User login

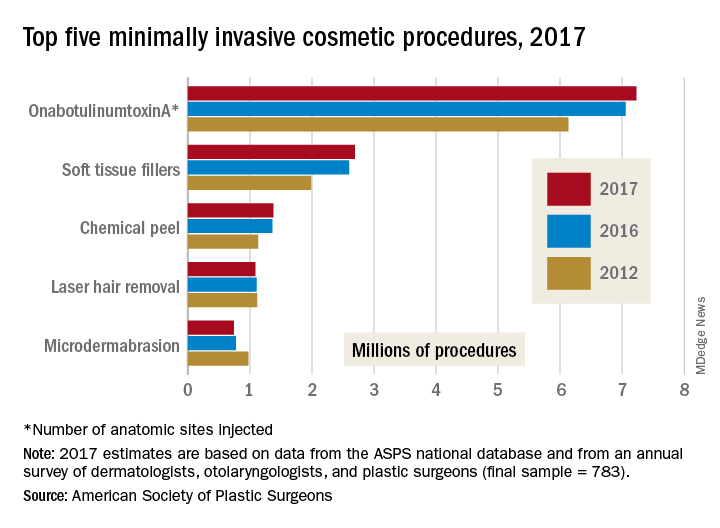

Cosmetic procedures show continued growth

and two declining, according to the American Society of Plastic Surgeons.

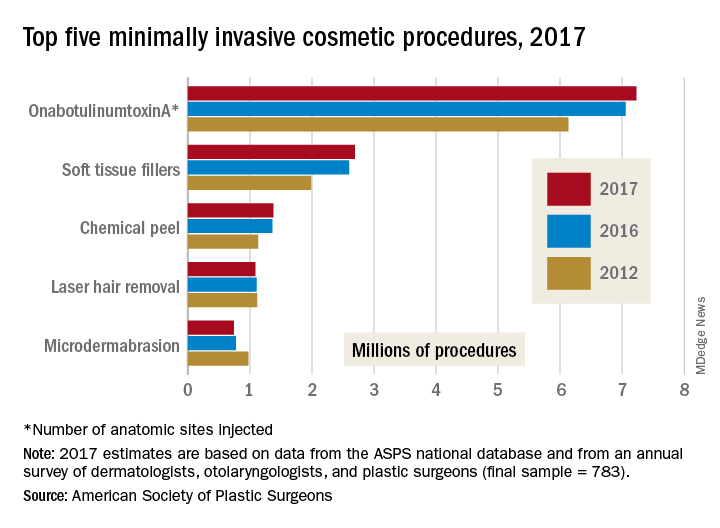

The gainers were the three most popular procedures: OnabotulinumtoxinA injections topped the list with 7.23 million anatomic sites injected – an increase of 2% over 2016 – followed by injection of soft tissue fillers with 2.69 million procedures (up 3%) and chemical peels with 1.38 million procedures (an increase of 1%), the ASPS said in its 2017 Plastic Surgery Statistics Report.

The two decliners among the top five were laser hair removal, which dropped 2% to 1.09 million procedures, and microdermabrasion, which continued a long-term decline by falling 4% to 740,000 procedures in 2017, the ASPS reported.

The minimally invasive cosmetic sector as a whole was up by 2% last year, bringing the number of total procedures to 15.7 million. Cosmetic surgical procedures were up by 1% from 2016 to 2017, reaching a total of 1.79 million. The five most popular cosmetic surgeries were breast augmentation (300,000 performed), liposuction (246,000), rhinoplasty (219,000), blepharoplasty (210,000), and abdominoplasty (130,000), according to the ASPS Tracking Operations and Outcomes for Plastic Surgeons database and an annual survey of board-certified dermatologists, otolaryngologists, and plastic surgeons (final sample = 783).

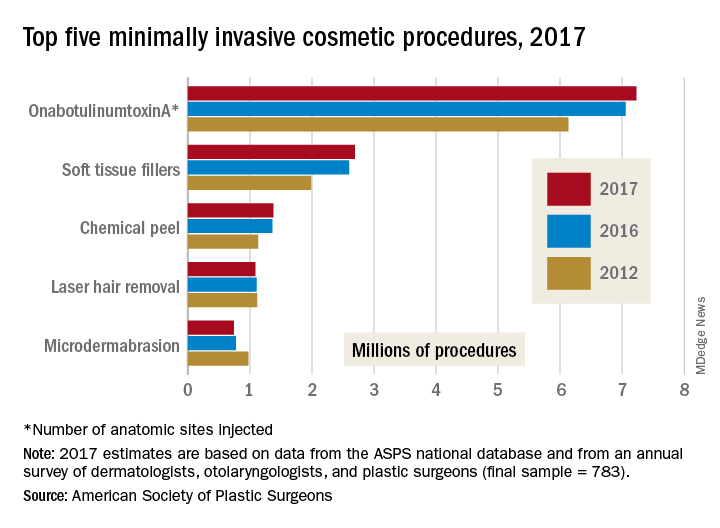

and two declining, according to the American Society of Plastic Surgeons.

The gainers were the three most popular procedures: OnabotulinumtoxinA injections topped the list with 7.23 million anatomic sites injected – an increase of 2% over 2016 – followed by injection of soft tissue fillers with 2.69 million procedures (up 3%) and chemical peels with 1.38 million procedures (an increase of 1%), the ASPS said in its 2017 Plastic Surgery Statistics Report.

The two decliners among the top five were laser hair removal, which dropped 2% to 1.09 million procedures, and microdermabrasion, which continued a long-term decline by falling 4% to 740,000 procedures in 2017, the ASPS reported.

The minimally invasive cosmetic sector as a whole was up by 2% last year, bringing the number of total procedures to 15.7 million. Cosmetic surgical procedures were up by 1% from 2016 to 2017, reaching a total of 1.79 million. The five most popular cosmetic surgeries were breast augmentation (300,000 performed), liposuction (246,000), rhinoplasty (219,000), blepharoplasty (210,000), and abdominoplasty (130,000), according to the ASPS Tracking Operations and Outcomes for Plastic Surgeons database and an annual survey of board-certified dermatologists, otolaryngologists, and plastic surgeons (final sample = 783).

and two declining, according to the American Society of Plastic Surgeons.

The gainers were the three most popular procedures: OnabotulinumtoxinA injections topped the list with 7.23 million anatomic sites injected – an increase of 2% over 2016 – followed by injection of soft tissue fillers with 2.69 million procedures (up 3%) and chemical peels with 1.38 million procedures (an increase of 1%), the ASPS said in its 2017 Plastic Surgery Statistics Report.

The two decliners among the top five were laser hair removal, which dropped 2% to 1.09 million procedures, and microdermabrasion, which continued a long-term decline by falling 4% to 740,000 procedures in 2017, the ASPS reported.

The minimally invasive cosmetic sector as a whole was up by 2% last year, bringing the number of total procedures to 15.7 million. Cosmetic surgical procedures were up by 1% from 2016 to 2017, reaching a total of 1.79 million. The five most popular cosmetic surgeries were breast augmentation (300,000 performed), liposuction (246,000), rhinoplasty (219,000), blepharoplasty (210,000), and abdominoplasty (130,000), according to the ASPS Tracking Operations and Outcomes for Plastic Surgeons database and an annual survey of board-certified dermatologists, otolaryngologists, and plastic surgeons (final sample = 783).

MI risk prediction after noncardiac surgery simplified

ORLANDO – The risk of perioperative MI or death associated with noncardiac surgery is vanishingly low in patients free of diabetes, hypertension, and smoking, Tanya Wilcox, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

How small is the risk? A mere 1 in 1,000, according to her analysis of more than 3.8 million major noncardiac surgeries in the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program database for 2009-2015, according to Dr. Wilcox of New York University.

Physicians are frequently asked by surgeons to clear patients for noncardiac surgery in terms of cardiovascular risk. Because current risk scores are complex, aren’t amenable to rapid bedside calculations, and may entail cardiac stress testing, Dr. Wilcox decided it was worth assessing the impact of three straightforward cardiovascular risk factors – current smoking and treatment for hypertension or diabetes – on 30-day postoperative MI-free survival. For this purpose she turned to the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program database, a validated, risk-adjusted, outcomes-based program to measure and improve the quality of surgical care utilizing data from 250 U.S. surgical centers.

Of the 3,817,113 patients who underwent major noncardiac surgery, 1,586,020 (42%) of them had none of the three cardiovascular risk factors of interest, 1,541,846 (40%) had one, 643,424 (17%) had two, and 45,823, or 1.2%, had all three. The patients’ mean age was 57, 75% were white, and 57% were women. About half of all patients underwent various operations within the realm of general surgery; next most frequent were orthopedic procedures, accounting for 18% of total noncardiac surgery. Of note, only 23% of patients with zero risk factors were American Society of Anesthesiologists Class 3-5, compared with 51% of those with one cardiovascular risk factor, 76% with two, and 71% with all three.

The incidence of acute MI or death within 30 days of noncardiac surgery climbed in stepwise fashion according to a patient’s risk factor burden. In a multivariate analysis adjusted for age, race, and gender, patients with any one of the cardiovascular risk factors had a 30-day risk of acute MI or death that was 1.52 times greater than those with no risk factors, patients with two risk factors were at 2.4-fold increased risk, and those with all three were at 3.63-fold greater risk than those with none. The degree of increased risk associated with any single risk factor ranged from 1.47-fold for hypertension to 1.94-fold for smoking.

“Further study is needed to determine whether aggressive risk factor modifications in the form of blood pressure control, glycemic control, and smoking cessation could reduce the incidence of postoperative MI,” Dr. Wilcox observed.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study.

ORLANDO – The risk of perioperative MI or death associated with noncardiac surgery is vanishingly low in patients free of diabetes, hypertension, and smoking, Tanya Wilcox, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

How small is the risk? A mere 1 in 1,000, according to her analysis of more than 3.8 million major noncardiac surgeries in the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program database for 2009-2015, according to Dr. Wilcox of New York University.

Physicians are frequently asked by surgeons to clear patients for noncardiac surgery in terms of cardiovascular risk. Because current risk scores are complex, aren’t amenable to rapid bedside calculations, and may entail cardiac stress testing, Dr. Wilcox decided it was worth assessing the impact of three straightforward cardiovascular risk factors – current smoking and treatment for hypertension or diabetes – on 30-day postoperative MI-free survival. For this purpose she turned to the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program database, a validated, risk-adjusted, outcomes-based program to measure and improve the quality of surgical care utilizing data from 250 U.S. surgical centers.

Of the 3,817,113 patients who underwent major noncardiac surgery, 1,586,020 (42%) of them had none of the three cardiovascular risk factors of interest, 1,541,846 (40%) had one, 643,424 (17%) had two, and 45,823, or 1.2%, had all three. The patients’ mean age was 57, 75% were white, and 57% were women. About half of all patients underwent various operations within the realm of general surgery; next most frequent were orthopedic procedures, accounting for 18% of total noncardiac surgery. Of note, only 23% of patients with zero risk factors were American Society of Anesthesiologists Class 3-5, compared with 51% of those with one cardiovascular risk factor, 76% with two, and 71% with all three.

The incidence of acute MI or death within 30 days of noncardiac surgery climbed in stepwise fashion according to a patient’s risk factor burden. In a multivariate analysis adjusted for age, race, and gender, patients with any one of the cardiovascular risk factors had a 30-day risk of acute MI or death that was 1.52 times greater than those with no risk factors, patients with two risk factors were at 2.4-fold increased risk, and those with all three were at 3.63-fold greater risk than those with none. The degree of increased risk associated with any single risk factor ranged from 1.47-fold for hypertension to 1.94-fold for smoking.

“Further study is needed to determine whether aggressive risk factor modifications in the form of blood pressure control, glycemic control, and smoking cessation could reduce the incidence of postoperative MI,” Dr. Wilcox observed.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study.

ORLANDO – The risk of perioperative MI or death associated with noncardiac surgery is vanishingly low in patients free of diabetes, hypertension, and smoking, Tanya Wilcox, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

How small is the risk? A mere 1 in 1,000, according to her analysis of more than 3.8 million major noncardiac surgeries in the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program database for 2009-2015, according to Dr. Wilcox of New York University.

Physicians are frequently asked by surgeons to clear patients for noncardiac surgery in terms of cardiovascular risk. Because current risk scores are complex, aren’t amenable to rapid bedside calculations, and may entail cardiac stress testing, Dr. Wilcox decided it was worth assessing the impact of three straightforward cardiovascular risk factors – current smoking and treatment for hypertension or diabetes – on 30-day postoperative MI-free survival. For this purpose she turned to the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program database, a validated, risk-adjusted, outcomes-based program to measure and improve the quality of surgical care utilizing data from 250 U.S. surgical centers.

Of the 3,817,113 patients who underwent major noncardiac surgery, 1,586,020 (42%) of them had none of the three cardiovascular risk factors of interest, 1,541,846 (40%) had one, 643,424 (17%) had two, and 45,823, or 1.2%, had all three. The patients’ mean age was 57, 75% were white, and 57% were women. About half of all patients underwent various operations within the realm of general surgery; next most frequent were orthopedic procedures, accounting for 18% of total noncardiac surgery. Of note, only 23% of patients with zero risk factors were American Society of Anesthesiologists Class 3-5, compared with 51% of those with one cardiovascular risk factor, 76% with two, and 71% with all three.

The incidence of acute MI or death within 30 days of noncardiac surgery climbed in stepwise fashion according to a patient’s risk factor burden. In a multivariate analysis adjusted for age, race, and gender, patients with any one of the cardiovascular risk factors had a 30-day risk of acute MI or death that was 1.52 times greater than those with no risk factors, patients with two risk factors were at 2.4-fold increased risk, and those with all three were at 3.63-fold greater risk than those with none. The degree of increased risk associated with any single risk factor ranged from 1.47-fold for hypertension to 1.94-fold for smoking.

“Further study is needed to determine whether aggressive risk factor modifications in the form of blood pressure control, glycemic control, and smoking cessation could reduce the incidence of postoperative MI,” Dr. Wilcox observed.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study.

REPORTING FROM ACC 2018

Key clinical point: Noncardiac surgery patients can breathe easier regarding perioperative cardiovascular risk provided they don’t smoke and aren’t hypertensive or diabetic.

Major finding: .

Study details: This was a retrospective analysis of more than 3.8 million noncardiac surgeries contained in the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program database for 2009-2015.

Disclosures: The study presenter reported having no financial conflicts.

Canakinumab cut gout attacks in CANTOS

AMSTERDAM – in an exploratory, post hoc analysis of data collected from more than 10,000 patients in the CANTOS multicenter, randomized trial.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

While this result is only a hypothesis-generating suggestion that blocking interleukin (IL)-1 beta can have a significant impact on the frequency of gout flares, it serves as a proof-of-concept that IL-1 beta blockade is a potentially clinically meaningful strategy for future efforts to block gout attacks, Daniel H. Solomon, MD, said at the European Congress of Rheumatology.

“IL-1 beta is incredibly important in the inflammation associated with gout. Gout is considered by many to be the canonical IL-1 beta disease,” and hence it was important to examine the impact that treatment with the IL-1 beta blocker canakinumab had on gout in the CANTOS trial, Dr. Solomon explained in a video interview.

The answer was that treatment with canakinumab was linked with a roughly 50% reduction in gout flares in the total study group. The same reduction was seen in both the subgroups of patients with and without a history of gout. The effect was seen across all three subgroups of patients, based on their baseline serum urate levels including those with normal, elevated, or very elevated levels and across all the other prespecified subgroups including divisions based on sex, age, baseline body mass index, and baseline level of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP).

It’s also unclear that canakinumab (Ilaris) is the best type of IL-1 beta blocking drug to use for prevention of gout flares. In CANTOS, this expensive drug was administered subcutaneously every 3 months. A more appropriate agent might be an oral, small-molecule drug that blocks IL-1 beta. Several examples of this type of agent are currently in clinical development, said Dr. Solomon, a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and a rheumatologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, both in Boston.

CANTOS (Canakinumab Anti-inflammatory Thrombosis Outcome Study) randomized 10,061 patients with a history of MI and a hsCRP level of at least 2 mg/L at centers in 39 countries. The study’s primary endpoint was the combined rate of cardiovascular death, MI, or stroke, and canakinumab treatment at the 150-mg dosage level linked with a 15% relative reduction in this endpoint, compared with placebo in this secondary-prevention study (N Engl J Med. 2017 Sept 21;377[12]:1119-31). The study also randomized patients to either of two other canakinumab dosages, 50 mg or 300 mg, administered every 3 months, and, while each of these produced reductions in the primary endpoint relative to placebo, the 150-mg dosage had the largest effect. In the gout analysis reported by Dr. Solomon, the three different canakinumab dosages produced somewhat different levels of gout-flare reductions, but, generally, the effect was similar across the three treatment groups.

In the total study population, regardless of gout history, treatment with 50 mg, 150 mg, and 300 mg canakinumab every 3 months was linked with a reduction in gout attacks of 46%, 57%, and 53%, respectively, compared with placebo-treated patients, Dr. Solomon reported. The three dosages also uniformly produced significantly drops in serum levels of hsCRP, compared with placebo, but canakinumab treatment had no impact on serum urate levels, indicating that the gout-reducing effects of the drug did not occur via a mechanism that involved serum urate.

Because CANTOS exclusively enrolled patients with established coronary disease, the new analysis could not address whether IL-1 beta blockade would also be an effective strategy for reducing gout flares in people without cardiovascular disease, Dr. Solomon cautioned. Although it probably would, he said. He also stressed that treatment with an IL-1 blocking drug should not be seen as a substitute for appropriate urate-lowering treatment in patients with elevated levels of serum urate.

SOURCE: Solomon DH et al. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77(Suppl 2):56. Abstract OP0014.

AMSTERDAM – in an exploratory, post hoc analysis of data collected from more than 10,000 patients in the CANTOS multicenter, randomized trial.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

While this result is only a hypothesis-generating suggestion that blocking interleukin (IL)-1 beta can have a significant impact on the frequency of gout flares, it serves as a proof-of-concept that IL-1 beta blockade is a potentially clinically meaningful strategy for future efforts to block gout attacks, Daniel H. Solomon, MD, said at the European Congress of Rheumatology.

“IL-1 beta is incredibly important in the inflammation associated with gout. Gout is considered by many to be the canonical IL-1 beta disease,” and hence it was important to examine the impact that treatment with the IL-1 beta blocker canakinumab had on gout in the CANTOS trial, Dr. Solomon explained in a video interview.

The answer was that treatment with canakinumab was linked with a roughly 50% reduction in gout flares in the total study group. The same reduction was seen in both the subgroups of patients with and without a history of gout. The effect was seen across all three subgroups of patients, based on their baseline serum urate levels including those with normal, elevated, or very elevated levels and across all the other prespecified subgroups including divisions based on sex, age, baseline body mass index, and baseline level of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP).

It’s also unclear that canakinumab (Ilaris) is the best type of IL-1 beta blocking drug to use for prevention of gout flares. In CANTOS, this expensive drug was administered subcutaneously every 3 months. A more appropriate agent might be an oral, small-molecule drug that blocks IL-1 beta. Several examples of this type of agent are currently in clinical development, said Dr. Solomon, a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and a rheumatologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, both in Boston.

CANTOS (Canakinumab Anti-inflammatory Thrombosis Outcome Study) randomized 10,061 patients with a history of MI and a hsCRP level of at least 2 mg/L at centers in 39 countries. The study’s primary endpoint was the combined rate of cardiovascular death, MI, or stroke, and canakinumab treatment at the 150-mg dosage level linked with a 15% relative reduction in this endpoint, compared with placebo in this secondary-prevention study (N Engl J Med. 2017 Sept 21;377[12]:1119-31). The study also randomized patients to either of two other canakinumab dosages, 50 mg or 300 mg, administered every 3 months, and, while each of these produced reductions in the primary endpoint relative to placebo, the 150-mg dosage had the largest effect. In the gout analysis reported by Dr. Solomon, the three different canakinumab dosages produced somewhat different levels of gout-flare reductions, but, generally, the effect was similar across the three treatment groups.

In the total study population, regardless of gout history, treatment with 50 mg, 150 mg, and 300 mg canakinumab every 3 months was linked with a reduction in gout attacks of 46%, 57%, and 53%, respectively, compared with placebo-treated patients, Dr. Solomon reported. The three dosages also uniformly produced significantly drops in serum levels of hsCRP, compared with placebo, but canakinumab treatment had no impact on serum urate levels, indicating that the gout-reducing effects of the drug did not occur via a mechanism that involved serum urate.

Because CANTOS exclusively enrolled patients with established coronary disease, the new analysis could not address whether IL-1 beta blockade would also be an effective strategy for reducing gout flares in people without cardiovascular disease, Dr. Solomon cautioned. Although it probably would, he said. He also stressed that treatment with an IL-1 blocking drug should not be seen as a substitute for appropriate urate-lowering treatment in patients with elevated levels of serum urate.

SOURCE: Solomon DH et al. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77(Suppl 2):56. Abstract OP0014.

AMSTERDAM – in an exploratory, post hoc analysis of data collected from more than 10,000 patients in the CANTOS multicenter, randomized trial.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

While this result is only a hypothesis-generating suggestion that blocking interleukin (IL)-1 beta can have a significant impact on the frequency of gout flares, it serves as a proof-of-concept that IL-1 beta blockade is a potentially clinically meaningful strategy for future efforts to block gout attacks, Daniel H. Solomon, MD, said at the European Congress of Rheumatology.

“IL-1 beta is incredibly important in the inflammation associated with gout. Gout is considered by many to be the canonical IL-1 beta disease,” and hence it was important to examine the impact that treatment with the IL-1 beta blocker canakinumab had on gout in the CANTOS trial, Dr. Solomon explained in a video interview.

The answer was that treatment with canakinumab was linked with a roughly 50% reduction in gout flares in the total study group. The same reduction was seen in both the subgroups of patients with and without a history of gout. The effect was seen across all three subgroups of patients, based on their baseline serum urate levels including those with normal, elevated, or very elevated levels and across all the other prespecified subgroups including divisions based on sex, age, baseline body mass index, and baseline level of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP).

It’s also unclear that canakinumab (Ilaris) is the best type of IL-1 beta blocking drug to use for prevention of gout flares. In CANTOS, this expensive drug was administered subcutaneously every 3 months. A more appropriate agent might be an oral, small-molecule drug that blocks IL-1 beta. Several examples of this type of agent are currently in clinical development, said Dr. Solomon, a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and a rheumatologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, both in Boston.

CANTOS (Canakinumab Anti-inflammatory Thrombosis Outcome Study) randomized 10,061 patients with a history of MI and a hsCRP level of at least 2 mg/L at centers in 39 countries. The study’s primary endpoint was the combined rate of cardiovascular death, MI, or stroke, and canakinumab treatment at the 150-mg dosage level linked with a 15% relative reduction in this endpoint, compared with placebo in this secondary-prevention study (N Engl J Med. 2017 Sept 21;377[12]:1119-31). The study also randomized patients to either of two other canakinumab dosages, 50 mg or 300 mg, administered every 3 months, and, while each of these produced reductions in the primary endpoint relative to placebo, the 150-mg dosage had the largest effect. In the gout analysis reported by Dr. Solomon, the three different canakinumab dosages produced somewhat different levels of gout-flare reductions, but, generally, the effect was similar across the three treatment groups.

In the total study population, regardless of gout history, treatment with 50 mg, 150 mg, and 300 mg canakinumab every 3 months was linked with a reduction in gout attacks of 46%, 57%, and 53%, respectively, compared with placebo-treated patients, Dr. Solomon reported. The three dosages also uniformly produced significantly drops in serum levels of hsCRP, compared with placebo, but canakinumab treatment had no impact on serum urate levels, indicating that the gout-reducing effects of the drug did not occur via a mechanism that involved serum urate.

Because CANTOS exclusively enrolled patients with established coronary disease, the new analysis could not address whether IL-1 beta blockade would also be an effective strategy for reducing gout flares in people without cardiovascular disease, Dr. Solomon cautioned. Although it probably would, he said. He also stressed that treatment with an IL-1 blocking drug should not be seen as a substitute for appropriate urate-lowering treatment in patients with elevated levels of serum urate.

SOURCE: Solomon DH et al. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77(Suppl 2):56. Abstract OP0014.

REPORTING FROM THE EULAR 2018 CONGRESS

Key clinical point: IL-1 blockade seems to be an effective way to cut the incidence of gout attacks.

Major finding: IL-1 blockade with canakinumab was linked with about a 50% cut in gout flares, compared with placebo.

Study details: CANTOS, a multicenter, randomized trial with 10,061 patients.

Disclosures: CANTOS was funded by Novartis, the company that markets canakinumab. Dr. Solomon has no relationships with Novartis. Brigham and Women’s Hospital, the center at which he works, has received research funding from Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Genentech, and Pfizer for studies that Dr. Solomon has helped direct.

Source: Solomon DH et al. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77(Suppl 2):56. Abstract OP0014.

Creating a digital pill

Technology battles medication noncompliance

Hospitalists and other physicians have long struggled with medication noncompliance, which can lead to sicker patients and higher rates of readmittance, and costs some $100-$289 billion a year.

There is a growing field of digital devices being developed to address this problem. The Food and Drug Administration has just approved the newest one: a medication with a sensor embedded that can tell doctors if, and when, patients take their medicine, according to an article in the New York Times.1 It’s expected to become available in 2018.

The digital medication is a version of the antipsychotic Abilify. Patients who agree to take it will sign consent forms allowing their doctors (and up to four other people) to receive electronic data showing the date and time pills are ingested.

The sensor, created by Proteus Digital Health, contains copper, magnesium, and silicon, all said to be safe ingredients found in foods. The electrical signal is created when stomach fluids contact the sensor; a patch worn on the rib cage detects that signal and sends the message.

Other companies are joining the race to create digital medication technologies; these are being tested in medications for patients with conditions including heart disease, diabetes, and HIV infection. Some researchers predict the technology might have applications for monitoring the opioid intake of postsurgical patients or patients in medication clinical trials.

Reference

1. Belluck P. “First Digital Pill Approved to Worries About Biomedical ‘Big Brother.’ ” New York Times. Nov 13, 2017.

Technology battles medication noncompliance

Technology battles medication noncompliance

Hospitalists and other physicians have long struggled with medication noncompliance, which can lead to sicker patients and higher rates of readmittance, and costs some $100-$289 billion a year.

There is a growing field of digital devices being developed to address this problem. The Food and Drug Administration has just approved the newest one: a medication with a sensor embedded that can tell doctors if, and when, patients take their medicine, according to an article in the New York Times.1 It’s expected to become available in 2018.

The digital medication is a version of the antipsychotic Abilify. Patients who agree to take it will sign consent forms allowing their doctors (and up to four other people) to receive electronic data showing the date and time pills are ingested.

The sensor, created by Proteus Digital Health, contains copper, magnesium, and silicon, all said to be safe ingredients found in foods. The electrical signal is created when stomach fluids contact the sensor; a patch worn on the rib cage detects that signal and sends the message.

Other companies are joining the race to create digital medication technologies; these are being tested in medications for patients with conditions including heart disease, diabetes, and HIV infection. Some researchers predict the technology might have applications for monitoring the opioid intake of postsurgical patients or patients in medication clinical trials.

Reference

1. Belluck P. “First Digital Pill Approved to Worries About Biomedical ‘Big Brother.’ ” New York Times. Nov 13, 2017.

Hospitalists and other physicians have long struggled with medication noncompliance, which can lead to sicker patients and higher rates of readmittance, and costs some $100-$289 billion a year.

There is a growing field of digital devices being developed to address this problem. The Food and Drug Administration has just approved the newest one: a medication with a sensor embedded that can tell doctors if, and when, patients take their medicine, according to an article in the New York Times.1 It’s expected to become available in 2018.

The digital medication is a version of the antipsychotic Abilify. Patients who agree to take it will sign consent forms allowing their doctors (and up to four other people) to receive electronic data showing the date and time pills are ingested.

The sensor, created by Proteus Digital Health, contains copper, magnesium, and silicon, all said to be safe ingredients found in foods. The electrical signal is created when stomach fluids contact the sensor; a patch worn on the rib cage detects that signal and sends the message.

Other companies are joining the race to create digital medication technologies; these are being tested in medications for patients with conditions including heart disease, diabetes, and HIV infection. Some researchers predict the technology might have applications for monitoring the opioid intake of postsurgical patients or patients in medication clinical trials.

Reference

1. Belluck P. “First Digital Pill Approved to Worries About Biomedical ‘Big Brother.’ ” New York Times. Nov 13, 2017.

Serious complications linked to rituximab in MS

NASHVILLE, TENN. – In a sign of the potential complications that can be spawned by B-cell–depleting therapies, a new report found that 5 of 30 patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS) had to discontinue or interrupt long-term treatment with rituximab (Rituxan) because of serious infections such as pneumonia, septic arthritis, and sinusitis.

The findings are a “big lesson to not just focus on opportunistic infections [with Rituxan use] but also consider nonopportunistic infections that could occur,” lead study author Cindy Darius, a registered nurse with the Johns Hopkins Multiple Sclerosis Center (JHMSC), Baltimore, said in an interview. She presented the research at the annual meeting of the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers.

As Ms. Darius noted, progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy has been the main focus of discussions about the use of rituximab in MS, as the disease has been noted in patients who have taken rituximab for other conditions.

But Ms. Darius said that the JHMSC observed a trend of patients with MS who took rituximab and developed “these weird infections that were more nonopportunistic infections. That prompted us to dig a little bit deeper: Are these infections happening sporadically, or could they have a connection with Rituxan?”

Ms. Darius and her colleagues retrospectively reviewed the records of 30 patients with MS who were prescribed rituximab by a single JHMSC physician since 2012. They found five cases of infectious complications, all in patients with RRMS:

- A woman, aged 30 years, whose rituximab regimen was interrupted after 4 years of treatment when she developed recurrent pneumonia.

- A man, aged 42 years, who took rituximab for a year then stopped after developing ringworm and two bouts of Staphylococcus aureus septic arthritis, and who had previously changed from natalizumab (Tysabri) to rituximab after seroconverting to the John Cunningham virus.

- A woman, aged 65 years, with Sjögren’s syndrome who stopped rituximab at 2 years after developing sinusitis, pneumonia, and herpes simplex virus keratitis.

- A woman, aged 38 years, who discontinued rituximab after 2 years because of recurrent urosepsis, sinusitis, and pyrexia of unknown origin.

- A woman, aged 56 years, who stopped rituximab after 2 years following intractable sinusitis and pneumonia that resulted in empyema and required a thoracotomy.

What might be causing the apparent side effects? Ms. Darius pointed out that the patients were already immunocompromised because of previous treatment with first- and/or second-line medications. She added that the complications “may be due to dosing that may be a little too high for the MS population.”

JHMSC is considering whether to give doses of the drug once a year instead of twice annually, she said. “Other providers are cutting the dose in half: Instead of 1,000 mg, they’re giving 500,” she added. “After the patient has been on the medication for a year or two, and you feel the disease process has stabilized, you may want to consider adjusting the dosage.”

Going forward, the researchers wrote that they “plan to determine the incidence of all serious infectious complications related to rituximab use among MS patients attending the JHMSC, and the influence of different dosing protocols between MS providers in this regard.”

No study funding was reported, and most study authors reported no relevant disclosures. One author reported receiving National Institutes of Health funding and another reported consulting for Biogen and Genentech.

SOURCE: Darius C et al. CMSC 2018, Abstract DX57.

NASHVILLE, TENN. – In a sign of the potential complications that can be spawned by B-cell–depleting therapies, a new report found that 5 of 30 patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS) had to discontinue or interrupt long-term treatment with rituximab (Rituxan) because of serious infections such as pneumonia, septic arthritis, and sinusitis.

The findings are a “big lesson to not just focus on opportunistic infections [with Rituxan use] but also consider nonopportunistic infections that could occur,” lead study author Cindy Darius, a registered nurse with the Johns Hopkins Multiple Sclerosis Center (JHMSC), Baltimore, said in an interview. She presented the research at the annual meeting of the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers.

As Ms. Darius noted, progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy has been the main focus of discussions about the use of rituximab in MS, as the disease has been noted in patients who have taken rituximab for other conditions.

But Ms. Darius said that the JHMSC observed a trend of patients with MS who took rituximab and developed “these weird infections that were more nonopportunistic infections. That prompted us to dig a little bit deeper: Are these infections happening sporadically, or could they have a connection with Rituxan?”

Ms. Darius and her colleagues retrospectively reviewed the records of 30 patients with MS who were prescribed rituximab by a single JHMSC physician since 2012. They found five cases of infectious complications, all in patients with RRMS:

- A woman, aged 30 years, whose rituximab regimen was interrupted after 4 years of treatment when she developed recurrent pneumonia.

- A man, aged 42 years, who took rituximab for a year then stopped after developing ringworm and two bouts of Staphylococcus aureus septic arthritis, and who had previously changed from natalizumab (Tysabri) to rituximab after seroconverting to the John Cunningham virus.

- A woman, aged 65 years, with Sjögren’s syndrome who stopped rituximab at 2 years after developing sinusitis, pneumonia, and herpes simplex virus keratitis.

- A woman, aged 38 years, who discontinued rituximab after 2 years because of recurrent urosepsis, sinusitis, and pyrexia of unknown origin.

- A woman, aged 56 years, who stopped rituximab after 2 years following intractable sinusitis and pneumonia that resulted in empyema and required a thoracotomy.

What might be causing the apparent side effects? Ms. Darius pointed out that the patients were already immunocompromised because of previous treatment with first- and/or second-line medications. She added that the complications “may be due to dosing that may be a little too high for the MS population.”

JHMSC is considering whether to give doses of the drug once a year instead of twice annually, she said. “Other providers are cutting the dose in half: Instead of 1,000 mg, they’re giving 500,” she added. “After the patient has been on the medication for a year or two, and you feel the disease process has stabilized, you may want to consider adjusting the dosage.”

Going forward, the researchers wrote that they “plan to determine the incidence of all serious infectious complications related to rituximab use among MS patients attending the JHMSC, and the influence of different dosing protocols between MS providers in this regard.”

No study funding was reported, and most study authors reported no relevant disclosures. One author reported receiving National Institutes of Health funding and another reported consulting for Biogen and Genentech.

SOURCE: Darius C et al. CMSC 2018, Abstract DX57.

NASHVILLE, TENN. – In a sign of the potential complications that can be spawned by B-cell–depleting therapies, a new report found that 5 of 30 patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS) had to discontinue or interrupt long-term treatment with rituximab (Rituxan) because of serious infections such as pneumonia, septic arthritis, and sinusitis.

The findings are a “big lesson to not just focus on opportunistic infections [with Rituxan use] but also consider nonopportunistic infections that could occur,” lead study author Cindy Darius, a registered nurse with the Johns Hopkins Multiple Sclerosis Center (JHMSC), Baltimore, said in an interview. She presented the research at the annual meeting of the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers.

As Ms. Darius noted, progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy has been the main focus of discussions about the use of rituximab in MS, as the disease has been noted in patients who have taken rituximab for other conditions.

But Ms. Darius said that the JHMSC observed a trend of patients with MS who took rituximab and developed “these weird infections that were more nonopportunistic infections. That prompted us to dig a little bit deeper: Are these infections happening sporadically, or could they have a connection with Rituxan?”

Ms. Darius and her colleagues retrospectively reviewed the records of 30 patients with MS who were prescribed rituximab by a single JHMSC physician since 2012. They found five cases of infectious complications, all in patients with RRMS:

- A woman, aged 30 years, whose rituximab regimen was interrupted after 4 years of treatment when she developed recurrent pneumonia.

- A man, aged 42 years, who took rituximab for a year then stopped after developing ringworm and two bouts of Staphylococcus aureus septic arthritis, and who had previously changed from natalizumab (Tysabri) to rituximab after seroconverting to the John Cunningham virus.

- A woman, aged 65 years, with Sjögren’s syndrome who stopped rituximab at 2 years after developing sinusitis, pneumonia, and herpes simplex virus keratitis.

- A woman, aged 38 years, who discontinued rituximab after 2 years because of recurrent urosepsis, sinusitis, and pyrexia of unknown origin.

- A woman, aged 56 years, who stopped rituximab after 2 years following intractable sinusitis and pneumonia that resulted in empyema and required a thoracotomy.

What might be causing the apparent side effects? Ms. Darius pointed out that the patients were already immunocompromised because of previous treatment with first- and/or second-line medications. She added that the complications “may be due to dosing that may be a little too high for the MS population.”

JHMSC is considering whether to give doses of the drug once a year instead of twice annually, she said. “Other providers are cutting the dose in half: Instead of 1,000 mg, they’re giving 500,” she added. “After the patient has been on the medication for a year or two, and you feel the disease process has stabilized, you may want to consider adjusting the dosage.”

Going forward, the researchers wrote that they “plan to determine the incidence of all serious infectious complications related to rituximab use among MS patients attending the JHMSC, and the influence of different dosing protocols between MS providers in this regard.”

No study funding was reported, and most study authors reported no relevant disclosures. One author reported receiving National Institutes of Health funding and another reported consulting for Biogen and Genentech.

SOURCE: Darius C et al. CMSC 2018, Abstract DX57.

REPORTING FROM THE CMSC ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: Much of the attention toward side effects in rituximab as an off-label treatment for multiple sclerosis has focused on progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, but other infections may affect this population over the long term.

Major finding: Of 30 patients treated with rituximab for MS, 5 developed infections that required suspension or cessation of the treatment.

Study details: A retrospective analysis of 30 patients with MS treated with rituximab since 2012.

Disclosures: No study funding was reported, and most study authors reported no relevant disclosures. One author reported receiving National Institutes of Health funding and another reported consulting for Biogen and Genentech.

Source: Darius C et al. CMSC 2018, Abstract DX57.

Sickle cell disease exacts a heavy vocational toll

WASHINGTON – Three-quarters of patients with sickle cell disease (SCD) reported missing work in the last year because of disease symptoms, according to results from a single-center study.

While the direct costs of SCD are easy to measure, it’s harder to capture the indirect costs patients may incur from this chronic, progressive disease, which range from lost days at work to the downstream consequences of “presenteeism.”

“Indirect costs are related to things that have value, but it’s a little bit harder to apply an exact value to it,” said Nicholas Vendetti of Pfizer. But this is a critical piece for understanding SCD, he said. “The burden of illness is unknown without productivity costs.”

Mr. Vendetti and his collaborators attempted to capture the indirect costs of SCD, and reported the results of a single-site study at the annual meeting of the Foundation for Sickle Cell Disease Research.

They recruited patients from Virginia Commonwealth University’s adult sickle cell clinic and trained interviewers to conduct structured interviews using the Institute for Medical Technology Assessment Productivity Cost Questionnaire. The interviewers asked about absenteeism, lost work, unpaid work activity, and “presenteeism,” defined as days when participants were at work but experienced decreased work output because of disease symptoms.

In the end, the study enrolled 186 patients aged 18 and older, a figure that “really exceeded what we expected when we started the protocol,” Mr. Vendetti said. Most participants were between the ages of 20 and 60 years – the most productive working years.

About 58% of participants were female. Nearly half (46%) had the HbSS genotype, while 30% had the HbSC genotype. About half (52%) were high school graduates, and about a third had some college. There were no advanced degrees earned in the study population, and 11.5% had not finished high school.

Initial questions about educational status and employment status “highlighted a very interesting aspect of the disease: 43.8% reported that they were currently unable to work as part of their disease process,” Mr. Vendetti said. Just 28% were employed for wages, 3% were self-employed, and about 7% reported being homemakers. The remainder were out of work, were students, or were retired.

Three-quarters of patients reported missing work in the last year because of SCD symptoms. This group reported missing a mean 36.75 days yearly. Assuming the average Virginia hourly wage of $25.53 per hour, this comes to an average of $7,506 in lost wages each year, Mr. Vendetti said.

Presenteeism had a large impact as well. Nearly 73% of patients said they were bothered at work – either psychologically or physically – by their symptoms in the last 4 weeks, and 90% over the past year. These patients estimated they were affected for about 100 working days yearly.

When asked on a scale of 0-10 how much work they were able to get done on days when their SCD was affecting productivity, “most patients are falling into that middle range” of a score of 4-6, Mr. Vendetti said. “Most patients are moderately affected.

“It’s hard to apply a dollar value to that, but it’s easy to see how it could affect the trajectory of your career,” he added.

Another aspect of the indirect cost of the sickle cell disease burden that’s even harder to tease out is whether those affected are unable to complete a significant amount of unpaid work. Again, about three-quarters of patients reported that SCD had affected their ability to do this kind of work, and these patients said this happened on an average 105 days each year.

Even though patients may not be hiring others to do housework they’re unable to complete, or to care for children on days when they’re too unwell to do so, that doesn’t mean there’s no impact on the patient and those around them, Mr. Vendetti said. “If you ask a family member or a friend for help, that creates a strain in the relationship.”

In terms of resources to address the indirect burden of SCD on careers, Mr. Vendetti pointed out that many states have vocational rehabilitation programs that offer a significant amount of support and assistance to help find a productive work path that still accommodates a chronic illness such as SCD. In Virginia, he said, individuals need to be on disability to avail themselves of the program.

Health care providers can educate themselves about these and other programs. “Most adult sickle cell disease patients didn’t even know they might be eligible” for vocational assistance, he said.

During discussion after the presentation, an audience member pointed out that parents and caregivers of children with SCD are probably also incurring significant indirect costs because of their care-giving burden and that this population should also be studied. Mr. Vendetti agreed. “This is potential that isn’t fulfilled” for all patients and families whose work and personal lives are so profoundly affected by SCD, he said. “This is a dream deferred.”

Mr. Vendetti is employed by Pfizer and is a Pfizer stockholder. A coauthor of the study is a Pfizer consultant.

WASHINGTON – Three-quarters of patients with sickle cell disease (SCD) reported missing work in the last year because of disease symptoms, according to results from a single-center study.

While the direct costs of SCD are easy to measure, it’s harder to capture the indirect costs patients may incur from this chronic, progressive disease, which range from lost days at work to the downstream consequences of “presenteeism.”

“Indirect costs are related to things that have value, but it’s a little bit harder to apply an exact value to it,” said Nicholas Vendetti of Pfizer. But this is a critical piece for understanding SCD, he said. “The burden of illness is unknown without productivity costs.”

Mr. Vendetti and his collaborators attempted to capture the indirect costs of SCD, and reported the results of a single-site study at the annual meeting of the Foundation for Sickle Cell Disease Research.

They recruited patients from Virginia Commonwealth University’s adult sickle cell clinic and trained interviewers to conduct structured interviews using the Institute for Medical Technology Assessment Productivity Cost Questionnaire. The interviewers asked about absenteeism, lost work, unpaid work activity, and “presenteeism,” defined as days when participants were at work but experienced decreased work output because of disease symptoms.

In the end, the study enrolled 186 patients aged 18 and older, a figure that “really exceeded what we expected when we started the protocol,” Mr. Vendetti said. Most participants were between the ages of 20 and 60 years – the most productive working years.

About 58% of participants were female. Nearly half (46%) had the HbSS genotype, while 30% had the HbSC genotype. About half (52%) were high school graduates, and about a third had some college. There were no advanced degrees earned in the study population, and 11.5% had not finished high school.

Initial questions about educational status and employment status “highlighted a very interesting aspect of the disease: 43.8% reported that they were currently unable to work as part of their disease process,” Mr. Vendetti said. Just 28% were employed for wages, 3% were self-employed, and about 7% reported being homemakers. The remainder were out of work, were students, or were retired.

Three-quarters of patients reported missing work in the last year because of SCD symptoms. This group reported missing a mean 36.75 days yearly. Assuming the average Virginia hourly wage of $25.53 per hour, this comes to an average of $7,506 in lost wages each year, Mr. Vendetti said.

Presenteeism had a large impact as well. Nearly 73% of patients said they were bothered at work – either psychologically or physically – by their symptoms in the last 4 weeks, and 90% over the past year. These patients estimated they were affected for about 100 working days yearly.

When asked on a scale of 0-10 how much work they were able to get done on days when their SCD was affecting productivity, “most patients are falling into that middle range” of a score of 4-6, Mr. Vendetti said. “Most patients are moderately affected.

“It’s hard to apply a dollar value to that, but it’s easy to see how it could affect the trajectory of your career,” he added.

Another aspect of the indirect cost of the sickle cell disease burden that’s even harder to tease out is whether those affected are unable to complete a significant amount of unpaid work. Again, about three-quarters of patients reported that SCD had affected their ability to do this kind of work, and these patients said this happened on an average 105 days each year.

Even though patients may not be hiring others to do housework they’re unable to complete, or to care for children on days when they’re too unwell to do so, that doesn’t mean there’s no impact on the patient and those around them, Mr. Vendetti said. “If you ask a family member or a friend for help, that creates a strain in the relationship.”

In terms of resources to address the indirect burden of SCD on careers, Mr. Vendetti pointed out that many states have vocational rehabilitation programs that offer a significant amount of support and assistance to help find a productive work path that still accommodates a chronic illness such as SCD. In Virginia, he said, individuals need to be on disability to avail themselves of the program.

Health care providers can educate themselves about these and other programs. “Most adult sickle cell disease patients didn’t even know they might be eligible” for vocational assistance, he said.

During discussion after the presentation, an audience member pointed out that parents and caregivers of children with SCD are probably also incurring significant indirect costs because of their care-giving burden and that this population should also be studied. Mr. Vendetti agreed. “This is potential that isn’t fulfilled” for all patients and families whose work and personal lives are so profoundly affected by SCD, he said. “This is a dream deferred.”

Mr. Vendetti is employed by Pfizer and is a Pfizer stockholder. A coauthor of the study is a Pfizer consultant.

WASHINGTON – Three-quarters of patients with sickle cell disease (SCD) reported missing work in the last year because of disease symptoms, according to results from a single-center study.

While the direct costs of SCD are easy to measure, it’s harder to capture the indirect costs patients may incur from this chronic, progressive disease, which range from lost days at work to the downstream consequences of “presenteeism.”

“Indirect costs are related to things that have value, but it’s a little bit harder to apply an exact value to it,” said Nicholas Vendetti of Pfizer. But this is a critical piece for understanding SCD, he said. “The burden of illness is unknown without productivity costs.”

Mr. Vendetti and his collaborators attempted to capture the indirect costs of SCD, and reported the results of a single-site study at the annual meeting of the Foundation for Sickle Cell Disease Research.

They recruited patients from Virginia Commonwealth University’s adult sickle cell clinic and trained interviewers to conduct structured interviews using the Institute for Medical Technology Assessment Productivity Cost Questionnaire. The interviewers asked about absenteeism, lost work, unpaid work activity, and “presenteeism,” defined as days when participants were at work but experienced decreased work output because of disease symptoms.

In the end, the study enrolled 186 patients aged 18 and older, a figure that “really exceeded what we expected when we started the protocol,” Mr. Vendetti said. Most participants were between the ages of 20 and 60 years – the most productive working years.

About 58% of participants were female. Nearly half (46%) had the HbSS genotype, while 30% had the HbSC genotype. About half (52%) were high school graduates, and about a third had some college. There were no advanced degrees earned in the study population, and 11.5% had not finished high school.

Initial questions about educational status and employment status “highlighted a very interesting aspect of the disease: 43.8% reported that they were currently unable to work as part of their disease process,” Mr. Vendetti said. Just 28% were employed for wages, 3% were self-employed, and about 7% reported being homemakers. The remainder were out of work, were students, or were retired.

Three-quarters of patients reported missing work in the last year because of SCD symptoms. This group reported missing a mean 36.75 days yearly. Assuming the average Virginia hourly wage of $25.53 per hour, this comes to an average of $7,506 in lost wages each year, Mr. Vendetti said.

Presenteeism had a large impact as well. Nearly 73% of patients said they were bothered at work – either psychologically or physically – by their symptoms in the last 4 weeks, and 90% over the past year. These patients estimated they were affected for about 100 working days yearly.

When asked on a scale of 0-10 how much work they were able to get done on days when their SCD was affecting productivity, “most patients are falling into that middle range” of a score of 4-6, Mr. Vendetti said. “Most patients are moderately affected.

“It’s hard to apply a dollar value to that, but it’s easy to see how it could affect the trajectory of your career,” he added.

Another aspect of the indirect cost of the sickle cell disease burden that’s even harder to tease out is whether those affected are unable to complete a significant amount of unpaid work. Again, about three-quarters of patients reported that SCD had affected their ability to do this kind of work, and these patients said this happened on an average 105 days each year.

Even though patients may not be hiring others to do housework they’re unable to complete, or to care for children on days when they’re too unwell to do so, that doesn’t mean there’s no impact on the patient and those around them, Mr. Vendetti said. “If you ask a family member or a friend for help, that creates a strain in the relationship.”

In terms of resources to address the indirect burden of SCD on careers, Mr. Vendetti pointed out that many states have vocational rehabilitation programs that offer a significant amount of support and assistance to help find a productive work path that still accommodates a chronic illness such as SCD. In Virginia, he said, individuals need to be on disability to avail themselves of the program.

Health care providers can educate themselves about these and other programs. “Most adult sickle cell disease patients didn’t even know they might be eligible” for vocational assistance, he said.

During discussion after the presentation, an audience member pointed out that parents and caregivers of children with SCD are probably also incurring significant indirect costs because of their care-giving burden and that this population should also be studied. Mr. Vendetti agreed. “This is potential that isn’t fulfilled” for all patients and families whose work and personal lives are so profoundly affected by SCD, he said. “This is a dream deferred.”

Mr. Vendetti is employed by Pfizer and is a Pfizer stockholder. A coauthor of the study is a Pfizer consultant.

REPORTING FROM FSCDR 2018

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Three-quarters of patients reported missing work in the last year because of SCD symptoms. This group reported missing a mean 37 days yearly.

Study details: Single-site survey-based study of 186 adults with SCD.

Disclosures: Pfizer sponsored the study. Mr. Vendetti is employed by Pfizer and holds Pfizer stock. A study coauthor is a Pfizer consultant.

Dual-targeting CAR T active against AML in mice and one man

STOCKHOLM – A novel compound chimeric antigen receptor (cCAR) T-cell construct directed against two different targets may one day serve as a standalone therapy, as a supplement to chemotherapy, or as a bridge to transplant for patients with refractory acute myeloid leukemia (AML), investigators asserted.

To date, however, only one patient – a man with treatment-refractory AML – has been treated with the cCAR T, which contains two independent complete units, one directed against CD33 to target bulky disease and the other targeted against CLL1 on leukemic stem cells.

The patient was a 44-year-old man with AML who remained refractory after four cycles of chemotherapy and had 20% bone marrow blasts. He achieved a complete response after infusion with the cCAR T cells and went on to bone marrow transplant with no evidence of minimal residual disease (MRD) at 3 months of follow-up, Dr. Liu said.

Although anti-CD19 CAR T cells have been demonstrated to have significant efficacy in relapsed or refractory B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia, AML is a tougher problem to solve because the heterogeneity of myeloid leukemia cells allows some cells to escape targeting by enhanced T cells, which leads to eventual relapse.

To get around this problem, the investigators created a CAR T with a one-two punch, with one component targeting the antigen CLL1, which is expressed on leukemic stem cells, and a second, separate component targeting CD33, a myeloid marker expressed on bulk AML disease cells in a majority of patients.

They first tested the cCAR T cells against several AML cell lines and primary human AML samples, then in mouse models of human AML.

In vitro assays showed that the construct had specific antitumor activity against cell lines engineered to express either of the target antigens and also against samples from AML patients. In mouse models created with engineered CLL1 or CD33 expressing cell lines and an AML cell line, the cCAR T cells caused significant reductions in tumor burden and led to prolonged survival, Dr. Liu said.

Since CAR T-cell therapy is associated with serious or life-threatening side effects, such as the cytokine-release syndrome, the investigators built an “off switch” into the cCAR T construct that could be activated by CAMPATH, a monoclonal antibody directed against CD52. Introducing this agent into the mice quickly neutralized the cCAR T therapy, Dr. Liu said.

Finally, the investigators tested the construct in the human patient. He received the cCAR T construct after conditioning with fludarabine and cyclophosphamide; he had a complete remission by day 19 after receiving the cells and was MRD negative. He went on to an allogeneic stem cell transplant on day 44, and he remained MRD negative 3 months after transplant.

Side effects associated with the treatment were a grade 1 cytokine release syndrome event, manifesting in fever and chills, lung infection, and red blood cell transfusion dependence but also platelet transfusion independence.

The investigators have initiated a phase 1 trial and plan to enroll 20 patients to further evaluate the efficacy and safety of the cCAR T construct.

The study was supported by iCell Gene Therapeutics. Dr. Liu reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Liu F et al. EHA Congress, Abstract S149.

STOCKHOLM – A novel compound chimeric antigen receptor (cCAR) T-cell construct directed against two different targets may one day serve as a standalone therapy, as a supplement to chemotherapy, or as a bridge to transplant for patients with refractory acute myeloid leukemia (AML), investigators asserted.

To date, however, only one patient – a man with treatment-refractory AML – has been treated with the cCAR T, which contains two independent complete units, one directed against CD33 to target bulky disease and the other targeted against CLL1 on leukemic stem cells.

The patient was a 44-year-old man with AML who remained refractory after four cycles of chemotherapy and had 20% bone marrow blasts. He achieved a complete response after infusion with the cCAR T cells and went on to bone marrow transplant with no evidence of minimal residual disease (MRD) at 3 months of follow-up, Dr. Liu said.

Although anti-CD19 CAR T cells have been demonstrated to have significant efficacy in relapsed or refractory B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia, AML is a tougher problem to solve because the heterogeneity of myeloid leukemia cells allows some cells to escape targeting by enhanced T cells, which leads to eventual relapse.

To get around this problem, the investigators created a CAR T with a one-two punch, with one component targeting the antigen CLL1, which is expressed on leukemic stem cells, and a second, separate component targeting CD33, a myeloid marker expressed on bulk AML disease cells in a majority of patients.

They first tested the cCAR T cells against several AML cell lines and primary human AML samples, then in mouse models of human AML.

In vitro assays showed that the construct had specific antitumor activity against cell lines engineered to express either of the target antigens and also against samples from AML patients. In mouse models created with engineered CLL1 or CD33 expressing cell lines and an AML cell line, the cCAR T cells caused significant reductions in tumor burden and led to prolonged survival, Dr. Liu said.

Since CAR T-cell therapy is associated with serious or life-threatening side effects, such as the cytokine-release syndrome, the investigators built an “off switch” into the cCAR T construct that could be activated by CAMPATH, a monoclonal antibody directed against CD52. Introducing this agent into the mice quickly neutralized the cCAR T therapy, Dr. Liu said.

Finally, the investigators tested the construct in the human patient. He received the cCAR T construct after conditioning with fludarabine and cyclophosphamide; he had a complete remission by day 19 after receiving the cells and was MRD negative. He went on to an allogeneic stem cell transplant on day 44, and he remained MRD negative 3 months after transplant.

Side effects associated with the treatment were a grade 1 cytokine release syndrome event, manifesting in fever and chills, lung infection, and red blood cell transfusion dependence but also platelet transfusion independence.

The investigators have initiated a phase 1 trial and plan to enroll 20 patients to further evaluate the efficacy and safety of the cCAR T construct.

The study was supported by iCell Gene Therapeutics. Dr. Liu reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Liu F et al. EHA Congress, Abstract S149.

STOCKHOLM – A novel compound chimeric antigen receptor (cCAR) T-cell construct directed against two different targets may one day serve as a standalone therapy, as a supplement to chemotherapy, or as a bridge to transplant for patients with refractory acute myeloid leukemia (AML), investigators asserted.

To date, however, only one patient – a man with treatment-refractory AML – has been treated with the cCAR T, which contains two independent complete units, one directed against CD33 to target bulky disease and the other targeted against CLL1 on leukemic stem cells.

The patient was a 44-year-old man with AML who remained refractory after four cycles of chemotherapy and had 20% bone marrow blasts. He achieved a complete response after infusion with the cCAR T cells and went on to bone marrow transplant with no evidence of minimal residual disease (MRD) at 3 months of follow-up, Dr. Liu said.

Although anti-CD19 CAR T cells have been demonstrated to have significant efficacy in relapsed or refractory B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia, AML is a tougher problem to solve because the heterogeneity of myeloid leukemia cells allows some cells to escape targeting by enhanced T cells, which leads to eventual relapse.

To get around this problem, the investigators created a CAR T with a one-two punch, with one component targeting the antigen CLL1, which is expressed on leukemic stem cells, and a second, separate component targeting CD33, a myeloid marker expressed on bulk AML disease cells in a majority of patients.

They first tested the cCAR T cells against several AML cell lines and primary human AML samples, then in mouse models of human AML.

In vitro assays showed that the construct had specific antitumor activity against cell lines engineered to express either of the target antigens and also against samples from AML patients. In mouse models created with engineered CLL1 or CD33 expressing cell lines and an AML cell line, the cCAR T cells caused significant reductions in tumor burden and led to prolonged survival, Dr. Liu said.

Since CAR T-cell therapy is associated with serious or life-threatening side effects, such as the cytokine-release syndrome, the investigators built an “off switch” into the cCAR T construct that could be activated by CAMPATH, a monoclonal antibody directed against CD52. Introducing this agent into the mice quickly neutralized the cCAR T therapy, Dr. Liu said.

Finally, the investigators tested the construct in the human patient. He received the cCAR T construct after conditioning with fludarabine and cyclophosphamide; he had a complete remission by day 19 after receiving the cells and was MRD negative. He went on to an allogeneic stem cell transplant on day 44, and he remained MRD negative 3 months after transplant.

Side effects associated with the treatment were a grade 1 cytokine release syndrome event, manifesting in fever and chills, lung infection, and red blood cell transfusion dependence but also platelet transfusion independence.

The investigators have initiated a phase 1 trial and plan to enroll 20 patients to further evaluate the efficacy and safety of the cCAR T construct.

The study was supported by iCell Gene Therapeutics. Dr. Liu reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Liu F et al. EHA Congress, Abstract S149.

REPORTING FROM THE EHA CONGRESS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The only human patient treated with the construct had a complete remission and successful bridge to transplant.

Study details: Preclinical study plus phase 1 data on one patient.

Disclosures: The study was supported by iCell Gene Therapeutics. Dr. Liu reported having no conflicts of interest.

Source: Liu F et al. EHA Congress, Abstract S149.

Midlife retinopathy predicts ischemic stroke

LOS ANGELES – The more severe retinopathy is at midlife, the greater the risk of ischemic stroke – particularly lacunar stroke – later on, according to investigators from Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

Retinopathy has been associated with strokes before, but the investigators wanted to see whether it could predict stroke type. The idea is that microvascular changes in the retina could mirror microvascular changes in the brain that could lead to stroke.

The positive findings mean that “retinal microvasculature may serve as a biomarker for cerebrovascular health. Retinal imaging may enable further risk stratification of cerebrovascular and neurodegenerative diseases for early, intensive preventive interventions,” said lead investigator Michelle Lin, MD, a stroke fellow at Johns Hopkins.

A full evaluation is beyond the scope of a quick ophthalmoscope check up in the office. The advent of smartphone fundoscopic cameras and optical coherence tomography – which provides images of retinal vasculature at micrometer-level resolution – will likely help retinal imaging reach its full potential in the clinic, she said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

Dr. Lin and her team reviewed 10,468 participants in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study database. They had baseline retinal photographs from 1993-1995 when they were 45-65 years old. The photos were checked for four types of retinopathy: arteriovenous nicking, focal arteriolar narrowing, retinal microaneurysms, and retinal hemorrhage. The presence of each one was given a score of 1, yielding a retinopathy severity score of 0-4, with 4 meaning subjects had all four types.

Over a median follow-up period of 18.8 years, 578 participants had an ischemic stroke, including 114 lacunar strokes, 292 nonlacunar strokes, and 172 cardioembolic strokes. Hemorrhagic strokes occurred in 95 subjects.

The incidence of ischemic stroke increased with the severity of baseline retinopathy, from 2.7 strokes per 1,000 participant-years among those with no retinopathy to 10.2 among those with a severity score of 3 or higher (P less than .001). The 15-year cumulative risk of ischemic stroke with any retinopathy was 3.4% versus 1.6% with no retinopathy (P less than .001).

After adjustment for age, sex, race, comorbidities, and other confounders, retinal microvasculopathy associated positively with ischemic stroke, especially lacunar stroke (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.84; 95% confidence interval, 1.23-2.74; P = .005).

Trends linking retinopathy severity to the incidence of nonlacunar, cardioembolic, and hemorrhagic strokes were not statistically significant. Factors associated with higher retinopathy grade included older age, black race, hypertension, and diabetes, among others.

There were slightly more women than men in the review. The average age at baseline was 59 years. Patients with stroke histories at baseline were excluded.

The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health. The investigators had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Lin MP et al. Neurology. 2018 Apr;90(15 Suppl.):CCI.001.

The findings are really not surprising. Retinal microvascular changes are a sign of end-organ damage. Small-vessel disease in the eye, small-vessel disease in the brain. This makes a lot of sense.

The question is: Which magic wand do we need to be able to measure and calculate these changes? These are not changes you are going to be able to detect easily when looking at the ocular fundus with your ophthalmoscope. These are very subtle changes we are taking about.

There’s new technology, like optical coherence tomography, and this is what will save us. People are working to provide us tools to automatically calculate retinal microvascular changes from fundus photographs. I have no doubt that within the next 2-3 years we will be able to use this technology. We are almost there; we are in the hands of engineers.

Valerie Biousse, MD , is a professor of neuro-ophthalmology at Emory University, Atlanta. She had no relevant disclosures.

The findings are really not surprising. Retinal microvascular changes are a sign of end-organ damage. Small-vessel disease in the eye, small-vessel disease in the brain. This makes a lot of sense.

The question is: Which magic wand do we need to be able to measure and calculate these changes? These are not changes you are going to be able to detect easily when looking at the ocular fundus with your ophthalmoscope. These are very subtle changes we are taking about.

There’s new technology, like optical coherence tomography, and this is what will save us. People are working to provide us tools to automatically calculate retinal microvascular changes from fundus photographs. I have no doubt that within the next 2-3 years we will be able to use this technology. We are almost there; we are in the hands of engineers.

Valerie Biousse, MD , is a professor of neuro-ophthalmology at Emory University, Atlanta. She had no relevant disclosures.

The findings are really not surprising. Retinal microvascular changes are a sign of end-organ damage. Small-vessel disease in the eye, small-vessel disease in the brain. This makes a lot of sense.

The question is: Which magic wand do we need to be able to measure and calculate these changes? These are not changes you are going to be able to detect easily when looking at the ocular fundus with your ophthalmoscope. These are very subtle changes we are taking about.

There’s new technology, like optical coherence tomography, and this is what will save us. People are working to provide us tools to automatically calculate retinal microvascular changes from fundus photographs. I have no doubt that within the next 2-3 years we will be able to use this technology. We are almost there; we are in the hands of engineers.

Valerie Biousse, MD , is a professor of neuro-ophthalmology at Emory University, Atlanta. She had no relevant disclosures.

LOS ANGELES – The more severe retinopathy is at midlife, the greater the risk of ischemic stroke – particularly lacunar stroke – later on, according to investigators from Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

Retinopathy has been associated with strokes before, but the investigators wanted to see whether it could predict stroke type. The idea is that microvascular changes in the retina could mirror microvascular changes in the brain that could lead to stroke.

The positive findings mean that “retinal microvasculature may serve as a biomarker for cerebrovascular health. Retinal imaging may enable further risk stratification of cerebrovascular and neurodegenerative diseases for early, intensive preventive interventions,” said lead investigator Michelle Lin, MD, a stroke fellow at Johns Hopkins.

A full evaluation is beyond the scope of a quick ophthalmoscope check up in the office. The advent of smartphone fundoscopic cameras and optical coherence tomography – which provides images of retinal vasculature at micrometer-level resolution – will likely help retinal imaging reach its full potential in the clinic, she said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

Dr. Lin and her team reviewed 10,468 participants in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study database. They had baseline retinal photographs from 1993-1995 when they were 45-65 years old. The photos were checked for four types of retinopathy: arteriovenous nicking, focal arteriolar narrowing, retinal microaneurysms, and retinal hemorrhage. The presence of each one was given a score of 1, yielding a retinopathy severity score of 0-4, with 4 meaning subjects had all four types.

Over a median follow-up period of 18.8 years, 578 participants had an ischemic stroke, including 114 lacunar strokes, 292 nonlacunar strokes, and 172 cardioembolic strokes. Hemorrhagic strokes occurred in 95 subjects.

The incidence of ischemic stroke increased with the severity of baseline retinopathy, from 2.7 strokes per 1,000 participant-years among those with no retinopathy to 10.2 among those with a severity score of 3 or higher (P less than .001). The 15-year cumulative risk of ischemic stroke with any retinopathy was 3.4% versus 1.6% with no retinopathy (P less than .001).

After adjustment for age, sex, race, comorbidities, and other confounders, retinal microvasculopathy associated positively with ischemic stroke, especially lacunar stroke (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.84; 95% confidence interval, 1.23-2.74; P = .005).

Trends linking retinopathy severity to the incidence of nonlacunar, cardioembolic, and hemorrhagic strokes were not statistically significant. Factors associated with higher retinopathy grade included older age, black race, hypertension, and diabetes, among others.

There were slightly more women than men in the review. The average age at baseline was 59 years. Patients with stroke histories at baseline were excluded.

The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health. The investigators had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Lin MP et al. Neurology. 2018 Apr;90(15 Suppl.):CCI.001.

LOS ANGELES – The more severe retinopathy is at midlife, the greater the risk of ischemic stroke – particularly lacunar stroke – later on, according to investigators from Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.