User login

Pediatric thyroid nodules: Experienced radiologists best ultrasound risk stratification

VICTORIA, B.C. – Ultrasound risk criteria for adults are no match for the training, skill, and gut instinct of an experienced radiologist when evaluating pediatric thyroid nodules, results of a retrospective cohort study reported at the annual meeting of the American Thyroid Association suggest.

“In 2015, the ATA commissioned a pediatric task force that developed valuable guidelines specific to our pediatric patients. These guidelines recommend performing an FNA [fine-needle aspiration biopsy] in any nodule with a concerning clinical history or a concerning ultrasound feature,” commented first author Ana L. Creo, MD, a pediatric endocrinology fellow at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

She and her colleagues analyzed findings from diagnostic ultrasound in 112 patients aged under 21 years who had 145 thyroid nodules that were ultimately assessed histologically or cytologically.

Results showed that the radiologists’ overall impression and the ATA risk-stratification system for adults had the same high sensitivity, picking up 9 out of 10 malignant cases, she reported. But the radiologists’ overall impression had much higher specificity, correctly classifying 8 out of 10 benign cases, versus about 5 out of 10 for the risk stratification.

“These findings may have implications in trying to avoid unnecessary FNAs, particularly in our population,” Dr. Creo summarized. “Our million dollar question is trying to get in the heads of the radiologists to figure out what really goes into that overall impression. And if we can apply a specific score to that, I think that would be most clinically useful.”

“Based upon these results, further work is needed to determine the usefulness of the adult ATA ultrasound risk stratification in children, moving towards an ultrasound-based stratification system specific to our pediatric patients,” she concluded.

One session cochair, Catherine A. Dinauer, MD, a pediatric endocrinologist and clinician at the Yale Pediatric Thyroid Center, New Haven, Conn., commented, “It seems as though we’re pretty good at picking up which nodules are malignant, but I still feel like so many of the nodules that are benign are suspicious by ultrasound. Trying to tease out what is it about those benign ones may allow us to figure out in which ones we could avoid biopsy. That’s where we see we are not that good at it.”

Nodule attributes that might help in this regard include subtypes of microcalcifications, irregular margins, and position of the nodule in the gland relative to the skin, she proposed.

The other session cochair, Yaron Tomer, MD, chair of the department of medicine and the Anita and Jack Saltz Chair in Diabetes Research at the Montefiore Medical Center, New York, stressed knowing one’s radiologist and questioned the generalizability of the findings.

“You have to know your own radiologist well and how well you can trust them. Probably, the investigators chose some of the top radiologists in their institution and maybe even in the nation, so we have to be careful as to whether this applies to places that don’t have access to such great radiologists,” he commented. “But I think even if the guidelines are not perfect, they are the best we have right now.”

Study details

The investigators studied pediatric patients (mean age, 15.5 years) with thyroid nodules who underwent initial ultrasound at the Mayo Clinic during 1996-2015, had at least a year of follow-up, and for whom histology or cytology results were available. Those with a known genetic tumor syndrome or a history of radiation exposure were excluded.

Two blinded radiologists assessed nodule ultrasound features using the Thyroid Imaging and Reporting Data System (TIRADS) (J Am Coll Radiol. 2015;12[12 Pt A]:1272-9) and then rendered their overall impression: malignant, indeterminate, or benign.

Next, an independent reviewer assigned each nodule an ATA adult risk category (Thyroid. 2016;26:1-133): high, intermediate, low, or very low suspicion.

Finally, both measures were compared against the reference standard of the nodule’s histology or cytology results.

Ultimately, 34% of the patients had malignant nodules, Dr. Creo reported. “This is likely quite a bit elevated from the true prevalence due to our intentional study design requiring follow-up, likely excluding some patients with benign nodules,” she commented.

Patients with benign and malignant nodules did not differ significantly on any of a variety of sociodemographic and clinical factors, such as family history and mode of detection.

For comparison of sensitivity, the investigators combined the ATA risk categories of high and intermediate suspicion and combined the overall radiologists’ impression of malignant and indeterminate. “We felt this best answered the practical clinical question of how many malignant nodules would be missed if FNA was not performed, assuming FNA would typically be performed if the ATA risk stratification was high or intermediate or if the radiologist’s overall impression was malignant or indeterminate,” Dr. Creo explained.

Results here showed that the ATA risk stratification and the radiologists’ overall impression had the same high sensitivity of 90%.

For comparison of specificity, the investigators compared the ATA risk category of high suspicion with the radiologists’ overall impression of malignant.

Results showed that the overall impression had specificity of 80%, whereas the risk category had a specificity of only about 52%. Findings were similar when analyses instead used ATA high suspicion and intermediate suspicion combined.

“The key ultrasound characteristics that drove the diagnosis included having a solid component, calcifications, irregular margins, and hypoechogenicity – all similar to those seen in pediatric studies and similar to those in adult studies as well,” Dr. Creo noted.

Compared with benign nodules, malignant nodules significantly more often had a greater than 75% solid component (84% vs. 64%; P = .01), contained calcifications (60% vs. 18%; P less than .0001), had irregular margins (70% vs. 46%; P = .0073), and were hypoechogenic (74% vs. 51%; P = .0073). Notably, size and presence of halo did not differ significantly.

“Our study adds to previous work in that it had a relatively large pediatric sample size, used strict inclusion criteria with at least a year of follow-up to increase the validity of the diagnosis, and had precise definitions of the ultrasound features,” concluded Dr. Creo, who disclosed that she had no relevant conflicts of interest.

At the same time, the study had limitations, such as its use of a referral population, likely loss to follow-up of some patients with benign nodules, and possible clustering effect. “Lastly, we had the benefit of extremely experienced pediatric radiologists, and their overall diagnostic accuracy may not universally apply across all radiologists,” she said.

VICTORIA, B.C. – Ultrasound risk criteria for adults are no match for the training, skill, and gut instinct of an experienced radiologist when evaluating pediatric thyroid nodules, results of a retrospective cohort study reported at the annual meeting of the American Thyroid Association suggest.

“In 2015, the ATA commissioned a pediatric task force that developed valuable guidelines specific to our pediatric patients. These guidelines recommend performing an FNA [fine-needle aspiration biopsy] in any nodule with a concerning clinical history or a concerning ultrasound feature,” commented first author Ana L. Creo, MD, a pediatric endocrinology fellow at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

She and her colleagues analyzed findings from diagnostic ultrasound in 112 patients aged under 21 years who had 145 thyroid nodules that were ultimately assessed histologically or cytologically.

Results showed that the radiologists’ overall impression and the ATA risk-stratification system for adults had the same high sensitivity, picking up 9 out of 10 malignant cases, she reported. But the radiologists’ overall impression had much higher specificity, correctly classifying 8 out of 10 benign cases, versus about 5 out of 10 for the risk stratification.

“These findings may have implications in trying to avoid unnecessary FNAs, particularly in our population,” Dr. Creo summarized. “Our million dollar question is trying to get in the heads of the radiologists to figure out what really goes into that overall impression. And if we can apply a specific score to that, I think that would be most clinically useful.”

“Based upon these results, further work is needed to determine the usefulness of the adult ATA ultrasound risk stratification in children, moving towards an ultrasound-based stratification system specific to our pediatric patients,” she concluded.

One session cochair, Catherine A. Dinauer, MD, a pediatric endocrinologist and clinician at the Yale Pediatric Thyroid Center, New Haven, Conn., commented, “It seems as though we’re pretty good at picking up which nodules are malignant, but I still feel like so many of the nodules that are benign are suspicious by ultrasound. Trying to tease out what is it about those benign ones may allow us to figure out in which ones we could avoid biopsy. That’s where we see we are not that good at it.”

Nodule attributes that might help in this regard include subtypes of microcalcifications, irregular margins, and position of the nodule in the gland relative to the skin, she proposed.

The other session cochair, Yaron Tomer, MD, chair of the department of medicine and the Anita and Jack Saltz Chair in Diabetes Research at the Montefiore Medical Center, New York, stressed knowing one’s radiologist and questioned the generalizability of the findings.

“You have to know your own radiologist well and how well you can trust them. Probably, the investigators chose some of the top radiologists in their institution and maybe even in the nation, so we have to be careful as to whether this applies to places that don’t have access to such great radiologists,” he commented. “But I think even if the guidelines are not perfect, they are the best we have right now.”

Study details

The investigators studied pediatric patients (mean age, 15.5 years) with thyroid nodules who underwent initial ultrasound at the Mayo Clinic during 1996-2015, had at least a year of follow-up, and for whom histology or cytology results were available. Those with a known genetic tumor syndrome or a history of radiation exposure were excluded.

Two blinded radiologists assessed nodule ultrasound features using the Thyroid Imaging and Reporting Data System (TIRADS) (J Am Coll Radiol. 2015;12[12 Pt A]:1272-9) and then rendered their overall impression: malignant, indeterminate, or benign.

Next, an independent reviewer assigned each nodule an ATA adult risk category (Thyroid. 2016;26:1-133): high, intermediate, low, or very low suspicion.

Finally, both measures were compared against the reference standard of the nodule’s histology or cytology results.

Ultimately, 34% of the patients had malignant nodules, Dr. Creo reported. “This is likely quite a bit elevated from the true prevalence due to our intentional study design requiring follow-up, likely excluding some patients with benign nodules,” she commented.

Patients with benign and malignant nodules did not differ significantly on any of a variety of sociodemographic and clinical factors, such as family history and mode of detection.

For comparison of sensitivity, the investigators combined the ATA risk categories of high and intermediate suspicion and combined the overall radiologists’ impression of malignant and indeterminate. “We felt this best answered the practical clinical question of how many malignant nodules would be missed if FNA was not performed, assuming FNA would typically be performed if the ATA risk stratification was high or intermediate or if the radiologist’s overall impression was malignant or indeterminate,” Dr. Creo explained.

Results here showed that the ATA risk stratification and the radiologists’ overall impression had the same high sensitivity of 90%.

For comparison of specificity, the investigators compared the ATA risk category of high suspicion with the radiologists’ overall impression of malignant.

Results showed that the overall impression had specificity of 80%, whereas the risk category had a specificity of only about 52%. Findings were similar when analyses instead used ATA high suspicion and intermediate suspicion combined.

“The key ultrasound characteristics that drove the diagnosis included having a solid component, calcifications, irregular margins, and hypoechogenicity – all similar to those seen in pediatric studies and similar to those in adult studies as well,” Dr. Creo noted.

Compared with benign nodules, malignant nodules significantly more often had a greater than 75% solid component (84% vs. 64%; P = .01), contained calcifications (60% vs. 18%; P less than .0001), had irregular margins (70% vs. 46%; P = .0073), and were hypoechogenic (74% vs. 51%; P = .0073). Notably, size and presence of halo did not differ significantly.

“Our study adds to previous work in that it had a relatively large pediatric sample size, used strict inclusion criteria with at least a year of follow-up to increase the validity of the diagnosis, and had precise definitions of the ultrasound features,” concluded Dr. Creo, who disclosed that she had no relevant conflicts of interest.

At the same time, the study had limitations, such as its use of a referral population, likely loss to follow-up of some patients with benign nodules, and possible clustering effect. “Lastly, we had the benefit of extremely experienced pediatric radiologists, and their overall diagnostic accuracy may not universally apply across all radiologists,” she said.

VICTORIA, B.C. – Ultrasound risk criteria for adults are no match for the training, skill, and gut instinct of an experienced radiologist when evaluating pediatric thyroid nodules, results of a retrospective cohort study reported at the annual meeting of the American Thyroid Association suggest.

“In 2015, the ATA commissioned a pediatric task force that developed valuable guidelines specific to our pediatric patients. These guidelines recommend performing an FNA [fine-needle aspiration biopsy] in any nodule with a concerning clinical history or a concerning ultrasound feature,” commented first author Ana L. Creo, MD, a pediatric endocrinology fellow at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

She and her colleagues analyzed findings from diagnostic ultrasound in 112 patients aged under 21 years who had 145 thyroid nodules that were ultimately assessed histologically or cytologically.

Results showed that the radiologists’ overall impression and the ATA risk-stratification system for adults had the same high sensitivity, picking up 9 out of 10 malignant cases, she reported. But the radiologists’ overall impression had much higher specificity, correctly classifying 8 out of 10 benign cases, versus about 5 out of 10 for the risk stratification.

“These findings may have implications in trying to avoid unnecessary FNAs, particularly in our population,” Dr. Creo summarized. “Our million dollar question is trying to get in the heads of the radiologists to figure out what really goes into that overall impression. And if we can apply a specific score to that, I think that would be most clinically useful.”

“Based upon these results, further work is needed to determine the usefulness of the adult ATA ultrasound risk stratification in children, moving towards an ultrasound-based stratification system specific to our pediatric patients,” she concluded.

One session cochair, Catherine A. Dinauer, MD, a pediatric endocrinologist and clinician at the Yale Pediatric Thyroid Center, New Haven, Conn., commented, “It seems as though we’re pretty good at picking up which nodules are malignant, but I still feel like so many of the nodules that are benign are suspicious by ultrasound. Trying to tease out what is it about those benign ones may allow us to figure out in which ones we could avoid biopsy. That’s where we see we are not that good at it.”

Nodule attributes that might help in this regard include subtypes of microcalcifications, irregular margins, and position of the nodule in the gland relative to the skin, she proposed.

The other session cochair, Yaron Tomer, MD, chair of the department of medicine and the Anita and Jack Saltz Chair in Diabetes Research at the Montefiore Medical Center, New York, stressed knowing one’s radiologist and questioned the generalizability of the findings.

“You have to know your own radiologist well and how well you can trust them. Probably, the investigators chose some of the top radiologists in their institution and maybe even in the nation, so we have to be careful as to whether this applies to places that don’t have access to such great radiologists,” he commented. “But I think even if the guidelines are not perfect, they are the best we have right now.”

Study details

The investigators studied pediatric patients (mean age, 15.5 years) with thyroid nodules who underwent initial ultrasound at the Mayo Clinic during 1996-2015, had at least a year of follow-up, and for whom histology or cytology results were available. Those with a known genetic tumor syndrome or a history of radiation exposure were excluded.

Two blinded radiologists assessed nodule ultrasound features using the Thyroid Imaging and Reporting Data System (TIRADS) (J Am Coll Radiol. 2015;12[12 Pt A]:1272-9) and then rendered their overall impression: malignant, indeterminate, or benign.

Next, an independent reviewer assigned each nodule an ATA adult risk category (Thyroid. 2016;26:1-133): high, intermediate, low, or very low suspicion.

Finally, both measures were compared against the reference standard of the nodule’s histology or cytology results.

Ultimately, 34% of the patients had malignant nodules, Dr. Creo reported. “This is likely quite a bit elevated from the true prevalence due to our intentional study design requiring follow-up, likely excluding some patients with benign nodules,” she commented.

Patients with benign and malignant nodules did not differ significantly on any of a variety of sociodemographic and clinical factors, such as family history and mode of detection.

For comparison of sensitivity, the investigators combined the ATA risk categories of high and intermediate suspicion and combined the overall radiologists’ impression of malignant and indeterminate. “We felt this best answered the practical clinical question of how many malignant nodules would be missed if FNA was not performed, assuming FNA would typically be performed if the ATA risk stratification was high or intermediate or if the radiologist’s overall impression was malignant or indeterminate,” Dr. Creo explained.

Results here showed that the ATA risk stratification and the radiologists’ overall impression had the same high sensitivity of 90%.

For comparison of specificity, the investigators compared the ATA risk category of high suspicion with the radiologists’ overall impression of malignant.

Results showed that the overall impression had specificity of 80%, whereas the risk category had a specificity of only about 52%. Findings were similar when analyses instead used ATA high suspicion and intermediate suspicion combined.

“The key ultrasound characteristics that drove the diagnosis included having a solid component, calcifications, irregular margins, and hypoechogenicity – all similar to those seen in pediatric studies and similar to those in adult studies as well,” Dr. Creo noted.

Compared with benign nodules, malignant nodules significantly more often had a greater than 75% solid component (84% vs. 64%; P = .01), contained calcifications (60% vs. 18%; P less than .0001), had irregular margins (70% vs. 46%; P = .0073), and were hypoechogenic (74% vs. 51%; P = .0073). Notably, size and presence of halo did not differ significantly.

“Our study adds to previous work in that it had a relatively large pediatric sample size, used strict inclusion criteria with at least a year of follow-up to increase the validity of the diagnosis, and had precise definitions of the ultrasound features,” concluded Dr. Creo, who disclosed that she had no relevant conflicts of interest.

At the same time, the study had limitations, such as its use of a referral population, likely loss to follow-up of some patients with benign nodules, and possible clustering effect. “Lastly, we had the benefit of extremely experienced pediatric radiologists, and their overall diagnostic accuracy may not universally apply across all radiologists,” she said.

AT ATA 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Radiologists’ overall impression and ATA risk stratification had the same good sensitivity (90% for each), but the former had higher specificity (80% vs. 52%).

Data source: A retrospective cohort study of 112 patients younger than 21 who had 145 thyroid nodules.

Disclosures: Dr. Creo disclosed that she had no relevant conflicts of interest.

Low vitamin D levels linked to increased ESRD risk in SLE patients

SAN DIEGO – , results from a single-center cohort study showed.

“We had previously proved that vitamin D supplementation helped lupus activity,” lead study author Michelle Petri, MD, MPH, said in an interview in advance of the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology. “Now, we prove that it specifically helps renal activity as measured by the urine protein. By helping to reduce urine protein, it helps to prevent permanent renal damage and end-stage renal disease.”

The first measure of vitamin D typically occurred in late 2009 or 2010 for existing patients and at the first visit of new patients after that. The researchers categorized patients based on their first measure of vitamin D as less than 20 ng/mL or 20 ng/mL or higher. At the first visit when vitamin D was measured, 27.3% had levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D less than 20 ng/mL. The mean age of patients was 47.3 years, 92% were female, 50% were white, and 41% were African American.

In the study, Dr. Petri and her associates used the Systemic Lupus International Collaborative Clinics/American College of Rheumatology Damage Index to calculate the risk of lifetime organ damage. After adjusting for age, gender, and ethnicity, low levels of vitamin D were significantly associated with increased risk of renal damage (RR, 1.66; P = .0206) and total organ damage (RR, 1.17; P = .0245), they found.

Skin damage was another concern, with an adjusted relative risk of 1.22, though it was not statistically significant (P = .3561). The investigators observed no association between low vitamin D and musculoskeletal damage, including osteoporotic fractures.

“There is a lot of interest in lupus right now, due to [singer Selena] Gomez’s kidney transplant for lupus nephritis,” said Dr. Petri, who also directs the Johns Hopkins Lupus Center. “So, I think there is interest in how to prevent the need for kidney transplant. Vitamin D helps kidney lupus – and we only need to achieve a level of 40 ng/mL, [which is] safe and easy to do.” She acknowledged the study’s single-center design as a limitation but underscored its large sample size as a strength.

The Hopkins Lupus Cohort is funded by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. Dr. Petri disclosed having received research support from Anthera, GlaxoSmithKline, EMD Serono, Eli Lilly, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Amgen, United Rheumatology, Global Academy, and Exagen.

SAN DIEGO – , results from a single-center cohort study showed.

“We had previously proved that vitamin D supplementation helped lupus activity,” lead study author Michelle Petri, MD, MPH, said in an interview in advance of the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology. “Now, we prove that it specifically helps renal activity as measured by the urine protein. By helping to reduce urine protein, it helps to prevent permanent renal damage and end-stage renal disease.”

The first measure of vitamin D typically occurred in late 2009 or 2010 for existing patients and at the first visit of new patients after that. The researchers categorized patients based on their first measure of vitamin D as less than 20 ng/mL or 20 ng/mL or higher. At the first visit when vitamin D was measured, 27.3% had levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D less than 20 ng/mL. The mean age of patients was 47.3 years, 92% were female, 50% were white, and 41% were African American.

In the study, Dr. Petri and her associates used the Systemic Lupus International Collaborative Clinics/American College of Rheumatology Damage Index to calculate the risk of lifetime organ damage. After adjusting for age, gender, and ethnicity, low levels of vitamin D were significantly associated with increased risk of renal damage (RR, 1.66; P = .0206) and total organ damage (RR, 1.17; P = .0245), they found.

Skin damage was another concern, with an adjusted relative risk of 1.22, though it was not statistically significant (P = .3561). The investigators observed no association between low vitamin D and musculoskeletal damage, including osteoporotic fractures.

“There is a lot of interest in lupus right now, due to [singer Selena] Gomez’s kidney transplant for lupus nephritis,” said Dr. Petri, who also directs the Johns Hopkins Lupus Center. “So, I think there is interest in how to prevent the need for kidney transplant. Vitamin D helps kidney lupus – and we only need to achieve a level of 40 ng/mL, [which is] safe and easy to do.” She acknowledged the study’s single-center design as a limitation but underscored its large sample size as a strength.

The Hopkins Lupus Cohort is funded by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. Dr. Petri disclosed having received research support from Anthera, GlaxoSmithKline, EMD Serono, Eli Lilly, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Amgen, United Rheumatology, Global Academy, and Exagen.

SAN DIEGO – , results from a single-center cohort study showed.

“We had previously proved that vitamin D supplementation helped lupus activity,” lead study author Michelle Petri, MD, MPH, said in an interview in advance of the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology. “Now, we prove that it specifically helps renal activity as measured by the urine protein. By helping to reduce urine protein, it helps to prevent permanent renal damage and end-stage renal disease.”

The first measure of vitamin D typically occurred in late 2009 or 2010 for existing patients and at the first visit of new patients after that. The researchers categorized patients based on their first measure of vitamin D as less than 20 ng/mL or 20 ng/mL or higher. At the first visit when vitamin D was measured, 27.3% had levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D less than 20 ng/mL. The mean age of patients was 47.3 years, 92% were female, 50% were white, and 41% were African American.

In the study, Dr. Petri and her associates used the Systemic Lupus International Collaborative Clinics/American College of Rheumatology Damage Index to calculate the risk of lifetime organ damage. After adjusting for age, gender, and ethnicity, low levels of vitamin D were significantly associated with increased risk of renal damage (RR, 1.66; P = .0206) and total organ damage (RR, 1.17; P = .0245), they found.

Skin damage was another concern, with an adjusted relative risk of 1.22, though it was not statistically significant (P = .3561). The investigators observed no association between low vitamin D and musculoskeletal damage, including osteoporotic fractures.

“There is a lot of interest in lupus right now, due to [singer Selena] Gomez’s kidney transplant for lupus nephritis,” said Dr. Petri, who also directs the Johns Hopkins Lupus Center. “So, I think there is interest in how to prevent the need for kidney transplant. Vitamin D helps kidney lupus – and we only need to achieve a level of 40 ng/mL, [which is] safe and easy to do.” She acknowledged the study’s single-center design as a limitation but underscored its large sample size as a strength.

The Hopkins Lupus Cohort is funded by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. Dr. Petri disclosed having received research support from Anthera, GlaxoSmithKline, EMD Serono, Eli Lilly, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Amgen, United Rheumatology, Global Academy, and Exagen.

AT ACR 2017

Key clinical point: Supplemental vitamin D should be part of the treatment plan for patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).

Major finding: SLE patients with low vitamin D levels face a significantly increased risk of renal damage (relatve risk, 1.66; P = .0206) and total organ damage (RR, 1.17; P = .0245).

Study details: A single-center cohort study of 1,392 patients with SLE.

Disclosures: The Hopkins Lupus Cohort is funded by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. Dr. Petri disclosed having received research support from Anthera, GlaxoSmithKline, EMD Serono, Eli Lilly, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Amgen, United Rheumatology, Global Academy, and Exagen.

FDA approves first Erdheim-Chester disease treatment

The kinase inhibitor – marketed as Zelboraf – was approved on Nov. 6. It is the first approved treatment for ECD and is already on the market as a treatment for patients with unresectable or metastatic melanoma with BRAF V600E mutation.

The FDA expedited approval of the drug under the Priority Review and Breakthrough Therapy programs. The drug also received an orphan status designation, which makes the sponsor eligible for incentives such as tax credits for clinical testing.

The agency based its approval on results from 22 patients with BRAF-V600-mutation positive ECD. Half of the patients (11) experienced a partial reduction in tumor size and 1 patient experienced a complete response, according to the FDA. Initial results from the phase 2, open-label VE-BASKET study were published in 2015 (N Engl J Med. 2015 Aug 20;373[8]:726-36).

Common side effects of vemurafenib include arthralgias, maculopapular rash, alopecia, fatigue, prolonged QT interval, and papilloma. Severe side effects include development of new cancers, growth of tumors in patients with BRAF wild-type melanoma, anaphylaxis and DRESS syndrome, severe skin reactions, heart abnormalities, hepatotoxicity, photosensitivity, uveitis, radiation sensitization and radiation recall, and Dupuytren’s contracture and plantar fascial fibromatosis. The drug is also considered teratogenic and women should be advised to use contraception while taking it, according to the FDA.

The full prescribing information is available at zelboraf.com.

[email protected]

On Twitter @maryellenny

The kinase inhibitor – marketed as Zelboraf – was approved on Nov. 6. It is the first approved treatment for ECD and is already on the market as a treatment for patients with unresectable or metastatic melanoma with BRAF V600E mutation.

The FDA expedited approval of the drug under the Priority Review and Breakthrough Therapy programs. The drug also received an orphan status designation, which makes the sponsor eligible for incentives such as tax credits for clinical testing.

The agency based its approval on results from 22 patients with BRAF-V600-mutation positive ECD. Half of the patients (11) experienced a partial reduction in tumor size and 1 patient experienced a complete response, according to the FDA. Initial results from the phase 2, open-label VE-BASKET study were published in 2015 (N Engl J Med. 2015 Aug 20;373[8]:726-36).

Common side effects of vemurafenib include arthralgias, maculopapular rash, alopecia, fatigue, prolonged QT interval, and papilloma. Severe side effects include development of new cancers, growth of tumors in patients with BRAF wild-type melanoma, anaphylaxis and DRESS syndrome, severe skin reactions, heart abnormalities, hepatotoxicity, photosensitivity, uveitis, radiation sensitization and radiation recall, and Dupuytren’s contracture and plantar fascial fibromatosis. The drug is also considered teratogenic and women should be advised to use contraception while taking it, according to the FDA.

The full prescribing information is available at zelboraf.com.

[email protected]

On Twitter @maryellenny

The kinase inhibitor – marketed as Zelboraf – was approved on Nov. 6. It is the first approved treatment for ECD and is already on the market as a treatment for patients with unresectable or metastatic melanoma with BRAF V600E mutation.

The FDA expedited approval of the drug under the Priority Review and Breakthrough Therapy programs. The drug also received an orphan status designation, which makes the sponsor eligible for incentives such as tax credits for clinical testing.

The agency based its approval on results from 22 patients with BRAF-V600-mutation positive ECD. Half of the patients (11) experienced a partial reduction in tumor size and 1 patient experienced a complete response, according to the FDA. Initial results from the phase 2, open-label VE-BASKET study were published in 2015 (N Engl J Med. 2015 Aug 20;373[8]:726-36).

Common side effects of vemurafenib include arthralgias, maculopapular rash, alopecia, fatigue, prolonged QT interval, and papilloma. Severe side effects include development of new cancers, growth of tumors in patients with BRAF wild-type melanoma, anaphylaxis and DRESS syndrome, severe skin reactions, heart abnormalities, hepatotoxicity, photosensitivity, uveitis, radiation sensitization and radiation recall, and Dupuytren’s contracture and plantar fascial fibromatosis. The drug is also considered teratogenic and women should be advised to use contraception while taking it, according to the FDA.

The full prescribing information is available at zelboraf.com.

[email protected]

On Twitter @maryellenny

Teach your adolescent patients about normal menses, so they know when it’s abnormal

CHICAGO – , according to S. Paige Hertweck, MD, chief of gynecology at Norton Children’s Hospital in Louisville, Ky.

“Remember to use the menstrual cycle as a vital sign,” Dr. Hertweck told attendees at the American Academy of Pediatrics annual meeting. “Even within the first year of menarche, most girls have a period at least every 90 days, so work up those who don’t.”

The median age of menarche is 12.4 years, typically beginning within 2-3 years of breast budding at Tanner Stage 4 breast development, she said. By 15 years of age, 98% of girls have begun menstruation.

Girls’ cycles typically last 21-45 days, an average of 32.2 days during their first year of menstruation, with flow for 7 days or less, requiring an average of 3-6 pads and/or tampons per day. Dr. Hertweck recommends you write down these features of normal menstruation so that your patients can tell you when their cycle is abnormal or menses doesn’t return.

“Cycle length is more variable for teens versus women 20-40 years old,” she said. However, “it’s not true that ‘anything goes’ for cycle length” in teens, she added. “Cycles that are consistently outside the range of 21-45 days are statistically uncommon.” Hence the need to evaluate causes of amenorrhea in girls whose cycles exceed 90 days.

Possible causes of amenorrhea include pregnancy, polycystic ovary syndrome, thyroid abnormalities, hyperprolactinemia, primary ovarian insufficiency, or hypogonadal amenorrhea, typically stimulated by the first instance of anorexia, Crohn’s disease, celiac disease, or a gluten intolerance.

Primary amenorrhea

Dr. Hertweck listed five benchmarks that indicate primary amenorrhea requiring evaluation. Those indicators include girls who have no menarche by age 15 years or within 3 years of breast budding, no breast development by age 13 years, or no menses by age 14 years with hirsutism or with a history of excessive exercise or of an eating disorder.

You can start by examining what normal menstruation relies on: an intact central nervous system with a functioning pituitary, an ovarian response, and a normal uterus, cervix, and vagina. You should check the patient’s follicle-stimulating hormone, thyroid-stimulating hormone, and prolactin levels to assess CNS functioning, and estradiol levels to assess ovarian response. A genital exam with a pelvic ultrasound can reveal any possible defects in the uterus, cervix, or vagina.

The presence of breasts without a uterus indicates normal estrogen production, so the missing uterus could be a congenital defect or result from androgen insensitivity, Dr. Hertweck explained. In those without breasts, gonadal dysgenesis or gonadal enzymatic deficiency may explain no estrogen production. If the patient has both breasts and a uterus, you should rule out pregnancy first and then track CNS changes via FSH, TSH, and prolactin levels.

Premature ovarian insufficiency

Approximately 1% of females experience premature ovarian insufficiency, which can be diagnosed as early as age 14 years and should be suspected in a patient with a uterus but without breasts who has low estradiol levels, CNS failure identified by a high FSH level, and gonadal failure.

Formal diagnosis requires two separate instances of FSH elevation, and chromosomal testing should be done to rule out gonadal dysgenesis. You also should test the serum anti-Müllerian hormone biomarker (readings above 8 are concerning) and look for two possible causes. The FMR1 (Fragile X) premutation carrier status could be a cause, or presence of 21-hydroxylase and/or adrenal antibodies indicate autoimmune polyglandular syndrome.

Catching premature ovarian insufficiency early enough may allow patients to preserve some fertility if they still have oocytes present. Aside from this, girls will need hormone replacement therapy to fulfill developmental emotional and physical needs, such as bone growth and overall health. Despite a history of treating teens with premature ovarian insufficiency like adults, you should follow the practice guidelines specific to adolescents by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists committee opinion statement (Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:193-7).

Menorrhagia: heavy menstrual bleeding

Even though average blood loss is estimated at 30 mL per period, that number means little in clinical practice because patients cannot measure the actual amount of menses. Better indicators of abnormally greater flow include flow lasting longer than 7 days, finding clots larger than a quarter, changing menstrual products every 1-2 hours, leaking onto clothing such that patients need to take extra clothes to school, and any heavy periods that occur with easy bruising or with a family history of bleeding disorders.

First-line treatment for heavy menstrual bleeding in teens is hormonal contraception, either combination oral contraceptive pills, the transdermal patch, or the intravaginal ring, which can be combined with other therapies.

An alternative for those under age 18 (per Food and Drug Administration labeling) is oral tranexamic acid, found in a crossover trial with an oral contraceptive pill to be just as effective at reducing average blood loss and improving quality of life, but with fewer side effects and better compliance. Before prescribing anything for heavy menstrual bleeding, however, you must consider possible causes and rule some out that require different management.

Aside from pregnancy, one potential cause of menorrhagia is infection such as chlamydia or gonorrhea, which should be considered even in those with a negative sexual history, Dr. Hertweck said. Other possible causes include an immature hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis, polycystic ovary syndrome (even with low hemoglobin), malignancy with a hormone-producing tumor, hypothalamic dysfunction (often stimulated by eating disorders, obesity, rapid weight loss, or gluten intolerance), or coagulopathy.

“Teens with menorrhagia may need to be screened for a bleeding disorder,” Dr. Hertweck said. At a minimum, she recommends checking complete blood count, ferritin, and TSH. “The most common bleeding disorders associated with heavy menstrual bleeding include platelet function disorders and von Willebrand.”

Up to half of teen girls with menorrhagia who visit a hematologist or multidisciplinary clinic receive a diagnosis of a bleeding disorder, Dr. Hertweck said. And up to half of those with menorrhagia at menarche may have von Willebrand, as do one in six adolescents who go to the emergency department because of heavy menstrual bleeding.

Von Willebrand syndrome

Von Willebrand syndrome is a deficiency or dysfunction of von Willebrand factor (vWF), a protein with binding sites for platelets, collagen, and factor VIII that “serves as a bridge between platelets and injury sites in vessel walls” and “protects factor VIII from rapid proteolytic degradation,” Dr. Hertweck said. Von Willebrand syndrome is the most common inherited congenital bleeding disorder. Although acquired von Willebrand syndrome is rare, it has grown in incidence among those with complex cardiovascular, hematologic, or immunologic disorders.

“Correct diagnosis is complex and not always straightforward,” Dr. Hertweck said, but “a positive response to questions in four categories is highly sensitive.” They are as follows:

• Menses lasting at least 7 days and interfering with a person’s daily activities.

• “History of treatment for anemia.

• Family history of a diagnosed bleeding disorder.

• History of excessive bleeding after tooth extraction, delivery, miscarriage, or surgery.

Diagnostic assays include platelet concentration of vWF antigen, an activity test of vWF-platelet binding, and factor VIII activity. However, you often need to repeat diagnostic testing because vWF antigens vary according to race, blood type, age, acute phase response, and menstrual cycle timing, Dr. Hertweck said.

“Remember to draw von Willebrand testing only during the first 3 days of the menstrual cycle when estrogen levels are at the nadir,” she said.

Because estrogen increases vWF, treatment for von Willebrand syndrome should be progestin only, either oral pills, medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA, or Depo-Provera injections), or an etonogestrel implant.

Dr. Hertweck presented several cases of abnormal menstruation and extreme conditions such as severe menorrhagia. Outside of von Willebrand in such patients, possible platelet disorders could include Glanzmann thrombasthenia (a platelet function disorder that is caused by an abnormality in the genes for glycoproteins IIb/IIIa) and platelet storage pool disorder, both of which should be diagnosed by a hematologist.

Dr. Hertweck reported having a research grant from Merck related to contraceptive implants in adolescents.

CHICAGO – , according to S. Paige Hertweck, MD, chief of gynecology at Norton Children’s Hospital in Louisville, Ky.

“Remember to use the menstrual cycle as a vital sign,” Dr. Hertweck told attendees at the American Academy of Pediatrics annual meeting. “Even within the first year of menarche, most girls have a period at least every 90 days, so work up those who don’t.”

The median age of menarche is 12.4 years, typically beginning within 2-3 years of breast budding at Tanner Stage 4 breast development, she said. By 15 years of age, 98% of girls have begun menstruation.

Girls’ cycles typically last 21-45 days, an average of 32.2 days during their first year of menstruation, with flow for 7 days or less, requiring an average of 3-6 pads and/or tampons per day. Dr. Hertweck recommends you write down these features of normal menstruation so that your patients can tell you when their cycle is abnormal or menses doesn’t return.

“Cycle length is more variable for teens versus women 20-40 years old,” she said. However, “it’s not true that ‘anything goes’ for cycle length” in teens, she added. “Cycles that are consistently outside the range of 21-45 days are statistically uncommon.” Hence the need to evaluate causes of amenorrhea in girls whose cycles exceed 90 days.

Possible causes of amenorrhea include pregnancy, polycystic ovary syndrome, thyroid abnormalities, hyperprolactinemia, primary ovarian insufficiency, or hypogonadal amenorrhea, typically stimulated by the first instance of anorexia, Crohn’s disease, celiac disease, or a gluten intolerance.

Primary amenorrhea

Dr. Hertweck listed five benchmarks that indicate primary amenorrhea requiring evaluation. Those indicators include girls who have no menarche by age 15 years or within 3 years of breast budding, no breast development by age 13 years, or no menses by age 14 years with hirsutism or with a history of excessive exercise or of an eating disorder.

You can start by examining what normal menstruation relies on: an intact central nervous system with a functioning pituitary, an ovarian response, and a normal uterus, cervix, and vagina. You should check the patient’s follicle-stimulating hormone, thyroid-stimulating hormone, and prolactin levels to assess CNS functioning, and estradiol levels to assess ovarian response. A genital exam with a pelvic ultrasound can reveal any possible defects in the uterus, cervix, or vagina.

The presence of breasts without a uterus indicates normal estrogen production, so the missing uterus could be a congenital defect or result from androgen insensitivity, Dr. Hertweck explained. In those without breasts, gonadal dysgenesis or gonadal enzymatic deficiency may explain no estrogen production. If the patient has both breasts and a uterus, you should rule out pregnancy first and then track CNS changes via FSH, TSH, and prolactin levels.

Premature ovarian insufficiency

Approximately 1% of females experience premature ovarian insufficiency, which can be diagnosed as early as age 14 years and should be suspected in a patient with a uterus but without breasts who has low estradiol levels, CNS failure identified by a high FSH level, and gonadal failure.

Formal diagnosis requires two separate instances of FSH elevation, and chromosomal testing should be done to rule out gonadal dysgenesis. You also should test the serum anti-Müllerian hormone biomarker (readings above 8 are concerning) and look for two possible causes. The FMR1 (Fragile X) premutation carrier status could be a cause, or presence of 21-hydroxylase and/or adrenal antibodies indicate autoimmune polyglandular syndrome.

Catching premature ovarian insufficiency early enough may allow patients to preserve some fertility if they still have oocytes present. Aside from this, girls will need hormone replacement therapy to fulfill developmental emotional and physical needs, such as bone growth and overall health. Despite a history of treating teens with premature ovarian insufficiency like adults, you should follow the practice guidelines specific to adolescents by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists committee opinion statement (Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:193-7).

Menorrhagia: heavy menstrual bleeding

Even though average blood loss is estimated at 30 mL per period, that number means little in clinical practice because patients cannot measure the actual amount of menses. Better indicators of abnormally greater flow include flow lasting longer than 7 days, finding clots larger than a quarter, changing menstrual products every 1-2 hours, leaking onto clothing such that patients need to take extra clothes to school, and any heavy periods that occur with easy bruising or with a family history of bleeding disorders.

First-line treatment for heavy menstrual bleeding in teens is hormonal contraception, either combination oral contraceptive pills, the transdermal patch, or the intravaginal ring, which can be combined with other therapies.

An alternative for those under age 18 (per Food and Drug Administration labeling) is oral tranexamic acid, found in a crossover trial with an oral contraceptive pill to be just as effective at reducing average blood loss and improving quality of life, but with fewer side effects and better compliance. Before prescribing anything for heavy menstrual bleeding, however, you must consider possible causes and rule some out that require different management.

Aside from pregnancy, one potential cause of menorrhagia is infection such as chlamydia or gonorrhea, which should be considered even in those with a negative sexual history, Dr. Hertweck said. Other possible causes include an immature hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis, polycystic ovary syndrome (even with low hemoglobin), malignancy with a hormone-producing tumor, hypothalamic dysfunction (often stimulated by eating disorders, obesity, rapid weight loss, or gluten intolerance), or coagulopathy.

“Teens with menorrhagia may need to be screened for a bleeding disorder,” Dr. Hertweck said. At a minimum, she recommends checking complete blood count, ferritin, and TSH. “The most common bleeding disorders associated with heavy menstrual bleeding include platelet function disorders and von Willebrand.”

Up to half of teen girls with menorrhagia who visit a hematologist or multidisciplinary clinic receive a diagnosis of a bleeding disorder, Dr. Hertweck said. And up to half of those with menorrhagia at menarche may have von Willebrand, as do one in six adolescents who go to the emergency department because of heavy menstrual bleeding.

Von Willebrand syndrome

Von Willebrand syndrome is a deficiency or dysfunction of von Willebrand factor (vWF), a protein with binding sites for platelets, collagen, and factor VIII that “serves as a bridge between platelets and injury sites in vessel walls” and “protects factor VIII from rapid proteolytic degradation,” Dr. Hertweck said. Von Willebrand syndrome is the most common inherited congenital bleeding disorder. Although acquired von Willebrand syndrome is rare, it has grown in incidence among those with complex cardiovascular, hematologic, or immunologic disorders.

“Correct diagnosis is complex and not always straightforward,” Dr. Hertweck said, but “a positive response to questions in four categories is highly sensitive.” They are as follows:

• Menses lasting at least 7 days and interfering with a person’s daily activities.

• “History of treatment for anemia.

• Family history of a diagnosed bleeding disorder.

• History of excessive bleeding after tooth extraction, delivery, miscarriage, or surgery.

Diagnostic assays include platelet concentration of vWF antigen, an activity test of vWF-platelet binding, and factor VIII activity. However, you often need to repeat diagnostic testing because vWF antigens vary according to race, blood type, age, acute phase response, and menstrual cycle timing, Dr. Hertweck said.

“Remember to draw von Willebrand testing only during the first 3 days of the menstrual cycle when estrogen levels are at the nadir,” she said.

Because estrogen increases vWF, treatment for von Willebrand syndrome should be progestin only, either oral pills, medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA, or Depo-Provera injections), or an etonogestrel implant.

Dr. Hertweck presented several cases of abnormal menstruation and extreme conditions such as severe menorrhagia. Outside of von Willebrand in such patients, possible platelet disorders could include Glanzmann thrombasthenia (a platelet function disorder that is caused by an abnormality in the genes for glycoproteins IIb/IIIa) and platelet storage pool disorder, both of which should be diagnosed by a hematologist.

Dr. Hertweck reported having a research grant from Merck related to contraceptive implants in adolescents.

CHICAGO – , according to S. Paige Hertweck, MD, chief of gynecology at Norton Children’s Hospital in Louisville, Ky.

“Remember to use the menstrual cycle as a vital sign,” Dr. Hertweck told attendees at the American Academy of Pediatrics annual meeting. “Even within the first year of menarche, most girls have a period at least every 90 days, so work up those who don’t.”

The median age of menarche is 12.4 years, typically beginning within 2-3 years of breast budding at Tanner Stage 4 breast development, she said. By 15 years of age, 98% of girls have begun menstruation.

Girls’ cycles typically last 21-45 days, an average of 32.2 days during their first year of menstruation, with flow for 7 days or less, requiring an average of 3-6 pads and/or tampons per day. Dr. Hertweck recommends you write down these features of normal menstruation so that your patients can tell you when their cycle is abnormal or menses doesn’t return.

“Cycle length is more variable for teens versus women 20-40 years old,” she said. However, “it’s not true that ‘anything goes’ for cycle length” in teens, she added. “Cycles that are consistently outside the range of 21-45 days are statistically uncommon.” Hence the need to evaluate causes of amenorrhea in girls whose cycles exceed 90 days.

Possible causes of amenorrhea include pregnancy, polycystic ovary syndrome, thyroid abnormalities, hyperprolactinemia, primary ovarian insufficiency, or hypogonadal amenorrhea, typically stimulated by the first instance of anorexia, Crohn’s disease, celiac disease, or a gluten intolerance.

Primary amenorrhea

Dr. Hertweck listed five benchmarks that indicate primary amenorrhea requiring evaluation. Those indicators include girls who have no menarche by age 15 years or within 3 years of breast budding, no breast development by age 13 years, or no menses by age 14 years with hirsutism or with a history of excessive exercise or of an eating disorder.

You can start by examining what normal menstruation relies on: an intact central nervous system with a functioning pituitary, an ovarian response, and a normal uterus, cervix, and vagina. You should check the patient’s follicle-stimulating hormone, thyroid-stimulating hormone, and prolactin levels to assess CNS functioning, and estradiol levels to assess ovarian response. A genital exam with a pelvic ultrasound can reveal any possible defects in the uterus, cervix, or vagina.

The presence of breasts without a uterus indicates normal estrogen production, so the missing uterus could be a congenital defect or result from androgen insensitivity, Dr. Hertweck explained. In those without breasts, gonadal dysgenesis or gonadal enzymatic deficiency may explain no estrogen production. If the patient has both breasts and a uterus, you should rule out pregnancy first and then track CNS changes via FSH, TSH, and prolactin levels.

Premature ovarian insufficiency

Approximately 1% of females experience premature ovarian insufficiency, which can be diagnosed as early as age 14 years and should be suspected in a patient with a uterus but without breasts who has low estradiol levels, CNS failure identified by a high FSH level, and gonadal failure.

Formal diagnosis requires two separate instances of FSH elevation, and chromosomal testing should be done to rule out gonadal dysgenesis. You also should test the serum anti-Müllerian hormone biomarker (readings above 8 are concerning) and look for two possible causes. The FMR1 (Fragile X) premutation carrier status could be a cause, or presence of 21-hydroxylase and/or adrenal antibodies indicate autoimmune polyglandular syndrome.

Catching premature ovarian insufficiency early enough may allow patients to preserve some fertility if they still have oocytes present. Aside from this, girls will need hormone replacement therapy to fulfill developmental emotional and physical needs, such as bone growth and overall health. Despite a history of treating teens with premature ovarian insufficiency like adults, you should follow the practice guidelines specific to adolescents by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists committee opinion statement (Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:193-7).

Menorrhagia: heavy menstrual bleeding

Even though average blood loss is estimated at 30 mL per period, that number means little in clinical practice because patients cannot measure the actual amount of menses. Better indicators of abnormally greater flow include flow lasting longer than 7 days, finding clots larger than a quarter, changing menstrual products every 1-2 hours, leaking onto clothing such that patients need to take extra clothes to school, and any heavy periods that occur with easy bruising or with a family history of bleeding disorders.

First-line treatment for heavy menstrual bleeding in teens is hormonal contraception, either combination oral contraceptive pills, the transdermal patch, or the intravaginal ring, which can be combined with other therapies.

An alternative for those under age 18 (per Food and Drug Administration labeling) is oral tranexamic acid, found in a crossover trial with an oral contraceptive pill to be just as effective at reducing average blood loss and improving quality of life, but with fewer side effects and better compliance. Before prescribing anything for heavy menstrual bleeding, however, you must consider possible causes and rule some out that require different management.

Aside from pregnancy, one potential cause of menorrhagia is infection such as chlamydia or gonorrhea, which should be considered even in those with a negative sexual history, Dr. Hertweck said. Other possible causes include an immature hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis, polycystic ovary syndrome (even with low hemoglobin), malignancy with a hormone-producing tumor, hypothalamic dysfunction (often stimulated by eating disorders, obesity, rapid weight loss, or gluten intolerance), or coagulopathy.

“Teens with menorrhagia may need to be screened for a bleeding disorder,” Dr. Hertweck said. At a minimum, she recommends checking complete blood count, ferritin, and TSH. “The most common bleeding disorders associated with heavy menstrual bleeding include platelet function disorders and von Willebrand.”

Up to half of teen girls with menorrhagia who visit a hematologist or multidisciplinary clinic receive a diagnosis of a bleeding disorder, Dr. Hertweck said. And up to half of those with menorrhagia at menarche may have von Willebrand, as do one in six adolescents who go to the emergency department because of heavy menstrual bleeding.

Von Willebrand syndrome

Von Willebrand syndrome is a deficiency or dysfunction of von Willebrand factor (vWF), a protein with binding sites for platelets, collagen, and factor VIII that “serves as a bridge between platelets and injury sites in vessel walls” and “protects factor VIII from rapid proteolytic degradation,” Dr. Hertweck said. Von Willebrand syndrome is the most common inherited congenital bleeding disorder. Although acquired von Willebrand syndrome is rare, it has grown in incidence among those with complex cardiovascular, hematologic, or immunologic disorders.

“Correct diagnosis is complex and not always straightforward,” Dr. Hertweck said, but “a positive response to questions in four categories is highly sensitive.” They are as follows:

• Menses lasting at least 7 days and interfering with a person’s daily activities.

• “History of treatment for anemia.

• Family history of a diagnosed bleeding disorder.

• History of excessive bleeding after tooth extraction, delivery, miscarriage, or surgery.

Diagnostic assays include platelet concentration of vWF antigen, an activity test of vWF-platelet binding, and factor VIII activity. However, you often need to repeat diagnostic testing because vWF antigens vary according to race, blood type, age, acute phase response, and menstrual cycle timing, Dr. Hertweck said.

“Remember to draw von Willebrand testing only during the first 3 days of the menstrual cycle when estrogen levels are at the nadir,” she said.

Because estrogen increases vWF, treatment for von Willebrand syndrome should be progestin only, either oral pills, medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA, or Depo-Provera injections), or an etonogestrel implant.

Dr. Hertweck presented several cases of abnormal menstruation and extreme conditions such as severe menorrhagia. Outside of von Willebrand in such patients, possible platelet disorders could include Glanzmann thrombasthenia (a platelet function disorder that is caused by an abnormality in the genes for glycoproteins IIb/IIIa) and platelet storage pool disorder, both of which should be diagnosed by a hematologist.

Dr. Hertweck reported having a research grant from Merck related to contraceptive implants in adolescents.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM AAP 2017

Return to Activities After Patellofemoral Arthroplasty

Take-Home Points

- PFA improved knee function and pain scores in patients with isolated patellofemoral arthritis.

- The majority (84.2%) of patients undergoing PFA were female.

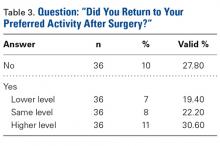

- Regardless of age or gender, 72.2% of patients returned to their desired preoperative activity after PFA, and 52.8% returned at the same or higher level.

- The rate of conversion from PFA to TKA was 6.3%.

- PFA is an alternative to TKA in active patients with isolated patellofemoral arthritis.

Compared with total knee arthroplasty (TKA), single-compartment knee arthroplasty may provide better physiologic function, faster recovery, and higher rates of return to activities in patients with unicompartmental knee disease.1-3 In 1955, McKeever4 introduced patellar arthroplasty for surgical management of isolated patellofemoral arthritis. In 1979, Lubinus5 improved on the technique and design by adding a femoral component. Since then, implants and techniques have been developed to effect better clinical outcomes. Patellofemoral arthroplasty (PFA) has many advantages over TKA in the treatment of patellofemoral arthritis. PFA is less invasive, requires shorter tourniquet times, has faster recovery, and spares the tibiofemoral compartment, leaving more native bone for potential conversion to TKA. Regarding activity and function, the resurfacing arthroplasty (vs TKA) allows maintenance of nearly normal knee kinematics.

Despite these advantages, the broader orthopedic surgery community has only cautiously accepted PFA. The procedure has high complication rates. Persistent instability, malalignment, wear, impingement, and tibiofemoral arthritis progression can occur after PFA.6 Although first-generation PFA prostheses often failed because of mechanical problems, loosening, maltracking, or instability,7 the most common indication for PFA revision has been, according to a recent large retrospective study,8 unexplained pain. More than 10 to 15 years after PFA, tibiofemoral arthritis may be the primary mechanism of failure.9 Nevertheless, compared with standard TKA for isolated patellofemoral arthritis, modern PFA does not have significantly different clinical outcomes, including complication and revision rates.6Numerous patient factors influence functional prognosis before and after knee arthroplasty, regardless of surgical technique and implant used. Age, comorbidities, athletic status, mental health, pain, functional limitations, excessive caution, “artificial joint”–related worries, and rehabilitation protocol all influence function.10 Return to activity and other quality-of-life indices are important aspects of postoperative patient satisfaction.

Methods

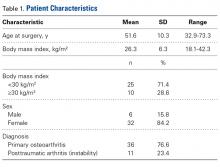

We conducted a retrospective cohort study to describe functional status after PFA for patellofemoral arthritis. We identified 48 consecutive PFAs (39 patients) performed by a team of 2 orthopedic surgeons (specialists in treating patellofemoral pathology) between 2009 and 2014.

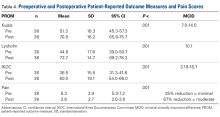

Three validated patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) were used to determine preoperative (baseline) and postoperative functional status: Kujala score, Lysholm score, and International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC) score. The Kujala score is a measure of knee function specific to the patellofemoral joint; the Lysholm score focuses on activities related to the knee; and the IKDC score is a general measure of knee function. Charts were reviewed to extract patients’ clinical data, including preoperative outcome scores, medical history, physical examination data, intraoperative characteristics, and postoperative course. By telephone, patients answered questions about their postoperative clinical course and completed final follow-up questionnaires. They were also asked which sporting or fitness activity they had preferred before surgery and whether they were able to return to that activity after surgery.

Statistical analysis included the study population’s descriptive statistics. Means and SDs were reported for continuous variables, and frequencies and percentages were reported for categorical variables. Paired t tests were used to analyze changes in PROM scores. For comparison of differences between characteristics of patients who did and did not return to their previous activity level, independent-samples t tests were used for continuous variables. Chi-square tests or Fisher exact tests were used to compare discrete variables. Statistical significance was set at P ≤ .05. All analyses were performed with SPSS Version 22.0 (IBM).

Results

Postoperative knee-specific PROM scores and general pain score (reported by the patient on a scale of 0-10) were statistically significantly improved (P < .001 for all measures) over preoperative scores (Table 4).

After surgery, 1 patient (2.6%) developed a pulmonary embolus, which was successfully identified and treated without incident. Five patients (10.4%) had another surgery on the same knee. Three patients (6.3%) underwent conversion to TKA: 1 for continued symptoms in the setting of newly diagnosed inflammatory arthritis, 1 for arthritic pain, and 1 for patellofemoral instability. Two patients (4.2%) underwent irrigation and débridement: 1 for hematoma and 1 for suspected (culture-negative) infection.

Discussion

Historically, the literature evaluating knee arthroplasty outcomes has focused on implant survivorship, pain relief, and patient satisfaction. Since the advent of partial knee arthroplasty options, more attention has been given to functional outcomes and return to activities after single-compartment knee resurfacing. TKA remains the gold standard by which newer, less invasive surgical options are measured. In a large prospective study, 97% of patients (age, >55 years) who had TKA for patellofemoral arthritis reported good or excellent clinical results, the majority being excellent.11 Post-TKA functional status and activity levels may not be rated as highly. After TKA, many patients switch to lower impact sports or reduce or stop their participation in sports.12 A small study of competitive adult tennis players found high levels of post-TKA satisfaction, ability to resume playing tennis, pain relief, and increased or continued enjoyment in playing.13 In a study of 355 patients (417 knees) who had underwent TKA, improvement in Knee Society function score showed a moderate correlation to an increase in weighted activity score (R = 0.362).14

Unicondylar knee arthroplasty (UKA) is becoming a popular treatment option for single-compartment tibiofemoral arthritis. A systematic review of 18 original studies of patients with knee osteoarthritis found that overall return to sports varied from 36% to 89% after TKA and from 75% to 100% after UKA.15 In another study, return-to-sports rates were similar for UKA (87%) and TKA (83%); the only significant difference was UKA patients returned quicker.16 The authors of a large meta-analysis conceded that significant heterogeneity of data prevented them from drawing definitive conclusions, but UKA patients seemed to return to low- and high-impact sports 2 weeks faster than their TKA counterparts.10 Overall, UKA and TKA patients (age, 51-71 years) had comparable return-to-sports rates at an average of 4 years after surgery.10 A smaller study corroborated faster return to sports for UKA over TKA patients and also found that, compared with TKA patients, UKA patients participated in sports more regularly and over a longer period.17 On the other hand, Walton and colleagues18 found similar return-to-sports rates but higher frequency of and satisfaction with sports participation in UKA over TKA patients.

A large retrospective study found no differences in rates of return to sports after TKA, UKA, patellar resurfacing, hip resurfacing, and total hip arthroplasty.19 Pain was the most common barrier to return. UKA patients who returned to sports tended to be younger than those who did not.20 Naal and colleagues3 found that 95% of UKA patients returned to their activities—hiking, walking, cycling, and swimming being most common. Although 90.3% of patients said surgery maintained or improved their ability to participate in sports, participation in high-impact sports (eg, running) decreased after surgery.

Outcomes of PFA vary because of evolving patient selection, implant design, surgical technique, and return-to-activity expectations.21,22 Most PFA outcome studies focus on implant survivorship, complication rates, and postoperative knee scores.23-28 PFA studies focused on return to activities are limited. Kooijman and colleagues7 and Mertl and colleagues29 reported good or excellent clinical results of PFA in 86% and 82% of patients, respectively. Neither study included a comprehensive analysis of postoperative functional status. Similarly, De Cloedt and colleagues30 reported good PFA outcomes in 43% of patients with degenerative joint disease and in 83% of patients with instability. Specific activity status was not described. Dahm and colleagues31 and Farr and colleagues32 suggested postoperative pain resolution motivates some PFA patients not only to resume preoperative activities but to start participating in new, higher level activities after pain has subsided. However, the studies did not examine the characteristics of patients who returned to baseline activities and did not examine return-to-sports rates.

Study Strengths and Limitations

Our study focused on the PFA patient population of a surgical team of 2 fellowship-trained orthopedic surgeons (specialists in treating patellofemoral pathology). Although generalization of our findings to other surgeons and different implants may be limited, the study design standardized treatment in a way that makes these findings more reliable. The 100% follow-up strengthens these findings as well. Last, though the patient population was relatively small, it was consistent with or larger than the PFA patient groups studied previously.

Conclusion

In this study, PROM and pain scores were significantly improved after PFA. That almost 75% of patients returned to their preferred activities and >50% of patients returned at the same or a higher activity level provides useful information for preoperative discussions with patients who want to remain active after PFA. Prospective studies are needed to evaluate the longevity and durability of PFA, particularly in active patients.

1. Laurencin CT, Zelicof SB, Scott RD, Ewald FC. Unicompartmental versus total knee arthroplasty in the same patient. A comparative study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1991;(273):151-156.

2. Kozinn SC, Scott R. Unicondylar knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1989;71(1):145-150.

3. Naal FD, Fischer M, Preuss A, et al. Return to sports and recreational activity after unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(10):1688-1695.

4. McKeever DC. Patellar prosthesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1955;37(5):1074-1084.

5. Lubinus HH. Patella glide bearing total replacement. Orthopedics. 1979;2(2):119-127.

6. Dy CJ, Franco N, Ma Y, Mazumdar M, McCarthy MM, Gonzalez Della Valle A. Complications after patello-femoral versus total knee replacement in the treatment of isolated patello-femoral osteoarthritis. A meta-analysis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2012;20(11):2174-2190.

7. Kooijman HJ, Driessen AP, van Horn JR. Long-term results of patellofemoral arthroplasty. A report of 56 arthroplasties with 17 years of follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2003;85(6):836-840.

8. Baker PN, Refaie R, Gregg P, Deehan D. Revision following patello-femoral arthroplasty. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2012;20(10):2047-2053.

9. Lonner JH, Bloomfield MR. The clinical outcome of patellofemoral arthroplasty. Orthop Clin North Am. 2013;44(3):271-280.

10. Papalia R, Del Buono A, Zampogna B, Maffulli N, Denaro V. Sport activity following joint arthroplasty: a systematic review. Br Med Bull. 2012;101:81-103.

11. Mont MA, Haas S, Mullick T, Hungerford DS. Total knee arthroplasty for patellofemoral arthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84(11):1977-1981.

12. Chatterji U, Ashworth MJ, Lewis PL, Dobson PJ. Effect of total knee arthroplasty on recreational and sporting activity. ANZ J Surg. 2005;75(6):405-408.

13. Mont MA, Rajadhyaksha AD, Marxen JL, Silberstein CE, Hungerford DS. Tennis after total knee arthroplasty. Am J Sports Med. 2002;30(2):163-166.

14. Marker DR, Mont MA, Seyler TM, McGrath MS, Kolisek FR, Bonutti PM. Does functional improvement following TKA correlate to increased sports activity? Iowa Orthop J. 2009;29:11-16.

15. Witjes S, Gouttebarge V, Kuijer PP, van Geenen RC, Poolman RW, Kerkhoffs GM. Return to sports and physical activity after total and unicondylar knee arthroplasty: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2016;46(2):269-292.

16. Ho JC, Stitzlein RN, Green CJ, Stoner T, Froimson MI. Return to sports activity following UKA and TKA. J Knee Surg. 2016;29(3):254-259.

17. Hopper GP, Leach WJ. Participation in sporting activities following knee replacement: total versus unicompartmental. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2008;16(10):973-979.

18. Walton NP, Jahromi I, Lewis PL, Dobson PJ, Angel KR, Campbell DG. Patient-perceived outcomes and return to sport and work: TKA versus mini-incision unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. J Knee Surg. 2006;19(2):112-116.

19. Wylde V, Blom A, Dieppe P, Hewlett S, Learmonth I. Return to sport after joint replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008;90(7):920-923.

20. Pietschmann MF, Wohlleb L, Weber P, et al. Sports activities after medial unicompartmental knee arthroplasty Oxford III—what can we expect? Int Orthop. 2013;37(1):31-37.

21. Lonner JH. Patellofemoral arthroplasty. Orthopedics. 2010;33(9):653.

22. Lustig S. Patellofemoral arthroplasty. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2014;100(1 suppl):S35-S43.

23. Krajca-Radcliffe JB, Coker TP. Patellofemoral arthroplasty. A 2- to 18-year followup study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;(330):143-151.

24. Mihalko WM, Boachie-Adjei Y, Spang JT, Fulkerson JP, Arendt EA, Saleh KJ. Controversies and techniques in the surgical management of patellofemoral arthritis. Instr Course Lect. 2008;57:365-380.

25. Lonner JH. Patellofemoral arthroplasty: pros, cons, and design considerations. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;(428):158-165.

26. Lonner JH. Patellofemoral arthroplasty: the impact of design on outcomes. Orthop Clin North Am. 2008;39(3):347-354.

27. Farr J 2nd, Barrett D. Optimizing patellofemoral arthroplasty. Knee. 2008;15(5):339-347.

28. Leadbetter WB, Seyler TM, Ragland PS, Mont MA. Indications, contraindications, and pitfalls of patellofemoral arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(suppl 4):122-137.

29. Mertl P, Van FT, Bonhomme P, Vives P. Femoropatellar osteoarthritis treated by prosthesis. Retrospective study of 50 implants [in French]. Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot. 1997;83(8):712-718.

30. De Cloedt P, Legaye J, Lokietek W. Femoro-patellar prosthesis. A retrospective study of 45 consecutive cases with a follow-up of 3-12 years [in French]. Acta Orthop Belg. 1999;65(2):170-175.

31. Dahm DL, Al-Rayashi W, Dajani K, Shah JP, Levy BA, Stuart MJ. Patellofemoral arthroplasty versus total knee arthroplasty in patients with isolated patellofemoral osteoarthritis. Am J Orthop. 2010;39(10):487-491.

32. Farr J, Arendt E, Dahm D, Daynes J. Patellofemoral arthroplasty in the athlete. Clin Sports Med. 2014;33(3):547-552.

Take-Home Points

- PFA improved knee function and pain scores in patients with isolated patellofemoral arthritis.

- The majority (84.2%) of patients undergoing PFA were female.

- Regardless of age or gender, 72.2% of patients returned to their desired preoperative activity after PFA, and 52.8% returned at the same or higher level.

- The rate of conversion from PFA to TKA was 6.3%.

- PFA is an alternative to TKA in active patients with isolated patellofemoral arthritis.

Compared with total knee arthroplasty (TKA), single-compartment knee arthroplasty may provide better physiologic function, faster recovery, and higher rates of return to activities in patients with unicompartmental knee disease.1-3 In 1955, McKeever4 introduced patellar arthroplasty for surgical management of isolated patellofemoral arthritis. In 1979, Lubinus5 improved on the technique and design by adding a femoral component. Since then, implants and techniques have been developed to effect better clinical outcomes. Patellofemoral arthroplasty (PFA) has many advantages over TKA in the treatment of patellofemoral arthritis. PFA is less invasive, requires shorter tourniquet times, has faster recovery, and spares the tibiofemoral compartment, leaving more native bone for potential conversion to TKA. Regarding activity and function, the resurfacing arthroplasty (vs TKA) allows maintenance of nearly normal knee kinematics.