User login

Implementation of a Communication Training Program Is Associated with Reduction of Antipsychotic Medication Use in Nursing Homes

Study Overview

Objective. To evaluate the effectiveness of OASIS, a large-scale, statewide communication training program, on the reduction of antipsychotic use in nursing homes (NHs).

Design. Quasi-experimental longitudinal study with external controls.

Setting and participants. The participants were residents living in NHs between 1 March 2011 and 31 August 2013. The intervention group consisted of NHs in Massachusetts that were enrolled in the OASIS intervention and the control group consisted of NHs in Massachusetts and New York. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Minimum Data Set (MDS) 3.0 data was analyzed to determine medication use and behavior of residents of NHs. Residents of these NHs were excluded if they had a US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved indication for antipsychotic use (eg, schizophrenia); were short-term residents (length of stay < 90 days); or had missing data on psychopharmacological medication use or behavior.

Intervention. The OASIS is an educational program that targeted both direct care and non-direct care staff in NHs to assist them in meeting the needs and challenges of caring for long-term care residents. Utilizing a train-the-trainer model, OASIS program coordinators and champions from each intervention NH participated in an 8-hour in-person training session that focused on enhancing communication skills between NH staff and residents with cognitive impairment. These trainers subsequently instructed the OASIS program to staff at their respective NHs using a team-based care approach. Addi-tional support of the OASIS educational program, such as telephone support, 12 webinars, 2 regional seminars, and 2 booster sessions, were provided to participating NHs.

Main outcome measures. The main outcome measure was facility-level prevalence of antipsychotic use in long-term NH residents captured by MDS in the 7 days preceding the MDS assessment. The secondary outcome measures were facility-level quarterly prevalence of psychotropic medications that may have been substituted for antipsychotic medications (ie, anxiolytics, antidepressants, and hypnotics) and behavioral disturbances (ie, physically abusive behavior, verbally abusive behavior, and rejecting care). All secondary outcomes were dichotomized in the 7 days preceding the MDS assessment and aggregated at the facility level for each quarter.

The analysis utilized an interrupted time series model of facility-level prevalence of antipsychotic medication use, other psychotropic medication use, and behavioral disturbances to evaluate the OASIS intervention’s effectiveness in participating facilities compared with control NHs. This methodology allowed the assessment of changes in the trend of antipsychotic use after the OASIS intervention controlling for historical trends. Data from the 18-month pre-intervention (baseline) period was compared with that of a 3-month training phase, a 6-month implementation phase, and a 3-month maintenance phase.

Main results. 93 NHs received OASIS intervention (27 with high prevalence of antipsychotic use) while 831 NHs did not (non-intervention control). The intervention NHs had a higher prevalence of antipsychotic use before OASIS training (baseline period) than the control NHs (34.1% vs. 22.7%, P < 0.001). The intervention NHs compared to controls were smaller in size (122 beds [interquartile range {IQR}, 88–152 beds] vs. 140 beds; [IQR, 104–200 beds]; P < 0.001), more likely to be for profit (77.4% vs. 62.0%, P = 0.009), had corporate ownership (93.5% vs. 74.6%, P < 0.001), and provided resident-only councils (78.5% vs. 52.9%, P < 0.001). The intervention NHs had higher registered nurse (RN) staffing hours per resident (0.8 vs. 0.7; P = 0.01) but lower certified nursing assistant (CNA) hours per resident (2.3 vs. 2.4; P = 0.04) than control NHs. There was no difference in licensed practical nurse hours per resident between groups.

All 93 intervention NHs completed the 8-hour in-person training session and attended an average of 6.5 (range, 0–12) subsequent support webinars. Thirteen NHs (14.0%) attended no regional seminars, 32 (34.4%) attended one, and 48 (51.6%) attended both. Four NHs (4.3%) attended one booster session, and 13 (14.0%) attended both. The NH staff most often trained in the OASIS training program were the directors of nursing, RNs, CNAs, and activities personnel. Support staff including housekeeping and dietary were trained in about half of the reporting intervention NHs, while physicians and nurse practitioners participated infrequently. Concurrent training programs in dementia care (Hand-in-Hand, Alzheimer Association training, MassPRO dementia care training) were implemented in 67.2% of intervention NHs.

In the intervention NHs, the prevalence of antipsych-otic prescribing decreased from 34.1% at baseline to 26.5% at the study end (7.6% absolute reduction, 22.3% relative reduction). In comparison, the prevalence of antipsychotic prescribing in control NHs decreased from 22.7% to 18.8% over the same period (3.9% absolute reduction, 17.2% relative reduction). During the OASIS implementation phase, the intervention NHs had a reduc-tion in prevalence of antipsychotic use (–1.20% [95% confidence interval {CI}, –1.85% to –0.09% per quarter]) greater than that of the control NHs (–0.23% [95% CI, –0.47% to 0.01% per quarter]), resulting in a net OASIS influence of –0.97% (95% CI, –1.85% to –0.09% per quarter; P = 0.03). The antipsychotic use reduction observed in the implementation phase was not sustained in the maintenance phase (difference of 0.93%; 95% CI, –0.66% to 2.54%; P = 0.48). No increases in other psychotropic medication use (anxiolytics, antidepressants, hypnotics) or behavioral disturbances (physically abusive behavior, verbally abusive behavior, and rejecting care) were observed during the OASIS training and implementation phases.

Conclusion. The OASIS communication training program reduced the prevalence of antipsychotic use in NHs during its implementation phase, but its effect was not sustained in the subsequent maintenance phase. The use of other psychotropic medications and behavior disturbances did not increase during the implementation of OASIS program. The findings from this study provided further support for utilizing nonpharmacologic programs to treat behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia in older adults who reside in NHs.

Commentary

The use of both conventional and atypical antipsychotic medications is associated with a dose-related, approximately 2-fold increased risk of sudden cardiac death in older adults [1,2]. In 2006, the FDA issued a public health advisory stating that both conventional and atypical anti-psychotic medications are associated with an increased risk of mortality in elderly patients treated for dementia-related psychosis. Despite this black box warning and growing recognition that antipsychotic medications are not indicated for the treatment of dementia-related psychosis, the off-label use of antipsychotic medications to treat behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia in older adults remains a common practice in nursing homes [3]. Thus, there is an urgent need to assess and develop effective interventions that reduce the practice of antipsychotic medication prescribing in long-term care. To that effect, the study reported by Tjia et al appropriately investigated the impact of the OASIS communication training program, a nonpharmacologic intervention, on the reduction of antipsychotic use in NHs.

This study was well designed and had a number of strengths. It utilized an interrupted time series model, one of the strongest quasi-experimental approaches due to its robustness to threats of internal validity, for evaluating longitudinal effects of an intervention intended to improve the quality of medication use. Moreover, this study included a large sample size and comparison facilities from the same geographical areas (NHs in Massachusetts and New York State) that served as external controls. Several potential weaknesses of the study were identified. Because facility-level aggregate data from NHs were used for analysis, individual level (long-term care resident) characteristics were not accounted for in the analysis. In addition, while the post-OASIS intervention questionnaire response rate was 65.6% (61 of 93 intervention NHs), a higher response rate would provide better characterization of NH staff that participated in OASIS program training, program completion rate, and a more complete representation of competing dementia care training programs concurrently implemented in these NHs.

Several studies, most utilizing various provider education methods, had explored whether these interventions could curb antipsychotic use in NHs with limited success. The largest successful intervention was reported by Meador et al [4], where a focused provider education program facilitated a relative reduction in antipsychotic medication use of 23% compared to control NHs. However, the implementation of this specific program was time- and resource-intensive, requiring geropsychiatry evaluation to all physicians (45 to 60 min), nurse-educator in-service programs for NH staff (5 to 6 one-hr sessions), management specialist consultation to NH administrators (4 hr), and evening meeting for the families of NH residents. The current study by Tjia et al, the largest study to date conducted in the context of competing dementia care training programs and increased awareness of the danger of antipsychotic use in the elderly, similarly showed a meaningful reduction in antipsychotic medication use in NHs that received the OASIS communication training program. The OASIS program appears to be less resource-intensive than the provider education program modeled by Meador et al, and its train-the-trainer model is likely more adaptable to meet the limitations (eg, low staffing and staff turnover) inherent in NHs. The beneficial effect of the OASIS program on reduction of antipsychotic medication prescribing was observed despite low participation by prescribers (11.5% of physicians and 11.5% of nurse practitioners). Although it is unclear why this was observed, this finding is intriguing in that a communication training program that reframes challenging behavior of NH residents with cognitive impairment as (1) communication of unmet needs, (2) train staff to anticipate resident needs, and (3) integrate resident strengths into daily care plans can alter provider prescription behavior. The implication of this is that provider practice in managing behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia can be improved by optimizing communication training in NH staff. Taken together, this study adds to evidence in favor of utilizing nonpharmacologic interventions to reduce antipsychotic use in long-term care.

Applications for Clinical Practice

OASIS, a communication training program for NH staff, reduces antipsychotic medication use in NHs during its implementation phase. Future studies need to investigate pragmatic methods to sustain the beneficial effect of OASIS after its implementation phase.

—Fred Ko, MD, MS, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY

1. Ray WA, Chung CP, Murray KT, et al. Atypical antipsychotic drugs and the risk of sudden cardiac death. N Engl J Med 2009;360:225–35.

2. Wang PS, Schneeweiss S, Avorn J, et al. Risk of death in elderly users of conventional vs. atypical antipsychotic medications. N Engl J Med 2005;353:2335–41.

3. Chen Y, Briesacher BA, Field TS, et al. Unexplained variation across US nursing homes in antipsychotic prescribing rates. Arch Intern Med 2010;170:89–95.

4. Meador KG, Taylor JA, Thapa PB, et al. Predictors of anti-

psychotic withdrawal or dose reduction in a randomized controlled trial of provider education. J Am Geriatr Soc 1997;45:207–10.

Study Overview

Objective. To evaluate the effectiveness of OASIS, a large-scale, statewide communication training program, on the reduction of antipsychotic use in nursing homes (NHs).

Design. Quasi-experimental longitudinal study with external controls.

Setting and participants. The participants were residents living in NHs between 1 March 2011 and 31 August 2013. The intervention group consisted of NHs in Massachusetts that were enrolled in the OASIS intervention and the control group consisted of NHs in Massachusetts and New York. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Minimum Data Set (MDS) 3.0 data was analyzed to determine medication use and behavior of residents of NHs. Residents of these NHs were excluded if they had a US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved indication for antipsychotic use (eg, schizophrenia); were short-term residents (length of stay < 90 days); or had missing data on psychopharmacological medication use or behavior.

Intervention. The OASIS is an educational program that targeted both direct care and non-direct care staff in NHs to assist them in meeting the needs and challenges of caring for long-term care residents. Utilizing a train-the-trainer model, OASIS program coordinators and champions from each intervention NH participated in an 8-hour in-person training session that focused on enhancing communication skills between NH staff and residents with cognitive impairment. These trainers subsequently instructed the OASIS program to staff at their respective NHs using a team-based care approach. Addi-tional support of the OASIS educational program, such as telephone support, 12 webinars, 2 regional seminars, and 2 booster sessions, were provided to participating NHs.

Main outcome measures. The main outcome measure was facility-level prevalence of antipsychotic use in long-term NH residents captured by MDS in the 7 days preceding the MDS assessment. The secondary outcome measures were facility-level quarterly prevalence of psychotropic medications that may have been substituted for antipsychotic medications (ie, anxiolytics, antidepressants, and hypnotics) and behavioral disturbances (ie, physically abusive behavior, verbally abusive behavior, and rejecting care). All secondary outcomes were dichotomized in the 7 days preceding the MDS assessment and aggregated at the facility level for each quarter.

The analysis utilized an interrupted time series model of facility-level prevalence of antipsychotic medication use, other psychotropic medication use, and behavioral disturbances to evaluate the OASIS intervention’s effectiveness in participating facilities compared with control NHs. This methodology allowed the assessment of changes in the trend of antipsychotic use after the OASIS intervention controlling for historical trends. Data from the 18-month pre-intervention (baseline) period was compared with that of a 3-month training phase, a 6-month implementation phase, and a 3-month maintenance phase.

Main results. 93 NHs received OASIS intervention (27 with high prevalence of antipsychotic use) while 831 NHs did not (non-intervention control). The intervention NHs had a higher prevalence of antipsychotic use before OASIS training (baseline period) than the control NHs (34.1% vs. 22.7%, P < 0.001). The intervention NHs compared to controls were smaller in size (122 beds [interquartile range {IQR}, 88–152 beds] vs. 140 beds; [IQR, 104–200 beds]; P < 0.001), more likely to be for profit (77.4% vs. 62.0%, P = 0.009), had corporate ownership (93.5% vs. 74.6%, P < 0.001), and provided resident-only councils (78.5% vs. 52.9%, P < 0.001). The intervention NHs had higher registered nurse (RN) staffing hours per resident (0.8 vs. 0.7; P = 0.01) but lower certified nursing assistant (CNA) hours per resident (2.3 vs. 2.4; P = 0.04) than control NHs. There was no difference in licensed practical nurse hours per resident between groups.

All 93 intervention NHs completed the 8-hour in-person training session and attended an average of 6.5 (range, 0–12) subsequent support webinars. Thirteen NHs (14.0%) attended no regional seminars, 32 (34.4%) attended one, and 48 (51.6%) attended both. Four NHs (4.3%) attended one booster session, and 13 (14.0%) attended both. The NH staff most often trained in the OASIS training program were the directors of nursing, RNs, CNAs, and activities personnel. Support staff including housekeeping and dietary were trained in about half of the reporting intervention NHs, while physicians and nurse practitioners participated infrequently. Concurrent training programs in dementia care (Hand-in-Hand, Alzheimer Association training, MassPRO dementia care training) were implemented in 67.2% of intervention NHs.

In the intervention NHs, the prevalence of antipsych-otic prescribing decreased from 34.1% at baseline to 26.5% at the study end (7.6% absolute reduction, 22.3% relative reduction). In comparison, the prevalence of antipsychotic prescribing in control NHs decreased from 22.7% to 18.8% over the same period (3.9% absolute reduction, 17.2% relative reduction). During the OASIS implementation phase, the intervention NHs had a reduc-tion in prevalence of antipsychotic use (–1.20% [95% confidence interval {CI}, –1.85% to –0.09% per quarter]) greater than that of the control NHs (–0.23% [95% CI, –0.47% to 0.01% per quarter]), resulting in a net OASIS influence of –0.97% (95% CI, –1.85% to –0.09% per quarter; P = 0.03). The antipsychotic use reduction observed in the implementation phase was not sustained in the maintenance phase (difference of 0.93%; 95% CI, –0.66% to 2.54%; P = 0.48). No increases in other psychotropic medication use (anxiolytics, antidepressants, hypnotics) or behavioral disturbances (physically abusive behavior, verbally abusive behavior, and rejecting care) were observed during the OASIS training and implementation phases.

Conclusion. The OASIS communication training program reduced the prevalence of antipsychotic use in NHs during its implementation phase, but its effect was not sustained in the subsequent maintenance phase. The use of other psychotropic medications and behavior disturbances did not increase during the implementation of OASIS program. The findings from this study provided further support for utilizing nonpharmacologic programs to treat behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia in older adults who reside in NHs.

Commentary

The use of both conventional and atypical antipsychotic medications is associated with a dose-related, approximately 2-fold increased risk of sudden cardiac death in older adults [1,2]. In 2006, the FDA issued a public health advisory stating that both conventional and atypical anti-psychotic medications are associated with an increased risk of mortality in elderly patients treated for dementia-related psychosis. Despite this black box warning and growing recognition that antipsychotic medications are not indicated for the treatment of dementia-related psychosis, the off-label use of antipsychotic medications to treat behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia in older adults remains a common practice in nursing homes [3]. Thus, there is an urgent need to assess and develop effective interventions that reduce the practice of antipsychotic medication prescribing in long-term care. To that effect, the study reported by Tjia et al appropriately investigated the impact of the OASIS communication training program, a nonpharmacologic intervention, on the reduction of antipsychotic use in NHs.

This study was well designed and had a number of strengths. It utilized an interrupted time series model, one of the strongest quasi-experimental approaches due to its robustness to threats of internal validity, for evaluating longitudinal effects of an intervention intended to improve the quality of medication use. Moreover, this study included a large sample size and comparison facilities from the same geographical areas (NHs in Massachusetts and New York State) that served as external controls. Several potential weaknesses of the study were identified. Because facility-level aggregate data from NHs were used for analysis, individual level (long-term care resident) characteristics were not accounted for in the analysis. In addition, while the post-OASIS intervention questionnaire response rate was 65.6% (61 of 93 intervention NHs), a higher response rate would provide better characterization of NH staff that participated in OASIS program training, program completion rate, and a more complete representation of competing dementia care training programs concurrently implemented in these NHs.

Several studies, most utilizing various provider education methods, had explored whether these interventions could curb antipsychotic use in NHs with limited success. The largest successful intervention was reported by Meador et al [4], where a focused provider education program facilitated a relative reduction in antipsychotic medication use of 23% compared to control NHs. However, the implementation of this specific program was time- and resource-intensive, requiring geropsychiatry evaluation to all physicians (45 to 60 min), nurse-educator in-service programs for NH staff (5 to 6 one-hr sessions), management specialist consultation to NH administrators (4 hr), and evening meeting for the families of NH residents. The current study by Tjia et al, the largest study to date conducted in the context of competing dementia care training programs and increased awareness of the danger of antipsychotic use in the elderly, similarly showed a meaningful reduction in antipsychotic medication use in NHs that received the OASIS communication training program. The OASIS program appears to be less resource-intensive than the provider education program modeled by Meador et al, and its train-the-trainer model is likely more adaptable to meet the limitations (eg, low staffing and staff turnover) inherent in NHs. The beneficial effect of the OASIS program on reduction of antipsychotic medication prescribing was observed despite low participation by prescribers (11.5% of physicians and 11.5% of nurse practitioners). Although it is unclear why this was observed, this finding is intriguing in that a communication training program that reframes challenging behavior of NH residents with cognitive impairment as (1) communication of unmet needs, (2) train staff to anticipate resident needs, and (3) integrate resident strengths into daily care plans can alter provider prescription behavior. The implication of this is that provider practice in managing behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia can be improved by optimizing communication training in NH staff. Taken together, this study adds to evidence in favor of utilizing nonpharmacologic interventions to reduce antipsychotic use in long-term care.

Applications for Clinical Practice

OASIS, a communication training program for NH staff, reduces antipsychotic medication use in NHs during its implementation phase. Future studies need to investigate pragmatic methods to sustain the beneficial effect of OASIS after its implementation phase.

—Fred Ko, MD, MS, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY

Study Overview

Objective. To evaluate the effectiveness of OASIS, a large-scale, statewide communication training program, on the reduction of antipsychotic use in nursing homes (NHs).

Design. Quasi-experimental longitudinal study with external controls.

Setting and participants. The participants were residents living in NHs between 1 March 2011 and 31 August 2013. The intervention group consisted of NHs in Massachusetts that were enrolled in the OASIS intervention and the control group consisted of NHs in Massachusetts and New York. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Minimum Data Set (MDS) 3.0 data was analyzed to determine medication use and behavior of residents of NHs. Residents of these NHs were excluded if they had a US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved indication for antipsychotic use (eg, schizophrenia); were short-term residents (length of stay < 90 days); or had missing data on psychopharmacological medication use or behavior.

Intervention. The OASIS is an educational program that targeted both direct care and non-direct care staff in NHs to assist them in meeting the needs and challenges of caring for long-term care residents. Utilizing a train-the-trainer model, OASIS program coordinators and champions from each intervention NH participated in an 8-hour in-person training session that focused on enhancing communication skills between NH staff and residents with cognitive impairment. These trainers subsequently instructed the OASIS program to staff at their respective NHs using a team-based care approach. Addi-tional support of the OASIS educational program, such as telephone support, 12 webinars, 2 regional seminars, and 2 booster sessions, were provided to participating NHs.

Main outcome measures. The main outcome measure was facility-level prevalence of antipsychotic use in long-term NH residents captured by MDS in the 7 days preceding the MDS assessment. The secondary outcome measures were facility-level quarterly prevalence of psychotropic medications that may have been substituted for antipsychotic medications (ie, anxiolytics, antidepressants, and hypnotics) and behavioral disturbances (ie, physically abusive behavior, verbally abusive behavior, and rejecting care). All secondary outcomes were dichotomized in the 7 days preceding the MDS assessment and aggregated at the facility level for each quarter.

The analysis utilized an interrupted time series model of facility-level prevalence of antipsychotic medication use, other psychotropic medication use, and behavioral disturbances to evaluate the OASIS intervention’s effectiveness in participating facilities compared with control NHs. This methodology allowed the assessment of changes in the trend of antipsychotic use after the OASIS intervention controlling for historical trends. Data from the 18-month pre-intervention (baseline) period was compared with that of a 3-month training phase, a 6-month implementation phase, and a 3-month maintenance phase.

Main results. 93 NHs received OASIS intervention (27 with high prevalence of antipsychotic use) while 831 NHs did not (non-intervention control). The intervention NHs had a higher prevalence of antipsychotic use before OASIS training (baseline period) than the control NHs (34.1% vs. 22.7%, P < 0.001). The intervention NHs compared to controls were smaller in size (122 beds [interquartile range {IQR}, 88–152 beds] vs. 140 beds; [IQR, 104–200 beds]; P < 0.001), more likely to be for profit (77.4% vs. 62.0%, P = 0.009), had corporate ownership (93.5% vs. 74.6%, P < 0.001), and provided resident-only councils (78.5% vs. 52.9%, P < 0.001). The intervention NHs had higher registered nurse (RN) staffing hours per resident (0.8 vs. 0.7; P = 0.01) but lower certified nursing assistant (CNA) hours per resident (2.3 vs. 2.4; P = 0.04) than control NHs. There was no difference in licensed practical nurse hours per resident between groups.

All 93 intervention NHs completed the 8-hour in-person training session and attended an average of 6.5 (range, 0–12) subsequent support webinars. Thirteen NHs (14.0%) attended no regional seminars, 32 (34.4%) attended one, and 48 (51.6%) attended both. Four NHs (4.3%) attended one booster session, and 13 (14.0%) attended both. The NH staff most often trained in the OASIS training program were the directors of nursing, RNs, CNAs, and activities personnel. Support staff including housekeeping and dietary were trained in about half of the reporting intervention NHs, while physicians and nurse practitioners participated infrequently. Concurrent training programs in dementia care (Hand-in-Hand, Alzheimer Association training, MassPRO dementia care training) were implemented in 67.2% of intervention NHs.

In the intervention NHs, the prevalence of antipsych-otic prescribing decreased from 34.1% at baseline to 26.5% at the study end (7.6% absolute reduction, 22.3% relative reduction). In comparison, the prevalence of antipsychotic prescribing in control NHs decreased from 22.7% to 18.8% over the same period (3.9% absolute reduction, 17.2% relative reduction). During the OASIS implementation phase, the intervention NHs had a reduc-tion in prevalence of antipsychotic use (–1.20% [95% confidence interval {CI}, –1.85% to –0.09% per quarter]) greater than that of the control NHs (–0.23% [95% CI, –0.47% to 0.01% per quarter]), resulting in a net OASIS influence of –0.97% (95% CI, –1.85% to –0.09% per quarter; P = 0.03). The antipsychotic use reduction observed in the implementation phase was not sustained in the maintenance phase (difference of 0.93%; 95% CI, –0.66% to 2.54%; P = 0.48). No increases in other psychotropic medication use (anxiolytics, antidepressants, hypnotics) or behavioral disturbances (physically abusive behavior, verbally abusive behavior, and rejecting care) were observed during the OASIS training and implementation phases.

Conclusion. The OASIS communication training program reduced the prevalence of antipsychotic use in NHs during its implementation phase, but its effect was not sustained in the subsequent maintenance phase. The use of other psychotropic medications and behavior disturbances did not increase during the implementation of OASIS program. The findings from this study provided further support for utilizing nonpharmacologic programs to treat behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia in older adults who reside in NHs.

Commentary

The use of both conventional and atypical antipsychotic medications is associated with a dose-related, approximately 2-fold increased risk of sudden cardiac death in older adults [1,2]. In 2006, the FDA issued a public health advisory stating that both conventional and atypical anti-psychotic medications are associated with an increased risk of mortality in elderly patients treated for dementia-related psychosis. Despite this black box warning and growing recognition that antipsychotic medications are not indicated for the treatment of dementia-related psychosis, the off-label use of antipsychotic medications to treat behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia in older adults remains a common practice in nursing homes [3]. Thus, there is an urgent need to assess and develop effective interventions that reduce the practice of antipsychotic medication prescribing in long-term care. To that effect, the study reported by Tjia et al appropriately investigated the impact of the OASIS communication training program, a nonpharmacologic intervention, on the reduction of antipsychotic use in NHs.

This study was well designed and had a number of strengths. It utilized an interrupted time series model, one of the strongest quasi-experimental approaches due to its robustness to threats of internal validity, for evaluating longitudinal effects of an intervention intended to improve the quality of medication use. Moreover, this study included a large sample size and comparison facilities from the same geographical areas (NHs in Massachusetts and New York State) that served as external controls. Several potential weaknesses of the study were identified. Because facility-level aggregate data from NHs were used for analysis, individual level (long-term care resident) characteristics were not accounted for in the analysis. In addition, while the post-OASIS intervention questionnaire response rate was 65.6% (61 of 93 intervention NHs), a higher response rate would provide better characterization of NH staff that participated in OASIS program training, program completion rate, and a more complete representation of competing dementia care training programs concurrently implemented in these NHs.

Several studies, most utilizing various provider education methods, had explored whether these interventions could curb antipsychotic use in NHs with limited success. The largest successful intervention was reported by Meador et al [4], where a focused provider education program facilitated a relative reduction in antipsychotic medication use of 23% compared to control NHs. However, the implementation of this specific program was time- and resource-intensive, requiring geropsychiatry evaluation to all physicians (45 to 60 min), nurse-educator in-service programs for NH staff (5 to 6 one-hr sessions), management specialist consultation to NH administrators (4 hr), and evening meeting for the families of NH residents. The current study by Tjia et al, the largest study to date conducted in the context of competing dementia care training programs and increased awareness of the danger of antipsychotic use in the elderly, similarly showed a meaningful reduction in antipsychotic medication use in NHs that received the OASIS communication training program. The OASIS program appears to be less resource-intensive than the provider education program modeled by Meador et al, and its train-the-trainer model is likely more adaptable to meet the limitations (eg, low staffing and staff turnover) inherent in NHs. The beneficial effect of the OASIS program on reduction of antipsychotic medication prescribing was observed despite low participation by prescribers (11.5% of physicians and 11.5% of nurse practitioners). Although it is unclear why this was observed, this finding is intriguing in that a communication training program that reframes challenging behavior of NH residents with cognitive impairment as (1) communication of unmet needs, (2) train staff to anticipate resident needs, and (3) integrate resident strengths into daily care plans can alter provider prescription behavior. The implication of this is that provider practice in managing behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia can be improved by optimizing communication training in NH staff. Taken together, this study adds to evidence in favor of utilizing nonpharmacologic interventions to reduce antipsychotic use in long-term care.

Applications for Clinical Practice

OASIS, a communication training program for NH staff, reduces antipsychotic medication use in NHs during its implementation phase. Future studies need to investigate pragmatic methods to sustain the beneficial effect of OASIS after its implementation phase.

—Fred Ko, MD, MS, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY

1. Ray WA, Chung CP, Murray KT, et al. Atypical antipsychotic drugs and the risk of sudden cardiac death. N Engl J Med 2009;360:225–35.

2. Wang PS, Schneeweiss S, Avorn J, et al. Risk of death in elderly users of conventional vs. atypical antipsychotic medications. N Engl J Med 2005;353:2335–41.

3. Chen Y, Briesacher BA, Field TS, et al. Unexplained variation across US nursing homes in antipsychotic prescribing rates. Arch Intern Med 2010;170:89–95.

4. Meador KG, Taylor JA, Thapa PB, et al. Predictors of anti-

psychotic withdrawal or dose reduction in a randomized controlled trial of provider education. J Am Geriatr Soc 1997;45:207–10.

1. Ray WA, Chung CP, Murray KT, et al. Atypical antipsychotic drugs and the risk of sudden cardiac death. N Engl J Med 2009;360:225–35.

2. Wang PS, Schneeweiss S, Avorn J, et al. Risk of death in elderly users of conventional vs. atypical antipsychotic medications. N Engl J Med 2005;353:2335–41.

3. Chen Y, Briesacher BA, Field TS, et al. Unexplained variation across US nursing homes in antipsychotic prescribing rates. Arch Intern Med 2010;170:89–95.

4. Meador KG, Taylor JA, Thapa PB, et al. Predictors of anti-

psychotic withdrawal or dose reduction in a randomized controlled trial of provider education. J Am Geriatr Soc 1997;45:207–10.

Nocturnal Seizures Linked to Severe Hypoxemia

Patients who have seizures while asleep are more likely to experience severe and longer episodes of hypoxemia compared with seizures while awake according to an examination of 48 recorded seizures from 20 adults with epilepsy. The analysis also suggested that an increased risk of sudden death may be caused by hypoxemia from nocturnal seizures.

Latreille V, Abdennadher M, Dworetzky BA et al. Nocturnal seizures are associated with more severe hypoxemia and increased risk of postictal generalized EEG suppression [published online ahead of print July 17, 2017]. Epilepsia. 2017;doi: 10.1111/epi.13841.

Patients who have seizures while asleep are more likely to experience severe and longer episodes of hypoxemia compared with seizures while awake according to an examination of 48 recorded seizures from 20 adults with epilepsy. The analysis also suggested that an increased risk of sudden death may be caused by hypoxemia from nocturnal seizures.

Latreille V, Abdennadher M, Dworetzky BA et al. Nocturnal seizures are associated with more severe hypoxemia and increased risk of postictal generalized EEG suppression [published online ahead of print July 17, 2017]. Epilepsia. 2017;doi: 10.1111/epi.13841.

Patients who have seizures while asleep are more likely to experience severe and longer episodes of hypoxemia compared with seizures while awake according to an examination of 48 recorded seizures from 20 adults with epilepsy. The analysis also suggested that an increased risk of sudden death may be caused by hypoxemia from nocturnal seizures.

Latreille V, Abdennadher M, Dworetzky BA et al. Nocturnal seizures are associated with more severe hypoxemia and increased risk of postictal generalized EEG suppression [published online ahead of print July 17, 2017]. Epilepsia. 2017;doi: 10.1111/epi.13841.

Finding a Noninvasive Approach to Epilepsy Diagnosis

A combination of metabolites and genomic indicators hold promise as a noninvasive biomarker for epilepsy suggests a recent study published in Epilepsia. Wu et al found that a metabolomic-genomic signature that included reduced lactate and increased creatine plus phosphocreatine and choline was able to predict the existence of an altered metabolic state in epileptic brain regions, suggesting it may eventually be an alternative to surgically invasive approaches to diagnosis.

Wu HC, Dachet F, Ghoddoussi F, et al. Altered metabolomic-genomic signature: a potential noninvasive biomarker of epilepsy [published online ahead of print July 17, 2017]. Epilepsia. 2017; doi: 10.1111/epi.13848.

A combination of metabolites and genomic indicators hold promise as a noninvasive biomarker for epilepsy suggests a recent study published in Epilepsia. Wu et al found that a metabolomic-genomic signature that included reduced lactate and increased creatine plus phosphocreatine and choline was able to predict the existence of an altered metabolic state in epileptic brain regions, suggesting it may eventually be an alternative to surgically invasive approaches to diagnosis.

Wu HC, Dachet F, Ghoddoussi F, et al. Altered metabolomic-genomic signature: a potential noninvasive biomarker of epilepsy [published online ahead of print July 17, 2017]. Epilepsia. 2017; doi: 10.1111/epi.13848.

A combination of metabolites and genomic indicators hold promise as a noninvasive biomarker for epilepsy suggests a recent study published in Epilepsia. Wu et al found that a metabolomic-genomic signature that included reduced lactate and increased creatine plus phosphocreatine and choline was able to predict the existence of an altered metabolic state in epileptic brain regions, suggesting it may eventually be an alternative to surgically invasive approaches to diagnosis.

Wu HC, Dachet F, Ghoddoussi F, et al. Altered metabolomic-genomic signature: a potential noninvasive biomarker of epilepsy [published online ahead of print July 17, 2017]. Epilepsia. 2017; doi: 10.1111/epi.13848.

Deep Brain Stimulation Offers Benefit for Intractable Epilepsy

Intracranial deep brain stimulation (DBS) may offer some benefit to patients with epilepsy who do not respond to more conservative therapy, but most of the evidence comes from short-term randomized controlled trials, according to a recent review from the Cochrane Library. Experts concluded that anterior thalamic DBS, responsive ictal onset zone stimulation, and hippocampal DBS can reduce the frequency of seizures in patients with refractory epilepsy.

Sprengers M, Vonck K, Carrette E, Marson AG, Boon P. Deep brain and cortical stimulation for epilepsy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Jul 18;7:CD008497.

Intracranial deep brain stimulation (DBS) may offer some benefit to patients with epilepsy who do not respond to more conservative therapy, but most of the evidence comes from short-term randomized controlled trials, according to a recent review from the Cochrane Library. Experts concluded that anterior thalamic DBS, responsive ictal onset zone stimulation, and hippocampal DBS can reduce the frequency of seizures in patients with refractory epilepsy.

Sprengers M, Vonck K, Carrette E, Marson AG, Boon P. Deep brain and cortical stimulation for epilepsy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Jul 18;7:CD008497.

Intracranial deep brain stimulation (DBS) may offer some benefit to patients with epilepsy who do not respond to more conservative therapy, but most of the evidence comes from short-term randomized controlled trials, according to a recent review from the Cochrane Library. Experts concluded that anterior thalamic DBS, responsive ictal onset zone stimulation, and hippocampal DBS can reduce the frequency of seizures in patients with refractory epilepsy.

Sprengers M, Vonck K, Carrette E, Marson AG, Boon P. Deep brain and cortical stimulation for epilepsy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Jul 18;7:CD008497.

Managing psychiatric illness during pregnancy and breastfeeding: Tools for decision making

Increasingly, women with psychiatric illness are undergoing pharmacologic treatment during pregnancy. In the United States, an estimated 8% of pregnant women are prescribed antidepressants, and the number of such cases has risen over the past 15 years.1 Women with a psychiatric diagnosis were once instructed either to discontinue all medication immediately on learning they were pregnant, or to forgo motherhood because their illness might have a negative effect on a child or because avoiding medication during pregnancy might lead to a relapse.

Fortunately, women with depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, or schizophrenia no longer are being told that they cannot become mothers. For many women, however, stopping medication is not an option. Furthermore, psychiatric illness sometimes is diagnosed initially during pregnancy and requires treatment.

Pregnant women and their physicians need accurate information about when to taper off medication, when to start or continue, and which medications are safest. Even for clinicians with a solid knowledge base, counseling a woman who needs or may need psychotropic medication during pregnancy and breastfeeding is a daunting task. Some clinicians still recommend no drug treatment as the safest and best option, given the potential risks to the fetus.

In this review we offer a methodologic approach for decision making about pharmacologic treatment during pregnancy. As the scientific literature is constantly being updated, it is imperative to have the most current information on psychotropics and to know how to individualize that information when counseling a pregnant woman and her family. Using this framework for analyzing the risks and benefits for both mother and fetus, clinicians can avoid the unanswerable question of which medication is the “safest.”

A patient’s mental health care provider is a useful resource for information about a woman’s mental health history and current stability, but he or she may not be expert or comfortable in recommending treatment for a pregnant patient. During pregnancy, a woman’s obstetrician often becomes the “expert” for all treatment decisions.

Antidepressants. Previous studies may have overestimated the association between prenatal use of antidepressants and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in children because they did not control for shared family factors, according to investigators who say that their recent study findings raise the possibility that "confounding by indication" might partially explain the observed association.1

In a population-based cohort study in Hong Kong, Man and colleagues analyzed the records of 190,618 maternal-child pairs.1 A total of 1,252 children were exposed to maternal antidepressant use during pregnancy. Medications included selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), non-SSRIs, and antipsychotics as monotherapy or in various combination regimens. Overall, 5,659 of the cohort children (3%) were diagnosed with or received treatment for ADHD.

When gestational medication users were compared with nongestational users, the crude hazard ratio (HR) of antidepressant use during pregnancy and ADHD was 2.26 (P<.01). After adjusting for potential confounding factors (such as maternal psychiatric disorders and use of other psychotropic drugs), this reduced to 1.39 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.07-1.82; P = .01). Children of mothers with psychiatric disorders had a higher risk of ADHD than did children of mothers without psychiatric disorders (HR, 1.84; 95% CI, 1.54-2.18; P<.01), even if the mothers had never used antidepressants.

While acknowledging the potential for type 2 error in the study analysis, the investigators proposed that the results "further strengthen our hypothesis that confounding by indication may play a major role in the observed positive association between gestational use of antidepressants and ADHD in offspring."

Lithium. Similarly, investigators of another recently published study found that the magnitude of the association between prenatal lithium use and increased risk of cardiac malformations in infants was smaller than previously shown.2 This finding may be important clinically because lithium is a first-line treatment for many US women of reproductive age with bipolar disorder.

Most earlier data were derived from a database registry, case reports, and small studies that often had conflicting results. However, Patorno and colleagues conducted a large retrospective cohort study that involved data on 1,325,563 pregnancies in women enrolled in Medicaid.2 Exposure to lithium was defined as at least 1 filled prescription during the first trimester, and the primary reference group included women with no lithium or lamotrigine (another mood stabilizer not associated with congenital malformations) dispensing during the 3 months before the start of pregnancy or during the first trimester.

A total of 663 pregnancies (0.05%) were exposed to lithium and 1,945 (0.15%) were exposed to lamotrigine during the first trimester. The adjusted risk ratios for cardiac malformations among infants exposed to lithium were 1.65 (95% CI, 1.02-2.68) as compared with nonexposed infants and 2.25 (95% CI, 1.17-4.34) as compared with lamotrigine-exposed infants. Notably, all right ventricular outflow tract obstruction defects identified in the infants exposed to lithium occurred with a daily dose of more than 600 mg.

Although the study results suggest an increased risk of cardiac malformations--of approximately 1 additional case per 100 live births--associated with lithium use in early pregnancy, the magnitude of risk is much lower than originally proposed based on early lithium registry data.

-- Kathy Christie, Senior Editor

References

- Man KC, Chan EW, Ip P, et al. Prenatal antidepressant use and risk of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in offspring: population based cohort study. BMJ. 2017;357:j2350.

- Patorno E, Huybrechts KR, Bateman BT, et al. Lithium use in pregnancy and risk of cardiac malformations. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(23):2245-2254.

Analyze risks and benefits of medication versus no medication

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has not approved any psychotropic medication for use during pregnancy. While a clinical study would provide more scientifically rigorous safety data, conducting a double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial in pregnant women with a psychiatric disorder is unethical. Thus, the literature consists mostly of reports on case series, retrospective chart reviews, prospective naturalistic studies, and analyses of large registry databases. Each has benefits and limitations. It is important to understand the limitations when making treatment decisions.

In 1979, the FDA developed a 5-lettersystem (A, B, C, D, X) for classifying the relative safety of medications used during pregnancy.2 Many clinicians and pregnant women relied on this system to decide which medications were safe. Unfortunately, the information in the system was inadequate for making informed decisions. For example, although a class B medication might have appeared safer than one in class C, the studies of risk in humans might not have been adequate to permit comparisons. Drug safety classifications were seldom changed, despite the availability of additional data.

In June 2015, the FDA changed the requirements for the Pregnancy and Lactation subsections of the labeling for human prescription drugs and biologic products. Drug manufacturers must now include in each subsection a risk summary, clinical considerations supporting patient care decisions and counseling, and detailed data. These subsections provide information on available human and animal studies, known or potential maternal or fetal adverse reactions, and dose adjustments needed during pregnancy and the postpartum period. In addition, the FDA added a subsection: Females and Males of Reproductive Potential.3

These changes acknowledge there is no list of “safe” medications. The safest medication generally is the one that works for a particular patient at the lowest effective dose. As each woman’s history of illness and effective treatment is different, the best medication may differ as well, even among women with the same illness. Therefore, medication should be individualized to the patient. A risk–benefit analysis comparing psychotropic medication treatment with no medication treatment must be performed for each patient according to her personal history and the best available data.

Read about the risks of untreated illness during pregnancy

What is the risk of untreated illness during pregnancy?

During pregnancy, women are treated for many medical disorders, including psychiatric illness. One general guideline is that, if a pregnant woman does not need a medication—whether it be for an allergy, hypertension, or another disorder—she should not take it. Conversely, if a medication is required for a patient’s well-being, her physician should continue it or switch to a safer one. This general guideline is the same for women with depression, anxiety, or a psychotic disorder.

Managing hypertension during pregnancy is an example of choosing treatment when the risk of the illness to the mother and the infant outweighs the likely small risk associated with taking a medication. Blood pressure is monitored, and, when it reaches a threshold, an antihypertensive is started promptly to avoid morbidity and mortality.

Psychiatric illness carries risks for both mother and fetus as well, but no data show a clear threshold for initiating pharmacologic treatment. Therefore, in prescribing medication the most important steps are to take a complete history and perform a thorough evaluation. Important information includes the number and severity of previous episodes, prior history of hospitalization or suicidal thoughts or attempts, and any history of psychotic or manic status.

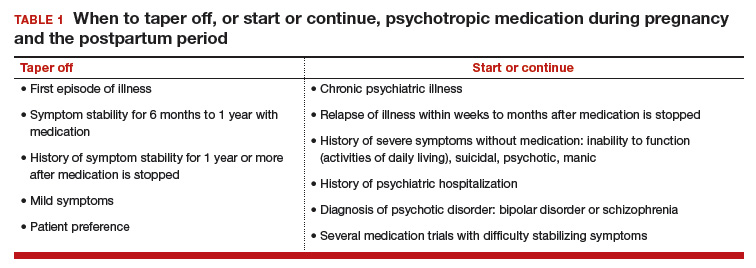

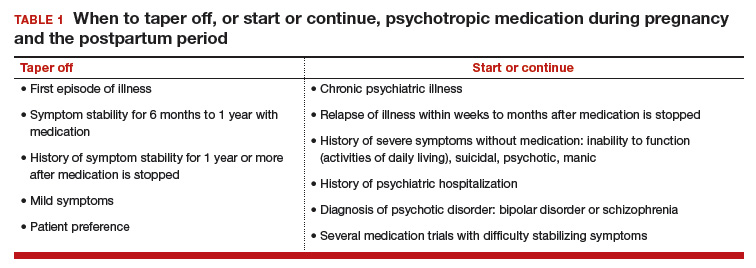

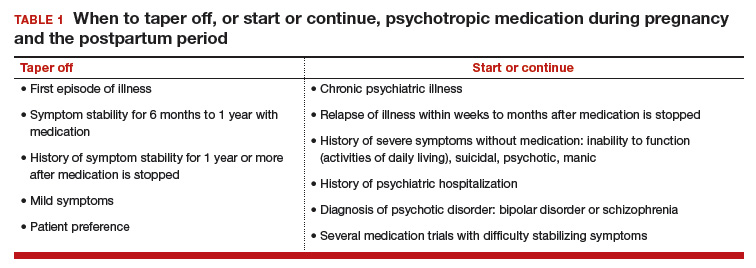

Whether to continue or discontinue medication is often decided after inquiring about other times a medication was discontinued. A patient who in the past stayed well for several years after stopping a medication may be able to taper off a medication and conceive during a window of wellness. Some women who have experienced only one episode of illness and have been stable for at least a year may be able to taper off a medication before conceiving (TABLE 1).

In the risk–benefit analysis, assess the need for pharmacologic treatment by considering the risk that untreated illness poses for both mother and fetus, the benefits of treatment for both, and the risk of medication exposure for the fetus.4

Mother: Risk of untreated illness versus benefit of treatment

A complete history and a current symptom evaluation are needed to assess the risk that nonpharmacologic treatment poses for the mother. Women with functional impairment, including inability to work, to perform activities of daily living, or to take care of other children, likely require treatment. Studies have found that women who discontinue treatment for a psychiatric illness around the time of conception are likely to experience a recurrence of illness during pregnancy, often in the first trimester, and must restart medication.5,6 For some diagnoses, particularly bipolar disorder, symptoms during a relapse can be more severe and more difficult to treat, and they carry a risk for both mother and fetus.7 A longitudinal study of pregnant women who stopped medication for bipolar disorder found a 71% rate of relapse.7 In cases in which there is a history of hospitalization, suicide attempt, or psychosis, discontinuing treatment is not an option; instead, the physician must determine which medication is safest for the particular patient.

Related article:

Does PTSD during pregnancy increase the likelihood of preterm birth?

Fetus: Risk of untreated illness versus benefit of treatment

Mothers with untreated psychiatric illness are at higher risk for poor prenatal care, substance abuse, and inadequate nutrition, all of which increase the risk of negative obstetric and neonatal outcomes.8 Evidence indicates that untreated maternal depression increases the risk of preterm delivery and low birth weight.9 Children born to mothers with depression have more behavioral problems, more psychiatric illness, more visits to pediatricians, lower IQ scores, and attachment issues.10 Some of the long-term negative effects of intrauterine stress, which include hypertension, coronary heart disease, and autoimmune disorders, persist into adulthood.11

Fetus: Risk of medication exposure

With any pharmacologic treatment, the timing of fetal exposure affects resultant risks and therefore must be considered in the management plan.

Before conception. Is there any effect on ovulation or fertilization?

Implantation. Does the exposure impair the blastocyst’s ability to implant in the uterine lining?

First trimester. This is the period of organogenesis. Regardless of drug exposure, there is a 2% to 4% baseline risk of a major malformation during any pregnancy. The risk of a particular malformation must be weighed against this baseline risk.

According to limited data, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) may increase the risk of early miscarriage.12 SSRIs also have been implicated in increasing the risk of cardiovascular malformations, although the data are conflicting.13,14

Antiepileptics such as valproate and carbamazepine are used as mood stabilizers in the treatment of bipolar disorder.15 Extensive data have shown an association with teratogenicity. Pregnant women who require either of these medications also should be prescribed folic acid 4 or 5 mg/day. Given the high risk of birth defects and cognitive delay, valproate no longer is recommended for women of reproductive potential.16

Lithium, one of the safest medications used in the treatment of bipolar disorder, is associated with a very small risk of Ebstein anomaly.17

Lamotrigine is used to treat bipolar depression and appears to have a good safety profile, along with a possible small increased risk of oral clefts.18,19

Atypical antipsychotics (such as aripiprazole, olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone) are often used first-line in the treatment of psychotic disorders and bipolar disorder in women who are not pregnant. Although the safety data on use of these drugs during pregnancy are limited, a recent analysis of pregnant Medicaid enrollees found no increased risk of birth defects after controlling for potential confounding factors.20 Common practice is to avoid these newer agents, given their limited data and the time needed for rare malformations to emerge (adequate numbers require many exposures during pregnancy).

Read additional fetal risks of medication exposure

Second trimester. This is a period of growth and neural development. A 2006 study suggested that SSRI exposure after pregnancy week 20 increases the risk of persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn (PPHN).21 In 2011, however, the FDA removed the PPHN warning label for SSRIs, citing inconsistent data. Whether the PPHN risk is increased with SSRI use is unclear, but the risk is presumed to be smaller than previously suggested.22 Stopping SSRIs before week 20 puts the mother at risk for relapse during pregnancy and increases her risk of developing postpartum depression. If we follow the recommendation to prescribe medication only for women who need it most, then stopping the medication at any time during pregnancy is not an option.

Third trimester. This is a period of continued growth and lung maturation.

Delivery. Is there a potential for impairment in parturition?

Neonatal adaptation. Newborns are active mainly in adapting to extrauterine life: They regulate their temperature and muscle tone and learn to coordinate sucking, swallowing, and breathing. Does medication exposure impair adaptation, or are signs or symptoms of withdrawal or toxicity present? The evidence that in utero SSRI exposure increases the risk of neonatal adaptation syndrome is consistent, but symptoms are mild and self-limited.23 Tapering off SSRIs before delivery currently is not recommended, as doing so increases the mother’s risk for postpartum depression and, according to one study, does not prevent symptoms of neonatal adaptation syndrome from developing.24

Behavioral teratogenicity. What are the long-term developmental outcomes for the child? Are there any differences in IQ, speech and language, or psychiatric illness? One study found an increased risk of autism with in utero exposure to sertraline, but the study had many methodologic flaws and its findings have not been replicated.25 Most studies have not found consistent differences in speech, IQ, or behavior between infants exposed and infants not exposed to antidepressants.26,27 By contrast, in utero exposure to anticonvulsants, particularly valproate, has led to significant developmental problems in children.28 The data on atypical antipsychotics are limited.

Related article:

Do antidepressants really cause autism?

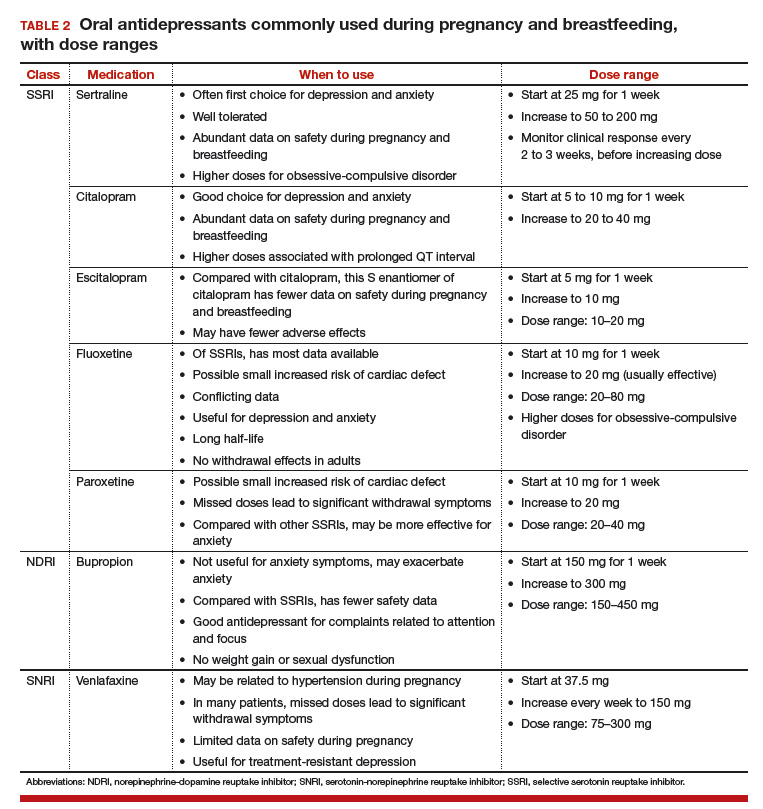

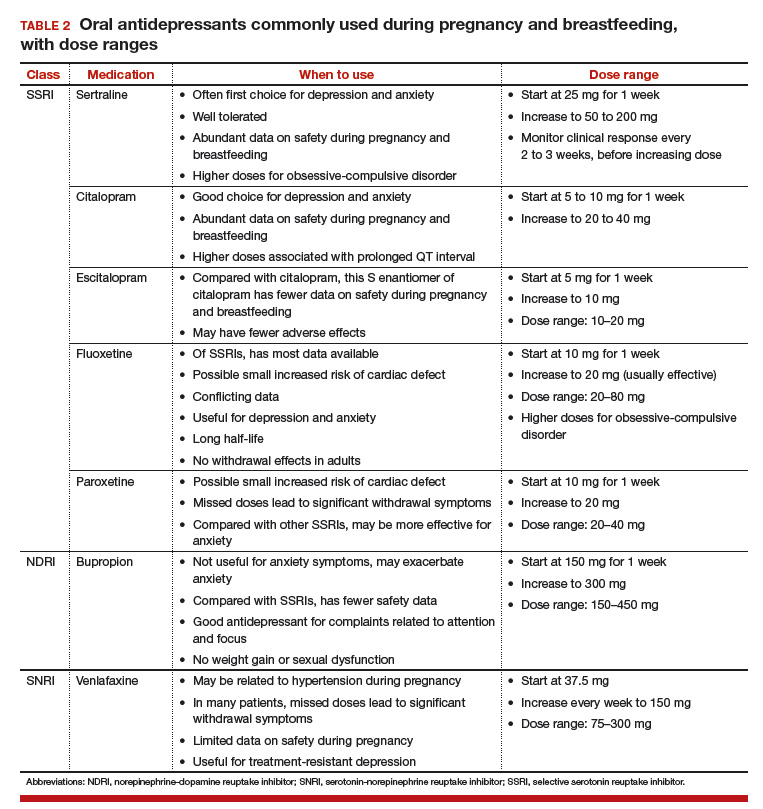

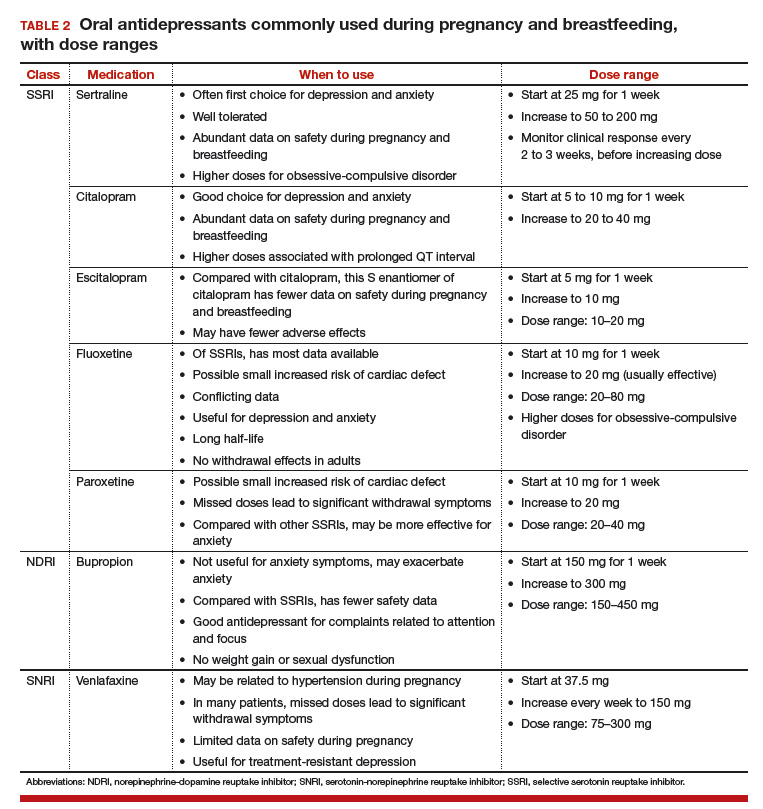

None of the medications used to treat depression, bipolar disorder, anxiety, or schizophrenia is considered first-line or safest therapy for the pregnant woman. For any woman who is doing well on a certain medication, but particularly for a pregnant woman, there is no compelling, data-supported reason to switch to another agent. For depression, options include all of the SSRIs, with the possible exception of paroxetine (TABLE 2). In conflicting studies, paroxetine was no different from any other SSRI in not being associated with cardiovascular defects.29

One goal in treatment is to use a medication that previously was effective in the remission of symptoms and to use it at the lowest dose possible. Treating simply to maintain a low dose of drug, however, and not to effect symptom remission, exposes the fetus to both the drug and the illness. Again, the lowest effective dose is the best choice.

Read about treatment during breastfeeding

Treatment during breastfeeding

Women are encouraged to breastfeed for physical and psychological health benefits, for both themselves and their babies. Many medications are compatible with breastfeeding.30 The amount of drug an infant receives through breast milk is considerably less than the amount received during the mother’s pregnancy. Breastfeeding generally is allowed if the calculated infant dose is less than 10% of the weight-adjusted maternal dose.31

The amount of drug transferred from maternal plasma into milk is highest for drugs with low protein binding and high lipid solubility.32 Drug clearance in infants must be considered as well. Renal clearance is decreased in newborns and does not reach adult levels until 5 or 6 months of age. In addition, liver metabolism is impaired in neonates and even more so in premature infants.33 Drugs that require extensive first-pass metabolism may have higher bioavailability, and this factor should be considered.

Some clinicians recommend pumping and discarding breast milk when the drug in it is at its peak level; although the drug is not eliminated, the infant ingests less of it.34 Most women who are anxious about breastfeeding while on medication “pump and dump” until they are more comfortable nursing and the infants are doing well. Except in cases of mother preference, most physicians with expertise in reproductive mental health generally recommend against pumping and discarding milk.

Through breast milk, infants ingest drugs in varying amounts. The amount depends on the qualities of the medication, the timing and duration of breastfeeding, and the characteristics of the infant. Few psychotropic drugs have significant effects on breastfed infants. Even lithium, previously contraindicated, is successfully used, with infant monitoring, during breastfeeding.35 Given breastfeeding’s benefits for both mother and child, many more women on psychotropic medications are choosing to breastfeed.

Related article:

USPSTF Recommendations to Support Breastfeeding

Balance the pros and cons

Deciding to use medication during pregnancy and breastfeeding involves considering the risk of untreated illness versus the benefit of treatment for both mother and fetus, and the risk of medication exposure for the fetus. Mother and fetus are inseparable, and neither can be isolated from the other in treatment decisions. Avoiding psychotropic medication during pregnancy is not always the safest option for mother or fetus. The patient and her clinician and support system must make an informed decision that is based on the best available data and that takes into account the mother’s history of illness and effective treatment. Many women with psychiatric illness no longer have to choose between mental health and starting a family, and their babies will be healthy.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Andrade SE, Raebel MA, Brown J, et al. Use of antidepressant medications during pregnancy: a multisite study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198(2):194.e1–e5.

- Hecht A. Drug safety labeling for doctors. FDA Consum. 1979;13(8):12–13.

- Ramoz LL, Patel-Shori NM. Recent changes in pregnancy and lactation labeling: retirement of risk categories. Pharmacotherapy. 2014;34(4):389–395.

- Yonkers KA, Wisner KL, Stewart DE, et al. The management of depression during pregnancy: a report from the American Psychiatric Association and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2009;31(5):403–413.

- Cohen LS, Altshuler LL, Harlow BL, et al. Relapse of major depression during pregnancy in women who maintain or discontinue antidepressant treatment. JAMA. 2006;295(5):499–507.

- O’Brien L, Laporte A, Koren G. Estimating the economic costs of antidepressant discontinuation during pregnancy. Can J Psychiatry. 2009;54(6):399–408.

- Viguera AC, Whitfield T, Baldessarini RJ, et al. Risk of recurrence in women with bipolar disorder during pregnancy: prospective study of mood stabilizer discontinuation. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(12):1817–1824.

- Bonari L, Pinto N, Ahn E, Einarson A, Steiner M, Koren G. Perinatal risks of untreated depression during pregnancy. Can J Psychiatry. 2004;49(11):726–735.

- Straub H, Adams M, Kim JJ, Silver RK. Antenatal depressive symptoms increase the likelihood of preterm birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207(4):329.e1–e4.

- Hayes LJ, Goodman SH, Carlson E. Maternal antenatal depression and infant disorganized attachment at 12 months. Attach Hum Dev. 2013;15(2):133–153.

- Field T. Prenatal depression effects on early development: a review. Infant Behav Dev. 2011;34(1):1–14.

- Kjaersgaard MI, Parner ET, Vestergaard M, et al. Prenatal antidepressant exposure and risk of spontaneous abortion—a population-based study. PLoS One. 2013;8(8):e72095.

- Nordeng H, van Gelder MM, Spigset O, Koren G, Einarson A, Eberhard-Gran M. Pregnancy outcome after exposure to antidepressants and the role of maternal depression: results from the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2012;32(2):186–194.

- Källén BA, Otterblad Olausson P. Maternal use of selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors in early pregnancy and infant congenital malformations. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2007;79(4):301–308.

- Tomson T, Battino D. Teratogenic effects of antiepileptic drugs. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11(9):803–813.

- Balon R, Riba M. Should women of childbearing potential be prescribed valproate? A call to action. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(4):525–526.

- Giles JJ, Bannigan JG. Teratogenic and developmental effects of lithium. Curr Pharm Design. 2006;12(12):1531–1541.

- Nguyen HT, Sharma V, McIntyre RS. Teratogenesis associated with antibipolar agents. Adv Ther. 2009;26(3):281–294.

- Campbell E, Kennedy F, Irwin B, et al. Malformation risks of antiepileptic drug monotherapies in pregnancy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2013;84(11):e2.

- Huybrechts KF, Hernández-Díaz S, Patorno E, et al. Antipsychotic use in pregnancy and the risk for congenital malformations. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73(9):938–946.

- Chambers CD, Hernández-Díaz S, Van Marter LJ, et al. Selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors and risk of persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(6):579–587.

- ‘t Jong GW, Einarson T, Koren G, Einarson A. Antidepressant use in pregnancy and persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn (PPHN): a systematic review. Reprod Toxicol. 2012;34(3):293–297.

- Oberlander TF, Misri S, Fitzgerald CE, Kostaras X, Rurak D, Riggs W. Pharmacologic factors associated with transient neonatal symptoms following prenatal psychotropic medication exposure. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(2):230–237.

- Warburton W, Hertzman C, Oberlander TF. A register study of the impact of stopping third trimester selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor exposure on neonatal health. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2010;121(6):471–479.

- Croen LA, Grether JK, Yoshida CK, Odouli R, Hendrick V. Antidepressant use during pregnancy and childhood autism spectrum disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(11):1104–1112.

- Batton B, Batton E, Weigler K, Aylward G, Batton D. In utero antidepressant exposure and neurodevelopment in preterm infants. Am J Perinatol. 2013;30(4):297–301.

- Austin MP, Karatas JC, Mishra P, Christl B, Kennedy D, Oei J. Infant neurodevelopment following in utero exposure to antidepressant medication. Acta Paediatr. 2013;102(11):1054–1059.

- Bromley RL, Mawer GE, Briggs M, et al. The prevalence of neurodevelopmental disorders in children prenatally exposed to antiepileptic drugs. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2013;84(6):637–643.

- Einarson A, Pistelli A, DeSantis M, et al. Evaluation of the risk of congenital cardiovascular defects associated with use of paroxetine during pregnancy. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(6):749–752.

- Davanzo R, Copertino M, De Cunto A, Minen F, Amaddeo A. Antidepressant drugs and breastfeeding: a review of the literature. Breastfeed Med. 2011;6(2):89–98.

- Ito S. Drug therapy for breast-feeding women. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(2):118–126.

- Suri RA, Altshuler LL, Burt VK, Hendrick VC. Managing psychiatric medications in the breast-feeding woman. Medscape Womens Health. 1998;3(1):1.

- Milsap RL, Jusko WJ. Pharmacokinetics in the infant. Environ Health Perspect. 1994;102(suppl 11):107–110.

- Newport DJ, Hostetter A, Arnold A, Stowe ZN. The treatment of postpartum depression: minimizing infant exposures. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63(suppl 7):31–44.

- Viguera AC, Newport DJ, Ritchie J, et al. Lithium in breast milk and nursing infants: clinical implications. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(2):342–345.

Increasingly, women with psychiatric illness are undergoing pharmacologic treatment during pregnancy. In the United States, an estimated 8% of pregnant women are prescribed antidepressants, and the number of such cases has risen over the past 15 years.1 Women with a psychiatric diagnosis were once instructed either to discontinue all medication immediately on learning they were pregnant, or to forgo motherhood because their illness might have a negative effect on a child or because avoiding medication during pregnancy might lead to a relapse.

Fortunately, women with depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, or schizophrenia no longer are being told that they cannot become mothers. For many women, however, stopping medication is not an option. Furthermore, psychiatric illness sometimes is diagnosed initially during pregnancy and requires treatment.

Pregnant women and their physicians need accurate information about when to taper off medication, when to start or continue, and which medications are safest. Even for clinicians with a solid knowledge base, counseling a woman who needs or may need psychotropic medication during pregnancy and breastfeeding is a daunting task. Some clinicians still recommend no drug treatment as the safest and best option, given the potential risks to the fetus.

In this review we offer a methodologic approach for decision making about pharmacologic treatment during pregnancy. As the scientific literature is constantly being updated, it is imperative to have the most current information on psychotropics and to know how to individualize that information when counseling a pregnant woman and her family. Using this framework for analyzing the risks and benefits for both mother and fetus, clinicians can avoid the unanswerable question of which medication is the “safest.”

A patient’s mental health care provider is a useful resource for information about a woman’s mental health history and current stability, but he or she may not be expert or comfortable in recommending treatment for a pregnant patient. During pregnancy, a woman’s obstetrician often becomes the “expert” for all treatment decisions.

Antidepressants. Previous studies may have overestimated the association between prenatal use of antidepressants and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in children because they did not control for shared family factors, according to investigators who say that their recent study findings raise the possibility that "confounding by indication" might partially explain the observed association.1

In a population-based cohort study in Hong Kong, Man and colleagues analyzed the records of 190,618 maternal-child pairs.1 A total of 1,252 children were exposed to maternal antidepressant use during pregnancy. Medications included selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), non-SSRIs, and antipsychotics as monotherapy or in various combination regimens. Overall, 5,659 of the cohort children (3%) were diagnosed with or received treatment for ADHD.

When gestational medication users were compared with nongestational users, the crude hazard ratio (HR) of antidepressant use during pregnancy and ADHD was 2.26 (P<.01). After adjusting for potential confounding factors (such as maternal psychiatric disorders and use of other psychotropic drugs), this reduced to 1.39 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.07-1.82; P = .01). Children of mothers with psychiatric disorders had a higher risk of ADHD than did children of mothers without psychiatric disorders (HR, 1.84; 95% CI, 1.54-2.18; P<.01), even if the mothers had never used antidepressants.

While acknowledging the potential for type 2 error in the study analysis, the investigators proposed that the results "further strengthen our hypothesis that confounding by indication may play a major role in the observed positive association between gestational use of antidepressants and ADHD in offspring."

Lithium. Similarly, investigators of another recently published study found that the magnitude of the association between prenatal lithium use and increased risk of cardiac malformations in infants was smaller than previously shown.2 This finding may be important clinically because lithium is a first-line treatment for many US women of reproductive age with bipolar disorder.

Most earlier data were derived from a database registry, case reports, and small studies that often had conflicting results. However, Patorno and colleagues conducted a large retrospective cohort study that involved data on 1,325,563 pregnancies in women enrolled in Medicaid.2 Exposure to lithium was defined as at least 1 filled prescription during the first trimester, and the primary reference group included women with no lithium or lamotrigine (another mood stabilizer not associated with congenital malformations) dispensing during the 3 months before the start of pregnancy or during the first trimester.

A total of 663 pregnancies (0.05%) were exposed to lithium and 1,945 (0.15%) were exposed to lamotrigine during the first trimester. The adjusted risk ratios for cardiac malformations among infants exposed to lithium were 1.65 (95% CI, 1.02-2.68) as compared with nonexposed infants and 2.25 (95% CI, 1.17-4.34) as compared with lamotrigine-exposed infants. Notably, all right ventricular outflow tract obstruction defects identified in the infants exposed to lithium occurred with a daily dose of more than 600 mg.

Although the study results suggest an increased risk of cardiac malformations--of approximately 1 additional case per 100 live births--associated with lithium use in early pregnancy, the magnitude of risk is much lower than originally proposed based on early lithium registry data.

-- Kathy Christie, Senior Editor

References

- Man KC, Chan EW, Ip P, et al. Prenatal antidepressant use and risk of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in offspring: population based cohort study. BMJ. 2017;357:j2350.

- Patorno E, Huybrechts KR, Bateman BT, et al. Lithium use in pregnancy and risk of cardiac malformations. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(23):2245-2254.

Analyze risks and benefits of medication versus no medication

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has not approved any psychotropic medication for use during pregnancy. While a clinical study would provide more scientifically rigorous safety data, conducting a double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial in pregnant women with a psychiatric disorder is unethical. Thus, the literature consists mostly of reports on case series, retrospective chart reviews, prospective naturalistic studies, and analyses of large registry databases. Each has benefits and limitations. It is important to understand the limitations when making treatment decisions.

In 1979, the FDA developed a 5-lettersystem (A, B, C, D, X) for classifying the relative safety of medications used during pregnancy.2 Many clinicians and pregnant women relied on this system to decide which medications were safe. Unfortunately, the information in the system was inadequate for making informed decisions. For example, although a class B medication might have appeared safer than one in class C, the studies of risk in humans might not have been adequate to permit comparisons. Drug safety classifications were seldom changed, despite the availability of additional data.

In June 2015, the FDA changed the requirements for the Pregnancy and Lactation subsections of the labeling for human prescription drugs and biologic products. Drug manufacturers must now include in each subsection a risk summary, clinical considerations supporting patient care decisions and counseling, and detailed data. These subsections provide information on available human and animal studies, known or potential maternal or fetal adverse reactions, and dose adjustments needed during pregnancy and the postpartum period. In addition, the FDA added a subsection: Females and Males of Reproductive Potential.3

These changes acknowledge there is no list of “safe” medications. The safest medication generally is the one that works for a particular patient at the lowest effective dose. As each woman’s history of illness and effective treatment is different, the best medication may differ as well, even among women with the same illness. Therefore, medication should be individualized to the patient. A risk–benefit analysis comparing psychotropic medication treatment with no medication treatment must be performed for each patient according to her personal history and the best available data.

Read about the risks of untreated illness during pregnancy

What is the risk of untreated illness during pregnancy?

During pregnancy, women are treated for many medical disorders, including psychiatric illness. One general guideline is that, if a pregnant woman does not need a medication—whether it be for an allergy, hypertension, or another disorder—she should not take it. Conversely, if a medication is required for a patient’s well-being, her physician should continue it or switch to a safer one. This general guideline is the same for women with depression, anxiety, or a psychotic disorder.

Managing hypertension during pregnancy is an example of choosing treatment when the risk of the illness to the mother and the infant outweighs the likely small risk associated with taking a medication. Blood pressure is monitored, and, when it reaches a threshold, an antihypertensive is started promptly to avoid morbidity and mortality.

Psychiatric illness carries risks for both mother and fetus as well, but no data show a clear threshold for initiating pharmacologic treatment. Therefore, in prescribing medication the most important steps are to take a complete history and perform a thorough evaluation. Important information includes the number and severity of previous episodes, prior history of hospitalization or suicidal thoughts or attempts, and any history of psychotic or manic status.