User login

MDedge Daily News: How European data privacy rules may cost you

Synthetic opioids drive increases in overdose deaths. Robocalls increase diabetic retinopathy screenings in low-income patients. And a new ranking points physicians toward practice-friendly South Dakota.

Listen to the MDedge Daily News podcast for all the details on today’s top news.

Synthetic opioids drive increases in overdose deaths. Robocalls increase diabetic retinopathy screenings in low-income patients. And a new ranking points physicians toward practice-friendly South Dakota.

Listen to the MDedge Daily News podcast for all the details on today’s top news.

Synthetic opioids drive increases in overdose deaths. Robocalls increase diabetic retinopathy screenings in low-income patients. And a new ranking points physicians toward practice-friendly South Dakota.

Listen to the MDedge Daily News podcast for all the details on today’s top news.

Higher preconception blood pressure linked to pregnancy loss

High preconception blood pressure is associated with a greater risk of pregnancy loss, according to analysis of data from a randomized clinical trial of aspirin and pregnancy outcomes.

Researchers in the EAGeR (Effects of Aspirin on Gestational and Reproduction) trial analyzed data from 1,228 women attempting pregnancy with a history of pregnancy loss. After researchers adjusted for treatment assignment, body mass index (BMI), race, marital status, smoking, parity, and time from last pregnancy loss, an increase in all blood pressure measures was associated with a 17% increase in the risk of pregnancy loss (Hypertension. doi: 10.1161/hypertensionaha.117.10705).

although the authors noted that group sizes were small.

Overall, one-quarter of the women enrolled in the study met the criteria for hypertension stage I, and 4.3% met the criteria for hypertension stage II.

“Screening and lifestyle interventions targeting maintenance of healthy blood pressure levels among reproductive-aged women may have additional important short-term benefits on reproductive health,” wrote Carrie J. Nobles, MD, of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, and coauthors.

The authors also saw an impact of early pregnancy blood pressure on pregnancy loss, with an 18% greater risk of loss with each 10–mm Hg increase in mean arterial pressure.

Higher blood pressure during preconception was also associated with a decrease in the chance of live birth, but this association disappeared after adjusting for other confounders.

The study also examined the relationship between preconception blood pressure and the probability of conception. While the unadjusted models suggested 10% lower odds of fecundability, adjusting for all covariates except for BMI found similar effect estimates.

“We observed no clear associations of preconception blood pressure with fecundability after adjustment for BMI, suggesting that pathways related to BMI, which is strongly related to fecundability, may explain the marginal association of blood pressure with fecundability,” the authors wrote.

There was also some evidence that aspirin may influence the association between higher preconception blood pressure and pregnancy loss, as this association was marginally stronger in the placebo group than in the group randomized to low-dose aspirin.

“Pregnancy loss and other adverse reproductive outcomes may serve as sensitive markers of early-stage progression toward cardiometabolic disease in young adults,” Dr. Noble and coauthors wrote. “Further elucidating the cardiometabolic risk factors for pregnancy loss may help identify early intervention strategies, such as regular physical activity and following a DASH-type (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) diet.”

The study was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. No conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Nobles CJ et al. Hypertension. 2018 Apr 2;71. doi: 10.1161/hypertensionaha.117.10705.

High preconception blood pressure is associated with a greater risk of pregnancy loss, according to analysis of data from a randomized clinical trial of aspirin and pregnancy outcomes.

Researchers in the EAGeR (Effects of Aspirin on Gestational and Reproduction) trial analyzed data from 1,228 women attempting pregnancy with a history of pregnancy loss. After researchers adjusted for treatment assignment, body mass index (BMI), race, marital status, smoking, parity, and time from last pregnancy loss, an increase in all blood pressure measures was associated with a 17% increase in the risk of pregnancy loss (Hypertension. doi: 10.1161/hypertensionaha.117.10705).

although the authors noted that group sizes were small.

Overall, one-quarter of the women enrolled in the study met the criteria for hypertension stage I, and 4.3% met the criteria for hypertension stage II.

“Screening and lifestyle interventions targeting maintenance of healthy blood pressure levels among reproductive-aged women may have additional important short-term benefits on reproductive health,” wrote Carrie J. Nobles, MD, of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, and coauthors.

The authors also saw an impact of early pregnancy blood pressure on pregnancy loss, with an 18% greater risk of loss with each 10–mm Hg increase in mean arterial pressure.

Higher blood pressure during preconception was also associated with a decrease in the chance of live birth, but this association disappeared after adjusting for other confounders.

The study also examined the relationship between preconception blood pressure and the probability of conception. While the unadjusted models suggested 10% lower odds of fecundability, adjusting for all covariates except for BMI found similar effect estimates.

“We observed no clear associations of preconception blood pressure with fecundability after adjustment for BMI, suggesting that pathways related to BMI, which is strongly related to fecundability, may explain the marginal association of blood pressure with fecundability,” the authors wrote.

There was also some evidence that aspirin may influence the association between higher preconception blood pressure and pregnancy loss, as this association was marginally stronger in the placebo group than in the group randomized to low-dose aspirin.

“Pregnancy loss and other adverse reproductive outcomes may serve as sensitive markers of early-stage progression toward cardiometabolic disease in young adults,” Dr. Noble and coauthors wrote. “Further elucidating the cardiometabolic risk factors for pregnancy loss may help identify early intervention strategies, such as regular physical activity and following a DASH-type (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) diet.”

The study was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. No conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Nobles CJ et al. Hypertension. 2018 Apr 2;71. doi: 10.1161/hypertensionaha.117.10705.

High preconception blood pressure is associated with a greater risk of pregnancy loss, according to analysis of data from a randomized clinical trial of aspirin and pregnancy outcomes.

Researchers in the EAGeR (Effects of Aspirin on Gestational and Reproduction) trial analyzed data from 1,228 women attempting pregnancy with a history of pregnancy loss. After researchers adjusted for treatment assignment, body mass index (BMI), race, marital status, smoking, parity, and time from last pregnancy loss, an increase in all blood pressure measures was associated with a 17% increase in the risk of pregnancy loss (Hypertension. doi: 10.1161/hypertensionaha.117.10705).

although the authors noted that group sizes were small.

Overall, one-quarter of the women enrolled in the study met the criteria for hypertension stage I, and 4.3% met the criteria for hypertension stage II.

“Screening and lifestyle interventions targeting maintenance of healthy blood pressure levels among reproductive-aged women may have additional important short-term benefits on reproductive health,” wrote Carrie J. Nobles, MD, of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, and coauthors.

The authors also saw an impact of early pregnancy blood pressure on pregnancy loss, with an 18% greater risk of loss with each 10–mm Hg increase in mean arterial pressure.

Higher blood pressure during preconception was also associated with a decrease in the chance of live birth, but this association disappeared after adjusting for other confounders.

The study also examined the relationship between preconception blood pressure and the probability of conception. While the unadjusted models suggested 10% lower odds of fecundability, adjusting for all covariates except for BMI found similar effect estimates.

“We observed no clear associations of preconception blood pressure with fecundability after adjustment for BMI, suggesting that pathways related to BMI, which is strongly related to fecundability, may explain the marginal association of blood pressure with fecundability,” the authors wrote.

There was also some evidence that aspirin may influence the association between higher preconception blood pressure and pregnancy loss, as this association was marginally stronger in the placebo group than in the group randomized to low-dose aspirin.

“Pregnancy loss and other adverse reproductive outcomes may serve as sensitive markers of early-stage progression toward cardiometabolic disease in young adults,” Dr. Noble and coauthors wrote. “Further elucidating the cardiometabolic risk factors for pregnancy loss may help identify early intervention strategies, such as regular physical activity and following a DASH-type (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) diet.”

The study was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. No conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCE: Nobles CJ et al. Hypertension. 2018 Apr 2;71. doi: 10.1161/hypertensionaha.117.10705.

FROM HYPERTENSION

Key clinical point: Maintaining normal blood pressure is even more important for women who previously have miscarried.

Major finding: Higher preconception blood pressure was associated with a 17% increase in the risk of pregnancy loss.

Study details: Analysis of data from a randomized clinical trial in 1,228 women.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. No conflicts of interest were declared.

Source: Nobles CJ et al. Hypertension. 2018 Apr 2;71. doi: 10.1161/hypertensionaha.117.10705.

Some Health Care Workers Are at Risk for Hearing Loss

As many as one-third of workers in some sectors of health care and social service may have hearing loss, according to the researchers at the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) who studied audiograms from hundreds of US companies. Theirs is the first known study to estimate and compare the prevalence of noise-exposed worker hearing loss by subsector within the Health Care and Social Assistance (HSA) sector.

Some subsectors had higher than expected prevalence of hearing loss for an industry that has had assumed “low exposure” to noise, NIOSH says. Most of the HSA subsector prevalence estimates ranged from 14% to 18%, but the Medical and Diagnostic Laboratories subsector had 31% prevalence, the Offices of All Other Miscellaneous Health Practitioners had 24% prevalence, and Child Day Care Services had a 52% higher risk compared with that of the reference industry.

NIOSH says successful noise reduction measures have been documented in hospital settings. Exposure to chemotherapy drugs can be better prevented and laboratories can be modified to reduce the level of noise. When noise can’t be removed or reduced to safe levels, NIOSH recommends implementing an effective hearing conservation program.

Hearing loss is the third most common chronic physical condition in the US, NIOSH says. But Elizabeth Masterson, PhD, epidemiologist and lead author of the study, says, “Occupational hearing loss is entirely preventable.”

As many as one-third of workers in some sectors of health care and social service may have hearing loss, according to the researchers at the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) who studied audiograms from hundreds of US companies. Theirs is the first known study to estimate and compare the prevalence of noise-exposed worker hearing loss by subsector within the Health Care and Social Assistance (HSA) sector.

Some subsectors had higher than expected prevalence of hearing loss for an industry that has had assumed “low exposure” to noise, NIOSH says. Most of the HSA subsector prevalence estimates ranged from 14% to 18%, but the Medical and Diagnostic Laboratories subsector had 31% prevalence, the Offices of All Other Miscellaneous Health Practitioners had 24% prevalence, and Child Day Care Services had a 52% higher risk compared with that of the reference industry.

NIOSH says successful noise reduction measures have been documented in hospital settings. Exposure to chemotherapy drugs can be better prevented and laboratories can be modified to reduce the level of noise. When noise can’t be removed or reduced to safe levels, NIOSH recommends implementing an effective hearing conservation program.

Hearing loss is the third most common chronic physical condition in the US, NIOSH says. But Elizabeth Masterson, PhD, epidemiologist and lead author of the study, says, “Occupational hearing loss is entirely preventable.”

As many as one-third of workers in some sectors of health care and social service may have hearing loss, according to the researchers at the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) who studied audiograms from hundreds of US companies. Theirs is the first known study to estimate and compare the prevalence of noise-exposed worker hearing loss by subsector within the Health Care and Social Assistance (HSA) sector.

Some subsectors had higher than expected prevalence of hearing loss for an industry that has had assumed “low exposure” to noise, NIOSH says. Most of the HSA subsector prevalence estimates ranged from 14% to 18%, but the Medical and Diagnostic Laboratories subsector had 31% prevalence, the Offices of All Other Miscellaneous Health Practitioners had 24% prevalence, and Child Day Care Services had a 52% higher risk compared with that of the reference industry.

NIOSH says successful noise reduction measures have been documented in hospital settings. Exposure to chemotherapy drugs can be better prevented and laboratories can be modified to reduce the level of noise. When noise can’t be removed or reduced to safe levels, NIOSH recommends implementing an effective hearing conservation program.

Hearing loss is the third most common chronic physical condition in the US, NIOSH says. But Elizabeth Masterson, PhD, epidemiologist and lead author of the study, says, “Occupational hearing loss is entirely preventable.”

Aripiprazole, brexpiprazole, and cariprazine: Not all the same

Aripiprazole, brexpiprazole, and cariprazine are dopamine receptor partial agonists, and on the surface, they appear similar. However, there are key differences in terms of available indications, formulations, pharmacodynamics, pharmacokinetics, dosing, drug interactions, tolerability, and other factors related to successful use.1 This review will cover the main points that the knowledgeable clinician will need to be mindful of when prescribing these agents.

Aripiprazole

Aripiprazole was launched in the United States in 20022 as the first dopamine receptor partial agonist approved for the treatment of schizophrenia; it later received additional indications for adults with manic or mixed episodes associated with bipolar I disorder and the maintenance treatment of bipolar I disorder, as well as for the adjunctive treatment of major depressive disorder (MDD). Pediatric indications include schizophrenia, acute treatment of manic or mixed episodes associated with bipolar I disorder, irritability associated with autistic disorder, and Tourette’s disorder.

Several formulations also became available, including a short-acting injection indicated for agitation associated with schizophrenia or bipolar mania, and oral disintegrating tablets and an oral solution that could substitute for the regular tablet. Presently the medication has gone “generic,” and not all formulations are being manufactured. The long-acting formulations of aripiprazole (aripiprazole monohydrate and aripiprazole lauroxil) are considered different products, each with its own product insert, with indications that are more limited in scope than for the oral forms.3,4

Although dopamine D2 receptor partial agonism is a relevant mechanism of action, partial agonist activity at serotonin 5-HT1A receptors and antagonist activity at 5-HT2A receptors also play a role.2 Actions at receptors other than dopamine D2, serotonin 5-HT1A, and serotonin 5-HT2A may explain some of the other clinical effects of aripiprazole. In terms of binding, aripiprazole has very high binding affinities (Ki) to dopamine D2 (0.34 nM), dopamine D3 (0.8 nM), and serotonin 5-HT2B (0.36 nM) receptors, and high binding affinities to serotonin 5-HT1A (1.7 nM) and serotonin 5-HT2A (3.4 nM) receptors.

Dosage recommendations for adults with schizophrenia suggest a starting and maintenance dose of 10 to 15 mg/d.2 Although the maximum dose is 30 mg/d, there is no evidence that doses >15 mg/d are superior to lower doses.5 In adolescents with schizophrenia, the product label recommends a starting dose of 2 mg/d, a maintenance dose of 10 mg/d, and a maximum dose of 30 mg/d. Recommendations for dosing in bipolar mania are similar. Dosing for the other indications is lower.

Efficacy in schizophrenia can be quantified using number needed to treat (NNT) for response vs placebo. The NNT answers the question “How many patients need to be randomized to aripiprazole vs placebo before expecting to encounter one additional responder?”6 From the 4 positive pivotal short-term acute schizophrenia trials for aripiprazole in adults,7-10 using the definition of response as a ≥30% decrease in the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) total score or a Clinical Global Impressions–Improvement (CGI-I) score of 1 (very much improved) or 2 (much improved), and pooling the data for aripiprazole doses 10 to 30 mg/d, response rates were 38% for aripiprazole vs 24% for placebo, resulting in a NNT of 8 (95% confidence interval [CI] 6 to 13).

From the 4 positive pivotal short-term acute bipolar mania trials for aripiprazole monotherapy in adults11-14 using the definition of response as a ≥50% decrease in the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) total score, and pooling the data for aripiprazole doses 15 to 30 mg/d, response rates were 47% for aripiprazole vs 31% for placebo, resulting in a NNT of 7 (95% CI 5 to 11).1 Similar results were observed in the adjunctive aripiprazole acute bipolar mania trial15 where the NNT for response was also 7.1

Continue to: From the 2 positive pivotal short-term...

From the 2 positive pivotal short-term acute MDD trials for aripiprazole,16,17 using the definition of response as a ≥50% decrease in the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) total score, and pooling the data (aripiprazole flexibly dosed 2 to 20 mg/d, with a median dose of 10 mg/d), response rates were 33% for aripiprazole vs 20% for placebo, resulting in a NNT of 8 (95% CI 6 to 17). After including a third trial not described in product labeling,18 the NNT became a more robust 7 (95% CI 5 to 11).1

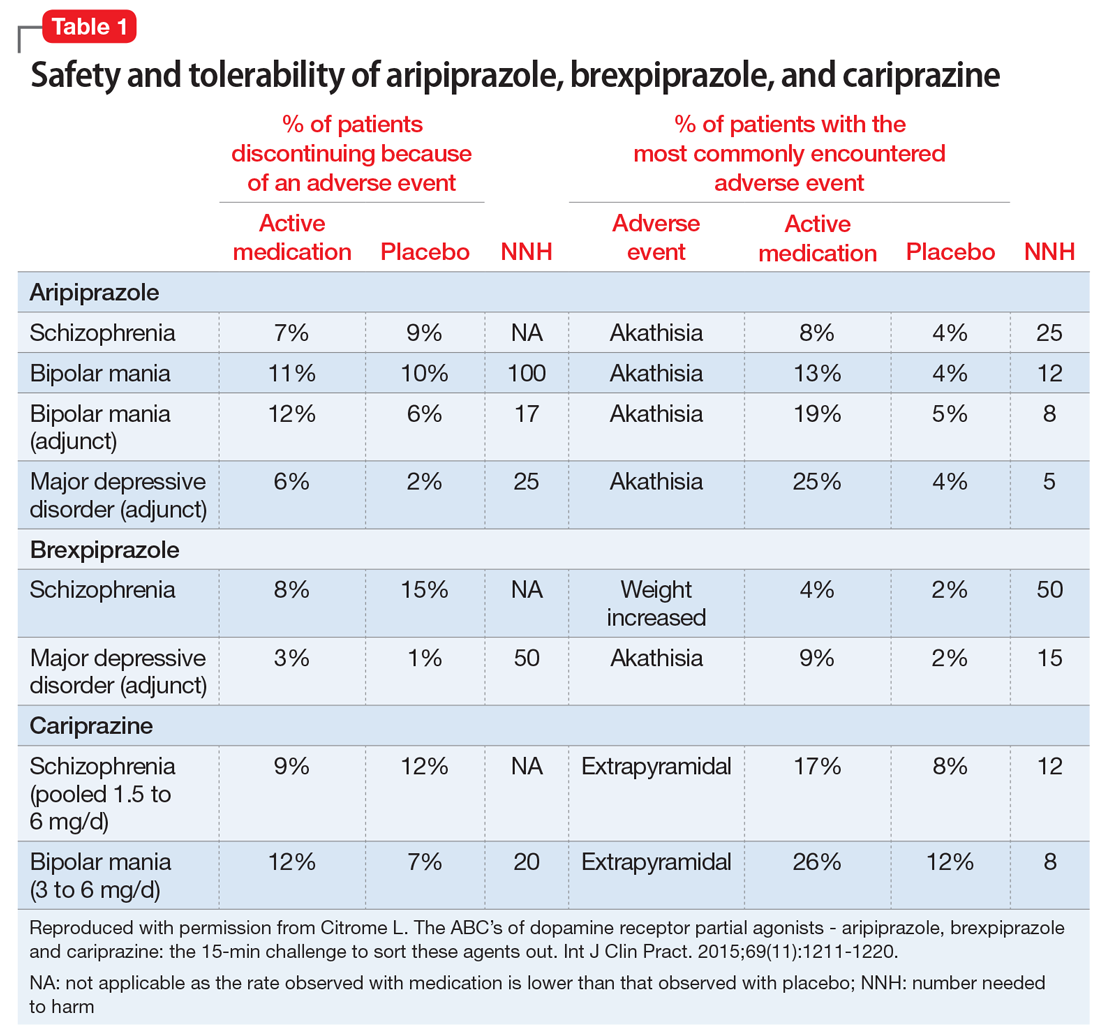

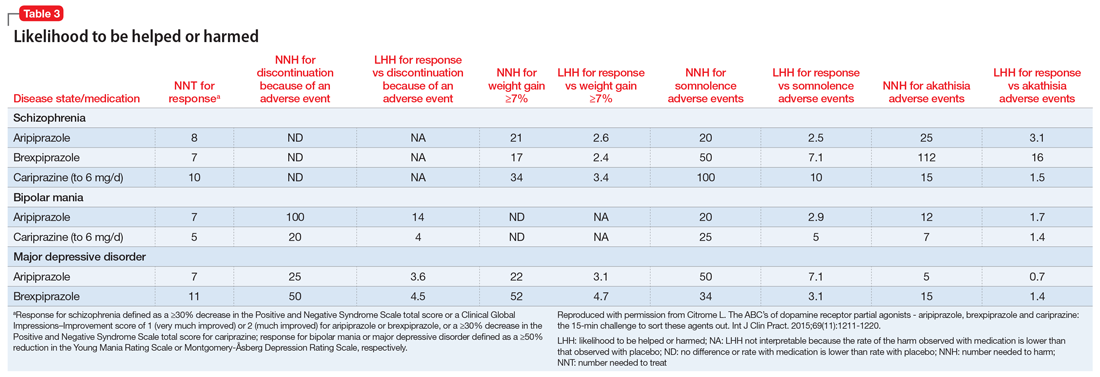

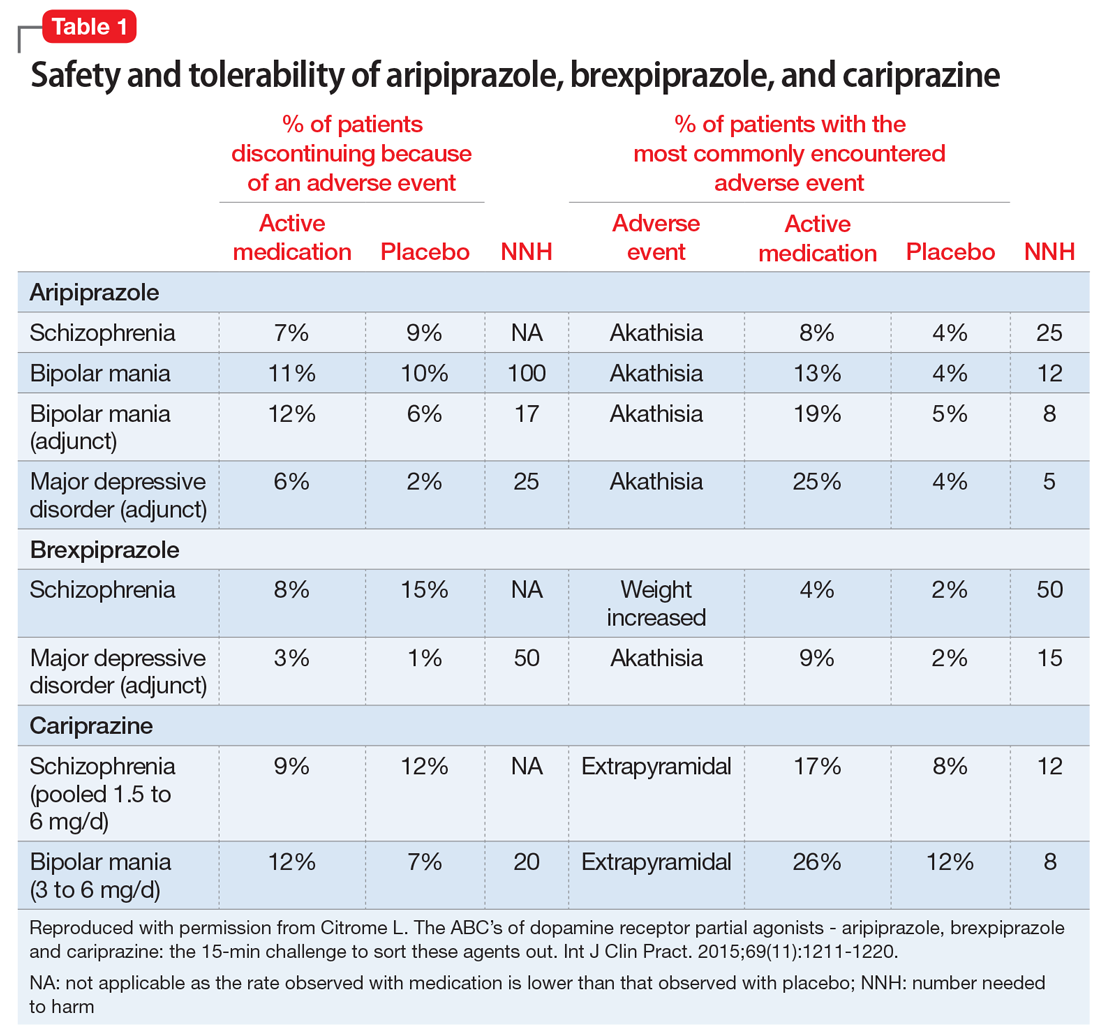

The most commonly encountered adverse events (incidence ≥5% and at least twice the rate of placebo) in the pivotal trials were akathisia (schizophrenia); akathisia, sedation, restlessness, tremor, and extrapyramidal disorder (bipolar mania, monotherapy); akathisia, insomnia, and extrapyramidal disorder (bipolar mania, adjunctive therapy); akathisia, restlessness, insomnia, constipation, fatigue, and blurred vision (MDD); and nausea (short-acting IM formulation). Table 11 summarizes the tolerability information regarding rate of discontinuation due to adverse events (an overall indicator of tolerability), and the incidence of the most common adverse event, together with the calculated number needed to harm (NNH). Rates of discontinuation because of an adverse event were not higher for active medication vs placebo for the schizophrenia studies, suggesting excellent overall tolerability; for the other disease states, NNH values ranged from 17 (adjunctive use of aripiprazole for bipolar mania) to 100 (aripiprazole monotherapy for bipolar mania), representing reasonable overall tolerability for these indications.

Brexpiprazole

Brexpiprazole was launched in the United States in 2015 for 2 indications: schizophrenia and the adjunctive treatment of MDD, both in adults.19 In terms of binding, brexpiprazole has very high binding affinities to serotonin 5-HT1A (0.12 nM), adrenergic α1B (0.17 nM), dopamine D2 (0.30 nM), serotonin 5-HT2A (0.47 nM), and adrenergic α2C (0.59 nM) receptors, and high binding affinities to dopamine D3 (1.1 nM), serotonin 5-HT2B (1.9 nM), adrenergic α1D (2.6 nM), serotonin 5-HT7 (3.7 nM), and adrenergic α1A (3.8 nM) receptors.

The 1-mg/d starting dose for brexpiprazole is lower than the recommended dose range of 2 to 4 mg/d for schizophrenia or the recommended dose of 2 mg/d for MDD.19 Thus brexpiprazole requires titration. The recommended rate of titration depends on the disease state being treated. For schizophrenia, the recommended titration schedule is to increase the dose to 2 mg/d on Day 5 through Day 7, then to 4 mg/d (the maximum recommended dose) on Day 8 based on the patient’s clinical response and tolerability. For MDD, there is the option of starting at 0.5 mg/d and the titration process is slower, with dosage increases occurring at weekly intervals, and with a maximum dose of 3 mg/d.

Using the identical definition of response in persons with schizophrenia as for the aripiprazole data described above, pooling together all the available data for the recommended target dose of brexpiprazole for schizophrenia (2 to 4 mg/d) from the 2 studies listed in the product label,20,21 the percentage of responders was 46%, compared with 31% for the pooled placebo groups, yielding a NNT of 7 (95% CI 5 to 12).22

Continue to: For MDD...

For MDD, using the definition of response as a ≥50% decrease in MADRS total score, and pooling the results for brexpiprazole 1, 2, and 3 mg/d from the 2 pivotal trials,23,24 23.2% of the patients receiving brexpiprazole were responders, vs 14.5% for placebo, yielding a NNT of 12 (95% CI 8 to 26).22 Including the 1.5-mg/d dose arm and the placebo arm from the phase II study for which results are also available but not included in product labelling, the NNT becomes a slightly more robust 11 (95% CI 8 to 20).22 Although the magnitude of the NNT effect size is stronger for aripiprazole than for brexpiprazole, the 95% CIs do overlap.

The most commonly encountered adverse event in the short-term trials in schizophrenia (incidence ≥4% and at least twice the rate of placebo) was increased weight. The most commonly encountered adverse events in the short-term trials in MDD (incidence ≥5% and at least twice the rate of placebo) were increased weight and akathisia. Rates of discontinuation because of an adverse event were not higher for active medication vs placebo for the schizophrenia studies, suggesting excellent overall tolerability, and for MDD the NNH vs placebo on discontinuation because of an adverse event was 50, representing reasonable overall tolerability for this indication as well (Table 11).

Cariprazine

Cariprazine was launched in the United States in 2015 for 2 indications: schizophrenia, and the acute treatment of manic or mixed episodes associated with bipolar I disorder, both in adults.25 In terms of binding, cariprazine has very high binding affinities to dopamine D3 (0.085 nM), dopamine D2L (0.49 nM), serotonin 5-HT2B (0.58 nM), and dopamine D2S (0.69 nM) receptors, and high binding affinity to serotonin 5-HT1A (2.6 nM) receptors. Cariprazine forms 2 major metabolites, desmethyl cariprazine and didesmethyl cariprazine, that have in vitro receptor binding profiles similar to the parent drug. This latter metabolite, didesmethyl cariprazine, has a half-life of 1 to 3 weeks, and is the active moiety responsible for the majority of cariprazine’s effect when in steady state. Thus, following discontinuation of cariprazine, the decline in plasma concentrations of active drug will be slow.

The starting dose for cariprazine for schizophrenia, 1.5 mg/d, can be therapeutic. The dosage can be increased to 3 mg/d on Day 2. Depending upon clinical response and tolerability, further dose adjustments can be made in 1.5-mg or 3-mg increments to a maximum dose of 6 mg/d. For the treatment of bipolar mania, cariprazine will need to be titrated from the starting dose of 1.5 mg/d to the recommended target dose range of 3 to 6 mg/d; this can be done on Day 2. Cariprazine has been tested in clinical trials at higher doses; however, doses that exceed 6 mg/d did not confer significant additional benefit.25

A more conservative definition of response was used in the reporting of the cariprazine acute schizophrenia studies. This was simply a ≥30% decrease in the PANSS total score, and did not include the option of including patients who scored a 1 or 2 on the CGI-I. For pooled doses of cariprazine 1.5 to 6 mg/d,26-28 the percentage of responders was 31%, compared with 21% for the pooled placebo groups, yielding a NNT of 10 (95% CI 7 to 18).1 Although the magnitude of the NNT effect size is weaker for cariprazine than the other dopamine receptor partial agonists, the 95% CI overlaps with that of aripiprazole and brexpiprazole. An appropriately designed head-to-head trial would be necessary to directly test noninferiority.

Continue to: Pooling the data...

Pooling the data from the 3 pivotal short-term acute bipolar mania trials for cariprazine monotherapy in adults29-31 and using the definition of response as a ≥50% decrease in the YMRS total score for the recommended target dose of 3 to 6 mg/d, the percentage of responders was 57%, compared with 36% for the pooled placebo groups, yielding a NNT of 5 (95% CI 4 to 8).1 The magnitude of the NNT effect size is stronger for cariprazine than for aripiprazole, but the 95% CIs overlap.

The most commonly encountered adverse events in the short-term trials (incidence ≥5% and at least twice the rate of placebo) were extrapyramidal symptoms and akathisia (schizophrenia); and extrapyramidal symptoms, akathisia, dyspepsia, vomiting, somnolence, and restlessness (bipolar mania). In the schizophrenia studies, rates of discontinuation because of an adverse event were not higher for active medication vs placebo, suggesting excellent overall tolerability, and for bipolar disorder the NNH vs placebo on discontinuation because of an adverse event was 20, representing reasonable overall tolerability for this indication as well (Table 1).

Differences to consider

Indications. Although all 3 medications are approved for the treatment of schizophrenia, both aripiprazole and brexpiprazole are also approved for adjunctive treatment of MDD, and both aripiprazole and cariprazine are also approved for acute treatment of manic or mixed episodes associated with bipolar I disorder. In addition, aripiprazole is approved for a number of different disease states in pediatric patients. Aripiprazole has also been approved in a number of different formulations (oral and IM), but brexpiprazole and cariprazine are presently available only as oral pills (tablets for brexpiprazole, capsules for cariprazine).

Contraindications. All 3 agents are contraindicated in patients with a known hypersensitivity reaction to the product. All 3 also have a “black-box” warning for increased mortality in geriatric patients with dementia-related psychosis, a warning that is found in all antipsychotic medication labels. Additional black-box warnings are included regarding suicidality in the product labels of aripiprazole and brexpiprazole by virtue of their approval for the treatment of MDD.

Pharmacodynamics. All 3 agents describe a similar mechanism of action in their respective product labels: “efficacy … could be mediated through a combination of partial agonist activity at central dopamine D2 and serotonin 5-HT1A receptors and antagonist activity at serotonin 5-HT2A receptors.”2,19,25

Continue to: However, binding affinities differ...

However, binding affinities differ substantially among the agents (for example, cariprazine has only moderate binding affinity at serotonin 5-HT2A receptors [18.8 nM]), and differences also exist in terms of intrinsic activity at the receptors where partial agonism is operative. Compared with aripiprazole, brexpiprazole has lower intrinsic activity at the dopamine D2 receptor (and thus is expected to cause less akathisia), and has an approximately 10-fold higher affinity for serotonin 5-HT1A and 5-HT2A receptors, also potentially enhancing tolerability and perhaps anxiolytic activity.32,33 When cariprazine was compared with aripiprazole in functional assays for dopamine D2 and D3 receptors, similar D2 and higher D3 antagonist-partial agonist affinity and a 3- to 10-fold greater D3 vs D2 selectivity was observed for cariprazine.34 Whether specifically targeting the dopamine D3 receptor over the dopamine D2 receptor is clinically advantageous remains unknown, but in preclinical studies, dopamine D3–preferring agents may exert pro-cognitive effects.35-37 All 3 agents have only moderate binding affinities to histamine H1 receptors, thus sedation should not be prominent for any of them. None of the 3 agents have appreciable binding at muscarinic receptors, thus adverse effects related to antimuscarinic activity should not be present as well.

Schizophrenia is a heterogenous disorder. We know from clinical practice that patients respond differently to specific antipsychotics. Having different pharmacodynamic “fingerprints” to choose from allows for flexibility in treatment. Moreover, dopamine receptor partial agonists provide an alternative to the array of dopamine receptor antagonists, such as the other second-generation antipsychotics and all first-generation antipsychotics.

Dosing. Although all 3 agents are dosed once daily, only for aripiprazole is the recommended starting dose the same as the recommended maintenance dose in adults with schizophrenia or bipolar mania. Although the starting dose for cariprazine for schizophrenia can be therapeutic (1.5 mg/d), for the treatment of bipolar mania, cariprazine will need to be titrated from the starting dose of 1.5 mg/d to the recommended target dose range of 3 to 6 mg/d.

Half-life. Aripiprazole and brexpiprazole share a similar elimination half-life: approximately 75 hours and 94 hours for aripiprazole and its active metabolite dehydro-aripiprazole, respectively, and 91 hours and 86 hours for brexpiprazole and its major metabolite, DM-3411 (inactive), respectively. Cariprazine is strikingly different, with an elimination half-life of 2 to 4 days, and approximately 1 to 3 weeks for its active metabolite didesmethyl cariprazine.

Drug interactions. Both aripiprazole and brexpiprazole are metabolized via cytochrome P450 (CYP) 2D6 and CYP3A4, and thus the dose may need to be adjusted in the presence of CYP2D6 inhibitors or CYP3A4 inhibitors/inducers; with inhibitors, the dose is decreased by half or more, and with inducers, the dose is doubled. In contrast, cariprazine is primarily metabolized by CYP3A4 and thus potential drug–drug interactions are primarily focused on CYP3A4 inhibitors (decrease cariprazine dose by half) and inducers (co-prescribing of cariprazine with a CYP3A4 inducer is not recommended).

Continue to: Tolerability

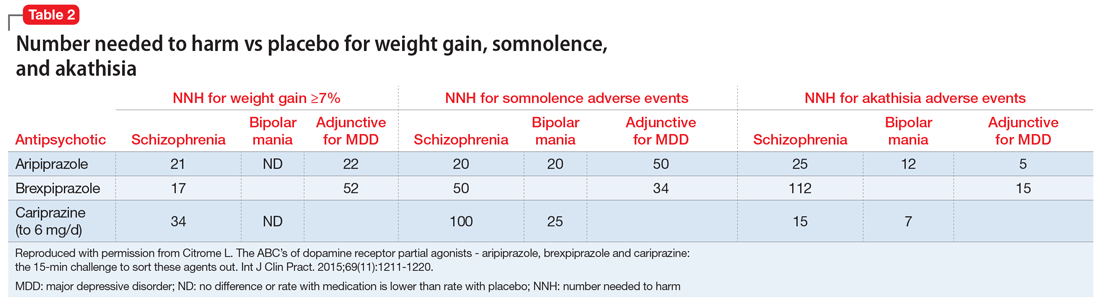

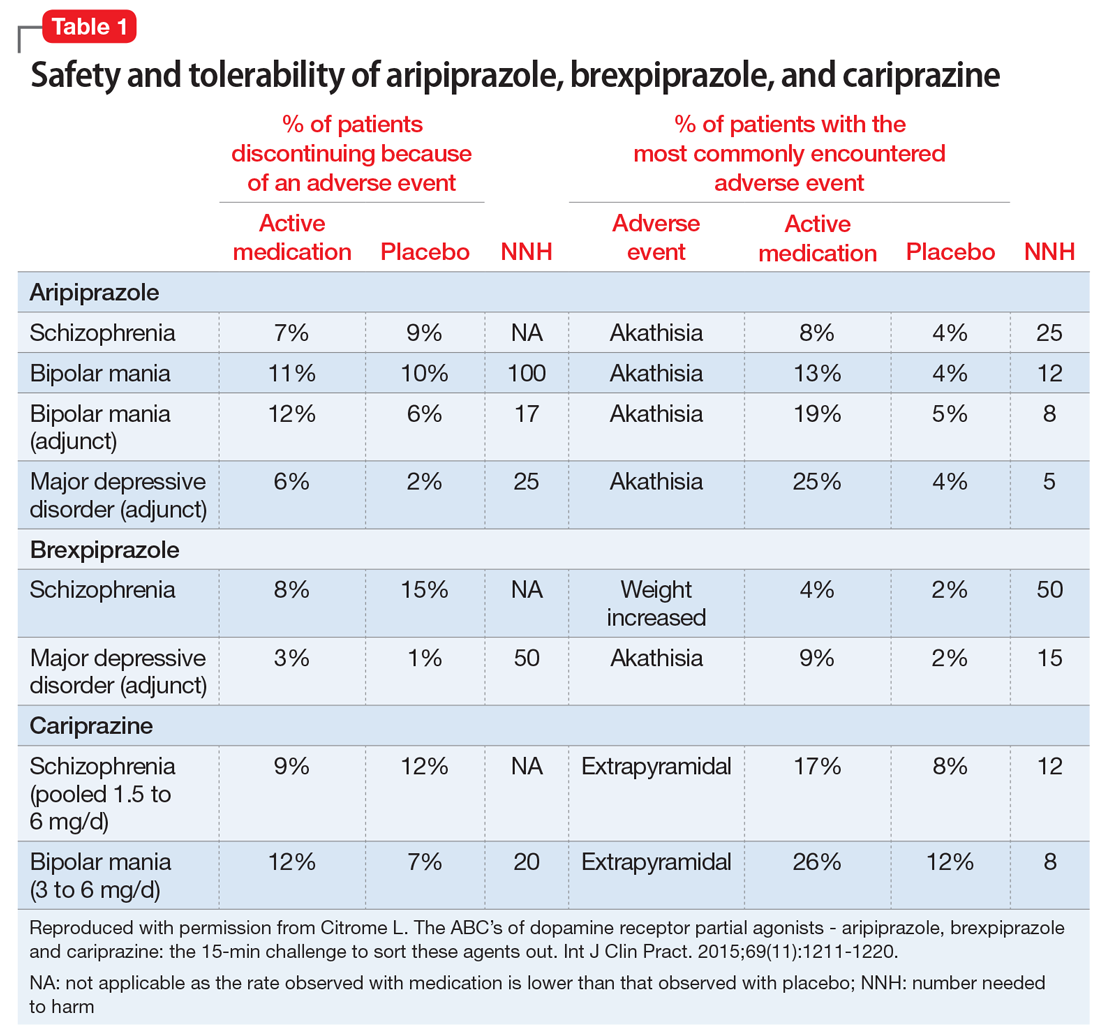

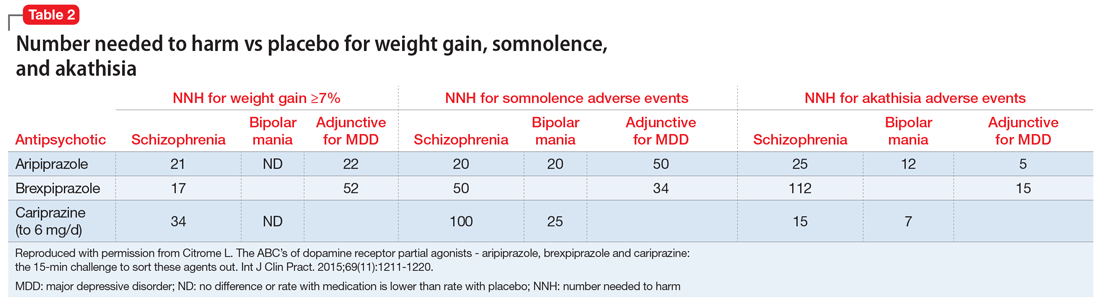

Tolerability. For all 3 agents, rates of discontinuation because of an adverse event were not higher for active medication vs placebo for the schizophrenia studies, suggesting excellent overall tolerability.2,19,25 For the other disease states, NNH values ranged from 17 (adjunctive use of aripiprazole for bipolar mania) to 100 (aripiprazole monotherapy for bipolar mania), representing reasonable overall tolerability. For the most commonly encountered adverse event for each medication, the NNH values ranged from 5 (akathisia for aripiprazole for adjunctive use in MDD) to 50 (increased weight for brexpiprazole for schizophrenia). Of special interest are the adverse events of weight gain ≥7% from baseline, somnolence adverse events, and akathisia adverse events; the NNH values vs placebo for these are listed in Table 21. Pragmatically, NNH values <10 are likely to be more clinically relevant. For aripiprazole, brexpiprazole, and cariprazine for the treatment of schizophrenia, none of the NNH values for weight gain, somnolence, or akathisia were <10; however, this was not the case for the mood disorders, where in general, akathisia was more frequently observed for each of the agents. For the indication of schizophrenia, the rank order for propensity for weight gain appears to be brexpiprazole > aripiprazole > cariprazine, the propensity for somnolence aripiprazole > brexpiprazole > cariprazine, and the propensity for akathisia cariprazine > aripiprazole > brexpiprazole; however, this is by indirect comparison, and appropriately designed head-to-head clinical trials will be necessary in order to accurately assess these potential differences.

Because of the partial agonist activity at the dopamine D2 receptor, aripiprazole, brexpiprazole, and cariprazine are less likely to cause hyperprolactinemia than other first-line first- or second-generation antipsychotics. Other differentiating features of the dopamine receptor partial agonists compared with other choices include a relative lack of effect on the QT interval.38 In general, as predicted by their relatively lower binding affinities to histamine H1 receptors, the dopamine receptor partial agonists are not especially sedating.39

Likelihood to be helped or harmed

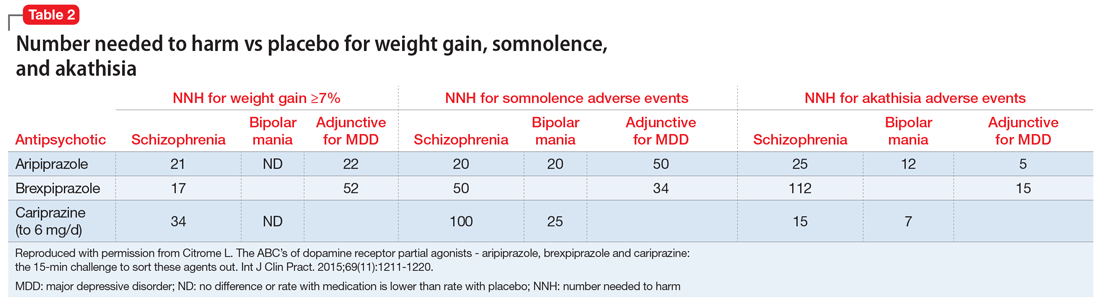

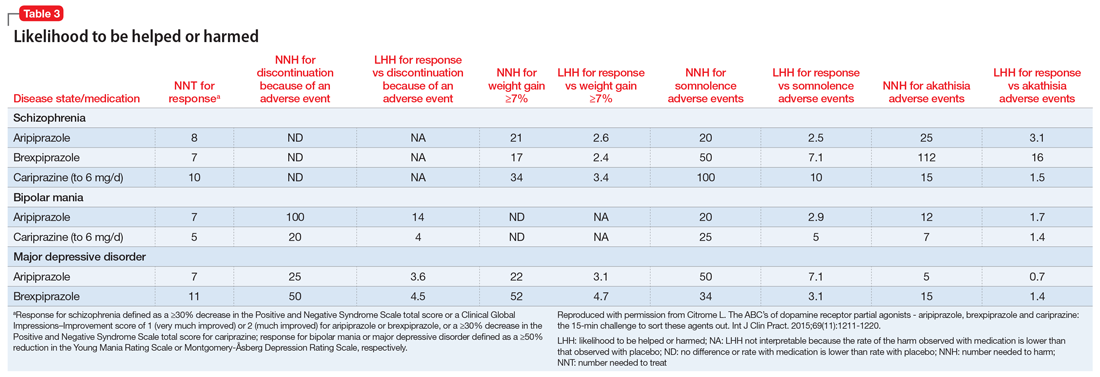

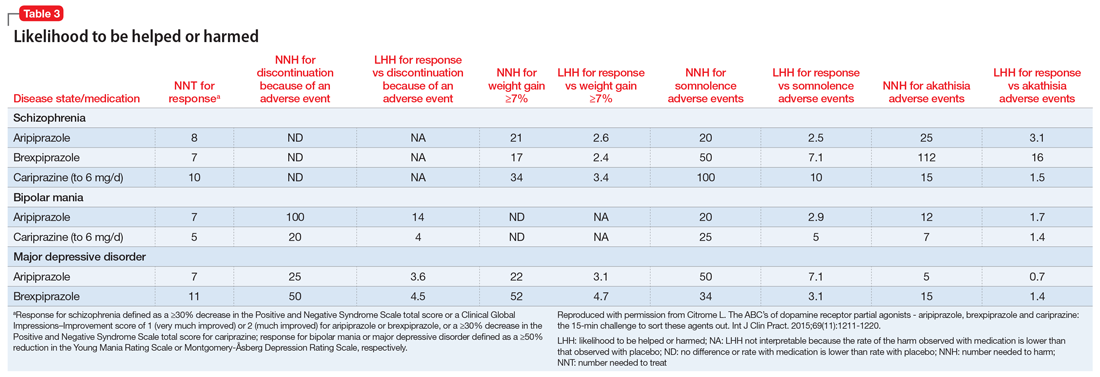

The concept of likelihood to be helped or harmed (LHH) can be useful to assess benefit vs risk, provided you select a relevant harm to contrast with the expected benefit.40 Table 31 provides the NNT for response, NNH for discontinuation because of an adverse event (where applicable), the NNHs for weight gain ≥7%, somnolence adverse events, and akathisia adverse events, together with the calculated LHH (where applicable). With the exception of aripiprazole for the treatment of MDD when comparing response vs akathisia, all LHH values are >1.0, and thus the benefit (response) would be encountered more often than the harm. When LHH values are ≥10, this can be interpreted that one would encounter a response at least 10 times more often than the adverse event of interest. This was observed for brexpiprazole for the treatment of schizophrenia when comparing response vs akathisia, for cariprazine for schizophrenia when comparing response vs somnolence, for aripiprazole for bipolar mania when comparing response vs discontinuation because of an adverse event, and for cariprazine for bipolar mania when comparing response vs somnolence.

Beyond acute studies

When treating patients with schizophrenia, delaying time to relapse is a main goal. In placebo-controlled randomized withdrawal studies of oral aripiprazole, brexpiprazole, and cariprazine in patients with schizophrenia, observed relapse rates vs placebo were reported, allowing the calculation of NNT vs placebo for the avoidance of relapse.41-44 These NNT values were similar and ranged from 4 to 5. For aripiprazole, relapse rates vs placebo in the 26-week study were 34% vs 57%, resulting in a NNT of 5 (95% CI 3 to 9); brexpiprazole, 52-week study, 13.5% vs 38.5%, NNT of 4 (95% CI 3 to 8); and cariprazine, 72-week study, 25% vs 47.5%, NNT of 5 (95% CI 3 to 11). In addition, cariprazine, 4.5 mg/d, has been directly compared with risperidone, 4 mg/d, in a 26-week double-blind study in non-geriatric adult patients with schizophrenia and predominant negative symptoms for at least 6 months.45 Cariprazine was superior to risperidone on the PANSS–Negative Factor Score, and response to treatment (decrease ≥20% in PANSS–Negative Factor Score) was achieved by more patients treated with cariprazine by 26 weeks than those treated with risperidone (69% vs 58%, NNT 9 [95% CI 5 to 44]).

Caveats

The harms discussed in this article are primarily from acute studies and do not reflect effects that can take time to develop, such as tardive dyskinesia, the long-term accumulation of body weight, and the development of insulin resistance/type 2 diabetes mellitus.40 The data presented are from carefully conducted registration trials that enrolled subjects who fulfilled restrictive inclusion/exclusion criteria. Such patients may differ from those encountered in routine clinical practice. Keep in mind that adverse events may differ in terms of impact and may not be clinically relevant if the adverse event is mild, time-limited, or easily managed. Moreover, different patients carry different propensities to experience different adverse events or to achieve a therapeutic response.

Continue to: Bottom Line

Bottom Line

Although aripiprazole, brexpiprazole, and cariprazine are all dopamine receptor partial agonists with demonstrated efficacy in psychiatric disorders, they differ in terms of available formulations, indications, pharmacodynamics, pharmacokinetics, titration requirements, and tolerability. Careful consideration of these factors can increase the likelihood of successful treatment.

Related Resources

- Citrome L. A review of the pharmacology, efficacy and tolerability of recently approved and upcoming oral antipsychotics: an evidence-based medicine approach. CNS Drugs. 2013;27(11):879-911.

- Citrome L, Ketter TA. When does a difference make a difference? Interpretation of number needed to treat, number needed to harm, and likelihood to be helped or harmed. Int J Clin Pract. 2013;67(5):407-411.

- U.S. Food & Drug Administration. Drugs@FDA: FDA Approved Drug Products. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Aripiprazole lauroxil • Aristada

Aripiprazole monohydrate • Abilify Maintena

Brexpiprazole • Rexulti

Cariprazine • Vraylar

1. C

2. Otsuka. Abilify (aripiprazole) tablets, ABILIFY DISCMELT (aripiprazole) orally disintegrating tablets, ABILIFY (aripiprazole) oral solution, Abilify (aripiprazole) injection for intramuscular use only. Prescribing information. http://www.otsuka-us.com/Documents/Abilify.PI.pdf. Revised February 2018. Accessed March 14, 2018.

3. Citrome L. Aripiprazole long-acting injectable formulations for schizophrenia: aripiprazole monohydrate and aripiprazole lauroxil. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2016;9(2):169-186.

4. Citrome L. Long-acting injectable antipsychotics update: lengthening the dosing interval and expanding the diagnostic indications. Expert Rev Neurother. 2017;17(10):1029-1043.

5. Mace S, Taylor D. Aripiprazole: dose-response relationship in schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. CNS Drugs. 2009;23(9):773-780.

6. Citrome L. Compelling or irrelevant? Using number needed to treat can help decide. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2008;117(6):412-419.

7. Kane JM, Carson WH, Saha AR, et al. Efficacy and safety of aripiprazole and haloperidol versus placebo in patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63(9):763-771.

8. Potkin SG, Saha AR, Kujawa MJ, et al. Aripiprazole, an antipsychotic with a novel mechanism of action, and risperidone vs placebo in patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(7):681-690.

9. McEvoy JP, Daniel DG, Carson WH Jr, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, study of the efficacy and safety of aripiprazole 10, 15 or 20 mg/day for the treatment of patients with acute exacerbations of schizophrenia. J Psychiatr Res. 2007;41(11):895-905.

10. Cutler AJ, Marcus RN, Hardy SA, et al. The efficacy and safety of lower doses of aripiprazole for the treatment of patients with acute exacerbation of schizophrenia. CNS Spectr. 2006;11(9):691-702.

11. Sachs G, Sanchez R, Marcus R, et al; Aripiprazole Study Group. Aripiprazole in the treatment of acute manic or mixed episodes in patients with bipolar I disorder: a 3-week placebo-controlled study. J Psychopharmacol. 2006;20(4):536-546.

12. Keck PE Jr, Marcus R, Tourkodimitris S, et al; Aripiprazole Study Group. A placebo-controlled, double-blind study of the efficacy and safety of aripiprazole in patients with acute bipolar mania. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(9):1651-1658.

13. Keck PE, Orsulak PJ, Cutler AJ, et al; CN138-135 Study Group. Aripiprazole monotherapy in the treatment of acute bipolar I mania: a randomized, double-blind, placebo- and lithium-controlled study. J Affect Disord. 2009;112(1-3):36-49.

14. Young AH, Oren DA, Lowy A, et al. Aripiprazole monotherapy in acute mania: 12-week randomised placebo- and haloperidol-controlled study. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;194(1):40-48.

15. Vieta E, T’joen C, McQuade RD, et al. Efficacy of adjunctive aripiprazole to either valproate or lithium in bipolar mania patients partially nonresponsive to valproate/lithium monotherapy: a placebo-controlled study. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(10):1316-1325.

16. Marcus RN, McQuade RD, Carson WH, et al. The efficacy and safety of aripiprazole as adjunctive therapy in major depressive disorder: a second multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;28(2):156-165.

17. Berman RM, Marcus RN, Swanink R, et al. The efficacy and safety of aripiprazole as adjunctive therapy in major depressive disorder: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(6):843-853.

18. Berman RM, Fava M, Thase ME, et al. Aripiprazole augmentation in major depressive disorder: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study in patients with inadequate response to antidepressants. CNS Spectr. 2009;14(4):197-206.

19. Otsuka. Rexulti (brexpiprazole) tablets, for oral use. Prescribing information. http://www.otsuka-us.com/Products/Documents/Rexulti.PI.pdf. Revised February 2018. Accessed March 14, 2018.

20. Correll CU, Skuban A, Ouyang J, et al. Efficacy and safety of brexpiprazole for the treatment of acute schizophrenia: a 6-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(9):870-880.

21. Kane JM, Skuban A, Ouyang J, et al. A multicenter, randomized, double-blind, controlled phase 3 trial of fixed-dose brexpiprazole for the treatment of adults with acute schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2015;164(1-3):127-135.

22. Citrome L. Brexpiprazole for schizophrenia and as adjunct for major depressive disorder: a systematic review of the efficacy and safety profile for this newly approved antipsychotic - what is the number needed to treat, number needed to harm and likelihood to be helped or harmed? Int J Clin Pract. 2015;69(9):978-997.

23. Thase ME, Youakim JM, Skuban A, et al. Efficacy and safety of adjunctive brexpiprazole 2 mg in major depressive disorder: a phase 3, randomized, placebo-controlled study in patients with inadequate response to antidepressants. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(9):1224-1231.

24. Thase ME, Youakim JM, Skuban A, et al. Adjunctive brexpiprazole 1 and 3 mg for patients with major depressive disorder following inadequate response to antidepressants: a phase 3, randomized, double-blind study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(9):1232-1240.

25. Allergan. Vraylar (cariprazine) capsules, for oral use. Prescribing information. https://www.allergan.com/assets/pdf/vraylar_pi. Revised November 2017. Accessed March 14, 2018.

26. Durgam S, Starace A, Li D, et al. An evaluation of the safety and efficacy of cariprazine in patients with acute exacerbation of schizophrenia: a phase II, randomized clinical trial. Schizophr Res. 2014;152(2-3):450-457.

27. Durgam S, Cutler AJ, Lu K, et al. Cariprazine in acute exacerbation of schizophrenia: a fixed-dose, phase 3, randomized, double-blind, placebo- and active-controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(12):e1574-e1582.

28. Kane JM, Zukin S, Wang Y, et al. Efficacy and safety of cariprazine in acute exacerbation of schizophrenia: results from an international, phase III clinical trial. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2015;35(4):367-373.

29. Calabrese JR, Keck PE Jr, Starace A, et al. Efficacy and safety of low- and high-dose cariprazine in acute and mixed mania associated with bipolar I disorder: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(3):284-292.

30. Durgam S, Starace A, Li D, et al. The efficacy and tolerability of cariprazine in acute mania associated with bipolar I disorder: a phase II trial. Bipolar Disord. 2015;17(1):63-75.

31. Sachs GS, Greenberg WM, Starace A, et al. Cariprazine in the treatment of acute mania in bipolar I disorder: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III trial. J Affect Disord. 2015;174:296-302.

32. Citrome L, Stensbøl TB, Maeda K. The preclinical profile of brexpiprazole: what is its clinical relevance for the treatment of psychiatric disorders? Expert Rev Neurother. 2015;15(10):1219-1229.

33. Maeda K, Sugino H, Akazawa H, et al. Brexpiprazole I: in vitro and in vivo characterization of a novel serotonin-dopamine activity modulator. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2014;350(3):589-604.

34. Kiss B, Horváth A, Némethy Z, et al. Cariprazine (RGH-188), a dopamine D(3) receptor-preferring, D(3)/D(2) dopamine receptor antagonist-partial agonist antipsychotic candidate: in vitro and neurochemical profile. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2010;333(1):328-340.

35. Zimnisky R, Chang G, Gyertyán I, et al. Cariprazine, a dopamine D3-receptor-preferring partial agonist, blocks phencyclidine-induced impairments of working memory, attention set-shifting, and recognition memory in the mouse. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2013; 226(1):91-100.

36. Neill JC, Grayson B, Kiss B, et al. Effects of cariprazine, a novel antipsychotic, on cognitive deficit and negative symptoms in a rodent model of schizophrenia symptomatology. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2016;26(1):3-14.

37. Gyertyán I, Kiss B, Sághy K, et al. Cariprazine (RGH-188), a potent D3/D2 dopamine receptor partial agonist, binds to dopamine D3 receptors in vivo and shows antipsychotic-like and procognitive effects in rodents. Neurochem Int. 2011;59(6):925-935.

38. Leucht S, Leucht C, Huhn M, et al. Sixty years of placebo-controlled antipsychotic drug trials in acute schizophrenia: systematic review, Bayesian meta-analysis, and meta-regression of efficacy predictors. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174(10):927-942.

39. Citrome L. Activating and sedating adverse effects of second-generation antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia and major depressive disorder: absolute risk increase and number needed to harm. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2017;37(2):138-147.

40. Citrome L, Kantrowitz J. Antipsychotics for the treatment of schizophrenia: likelihood to be helped or harmed, understanding proximal and distal benefits and risks. Expert Rev Neurother. 2008;8(7):1079-1091.

41. Pigott TA, Carson WH, Saha AR, et al; Aripiprazole Study Group. Aripiprazole for the prevention of relapse in stabilized patients with chronic schizophrenia: a placebo-controlled 26-week study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(9):1048-1056.

42. Fleischhacker WW, Hobart M, Ouyang J, et al. Efficacy and safety of brexpiprazole (OPC-34712) as maintenance treatment in adults with schizophrenia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2016;20(1):11-21.

43. Durgam S, Earley W, Li R, et al. Long-term cariprazine treatment for the prevention of relapse in patients with schizophrenia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Schizophr Res. 2016;176(2-3):264-271.

44. Citrome L. Schizophrenia relapse, patient considerations, and potential role of lurasidone. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2016;10:1529-1537.

45. Németh G, Laszlovszky I, Czobor P, et al. Cariprazine versus risperidone monotherapy for treatment of predominant negative symptoms in patients with schizophrenia: a randomised, double-blind, controlled trial. Lancet. 2017;389(10074):1103-1113.

Aripiprazole, brexpiprazole, and cariprazine are dopamine receptor partial agonists, and on the surface, they appear similar. However, there are key differences in terms of available indications, formulations, pharmacodynamics, pharmacokinetics, dosing, drug interactions, tolerability, and other factors related to successful use.1 This review will cover the main points that the knowledgeable clinician will need to be mindful of when prescribing these agents.

Aripiprazole

Aripiprazole was launched in the United States in 20022 as the first dopamine receptor partial agonist approved for the treatment of schizophrenia; it later received additional indications for adults with manic or mixed episodes associated with bipolar I disorder and the maintenance treatment of bipolar I disorder, as well as for the adjunctive treatment of major depressive disorder (MDD). Pediatric indications include schizophrenia, acute treatment of manic or mixed episodes associated with bipolar I disorder, irritability associated with autistic disorder, and Tourette’s disorder.

Several formulations also became available, including a short-acting injection indicated for agitation associated with schizophrenia or bipolar mania, and oral disintegrating tablets and an oral solution that could substitute for the regular tablet. Presently the medication has gone “generic,” and not all formulations are being manufactured. The long-acting formulations of aripiprazole (aripiprazole monohydrate and aripiprazole lauroxil) are considered different products, each with its own product insert, with indications that are more limited in scope than for the oral forms.3,4

Although dopamine D2 receptor partial agonism is a relevant mechanism of action, partial agonist activity at serotonin 5-HT1A receptors and antagonist activity at 5-HT2A receptors also play a role.2 Actions at receptors other than dopamine D2, serotonin 5-HT1A, and serotonin 5-HT2A may explain some of the other clinical effects of aripiprazole. In terms of binding, aripiprazole has very high binding affinities (Ki) to dopamine D2 (0.34 nM), dopamine D3 (0.8 nM), and serotonin 5-HT2B (0.36 nM) receptors, and high binding affinities to serotonin 5-HT1A (1.7 nM) and serotonin 5-HT2A (3.4 nM) receptors.

Dosage recommendations for adults with schizophrenia suggest a starting and maintenance dose of 10 to 15 mg/d.2 Although the maximum dose is 30 mg/d, there is no evidence that doses >15 mg/d are superior to lower doses.5 In adolescents with schizophrenia, the product label recommends a starting dose of 2 mg/d, a maintenance dose of 10 mg/d, and a maximum dose of 30 mg/d. Recommendations for dosing in bipolar mania are similar. Dosing for the other indications is lower.

Efficacy in schizophrenia can be quantified using number needed to treat (NNT) for response vs placebo. The NNT answers the question “How many patients need to be randomized to aripiprazole vs placebo before expecting to encounter one additional responder?”6 From the 4 positive pivotal short-term acute schizophrenia trials for aripiprazole in adults,7-10 using the definition of response as a ≥30% decrease in the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) total score or a Clinical Global Impressions–Improvement (CGI-I) score of 1 (very much improved) or 2 (much improved), and pooling the data for aripiprazole doses 10 to 30 mg/d, response rates were 38% for aripiprazole vs 24% for placebo, resulting in a NNT of 8 (95% confidence interval [CI] 6 to 13).

From the 4 positive pivotal short-term acute bipolar mania trials for aripiprazole monotherapy in adults11-14 using the definition of response as a ≥50% decrease in the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) total score, and pooling the data for aripiprazole doses 15 to 30 mg/d, response rates were 47% for aripiprazole vs 31% for placebo, resulting in a NNT of 7 (95% CI 5 to 11).1 Similar results were observed in the adjunctive aripiprazole acute bipolar mania trial15 where the NNT for response was also 7.1

Continue to: From the 2 positive pivotal short-term...

From the 2 positive pivotal short-term acute MDD trials for aripiprazole,16,17 using the definition of response as a ≥50% decrease in the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) total score, and pooling the data (aripiprazole flexibly dosed 2 to 20 mg/d, with a median dose of 10 mg/d), response rates were 33% for aripiprazole vs 20% for placebo, resulting in a NNT of 8 (95% CI 6 to 17). After including a third trial not described in product labeling,18 the NNT became a more robust 7 (95% CI 5 to 11).1

The most commonly encountered adverse events (incidence ≥5% and at least twice the rate of placebo) in the pivotal trials were akathisia (schizophrenia); akathisia, sedation, restlessness, tremor, and extrapyramidal disorder (bipolar mania, monotherapy); akathisia, insomnia, and extrapyramidal disorder (bipolar mania, adjunctive therapy); akathisia, restlessness, insomnia, constipation, fatigue, and blurred vision (MDD); and nausea (short-acting IM formulation). Table 11 summarizes the tolerability information regarding rate of discontinuation due to adverse events (an overall indicator of tolerability), and the incidence of the most common adverse event, together with the calculated number needed to harm (NNH). Rates of discontinuation because of an adverse event were not higher for active medication vs placebo for the schizophrenia studies, suggesting excellent overall tolerability; for the other disease states, NNH values ranged from 17 (adjunctive use of aripiprazole for bipolar mania) to 100 (aripiprazole monotherapy for bipolar mania), representing reasonable overall tolerability for these indications.

Brexpiprazole

Brexpiprazole was launched in the United States in 2015 for 2 indications: schizophrenia and the adjunctive treatment of MDD, both in adults.19 In terms of binding, brexpiprazole has very high binding affinities to serotonin 5-HT1A (0.12 nM), adrenergic α1B (0.17 nM), dopamine D2 (0.30 nM), serotonin 5-HT2A (0.47 nM), and adrenergic α2C (0.59 nM) receptors, and high binding affinities to dopamine D3 (1.1 nM), serotonin 5-HT2B (1.9 nM), adrenergic α1D (2.6 nM), serotonin 5-HT7 (3.7 nM), and adrenergic α1A (3.8 nM) receptors.

The 1-mg/d starting dose for brexpiprazole is lower than the recommended dose range of 2 to 4 mg/d for schizophrenia or the recommended dose of 2 mg/d for MDD.19 Thus brexpiprazole requires titration. The recommended rate of titration depends on the disease state being treated. For schizophrenia, the recommended titration schedule is to increase the dose to 2 mg/d on Day 5 through Day 7, then to 4 mg/d (the maximum recommended dose) on Day 8 based on the patient’s clinical response and tolerability. For MDD, there is the option of starting at 0.5 mg/d and the titration process is slower, with dosage increases occurring at weekly intervals, and with a maximum dose of 3 mg/d.

Using the identical definition of response in persons with schizophrenia as for the aripiprazole data described above, pooling together all the available data for the recommended target dose of brexpiprazole for schizophrenia (2 to 4 mg/d) from the 2 studies listed in the product label,20,21 the percentage of responders was 46%, compared with 31% for the pooled placebo groups, yielding a NNT of 7 (95% CI 5 to 12).22

Continue to: For MDD...

For MDD, using the definition of response as a ≥50% decrease in MADRS total score, and pooling the results for brexpiprazole 1, 2, and 3 mg/d from the 2 pivotal trials,23,24 23.2% of the patients receiving brexpiprazole were responders, vs 14.5% for placebo, yielding a NNT of 12 (95% CI 8 to 26).22 Including the 1.5-mg/d dose arm and the placebo arm from the phase II study for which results are also available but not included in product labelling, the NNT becomes a slightly more robust 11 (95% CI 8 to 20).22 Although the magnitude of the NNT effect size is stronger for aripiprazole than for brexpiprazole, the 95% CIs do overlap.

The most commonly encountered adverse event in the short-term trials in schizophrenia (incidence ≥4% and at least twice the rate of placebo) was increased weight. The most commonly encountered adverse events in the short-term trials in MDD (incidence ≥5% and at least twice the rate of placebo) were increased weight and akathisia. Rates of discontinuation because of an adverse event were not higher for active medication vs placebo for the schizophrenia studies, suggesting excellent overall tolerability, and for MDD the NNH vs placebo on discontinuation because of an adverse event was 50, representing reasonable overall tolerability for this indication as well (Table 11).

Cariprazine

Cariprazine was launched in the United States in 2015 for 2 indications: schizophrenia, and the acute treatment of manic or mixed episodes associated with bipolar I disorder, both in adults.25 In terms of binding, cariprazine has very high binding affinities to dopamine D3 (0.085 nM), dopamine D2L (0.49 nM), serotonin 5-HT2B (0.58 nM), and dopamine D2S (0.69 nM) receptors, and high binding affinity to serotonin 5-HT1A (2.6 nM) receptors. Cariprazine forms 2 major metabolites, desmethyl cariprazine and didesmethyl cariprazine, that have in vitro receptor binding profiles similar to the parent drug. This latter metabolite, didesmethyl cariprazine, has a half-life of 1 to 3 weeks, and is the active moiety responsible for the majority of cariprazine’s effect when in steady state. Thus, following discontinuation of cariprazine, the decline in plasma concentrations of active drug will be slow.

The starting dose for cariprazine for schizophrenia, 1.5 mg/d, can be therapeutic. The dosage can be increased to 3 mg/d on Day 2. Depending upon clinical response and tolerability, further dose adjustments can be made in 1.5-mg or 3-mg increments to a maximum dose of 6 mg/d. For the treatment of bipolar mania, cariprazine will need to be titrated from the starting dose of 1.5 mg/d to the recommended target dose range of 3 to 6 mg/d; this can be done on Day 2. Cariprazine has been tested in clinical trials at higher doses; however, doses that exceed 6 mg/d did not confer significant additional benefit.25

A more conservative definition of response was used in the reporting of the cariprazine acute schizophrenia studies. This was simply a ≥30% decrease in the PANSS total score, and did not include the option of including patients who scored a 1 or 2 on the CGI-I. For pooled doses of cariprazine 1.5 to 6 mg/d,26-28 the percentage of responders was 31%, compared with 21% for the pooled placebo groups, yielding a NNT of 10 (95% CI 7 to 18).1 Although the magnitude of the NNT effect size is weaker for cariprazine than the other dopamine receptor partial agonists, the 95% CI overlaps with that of aripiprazole and brexpiprazole. An appropriately designed head-to-head trial would be necessary to directly test noninferiority.

Continue to: Pooling the data...

Pooling the data from the 3 pivotal short-term acute bipolar mania trials for cariprazine monotherapy in adults29-31 and using the definition of response as a ≥50% decrease in the YMRS total score for the recommended target dose of 3 to 6 mg/d, the percentage of responders was 57%, compared with 36% for the pooled placebo groups, yielding a NNT of 5 (95% CI 4 to 8).1 The magnitude of the NNT effect size is stronger for cariprazine than for aripiprazole, but the 95% CIs overlap.

The most commonly encountered adverse events in the short-term trials (incidence ≥5% and at least twice the rate of placebo) were extrapyramidal symptoms and akathisia (schizophrenia); and extrapyramidal symptoms, akathisia, dyspepsia, vomiting, somnolence, and restlessness (bipolar mania). In the schizophrenia studies, rates of discontinuation because of an adverse event were not higher for active medication vs placebo, suggesting excellent overall tolerability, and for bipolar disorder the NNH vs placebo on discontinuation because of an adverse event was 20, representing reasonable overall tolerability for this indication as well (Table 1).

Differences to consider

Indications. Although all 3 medications are approved for the treatment of schizophrenia, both aripiprazole and brexpiprazole are also approved for adjunctive treatment of MDD, and both aripiprazole and cariprazine are also approved for acute treatment of manic or mixed episodes associated with bipolar I disorder. In addition, aripiprazole is approved for a number of different disease states in pediatric patients. Aripiprazole has also been approved in a number of different formulations (oral and IM), but brexpiprazole and cariprazine are presently available only as oral pills (tablets for brexpiprazole, capsules for cariprazine).

Contraindications. All 3 agents are contraindicated in patients with a known hypersensitivity reaction to the product. All 3 also have a “black-box” warning for increased mortality in geriatric patients with dementia-related psychosis, a warning that is found in all antipsychotic medication labels. Additional black-box warnings are included regarding suicidality in the product labels of aripiprazole and brexpiprazole by virtue of their approval for the treatment of MDD.

Pharmacodynamics. All 3 agents describe a similar mechanism of action in their respective product labels: “efficacy … could be mediated through a combination of partial agonist activity at central dopamine D2 and serotonin 5-HT1A receptors and antagonist activity at serotonin 5-HT2A receptors.”2,19,25

Continue to: However, binding affinities differ...

However, binding affinities differ substantially among the agents (for example, cariprazine has only moderate binding affinity at serotonin 5-HT2A receptors [18.8 nM]), and differences also exist in terms of intrinsic activity at the receptors where partial agonism is operative. Compared with aripiprazole, brexpiprazole has lower intrinsic activity at the dopamine D2 receptor (and thus is expected to cause less akathisia), and has an approximately 10-fold higher affinity for serotonin 5-HT1A and 5-HT2A receptors, also potentially enhancing tolerability and perhaps anxiolytic activity.32,33 When cariprazine was compared with aripiprazole in functional assays for dopamine D2 and D3 receptors, similar D2 and higher D3 antagonist-partial agonist affinity and a 3- to 10-fold greater D3 vs D2 selectivity was observed for cariprazine.34 Whether specifically targeting the dopamine D3 receptor over the dopamine D2 receptor is clinically advantageous remains unknown, but in preclinical studies, dopamine D3–preferring agents may exert pro-cognitive effects.35-37 All 3 agents have only moderate binding affinities to histamine H1 receptors, thus sedation should not be prominent for any of them. None of the 3 agents have appreciable binding at muscarinic receptors, thus adverse effects related to antimuscarinic activity should not be present as well.

Schizophrenia is a heterogenous disorder. We know from clinical practice that patients respond differently to specific antipsychotics. Having different pharmacodynamic “fingerprints” to choose from allows for flexibility in treatment. Moreover, dopamine receptor partial agonists provide an alternative to the array of dopamine receptor antagonists, such as the other second-generation antipsychotics and all first-generation antipsychotics.

Dosing. Although all 3 agents are dosed once daily, only for aripiprazole is the recommended starting dose the same as the recommended maintenance dose in adults with schizophrenia or bipolar mania. Although the starting dose for cariprazine for schizophrenia can be therapeutic (1.5 mg/d), for the treatment of bipolar mania, cariprazine will need to be titrated from the starting dose of 1.5 mg/d to the recommended target dose range of 3 to 6 mg/d.

Half-life. Aripiprazole and brexpiprazole share a similar elimination half-life: approximately 75 hours and 94 hours for aripiprazole and its active metabolite dehydro-aripiprazole, respectively, and 91 hours and 86 hours for brexpiprazole and its major metabolite, DM-3411 (inactive), respectively. Cariprazine is strikingly different, with an elimination half-life of 2 to 4 days, and approximately 1 to 3 weeks for its active metabolite didesmethyl cariprazine.

Drug interactions. Both aripiprazole and brexpiprazole are metabolized via cytochrome P450 (CYP) 2D6 and CYP3A4, and thus the dose may need to be adjusted in the presence of CYP2D6 inhibitors or CYP3A4 inhibitors/inducers; with inhibitors, the dose is decreased by half or more, and with inducers, the dose is doubled. In contrast, cariprazine is primarily metabolized by CYP3A4 and thus potential drug–drug interactions are primarily focused on CYP3A4 inhibitors (decrease cariprazine dose by half) and inducers (co-prescribing of cariprazine with a CYP3A4 inducer is not recommended).

Continue to: Tolerability

Tolerability. For all 3 agents, rates of discontinuation because of an adverse event were not higher for active medication vs placebo for the schizophrenia studies, suggesting excellent overall tolerability.2,19,25 For the other disease states, NNH values ranged from 17 (adjunctive use of aripiprazole for bipolar mania) to 100 (aripiprazole monotherapy for bipolar mania), representing reasonable overall tolerability. For the most commonly encountered adverse event for each medication, the NNH values ranged from 5 (akathisia for aripiprazole for adjunctive use in MDD) to 50 (increased weight for brexpiprazole for schizophrenia). Of special interest are the adverse events of weight gain ≥7% from baseline, somnolence adverse events, and akathisia adverse events; the NNH values vs placebo for these are listed in Table 21. Pragmatically, NNH values <10 are likely to be more clinically relevant. For aripiprazole, brexpiprazole, and cariprazine for the treatment of schizophrenia, none of the NNH values for weight gain, somnolence, or akathisia were <10; however, this was not the case for the mood disorders, where in general, akathisia was more frequently observed for each of the agents. For the indication of schizophrenia, the rank order for propensity for weight gain appears to be brexpiprazole > aripiprazole > cariprazine, the propensity for somnolence aripiprazole > brexpiprazole > cariprazine, and the propensity for akathisia cariprazine > aripiprazole > brexpiprazole; however, this is by indirect comparison, and appropriately designed head-to-head clinical trials will be necessary in order to accurately assess these potential differences.

Because of the partial agonist activity at the dopamine D2 receptor, aripiprazole, brexpiprazole, and cariprazine are less likely to cause hyperprolactinemia than other first-line first- or second-generation antipsychotics. Other differentiating features of the dopamine receptor partial agonists compared with other choices include a relative lack of effect on the QT interval.38 In general, as predicted by their relatively lower binding affinities to histamine H1 receptors, the dopamine receptor partial agonists are not especially sedating.39

Likelihood to be helped or harmed

The concept of likelihood to be helped or harmed (LHH) can be useful to assess benefit vs risk, provided you select a relevant harm to contrast with the expected benefit.40 Table 31 provides the NNT for response, NNH for discontinuation because of an adverse event (where applicable), the NNHs for weight gain ≥7%, somnolence adverse events, and akathisia adverse events, together with the calculated LHH (where applicable). With the exception of aripiprazole for the treatment of MDD when comparing response vs akathisia, all LHH values are >1.0, and thus the benefit (response) would be encountered more often than the harm. When LHH values are ≥10, this can be interpreted that one would encounter a response at least 10 times more often than the adverse event of interest. This was observed for brexpiprazole for the treatment of schizophrenia when comparing response vs akathisia, for cariprazine for schizophrenia when comparing response vs somnolence, for aripiprazole for bipolar mania when comparing response vs discontinuation because of an adverse event, and for cariprazine for bipolar mania when comparing response vs somnolence.

Beyond acute studies

When treating patients with schizophrenia, delaying time to relapse is a main goal. In placebo-controlled randomized withdrawal studies of oral aripiprazole, brexpiprazole, and cariprazine in patients with schizophrenia, observed relapse rates vs placebo were reported, allowing the calculation of NNT vs placebo for the avoidance of relapse.41-44 These NNT values were similar and ranged from 4 to 5. For aripiprazole, relapse rates vs placebo in the 26-week study were 34% vs 57%, resulting in a NNT of 5 (95% CI 3 to 9); brexpiprazole, 52-week study, 13.5% vs 38.5%, NNT of 4 (95% CI 3 to 8); and cariprazine, 72-week study, 25% vs 47.5%, NNT of 5 (95% CI 3 to 11). In addition, cariprazine, 4.5 mg/d, has been directly compared with risperidone, 4 mg/d, in a 26-week double-blind study in non-geriatric adult patients with schizophrenia and predominant negative symptoms for at least 6 months.45 Cariprazine was superior to risperidone on the PANSS–Negative Factor Score, and response to treatment (decrease ≥20% in PANSS–Negative Factor Score) was achieved by more patients treated with cariprazine by 26 weeks than those treated with risperidone (69% vs 58%, NNT 9 [95% CI 5 to 44]).

Caveats

The harms discussed in this article are primarily from acute studies and do not reflect effects that can take time to develop, such as tardive dyskinesia, the long-term accumulation of body weight, and the development of insulin resistance/type 2 diabetes mellitus.40 The data presented are from carefully conducted registration trials that enrolled subjects who fulfilled restrictive inclusion/exclusion criteria. Such patients may differ from those encountered in routine clinical practice. Keep in mind that adverse events may differ in terms of impact and may not be clinically relevant if the adverse event is mild, time-limited, or easily managed. Moreover, different patients carry different propensities to experience different adverse events or to achieve a therapeutic response.

Continue to: Bottom Line

Bottom Line

Although aripiprazole, brexpiprazole, and cariprazine are all dopamine receptor partial agonists with demonstrated efficacy in psychiatric disorders, they differ in terms of available formulations, indications, pharmacodynamics, pharmacokinetics, titration requirements, and tolerability. Careful consideration of these factors can increase the likelihood of successful treatment.

Related Resources

- Citrome L. A review of the pharmacology, efficacy and tolerability of recently approved and upcoming oral antipsychotics: an evidence-based medicine approach. CNS Drugs. 2013;27(11):879-911.

- Citrome L, Ketter TA. When does a difference make a difference? Interpretation of number needed to treat, number needed to harm, and likelihood to be helped or harmed. Int J Clin Pract. 2013;67(5):407-411.

- U.S. Food & Drug Administration. Drugs@FDA: FDA Approved Drug Products. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf.

Drug Brand Names

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Aripiprazole lauroxil • Aristada

Aripiprazole monohydrate • Abilify Maintena

Brexpiprazole • Rexulti

Cariprazine • Vraylar

Aripiprazole, brexpiprazole, and cariprazine are dopamine receptor partial agonists, and on the surface, they appear similar. However, there are key differences in terms of available indications, formulations, pharmacodynamics, pharmacokinetics, dosing, drug interactions, tolerability, and other factors related to successful use.1 This review will cover the main points that the knowledgeable clinician will need to be mindful of when prescribing these agents.

Aripiprazole

Aripiprazole was launched in the United States in 20022 as the first dopamine receptor partial agonist approved for the treatment of schizophrenia; it later received additional indications for adults with manic or mixed episodes associated with bipolar I disorder and the maintenance treatment of bipolar I disorder, as well as for the adjunctive treatment of major depressive disorder (MDD). Pediatric indications include schizophrenia, acute treatment of manic or mixed episodes associated with bipolar I disorder, irritability associated with autistic disorder, and Tourette’s disorder.

Several formulations also became available, including a short-acting injection indicated for agitation associated with schizophrenia or bipolar mania, and oral disintegrating tablets and an oral solution that could substitute for the regular tablet. Presently the medication has gone “generic,” and not all formulations are being manufactured. The long-acting formulations of aripiprazole (aripiprazole monohydrate and aripiprazole lauroxil) are considered different products, each with its own product insert, with indications that are more limited in scope than for the oral forms.3,4

Although dopamine D2 receptor partial agonism is a relevant mechanism of action, partial agonist activity at serotonin 5-HT1A receptors and antagonist activity at 5-HT2A receptors also play a role.2 Actions at receptors other than dopamine D2, serotonin 5-HT1A, and serotonin 5-HT2A may explain some of the other clinical effects of aripiprazole. In terms of binding, aripiprazole has very high binding affinities (Ki) to dopamine D2 (0.34 nM), dopamine D3 (0.8 nM), and serotonin 5-HT2B (0.36 nM) receptors, and high binding affinities to serotonin 5-HT1A (1.7 nM) and serotonin 5-HT2A (3.4 nM) receptors.

Dosage recommendations for adults with schizophrenia suggest a starting and maintenance dose of 10 to 15 mg/d.2 Although the maximum dose is 30 mg/d, there is no evidence that doses >15 mg/d are superior to lower doses.5 In adolescents with schizophrenia, the product label recommends a starting dose of 2 mg/d, a maintenance dose of 10 mg/d, and a maximum dose of 30 mg/d. Recommendations for dosing in bipolar mania are similar. Dosing for the other indications is lower.

Efficacy in schizophrenia can be quantified using number needed to treat (NNT) for response vs placebo. The NNT answers the question “How many patients need to be randomized to aripiprazole vs placebo before expecting to encounter one additional responder?”6 From the 4 positive pivotal short-term acute schizophrenia trials for aripiprazole in adults,7-10 using the definition of response as a ≥30% decrease in the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) total score or a Clinical Global Impressions–Improvement (CGI-I) score of 1 (very much improved) or 2 (much improved), and pooling the data for aripiprazole doses 10 to 30 mg/d, response rates were 38% for aripiprazole vs 24% for placebo, resulting in a NNT of 8 (95% confidence interval [CI] 6 to 13).

From the 4 positive pivotal short-term acute bipolar mania trials for aripiprazole monotherapy in adults11-14 using the definition of response as a ≥50% decrease in the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) total score, and pooling the data for aripiprazole doses 15 to 30 mg/d, response rates were 47% for aripiprazole vs 31% for placebo, resulting in a NNT of 7 (95% CI 5 to 11).1 Similar results were observed in the adjunctive aripiprazole acute bipolar mania trial15 where the NNT for response was also 7.1

Continue to: From the 2 positive pivotal short-term...

From the 2 positive pivotal short-term acute MDD trials for aripiprazole,16,17 using the definition of response as a ≥50% decrease in the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) total score, and pooling the data (aripiprazole flexibly dosed 2 to 20 mg/d, with a median dose of 10 mg/d), response rates were 33% for aripiprazole vs 20% for placebo, resulting in a NNT of 8 (95% CI 6 to 17). After including a third trial not described in product labeling,18 the NNT became a more robust 7 (95% CI 5 to 11).1

The most commonly encountered adverse events (incidence ≥5% and at least twice the rate of placebo) in the pivotal trials were akathisia (schizophrenia); akathisia, sedation, restlessness, tremor, and extrapyramidal disorder (bipolar mania, monotherapy); akathisia, insomnia, and extrapyramidal disorder (bipolar mania, adjunctive therapy); akathisia, restlessness, insomnia, constipation, fatigue, and blurred vision (MDD); and nausea (short-acting IM formulation). Table 11 summarizes the tolerability information regarding rate of discontinuation due to adverse events (an overall indicator of tolerability), and the incidence of the most common adverse event, together with the calculated number needed to harm (NNH). Rates of discontinuation because of an adverse event were not higher for active medication vs placebo for the schizophrenia studies, suggesting excellent overall tolerability; for the other disease states, NNH values ranged from 17 (adjunctive use of aripiprazole for bipolar mania) to 100 (aripiprazole monotherapy for bipolar mania), representing reasonable overall tolerability for these indications.

Brexpiprazole

Brexpiprazole was launched in the United States in 2015 for 2 indications: schizophrenia and the adjunctive treatment of MDD, both in adults.19 In terms of binding, brexpiprazole has very high binding affinities to serotonin 5-HT1A (0.12 nM), adrenergic α1B (0.17 nM), dopamine D2 (0.30 nM), serotonin 5-HT2A (0.47 nM), and adrenergic α2C (0.59 nM) receptors, and high binding affinities to dopamine D3 (1.1 nM), serotonin 5-HT2B (1.9 nM), adrenergic α1D (2.6 nM), serotonin 5-HT7 (3.7 nM), and adrenergic α1A (3.8 nM) receptors.