User login

We can achieve opioid-free analgesia after childbirth: Stop prescribing opioids after vaginal delivery and reduce their use after cesarean

CASE New mother receives unneeded opioids after CD

A house officer wrote orders for a healthy patient who had just had an uncomplicated cesarean delivery (CD). The hospital’s tradition dictates orders for oxycodone plus acetaminophen tablets in addition to ibuprofen for all new mothers. At the time of the patient’s discharge, the same house officer prescribed 30 tablets of oxycodone plus acetaminophen “just in case,” although the patient had required only a few tablets while in the hospital on postoperative day 2 and none on the day of discharge.

Stuck in the habit

Prescribing postpartum opioids in the United States is almost habitual. Both optimizing patient satisfaction and minimizing patient phone calls may be driving this well-established pattern. Interestingly, a survey study of obstetric providers in 14 countries found that clinicians in 13 countries prescribe opioids “almost never” after vaginal delivery.1 The United States was the 1 outlier, with providers reporting prescribing opioids “on a regular basis” after vaginal birth. Similarly, providers in 10 countries reported prescribing opioids “almost never” after CD, while those in the United States reported prescribing opioids “almost always” in this context.

Moreover, mounting data suggest that many patients do not require the quantity of opioids prescribed and that our overprescribing may be causing more harm than good.

The problem of overprescribing opioids after childbirth

Opioid analgesia has long been the mainstay of treatment for postpartum pain, which when poorly controlled is associated with the development of postpartum depression and chronic pain.2 However, common adverse effects of opioids, including nausea, drowsiness, and dizziness, similarly can interfere with self-care and infant care. Of additional concern, a 2016 claims data study found that 1 of 300 opioid-naïve women who were prescribed opioids at discharge after CD used these medications persistently in the first year postpartum.3

Many women do not use the opioids that are prescribed to them at discharge, thus making tablets available for potential diversion into the community—a commonly recognized source of opioid misuse and abuse.4,5 In a 2018 Committee Opinion on postpartum pain management, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) stated that “a stepwise, multimodal approach emphasizing nonopioid analgesia as first-line therapy is safe and effective for vaginal deliveries and cesarean deliveries.”6 The Committee Opinion also asserted that “opioid medication is an adjunct for patients with uncontrolled pain despite adequate first-line therapy.”6

Despite efforts by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and ACOG to improve opioid prescribing patterns after childbirth, the vast majority of women receive opioids in the hospital and at discharge not only after CD, but after vaginal delivery as well.4,7 Why has tradition prevailed over data, and why have we not changed?

Continue to: Common misconceptions about reducing opioid use...

Common misconceptions about reducing opioid use

Two misconceptions persist regarding reducing opioid prescriptions for postpartum pain.

Misconception #1: Patients will be in pain

Randomized controlled trials that compared nonopioid with opioid regimens in the emergency room setting and opioid use after outpatient general surgery procedures have demonstrated that pain control for patients receiving opioids was equivalent to that for patients with pain managed with nonopioid regimens.8-10 In the obstetric setting, a survey study of 720 women who underwent CD found that higher quantities of opioid tablets prescribed at discharge were not associated with improved pain, higher satisfaction, or lower refill rates at 2 weeks postpartum.4 However, greater quantities of opioids prescribed at the time of discharge were associated with greater opioid consumption.

Recently, several quality improvement studies implemented various interventions and successfully decreased postpartum opioid consumption without compromising pain management. One quality improvement project eliminated the routine use of opioids after CD and decreased the proportion of patients using any opioids in the hospital from 68% to 45%, with no changes in pain scores.11 A similar study implemented an enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) program for women after CD; mean in-patient opioid use decreased from 10.7 to 5.4 average daily morphine equivalents, with improvement in the proportion of time that patients reported their pain as acceptable.12

Misconception #2: Clinicians will be overwhelmed with pages and phone calls

Providers commonly fear that decreasing opioid use will lead to an increased volume of pages and phone calls from patients requesting additional medication. However, data suggest otherwise. For example, a quality improvement study that eliminated the routine use of opioids after CD tracked the number of phone calls that were received requesting rescue opioid prescriptions after discharge.11 Although the percentage of women discharged with opioids decreased from 90.6% to 40.3%, the requests for rescue opioid prescriptions did not change. Of 191 women, 4 requested a rescue prescription prior to the intervention compared with no women after the intervention. At the same time, according to unpublished data (Dr. Holland), satisfaction among nurses, house staff, and faculty did not change.

Similarly, a quality improvement project that implemented shared decision-making to inform the quantity of opioids prescribed at discharge demonstrated that the number of tablets prescribed decreased from 33.2 to 26.5, and there was no change in the rate of patients requesting opioid refills.13

Success stories: Strategies for reducing opioid use after childbirth

While overall rates of opioid prescribing after vaginal delivery and CD remain high throughout the United States, various institutions have developed successful and reproducible strategies to reduce opioid use after childbirth both in the hospital and at discharge. We highlight 3 strategies below.

Strategy 1: ERAS initiatives

An integrated health care system in northern California studied the effects of an ERAS protocol for CD across 15 medical centers.12 The intervention centered on 4 pillars: multimodal pain management, early mobility, optimal nutrition, and patient engagement through education. Specifically, multimodal pain management consisted of the following:

- intrathecal opioids during CD

- scheduled intravenous acetaminophen for 24 hours followed by oral acetaminophen every 6 hours

- nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) every 6 hours

- oral oxycodone for breakthrough pain

- decoupling of opioid medication from nonopioids in the post-CD order set

- decoupling of opioid and nonopioid medications in the discharge order set along with a reduction from 30 to 20 tablets as the default discharge quantity.

Continue to: Among 4,689 and 4,624 patients who underwent CD...

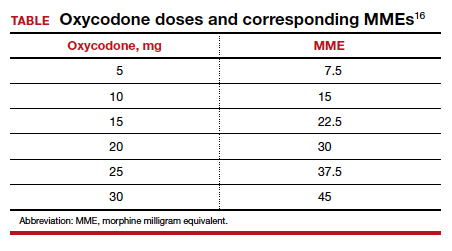

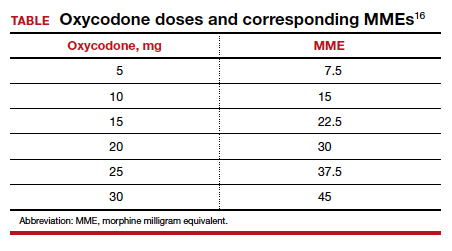

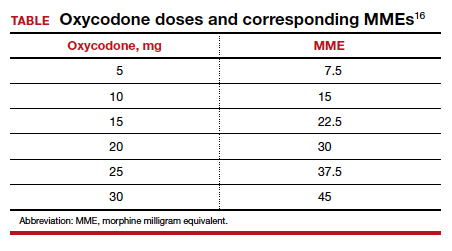

Among 4,689 and 4,624 patients who underwent CD before and after the intervention, the daily morphine milligram equivalents (MME) consumed in the hospital decreased from 10.7 to 5.4. The percentage of women who required no opioids while in the hospital increased from 8.3% to 21.4% after ERAS implementation, while the percentage of time that patients reported acceptable pain scores increased from 82.1% to 86.4%. The average number of opioid tablets prescribed at discharge also decreased, from 37 to 26 MME.12 (The TABLE shows oxycodone doses converted to MMEs.)

A similar initiative at a network of 5 hospitals in Texas showed that implementation of a “multimodal pain power plan” (which incorporated postpartum activity goals with standardized order sets) decreased opioid use after both vaginal delivery and CD.14

Strategy 2: Order set change to eliminate routine use of opioids

A tertiary care center in Boston, Massachusetts, implemented a quality improvement project aimed at eliminating the routine use of opioid medication after CD through an order set change.11 The intervention consisted of the following:

- intrathecal morphine

- multimodal postoperative pain management including scheduled oral acetaminophen for 72 hours followed by as-needed oral acetaminophen, scheduled NSAIDs for 72 hours followed by as-needed NSAIDs

- no postoperative order for opioids unless the patient had a contraindication to acetaminophen or NSAIDs, had a history of opioid dependence, or underwent complex surgery

- counseling patients that opioids were available for breakthrough pain if needed. In this case, nursing staff would page the responding clinician, who would order oxycodone 5 mg every 6 hours for 6 doses.

- specific criteria for discharge quantities of opioids: if the patient required no opioids in the hospital, she received no opioids at discharge; if the patient required opioids in the hospital but none at the time of discharge, she received no more than 10 tablets of oxycodone 5 mg; if the patient required opioids at the time of discharge, she received a maximum of 20 tablets of oxycodone 5 mg.

Among 191 and 181 women undergoing CD before and after the intervention, the percentage of patients who received any opioids in the hospital decreased from 68.1% to 45.3%.11 Similarly, the percentage of patients receiving a discharge prescription for opioids decreased from 90.6% to 40.3%, while patient pain scores and satisfaction with pain control remained unchanged.

Strategy 3: Shared decision-making tool

Another tertiary care center in Boston evaluated the effects of a shared decision-making tool on opioid discharge prescribing after CD.15 The intervention consisted of a 10-minute clinician-facilitated session incorporating:

- education around anticipated patterns of postoperative pain

- expected outpatient opioid use after CD

- risks and benefits of opioids and nonopioids

- education around opioid disposal and access to refills.

Among the 50 women enrolled in the study, the number of oxycodone 5-mg tablets prescribed at discharge decreased from the institutional standard of 40 to 20. Ninety percent of women reported being satisfied or very satisfied with their pain control, while only 4 of 50 women required an opioid refill. A follow-up quality improvement project, which implemented the shared decision-making model along with a standardized multimodal pain management protocol, demonstrated a similar decrease in the quantity of opioids prescribed at discharge.13

Continue to: Change is here to stay: A new culture of postpartum analgesia...

Change is here to stay: A new culture of postpartum analgesia

The CDC continues to champion responsible opioid prescribing, while ACOG advocates for a reassessment of the way that opioids are utilized postpartum. The majority of women in the United States, however, continue to receive opioids after both vaginal delivery and CD. Consciously or not, we clinicians may be contributing to an outdated tradition that is potentially harmful both to patients and society. Reproducible strategies exist to reduce opioid use without compromising pain control or overwhelming clinicians with phone calls. It is time to embrace the change.

- Wong CA, Girard T. Undertreated or overtreated? Opioids for postdelivery analgesia. Br J Anaesth. 2018;121:339-342.

- Eisenach JC, Pan PH, Smiley R, et al. Severity of acute pain after childbirth, but not type of delivery, predicts persistent pain and postpartum depression. Pain. 2008;140:87-94.

- Bateman BT, Franklin JM, Bykov K, et al. Persistent opioid use following cesarean delivery: patterns and predictors among opioid-naïve women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215:353.e1- 353.e18.

- Bateman BT, Cole NM, Maeda A, et al. Patterns of opioid prescription and use after cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:29-35.

- Osmundson SS, Schornack LA, Grasch JL, et al. Postdischarge opioid use after cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:36-41.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG committee opinion no. 742: postpartum pain management. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132:e35-e43.

- Mills JR, Huizinga MM, Robinson SB, et al. Draft opioid prescribing guidelines for uncomplicated normal spontaneous vaginal birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:81-90.

- Chang AK, Bijur PE, Esses D, et al. Effect of a single dose of oral opioid and nonopioid analgesics on acute extremity pain in the emergency department: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;318:1661-1667.

- Mitchell A, van Zanten SV, Inglis K, et al. A randomized controlled trial comparing acetaminophen plus ibuprofen versus acetaminophen plus codeine plus caffeine after outpatient general surgery. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;206:472-479.

- Mitchell A, McCrea P, Inglis K, et al. A randomized, controlled trial comparing acetaminophen plus ibuprofen versus acetaminophen plus codeine plus caffeine (Tylenol 3) after outpatient breast surgery. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:3792-3800.

- Holland E, Bateman BT, Cole N, et al. Evaluation of a quality improvement intervention that eliminated routine use of opioids after cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:91-97.

- Hedderson M, Lee D, Hunt E, et al. Enhanced recovery after surgery to change process measures and reduce opioid use after cesarean delivery: a quality improvement initiative. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;134:511-519.

- Prabhu M, Dubois H, James K, et al. Implementation of a quality improvement initiative to decrease opioid prescribing after cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132:631-636.

- Rogers RG, Nix M, Chipman Z, et al. Decreasing opioid use postpartum: a quality improvement initiative. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;134:932-940.

- Prabhu M, McQuaid-Hanson E, Hopp S, et al. A shared decision-making intervention to guide opioid prescribing after cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:42-46.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Calculating total daily dose of opioids for safer dosage. www.cdc.gov/ drugoverdose/pdf/calculating_total_daily_dose-a.pdf. Accessed December 31, 2019.

CASE New mother receives unneeded opioids after CD

A house officer wrote orders for a healthy patient who had just had an uncomplicated cesarean delivery (CD). The hospital’s tradition dictates orders for oxycodone plus acetaminophen tablets in addition to ibuprofen for all new mothers. At the time of the patient’s discharge, the same house officer prescribed 30 tablets of oxycodone plus acetaminophen “just in case,” although the patient had required only a few tablets while in the hospital on postoperative day 2 and none on the day of discharge.

Stuck in the habit

Prescribing postpartum opioids in the United States is almost habitual. Both optimizing patient satisfaction and minimizing patient phone calls may be driving this well-established pattern. Interestingly, a survey study of obstetric providers in 14 countries found that clinicians in 13 countries prescribe opioids “almost never” after vaginal delivery.1 The United States was the 1 outlier, with providers reporting prescribing opioids “on a regular basis” after vaginal birth. Similarly, providers in 10 countries reported prescribing opioids “almost never” after CD, while those in the United States reported prescribing opioids “almost always” in this context.

Moreover, mounting data suggest that many patients do not require the quantity of opioids prescribed and that our overprescribing may be causing more harm than good.

The problem of overprescribing opioids after childbirth

Opioid analgesia has long been the mainstay of treatment for postpartum pain, which when poorly controlled is associated with the development of postpartum depression and chronic pain.2 However, common adverse effects of opioids, including nausea, drowsiness, and dizziness, similarly can interfere with self-care and infant care. Of additional concern, a 2016 claims data study found that 1 of 300 opioid-naïve women who were prescribed opioids at discharge after CD used these medications persistently in the first year postpartum.3

Many women do not use the opioids that are prescribed to them at discharge, thus making tablets available for potential diversion into the community—a commonly recognized source of opioid misuse and abuse.4,5 In a 2018 Committee Opinion on postpartum pain management, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) stated that “a stepwise, multimodal approach emphasizing nonopioid analgesia as first-line therapy is safe and effective for vaginal deliveries and cesarean deliveries.”6 The Committee Opinion also asserted that “opioid medication is an adjunct for patients with uncontrolled pain despite adequate first-line therapy.”6

Despite efforts by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and ACOG to improve opioid prescribing patterns after childbirth, the vast majority of women receive opioids in the hospital and at discharge not only after CD, but after vaginal delivery as well.4,7 Why has tradition prevailed over data, and why have we not changed?

Continue to: Common misconceptions about reducing opioid use...

Common misconceptions about reducing opioid use

Two misconceptions persist regarding reducing opioid prescriptions for postpartum pain.

Misconception #1: Patients will be in pain

Randomized controlled trials that compared nonopioid with opioid regimens in the emergency room setting and opioid use after outpatient general surgery procedures have demonstrated that pain control for patients receiving opioids was equivalent to that for patients with pain managed with nonopioid regimens.8-10 In the obstetric setting, a survey study of 720 women who underwent CD found that higher quantities of opioid tablets prescribed at discharge were not associated with improved pain, higher satisfaction, or lower refill rates at 2 weeks postpartum.4 However, greater quantities of opioids prescribed at the time of discharge were associated with greater opioid consumption.

Recently, several quality improvement studies implemented various interventions and successfully decreased postpartum opioid consumption without compromising pain management. One quality improvement project eliminated the routine use of opioids after CD and decreased the proportion of patients using any opioids in the hospital from 68% to 45%, with no changes in pain scores.11 A similar study implemented an enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) program for women after CD; mean in-patient opioid use decreased from 10.7 to 5.4 average daily morphine equivalents, with improvement in the proportion of time that patients reported their pain as acceptable.12

Misconception #2: Clinicians will be overwhelmed with pages and phone calls

Providers commonly fear that decreasing opioid use will lead to an increased volume of pages and phone calls from patients requesting additional medication. However, data suggest otherwise. For example, a quality improvement study that eliminated the routine use of opioids after CD tracked the number of phone calls that were received requesting rescue opioid prescriptions after discharge.11 Although the percentage of women discharged with opioids decreased from 90.6% to 40.3%, the requests for rescue opioid prescriptions did not change. Of 191 women, 4 requested a rescue prescription prior to the intervention compared with no women after the intervention. At the same time, according to unpublished data (Dr. Holland), satisfaction among nurses, house staff, and faculty did not change.

Similarly, a quality improvement project that implemented shared decision-making to inform the quantity of opioids prescribed at discharge demonstrated that the number of tablets prescribed decreased from 33.2 to 26.5, and there was no change in the rate of patients requesting opioid refills.13

Success stories: Strategies for reducing opioid use after childbirth

While overall rates of opioid prescribing after vaginal delivery and CD remain high throughout the United States, various institutions have developed successful and reproducible strategies to reduce opioid use after childbirth both in the hospital and at discharge. We highlight 3 strategies below.

Strategy 1: ERAS initiatives

An integrated health care system in northern California studied the effects of an ERAS protocol for CD across 15 medical centers.12 The intervention centered on 4 pillars: multimodal pain management, early mobility, optimal nutrition, and patient engagement through education. Specifically, multimodal pain management consisted of the following:

- intrathecal opioids during CD

- scheduled intravenous acetaminophen for 24 hours followed by oral acetaminophen every 6 hours

- nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) every 6 hours

- oral oxycodone for breakthrough pain

- decoupling of opioid medication from nonopioids in the post-CD order set

- decoupling of opioid and nonopioid medications in the discharge order set along with a reduction from 30 to 20 tablets as the default discharge quantity.

Continue to: Among 4,689 and 4,624 patients who underwent CD...

Among 4,689 and 4,624 patients who underwent CD before and after the intervention, the daily morphine milligram equivalents (MME) consumed in the hospital decreased from 10.7 to 5.4. The percentage of women who required no opioids while in the hospital increased from 8.3% to 21.4% after ERAS implementation, while the percentage of time that patients reported acceptable pain scores increased from 82.1% to 86.4%. The average number of opioid tablets prescribed at discharge also decreased, from 37 to 26 MME.12 (The TABLE shows oxycodone doses converted to MMEs.)

A similar initiative at a network of 5 hospitals in Texas showed that implementation of a “multimodal pain power plan” (which incorporated postpartum activity goals with standardized order sets) decreased opioid use after both vaginal delivery and CD.14

Strategy 2: Order set change to eliminate routine use of opioids

A tertiary care center in Boston, Massachusetts, implemented a quality improvement project aimed at eliminating the routine use of opioid medication after CD through an order set change.11 The intervention consisted of the following:

- intrathecal morphine

- multimodal postoperative pain management including scheduled oral acetaminophen for 72 hours followed by as-needed oral acetaminophen, scheduled NSAIDs for 72 hours followed by as-needed NSAIDs

- no postoperative order for opioids unless the patient had a contraindication to acetaminophen or NSAIDs, had a history of opioid dependence, or underwent complex surgery

- counseling patients that opioids were available for breakthrough pain if needed. In this case, nursing staff would page the responding clinician, who would order oxycodone 5 mg every 6 hours for 6 doses.

- specific criteria for discharge quantities of opioids: if the patient required no opioids in the hospital, she received no opioids at discharge; if the patient required opioids in the hospital but none at the time of discharge, she received no more than 10 tablets of oxycodone 5 mg; if the patient required opioids at the time of discharge, she received a maximum of 20 tablets of oxycodone 5 mg.

Among 191 and 181 women undergoing CD before and after the intervention, the percentage of patients who received any opioids in the hospital decreased from 68.1% to 45.3%.11 Similarly, the percentage of patients receiving a discharge prescription for opioids decreased from 90.6% to 40.3%, while patient pain scores and satisfaction with pain control remained unchanged.

Strategy 3: Shared decision-making tool

Another tertiary care center in Boston evaluated the effects of a shared decision-making tool on opioid discharge prescribing after CD.15 The intervention consisted of a 10-minute clinician-facilitated session incorporating:

- education around anticipated patterns of postoperative pain

- expected outpatient opioid use after CD

- risks and benefits of opioids and nonopioids

- education around opioid disposal and access to refills.

Among the 50 women enrolled in the study, the number of oxycodone 5-mg tablets prescribed at discharge decreased from the institutional standard of 40 to 20. Ninety percent of women reported being satisfied or very satisfied with their pain control, while only 4 of 50 women required an opioid refill. A follow-up quality improvement project, which implemented the shared decision-making model along with a standardized multimodal pain management protocol, demonstrated a similar decrease in the quantity of opioids prescribed at discharge.13

Continue to: Change is here to stay: A new culture of postpartum analgesia...

Change is here to stay: A new culture of postpartum analgesia

The CDC continues to champion responsible opioid prescribing, while ACOG advocates for a reassessment of the way that opioids are utilized postpartum. The majority of women in the United States, however, continue to receive opioids after both vaginal delivery and CD. Consciously or not, we clinicians may be contributing to an outdated tradition that is potentially harmful both to patients and society. Reproducible strategies exist to reduce opioid use without compromising pain control or overwhelming clinicians with phone calls. It is time to embrace the change.

CASE New mother receives unneeded opioids after CD

A house officer wrote orders for a healthy patient who had just had an uncomplicated cesarean delivery (CD). The hospital’s tradition dictates orders for oxycodone plus acetaminophen tablets in addition to ibuprofen for all new mothers. At the time of the patient’s discharge, the same house officer prescribed 30 tablets of oxycodone plus acetaminophen “just in case,” although the patient had required only a few tablets while in the hospital on postoperative day 2 and none on the day of discharge.

Stuck in the habit

Prescribing postpartum opioids in the United States is almost habitual. Both optimizing patient satisfaction and minimizing patient phone calls may be driving this well-established pattern. Interestingly, a survey study of obstetric providers in 14 countries found that clinicians in 13 countries prescribe opioids “almost never” after vaginal delivery.1 The United States was the 1 outlier, with providers reporting prescribing opioids “on a regular basis” after vaginal birth. Similarly, providers in 10 countries reported prescribing opioids “almost never” after CD, while those in the United States reported prescribing opioids “almost always” in this context.

Moreover, mounting data suggest that many patients do not require the quantity of opioids prescribed and that our overprescribing may be causing more harm than good.

The problem of overprescribing opioids after childbirth

Opioid analgesia has long been the mainstay of treatment for postpartum pain, which when poorly controlled is associated with the development of postpartum depression and chronic pain.2 However, common adverse effects of opioids, including nausea, drowsiness, and dizziness, similarly can interfere with self-care and infant care. Of additional concern, a 2016 claims data study found that 1 of 300 opioid-naïve women who were prescribed opioids at discharge after CD used these medications persistently in the first year postpartum.3

Many women do not use the opioids that are prescribed to them at discharge, thus making tablets available for potential diversion into the community—a commonly recognized source of opioid misuse and abuse.4,5 In a 2018 Committee Opinion on postpartum pain management, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) stated that “a stepwise, multimodal approach emphasizing nonopioid analgesia as first-line therapy is safe and effective for vaginal deliveries and cesarean deliveries.”6 The Committee Opinion also asserted that “opioid medication is an adjunct for patients with uncontrolled pain despite adequate first-line therapy.”6

Despite efforts by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and ACOG to improve opioid prescribing patterns after childbirth, the vast majority of women receive opioids in the hospital and at discharge not only after CD, but after vaginal delivery as well.4,7 Why has tradition prevailed over data, and why have we not changed?

Continue to: Common misconceptions about reducing opioid use...

Common misconceptions about reducing opioid use

Two misconceptions persist regarding reducing opioid prescriptions for postpartum pain.

Misconception #1: Patients will be in pain

Randomized controlled trials that compared nonopioid with opioid regimens in the emergency room setting and opioid use after outpatient general surgery procedures have demonstrated that pain control for patients receiving opioids was equivalent to that for patients with pain managed with nonopioid regimens.8-10 In the obstetric setting, a survey study of 720 women who underwent CD found that higher quantities of opioid tablets prescribed at discharge were not associated with improved pain, higher satisfaction, or lower refill rates at 2 weeks postpartum.4 However, greater quantities of opioids prescribed at the time of discharge were associated with greater opioid consumption.

Recently, several quality improvement studies implemented various interventions and successfully decreased postpartum opioid consumption without compromising pain management. One quality improvement project eliminated the routine use of opioids after CD and decreased the proportion of patients using any opioids in the hospital from 68% to 45%, with no changes in pain scores.11 A similar study implemented an enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) program for women after CD; mean in-patient opioid use decreased from 10.7 to 5.4 average daily morphine equivalents, with improvement in the proportion of time that patients reported their pain as acceptable.12

Misconception #2: Clinicians will be overwhelmed with pages and phone calls

Providers commonly fear that decreasing opioid use will lead to an increased volume of pages and phone calls from patients requesting additional medication. However, data suggest otherwise. For example, a quality improvement study that eliminated the routine use of opioids after CD tracked the number of phone calls that were received requesting rescue opioid prescriptions after discharge.11 Although the percentage of women discharged with opioids decreased from 90.6% to 40.3%, the requests for rescue opioid prescriptions did not change. Of 191 women, 4 requested a rescue prescription prior to the intervention compared with no women after the intervention. At the same time, according to unpublished data (Dr. Holland), satisfaction among nurses, house staff, and faculty did not change.

Similarly, a quality improvement project that implemented shared decision-making to inform the quantity of opioids prescribed at discharge demonstrated that the number of tablets prescribed decreased from 33.2 to 26.5, and there was no change in the rate of patients requesting opioid refills.13

Success stories: Strategies for reducing opioid use after childbirth

While overall rates of opioid prescribing after vaginal delivery and CD remain high throughout the United States, various institutions have developed successful and reproducible strategies to reduce opioid use after childbirth both in the hospital and at discharge. We highlight 3 strategies below.

Strategy 1: ERAS initiatives

An integrated health care system in northern California studied the effects of an ERAS protocol for CD across 15 medical centers.12 The intervention centered on 4 pillars: multimodal pain management, early mobility, optimal nutrition, and patient engagement through education. Specifically, multimodal pain management consisted of the following:

- intrathecal opioids during CD

- scheduled intravenous acetaminophen for 24 hours followed by oral acetaminophen every 6 hours

- nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) every 6 hours

- oral oxycodone for breakthrough pain

- decoupling of opioid medication from nonopioids in the post-CD order set

- decoupling of opioid and nonopioid medications in the discharge order set along with a reduction from 30 to 20 tablets as the default discharge quantity.

Continue to: Among 4,689 and 4,624 patients who underwent CD...

Among 4,689 and 4,624 patients who underwent CD before and after the intervention, the daily morphine milligram equivalents (MME) consumed in the hospital decreased from 10.7 to 5.4. The percentage of women who required no opioids while in the hospital increased from 8.3% to 21.4% after ERAS implementation, while the percentage of time that patients reported acceptable pain scores increased from 82.1% to 86.4%. The average number of opioid tablets prescribed at discharge also decreased, from 37 to 26 MME.12 (The TABLE shows oxycodone doses converted to MMEs.)

A similar initiative at a network of 5 hospitals in Texas showed that implementation of a “multimodal pain power plan” (which incorporated postpartum activity goals with standardized order sets) decreased opioid use after both vaginal delivery and CD.14

Strategy 2: Order set change to eliminate routine use of opioids

A tertiary care center in Boston, Massachusetts, implemented a quality improvement project aimed at eliminating the routine use of opioid medication after CD through an order set change.11 The intervention consisted of the following:

- intrathecal morphine

- multimodal postoperative pain management including scheduled oral acetaminophen for 72 hours followed by as-needed oral acetaminophen, scheduled NSAIDs for 72 hours followed by as-needed NSAIDs

- no postoperative order for opioids unless the patient had a contraindication to acetaminophen or NSAIDs, had a history of opioid dependence, or underwent complex surgery

- counseling patients that opioids were available for breakthrough pain if needed. In this case, nursing staff would page the responding clinician, who would order oxycodone 5 mg every 6 hours for 6 doses.

- specific criteria for discharge quantities of opioids: if the patient required no opioids in the hospital, she received no opioids at discharge; if the patient required opioids in the hospital but none at the time of discharge, she received no more than 10 tablets of oxycodone 5 mg; if the patient required opioids at the time of discharge, she received a maximum of 20 tablets of oxycodone 5 mg.

Among 191 and 181 women undergoing CD before and after the intervention, the percentage of patients who received any opioids in the hospital decreased from 68.1% to 45.3%.11 Similarly, the percentage of patients receiving a discharge prescription for opioids decreased from 90.6% to 40.3%, while patient pain scores and satisfaction with pain control remained unchanged.

Strategy 3: Shared decision-making tool

Another tertiary care center in Boston evaluated the effects of a shared decision-making tool on opioid discharge prescribing after CD.15 The intervention consisted of a 10-minute clinician-facilitated session incorporating:

- education around anticipated patterns of postoperative pain

- expected outpatient opioid use after CD

- risks and benefits of opioids and nonopioids

- education around opioid disposal and access to refills.

Among the 50 women enrolled in the study, the number of oxycodone 5-mg tablets prescribed at discharge decreased from the institutional standard of 40 to 20. Ninety percent of women reported being satisfied or very satisfied with their pain control, while only 4 of 50 women required an opioid refill. A follow-up quality improvement project, which implemented the shared decision-making model along with a standardized multimodal pain management protocol, demonstrated a similar decrease in the quantity of opioids prescribed at discharge.13

Continue to: Change is here to stay: A new culture of postpartum analgesia...

Change is here to stay: A new culture of postpartum analgesia

The CDC continues to champion responsible opioid prescribing, while ACOG advocates for a reassessment of the way that opioids are utilized postpartum. The majority of women in the United States, however, continue to receive opioids after both vaginal delivery and CD. Consciously or not, we clinicians may be contributing to an outdated tradition that is potentially harmful both to patients and society. Reproducible strategies exist to reduce opioid use without compromising pain control or overwhelming clinicians with phone calls. It is time to embrace the change.

- Wong CA, Girard T. Undertreated or overtreated? Opioids for postdelivery analgesia. Br J Anaesth. 2018;121:339-342.

- Eisenach JC, Pan PH, Smiley R, et al. Severity of acute pain after childbirth, but not type of delivery, predicts persistent pain and postpartum depression. Pain. 2008;140:87-94.

- Bateman BT, Franklin JM, Bykov K, et al. Persistent opioid use following cesarean delivery: patterns and predictors among opioid-naïve women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215:353.e1- 353.e18.

- Bateman BT, Cole NM, Maeda A, et al. Patterns of opioid prescription and use after cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:29-35.

- Osmundson SS, Schornack LA, Grasch JL, et al. Postdischarge opioid use after cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:36-41.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG committee opinion no. 742: postpartum pain management. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132:e35-e43.

- Mills JR, Huizinga MM, Robinson SB, et al. Draft opioid prescribing guidelines for uncomplicated normal spontaneous vaginal birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:81-90.

- Chang AK, Bijur PE, Esses D, et al. Effect of a single dose of oral opioid and nonopioid analgesics on acute extremity pain in the emergency department: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;318:1661-1667.

- Mitchell A, van Zanten SV, Inglis K, et al. A randomized controlled trial comparing acetaminophen plus ibuprofen versus acetaminophen plus codeine plus caffeine after outpatient general surgery. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;206:472-479.

- Mitchell A, McCrea P, Inglis K, et al. A randomized, controlled trial comparing acetaminophen plus ibuprofen versus acetaminophen plus codeine plus caffeine (Tylenol 3) after outpatient breast surgery. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:3792-3800.

- Holland E, Bateman BT, Cole N, et al. Evaluation of a quality improvement intervention that eliminated routine use of opioids after cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:91-97.

- Hedderson M, Lee D, Hunt E, et al. Enhanced recovery after surgery to change process measures and reduce opioid use after cesarean delivery: a quality improvement initiative. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;134:511-519.

- Prabhu M, Dubois H, James K, et al. Implementation of a quality improvement initiative to decrease opioid prescribing after cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132:631-636.

- Rogers RG, Nix M, Chipman Z, et al. Decreasing opioid use postpartum: a quality improvement initiative. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;134:932-940.

- Prabhu M, McQuaid-Hanson E, Hopp S, et al. A shared decision-making intervention to guide opioid prescribing after cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:42-46.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Calculating total daily dose of opioids for safer dosage. www.cdc.gov/ drugoverdose/pdf/calculating_total_daily_dose-a.pdf. Accessed December 31, 2019.

- Wong CA, Girard T. Undertreated or overtreated? Opioids for postdelivery analgesia. Br J Anaesth. 2018;121:339-342.

- Eisenach JC, Pan PH, Smiley R, et al. Severity of acute pain after childbirth, but not type of delivery, predicts persistent pain and postpartum depression. Pain. 2008;140:87-94.

- Bateman BT, Franklin JM, Bykov K, et al. Persistent opioid use following cesarean delivery: patterns and predictors among opioid-naïve women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215:353.e1- 353.e18.

- Bateman BT, Cole NM, Maeda A, et al. Patterns of opioid prescription and use after cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:29-35.

- Osmundson SS, Schornack LA, Grasch JL, et al. Postdischarge opioid use after cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:36-41.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG committee opinion no. 742: postpartum pain management. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132:e35-e43.

- Mills JR, Huizinga MM, Robinson SB, et al. Draft opioid prescribing guidelines for uncomplicated normal spontaneous vaginal birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:81-90.

- Chang AK, Bijur PE, Esses D, et al. Effect of a single dose of oral opioid and nonopioid analgesics on acute extremity pain in the emergency department: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;318:1661-1667.

- Mitchell A, van Zanten SV, Inglis K, et al. A randomized controlled trial comparing acetaminophen plus ibuprofen versus acetaminophen plus codeine plus caffeine after outpatient general surgery. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;206:472-479.

- Mitchell A, McCrea P, Inglis K, et al. A randomized, controlled trial comparing acetaminophen plus ibuprofen versus acetaminophen plus codeine plus caffeine (Tylenol 3) after outpatient breast surgery. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:3792-3800.

- Holland E, Bateman BT, Cole N, et al. Evaluation of a quality improvement intervention that eliminated routine use of opioids after cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:91-97.

- Hedderson M, Lee D, Hunt E, et al. Enhanced recovery after surgery to change process measures and reduce opioid use after cesarean delivery: a quality improvement initiative. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;134:511-519.

- Prabhu M, Dubois H, James K, et al. Implementation of a quality improvement initiative to decrease opioid prescribing after cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132:631-636.

- Rogers RG, Nix M, Chipman Z, et al. Decreasing opioid use postpartum: a quality improvement initiative. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;134:932-940.

- Prabhu M, McQuaid-Hanson E, Hopp S, et al. A shared decision-making intervention to guide opioid prescribing after cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:42-46.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Calculating total daily dose of opioids for safer dosage. www.cdc.gov/ drugoverdose/pdf/calculating_total_daily_dose-a.pdf. Accessed December 31, 2019.

CAR T cells produce complete responses in T-cell malignancies

ORLANDO – Anti-CD5 chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells can produce complete responses (CRs) in patients with relapsed or refractory T-cell malignancies, according to findings from a phase 1 trial.

Three of 11 patients achieved a CR after CAR T-cell therapy, and one patient achieved a mixed response that deepened to a CR after transplant. Three responders, all of whom had T-cell lymphoma, were still alive and in CR at last follow-up.

There were no cases of severe cytokine release syndrome (CRS) or severe neurotoxicity, no serious infectious complications, and no nonhematologic grade 4 adverse events in this trial.

LaQuisa C. Hill, MD, of Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, presented these results at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

“While CD19 CAR T cells have revolutionized the treatment of relapsed/refractory B-cell malignancies, development of CAR T-cell platforms targeting T-cell-driven malignancies have been hindered by three main factors: CAR T-cell fratricide due to shared expression of target antigens leading to impaired expansion, ablation of normal T cells continuing to cause profound immunodeficiency, and the potential of transduced tumor cells providing a means of tumor escape,” Dr. Hill said.

Researchers have theorized that anti-CD5 CAR T cells can overcome these obstacles. In preclinical studies, anti-CD5 CAR T cells eliminated malignant blasts in vitro and in vivo and resulted in “limited and transient” fratricide (Blood. 2015 Aug 20;126[8]:983-92).

With this in mind, Dr. Hill and her colleagues tested CD5.28z CAR T cells in a phase 1 trial (NCT03081910). Eleven patients have been treated thus far – five with T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL), three with peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL), two with angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma (AITL), and one with Sézary syndrome.

The patients’ median age at baseline was 62 years (range, 21-71 years), and 63% were men. They had received a median of 5 prior therapies (range, 3-18). Two patients had relapsed after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT), three had relapsed after autologous HSCT, and five were primary refractory.

Patients underwent lymphodepletion with fludarabine and cyclophosphamide, then received CAR T cells at doses of 1 x 107 or 5 x 107.

Response

Three lymphoma patients – two with AITL and one with PTCL – were still alive and in CR at last follow-up. The PTCL patient achieved a CR after CAR T-cell therapy and declined a subsequent HSCT. The patient has not received additional therapy and has retained the CR for 7 months.

One AITL patient achieved a CR and declined transplant as well. He relapsed after 7 months but received subsequent therapy and achieved another CR. The other AITL patient had a mixed response to CAR T-cell therapy but proceeded to allogeneic HSCT and achieved a CR that has lasted 9 months.

The remaining three lymphoma patients – two with PTCL and one with Sézary syndrome – progressed and died.

One T-ALL patient achieved a CR lasting 6 weeks, but the patient died while undergoing transplant workup. Two T-ALL patients did not respond to treatment and died. The remaining two patients progressed, and one of them died. The other patient who progressed is still alive and in CR after receiving subsequent therapy.

Factors associated with response

Dr. Hill said a shortened manufacturing process may be associated with enhanced response, as all responders received CAR T cells produced via a shorter manufacturing process. The shortened process involves freezing cells on day 4-5 post transduction, as opposed to day 7.

“While the numbers are too small to make any definitive conclusions, this seems to correlate with less terminal differentiation, which might improve potency,” Dr. Hill said. “However, additional analyses are ongoing.”

Dr. Hill also pointed out that CAR T-cell expansion was observed in all patients, with higher peak levels observed at the higher dose. In addition, CAR T-cell persistence was durable at both dose levels.

“We have been able to detect the CAR transgene at all follow-up time points, out to 9 months for some patients,” Dr. Hill said. “While limited persistence may play a role in nonresponders, it does not appear to be the only factor.”

Safety

“Surprisingly, no selective ablation of normal T cells has been observed,” Dr. Hill said. “As CAR T cells dwindled [after infusion], we were able to see recovery of normal T cells, all of which expressed normal levels of CD5. This was observed in all patients on study, except for one patient who had prolonged pancytopenia.”

Cytopenias were the most common grade 3/4 adverse events, including neutropenia (n = 8), anemia (n = 7), and thrombocytopenia (n = 5). Other grade 3/4 events included elevated aspartate aminotransferase (n = 2), hypoalbuminemia (n = 1), hyponatremia (n = 1), hypophosphatemia (n = 1), and elevated alanine aminotransferase (n = 1). There were no grade 5 adverse events.

Two patients developed grade 1 CRS, and two had grade 2 CRS. Both patients with grade 2 CRS were treated with tocilizumab, and their symptoms resolved.

One patient developed grade 2 immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome, but this resolved with supportive care.

One patient had a central line–associated bloodstream infection (coagulase-negative staphylococci), and one had cytomegalovirus and BK virus reactivation. There were no fungal infections.

“We have demonstrated that CD5 CAR T cells can be manufactured from heavily pretreated patients with T-cell malignancies, and therapy is well tolerated,” Dr. Hill said. “We have seen strong and promising activity in T-cell lymphoma, which we hope to be able to translate to T-ALL as well.”

Dr. Hill said she and her colleagues hope to improve upon these results with a higher dose level of CD5 CAR T cells (1 x 108), which the team plans to start testing soon. The researchers may also investigate other target antigens, such as CD7, as well as the use of donor-derived CAR T cells for patients who have relapsed after allogeneic HSCT.

Dr. Hill said she has no relevant disclosures. Baylor College of Medicine is sponsoring this trial.

SOURCE: Hill L et al. ASH 2019. Abstract 199.

ORLANDO – Anti-CD5 chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells can produce complete responses (CRs) in patients with relapsed or refractory T-cell malignancies, according to findings from a phase 1 trial.

Three of 11 patients achieved a CR after CAR T-cell therapy, and one patient achieved a mixed response that deepened to a CR after transplant. Three responders, all of whom had T-cell lymphoma, were still alive and in CR at last follow-up.

There were no cases of severe cytokine release syndrome (CRS) or severe neurotoxicity, no serious infectious complications, and no nonhematologic grade 4 adverse events in this trial.

LaQuisa C. Hill, MD, of Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, presented these results at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

“While CD19 CAR T cells have revolutionized the treatment of relapsed/refractory B-cell malignancies, development of CAR T-cell platforms targeting T-cell-driven malignancies have been hindered by three main factors: CAR T-cell fratricide due to shared expression of target antigens leading to impaired expansion, ablation of normal T cells continuing to cause profound immunodeficiency, and the potential of transduced tumor cells providing a means of tumor escape,” Dr. Hill said.

Researchers have theorized that anti-CD5 CAR T cells can overcome these obstacles. In preclinical studies, anti-CD5 CAR T cells eliminated malignant blasts in vitro and in vivo and resulted in “limited and transient” fratricide (Blood. 2015 Aug 20;126[8]:983-92).

With this in mind, Dr. Hill and her colleagues tested CD5.28z CAR T cells in a phase 1 trial (NCT03081910). Eleven patients have been treated thus far – five with T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL), three with peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL), two with angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma (AITL), and one with Sézary syndrome.

The patients’ median age at baseline was 62 years (range, 21-71 years), and 63% were men. They had received a median of 5 prior therapies (range, 3-18). Two patients had relapsed after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT), three had relapsed after autologous HSCT, and five were primary refractory.

Patients underwent lymphodepletion with fludarabine and cyclophosphamide, then received CAR T cells at doses of 1 x 107 or 5 x 107.

Response

Three lymphoma patients – two with AITL and one with PTCL – were still alive and in CR at last follow-up. The PTCL patient achieved a CR after CAR T-cell therapy and declined a subsequent HSCT. The patient has not received additional therapy and has retained the CR for 7 months.

One AITL patient achieved a CR and declined transplant as well. He relapsed after 7 months but received subsequent therapy and achieved another CR. The other AITL patient had a mixed response to CAR T-cell therapy but proceeded to allogeneic HSCT and achieved a CR that has lasted 9 months.

The remaining three lymphoma patients – two with PTCL and one with Sézary syndrome – progressed and died.

One T-ALL patient achieved a CR lasting 6 weeks, but the patient died while undergoing transplant workup. Two T-ALL patients did not respond to treatment and died. The remaining two patients progressed, and one of them died. The other patient who progressed is still alive and in CR after receiving subsequent therapy.

Factors associated with response

Dr. Hill said a shortened manufacturing process may be associated with enhanced response, as all responders received CAR T cells produced via a shorter manufacturing process. The shortened process involves freezing cells on day 4-5 post transduction, as opposed to day 7.

“While the numbers are too small to make any definitive conclusions, this seems to correlate with less terminal differentiation, which might improve potency,” Dr. Hill said. “However, additional analyses are ongoing.”

Dr. Hill also pointed out that CAR T-cell expansion was observed in all patients, with higher peak levels observed at the higher dose. In addition, CAR T-cell persistence was durable at both dose levels.

“We have been able to detect the CAR transgene at all follow-up time points, out to 9 months for some patients,” Dr. Hill said. “While limited persistence may play a role in nonresponders, it does not appear to be the only factor.”

Safety

“Surprisingly, no selective ablation of normal T cells has been observed,” Dr. Hill said. “As CAR T cells dwindled [after infusion], we were able to see recovery of normal T cells, all of which expressed normal levels of CD5. This was observed in all patients on study, except for one patient who had prolonged pancytopenia.”

Cytopenias were the most common grade 3/4 adverse events, including neutropenia (n = 8), anemia (n = 7), and thrombocytopenia (n = 5). Other grade 3/4 events included elevated aspartate aminotransferase (n = 2), hypoalbuminemia (n = 1), hyponatremia (n = 1), hypophosphatemia (n = 1), and elevated alanine aminotransferase (n = 1). There were no grade 5 adverse events.

Two patients developed grade 1 CRS, and two had grade 2 CRS. Both patients with grade 2 CRS were treated with tocilizumab, and their symptoms resolved.

One patient developed grade 2 immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome, but this resolved with supportive care.

One patient had a central line–associated bloodstream infection (coagulase-negative staphylococci), and one had cytomegalovirus and BK virus reactivation. There were no fungal infections.

“We have demonstrated that CD5 CAR T cells can be manufactured from heavily pretreated patients with T-cell malignancies, and therapy is well tolerated,” Dr. Hill said. “We have seen strong and promising activity in T-cell lymphoma, which we hope to be able to translate to T-ALL as well.”

Dr. Hill said she and her colleagues hope to improve upon these results with a higher dose level of CD5 CAR T cells (1 x 108), which the team plans to start testing soon. The researchers may also investigate other target antigens, such as CD7, as well as the use of donor-derived CAR T cells for patients who have relapsed after allogeneic HSCT.

Dr. Hill said she has no relevant disclosures. Baylor College of Medicine is sponsoring this trial.

SOURCE: Hill L et al. ASH 2019. Abstract 199.

ORLANDO – Anti-CD5 chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells can produce complete responses (CRs) in patients with relapsed or refractory T-cell malignancies, according to findings from a phase 1 trial.

Three of 11 patients achieved a CR after CAR T-cell therapy, and one patient achieved a mixed response that deepened to a CR after transplant. Three responders, all of whom had T-cell lymphoma, were still alive and in CR at last follow-up.

There were no cases of severe cytokine release syndrome (CRS) or severe neurotoxicity, no serious infectious complications, and no nonhematologic grade 4 adverse events in this trial.

LaQuisa C. Hill, MD, of Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, presented these results at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

“While CD19 CAR T cells have revolutionized the treatment of relapsed/refractory B-cell malignancies, development of CAR T-cell platforms targeting T-cell-driven malignancies have been hindered by three main factors: CAR T-cell fratricide due to shared expression of target antigens leading to impaired expansion, ablation of normal T cells continuing to cause profound immunodeficiency, and the potential of transduced tumor cells providing a means of tumor escape,” Dr. Hill said.

Researchers have theorized that anti-CD5 CAR T cells can overcome these obstacles. In preclinical studies, anti-CD5 CAR T cells eliminated malignant blasts in vitro and in vivo and resulted in “limited and transient” fratricide (Blood. 2015 Aug 20;126[8]:983-92).

With this in mind, Dr. Hill and her colleagues tested CD5.28z CAR T cells in a phase 1 trial (NCT03081910). Eleven patients have been treated thus far – five with T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL), three with peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL), two with angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma (AITL), and one with Sézary syndrome.

The patients’ median age at baseline was 62 years (range, 21-71 years), and 63% were men. They had received a median of 5 prior therapies (range, 3-18). Two patients had relapsed after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT), three had relapsed after autologous HSCT, and five were primary refractory.

Patients underwent lymphodepletion with fludarabine and cyclophosphamide, then received CAR T cells at doses of 1 x 107 or 5 x 107.

Response

Three lymphoma patients – two with AITL and one with PTCL – were still alive and in CR at last follow-up. The PTCL patient achieved a CR after CAR T-cell therapy and declined a subsequent HSCT. The patient has not received additional therapy and has retained the CR for 7 months.

One AITL patient achieved a CR and declined transplant as well. He relapsed after 7 months but received subsequent therapy and achieved another CR. The other AITL patient had a mixed response to CAR T-cell therapy but proceeded to allogeneic HSCT and achieved a CR that has lasted 9 months.

The remaining three lymphoma patients – two with PTCL and one with Sézary syndrome – progressed and died.

One T-ALL patient achieved a CR lasting 6 weeks, but the patient died while undergoing transplant workup. Two T-ALL patients did not respond to treatment and died. The remaining two patients progressed, and one of them died. The other patient who progressed is still alive and in CR after receiving subsequent therapy.

Factors associated with response

Dr. Hill said a shortened manufacturing process may be associated with enhanced response, as all responders received CAR T cells produced via a shorter manufacturing process. The shortened process involves freezing cells on day 4-5 post transduction, as opposed to day 7.

“While the numbers are too small to make any definitive conclusions, this seems to correlate with less terminal differentiation, which might improve potency,” Dr. Hill said. “However, additional analyses are ongoing.”

Dr. Hill also pointed out that CAR T-cell expansion was observed in all patients, with higher peak levels observed at the higher dose. In addition, CAR T-cell persistence was durable at both dose levels.

“We have been able to detect the CAR transgene at all follow-up time points, out to 9 months for some patients,” Dr. Hill said. “While limited persistence may play a role in nonresponders, it does not appear to be the only factor.”

Safety

“Surprisingly, no selective ablation of normal T cells has been observed,” Dr. Hill said. “As CAR T cells dwindled [after infusion], we were able to see recovery of normal T cells, all of which expressed normal levels of CD5. This was observed in all patients on study, except for one patient who had prolonged pancytopenia.”

Cytopenias were the most common grade 3/4 adverse events, including neutropenia (n = 8), anemia (n = 7), and thrombocytopenia (n = 5). Other grade 3/4 events included elevated aspartate aminotransferase (n = 2), hypoalbuminemia (n = 1), hyponatremia (n = 1), hypophosphatemia (n = 1), and elevated alanine aminotransferase (n = 1). There were no grade 5 adverse events.

Two patients developed grade 1 CRS, and two had grade 2 CRS. Both patients with grade 2 CRS were treated with tocilizumab, and their symptoms resolved.

One patient developed grade 2 immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome, but this resolved with supportive care.

One patient had a central line–associated bloodstream infection (coagulase-negative staphylococci), and one had cytomegalovirus and BK virus reactivation. There were no fungal infections.

“We have demonstrated that CD5 CAR T cells can be manufactured from heavily pretreated patients with T-cell malignancies, and therapy is well tolerated,” Dr. Hill said. “We have seen strong and promising activity in T-cell lymphoma, which we hope to be able to translate to T-ALL as well.”

Dr. Hill said she and her colleagues hope to improve upon these results with a higher dose level of CD5 CAR T cells (1 x 108), which the team plans to start testing soon. The researchers may also investigate other target antigens, such as CD7, as well as the use of donor-derived CAR T cells for patients who have relapsed after allogeneic HSCT.

Dr. Hill said she has no relevant disclosures. Baylor College of Medicine is sponsoring this trial.

SOURCE: Hill L et al. ASH 2019. Abstract 199.

REPORTING FROM ASH 2019

Big practices outpace small ones in Medicare pay bonuses

More physician practices are earning positive payments under Medicare’s Merit-Based Incentive Payment System, but smaller practices won’t fare quite as well as larger ones in 2020.

Under the Quality Payment Program, 97% of MIPS-eligible clinicians are scheduled to receive an incentive payment this year, based on meeting performance criteria in 2018. That’s up five percentage points from the 2017 performance year, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services reported Jan. 6. But 2% of clinicians will see a negative adjustment for not having met those criteria.

Among small practices, however, the rate of MIPS-eligible clinicians earning a positive payment adjustment in 2020 is about 84%. While lower than the overall rate, that’s still a 10 percentage point improvement from the previous performance year. But 13% of MIPS-eligible clinicians in small practices face a negative adjustment.

The bonus rate among rural practices mirrors the national rate, with more than 97% of rural practices eligible to receive a bonus in 2020. In 2019, 93% of MIPS-eligible clinicians in rural settings received a positive adjustment.

More small and rural practices will see positive payment adjustments in 2020, compared with 2019, CMS Administrator Seema Verma said. “This shows we are making strides toward making MIPS a practical program for every clinician, regardless of size.”

While most clinicians earned a positive adjustment, Ms. Verma acknowledged that the dollar value of the adjustment remains relatively small.

For clinicians who met the exceptional performance criteria for 2020 based on work in 2018, the maximum adjustment will be 1.68%. For those who failed to meet the exceptional performance threshold, the maximum positive adjustment will be 0.2%. The range of negative payment adjustments will be between –0.01% and –5%.

Those positive payment adjustments are modest in part because adjustments overall must be budget neutral, Ms. Verma explained. But CMS expects that to change in future years. As the program matures, increased performance thresholds will shrink distribution of positive payment adjustments for high-performing clinicians. That will lead to larger positive payment adjustments for those who do earn them.

More physician practices are earning positive payments under Medicare’s Merit-Based Incentive Payment System, but smaller practices won’t fare quite as well as larger ones in 2020.

Under the Quality Payment Program, 97% of MIPS-eligible clinicians are scheduled to receive an incentive payment this year, based on meeting performance criteria in 2018. That’s up five percentage points from the 2017 performance year, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services reported Jan. 6. But 2% of clinicians will see a negative adjustment for not having met those criteria.

Among small practices, however, the rate of MIPS-eligible clinicians earning a positive payment adjustment in 2020 is about 84%. While lower than the overall rate, that’s still a 10 percentage point improvement from the previous performance year. But 13% of MIPS-eligible clinicians in small practices face a negative adjustment.

The bonus rate among rural practices mirrors the national rate, with more than 97% of rural practices eligible to receive a bonus in 2020. In 2019, 93% of MIPS-eligible clinicians in rural settings received a positive adjustment.

More small and rural practices will see positive payment adjustments in 2020, compared with 2019, CMS Administrator Seema Verma said. “This shows we are making strides toward making MIPS a practical program for every clinician, regardless of size.”

While most clinicians earned a positive adjustment, Ms. Verma acknowledged that the dollar value of the adjustment remains relatively small.

For clinicians who met the exceptional performance criteria for 2020 based on work in 2018, the maximum adjustment will be 1.68%. For those who failed to meet the exceptional performance threshold, the maximum positive adjustment will be 0.2%. The range of negative payment adjustments will be between –0.01% and –5%.

Those positive payment adjustments are modest in part because adjustments overall must be budget neutral, Ms. Verma explained. But CMS expects that to change in future years. As the program matures, increased performance thresholds will shrink distribution of positive payment adjustments for high-performing clinicians. That will lead to larger positive payment adjustments for those who do earn them.

More physician practices are earning positive payments under Medicare’s Merit-Based Incentive Payment System, but smaller practices won’t fare quite as well as larger ones in 2020.

Under the Quality Payment Program, 97% of MIPS-eligible clinicians are scheduled to receive an incentive payment this year, based on meeting performance criteria in 2018. That’s up five percentage points from the 2017 performance year, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services reported Jan. 6. But 2% of clinicians will see a negative adjustment for not having met those criteria.

Among small practices, however, the rate of MIPS-eligible clinicians earning a positive payment adjustment in 2020 is about 84%. While lower than the overall rate, that’s still a 10 percentage point improvement from the previous performance year. But 13% of MIPS-eligible clinicians in small practices face a negative adjustment.

The bonus rate among rural practices mirrors the national rate, with more than 97% of rural practices eligible to receive a bonus in 2020. In 2019, 93% of MIPS-eligible clinicians in rural settings received a positive adjustment.

More small and rural practices will see positive payment adjustments in 2020, compared with 2019, CMS Administrator Seema Verma said. “This shows we are making strides toward making MIPS a practical program for every clinician, regardless of size.”

While most clinicians earned a positive adjustment, Ms. Verma acknowledged that the dollar value of the adjustment remains relatively small.

For clinicians who met the exceptional performance criteria for 2020 based on work in 2018, the maximum adjustment will be 1.68%. For those who failed to meet the exceptional performance threshold, the maximum positive adjustment will be 0.2%. The range of negative payment adjustments will be between –0.01% and –5%.

Those positive payment adjustments are modest in part because adjustments overall must be budget neutral, Ms. Verma explained. But CMS expects that to change in future years. As the program matures, increased performance thresholds will shrink distribution of positive payment adjustments for high-performing clinicians. That will lead to larger positive payment adjustments for those who do earn them.

Medical malpractice: Its evolution to today’s risk of the “big verdict”

Medical malpractice (more formally, professional liability, but we will use the term malpractice) has been of concern to ObGyns for many years, and for good reasons. This specialty has some of the highest incidents of malpractice claims, some of the largest verdicts, and some of the highest malpractice insurance rates. We look more closely at ObGyn malpractice issues in a 3-part “What’s the Verdict” series over the next few months.

In part 1, we discuss the background on malpractice and reasons why malpractice rates have been so high—including large verdicts and lawsuit-prone physicians. In the second part we will look at recent experience and developments in malpractice exposure—who is sued and why. Finally, in the third part we will consider suggestions for reducing the likelihood of a malpractice lawsuit, with a special focus on recent research regarding apologies.

Two reports of recent trials involving ObGyn care illustrate the risk of “the big verdict.”1,2 (Note that the following vignettes are drawn from actual cases but are outlines of those cases and not complete descriptions of the claims. Because the information does not come from formal court records, the facts may be inaccurate and are incomplete; they should be viewed as illustrations only.)

CASE 1 Delayed delivery, $19M verdict

At 39 weeks’ gestation, a woman was admitted to the hospital in spontaneous labor. Artificial rupture of membranes with clear amniotic fluid was noted. Active contractions occurred for 11 hours. Oxytocin was then initiated, and 17 minutes later, profound fetal bradycardia was detected. There was recurrent evidence of fetal distress with meconium. After a nursing staff change a second nurse restarted oxytocin for a prolonged period. The physician allowed labor to continue despite fetal distress, and performed a cesarean delivery (CD) 4.5 hours later. Five hours postdelivery the neonate was noted to have a pneumothorax, lung damage, and respiratory failure. The infant died at 18 days of age.

The jury felt that there was negligence—failure to timely diagnose fetal distress and failure to timely perform CD, all of which resulted in a verdict for the plaintiff. The jury awarded in excess of $19 million.1

CASE 2 An undiagnosed tumor, $20M verdict

A patient underwent bilateral mastectomy. Following surgery, she reported pain and swelling at the surgical site for 2 years, and the defendant physician “dismissed” her complaint, refusing to evaluate it as the provider felt it was related to scar tissue. Three years after the mastectomies, the patient underwent surgical exploration and removal of 3 ribs and sternum secondary to a desmoid tumor. Surgical mesh and chest reconstruction was required, necessitating long-term opioids and sleeping medications that “will slow her wits, dull her senses and limit activities of daily living.” Of note, discrepancies were found in the medical records maintained by the defendant. (There was, for example, no report in the record of the plaintiff’s pain until late in the process.) The plaintiff based her claim on the fact that her pain and lump were neither evaluated nor discovered until it was too late.

The jury awarded $20 million. The verdict was reduced to $2 million by the court based on state statutory limits on malpractice damages.2,3

Continue to: Medical malpractice: Evolution of a standard of care...

Medical malpractice: Evolution of a standard of care

Medical malpractice is not a modern invention. Some historians trace malpractice to the Code of Hammurabi (2030 BC), through Roman law,4 into English common law.5 It was sufficiently established by 1765 that the classic legal treatise of the century referred to medical malpractice.6,7 Although medical malpractice existed for a long time, actual malpractice cases were relatively rare before the last half of the 20th century.8

Defensive medicine born out of necessity. The number of malpractice cases increased substantially—described as a “geometric increase”—after 1960, with a 300% rise between 1965 and 1970.7,9 This “malpractice maelstrom of the 70s”7 resulted in dramatic increases in malpractice insurance costs and invited the practice of defensive medicine—medically unnecessary or unjustified tests and services.10Although there is controversy about what is defensive medicine and what is reasonably cautious medicine, the practice may account for 3% of total health care spending.11 Mello and others have estimated that there may be a $55 billion annual cost related to the medical malpractice system.12

Several malpractice crises and waves of malpractice or tort reform ensued,13 beginning in the 1970s and extending into the 2000s.11 Malpractice law is primarily a matter of state law, so reform essentially has been at the state level—as we will see in the second part in this series.

Defining a standard of care

Medical malpractice is the application of standard legal principles to medical practice. Those principles generally are torts (intentional torts and negligence), and sometimes contracts.14 Eventually, medical malpractice came to focus primarily on negligence. The legal purposes of imposing negligence liability are compensation (to repay the plaintiff the costs of the harm caused by the defendant) and deterrence (to discourage careless conduct that can harm others.)

Negligence is essentially carelessness that falls below the acceptable standard of care. Negligence may arise, for example, from15:

- doing something (giving a drug to a patient with a known allergy to it)

- not doing something (failing to test for a possible tumor, as in the second case above)

- not giving appropriate informed consent

- failing to conduct an adequate examination

- abandoning a patient

- failing to refer a patient to a specialist (or conduct a consultation).

(In recent years, law reforms directed specifically at medical malpractice have somewhat separated medical malpractice from other tort law.)

In malpractice cases, the core question is whether the provider did (or did not) do something that a reasonably careful physician would have done. It is axiomatic that not all bad outcomes are negligent. Indeed, not all mistakes are negligent—only the mistakes that were unreasonable given all of the circumstances. In the first case above, for example, given all of the facts that preceded it, the delay of the physician for 4.5 hours after the fetal distress started was, as seen by the jury, not just a mistake but an unreasonable mistake. Hence, it was negligent. In the second case, the failure to investigate the pain and swelling in the surgical site for 2 years (or failure to refer the patient to another physician) was seen by the jury as an unreasonable mistake—one that would not have been made by a reasonably careful practitioner.

Continue to: The big verdict...

The big verdict

Everyone—every professional providing service, every manufacturer, every driver—eventually will make an unreasonable mistake (ie, commit negligence). If that negligence results in harming someone else, our standard legal response is that the negligent person should be financially responsible for the harm to the other. So, a driver who fails to stop at a red light and hits another car is responsible for those damages. But the damages may vary—perhaps a banged-up fender, or, in another instance, with the same negligence, perhaps terrible personal injuries that will disable the other driver for life. Thus, the damages can vary for the same level of carelessness. The “big verdict” may therefore fall on someone who was not especially careless.

Big verdicts often involve long-term care. The opening case vignettes illustrate a concern of medical malpractice generally—especially for ObGyn practice—the very high verdict. Very high verdicts generally reflect catastrophic damages that will continue for a long time. Bixenstine and colleagues found, for example, that catastrophic payouts often involved “patient age less than 1 year, quadriplegia, brain damage, or lifelong care.”16 In the case of serious injuries during delivery, for example, the harm to the child may last a lifetime and require years and years of intensive medical services.

Million-dollar-plus payouts are on the rise. The percentage of paid claims (through settlement or trial) that are above $1 million is increasing. These million-dollar cases represent 36% of the total dollars paid in ObGyn malpractice claims, even though they represent only 8% of the number of claims paid.16 The increase in the big verdict cases (above $1 million) suggests that ObGyn practitioners should consider their malpractice policy limits—a million dollars may not be enough.

In big verdict cases, the great harm to the plaintiff is often combined with facts that produce extraordinary sympathy for the plaintiff. Sometimes there is decidedly unsympathetic conduct by the defendant as well. In the second case, for example, the problems with the medical record may have suggested to the jury that the doctor was either trying to hide something or did not care enough about the patient even to note a serious complaint. In a case we reviewed in an earlier “What’s the Verdict” column, a physician left the room for several minutes during a critical time—to take a call from a stockbroker.16-18

The big verdict does not necessarily suggest that the defendant was especially or grossly negligent.16 It was a bad injury that occurred, for instance. On the other hand, the physician with several malpractice judgments may suggest that this is a problem physician.

Physicians facing multiple lawsuits are the exceptions

A number of studies have demonstrated that only a small proportion of physicians are responsible for a disproportionate number of paid medical malpractice claims. (“Paid claims” are those in which the plaintiff receives money from the doctor’s insurance. “Filed claims” are all malpractice lawsuits filed. Many claims are filed, but few are paid.)