User login

Depression and substance abuse

The crisis of poor physical health and early mortality of psychiatric patients

It is well established that general medical conditions can be associated with various psychiatric disorders. But the reverse is less recognized: That serious mental illness is associated with many physical maladies, often leading to early mortality. Thus, it is a bidirectional medical reality.

The multisystem adverse effects of psychotropic medications, such as metabolic dysregulation, often are blamed for the serious medical problems afflicting psychiatrically ill patients. However, evidence is mounting that while iatrogenic effects play a role, the larger effect appears to be due to a genetic link between psychiatric disorders and cardiovascular risk.1 Unhealthy lifestyles, including sedentary living, poor dietary habits, smoking, and alcohol/substance use, also play a role in the rapid deterioration of physical health and early mortality of individuals afflicted by mood disorders, psychotic disorders, and anxiety disorders. The mantra of “healthy body, healthy mind” is well known, but “unhealthy mind, unhealthy body” should be equally emphasized as a reason for high morbidity and premature mortality in patients with serious mental disorders.

Consider the following alarming findings:

- A recent study revealed that even before the onset of the first psychotic episode, young patients with schizophrenia already suffer from a wide variety of medical conditions.2 In a large sample of 954,351 Danish persons followed from birth to adulthood, of whom 4,371 developed schizophrenia, 95.6% of patients with schizophrenia had a history of hospitalization for somatic problems, including gastrointestinal, endocrine, genitourinary, metabolic, and circulatory system diseases; cancer; and epilepsy. Those findings suggest genetic, physiological, immunological, or developmental overlap between schizophrenia and medical conditions.

- A survey of 67,609 individuals with mood, anxiety, eating, impulse control, or substance use disorders followed for 10 years found that persons with those psychiatric disorders had a significantly higher risk of chronic medical conditions, including heart disease, stroke, hypertension, diabetes, asthma, arthritis, lung disease, peptic ulcer, and cancer.3

- A 7-year follow-up study of 1,138,853 individuals with schizophrenia in the United States found a 350% increase in mortality among this group of patients, who ranged in age from 20 to 64 years, compared with the general population, matched for age, sex, race, ethnicity, and geographic regions.4 An editorial accompanying this study urged psychiatrists to urgently address the “deadly consequences” of major psychiatric disorders.5

- A study of 18,380 individuals with schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or bipolar disorder in London found that these patients were frequently hospitalized for general medical conditions, most commonly urinary, digestive, respiratory, endocrine/metabolic, hematologic, neurologic, dermatologic, and infectious disorders, neoplasm, and poisoning.6 The authors attributed those nonpsychiatric hospitalizations to self-neglect, self-harm, and poor health care access, as well as to “medically unexplained” causes.

- An extremely elevated mortality rate (24-fold higher than the general population) was reported in a 12-month study of young individuals (age 16 to 30 years) diagnosed with psychosis.7 The investigators also found that 61% of the cohort did not fill their antipsychotic prescriptions during that year, and 62% had ≥1 hospitalizations and/or emergency room visits during that year. The relationship between high mortality and lack of treatment with antipsychotics in schizophrenia was confirmed by another recent study,8 a 7-year follow-up of 29,823 persons with schizophrenia in Sweden that measured all-cause mortality. These researchers found the highest mortality among patients not receiving any antipsychotics, while the lowest mortality was among those receiving a long-acting injectable second-generation antipsychotic.

- A recent systematic review of 16 studies that examined glucose homeostasis in first-episode psychosis9 revealed that even at the onset of schizophrenia, glucose homeostasis was already altered, suggesting that predisposition to type 2 diabetes mellitus is a medical condition associated with schizophrenia, and not simply an iatrogenic effect of antipsychotic pharmacotherapy. This adds fodder to the possibility of a genetic overlap between schizophrenia and somatic disorders, including diabetes.10

- In a meta-analysis of 47 studies of young people at “ultra-high risk” for schizophrenia, cardiovascular risk was found to be high, mostly as a result of lifestyle factors such as low levels of physical activity and high rates of smoking and alcohol use, even before the onset of psychosis.11

- The risk of stroke was found to be higher in 80,569 patients with schizophrenia compared with 241,707 age- and sex-matched control subjects.12

- A meta-analysis of the risk of stroke in 6 cohorts with schizophrenia found that there is a higher risk for stroke in schizophrenia, and that this may be related to natural history of the illness itself, not just due to comorbid metabolic risk factors.13

- The high rate of cardiovascular disease in depression has been attributed to neuroinflammation14 or possibly to increased platelet reactivity.15

Continue to: As psychiatric physicians...

As psychiatric physicians, we always screen our patients for past and current medical conditions that are comorbid with their psychiatric disorders. We are aware of the lifestyle factors that increase these patients’ physical morbidity and mortality, above and beyond their suicide-related mortality. Our patients with schizophrenia and mood disorders have triple the smoking rates of the general population, and they tend to be sedentary with poor eating habits that lead to obesity, obstructive sleep apnea, diabetes, hypertension, and dyslipidemia, which increases their risk for heart attack, stroke, and cancer. Self-neglect during acute episodes of depression or psychosis increases the risk of infection, malnutrition, and tooth decay. We also see skin damage in obsessive-compulsive disorder patients who are compelled to wash their hands numerous times a day, the life-threatening effects of anorexia nervosa, and various types of medical ailments caused by incomplete suicidal attempts. Poverty and substance use among chronically mentally ill patients also increase the odds of physical ailments.

So we need to act diligently to reduce the alarming medical morbidity and mortality of the psychiatric population. Collaborative care with a primary care provider is a must, not an option, for every patient, because studies indicate that without collaborative care, patients receive inadequate primary care.16 Providing rapid access to standard medical care is the single most critical step for the prevention or amelioration of physical disorders in our psychiatric patients, concurrently with stabilizing their ailing brains and minds. If we focus only on treating psychopathology, then we will win the battle against mental illness, but lose the war of life and death.

1. Azad MC, Shoesmith WD, Al Mamun M, et al. Cardiovascular diseases among patients with schizophrenia. Asian J Psychiatr. 2016;19:28-36.

2. Sørensen HJ, Nielsen PR, Benros ME, et al. Somatic diseases and conditions before the first diagnosis of schizophrenia: a nationwide population-based cohort study in more than 900 000 individuals. Schizophr Bull. 2015;41(2):513-521.

3. Scott KM, Lim C, Al-Hamzawi A, et al. Association of mental disorders with subsequent chronic physical conditions: world mental health surveys from 17 countries. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73(2):150-158.

4. Olfson M, Gerhard T, Huang C, et al. Premature mortality among adults with schizophrenia in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(12):1172-1181.

5. Suetani S, Whiteford HA, McGrath JJ. An urgent call to address the deadly consequences of serious mental disorders. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(12):1166-1167.

6. Jayatilleke N, Hayes RD, Chang CK, et al. Acute general hospital admissions in people with serious mental illness [published online February 28, 2018]. Psychol Med. 2018;1-8.

7. Schoenbaum M, Sutherland JM, Chappel A, et al. Twelve-month health care use and mortality in commercially insured young people with incident psychosis in the United States. Schizophr Bull. 2017;43(6):1262-1272.

8. Taipale H, Mittendorfer-Rutz E, Alexanderson K, et al. Antipsychotics and mortality in a nationwide cohort of 29,823 patients with schizophrenia [published online December 20, 2017]. Schizophr Res. pii: S0920-9964(17)30762-4. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2017.12.010.

9. Pillinger T, Beck K, Gobjila C, et al. Impaired glucose homeostasis in first-episode schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(3):261-269.

10. Dieset I, Andreassen OA, Haukvik UK. Somatic comorbidity in schizophrenia: some possible biological mechanisms across the life span. Schizophr Bull. 2016;42(6):1316-1319.

11. Carney R, Cotter J, Bradshaw T, et al. Cardiometabolic risk factors in young people at ultra-high risk for psychosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Res. 2016;170(2-3):290-300.

12. Tsai KY, Lee CC, Chou YM, et al. The incidence and relative risk of stroke in patients with schizophrenia: a five-year follow-up study. Schizophr Res. 2012;138(1):41-47.

13. Li M, Fan YL, Tang ZY, et al. Schizophrenia and risk of stroke: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. Int J Cardiol. 2014;173(3):588-590.

14. Halaris A. Inflammation-associated co-morbidity between depression and cardiovascular disease. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2017;31:45-70.

15. Nemeroff CB, Musselman DL. Are platelets the link between depression and ischemic heart disease? Am Heart J. 2000;140(suppl 4):57-62.

16. Nasrallah HA, Meyer JM, Goff DC, et al. Low rates of treatment for hypertension, dyslipidemia and diabetes in schizophrenia: data from the CATIE schizophrenia trial sample at baseline. Schizophr Res. 2006;86(1-3):15-22.

It is well established that general medical conditions can be associated with various psychiatric disorders. But the reverse is less recognized: That serious mental illness is associated with many physical maladies, often leading to early mortality. Thus, it is a bidirectional medical reality.

The multisystem adverse effects of psychotropic medications, such as metabolic dysregulation, often are blamed for the serious medical problems afflicting psychiatrically ill patients. However, evidence is mounting that while iatrogenic effects play a role, the larger effect appears to be due to a genetic link between psychiatric disorders and cardiovascular risk.1 Unhealthy lifestyles, including sedentary living, poor dietary habits, smoking, and alcohol/substance use, also play a role in the rapid deterioration of physical health and early mortality of individuals afflicted by mood disorders, psychotic disorders, and anxiety disorders. The mantra of “healthy body, healthy mind” is well known, but “unhealthy mind, unhealthy body” should be equally emphasized as a reason for high morbidity and premature mortality in patients with serious mental disorders.

Consider the following alarming findings:

- A recent study revealed that even before the onset of the first psychotic episode, young patients with schizophrenia already suffer from a wide variety of medical conditions.2 In a large sample of 954,351 Danish persons followed from birth to adulthood, of whom 4,371 developed schizophrenia, 95.6% of patients with schizophrenia had a history of hospitalization for somatic problems, including gastrointestinal, endocrine, genitourinary, metabolic, and circulatory system diseases; cancer; and epilepsy. Those findings suggest genetic, physiological, immunological, or developmental overlap between schizophrenia and medical conditions.

- A survey of 67,609 individuals with mood, anxiety, eating, impulse control, or substance use disorders followed for 10 years found that persons with those psychiatric disorders had a significantly higher risk of chronic medical conditions, including heart disease, stroke, hypertension, diabetes, asthma, arthritis, lung disease, peptic ulcer, and cancer.3

- A 7-year follow-up study of 1,138,853 individuals with schizophrenia in the United States found a 350% increase in mortality among this group of patients, who ranged in age from 20 to 64 years, compared with the general population, matched for age, sex, race, ethnicity, and geographic regions.4 An editorial accompanying this study urged psychiatrists to urgently address the “deadly consequences” of major psychiatric disorders.5

- A study of 18,380 individuals with schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or bipolar disorder in London found that these patients were frequently hospitalized for general medical conditions, most commonly urinary, digestive, respiratory, endocrine/metabolic, hematologic, neurologic, dermatologic, and infectious disorders, neoplasm, and poisoning.6 The authors attributed those nonpsychiatric hospitalizations to self-neglect, self-harm, and poor health care access, as well as to “medically unexplained” causes.

- An extremely elevated mortality rate (24-fold higher than the general population) was reported in a 12-month study of young individuals (age 16 to 30 years) diagnosed with psychosis.7 The investigators also found that 61% of the cohort did not fill their antipsychotic prescriptions during that year, and 62% had ≥1 hospitalizations and/or emergency room visits during that year. The relationship between high mortality and lack of treatment with antipsychotics in schizophrenia was confirmed by another recent study,8 a 7-year follow-up of 29,823 persons with schizophrenia in Sweden that measured all-cause mortality. These researchers found the highest mortality among patients not receiving any antipsychotics, while the lowest mortality was among those receiving a long-acting injectable second-generation antipsychotic.

- A recent systematic review of 16 studies that examined glucose homeostasis in first-episode psychosis9 revealed that even at the onset of schizophrenia, glucose homeostasis was already altered, suggesting that predisposition to type 2 diabetes mellitus is a medical condition associated with schizophrenia, and not simply an iatrogenic effect of antipsychotic pharmacotherapy. This adds fodder to the possibility of a genetic overlap between schizophrenia and somatic disorders, including diabetes.10

- In a meta-analysis of 47 studies of young people at “ultra-high risk” for schizophrenia, cardiovascular risk was found to be high, mostly as a result of lifestyle factors such as low levels of physical activity and high rates of smoking and alcohol use, even before the onset of psychosis.11

- The risk of stroke was found to be higher in 80,569 patients with schizophrenia compared with 241,707 age- and sex-matched control subjects.12

- A meta-analysis of the risk of stroke in 6 cohorts with schizophrenia found that there is a higher risk for stroke in schizophrenia, and that this may be related to natural history of the illness itself, not just due to comorbid metabolic risk factors.13

- The high rate of cardiovascular disease in depression has been attributed to neuroinflammation14 or possibly to increased platelet reactivity.15

Continue to: As psychiatric physicians...

As psychiatric physicians, we always screen our patients for past and current medical conditions that are comorbid with their psychiatric disorders. We are aware of the lifestyle factors that increase these patients’ physical morbidity and mortality, above and beyond their suicide-related mortality. Our patients with schizophrenia and mood disorders have triple the smoking rates of the general population, and they tend to be sedentary with poor eating habits that lead to obesity, obstructive sleep apnea, diabetes, hypertension, and dyslipidemia, which increases their risk for heart attack, stroke, and cancer. Self-neglect during acute episodes of depression or psychosis increases the risk of infection, malnutrition, and tooth decay. We also see skin damage in obsessive-compulsive disorder patients who are compelled to wash their hands numerous times a day, the life-threatening effects of anorexia nervosa, and various types of medical ailments caused by incomplete suicidal attempts. Poverty and substance use among chronically mentally ill patients also increase the odds of physical ailments.

So we need to act diligently to reduce the alarming medical morbidity and mortality of the psychiatric population. Collaborative care with a primary care provider is a must, not an option, for every patient, because studies indicate that without collaborative care, patients receive inadequate primary care.16 Providing rapid access to standard medical care is the single most critical step for the prevention or amelioration of physical disorders in our psychiatric patients, concurrently with stabilizing their ailing brains and minds. If we focus only on treating psychopathology, then we will win the battle against mental illness, but lose the war of life and death.

It is well established that general medical conditions can be associated with various psychiatric disorders. But the reverse is less recognized: That serious mental illness is associated with many physical maladies, often leading to early mortality. Thus, it is a bidirectional medical reality.

The multisystem adverse effects of psychotropic medications, such as metabolic dysregulation, often are blamed for the serious medical problems afflicting psychiatrically ill patients. However, evidence is mounting that while iatrogenic effects play a role, the larger effect appears to be due to a genetic link between psychiatric disorders and cardiovascular risk.1 Unhealthy lifestyles, including sedentary living, poor dietary habits, smoking, and alcohol/substance use, also play a role in the rapid deterioration of physical health and early mortality of individuals afflicted by mood disorders, psychotic disorders, and anxiety disorders. The mantra of “healthy body, healthy mind” is well known, but “unhealthy mind, unhealthy body” should be equally emphasized as a reason for high morbidity and premature mortality in patients with serious mental disorders.

Consider the following alarming findings:

- A recent study revealed that even before the onset of the first psychotic episode, young patients with schizophrenia already suffer from a wide variety of medical conditions.2 In a large sample of 954,351 Danish persons followed from birth to adulthood, of whom 4,371 developed schizophrenia, 95.6% of patients with schizophrenia had a history of hospitalization for somatic problems, including gastrointestinal, endocrine, genitourinary, metabolic, and circulatory system diseases; cancer; and epilepsy. Those findings suggest genetic, physiological, immunological, or developmental overlap between schizophrenia and medical conditions.

- A survey of 67,609 individuals with mood, anxiety, eating, impulse control, or substance use disorders followed for 10 years found that persons with those psychiatric disorders had a significantly higher risk of chronic medical conditions, including heart disease, stroke, hypertension, diabetes, asthma, arthritis, lung disease, peptic ulcer, and cancer.3

- A 7-year follow-up study of 1,138,853 individuals with schizophrenia in the United States found a 350% increase in mortality among this group of patients, who ranged in age from 20 to 64 years, compared with the general population, matched for age, sex, race, ethnicity, and geographic regions.4 An editorial accompanying this study urged psychiatrists to urgently address the “deadly consequences” of major psychiatric disorders.5

- A study of 18,380 individuals with schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or bipolar disorder in London found that these patients were frequently hospitalized for general medical conditions, most commonly urinary, digestive, respiratory, endocrine/metabolic, hematologic, neurologic, dermatologic, and infectious disorders, neoplasm, and poisoning.6 The authors attributed those nonpsychiatric hospitalizations to self-neglect, self-harm, and poor health care access, as well as to “medically unexplained” causes.

- An extremely elevated mortality rate (24-fold higher than the general population) was reported in a 12-month study of young individuals (age 16 to 30 years) diagnosed with psychosis.7 The investigators also found that 61% of the cohort did not fill their antipsychotic prescriptions during that year, and 62% had ≥1 hospitalizations and/or emergency room visits during that year. The relationship between high mortality and lack of treatment with antipsychotics in schizophrenia was confirmed by another recent study,8 a 7-year follow-up of 29,823 persons with schizophrenia in Sweden that measured all-cause mortality. These researchers found the highest mortality among patients not receiving any antipsychotics, while the lowest mortality was among those receiving a long-acting injectable second-generation antipsychotic.

- A recent systematic review of 16 studies that examined glucose homeostasis in first-episode psychosis9 revealed that even at the onset of schizophrenia, glucose homeostasis was already altered, suggesting that predisposition to type 2 diabetes mellitus is a medical condition associated with schizophrenia, and not simply an iatrogenic effect of antipsychotic pharmacotherapy. This adds fodder to the possibility of a genetic overlap between schizophrenia and somatic disorders, including diabetes.10

- In a meta-analysis of 47 studies of young people at “ultra-high risk” for schizophrenia, cardiovascular risk was found to be high, mostly as a result of lifestyle factors such as low levels of physical activity and high rates of smoking and alcohol use, even before the onset of psychosis.11

- The risk of stroke was found to be higher in 80,569 patients with schizophrenia compared with 241,707 age- and sex-matched control subjects.12

- A meta-analysis of the risk of stroke in 6 cohorts with schizophrenia found that there is a higher risk for stroke in schizophrenia, and that this may be related to natural history of the illness itself, not just due to comorbid metabolic risk factors.13

- The high rate of cardiovascular disease in depression has been attributed to neuroinflammation14 or possibly to increased platelet reactivity.15

Continue to: As psychiatric physicians...

As psychiatric physicians, we always screen our patients for past and current medical conditions that are comorbid with their psychiatric disorders. We are aware of the lifestyle factors that increase these patients’ physical morbidity and mortality, above and beyond their suicide-related mortality. Our patients with schizophrenia and mood disorders have triple the smoking rates of the general population, and they tend to be sedentary with poor eating habits that lead to obesity, obstructive sleep apnea, diabetes, hypertension, and dyslipidemia, which increases their risk for heart attack, stroke, and cancer. Self-neglect during acute episodes of depression or psychosis increases the risk of infection, malnutrition, and tooth decay. We also see skin damage in obsessive-compulsive disorder patients who are compelled to wash their hands numerous times a day, the life-threatening effects of anorexia nervosa, and various types of medical ailments caused by incomplete suicidal attempts. Poverty and substance use among chronically mentally ill patients also increase the odds of physical ailments.

So we need to act diligently to reduce the alarming medical morbidity and mortality of the psychiatric population. Collaborative care with a primary care provider is a must, not an option, for every patient, because studies indicate that without collaborative care, patients receive inadequate primary care.16 Providing rapid access to standard medical care is the single most critical step for the prevention or amelioration of physical disorders in our psychiatric patients, concurrently with stabilizing their ailing brains and minds. If we focus only on treating psychopathology, then we will win the battle against mental illness, but lose the war of life and death.

1. Azad MC, Shoesmith WD, Al Mamun M, et al. Cardiovascular diseases among patients with schizophrenia. Asian J Psychiatr. 2016;19:28-36.

2. Sørensen HJ, Nielsen PR, Benros ME, et al. Somatic diseases and conditions before the first diagnosis of schizophrenia: a nationwide population-based cohort study in more than 900 000 individuals. Schizophr Bull. 2015;41(2):513-521.

3. Scott KM, Lim C, Al-Hamzawi A, et al. Association of mental disorders with subsequent chronic physical conditions: world mental health surveys from 17 countries. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73(2):150-158.

4. Olfson M, Gerhard T, Huang C, et al. Premature mortality among adults with schizophrenia in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(12):1172-1181.

5. Suetani S, Whiteford HA, McGrath JJ. An urgent call to address the deadly consequences of serious mental disorders. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(12):1166-1167.

6. Jayatilleke N, Hayes RD, Chang CK, et al. Acute general hospital admissions in people with serious mental illness [published online February 28, 2018]. Psychol Med. 2018;1-8.

7. Schoenbaum M, Sutherland JM, Chappel A, et al. Twelve-month health care use and mortality in commercially insured young people with incident psychosis in the United States. Schizophr Bull. 2017;43(6):1262-1272.

8. Taipale H, Mittendorfer-Rutz E, Alexanderson K, et al. Antipsychotics and mortality in a nationwide cohort of 29,823 patients with schizophrenia [published online December 20, 2017]. Schizophr Res. pii: S0920-9964(17)30762-4. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2017.12.010.

9. Pillinger T, Beck K, Gobjila C, et al. Impaired glucose homeostasis in first-episode schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(3):261-269.

10. Dieset I, Andreassen OA, Haukvik UK. Somatic comorbidity in schizophrenia: some possible biological mechanisms across the life span. Schizophr Bull. 2016;42(6):1316-1319.

11. Carney R, Cotter J, Bradshaw T, et al. Cardiometabolic risk factors in young people at ultra-high risk for psychosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Res. 2016;170(2-3):290-300.

12. Tsai KY, Lee CC, Chou YM, et al. The incidence and relative risk of stroke in patients with schizophrenia: a five-year follow-up study. Schizophr Res. 2012;138(1):41-47.

13. Li M, Fan YL, Tang ZY, et al. Schizophrenia and risk of stroke: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. Int J Cardiol. 2014;173(3):588-590.

14. Halaris A. Inflammation-associated co-morbidity between depression and cardiovascular disease. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2017;31:45-70.

15. Nemeroff CB, Musselman DL. Are platelets the link between depression and ischemic heart disease? Am Heart J. 2000;140(suppl 4):57-62.

16. Nasrallah HA, Meyer JM, Goff DC, et al. Low rates of treatment for hypertension, dyslipidemia and diabetes in schizophrenia: data from the CATIE schizophrenia trial sample at baseline. Schizophr Res. 2006;86(1-3):15-22.

1. Azad MC, Shoesmith WD, Al Mamun M, et al. Cardiovascular diseases among patients with schizophrenia. Asian J Psychiatr. 2016;19:28-36.

2. Sørensen HJ, Nielsen PR, Benros ME, et al. Somatic diseases and conditions before the first diagnosis of schizophrenia: a nationwide population-based cohort study in more than 900 000 individuals. Schizophr Bull. 2015;41(2):513-521.

3. Scott KM, Lim C, Al-Hamzawi A, et al. Association of mental disorders with subsequent chronic physical conditions: world mental health surveys from 17 countries. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73(2):150-158.

4. Olfson M, Gerhard T, Huang C, et al. Premature mortality among adults with schizophrenia in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(12):1172-1181.

5. Suetani S, Whiteford HA, McGrath JJ. An urgent call to address the deadly consequences of serious mental disorders. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(12):1166-1167.

6. Jayatilleke N, Hayes RD, Chang CK, et al. Acute general hospital admissions in people with serious mental illness [published online February 28, 2018]. Psychol Med. 2018;1-8.

7. Schoenbaum M, Sutherland JM, Chappel A, et al. Twelve-month health care use and mortality in commercially insured young people with incident psychosis in the United States. Schizophr Bull. 2017;43(6):1262-1272.

8. Taipale H, Mittendorfer-Rutz E, Alexanderson K, et al. Antipsychotics and mortality in a nationwide cohort of 29,823 patients with schizophrenia [published online December 20, 2017]. Schizophr Res. pii: S0920-9964(17)30762-4. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2017.12.010.

9. Pillinger T, Beck K, Gobjila C, et al. Impaired glucose homeostasis in first-episode schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(3):261-269.

10. Dieset I, Andreassen OA, Haukvik UK. Somatic comorbidity in schizophrenia: some possible biological mechanisms across the life span. Schizophr Bull. 2016;42(6):1316-1319.

11. Carney R, Cotter J, Bradshaw T, et al. Cardiometabolic risk factors in young people at ultra-high risk for psychosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Res. 2016;170(2-3):290-300.

12. Tsai KY, Lee CC, Chou YM, et al. The incidence and relative risk of stroke in patients with schizophrenia: a five-year follow-up study. Schizophr Res. 2012;138(1):41-47.

13. Li M, Fan YL, Tang ZY, et al. Schizophrenia and risk of stroke: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. Int J Cardiol. 2014;173(3):588-590.

14. Halaris A. Inflammation-associated co-morbidity between depression and cardiovascular disease. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2017;31:45-70.

15. Nemeroff CB, Musselman DL. Are platelets the link between depression and ischemic heart disease? Am Heart J. 2000;140(suppl 4):57-62.

16. Nasrallah HA, Meyer JM, Goff DC, et al. Low rates of treatment for hypertension, dyslipidemia and diabetes in schizophrenia: data from the CATIE schizophrenia trial sample at baseline. Schizophr Res. 2006;86(1-3):15-22.

How precision psychiatry helped my patient; Ketamine: The next ‘opioid crisis’?

How precision psychiatry helped my patient

I applaud Dr. Nasrallah’s editorial “The dawn of precision psychiatry” (From the Editor,

Ms. G, age 14, presented with periodic emotional “meltdowns,” which would occur in any setting, and I determined that they were precipitated by a high glycemic intake. By carefully controlling her glycemic intake and starting her on caprylic acid (a medium-chain triglyceride, which was used to maintain a ketotic state), 1 tablespoon 3 times daily, we were able to reduce the frequency of her episodes by 80% to 90%. Using data from commercially available DNA testing, I determined that she had single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in an alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase gene, which is primarily located in the prefrontal cortex (PFC), and whose function is supported by thiamine and impaired by high glycemic intake.1 After adding oral thiamine hydrochloride, 100 mg twice a day, and correcting other abnormalities (eg, she was hypothyroid), her episodes are now rare. She is functioning well, has been getting high grades, and recently wrote a 40-page short story.

Once she improved, she was able to describe having a partial seizure, with a rising sensation, which often improves with ketosis. Clearly, disruption of her PFC energetics due to the SNPs described above contributed to the disinhibition of the temporal lobe structures. Furthermore, she has an APOE3/4 status, which puts her at risk for Alzheimer’s disease. Her mother was educated about the importance of good health habits, which is personalized and preventative medicine.

Robert Hedaya, MD, DLFAPA

Clinical Professor

MedStar Georgetown University Hospital

Washington, DC

Faculty

Institute for Functional Medicine

Gig Harbor, Washington, DC

Founder

National Center for Whole Psychiatry

Rockville, Maryland

Reference

1. Tretter L, Adam-Vizi V. Alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase: a target and generator of oxidative stress. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2005;360(1464):2335-2345.

Dr. Nasrallah responds

My thanks to Dr. Hedaya for his letter and for providing an excellent example of precision psychiatry. His brief case vignette brings it to life! I commend him for practicing on the cutting-edge of psychiatry’s scientific frontier.

Continue to: Ketamine: The next 'opioid crisis'?

Ketamine: The next ‘opioid crisis’?

The chief of the FDA, Scott Gottlieb, MD, recently discussed the

There are many similarities between the use of opioids to treat pain and the potential use of ketamine to treat suicidality. Physical and mental pain are subjective, qualitative, and difficult to quantify, which makes it difficult to develop accurate measurements of symptom severity. Chronic physical pain and suicidality are not illnesses, but symptoms of myriad types of pathologies with differing etiologies and treatment options.5 Due to the ambiguous and subjective experience of physical and mental pain, we tend to lump them together as 1 pathological category without understanding pathophysiologic differences. The most commonly reported types of pain include low back pain, migraine/headache, neck pain, and facial pain.6 However, each of these pain types would likely have a different pathophysiology and treatment. Likewise, suicide can be associated with various psychiatric conditions,7 and suicidality resulting from these conditions may require a different etiology and treatment.

We already know that both opioids and ketamine are addictive. For example, there is a report of a nurse stealing a hospital’s supply of ketamine and self-treating for depression, which led to an inpatient detox admission after she developed toxicity and addiction.8 Some ketamine research supports its safe use, but it may be biased due to conflicts of interest. For example, several authors of a recent study proclaiming the effectiveness of a single dose of ketamine in treating suicidal ideation

Warnings stating how both opioid and ketamine should be used were published years ago but have since been ignored. For example, a 1977 article advocated that opioids should only be used for a “short duration and limited to patients with acute diseases or inoperable or metastatic cancer who require long-term relief.”10 The rationale for this distinction was foretelling of the current opioid epidemic: “Continued and prolonged use of narcotics in patients with chronic benign pain is not recommended because of serious behavioral consequences, the development of tolerance, and addiction liability. Long-term use of analgesic drugs in chronic pain usually produces negative behavioral complications that are more difficult to manage than the pain it was desired to eliminate.”10 We knew better then.

The earliest report of ketamine dependency I could find was published in 1987, which predates its classification as a controlled substance.11 More recently, ketamine dependency has been associated with adverse effects that are similar to “not only cocaine and amphetamine but also with opiates, alcohol and cannabis, as well as the psychological attractions of its distinctive psychedelic properties.”12 We should consider ourselves warned.

Michael Shapiro, MD

Assistant Professor

Department of Psychiatry

University of Florida

Gainesville, Florida

References

1. Jayne O’Donnell. FDA chief supports opioid prescription limits, regrets agency’s prior inaction. USA TODAY. https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/politics/2017/10/23/fda-chief-supports-opioid-prescription-limits-regrets-agencys-prior-inaction/774007001. Published October 23, 2017. Accessed January 25, 2018.

2. Bill Whitaker. Ex-DEA agent: opioid crisis fueled by drug industry and Congress. CBS News. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/ex-dea-agent-opioid-crisis-fueled-by-drug-industry-and-congress. Published October 15, 2017. Accessed January 25, 2018.

3. Drug Enforcement Administration. Diversion of Control Division. Ketamine. https://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/drug_chem_info/ketamine.pdf. Published August 2013. Accessed January 25, 2018.

4. Bell RF. Ketamine for chronic noncancer pain: concerns regarding toxicity. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2012;6(2):183-187.

5. Barzilay S, Apter A. Psychological models of suicide. Arch Suicide Res. 2014;18(4):295-312.

6. American Academy of Pain Medicine. AAPM facts and figures on pain. http://www.painmed.org/patientcenter/facts_on_pain.aspx.

7. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

8. Bonnet U. Long-term ketamine self-injections in major depressive disorder: focus on tolerance in ketamine’s antidepressant response and the development of ketamine addiction. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2015;47(4):276-85.

9. Wilkinson ST, Ballard ED, Bloch MH, et al. The effect of a single dose of intravenous ketamine on suicidal ideation: a systematic review and individual participant data meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry 2017. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2017.17040472

10. Halpern LM. Analgesic drugs in the management of pain. Arch Surg. 1977;112(7):861-869.

11. Kamaya H, Krishna PR. Anesthesiology. 1987;67(5):861-862.

12. Jansen KL, Darracot-Cankovic R. The nonmedical use of ketamine, part two: a review of problem use and dependence. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2001;33(2):151-158.

How precision psychiatry helped my patient

I applaud Dr. Nasrallah’s editorial “The dawn of precision psychiatry” (From the Editor,

Ms. G, age 14, presented with periodic emotional “meltdowns,” which would occur in any setting, and I determined that they were precipitated by a high glycemic intake. By carefully controlling her glycemic intake and starting her on caprylic acid (a medium-chain triglyceride, which was used to maintain a ketotic state), 1 tablespoon 3 times daily, we were able to reduce the frequency of her episodes by 80% to 90%. Using data from commercially available DNA testing, I determined that she had single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in an alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase gene, which is primarily located in the prefrontal cortex (PFC), and whose function is supported by thiamine and impaired by high glycemic intake.1 After adding oral thiamine hydrochloride, 100 mg twice a day, and correcting other abnormalities (eg, she was hypothyroid), her episodes are now rare. She is functioning well, has been getting high grades, and recently wrote a 40-page short story.

Once she improved, she was able to describe having a partial seizure, with a rising sensation, which often improves with ketosis. Clearly, disruption of her PFC energetics due to the SNPs described above contributed to the disinhibition of the temporal lobe structures. Furthermore, she has an APOE3/4 status, which puts her at risk for Alzheimer’s disease. Her mother was educated about the importance of good health habits, which is personalized and preventative medicine.

Robert Hedaya, MD, DLFAPA

Clinical Professor

MedStar Georgetown University Hospital

Washington, DC

Faculty

Institute for Functional Medicine

Gig Harbor, Washington, DC

Founder

National Center for Whole Psychiatry

Rockville, Maryland

Reference

1. Tretter L, Adam-Vizi V. Alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase: a target and generator of oxidative stress. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2005;360(1464):2335-2345.

Dr. Nasrallah responds

My thanks to Dr. Hedaya for his letter and for providing an excellent example of precision psychiatry. His brief case vignette brings it to life! I commend him for practicing on the cutting-edge of psychiatry’s scientific frontier.

Continue to: Ketamine: The next 'opioid crisis'?

Ketamine: The next ‘opioid crisis’?

The chief of the FDA, Scott Gottlieb, MD, recently discussed the

There are many similarities between the use of opioids to treat pain and the potential use of ketamine to treat suicidality. Physical and mental pain are subjective, qualitative, and difficult to quantify, which makes it difficult to develop accurate measurements of symptom severity. Chronic physical pain and suicidality are not illnesses, but symptoms of myriad types of pathologies with differing etiologies and treatment options.5 Due to the ambiguous and subjective experience of physical and mental pain, we tend to lump them together as 1 pathological category without understanding pathophysiologic differences. The most commonly reported types of pain include low back pain, migraine/headache, neck pain, and facial pain.6 However, each of these pain types would likely have a different pathophysiology and treatment. Likewise, suicide can be associated with various psychiatric conditions,7 and suicidality resulting from these conditions may require a different etiology and treatment.

We already know that both opioids and ketamine are addictive. For example, there is a report of a nurse stealing a hospital’s supply of ketamine and self-treating for depression, which led to an inpatient detox admission after she developed toxicity and addiction.8 Some ketamine research supports its safe use, but it may be biased due to conflicts of interest. For example, several authors of a recent study proclaiming the effectiveness of a single dose of ketamine in treating suicidal ideation

Warnings stating how both opioid and ketamine should be used were published years ago but have since been ignored. For example, a 1977 article advocated that opioids should only be used for a “short duration and limited to patients with acute diseases or inoperable or metastatic cancer who require long-term relief.”10 The rationale for this distinction was foretelling of the current opioid epidemic: “Continued and prolonged use of narcotics in patients with chronic benign pain is not recommended because of serious behavioral consequences, the development of tolerance, and addiction liability. Long-term use of analgesic drugs in chronic pain usually produces negative behavioral complications that are more difficult to manage than the pain it was desired to eliminate.”10 We knew better then.

The earliest report of ketamine dependency I could find was published in 1987, which predates its classification as a controlled substance.11 More recently, ketamine dependency has been associated with adverse effects that are similar to “not only cocaine and amphetamine but also with opiates, alcohol and cannabis, as well as the psychological attractions of its distinctive psychedelic properties.”12 We should consider ourselves warned.

Michael Shapiro, MD

Assistant Professor

Department of Psychiatry

University of Florida

Gainesville, Florida

References

1. Jayne O’Donnell. FDA chief supports opioid prescription limits, regrets agency’s prior inaction. USA TODAY. https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/politics/2017/10/23/fda-chief-supports-opioid-prescription-limits-regrets-agencys-prior-inaction/774007001. Published October 23, 2017. Accessed January 25, 2018.

2. Bill Whitaker. Ex-DEA agent: opioid crisis fueled by drug industry and Congress. CBS News. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/ex-dea-agent-opioid-crisis-fueled-by-drug-industry-and-congress. Published October 15, 2017. Accessed January 25, 2018.

3. Drug Enforcement Administration. Diversion of Control Division. Ketamine. https://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/drug_chem_info/ketamine.pdf. Published August 2013. Accessed January 25, 2018.

4. Bell RF. Ketamine for chronic noncancer pain: concerns regarding toxicity. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2012;6(2):183-187.

5. Barzilay S, Apter A. Psychological models of suicide. Arch Suicide Res. 2014;18(4):295-312.

6. American Academy of Pain Medicine. AAPM facts and figures on pain. http://www.painmed.org/patientcenter/facts_on_pain.aspx.

7. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

8. Bonnet U. Long-term ketamine self-injections in major depressive disorder: focus on tolerance in ketamine’s antidepressant response and the development of ketamine addiction. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2015;47(4):276-85.

9. Wilkinson ST, Ballard ED, Bloch MH, et al. The effect of a single dose of intravenous ketamine on suicidal ideation: a systematic review and individual participant data meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry 2017. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2017.17040472

10. Halpern LM. Analgesic drugs in the management of pain. Arch Surg. 1977;112(7):861-869.

11. Kamaya H, Krishna PR. Anesthesiology. 1987;67(5):861-862.

12. Jansen KL, Darracot-Cankovic R. The nonmedical use of ketamine, part two: a review of problem use and dependence. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2001;33(2):151-158.

How precision psychiatry helped my patient

I applaud Dr. Nasrallah’s editorial “The dawn of precision psychiatry” (From the Editor,

Ms. G, age 14, presented with periodic emotional “meltdowns,” which would occur in any setting, and I determined that they were precipitated by a high glycemic intake. By carefully controlling her glycemic intake and starting her on caprylic acid (a medium-chain triglyceride, which was used to maintain a ketotic state), 1 tablespoon 3 times daily, we were able to reduce the frequency of her episodes by 80% to 90%. Using data from commercially available DNA testing, I determined that she had single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in an alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase gene, which is primarily located in the prefrontal cortex (PFC), and whose function is supported by thiamine and impaired by high glycemic intake.1 After adding oral thiamine hydrochloride, 100 mg twice a day, and correcting other abnormalities (eg, she was hypothyroid), her episodes are now rare. She is functioning well, has been getting high grades, and recently wrote a 40-page short story.

Once she improved, she was able to describe having a partial seizure, with a rising sensation, which often improves with ketosis. Clearly, disruption of her PFC energetics due to the SNPs described above contributed to the disinhibition of the temporal lobe structures. Furthermore, she has an APOE3/4 status, which puts her at risk for Alzheimer’s disease. Her mother was educated about the importance of good health habits, which is personalized and preventative medicine.

Robert Hedaya, MD, DLFAPA

Clinical Professor

MedStar Georgetown University Hospital

Washington, DC

Faculty

Institute for Functional Medicine

Gig Harbor, Washington, DC

Founder

National Center for Whole Psychiatry

Rockville, Maryland

Reference

1. Tretter L, Adam-Vizi V. Alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase: a target and generator of oxidative stress. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2005;360(1464):2335-2345.

Dr. Nasrallah responds

My thanks to Dr. Hedaya for his letter and for providing an excellent example of precision psychiatry. His brief case vignette brings it to life! I commend him for practicing on the cutting-edge of psychiatry’s scientific frontier.

Continue to: Ketamine: The next 'opioid crisis'?

Ketamine: The next ‘opioid crisis’?

The chief of the FDA, Scott Gottlieb, MD, recently discussed the

There are many similarities between the use of opioids to treat pain and the potential use of ketamine to treat suicidality. Physical and mental pain are subjective, qualitative, and difficult to quantify, which makes it difficult to develop accurate measurements of symptom severity. Chronic physical pain and suicidality are not illnesses, but symptoms of myriad types of pathologies with differing etiologies and treatment options.5 Due to the ambiguous and subjective experience of physical and mental pain, we tend to lump them together as 1 pathological category without understanding pathophysiologic differences. The most commonly reported types of pain include low back pain, migraine/headache, neck pain, and facial pain.6 However, each of these pain types would likely have a different pathophysiology and treatment. Likewise, suicide can be associated with various psychiatric conditions,7 and suicidality resulting from these conditions may require a different etiology and treatment.

We already know that both opioids and ketamine are addictive. For example, there is a report of a nurse stealing a hospital’s supply of ketamine and self-treating for depression, which led to an inpatient detox admission after she developed toxicity and addiction.8 Some ketamine research supports its safe use, but it may be biased due to conflicts of interest. For example, several authors of a recent study proclaiming the effectiveness of a single dose of ketamine in treating suicidal ideation

Warnings stating how both opioid and ketamine should be used were published years ago but have since been ignored. For example, a 1977 article advocated that opioids should only be used for a “short duration and limited to patients with acute diseases or inoperable or metastatic cancer who require long-term relief.”10 The rationale for this distinction was foretelling of the current opioid epidemic: “Continued and prolonged use of narcotics in patients with chronic benign pain is not recommended because of serious behavioral consequences, the development of tolerance, and addiction liability. Long-term use of analgesic drugs in chronic pain usually produces negative behavioral complications that are more difficult to manage than the pain it was desired to eliminate.”10 We knew better then.

The earliest report of ketamine dependency I could find was published in 1987, which predates its classification as a controlled substance.11 More recently, ketamine dependency has been associated with adverse effects that are similar to “not only cocaine and amphetamine but also with opiates, alcohol and cannabis, as well as the psychological attractions of its distinctive psychedelic properties.”12 We should consider ourselves warned.

Michael Shapiro, MD

Assistant Professor

Department of Psychiatry

University of Florida

Gainesville, Florida

References

1. Jayne O’Donnell. FDA chief supports opioid prescription limits, regrets agency’s prior inaction. USA TODAY. https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/politics/2017/10/23/fda-chief-supports-opioid-prescription-limits-regrets-agencys-prior-inaction/774007001. Published October 23, 2017. Accessed January 25, 2018.

2. Bill Whitaker. Ex-DEA agent: opioid crisis fueled by drug industry and Congress. CBS News. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/ex-dea-agent-opioid-crisis-fueled-by-drug-industry-and-congress. Published October 15, 2017. Accessed January 25, 2018.

3. Drug Enforcement Administration. Diversion of Control Division. Ketamine. https://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/drug_chem_info/ketamine.pdf. Published August 2013. Accessed January 25, 2018.

4. Bell RF. Ketamine for chronic noncancer pain: concerns regarding toxicity. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2012;6(2):183-187.

5. Barzilay S, Apter A. Psychological models of suicide. Arch Suicide Res. 2014;18(4):295-312.

6. American Academy of Pain Medicine. AAPM facts and figures on pain. http://www.painmed.org/patientcenter/facts_on_pain.aspx.

7. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

8. Bonnet U. Long-term ketamine self-injections in major depressive disorder: focus on tolerance in ketamine’s antidepressant response and the development of ketamine addiction. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2015;47(4):276-85.

9. Wilkinson ST, Ballard ED, Bloch MH, et al. The effect of a single dose of intravenous ketamine on suicidal ideation: a systematic review and individual participant data meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry 2017. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2017.17040472

10. Halpern LM. Analgesic drugs in the management of pain. Arch Surg. 1977;112(7):861-869.

11. Kamaya H, Krishna PR. Anesthesiology. 1987;67(5):861-862.

12. Jansen KL, Darracot-Cankovic R. The nonmedical use of ketamine, part two: a review of problem use and dependence. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2001;33(2):151-158.

A 10-year-old boy with ‘voices in my head’: Is it a psychotic disorder?

CASE Auditory hallucinations?

M, age 10, has had multiple visits to the pediatric emergency department (PED) with the chief concern of excessive urinary frequency. At each visit, the medical workup has been negative and he was discharged home. After a few months, M’s parents bring their son back to the PED because he reports hearing “voices in my head” and “feeling tense and scared.” When these feelings become too overwhelming, M stops eating and experiences substantial fear and anxiety that require his mother’s repeated reassurances. M’s mother reports that 2 weeks before his most recent PED visit, he became increasingly anxious and disturbed, and said he was afraid most of the time, and worried about the safety of his family for no apparent reason.

The psychiatrist evaluates M in the PED and diagnoses him with unspecified schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorder based on his persistent report of auditory and tactile hallucinations, including hearing a voice of a man telling him he was going to choke on his food and feeling someone touch his arm to soothe him during his anxious moments. M does not meet criteria for acute inpatient hospitalization, and is discharged home with referral to follow-up at our child and adolescent psychiatry outpatient clinic.

On subsequent evaluation in our clinic, M reports most of the same about his experience hearing “voices in my head” that repeatedly suggest “I might choke on my food and end up seriously ill in the hospital.” He started to hear the “voices” after he witnessed his sister choke while eating a few days earlier. He also mentions that the “voices” tell him “you have to use the restroom.” As a result, he uses the restroom several times before leaving for home and is frequently late for school. His parents accommodate his behavior—his mother allows him to use the bathroom multiple times, and his father overlooks the behavior as part of school anxiety.

At school, his teacher reports a concern for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) based on M’s continuous inattentiveness in class and dropping grades. He asks for bathroom breaks up to 15 times a day, which disrupts his class work.

These behaviors have led to a gradual 1-year decline in his overall functioning, including difficulty at school for requesting too many bathroom breaks; having to repeat the 3rd grade; and incurring multiple hospital visits for evaluation of his various complaints. M has become socially isolated and withdrawn from friends and family.

M’s developmental history is normal and his family history is negative for any psychiatric disorder. Medical history and physical examination are unremarkable. CT scan of his head is unremarkable, and all hematologic and biochemistry laboratory test values are within normal range.

[polldaddy:9971376]

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

Several factors may contribute to an increased chance of misdiagnosis of a psychiatric illness

On closer sequential evaluations with M and his family, we determined that the “voices” he was hearing were actually intrusive thoughts, and not hallucinations. M clarified this by saying that first he feels a “pressure”-like sensation in his head, followed by repeated intrusive thoughts of voiding his bladder that compel him to go to the restroom to try to urinate. He feels temporary relief after complying with the urge, even when he passes only a small amount of urine or just washes his hands. After a brief period of relief, this process repeats itself. Further, he was able to clarify his experience while eating food, where he first felt a “pressure”-like sensation in his head, followed by intrusive thoughts of choking that result in him not eating.

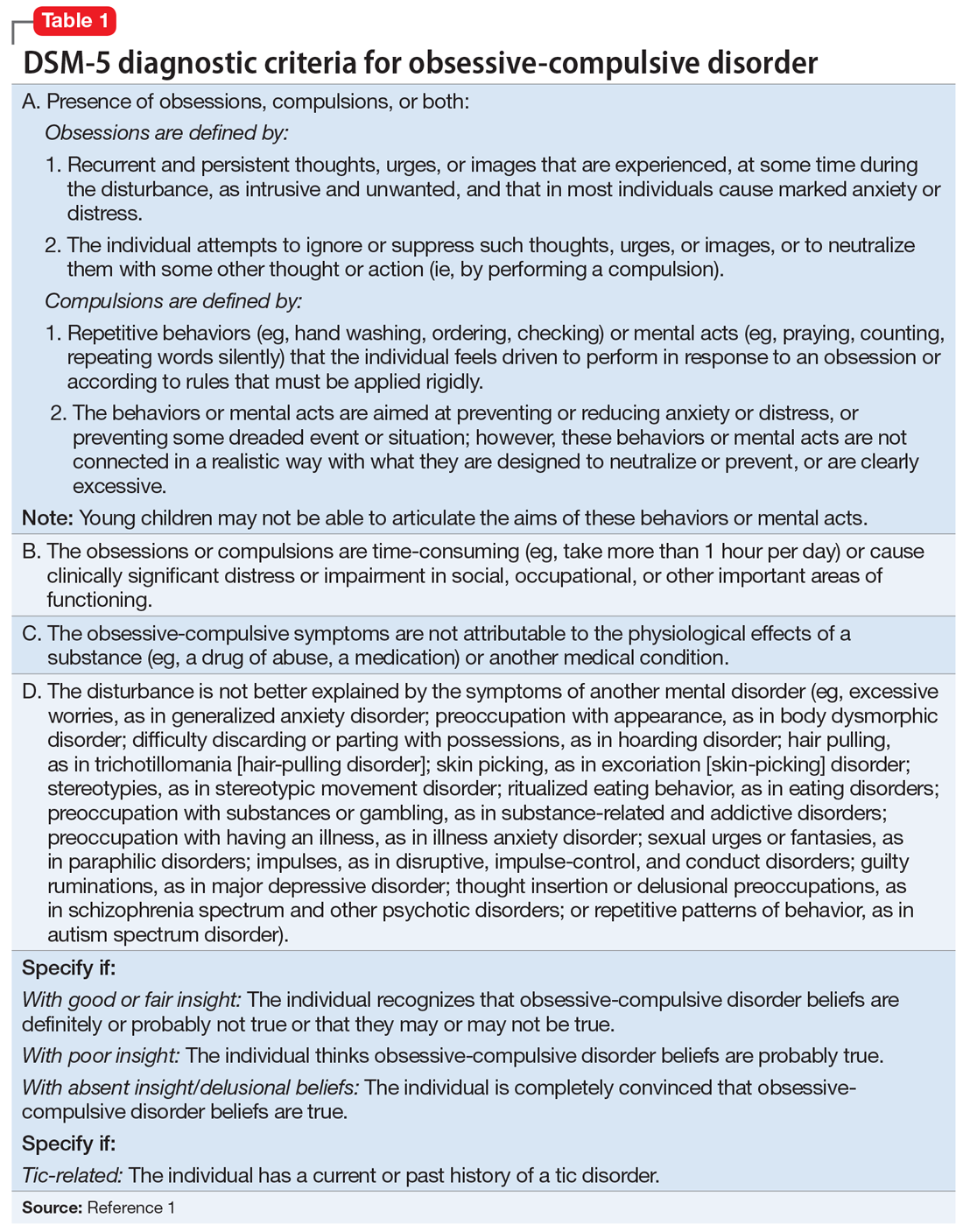

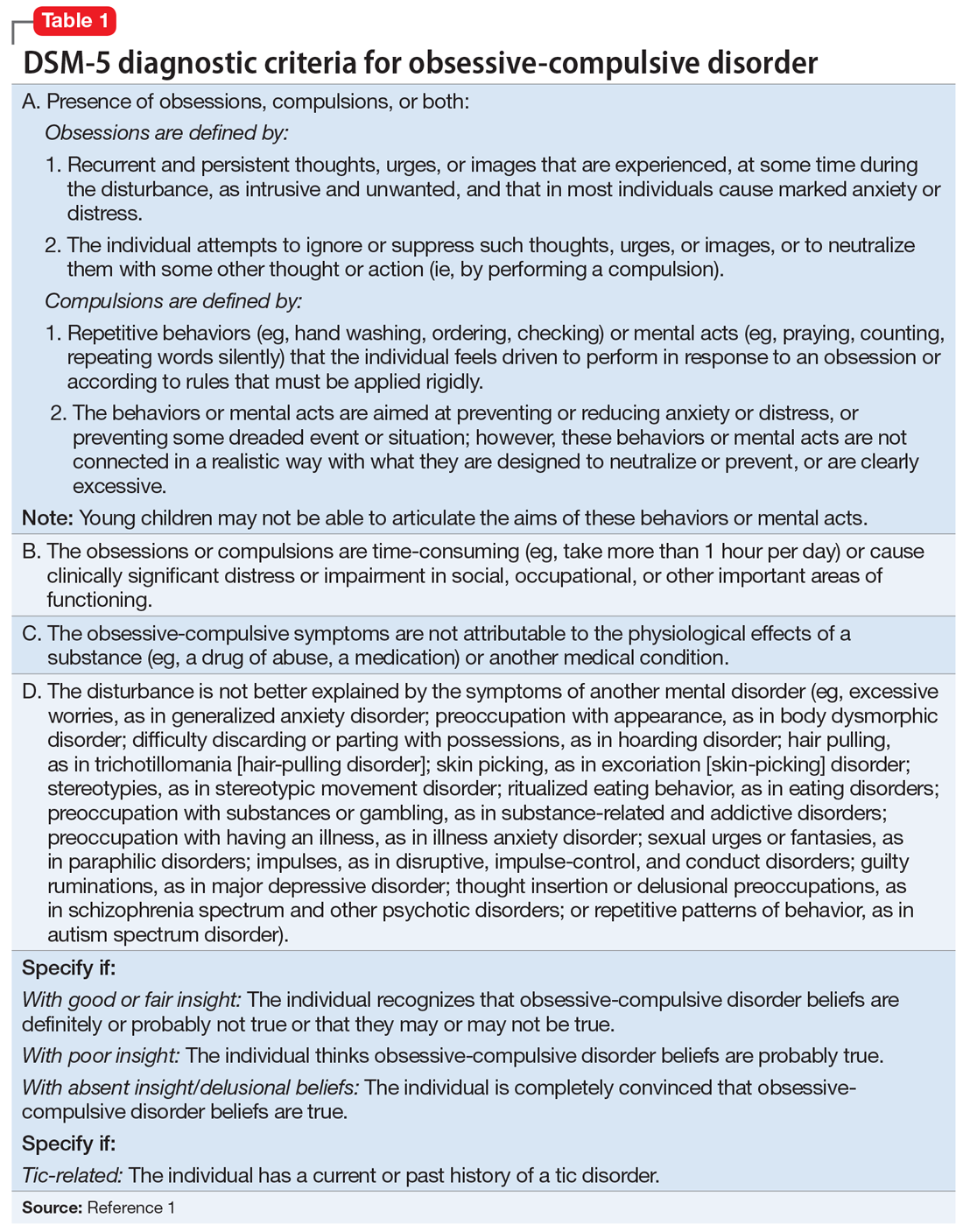

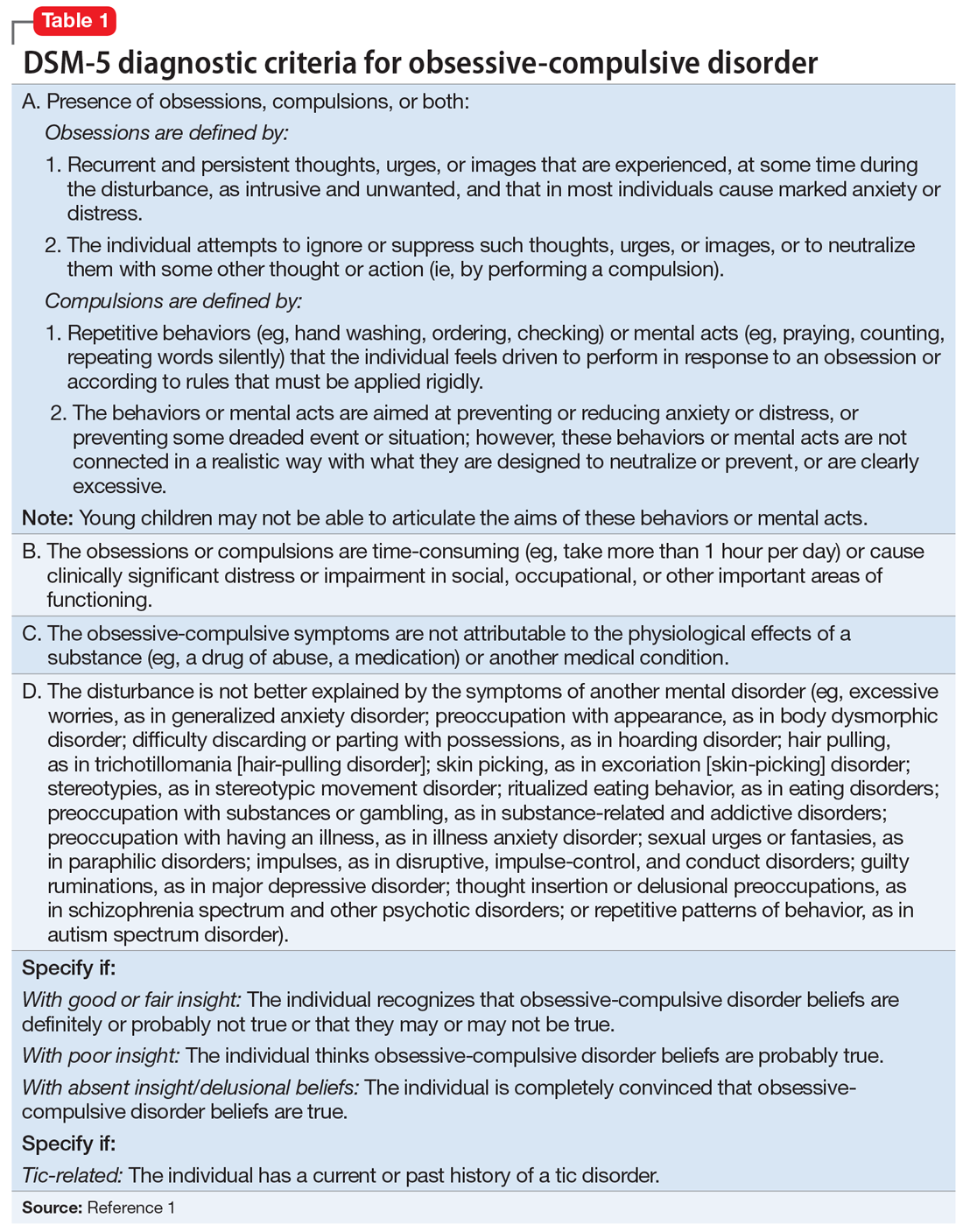

This led us to a more appropriate diagnosis of OCD (Table 11). The incidence of OCD has 2 peaks, with different gender distributions. The first peak occurs in childhood, with symptoms mostly arising between 7 and 12 years of age and affecting boys more often than girls. The second peak occurs in early adulthood, at a mean age of 21 years, with a slight female majority.2 However, OCD is often under recognized and undertreated, perhaps due to its extensive heterogeneity; symptom presentations and comorbidity patterns can vary noticeably between individual patients as well as age groups.

OCD is characterized by the presence of obsessions or compulsions that wax and wane in severity, are time-consuming (at least 1 hour per day), and cause subjective distress or interfere with life of the patient or the family. Adults with OCD recognize at some level that the obsessions and/or compulsions are excessive and unreasonable, although children are not required to have this insight to meet criteria for the diagnosis.1 Rating scales, such as the Children’s Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale, Dimensional Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale, and Family Accommodation Scale, are useful to obtain detailed information regarding OCD symptoms, tics, and other factors relevant to the diagnosis.

Continue to: M's symptomatology...

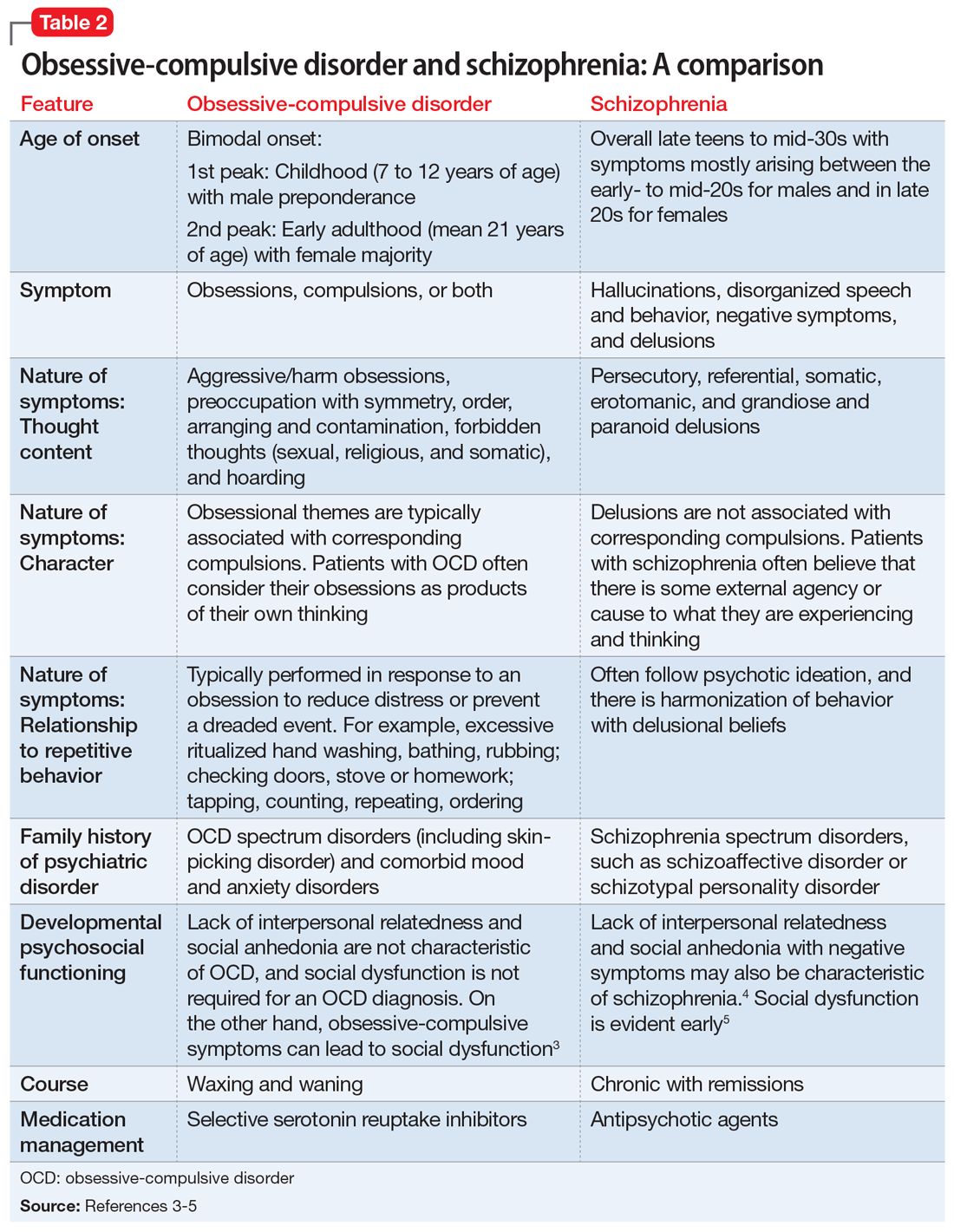

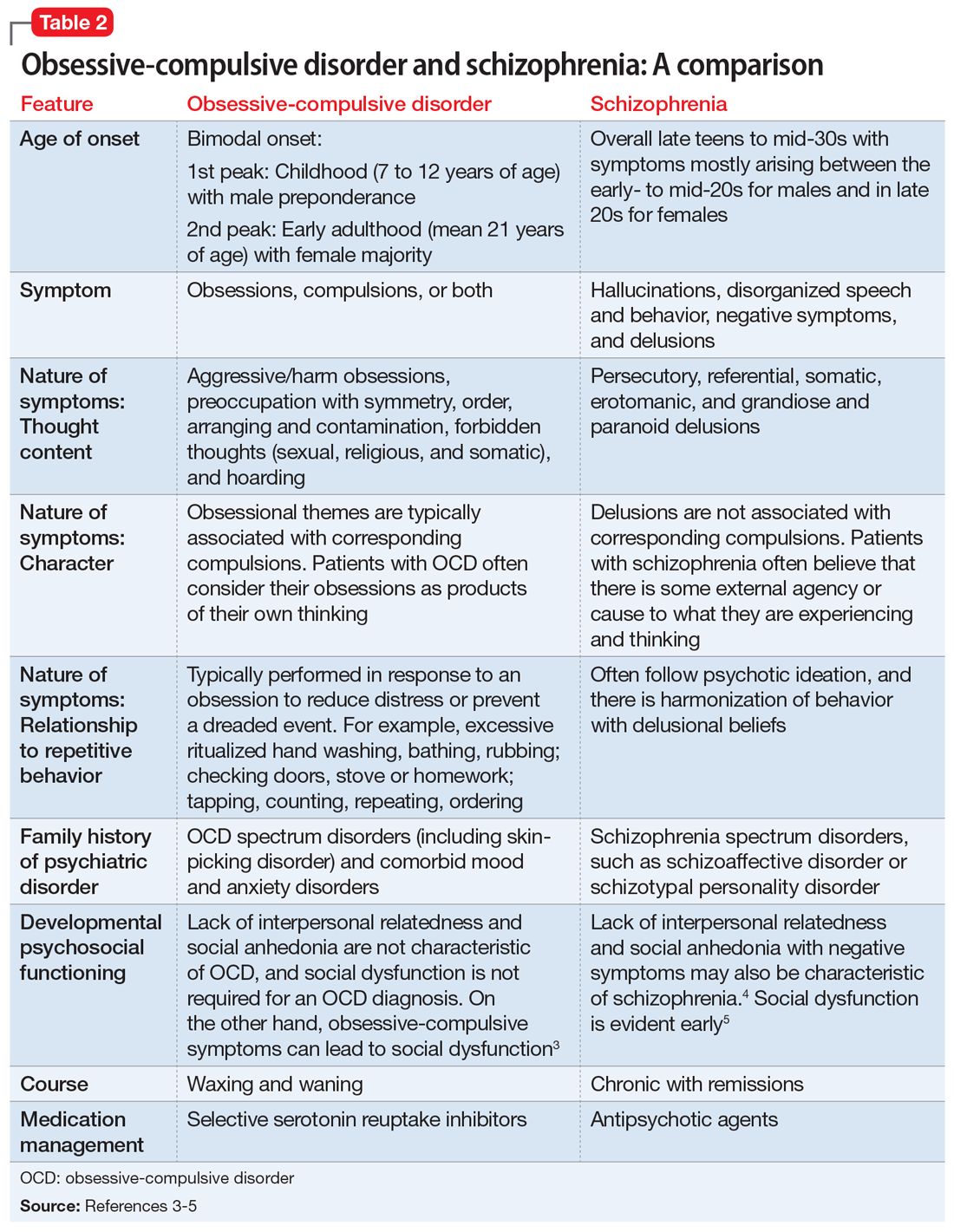

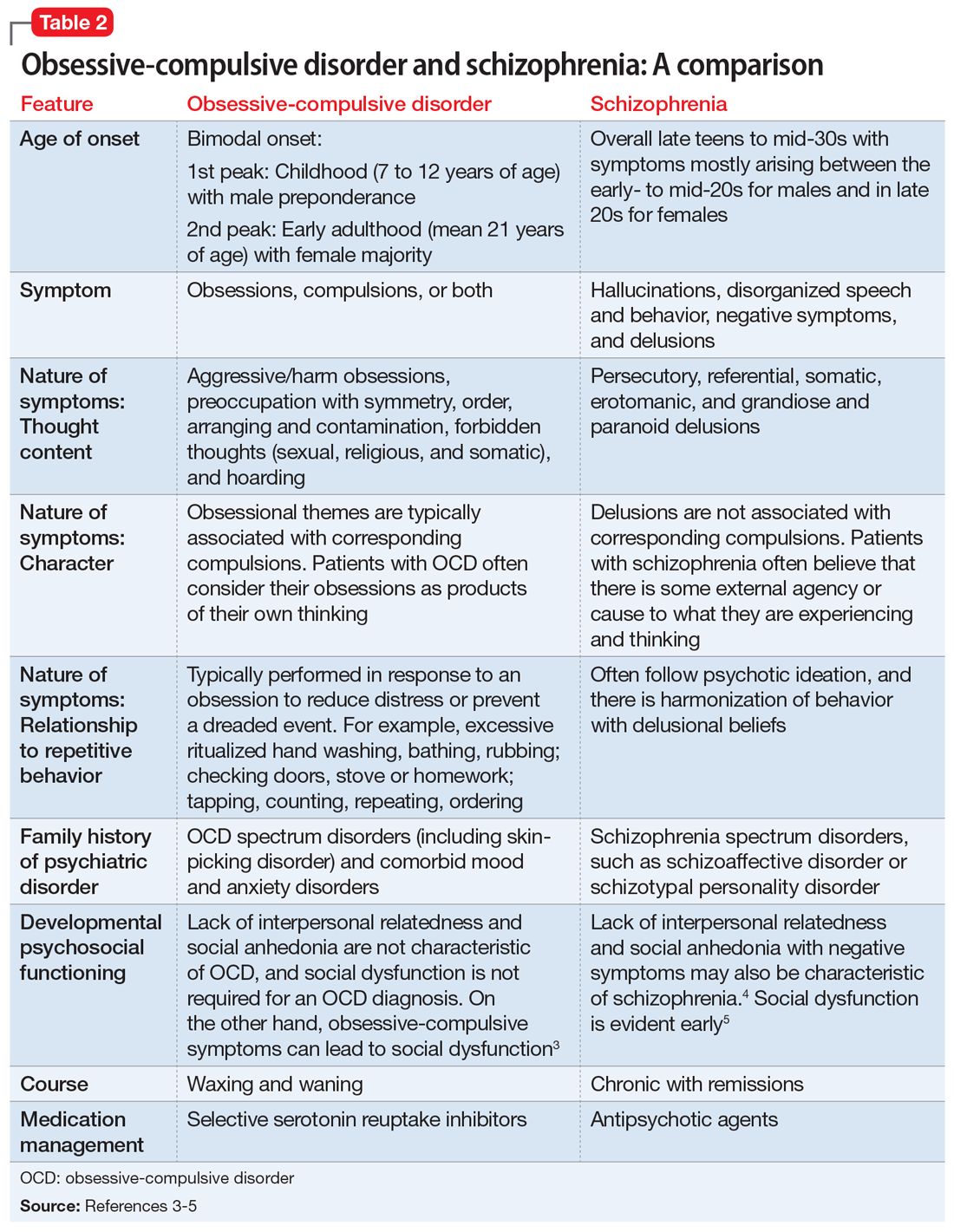

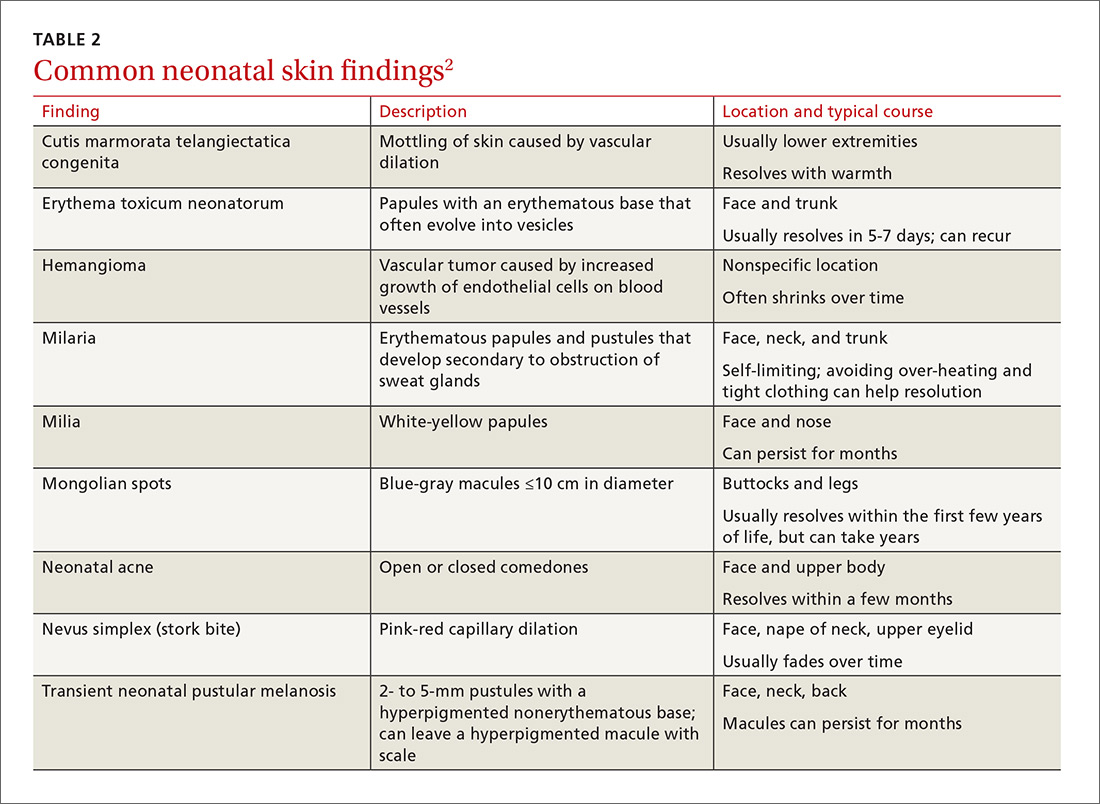

M’s symptomatology did not appear to be psychotic. He was screened for positive or negative symptoms of psychosis, which he and his family clearly denied. Moreover, M’s compulsions (going to the restroom) were typically performed in response to his obsessions (urge to void his bladder) to reduce his distress, which is different from schizophrenia, in which repetitive behaviors are performed in response to psychotic ideation, and not obsessions (Table 23-5).

M’s inattentiveness in the classroom was found to be related to his obsessions and compulsions, and not part of a symptom cluster characterizing ADHD. Teachers often interpret inattention and poor classroom performance as ADHD, but having detailed conversations with teachers often is helpful in understanding the nature of a child’s symptomology and making the appropriate diagnosis.

Establishing the correct clinical diagnosis is critical because it is the starting point in treatment. First-line medication for one condition may exacerbate the symptoms of others. For example, in addition to having a large adverse-effect burden, antipsychotics can induce de novo obsessive–compulsive symptoms (OCS) or exacerbate preexisting OCS, and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) may exacerbate psychosis in schizo-obsessive patients with a history of impulsivity and aggressiveness.6 Similarly, stimulant medications for ADHD may exacerbate OCS and may even induce them on their own.7,8

[polldaddy:9971377]

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

Studies have reported an average of 2.5 years from the onset of OCD symptoms to diagnosis in the United States.9 A key reason for this delay, which is more frequently encountered in pediatric patients, is secrecy. Children often feel embarrassed about their symptoms and conceal them until the interference with their functioning becomes extremely disabling. In some cases, symptoms may closely resemble normal childhood routines. In fact, some repetitive behaviors may be normal in some developmental stages, and OCD could be conceptualized as a pathological condition with continuity of normal behaviors during different developmental periods.10

Also, symptoms may go unnoticed for quite some time as unsuspecting and well-intentioned parents and family members become overly involved in the child’s rituals (eg, allowing for increasing frequent prolonged bathroom breaks or frequent change of clothing, etc.). This well-established phenomenon, termed accommodation, is defined as participation of family members in a child’s OCD–related rituals.11 Especially when symptoms are mild or the child is functioning well, accommodation can make it difficult for parents to realize the presence or nature of a problem, as they might tend to minimize their child’s symptoms as representing a unique personality trait or a special “quirk.” Parents generally will seek treatment when their child’s symptoms become more impairing and begin to interfere with social functioning, school performance, or family functioning.

The clinical picture is further complicated by comorbidity. Approximately 60% to 80% of children and adolescents with OCD have ≥1 comorbid psychiatric disorders. Some of the most common include tic disorders, ADHD, anxiety disorders, and mood or eating disorders.9

[polldaddy:9971379]

Continue to: TREATMENT Combination therapy

TREATMENT Combination therapy

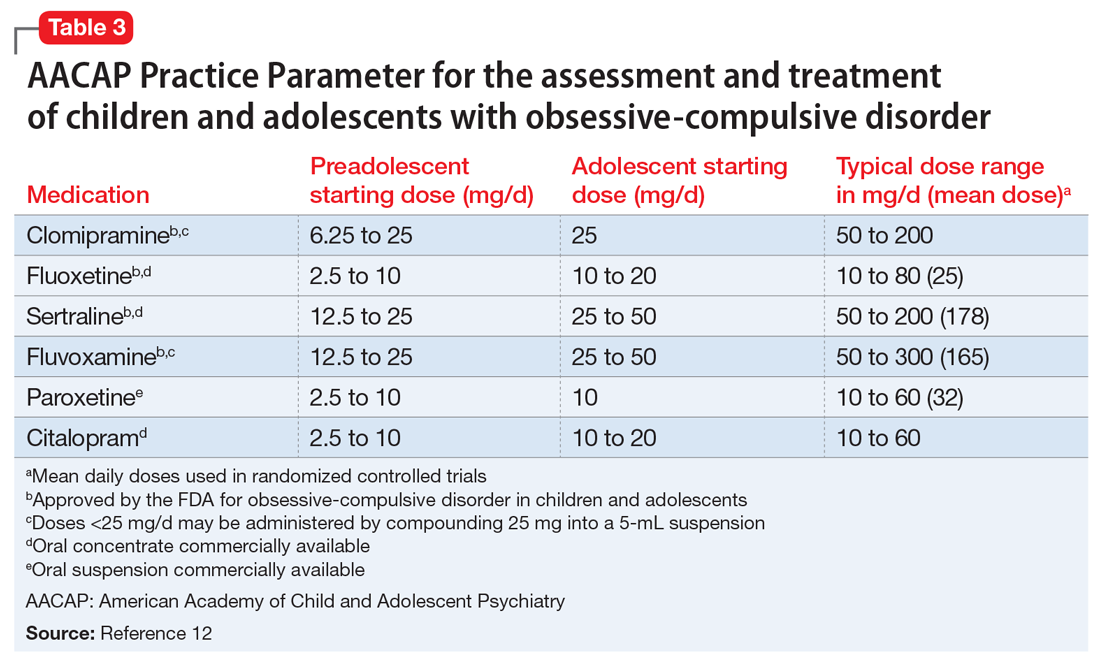

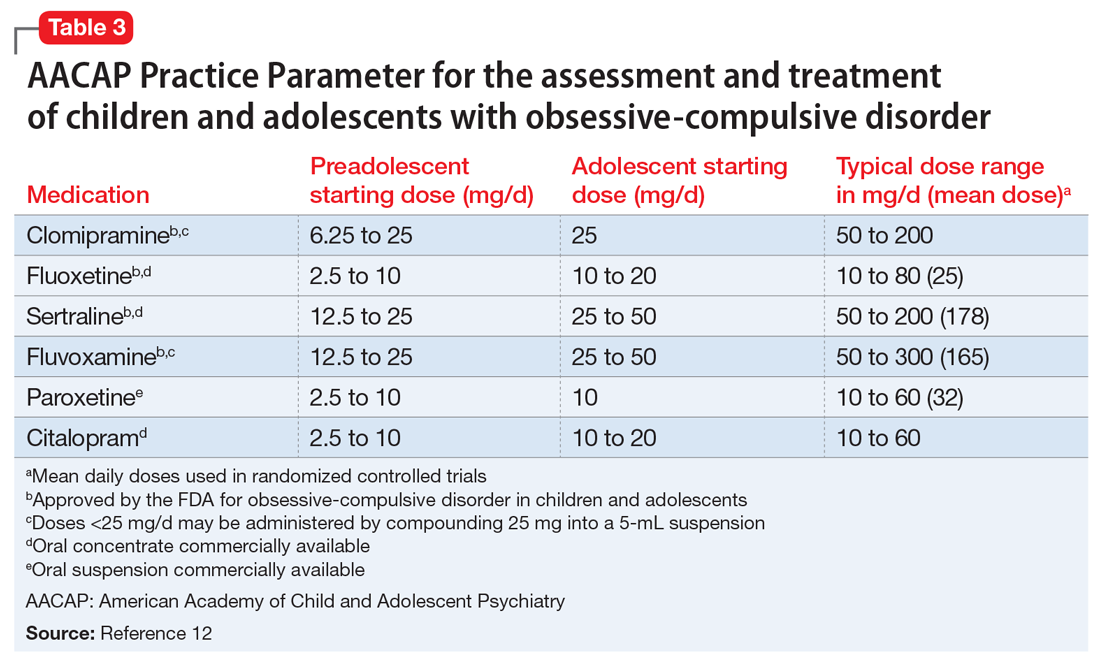

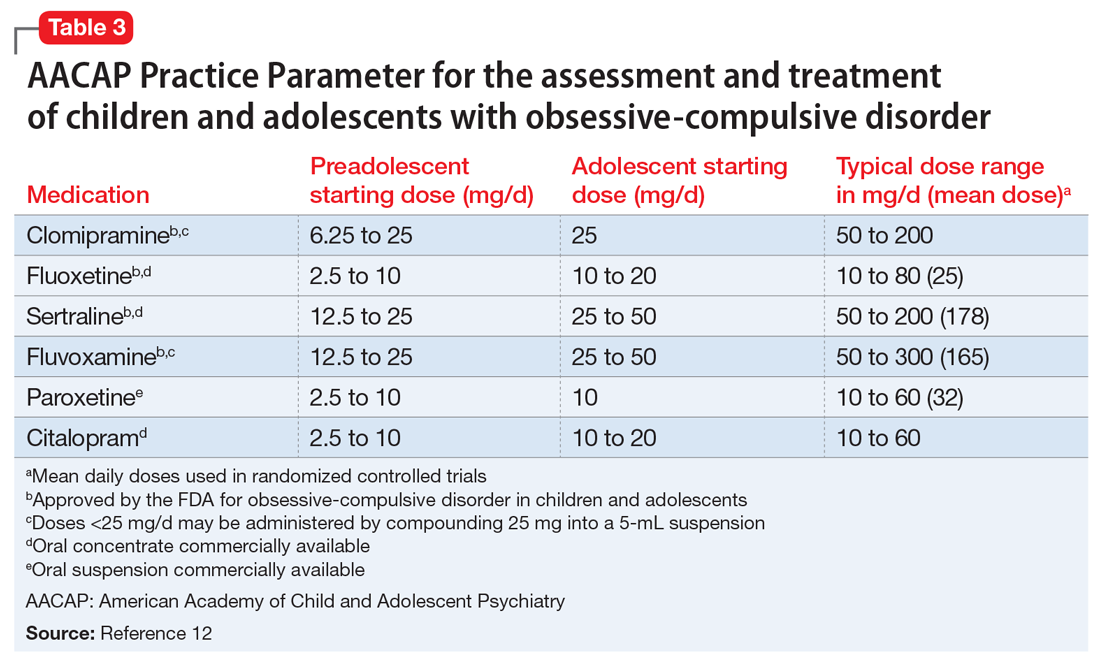

In keeping with American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry guidelines on treating OCD (Table 312), we start M on fluoxetine 10 mg/d. He also begins CBT. Fluoxetine is slowly titrated to 40 mg/d while M engages in learning and utilizing CBT techniques to manage his OCD.

The authors’ observations

The combination of CBT and medication has been suggested as the treatment of choice for moderate and severe OCD.12 The Pediatric OCD Treatment Study, a 5-year, 3-site outcome study designed to compare placebo, sertraline, CBT, and combined CBT and sertraline, concluded that the combined treatment (CBT plus sertraline) was more effective than CBT alone or sertraline alone.13 The effect sizes for the combined treatment, CBT alone, and sertraline alone were 1.4, 0.97, and 0.67, respectively. Remission rates for SSRIs alone are <33%.13,14

SSRIs are the first-line medication for OCD in children, adolescents, and adults (Table 312). Well-designed clinical trials have demonstrated the efficacy and safety of the SSRIs fluoxetine, sertraline, and fluvoxamine (alone or combined with CBT) in children and adolescents with OCD.13 Other SSRIs, such as citalopram, paroxetine, and escitalopram, also have demonstrated efficacy in children and adolescents with OCD, even though the FDA has not yet approved their use in pediatric patients.12 Despite a positive trial of paroxetine in pediatric OCD,12 there have been concerns related to its higher rates of treatment-emergent suicidality,15 lower likelihood of treatment response,16 and its particularly short half-life in pediatric patients.17

Clomipramine is a tricyclic antidepressant with serotonergic properties that is used alone or to boost the effect of an SSRI when there is a partial response. It should be introduced at a low dose in pediatric patients (before age 12) and closely monitored for anticholinergic and cardiac adverse effects. A systemic review and meta-analysis of early treatment responses of SSRIs and clomipramine in pediatric OCD indicated that the greatest benefits occurred early in treatment.18 Clomipramine was associated with a greater measured benefit compared with placebo than SSRIs; there was no evidence of a relationship between SSRI dosing and treatment effect, although data were limited. Adults and children with OCD demonstrated a similar degree and time course of response to SSRIs in OCD.18

Treatment should start with a low dose to reduce the risk of adverse effects with an adequate trial for 10 to 16 weeks at adequate doses. Most experts suggest that treatment should continue for at least 12 months after symptom resolution or stabilization, followed by a very gradual cessation.19

Continue to: OUTCOME Improvement in functioning

OUTCOME Improvement in functioning

After 12 months of combined CBT and fluoxetine, M’s global assessment of functioning (GAF) scale score improves from 35 to 80, indicating major improvement in overall functional level.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Uzoma Osuchukwu, MD, ex-fellow, Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, Harlem Hospital Center, New York, New York, for his assistance with this article.

Bottom Line

Obsessive-compulsive disorder may masquerade as a schizophrenia spectrum disorder, particularly in younger patients. Accurate differentiation is crucial because antipsychotics can induce de novo obsessive-compulsive symptoms (OCS) or exacerbate preexisting OCS, and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors may exacerbate psychosis in schizo-obsessive patients with a history of impulsivity and aggressiveness.

Related Resource

- Raveendranathan D, Shiva L, Sharma E, et al. Obsessive compulsive disorder masquerading as psychosis. Indian J Psychol Med. 2012;34(2):179-180.

Drug Brand Names

Citalopram • Celexa

Clomipramine • Anafranil

Escitalopram • Lexapro

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Fluvoxamine • Luvox

Paroxetine • Paxil

Sertraline • Zoloft

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Geller D, Biederman J, Jones J, et al. Is juvenile obsessive-compulsive disorder a developmental subtype of the disorder? A review of the pediatric literature. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry.1998;37(4):420-427.

3. Huppert JD, Simpson HB, Nissenson KJ, et al. Quality of life and functional impairment in obsessive-compulsive disorder: A comparison of patients with and without comorbidity, patients in remission, and healthy controls. Depress Anxiety. 2009;26(1):39-45.

4. Sobel W, Wolski R, Cancro R, et al. Interpersonal relatedness and paranoid schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry.1996;153(8):1084-1087.

5. Meares A. The diagnosis of prepsychotic schizophrenia. Lancet. 1959;1(7063):55-58.

6. Poyurovsky M, Weizman A, Weizman R. Obsessive-compulsive disorder in schizophrenia: Clinical characteristics and treatment. CNS Drugs. 2004;18(14):989-1010.

7. Kouris S. Methylphenidate-induced obsessive-compulsiveness. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998;37(2):135.

8. Woolley JB, Heyman I. Dexamphetamine for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(1):183.

9. Geller DA. Obsessive-compulsive and spectrum disorders in children and adolescents. Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2006;29(2):352-370.

10. Evans DW, Milanak ME, Medeiros B, et al. Magical beliefs and rituals in young children. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2002;33(1):43-58.

11. Amir N, Freshman M, Foa E. Family distress and involvement in relatives of obsessive-compulsive disorder patients. J Anxiety Disord. 2000;14(3):209-217.

12. Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;51(1):98-113.

13. Pediatric OCD Treatment Study (POTS) Team. Cognitive-behavior therapy, sertraline, and their combination for children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder: The Pediatric OCD Treatment Study (POTS) randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;292(16):1969-1976.

14. Franklin ME, Sapyta J, Freeman JB, et al. Cognitive behavior therapy augmentation of pharmacotherapy in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder: The Pediatric OCD Treatment Study II (POTS II) randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2011;306(11):1224-1232.

15. Wagner KD, Asarnow JR, Vitiello B, et al. Out of the black box: treatment of resistant depression in adolescents and the antidepressant controversy. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2012;22(1):5-10.

16. Sakolsky DJ, Perel JM, Emslie GJ, et al. Antidepressant exposure as a predictor of clinical outcomes in the treatment of resistant depression in adolescents (TORDIA) study. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;31(1):92-97.

17. Findling RL. How (not) to dose antidepressants and antipsychotics for children. Current Psychiatry. 2007;6(6):79-83.

18. Varigonda AL, Jakubovski E, Bloch MH. Systematic review and meta-analysis: early treatment responses of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and clomipramine in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2016 Oct;55(10):851-859.e2.

19. Mancuso E, Faro A, Joshi G, et al. Treatment of pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder: a review. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2010;20(4):299-308.

CASE Auditory hallucinations?

M, age 10, has had multiple visits to the pediatric emergency department (PED) with the chief concern of excessive urinary frequency. At each visit, the medical workup has been negative and he was discharged home. After a few months, M’s parents bring their son back to the PED because he reports hearing “voices in my head” and “feeling tense and scared.” When these feelings become too overwhelming, M stops eating and experiences substantial fear and anxiety that require his mother’s repeated reassurances. M’s mother reports that 2 weeks before his most recent PED visit, he became increasingly anxious and disturbed, and said he was afraid most of the time, and worried about the safety of his family for no apparent reason.

The psychiatrist evaluates M in the PED and diagnoses him with unspecified schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorder based on his persistent report of auditory and tactile hallucinations, including hearing a voice of a man telling him he was going to choke on his food and feeling someone touch his arm to soothe him during his anxious moments. M does not meet criteria for acute inpatient hospitalization, and is discharged home with referral to follow-up at our child and adolescent psychiatry outpatient clinic.

On subsequent evaluation in our clinic, M reports most of the same about his experience hearing “voices in my head” that repeatedly suggest “I might choke on my food and end up seriously ill in the hospital.” He started to hear the “voices” after he witnessed his sister choke while eating a few days earlier. He also mentions that the “voices” tell him “you have to use the restroom.” As a result, he uses the restroom several times before leaving for home and is frequently late for school. His parents accommodate his behavior—his mother allows him to use the bathroom multiple times, and his father overlooks the behavior as part of school anxiety.

At school, his teacher reports a concern for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) based on M’s continuous inattentiveness in class and dropping grades. He asks for bathroom breaks up to 15 times a day, which disrupts his class work.

These behaviors have led to a gradual 1-year decline in his overall functioning, including difficulty at school for requesting too many bathroom breaks; having to repeat the 3rd grade; and incurring multiple hospital visits for evaluation of his various complaints. M has become socially isolated and withdrawn from friends and family.

M’s developmental history is normal and his family history is negative for any psychiatric disorder. Medical history and physical examination are unremarkable. CT scan of his head is unremarkable, and all hematologic and biochemistry laboratory test values are within normal range.

[polldaddy:9971376]

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

Several factors may contribute to an increased chance of misdiagnosis of a psychiatric illness

On closer sequential evaluations with M and his family, we determined that the “voices” he was hearing were actually intrusive thoughts, and not hallucinations. M clarified this by saying that first he feels a “pressure”-like sensation in his head, followed by repeated intrusive thoughts of voiding his bladder that compel him to go to the restroom to try to urinate. He feels temporary relief after complying with the urge, even when he passes only a small amount of urine or just washes his hands. After a brief period of relief, this process repeats itself. Further, he was able to clarify his experience while eating food, where he first felt a “pressure”-like sensation in his head, followed by intrusive thoughts of choking that result in him not eating.

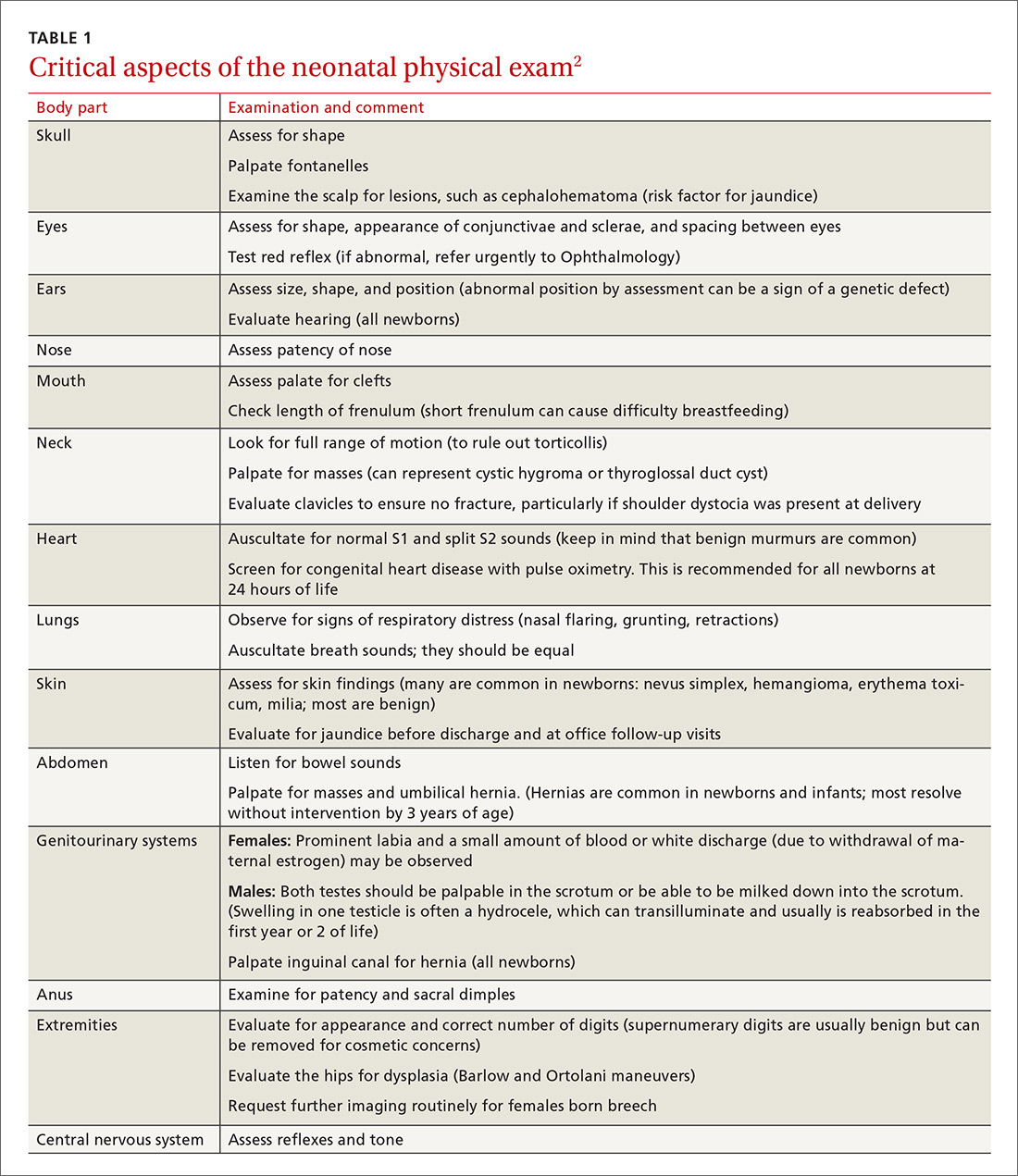

This led us to a more appropriate diagnosis of OCD (Table 11). The incidence of OCD has 2 peaks, with different gender distributions. The first peak occurs in childhood, with symptoms mostly arising between 7 and 12 years of age and affecting boys more often than girls. The second peak occurs in early adulthood, at a mean age of 21 years, with a slight female majority.2 However, OCD is often under recognized and undertreated, perhaps due to its extensive heterogeneity; symptom presentations and comorbidity patterns can vary noticeably between individual patients as well as age groups.

OCD is characterized by the presence of obsessions or compulsions that wax and wane in severity, are time-consuming (at least 1 hour per day), and cause subjective distress or interfere with life of the patient or the family. Adults with OCD recognize at some level that the obsessions and/or compulsions are excessive and unreasonable, although children are not required to have this insight to meet criteria for the diagnosis.1 Rating scales, such as the Children’s Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale, Dimensional Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale, and Family Accommodation Scale, are useful to obtain detailed information regarding OCD symptoms, tics, and other factors relevant to the diagnosis.

Continue to: M's symptomatology...

M’s symptomatology did not appear to be psychotic. He was screened for positive or negative symptoms of psychosis, which he and his family clearly denied. Moreover, M’s compulsions (going to the restroom) were typically performed in response to his obsessions (urge to void his bladder) to reduce his distress, which is different from schizophrenia, in which repetitive behaviors are performed in response to psychotic ideation, and not obsessions (Table 23-5).

M’s inattentiveness in the classroom was found to be related to his obsessions and compulsions, and not part of a symptom cluster characterizing ADHD. Teachers often interpret inattention and poor classroom performance as ADHD, but having detailed conversations with teachers often is helpful in understanding the nature of a child’s symptomology and making the appropriate diagnosis.

Establishing the correct clinical diagnosis is critical because it is the starting point in treatment. First-line medication for one condition may exacerbate the symptoms of others. For example, in addition to having a large adverse-effect burden, antipsychotics can induce de novo obsessive–compulsive symptoms (OCS) or exacerbate preexisting OCS, and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) may exacerbate psychosis in schizo-obsessive patients with a history of impulsivity and aggressiveness.6 Similarly, stimulant medications for ADHD may exacerbate OCS and may even induce them on their own.7,8

[polldaddy:9971377]

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

Studies have reported an average of 2.5 years from the onset of OCD symptoms to diagnosis in the United States.9 A key reason for this delay, which is more frequently encountered in pediatric patients, is secrecy. Children often feel embarrassed about their symptoms and conceal them until the interference with their functioning becomes extremely disabling. In some cases, symptoms may closely resemble normal childhood routines. In fact, some repetitive behaviors may be normal in some developmental stages, and OCD could be conceptualized as a pathological condition with continuity of normal behaviors during different developmental periods.10

Also, symptoms may go unnoticed for quite some time as unsuspecting and well-intentioned parents and family members become overly involved in the child’s rituals (eg, allowing for increasing frequent prolonged bathroom breaks or frequent change of clothing, etc.). This well-established phenomenon, termed accommodation, is defined as participation of family members in a child’s OCD–related rituals.11 Especially when symptoms are mild or the child is functioning well, accommodation can make it difficult for parents to realize the presence or nature of a problem, as they might tend to minimize their child’s symptoms as representing a unique personality trait or a special “quirk.” Parents generally will seek treatment when their child’s symptoms become more impairing and begin to interfere with social functioning, school performance, or family functioning.

The clinical picture is further complicated by comorbidity. Approximately 60% to 80% of children and adolescents with OCD have ≥1 comorbid psychiatric disorders. Some of the most common include tic disorders, ADHD, anxiety disorders, and mood or eating disorders.9

[polldaddy:9971379]

Continue to: TREATMENT Combination therapy

TREATMENT Combination therapy

In keeping with American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry guidelines on treating OCD (Table 312), we start M on fluoxetine 10 mg/d. He also begins CBT. Fluoxetine is slowly titrated to 40 mg/d while M engages in learning and utilizing CBT techniques to manage his OCD.

The authors’ observations

The combination of CBT and medication has been suggested as the treatment of choice for moderate and severe OCD.12 The Pediatric OCD Treatment Study, a 5-year, 3-site outcome study designed to compare placebo, sertraline, CBT, and combined CBT and sertraline, concluded that the combined treatment (CBT plus sertraline) was more effective than CBT alone or sertraline alone.13 The effect sizes for the combined treatment, CBT alone, and sertraline alone were 1.4, 0.97, and 0.67, respectively. Remission rates for SSRIs alone are <33%.13,14

SSRIs are the first-line medication for OCD in children, adolescents, and adults (Table 312). Well-designed clinical trials have demonstrated the efficacy and safety of the SSRIs fluoxetine, sertraline, and fluvoxamine (alone or combined with CBT) in children and adolescents with OCD.13 Other SSRIs, such as citalopram, paroxetine, and escitalopram, also have demonstrated efficacy in children and adolescents with OCD, even though the FDA has not yet approved their use in pediatric patients.12 Despite a positive trial of paroxetine in pediatric OCD,12 there have been concerns related to its higher rates of treatment-emergent suicidality,15 lower likelihood of treatment response,16 and its particularly short half-life in pediatric patients.17