User login

Levofloxacin-Induced Purpura Annularis Telangiectodes of Majocchi

To the Editor:

Purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi (PATM) is a type of pigmented purpuric dermatosis (PPD). Patients present with nonblanchable, annular, symmetric, purpuric, and telangiectatic patches, often on the legs, with histology revealing a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate and extravasated erythrocytes.1,2 A variety of medications have been linked to the development of PPD. We describe a case of levofloxacin-induced PATM.

RELATED ARTICLE: Granulomatous Changes Associated With Pigmented Purpuric Dermatosis

A 42-year-old man presented with a rash on the arms, trunk, abdomen, and legs of 1 month’s duration. He reported no associated itching, bleeding, or pain, and no history of a similar rash. He had a history of hypothyroidism and had been taking levothyroxine for years. He had no known allergies and no history of childhood eczema, asthma, or allergic rhinitis. Notably, the rash started shortly after the patient finished a 2-week course of levofloxacin, an antibiotic he had not taken in the past. The patient resided with his wife, 3 children, and a pet dog, and no family members had the rash. Prior to presentation, the patient had tried econazole cream and then triamcinolone acetonide cream 0.5% without any clinical improvement.

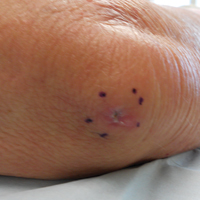

A complete review of systems was unremarkable. Physical examination revealed scattered, reddish brown, annular, nonscaly patches on the back, abdomen (Figure 1), arms, and legs with nonblanching petechiae within the patches.

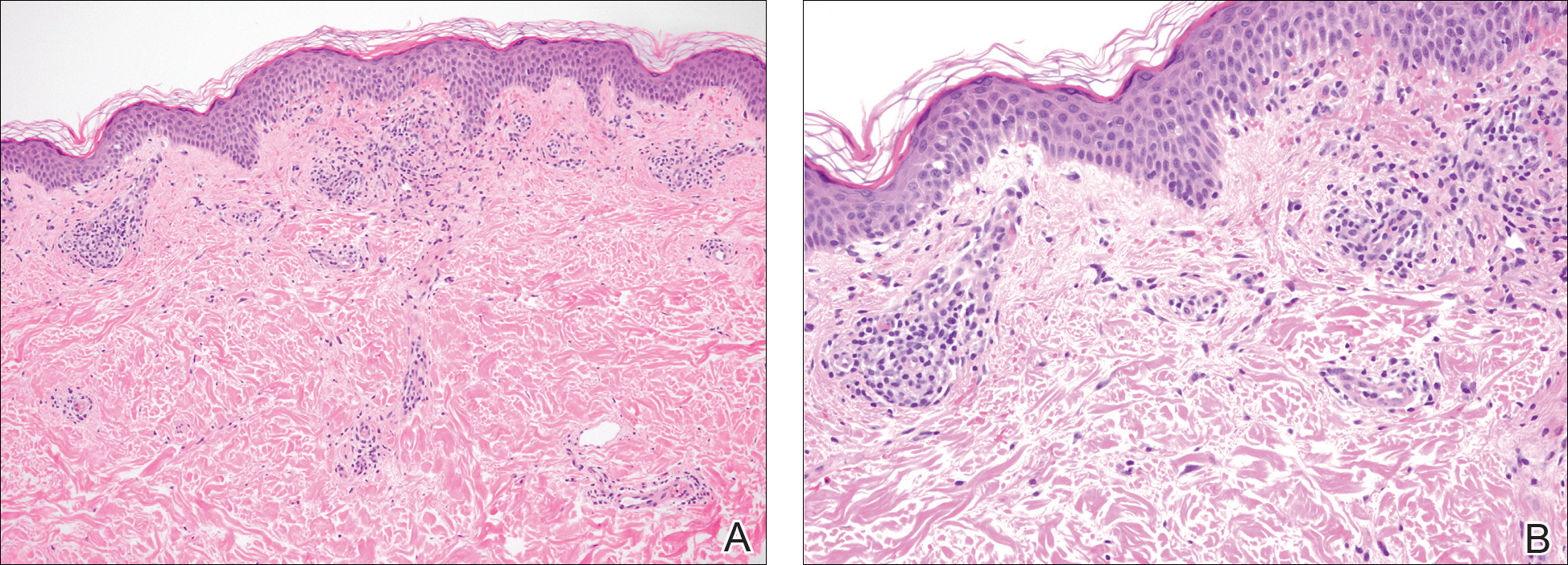

A punch biopsy of the left inner thigh demonstrated patchy interface dermatitis, superficial perivascular inflammation, and numerous extravasated red blood cells in the papillary dermis (Figure 2). The histologic features were compatible with the clinical impression of PATM. The patient presented for a follow-up visit 2 weeks later with no new lesions and the old lesions were rapidly fading (Figure 3).

Pigmented purpuric dermatoses are a group of conditions that have different clinical morphologies but similar histopathologic examinations.2 All PPDs are characterized by nonblanching, nonpalpable, purpuric lesions that often are bilaterally symmetrical and present on the legs.2,3 Although the precise etiology of these conditions is not known, most cases include a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate along with the presence of extravasated erythrocytes and hemosiderin deposition in the dermis.2 Of note, PATM often is idiopathic and patients usually present with no associated comorbidities.3 The currently established PPDs include progressive pigmentary dermatosis (Schamberg disease), PATM, pigmented purpuric lichenoid dermatosis of Gougerot and Blum, lichen aureus, and eczematidlike purpura of Doucas and Kapetanakis.2,4

RELATED ARTICLE: Granulomatous Pigmented Purpuric Dermatosis

The lesions of PATM are symmetrically distributed on the bilateral legs and may be symptomatic in most cases, with severe pruritus being reported in several drug-induced PATM cases.3,5 Although the exact etiology of PPDs currently is unknown, some contributing factors that are thought to play a role include exercise, venous stasis, gravitational dependence, capillary fragility, hypertension, drugs, chemical exposure or ingestions, and contact allergy to dyes.3 Some of the drugs known to cause drug-induced PPDs fall into the class of sedatives, stimulants, antibiotics, cardiovascular drugs, vitamins, and nutritional supplements.3,6 Some medications that have been reported to cause PPDs include acetaminophen, aspirin, carbamazepine, diltiazem, furosemide, glipizide, hydralazine, infliximab, isotretinoin, lorazepam, minocycline, nitroglycerine, and sildenafil.3,7-15

Although the mechanism of drug-induced PPD is not completely understood, it is thought that the ingested substance leads to an immunologic response in the capillary endothelium, which results in a cell-mediated immune response causing vascular damage.3 The ingested substance may act as a hapten, stimulating antibody formation and immune-mediated injury, leading to the clinical presentation of nonblanching, symmetric, purpuric, telangiectatic, and atrophic patches at the site of injury.1,3

Levofloxacin is a broad-spectrum antibiotic that has activity against both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. It inhibits the enzymes DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV, preventing bacteria from undergoing proper DNA synthesis.16 Our patient’s rash began shortly after a 2-week course of levofloxacin and faded within a few weeks of discontinuing the drug; the clinical presentation, time course, and histologic appearance of the lesions were consistent with the diagnosis of drug-induced PPD. Of note, solar capillaritis has been reported following a phototoxic reaction induced by levofloxacin.17 Our case differs in that our patient had annular lesions on both photoprotected and photoexposed skin.

The first-line interventions for the treatment of PPDs are nonpharmacologic, such as discontinuation of an offending drug or allergen or wearing supportive stockings if there are signs of venous stasis. Other interventions include the use of a medium- or high-potency topical corticosteroid once to twice daily to affected areas for 4 to 6 weeks.18 Some case series also have shown improvement with narrowband UVB treatment after 24 to 28 treatment sessions or with psoralen plus UVA phototherapy within 7 to 20 treatments.19,20 If the above measures are unsuccessful in resolving symptoms, other treatment alternatives may include pentoxifylline, griseofulvin, colchicine, cyclosporine, and methotrexate. The potential benefit of treatment must be weighed against the side-effect profile of these medications.2,21-24 Of note, oral rutoside (50 mg twice daily) and ascorbic acid (500 mg twice daily) were administered to 3 patients with chronic progressive pigmented purpura. At the end of the 4-week treatment period, complete clearance of skin lesions was seen in all patients with no adverse reactions noted.25

Despite these treatment options, PATM does not necessitate treatment given its benign course and often self-resolving nature.26 In cases of drug-induced PPD such as in our patient, discontinuation of the offending drug often may lead to resolution.

In summary, PATM is a PPD that has been associated with different etiologic factors. If PATM is suspected to be caused by a drug, discontinuation of the offending agent usually results in resolution of symptoms, as it did in our case with fading of lesions within a few weeks after the patient was no longer taking levofloxacin.

- Hale EK. Purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi. Dermatol Online J. 2003;9:17.

- Hoesly FJ, Huerter CJ, Shehan JM. Purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi: case report and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:1129-1133.

- Kaplan R, Meehan SA, Leger M. A case of isotretinoin-induced purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi and review of substance-induced pigmented purpuric dermatosis. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:182-184.

- Newton RC, Raimer SS. Pigmented purpuric eruptions. Dermatol Clin. 1985;3:165-169.

- Ratnam KV, Su WP, Peters MS. Purpura simplex (inflammatory purpura without vasculitis): a clinicopathologic study of 174 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:642-647.

- Pang BK, Su D, Ratnam KV. Drug-induced purpura simplex: clinical and histological characteristics. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1993;22:870-872.

- Abeck D, Gross GE, Kuwert C, et al. Acetaminophen-induced progressive pigmentary purpura (Schamberg’s disease). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:123-124.

- Lipsker D, Cribier B, Heid E, et al. Cutaneous lymphoma manifesting as pigmented, purpuric capillaries [in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1999;126:321-326.

- Peterson WC Jr, Manick KP. Purpuric eruptions associated with use of carbromal and meprobamate. Arch Dermatol. 1967;95:40-42.

- Nishioka K, Katayama I, Masuzawa M, et al. Drug-induced chronic pigmented purpura. J Dermatol. 1989;16:220-222.

- Voelter WW. Pigmented purpuric dermatosis-like reaction to topical fluorouracil. Arch Dermatol. 1983;119:875-876.

- Adams BB, Gadenne AS. Glipizide-induced pigmented purpuric dermatosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41(5, pt 2):827-829.

- Tsao H, Lerner LH. Pigmented purpuric eruption associated with injection medroxyprogesterone acetate. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43(2, pt 1):308-310.

- Koçak AY, Akay BN, Heper AO. Sildenafil-induced pigmented purpuric dermatosis. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2013;32:91-92.

- Nishioka K, Sarashi C, Katayama I. Chronic pigmented purpura induced by chemical substances. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1980;5:213-218.

- Drlica K, Zhao X. DNA gyrase, topoisomerase IV, and the 4-quinolones. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1997;61:377-392.

- Rubegni P, Feci L, Pellegrino M, et al. Photolocalized purpura during levofloxacin therapy. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2012;28:105-107.

- Sardana K, Sarkar R, Sehgal VN. Pigmented purpuric dermatoses: an overview. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:482-488.

- Fathy H, Abdelgaber S. Treatment of pigmented purpuric dermatoses with narrow-band UVB: a report of six cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:603-606.

- Krizsa J, Hunyadi J, Dobozy A. PUVA treatment of pigmented purpuric lichenoid dermatitis (Gougerot-Blum). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27(5, pt 1):778-780.

- Panda S, Malakar S, Lahiri K. Oral pentoxifylline vs topical betamethasone in Schamberg disease: a comparative randomized investigator-blinded parallel-group trial. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:491-493.

- Tamaki K, Yasaka N, Osada A, et al. Successful treatment of pigmented purpuric dermatosis with griseofulvin. Br J Dermatol. 1995;132:159-160.

- Geller M. Benefit of colchicine in the treatment of Schamberg’s disease. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2000;85:246.

- Okada K, Ishikawa O, Miyachi Y. Purpura pigmentosa chronica successfully treated with oral cyclosporin A. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:180-181.

- Reinhold U, Seiter S, Ugurel S, et al. Treatment of progressive pigmented purpura with oral bioflavonoids and ascorbic acid: an open pilot study in 3 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41(2, pt 1):207-208.

- Wang A, Shuja F, Chan A, et al. Unilateral purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi in an elderly male: an atypical presentation. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:19263.

To the Editor:

Purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi (PATM) is a type of pigmented purpuric dermatosis (PPD). Patients present with nonblanchable, annular, symmetric, purpuric, and telangiectatic patches, often on the legs, with histology revealing a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate and extravasated erythrocytes.1,2 A variety of medications have been linked to the development of PPD. We describe a case of levofloxacin-induced PATM.

RELATED ARTICLE: Granulomatous Changes Associated With Pigmented Purpuric Dermatosis

A 42-year-old man presented with a rash on the arms, trunk, abdomen, and legs of 1 month’s duration. He reported no associated itching, bleeding, or pain, and no history of a similar rash. He had a history of hypothyroidism and had been taking levothyroxine for years. He had no known allergies and no history of childhood eczema, asthma, or allergic rhinitis. Notably, the rash started shortly after the patient finished a 2-week course of levofloxacin, an antibiotic he had not taken in the past. The patient resided with his wife, 3 children, and a pet dog, and no family members had the rash. Prior to presentation, the patient had tried econazole cream and then triamcinolone acetonide cream 0.5% without any clinical improvement.

A complete review of systems was unremarkable. Physical examination revealed scattered, reddish brown, annular, nonscaly patches on the back, abdomen (Figure 1), arms, and legs with nonblanching petechiae within the patches.

A punch biopsy of the left inner thigh demonstrated patchy interface dermatitis, superficial perivascular inflammation, and numerous extravasated red blood cells in the papillary dermis (Figure 2). The histologic features were compatible with the clinical impression of PATM. The patient presented for a follow-up visit 2 weeks later with no new lesions and the old lesions were rapidly fading (Figure 3).

Pigmented purpuric dermatoses are a group of conditions that have different clinical morphologies but similar histopathologic examinations.2 All PPDs are characterized by nonblanching, nonpalpable, purpuric lesions that often are bilaterally symmetrical and present on the legs.2,3 Although the precise etiology of these conditions is not known, most cases include a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate along with the presence of extravasated erythrocytes and hemosiderin deposition in the dermis.2 Of note, PATM often is idiopathic and patients usually present with no associated comorbidities.3 The currently established PPDs include progressive pigmentary dermatosis (Schamberg disease), PATM, pigmented purpuric lichenoid dermatosis of Gougerot and Blum, lichen aureus, and eczematidlike purpura of Doucas and Kapetanakis.2,4

RELATED ARTICLE: Granulomatous Pigmented Purpuric Dermatosis

The lesions of PATM are symmetrically distributed on the bilateral legs and may be symptomatic in most cases, with severe pruritus being reported in several drug-induced PATM cases.3,5 Although the exact etiology of PPDs currently is unknown, some contributing factors that are thought to play a role include exercise, venous stasis, gravitational dependence, capillary fragility, hypertension, drugs, chemical exposure or ingestions, and contact allergy to dyes.3 Some of the drugs known to cause drug-induced PPDs fall into the class of sedatives, stimulants, antibiotics, cardiovascular drugs, vitamins, and nutritional supplements.3,6 Some medications that have been reported to cause PPDs include acetaminophen, aspirin, carbamazepine, diltiazem, furosemide, glipizide, hydralazine, infliximab, isotretinoin, lorazepam, minocycline, nitroglycerine, and sildenafil.3,7-15

Although the mechanism of drug-induced PPD is not completely understood, it is thought that the ingested substance leads to an immunologic response in the capillary endothelium, which results in a cell-mediated immune response causing vascular damage.3 The ingested substance may act as a hapten, stimulating antibody formation and immune-mediated injury, leading to the clinical presentation of nonblanching, symmetric, purpuric, telangiectatic, and atrophic patches at the site of injury.1,3

Levofloxacin is a broad-spectrum antibiotic that has activity against both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. It inhibits the enzymes DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV, preventing bacteria from undergoing proper DNA synthesis.16 Our patient’s rash began shortly after a 2-week course of levofloxacin and faded within a few weeks of discontinuing the drug; the clinical presentation, time course, and histologic appearance of the lesions were consistent with the diagnosis of drug-induced PPD. Of note, solar capillaritis has been reported following a phototoxic reaction induced by levofloxacin.17 Our case differs in that our patient had annular lesions on both photoprotected and photoexposed skin.

The first-line interventions for the treatment of PPDs are nonpharmacologic, such as discontinuation of an offending drug or allergen or wearing supportive stockings if there are signs of venous stasis. Other interventions include the use of a medium- or high-potency topical corticosteroid once to twice daily to affected areas for 4 to 6 weeks.18 Some case series also have shown improvement with narrowband UVB treatment after 24 to 28 treatment sessions or with psoralen plus UVA phototherapy within 7 to 20 treatments.19,20 If the above measures are unsuccessful in resolving symptoms, other treatment alternatives may include pentoxifylline, griseofulvin, colchicine, cyclosporine, and methotrexate. The potential benefit of treatment must be weighed against the side-effect profile of these medications.2,21-24 Of note, oral rutoside (50 mg twice daily) and ascorbic acid (500 mg twice daily) were administered to 3 patients with chronic progressive pigmented purpura. At the end of the 4-week treatment period, complete clearance of skin lesions was seen in all patients with no adverse reactions noted.25

Despite these treatment options, PATM does not necessitate treatment given its benign course and often self-resolving nature.26 In cases of drug-induced PPD such as in our patient, discontinuation of the offending drug often may lead to resolution.

In summary, PATM is a PPD that has been associated with different etiologic factors. If PATM is suspected to be caused by a drug, discontinuation of the offending agent usually results in resolution of symptoms, as it did in our case with fading of lesions within a few weeks after the patient was no longer taking levofloxacin.

To the Editor:

Purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi (PATM) is a type of pigmented purpuric dermatosis (PPD). Patients present with nonblanchable, annular, symmetric, purpuric, and telangiectatic patches, often on the legs, with histology revealing a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate and extravasated erythrocytes.1,2 A variety of medications have been linked to the development of PPD. We describe a case of levofloxacin-induced PATM.

RELATED ARTICLE: Granulomatous Changes Associated With Pigmented Purpuric Dermatosis

A 42-year-old man presented with a rash on the arms, trunk, abdomen, and legs of 1 month’s duration. He reported no associated itching, bleeding, or pain, and no history of a similar rash. He had a history of hypothyroidism and had been taking levothyroxine for years. He had no known allergies and no history of childhood eczema, asthma, or allergic rhinitis. Notably, the rash started shortly after the patient finished a 2-week course of levofloxacin, an antibiotic he had not taken in the past. The patient resided with his wife, 3 children, and a pet dog, and no family members had the rash. Prior to presentation, the patient had tried econazole cream and then triamcinolone acetonide cream 0.5% without any clinical improvement.

A complete review of systems was unremarkable. Physical examination revealed scattered, reddish brown, annular, nonscaly patches on the back, abdomen (Figure 1), arms, and legs with nonblanching petechiae within the patches.

A punch biopsy of the left inner thigh demonstrated patchy interface dermatitis, superficial perivascular inflammation, and numerous extravasated red blood cells in the papillary dermis (Figure 2). The histologic features were compatible with the clinical impression of PATM. The patient presented for a follow-up visit 2 weeks later with no new lesions and the old lesions were rapidly fading (Figure 3).

Pigmented purpuric dermatoses are a group of conditions that have different clinical morphologies but similar histopathologic examinations.2 All PPDs are characterized by nonblanching, nonpalpable, purpuric lesions that often are bilaterally symmetrical and present on the legs.2,3 Although the precise etiology of these conditions is not known, most cases include a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate along with the presence of extravasated erythrocytes and hemosiderin deposition in the dermis.2 Of note, PATM often is idiopathic and patients usually present with no associated comorbidities.3 The currently established PPDs include progressive pigmentary dermatosis (Schamberg disease), PATM, pigmented purpuric lichenoid dermatosis of Gougerot and Blum, lichen aureus, and eczematidlike purpura of Doucas and Kapetanakis.2,4

RELATED ARTICLE: Granulomatous Pigmented Purpuric Dermatosis

The lesions of PATM are symmetrically distributed on the bilateral legs and may be symptomatic in most cases, with severe pruritus being reported in several drug-induced PATM cases.3,5 Although the exact etiology of PPDs currently is unknown, some contributing factors that are thought to play a role include exercise, venous stasis, gravitational dependence, capillary fragility, hypertension, drugs, chemical exposure or ingestions, and contact allergy to dyes.3 Some of the drugs known to cause drug-induced PPDs fall into the class of sedatives, stimulants, antibiotics, cardiovascular drugs, vitamins, and nutritional supplements.3,6 Some medications that have been reported to cause PPDs include acetaminophen, aspirin, carbamazepine, diltiazem, furosemide, glipizide, hydralazine, infliximab, isotretinoin, lorazepam, minocycline, nitroglycerine, and sildenafil.3,7-15

Although the mechanism of drug-induced PPD is not completely understood, it is thought that the ingested substance leads to an immunologic response in the capillary endothelium, which results in a cell-mediated immune response causing vascular damage.3 The ingested substance may act as a hapten, stimulating antibody formation and immune-mediated injury, leading to the clinical presentation of nonblanching, symmetric, purpuric, telangiectatic, and atrophic patches at the site of injury.1,3

Levofloxacin is a broad-spectrum antibiotic that has activity against both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. It inhibits the enzymes DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV, preventing bacteria from undergoing proper DNA synthesis.16 Our patient’s rash began shortly after a 2-week course of levofloxacin and faded within a few weeks of discontinuing the drug; the clinical presentation, time course, and histologic appearance of the lesions were consistent with the diagnosis of drug-induced PPD. Of note, solar capillaritis has been reported following a phototoxic reaction induced by levofloxacin.17 Our case differs in that our patient had annular lesions on both photoprotected and photoexposed skin.

The first-line interventions for the treatment of PPDs are nonpharmacologic, such as discontinuation of an offending drug or allergen or wearing supportive stockings if there are signs of venous stasis. Other interventions include the use of a medium- or high-potency topical corticosteroid once to twice daily to affected areas for 4 to 6 weeks.18 Some case series also have shown improvement with narrowband UVB treatment after 24 to 28 treatment sessions or with psoralen plus UVA phototherapy within 7 to 20 treatments.19,20 If the above measures are unsuccessful in resolving symptoms, other treatment alternatives may include pentoxifylline, griseofulvin, colchicine, cyclosporine, and methotrexate. The potential benefit of treatment must be weighed against the side-effect profile of these medications.2,21-24 Of note, oral rutoside (50 mg twice daily) and ascorbic acid (500 mg twice daily) were administered to 3 patients with chronic progressive pigmented purpura. At the end of the 4-week treatment period, complete clearance of skin lesions was seen in all patients with no adverse reactions noted.25

Despite these treatment options, PATM does not necessitate treatment given its benign course and often self-resolving nature.26 In cases of drug-induced PPD such as in our patient, discontinuation of the offending drug often may lead to resolution.

In summary, PATM is a PPD that has been associated with different etiologic factors. If PATM is suspected to be caused by a drug, discontinuation of the offending agent usually results in resolution of symptoms, as it did in our case with fading of lesions within a few weeks after the patient was no longer taking levofloxacin.

- Hale EK. Purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi. Dermatol Online J. 2003;9:17.

- Hoesly FJ, Huerter CJ, Shehan JM. Purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi: case report and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:1129-1133.

- Kaplan R, Meehan SA, Leger M. A case of isotretinoin-induced purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi and review of substance-induced pigmented purpuric dermatosis. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:182-184.

- Newton RC, Raimer SS. Pigmented purpuric eruptions. Dermatol Clin. 1985;3:165-169.

- Ratnam KV, Su WP, Peters MS. Purpura simplex (inflammatory purpura without vasculitis): a clinicopathologic study of 174 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:642-647.

- Pang BK, Su D, Ratnam KV. Drug-induced purpura simplex: clinical and histological characteristics. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1993;22:870-872.

- Abeck D, Gross GE, Kuwert C, et al. Acetaminophen-induced progressive pigmentary purpura (Schamberg’s disease). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:123-124.

- Lipsker D, Cribier B, Heid E, et al. Cutaneous lymphoma manifesting as pigmented, purpuric capillaries [in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1999;126:321-326.

- Peterson WC Jr, Manick KP. Purpuric eruptions associated with use of carbromal and meprobamate. Arch Dermatol. 1967;95:40-42.

- Nishioka K, Katayama I, Masuzawa M, et al. Drug-induced chronic pigmented purpura. J Dermatol. 1989;16:220-222.

- Voelter WW. Pigmented purpuric dermatosis-like reaction to topical fluorouracil. Arch Dermatol. 1983;119:875-876.

- Adams BB, Gadenne AS. Glipizide-induced pigmented purpuric dermatosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41(5, pt 2):827-829.

- Tsao H, Lerner LH. Pigmented purpuric eruption associated with injection medroxyprogesterone acetate. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43(2, pt 1):308-310.

- Koçak AY, Akay BN, Heper AO. Sildenafil-induced pigmented purpuric dermatosis. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2013;32:91-92.

- Nishioka K, Sarashi C, Katayama I. Chronic pigmented purpura induced by chemical substances. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1980;5:213-218.

- Drlica K, Zhao X. DNA gyrase, topoisomerase IV, and the 4-quinolones. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1997;61:377-392.

- Rubegni P, Feci L, Pellegrino M, et al. Photolocalized purpura during levofloxacin therapy. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2012;28:105-107.

- Sardana K, Sarkar R, Sehgal VN. Pigmented purpuric dermatoses: an overview. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:482-488.

- Fathy H, Abdelgaber S. Treatment of pigmented purpuric dermatoses with narrow-band UVB: a report of six cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:603-606.

- Krizsa J, Hunyadi J, Dobozy A. PUVA treatment of pigmented purpuric lichenoid dermatitis (Gougerot-Blum). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27(5, pt 1):778-780.

- Panda S, Malakar S, Lahiri K. Oral pentoxifylline vs topical betamethasone in Schamberg disease: a comparative randomized investigator-blinded parallel-group trial. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:491-493.

- Tamaki K, Yasaka N, Osada A, et al. Successful treatment of pigmented purpuric dermatosis with griseofulvin. Br J Dermatol. 1995;132:159-160.

- Geller M. Benefit of colchicine in the treatment of Schamberg’s disease. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2000;85:246.

- Okada K, Ishikawa O, Miyachi Y. Purpura pigmentosa chronica successfully treated with oral cyclosporin A. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:180-181.

- Reinhold U, Seiter S, Ugurel S, et al. Treatment of progressive pigmented purpura with oral bioflavonoids and ascorbic acid: an open pilot study in 3 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41(2, pt 1):207-208.

- Wang A, Shuja F, Chan A, et al. Unilateral purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi in an elderly male: an atypical presentation. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:19263.

- Hale EK. Purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi. Dermatol Online J. 2003;9:17.

- Hoesly FJ, Huerter CJ, Shehan JM. Purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi: case report and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:1129-1133.

- Kaplan R, Meehan SA, Leger M. A case of isotretinoin-induced purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi and review of substance-induced pigmented purpuric dermatosis. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:182-184.

- Newton RC, Raimer SS. Pigmented purpuric eruptions. Dermatol Clin. 1985;3:165-169.

- Ratnam KV, Su WP, Peters MS. Purpura simplex (inflammatory purpura without vasculitis): a clinicopathologic study of 174 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:642-647.

- Pang BK, Su D, Ratnam KV. Drug-induced purpura simplex: clinical and histological characteristics. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1993;22:870-872.

- Abeck D, Gross GE, Kuwert C, et al. Acetaminophen-induced progressive pigmentary purpura (Schamberg’s disease). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:123-124.

- Lipsker D, Cribier B, Heid E, et al. Cutaneous lymphoma manifesting as pigmented, purpuric capillaries [in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1999;126:321-326.

- Peterson WC Jr, Manick KP. Purpuric eruptions associated with use of carbromal and meprobamate. Arch Dermatol. 1967;95:40-42.

- Nishioka K, Katayama I, Masuzawa M, et al. Drug-induced chronic pigmented purpura. J Dermatol. 1989;16:220-222.

- Voelter WW. Pigmented purpuric dermatosis-like reaction to topical fluorouracil. Arch Dermatol. 1983;119:875-876.

- Adams BB, Gadenne AS. Glipizide-induced pigmented purpuric dermatosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41(5, pt 2):827-829.

- Tsao H, Lerner LH. Pigmented purpuric eruption associated with injection medroxyprogesterone acetate. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43(2, pt 1):308-310.

- Koçak AY, Akay BN, Heper AO. Sildenafil-induced pigmented purpuric dermatosis. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2013;32:91-92.

- Nishioka K, Sarashi C, Katayama I. Chronic pigmented purpura induced by chemical substances. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1980;5:213-218.

- Drlica K, Zhao X. DNA gyrase, topoisomerase IV, and the 4-quinolones. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1997;61:377-392.

- Rubegni P, Feci L, Pellegrino M, et al. Photolocalized purpura during levofloxacin therapy. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2012;28:105-107.

- Sardana K, Sarkar R, Sehgal VN. Pigmented purpuric dermatoses: an overview. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:482-488.

- Fathy H, Abdelgaber S. Treatment of pigmented purpuric dermatoses with narrow-band UVB: a report of six cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:603-606.

- Krizsa J, Hunyadi J, Dobozy A. PUVA treatment of pigmented purpuric lichenoid dermatitis (Gougerot-Blum). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27(5, pt 1):778-780.

- Panda S, Malakar S, Lahiri K. Oral pentoxifylline vs topical betamethasone in Schamberg disease: a comparative randomized investigator-blinded parallel-group trial. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:491-493.

- Tamaki K, Yasaka N, Osada A, et al. Successful treatment of pigmented purpuric dermatosis with griseofulvin. Br J Dermatol. 1995;132:159-160.

- Geller M. Benefit of colchicine in the treatment of Schamberg’s disease. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2000;85:246.

- Okada K, Ishikawa O, Miyachi Y. Purpura pigmentosa chronica successfully treated with oral cyclosporin A. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:180-181.

- Reinhold U, Seiter S, Ugurel S, et al. Treatment of progressive pigmented purpura with oral bioflavonoids and ascorbic acid: an open pilot study in 3 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41(2, pt 1):207-208.

- Wang A, Shuja F, Chan A, et al. Unilateral purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi in an elderly male: an atypical presentation. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:19263.

Practice Point

- Purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi, a type of pigmented purpuric dermatosis, may on occasion be triggered by a medication; therefore, a careful medication history may prove to be an important part of the workup for this eruption.

Adverse effects low in long-term crisaborole eczema study

, suggesting that the therapy has the potential to treat atopic dermatitis without the side effects of the current topical treatments, said Lawrence F. Eichenfield, MD, of Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego, and his associates.

The multicenter, long-term, open-label safety study of 48 weeks assessed 517 patients with mild to moderate atopic dermatitis after they had finished a 28-day phase 3 study of 2% crisaborole ointment. The patients in the extension study were told to apply crisaborole twice daily for 28 days, with an off-treatment period initiated if their disease severity was clear or almost clear after the 28 days. They were told to stop the treatment if they had no improvement in their Investigator’s Static Global Assessment score after three consecutive treatment periods.

Treatment-related adverse events occurred in 10% of patients; 86% of them were mild or moderate. Dermatitis atopic – defined as worsening, exacerbation, flare, or flare-up – occurred in 3% of patients; application-site burning or stinging in 2%; and application-site infection in 1%. The median duration was 18 days for dermatitis atopic, 5 days for application-site burning or stinging, and 12 days for application-site infection. The frequency of these adverse events did not increase over time, the investigators said.

Most patients (78%) did not need rescue therapy, 79% later resumed crisaborole therapy at a later date, and 76% stayed in the study until week 48 or the end of the study.

Read more in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology (2017 Oct;77[4]:641-9).

, suggesting that the therapy has the potential to treat atopic dermatitis without the side effects of the current topical treatments, said Lawrence F. Eichenfield, MD, of Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego, and his associates.

The multicenter, long-term, open-label safety study of 48 weeks assessed 517 patients with mild to moderate atopic dermatitis after they had finished a 28-day phase 3 study of 2% crisaborole ointment. The patients in the extension study were told to apply crisaborole twice daily for 28 days, with an off-treatment period initiated if their disease severity was clear or almost clear after the 28 days. They were told to stop the treatment if they had no improvement in their Investigator’s Static Global Assessment score after three consecutive treatment periods.

Treatment-related adverse events occurred in 10% of patients; 86% of them were mild or moderate. Dermatitis atopic – defined as worsening, exacerbation, flare, or flare-up – occurred in 3% of patients; application-site burning or stinging in 2%; and application-site infection in 1%. The median duration was 18 days for dermatitis atopic, 5 days for application-site burning or stinging, and 12 days for application-site infection. The frequency of these adverse events did not increase over time, the investigators said.

Most patients (78%) did not need rescue therapy, 79% later resumed crisaborole therapy at a later date, and 76% stayed in the study until week 48 or the end of the study.

Read more in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology (2017 Oct;77[4]:641-9).

, suggesting that the therapy has the potential to treat atopic dermatitis without the side effects of the current topical treatments, said Lawrence F. Eichenfield, MD, of Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego, and his associates.

The multicenter, long-term, open-label safety study of 48 weeks assessed 517 patients with mild to moderate atopic dermatitis after they had finished a 28-day phase 3 study of 2% crisaborole ointment. The patients in the extension study were told to apply crisaborole twice daily for 28 days, with an off-treatment period initiated if their disease severity was clear or almost clear after the 28 days. They were told to stop the treatment if they had no improvement in their Investigator’s Static Global Assessment score after three consecutive treatment periods.

Treatment-related adverse events occurred in 10% of patients; 86% of them were mild or moderate. Dermatitis atopic – defined as worsening, exacerbation, flare, or flare-up – occurred in 3% of patients; application-site burning or stinging in 2%; and application-site infection in 1%. The median duration was 18 days for dermatitis atopic, 5 days for application-site burning or stinging, and 12 days for application-site infection. The frequency of these adverse events did not increase over time, the investigators said.

Most patients (78%) did not need rescue therapy, 79% later resumed crisaborole therapy at a later date, and 76% stayed in the study until week 48 or the end of the study.

Read more in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology (2017 Oct;77[4]:641-9).

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF DERMATOLOGY

MACRA in a nutshell

Much has been written over the past year about the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA), and its primary vehicle, the Merit-Based Incentive System (MIPS); but many small practices seem reluctant to take it seriously, despite the fact that it puts yet another significant percentage of our Medicare reimbursements at risk.

Those much-publicized attempts to “repeal and replace” the Affordable Care Act earlier this year undoubtedly contributed to the apathy; but the ACA is apparently here to stay, and the first MIPS “performance period” ends on Dec. 31, so now would be an excellent time to get up to speed. Herewith, the basics:

Each practice must choose between two payment tracks: either MIPS or one of the so-called Alternate Payment Models (APM). The MIPS track will use the four reporting programs just mentioned to compile a composite score between 0 and 100 each year for every practitioner, based on four performance metrics: quality measures listed in Qualified Clinical Data Registries (QCDRs), such as Approved Quality Improvement (AQI); total resources used by each practitioner, as measured by VBM; “improvement activities” (MOC); and MU, in some new, as-yet-undefined form. You can earn a bonus of 4% of reimbursement in 2019, rising to 5% in 2020, 7% in 2021, and 9% in 2022 – or you can be penalized those amounts (“negative adjustments”) if your performance doesn’t measure up.

The final MACRA regulations, issued last October, allow a more gradual MIPS implementation that should decrease the penalty burden for small practices, at least initially. For example, you can avoid a penalty in 2019 – but not qualify for a bonus – by reporting your performance in only one quality-of-care or practice-improvement category by the end of this year. A decrease in penalties, however, means a smaller pot for bonuses – and reprieves will be temporary.

The alternative, APM, is difficult to discuss, as very few models have been presented – or even defined – to date. Only Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs) have been introduced in any quantity, and most of those have failed miserably in real-world settings. The Episode of Care (EOC) model, which pays providers a fixed amount for all services rendered in a bundle (“episode”) of care, has been discussed at some length, but this remains untested and in the end may turn out to be just another variant of capitation.

So, which to choose? Long term, I strongly suggest that everyone prepare for the APM track as soon as APMs that are better and more efficient become available, as it appears that there will be more financial security there, with less risk of penalties; but you will probably need to start in the MIPS program, since most projections indicate that the great majority of practitioners, particularly those in smaller operations, will do so.

While some may be prompted to join a larger organization or network to decrease their risk of MIPS penalties and gain quicker access to the APM track – which may well be one of the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ surreptitious goals in introducing MACRA in the first place – there are steps that those individuals and small groups who choose to remain independent can take now to maximize their chances of landing on the bonus side of the MIPS ledger.

If the alphabet soup above has your head swimming, join the club – you’re far from alone; but don’t be discouraged. CMS has indicated its willingness to make changes aimed at decreasing the administrative burden and, in its words, “making the transition to MACRA as simple and as flexible as possible.”

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at [email protected].

Much has been written over the past year about the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA), and its primary vehicle, the Merit-Based Incentive System (MIPS); but many small practices seem reluctant to take it seriously, despite the fact that it puts yet another significant percentage of our Medicare reimbursements at risk.

Those much-publicized attempts to “repeal and replace” the Affordable Care Act earlier this year undoubtedly contributed to the apathy; but the ACA is apparently here to stay, and the first MIPS “performance period” ends on Dec. 31, so now would be an excellent time to get up to speed. Herewith, the basics:

Each practice must choose between two payment tracks: either MIPS or one of the so-called Alternate Payment Models (APM). The MIPS track will use the four reporting programs just mentioned to compile a composite score between 0 and 100 each year for every practitioner, based on four performance metrics: quality measures listed in Qualified Clinical Data Registries (QCDRs), such as Approved Quality Improvement (AQI); total resources used by each practitioner, as measured by VBM; “improvement activities” (MOC); and MU, in some new, as-yet-undefined form. You can earn a bonus of 4% of reimbursement in 2019, rising to 5% in 2020, 7% in 2021, and 9% in 2022 – or you can be penalized those amounts (“negative adjustments”) if your performance doesn’t measure up.

The final MACRA regulations, issued last October, allow a more gradual MIPS implementation that should decrease the penalty burden for small practices, at least initially. For example, you can avoid a penalty in 2019 – but not qualify for a bonus – by reporting your performance in only one quality-of-care or practice-improvement category by the end of this year. A decrease in penalties, however, means a smaller pot for bonuses – and reprieves will be temporary.

The alternative, APM, is difficult to discuss, as very few models have been presented – or even defined – to date. Only Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs) have been introduced in any quantity, and most of those have failed miserably in real-world settings. The Episode of Care (EOC) model, which pays providers a fixed amount for all services rendered in a bundle (“episode”) of care, has been discussed at some length, but this remains untested and in the end may turn out to be just another variant of capitation.

So, which to choose? Long term, I strongly suggest that everyone prepare for the APM track as soon as APMs that are better and more efficient become available, as it appears that there will be more financial security there, with less risk of penalties; but you will probably need to start in the MIPS program, since most projections indicate that the great majority of practitioners, particularly those in smaller operations, will do so.

While some may be prompted to join a larger organization or network to decrease their risk of MIPS penalties and gain quicker access to the APM track – which may well be one of the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ surreptitious goals in introducing MACRA in the first place – there are steps that those individuals and small groups who choose to remain independent can take now to maximize their chances of landing on the bonus side of the MIPS ledger.

If the alphabet soup above has your head swimming, join the club – you’re far from alone; but don’t be discouraged. CMS has indicated its willingness to make changes aimed at decreasing the administrative burden and, in its words, “making the transition to MACRA as simple and as flexible as possible.”

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at [email protected].

Much has been written over the past year about the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA), and its primary vehicle, the Merit-Based Incentive System (MIPS); but many small practices seem reluctant to take it seriously, despite the fact that it puts yet another significant percentage of our Medicare reimbursements at risk.

Those much-publicized attempts to “repeal and replace” the Affordable Care Act earlier this year undoubtedly contributed to the apathy; but the ACA is apparently here to stay, and the first MIPS “performance period” ends on Dec. 31, so now would be an excellent time to get up to speed. Herewith, the basics:

Each practice must choose between two payment tracks: either MIPS or one of the so-called Alternate Payment Models (APM). The MIPS track will use the four reporting programs just mentioned to compile a composite score between 0 and 100 each year for every practitioner, based on four performance metrics: quality measures listed in Qualified Clinical Data Registries (QCDRs), such as Approved Quality Improvement (AQI); total resources used by each practitioner, as measured by VBM; “improvement activities” (MOC); and MU, in some new, as-yet-undefined form. You can earn a bonus of 4% of reimbursement in 2019, rising to 5% in 2020, 7% in 2021, and 9% in 2022 – or you can be penalized those amounts (“negative adjustments”) if your performance doesn’t measure up.

The final MACRA regulations, issued last October, allow a more gradual MIPS implementation that should decrease the penalty burden for small practices, at least initially. For example, you can avoid a penalty in 2019 – but not qualify for a bonus – by reporting your performance in only one quality-of-care or practice-improvement category by the end of this year. A decrease in penalties, however, means a smaller pot for bonuses – and reprieves will be temporary.

The alternative, APM, is difficult to discuss, as very few models have been presented – or even defined – to date. Only Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs) have been introduced in any quantity, and most of those have failed miserably in real-world settings. The Episode of Care (EOC) model, which pays providers a fixed amount for all services rendered in a bundle (“episode”) of care, has been discussed at some length, but this remains untested and in the end may turn out to be just another variant of capitation.

So, which to choose? Long term, I strongly suggest that everyone prepare for the APM track as soon as APMs that are better and more efficient become available, as it appears that there will be more financial security there, with less risk of penalties; but you will probably need to start in the MIPS program, since most projections indicate that the great majority of practitioners, particularly those in smaller operations, will do so.

While some may be prompted to join a larger organization or network to decrease their risk of MIPS penalties and gain quicker access to the APM track – which may well be one of the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ surreptitious goals in introducing MACRA in the first place – there are steps that those individuals and small groups who choose to remain independent can take now to maximize their chances of landing on the bonus side of the MIPS ledger.

If the alphabet soup above has your head swimming, join the club – you’re far from alone; but don’t be discouraged. CMS has indicated its willingness to make changes aimed at decreasing the administrative burden and, in its words, “making the transition to MACRA as simple and as flexible as possible.”

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at [email protected].

Chromoblastomycosis Infection From a House Plant

To the Editor:

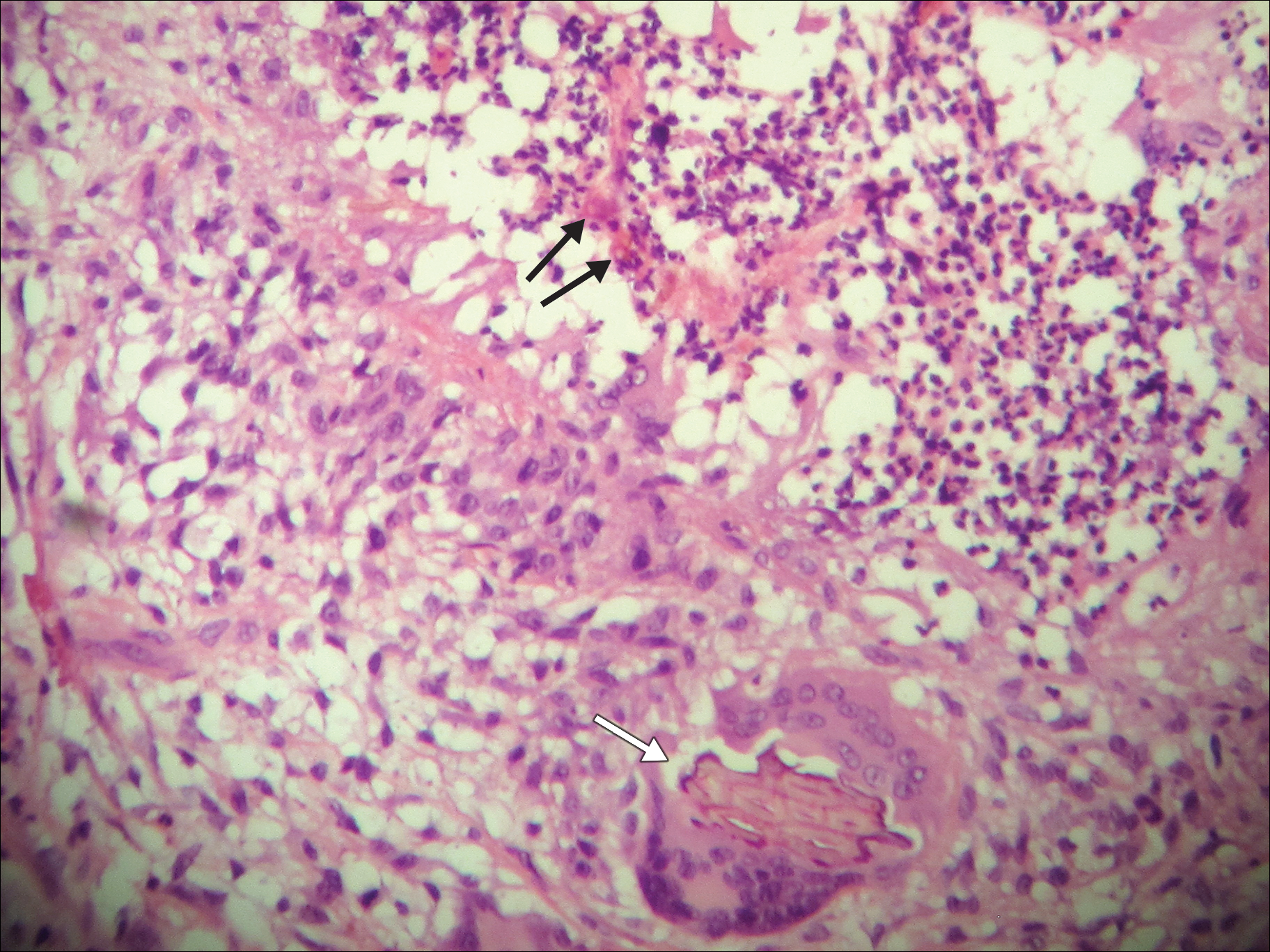

A 69-year-old woman with no history of immunodeficiency presented 1 month after a thorn from her locally grown Madagascar palm plant (Pachypodium lamerei) pierced the skin. The patient developed a painful nodule at the site on the left elbow (Figure 1). An excisional biopsy by an outside dermatologist was performed, which showed granulomatous inflammation within the dermis with epidermal hyperplasia and the presence of golden brown spherules (medlar bodies). The diagnosis was a dermal fungal infection consistent with chromoblastomycosis. A curative surgical excision was performed, and medlar bodies were seen adjacent to a polarizable foreign body consistent with plant material on histology (Figure 2). Because the lesion was localized, adjuvant medical treatment was not deemed necessary. The patient has not had any recurrence in the last 1.5 years since the resection.

The categorization of chromoblastomycosis includes a chronic fungal infection of the cutaneous and subcutaneous tissues by dematiaceous (pigmented) fungi. This definition is such that there are a multitude of organisms that can be the primary cause of this diagnosis. Generally, infection follows a traumatic permeation of the skin by a foreign body contaminated by the causative organism in agricultural workers. The most common dematiaceous pathogens are Fonsecaea pedrosoi, Phialophora verrucosa, and Cladosporium carrionii; however, the specific causative organism varies heavily on geographic location. With inoculation by a foreign body, a small papule develops at the site of the lesion. Several years after the primary infection, nodules and verrucous erythematous plaques develop in the same area, and patients present with concerns of pain and pruritus.1 Lesions usually are localized to the initial area of inoculation, generally a break in the skin by the offending foreign body, on the legs, arms, or hands, but hematogenous or lymphatic dissemination with distant transmission due to scratching also can occur. Ulceration due to secondary bacterial infection is another possible manifestation, resulting in a foul odor and less commonly lymphedema. Rarely, squamous cell carcinoma is a complication.2

RELATED ARTICLE: Fungal Foes: Presentations of Chromoblastomycosis Post–Hurricane Ike

On histopathology, thick-walled sclerotic bodies termed medlar bodies or copper pennies are pathognomonic for chromoblastomycosis and represent the fungal elements. Grossly, black dots can be seen on the skin in the affected areas from the transepidermal elimination of the fungi.1,2 However, there is no specificity for determining the causative organism in this manner, or even with culture, as it is difficult to differentiate the species morphologically. More advanced tests can help, such as polymerase chain reaction or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, where available.2 Hematoxylin and eosin stain also shows epidermal hyperplasia and dermal mononuclear infiltrate.

Treatment modalities include surgical excision, cryotherapy, pharmacologic treatment, and combination therapy. Localized lesions often can be resected, but more severe infections can require pharmacologic treatment. Unfortunately, there tends to be a high risk for relapse with most antifungal modalities. The combination of itraconazole and terbinafine has been shown to offer the best medical therapy with lower risk for refractoriness to treatment by producing a synergistic effect between the 2 antifungals.2,3 Many surgical treatments often are combined with oral antifungals to try to attain complete eradication in deep or extensive lesions, as seen in a case in which oral terbinafine was used prior to surgery to reduce the size of the lesion, followed by complete resection.4 With localized lesions that are resectable, a wide and deep incision often can be curative. Cryotherapy also may be coupled with surgical excision or pharmacologic therapy. Most literature suggests that cryotherapy or the use of antifungals prior to excision offers improved outcomes.2,5 Prognosis tends to be good for chromoblastomycoses, particularly with smaller lesions. Complete eradication varies greatly on the size and depth of the lesion, independent of the causative pathogen.

Our patient’s presentation with chromoblastomycosis is unique because of the source of infection, which was a plant grown from seeds in a local nursery in South Florida and then sold to the patient. The majority of chromoblastomycosis infections occur in agricultural workers, typically in tropical climates such as South and Central America, the Caribbean, and Mexico.1,2 Historically, infections in the United States have been uncommon, with the majority presenting in patients on prolonged corticosteroid therapy or with other immunosuppressive conditions.6,7

- Torres-Guerrero E, Isa-Isa R, Isa M, et al. Chromoblastomycosis. Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:403-408.

- Ameen M. Managing chromoblastomycosis. Trop Doct. 2010;40:65-67.

- Zhang J, Xi L, Lu C, et al. Successful treatment for chromoblastomycosis caused by Fonsecaea monophora: a report of three cases in Guangdong, China. Mycoses. 2009;52:176-181.

- Tamura K, Matsuyama T, Yahagi E, et al. A case of chromomycosis treated by surgical therapy combined with preceded oral administration of terbinafine to reduce the size of the lesion. Tokai J Exp Clin Med. 2012;37:6-10.

- Patel U, Chu J, Patel R, et al. Subcutaneous dematiaceous fungal infection. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:19.

- Basílio FM, Hammerschmidt M, Mukai MM, et al. Mucormycosis and chromoblastomycosis occurring in a patient with leprosy type 2 reaction under prolonged corticosteroid and thalidomide therapy. An Bras Dermatol. 2012;87:767-771.

- Parente JN, Talhari C, Ginter-Hanselmayer G, et al. Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis in immunocompetent patients: two new cases caused by Exophiala jeanselmei and Cladophialophora carrionii. Mycoses. 2001;54:265-269.

To the Editor:

A 69-year-old woman with no history of immunodeficiency presented 1 month after a thorn from her locally grown Madagascar palm plant (Pachypodium lamerei) pierced the skin. The patient developed a painful nodule at the site on the left elbow (Figure 1). An excisional biopsy by an outside dermatologist was performed, which showed granulomatous inflammation within the dermis with epidermal hyperplasia and the presence of golden brown spherules (medlar bodies). The diagnosis was a dermal fungal infection consistent with chromoblastomycosis. A curative surgical excision was performed, and medlar bodies were seen adjacent to a polarizable foreign body consistent with plant material on histology (Figure 2). Because the lesion was localized, adjuvant medical treatment was not deemed necessary. The patient has not had any recurrence in the last 1.5 years since the resection.

The categorization of chromoblastomycosis includes a chronic fungal infection of the cutaneous and subcutaneous tissues by dematiaceous (pigmented) fungi. This definition is such that there are a multitude of organisms that can be the primary cause of this diagnosis. Generally, infection follows a traumatic permeation of the skin by a foreign body contaminated by the causative organism in agricultural workers. The most common dematiaceous pathogens are Fonsecaea pedrosoi, Phialophora verrucosa, and Cladosporium carrionii; however, the specific causative organism varies heavily on geographic location. With inoculation by a foreign body, a small papule develops at the site of the lesion. Several years after the primary infection, nodules and verrucous erythematous plaques develop in the same area, and patients present with concerns of pain and pruritus.1 Lesions usually are localized to the initial area of inoculation, generally a break in the skin by the offending foreign body, on the legs, arms, or hands, but hematogenous or lymphatic dissemination with distant transmission due to scratching also can occur. Ulceration due to secondary bacterial infection is another possible manifestation, resulting in a foul odor and less commonly lymphedema. Rarely, squamous cell carcinoma is a complication.2

RELATED ARTICLE: Fungal Foes: Presentations of Chromoblastomycosis Post–Hurricane Ike

On histopathology, thick-walled sclerotic bodies termed medlar bodies or copper pennies are pathognomonic for chromoblastomycosis and represent the fungal elements. Grossly, black dots can be seen on the skin in the affected areas from the transepidermal elimination of the fungi.1,2 However, there is no specificity for determining the causative organism in this manner, or even with culture, as it is difficult to differentiate the species morphologically. More advanced tests can help, such as polymerase chain reaction or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, where available.2 Hematoxylin and eosin stain also shows epidermal hyperplasia and dermal mononuclear infiltrate.

Treatment modalities include surgical excision, cryotherapy, pharmacologic treatment, and combination therapy. Localized lesions often can be resected, but more severe infections can require pharmacologic treatment. Unfortunately, there tends to be a high risk for relapse with most antifungal modalities. The combination of itraconazole and terbinafine has been shown to offer the best medical therapy with lower risk for refractoriness to treatment by producing a synergistic effect between the 2 antifungals.2,3 Many surgical treatments often are combined with oral antifungals to try to attain complete eradication in deep or extensive lesions, as seen in a case in which oral terbinafine was used prior to surgery to reduce the size of the lesion, followed by complete resection.4 With localized lesions that are resectable, a wide and deep incision often can be curative. Cryotherapy also may be coupled with surgical excision or pharmacologic therapy. Most literature suggests that cryotherapy or the use of antifungals prior to excision offers improved outcomes.2,5 Prognosis tends to be good for chromoblastomycoses, particularly with smaller lesions. Complete eradication varies greatly on the size and depth of the lesion, independent of the causative pathogen.

Our patient’s presentation with chromoblastomycosis is unique because of the source of infection, which was a plant grown from seeds in a local nursery in South Florida and then sold to the patient. The majority of chromoblastomycosis infections occur in agricultural workers, typically in tropical climates such as South and Central America, the Caribbean, and Mexico.1,2 Historically, infections in the United States have been uncommon, with the majority presenting in patients on prolonged corticosteroid therapy or with other immunosuppressive conditions.6,7

To the Editor:

A 69-year-old woman with no history of immunodeficiency presented 1 month after a thorn from her locally grown Madagascar palm plant (Pachypodium lamerei) pierced the skin. The patient developed a painful nodule at the site on the left elbow (Figure 1). An excisional biopsy by an outside dermatologist was performed, which showed granulomatous inflammation within the dermis with epidermal hyperplasia and the presence of golden brown spherules (medlar bodies). The diagnosis was a dermal fungal infection consistent with chromoblastomycosis. A curative surgical excision was performed, and medlar bodies were seen adjacent to a polarizable foreign body consistent with plant material on histology (Figure 2). Because the lesion was localized, adjuvant medical treatment was not deemed necessary. The patient has not had any recurrence in the last 1.5 years since the resection.

The categorization of chromoblastomycosis includes a chronic fungal infection of the cutaneous and subcutaneous tissues by dematiaceous (pigmented) fungi. This definition is such that there are a multitude of organisms that can be the primary cause of this diagnosis. Generally, infection follows a traumatic permeation of the skin by a foreign body contaminated by the causative organism in agricultural workers. The most common dematiaceous pathogens are Fonsecaea pedrosoi, Phialophora verrucosa, and Cladosporium carrionii; however, the specific causative organism varies heavily on geographic location. With inoculation by a foreign body, a small papule develops at the site of the lesion. Several years after the primary infection, nodules and verrucous erythematous plaques develop in the same area, and patients present with concerns of pain and pruritus.1 Lesions usually are localized to the initial area of inoculation, generally a break in the skin by the offending foreign body, on the legs, arms, or hands, but hematogenous or lymphatic dissemination with distant transmission due to scratching also can occur. Ulceration due to secondary bacterial infection is another possible manifestation, resulting in a foul odor and less commonly lymphedema. Rarely, squamous cell carcinoma is a complication.2

RELATED ARTICLE: Fungal Foes: Presentations of Chromoblastomycosis Post–Hurricane Ike

On histopathology, thick-walled sclerotic bodies termed medlar bodies or copper pennies are pathognomonic for chromoblastomycosis and represent the fungal elements. Grossly, black dots can be seen on the skin in the affected areas from the transepidermal elimination of the fungi.1,2 However, there is no specificity for determining the causative organism in this manner, or even with culture, as it is difficult to differentiate the species morphologically. More advanced tests can help, such as polymerase chain reaction or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, where available.2 Hematoxylin and eosin stain also shows epidermal hyperplasia and dermal mononuclear infiltrate.

Treatment modalities include surgical excision, cryotherapy, pharmacologic treatment, and combination therapy. Localized lesions often can be resected, but more severe infections can require pharmacologic treatment. Unfortunately, there tends to be a high risk for relapse with most antifungal modalities. The combination of itraconazole and terbinafine has been shown to offer the best medical therapy with lower risk for refractoriness to treatment by producing a synergistic effect between the 2 antifungals.2,3 Many surgical treatments often are combined with oral antifungals to try to attain complete eradication in deep or extensive lesions, as seen in a case in which oral terbinafine was used prior to surgery to reduce the size of the lesion, followed by complete resection.4 With localized lesions that are resectable, a wide and deep incision often can be curative. Cryotherapy also may be coupled with surgical excision or pharmacologic therapy. Most literature suggests that cryotherapy or the use of antifungals prior to excision offers improved outcomes.2,5 Prognosis tends to be good for chromoblastomycoses, particularly with smaller lesions. Complete eradication varies greatly on the size and depth of the lesion, independent of the causative pathogen.

Our patient’s presentation with chromoblastomycosis is unique because of the source of infection, which was a plant grown from seeds in a local nursery in South Florida and then sold to the patient. The majority of chromoblastomycosis infections occur in agricultural workers, typically in tropical climates such as South and Central America, the Caribbean, and Mexico.1,2 Historically, infections in the United States have been uncommon, with the majority presenting in patients on prolonged corticosteroid therapy or with other immunosuppressive conditions.6,7

- Torres-Guerrero E, Isa-Isa R, Isa M, et al. Chromoblastomycosis. Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:403-408.

- Ameen M. Managing chromoblastomycosis. Trop Doct. 2010;40:65-67.

- Zhang J, Xi L, Lu C, et al. Successful treatment for chromoblastomycosis caused by Fonsecaea monophora: a report of three cases in Guangdong, China. Mycoses. 2009;52:176-181.

- Tamura K, Matsuyama T, Yahagi E, et al. A case of chromomycosis treated by surgical therapy combined with preceded oral administration of terbinafine to reduce the size of the lesion. Tokai J Exp Clin Med. 2012;37:6-10.

- Patel U, Chu J, Patel R, et al. Subcutaneous dematiaceous fungal infection. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:19.

- Basílio FM, Hammerschmidt M, Mukai MM, et al. Mucormycosis and chromoblastomycosis occurring in a patient with leprosy type 2 reaction under prolonged corticosteroid and thalidomide therapy. An Bras Dermatol. 2012;87:767-771.

- Parente JN, Talhari C, Ginter-Hanselmayer G, et al. Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis in immunocompetent patients: two new cases caused by Exophiala jeanselmei and Cladophialophora carrionii. Mycoses. 2001;54:265-269.

- Torres-Guerrero E, Isa-Isa R, Isa M, et al. Chromoblastomycosis. Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:403-408.

- Ameen M. Managing chromoblastomycosis. Trop Doct. 2010;40:65-67.

- Zhang J, Xi L, Lu C, et al. Successful treatment for chromoblastomycosis caused by Fonsecaea monophora: a report of three cases in Guangdong, China. Mycoses. 2009;52:176-181.

- Tamura K, Matsuyama T, Yahagi E, et al. A case of chromomycosis treated by surgical therapy combined with preceded oral administration of terbinafine to reduce the size of the lesion. Tokai J Exp Clin Med. 2012;37:6-10.

- Patel U, Chu J, Patel R, et al. Subcutaneous dematiaceous fungal infection. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:19.

- Basílio FM, Hammerschmidt M, Mukai MM, et al. Mucormycosis and chromoblastomycosis occurring in a patient with leprosy type 2 reaction under prolonged corticosteroid and thalidomide therapy. An Bras Dermatol. 2012;87:767-771.

- Parente JN, Talhari C, Ginter-Hanselmayer G, et al. Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis in immunocompetent patients: two new cases caused by Exophiala jeanselmei and Cladophialophora carrionii. Mycoses. 2001;54:265-269.

Practice Points

- Chromoblastomycosis is an uncommon fungal infection that should be considered in cases of traumatic injuries to the skin.

- Biopsies of growing or nonhealing nodules will demonstrate characteristic golden brown spherules (medlar bodies).

- In localized cases, surgical excision may be curative.

Observational Study of Peripheral Intravenous Catheter Outcomes in Adult Hospitalized Patients: A Multivariable Analysis of Peripheral Intravenous Catheter Failure

INTRODUCTION

Peripheral intravenous catheter (PIV) insertion is the fastest, simplest, and most cost-effective method to gain vascular access, and it is used for short-term intravenous (IV) fluids, medications, blood products, and contrast media.1 It is the most common invasive device in hospitalized patients,2 with up to 70% of hospital patients receiving a PIV.3 Unacceptable PIV failure rates have been reported as high as 69%.4-7 Failure is most frequently due to phlebitis (vein wall irritation/inflammation), occlusion (blockage), infiltration or extravasation (IV fluids/vesicant therapy entering surrounding tissue), partial dislodgement or accidental removal, leakage, and infection.4,6,8 These failures have important implications for patients, who endure the discomfort of PIV complications and catheter replacements, and healthcare staff and budgets.

To reduce the incidence of catheter failure and avoid preventable PIV replacements, a clear understanding of why catheters fail is required. Previous research has identified that catheter gauge,9-11 insertion site,12-14 and inserter skill10,15 have an impact on PIV failure. Limitations of existing research are small study sizes,16-18 retrospective design,19 or secondary analysis of an existing data set; all potentially introduce sampling bias.10,20

To overcome these potential biases, we developed a data collection instrument based on the catheter-associated risk factors described in the literature,9-11,13 and other potential insertion and maintenance risks for PIV failure (eg, multiple insertion attempts, medications administered), with data collected prospectively. The study aim was to improve patient outcomes by identifying PIV insertion and maintenance risk factors amenable to modification through education or alternative clinical interventions, such as catheter gauge selection or insertion site.

METHODS

Study Design and Participants

We conducted this prospective cohort study in a large tertiary hospital in Queensland, Australia. Ethics committee approval was obtained from the hospital (HREC/14/QRBW/76) and Griffith University (NRS/26/14/HREC). The study was registered with the Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ACTRN12615000738527). Patients in medical and surgical wards were screened Monday, Wednesday, and Friday between October 2014 and December 2015. Patients over 18 years with a PIV (BD InsyteTM AutoguardTM BC; Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ) inserted within 24 hours, and who were able to provide written informed consent, were eligible and recruited sequentially. Patients classified as palliative by the treating clinical team were excluded.

Sample Size Calculation

The “10 events per variable” rule was used to determine the sample size required to study 50 potential risk factors.21,22 This determined that 1000 patients, with an average of 1.5 PIVs each and an expected PIV failure of 30% (500 events), were required.

Data Collection

At recruitment, baseline patient information was collected by a research nurse (ReNs) (demographics, admitting diagnosis, comorbidities, skin type,23 and vein condition) and entered into an electronic data platform supported by Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap).24 Baseline data also included catheter variables (eg, gauge, insertion site, catheterized vein) and insertion details (eg, department of insertion, inserting clinician, number of insertion attempts). We included every PIV the participant had during their admission until hospital discharge or insertion of a central venous access device. PIV sites were reviewed Monday, Wednesday, and Friday by ReNs for site complications (eg, redness, pain, swelling, palpable cord). Potential risk factors for failure were also recorded (eg, infusates and additives, antibiotic type and dosage, flushing regimen, number of times the PIV was accessed each day for administration of IV medications or fluids, dressing type and condition, securement method for the catheter and tubing, presence of extension tubing or 3-way taps, patient mobility status, and delirium). A project manager trained and supervised ReNs for protocol compliance and audited study data quality. We considered PIV failure to have occurred if the catheter had complications at removal identified by the ReNs assessment, from medical charts, or by speaking to the patient and beside nurse. We grouped the failures in 1 of 3 types: (1) occlusion or infiltration, defined as blockage, IV fluids moving into surrounding tissue, induration, or swelling greater than 1 cm from the insertion site at or within 24 hours of removal; (2) phlebitis, defined as per clinicians’ definitions or one or more of the following signs and symptoms: pain or tenderness scored at 2 or more on a 1 to 10 increasing severity pain scale, or redness or a palpable cord (either extending greater than 1 cm from the insertion site) at or within 24 hours of PIV removal; and (3) dislodgement (partial or complete). If multiple complications were present, all were recorded.

Statistical Analysis

Data were downloaded from REDcap to Stata 14.2 (StataCorp., College Station, TX) for data management and analysis. Missing data were not imputed. Nominal data observations were collapsed into a single observation per device. Patient and device variables were described as frequencies and proportions, means and standard deviations, or medians and interquartile ranges. Failure incidence rates were calculated, and a Kaplan-Meier survival curve was plotted. In general, Cox proportional hazards models were fitted (Efron method) to handle tied failures (clustering by patient). Variables significant at P < 0.20 on univariable analyses were subjected to multivariable regression. Generally, the largest category was set as referent. Correlations between variables were checked (Spearman’s rank for binary variables, R-squared value of linear regressions for continuous/categorical or continuous/continuous variables). Correlations were considered significant if r > 0.5 and the lower bound of the 95% confidence interval (CI) was >0.5 (where calculated). Covariate interactions were explored, and effects at P < 0.05 noted. The 4 steps of multivariable model building were (1) baseline covariates only with manual stepwise removal of covariates at P ≥ 0.05, (2) treatment covariates only with manual stepwise removal of covariates at P ≥ 0.05, (3) a combination of the derived models from (1) and (2) and manual stepwise removal of covariates at P ≥ 0.05, and (4) manual stepwise addition and removal (at P ≥ 0.05) of variables dropped during the previous steps and interaction testing. Final models were checked as follows: global proportional-hazards assumption test, concordance probability (that predictions and outcomes were in agreement), and Nelson-Aalen cumulative hazard function plotted against the Cox-Snell residuals.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

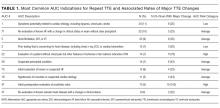

In total, 1000 patients with 1578 PIVs were recruited. The average age was 54 years and the majority were surgical patients (673; 67%). Almost half of patients (455; 46%) had 2 or more comorbidities, and 334 (33%) were obese (body mass index greater than 30). Sample characteristics are shown by the type of catheter failure in Table 1.

PIV Characteristics

All 1578 PIVs were followed until removal, with only 7 PIVs (0.44%) having missing data for the 3 outcomes of interest (these were coded as nonfailures for analysis). Sixty percent of participants had more than 1 PIV followed in the study. Doctors and physicians inserted 1278 (83%) catheters. A total of 550 (35%) were placed in the ward, with 428 (28%) inserted in the emergency department or ambulance. A third of the catheters (540; 34%) were 18-gauge or larger in diameter, and 1000 (64%) were located in the cubital fossa or hand. Multiple insertion attempts were required to place 315 (23%) PIVs. No PIVs were inserted with ultrasound, as this is rarely used in this hospital. The flushing policy was for the administration of 9% sodium chloride every 8 hours if no IV medications or fluids were ordered. Table 2 contains further details of device-related characteristics. Although the hospital policy was for catheter removal by 72 hours, dwell time ranged from <1 to 14 days, with an average of 2.4 days.

PIV Complications

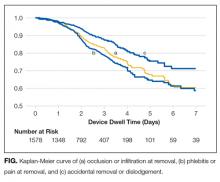

Catheter failure (any cause) occurred in 512 (32%) catheters, which is a failure rate of 136 per 1000 catheter days (95% CI, 125-148). A total of 346 patients out of 1000 (35%) had at least 1 failed PIV during the study. Failures were 267 phlebitis (17%), 228 occlusion/infiltration (14%), and/or 154 dislodgement (10%; Figure), with some PIVs exhibiting multiple concurrent complications (Table 2).

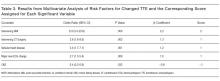

Multivariable AnalysisOcclusion/Infiltration

The multivariable analysis (Table 3) showed occlusion or infiltration was statistically significantly associated with female patients (hazard ratio [HR], 1.48; 95% CI, 1.10-2.00), with a 22-gauge catheter (HR, 1.43; 95% CI, 1.02-2.00), IV flucloxacillin (HR, 1.98; 95% CI, 1.19-3.31), and with frequent PIV access (HR, 1.12; 95% CI, 1.04-1.21; ie, with each increase of 1 in the mean medications/fluids administrations per day, relative PIV failure increased 112%). Less occlusion and infiltration were statistically significantly associated with securement by using additional nonsterile tape (HR, 0.46; 95% CI, 0.33-0.63), elasticized tubular bandages (HR, 0.49; 95% CI, 0.35-0.70 ), or other types of additional securement for the PIV (HR, 0.35; 95% CI, 0.26-0.47).

Phlebitis

Phlebitis was statistically significantly associated with female patients (HR, 1.81; 95% CI, 1.40-2.35), bruising at the insertion site (HR, 2.16; 95% CI, 1.26-3.71), insertion in patients’ dominant side (HR, 1.39; 95% CI, 1.09-1.77), IV flucloxicillin (HR, 2.01; 95% CI, 1.26-3.21), or with frequent PIV access (HR, 1.14; 95% CI, 1.08-1.21). Older age, (HR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.98-0.99; ie, each year older was associated with 1% less phlebitis), securement with additional nonsterile tape (HR, 0.63; 95% CI, 0.48-0.82) or with any other additional securement (HR, 0.53; 95% CI, 0.39-0.70), or the administration of IV cephazolin (HR, 0.63; 95% CI, 0.44-0.89) were associated with lower phlebitis risk.

Dislodgement

Statistically significant predictors associated with an increased risk of PIV dislodgement included paramedic insertion (HR, 1.78; 95% CI, 1.03-3.06) and frequent PIV access (HR, 1.11; 95% CI, 1.03-1.20). A decreased risk was associated with the additional securement of the PIV, including nonsterile tape (HR, 0.44; 95% CI, 0.31-0.63) or other forms of additional securement (HR, 0.32; 95% CI, 0.22-0.46).

DISCUSSION

One in 3 PIVs failed in this study, with phlebitis as the most common cause of PIV failure. The 17% phlebitis rate reflected clinician-reported phlebitis or phlebitis observed by research staff using a 1-criteria definition because any sign or symptom can trigger PIV removal (eg, pain), even if other signs or symptoms are not present. Reported phlebitis rates are lower if definitions require 2 signs or symptoms.4,6 With over 71 different phlebitis assessment scales in use, and none well validated, the best method for diagnosing phlebitis remains unclear and explains the variation in reported rates.25 Occlusion/infiltration and dislodgement were also highly prevalent forms of PIV failure at 14% and 10%, respectively. Occlusion and infiltration were combined because clinical staff use these terms interchangeably, and differential diagnostic tools are not used in practice. Both result in the same outcome (therapy interruption and PIV removal), and this combination of outcomes has been used previously.23 No PIV-associated bloodstream infections occurred, despite the heightened awareness of these infections in the literature.3

Females had significantly more occlusion/infiltration and phlebitis than males, in keeping with previous studies.7,9,10 This could be because of females’ smaller vein caliber, although the effect remained after adjustment for PIV gauge.7,26 The effect of aging on vascular endothelium and structural integrity may explain the observed decrease in phlebitis of 1% with each older year of age.27 However, gender and age effects could be explained by psychosocial factors (eg, older people may be less likely to admit pain, or we may question them less sympathetically), but, regardless, women and younger patients should be monitored more closely.