User login

Allo-HSCT cures adult with congenital dyserythropoietic anemia

Physicians have reported what they believe is the first case of an allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (allo-HSCT) curing an adult with congenital dyserythropoietic anemia (CDA).

The patient, David Levy, was previously transfusion-dependent and suffered from iron overload, severe pain, and other adverse effects of his illness.

Levy was denied a transplant for years, but, in 2014, he received a non-myeloablative allo-HSCT from a matched, unrelated donor.

Now, Levy no longer requires transfusions, iron chelation, or immunosuppression, and says he is able to live a normal life.

Damiano Rondelli, MD, of the University of Illinois at Chicago, and his colleagues described Levy’s case in a letter to Bone Marrow Transplantation.

Levy was diagnosed with CDA at 4 months of age and was treated with regular blood transfusions for most of his life. He was 24 when the pain from his illness became so severe that he had to withdraw from graduate school.

“I spent the following years doing nothing—no work, no school, no social contact—because all I could focus on was managing my pain and getting my health back on track,” Levy said.

By age 32, Levy required transfusions every 2 to 3 weeks, had undergone a splenectomy, had an enlarged liver, and was suffering from fatigue, heart palpitations, and iron overload.

“It was bad,” Levy said. “I had been through enough pain. I was angry and depressed, and I wanted a cure. That’s why I started emailing Dr Rondelli.”

Dr Rondelli said that because of Levy’s range of illnesses and inability to tolerate chemotherapy and radiation, several institutions had denied him the possibility of a transplant.

However, Dr Rondelli and his colleagues had reported success with chemotherapy-free allo-HSCT in patients with sickle cell disease. So Dr Rondelli performed Levy’s transplant in 2014.

Levy received a peripheral blood stem cell transplant from an unrelated donor who was a 10/10 HLA match but ABO incompatible. He received conditioning with rabbit anti-thymocyte globulin, fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and total body irradiation.

Levy also received graft-vs-host disease (GVHD) prophylaxis consisting of high-dose cyclophosphamide, mycophenolate mofetil, and sirolimus. And he received standard antibacterial, antifungal, antiviral, and anti-Pneumocystis jiroveci prophylaxis.

Levy experienced platelet engraftment on day 20 and neutrophil engraftment on day 21. Whole-blood donor-cell chimerism was 98.7% on day 30 and 100% on day 60 and beyond.

Levy did develop transient hemolytic anemia due to the ABO incompatibility. He was given a total of 10 units of packed red blood cells until day 78.

Levy was tapered off all immunosuppression at 12 months and has shown no signs of acute or chronic GVHD.

At 24 months after HSCT, Levy’s hemoglobin was 13.7 g/dL, and his ferritin was 376 ng/mL. He has had no iron chelation since the transplant.

“The transplant was hard, and I had some complications, but I am back to normal now,” said Levy, who is now 35.

“I still have some pain and some lingering issues from the years my condition was not properly managed, but I can be independent now. That is the most important thing to me.”

Levy is finishing his doctorate in psychology and running group therapy sessions at a behavioral health hospital.

Dr Rondelli said the potential of this treatment approach is promising.

“The use of this transplant protocol may represent a safe therapeutic strategy to treat adult patients with many types of congenital anemias—perhaps the only possible cure,” he said.

“For many adult patients with a blood disorder, treatment options have been limited because they are often not sick enough to qualify for a risky procedure, or they are too sick to tolerate the toxic drugs used alongside a standard transplant. This procedure gives some adults the option of a stem cell transplant, which was not previously available.” ![]()

Physicians have reported what they believe is the first case of an allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (allo-HSCT) curing an adult with congenital dyserythropoietic anemia (CDA).

The patient, David Levy, was previously transfusion-dependent and suffered from iron overload, severe pain, and other adverse effects of his illness.

Levy was denied a transplant for years, but, in 2014, he received a non-myeloablative allo-HSCT from a matched, unrelated donor.

Now, Levy no longer requires transfusions, iron chelation, or immunosuppression, and says he is able to live a normal life.

Damiano Rondelli, MD, of the University of Illinois at Chicago, and his colleagues described Levy’s case in a letter to Bone Marrow Transplantation.

Levy was diagnosed with CDA at 4 months of age and was treated with regular blood transfusions for most of his life. He was 24 when the pain from his illness became so severe that he had to withdraw from graduate school.

“I spent the following years doing nothing—no work, no school, no social contact—because all I could focus on was managing my pain and getting my health back on track,” Levy said.

By age 32, Levy required transfusions every 2 to 3 weeks, had undergone a splenectomy, had an enlarged liver, and was suffering from fatigue, heart palpitations, and iron overload.

“It was bad,” Levy said. “I had been through enough pain. I was angry and depressed, and I wanted a cure. That’s why I started emailing Dr Rondelli.”

Dr Rondelli said that because of Levy’s range of illnesses and inability to tolerate chemotherapy and radiation, several institutions had denied him the possibility of a transplant.

However, Dr Rondelli and his colleagues had reported success with chemotherapy-free allo-HSCT in patients with sickle cell disease. So Dr Rondelli performed Levy’s transplant in 2014.

Levy received a peripheral blood stem cell transplant from an unrelated donor who was a 10/10 HLA match but ABO incompatible. He received conditioning with rabbit anti-thymocyte globulin, fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and total body irradiation.

Levy also received graft-vs-host disease (GVHD) prophylaxis consisting of high-dose cyclophosphamide, mycophenolate mofetil, and sirolimus. And he received standard antibacterial, antifungal, antiviral, and anti-Pneumocystis jiroveci prophylaxis.

Levy experienced platelet engraftment on day 20 and neutrophil engraftment on day 21. Whole-blood donor-cell chimerism was 98.7% on day 30 and 100% on day 60 and beyond.

Levy did develop transient hemolytic anemia due to the ABO incompatibility. He was given a total of 10 units of packed red blood cells until day 78.

Levy was tapered off all immunosuppression at 12 months and has shown no signs of acute or chronic GVHD.

At 24 months after HSCT, Levy’s hemoglobin was 13.7 g/dL, and his ferritin was 376 ng/mL. He has had no iron chelation since the transplant.

“The transplant was hard, and I had some complications, but I am back to normal now,” said Levy, who is now 35.

“I still have some pain and some lingering issues from the years my condition was not properly managed, but I can be independent now. That is the most important thing to me.”

Levy is finishing his doctorate in psychology and running group therapy sessions at a behavioral health hospital.

Dr Rondelli said the potential of this treatment approach is promising.

“The use of this transplant protocol may represent a safe therapeutic strategy to treat adult patients with many types of congenital anemias—perhaps the only possible cure,” he said.

“For many adult patients with a blood disorder, treatment options have been limited because they are often not sick enough to qualify for a risky procedure, or they are too sick to tolerate the toxic drugs used alongside a standard transplant. This procedure gives some adults the option of a stem cell transplant, which was not previously available.” ![]()

Physicians have reported what they believe is the first case of an allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (allo-HSCT) curing an adult with congenital dyserythropoietic anemia (CDA).

The patient, David Levy, was previously transfusion-dependent and suffered from iron overload, severe pain, and other adverse effects of his illness.

Levy was denied a transplant for years, but, in 2014, he received a non-myeloablative allo-HSCT from a matched, unrelated donor.

Now, Levy no longer requires transfusions, iron chelation, or immunosuppression, and says he is able to live a normal life.

Damiano Rondelli, MD, of the University of Illinois at Chicago, and his colleagues described Levy’s case in a letter to Bone Marrow Transplantation.

Levy was diagnosed with CDA at 4 months of age and was treated with regular blood transfusions for most of his life. He was 24 when the pain from his illness became so severe that he had to withdraw from graduate school.

“I spent the following years doing nothing—no work, no school, no social contact—because all I could focus on was managing my pain and getting my health back on track,” Levy said.

By age 32, Levy required transfusions every 2 to 3 weeks, had undergone a splenectomy, had an enlarged liver, and was suffering from fatigue, heart palpitations, and iron overload.

“It was bad,” Levy said. “I had been through enough pain. I was angry and depressed, and I wanted a cure. That’s why I started emailing Dr Rondelli.”

Dr Rondelli said that because of Levy’s range of illnesses and inability to tolerate chemotherapy and radiation, several institutions had denied him the possibility of a transplant.

However, Dr Rondelli and his colleagues had reported success with chemotherapy-free allo-HSCT in patients with sickle cell disease. So Dr Rondelli performed Levy’s transplant in 2014.

Levy received a peripheral blood stem cell transplant from an unrelated donor who was a 10/10 HLA match but ABO incompatible. He received conditioning with rabbit anti-thymocyte globulin, fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and total body irradiation.

Levy also received graft-vs-host disease (GVHD) prophylaxis consisting of high-dose cyclophosphamide, mycophenolate mofetil, and sirolimus. And he received standard antibacterial, antifungal, antiviral, and anti-Pneumocystis jiroveci prophylaxis.

Levy experienced platelet engraftment on day 20 and neutrophil engraftment on day 21. Whole-blood donor-cell chimerism was 98.7% on day 30 and 100% on day 60 and beyond.

Levy did develop transient hemolytic anemia due to the ABO incompatibility. He was given a total of 10 units of packed red blood cells until day 78.

Levy was tapered off all immunosuppression at 12 months and has shown no signs of acute or chronic GVHD.

At 24 months after HSCT, Levy’s hemoglobin was 13.7 g/dL, and his ferritin was 376 ng/mL. He has had no iron chelation since the transplant.

“The transplant was hard, and I had some complications, but I am back to normal now,” said Levy, who is now 35.

“I still have some pain and some lingering issues from the years my condition was not properly managed, but I can be independent now. That is the most important thing to me.”

Levy is finishing his doctorate in psychology and running group therapy sessions at a behavioral health hospital.

Dr Rondelli said the potential of this treatment approach is promising.

“The use of this transplant protocol may represent a safe therapeutic strategy to treat adult patients with many types of congenital anemias—perhaps the only possible cure,” he said.

“For many adult patients with a blood disorder, treatment options have been limited because they are often not sick enough to qualify for a risky procedure, or they are too sick to tolerate the toxic drugs used alongside a standard transplant. This procedure gives some adults the option of a stem cell transplant, which was not previously available.” ![]()

New insight into high-hyperdiploid ALL

New research appears to explain how 10q21.2 influences the risk of high-hyperdiploid acute lymphoblastic leukemia (HD-ALL).

Previous research indicated that variation in the gene ARID5B at 10q21.2 is associated with HD-ALL.

Now, researchers have reported that the 10q21.2 risk locus for HD-ALL is mediated through the single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) rs7090445, which disrupts RUNX3 transcription factor binding.

Specifically, the rs7090445-C allele confers an increased risk of HD-ALL through reduced RUNX3-mediated expression of ARID5B.

The researchers described these findings in Nature Communications.

“This study expands our understanding of how genetic risk factors can influence the development of acute lymphoblastic leukemia . . .,” said study author Richard Houlston, MD, PhD, of The Institute of Cancer Research in London, UK.

Dr Houlston and his colleagues focused this research on 10q21.2 because it had previously been implicated in HD-ALL, but it wasn’t clear how the region affects the risk of HD-ALL.

The team said they found that a SNP in the region, rs7090445, is “highly associated” with HD-ALL.

Further investigation revealed that variation at rs7090445 disrupts RUNX3 binding and reduces the expression of ARID5B, as RUNX3 regulates ARID5B expression.

The researchers also discovered that the rs7090445-C risk allele, which is associated with reduced ARID5B expression, is amplified in HD-ALL. The risk allele is “preferentially retained” on additional copies of chromosome 10 in HD-ALL blasts.

“We implicate reduced expression of a gene called ARID5B in the production and release of the immature ‘blast’ cells that characterize [HD-ALL],” Dr Houlston said. “Our study gives a new insight into the causes of the disease and may open up new strategies for prevention.” ![]()

New research appears to explain how 10q21.2 influences the risk of high-hyperdiploid acute lymphoblastic leukemia (HD-ALL).

Previous research indicated that variation in the gene ARID5B at 10q21.2 is associated with HD-ALL.

Now, researchers have reported that the 10q21.2 risk locus for HD-ALL is mediated through the single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) rs7090445, which disrupts RUNX3 transcription factor binding.

Specifically, the rs7090445-C allele confers an increased risk of HD-ALL through reduced RUNX3-mediated expression of ARID5B.

The researchers described these findings in Nature Communications.

“This study expands our understanding of how genetic risk factors can influence the development of acute lymphoblastic leukemia . . .,” said study author Richard Houlston, MD, PhD, of The Institute of Cancer Research in London, UK.

Dr Houlston and his colleagues focused this research on 10q21.2 because it had previously been implicated in HD-ALL, but it wasn’t clear how the region affects the risk of HD-ALL.

The team said they found that a SNP in the region, rs7090445, is “highly associated” with HD-ALL.

Further investigation revealed that variation at rs7090445 disrupts RUNX3 binding and reduces the expression of ARID5B, as RUNX3 regulates ARID5B expression.

The researchers also discovered that the rs7090445-C risk allele, which is associated with reduced ARID5B expression, is amplified in HD-ALL. The risk allele is “preferentially retained” on additional copies of chromosome 10 in HD-ALL blasts.

“We implicate reduced expression of a gene called ARID5B in the production and release of the immature ‘blast’ cells that characterize [HD-ALL],” Dr Houlston said. “Our study gives a new insight into the causes of the disease and may open up new strategies for prevention.” ![]()

New research appears to explain how 10q21.2 influences the risk of high-hyperdiploid acute lymphoblastic leukemia (HD-ALL).

Previous research indicated that variation in the gene ARID5B at 10q21.2 is associated with HD-ALL.

Now, researchers have reported that the 10q21.2 risk locus for HD-ALL is mediated through the single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) rs7090445, which disrupts RUNX3 transcription factor binding.

Specifically, the rs7090445-C allele confers an increased risk of HD-ALL through reduced RUNX3-mediated expression of ARID5B.

The researchers described these findings in Nature Communications.

“This study expands our understanding of how genetic risk factors can influence the development of acute lymphoblastic leukemia . . .,” said study author Richard Houlston, MD, PhD, of The Institute of Cancer Research in London, UK.

Dr Houlston and his colleagues focused this research on 10q21.2 because it had previously been implicated in HD-ALL, but it wasn’t clear how the region affects the risk of HD-ALL.

The team said they found that a SNP in the region, rs7090445, is “highly associated” with HD-ALL.

Further investigation revealed that variation at rs7090445 disrupts RUNX3 binding and reduces the expression of ARID5B, as RUNX3 regulates ARID5B expression.

The researchers also discovered that the rs7090445-C risk allele, which is associated with reduced ARID5B expression, is amplified in HD-ALL. The risk allele is “preferentially retained” on additional copies of chromosome 10 in HD-ALL blasts.

“We implicate reduced expression of a gene called ARID5B in the production and release of the immature ‘blast’ cells that characterize [HD-ALL],” Dr Houlston said. “Our study gives a new insight into the causes of the disease and may open up new strategies for prevention.” ![]()

Suspecting Pituitary Disorders: “What's Next?”

Reinforcing mesh at ostomy site prevents parastomal hernia

For patients undergoing elective permanent colostomy, prophylactic augmentation of the abdominal wall using mesh at the ostomy site prevents the development of parastomal hernia, according to a report published in the April issue of Annals of Surgery.

The incidence of parastomal hernia is expected to rise because of the increasing number of cancer patients surviving with a colostomy, and the rising number of obese patients who have increased tension on the abdominal wall because of their elevated intra-abdominal pressure and larger abdominal radius. Researchers in the Netherlands performed a prospective randomized study, the PREVENT trial, to assess whether augmenting the abdominal wall at the ostomy site, using a lightweight mesh, would be safe, feasible, and effective at preventing parastomal hernia. They reported their findings after 1 year of follow-up; the study will continue until longer-term results are available at 5 years.

In the intervention group, a retromuscular space was created to accommodate the mesh by dissecting the muscle from the posterior fascia or peritoneum to the lateral border via a median laparotomy. An incision was made in the center of the mesh to allow passage of the colon, and the mesh was placed on the posterior rectus sheath and anchored laterally with two absorbable sutures. “On the medial side, the mesh was incorporated in the running suture closing the fascia, thus preventing contact between the mesh and the viscera,” the investigators said (Ann Surg. 2017;265:663-9).

The primary end point – the incidence of parastomal hernia at 1 year – occurred in 3 patients (4.5%) in the intervention group and 16 (24.2%) in the control group, a significant difference. There were no mesh-related complications such as infection, strictures, or adhesions. “The majority of the parastomal hernias that required surgical repair were in the control group, which supports the concept that if a hernia develops in a patient with mesh, it is smaller and less likely to cause complaints,” Dr. Brandsma and his associates said.

Significantly fewer patients in the mesh group (9%) than in the control group (21%) reported stoma-related complaints such as pain, leakage, and skin problems. Scores on measures of quality of life and pain severity were no different between the two study groups.

“Prophylactic augmentation of the abdominal wall with a retromuscular polypropylene mesh at the ostomy site is a safe and feasible procedure with no adverse events. It significantly reduces the incidence of parastomal hernia,” the investigators concluded.

This study was supported by Canisius Wilhelmina Hospital’s surgery research fund, the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development, and Covidien/Medtronic. Dr. Brandsma and his associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

For patients undergoing elective permanent colostomy, prophylactic augmentation of the abdominal wall using mesh at the ostomy site prevents the development of parastomal hernia, according to a report published in the April issue of Annals of Surgery.

The incidence of parastomal hernia is expected to rise because of the increasing number of cancer patients surviving with a colostomy, and the rising number of obese patients who have increased tension on the abdominal wall because of their elevated intra-abdominal pressure and larger abdominal radius. Researchers in the Netherlands performed a prospective randomized study, the PREVENT trial, to assess whether augmenting the abdominal wall at the ostomy site, using a lightweight mesh, would be safe, feasible, and effective at preventing parastomal hernia. They reported their findings after 1 year of follow-up; the study will continue until longer-term results are available at 5 years.

In the intervention group, a retromuscular space was created to accommodate the mesh by dissecting the muscle from the posterior fascia or peritoneum to the lateral border via a median laparotomy. An incision was made in the center of the mesh to allow passage of the colon, and the mesh was placed on the posterior rectus sheath and anchored laterally with two absorbable sutures. “On the medial side, the mesh was incorporated in the running suture closing the fascia, thus preventing contact between the mesh and the viscera,” the investigators said (Ann Surg. 2017;265:663-9).

The primary end point – the incidence of parastomal hernia at 1 year – occurred in 3 patients (4.5%) in the intervention group and 16 (24.2%) in the control group, a significant difference. There were no mesh-related complications such as infection, strictures, or adhesions. “The majority of the parastomal hernias that required surgical repair were in the control group, which supports the concept that if a hernia develops in a patient with mesh, it is smaller and less likely to cause complaints,” Dr. Brandsma and his associates said.

Significantly fewer patients in the mesh group (9%) than in the control group (21%) reported stoma-related complaints such as pain, leakage, and skin problems. Scores on measures of quality of life and pain severity were no different between the two study groups.

“Prophylactic augmentation of the abdominal wall with a retromuscular polypropylene mesh at the ostomy site is a safe and feasible procedure with no adverse events. It significantly reduces the incidence of parastomal hernia,” the investigators concluded.

This study was supported by Canisius Wilhelmina Hospital’s surgery research fund, the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development, and Covidien/Medtronic. Dr. Brandsma and his associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

For patients undergoing elective permanent colostomy, prophylactic augmentation of the abdominal wall using mesh at the ostomy site prevents the development of parastomal hernia, according to a report published in the April issue of Annals of Surgery.

The incidence of parastomal hernia is expected to rise because of the increasing number of cancer patients surviving with a colostomy, and the rising number of obese patients who have increased tension on the abdominal wall because of their elevated intra-abdominal pressure and larger abdominal radius. Researchers in the Netherlands performed a prospective randomized study, the PREVENT trial, to assess whether augmenting the abdominal wall at the ostomy site, using a lightweight mesh, would be safe, feasible, and effective at preventing parastomal hernia. They reported their findings after 1 year of follow-up; the study will continue until longer-term results are available at 5 years.

In the intervention group, a retromuscular space was created to accommodate the mesh by dissecting the muscle from the posterior fascia or peritoneum to the lateral border via a median laparotomy. An incision was made in the center of the mesh to allow passage of the colon, and the mesh was placed on the posterior rectus sheath and anchored laterally with two absorbable sutures. “On the medial side, the mesh was incorporated in the running suture closing the fascia, thus preventing contact between the mesh and the viscera,” the investigators said (Ann Surg. 2017;265:663-9).

The primary end point – the incidence of parastomal hernia at 1 year – occurred in 3 patients (4.5%) in the intervention group and 16 (24.2%) in the control group, a significant difference. There were no mesh-related complications such as infection, strictures, or adhesions. “The majority of the parastomal hernias that required surgical repair were in the control group, which supports the concept that if a hernia develops in a patient with mesh, it is smaller and less likely to cause complaints,” Dr. Brandsma and his associates said.

Significantly fewer patients in the mesh group (9%) than in the control group (21%) reported stoma-related complaints such as pain, leakage, and skin problems. Scores on measures of quality of life and pain severity were no different between the two study groups.

“Prophylactic augmentation of the abdominal wall with a retromuscular polypropylene mesh at the ostomy site is a safe and feasible procedure with no adverse events. It significantly reduces the incidence of parastomal hernia,” the investigators concluded.

This study was supported by Canisius Wilhelmina Hospital’s surgery research fund, the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development, and Covidien/Medtronic. Dr. Brandsma and his associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM THE ANNALS OF SURGERY

Key clinical point: For patients undergoing permanent colostomy, prophylactic augmentation of the abdominal wall using mesh at the ostomy site prevents the development of parastomal hernia.

Major finding: The primary end point – the incidence of parastomal hernia at 1 year – occurred in 3 patients (4.5%) in the intervention group and 16 (24.2%) in the control group.

Data source: A prospective, multicenter, randomized cohort study comparing prophylactic mesh against standard care in 133 adults undergoing elective end-colostomy during a 3-year period.

Disclosures: This study was supported by Canisius Wilhelmina Hospital’s surgery research fund, the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development, and Covidien/Medtronic. Dr. Brandsma and his associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Anti-TNF agents show clinical benefit in refractory sarcoidosis

FROM SEMINARS IN ARTHRITIS & RHEUMATISM

Around two-thirds of patients with severe or refractory sarcoidosis show a significant clinical response to tumor necrosis factor (TNF) antagonists, according to findings from a retrospective, multicenter cohort study.

Biologic agents targeting TNF, such as etanercept, infliximab, and adalimumab, have been introduced as a third-line option for patients with disease that is refractory to other treatments. However, Yvan Jamilloux, MD, of the Hospices Civils de Lyon (France) and his coauthors reported that there are still insufficient data available on efficacy and safety of these drugs in the context of sarcoidosis.

Dr. Jamilloux and his colleagues analyzed data from 132 sarcoidosis patients who received TNF antagonists, 122 (92%) of whom had severe sarcoidosis (Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2017 Mar 8. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2017.03.005).

Overall, 64% of patients showed clinical improvements in response to TNF antagonists; 18% had a complete response, and 46% had a partial response. However, 33 (25%) patients showed no change, and 14 (11%) had continued disease progression despite treatment with TNF antagonists. In another 16 patients who received a second TNF antagonist, 10 (63%) had a complete or partial clinical response. The investigators could find no differences in response between anti-TNF agents or between monotherapy and a combination with an immunosuppressant.

Pulmonary involvement was associated with a significantly lower clinical response, but none of the other factors examined in a multivariate analysis (sex, age, ethnicity, organ involvement, disease duration, steroid dosage, or prior immunosuppressant use) distinguished responders and nonresponders.

The authors noted that these response rates were lower than those seen in the literature and suggested this may be attributable to the multicenter design, more patients with longer-lasting and more refractory disease, and longer times under biologic therapy (median 12 months).

The researchers reported significant improvements in central nervous system, peripheral nervous system, heart, skin, and upper respiratory tract involvements based on declines in Extrapulmonary Physician Organ Severity Tool (ePOST) scores. There were also improvements in the eye, muscle, and lung, but these were not statistically significant.

TNF-antagonist therapy was associated with a high rate of adverse events. Around half of all patients (52%) experienced adverse events, such as pneumonia, urinary tract infections, bacterial sepsis, and herpes zoster. In 31 patients (23%), these led to treatment cessation.

Nine patients also had severe allergic reactions, four had paradoxical granulomatous reactions, three developed neutralizing antibodies against anti-TNF agents, two patients had demyelinating lesions, and one had a serum sickness-like reaction. All of these events led to discontinuation.

Overall, 128 (97%) of the patients in the study had received corticosteroids as first-line therapy, and 125 (95%) had received at least one second-line immunosuppressive drug over a median duration of 16 months. Most were treated with infliximab (91%) as the first-line TNF antagonist, followed by adalimumab (6%), etanercept (2%), and certolizumab pegol (1%).

Treatment with TNF antagonists was associated with significant reductions in corticosteroid use; the mean daily prednisone dose decreased from 23 mg/day to 11 mg/day over the median 20.5-month follow-up. This was seen even in the 33 patients who showed no change in their disease course after TNF-antagonist therapy.

No conflicts of interest were declared.

This uncontrolled, unblinded retrospective observational study reports the outcomes of anti-TNF therapy in a heterogenous group of refractory sarcoid patients, with only 12% of the severe sarcoidosis population studied having the indication for treatment based on lung involvement. Further, it is notable that the patients with primarily pulmonary involvement had a poorer response to anti-TNF therapy. Over half of the patients had an adverse event related to the treatment, with nearly a quarter having to discontinue therapy. Given the limitations of this type of study, the low numbers of pulmonary sarcoid patients included, the lack of an efficacy signal in pulmonary sarcoid, and the high rate of serious adverse events – the role of anti-TNF agents for pulmonary sarcoid remains unclear and limited. However

This uncontrolled, unblinded retrospective observational study reports the outcomes of anti-TNF therapy in a heterogenous group of refractory sarcoid patients, with only 12% of the severe sarcoidosis population studied having the indication for treatment based on lung involvement. Further, it is notable that the patients with primarily pulmonary involvement had a poorer response to anti-TNF therapy. Over half of the patients had an adverse event related to the treatment, with nearly a quarter having to discontinue therapy. Given the limitations of this type of study, the low numbers of pulmonary sarcoid patients included, the lack of an efficacy signal in pulmonary sarcoid, and the high rate of serious adverse events – the role of anti-TNF agents for pulmonary sarcoid remains unclear and limited. However

This uncontrolled, unblinded retrospective observational study reports the outcomes of anti-TNF therapy in a heterogenous group of refractory sarcoid patients, with only 12% of the severe sarcoidosis population studied having the indication for treatment based on lung involvement. Further, it is notable that the patients with primarily pulmonary involvement had a poorer response to anti-TNF therapy. Over half of the patients had an adverse event related to the treatment, with nearly a quarter having to discontinue therapy. Given the limitations of this type of study, the low numbers of pulmonary sarcoid patients included, the lack of an efficacy signal in pulmonary sarcoid, and the high rate of serious adverse events – the role of anti-TNF agents for pulmonary sarcoid remains unclear and limited. However

FROM SEMINARS IN ARTHRITIS & RHEUMATISM

Around two-thirds of patients with severe or refractory sarcoidosis show a significant clinical response to tumor necrosis factor (TNF) antagonists, according to findings from a retrospective, multicenter cohort study.

Biologic agents targeting TNF, such as etanercept, infliximab, and adalimumab, have been introduced as a third-line option for patients with disease that is refractory to other treatments. However, Yvan Jamilloux, MD, of the Hospices Civils de Lyon (France) and his coauthors reported that there are still insufficient data available on efficacy and safety of these drugs in the context of sarcoidosis.

Dr. Jamilloux and his colleagues analyzed data from 132 sarcoidosis patients who received TNF antagonists, 122 (92%) of whom had severe sarcoidosis (Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2017 Mar 8. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2017.03.005).

Overall, 64% of patients showed clinical improvements in response to TNF antagonists; 18% had a complete response, and 46% had a partial response. However, 33 (25%) patients showed no change, and 14 (11%) had continued disease progression despite treatment with TNF antagonists. In another 16 patients who received a second TNF antagonist, 10 (63%) had a complete or partial clinical response. The investigators could find no differences in response between anti-TNF agents or between monotherapy and a combination with an immunosuppressant.

Pulmonary involvement was associated with a significantly lower clinical response, but none of the other factors examined in a multivariate analysis (sex, age, ethnicity, organ involvement, disease duration, steroid dosage, or prior immunosuppressant use) distinguished responders and nonresponders.

The authors noted that these response rates were lower than those seen in the literature and suggested this may be attributable to the multicenter design, more patients with longer-lasting and more refractory disease, and longer times under biologic therapy (median 12 months).

The researchers reported significant improvements in central nervous system, peripheral nervous system, heart, skin, and upper respiratory tract involvements based on declines in Extrapulmonary Physician Organ Severity Tool (ePOST) scores. There were also improvements in the eye, muscle, and lung, but these were not statistically significant.

TNF-antagonist therapy was associated with a high rate of adverse events. Around half of all patients (52%) experienced adverse events, such as pneumonia, urinary tract infections, bacterial sepsis, and herpes zoster. In 31 patients (23%), these led to treatment cessation.

Nine patients also had severe allergic reactions, four had paradoxical granulomatous reactions, three developed neutralizing antibodies against anti-TNF agents, two patients had demyelinating lesions, and one had a serum sickness-like reaction. All of these events led to discontinuation.

Overall, 128 (97%) of the patients in the study had received corticosteroids as first-line therapy, and 125 (95%) had received at least one second-line immunosuppressive drug over a median duration of 16 months. Most were treated with infliximab (91%) as the first-line TNF antagonist, followed by adalimumab (6%), etanercept (2%), and certolizumab pegol (1%).

Treatment with TNF antagonists was associated with significant reductions in corticosteroid use; the mean daily prednisone dose decreased from 23 mg/day to 11 mg/day over the median 20.5-month follow-up. This was seen even in the 33 patients who showed no change in their disease course after TNF-antagonist therapy.

No conflicts of interest were declared.

FROM SEMINARS IN ARTHRITIS & RHEUMATISM

Around two-thirds of patients with severe or refractory sarcoidosis show a significant clinical response to tumor necrosis factor (TNF) antagonists, according to findings from a retrospective, multicenter cohort study.

Biologic agents targeting TNF, such as etanercept, infliximab, and adalimumab, have been introduced as a third-line option for patients with disease that is refractory to other treatments. However, Yvan Jamilloux, MD, of the Hospices Civils de Lyon (France) and his coauthors reported that there are still insufficient data available on efficacy and safety of these drugs in the context of sarcoidosis.

Dr. Jamilloux and his colleagues analyzed data from 132 sarcoidosis patients who received TNF antagonists, 122 (92%) of whom had severe sarcoidosis (Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2017 Mar 8. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2017.03.005).

Overall, 64% of patients showed clinical improvements in response to TNF antagonists; 18% had a complete response, and 46% had a partial response. However, 33 (25%) patients showed no change, and 14 (11%) had continued disease progression despite treatment with TNF antagonists. In another 16 patients who received a second TNF antagonist, 10 (63%) had a complete or partial clinical response. The investigators could find no differences in response between anti-TNF agents or between monotherapy and a combination with an immunosuppressant.

Pulmonary involvement was associated with a significantly lower clinical response, but none of the other factors examined in a multivariate analysis (sex, age, ethnicity, organ involvement, disease duration, steroid dosage, or prior immunosuppressant use) distinguished responders and nonresponders.

The authors noted that these response rates were lower than those seen in the literature and suggested this may be attributable to the multicenter design, more patients with longer-lasting and more refractory disease, and longer times under biologic therapy (median 12 months).

The researchers reported significant improvements in central nervous system, peripheral nervous system, heart, skin, and upper respiratory tract involvements based on declines in Extrapulmonary Physician Organ Severity Tool (ePOST) scores. There were also improvements in the eye, muscle, and lung, but these were not statistically significant.

TNF-antagonist therapy was associated with a high rate of adverse events. Around half of all patients (52%) experienced adverse events, such as pneumonia, urinary tract infections, bacterial sepsis, and herpes zoster. In 31 patients (23%), these led to treatment cessation.

Nine patients also had severe allergic reactions, four had paradoxical granulomatous reactions, three developed neutralizing antibodies against anti-TNF agents, two patients had demyelinating lesions, and one had a serum sickness-like reaction. All of these events led to discontinuation.

Overall, 128 (97%) of the patients in the study had received corticosteroids as first-line therapy, and 125 (95%) had received at least one second-line immunosuppressive drug over a median duration of 16 months. Most were treated with infliximab (91%) as the first-line TNF antagonist, followed by adalimumab (6%), etanercept (2%), and certolizumab pegol (1%).

Treatment with TNF antagonists was associated with significant reductions in corticosteroid use; the mean daily prednisone dose decreased from 23 mg/day to 11 mg/day over the median 20.5-month follow-up. This was seen even in the 33 patients who showed no change in their disease course after TNF-antagonist therapy.

No conflicts of interest were declared.

Key clinical point:

Major finding: A total of 18% had a complete response, and 46% had a partial response, to TNF antagonists.

Data source: A retrospective, multicenter study in 132 sarcoidosis patients who received TNF antagonists.

Disclosures: No conflicts of interest were declared.

HIV vaccine could prevent 30 million cases by 2035

Global cases of HIV from 2015 to 2035 would be reduced by over 50% if the Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS 95/95/95 target is met and a moderately effective HIV vaccine is introduced by 2020, according to new research published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

A custom model based on current rates of diagnosis and treatment in 127 countries predicts that a total of 49 million new cases of HIV would occur globally from 2015 to 2035, investigators said. Achieving the UNAIDS goal of 95% disease diagnosis, 95% antiretroviral coverage, and 95% viral suppression by 2030 would avert 25 million cases by 2035. Achieving the more modest 90/90/90 target would avert 22 million cases within the same time period.

“Recent results from the HVTN 100 vaccine trial have bolstered optimism for the development and deployment of an HIV vaccine in the near term,” the investigators said. “HIV vaccination would enable a strategic shift from reactive to proactive control, as suggested by our finding that an HIV vaccine with even moderate efficacy rolled out in 2020 could avert 17 million new infections by 2035 relative to expectations under status quo interventions.”

Find the full study in PNAS (doi: 10.1073/pnas.1620788114)

[email protected]

On Twitter @IDPractitioner

Global cases of HIV from 2015 to 2035 would be reduced by over 50% if the Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS 95/95/95 target is met and a moderately effective HIV vaccine is introduced by 2020, according to new research published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

A custom model based on current rates of diagnosis and treatment in 127 countries predicts that a total of 49 million new cases of HIV would occur globally from 2015 to 2035, investigators said. Achieving the UNAIDS goal of 95% disease diagnosis, 95% antiretroviral coverage, and 95% viral suppression by 2030 would avert 25 million cases by 2035. Achieving the more modest 90/90/90 target would avert 22 million cases within the same time period.

“Recent results from the HVTN 100 vaccine trial have bolstered optimism for the development and deployment of an HIV vaccine in the near term,” the investigators said. “HIV vaccination would enable a strategic shift from reactive to proactive control, as suggested by our finding that an HIV vaccine with even moderate efficacy rolled out in 2020 could avert 17 million new infections by 2035 relative to expectations under status quo interventions.”

Find the full study in PNAS (doi: 10.1073/pnas.1620788114)

[email protected]

On Twitter @IDPractitioner

Global cases of HIV from 2015 to 2035 would be reduced by over 50% if the Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS 95/95/95 target is met and a moderately effective HIV vaccine is introduced by 2020, according to new research published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

A custom model based on current rates of diagnosis and treatment in 127 countries predicts that a total of 49 million new cases of HIV would occur globally from 2015 to 2035, investigators said. Achieving the UNAIDS goal of 95% disease diagnosis, 95% antiretroviral coverage, and 95% viral suppression by 2030 would avert 25 million cases by 2035. Achieving the more modest 90/90/90 target would avert 22 million cases within the same time period.

“Recent results from the HVTN 100 vaccine trial have bolstered optimism for the development and deployment of an HIV vaccine in the near term,” the investigators said. “HIV vaccination would enable a strategic shift from reactive to proactive control, as suggested by our finding that an HIV vaccine with even moderate efficacy rolled out in 2020 could avert 17 million new infections by 2035 relative to expectations under status quo interventions.”

Find the full study in PNAS (doi: 10.1073/pnas.1620788114)

[email protected]

On Twitter @IDPractitioner

Reversible Cutaneous Side Effects of Vismodegib Treatment

To the Editor:

Vismodegib, a first-in-class inhibitor of the hedgehog signaling pathway, is useful in the treatment of advanced basal cell carcinomas (BCCs).1 Common side effects of vismodegib include alopecia (58%), muscle spasms (71%), and dysgeusia (71%).2 Some of these side effects have been hypothesized to be mechanism related.3,4 Keratoacanthomas have been reported to occur after vismodegib treatment of BCC.5 We report 3 cases illustrating reversible cutaneous side effects of vismodegib: alopecia, follicular dermatitis, and drug hypersensitivity reaction.

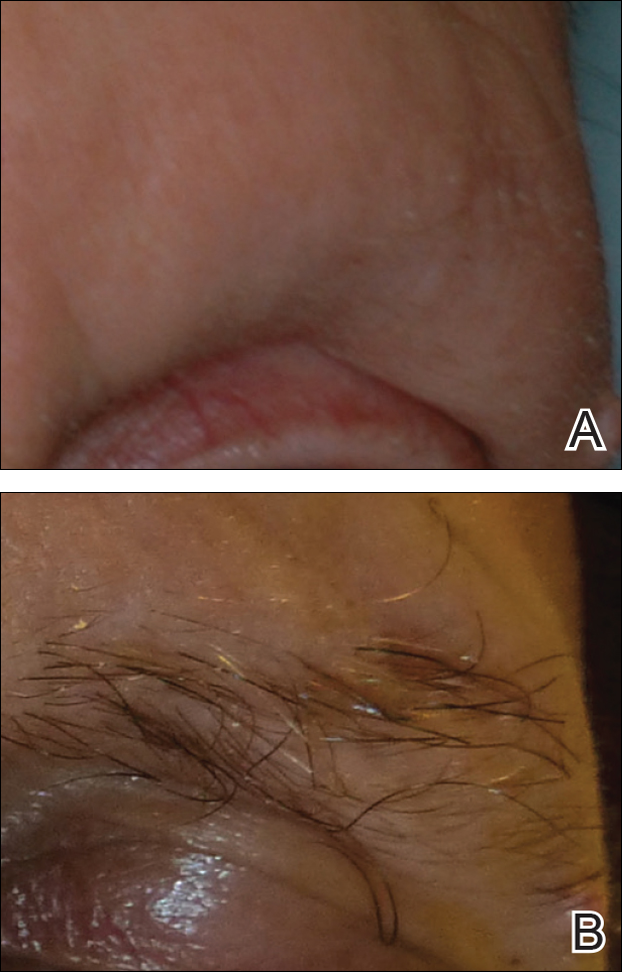

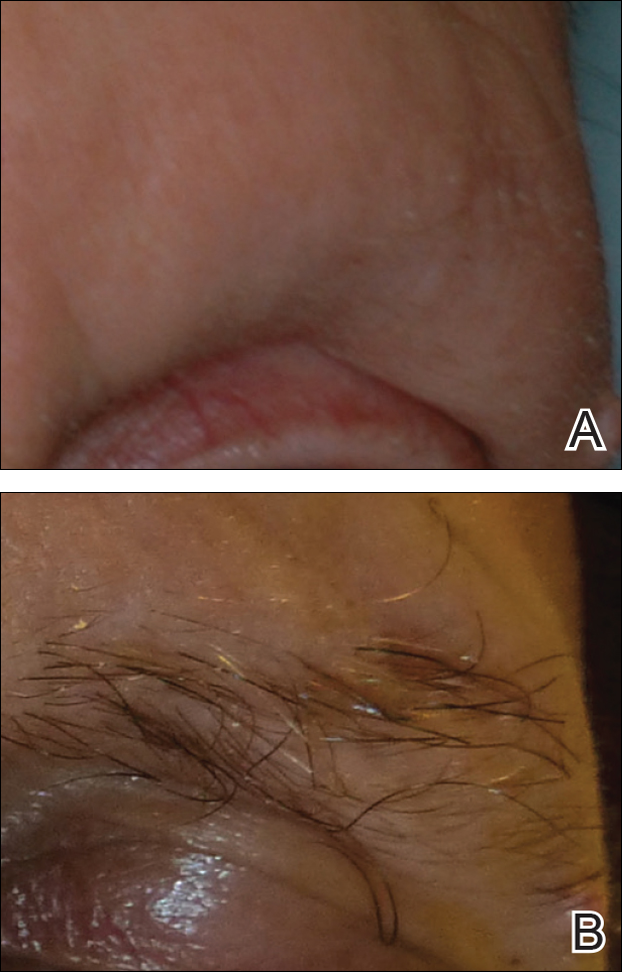

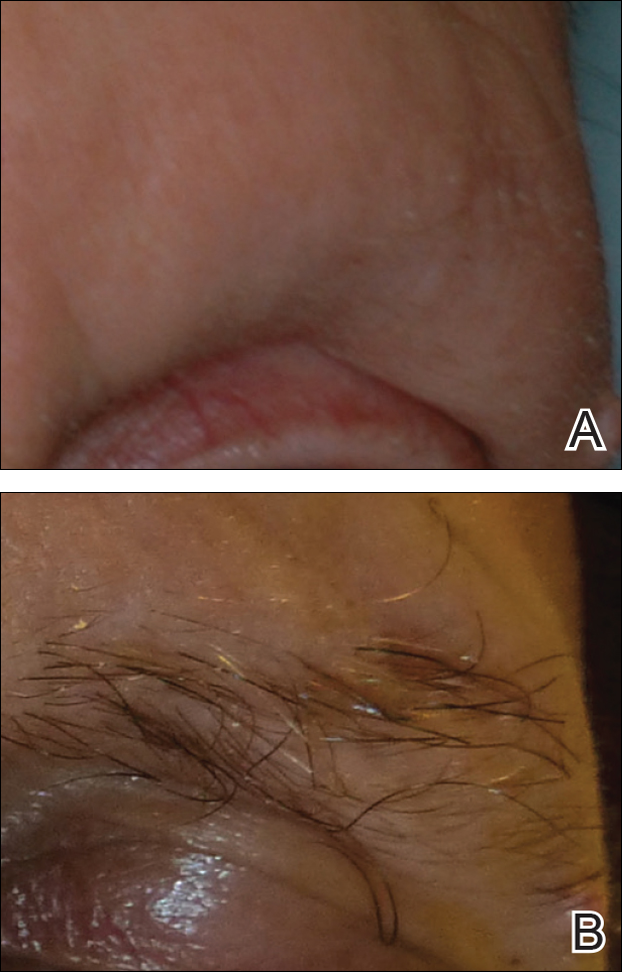

A 53-year-old man with a locally advanced BCC of the right medial canthus began experiencing progressive and diffuse hair loss on the beard area, parietal scalp, eyelashes, and eyebrows after 2 months of vismodegib treatment. At 12 months of treatment, he had complete loss of eyelashes and eyebrows (Figure, A). After vismodegib was discontinued due to disease progression, all of his hair began regrowing within several months, with complete hair regrowth observed at 20 months after the last dose (Figure, B).

A 55-year-old man with several locally advanced BCCs developed new-onset mildly pruritic, acneform lesions on the chest and back after 4 months of vismodegib treatment. Biopsy of the lesions showed a folliculocentric mixed dermal infiltrate. The patient did not have a history of follicular dermatitis. The dermatitis resolved several months after onset without treatment, despite continued vismodegib.

A 55-year-old man with locally advanced BCCs developed erythematous dermal plaques on the arms and chest after 2 months of vismodegib treatment. Lesions were asymptomatic. He was not using any other medications and did not have any contact allergen exposures. Punch biopsy showed superficial and deep perivascular dermatitis with occasional eosinophils, consistent with drug hypersensitivity. Although lesions spontaneously resolved without treatment after 1 month, he experienced a couple more bouts of these lesions over the next year. He continued vismodegib for 2 years without return of this eruption.

The average time frame for hair regrowth after vismodegib cessation has not been characterized and awaits future larger studies. The frequency of follicular dermatitis and drug eruption also has not been determined and may require careful observation by dermatologists in larger numbers of treated patients.

Because the hedgehog pathway is critical for normal hair follicle function, follicle-based toxicities of vismodegib including alopecia and folliculitis could be hypothesized to reflect effective blockade of the pathway.6 Currently, there are no data that these changes correlate with tumor response.

Although alopecia is a recognized side effect of vismodegib, regrowth has not been previously reported.1,2 Knowledge of the reversibility of alopecia as well as other toxicities has the potential to influence patient decision-making on drug initiation and adherence.

- Sekulic A, Migden MR, Oro AE, et al. Efficacy and safety of vismodegib in advanced basal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2171-2179.

- Chang AL, Solomon JA, Hainsworth JD, et al. Expanded access study of patients with advanced basal cell carcinoma treated with the Hedgehog pathway inhibitor, vismodegib. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:60-69.

- St-Jacques B, Dassule HR, Karavanova I, et al. Sonic hedgehog signaling is essential for hair development. Curr Biol. 1998;8:1058-1068.

- Hall JM, Bell ML, Finger TE. Disruption of sonic hedgehog signaling alters growth and patterning of lingual taste papillae. Dev Biol. 2003;255:263-277.

- Aasi S, Silkiss R, Tang JY, et al. New onset of keratoacanthomas after vismodegib treatment for locally advanced basal cell carcinomas: a report of 2 cases. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:242-243.

- Rittie L, Stoll SW, Kang S, et al. Hedgehog signaling maintains hair follicle stem cell phenotype in young and aged human skin. Aging Cell. 2009;8:738-751.

To the Editor:

Vismodegib, a first-in-class inhibitor of the hedgehog signaling pathway, is useful in the treatment of advanced basal cell carcinomas (BCCs).1 Common side effects of vismodegib include alopecia (58%), muscle spasms (71%), and dysgeusia (71%).2 Some of these side effects have been hypothesized to be mechanism related.3,4 Keratoacanthomas have been reported to occur after vismodegib treatment of BCC.5 We report 3 cases illustrating reversible cutaneous side effects of vismodegib: alopecia, follicular dermatitis, and drug hypersensitivity reaction.

A 53-year-old man with a locally advanced BCC of the right medial canthus began experiencing progressive and diffuse hair loss on the beard area, parietal scalp, eyelashes, and eyebrows after 2 months of vismodegib treatment. At 12 months of treatment, he had complete loss of eyelashes and eyebrows (Figure, A). After vismodegib was discontinued due to disease progression, all of his hair began regrowing within several months, with complete hair regrowth observed at 20 months after the last dose (Figure, B).

A 55-year-old man with several locally advanced BCCs developed new-onset mildly pruritic, acneform lesions on the chest and back after 4 months of vismodegib treatment. Biopsy of the lesions showed a folliculocentric mixed dermal infiltrate. The patient did not have a history of follicular dermatitis. The dermatitis resolved several months after onset without treatment, despite continued vismodegib.

A 55-year-old man with locally advanced BCCs developed erythematous dermal plaques on the arms and chest after 2 months of vismodegib treatment. Lesions were asymptomatic. He was not using any other medications and did not have any contact allergen exposures. Punch biopsy showed superficial and deep perivascular dermatitis with occasional eosinophils, consistent with drug hypersensitivity. Although lesions spontaneously resolved without treatment after 1 month, he experienced a couple more bouts of these lesions over the next year. He continued vismodegib for 2 years without return of this eruption.

The average time frame for hair regrowth after vismodegib cessation has not been characterized and awaits future larger studies. The frequency of follicular dermatitis and drug eruption also has not been determined and may require careful observation by dermatologists in larger numbers of treated patients.

Because the hedgehog pathway is critical for normal hair follicle function, follicle-based toxicities of vismodegib including alopecia and folliculitis could be hypothesized to reflect effective blockade of the pathway.6 Currently, there are no data that these changes correlate with tumor response.

Although alopecia is a recognized side effect of vismodegib, regrowth has not been previously reported.1,2 Knowledge of the reversibility of alopecia as well as other toxicities has the potential to influence patient decision-making on drug initiation and adherence.

To the Editor:

Vismodegib, a first-in-class inhibitor of the hedgehog signaling pathway, is useful in the treatment of advanced basal cell carcinomas (BCCs).1 Common side effects of vismodegib include alopecia (58%), muscle spasms (71%), and dysgeusia (71%).2 Some of these side effects have been hypothesized to be mechanism related.3,4 Keratoacanthomas have been reported to occur after vismodegib treatment of BCC.5 We report 3 cases illustrating reversible cutaneous side effects of vismodegib: alopecia, follicular dermatitis, and drug hypersensitivity reaction.

A 53-year-old man with a locally advanced BCC of the right medial canthus began experiencing progressive and diffuse hair loss on the beard area, parietal scalp, eyelashes, and eyebrows after 2 months of vismodegib treatment. At 12 months of treatment, he had complete loss of eyelashes and eyebrows (Figure, A). After vismodegib was discontinued due to disease progression, all of his hair began regrowing within several months, with complete hair regrowth observed at 20 months after the last dose (Figure, B).

A 55-year-old man with several locally advanced BCCs developed new-onset mildly pruritic, acneform lesions on the chest and back after 4 months of vismodegib treatment. Biopsy of the lesions showed a folliculocentric mixed dermal infiltrate. The patient did not have a history of follicular dermatitis. The dermatitis resolved several months after onset without treatment, despite continued vismodegib.

A 55-year-old man with locally advanced BCCs developed erythematous dermal plaques on the arms and chest after 2 months of vismodegib treatment. Lesions were asymptomatic. He was not using any other medications and did not have any contact allergen exposures. Punch biopsy showed superficial and deep perivascular dermatitis with occasional eosinophils, consistent with drug hypersensitivity. Although lesions spontaneously resolved without treatment after 1 month, he experienced a couple more bouts of these lesions over the next year. He continued vismodegib for 2 years without return of this eruption.

The average time frame for hair regrowth after vismodegib cessation has not been characterized and awaits future larger studies. The frequency of follicular dermatitis and drug eruption also has not been determined and may require careful observation by dermatologists in larger numbers of treated patients.

Because the hedgehog pathway is critical for normal hair follicle function, follicle-based toxicities of vismodegib including alopecia and folliculitis could be hypothesized to reflect effective blockade of the pathway.6 Currently, there are no data that these changes correlate with tumor response.

Although alopecia is a recognized side effect of vismodegib, regrowth has not been previously reported.1,2 Knowledge of the reversibility of alopecia as well as other toxicities has the potential to influence patient decision-making on drug initiation and adherence.

- Sekulic A, Migden MR, Oro AE, et al. Efficacy and safety of vismodegib in advanced basal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2171-2179.

- Chang AL, Solomon JA, Hainsworth JD, et al. Expanded access study of patients with advanced basal cell carcinoma treated with the Hedgehog pathway inhibitor, vismodegib. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:60-69.

- St-Jacques B, Dassule HR, Karavanova I, et al. Sonic hedgehog signaling is essential for hair development. Curr Biol. 1998;8:1058-1068.

- Hall JM, Bell ML, Finger TE. Disruption of sonic hedgehog signaling alters growth and patterning of lingual taste papillae. Dev Biol. 2003;255:263-277.

- Aasi S, Silkiss R, Tang JY, et al. New onset of keratoacanthomas after vismodegib treatment for locally advanced basal cell carcinomas: a report of 2 cases. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:242-243.

- Rittie L, Stoll SW, Kang S, et al. Hedgehog signaling maintains hair follicle stem cell phenotype in young and aged human skin. Aging Cell. 2009;8:738-751.

- Sekulic A, Migden MR, Oro AE, et al. Efficacy and safety of vismodegib in advanced basal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2171-2179.

- Chang AL, Solomon JA, Hainsworth JD, et al. Expanded access study of patients with advanced basal cell carcinoma treated with the Hedgehog pathway inhibitor, vismodegib. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:60-69.

- St-Jacques B, Dassule HR, Karavanova I, et al. Sonic hedgehog signaling is essential for hair development. Curr Biol. 1998;8:1058-1068.

- Hall JM, Bell ML, Finger TE. Disruption of sonic hedgehog signaling alters growth and patterning of lingual taste papillae. Dev Biol. 2003;255:263-277.

- Aasi S, Silkiss R, Tang JY, et al. New onset of keratoacanthomas after vismodegib treatment for locally advanced basal cell carcinomas: a report of 2 cases. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:242-243.

- Rittie L, Stoll SW, Kang S, et al. Hedgehog signaling maintains hair follicle stem cell phenotype in young and aged human skin. Aging Cell. 2009;8:738-751.

Practice Points

- Hair loss is a common late side effect of vismodegib usage and is reversible, but regrowth takes many months.

- Mild folliculitis that resolves spontaneously has been observed in patients using vismodegib.

- Dermal hypersensitivity has been observed in patients on vismodegib, though the exact frequency of this type of dermatitis is not known.

Real-world EGFR and ALK testing of NSCLC falls short

ORLANDO – A large proportion of patients with advanced non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) are not being tested for tumor associated–epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) alterations according to national guidelines. This situation may be leading to suboptimal treatment, a large retrospective cohort study suggests.

Guidelines from the American Society of Clinical Oncology and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network recommend testing before first-line therapy for all treatment-eligible patients with nonsquamous histology and for those patients with squamous histology who are nonsmokers or who have mixed cell types or small tumor samples. Additionally, the guidelines recommend that results be made available within 2 weeks of the lab’s receipt of the sample so that they can be used to inform treatment decisions.

Overall, 22% of patients with nonsquamous tumors had no evidence of EGFR and ALK testing in their records. The large majority of patients with squamous tumors did not have any evidence of testing either, and it was unclear how well testing corresponded with the criteria.

In roughly a third of cases in which testing was done, the time between diagnosis of advanced disease and availability of test results exceeded 4 weeks. Among patients with positive test results, those whose results came back after the start of first-line therapy, were about half as likely to appropriately receive a therapy that targeted their tumor’s molecular aberration.

“We observed variation in adherence to [the American Society of Clinical Oncology] and [the National Comprehensive Cancer Network] guidelines around biomarker testing in advanced NSCLC, and we saw significant variation in testing in the squamous population and the nonsquamous population across practices,” presenting author Jay Rughani, manager of Life Sciences at Flatiron Health, New York, commented in an interview. Observed delays in availability of test results were mainly driven by delays between diagnosis and submission of samples to the lab for testing.

“There may be an opportunity to educate the oncology community around testing, certainly for all nonsquamous patients, because this is a case where they all should have been tested,” he said. “And there is also an opportunity to ensure testing of the appropriate squamous cell patients, while discouraging the testing of the majority who aren’t candidates, so there may be an opportunity for education around smoking status.”

Slow uptake of the national guidelines is unlikely to explain the observed variations in testing, according to Mr. Rughani. “Since we looked at patients diagnosed after Jan. 1, 2014, our impression was that the guidelines were sort of disseminated enough and widely known enough by that point, particularly around EGFR and ALK, that we wouldn’t expect any lag there. If we had done this for PD-L1 [programmed death ligand 1] testing, perhaps we might have thought about some lag in adoption.”

The impact of variations in testing and receipt of inappropriate initial therapy on clinical outcomes is yet to be determined. “As a follow-on, some of the work we have been doing is trying to understand, for these separate cohorts of patients, depending on what they received in the front line, what their overall survival was and what their surrogate endpoints were,” Mr. Rughani concluded.

Study details

For the study, the investigators identified 16,316 patients with advanced NSCLC from 206 community clinics across the United States participating in the Flatiron Network. All patients were treated between 2014 and 2016.

Cross-checking of the total Flatiron population against the National Program of Cancer Registries and Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results databases suggested that it is a good national representation, according to Mr. Rughani.

A record review showed that the rate of EGFR and ALK testing among study patients ranged widely across clinics, from 0% to 100% for both the nonsquamous cases and the squamous cases, according to results reported in a poster session. The median was 79% for the former and 16% for the latter.

Overall, 22% of the nonsquamous cohort and 79% of the squamous cohort did not have any evidence of testing in their records. For the latter, a sampling of records was unable to verify whether testing was appropriately matched to eligibility criteria.

When testing was performed, 35% of EGFR test results and 37% of ALK test results were not available to the treating clinician until more than 4 weeks after the date of the advanced cancer diagnosis.

“The delays were mostly attributed to nonlab factors. When we isolated the time that the lab took to turn it around, it was under 2 weeks for the vast majority of patients,” Mr. Rughani reported. Possible nonlab culprit factors include clinic work flows, insurance-related issues, and families’ and patients’ hesitancy to be tested, he said.

Delays in receipt of positive test results appeared to influence choice of first-line therapy. Among patients in whom these results were available before first-line therapy, 80% of those found to have an EGFR-mutated tumor received an EGFR–tyrosine kinase inhibitor, and 77% of those found to have ALK-rearranged tumors received an ALK inhibitor.

In sharp contrast, among patients in whom positive test results did not become available until after the start of first-line therapy, respective values were just 43% and 42%.

“Anecdotally, we saw that some patients would go on to Avastin [bevacizumab] in the front line when the results were delayed, and then, ultimately, they would have the opportunity to receive an EGFR[–tyrosine kinase inhibitor] or something like that in later lines,” commented Mr. Rughani. “So, that impacted treatment decisions there.”

Mr. Rughani disclosed stock and other ownership interests in Flatiron Health.

ORLANDO – A large proportion of patients with advanced non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) are not being tested for tumor associated–epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) alterations according to national guidelines. This situation may be leading to suboptimal treatment, a large retrospective cohort study suggests.

Guidelines from the American Society of Clinical Oncology and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network recommend testing before first-line therapy for all treatment-eligible patients with nonsquamous histology and for those patients with squamous histology who are nonsmokers or who have mixed cell types or small tumor samples. Additionally, the guidelines recommend that results be made available within 2 weeks of the lab’s receipt of the sample so that they can be used to inform treatment decisions.

Overall, 22% of patients with nonsquamous tumors had no evidence of EGFR and ALK testing in their records. The large majority of patients with squamous tumors did not have any evidence of testing either, and it was unclear how well testing corresponded with the criteria.

In roughly a third of cases in which testing was done, the time between diagnosis of advanced disease and availability of test results exceeded 4 weeks. Among patients with positive test results, those whose results came back after the start of first-line therapy, were about half as likely to appropriately receive a therapy that targeted their tumor’s molecular aberration.

“We observed variation in adherence to [the American Society of Clinical Oncology] and [the National Comprehensive Cancer Network] guidelines around biomarker testing in advanced NSCLC, and we saw significant variation in testing in the squamous population and the nonsquamous population across practices,” presenting author Jay Rughani, manager of Life Sciences at Flatiron Health, New York, commented in an interview. Observed delays in availability of test results were mainly driven by delays between diagnosis and submission of samples to the lab for testing.

“There may be an opportunity to educate the oncology community around testing, certainly for all nonsquamous patients, because this is a case where they all should have been tested,” he said. “And there is also an opportunity to ensure testing of the appropriate squamous cell patients, while discouraging the testing of the majority who aren’t candidates, so there may be an opportunity for education around smoking status.”

Slow uptake of the national guidelines is unlikely to explain the observed variations in testing, according to Mr. Rughani. “Since we looked at patients diagnosed after Jan. 1, 2014, our impression was that the guidelines were sort of disseminated enough and widely known enough by that point, particularly around EGFR and ALK, that we wouldn’t expect any lag there. If we had done this for PD-L1 [programmed death ligand 1] testing, perhaps we might have thought about some lag in adoption.”

The impact of variations in testing and receipt of inappropriate initial therapy on clinical outcomes is yet to be determined. “As a follow-on, some of the work we have been doing is trying to understand, for these separate cohorts of patients, depending on what they received in the front line, what their overall survival was and what their surrogate endpoints were,” Mr. Rughani concluded.

Study details

For the study, the investigators identified 16,316 patients with advanced NSCLC from 206 community clinics across the United States participating in the Flatiron Network. All patients were treated between 2014 and 2016.

Cross-checking of the total Flatiron population against the National Program of Cancer Registries and Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results databases suggested that it is a good national representation, according to Mr. Rughani.

A record review showed that the rate of EGFR and ALK testing among study patients ranged widely across clinics, from 0% to 100% for both the nonsquamous cases and the squamous cases, according to results reported in a poster session. The median was 79% for the former and 16% for the latter.

Overall, 22% of the nonsquamous cohort and 79% of the squamous cohort did not have any evidence of testing in their records. For the latter, a sampling of records was unable to verify whether testing was appropriately matched to eligibility criteria.

When testing was performed, 35% of EGFR test results and 37% of ALK test results were not available to the treating clinician until more than 4 weeks after the date of the advanced cancer diagnosis.

“The delays were mostly attributed to nonlab factors. When we isolated the time that the lab took to turn it around, it was under 2 weeks for the vast majority of patients,” Mr. Rughani reported. Possible nonlab culprit factors include clinic work flows, insurance-related issues, and families’ and patients’ hesitancy to be tested, he said.

Delays in receipt of positive test results appeared to influence choice of first-line therapy. Among patients in whom these results were available before first-line therapy, 80% of those found to have an EGFR-mutated tumor received an EGFR–tyrosine kinase inhibitor, and 77% of those found to have ALK-rearranged tumors received an ALK inhibitor.

In sharp contrast, among patients in whom positive test results did not become available until after the start of first-line therapy, respective values were just 43% and 42%.

“Anecdotally, we saw that some patients would go on to Avastin [bevacizumab] in the front line when the results were delayed, and then, ultimately, they would have the opportunity to receive an EGFR[–tyrosine kinase inhibitor] or something like that in later lines,” commented Mr. Rughani. “So, that impacted treatment decisions there.”

Mr. Rughani disclosed stock and other ownership interests in Flatiron Health.

ORLANDO – A large proportion of patients with advanced non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) are not being tested for tumor associated–epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) alterations according to national guidelines. This situation may be leading to suboptimal treatment, a large retrospective cohort study suggests.

Guidelines from the American Society of Clinical Oncology and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network recommend testing before first-line therapy for all treatment-eligible patients with nonsquamous histology and for those patients with squamous histology who are nonsmokers or who have mixed cell types or small tumor samples. Additionally, the guidelines recommend that results be made available within 2 weeks of the lab’s receipt of the sample so that they can be used to inform treatment decisions.

Overall, 22% of patients with nonsquamous tumors had no evidence of EGFR and ALK testing in their records. The large majority of patients with squamous tumors did not have any evidence of testing either, and it was unclear how well testing corresponded with the criteria.

In roughly a third of cases in which testing was done, the time between diagnosis of advanced disease and availability of test results exceeded 4 weeks. Among patients with positive test results, those whose results came back after the start of first-line therapy, were about half as likely to appropriately receive a therapy that targeted their tumor’s molecular aberration.

“We observed variation in adherence to [the American Society of Clinical Oncology] and [the National Comprehensive Cancer Network] guidelines around biomarker testing in advanced NSCLC, and we saw significant variation in testing in the squamous population and the nonsquamous population across practices,” presenting author Jay Rughani, manager of Life Sciences at Flatiron Health, New York, commented in an interview. Observed delays in availability of test results were mainly driven by delays between diagnosis and submission of samples to the lab for testing.

“There may be an opportunity to educate the oncology community around testing, certainly for all nonsquamous patients, because this is a case where they all should have been tested,” he said. “And there is also an opportunity to ensure testing of the appropriate squamous cell patients, while discouraging the testing of the majority who aren’t candidates, so there may be an opportunity for education around smoking status.”

Slow uptake of the national guidelines is unlikely to explain the observed variations in testing, according to Mr. Rughani. “Since we looked at patients diagnosed after Jan. 1, 2014, our impression was that the guidelines were sort of disseminated enough and widely known enough by that point, particularly around EGFR and ALK, that we wouldn’t expect any lag there. If we had done this for PD-L1 [programmed death ligand 1] testing, perhaps we might have thought about some lag in adoption.”

The impact of variations in testing and receipt of inappropriate initial therapy on clinical outcomes is yet to be determined. “As a follow-on, some of the work we have been doing is trying to understand, for these separate cohorts of patients, depending on what they received in the front line, what their overall survival was and what their surrogate endpoints were,” Mr. Rughani concluded.

Study details

For the study, the investigators identified 16,316 patients with advanced NSCLC from 206 community clinics across the United States participating in the Flatiron Network. All patients were treated between 2014 and 2016.

Cross-checking of the total Flatiron population against the National Program of Cancer Registries and Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results databases suggested that it is a good national representation, according to Mr. Rughani.

A record review showed that the rate of EGFR and ALK testing among study patients ranged widely across clinics, from 0% to 100% for both the nonsquamous cases and the squamous cases, according to results reported in a poster session. The median was 79% for the former and 16% for the latter.

Overall, 22% of the nonsquamous cohort and 79% of the squamous cohort did not have any evidence of testing in their records. For the latter, a sampling of records was unable to verify whether testing was appropriately matched to eligibility criteria.

When testing was performed, 35% of EGFR test results and 37% of ALK test results were not available to the treating clinician until more than 4 weeks after the date of the advanced cancer diagnosis.

“The delays were mostly attributed to nonlab factors. When we isolated the time that the lab took to turn it around, it was under 2 weeks for the vast majority of patients,” Mr. Rughani reported. Possible nonlab culprit factors include clinic work flows, insurance-related issues, and families’ and patients’ hesitancy to be tested, he said.

Delays in receipt of positive test results appeared to influence choice of first-line therapy. Among patients in whom these results were available before first-line therapy, 80% of those found to have an EGFR-mutated tumor received an EGFR–tyrosine kinase inhibitor, and 77% of those found to have ALK-rearranged tumors received an ALK inhibitor.

In sharp contrast, among patients in whom positive test results did not become available until after the start of first-line therapy, respective values were just 43% and 42%.

“Anecdotally, we saw that some patients would go on to Avastin [bevacizumab] in the front line when the results were delayed, and then, ultimately, they would have the opportunity to receive an EGFR[–tyrosine kinase inhibitor] or something like that in later lines,” commented Mr. Rughani. “So, that impacted treatment decisions there.”

Mr. Rughani disclosed stock and other ownership interests in Flatiron Health.

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Overall, 22% of patients with nonsquamous advanced NSCLC had no evidence of EGFR and ALK tumor testing in their records.

Data source: A retrospective cohort study of 16,316 community oncology patients with advanced NSCLC.

Disclosures: Mr. Rughani disclosed that he is an employee of and has stock or other ownership interests in Flatiron Health.

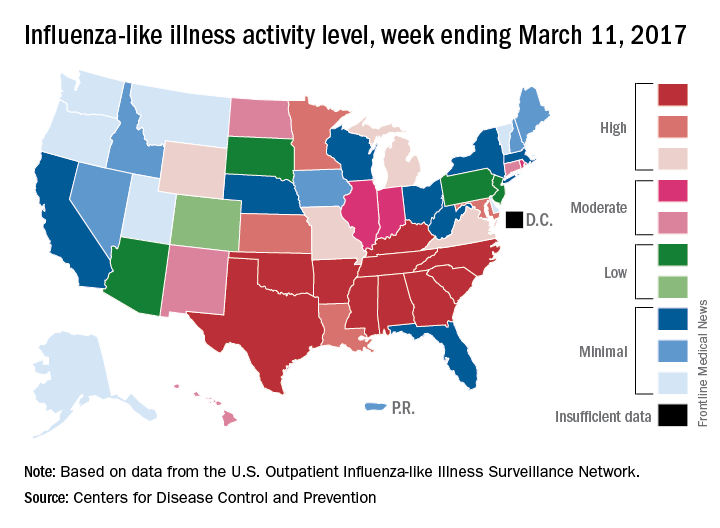

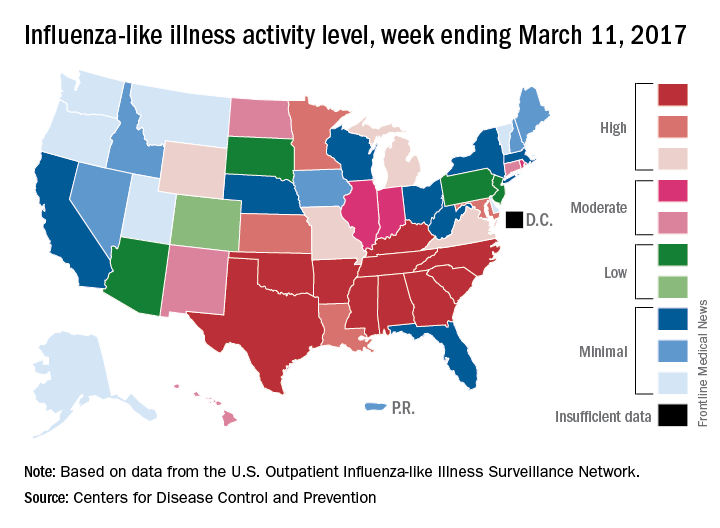

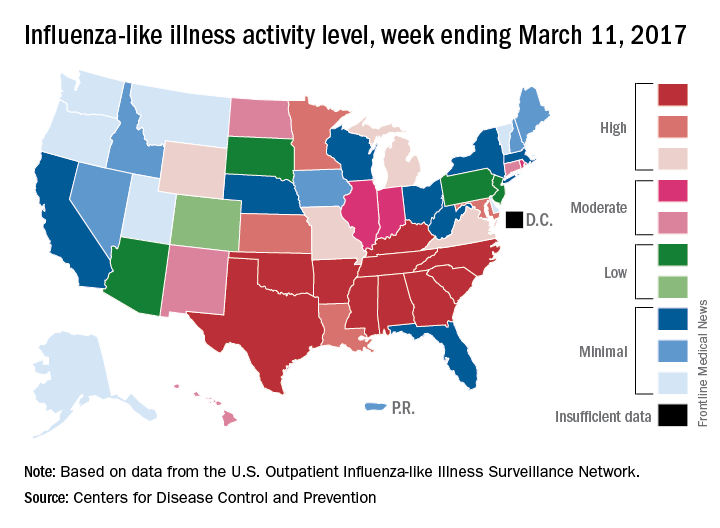

U.S. influenza activity remains steady

The decline in U.S. influenza activity that started in February paused during the week ending March 11, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The proportion of outpatient visits for influenza-like illness (ILI) stayed at 3.7% for a second consecutive week after declining for 3 weeks in a row. The peak for the season, 5.2%, came during the week ending Feb. 11, CDC data show. The national baseline is 2.2%.

Five ILI-related pediatric deaths were reported to the CDC for the week – all of which occurred during previous weeks – bringing the total to 53 for the 2016-2017 season, the CDC said.

The decline in U.S. influenza activity that started in February paused during the week ending March 11, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The proportion of outpatient visits for influenza-like illness (ILI) stayed at 3.7% for a second consecutive week after declining for 3 weeks in a row. The peak for the season, 5.2%, came during the week ending Feb. 11, CDC data show. The national baseline is 2.2%.

Five ILI-related pediatric deaths were reported to the CDC for the week – all of which occurred during previous weeks – bringing the total to 53 for the 2016-2017 season, the CDC said.

The decline in U.S. influenza activity that started in February paused during the week ending March 11, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The proportion of outpatient visits for influenza-like illness (ILI) stayed at 3.7% for a second consecutive week after declining for 3 weeks in a row. The peak for the season, 5.2%, came during the week ending Feb. 11, CDC data show. The national baseline is 2.2%.

Five ILI-related pediatric deaths were reported to the CDC for the week – all of which occurred during previous weeks – bringing the total to 53 for the 2016-2017 season, the CDC said.

LVADs achieve cardiac palliation in muscular dystrophies

At one time, respiratory failure was the primary cause of death in young men and boys with muscular dystrophies, but since improvements in ventilator support have addressed this problem, cardiac complications such as cardiomyopathy have become the main cause of death in this group, with the highest risk of death in people with Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD). Researchers from Rome have reported that the novel use of ventricular assist devices in this population can prolong life.

Gianluigi Perri, MD, PhD, of University Hospital and Bambino Gesù Children Hospital in Rome, and his coauthors, shared their experience treating seven patients with dystrophinopathies and dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) with left ventricular assist devices (LVADs) from February 2011 to February 2016 (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017 March;153:669-74). “Our experience indicates that the use of an LVAD as destination therapy in patients with dystrophinopathies with end-stage DCM is feasible, suggesting that it may be suitable as a palliative therapy for the treatment of these patients with no other therapeutic options,” Dr. Perri and his coauthors said.