User login

In utero exposure to valproate and other AEDs linked to low test scores

In utero exposure to some antiepileptic drugs was linked to decreased educational achievement at the age of 7 years, in results of a matched-case control study.

Compared with controls, children exposed in the womb to sodium valproate alone, or to multiple antiepileptics (AEDs), had lower scores on U.K standardized tests routinely administered to 7-year-olds, according to results published in the Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry.

The results provide evidence showing that in utero exposure to some AEDs may lead to developmental issues in children, according to lead author Arron S. Lacey, Wales Epilepsy Research Network, Swansea University Medical School, Swansea, England, and coauthors.

“Women with epilepsy should be informed of this risk, and alternative treatment regimens should be discussed before their pregnancy with a physician that specializes in epilepsy,” Dr. Lacey concluded in a discussion of their study results.

In the United Kingdom, already-stringent guidance on valproate in pregnancy was strengthened on March 23 when the European Medicines Agency announced new measures designed to avoid valproate exposure in pregnancy because of risk of malformations and developmental issues. The measures include a ban on valproate-containing medicines for the treatment of epilepsy during pregnancy unless no other effective treatment is available.

The risks of AEDs, and valproate in particular, in pregnancy have been documented in multiple studies suggesting that exposure may lead to cognitive impairment, neurodevelopmental disorders, and impaired IQ. However, the available data are largely from psychometric studies, Dr. Lacey and colleagues noted in their report. “It is important to know whether the psychometric differences demonstrated in research conditions translate to children in the community,” they wrote.

To address this, Dr. Lacey and coinvestigators conducted a study of standardized academic test results in children in Wales born to mothers with epilepsy who had been prescribed AEDs during pregnancy. They reviewed health records and identified 440 AED-exposed children who had available results for Key Stage 1 tests for mathematics, language, and science at the age of 7 years.

Among children whose mothers had been prescribed valproate during pregnancy, the proportion achieving U.K. minimum standards for all subjects was 12.7% lower than a matched control group, investigators said.

Children of mothers who had been prescribed multiple AEDs had an even lower proportion achieving the minimum standard for all subjects, at 20.7% less than the control group, they added.

By contrast, children whose mothers were prescribed carbamazepine did not have any significant differences in educational achievement, compared with controls.

Some previous studies found as association between exposure to carbamazepine and cognitive impairment, while others found no such association. “Our study supports the latter, with no evidence of decreased educational attainment at school age,” the investigators said in their article.

Some study authors reported competing interests related to Eisai, Sanofi, UCB, and others.

SOURCE: Lacey AS et al. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2018 Mar 25. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-201-317515.

Performing a matched-case control study that links health records and national educational data is an innovative approach to assessing educational achievement in children born to mothers with epilepsy, according to Richard F.M. Chin, MD.

Lacey and colleagues demonstrated that in utero exposure to sodium valproate alone or antiepileptic drugs in combination was associated with significant decreases in educational achievement in national educational tests given to 7-year-old children, Dr Chin wrote in an editorial.

That finding may not seem new, given that multiple previous studies have linked in utero antiepileptic exposure to lower IQ, more frequent behavioral issues, and higher risk of psychiatric disorders. However, previous studies depended on detailed, resource-intensive, one-on-one assessments, or parent responses to questionnaires with potentially biased responses, Dr. Chin said. In contrast, Lacey and colleagues incorporating validated epilepsy diagnoses and made use of already available educational attainment data from the epilepsy cases and matched controls.

Because of that, their results may be more likely than previous studies to be representative of the general population, according to Dr. Chin.

“Such a relatively cost-effective and efficient approach has vast potential to be applicable for a number of other conditions and is at the heart of the emerging health informatics revolution,” he wrote.

Richard F.M. Chin is with the Muir Maxwell Epilepsy Centre, University of Edinburgh, Scotland. These comments are derived from his editorial published in the Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry (2018 Mar 25. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2017-317924 ). Dr. Chin declared no competing interests related to the editorial.

Performing a matched-case control study that links health records and national educational data is an innovative approach to assessing educational achievement in children born to mothers with epilepsy, according to Richard F.M. Chin, MD.

Lacey and colleagues demonstrated that in utero exposure to sodium valproate alone or antiepileptic drugs in combination was associated with significant decreases in educational achievement in national educational tests given to 7-year-old children, Dr Chin wrote in an editorial.

That finding may not seem new, given that multiple previous studies have linked in utero antiepileptic exposure to lower IQ, more frequent behavioral issues, and higher risk of psychiatric disorders. However, previous studies depended on detailed, resource-intensive, one-on-one assessments, or parent responses to questionnaires with potentially biased responses, Dr. Chin said. In contrast, Lacey and colleagues incorporating validated epilepsy diagnoses and made use of already available educational attainment data from the epilepsy cases and matched controls.

Because of that, their results may be more likely than previous studies to be representative of the general population, according to Dr. Chin.

“Such a relatively cost-effective and efficient approach has vast potential to be applicable for a number of other conditions and is at the heart of the emerging health informatics revolution,” he wrote.

Richard F.M. Chin is with the Muir Maxwell Epilepsy Centre, University of Edinburgh, Scotland. These comments are derived from his editorial published in the Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry (2018 Mar 25. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2017-317924 ). Dr. Chin declared no competing interests related to the editorial.

Performing a matched-case control study that links health records and national educational data is an innovative approach to assessing educational achievement in children born to mothers with epilepsy, according to Richard F.M. Chin, MD.

Lacey and colleagues demonstrated that in utero exposure to sodium valproate alone or antiepileptic drugs in combination was associated with significant decreases in educational achievement in national educational tests given to 7-year-old children, Dr Chin wrote in an editorial.

That finding may not seem new, given that multiple previous studies have linked in utero antiepileptic exposure to lower IQ, more frequent behavioral issues, and higher risk of psychiatric disorders. However, previous studies depended on detailed, resource-intensive, one-on-one assessments, or parent responses to questionnaires with potentially biased responses, Dr. Chin said. In contrast, Lacey and colleagues incorporating validated epilepsy diagnoses and made use of already available educational attainment data from the epilepsy cases and matched controls.

Because of that, their results may be more likely than previous studies to be representative of the general population, according to Dr. Chin.

“Such a relatively cost-effective and efficient approach has vast potential to be applicable for a number of other conditions and is at the heart of the emerging health informatics revolution,” he wrote.

Richard F.M. Chin is with the Muir Maxwell Epilepsy Centre, University of Edinburgh, Scotland. These comments are derived from his editorial published in the Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry (2018 Mar 25. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2017-317924 ). Dr. Chin declared no competing interests related to the editorial.

In utero exposure to some antiepileptic drugs was linked to decreased educational achievement at the age of 7 years, in results of a matched-case control study.

Compared with controls, children exposed in the womb to sodium valproate alone, or to multiple antiepileptics (AEDs), had lower scores on U.K standardized tests routinely administered to 7-year-olds, according to results published in the Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry.

The results provide evidence showing that in utero exposure to some AEDs may lead to developmental issues in children, according to lead author Arron S. Lacey, Wales Epilepsy Research Network, Swansea University Medical School, Swansea, England, and coauthors.

“Women with epilepsy should be informed of this risk, and alternative treatment regimens should be discussed before their pregnancy with a physician that specializes in epilepsy,” Dr. Lacey concluded in a discussion of their study results.

In the United Kingdom, already-stringent guidance on valproate in pregnancy was strengthened on March 23 when the European Medicines Agency announced new measures designed to avoid valproate exposure in pregnancy because of risk of malformations and developmental issues. The measures include a ban on valproate-containing medicines for the treatment of epilepsy during pregnancy unless no other effective treatment is available.

The risks of AEDs, and valproate in particular, in pregnancy have been documented in multiple studies suggesting that exposure may lead to cognitive impairment, neurodevelopmental disorders, and impaired IQ. However, the available data are largely from psychometric studies, Dr. Lacey and colleagues noted in their report. “It is important to know whether the psychometric differences demonstrated in research conditions translate to children in the community,” they wrote.

To address this, Dr. Lacey and coinvestigators conducted a study of standardized academic test results in children in Wales born to mothers with epilepsy who had been prescribed AEDs during pregnancy. They reviewed health records and identified 440 AED-exposed children who had available results for Key Stage 1 tests for mathematics, language, and science at the age of 7 years.

Among children whose mothers had been prescribed valproate during pregnancy, the proportion achieving U.K. minimum standards for all subjects was 12.7% lower than a matched control group, investigators said.

Children of mothers who had been prescribed multiple AEDs had an even lower proportion achieving the minimum standard for all subjects, at 20.7% less than the control group, they added.

By contrast, children whose mothers were prescribed carbamazepine did not have any significant differences in educational achievement, compared with controls.

Some previous studies found as association between exposure to carbamazepine and cognitive impairment, while others found no such association. “Our study supports the latter, with no evidence of decreased educational attainment at school age,” the investigators said in their article.

Some study authors reported competing interests related to Eisai, Sanofi, UCB, and others.

SOURCE: Lacey AS et al. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2018 Mar 25. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-201-317515.

In utero exposure to some antiepileptic drugs was linked to decreased educational achievement at the age of 7 years, in results of a matched-case control study.

Compared with controls, children exposed in the womb to sodium valproate alone, or to multiple antiepileptics (AEDs), had lower scores on U.K standardized tests routinely administered to 7-year-olds, according to results published in the Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry.

The results provide evidence showing that in utero exposure to some AEDs may lead to developmental issues in children, according to lead author Arron S. Lacey, Wales Epilepsy Research Network, Swansea University Medical School, Swansea, England, and coauthors.

“Women with epilepsy should be informed of this risk, and alternative treatment regimens should be discussed before their pregnancy with a physician that specializes in epilepsy,” Dr. Lacey concluded in a discussion of their study results.

In the United Kingdom, already-stringent guidance on valproate in pregnancy was strengthened on March 23 when the European Medicines Agency announced new measures designed to avoid valproate exposure in pregnancy because of risk of malformations and developmental issues. The measures include a ban on valproate-containing medicines for the treatment of epilepsy during pregnancy unless no other effective treatment is available.

The risks of AEDs, and valproate in particular, in pregnancy have been documented in multiple studies suggesting that exposure may lead to cognitive impairment, neurodevelopmental disorders, and impaired IQ. However, the available data are largely from psychometric studies, Dr. Lacey and colleagues noted in their report. “It is important to know whether the psychometric differences demonstrated in research conditions translate to children in the community,” they wrote.

To address this, Dr. Lacey and coinvestigators conducted a study of standardized academic test results in children in Wales born to mothers with epilepsy who had been prescribed AEDs during pregnancy. They reviewed health records and identified 440 AED-exposed children who had available results for Key Stage 1 tests for mathematics, language, and science at the age of 7 years.

Among children whose mothers had been prescribed valproate during pregnancy, the proportion achieving U.K. minimum standards for all subjects was 12.7% lower than a matched control group, investigators said.

Children of mothers who had been prescribed multiple AEDs had an even lower proportion achieving the minimum standard for all subjects, at 20.7% less than the control group, they added.

By contrast, children whose mothers were prescribed carbamazepine did not have any significant differences in educational achievement, compared with controls.

Some previous studies found as association between exposure to carbamazepine and cognitive impairment, while others found no such association. “Our study supports the latter, with no evidence of decreased educational attainment at school age,” the investigators said in their article.

Some study authors reported competing interests related to Eisai, Sanofi, UCB, and others.

SOURCE: Lacey AS et al. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2018 Mar 25. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-201-317515.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF NEUROLOGY, NEUROSURGERY & PSYCHIATRY

Key clinical point: In utero exposure to sodium valproate or to multiple antiepileptic drugs was associated with decreased educational achievement at the age of 7 years.

Major finding: Compared with a control group, the proportion of 7-year-old students achieving U.K. minimum standards for all subjects was 12.7% lower in children born to mothers with epilepsy prescribed valproate during pregnancy.

Study details: An analysis of standardized national test scores for 440 U.K. children who had been born to mothers with epilepsy, compared with test scores for a matched control group.

Disclosures: Some study authors reported competing interests related to Eisai, Sanofi, UCB, and others.

Source: Lacey AS et al. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2018 Mar 25. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-201-317515.

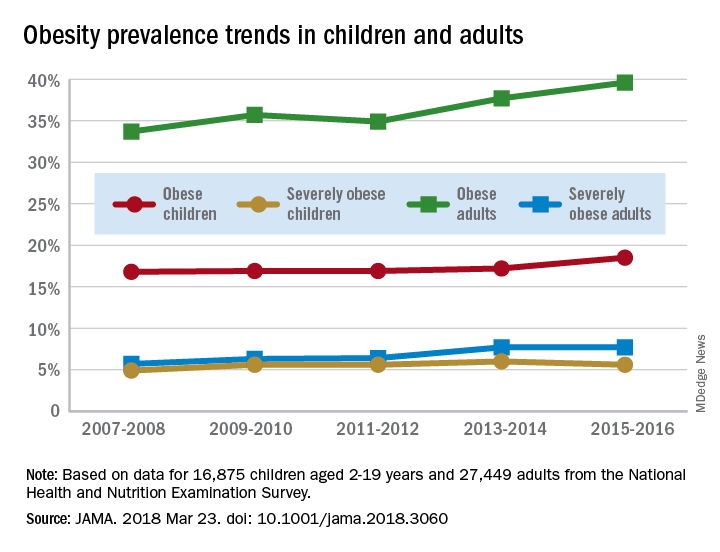

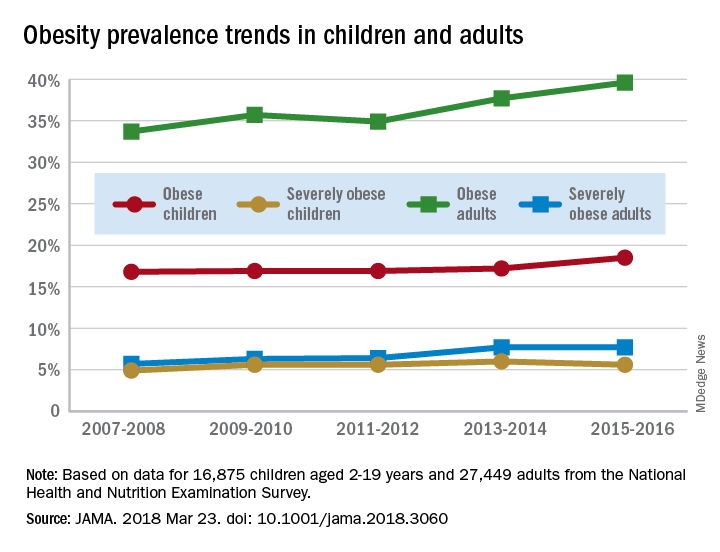

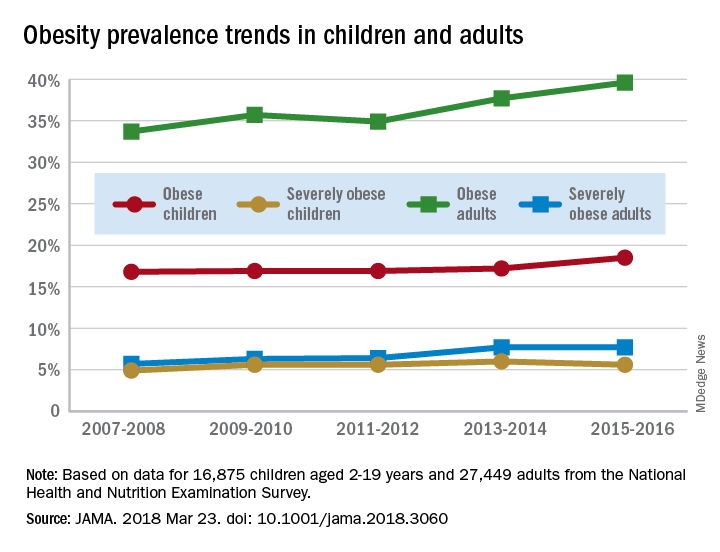

Obesity in adults continues to rise

according to data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

The age-standardized prevalence of obesity – defined as a body mass index of 30 or more – among adults aged 20 years and over increased from 33.7% for the 2-year period of 2007-2008 to 39.6% in 2015-2016, while the prevalence of severe obesity – defined as a body mass index of 40 kg/m2 or more – went from 5.7% to 7.7% over that same period, Craig M. Hales, MD, and his associates at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Hyattsville, Md., and Atlanta said in a research letter published in JAMA.

The prevalence of obesity in children aged 2-19 years – defined as BMI at or above the sex-specific 95th percentile – increased, but not significantly, from 16.8% in 2007-2008 to 18.5% in 2015-2016, with most of that increase coming in the last 2 years. Severe obesity – BMI at or above 120% of the sex-specific 95th percentile – rose from 4.9% to 5.6% over those 10 years, but the last 2-year period saw the rate drop from 6% in 2013-2014, the investigators reported.

For the most recent reporting period, boys were more likely than girls to be obese (19.1% vs. 17.8%) and severely obese (6.3% vs. 4.9%), and both obesity and severe obesity were more common with increasing age. Obesity prevalence went from 13.9% in those aged 2-5 years to 20.6% in 12- to 19-year-olds, and severe obesity was 1.8% in the youngest group and 7.7% in the oldest, with the middle-age group (6-11 years) in the middle in both categories, they said

Among the adults, obesity was more common in women than men (41.1% vs. 37.9%) for 2015-2016, as was severe obesity (9.7% vs. 5.6%). Obesity and severe obesity were both highest in those aged 40-59 years, but obesity prevalence was lowest in the younger group (20-39 years) and severe obesity was least common in the older group (60 years and older), Dr. Hales and his associates said.

The analysis involved 16,875 children and 27,449 adults over the 10-year period. The investigators did not report any conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Hales CM et al. JAMA 2018 Mar 23. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.3060.

according to data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

The age-standardized prevalence of obesity – defined as a body mass index of 30 or more – among adults aged 20 years and over increased from 33.7% for the 2-year period of 2007-2008 to 39.6% in 2015-2016, while the prevalence of severe obesity – defined as a body mass index of 40 kg/m2 or more – went from 5.7% to 7.7% over that same period, Craig M. Hales, MD, and his associates at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Hyattsville, Md., and Atlanta said in a research letter published in JAMA.

The prevalence of obesity in children aged 2-19 years – defined as BMI at or above the sex-specific 95th percentile – increased, but not significantly, from 16.8% in 2007-2008 to 18.5% in 2015-2016, with most of that increase coming in the last 2 years. Severe obesity – BMI at or above 120% of the sex-specific 95th percentile – rose from 4.9% to 5.6% over those 10 years, but the last 2-year period saw the rate drop from 6% in 2013-2014, the investigators reported.

For the most recent reporting period, boys were more likely than girls to be obese (19.1% vs. 17.8%) and severely obese (6.3% vs. 4.9%), and both obesity and severe obesity were more common with increasing age. Obesity prevalence went from 13.9% in those aged 2-5 years to 20.6% in 12- to 19-year-olds, and severe obesity was 1.8% in the youngest group and 7.7% in the oldest, with the middle-age group (6-11 years) in the middle in both categories, they said

Among the adults, obesity was more common in women than men (41.1% vs. 37.9%) for 2015-2016, as was severe obesity (9.7% vs. 5.6%). Obesity and severe obesity were both highest in those aged 40-59 years, but obesity prevalence was lowest in the younger group (20-39 years) and severe obesity was least common in the older group (60 years and older), Dr. Hales and his associates said.

The analysis involved 16,875 children and 27,449 adults over the 10-year period. The investigators did not report any conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Hales CM et al. JAMA 2018 Mar 23. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.3060.

according to data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

The age-standardized prevalence of obesity – defined as a body mass index of 30 or more – among adults aged 20 years and over increased from 33.7% for the 2-year period of 2007-2008 to 39.6% in 2015-2016, while the prevalence of severe obesity – defined as a body mass index of 40 kg/m2 or more – went from 5.7% to 7.7% over that same period, Craig M. Hales, MD, and his associates at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Hyattsville, Md., and Atlanta said in a research letter published in JAMA.

The prevalence of obesity in children aged 2-19 years – defined as BMI at or above the sex-specific 95th percentile – increased, but not significantly, from 16.8% in 2007-2008 to 18.5% in 2015-2016, with most of that increase coming in the last 2 years. Severe obesity – BMI at or above 120% of the sex-specific 95th percentile – rose from 4.9% to 5.6% over those 10 years, but the last 2-year period saw the rate drop from 6% in 2013-2014, the investigators reported.

For the most recent reporting period, boys were more likely than girls to be obese (19.1% vs. 17.8%) and severely obese (6.3% vs. 4.9%), and both obesity and severe obesity were more common with increasing age. Obesity prevalence went from 13.9% in those aged 2-5 years to 20.6% in 12- to 19-year-olds, and severe obesity was 1.8% in the youngest group and 7.7% in the oldest, with the middle-age group (6-11 years) in the middle in both categories, they said

Among the adults, obesity was more common in women than men (41.1% vs. 37.9%) for 2015-2016, as was severe obesity (9.7% vs. 5.6%). Obesity and severe obesity were both highest in those aged 40-59 years, but obesity prevalence was lowest in the younger group (20-39 years) and severe obesity was least common in the older group (60 years and older), Dr. Hales and his associates said.

The analysis involved 16,875 children and 27,449 adults over the 10-year period. The investigators did not report any conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Hales CM et al. JAMA 2018 Mar 23. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.3060.

FROM JAMA

Switching to tenofovir alafenamide may benefit HBV patients

PHILADELPHIA – Tenofovir alafenamide, the newest kid on the block for treatment of chronic hepatitis B, not only has less bone and renal effects than tenofovir disoproxil, but now also appears to improve those parameters in patients switched over from the older tenofovir formulation, according to Paul Kwo, MD.

“Renal function, as well as hip and spine bone mineral density measurements, all improve after you flip,” said Dr. Kwo, director of hepatology at Stanford (Calif.) University.

Dr. Kwo described some of the latest data on the newer tenofovir formulation in a hepatitis B update he gave at the conference, jointly provided by Rutgers and Global Academy for Medical Education.

Tenofovir alafenamide, a nucleoside analogue reverse transcriptase inhibitor, was approved in November 2016 for treatment of adults with chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection and compensated liver disease.

It has similar efficacy to tenofovir disoproxil, with fewer bone and renal effects, according to results of two large international phase 3 trials.

Some of the latest data, presented in October 2017 at The Liver Meeting in Washington, show that switching patients from tenofovir disoproxil to tenofovir alafenamide improved creatinine clearance and increased rates of alanine aminotransferase normalization, with sustained rates of virologic control, over 48 weeks of treatment.

Similar results were seen for bone mineral density. “It goes up over time, and you approach bone mineral density levels that are similar to [levels in] those who are on tenofovir alafenamide long term,” Dr. Kwo said, commenting on results of the study.

Compared with tenofovir disoproxil, tenofovir alafenamide is a slightly different prodrug of tenofovir, according to Dr. Kwo.

The approved dose of tenofovir alafenamide is 25 mg, compared with 300 mg for tenofovir disoproxil. “It’s more stable in the serum, so you don’t need higher levels, and you have fewer off-target effects,” Dr. Kwo said.

The two agents are “Coke and Pepsi” in terms of efficacy, he added, noting that comparative studies showed similar efficacy on endpoints of percentage HBV DNA less than 29 IU/mL and log10 HBV DNA change.

Very low rates of resistance are seen with first-line therapies for chronic hepatitis B, including entecavir and tenofovir disoproxil. “We wouldn’t expect (tenofovir alafenamide) to be any different, but nonetheless the surveillance has to happen,” Dr. Kwo said.

Tenofovir alafenamide is not yet listed in the official recommendations of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, but it is in current guidelines from the European Association for the Study of the Liver.

The published EASL guidelines provide guidance on how tenofovir alafenamide fits into the treatment armamentarium for HBV.

Going by the EASL recommendations, age greater than 60 years, bone disease, and renal alterations are all good reasons to use tenofovir alafenamide as first-line therapy for hepatitis B, according to Dr. Kwo.

Dr. Kwo reported disclosures related to AbbVie, Allergan, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Conatus Pharmaceuticals, Dova Pharmaceuticals, DURECT, Gilead Sciences, Merck, and Shionogi.

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same company.

PHILADELPHIA – Tenofovir alafenamide, the newest kid on the block for treatment of chronic hepatitis B, not only has less bone and renal effects than tenofovir disoproxil, but now also appears to improve those parameters in patients switched over from the older tenofovir formulation, according to Paul Kwo, MD.

“Renal function, as well as hip and spine bone mineral density measurements, all improve after you flip,” said Dr. Kwo, director of hepatology at Stanford (Calif.) University.

Dr. Kwo described some of the latest data on the newer tenofovir formulation in a hepatitis B update he gave at the conference, jointly provided by Rutgers and Global Academy for Medical Education.

Tenofovir alafenamide, a nucleoside analogue reverse transcriptase inhibitor, was approved in November 2016 for treatment of adults with chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection and compensated liver disease.

It has similar efficacy to tenofovir disoproxil, with fewer bone and renal effects, according to results of two large international phase 3 trials.

Some of the latest data, presented in October 2017 at The Liver Meeting in Washington, show that switching patients from tenofovir disoproxil to tenofovir alafenamide improved creatinine clearance and increased rates of alanine aminotransferase normalization, with sustained rates of virologic control, over 48 weeks of treatment.

Similar results were seen for bone mineral density. “It goes up over time, and you approach bone mineral density levels that are similar to [levels in] those who are on tenofovir alafenamide long term,” Dr. Kwo said, commenting on results of the study.

Compared with tenofovir disoproxil, tenofovir alafenamide is a slightly different prodrug of tenofovir, according to Dr. Kwo.

The approved dose of tenofovir alafenamide is 25 mg, compared with 300 mg for tenofovir disoproxil. “It’s more stable in the serum, so you don’t need higher levels, and you have fewer off-target effects,” Dr. Kwo said.

The two agents are “Coke and Pepsi” in terms of efficacy, he added, noting that comparative studies showed similar efficacy on endpoints of percentage HBV DNA less than 29 IU/mL and log10 HBV DNA change.

Very low rates of resistance are seen with first-line therapies for chronic hepatitis B, including entecavir and tenofovir disoproxil. “We wouldn’t expect (tenofovir alafenamide) to be any different, but nonetheless the surveillance has to happen,” Dr. Kwo said.

Tenofovir alafenamide is not yet listed in the official recommendations of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, but it is in current guidelines from the European Association for the Study of the Liver.

The published EASL guidelines provide guidance on how tenofovir alafenamide fits into the treatment armamentarium for HBV.

Going by the EASL recommendations, age greater than 60 years, bone disease, and renal alterations are all good reasons to use tenofovir alafenamide as first-line therapy for hepatitis B, according to Dr. Kwo.

Dr. Kwo reported disclosures related to AbbVie, Allergan, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Conatus Pharmaceuticals, Dova Pharmaceuticals, DURECT, Gilead Sciences, Merck, and Shionogi.

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same company.

PHILADELPHIA – Tenofovir alafenamide, the newest kid on the block for treatment of chronic hepatitis B, not only has less bone and renal effects than tenofovir disoproxil, but now also appears to improve those parameters in patients switched over from the older tenofovir formulation, according to Paul Kwo, MD.

“Renal function, as well as hip and spine bone mineral density measurements, all improve after you flip,” said Dr. Kwo, director of hepatology at Stanford (Calif.) University.

Dr. Kwo described some of the latest data on the newer tenofovir formulation in a hepatitis B update he gave at the conference, jointly provided by Rutgers and Global Academy for Medical Education.

Tenofovir alafenamide, a nucleoside analogue reverse transcriptase inhibitor, was approved in November 2016 for treatment of adults with chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection and compensated liver disease.

It has similar efficacy to tenofovir disoproxil, with fewer bone and renal effects, according to results of two large international phase 3 trials.

Some of the latest data, presented in October 2017 at The Liver Meeting in Washington, show that switching patients from tenofovir disoproxil to tenofovir alafenamide improved creatinine clearance and increased rates of alanine aminotransferase normalization, with sustained rates of virologic control, over 48 weeks of treatment.

Similar results were seen for bone mineral density. “It goes up over time, and you approach bone mineral density levels that are similar to [levels in] those who are on tenofovir alafenamide long term,” Dr. Kwo said, commenting on results of the study.

Compared with tenofovir disoproxil, tenofovir alafenamide is a slightly different prodrug of tenofovir, according to Dr. Kwo.

The approved dose of tenofovir alafenamide is 25 mg, compared with 300 mg for tenofovir disoproxil. “It’s more stable in the serum, so you don’t need higher levels, and you have fewer off-target effects,” Dr. Kwo said.

The two agents are “Coke and Pepsi” in terms of efficacy, he added, noting that comparative studies showed similar efficacy on endpoints of percentage HBV DNA less than 29 IU/mL and log10 HBV DNA change.

Very low rates of resistance are seen with first-line therapies for chronic hepatitis B, including entecavir and tenofovir disoproxil. “We wouldn’t expect (tenofovir alafenamide) to be any different, but nonetheless the surveillance has to happen,” Dr. Kwo said.

Tenofovir alafenamide is not yet listed in the official recommendations of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, but it is in current guidelines from the European Association for the Study of the Liver.

The published EASL guidelines provide guidance on how tenofovir alafenamide fits into the treatment armamentarium for HBV.

Going by the EASL recommendations, age greater than 60 years, bone disease, and renal alterations are all good reasons to use tenofovir alafenamide as first-line therapy for hepatitis B, according to Dr. Kwo.

Dr. Kwo reported disclosures related to AbbVie, Allergan, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Conatus Pharmaceuticals, Dova Pharmaceuticals, DURECT, Gilead Sciences, Merck, and Shionogi.

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same company.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM DIGESTIVE DISEASES: NEW ADVANCES

Major message: Most heart failure is preventable

SNOWMASS, COLO. – More than 960,000 new cases of heart failure will occur in the United States this year – and most of them could have been prevented, Gregg C. Fonarow, MD, asserted at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

Preventing heart failure doesn’t require heroic measures. It entails identifying high-risk individuals while they are still asymptomatic and free of structural heart disease – that is, patients who are stage A, pre–heart failure, in the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association classification system for heart failure – and then addressing their modifiable risk factors via evidence-based, guideline-directed medical therapy, said Dr. Fonarow, professor of cardiovascular medicine and cochief of cardiology at the University of California, Los Angeles, and director of the Ahmanson-UCLA Cardiomyopathy Center.

A special word about obesity: A Framingham Heart Study analysis concluded that, after controlling for other cardiovascular risk factors, obese individuals had double the risk of new-onset heart failure, compared with normal weight subjects, during a mean follow-up of 14 years. For each one-unit increase in body mass index, the adjusted risk of heart failure climbed by 5% in men and 7% in women (N Engl J Med. 2002 Aug 1;347[5]:305-13). And that spells trouble down the line.

“You can imagine, with the marked increase in overweight and obesity status now affecting over half of U.S. adults, what this will mean for a potential rise in heart failure prevalence and incidence unless we do something further to modify this,” the cardiologist observed.

Dr. Fonarow is a member of the writing group for the ACC/AHA guidelines on management of heart failure. They recommend as a risk reduction strategy identification of patients with stage A pre–heart failure and addressing their risk factors: treating their hypertension and lipid disorders, gaining control over metabolic syndrome, discouraging heavy alcohol intake, and encouraging smoking cessation and regular exercise (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013 Oct 15;62[16]:e147-239).

What kind of reduction in heart failure risk can be expected via these measures?

Antihypertensive therapy

More than a quarter century ago, the landmark SHEP trial (Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program) in more than 4,700 hypertensive seniors showed that treatment with diuretics and beta-blockers resulted in a 49% reduction in heart failure events, compared with placebo. And this has been a consistent finding in other studies: A meta-analysis of all 12 major randomized trials of antihypertensive therapy conducted over a 20-year period showed that treatment resulted in a whopping 52% reduction in the risk of heart failure (J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995 Apr; 27[5]:1214-8).

“If you ask most people why they’re on antihypertensive medication, they say, ‘Oh, to prevent heart attacks and stroke.’ But in fact the greatest relative risk reduction that we see is this remarkable reduction in the risk of developing heart failure with blood pressure treatment,” Dr. Fonarow said.

There has been some argument within medicine as to whether aggressive blood pressure lowering is appropriate in individuals over age 80. But in the HYVET trial (Hypertension in the Very Elderly Trial) conducted in that age group, the use of diuretics and/or ACE inhibitors to lower systolic blood pressure from roughly 155 mm Hg to 145 mm Hg resulted in a dramatic 64% reduction in the rate of new-onset heart failure (N Engl J Med. 2008 May 1;358[18]:1887-98).

How low to go with blood pressure reduction in order to maximize the heart failure risk reduction benefit? In the SPRINT trial (Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial) of 9,361 hypertensive patients with a history of cardiovascular disease or multiple risk factors, participants randomized to a goal of less than 120 mm Hg enjoyed a 38% lower risk of heart failure events, compared with those whose target was less than 140 mm Hg (N Engl J Med. 2015 Nov 26;373[22]:2103-16).

A secondary analysis from SPRINT showed that the risk of acute decompensated heart failure was 37% lower in patients treated to the target of less than 120 mm Hg. That finding takes on particular importance because SPRINT participants who developed acute decompensated heart failure had a 27-fold increase in cardiovascular death (Circ Heart Fail. 2017 Apr; doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.116.003613).

Lipid lowering

A meta-analysis of four major, randomized clinical trials of intensive versus moderate statin therapy in 27,546 patients with stable coronary artery disease or acute coronary syndrome concluded that intensive therapy resulted in a 27% reduction in the risk of hospitalization for heart failure (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006 Jun 6;47[11]:2326-31).

SGLT-2 inhibition

Until the randomized EMPA-REG OUTCOME trial of the sodium-glucose transporter 2 (SGLT-2) inhibitor empagliflozin(Jardiance), no glucose-lowering drug available for treatment of type 2 diabetes had shown any benefit in terms of reducing diabetic patients’ elevated risk of heart failure. Neither had weight loss. Abundant evidence showed that glycemic control had no impact on the risk of heart failure events. So EMPA-REG OUTCOME was cause for celebration among heart failure specialists, with its demonstration of a 35% reduction in the risk of hospitalization for heart failure, compared with placebo in more than 7,000 randomized patients. The risk of death because of heart failure was chopped by 68%. Sharp reductions in other cardiovascular events were also seen with empagliflozin (N Engl J Med. 2015 Nov 26;373[22]:2117-28).

Similar benefits were subsequently documented with another SGLT-2 inhibitor, canagliflozin(Invokana), in the CANVAS study program (N Engl J Med. 2017 Aug 17;377:644-57).

The reduction in cardiovascular mortality achieved with empagliflozin in EMPA-REG OUTCOME was actually bigger than seen with ACE inhibitors and angiotensin-receptor blockers (ARBs) in earlier landmark heart failure trials (Eur J Heart Fail. 2017 Jan;19[1]:43-53).

Dr. Fonarow views these data as “compelling.” These trials mark a huge step forward in the prevention of heart failure.

“We now for the first time in patients with diabetes have the ability to markedly prevent heart failure as well as cardiovascular death,” the cardiologist commented. “It is critical for cardiologists and heart failure specialists to play an active role in this [pharmacologic diabetes] management, as choice of therapy is a key determinant of outcomes, including survival.”

ACE inhibitors and ARBs

The ACC/AHA heart failure guidelines give a Class I recommendation to the routine use of ACE inhibitors or ARBs in patients at high risk for developing heart failure because of a history of diabetes, hypertension with associated cardiovascular risk factors, or any form of atherosclerotic vascular disease.

Lifestyle modification

Heavy drinking is known to raise the risk of heart failure. However, moderate alcohol consumption may be protective. In a classic prospective cohort study, individuals who reported consuming 1.5-4 drinks per day in the previous month had a 47% reduction in subsequent new-onset heart failure, compared with teetotalers in a multivariate analysis adjusted for conventional cardiovascular risk factors. Those who drank less than 1.5 drinks per day had a 21% reduction in heart failure risk, compared with the nondrinkers (JAMA. 2001 Apr 18;285[15]:1971-7).

In the prospective observational Physicians’ Health Study of nearly 21,000 men, adherence to six modifiable healthy lifestyle factors was associated with an incremental stepwise reduction in lifetime risk of developing heart failure. The six lifestyle factors – a forerunner of the AHA’s Life’s Simple 7 – were maintaining a normal body weight, stopping smoking, getting exercise, drinking alcohol in moderation, consuming breakfast cereals, and eating fruits and vegetables. Male physicians who shunned all six had a 21.2% lifetime risk of heart failure; those who followed at least four of the healthy lifestyle factors had a 10.1% risk (JAMA 2009 Jul 22;302[4]:394-400).

In a separate analysis from the Physicians’ Health Study, men who engaged in vigorous exercise to the point of breaking a sweat as little as one to three times per month had an 18% lower risk of developing heart failure during follow-up, compared with inactive men (Circulation 2009 Jan 6;119[1]:44-52).

What’s next in prevention of heart failure

Heart failure is one of the most expensive health care problems in the United States, and one of the deadliest. Today an estimated 6.5 million Americans have symptomatic heart failure. But that’s just the tip of the iceberg.

“Countless millions more are likely to manifest heart failure in the future,” Dr. Fonarow warned, noting the vast prevalence of identifiable risk factors.

It’s time for a high-visibility public health campaign designed to foster community education and engagement regarding heart failure prevention, he added.

“We have a lot of action and events around preventing atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. But can you think of any campaign you’ve seen focusing specifically on heart failure? Heart failure isn’t one of the endpoints in the ACC/AHA Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease Risk Calculator or even the new hypertension risk calculator, so we need to take this a whole lot more seriously,” the cardiologist said.

The 2017 focused update of the ACC/AHA heart failure guidelines endorsed a novel strategy of primary care–centered, biomarker-based screening of patients with cardiovascular risk factors as a means of triggering early intervention to prevent heart failure (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017 Aug 8;70[6]:776-803). This strategy, which received a Class IIa recommendation, involves screening measurement of a natriuretic peptide biomarker.

The recommendation was based on evidence including the STOP-HF randomized trial (St. Vincent’s Screening to Prevent Heart Failure Study), in which 1,374 asymptomatic Irish patients with cardiovascular risk factors were randomized to routine primary care or primary care plus screening with brain-type natriuretic peptide testing. Patients with a brain-type natriuretic peptide level of 50 pg/mL or more were directed to team-based care involving a collaboration between their primary care physician and a specialist cardiovascular service focused on optimizing guideline-directed medical therapy. During a mean follow-up of 4.2 years, the primary endpoint of new-onset left ventricular dysfunction occurred in 5.3% of the intervention group and 8.7% of controls, for a 45% relative risk reduction (JAMA 2013 Jul 3;310[1]:66-74).

Dr. Fonarow reported receiving research grants from and serving as a consultant to the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and a handful of medical companies.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – More than 960,000 new cases of heart failure will occur in the United States this year – and most of them could have been prevented, Gregg C. Fonarow, MD, asserted at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

Preventing heart failure doesn’t require heroic measures. It entails identifying high-risk individuals while they are still asymptomatic and free of structural heart disease – that is, patients who are stage A, pre–heart failure, in the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association classification system for heart failure – and then addressing their modifiable risk factors via evidence-based, guideline-directed medical therapy, said Dr. Fonarow, professor of cardiovascular medicine and cochief of cardiology at the University of California, Los Angeles, and director of the Ahmanson-UCLA Cardiomyopathy Center.

A special word about obesity: A Framingham Heart Study analysis concluded that, after controlling for other cardiovascular risk factors, obese individuals had double the risk of new-onset heart failure, compared with normal weight subjects, during a mean follow-up of 14 years. For each one-unit increase in body mass index, the adjusted risk of heart failure climbed by 5% in men and 7% in women (N Engl J Med. 2002 Aug 1;347[5]:305-13). And that spells trouble down the line.

“You can imagine, with the marked increase in overweight and obesity status now affecting over half of U.S. adults, what this will mean for a potential rise in heart failure prevalence and incidence unless we do something further to modify this,” the cardiologist observed.

Dr. Fonarow is a member of the writing group for the ACC/AHA guidelines on management of heart failure. They recommend as a risk reduction strategy identification of patients with stage A pre–heart failure and addressing their risk factors: treating their hypertension and lipid disorders, gaining control over metabolic syndrome, discouraging heavy alcohol intake, and encouraging smoking cessation and regular exercise (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013 Oct 15;62[16]:e147-239).

What kind of reduction in heart failure risk can be expected via these measures?

Antihypertensive therapy

More than a quarter century ago, the landmark SHEP trial (Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program) in more than 4,700 hypertensive seniors showed that treatment with diuretics and beta-blockers resulted in a 49% reduction in heart failure events, compared with placebo. And this has been a consistent finding in other studies: A meta-analysis of all 12 major randomized trials of antihypertensive therapy conducted over a 20-year period showed that treatment resulted in a whopping 52% reduction in the risk of heart failure (J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995 Apr; 27[5]:1214-8).

“If you ask most people why they’re on antihypertensive medication, they say, ‘Oh, to prevent heart attacks and stroke.’ But in fact the greatest relative risk reduction that we see is this remarkable reduction in the risk of developing heart failure with blood pressure treatment,” Dr. Fonarow said.

There has been some argument within medicine as to whether aggressive blood pressure lowering is appropriate in individuals over age 80. But in the HYVET trial (Hypertension in the Very Elderly Trial) conducted in that age group, the use of diuretics and/or ACE inhibitors to lower systolic blood pressure from roughly 155 mm Hg to 145 mm Hg resulted in a dramatic 64% reduction in the rate of new-onset heart failure (N Engl J Med. 2008 May 1;358[18]:1887-98).

How low to go with blood pressure reduction in order to maximize the heart failure risk reduction benefit? In the SPRINT trial (Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial) of 9,361 hypertensive patients with a history of cardiovascular disease or multiple risk factors, participants randomized to a goal of less than 120 mm Hg enjoyed a 38% lower risk of heart failure events, compared with those whose target was less than 140 mm Hg (N Engl J Med. 2015 Nov 26;373[22]:2103-16).

A secondary analysis from SPRINT showed that the risk of acute decompensated heart failure was 37% lower in patients treated to the target of less than 120 mm Hg. That finding takes on particular importance because SPRINT participants who developed acute decompensated heart failure had a 27-fold increase in cardiovascular death (Circ Heart Fail. 2017 Apr; doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.116.003613).

Lipid lowering

A meta-analysis of four major, randomized clinical trials of intensive versus moderate statin therapy in 27,546 patients with stable coronary artery disease or acute coronary syndrome concluded that intensive therapy resulted in a 27% reduction in the risk of hospitalization for heart failure (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006 Jun 6;47[11]:2326-31).

SGLT-2 inhibition

Until the randomized EMPA-REG OUTCOME trial of the sodium-glucose transporter 2 (SGLT-2) inhibitor empagliflozin(Jardiance), no glucose-lowering drug available for treatment of type 2 diabetes had shown any benefit in terms of reducing diabetic patients’ elevated risk of heart failure. Neither had weight loss. Abundant evidence showed that glycemic control had no impact on the risk of heart failure events. So EMPA-REG OUTCOME was cause for celebration among heart failure specialists, with its demonstration of a 35% reduction in the risk of hospitalization for heart failure, compared with placebo in more than 7,000 randomized patients. The risk of death because of heart failure was chopped by 68%. Sharp reductions in other cardiovascular events were also seen with empagliflozin (N Engl J Med. 2015 Nov 26;373[22]:2117-28).

Similar benefits were subsequently documented with another SGLT-2 inhibitor, canagliflozin(Invokana), in the CANVAS study program (N Engl J Med. 2017 Aug 17;377:644-57).

The reduction in cardiovascular mortality achieved with empagliflozin in EMPA-REG OUTCOME was actually bigger than seen with ACE inhibitors and angiotensin-receptor blockers (ARBs) in earlier landmark heart failure trials (Eur J Heart Fail. 2017 Jan;19[1]:43-53).

Dr. Fonarow views these data as “compelling.” These trials mark a huge step forward in the prevention of heart failure.

“We now for the first time in patients with diabetes have the ability to markedly prevent heart failure as well as cardiovascular death,” the cardiologist commented. “It is critical for cardiologists and heart failure specialists to play an active role in this [pharmacologic diabetes] management, as choice of therapy is a key determinant of outcomes, including survival.”

ACE inhibitors and ARBs

The ACC/AHA heart failure guidelines give a Class I recommendation to the routine use of ACE inhibitors or ARBs in patients at high risk for developing heart failure because of a history of diabetes, hypertension with associated cardiovascular risk factors, or any form of atherosclerotic vascular disease.

Lifestyle modification

Heavy drinking is known to raise the risk of heart failure. However, moderate alcohol consumption may be protective. In a classic prospective cohort study, individuals who reported consuming 1.5-4 drinks per day in the previous month had a 47% reduction in subsequent new-onset heart failure, compared with teetotalers in a multivariate analysis adjusted for conventional cardiovascular risk factors. Those who drank less than 1.5 drinks per day had a 21% reduction in heart failure risk, compared with the nondrinkers (JAMA. 2001 Apr 18;285[15]:1971-7).

In the prospective observational Physicians’ Health Study of nearly 21,000 men, adherence to six modifiable healthy lifestyle factors was associated with an incremental stepwise reduction in lifetime risk of developing heart failure. The six lifestyle factors – a forerunner of the AHA’s Life’s Simple 7 – were maintaining a normal body weight, stopping smoking, getting exercise, drinking alcohol in moderation, consuming breakfast cereals, and eating fruits and vegetables. Male physicians who shunned all six had a 21.2% lifetime risk of heart failure; those who followed at least four of the healthy lifestyle factors had a 10.1% risk (JAMA 2009 Jul 22;302[4]:394-400).

In a separate analysis from the Physicians’ Health Study, men who engaged in vigorous exercise to the point of breaking a sweat as little as one to three times per month had an 18% lower risk of developing heart failure during follow-up, compared with inactive men (Circulation 2009 Jan 6;119[1]:44-52).

What’s next in prevention of heart failure

Heart failure is one of the most expensive health care problems in the United States, and one of the deadliest. Today an estimated 6.5 million Americans have symptomatic heart failure. But that’s just the tip of the iceberg.

“Countless millions more are likely to manifest heart failure in the future,” Dr. Fonarow warned, noting the vast prevalence of identifiable risk factors.

It’s time for a high-visibility public health campaign designed to foster community education and engagement regarding heart failure prevention, he added.

“We have a lot of action and events around preventing atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. But can you think of any campaign you’ve seen focusing specifically on heart failure? Heart failure isn’t one of the endpoints in the ACC/AHA Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease Risk Calculator or even the new hypertension risk calculator, so we need to take this a whole lot more seriously,” the cardiologist said.

The 2017 focused update of the ACC/AHA heart failure guidelines endorsed a novel strategy of primary care–centered, biomarker-based screening of patients with cardiovascular risk factors as a means of triggering early intervention to prevent heart failure (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017 Aug 8;70[6]:776-803). This strategy, which received a Class IIa recommendation, involves screening measurement of a natriuretic peptide biomarker.

The recommendation was based on evidence including the STOP-HF randomized trial (St. Vincent’s Screening to Prevent Heart Failure Study), in which 1,374 asymptomatic Irish patients with cardiovascular risk factors were randomized to routine primary care or primary care plus screening with brain-type natriuretic peptide testing. Patients with a brain-type natriuretic peptide level of 50 pg/mL or more were directed to team-based care involving a collaboration between their primary care physician and a specialist cardiovascular service focused on optimizing guideline-directed medical therapy. During a mean follow-up of 4.2 years, the primary endpoint of new-onset left ventricular dysfunction occurred in 5.3% of the intervention group and 8.7% of controls, for a 45% relative risk reduction (JAMA 2013 Jul 3;310[1]:66-74).

Dr. Fonarow reported receiving research grants from and serving as a consultant to the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and a handful of medical companies.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – More than 960,000 new cases of heart failure will occur in the United States this year – and most of them could have been prevented, Gregg C. Fonarow, MD, asserted at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

Preventing heart failure doesn’t require heroic measures. It entails identifying high-risk individuals while they are still asymptomatic and free of structural heart disease – that is, patients who are stage A, pre–heart failure, in the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association classification system for heart failure – and then addressing their modifiable risk factors via evidence-based, guideline-directed medical therapy, said Dr. Fonarow, professor of cardiovascular medicine and cochief of cardiology at the University of California, Los Angeles, and director of the Ahmanson-UCLA Cardiomyopathy Center.

A special word about obesity: A Framingham Heart Study analysis concluded that, after controlling for other cardiovascular risk factors, obese individuals had double the risk of new-onset heart failure, compared with normal weight subjects, during a mean follow-up of 14 years. For each one-unit increase in body mass index, the adjusted risk of heart failure climbed by 5% in men and 7% in women (N Engl J Med. 2002 Aug 1;347[5]:305-13). And that spells trouble down the line.

“You can imagine, with the marked increase in overweight and obesity status now affecting over half of U.S. adults, what this will mean for a potential rise in heart failure prevalence and incidence unless we do something further to modify this,” the cardiologist observed.

Dr. Fonarow is a member of the writing group for the ACC/AHA guidelines on management of heart failure. They recommend as a risk reduction strategy identification of patients with stage A pre–heart failure and addressing their risk factors: treating their hypertension and lipid disorders, gaining control over metabolic syndrome, discouraging heavy alcohol intake, and encouraging smoking cessation and regular exercise (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013 Oct 15;62[16]:e147-239).

What kind of reduction in heart failure risk can be expected via these measures?

Antihypertensive therapy

More than a quarter century ago, the landmark SHEP trial (Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program) in more than 4,700 hypertensive seniors showed that treatment with diuretics and beta-blockers resulted in a 49% reduction in heart failure events, compared with placebo. And this has been a consistent finding in other studies: A meta-analysis of all 12 major randomized trials of antihypertensive therapy conducted over a 20-year period showed that treatment resulted in a whopping 52% reduction in the risk of heart failure (J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995 Apr; 27[5]:1214-8).

“If you ask most people why they’re on antihypertensive medication, they say, ‘Oh, to prevent heart attacks and stroke.’ But in fact the greatest relative risk reduction that we see is this remarkable reduction in the risk of developing heart failure with blood pressure treatment,” Dr. Fonarow said.

There has been some argument within medicine as to whether aggressive blood pressure lowering is appropriate in individuals over age 80. But in the HYVET trial (Hypertension in the Very Elderly Trial) conducted in that age group, the use of diuretics and/or ACE inhibitors to lower systolic blood pressure from roughly 155 mm Hg to 145 mm Hg resulted in a dramatic 64% reduction in the rate of new-onset heart failure (N Engl J Med. 2008 May 1;358[18]:1887-98).

How low to go with blood pressure reduction in order to maximize the heart failure risk reduction benefit? In the SPRINT trial (Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial) of 9,361 hypertensive patients with a history of cardiovascular disease or multiple risk factors, participants randomized to a goal of less than 120 mm Hg enjoyed a 38% lower risk of heart failure events, compared with those whose target was less than 140 mm Hg (N Engl J Med. 2015 Nov 26;373[22]:2103-16).

A secondary analysis from SPRINT showed that the risk of acute decompensated heart failure was 37% lower in patients treated to the target of less than 120 mm Hg. That finding takes on particular importance because SPRINT participants who developed acute decompensated heart failure had a 27-fold increase in cardiovascular death (Circ Heart Fail. 2017 Apr; doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.116.003613).

Lipid lowering

A meta-analysis of four major, randomized clinical trials of intensive versus moderate statin therapy in 27,546 patients with stable coronary artery disease or acute coronary syndrome concluded that intensive therapy resulted in a 27% reduction in the risk of hospitalization for heart failure (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006 Jun 6;47[11]:2326-31).

SGLT-2 inhibition

Until the randomized EMPA-REG OUTCOME trial of the sodium-glucose transporter 2 (SGLT-2) inhibitor empagliflozin(Jardiance), no glucose-lowering drug available for treatment of type 2 diabetes had shown any benefit in terms of reducing diabetic patients’ elevated risk of heart failure. Neither had weight loss. Abundant evidence showed that glycemic control had no impact on the risk of heart failure events. So EMPA-REG OUTCOME was cause for celebration among heart failure specialists, with its demonstration of a 35% reduction in the risk of hospitalization for heart failure, compared with placebo in more than 7,000 randomized patients. The risk of death because of heart failure was chopped by 68%. Sharp reductions in other cardiovascular events were also seen with empagliflozin (N Engl J Med. 2015 Nov 26;373[22]:2117-28).

Similar benefits were subsequently documented with another SGLT-2 inhibitor, canagliflozin(Invokana), in the CANVAS study program (N Engl J Med. 2017 Aug 17;377:644-57).

The reduction in cardiovascular mortality achieved with empagliflozin in EMPA-REG OUTCOME was actually bigger than seen with ACE inhibitors and angiotensin-receptor blockers (ARBs) in earlier landmark heart failure trials (Eur J Heart Fail. 2017 Jan;19[1]:43-53).

Dr. Fonarow views these data as “compelling.” These trials mark a huge step forward in the prevention of heart failure.

“We now for the first time in patients with diabetes have the ability to markedly prevent heart failure as well as cardiovascular death,” the cardiologist commented. “It is critical for cardiologists and heart failure specialists to play an active role in this [pharmacologic diabetes] management, as choice of therapy is a key determinant of outcomes, including survival.”

ACE inhibitors and ARBs

The ACC/AHA heart failure guidelines give a Class I recommendation to the routine use of ACE inhibitors or ARBs in patients at high risk for developing heart failure because of a history of diabetes, hypertension with associated cardiovascular risk factors, or any form of atherosclerotic vascular disease.

Lifestyle modification

Heavy drinking is known to raise the risk of heart failure. However, moderate alcohol consumption may be protective. In a classic prospective cohort study, individuals who reported consuming 1.5-4 drinks per day in the previous month had a 47% reduction in subsequent new-onset heart failure, compared with teetotalers in a multivariate analysis adjusted for conventional cardiovascular risk factors. Those who drank less than 1.5 drinks per day had a 21% reduction in heart failure risk, compared with the nondrinkers (JAMA. 2001 Apr 18;285[15]:1971-7).

In the prospective observational Physicians’ Health Study of nearly 21,000 men, adherence to six modifiable healthy lifestyle factors was associated with an incremental stepwise reduction in lifetime risk of developing heart failure. The six lifestyle factors – a forerunner of the AHA’s Life’s Simple 7 – were maintaining a normal body weight, stopping smoking, getting exercise, drinking alcohol in moderation, consuming breakfast cereals, and eating fruits and vegetables. Male physicians who shunned all six had a 21.2% lifetime risk of heart failure; those who followed at least four of the healthy lifestyle factors had a 10.1% risk (JAMA 2009 Jul 22;302[4]:394-400).

In a separate analysis from the Physicians’ Health Study, men who engaged in vigorous exercise to the point of breaking a sweat as little as one to three times per month had an 18% lower risk of developing heart failure during follow-up, compared with inactive men (Circulation 2009 Jan 6;119[1]:44-52).

What’s next in prevention of heart failure

Heart failure is one of the most expensive health care problems in the United States, and one of the deadliest. Today an estimated 6.5 million Americans have symptomatic heart failure. But that’s just the tip of the iceberg.

“Countless millions more are likely to manifest heart failure in the future,” Dr. Fonarow warned, noting the vast prevalence of identifiable risk factors.

It’s time for a high-visibility public health campaign designed to foster community education and engagement regarding heart failure prevention, he added.

“We have a lot of action and events around preventing atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. But can you think of any campaign you’ve seen focusing specifically on heart failure? Heart failure isn’t one of the endpoints in the ACC/AHA Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease Risk Calculator or even the new hypertension risk calculator, so we need to take this a whole lot more seriously,” the cardiologist said.

The 2017 focused update of the ACC/AHA heart failure guidelines endorsed a novel strategy of primary care–centered, biomarker-based screening of patients with cardiovascular risk factors as a means of triggering early intervention to prevent heart failure (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017 Aug 8;70[6]:776-803). This strategy, which received a Class IIa recommendation, involves screening measurement of a natriuretic peptide biomarker.

The recommendation was based on evidence including the STOP-HF randomized trial (St. Vincent’s Screening to Prevent Heart Failure Study), in which 1,374 asymptomatic Irish patients with cardiovascular risk factors were randomized to routine primary care or primary care plus screening with brain-type natriuretic peptide testing. Patients with a brain-type natriuretic peptide level of 50 pg/mL or more were directed to team-based care involving a collaboration between their primary care physician and a specialist cardiovascular service focused on optimizing guideline-directed medical therapy. During a mean follow-up of 4.2 years, the primary endpoint of new-onset left ventricular dysfunction occurred in 5.3% of the intervention group and 8.7% of controls, for a 45% relative risk reduction (JAMA 2013 Jul 3;310[1]:66-74).

Dr. Fonarow reported receiving research grants from and serving as a consultant to the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and a handful of medical companies.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE ANNUAL CARDIOVASCULAR CONFERENCE AT SNOWMASS

‘If this is an emergency, call 911’

This is the mantra that the world hears when they call most, if not all, hospitals and medical clinics for the symptomatic relief of a myriad of health care complaints. Exactly what is the definition of an emergency is uncertain. We all could include severe chest pain, shortness of breath or sudden collapse or loss of consciousness.

To a patient, an emergency might just include the pressing need to speak to their doctor about the occurrence of symptoms and or anxieties that suddenly have occurred. In the past, before the telephone was invented, a friend or family member was sent by horseback or a Ford V8 to find the local doctor. With the advent of the telephone, doctors actually listed their number in a phone directory to facilitate contact with their patient.

Enter the current situation. Many patients still perceive the need to call their doctor for everything from a mild cough or headache or an actual fever to just not feeling well. This perceived patient need to seek expert medical help short of an ambulance ride to the emergency room leads the patient into the frustrating downward spiral associated with this bizarre need to communicate with their doctor.

I presume many patients assume that they may be able to actually talk to their doctor by telephone. They learn, as I have, that presumption is an arcane curiosity. First of all, most of my young colleagues, like most of their generation, do not own a land line and therefore are not listed in any known telephone directory. They work in an environment driven by the pressure to see more and more patients, and at the end of the day they are pretty much ready to “hang it up.” But many in my generation worked hard, and we still answered the telephone, and many of us actually made house calls.

But, should you have your doctor’s telephone number and make the call, you are immediately put in touch with a triage nurse who demands to know the intimate details of your problem in order to assist you in speaking to the doctor. Having divulged your symptoms in their gory details and achieved an appropriate threshold, you will be placed on hold while being connected to the clinic nurse. Once again you will be asked to divulge your intimate symptoms and again will be passed on to the doctor’s physician assistant who is familiar with the innermost knowledge of your doctor. But, again, if you persist you may again be put on hold to talk to your doctor or asked to leave a message with the physician assistant, since the doctor is seeing a patient or does not take calls during office hours. “Perhaps you would like to leave an email, and the doctor will contact you.”

Now, I have to admit that many of my friends find this process acceptable and use a variety of digital devices like “My Chart” to communicate with their doctor. But having grown up in the shadow of the horse and buggy era, and having adapted to the contemporary world, I give my patients my cell phone number. I will give it to you, too.

Dr. Goldstein, medical editor of Cardiology News, is professor of medicine at Wayne State University and division head emeritus of cardiovascular medicine at Henry Ford Hospital, both in Detroit. He is on data safety monitoring committees for the National Institutes of Health and several pharmaceutical companies.

This is the mantra that the world hears when they call most, if not all, hospitals and medical clinics for the symptomatic relief of a myriad of health care complaints. Exactly what is the definition of an emergency is uncertain. We all could include severe chest pain, shortness of breath or sudden collapse or loss of consciousness.

To a patient, an emergency might just include the pressing need to speak to their doctor about the occurrence of symptoms and or anxieties that suddenly have occurred. In the past, before the telephone was invented, a friend or family member was sent by horseback or a Ford V8 to find the local doctor. With the advent of the telephone, doctors actually listed their number in a phone directory to facilitate contact with their patient.

Enter the current situation. Many patients still perceive the need to call their doctor for everything from a mild cough or headache or an actual fever to just not feeling well. This perceived patient need to seek expert medical help short of an ambulance ride to the emergency room leads the patient into the frustrating downward spiral associated with this bizarre need to communicate with their doctor.

I presume many patients assume that they may be able to actually talk to their doctor by telephone. They learn, as I have, that presumption is an arcane curiosity. First of all, most of my young colleagues, like most of their generation, do not own a land line and therefore are not listed in any known telephone directory. They work in an environment driven by the pressure to see more and more patients, and at the end of the day they are pretty much ready to “hang it up.” But many in my generation worked hard, and we still answered the telephone, and many of us actually made house calls.

But, should you have your doctor’s telephone number and make the call, you are immediately put in touch with a triage nurse who demands to know the intimate details of your problem in order to assist you in speaking to the doctor. Having divulged your symptoms in their gory details and achieved an appropriate threshold, you will be placed on hold while being connected to the clinic nurse. Once again you will be asked to divulge your intimate symptoms and again will be passed on to the doctor’s physician assistant who is familiar with the innermost knowledge of your doctor. But, again, if you persist you may again be put on hold to talk to your doctor or asked to leave a message with the physician assistant, since the doctor is seeing a patient or does not take calls during office hours. “Perhaps you would like to leave an email, and the doctor will contact you.”

Now, I have to admit that many of my friends find this process acceptable and use a variety of digital devices like “My Chart” to communicate with their doctor. But having grown up in the shadow of the horse and buggy era, and having adapted to the contemporary world, I give my patients my cell phone number. I will give it to you, too.

Dr. Goldstein, medical editor of Cardiology News, is professor of medicine at Wayne State University and division head emeritus of cardiovascular medicine at Henry Ford Hospital, both in Detroit. He is on data safety monitoring committees for the National Institutes of Health and several pharmaceutical companies.

This is the mantra that the world hears when they call most, if not all, hospitals and medical clinics for the symptomatic relief of a myriad of health care complaints. Exactly what is the definition of an emergency is uncertain. We all could include severe chest pain, shortness of breath or sudden collapse or loss of consciousness.

To a patient, an emergency might just include the pressing need to speak to their doctor about the occurrence of symptoms and or anxieties that suddenly have occurred. In the past, before the telephone was invented, a friend or family member was sent by horseback or a Ford V8 to find the local doctor. With the advent of the telephone, doctors actually listed their number in a phone directory to facilitate contact with their patient.

Enter the current situation. Many patients still perceive the need to call their doctor for everything from a mild cough or headache or an actual fever to just not feeling well. This perceived patient need to seek expert medical help short of an ambulance ride to the emergency room leads the patient into the frustrating downward spiral associated with this bizarre need to communicate with their doctor.

I presume many patients assume that they may be able to actually talk to their doctor by telephone. They learn, as I have, that presumption is an arcane curiosity. First of all, most of my young colleagues, like most of their generation, do not own a land line and therefore are not listed in any known telephone directory. They work in an environment driven by the pressure to see more and more patients, and at the end of the day they are pretty much ready to “hang it up.” But many in my generation worked hard, and we still answered the telephone, and many of us actually made house calls.

But, should you have your doctor’s telephone number and make the call, you are immediately put in touch with a triage nurse who demands to know the intimate details of your problem in order to assist you in speaking to the doctor. Having divulged your symptoms in their gory details and achieved an appropriate threshold, you will be placed on hold while being connected to the clinic nurse. Once again you will be asked to divulge your intimate symptoms and again will be passed on to the doctor’s physician assistant who is familiar with the innermost knowledge of your doctor. But, again, if you persist you may again be put on hold to talk to your doctor or asked to leave a message with the physician assistant, since the doctor is seeing a patient or does not take calls during office hours. “Perhaps you would like to leave an email, and the doctor will contact you.”

Now, I have to admit that many of my friends find this process acceptable and use a variety of digital devices like “My Chart” to communicate with their doctor. But having grown up in the shadow of the horse and buggy era, and having adapted to the contemporary world, I give my patients my cell phone number. I will give it to you, too.

Dr. Goldstein, medical editor of Cardiology News, is professor of medicine at Wayne State University and division head emeritus of cardiovascular medicine at Henry Ford Hospital, both in Detroit. He is on data safety monitoring committees for the National Institutes of Health and several pharmaceutical companies.

Hospitalist movers and shakers – March 2018

Jason Blair, DO, recently was named an honorary Fellow by the American College of Osteopathic Internists (ACOI) for excellence in the practice of internal medicine. Dr. Blair currently is a hospitalist at Lake Regional Health System in Osage Beach, Mo.

The degree of Fellow is given to physicians who demonstrate continuing professional accomplishments, scholarship, and professional activities, including teaching, research, and community service. The ACOI represents more than 5,000 osteopathic internists and subspecialists nationwide. Dr. Blair joined Lake Regional in 2017.

Dr. Howell is the division director of the Collaborative Inpatient Medicine Service (CIMS) and a professor of medicine at the Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center in Baltimore. He received the award for his work with project EQUIP (Excellence in Quality, Utilization Integration, and Patient-Centered Care) to improve quality and efficiency and to reduce mortality, emergency department boarding, and patient lengths of stay.

David Svec, MD, MBA, has been named the new chief medical officer at Stanford Health Care – ValleyCare in Pleasanton, Calif. Dr. Svec has served as a hospitalist and internal medicine specialist at ValleyCare for the past 6 years. Previously, he was ValleyCare’s medical director of the hospitalist team and a clinical assistant professor of medicine. Dr. Svec helped develop the hospitalist program at ValleyCare and will continue to work in that capacity while advancing into his new role.

As CMO, Dr. Svec will carry on the mission of Stanford Health Care, including increasing innovative programs, monitoring outcome measures, and developing and implementing improvement plans.

Dr. Svec earned Stanford Health Care’s 2016 David A. Rytand Clinical Teaching Award, the 2016 Lawrence Mathers Award: Exceptional Commitment to Teaching/Active Involvement in Medical Student Education, and the 2014 Arthur L. Bloomfield Award for Excellence in Clinical Teaching.

Brent Baboolal, MD, recently was selected by the International Association of HealthCare Professionals to be part of the Leading Physicians of the World. Dr. Baboolal is an internist and a hospitalist serving the Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital in Dallas.

Trained in Grenada, Dr. Baboolal came to the United States in 2009 and began work at Stamford (Conn.) Hospital. He is board certified by the American Board of Internal Medicine and is renowned as a leading internist and hospitalist. He is a former associate professor at the University of Texas School of Nursing.

BUSINESS MOVES

Sound Physicians in Tacoma, Wash., recently announced that it will take over providing hospitalist services for SSM Health DePaul Hospital and SSM Health St. Mary’s Hospital in St. Louis. Sound Physicians already had been running critical care at SSM Health St. Clare Hospital, Fenton, Mo.

SSM Health is a Catholic, faith-based, nonprofit health system serving communities in Illinois, Missouri, Oklahoma, and Wisconsin.

“We have been impressed with their efficiency and professionalism of establishing Sound Physicians’ infrastructure that supports providers and implementing processes to drive improved outcomes,” said Rajiv Patel, MD, vice president of medical affairs for SSM Health DePaul Hospital.

Sound Physicians prides itself on improving quality and lowering costs of acute care for health organizations and facilities. Sound provides emergency medicine, hospital medicine, critical care, transitional care, and advisory services for its partners nationwide.