User login

Large Indurated Plaque on the Chest With Ulceration and Necrosis

The Diagnosis: Carcinoma en Cuirasse

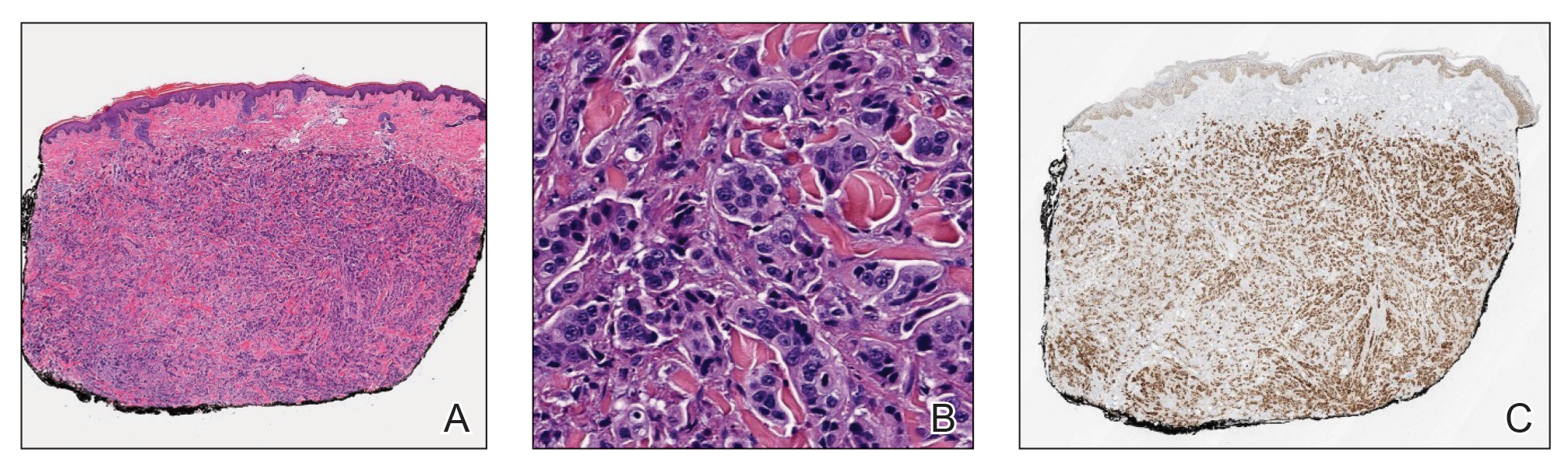

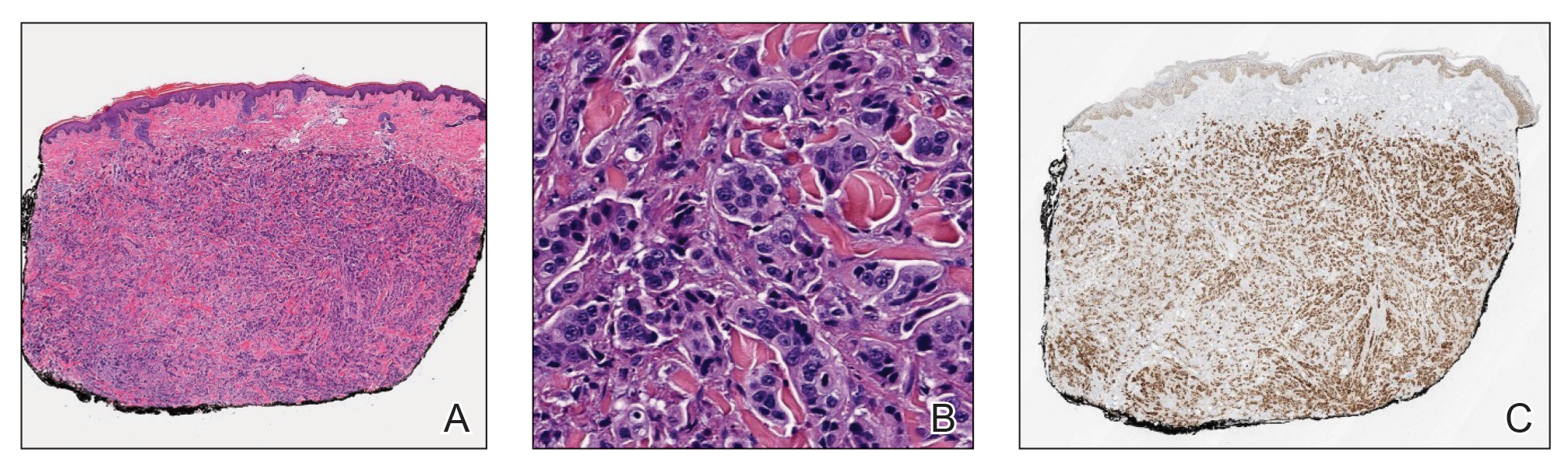

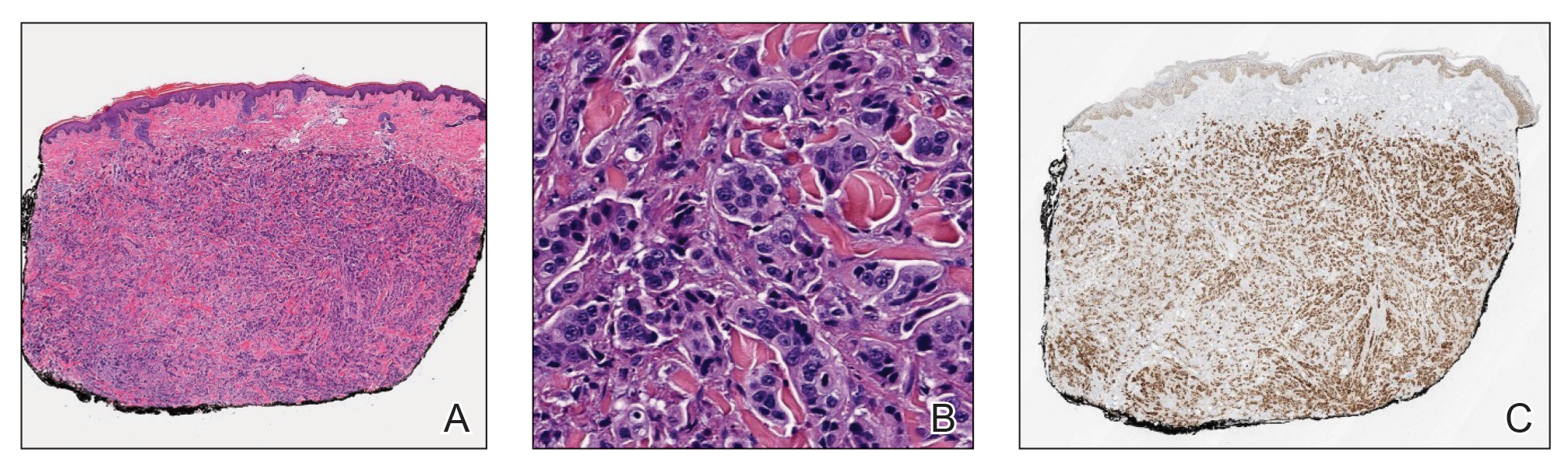

Histopathology demonstrated a cellular infiltrate filling the dermis with sparing of the papillary and superficial reticular dermis (Figure 1A). The cells were arranged in strands and cords that infiltrated between sclerotic collagen bundles. Cytomorphologically, the cells ranged from epithelioid with large vesicular nuclei and prominent nucleoli to cuboidal with hyperchromatic nuclei with irregular contours and a high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio (Figure 1B). Occasional mitotic figures were identified, and cells demonstrated diffuse nuclear positivity for GATA-3 (Figure 1C); 55% of the cells demonstrated estrogen receptor positivity, and immunohistochemistry of progesterone receptors was negative. These findings confirmed our patient’s diagnosis of breast carcinoma en cuirasse (CeC) as the primary manifestation of metastatic invasive ductal carcinoma. Our patient was treated with intravenous chemotherapy and tamoxifen.

Histopathologic findings of morphea include thickened hyalinized collagen bundles and loss of adventitial fat.1 A diagnosis of chronic radiation dermatitis was inconsistent with our patient’s medical history and biopsy results, as pathology should reveal hyalinized collagen or stellate radiation fibroblasts.2,3 Nests of squamous epithelial cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and large vesicular nuclei were not seen, excluding squamous cell carcinoma as a possible diagnosis.4 Although sclerosing sweat duct carcinoma is characterized by infiltrating cords in sclerotic dermis, the cells were not arranged in ductlike structures 1– to 2–cell layers thick, excluding this diagnosis.5

Carcinoma en cuirasse—named for skin involvement that appears similar to the metal breastplate of a cuirassier—is a rare form of cutaneous metastasis that typically presents with extensive infiltrative plaques resulting in fibrosis of the skin and subcutaneous tissue.6,7 Carcinoma en cuirasse most commonly metastasizes from the breast but also may represent metastases from the lungs, gastrointestinal tract, or genitourinary systems.8 In the setting of a primary breast malignancy, metastatic plaques of CeC tend to represent tumor recurrence following a mastectomy procedure; however, in rare cases CeC can present as the primary manifestation of breast cancer or as a result of untreated malignancy.6,9 In our patient, CeC was the primary manifestation of metastatic invasive ductal carcinoma with additional paraneoplastic ichthyosis (Figure 2).

Carcinoma en cuirasse comprises 3% to 6% of cutaneous metastases originating from the breast.10,11 Breast cancer is the most common primary neoplasm displaying extracutaneous metastasis, comprising 70% of all cutaneous metastases in females.11 Cutaneous metastasis often indicates late stage of disease, portending a poor prognosis. In our patient, the cutaneous nodules were present for approximately 3 years prior to the diagnosis of stage IV invasive ductal cell carcinoma with metastasis to the skin and lungs. Prior to admission, she had not been diagnosed with breast cancer, thus no treatments had been administered. It is uncommon for CeC to present as the initial finding and without prior treatment of the underlying malignancy. The median length of survival after diagnosis of cutaneous metastasis from breast cancer is 13.8 months, with a 10-year survival rate of 3.1%.12

In addition to cutaneous metastasis, breast cancer also may present with paraneoplastic dermatoses such as ichthyosis.13 Ichthyosis is characterized by extreme dryness, flaking, thickening, and mild pruritus.14 It most commonly is an inherited condition, but it may be acquired due to malignancy. Acquired ichthyosis may manifest in systemic diseases including systemic lupus erythematosus, sarcoidosis, and hypothyroidism.15 Although acquired ichthyosis is rare, it has been reported in cases of internal malignancy, most commonly lymphoproliferative malignancies and less frequently carcinoma of the breasts, cervix, and lungs. Patients who acquire ichthyosis in association with malignancy usually present with late-stage disease.15 Our patient acquired ichthyosis 3 months prior to admission and had never experienced it previously. Although the exact mechanism for acquiring ichthyosis remains unknown, it is uncertain if ichthyosis associated with malignancy is paraneoplastic or a result of chemotherapy.14,16 In this case, the patient had not yet started chemotherapy at the time of the ichthyosis diagnosis, suggesting a paraneoplastic etiology.

Carcinoma en cuirasse and paraneoplastic ichthyosis individually are extremely rare manifestations of breast cancer. Thus, it is even rarer for these conditions to present concurrently. Treatment options for CeC include chemotherapy, radiotherapy, hormonal antagonists, and snake venom.11 Systemic chemotherapy targeting the histopathologic type of the primary tumor is the treatment of choice. Other treatment methods usually are chosen for late stages of disease progression.10 Paraneoplastic ichthyosis has been reported to show improvement with treatment of the underlying primary malignancy by surgical removal or chemotherapy.14,17 Tamoxifen less commonly is used for systemic treatment of CeC, but one case in the literature reported favorable outcomes.18

We describe 2 rare cutaneous manifestations of breast cancer occurring concomitantly: CeC and paraneoplastic ichthyosis. The combination of clinical and pathologic findings presented in this case solidified the diagnosis of metastatic invasive ductal carcinoma. We aim to improve recognition of paraneoplastic skin findings to accelerate the process of effective and efficient treatment.

- Walker D, Susa JS, Currimbhoy S, et al. Histopathological changes in morphea and their clinical correlates: results from the Morphea in Adults and Children Cohort V. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:1124-1130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2016.12.020

- Borrelli MR, Shen AH, Lee GK, et al. Radiation-induced skin fibrosis: pathogenesis, current treatment options, and emerging therapeutics. Ann Plast Surg. 2019;83(4 suppl 1):S59-S64. https://doi.org/10.1097/SAP.0000000000002098

- Boncher J, Bergfeld WF. Fluoroscopy-induced chronic radiation dermatitis: a report of two additional cases and a brief review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:63-67. https://doi.org/10.1111/j .1600-0560.2011.01754.x

- Cassarino DS, Derienzo DP, Barr RJ. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: a comprehensive clinicopathologic classification. part one. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:191-206. https://doi.org/10.1111 /j.0303-6987.2006.00516_1.x

- Harvey DT, Hu J, Long JA, et al. Sclerosing sweat duct carcinoma of the lower extremity treated with Mohs micrographic surgery. JAAD Case Rep. 2016;2:284-286. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdcr.2016.05.017

- Sharma V, Kumar A. Carcinoma en cuirasse. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:2562. doi:10.1056/NEJMicm2111669

- Oliveira GM, Zachetti DB, Barros HR, et al. Breast carcinoma en cuirasse—case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:608-610. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20131926

- Alcaraz I, Cerroni L, Rütten A, et al. Cutaneous metastases from internal malignancies: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:347-393. doi:10.1097 /DAD.0b013e31823069cf

- Glazebrook AJ, Tomaszewski W. Ichthyosiform atrophy of the skin in Hodgkin’s disease: report of a case, with reference to vitamin A metabolism. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1944;50:85-89. doi:10.1001 /archderm.1944.01510140008002

- Mordenti C, Concetta F, Cerroni M, et al. Cutaneous metastatic breast carcinoma: a study of 164 patients. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2000;9:143-148.

- Culver AL, Metter DM, Pippen JE Jr. Carcinoma en cuirasse. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2019;32:263-265. doi:10.1080/08998280.2018.1564966

- Schoenlaub P, Sarraux A, Grosshans E, et al. Survival after cutaneous metastasis: a study of 200 cases [in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2001;128:1310-1315.

- Tan AR. Cutaneous manifestations of breast cancer. Semin Oncol. 2016;43:331-334. doi:10.1053/j.seminoncol.2016.02.030

- Song Y, Wu Y, Fan T. Dermatosis as the initial manifestation of malignant breast tumors: retrospective analysis of 4 cases. Breast Care. 2010;5:174-176. doi:10.1159/000314265

- Polisky RB, Bronson DM. Acquired ichthyosis in a patient with adenocarcinoma of the breast. Cutis. 1986;38:359-360.

- Haste AR. Acquired ichthyosis from breast cancer. Br Med J. 1967;4:96-98.

- Riesco Martínez MC, Muñoz Martín AJ, Zamberk Majlis P, et al. Acquired ichthyosis as a paraneoplastic syndrome in Hodgkin’s disease. Clin Transl Oncol. 2009;11:552-553. doi:10.1007/s12094-009-0402-2

- Siddiqui MA, Zaman MN. Primary carcinoma en cuirasse. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44:221-222. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb02455.xssss

The Diagnosis: Carcinoma en Cuirasse

Histopathology demonstrated a cellular infiltrate filling the dermis with sparing of the papillary and superficial reticular dermis (Figure 1A). The cells were arranged in strands and cords that infiltrated between sclerotic collagen bundles. Cytomorphologically, the cells ranged from epithelioid with large vesicular nuclei and prominent nucleoli to cuboidal with hyperchromatic nuclei with irregular contours and a high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio (Figure 1B). Occasional mitotic figures were identified, and cells demonstrated diffuse nuclear positivity for GATA-3 (Figure 1C); 55% of the cells demonstrated estrogen receptor positivity, and immunohistochemistry of progesterone receptors was negative. These findings confirmed our patient’s diagnosis of breast carcinoma en cuirasse (CeC) as the primary manifestation of metastatic invasive ductal carcinoma. Our patient was treated with intravenous chemotherapy and tamoxifen.

Histopathologic findings of morphea include thickened hyalinized collagen bundles and loss of adventitial fat.1 A diagnosis of chronic radiation dermatitis was inconsistent with our patient’s medical history and biopsy results, as pathology should reveal hyalinized collagen or stellate radiation fibroblasts.2,3 Nests of squamous epithelial cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and large vesicular nuclei were not seen, excluding squamous cell carcinoma as a possible diagnosis.4 Although sclerosing sweat duct carcinoma is characterized by infiltrating cords in sclerotic dermis, the cells were not arranged in ductlike structures 1– to 2–cell layers thick, excluding this diagnosis.5

Carcinoma en cuirasse—named for skin involvement that appears similar to the metal breastplate of a cuirassier—is a rare form of cutaneous metastasis that typically presents with extensive infiltrative plaques resulting in fibrosis of the skin and subcutaneous tissue.6,7 Carcinoma en cuirasse most commonly metastasizes from the breast but also may represent metastases from the lungs, gastrointestinal tract, or genitourinary systems.8 In the setting of a primary breast malignancy, metastatic plaques of CeC tend to represent tumor recurrence following a mastectomy procedure; however, in rare cases CeC can present as the primary manifestation of breast cancer or as a result of untreated malignancy.6,9 In our patient, CeC was the primary manifestation of metastatic invasive ductal carcinoma with additional paraneoplastic ichthyosis (Figure 2).

Carcinoma en cuirasse comprises 3% to 6% of cutaneous metastases originating from the breast.10,11 Breast cancer is the most common primary neoplasm displaying extracutaneous metastasis, comprising 70% of all cutaneous metastases in females.11 Cutaneous metastasis often indicates late stage of disease, portending a poor prognosis. In our patient, the cutaneous nodules were present for approximately 3 years prior to the diagnosis of stage IV invasive ductal cell carcinoma with metastasis to the skin and lungs. Prior to admission, she had not been diagnosed with breast cancer, thus no treatments had been administered. It is uncommon for CeC to present as the initial finding and without prior treatment of the underlying malignancy. The median length of survival after diagnosis of cutaneous metastasis from breast cancer is 13.8 months, with a 10-year survival rate of 3.1%.12

In addition to cutaneous metastasis, breast cancer also may present with paraneoplastic dermatoses such as ichthyosis.13 Ichthyosis is characterized by extreme dryness, flaking, thickening, and mild pruritus.14 It most commonly is an inherited condition, but it may be acquired due to malignancy. Acquired ichthyosis may manifest in systemic diseases including systemic lupus erythematosus, sarcoidosis, and hypothyroidism.15 Although acquired ichthyosis is rare, it has been reported in cases of internal malignancy, most commonly lymphoproliferative malignancies and less frequently carcinoma of the breasts, cervix, and lungs. Patients who acquire ichthyosis in association with malignancy usually present with late-stage disease.15 Our patient acquired ichthyosis 3 months prior to admission and had never experienced it previously. Although the exact mechanism for acquiring ichthyosis remains unknown, it is uncertain if ichthyosis associated with malignancy is paraneoplastic or a result of chemotherapy.14,16 In this case, the patient had not yet started chemotherapy at the time of the ichthyosis diagnosis, suggesting a paraneoplastic etiology.

Carcinoma en cuirasse and paraneoplastic ichthyosis individually are extremely rare manifestations of breast cancer. Thus, it is even rarer for these conditions to present concurrently. Treatment options for CeC include chemotherapy, radiotherapy, hormonal antagonists, and snake venom.11 Systemic chemotherapy targeting the histopathologic type of the primary tumor is the treatment of choice. Other treatment methods usually are chosen for late stages of disease progression.10 Paraneoplastic ichthyosis has been reported to show improvement with treatment of the underlying primary malignancy by surgical removal or chemotherapy.14,17 Tamoxifen less commonly is used for systemic treatment of CeC, but one case in the literature reported favorable outcomes.18

We describe 2 rare cutaneous manifestations of breast cancer occurring concomitantly: CeC and paraneoplastic ichthyosis. The combination of clinical and pathologic findings presented in this case solidified the diagnosis of metastatic invasive ductal carcinoma. We aim to improve recognition of paraneoplastic skin findings to accelerate the process of effective and efficient treatment.

The Diagnosis: Carcinoma en Cuirasse

Histopathology demonstrated a cellular infiltrate filling the dermis with sparing of the papillary and superficial reticular dermis (Figure 1A). The cells were arranged in strands and cords that infiltrated between sclerotic collagen bundles. Cytomorphologically, the cells ranged from epithelioid with large vesicular nuclei and prominent nucleoli to cuboidal with hyperchromatic nuclei with irregular contours and a high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio (Figure 1B). Occasional mitotic figures were identified, and cells demonstrated diffuse nuclear positivity for GATA-3 (Figure 1C); 55% of the cells demonstrated estrogen receptor positivity, and immunohistochemistry of progesterone receptors was negative. These findings confirmed our patient’s diagnosis of breast carcinoma en cuirasse (CeC) as the primary manifestation of metastatic invasive ductal carcinoma. Our patient was treated with intravenous chemotherapy and tamoxifen.

Histopathologic findings of morphea include thickened hyalinized collagen bundles and loss of adventitial fat.1 A diagnosis of chronic radiation dermatitis was inconsistent with our patient’s medical history and biopsy results, as pathology should reveal hyalinized collagen or stellate radiation fibroblasts.2,3 Nests of squamous epithelial cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and large vesicular nuclei were not seen, excluding squamous cell carcinoma as a possible diagnosis.4 Although sclerosing sweat duct carcinoma is characterized by infiltrating cords in sclerotic dermis, the cells were not arranged in ductlike structures 1– to 2–cell layers thick, excluding this diagnosis.5

Carcinoma en cuirasse—named for skin involvement that appears similar to the metal breastplate of a cuirassier—is a rare form of cutaneous metastasis that typically presents with extensive infiltrative plaques resulting in fibrosis of the skin and subcutaneous tissue.6,7 Carcinoma en cuirasse most commonly metastasizes from the breast but also may represent metastases from the lungs, gastrointestinal tract, or genitourinary systems.8 In the setting of a primary breast malignancy, metastatic plaques of CeC tend to represent tumor recurrence following a mastectomy procedure; however, in rare cases CeC can present as the primary manifestation of breast cancer or as a result of untreated malignancy.6,9 In our patient, CeC was the primary manifestation of metastatic invasive ductal carcinoma with additional paraneoplastic ichthyosis (Figure 2).

Carcinoma en cuirasse comprises 3% to 6% of cutaneous metastases originating from the breast.10,11 Breast cancer is the most common primary neoplasm displaying extracutaneous metastasis, comprising 70% of all cutaneous metastases in females.11 Cutaneous metastasis often indicates late stage of disease, portending a poor prognosis. In our patient, the cutaneous nodules were present for approximately 3 years prior to the diagnosis of stage IV invasive ductal cell carcinoma with metastasis to the skin and lungs. Prior to admission, she had not been diagnosed with breast cancer, thus no treatments had been administered. It is uncommon for CeC to present as the initial finding and without prior treatment of the underlying malignancy. The median length of survival after diagnosis of cutaneous metastasis from breast cancer is 13.8 months, with a 10-year survival rate of 3.1%.12

In addition to cutaneous metastasis, breast cancer also may present with paraneoplastic dermatoses such as ichthyosis.13 Ichthyosis is characterized by extreme dryness, flaking, thickening, and mild pruritus.14 It most commonly is an inherited condition, but it may be acquired due to malignancy. Acquired ichthyosis may manifest in systemic diseases including systemic lupus erythematosus, sarcoidosis, and hypothyroidism.15 Although acquired ichthyosis is rare, it has been reported in cases of internal malignancy, most commonly lymphoproliferative malignancies and less frequently carcinoma of the breasts, cervix, and lungs. Patients who acquire ichthyosis in association with malignancy usually present with late-stage disease.15 Our patient acquired ichthyosis 3 months prior to admission and had never experienced it previously. Although the exact mechanism for acquiring ichthyosis remains unknown, it is uncertain if ichthyosis associated with malignancy is paraneoplastic or a result of chemotherapy.14,16 In this case, the patient had not yet started chemotherapy at the time of the ichthyosis diagnosis, suggesting a paraneoplastic etiology.

Carcinoma en cuirasse and paraneoplastic ichthyosis individually are extremely rare manifestations of breast cancer. Thus, it is even rarer for these conditions to present concurrently. Treatment options for CeC include chemotherapy, radiotherapy, hormonal antagonists, and snake venom.11 Systemic chemotherapy targeting the histopathologic type of the primary tumor is the treatment of choice. Other treatment methods usually are chosen for late stages of disease progression.10 Paraneoplastic ichthyosis has been reported to show improvement with treatment of the underlying primary malignancy by surgical removal or chemotherapy.14,17 Tamoxifen less commonly is used for systemic treatment of CeC, but one case in the literature reported favorable outcomes.18

We describe 2 rare cutaneous manifestations of breast cancer occurring concomitantly: CeC and paraneoplastic ichthyosis. The combination of clinical and pathologic findings presented in this case solidified the diagnosis of metastatic invasive ductal carcinoma. We aim to improve recognition of paraneoplastic skin findings to accelerate the process of effective and efficient treatment.

- Walker D, Susa JS, Currimbhoy S, et al. Histopathological changes in morphea and their clinical correlates: results from the Morphea in Adults and Children Cohort V. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:1124-1130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2016.12.020

- Borrelli MR, Shen AH, Lee GK, et al. Radiation-induced skin fibrosis: pathogenesis, current treatment options, and emerging therapeutics. Ann Plast Surg. 2019;83(4 suppl 1):S59-S64. https://doi.org/10.1097/SAP.0000000000002098

- Boncher J, Bergfeld WF. Fluoroscopy-induced chronic radiation dermatitis: a report of two additional cases and a brief review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:63-67. https://doi.org/10.1111/j .1600-0560.2011.01754.x

- Cassarino DS, Derienzo DP, Barr RJ. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: a comprehensive clinicopathologic classification. part one. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:191-206. https://doi.org/10.1111 /j.0303-6987.2006.00516_1.x

- Harvey DT, Hu J, Long JA, et al. Sclerosing sweat duct carcinoma of the lower extremity treated with Mohs micrographic surgery. JAAD Case Rep. 2016;2:284-286. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdcr.2016.05.017

- Sharma V, Kumar A. Carcinoma en cuirasse. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:2562. doi:10.1056/NEJMicm2111669

- Oliveira GM, Zachetti DB, Barros HR, et al. Breast carcinoma en cuirasse—case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:608-610. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20131926

- Alcaraz I, Cerroni L, Rütten A, et al. Cutaneous metastases from internal malignancies: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:347-393. doi:10.1097 /DAD.0b013e31823069cf

- Glazebrook AJ, Tomaszewski W. Ichthyosiform atrophy of the skin in Hodgkin’s disease: report of a case, with reference to vitamin A metabolism. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1944;50:85-89. doi:10.1001 /archderm.1944.01510140008002

- Mordenti C, Concetta F, Cerroni M, et al. Cutaneous metastatic breast carcinoma: a study of 164 patients. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2000;9:143-148.

- Culver AL, Metter DM, Pippen JE Jr. Carcinoma en cuirasse. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2019;32:263-265. doi:10.1080/08998280.2018.1564966

- Schoenlaub P, Sarraux A, Grosshans E, et al. Survival after cutaneous metastasis: a study of 200 cases [in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2001;128:1310-1315.

- Tan AR. Cutaneous manifestations of breast cancer. Semin Oncol. 2016;43:331-334. doi:10.1053/j.seminoncol.2016.02.030

- Song Y, Wu Y, Fan T. Dermatosis as the initial manifestation of malignant breast tumors: retrospective analysis of 4 cases. Breast Care. 2010;5:174-176. doi:10.1159/000314265

- Polisky RB, Bronson DM. Acquired ichthyosis in a patient with adenocarcinoma of the breast. Cutis. 1986;38:359-360.

- Haste AR. Acquired ichthyosis from breast cancer. Br Med J. 1967;4:96-98.

- Riesco Martínez MC, Muñoz Martín AJ, Zamberk Majlis P, et al. Acquired ichthyosis as a paraneoplastic syndrome in Hodgkin’s disease. Clin Transl Oncol. 2009;11:552-553. doi:10.1007/s12094-009-0402-2

- Siddiqui MA, Zaman MN. Primary carcinoma en cuirasse. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44:221-222. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb02455.xssss

- Walker D, Susa JS, Currimbhoy S, et al. Histopathological changes in morphea and their clinical correlates: results from the Morphea in Adults and Children Cohort V. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:1124-1130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2016.12.020

- Borrelli MR, Shen AH, Lee GK, et al. Radiation-induced skin fibrosis: pathogenesis, current treatment options, and emerging therapeutics. Ann Plast Surg. 2019;83(4 suppl 1):S59-S64. https://doi.org/10.1097/SAP.0000000000002098

- Boncher J, Bergfeld WF. Fluoroscopy-induced chronic radiation dermatitis: a report of two additional cases and a brief review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2012;39:63-67. https://doi.org/10.1111/j .1600-0560.2011.01754.x

- Cassarino DS, Derienzo DP, Barr RJ. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: a comprehensive clinicopathologic classification. part one. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:191-206. https://doi.org/10.1111 /j.0303-6987.2006.00516_1.x

- Harvey DT, Hu J, Long JA, et al. Sclerosing sweat duct carcinoma of the lower extremity treated with Mohs micrographic surgery. JAAD Case Rep. 2016;2:284-286. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdcr.2016.05.017

- Sharma V, Kumar A. Carcinoma en cuirasse. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:2562. doi:10.1056/NEJMicm2111669

- Oliveira GM, Zachetti DB, Barros HR, et al. Breast carcinoma en cuirasse—case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:608-610. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20131926

- Alcaraz I, Cerroni L, Rütten A, et al. Cutaneous metastases from internal malignancies: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:347-393. doi:10.1097 /DAD.0b013e31823069cf

- Glazebrook AJ, Tomaszewski W. Ichthyosiform atrophy of the skin in Hodgkin’s disease: report of a case, with reference to vitamin A metabolism. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1944;50:85-89. doi:10.1001 /archderm.1944.01510140008002

- Mordenti C, Concetta F, Cerroni M, et al. Cutaneous metastatic breast carcinoma: a study of 164 patients. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2000;9:143-148.

- Culver AL, Metter DM, Pippen JE Jr. Carcinoma en cuirasse. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2019;32:263-265. doi:10.1080/08998280.2018.1564966

- Schoenlaub P, Sarraux A, Grosshans E, et al. Survival after cutaneous metastasis: a study of 200 cases [in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2001;128:1310-1315.

- Tan AR. Cutaneous manifestations of breast cancer. Semin Oncol. 2016;43:331-334. doi:10.1053/j.seminoncol.2016.02.030

- Song Y, Wu Y, Fan T. Dermatosis as the initial manifestation of malignant breast tumors: retrospective analysis of 4 cases. Breast Care. 2010;5:174-176. doi:10.1159/000314265

- Polisky RB, Bronson DM. Acquired ichthyosis in a patient with adenocarcinoma of the breast. Cutis. 1986;38:359-360.

- Haste AR. Acquired ichthyosis from breast cancer. Br Med J. 1967;4:96-98.

- Riesco Martínez MC, Muñoz Martín AJ, Zamberk Majlis P, et al. Acquired ichthyosis as a paraneoplastic syndrome in Hodgkin’s disease. Clin Transl Oncol. 2009;11:552-553. doi:10.1007/s12094-009-0402-2

- Siddiqui MA, Zaman MN. Primary carcinoma en cuirasse. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44:221-222. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb02455.xssss

A 47-year-old woman with no notable medical history presented to the emergency department with shortness of breath on simple exertion as well as a large lesion on the chest that had slowly increased in size over the last 3 years. The lesion was not painful or pruritic, and she had been treating it with topical emollients without substantial improvement. Physical examination revealed a large indurated plaque with areas of ulceration and necrosis spanning the mid to lateral chest. Additionally, ichthyotic brown scaling was present on the arms and legs. Upon further questioning, the patient reported that the scales on the extremities appeared in the last 3 months and were not previously noted. She had no recent routine cancer screenings, and her family history was notable for a brother with brain cancer. A punch biopsy of the chest plaque was performed.

Fellowships in Complex Medical Dermatology

Complex medical dermatology has become an emerging field in dermatology. Although a rather protean and broad term, complex medical dermatology encompasses patients with autoimmune conditions, bullous disease, connective tissue disease, vasculitis, severe dermatoses requiring immunomodulation, and inpatient consultations. Importantly, dermatology inpatient consultations aid in lowering health care costs due to accurate diagnoses, correct treatment, and decreased hospital stays.1 A fellowship is not required for holding an inpatient role in the hospital system as a dermatologist but can be beneficial. There are combined internal medicine–dermatology programs available for medical students applying to dermatology residency, but a complex medical dermatology fellowship is an option after residency for those who are interested. I believe that a focused complex medical dermatology fellowship differs from the training offered in combined internal medicine–dermatology residency. My fellow colleagues in combined internal medicine–dermatology programs are exposed to systemic manifestations of cutaneous disease and are experts in the interplay between the skin and other organ systems. However, the focus of their programs is with the intention of becoming double boarded in internal medicine and dermatology with comprehensive exposure to both fields. In my fellowship, I am able to tailor my schedule to focus on any dermatologic disease such as connective tissue disease, pruritus, graft vs host disease, and Merkel cell carcinoma. I ultimately can determine a niche in dermatology and hone my skills for a year under supervision.

Available Fellowships

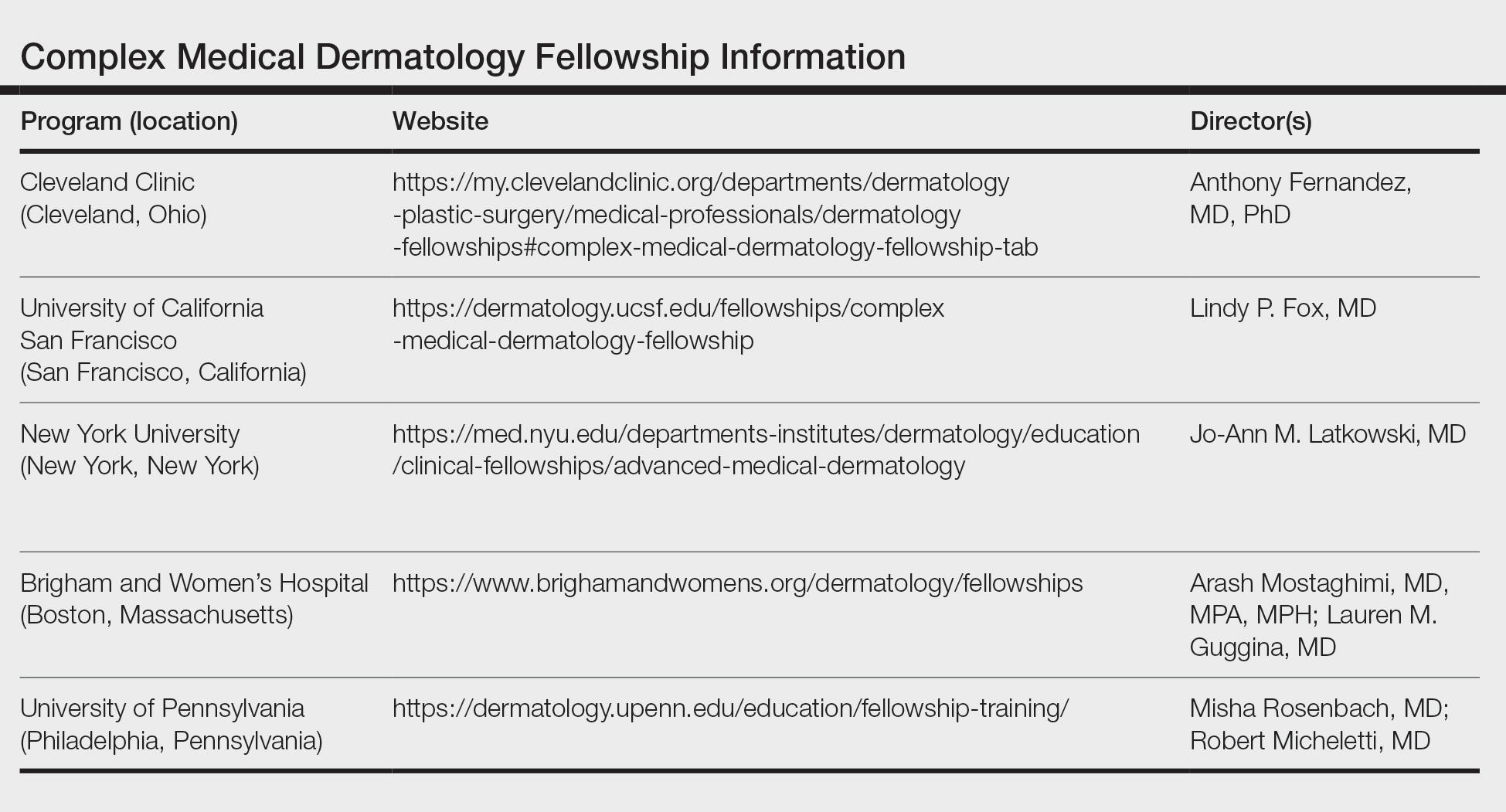

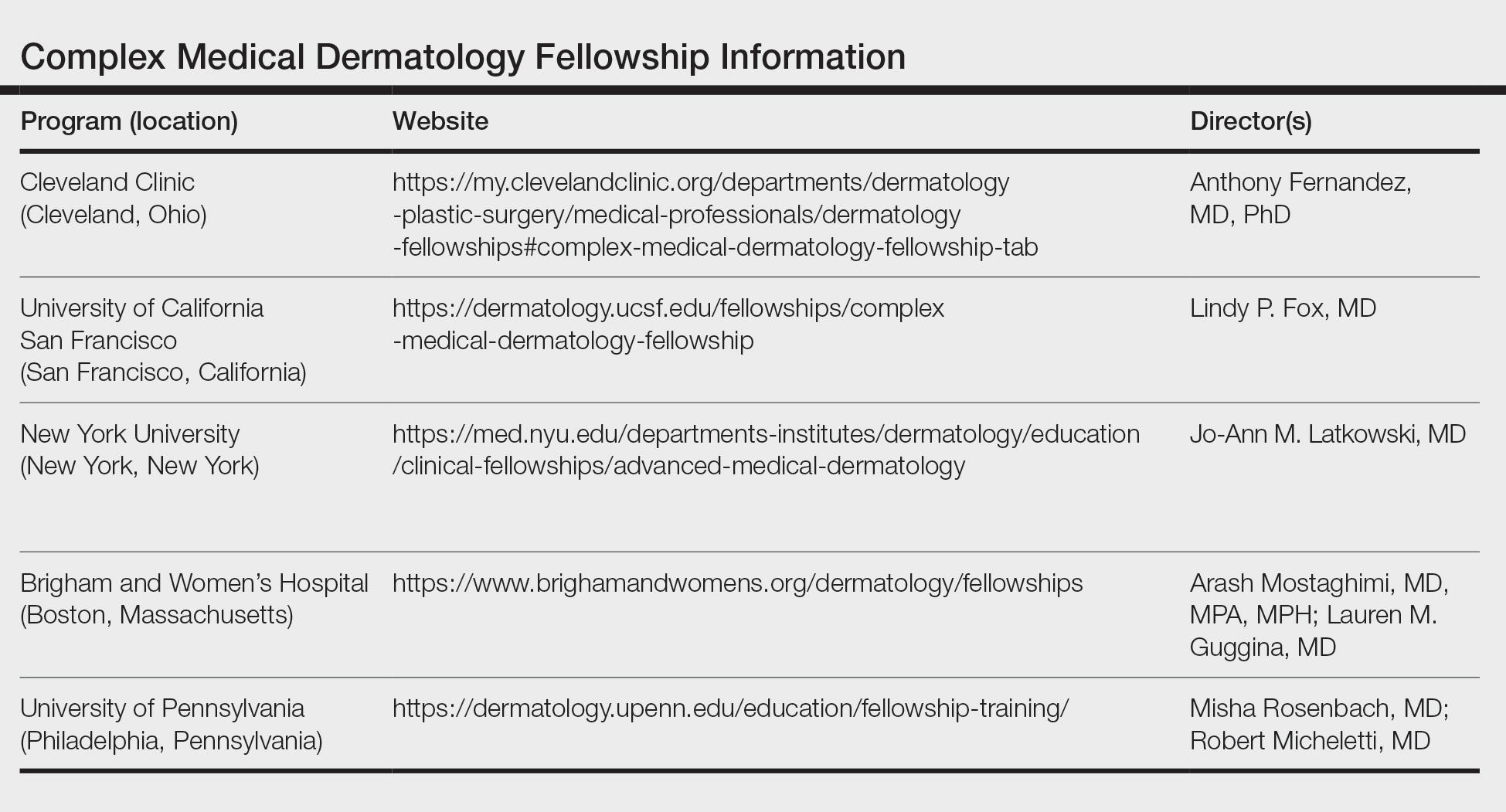

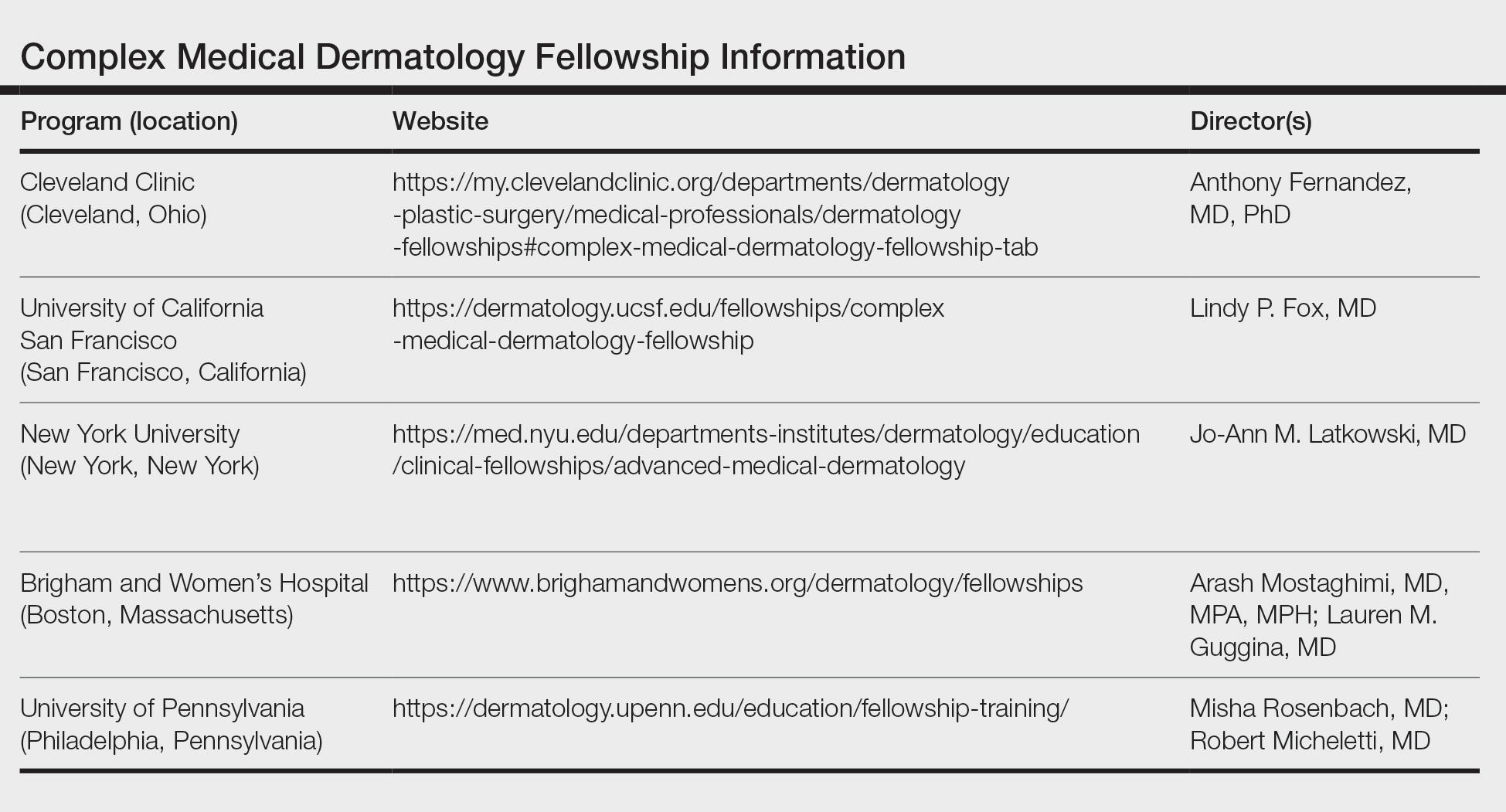

Fellowship Locations—Importantly, the complex medical dermatology fellowship is not accredited by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, which can make it difficult to identify and apply to programs. The complex medical dermatology fellowship is different than a rheumatology-dermatology fellowship, cutaneous oncology fellowship, pediatric dermatology fellowship, or other subspecialty fellowships such as those in itch or autoimmune blistering diseases. The fellowship often encompasses gaining clinical expertise in many of these conditions. I performed a thorough search online and spoke with complex medical dermatologists to compile a list of programs that offer a complex medical dermatology fellowship: Brigham and Women’s Hospital (Boston, Massachusetts); University of California San Francisco (San Francisco, California); University of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania); Cleveland Clinic (Cleveland, Ohio); and New York University (New York, New York)(Table). Only 1 spot is offered at each of these programs.

Reason to Pursue the Fellowship—There are many reasons to pursue a fellowship in complex medical dermatology such as a desire to enhance exposure to the field, to practice in an academic center and develop a niche within dermatology, to practice dermatology in an inpatient setting, to improve delivery of health care to medically challenging populations in a community setting, and to become an expert on cutaneous manifestations of internal and systemic disease.

Application—There is no standardized application or deadline for this fellowship; however, there is a concerted attempt from some of the programs to offer interviews and decisions at a similar time. Deadlines and contact information are listed on the program websites, along with more details (Table).

Recommendations—I would recommend reaching out at the beginning of postgraduate year (PGY) 4 to these programs and voicing your interest in the fellowship. It is possible to set up an away rotation at some of the programs, and if your program offers elective time, pursuing an away rotation during PGY-3 or early in PGY-4 can prove to be advantageous. Furthermore, during my application cycle I toured the University of California San Francisco, University of Pennsylvania, and Brigham and Women’s Hospital to gain further insight into each program.

Brigham and Women’s Complex Medical Dermatology Fellowship

I am currently the complex medical dermatology fellow at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and it has been an outstanding experience thus far. The program offers numerous subspecialty clinics focusing solely on cutaneous-oncodermatology, psoriasis, rheumatology-dermatology, skin of color, mole mapping backed by artificial intelligence, cosmetics, high-risk skin cancer, neutrophilic dermatoses, patch testing, phototherapy, psychodermatology, and transplant dermatology. In addition to a wide variety of subspecialty clinics, fellows have the opportunity to participate in inpatient dermatology rounds and act as a junior attending. I appreciate the flexibility of this program combined with the ability to work alongside worldwide experts. There are numerous teaching opportunities, and all of the faculty are amiable and intelligent and emphasize wellness, education, and autonomy. Overall, my experience and decision to pursue a complex medical dermatology fellowship has been extremely rewarding and invaluable. I am gaining additional skills to aid medically challenging patients while pursuing my true passion in dermatology.

1. Sahni DR. Inpatient dermatology consultation services in hospital institutions. Cutis. 2023;111:E11-E12. doi:10.12788/cutis.0776.

Complex medical dermatology has become an emerging field in dermatology. Although a rather protean and broad term, complex medical dermatology encompasses patients with autoimmune conditions, bullous disease, connective tissue disease, vasculitis, severe dermatoses requiring immunomodulation, and inpatient consultations. Importantly, dermatology inpatient consultations aid in lowering health care costs due to accurate diagnoses, correct treatment, and decreased hospital stays.1 A fellowship is not required for holding an inpatient role in the hospital system as a dermatologist but can be beneficial. There are combined internal medicine–dermatology programs available for medical students applying to dermatology residency, but a complex medical dermatology fellowship is an option after residency for those who are interested. I believe that a focused complex medical dermatology fellowship differs from the training offered in combined internal medicine–dermatology residency. My fellow colleagues in combined internal medicine–dermatology programs are exposed to systemic manifestations of cutaneous disease and are experts in the interplay between the skin and other organ systems. However, the focus of their programs is with the intention of becoming double boarded in internal medicine and dermatology with comprehensive exposure to both fields. In my fellowship, I am able to tailor my schedule to focus on any dermatologic disease such as connective tissue disease, pruritus, graft vs host disease, and Merkel cell carcinoma. I ultimately can determine a niche in dermatology and hone my skills for a year under supervision.

Available Fellowships

Fellowship Locations—Importantly, the complex medical dermatology fellowship is not accredited by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, which can make it difficult to identify and apply to programs. The complex medical dermatology fellowship is different than a rheumatology-dermatology fellowship, cutaneous oncology fellowship, pediatric dermatology fellowship, or other subspecialty fellowships such as those in itch or autoimmune blistering diseases. The fellowship often encompasses gaining clinical expertise in many of these conditions. I performed a thorough search online and spoke with complex medical dermatologists to compile a list of programs that offer a complex medical dermatology fellowship: Brigham and Women’s Hospital (Boston, Massachusetts); University of California San Francisco (San Francisco, California); University of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania); Cleveland Clinic (Cleveland, Ohio); and New York University (New York, New York)(Table). Only 1 spot is offered at each of these programs.

Reason to Pursue the Fellowship—There are many reasons to pursue a fellowship in complex medical dermatology such as a desire to enhance exposure to the field, to practice in an academic center and develop a niche within dermatology, to practice dermatology in an inpatient setting, to improve delivery of health care to medically challenging populations in a community setting, and to become an expert on cutaneous manifestations of internal and systemic disease.

Application—There is no standardized application or deadline for this fellowship; however, there is a concerted attempt from some of the programs to offer interviews and decisions at a similar time. Deadlines and contact information are listed on the program websites, along with more details (Table).

Recommendations—I would recommend reaching out at the beginning of postgraduate year (PGY) 4 to these programs and voicing your interest in the fellowship. It is possible to set up an away rotation at some of the programs, and if your program offers elective time, pursuing an away rotation during PGY-3 or early in PGY-4 can prove to be advantageous. Furthermore, during my application cycle I toured the University of California San Francisco, University of Pennsylvania, and Brigham and Women’s Hospital to gain further insight into each program.

Brigham and Women’s Complex Medical Dermatology Fellowship

I am currently the complex medical dermatology fellow at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and it has been an outstanding experience thus far. The program offers numerous subspecialty clinics focusing solely on cutaneous-oncodermatology, psoriasis, rheumatology-dermatology, skin of color, mole mapping backed by artificial intelligence, cosmetics, high-risk skin cancer, neutrophilic dermatoses, patch testing, phototherapy, psychodermatology, and transplant dermatology. In addition to a wide variety of subspecialty clinics, fellows have the opportunity to participate in inpatient dermatology rounds and act as a junior attending. I appreciate the flexibility of this program combined with the ability to work alongside worldwide experts. There are numerous teaching opportunities, and all of the faculty are amiable and intelligent and emphasize wellness, education, and autonomy. Overall, my experience and decision to pursue a complex medical dermatology fellowship has been extremely rewarding and invaluable. I am gaining additional skills to aid medically challenging patients while pursuing my true passion in dermatology.

Complex medical dermatology has become an emerging field in dermatology. Although a rather protean and broad term, complex medical dermatology encompasses patients with autoimmune conditions, bullous disease, connective tissue disease, vasculitis, severe dermatoses requiring immunomodulation, and inpatient consultations. Importantly, dermatology inpatient consultations aid in lowering health care costs due to accurate diagnoses, correct treatment, and decreased hospital stays.1 A fellowship is not required for holding an inpatient role in the hospital system as a dermatologist but can be beneficial. There are combined internal medicine–dermatology programs available for medical students applying to dermatology residency, but a complex medical dermatology fellowship is an option after residency for those who are interested. I believe that a focused complex medical dermatology fellowship differs from the training offered in combined internal medicine–dermatology residency. My fellow colleagues in combined internal medicine–dermatology programs are exposed to systemic manifestations of cutaneous disease and are experts in the interplay between the skin and other organ systems. However, the focus of their programs is with the intention of becoming double boarded in internal medicine and dermatology with comprehensive exposure to both fields. In my fellowship, I am able to tailor my schedule to focus on any dermatologic disease such as connective tissue disease, pruritus, graft vs host disease, and Merkel cell carcinoma. I ultimately can determine a niche in dermatology and hone my skills for a year under supervision.

Available Fellowships

Fellowship Locations—Importantly, the complex medical dermatology fellowship is not accredited by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, which can make it difficult to identify and apply to programs. The complex medical dermatology fellowship is different than a rheumatology-dermatology fellowship, cutaneous oncology fellowship, pediatric dermatology fellowship, or other subspecialty fellowships such as those in itch or autoimmune blistering diseases. The fellowship often encompasses gaining clinical expertise in many of these conditions. I performed a thorough search online and spoke with complex medical dermatologists to compile a list of programs that offer a complex medical dermatology fellowship: Brigham and Women’s Hospital (Boston, Massachusetts); University of California San Francisco (San Francisco, California); University of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania); Cleveland Clinic (Cleveland, Ohio); and New York University (New York, New York)(Table). Only 1 spot is offered at each of these programs.

Reason to Pursue the Fellowship—There are many reasons to pursue a fellowship in complex medical dermatology such as a desire to enhance exposure to the field, to practice in an academic center and develop a niche within dermatology, to practice dermatology in an inpatient setting, to improve delivery of health care to medically challenging populations in a community setting, and to become an expert on cutaneous manifestations of internal and systemic disease.

Application—There is no standardized application or deadline for this fellowship; however, there is a concerted attempt from some of the programs to offer interviews and decisions at a similar time. Deadlines and contact information are listed on the program websites, along with more details (Table).

Recommendations—I would recommend reaching out at the beginning of postgraduate year (PGY) 4 to these programs and voicing your interest in the fellowship. It is possible to set up an away rotation at some of the programs, and if your program offers elective time, pursuing an away rotation during PGY-3 or early in PGY-4 can prove to be advantageous. Furthermore, during my application cycle I toured the University of California San Francisco, University of Pennsylvania, and Brigham and Women’s Hospital to gain further insight into each program.

Brigham and Women’s Complex Medical Dermatology Fellowship

I am currently the complex medical dermatology fellow at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and it has been an outstanding experience thus far. The program offers numerous subspecialty clinics focusing solely on cutaneous-oncodermatology, psoriasis, rheumatology-dermatology, skin of color, mole mapping backed by artificial intelligence, cosmetics, high-risk skin cancer, neutrophilic dermatoses, patch testing, phototherapy, psychodermatology, and transplant dermatology. In addition to a wide variety of subspecialty clinics, fellows have the opportunity to participate in inpatient dermatology rounds and act as a junior attending. I appreciate the flexibility of this program combined with the ability to work alongside worldwide experts. There are numerous teaching opportunities, and all of the faculty are amiable and intelligent and emphasize wellness, education, and autonomy. Overall, my experience and decision to pursue a complex medical dermatology fellowship has been extremely rewarding and invaluable. I am gaining additional skills to aid medically challenging patients while pursuing my true passion in dermatology.

1. Sahni DR. Inpatient dermatology consultation services in hospital institutions. Cutis. 2023;111:E11-E12. doi:10.12788/cutis.0776.

1. Sahni DR. Inpatient dermatology consultation services in hospital institutions. Cutis. 2023;111:E11-E12. doi:10.12788/cutis.0776.

RESIDENT PEARL

- Complex medical dermatology is a rewarding and fascinating subspecialty of dermatology, and additional training can be accomplished through a fellowship at a variety of prestigious institutions.

Sickle Cell: Good Outcomes for Haploidentical Transplants

Of 42 patients aged 15-45 who were fully treated, 95% survived to 2 years post transplant (overall survival, (95% CI, 81.5%-98.7%), and 88% reached the primary endpoint of event-free survival at 2 years (95% CI, 73.5%-94.8%), according to the findings, which were released at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

At an ASH news briefing, study lead author Adetola A. Kassim, MBBS, MS, of Vanderbilt University Medical Center, in Nashville, Tennessee, said the results support haploidentical stem cell transplants “as a suitable and tolerable curative therapy for adults with sickle cell disease and severe end-organ toxicity such as stroke or pulmonary hypertension, a population typically excluded from participating in gene therapy.”

Dr. Kassim added that the findings are especially promising since there are so many potential donors in stem-cell transplants: “Your siblings can be donors, your parents can be donors, your cousins can be donors. First-, second-, and third-degree relatives can be donors. So there’s really endless donors within the family.”

In an interview, Mayo Clinic SCD specialist Asmaa Ferdjallah, MD, MPH, of Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, who was not involved with the study but is familiar with its findings, said stem cell transplant is the only option to cure SCD.

“This is advantageous because SCD is otherwise a chronic disease that is marked by chronic pain, risk of stroke, frequent interruptions of school/work due to sick days, and decreased life span,” she said. “Most patients, assuming they can tolerate the conditioning chemotherapy that is given before transplant, are eligible.”

Matched sibling donors are preferable, but they can be hard to find, she said. It hasn’t been clear whether half-matched donors are feasible options in SCD, she said. “This means that, if you are a patient with sickle cell disease, and you don’t have a suitable matched donor, haploidentical transplant is not a recommendation we can make outside of enrollment in a clinical trial.”

For the study, researchers enlisted 54 patients with SCD and prior stroke, recurrent acute chest syndrome or pain, chronic transfusion regimen, or tricuspid valve regurgitant jet velocity ≥2.7 m/sec. Participants had to have an HLA-haploidentical first-degree relative donor who would donate bone marrow.

“The median age was 22.8 years at enrollment; 47/54 (87%) of enrolled participants had hemoglobin SS disease, 40/54 (74.1%) had a Lansky/Karnofsky score of 90-100 at baseline, and 41/54 (75.9%) had an HLA match score of 4/8,” the researchers reported. “Recurrent vaso-occlusive pain episodes (38.9%), acute chest syndrome (16.8%), and overt stroke (16.7%) were the most common indications for transplant.”

“We knew going into this that we were going to get very high-risk patients,” Dr. Kassim said.

Forty-two patients went through with transplants. As for adverse events, 2 patients died, all within the first year, of organ failure and acute respiratory distress syndrome; 4.8% of participants had primary graft failure, and 2.4% had secondary graft failure before day 100. “The cumulative incidence of grades II-IV acute GVHD [graft-versus-host disease] at day 100 was 26.2% (95% CI, 14.0%-40.2%), and grades III-IV acute GVHD at day 100 was 4.8% (95% CI, 0.9%-14.4%).”

The outcomes are similar to those in transplants with matched sibling donors, Dr. Kassim said.

Dr. Ferdjallah said the new study is “robust” and impressive, although it’s small.

“As a clinician, these are the kind of outcomes I have been hoping for,” Dr. Ferdjallah said. “I have been very reluctant to suggest haploidentical transplant for my sickle cell disease patients. However, reviewing the results of this study with my motivated patients and families can help us both to use shared medical decision-making and come together with what is best for that specific patient.”

As for adverse events, she said they “confirm a fear of using haploidentical transplant, which is graft failure. Fortunately, out of 42 who proceeded to transplant, only 2 had primary graft failure and 1 had secondary graft failure. This is not overtly a large number. Of course, we would hope for more durable engraftment. The other side effects including GVHD and infection are all to be expected.”

As for cost, Dr. Kassim said the transplants run from $200,000 to $400,000 vs over $2 million for gene therapy, and Dr. Ferdjallah said insurance is likely to cover the treatment.

Moving ahead, Dr. Ferdjallah said she looks forward to getting study data about pediatric patients specifically. For now, “we should consider HLA-haploidentical seriously in patients with sickle cell disease and no available HLA-matched donors.”

Grants to the Blood and Marrow Transplant Clinical Trials Network from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and National Cancer Institute funded the study. Dr. Kassim had no disclosures. Some other authors disclosed various and multiple relationships with industry. Dr. Ferdjallah has no disclosures.

Of 42 patients aged 15-45 who were fully treated, 95% survived to 2 years post transplant (overall survival, (95% CI, 81.5%-98.7%), and 88% reached the primary endpoint of event-free survival at 2 years (95% CI, 73.5%-94.8%), according to the findings, which were released at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

At an ASH news briefing, study lead author Adetola A. Kassim, MBBS, MS, of Vanderbilt University Medical Center, in Nashville, Tennessee, said the results support haploidentical stem cell transplants “as a suitable and tolerable curative therapy for adults with sickle cell disease and severe end-organ toxicity such as stroke or pulmonary hypertension, a population typically excluded from participating in gene therapy.”

Dr. Kassim added that the findings are especially promising since there are so many potential donors in stem-cell transplants: “Your siblings can be donors, your parents can be donors, your cousins can be donors. First-, second-, and third-degree relatives can be donors. So there’s really endless donors within the family.”

In an interview, Mayo Clinic SCD specialist Asmaa Ferdjallah, MD, MPH, of Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, who was not involved with the study but is familiar with its findings, said stem cell transplant is the only option to cure SCD.

“This is advantageous because SCD is otherwise a chronic disease that is marked by chronic pain, risk of stroke, frequent interruptions of school/work due to sick days, and decreased life span,” she said. “Most patients, assuming they can tolerate the conditioning chemotherapy that is given before transplant, are eligible.”

Matched sibling donors are preferable, but they can be hard to find, she said. It hasn’t been clear whether half-matched donors are feasible options in SCD, she said. “This means that, if you are a patient with sickle cell disease, and you don’t have a suitable matched donor, haploidentical transplant is not a recommendation we can make outside of enrollment in a clinical trial.”

For the study, researchers enlisted 54 patients with SCD and prior stroke, recurrent acute chest syndrome or pain, chronic transfusion regimen, or tricuspid valve regurgitant jet velocity ≥2.7 m/sec. Participants had to have an HLA-haploidentical first-degree relative donor who would donate bone marrow.

“The median age was 22.8 years at enrollment; 47/54 (87%) of enrolled participants had hemoglobin SS disease, 40/54 (74.1%) had a Lansky/Karnofsky score of 90-100 at baseline, and 41/54 (75.9%) had an HLA match score of 4/8,” the researchers reported. “Recurrent vaso-occlusive pain episodes (38.9%), acute chest syndrome (16.8%), and overt stroke (16.7%) were the most common indications for transplant.”

“We knew going into this that we were going to get very high-risk patients,” Dr. Kassim said.

Forty-two patients went through with transplants. As for adverse events, 2 patients died, all within the first year, of organ failure and acute respiratory distress syndrome; 4.8% of participants had primary graft failure, and 2.4% had secondary graft failure before day 100. “The cumulative incidence of grades II-IV acute GVHD [graft-versus-host disease] at day 100 was 26.2% (95% CI, 14.0%-40.2%), and grades III-IV acute GVHD at day 100 was 4.8% (95% CI, 0.9%-14.4%).”

The outcomes are similar to those in transplants with matched sibling donors, Dr. Kassim said.

Dr. Ferdjallah said the new study is “robust” and impressive, although it’s small.

“As a clinician, these are the kind of outcomes I have been hoping for,” Dr. Ferdjallah said. “I have been very reluctant to suggest haploidentical transplant for my sickle cell disease patients. However, reviewing the results of this study with my motivated patients and families can help us both to use shared medical decision-making and come together with what is best for that specific patient.”

As for adverse events, she said they “confirm a fear of using haploidentical transplant, which is graft failure. Fortunately, out of 42 who proceeded to transplant, only 2 had primary graft failure and 1 had secondary graft failure. This is not overtly a large number. Of course, we would hope for more durable engraftment. The other side effects including GVHD and infection are all to be expected.”

As for cost, Dr. Kassim said the transplants run from $200,000 to $400,000 vs over $2 million for gene therapy, and Dr. Ferdjallah said insurance is likely to cover the treatment.

Moving ahead, Dr. Ferdjallah said she looks forward to getting study data about pediatric patients specifically. For now, “we should consider HLA-haploidentical seriously in patients with sickle cell disease and no available HLA-matched donors.”

Grants to the Blood and Marrow Transplant Clinical Trials Network from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and National Cancer Institute funded the study. Dr. Kassim had no disclosures. Some other authors disclosed various and multiple relationships with industry. Dr. Ferdjallah has no disclosures.

Of 42 patients aged 15-45 who were fully treated, 95% survived to 2 years post transplant (overall survival, (95% CI, 81.5%-98.7%), and 88% reached the primary endpoint of event-free survival at 2 years (95% CI, 73.5%-94.8%), according to the findings, which were released at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

At an ASH news briefing, study lead author Adetola A. Kassim, MBBS, MS, of Vanderbilt University Medical Center, in Nashville, Tennessee, said the results support haploidentical stem cell transplants “as a suitable and tolerable curative therapy for adults with sickle cell disease and severe end-organ toxicity such as stroke or pulmonary hypertension, a population typically excluded from participating in gene therapy.”

Dr. Kassim added that the findings are especially promising since there are so many potential donors in stem-cell transplants: “Your siblings can be donors, your parents can be donors, your cousins can be donors. First-, second-, and third-degree relatives can be donors. So there’s really endless donors within the family.”

In an interview, Mayo Clinic SCD specialist Asmaa Ferdjallah, MD, MPH, of Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, who was not involved with the study but is familiar with its findings, said stem cell transplant is the only option to cure SCD.

“This is advantageous because SCD is otherwise a chronic disease that is marked by chronic pain, risk of stroke, frequent interruptions of school/work due to sick days, and decreased life span,” she said. “Most patients, assuming they can tolerate the conditioning chemotherapy that is given before transplant, are eligible.”

Matched sibling donors are preferable, but they can be hard to find, she said. It hasn’t been clear whether half-matched donors are feasible options in SCD, she said. “This means that, if you are a patient with sickle cell disease, and you don’t have a suitable matched donor, haploidentical transplant is not a recommendation we can make outside of enrollment in a clinical trial.”

For the study, researchers enlisted 54 patients with SCD and prior stroke, recurrent acute chest syndrome or pain, chronic transfusion regimen, or tricuspid valve regurgitant jet velocity ≥2.7 m/sec. Participants had to have an HLA-haploidentical first-degree relative donor who would donate bone marrow.

“The median age was 22.8 years at enrollment; 47/54 (87%) of enrolled participants had hemoglobin SS disease, 40/54 (74.1%) had a Lansky/Karnofsky score of 90-100 at baseline, and 41/54 (75.9%) had an HLA match score of 4/8,” the researchers reported. “Recurrent vaso-occlusive pain episodes (38.9%), acute chest syndrome (16.8%), and overt stroke (16.7%) were the most common indications for transplant.”

“We knew going into this that we were going to get very high-risk patients,” Dr. Kassim said.

Forty-two patients went through with transplants. As for adverse events, 2 patients died, all within the first year, of organ failure and acute respiratory distress syndrome; 4.8% of participants had primary graft failure, and 2.4% had secondary graft failure before day 100. “The cumulative incidence of grades II-IV acute GVHD [graft-versus-host disease] at day 100 was 26.2% (95% CI, 14.0%-40.2%), and grades III-IV acute GVHD at day 100 was 4.8% (95% CI, 0.9%-14.4%).”

The outcomes are similar to those in transplants with matched sibling donors, Dr. Kassim said.

Dr. Ferdjallah said the new study is “robust” and impressive, although it’s small.

“As a clinician, these are the kind of outcomes I have been hoping for,” Dr. Ferdjallah said. “I have been very reluctant to suggest haploidentical transplant for my sickle cell disease patients. However, reviewing the results of this study with my motivated patients and families can help us both to use shared medical decision-making and come together with what is best for that specific patient.”

As for adverse events, she said they “confirm a fear of using haploidentical transplant, which is graft failure. Fortunately, out of 42 who proceeded to transplant, only 2 had primary graft failure and 1 had secondary graft failure. This is not overtly a large number. Of course, we would hope for more durable engraftment. The other side effects including GVHD and infection are all to be expected.”

As for cost, Dr. Kassim said the transplants run from $200,000 to $400,000 vs over $2 million for gene therapy, and Dr. Ferdjallah said insurance is likely to cover the treatment.

Moving ahead, Dr. Ferdjallah said she looks forward to getting study data about pediatric patients specifically. For now, “we should consider HLA-haploidentical seriously in patients with sickle cell disease and no available HLA-matched donors.”

Grants to the Blood and Marrow Transplant Clinical Trials Network from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and National Cancer Institute funded the study. Dr. Kassim had no disclosures. Some other authors disclosed various and multiple relationships with industry. Dr. Ferdjallah has no disclosures.

FROM ASH 2023

Measurable residual disease–guided therapy promising for CLL

The targeted therapy combination was also associated with better progression-free survival among patients with CLL with worse prognostic features, including immunoglobulin heavy chain variable (IGHV) unmutated disease and cytogenetic abnormalities, such as the 11q deletion, trisomy 12, and 13q deletion.

Personalizing treatment duration of ibrutinib-venetoclax, as determined by measurable residual disease (MRD), allowed more than half of patients assigned to the combination therapy to stop therapy by 3 years because they had achieved MRD negativity, reported Peter Hillmen, MBChB, PhD, from the Leeds Institute of Medical Research at St James’s University Hospital in Leeds, United Kingdom.

The shorter course of therapy could help to ameliorate toxicities and lower the risk for the development of drug-resistant disease, he said.

“This is the first trial to show that an MRD-guided approach with treatment beyond [MRD] negativity has a significant advantage over chemoimmunotherapy, both in terms of [progression-free] and overall survival. Over 90% of patients achieve an MRD-negative in this combination in the peripheral blood,” said Dr. Hillmen in a media briefing prior to his presentation of the data in an oral abstract session here at the American Society of Hematology annual meeting.

The study results were also published online in The New England Journal of Medicine to coincide with the presentation.

Adaptive Trial

The FLAIR study is a phase 3 open-label platform trial that initially compared ibrutinib-rituximab with fludarabine-cyclophosphamide-rituximab (FCR) in patients with untreated CLL. However, in 2017 the trial was adapted to include both an ibrutinib monotherapy and an ibrutinib-venetoclax arm with therapy duration determined by MRD.

At ASH 2023, Dr. Hillmen presented data from an interim analysis of 523 patients comparing ibrutinib-venetoclax with FCR.

In the ibrutinib-venetoclax group, patients received oral ibrutinib 420 mg daily, with venetoclax added after 2 months, beginning with a 20-mg dose ramped up to 400 mg in a weekly dose-escalation schedule. The combination could be given for 2-6 years, depending on MRD responses. FCR was delivered in up to six cycles of 28 days each. Two thirds of patients assigned to FCR completed all six cycles.

After a median follow-up of 43.7 months, 12 patients (4.6%) randomly assigned to ibrutinib-venetoclax had disease progression or died compared with 75 patients (28.5%) assigned to FCR. The estimated 3-year progression-free survival with ibrutinib-venetoclax was 97.2%, compared with 76.8% with FCR, translating into a hazard ratio (HR) for progression or death with the targeted therapy combination of 0.13 (P <.001).

Among patients with unmutated IGHV, the combination led to improved progression-free survival compared with FCR (hazard ratio [HR] for progression or death, 0.07); for patients with mutated IGHV, however, the combination did not improve progression-free survival (HR, 0.54; 95% CI, 0.21-1.38).

In all, eight patients (3.5%) assigned to ibrutinib-venetoclax and 23 assigned to FCR (9.5%) died.

The 3-year overall survival rates were 98% in the targeted therapy group vs 93% in the FCR group (HR for progression or death, 0.31).

At 2 years, 52.4% of patients assigned to ibrutinib-venetoclax had undetectable MRD in bone marrow compared with 49.8% with FCR. At 5 years, the respective percentages for MRD in bone marrow were 65.9% vs 49.8% and 92.7% vs 67.9% for MRD in peripheral blood.

The safety analysis showed higher rates of blood and lymphatic system disorders with FCR, whereas cardiac, metabolic/nutrition disorders, and eye disorders occurred more frequent with ibrutinib-venetoclax.

A total of 24 secondary cancers were diagnosed in 17 patients randomly assigned to ibrutinib-venetoclax and 45 secondary cancers among 34 patients randomly assigned to FCR. One patient assigned to ibrutinib-venetoclax developed myelodysplastic syndrome/acute myeloid leukemia (AML), as did eight patients assigned to FCR. One patient in the ibrutinib-venetoclax arm and four patients in the FCR arm had Richter’s transformation.

The incidence rate for other cancers was 2.6 per 100 person-years with ibrutinib-venetoclax compared with 5.4 per 100 person-years with FCR.

The most frequently occurring cancers in each arm were basal cell or squamous cell carcinomas. The incidence of myelodysplastic syndromes, AML lymphoma, and prostate/urologic cancers was higher among patients on FCR.

This research “unequivocally shows the superiority of targeted therapy over traditional cytotoxic chemotherapy,” commented briefing moderator Mikkael A. Sekeres, MD, from the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine.

The ibrutinib-venetoclax combination has the potential to reduce the incidence of myelodysplastic syndromes secondary to CLL therapy, Dr. Sekeres suggested.

“As someone who specializes in leukemia and myelodysplastic syndromes, I have the feeling I won’t be seeing these CLL patients in my clinic — years after being treated for CLL — much longer,” he said.

In an interview with this news organization, Lee Greenberger, PhD, said that “I think that duration-adapted therapy is a great story. Using MRD negativity is a perfectly justified way, I think, to go about a new combination that’s going to be really potent for CLL patients and probably give them many years of treatment and then to get off the drug, because ultimately the goal is to get cures.”

This combination, though highly efficacious, is unlikely to be curative; however, because even when MRD is undetectable, “it will come back,” said Dr. Greenberger, chief scientific officer for the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society.

Dr. Greenberger added that MRD testing of bone marrow, which provides a more detailed picture of MRD status than testing of peripheral blood, is feasible in academic medical centers but may be a barrier to MRD-adapted therapy in community oncology practices.

The FLAIR study is supported by grants from Cancer Research UK, Janssen, Pharmacyclics, and AbbVie. Dr. Hillmen disclosed employment and equity participation with Apellis Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Sekeres disclosed board activities for Geron, Novartis, and Bristol-Myers Squibb and owner of stock options Kurome. Dr. Greenberger reported no relevant financial disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The targeted therapy combination was also associated with better progression-free survival among patients with CLL with worse prognostic features, including immunoglobulin heavy chain variable (IGHV) unmutated disease and cytogenetic abnormalities, such as the 11q deletion, trisomy 12, and 13q deletion.

Personalizing treatment duration of ibrutinib-venetoclax, as determined by measurable residual disease (MRD), allowed more than half of patients assigned to the combination therapy to stop therapy by 3 years because they had achieved MRD negativity, reported Peter Hillmen, MBChB, PhD, from the Leeds Institute of Medical Research at St James’s University Hospital in Leeds, United Kingdom.

The shorter course of therapy could help to ameliorate toxicities and lower the risk for the development of drug-resistant disease, he said.

“This is the first trial to show that an MRD-guided approach with treatment beyond [MRD] negativity has a significant advantage over chemoimmunotherapy, both in terms of [progression-free] and overall survival. Over 90% of patients achieve an MRD-negative in this combination in the peripheral blood,” said Dr. Hillmen in a media briefing prior to his presentation of the data in an oral abstract session here at the American Society of Hematology annual meeting.

The study results were also published online in The New England Journal of Medicine to coincide with the presentation.

Adaptive Trial

The FLAIR study is a phase 3 open-label platform trial that initially compared ibrutinib-rituximab with fludarabine-cyclophosphamide-rituximab (FCR) in patients with untreated CLL. However, in 2017 the trial was adapted to include both an ibrutinib monotherapy and an ibrutinib-venetoclax arm with therapy duration determined by MRD.

At ASH 2023, Dr. Hillmen presented data from an interim analysis of 523 patients comparing ibrutinib-venetoclax with FCR.

In the ibrutinib-venetoclax group, patients received oral ibrutinib 420 mg daily, with venetoclax added after 2 months, beginning with a 20-mg dose ramped up to 400 mg in a weekly dose-escalation schedule. The combination could be given for 2-6 years, depending on MRD responses. FCR was delivered in up to six cycles of 28 days each. Two thirds of patients assigned to FCR completed all six cycles.

After a median follow-up of 43.7 months, 12 patients (4.6%) randomly assigned to ibrutinib-venetoclax had disease progression or died compared with 75 patients (28.5%) assigned to FCR. The estimated 3-year progression-free survival with ibrutinib-venetoclax was 97.2%, compared with 76.8% with FCR, translating into a hazard ratio (HR) for progression or death with the targeted therapy combination of 0.13 (P <.001).

Among patients with unmutated IGHV, the combination led to improved progression-free survival compared with FCR (hazard ratio [HR] for progression or death, 0.07); for patients with mutated IGHV, however, the combination did not improve progression-free survival (HR, 0.54; 95% CI, 0.21-1.38).

In all, eight patients (3.5%) assigned to ibrutinib-venetoclax and 23 assigned to FCR (9.5%) died.

The 3-year overall survival rates were 98% in the targeted therapy group vs 93% in the FCR group (HR for progression or death, 0.31).

At 2 years, 52.4% of patients assigned to ibrutinib-venetoclax had undetectable MRD in bone marrow compared with 49.8% with FCR. At 5 years, the respective percentages for MRD in bone marrow were 65.9% vs 49.8% and 92.7% vs 67.9% for MRD in peripheral blood.

The safety analysis showed higher rates of blood and lymphatic system disorders with FCR, whereas cardiac, metabolic/nutrition disorders, and eye disorders occurred more frequent with ibrutinib-venetoclax.

A total of 24 secondary cancers were diagnosed in 17 patients randomly assigned to ibrutinib-venetoclax and 45 secondary cancers among 34 patients randomly assigned to FCR. One patient assigned to ibrutinib-venetoclax developed myelodysplastic syndrome/acute myeloid leukemia (AML), as did eight patients assigned to FCR. One patient in the ibrutinib-venetoclax arm and four patients in the FCR arm had Richter’s transformation.

The incidence rate for other cancers was 2.6 per 100 person-years with ibrutinib-venetoclax compared with 5.4 per 100 person-years with FCR.

The most frequently occurring cancers in each arm were basal cell or squamous cell carcinomas. The incidence of myelodysplastic syndromes, AML lymphoma, and prostate/urologic cancers was higher among patients on FCR.

This research “unequivocally shows the superiority of targeted therapy over traditional cytotoxic chemotherapy,” commented briefing moderator Mikkael A. Sekeres, MD, from the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine.

The ibrutinib-venetoclax combination has the potential to reduce the incidence of myelodysplastic syndromes secondary to CLL therapy, Dr. Sekeres suggested.

“As someone who specializes in leukemia and myelodysplastic syndromes, I have the feeling I won’t be seeing these CLL patients in my clinic — years after being treated for CLL — much longer,” he said.

In an interview with this news organization, Lee Greenberger, PhD, said that “I think that duration-adapted therapy is a great story. Using MRD negativity is a perfectly justified way, I think, to go about a new combination that’s going to be really potent for CLL patients and probably give them many years of treatment and then to get off the drug, because ultimately the goal is to get cures.”

This combination, though highly efficacious, is unlikely to be curative; however, because even when MRD is undetectable, “it will come back,” said Dr. Greenberger, chief scientific officer for the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society.

Dr. Greenberger added that MRD testing of bone marrow, which provides a more detailed picture of MRD status than testing of peripheral blood, is feasible in academic medical centers but may be a barrier to MRD-adapted therapy in community oncology practices.

The FLAIR study is supported by grants from Cancer Research UK, Janssen, Pharmacyclics, and AbbVie. Dr. Hillmen disclosed employment and equity participation with Apellis Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Sekeres disclosed board activities for Geron, Novartis, and Bristol-Myers Squibb and owner of stock options Kurome. Dr. Greenberger reported no relevant financial disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The targeted therapy combination was also associated with better progression-free survival among patients with CLL with worse prognostic features, including immunoglobulin heavy chain variable (IGHV) unmutated disease and cytogenetic abnormalities, such as the 11q deletion, trisomy 12, and 13q deletion.

Personalizing treatment duration of ibrutinib-venetoclax, as determined by measurable residual disease (MRD), allowed more than half of patients assigned to the combination therapy to stop therapy by 3 years because they had achieved MRD negativity, reported Peter Hillmen, MBChB, PhD, from the Leeds Institute of Medical Research at St James’s University Hospital in Leeds, United Kingdom.

The shorter course of therapy could help to ameliorate toxicities and lower the risk for the development of drug-resistant disease, he said.

“This is the first trial to show that an MRD-guided approach with treatment beyond [MRD] negativity has a significant advantage over chemoimmunotherapy, both in terms of [progression-free] and overall survival. Over 90% of patients achieve an MRD-negative in this combination in the peripheral blood,” said Dr. Hillmen in a media briefing prior to his presentation of the data in an oral abstract session here at the American Society of Hematology annual meeting.

The study results were also published online in The New England Journal of Medicine to coincide with the presentation.

Adaptive Trial

The FLAIR study is a phase 3 open-label platform trial that initially compared ibrutinib-rituximab with fludarabine-cyclophosphamide-rituximab (FCR) in patients with untreated CLL. However, in 2017 the trial was adapted to include both an ibrutinib monotherapy and an ibrutinib-venetoclax arm with therapy duration determined by MRD.

At ASH 2023, Dr. Hillmen presented data from an interim analysis of 523 patients comparing ibrutinib-venetoclax with FCR.

In the ibrutinib-venetoclax group, patients received oral ibrutinib 420 mg daily, with venetoclax added after 2 months, beginning with a 20-mg dose ramped up to 400 mg in a weekly dose-escalation schedule. The combination could be given for 2-6 years, depending on MRD responses. FCR was delivered in up to six cycles of 28 days each. Two thirds of patients assigned to FCR completed all six cycles.

After a median follow-up of 43.7 months, 12 patients (4.6%) randomly assigned to ibrutinib-venetoclax had disease progression or died compared with 75 patients (28.5%) assigned to FCR. The estimated 3-year progression-free survival with ibrutinib-venetoclax was 97.2%, compared with 76.8% with FCR, translating into a hazard ratio (HR) for progression or death with the targeted therapy combination of 0.13 (P <.001).

Among patients with unmutated IGHV, the combination led to improved progression-free survival compared with FCR (hazard ratio [HR] for progression or death, 0.07); for patients with mutated IGHV, however, the combination did not improve progression-free survival (HR, 0.54; 95% CI, 0.21-1.38).

In all, eight patients (3.5%) assigned to ibrutinib-venetoclax and 23 assigned to FCR (9.5%) died.

The 3-year overall survival rates were 98% in the targeted therapy group vs 93% in the FCR group (HR for progression or death, 0.31).

At 2 years, 52.4% of patients assigned to ibrutinib-venetoclax had undetectable MRD in bone marrow compared with 49.8% with FCR. At 5 years, the respective percentages for MRD in bone marrow were 65.9% vs 49.8% and 92.7% vs 67.9% for MRD in peripheral blood.

The safety analysis showed higher rates of blood and lymphatic system disorders with FCR, whereas cardiac, metabolic/nutrition disorders, and eye disorders occurred more frequent with ibrutinib-venetoclax.

A total of 24 secondary cancers were diagnosed in 17 patients randomly assigned to ibrutinib-venetoclax and 45 secondary cancers among 34 patients randomly assigned to FCR. One patient assigned to ibrutinib-venetoclax developed myelodysplastic syndrome/acute myeloid leukemia (AML), as did eight patients assigned to FCR. One patient in the ibrutinib-venetoclax arm and four patients in the FCR arm had Richter’s transformation.

The incidence rate for other cancers was 2.6 per 100 person-years with ibrutinib-venetoclax compared with 5.4 per 100 person-years with FCR.

The most frequently occurring cancers in each arm were basal cell or squamous cell carcinomas. The incidence of myelodysplastic syndromes, AML lymphoma, and prostate/urologic cancers was higher among patients on FCR.

This research “unequivocally shows the superiority of targeted therapy over traditional cytotoxic chemotherapy,” commented briefing moderator Mikkael A. Sekeres, MD, from the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine.

The ibrutinib-venetoclax combination has the potential to reduce the incidence of myelodysplastic syndromes secondary to CLL therapy, Dr. Sekeres suggested.

“As someone who specializes in leukemia and myelodysplastic syndromes, I have the feeling I won’t be seeing these CLL patients in my clinic — years after being treated for CLL — much longer,” he said.

In an interview with this news organization, Lee Greenberger, PhD, said that “I think that duration-adapted therapy is a great story. Using MRD negativity is a perfectly justified way, I think, to go about a new combination that’s going to be really potent for CLL patients and probably give them many years of treatment and then to get off the drug, because ultimately the goal is to get cures.”

This combination, though highly efficacious, is unlikely to be curative; however, because even when MRD is undetectable, “it will come back,” said Dr. Greenberger, chief scientific officer for the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society.

Dr. Greenberger added that MRD testing of bone marrow, which provides a more detailed picture of MRD status than testing of peripheral blood, is feasible in academic medical centers but may be a barrier to MRD-adapted therapy in community oncology practices.

The FLAIR study is supported by grants from Cancer Research UK, Janssen, Pharmacyclics, and AbbVie. Dr. Hillmen disclosed employment and equity participation with Apellis Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Sekeres disclosed board activities for Geron, Novartis, and Bristol-Myers Squibb and owner of stock options Kurome. Dr. Greenberger reported no relevant financial disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ASH 2023

Mantle Cell Lymphoma: Drug Combo Improves PFS

Still, “in the countries where ibrutinib is indicated, this combination should be a new standard therapy for relapsed/refractory mantle cell lymphoma,” Michael Wang, MD, of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, said in a media briefing at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

Its use would be off label, according to the authors of the industry-funded trial, because no nation has approved the combination therapy for MCL, a rare, aggressive form of non-Hodgkin lymphoma.