User login

PrEP Prescriptions Are on the Rise

The CDC estimates that > 1.2 million people in the US could benefit from pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). The National HIV/AIDS Strategy (NHAS) aims to increase the number of adults prescribed PrEP by at least 500% by 2020, or about 47,832 people.

So far, prescriptions for PrEP increased by > 300% between 2014 and 2015. In 2015, 33,273 people had been prescribed PrEP, triple the NHAS target for that year, says Richard Wolitski, PhD, director, Office of HIV/AIDS and Infectious Disease Policy.

But according to 1 study, only 10% of the new prescriptions were for African Americans and 12% for Latinos, even though in 2016 African Americans accounted for 44% of new HIV diagnoses and Latinos for 25%. By contrast, 74% of new prescriptions were written for whites who made up only 26% of new diagnoses in 2016.

Such disparities highlight the need to continue to monitor uptake and expand efforts to increase use of PrEP, Wolitski says in his blog for HIV.gov. Studies show that daily PrEP can reduce the risk of acquiring HIV via sex by > 90% and > 70% among injection drug users.

The NHAS has added a PrEP indicator as 1 of 3 developmental indicators, introduced in 2016. Wolitski advocates multiple strategies for HIV prevention, including policies, programs, education, and monitoring. But he emphasizes that preventing HIV is only one component of an individual’s overall health and well-being—it’s also necessary to address other “competing needs,” such as access to jobs and housing, coordinated systems of care, and collaborations with social services.

The CDC estimates that > 1.2 million people in the US could benefit from pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). The National HIV/AIDS Strategy (NHAS) aims to increase the number of adults prescribed PrEP by at least 500% by 2020, or about 47,832 people.

So far, prescriptions for PrEP increased by > 300% between 2014 and 2015. In 2015, 33,273 people had been prescribed PrEP, triple the NHAS target for that year, says Richard Wolitski, PhD, director, Office of HIV/AIDS and Infectious Disease Policy.

But according to 1 study, only 10% of the new prescriptions were for African Americans and 12% for Latinos, even though in 2016 African Americans accounted for 44% of new HIV diagnoses and Latinos for 25%. By contrast, 74% of new prescriptions were written for whites who made up only 26% of new diagnoses in 2016.

Such disparities highlight the need to continue to monitor uptake and expand efforts to increase use of PrEP, Wolitski says in his blog for HIV.gov. Studies show that daily PrEP can reduce the risk of acquiring HIV via sex by > 90% and > 70% among injection drug users.

The NHAS has added a PrEP indicator as 1 of 3 developmental indicators, introduced in 2016. Wolitski advocates multiple strategies for HIV prevention, including policies, programs, education, and monitoring. But he emphasizes that preventing HIV is only one component of an individual’s overall health and well-being—it’s also necessary to address other “competing needs,” such as access to jobs and housing, coordinated systems of care, and collaborations with social services.

The CDC estimates that > 1.2 million people in the US could benefit from pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). The National HIV/AIDS Strategy (NHAS) aims to increase the number of adults prescribed PrEP by at least 500% by 2020, or about 47,832 people.

So far, prescriptions for PrEP increased by > 300% between 2014 and 2015. In 2015, 33,273 people had been prescribed PrEP, triple the NHAS target for that year, says Richard Wolitski, PhD, director, Office of HIV/AIDS and Infectious Disease Policy.

But according to 1 study, only 10% of the new prescriptions were for African Americans and 12% for Latinos, even though in 2016 African Americans accounted for 44% of new HIV diagnoses and Latinos for 25%. By contrast, 74% of new prescriptions were written for whites who made up only 26% of new diagnoses in 2016.

Such disparities highlight the need to continue to monitor uptake and expand efforts to increase use of PrEP, Wolitski says in his blog for HIV.gov. Studies show that daily PrEP can reduce the risk of acquiring HIV via sex by > 90% and > 70% among injection drug users.

The NHAS has added a PrEP indicator as 1 of 3 developmental indicators, introduced in 2016. Wolitski advocates multiple strategies for HIV prevention, including policies, programs, education, and monitoring. But he emphasizes that preventing HIV is only one component of an individual’s overall health and well-being—it’s also necessary to address other “competing needs,” such as access to jobs and housing, coordinated systems of care, and collaborations with social services.

Team modifies platelets to improve coagulation

Researchers say they have found a way to improve the coagulability of platelets—by loading them with thrombin encapsulated in liposomes.

Platelets modified in this way decreased clotting time and enhanced clot strength in blood samples from healthy subjects.

The platelets also reduced clotting time in samples from patients with hemophilia A and decreased thrombin generation time in samples from patients with trauma-induced coagulopathy (TIC).

“Coagulation, which depends on a series of complex biochemical reactions, works great for scrapes and paper cuts,” said study author Christian Kastrup, PhD, of the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada.

“But trauma often overwhelms this intricate, delicate process. We wanted to make it more resilient.”

Dr Kastrup and his colleagues described this endeavor in the Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis.

The researchers inserted thrombin into nanoliposomes and mixed them with platelets. After the platelets absorbed the nanoparticles, the team immersed the cells in blood samples for testing.

In platelet-rich plasma (PRP), the clot initiation time was about 26% faster with the modified platelets than with normal platelets—8.8 ± 1.7 min and 11.9 ± 2.5 min, respectively. And the clot strength was about 16% greater—13.4 ± 1.7 kdyne cm-1 and 11.5 ± 1.6 kdyne cm-1, respectively.

In whole blood, the clot initiation time was about 13% faster with modified platelets than with normal platelets—11.2 ± 1.2 min and 12.9 ± 1.2 min, respectively. And the clot strength was about 22% greater—5.0 ± 0.6 kdyne cm-1 and 4.1 ± 0.4 kdyne cm-1, respectively.

The researchers also found the modified platelets offset the effect of acidosis. Acidifying PRP increased thrombin generation time by 1.0 (± 0.4) min, but the modified platelets decreased thrombin generation time by 1.6 (± 0.2) min.

The modified platelets lessened the effects of antiplatelet agents as well. Aspirin or naproxen slowed thrombin generation time by 1.3 (± 0.5) min.

However, the modified platelets generated thrombin 0.4 (± 0.4) min faster in the presence of aspirin and 0.6 (± 0.4) min faster in the presence of naproxen, compared to normal platelets.

The researchers also tested the modified platelets in samples from patients with hemophilia A. Normal PRP had a clot initiation time of 5.3 (± 0.5) min, and clotting time for hemophilia A PRP was 33% slower.

In the presence of the modified platelets, clotting time was 17% slower in hemophilia A PRP than in normal PRP.

Finally, the researchers tested the modified platelets in plasma from 2 patients with TIC. With normal platelets, thrombin generation times were 5.0 (± 0.1) min and 6.7 (± 0.2) min.

With the modified platelets, thrombin generation times decreased to 3.9 (± 0.1) min and 5.9 (± 0.1) min, respectively.

If these modified platelets prove effective in subsequent preclinical and clinical testing, Dr Kastrup envisions that trauma centers could have bags of plasma containing modified platelets on hand for patients with severe bleeding. The modification could conceivably be done at the time donated blood is processed.

“Trauma is the leading killer of people under 45 years old, and blood loss is the second most common cause of such deaths,” Dr Kastrup noted. “By tweaking the body’s own clotting mechanism, we might be able to make trauma more survivable.”

Researchers say they have found a way to improve the coagulability of platelets—by loading them with thrombin encapsulated in liposomes.

Platelets modified in this way decreased clotting time and enhanced clot strength in blood samples from healthy subjects.

The platelets also reduced clotting time in samples from patients with hemophilia A and decreased thrombin generation time in samples from patients with trauma-induced coagulopathy (TIC).

“Coagulation, which depends on a series of complex biochemical reactions, works great for scrapes and paper cuts,” said study author Christian Kastrup, PhD, of the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada.

“But trauma often overwhelms this intricate, delicate process. We wanted to make it more resilient.”

Dr Kastrup and his colleagues described this endeavor in the Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis.

The researchers inserted thrombin into nanoliposomes and mixed them with platelets. After the platelets absorbed the nanoparticles, the team immersed the cells in blood samples for testing.

In platelet-rich plasma (PRP), the clot initiation time was about 26% faster with the modified platelets than with normal platelets—8.8 ± 1.7 min and 11.9 ± 2.5 min, respectively. And the clot strength was about 16% greater—13.4 ± 1.7 kdyne cm-1 and 11.5 ± 1.6 kdyne cm-1, respectively.

In whole blood, the clot initiation time was about 13% faster with modified platelets than with normal platelets—11.2 ± 1.2 min and 12.9 ± 1.2 min, respectively. And the clot strength was about 22% greater—5.0 ± 0.6 kdyne cm-1 and 4.1 ± 0.4 kdyne cm-1, respectively.

The researchers also found the modified platelets offset the effect of acidosis. Acidifying PRP increased thrombin generation time by 1.0 (± 0.4) min, but the modified platelets decreased thrombin generation time by 1.6 (± 0.2) min.

The modified platelets lessened the effects of antiplatelet agents as well. Aspirin or naproxen slowed thrombin generation time by 1.3 (± 0.5) min.

However, the modified platelets generated thrombin 0.4 (± 0.4) min faster in the presence of aspirin and 0.6 (± 0.4) min faster in the presence of naproxen, compared to normal platelets.

The researchers also tested the modified platelets in samples from patients with hemophilia A. Normal PRP had a clot initiation time of 5.3 (± 0.5) min, and clotting time for hemophilia A PRP was 33% slower.

In the presence of the modified platelets, clotting time was 17% slower in hemophilia A PRP than in normal PRP.

Finally, the researchers tested the modified platelets in plasma from 2 patients with TIC. With normal platelets, thrombin generation times were 5.0 (± 0.1) min and 6.7 (± 0.2) min.

With the modified platelets, thrombin generation times decreased to 3.9 (± 0.1) min and 5.9 (± 0.1) min, respectively.

If these modified platelets prove effective in subsequent preclinical and clinical testing, Dr Kastrup envisions that trauma centers could have bags of plasma containing modified platelets on hand for patients with severe bleeding. The modification could conceivably be done at the time donated blood is processed.

“Trauma is the leading killer of people under 45 years old, and blood loss is the second most common cause of such deaths,” Dr Kastrup noted. “By tweaking the body’s own clotting mechanism, we might be able to make trauma more survivable.”

Researchers say they have found a way to improve the coagulability of platelets—by loading them with thrombin encapsulated in liposomes.

Platelets modified in this way decreased clotting time and enhanced clot strength in blood samples from healthy subjects.

The platelets also reduced clotting time in samples from patients with hemophilia A and decreased thrombin generation time in samples from patients with trauma-induced coagulopathy (TIC).

“Coagulation, which depends on a series of complex biochemical reactions, works great for scrapes and paper cuts,” said study author Christian Kastrup, PhD, of the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada.

“But trauma often overwhelms this intricate, delicate process. We wanted to make it more resilient.”

Dr Kastrup and his colleagues described this endeavor in the Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis.

The researchers inserted thrombin into nanoliposomes and mixed them with platelets. After the platelets absorbed the nanoparticles, the team immersed the cells in blood samples for testing.

In platelet-rich plasma (PRP), the clot initiation time was about 26% faster with the modified platelets than with normal platelets—8.8 ± 1.7 min and 11.9 ± 2.5 min, respectively. And the clot strength was about 16% greater—13.4 ± 1.7 kdyne cm-1 and 11.5 ± 1.6 kdyne cm-1, respectively.

In whole blood, the clot initiation time was about 13% faster with modified platelets than with normal platelets—11.2 ± 1.2 min and 12.9 ± 1.2 min, respectively. And the clot strength was about 22% greater—5.0 ± 0.6 kdyne cm-1 and 4.1 ± 0.4 kdyne cm-1, respectively.

The researchers also found the modified platelets offset the effect of acidosis. Acidifying PRP increased thrombin generation time by 1.0 (± 0.4) min, but the modified platelets decreased thrombin generation time by 1.6 (± 0.2) min.

The modified platelets lessened the effects of antiplatelet agents as well. Aspirin or naproxen slowed thrombin generation time by 1.3 (± 0.5) min.

However, the modified platelets generated thrombin 0.4 (± 0.4) min faster in the presence of aspirin and 0.6 (± 0.4) min faster in the presence of naproxen, compared to normal platelets.

The researchers also tested the modified platelets in samples from patients with hemophilia A. Normal PRP had a clot initiation time of 5.3 (± 0.5) min, and clotting time for hemophilia A PRP was 33% slower.

In the presence of the modified platelets, clotting time was 17% slower in hemophilia A PRP than in normal PRP.

Finally, the researchers tested the modified platelets in plasma from 2 patients with TIC. With normal platelets, thrombin generation times were 5.0 (± 0.1) min and 6.7 (± 0.2) min.

With the modified platelets, thrombin generation times decreased to 3.9 (± 0.1) min and 5.9 (± 0.1) min, respectively.

If these modified platelets prove effective in subsequent preclinical and clinical testing, Dr Kastrup envisions that trauma centers could have bags of plasma containing modified platelets on hand for patients with severe bleeding. The modification could conceivably be done at the time donated blood is processed.

“Trauma is the leading killer of people under 45 years old, and blood loss is the second most common cause of such deaths,” Dr Kastrup noted. “By tweaking the body’s own clotting mechanism, we might be able to make trauma more survivable.”

FDA lifts hold on trials of BPX-501

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has lifted the clinical hold on studies of BPX-501 in the US.

BPX-501 is an adjunct T-cell therapy intended to be given after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT).

The product is being tested in phase 1/2 trials of children and adults with hematologic disorders.

The FDA placed all US trials of BPX-501 on hold earlier this year due to 3 cases of encephalopathy that were considered possibly related to BPX-501.

The hold did not affect a registrational trial of BPX-501—known as BP-004—that is underway in Europe.

Now, the FDA has lifted the hold on the US trials after discussions with Bellicum Pharmaceuticals, Inc., the company developing BPX-501.

Bellicum agreed to amend study protocols to include guidance on monitoring and management of neurologic adverse events. The company said it will be working with US clinical sites to resume patient recruitment in BPX-501 trials based on the amended protocols.

About BPX-501

BPX-501 is intended to speed immune reconstitution, fight infection, and enhance the graft-versus-leukemia effect of HSCT while also minimizing graft-vs-host disease (GVHD) and other T-cell-mediated transplant complications.

BPX-501 contains a safety switch, CaspaCIDe®, that can be activated with the drug rimiducid. The drug can be used to eliminate alloreactive BPX-501 T cells if uncontrollable GVHD or other T-cell-mediated complications occur.

The FDA and the European Commission granted BPX-501 and rimiducid orphan drug designation for use in HSCT recipients.

BPX-501 and rimiducid have demonstrated efficacy in the BP-004 trial. Results from this trial have been presented at the EBMT Annual Meeting in 2016 (abstract WP16 and abstract O007), the 2017 EHA Congress, and the 2017 ASH Annual Meeting.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has lifted the clinical hold on studies of BPX-501 in the US.

BPX-501 is an adjunct T-cell therapy intended to be given after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT).

The product is being tested in phase 1/2 trials of children and adults with hematologic disorders.

The FDA placed all US trials of BPX-501 on hold earlier this year due to 3 cases of encephalopathy that were considered possibly related to BPX-501.

The hold did not affect a registrational trial of BPX-501—known as BP-004—that is underway in Europe.

Now, the FDA has lifted the hold on the US trials after discussions with Bellicum Pharmaceuticals, Inc., the company developing BPX-501.

Bellicum agreed to amend study protocols to include guidance on monitoring and management of neurologic adverse events. The company said it will be working with US clinical sites to resume patient recruitment in BPX-501 trials based on the amended protocols.

About BPX-501

BPX-501 is intended to speed immune reconstitution, fight infection, and enhance the graft-versus-leukemia effect of HSCT while also minimizing graft-vs-host disease (GVHD) and other T-cell-mediated transplant complications.

BPX-501 contains a safety switch, CaspaCIDe®, that can be activated with the drug rimiducid. The drug can be used to eliminate alloreactive BPX-501 T cells if uncontrollable GVHD or other T-cell-mediated complications occur.

The FDA and the European Commission granted BPX-501 and rimiducid orphan drug designation for use in HSCT recipients.

BPX-501 and rimiducid have demonstrated efficacy in the BP-004 trial. Results from this trial have been presented at the EBMT Annual Meeting in 2016 (abstract WP16 and abstract O007), the 2017 EHA Congress, and the 2017 ASH Annual Meeting.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has lifted the clinical hold on studies of BPX-501 in the US.

BPX-501 is an adjunct T-cell therapy intended to be given after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT).

The product is being tested in phase 1/2 trials of children and adults with hematologic disorders.

The FDA placed all US trials of BPX-501 on hold earlier this year due to 3 cases of encephalopathy that were considered possibly related to BPX-501.

The hold did not affect a registrational trial of BPX-501—known as BP-004—that is underway in Europe.

Now, the FDA has lifted the hold on the US trials after discussions with Bellicum Pharmaceuticals, Inc., the company developing BPX-501.

Bellicum agreed to amend study protocols to include guidance on monitoring and management of neurologic adverse events. The company said it will be working with US clinical sites to resume patient recruitment in BPX-501 trials based on the amended protocols.

About BPX-501

BPX-501 is intended to speed immune reconstitution, fight infection, and enhance the graft-versus-leukemia effect of HSCT while also minimizing graft-vs-host disease (GVHD) and other T-cell-mediated transplant complications.

BPX-501 contains a safety switch, CaspaCIDe®, that can be activated with the drug rimiducid. The drug can be used to eliminate alloreactive BPX-501 T cells if uncontrollable GVHD or other T-cell-mediated complications occur.

The FDA and the European Commission granted BPX-501 and rimiducid orphan drug designation for use in HSCT recipients.

BPX-501 and rimiducid have demonstrated efficacy in the BP-004 trial. Results from this trial have been presented at the EBMT Annual Meeting in 2016 (abstract WP16 and abstract O007), the 2017 EHA Congress, and the 2017 ASH Annual Meeting.

Study of DBA provides new insight into hematopoiesis

In studying Diamond-Blackfan anemia (DBA), researchers have found evidence to suggest that ribosome levels play a key role in hematopoiesis.

The researchers found that a reduction in ribosomes is responsible for the disruption in red blood cell production observed in patients with DBA.

This reduction in ribosomes impairs the translation of certain messenger RNAs (mRNAs), which inhibits erythroid lineage commitment in hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSCPs).

The researchers said this work has provided insight into how lineage commitment functions normally and in the setting of DBA.

Vijay Sankaran, MD, PhD, of Boston Children’s Hospital in Massachusetts, and his colleagues described these findings in Cell.

The team noted that most cases of DBA are caused by heterozygous loss-of-function mutations in ribosomal protein (RP) genes, which result in RP haploinsufficiency.

Past research revealed DBA-causing mutations in the transcription factor GATA1. Subsequent work showed that RP haploinsufficiency results in reduced translation of GATA1 mRNA, and increasing GATA1 protein levels can reduce the erythroid defects in DBA cells.

However, the mechanisms underlying these phenomena were unclear.

In the current study, the researchers found that DBA-associated perturbations reduced ribosome levels but did not affect the composition of ribosomes.

“There has been controversy over whether a ribosomal protein mutation changes the composition of the ribosomes or the quantity of the ribosomes,” Dr Sankaran said. “We know now that it is the latter.”

The researchers said the reduction of ribosome levels was largely promoted through reduced translation of RP mRNAs.

The team identified 525 transcripts with translation efficiencies that were downregulated by RP haploinsufficiency. They said a subset of these transcripts, including GATA1, have proven essential for hematopoietic cell growth and are upregulated during early erythropoiesis.

The researchers confirmed their prior findings that translation of GATA1 mRNA is decreased by about 2-fold in differentiating HSPCs with RP haploinsufficiency.

The team also found that GATA1 has “unique” 5’ untranslated region features that confer sensitivity to ribosome levels.

Taken together, these findings suggest the presence of GATA1 proteins in HSPCs helps prime them for erythroid lineage commitment. Without enough ribosomes to produce enough GATA1 proteins, the HSPCs never receive the signal to become red blood cells.

“This raises the question of whether we can design a gene therapy to overcome the GATA1 deficiency,” Dr Sankaran said. “We now have a tremendous interest in this approach and believe it can be done.”

In studying Diamond-Blackfan anemia (DBA), researchers have found evidence to suggest that ribosome levels play a key role in hematopoiesis.

The researchers found that a reduction in ribosomes is responsible for the disruption in red blood cell production observed in patients with DBA.

This reduction in ribosomes impairs the translation of certain messenger RNAs (mRNAs), which inhibits erythroid lineage commitment in hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSCPs).

The researchers said this work has provided insight into how lineage commitment functions normally and in the setting of DBA.

Vijay Sankaran, MD, PhD, of Boston Children’s Hospital in Massachusetts, and his colleagues described these findings in Cell.

The team noted that most cases of DBA are caused by heterozygous loss-of-function mutations in ribosomal protein (RP) genes, which result in RP haploinsufficiency.

Past research revealed DBA-causing mutations in the transcription factor GATA1. Subsequent work showed that RP haploinsufficiency results in reduced translation of GATA1 mRNA, and increasing GATA1 protein levels can reduce the erythroid defects in DBA cells.

However, the mechanisms underlying these phenomena were unclear.

In the current study, the researchers found that DBA-associated perturbations reduced ribosome levels but did not affect the composition of ribosomes.

“There has been controversy over whether a ribosomal protein mutation changes the composition of the ribosomes or the quantity of the ribosomes,” Dr Sankaran said. “We know now that it is the latter.”

The researchers said the reduction of ribosome levels was largely promoted through reduced translation of RP mRNAs.

The team identified 525 transcripts with translation efficiencies that were downregulated by RP haploinsufficiency. They said a subset of these transcripts, including GATA1, have proven essential for hematopoietic cell growth and are upregulated during early erythropoiesis.

The researchers confirmed their prior findings that translation of GATA1 mRNA is decreased by about 2-fold in differentiating HSPCs with RP haploinsufficiency.

The team also found that GATA1 has “unique” 5’ untranslated region features that confer sensitivity to ribosome levels.

Taken together, these findings suggest the presence of GATA1 proteins in HSPCs helps prime them for erythroid lineage commitment. Without enough ribosomes to produce enough GATA1 proteins, the HSPCs never receive the signal to become red blood cells.

“This raises the question of whether we can design a gene therapy to overcome the GATA1 deficiency,” Dr Sankaran said. “We now have a tremendous interest in this approach and believe it can be done.”

In studying Diamond-Blackfan anemia (DBA), researchers have found evidence to suggest that ribosome levels play a key role in hematopoiesis.

The researchers found that a reduction in ribosomes is responsible for the disruption in red blood cell production observed in patients with DBA.

This reduction in ribosomes impairs the translation of certain messenger RNAs (mRNAs), which inhibits erythroid lineage commitment in hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSCPs).

The researchers said this work has provided insight into how lineage commitment functions normally and in the setting of DBA.

Vijay Sankaran, MD, PhD, of Boston Children’s Hospital in Massachusetts, and his colleagues described these findings in Cell.

The team noted that most cases of DBA are caused by heterozygous loss-of-function mutations in ribosomal protein (RP) genes, which result in RP haploinsufficiency.

Past research revealed DBA-causing mutations in the transcription factor GATA1. Subsequent work showed that RP haploinsufficiency results in reduced translation of GATA1 mRNA, and increasing GATA1 protein levels can reduce the erythroid defects in DBA cells.

However, the mechanisms underlying these phenomena were unclear.

In the current study, the researchers found that DBA-associated perturbations reduced ribosome levels but did not affect the composition of ribosomes.

“There has been controversy over whether a ribosomal protein mutation changes the composition of the ribosomes or the quantity of the ribosomes,” Dr Sankaran said. “We know now that it is the latter.”

The researchers said the reduction of ribosome levels was largely promoted through reduced translation of RP mRNAs.

The team identified 525 transcripts with translation efficiencies that were downregulated by RP haploinsufficiency. They said a subset of these transcripts, including GATA1, have proven essential for hematopoietic cell growth and are upregulated during early erythropoiesis.

The researchers confirmed their prior findings that translation of GATA1 mRNA is decreased by about 2-fold in differentiating HSPCs with RP haploinsufficiency.

The team also found that GATA1 has “unique” 5’ untranslated region features that confer sensitivity to ribosome levels.

Taken together, these findings suggest the presence of GATA1 proteins in HSPCs helps prime them for erythroid lineage commitment. Without enough ribosomes to produce enough GATA1 proteins, the HSPCs never receive the signal to become red blood cells.

“This raises the question of whether we can design a gene therapy to overcome the GATA1 deficiency,” Dr Sankaran said. “We now have a tremendous interest in this approach and believe it can be done.”

Abstract: Coronary Computed Tomography Angiography vs Functional Stress Testing for Patients With Suspected Coronary Artery Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Foy, A.J., et al, JAMA Intern Med 177(11):1623, November 1, 2017

BACKGROUND: Coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA) is more accurate than functional stress testing for the diagnosis of coronary artery disease, but it is unclear whether this superiority leads to better clinical outcomes.

METHODS: The authors performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of 13 randomized, controlled trials that included 20,092 patients (mean age 58) and compared CCTA (n=10,315) with functional stress testing (n=9,777) in patients being evaluated for coronary artery disease. The primary endpoints included clinical outcomes and changes in therapy.

RESULTS: There was no difference between the groups in the overall mortality rate or the rate of cardiac hospitalization (2.7% in both groups). The CCTA group had a lower incidence of myocardial infarction (0.7% vs. 1.1% in the stress test group), and a higher incidence of revascularization (7.2 vs. 4.5), invasive coronary angiography (11.7% vs. 9.1%), and a new CAD diagnosis (18.3% vs. 8.3%). The CCTA group also had a higher rate of use of aspirin (21.6% vs. 8.2%) and statins (20.0% vs. 7.3%).

CONCLUSIONS: When compared with functional stress testing, CCTA appears to be associated with a decreased incidence of myocardial infarction in patients with chest pain, but an increased probability of revascularization, invasive angiography and medication change. However, rates of cardiac hospitalization and overall mortality were similar in patients evaluated with CCTA vs. functional stress testing. 23 references ([email protected] – no reprints)

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Foy, A.J., et al, JAMA Intern Med 177(11):1623, November 1, 2017

BACKGROUND: Coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA) is more accurate than functional stress testing for the diagnosis of coronary artery disease, but it is unclear whether this superiority leads to better clinical outcomes.

METHODS: The authors performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of 13 randomized, controlled trials that included 20,092 patients (mean age 58) and compared CCTA (n=10,315) with functional stress testing (n=9,777) in patients being evaluated for coronary artery disease. The primary endpoints included clinical outcomes and changes in therapy.

RESULTS: There was no difference between the groups in the overall mortality rate or the rate of cardiac hospitalization (2.7% in both groups). The CCTA group had a lower incidence of myocardial infarction (0.7% vs. 1.1% in the stress test group), and a higher incidence of revascularization (7.2 vs. 4.5), invasive coronary angiography (11.7% vs. 9.1%), and a new CAD diagnosis (18.3% vs. 8.3%). The CCTA group also had a higher rate of use of aspirin (21.6% vs. 8.2%) and statins (20.0% vs. 7.3%).

CONCLUSIONS: When compared with functional stress testing, CCTA appears to be associated with a decreased incidence of myocardial infarction in patients with chest pain, but an increased probability of revascularization, invasive angiography and medication change. However, rates of cardiac hospitalization and overall mortality were similar in patients evaluated with CCTA vs. functional stress testing. 23 references ([email protected] – no reprints)

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Foy, A.J., et al, JAMA Intern Med 177(11):1623, November 1, 2017

BACKGROUND: Coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA) is more accurate than functional stress testing for the diagnosis of coronary artery disease, but it is unclear whether this superiority leads to better clinical outcomes.

METHODS: The authors performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of 13 randomized, controlled trials that included 20,092 patients (mean age 58) and compared CCTA (n=10,315) with functional stress testing (n=9,777) in patients being evaluated for coronary artery disease. The primary endpoints included clinical outcomes and changes in therapy.

RESULTS: There was no difference between the groups in the overall mortality rate or the rate of cardiac hospitalization (2.7% in both groups). The CCTA group had a lower incidence of myocardial infarction (0.7% vs. 1.1% in the stress test group), and a higher incidence of revascularization (7.2 vs. 4.5), invasive coronary angiography (11.7% vs. 9.1%), and a new CAD diagnosis (18.3% vs. 8.3%). The CCTA group also had a higher rate of use of aspirin (21.6% vs. 8.2%) and statins (20.0% vs. 7.3%).

CONCLUSIONS: When compared with functional stress testing, CCTA appears to be associated with a decreased incidence of myocardial infarction in patients with chest pain, but an increased probability of revascularization, invasive angiography and medication change. However, rates of cardiac hospitalization and overall mortality were similar in patients evaluated with CCTA vs. functional stress testing. 23 references ([email protected] – no reprints)

Learn more about the Primary Care Medical Abstracts and podcasts, for which you can earn up to 9 CME credits per month.

Copyright © The Center for Medical Education

Pharmacologic Treatments for Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis

IN THIS ARTICLE

- Confirming the diagnosis

- Pirfenidone treatment

- Nintedanib treatment

A 64-year-old man has a one-year history of dyspnea on exertion and a nonproductive cough. His symptoms are gradually worsening and increasingly bothersome to him.

His medical history includes mild seasonal allergies and GERD, which is well-controlled by oral antihistamines and proton pump inhibitors. He has spent the past 30 years working a desk job as an accountant. He denies a history of smoking, exposure to secondhand smoke, and initiation of new medication.

He admits to increased fatigue, but denies fever, chills, lymphadenopathy, weight change, chest pain, wheezing, abdominal pain, diarrhea, vomiting, claudication, and swelling in the extremities. The rest of the review of systems is negative.

Lab results—complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, TSH, antinuclear antibodies, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein—are within normal limits. Spirometry shows very mild restriction. A chest x-ray is abnormal but nonspecific, showing peripheral opacities. An ECG shows normal sinus rhythm.

The patient is given a trial of an inhaled steroid, which yields no improvement. Six months later, the patient is seen by a pulmonologist. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is diagnosed based on high-resolution CT (HRCT) and lung biopsy results.

IPF is a chronic, progressive, fibrosing interstitial disease that is limited to lung tissue. It most commonly manifests in older adults with vague symptoms of dyspnea on exertion and nonproductive cough, but symptoms can also include fatigue, muscle and joint aches, clubbing of the fingernails, and weight loss.1 The average life expectancy following diagnosis of IPF is two to five years, and the mortality rate is estimated at 64.3 per million men and 58.4 per million women per year.2,3

Continue to: DIAGNOSIS

DIAGNOSIS

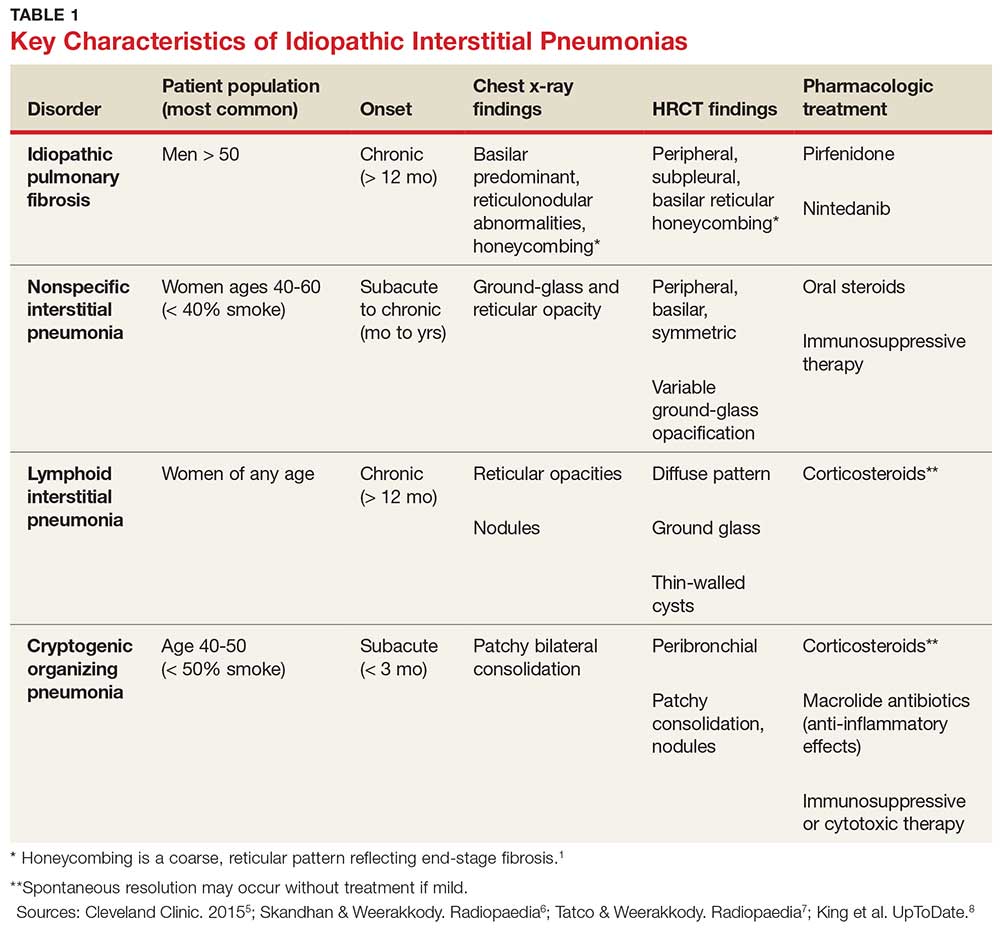

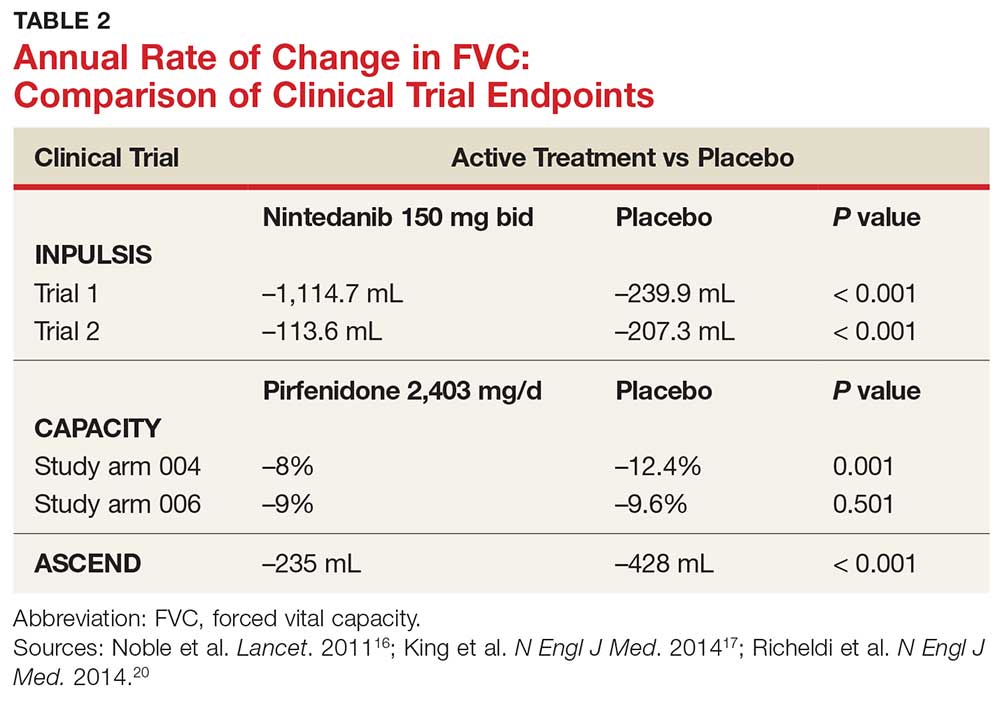

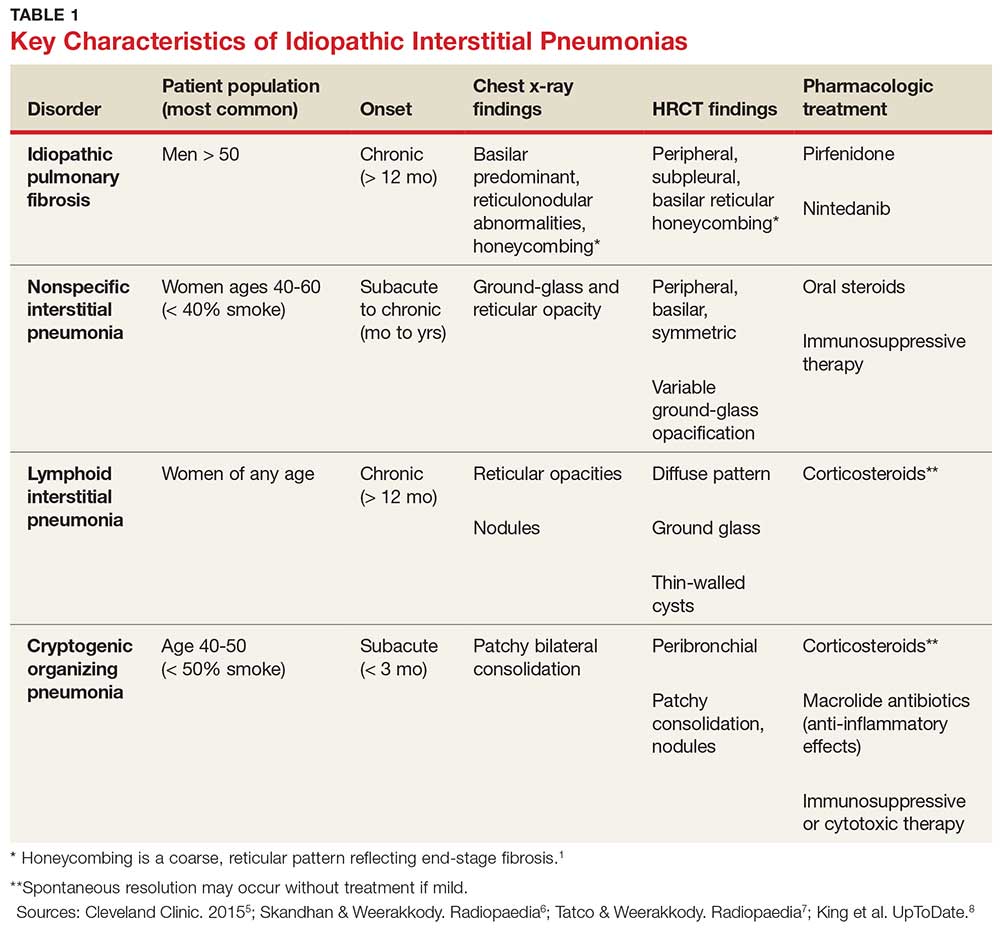

IPF belongs in the general class of idiopathic interstitial pneumonias (IIPs), which are characterized by varying degrees of inflammation and fibrosis of lung interstitium.4 All subtypes of IIPs cause dyspnea and diffuse abnormalities on HRCT, and all vary from each other histologically. Table 1 outlines the key features of each.5-8

Because of its vague symptomology and the extensive workup needed to rule out other diseases, patients with IPF often have symptoms for one to two years before a diagnosis is made.1 Physical exam may reveal fine inspiratory rales in both lung bases and digital clubbing; eventual signs of pulmonary hypertension and right-sided heart failure may be appreciated.1,9

There are no specific diagnostic laboratory tests to confirm IPF; however, baseline labwork (as outlined in the case presentation) is typically ordered to rule out infection, thyroid disease, or connective tissue disease.10 Many patients are referred to a cardiologist before being seen by a pulmonologist; cardiac stress testing may be done, and an echocardiogram may be performed to rule out heart failure.

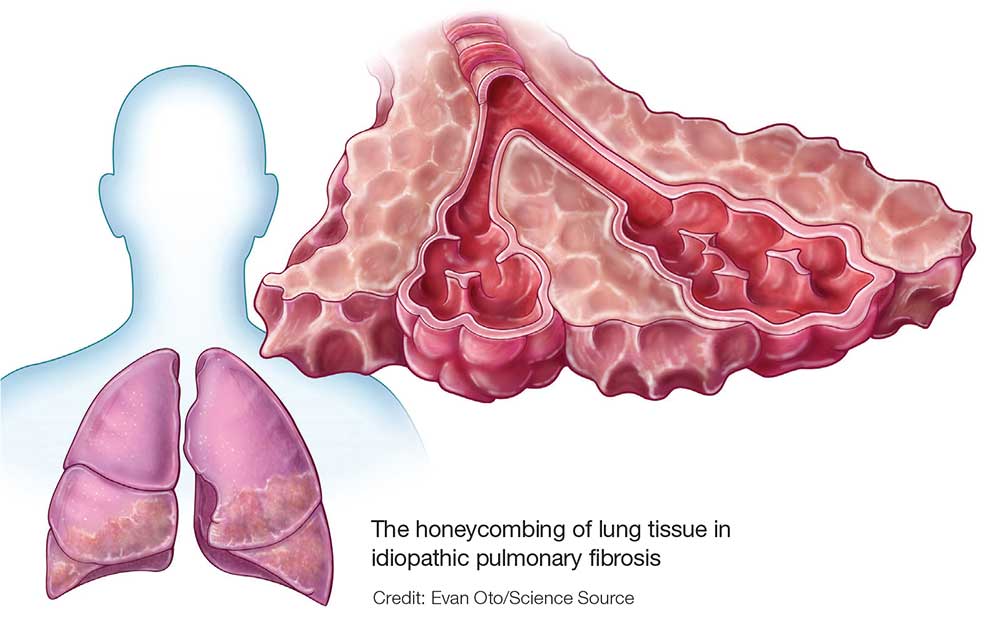

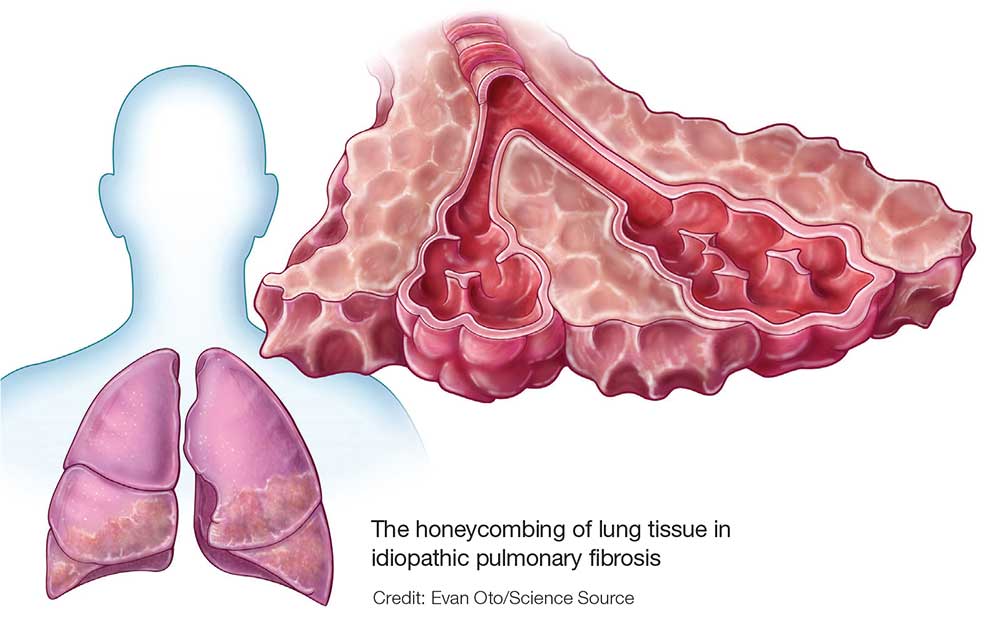

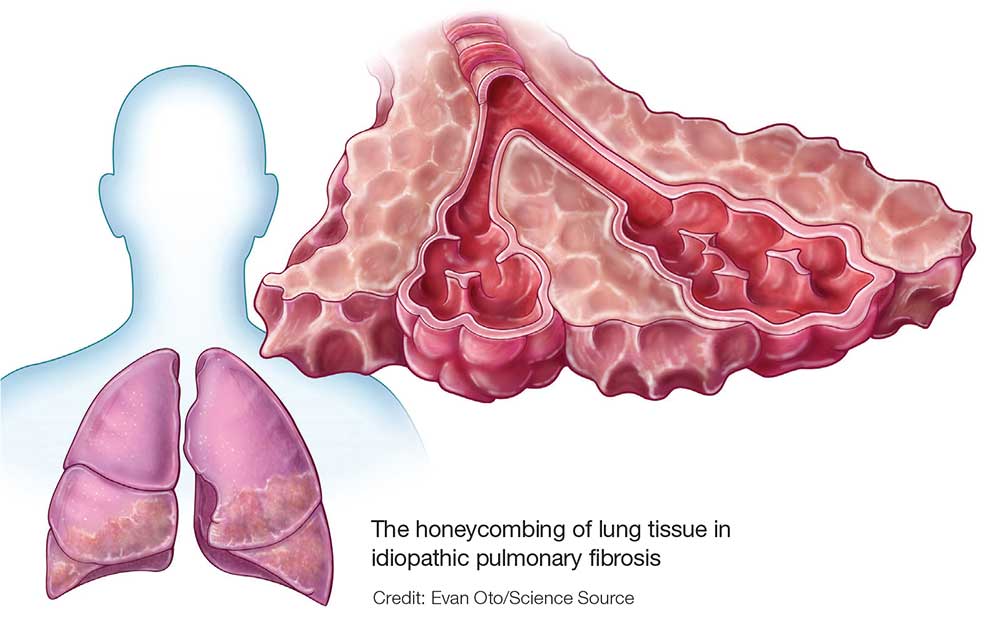

Diagnostic testing may include pulmonary function testing, HRCT of the chest, and lung biopsy.10 Tissue samples from patients with IPF reveal different stages of disease, including dense fibrosis with honeycombing, subpleural or paraseptal distribution, fibroblast foci, and normal tissue.11 Pulmonary function test results will show a restrictive pattern. Both forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) and forced vital capacity (FVC) will be reduced, and the FEV1/FVC ratio preserved. Due to decreased functional lung volume, diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (DLCO) will also be reduced.4,12

The differential is broad and includes allergic asthma, bronchitis, COPD, lung cancer, hypersensitivity pneumonitis, asbestosis, or pulmonary embolism.

Continue to: TREATMENT HISTORY

TREATMENT HISTORY

IPF has a long history of tried and failed treatment options. The American Thoracic Society (ATS), in concert with other professional organizations, has published comprehensive guidelines and recommendations pertaining to the use of pharmacologic medications to control disease progression. Warfarin and other anticoagulants have been studied, based on the observation that a procoagulant state promotes fibrotic changes in the lung tissue.13 However, anticoagulant use is not recommended in patients with IPF due to lack of efficacy and high potential for harm.13

Immunosuppressants have also been in the spotlight as possible treatment for IPF, but a clinical study investigating the efficacy of a three-drug regimen including prednisone, azathioprine, and N-acetylcysteine was stopped early due to increased risk for harm. Endothelin antagonists and potent tyrosine kinase inhibitors are also not recommended in the most recent edition of IPF guidelines, as they lack benefit.13

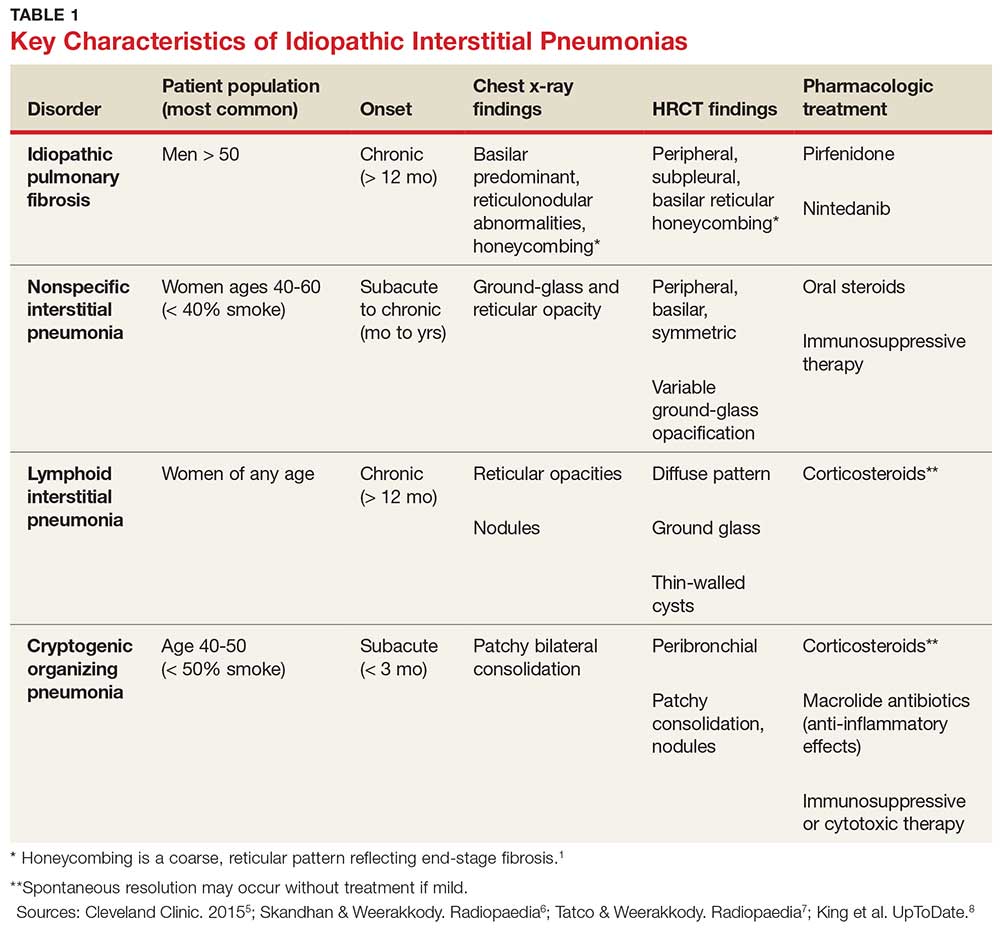

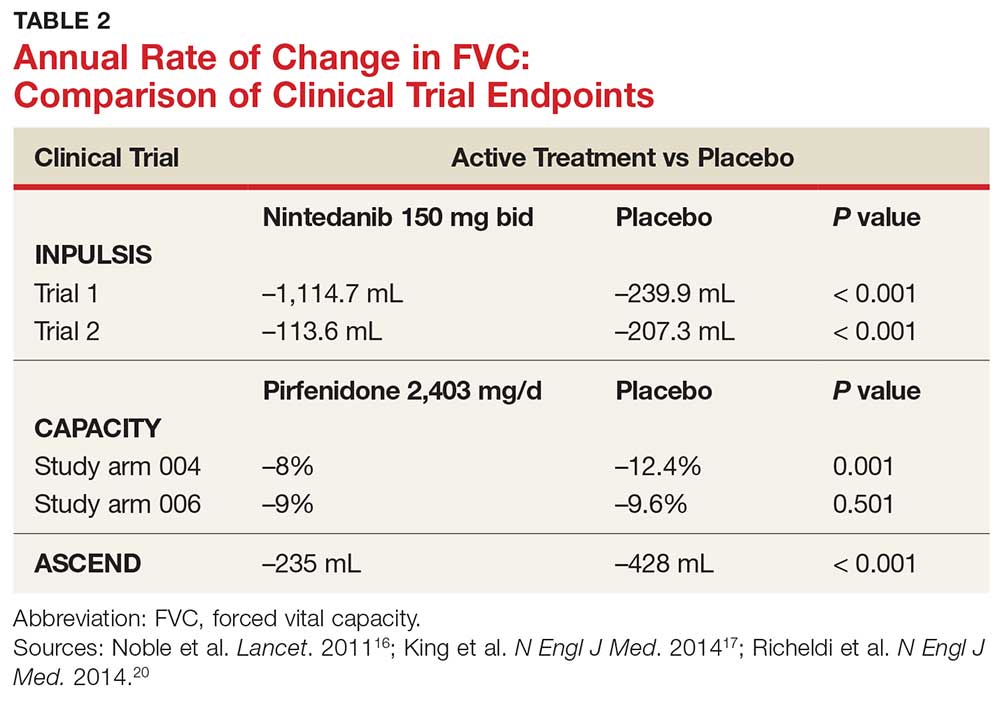

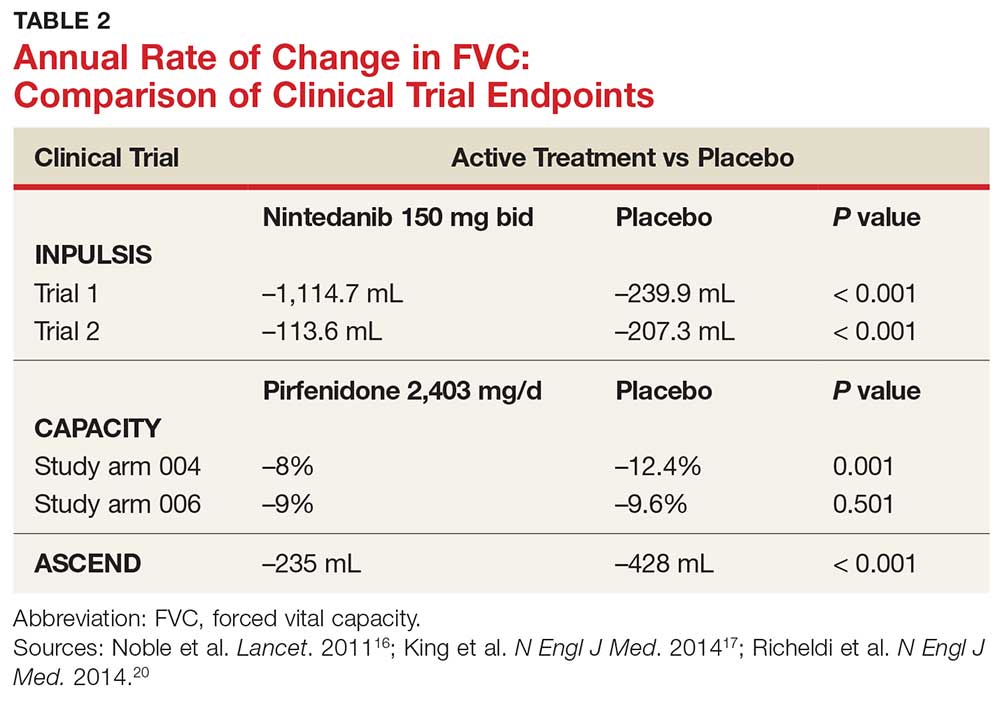

In fact, prior to the 2015 edition of the guidelines, no single medication was routinely recommended for patients with IPF. But this is now changing, following the 2014 FDA approval of two new drugs, nintedanib and pirfenidone, designed specifically to treat IPF.14 These drugs have shown promise in clinical trials (results of which are summarized in Table 2).

Continue to: NEW PHARMACOLOGIC OPTIONS

NEW PHARMACOLOGIC OPTIONS

Pirfenidone

In 2008, a study was conducted in Japan to determine the mechanism of action of pirfenidone.15 Through in vitro studies of healthy adult lung fibroblasts with added pro-fibrotic factor and transforming growth factor (TGF-ß 1), the researchers found that pirfenidone was effective at decreasing the production of a collagen-binding protein called HSP47. This protein is ubiquitous in fibrotic tissue. The study also showed that pirfenidone decreased the production of collagen type 1, which, when uninhibited, increases fibrosis.15

CAPACITY trials. In the CAPACITY trials, two phase 3 multinational studies conducted from 2006 to 2008, patients were given either pirfenidone or placebo.16 In the first study arm, patients were assigned to pirfenidone 2,403 mg/d (n = 174), pirfenidone 1,197 mg/d (n = 87), or placebo (n = 174). In the second study arm, 171 patients received pirfenidone 2,403 mg/d and 173 patients received placebo. Endpoints were measured at baseline and up to week 72.

The first study arm found that the mean rate of decline of FVC—the primary endpoint—was 4.4% less in the treatment group than in the placebo group (p = 0.001), and there was a 36% decrease in risk for death or disease progression in the treatment group (HR, 0.64; p, 0.023). (Endpoints were defined as: time to confirmed > 10% decline in percentage predicted FVC, > 15% decline in percentage predicted DLCO, or death.) The researchers found no clinically significant change in the six-minute walk test—a secondary endpoint of the study.16

The second study arm, however, found no statistically significant change in FVC between the treatment and placebo groups (with a 0.6% smaller decrease in FVC in the pirfenidone group), nor did they see a difference in progression-free survival. However, there was a significant change in the six-minute walk test between the treatment and placebo groups (p = 0.0009). Throughout the study, the most common adverse effects included nausea (36%), rash (32%), and dyspepsia (19%).16

ASCEND trial. The 2014 Assessment of Pirfenidone to Confirm Efficacy and Safety in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (ASCEND) trial was a phase 3, multinational, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the use of pirfenidone 2,403 mg/d.17 The study was conducted from 2012 to 2013. Of the total number of patients (N = 522), half received pirfenidone and half received placebo. After 52 weeks of treatment (the end of the study), the researchers found a smaller decline in FVC—the primary endpoint—in the treatment group compared to placebo (mean decline, 235 mL vs 428 mL, respectively [p < 0.001]). Regarding the six-minute walk test, the investigators found that 25.9% of the treatment group exhibited a decrease of ≥ 50 meters, compared to 35.7% of the placebo group (p = 0.04). (Progression-free survival was defined as a confirmed ≥ 10% decrease in predicted FVC, a confirmed decrease of 50 meters in the six-minute walk test, or death.)

The pirfenidone group in the ASCEND trial showed a 43% reduced risk for death or disease progression (HR, 0.57; p, < 0.001).16,17 All-cause mortality was lower in the pirfenidone group (4%) than in the placebo group (7.2%), but this was not statistically significant. Deaths from IPF in the pirfenidone group totaled three patients (1.1%) versus seven patients (2.5%) in the placebo group; this was also not statistically significant. The most common adverse effects seen during the study were nausea (36%), rash (28.1%), and headache (25.9%).17

Recommendations for use. Liver function testing should be performed at baseline, monthly for six months, and every three months afterward, as elevations in liver enzymes have been observed.18 Pirfenidone is a CYP1A2 substrate; moderate-to-strong CYP1A2 inhibitors should therefore be discontinued prior to initiation, as they are likely to decrease exposure and efficacy of pirfenidone. There are currently no black box warnings.18

Continue to: Nintedanib

Nintedanib

Hostettler et al studied lung samples from patients with IPF to determine the mechanism of action of nintedanib.19 Evaluation of fibroblasts derived from IPF samples revealed that they contained higher levels of platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) than did nonfibrotic control cells. They also found that nintedanib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor, significantly inhibited the phosphorylation of fibrotic-inducing growth factors—PDGF as well as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF).

INPULSIS trials. A phase 3 replicate of randomized, double-blind, multinational studies, the INPULSIS trials were performed between 2011 and 2012.20 Two study arms were used to evaluate a total of 638 patients who received nintedanib 150 mg bid for 52 weeks. The primary endpoint was annual rate of decline of FVC.

The researchers also evaluated efficacy through two other endpoints: patient-reported quality of life and symptoms via the St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) and evaluation of time to acute exacerbation. The latter was defined as worsening or new dyspnea, new diffuse pulmonary infiltrates visualized on chest radiography and/or HRCT, or the development of parenchymal abnormalities with no pneumothorax or pleural effusion since the preceding visit; and exclusion of any known causes of acute worsening, including infection, heart failure, pulmonary embolism, and any identifiable cause of acute lung injury.20

INPULSIS 1 (first arm) included 309 patients in the treatment group. Results showed an adjusted annual rate of decline in FVC of 114.7 mL/year, versus 239.9 mL/year in the placebo group (p < 0.001). In the treatment group, 52.8% exhibited ≤ 5% decline in FVC, compared to 38.2% in the placebo group (p = 0.001). No significant between-group differences were found in SGRQ score or time to acute exacerbation.20

INPULSIS 2 had 329 patients receiving nintedanib. An annual rate of decline in FVC of 113.6 mL/year from baseline was observed in the treatment group, compared to 207.3 mL/year in the placebo group (p < 0.001). In the treatment group, 53.2% showed ≤ 5% decline in FVC, versus 39.3% in the placebo group (p = 0.001). There was also a significantly smaller increase in total SGRQ score (meaning, less deterioration in quality of life) in the nintedanib group versus the placebo group (p = 0.02). A statistically significant increase in time to first acute exacerbation was observed in the nintedanib group (p = 0.005).20

There was no significant difference between groups in death from any cause, death from respiratory causation, or death that occurred between randomization and 28 days post treatment. The most common adverse effects seen throughout the two trials included diarrhea (trial 1, 61.5%; trial 2, 63.2%), nausea (trial 1, 22.7%; trial 2, 26.1%), and nasopharyngitis (trial 1, 12.6%; trial 2, 14.6%).20

Recommendations for use. Liver function testing should be performed at baseline, at regular intervals during the first three months, then periodically thereafter; patients in the treatment group of both INPULSIS trials had elevated liver enzymes, and cases of drug-induced liver injury have been observed with use of nintedanib.21 This medication may increase risk for bleeding due to its mechanism of action (VEGFR inhibition). Coadministration with CYP3A4 inhibitors may increase concentration of nintedanib; therefore, close monitoring is recommended. Avoid coadministration with CYP3A4 inducers, as this may decrease concentration of nintedanib by 50%. There are currently no black box warnings.21

Continue to: Patient monitoring

Patient monitoring

The ATS recommends measuring FVC and DLCO every three to six months, or sooner if clinically indicated.13 Pulse oximetry should be measured at rest and on exertion in all patients, regardless of symptoms, to assure proper saturation and identify the need for supplemental oxygen; this should also be done every three to six months.

The ATS recommends prompt detection and treatment of comorbidities such as pulmonary hypertension, emphysema, airflow obstruction, GERD, sleep apnea, and coronary artery disease.13 These recommendations are based on the organization’s 2015 guidelines.

OUTCOME FOR THE CASE PATIENT

The patient was started on pirfenidone (2,403 mg/d). He is continuing treatment and showing improvements in quality of life and slowed deterioration of lung function.

CONCLUSION

IPF causes progressive fibrosis of lung interstitium. The etiology is unknown, the symptoms and signs are vague, and mean life expectancy following diagnosis is two to five years. The most recent IPF guidelines recommend avoiding use of anticoagulants and immunosuppressants (eg, steroids, azathioprine, and N-acetylcysteine), due to their proven ineffectiveness and harm to patients with IPF.

Since the FDA’s approval of pirfenidone and nintedanib, the ATS has made recommendations for their use in patients with IPF. Despite mixed results in clinical trials, both drugs have demonstrated the ability to slow the decline in FVC over time, with relatively benign adverse effects. It is difficult to compare pirfenidone and nintedanib, or to recommend use of one drug over the other. However, it is promising that patients with this routinely fatal disease now have treatment options that can potentially modulate their disease progression.

1. Kim DS, Collard HR, King TE Jr. Classification and natural history of the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2006;3(4):285-292.

2. Frankel SK, Schwarz MI. Update in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2009;15(5):463-469.

3. Olson AL, Swigris JJ, Lezotte DC, et al. Mortality from pulmonary fibrosis increased in the United States from 1992 to 2003. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176(3):277-284.

4. Chapman JT. Interstitial lung disease. Cleveland Clinic. August 2010. www.clevelandclinicmeded.com/medical pubs/diseasemanagement/pulmonary/interstitial-lung-disease. Accessed March 12, 2018.

5. Cleveland Clinic. Nonspecific interstitial pneumonia. January 16, 2015. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/articles/nonspecific-interstitial-pneumonia. Accessed March 12, 2018.

6. Skandhan AKP, Weerakkody Y. Non-specific interstitial pneumonia. Radiopaedia. https://radiopaedia.org/articles/non-specific-interstitial-pneumonia-1. Accessed March 12, 2018.

7. Tatco V, Weerakkody Y. Lymphocytic interstitial pneumonitis. Radiopaedia. https://radiopaedia.org/articles/lymphocytic-interstitial-pneumonitis-1. Accessed March 12, 2018.

8. King TE Jr, Flaherty KR, Hollingsworth H. Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia. UpToDate. www.uptodate.com/contents/cryptogenic-organizing-pneumonia#H12. Accessed March 12, 2018.

9. Patel NM, Lederer DJ, Borczuk AC, Kawut SM. Pulmonary hypertension in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Chest. 2007; 132(3):998-1006.

10. Lee J. Overview of idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. April 2016. www.merckmanuals.com/professional/pulmonary-disorders/interstitial-lung-diseases/overview-of-idiopathic-interstitial-pneumonias. Accessed March 12, 2018.

11. Lynch DA, Sverzellati N, Travis WD, et al. Diagnostic criteria for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a Fleischner Society White Paper. Lancet Respir Med. 2018;6(2):138-153.

12. Martinez FJ, Flaherty K. Pulmonary function testing in idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2006; 3(4):315-321.

13. Raghu G, Rochwerg B, Zhang Y, et al; American Thoracic Society; European Respiratory Society; Japanese Respiratory Society; Latin American Thoracic Association. An official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT clinical practice guideline: treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. An update of the 2011 Clinical Practice Guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015; 192(2):e3-e19.

14. Chowdhury BA; FDA. Two FDA drug approvals for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF). October 15, 2014. https://blogs.fda.gov/fdavoice/index.php/2014/10/two-fda-drug-approvals-for-idiopathic-pulmonary-fibrosis-ipf/. Accessed March 12, 2018.

15. Nakayama S, Mukae H, Sakamoto N, et al. Pirfenidone inhibits the expression of HSP47 in TGF-beta1-stimulated human lung fibroblasts. Life Sci. 2008; 82(3-4):210-217.

16. Noble PW, Albera C, Bradford WZ, et al; CAPACITY Study Group. Pirfenidone in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (CAPACITY): two randomized trials. Lancet. 2011;377: 1760-1769.

17. King TE Jr, Bradford WZ, Castro-Bernardini S, et al; ASCEND Study Group. A phase 3 trial of pirfenidone in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(22): 2083-2092.

18. Esbriet [package insert]. South San Francisco, CA: Genentech, Inc; 2016.

19. Hostettler KE, Zhong J, Papakonstantinou E, et al. Anti-fibrotic effects of nintedanib in lung fibroblasts derived from patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respir Res. 2014;15(1):157.

20. Richeldi L, du Bois RM, Raghu G, et al; INPULSIS Trial Investigators. Efficacy and safety of nintedanib in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(22):2071-2082.

21. OFEV [package insert]. Ridgefield, CT: Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc; 2018.

IN THIS ARTICLE

- Confirming the diagnosis

- Pirfenidone treatment

- Nintedanib treatment

A 64-year-old man has a one-year history of dyspnea on exertion and a nonproductive cough. His symptoms are gradually worsening and increasingly bothersome to him.

His medical history includes mild seasonal allergies and GERD, which is well-controlled by oral antihistamines and proton pump inhibitors. He has spent the past 30 years working a desk job as an accountant. He denies a history of smoking, exposure to secondhand smoke, and initiation of new medication.

He admits to increased fatigue, but denies fever, chills, lymphadenopathy, weight change, chest pain, wheezing, abdominal pain, diarrhea, vomiting, claudication, and swelling in the extremities. The rest of the review of systems is negative.

Lab results—complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, TSH, antinuclear antibodies, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein—are within normal limits. Spirometry shows very mild restriction. A chest x-ray is abnormal but nonspecific, showing peripheral opacities. An ECG shows normal sinus rhythm.

The patient is given a trial of an inhaled steroid, which yields no improvement. Six months later, the patient is seen by a pulmonologist. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is diagnosed based on high-resolution CT (HRCT) and lung biopsy results.

IPF is a chronic, progressive, fibrosing interstitial disease that is limited to lung tissue. It most commonly manifests in older adults with vague symptoms of dyspnea on exertion and nonproductive cough, but symptoms can also include fatigue, muscle and joint aches, clubbing of the fingernails, and weight loss.1 The average life expectancy following diagnosis of IPF is two to five years, and the mortality rate is estimated at 64.3 per million men and 58.4 per million women per year.2,3

Continue to: DIAGNOSIS

DIAGNOSIS

IPF belongs in the general class of idiopathic interstitial pneumonias (IIPs), which are characterized by varying degrees of inflammation and fibrosis of lung interstitium.4 All subtypes of IIPs cause dyspnea and diffuse abnormalities on HRCT, and all vary from each other histologically. Table 1 outlines the key features of each.5-8

Because of its vague symptomology and the extensive workup needed to rule out other diseases, patients with IPF often have symptoms for one to two years before a diagnosis is made.1 Physical exam may reveal fine inspiratory rales in both lung bases and digital clubbing; eventual signs of pulmonary hypertension and right-sided heart failure may be appreciated.1,9

There are no specific diagnostic laboratory tests to confirm IPF; however, baseline labwork (as outlined in the case presentation) is typically ordered to rule out infection, thyroid disease, or connective tissue disease.10 Many patients are referred to a cardiologist before being seen by a pulmonologist; cardiac stress testing may be done, and an echocardiogram may be performed to rule out heart failure.

Diagnostic testing may include pulmonary function testing, HRCT of the chest, and lung biopsy.10 Tissue samples from patients with IPF reveal different stages of disease, including dense fibrosis with honeycombing, subpleural or paraseptal distribution, fibroblast foci, and normal tissue.11 Pulmonary function test results will show a restrictive pattern. Both forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) and forced vital capacity (FVC) will be reduced, and the FEV1/FVC ratio preserved. Due to decreased functional lung volume, diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (DLCO) will also be reduced.4,12

The differential is broad and includes allergic asthma, bronchitis, COPD, lung cancer, hypersensitivity pneumonitis, asbestosis, or pulmonary embolism.

Continue to: TREATMENT HISTORY

TREATMENT HISTORY

IPF has a long history of tried and failed treatment options. The American Thoracic Society (ATS), in concert with other professional organizations, has published comprehensive guidelines and recommendations pertaining to the use of pharmacologic medications to control disease progression. Warfarin and other anticoagulants have been studied, based on the observation that a procoagulant state promotes fibrotic changes in the lung tissue.13 However, anticoagulant use is not recommended in patients with IPF due to lack of efficacy and high potential for harm.13

Immunosuppressants have also been in the spotlight as possible treatment for IPF, but a clinical study investigating the efficacy of a three-drug regimen including prednisone, azathioprine, and N-acetylcysteine was stopped early due to increased risk for harm. Endothelin antagonists and potent tyrosine kinase inhibitors are also not recommended in the most recent edition of IPF guidelines, as they lack benefit.13

In fact, prior to the 2015 edition of the guidelines, no single medication was routinely recommended for patients with IPF. But this is now changing, following the 2014 FDA approval of two new drugs, nintedanib and pirfenidone, designed specifically to treat IPF.14 These drugs have shown promise in clinical trials (results of which are summarized in Table 2).

Continue to: NEW PHARMACOLOGIC OPTIONS

NEW PHARMACOLOGIC OPTIONS

Pirfenidone

In 2008, a study was conducted in Japan to determine the mechanism of action of pirfenidone.15 Through in vitro studies of healthy adult lung fibroblasts with added pro-fibrotic factor and transforming growth factor (TGF-ß 1), the researchers found that pirfenidone was effective at decreasing the production of a collagen-binding protein called HSP47. This protein is ubiquitous in fibrotic tissue. The study also showed that pirfenidone decreased the production of collagen type 1, which, when uninhibited, increases fibrosis.15

CAPACITY trials. In the CAPACITY trials, two phase 3 multinational studies conducted from 2006 to 2008, patients were given either pirfenidone or placebo.16 In the first study arm, patients were assigned to pirfenidone 2,403 mg/d (n = 174), pirfenidone 1,197 mg/d (n = 87), or placebo (n = 174). In the second study arm, 171 patients received pirfenidone 2,403 mg/d and 173 patients received placebo. Endpoints were measured at baseline and up to week 72.

The first study arm found that the mean rate of decline of FVC—the primary endpoint—was 4.4% less in the treatment group than in the placebo group (p = 0.001), and there was a 36% decrease in risk for death or disease progression in the treatment group (HR, 0.64; p, 0.023). (Endpoints were defined as: time to confirmed > 10% decline in percentage predicted FVC, > 15% decline in percentage predicted DLCO, or death.) The researchers found no clinically significant change in the six-minute walk test—a secondary endpoint of the study.16

The second study arm, however, found no statistically significant change in FVC between the treatment and placebo groups (with a 0.6% smaller decrease in FVC in the pirfenidone group), nor did they see a difference in progression-free survival. However, there was a significant change in the six-minute walk test between the treatment and placebo groups (p = 0.0009). Throughout the study, the most common adverse effects included nausea (36%), rash (32%), and dyspepsia (19%).16

ASCEND trial. The 2014 Assessment of Pirfenidone to Confirm Efficacy and Safety in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (ASCEND) trial was a phase 3, multinational, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the use of pirfenidone 2,403 mg/d.17 The study was conducted from 2012 to 2013. Of the total number of patients (N = 522), half received pirfenidone and half received placebo. After 52 weeks of treatment (the end of the study), the researchers found a smaller decline in FVC—the primary endpoint—in the treatment group compared to placebo (mean decline, 235 mL vs 428 mL, respectively [p < 0.001]). Regarding the six-minute walk test, the investigators found that 25.9% of the treatment group exhibited a decrease of ≥ 50 meters, compared to 35.7% of the placebo group (p = 0.04). (Progression-free survival was defined as a confirmed ≥ 10% decrease in predicted FVC, a confirmed decrease of 50 meters in the six-minute walk test, or death.)

The pirfenidone group in the ASCEND trial showed a 43% reduced risk for death or disease progression (HR, 0.57; p, < 0.001).16,17 All-cause mortality was lower in the pirfenidone group (4%) than in the placebo group (7.2%), but this was not statistically significant. Deaths from IPF in the pirfenidone group totaled three patients (1.1%) versus seven patients (2.5%) in the placebo group; this was also not statistically significant. The most common adverse effects seen during the study were nausea (36%), rash (28.1%), and headache (25.9%).17

Recommendations for use. Liver function testing should be performed at baseline, monthly for six months, and every three months afterward, as elevations in liver enzymes have been observed.18 Pirfenidone is a CYP1A2 substrate; moderate-to-strong CYP1A2 inhibitors should therefore be discontinued prior to initiation, as they are likely to decrease exposure and efficacy of pirfenidone. There are currently no black box warnings.18

Continue to: Nintedanib

Nintedanib

Hostettler et al studied lung samples from patients with IPF to determine the mechanism of action of nintedanib.19 Evaluation of fibroblasts derived from IPF samples revealed that they contained higher levels of platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) than did nonfibrotic control cells. They also found that nintedanib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor, significantly inhibited the phosphorylation of fibrotic-inducing growth factors—PDGF as well as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF).

INPULSIS trials. A phase 3 replicate of randomized, double-blind, multinational studies, the INPULSIS trials were performed between 2011 and 2012.20 Two study arms were used to evaluate a total of 638 patients who received nintedanib 150 mg bid for 52 weeks. The primary endpoint was annual rate of decline of FVC.

The researchers also evaluated efficacy through two other endpoints: patient-reported quality of life and symptoms via the St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) and evaluation of time to acute exacerbation. The latter was defined as worsening or new dyspnea, new diffuse pulmonary infiltrates visualized on chest radiography and/or HRCT, or the development of parenchymal abnormalities with no pneumothorax or pleural effusion since the preceding visit; and exclusion of any known causes of acute worsening, including infection, heart failure, pulmonary embolism, and any identifiable cause of acute lung injury.20

INPULSIS 1 (first arm) included 309 patients in the treatment group. Results showed an adjusted annual rate of decline in FVC of 114.7 mL/year, versus 239.9 mL/year in the placebo group (p < 0.001). In the treatment group, 52.8% exhibited ≤ 5% decline in FVC, compared to 38.2% in the placebo group (p = 0.001). No significant between-group differences were found in SGRQ score or time to acute exacerbation.20

INPULSIS 2 had 329 patients receiving nintedanib. An annual rate of decline in FVC of 113.6 mL/year from baseline was observed in the treatment group, compared to 207.3 mL/year in the placebo group (p < 0.001). In the treatment group, 53.2% showed ≤ 5% decline in FVC, versus 39.3% in the placebo group (p = 0.001). There was also a significantly smaller increase in total SGRQ score (meaning, less deterioration in quality of life) in the nintedanib group versus the placebo group (p = 0.02). A statistically significant increase in time to first acute exacerbation was observed in the nintedanib group (p = 0.005).20

There was no significant difference between groups in death from any cause, death from respiratory causation, or death that occurred between randomization and 28 days post treatment. The most common adverse effects seen throughout the two trials included diarrhea (trial 1, 61.5%; trial 2, 63.2%), nausea (trial 1, 22.7%; trial 2, 26.1%), and nasopharyngitis (trial 1, 12.6%; trial 2, 14.6%).20

Recommendations for use. Liver function testing should be performed at baseline, at regular intervals during the first three months, then periodically thereafter; patients in the treatment group of both INPULSIS trials had elevated liver enzymes, and cases of drug-induced liver injury have been observed with use of nintedanib.21 This medication may increase risk for bleeding due to its mechanism of action (VEGFR inhibition). Coadministration with CYP3A4 inhibitors may increase concentration of nintedanib; therefore, close monitoring is recommended. Avoid coadministration with CYP3A4 inducers, as this may decrease concentration of nintedanib by 50%. There are currently no black box warnings.21

Continue to: Patient monitoring

Patient monitoring

The ATS recommends measuring FVC and DLCO every three to six months, or sooner if clinically indicated.13 Pulse oximetry should be measured at rest and on exertion in all patients, regardless of symptoms, to assure proper saturation and identify the need for supplemental oxygen; this should also be done every three to six months.

The ATS recommends prompt detection and treatment of comorbidities such as pulmonary hypertension, emphysema, airflow obstruction, GERD, sleep apnea, and coronary artery disease.13 These recommendations are based on the organization’s 2015 guidelines.

OUTCOME FOR THE CASE PATIENT

The patient was started on pirfenidone (2,403 mg/d). He is continuing treatment and showing improvements in quality of life and slowed deterioration of lung function.

CONCLUSION

IPF causes progressive fibrosis of lung interstitium. The etiology is unknown, the symptoms and signs are vague, and mean life expectancy following diagnosis is two to five years. The most recent IPF guidelines recommend avoiding use of anticoagulants and immunosuppressants (eg, steroids, azathioprine, and N-acetylcysteine), due to their proven ineffectiveness and harm to patients with IPF.

Since the FDA’s approval of pirfenidone and nintedanib, the ATS has made recommendations for their use in patients with IPF. Despite mixed results in clinical trials, both drugs have demonstrated the ability to slow the decline in FVC over time, with relatively benign adverse effects. It is difficult to compare pirfenidone and nintedanib, or to recommend use of one drug over the other. However, it is promising that patients with this routinely fatal disease now have treatment options that can potentially modulate their disease progression.

IN THIS ARTICLE

- Confirming the diagnosis

- Pirfenidone treatment

- Nintedanib treatment

A 64-year-old man has a one-year history of dyspnea on exertion and a nonproductive cough. His symptoms are gradually worsening and increasingly bothersome to him.

His medical history includes mild seasonal allergies and GERD, which is well-controlled by oral antihistamines and proton pump inhibitors. He has spent the past 30 years working a desk job as an accountant. He denies a history of smoking, exposure to secondhand smoke, and initiation of new medication.

He admits to increased fatigue, but denies fever, chills, lymphadenopathy, weight change, chest pain, wheezing, abdominal pain, diarrhea, vomiting, claudication, and swelling in the extremities. The rest of the review of systems is negative.

Lab results—complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, TSH, antinuclear antibodies, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein—are within normal limits. Spirometry shows very mild restriction. A chest x-ray is abnormal but nonspecific, showing peripheral opacities. An ECG shows normal sinus rhythm.

The patient is given a trial of an inhaled steroid, which yields no improvement. Six months later, the patient is seen by a pulmonologist. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is diagnosed based on high-resolution CT (HRCT) and lung biopsy results.

IPF is a chronic, progressive, fibrosing interstitial disease that is limited to lung tissue. It most commonly manifests in older adults with vague symptoms of dyspnea on exertion and nonproductive cough, but symptoms can also include fatigue, muscle and joint aches, clubbing of the fingernails, and weight loss.1 The average life expectancy following diagnosis of IPF is two to five years, and the mortality rate is estimated at 64.3 per million men and 58.4 per million women per year.2,3

Continue to: DIAGNOSIS

DIAGNOSIS

IPF belongs in the general class of idiopathic interstitial pneumonias (IIPs), which are characterized by varying degrees of inflammation and fibrosis of lung interstitium.4 All subtypes of IIPs cause dyspnea and diffuse abnormalities on HRCT, and all vary from each other histologically. Table 1 outlines the key features of each.5-8

Because of its vague symptomology and the extensive workup needed to rule out other diseases, patients with IPF often have symptoms for one to two years before a diagnosis is made.1 Physical exam may reveal fine inspiratory rales in both lung bases and digital clubbing; eventual signs of pulmonary hypertension and right-sided heart failure may be appreciated.1,9

There are no specific diagnostic laboratory tests to confirm IPF; however, baseline labwork (as outlined in the case presentation) is typically ordered to rule out infection, thyroid disease, or connective tissue disease.10 Many patients are referred to a cardiologist before being seen by a pulmonologist; cardiac stress testing may be done, and an echocardiogram may be performed to rule out heart failure.

Diagnostic testing may include pulmonary function testing, HRCT of the chest, and lung biopsy.10 Tissue samples from patients with IPF reveal different stages of disease, including dense fibrosis with honeycombing, subpleural or paraseptal distribution, fibroblast foci, and normal tissue.11 Pulmonary function test results will show a restrictive pattern. Both forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) and forced vital capacity (FVC) will be reduced, and the FEV1/FVC ratio preserved. Due to decreased functional lung volume, diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (DLCO) will also be reduced.4,12

The differential is broad and includes allergic asthma, bronchitis, COPD, lung cancer, hypersensitivity pneumonitis, asbestosis, or pulmonary embolism.

Continue to: TREATMENT HISTORY

TREATMENT HISTORY

IPF has a long history of tried and failed treatment options. The American Thoracic Society (ATS), in concert with other professional organizations, has published comprehensive guidelines and recommendations pertaining to the use of pharmacologic medications to control disease progression. Warfarin and other anticoagulants have been studied, based on the observation that a procoagulant state promotes fibrotic changes in the lung tissue.13 However, anticoagulant use is not recommended in patients with IPF due to lack of efficacy and high potential for harm.13

Immunosuppressants have also been in the spotlight as possible treatment for IPF, but a clinical study investigating the efficacy of a three-drug regimen including prednisone, azathioprine, and N-acetylcysteine was stopped early due to increased risk for harm. Endothelin antagonists and potent tyrosine kinase inhibitors are also not recommended in the most recent edition of IPF guidelines, as they lack benefit.13

In fact, prior to the 2015 edition of the guidelines, no single medication was routinely recommended for patients with IPF. But this is now changing, following the 2014 FDA approval of two new drugs, nintedanib and pirfenidone, designed specifically to treat IPF.14 These drugs have shown promise in clinical trials (results of which are summarized in Table 2).

Continue to: NEW PHARMACOLOGIC OPTIONS

NEW PHARMACOLOGIC OPTIONS

Pirfenidone

In 2008, a study was conducted in Japan to determine the mechanism of action of pirfenidone.15 Through in vitro studies of healthy adult lung fibroblasts with added pro-fibrotic factor and transforming growth factor (TGF-ß 1), the researchers found that pirfenidone was effective at decreasing the production of a collagen-binding protein called HSP47. This protein is ubiquitous in fibrotic tissue. The study also showed that pirfenidone decreased the production of collagen type 1, which, when uninhibited, increases fibrosis.15

CAPACITY trials. In the CAPACITY trials, two phase 3 multinational studies conducted from 2006 to 2008, patients were given either pirfenidone or placebo.16 In the first study arm, patients were assigned to pirfenidone 2,403 mg/d (n = 174), pirfenidone 1,197 mg/d (n = 87), or placebo (n = 174). In the second study arm, 171 patients received pirfenidone 2,403 mg/d and 173 patients received placebo. Endpoints were measured at baseline and up to week 72.

The first study arm found that the mean rate of decline of FVC—the primary endpoint—was 4.4% less in the treatment group than in the placebo group (p = 0.001), and there was a 36% decrease in risk for death or disease progression in the treatment group (HR, 0.64; p, 0.023). (Endpoints were defined as: time to confirmed > 10% decline in percentage predicted FVC, > 15% decline in percentage predicted DLCO, or death.) The researchers found no clinically significant change in the six-minute walk test—a secondary endpoint of the study.16

The second study arm, however, found no statistically significant change in FVC between the treatment and placebo groups (with a 0.6% smaller decrease in FVC in the pirfenidone group), nor did they see a difference in progression-free survival. However, there was a significant change in the six-minute walk test between the treatment and placebo groups (p = 0.0009). Throughout the study, the most common adverse effects included nausea (36%), rash (32%), and dyspepsia (19%).16

ASCEND trial. The 2014 Assessment of Pirfenidone to Confirm Efficacy and Safety in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (ASCEND) trial was a phase 3, multinational, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the use of pirfenidone 2,403 mg/d.17 The study was conducted from 2012 to 2013. Of the total number of patients (N = 522), half received pirfenidone and half received placebo. After 52 weeks of treatment (the end of the study), the researchers found a smaller decline in FVC—the primary endpoint—in the treatment group compared to placebo (mean decline, 235 mL vs 428 mL, respectively [p < 0.001]). Regarding the six-minute walk test, the investigators found that 25.9% of the treatment group exhibited a decrease of ≥ 50 meters, compared to 35.7% of the placebo group (p = 0.04). (Progression-free survival was defined as a confirmed ≥ 10% decrease in predicted FVC, a confirmed decrease of 50 meters in the six-minute walk test, or death.)

The pirfenidone group in the ASCEND trial showed a 43% reduced risk for death or disease progression (HR, 0.57; p, < 0.001).16,17 All-cause mortality was lower in the pirfenidone group (4%) than in the placebo group (7.2%), but this was not statistically significant. Deaths from IPF in the pirfenidone group totaled three patients (1.1%) versus seven patients (2.5%) in the placebo group; this was also not statistically significant. The most common adverse effects seen during the study were nausea (36%), rash (28.1%), and headache (25.9%).17

Recommendations for use. Liver function testing should be performed at baseline, monthly for six months, and every three months afterward, as elevations in liver enzymes have been observed.18 Pirfenidone is a CYP1A2 substrate; moderate-to-strong CYP1A2 inhibitors should therefore be discontinued prior to initiation, as they are likely to decrease exposure and efficacy of pirfenidone. There are currently no black box warnings.18

Continue to: Nintedanib

Nintedanib

Hostettler et al studied lung samples from patients with IPF to determine the mechanism of action of nintedanib.19 Evaluation of fibroblasts derived from IPF samples revealed that they contained higher levels of platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) than did nonfibrotic control cells. They also found that nintedanib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor, significantly inhibited the phosphorylation of fibrotic-inducing growth factors—PDGF as well as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF).

INPULSIS trials. A phase 3 replicate of randomized, double-blind, multinational studies, the INPULSIS trials were performed between 2011 and 2012.20 Two study arms were used to evaluate a total of 638 patients who received nintedanib 150 mg bid for 52 weeks. The primary endpoint was annual rate of decline of FVC.

The researchers also evaluated efficacy through two other endpoints: patient-reported quality of life and symptoms via the St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) and evaluation of time to acute exacerbation. The latter was defined as worsening or new dyspnea, new diffuse pulmonary infiltrates visualized on chest radiography and/or HRCT, or the development of parenchymal abnormalities with no pneumothorax or pleural effusion since the preceding visit; and exclusion of any known causes of acute worsening, including infection, heart failure, pulmonary embolism, and any identifiable cause of acute lung injury.20

INPULSIS 1 (first arm) included 309 patients in the treatment group. Results showed an adjusted annual rate of decline in FVC of 114.7 mL/year, versus 239.9 mL/year in the placebo group (p < 0.001). In the treatment group, 52.8% exhibited ≤ 5% decline in FVC, compared to 38.2% in the placebo group (p = 0.001). No significant between-group differences were found in SGRQ score or time to acute exacerbation.20