User login

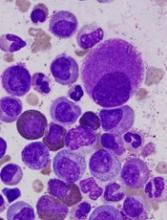

Drug approved for kids with sickle cell anemia

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved a hydroxyurea product (Addmedica’s Siklos) for use in pediatric patients with sickle cell anemia.

Siklos is intended to reduce the frequency of painful crises and the need for blood transfusions in pediatric patients age 2 and older who have sickle cell anemia and recurrent moderate to severe painful crises.

The recommended dose of Siklos is 20 mg/kg once daily.

The FDA granted priority review and orphan drug designation to the application for Siklos.

The agency’s approval of Siklos was based on data from the ESCORT HU study (NCT02516579). The trial was an evaluation of Siklos in 405 patients, ages 2 to 18, with sickle cell disease (SCD).

Thirty-five percent of these patients (n=141) had not received hydroxyurea prior to study enrollment and were therefore evaluable for efficacy. The median follow-up was 23 months (range, 12 to 80 months).

The researchers found that Siklos prompted an increase in fetal hemoglobin. Median fetal hemoglobin percentages were 5.6% (range, 1.3 to 15.0) at baseline and 12.8% (range, 2.1 to 37.2) at around 6 months after Siklos initiation (the value closest to 6 months collected between 5 and 14 months).

In addition, the percentage of patients with at least 1 vaso-occlusive episode, 1 episode of acute chest syndrome, 1 hospitalization due to SCD, or 1 blood transfusion decreased after 12 months of Siklos treatment.

The proportion of patients with at least 1 vaso-occlusive episode was 69.2% at baseline and 42.5% at 12 months. The proportion with at least 1 episode of acute chest syndrome was 23.6% and 5.7%, respectively.

The proportion with at least 1 hospitalization due to SCD was 75.5% and 41.8%, respectively. And the proportion with at least 1 blood transfusion was 45.9% and 23.0%, respectively.

The most common adverse events (occurring in at least 10% of patients) were infections (39.8%), gastrointestinal disorders (13.1%), neutropenia (12.6%), nervous system disorders (11.1%), and metabolic and nutrition disorders (10.9%).

Full prescribing information for Siklos is available on the FDA website. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved a hydroxyurea product (Addmedica’s Siklos) for use in pediatric patients with sickle cell anemia.

Siklos is intended to reduce the frequency of painful crises and the need for blood transfusions in pediatric patients age 2 and older who have sickle cell anemia and recurrent moderate to severe painful crises.

The recommended dose of Siklos is 20 mg/kg once daily.

The FDA granted priority review and orphan drug designation to the application for Siklos.

The agency’s approval of Siklos was based on data from the ESCORT HU study (NCT02516579). The trial was an evaluation of Siklos in 405 patients, ages 2 to 18, with sickle cell disease (SCD).

Thirty-five percent of these patients (n=141) had not received hydroxyurea prior to study enrollment and were therefore evaluable for efficacy. The median follow-up was 23 months (range, 12 to 80 months).

The researchers found that Siklos prompted an increase in fetal hemoglobin. Median fetal hemoglobin percentages were 5.6% (range, 1.3 to 15.0) at baseline and 12.8% (range, 2.1 to 37.2) at around 6 months after Siklos initiation (the value closest to 6 months collected between 5 and 14 months).

In addition, the percentage of patients with at least 1 vaso-occlusive episode, 1 episode of acute chest syndrome, 1 hospitalization due to SCD, or 1 blood transfusion decreased after 12 months of Siklos treatment.

The proportion of patients with at least 1 vaso-occlusive episode was 69.2% at baseline and 42.5% at 12 months. The proportion with at least 1 episode of acute chest syndrome was 23.6% and 5.7%, respectively.

The proportion with at least 1 hospitalization due to SCD was 75.5% and 41.8%, respectively. And the proportion with at least 1 blood transfusion was 45.9% and 23.0%, respectively.

The most common adverse events (occurring in at least 10% of patients) were infections (39.8%), gastrointestinal disorders (13.1%), neutropenia (12.6%), nervous system disorders (11.1%), and metabolic and nutrition disorders (10.9%).

Full prescribing information for Siklos is available on the FDA website. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved a hydroxyurea product (Addmedica’s Siklos) for use in pediatric patients with sickle cell anemia.

Siklos is intended to reduce the frequency of painful crises and the need for blood transfusions in pediatric patients age 2 and older who have sickle cell anemia and recurrent moderate to severe painful crises.

The recommended dose of Siklos is 20 mg/kg once daily.

The FDA granted priority review and orphan drug designation to the application for Siklos.

The agency’s approval of Siklos was based on data from the ESCORT HU study (NCT02516579). The trial was an evaluation of Siklos in 405 patients, ages 2 to 18, with sickle cell disease (SCD).

Thirty-five percent of these patients (n=141) had not received hydroxyurea prior to study enrollment and were therefore evaluable for efficacy. The median follow-up was 23 months (range, 12 to 80 months).

The researchers found that Siklos prompted an increase in fetal hemoglobin. Median fetal hemoglobin percentages were 5.6% (range, 1.3 to 15.0) at baseline and 12.8% (range, 2.1 to 37.2) at around 6 months after Siklos initiation (the value closest to 6 months collected between 5 and 14 months).

In addition, the percentage of patients with at least 1 vaso-occlusive episode, 1 episode of acute chest syndrome, 1 hospitalization due to SCD, or 1 blood transfusion decreased after 12 months of Siklos treatment.

The proportion of patients with at least 1 vaso-occlusive episode was 69.2% at baseline and 42.5% at 12 months. The proportion with at least 1 episode of acute chest syndrome was 23.6% and 5.7%, respectively.

The proportion with at least 1 hospitalization due to SCD was 75.5% and 41.8%, respectively. And the proportion with at least 1 blood transfusion was 45.9% and 23.0%, respectively.

The most common adverse events (occurring in at least 10% of patients) were infections (39.8%), gastrointestinal disorders (13.1%), neutropenia (12.6%), nervous system disorders (11.1%), and metabolic and nutrition disorders (10.9%).

Full prescribing information for Siklos is available on the FDA website. ![]()

Nilotinib label updated with info on discontinuation

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved an update to the product label for nilotinib (Tasigna) that includes information about how to discontinue the drug in certain patients.

Nilotinib, which was first approved by the FDA in 2007, is indicated for the treatment of patients with Philadelphia chromosome positive (Ph+) chronic myeloid leukemia (CML).

The updated prescribing information for the drug now outlines which of these patients may be eligible to stop receiving nilotinib.

Patients with chronic phase, Ph+ CML who have been taking nilotinib for 3 years or more (as first-line treatment or after failure with imatinib) and have achieved a sustained deep molecular response may be eligible to stop treatment.

Patients must have maintained a molecular response of at least MR4.0 for 1 year prior to discontinuation and achieved an MR4.5 at their last assessment.

Patients must have typical BCR-ABL transcripts (e13a2/b2a2 or e14a2/b3a2), no history of accelerated phase or blast crisis, and no past attempts at treatment discontinuation that resulted in relapse.

After discontinuation, patients must be monitored for possible loss of major molecular response (MMR). BCR-ABL transcript levels must be assessed and a complete blood count with differential performed monthly for 1 year, then every 6 weeks for the second year, and every 12 weeks thereafter.

BCR-ABL transcript levels should be measured using the MolecularMD MRDxTM BCR-ABL test, an FDA-authorized companion diagnostic validated to measure down to MR4.5.

If patients lose MMR, they must restart nilotinib within 4 weeks and receive the dose level they were receiving prior to discontinuation.

BCR-ABL transcript levels should be monitored every 2 weeks until they are lower than MMR for 4 consecutive measurements. Patients can then return to the original monitoring schedule.

The update of nilotinib’s label to include this information was based on results from 2 single-arm trials—ENESTfreedom and ENESTop.

ENESTfreedom

This phase 2 trial included 215 patients with Ph+, chronic phase CML. Researchers evaluated stopping treatment in 190 patients who had achieved a response of MR4.5 with nilotinib as first-line treatment. The patients had sustained deep molecular response for 1 year prior to treatment discontinuation.

Ninety-six weeks after stopping treatment, 48.9% of patients were still in MMR, also known as treatment-free remission (TFR).

Of the 88 patients who restarted nilotinib due to loss of MMR by the cut-off date, 98.9% were able to regain MMR (n=87). One patient discontinued the study at 7.1 weeks without regaining MMR after reinitiating treatment with nilotinib. Eighty-one patients (92.0%) regained MR4.5 by the cut-off date.

Common adverse events (AEs) in patients who discontinued nilotinib included musculoskeletal symptoms such as body aches, bone pain, and pain in extremities. However, these AEs decreased over time.

The incidence of musculoskeletal pain-related AEs decreased from 34.0% to 9.0% during the first and second 48 weeks of the TFR phase, respectively. In comparison, the incidence of such AEs was 17.0% during the treatment consolidation phase.

ENESTop

This phase 2 trial included 163 patients with Ph+, chronic phase CML. Researchers evaluated stopping treatment in 126 patients who had previously received imatinib, then switched to nilotinib and sustained a molecular response for 1 year prior to stopping nilotinib.

At 96 weeks, 53.2% of patients were still in TFR.

Fifty-six patients with confirmed loss of MR4.0 or loss of MMR restarted nilotinib by the cut-off date. Of these patients, 92.9% (n=52) regained both MR4.0 and MR4.5.

As in ENESTfreedom, patients who discontinued nilotinib had musculoskeletal symptoms that decreased over time.

The incidence of musculoskeletal pain-related AEs decreased from 47.9% to 15.1% during the first and second 48 weeks of the TFR phase, respectively. In comparison, the incidence of such AEs was 13.7% during the treatment consolidation phase.

Additional data from ENESTop and ENESTfreedom, as well as the recommendations for stopping nilotinib, are included in the updated prescribing information, which is available at https://www.us.tasigna.com/. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved an update to the product label for nilotinib (Tasigna) that includes information about how to discontinue the drug in certain patients.

Nilotinib, which was first approved by the FDA in 2007, is indicated for the treatment of patients with Philadelphia chromosome positive (Ph+) chronic myeloid leukemia (CML).

The updated prescribing information for the drug now outlines which of these patients may be eligible to stop receiving nilotinib.

Patients with chronic phase, Ph+ CML who have been taking nilotinib for 3 years or more (as first-line treatment or after failure with imatinib) and have achieved a sustained deep molecular response may be eligible to stop treatment.

Patients must have maintained a molecular response of at least MR4.0 for 1 year prior to discontinuation and achieved an MR4.5 at their last assessment.

Patients must have typical BCR-ABL transcripts (e13a2/b2a2 or e14a2/b3a2), no history of accelerated phase or blast crisis, and no past attempts at treatment discontinuation that resulted in relapse.

After discontinuation, patients must be monitored for possible loss of major molecular response (MMR). BCR-ABL transcript levels must be assessed and a complete blood count with differential performed monthly for 1 year, then every 6 weeks for the second year, and every 12 weeks thereafter.

BCR-ABL transcript levels should be measured using the MolecularMD MRDxTM BCR-ABL test, an FDA-authorized companion diagnostic validated to measure down to MR4.5.

If patients lose MMR, they must restart nilotinib within 4 weeks and receive the dose level they were receiving prior to discontinuation.

BCR-ABL transcript levels should be monitored every 2 weeks until they are lower than MMR for 4 consecutive measurements. Patients can then return to the original monitoring schedule.

The update of nilotinib’s label to include this information was based on results from 2 single-arm trials—ENESTfreedom and ENESTop.

ENESTfreedom

This phase 2 trial included 215 patients with Ph+, chronic phase CML. Researchers evaluated stopping treatment in 190 patients who had achieved a response of MR4.5 with nilotinib as first-line treatment. The patients had sustained deep molecular response for 1 year prior to treatment discontinuation.

Ninety-six weeks after stopping treatment, 48.9% of patients were still in MMR, also known as treatment-free remission (TFR).

Of the 88 patients who restarted nilotinib due to loss of MMR by the cut-off date, 98.9% were able to regain MMR (n=87). One patient discontinued the study at 7.1 weeks without regaining MMR after reinitiating treatment with nilotinib. Eighty-one patients (92.0%) regained MR4.5 by the cut-off date.

Common adverse events (AEs) in patients who discontinued nilotinib included musculoskeletal symptoms such as body aches, bone pain, and pain in extremities. However, these AEs decreased over time.

The incidence of musculoskeletal pain-related AEs decreased from 34.0% to 9.0% during the first and second 48 weeks of the TFR phase, respectively. In comparison, the incidence of such AEs was 17.0% during the treatment consolidation phase.

ENESTop

This phase 2 trial included 163 patients with Ph+, chronic phase CML. Researchers evaluated stopping treatment in 126 patients who had previously received imatinib, then switched to nilotinib and sustained a molecular response for 1 year prior to stopping nilotinib.

At 96 weeks, 53.2% of patients were still in TFR.

Fifty-six patients with confirmed loss of MR4.0 or loss of MMR restarted nilotinib by the cut-off date. Of these patients, 92.9% (n=52) regained both MR4.0 and MR4.5.

As in ENESTfreedom, patients who discontinued nilotinib had musculoskeletal symptoms that decreased over time.

The incidence of musculoskeletal pain-related AEs decreased from 47.9% to 15.1% during the first and second 48 weeks of the TFR phase, respectively. In comparison, the incidence of such AEs was 13.7% during the treatment consolidation phase.

Additional data from ENESTop and ENESTfreedom, as well as the recommendations for stopping nilotinib, are included in the updated prescribing information, which is available at https://www.us.tasigna.com/. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved an update to the product label for nilotinib (Tasigna) that includes information about how to discontinue the drug in certain patients.

Nilotinib, which was first approved by the FDA in 2007, is indicated for the treatment of patients with Philadelphia chromosome positive (Ph+) chronic myeloid leukemia (CML).

The updated prescribing information for the drug now outlines which of these patients may be eligible to stop receiving nilotinib.

Patients with chronic phase, Ph+ CML who have been taking nilotinib for 3 years or more (as first-line treatment or after failure with imatinib) and have achieved a sustained deep molecular response may be eligible to stop treatment.

Patients must have maintained a molecular response of at least MR4.0 for 1 year prior to discontinuation and achieved an MR4.5 at their last assessment.

Patients must have typical BCR-ABL transcripts (e13a2/b2a2 or e14a2/b3a2), no history of accelerated phase or blast crisis, and no past attempts at treatment discontinuation that resulted in relapse.

After discontinuation, patients must be monitored for possible loss of major molecular response (MMR). BCR-ABL transcript levels must be assessed and a complete blood count with differential performed monthly for 1 year, then every 6 weeks for the second year, and every 12 weeks thereafter.

BCR-ABL transcript levels should be measured using the MolecularMD MRDxTM BCR-ABL test, an FDA-authorized companion diagnostic validated to measure down to MR4.5.

If patients lose MMR, they must restart nilotinib within 4 weeks and receive the dose level they were receiving prior to discontinuation.

BCR-ABL transcript levels should be monitored every 2 weeks until they are lower than MMR for 4 consecutive measurements. Patients can then return to the original monitoring schedule.

The update of nilotinib’s label to include this information was based on results from 2 single-arm trials—ENESTfreedom and ENESTop.

ENESTfreedom

This phase 2 trial included 215 patients with Ph+, chronic phase CML. Researchers evaluated stopping treatment in 190 patients who had achieved a response of MR4.5 with nilotinib as first-line treatment. The patients had sustained deep molecular response for 1 year prior to treatment discontinuation.

Ninety-six weeks after stopping treatment, 48.9% of patients were still in MMR, also known as treatment-free remission (TFR).

Of the 88 patients who restarted nilotinib due to loss of MMR by the cut-off date, 98.9% were able to regain MMR (n=87). One patient discontinued the study at 7.1 weeks without regaining MMR after reinitiating treatment with nilotinib. Eighty-one patients (92.0%) regained MR4.5 by the cut-off date.

Common adverse events (AEs) in patients who discontinued nilotinib included musculoskeletal symptoms such as body aches, bone pain, and pain in extremities. However, these AEs decreased over time.

The incidence of musculoskeletal pain-related AEs decreased from 34.0% to 9.0% during the first and second 48 weeks of the TFR phase, respectively. In comparison, the incidence of such AEs was 17.0% during the treatment consolidation phase.

ENESTop

This phase 2 trial included 163 patients with Ph+, chronic phase CML. Researchers evaluated stopping treatment in 126 patients who had previously received imatinib, then switched to nilotinib and sustained a molecular response for 1 year prior to stopping nilotinib.

At 96 weeks, 53.2% of patients were still in TFR.

Fifty-six patients with confirmed loss of MR4.0 or loss of MMR restarted nilotinib by the cut-off date. Of these patients, 92.9% (n=52) regained both MR4.0 and MR4.5.

As in ENESTfreedom, patients who discontinued nilotinib had musculoskeletal symptoms that decreased over time.

The incidence of musculoskeletal pain-related AEs decreased from 47.9% to 15.1% during the first and second 48 weeks of the TFR phase, respectively. In comparison, the incidence of such AEs was 13.7% during the treatment consolidation phase.

Additional data from ENESTop and ENESTfreedom, as well as the recommendations for stopping nilotinib, are included in the updated prescribing information, which is available at https://www.us.tasigna.com/. ![]()

Isolation precautions are associated with higher costs, longer LOS

Clinical question: What are the effects of isolation precautions on hospital outcomes and cost of care?

Background: Previous studies have found that isolation precautions negatively affect various aspects of patient care, including frequency of contact with clinicians, adverse events in the hospital, measures of patient well-being, and patient experience scores. It is not known how isolation precautions affect other hospital-based metrics, such as 30-day readmissions, length of stay (LOS), in-hospital mortality, and cost of care.

Study design: Multisite, retrospective, propensity score–matched cohort study.

Setting: Three academic tertiary care hospitals in Toronto.

Synopsis: The authors used administrative databases and propensity-score modeling to match isolated patients and nonisolated controls. Researchers included 17,649 control patients, 737 patients isolated for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (contact isolation), and 1,502 patients isolated for respiratory illnesses (contact and droplet isolation) in the study. Patients isolated for MRSA had a higher 30-day readmission rate than did controls (19% vs. 14.7%), a longer average length of stay (11.9 days vs. 9.1 days), and higher direct costs ($11,009 vs. $7,670). Patients isolated for respiratory illnesses had a longer average length of stay (8.5 days vs. 7.6 days) and higher direct costs ($7,194 vs. $6,294). No differences in adverse events rates or in-hospital mortality were observed between control patients and patients in either isolation group.

Some of the differences observed may be from illness severity rather than from the effects of isolation, especially in the MRSA group. There was no difference observed in rates of adverse outcomes, such as falls or medication errors, or in rates of formal patient complaints to the hospital. It is possible that propensity score modeling corrected for unidentified biases in prior studies that found differences in these types of outcomes.

Bottom line: Isolation precautions are associated with higher costs and longer LOS in hospitalized general medicine patients.

Citation: Tran K et al. The effect of hospital isolation precautions on patient outcomes and cost of care: A multisite, retrospective, propensity score-matched cohort study. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(3):262-8.

Dr. Wachter is an assistant professor of medicine at Duke University.

Clinical question: What are the effects of isolation precautions on hospital outcomes and cost of care?

Background: Previous studies have found that isolation precautions negatively affect various aspects of patient care, including frequency of contact with clinicians, adverse events in the hospital, measures of patient well-being, and patient experience scores. It is not known how isolation precautions affect other hospital-based metrics, such as 30-day readmissions, length of stay (LOS), in-hospital mortality, and cost of care.

Study design: Multisite, retrospective, propensity score–matched cohort study.

Setting: Three academic tertiary care hospitals in Toronto.

Synopsis: The authors used administrative databases and propensity-score modeling to match isolated patients and nonisolated controls. Researchers included 17,649 control patients, 737 patients isolated for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (contact isolation), and 1,502 patients isolated for respiratory illnesses (contact and droplet isolation) in the study. Patients isolated for MRSA had a higher 30-day readmission rate than did controls (19% vs. 14.7%), a longer average length of stay (11.9 days vs. 9.1 days), and higher direct costs ($11,009 vs. $7,670). Patients isolated for respiratory illnesses had a longer average length of stay (8.5 days vs. 7.6 days) and higher direct costs ($7,194 vs. $6,294). No differences in adverse events rates or in-hospital mortality were observed between control patients and patients in either isolation group.

Some of the differences observed may be from illness severity rather than from the effects of isolation, especially in the MRSA group. There was no difference observed in rates of adverse outcomes, such as falls or medication errors, or in rates of formal patient complaints to the hospital. It is possible that propensity score modeling corrected for unidentified biases in prior studies that found differences in these types of outcomes.

Bottom line: Isolation precautions are associated with higher costs and longer LOS in hospitalized general medicine patients.

Citation: Tran K et al. The effect of hospital isolation precautions on patient outcomes and cost of care: A multisite, retrospective, propensity score-matched cohort study. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(3):262-8.

Dr. Wachter is an assistant professor of medicine at Duke University.

Clinical question: What are the effects of isolation precautions on hospital outcomes and cost of care?

Background: Previous studies have found that isolation precautions negatively affect various aspects of patient care, including frequency of contact with clinicians, adverse events in the hospital, measures of patient well-being, and patient experience scores. It is not known how isolation precautions affect other hospital-based metrics, such as 30-day readmissions, length of stay (LOS), in-hospital mortality, and cost of care.

Study design: Multisite, retrospective, propensity score–matched cohort study.

Setting: Three academic tertiary care hospitals in Toronto.

Synopsis: The authors used administrative databases and propensity-score modeling to match isolated patients and nonisolated controls. Researchers included 17,649 control patients, 737 patients isolated for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (contact isolation), and 1,502 patients isolated for respiratory illnesses (contact and droplet isolation) in the study. Patients isolated for MRSA had a higher 30-day readmission rate than did controls (19% vs. 14.7%), a longer average length of stay (11.9 days vs. 9.1 days), and higher direct costs ($11,009 vs. $7,670). Patients isolated for respiratory illnesses had a longer average length of stay (8.5 days vs. 7.6 days) and higher direct costs ($7,194 vs. $6,294). No differences in adverse events rates or in-hospital mortality were observed between control patients and patients in either isolation group.

Some of the differences observed may be from illness severity rather than from the effects of isolation, especially in the MRSA group. There was no difference observed in rates of adverse outcomes, such as falls or medication errors, or in rates of formal patient complaints to the hospital. It is possible that propensity score modeling corrected for unidentified biases in prior studies that found differences in these types of outcomes.

Bottom line: Isolation precautions are associated with higher costs and longer LOS in hospitalized general medicine patients.

Citation: Tran K et al. The effect of hospital isolation precautions on patient outcomes and cost of care: A multisite, retrospective, propensity score-matched cohort study. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(3):262-8.

Dr. Wachter is an assistant professor of medicine at Duke University.

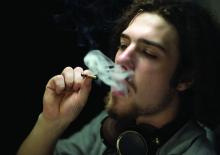

When cannabis use becomes another disorder

Despite the justified concern about rising opiate use in the United States, cannabis remains the most commonly used substance in the 12- to 17-year-old population.1 Cannabis use is widespread, particularly in states in which it has been decriminalized or legalized. While use of alcohol and nicotine has fallen among high school students from the years 2010 to 2015, marijuana use has remained relatively constant.2 In addition, the potency of cannabis with regard to tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) content has increased over the years. Despite the common belief among the public that cannabis use is benign, accumulating research is revealing a number of concerning consequences, especially in vulnerable populations and those who use cannabis regularly.

Case summary

Case discussion

Treatment for these adverse effects of cannabis is cessation of the drug. This can be accomplished through hard work with a counselor, who may recommend any of a number of treatments, including contingency management, cognitive behavioral therapy, systematic multidimensional family therapy, and motivational enhancement therapy, among others.5 While common lore is that it is impossible to stop cannabis use, the effect sizes of these treatments is in the moderate to large range. There are viable options to stop cannabis use, especially when it becomes problematic.

Dr. Althoff is associate professor of psychiatry, psychology, and pediatrics at the University of Vermont, Burlington. He is director of the division of behavioral genetics and conducts research on the development of self-regulation in children. Email him at [email protected].

References

1. “Results from the 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings,” Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2013.

2. “Monitoring the Future Survey, 2015,” National Institute on Drug Abuse.

3. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2012 Jul;5(7):719-26.

4. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007 Nov;8(11):885-95.

5. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2016 Sep;113(39): 653-9.

Despite the justified concern about rising opiate use in the United States, cannabis remains the most commonly used substance in the 12- to 17-year-old population.1 Cannabis use is widespread, particularly in states in which it has been decriminalized or legalized. While use of alcohol and nicotine has fallen among high school students from the years 2010 to 2015, marijuana use has remained relatively constant.2 In addition, the potency of cannabis with regard to tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) content has increased over the years. Despite the common belief among the public that cannabis use is benign, accumulating research is revealing a number of concerning consequences, especially in vulnerable populations and those who use cannabis regularly.

Case summary

Case discussion

Treatment for these adverse effects of cannabis is cessation of the drug. This can be accomplished through hard work with a counselor, who may recommend any of a number of treatments, including contingency management, cognitive behavioral therapy, systematic multidimensional family therapy, and motivational enhancement therapy, among others.5 While common lore is that it is impossible to stop cannabis use, the effect sizes of these treatments is in the moderate to large range. There are viable options to stop cannabis use, especially when it becomes problematic.

Dr. Althoff is associate professor of psychiatry, psychology, and pediatrics at the University of Vermont, Burlington. He is director of the division of behavioral genetics and conducts research on the development of self-regulation in children. Email him at [email protected].

References

1. “Results from the 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings,” Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2013.

2. “Monitoring the Future Survey, 2015,” National Institute on Drug Abuse.

3. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2012 Jul;5(7):719-26.

4. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007 Nov;8(11):885-95.

5. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2016 Sep;113(39): 653-9.

Despite the justified concern about rising opiate use in the United States, cannabis remains the most commonly used substance in the 12- to 17-year-old population.1 Cannabis use is widespread, particularly in states in which it has been decriminalized or legalized. While use of alcohol and nicotine has fallen among high school students from the years 2010 to 2015, marijuana use has remained relatively constant.2 In addition, the potency of cannabis with regard to tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) content has increased over the years. Despite the common belief among the public that cannabis use is benign, accumulating research is revealing a number of concerning consequences, especially in vulnerable populations and those who use cannabis regularly.

Case summary

Case discussion

Treatment for these adverse effects of cannabis is cessation of the drug. This can be accomplished through hard work with a counselor, who may recommend any of a number of treatments, including contingency management, cognitive behavioral therapy, systematic multidimensional family therapy, and motivational enhancement therapy, among others.5 While common lore is that it is impossible to stop cannabis use, the effect sizes of these treatments is in the moderate to large range. There are viable options to stop cannabis use, especially when it becomes problematic.

Dr. Althoff is associate professor of psychiatry, psychology, and pediatrics at the University of Vermont, Burlington. He is director of the division of behavioral genetics and conducts research on the development of self-regulation in children. Email him at [email protected].

References

1. “Results from the 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings,” Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2013.

2. “Monitoring the Future Survey, 2015,” National Institute on Drug Abuse.

3. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2012 Jul;5(7):719-26.

4. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007 Nov;8(11):885-95.

5. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2016 Sep;113(39): 653-9.

She’s Not My Mother: A 24-Year-Old Man With Capgras Delusion

Many patients admitted to inpatient psychiatric hospitals present with delusions; however, the Capgras delusion is a rare type that often appears as a sequela of certain medical and neurologic conditions.1 The Capgras delusion is a condition in which a person believes that either an individual or a group of people has been replaced by doubles or imposters.

In 1923, French psychiatrist Joseph Capgras first described the delusion. He and Jean Reboul-Lachaux coauthored a paper on a 53-year-old woman. The patient was a paranoid megalomaniac who “transformed everyone in her entourage, even those closest to her, such as her husband and daughter, into various and numerous doubles.”2 She believed she was famous, wealthy, and of royal lineage. Although 3 of her children had died, she believed that they were abducted, and that her only surviving child was replaced by a look-alike.2,3 Although the prevalence of such delusions in the general population has not been fully studied, a psychiatric hospital in Turkey found a 1.3% prevalence (1.8% women and 0.9% men) in 920 admissions over 5 years.4

The Capgras delusion is one of many delusions related to the misidentification of people, places, or objects; these delusions collectively are known as delusional misidentification syndrome (DMS).5,6 The Fregoli delusion involves the belief that several different people are the same person in disguise. Intermetamorphosis is the belief that an individual has been transformed internally and externally to another person. Subjective doubles is the belief that a doppelganger of the afflicted person exists, living and functioning independently in the world. Reduplicative paramnesia is the belief that a person, place, or object has been duplicated. A rarer example of DMS is the Cotard delusion, which is the belief that the patient himself or herself is dead, putrefying, exsanguinating, or lacking internal organs.

The most common of the DMS is the Capgras delusion. One common presentation of Capgras delusion involves the spouse of the patient, who believes that an imposter of the same sex as their spouse has taken over his or her body. Rarer delusions are those in which a person misidentifies him or herself as the imposter.3,5,6

Case Presentation

This case involved a 24-year-old male veteran who had received a wide range of mental health diagnoses in the past, including major depressive disorder (MDD) with psychotic features, generalized anxiety disorder, cannabis use disorder, adjustment disorder, and borderline personality disorder. He also had a medical history related to a motor vehicle accident with subsequent intestinal rupture and colostomy placement that had occurred a year and a half prior to presentation. He had no history of brain trauma.

The patient voluntarily presented to the hospital for increased suicidal thoughts and was admitted voluntarily for stabilization and self-harm prevention. He stated that “I feel everything is unreal. I feel suicidal and guilt” and endorsed a plan to either walk into traffic or shoot himself in the head due to increasingly distressing thoughts and memories. According to the patient, he had reported to the police that he raped his ex-girlfriend a year previously, although she denied the claim to the police.

The patient further disclosed that he did not believe his mother was real. “Last year my sister told me it was not 2016, but it was 2022,” he said. “She told me that I have hurt my mother with a padlock—that you could no longer identify her face. I don’t remember having done this. I have lived with her since that time, so I don’t think it’s really [my mother].” He believed that his mother was replaced by “government employees” who were sent to elicit confessions for his behavior while in the military. He expressed guilt over several actions he had performed while in military service, such as punching a wall during boot camp, stealing “soak-up” pads, and napping during work hours. His mother was contacted by a staff psychiatrist in the inpatient unit and denied that any assault had taken place.

The patient’s psychiatric review of systems was positive for visual hallucinations (specifically “blurs” next to his bed in the morning that disappeared as he tried to touch them), depressed mood, anxiety, hopelessness, and insomnia. Pertinent negatives of the review of systems included a denial of manic symptoms and auditory hallucinations. For additional details of his past psychiatric history, the patient admitted that his motor vehicle accident, intestinal rupture, and colostomy were the result of his 1 suicide attempt a year and a half prior after a verbal dispute with the same ex-girlfriend that he believed he had raped. After undergoing extensive medical and surgical treatment, he began seeing an outpatient psychiatrist as well as attending substance use counseling to curtail his marijuana use. He was prescribed a combination of duloxetine and risperidone as an outpatient, which he was taking with intermittent adherence.

Regarding substance use, the patient admitted to using marijuana regularly in the past but quit completely 1 month prior and denied any other drug use or alcohol use. He reported a family history of a sister who was undergoing treatment for bipolar disorder. In his social history, the patient disclosed that he was raised by both parents and described a good childhood with a life absent of abuse in any form. He was single with no children. Although he was unemployed, he lived off the funds from an insurance settlement from his motor vehicle accident. He was living in a trailer with his brother and mother. He also denied having access to firearms.

The patient was overweight, neatly groomed, had good eye contact, and was calm and cooperative. He seemed anxious as evidenced by his continuous shaking of his feet; although speech was normal in rate and tone. He reported his mood as “depressed and anxious” with congruent and tearful affect. His thought process was concrete, although his thought content contained delusions, suicidal ideation, and paranoia. He denied any homicidal thoughts or thoughts of harming others. He did not present with any auditory or visual hallucinations. Insight and judgment were poor. The mental status examination revealed no notable deficits in cognition.

The patient’s differential diagnosis included schizophreniform disorder, exacerbation of MDD with psychotic features, and the psychotic component of cannabis use disorder. His outpatient risperidone and duloxetine were not restarted. Aripiprazole 15 mg daily was prescribed for his delusions, paranoia, and visual hallucinations. The patient also received a prescription for hydroxyzine 50 mg every 6 hours as needed for anxiety.

Because of the nature of his delusions, comorbid medical and neurologic conditions were considered. Neurology consultation recommended a noncontrast head computer tomography (CT) scan and an electroencephalogram (EEG). Laboratory workup included HIV antibody, thyroid panel, chemistry panel, complete blood count, hepatitis B serum antigen, urine drug screen, hepatitis C virus, and rapid plasma reagin. All laboratory results were benign and unremarkable, and the urine drug screen was negative. The noncontrast CT revealed no acute findings, and the EEG revealed no recorded epileptiform abnormalities or seizures.

Throughout his hospital course, the patient remained cooperative with treatment. Three days into the hospitalization, he stated that he believed the entire family had been replaced by imposters. He began to distrust members of his family and was reticent to communicate with them when they attempted to contact him. He also experienced fragmented sleep during his hospital stay, and trazodone 50 mg at bedtime was added.

After aripiprazole was increased to 20 mg daily on hospital day 2 and then to 30 mg daily on hospital day 3 due to the patient’s delusions, he began to doubt the validity of his beliefs. After showing gradual improvement over 6 days, the patient reported that he no longer believed that those memories were real. His sleep, depressed mood, anxiety, and paranoia had markedly improved toward the end of the hospitalization and suicidal ideation/intent resolved. The patient was discharged home to his mother and brother after 6 days of hospitalization with aripiprazole 30 mg daily and trazodone 50 mg at bedtime.

Discussion

The Capgras delusion can present in several different contexts. A psychiatric differential diagnosis includes disorders in the schizophrenia spectrum (brief psychotic disorder, schizophreniform disorder, and schizophrenia), schizoaffective disorder, delusional disorder, and substance-induced psychotic disorder. In addition to psychiatric disorders, the Capgras delusion has been shown to occur in several medical conditions, which include stroke, central nervous system tumors, subarachnoid hemorrhage, vitamin B12 deficiency, hepatic encephalopathy, hypothyroidism, hyperparathyroidism, epilepsy, and dementia.1,2,4,7

A 2007 retrospective study by Josephs examined 47 patients diagnosed with the Capgras delusion from several tertiary care centers. Of those patients, 38 (81%) had a neurodegenerative disease, most commonly Lewy body dementia (LBD).1 In his review of the Josephs study, Devinsky proposed that the loss of striatal D2 receptors in LBD may be implicated in the manifestation of Capgras delusions.2 The data suggest multiple brain regions may be involved, including the frontal lobes, right temporal lobe, right parietal lobe, parahippocampus, and amygdala.1,2 Most patients in the Josephs study demonstrated global atrophy on imaging studies. One hypothesis is that it is the disconnection of the frontal lobe to other brain regions that may be implicated.1,2,4 This results in intact recognition of facial features of familiar people, impaired emotional recognition, and impaired self-correction due to executive dysfunction.

Methamphetamine also has been implicated in a small number of cases of Capgras; the proposed mechanism involves dopaminergic neuronal impairment/loss.1,2 Additionally, Capgras delusions have been described in cases of patients treated with antimalarial medications, such as chloroquine.8 Younger patients with the Capgras delusion were more likely to have purely psychiatric comorbidities—such as schizophrenia, substance-induced psychosis, or schizoaffective disorder—as opposed to underlying medical conditions.1 In the case presented here, the Capgras delusion was thought to be due to a disorder in the schizophrenia spectrum, specifically schizophreniform disorder.

Because an increasing amount of evidence indicates that the Capgras delusion is associated with certain medical conditions, a workup should be performed to rule out underlying medical etiology. Of note, no official guidelines for the workup have been produced for the Capgras delusion. However, the workup may include brain imaging, such as magnetic resonance imaging and/or CT scan to rule out mass lesions, vascular malformations, stroke, or neuro-infectious processes; laboratory tests, such as vitamin B12, liver panel, HIV, rapid plasma reagin, hepatitis B and C viruses, parathyroid hormone levels, urine drug screen, and thyroid panel can be ordered to rule out other medical causes.1,2,6,7,9

Consultations with internal medicine and neurology departments may be beneficial. Although treatment of the underlying condition may lead to an improvement in the symptoms, full remission in all cases has not been consistently demonstrated in the current literature.5,7,9,10 Patients with the Capgras delusion are challenging to treat, because their delusions have been shown to be refractory to antipsychotic therapy. However, antipsychotics are currently the mainstay of treatment. Some case studies have shown efficacy with pimozide, tricyclic antidepressants, and mirtazapine.6,9

One case study in 2014 in India of a 45-year-old woman who believed her husband and son were replaced by imposters out to kill her, showed a 40% to 50% reduction of paranoia, irritability, and suspicious scanning behaviors with a combination of risperidone and trihexyphenidyl. Despite the improvements, the woman continued to have delusions.7

A notable feature associated with those experiencing the Capgras delusion is the increased risk of violent behaviors, often because of suspiciousness and paranoia. A 2004 review suggested the risk of violence and homicidality is much higher in male patients compared with that of female patients with the Capgras delusion.9 This is despite evidence suggesting that the prevalence of the Capgras delusion seems to be greater in women.6,9 Moreover, patients often demonstrated social withdrawal and self-isolation prior to violent acts. The victims often were family members or those who live with the patient, which is consistent with the evidence that those most familiar to patients are more likely to be misidentified.1,2,7,9,10

A 1989 case series that examined 8 cases of the Capgras delusion listed the following violent behaviors: shot and killed father, pointed knife at mother, held knife to mother’s throat, punched parents, threatened to stab husband with scissors, nonspecifically threatened physical harm to family, injured mother with axe, and threatened to stab son with knife and burn him. Seven of the 8 patients lived with the misidentified persons, and 5 of the 8 patients were treatment resistant. The study posited that chronicity of the delusion, content of the delusion, and accessibility of misidentified persons seemed to increase the risk of violent behaviors. These authors went on to suggest that despite the appearance of stability, patients may react violently to minute changes.10 Overall literature seems to suggest the importance of performing a violence and homicidality assessment with special attention to assessment for themes of hostility toward misidentified individuals.9,10

Conclusion

The Capgras delusion is an uncommon symptom associated with varied psychiatric, medical, iatrogenic, and neurologic conditions. Treatment of underlying medical conditions may improve or resolve the delusions. However, in this case, the patient did not seem to have any underlying medical conditions, and it was thought that he may have been experiencing a prodrome within the schizophrenia spectrum. This is consistent with the literature, which suggests that those with the delusions at younger ages may have a psychiatric etiology.

Although this patient was responsive to aripiprazole, the Capgras delusion has been known to be resistant to antipsychotic therapy. It is worth considering a medical and neurologic workup with the addition of a psychiatry referral. Further, while the patient in the presented case had the delusion that he had assaulted his mother, whom he misidentified as an imposter, the patient did not demonstrate any hostility and denied thoughts of harming her. However, given the increased risk of violence in patients with the Capgras delusion, a homicidality and violence assessment should be performed. While further recommendations are outside the scope of this article, the provider should be cognizant of local duty-to-warn and duty-to-protect laws regarding potentially homicidal patients.

1. Josephs KA. The Capgras delusion and its relationship to neurodegenerative disease. Arch Neurol. 2007;64(12):1762-1766.

2. Devinsky O. Behavioral neurology. The neurology of the Capgras delusion. Rev Neurol Dis. 2008;5(2):97-100.

3. Sadock BJ, Sadock VA. Kaplan & Sadock’s Synopsis of Psychiatry: Behavioral Sciences/Clinical Psychiatry. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2007.

4. Tamam L, Karatas G, Zeren T, Ozpyraz N. The prevalence of Capgras syndrome in a university hospital setting. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2003;15(5):290-295.

5. Klein CA, Hirchan S. The masks of identities: who’s who? Delusional misidentification syndromes. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2014;42(3):369-378.

6. Atta K. Forlenza N, Gujski M, Hashmi S, Isaac G. Delusional misidentification syndromes: separate disorders or unusual presentations of existing DSM-IV categories? Psychiatry (Edgemont). 2006;3(9):56-61.

7. Sathe H, Karia S, De Sousa A, Shah N. Capgras syndrome: a case report. Paripex Indian J Res. 2014;3(8):134-135. 8. Bhatia MS, Singhal PK, Agrawal P, Malik SC. Capgras’ syndrome in chloroquine induced psychosis. Indian J Psychiatry. 1988;30(3):311-313.

9. Bourget D, Whitehurst L. Capgras syndrome: a review of the neurophysiological correlates and presenting clinical features in cases involving physical violence. Can J Psychiatry. 2004;49(11):719-725.

10. Silva JA, Leong GB, Weinstock R, Boyer CL. Capgras syndrome and dangerousness. Bull Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 1989;17(1):5-14.

Many patients admitted to inpatient psychiatric hospitals present with delusions; however, the Capgras delusion is a rare type that often appears as a sequela of certain medical and neurologic conditions.1 The Capgras delusion is a condition in which a person believes that either an individual or a group of people has been replaced by doubles or imposters.

In 1923, French psychiatrist Joseph Capgras first described the delusion. He and Jean Reboul-Lachaux coauthored a paper on a 53-year-old woman. The patient was a paranoid megalomaniac who “transformed everyone in her entourage, even those closest to her, such as her husband and daughter, into various and numerous doubles.”2 She believed she was famous, wealthy, and of royal lineage. Although 3 of her children had died, she believed that they were abducted, and that her only surviving child was replaced by a look-alike.2,3 Although the prevalence of such delusions in the general population has not been fully studied, a psychiatric hospital in Turkey found a 1.3% prevalence (1.8% women and 0.9% men) in 920 admissions over 5 years.4

The Capgras delusion is one of many delusions related to the misidentification of people, places, or objects; these delusions collectively are known as delusional misidentification syndrome (DMS).5,6 The Fregoli delusion involves the belief that several different people are the same person in disguise. Intermetamorphosis is the belief that an individual has been transformed internally and externally to another person. Subjective doubles is the belief that a doppelganger of the afflicted person exists, living and functioning independently in the world. Reduplicative paramnesia is the belief that a person, place, or object has been duplicated. A rarer example of DMS is the Cotard delusion, which is the belief that the patient himself or herself is dead, putrefying, exsanguinating, or lacking internal organs.

The most common of the DMS is the Capgras delusion. One common presentation of Capgras delusion involves the spouse of the patient, who believes that an imposter of the same sex as their spouse has taken over his or her body. Rarer delusions are those in which a person misidentifies him or herself as the imposter.3,5,6

Case Presentation

This case involved a 24-year-old male veteran who had received a wide range of mental health diagnoses in the past, including major depressive disorder (MDD) with psychotic features, generalized anxiety disorder, cannabis use disorder, adjustment disorder, and borderline personality disorder. He also had a medical history related to a motor vehicle accident with subsequent intestinal rupture and colostomy placement that had occurred a year and a half prior to presentation. He had no history of brain trauma.

The patient voluntarily presented to the hospital for increased suicidal thoughts and was admitted voluntarily for stabilization and self-harm prevention. He stated that “I feel everything is unreal. I feel suicidal and guilt” and endorsed a plan to either walk into traffic or shoot himself in the head due to increasingly distressing thoughts and memories. According to the patient, he had reported to the police that he raped his ex-girlfriend a year previously, although she denied the claim to the police.

The patient further disclosed that he did not believe his mother was real. “Last year my sister told me it was not 2016, but it was 2022,” he said. “She told me that I have hurt my mother with a padlock—that you could no longer identify her face. I don’t remember having done this. I have lived with her since that time, so I don’t think it’s really [my mother].” He believed that his mother was replaced by “government employees” who were sent to elicit confessions for his behavior while in the military. He expressed guilt over several actions he had performed while in military service, such as punching a wall during boot camp, stealing “soak-up” pads, and napping during work hours. His mother was contacted by a staff psychiatrist in the inpatient unit and denied that any assault had taken place.

The patient’s psychiatric review of systems was positive for visual hallucinations (specifically “blurs” next to his bed in the morning that disappeared as he tried to touch them), depressed mood, anxiety, hopelessness, and insomnia. Pertinent negatives of the review of systems included a denial of manic symptoms and auditory hallucinations. For additional details of his past psychiatric history, the patient admitted that his motor vehicle accident, intestinal rupture, and colostomy were the result of his 1 suicide attempt a year and a half prior after a verbal dispute with the same ex-girlfriend that he believed he had raped. After undergoing extensive medical and surgical treatment, he began seeing an outpatient psychiatrist as well as attending substance use counseling to curtail his marijuana use. He was prescribed a combination of duloxetine and risperidone as an outpatient, which he was taking with intermittent adherence.

Regarding substance use, the patient admitted to using marijuana regularly in the past but quit completely 1 month prior and denied any other drug use or alcohol use. He reported a family history of a sister who was undergoing treatment for bipolar disorder. In his social history, the patient disclosed that he was raised by both parents and described a good childhood with a life absent of abuse in any form. He was single with no children. Although he was unemployed, he lived off the funds from an insurance settlement from his motor vehicle accident. He was living in a trailer with his brother and mother. He also denied having access to firearms.

The patient was overweight, neatly groomed, had good eye contact, and was calm and cooperative. He seemed anxious as evidenced by his continuous shaking of his feet; although speech was normal in rate and tone. He reported his mood as “depressed and anxious” with congruent and tearful affect. His thought process was concrete, although his thought content contained delusions, suicidal ideation, and paranoia. He denied any homicidal thoughts or thoughts of harming others. He did not present with any auditory or visual hallucinations. Insight and judgment were poor. The mental status examination revealed no notable deficits in cognition.

The patient’s differential diagnosis included schizophreniform disorder, exacerbation of MDD with psychotic features, and the psychotic component of cannabis use disorder. His outpatient risperidone and duloxetine were not restarted. Aripiprazole 15 mg daily was prescribed for his delusions, paranoia, and visual hallucinations. The patient also received a prescription for hydroxyzine 50 mg every 6 hours as needed for anxiety.

Because of the nature of his delusions, comorbid medical and neurologic conditions were considered. Neurology consultation recommended a noncontrast head computer tomography (CT) scan and an electroencephalogram (EEG). Laboratory workup included HIV antibody, thyroid panel, chemistry panel, complete blood count, hepatitis B serum antigen, urine drug screen, hepatitis C virus, and rapid plasma reagin. All laboratory results were benign and unremarkable, and the urine drug screen was negative. The noncontrast CT revealed no acute findings, and the EEG revealed no recorded epileptiform abnormalities or seizures.

Throughout his hospital course, the patient remained cooperative with treatment. Three days into the hospitalization, he stated that he believed the entire family had been replaced by imposters. He began to distrust members of his family and was reticent to communicate with them when they attempted to contact him. He also experienced fragmented sleep during his hospital stay, and trazodone 50 mg at bedtime was added.

After aripiprazole was increased to 20 mg daily on hospital day 2 and then to 30 mg daily on hospital day 3 due to the patient’s delusions, he began to doubt the validity of his beliefs. After showing gradual improvement over 6 days, the patient reported that he no longer believed that those memories were real. His sleep, depressed mood, anxiety, and paranoia had markedly improved toward the end of the hospitalization and suicidal ideation/intent resolved. The patient was discharged home to his mother and brother after 6 days of hospitalization with aripiprazole 30 mg daily and trazodone 50 mg at bedtime.

Discussion

The Capgras delusion can present in several different contexts. A psychiatric differential diagnosis includes disorders in the schizophrenia spectrum (brief psychotic disorder, schizophreniform disorder, and schizophrenia), schizoaffective disorder, delusional disorder, and substance-induced psychotic disorder. In addition to psychiatric disorders, the Capgras delusion has been shown to occur in several medical conditions, which include stroke, central nervous system tumors, subarachnoid hemorrhage, vitamin B12 deficiency, hepatic encephalopathy, hypothyroidism, hyperparathyroidism, epilepsy, and dementia.1,2,4,7

A 2007 retrospective study by Josephs examined 47 patients diagnosed with the Capgras delusion from several tertiary care centers. Of those patients, 38 (81%) had a neurodegenerative disease, most commonly Lewy body dementia (LBD).1 In his review of the Josephs study, Devinsky proposed that the loss of striatal D2 receptors in LBD may be implicated in the manifestation of Capgras delusions.2 The data suggest multiple brain regions may be involved, including the frontal lobes, right temporal lobe, right parietal lobe, parahippocampus, and amygdala.1,2 Most patients in the Josephs study demonstrated global atrophy on imaging studies. One hypothesis is that it is the disconnection of the frontal lobe to other brain regions that may be implicated.1,2,4 This results in intact recognition of facial features of familiar people, impaired emotional recognition, and impaired self-correction due to executive dysfunction.

Methamphetamine also has been implicated in a small number of cases of Capgras; the proposed mechanism involves dopaminergic neuronal impairment/loss.1,2 Additionally, Capgras delusions have been described in cases of patients treated with antimalarial medications, such as chloroquine.8 Younger patients with the Capgras delusion were more likely to have purely psychiatric comorbidities—such as schizophrenia, substance-induced psychosis, or schizoaffective disorder—as opposed to underlying medical conditions.1 In the case presented here, the Capgras delusion was thought to be due to a disorder in the schizophrenia spectrum, specifically schizophreniform disorder.

Because an increasing amount of evidence indicates that the Capgras delusion is associated with certain medical conditions, a workup should be performed to rule out underlying medical etiology. Of note, no official guidelines for the workup have been produced for the Capgras delusion. However, the workup may include brain imaging, such as magnetic resonance imaging and/or CT scan to rule out mass lesions, vascular malformations, stroke, or neuro-infectious processes; laboratory tests, such as vitamin B12, liver panel, HIV, rapid plasma reagin, hepatitis B and C viruses, parathyroid hormone levels, urine drug screen, and thyroid panel can be ordered to rule out other medical causes.1,2,6,7,9

Consultations with internal medicine and neurology departments may be beneficial. Although treatment of the underlying condition may lead to an improvement in the symptoms, full remission in all cases has not been consistently demonstrated in the current literature.5,7,9,10 Patients with the Capgras delusion are challenging to treat, because their delusions have been shown to be refractory to antipsychotic therapy. However, antipsychotics are currently the mainstay of treatment. Some case studies have shown efficacy with pimozide, tricyclic antidepressants, and mirtazapine.6,9

One case study in 2014 in India of a 45-year-old woman who believed her husband and son were replaced by imposters out to kill her, showed a 40% to 50% reduction of paranoia, irritability, and suspicious scanning behaviors with a combination of risperidone and trihexyphenidyl. Despite the improvements, the woman continued to have delusions.7

A notable feature associated with those experiencing the Capgras delusion is the increased risk of violent behaviors, often because of suspiciousness and paranoia. A 2004 review suggested the risk of violence and homicidality is much higher in male patients compared with that of female patients with the Capgras delusion.9 This is despite evidence suggesting that the prevalence of the Capgras delusion seems to be greater in women.6,9 Moreover, patients often demonstrated social withdrawal and self-isolation prior to violent acts. The victims often were family members or those who live with the patient, which is consistent with the evidence that those most familiar to patients are more likely to be misidentified.1,2,7,9,10

A 1989 case series that examined 8 cases of the Capgras delusion listed the following violent behaviors: shot and killed father, pointed knife at mother, held knife to mother’s throat, punched parents, threatened to stab husband with scissors, nonspecifically threatened physical harm to family, injured mother with axe, and threatened to stab son with knife and burn him. Seven of the 8 patients lived with the misidentified persons, and 5 of the 8 patients were treatment resistant. The study posited that chronicity of the delusion, content of the delusion, and accessibility of misidentified persons seemed to increase the risk of violent behaviors. These authors went on to suggest that despite the appearance of stability, patients may react violently to minute changes.10 Overall literature seems to suggest the importance of performing a violence and homicidality assessment with special attention to assessment for themes of hostility toward misidentified individuals.9,10

Conclusion

The Capgras delusion is an uncommon symptom associated with varied psychiatric, medical, iatrogenic, and neurologic conditions. Treatment of underlying medical conditions may improve or resolve the delusions. However, in this case, the patient did not seem to have any underlying medical conditions, and it was thought that he may have been experiencing a prodrome within the schizophrenia spectrum. This is consistent with the literature, which suggests that those with the delusions at younger ages may have a psychiatric etiology.

Although this patient was responsive to aripiprazole, the Capgras delusion has been known to be resistant to antipsychotic therapy. It is worth considering a medical and neurologic workup with the addition of a psychiatry referral. Further, while the patient in the presented case had the delusion that he had assaulted his mother, whom he misidentified as an imposter, the patient did not demonstrate any hostility and denied thoughts of harming her. However, given the increased risk of violence in patients with the Capgras delusion, a homicidality and violence assessment should be performed. While further recommendations are outside the scope of this article, the provider should be cognizant of local duty-to-warn and duty-to-protect laws regarding potentially homicidal patients.

Many patients admitted to inpatient psychiatric hospitals present with delusions; however, the Capgras delusion is a rare type that often appears as a sequela of certain medical and neurologic conditions.1 The Capgras delusion is a condition in which a person believes that either an individual or a group of people has been replaced by doubles or imposters.

In 1923, French psychiatrist Joseph Capgras first described the delusion. He and Jean Reboul-Lachaux coauthored a paper on a 53-year-old woman. The patient was a paranoid megalomaniac who “transformed everyone in her entourage, even those closest to her, such as her husband and daughter, into various and numerous doubles.”2 She believed she was famous, wealthy, and of royal lineage. Although 3 of her children had died, she believed that they were abducted, and that her only surviving child was replaced by a look-alike.2,3 Although the prevalence of such delusions in the general population has not been fully studied, a psychiatric hospital in Turkey found a 1.3% prevalence (1.8% women and 0.9% men) in 920 admissions over 5 years.4

The Capgras delusion is one of many delusions related to the misidentification of people, places, or objects; these delusions collectively are known as delusional misidentification syndrome (DMS).5,6 The Fregoli delusion involves the belief that several different people are the same person in disguise. Intermetamorphosis is the belief that an individual has been transformed internally and externally to another person. Subjective doubles is the belief that a doppelganger of the afflicted person exists, living and functioning independently in the world. Reduplicative paramnesia is the belief that a person, place, or object has been duplicated. A rarer example of DMS is the Cotard delusion, which is the belief that the patient himself or herself is dead, putrefying, exsanguinating, or lacking internal organs.

The most common of the DMS is the Capgras delusion. One common presentation of Capgras delusion involves the spouse of the patient, who believes that an imposter of the same sex as their spouse has taken over his or her body. Rarer delusions are those in which a person misidentifies him or herself as the imposter.3,5,6

Case Presentation

This case involved a 24-year-old male veteran who had received a wide range of mental health diagnoses in the past, including major depressive disorder (MDD) with psychotic features, generalized anxiety disorder, cannabis use disorder, adjustment disorder, and borderline personality disorder. He also had a medical history related to a motor vehicle accident with subsequent intestinal rupture and colostomy placement that had occurred a year and a half prior to presentation. He had no history of brain trauma.

The patient voluntarily presented to the hospital for increased suicidal thoughts and was admitted voluntarily for stabilization and self-harm prevention. He stated that “I feel everything is unreal. I feel suicidal and guilt” and endorsed a plan to either walk into traffic or shoot himself in the head due to increasingly distressing thoughts and memories. According to the patient, he had reported to the police that he raped his ex-girlfriend a year previously, although she denied the claim to the police.

The patient further disclosed that he did not believe his mother was real. “Last year my sister told me it was not 2016, but it was 2022,” he said. “She told me that I have hurt my mother with a padlock—that you could no longer identify her face. I don’t remember having done this. I have lived with her since that time, so I don’t think it’s really [my mother].” He believed that his mother was replaced by “government employees” who were sent to elicit confessions for his behavior while in the military. He expressed guilt over several actions he had performed while in military service, such as punching a wall during boot camp, stealing “soak-up” pads, and napping during work hours. His mother was contacted by a staff psychiatrist in the inpatient unit and denied that any assault had taken place.

The patient’s psychiatric review of systems was positive for visual hallucinations (specifically “blurs” next to his bed in the morning that disappeared as he tried to touch them), depressed mood, anxiety, hopelessness, and insomnia. Pertinent negatives of the review of systems included a denial of manic symptoms and auditory hallucinations. For additional details of his past psychiatric history, the patient admitted that his motor vehicle accident, intestinal rupture, and colostomy were the result of his 1 suicide attempt a year and a half prior after a verbal dispute with the same ex-girlfriend that he believed he had raped. After undergoing extensive medical and surgical treatment, he began seeing an outpatient psychiatrist as well as attending substance use counseling to curtail his marijuana use. He was prescribed a combination of duloxetine and risperidone as an outpatient, which he was taking with intermittent adherence.

Regarding substance use, the patient admitted to using marijuana regularly in the past but quit completely 1 month prior and denied any other drug use or alcohol use. He reported a family history of a sister who was undergoing treatment for bipolar disorder. In his social history, the patient disclosed that he was raised by both parents and described a good childhood with a life absent of abuse in any form. He was single with no children. Although he was unemployed, he lived off the funds from an insurance settlement from his motor vehicle accident. He was living in a trailer with his brother and mother. He also denied having access to firearms.

The patient was overweight, neatly groomed, had good eye contact, and was calm and cooperative. He seemed anxious as evidenced by his continuous shaking of his feet; although speech was normal in rate and tone. He reported his mood as “depressed and anxious” with congruent and tearful affect. His thought process was concrete, although his thought content contained delusions, suicidal ideation, and paranoia. He denied any homicidal thoughts or thoughts of harming others. He did not present with any auditory or visual hallucinations. Insight and judgment were poor. The mental status examination revealed no notable deficits in cognition.

The patient’s differential diagnosis included schizophreniform disorder, exacerbation of MDD with psychotic features, and the psychotic component of cannabis use disorder. His outpatient risperidone and duloxetine were not restarted. Aripiprazole 15 mg daily was prescribed for his delusions, paranoia, and visual hallucinations. The patient also received a prescription for hydroxyzine 50 mg every 6 hours as needed for anxiety.

Because of the nature of his delusions, comorbid medical and neurologic conditions were considered. Neurology consultation recommended a noncontrast head computer tomography (CT) scan and an electroencephalogram (EEG). Laboratory workup included HIV antibody, thyroid panel, chemistry panel, complete blood count, hepatitis B serum antigen, urine drug screen, hepatitis C virus, and rapid plasma reagin. All laboratory results were benign and unremarkable, and the urine drug screen was negative. The noncontrast CT revealed no acute findings, and the EEG revealed no recorded epileptiform abnormalities or seizures.

Throughout his hospital course, the patient remained cooperative with treatment. Three days into the hospitalization, he stated that he believed the entire family had been replaced by imposters. He began to distrust members of his family and was reticent to communicate with them when they attempted to contact him. He also experienced fragmented sleep during his hospital stay, and trazodone 50 mg at bedtime was added.

After aripiprazole was increased to 20 mg daily on hospital day 2 and then to 30 mg daily on hospital day 3 due to the patient’s delusions, he began to doubt the validity of his beliefs. After showing gradual improvement over 6 days, the patient reported that he no longer believed that those memories were real. His sleep, depressed mood, anxiety, and paranoia had markedly improved toward the end of the hospitalization and suicidal ideation/intent resolved. The patient was discharged home to his mother and brother after 6 days of hospitalization with aripiprazole 30 mg daily and trazodone 50 mg at bedtime.

Discussion

The Capgras delusion can present in several different contexts. A psychiatric differential diagnosis includes disorders in the schizophrenia spectrum (brief psychotic disorder, schizophreniform disorder, and schizophrenia), schizoaffective disorder, delusional disorder, and substance-induced psychotic disorder. In addition to psychiatric disorders, the Capgras delusion has been shown to occur in several medical conditions, which include stroke, central nervous system tumors, subarachnoid hemorrhage, vitamin B12 deficiency, hepatic encephalopathy, hypothyroidism, hyperparathyroidism, epilepsy, and dementia.1,2,4,7

A 2007 retrospective study by Josephs examined 47 patients diagnosed with the Capgras delusion from several tertiary care centers. Of those patients, 38 (81%) had a neurodegenerative disease, most commonly Lewy body dementia (LBD).1 In his review of the Josephs study, Devinsky proposed that the loss of striatal D2 receptors in LBD may be implicated in the manifestation of Capgras delusions.2 The data suggest multiple brain regions may be involved, including the frontal lobes, right temporal lobe, right parietal lobe, parahippocampus, and amygdala.1,2 Most patients in the Josephs study demonstrated global atrophy on imaging studies. One hypothesis is that it is the disconnection of the frontal lobe to other brain regions that may be implicated.1,2,4 This results in intact recognition of facial features of familiar people, impaired emotional recognition, and impaired self-correction due to executive dysfunction.

Methamphetamine also has been implicated in a small number of cases of Capgras; the proposed mechanism involves dopaminergic neuronal impairment/loss.1,2 Additionally, Capgras delusions have been described in cases of patients treated with antimalarial medications, such as chloroquine.8 Younger patients with the Capgras delusion were more likely to have purely psychiatric comorbidities—such as schizophrenia, substance-induced psychosis, or schizoaffective disorder—as opposed to underlying medical conditions.1 In the case presented here, the Capgras delusion was thought to be due to a disorder in the schizophrenia spectrum, specifically schizophreniform disorder.

Because an increasing amount of evidence indicates that the Capgras delusion is associated with certain medical conditions, a workup should be performed to rule out underlying medical etiology. Of note, no official guidelines for the workup have been produced for the Capgras delusion. However, the workup may include brain imaging, such as magnetic resonance imaging and/or CT scan to rule out mass lesions, vascular malformations, stroke, or neuro-infectious processes; laboratory tests, such as vitamin B12, liver panel, HIV, rapid plasma reagin, hepatitis B and C viruses, parathyroid hormone levels, urine drug screen, and thyroid panel can be ordered to rule out other medical causes.1,2,6,7,9

Consultations with internal medicine and neurology departments may be beneficial. Although treatment of the underlying condition may lead to an improvement in the symptoms, full remission in all cases has not been consistently demonstrated in the current literature.5,7,9,10 Patients with the Capgras delusion are challenging to treat, because their delusions have been shown to be refractory to antipsychotic therapy. However, antipsychotics are currently the mainstay of treatment. Some case studies have shown efficacy with pimozide, tricyclic antidepressants, and mirtazapine.6,9

One case study in 2014 in India of a 45-year-old woman who believed her husband and son were replaced by imposters out to kill her, showed a 40% to 50% reduction of paranoia, irritability, and suspicious scanning behaviors with a combination of risperidone and trihexyphenidyl. Despite the improvements, the woman continued to have delusions.7

A notable feature associated with those experiencing the Capgras delusion is the increased risk of violent behaviors, often because of suspiciousness and paranoia. A 2004 review suggested the risk of violence and homicidality is much higher in male patients compared with that of female patients with the Capgras delusion.9 This is despite evidence suggesting that the prevalence of the Capgras delusion seems to be greater in women.6,9 Moreover, patients often demonstrated social withdrawal and self-isolation prior to violent acts. The victims often were family members or those who live with the patient, which is consistent with the evidence that those most familiar to patients are more likely to be misidentified.1,2,7,9,10