User login

AHA: Chagas disease and its heart effects have come to the U.S.

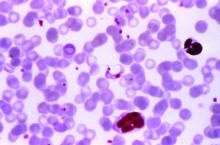

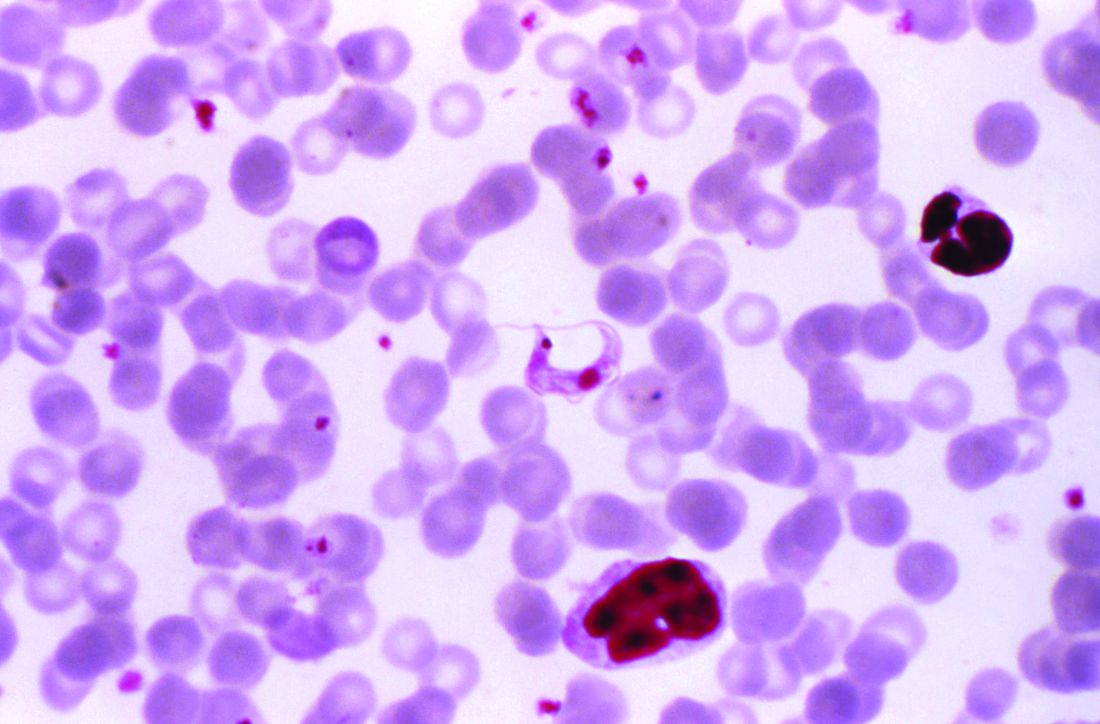

Chagas disease, a cause of serious cardiovascular problems and sudden death, was previously localized mainly in the tropics, but now affects at least 300,000 people in the United States and is growing in prevalence in other traditionally nonendemic areas, including Europe, Australia, and Japan. The American Heart Association and the Inter-American Society of Cardiology have released a statement to “increase global awareness among providers who may encounter patients with Chagas disease outside of traditionally endemic environments.”

The document summarizes the most up-to-date information on diagnosis, screening, and treatment of Trypanosoma cruzi (the protozoan cause of Chagas) infection, focusing primarily on its cardiovascular aspects, and was developed by Maria Carmo Pereira Nunes, MD, chair, and her colleagues on the American Heart Association Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis and Kawasaki Disease Committee.

Chagas disease is transmitted by a blood-sucking insect vector Triatoma infestans and, less frequently, from mother to fetus or by contaminated food or drink, and about one third of infected individuals develop chronic heart disease.

Although 60%-70% of people infected with T. cruzi never develop any symptoms, those who do can develop heart disease, including heart failure, stroke, life threatening ventricular arrhythmias, and cardiac arrest, according to the statement published in Circulation.

Chronic Chagas-related heart disease develops after several decades of the indeterminate, or subclinical, form of the disease following the initial acute infection. Potential risk factors for progression to the chronic stage include African ancestry, age, severity of acute infection, nutritional status, alcoholism, and their concomitant diseases.

In most studies, sudden death is the most common overall cause of death in patients with Chagas-related cardiomyopathy (55%-60%), followed by heart failure (25%-30%) and embolic events (10%-15%), according to the authors.

Benznidazole and nifurtimox are the only drugs with proven efficacy against Chagas disease, with benznidazole as the first-line treatment because it has better tolerance, is more widely available, and has more published data published on its efficacy. Furthermore, it is available in the United States, after the Food and Drug Administration granted fast-track approved 2017 for treatment of Chagas disease. Use of nifurtimox in the United States entails consultation with the Centers for Disease Control and prevention, according to the statement.

“More data are needed on the best practices for the treatment of Chagas cardiomyopathy. Because no specific clinical trials have been conducted, care for

patients with Chagas-induced ventricular dysfunction is extrapolated from general heart failure recommendations with unclear efficacy (and potential harm),” Dr. Pereira Nunes and her colleagues concluded.

One author disclosed receiving a research grant from Merck and speakers’ bureau and/or honoraria from Bayer; Biotronik, and Medtronic. The others had no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Nunes, MCP, et al., Circulation. 2018 Aug 20; doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000599.

Chagas disease, a cause of serious cardiovascular problems and sudden death, was previously localized mainly in the tropics, but now affects at least 300,000 people in the United States and is growing in prevalence in other traditionally nonendemic areas, including Europe, Australia, and Japan. The American Heart Association and the Inter-American Society of Cardiology have released a statement to “increase global awareness among providers who may encounter patients with Chagas disease outside of traditionally endemic environments.”

The document summarizes the most up-to-date information on diagnosis, screening, and treatment of Trypanosoma cruzi (the protozoan cause of Chagas) infection, focusing primarily on its cardiovascular aspects, and was developed by Maria Carmo Pereira Nunes, MD, chair, and her colleagues on the American Heart Association Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis and Kawasaki Disease Committee.

Chagas disease is transmitted by a blood-sucking insect vector Triatoma infestans and, less frequently, from mother to fetus or by contaminated food or drink, and about one third of infected individuals develop chronic heart disease.

Although 60%-70% of people infected with T. cruzi never develop any symptoms, those who do can develop heart disease, including heart failure, stroke, life threatening ventricular arrhythmias, and cardiac arrest, according to the statement published in Circulation.

Chronic Chagas-related heart disease develops after several decades of the indeterminate, or subclinical, form of the disease following the initial acute infection. Potential risk factors for progression to the chronic stage include African ancestry, age, severity of acute infection, nutritional status, alcoholism, and their concomitant diseases.

In most studies, sudden death is the most common overall cause of death in patients with Chagas-related cardiomyopathy (55%-60%), followed by heart failure (25%-30%) and embolic events (10%-15%), according to the authors.

Benznidazole and nifurtimox are the only drugs with proven efficacy against Chagas disease, with benznidazole as the first-line treatment because it has better tolerance, is more widely available, and has more published data published on its efficacy. Furthermore, it is available in the United States, after the Food and Drug Administration granted fast-track approved 2017 for treatment of Chagas disease. Use of nifurtimox in the United States entails consultation with the Centers for Disease Control and prevention, according to the statement.

“More data are needed on the best practices for the treatment of Chagas cardiomyopathy. Because no specific clinical trials have been conducted, care for

patients with Chagas-induced ventricular dysfunction is extrapolated from general heart failure recommendations with unclear efficacy (and potential harm),” Dr. Pereira Nunes and her colleagues concluded.

One author disclosed receiving a research grant from Merck and speakers’ bureau and/or honoraria from Bayer; Biotronik, and Medtronic. The others had no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Nunes, MCP, et al., Circulation. 2018 Aug 20; doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000599.

Chagas disease, a cause of serious cardiovascular problems and sudden death, was previously localized mainly in the tropics, but now affects at least 300,000 people in the United States and is growing in prevalence in other traditionally nonendemic areas, including Europe, Australia, and Japan. The American Heart Association and the Inter-American Society of Cardiology have released a statement to “increase global awareness among providers who may encounter patients with Chagas disease outside of traditionally endemic environments.”

The document summarizes the most up-to-date information on diagnosis, screening, and treatment of Trypanosoma cruzi (the protozoan cause of Chagas) infection, focusing primarily on its cardiovascular aspects, and was developed by Maria Carmo Pereira Nunes, MD, chair, and her colleagues on the American Heart Association Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis and Kawasaki Disease Committee.

Chagas disease is transmitted by a blood-sucking insect vector Triatoma infestans and, less frequently, from mother to fetus or by contaminated food or drink, and about one third of infected individuals develop chronic heart disease.

Although 60%-70% of people infected with T. cruzi never develop any symptoms, those who do can develop heart disease, including heart failure, stroke, life threatening ventricular arrhythmias, and cardiac arrest, according to the statement published in Circulation.

Chronic Chagas-related heart disease develops after several decades of the indeterminate, or subclinical, form of the disease following the initial acute infection. Potential risk factors for progression to the chronic stage include African ancestry, age, severity of acute infection, nutritional status, alcoholism, and their concomitant diseases.

In most studies, sudden death is the most common overall cause of death in patients with Chagas-related cardiomyopathy (55%-60%), followed by heart failure (25%-30%) and embolic events (10%-15%), according to the authors.

Benznidazole and nifurtimox are the only drugs with proven efficacy against Chagas disease, with benznidazole as the first-line treatment because it has better tolerance, is more widely available, and has more published data published on its efficacy. Furthermore, it is available in the United States, after the Food and Drug Administration granted fast-track approved 2017 for treatment of Chagas disease. Use of nifurtimox in the United States entails consultation with the Centers for Disease Control and prevention, according to the statement.

“More data are needed on the best practices for the treatment of Chagas cardiomyopathy. Because no specific clinical trials have been conducted, care for

patients with Chagas-induced ventricular dysfunction is extrapolated from general heart failure recommendations with unclear efficacy (and potential harm),” Dr. Pereira Nunes and her colleagues concluded.

One author disclosed receiving a research grant from Merck and speakers’ bureau and/or honoraria from Bayer; Biotronik, and Medtronic. The others had no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Nunes, MCP, et al., Circulation. 2018 Aug 20; doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000599.

FROM CIRCULATION

Access to care drives disparity between urban, rural cancer patients

New research suggests that better access to quality care may reduce disparities in survival between cancer patients living in rural areas of the US and those living in urban areas.

The study showed that urban and rural cancer patients had similar survival outcomes when they were enrolled in clinical trials.

These results, published in JAMA Network Open, cast new light on decades of research showing that cancer patients living in rural areas don’t live as long as urban cancer patients.

“These findings were a surprise, since we thought we might find the same disparities others had found,” said study author Joseph Unger, PhD, of Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, Washington.

“But clinical trials are a key difference here. In trials, patients are uniformly assessed, treated, and followed under a strict, guideline-driven protocol. This suggests that giving people with cancer access to uniform treatment strategies could help resolve the disparities in outcomes that we see between rural and urban patients.”

Dr Unger and his colleagues studied data on 36,995 patients who were enrolled in 44 phase 3 or phase 2/3 SWOG trials from 1986 through 2012. All 50 states were represented.

Patients had 17 different cancer types, including acute myeloid leukemia (AML), non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), and multiple myeloma (MM).

Using US Department of Agriculture population classifications known as Rural-Urban Continuum Codes, the researchers categorized the patients as either rural or urban and analyzed their outcomes.

A minority of patients (19.4%, n=7184) were from rural locations. They were significantly more likely than urban patients to be 65 or older (P<0.001) and significantly less likely to be black (vs all other races; P<0.001).

However, there was no significant between-group difference in sex (P=0.53), and all major US geographic regions (West, Midwest, South, and Northeast) were represented.

Results

The researchers limited their analysis of survival to the first 5 years after trial enrollment to emphasize outcomes related to cancer and its treatment. They looked at overall survival (OS) as well as cancer-specific survival.

The team found no meaningful difference in OS or cancer-specific survival between rural and urban patients for 16 of the 17 cancer types.

The exception was estrogen receptor-negative, progesterone receptor-negative breast cancer. Rural patients with this cancer didn’t live as long as their urban counterparts. The hazard ratio (HR) was 1.27 (95% CI, 1.06-1.51; P=0.008) for OS and 1.26 (95% CI, 1.04-1.52; P=0.02) for cancer-specific survival.

The researchers believe this finding could be attributed to a few factors, including timely access to follow-up chemotherapy after patients’ first round of cancer treatment.

Although there were no significant survival differences for patients with hematologic malignancies, rural patients had slightly better OS if they had advanced indolent NHL or AML but slightly worse OS if they had MM or advanced aggressive NHL. The HRs were as follows:

- Advanced indolent NHL—HR=0.91 (95% CI, 0.64-1.29; P=0.60)

- AML—HR=0.94 (95% CI, 0.83-1.06; P=0.29)

- MM—HR=1.05 (95% CI, 0.93-1.18, P=0.46)

- Advanced aggressive NHL—HR=1.05 (95% CI, 0.87-1.27; P=0.60).

Rural patients had slightly better cancer-specific survival if they had advanced indolent NHL but slightly worse cancer-specific survival if they had AML, MM, or advanced aggressive NHL. The HRs were as follows:

- Advanced indolent NHL—HR=0.98 (95% CI, 0.66-1.45; P=0.90)

- AML—HR=1.01 (95% CI, 0.86-1.20; P=0.87)

- MM—HR=1.04 (95% CI, 0.90-1.20; P=0.60)

- Advanced aggressive NHL—HR=1.08 (95% CI, 0.87-1.34; P=0.50).

The researchers said these findings suggest it is access to care, and not other characteristics, that drive the survival disparities typically observed between urban and rural cancer patients.

“If people diagnosed with cancer, regardless of where they live, receive similar care and have similar outcomes, then a reasonable inference is that the best way to improve outcomes for rural patients is to improve their access to quality care,” Dr Unger said.

This research was supported by the National Cancer Institute and the HOPE Foundation. The researchers reported financial relationships with various pharmaceutical companies.

New research suggests that better access to quality care may reduce disparities in survival between cancer patients living in rural areas of the US and those living in urban areas.

The study showed that urban and rural cancer patients had similar survival outcomes when they were enrolled in clinical trials.

These results, published in JAMA Network Open, cast new light on decades of research showing that cancer patients living in rural areas don’t live as long as urban cancer patients.

“These findings were a surprise, since we thought we might find the same disparities others had found,” said study author Joseph Unger, PhD, of Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, Washington.

“But clinical trials are a key difference here. In trials, patients are uniformly assessed, treated, and followed under a strict, guideline-driven protocol. This suggests that giving people with cancer access to uniform treatment strategies could help resolve the disparities in outcomes that we see between rural and urban patients.”

Dr Unger and his colleagues studied data on 36,995 patients who were enrolled in 44 phase 3 or phase 2/3 SWOG trials from 1986 through 2012. All 50 states were represented.

Patients had 17 different cancer types, including acute myeloid leukemia (AML), non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), and multiple myeloma (MM).

Using US Department of Agriculture population classifications known as Rural-Urban Continuum Codes, the researchers categorized the patients as either rural or urban and analyzed their outcomes.

A minority of patients (19.4%, n=7184) were from rural locations. They were significantly more likely than urban patients to be 65 or older (P<0.001) and significantly less likely to be black (vs all other races; P<0.001).

However, there was no significant between-group difference in sex (P=0.53), and all major US geographic regions (West, Midwest, South, and Northeast) were represented.

Results

The researchers limited their analysis of survival to the first 5 years after trial enrollment to emphasize outcomes related to cancer and its treatment. They looked at overall survival (OS) as well as cancer-specific survival.

The team found no meaningful difference in OS or cancer-specific survival between rural and urban patients for 16 of the 17 cancer types.

The exception was estrogen receptor-negative, progesterone receptor-negative breast cancer. Rural patients with this cancer didn’t live as long as their urban counterparts. The hazard ratio (HR) was 1.27 (95% CI, 1.06-1.51; P=0.008) for OS and 1.26 (95% CI, 1.04-1.52; P=0.02) for cancer-specific survival.

The researchers believe this finding could be attributed to a few factors, including timely access to follow-up chemotherapy after patients’ first round of cancer treatment.

Although there were no significant survival differences for patients with hematologic malignancies, rural patients had slightly better OS if they had advanced indolent NHL or AML but slightly worse OS if they had MM or advanced aggressive NHL. The HRs were as follows:

- Advanced indolent NHL—HR=0.91 (95% CI, 0.64-1.29; P=0.60)

- AML—HR=0.94 (95% CI, 0.83-1.06; P=0.29)

- MM—HR=1.05 (95% CI, 0.93-1.18, P=0.46)

- Advanced aggressive NHL—HR=1.05 (95% CI, 0.87-1.27; P=0.60).

Rural patients had slightly better cancer-specific survival if they had advanced indolent NHL but slightly worse cancer-specific survival if they had AML, MM, or advanced aggressive NHL. The HRs were as follows:

- Advanced indolent NHL—HR=0.98 (95% CI, 0.66-1.45; P=0.90)

- AML—HR=1.01 (95% CI, 0.86-1.20; P=0.87)

- MM—HR=1.04 (95% CI, 0.90-1.20; P=0.60)

- Advanced aggressive NHL—HR=1.08 (95% CI, 0.87-1.34; P=0.50).

The researchers said these findings suggest it is access to care, and not other characteristics, that drive the survival disparities typically observed between urban and rural cancer patients.

“If people diagnosed with cancer, regardless of where they live, receive similar care and have similar outcomes, then a reasonable inference is that the best way to improve outcomes for rural patients is to improve their access to quality care,” Dr Unger said.

This research was supported by the National Cancer Institute and the HOPE Foundation. The researchers reported financial relationships with various pharmaceutical companies.

New research suggests that better access to quality care may reduce disparities in survival between cancer patients living in rural areas of the US and those living in urban areas.

The study showed that urban and rural cancer patients had similar survival outcomes when they were enrolled in clinical trials.

These results, published in JAMA Network Open, cast new light on decades of research showing that cancer patients living in rural areas don’t live as long as urban cancer patients.

“These findings were a surprise, since we thought we might find the same disparities others had found,” said study author Joseph Unger, PhD, of Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, Washington.

“But clinical trials are a key difference here. In trials, patients are uniformly assessed, treated, and followed under a strict, guideline-driven protocol. This suggests that giving people with cancer access to uniform treatment strategies could help resolve the disparities in outcomes that we see between rural and urban patients.”

Dr Unger and his colleagues studied data on 36,995 patients who were enrolled in 44 phase 3 or phase 2/3 SWOG trials from 1986 through 2012. All 50 states were represented.

Patients had 17 different cancer types, including acute myeloid leukemia (AML), non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), and multiple myeloma (MM).

Using US Department of Agriculture population classifications known as Rural-Urban Continuum Codes, the researchers categorized the patients as either rural or urban and analyzed their outcomes.

A minority of patients (19.4%, n=7184) were from rural locations. They were significantly more likely than urban patients to be 65 or older (P<0.001) and significantly less likely to be black (vs all other races; P<0.001).

However, there was no significant between-group difference in sex (P=0.53), and all major US geographic regions (West, Midwest, South, and Northeast) were represented.

Results

The researchers limited their analysis of survival to the first 5 years after trial enrollment to emphasize outcomes related to cancer and its treatment. They looked at overall survival (OS) as well as cancer-specific survival.

The team found no meaningful difference in OS or cancer-specific survival between rural and urban patients for 16 of the 17 cancer types.

The exception was estrogen receptor-negative, progesterone receptor-negative breast cancer. Rural patients with this cancer didn’t live as long as their urban counterparts. The hazard ratio (HR) was 1.27 (95% CI, 1.06-1.51; P=0.008) for OS and 1.26 (95% CI, 1.04-1.52; P=0.02) for cancer-specific survival.

The researchers believe this finding could be attributed to a few factors, including timely access to follow-up chemotherapy after patients’ first round of cancer treatment.

Although there were no significant survival differences for patients with hematologic malignancies, rural patients had slightly better OS if they had advanced indolent NHL or AML but slightly worse OS if they had MM or advanced aggressive NHL. The HRs were as follows:

- Advanced indolent NHL—HR=0.91 (95% CI, 0.64-1.29; P=0.60)

- AML—HR=0.94 (95% CI, 0.83-1.06; P=0.29)

- MM—HR=1.05 (95% CI, 0.93-1.18, P=0.46)

- Advanced aggressive NHL—HR=1.05 (95% CI, 0.87-1.27; P=0.60).

Rural patients had slightly better cancer-specific survival if they had advanced indolent NHL but slightly worse cancer-specific survival if they had AML, MM, or advanced aggressive NHL. The HRs were as follows:

- Advanced indolent NHL—HR=0.98 (95% CI, 0.66-1.45; P=0.90)

- AML—HR=1.01 (95% CI, 0.86-1.20; P=0.87)

- MM—HR=1.04 (95% CI, 0.90-1.20; P=0.60)

- Advanced aggressive NHL—HR=1.08 (95% CI, 0.87-1.34; P=0.50).

The researchers said these findings suggest it is access to care, and not other characteristics, that drive the survival disparities typically observed between urban and rural cancer patients.

“If people diagnosed with cancer, regardless of where they live, receive similar care and have similar outcomes, then a reasonable inference is that the best way to improve outcomes for rural patients is to improve their access to quality care,” Dr Unger said.

This research was supported by the National Cancer Institute and the HOPE Foundation. The researchers reported financial relationships with various pharmaceutical companies.

The emotionally exhausted physician

CASE ‘I’m stuck’

Dr. D, age 48, an internist practicing general medicine who is a married mother of 2 teenagers, presents with emotional exhaustion. Her medical history is unremarkable other than hyperlipidemia controlled by diet. She describes an episode of reactive depressive symptoms and anxiety when in college, which was related to the stress of final exams, finances, and the dissolution of a long-standing relationship. Regardless, she functioned well and graduated summa cum laude. She says her current feelings of being “stuck” have gradually increased during the past 3 to 4 years. Although she describes being mildly anxious and dysphoric, she also said she feels like her “wheels are spinning” and that she doesn’t even seem to care. Dr. D had been a high achiever, yet says she feels like she isn’t getting anywhere at work or at home.

[polldaddy:10064977]

The authors’ observations

As psychiatrists in the business of diagnosis and treatment, we immediately considered common diagnoses, such as major depressive disorder and persistent depressive disorder. However, despite our training in pathology, we believe patients should be considered well until proven sick. This paradigm shift is in line with the definition of mental health per the World Health Organization: “A state of well-being in which every individual realizes his or her own potential, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to her or his community.”1

In Dr. D’s case, there was not enough information yet to fully support any of the diagnoses. She did not exhibit enough depressive symptoms to support a diagnosis of a depressive disorder. She said that she didn’t feel like she was getting anywhere at work or home. Yet there was no objective information that suggested impairment in functioning, which would preclude a diagnosis of adjustment disorder. At this point, we would support the “V code” diagnosis of phase of life problem, or even what is rarely seen in a psychiatric evaluation: “no diagnosis.”

EVALUATION Is work the problem?

We diligently conduct a thorough review of systems with Dr. D and confirm there is not enough information to diagnose a depressive disorder, anxiety disorder, or other psychiatric disorder. Collateral history suggests her teenagers are well-adjusted and doing well in high school, and she is well-respected at work with reportedly excellent performance ratings. We identify strongly with her and her situation.

Dr. D admits she is an idealist and half-jokingly says she entered into medicine “to save the world.” Yet she laments the long hours and finding herself mired in paperwork. She is barely making it to her kids’ school events and says she can’t believe her first child will be graduating within a year. She has had some particularly challenging patients recently, and although she is still diligent about their care, she is shocked she doesn’t seem to care as much about “solving the medical puzzle.” This came to light for her when a longtime patient observed that Dr. D didn’t seem herself and asked, “Are you all right, Doc?”

Dr. D is professionally dressed and has excellent grooming and hygiene. She looks tired, yet has a full affect, a witty conversational style, and responds appropriately to humor.

[polldaddy:10064980]

The authors’ observations

It can be difficult to know what to do next when there isn’t an established “playbook” for a problem without a diagnosis. We realized Dr. D was describing burnout, a syndrome of depersonalization (detached and not caring, to the point of viewing people as objects), emotional exhaustion, and low personal accomplishment that leads to decreased effectiveness at work.2 DSM-5 does not include “burnout” as a diagnosis3; however, if symptoms evolve to the point where they affect occupational or social functioning, burnout can be similar to adjustment disorder. Treatment with an antidepressant medication is not appropriate. It is possible that CBT might be helpful for many patients, yet there is no evidence that Dr. D has any cognitive distortions. Although we already had some collateral information, it is never wrong to gather additional collateral. However, because burnout is common, we may not need additional information. We could reassure her and send her on her way, but we want to add therapeutic value. We advocated exploring issues in her life and work related to meaning.

Continue to: Physician burnout

Physician burnout

Burnout is an alarmingly common problem among physicians that affects approximately half of psychiatrists. In 2014, 54.4% of physicians, and slightly less than 50% of psychiatrists, had at least 1 symptom of burnout.4 This was up from the 45.5% of physicians and a little more than 40% of psychiatrists who reported burnout in 2011,4 which suggests that as medicine continues to change, doctors may increasingly feel the brunt of this change. The rate of burnout is highest in front-line specialties (family medicine, general internal medicine, and emergency medicine) and lowest in preventive medicine.5 Physician burnout leads to real-world occupational issues, such as medical errors, poor relationships with coworkers and patients, decreased patient satisfaction, and medical malpractice suits.6,7

Even though burnout is clearly a concern for our colleagues, don’t expect them to proactively line up outside our offices. In a survey of 7,197 surgeons, 86.6% of respondents answered it was not important that “I have regular meetings with a psychologist/psychiatrist to discuss stress.”8 At the same time, the idea of meeting with a psychologist/psychiatrist was rated more highly by surgeons who were burnt out and found to be a factor independently associated with burnout.8 Perhaps we have some work to do in marketing our services in a way that welcomes our colleagues.

Although physician burnout has been a focus of recent studies, burnout in general has been studied for decades in other working populations. There are 2 useful models describing burnout:

- The job demand-control(-support) model suggests that individuals experience strain and subsequent ill effects when the demands of their job exceed the control they have,9 and social support from supervisors and colleagues can buffer the harmful effects of job strain.10

- The effort-reward imbalance model suggests that high-effort, low-reward occupational conditions are particularly stressful.11

Both models are simple, intuitive, and suggest solutions.

When engaging your physician colleagues about their burnout, remember that physicians are people, too, and have the same difficulties that everyone else does in successfully practicing healthy behaviors. As physicians, we have significant demands on our time that make it difficult to control our ability to eat, sleep, and exercise. In general, the food available where we work is not nutritious,12 half of us are overweight or obese,13 and working more than 40 hours per week increases the likelihood we’ll have a higher body mass index.14 We don’t sleep well, either—we get less sleep than the general population,15 and more sleep equates to less burnout.16 Regarding exercise, doctors who cannot prioritize exercise tend to have more burnout.17

Continue to: When evaluating a physician colleague for symptoms of burnout...

When evaluating a physician colleague for symptoms of burnout, start by assessing the basics: eating, sleeping, and moving. In Dr. D’s case, this also included taking a quick inventory of what demands were on her proverbial plate. Taking inventory of these demands (ie, demand-control[-support] model) may lead to new insights about what she can control. Prioritization is important to determine where efforts go (ie, effort-reward imbalance model). This is where your skills as a psychiatrist can especially help, as you explore values and bring trade-offs to light.

EVALUATION Permission not to be perfect

As we interview Dr. D, we realize she has some obsessive-compulsive personality traits that are mostly self-serving. She places a high value on being thorough and having elegant clinical notes. Yet this value competes with her desire to be efficient and get home on time to see her kids’ school events. You point this out to her and see if she can come up with some solutions. You also discuss with Dr. D the tension everyone feels between valuing career and valuing family and friends. You normalize her situation, and give her permission to pick something about which she will allow herself not to be perfect.

[polldaddy:10064981]

The authors’ observations

Since perfectionism is a common trait among physicians,18 failure doesn’t seem to be compatible with their DNA. We encourage other physicians to be scientific about their own lives, just as they are in the profession they have chosen. Physicians can delude themselves into thinking they can have it all, not recognizing that every choice has its cost. For example, a physician who decides that it’s okay to publish one fewer research paper this year might have more time to enjoy spending time with his or her children. In our work with physicians, we strive to normalize their experiences, helping them reframe their perfectionistic viewpoint to recognize that everyone struggles with work-life balance issues. We validate that physicians have difficult choices to make in finding what works for them, and we challenge and support them in exploring these choices.

Choosing where to put one’s efforts is also contingent upon the expected rewards. Sometime before the daily grind of our careers in medicine started, we had strong visions of what such careers would mean to us. We visualized the ideal of helping people and making a difference. Then, at some point, many of us took this for granted and forgot about the intrinsic rewards of our work. In a 2014-2015 survey of U.S. physicians across all specialties, only 64.6% of respondents who were highly burned out said they found their work personally rewarding. This is a sharp contrast to the 97.5% of respondents who were not burned out who reported that they found their work personally rewarding.19

As psychiatrists, we can challenge our physician colleagues to dare to dream again. We can help them rediscover the rewarding aspects of their work (ie, per effort-reward imbalance model) that drew them into medicine in the first place. This may include exploring their future legacy. How do they want to be remembered at retirement? Such consideration is linked to mental simulation and meaning in their lives.20 We guide our colleagues to reframe their current situation to see the myriad of choices they have based upon their own specific value system. If family and friends are currently taking priority over work, it also helps to reframe that working allows us to make a good living so we can fully enjoy that time spent with family and friends.

Continue to: If we do our jobs well...

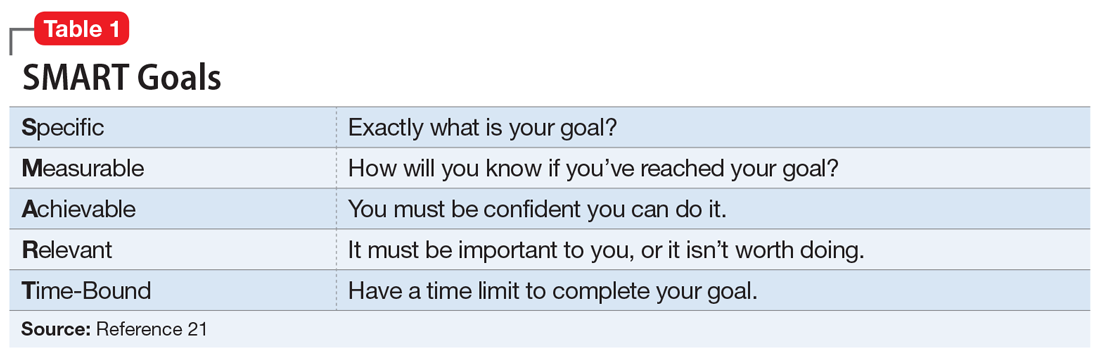

If we do our jobs well, the next part is easy. We have them set specific short- and long-term goals related to their situation. This is something we do every day in our practices. It may help to make sure we’re using SMART (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, Time-Bound), a well-known mnemonic used for goals (Table 121), and brush up on our motivational interviewing skills (see Related Resources). It is especially important to make sure our colleagues have goals that are relevant—the “R” in the SMART mnemonic—to their situation.

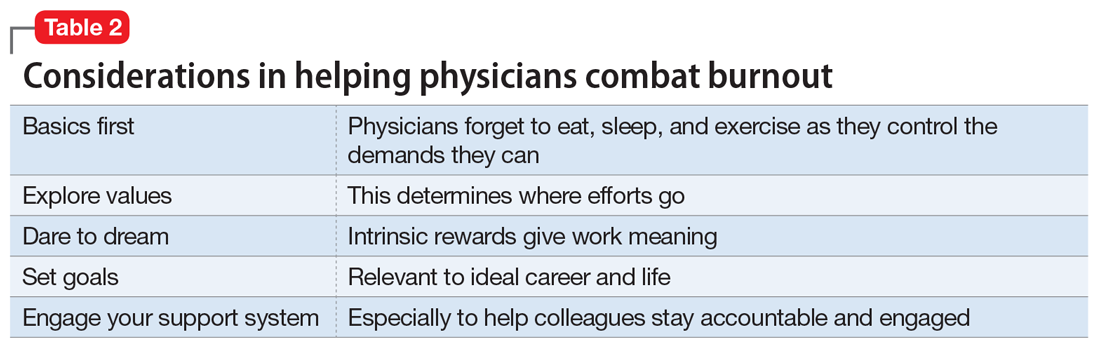

Finally, we do a better job of reaching our goals and engaging more at work and at home when we have good social support. For physicians, co-worker support has been found to be directly related to our well-being as well as buffering the negative effects of work demands.22 Furthermore, our colleagues are the most acceptable sources of support when we are faced with stressful situations.23 Thus, as psychiatrists, we can doubly help our physician patients by providing collegial support and doing our usual job of holding them accountable to their goals (Table 2).

OUTCOME Goal-setting, priorities, accountability

As we’re exploring goals with Dr. D, she makes a conscious decision to spend less time on documentation and start focusing on being present with her patients. She returns in 1 month to tell you time management is still a struggle, but her visit with you was instrumental in making her realize how important it was to get home on time for her kids’ activities. She says it greatly helped that you kept her accountable, yet also validated her struggles and gave her permission to design her life within the constraints of her situation and without the burden of having to be perfect at everything.

Bottom Line

We can best help our physician colleagues who are experiencing burnout by shifting our paradigm to a wellness model that focuses on helping them reach their potential and balance their professional and personal lives.

Related Resources

- Balch CM, Shanafelt TD. Combating stress and burnout in surgical practice: a review. Thorac Surg Clin. 2011;21(3):417-430.

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: preparing people for change, 2nd ed. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2002.

- Stanford Medicine WellMD. Stress & Burnout. https://wellmd.stanford.edu.

1. World Health Organization. Mental health: a state of well-being. http://www.who.int/features/factfiles/mental_health/en/. Updated August 2014. Accessed March 17, 2017.

2. Maslach C, Jackson S, Leiter M. Maslach burnout inventory manual, 3rd ed. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1996.

3. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

4. Shanafelt TD, Hasan O, Dyrbye LN, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(12):1600-1613.

5. Shanafelt TD, Boone S, Tan L, et al. Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among US physicians relative to the general US population. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(18):1377-1385.

6. Shanafelt TD, Sloan JA, Habermann TM. The well-being of physicians. Am J Med. 2003;114(6):513-519.

7. Balch CM, Shanafelt TD. Combating stress and burnout in surgical practice: a review. Adv Surg. 2010;44:29-47.

8. Shanafelt TD, Oreskovich MR, Dyrbye LN, et al. Avoiding burnout: the personal health habits and wellness practices of US Surgeons. Ann Surg. 2012;255(4):625-633.

9. Karasek RA Jr. Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: implications for job redesign. Adm Sci Q. 1979;24(2):285-308.

10. Johnson JV. Collective control: strategies for survival in the workplace. Int J Health Serv. 1989;19(3):469-480.

11. Siegrist J. Adverse health effects of high-effort/low-reward conditions. J Occup Health Psychol. 1996;1(1):27-41.

12. Lesser LI, Cohen DA, Brook RH. Changing eating habits for the medical profession. JAMA. 2012;308(10):983-984.

13. Bleich SN, Bennett WL, Gudzune KA, et al. Impact of physician BMI on obesity care and beliefs. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2012;20(5):999-1005.

14. Stanford FC, Durkin MW, Blair SN, et al. Determining levels of physical activity in attending physicians, resident and fellow physicians, and medical students in the USA. Br J Sports Med. 2012;46(5):360-364.

15. Tucker P, Bejerot E, Kecklund G, et al. Stress Research Institute at Stockholm University. Stress Research Report-doctors’ work hours in Sweden: their impact on sleep, health, work-family balance, patient care and thoughts about work. https://www.stressforskning.su.se/polopoly_fs/1.233341.1429526778!/menu/standard/file/sfr325.pdf. Accessed March 17, 2017.

16. Wisetborisut A, Angkurawaranon C, Jiraporncharoen W, et al. Shift work and burnout among health care workers. Occup Med (Lond). 2014;64(4):279-286.

17. Eckleberry-Hunt J, Lick D, Boura J, et al. An exploratory study of resident burnout and wellness. Acad Med. 2009;84(2):269-277.

18. Peters M, King J. Perfectionism in doctors. BMJ. 2012;344:e1674. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.e1674.

19. Jager AJ, Tutty MA, Kao AC. Association between physician burnout and identification with medicine as a calling. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92(3):415-422.

20. Waytz A, Hershfield HE, Tamir DI. Neural and behavioral evidence for the role of mental simulation in meaning in life. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2015;108(2):336-355.

21. SMART Criteria. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SMART_criteria. Accessed March 17, 2017.

22. Hu YY, Fix ML, Hevelone ND, et al. Physicians’ needs in coping with emotional stressors: the case for peer support. Arch Surg. 2012;147(3):212-217.

23. Wallace JE, Lemaire J. On physician well being–you’ll get by with a little help from your friends. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64(12):2565-2577.

CASE ‘I’m stuck’

Dr. D, age 48, an internist practicing general medicine who is a married mother of 2 teenagers, presents with emotional exhaustion. Her medical history is unremarkable other than hyperlipidemia controlled by diet. She describes an episode of reactive depressive symptoms and anxiety when in college, which was related to the stress of final exams, finances, and the dissolution of a long-standing relationship. Regardless, she functioned well and graduated summa cum laude. She says her current feelings of being “stuck” have gradually increased during the past 3 to 4 years. Although she describes being mildly anxious and dysphoric, she also said she feels like her “wheels are spinning” and that she doesn’t even seem to care. Dr. D had been a high achiever, yet says she feels like she isn’t getting anywhere at work or at home.

[polldaddy:10064977]

The authors’ observations

As psychiatrists in the business of diagnosis and treatment, we immediately considered common diagnoses, such as major depressive disorder and persistent depressive disorder. However, despite our training in pathology, we believe patients should be considered well until proven sick. This paradigm shift is in line with the definition of mental health per the World Health Organization: “A state of well-being in which every individual realizes his or her own potential, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to her or his community.”1

In Dr. D’s case, there was not enough information yet to fully support any of the diagnoses. She did not exhibit enough depressive symptoms to support a diagnosis of a depressive disorder. She said that she didn’t feel like she was getting anywhere at work or home. Yet there was no objective information that suggested impairment in functioning, which would preclude a diagnosis of adjustment disorder. At this point, we would support the “V code” diagnosis of phase of life problem, or even what is rarely seen in a psychiatric evaluation: “no diagnosis.”

EVALUATION Is work the problem?

We diligently conduct a thorough review of systems with Dr. D and confirm there is not enough information to diagnose a depressive disorder, anxiety disorder, or other psychiatric disorder. Collateral history suggests her teenagers are well-adjusted and doing well in high school, and she is well-respected at work with reportedly excellent performance ratings. We identify strongly with her and her situation.

Dr. D admits she is an idealist and half-jokingly says she entered into medicine “to save the world.” Yet she laments the long hours and finding herself mired in paperwork. She is barely making it to her kids’ school events and says she can’t believe her first child will be graduating within a year. She has had some particularly challenging patients recently, and although she is still diligent about their care, she is shocked she doesn’t seem to care as much about “solving the medical puzzle.” This came to light for her when a longtime patient observed that Dr. D didn’t seem herself and asked, “Are you all right, Doc?”

Dr. D is professionally dressed and has excellent grooming and hygiene. She looks tired, yet has a full affect, a witty conversational style, and responds appropriately to humor.

[polldaddy:10064980]

The authors’ observations

It can be difficult to know what to do next when there isn’t an established “playbook” for a problem without a diagnosis. We realized Dr. D was describing burnout, a syndrome of depersonalization (detached and not caring, to the point of viewing people as objects), emotional exhaustion, and low personal accomplishment that leads to decreased effectiveness at work.2 DSM-5 does not include “burnout” as a diagnosis3; however, if symptoms evolve to the point where they affect occupational or social functioning, burnout can be similar to adjustment disorder. Treatment with an antidepressant medication is not appropriate. It is possible that CBT might be helpful for many patients, yet there is no evidence that Dr. D has any cognitive distortions. Although we already had some collateral information, it is never wrong to gather additional collateral. However, because burnout is common, we may not need additional information. We could reassure her and send her on her way, but we want to add therapeutic value. We advocated exploring issues in her life and work related to meaning.

Continue to: Physician burnout

Physician burnout

Burnout is an alarmingly common problem among physicians that affects approximately half of psychiatrists. In 2014, 54.4% of physicians, and slightly less than 50% of psychiatrists, had at least 1 symptom of burnout.4 This was up from the 45.5% of physicians and a little more than 40% of psychiatrists who reported burnout in 2011,4 which suggests that as medicine continues to change, doctors may increasingly feel the brunt of this change. The rate of burnout is highest in front-line specialties (family medicine, general internal medicine, and emergency medicine) and lowest in preventive medicine.5 Physician burnout leads to real-world occupational issues, such as medical errors, poor relationships with coworkers and patients, decreased patient satisfaction, and medical malpractice suits.6,7

Even though burnout is clearly a concern for our colleagues, don’t expect them to proactively line up outside our offices. In a survey of 7,197 surgeons, 86.6% of respondents answered it was not important that “I have regular meetings with a psychologist/psychiatrist to discuss stress.”8 At the same time, the idea of meeting with a psychologist/psychiatrist was rated more highly by surgeons who were burnt out and found to be a factor independently associated with burnout.8 Perhaps we have some work to do in marketing our services in a way that welcomes our colleagues.

Although physician burnout has been a focus of recent studies, burnout in general has been studied for decades in other working populations. There are 2 useful models describing burnout:

- The job demand-control(-support) model suggests that individuals experience strain and subsequent ill effects when the demands of their job exceed the control they have,9 and social support from supervisors and colleagues can buffer the harmful effects of job strain.10

- The effort-reward imbalance model suggests that high-effort, low-reward occupational conditions are particularly stressful.11

Both models are simple, intuitive, and suggest solutions.

When engaging your physician colleagues about their burnout, remember that physicians are people, too, and have the same difficulties that everyone else does in successfully practicing healthy behaviors. As physicians, we have significant demands on our time that make it difficult to control our ability to eat, sleep, and exercise. In general, the food available where we work is not nutritious,12 half of us are overweight or obese,13 and working more than 40 hours per week increases the likelihood we’ll have a higher body mass index.14 We don’t sleep well, either—we get less sleep than the general population,15 and more sleep equates to less burnout.16 Regarding exercise, doctors who cannot prioritize exercise tend to have more burnout.17

Continue to: When evaluating a physician colleague for symptoms of burnout...

When evaluating a physician colleague for symptoms of burnout, start by assessing the basics: eating, sleeping, and moving. In Dr. D’s case, this also included taking a quick inventory of what demands were on her proverbial plate. Taking inventory of these demands (ie, demand-control[-support] model) may lead to new insights about what she can control. Prioritization is important to determine where efforts go (ie, effort-reward imbalance model). This is where your skills as a psychiatrist can especially help, as you explore values and bring trade-offs to light.

EVALUATION Permission not to be perfect

As we interview Dr. D, we realize she has some obsessive-compulsive personality traits that are mostly self-serving. She places a high value on being thorough and having elegant clinical notes. Yet this value competes with her desire to be efficient and get home on time to see her kids’ school events. You point this out to her and see if she can come up with some solutions. You also discuss with Dr. D the tension everyone feels between valuing career and valuing family and friends. You normalize her situation, and give her permission to pick something about which she will allow herself not to be perfect.

[polldaddy:10064981]

The authors’ observations

Since perfectionism is a common trait among physicians,18 failure doesn’t seem to be compatible with their DNA. We encourage other physicians to be scientific about their own lives, just as they are in the profession they have chosen. Physicians can delude themselves into thinking they can have it all, not recognizing that every choice has its cost. For example, a physician who decides that it’s okay to publish one fewer research paper this year might have more time to enjoy spending time with his or her children. In our work with physicians, we strive to normalize their experiences, helping them reframe their perfectionistic viewpoint to recognize that everyone struggles with work-life balance issues. We validate that physicians have difficult choices to make in finding what works for them, and we challenge and support them in exploring these choices.

Choosing where to put one’s efforts is also contingent upon the expected rewards. Sometime before the daily grind of our careers in medicine started, we had strong visions of what such careers would mean to us. We visualized the ideal of helping people and making a difference. Then, at some point, many of us took this for granted and forgot about the intrinsic rewards of our work. In a 2014-2015 survey of U.S. physicians across all specialties, only 64.6% of respondents who were highly burned out said they found their work personally rewarding. This is a sharp contrast to the 97.5% of respondents who were not burned out who reported that they found their work personally rewarding.19

As psychiatrists, we can challenge our physician colleagues to dare to dream again. We can help them rediscover the rewarding aspects of their work (ie, per effort-reward imbalance model) that drew them into medicine in the first place. This may include exploring their future legacy. How do they want to be remembered at retirement? Such consideration is linked to mental simulation and meaning in their lives.20 We guide our colleagues to reframe their current situation to see the myriad of choices they have based upon their own specific value system. If family and friends are currently taking priority over work, it also helps to reframe that working allows us to make a good living so we can fully enjoy that time spent with family and friends.

Continue to: If we do our jobs well...

If we do our jobs well, the next part is easy. We have them set specific short- and long-term goals related to their situation. This is something we do every day in our practices. It may help to make sure we’re using SMART (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, Time-Bound), a well-known mnemonic used for goals (Table 121), and brush up on our motivational interviewing skills (see Related Resources). It is especially important to make sure our colleagues have goals that are relevant—the “R” in the SMART mnemonic—to their situation.

Finally, we do a better job of reaching our goals and engaging more at work and at home when we have good social support. For physicians, co-worker support has been found to be directly related to our well-being as well as buffering the negative effects of work demands.22 Furthermore, our colleagues are the most acceptable sources of support when we are faced with stressful situations.23 Thus, as psychiatrists, we can doubly help our physician patients by providing collegial support and doing our usual job of holding them accountable to their goals (Table 2).

OUTCOME Goal-setting, priorities, accountability

As we’re exploring goals with Dr. D, she makes a conscious decision to spend less time on documentation and start focusing on being present with her patients. She returns in 1 month to tell you time management is still a struggle, but her visit with you was instrumental in making her realize how important it was to get home on time for her kids’ activities. She says it greatly helped that you kept her accountable, yet also validated her struggles and gave her permission to design her life within the constraints of her situation and without the burden of having to be perfect at everything.

Bottom Line

We can best help our physician colleagues who are experiencing burnout by shifting our paradigm to a wellness model that focuses on helping them reach their potential and balance their professional and personal lives.

Related Resources

- Balch CM, Shanafelt TD. Combating stress and burnout in surgical practice: a review. Thorac Surg Clin. 2011;21(3):417-430.

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: preparing people for change, 2nd ed. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2002.

- Stanford Medicine WellMD. Stress & Burnout. https://wellmd.stanford.edu.

CASE ‘I’m stuck’

Dr. D, age 48, an internist practicing general medicine who is a married mother of 2 teenagers, presents with emotional exhaustion. Her medical history is unremarkable other than hyperlipidemia controlled by diet. She describes an episode of reactive depressive symptoms and anxiety when in college, which was related to the stress of final exams, finances, and the dissolution of a long-standing relationship. Regardless, she functioned well and graduated summa cum laude. She says her current feelings of being “stuck” have gradually increased during the past 3 to 4 years. Although she describes being mildly anxious and dysphoric, she also said she feels like her “wheels are spinning” and that she doesn’t even seem to care. Dr. D had been a high achiever, yet says she feels like she isn’t getting anywhere at work or at home.

[polldaddy:10064977]

The authors’ observations

As psychiatrists in the business of diagnosis and treatment, we immediately considered common diagnoses, such as major depressive disorder and persistent depressive disorder. However, despite our training in pathology, we believe patients should be considered well until proven sick. This paradigm shift is in line with the definition of mental health per the World Health Organization: “A state of well-being in which every individual realizes his or her own potential, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to her or his community.”1

In Dr. D’s case, there was not enough information yet to fully support any of the diagnoses. She did not exhibit enough depressive symptoms to support a diagnosis of a depressive disorder. She said that she didn’t feel like she was getting anywhere at work or home. Yet there was no objective information that suggested impairment in functioning, which would preclude a diagnosis of adjustment disorder. At this point, we would support the “V code” diagnosis of phase of life problem, or even what is rarely seen in a psychiatric evaluation: “no diagnosis.”

EVALUATION Is work the problem?

We diligently conduct a thorough review of systems with Dr. D and confirm there is not enough information to diagnose a depressive disorder, anxiety disorder, or other psychiatric disorder. Collateral history suggests her teenagers are well-adjusted and doing well in high school, and she is well-respected at work with reportedly excellent performance ratings. We identify strongly with her and her situation.

Dr. D admits she is an idealist and half-jokingly says she entered into medicine “to save the world.” Yet she laments the long hours and finding herself mired in paperwork. She is barely making it to her kids’ school events and says she can’t believe her first child will be graduating within a year. She has had some particularly challenging patients recently, and although she is still diligent about their care, she is shocked she doesn’t seem to care as much about “solving the medical puzzle.” This came to light for her when a longtime patient observed that Dr. D didn’t seem herself and asked, “Are you all right, Doc?”

Dr. D is professionally dressed and has excellent grooming and hygiene. She looks tired, yet has a full affect, a witty conversational style, and responds appropriately to humor.

[polldaddy:10064980]

The authors’ observations

It can be difficult to know what to do next when there isn’t an established “playbook” for a problem without a diagnosis. We realized Dr. D was describing burnout, a syndrome of depersonalization (detached and not caring, to the point of viewing people as objects), emotional exhaustion, and low personal accomplishment that leads to decreased effectiveness at work.2 DSM-5 does not include “burnout” as a diagnosis3; however, if symptoms evolve to the point where they affect occupational or social functioning, burnout can be similar to adjustment disorder. Treatment with an antidepressant medication is not appropriate. It is possible that CBT might be helpful for many patients, yet there is no evidence that Dr. D has any cognitive distortions. Although we already had some collateral information, it is never wrong to gather additional collateral. However, because burnout is common, we may not need additional information. We could reassure her and send her on her way, but we want to add therapeutic value. We advocated exploring issues in her life and work related to meaning.

Continue to: Physician burnout

Physician burnout

Burnout is an alarmingly common problem among physicians that affects approximately half of psychiatrists. In 2014, 54.4% of physicians, and slightly less than 50% of psychiatrists, had at least 1 symptom of burnout.4 This was up from the 45.5% of physicians and a little more than 40% of psychiatrists who reported burnout in 2011,4 which suggests that as medicine continues to change, doctors may increasingly feel the brunt of this change. The rate of burnout is highest in front-line specialties (family medicine, general internal medicine, and emergency medicine) and lowest in preventive medicine.5 Physician burnout leads to real-world occupational issues, such as medical errors, poor relationships with coworkers and patients, decreased patient satisfaction, and medical malpractice suits.6,7

Even though burnout is clearly a concern for our colleagues, don’t expect them to proactively line up outside our offices. In a survey of 7,197 surgeons, 86.6% of respondents answered it was not important that “I have regular meetings with a psychologist/psychiatrist to discuss stress.”8 At the same time, the idea of meeting with a psychologist/psychiatrist was rated more highly by surgeons who were burnt out and found to be a factor independently associated with burnout.8 Perhaps we have some work to do in marketing our services in a way that welcomes our colleagues.

Although physician burnout has been a focus of recent studies, burnout in general has been studied for decades in other working populations. There are 2 useful models describing burnout:

- The job demand-control(-support) model suggests that individuals experience strain and subsequent ill effects when the demands of their job exceed the control they have,9 and social support from supervisors and colleagues can buffer the harmful effects of job strain.10

- The effort-reward imbalance model suggests that high-effort, low-reward occupational conditions are particularly stressful.11

Both models are simple, intuitive, and suggest solutions.

When engaging your physician colleagues about their burnout, remember that physicians are people, too, and have the same difficulties that everyone else does in successfully practicing healthy behaviors. As physicians, we have significant demands on our time that make it difficult to control our ability to eat, sleep, and exercise. In general, the food available where we work is not nutritious,12 half of us are overweight or obese,13 and working more than 40 hours per week increases the likelihood we’ll have a higher body mass index.14 We don’t sleep well, either—we get less sleep than the general population,15 and more sleep equates to less burnout.16 Regarding exercise, doctors who cannot prioritize exercise tend to have more burnout.17

Continue to: When evaluating a physician colleague for symptoms of burnout...

When evaluating a physician colleague for symptoms of burnout, start by assessing the basics: eating, sleeping, and moving. In Dr. D’s case, this also included taking a quick inventory of what demands were on her proverbial plate. Taking inventory of these demands (ie, demand-control[-support] model) may lead to new insights about what she can control. Prioritization is important to determine where efforts go (ie, effort-reward imbalance model). This is where your skills as a psychiatrist can especially help, as you explore values and bring trade-offs to light.

EVALUATION Permission not to be perfect

As we interview Dr. D, we realize she has some obsessive-compulsive personality traits that are mostly self-serving. She places a high value on being thorough and having elegant clinical notes. Yet this value competes with her desire to be efficient and get home on time to see her kids’ school events. You point this out to her and see if she can come up with some solutions. You also discuss with Dr. D the tension everyone feels between valuing career and valuing family and friends. You normalize her situation, and give her permission to pick something about which she will allow herself not to be perfect.

[polldaddy:10064981]

The authors’ observations

Since perfectionism is a common trait among physicians,18 failure doesn’t seem to be compatible with their DNA. We encourage other physicians to be scientific about their own lives, just as they are in the profession they have chosen. Physicians can delude themselves into thinking they can have it all, not recognizing that every choice has its cost. For example, a physician who decides that it’s okay to publish one fewer research paper this year might have more time to enjoy spending time with his or her children. In our work with physicians, we strive to normalize their experiences, helping them reframe their perfectionistic viewpoint to recognize that everyone struggles with work-life balance issues. We validate that physicians have difficult choices to make in finding what works for them, and we challenge and support them in exploring these choices.

Choosing where to put one’s efforts is also contingent upon the expected rewards. Sometime before the daily grind of our careers in medicine started, we had strong visions of what such careers would mean to us. We visualized the ideal of helping people and making a difference. Then, at some point, many of us took this for granted and forgot about the intrinsic rewards of our work. In a 2014-2015 survey of U.S. physicians across all specialties, only 64.6% of respondents who were highly burned out said they found their work personally rewarding. This is a sharp contrast to the 97.5% of respondents who were not burned out who reported that they found their work personally rewarding.19

As psychiatrists, we can challenge our physician colleagues to dare to dream again. We can help them rediscover the rewarding aspects of their work (ie, per effort-reward imbalance model) that drew them into medicine in the first place. This may include exploring their future legacy. How do they want to be remembered at retirement? Such consideration is linked to mental simulation and meaning in their lives.20 We guide our colleagues to reframe their current situation to see the myriad of choices they have based upon their own specific value system. If family and friends are currently taking priority over work, it also helps to reframe that working allows us to make a good living so we can fully enjoy that time spent with family and friends.

Continue to: If we do our jobs well...

If we do our jobs well, the next part is easy. We have them set specific short- and long-term goals related to their situation. This is something we do every day in our practices. It may help to make sure we’re using SMART (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, Time-Bound), a well-known mnemonic used for goals (Table 121), and brush up on our motivational interviewing skills (see Related Resources). It is especially important to make sure our colleagues have goals that are relevant—the “R” in the SMART mnemonic—to their situation.

Finally, we do a better job of reaching our goals and engaging more at work and at home when we have good social support. For physicians, co-worker support has been found to be directly related to our well-being as well as buffering the negative effects of work demands.22 Furthermore, our colleagues are the most acceptable sources of support when we are faced with stressful situations.23 Thus, as psychiatrists, we can doubly help our physician patients by providing collegial support and doing our usual job of holding them accountable to their goals (Table 2).

OUTCOME Goal-setting, priorities, accountability

As we’re exploring goals with Dr. D, she makes a conscious decision to spend less time on documentation and start focusing on being present with her patients. She returns in 1 month to tell you time management is still a struggle, but her visit with you was instrumental in making her realize how important it was to get home on time for her kids’ activities. She says it greatly helped that you kept her accountable, yet also validated her struggles and gave her permission to design her life within the constraints of her situation and without the burden of having to be perfect at everything.

Bottom Line

We can best help our physician colleagues who are experiencing burnout by shifting our paradigm to a wellness model that focuses on helping them reach their potential and balance their professional and personal lives.

Related Resources

- Balch CM, Shanafelt TD. Combating stress and burnout in surgical practice: a review. Thorac Surg Clin. 2011;21(3):417-430.

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: preparing people for change, 2nd ed. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2002.

- Stanford Medicine WellMD. Stress & Burnout. https://wellmd.stanford.edu.

1. World Health Organization. Mental health: a state of well-being. http://www.who.int/features/factfiles/mental_health/en/. Updated August 2014. Accessed March 17, 2017.

2. Maslach C, Jackson S, Leiter M. Maslach burnout inventory manual, 3rd ed. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1996.

3. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

4. Shanafelt TD, Hasan O, Dyrbye LN, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(12):1600-1613.

5. Shanafelt TD, Boone S, Tan L, et al. Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among US physicians relative to the general US population. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(18):1377-1385.

6. Shanafelt TD, Sloan JA, Habermann TM. The well-being of physicians. Am J Med. 2003;114(6):513-519.

7. Balch CM, Shanafelt TD. Combating stress and burnout in surgical practice: a review. Adv Surg. 2010;44:29-47.

8. Shanafelt TD, Oreskovich MR, Dyrbye LN, et al. Avoiding burnout: the personal health habits and wellness practices of US Surgeons. Ann Surg. 2012;255(4):625-633.

9. Karasek RA Jr. Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: implications for job redesign. Adm Sci Q. 1979;24(2):285-308.

10. Johnson JV. Collective control: strategies for survival in the workplace. Int J Health Serv. 1989;19(3):469-480.

11. Siegrist J. Adverse health effects of high-effort/low-reward conditions. J Occup Health Psychol. 1996;1(1):27-41.

12. Lesser LI, Cohen DA, Brook RH. Changing eating habits for the medical profession. JAMA. 2012;308(10):983-984.

13. Bleich SN, Bennett WL, Gudzune KA, et al. Impact of physician BMI on obesity care and beliefs. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2012;20(5):999-1005.

14. Stanford FC, Durkin MW, Blair SN, et al. Determining levels of physical activity in attending physicians, resident and fellow physicians, and medical students in the USA. Br J Sports Med. 2012;46(5):360-364.

15. Tucker P, Bejerot E, Kecklund G, et al. Stress Research Institute at Stockholm University. Stress Research Report-doctors’ work hours in Sweden: their impact on sleep, health, work-family balance, patient care and thoughts about work. https://www.stressforskning.su.se/polopoly_fs/1.233341.1429526778!/menu/standard/file/sfr325.pdf. Accessed March 17, 2017.

16. Wisetborisut A, Angkurawaranon C, Jiraporncharoen W, et al. Shift work and burnout among health care workers. Occup Med (Lond). 2014;64(4):279-286.

17. Eckleberry-Hunt J, Lick D, Boura J, et al. An exploratory study of resident burnout and wellness. Acad Med. 2009;84(2):269-277.

18. Peters M, King J. Perfectionism in doctors. BMJ. 2012;344:e1674. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.e1674.

19. Jager AJ, Tutty MA, Kao AC. Association between physician burnout and identification with medicine as a calling. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92(3):415-422.

20. Waytz A, Hershfield HE, Tamir DI. Neural and behavioral evidence for the role of mental simulation in meaning in life. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2015;108(2):336-355.

21. SMART Criteria. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SMART_criteria. Accessed March 17, 2017.

22. Hu YY, Fix ML, Hevelone ND, et al. Physicians’ needs in coping with emotional stressors: the case for peer support. Arch Surg. 2012;147(3):212-217.

23. Wallace JE, Lemaire J. On physician well being–you’ll get by with a little help from your friends. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64(12):2565-2577.

1. World Health Organization. Mental health: a state of well-being. http://www.who.int/features/factfiles/mental_health/en/. Updated August 2014. Accessed March 17, 2017.

2. Maslach C, Jackson S, Leiter M. Maslach burnout inventory manual, 3rd ed. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1996.

3. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

4. Shanafelt TD, Hasan O, Dyrbye LN, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(12):1600-1613.

5. Shanafelt TD, Boone S, Tan L, et al. Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among US physicians relative to the general US population. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(18):1377-1385.

6. Shanafelt TD, Sloan JA, Habermann TM. The well-being of physicians. Am J Med. 2003;114(6):513-519.

7. Balch CM, Shanafelt TD. Combating stress and burnout in surgical practice: a review. Adv Surg. 2010;44:29-47.

8. Shanafelt TD, Oreskovich MR, Dyrbye LN, et al. Avoiding burnout: the personal health habits and wellness practices of US Surgeons. Ann Surg. 2012;255(4):625-633.

9. Karasek RA Jr. Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: implications for job redesign. Adm Sci Q. 1979;24(2):285-308.

10. Johnson JV. Collective control: strategies for survival in the workplace. Int J Health Serv. 1989;19(3):469-480.

11. Siegrist J. Adverse health effects of high-effort/low-reward conditions. J Occup Health Psychol. 1996;1(1):27-41.

12. Lesser LI, Cohen DA, Brook RH. Changing eating habits for the medical profession. JAMA. 2012;308(10):983-984.

13. Bleich SN, Bennett WL, Gudzune KA, et al. Impact of physician BMI on obesity care and beliefs. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2012;20(5):999-1005.

14. Stanford FC, Durkin MW, Blair SN, et al. Determining levels of physical activity in attending physicians, resident and fellow physicians, and medical students in the USA. Br J Sports Med. 2012;46(5):360-364.

15. Tucker P, Bejerot E, Kecklund G, et al. Stress Research Institute at Stockholm University. Stress Research Report-doctors’ work hours in Sweden: their impact on sleep, health, work-family balance, patient care and thoughts about work. https://www.stressforskning.su.se/polopoly_fs/1.233341.1429526778!/menu/standard/file/sfr325.pdf. Accessed March 17, 2017.

16. Wisetborisut A, Angkurawaranon C, Jiraporncharoen W, et al. Shift work and burnout among health care workers. Occup Med (Lond). 2014;64(4):279-286.

17. Eckleberry-Hunt J, Lick D, Boura J, et al. An exploratory study of resident burnout and wellness. Acad Med. 2009;84(2):269-277.

18. Peters M, King J. Perfectionism in doctors. BMJ. 2012;344:e1674. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.e1674.

19. Jager AJ, Tutty MA, Kao AC. Association between physician burnout and identification with medicine as a calling. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92(3):415-422.

20. Waytz A, Hershfield HE, Tamir DI. Neural and behavioral evidence for the role of mental simulation in meaning in life. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2015;108(2):336-355.

21. SMART Criteria. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SMART_criteria. Accessed March 17, 2017.

22. Hu YY, Fix ML, Hevelone ND, et al. Physicians’ needs in coping with emotional stressors: the case for peer support. Arch Surg. 2012;147(3):212-217.

23. Wallace JE, Lemaire J. On physician well being–you’ll get by with a little help from your friends. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64(12):2565-2577.

Partial hold placed on trial of drug for AML, MDS

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has placed a partial clinical hold on a phase 1b/2 study of OXi4503, a vascular disrupting agent.

In this trial (NCT02576301), researchers are evaluating OXi4503, alone and in combination with cytarabine, in patients with relapsed/refractory acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS).

The partial clinical hold applies to the 12.2 mg/m2 dose of OXi4503.

The FDA is allowing the continued treatment and enrollment of patients using a dose of 9.76 mg/m2.

The agency said additional data on patients receiving OXi4503 at 9.76 mg/m2 must be evaluated before dosing at 12.2 mg/m2 can be resumed.

The partial clinical hold is a result of 2 potential dose-limiting toxicities (DLTs) observed at the 12.2 mg/m2 dose level.

One DLT was hypotension, which occurred shortly after initial treatment with OXi4503. The other DLT was acute hypoxic respiratory failure, which occurred approximately 2 weeks after receiving OXi4503 and cytarabine.

Both events were deemed “possibly related” to OXi4503, and both patients recovered following treatment.

The study protocol generally defines a DLT as any grade 3 serious adverse event where a relationship to OXi4503 cannot be ruled out.

“Although it is disappointing that we are not currently continuing with the higher dose of OXi4503, we look forward to gathering more safety and efficacy data at the previous dose level, where we observed 2 complete remissions in the 4 patients that we treated,” said William D. Schwieterman, MD, chief executive officer of Mateon Therapeutics, Inc., the company developing OXi4503.

About OXi4503

According to Mateon Therapeutics, OXi4503 has a dual mechanism of action that disrupts the shape of tumor bone marrow endothelial cells through reversible binding to tubulin at the colchicine binding site, downregulating intercellular adhesion molecules.

This alters the endothelial cell shape, releasing quiescent adherent tumor cells from bone marrow endothelial cells and activating the cell cycle, which makes the tumor cells vulnerable to chemotherapy.

OXi4503 also kills tumor cells directly via myeloperoxidase activation of an orthoquinone cytotoxic mediator.

In preclinical research, OXi4503 demonstrated activity against AML, both when given alone and in combination with bevacizumab. These results were published in Blood in 2010.

Clinical trials

In a phase 1 trial (NCT01085656), researchers evaluated OXi4503 in patients with relapsed or refractory AML or MDS. The goals were to determine the safety profile, maximum tolerated dose, and biologic activity of OXi4503.

The researchers said OXi4503 demonstrated preliminary evidence of disease response in heavily pre-treated, refractory AML and advanced MDS.

The maximum tolerated dose of OXi4503 was not identified, but adverse events attributable to the drug included hypertension, bone pain, fever, anemia, thrombocytopenia, and coagulopathies.

Results from this study were presented at the 2013 ASH Annual Meeting.

In 2015, Mateon Therapeutics initiated the phase 1b/2 study of OXi4503 (NCT02576301) that is now on partial clinical hold.

The phase 1 portion of this study was designed to assess the safety, pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and preliminary efficacy of single-agent OXi4503 in patients with relapsed/refractory AML and MDS.

The phase 1 portion was also intended to determine the safety, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of OXi4503 plus intermediate-dose cytarabine.

The goal of the phase 2 portion is to assess the preliminary efficacy of OXi4503 and cytarabine in patients with AML and MDS.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has placed a partial clinical hold on a phase 1b/2 study of OXi4503, a vascular disrupting agent.

In this trial (NCT02576301), researchers are evaluating OXi4503, alone and in combination with cytarabine, in patients with relapsed/refractory acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS).

The partial clinical hold applies to the 12.2 mg/m2 dose of OXi4503.

The FDA is allowing the continued treatment and enrollment of patients using a dose of 9.76 mg/m2.

The agency said additional data on patients receiving OXi4503 at 9.76 mg/m2 must be evaluated before dosing at 12.2 mg/m2 can be resumed.

The partial clinical hold is a result of 2 potential dose-limiting toxicities (DLTs) observed at the 12.2 mg/m2 dose level.

One DLT was hypotension, which occurred shortly after initial treatment with OXi4503. The other DLT was acute hypoxic respiratory failure, which occurred approximately 2 weeks after receiving OXi4503 and cytarabine.

Both events were deemed “possibly related” to OXi4503, and both patients recovered following treatment.

The study protocol generally defines a DLT as any grade 3 serious adverse event where a relationship to OXi4503 cannot be ruled out.