User login

Mindfulness yoga reduced stress and motor symptoms in patients with Parkinson’s disease

Among patients with mild or moderate Parkinson’s disease, mindfulness yoga was as effective as stretching and resistance training in improving motor function and mobility, a randomized trial found.

In addition, mindfulness yoga reduced anxiety and depressive symptoms and increased spiritual well-being and health-related quality of life more than stretching and resistance training, researchers reported in JAMA Neurology.

Although guidelines support exercise for patients with Parkinson’s disease, investigators had not examined whether yoga is superior to conventional exercise for stress and symptom management in this patient population. Jojo Y. Y. Kwok, PhD, a research assistant professor of nursing at the University of Hong Kong, and her colleagues conducted an assessor-masked, randomized trial that included 138 adults with idiopathic Parkinson’s disease who were able to stand on their own and walk with or without an assistive device. The trial was conducted at 4 community rehabilitation centers in Hong Kong between December 1, 2016, and May 31, 2017. Participants were randomized to 8 weeks of mindfulness yoga delivered weekly in 90-minute group sessions (71) or stretching and resistance training delivered in weekly 60-minute group sessions (67).

The primary outcomes was psychological distress in terms of anxiety and depressive symptoms assessed with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). Secondary outcomes included motor symptom severity, mobility, spiritual well-being in terms of perceived hardship and equanimity, and health-related quality of life. The researchers assessed patients at baseline, 8 weeks, and 20 weeks.

The average age of the participants was 63.7 years; 65 (47.1%) were men. Generalized estimating equation analyses found that patients in the yoga group had significantly better outcomes, including for anxiety (time-by-group interaction, beta, –1.79 at 8 weeks and –2.05 at 20 weeks), and depressive symptoms (beta, –2.75 at 8 weeks and –2.75 at 20 weeks). These improvements were considered “statistically and clinically significant, the authors wrote. There were no significant improvements in anxiety or depressive symptoms in the stretching and resistance training group at the different time points.

Outcomes in the yoga group were also better with regards to disease-specific health-related quality of life (beta, –7.77 at 8 weeks and –7.99 at 20 weeks). Those who were in the mindfulness yoga group also had greater improvements in measures of perceived hardship and equanimity, compared with the stretching and resistance training group.

Referring to the improved psychological outcomes in the yoga group, the authors wrote, “these benefits were remarkable because the participants who received the [mindfulness yoga] intervention attended a mean of only 6 sessions.”

There were significant reductions in motor symptoms in both groups, which were significantly higher among those undergoing stretching, but the differences in the mean scores between the two groups were “clinically insignificant,” they wrote.

Three participants in the yoga group and 2 in the control group reported temporary mild knee pain. No serious adverse events were reported.

Expectation bias, selection bias, and the dropout rates of 15.2% at 8 weeks and 18.8% at 20 weeks are limitations of the study, the authors noted.

“These findings suggest that ,” Dr. Kwok and her colleagues concluded. “Considering that PD is not only a physically limiting condition but also a psychologically distressing life event, health care professionals should adopt a holistic approach in PD rehabilitation. Future rehabilitation programs could consider integrating mindfulness skills into physical therapy to enhance the holistic well-being of people with neurodegenerative conditions.”

The trial was supported by the Professional Development Fund of the Association of Hong Kong Nursing Staff. The authors had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Kwok JYY et al. JAMA Neurol. 2019 Apr 8. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.0534.

Among patients with mild or moderate Parkinson’s disease, mindfulness yoga was as effective as stretching and resistance training in improving motor function and mobility, a randomized trial found.

In addition, mindfulness yoga reduced anxiety and depressive symptoms and increased spiritual well-being and health-related quality of life more than stretching and resistance training, researchers reported in JAMA Neurology.

Although guidelines support exercise for patients with Parkinson’s disease, investigators had not examined whether yoga is superior to conventional exercise for stress and symptom management in this patient population. Jojo Y. Y. Kwok, PhD, a research assistant professor of nursing at the University of Hong Kong, and her colleagues conducted an assessor-masked, randomized trial that included 138 adults with idiopathic Parkinson’s disease who were able to stand on their own and walk with or without an assistive device. The trial was conducted at 4 community rehabilitation centers in Hong Kong between December 1, 2016, and May 31, 2017. Participants were randomized to 8 weeks of mindfulness yoga delivered weekly in 90-minute group sessions (71) or stretching and resistance training delivered in weekly 60-minute group sessions (67).

The primary outcomes was psychological distress in terms of anxiety and depressive symptoms assessed with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). Secondary outcomes included motor symptom severity, mobility, spiritual well-being in terms of perceived hardship and equanimity, and health-related quality of life. The researchers assessed patients at baseline, 8 weeks, and 20 weeks.

The average age of the participants was 63.7 years; 65 (47.1%) were men. Generalized estimating equation analyses found that patients in the yoga group had significantly better outcomes, including for anxiety (time-by-group interaction, beta, –1.79 at 8 weeks and –2.05 at 20 weeks), and depressive symptoms (beta, –2.75 at 8 weeks and –2.75 at 20 weeks). These improvements were considered “statistically and clinically significant, the authors wrote. There were no significant improvements in anxiety or depressive symptoms in the stretching and resistance training group at the different time points.

Outcomes in the yoga group were also better with regards to disease-specific health-related quality of life (beta, –7.77 at 8 weeks and –7.99 at 20 weeks). Those who were in the mindfulness yoga group also had greater improvements in measures of perceived hardship and equanimity, compared with the stretching and resistance training group.

Referring to the improved psychological outcomes in the yoga group, the authors wrote, “these benefits were remarkable because the participants who received the [mindfulness yoga] intervention attended a mean of only 6 sessions.”

There were significant reductions in motor symptoms in both groups, which were significantly higher among those undergoing stretching, but the differences in the mean scores between the two groups were “clinically insignificant,” they wrote.

Three participants in the yoga group and 2 in the control group reported temporary mild knee pain. No serious adverse events were reported.

Expectation bias, selection bias, and the dropout rates of 15.2% at 8 weeks and 18.8% at 20 weeks are limitations of the study, the authors noted.

“These findings suggest that ,” Dr. Kwok and her colleagues concluded. “Considering that PD is not only a physically limiting condition but also a psychologically distressing life event, health care professionals should adopt a holistic approach in PD rehabilitation. Future rehabilitation programs could consider integrating mindfulness skills into physical therapy to enhance the holistic well-being of people with neurodegenerative conditions.”

The trial was supported by the Professional Development Fund of the Association of Hong Kong Nursing Staff. The authors had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Kwok JYY et al. JAMA Neurol. 2019 Apr 8. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.0534.

Among patients with mild or moderate Parkinson’s disease, mindfulness yoga was as effective as stretching and resistance training in improving motor function and mobility, a randomized trial found.

In addition, mindfulness yoga reduced anxiety and depressive symptoms and increased spiritual well-being and health-related quality of life more than stretching and resistance training, researchers reported in JAMA Neurology.

Although guidelines support exercise for patients with Parkinson’s disease, investigators had not examined whether yoga is superior to conventional exercise for stress and symptom management in this patient population. Jojo Y. Y. Kwok, PhD, a research assistant professor of nursing at the University of Hong Kong, and her colleagues conducted an assessor-masked, randomized trial that included 138 adults with idiopathic Parkinson’s disease who were able to stand on their own and walk with or without an assistive device. The trial was conducted at 4 community rehabilitation centers in Hong Kong between December 1, 2016, and May 31, 2017. Participants were randomized to 8 weeks of mindfulness yoga delivered weekly in 90-minute group sessions (71) or stretching and resistance training delivered in weekly 60-minute group sessions (67).

The primary outcomes was psychological distress in terms of anxiety and depressive symptoms assessed with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). Secondary outcomes included motor symptom severity, mobility, spiritual well-being in terms of perceived hardship and equanimity, and health-related quality of life. The researchers assessed patients at baseline, 8 weeks, and 20 weeks.

The average age of the participants was 63.7 years; 65 (47.1%) were men. Generalized estimating equation analyses found that patients in the yoga group had significantly better outcomes, including for anxiety (time-by-group interaction, beta, –1.79 at 8 weeks and –2.05 at 20 weeks), and depressive symptoms (beta, –2.75 at 8 weeks and –2.75 at 20 weeks). These improvements were considered “statistically and clinically significant, the authors wrote. There were no significant improvements in anxiety or depressive symptoms in the stretching and resistance training group at the different time points.

Outcomes in the yoga group were also better with regards to disease-specific health-related quality of life (beta, –7.77 at 8 weeks and –7.99 at 20 weeks). Those who were in the mindfulness yoga group also had greater improvements in measures of perceived hardship and equanimity, compared with the stretching and resistance training group.

Referring to the improved psychological outcomes in the yoga group, the authors wrote, “these benefits were remarkable because the participants who received the [mindfulness yoga] intervention attended a mean of only 6 sessions.”

There were significant reductions in motor symptoms in both groups, which were significantly higher among those undergoing stretching, but the differences in the mean scores between the two groups were “clinically insignificant,” they wrote.

Three participants in the yoga group and 2 in the control group reported temporary mild knee pain. No serious adverse events were reported.

Expectation bias, selection bias, and the dropout rates of 15.2% at 8 weeks and 18.8% at 20 weeks are limitations of the study, the authors noted.

“These findings suggest that ,” Dr. Kwok and her colleagues concluded. “Considering that PD is not only a physically limiting condition but also a psychologically distressing life event, health care professionals should adopt a holistic approach in PD rehabilitation. Future rehabilitation programs could consider integrating mindfulness skills into physical therapy to enhance the holistic well-being of people with neurodegenerative conditions.”

The trial was supported by the Professional Development Fund of the Association of Hong Kong Nursing Staff. The authors had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Kwok JYY et al. JAMA Neurol. 2019 Apr 8. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.0534.

FROM JAMA NEUROLOGY

How common are noninfectious complications of Foley catheters?

CLINICAL QUESTION: How common are noninfectious complications of Foley catheters?

BACKGROUND: Approximately 20% of hospitalized patients have a Foley catheter inserted at some time during their admission. Infectious complications associated with the use of Foley catheters are widely recognized; however, much less is known about noninfectious complications.

STUDY DESIGN: Prospective cohort study.

SETTING: Four U.S. hospitals in two states.SYNOPSIS: The study included 2,076 hospitalized patients with a Foley catheter. They were followed for 30 days after its insertion, even if catheter removal occurred during this time period. Data about infectious and noninfectious complications were collected through patient interviews.

At least one complication was noted in 1,184 of 2,076 patients (57%) during the 30-day period following Foley catheter insertion. While infectious complications occurred in 219 of 2,076 patients (10.5%), noninfectious complications (such as pain, urinary urgency, hematuria) were reported by 1,150 patients (55.4%; P less than .001). For those with catheters still in place, the most common complication was pain or discomfort (54.5%). Postremoval leaking urine (20.3%) and/or urgency and bladder spasms (24.0%) were the most common complications.

The study only included patients who had a Foley catheter placed during a hospitalization; the results may not apply to patients who receive catheters in other settings.

BOTTOM LINE: Noninfectious complications affect over half of patients with a Foley catheters. These types of complications should be targeted in future harm prevention efforts and should be considered when deciding to place a Foley catheter.

CITATION: Saint S et al. A multicenter study of patient-reported infectious and noninfectious complications associated with indwelling urethral catheters. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(8):1078-85.

Dr. Clarke is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine at Emory University, Atlanta.

CLINICAL QUESTION: How common are noninfectious complications of Foley catheters?

BACKGROUND: Approximately 20% of hospitalized patients have a Foley catheter inserted at some time during their admission. Infectious complications associated with the use of Foley catheters are widely recognized; however, much less is known about noninfectious complications.

STUDY DESIGN: Prospective cohort study.

SETTING: Four U.S. hospitals in two states.SYNOPSIS: The study included 2,076 hospitalized patients with a Foley catheter. They were followed for 30 days after its insertion, even if catheter removal occurred during this time period. Data about infectious and noninfectious complications were collected through patient interviews.

At least one complication was noted in 1,184 of 2,076 patients (57%) during the 30-day period following Foley catheter insertion. While infectious complications occurred in 219 of 2,076 patients (10.5%), noninfectious complications (such as pain, urinary urgency, hematuria) were reported by 1,150 patients (55.4%; P less than .001). For those with catheters still in place, the most common complication was pain or discomfort (54.5%). Postremoval leaking urine (20.3%) and/or urgency and bladder spasms (24.0%) were the most common complications.

The study only included patients who had a Foley catheter placed during a hospitalization; the results may not apply to patients who receive catheters in other settings.

BOTTOM LINE: Noninfectious complications affect over half of patients with a Foley catheters. These types of complications should be targeted in future harm prevention efforts and should be considered when deciding to place a Foley catheter.

CITATION: Saint S et al. A multicenter study of patient-reported infectious and noninfectious complications associated with indwelling urethral catheters. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(8):1078-85.

Dr. Clarke is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine at Emory University, Atlanta.

CLINICAL QUESTION: How common are noninfectious complications of Foley catheters?

BACKGROUND: Approximately 20% of hospitalized patients have a Foley catheter inserted at some time during their admission. Infectious complications associated with the use of Foley catheters are widely recognized; however, much less is known about noninfectious complications.

STUDY DESIGN: Prospective cohort study.

SETTING: Four U.S. hospitals in two states.SYNOPSIS: The study included 2,076 hospitalized patients with a Foley catheter. They were followed for 30 days after its insertion, even if catheter removal occurred during this time period. Data about infectious and noninfectious complications were collected through patient interviews.

At least one complication was noted in 1,184 of 2,076 patients (57%) during the 30-day period following Foley catheter insertion. While infectious complications occurred in 219 of 2,076 patients (10.5%), noninfectious complications (such as pain, urinary urgency, hematuria) were reported by 1,150 patients (55.4%; P less than .001). For those with catheters still in place, the most common complication was pain or discomfort (54.5%). Postremoval leaking urine (20.3%) and/or urgency and bladder spasms (24.0%) were the most common complications.

The study only included patients who had a Foley catheter placed during a hospitalization; the results may not apply to patients who receive catheters in other settings.

BOTTOM LINE: Noninfectious complications affect over half of patients with a Foley catheters. These types of complications should be targeted in future harm prevention efforts and should be considered when deciding to place a Foley catheter.

CITATION: Saint S et al. A multicenter study of patient-reported infectious and noninfectious complications associated with indwelling urethral catheters. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(8):1078-85.

Dr. Clarke is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine at Emory University, Atlanta.

Robotics will expand endoscopy’s vision and reach

Think about what a puppet can do: Not much, since it’s typically controlled by a single hand. Then consider the skills of a marionette in the hands – both of them – of a talented performer: It can gesture and jump and even dance. A whole new world of movement opens up thanks to the capacity for fine-tuned control.

When it comes to GI endoscopy, revolutionary two-handed marionette-style control beckons on the horizon thanks to robotics. That’s the word from Josh DeFonzo, chief operating officer of Auris Health, who will present a keynote speech on “Opportunities in GI Over the Next Decade” at the 2019 AGA Tech Summit, sponsored by the AGA Center for GI Innovation and Technology.

“I’ll be talking about where opportunities will lie in the GI space over the next decade,” Mr. DeFonzo said. “One of the major themes will be the need to accelerate technical capabilities in endoscopy. Noninvasive treatment is quite challenging for interventional endoscopists. They generally don’t have the tools they need to reach where they need to reach, see where they need to see, and perform complex tasks, at least not at scale.”

This is all changing thanks to the work of companies like Auris Health, which is working to advance endoscopy through flexible robotics. Auris Health, which was recently acquired by Johnson & Johnson, is offering robotic endoscopy to pulmonologists and developing it for gastroenterology.

The challenges of existing endoscopic technology, Mr. DeFonzo said, revolve around the limitations of access. “In the world of GI, it’s not difficult to get to polyps or cancerous lesions. It’s harder to do something when you’re there,” he said. “In the colon, stomach, and esophagus, you’re in a cylindrical hallway with a cylindrical device, and both are moving. You don’t have the stability to achieve traction, and you are usually limited to a single hand and single working channel.”

Robotic endoscopic technology offers physicians the ability to overcome these barriers through two-handed control and other advances. “It’s all about reach, vision, control, and the ability to perform tasks as a result of those three things,” he said. “The hope is empower endoscopists with more tools and capabilities to prevent patients from having to undergo surgery.”

Within the next 5 years, he predicts, physicians will be able to use robotic endoscopy to remove potentially cancerous lesions during colonoscopy instead of referring patients for colectomy. And over the longer term, perhaps over more than a decade, he expects patients will be able to undergo endoscopic removal of those lesions during colonoscopy instead of being referred.

Meanwhile, he said, scientists are advancing areas such as two-handed robotic control, Google Maps-style navigation based on preoperative scans, and pattern recognition to detect abnormalities such as lesions.

Think about what a puppet can do: Not much, since it’s typically controlled by a single hand. Then consider the skills of a marionette in the hands – both of them – of a talented performer: It can gesture and jump and even dance. A whole new world of movement opens up thanks to the capacity for fine-tuned control.

When it comes to GI endoscopy, revolutionary two-handed marionette-style control beckons on the horizon thanks to robotics. That’s the word from Josh DeFonzo, chief operating officer of Auris Health, who will present a keynote speech on “Opportunities in GI Over the Next Decade” at the 2019 AGA Tech Summit, sponsored by the AGA Center for GI Innovation and Technology.

“I’ll be talking about where opportunities will lie in the GI space over the next decade,” Mr. DeFonzo said. “One of the major themes will be the need to accelerate technical capabilities in endoscopy. Noninvasive treatment is quite challenging for interventional endoscopists. They generally don’t have the tools they need to reach where they need to reach, see where they need to see, and perform complex tasks, at least not at scale.”

This is all changing thanks to the work of companies like Auris Health, which is working to advance endoscopy through flexible robotics. Auris Health, which was recently acquired by Johnson & Johnson, is offering robotic endoscopy to pulmonologists and developing it for gastroenterology.

The challenges of existing endoscopic technology, Mr. DeFonzo said, revolve around the limitations of access. “In the world of GI, it’s not difficult to get to polyps or cancerous lesions. It’s harder to do something when you’re there,” he said. “In the colon, stomach, and esophagus, you’re in a cylindrical hallway with a cylindrical device, and both are moving. You don’t have the stability to achieve traction, and you are usually limited to a single hand and single working channel.”

Robotic endoscopic technology offers physicians the ability to overcome these barriers through two-handed control and other advances. “It’s all about reach, vision, control, and the ability to perform tasks as a result of those three things,” he said. “The hope is empower endoscopists with more tools and capabilities to prevent patients from having to undergo surgery.”

Within the next 5 years, he predicts, physicians will be able to use robotic endoscopy to remove potentially cancerous lesions during colonoscopy instead of referring patients for colectomy. And over the longer term, perhaps over more than a decade, he expects patients will be able to undergo endoscopic removal of those lesions during colonoscopy instead of being referred.

Meanwhile, he said, scientists are advancing areas such as two-handed robotic control, Google Maps-style navigation based on preoperative scans, and pattern recognition to detect abnormalities such as lesions.

Think about what a puppet can do: Not much, since it’s typically controlled by a single hand. Then consider the skills of a marionette in the hands – both of them – of a talented performer: It can gesture and jump and even dance. A whole new world of movement opens up thanks to the capacity for fine-tuned control.

When it comes to GI endoscopy, revolutionary two-handed marionette-style control beckons on the horizon thanks to robotics. That’s the word from Josh DeFonzo, chief operating officer of Auris Health, who will present a keynote speech on “Opportunities in GI Over the Next Decade” at the 2019 AGA Tech Summit, sponsored by the AGA Center for GI Innovation and Technology.

“I’ll be talking about where opportunities will lie in the GI space over the next decade,” Mr. DeFonzo said. “One of the major themes will be the need to accelerate technical capabilities in endoscopy. Noninvasive treatment is quite challenging for interventional endoscopists. They generally don’t have the tools they need to reach where they need to reach, see where they need to see, and perform complex tasks, at least not at scale.”

This is all changing thanks to the work of companies like Auris Health, which is working to advance endoscopy through flexible robotics. Auris Health, which was recently acquired by Johnson & Johnson, is offering robotic endoscopy to pulmonologists and developing it for gastroenterology.

The challenges of existing endoscopic technology, Mr. DeFonzo said, revolve around the limitations of access. “In the world of GI, it’s not difficult to get to polyps or cancerous lesions. It’s harder to do something when you’re there,” he said. “In the colon, stomach, and esophagus, you’re in a cylindrical hallway with a cylindrical device, and both are moving. You don’t have the stability to achieve traction, and you are usually limited to a single hand and single working channel.”

Robotic endoscopic technology offers physicians the ability to overcome these barriers through two-handed control and other advances. “It’s all about reach, vision, control, and the ability to perform tasks as a result of those three things,” he said. “The hope is empower endoscopists with more tools and capabilities to prevent patients from having to undergo surgery.”

Within the next 5 years, he predicts, physicians will be able to use robotic endoscopy to remove potentially cancerous lesions during colonoscopy instead of referring patients for colectomy. And over the longer term, perhaps over more than a decade, he expects patients will be able to undergo endoscopic removal of those lesions during colonoscopy instead of being referred.

Meanwhile, he said, scientists are advancing areas such as two-handed robotic control, Google Maps-style navigation based on preoperative scans, and pattern recognition to detect abnormalities such as lesions.

FROM THE 2019 AGA TECH SUMMIT

Apply for the Community Awareness and Prevention Grant

The application deadline for the Community Awareness and Prevention Project Grant is April 15. This award is intended to help vascular surgeons conduct community-based projects that address emerging issues in vascular health, wellness and disease prevention. The SVS Foundation encourages applicants to establish collaborative community partnerships with organizations who share our goals for maximizing public health and can contribute to the success of the project. Read more about the grant here.

The application deadline for the Community Awareness and Prevention Project Grant is April 15. This award is intended to help vascular surgeons conduct community-based projects that address emerging issues in vascular health, wellness and disease prevention. The SVS Foundation encourages applicants to establish collaborative community partnerships with organizations who share our goals for maximizing public health and can contribute to the success of the project. Read more about the grant here.

The application deadline for the Community Awareness and Prevention Project Grant is April 15. This award is intended to help vascular surgeons conduct community-based projects that address emerging issues in vascular health, wellness and disease prevention. The SVS Foundation encourages applicants to establish collaborative community partnerships with organizations who share our goals for maximizing public health and can contribute to the success of the project. Read more about the grant here.

VAM Online Planner Available Now

Begin planning your Vascular Annual Meeting experience with the SVS Online Planner. This includes the entire VAM schedule, plus the schedule for the Society for Vascular Nursing’s annual conference. The full schedule for the Vascular Quality Initiative's meeting, VQI@VAM, also will be available in the future. Users can easily find such information as presenters, certain topics, session types, intended audience and credit availability. Find the online planner on the VAM site here.

Begin planning your Vascular Annual Meeting experience with the SVS Online Planner. This includes the entire VAM schedule, plus the schedule for the Society for Vascular Nursing’s annual conference. The full schedule for the Vascular Quality Initiative's meeting, VQI@VAM, also will be available in the future. Users can easily find such information as presenters, certain topics, session types, intended audience and credit availability. Find the online planner on the VAM site here.

Begin planning your Vascular Annual Meeting experience with the SVS Online Planner. This includes the entire VAM schedule, plus the schedule for the Society for Vascular Nursing’s annual conference. The full schedule for the Vascular Quality Initiative's meeting, VQI@VAM, also will be available in the future. Users can easily find such information as presenters, certain topics, session types, intended audience and credit availability. Find the online planner on the VAM site here.

Bronchiolitis is a feared complication of connective tissue disease

MAUI, HAWAII – who develop shortness of breath and cough or a precipitous drop in their forced expiratory volume on pulmonary function testing, Aryeh Fischer, MD, said at the 2019 Rheumatology Winter Clinical Symposium.

“This is an underappreciated – and I think among the most potentially devastating – of the lung diseases we as rheumatologists will encounter in our patients,” said Dr. Fischer, a rheumatologist at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, with a special interest in autoimmune lung disease.

“If you’re seeing patients with rheumatoid arthritis, SLE, or Sjögren’s and they’ve got bad asthma they can’t get under control, you’ve got to think about bronchiolitis because I can tell you your lung doc quite often is not thinking about this,” he added.

Bronchiolitis involves inflammation, narrowing, or obliteration of the small airways. The diagnosis is often missed because of the false sense of reassurance provided by the normal chest x-ray and regular CT findings, which are a feature of the disease.

“This is really important: You have to get a high-resolution CT that includes expiratory images, because that’s the only way you’re going to be able to tell if your patient has small airways disease,” he explained. “You must, must, must do an expiratory CT.”

A normal expiratory CT image should be gray, since the lungs are empty. Air is black on CT, so large areas of black intermixed with gray on an expiratory CT – a finding known as mosaicism – indicate air trapping due to small airways disease, Dr. Fischer noted.

Surgical lung biopsy will yield a pathologic report documenting isolated constrictive, follicular, and/or lymphocytic bronchiolitis. However, the terminology can be confusing: What pathologists describe as constrictive bronchiolitis is called obliterative by pulmonologists and radiologists.

Pulmonary function testing shows an obstructive defect. The diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide (DLCO) is fairly normal, the forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) is sharply reduced, and the forced vital capacity (FVC) is near normal, with a resultant abnormally low FEV1/FVC ratio. A patient with bronchiolitis may or may not have a response to bronchodilators.

“I tell you, I’ve seen a bunch of these patients. They typically have a precipitous drop in their FEV1 and then stay stable at a very low level of lung function without much opportunity for improvement,” Dr. Fischer said. “Stability equals success in these patients. It’s really unusual to see much improvement.”

In theory, patients with follicular or lymphocytic bronchiolitis have an ongoing inflammatory process that should be amenable to rheumatologic ministrations. But there is no convincing evidence of treatment efficacy to date. And in obliterative bronchiolitis, marked by airway scarring, there is no reason to think anti-inflammatory therapies should be helpful. Anecdotally, Dr. Fischer said, he has seen immunosuppression help patients with obliterative bronchiolitis.

“Actually, the only proven therapy is lung transplantation,” he said.

He recommended that his fellow rheumatologists periodically use office spirometry to check the FEV1 in their patients with rheumatoid arthritis, Sjögren’s, or SLE, the forms of connective tissue disease most often associated with bronchiolitis. Compared with all the other testing rheumatologists routinely order in their patients, having them blow into a tube is a simple enough matter.

“We really don’t have anything to impact the natural history, but I like the notion of not being surprised. What are you going to do with that [abnormal] FEV1 data? I have no idea. But maybe it’s better to know earlier,” he said.

Dr. Fischer reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding his presentation.

MAUI, HAWAII – who develop shortness of breath and cough or a precipitous drop in their forced expiratory volume on pulmonary function testing, Aryeh Fischer, MD, said at the 2019 Rheumatology Winter Clinical Symposium.

“This is an underappreciated – and I think among the most potentially devastating – of the lung diseases we as rheumatologists will encounter in our patients,” said Dr. Fischer, a rheumatologist at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, with a special interest in autoimmune lung disease.

“If you’re seeing patients with rheumatoid arthritis, SLE, or Sjögren’s and they’ve got bad asthma they can’t get under control, you’ve got to think about bronchiolitis because I can tell you your lung doc quite often is not thinking about this,” he added.

Bronchiolitis involves inflammation, narrowing, or obliteration of the small airways. The diagnosis is often missed because of the false sense of reassurance provided by the normal chest x-ray and regular CT findings, which are a feature of the disease.

“This is really important: You have to get a high-resolution CT that includes expiratory images, because that’s the only way you’re going to be able to tell if your patient has small airways disease,” he explained. “You must, must, must do an expiratory CT.”

A normal expiratory CT image should be gray, since the lungs are empty. Air is black on CT, so large areas of black intermixed with gray on an expiratory CT – a finding known as mosaicism – indicate air trapping due to small airways disease, Dr. Fischer noted.

Surgical lung biopsy will yield a pathologic report documenting isolated constrictive, follicular, and/or lymphocytic bronchiolitis. However, the terminology can be confusing: What pathologists describe as constrictive bronchiolitis is called obliterative by pulmonologists and radiologists.

Pulmonary function testing shows an obstructive defect. The diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide (DLCO) is fairly normal, the forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) is sharply reduced, and the forced vital capacity (FVC) is near normal, with a resultant abnormally low FEV1/FVC ratio. A patient with bronchiolitis may or may not have a response to bronchodilators.

“I tell you, I’ve seen a bunch of these patients. They typically have a precipitous drop in their FEV1 and then stay stable at a very low level of lung function without much opportunity for improvement,” Dr. Fischer said. “Stability equals success in these patients. It’s really unusual to see much improvement.”

In theory, patients with follicular or lymphocytic bronchiolitis have an ongoing inflammatory process that should be amenable to rheumatologic ministrations. But there is no convincing evidence of treatment efficacy to date. And in obliterative bronchiolitis, marked by airway scarring, there is no reason to think anti-inflammatory therapies should be helpful. Anecdotally, Dr. Fischer said, he has seen immunosuppression help patients with obliterative bronchiolitis.

“Actually, the only proven therapy is lung transplantation,” he said.

He recommended that his fellow rheumatologists periodically use office spirometry to check the FEV1 in their patients with rheumatoid arthritis, Sjögren’s, or SLE, the forms of connective tissue disease most often associated with bronchiolitis. Compared with all the other testing rheumatologists routinely order in their patients, having them blow into a tube is a simple enough matter.

“We really don’t have anything to impact the natural history, but I like the notion of not being surprised. What are you going to do with that [abnormal] FEV1 data? I have no idea. But maybe it’s better to know earlier,” he said.

Dr. Fischer reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding his presentation.

MAUI, HAWAII – who develop shortness of breath and cough or a precipitous drop in their forced expiratory volume on pulmonary function testing, Aryeh Fischer, MD, said at the 2019 Rheumatology Winter Clinical Symposium.

“This is an underappreciated – and I think among the most potentially devastating – of the lung diseases we as rheumatologists will encounter in our patients,” said Dr. Fischer, a rheumatologist at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, with a special interest in autoimmune lung disease.

“If you’re seeing patients with rheumatoid arthritis, SLE, or Sjögren’s and they’ve got bad asthma they can’t get under control, you’ve got to think about bronchiolitis because I can tell you your lung doc quite often is not thinking about this,” he added.

Bronchiolitis involves inflammation, narrowing, or obliteration of the small airways. The diagnosis is often missed because of the false sense of reassurance provided by the normal chest x-ray and regular CT findings, which are a feature of the disease.

“This is really important: You have to get a high-resolution CT that includes expiratory images, because that’s the only way you’re going to be able to tell if your patient has small airways disease,” he explained. “You must, must, must do an expiratory CT.”

A normal expiratory CT image should be gray, since the lungs are empty. Air is black on CT, so large areas of black intermixed with gray on an expiratory CT – a finding known as mosaicism – indicate air trapping due to small airways disease, Dr. Fischer noted.

Surgical lung biopsy will yield a pathologic report documenting isolated constrictive, follicular, and/or lymphocytic bronchiolitis. However, the terminology can be confusing: What pathologists describe as constrictive bronchiolitis is called obliterative by pulmonologists and radiologists.

Pulmonary function testing shows an obstructive defect. The diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide (DLCO) is fairly normal, the forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) is sharply reduced, and the forced vital capacity (FVC) is near normal, with a resultant abnormally low FEV1/FVC ratio. A patient with bronchiolitis may or may not have a response to bronchodilators.

“I tell you, I’ve seen a bunch of these patients. They typically have a precipitous drop in their FEV1 and then stay stable at a very low level of lung function without much opportunity for improvement,” Dr. Fischer said. “Stability equals success in these patients. It’s really unusual to see much improvement.”

In theory, patients with follicular or lymphocytic bronchiolitis have an ongoing inflammatory process that should be amenable to rheumatologic ministrations. But there is no convincing evidence of treatment efficacy to date. And in obliterative bronchiolitis, marked by airway scarring, there is no reason to think anti-inflammatory therapies should be helpful. Anecdotally, Dr. Fischer said, he has seen immunosuppression help patients with obliterative bronchiolitis.

“Actually, the only proven therapy is lung transplantation,” he said.

He recommended that his fellow rheumatologists periodically use office spirometry to check the FEV1 in their patients with rheumatoid arthritis, Sjögren’s, or SLE, the forms of connective tissue disease most often associated with bronchiolitis. Compared with all the other testing rheumatologists routinely order in their patients, having them blow into a tube is a simple enough matter.

“We really don’t have anything to impact the natural history, but I like the notion of not being surprised. What are you going to do with that [abnormal] FEV1 data? I have no idea. But maybe it’s better to know earlier,” he said.

Dr. Fischer reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding his presentation.

REPORTING FROM RWCS 2019

More Than His Car Is Bent Out of Shape

ANSWER

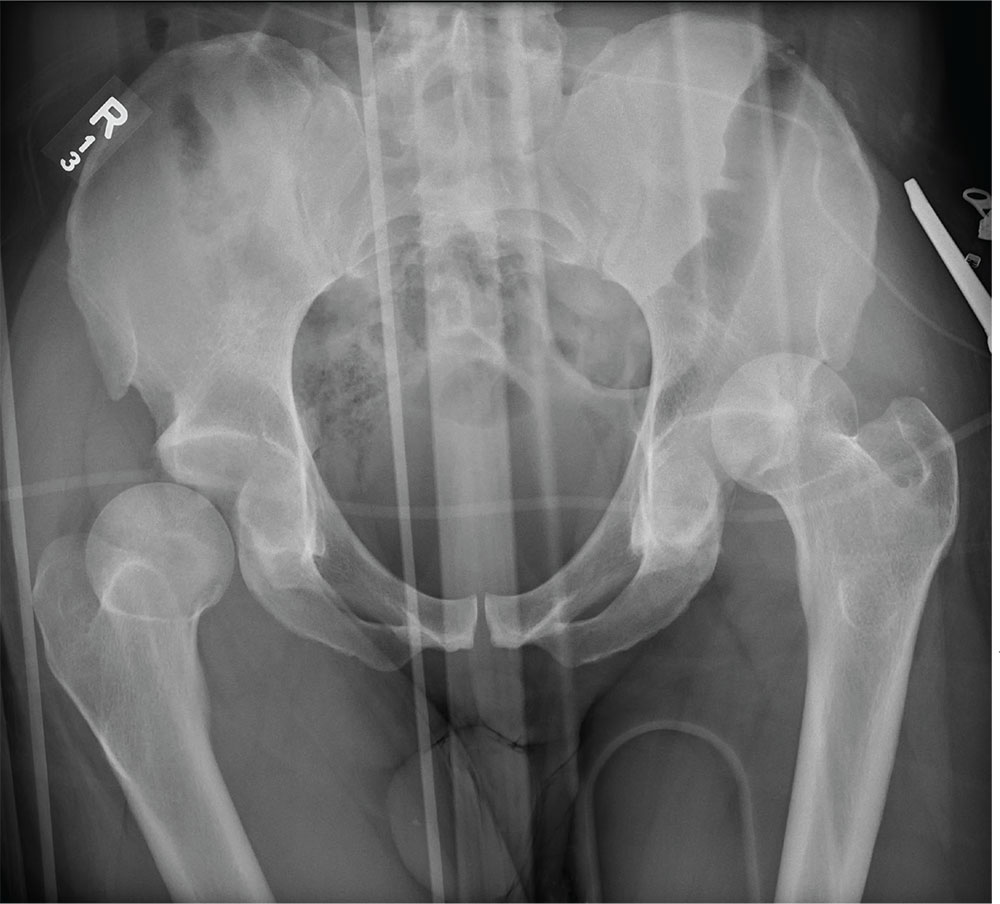

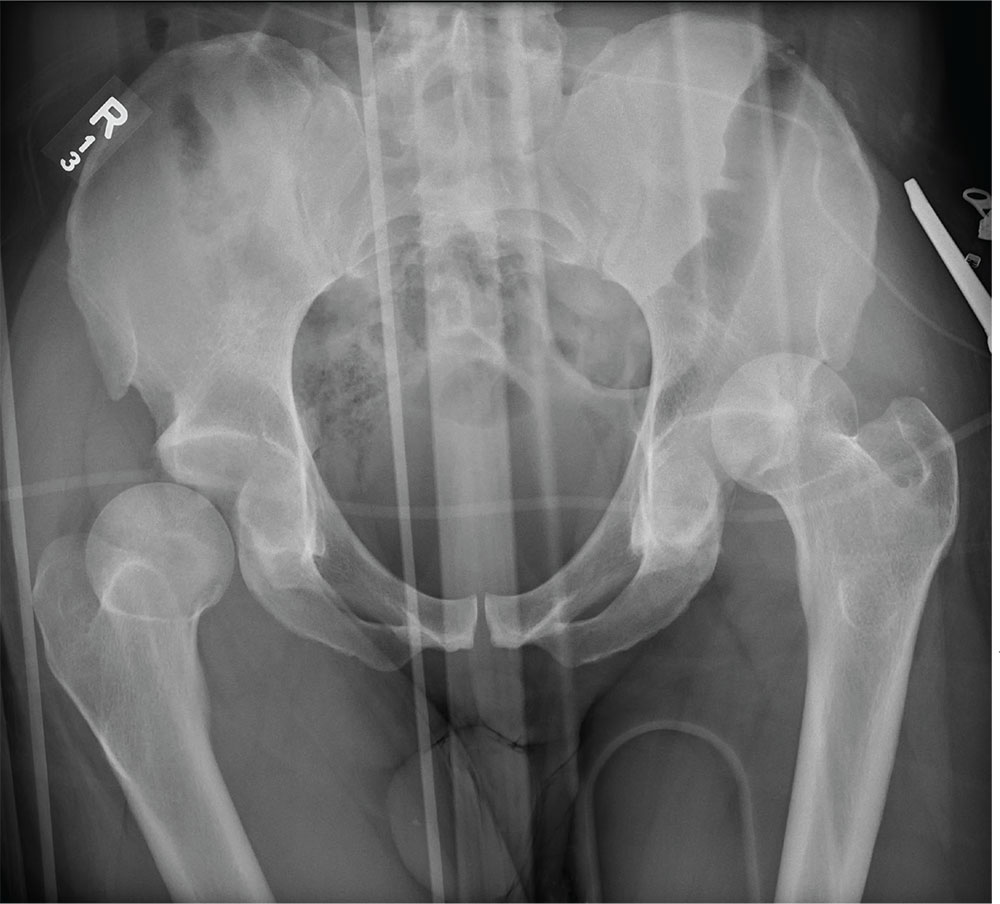

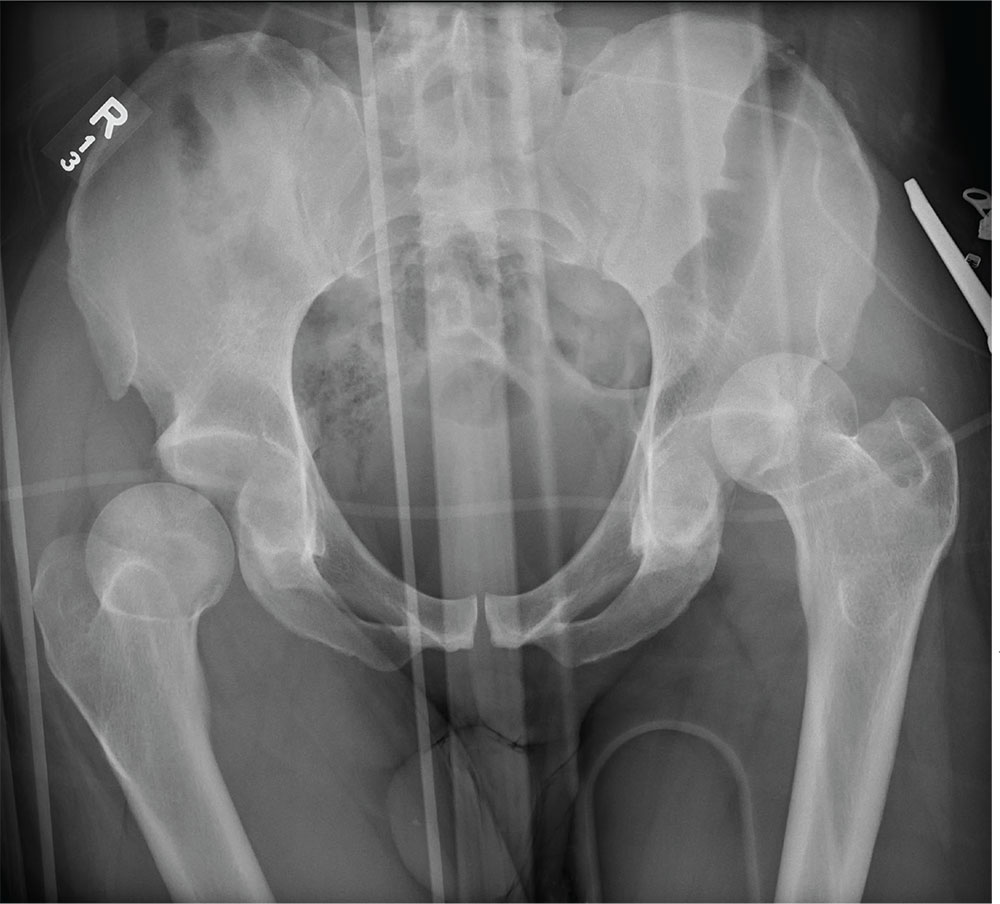

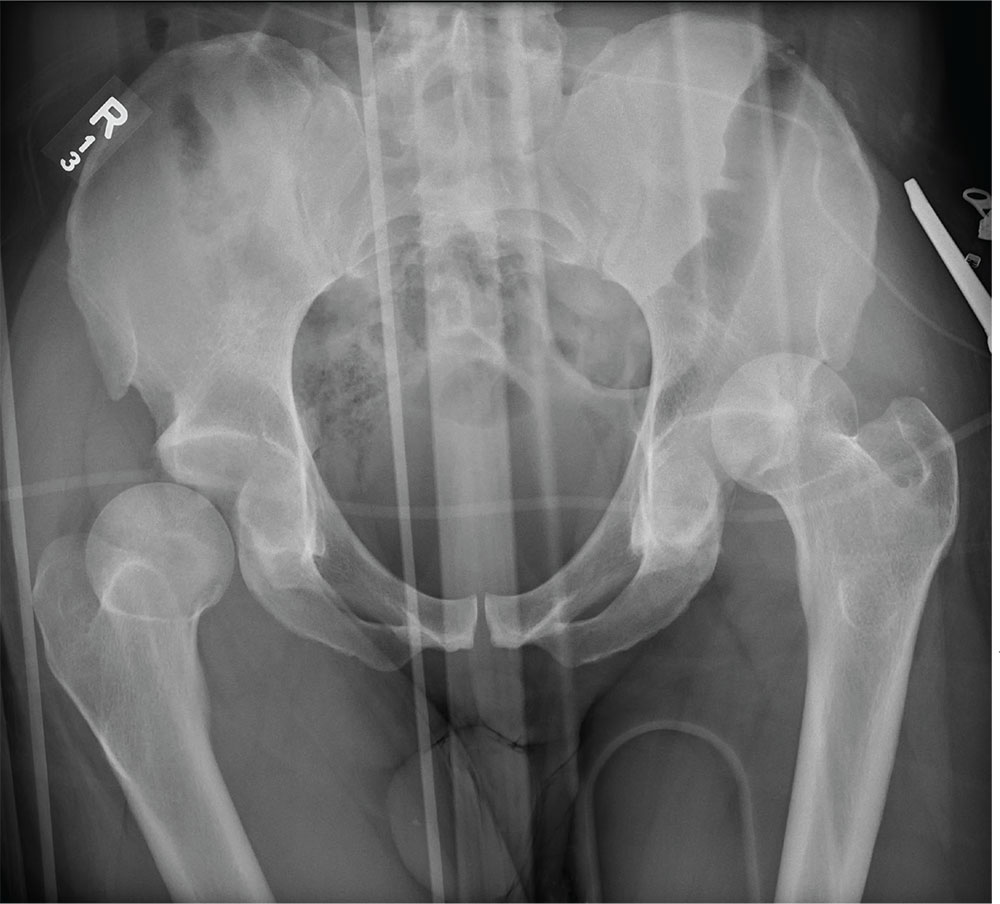

The radiograph demonstrates bilateral hip dislocations. On the right, the femoral head appears to be posteriorly dislocated and slightly internally rotated. On the left, the femoral head appears to be anteriorly and superiorly dislocated (although evaluation is limited by a single view). Neither side appears to have any obvious fractures.

The patient’s dislocations were promptly reduced in the trauma bay by the orthopedic service before he was sent for CT.

ANSWER

The radiograph demonstrates bilateral hip dislocations. On the right, the femoral head appears to be posteriorly dislocated and slightly internally rotated. On the left, the femoral head appears to be anteriorly and superiorly dislocated (although evaluation is limited by a single view). Neither side appears to have any obvious fractures.

The patient’s dislocations were promptly reduced in the trauma bay by the orthopedic service before he was sent for CT.

ANSWER

The radiograph demonstrates bilateral hip dislocations. On the right, the femoral head appears to be posteriorly dislocated and slightly internally rotated. On the left, the femoral head appears to be anteriorly and superiorly dislocated (although evaluation is limited by a single view). Neither side appears to have any obvious fractures.

The patient’s dislocations were promptly reduced in the trauma bay by the orthopedic service before he was sent for CT.

A 30-year-old man is broug

Upon arrival, he is immediately intubated because emergency personnel had difficulty intubating him in the field. He has a Glasgow Coma Scale score of 3T. The patient’s blood pressure is 90/40 mm Hg and his heart rate, 150 beats/min. He appears to have deformities in his lower extremities.

You obtain portable radiographs of the chest and pelvis. The latter is shown. What is your impression?

Preclinical findings highlight value of Lynch syndrome for cancer vaccine development

ATLANTA – Lynch syndrome serves as an excellent platform for the development of immunoprevention cancer vaccines, and findings from a preclinical Lynch syndrome mouse model support ongoing research, according to Steven M. Lipkin, MD, PhD.

A novel vaccine, which included peptides encoding four intestinal cancer frameshift peptide (FSP) neoantigens derived from coding microsatellite (cMS) mutations in the genes Nacad, Maz, Xirp1, and Senp6 elicited strong antigen-specific cellular immune responses in the model, Dr. Lipkin, the Gladys and Roland Harriman Professor of Medicine and vice chair for research in the Sanford and Joan Weill Department of Medicine, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, reported at the annual meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research.

CD4-specific T cell responses were detected for Maz, Nacad, and Senp6, and CD8-positive T cells were detected for Xirp1 and Nacad, he noted, explaining that the findings come in the wake of a recently completed clinical phase 1/2a trial that successfully demonstrated safety and immunogenicity of an FSP neoantigen-based vaccine in microsatellite unstable (MSI) colorectal cancer patients.

The current effort to further develop a cancer preventive vaccine against MSI cancers in Lynch syndrome using a preclinical mouse model involved a systematic database search to identify cMS sequences in the murine genome. Intestinal tumors obtained from Lynch syndrome mice were evaluated for mutations affecting these candidate cMS, and of 13 with a mutation frequency of 15% or higher, the 4 FSP neoantigens ultimately included in the vaccine elicited strong antigen-specific cellular immune responses.

Vaccination with peptides encoding these four intestinal cancer FSP neoantigens promoted antineoantigen immunity, reduced intestinal tumorigenicity, and prolonged overall survival, Dr. Lipkin said.

Further, based on preclinical data suggesting that naproxen in this setting might provide better risk-reducing effects, compared with aspirin (which has previously been shown to reduce colorectal cancer risk in Lynch syndrome patients), its addition to the vaccine did, indeed, improve response, he noted, explaining that naproxen worked as “sort of a super-aspirin,” that improved overall survival, compared with vaccine alone or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents alone.

In a video interview, Dr. Lipkin describes his research and its potential implications for the immunoprevention of Lynch syndrome and other cancers.

Vaccination with as few as four mutations that occur across Lynch syndrome tumors induced complete cures in some mice and delays in disease onset in others, he said.

“[This is] a very simple approach, very effective,” he added, noting that the T cells are now being studied to better understand the biology of the effects. “The idea of immunoprevention ... is actually very exciting and ... can be expanded beyond this.”

Lynch syndrome is a “great place to start,” because of the high rate of mutations, which are the most immunogenic types of mutations, he said.

“If we can get this basic paradigm to work, I think we can expand it to other types of mutations – for example, KRAS or BRAF, which are seen frequently in lung cancers, colon cancers, stomach cancers, pancreatic cancers, and others,” he said, noting that a proposal for a phase 1 clinical trial has been submitted.

ATLANTA – Lynch syndrome serves as an excellent platform for the development of immunoprevention cancer vaccines, and findings from a preclinical Lynch syndrome mouse model support ongoing research, according to Steven M. Lipkin, MD, PhD.

A novel vaccine, which included peptides encoding four intestinal cancer frameshift peptide (FSP) neoantigens derived from coding microsatellite (cMS) mutations in the genes Nacad, Maz, Xirp1, and Senp6 elicited strong antigen-specific cellular immune responses in the model, Dr. Lipkin, the Gladys and Roland Harriman Professor of Medicine and vice chair for research in the Sanford and Joan Weill Department of Medicine, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, reported at the annual meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research.

CD4-specific T cell responses were detected for Maz, Nacad, and Senp6, and CD8-positive T cells were detected for Xirp1 and Nacad, he noted, explaining that the findings come in the wake of a recently completed clinical phase 1/2a trial that successfully demonstrated safety and immunogenicity of an FSP neoantigen-based vaccine in microsatellite unstable (MSI) colorectal cancer patients.

The current effort to further develop a cancer preventive vaccine against MSI cancers in Lynch syndrome using a preclinical mouse model involved a systematic database search to identify cMS sequences in the murine genome. Intestinal tumors obtained from Lynch syndrome mice were evaluated for mutations affecting these candidate cMS, and of 13 with a mutation frequency of 15% or higher, the 4 FSP neoantigens ultimately included in the vaccine elicited strong antigen-specific cellular immune responses.

Vaccination with peptides encoding these four intestinal cancer FSP neoantigens promoted antineoantigen immunity, reduced intestinal tumorigenicity, and prolonged overall survival, Dr. Lipkin said.

Further, based on preclinical data suggesting that naproxen in this setting might provide better risk-reducing effects, compared with aspirin (which has previously been shown to reduce colorectal cancer risk in Lynch syndrome patients), its addition to the vaccine did, indeed, improve response, he noted, explaining that naproxen worked as “sort of a super-aspirin,” that improved overall survival, compared with vaccine alone or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents alone.

In a video interview, Dr. Lipkin describes his research and its potential implications for the immunoprevention of Lynch syndrome and other cancers.

Vaccination with as few as four mutations that occur across Lynch syndrome tumors induced complete cures in some mice and delays in disease onset in others, he said.

“[This is] a very simple approach, very effective,” he added, noting that the T cells are now being studied to better understand the biology of the effects. “The idea of immunoprevention ... is actually very exciting and ... can be expanded beyond this.”

Lynch syndrome is a “great place to start,” because of the high rate of mutations, which are the most immunogenic types of mutations, he said.

“If we can get this basic paradigm to work, I think we can expand it to other types of mutations – for example, KRAS or BRAF, which are seen frequently in lung cancers, colon cancers, stomach cancers, pancreatic cancers, and others,” he said, noting that a proposal for a phase 1 clinical trial has been submitted.

ATLANTA – Lynch syndrome serves as an excellent platform for the development of immunoprevention cancer vaccines, and findings from a preclinical Lynch syndrome mouse model support ongoing research, according to Steven M. Lipkin, MD, PhD.

A novel vaccine, which included peptides encoding four intestinal cancer frameshift peptide (FSP) neoantigens derived from coding microsatellite (cMS) mutations in the genes Nacad, Maz, Xirp1, and Senp6 elicited strong antigen-specific cellular immune responses in the model, Dr. Lipkin, the Gladys and Roland Harriman Professor of Medicine and vice chair for research in the Sanford and Joan Weill Department of Medicine, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, reported at the annual meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research.

CD4-specific T cell responses were detected for Maz, Nacad, and Senp6, and CD8-positive T cells were detected for Xirp1 and Nacad, he noted, explaining that the findings come in the wake of a recently completed clinical phase 1/2a trial that successfully demonstrated safety and immunogenicity of an FSP neoantigen-based vaccine in microsatellite unstable (MSI) colorectal cancer patients.

The current effort to further develop a cancer preventive vaccine against MSI cancers in Lynch syndrome using a preclinical mouse model involved a systematic database search to identify cMS sequences in the murine genome. Intestinal tumors obtained from Lynch syndrome mice were evaluated for mutations affecting these candidate cMS, and of 13 with a mutation frequency of 15% or higher, the 4 FSP neoantigens ultimately included in the vaccine elicited strong antigen-specific cellular immune responses.

Vaccination with peptides encoding these four intestinal cancer FSP neoantigens promoted antineoantigen immunity, reduced intestinal tumorigenicity, and prolonged overall survival, Dr. Lipkin said.

Further, based on preclinical data suggesting that naproxen in this setting might provide better risk-reducing effects, compared with aspirin (which has previously been shown to reduce colorectal cancer risk in Lynch syndrome patients), its addition to the vaccine did, indeed, improve response, he noted, explaining that naproxen worked as “sort of a super-aspirin,” that improved overall survival, compared with vaccine alone or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents alone.

In a video interview, Dr. Lipkin describes his research and its potential implications for the immunoprevention of Lynch syndrome and other cancers.

Vaccination with as few as four mutations that occur across Lynch syndrome tumors induced complete cures in some mice and delays in disease onset in others, he said.

“[This is] a very simple approach, very effective,” he added, noting that the T cells are now being studied to better understand the biology of the effects. “The idea of immunoprevention ... is actually very exciting and ... can be expanded beyond this.”

Lynch syndrome is a “great place to start,” because of the high rate of mutations, which are the most immunogenic types of mutations, he said.

“If we can get this basic paradigm to work, I think we can expand it to other types of mutations – for example, KRAS or BRAF, which are seen frequently in lung cancers, colon cancers, stomach cancers, pancreatic cancers, and others,” he said, noting that a proposal for a phase 1 clinical trial has been submitted.

REPORTING FROM AACR 2019

CV disease and mortality risk higher with younger age of type 2 diabetes diagnosis

Individuals who are younger when diagnosed with type 2 diabetes are at greater risk of cardiovascular disease and death, compared with those diagnosed at an older age, according to a retrospective study involving almost 2 million people.

People diagnosed with type 2 diabetes at age 40 or younger were at greatest risk of most outcomes, reported lead author Naveed Sattar, MD, PhD, professor of metabolic medicine, University of Glasgow, Scotland, and his colleagues. “Treatment target recommendations in regards to the risk factor control may need to be more aggressive in people developing diabetes at younger ages,” they wrote in Circulation.

In contrast, developing type 2 diabetes over the age of 80 years had little impact on risks.

“[R]eassessment of treatment goals in elderly might be useful,” the investigators wrote. “Diabetes screening needs for the elderly (above 80) should also be reevaluated.”

The study involved 318,083 patients with type 2 diabetes registered in the Swedish National Diabetes Registry between 1998 and 2012. Each patient was matched with 5 individuals from the general population based on sex, age, and country of residence, providing a control population of 1,575,108. Outcomes assessed included non-cardiovascular mortality, cardiovascular mortality, all causemortality, hospitalization for heart failure, coronary heart disease, stroke, atrial fibrillation, and acute myocardial infarction. Patients were followed for cardiovascular outcomes from 1998 to December 2013, while mortality surveillance continued through 2014.

In comparison with controls, patients 40 years or less had the highest excess risk of the most outcomes. *Excess risk of heart failure was elevated almost 5-fold (hazard ratio (HR), R 4.77), and risk of coronary heart disease wasn’t far behind (HR, 4.33). Risks of acute MI (HR, 3.41), stroke (HR, 3.58), and atrial fibrillation (HR, 1.95) were also elevated. Cardiovascular-related mortality was increased almost 3-fold (HR, 2.72), while total mortality (HR, 2.05) and non-cardiovascular mortality (HR, 1.95) were raised to a lesser degree.

“Thereafter, incremental risks generally declined with each higher decade age at diagnosis” of type 2 diabetes,” the investigators wrote.

After 80 years of age, all relative mortality risk factors dropped to less than 1, indicating lower risk than controls. Although non-fatal outcomes were still greater than 1 in this age group, these risks were “substantially attenuated compared with relative incremental risks in those diagnosed with T2DM at younger ages,” the investigators wrote.

The study was funded by the Swedish Association of Local Authorities Regions, the Swedish Heart and Lung Foundation, and the Swedish Research Council.

The investigators disclosed financial relationships with Amgen, AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, and other pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Sattar et al. Circulation. 2019 Apr 8. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.037885.

Individuals who are younger when diagnosed with type 2 diabetes are at greater risk of cardiovascular disease and death, compared with those diagnosed at an older age, according to a retrospective study involving almost 2 million people.

People diagnosed with type 2 diabetes at age 40 or younger were at greatest risk of most outcomes, reported lead author Naveed Sattar, MD, PhD, professor of metabolic medicine, University of Glasgow, Scotland, and his colleagues. “Treatment target recommendations in regards to the risk factor control may need to be more aggressive in people developing diabetes at younger ages,” they wrote in Circulation.

In contrast, developing type 2 diabetes over the age of 80 years had little impact on risks.

“[R]eassessment of treatment goals in elderly might be useful,” the investigators wrote. “Diabetes screening needs for the elderly (above 80) should also be reevaluated.”

The study involved 318,083 patients with type 2 diabetes registered in the Swedish National Diabetes Registry between 1998 and 2012. Each patient was matched with 5 individuals from the general population based on sex, age, and country of residence, providing a control population of 1,575,108. Outcomes assessed included non-cardiovascular mortality, cardiovascular mortality, all causemortality, hospitalization for heart failure, coronary heart disease, stroke, atrial fibrillation, and acute myocardial infarction. Patients were followed for cardiovascular outcomes from 1998 to December 2013, while mortality surveillance continued through 2014.

In comparison with controls, patients 40 years or less had the highest excess risk of the most outcomes. *Excess risk of heart failure was elevated almost 5-fold (hazard ratio (HR), R 4.77), and risk of coronary heart disease wasn’t far behind (HR, 4.33). Risks of acute MI (HR, 3.41), stroke (HR, 3.58), and atrial fibrillation (HR, 1.95) were also elevated. Cardiovascular-related mortality was increased almost 3-fold (HR, 2.72), while total mortality (HR, 2.05) and non-cardiovascular mortality (HR, 1.95) were raised to a lesser degree.

“Thereafter, incremental risks generally declined with each higher decade age at diagnosis” of type 2 diabetes,” the investigators wrote.

After 80 years of age, all relative mortality risk factors dropped to less than 1, indicating lower risk than controls. Although non-fatal outcomes were still greater than 1 in this age group, these risks were “substantially attenuated compared with relative incremental risks in those diagnosed with T2DM at younger ages,” the investigators wrote.

The study was funded by the Swedish Association of Local Authorities Regions, the Swedish Heart and Lung Foundation, and the Swedish Research Council.

The investigators disclosed financial relationships with Amgen, AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, and other pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Sattar et al. Circulation. 2019 Apr 8. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.037885.

Individuals who are younger when diagnosed with type 2 diabetes are at greater risk of cardiovascular disease and death, compared with those diagnosed at an older age, according to a retrospective study involving almost 2 million people.

People diagnosed with type 2 diabetes at age 40 or younger were at greatest risk of most outcomes, reported lead author Naveed Sattar, MD, PhD, professor of metabolic medicine, University of Glasgow, Scotland, and his colleagues. “Treatment target recommendations in regards to the risk factor control may need to be more aggressive in people developing diabetes at younger ages,” they wrote in Circulation.

In contrast, developing type 2 diabetes over the age of 80 years had little impact on risks.

“[R]eassessment of treatment goals in elderly might be useful,” the investigators wrote. “Diabetes screening needs for the elderly (above 80) should also be reevaluated.”

The study involved 318,083 patients with type 2 diabetes registered in the Swedish National Diabetes Registry between 1998 and 2012. Each patient was matched with 5 individuals from the general population based on sex, age, and country of residence, providing a control population of 1,575,108. Outcomes assessed included non-cardiovascular mortality, cardiovascular mortality, all causemortality, hospitalization for heart failure, coronary heart disease, stroke, atrial fibrillation, and acute myocardial infarction. Patients were followed for cardiovascular outcomes from 1998 to December 2013, while mortality surveillance continued through 2014.

In comparison with controls, patients 40 years or less had the highest excess risk of the most outcomes. *Excess risk of heart failure was elevated almost 5-fold (hazard ratio (HR), R 4.77), and risk of coronary heart disease wasn’t far behind (HR, 4.33). Risks of acute MI (HR, 3.41), stroke (HR, 3.58), and atrial fibrillation (HR, 1.95) were also elevated. Cardiovascular-related mortality was increased almost 3-fold (HR, 2.72), while total mortality (HR, 2.05) and non-cardiovascular mortality (HR, 1.95) were raised to a lesser degree.

“Thereafter, incremental risks generally declined with each higher decade age at diagnosis” of type 2 diabetes,” the investigators wrote.

After 80 years of age, all relative mortality risk factors dropped to less than 1, indicating lower risk than controls. Although non-fatal outcomes were still greater than 1 in this age group, these risks were “substantially attenuated compared with relative incremental risks in those diagnosed with T2DM at younger ages,” the investigators wrote.

The study was funded by the Swedish Association of Local Authorities Regions, the Swedish Heart and Lung Foundation, and the Swedish Research Council.

The investigators disclosed financial relationships with Amgen, AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, and other pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Sattar et al. Circulation. 2019 Apr 8. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.037885.

FROM CIRCULATION

Key clinical point: Patients who are younger when diagnosed with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) are at greater risk of cardiovascular disease and death than patients diagnosed at an older age.

Major finding: Patients diagnosed with T2DM at age 40 or younger had twice the risk of death from any cause, compared with age-matched controls (hazard ratio, 2.05).

Study details: A retrospective analysis of type 2 diabetes and associations with cardiovascular and mortality risks, using data from 318,083 patients in the Swedish National Diabetes Registry.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the Swedish Association of Local Authorities Regions, the Swedish Heart and Lung Foundation, and the Swedish Research Council. The investigators disclosed financial relationships with Amgen, Astra-Zeneca, Eli Lilly, and others.

Source: Sattar et al. Circulation. 2019 Apr 8. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.037885.

Managing Eating Disorders on a General Pediatrics Unit: A Centralized Video Monitoring Pilot

Hospitalizations for nutritional rehabilitation of patients with restrictive eating disorders are increasing.1 Among primary mental health admissions at free-standing children’s hospitals, eating disorders represent 5.5% of hospitalizations and are associated with the longest length of stay (LOS; mean 14.3 days) and costliest care (mean $46,130).2 Admission is necessary to ensure initial weight restoration and monitoring for symptoms of refeeding syndrome, including electrolyte shifts and vital sign abnormalities.3-5

Supervision is generally considered an essential element of caring for hospitalized patients with eating disorders, who may experience difficulty adhering to nutritional treatment, perform excessive movement or exercise, or demonstrate purging or self-harming behaviors. Supervision is presumed to prevent counterproductive behaviors, facilitating weight gain and earlier discharge to psychiatric treatment. Best practices for patient supervision to address these challenges have not been established but often include meal time or continuous one-to-one supervision by nursing assistants (NAs) or other staff.6,7 While meal supervision has been shown to decrease medical LOS, it is costly, reduces staff availability for the care of other patient care, and can be a barrier to caring for patients with eating disorders in many institutions.8

Although not previously used in patients with eating disorders, centralized video monitoring (CVM) may provide an additional mode of supervision. CVM is an emerging technology consisting of real-time video streaming, without video recording, enabling tracking of patient movement, redirection of behaviors, and communication with unit nurses when necessary. CVM has been used in multiple patient safety initiatives to reduce falls, address staffing shortages, reduce costs,9,10 supervise patients at risk for self-harm or elopement, and prevent controlled medication diversion.10,11

We sought to pilot a novel use of CVM to replace our institution’s standard practice of continuous one-to-one nursing assistant (NA) supervision of patients admitted for medical stabilization of an eating disorder. Our objective was to evaluate the supervision cost and feasibility of CVM, using LOS and days to weight gain as balancing measures.

METHODS

Setting and Participants

This retrospective cohort study included patients 12-18 years old admitted to the pediatric hospital medicine service on a general unit of an academic quaternary care children’s hospital for medical stabilization of an eating disorder between September 2013 and March 2017. Patients were identified using administrative data based on primary or secondary diagnosis of anorexia nervosa, eating disorder not other wise specified, or another specified eating disorder (ICD 9 3071, 20759, or ICD 10 f5000, 5001, f5089, f509).12,13 This research study was considered exempt by the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health’s Institutional Review Board.

Supervision Interventions

A standard medical stabilization protocol was used for patients admitted with an eating disorder throughout the study period (Appendix). All patients received continuous one-to-one NA supervision until they reached the target calorie intake and demonstrated the ability to follow the nutritional meal protocol. Beginning July 2015, patients received continuous CVM supervision unless they expressed suicidal ideation (SI), which triggered one-to-one NA supervision until they no longer endorsed suicidality.

Centralized Video Monitoring Implementation

Institutional CVM technology was AvaSys TeleSitter Solution (AvaSure, Inc). Our institution purchased CVM devices for use in adult settings, and one was assigned for pediatric CVM. Mobile CVM video carts were deployed to patient rooms and generated live video streams, without recorded capture, which were supervised by CVM technicians. These technicians were NAs hired and trained specifically for this role; worked four-, eight-, and 12-hour shifts; and observed up to eight camera feeds on a single monitor in a centralized room. Patients and family members could refuse CVM, which would trigger one-to-one NA supervision. Patients were not observed by CVM while in the restroom; staff were notified by either the patient or technician, and one-to-one supervision was provided. CVM had two-way audio communication, which allowed technicians to redirect patients verbally. Technicians could contact nursing staff directly by phone when additional intervention was needed.

Supervision Costs

NA supervision costs were estimated at $19/hour, based upon institutional human resources average NA salaries at that time. No additional mealtime supervision was included, as in-person supervision was already occurring.

CVM supervision costs were defined as the sum of the device cost plus CVM technician costs and two hours of one-to-one NA mealtime supervision per day. The CVM device cost was estimated at $2.10/hour, assuming a 10-year machine life expectancy (single unit cost $82,893 in 2015, 3,944 hours of use in fiscal year of 2018). CVM technician costs were $19/hour, based upon institutional human resources average CVM technician salaries at that time. Because technicians monitored an average of six patients simultaneously during this study, one-sixth of a CVM technician’s salary (ie, $3.17/hour) was used for each hour of CVM monitoring. Patients with mixed (NA and CVM) supervision were analyzed with those having CVM supervision. These patients’ costs were the sum of their NA supervision costs plus their CVM supervision costs.

Data Collection

Descriptive variables including age, gender, race/ethnicity, insurance, and LOS were collected from administrative data. The duration and type of supervision for all patients were collected from daily staffing logs. The eating disorder protocol standardized the process of obtaining daily weights (Appendix). Days to weight gain following admission were defined as the total number of days from admission to the first day of weight gain that was followed by another day of weight gain or maintaining the same weight

Data Analysis

Patient and hospitalization characteristics were summarized. A sample size of at least 14 in each group was estimated as necessary to detect a 50% reduction in supervision cost between the groups using alpha = 0.05, a power of 80%, a mean cost of $4,400 in the NA group, and a standard deviation of $1,600.Wilcoxon rank-sum tests were used to assess differences in median supervision cost between NA and CVM use. Differences in mean LOS and days to weight gain between NA and CVM use were assessed with t-tests because these data were normally distributed.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics and Supervision Costs

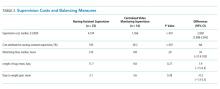

The study included 37 consecutive admissions (NA = 23 and CVM = 14) with 35 unique patients. Patients were female, primarily non-Hispanic White, and privately insured (Table 1). Median supervision cost for the NA was statistically significantly more expensive at $4,104/admission versus $1,166/admission for CVM (P < .001, Table 2).

Balancing Measures, Acceptability, and Feasibility

Mean LOS was 11.7 days for NA and 9.8 days for CVM (P = .27; Table 2). The mean number of days to weight gain was 3.1 and 3.6 days, respectively (P = .28). No patients converted from CVM to NA supervision. One patient with SI converted to CVM after SI resolved and two patients required ongoing NA supervision due to continued SI. There were no reported refusals, technology failures, or unplanned discontinuations of CVM. One patient/family reported excessive CVM redirection of behavior.

DISCUSSION

This is the first description of CVM use in adolescent patients or patients with eating disorders. Our results suggest that CVM appears feasible and less costly in this population than one-to-one NA supervision, without statistically significant differences in LOS or time to weight gain. Patients with CVM with any NA supervision (except mealtime alone) were analyzed in the CVM group; therefore, this study may underestimate cost savings from CVM supervision. This innovative use of CVM may represent an opportunity for hospitals to repurpose monitoring technology for more efficient supervision of patients with eating disorders.

This pediatric pilot study adds to the growing body of literature in adult patients suggesting CVM supervision may be a feasible inpatient cost-reduction strategy.9,10 One single-center study demonstrated that the use of CVM with adult inpatients led to fewer unsafe behaviors, eg, patient removal of intravenous catheters and oxygen therapy. Personnel savings exceeded the original investment cost of the monitor within one fiscal quarter.9 Results of another study suggest that CVM use with hospitalized adults who required supervision to prevent falls was associated with improved patient and family satisfaction.14 In the absence of a gold standard for supervision of patients hospitalized with eating disorders, CVM technology is a tool that may balance cost, care quality, and patient experience. Given the upfront investment in CVM units, this technology may be most appropriate for institutions already using CVM for other inpatient indications.

Although our institutional cost of CVM use was similar to that reported by other institutions,11,15 the single-center design of this pilot study limits the generalizability of our findings. Unadjusted results of this observational study may be confounded by indication bias. As this was a pilot study, it was powered to detect a clinically significant difference in cost between NA and CVM supervision. While statistically significant differences were not seen in LOS or weight gain, this pilot study was not powered to detect potential differences or to adjust for all potential confounders (eg, other mental health conditions or comorbidities, eating disorder type, previous hospitalizations). Future studies should include these considerations in estimating sample sizes. The ability to conduct a robust cost-effectiveness analysis was also limited by cost data availability and reliance on staffing assumptions to calculate supervision costs. However, these findings will be important for valid effect size estimates for future interventional studies that rigorously evaluate CVM effectiveness and safety. Patients and families were not formally surveyed about their experiences with CVM, and the patient and family experience is another important outcome to consider in future studies.

CONCLUSION

The results of this pilot study suggest that supervision costs for patients admitted for medical stabilization of eating disorders were statistically significantly lower with CVM when compared with one-to-one NA supervision, without a change in hospitalization LOS or time to weight gain. These findings are particularly important as hospitals seek opportunities to reduce costs while providing safe and effective care. Future efforts should focus on evaluating clinical outcomes and patient experiences with this technology and strategies to maximize efficiency to offset the initial device cost.

Disclosures

The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose. The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose.

1. Zhao Y, Encinosa W. An update on hospitalizations for eating disorders, 1999 to 2009: statistical brief #120. In: Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2006. PubMed

2. Bardach NS, Coker TR, Zima BT, et al. Common and costly hospitalizations for pediatric mental health disorders. Pediatrics. 2014;133(4):602-609. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-3165. PubMed

3. Society for Adolescent H, Medicine, Golden NH, et al. Position Paper of the Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine: medical management of restrictive eating disorders in adolescents and young adults. J Adolesc Health. 2015;56(1):121-125. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.10.259. PubMed

4. Katzman DK. Medical complications in adolescents with anorexia nervosa: a review of the literature. Int J Eat Disord. 2005;37(S1):S52-S59; discussion S87-S59. doi: 10.1002/eat.20118. PubMed

5. Strandjord SE, Sieke EH, Richmond M, Khadilkar A, Rome ES. Medical stabilization of adolescents with nutritional insufficiency: a clinical care path. Eat Weight Disord. 2016;21(3):403-410. doi: 10.1007/s40519-015-0245-5. PubMed

6. Kells M, Davidson K, Hitchko L, O’Neil K, Schubert-Bob P, McCabe M. Examining supervised meals in patients with restrictive eating disorders. Appl Nurs Res. 2013;26(2):76-79. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2012.06.003. PubMed

7. Leclerc A, Turrini T, Sherwood K, Katzman DK. Evaluation of a nutrition rehabilitation protocol in hospitalized adolescents with restrictive eating disorders. J Adolesc Health. 2013;53(5):585-589. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.06.001. PubMed

8. Kells M, Schubert-Bob P, Nagle K, et al. Meal supervision during medical hospitalization for eating disorders. Clin Nurs Res. 2017;26(4):525-537. doi: 10.1177/1054773816637598. PubMed

9. Jeffers S, Searcey P, Boyle K, et al. Centralized video monitoring for patient safety: a Denver Health Lean journey. Nurs Econ. 2013;31(6):298-306. PubMed

10. Sand-Jecklin K, Johnson JR, Tylka S. Protecting patient safety: can video monitoring prevent falls in high-risk patient populations? J Nurs Care Qual. 2016;31(2):131-138. doi: 10.1097/NCQ.0000000000000163. PubMed

11. Burtson PL, Vento L. Sitter reduction through mobile video monitoring: a nurse-driven sitter protocol and administrative oversight. J Nurs Adm. 2015;45(7-8):363-369. doi: 10.1097/NNA.0000000000000216. PubMed

12. Prevention CfDCa. ICD-9-CM Guidelines, 9th ed. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/icd/icd9cm_guidelines_2011.pdf. Accessed April 11, 2018.

13. Prevention CfDca. IDC-9-CM Code Conversion Table. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/icd/icd-9-cm_fy14_cnvtbl_final.pdf. Accessed April 11, 2018.

14. Cournan M, Fusco-Gessick B, Wright L. Improving patient safety through video monitoring. Rehabil Nurs. 2016. doi: 10.1002/rnj.308. PubMed

15. Rochefort CM, Ward L, Ritchie JA, Girard N, Tamblyn RM. Patient and nurse staffing characteristics associated with high sitter use costs. J Adv Nurs. 2012;68(8):1758-1767. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05864.x. PubMed

Hospitalizations for nutritional rehabilitation of patients with restrictive eating disorders are increasing.1 Among primary mental health admissions at free-standing children’s hospitals, eating disorders represent 5.5% of hospitalizations and are associated with the longest length of stay (LOS; mean 14.3 days) and costliest care (mean $46,130).2 Admission is necessary to ensure initial weight restoration and monitoring for symptoms of refeeding syndrome, including electrolyte shifts and vital sign abnormalities.3-5