User login

Apps for applying to ObGyn residency programs in the era of virtual interviews

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has upended the traditional 2020–2021 application season for ObGyn residency programs. In May 2020, the 2 national ObGyn education organizations, the Association of Professors of Gynecology and Obstetrics (APGO) and Council on Resident Education in ObGyn (CREOG), issued guidelines to ensure a fair and equitable application process.1 These guidelines are consistent with recommendations from the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) and the Coalition for Physician Accountability. Important recommendations include:

- limiting away rotations

- being flexible in the number of specialty-specific letters of recommendation required

- encouraging residency programs to develop alternate means of conveying information about their curriculum.

In addition, these statements provide timing on when programs should release interview offers and when to begin interviews. Finally, programs are required to commit to online interviews and virtual visits for all applicants, including local students, rather than in-person interviews.

Here, we focus on identifying apps that students can use to help them with the application process—apps for the nuts and bolts of applying and interviewing and apps to learn more about individual programs.

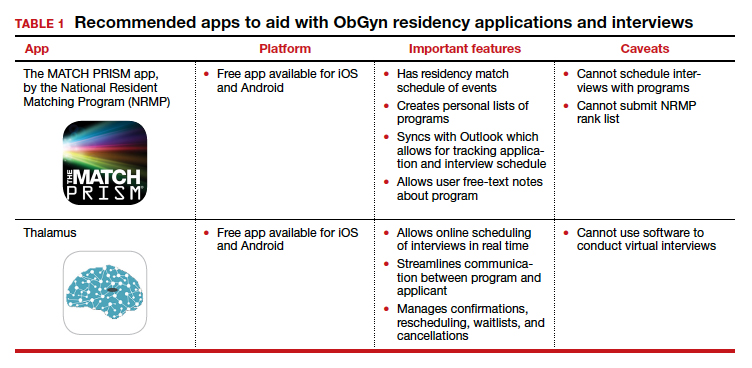

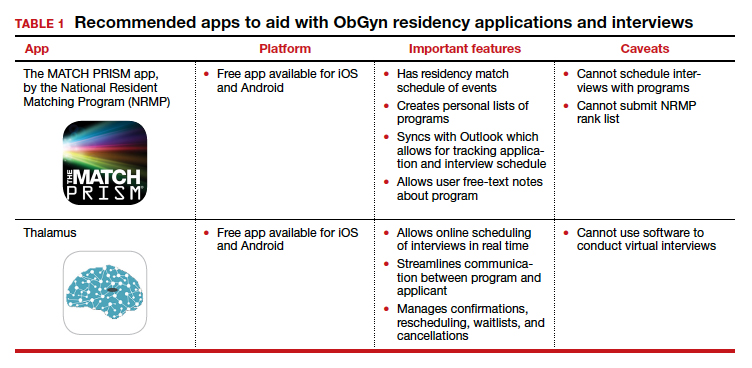

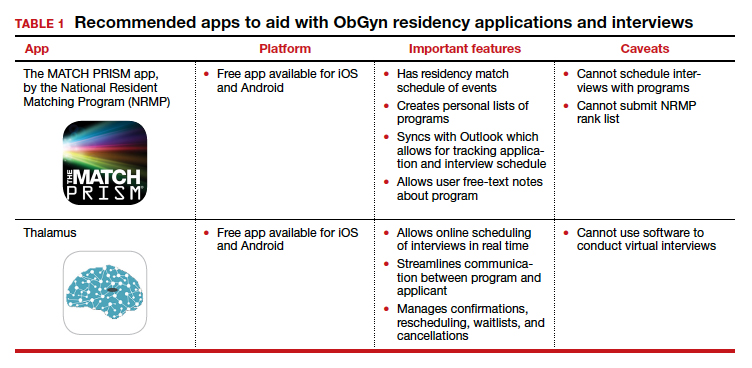

Students must use the Electronic Residency Application Service (ERAS) platform from AAMC to enter their information and register with the National Resident Matching Program (NRMP). Students also must use the ERAS to submit their applications to their selected residency programs. The ERAS platform does not include an app to aid in the completion or submission of an application. The NRMP has developed the MATCH PRISM app, but this does not allow students to register for the match or submit their rank list. To learn about how to schedule interviews, residency programs may use one of the following sources: ERAS, Interview Broker, or Thalamus. Moreover, APGO/CREOG has partnered with Thalamus for the upcoming application cycle, which provides residency programs and applicants tools for application management, interview scheduling, and itinerary building. Thalamus offers a free app.

This year offers some unique challenges. The application process for ObGyn residencies is likely to be more competitive, and students face the added stress of having to navigate the interview season:

- without away rotations (audition interviews)

- without in-person visits of the city/hospital/program or social events before or after interview day

- with an all-virtual interview day.

Continue to: To find information on individual residency programs...

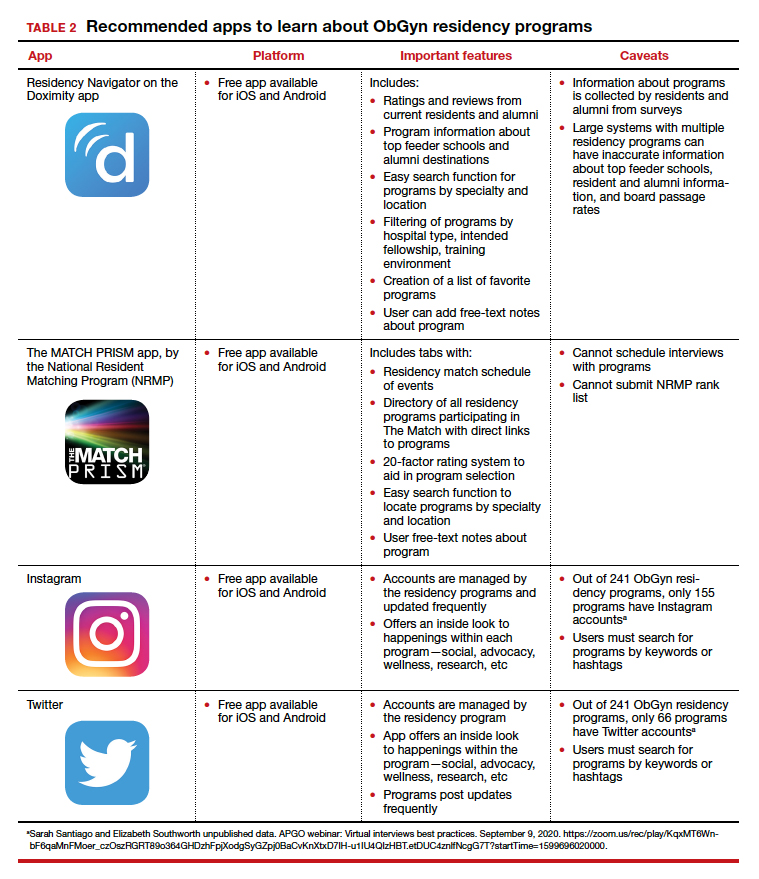

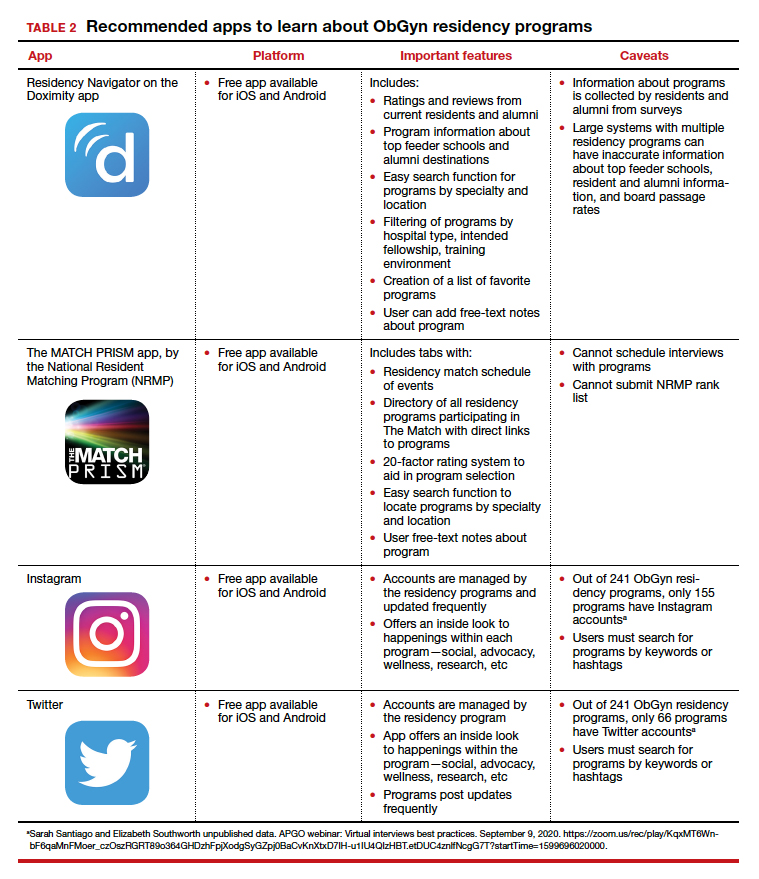

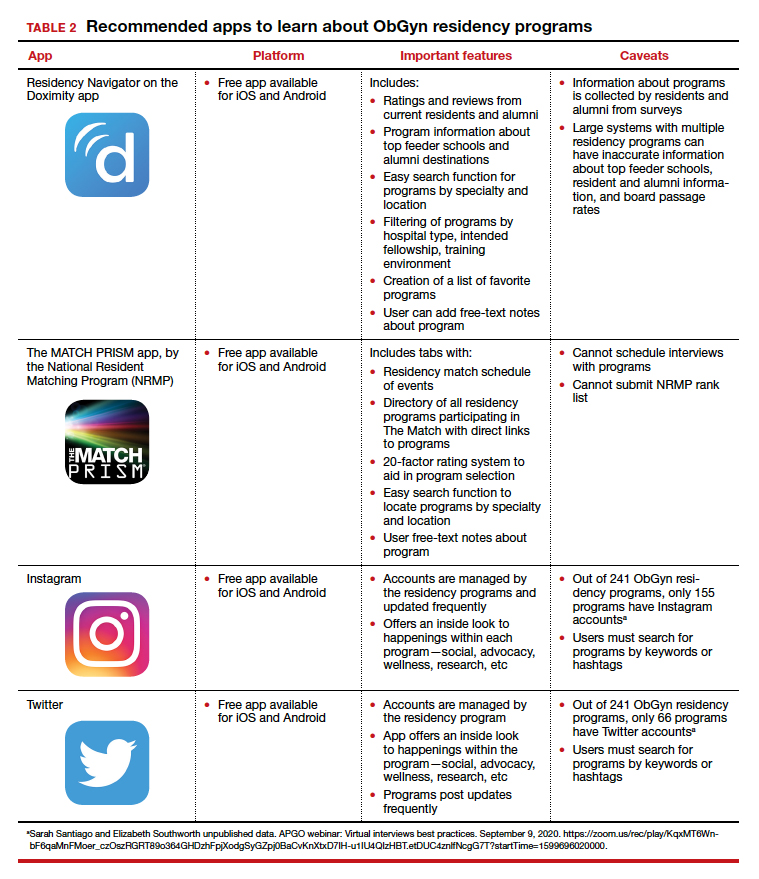

To find information on individual residency programs, the APGO website lists the FREIDA and APGO Residency Directories, which are not apps. Students are also aware of the Doximity Residency Navigator, which does include an app. The NRMP MATCH PRISM app is another resource, as it provides students with a directory of residency programs and information about each program.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recognizes that residency program websites and social media will be crucial in helping applicants learn about individual programs, faculty, and residents. As such, ACOG hosted a Virtual Residency Showcase in September 2020 in which programs posted content on Instagram and Twitter using the hashtag #ACOG-ResWeek20.2 Similarly, APGO and CREOG produced a report containing a social media directory, which lists individual residency programs and whether or not they have a social media handle/account.3 In a recent webinar,4 Drs. Sarah Santiago and Elizabeth Southworth noted that the number of residency programs that have an Instagram account more than doubled (from 60 to 128) between May and September 2020.

We present 2 tables describing the important features and caveats of apps available to students to assist them with residency applications this year—TABLE 1 summarizes apps to aid with applications and interviews; TABLE 2 lists apps designed for students to learn more about individual residency programs. We wish all of this year’s students every success in their search for the right program. ●

- Association of Professors of Gynecology and Obstetrics, Council on Resident Education in ObGyn. Updated APGO and CREOG Residency Application Response to COVID-19. https://www.apgo.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05 /Updated-APGO-CREOG-Residency-Response-to -COVID-19-.pdf. Accessed October 27, 2020.

- https://www.acog.org/education-and-events/webinars /virtual-residency-showcase. Accessed October 4, 2020.

- Social media directory-ObGyn. https://docs.google.com /spreadsheets/d/e/2PACX-1vQ6boyn7FWV9tEhfQp1o3 XJgNIPNBQ3qCYf4IpV-rOPcd212J-HNR84p0r85nXrAz MvOmcNlgjywDP/pubhtml?gid=1472916499&single =true. Accessed October 27, 2020.

- APGO webinar: Virtual interviews best practices. September 9, 2020. https://zoom.us/rec/play/KqxMT6Wnb F6qaMnFMoer_czOszRGRT89o364GHDzhFpjXodgSyGZpj 0BaCvKnXtxD7IH-u1IU4QIzHBT.etDUC4znlfNcgG7T?start Time=1599696020000. Accessed October 4, 2020.

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has upended the traditional 2020–2021 application season for ObGyn residency programs. In May 2020, the 2 national ObGyn education organizations, the Association of Professors of Gynecology and Obstetrics (APGO) and Council on Resident Education in ObGyn (CREOG), issued guidelines to ensure a fair and equitable application process.1 These guidelines are consistent with recommendations from the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) and the Coalition for Physician Accountability. Important recommendations include:

- limiting away rotations

- being flexible in the number of specialty-specific letters of recommendation required

- encouraging residency programs to develop alternate means of conveying information about their curriculum.

In addition, these statements provide timing on when programs should release interview offers and when to begin interviews. Finally, programs are required to commit to online interviews and virtual visits for all applicants, including local students, rather than in-person interviews.

Here, we focus on identifying apps that students can use to help them with the application process—apps for the nuts and bolts of applying and interviewing and apps to learn more about individual programs.

Students must use the Electronic Residency Application Service (ERAS) platform from AAMC to enter their information and register with the National Resident Matching Program (NRMP). Students also must use the ERAS to submit their applications to their selected residency programs. The ERAS platform does not include an app to aid in the completion or submission of an application. The NRMP has developed the MATCH PRISM app, but this does not allow students to register for the match or submit their rank list. To learn about how to schedule interviews, residency programs may use one of the following sources: ERAS, Interview Broker, or Thalamus. Moreover, APGO/CREOG has partnered with Thalamus for the upcoming application cycle, which provides residency programs and applicants tools for application management, interview scheduling, and itinerary building. Thalamus offers a free app.

This year offers some unique challenges. The application process for ObGyn residencies is likely to be more competitive, and students face the added stress of having to navigate the interview season:

- without away rotations (audition interviews)

- without in-person visits of the city/hospital/program or social events before or after interview day

- with an all-virtual interview day.

Continue to: To find information on individual residency programs...

To find information on individual residency programs, the APGO website lists the FREIDA and APGO Residency Directories, which are not apps. Students are also aware of the Doximity Residency Navigator, which does include an app. The NRMP MATCH PRISM app is another resource, as it provides students with a directory of residency programs and information about each program.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recognizes that residency program websites and social media will be crucial in helping applicants learn about individual programs, faculty, and residents. As such, ACOG hosted a Virtual Residency Showcase in September 2020 in which programs posted content on Instagram and Twitter using the hashtag #ACOG-ResWeek20.2 Similarly, APGO and CREOG produced a report containing a social media directory, which lists individual residency programs and whether or not they have a social media handle/account.3 In a recent webinar,4 Drs. Sarah Santiago and Elizabeth Southworth noted that the number of residency programs that have an Instagram account more than doubled (from 60 to 128) between May and September 2020.

We present 2 tables describing the important features and caveats of apps available to students to assist them with residency applications this year—TABLE 1 summarizes apps to aid with applications and interviews; TABLE 2 lists apps designed for students to learn more about individual residency programs. We wish all of this year’s students every success in their search for the right program. ●

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has upended the traditional 2020–2021 application season for ObGyn residency programs. In May 2020, the 2 national ObGyn education organizations, the Association of Professors of Gynecology and Obstetrics (APGO) and Council on Resident Education in ObGyn (CREOG), issued guidelines to ensure a fair and equitable application process.1 These guidelines are consistent with recommendations from the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) and the Coalition for Physician Accountability. Important recommendations include:

- limiting away rotations

- being flexible in the number of specialty-specific letters of recommendation required

- encouraging residency programs to develop alternate means of conveying information about their curriculum.

In addition, these statements provide timing on when programs should release interview offers and when to begin interviews. Finally, programs are required to commit to online interviews and virtual visits for all applicants, including local students, rather than in-person interviews.

Here, we focus on identifying apps that students can use to help them with the application process—apps for the nuts and bolts of applying and interviewing and apps to learn more about individual programs.

Students must use the Electronic Residency Application Service (ERAS) platform from AAMC to enter their information and register with the National Resident Matching Program (NRMP). Students also must use the ERAS to submit their applications to their selected residency programs. The ERAS platform does not include an app to aid in the completion or submission of an application. The NRMP has developed the MATCH PRISM app, but this does not allow students to register for the match or submit their rank list. To learn about how to schedule interviews, residency programs may use one of the following sources: ERAS, Interview Broker, or Thalamus. Moreover, APGO/CREOG has partnered with Thalamus for the upcoming application cycle, which provides residency programs and applicants tools for application management, interview scheduling, and itinerary building. Thalamus offers a free app.

This year offers some unique challenges. The application process for ObGyn residencies is likely to be more competitive, and students face the added stress of having to navigate the interview season:

- without away rotations (audition interviews)

- without in-person visits of the city/hospital/program or social events before or after interview day

- with an all-virtual interview day.

Continue to: To find information on individual residency programs...

To find information on individual residency programs, the APGO website lists the FREIDA and APGO Residency Directories, which are not apps. Students are also aware of the Doximity Residency Navigator, which does include an app. The NRMP MATCH PRISM app is another resource, as it provides students with a directory of residency programs and information about each program.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recognizes that residency program websites and social media will be crucial in helping applicants learn about individual programs, faculty, and residents. As such, ACOG hosted a Virtual Residency Showcase in September 2020 in which programs posted content on Instagram and Twitter using the hashtag #ACOG-ResWeek20.2 Similarly, APGO and CREOG produced a report containing a social media directory, which lists individual residency programs and whether or not they have a social media handle/account.3 In a recent webinar,4 Drs. Sarah Santiago and Elizabeth Southworth noted that the number of residency programs that have an Instagram account more than doubled (from 60 to 128) between May and September 2020.

We present 2 tables describing the important features and caveats of apps available to students to assist them with residency applications this year—TABLE 1 summarizes apps to aid with applications and interviews; TABLE 2 lists apps designed for students to learn more about individual residency programs. We wish all of this year’s students every success in their search for the right program. ●

- Association of Professors of Gynecology and Obstetrics, Council on Resident Education in ObGyn. Updated APGO and CREOG Residency Application Response to COVID-19. https://www.apgo.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05 /Updated-APGO-CREOG-Residency-Response-to -COVID-19-.pdf. Accessed October 27, 2020.

- https://www.acog.org/education-and-events/webinars /virtual-residency-showcase. Accessed October 4, 2020.

- Social media directory-ObGyn. https://docs.google.com /spreadsheets/d/e/2PACX-1vQ6boyn7FWV9tEhfQp1o3 XJgNIPNBQ3qCYf4IpV-rOPcd212J-HNR84p0r85nXrAz MvOmcNlgjywDP/pubhtml?gid=1472916499&single =true. Accessed October 27, 2020.

- APGO webinar: Virtual interviews best practices. September 9, 2020. https://zoom.us/rec/play/KqxMT6Wnb F6qaMnFMoer_czOszRGRT89o364GHDzhFpjXodgSyGZpj 0BaCvKnXtxD7IH-u1IU4QIzHBT.etDUC4znlfNcgG7T?start Time=1599696020000. Accessed October 4, 2020.

- Association of Professors of Gynecology and Obstetrics, Council on Resident Education in ObGyn. Updated APGO and CREOG Residency Application Response to COVID-19. https://www.apgo.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05 /Updated-APGO-CREOG-Residency-Response-to -COVID-19-.pdf. Accessed October 27, 2020.

- https://www.acog.org/education-and-events/webinars /virtual-residency-showcase. Accessed October 4, 2020.

- Social media directory-ObGyn. https://docs.google.com /spreadsheets/d/e/2PACX-1vQ6boyn7FWV9tEhfQp1o3 XJgNIPNBQ3qCYf4IpV-rOPcd212J-HNR84p0r85nXrAz MvOmcNlgjywDP/pubhtml?gid=1472916499&single =true. Accessed October 27, 2020.

- APGO webinar: Virtual interviews best practices. September 9, 2020. https://zoom.us/rec/play/KqxMT6Wnb F6qaMnFMoer_czOszRGRT89o364GHDzhFpjXodgSyGZpj 0BaCvKnXtxD7IH-u1IU4QIzHBT.etDUC4znlfNcgG7T?start Time=1599696020000. Accessed October 4, 2020.

When Female Patients with MS Ask About Breastfeeding, Here’s What to Tell Them

Chances are your female patients of childbearing age with multiple sclerosis—particularly if they become pregnant—will ask about breastfeeding. What are they likely to ask, and how should you answer? Here’s a quick rundown.

What kind of impact will breastfeeding have on my child?

We know that MS is not a genetic disease per se-it is neither autosomal recessive nor dominant. But there is an increased risk among family members, particularly first-degree relatives. If a patient asks, you can tell them it appears that infants who are breastfed are less likely to develop pediatric-onset MS.

In 2017, Brenton and colleagues asked individuals who experienced pediatric-onset MS (n=36) and those in a control group (n=72) to complete a questionnaire that covered breastfeeding history and other birth and demographic features. While most demographic and birth features were similar, 36% of those in the pediatric-onset MS group reported being breastfed, compared with 71% of controls. Individuals who were not breastfed were nearly 4.5 times more likely to be diagnosed with pediatric-onset MS.

How will breastfeeding impact my risk of MS relapse after giving birth?

The issue of breastfeeding and MS relapses is somewhat controversial. In 1988, Nelson and colleagues found that among 191 women with MS who became pregnant, 10% relapsed during pregnancy, but relapse rate rose to 34% during the 9 months after birth. Moreover, nearly 4 in 10 of those who breastfed experienced exacerbations, versus 3 in 10 among those who did not.

However, more recent studies demonstrate no association with breastfeeding and relapse. Just this year, Gould and colleagues published a study showing that among 466 pregnancies, annualized relapse rates declined during pregnancy, and there was no increase seen in the postpartum period. Moreover, women who exclusively breastfed saw their risk of an early postpartum relapse lowered by 63%.

In late 2019, Krysko and colleagues published a meta-analysis of 24 studies involving nearly 3,000 women with MS which showed that breastfeeds were 43% less likely to experience postpartum relapse compared with their non-breastfeeding counterparts. The link was stronger in studies where women breastfed exclusively.

The bottom line: There is a plurality of physicians who believe that breastfeeding has a protective effect – and most will tell you that you should recommend exclusive breastfeeding.

What medicines can I take that will not adversely affect me and my baby?

Once a woman knows that breastfeeding could help her offspring avoid developing MS, and minimize her chance of a postpartum relapse, she will likely ask what to do about medications. You answer will depends on what she’s taking.

- Drugs she can take with relative peace of mind. Most experts believe it is safe to take corticosteroids and breastfeed. In fact, women who relapse while breastfeeding will in all likelihood be given intravenous corticosteroids, such as methylprednisolone. These medications are present in the blood at very low levels, peak an hour after infusion, and quickly dissipate. So, it’s important to tell your patients to delay breastfeeding by 2 to 4 hours after they receive the steroid.

- Drugs that are potentially concerning and require close monitoring. For the so-called platform therapies—such as interferon beta/glatiramer acetate, natalizumab, and their generic equivalents—there are no large studies that clearly demonstrate safety. Still, they are generally thought to be safe. Be sure to heed FDA labeling: weigh breastfeeding benefit against the potential risk

- Drug to avoid entirely. Under no circumstances should breastfeeding women receive teriflunomide, cladribine, alemtuzumab, or mitoxantrone. The jury is still out on rituximab—which is not yet approved for MS in the United States—and ocrelizumab. For now, err on the safe side and switch to another therapy.

Chances are your female patients of childbearing age with multiple sclerosis—particularly if they become pregnant—will ask about breastfeeding. What are they likely to ask, and how should you answer? Here’s a quick rundown.

What kind of impact will breastfeeding have on my child?

We know that MS is not a genetic disease per se-it is neither autosomal recessive nor dominant. But there is an increased risk among family members, particularly first-degree relatives. If a patient asks, you can tell them it appears that infants who are breastfed are less likely to develop pediatric-onset MS.

In 2017, Brenton and colleagues asked individuals who experienced pediatric-onset MS (n=36) and those in a control group (n=72) to complete a questionnaire that covered breastfeeding history and other birth and demographic features. While most demographic and birth features were similar, 36% of those in the pediatric-onset MS group reported being breastfed, compared with 71% of controls. Individuals who were not breastfed were nearly 4.5 times more likely to be diagnosed with pediatric-onset MS.

How will breastfeeding impact my risk of MS relapse after giving birth?

The issue of breastfeeding and MS relapses is somewhat controversial. In 1988, Nelson and colleagues found that among 191 women with MS who became pregnant, 10% relapsed during pregnancy, but relapse rate rose to 34% during the 9 months after birth. Moreover, nearly 4 in 10 of those who breastfed experienced exacerbations, versus 3 in 10 among those who did not.

However, more recent studies demonstrate no association with breastfeeding and relapse. Just this year, Gould and colleagues published a study showing that among 466 pregnancies, annualized relapse rates declined during pregnancy, and there was no increase seen in the postpartum period. Moreover, women who exclusively breastfed saw their risk of an early postpartum relapse lowered by 63%.

In late 2019, Krysko and colleagues published a meta-analysis of 24 studies involving nearly 3,000 women with MS which showed that breastfeeds were 43% less likely to experience postpartum relapse compared with their non-breastfeeding counterparts. The link was stronger in studies where women breastfed exclusively.

The bottom line: There is a plurality of physicians who believe that breastfeeding has a protective effect – and most will tell you that you should recommend exclusive breastfeeding.

What medicines can I take that will not adversely affect me and my baby?

Once a woman knows that breastfeeding could help her offspring avoid developing MS, and minimize her chance of a postpartum relapse, she will likely ask what to do about medications. You answer will depends on what she’s taking.

- Drugs she can take with relative peace of mind. Most experts believe it is safe to take corticosteroids and breastfeed. In fact, women who relapse while breastfeeding will in all likelihood be given intravenous corticosteroids, such as methylprednisolone. These medications are present in the blood at very low levels, peak an hour after infusion, and quickly dissipate. So, it’s important to tell your patients to delay breastfeeding by 2 to 4 hours after they receive the steroid.

- Drugs that are potentially concerning and require close monitoring. For the so-called platform therapies—such as interferon beta/glatiramer acetate, natalizumab, and their generic equivalents—there are no large studies that clearly demonstrate safety. Still, they are generally thought to be safe. Be sure to heed FDA labeling: weigh breastfeeding benefit against the potential risk

- Drug to avoid entirely. Under no circumstances should breastfeeding women receive teriflunomide, cladribine, alemtuzumab, or mitoxantrone. The jury is still out on rituximab—which is not yet approved for MS in the United States—and ocrelizumab. For now, err on the safe side and switch to another therapy.

Chances are your female patients of childbearing age with multiple sclerosis—particularly if they become pregnant—will ask about breastfeeding. What are they likely to ask, and how should you answer? Here’s a quick rundown.

What kind of impact will breastfeeding have on my child?

We know that MS is not a genetic disease per se-it is neither autosomal recessive nor dominant. But there is an increased risk among family members, particularly first-degree relatives. If a patient asks, you can tell them it appears that infants who are breastfed are less likely to develop pediatric-onset MS.

In 2017, Brenton and colleagues asked individuals who experienced pediatric-onset MS (n=36) and those in a control group (n=72) to complete a questionnaire that covered breastfeeding history and other birth and demographic features. While most demographic and birth features were similar, 36% of those in the pediatric-onset MS group reported being breastfed, compared with 71% of controls. Individuals who were not breastfed were nearly 4.5 times more likely to be diagnosed with pediatric-onset MS.

How will breastfeeding impact my risk of MS relapse after giving birth?

The issue of breastfeeding and MS relapses is somewhat controversial. In 1988, Nelson and colleagues found that among 191 women with MS who became pregnant, 10% relapsed during pregnancy, but relapse rate rose to 34% during the 9 months after birth. Moreover, nearly 4 in 10 of those who breastfed experienced exacerbations, versus 3 in 10 among those who did not.

However, more recent studies demonstrate no association with breastfeeding and relapse. Just this year, Gould and colleagues published a study showing that among 466 pregnancies, annualized relapse rates declined during pregnancy, and there was no increase seen in the postpartum period. Moreover, women who exclusively breastfed saw their risk of an early postpartum relapse lowered by 63%.

In late 2019, Krysko and colleagues published a meta-analysis of 24 studies involving nearly 3,000 women with MS which showed that breastfeeds were 43% less likely to experience postpartum relapse compared with their non-breastfeeding counterparts. The link was stronger in studies where women breastfed exclusively.

The bottom line: There is a plurality of physicians who believe that breastfeeding has a protective effect – and most will tell you that you should recommend exclusive breastfeeding.

What medicines can I take that will not adversely affect me and my baby?

Once a woman knows that breastfeeding could help her offspring avoid developing MS, and minimize her chance of a postpartum relapse, she will likely ask what to do about medications. You answer will depends on what she’s taking.

- Drugs she can take with relative peace of mind. Most experts believe it is safe to take corticosteroids and breastfeed. In fact, women who relapse while breastfeeding will in all likelihood be given intravenous corticosteroids, such as methylprednisolone. These medications are present in the blood at very low levels, peak an hour after infusion, and quickly dissipate. So, it’s important to tell your patients to delay breastfeeding by 2 to 4 hours after they receive the steroid.

- Drugs that are potentially concerning and require close monitoring. For the so-called platform therapies—such as interferon beta/glatiramer acetate, natalizumab, and their generic equivalents—there are no large studies that clearly demonstrate safety. Still, they are generally thought to be safe. Be sure to heed FDA labeling: weigh breastfeeding benefit against the potential risk

- Drug to avoid entirely. Under no circumstances should breastfeeding women receive teriflunomide, cladribine, alemtuzumab, or mitoxantrone. The jury is still out on rituximab—which is not yet approved for MS in the United States—and ocrelizumab. For now, err on the safe side and switch to another therapy.

How mental health care would look under a Trump vs. Biden administration

The COVID-19 pandemic is one of the most pressing public health challenges the United States has ever faced, and the resulting financial ruin and social isolation are creating a mental health pandemic that will continue well after COVID-19 lockdowns end. To understand which presidential candidate would best lead the mental health recovery, we identified three of the most critical issues in mental health and compared the plans of the two candidates.

Fighting the opioid epidemic

Over the last several years, the opioid epidemic has devastated American families and communities. Prior to the pandemic, drug overdoses were the leading cause of death for American adults under 50 years of age. The effects of COVID-19–enabled overdose deaths to rise even higher. Multiple elements of the pandemic – isolation, unemployment, and increased anxiety and depression – make those struggling with substance use even more vulnerable, and immediate and comprehensive action is needed to address this national tragedy.

Donald J. Trump: President Trump has been vocal and active in addressing this problem since he took office. One of the Trump administration’s successes is launching the Opioid and Drug Abuse Commission and rolling out a five-point strategy built around improving services, data, research, overdose-reversing drugs, and pain management. Last year, the Trump administration funded $10 billion over 5 years to combat both the opioid epidemic and mental health issues by building upon the 21st Century CURES Act. However, in this same budget, the administration proposed cutting funding by $600 million for SAMHSA, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, which is the top government agency for addressing and providing care for substance use.

President Trump also created an assistant secretary for mental health and substance use position in the Department of Health & Human Services, and appointed Elinore F. McCance-Katz, MD, PhD, a psychiatrist with a strong track record on fighting opioid abuse in Rhode Island, to the post.

Joe Biden: Former Vice President Biden emphasizes that substance use is “a disease of the brain,” refuting the long-held misconception that addiction is an issue of willpower. This stigmatization is very personal given that his own son Hunter reportedly suffered through mental health and substance use issues since his teenage years. However, Biden also had a major role in pushing forward the federal “war on drugs,” including his role in crafting the “Len Bias law.”

Mr. Biden has since released a multifaceted plan for reducing substance use, aiming to make prevention and treatment services more available through a $125 billion federal investment. There are also measures to hold pharmaceutical companies accountable for triggering the crisis, stop the flow of fentanyl to the United States, and restrict incentive payments from manufacturers to doctors so as to limit the dosing and usage of powerful opioids.

Accessing health care

One of the main dividing lines in this election has been the battle to either gut or build upon the Affordable Care Act (ACA). This will have deep ramifications on people’s access to health mental health services. Since COVID-19 started, more than 50% of Americans have reported worsening mental health. This makes it crucial that each candidate’s mental health plan is judged by how they would expand access to insurance, address unenforced parity laws, and protect those who have a mental health disorder as a preexisting condition.

Mr. Trump: Following a failed Senate vote to repeal this law, the Trump administration took a piecemeal approach to dismantling the ACA that included removing the individual mandate, enabling states to introduce Medicaid work requirements, and reducing cost-sharing subsidies to insurers.

If a re-elected Trump administration pursued a complete repeal of the ACA law, many individuals with previous access to mental health and substance abuse treatment via Medicaid expansion may lose access altogether. In addition, key mechanisms aimed at making sure that mental health services are covered by private health plans may be lost, which could undermine policies to address opioids and suicide. On the other hand, the Trump administration’s move during the pandemic to expand telemedicine services has also expanded access to mental health services.

Mr. Biden: Mr. Biden’s plan would build upon the ACA by working to achieve parity between the treatment of mental health and physical health. The ACA itself strengthened the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act (federal parity law), which Mr. Biden championed as vice president, by mandating that all private insurance cover mental health and substance abuse treatment. This act still exempts some health plans, such as larger employers; and many insurers have used loopholes in the policy to illegally deny what could be life-saving coverage.

It follows that those who can afford Mr. Biden’s proposed public option Medicare buy-in would receive more comprehensive mental health benefits. He also says he would invest in school and college mental health professionals, an important opportunity for early intervention given 75% of lifetime mental illness starts by age 24 years. While Mr. Biden has not stated a specific plan for addressing minority groups, whose mental health has been disproportionately affected by COVID-19, he has acknowledged that this unmet need should be targeted.

Addressing suicide

More than 3,000 Americans attempt suicide every day. Suicide is the second leading cause of death for America’s youth and one of the top 10 leading causes of death across the population. Numerous strategies are necessary to address suicide, but one of the most decisive is gun control. Gun violence is inextricably tied to suicide: States where gun prevalence is higher see about four times the number of suicides because of guns, whereas nonfirearm suicide rates are the same as those seen elsewhere. In 2017, of the nearly 40,000 people who died of gun violence, 60% were attributable to suicides. Since the pandemic started, there have been increases in reported suicidal thoughts and a nearly 1,000% increase in use of the national crisis hotline. This is especially concerning given the uptick during the pandemic of gun purchases; as of September, more guns have been purchased this year than any year before.

Mr. Trump: Prior to coronavirus, the Trump administration was unwilling to enact gun control legislation. In early 2017, Mr. Trump removed an Obama-era bill that would have expanded the background check database. It would have added those deemed legally unfit to handle their own funds and those who received Social Security funds for mental health reasons. During the lockdown, the administration made an advisory ruling declaring gun shops as essential businesses that states should keep open.

Mr. Biden: The former vice president has a history of supporting gun control measures in his time as a senator and vice president. In the Senate, Mr. Biden supported both the Brady handgun bill in 1993 and a ban on assault weapons in 1994. As vice president, he was tasked by President Obama to push for a renewed assault weapons ban and a background check bill (Manchin-Toomey bill).

During his 2020 presidential campaign, Mr. Biden has suggested creating universal background checks and reinstating bans on assault rifle sales. He has said that he is also open to having a federal buyback program for assault rifles from gun owners.

Why this matters

The winner of the 2020 election will lead an electorate that is reeling from the health, economic, and social consequences COVID-19. The next administration needs to act swiftly to address the mental health pandemic and have a keen awareness of what is ahead. As Americans make their voting decision, consider who has the best plans not only to contain the virus but also the mental health crises that are ravaging our nation.

Dr. Vasan is a clinical assistant professor of psychiatry at Stanford (Calif.) University, where she is founder and executive director of Brainstorm: The Stanford Lab for Mental Health Innovation. She also serves as chief medical officer of Real, and chair of the American Psychiatric Association Committee on Innovation. Dr. Vasan has no conflicts of interest. Mr. Agbafe is a fellow at Stanford Brainstorm and a first-year medical student at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. He has no conflicts of interest. Ms. Li is a policy intern at Stanford Brainstorm and an undergraduate student in the department of economics at the University of California, Berkeley. She has no conflicts of interest.

The COVID-19 pandemic is one of the most pressing public health challenges the United States has ever faced, and the resulting financial ruin and social isolation are creating a mental health pandemic that will continue well after COVID-19 lockdowns end. To understand which presidential candidate would best lead the mental health recovery, we identified three of the most critical issues in mental health and compared the plans of the two candidates.

Fighting the opioid epidemic

Over the last several years, the opioid epidemic has devastated American families and communities. Prior to the pandemic, drug overdoses were the leading cause of death for American adults under 50 years of age. The effects of COVID-19–enabled overdose deaths to rise even higher. Multiple elements of the pandemic – isolation, unemployment, and increased anxiety and depression – make those struggling with substance use even more vulnerable, and immediate and comprehensive action is needed to address this national tragedy.

Donald J. Trump: President Trump has been vocal and active in addressing this problem since he took office. One of the Trump administration’s successes is launching the Opioid and Drug Abuse Commission and rolling out a five-point strategy built around improving services, data, research, overdose-reversing drugs, and pain management. Last year, the Trump administration funded $10 billion over 5 years to combat both the opioid epidemic and mental health issues by building upon the 21st Century CURES Act. However, in this same budget, the administration proposed cutting funding by $600 million for SAMHSA, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, which is the top government agency for addressing and providing care for substance use.

President Trump also created an assistant secretary for mental health and substance use position in the Department of Health & Human Services, and appointed Elinore F. McCance-Katz, MD, PhD, a psychiatrist with a strong track record on fighting opioid abuse in Rhode Island, to the post.

Joe Biden: Former Vice President Biden emphasizes that substance use is “a disease of the brain,” refuting the long-held misconception that addiction is an issue of willpower. This stigmatization is very personal given that his own son Hunter reportedly suffered through mental health and substance use issues since his teenage years. However, Biden also had a major role in pushing forward the federal “war on drugs,” including his role in crafting the “Len Bias law.”

Mr. Biden has since released a multifaceted plan for reducing substance use, aiming to make prevention and treatment services more available through a $125 billion federal investment. There are also measures to hold pharmaceutical companies accountable for triggering the crisis, stop the flow of fentanyl to the United States, and restrict incentive payments from manufacturers to doctors so as to limit the dosing and usage of powerful opioids.

Accessing health care

One of the main dividing lines in this election has been the battle to either gut or build upon the Affordable Care Act (ACA). This will have deep ramifications on people’s access to health mental health services. Since COVID-19 started, more than 50% of Americans have reported worsening mental health. This makes it crucial that each candidate’s mental health plan is judged by how they would expand access to insurance, address unenforced parity laws, and protect those who have a mental health disorder as a preexisting condition.

Mr. Trump: Following a failed Senate vote to repeal this law, the Trump administration took a piecemeal approach to dismantling the ACA that included removing the individual mandate, enabling states to introduce Medicaid work requirements, and reducing cost-sharing subsidies to insurers.

If a re-elected Trump administration pursued a complete repeal of the ACA law, many individuals with previous access to mental health and substance abuse treatment via Medicaid expansion may lose access altogether. In addition, key mechanisms aimed at making sure that mental health services are covered by private health plans may be lost, which could undermine policies to address opioids and suicide. On the other hand, the Trump administration’s move during the pandemic to expand telemedicine services has also expanded access to mental health services.

Mr. Biden: Mr. Biden’s plan would build upon the ACA by working to achieve parity between the treatment of mental health and physical health. The ACA itself strengthened the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act (federal parity law), which Mr. Biden championed as vice president, by mandating that all private insurance cover mental health and substance abuse treatment. This act still exempts some health plans, such as larger employers; and many insurers have used loopholes in the policy to illegally deny what could be life-saving coverage.

It follows that those who can afford Mr. Biden’s proposed public option Medicare buy-in would receive more comprehensive mental health benefits. He also says he would invest in school and college mental health professionals, an important opportunity for early intervention given 75% of lifetime mental illness starts by age 24 years. While Mr. Biden has not stated a specific plan for addressing minority groups, whose mental health has been disproportionately affected by COVID-19, he has acknowledged that this unmet need should be targeted.

Addressing suicide

More than 3,000 Americans attempt suicide every day. Suicide is the second leading cause of death for America’s youth and one of the top 10 leading causes of death across the population. Numerous strategies are necessary to address suicide, but one of the most decisive is gun control. Gun violence is inextricably tied to suicide: States where gun prevalence is higher see about four times the number of suicides because of guns, whereas nonfirearm suicide rates are the same as those seen elsewhere. In 2017, of the nearly 40,000 people who died of gun violence, 60% were attributable to suicides. Since the pandemic started, there have been increases in reported suicidal thoughts and a nearly 1,000% increase in use of the national crisis hotline. This is especially concerning given the uptick during the pandemic of gun purchases; as of September, more guns have been purchased this year than any year before.

Mr. Trump: Prior to coronavirus, the Trump administration was unwilling to enact gun control legislation. In early 2017, Mr. Trump removed an Obama-era bill that would have expanded the background check database. It would have added those deemed legally unfit to handle their own funds and those who received Social Security funds for mental health reasons. During the lockdown, the administration made an advisory ruling declaring gun shops as essential businesses that states should keep open.

Mr. Biden: The former vice president has a history of supporting gun control measures in his time as a senator and vice president. In the Senate, Mr. Biden supported both the Brady handgun bill in 1993 and a ban on assault weapons in 1994. As vice president, he was tasked by President Obama to push for a renewed assault weapons ban and a background check bill (Manchin-Toomey bill).

During his 2020 presidential campaign, Mr. Biden has suggested creating universal background checks and reinstating bans on assault rifle sales. He has said that he is also open to having a federal buyback program for assault rifles from gun owners.

Why this matters

The winner of the 2020 election will lead an electorate that is reeling from the health, economic, and social consequences COVID-19. The next administration needs to act swiftly to address the mental health pandemic and have a keen awareness of what is ahead. As Americans make their voting decision, consider who has the best plans not only to contain the virus but also the mental health crises that are ravaging our nation.

Dr. Vasan is a clinical assistant professor of psychiatry at Stanford (Calif.) University, where she is founder and executive director of Brainstorm: The Stanford Lab for Mental Health Innovation. She also serves as chief medical officer of Real, and chair of the American Psychiatric Association Committee on Innovation. Dr. Vasan has no conflicts of interest. Mr. Agbafe is a fellow at Stanford Brainstorm and a first-year medical student at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. He has no conflicts of interest. Ms. Li is a policy intern at Stanford Brainstorm and an undergraduate student in the department of economics at the University of California, Berkeley. She has no conflicts of interest.

The COVID-19 pandemic is one of the most pressing public health challenges the United States has ever faced, and the resulting financial ruin and social isolation are creating a mental health pandemic that will continue well after COVID-19 lockdowns end. To understand which presidential candidate would best lead the mental health recovery, we identified three of the most critical issues in mental health and compared the plans of the two candidates.

Fighting the opioid epidemic

Over the last several years, the opioid epidemic has devastated American families and communities. Prior to the pandemic, drug overdoses were the leading cause of death for American adults under 50 years of age. The effects of COVID-19–enabled overdose deaths to rise even higher. Multiple elements of the pandemic – isolation, unemployment, and increased anxiety and depression – make those struggling with substance use even more vulnerable, and immediate and comprehensive action is needed to address this national tragedy.

Donald J. Trump: President Trump has been vocal and active in addressing this problem since he took office. One of the Trump administration’s successes is launching the Opioid and Drug Abuse Commission and rolling out a five-point strategy built around improving services, data, research, overdose-reversing drugs, and pain management. Last year, the Trump administration funded $10 billion over 5 years to combat both the opioid epidemic and mental health issues by building upon the 21st Century CURES Act. However, in this same budget, the administration proposed cutting funding by $600 million for SAMHSA, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, which is the top government agency for addressing and providing care for substance use.

President Trump also created an assistant secretary for mental health and substance use position in the Department of Health & Human Services, and appointed Elinore F. McCance-Katz, MD, PhD, a psychiatrist with a strong track record on fighting opioid abuse in Rhode Island, to the post.

Joe Biden: Former Vice President Biden emphasizes that substance use is “a disease of the brain,” refuting the long-held misconception that addiction is an issue of willpower. This stigmatization is very personal given that his own son Hunter reportedly suffered through mental health and substance use issues since his teenage years. However, Biden also had a major role in pushing forward the federal “war on drugs,” including his role in crafting the “Len Bias law.”

Mr. Biden has since released a multifaceted plan for reducing substance use, aiming to make prevention and treatment services more available through a $125 billion federal investment. There are also measures to hold pharmaceutical companies accountable for triggering the crisis, stop the flow of fentanyl to the United States, and restrict incentive payments from manufacturers to doctors so as to limit the dosing and usage of powerful opioids.

Accessing health care

One of the main dividing lines in this election has been the battle to either gut or build upon the Affordable Care Act (ACA). This will have deep ramifications on people’s access to health mental health services. Since COVID-19 started, more than 50% of Americans have reported worsening mental health. This makes it crucial that each candidate’s mental health plan is judged by how they would expand access to insurance, address unenforced parity laws, and protect those who have a mental health disorder as a preexisting condition.

Mr. Trump: Following a failed Senate vote to repeal this law, the Trump administration took a piecemeal approach to dismantling the ACA that included removing the individual mandate, enabling states to introduce Medicaid work requirements, and reducing cost-sharing subsidies to insurers.

If a re-elected Trump administration pursued a complete repeal of the ACA law, many individuals with previous access to mental health and substance abuse treatment via Medicaid expansion may lose access altogether. In addition, key mechanisms aimed at making sure that mental health services are covered by private health plans may be lost, which could undermine policies to address opioids and suicide. On the other hand, the Trump administration’s move during the pandemic to expand telemedicine services has also expanded access to mental health services.

Mr. Biden: Mr. Biden’s plan would build upon the ACA by working to achieve parity between the treatment of mental health and physical health. The ACA itself strengthened the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act (federal parity law), which Mr. Biden championed as vice president, by mandating that all private insurance cover mental health and substance abuse treatment. This act still exempts some health plans, such as larger employers; and many insurers have used loopholes in the policy to illegally deny what could be life-saving coverage.

It follows that those who can afford Mr. Biden’s proposed public option Medicare buy-in would receive more comprehensive mental health benefits. He also says he would invest in school and college mental health professionals, an important opportunity for early intervention given 75% of lifetime mental illness starts by age 24 years. While Mr. Biden has not stated a specific plan for addressing minority groups, whose mental health has been disproportionately affected by COVID-19, he has acknowledged that this unmet need should be targeted.

Addressing suicide

More than 3,000 Americans attempt suicide every day. Suicide is the second leading cause of death for America’s youth and one of the top 10 leading causes of death across the population. Numerous strategies are necessary to address suicide, but one of the most decisive is gun control. Gun violence is inextricably tied to suicide: States where gun prevalence is higher see about four times the number of suicides because of guns, whereas nonfirearm suicide rates are the same as those seen elsewhere. In 2017, of the nearly 40,000 people who died of gun violence, 60% were attributable to suicides. Since the pandemic started, there have been increases in reported suicidal thoughts and a nearly 1,000% increase in use of the national crisis hotline. This is especially concerning given the uptick during the pandemic of gun purchases; as of September, more guns have been purchased this year than any year before.

Mr. Trump: Prior to coronavirus, the Trump administration was unwilling to enact gun control legislation. In early 2017, Mr. Trump removed an Obama-era bill that would have expanded the background check database. It would have added those deemed legally unfit to handle their own funds and those who received Social Security funds for mental health reasons. During the lockdown, the administration made an advisory ruling declaring gun shops as essential businesses that states should keep open.

Mr. Biden: The former vice president has a history of supporting gun control measures in his time as a senator and vice president. In the Senate, Mr. Biden supported both the Brady handgun bill in 1993 and a ban on assault weapons in 1994. As vice president, he was tasked by President Obama to push for a renewed assault weapons ban and a background check bill (Manchin-Toomey bill).

During his 2020 presidential campaign, Mr. Biden has suggested creating universal background checks and reinstating bans on assault rifle sales. He has said that he is also open to having a federal buyback program for assault rifles from gun owners.

Why this matters

The winner of the 2020 election will lead an electorate that is reeling from the health, economic, and social consequences COVID-19. The next administration needs to act swiftly to address the mental health pandemic and have a keen awareness of what is ahead. As Americans make their voting decision, consider who has the best plans not only to contain the virus but also the mental health crises that are ravaging our nation.

Dr. Vasan is a clinical assistant professor of psychiatry at Stanford (Calif.) University, where she is founder and executive director of Brainstorm: The Stanford Lab for Mental Health Innovation. She also serves as chief medical officer of Real, and chair of the American Psychiatric Association Committee on Innovation. Dr. Vasan has no conflicts of interest. Mr. Agbafe is a fellow at Stanford Brainstorm and a first-year medical student at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. He has no conflicts of interest. Ms. Li is a policy intern at Stanford Brainstorm and an undergraduate student in the department of economics at the University of California, Berkeley. She has no conflicts of interest.

Biologics may protect psoriasis patients against severe COVID-19

presented at the virtual annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

“Biologics seem to be very protective against severe, poor-prognosis COVID-19, but they do not prevent infection with the virus,” reported Giovanni Damiani, MD, a dermatologist at the University of Milan.

This apparent protective effect of biologic agents against severe and even fatal COVID-19 is all the more impressive because the psoriasis patients included in the Italian study – as is true of those elsewhere throughout the world – had relatively high rates of obesity, smoking, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, known risk factors for severe COVID-19, he added.

He presented a case-control study including 1,193 adult psoriasis patients on biologics or apremilast (Otezla) at Milan’s San Donato Hospital during the period from Feb. 21 to April 9, 2020. The control group comprised more than 10 million individuals, the entire adult population of the Lombardy region, of which Milan is the capital. This was the hardest-hit area in all of Italy during the first wave of COVID-19.

Twenty-two of the 1,193 psoriasis patients experienced confirmed COVID-19 during the study period. Seventeen were quarantined at home because their disease was mild. Five were hospitalized. But no psoriasis patients were placed in intensive care, and none died.

Psoriasis patients on biologics were significantly more likely than the general Lombardian population to test positive for COVID-19, with an unadjusted odds ratio of 3.43. They were at 9.05-fold increased risk of home quarantine for mild disease, and at 3.59-fold greater risk than controls for hospitalization for COVID-19. However, they were not at significantly increased risk of ICU admission. And while they actually had a 59% relative risk reduction for death, this didn’t achieve statistical significance.

Forty-five percent of the psoriasis patients were on an interleukin-17 (IL-17) inhibitor, 22% were on a tumor necrosis factor–alpha inhibitor, and 20% were taking an IL-12/23 inhibitor. Of note, none of 77 patients on apremilast developed COVID-19, even though it is widely considered a less potent psoriasis therapy than the injectable monoclonal antibody biologics.

The French experience

Anne-Claire Fougerousse, MD, and her French coinvestigators conducted a study designed to address a different question: Is it safe to start psoriasis patients on biologics or older conventional systemic agents such as methotrexate during the pandemic?

She presented a French national cross-sectional study of 1,418 adult psoriasis patients on a biologic or standard systemic therapy during a snapshot in time near the peak of the first wave of the pandemic in France: the period from April 27 to May 7, 2020. The group included 1,188 psoriasis patients on maintenance therapy and 230 who had initiated systemic treatment within the past 4 months. More than one-third of the patients had at least one risk factor for severe COVID-19.

Although testing wasn’t available to confirm all cases, 54 patients developed probable COVID-19 during the study period. Only five required hospitalization. None died. The two hospitalized psoriasis patients admitted to an ICU had obesity as a risk factor for severe COVID-19, as did another of the five hospitalized patients, reported Dr. Fougerousse, a dermatologist at the Bégin Military Teaching Hospital in Saint-Mandé, France. Hospitalization for COVID-19 was required in 0.43% of the French treatment initiators, not significantly different from the 0.34% rate in patients on maintenance systemic therapy. A study limitation was the lack of a control group.

Nonetheless, the data did answer the investigators’ main question: “This is the first data showing no increased incidence of severe COVID-19 in psoriasis patients receiving systemic therapy in the treatment initiation period compared to those on maintenance therapy. This may now allow physicians to initiate conventional systemic or biologic therapy in patients with severe psoriasis on a case-by-case basis in the context of the persistent COVID-19 pandemic,” Dr. Fougerousse concluded.

Proposed mechanism of benefit

The Italian study findings that biologics boost the risk of infection with the SARS-CoV-2 virus in psoriasis patients while potentially protecting them against ICU admission and death are backed by a biologically plausible albeit as yet unproven mechanism of action, Dr. Damiani asserted.

He elaborated: A vast body of high-quality clinical trials data demonstrates that these targeted immunosuppressive agents are associated with modestly increased risk of viral infections, including both skin and respiratory tract infections. So there is no reason to suppose these agents would offer protection against the first phase of COVID-19, involving SARS-CoV-2 infection, nor protect against the second (pulmonary phase), whose hallmarks are dyspnea with or without hypoxia. But progression to the third phase, involving hyperinflammation and hypercoagulation – dubbed the cytokine storm – could be a different matter.

“Of particular interest was that our patients on IL-17 inhibitors displayed a really great outcome. Interleukin-17 has procoagulant and prothrombotic effects, organizes bronchoalveolar remodeling, has a profibrotic effect, induces mitochondrial dysfunction, and encourages dendritic cell migration in peribronchial lymph nodes. Therefore, by antagonizing this interleukin, we may have a better prognosis, although further studies are needed to be certain,” Dr. Damiani commented.

Publication of his preliminary findings drew the attention of a group of highly respected thought leaders in psoriasis, including James G. Krueger, MD, head of the laboratory for investigative dermatology and codirector of the center for clinical and investigative science at Rockefeller University, New York.

The Italian report prompted them to analyze data from the phase 4, double-blind, randomized ObePso-S study investigating the effects of the IL-17 inhibitor secukinumab (Cosentyx) on systemic inflammatory markers and gene expression in psoriasis patients. The investigators demonstrated that IL-17–mediated inflammation in psoriasis patients was associated with increased expression of the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor in lesional skin, and that treatment with secukinumab dropped ACE2 expression to levels seen in nonlesional skin. Given that ACE2 is the chief portal of entry for SARS-CoV-2 and that IL-17 exerts systemic proinflammatory effects, it’s plausible that inhibition of IL-17–mediated inflammation via dampening of ACE2 expression in noncutaneous epithelia “could prove to be advantageous in patients with psoriasis who are at risk for SARS-CoV-2 infection,” according to Dr. Krueger and his coinvestigators in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology.

Dr. Damiani and Dr. Fougerousse reported having no financial conflicts regarding their studies. The secukinumab/ACE2 receptor study was funded by Novartis.

presented at the virtual annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

“Biologics seem to be very protective against severe, poor-prognosis COVID-19, but they do not prevent infection with the virus,” reported Giovanni Damiani, MD, a dermatologist at the University of Milan.

This apparent protective effect of biologic agents against severe and even fatal COVID-19 is all the more impressive because the psoriasis patients included in the Italian study – as is true of those elsewhere throughout the world – had relatively high rates of obesity, smoking, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, known risk factors for severe COVID-19, he added.

He presented a case-control study including 1,193 adult psoriasis patients on biologics or apremilast (Otezla) at Milan’s San Donato Hospital during the period from Feb. 21 to April 9, 2020. The control group comprised more than 10 million individuals, the entire adult population of the Lombardy region, of which Milan is the capital. This was the hardest-hit area in all of Italy during the first wave of COVID-19.

Twenty-two of the 1,193 psoriasis patients experienced confirmed COVID-19 during the study period. Seventeen were quarantined at home because their disease was mild. Five were hospitalized. But no psoriasis patients were placed in intensive care, and none died.

Psoriasis patients on biologics were significantly more likely than the general Lombardian population to test positive for COVID-19, with an unadjusted odds ratio of 3.43. They were at 9.05-fold increased risk of home quarantine for mild disease, and at 3.59-fold greater risk than controls for hospitalization for COVID-19. However, they were not at significantly increased risk of ICU admission. And while they actually had a 59% relative risk reduction for death, this didn’t achieve statistical significance.

Forty-five percent of the psoriasis patients were on an interleukin-17 (IL-17) inhibitor, 22% were on a tumor necrosis factor–alpha inhibitor, and 20% were taking an IL-12/23 inhibitor. Of note, none of 77 patients on apremilast developed COVID-19, even though it is widely considered a less potent psoriasis therapy than the injectable monoclonal antibody biologics.

The French experience

Anne-Claire Fougerousse, MD, and her French coinvestigators conducted a study designed to address a different question: Is it safe to start psoriasis patients on biologics or older conventional systemic agents such as methotrexate during the pandemic?

She presented a French national cross-sectional study of 1,418 adult psoriasis patients on a biologic or standard systemic therapy during a snapshot in time near the peak of the first wave of the pandemic in France: the period from April 27 to May 7, 2020. The group included 1,188 psoriasis patients on maintenance therapy and 230 who had initiated systemic treatment within the past 4 months. More than one-third of the patients had at least one risk factor for severe COVID-19.

Although testing wasn’t available to confirm all cases, 54 patients developed probable COVID-19 during the study period. Only five required hospitalization. None died. The two hospitalized psoriasis patients admitted to an ICU had obesity as a risk factor for severe COVID-19, as did another of the five hospitalized patients, reported Dr. Fougerousse, a dermatologist at the Bégin Military Teaching Hospital in Saint-Mandé, France. Hospitalization for COVID-19 was required in 0.43% of the French treatment initiators, not significantly different from the 0.34% rate in patients on maintenance systemic therapy. A study limitation was the lack of a control group.

Nonetheless, the data did answer the investigators’ main question: “This is the first data showing no increased incidence of severe COVID-19 in psoriasis patients receiving systemic therapy in the treatment initiation period compared to those on maintenance therapy. This may now allow physicians to initiate conventional systemic or biologic therapy in patients with severe psoriasis on a case-by-case basis in the context of the persistent COVID-19 pandemic,” Dr. Fougerousse concluded.

Proposed mechanism of benefit

The Italian study findings that biologics boost the risk of infection with the SARS-CoV-2 virus in psoriasis patients while potentially protecting them against ICU admission and death are backed by a biologically plausible albeit as yet unproven mechanism of action, Dr. Damiani asserted.

He elaborated: A vast body of high-quality clinical trials data demonstrates that these targeted immunosuppressive agents are associated with modestly increased risk of viral infections, including both skin and respiratory tract infections. So there is no reason to suppose these agents would offer protection against the first phase of COVID-19, involving SARS-CoV-2 infection, nor protect against the second (pulmonary phase), whose hallmarks are dyspnea with or without hypoxia. But progression to the third phase, involving hyperinflammation and hypercoagulation – dubbed the cytokine storm – could be a different matter.

“Of particular interest was that our patients on IL-17 inhibitors displayed a really great outcome. Interleukin-17 has procoagulant and prothrombotic effects, organizes bronchoalveolar remodeling, has a profibrotic effect, induces mitochondrial dysfunction, and encourages dendritic cell migration in peribronchial lymph nodes. Therefore, by antagonizing this interleukin, we may have a better prognosis, although further studies are needed to be certain,” Dr. Damiani commented.

Publication of his preliminary findings drew the attention of a group of highly respected thought leaders in psoriasis, including James G. Krueger, MD, head of the laboratory for investigative dermatology and codirector of the center for clinical and investigative science at Rockefeller University, New York.

The Italian report prompted them to analyze data from the phase 4, double-blind, randomized ObePso-S study investigating the effects of the IL-17 inhibitor secukinumab (Cosentyx) on systemic inflammatory markers and gene expression in psoriasis patients. The investigators demonstrated that IL-17–mediated inflammation in psoriasis patients was associated with increased expression of the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor in lesional skin, and that treatment with secukinumab dropped ACE2 expression to levels seen in nonlesional skin. Given that ACE2 is the chief portal of entry for SARS-CoV-2 and that IL-17 exerts systemic proinflammatory effects, it’s plausible that inhibition of IL-17–mediated inflammation via dampening of ACE2 expression in noncutaneous epithelia “could prove to be advantageous in patients with psoriasis who are at risk for SARS-CoV-2 infection,” according to Dr. Krueger and his coinvestigators in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology.

Dr. Damiani and Dr. Fougerousse reported having no financial conflicts regarding their studies. The secukinumab/ACE2 receptor study was funded by Novartis.

presented at the virtual annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

“Biologics seem to be very protective against severe, poor-prognosis COVID-19, but they do not prevent infection with the virus,” reported Giovanni Damiani, MD, a dermatologist at the University of Milan.

This apparent protective effect of biologic agents against severe and even fatal COVID-19 is all the more impressive because the psoriasis patients included in the Italian study – as is true of those elsewhere throughout the world – had relatively high rates of obesity, smoking, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, known risk factors for severe COVID-19, he added.

He presented a case-control study including 1,193 adult psoriasis patients on biologics or apremilast (Otezla) at Milan’s San Donato Hospital during the period from Feb. 21 to April 9, 2020. The control group comprised more than 10 million individuals, the entire adult population of the Lombardy region, of which Milan is the capital. This was the hardest-hit area in all of Italy during the first wave of COVID-19.

Twenty-two of the 1,193 psoriasis patients experienced confirmed COVID-19 during the study period. Seventeen were quarantined at home because their disease was mild. Five were hospitalized. But no psoriasis patients were placed in intensive care, and none died.

Psoriasis patients on biologics were significantly more likely than the general Lombardian population to test positive for COVID-19, with an unadjusted odds ratio of 3.43. They were at 9.05-fold increased risk of home quarantine for mild disease, and at 3.59-fold greater risk than controls for hospitalization for COVID-19. However, they were not at significantly increased risk of ICU admission. And while they actually had a 59% relative risk reduction for death, this didn’t achieve statistical significance.

Forty-five percent of the psoriasis patients were on an interleukin-17 (IL-17) inhibitor, 22% were on a tumor necrosis factor–alpha inhibitor, and 20% were taking an IL-12/23 inhibitor. Of note, none of 77 patients on apremilast developed COVID-19, even though it is widely considered a less potent psoriasis therapy than the injectable monoclonal antibody biologics.

The French experience

Anne-Claire Fougerousse, MD, and her French coinvestigators conducted a study designed to address a different question: Is it safe to start psoriasis patients on biologics or older conventional systemic agents such as methotrexate during the pandemic?

She presented a French national cross-sectional study of 1,418 adult psoriasis patients on a biologic or standard systemic therapy during a snapshot in time near the peak of the first wave of the pandemic in France: the period from April 27 to May 7, 2020. The group included 1,188 psoriasis patients on maintenance therapy and 230 who had initiated systemic treatment within the past 4 months. More than one-third of the patients had at least one risk factor for severe COVID-19.

Although testing wasn’t available to confirm all cases, 54 patients developed probable COVID-19 during the study period. Only five required hospitalization. None died. The two hospitalized psoriasis patients admitted to an ICU had obesity as a risk factor for severe COVID-19, as did another of the five hospitalized patients, reported Dr. Fougerousse, a dermatologist at the Bégin Military Teaching Hospital in Saint-Mandé, France. Hospitalization for COVID-19 was required in 0.43% of the French treatment initiators, not significantly different from the 0.34% rate in patients on maintenance systemic therapy. A study limitation was the lack of a control group.

Nonetheless, the data did answer the investigators’ main question: “This is the first data showing no increased incidence of severe COVID-19 in psoriasis patients receiving systemic therapy in the treatment initiation period compared to those on maintenance therapy. This may now allow physicians to initiate conventional systemic or biologic therapy in patients with severe psoriasis on a case-by-case basis in the context of the persistent COVID-19 pandemic,” Dr. Fougerousse concluded.

Proposed mechanism of benefit

The Italian study findings that biologics boost the risk of infection with the SARS-CoV-2 virus in psoriasis patients while potentially protecting them against ICU admission and death are backed by a biologically plausible albeit as yet unproven mechanism of action, Dr. Damiani asserted.

He elaborated: A vast body of high-quality clinical trials data demonstrates that these targeted immunosuppressive agents are associated with modestly increased risk of viral infections, including both skin and respiratory tract infections. So there is no reason to suppose these agents would offer protection against the first phase of COVID-19, involving SARS-CoV-2 infection, nor protect against the second (pulmonary phase), whose hallmarks are dyspnea with or without hypoxia. But progression to the third phase, involving hyperinflammation and hypercoagulation – dubbed the cytokine storm – could be a different matter.

“Of particular interest was that our patients on IL-17 inhibitors displayed a really great outcome. Interleukin-17 has procoagulant and prothrombotic effects, organizes bronchoalveolar remodeling, has a profibrotic effect, induces mitochondrial dysfunction, and encourages dendritic cell migration in peribronchial lymph nodes. Therefore, by antagonizing this interleukin, we may have a better prognosis, although further studies are needed to be certain,” Dr. Damiani commented.

Publication of his preliminary findings drew the attention of a group of highly respected thought leaders in psoriasis, including James G. Krueger, MD, head of the laboratory for investigative dermatology and codirector of the center for clinical and investigative science at Rockefeller University, New York.

The Italian report prompted them to analyze data from the phase 4, double-blind, randomized ObePso-S study investigating the effects of the IL-17 inhibitor secukinumab (Cosentyx) on systemic inflammatory markers and gene expression in psoriasis patients. The investigators demonstrated that IL-17–mediated inflammation in psoriasis patients was associated with increased expression of the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor in lesional skin, and that treatment with secukinumab dropped ACE2 expression to levels seen in nonlesional skin. Given that ACE2 is the chief portal of entry for SARS-CoV-2 and that IL-17 exerts systemic proinflammatory effects, it’s plausible that inhibition of IL-17–mediated inflammation via dampening of ACE2 expression in noncutaneous epithelia “could prove to be advantageous in patients with psoriasis who are at risk for SARS-CoV-2 infection,” according to Dr. Krueger and his coinvestigators in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology.

Dr. Damiani and Dr. Fougerousse reported having no financial conflicts regarding their studies. The secukinumab/ACE2 receptor study was funded by Novartis.

FROM THE EADV CONGRESS

Updated heart failure measures add newer meds

Safety measures for lab monitoring of mineralocorticoid receptor agonist therapy, performance measures for sacubitril/valsartan, cardiac resynchronization therapy and titration of medications, and quality measures based on patient-reported outcomes are among the updates the joint task force of the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association have made to performance and quality measures for managing adults with heart failure.

The revisions, published online Nov. 2 in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, update the 2011 ACC/AHA heart failure measure set, writing committee vice chair Gregg C. Fonarow, MD, said in an interview. The 2011 measure set predates the 2015 approval of the angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor (ARNI) sacubitril/valsartan for heart failure in adults.

Measures stress dosages, strength of evidence

“For the first time the heart failure performance measure sets also focus on not just the use of guideline-recommended medication at any dose, but on utilizing the doses that are evidence-based and guideline recommended so long as they are well tolerated,” said Dr. Fonarow, interim chief of cardiology at the University of California, Los Angeles. “The measure set now includes assessment of patients being treated with doses of medications at 50% or greater of target dose in the absence of contraindications or documented intolerance.”

The update includes seven new performance measures, two quality measures, and one structural measure. The performance measures come from the strongest recommendations – that is, a class of recommendation of 1 (strong) or 3 (no benefit or harmful, process to be avoided) – in the 2017 ACC/AHA/Heart Failure Society of American heart failure guideline update published in Circulation.

In addition to the 2017 update, the writing committee also reviewed existing performance measures. “Those management strategies, diagnostic testing, medications, and devices with the strongest evidence and highest level of guideline recommendations were further considered for inclusion in the performance measure set,” Dr. Fonarow said. “The measures went through extensive review by peer reviewers and approval from the organizations represented.”

Specifically, the update includes measures for monitoring serum potassium after starting mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists therapy, and cardiac resynchronization therapy for patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction already on guideline-directed therapy. “This therapy can significantly improve functional capacity and outcomes in appropriately selected patients,” Dr. Fonarow said.

New and retired measures

The update adds two performance measures for titration of medications based on dose, either reaching 50% of the recommended dose for a variety of medications, including ARNI, or documenting that the dose wasn’t tolerated for other reason for not using the dose.

The new structural measure calls for facility participation in a heart failure registry. The revised measure set now consists of 18 measures in all.

The update retired one measure from the 2011 set: left ventricular ejection fraction assessment for inpatients. The committee cited its use above 97% as the reason, but LVEF in outpatients remains a measure.

The following tree measures have been revised:

- Patient self-care education has moved from performance measure to quality measure because of concerns about the accuracy of self-care education documentation and limited evidence of improved outcomes with better documentation.

- ACE inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker therapy for left ventricular systolic dysfunction adds ARNI therapy to align with the 2017 ACC/AHA/HFSA update.

- Postdischarge appointments shifts from performance to quality measure and include a 7-day limit.

Measures future research should focus on, noted Dr. Fonarow, include the use of sodium glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors for heart failure, including in patients without diabetes. “Since the ACC/AHA heart failure guidelines had not yet been updated to recommend these therapies they could not be included in this performance measure set,” he said.