User login

What are the benefits and risks of daily low-dose aspirin for primary prevention of CV events?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A 2013 systematic review of RCTs, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses examined the prophylactic use of low-dose aspirin for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease (CVD) among adults 18 years and older.1 Twenty-seven papers met inclusion criteria; the total number of patients wasn’t reported.

A composite finding of nonfatal MI, nonfatal stroke, and CVD death indicated a number needed to treat (NNT) of 138 over 10 years of therapy (relative risk [RR]=0.90; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.85-0.96). CVD death wasn’t disaggregated from this composite, but an analysis of all-cause mortality didn’t reach statistical significance (RR=0.94; 95% CI, 0.88-1.00). RR for nonfatal stroke alone also wasn’t disaggregated.

Risk of gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding was found to be a number needed to harm (NNH) of 108 over 10 years (RR=1.37; 95% CI, 1.15-1.62) whereas risk of hemorrhagic stroke didn’t reach statistical significance (RR=1.32; 95% CI, 1.00-1.74). This population-level review didn’t report disaggregated findings by age or baseline atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk.

Another review finds benefit only for prevention of nonfatal MI

A 2016 systematic review included 2 good-quality and 9 fair-quality RCTs evaluating the benefits of low-dose aspirin compared with placebo or no treatment for primary prevention of CVD events in 118,445 patients ages 40 years and older.2 The review found benefit only for nonfatal MI, with an NNT of 126 over 10 years (RR=0.78; 95% CI, 0.71-0.87). There was no change in RR for nonfatal stroke (RR=0.95; 95% CI, 0.85-1.06); negligible impact on all-cause mortality (RR=0.95; 95% CI, 0.89-0.99); and no statistically significant benefit for CVD-specific mortality (RR=0.94; 95% CI, 0.86-1.03).

Aspirin carries risk of GI hemorrhage, but not hemorrhagic stroke

A companion 2016 systematic review of 16 RCTs, cohort studies, and meta-analyses evaluated the risk of serious bleeding in patients using low-dose aspirin for primary prevention of either CVD or cancer.3 The review (number of patients not reported) found that estimated excess bleeding events differed substantially depending on varying sources for baseline bleeding rates in aspirin nonusers.

The most conservative comparison yielded an NNH of 72 over 10 years of therapy (1.39 excess major GI bleeding events per 1000 person-years, 95% CI, 0.70-2.28). Comparison with other baseline bleeding rates in trial data yielded less risk of harm, with an NNH of 357 over 10 years (0.28 excess major GI bleeding events per 1000 person-years; 95% CI, 0.14-0.46). Excess risk for hemorrhagic stroke was not statistically significant (0.32 excess events per 1000 person-years; 95% CI, −0.05 to 0.82).

RECOMMENDATIONS

The US Preventive Services Task Force gives a Grade B recommendation (recommended, based on moderate to substantial benefit) to the use of aspirin to prevent CVD among adults ages 50 to 59 years with an ASCVD risk ≥10% who don’t have increased bleeding risk and are capable of 10 years of pharmacologic adherence with a similar expected longevity.4 The Task Force assigns a Grade C recommendation (individual and professional choice) to patients 60 to 69 years of age with the same constellation of risk factors and health status. Insufficient evidence was available to make recommendations for other age cohorts.

The American College of Chest Physicians recommends 75 to 100 mg of aspirin daily for adults 50 years or older who have moderate to high CV risk, defined as ≥10%.5

A working group of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) released a statement in 2014 recommending aspirin for primary prevention in adults with a CV risk ≥20% and no risk factors for bleeding. For patients with a CVD risk between 10% and 20%, the ESC recommends deferring to patient preference.6

1. Sutcliffe P, Connock M, Gurung T, et al. Aspirin in primary prevention of cardiovascular disease and cancer: a systematic review of the balance of evidence from reviews of randomized trials. PLoS One. 2013;8:e81970.

2. Guirguis-Blake JM, Evans CV, Senger CA, et al. Aspirin for the primary prevention of cardiovascular events: a systematic evidence review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164:804-813.

3. Whitlock EP, Burda BU, Williams SB, et al. Bleeding risks with aspirin use for primary prevention in adults: a systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164:826-835.

4. Bibbins-Domingo K, US Preventive Services Task Force. Aspirin use for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease and colorectal cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164:836-845.

5. Vandvik PO, Lincoff AM, Gore JM, et al. Primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 Suppl):e637S-e668S.

6. Halvorsen S, Andreotti F, ten Berg JM, et al. Aspirin therapy in primary cardiovascular disease prevention: a position paper of the European Society of Cardiology Working Group on Thrombosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:319-327.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A 2013 systematic review of RCTs, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses examined the prophylactic use of low-dose aspirin for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease (CVD) among adults 18 years and older.1 Twenty-seven papers met inclusion criteria; the total number of patients wasn’t reported.

A composite finding of nonfatal MI, nonfatal stroke, and CVD death indicated a number needed to treat (NNT) of 138 over 10 years of therapy (relative risk [RR]=0.90; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.85-0.96). CVD death wasn’t disaggregated from this composite, but an analysis of all-cause mortality didn’t reach statistical significance (RR=0.94; 95% CI, 0.88-1.00). RR for nonfatal stroke alone also wasn’t disaggregated.

Risk of gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding was found to be a number needed to harm (NNH) of 108 over 10 years (RR=1.37; 95% CI, 1.15-1.62) whereas risk of hemorrhagic stroke didn’t reach statistical significance (RR=1.32; 95% CI, 1.00-1.74). This population-level review didn’t report disaggregated findings by age or baseline atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk.

Another review finds benefit only for prevention of nonfatal MI

A 2016 systematic review included 2 good-quality and 9 fair-quality RCTs evaluating the benefits of low-dose aspirin compared with placebo or no treatment for primary prevention of CVD events in 118,445 patients ages 40 years and older.2 The review found benefit only for nonfatal MI, with an NNT of 126 over 10 years (RR=0.78; 95% CI, 0.71-0.87). There was no change in RR for nonfatal stroke (RR=0.95; 95% CI, 0.85-1.06); negligible impact on all-cause mortality (RR=0.95; 95% CI, 0.89-0.99); and no statistically significant benefit for CVD-specific mortality (RR=0.94; 95% CI, 0.86-1.03).

Aspirin carries risk of GI hemorrhage, but not hemorrhagic stroke

A companion 2016 systematic review of 16 RCTs, cohort studies, and meta-analyses evaluated the risk of serious bleeding in patients using low-dose aspirin for primary prevention of either CVD or cancer.3 The review (number of patients not reported) found that estimated excess bleeding events differed substantially depending on varying sources for baseline bleeding rates in aspirin nonusers.

The most conservative comparison yielded an NNH of 72 over 10 years of therapy (1.39 excess major GI bleeding events per 1000 person-years, 95% CI, 0.70-2.28). Comparison with other baseline bleeding rates in trial data yielded less risk of harm, with an NNH of 357 over 10 years (0.28 excess major GI bleeding events per 1000 person-years; 95% CI, 0.14-0.46). Excess risk for hemorrhagic stroke was not statistically significant (0.32 excess events per 1000 person-years; 95% CI, −0.05 to 0.82).

RECOMMENDATIONS

The US Preventive Services Task Force gives a Grade B recommendation (recommended, based on moderate to substantial benefit) to the use of aspirin to prevent CVD among adults ages 50 to 59 years with an ASCVD risk ≥10% who don’t have increased bleeding risk and are capable of 10 years of pharmacologic adherence with a similar expected longevity.4 The Task Force assigns a Grade C recommendation (individual and professional choice) to patients 60 to 69 years of age with the same constellation of risk factors and health status. Insufficient evidence was available to make recommendations for other age cohorts.

The American College of Chest Physicians recommends 75 to 100 mg of aspirin daily for adults 50 years or older who have moderate to high CV risk, defined as ≥10%.5

A working group of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) released a statement in 2014 recommending aspirin for primary prevention in adults with a CV risk ≥20% and no risk factors for bleeding. For patients with a CVD risk between 10% and 20%, the ESC recommends deferring to patient preference.6

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A 2013 systematic review of RCTs, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses examined the prophylactic use of low-dose aspirin for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease (CVD) among adults 18 years and older.1 Twenty-seven papers met inclusion criteria; the total number of patients wasn’t reported.

A composite finding of nonfatal MI, nonfatal stroke, and CVD death indicated a number needed to treat (NNT) of 138 over 10 years of therapy (relative risk [RR]=0.90; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.85-0.96). CVD death wasn’t disaggregated from this composite, but an analysis of all-cause mortality didn’t reach statistical significance (RR=0.94; 95% CI, 0.88-1.00). RR for nonfatal stroke alone also wasn’t disaggregated.

Risk of gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding was found to be a number needed to harm (NNH) of 108 over 10 years (RR=1.37; 95% CI, 1.15-1.62) whereas risk of hemorrhagic stroke didn’t reach statistical significance (RR=1.32; 95% CI, 1.00-1.74). This population-level review didn’t report disaggregated findings by age or baseline atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk.

Another review finds benefit only for prevention of nonfatal MI

A 2016 systematic review included 2 good-quality and 9 fair-quality RCTs evaluating the benefits of low-dose aspirin compared with placebo or no treatment for primary prevention of CVD events in 118,445 patients ages 40 years and older.2 The review found benefit only for nonfatal MI, with an NNT of 126 over 10 years (RR=0.78; 95% CI, 0.71-0.87). There was no change in RR for nonfatal stroke (RR=0.95; 95% CI, 0.85-1.06); negligible impact on all-cause mortality (RR=0.95; 95% CI, 0.89-0.99); and no statistically significant benefit for CVD-specific mortality (RR=0.94; 95% CI, 0.86-1.03).

Aspirin carries risk of GI hemorrhage, but not hemorrhagic stroke

A companion 2016 systematic review of 16 RCTs, cohort studies, and meta-analyses evaluated the risk of serious bleeding in patients using low-dose aspirin for primary prevention of either CVD or cancer.3 The review (number of patients not reported) found that estimated excess bleeding events differed substantially depending on varying sources for baseline bleeding rates in aspirin nonusers.

The most conservative comparison yielded an NNH of 72 over 10 years of therapy (1.39 excess major GI bleeding events per 1000 person-years, 95% CI, 0.70-2.28). Comparison with other baseline bleeding rates in trial data yielded less risk of harm, with an NNH of 357 over 10 years (0.28 excess major GI bleeding events per 1000 person-years; 95% CI, 0.14-0.46). Excess risk for hemorrhagic stroke was not statistically significant (0.32 excess events per 1000 person-years; 95% CI, −0.05 to 0.82).

RECOMMENDATIONS

The US Preventive Services Task Force gives a Grade B recommendation (recommended, based on moderate to substantial benefit) to the use of aspirin to prevent CVD among adults ages 50 to 59 years with an ASCVD risk ≥10% who don’t have increased bleeding risk and are capable of 10 years of pharmacologic adherence with a similar expected longevity.4 The Task Force assigns a Grade C recommendation (individual and professional choice) to patients 60 to 69 years of age with the same constellation of risk factors and health status. Insufficient evidence was available to make recommendations for other age cohorts.

The American College of Chest Physicians recommends 75 to 100 mg of aspirin daily for adults 50 years or older who have moderate to high CV risk, defined as ≥10%.5

A working group of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) released a statement in 2014 recommending aspirin for primary prevention in adults with a CV risk ≥20% and no risk factors for bleeding. For patients with a CVD risk between 10% and 20%, the ESC recommends deferring to patient preference.6

1. Sutcliffe P, Connock M, Gurung T, et al. Aspirin in primary prevention of cardiovascular disease and cancer: a systematic review of the balance of evidence from reviews of randomized trials. PLoS One. 2013;8:e81970.

2. Guirguis-Blake JM, Evans CV, Senger CA, et al. Aspirin for the primary prevention of cardiovascular events: a systematic evidence review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164:804-813.

3. Whitlock EP, Burda BU, Williams SB, et al. Bleeding risks with aspirin use for primary prevention in adults: a systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164:826-835.

4. Bibbins-Domingo K, US Preventive Services Task Force. Aspirin use for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease and colorectal cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164:836-845.

5. Vandvik PO, Lincoff AM, Gore JM, et al. Primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 Suppl):e637S-e668S.

6. Halvorsen S, Andreotti F, ten Berg JM, et al. Aspirin therapy in primary cardiovascular disease prevention: a position paper of the European Society of Cardiology Working Group on Thrombosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:319-327.

1. Sutcliffe P, Connock M, Gurung T, et al. Aspirin in primary prevention of cardiovascular disease and cancer: a systematic review of the balance of evidence from reviews of randomized trials. PLoS One. 2013;8:e81970.

2. Guirguis-Blake JM, Evans CV, Senger CA, et al. Aspirin for the primary prevention of cardiovascular events: a systematic evidence review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164:804-813.

3. Whitlock EP, Burda BU, Williams SB, et al. Bleeding risks with aspirin use for primary prevention in adults: a systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164:826-835.

4. Bibbins-Domingo K, US Preventive Services Task Force. Aspirin use for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease and colorectal cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164:836-845.

5. Vandvik PO, Lincoff AM, Gore JM, et al. Primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 Suppl):e637S-e668S.

6. Halvorsen S, Andreotti F, ten Berg JM, et al. Aspirin therapy in primary cardiovascular disease prevention: a position paper of the European Society of Cardiology Working Group on Thrombosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:319-327.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network

EVIDENCE BASED ANSWER:

One nonfatal myocardial infarction (MI) will be avoided for every 126 to 138 adults who take daily aspirin for 10 years (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, systematic reviews and meta-analyses of multiple randomized controlled trials [RCTs]).

Taking low-dose aspirin for primary prevention shows no clear mortality benefit. A benefit for primary prevention of stroke is less certain. Although no evidence establishes increased risk of hemorrhagic stroke from daily low-dose aspirin, one gastrointestinal hemorrhage will occur for every 72 to 357 adults who take aspirin for longer than 10 years (SOR: A, systematic reviews and meta-analyses of multiple RCTs and cohort studies).

We need to treat gun violence like an epidemic

In an interesting bit of timing, just one month before the tragic shooting at the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, the AMA Journal of Ethics devoted its entire January issue to the role of physicians in preventing violence. Part of the discussion centered on the idea of treating gun violence as an infectious disease epidemic.1

Dr. Gary Slutkin, an infectious disease specialist and former Centers for Disease Control and Prevention epidemiologist, is a proponent of this approach. His research has demonstrated that epidemic disease control measures are effective in reducing violence and violence-related deaths.2-5

Just look at incidence. Violent deaths in the United States are at an epidemic proportion, just like deaths due to narcotic overdoses. In 2015, there were approximately 33,091 deaths due to narcotic overdoses and 36,252 deaths due to gun violence.6,7

Geographic and social factors. Like infectious disease epidemics, violence tends to cluster in certain geographic areas and social networks. The cause of violence is multifactorial, just like other infectious disease epidemics, such as tuberculosis. Poverty, poor education, and inadequate family structure act as modulating factors that increase the rate of violence in those exposed to it.

Enlisting the community. This contagious disease prevention approach uses community health workers to map areas of high transmission, reach out to those exposed, and intervene to reduce risk factors. For example, gang-related deaths are often due to retaliation. A thorough investigation of a patient who arrives in the emergency department (ED) with a gunshot wound can reveal the next likely perpetrators and victims. Then community violence prevention workers can go directly to these people and others in their social networks, such as parents and friends, to attempt to prevent the next shooting. This approach, dubbed “Cure Violence” (CureViolence.org), has resulted in up to a 70% decrease in violence in some areas of Chicago.2 Some neighborhoods of Baltimore and New York have seen similar reductions.3-5

What can family practitioners do? Dr. Slutkin believes his approach could be expanded from EDs to other health care settings, like primary care, where we can identify people at risk and refer them to community violence prevention resources. Imagine it—a day when violence goes the way of polio.

1. Slutkin G, Ransford C, Zvetina D. How the health sector can reduce violence by treating it as a contagion. AMA J Ethics. 2018;20:47-55.

2. Skogan WG, Hartnett SM, Bump N, et al. Evaluation of CeaseFire-Chicago. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Institute for Policy Research; 2008. Available at: https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/227181.pdf. Accessed September 11, 2017.

3. Webster DW, Whitehill JM, Vernick JS, et al. Evaluation of Baltimore’s Safe Streets program: effects on attitudes, participants’ experiences, and gun violence. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health; January 11, 2012. Available at: http://baltimorehealth.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/2012_01_10_JHSPH_Safe_Streets_evaluation.pdf. Accessed September 11, 2017.

4. Delgado SA, Alsabahi L, Wolff K, et al. Demoralizing violence: the effects of Cure Violence in the South Bronx and East New York, Brooklyn. John Jay College of Criminal Justice Research and Evaluation Center. Available at: https://johnjayrec.nyc/2017/10/02/cvinsobronxeastny/. Published October 2, 2017. Accessed November 15, 2017.

5. Picard-Fritsche S, Cerniglia L. Testing a public approach to gun violence: an evaluation of Crown Heights Save Our Streets, a replication of the Cure Violence Model. Center for Court Innovation; 2013. Available at: https://www.courtinnovation.org/sites/default/files/documents/SOS_Evaluation.pdf. Accessed November 28, 2017.

6. Murphy SL, Xu J, Kochanek KD, et al. Deaths: Final Data for 2015. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2017;66:1-75.

7. Rudd RA, Seth P, David F, et al. Increases in drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths — United States, 2010–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:1445-1452.

In an interesting bit of timing, just one month before the tragic shooting at the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, the AMA Journal of Ethics devoted its entire January issue to the role of physicians in preventing violence. Part of the discussion centered on the idea of treating gun violence as an infectious disease epidemic.1

Dr. Gary Slutkin, an infectious disease specialist and former Centers for Disease Control and Prevention epidemiologist, is a proponent of this approach. His research has demonstrated that epidemic disease control measures are effective in reducing violence and violence-related deaths.2-5

Just look at incidence. Violent deaths in the United States are at an epidemic proportion, just like deaths due to narcotic overdoses. In 2015, there were approximately 33,091 deaths due to narcotic overdoses and 36,252 deaths due to gun violence.6,7

Geographic and social factors. Like infectious disease epidemics, violence tends to cluster in certain geographic areas and social networks. The cause of violence is multifactorial, just like other infectious disease epidemics, such as tuberculosis. Poverty, poor education, and inadequate family structure act as modulating factors that increase the rate of violence in those exposed to it.

Enlisting the community. This contagious disease prevention approach uses community health workers to map areas of high transmission, reach out to those exposed, and intervene to reduce risk factors. For example, gang-related deaths are often due to retaliation. A thorough investigation of a patient who arrives in the emergency department (ED) with a gunshot wound can reveal the next likely perpetrators and victims. Then community violence prevention workers can go directly to these people and others in their social networks, such as parents and friends, to attempt to prevent the next shooting. This approach, dubbed “Cure Violence” (CureViolence.org), has resulted in up to a 70% decrease in violence in some areas of Chicago.2 Some neighborhoods of Baltimore and New York have seen similar reductions.3-5

What can family practitioners do? Dr. Slutkin believes his approach could be expanded from EDs to other health care settings, like primary care, where we can identify people at risk and refer them to community violence prevention resources. Imagine it—a day when violence goes the way of polio.

In an interesting bit of timing, just one month before the tragic shooting at the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, the AMA Journal of Ethics devoted its entire January issue to the role of physicians in preventing violence. Part of the discussion centered on the idea of treating gun violence as an infectious disease epidemic.1

Dr. Gary Slutkin, an infectious disease specialist and former Centers for Disease Control and Prevention epidemiologist, is a proponent of this approach. His research has demonstrated that epidemic disease control measures are effective in reducing violence and violence-related deaths.2-5

Just look at incidence. Violent deaths in the United States are at an epidemic proportion, just like deaths due to narcotic overdoses. In 2015, there were approximately 33,091 deaths due to narcotic overdoses and 36,252 deaths due to gun violence.6,7

Geographic and social factors. Like infectious disease epidemics, violence tends to cluster in certain geographic areas and social networks. The cause of violence is multifactorial, just like other infectious disease epidemics, such as tuberculosis. Poverty, poor education, and inadequate family structure act as modulating factors that increase the rate of violence in those exposed to it.

Enlisting the community. This contagious disease prevention approach uses community health workers to map areas of high transmission, reach out to those exposed, and intervene to reduce risk factors. For example, gang-related deaths are often due to retaliation. A thorough investigation of a patient who arrives in the emergency department (ED) with a gunshot wound can reveal the next likely perpetrators and victims. Then community violence prevention workers can go directly to these people and others in their social networks, such as parents and friends, to attempt to prevent the next shooting. This approach, dubbed “Cure Violence” (CureViolence.org), has resulted in up to a 70% decrease in violence in some areas of Chicago.2 Some neighborhoods of Baltimore and New York have seen similar reductions.3-5

What can family practitioners do? Dr. Slutkin believes his approach could be expanded from EDs to other health care settings, like primary care, where we can identify people at risk and refer them to community violence prevention resources. Imagine it—a day when violence goes the way of polio.

1. Slutkin G, Ransford C, Zvetina D. How the health sector can reduce violence by treating it as a contagion. AMA J Ethics. 2018;20:47-55.

2. Skogan WG, Hartnett SM, Bump N, et al. Evaluation of CeaseFire-Chicago. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Institute for Policy Research; 2008. Available at: https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/227181.pdf. Accessed September 11, 2017.

3. Webster DW, Whitehill JM, Vernick JS, et al. Evaluation of Baltimore’s Safe Streets program: effects on attitudes, participants’ experiences, and gun violence. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health; January 11, 2012. Available at: http://baltimorehealth.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/2012_01_10_JHSPH_Safe_Streets_evaluation.pdf. Accessed September 11, 2017.

4. Delgado SA, Alsabahi L, Wolff K, et al. Demoralizing violence: the effects of Cure Violence in the South Bronx and East New York, Brooklyn. John Jay College of Criminal Justice Research and Evaluation Center. Available at: https://johnjayrec.nyc/2017/10/02/cvinsobronxeastny/. Published October 2, 2017. Accessed November 15, 2017.

5. Picard-Fritsche S, Cerniglia L. Testing a public approach to gun violence: an evaluation of Crown Heights Save Our Streets, a replication of the Cure Violence Model. Center for Court Innovation; 2013. Available at: https://www.courtinnovation.org/sites/default/files/documents/SOS_Evaluation.pdf. Accessed November 28, 2017.

6. Murphy SL, Xu J, Kochanek KD, et al. Deaths: Final Data for 2015. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2017;66:1-75.

7. Rudd RA, Seth P, David F, et al. Increases in drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths — United States, 2010–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:1445-1452.

1. Slutkin G, Ransford C, Zvetina D. How the health sector can reduce violence by treating it as a contagion. AMA J Ethics. 2018;20:47-55.

2. Skogan WG, Hartnett SM, Bump N, et al. Evaluation of CeaseFire-Chicago. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Institute for Policy Research; 2008. Available at: https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/227181.pdf. Accessed September 11, 2017.

3. Webster DW, Whitehill JM, Vernick JS, et al. Evaluation of Baltimore’s Safe Streets program: effects on attitudes, participants’ experiences, and gun violence. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health; January 11, 2012. Available at: http://baltimorehealth.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/2012_01_10_JHSPH_Safe_Streets_evaluation.pdf. Accessed September 11, 2017.

4. Delgado SA, Alsabahi L, Wolff K, et al. Demoralizing violence: the effects of Cure Violence in the South Bronx and East New York, Brooklyn. John Jay College of Criminal Justice Research and Evaluation Center. Available at: https://johnjayrec.nyc/2017/10/02/cvinsobronxeastny/. Published October 2, 2017. Accessed November 15, 2017.

5. Picard-Fritsche S, Cerniglia L. Testing a public approach to gun violence: an evaluation of Crown Heights Save Our Streets, a replication of the Cure Violence Model. Center for Court Innovation; 2013. Available at: https://www.courtinnovation.org/sites/default/files/documents/SOS_Evaluation.pdf. Accessed November 28, 2017.

6. Murphy SL, Xu J, Kochanek KD, et al. Deaths: Final Data for 2015. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2017;66:1-75.

7. Rudd RA, Seth P, David F, et al. Increases in drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths — United States, 2010–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:1445-1452.

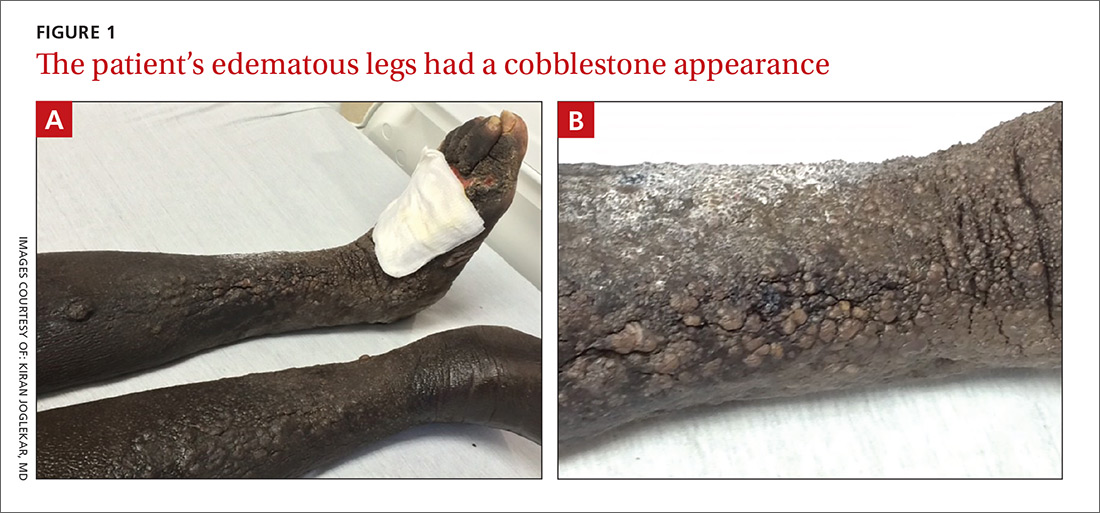

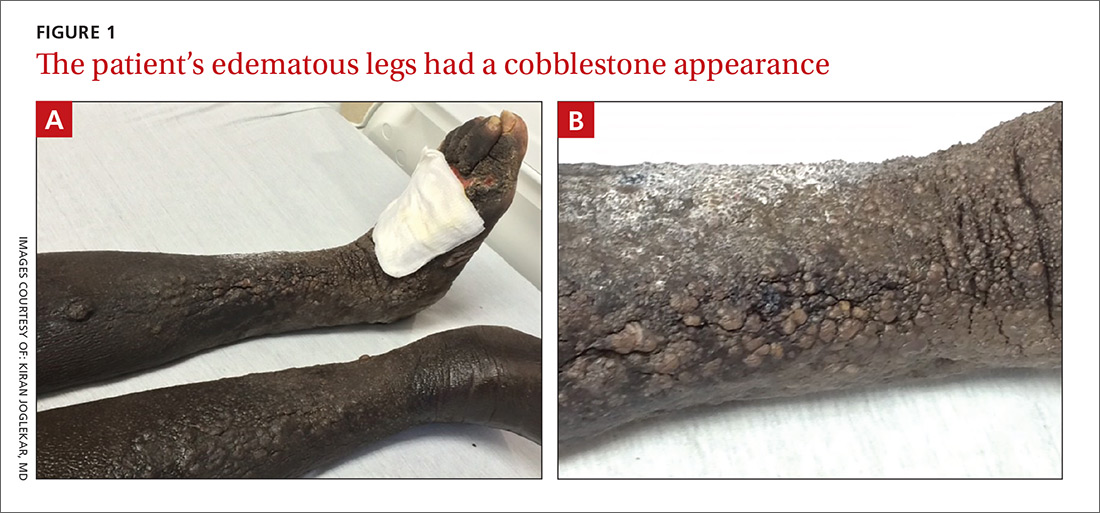

Bilateral nonpitting edema and xerotic skin

A 60-year-old African American woman who had congestive heart failure (CHF) with reduced ejection fraction, untreated hepatitis C virus infection, and chronic kidney disease presented to the emergency department (ED) with a 6-month history of bilateral lower extremity edema. Use of diuretics and antibiotic therapy for suspected CHF exacerbation and cellulitis, directed by her primary care physician, had no effect. In the month prior to presenting to the ED, the patient took 2 different antibiotics, each for 10 days: clindamycin 300 mg every 6 hours and doxycycline 100 mg every 12 hours. Additionally, she was taking furosemide 40 mg/d with good urine output, but no appreciable improvement in lower extremity edema.

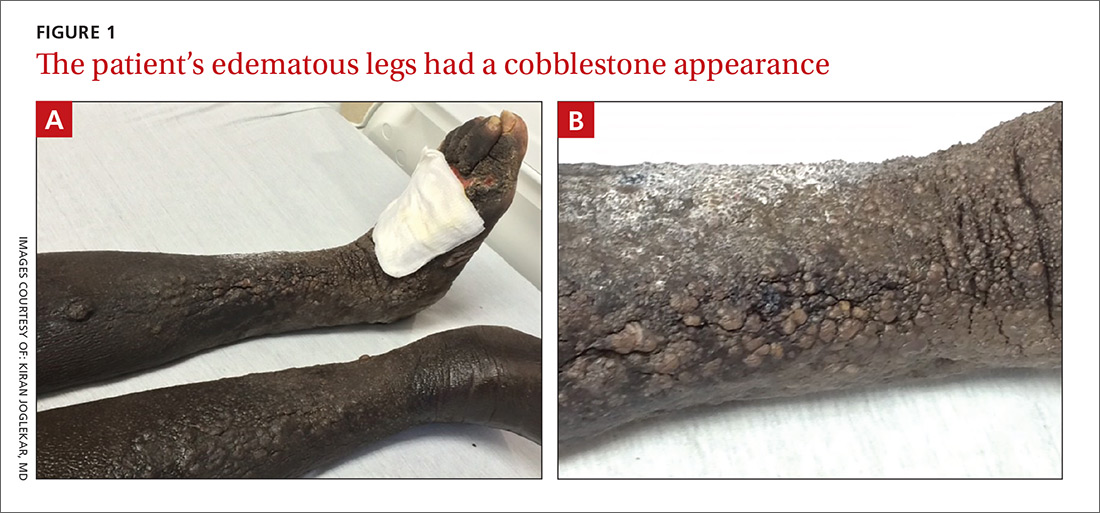

The physical examination revealed bilateral nonpitting edema. Weeping pearly papules, xerotic skin, and a cobblestone appearance extended from the dorsa of the patient’s feet to her knees (FIGURES 1A and 1B). The patient underwent Doppler ultrasound of the lower extremities and a skin biopsy.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa

The Doppler ultrasound was negative, and the biopsy ruled out malignancy and infection; however, the pathology report was histologically consistent with a diagnosis of elephantiasis nostras verrucosa (ENV).

ENV is a disfiguring, nonfilarial lymphedema that affects the lower extremities and is characterized by progressive cobblestoning and verrucous distortion of gravity-dependent areas.1 The skin changes are caused by lymphatic damage and obstruction from an accumulation of protein-rich fluid in the dermis and subcutaneous tissues.1,2

The term ENV was first coined by Aldo Castellani in 1934 to differentiate the condition from elephantiasis tropica (filariasis), which is caused by parasitic Wuchereria worms.3 ENV is also known as lymphangitis recurrens elephantogenica, elephantiasis verrucosa, elephantiasis nostra, mossy leg, and elephantiasis of the temperate zone.1

ENV is notably uncommon; its exact incidence is unknown. The etiology is multifactorial but can include obesity, chronic lymphedema, CHF, and recurrent cellulitis (the latter 2 were noted in our patient’s history).1

Although the diagnosis can be made based on patient history and physical examination alone, skin biopsy is warranted to rule out underlying malignancy or fungal infection.1,4 Histologic findings suggestive of ENV include pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, lymph channel dilation, widened tissue spaces, and loss of dermal papillae.1 In our patient’s case, the pathology report revealed dermal fibrosis, dilated lymph channels, and a mixed inflammatory infiltrate. Her lab work, which included a complete blood count and basic metabolic panel, was significant for neutrophilic leukocytosis (white blood cell count, 30,000 cells/mcL), chronic kidney disease, and elevated inflammatory markers.

The differential includes other types of edema and infections

Several other diseases must be differentiated from ENV, including:

Venous stasis dermatitis. Unlike ENV, this condition involves pitting edema with erythema and does not have a verrucous appearance.2,4

Lipedema. Histologically, lipedema shows no changes. It typically spares the feet, has an early age of onset, and is associated with a positive family history.1,2,4

Lipodermatosclerosis. This condition is caused by venous stasis with swelling of the proximal lower extremity and fibrosis of the distal parts. The affected leg develops an “inverted wine bottle” appearance.2,4

Pretibial myxedema. Patients with pretibial myxedema will have thyroid function test abnormalities and exhibit other signs of hyperthyroidism. If suspected, the laboratory evaluation should include thyroid-stimulating hormone levels.2,4

Filariasis. Endemic to tropical regions, filariasis is a parasitic infection. A travel history helps to differentiate this from ENV. If suspected, include a Giemsa blood smear in the laboratory evaluation.2

Chromoblastomycosis. This chronic fungal infection is typically contracted in rural tropical or subtropical regions. The causative fungi, which are present in soil, enter the skin through minor wounds (eg, thorns or splinters). The wounds are typically forgotten by the time the patient seeks medical attention. Biopsy can effectively rule out this condition.1,2,5

Treatment centers on preserving function, preventing complications

Currently, no standard treatment exists for ENV.1,4 Therapies are aimed at treating the underlying cause, preserving function in the affected limb, and preventing complications. Conservative therapy includes elevation of the affected limb and use of compression devices for edema. Antibiotics can be administered for associated cellulitis. There have been few case reports of successful treatment with oral retinoids. If medical therapy fails, surgical debridement serves as a last resort.1,4,6

Our patient improved after a week with antibiotic therapy (IV piperacillin/tazobactam 3.375 g every 6 hours) and other conservative measures, such as leg elevation.

CORRESPONDENCE

Kavita Natrajan, MBBS, George Washington University/Medical Faculty Associates, Division of Hematology and Oncology, 2150 Pennsylvania Avenue NW, DC 20037; [email protected].

1. Sisto K, Khachemoune A. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa: a review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2008;9:141-146.

2. Liaw FY, Huang CF, Wu YC, et al. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa: swelling with verrucose appearance of lower limbs. Can Fam Physician. 2012;58:e551-e553.

3. Castellani A. Researches on elephantiasis nostras and elephantiasis tropica with special regard to their initial stage of recurring lymphangitis (lymphangitis recurrens elephantogenica). J Trop Med Hyg. 1969;72:89-97.

4. Baird D, Bode D, Akers T, et al. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa (ENV): a complication of congestive heart failure and obesity. J Am Board Fam Med. 2010;23:413-417.

5. Queiroz-Telles F, Fahal AH, Falci R, et. al. Neglected endemic mycoses. Lancet Inf Dis. 2017;17:e367-e377.

6. Han HH, Lim SY, Oh DY. Successful surgical treatment for elephantiasis nostras verrucosa using a new designed column flap. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2015;14:299-302.

A 60-year-old African American woman who had congestive heart failure (CHF) with reduced ejection fraction, untreated hepatitis C virus infection, and chronic kidney disease presented to the emergency department (ED) with a 6-month history of bilateral lower extremity edema. Use of diuretics and antibiotic therapy for suspected CHF exacerbation and cellulitis, directed by her primary care physician, had no effect. In the month prior to presenting to the ED, the patient took 2 different antibiotics, each for 10 days: clindamycin 300 mg every 6 hours and doxycycline 100 mg every 12 hours. Additionally, she was taking furosemide 40 mg/d with good urine output, but no appreciable improvement in lower extremity edema.

The physical examination revealed bilateral nonpitting edema. Weeping pearly papules, xerotic skin, and a cobblestone appearance extended from the dorsa of the patient’s feet to her knees (FIGURES 1A and 1B). The patient underwent Doppler ultrasound of the lower extremities and a skin biopsy.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa

The Doppler ultrasound was negative, and the biopsy ruled out malignancy and infection; however, the pathology report was histologically consistent with a diagnosis of elephantiasis nostras verrucosa (ENV).

ENV is a disfiguring, nonfilarial lymphedema that affects the lower extremities and is characterized by progressive cobblestoning and verrucous distortion of gravity-dependent areas.1 The skin changes are caused by lymphatic damage and obstruction from an accumulation of protein-rich fluid in the dermis and subcutaneous tissues.1,2

The term ENV was first coined by Aldo Castellani in 1934 to differentiate the condition from elephantiasis tropica (filariasis), which is caused by parasitic Wuchereria worms.3 ENV is also known as lymphangitis recurrens elephantogenica, elephantiasis verrucosa, elephantiasis nostra, mossy leg, and elephantiasis of the temperate zone.1

ENV is notably uncommon; its exact incidence is unknown. The etiology is multifactorial but can include obesity, chronic lymphedema, CHF, and recurrent cellulitis (the latter 2 were noted in our patient’s history).1

Although the diagnosis can be made based on patient history and physical examination alone, skin biopsy is warranted to rule out underlying malignancy or fungal infection.1,4 Histologic findings suggestive of ENV include pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, lymph channel dilation, widened tissue spaces, and loss of dermal papillae.1 In our patient’s case, the pathology report revealed dermal fibrosis, dilated lymph channels, and a mixed inflammatory infiltrate. Her lab work, which included a complete blood count and basic metabolic panel, was significant for neutrophilic leukocytosis (white blood cell count, 30,000 cells/mcL), chronic kidney disease, and elevated inflammatory markers.

The differential includes other types of edema and infections

Several other diseases must be differentiated from ENV, including:

Venous stasis dermatitis. Unlike ENV, this condition involves pitting edema with erythema and does not have a verrucous appearance.2,4

Lipedema. Histologically, lipedema shows no changes. It typically spares the feet, has an early age of onset, and is associated with a positive family history.1,2,4

Lipodermatosclerosis. This condition is caused by venous stasis with swelling of the proximal lower extremity and fibrosis of the distal parts. The affected leg develops an “inverted wine bottle” appearance.2,4

Pretibial myxedema. Patients with pretibial myxedema will have thyroid function test abnormalities and exhibit other signs of hyperthyroidism. If suspected, the laboratory evaluation should include thyroid-stimulating hormone levels.2,4

Filariasis. Endemic to tropical regions, filariasis is a parasitic infection. A travel history helps to differentiate this from ENV. If suspected, include a Giemsa blood smear in the laboratory evaluation.2

Chromoblastomycosis. This chronic fungal infection is typically contracted in rural tropical or subtropical regions. The causative fungi, which are present in soil, enter the skin through minor wounds (eg, thorns or splinters). The wounds are typically forgotten by the time the patient seeks medical attention. Biopsy can effectively rule out this condition.1,2,5

Treatment centers on preserving function, preventing complications

Currently, no standard treatment exists for ENV.1,4 Therapies are aimed at treating the underlying cause, preserving function in the affected limb, and preventing complications. Conservative therapy includes elevation of the affected limb and use of compression devices for edema. Antibiotics can be administered for associated cellulitis. There have been few case reports of successful treatment with oral retinoids. If medical therapy fails, surgical debridement serves as a last resort.1,4,6

Our patient improved after a week with antibiotic therapy (IV piperacillin/tazobactam 3.375 g every 6 hours) and other conservative measures, such as leg elevation.

CORRESPONDENCE

Kavita Natrajan, MBBS, George Washington University/Medical Faculty Associates, Division of Hematology and Oncology, 2150 Pennsylvania Avenue NW, DC 20037; [email protected].

A 60-year-old African American woman who had congestive heart failure (CHF) with reduced ejection fraction, untreated hepatitis C virus infection, and chronic kidney disease presented to the emergency department (ED) with a 6-month history of bilateral lower extremity edema. Use of diuretics and antibiotic therapy for suspected CHF exacerbation and cellulitis, directed by her primary care physician, had no effect. In the month prior to presenting to the ED, the patient took 2 different antibiotics, each for 10 days: clindamycin 300 mg every 6 hours and doxycycline 100 mg every 12 hours. Additionally, she was taking furosemide 40 mg/d with good urine output, but no appreciable improvement in lower extremity edema.

The physical examination revealed bilateral nonpitting edema. Weeping pearly papules, xerotic skin, and a cobblestone appearance extended from the dorsa of the patient’s feet to her knees (FIGURES 1A and 1B). The patient underwent Doppler ultrasound of the lower extremities and a skin biopsy.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa

The Doppler ultrasound was negative, and the biopsy ruled out malignancy and infection; however, the pathology report was histologically consistent with a diagnosis of elephantiasis nostras verrucosa (ENV).

ENV is a disfiguring, nonfilarial lymphedema that affects the lower extremities and is characterized by progressive cobblestoning and verrucous distortion of gravity-dependent areas.1 The skin changes are caused by lymphatic damage and obstruction from an accumulation of protein-rich fluid in the dermis and subcutaneous tissues.1,2

The term ENV was first coined by Aldo Castellani in 1934 to differentiate the condition from elephantiasis tropica (filariasis), which is caused by parasitic Wuchereria worms.3 ENV is also known as lymphangitis recurrens elephantogenica, elephantiasis verrucosa, elephantiasis nostra, mossy leg, and elephantiasis of the temperate zone.1

ENV is notably uncommon; its exact incidence is unknown. The etiology is multifactorial but can include obesity, chronic lymphedema, CHF, and recurrent cellulitis (the latter 2 were noted in our patient’s history).1

Although the diagnosis can be made based on patient history and physical examination alone, skin biopsy is warranted to rule out underlying malignancy or fungal infection.1,4 Histologic findings suggestive of ENV include pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, lymph channel dilation, widened tissue spaces, and loss of dermal papillae.1 In our patient’s case, the pathology report revealed dermal fibrosis, dilated lymph channels, and a mixed inflammatory infiltrate. Her lab work, which included a complete blood count and basic metabolic panel, was significant for neutrophilic leukocytosis (white blood cell count, 30,000 cells/mcL), chronic kidney disease, and elevated inflammatory markers.

The differential includes other types of edema and infections

Several other diseases must be differentiated from ENV, including:

Venous stasis dermatitis. Unlike ENV, this condition involves pitting edema with erythema and does not have a verrucous appearance.2,4

Lipedema. Histologically, lipedema shows no changes. It typically spares the feet, has an early age of onset, and is associated with a positive family history.1,2,4

Lipodermatosclerosis. This condition is caused by venous stasis with swelling of the proximal lower extremity and fibrosis of the distal parts. The affected leg develops an “inverted wine bottle” appearance.2,4

Pretibial myxedema. Patients with pretibial myxedema will have thyroid function test abnormalities and exhibit other signs of hyperthyroidism. If suspected, the laboratory evaluation should include thyroid-stimulating hormone levels.2,4

Filariasis. Endemic to tropical regions, filariasis is a parasitic infection. A travel history helps to differentiate this from ENV. If suspected, include a Giemsa blood smear in the laboratory evaluation.2

Chromoblastomycosis. This chronic fungal infection is typically contracted in rural tropical or subtropical regions. The causative fungi, which are present in soil, enter the skin through minor wounds (eg, thorns or splinters). The wounds are typically forgotten by the time the patient seeks medical attention. Biopsy can effectively rule out this condition.1,2,5

Treatment centers on preserving function, preventing complications

Currently, no standard treatment exists for ENV.1,4 Therapies are aimed at treating the underlying cause, preserving function in the affected limb, and preventing complications. Conservative therapy includes elevation of the affected limb and use of compression devices for edema. Antibiotics can be administered for associated cellulitis. There have been few case reports of successful treatment with oral retinoids. If medical therapy fails, surgical debridement serves as a last resort.1,4,6

Our patient improved after a week with antibiotic therapy (IV piperacillin/tazobactam 3.375 g every 6 hours) and other conservative measures, such as leg elevation.

CORRESPONDENCE

Kavita Natrajan, MBBS, George Washington University/Medical Faculty Associates, Division of Hematology and Oncology, 2150 Pennsylvania Avenue NW, DC 20037; [email protected].

1. Sisto K, Khachemoune A. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa: a review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2008;9:141-146.

2. Liaw FY, Huang CF, Wu YC, et al. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa: swelling with verrucose appearance of lower limbs. Can Fam Physician. 2012;58:e551-e553.

3. Castellani A. Researches on elephantiasis nostras and elephantiasis tropica with special regard to their initial stage of recurring lymphangitis (lymphangitis recurrens elephantogenica). J Trop Med Hyg. 1969;72:89-97.

4. Baird D, Bode D, Akers T, et al. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa (ENV): a complication of congestive heart failure and obesity. J Am Board Fam Med. 2010;23:413-417.

5. Queiroz-Telles F, Fahal AH, Falci R, et. al. Neglected endemic mycoses. Lancet Inf Dis. 2017;17:e367-e377.

6. Han HH, Lim SY, Oh DY. Successful surgical treatment for elephantiasis nostras verrucosa using a new designed column flap. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2015;14:299-302.

1. Sisto K, Khachemoune A. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa: a review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2008;9:141-146.

2. Liaw FY, Huang CF, Wu YC, et al. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa: swelling with verrucose appearance of lower limbs. Can Fam Physician. 2012;58:e551-e553.

3. Castellani A. Researches on elephantiasis nostras and elephantiasis tropica with special regard to their initial stage of recurring lymphangitis (lymphangitis recurrens elephantogenica). J Trop Med Hyg. 1969;72:89-97.

4. Baird D, Bode D, Akers T, et al. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa (ENV): a complication of congestive heart failure and obesity. J Am Board Fam Med. 2010;23:413-417.

5. Queiroz-Telles F, Fahal AH, Falci R, et. al. Neglected endemic mycoses. Lancet Inf Dis. 2017;17:e367-e377.

6. Han HH, Lim SY, Oh DY. Successful surgical treatment for elephantiasis nostras verrucosa using a new designed column flap. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2015;14:299-302.

Treating migraines: It’s different for kids

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 15-year-old girl presents to your clinic with poorly controlled chronic migraines that are preventing her from attending school 3 to 4 days per month. As part of her treatment regimen, you are considering migraine prevention strategies.

Should you prescribe amitriptyline or topiramate for preventive migraine therapy?

Migraine headaches are the most common reason for headache presentation in pediatric neurology outpatient clinics, affecting 5% to 10% of the pediatric population worldwide.2 Current recommendations regarding prophylactic migraine therapy in childhood are based on consensus opinions.3,4 And the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has not approved any medications for preventing migraines in children younger than 12 years of age. However, surveys of pediatric headache specialists suggest that amitriptyline and topiramate are among the most commonly prescribed medications for childhood migraine prophylaxis.3,4

There is low-quality evidence from individual randomized controlled trials (RCTs) about the effectiveness of topiramate. A meta-analysis by El-Chammas and colleagues included 3 RCTs comparing topiramate to placebo for the prevention of episodic migraines (migraine headaches that occur <15 times/month) in a combined total of 283 children younger than 18 years of age.5 Topiramate demonstrated a nonclinically significant, but statistically significant, reduction of less than one headache per month (-0.71; 95% confidence interval [CI], -1.19 to -0.24). This is based on moderate quality evidence due to a high placebo response rate and study durations of only 12 weeks.5 The FDA has approved topiramate for migraine prevention in children ages 12 to 17 years.6

Adult guidelines. The findings described above are consistent with the most recent adult guidelines from the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society.7 In a joint publication from 2012, these societies recommended both topiramate and amitriptyline for the prevention of migraines in adults based on high-quality (Level A evidence) and medium-quality evidence (Level B), respectively.7

[polldaddy:9973304]

STUDY SUMMARY

Both drugs are no better than placebo in children

A multicenter, double-blind RCT by Powers and colleagues compared the effectiveness of amitriptyline, topiramate, and placebo in the prevention of pediatric migraines.1 Target dosing for amitriptyline and topiramate was set at 1 mg/kg/d and 2 mg/kg/d, respectively. Titration toward these doses occurred over an 8-week period based on reported adverse effects. Patients then continued their maximum tolerated dose for an additional 16 weeks.

Patients were predominantly white (70%), female (68%), and 8 to 17 years of age. They had at least 4 headache days over a prospective 28-day pre-treatment period and a Pediatric Migraine Disability Assessment Scale (PedMIDAS) score of 11 to 139 (mild to moderate disability=11-50; severe disability >50).1,8 The primary endpoint consisted of at least a 50% relative reduction (RR) in the number of headache days over the 28-day pre-therapy (baseline) period compared with the final 28 days of the trial.1

The authors of the study included 328 patients in the primary efficacy analysis and randomly assigned them in a 2:2:1 ratio to receive either amitriptyline (132 patients), topiramate (130 patients), or placebo (66 patients), respectively. After 24 weeks of therapy, there was no significant difference between the amitriptyline, topiramate, and placebo groups in the primary endpoint (52% amitriptyline, 55% topiramate, 61% placebo; adjusted odds ratio [OR]=0.71; 98% CI, 0.34-1.48; P=.26 between amitriptyline and placebo; OR=0.81; 98% CI, 0.39-1.68; P=.48 between topiramate and placebo; OR=0.88; 98% CI, 0.49-1.59; P=.49 between amitriptyline and topiramate).

There was also no difference in the secondary outcomes of absolute reduction in headache days and headache-related disability as determined by PedMIDAS. The study was stopped early for futility. Compared with placebo, amitriptyline significantly increased fatigue (number needed to harm [NNH]=8) and dry mouth (NNH=9) and was associated with 3 serious adverse events of altered mood. Compared with placebo, topiramate significantly increased paresthesia (NNH=4) and weight loss (NNH=13) and was associated with one serious adverse event—a suicide attempt.1

WHAT’S NEW?

Higher-level evidence demonstrates lack of efficacy

This RCT provides new, higher-level evidence that demonstrates the lack of efficacy of amitriptyline and topiramate in the prevention of pediatric migraines. It also highlights the risk of increased adverse events with topiramate and amitriptyline.

Two of the 3 topiramate trials used in the older meta-analysis by El-Chammas and colleagues5 and this new RCT1 were included in an updated meta-analysis by Le and colleagues (total participants 465) published in 2017.2 This newer meta-analysis found no statistical benefit associated with the use of topiramate over placebo. It demonstrated a nonsignificant decrease in the number of patients with at least a 50% relative reduction in headache frequency (risk ratio = 1.26; 95% CI, 0.94-1.67) and in the overall number of headache days (mean difference = -0.77; 95% CI, -2.31 to 0.76) in patients younger than 18 years of age.2 Both meta-analyses, however, showed an increase in the rate of adverse events in patients using topiramate vs placebo.2,5

CAVEATS

Is there a gender predominance?

El-Chammas and colleagues5 describe male pediatric patients as being the predominant pediatric gender with migraines. However, they do not quote an incidence rate or cite the reference for this statement. No other reference to gender predominance was noted in the literature. The current study,1 in addition to the total population of the meta-analysis by Le and colleagues,2 included women as the predominant patient population. Hopefully, future studies will help to delineate if there is a gender predominance and, if so, whether the current treatment data apply to both genders.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

None to speak of

There are no barriers to implementing this recommendation immediately in all primary care settings.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

1. Powers SW, Coffey CS, Chamberlin LA, et al; for the CHAMP Investigators. Trial of amitriptyline, topiramate, and placebo for pediatric migraine. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:115-124.

2. Le K, Yu D, Wang J, et al. Is topiramate effective for migraine prevention in patients less than 18 years of age? A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Headache Pain. 2017;18:69.

3. Lewis D, Ashwal S, Hershey A, et al. Practice parameter: pharmacological treatment of migraine headache in children and adolescents: report of the American Academy of Neurology Quality Standards Subcommittee and the Practice Committee of the Child Neurology Society. Neurology. 2004;63:2215-2224.

4. Hershey AD. Current approaches to the diagnosis and management of paediatric migraine. Lancet Neurology. 2010;9:190-204.

5. El-Chammas K, Keyes J, Thompson N, et al. Pharmacologic treatment of pediatric headaches: a meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167:250-258.

6. Qudexy XR. Highlights of prescribing information. Available at: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2017/205122s003s005lbl.pdf. Accessed March 15, 2018.

7. Silberstein SD, Holland S, Freitag F, et al. Evidence-based guideline update: pharmacologic treatment for episodic migraine prevention in adults: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society. Neurology. 2012;78:1337-1345.

8. Hershey AD, Powers SW, Vockell AL, et al. PedMIDAS: development of a questionnaire to assess disability of migraines in children. Neurology. 2001;57:2034-2039.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 15-year-old girl presents to your clinic with poorly controlled chronic migraines that are preventing her from attending school 3 to 4 days per month. As part of her treatment regimen, you are considering migraine prevention strategies.

Should you prescribe amitriptyline or topiramate for preventive migraine therapy?

Migraine headaches are the most common reason for headache presentation in pediatric neurology outpatient clinics, affecting 5% to 10% of the pediatric population worldwide.2 Current recommendations regarding prophylactic migraine therapy in childhood are based on consensus opinions.3,4 And the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has not approved any medications for preventing migraines in children younger than 12 years of age. However, surveys of pediatric headache specialists suggest that amitriptyline and topiramate are among the most commonly prescribed medications for childhood migraine prophylaxis.3,4

There is low-quality evidence from individual randomized controlled trials (RCTs) about the effectiveness of topiramate. A meta-analysis by El-Chammas and colleagues included 3 RCTs comparing topiramate to placebo for the prevention of episodic migraines (migraine headaches that occur <15 times/month) in a combined total of 283 children younger than 18 years of age.5 Topiramate demonstrated a nonclinically significant, but statistically significant, reduction of less than one headache per month (-0.71; 95% confidence interval [CI], -1.19 to -0.24). This is based on moderate quality evidence due to a high placebo response rate and study durations of only 12 weeks.5 The FDA has approved topiramate for migraine prevention in children ages 12 to 17 years.6

Adult guidelines. The findings described above are consistent with the most recent adult guidelines from the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society.7 In a joint publication from 2012, these societies recommended both topiramate and amitriptyline for the prevention of migraines in adults based on high-quality (Level A evidence) and medium-quality evidence (Level B), respectively.7

[polldaddy:9973304]

STUDY SUMMARY

Both drugs are no better than placebo in children

A multicenter, double-blind RCT by Powers and colleagues compared the effectiveness of amitriptyline, topiramate, and placebo in the prevention of pediatric migraines.1 Target dosing for amitriptyline and topiramate was set at 1 mg/kg/d and 2 mg/kg/d, respectively. Titration toward these doses occurred over an 8-week period based on reported adverse effects. Patients then continued their maximum tolerated dose for an additional 16 weeks.

Patients were predominantly white (70%), female (68%), and 8 to 17 years of age. They had at least 4 headache days over a prospective 28-day pre-treatment period and a Pediatric Migraine Disability Assessment Scale (PedMIDAS) score of 11 to 139 (mild to moderate disability=11-50; severe disability >50).1,8 The primary endpoint consisted of at least a 50% relative reduction (RR) in the number of headache days over the 28-day pre-therapy (baseline) period compared with the final 28 days of the trial.1

The authors of the study included 328 patients in the primary efficacy analysis and randomly assigned them in a 2:2:1 ratio to receive either amitriptyline (132 patients), topiramate (130 patients), or placebo (66 patients), respectively. After 24 weeks of therapy, there was no significant difference between the amitriptyline, topiramate, and placebo groups in the primary endpoint (52% amitriptyline, 55% topiramate, 61% placebo; adjusted odds ratio [OR]=0.71; 98% CI, 0.34-1.48; P=.26 between amitriptyline and placebo; OR=0.81; 98% CI, 0.39-1.68; P=.48 between topiramate and placebo; OR=0.88; 98% CI, 0.49-1.59; P=.49 between amitriptyline and topiramate).

There was also no difference in the secondary outcomes of absolute reduction in headache days and headache-related disability as determined by PedMIDAS. The study was stopped early for futility. Compared with placebo, amitriptyline significantly increased fatigue (number needed to harm [NNH]=8) and dry mouth (NNH=9) and was associated with 3 serious adverse events of altered mood. Compared with placebo, topiramate significantly increased paresthesia (NNH=4) and weight loss (NNH=13) and was associated with one serious adverse event—a suicide attempt.1

WHAT’S NEW?

Higher-level evidence demonstrates lack of efficacy

This RCT provides new, higher-level evidence that demonstrates the lack of efficacy of amitriptyline and topiramate in the prevention of pediatric migraines. It also highlights the risk of increased adverse events with topiramate and amitriptyline.

Two of the 3 topiramate trials used in the older meta-analysis by El-Chammas and colleagues5 and this new RCT1 were included in an updated meta-analysis by Le and colleagues (total participants 465) published in 2017.2 This newer meta-analysis found no statistical benefit associated with the use of topiramate over placebo. It demonstrated a nonsignificant decrease in the number of patients with at least a 50% relative reduction in headache frequency (risk ratio = 1.26; 95% CI, 0.94-1.67) and in the overall number of headache days (mean difference = -0.77; 95% CI, -2.31 to 0.76) in patients younger than 18 years of age.2 Both meta-analyses, however, showed an increase in the rate of adverse events in patients using topiramate vs placebo.2,5

CAVEATS

Is there a gender predominance?

El-Chammas and colleagues5 describe male pediatric patients as being the predominant pediatric gender with migraines. However, they do not quote an incidence rate or cite the reference for this statement. No other reference to gender predominance was noted in the literature. The current study,1 in addition to the total population of the meta-analysis by Le and colleagues,2 included women as the predominant patient population. Hopefully, future studies will help to delineate if there is a gender predominance and, if so, whether the current treatment data apply to both genders.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

None to speak of

There are no barriers to implementing this recommendation immediately in all primary care settings.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 15-year-old girl presents to your clinic with poorly controlled chronic migraines that are preventing her from attending school 3 to 4 days per month. As part of her treatment regimen, you are considering migraine prevention strategies.

Should you prescribe amitriptyline or topiramate for preventive migraine therapy?

Migraine headaches are the most common reason for headache presentation in pediatric neurology outpatient clinics, affecting 5% to 10% of the pediatric population worldwide.2 Current recommendations regarding prophylactic migraine therapy in childhood are based on consensus opinions.3,4 And the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has not approved any medications for preventing migraines in children younger than 12 years of age. However, surveys of pediatric headache specialists suggest that amitriptyline and topiramate are among the most commonly prescribed medications for childhood migraine prophylaxis.3,4

There is low-quality evidence from individual randomized controlled trials (RCTs) about the effectiveness of topiramate. A meta-analysis by El-Chammas and colleagues included 3 RCTs comparing topiramate to placebo for the prevention of episodic migraines (migraine headaches that occur <15 times/month) in a combined total of 283 children younger than 18 years of age.5 Topiramate demonstrated a nonclinically significant, but statistically significant, reduction of less than one headache per month (-0.71; 95% confidence interval [CI], -1.19 to -0.24). This is based on moderate quality evidence due to a high placebo response rate and study durations of only 12 weeks.5 The FDA has approved topiramate for migraine prevention in children ages 12 to 17 years.6

Adult guidelines. The findings described above are consistent with the most recent adult guidelines from the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society.7 In a joint publication from 2012, these societies recommended both topiramate and amitriptyline for the prevention of migraines in adults based on high-quality (Level A evidence) and medium-quality evidence (Level B), respectively.7

[polldaddy:9973304]

STUDY SUMMARY

Both drugs are no better than placebo in children

A multicenter, double-blind RCT by Powers and colleagues compared the effectiveness of amitriptyline, topiramate, and placebo in the prevention of pediatric migraines.1 Target dosing for amitriptyline and topiramate was set at 1 mg/kg/d and 2 mg/kg/d, respectively. Titration toward these doses occurred over an 8-week period based on reported adverse effects. Patients then continued their maximum tolerated dose for an additional 16 weeks.

Patients were predominantly white (70%), female (68%), and 8 to 17 years of age. They had at least 4 headache days over a prospective 28-day pre-treatment period and a Pediatric Migraine Disability Assessment Scale (PedMIDAS) score of 11 to 139 (mild to moderate disability=11-50; severe disability >50).1,8 The primary endpoint consisted of at least a 50% relative reduction (RR) in the number of headache days over the 28-day pre-therapy (baseline) period compared with the final 28 days of the trial.1

The authors of the study included 328 patients in the primary efficacy analysis and randomly assigned them in a 2:2:1 ratio to receive either amitriptyline (132 patients), topiramate (130 patients), or placebo (66 patients), respectively. After 24 weeks of therapy, there was no significant difference between the amitriptyline, topiramate, and placebo groups in the primary endpoint (52% amitriptyline, 55% topiramate, 61% placebo; adjusted odds ratio [OR]=0.71; 98% CI, 0.34-1.48; P=.26 between amitriptyline and placebo; OR=0.81; 98% CI, 0.39-1.68; P=.48 between topiramate and placebo; OR=0.88; 98% CI, 0.49-1.59; P=.49 between amitriptyline and topiramate).

There was also no difference in the secondary outcomes of absolute reduction in headache days and headache-related disability as determined by PedMIDAS. The study was stopped early for futility. Compared with placebo, amitriptyline significantly increased fatigue (number needed to harm [NNH]=8) and dry mouth (NNH=9) and was associated with 3 serious adverse events of altered mood. Compared with placebo, topiramate significantly increased paresthesia (NNH=4) and weight loss (NNH=13) and was associated with one serious adverse event—a suicide attempt.1

WHAT’S NEW?

Higher-level evidence demonstrates lack of efficacy

This RCT provides new, higher-level evidence that demonstrates the lack of efficacy of amitriptyline and topiramate in the prevention of pediatric migraines. It also highlights the risk of increased adverse events with topiramate and amitriptyline.

Two of the 3 topiramate trials used in the older meta-analysis by El-Chammas and colleagues5 and this new RCT1 were included in an updated meta-analysis by Le and colleagues (total participants 465) published in 2017.2 This newer meta-analysis found no statistical benefit associated with the use of topiramate over placebo. It demonstrated a nonsignificant decrease in the number of patients with at least a 50% relative reduction in headache frequency (risk ratio = 1.26; 95% CI, 0.94-1.67) and in the overall number of headache days (mean difference = -0.77; 95% CI, -2.31 to 0.76) in patients younger than 18 years of age.2 Both meta-analyses, however, showed an increase in the rate of adverse events in patients using topiramate vs placebo.2,5

CAVEATS

Is there a gender predominance?

El-Chammas and colleagues5 describe male pediatric patients as being the predominant pediatric gender with migraines. However, they do not quote an incidence rate or cite the reference for this statement. No other reference to gender predominance was noted in the literature. The current study,1 in addition to the total population of the meta-analysis by Le and colleagues,2 included women as the predominant patient population. Hopefully, future studies will help to delineate if there is a gender predominance and, if so, whether the current treatment data apply to both genders.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

None to speak of

There are no barriers to implementing this recommendation immediately in all primary care settings.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

1. Powers SW, Coffey CS, Chamberlin LA, et al; for the CHAMP Investigators. Trial of amitriptyline, topiramate, and placebo for pediatric migraine. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:115-124.

2. Le K, Yu D, Wang J, et al. Is topiramate effective for migraine prevention in patients less than 18 years of age? A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Headache Pain. 2017;18:69.

3. Lewis D, Ashwal S, Hershey A, et al. Practice parameter: pharmacological treatment of migraine headache in children and adolescents: report of the American Academy of Neurology Quality Standards Subcommittee and the Practice Committee of the Child Neurology Society. Neurology. 2004;63:2215-2224.

4. Hershey AD. Current approaches to the diagnosis and management of paediatric migraine. Lancet Neurology. 2010;9:190-204.

5. El-Chammas K, Keyes J, Thompson N, et al. Pharmacologic treatment of pediatric headaches: a meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167:250-258.

6. Qudexy XR. Highlights of prescribing information. Available at: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2017/205122s003s005lbl.pdf. Accessed March 15, 2018.

7. Silberstein SD, Holland S, Freitag F, et al. Evidence-based guideline update: pharmacologic treatment for episodic migraine prevention in adults: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society. Neurology. 2012;78:1337-1345.

8. Hershey AD, Powers SW, Vockell AL, et al. PedMIDAS: development of a questionnaire to assess disability of migraines in children. Neurology. 2001;57:2034-2039.

1. Powers SW, Coffey CS, Chamberlin LA, et al; for the CHAMP Investigators. Trial of amitriptyline, topiramate, and placebo for pediatric migraine. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:115-124.

2. Le K, Yu D, Wang J, et al. Is topiramate effective for migraine prevention in patients less than 18 years of age? A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Headache Pain. 2017;18:69.

3. Lewis D, Ashwal S, Hershey A, et al. Practice parameter: pharmacological treatment of migraine headache in children and adolescents: report of the American Academy of Neurology Quality Standards Subcommittee and the Practice Committee of the Child Neurology Society. Neurology. 2004;63:2215-2224.

4. Hershey AD. Current approaches to the diagnosis and management of paediatric migraine. Lancet Neurology. 2010;9:190-204.

5. El-Chammas K, Keyes J, Thompson N, et al. Pharmacologic treatment of pediatric headaches: a meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167:250-258.

6. Qudexy XR. Highlights of prescribing information. Available at: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2017/205122s003s005lbl.pdf. Accessed March 15, 2018.

7. Silberstein SD, Holland S, Freitag F, et al. Evidence-based guideline update: pharmacologic treatment for episodic migraine prevention in adults: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society. Neurology. 2012;78:1337-1345.

8. Hershey AD, Powers SW, Vockell AL, et al. PedMIDAS: development of a questionnaire to assess disability of migraines in children. Neurology. 2001;57:2034-2039.

Copyright © 2018. The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

PRACTICE CHANGER

Do not prescribe amitriptyline or topiramate as preventive therapy for migraine in children; both drugs are no better than placebo for this population and are associated with increased rates of adverse events.1,2

STRENGTH OF RECOMMENDATION

A: Based on a single double-blind randomized control trial (RCT) and supported by a meta-analysis of 4 RCTs.

1. Powers SW, Coffey CS, Chamberlin LA, et al; for the CHAMP Investigators. Trial of amitriptyline, topiramate, and placebo for pediatric migraine. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:115-124.

2. Le K, Yu D, Wang J, et al. Is topiramate effective for migraine prevention in patients less than 18 years of age? A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Headache Pain. 2017;18:69.

Severe right upper chest pain • tender right sternoclavicular joint • Dx?

THE CASE

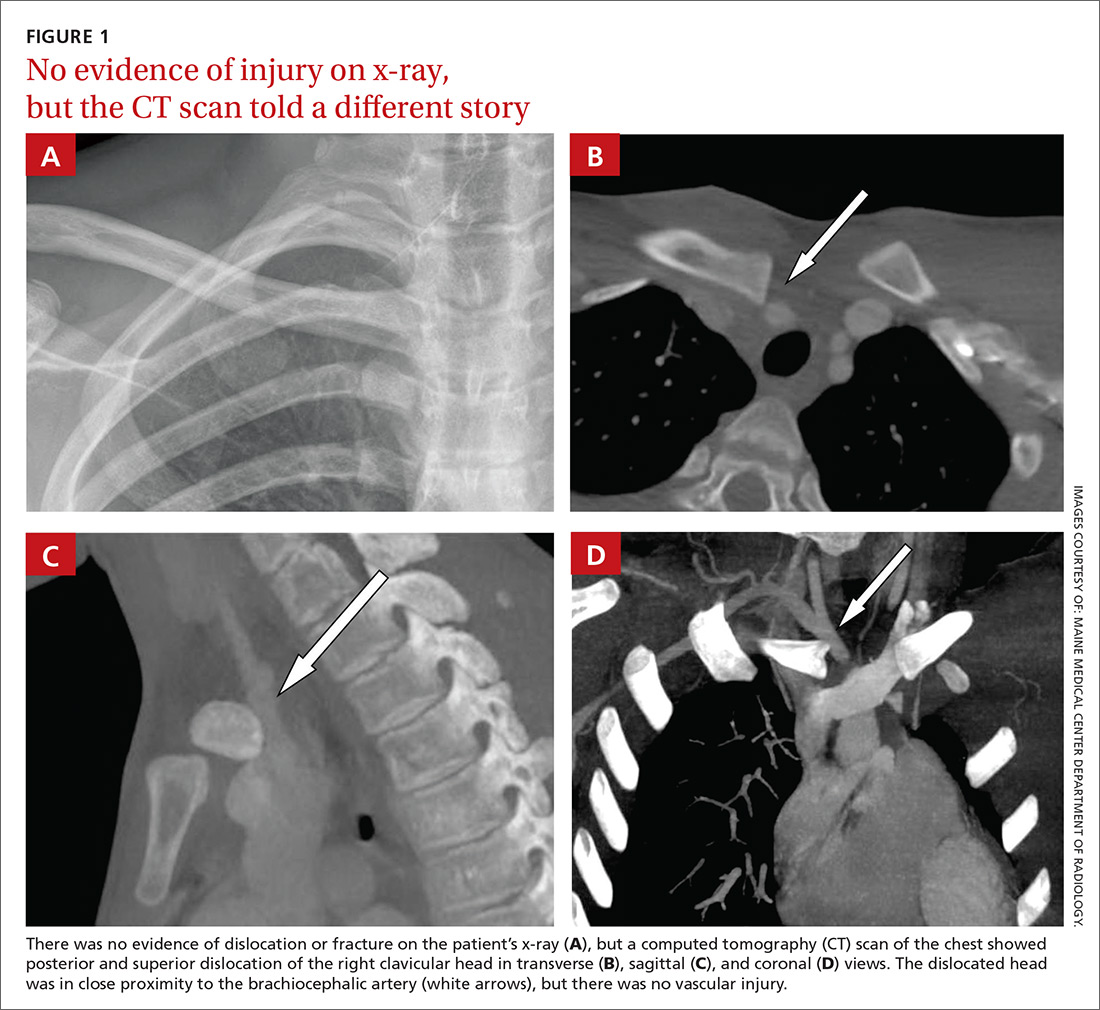

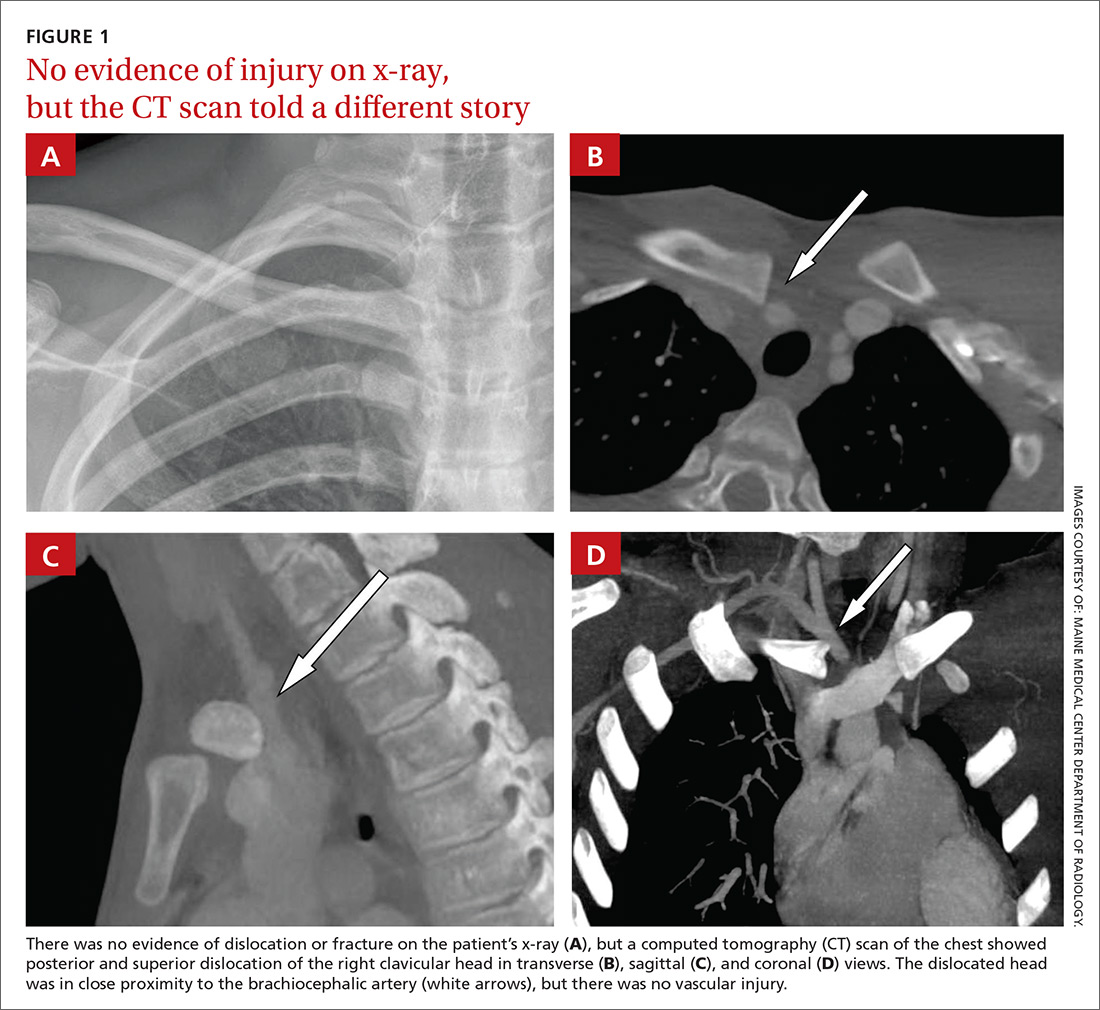

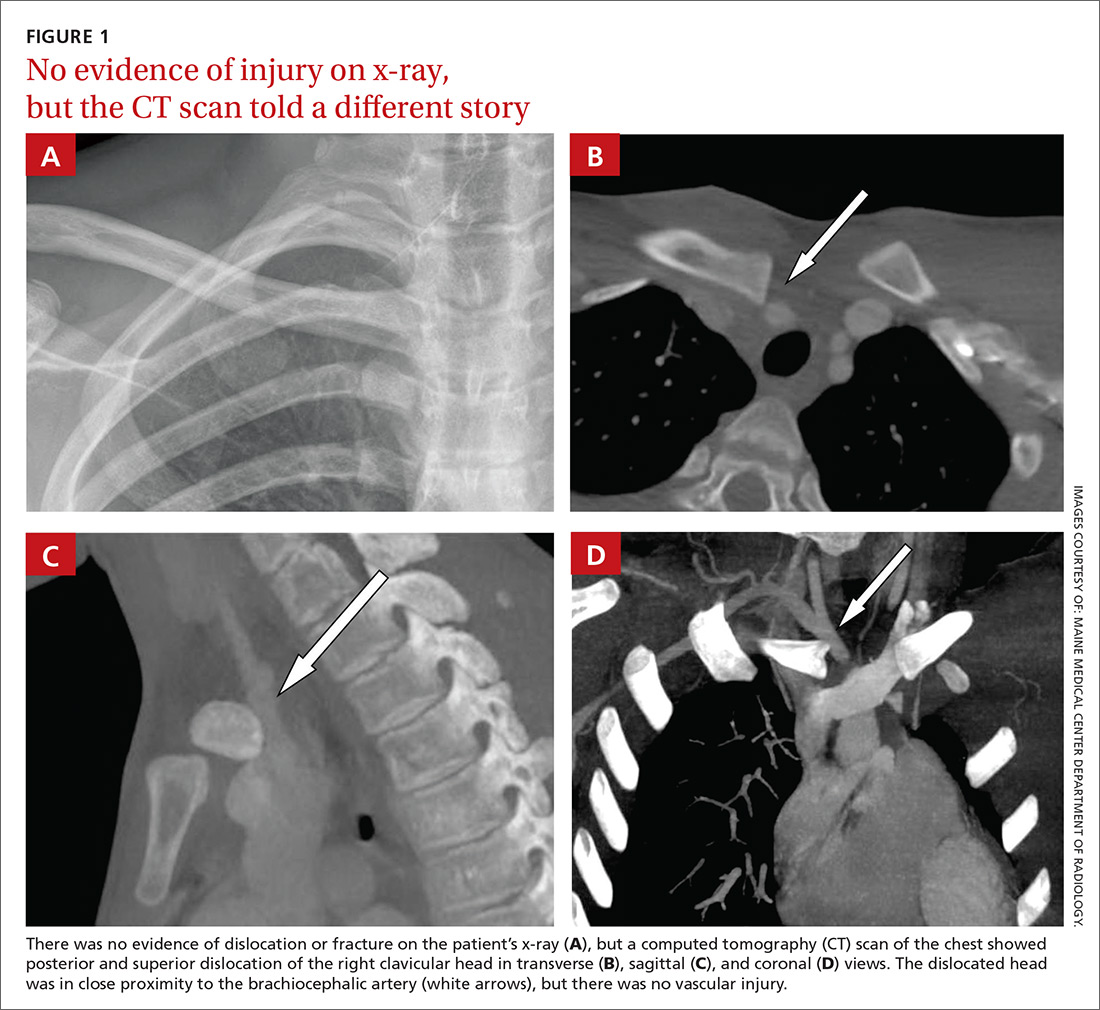

A 16-year-old hockey player presented to our emergency department with sharp pain in his right upper chest after “checking” another player during a game. The pain did not resolve with rest and was worse with movement and breathing. The patient did not have dysphagia, dyspnea, paresthesias, or hoarseness. The physical examination revealed tenderness over the right sternoclavicular joint (SCJ) without swelling or deformity. A distal neurovascular exam was intact, and a chest x-ray showed no evidence of dislocation or fracture (FIGURE 1A). The patient’s pain was refractory to multiple intravenous (IV) pain medications.

THE DIAGNOSIS

A computed tomography (CT) scan with IV contrast of the chest demonstrated posterior and superior dislocation of the right clavicular head. Despite the close proximity of the dislocated head to the brachiocephalic artery (FIGURE 1B-1D), there was no vascular injury.

DISCUSSION

Posterior sternoclavicular dislocations (PSCDs) can be difficult to diagnose. Edema can mask the characteristic skin depression that one would expect with a posterior dislocation.1 Chest radiographs are often normal (as was true in this case). Patients may present with an abnormal pulse, paresthesias, hoarseness, dysphagia, and/or dyspnea. However, for more than half of these patients, their only signs and symptoms will be pain, swelling, and limited range of motion.1 As a result, a PSCD may be misdiagnosed as a ligamentous or soft tissue injury.1

An uncommon injury that can result in serious complications

PSCDs represent 3% to 5% of all SCJ dislocations, which comprise <5% of all shoulder girdle injuries.1 Nevertheless, prompt and accurate diagnosis is critical, as these dislocations involve a high risk for injury to the posterior structures, particularly the brachiocephalic vein, right common carotid artery, and aortic arch.

One study found that nearly 75% of patients had a significant structure <1 cm posterior to the SCJ.2 This proximity can result in neurovascular complications—some of which are devastating—in up to 30% of patients with PSCDs.3 A case report from 2011, for example, describes a 19-year-old man who had an undiagnosed PSCD that caused a pseudoaneurysm in his subclavian artery and a subsequent thrombotic cerebrovascular accident.4

Which injuries should raise your suspicions? Injuries in which lateral compression on the shoulder has caused it to roll forward and those in which a posteriorly directed force has been applied to the medial clavicle (as might occur in tackle sports or motor vehicle rollovers) should increase suspicion of a PSCD.1

Proper diagnosis requires CT angiography of the chest to assess the injury and evaluate the underlying structures. If CT is not available, additional chest film views, such as a serendipity view (anteroposterior view with 40° cephalic tilt) or Heinig view (oblique projection perpendicular to SCJ), may be obtained; an ultrasound is also an option.5

PSCD = surgical emergency

Following diagnosis, immediate orthopedic consultation is required. A PSCD is a surgical emergency. Reduction (open or closed) must be performed under general anesthesia with vascular and/or cardiothoracic surgery specialists available, as the reduction itself could injure one of the great vessels. Fortunately, most patients do quite well following surgery, with the majority achieving good-to-excellent results.6

Our patient was admitted to the hospital and underwent orthopedic surgery the following morning. Vascular and cardiothoracic surgeons were consulted and available in the event of a complication. A Salter-Harris type 2 fracture of the medial clavicle was identified intraoperatively, and an open reduction with internal fixation was performed. The patient had an uneventful recovery and resumed his usual activities, including playing hockey.

THE TAKEAWAY

PSCDs, although uncommon, can be life-threatening. Since the physical exam is unreliable and standard radiographs are often normal, accurate diagnosis relies largely on increased clinical suspicion. When there is a history of shoulder trauma, medial clavicle pain, and SCJ edema or tenderness, a PSCD should be suspected.7

Confirm the diagnosis with CT angiogram, and remember that a PSCD is a surgical emergency that requires coordination with orthopedic and vascular/cardiothoracic surgeons.

1. Chaudhry S. Pediatric posterior sternoclavicular joint injuries. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2015;23:468-475.

2. Ponce BA, Kundukulam JA, Pflugner R, et al. Sternoclavicular joint surgery: how far does danger lurk below? J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22:993-999.

3. Daya MR, Bengtzen RR. Shoulder. In: Rosen’s Emergency Medicine: Concepts and Clinical Practice. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2014:618-642.

4. Marcus MS, Tan V. Cerebrovascular accident in a 19-year-old patient: a case report of posterior sternoclavicular dislocation. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20:e1-e4.

5. Morell DJ, Thyagarajan DS. Sternoclavicular joint dislocation and its management: a review of the literature. World J Orthop. 2016;7:244-250.