User login

Psychosocial factors and treatment satisfaction after radical prostatectomy

More than 164,690 men are expected to be diagnosed with prostate cancer in the United States in 2018.1 Men with prostate cancer face not only stress associated with the diagnosis but also decisional conflict regarding different treatment options.2 Most men diagnosed with clinically localized prostate cancer receive 1 or more of the following treatments: radical prostatectomy, external-beam radiation therapy, and/or brachytherapy, all of which are associated with posttreatment urological or sexual side effects including bowel, urinary, or erectile dysfunction.3-5 Men who choose active surveillance may experience increased anxiety associated with the constant vigilance and monitoring of their tumor status along with the uncertainty of not definitively removing or radiating their prostate.6 In addition to direct functional limitations of sexual and urological side effects, treatment can also lead to secondary psychosocial effects, including depression, self-blame, embarrassment, guilt, lower masculine self-esteem, increased reticence to participate socially or engage in sexual activity, and relationship distress.7-9 Therefore, health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and treatment satisfaction are important for this population.

Urological and sexual side effects of prostate cancer treatments are often a primary focus during treatment decision making between patients and providers. However, little prospective empirical data exist regarding the role of HRQoL and other nonurological physical and psychosocial outcomes on overall treatment satisfaction. The purpose of this study was to prospectively evaluate the role of both urological and nonurological outcomes on overall treatment satisfaction in men diagnosed with prostate cancer. We hypothesize that such an understanding can help describe changes in physical and psychosocial factors that are important to men beyond traditional urological outcomes, including their association with overall treatment satisfaction.

Methods

This was a prospective longitudinal assessment of patients from the Department of Urology at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago. Patients were eligible if they met the following inclusion criteria: they had been diagnosed with clinically localized or locally advanced prostate cancer; they had not yet received a primary treatment (eg, surgery, radiation, active surveillance) before their baseline assessment; they were 18 years or older; and they were able to read, write, speak, and understand English. Patients were excluded if they had a physical debilitation that would make participation not feasible or would create undue hardship, or if they had a history of diagnosed severe mental illness or hospitalization for chronic psychiatric reasons, as identified by referring physicians.

Eligible participants were approached before their treatment decision (if any). Patient enrollment occurred in 2 ways. For patients invited to participate during their clinic visit, the research assistant explained the study and obtained written informed consent for interested patients. A unique user identification and password was created for each patient, and they practiced using the touch screen computer while the research assistant observed and provided guidance as needed. When the patients were ready to start their pretreatment online interview, they completed the questionnaires by themselves. For patients who were invited to participate but were not scheduled to return in the foreseeable future, enrollment was carried out differently. In those cases, participating physicians contacted eligible patients who were not scheduled for a visit and informed them of the study opportunity. Interested patients were contacted by the research assistant who provided them with the study website address, which directed them to the online consent form. After a patient had completed the consent form, he was prompted to self-register. He received a unique user identification and password that could be used to complete the baseline assessment and subsequent assessments. However, for interested patients who did not have access to a computer or Internet connection, the research assistant provided them with paper consent forms and paper versions of all study assessments. After participants had completed the baseline assessment, the research assistant provided them with a written schedule of future assessments, which were expected to occur at 1 month posttreatment, 3 months posttreatment, 6 months posttreatment, and 12 months posttreatment.

For all follow-up appointments, participants could complete assessments either at clinic visits or from home using a secure online assessment platform called Assessment Center.10 The research assistant used a patient log to track participants and their progress in the study, which included study number, patient name (or initials), registration date, date of birth, sex, and timeline of completed or future assessments. The research assistant called or emailed participants (depending on patient preference) about a week before each of their follow-up assessments to facilitate adherence. If the participant did not log into the system by the target day, the research assistant contacted him the following day (target day +1) with a phone or email reminder to log into the system and complete the assessments. If the participant did not log in by midnight 1 day after the target day, the research assistant attempted to contact him one last time (target day +2) with either a reminder to log into the system or to ascertain his status that might be related to his noncompletion. Overall, a participant was called or e-mailed 1 to 3 times to remind him of his assessment. If he was unresponsive after 3 attempts, he was recorded as having withdrawn for an unknown reason.

At baseline and each follow-up time point, study participants completed a battery of patient-reported outcome measures, with most coming from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS)11 and the Surgical Outcomes Measurement System (SOMS).12 PROMIS is a National Institutes of Health (NIH) funded measurement system that has helped standardize and improve self-reported assessment of health status, symptoms, side effects, and different aspects of HRQoL, including physical, emotional, cognitive, and social health. SOMS is a suite of patient-reported outcome measures assessing important aspects of HRQoL after surgery. It was developed with feedback from surgeons, postoperative patients, and surgical nurses. PROMIS items were directly incorporated into numerous SOMS measures to facilitate easier comparisons and score crosswalks across measures and patient populations. In addition to PROMIS and SOMS measures, we also administered several well-known instruments of urological and sexual function, including the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF) and American Urological Association Symptom Score Index (AUASS).13,14

Outcome measures were compared across sociodemographic and clinical variables at each time point using t tests for numerical variables (age) and with chi-square or Fisher exact tests for categorical variables; those variables with significant differences were used as covariates in statistical models. To examine differences in patient-reported scores over time, we used repeated measures analysis of covariance with general linear modeling methods. We used Pearson correlation coefficients to evaluate for correlations between quality-of-life outcomes and treatment satisfaction.

Not all participants completed each of the follow-up surveys, and reasons for dropout were prospectively documented. Most participants elected surgical resection as their primary treatment compared with the fewer than 10% of patients who chose radiation or chemotherapy as their primary treatment and about 20% of men who chose active surveillance after their initial diagnosis. Therefore, our analysis focused on patients who elected surgical resection. For comparison purposes, we included the HRQoL results from active surveillance patients.

Results

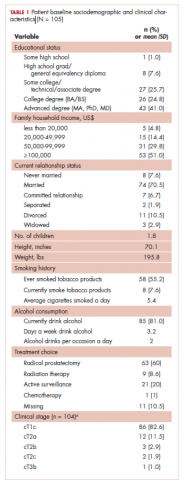

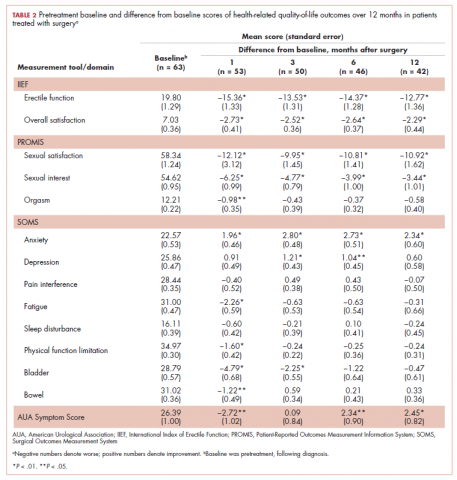

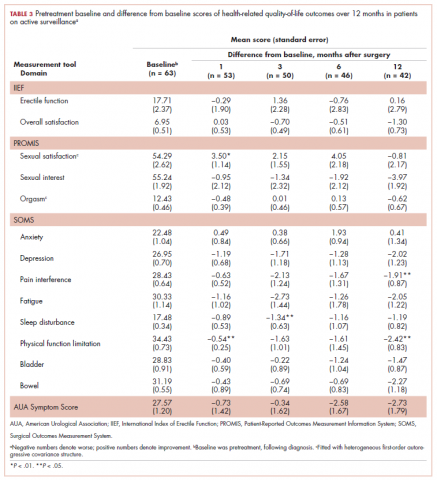

A total of 105 patients diagnosed with prostate cancer were enrolled in the study. Response rates decreased throughout the study (n = 75 at 1 month; n = 71 at 3 months; n = 64 at 6 months; n = 54 at 12 months). Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of participants are shown in Table 1. The mean change from pretreatment (baseline) scores for each measure in patients treated with surgery is shown in Table 2, and the mean change from pretreatment scores in patients who elected active surveillance is shown in Table 3 (in both tables, a negative score denotes worsened function, and a positive change denotes improvement).

After surgery, patients reported significantly lower erectile function and sexual satisfaction scores. These included statistically significant decreases for IIEF Erectile Function, IIEF Overall Satisfaction, PROMIS Sexual Satisfaction, PROMIS Sexual Interest, and PROMIS Orgasm. In patients treated with surgery, there were significant improvements in anxiety observed for patients at each follow-up time, whereas significantly worse bladder problems were observed on SOMS Bladder at 1 and 3 months but returned to baseline by 12 months after surgery. AUASS was worse at 1 month but significantly improved at 6 and 12 months. Fatigue scores significantly worsened at 1 month but were no longer significant at 6 and 12 months. Physical Function was worsened at 1 month but not throughout the rest of the study. Bowel Problems (SOMS) were significantly worse at 1 month, but changes became nonsignificant on subsequent assessments. The only 2 domains that did not demonstrate any significant changes o

In active surveillance patients, sexual function domains were generally unchanged over the course of the study. However, unlike treated patients, there was no significant improvement in anxiety, depression, pain, fatigue, or sleep. In fact, most of these domains demonstrated worsened functioning, although these were not statistically significant. Urinary domains generally remained unchanged.

Pearson correlation coefficients between HRQoL measures and overall treatment satisfaction (assessed by the question, Are you satisfied with the results of your operation?) at each follow-up time point in patients treated with surgery are shown in Table 4. Relations between treatment satisfaction and sexual outcomes were generally statistically insignificant (r, .08-.56). However, sleep disturbance, depression, pain interference, fatigue, embarrassment, and bladder problems all demonstrated statistically significant positive associations with treatment satisfaction, with coefficients ranging from small to medium in magnitude (r, .32-.61). Other outcomes such as anxiety, physical function, and bowel problems demonstrated small to medium statistically significant associations with treatment satisfaction (r, .04-.60) but not at every time point. We performed t tests to examine treatment satisfaction in patients with detectable initial posttreatment prostate-specific antigen (PSA; >0.01 ng/mL). We found no difference in treatment satisfaction between patients with detectable PSA values and those with undetectable PSA at each time point.

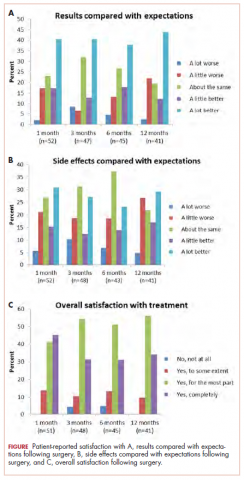

When the patients were asked, Compared with what you expected, how do you rate the results of your operation?, most of those treated with surgery reported that the results of their operation were better than they had expected (Figure 1A; p. e137). More than 75% of the patients had results that were as expected or better than expected. When asked, Compared with what you expected, how do you rate your side effects of the operation?, almost 70% of patients reported side effects no worse than expected (Figure 1B). When asked, Are you satisfied with the results of your operation?, most patients reported that overall, they were satisfied with the results of their operation (Figure 1C).

At 12 months, none of the patients reported overall dissatisfaction with their treatment choice. More than 90% of patients were mostly or completely satisfied with the results of their operation.

Discussion

This prospective study assessed the HRQoL from pretreatment through 12 months posttreatment in men diagnosed with clinically localized prostate cancer that had been treated with surgery. Although the indicators of sexual function significantly decreased over time, they were not meaningfully associated with overall treatment satisfaction. Instead, a host of other factors, including psychosocial (eg, anxiety, depression, body image dissatisfaction, embarrassment), nonurological physical symptoms (pain interference, physical function, sleep disturbance, fatigue), and bladder problems, were significantly related to overall treatment satisfaction. Although this may not be surprising in other clinical oncology paradigms, the sheer surfeit of focus and attention on sexual function has overshadowed aspects of HRQoL that many men report are important to them, despite worsened sexual function outcomes.

Understanding potential treatment-related changes in HRQoL can be challenging for men when choosing providers and different therapeutic options. The increasing complexity of treatment in prostate cancer has created an opportunity to not only understand efficacy on cancer control but also focus on meaningful patient-reported outcomes. Hospitals and medical groups are increasingly aware of the importance of improving the patient care experience. Objective measures of patient satisfaction for health care providers, such as the Press-Ganey and Net Promoter score, exist to measure and improve patient experience. In prostate cancer, clinicians and large groups, including governmental agencies such as the US Preventive Services Task Force, have often focused on declines in urinary and erectile function15 without considering the full impact of prostate cancer treatment on global HRQoL. Our study was a prospective, longitudinal, self-reported examination of the impact, positive and negative, of prostate cancer treatment over a 12-month period.

Numerous studies have documented the treatment-related side effects of erectile, urinary, and bowel dysfunction in patients treated for prostate cancer, which may occur after definitive local therapies.5,16-18 The present study shows a similar impact on urinary, bowel, and erectile domains after treatment. Although erectile function scores remained lower through the course of the 12-month study, bowel and bladder domains returned to baseline by month 12. Unlike other studies, we also examined psychosocial and nonurological aspects of prostate cancer treatment. We found that there was a measurable and significant positive impact on other HRQoL measurements such as decreased anxiety. Despite a variety of declines across HRQoL domains, most patients reported that their results were largely as they had expected, and their side effects were the same or better than they had expected. No patient in the cohort reported being dissatisfied with his overall treatment, and more than 90% of patients were mostly or completely satisfied with their treatment choice. This highlights the point that while sexual and other urological domains of HRQoL are important, impairments in these areas do not necessarily reflect how many patients perceive success or satisfaction with their treatment choice. We also showed correlations between treatment satisfaction and improvement in sleep, anxiety, depression, and fatigue. It is worth noting that although there were decreases in the erectile and sexual function domains after treatment, those factors were not correlated with overall treatment satisfaction. Those factors may not routinely be assessed before, during, and after treatment for prostate cancer in most clinical encounters. However, because they were strongly associated with satisfaction with treatment outcomes in this study, identification in impairments may lead to opportunities to intervene and improve the patient experience. Therefore, important “teachable moments” may be missed (for both patients and providers) during treatment decision-making encounters if other factors beyond sexual and urological outcomes are not adequately considered and addressed. Furthermore, the results of our study may help clinicians counsel patients on their expectations for their recovery after surgery and identify particular issues related to HRQoL to pay close attention to in follow-up visits.

Strengths of our study include its prospective nature, which allowed evaluation of HRQoL outcomes at multiple time points throughout the first year after treatment. In addition, we used existing patient-reported outcome tools validated by the NIH to assess changes in HRQoL. PROMIS is an NIH-supported tool that can be leveraged in the pre- and posttreatment periods to identify patients who have impairments with HRQoL. It can provide clinicians with a unique opportunity to detect and intervene in setbacks and side effects to improve patient satisfaction and HRQoL.

Limitations of the current study include that most patients selected surgery for their treatment choice and that not all patients completed all longitudinal questionnaires, although this is expected in longitudinal studies of this nature. Although all the patients were approached and encouraged to participate, many did not participate and were not captured. In addition, not all patients completed end-of-study surveys. These factors may have biased our results because of unmeasurable factors related to nonparticipation or dropout. Our study encompassed the preoperative period up to 12 months postoperatively, which may fail to identify improvements or declines in HRQoL that may occur more than 12 months postoperatively, particularly related to continence and erectile function. The participants were enrolled by 6 surgeons, and we were not able to standardize the preoperative counseling either preoperatively or postoperatively, which may have biased our results. Finally, our study population consisted of predominantly white, married men of higher socioeconomic status; therefore, our results may not be generalizable to newly diagnosed prostate cancer patients overall.

Conclusions

By using validated self-administered questionnaires, we found that despite decreased sexual and urinary function, patients treated for prostate cancer were satisfied with their treatment choice. Correlates to higher patient satisfaction included decreased anxiety, depression, fatigue, and sleep disturbances.

1. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:7‐30.

2. Berry DL, Ellis WJ, Woods NF, Schwien C, Mullen KH, Yang C. Treatment decision-making by men with localized prostate cancer: the influence of personal factors. Urol Oncol. 2003;21(2):93-100.

3. Dubbelman YD, Dohle GR, Schröder FH. Sexual function before and after radical retropubic prostatectomy: a systematic review of prognostic indicators for a successful outcome. Eur Urol. 2006;50(4):711-718; discussion 718-720.

4. McCullough AR. Sexual dysfunction after radical prostatectomy. Rev Urol. 2005;7(2 suppl):S3-S10.

5. Sanda MG, Dunn RL, Michalski J, et al. Quality of life and satisfaction with outcome among prostate-cancer survivors. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(12):1250-1261.

6. Latini DM, Hart SL, Knight SJ, et al. The relationship between anxiety and time to treatment for patients with prostate cancer on surveillance. J Urol. 2007;178(3, pt 1):826-831; discussion 831-832.

7. Meyer JP, Gillatt DA, Lockyer R, Macdonagh R. The effect of erectile dysfunction on the quality of life of men after radical prostatectomy. BJU Int. 2003;92(9):929-931.

8. Casey RG, Corcoran NM, Goldenberg SL. Quality of life issues in men undergoing androgen deprivation therapy: a review. Asian J Androl. 2012;14(2):226-231.

9. Segrin C, Badger TA, Harrington J. Interdependent psychological quality of life in dyads adjusting to prostate cancer. Health Psychol. 2012;31(1):70-79.

10. Gershon RC, Rothrock N, Hanrahan R, Bass M, Cella D. The use of PROMIS and assessment center to deliver patient-reported outcome measures in clinical research. J Appl Meas. 2010;11(3):304-314.

11. Cella D, Yount S, Rothrock N, et al. The patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS): progress of an NIH roadmap cooperative group during its first two years. Med Care. 2007;45(5 suppl 1):S3-S11.

12. Zapf M, Denham W, Barrera E, et al. Patient-centered outcomes after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 2013;27(12):4491-4498.

13. Barry MJ, Fowler FJ Jr, O'Leary MP, et al. The American Urological Association symptom index for benign prostatic hyperplasia. The Measurement Committee of the American Urological Association. J Urol. 1992;148(5):1549-1557; discussion 1564.

14. Rosen RC, Riley A, Wagner G, Osterloh IH, Kirkpatrick J, Mishra A. The international index of erectile function (IIEF): a multidimensional scale for assessment of erectile dysfunction. Urology. 1997;49(6):822-830.

15. United States Preventive Services Task Force. Final update summary: prostate cancer: screening. http:// www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/ Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/prostate-cancer-screening. Updated July 2015. Accessed April 14, 2017

16. Litwin MS, Gore JL, Kwan L, et al. Quality of life after surgery, external beam irradiation, or brachytherapy for early-stage prostate cancer. Cancer. 2007;109(11):2239-2247.

17. Miwa S, Mizokami A, Konaka H, et al. Prospective longitudinal comparative study of health-related quality of life and treatment satisfaction in patients treated with hormone therapy, radical retropubic prostatectomy, and high or low dose rate brachytherapy for prostate cancer. Prostate Int. 2013;1(3):117-124.

18. Miller DC, Sanda MG, Dunn RL et al. Long-term outcomes among localized prostate cancer survivors: health-related quality-of-life changes after radical prostatectomy, external radiation, and brachytherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(12):2772-2780.

More than 164,690 men are expected to be diagnosed with prostate cancer in the United States in 2018.1 Men with prostate cancer face not only stress associated with the diagnosis but also decisional conflict regarding different treatment options.2 Most men diagnosed with clinically localized prostate cancer receive 1 or more of the following treatments: radical prostatectomy, external-beam radiation therapy, and/or brachytherapy, all of which are associated with posttreatment urological or sexual side effects including bowel, urinary, or erectile dysfunction.3-5 Men who choose active surveillance may experience increased anxiety associated with the constant vigilance and monitoring of their tumor status along with the uncertainty of not definitively removing or radiating their prostate.6 In addition to direct functional limitations of sexual and urological side effects, treatment can also lead to secondary psychosocial effects, including depression, self-blame, embarrassment, guilt, lower masculine self-esteem, increased reticence to participate socially or engage in sexual activity, and relationship distress.7-9 Therefore, health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and treatment satisfaction are important for this population.

Urological and sexual side effects of prostate cancer treatments are often a primary focus during treatment decision making between patients and providers. However, little prospective empirical data exist regarding the role of HRQoL and other nonurological physical and psychosocial outcomes on overall treatment satisfaction. The purpose of this study was to prospectively evaluate the role of both urological and nonurological outcomes on overall treatment satisfaction in men diagnosed with prostate cancer. We hypothesize that such an understanding can help describe changes in physical and psychosocial factors that are important to men beyond traditional urological outcomes, including their association with overall treatment satisfaction.

Methods

This was a prospective longitudinal assessment of patients from the Department of Urology at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago. Patients were eligible if they met the following inclusion criteria: they had been diagnosed with clinically localized or locally advanced prostate cancer; they had not yet received a primary treatment (eg, surgery, radiation, active surveillance) before their baseline assessment; they were 18 years or older; and they were able to read, write, speak, and understand English. Patients were excluded if they had a physical debilitation that would make participation not feasible or would create undue hardship, or if they had a history of diagnosed severe mental illness or hospitalization for chronic psychiatric reasons, as identified by referring physicians.

Eligible participants were approached before their treatment decision (if any). Patient enrollment occurred in 2 ways. For patients invited to participate during their clinic visit, the research assistant explained the study and obtained written informed consent for interested patients. A unique user identification and password was created for each patient, and they practiced using the touch screen computer while the research assistant observed and provided guidance as needed. When the patients were ready to start their pretreatment online interview, they completed the questionnaires by themselves. For patients who were invited to participate but were not scheduled to return in the foreseeable future, enrollment was carried out differently. In those cases, participating physicians contacted eligible patients who were not scheduled for a visit and informed them of the study opportunity. Interested patients were contacted by the research assistant who provided them with the study website address, which directed them to the online consent form. After a patient had completed the consent form, he was prompted to self-register. He received a unique user identification and password that could be used to complete the baseline assessment and subsequent assessments. However, for interested patients who did not have access to a computer or Internet connection, the research assistant provided them with paper consent forms and paper versions of all study assessments. After participants had completed the baseline assessment, the research assistant provided them with a written schedule of future assessments, which were expected to occur at 1 month posttreatment, 3 months posttreatment, 6 months posttreatment, and 12 months posttreatment.

For all follow-up appointments, participants could complete assessments either at clinic visits or from home using a secure online assessment platform called Assessment Center.10 The research assistant used a patient log to track participants and their progress in the study, which included study number, patient name (or initials), registration date, date of birth, sex, and timeline of completed or future assessments. The research assistant called or emailed participants (depending on patient preference) about a week before each of their follow-up assessments to facilitate adherence. If the participant did not log into the system by the target day, the research assistant contacted him the following day (target day +1) with a phone or email reminder to log into the system and complete the assessments. If the participant did not log in by midnight 1 day after the target day, the research assistant attempted to contact him one last time (target day +2) with either a reminder to log into the system or to ascertain his status that might be related to his noncompletion. Overall, a participant was called or e-mailed 1 to 3 times to remind him of his assessment. If he was unresponsive after 3 attempts, he was recorded as having withdrawn for an unknown reason.

At baseline and each follow-up time point, study participants completed a battery of patient-reported outcome measures, with most coming from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS)11 and the Surgical Outcomes Measurement System (SOMS).12 PROMIS is a National Institutes of Health (NIH) funded measurement system that has helped standardize and improve self-reported assessment of health status, symptoms, side effects, and different aspects of HRQoL, including physical, emotional, cognitive, and social health. SOMS is a suite of patient-reported outcome measures assessing important aspects of HRQoL after surgery. It was developed with feedback from surgeons, postoperative patients, and surgical nurses. PROMIS items were directly incorporated into numerous SOMS measures to facilitate easier comparisons and score crosswalks across measures and patient populations. In addition to PROMIS and SOMS measures, we also administered several well-known instruments of urological and sexual function, including the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF) and American Urological Association Symptom Score Index (AUASS).13,14

Outcome measures were compared across sociodemographic and clinical variables at each time point using t tests for numerical variables (age) and with chi-square or Fisher exact tests for categorical variables; those variables with significant differences were used as covariates in statistical models. To examine differences in patient-reported scores over time, we used repeated measures analysis of covariance with general linear modeling methods. We used Pearson correlation coefficients to evaluate for correlations between quality-of-life outcomes and treatment satisfaction.

Not all participants completed each of the follow-up surveys, and reasons for dropout were prospectively documented. Most participants elected surgical resection as their primary treatment compared with the fewer than 10% of patients who chose radiation or chemotherapy as their primary treatment and about 20% of men who chose active surveillance after their initial diagnosis. Therefore, our analysis focused on patients who elected surgical resection. For comparison purposes, we included the HRQoL results from active surveillance patients.

Results

A total of 105 patients diagnosed with prostate cancer were enrolled in the study. Response rates decreased throughout the study (n = 75 at 1 month; n = 71 at 3 months; n = 64 at 6 months; n = 54 at 12 months). Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of participants are shown in Table 1. The mean change from pretreatment (baseline) scores for each measure in patients treated with surgery is shown in Table 2, and the mean change from pretreatment scores in patients who elected active surveillance is shown in Table 3 (in both tables, a negative score denotes worsened function, and a positive change denotes improvement).

After surgery, patients reported significantly lower erectile function and sexual satisfaction scores. These included statistically significant decreases for IIEF Erectile Function, IIEF Overall Satisfaction, PROMIS Sexual Satisfaction, PROMIS Sexual Interest, and PROMIS Orgasm. In patients treated with surgery, there were significant improvements in anxiety observed for patients at each follow-up time, whereas significantly worse bladder problems were observed on SOMS Bladder at 1 and 3 months but returned to baseline by 12 months after surgery. AUASS was worse at 1 month but significantly improved at 6 and 12 months. Fatigue scores significantly worsened at 1 month but were no longer significant at 6 and 12 months. Physical Function was worsened at 1 month but not throughout the rest of the study. Bowel Problems (SOMS) were significantly worse at 1 month, but changes became nonsignificant on subsequent assessments. The only 2 domains that did not demonstrate any significant changes o

In active surveillance patients, sexual function domains were generally unchanged over the course of the study. However, unlike treated patients, there was no significant improvement in anxiety, depression, pain, fatigue, or sleep. In fact, most of these domains demonstrated worsened functioning, although these were not statistically significant. Urinary domains generally remained unchanged.

Pearson correlation coefficients between HRQoL measures and overall treatment satisfaction (assessed by the question, Are you satisfied with the results of your operation?) at each follow-up time point in patients treated with surgery are shown in Table 4. Relations between treatment satisfaction and sexual outcomes were generally statistically insignificant (r, .08-.56). However, sleep disturbance, depression, pain interference, fatigue, embarrassment, and bladder problems all demonstrated statistically significant positive associations with treatment satisfaction, with coefficients ranging from small to medium in magnitude (r, .32-.61). Other outcomes such as anxiety, physical function, and bowel problems demonstrated small to medium statistically significant associations with treatment satisfaction (r, .04-.60) but not at every time point. We performed t tests to examine treatment satisfaction in patients with detectable initial posttreatment prostate-specific antigen (PSA; >0.01 ng/mL). We found no difference in treatment satisfaction between patients with detectable PSA values and those with undetectable PSA at each time point.

When the patients were asked, Compared with what you expected, how do you rate the results of your operation?, most of those treated with surgery reported that the results of their operation were better than they had expected (Figure 1A; p. e137). More than 75% of the patients had results that were as expected or better than expected. When asked, Compared with what you expected, how do you rate your side effects of the operation?, almost 70% of patients reported side effects no worse than expected (Figure 1B). When asked, Are you satisfied with the results of your operation?, most patients reported that overall, they were satisfied with the results of their operation (Figure 1C).

At 12 months, none of the patients reported overall dissatisfaction with their treatment choice. More than 90% of patients were mostly or completely satisfied with the results of their operation.

Discussion

This prospective study assessed the HRQoL from pretreatment through 12 months posttreatment in men diagnosed with clinically localized prostate cancer that had been treated with surgery. Although the indicators of sexual function significantly decreased over time, they were not meaningfully associated with overall treatment satisfaction. Instead, a host of other factors, including psychosocial (eg, anxiety, depression, body image dissatisfaction, embarrassment), nonurological physical symptoms (pain interference, physical function, sleep disturbance, fatigue), and bladder problems, were significantly related to overall treatment satisfaction. Although this may not be surprising in other clinical oncology paradigms, the sheer surfeit of focus and attention on sexual function has overshadowed aspects of HRQoL that many men report are important to them, despite worsened sexual function outcomes.

Understanding potential treatment-related changes in HRQoL can be challenging for men when choosing providers and different therapeutic options. The increasing complexity of treatment in prostate cancer has created an opportunity to not only understand efficacy on cancer control but also focus on meaningful patient-reported outcomes. Hospitals and medical groups are increasingly aware of the importance of improving the patient care experience. Objective measures of patient satisfaction for health care providers, such as the Press-Ganey and Net Promoter score, exist to measure and improve patient experience. In prostate cancer, clinicians and large groups, including governmental agencies such as the US Preventive Services Task Force, have often focused on declines in urinary and erectile function15 without considering the full impact of prostate cancer treatment on global HRQoL. Our study was a prospective, longitudinal, self-reported examination of the impact, positive and negative, of prostate cancer treatment over a 12-month period.

Numerous studies have documented the treatment-related side effects of erectile, urinary, and bowel dysfunction in patients treated for prostate cancer, which may occur after definitive local therapies.5,16-18 The present study shows a similar impact on urinary, bowel, and erectile domains after treatment. Although erectile function scores remained lower through the course of the 12-month study, bowel and bladder domains returned to baseline by month 12. Unlike other studies, we also examined psychosocial and nonurological aspects of prostate cancer treatment. We found that there was a measurable and significant positive impact on other HRQoL measurements such as decreased anxiety. Despite a variety of declines across HRQoL domains, most patients reported that their results were largely as they had expected, and their side effects were the same or better than they had expected. No patient in the cohort reported being dissatisfied with his overall treatment, and more than 90% of patients were mostly or completely satisfied with their treatment choice. This highlights the point that while sexual and other urological domains of HRQoL are important, impairments in these areas do not necessarily reflect how many patients perceive success or satisfaction with their treatment choice. We also showed correlations between treatment satisfaction and improvement in sleep, anxiety, depression, and fatigue. It is worth noting that although there were decreases in the erectile and sexual function domains after treatment, those factors were not correlated with overall treatment satisfaction. Those factors may not routinely be assessed before, during, and after treatment for prostate cancer in most clinical encounters. However, because they were strongly associated with satisfaction with treatment outcomes in this study, identification in impairments may lead to opportunities to intervene and improve the patient experience. Therefore, important “teachable moments” may be missed (for both patients and providers) during treatment decision-making encounters if other factors beyond sexual and urological outcomes are not adequately considered and addressed. Furthermore, the results of our study may help clinicians counsel patients on their expectations for their recovery after surgery and identify particular issues related to HRQoL to pay close attention to in follow-up visits.

Strengths of our study include its prospective nature, which allowed evaluation of HRQoL outcomes at multiple time points throughout the first year after treatment. In addition, we used existing patient-reported outcome tools validated by the NIH to assess changes in HRQoL. PROMIS is an NIH-supported tool that can be leveraged in the pre- and posttreatment periods to identify patients who have impairments with HRQoL. It can provide clinicians with a unique opportunity to detect and intervene in setbacks and side effects to improve patient satisfaction and HRQoL.

Limitations of the current study include that most patients selected surgery for their treatment choice and that not all patients completed all longitudinal questionnaires, although this is expected in longitudinal studies of this nature. Although all the patients were approached and encouraged to participate, many did not participate and were not captured. In addition, not all patients completed end-of-study surveys. These factors may have biased our results because of unmeasurable factors related to nonparticipation or dropout. Our study encompassed the preoperative period up to 12 months postoperatively, which may fail to identify improvements or declines in HRQoL that may occur more than 12 months postoperatively, particularly related to continence and erectile function. The participants were enrolled by 6 surgeons, and we were not able to standardize the preoperative counseling either preoperatively or postoperatively, which may have biased our results. Finally, our study population consisted of predominantly white, married men of higher socioeconomic status; therefore, our results may not be generalizable to newly diagnosed prostate cancer patients overall.

Conclusions

By using validated self-administered questionnaires, we found that despite decreased sexual and urinary function, patients treated for prostate cancer were satisfied with their treatment choice. Correlates to higher patient satisfaction included decreased anxiety, depression, fatigue, and sleep disturbances.

More than 164,690 men are expected to be diagnosed with prostate cancer in the United States in 2018.1 Men with prostate cancer face not only stress associated with the diagnosis but also decisional conflict regarding different treatment options.2 Most men diagnosed with clinically localized prostate cancer receive 1 or more of the following treatments: radical prostatectomy, external-beam radiation therapy, and/or brachytherapy, all of which are associated with posttreatment urological or sexual side effects including bowel, urinary, or erectile dysfunction.3-5 Men who choose active surveillance may experience increased anxiety associated with the constant vigilance and monitoring of their tumor status along with the uncertainty of not definitively removing or radiating their prostate.6 In addition to direct functional limitations of sexual and urological side effects, treatment can also lead to secondary psychosocial effects, including depression, self-blame, embarrassment, guilt, lower masculine self-esteem, increased reticence to participate socially or engage in sexual activity, and relationship distress.7-9 Therefore, health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and treatment satisfaction are important for this population.

Urological and sexual side effects of prostate cancer treatments are often a primary focus during treatment decision making between patients and providers. However, little prospective empirical data exist regarding the role of HRQoL and other nonurological physical and psychosocial outcomes on overall treatment satisfaction. The purpose of this study was to prospectively evaluate the role of both urological and nonurological outcomes on overall treatment satisfaction in men diagnosed with prostate cancer. We hypothesize that such an understanding can help describe changes in physical and psychosocial factors that are important to men beyond traditional urological outcomes, including their association with overall treatment satisfaction.

Methods

This was a prospective longitudinal assessment of patients from the Department of Urology at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago. Patients were eligible if they met the following inclusion criteria: they had been diagnosed with clinically localized or locally advanced prostate cancer; they had not yet received a primary treatment (eg, surgery, radiation, active surveillance) before their baseline assessment; they were 18 years or older; and they were able to read, write, speak, and understand English. Patients were excluded if they had a physical debilitation that would make participation not feasible or would create undue hardship, or if they had a history of diagnosed severe mental illness or hospitalization for chronic psychiatric reasons, as identified by referring physicians.

Eligible participants were approached before their treatment decision (if any). Patient enrollment occurred in 2 ways. For patients invited to participate during their clinic visit, the research assistant explained the study and obtained written informed consent for interested patients. A unique user identification and password was created for each patient, and they practiced using the touch screen computer while the research assistant observed and provided guidance as needed. When the patients were ready to start their pretreatment online interview, they completed the questionnaires by themselves. For patients who were invited to participate but were not scheduled to return in the foreseeable future, enrollment was carried out differently. In those cases, participating physicians contacted eligible patients who were not scheduled for a visit and informed them of the study opportunity. Interested patients were contacted by the research assistant who provided them with the study website address, which directed them to the online consent form. After a patient had completed the consent form, he was prompted to self-register. He received a unique user identification and password that could be used to complete the baseline assessment and subsequent assessments. However, for interested patients who did not have access to a computer or Internet connection, the research assistant provided them with paper consent forms and paper versions of all study assessments. After participants had completed the baseline assessment, the research assistant provided them with a written schedule of future assessments, which were expected to occur at 1 month posttreatment, 3 months posttreatment, 6 months posttreatment, and 12 months posttreatment.

For all follow-up appointments, participants could complete assessments either at clinic visits or from home using a secure online assessment platform called Assessment Center.10 The research assistant used a patient log to track participants and their progress in the study, which included study number, patient name (or initials), registration date, date of birth, sex, and timeline of completed or future assessments. The research assistant called or emailed participants (depending on patient preference) about a week before each of their follow-up assessments to facilitate adherence. If the participant did not log into the system by the target day, the research assistant contacted him the following day (target day +1) with a phone or email reminder to log into the system and complete the assessments. If the participant did not log in by midnight 1 day after the target day, the research assistant attempted to contact him one last time (target day +2) with either a reminder to log into the system or to ascertain his status that might be related to his noncompletion. Overall, a participant was called or e-mailed 1 to 3 times to remind him of his assessment. If he was unresponsive after 3 attempts, he was recorded as having withdrawn for an unknown reason.

At baseline and each follow-up time point, study participants completed a battery of patient-reported outcome measures, with most coming from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS)11 and the Surgical Outcomes Measurement System (SOMS).12 PROMIS is a National Institutes of Health (NIH) funded measurement system that has helped standardize and improve self-reported assessment of health status, symptoms, side effects, and different aspects of HRQoL, including physical, emotional, cognitive, and social health. SOMS is a suite of patient-reported outcome measures assessing important aspects of HRQoL after surgery. It was developed with feedback from surgeons, postoperative patients, and surgical nurses. PROMIS items were directly incorporated into numerous SOMS measures to facilitate easier comparisons and score crosswalks across measures and patient populations. In addition to PROMIS and SOMS measures, we also administered several well-known instruments of urological and sexual function, including the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF) and American Urological Association Symptom Score Index (AUASS).13,14

Outcome measures were compared across sociodemographic and clinical variables at each time point using t tests for numerical variables (age) and with chi-square or Fisher exact tests for categorical variables; those variables with significant differences were used as covariates in statistical models. To examine differences in patient-reported scores over time, we used repeated measures analysis of covariance with general linear modeling methods. We used Pearson correlation coefficients to evaluate for correlations between quality-of-life outcomes and treatment satisfaction.

Not all participants completed each of the follow-up surveys, and reasons for dropout were prospectively documented. Most participants elected surgical resection as their primary treatment compared with the fewer than 10% of patients who chose radiation or chemotherapy as their primary treatment and about 20% of men who chose active surveillance after their initial diagnosis. Therefore, our analysis focused on patients who elected surgical resection. For comparison purposes, we included the HRQoL results from active surveillance patients.

Results

A total of 105 patients diagnosed with prostate cancer were enrolled in the study. Response rates decreased throughout the study (n = 75 at 1 month; n = 71 at 3 months; n = 64 at 6 months; n = 54 at 12 months). Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of participants are shown in Table 1. The mean change from pretreatment (baseline) scores for each measure in patients treated with surgery is shown in Table 2, and the mean change from pretreatment scores in patients who elected active surveillance is shown in Table 3 (in both tables, a negative score denotes worsened function, and a positive change denotes improvement).

After surgery, patients reported significantly lower erectile function and sexual satisfaction scores. These included statistically significant decreases for IIEF Erectile Function, IIEF Overall Satisfaction, PROMIS Sexual Satisfaction, PROMIS Sexual Interest, and PROMIS Orgasm. In patients treated with surgery, there were significant improvements in anxiety observed for patients at each follow-up time, whereas significantly worse bladder problems were observed on SOMS Bladder at 1 and 3 months but returned to baseline by 12 months after surgery. AUASS was worse at 1 month but significantly improved at 6 and 12 months. Fatigue scores significantly worsened at 1 month but were no longer significant at 6 and 12 months. Physical Function was worsened at 1 month but not throughout the rest of the study. Bowel Problems (SOMS) were significantly worse at 1 month, but changes became nonsignificant on subsequent assessments. The only 2 domains that did not demonstrate any significant changes o

In active surveillance patients, sexual function domains were generally unchanged over the course of the study. However, unlike treated patients, there was no significant improvement in anxiety, depression, pain, fatigue, or sleep. In fact, most of these domains demonstrated worsened functioning, although these were not statistically significant. Urinary domains generally remained unchanged.

Pearson correlation coefficients between HRQoL measures and overall treatment satisfaction (assessed by the question, Are you satisfied with the results of your operation?) at each follow-up time point in patients treated with surgery are shown in Table 4. Relations between treatment satisfaction and sexual outcomes were generally statistically insignificant (r, .08-.56). However, sleep disturbance, depression, pain interference, fatigue, embarrassment, and bladder problems all demonstrated statistically significant positive associations with treatment satisfaction, with coefficients ranging from small to medium in magnitude (r, .32-.61). Other outcomes such as anxiety, physical function, and bowel problems demonstrated small to medium statistically significant associations with treatment satisfaction (r, .04-.60) but not at every time point. We performed t tests to examine treatment satisfaction in patients with detectable initial posttreatment prostate-specific antigen (PSA; >0.01 ng/mL). We found no difference in treatment satisfaction between patients with detectable PSA values and those with undetectable PSA at each time point.

When the patients were asked, Compared with what you expected, how do you rate the results of your operation?, most of those treated with surgery reported that the results of their operation were better than they had expected (Figure 1A; p. e137). More than 75% of the patients had results that were as expected or better than expected. When asked, Compared with what you expected, how do you rate your side effects of the operation?, almost 70% of patients reported side effects no worse than expected (Figure 1B). When asked, Are you satisfied with the results of your operation?, most patients reported that overall, they were satisfied with the results of their operation (Figure 1C).

At 12 months, none of the patients reported overall dissatisfaction with their treatment choice. More than 90% of patients were mostly or completely satisfied with the results of their operation.

Discussion

This prospective study assessed the HRQoL from pretreatment through 12 months posttreatment in men diagnosed with clinically localized prostate cancer that had been treated with surgery. Although the indicators of sexual function significantly decreased over time, they were not meaningfully associated with overall treatment satisfaction. Instead, a host of other factors, including psychosocial (eg, anxiety, depression, body image dissatisfaction, embarrassment), nonurological physical symptoms (pain interference, physical function, sleep disturbance, fatigue), and bladder problems, were significantly related to overall treatment satisfaction. Although this may not be surprising in other clinical oncology paradigms, the sheer surfeit of focus and attention on sexual function has overshadowed aspects of HRQoL that many men report are important to them, despite worsened sexual function outcomes.

Understanding potential treatment-related changes in HRQoL can be challenging for men when choosing providers and different therapeutic options. The increasing complexity of treatment in prostate cancer has created an opportunity to not only understand efficacy on cancer control but also focus on meaningful patient-reported outcomes. Hospitals and medical groups are increasingly aware of the importance of improving the patient care experience. Objective measures of patient satisfaction for health care providers, such as the Press-Ganey and Net Promoter score, exist to measure and improve patient experience. In prostate cancer, clinicians and large groups, including governmental agencies such as the US Preventive Services Task Force, have often focused on declines in urinary and erectile function15 without considering the full impact of prostate cancer treatment on global HRQoL. Our study was a prospective, longitudinal, self-reported examination of the impact, positive and negative, of prostate cancer treatment over a 12-month period.

Numerous studies have documented the treatment-related side effects of erectile, urinary, and bowel dysfunction in patients treated for prostate cancer, which may occur after definitive local therapies.5,16-18 The present study shows a similar impact on urinary, bowel, and erectile domains after treatment. Although erectile function scores remained lower through the course of the 12-month study, bowel and bladder domains returned to baseline by month 12. Unlike other studies, we also examined psychosocial and nonurological aspects of prostate cancer treatment. We found that there was a measurable and significant positive impact on other HRQoL measurements such as decreased anxiety. Despite a variety of declines across HRQoL domains, most patients reported that their results were largely as they had expected, and their side effects were the same or better than they had expected. No patient in the cohort reported being dissatisfied with his overall treatment, and more than 90% of patients were mostly or completely satisfied with their treatment choice. This highlights the point that while sexual and other urological domains of HRQoL are important, impairments in these areas do not necessarily reflect how many patients perceive success or satisfaction with their treatment choice. We also showed correlations between treatment satisfaction and improvement in sleep, anxiety, depression, and fatigue. It is worth noting that although there were decreases in the erectile and sexual function domains after treatment, those factors were not correlated with overall treatment satisfaction. Those factors may not routinely be assessed before, during, and after treatment for prostate cancer in most clinical encounters. However, because they were strongly associated with satisfaction with treatment outcomes in this study, identification in impairments may lead to opportunities to intervene and improve the patient experience. Therefore, important “teachable moments” may be missed (for both patients and providers) during treatment decision-making encounters if other factors beyond sexual and urological outcomes are not adequately considered and addressed. Furthermore, the results of our study may help clinicians counsel patients on their expectations for their recovery after surgery and identify particular issues related to HRQoL to pay close attention to in follow-up visits.

Strengths of our study include its prospective nature, which allowed evaluation of HRQoL outcomes at multiple time points throughout the first year after treatment. In addition, we used existing patient-reported outcome tools validated by the NIH to assess changes in HRQoL. PROMIS is an NIH-supported tool that can be leveraged in the pre- and posttreatment periods to identify patients who have impairments with HRQoL. It can provide clinicians with a unique opportunity to detect and intervene in setbacks and side effects to improve patient satisfaction and HRQoL.

Limitations of the current study include that most patients selected surgery for their treatment choice and that not all patients completed all longitudinal questionnaires, although this is expected in longitudinal studies of this nature. Although all the patients were approached and encouraged to participate, many did not participate and were not captured. In addition, not all patients completed end-of-study surveys. These factors may have biased our results because of unmeasurable factors related to nonparticipation or dropout. Our study encompassed the preoperative period up to 12 months postoperatively, which may fail to identify improvements or declines in HRQoL that may occur more than 12 months postoperatively, particularly related to continence and erectile function. The participants were enrolled by 6 surgeons, and we were not able to standardize the preoperative counseling either preoperatively or postoperatively, which may have biased our results. Finally, our study population consisted of predominantly white, married men of higher socioeconomic status; therefore, our results may not be generalizable to newly diagnosed prostate cancer patients overall.

Conclusions

By using validated self-administered questionnaires, we found that despite decreased sexual and urinary function, patients treated for prostate cancer were satisfied with their treatment choice. Correlates to higher patient satisfaction included decreased anxiety, depression, fatigue, and sleep disturbances.

1. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:7‐30.

2. Berry DL, Ellis WJ, Woods NF, Schwien C, Mullen KH, Yang C. Treatment decision-making by men with localized prostate cancer: the influence of personal factors. Urol Oncol. 2003;21(2):93-100.

3. Dubbelman YD, Dohle GR, Schröder FH. Sexual function before and after radical retropubic prostatectomy: a systematic review of prognostic indicators for a successful outcome. Eur Urol. 2006;50(4):711-718; discussion 718-720.

4. McCullough AR. Sexual dysfunction after radical prostatectomy. Rev Urol. 2005;7(2 suppl):S3-S10.

5. Sanda MG, Dunn RL, Michalski J, et al. Quality of life and satisfaction with outcome among prostate-cancer survivors. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(12):1250-1261.

6. Latini DM, Hart SL, Knight SJ, et al. The relationship between anxiety and time to treatment for patients with prostate cancer on surveillance. J Urol. 2007;178(3, pt 1):826-831; discussion 831-832.

7. Meyer JP, Gillatt DA, Lockyer R, Macdonagh R. The effect of erectile dysfunction on the quality of life of men after radical prostatectomy. BJU Int. 2003;92(9):929-931.

8. Casey RG, Corcoran NM, Goldenberg SL. Quality of life issues in men undergoing androgen deprivation therapy: a review. Asian J Androl. 2012;14(2):226-231.

9. Segrin C, Badger TA, Harrington J. Interdependent psychological quality of life in dyads adjusting to prostate cancer. Health Psychol. 2012;31(1):70-79.

10. Gershon RC, Rothrock N, Hanrahan R, Bass M, Cella D. The use of PROMIS and assessment center to deliver patient-reported outcome measures in clinical research. J Appl Meas. 2010;11(3):304-314.

11. Cella D, Yount S, Rothrock N, et al. The patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS): progress of an NIH roadmap cooperative group during its first two years. Med Care. 2007;45(5 suppl 1):S3-S11.

12. Zapf M, Denham W, Barrera E, et al. Patient-centered outcomes after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 2013;27(12):4491-4498.

13. Barry MJ, Fowler FJ Jr, O'Leary MP, et al. The American Urological Association symptom index for benign prostatic hyperplasia. The Measurement Committee of the American Urological Association. J Urol. 1992;148(5):1549-1557; discussion 1564.

14. Rosen RC, Riley A, Wagner G, Osterloh IH, Kirkpatrick J, Mishra A. The international index of erectile function (IIEF): a multidimensional scale for assessment of erectile dysfunction. Urology. 1997;49(6):822-830.

15. United States Preventive Services Task Force. Final update summary: prostate cancer: screening. http:// www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/ Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/prostate-cancer-screening. Updated July 2015. Accessed April 14, 2017

16. Litwin MS, Gore JL, Kwan L, et al. Quality of life after surgery, external beam irradiation, or brachytherapy for early-stage prostate cancer. Cancer. 2007;109(11):2239-2247.

17. Miwa S, Mizokami A, Konaka H, et al. Prospective longitudinal comparative study of health-related quality of life and treatment satisfaction in patients treated with hormone therapy, radical retropubic prostatectomy, and high or low dose rate brachytherapy for prostate cancer. Prostate Int. 2013;1(3):117-124.

18. Miller DC, Sanda MG, Dunn RL et al. Long-term outcomes among localized prostate cancer survivors: health-related quality-of-life changes after radical prostatectomy, external radiation, and brachytherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(12):2772-2780.

1. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:7‐30.

2. Berry DL, Ellis WJ, Woods NF, Schwien C, Mullen KH, Yang C. Treatment decision-making by men with localized prostate cancer: the influence of personal factors. Urol Oncol. 2003;21(2):93-100.

3. Dubbelman YD, Dohle GR, Schröder FH. Sexual function before and after radical retropubic prostatectomy: a systematic review of prognostic indicators for a successful outcome. Eur Urol. 2006;50(4):711-718; discussion 718-720.

4. McCullough AR. Sexual dysfunction after radical prostatectomy. Rev Urol. 2005;7(2 suppl):S3-S10.

5. Sanda MG, Dunn RL, Michalski J, et al. Quality of life and satisfaction with outcome among prostate-cancer survivors. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(12):1250-1261.

6. Latini DM, Hart SL, Knight SJ, et al. The relationship between anxiety and time to treatment for patients with prostate cancer on surveillance. J Urol. 2007;178(3, pt 1):826-831; discussion 831-832.

7. Meyer JP, Gillatt DA, Lockyer R, Macdonagh R. The effect of erectile dysfunction on the quality of life of men after radical prostatectomy. BJU Int. 2003;92(9):929-931.

8. Casey RG, Corcoran NM, Goldenberg SL. Quality of life issues in men undergoing androgen deprivation therapy: a review. Asian J Androl. 2012;14(2):226-231.

9. Segrin C, Badger TA, Harrington J. Interdependent psychological quality of life in dyads adjusting to prostate cancer. Health Psychol. 2012;31(1):70-79.

10. Gershon RC, Rothrock N, Hanrahan R, Bass M, Cella D. The use of PROMIS and assessment center to deliver patient-reported outcome measures in clinical research. J Appl Meas. 2010;11(3):304-314.

11. Cella D, Yount S, Rothrock N, et al. The patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS): progress of an NIH roadmap cooperative group during its first two years. Med Care. 2007;45(5 suppl 1):S3-S11.

12. Zapf M, Denham W, Barrera E, et al. Patient-centered outcomes after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 2013;27(12):4491-4498.

13. Barry MJ, Fowler FJ Jr, O'Leary MP, et al. The American Urological Association symptom index for benign prostatic hyperplasia. The Measurement Committee of the American Urological Association. J Urol. 1992;148(5):1549-1557; discussion 1564.

14. Rosen RC, Riley A, Wagner G, Osterloh IH, Kirkpatrick J, Mishra A. The international index of erectile function (IIEF): a multidimensional scale for assessment of erectile dysfunction. Urology. 1997;49(6):822-830.

15. United States Preventive Services Task Force. Final update summary: prostate cancer: screening. http:// www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/ Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/prostate-cancer-screening. Updated July 2015. Accessed April 14, 2017

16. Litwin MS, Gore JL, Kwan L, et al. Quality of life after surgery, external beam irradiation, or brachytherapy for early-stage prostate cancer. Cancer. 2007;109(11):2239-2247.

17. Miwa S, Mizokami A, Konaka H, et al. Prospective longitudinal comparative study of health-related quality of life and treatment satisfaction in patients treated with hormone therapy, radical retropubic prostatectomy, and high or low dose rate brachytherapy for prostate cancer. Prostate Int. 2013;1(3):117-124.

18. Miller DC, Sanda MG, Dunn RL et al. Long-term outcomes among localized prostate cancer survivors: health-related quality-of-life changes after radical prostatectomy, external radiation, and brachytherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(12):2772-2780.

ACIP votes to recommend new strains for the 2018-2019 flu vaccine

Thirteen members of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) voted to approve the influenza vaccine recommendations for 2018-2019, while one member abstained from voting at the summer ACIP meeting.

The 2018-2019 recommendation maintains the core recommendation that influenza vaccines should be administered to all persons 6 months or older who have no contraindications.

FluMist Quadrivalent (LAIV4) also is being updated for the 2018-2019 season. At the February meeting of ACIP, the committee approved language that providers may provide any licensed, age-appropriate influenza vaccine, and LAIV4 is considered in this set of vaccine options.

Prior to this approval, there was a discussion of the safety of the 2017-2018 vaccine. For many of the available vaccines, there were no new safety concerns raised from reports during the flu season. Monitoring during the 2018-2019 will yield more safety monitoring data concerning pregnancy and influenza vaccinations and anaphylaxis in persons with an egg allergy.

The committee’s recommendations must be approved by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s director before they are considered official recommendations.

Thirteen members of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) voted to approve the influenza vaccine recommendations for 2018-2019, while one member abstained from voting at the summer ACIP meeting.

The 2018-2019 recommendation maintains the core recommendation that influenza vaccines should be administered to all persons 6 months or older who have no contraindications.

FluMist Quadrivalent (LAIV4) also is being updated for the 2018-2019 season. At the February meeting of ACIP, the committee approved language that providers may provide any licensed, age-appropriate influenza vaccine, and LAIV4 is considered in this set of vaccine options.

Prior to this approval, there was a discussion of the safety of the 2017-2018 vaccine. For many of the available vaccines, there were no new safety concerns raised from reports during the flu season. Monitoring during the 2018-2019 will yield more safety monitoring data concerning pregnancy and influenza vaccinations and anaphylaxis in persons with an egg allergy.

The committee’s recommendations must be approved by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s director before they are considered official recommendations.

Thirteen members of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) voted to approve the influenza vaccine recommendations for 2018-2019, while one member abstained from voting at the summer ACIP meeting.

The 2018-2019 recommendation maintains the core recommendation that influenza vaccines should be administered to all persons 6 months or older who have no contraindications.

FluMist Quadrivalent (LAIV4) also is being updated for the 2018-2019 season. At the February meeting of ACIP, the committee approved language that providers may provide any licensed, age-appropriate influenza vaccine, and LAIV4 is considered in this set of vaccine options.

Prior to this approval, there was a discussion of the safety of the 2017-2018 vaccine. For many of the available vaccines, there were no new safety concerns raised from reports during the flu season. Monitoring during the 2018-2019 will yield more safety monitoring data concerning pregnancy and influenza vaccinations and anaphylaxis in persons with an egg allergy.

The committee’s recommendations must be approved by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s director before they are considered official recommendations.

REPORTING FROM AN ACIP MEETING

Preview of ADA/EASD statement on hyperglycemia

A move toward more individualized treatment of hyperglycemia is coming in the next American Diabetes Association/European Association for the Study of Diabetes Consensus Report, according to John B. Buse, MD, PhD, cochair of the committee writing the new consensus statement.

He will present a draft of the statement on the management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes at the ADA’s annual scientific sessions in Orlando.

When finalized – after revisions based on comments and feedback from diabetes care providers – clinical researchers, patient groups, payers, regulators, and stakeholders – the statement will update the last revision, issued in 2015.

“We are taking a new look at hyperglycemia based on the many studies conducted since 2014, particularly the cardiovascular outcomes trials,” Dr. Buse, the Verne S. Caviness Distinguished Professor in the division of endocrinology and metabolism and chief of endocrinology at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, said in a statement.

But it’s a good bet that ADA scientific sessions attendees will see a move toward more specific recommendations based on patient characteristics and fewer one-size-fits-all recommendations. Specific characteristics like obesity, cardiovascular disease, and chronic kidney disease will likely be addressed in the new consensus statement.

One aspect of patient care that will see more attention in the ultimate statement is personalized care. “We will certainly highlight the need to individualize all aspects of care in a patient-centered way, taking into account both specific patient attributes and preferences,” Dr. Buse said.

The draft statement will be presented on Tuesday, June 26, at 8:00 a.m., so it may be worth staying for that last day of the meeting.

The final draft of the new statement will be released in October at the EASD annual meeting in Berlin, noted Dr. Buse, also director of the diabetes center at the university.

A move toward more individualized treatment of hyperglycemia is coming in the next American Diabetes Association/European Association for the Study of Diabetes Consensus Report, according to John B. Buse, MD, PhD, cochair of the committee writing the new consensus statement.

He will present a draft of the statement on the management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes at the ADA’s annual scientific sessions in Orlando.

When finalized – after revisions based on comments and feedback from diabetes care providers – clinical researchers, patient groups, payers, regulators, and stakeholders – the statement will update the last revision, issued in 2015.

“We are taking a new look at hyperglycemia based on the many studies conducted since 2014, particularly the cardiovascular outcomes trials,” Dr. Buse, the Verne S. Caviness Distinguished Professor in the division of endocrinology and metabolism and chief of endocrinology at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, said in a statement.

But it’s a good bet that ADA scientific sessions attendees will see a move toward more specific recommendations based on patient characteristics and fewer one-size-fits-all recommendations. Specific characteristics like obesity, cardiovascular disease, and chronic kidney disease will likely be addressed in the new consensus statement.

One aspect of patient care that will see more attention in the ultimate statement is personalized care. “We will certainly highlight the need to individualize all aspects of care in a patient-centered way, taking into account both specific patient attributes and preferences,” Dr. Buse said.

The draft statement will be presented on Tuesday, June 26, at 8:00 a.m., so it may be worth staying for that last day of the meeting.

The final draft of the new statement will be released in October at the EASD annual meeting in Berlin, noted Dr. Buse, also director of the diabetes center at the university.

A move toward more individualized treatment of hyperglycemia is coming in the next American Diabetes Association/European Association for the Study of Diabetes Consensus Report, according to John B. Buse, MD, PhD, cochair of the committee writing the new consensus statement.

He will present a draft of the statement on the management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes at the ADA’s annual scientific sessions in Orlando.

When finalized – after revisions based on comments and feedback from diabetes care providers – clinical researchers, patient groups, payers, regulators, and stakeholders – the statement will update the last revision, issued in 2015.

“We are taking a new look at hyperglycemia based on the many studies conducted since 2014, particularly the cardiovascular outcomes trials,” Dr. Buse, the Verne S. Caviness Distinguished Professor in the division of endocrinology and metabolism and chief of endocrinology at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, said in a statement.

But it’s a good bet that ADA scientific sessions attendees will see a move toward more specific recommendations based on patient characteristics and fewer one-size-fits-all recommendations. Specific characteristics like obesity, cardiovascular disease, and chronic kidney disease will likely be addressed in the new consensus statement.

One aspect of patient care that will see more attention in the ultimate statement is personalized care. “We will certainly highlight the need to individualize all aspects of care in a patient-centered way, taking into account both specific patient attributes and preferences,” Dr. Buse said.

The draft statement will be presented on Tuesday, June 26, at 8:00 a.m., so it may be worth staying for that last day of the meeting.

The final draft of the new statement will be released in October at the EASD annual meeting in Berlin, noted Dr. Buse, also director of the diabetes center at the university.

The magic of microblading

The use of permanent cosmetics dates back thousands of years in history. and has rapidly become one of the most popular cosmetic procedures in the United States. However, it has not completely replaced traditional eyebrow micropigmentation techniques: Many people may not be candidates for microblading because of how the pigment is manually deposited in the skin through tiny “tears” in the skin with this procedure.

The use of microblading has increased exponentially since 2015, as reflected by the millions of searches on popular social media sites. With the increase in the popularity and volume of tattoo artists performing these procedures, there has also been an increase in side effects and complications from microblading provided by poorly trained and unlicensed “artists,” a problem facilitated by the absence of adequate training requirements and/or regulatory oversight in many states.

Microblading is a revolutionary technique that can transform the lives of patients with hypotrichosis of the eyebrows, trichotillomania, eyebrow loss due to internal disease (such as thyroid disease), chemotherapy-induced eyebrow loss, or alopecia – or simply those seeking it for cosmetic improvement. The art of shaping the eyebrow depends on the natural growth of the brow (if any), facial symmetry, and meticulous measurement and mapping of the brow position based on facial landmarks and bone structure. The color of pigment selection is based on Fitzpatrick skin type and skin color undertones.

While dermatologists usually do not perform microblading, we may see patients with these complications. Practitioners treating patients who have had eyebrow microblading should also be aware of how to prevent premature fading of the eyebrow tattoo pigment. Tattooed eyebrows should be covered with petroleum jelly prior to the use of alpha hydroxy acids, vitamin C, chemical peels, hydroquinone, or retinols because these preparations can fade the pigment rapidly even if applied far from the microblading site. Any UV exposure, heat (such as steam from a facial), LED light exposure, or radio frequency can fade the pigment and exacerbate postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. Patients who have a history of hypertrophic scarring or keloids or are using isotretinoin concurrently should avoid microblading entirely. Resurfacing lasers and intense pulsed-light lasers should be used with caution as these aesthetic procedures will cause fading of the eyebrow pigment even if applied at a considerable distance from the eyebrow. Microbladed eyebrows should be covered with 20% zinc oxide paste prior to the use of any intense pulsed-light or resurfacing lasers.