User login

Flashback to 2014

The development of therapies for chronic hepatitis C viral (HCV) infection has been a highlight of progress in hepatology and infectious disease over the last 25 years. From initial empiric approaches with interferon and ribavirin, to targeted and custom designed direct-acting antivirals (DAAs), there has been rapid improvement in efficacy and side effect profiles. Since we are dealing with a viral infection, loss of viremia after stopping therapy (sustained viral response, SVR) has been the marker of therapeutic success. SVR, however, is still a surrogate for clinical outcome and the analysis of 5-year follow-up in the December 2014 issue reported that in patients with SVR there was a reduction in risk of death, hepatocellular carcinoma, and liver transplantation.

Observational studies have the potential for significant biases as decisions to treat are frequently based on the likelihood of a successful outcome. A randomized clinical trial for DAAs compared to control would of course be unethical at this stage. The scale of use of DAAs should allow a clear answer to this question within the next 2 years.

The development of therapies for chronic hepatitis C viral (HCV) infection has been a highlight of progress in hepatology and infectious disease over the last 25 years. From initial empiric approaches with interferon and ribavirin, to targeted and custom designed direct-acting antivirals (DAAs), there has been rapid improvement in efficacy and side effect profiles. Since we are dealing with a viral infection, loss of viremia after stopping therapy (sustained viral response, SVR) has been the marker of therapeutic success. SVR, however, is still a surrogate for clinical outcome and the analysis of 5-year follow-up in the December 2014 issue reported that in patients with SVR there was a reduction in risk of death, hepatocellular carcinoma, and liver transplantation.

Observational studies have the potential for significant biases as decisions to treat are frequently based on the likelihood of a successful outcome. A randomized clinical trial for DAAs compared to control would of course be unethical at this stage. The scale of use of DAAs should allow a clear answer to this question within the next 2 years.

The development of therapies for chronic hepatitis C viral (HCV) infection has been a highlight of progress in hepatology and infectious disease over the last 25 years. From initial empiric approaches with interferon and ribavirin, to targeted and custom designed direct-acting antivirals (DAAs), there has been rapid improvement in efficacy and side effect profiles. Since we are dealing with a viral infection, loss of viremia after stopping therapy (sustained viral response, SVR) has been the marker of therapeutic success. SVR, however, is still a surrogate for clinical outcome and the analysis of 5-year follow-up in the December 2014 issue reported that in patients with SVR there was a reduction in risk of death, hepatocellular carcinoma, and liver transplantation.

Observational studies have the potential for significant biases as decisions to treat are frequently based on the likelihood of a successful outcome. A randomized clinical trial for DAAs compared to control would of course be unethical at this stage. The scale of use of DAAs should allow a clear answer to this question within the next 2 years.

Malperfusion key in aortic dissection repair outcomes

Early repair is the standard of care for patients with type A aortic dissection, but the presence of malperfusion rather than the timing of surgery may be a major determinant in patient survival both in the hospital and in the long term, according to an analysis of patients with acute type A aortic dissection over a 17-year period at the University of Bristol (England).

“Malperfusion at presentation rather than the timing of intervention is the major risk factor for death in both the short term and long term in patients undergoing surgical repair of type A aortic dissection,” Pradeep Narayan, FRCS, and his colleagues said in reporting their findings in the July issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (154:81-6). Nonetheless, Dr. Narayan and his colleagues acknowledged that early operation prevents the development of malperfusion and is the best option for restoring normal perfusion for patients who already have malperfusion.

Their study analyzed results from two different groups of patients who had surgery for repair of acute type A aortic dissection over a 17-year period: 72 in the early surgery group that had operative repair within 12 hours of symptom onset; and 80 in the late-surgery group that had the operation 12 hours or more after symptoms first appeared. A total of 205 patients underwent surgical repair for acute type A aortic dissection in that period, but only 152 cases had recorded the timing of surgery from onset of symptoms. The median time between arrival at the center and surgery was 3 hours.

Dr. Narayan and his coauthors reported that 39% (60) of the 152 patients had malperfusion. Organ malperfusion was actually more common in the early surgery group, although the difference was not significant: 48.6% vs. 31.3% in the late-surgery group (P = .29). Early mortality was also similar between the two groups: 19.4% in the early surgery group and 13.8% in the late surgery group (P = .8). In terms of late survival, the study found no difference between the two groups.

Dr. Narayan and his coauthors reported that malperfusion and concomitant coronary artery bypass grafting were independent predictors of survival, with hazard ratios of 2.65 (P = .01) and 3.03 (P = .03), respectively. As a nonlinear variable, time to surgery showed an inverse relationship with late mortality (HR, 0.51; P = .26), but as a linear variable when adjusted for other covariates, including malperfusion, it did not affect survival (HR, 1.01; P = .09).

“The main finding of the present study is that almost 40% of patients undergoing repair of type A aortic dissection had evidence of malperfusion,” Dr. Narayan and his coauthors said. “The second important finding is that the presence of malperfusion was associated with significantly increased risk of death in both the short-term and long-term follow-up.” While a delayed operation was associated with a reduced risk of death, it was not significant when accounting for malperfusion.

Dr. Narayan and his coauthors acknowledged limitations of their study, the most important of which was the including of different types of malperfusion as a single variable. Also, the small sample size may explain the lack of statistically significant differences between the two groups.

Dr. Narayan and his coauthors had no financial relationships to disclose.

Malperfusion has the potential to serve as a marker for the need for surgery in type A aortic dissection, but the inability to identify the true risk of developing malperfusion in the first 12-24 hours after acute type A dissection means that the indication for early surgery will remain unchanged, James I. Fann, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University says in his invited commentary (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;154:87-8).

“The findings of Narayan and colleagues impel us to review the history of the development of the classification and treatment (or in fact vice versa) of acute type A dissection and to acknowledge that early timing of surgery in these high-risk patients was originally proposed to prevent malperfusion and to respond to the most catastrophic complications,” Dr. Fann said.

But Dr. Fann cautioned against “being dismissive” of their findings, because such questioning and re-evaluation are essential in developing appropriate treatments. “Now, the question is whether we can identify the cohort of patients who are at lower risk for the development of malperfusion and tailor their treatment,” he said.

Dr. Fann had no financial relationships to disclose.

Malperfusion has the potential to serve as a marker for the need for surgery in type A aortic dissection, but the inability to identify the true risk of developing malperfusion in the first 12-24 hours after acute type A dissection means that the indication for early surgery will remain unchanged, James I. Fann, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University says in his invited commentary (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;154:87-8).

“The findings of Narayan and colleagues impel us to review the history of the development of the classification and treatment (or in fact vice versa) of acute type A dissection and to acknowledge that early timing of surgery in these high-risk patients was originally proposed to prevent malperfusion and to respond to the most catastrophic complications,” Dr. Fann said.

But Dr. Fann cautioned against “being dismissive” of their findings, because such questioning and re-evaluation are essential in developing appropriate treatments. “Now, the question is whether we can identify the cohort of patients who are at lower risk for the development of malperfusion and tailor their treatment,” he said.

Dr. Fann had no financial relationships to disclose.

Malperfusion has the potential to serve as a marker for the need for surgery in type A aortic dissection, but the inability to identify the true risk of developing malperfusion in the first 12-24 hours after acute type A dissection means that the indication for early surgery will remain unchanged, James I. Fann, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University says in his invited commentary (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;154:87-8).

“The findings of Narayan and colleagues impel us to review the history of the development of the classification and treatment (or in fact vice versa) of acute type A dissection and to acknowledge that early timing of surgery in these high-risk patients was originally proposed to prevent malperfusion and to respond to the most catastrophic complications,” Dr. Fann said.

But Dr. Fann cautioned against “being dismissive” of their findings, because such questioning and re-evaluation are essential in developing appropriate treatments. “Now, the question is whether we can identify the cohort of patients who are at lower risk for the development of malperfusion and tailor their treatment,” he said.

Dr. Fann had no financial relationships to disclose.

Early repair is the standard of care for patients with type A aortic dissection, but the presence of malperfusion rather than the timing of surgery may be a major determinant in patient survival both in the hospital and in the long term, according to an analysis of patients with acute type A aortic dissection over a 17-year period at the University of Bristol (England).

“Malperfusion at presentation rather than the timing of intervention is the major risk factor for death in both the short term and long term in patients undergoing surgical repair of type A aortic dissection,” Pradeep Narayan, FRCS, and his colleagues said in reporting their findings in the July issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (154:81-6). Nonetheless, Dr. Narayan and his colleagues acknowledged that early operation prevents the development of malperfusion and is the best option for restoring normal perfusion for patients who already have malperfusion.

Their study analyzed results from two different groups of patients who had surgery for repair of acute type A aortic dissection over a 17-year period: 72 in the early surgery group that had operative repair within 12 hours of symptom onset; and 80 in the late-surgery group that had the operation 12 hours or more after symptoms first appeared. A total of 205 patients underwent surgical repair for acute type A aortic dissection in that period, but only 152 cases had recorded the timing of surgery from onset of symptoms. The median time between arrival at the center and surgery was 3 hours.

Dr. Narayan and his coauthors reported that 39% (60) of the 152 patients had malperfusion. Organ malperfusion was actually more common in the early surgery group, although the difference was not significant: 48.6% vs. 31.3% in the late-surgery group (P = .29). Early mortality was also similar between the two groups: 19.4% in the early surgery group and 13.8% in the late surgery group (P = .8). In terms of late survival, the study found no difference between the two groups.

Dr. Narayan and his coauthors reported that malperfusion and concomitant coronary artery bypass grafting were independent predictors of survival, with hazard ratios of 2.65 (P = .01) and 3.03 (P = .03), respectively. As a nonlinear variable, time to surgery showed an inverse relationship with late mortality (HR, 0.51; P = .26), but as a linear variable when adjusted for other covariates, including malperfusion, it did not affect survival (HR, 1.01; P = .09).

“The main finding of the present study is that almost 40% of patients undergoing repair of type A aortic dissection had evidence of malperfusion,” Dr. Narayan and his coauthors said. “The second important finding is that the presence of malperfusion was associated with significantly increased risk of death in both the short-term and long-term follow-up.” While a delayed operation was associated with a reduced risk of death, it was not significant when accounting for malperfusion.

Dr. Narayan and his coauthors acknowledged limitations of their study, the most important of which was the including of different types of malperfusion as a single variable. Also, the small sample size may explain the lack of statistically significant differences between the two groups.

Dr. Narayan and his coauthors had no financial relationships to disclose.

Early repair is the standard of care for patients with type A aortic dissection, but the presence of malperfusion rather than the timing of surgery may be a major determinant in patient survival both in the hospital and in the long term, according to an analysis of patients with acute type A aortic dissection over a 17-year period at the University of Bristol (England).

“Malperfusion at presentation rather than the timing of intervention is the major risk factor for death in both the short term and long term in patients undergoing surgical repair of type A aortic dissection,” Pradeep Narayan, FRCS, and his colleagues said in reporting their findings in the July issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (154:81-6). Nonetheless, Dr. Narayan and his colleagues acknowledged that early operation prevents the development of malperfusion and is the best option for restoring normal perfusion for patients who already have malperfusion.

Their study analyzed results from two different groups of patients who had surgery for repair of acute type A aortic dissection over a 17-year period: 72 in the early surgery group that had operative repair within 12 hours of symptom onset; and 80 in the late-surgery group that had the operation 12 hours or more after symptoms first appeared. A total of 205 patients underwent surgical repair for acute type A aortic dissection in that period, but only 152 cases had recorded the timing of surgery from onset of symptoms. The median time between arrival at the center and surgery was 3 hours.

Dr. Narayan and his coauthors reported that 39% (60) of the 152 patients had malperfusion. Organ malperfusion was actually more common in the early surgery group, although the difference was not significant: 48.6% vs. 31.3% in the late-surgery group (P = .29). Early mortality was also similar between the two groups: 19.4% in the early surgery group and 13.8% in the late surgery group (P = .8). In terms of late survival, the study found no difference between the two groups.

Dr. Narayan and his coauthors reported that malperfusion and concomitant coronary artery bypass grafting were independent predictors of survival, with hazard ratios of 2.65 (P = .01) and 3.03 (P = .03), respectively. As a nonlinear variable, time to surgery showed an inverse relationship with late mortality (HR, 0.51; P = .26), but as a linear variable when adjusted for other covariates, including malperfusion, it did not affect survival (HR, 1.01; P = .09).

“The main finding of the present study is that almost 40% of patients undergoing repair of type A aortic dissection had evidence of malperfusion,” Dr. Narayan and his coauthors said. “The second important finding is that the presence of malperfusion was associated with significantly increased risk of death in both the short-term and long-term follow-up.” While a delayed operation was associated with a reduced risk of death, it was not significant when accounting for malperfusion.

Dr. Narayan and his coauthors acknowledged limitations of their study, the most important of which was the including of different types of malperfusion as a single variable. Also, the small sample size may explain the lack of statistically significant differences between the two groups.

Dr. Narayan and his coauthors had no financial relationships to disclose.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THORACIC AND CARDIOVASCULAR SURGERY

Key clinical point: Malperfusion is a main determinant of outcomes for patients having surgical repair for acute type A aortic dissection.

Major finding: Patients in the early surgery group (surgery within 12 hours of onset) were more likely to have malperfusion than those who had surgery later, 47% vs. 31%.

Data source: Single-center analysis of 152 operations for repair of acute type A aortic dissections over a 17-year period.

Disclosures: Dr. Narayan and his coauthors had no financial relationships to disclose.

Short, simple antibiotic courses effective in latent TB

Latent tuberculosis infection can be safely and effectively treated with 3- and 4-month medication regimens, including those using once-weekly dosing, according to results from a new meta-analysis.

The findings, published online July 31 in Annals of Internal Medicine, bolster evidence that shorter antibiotic regimens using rifamycins alone or in combination with other drugs are a viable alternative to the longer courses (Ann Intern Med. 2017;167:248-55).

For their research, Dominik Zenner, MD, an epidemiologist with Public Health England in London, and his colleagues updated a meta-analysis they published in 2014. The team added 8 new randomized studies to the 53 that had been included in the earlier paper (Ann Intern Med. 2014 Sep;161:419-28).

Using pairwise comparisons and a Bayesian network analysis, Dr. Zenner and his colleagues found comparable efficacy among isoniazid regimens of 6 months or more; rifampicin-isoniazid regimens of 3 or 4 months, rifampicin-only regimens, and rifampicin-pyrazinamide regimens, compared with placebo (P less than .05 for all).

Importantly, a rifapentine-based regimen in which patients took a weekly dose for 12 weeks was as effective as the others.

“We think that you can get away with shorter regimens,” Dr. Zenner said in an interview. Although 3- to 4-month courses are already recommended in some countries, including the United Kingdom, for most patients with latent TB, “clinicians in some settings have been quite slow to adopt them,” he said.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention currently recommend multiple treatment strategies for latent TB, depending on patient characteristics. These include 6 or 9 months of isoniazid; 3 months of once-weekly isoniazid and rifapentine; or 4 months of daily rifampin.

In the meta-analysis, rifamycin-only regimens performed as well as did those regimens that also used isoniazid, the study showed, suggesting that, for most patients who can safely be treated with rifamycins, “there is no added gain of using isoniazid,” Dr. Zenner said.

He noted that the longer isoniazid-alone regimens are nonetheless effective and appropriate for some, including people who might have potential drug interactions, such as HIV patients taking antiretroviral medications.

About 2 billion people worldwide are estimated to have latent TB, and most will not go on to develop active TB. However, because latent TB acts as the reservoir for active TB, screening of high-risk groups and close contacts of TB patients and treating latent infections is a public health priority.

But many of these asymptomatic patients will get lost between a positive screen result and successful treatment completion, Dr. Zenner said.

“We have huge drop-offs in the cascade of treatment, and treatment completion is one of the worries,” he said. “Whether it makes a huge difference in compliance to take only 12 doses is not sufficiently studied, but it does make a lot of sense. By reducing the pill burden, as we call it, we think that we will see quite good adherence rates – but that’s a subject of further detailed study.”

The investigators noted as a limitation of their study that hepatotoxicity outcomes were not available for all studies and that some of the included trials had a potential for bias. They did not see statistically significant differences in treatment efficacy between regimens in HIV-positive and HIV-negative patients, but noted in their analysis that “efficacy may have been weaker in HIV-positive populations.”

The U.K. National Institute for Health Research provided some funding for Dr. Zenner and his colleagues’ study. One coauthor, Helen Stagg, PhD, reported nonfinancial support from Sanofi during the study, and financial support from Otsuka for unrelated work.

Latent tuberculosis infection can be safely and effectively treated with 3- and 4-month medication regimens, including those using once-weekly dosing, according to results from a new meta-analysis.

The findings, published online July 31 in Annals of Internal Medicine, bolster evidence that shorter antibiotic regimens using rifamycins alone or in combination with other drugs are a viable alternative to the longer courses (Ann Intern Med. 2017;167:248-55).

For their research, Dominik Zenner, MD, an epidemiologist with Public Health England in London, and his colleagues updated a meta-analysis they published in 2014. The team added 8 new randomized studies to the 53 that had been included in the earlier paper (Ann Intern Med. 2014 Sep;161:419-28).

Using pairwise comparisons and a Bayesian network analysis, Dr. Zenner and his colleagues found comparable efficacy among isoniazid regimens of 6 months or more; rifampicin-isoniazid regimens of 3 or 4 months, rifampicin-only regimens, and rifampicin-pyrazinamide regimens, compared with placebo (P less than .05 for all).

Importantly, a rifapentine-based regimen in which patients took a weekly dose for 12 weeks was as effective as the others.

“We think that you can get away with shorter regimens,” Dr. Zenner said in an interview. Although 3- to 4-month courses are already recommended in some countries, including the United Kingdom, for most patients with latent TB, “clinicians in some settings have been quite slow to adopt them,” he said.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention currently recommend multiple treatment strategies for latent TB, depending on patient characteristics. These include 6 or 9 months of isoniazid; 3 months of once-weekly isoniazid and rifapentine; or 4 months of daily rifampin.

In the meta-analysis, rifamycin-only regimens performed as well as did those regimens that also used isoniazid, the study showed, suggesting that, for most patients who can safely be treated with rifamycins, “there is no added gain of using isoniazid,” Dr. Zenner said.

He noted that the longer isoniazid-alone regimens are nonetheless effective and appropriate for some, including people who might have potential drug interactions, such as HIV patients taking antiretroviral medications.

About 2 billion people worldwide are estimated to have latent TB, and most will not go on to develop active TB. However, because latent TB acts as the reservoir for active TB, screening of high-risk groups and close contacts of TB patients and treating latent infections is a public health priority.

But many of these asymptomatic patients will get lost between a positive screen result and successful treatment completion, Dr. Zenner said.

“We have huge drop-offs in the cascade of treatment, and treatment completion is one of the worries,” he said. “Whether it makes a huge difference in compliance to take only 12 doses is not sufficiently studied, but it does make a lot of sense. By reducing the pill burden, as we call it, we think that we will see quite good adherence rates – but that’s a subject of further detailed study.”

The investigators noted as a limitation of their study that hepatotoxicity outcomes were not available for all studies and that some of the included trials had a potential for bias. They did not see statistically significant differences in treatment efficacy between regimens in HIV-positive and HIV-negative patients, but noted in their analysis that “efficacy may have been weaker in HIV-positive populations.”

The U.K. National Institute for Health Research provided some funding for Dr. Zenner and his colleagues’ study. One coauthor, Helen Stagg, PhD, reported nonfinancial support from Sanofi during the study, and financial support from Otsuka for unrelated work.

Latent tuberculosis infection can be safely and effectively treated with 3- and 4-month medication regimens, including those using once-weekly dosing, according to results from a new meta-analysis.

The findings, published online July 31 in Annals of Internal Medicine, bolster evidence that shorter antibiotic regimens using rifamycins alone or in combination with other drugs are a viable alternative to the longer courses (Ann Intern Med. 2017;167:248-55).

For their research, Dominik Zenner, MD, an epidemiologist with Public Health England in London, and his colleagues updated a meta-analysis they published in 2014. The team added 8 new randomized studies to the 53 that had been included in the earlier paper (Ann Intern Med. 2014 Sep;161:419-28).

Using pairwise comparisons and a Bayesian network analysis, Dr. Zenner and his colleagues found comparable efficacy among isoniazid regimens of 6 months or more; rifampicin-isoniazid regimens of 3 or 4 months, rifampicin-only regimens, and rifampicin-pyrazinamide regimens, compared with placebo (P less than .05 for all).

Importantly, a rifapentine-based regimen in which patients took a weekly dose for 12 weeks was as effective as the others.

“We think that you can get away with shorter regimens,” Dr. Zenner said in an interview. Although 3- to 4-month courses are already recommended in some countries, including the United Kingdom, for most patients with latent TB, “clinicians in some settings have been quite slow to adopt them,” he said.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention currently recommend multiple treatment strategies for latent TB, depending on patient characteristics. These include 6 or 9 months of isoniazid; 3 months of once-weekly isoniazid and rifapentine; or 4 months of daily rifampin.

In the meta-analysis, rifamycin-only regimens performed as well as did those regimens that also used isoniazid, the study showed, suggesting that, for most patients who can safely be treated with rifamycins, “there is no added gain of using isoniazid,” Dr. Zenner said.

He noted that the longer isoniazid-alone regimens are nonetheless effective and appropriate for some, including people who might have potential drug interactions, such as HIV patients taking antiretroviral medications.

About 2 billion people worldwide are estimated to have latent TB, and most will not go on to develop active TB. However, because latent TB acts as the reservoir for active TB, screening of high-risk groups and close contacts of TB patients and treating latent infections is a public health priority.

But many of these asymptomatic patients will get lost between a positive screen result and successful treatment completion, Dr. Zenner said.

“We have huge drop-offs in the cascade of treatment, and treatment completion is one of the worries,” he said. “Whether it makes a huge difference in compliance to take only 12 doses is not sufficiently studied, but it does make a lot of sense. By reducing the pill burden, as we call it, we think that we will see quite good adherence rates – but that’s a subject of further detailed study.”

The investigators noted as a limitation of their study that hepatotoxicity outcomes were not available for all studies and that some of the included trials had a potential for bias. They did not see statistically significant differences in treatment efficacy between regimens in HIV-positive and HIV-negative patients, but noted in their analysis that “efficacy may have been weaker in HIV-positive populations.”

The U.K. National Institute for Health Research provided some funding for Dr. Zenner and his colleagues’ study. One coauthor, Helen Stagg, PhD, reported nonfinancial support from Sanofi during the study, and financial support from Otsuka for unrelated work.

FROM ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Rifamycin-only treatment of latent TB works as well as combination regimens, and shorter dosing schedules show no loss in efficacy vs. longer ones.

Major finding: Rifamycin-only regimens, rifampicin-isoniazid regimens of 3 or 4 months, rifampicin-pyrazinamide regimens were all effective, compared with placebo and with isoniazid regimens of 6, 12 and 72 months.

Data source: A network meta-analysis of 61 randomized trials, 8 of them published in last 3 years

Disclosures: The National Institute for Health Research (UK) funded some co-authors; one co-author disclosed a financial relationship with a pharmaceutical firm.

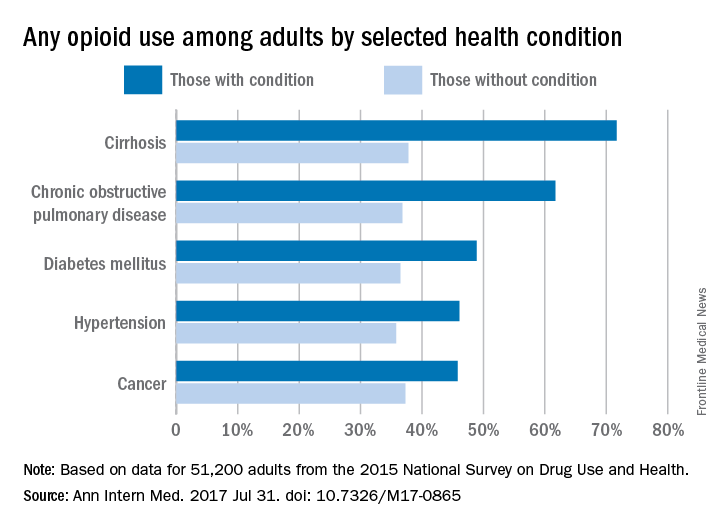

Opioid use higher in adults with health conditions

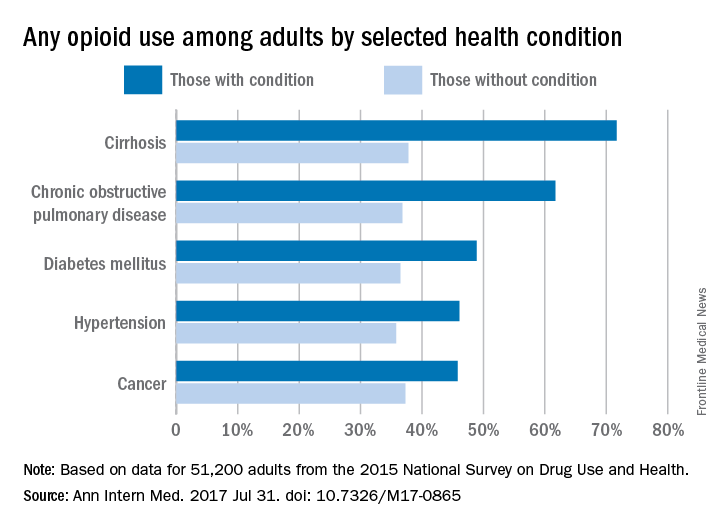

Use of prescription opioids is higher among adults with health conditions such as cirrhosis and diabetes, compared with those who do not have the conditions, according to an analysis of national survey data.

In 2015, reported use of opioids was 71.7% in adults with cirrhosis, compared with 37.8% for those who did not have cirrhosis. That is the largest difference among any of the various health conditions included in a report by Beth Han, MD, PhD, of the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration in Rockville, Md., which conducts the ongoing survey, and her associates (Ann Intern Med. 2017 July 31. doi: 10.7326/M17-0865).

Of those with cirrhosis who reported any use of prescription opioids, 86.1% said that they did so without misuse, while the other four conditions had rates ranging from 91.3% to 93.9%. Among those with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, 6.2% misused opioids without use disorder, and 2.5% had opioid use disorder. These estimates were not available for cirrhosis because of low statistical precision, but the corresponding figures were 6.9% and 1.5% for diabetes, 6% and 2.1% for hypertension, and 5.3% and 0.8% for cancer, the investigators said.

Overall prescription opioid use in 2015 was 37.8% for the civilian, noninstitutionalized adult population, about 91.8 million individuals. Estimates suggest that 4.7% (1.5 million) of all adults misused them in some way, and that 0.8% (1.9 million) had a use disorder, they reported.

“Among adults with misuse of prescription opioids, 59.9% used them without a prescription at least once in 2015, and 40.8% obtained them from friends or relatives for free for their most recent episode of misuse. Such widespread social availability of prescription opioids suggests that they are commonly dispensed in amounts not fully consumed by the patients to whom they are prescribed,” the authors wrote.

Funding for the study came from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, the National Institute on Drug Abuse, and the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation of the Department of Health and Human Services. One investigator reported stock holdings in 3M, General Electric, and Pfizer, and another reported stock holdings in Eli Lilly, General Electric, and Sanofi. Dr. Han and the other three investigators disclosed that they had no conflicts of interest.

Talk to any busy full-time primary care physician, and it becomes evident that writing an opioid prescription is much easier than exploring other options for addressing chronic pain in the course of a 15-minute visit. The same stressful work conditions likely also make it difficult for primary care providers to appropriately monitor patients who take opioids in the long term with urine drug tests and pill counts to assess for opioid diversion or other substance use.

A potential solution to the problem of the overburdened primary care physician is to distribute some of the work to other members of the health care team. Indeed, we have found that using a nurse care manager with a registry increased receipt of guideline-concordant care (urine drug testing and patient-provider agreements) among patients receiving long-term opioid therapy. The intervention also resulted in reductions in opioid doses at a large urban safety-net hospital and three community health centers.

Karen E. Lasser, MD, is with Boston Medical Center and Boston University. Her remarks are excerpted from an editorial response (Ann Intern Med. 2017 Jul 31. doi: 10.7326/M17-1559) to Dr. Han’s study.

Talk to any busy full-time primary care physician, and it becomes evident that writing an opioid prescription is much easier than exploring other options for addressing chronic pain in the course of a 15-minute visit. The same stressful work conditions likely also make it difficult for primary care providers to appropriately monitor patients who take opioids in the long term with urine drug tests and pill counts to assess for opioid diversion or other substance use.

A potential solution to the problem of the overburdened primary care physician is to distribute some of the work to other members of the health care team. Indeed, we have found that using a nurse care manager with a registry increased receipt of guideline-concordant care (urine drug testing and patient-provider agreements) among patients receiving long-term opioid therapy. The intervention also resulted in reductions in opioid doses at a large urban safety-net hospital and three community health centers.

Karen E. Lasser, MD, is with Boston Medical Center and Boston University. Her remarks are excerpted from an editorial response (Ann Intern Med. 2017 Jul 31. doi: 10.7326/M17-1559) to Dr. Han’s study.

Talk to any busy full-time primary care physician, and it becomes evident that writing an opioid prescription is much easier than exploring other options for addressing chronic pain in the course of a 15-minute visit. The same stressful work conditions likely also make it difficult for primary care providers to appropriately monitor patients who take opioids in the long term with urine drug tests and pill counts to assess for opioid diversion or other substance use.

A potential solution to the problem of the overburdened primary care physician is to distribute some of the work to other members of the health care team. Indeed, we have found that using a nurse care manager with a registry increased receipt of guideline-concordant care (urine drug testing and patient-provider agreements) among patients receiving long-term opioid therapy. The intervention also resulted in reductions in opioid doses at a large urban safety-net hospital and three community health centers.

Karen E. Lasser, MD, is with Boston Medical Center and Boston University. Her remarks are excerpted from an editorial response (Ann Intern Med. 2017 Jul 31. doi: 10.7326/M17-1559) to Dr. Han’s study.

Use of prescription opioids is higher among adults with health conditions such as cirrhosis and diabetes, compared with those who do not have the conditions, according to an analysis of national survey data.

In 2015, reported use of opioids was 71.7% in adults with cirrhosis, compared with 37.8% for those who did not have cirrhosis. That is the largest difference among any of the various health conditions included in a report by Beth Han, MD, PhD, of the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration in Rockville, Md., which conducts the ongoing survey, and her associates (Ann Intern Med. 2017 July 31. doi: 10.7326/M17-0865).

Of those with cirrhosis who reported any use of prescription opioids, 86.1% said that they did so without misuse, while the other four conditions had rates ranging from 91.3% to 93.9%. Among those with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, 6.2% misused opioids without use disorder, and 2.5% had opioid use disorder. These estimates were not available for cirrhosis because of low statistical precision, but the corresponding figures were 6.9% and 1.5% for diabetes, 6% and 2.1% for hypertension, and 5.3% and 0.8% for cancer, the investigators said.

Overall prescription opioid use in 2015 was 37.8% for the civilian, noninstitutionalized adult population, about 91.8 million individuals. Estimates suggest that 4.7% (1.5 million) of all adults misused them in some way, and that 0.8% (1.9 million) had a use disorder, they reported.

“Among adults with misuse of prescription opioids, 59.9% used them without a prescription at least once in 2015, and 40.8% obtained them from friends or relatives for free for their most recent episode of misuse. Such widespread social availability of prescription opioids suggests that they are commonly dispensed in amounts not fully consumed by the patients to whom they are prescribed,” the authors wrote.

Funding for the study came from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, the National Institute on Drug Abuse, and the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation of the Department of Health and Human Services. One investigator reported stock holdings in 3M, General Electric, and Pfizer, and another reported stock holdings in Eli Lilly, General Electric, and Sanofi. Dr. Han and the other three investigators disclosed that they had no conflicts of interest.

Use of prescription opioids is higher among adults with health conditions such as cirrhosis and diabetes, compared with those who do not have the conditions, according to an analysis of national survey data.

In 2015, reported use of opioids was 71.7% in adults with cirrhosis, compared with 37.8% for those who did not have cirrhosis. That is the largest difference among any of the various health conditions included in a report by Beth Han, MD, PhD, of the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration in Rockville, Md., which conducts the ongoing survey, and her associates (Ann Intern Med. 2017 July 31. doi: 10.7326/M17-0865).

Of those with cirrhosis who reported any use of prescription opioids, 86.1% said that they did so without misuse, while the other four conditions had rates ranging from 91.3% to 93.9%. Among those with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, 6.2% misused opioids without use disorder, and 2.5% had opioid use disorder. These estimates were not available for cirrhosis because of low statistical precision, but the corresponding figures were 6.9% and 1.5% for diabetes, 6% and 2.1% for hypertension, and 5.3% and 0.8% for cancer, the investigators said.

Overall prescription opioid use in 2015 was 37.8% for the civilian, noninstitutionalized adult population, about 91.8 million individuals. Estimates suggest that 4.7% (1.5 million) of all adults misused them in some way, and that 0.8% (1.9 million) had a use disorder, they reported.

“Among adults with misuse of prescription opioids, 59.9% used them without a prescription at least once in 2015, and 40.8% obtained them from friends or relatives for free for their most recent episode of misuse. Such widespread social availability of prescription opioids suggests that they are commonly dispensed in amounts not fully consumed by the patients to whom they are prescribed,” the authors wrote.

Funding for the study came from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, the National Institute on Drug Abuse, and the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation of the Department of Health and Human Services. One investigator reported stock holdings in 3M, General Electric, and Pfizer, and another reported stock holdings in Eli Lilly, General Electric, and Sanofi. Dr. Han and the other three investigators disclosed that they had no conflicts of interest.

FROM ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

Tips for Living With Narcolepsy

Click here to download the PDF.

Click here to download the PDF.

Click here to download the PDF.

Thyroid-nodule size boosts serum thyroglobulin’s diagnostic value

BOSTON – Normalizing the serum thyroglobulin level by thyroid nodule size in patients surgically treated for a thyroid nodule produced a strongly significant link between the level of this marker and nodule malignancy in a review of nearly 200 patients treated at any of three Montreal centers.

After normalization, the serum thyroglobulin of patients with a malignant nodule averaged 51 mcg/L*cm, more than double the average 23 mcg/L*cm among patients with benign nodules, Neil Verma, MD, said at the World Congress on Thyroid Cancer.

But the senior investigator on the study said that, even if the MTNS+ gets a little more accurate by using a nodule size-normalized serum thyroglobulin level, the clinical utility of the MTNS+ will soon be completely eclipsed by widespread reliance on molecular tests, whereas the MTNS+ combines many clinical and conventional laboratory measures. It‘s only a matter of cost, said Richard J. Payne, MD, a head and neck surgeon at McGill.

Routine reimbursement for molecular diagnostic tests for the malignancy of thyroid nodules was discussed at a recent meeting of Canadian head and neck surgeons, who decided to lobby provincial governments to try to get it covered, according to Dr. Payne. “I’d be very surprised if we don’t have government coverage within 4-5 years,” in part because the cost for molecular testing will likely fall significantly in that time frame, he predicted.

The analysis reported by Dr. Verma included 196 patients with thyroid nodules who underwent a partial or total thyroidectomy at any of three McGill teaching hospitals during 2010-2015. He determined the benign or malignant status of their nodules based on their histology. The analysis he presented also showed that malignancy had no clear relationship to nodule size. Nodules that were less than 2 cm in diameter were about as likely to be malignant as were those that were 3 cm or larger in diameter, Dr. Verma reported.

Size-normalized serum thyroglobulin will now be incorporated into the MTNS+, which will be the fourth change to the original MTNS scoring system since it was developed more than a decade ago, noted Dr. Payne. But, while the MTNS+ allows better prediction of malignant potential than does the Bethesda system for evaluating nodule cytopathology in a fine-needle aspirate, it still falls short of molecular testing in its predictive accuracy, Dr. Payne said.

Dr. Verma and Dr. Payne had no disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

BOSTON – Normalizing the serum thyroglobulin level by thyroid nodule size in patients surgically treated for a thyroid nodule produced a strongly significant link between the level of this marker and nodule malignancy in a review of nearly 200 patients treated at any of three Montreal centers.

After normalization, the serum thyroglobulin of patients with a malignant nodule averaged 51 mcg/L*cm, more than double the average 23 mcg/L*cm among patients with benign nodules, Neil Verma, MD, said at the World Congress on Thyroid Cancer.

But the senior investigator on the study said that, even if the MTNS+ gets a little more accurate by using a nodule size-normalized serum thyroglobulin level, the clinical utility of the MTNS+ will soon be completely eclipsed by widespread reliance on molecular tests, whereas the MTNS+ combines many clinical and conventional laboratory measures. It‘s only a matter of cost, said Richard J. Payne, MD, a head and neck surgeon at McGill.

Routine reimbursement for molecular diagnostic tests for the malignancy of thyroid nodules was discussed at a recent meeting of Canadian head and neck surgeons, who decided to lobby provincial governments to try to get it covered, according to Dr. Payne. “I’d be very surprised if we don’t have government coverage within 4-5 years,” in part because the cost for molecular testing will likely fall significantly in that time frame, he predicted.

The analysis reported by Dr. Verma included 196 patients with thyroid nodules who underwent a partial or total thyroidectomy at any of three McGill teaching hospitals during 2010-2015. He determined the benign or malignant status of their nodules based on their histology. The analysis he presented also showed that malignancy had no clear relationship to nodule size. Nodules that were less than 2 cm in diameter were about as likely to be malignant as were those that were 3 cm or larger in diameter, Dr. Verma reported.

Size-normalized serum thyroglobulin will now be incorporated into the MTNS+, which will be the fourth change to the original MTNS scoring system since it was developed more than a decade ago, noted Dr. Payne. But, while the MTNS+ allows better prediction of malignant potential than does the Bethesda system for evaluating nodule cytopathology in a fine-needle aspirate, it still falls short of molecular testing in its predictive accuracy, Dr. Payne said.

Dr. Verma and Dr. Payne had no disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

BOSTON – Normalizing the serum thyroglobulin level by thyroid nodule size in patients surgically treated for a thyroid nodule produced a strongly significant link between the level of this marker and nodule malignancy in a review of nearly 200 patients treated at any of three Montreal centers.

After normalization, the serum thyroglobulin of patients with a malignant nodule averaged 51 mcg/L*cm, more than double the average 23 mcg/L*cm among patients with benign nodules, Neil Verma, MD, said at the World Congress on Thyroid Cancer.

But the senior investigator on the study said that, even if the MTNS+ gets a little more accurate by using a nodule size-normalized serum thyroglobulin level, the clinical utility of the MTNS+ will soon be completely eclipsed by widespread reliance on molecular tests, whereas the MTNS+ combines many clinical and conventional laboratory measures. It‘s only a matter of cost, said Richard J. Payne, MD, a head and neck surgeon at McGill.

Routine reimbursement for molecular diagnostic tests for the malignancy of thyroid nodules was discussed at a recent meeting of Canadian head and neck surgeons, who decided to lobby provincial governments to try to get it covered, according to Dr. Payne. “I’d be very surprised if we don’t have government coverage within 4-5 years,” in part because the cost for molecular testing will likely fall significantly in that time frame, he predicted.

The analysis reported by Dr. Verma included 196 patients with thyroid nodules who underwent a partial or total thyroidectomy at any of three McGill teaching hospitals during 2010-2015. He determined the benign or malignant status of their nodules based on their histology. The analysis he presented also showed that malignancy had no clear relationship to nodule size. Nodules that were less than 2 cm in diameter were about as likely to be malignant as were those that were 3 cm or larger in diameter, Dr. Verma reported.

Size-normalized serum thyroglobulin will now be incorporated into the MTNS+, which will be the fourth change to the original MTNS scoring system since it was developed more than a decade ago, noted Dr. Payne. But, while the MTNS+ allows better prediction of malignant potential than does the Bethesda system for evaluating nodule cytopathology in a fine-needle aspirate, it still falls short of molecular testing in its predictive accuracy, Dr. Payne said.

Dr. Verma and Dr. Payne had no disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT WCTC 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The average size-normalized serum thyroglobulin level was 51 mcg/L*cm in patients with malignant nodules and 23 mcg/L*cm with benign nodules.

Data source: Review of 196 patients who underwent partial or complete thyroidectomy at any of three Montreal centers.

Disclosures: Dr. Verma and Dr. Payne had no disclosures.

Are women of advanced maternal age at increased risk for severe maternal morbidity?

EXPERT COMMENTARY

While numerous studies have investigated the risk of perinatal outcomes with advancing maternal age, the primary objective of a recent study by Lisonkova and colleagues was to examine the association between advancing maternal age and severe maternal morbidities and mortality.

Details of the study

The population-based retrospective cohort study compared age-specific rates of severe maternal morbidities and mortality among 828,269 pregnancies in Washington state between 2003 and 2013. Singleton births to women 15 to 60 years of age were included; out-of-hospital births were excluded. Information was obtained by linking the Birth Events Record Database (which includes information on maternal, pregnancy, and labor and delivery characteristics and birth outcomes), and the Comprehensive Hospital Abstract Reporting System database (which includes diagnostic and procedural codes for all hospitalizations in Washington state).

The primary objective was to examine the association between age and severe maternal morbidities. Maternal morbidities were divided into categories: antepartum hemorrhage, respiratory morbidity, thromboembolism, cerebrovascular morbidity, acute cardiac morbidity, severe postpartum hemorrhage, maternal sepsis, renal failure, obstetric shock, complications of anesthesia and obstetric interventions, and need for life-saving procedures. A composite outcome, comprised of severe maternal morbidities, intensive care unit admission, and maternal mortality, was also created.

Rates of severe morbidities were compared for age groups 15 to 19, 20 to 24, 25 to 29, 30 to 34, 35 to 39, 40 to 44, and ≥45 years to the referent category (25 to 29 years). Additional comparisons were also performed for ages 45 to 49 and ≥50 years for the composite and for morbidities with high incidence. Logistic regression and sensitivity analyses were used to control for demographic and prepregnancy characteristics, underlying medical conditions, assisted conception, and delivery characteristics.

Severe maternal morbidities demonstrated a J-shaped association with age: the lowest rates of morbidity were observed in women 20 to 34 years of age, and steeply increasing rates of morbidity were observed for women aged 40 and older. One notable exception was the rate of sepsis, which was increased in teen mothers compared with all other groups.

The unadjusted rate of the composite outcome of severe maternal morbidity and mortality was 2.1% in teenagers, 1.5% among women 25 to 29 years, 2.3% among those aged 40 to 44, and 3.6% among women aged 45 and older.

Although rates were somewhat attenuated after adjustment for demographic and prepregnancy characteristics, chronic medical conditions, assisted conception, and delivery characteristics, most morbidities remained significantly increased among women aged 39 years and older, including the composite outcome. Among the individual morbidities considered, increased risk was highest for renal failure, amniotic fluid embolism, cardiac morbidity, and shock, with adjusted odds ratios of 2.0 or greater for women older than 39 years.

Related article:

Reducing maternal mortality in the United States—Let’s get organized!

Study strengths and weaknesses

This study contributes substantially to the existing literature that demonstrates higher rates of pregnancy-associated morbidities in women of increasing maternal age.1,2 Prior studies in this area focused on perinatal morbidity and mortality and on obstetric outcomes such as cesarean delivery.3–5 This large-scale study examined the association between advancing maternal age and a variety of serious maternal morbidities. In another study, Callaghan and Berg found a similar pattern among mortalities, with high rates of mortality attributable to hemorrhage, embolism, and cardiomyopathy in women aged 40 years and older.1

Exclusion of multiple gestations. As in any study, we must consider the methodology, and it is notable that Lisonkova and colleagues’ study excluded multiple gestations. Given the association with advanced maternal age, assisted reproductive technology, and the incidence of multiple gestations, a high rate of multiple gestations would be expected among women of advanced maternal age. (Generally, maternal age of at least 35 years is considered “advanced,” with greater than 40 years “very advanced.”) Since multiple gestations tend to be associated with increases in morbidity, excluding these pregnancies would likely bias the study results toward the null. If multiple gestations had been included, the rates of serious maternal morbidities in older women might be even higher than those demonstrated, potentially strengthening the associations reported here.

This large, retrospective study (level II evidence) suggests that women of advancing age are at significantly increased risk of severe maternal morbidities, even after controlling for preexisting medical conditions. We therefore recommend that clinicians inform and counsel women who are considering pregnancy at an advanced age, and those considering oocyte cryopreservation as a means of extending their reproductive life span, about the increased maternal morbidities associated with pregnancy at age 40 and older.

-- Amy E. Judy, MD, MPH, and Yasser Y. El-Sayed, MD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Callaghan WM, Berg CJ. Pregnancy-related mortality among women aged 35 years and older, United States, 1991–1997. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102(5 pt 1):1015–1021.

- McCall SJ, Nair M, Knight M. Factors associated with maternal mortality at advanced maternal age: a population-based case-control study. BJOG. 2017;124(8):1225–1233.

- Yogev Y, Melamed N, Bardin R, Tenenbaum-Gavish K, Ben-Shitrit G, Ben-Haroush A. Pregnancy outcome at extremely advanced maternal age. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203(6):558.e1–e7.

- Gilbert WM, Nesbitt TS, Danielsen B. Childbearing beyond age 40: pregnancy outcome in 24,032 cases. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;93(1):9–14.

- Luke B, Brown MB. Elevated risks of pregnancy complications and adverse outcomes with increasing maternal age. Hum Reprod. 2007;22(5):1264–1272.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

While numerous studies have investigated the risk of perinatal outcomes with advancing maternal age, the primary objective of a recent study by Lisonkova and colleagues was to examine the association between advancing maternal age and severe maternal morbidities and mortality.

Details of the study

The population-based retrospective cohort study compared age-specific rates of severe maternal morbidities and mortality among 828,269 pregnancies in Washington state between 2003 and 2013. Singleton births to women 15 to 60 years of age were included; out-of-hospital births were excluded. Information was obtained by linking the Birth Events Record Database (which includes information on maternal, pregnancy, and labor and delivery characteristics and birth outcomes), and the Comprehensive Hospital Abstract Reporting System database (which includes diagnostic and procedural codes for all hospitalizations in Washington state).

The primary objective was to examine the association between age and severe maternal morbidities. Maternal morbidities were divided into categories: antepartum hemorrhage, respiratory morbidity, thromboembolism, cerebrovascular morbidity, acute cardiac morbidity, severe postpartum hemorrhage, maternal sepsis, renal failure, obstetric shock, complications of anesthesia and obstetric interventions, and need for life-saving procedures. A composite outcome, comprised of severe maternal morbidities, intensive care unit admission, and maternal mortality, was also created.

Rates of severe morbidities were compared for age groups 15 to 19, 20 to 24, 25 to 29, 30 to 34, 35 to 39, 40 to 44, and ≥45 years to the referent category (25 to 29 years). Additional comparisons were also performed for ages 45 to 49 and ≥50 years for the composite and for morbidities with high incidence. Logistic regression and sensitivity analyses were used to control for demographic and prepregnancy characteristics, underlying medical conditions, assisted conception, and delivery characteristics.

Severe maternal morbidities demonstrated a J-shaped association with age: the lowest rates of morbidity were observed in women 20 to 34 years of age, and steeply increasing rates of morbidity were observed for women aged 40 and older. One notable exception was the rate of sepsis, which was increased in teen mothers compared with all other groups.

The unadjusted rate of the composite outcome of severe maternal morbidity and mortality was 2.1% in teenagers, 1.5% among women 25 to 29 years, 2.3% among those aged 40 to 44, and 3.6% among women aged 45 and older.

Although rates were somewhat attenuated after adjustment for demographic and prepregnancy characteristics, chronic medical conditions, assisted conception, and delivery characteristics, most morbidities remained significantly increased among women aged 39 years and older, including the composite outcome. Among the individual morbidities considered, increased risk was highest for renal failure, amniotic fluid embolism, cardiac morbidity, and shock, with adjusted odds ratios of 2.0 or greater for women older than 39 years.

Related article:

Reducing maternal mortality in the United States—Let’s get organized!

Study strengths and weaknesses

This study contributes substantially to the existing literature that demonstrates higher rates of pregnancy-associated morbidities in women of increasing maternal age.1,2 Prior studies in this area focused on perinatal morbidity and mortality and on obstetric outcomes such as cesarean delivery.3–5 This large-scale study examined the association between advancing maternal age and a variety of serious maternal morbidities. In another study, Callaghan and Berg found a similar pattern among mortalities, with high rates of mortality attributable to hemorrhage, embolism, and cardiomyopathy in women aged 40 years and older.1

Exclusion of multiple gestations. As in any study, we must consider the methodology, and it is notable that Lisonkova and colleagues’ study excluded multiple gestations. Given the association with advanced maternal age, assisted reproductive technology, and the incidence of multiple gestations, a high rate of multiple gestations would be expected among women of advanced maternal age. (Generally, maternal age of at least 35 years is considered “advanced,” with greater than 40 years “very advanced.”) Since multiple gestations tend to be associated with increases in morbidity, excluding these pregnancies would likely bias the study results toward the null. If multiple gestations had been included, the rates of serious maternal morbidities in older women might be even higher than those demonstrated, potentially strengthening the associations reported here.

This large, retrospective study (level II evidence) suggests that women of advancing age are at significantly increased risk of severe maternal morbidities, even after controlling for preexisting medical conditions. We therefore recommend that clinicians inform and counsel women who are considering pregnancy at an advanced age, and those considering oocyte cryopreservation as a means of extending their reproductive life span, about the increased maternal morbidities associated with pregnancy at age 40 and older.

-- Amy E. Judy, MD, MPH, and Yasser Y. El-Sayed, MD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

While numerous studies have investigated the risk of perinatal outcomes with advancing maternal age, the primary objective of a recent study by Lisonkova and colleagues was to examine the association between advancing maternal age and severe maternal morbidities and mortality.

Details of the study

The population-based retrospective cohort study compared age-specific rates of severe maternal morbidities and mortality among 828,269 pregnancies in Washington state between 2003 and 2013. Singleton births to women 15 to 60 years of age were included; out-of-hospital births were excluded. Information was obtained by linking the Birth Events Record Database (which includes information on maternal, pregnancy, and labor and delivery characteristics and birth outcomes), and the Comprehensive Hospital Abstract Reporting System database (which includes diagnostic and procedural codes for all hospitalizations in Washington state).

The primary objective was to examine the association between age and severe maternal morbidities. Maternal morbidities were divided into categories: antepartum hemorrhage, respiratory morbidity, thromboembolism, cerebrovascular morbidity, acute cardiac morbidity, severe postpartum hemorrhage, maternal sepsis, renal failure, obstetric shock, complications of anesthesia and obstetric interventions, and need for life-saving procedures. A composite outcome, comprised of severe maternal morbidities, intensive care unit admission, and maternal mortality, was also created.

Rates of severe morbidities were compared for age groups 15 to 19, 20 to 24, 25 to 29, 30 to 34, 35 to 39, 40 to 44, and ≥45 years to the referent category (25 to 29 years). Additional comparisons were also performed for ages 45 to 49 and ≥50 years for the composite and for morbidities with high incidence. Logistic regression and sensitivity analyses were used to control for demographic and prepregnancy characteristics, underlying medical conditions, assisted conception, and delivery characteristics.

Severe maternal morbidities demonstrated a J-shaped association with age: the lowest rates of morbidity were observed in women 20 to 34 years of age, and steeply increasing rates of morbidity were observed for women aged 40 and older. One notable exception was the rate of sepsis, which was increased in teen mothers compared with all other groups.

The unadjusted rate of the composite outcome of severe maternal morbidity and mortality was 2.1% in teenagers, 1.5% among women 25 to 29 years, 2.3% among those aged 40 to 44, and 3.6% among women aged 45 and older.

Although rates were somewhat attenuated after adjustment for demographic and prepregnancy characteristics, chronic medical conditions, assisted conception, and delivery characteristics, most morbidities remained significantly increased among women aged 39 years and older, including the composite outcome. Among the individual morbidities considered, increased risk was highest for renal failure, amniotic fluid embolism, cardiac morbidity, and shock, with adjusted odds ratios of 2.0 or greater for women older than 39 years.

Related article:

Reducing maternal mortality in the United States—Let’s get organized!

Study strengths and weaknesses

This study contributes substantially to the existing literature that demonstrates higher rates of pregnancy-associated morbidities in women of increasing maternal age.1,2 Prior studies in this area focused on perinatal morbidity and mortality and on obstetric outcomes such as cesarean delivery.3–5 This large-scale study examined the association between advancing maternal age and a variety of serious maternal morbidities. In another study, Callaghan and Berg found a similar pattern among mortalities, with high rates of mortality attributable to hemorrhage, embolism, and cardiomyopathy in women aged 40 years and older.1

Exclusion of multiple gestations. As in any study, we must consider the methodology, and it is notable that Lisonkova and colleagues’ study excluded multiple gestations. Given the association with advanced maternal age, assisted reproductive technology, and the incidence of multiple gestations, a high rate of multiple gestations would be expected among women of advanced maternal age. (Generally, maternal age of at least 35 years is considered “advanced,” with greater than 40 years “very advanced.”) Since multiple gestations tend to be associated with increases in morbidity, excluding these pregnancies would likely bias the study results toward the null. If multiple gestations had been included, the rates of serious maternal morbidities in older women might be even higher than those demonstrated, potentially strengthening the associations reported here.

This large, retrospective study (level II evidence) suggests that women of advancing age are at significantly increased risk of severe maternal morbidities, even after controlling for preexisting medical conditions. We therefore recommend that clinicians inform and counsel women who are considering pregnancy at an advanced age, and those considering oocyte cryopreservation as a means of extending their reproductive life span, about the increased maternal morbidities associated with pregnancy at age 40 and older.

-- Amy E. Judy, MD, MPH, and Yasser Y. El-Sayed, MD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Callaghan WM, Berg CJ. Pregnancy-related mortality among women aged 35 years and older, United States, 1991–1997. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102(5 pt 1):1015–1021.

- McCall SJ, Nair M, Knight M. Factors associated with maternal mortality at advanced maternal age: a population-based case-control study. BJOG. 2017;124(8):1225–1233.

- Yogev Y, Melamed N, Bardin R, Tenenbaum-Gavish K, Ben-Shitrit G, Ben-Haroush A. Pregnancy outcome at extremely advanced maternal age. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203(6):558.e1–e7.

- Gilbert WM, Nesbitt TS, Danielsen B. Childbearing beyond age 40: pregnancy outcome in 24,032 cases. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;93(1):9–14.

- Luke B, Brown MB. Elevated risks of pregnancy complications and adverse outcomes with increasing maternal age. Hum Reprod. 2007;22(5):1264–1272.

- Callaghan WM, Berg CJ. Pregnancy-related mortality among women aged 35 years and older, United States, 1991–1997. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102(5 pt 1):1015–1021.

- McCall SJ, Nair M, Knight M. Factors associated with maternal mortality at advanced maternal age: a population-based case-control study. BJOG. 2017;124(8):1225–1233.

- Yogev Y, Melamed N, Bardin R, Tenenbaum-Gavish K, Ben-Shitrit G, Ben-Haroush A. Pregnancy outcome at extremely advanced maternal age. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203(6):558.e1–e7.

- Gilbert WM, Nesbitt TS, Danielsen B. Childbearing beyond age 40: pregnancy outcome in 24,032 cases. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;93(1):9–14.

- Luke B, Brown MB. Elevated risks of pregnancy complications and adverse outcomes with increasing maternal age. Hum Reprod. 2007;22(5):1264–1272.

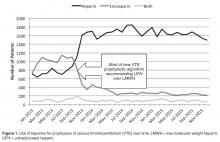

Clinical Outcomes After Conversion from Low-Molecular-Weight Heparin to Unfractionated Heparin for Venous Thromboembolism Prophylaxis

From the Anne Arundel Health System Research Institute, Annapolis, MD.

Abstract

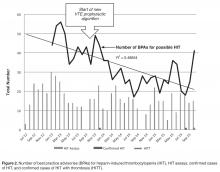

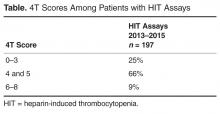

- Objective: To measure clinical outcomes associated with heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) and acquisition costs of heparin after implementing a new order set promoting unfractionated heparin (UFH) use instead of low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) for venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis.

- Methods: This was single-center, retrospective, pre-post intervention analysis utilizing pharmacy, laboratory, and clinical data sources. Subjects were patients receiving VTE thromboprophyalxis with heparin at an acute care hospital. Usage rates for UFH and LMWH, acquisition costs for heparins, number of HIT assays, best practice advisories for HIT, and confirmed cases of HIT and HIT with thrombosis were assessed.

- Results: After order set intervention, UFH use increased from 43% of all prophylaxis orders to 86%. Net annual savings in acquisition costs for VTE prophylaxis was $131,000. After the intervention, HIT best practice advisories and number of monthly HIT assays fell 35% and 15%, respectively. In the 9-month pre-intervention period, HIT and HITT occurred in zero of 6717 patients receiving VTE prophylaxis. In the 25 months of post-intervention follow-up, HIT occurred in 3 of 44,240 patients (P = 0.86) receiving VTE prophylaxis, 2 of whom had HITT, all after receiving UFH. The median duration of UFH and LMWH use was 3.0 and 3.5 days, respectively.

- Conclusion: UFH use in hospitals can be safely maintained or increased among patient subpopulations that are not at high risk for HIT. A more nuanced approach to prophylaxis, taking into account individual patient risk and expected duration of therapy, may provide desired cost savings without provoking HIT.

Key words: heparin; heparin-induced thrombocytopenia; venous thromboembolism prophylaxis; cost-effectiveness.

Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) and its more severe clinical complication, HIT with thrombosis (HITT), complicate the use of heparin products for venous thromboembolic (VTE) prophylaxis. The clinical characteristics and time course of thrombocytopenia in relation to heparin are well characterized (typically 30%–50% drop in platelet count 5–10 days after exposure), if not absolute. Risk calculation tools help to judge the clinical probability and guide ordering of appropriate confirmatory tests [1]. The incidence of HIT is higher with unfractionated heparin (UFH) than with low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH). A meta-analysis of 5 randomized or prospective nonrandomized trials indicated a risk of 2.6% (95% CI, 1.5%–3.8%) for UFH and 0.2% (95% CI, 0.1%–0.4%) for LMWH [2], though the analyzed studies were heavily weighted by studies of orthopedic surgery patients, a high-risk group. However, not all patients are at equal risk for HIT, suggesting that LMWH may not be necessary for all patients [3]. Unfortunately, LMWH is considerably more expensive for hospitals to purchase than UFH, raising costs for a prophylactic treatment that is widely utilized. However, the higher incidence of HIT and HITT associated with UFH can erode any cost savings because of the additional cost of diagnosing HIT and need for temporary or long-term treatment with even more expensive alternative anticoagulants. Indeed, a recent retrospective study suggested that the excess costs of evaluating and treating HIT were approximately $267,000 per year in Canadian dollars [4].But contrary data has also been reported. A retrospective study of the consequences of increased prophylactic UFH use found no increase in ordered HIT assays or in the results of HIT testing or of inferred positive cases despite a growth of 71% in the number of patients receiving UFH prophylaxis [5].

In 2013, the pharmacy and therapeutics committee made a decision to encourage the use of UFH over LMWH for VTE prophylaxis by making changes to order sets to favor UFH over LMWH (enoxaparin). Given the uncertainty about excess risk of HIT, a monitoring work group was created to assess for any increase of either HIT or HITT that might follow, including any patient readmitted with thrombosis within 30 days of a discharge. In this paper, we report the impact of a hospital-wide conversion to UFH for VTE prophylaxis on the incidence of VTE, HIT, and HITT and acquisition costs of UFH and LMWH and use of alternative prophylactic anticoagulant medications.

Methods

Setting

Anne Arundel Medical Center is a 383-bed acute care hospital with about 30,000 adult admissions and 10,000 inpatient surgeries annually. The average length of stay is approximately 3.6 days with a patient median age of 59 years. Caucasians comprise 75.3% of the admitted populations and African Americans 21.4%. Most patients are on Medicare (59%), while 29.5% have private insurance, 6.6% are on Medicaid, and 4.7% self-pay. The 9 most common medical principal diagnoses are sepsis, heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, pneumonia, myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke, urinary tract infection, cardiac arrhythmia, and other infection. The 6 most common procedures include newborn delivery (with and without caesarean section), joint replacement surgery, bariatric procedures, cardiac catheterizations, other abdominal surgeries, and thoracotomy. The predominant medical care model is internal medicine and physician assistant acute care hospitalists attending both medicine and surgical patients. Obstetrical hospitalists care for admitted obstetric patients. Patients admitted to the intensive care units had only critical care trained physician specialists as attending physicians. No trainees cared for the patients described in this study.

P&T Committee

The P&T committee is a multidisciplinary group of health care professionals selected for appointment by the chairs of the committee (chair of medicine and director of pharmacy) and approved by the president of the medical staff. The committee has oversight responsibility for all medication policies, order sets involving medications, as well as the monitoring of clinical outcomes as they regard medications.

Electronic Medical Record and Best Practice Advisory

Throughout this study period both pre-and post-intervention, the EMR in use was Epic (Verona WI), used for all ordering and lab results. A best practice advisory was in place in the EMR that alerted providers to all cases of thrombocytopenia < 100,000/mm3 when there was concurrent order for any heparin. The best practice advisory highlighted the thrombocytopenia, advised the providers to consider HIT as a diagnosis and to order confirmation tests if clinically appropriate, providing a direct link to the HIT assay order screen. The best practice advisory did not access information from prior admissions where heparin might have been used nor determine the percentage drop from the baseline platelet count.

HIT Case Definition and Assays

The 2 laboratory tests for HIT on which this study is based are the heparin-induced platelet antibody test (also known as anti-PF4) and the serotonin release assay. The heparin-induced platelet antibody test is an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) that detects IgG, IgM, and IgA antibodies against the platelet factor 4 (PF4/heparin complex). This test was reported as positive if the optical density was 0.4 or higher and generated an automatic request for a serotonin release assay (SRA), which is a functional assay that measures heparin-dependent platelet activation. The decision to order the SRA was therefore a “reflex” test and not made with any knowledge of clinical characteristics of the case. The HIT assays were performed by a reference lab, Quest Diagnostics, in the Chantilly, VA facility. HIT was said to be present when both a characteristic pattern of thrombocytopenia occurring after heparin use was seen [1]and when the confirmatory SRA was positive at a level of > 20% release.

Order Set Modifications

After the P&T committee decision to emphasize UFH for VTE prophylaxis in October 2013, the relevant electronic order sets were altered to highlight the fact that UFH was the first choice for VTE prophylaxis. The order sets still allowed LMWH (enoxaparin) or alternative anticoagulants at the prescribers’ discretion but indicated they were a second choice. Doses of UFH and LMWH in the order sets were standard based upon weight and estimates of creatinine clearance and, in the case of dosing frequency for UFH, based upon the risk of VTE. Order sets for the therapeutic treatment of VTE were not changed.

Data Collection and Analysis

The clinical research committee, the local oversight board for research and performance improvement analyses, reviewed this project and determined that it qualified as a performance improvement analysis based upon the standards of the U.S. Office of Human Research Protections. Some data were extracted from patient medical records and stored in a customized and password-protected database. Access to the database was limited to members of the analysis team and stripped of all patient identifiers under the HIPAA privacy rule standard for de-identification from 45 CFR 164.514(b) immediately following the collection of all data elements from the medical record.

An internal pharmacy database was used to determine the volume and actual acquisition cost of prophylactic anticoagulant doses administered during both pre- and post-intervention time periods. To determine if clinical suspicion for HIT increased after the intervention, a definitive listing of all ordered HIT assays was obtained from laboratory billing records for the 9 months (January 2013–September 2013) before the conversion and for 25 months after the intervention (beginning in November 2013 so as not to include the conversion month). To determine if the HIT assays were associated with a higher risk score, we identified all cases in which the HIT assay was ordered and retroactively measured the probability score known as the 4T score [1].Simultaneously, separate clinical work groups reviewed all cases of hospital-acquired thrombosis, whatever their cause, including patients readmitted with thrombosis up to 30 days after discharge and episodes of bleeding due to anti-coagulant use. A chi square analysis of the incidence of HIT pre- and post-intervention was performed.

Results

Heparin Use and Acquisition Costs

HIT Assays and Incidence of HIT and HITT

In the 9 months pre-intervention, HIT and HITT occurred in zero of 6717 patients receiving at least 1 dose of VTE prophylaxis. In the 25 months of post-intervention follow-up, 44,240 patients received prophylaxis with either heparin. HIT (clinical suspicion with positive antibody and confirmatory SRA) occurred in 3 patients, 2 of whom had HITT, all after UFH. This incidence was not statistically significant using chi square analysis (P = 0.86).

Discussion