a scarcity of data on the benefits and harms of metformin use on pregnancy outcomes in these women.

The MiTy trial was therefore undertaken to determine whether metformin could improve outcomes.

The team recruited 502 women from 29 sites in Canada and Australia who had type 2 diabetes prior to pregnancy or were diagnosed during pregnancy, before 20 weeks’ gestation. The women were randomized to metformin 1 g twice daily or placebo, in addition to their usual insulin regimen, at between 6 and 28 weeks’ gestation.

Type 2 diabetes was diagnosed prior to pregnancy in 83% of women in the metformin group and in 90% of those assigned to placebo. The mean hemoglobin A1c level at randomization was 47 mmol/mol (6.5%) in both groups.

The average maternal age at baseline was approximately 35 years and mean gestational age at randomization was 16 weeks. Mean prepregnancy BMI was approximately 34 kg/m2.

Of note, only 30% were of European ethnicity.

Less weight gain, lower A1c, less insulin needed with metformin

Dr. Feig reported that there was no significant difference between the treatment groups in terms of the proportion of women with the composite primary outcome of pregnancy loss, preterm birth, birth injury, respiratory distress, neonatal hypoglycemia, or admission to neonatal intensive care lasting more than 24 hours (P = 0.86).

However, women in the metformin group had significantly less overall weight gain during pregnancy than did those in the placebo group, at –1.8 kg (P < .0001).

They also had a significantly lower last A1c level in pregnancy, at 41 mmol/mol (5.9%) versus 43.2 mmol/mol (6.1%) in those given placebo (P = .015), and required fewer insulin doses, at 1.1 versus 1.5 units/kg/day (P < .0001), which translated to a reduction of almost 44 units/day.

Women given metformin were also less likely to require Cesarean section delivery, at 53.4% versus 62.7% in the placebo group (P = .03), although there was no difference between groups in terms of gestational hypertension or preeclampsia.

The most common adverse events were gastrointestinal complications, which occurred in 27.3% of women in the metformin group and 22.3% of those given placebo.

There were no significant differences between the metformin and placebo groups in rates of pregnancy loss (P = .81), preterm birth (P = .16), birth injury (P = .37), respiratory distress (P = .49), and congenital anomalies (P = .16).

Average birth weight lower with metformin

However, Dr. Feig showed that the average birth weight was lower for offspring of women given metformin than those assigned to placebo, at 3.2 kg (7.05 lb) versus 3.4 kg (7.4 lb) (P = .002).

Women given metformin were also less likely to have a baby with a birth weight of 4 kg (8.8 lb) or more, at 12.1% versus 19.2%, or a relative risk of 0.65 (P = .046), and a baby that was extremely large for gestational age, at 8.6% versus 14.8%, or a relative risk of 0.58 (P = .046).

But of concern, metformin was associated with an increased risk of small-for-gestational-age babies, at 12.9% versus 6.6% with placebo, or a relative risk of 1.96 (P = .03).

Dr. Feig suggested that this may be due to a direct effect of metformin “because as we know metformin inhibits the mTOR pathway,” which is a “primary nutrient sensor in the placenta” and could “attenuate nutrient flux and fetal growth.”

She said it is not clear whether the small-for-gestational-age babies were “healthy or unhealthy.”

To investigate further, the team has launched the MiTy Kids study, which will follow the offspring in the MiTy trial to determine whether metformin during pregnancy is associated with a reduction in adiposity and improvement in insulin resistance in the babies at 2 years of age.

Who should be given metformin?

During the discussion, Helen R. Murphy, MD, PhD, Norwich Medical School, University of East Anglia, England, asked whether Dr. Feig would recommend continuing metformin in pregnancy if it was started preconception for fertility issues rather than diabetes.

She replied: “If they don’t have diabetes and it’s simply for PCOS [polycystic ovary syndrome], then I have either stopped it as soon as they got pregnant or sometimes continued it through the first trimester, and then stopped.

“If the person has diabetes, however, I think given this work, for most people I would continue it,” she said.

The study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Lunenfeld-Tanenbaum Research Institute, and the University of Toronto. The authors have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

including reduced weight gain, reduced insulin doses, and fewer large-for-gestational-age babies, suggest the results of a randomized controlled trial.

However, the drug was associated with an increased risk of small-for-gestational-age babies, which poses the question as to risk versus benefit of metformin on the health of offspring.

“Better understanding of the short- and long-term implications of these effects on infants will be important to properly advise patients with type 2 diabetes contemplating use of metformin during pregnancy,” said lead author Denice S. Feig, MD, Mount Sinai Hospital, Toronto.

The research was presented at the Diabetes UK Professional Conference: Online Series on Nov. 17 and recently published in The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology.

Summing up, Dr. Feig said that, on balance, she would be inclined to give metformin to most pregnant women with type 2 diabetes, perhaps with the exception of those who may have risk factors for small-for-gestational-age babies; for example, women who’ve had intrauterine growth restriction, who are smokers, and have significant renal disease, or have a lower body mass index.

Increased prevalence of type 2 diabetes in pregnancy

Dr. Feig said that across the developed world there have been huge increases in the prevalence of type 2 diabetes in pregnancy in recent years.

Insulin is the standard treatment for the management of type 2 diabetes in pregnancy, but these women have marked insulin resistance that worsens in pregnancy, which means their insulin requirements increase, leading to weight gain, painful injections, high cost, and noncompliance.

So despite treatment with insulin, these women continue to face increased rates of adverse maternal and fetal outcomes.

And although metformin is increasingly being used in women with type 2 diabetes during pregnancy, there is a scarcity of data on the benefits and harms of metformin use on pregnancy outcomes in these women.

The MiTy trial was therefore undertaken to determine whether metformin could improve outcomes.

The team recruited 502 women from 29 sites in Canada and Australia who had type 2 diabetes prior to pregnancy or were diagnosed during pregnancy, before 20 weeks’ gestation. The women were randomized to metformin 1 g twice daily or placebo, in addition to their usual insulin regimen, at between 6 and 28 weeks’ gestation.

Type 2 diabetes was diagnosed prior to pregnancy in 83% of women in the metformin group and in 90% of those assigned to placebo. The mean hemoglobin A1c level at randomization was 47 mmol/mol (6.5%) in both groups.

The average maternal age at baseline was approximately 35 years and mean gestational age at randomization was 16 weeks. Mean prepregnancy BMI was approximately 34 kg/m2.

Of note, only 30% were of European ethnicity.

Less weight gain, lower A1c, less insulin needed with metformin

Dr. Feig reported that there was no significant difference between the treatment groups in terms of the proportion of women with the composite primary outcome of pregnancy loss, preterm birth, birth injury, respiratory distress, neonatal hypoglycemia, or admission to neonatal intensive care lasting more than 24 hours (P = 0.86).

However, women in the metformin group had significantly less overall weight gain during pregnancy than did those in the placebo group, at –1.8 kg (P < .0001).

They also had a significantly lower last A1c level in pregnancy, at 41 mmol/mol (5.9%) versus 43.2 mmol/mol (6.1%) in those given placebo (P = .015), and required fewer insulin doses, at 1.1 versus 1.5 units/kg/day (P < .0001), which translated to a reduction of almost 44 units/day.

Women given metformin were also less likely to require Cesarean section delivery, at 53.4% versus 62.7% in the placebo group (P = .03), although there was no difference between groups in terms of gestational hypertension or preeclampsia.

The most common adverse events were gastrointestinal complications, which occurred in 27.3% of women in the metformin group and 22.3% of those given placebo.

There were no significant differences between the metformin and placebo groups in rates of pregnancy loss (P = .81), preterm birth (P = .16), birth injury (P = .37), respiratory distress (P = .49), and congenital anomalies (P = .16).

Average birth weight lower with metformin

However, Dr. Feig showed that the average birth weight was lower for offspring of women given metformin than those assigned to placebo, at 3.2 kg (7.05 lb) versus 3.4 kg (7.4 lb) (P = .002).

Women given metformin were also less likely to have a baby with a birth weight of 4 kg (8.8 lb) or more, at 12.1% versus 19.2%, or a relative risk of 0.65 (P = .046), and a baby that was extremely large for gestational age, at 8.6% versus 14.8%, or a relative risk of 0.58 (P = .046).

But of concern, metformin was associated with an increased risk of small-for-gestational-age babies, at 12.9% versus 6.6% with placebo, or a relative risk of 1.96 (P = .03).

Dr. Feig suggested that this may be due to a direct effect of metformin “because as we know metformin inhibits the mTOR pathway,” which is a “primary nutrient sensor in the placenta” and could “attenuate nutrient flux and fetal growth.”

She said it is not clear whether the small-for-gestational-age babies were “healthy or unhealthy.”

To investigate further, the team has launched the MiTy Kids study, which will follow the offspring in the MiTy trial to determine whether metformin during pregnancy is associated with a reduction in adiposity and improvement in insulin resistance in the babies at 2 years of age.

Who should be given metformin?

During the discussion, Helen R. Murphy, MD, PhD, Norwich Medical School, University of East Anglia, England, asked whether Dr. Feig would recommend continuing metformin in pregnancy if it was started preconception for fertility issues rather than diabetes.

She replied: “If they don’t have diabetes and it’s simply for PCOS [polycystic ovary syndrome], then I have either stopped it as soon as they got pregnant or sometimes continued it through the first trimester, and then stopped.

“If the person has diabetes, however, I think given this work, for most people I would continue it,” she said.

The study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Lunenfeld-Tanenbaum Research Institute, and the University of Toronto. The authors have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Immunodeficiency strongly linked to mental illness, suicidal behavior

Patients with a primary humoral immunodeficiency (PID) are 91% more likely to have a psychiatric disorder and 84% more likely to exhibit suicidal behavior, compared against those without the condition, new research shows.

Results showed that this association, which was stronger in women, could not be fully explained by comorbid autoimmune diseases or by familial confounding.

These findings have important clinical implications, study investigator Josef Isung, MD, PhD, Centre for Psychiatry Research, Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, Sweden, told Medscape Medical News.

Clinicians managing patients with PID “should be aware of this increased association with psychiatric disorders and perhaps screen for them,” said Isung.

The study was published in the November issue of JAMA Psychiatry.

Registry study

Mounting evidence suggests immune disruption plays a role in psychiatric disorders through a range of mechanisms, including altered neurodevelopment. However, little is known about the neuropsychiatric consequences resulting from the underproduction of homeostatic antibodies.

They’re associated with an increased risk for recurrent infections and of developing autoimmune diseases.

The immunodeficiency can be severe, even life threatening, but can also be relatively mild. One of the less severe PID types is selective IgA deficiency, which is linked to increased infections within the mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT), an important immune barrier.

Experts have long suspected that infections within the MALT are associated with certain forms of psychopathology in children, particularly obsessive-compulsive disorder and chronic tic disorders.

While patients with this selective IgA subtype may be at some increased risk for infection and autoimmune disease, their overall health otherwise is good, said Isung.

The prevalence of PIDs ranges from about 1:250 to 1:20,000, depending on the type of humoral immunodeficiency, although most would fall into the relatively rare category, he added.

Using several linked national Swedish registries, researchers identified individuals with any PID diagnosis affecting immunoglobulin levels, their full siblings, and those with a lifetime diagnosis of selective IgA deficiency. In addition, they collected data on autoimmune diseases.

The study outcome was a lifetime record of a psychiatric disorder, a suicide attempt, or death by suicide.

Strong link to autism

Researchers identified 8378 patients (59% women) with PID affecting immunoglobulin levels (median age at first diagnosis, 47.8 years). They compared this group with almost 14.3 million subjects without PID.

In those with PID, 27.6% had an autoimmune disease vs 6.8% of those without PID, a statistically significant difference (P < .001).

About 20.5% of those with PID and 10.7% of unexposed subjects had at least one diagnosis of a psychiatric disorder.

In a model adjusted for year of birth, sex, and history of autoimmune disease, subjects with PID had a 91% higher likelihood of any psychiatric disorder (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] 1.91; 95% CI, 1.81 - 2.01; P < .001) vs their counterparts without PID.

The AORs for individual psychiatric disorders ranged from 1.34 (95% CI, 1.17 - 1.54; P < .001) for schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders to 2.99 (95% CI, 2.42 - 3.70; P < .001) for autism spectrum disorders (ASDs)

It’s unclear why the association with PID was strongest for autism, “but being a neurodevelopmental disorder, maybe autism is logically more associated with this type of disruption,” said Isung.

Research suggests that immunologic disruption may play a role in ASD, either through altered maternal immune function in utero or through immune disruption after birth, the researchers note.

Compared to those without PID, individuals with it had a significantly increased likelihood of any suicidal behavior (AOR, 1.84; 95% CI, 1.66 - 2.04, P < .001) as well as individual outcomes of death by suicide and suicide attempts.

The association with psychiatric disorders and suicidal behavior was markedly stronger for exposure to both PID and autoimmune disease than for exposure to either of these alone, which suggest an additive effect for these immune-related conditions.

Sex differences

“It was unclear to us why women seemed particularly vulnerable,” said Isung. He noted that PIDs are generally about as common in women as in men, but women tend to have higher rates of psychiatric disorders.

The analysis of the sibling cohort also revealed an elevated risk for psychiatric disorders, including ASD and suicidal behavior, but to a lesser degree.

“From this we could infer that at least part of the associations would be genetic, but part would be related to the disruption in itself,” said Isung.

An analysis examining selective IgA subtype also revealed a link with psychiatric disorders and suicidal behavior, suggesting this link is not exclusive to severe PID cases.

“Our conclusion here was that it seems like PID itself, or the immune disruption in itself, could explain the association rather than the burden of illness,” said Isung.

However, he acknowledged that the long-term stress and mental health fallout of having a chronic illness like PID may also explain some of the increased risk for psychiatric disorders.

This study, he said, provides more evidence that immune disruptions affect neurodevelopment and the brain. However, he added, the underlying mechanism still isn’t fully understood.

The results highlight the need to raise awareness of the association between immunodeficiency and mental illness, including suicidality among clinicians, patients, and advocates.

These findings may also have implications in patients with other immune deficiencies, said Isung, noting, “it would be interesting to further explore associations with other immunocompromised populations.”

No surprises

Commenting on the findings for Medscape Medical News, Igor Galynker, MD, professor of psychiatry at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York City, said the study was “very well-done” and used “reliable and well-controlled” databases.

However, he added, the results “are neither particularly dramatic nor conclusive” as it makes sense that medical illnesses like PID would “increase risk of psychopathology,” said Galynker.

PID patients are much more likely to have contact with clinicians and to receive a psychiatric diagnosis, he said.

“People with a chronic illness are more stressed and generally have high incidences of depression, anxiety, and suicidal behavior. In addition to that, they may be more likely to be diagnosed with those conditions because they see a clinician more frequently.”

However, that reasoning doesn’t apply to autism, which manifests in early childhood and so is unlikely to be the result of stress, said Galynker, which is why he believes the finding that ASD is the psychiatric outcome most strongly associated with PID is “the most convincing.”

Galynker wasn’t surprised that the association between PID and psychiatric illnesses, and suicidal behaviors, was stronger among women.

“Women attempt suicide four times more often than men to begin with, so you would expect this to be more pronounced” in those with PID.

The study was supported by grants from the Centre for Psychiatry Research, Department of Clinical Neuroscience, Karolinska Institute; Stockholm Care Services; the Soderstrom Konig Foundation; and the Fredrik & Ingrid Thurings Foundation. Isung and Galynker have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Patients with a primary humoral immunodeficiency (PID) are 91% more likely to have a psychiatric disorder and 84% more likely to exhibit suicidal behavior, compared against those without the condition, new research shows.