User login

5 drug interactions you don’t want to miss

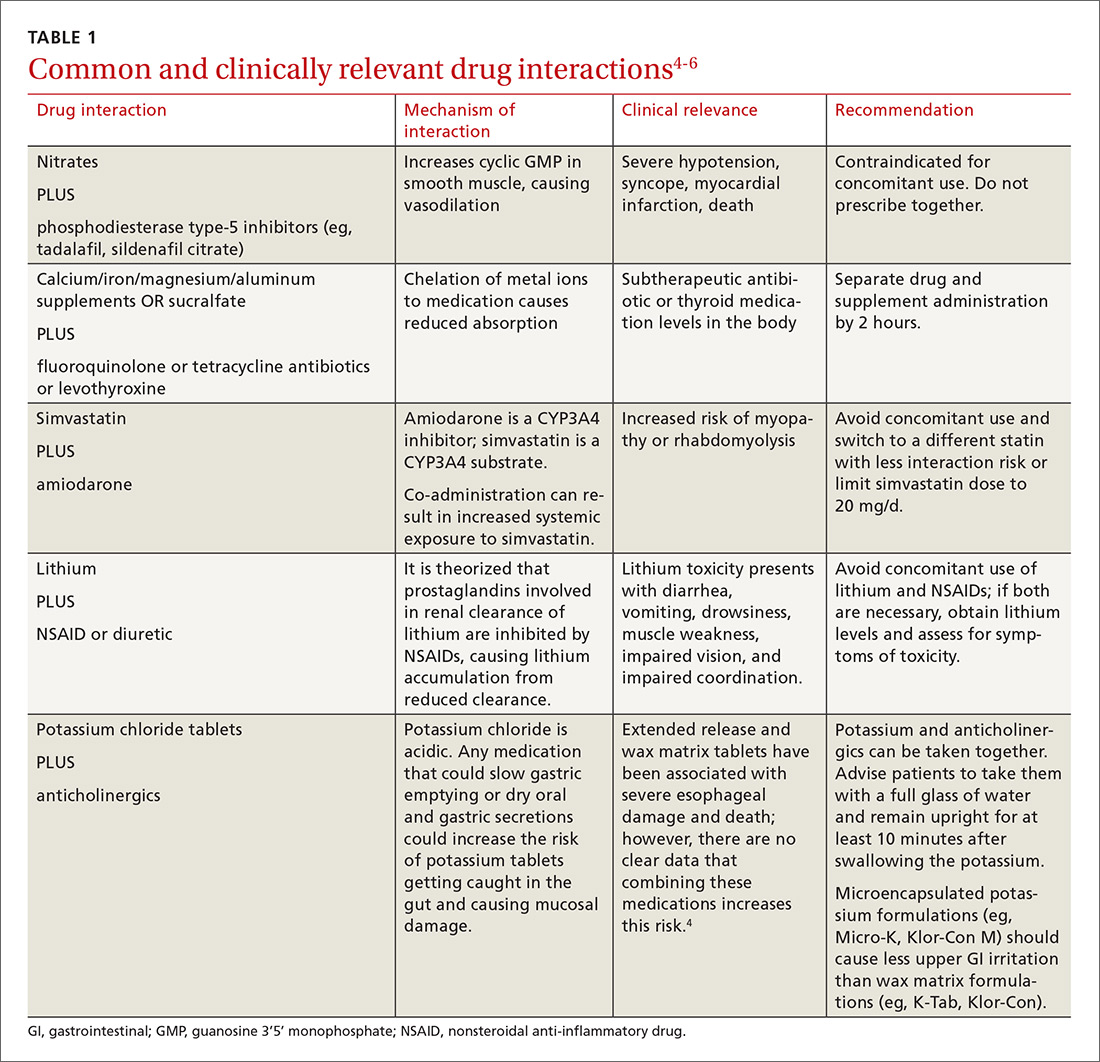

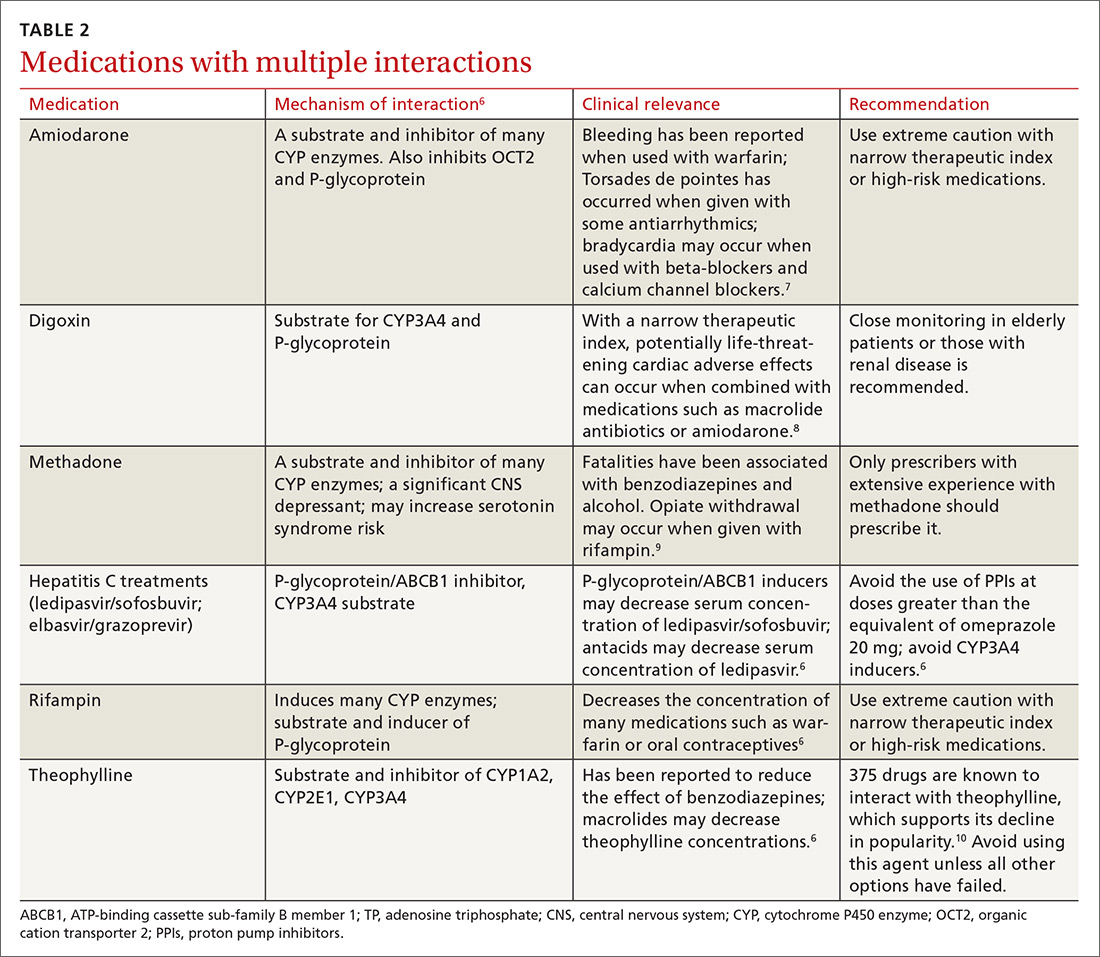

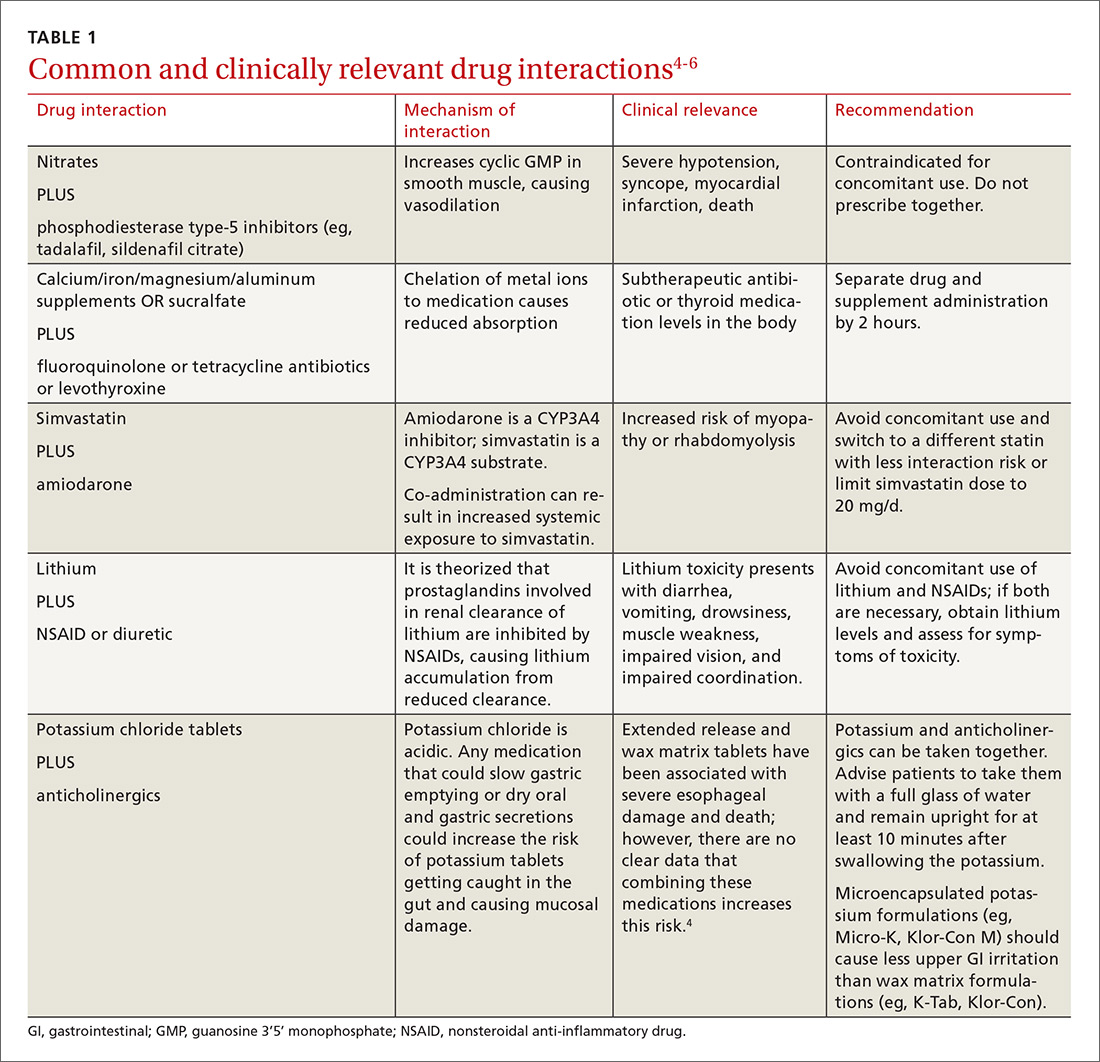

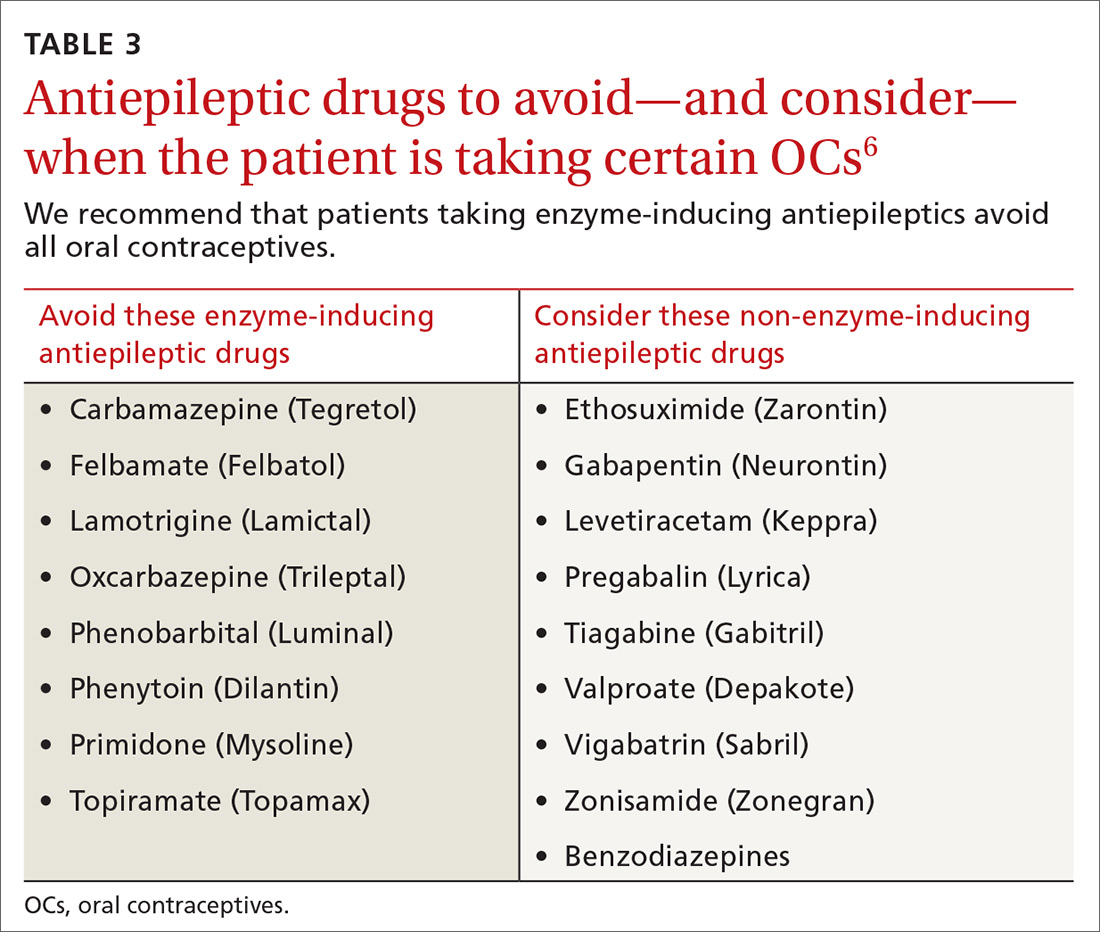

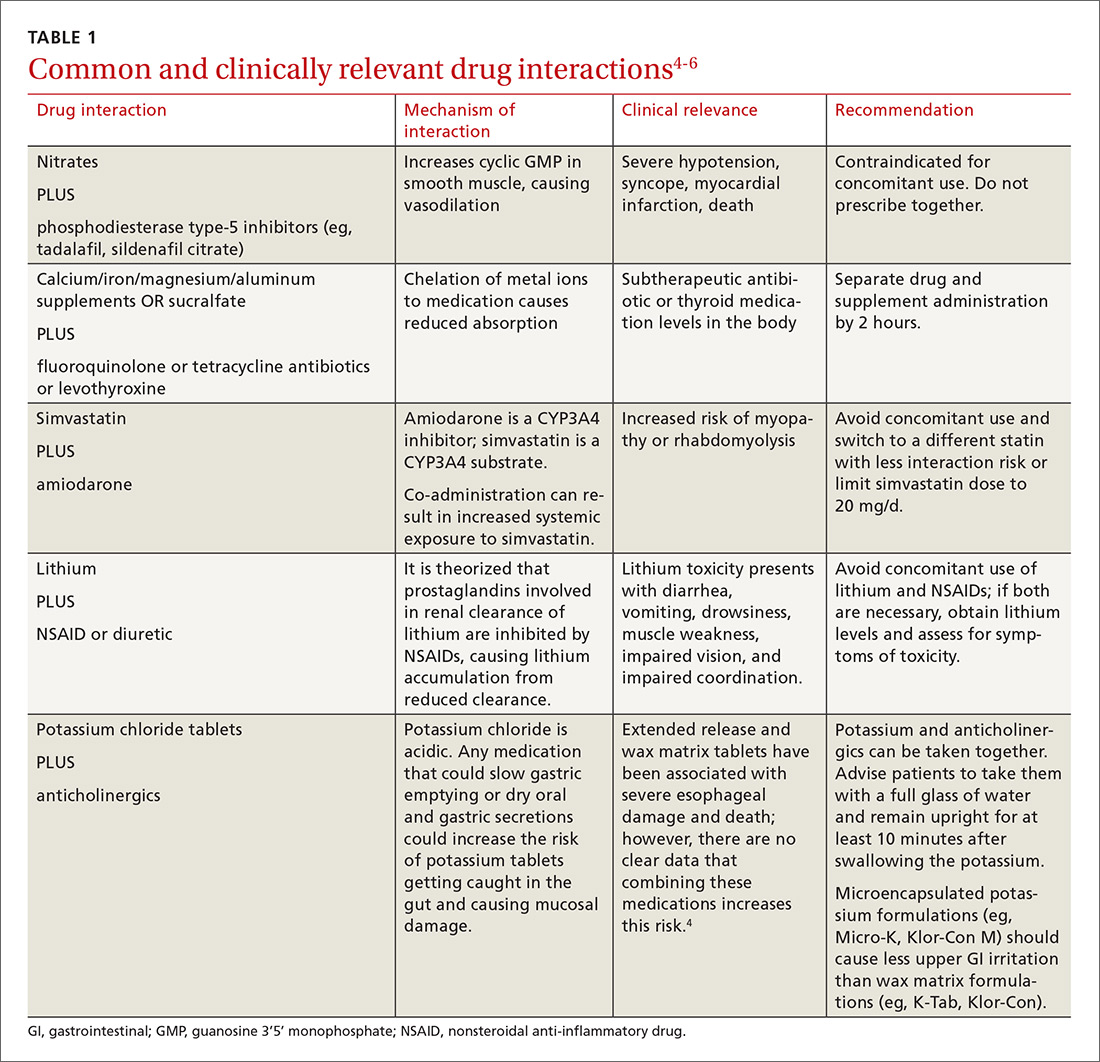

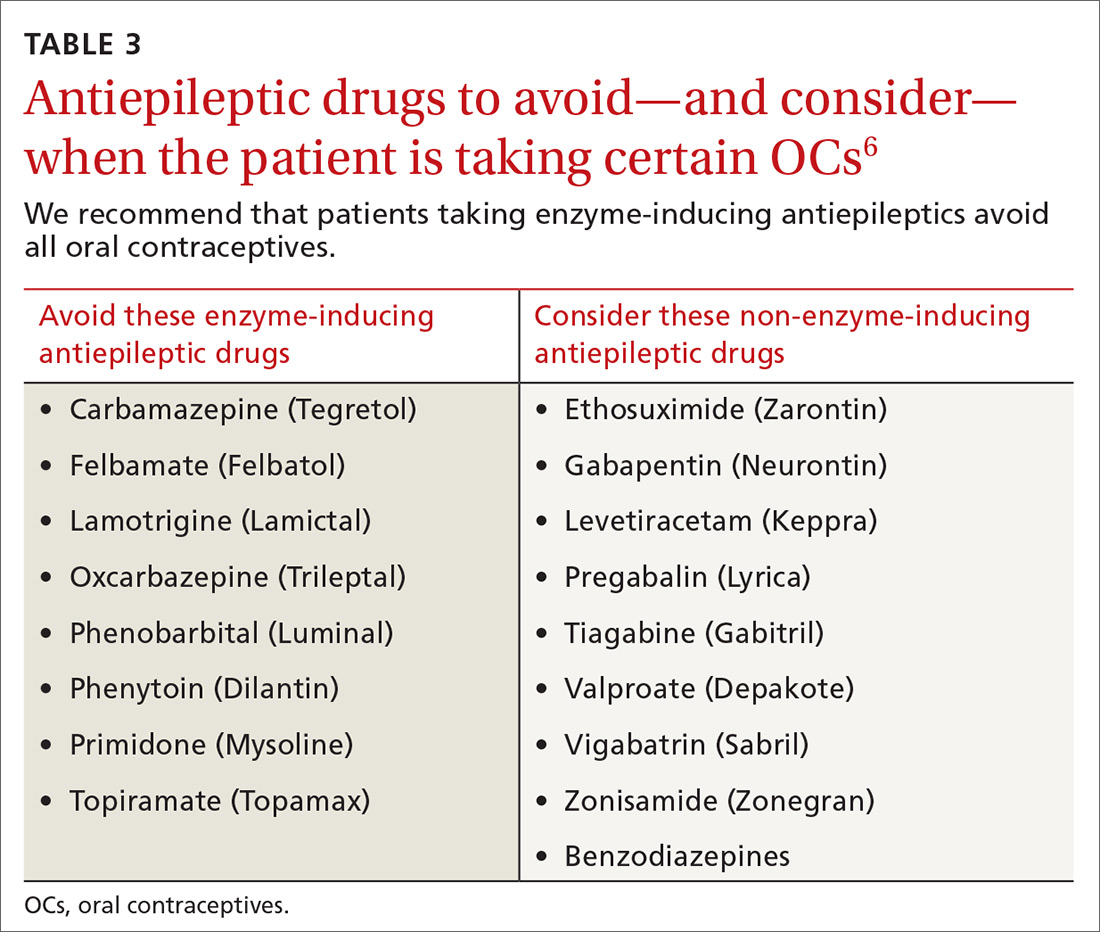

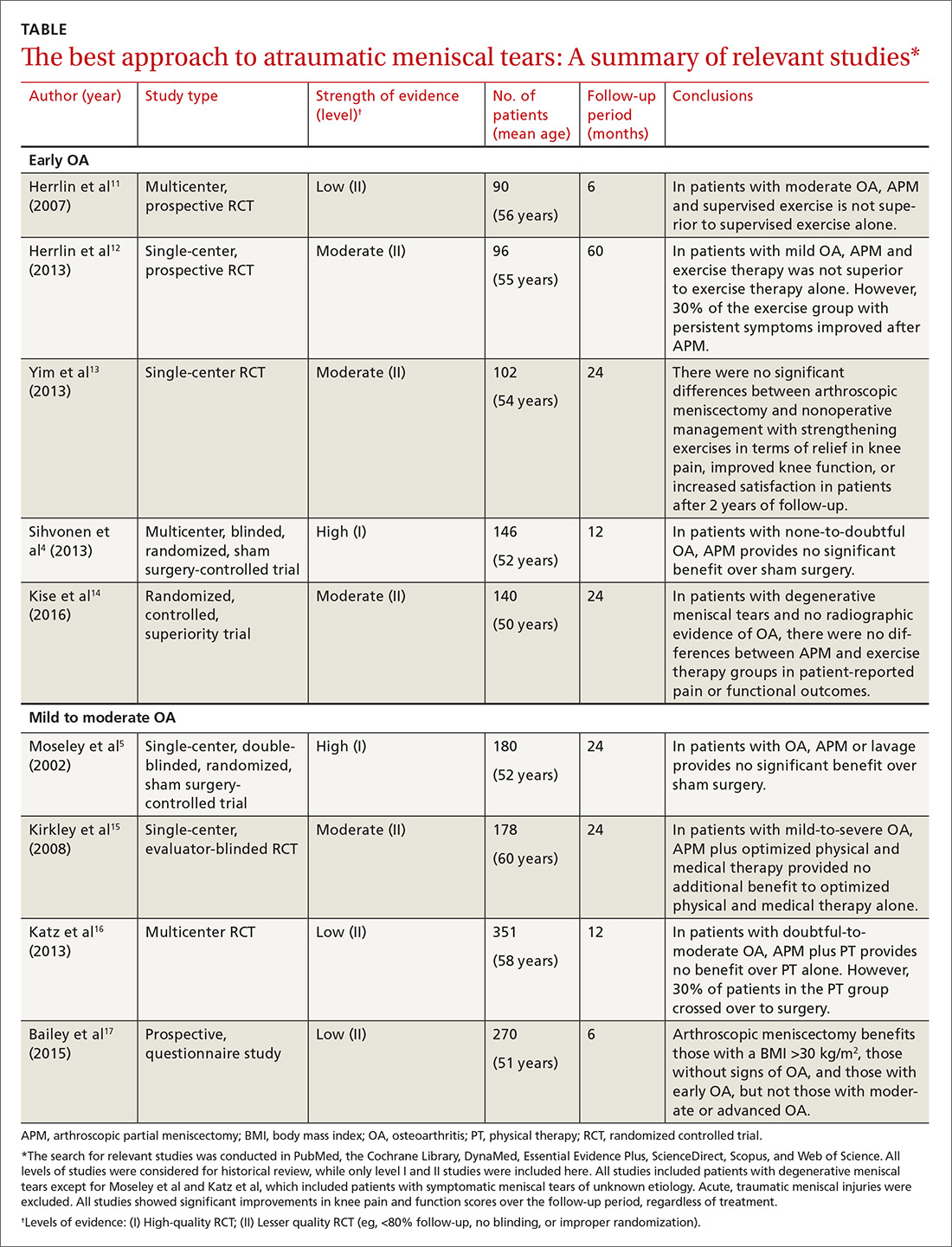

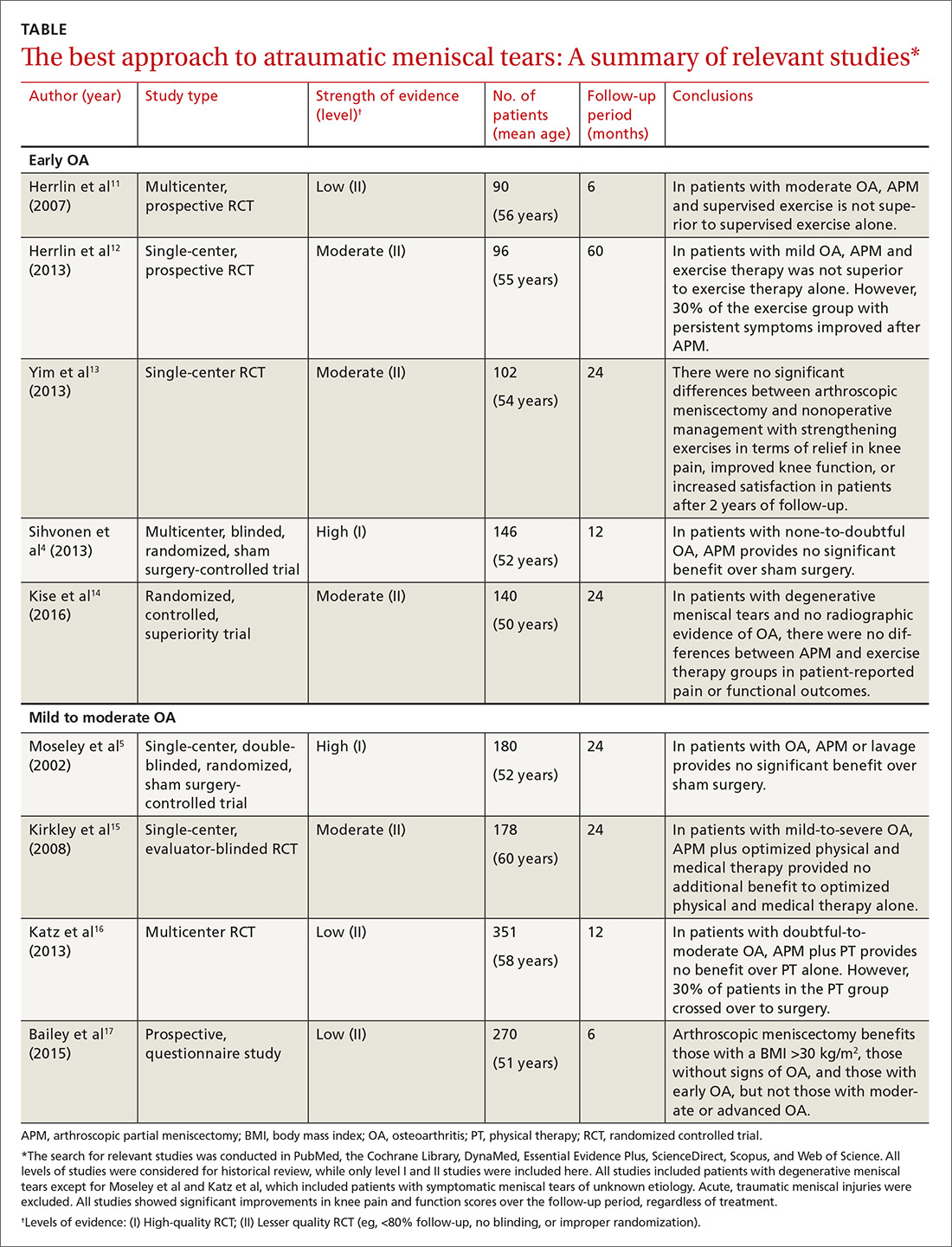

There is a strong relationship between the number of medications taken and the likelihood of a potentially serious drug-drug interaction.1,2 Drug interaction software programs can help alert prescribers to potential problems, but these programs sometimes fail to detect important interactions or generate so many clinically insignificant alerts that they become a nuisance.3 This review provides guidance about 5 clinically relevant drug interactions, including those that are common (TABLE 14-6)—and those that are less common, but no less important (TABLE 26-10).

1. Antiepileptics & contraceptives

Many antiepileptic medications decrease the efficacy of certain contraceptives

Contraception management in women with epilepsy is critical due to potential maternal and fetal complications. Many antiepileptic drugs (AEDs), including carbamazepine, ethosuximide, fosphenytoin, phenobarbital, phenytoin, primidone, topiramate, and valproate, are potentially teratogenic.11 A retrospective, observational study of 115 women of childbearing age who had epilepsy and were seen at a neurology clinic found that 74% were not using documented contraception.11 Of the minority of study participants using contraception, most were using oral contraceptives (OCs) that could potentially interact with AEDs.

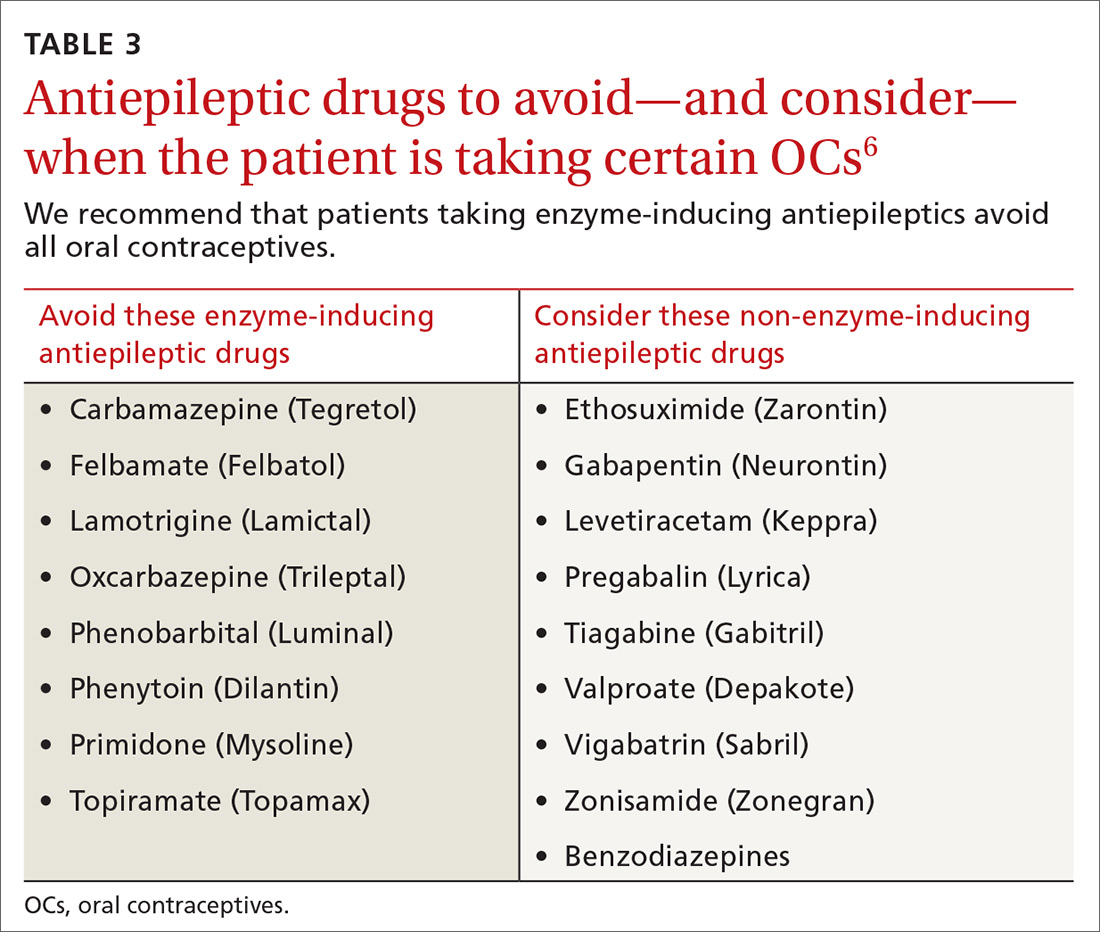

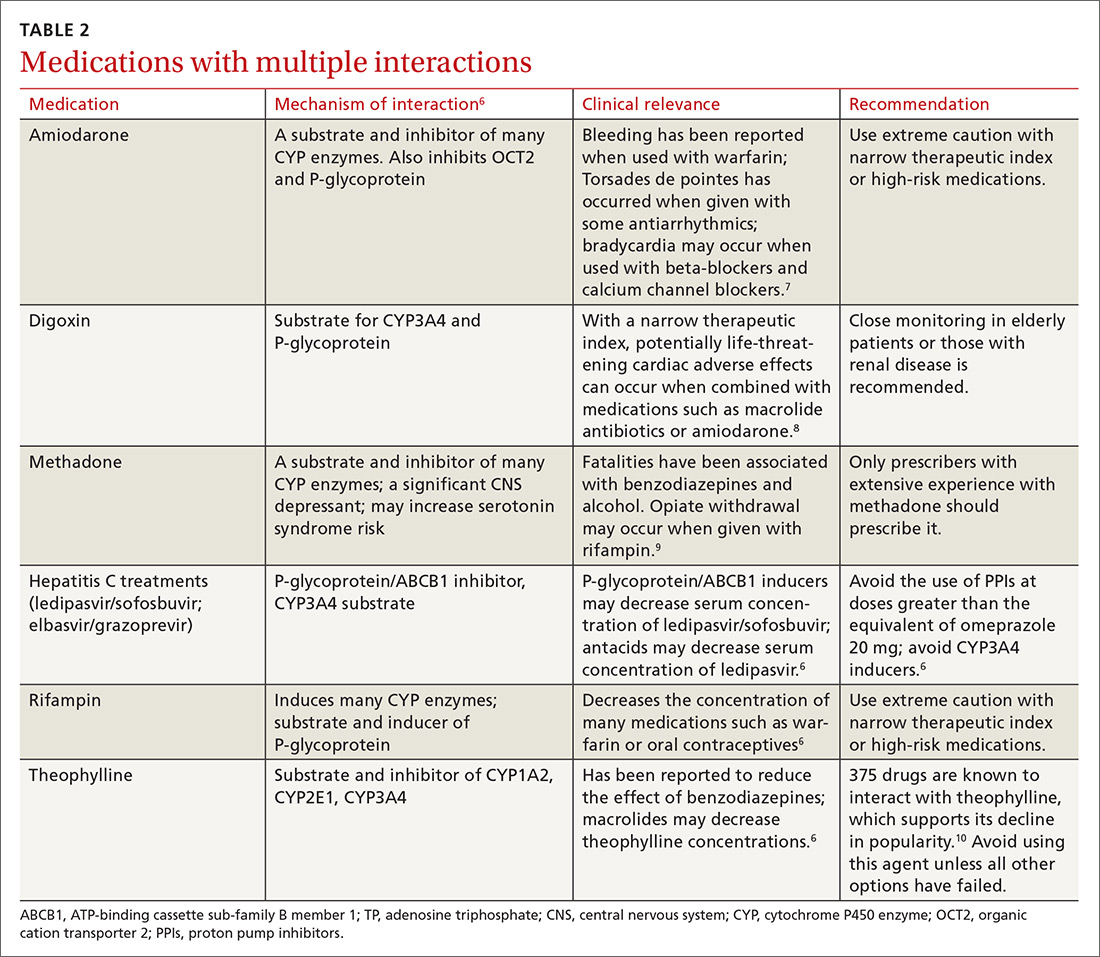

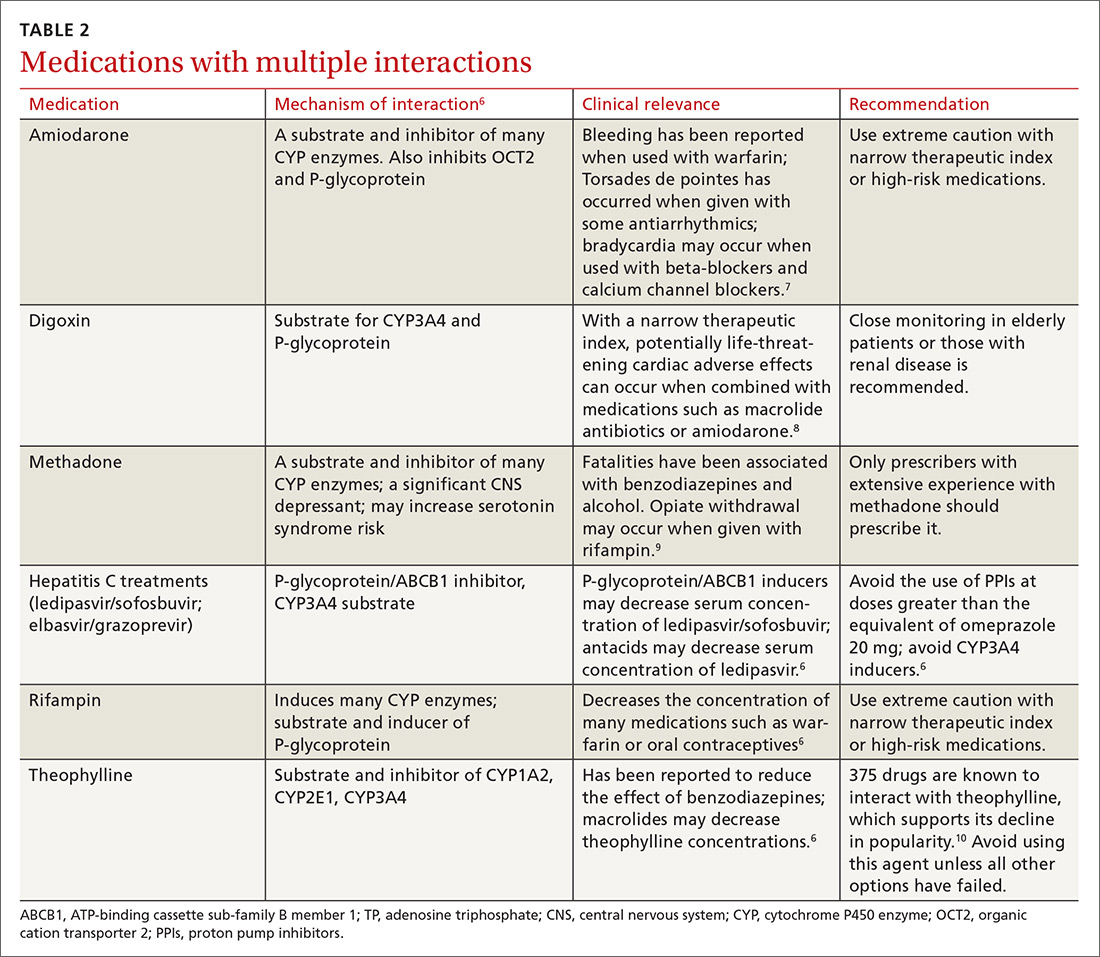

CYP inducers. Estrogen and progesterone are metabolized by the cytochrome P450 3A4 enzyme. Some AEDs induce this enzyme, which can enhance the metabolism of OCs, thus reducing their efficacy.12 It is not known, however, if this interaction results in increased pregnancy rates.13 Most newer AEDs (TABLE 36) do not induce cytochrome P450 3A4 and, thus, do not appear to affect OC efficacy, and may be safer for women with seizure disorders.12 While enzyme-inducing AEDs may decrease the efficacy of progesterone-only OCs and the morning-after pill,12,14,15 progesterone-containing intrauterine devices (IUDs), long-acting progesterone injections, and non-hormonal contraceptive methods appear to be unaffected.14-17

OCs and seizure frequency. There is no strong evidence that OCs affect seizure frequency in epileptic women, although changes in hormone levels during the menstrual cycle do affect seizure susceptibility.12 Combination OCs decrease lamotrigine levels and, therefore, may increase the risk of seizures, but progesterone-only pills do not produce this effect.12,16

Do guidelines exist? There are no specific evidence-based guidelines that pertain to the use of AEDs and contraception together, but some organizations have issued recommendations.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends using a 30- to 35-mcg estrogen-containing OC rather than a lower dose in women taking an enzyme-inducing AED. The group also recommends using condoms with OCs or using IUDs.18

The American Academy of Neurology suggests that women taking OCs and enzyme-inducing AEDs use an OC containing at least 50 mcg estrogen.19

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommends that women taking enzyme-inducing AEDs avoid progestin-only pills.20

The Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare agrees that enzyme-inducing drugs may decrease efficacy and recommend considering IUDs and injectable contraceptive methods.21

2. SSRIs & NSAIDs.

SSRIs increase the GI bleeding risk associated with NSAIDs alone

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are commonly prescribed worldwide.22,23 A well-established adverse effect of NSAIDs is gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding, and there is increasing evidence that concomitant use of an SSRI can further increase that risk through a variety of mechanisms.23

SSRIs decrease platelet serotonin levels resulting in defective platelet aggregation and impaired hemostasis. Studies have also shown that SSRIs increase gastric acidity, which leads to increased risk of peptic ulcer disease and GI bleeding.23 These mechanisms, combined with the inhibition of gastroprotective prostaglandin cyclooxygenase-1 and platelets by NSAIDs, further potentiate GI bleeding risk.24

Patients at high risk for bleeding with concomitant SSRIs and NSAIDs include older patients, patients with other risk factors for GI bleeding (eg, chronic steroid use), and patients with a history of GI bleeding.23

The evidence. A 2014 meta-analysis found that when SSRIs were used in combination with NSAIDs, the risk of GI bleeding was significantly increased, compared with SSRI monotherapy.23

Case control studies found the risk of upper GI bleeding with SSRIs had a number needed to harm (NNH) of 3177 for a low-risk population and 881 for a high-risk population with an odds ratio (OR) of 1.66 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.44-1.92; P<.00001).23 When SSRIs were used in combination with NSAIDs, the NNH decreased to 645 for a low-risk population and 179 for a high-risk population (OR=4.25; 95% CI, 2.82-6.42; P<.0001).23

Another meta-analysis found that the OR for bleeding risk increased to 6.33 (95% CI, 3.40-11.8; P<.00001; NNH=106) with concomitant use of NSAIDs and SSRIs, compared with 2.36 (95% CI, 1.44-3.85; P=.0006; NNH=411) for SSRI use alone.25

The studies did not evaluate results based on the indication, dose, or duration of SSRI or NSAID treatment. If both an SSRI and an NSAID must be used, select a cyclooxygenase-2 selective NSAID at the lowest effective dose and consider the addition of a proton pump inhibitor to decrease the risk of a GI bleed.23,26

3. Direct oral anticoagulants and antiepileptics

Don’t use DOACs in patients taking certain antiepileptic medications

Drug interactions with anticoagulants, such as warfarin, are well documented and have been publicized for years, but physicians must also be aware of the potential for interaction between the direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) and AEDs.

Apixaban, rivaroxaban, and dabigatran appear to interact withthe AEDs carbamazepine, phenytoin, and phenobarbital.27,28 These interactions occur due to AED induction of the CYP3A4 enzyme and effects on the P-glycoprotein (P-gp) efflux pump.27,29 When taken together, the AED induces metabolism and elimination of the DOAC medication to occur more quickly than it would normally, resulting in subtherapeutic concentrations of the DOAC. This could theoretically result in a venous thromboembolic event or stroke.

A caveat. One thing to consider is that studies demonstrating interaction between the DOAC and AED drug classes have been performed in healthy volunteers, making it difficult to extrapolate how this interaction may increase the risk for thrombotic events in other patients.

Some studies demonstrated reductions in drug levels of up to 50% with strong CYP3A4 and P-glycoprotein inducers.30 Common inducers include carbamazepine, rifampin, and St. John’s Wort.6 Patients taking such agents could theoretically have decreased exposure to the DOAC, resulting in an increase in thromboembolic risk.31

4. Statins & certain CYP inhibitors

Combining simvastatin with fibrates warrants extra attention

The efficacy of statin medications in the prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) is clear. However, the clinical significance of many identified drug interactions involving statins is difficult to interpret. Interactions that cause increased serum concentrations of statins can increase the risk for liver enzyme elevations and skeletal muscle abnormalities (myalgias to rhabdomyolysis).32 Strong inhibitors of CYP3A4 (amiodarone, cyclosporine, ketoconazole, etc.) significantly increase concentrations of lovastatin, simvastatin, and atorvastatin. Pitavastatin, pravastatin, and rosuvastatin are not susceptible to any CYP-mediated drug interactions;33 therefore, rosuvastatin (a high-intensity statin) is usually recommended over other statins for patients taking strong inhibitors of CYP3A4.

When to limit simvastatin. Doses of simvastatin should not exceed 10 mg/d when combined with diltiazem, dronedarone, or verapamil, and doses should not exceed 20 mg/d when used with amiodarone, amlodipine, or ranolazine.6 These recommendations are in response to results from the SEARCH (Study of the Effectiveness of Additional Reductions in cholesterol and homocysteine) trial, which found a higher incidence of myopathies and rhabdomyolysis in patients taking 80 mg of simvastatin compared with those taking 20-mg doses.34 CYP3A4-inducing medications, especially diltiazem, were thought to also contribute to an increased risk.34

Avoid gemfibrozil with statins. Using fibrates with statins is beneficial for some patients; however, gemfibrozil significantly interacts with statins by inhibiting CYP2C8 and organic anion transporting polypeptide 1B1 (OATP1B1).33 The safer choice is fenofibrate because it does not interfere with statin metabolism and can be safely used in combination with statins.6

A retrospective review of the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (AERS) database found that 88% of fibrate and statin combinations that resulted in rhabdomyolysis were associated with gemfibrozil/cerivastatin (cerivastatin is no longer available in the United States).35

5. One serotonergic drug & another

Serotonin syndrome is associated with more than just SSRIs

Serotonin syndrome is a constellation of symptoms (hyperthermia, hyperreflexia, muscle clonus, tremor and altered mental status) caused by increases in serotonin levels in the central and peripheral nervous systems that can lead to mild or life-threatening complications such as seizures, muscle breakdown, or hyperthermia. Serotonin syndrome is most likely to occur within 24 hours after a dose increase, after starting a new medication that increases serotonin levels, or after a drug overdose.36

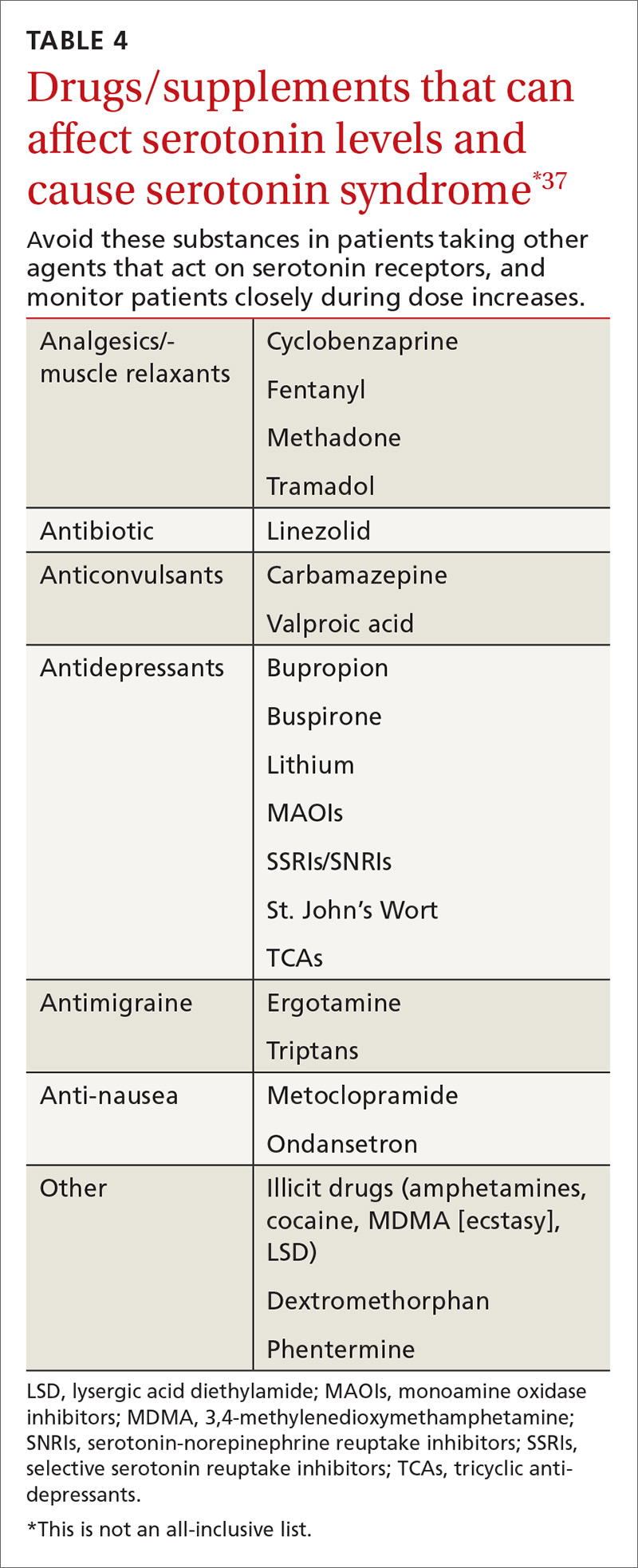

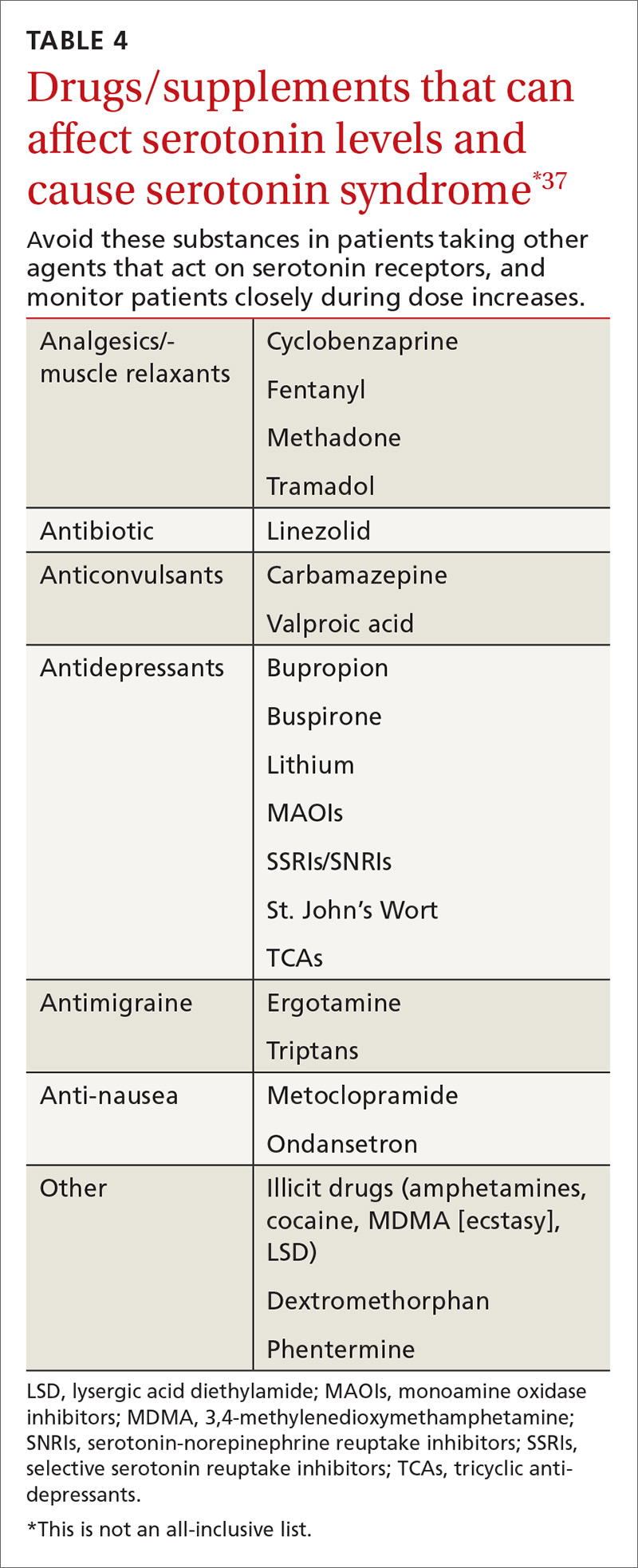

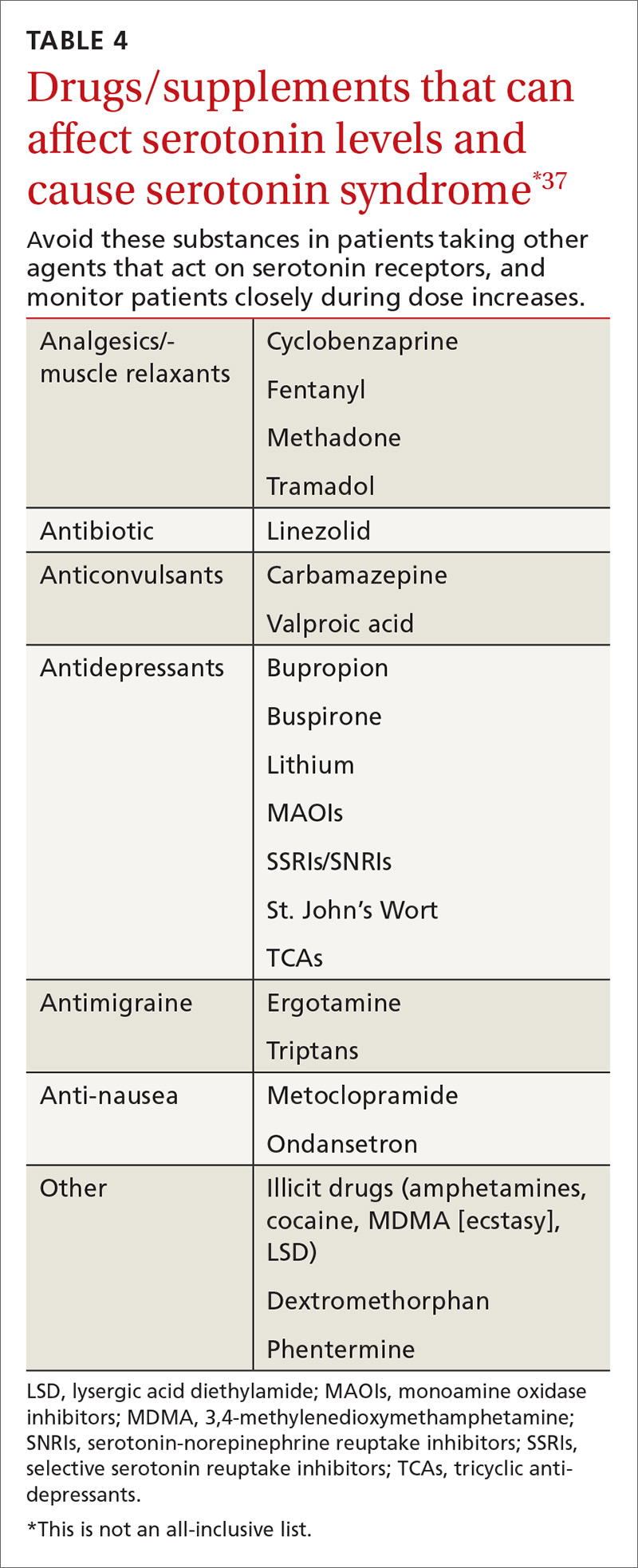

SSRIs are the most commonly reported drug associated with serotonin syndrome; however, other medications (TABLE 437) may be responsible, especially when used in combination with agents that act on serotonin receptors or in patients with impaired metabolism of the drugs being used.37

Other culprits. Serotonergic effects can also be associated with illicit drugs, some nonprescription medications, and supplements. And in March 2016, the FDA issued a warning about the risks of taking opioids with serotonergic medications.38 Although labeling changes have been recommended for all opioids, the cases of serotonin syndrome were reported more often with normal doses of fentanyl and methadone.

There are 2 mechanisms by which drugs may increase a patient’s risk for serotonin syndrome. The first is a pharmacodynamic interaction, which can occur when 2 or more medications act at the same receptor site (serotonin receptors in this example), which may result in an additive or synergistic effect.39

The second mechanism is a pharmacokinetic alteration (an agent alters absorption, distribution, metabolism, or excretion) of CYP enzymes.40 Of the more commonly used antidepressants, citalopram, escitalopram, venlafaxine, and mirtazapine seem to have the least potential for clinically significant pharmacokinetic interactions.41

Guidelines? Currently there are no guidelines for preventing serotonin syndrome. Clinicians should exercise caution in patients at high risk for drug adverse events, such as the elderly, patients taking multiple medications, and patients with comorbidities. Healthy low-risk patients can generally take 2 or 3 serotonergic medications at therapeutic doses without a major risk of harm.

CORRESPONDENCE

Mary Onysko, PharmD, BCPS, 191 East Orchard Road, Suite 200, Littleton, CO 80121; [email protected].

1. Aparasu R, Baer R, Aparasu A. Clinically important potential drug-drug interactions in outpatient settings. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2007;3:426-437.

2. Johnell K, Klarin I. The relationship between number of drugs and potential drug-drug interactions in the elderly: a study of over 600,000 elderly patients from the Swedish Prescribed Drug Register. Drug Saf. 2007;30:911-918.

3. Pharmacist’s Letter. Online continuing medical education and webinars. Drug interaction overload: Problems and solutions for drug interaction alerts. Volume 2012, Course No. 216. Self-Study Course #120216. Available at: http://pharmacistsletter.therapeuticresearch.com/ce/cecourse.aspx?pc=15-219&quiz=1. Accessed June 9, 2016.

4. PL Detail-Document, Potassium and Anticholinergic Drug Interaction. Pharmacist’s Letter/Prescriber’s Letter. October 2011.

5. Micromedex Solutions. Available at: http://www.micromedexsolutions.com. Accessed May 3, 2016.

6. Lexi-Comp Online. Available at: http://online.lexi.com/lco/action/home. Accessed May 22, 2016.

7. Marcus FI. Drug interactions with amiodarone. Am Heart J. 1983;106(4 Pt 2):924-930.

8. Digoxin: serious drug interactions. Prescrire Int. 2010;19:68-70.

9. McCance-Katz EF, Sullivan LE, Nallani S. Drug interactions of clinical importance among the opioids, methadone and buprenorphine, and other frequently prescribed medications: a review. Am J Addict. 2010;19:4-16.

10. Drugs.com. Theophylline drug interactions. Available at: https://www.drugs.com/drug-interactions/theophylline.html. Accessed June 23, 2016.

11. Bhakta J, Bainbridge J, Borgelt L. Teratogenic medications and concurrent contraceptive use in women of childbearing ability with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2015;52(Pt A):212-217.

12. Reddy DS. Clinical pharmacokinetic interactions between antiepileptic drugs and hormonal contraceptives. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2010;3:183-192.

13. Carl JS, Weaver SP, Tweed E. Effect of antiepileptic drugs on oral contraceptives. Am Fam Physician. 2008;78:634-635.

14. O’Brien MD, Guillebaud J. Contraception for women with epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2006;47:1419-1422.

15. Schwenkhagen AM, Stodieck SR. Which contraception for women with epilepsy? Seizure. 2008;17:145-150.

16. Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare Clinical Effectiveness Unit. Antiepileptic drugs and contraception. CEU statement. January 2010. Available at: https://www.fsrh.org/standards-and-guidance/documents/ceu-clinical-guidance-drug-interactions-with-hormonal/. Accessed April 25, 2016.

17. Perruca E. Clinically relevant drug interactions with antiepileptic drugs. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;61:246-255.

18. ACOG practice bulletin. Number 73: Use of hormonal contraception in women with coexisting medical conditions. ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins-Gynecology. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107:1453-1472.

19. Report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Practice parameter: management issues for women with epilepsy (summary statement). Neurology. 1998;51:944-948.

20. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Do not do recommendation. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/donotdo/the-progestogenonly-pill-is-not-recommended-as-reliable-contraception-inwomen-and-girls-taking-enzymeinducing-anti-epileptic-drugs-aeds. Accessed September 21, 2017.

21. Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare. Clinical guidance: drug interactions with hormonal contraception. Available at: https://www.fsrh.org/standards-and-guidance/documents/ceu-clinical-guidance-drug-interactions-with-hormonal/. Accessed September 21, 2017.

22. de Jong JCF, van den Berg PB, Tobi H, et al. Combined use of SSRIs and NSAIDs increases the risk of gastrointestinal adverse effects. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2003;55:591-595.

23. Anglin R, Yuan Y, Moayyedi P, et al. Risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors with or without concurrent nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory use: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:811-819.

24. Mort JR, Aparasu RR, Baer RK, et al. Interaction between selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: review of the literature. Pharmacotherapy. 2006;26:1307-1313.

25. Loke YK, Trivedi AN, Singh S. Meta-analysis: gastrointestinal bleeding due to interaction between selective serotonin uptake inhibitors and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27:31-40.

26. Venerito M, Wex T, Malfertheiner P. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced gastroduodenal bleeding: risk factors and prevention strategies. Pharmaceuticals. 2010;3:2225-2237.

27. Boehringer S, Williams CD, Yawn BP, et al. Managing interactions with direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs). Pharmacist’s Letter. May 2016.

28. Johannessen SI, Landmark CJ. Antiepileptic drug interactions – principles and clinical implications. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2010;8:254-267.

29. Mohrien K, Oliphant CS, Self TH. Drug interactions with novel oral anticoagulants. Consultant. 2013;53:918-919. Available at: http://www.consultant360.com/articles/drug-interactions-novel-oral-anticoagulants. Accessed May 3, 2016.

30. Wiggins BS, Northup A, Johnson D, et al. Reduced anticoagulant effect of dabigatran in a patient receiving concomitant phenytoin. Pharmacotherapy. 2016;36:e5-e7.

31. Burnett AE, Mahan CE, Vazquez SR, et al. Guidance for the practical management of the direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) in VTE treatment. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2016;41:206-232.

32. Thompson PD, Clarkson P, Karas RH. Statin-associated myopathy. JAMA. 2003;289:1681-1690.

33. Hirota T, Leiri I. Drug-drug interactions that interfere with statin metabolism. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2015;11:1435-1447.

34. Study of the Effectiveness of Additional Reductions in Cholesterol and Homocysteine (SEARCH) Collaborative Group. Intensive lowering of LDL cholesterol wih 80 mg versus 20 mg simvastatin daily in 12,064 survivors of myocardial inffarction: a double-blind randomised trial. Lancet. 2010;376:1658-1669.

35. Jones PH, Davidson MH. Reporting rate of rhabdomyolysis with fenofibrate + statin versus gemfibrozil + any statin. Am J Cardiol. 2005;95:120-122.

36. Birmes P, Coppin D, Schmitt L, et al. Serotonin syndrome: a brief review. CMAJ. 2003;168:1439-1442.

37. Boyer EW, Shannon M. The serotonin syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1112-1120.

38. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA warns about several safety issues with opioid pain medicines; requires label changes. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm489676.htm. Accessed June 15, 2016.

39. Sultana J, Spina E, Trifirò G. Antidepressant use in the elderly: the role of pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics in drug safety. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2015;11:883-892.

40. Sproule BA, Naranjo CA, Brenmer KE, et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and CNS drug interactions. A critical review of the evidence. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1997;33:454-471.

41. Spina E, Santoro V, D’Arrigo C. Clinically relevant pharmacokinetic drug interactions with second-generation antidepressants: an update. Clin Ther. 2008;30:1206-1227.

There is a strong relationship between the number of medications taken and the likelihood of a potentially serious drug-drug interaction.1,2 Drug interaction software programs can help alert prescribers to potential problems, but these programs sometimes fail to detect important interactions or generate so many clinically insignificant alerts that they become a nuisance.3 This review provides guidance about 5 clinically relevant drug interactions, including those that are common (TABLE 14-6)—and those that are less common, but no less important (TABLE 26-10).

1. Antiepileptics & contraceptives

Many antiepileptic medications decrease the efficacy of certain contraceptives

Contraception management in women with epilepsy is critical due to potential maternal and fetal complications. Many antiepileptic drugs (AEDs), including carbamazepine, ethosuximide, fosphenytoin, phenobarbital, phenytoin, primidone, topiramate, and valproate, are potentially teratogenic.11 A retrospective, observational study of 115 women of childbearing age who had epilepsy and were seen at a neurology clinic found that 74% were not using documented contraception.11 Of the minority of study participants using contraception, most were using oral contraceptives (OCs) that could potentially interact with AEDs.

CYP inducers. Estrogen and progesterone are metabolized by the cytochrome P450 3A4 enzyme. Some AEDs induce this enzyme, which can enhance the metabolism of OCs, thus reducing their efficacy.12 It is not known, however, if this interaction results in increased pregnancy rates.13 Most newer AEDs (TABLE 36) do not induce cytochrome P450 3A4 and, thus, do not appear to affect OC efficacy, and may be safer for women with seizure disorders.12 While enzyme-inducing AEDs may decrease the efficacy of progesterone-only OCs and the morning-after pill,12,14,15 progesterone-containing intrauterine devices (IUDs), long-acting progesterone injections, and non-hormonal contraceptive methods appear to be unaffected.14-17

OCs and seizure frequency. There is no strong evidence that OCs affect seizure frequency in epileptic women, although changes in hormone levels during the menstrual cycle do affect seizure susceptibility.12 Combination OCs decrease lamotrigine levels and, therefore, may increase the risk of seizures, but progesterone-only pills do not produce this effect.12,16

Do guidelines exist? There are no specific evidence-based guidelines that pertain to the use of AEDs and contraception together, but some organizations have issued recommendations.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends using a 30- to 35-mcg estrogen-containing OC rather than a lower dose in women taking an enzyme-inducing AED. The group also recommends using condoms with OCs or using IUDs.18

The American Academy of Neurology suggests that women taking OCs and enzyme-inducing AEDs use an OC containing at least 50 mcg estrogen.19

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommends that women taking enzyme-inducing AEDs avoid progestin-only pills.20

The Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare agrees that enzyme-inducing drugs may decrease efficacy and recommend considering IUDs and injectable contraceptive methods.21

2. SSRIs & NSAIDs.

SSRIs increase the GI bleeding risk associated with NSAIDs alone

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are commonly prescribed worldwide.22,23 A well-established adverse effect of NSAIDs is gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding, and there is increasing evidence that concomitant use of an SSRI can further increase that risk through a variety of mechanisms.23

SSRIs decrease platelet serotonin levels resulting in defective platelet aggregation and impaired hemostasis. Studies have also shown that SSRIs increase gastric acidity, which leads to increased risk of peptic ulcer disease and GI bleeding.23 These mechanisms, combined with the inhibition of gastroprotective prostaglandin cyclooxygenase-1 and platelets by NSAIDs, further potentiate GI bleeding risk.24

Patients at high risk for bleeding with concomitant SSRIs and NSAIDs include older patients, patients with other risk factors for GI bleeding (eg, chronic steroid use), and patients with a history of GI bleeding.23

The evidence. A 2014 meta-analysis found that when SSRIs were used in combination with NSAIDs, the risk of GI bleeding was significantly increased, compared with SSRI monotherapy.23

Case control studies found the risk of upper GI bleeding with SSRIs had a number needed to harm (NNH) of 3177 for a low-risk population and 881 for a high-risk population with an odds ratio (OR) of 1.66 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.44-1.92; P<.00001).23 When SSRIs were used in combination with NSAIDs, the NNH decreased to 645 for a low-risk population and 179 for a high-risk population (OR=4.25; 95% CI, 2.82-6.42; P<.0001).23

Another meta-analysis found that the OR for bleeding risk increased to 6.33 (95% CI, 3.40-11.8; P<.00001; NNH=106) with concomitant use of NSAIDs and SSRIs, compared with 2.36 (95% CI, 1.44-3.85; P=.0006; NNH=411) for SSRI use alone.25

The studies did not evaluate results based on the indication, dose, or duration of SSRI or NSAID treatment. If both an SSRI and an NSAID must be used, select a cyclooxygenase-2 selective NSAID at the lowest effective dose and consider the addition of a proton pump inhibitor to decrease the risk of a GI bleed.23,26

3. Direct oral anticoagulants and antiepileptics

Don’t use DOACs in patients taking certain antiepileptic medications

Drug interactions with anticoagulants, such as warfarin, are well documented and have been publicized for years, but physicians must also be aware of the potential for interaction between the direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) and AEDs.

Apixaban, rivaroxaban, and dabigatran appear to interact withthe AEDs carbamazepine, phenytoin, and phenobarbital.27,28 These interactions occur due to AED induction of the CYP3A4 enzyme and effects on the P-glycoprotein (P-gp) efflux pump.27,29 When taken together, the AED induces metabolism and elimination of the DOAC medication to occur more quickly than it would normally, resulting in subtherapeutic concentrations of the DOAC. This could theoretically result in a venous thromboembolic event or stroke.

A caveat. One thing to consider is that studies demonstrating interaction between the DOAC and AED drug classes have been performed in healthy volunteers, making it difficult to extrapolate how this interaction may increase the risk for thrombotic events in other patients.

Some studies demonstrated reductions in drug levels of up to 50% with strong CYP3A4 and P-glycoprotein inducers.30 Common inducers include carbamazepine, rifampin, and St. John’s Wort.6 Patients taking such agents could theoretically have decreased exposure to the DOAC, resulting in an increase in thromboembolic risk.31

4. Statins & certain CYP inhibitors

Combining simvastatin with fibrates warrants extra attention

The efficacy of statin medications in the prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) is clear. However, the clinical significance of many identified drug interactions involving statins is difficult to interpret. Interactions that cause increased serum concentrations of statins can increase the risk for liver enzyme elevations and skeletal muscle abnormalities (myalgias to rhabdomyolysis).32 Strong inhibitors of CYP3A4 (amiodarone, cyclosporine, ketoconazole, etc.) significantly increase concentrations of lovastatin, simvastatin, and atorvastatin. Pitavastatin, pravastatin, and rosuvastatin are not susceptible to any CYP-mediated drug interactions;33 therefore, rosuvastatin (a high-intensity statin) is usually recommended over other statins for patients taking strong inhibitors of CYP3A4.

When to limit simvastatin. Doses of simvastatin should not exceed 10 mg/d when combined with diltiazem, dronedarone, or verapamil, and doses should not exceed 20 mg/d when used with amiodarone, amlodipine, or ranolazine.6 These recommendations are in response to results from the SEARCH (Study of the Effectiveness of Additional Reductions in cholesterol and homocysteine) trial, which found a higher incidence of myopathies and rhabdomyolysis in patients taking 80 mg of simvastatin compared with those taking 20-mg doses.34 CYP3A4-inducing medications, especially diltiazem, were thought to also contribute to an increased risk.34

Avoid gemfibrozil with statins. Using fibrates with statins is beneficial for some patients; however, gemfibrozil significantly interacts with statins by inhibiting CYP2C8 and organic anion transporting polypeptide 1B1 (OATP1B1).33 The safer choice is fenofibrate because it does not interfere with statin metabolism and can be safely used in combination with statins.6

A retrospective review of the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (AERS) database found that 88% of fibrate and statin combinations that resulted in rhabdomyolysis were associated with gemfibrozil/cerivastatin (cerivastatin is no longer available in the United States).35

5. One serotonergic drug & another

Serotonin syndrome is associated with more than just SSRIs

Serotonin syndrome is a constellation of symptoms (hyperthermia, hyperreflexia, muscle clonus, tremor and altered mental status) caused by increases in serotonin levels in the central and peripheral nervous systems that can lead to mild or life-threatening complications such as seizures, muscle breakdown, or hyperthermia. Serotonin syndrome is most likely to occur within 24 hours after a dose increase, after starting a new medication that increases serotonin levels, or after a drug overdose.36

SSRIs are the most commonly reported drug associated with serotonin syndrome; however, other medications (TABLE 437) may be responsible, especially when used in combination with agents that act on serotonin receptors or in patients with impaired metabolism of the drugs being used.37

Other culprits. Serotonergic effects can also be associated with illicit drugs, some nonprescription medications, and supplements. And in March 2016, the FDA issued a warning about the risks of taking opioids with serotonergic medications.38 Although labeling changes have been recommended for all opioids, the cases of serotonin syndrome were reported more often with normal doses of fentanyl and methadone.

There are 2 mechanisms by which drugs may increase a patient’s risk for serotonin syndrome. The first is a pharmacodynamic interaction, which can occur when 2 or more medications act at the same receptor site (serotonin receptors in this example), which may result in an additive or synergistic effect.39

The second mechanism is a pharmacokinetic alteration (an agent alters absorption, distribution, metabolism, or excretion) of CYP enzymes.40 Of the more commonly used antidepressants, citalopram, escitalopram, venlafaxine, and mirtazapine seem to have the least potential for clinically significant pharmacokinetic interactions.41

Guidelines? Currently there are no guidelines for preventing serotonin syndrome. Clinicians should exercise caution in patients at high risk for drug adverse events, such as the elderly, patients taking multiple medications, and patients with comorbidities. Healthy low-risk patients can generally take 2 or 3 serotonergic medications at therapeutic doses without a major risk of harm.

CORRESPONDENCE

Mary Onysko, PharmD, BCPS, 191 East Orchard Road, Suite 200, Littleton, CO 80121; [email protected].

There is a strong relationship between the number of medications taken and the likelihood of a potentially serious drug-drug interaction.1,2 Drug interaction software programs can help alert prescribers to potential problems, but these programs sometimes fail to detect important interactions or generate so many clinically insignificant alerts that they become a nuisance.3 This review provides guidance about 5 clinically relevant drug interactions, including those that are common (TABLE 14-6)—and those that are less common, but no less important (TABLE 26-10).

1. Antiepileptics & contraceptives

Many antiepileptic medications decrease the efficacy of certain contraceptives

Contraception management in women with epilepsy is critical due to potential maternal and fetal complications. Many antiepileptic drugs (AEDs), including carbamazepine, ethosuximide, fosphenytoin, phenobarbital, phenytoin, primidone, topiramate, and valproate, are potentially teratogenic.11 A retrospective, observational study of 115 women of childbearing age who had epilepsy and were seen at a neurology clinic found that 74% were not using documented contraception.11 Of the minority of study participants using contraception, most were using oral contraceptives (OCs) that could potentially interact with AEDs.

CYP inducers. Estrogen and progesterone are metabolized by the cytochrome P450 3A4 enzyme. Some AEDs induce this enzyme, which can enhance the metabolism of OCs, thus reducing their efficacy.12 It is not known, however, if this interaction results in increased pregnancy rates.13 Most newer AEDs (TABLE 36) do not induce cytochrome P450 3A4 and, thus, do not appear to affect OC efficacy, and may be safer for women with seizure disorders.12 While enzyme-inducing AEDs may decrease the efficacy of progesterone-only OCs and the morning-after pill,12,14,15 progesterone-containing intrauterine devices (IUDs), long-acting progesterone injections, and non-hormonal contraceptive methods appear to be unaffected.14-17

OCs and seizure frequency. There is no strong evidence that OCs affect seizure frequency in epileptic women, although changes in hormone levels during the menstrual cycle do affect seizure susceptibility.12 Combination OCs decrease lamotrigine levels and, therefore, may increase the risk of seizures, but progesterone-only pills do not produce this effect.12,16

Do guidelines exist? There are no specific evidence-based guidelines that pertain to the use of AEDs and contraception together, but some organizations have issued recommendations.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends using a 30- to 35-mcg estrogen-containing OC rather than a lower dose in women taking an enzyme-inducing AED. The group also recommends using condoms with OCs or using IUDs.18

The American Academy of Neurology suggests that women taking OCs and enzyme-inducing AEDs use an OC containing at least 50 mcg estrogen.19

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommends that women taking enzyme-inducing AEDs avoid progestin-only pills.20

The Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare agrees that enzyme-inducing drugs may decrease efficacy and recommend considering IUDs and injectable contraceptive methods.21

2. SSRIs & NSAIDs.

SSRIs increase the GI bleeding risk associated with NSAIDs alone

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are commonly prescribed worldwide.22,23 A well-established adverse effect of NSAIDs is gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding, and there is increasing evidence that concomitant use of an SSRI can further increase that risk through a variety of mechanisms.23

SSRIs decrease platelet serotonin levels resulting in defective platelet aggregation and impaired hemostasis. Studies have also shown that SSRIs increase gastric acidity, which leads to increased risk of peptic ulcer disease and GI bleeding.23 These mechanisms, combined with the inhibition of gastroprotective prostaglandin cyclooxygenase-1 and platelets by NSAIDs, further potentiate GI bleeding risk.24

Patients at high risk for bleeding with concomitant SSRIs and NSAIDs include older patients, patients with other risk factors for GI bleeding (eg, chronic steroid use), and patients with a history of GI bleeding.23

The evidence. A 2014 meta-analysis found that when SSRIs were used in combination with NSAIDs, the risk of GI bleeding was significantly increased, compared with SSRI monotherapy.23

Case control studies found the risk of upper GI bleeding with SSRIs had a number needed to harm (NNH) of 3177 for a low-risk population and 881 for a high-risk population with an odds ratio (OR) of 1.66 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.44-1.92; P<.00001).23 When SSRIs were used in combination with NSAIDs, the NNH decreased to 645 for a low-risk population and 179 for a high-risk population (OR=4.25; 95% CI, 2.82-6.42; P<.0001).23

Another meta-analysis found that the OR for bleeding risk increased to 6.33 (95% CI, 3.40-11.8; P<.00001; NNH=106) with concomitant use of NSAIDs and SSRIs, compared with 2.36 (95% CI, 1.44-3.85; P=.0006; NNH=411) for SSRI use alone.25

The studies did not evaluate results based on the indication, dose, or duration of SSRI or NSAID treatment. If both an SSRI and an NSAID must be used, select a cyclooxygenase-2 selective NSAID at the lowest effective dose and consider the addition of a proton pump inhibitor to decrease the risk of a GI bleed.23,26

3. Direct oral anticoagulants and antiepileptics

Don’t use DOACs in patients taking certain antiepileptic medications

Drug interactions with anticoagulants, such as warfarin, are well documented and have been publicized for years, but physicians must also be aware of the potential for interaction between the direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) and AEDs.

Apixaban, rivaroxaban, and dabigatran appear to interact withthe AEDs carbamazepine, phenytoin, and phenobarbital.27,28 These interactions occur due to AED induction of the CYP3A4 enzyme and effects on the P-glycoprotein (P-gp) efflux pump.27,29 When taken together, the AED induces metabolism and elimination of the DOAC medication to occur more quickly than it would normally, resulting in subtherapeutic concentrations of the DOAC. This could theoretically result in a venous thromboembolic event or stroke.

A caveat. One thing to consider is that studies demonstrating interaction between the DOAC and AED drug classes have been performed in healthy volunteers, making it difficult to extrapolate how this interaction may increase the risk for thrombotic events in other patients.

Some studies demonstrated reductions in drug levels of up to 50% with strong CYP3A4 and P-glycoprotein inducers.30 Common inducers include carbamazepine, rifampin, and St. John’s Wort.6 Patients taking such agents could theoretically have decreased exposure to the DOAC, resulting in an increase in thromboembolic risk.31

4. Statins & certain CYP inhibitors

Combining simvastatin with fibrates warrants extra attention

The efficacy of statin medications in the prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) is clear. However, the clinical significance of many identified drug interactions involving statins is difficult to interpret. Interactions that cause increased serum concentrations of statins can increase the risk for liver enzyme elevations and skeletal muscle abnormalities (myalgias to rhabdomyolysis).32 Strong inhibitors of CYP3A4 (amiodarone, cyclosporine, ketoconazole, etc.) significantly increase concentrations of lovastatin, simvastatin, and atorvastatin. Pitavastatin, pravastatin, and rosuvastatin are not susceptible to any CYP-mediated drug interactions;33 therefore, rosuvastatin (a high-intensity statin) is usually recommended over other statins for patients taking strong inhibitors of CYP3A4.

When to limit simvastatin. Doses of simvastatin should not exceed 10 mg/d when combined with diltiazem, dronedarone, or verapamil, and doses should not exceed 20 mg/d when used with amiodarone, amlodipine, or ranolazine.6 These recommendations are in response to results from the SEARCH (Study of the Effectiveness of Additional Reductions in cholesterol and homocysteine) trial, which found a higher incidence of myopathies and rhabdomyolysis in patients taking 80 mg of simvastatin compared with those taking 20-mg doses.34 CYP3A4-inducing medications, especially diltiazem, were thought to also contribute to an increased risk.34

Avoid gemfibrozil with statins. Using fibrates with statins is beneficial for some patients; however, gemfibrozil significantly interacts with statins by inhibiting CYP2C8 and organic anion transporting polypeptide 1B1 (OATP1B1).33 The safer choice is fenofibrate because it does not interfere with statin metabolism and can be safely used in combination with statins.6

A retrospective review of the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (AERS) database found that 88% of fibrate and statin combinations that resulted in rhabdomyolysis were associated with gemfibrozil/cerivastatin (cerivastatin is no longer available in the United States).35

5. One serotonergic drug & another

Serotonin syndrome is associated with more than just SSRIs

Serotonin syndrome is a constellation of symptoms (hyperthermia, hyperreflexia, muscle clonus, tremor and altered mental status) caused by increases in serotonin levels in the central and peripheral nervous systems that can lead to mild or life-threatening complications such as seizures, muscle breakdown, or hyperthermia. Serotonin syndrome is most likely to occur within 24 hours after a dose increase, after starting a new medication that increases serotonin levels, or after a drug overdose.36

SSRIs are the most commonly reported drug associated with serotonin syndrome; however, other medications (TABLE 437) may be responsible, especially when used in combination with agents that act on serotonin receptors or in patients with impaired metabolism of the drugs being used.37

Other culprits. Serotonergic effects can also be associated with illicit drugs, some nonprescription medications, and supplements. And in March 2016, the FDA issued a warning about the risks of taking opioids with serotonergic medications.38 Although labeling changes have been recommended for all opioids, the cases of serotonin syndrome were reported more often with normal doses of fentanyl and methadone.

There are 2 mechanisms by which drugs may increase a patient’s risk for serotonin syndrome. The first is a pharmacodynamic interaction, which can occur when 2 or more medications act at the same receptor site (serotonin receptors in this example), which may result in an additive or synergistic effect.39

The second mechanism is a pharmacokinetic alteration (an agent alters absorption, distribution, metabolism, or excretion) of CYP enzymes.40 Of the more commonly used antidepressants, citalopram, escitalopram, venlafaxine, and mirtazapine seem to have the least potential for clinically significant pharmacokinetic interactions.41

Guidelines? Currently there are no guidelines for preventing serotonin syndrome. Clinicians should exercise caution in patients at high risk for drug adverse events, such as the elderly, patients taking multiple medications, and patients with comorbidities. Healthy low-risk patients can generally take 2 or 3 serotonergic medications at therapeutic doses without a major risk of harm.

CORRESPONDENCE

Mary Onysko, PharmD, BCPS, 191 East Orchard Road, Suite 200, Littleton, CO 80121; [email protected].

1. Aparasu R, Baer R, Aparasu A. Clinically important potential drug-drug interactions in outpatient settings. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2007;3:426-437.

2. Johnell K, Klarin I. The relationship between number of drugs and potential drug-drug interactions in the elderly: a study of over 600,000 elderly patients from the Swedish Prescribed Drug Register. Drug Saf. 2007;30:911-918.

3. Pharmacist’s Letter. Online continuing medical education and webinars. Drug interaction overload: Problems and solutions for drug interaction alerts. Volume 2012, Course No. 216. Self-Study Course #120216. Available at: http://pharmacistsletter.therapeuticresearch.com/ce/cecourse.aspx?pc=15-219&quiz=1. Accessed June 9, 2016.

4. PL Detail-Document, Potassium and Anticholinergic Drug Interaction. Pharmacist’s Letter/Prescriber’s Letter. October 2011.

5. Micromedex Solutions. Available at: http://www.micromedexsolutions.com. Accessed May 3, 2016.

6. Lexi-Comp Online. Available at: http://online.lexi.com/lco/action/home. Accessed May 22, 2016.

7. Marcus FI. Drug interactions with amiodarone. Am Heart J. 1983;106(4 Pt 2):924-930.

8. Digoxin: serious drug interactions. Prescrire Int. 2010;19:68-70.

9. McCance-Katz EF, Sullivan LE, Nallani S. Drug interactions of clinical importance among the opioids, methadone and buprenorphine, and other frequently prescribed medications: a review. Am J Addict. 2010;19:4-16.

10. Drugs.com. Theophylline drug interactions. Available at: https://www.drugs.com/drug-interactions/theophylline.html. Accessed June 23, 2016.

11. Bhakta J, Bainbridge J, Borgelt L. Teratogenic medications and concurrent contraceptive use in women of childbearing ability with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2015;52(Pt A):212-217.

12. Reddy DS. Clinical pharmacokinetic interactions between antiepileptic drugs and hormonal contraceptives. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2010;3:183-192.

13. Carl JS, Weaver SP, Tweed E. Effect of antiepileptic drugs on oral contraceptives. Am Fam Physician. 2008;78:634-635.

14. O’Brien MD, Guillebaud J. Contraception for women with epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2006;47:1419-1422.

15. Schwenkhagen AM, Stodieck SR. Which contraception for women with epilepsy? Seizure. 2008;17:145-150.

16. Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare Clinical Effectiveness Unit. Antiepileptic drugs and contraception. CEU statement. January 2010. Available at: https://www.fsrh.org/standards-and-guidance/documents/ceu-clinical-guidance-drug-interactions-with-hormonal/. Accessed April 25, 2016.

17. Perruca E. Clinically relevant drug interactions with antiepileptic drugs. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;61:246-255.

18. ACOG practice bulletin. Number 73: Use of hormonal contraception in women with coexisting medical conditions. ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins-Gynecology. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107:1453-1472.

19. Report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Practice parameter: management issues for women with epilepsy (summary statement). Neurology. 1998;51:944-948.

20. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Do not do recommendation. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/donotdo/the-progestogenonly-pill-is-not-recommended-as-reliable-contraception-inwomen-and-girls-taking-enzymeinducing-anti-epileptic-drugs-aeds. Accessed September 21, 2017.

21. Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare. Clinical guidance: drug interactions with hormonal contraception. Available at: https://www.fsrh.org/standards-and-guidance/documents/ceu-clinical-guidance-drug-interactions-with-hormonal/. Accessed September 21, 2017.

22. de Jong JCF, van den Berg PB, Tobi H, et al. Combined use of SSRIs and NSAIDs increases the risk of gastrointestinal adverse effects. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2003;55:591-595.

23. Anglin R, Yuan Y, Moayyedi P, et al. Risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors with or without concurrent nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory use: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:811-819.

24. Mort JR, Aparasu RR, Baer RK, et al. Interaction between selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: review of the literature. Pharmacotherapy. 2006;26:1307-1313.

25. Loke YK, Trivedi AN, Singh S. Meta-analysis: gastrointestinal bleeding due to interaction between selective serotonin uptake inhibitors and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27:31-40.

26. Venerito M, Wex T, Malfertheiner P. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced gastroduodenal bleeding: risk factors and prevention strategies. Pharmaceuticals. 2010;3:2225-2237.

27. Boehringer S, Williams CD, Yawn BP, et al. Managing interactions with direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs). Pharmacist’s Letter. May 2016.

28. Johannessen SI, Landmark CJ. Antiepileptic drug interactions – principles and clinical implications. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2010;8:254-267.

29. Mohrien K, Oliphant CS, Self TH. Drug interactions with novel oral anticoagulants. Consultant. 2013;53:918-919. Available at: http://www.consultant360.com/articles/drug-interactions-novel-oral-anticoagulants. Accessed May 3, 2016.

30. Wiggins BS, Northup A, Johnson D, et al. Reduced anticoagulant effect of dabigatran in a patient receiving concomitant phenytoin. Pharmacotherapy. 2016;36:e5-e7.

31. Burnett AE, Mahan CE, Vazquez SR, et al. Guidance for the practical management of the direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) in VTE treatment. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2016;41:206-232.

32. Thompson PD, Clarkson P, Karas RH. Statin-associated myopathy. JAMA. 2003;289:1681-1690.

33. Hirota T, Leiri I. Drug-drug interactions that interfere with statin metabolism. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2015;11:1435-1447.

34. Study of the Effectiveness of Additional Reductions in Cholesterol and Homocysteine (SEARCH) Collaborative Group. Intensive lowering of LDL cholesterol wih 80 mg versus 20 mg simvastatin daily in 12,064 survivors of myocardial inffarction: a double-blind randomised trial. Lancet. 2010;376:1658-1669.

35. Jones PH, Davidson MH. Reporting rate of rhabdomyolysis with fenofibrate + statin versus gemfibrozil + any statin. Am J Cardiol. 2005;95:120-122.

36. Birmes P, Coppin D, Schmitt L, et al. Serotonin syndrome: a brief review. CMAJ. 2003;168:1439-1442.

37. Boyer EW, Shannon M. The serotonin syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1112-1120.

38. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA warns about several safety issues with opioid pain medicines; requires label changes. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm489676.htm. Accessed June 15, 2016.

39. Sultana J, Spina E, Trifirò G. Antidepressant use in the elderly: the role of pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics in drug safety. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2015;11:883-892.

40. Sproule BA, Naranjo CA, Brenmer KE, et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and CNS drug interactions. A critical review of the evidence. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1997;33:454-471.

41. Spina E, Santoro V, D’Arrigo C. Clinically relevant pharmacokinetic drug interactions with second-generation antidepressants: an update. Clin Ther. 2008;30:1206-1227.

1. Aparasu R, Baer R, Aparasu A. Clinically important potential drug-drug interactions in outpatient settings. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2007;3:426-437.

2. Johnell K, Klarin I. The relationship between number of drugs and potential drug-drug interactions in the elderly: a study of over 600,000 elderly patients from the Swedish Prescribed Drug Register. Drug Saf. 2007;30:911-918.

3. Pharmacist’s Letter. Online continuing medical education and webinars. Drug interaction overload: Problems and solutions for drug interaction alerts. Volume 2012, Course No. 216. Self-Study Course #120216. Available at: http://pharmacistsletter.therapeuticresearch.com/ce/cecourse.aspx?pc=15-219&quiz=1. Accessed June 9, 2016.

4. PL Detail-Document, Potassium and Anticholinergic Drug Interaction. Pharmacist’s Letter/Prescriber’s Letter. October 2011.

5. Micromedex Solutions. Available at: http://www.micromedexsolutions.com. Accessed May 3, 2016.

6. Lexi-Comp Online. Available at: http://online.lexi.com/lco/action/home. Accessed May 22, 2016.

7. Marcus FI. Drug interactions with amiodarone. Am Heart J. 1983;106(4 Pt 2):924-930.

8. Digoxin: serious drug interactions. Prescrire Int. 2010;19:68-70.

9. McCance-Katz EF, Sullivan LE, Nallani S. Drug interactions of clinical importance among the opioids, methadone and buprenorphine, and other frequently prescribed medications: a review. Am J Addict. 2010;19:4-16.

10. Drugs.com. Theophylline drug interactions. Available at: https://www.drugs.com/drug-interactions/theophylline.html. Accessed June 23, 2016.

11. Bhakta J, Bainbridge J, Borgelt L. Teratogenic medications and concurrent contraceptive use in women of childbearing ability with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2015;52(Pt A):212-217.

12. Reddy DS. Clinical pharmacokinetic interactions between antiepileptic drugs and hormonal contraceptives. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2010;3:183-192.

13. Carl JS, Weaver SP, Tweed E. Effect of antiepileptic drugs on oral contraceptives. Am Fam Physician. 2008;78:634-635.

14. O’Brien MD, Guillebaud J. Contraception for women with epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2006;47:1419-1422.

15. Schwenkhagen AM, Stodieck SR. Which contraception for women with epilepsy? Seizure. 2008;17:145-150.

16. Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare Clinical Effectiveness Unit. Antiepileptic drugs and contraception. CEU statement. January 2010. Available at: https://www.fsrh.org/standards-and-guidance/documents/ceu-clinical-guidance-drug-interactions-with-hormonal/. Accessed April 25, 2016.

17. Perruca E. Clinically relevant drug interactions with antiepileptic drugs. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;61:246-255.

18. ACOG practice bulletin. Number 73: Use of hormonal contraception in women with coexisting medical conditions. ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins-Gynecology. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107:1453-1472.

19. Report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Practice parameter: management issues for women with epilepsy (summary statement). Neurology. 1998;51:944-948.

20. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Do not do recommendation. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/donotdo/the-progestogenonly-pill-is-not-recommended-as-reliable-contraception-inwomen-and-girls-taking-enzymeinducing-anti-epileptic-drugs-aeds. Accessed September 21, 2017.

21. Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare. Clinical guidance: drug interactions with hormonal contraception. Available at: https://www.fsrh.org/standards-and-guidance/documents/ceu-clinical-guidance-drug-interactions-with-hormonal/. Accessed September 21, 2017.

22. de Jong JCF, van den Berg PB, Tobi H, et al. Combined use of SSRIs and NSAIDs increases the risk of gastrointestinal adverse effects. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2003;55:591-595.

23. Anglin R, Yuan Y, Moayyedi P, et al. Risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors with or without concurrent nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory use: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:811-819.

24. Mort JR, Aparasu RR, Baer RK, et al. Interaction between selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: review of the literature. Pharmacotherapy. 2006;26:1307-1313.

25. Loke YK, Trivedi AN, Singh S. Meta-analysis: gastrointestinal bleeding due to interaction between selective serotonin uptake inhibitors and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27:31-40.

26. Venerito M, Wex T, Malfertheiner P. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced gastroduodenal bleeding: risk factors and prevention strategies. Pharmaceuticals. 2010;3:2225-2237.

27. Boehringer S, Williams CD, Yawn BP, et al. Managing interactions with direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs). Pharmacist’s Letter. May 2016.

28. Johannessen SI, Landmark CJ. Antiepileptic drug interactions – principles and clinical implications. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2010;8:254-267.

29. Mohrien K, Oliphant CS, Self TH. Drug interactions with novel oral anticoagulants. Consultant. 2013;53:918-919. Available at: http://www.consultant360.com/articles/drug-interactions-novel-oral-anticoagulants. Accessed May 3, 2016.

30. Wiggins BS, Northup A, Johnson D, et al. Reduced anticoagulant effect of dabigatran in a patient receiving concomitant phenytoin. Pharmacotherapy. 2016;36:e5-e7.

31. Burnett AE, Mahan CE, Vazquez SR, et al. Guidance for the practical management of the direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) in VTE treatment. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2016;41:206-232.

32. Thompson PD, Clarkson P, Karas RH. Statin-associated myopathy. JAMA. 2003;289:1681-1690.

33. Hirota T, Leiri I. Drug-drug interactions that interfere with statin metabolism. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2015;11:1435-1447.

34. Study of the Effectiveness of Additional Reductions in Cholesterol and Homocysteine (SEARCH) Collaborative Group. Intensive lowering of LDL cholesterol wih 80 mg versus 20 mg simvastatin daily in 12,064 survivors of myocardial inffarction: a double-blind randomised trial. Lancet. 2010;376:1658-1669.

35. Jones PH, Davidson MH. Reporting rate of rhabdomyolysis with fenofibrate + statin versus gemfibrozil + any statin. Am J Cardiol. 2005;95:120-122.

36. Birmes P, Coppin D, Schmitt L, et al. Serotonin syndrome: a brief review. CMAJ. 2003;168:1439-1442.

37. Boyer EW, Shannon M. The serotonin syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1112-1120.

38. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA warns about several safety issues with opioid pain medicines; requires label changes. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm489676.htm. Accessed June 15, 2016.

39. Sultana J, Spina E, Trifirò G. Antidepressant use in the elderly: the role of pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics in drug safety. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2015;11:883-892.

40. Sproule BA, Naranjo CA, Brenmer KE, et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and CNS drug interactions. A critical review of the evidence. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1997;33:454-471.

41. Spina E, Santoro V, D’Arrigo C. Clinically relevant pharmacokinetic drug interactions with second-generation antidepressants: an update. Clin Ther. 2008;30:1206-1227.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

› Recommend progesterone-containing intrauterine devices or long-acting progesterone injections for women using antiepileptic drugs. B

› Be aware that there is an increased risk of gastrointestinal bleeding when nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are used with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. A

› Do not prescribe novel oral anticoagulants for patients taking carbamazepine, phenytoin, or phenobarbital. B

› Choose fenofibrate over gemfibrozil when combining a fibrate and a statin. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

Contraceptive care best practices

While the unintended pregnancy rate for women ages 15 to 44 years decreased by 18% between 2008 and 2011, almost half of pregnancies in the United States remain unintended.1 On a more positive note, however, women who use birth control consistently and correctly account for only 5% of unintended pregnancies.2 As family physicians (FPs), we can support and facilitate our female patients’ efforts to consistently use highly effective forms of contraception. The 5 initiatives detailed here can help toward that end.

1. Routinely screen patients for their reproductive intentions

All women of reproductive age should be screened routinely for their pregnancy intentions. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) encourages clinicians to ask women about pregnancy intendedness and encourages patients to develop a reproductive life plan, or a set of personal goals about whether or when to have children.3 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has also developed a reproductive life plan tool for health professionals to encourage women and men to reflect upon their plans.4 So just as we regularly screen and document cigarette use and blood pressure (BP), so too, should we routinely screen women for their reproductive goals.

Ask women this one question. The Oregon Foundation for Reproductive Health launched the One Key Question Initiative, which proposes that the care team ask women ages 18 to 50: “Would you like to become pregnant in the next year?”5 A common workflow includes the medical assistant asking women about pregnancy intentions and providing a preconception and/or contraceptive handout, if appropriate. The physician provides additional counseling as needed. Pilot studies of One Key Question indicate that 30% to 40% of women screened needed follow-up counseling, suggesting the need for clinicians to be proactive in asking about reproductive plans. (Additional information on the Initiative is available on the Foundation’s Web site at http://www.orfrh.org/.)

This approach assumes women feel in control of their reproduction; however, this may not be the reality for many, especially low-income women.6 Additionally, women commonly cite planning a pregnancy as appropriate only when they are in an ideal relationship and when they are living in a financially stable environment—conditions that some women may never achieve.

Another caveat is that women may not have explicit pregnancy intentions, in which case, this particular approach may not be effective. A study of low-income women found only 60% intended to use the method prescribed after contraception counseling, with 37% of those stopping because of adverse effects, 23% saying they wanted another method, and 17% citing method complexity.7

Reproductive coercion from male partners, ranging from pressure to become pregnant to method sabotage, is also common in low-income women.8 Regular conversations that prioritize a woman’s values and experience are needed to promote reproductive autonomy.

2. Decouple provision of contraception from unnecessary exams

Pelvic exams and pap smears should not be required prior to offering patients hormonal contraception, according to the Choosing Wisely campaign of the American Board of Internal Medicine and ACOG.9,10 Hormonal contraception may instead be provided safely based on a medical history and BP assessment. Adolescents, minority groups, obese women, and victims of sexual trauma, in particular may avoid asking about birth control because of anxiety and fear of pain from these exams.11 The American College of Physicians recommends against speculum and bimanual exams in asymptomatic, non-pregnant, adult women.12 Pap smears and sexually transmitted infection (STI) testing should be performed at their normally scheduled intervals as recommended by the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) and not be tied to contraceptive provision.13

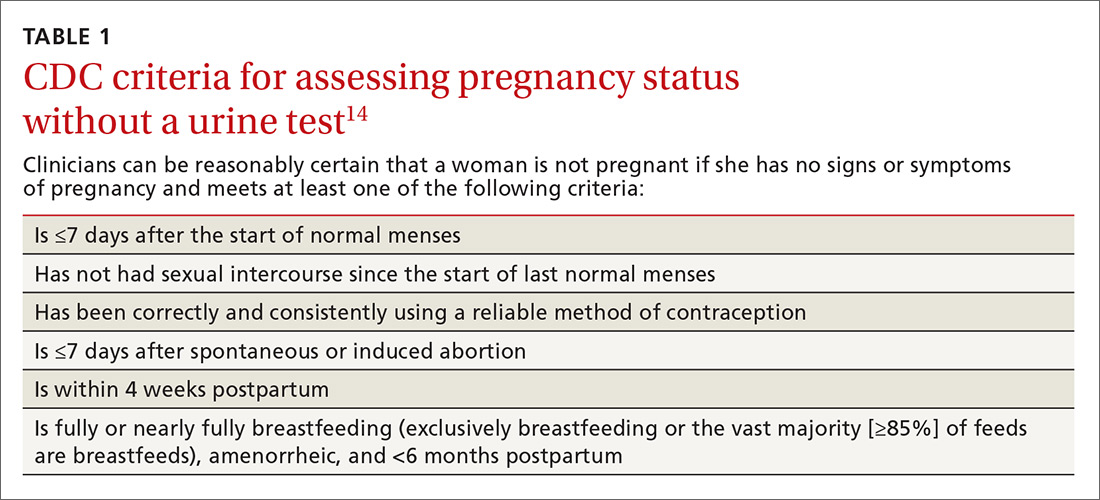

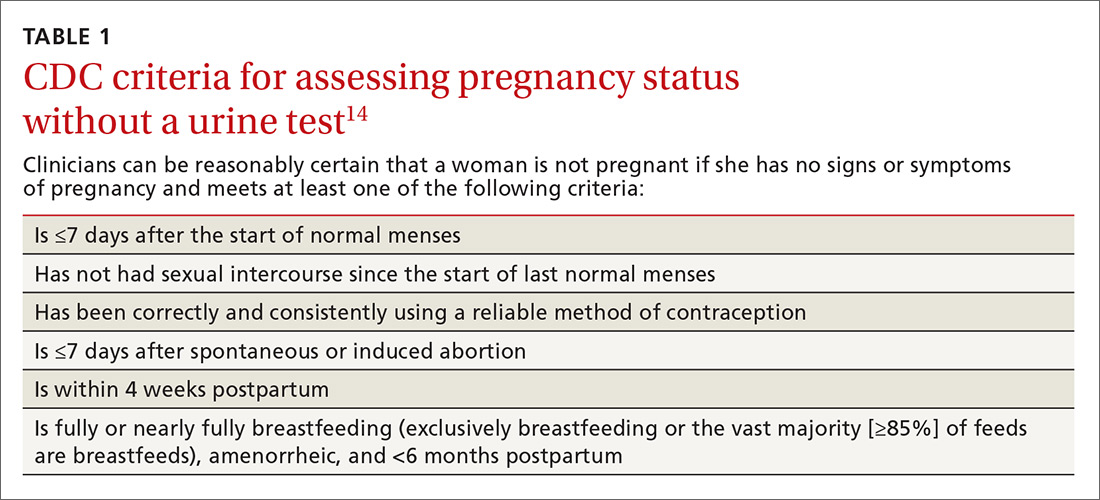

Assess pregnancy status using criteria,rather than a pregnancy text

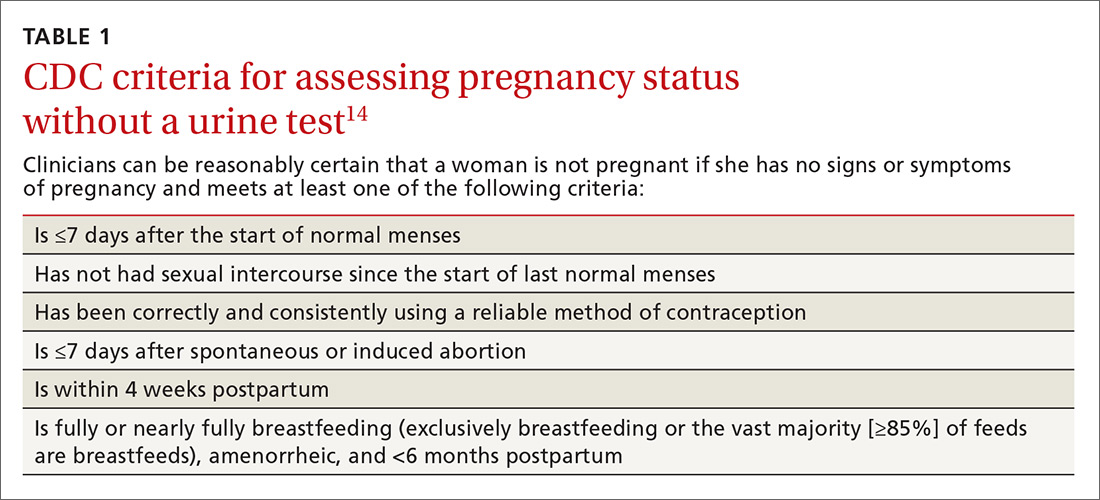

Use the CDC’s criteria to assess pregnancy status rather than relying on a urine pregnancy test prior to providing contraception. Once you are reasonably sure that a woman is not pregnant (TABLE 114), contraception may be started. Some physicians have traditionally requested that a woman delay starting contraception until the next menses to ensure that she is not already pregnant. However, given the evidence that hormonal contraception does not cause birth defects, such a delay is not warranted and puts the woman at risk of an unintended pregnancy during the gap.15

Furthermore, there is an approximate 2-week window in which a woman could have a negative urine pregnancy test despite being pregnant, so the test alone is not completely reliable. In addition, obese women may experience irregular cycles, further complicating the traditional approach.16

Another largely unnecessary step … The US Selected Practice Recommendations (US SPR) from the CDC notes that additional STI screening prior to an intrauterine device (IUD) insertion is unnecessary for most women if appropriate screening guidelines have been previously followed.14 For those who have not been screened according to guidelines, the CDC recommends same-day screening and IUD insertion. You can then treat an STI without removing the IUD. Women with purulent cervicitis or a current chlamydial or gonorrheal infection should delay IUD insertion until after treatment.

3. Expand long-acting reversible contraception counseling and access

Offer long-acting reversible contraception (LARC), such as IUDs and implants, as first-line options for most women. ACOG endorses LARC as the most effective reversible method for most women, including those who have not given birth and adolescents.17 Unfortunately, a 2012 study found that family physicians were less likely than OB-GYNs to have enough time for contraceptive counseling and fewer than half felt competent inserting IUDs.18 While 79% of OB-GYNs routinely discussed IUDs with their patients, only 47% of family physicians did. In 2014, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) endorsed a LARC-first tiered counseling approach for adolescents.19

A test of LARC-first counseling

The Contraceptive CHOICE project, a St. Louis, Missouri-based initiative, was launched to reduce unintended pregnancies in women ages 14 to 45 years by offering LARC-first counseling and free contraception of their choice.20 This project involved more than 9000 women at high risk for unintended pregnancy. Same-day LARC insertion was available. Seventy-five percent of women chose a LARC method and they reported greater continuation at 12 and 24 months, when compared to women who did not choose a LARC method. LARC users also reported higher satisfaction at one year. Provision of contraception through the project contributed to a reduction in repeat abortions as well as decreased rates of teenage pregnancy, birth, and abortion. Three years after the start of the project, IUDs had continuation rates of nearly 70%, implants of 56%, and non-LARC methods of 31%.21

When counseling women, it’s important to remember that effectiveness may not be the only criterium a woman uses when choosing a method. A 2010 study found that for 91% of women at high risk for unintended pregnancy, no single method possessed all the features they deemed “extremely important.”22 Clinicians should take a patient-centered approach to find birth control that fits each patient’s priorities.

Clinicians need proper training in LARC methods

Only 20% of FPs regularly insert IUDs, and 11% offer contraceptive implants, according to estimates from physicians recertifying with the American Board of Family Medicine in 2014.23 Access to training during residency is a key component to increasing these rates. FPs who practice obstetrics should be trained in postpartum LARC insertion and offer this option prior to hospital discharge as well as during the postpartum office visit.

Performing LARC insertions on the same day as counseling is ideal, and clinics should strive to reduce barriers to same-day procedures. Time constraints may be addressed by shifting tasks among the medical team. In the CHOICE project, contraceptive counselors—half of whom had no clinical experience—were trained to provide tiered counseling to participants. By working with a cross-trained health care team and offering prepared resources, clinicians can save time and improve access.

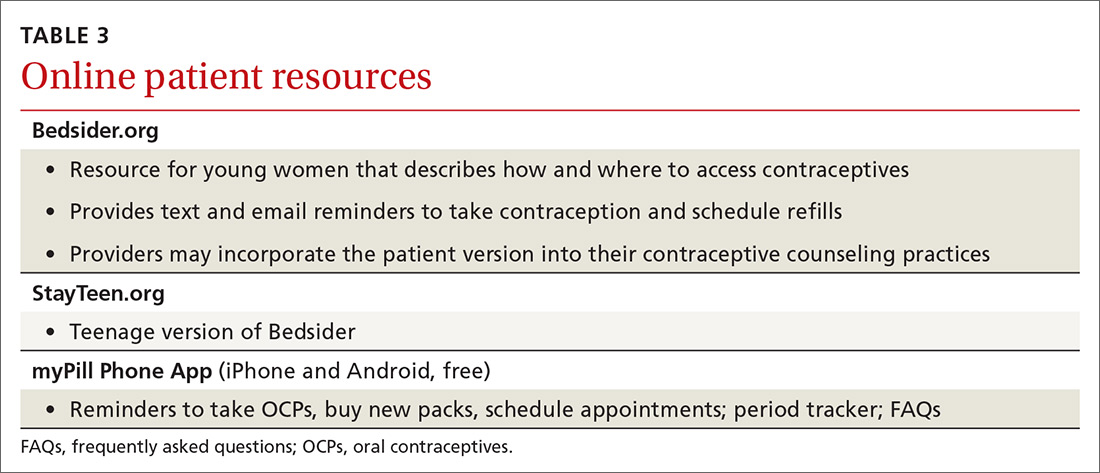

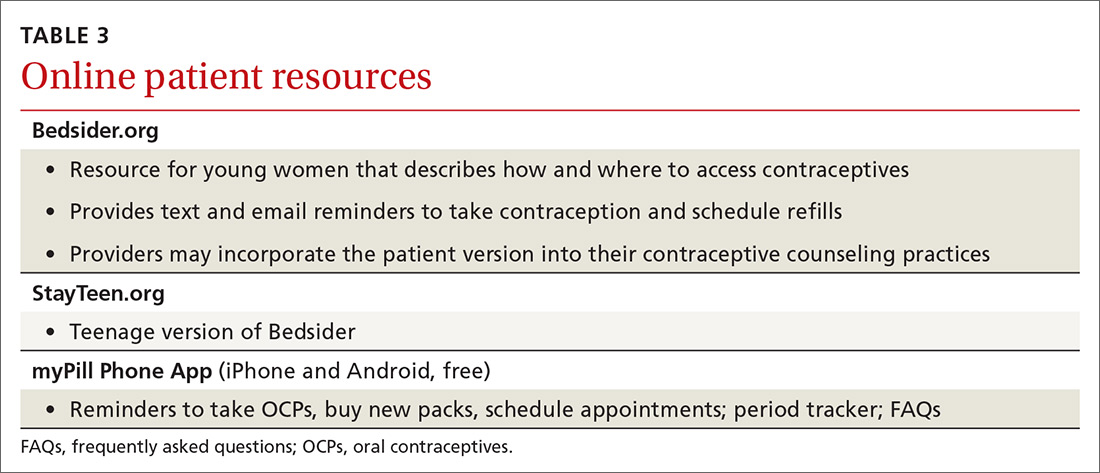

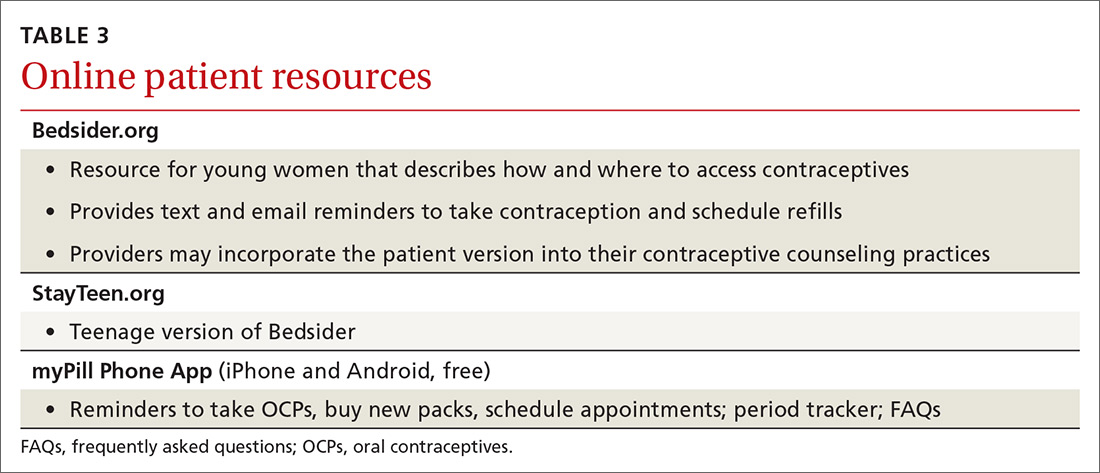

Physicians may want to incorporate the free online resources Bedsider.org or Stayteen.org to help women learn about contraceptive methods.24 The user-friendly Web sites, operated by the National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy, describe various forms of contraception and offer text and email reminders. Incorporating Bedsider into the counseling workflow and discussing the various reminder tools available may improve patients’ knowledge and enhance their compliance.

Additional barriers for practices may include high upfront costs associated with stocking devices. Practices that may be unable to sustain the costs surrounding enhanced contraception counseling and provision can collaborate with family planning clinics that are able to offer same-day services. A study of clinics in California found that Title X clinics were more likely to provide on-site LARC services than non-Title X public and private providers.25

4. Follow CDC guidelines for initiating and continuing contraception

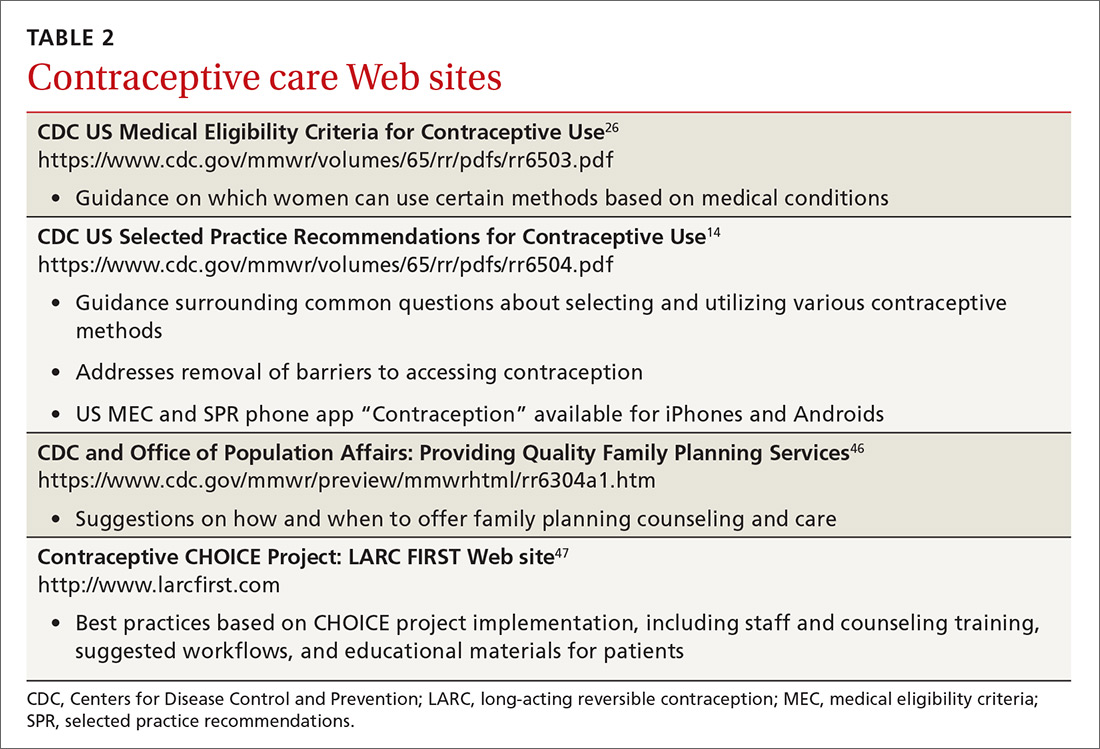

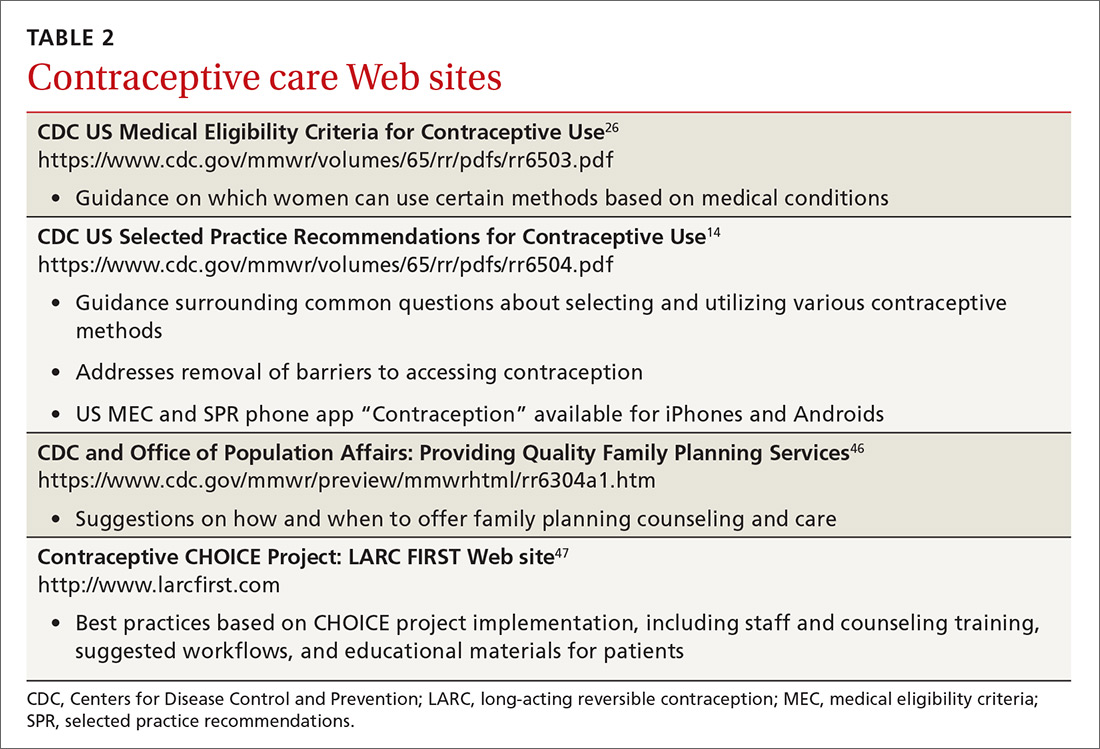

Follow the US SPR for guidance on initiating and continuing contraceptive methods.14 The CDC’s Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use is another vital resource, providing recommendations for contraceptive methods to patients who have specific medical conditions or characteristics.26

Utilize the “quick start” method for hormonal contraception, where birth control is started on the same day as its prescription regardless of timing of the menstrual cycle. If you can’t be reasonably certain that a woman is not pregnant based on the criteria listed in TABLE 1,14 conduct a pregnancy test (while recognizing the aforementioned 2-week window of limitations) and counsel the patient to use back-up protection for the first 7 days along with repeating a pregnancy test in 2 weeks’ time.

The quick start method may lead to higher adherence than delayed initiation.27 Differences in continuation rates between women who use the quick start method and those who follow the delayed approach may disappear over time.28

Prescribe and provide a year’s supply of oral contraceptive pills (OCPs) as recommended by the CDC US SPR.14 It is important to note that pharmacists are usually restricted by insurance companies to only fill a one or 3 month’s supply.

In January 2016, Oregon began requiring private and state health insurance providers to reimburse for a year’s supply of prescription contraception; in January 2017, insurers in Washington, DC, were also required to offer women a year’s supply of prescription contraception.29,30 Several other states have followed suit. The California Health Benefits Review Program estimates a savings of $42.8 million a year from fewer office visits and 15,000 fewer unintended pregnancies if their state enacts a similar policy.31

Pharmacist initiatives are worth watching. In January 2016, Oregon pharmacists with additional training were allowed to prescribe OCs and hormonal patches to women 18 years and older.32 In April 2016, a similar law went into effect in California, but without a minimum age requirement and with the additional coverage of vaginal rings and Depo-Provera (depo) injections.33 Pharmacists in both states must review a health questionnaire completed by the woman and can refer to a physician as necessary.

The CDC recommends that clinicians extend the allowed window for repeat depo injections to 15 weeks.14 Common institutional protocol is to give repeat injections every 11 to 13 weeks. If past that window, protocol often dictates the woman abstain from unprotected sex for 2 weeks and then return for a negative pregnancy test (or await menses) before the next injection. However, the CDC notes that depo is effective for longer than the 13-week period.14 No additional birth control or pregnancy testing is needed and the woman can receive the next depo shot if she is up to 15 weeks from the previous shot.

One study found no additional pregnancy risks for those who were up to 4 weeks “late” for their next shot, suggesting there is potential for an even larger grace period.34 The World Health Organization advises allowing a repeat injection up to 4 weeks late.35 We encourage institutions to change their policies to comply with the CDC’s 15-week window.

Another initiative is over-the-counter (OTC) access to OCs, which the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) and ACOG support.36,37 ACOG notes that “no drug or intervention is completely without risk of harm” and that the risk of venous thromboembolism for OC users is lower than the risk of pregnancy.37 Women can successfully self-screen for contraindications using a checklist. Concerns about women potentially being less adherent or less likely to choose LARCs are not reasons to preclude access to other methods. The AAFP supports insurance coverage of OCs, regardless of prescription status.36

5. Routinely counsel about, and advance-prescribe, emergency contraception pills

Physicians should counsel and advance-prescribe emergency contraception pills (ECPs) to women, including adolescents, using less reliable contraception, as recommended by ACOG, AAP, and the CDC.14,37,38 It’s also important to provide information on the copper IUD as the most effective method of emergency contraception, with nearly 100% efficacy if placed within 5 days.39 An easy-to-read patient hand-out in English and Spanish on EC options can be found at http://beyondthepill.ucsf.edu/tools-materials.

Only 3% of respondents participating in the 2006-2010 National Survey of Family Growth received counseling about emergency contraception in the past year.40 ECPs are most effective when used within 24 hours but have some efficacy up to 5 days.37 Due to the Affordable Care Act, most insurance plans will cover ECPs if purchased with a prescription, but coverage varies by state.41 Ulipristal acetate (UPA) ECP is only available with a prescription. Advance prescriptions can alleviate financial burdens on women when they need to access ECPs quickly.

Women should wait at least 5 days before resuming or starting hormonal contraception after taking UPA-based ECP, as it may reduce the ovulation-delaying effect of the ECP.14 For IUDs, implants, and depo, which require a visit to a health care provider, physicians evaluating earlier provision should consider the risks of reduced efficacy against the many barriers to access.

UPA-based ECPs (such as ella) may be more effective for overweight and obese women than levonorgestrel-based ECPs (such as Plan B and Next Choice).14 Consider advance-prescribing UPA ECPs to women with a body mass index (BMI) >25 kg/m2.42 Such considerations are important as the prevalence of obesity in women between 2013 and 2014 was 40.4%.43

In May 2016, the FDA noted that while current data are insufficient regarding whether the effectiveness of levonorgestrel ECPs is reduced in overweight or obese women, there are no safety concerns regarding their use in this population.44 Therefore, a woman with a BMI >25 kg/m2 should use UPA ECPs if available; but if not, she can still use levonorgestrel ECPs. One study, however, has found that UPA ECPs are only as effective as a placebo when BMI is ≥35 kg/m2, at which point a copper IUD may be the only effective form of emergency contraception.45

Transitioning from customary practices to best practices

Following these practical steps, FPs can improve contraceptive care for women. However, to make a significant impact, clinicians must be willing to change customary practices that are based on tradition, routines, or outdated protocols in favor of those based on current evidence.

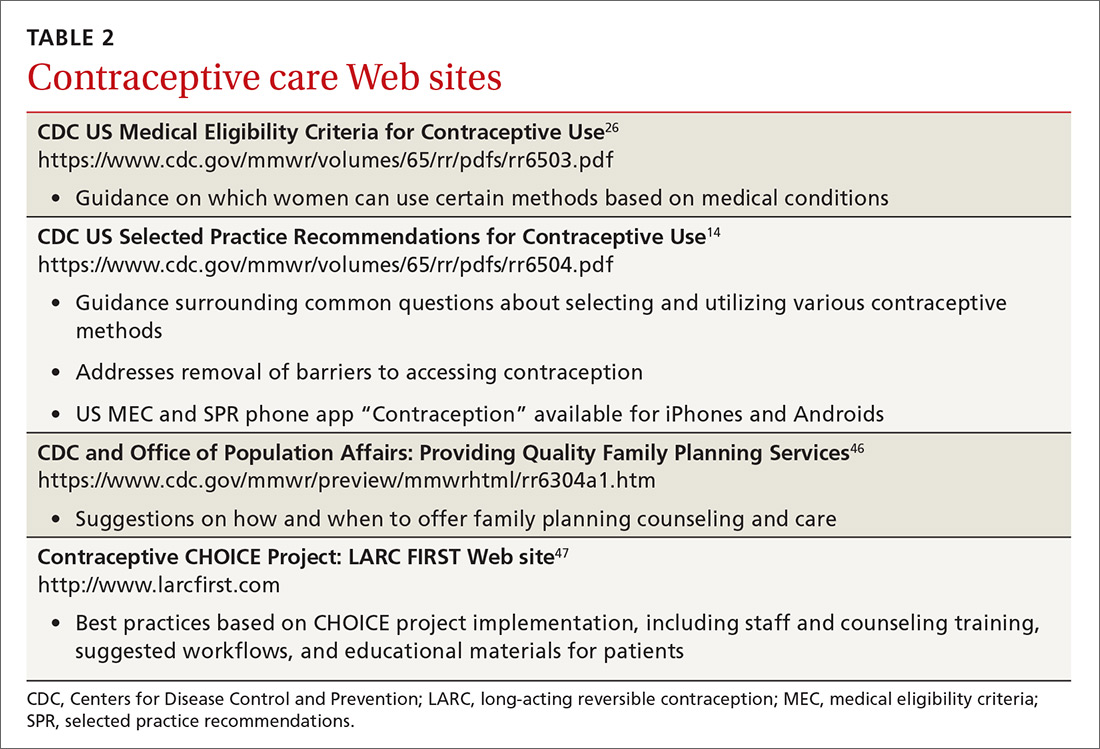

One good place to start the transition to best practices is to familiarize yourself with the 2016 US Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use26 and Selected Practice Recommendations for Contraceptive Use.14 TABLES 214,26,46,47 and 3 offer additional resources that can enhance contraceptive counseling and further promote access to contraceptive care.

The contraceptive coverage guarantee under the Affordable Care Act has allowed many women to make contraceptive choices based on personal needs and preferences rather than cost. The new contraceptive coverage exemptions issued under the Trump administration will bring cost back as the driving decision factor for women whose employers choose not to provide contraceptive coverage. Providers should be aware of the typical costs associated with the various contraceptive options offered in their practice and community.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jessica Dalby, MD, Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, 1102 South Park St, Suite 100, Madison, WI 53715; [email protected].

1. Finer LB, Zolna MR. Declines in unintended pregnancy in the United States, 2008–2011. N Engl J Med. 2016; 374:843-852.

2. Sonfield A, Hasstedt K, Gold RB. Moving Forward: Family Planning in the Era of Health Reform. New York: Guttmacher Institute. 2014. Available at: https://www.guttmacher.org/report/moving-forward-family-planning-era-health-reform. Accessed October 5, 2017.

3. Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women. Reproductive Life Planning to Reduce Unintended Pregnancy: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. 2016. Available at: https://www.acog.org/Resources-And-Publications/Committee-Opinions/Committee-on-Health-Care-for-Underserved-Women/Reproductive-Life-Planning-to-Reduce-Unintended-Pregnancy. Accessed October 5, 2017.

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Reproductive Life Plan Tool for Health Care Providers. 2016. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/preconception/rlptool.html. Accessed August 31, 2016.

5. Oregon Health Authority. Effective Contraceptive Use among Women at Risk of Unintended Pregnancy Guidance Document. 2014. Available at: http://www.oregon.gov/oha/HPA/ANALYTICS/CCOData/Effective%20Contraceptive%20Use%20Guidance%20Document.pdf. Accessed October 5, 2017.

6. Borrero S, Nikolajski C, Steinberg JR, et al. “It just happens”: a qualitative study exploring low-income women’s perspectives on pregnancy intention and planning. Contraception. 2015;91:150-156.

7. Yee LM, Farner KC, King E, et al. What do women want? Experiences of low-income women with postpartum contraception and contraceptive counseling. J Pregnancy Child Health. 2015;2.

8. Kalichman SC, Williams EA, Cherry C, et al. Sexual coercion, domestic violence, and negotiating condom use among low-income African American women. J Womens Health. 1998;7:371-378.

9. ABIM Foundation. Pelvic Exams, Pap Tests and Oral Contraceptives. 2016. Available at: http://www.choosingwisely.org/patient-resources/pelvic-exams-pap-tests-and-oral-contraceptives/. Accessed May 31, 2016.

10. Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women. Access to Contraception: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. 2015. Number 615. Available at: https://www.acog.org/-/media/Committee-Opinions/Committee-on-Health-Care-for-Underserved-Women/co615.pdf?dmc=1&ts=201710. Accessed October 5, 2017.

11. Bates CK, Carroll N, Potter J. The challenging pelvic examination. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26:651-657.

12. Qaseem A, Humphrey LL, Harris R, et al. Screening pelvic examination in adult women: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161:67-72.

13. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Cervical Cancer: Screening. 2012. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/cervical-cancer-screening. Accessed May 25, 2016.

14. Curtis KM, Jatlaoui TC, Tepper NK, et al. U.S. selected practice recommendations for contraceptive use, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:1-66.

15. Lesnewski R, Prine L. Initiating hormonal contraception. Am Fam Physician. 2006;74:105-112.

16. Jacobsen BK, Knutsen SF, Oda K, et al. Obesity at age 20 and the risk of miscarriages, irregular periods and reported problems of becoming pregnant: the Adventist Health Study-2. Eur J Epidemiol. 2012; 27:923-931.

17. Committee on Gynecologic Practice. Increasing Access to Contraceptive Implants and Intrauterine Devices to Reduce Unintended Pregnancy: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. 2015. Number 642. Available at: https://www.acog.org/Resources-And-Publications/Committee-Opinions/Committee-on-Gynecologic-Practice/Increasing-Access-to-Contraceptive-Implants-and-Intrauterine-Devices-to-Reduce-Unintended-Pregnancy. Accessed October 5, 2017.

18. Harper CC, Henderson JT, Raine TR, et al. Evidence-based IUD practice: family physicians and obstetrician-gynecologists. Fam Med. 2012;44:637-645.