User login

Recovery of Hair in the Psoriatic Plaques of a Patient With Coexistent Alopecia Universalis

To the Editor:

Both alopecia areata (AA) and psoriasis vulgaris are chronic relapsing autoimmune diseases, with AA causing nonscarring hair loss in approximately 0.1% to 0.2%1 of the population with a lifetime risk of 1.7%,2 and psoriasis more broadly impacting 1.5% to 2% of the population.3 The helper T cell (TH1) cytokine milieu is pathogenic in both conditions.4-6 IFN-γ knockout mice, unlike their wild-type counterparts, do not exhibit AA.7 Psoriasis is notably improved by IL-10 injections, which dampen the TH1 response.8 Distinct from AA, TH17 and TH22 cells have been implicated as key players in psoriasis pathogenesis, along with the associated IL-17 and IL-22 cytokines.9-12

Few cases of patients with concurrent AA and psoriasis have been described. Interestingly, these cases document normal hair regrowth in the areas of psoriasis.13-16 These cases may offer unique insight into the immune factors driving each disease. We describe a case of a man with both alopecia universalis (AU) and psoriasis who developed hair regrowth in some of the psoriatic plaques.

A 34-year-old man with concurrent AU and psoriasis who had not used any systemic or topical medication for either condition in the last year presented to our clinic seeking treatment. The patient had a history of alopecia totalis as a toddler that completely resolved by 4 years of age with the use of squaric acid dibutylester (SADBE). At 31 years of age, the alopecia recurred and was localized to the scalp. It was partially responsive to intralesional triamcinolone acetonide. The patient’s alopecia worsened over the 2 years following recurrence, ultimately progressing to AU. Two months after the alopecia recurrence, he developed the first psoriatic plaques. As the plaque psoriasis progressed, systemic therapy was initiated, first methotrexate and then etanercept. Shortly after developing AU, he lost his health insurance and discontinued all therapy. The patient’s psoriasis began to recur approximately 3 months after stopping etanercept. He was not using any other psoriasis medications. At that time, he noted terminal hair regrowth within some of the psoriatic plaques. No terminal hairs grew outside of the psoriatic plaques, and all regions with growth had previously been without hair for an extended period of time. The patient presented to our clinic approximately 1 year later. He had no other medical conditions and no relevant family history.

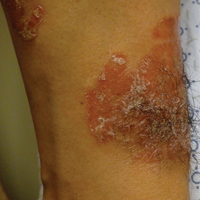

On initial physical examination, he had nonscarring hair loss involving nearly 100% of the body with psoriatic plaques on approximately 30% of the body surface area. Regions of terminal hair growth were confined to some but not all of the psoriatic plaques (Figure). Interestingly, the terminal hairs were primarily localized to the thickest central regions of the plaques. The patient’s psoriasis was treated with a combination of topical clobetasol and calcipotriene. In addition, he was started on tacrolimus ointment to the face and eyebrows for the AA. Maintenance of terminal hair within a region of topically treated psoriasis on the forearm persisted at the 2-month follow-up despite complete clearance of the corresponding psoriatic plaque. A small psoriatic plaque on the scalp cleared early with topical therapy without noticeable hair regrowth. The patient subsequently was started on contact immunotherapy with SADBE and intralesional triamcinolone acetonide for the scalp alopecia without satisfactory response. He decided to discontinue further attempts at treating the alopecia and requested to be restarted on etanercept therapy for recalcitrant psoriatic plaques. His psoriasis responded well to this therapy and he continues to be followed in our psoriasis clinic. One year after clearance of the treated psoriatic plaques, the corresponding terminal hairs persist.

Contact immunotherapy, most commonly with diphenylcyclopropenone or SADBE, is reported to have a 50% to 60% success rate in extensive AA, with a broad range of 9% to 87%17; however, randomized controlled trials testing the efficacy of contact immunotherapy are lacking. Although the mechanism of action of these topical sensitizers is not clearly delineated, it has been postulated that by inducing a new type of inflammatory response in the region, the immunologic milieu is changed, allowing the hair to grow. Some proposed mechanisms include promoting perifollicular lymphocyte apoptosis, preventing new recruitment of autoreactive lymphocytes, and allowing for the correction of aberrant major histocompatibility complex expression on the hair matrix epithelium to regain follicle immune privilege.18-20

Iatrogenic immunotherapy may work analogously to the natural immune system deviation demonstrated in our patient. Psoriasis and AA are believed to form competing immune cells and cytokine milieus, thus explaining how an individual with AA could regain normal hair growth in areas of psoriasis.15,16 The Renbök phenomenon, or reverse Köbner phenomenon, coined by Happle et al13 can be used to describe both the iatrogenic and natural cases of dermatologic disease improvement in response to secondary insults.14

A complex cascade of immune cells and cytokines coordinate AA pathogenesis. In the acute stage of AA, an inflammatory infiltrate of CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, and antigen-presenting cells target anagen phase follicles, with a higher CD4+:CD8+ ratio in clinically active disease.21-23 Subcutaneous injections of either CD4+ or CD8+ lymphocyte subsets from mice with AA into normal-haired mice induces disease. However, CD8+ T cell injections rapidly produce apparent hair loss, whereas CD4+ T cells cause hair loss after several weeks, suggesting that CD8+ T cells directly modulate AA hair loss and CD4+ T cells act as an aide.24 The growth, differentiation, and survival of CD8+ T cells are stimulated by IL-2 and IFN-γ. Alopecia areata biopsies demonstrate a prevalence of TH1 cytokines, and patients with localized AA, alopecia totalis, and AU have notably higher serum IFN-γ levels compared to controls.25 In murine models, IL-1α and IL-1β increase during the catagen phase of the hair cycle and peak during the telogen phase.26 Excessive IL-1β expression is detected in the early stages of human disease, and certain IL-1β polymorphisms are associated with severe forms of AA.26 The role of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α in AA is not well understood. In vitro studies show it inhibits hair growth, suggesting the cytokine may play a role in AA.27 However, anti–TNF-α therapy is not effective in AA, and case reports propose these therapies rarely induce AA.28-31

The TH1 response is likewise critical to psoriatic plaque development. IFN-γ and TNF-α are overexpressed in psoriatic plaques.32 IFN-γ has an antiproliferative and differentiation-inducing effect on normal keratinocytes, but psoriatic epithelial cells in vitro respond differently to the cytokine with a notably diminished growth inhibition.33,34 One explanation for the role of IFN-γ is that it stimulates dendritic cells to produce IL-1 and IL-23.35 IL-23 activates TH17 cells36; TH1 and TH17 conditions produce IL-22 whose serum level correlates with disease severity.37-39 IL-22 induces keratinocyte proliferation and migration and inhibits keratinocyte differentiation, helping account for hallmarks of the disease.40 Patients with psoriasis have increased levels of TH1, TH17, and TH22 cells, as well as their associated cytokines, in the skin and blood compared to controls.4,11,32,39,41

Alopecia areata and psoriasis are regulated by complex and still not entirely understood immune interactions. The fact that many of the same therapies are used to treat both diseases emphasizes both their overlapping characteristics and the lack of targeted therapy. It is unclear if and how the topical or systemic therapies used in our patient to treat one disease affected the natural history of the other condition. It is important to highlight, however, that the patient had not been treated for months when he developed the psoriatic plaques with hair regrowth. Other case reports also document hair regrowth in untreated plaques,13,16 making it unlikely to be a side effect of the medication regimen. For both psoriasis and AA, the immune cell composition and cytokine levels in the skin or serum vary throughout a patient’s disease course depending on severity of disease or response to treatment.6,39,42,43 Therefore, we hypothesize that the 2 conditions interact in a similarly distinct manner based on each disease’s stage and intensity in the patient. Both our patient’s course thus far and the various presentations described by other groups support this hypothesis. Our patient had a small region of psoriasis on the scalp that cleared without any terminal hair growth. He also had larger plaques on the forearms that developed hair growth most predominantly within the thicker regions of the plaques. His unique presentation highlights the fluidity of the immune factors driving psoriasis vulgaris and AA.

- Safavi K. Prevalence of alopecia areata in the First National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Arch Dermatol. 1992;128:702.

- Safavi KH, Muller SA, Suman VJ, et al. Incidence of alopecia areata in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1975 through 1989. Mayo Clin Proc. 1995;70:628-633.

- Wolff K, Johnson RA. Fitzpatrick’s Color Atlas and Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology. 6th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009.

- Austin LM, Ozawa M, Kikuchi T, et al. The majority of epidermal T cells in psoriasis vulgaris lesions can produce type 1 cytokines, interferon-gamma, interleukin-2, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha, defining TC1 (cytotoxic T lymphocyte) and TH1 effector populations: a type 1 differentiation bias is also measured in circulating blood T cells in psoriatic patients. J Invest Dermatol. 1999;113:752-759.

- Ghoreishi M, Martinka M, Dutz JP. Type 1 interferon signature in the scalp lesions of alopecia areata. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:57-62.

- Rossi A, Cantisani C, Carlesimo M, et al. Serum concentrations of IL-2, IL-6, IL-12 and TNF-α in patients with alopecia areata. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2012;25:781-788.

- Freyschmidt-Paul P, McElwee KJ, Hoffmann R, et al. Interferon-gamma-deficient mice are resistant to the development of alopecia areata. Br J Dermatol. 2006;155:515-521.

- Reich K, Garbe C, Blaschke V, et al. Response of psoriasis to interleukin-10 is associated with suppression of cutaneous type 1 inflammation, downregulation of the epidermal interleukin-8/CXCR2 pathway and normalization of keratinocyte maturation. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;116:319-329.

- Teunissen MB, Koomen CW, de Waal Malefyt R, et al. Interleukin-17 and interferon-gamma synergize in the enhancement of proinflammatory cytokine production by human keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 1998;111:645-649.

- Zheng Y, Danilenko DM, Valdez P, et al. Interleukin-22, a T(H)17 cytokine, mediates IL-23-induced dermal inflammation and acanthosis. Nature. 2007;445:648-651.

- Boniface K, Guignouard E, Pedretti N, et al. A role for T cell-derived interleukin 22 in psoriatic skin inflammation. Clin Exp Immunol. 2007;150:407-415.

- Zaba LC, Suárez-Fariñas M, Fuentes-Duculan J, et al. Effective treatment of psoriasis with etanercept is linked to suppression of IL-17 signaling, not immediate response TNF genes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124:1022-1030.e395.

- Happle R, van der Steen PHM, Perret CM. The Renbök phenomenon: an inverse Köebner reaction observed in alopecia areata. Eur J Dermatol. 1991;2:39-40.

- Ito T, Hashizume H, Takigawa M. Contact immunotherapy-induced Renbök phenomenon in a patient with alopecia areata and psoriasis vulgaris. Eur J Dermatol. 2010;20:126-127.

- Criado PR, Valente NY, Michalany NS, et al. An unusual association between scalp psoriasis and ophiasic alopecia areata: the Renbök phenomenon. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2007;32:320-321.

- Harris JE, Seykora JT, Lee RA. Renbök phenomenon and contact sensitization in a patient with alopecia universalis. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:422-425.

- Alkhalifah A. Topical and intralesional therapies for alopecia areata. Dermatol Ther. 2011;24:355-363.

- Herbst V, Zöller M, Kissling S, et al. Diphenylcyclopropenone treatment of alopecia areata induces apoptosis of perifollicular lymphocytes. Eur J Dermatol. 2006;16:537-542.

- Zöller M, Freyschmidt-Paul P, Vitacolonna M, et al. Chronic delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction as a means to treat alopecia areata. Clin Exp Immunol. 2004;135:398-408.

- Bröcker EB, Echternacht-Happle K, Hamm H, et al. Abnormal expression of class I and class II major histocompatibility antigens in alopecia areata: modulation by topical immunotherapy. J Invest Dermatol. 1987;88:564-568.

- Todes-Taylor N, Turner R, Wood GS, et al. T cell subpopulations in alopecia areata. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;11:216-223.

- Perret C, Wiesner-Menzel L, Happle R. Immunohistochemical analysis of T-cell subsets in the peribulbar and intrabulbar infiltrates of alopecia areata. Acta Derm Venereol. 1984;64:26-30.

- Wiesner-Menzel L, Happle R. Intrabulbar and peribulbar accumulation of dendritic OKT 6-positive cells in alopecia areata. Arch Dermatol Res. 1984;276:333-334.

- McElwee KJ, Freyschmidt-Paul P, Hoffmann R, et al. Transfer of CD8+ cells induces localized hair loss whereas CD4+/CD25– cells promote systemic alopecia areata and CD4+/CD25+ cells blockade disease onset in the C3H/HeJ mouse model. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;124:947-957.

- Arca E, Muşabak U, Akar A, et al. Interferon-gamma in alopecia areata. Eur J Dermatol. 2004;14:33-36.

- Hoffmann R. The potential role of cytokines and T cells in alopecia areata. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 1999;4:235-238.

- Philpott MP, Sanders DA, Bowen J, et al. Effects of interleukins, colony-stimulating factor and tumour necrosis factor on human hair follicle growth in vitro: a possible role for interleukin-1 and tumour necrosis factor-alpha in alopecia areata. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:942-948.

- Le Bidre E, Chaby G, Martin L, et al. Alopecia areata during anti-TNF alpha therapy: nine cases. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2011;138:285-293.

- Ferran M, Calvet J, Almirall M, et al. Alopecia areata as another immune-mediated disease developed in patients treated with tumour necrosis factor-α blocker agents: report of five cases and review of the literature. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:479-484.

- Pan Y, Rao NA. Alopecia areata during etanercept therapy. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2009;17:127-129.

- Pelivani N, Hassan AS, Braathen LR, et al. Alopecia areata universalis elicited during treatment with adalimumab. Dermatology. 2008;216:320-323.

- Uyemura K, Yamamura M, Fivenson DF, et al. The cytokine network in lesional and lesion-free psoriatic skin is characterized by a T-helper type 1 cell-mediated response. J Invest Dermatol. 1993;101:701-705.

- Baker BS, Powles AV, Valdimarsson H, et al. An altered response by psoriatic keratinocytes to gamma interferon. Scan J Immunol. 1988;28:735-740.

- Jackson M, Howie SE, Weller R, et al. Psoriatic keratinocytes show reduced IRF-1 and STAT-1alpha activation in response to gamma-IFN. FASEB J. 1999;13:495-502.

- Perera GK, Di Meglio P, Nestle FO. Psoriasis. Annu Rev Pathol. 2012;7:385-422.

- McGeachy MJ, Chen Y, Tato CM, et al. The interleukin 23 receptor is essential for the terminal differentiation of interleukin 17-producing effector T helper cells in vivo. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:314-324.

- Volpe E, Servant N, Zollinger R, et al. A critical function for transforming growth factor-beta, interleukin 23 and proinflammatory cytokines in driving and modulating human T(H)-17 responses. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:650-657.

- Boniface K, Blumenschein WM, Brovont-Porth K, et al. Human Th17 cells comprise heterogeneous subsets including IFN-gamma-producing cells with distinct properties from the Th1 lineage. J Immunol. 2010;185:679-687.

- Kagami S, Rizzo HL, Lee JJ, et al. Circulating Th17, Th22, and Th1 cells are increased in psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol. 2010;130:1373-1383.

- Boniface K, Bernard FX, Garcia M, et al. IL-22 inhibits epidermal differentiation and induces proinflammatory gene expression and migration of human keratinocytes. J Immunol. 2005;174:3695-3702.

- Harper EG, Guo C, Rizzo H, et al. Th17 cytokines stimulate CCL20 expression in keratinocytes in vitro and in vivo: implications for psoriasis pathogenesis. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:2175-2183.

- Bowcock AM, Krueger JG. Getting under the skin: the immunogenetics of psoriasis. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:699-711.

- Hoffmann R, Wenzel E, Huth A, et al. Cytokine mRNA levels in alopecia areata before and after treatment with the contact allergen diphenylcyclopropenone. J Invest Dermatol. 1994;103:530-533.

To the Editor:

Both alopecia areata (AA) and psoriasis vulgaris are chronic relapsing autoimmune diseases, with AA causing nonscarring hair loss in approximately 0.1% to 0.2%1 of the population with a lifetime risk of 1.7%,2 and psoriasis more broadly impacting 1.5% to 2% of the population.3 The helper T cell (TH1) cytokine milieu is pathogenic in both conditions.4-6 IFN-γ knockout mice, unlike their wild-type counterparts, do not exhibit AA.7 Psoriasis is notably improved by IL-10 injections, which dampen the TH1 response.8 Distinct from AA, TH17 and TH22 cells have been implicated as key players in psoriasis pathogenesis, along with the associated IL-17 and IL-22 cytokines.9-12

Few cases of patients with concurrent AA and psoriasis have been described. Interestingly, these cases document normal hair regrowth in the areas of psoriasis.13-16 These cases may offer unique insight into the immune factors driving each disease. We describe a case of a man with both alopecia universalis (AU) and psoriasis who developed hair regrowth in some of the psoriatic plaques.

A 34-year-old man with concurrent AU and psoriasis who had not used any systemic or topical medication for either condition in the last year presented to our clinic seeking treatment. The patient had a history of alopecia totalis as a toddler that completely resolved by 4 years of age with the use of squaric acid dibutylester (SADBE). At 31 years of age, the alopecia recurred and was localized to the scalp. It was partially responsive to intralesional triamcinolone acetonide. The patient’s alopecia worsened over the 2 years following recurrence, ultimately progressing to AU. Two months after the alopecia recurrence, he developed the first psoriatic plaques. As the plaque psoriasis progressed, systemic therapy was initiated, first methotrexate and then etanercept. Shortly after developing AU, he lost his health insurance and discontinued all therapy. The patient’s psoriasis began to recur approximately 3 months after stopping etanercept. He was not using any other psoriasis medications. At that time, he noted terminal hair regrowth within some of the psoriatic plaques. No terminal hairs grew outside of the psoriatic plaques, and all regions with growth had previously been without hair for an extended period of time. The patient presented to our clinic approximately 1 year later. He had no other medical conditions and no relevant family history.

On initial physical examination, he had nonscarring hair loss involving nearly 100% of the body with psoriatic plaques on approximately 30% of the body surface area. Regions of terminal hair growth were confined to some but not all of the psoriatic plaques (Figure). Interestingly, the terminal hairs were primarily localized to the thickest central regions of the plaques. The patient’s psoriasis was treated with a combination of topical clobetasol and calcipotriene. In addition, he was started on tacrolimus ointment to the face and eyebrows for the AA. Maintenance of terminal hair within a region of topically treated psoriasis on the forearm persisted at the 2-month follow-up despite complete clearance of the corresponding psoriatic plaque. A small psoriatic plaque on the scalp cleared early with topical therapy without noticeable hair regrowth. The patient subsequently was started on contact immunotherapy with SADBE and intralesional triamcinolone acetonide for the scalp alopecia without satisfactory response. He decided to discontinue further attempts at treating the alopecia and requested to be restarted on etanercept therapy for recalcitrant psoriatic plaques. His psoriasis responded well to this therapy and he continues to be followed in our psoriasis clinic. One year after clearance of the treated psoriatic plaques, the corresponding terminal hairs persist.

Contact immunotherapy, most commonly with diphenylcyclopropenone or SADBE, is reported to have a 50% to 60% success rate in extensive AA, with a broad range of 9% to 87%17; however, randomized controlled trials testing the efficacy of contact immunotherapy are lacking. Although the mechanism of action of these topical sensitizers is not clearly delineated, it has been postulated that by inducing a new type of inflammatory response in the region, the immunologic milieu is changed, allowing the hair to grow. Some proposed mechanisms include promoting perifollicular lymphocyte apoptosis, preventing new recruitment of autoreactive lymphocytes, and allowing for the correction of aberrant major histocompatibility complex expression on the hair matrix epithelium to regain follicle immune privilege.18-20

Iatrogenic immunotherapy may work analogously to the natural immune system deviation demonstrated in our patient. Psoriasis and AA are believed to form competing immune cells and cytokine milieus, thus explaining how an individual with AA could regain normal hair growth in areas of psoriasis.15,16 The Renbök phenomenon, or reverse Köbner phenomenon, coined by Happle et al13 can be used to describe both the iatrogenic and natural cases of dermatologic disease improvement in response to secondary insults.14

A complex cascade of immune cells and cytokines coordinate AA pathogenesis. In the acute stage of AA, an inflammatory infiltrate of CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, and antigen-presenting cells target anagen phase follicles, with a higher CD4+:CD8+ ratio in clinically active disease.21-23 Subcutaneous injections of either CD4+ or CD8+ lymphocyte subsets from mice with AA into normal-haired mice induces disease. However, CD8+ T cell injections rapidly produce apparent hair loss, whereas CD4+ T cells cause hair loss after several weeks, suggesting that CD8+ T cells directly modulate AA hair loss and CD4+ T cells act as an aide.24 The growth, differentiation, and survival of CD8+ T cells are stimulated by IL-2 and IFN-γ. Alopecia areata biopsies demonstrate a prevalence of TH1 cytokines, and patients with localized AA, alopecia totalis, and AU have notably higher serum IFN-γ levels compared to controls.25 In murine models, IL-1α and IL-1β increase during the catagen phase of the hair cycle and peak during the telogen phase.26 Excessive IL-1β expression is detected in the early stages of human disease, and certain IL-1β polymorphisms are associated with severe forms of AA.26 The role of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α in AA is not well understood. In vitro studies show it inhibits hair growth, suggesting the cytokine may play a role in AA.27 However, anti–TNF-α therapy is not effective in AA, and case reports propose these therapies rarely induce AA.28-31

The TH1 response is likewise critical to psoriatic plaque development. IFN-γ and TNF-α are overexpressed in psoriatic plaques.32 IFN-γ has an antiproliferative and differentiation-inducing effect on normal keratinocytes, but psoriatic epithelial cells in vitro respond differently to the cytokine with a notably diminished growth inhibition.33,34 One explanation for the role of IFN-γ is that it stimulates dendritic cells to produce IL-1 and IL-23.35 IL-23 activates TH17 cells36; TH1 and TH17 conditions produce IL-22 whose serum level correlates with disease severity.37-39 IL-22 induces keratinocyte proliferation and migration and inhibits keratinocyte differentiation, helping account for hallmarks of the disease.40 Patients with psoriasis have increased levels of TH1, TH17, and TH22 cells, as well as their associated cytokines, in the skin and blood compared to controls.4,11,32,39,41

Alopecia areata and psoriasis are regulated by complex and still not entirely understood immune interactions. The fact that many of the same therapies are used to treat both diseases emphasizes both their overlapping characteristics and the lack of targeted therapy. It is unclear if and how the topical or systemic therapies used in our patient to treat one disease affected the natural history of the other condition. It is important to highlight, however, that the patient had not been treated for months when he developed the psoriatic plaques with hair regrowth. Other case reports also document hair regrowth in untreated plaques,13,16 making it unlikely to be a side effect of the medication regimen. For both psoriasis and AA, the immune cell composition and cytokine levels in the skin or serum vary throughout a patient’s disease course depending on severity of disease or response to treatment.6,39,42,43 Therefore, we hypothesize that the 2 conditions interact in a similarly distinct manner based on each disease’s stage and intensity in the patient. Both our patient’s course thus far and the various presentations described by other groups support this hypothesis. Our patient had a small region of psoriasis on the scalp that cleared without any terminal hair growth. He also had larger plaques on the forearms that developed hair growth most predominantly within the thicker regions of the plaques. His unique presentation highlights the fluidity of the immune factors driving psoriasis vulgaris and AA.

To the Editor:

Both alopecia areata (AA) and psoriasis vulgaris are chronic relapsing autoimmune diseases, with AA causing nonscarring hair loss in approximately 0.1% to 0.2%1 of the population with a lifetime risk of 1.7%,2 and psoriasis more broadly impacting 1.5% to 2% of the population.3 The helper T cell (TH1) cytokine milieu is pathogenic in both conditions.4-6 IFN-γ knockout mice, unlike their wild-type counterparts, do not exhibit AA.7 Psoriasis is notably improved by IL-10 injections, which dampen the TH1 response.8 Distinct from AA, TH17 and TH22 cells have been implicated as key players in psoriasis pathogenesis, along with the associated IL-17 and IL-22 cytokines.9-12

Few cases of patients with concurrent AA and psoriasis have been described. Interestingly, these cases document normal hair regrowth in the areas of psoriasis.13-16 These cases may offer unique insight into the immune factors driving each disease. We describe a case of a man with both alopecia universalis (AU) and psoriasis who developed hair regrowth in some of the psoriatic plaques.

A 34-year-old man with concurrent AU and psoriasis who had not used any systemic or topical medication for either condition in the last year presented to our clinic seeking treatment. The patient had a history of alopecia totalis as a toddler that completely resolved by 4 years of age with the use of squaric acid dibutylester (SADBE). At 31 years of age, the alopecia recurred and was localized to the scalp. It was partially responsive to intralesional triamcinolone acetonide. The patient’s alopecia worsened over the 2 years following recurrence, ultimately progressing to AU. Two months after the alopecia recurrence, he developed the first psoriatic plaques. As the plaque psoriasis progressed, systemic therapy was initiated, first methotrexate and then etanercept. Shortly after developing AU, he lost his health insurance and discontinued all therapy. The patient’s psoriasis began to recur approximately 3 months after stopping etanercept. He was not using any other psoriasis medications. At that time, he noted terminal hair regrowth within some of the psoriatic plaques. No terminal hairs grew outside of the psoriatic plaques, and all regions with growth had previously been without hair for an extended period of time. The patient presented to our clinic approximately 1 year later. He had no other medical conditions and no relevant family history.

On initial physical examination, he had nonscarring hair loss involving nearly 100% of the body with psoriatic plaques on approximately 30% of the body surface area. Regions of terminal hair growth were confined to some but not all of the psoriatic plaques (Figure). Interestingly, the terminal hairs were primarily localized to the thickest central regions of the plaques. The patient’s psoriasis was treated with a combination of topical clobetasol and calcipotriene. In addition, he was started on tacrolimus ointment to the face and eyebrows for the AA. Maintenance of terminal hair within a region of topically treated psoriasis on the forearm persisted at the 2-month follow-up despite complete clearance of the corresponding psoriatic plaque. A small psoriatic plaque on the scalp cleared early with topical therapy without noticeable hair regrowth. The patient subsequently was started on contact immunotherapy with SADBE and intralesional triamcinolone acetonide for the scalp alopecia without satisfactory response. He decided to discontinue further attempts at treating the alopecia and requested to be restarted on etanercept therapy for recalcitrant psoriatic plaques. His psoriasis responded well to this therapy and he continues to be followed in our psoriasis clinic. One year after clearance of the treated psoriatic plaques, the corresponding terminal hairs persist.

Contact immunotherapy, most commonly with diphenylcyclopropenone or SADBE, is reported to have a 50% to 60% success rate in extensive AA, with a broad range of 9% to 87%17; however, randomized controlled trials testing the efficacy of contact immunotherapy are lacking. Although the mechanism of action of these topical sensitizers is not clearly delineated, it has been postulated that by inducing a new type of inflammatory response in the region, the immunologic milieu is changed, allowing the hair to grow. Some proposed mechanisms include promoting perifollicular lymphocyte apoptosis, preventing new recruitment of autoreactive lymphocytes, and allowing for the correction of aberrant major histocompatibility complex expression on the hair matrix epithelium to regain follicle immune privilege.18-20

Iatrogenic immunotherapy may work analogously to the natural immune system deviation demonstrated in our patient. Psoriasis and AA are believed to form competing immune cells and cytokine milieus, thus explaining how an individual with AA could regain normal hair growth in areas of psoriasis.15,16 The Renbök phenomenon, or reverse Köbner phenomenon, coined by Happle et al13 can be used to describe both the iatrogenic and natural cases of dermatologic disease improvement in response to secondary insults.14

A complex cascade of immune cells and cytokines coordinate AA pathogenesis. In the acute stage of AA, an inflammatory infiltrate of CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, and antigen-presenting cells target anagen phase follicles, with a higher CD4+:CD8+ ratio in clinically active disease.21-23 Subcutaneous injections of either CD4+ or CD8+ lymphocyte subsets from mice with AA into normal-haired mice induces disease. However, CD8+ T cell injections rapidly produce apparent hair loss, whereas CD4+ T cells cause hair loss after several weeks, suggesting that CD8+ T cells directly modulate AA hair loss and CD4+ T cells act as an aide.24 The growth, differentiation, and survival of CD8+ T cells are stimulated by IL-2 and IFN-γ. Alopecia areata biopsies demonstrate a prevalence of TH1 cytokines, and patients with localized AA, alopecia totalis, and AU have notably higher serum IFN-γ levels compared to controls.25 In murine models, IL-1α and IL-1β increase during the catagen phase of the hair cycle and peak during the telogen phase.26 Excessive IL-1β expression is detected in the early stages of human disease, and certain IL-1β polymorphisms are associated with severe forms of AA.26 The role of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α in AA is not well understood. In vitro studies show it inhibits hair growth, suggesting the cytokine may play a role in AA.27 However, anti–TNF-α therapy is not effective in AA, and case reports propose these therapies rarely induce AA.28-31

The TH1 response is likewise critical to psoriatic plaque development. IFN-γ and TNF-α are overexpressed in psoriatic plaques.32 IFN-γ has an antiproliferative and differentiation-inducing effect on normal keratinocytes, but psoriatic epithelial cells in vitro respond differently to the cytokine with a notably diminished growth inhibition.33,34 One explanation for the role of IFN-γ is that it stimulates dendritic cells to produce IL-1 and IL-23.35 IL-23 activates TH17 cells36; TH1 and TH17 conditions produce IL-22 whose serum level correlates with disease severity.37-39 IL-22 induces keratinocyte proliferation and migration and inhibits keratinocyte differentiation, helping account for hallmarks of the disease.40 Patients with psoriasis have increased levels of TH1, TH17, and TH22 cells, as well as their associated cytokines, in the skin and blood compared to controls.4,11,32,39,41

Alopecia areata and psoriasis are regulated by complex and still not entirely understood immune interactions. The fact that many of the same therapies are used to treat both diseases emphasizes both their overlapping characteristics and the lack of targeted therapy. It is unclear if and how the topical or systemic therapies used in our patient to treat one disease affected the natural history of the other condition. It is important to highlight, however, that the patient had not been treated for months when he developed the psoriatic plaques with hair regrowth. Other case reports also document hair regrowth in untreated plaques,13,16 making it unlikely to be a side effect of the medication regimen. For both psoriasis and AA, the immune cell composition and cytokine levels in the skin or serum vary throughout a patient’s disease course depending on severity of disease or response to treatment.6,39,42,43 Therefore, we hypothesize that the 2 conditions interact in a similarly distinct manner based on each disease’s stage and intensity in the patient. Both our patient’s course thus far and the various presentations described by other groups support this hypothesis. Our patient had a small region of psoriasis on the scalp that cleared without any terminal hair growth. He also had larger plaques on the forearms that developed hair growth most predominantly within the thicker regions of the plaques. His unique presentation highlights the fluidity of the immune factors driving psoriasis vulgaris and AA.

- Safavi K. Prevalence of alopecia areata in the First National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Arch Dermatol. 1992;128:702.

- Safavi KH, Muller SA, Suman VJ, et al. Incidence of alopecia areata in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1975 through 1989. Mayo Clin Proc. 1995;70:628-633.

- Wolff K, Johnson RA. Fitzpatrick’s Color Atlas and Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology. 6th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009.

- Austin LM, Ozawa M, Kikuchi T, et al. The majority of epidermal T cells in psoriasis vulgaris lesions can produce type 1 cytokines, interferon-gamma, interleukin-2, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha, defining TC1 (cytotoxic T lymphocyte) and TH1 effector populations: a type 1 differentiation bias is also measured in circulating blood T cells in psoriatic patients. J Invest Dermatol. 1999;113:752-759.

- Ghoreishi M, Martinka M, Dutz JP. Type 1 interferon signature in the scalp lesions of alopecia areata. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:57-62.

- Rossi A, Cantisani C, Carlesimo M, et al. Serum concentrations of IL-2, IL-6, IL-12 and TNF-α in patients with alopecia areata. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2012;25:781-788.

- Freyschmidt-Paul P, McElwee KJ, Hoffmann R, et al. Interferon-gamma-deficient mice are resistant to the development of alopecia areata. Br J Dermatol. 2006;155:515-521.

- Reich K, Garbe C, Blaschke V, et al. Response of psoriasis to interleukin-10 is associated with suppression of cutaneous type 1 inflammation, downregulation of the epidermal interleukin-8/CXCR2 pathway and normalization of keratinocyte maturation. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;116:319-329.

- Teunissen MB, Koomen CW, de Waal Malefyt R, et al. Interleukin-17 and interferon-gamma synergize in the enhancement of proinflammatory cytokine production by human keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 1998;111:645-649.

- Zheng Y, Danilenko DM, Valdez P, et al. Interleukin-22, a T(H)17 cytokine, mediates IL-23-induced dermal inflammation and acanthosis. Nature. 2007;445:648-651.

- Boniface K, Guignouard E, Pedretti N, et al. A role for T cell-derived interleukin 22 in psoriatic skin inflammation. Clin Exp Immunol. 2007;150:407-415.

- Zaba LC, Suárez-Fariñas M, Fuentes-Duculan J, et al. Effective treatment of psoriasis with etanercept is linked to suppression of IL-17 signaling, not immediate response TNF genes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124:1022-1030.e395.

- Happle R, van der Steen PHM, Perret CM. The Renbök phenomenon: an inverse Köebner reaction observed in alopecia areata. Eur J Dermatol. 1991;2:39-40.

- Ito T, Hashizume H, Takigawa M. Contact immunotherapy-induced Renbök phenomenon in a patient with alopecia areata and psoriasis vulgaris. Eur J Dermatol. 2010;20:126-127.

- Criado PR, Valente NY, Michalany NS, et al. An unusual association between scalp psoriasis and ophiasic alopecia areata: the Renbök phenomenon. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2007;32:320-321.

- Harris JE, Seykora JT, Lee RA. Renbök phenomenon and contact sensitization in a patient with alopecia universalis. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:422-425.

- Alkhalifah A. Topical and intralesional therapies for alopecia areata. Dermatol Ther. 2011;24:355-363.

- Herbst V, Zöller M, Kissling S, et al. Diphenylcyclopropenone treatment of alopecia areata induces apoptosis of perifollicular lymphocytes. Eur J Dermatol. 2006;16:537-542.

- Zöller M, Freyschmidt-Paul P, Vitacolonna M, et al. Chronic delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction as a means to treat alopecia areata. Clin Exp Immunol. 2004;135:398-408.

- Bröcker EB, Echternacht-Happle K, Hamm H, et al. Abnormal expression of class I and class II major histocompatibility antigens in alopecia areata: modulation by topical immunotherapy. J Invest Dermatol. 1987;88:564-568.

- Todes-Taylor N, Turner R, Wood GS, et al. T cell subpopulations in alopecia areata. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;11:216-223.

- Perret C, Wiesner-Menzel L, Happle R. Immunohistochemical analysis of T-cell subsets in the peribulbar and intrabulbar infiltrates of alopecia areata. Acta Derm Venereol. 1984;64:26-30.

- Wiesner-Menzel L, Happle R. Intrabulbar and peribulbar accumulation of dendritic OKT 6-positive cells in alopecia areata. Arch Dermatol Res. 1984;276:333-334.

- McElwee KJ, Freyschmidt-Paul P, Hoffmann R, et al. Transfer of CD8+ cells induces localized hair loss whereas CD4+/CD25– cells promote systemic alopecia areata and CD4+/CD25+ cells blockade disease onset in the C3H/HeJ mouse model. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;124:947-957.

- Arca E, Muşabak U, Akar A, et al. Interferon-gamma in alopecia areata. Eur J Dermatol. 2004;14:33-36.

- Hoffmann R. The potential role of cytokines and T cells in alopecia areata. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 1999;4:235-238.

- Philpott MP, Sanders DA, Bowen J, et al. Effects of interleukins, colony-stimulating factor and tumour necrosis factor on human hair follicle growth in vitro: a possible role for interleukin-1 and tumour necrosis factor-alpha in alopecia areata. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:942-948.

- Le Bidre E, Chaby G, Martin L, et al. Alopecia areata during anti-TNF alpha therapy: nine cases. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2011;138:285-293.

- Ferran M, Calvet J, Almirall M, et al. Alopecia areata as another immune-mediated disease developed in patients treated with tumour necrosis factor-α blocker agents: report of five cases and review of the literature. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:479-484.

- Pan Y, Rao NA. Alopecia areata during etanercept therapy. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2009;17:127-129.

- Pelivani N, Hassan AS, Braathen LR, et al. Alopecia areata universalis elicited during treatment with adalimumab. Dermatology. 2008;216:320-323.

- Uyemura K, Yamamura M, Fivenson DF, et al. The cytokine network in lesional and lesion-free psoriatic skin is characterized by a T-helper type 1 cell-mediated response. J Invest Dermatol. 1993;101:701-705.

- Baker BS, Powles AV, Valdimarsson H, et al. An altered response by psoriatic keratinocytes to gamma interferon. Scan J Immunol. 1988;28:735-740.

- Jackson M, Howie SE, Weller R, et al. Psoriatic keratinocytes show reduced IRF-1 and STAT-1alpha activation in response to gamma-IFN. FASEB J. 1999;13:495-502.

- Perera GK, Di Meglio P, Nestle FO. Psoriasis. Annu Rev Pathol. 2012;7:385-422.

- McGeachy MJ, Chen Y, Tato CM, et al. The interleukin 23 receptor is essential for the terminal differentiation of interleukin 17-producing effector T helper cells in vivo. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:314-324.

- Volpe E, Servant N, Zollinger R, et al. A critical function for transforming growth factor-beta, interleukin 23 and proinflammatory cytokines in driving and modulating human T(H)-17 responses. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:650-657.

- Boniface K, Blumenschein WM, Brovont-Porth K, et al. Human Th17 cells comprise heterogeneous subsets including IFN-gamma-producing cells with distinct properties from the Th1 lineage. J Immunol. 2010;185:679-687.

- Kagami S, Rizzo HL, Lee JJ, et al. Circulating Th17, Th22, and Th1 cells are increased in psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol. 2010;130:1373-1383.

- Boniface K, Bernard FX, Garcia M, et al. IL-22 inhibits epidermal differentiation and induces proinflammatory gene expression and migration of human keratinocytes. J Immunol. 2005;174:3695-3702.

- Harper EG, Guo C, Rizzo H, et al. Th17 cytokines stimulate CCL20 expression in keratinocytes in vitro and in vivo: implications for psoriasis pathogenesis. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:2175-2183.

- Bowcock AM, Krueger JG. Getting under the skin: the immunogenetics of psoriasis. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:699-711.

- Hoffmann R, Wenzel E, Huth A, et al. Cytokine mRNA levels in alopecia areata before and after treatment with the contact allergen diphenylcyclopropenone. J Invest Dermatol. 1994;103:530-533.

- Safavi K. Prevalence of alopecia areata in the First National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Arch Dermatol. 1992;128:702.

- Safavi KH, Muller SA, Suman VJ, et al. Incidence of alopecia areata in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1975 through 1989. Mayo Clin Proc. 1995;70:628-633.

- Wolff K, Johnson RA. Fitzpatrick’s Color Atlas and Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology. 6th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009.

- Austin LM, Ozawa M, Kikuchi T, et al. The majority of epidermal T cells in psoriasis vulgaris lesions can produce type 1 cytokines, interferon-gamma, interleukin-2, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha, defining TC1 (cytotoxic T lymphocyte) and TH1 effector populations: a type 1 differentiation bias is also measured in circulating blood T cells in psoriatic patients. J Invest Dermatol. 1999;113:752-759.

- Ghoreishi M, Martinka M, Dutz JP. Type 1 interferon signature in the scalp lesions of alopecia areata. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:57-62.

- Rossi A, Cantisani C, Carlesimo M, et al. Serum concentrations of IL-2, IL-6, IL-12 and TNF-α in patients with alopecia areata. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2012;25:781-788.

- Freyschmidt-Paul P, McElwee KJ, Hoffmann R, et al. Interferon-gamma-deficient mice are resistant to the development of alopecia areata. Br J Dermatol. 2006;155:515-521.

- Reich K, Garbe C, Blaschke V, et al. Response of psoriasis to interleukin-10 is associated with suppression of cutaneous type 1 inflammation, downregulation of the epidermal interleukin-8/CXCR2 pathway and normalization of keratinocyte maturation. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;116:319-329.

- Teunissen MB, Koomen CW, de Waal Malefyt R, et al. Interleukin-17 and interferon-gamma synergize in the enhancement of proinflammatory cytokine production by human keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 1998;111:645-649.

- Zheng Y, Danilenko DM, Valdez P, et al. Interleukin-22, a T(H)17 cytokine, mediates IL-23-induced dermal inflammation and acanthosis. Nature. 2007;445:648-651.

- Boniface K, Guignouard E, Pedretti N, et al. A role for T cell-derived interleukin 22 in psoriatic skin inflammation. Clin Exp Immunol. 2007;150:407-415.

- Zaba LC, Suárez-Fariñas M, Fuentes-Duculan J, et al. Effective treatment of psoriasis with etanercept is linked to suppression of IL-17 signaling, not immediate response TNF genes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124:1022-1030.e395.

- Happle R, van der Steen PHM, Perret CM. The Renbök phenomenon: an inverse Köebner reaction observed in alopecia areata. Eur J Dermatol. 1991;2:39-40.

- Ito T, Hashizume H, Takigawa M. Contact immunotherapy-induced Renbök phenomenon in a patient with alopecia areata and psoriasis vulgaris. Eur J Dermatol. 2010;20:126-127.

- Criado PR, Valente NY, Michalany NS, et al. An unusual association between scalp psoriasis and ophiasic alopecia areata: the Renbök phenomenon. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2007;32:320-321.

- Harris JE, Seykora JT, Lee RA. Renbök phenomenon and contact sensitization in a patient with alopecia universalis. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:422-425.

- Alkhalifah A. Topical and intralesional therapies for alopecia areata. Dermatol Ther. 2011;24:355-363.

- Herbst V, Zöller M, Kissling S, et al. Diphenylcyclopropenone treatment of alopecia areata induces apoptosis of perifollicular lymphocytes. Eur J Dermatol. 2006;16:537-542.

- Zöller M, Freyschmidt-Paul P, Vitacolonna M, et al. Chronic delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction as a means to treat alopecia areata. Clin Exp Immunol. 2004;135:398-408.

- Bröcker EB, Echternacht-Happle K, Hamm H, et al. Abnormal expression of class I and class II major histocompatibility antigens in alopecia areata: modulation by topical immunotherapy. J Invest Dermatol. 1987;88:564-568.

- Todes-Taylor N, Turner R, Wood GS, et al. T cell subpopulations in alopecia areata. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;11:216-223.

- Perret C, Wiesner-Menzel L, Happle R. Immunohistochemical analysis of T-cell subsets in the peribulbar and intrabulbar infiltrates of alopecia areata. Acta Derm Venereol. 1984;64:26-30.

- Wiesner-Menzel L, Happle R. Intrabulbar and peribulbar accumulation of dendritic OKT 6-positive cells in alopecia areata. Arch Dermatol Res. 1984;276:333-334.

- McElwee KJ, Freyschmidt-Paul P, Hoffmann R, et al. Transfer of CD8+ cells induces localized hair loss whereas CD4+/CD25– cells promote systemic alopecia areata and CD4+/CD25+ cells blockade disease onset in the C3H/HeJ mouse model. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;124:947-957.

- Arca E, Muşabak U, Akar A, et al. Interferon-gamma in alopecia areata. Eur J Dermatol. 2004;14:33-36.

- Hoffmann R. The potential role of cytokines and T cells in alopecia areata. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 1999;4:235-238.

- Philpott MP, Sanders DA, Bowen J, et al. Effects of interleukins, colony-stimulating factor and tumour necrosis factor on human hair follicle growth in vitro: a possible role for interleukin-1 and tumour necrosis factor-alpha in alopecia areata. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:942-948.

- Le Bidre E, Chaby G, Martin L, et al. Alopecia areata during anti-TNF alpha therapy: nine cases. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2011;138:285-293.

- Ferran M, Calvet J, Almirall M, et al. Alopecia areata as another immune-mediated disease developed in patients treated with tumour necrosis factor-α blocker agents: report of five cases and review of the literature. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:479-484.

- Pan Y, Rao NA. Alopecia areata during etanercept therapy. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2009;17:127-129.

- Pelivani N, Hassan AS, Braathen LR, et al. Alopecia areata universalis elicited during treatment with adalimumab. Dermatology. 2008;216:320-323.

- Uyemura K, Yamamura M, Fivenson DF, et al. The cytokine network in lesional and lesion-free psoriatic skin is characterized by a T-helper type 1 cell-mediated response. J Invest Dermatol. 1993;101:701-705.

- Baker BS, Powles AV, Valdimarsson H, et al. An altered response by psoriatic keratinocytes to gamma interferon. Scan J Immunol. 1988;28:735-740.

- Jackson M, Howie SE, Weller R, et al. Psoriatic keratinocytes show reduced IRF-1 and STAT-1alpha activation in response to gamma-IFN. FASEB J. 1999;13:495-502.

- Perera GK, Di Meglio P, Nestle FO. Psoriasis. Annu Rev Pathol. 2012;7:385-422.

- McGeachy MJ, Chen Y, Tato CM, et al. The interleukin 23 receptor is essential for the terminal differentiation of interleukin 17-producing effector T helper cells in vivo. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:314-324.

- Volpe E, Servant N, Zollinger R, et al. A critical function for transforming growth factor-beta, interleukin 23 and proinflammatory cytokines in driving and modulating human T(H)-17 responses. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:650-657.

- Boniface K, Blumenschein WM, Brovont-Porth K, et al. Human Th17 cells comprise heterogeneous subsets including IFN-gamma-producing cells with distinct properties from the Th1 lineage. J Immunol. 2010;185:679-687.

- Kagami S, Rizzo HL, Lee JJ, et al. Circulating Th17, Th22, and Th1 cells are increased in psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol. 2010;130:1373-1383.

- Boniface K, Bernard FX, Garcia M, et al. IL-22 inhibits epidermal differentiation and induces proinflammatory gene expression and migration of human keratinocytes. J Immunol. 2005;174:3695-3702.

- Harper EG, Guo C, Rizzo H, et al. Th17 cytokines stimulate CCL20 expression in keratinocytes in vitro and in vivo: implications for psoriasis pathogenesis. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:2175-2183.

- Bowcock AM, Krueger JG. Getting under the skin: the immunogenetics of psoriasis. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:699-711.

- Hoffmann R, Wenzel E, Huth A, et al. Cytokine mRNA levels in alopecia areata before and after treatment with the contact allergen diphenylcyclopropenone. J Invest Dermatol. 1994;103:530-533.

Practice Points

- The Renbök phenomenon, or reverse Köbner phenomenon, describes cases where secondary insults improve dermatologic disease.

- Current evidence suggests that alopecia areata (AA) is driven by a helper T cell (TH1) response whereas psoriasis vulgaris is driven by TH1, TH17, and TH22.

- Patients with concurrent AA and psoriasis can develop normal hair regrowth confined to the psoriatic plaques. Developing methods to artificially alter the cytokine milieu in affected skin may lead to new therapeutic options for each condition.

Beyond Residency: No more black and white

The obstetrics and gynecology written board exam made everything seem cut and dry. A patient with fibroids causing heavy bleeding? Management options include hormone treatment, minor surgical procedures, or major surgical procedures like myomectomy or hysterectomy. A pregnant patient in labor with a fetal heart rate deceleration? The next step is to shut off the oxytocin infusion, turn the patient on her left side, administer intravenous fluids, and give her oxygen via a nasal cannula. A patient who has ruptured her membranes at 28 weeks? That’s an easy one: magnesium for neuroprotection, latency antibiotics, prenatal steroids, neonatalogy consult. Straightforward.

At the end of June, I was grateful for my residency experience – even though some of it seemed hectic and haphazard – because it ensured that I understood the reasoning behind these multiple-choice questions. But then I started my maternal-fetal medicine fellowship this past July. I was learning the names of new residents, attendings, and nurses, and having to orient myself to an entirely different hospital system. Even labor and delivery board sign-out was completely different. I reassured myself by thinking: Obstetrics is obstetrics. The rules and guidelines of obstetrics are universal, practiced at every level, and always make sense, right?

One day I had a patient come in with chronic, refractory immune thrombocytopenia. Her plan for delivery was induction at 37 weeks after our hematology colleagues used medications we had never heard of to finally get her platelets into the 100s. But upon admission, her platelets were down to the 70s. I wondered, should we induce anyway because her platelets are likely to drop even further if we wait? Or do we give her the slew of medications that didn’t completely work initially as a last-ditch effort to boost her platelets again before delivery? I looked at practice bulletins, hematology guidelines, and numerous other publications and still I could not find a protocol for this specific kind of patient. After discussion with anesthesiologists, hematologists, maternal-fetal medicine specialists, labor and delivery nurses, and the patient herself, we came up with a plan. We gave her additional doses of thrombopoietic agents and steroids and continued to monitor her platelet count. Within a week, she had an uncomplicated vaginal delivery with an epidural.*

Taking a lead role in the decision-making process and organizing a management plan made me feel like I was the quarterback of a football team, with a healthy mother and baby substituting for a game-winning touchdown. The decisions we make in maternal-fetal medicine are not supposed to be easy. However, I’ve heard over and over that when our colleagues ask for our input, the guidance they want to hear is “deliver” or “don’t deliver.” Over the last several months, I’ve learned that there is so much more to it than that. I now examine the entire patient and fetus in two ways: as one physiologically inseparable unit, and as two patients, weighing the neonatal risks of delivery against the maternal risks of the pregnancy itself. Determining an appropriate time for delivery is just part of it.

There are also the questions about antepartum fetal testing. Should we do additional monitoring for patients with isolated polyhydramnios? What about patients who are at advanced maternal age? What about patients whose fetuses have “decreased growth velocity” but not growth restriction? Should these patients get umbilical artery Dopplers, too? ACOG and the SMFM often do not give us specific monitoring guidelines, which forces us to make a plan based on each individual clinical scenario.

In other words, we must practice in that ever-changing, ever-frustrating, and confusing gray area. I hope in fellowship I learn to not only navigate through this area effectively, but to one day confidently hold out my hand to others to help guide them through it, too.

Dr. Grossman recently completed her residency in obstetrics and gynecology at Albert Einstein College of Medicine–Montefiore Hospital in the Bronx, N.Y., and is currently a first-year maternal-fetal medicine fellow at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York. She reported having no financial disclosures.

*This article was update April 21, 2107.

The obstetrics and gynecology written board exam made everything seem cut and dry. A patient with fibroids causing heavy bleeding? Management options include hormone treatment, minor surgical procedures, or major surgical procedures like myomectomy or hysterectomy. A pregnant patient in labor with a fetal heart rate deceleration? The next step is to shut off the oxytocin infusion, turn the patient on her left side, administer intravenous fluids, and give her oxygen via a nasal cannula. A patient who has ruptured her membranes at 28 weeks? That’s an easy one: magnesium for neuroprotection, latency antibiotics, prenatal steroids, neonatalogy consult. Straightforward.

At the end of June, I was grateful for my residency experience – even though some of it seemed hectic and haphazard – because it ensured that I understood the reasoning behind these multiple-choice questions. But then I started my maternal-fetal medicine fellowship this past July. I was learning the names of new residents, attendings, and nurses, and having to orient myself to an entirely different hospital system. Even labor and delivery board sign-out was completely different. I reassured myself by thinking: Obstetrics is obstetrics. The rules and guidelines of obstetrics are universal, practiced at every level, and always make sense, right?

One day I had a patient come in with chronic, refractory immune thrombocytopenia. Her plan for delivery was induction at 37 weeks after our hematology colleagues used medications we had never heard of to finally get her platelets into the 100s. But upon admission, her platelets were down to the 70s. I wondered, should we induce anyway because her platelets are likely to drop even further if we wait? Or do we give her the slew of medications that didn’t completely work initially as a last-ditch effort to boost her platelets again before delivery? I looked at practice bulletins, hematology guidelines, and numerous other publications and still I could not find a protocol for this specific kind of patient. After discussion with anesthesiologists, hematologists, maternal-fetal medicine specialists, labor and delivery nurses, and the patient herself, we came up with a plan. We gave her additional doses of thrombopoietic agents and steroids and continued to monitor her platelet count. Within a week, she had an uncomplicated vaginal delivery with an epidural.*

Taking a lead role in the decision-making process and organizing a management plan made me feel like I was the quarterback of a football team, with a healthy mother and baby substituting for a game-winning touchdown. The decisions we make in maternal-fetal medicine are not supposed to be easy. However, I’ve heard over and over that when our colleagues ask for our input, the guidance they want to hear is “deliver” or “don’t deliver.” Over the last several months, I’ve learned that there is so much more to it than that. I now examine the entire patient and fetus in two ways: as one physiologically inseparable unit, and as two patients, weighing the neonatal risks of delivery against the maternal risks of the pregnancy itself. Determining an appropriate time for delivery is just part of it.

There are also the questions about antepartum fetal testing. Should we do additional monitoring for patients with isolated polyhydramnios? What about patients who are at advanced maternal age? What about patients whose fetuses have “decreased growth velocity” but not growth restriction? Should these patients get umbilical artery Dopplers, too? ACOG and the SMFM often do not give us specific monitoring guidelines, which forces us to make a plan based on each individual clinical scenario.

In other words, we must practice in that ever-changing, ever-frustrating, and confusing gray area. I hope in fellowship I learn to not only navigate through this area effectively, but to one day confidently hold out my hand to others to help guide them through it, too.

Dr. Grossman recently completed her residency in obstetrics and gynecology at Albert Einstein College of Medicine–Montefiore Hospital in the Bronx, N.Y., and is currently a first-year maternal-fetal medicine fellow at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York. She reported having no financial disclosures.

*This article was update April 21, 2107.

The obstetrics and gynecology written board exam made everything seem cut and dry. A patient with fibroids causing heavy bleeding? Management options include hormone treatment, minor surgical procedures, or major surgical procedures like myomectomy or hysterectomy. A pregnant patient in labor with a fetal heart rate deceleration? The next step is to shut off the oxytocin infusion, turn the patient on her left side, administer intravenous fluids, and give her oxygen via a nasal cannula. A patient who has ruptured her membranes at 28 weeks? That’s an easy one: magnesium for neuroprotection, latency antibiotics, prenatal steroids, neonatalogy consult. Straightforward.

At the end of June, I was grateful for my residency experience – even though some of it seemed hectic and haphazard – because it ensured that I understood the reasoning behind these multiple-choice questions. But then I started my maternal-fetal medicine fellowship this past July. I was learning the names of new residents, attendings, and nurses, and having to orient myself to an entirely different hospital system. Even labor and delivery board sign-out was completely different. I reassured myself by thinking: Obstetrics is obstetrics. The rules and guidelines of obstetrics are universal, practiced at every level, and always make sense, right?

One day I had a patient come in with chronic, refractory immune thrombocytopenia. Her plan for delivery was induction at 37 weeks after our hematology colleagues used medications we had never heard of to finally get her platelets into the 100s. But upon admission, her platelets were down to the 70s. I wondered, should we induce anyway because her platelets are likely to drop even further if we wait? Or do we give her the slew of medications that didn’t completely work initially as a last-ditch effort to boost her platelets again before delivery? I looked at practice bulletins, hematology guidelines, and numerous other publications and still I could not find a protocol for this specific kind of patient. After discussion with anesthesiologists, hematologists, maternal-fetal medicine specialists, labor and delivery nurses, and the patient herself, we came up with a plan. We gave her additional doses of thrombopoietic agents and steroids and continued to monitor her platelet count. Within a week, she had an uncomplicated vaginal delivery with an epidural.*

Taking a lead role in the decision-making process and organizing a management plan made me feel like I was the quarterback of a football team, with a healthy mother and baby substituting for a game-winning touchdown. The decisions we make in maternal-fetal medicine are not supposed to be easy. However, I’ve heard over and over that when our colleagues ask for our input, the guidance they want to hear is “deliver” or “don’t deliver.” Over the last several months, I’ve learned that there is so much more to it than that. I now examine the entire patient and fetus in two ways: as one physiologically inseparable unit, and as two patients, weighing the neonatal risks of delivery against the maternal risks of the pregnancy itself. Determining an appropriate time for delivery is just part of it.

There are also the questions about antepartum fetal testing. Should we do additional monitoring for patients with isolated polyhydramnios? What about patients who are at advanced maternal age? What about patients whose fetuses have “decreased growth velocity” but not growth restriction? Should these patients get umbilical artery Dopplers, too? ACOG and the SMFM often do not give us specific monitoring guidelines, which forces us to make a plan based on each individual clinical scenario.

In other words, we must practice in that ever-changing, ever-frustrating, and confusing gray area. I hope in fellowship I learn to not only navigate through this area effectively, but to one day confidently hold out my hand to others to help guide them through it, too.

Dr. Grossman recently completed her residency in obstetrics and gynecology at Albert Einstein College of Medicine–Montefiore Hospital in the Bronx, N.Y., and is currently a first-year maternal-fetal medicine fellow at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York. She reported having no financial disclosures.

*This article was update April 21, 2107.

AGA tools help GIs manage patients with obesity

Patients with obesity need a multidisciplinary approach to achieve a healthy weight. AGA understands the importance of embracing obesity as a chronic, relapsing disease and supports a multidisciplinary approach to the management of obesity led by gastroenterologists.

To watch

AGA Solutions to Successful Obesity Program Integration: Andres Acosta, MD, PhD, assistant professor in medicine, clinical enteric neuroscience translational and epidemiological research, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, and Sarah Streett, MD, AGAF, clinical associate professor and director of IBD, Stanford (Calif.) University, discuss the AGA Obesity Guide and how GIs can begin to implement the program in their practices. Watch the on-demand webinar in the AGA Community resource library.

To read

POWER: Practice Guide on Obesity and Weight Management, Education and Resources: This practice guide on obesity and weight management will help you develop a multidisciplinary team and obesity care model for your practice.

Episode-of-Care Framework for the Management of Obesity: Moving toward high-value, high-quality care – AGA established an obesity episode-of-care model to develop a framework to support value-based management of patients with obesity, focusing on the provision of nonsurgical and endoscopic services.

These resources are available at www.gastro.org/obesity.

To discuss

Visit the AGA Community to join the discussion on managing your patient with obesity.

Patients with obesity need a multidisciplinary approach to achieve a healthy weight. AGA understands the importance of embracing obesity as a chronic, relapsing disease and supports a multidisciplinary approach to the management of obesity led by gastroenterologists.

To watch

AGA Solutions to Successful Obesity Program Integration: Andres Acosta, MD, PhD, assistant professor in medicine, clinical enteric neuroscience translational and epidemiological research, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, and Sarah Streett, MD, AGAF, clinical associate professor and director of IBD, Stanford (Calif.) University, discuss the AGA Obesity Guide and how GIs can begin to implement the program in their practices. Watch the on-demand webinar in the AGA Community resource library.

To read

POWER: Practice Guide on Obesity and Weight Management, Education and Resources: This practice guide on obesity and weight management will help you develop a multidisciplinary team and obesity care model for your practice.

Episode-of-Care Framework for the Management of Obesity: Moving toward high-value, high-quality care – AGA established an obesity episode-of-care model to develop a framework to support value-based management of patients with obesity, focusing on the provision of nonsurgical and endoscopic services.

These resources are available at www.gastro.org/obesity.

To discuss

Visit the AGA Community to join the discussion on managing your patient with obesity.

Patients with obesity need a multidisciplinary approach to achieve a healthy weight. AGA understands the importance of embracing obesity as a chronic, relapsing disease and supports a multidisciplinary approach to the management of obesity led by gastroenterologists.

To watch

AGA Solutions to Successful Obesity Program Integration: Andres Acosta, MD, PhD, assistant professor in medicine, clinical enteric neuroscience translational and epidemiological research, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, and Sarah Streett, MD, AGAF, clinical associate professor and director of IBD, Stanford (Calif.) University, discuss the AGA Obesity Guide and how GIs can begin to implement the program in their practices. Watch the on-demand webinar in the AGA Community resource library.

To read

POWER: Practice Guide on Obesity and Weight Management, Education and Resources: This practice guide on obesity and weight management will help you develop a multidisciplinary team and obesity care model for your practice.

Episode-of-Care Framework for the Management of Obesity: Moving toward high-value, high-quality care – AGA established an obesity episode-of-care model to develop a framework to support value-based management of patients with obesity, focusing on the provision of nonsurgical and endoscopic services.

These resources are available at www.gastro.org/obesity.

To discuss

Visit the AGA Community to join the discussion on managing your patient with obesity.

DTC genetic health risk tests: Beware

The Food and Drug Administration recently authorized 23andMe to provide consumers with results of germline DNA sequence variants associated with risk for 10 health conditions, among them hereditary hemochromatosis, alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency, celiac disease, Alzheimer’s disease, and Parkinson’s disease. After they submit a saliva sample and pay a test fee, customers ordering the online test will receive a report delineating their ancestry markers and informing them whether they carry any of the genetic variants associated with selected health risks included on the targeted DNA sequencing panel.

As more consumers partake in “recreational genomic testing,” clinicians should understand the limitations of DTC genetic tests and should be prepared to discuss with patients why these should not supersede clinical diagnostic evaluations.

Dr. Stoffel is a gastroenterologist, assistant professor of internal medicine, and director of the cancer genetics clinic at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. She has no disclosures.

The Food and Drug Administration recently authorized 23andMe to provide consumers with results of germline DNA sequence variants associated with risk for 10 health conditions, among them hereditary hemochromatosis, alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency, celiac disease, Alzheimer’s disease, and Parkinson’s disease. After they submit a saliva sample and pay a test fee, customers ordering the online test will receive a report delineating their ancestry markers and informing them whether they carry any of the genetic variants associated with selected health risks included on the targeted DNA sequencing panel.

As more consumers partake in “recreational genomic testing,” clinicians should understand the limitations of DTC genetic tests and should be prepared to discuss with patients why these should not supersede clinical diagnostic evaluations.

Dr. Stoffel is a gastroenterologist, assistant professor of internal medicine, and director of the cancer genetics clinic at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. She has no disclosures.

The Food and Drug Administration recently authorized 23andMe to provide consumers with results of germline DNA sequence variants associated with risk for 10 health conditions, among them hereditary hemochromatosis, alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency, celiac disease, Alzheimer’s disease, and Parkinson’s disease. After they submit a saliva sample and pay a test fee, customers ordering the online test will receive a report delineating their ancestry markers and informing them whether they carry any of the genetic variants associated with selected health risks included on the targeted DNA sequencing panel.

As more consumers partake in “recreational genomic testing,” clinicians should understand the limitations of DTC genetic tests and should be prepared to discuss with patients why these should not supersede clinical diagnostic evaluations.

Dr. Stoffel is a gastroenterologist, assistant professor of internal medicine, and director of the cancer genetics clinic at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. She has no disclosures.

Revaccinate HIV-infected teens with hepatitis B vaccine

Consider revaccinating all perinatally HIV-infected adolescents who did not initiate highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) at the time of initial infant hepatitis B virus (HBV) vaccination, with a three-dose HBV schedule, recommended researchers at Mahidol University, Bangkok, in a recent study.

In a prospective study from March 2012 to March 2014 ultimately involving 162 perinatally HIV-infected adolescents with immune reconstitution, only 3.6% were receiving HAART at the time of initial infant HBV vaccination and 96.3% had undetectable antihepatitis B surface antibodies (anti-HBs) at baseline. Adolescents with breakthrough HBV infection had been excluded from the cohort.

In a multivariate analysis, there was no independent factor that was associated with the presence of immune memory defined as anti-HBs greater than or equal to 100 mIU/mL, wrote lead researcher Keswadee Lapphra, MD, and her associates.

In a previous study, 71% of three-dose revaccinated persons retained protective antibodies against HBV at 3-year follow-up; this was a similar rate to that reported in healthy HIV-infected children after their infant primary HBV series (Vaccine. 2011 May 23;29[23]:3977-81), they said.

Read more at (Ped Inf Dis J. 2017. doi: 10.1097/inf.0000000000001613).

Consider revaccinating all perinatally HIV-infected adolescents who did not initiate highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) at the time of initial infant hepatitis B virus (HBV) vaccination, with a three-dose HBV schedule, recommended researchers at Mahidol University, Bangkok, in a recent study.

In a prospective study from March 2012 to March 2014 ultimately involving 162 perinatally HIV-infected adolescents with immune reconstitution, only 3.6% were receiving HAART at the time of initial infant HBV vaccination and 96.3% had undetectable antihepatitis B surface antibodies (anti-HBs) at baseline. Adolescents with breakthrough HBV infection had been excluded from the cohort.

In a multivariate analysis, there was no independent factor that was associated with the presence of immune memory defined as anti-HBs greater than or equal to 100 mIU/mL, wrote lead researcher Keswadee Lapphra, MD, and her associates.

In a previous study, 71% of three-dose revaccinated persons retained protective antibodies against HBV at 3-year follow-up; this was a similar rate to that reported in healthy HIV-infected children after their infant primary HBV series (Vaccine. 2011 May 23;29[23]:3977-81), they said.

Read more at (Ped Inf Dis J. 2017. doi: 10.1097/inf.0000000000001613).

Consider revaccinating all perinatally HIV-infected adolescents who did not initiate highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) at the time of initial infant hepatitis B virus (HBV) vaccination, with a three-dose HBV schedule, recommended researchers at Mahidol University, Bangkok, in a recent study.

In a prospective study from March 2012 to March 2014 ultimately involving 162 perinatally HIV-infected adolescents with immune reconstitution, only 3.6% were receiving HAART at the time of initial infant HBV vaccination and 96.3% had undetectable antihepatitis B surface antibodies (anti-HBs) at baseline. Adolescents with breakthrough HBV infection had been excluded from the cohort.

In a multivariate analysis, there was no independent factor that was associated with the presence of immune memory defined as anti-HBs greater than or equal to 100 mIU/mL, wrote lead researcher Keswadee Lapphra, MD, and her associates.

In a previous study, 71% of three-dose revaccinated persons retained protective antibodies against HBV at 3-year follow-up; this was a similar rate to that reported in healthy HIV-infected children after their infant primary HBV series (Vaccine. 2011 May 23;29[23]:3977-81), they said.

Read more at (Ped Inf Dis J. 2017. doi: 10.1097/inf.0000000000001613).

FROM THE PEDIATRIC INFECTIOUS DISEASE JOURNAL

ASBS annual meeting to explore treatment controversies

ACS Surgery News will be in Las Vegas this week at the annual meeting of the American Society of Breast Surgeons reporting on the latest in multidisciplinary management of benign and not-so-benign breast disease. Our reporters will cover controversies in neoadjuvant therapy, including managing axilla and skipping surgery with biopsy proven pathological complete response (pCR), as well as the use of axillary ultrasound on a clinically negative axilla, and what to do for in situ carcinoma and borderline cases. Coverage will also include the latest updates in high-risk and genetic predisposition, breast cancer subtypes, lymphedema, and recurrent and metastatic breast cancer, and guidance for coding and reimbursement.

Highly anticipated presentations include:

• Many Women are Choosing Unnecessarily Radical Surgeries for Early-Stage Cancer

• Debunking the Myth of Lymphedema Risk

• Aggressive Inflammatory Breast Cancer Treatment Yields Low Local/Regional Recurrence

Our team will provide daily coverage, beginning Thursday, April 27.

ACS Surgery News will be in Las Vegas this week at the annual meeting of the American Society of Breast Surgeons reporting on the latest in multidisciplinary management of benign and not-so-benign breast disease. Our reporters will cover controversies in neoadjuvant therapy, including managing axilla and skipping surgery with biopsy proven pathological complete response (pCR), as well as the use of axillary ultrasound on a clinically negative axilla, and what to do for in situ carcinoma and borderline cases. Coverage will also include the latest updates in high-risk and genetic predisposition, breast cancer subtypes, lymphedema, and recurrent and metastatic breast cancer, and guidance for coding and reimbursement.

Highly anticipated presentations include:

• Many Women are Choosing Unnecessarily Radical Surgeries for Early-Stage Cancer

• Debunking the Myth of Lymphedema Risk

• Aggressive Inflammatory Breast Cancer Treatment Yields Low Local/Regional Recurrence

Our team will provide daily coverage, beginning Thursday, April 27.

ACS Surgery News will be in Las Vegas this week at the annual meeting of the American Society of Breast Surgeons reporting on the latest in multidisciplinary management of benign and not-so-benign breast disease. Our reporters will cover controversies in neoadjuvant therapy, including managing axilla and skipping surgery with biopsy proven pathological complete response (pCR), as well as the use of axillary ultrasound on a clinically negative axilla, and what to do for in situ carcinoma and borderline cases. Coverage will also include the latest updates in high-risk and genetic predisposition, breast cancer subtypes, lymphedema, and recurrent and metastatic breast cancer, and guidance for coding and reimbursement.

Highly anticipated presentations include:

• Many Women are Choosing Unnecessarily Radical Surgeries for Early-Stage Cancer

• Debunking the Myth of Lymphedema Risk

• Aggressive Inflammatory Breast Cancer Treatment Yields Low Local/Regional Recurrence