User login

Anticoagulant resumption after ICH aids patients

HOUSTON – Even when patients on an oral anticoagulant have the dreaded complication of an intracerebral hemorrhage, resumption of their oral anticoagulation regimen appears to produce the best midterm outcomes, based on a meta-analysis of data from more than 1,000 patients collected in three observational studies.

Resumption of oral anticoagulation therapy (OAT) is a “major dilemma” when managing patients who developed an intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) while on OAT, said Alessandro Biffi, MD, explaining why he performed this meta-analysis that he presented at the International Stroke Conference sponsored by the American Heart Association.

He used individual patient data collected from a total of 1,027 patients enrolled in any of three different observational studies: the German-wide Multicenter Analysis of Oral Anticoagulation Associated Intracerebral Hemorrhage (RETRACE) study, the MGH longitudinal ICH study, or the Ethnic/Racial Variations of Intracerebral Hemorrhage (ERICH) study. Overall 26% of the patients resumed OAT following their ICH, although the rate ranged from a low of 20% in one study to a high of 42% in another. The vast majority of patients received a vitamin K antagonist as their anticoagulant; very few received a new oral anticoagulant.

Using propensity score matching to compare similar patients who resumed or stayed off OAT, Dr. Biffi found that, during the year following the index ICH, mortality was 71%-74% lower among patients who resumed OAT. Recurrent all-cause stroke was 49%-55% lower with resumed OAT, and favorable functional outcomes (a score of 0-3 on the modified Rankin scale) were more than fourfold higher with OAT resumption, he reported.

Dr. Biffi calculated these relative rates, both for patients with a lumbar location of their ICH and for those with a nonlumbar location, and found that location had no influence on responsiveness to OAT. Patients with an index ICH in a lumbar location had a trend toward more recurrent ICH on OAT, a 26% higher rate relative to patients not resumed on OAT, but this difference fell short of statistical significance.

The only factor he found that linked with whether or not patients resumed OAT was the severity of their index ICH. The more severe their bleed, the less likely were patients to resume. Aside from that, “there is a lot of variation in practice,” he said. “We are gathering additional data” to try to further address this question.

Dr. Biffi had no disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

Resuming oral anticoagulation following an intracerebral hemorrhage is one of the most vexing problems today in vascular neurology. It’s a situation that often happens, and it will grow increasingly more common as the number of patients with atrial fibrillation escalates and even more people start oral anticoagulation.

It’s also very important to remember that patients like these who need oral anticoagulation but now have a history of ICH must have all their other cardiovascular disease risk factors very well controlled: their blood pressure, their diabetes, their smoking, etc. Oral anticoagulation may be important for these patients, but tight risk factor control is even more important.

I agree with Dr. Biffi that a prospective, randomized trial is the best way to get more information to help guide resuming oral anticoagulation. Observational studies are significantly limited by ascertainment bias, and for these patients there are also many variables – at least a dozen – that can influence whether or not a patient resumes oral anticoagulation. Dr. Biffi’s findings are interesting, but the limitations of his data prevent the results from being truly compelling.

It would be very helpful to have data from a trial that randomized ICH patients who required anticoagulation to a full-dose NOAC, a reduced-dose NOAC, or aspirin and see which group had the best long-term outcome. Whatever the results, it would change practice. It’s intriguing to speculate that a reduced-dose NOAC might provide adequate ischemic protection with a reduced risk for more bleeding.

Mark J. Alberts, MD , is chief of neurology at Hartford (Conn.) Hospital. He had no disclosures. He made these comments in an interview and during a press conference.

Resuming oral anticoagulation following an intracerebral hemorrhage is one of the most vexing problems today in vascular neurology. It’s a situation that often happens, and it will grow increasingly more common as the number of patients with atrial fibrillation escalates and even more people start oral anticoagulation.

It’s also very important to remember that patients like these who need oral anticoagulation but now have a history of ICH must have all their other cardiovascular disease risk factors very well controlled: their blood pressure, their diabetes, their smoking, etc. Oral anticoagulation may be important for these patients, but tight risk factor control is even more important.

I agree with Dr. Biffi that a prospective, randomized trial is the best way to get more information to help guide resuming oral anticoagulation. Observational studies are significantly limited by ascertainment bias, and for these patients there are also many variables – at least a dozen – that can influence whether or not a patient resumes oral anticoagulation. Dr. Biffi’s findings are interesting, but the limitations of his data prevent the results from being truly compelling.

It would be very helpful to have data from a trial that randomized ICH patients who required anticoagulation to a full-dose NOAC, a reduced-dose NOAC, or aspirin and see which group had the best long-term outcome. Whatever the results, it would change practice. It’s intriguing to speculate that a reduced-dose NOAC might provide adequate ischemic protection with a reduced risk for more bleeding.

Mark J. Alberts, MD , is chief of neurology at Hartford (Conn.) Hospital. He had no disclosures. He made these comments in an interview and during a press conference.

Resuming oral anticoagulation following an intracerebral hemorrhage is one of the most vexing problems today in vascular neurology. It’s a situation that often happens, and it will grow increasingly more common as the number of patients with atrial fibrillation escalates and even more people start oral anticoagulation.

It’s also very important to remember that patients like these who need oral anticoagulation but now have a history of ICH must have all their other cardiovascular disease risk factors very well controlled: their blood pressure, their diabetes, their smoking, etc. Oral anticoagulation may be important for these patients, but tight risk factor control is even more important.

I agree with Dr. Biffi that a prospective, randomized trial is the best way to get more information to help guide resuming oral anticoagulation. Observational studies are significantly limited by ascertainment bias, and for these patients there are also many variables – at least a dozen – that can influence whether or not a patient resumes oral anticoagulation. Dr. Biffi’s findings are interesting, but the limitations of his data prevent the results from being truly compelling.

It would be very helpful to have data from a trial that randomized ICH patients who required anticoagulation to a full-dose NOAC, a reduced-dose NOAC, or aspirin and see which group had the best long-term outcome. Whatever the results, it would change practice. It’s intriguing to speculate that a reduced-dose NOAC might provide adequate ischemic protection with a reduced risk for more bleeding.

Mark J. Alberts, MD , is chief of neurology at Hartford (Conn.) Hospital. He had no disclosures. He made these comments in an interview and during a press conference.

HOUSTON – Even when patients on an oral anticoagulant have the dreaded complication of an intracerebral hemorrhage, resumption of their oral anticoagulation regimen appears to produce the best midterm outcomes, based on a meta-analysis of data from more than 1,000 patients collected in three observational studies.

Resumption of oral anticoagulation therapy (OAT) is a “major dilemma” when managing patients who developed an intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) while on OAT, said Alessandro Biffi, MD, explaining why he performed this meta-analysis that he presented at the International Stroke Conference sponsored by the American Heart Association.

He used individual patient data collected from a total of 1,027 patients enrolled in any of three different observational studies: the German-wide Multicenter Analysis of Oral Anticoagulation Associated Intracerebral Hemorrhage (RETRACE) study, the MGH longitudinal ICH study, or the Ethnic/Racial Variations of Intracerebral Hemorrhage (ERICH) study. Overall 26% of the patients resumed OAT following their ICH, although the rate ranged from a low of 20% in one study to a high of 42% in another. The vast majority of patients received a vitamin K antagonist as their anticoagulant; very few received a new oral anticoagulant.

Using propensity score matching to compare similar patients who resumed or stayed off OAT, Dr. Biffi found that, during the year following the index ICH, mortality was 71%-74% lower among patients who resumed OAT. Recurrent all-cause stroke was 49%-55% lower with resumed OAT, and favorable functional outcomes (a score of 0-3 on the modified Rankin scale) were more than fourfold higher with OAT resumption, he reported.

Dr. Biffi calculated these relative rates, both for patients with a lumbar location of their ICH and for those with a nonlumbar location, and found that location had no influence on responsiveness to OAT. Patients with an index ICH in a lumbar location had a trend toward more recurrent ICH on OAT, a 26% higher rate relative to patients not resumed on OAT, but this difference fell short of statistical significance.

The only factor he found that linked with whether or not patients resumed OAT was the severity of their index ICH. The more severe their bleed, the less likely were patients to resume. Aside from that, “there is a lot of variation in practice,” he said. “We are gathering additional data” to try to further address this question.

Dr. Biffi had no disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

HOUSTON – Even when patients on an oral anticoagulant have the dreaded complication of an intracerebral hemorrhage, resumption of their oral anticoagulation regimen appears to produce the best midterm outcomes, based on a meta-analysis of data from more than 1,000 patients collected in three observational studies.

Resumption of oral anticoagulation therapy (OAT) is a “major dilemma” when managing patients who developed an intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) while on OAT, said Alessandro Biffi, MD, explaining why he performed this meta-analysis that he presented at the International Stroke Conference sponsored by the American Heart Association.

He used individual patient data collected from a total of 1,027 patients enrolled in any of three different observational studies: the German-wide Multicenter Analysis of Oral Anticoagulation Associated Intracerebral Hemorrhage (RETRACE) study, the MGH longitudinal ICH study, or the Ethnic/Racial Variations of Intracerebral Hemorrhage (ERICH) study. Overall 26% of the patients resumed OAT following their ICH, although the rate ranged from a low of 20% in one study to a high of 42% in another. The vast majority of patients received a vitamin K antagonist as their anticoagulant; very few received a new oral anticoagulant.

Using propensity score matching to compare similar patients who resumed or stayed off OAT, Dr. Biffi found that, during the year following the index ICH, mortality was 71%-74% lower among patients who resumed OAT. Recurrent all-cause stroke was 49%-55% lower with resumed OAT, and favorable functional outcomes (a score of 0-3 on the modified Rankin scale) were more than fourfold higher with OAT resumption, he reported.

Dr. Biffi calculated these relative rates, both for patients with a lumbar location of their ICH and for those with a nonlumbar location, and found that location had no influence on responsiveness to OAT. Patients with an index ICH in a lumbar location had a trend toward more recurrent ICH on OAT, a 26% higher rate relative to patients not resumed on OAT, but this difference fell short of statistical significance.

The only factor he found that linked with whether or not patients resumed OAT was the severity of their index ICH. The more severe their bleed, the less likely were patients to resume. Aside from that, “there is a lot of variation in practice,” he said. “We are gathering additional data” to try to further address this question.

Dr. Biffi had no disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT THE INTERNATIONAL STROKE CONFERENCE

Key clinical point:

Major finding: One-year mortality was 71%-74% lower among patients who resumed oral anticoagulation relative to those who did not.

Data source: Meta-analysis of data from 1,027 patients collected in three observational studies.

Disclosures: Dr. Biffi had no disclosures.

Prenatal surveillance vital in monochorionic twin pregnancies

Prenatal care is important for every pregnancy. It ensures the health and safety of the mother and baby throughout gestation, and alerts the ob.gyn. to any possible complications that may arise. Today, more than ever before, we have a wide array of powerful tools to augment the care we provide for our patients – from imaging technologies, to genomic screens, to advances in fetal surgery. However, every pregnancy can present its own set of challenges, and successful delivery of a healthy newborn cannot be taken for granted.

The importance of proper prenatal care is most essential to women with higher-risk pregnancies, which includes those involving multiple fetuses. From the babies’ perspective, complications of multiple fetuses can include intrauterine growth restriction, cerebral palsy, and stillbirth; from the mother’s perspective, complications of multiple fetuses can include preterm labor, gestational diabetes mellitus, preeclampsia, and placental abruption.

This month, we focus on the range of tools and approaches used to treat complications that can occur in monochorionic twin pregnancies, including twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome, selective fetal growth restriction, twin anemia polycythemia sequence, and twin reversed arterial perfusion. Despite the challenges these conditions pose, increased ultrasonographic and echocardiographic surveillance allow for earlier detection and possible intervention to slow progression or, in some cases, correct defects that would have terminated the pregnancy not too long ago. Additionally, fetal therapy programs utilizing in-utero surgical techniques, such as fetoscopic laser coagulation, have significantly broadened the management and treatment options we can now offer these patients.

Dr. M. Ozhan Turan, an associate professor and director of fetal therapy and complex obstetric surgery in the department of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, provides an overview of these techniques and technologies which, when applied appropriately, can significantly improve pregnancy outcomes.

Dr. Reece, who specializes in maternal-fetal medicine, is vice president for medical affairs at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, as well as the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and dean of the school of medicine. Dr. Reece said he had no relevant financial disclosures. He is the medical editor of this column. Contact him at [email protected].

Prenatal care is important for every pregnancy. It ensures the health and safety of the mother and baby throughout gestation, and alerts the ob.gyn. to any possible complications that may arise. Today, more than ever before, we have a wide array of powerful tools to augment the care we provide for our patients – from imaging technologies, to genomic screens, to advances in fetal surgery. However, every pregnancy can present its own set of challenges, and successful delivery of a healthy newborn cannot be taken for granted.

The importance of proper prenatal care is most essential to women with higher-risk pregnancies, which includes those involving multiple fetuses. From the babies’ perspective, complications of multiple fetuses can include intrauterine growth restriction, cerebral palsy, and stillbirth; from the mother’s perspective, complications of multiple fetuses can include preterm labor, gestational diabetes mellitus, preeclampsia, and placental abruption.

This month, we focus on the range of tools and approaches used to treat complications that can occur in monochorionic twin pregnancies, including twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome, selective fetal growth restriction, twin anemia polycythemia sequence, and twin reversed arterial perfusion. Despite the challenges these conditions pose, increased ultrasonographic and echocardiographic surveillance allow for earlier detection and possible intervention to slow progression or, in some cases, correct defects that would have terminated the pregnancy not too long ago. Additionally, fetal therapy programs utilizing in-utero surgical techniques, such as fetoscopic laser coagulation, have significantly broadened the management and treatment options we can now offer these patients.

Dr. M. Ozhan Turan, an associate professor and director of fetal therapy and complex obstetric surgery in the department of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, provides an overview of these techniques and technologies which, when applied appropriately, can significantly improve pregnancy outcomes.

Dr. Reece, who specializes in maternal-fetal medicine, is vice president for medical affairs at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, as well as the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and dean of the school of medicine. Dr. Reece said he had no relevant financial disclosures. He is the medical editor of this column. Contact him at [email protected].

Prenatal care is important for every pregnancy. It ensures the health and safety of the mother and baby throughout gestation, and alerts the ob.gyn. to any possible complications that may arise. Today, more than ever before, we have a wide array of powerful tools to augment the care we provide for our patients – from imaging technologies, to genomic screens, to advances in fetal surgery. However, every pregnancy can present its own set of challenges, and successful delivery of a healthy newborn cannot be taken for granted.

The importance of proper prenatal care is most essential to women with higher-risk pregnancies, which includes those involving multiple fetuses. From the babies’ perspective, complications of multiple fetuses can include intrauterine growth restriction, cerebral palsy, and stillbirth; from the mother’s perspective, complications of multiple fetuses can include preterm labor, gestational diabetes mellitus, preeclampsia, and placental abruption.

This month, we focus on the range of tools and approaches used to treat complications that can occur in monochorionic twin pregnancies, including twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome, selective fetal growth restriction, twin anemia polycythemia sequence, and twin reversed arterial perfusion. Despite the challenges these conditions pose, increased ultrasonographic and echocardiographic surveillance allow for earlier detection and possible intervention to slow progression or, in some cases, correct defects that would have terminated the pregnancy not too long ago. Additionally, fetal therapy programs utilizing in-utero surgical techniques, such as fetoscopic laser coagulation, have significantly broadened the management and treatment options we can now offer these patients.

Dr. M. Ozhan Turan, an associate professor and director of fetal therapy and complex obstetric surgery in the department of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, provides an overview of these techniques and technologies which, when applied appropriately, can significantly improve pregnancy outcomes.

Dr. Reece, who specializes in maternal-fetal medicine, is vice president for medical affairs at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, as well as the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and dean of the school of medicine. Dr. Reece said he had no relevant financial disclosures. He is the medical editor of this column. Contact him at [email protected].

For mantle cell lymphoma, VR-CAP beat R-CHOP

For patients with newly diagnosed mantle cell lymphoma, duration and quality of response were superior with a regimen of bortezomib, rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and prednisone (VR-CAP) when compared with rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP), based on a post hoc analysis of the randomized, phase III LYM-3002 trial.

The difference was especially evident among patients who had a low- or medium-risk mantle cell lymphoma international prognostic index, Gregor Verhoef, MD, of University Hospital Leuven (Belgium) and his associates wrote in Haematologica.

In LYM-3002, 487 patients with newly diagnosed stage II-IV mantle cell lymphoma received six to eight 21-day cycles of intravenous VR-CAP or R-CHOP. Although overall response rates were similar for both groups, VR-CAP was associated with better duration of response and progression-free survival (PFS) and extended time to next treatment. To further explore these differences, the post hoc analysis stratified outcomes by response categories and analyzed depth of response based on computed tomography (CT) scans. Patients had a median age of about 65 years, and most were white males with stage-IV disease at diagnosis and an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 1 (Haematologica. 2017 Feb 9. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2016.152496).The superiority of VR-CAP held up across response categories. Complete responders to VR-CAP had more than twice the median PFS as did complete responders to R-CHOP (40.9 vs. 19.8 months; hazard ratio, 0.58; 95% confidence interval, 0.39-0.84; P = .004). Among partial responders, median PFS was 17.1 vs. 11.7 months, respectively (HR, 0.62; 95% CI, 0.43-0.89; P = .01). Respective median duration of overall response was 42.1 months for VR-CAP vs. 18.5 months among complete responders (HR, 0.42; P less than .001), and 20.2 vs. 9.6 months among partial responders (HR, 0.57; P = .006).

Median time to next treatment also favored VR-CAP over R-CHOP among both complete responders (not evaluable vs. 26.6 months; HR, 0.42; P less than .001) and partial responders (35.3 vs. 24.3 months; HR, 0.57; P = .006), the researchers said. Further, CT scans showed that proportionally more patients in each response category became lesion-negative on VR-CAP than on R-CHOP. Among complete responders, rates of lesion negativity were 72% and 59%, respectively. Among partial responders, rates were 48% and 28%.

The effects of VR-CAP were most evident among patients with a low or medium-risk mantle cell lymphoma international prognostic index. Perhaps high-risk status signifies more rapidly proliferative disease, which negates the deeper responses with VR-CAP, compared with R-CHOP, they added.

The LYM-3002 study was supported by Janssen Research & Development and Millennium Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Verhoef had no disclosures. Nine coinvestigators disclosed ties to Janssen, Roche, GlaxoSmithKline, and several other pharmaceutical companies.

For patients with newly diagnosed mantle cell lymphoma, duration and quality of response were superior with a regimen of bortezomib, rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and prednisone (VR-CAP) when compared with rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP), based on a post hoc analysis of the randomized, phase III LYM-3002 trial.

The difference was especially evident among patients who had a low- or medium-risk mantle cell lymphoma international prognostic index, Gregor Verhoef, MD, of University Hospital Leuven (Belgium) and his associates wrote in Haematologica.

In LYM-3002, 487 patients with newly diagnosed stage II-IV mantle cell lymphoma received six to eight 21-day cycles of intravenous VR-CAP or R-CHOP. Although overall response rates were similar for both groups, VR-CAP was associated with better duration of response and progression-free survival (PFS) and extended time to next treatment. To further explore these differences, the post hoc analysis stratified outcomes by response categories and analyzed depth of response based on computed tomography (CT) scans. Patients had a median age of about 65 years, and most were white males with stage-IV disease at diagnosis and an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 1 (Haematologica. 2017 Feb 9. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2016.152496).The superiority of VR-CAP held up across response categories. Complete responders to VR-CAP had more than twice the median PFS as did complete responders to R-CHOP (40.9 vs. 19.8 months; hazard ratio, 0.58; 95% confidence interval, 0.39-0.84; P = .004). Among partial responders, median PFS was 17.1 vs. 11.7 months, respectively (HR, 0.62; 95% CI, 0.43-0.89; P = .01). Respective median duration of overall response was 42.1 months for VR-CAP vs. 18.5 months among complete responders (HR, 0.42; P less than .001), and 20.2 vs. 9.6 months among partial responders (HR, 0.57; P = .006).

Median time to next treatment also favored VR-CAP over R-CHOP among both complete responders (not evaluable vs. 26.6 months; HR, 0.42; P less than .001) and partial responders (35.3 vs. 24.3 months; HR, 0.57; P = .006), the researchers said. Further, CT scans showed that proportionally more patients in each response category became lesion-negative on VR-CAP than on R-CHOP. Among complete responders, rates of lesion negativity were 72% and 59%, respectively. Among partial responders, rates were 48% and 28%.

The effects of VR-CAP were most evident among patients with a low or medium-risk mantle cell lymphoma international prognostic index. Perhaps high-risk status signifies more rapidly proliferative disease, which negates the deeper responses with VR-CAP, compared with R-CHOP, they added.

The LYM-3002 study was supported by Janssen Research & Development and Millennium Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Verhoef had no disclosures. Nine coinvestigators disclosed ties to Janssen, Roche, GlaxoSmithKline, and several other pharmaceutical companies.

For patients with newly diagnosed mantle cell lymphoma, duration and quality of response were superior with a regimen of bortezomib, rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and prednisone (VR-CAP) when compared with rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP), based on a post hoc analysis of the randomized, phase III LYM-3002 trial.

The difference was especially evident among patients who had a low- or medium-risk mantle cell lymphoma international prognostic index, Gregor Verhoef, MD, of University Hospital Leuven (Belgium) and his associates wrote in Haematologica.

In LYM-3002, 487 patients with newly diagnosed stage II-IV mantle cell lymphoma received six to eight 21-day cycles of intravenous VR-CAP or R-CHOP. Although overall response rates were similar for both groups, VR-CAP was associated with better duration of response and progression-free survival (PFS) and extended time to next treatment. To further explore these differences, the post hoc analysis stratified outcomes by response categories and analyzed depth of response based on computed tomography (CT) scans. Patients had a median age of about 65 years, and most were white males with stage-IV disease at diagnosis and an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 1 (Haematologica. 2017 Feb 9. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2016.152496).The superiority of VR-CAP held up across response categories. Complete responders to VR-CAP had more than twice the median PFS as did complete responders to R-CHOP (40.9 vs. 19.8 months; hazard ratio, 0.58; 95% confidence interval, 0.39-0.84; P = .004). Among partial responders, median PFS was 17.1 vs. 11.7 months, respectively (HR, 0.62; 95% CI, 0.43-0.89; P = .01). Respective median duration of overall response was 42.1 months for VR-CAP vs. 18.5 months among complete responders (HR, 0.42; P less than .001), and 20.2 vs. 9.6 months among partial responders (HR, 0.57; P = .006).

Median time to next treatment also favored VR-CAP over R-CHOP among both complete responders (not evaluable vs. 26.6 months; HR, 0.42; P less than .001) and partial responders (35.3 vs. 24.3 months; HR, 0.57; P = .006), the researchers said. Further, CT scans showed that proportionally more patients in each response category became lesion-negative on VR-CAP than on R-CHOP. Among complete responders, rates of lesion negativity were 72% and 59%, respectively. Among partial responders, rates were 48% and 28%.

The effects of VR-CAP were most evident among patients with a low or medium-risk mantle cell lymphoma international prognostic index. Perhaps high-risk status signifies more rapidly proliferative disease, which negates the deeper responses with VR-CAP, compared with R-CHOP, they added.

The LYM-3002 study was supported by Janssen Research & Development and Millennium Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Verhoef had no disclosures. Nine coinvestigators disclosed ties to Janssen, Roche, GlaxoSmithKline, and several other pharmaceutical companies.

FROM HAEMATOLOGICA

Key clinical point: A regimen of bortezomib, rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and prednisone (VR-CAP) led to superior duration and quality of response when compared with rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP) in patients with newly diagnosed mantle cell lymphoma.

Major finding: Among complete responders, median progression-free survival on VR-CAP was nearly twice that of R-CHOP (40.9 vs. 19.8 months; hazard ratio, 0.58; 95% confidence interval, 0.39-0.84; P = .004).

Data source: A post hoc analysis of a phase III trial comparing VR-CAP with R-CHOP in 487 patients with newly diagnosed, measurable stage II-IV mantle cell lymphoma (LYM-3002).

Disclosures: The LYM-3002 study was supported by Janssen Research & Development and Millennium Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Verhoef had no disclosures. Nine coinvestigators disclosed ties to Janssen, Roche, GlaxoSmithKline, and several other pharmaceutical companies.

Anticoagulation Management Outcomes in Veterans: Office vs Telephone Visits

Oral anticoagulation with warfarin is used for the treatment and prevention of a variety of thrombotic disorders, including deep venous thrombosis (DVT), pulmonary embolism (PE), stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation (AF) and atrial flutter, and other hypercoagulable conditions. Although a mainstay in the treatment for these conditions, warfarin requires close monitoring due to its narrow therapeutic range, extensive drug and dietary interactions, and dosage variability among patients.1 Patients outside the therapeutic range are at risk of having a thrombotic or bleeding event that could lead to hospitalization or fatality.1 To reduce the risk of these events, patients on warfarin are managed by dose adjustment based on the international normalized ratio (INR). Research has shown that patients on warfarin in pharmacist-managed specialty anticoagulation clinics have more consistent monitoring and lower rates of adverse events (AEs) compared with traditional physician or nurse clinics.2-6 Management through these clinics can be achieved through office visits or telephone visits.

There are advantages and disadvantages to each model of anticoagulation management for patients.Telephone clinics provide time and cost savings, increased access to care, and convenience. However, disadvantages include missed phone calls or inability to contact the patient, difficulty for the patient to hear the provider’s instructions over the phone, and patient unavailability when a critical INR is of concern. Office visits are beneficial in that providers can provide both written and verbal instruction to patients, perform visual or physical patient assessments, and provide timely care if needed. Disadvantages of office visits may include long wait times and inconvenience for patients who live far away.

Telephone anticoagulation clinics have been evaluated for their efficacy and cost-effectiveness in several studies.5,7,8 However, few studies are available that compare patient outcomes between office visits and telephone visits. Two prior studies comparing groups of anticoagulation patients managed by telephone or by office visit concluded that there is no difference in outcomes between the 2 management models.9,10 However, a retrospective study by Stoudenmire and colleagues examined extreme INR values (≤ 1.5 or ≥ 4.5) in each management model and found that telephone clinic patients have a significant increase in extreme INR values but no difference in AEs between the 2 management models.11

The VA North Texas Health Care System (VANTHCS) includes a major medical center, 3 outlying medical facilities, and 5 community-based outpatient clinics (CBOCs). A centralized pharmacist-managed anticoagulation clinic is used to manage more than 2,500 VANTHCS anticoagulation patients. To meet the National Patient Safety Goal measures and provide consistent management across the system, all anticoagulation patients from CBOCs and medical facilities are enrolled in the clinic.12 To facilitate access to care, many patients transitioned from office visits to telephone visits. It was essential to evaluate the transition of patients from office to telephone visits to ensure continued stability and continuity of care across both models. The objective of this study was to determine whether a difference in anticoagulation outcomes exists when patients are transitioned from office to telephone visits.

Methods

The VANTHCS anticoagulation clinic policy for office visits requires that patients arrive at the Dallas VAMC 2 hours before their appointment for INR lab draw. During the office visit, the anticoagulation pharmacist evaluates the INR and pertinent changes since the previous visit. The patient is provided verbal instructions and a written dosage adjustment card. Telephone clinic protocol is similar to office visits with a few exceptions. Any patient, regardless of INR stability, may be enrolled in the telephone clinic as long as the patient provides consent and has a working telephone with voice mail. Patients enrolled in the telephone clinic access blood draws at the nearest VA facility and are given a questionnaire that includes pertinent questions asked during an office visit. Anticoagulation pharmacists evaluate the questionnaire and INR then contact the patient within 1 business day to provide the patient with instructions. If a patient fails to answer the telephone, the anticoagulation pharmacist leaves a voicemail message.

Study Design

This retrospective study was conducted by chart review using Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) at VANTHCS on patients who met inclusion criteria between January 1, 2011 and May 31, 2014, and it was approved by the institutional review board and research and development committee. The study included patients aged ≥ 18 years on warfarin therapy managed by the VANTHCS anticoagulation clinic who were previously managed in office visits for ≥ 180 days before the telephone transition, then in telephone visits for another ≥ 180 days. Only INR values obtained through the VANTHCS anticoagulation clinic were assessed.

Patients were excluded from the study if they were not managed by the VANTHCS anticoagulation clinic or received direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs). The INR values were excluded if they were nonclinic related INR values (ie, results reported that do not reflect management by the anticoagulation clinic), the first INR after hospitalization, or INRs obtained during the first month of initial warfarin treatment for a patient.

For all patients included in the study, demographic information, goal INR range (2 to 3 or 2.5 to 3.5), indication for warfarin therapy, and duration of warfarin therapy (defined as the first prescription filled for warfarin at the VA) were obtained. Individual INR values were obtained for each patient during the period of investigation and type of visit (office or telephone) for each INR drawn was specified. Any major bleeding or thrombotic events (bleed requiring an emergency department [ED] visit, hospitalization, vitamin K administration, blood transfusion, and/or warfarin therapy hold/discontinuation) were documented. Procedures and number of hospitalizations also during the investigation were recorded.

The primary outcomes measures evaluated INRs for time in therapeutic range (TTR) using the Rosendaal method and percentage of INRs within range.13 The therapeutic range was either 2 to 3 or 2.5 to 3.5 (the “strict range” for INR management). Because many patients fluctuate around the strict range and it is common to avoid therapy adjustment based on slightly elevated or lower values, a “nonstrict” range (1.8 to 3.2 or 2.3 to 3.7) also was evaluated.14 The secondary outcomes examined differences between the 2 management models in rates of major AEs, including thrombosis and major bleeding events as defined earlier.Frequencies, percentages, and other descriptive statistics were used to describe nominal data. A paired t test was used to compare TTR of patients transitioned from office to telephone visits. A P value of < .05 was used for statistical significance.

Results

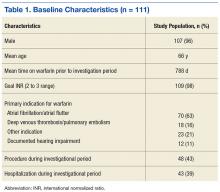

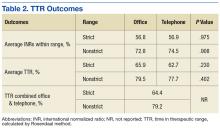

A total of 111 patients met inclusion criteria (Table 1). Most patients were elderly males with AF or atrial flutter as their primary indication for warfarin therapy. No statistically significant difference was found for percentage INRs in strict range (56.8% in office vs 56.9% in telephone, P = .98) or TTR (65.9% in office vs 62.72% in telephone, P = .23) for patients who transitioned from office to telephone visits (Table 2). Similar results were found within the nonstrict range.

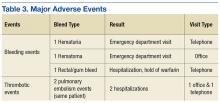

In examining safety, 5 major AEs occurred. One patient had 2 thrombotic pulmonary embolism events. This patient had a history of nonadherence with warfarin therapy. Three major bleeding events occurred (2 in the telephone group and 1 in the office group). Two bleeding events led to ED visits, and 1 event led to hospitalization. Although 43% of patients had a procedure during the study period, only a portion of patients received bridging with low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH). None of the 3 reported bleeding events discovered during the study were associated with recent LMWH use. No events were fatal (Table 3).

Discussion

This study demonstrates that patients transitioned from office to telephone visits for warfarin management will have no significant change in their TTR. Additionally, patients had similar rates of major AEs before and after transition, although there were few events overall.

Previous research comparing anticoagulation outcomes in telephone vs office visits also has described outcomes to be similar between these 2 management models. Wittkowsky and colleagues examined 2 university-affiliated clinics to evaluate warfarin outcomes and AEs in patients in each management model (office vs telephone) and found no difference in outcomes between the 2 management models.9

Staresinic and colleagues designed a prospective study of 192 patients to evaluate TTR and AEs of the 2 management models at the William S. Middleton Memorial Veterans Hospital in Madison, Wisconsin.10 This study found no difference between the 2 groups in percentage of time maintained within INR range or AEs and concluded that the telephone model was effective for anticoagulant management.

A retrospective study by Stoudenmire and colleagues evaluated office vs telephone management effects on extreme INR values (≤ 1.5 or ≥ 4.5), TTR, and AEs.11 This study found overall TTR and AEs to be similar between groups, but the telephone clinic had a 2-fold increase in extreme INR values compared with the office clinic.11

The current study differs from the previously discussed studies in that it evaluated outcomes for the same patients before and after the transition to telephone. This study did not exclude specific patients from telephone clinic. In the Wittkowsky study, patients were enrolled in the telephone clinic based on criteria such as patient disability or living long distances from the clinic.9 Additionally, in the current study, patients transitioned to telephone visits did not have scheduled office visits for anticoagulation management. In contrast, patients in the Staresinic study had routine anticoagulation office visits every 3 months, thus it was not a true telephone-only clinic.10

This study’s findings support prior studies’ findings that telephone clinics are acceptable for anticoagulation management. Furthermore, safety does not seem to be affected when transitioning patients, although there were few AEs to review. Providers can use telephone clinics to potentially decrease cost and facilitate access to care for patients.

Limitations

Patients were required to be in office and telephone for a sequential 6 months, and this may have produced selection biases toward patients who adhered to appointments and who were on long-term warfarin therapy. Many patients that were excluded from the study transitioned back and forth between the 2 management models. Due to the retrospective nature of this study, the authors were unable to control for all confounding variables. Patients also were not randomly assigned to be transitioned from office to telephone. Although a strength of this study was the limited telephone clinic selection criteria, there may be a few individual situations in which the pharmacist’s clinical judgment influenced the transition to the telephone clinic, creating selection bias.

There may be time bias present as clinical guidelines, providers, and clinic population size differed over the study period and might have influenced management. The population of VA patients was mainly elderly males; therefore, the study results may not be applicable to other populations. Last, the results of the study are reflective of the VANTHCS clinic structure and may not be applicable to other clinic designs.

Conclusion

Veterans in a pharmacist-managed anticoagulation clinic experienced the same outcomes in terms of TTR and major AEs when transitioned from the traditional face-to-face office visits to telephone visits. The study supports the safety and efficacy of transitioning patients from a pharmacist-managed anticoagulation office clinic to telephone clinic.

1. Ansell J, Hirsh J, Hylek E, Jacobson A, Crowther M, Palareti G; American College of Chest Physicians. Pharmacology and management of the vitamin K antagonists: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines (8th edition). Chest. 2008;133(suppl 6):160S-198S.

2. Rudd KM, Dier JG. Comparison of two different models of anticoagulation management services with usual medical care. Pharmacotherapy. 2010;30(4):330-338.

3. Bungard TJ, Gardner L, Archer SL, et al. Evaluation of a pharmacist-managed anticoagulation clinic: improving patient care. Open Med. 2009;3(1):e16-e21.

4. Chiquette E, Amato MG, Bussey HI. Comparison of an anticoagulation clinic with usual medical care: anticoagulation control, patient outcomes, and health care costs. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158(15):1641-1647.

5. Waterman AD, Banet G, Milligan PE, et al. Patient and physician satisfaction with a telephone-based anticoagulation service. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(7):460-463.

6. Hasan SS, Shamala R, Syed IA, et al. Factors affecting warfarin-related knowledge and INR control of patients attending physician- and pharmacist-managed anticoagulation clinics. J Pharm Pract. 2011;24(5):485-493.

7. Hassan S, Naboush A, Radbel J, et al. Telephone-based anticoagulation management in the homebound setting: a retrospective observational study. Int J Gen Med. 2013;6:869-875.

8. Moherman LJ, Kolar MM. Complication rates for a telephone-based anticoagulation service. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 1999;56(15):1540-1542.

9. Wittkowsky AK, Nutescu EA, Blackburn J, et al. Outcomes of oral anticoagulant therapy managed by telephone vs in-office visits in an anticoagulation clinic setting. Chest. 2006;130(5):1385-1389.

10. Staresinic AG, Sorkness CA, Goodman BM, Pigarelli DW. Comparison of outcomes using 2 delivery models of anticoagulation care. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(9):997-1002.

11. Stoudenmire LG, DeRemer CE, Elewa H. Telephone versus office-based management of warfarin: impact on international normalized ratios and outcomes. Int J Hematol. 2014;100(2):119-124.

12. The Joint Commission. National Patient Safety Goals Effective January 1, 2015. http://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/6/2015_NPSG_AHC1.PDF. Published 2014. Accessed November 23, 2016.

13. Rosendaal FR, Cannegieter SC, van der Meer FJ, Briët E. A method to determine the optimal intensity of oral anticoagulant therapy. Thromb Haemost. 1993;69(3):236-239.

14. Guyatt GH, Akl EA, Crowther M, Gutterman DD, Schuünemann HJ; American College of Chest Physicians Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis Panel. Executive summary: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(suppl 2):7S-47S.

Oral anticoagulation with warfarin is used for the treatment and prevention of a variety of thrombotic disorders, including deep venous thrombosis (DVT), pulmonary embolism (PE), stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation (AF) and atrial flutter, and other hypercoagulable conditions. Although a mainstay in the treatment for these conditions, warfarin requires close monitoring due to its narrow therapeutic range, extensive drug and dietary interactions, and dosage variability among patients.1 Patients outside the therapeutic range are at risk of having a thrombotic or bleeding event that could lead to hospitalization or fatality.1 To reduce the risk of these events, patients on warfarin are managed by dose adjustment based on the international normalized ratio (INR). Research has shown that patients on warfarin in pharmacist-managed specialty anticoagulation clinics have more consistent monitoring and lower rates of adverse events (AEs) compared with traditional physician or nurse clinics.2-6 Management through these clinics can be achieved through office visits or telephone visits.

There are advantages and disadvantages to each model of anticoagulation management for patients.Telephone clinics provide time and cost savings, increased access to care, and convenience. However, disadvantages include missed phone calls or inability to contact the patient, difficulty for the patient to hear the provider’s instructions over the phone, and patient unavailability when a critical INR is of concern. Office visits are beneficial in that providers can provide both written and verbal instruction to patients, perform visual or physical patient assessments, and provide timely care if needed. Disadvantages of office visits may include long wait times and inconvenience for patients who live far away.

Telephone anticoagulation clinics have been evaluated for their efficacy and cost-effectiveness in several studies.5,7,8 However, few studies are available that compare patient outcomes between office visits and telephone visits. Two prior studies comparing groups of anticoagulation patients managed by telephone or by office visit concluded that there is no difference in outcomes between the 2 management models.9,10 However, a retrospective study by Stoudenmire and colleagues examined extreme INR values (≤ 1.5 or ≥ 4.5) in each management model and found that telephone clinic patients have a significant increase in extreme INR values but no difference in AEs between the 2 management models.11

The VA North Texas Health Care System (VANTHCS) includes a major medical center, 3 outlying medical facilities, and 5 community-based outpatient clinics (CBOCs). A centralized pharmacist-managed anticoagulation clinic is used to manage more than 2,500 VANTHCS anticoagulation patients. To meet the National Patient Safety Goal measures and provide consistent management across the system, all anticoagulation patients from CBOCs and medical facilities are enrolled in the clinic.12 To facilitate access to care, many patients transitioned from office visits to telephone visits. It was essential to evaluate the transition of patients from office to telephone visits to ensure continued stability and continuity of care across both models. The objective of this study was to determine whether a difference in anticoagulation outcomes exists when patients are transitioned from office to telephone visits.

Methods

The VANTHCS anticoagulation clinic policy for office visits requires that patients arrive at the Dallas VAMC 2 hours before their appointment for INR lab draw. During the office visit, the anticoagulation pharmacist evaluates the INR and pertinent changes since the previous visit. The patient is provided verbal instructions and a written dosage adjustment card. Telephone clinic protocol is similar to office visits with a few exceptions. Any patient, regardless of INR stability, may be enrolled in the telephone clinic as long as the patient provides consent and has a working telephone with voice mail. Patients enrolled in the telephone clinic access blood draws at the nearest VA facility and are given a questionnaire that includes pertinent questions asked during an office visit. Anticoagulation pharmacists evaluate the questionnaire and INR then contact the patient within 1 business day to provide the patient with instructions. If a patient fails to answer the telephone, the anticoagulation pharmacist leaves a voicemail message.

Study Design

This retrospective study was conducted by chart review using Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) at VANTHCS on patients who met inclusion criteria between January 1, 2011 and May 31, 2014, and it was approved by the institutional review board and research and development committee. The study included patients aged ≥ 18 years on warfarin therapy managed by the VANTHCS anticoagulation clinic who were previously managed in office visits for ≥ 180 days before the telephone transition, then in telephone visits for another ≥ 180 days. Only INR values obtained through the VANTHCS anticoagulation clinic were assessed.

Patients were excluded from the study if they were not managed by the VANTHCS anticoagulation clinic or received direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs). The INR values were excluded if they were nonclinic related INR values (ie, results reported that do not reflect management by the anticoagulation clinic), the first INR after hospitalization, or INRs obtained during the first month of initial warfarin treatment for a patient.

For all patients included in the study, demographic information, goal INR range (2 to 3 or 2.5 to 3.5), indication for warfarin therapy, and duration of warfarin therapy (defined as the first prescription filled for warfarin at the VA) were obtained. Individual INR values were obtained for each patient during the period of investigation and type of visit (office or telephone) for each INR drawn was specified. Any major bleeding or thrombotic events (bleed requiring an emergency department [ED] visit, hospitalization, vitamin K administration, blood transfusion, and/or warfarin therapy hold/discontinuation) were documented. Procedures and number of hospitalizations also during the investigation were recorded.

The primary outcomes measures evaluated INRs for time in therapeutic range (TTR) using the Rosendaal method and percentage of INRs within range.13 The therapeutic range was either 2 to 3 or 2.5 to 3.5 (the “strict range” for INR management). Because many patients fluctuate around the strict range and it is common to avoid therapy adjustment based on slightly elevated or lower values, a “nonstrict” range (1.8 to 3.2 or 2.3 to 3.7) also was evaluated.14 The secondary outcomes examined differences between the 2 management models in rates of major AEs, including thrombosis and major bleeding events as defined earlier.Frequencies, percentages, and other descriptive statistics were used to describe nominal data. A paired t test was used to compare TTR of patients transitioned from office to telephone visits. A P value of < .05 was used for statistical significance.

Results

A total of 111 patients met inclusion criteria (Table 1). Most patients were elderly males with AF or atrial flutter as their primary indication for warfarin therapy. No statistically significant difference was found for percentage INRs in strict range (56.8% in office vs 56.9% in telephone, P = .98) or TTR (65.9% in office vs 62.72% in telephone, P = .23) for patients who transitioned from office to telephone visits (Table 2). Similar results were found within the nonstrict range.

In examining safety, 5 major AEs occurred. One patient had 2 thrombotic pulmonary embolism events. This patient had a history of nonadherence with warfarin therapy. Three major bleeding events occurred (2 in the telephone group and 1 in the office group). Two bleeding events led to ED visits, and 1 event led to hospitalization. Although 43% of patients had a procedure during the study period, only a portion of patients received bridging with low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH). None of the 3 reported bleeding events discovered during the study were associated with recent LMWH use. No events were fatal (Table 3).

Discussion

This study demonstrates that patients transitioned from office to telephone visits for warfarin management will have no significant change in their TTR. Additionally, patients had similar rates of major AEs before and after transition, although there were few events overall.

Previous research comparing anticoagulation outcomes in telephone vs office visits also has described outcomes to be similar between these 2 management models. Wittkowsky and colleagues examined 2 university-affiliated clinics to evaluate warfarin outcomes and AEs in patients in each management model (office vs telephone) and found no difference in outcomes between the 2 management models.9

Staresinic and colleagues designed a prospective study of 192 patients to evaluate TTR and AEs of the 2 management models at the William S. Middleton Memorial Veterans Hospital in Madison, Wisconsin.10 This study found no difference between the 2 groups in percentage of time maintained within INR range or AEs and concluded that the telephone model was effective for anticoagulant management.

A retrospective study by Stoudenmire and colleagues evaluated office vs telephone management effects on extreme INR values (≤ 1.5 or ≥ 4.5), TTR, and AEs.11 This study found overall TTR and AEs to be similar between groups, but the telephone clinic had a 2-fold increase in extreme INR values compared with the office clinic.11

The current study differs from the previously discussed studies in that it evaluated outcomes for the same patients before and after the transition to telephone. This study did not exclude specific patients from telephone clinic. In the Wittkowsky study, patients were enrolled in the telephone clinic based on criteria such as patient disability or living long distances from the clinic.9 Additionally, in the current study, patients transitioned to telephone visits did not have scheduled office visits for anticoagulation management. In contrast, patients in the Staresinic study had routine anticoagulation office visits every 3 months, thus it was not a true telephone-only clinic.10

This study’s findings support prior studies’ findings that telephone clinics are acceptable for anticoagulation management. Furthermore, safety does not seem to be affected when transitioning patients, although there were few AEs to review. Providers can use telephone clinics to potentially decrease cost and facilitate access to care for patients.

Limitations

Patients were required to be in office and telephone for a sequential 6 months, and this may have produced selection biases toward patients who adhered to appointments and who were on long-term warfarin therapy. Many patients that were excluded from the study transitioned back and forth between the 2 management models. Due to the retrospective nature of this study, the authors were unable to control for all confounding variables. Patients also were not randomly assigned to be transitioned from office to telephone. Although a strength of this study was the limited telephone clinic selection criteria, there may be a few individual situations in which the pharmacist’s clinical judgment influenced the transition to the telephone clinic, creating selection bias.

There may be time bias present as clinical guidelines, providers, and clinic population size differed over the study period and might have influenced management. The population of VA patients was mainly elderly males; therefore, the study results may not be applicable to other populations. Last, the results of the study are reflective of the VANTHCS clinic structure and may not be applicable to other clinic designs.

Conclusion

Veterans in a pharmacist-managed anticoagulation clinic experienced the same outcomes in terms of TTR and major AEs when transitioned from the traditional face-to-face office visits to telephone visits. The study supports the safety and efficacy of transitioning patients from a pharmacist-managed anticoagulation office clinic to telephone clinic.

Oral anticoagulation with warfarin is used for the treatment and prevention of a variety of thrombotic disorders, including deep venous thrombosis (DVT), pulmonary embolism (PE), stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation (AF) and atrial flutter, and other hypercoagulable conditions. Although a mainstay in the treatment for these conditions, warfarin requires close monitoring due to its narrow therapeutic range, extensive drug and dietary interactions, and dosage variability among patients.1 Patients outside the therapeutic range are at risk of having a thrombotic or bleeding event that could lead to hospitalization or fatality.1 To reduce the risk of these events, patients on warfarin are managed by dose adjustment based on the international normalized ratio (INR). Research has shown that patients on warfarin in pharmacist-managed specialty anticoagulation clinics have more consistent monitoring and lower rates of adverse events (AEs) compared with traditional physician or nurse clinics.2-6 Management through these clinics can be achieved through office visits or telephone visits.

There are advantages and disadvantages to each model of anticoagulation management for patients.Telephone clinics provide time and cost savings, increased access to care, and convenience. However, disadvantages include missed phone calls or inability to contact the patient, difficulty for the patient to hear the provider’s instructions over the phone, and patient unavailability when a critical INR is of concern. Office visits are beneficial in that providers can provide both written and verbal instruction to patients, perform visual or physical patient assessments, and provide timely care if needed. Disadvantages of office visits may include long wait times and inconvenience for patients who live far away.

Telephone anticoagulation clinics have been evaluated for their efficacy and cost-effectiveness in several studies.5,7,8 However, few studies are available that compare patient outcomes between office visits and telephone visits. Two prior studies comparing groups of anticoagulation patients managed by telephone or by office visit concluded that there is no difference in outcomes between the 2 management models.9,10 However, a retrospective study by Stoudenmire and colleagues examined extreme INR values (≤ 1.5 or ≥ 4.5) in each management model and found that telephone clinic patients have a significant increase in extreme INR values but no difference in AEs between the 2 management models.11

The VA North Texas Health Care System (VANTHCS) includes a major medical center, 3 outlying medical facilities, and 5 community-based outpatient clinics (CBOCs). A centralized pharmacist-managed anticoagulation clinic is used to manage more than 2,500 VANTHCS anticoagulation patients. To meet the National Patient Safety Goal measures and provide consistent management across the system, all anticoagulation patients from CBOCs and medical facilities are enrolled in the clinic.12 To facilitate access to care, many patients transitioned from office visits to telephone visits. It was essential to evaluate the transition of patients from office to telephone visits to ensure continued stability and continuity of care across both models. The objective of this study was to determine whether a difference in anticoagulation outcomes exists when patients are transitioned from office to telephone visits.

Methods

The VANTHCS anticoagulation clinic policy for office visits requires that patients arrive at the Dallas VAMC 2 hours before their appointment for INR lab draw. During the office visit, the anticoagulation pharmacist evaluates the INR and pertinent changes since the previous visit. The patient is provided verbal instructions and a written dosage adjustment card. Telephone clinic protocol is similar to office visits with a few exceptions. Any patient, regardless of INR stability, may be enrolled in the telephone clinic as long as the patient provides consent and has a working telephone with voice mail. Patients enrolled in the telephone clinic access blood draws at the nearest VA facility and are given a questionnaire that includes pertinent questions asked during an office visit. Anticoagulation pharmacists evaluate the questionnaire and INR then contact the patient within 1 business day to provide the patient with instructions. If a patient fails to answer the telephone, the anticoagulation pharmacist leaves a voicemail message.

Study Design

This retrospective study was conducted by chart review using Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) at VANTHCS on patients who met inclusion criteria between January 1, 2011 and May 31, 2014, and it was approved by the institutional review board and research and development committee. The study included patients aged ≥ 18 years on warfarin therapy managed by the VANTHCS anticoagulation clinic who were previously managed in office visits for ≥ 180 days before the telephone transition, then in telephone visits for another ≥ 180 days. Only INR values obtained through the VANTHCS anticoagulation clinic were assessed.

Patients were excluded from the study if they were not managed by the VANTHCS anticoagulation clinic or received direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs). The INR values were excluded if they were nonclinic related INR values (ie, results reported that do not reflect management by the anticoagulation clinic), the first INR after hospitalization, or INRs obtained during the first month of initial warfarin treatment for a patient.

For all patients included in the study, demographic information, goal INR range (2 to 3 or 2.5 to 3.5), indication for warfarin therapy, and duration of warfarin therapy (defined as the first prescription filled for warfarin at the VA) were obtained. Individual INR values were obtained for each patient during the period of investigation and type of visit (office or telephone) for each INR drawn was specified. Any major bleeding or thrombotic events (bleed requiring an emergency department [ED] visit, hospitalization, vitamin K administration, blood transfusion, and/or warfarin therapy hold/discontinuation) were documented. Procedures and number of hospitalizations also during the investigation were recorded.

The primary outcomes measures evaluated INRs for time in therapeutic range (TTR) using the Rosendaal method and percentage of INRs within range.13 The therapeutic range was either 2 to 3 or 2.5 to 3.5 (the “strict range” for INR management). Because many patients fluctuate around the strict range and it is common to avoid therapy adjustment based on slightly elevated or lower values, a “nonstrict” range (1.8 to 3.2 or 2.3 to 3.7) also was evaluated.14 The secondary outcomes examined differences between the 2 management models in rates of major AEs, including thrombosis and major bleeding events as defined earlier.Frequencies, percentages, and other descriptive statistics were used to describe nominal data. A paired t test was used to compare TTR of patients transitioned from office to telephone visits. A P value of < .05 was used for statistical significance.

Results

A total of 111 patients met inclusion criteria (Table 1). Most patients were elderly males with AF or atrial flutter as their primary indication for warfarin therapy. No statistically significant difference was found for percentage INRs in strict range (56.8% in office vs 56.9% in telephone, P = .98) or TTR (65.9% in office vs 62.72% in telephone, P = .23) for patients who transitioned from office to telephone visits (Table 2). Similar results were found within the nonstrict range.

In examining safety, 5 major AEs occurred. One patient had 2 thrombotic pulmonary embolism events. This patient had a history of nonadherence with warfarin therapy. Three major bleeding events occurred (2 in the telephone group and 1 in the office group). Two bleeding events led to ED visits, and 1 event led to hospitalization. Although 43% of patients had a procedure during the study period, only a portion of patients received bridging with low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH). None of the 3 reported bleeding events discovered during the study were associated with recent LMWH use. No events were fatal (Table 3).

Discussion

This study demonstrates that patients transitioned from office to telephone visits for warfarin management will have no significant change in their TTR. Additionally, patients had similar rates of major AEs before and after transition, although there were few events overall.

Previous research comparing anticoagulation outcomes in telephone vs office visits also has described outcomes to be similar between these 2 management models. Wittkowsky and colleagues examined 2 university-affiliated clinics to evaluate warfarin outcomes and AEs in patients in each management model (office vs telephone) and found no difference in outcomes between the 2 management models.9

Staresinic and colleagues designed a prospective study of 192 patients to evaluate TTR and AEs of the 2 management models at the William S. Middleton Memorial Veterans Hospital in Madison, Wisconsin.10 This study found no difference between the 2 groups in percentage of time maintained within INR range or AEs and concluded that the telephone model was effective for anticoagulant management.

A retrospective study by Stoudenmire and colleagues evaluated office vs telephone management effects on extreme INR values (≤ 1.5 or ≥ 4.5), TTR, and AEs.11 This study found overall TTR and AEs to be similar between groups, but the telephone clinic had a 2-fold increase in extreme INR values compared with the office clinic.11

The current study differs from the previously discussed studies in that it evaluated outcomes for the same patients before and after the transition to telephone. This study did not exclude specific patients from telephone clinic. In the Wittkowsky study, patients were enrolled in the telephone clinic based on criteria such as patient disability or living long distances from the clinic.9 Additionally, in the current study, patients transitioned to telephone visits did not have scheduled office visits for anticoagulation management. In contrast, patients in the Staresinic study had routine anticoagulation office visits every 3 months, thus it was not a true telephone-only clinic.10

This study’s findings support prior studies’ findings that telephone clinics are acceptable for anticoagulation management. Furthermore, safety does not seem to be affected when transitioning patients, although there were few AEs to review. Providers can use telephone clinics to potentially decrease cost and facilitate access to care for patients.

Limitations

Patients were required to be in office and telephone for a sequential 6 months, and this may have produced selection biases toward patients who adhered to appointments and who were on long-term warfarin therapy. Many patients that were excluded from the study transitioned back and forth between the 2 management models. Due to the retrospective nature of this study, the authors were unable to control for all confounding variables. Patients also were not randomly assigned to be transitioned from office to telephone. Although a strength of this study was the limited telephone clinic selection criteria, there may be a few individual situations in which the pharmacist’s clinical judgment influenced the transition to the telephone clinic, creating selection bias.

There may be time bias present as clinical guidelines, providers, and clinic population size differed over the study period and might have influenced management. The population of VA patients was mainly elderly males; therefore, the study results may not be applicable to other populations. Last, the results of the study are reflective of the VANTHCS clinic structure and may not be applicable to other clinic designs.

Conclusion

Veterans in a pharmacist-managed anticoagulation clinic experienced the same outcomes in terms of TTR and major AEs when transitioned from the traditional face-to-face office visits to telephone visits. The study supports the safety and efficacy of transitioning patients from a pharmacist-managed anticoagulation office clinic to telephone clinic.

1. Ansell J, Hirsh J, Hylek E, Jacobson A, Crowther M, Palareti G; American College of Chest Physicians. Pharmacology and management of the vitamin K antagonists: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines (8th edition). Chest. 2008;133(suppl 6):160S-198S.

2. Rudd KM, Dier JG. Comparison of two different models of anticoagulation management services with usual medical care. Pharmacotherapy. 2010;30(4):330-338.

3. Bungard TJ, Gardner L, Archer SL, et al. Evaluation of a pharmacist-managed anticoagulation clinic: improving patient care. Open Med. 2009;3(1):e16-e21.

4. Chiquette E, Amato MG, Bussey HI. Comparison of an anticoagulation clinic with usual medical care: anticoagulation control, patient outcomes, and health care costs. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158(15):1641-1647.

5. Waterman AD, Banet G, Milligan PE, et al. Patient and physician satisfaction with a telephone-based anticoagulation service. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(7):460-463.

6. Hasan SS, Shamala R, Syed IA, et al. Factors affecting warfarin-related knowledge and INR control of patients attending physician- and pharmacist-managed anticoagulation clinics. J Pharm Pract. 2011;24(5):485-493.

7. Hassan S, Naboush A, Radbel J, et al. Telephone-based anticoagulation management in the homebound setting: a retrospective observational study. Int J Gen Med. 2013;6:869-875.

8. Moherman LJ, Kolar MM. Complication rates for a telephone-based anticoagulation service. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 1999;56(15):1540-1542.

9. Wittkowsky AK, Nutescu EA, Blackburn J, et al. Outcomes of oral anticoagulant therapy managed by telephone vs in-office visits in an anticoagulation clinic setting. Chest. 2006;130(5):1385-1389.

10. Staresinic AG, Sorkness CA, Goodman BM, Pigarelli DW. Comparison of outcomes using 2 delivery models of anticoagulation care. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(9):997-1002.

11. Stoudenmire LG, DeRemer CE, Elewa H. Telephone versus office-based management of warfarin: impact on international normalized ratios and outcomes. Int J Hematol. 2014;100(2):119-124.

12. The Joint Commission. National Patient Safety Goals Effective January 1, 2015. http://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/6/2015_NPSG_AHC1.PDF. Published 2014. Accessed November 23, 2016.

13. Rosendaal FR, Cannegieter SC, van der Meer FJ, Briët E. A method to determine the optimal intensity of oral anticoagulant therapy. Thromb Haemost. 1993;69(3):236-239.

14. Guyatt GH, Akl EA, Crowther M, Gutterman DD, Schuünemann HJ; American College of Chest Physicians Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis Panel. Executive summary: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(suppl 2):7S-47S.

1. Ansell J, Hirsh J, Hylek E, Jacobson A, Crowther M, Palareti G; American College of Chest Physicians. Pharmacology and management of the vitamin K antagonists: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines (8th edition). Chest. 2008;133(suppl 6):160S-198S.

2. Rudd KM, Dier JG. Comparison of two different models of anticoagulation management services with usual medical care. Pharmacotherapy. 2010;30(4):330-338.

3. Bungard TJ, Gardner L, Archer SL, et al. Evaluation of a pharmacist-managed anticoagulation clinic: improving patient care. Open Med. 2009;3(1):e16-e21.

4. Chiquette E, Amato MG, Bussey HI. Comparison of an anticoagulation clinic with usual medical care: anticoagulation control, patient outcomes, and health care costs. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158(15):1641-1647.

5. Waterman AD, Banet G, Milligan PE, et al. Patient and physician satisfaction with a telephone-based anticoagulation service. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(7):460-463.

6. Hasan SS, Shamala R, Syed IA, et al. Factors affecting warfarin-related knowledge and INR control of patients attending physician- and pharmacist-managed anticoagulation clinics. J Pharm Pract. 2011;24(5):485-493.

7. Hassan S, Naboush A, Radbel J, et al. Telephone-based anticoagulation management in the homebound setting: a retrospective observational study. Int J Gen Med. 2013;6:869-875.

8. Moherman LJ, Kolar MM. Complication rates for a telephone-based anticoagulation service. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 1999;56(15):1540-1542.

9. Wittkowsky AK, Nutescu EA, Blackburn J, et al. Outcomes of oral anticoagulant therapy managed by telephone vs in-office visits in an anticoagulation clinic setting. Chest. 2006;130(5):1385-1389.

10. Staresinic AG, Sorkness CA, Goodman BM, Pigarelli DW. Comparison of outcomes using 2 delivery models of anticoagulation care. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(9):997-1002.

11. Stoudenmire LG, DeRemer CE, Elewa H. Telephone versus office-based management of warfarin: impact on international normalized ratios and outcomes. Int J Hematol. 2014;100(2):119-124.

12. The Joint Commission. National Patient Safety Goals Effective January 1, 2015. http://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/6/2015_NPSG_AHC1.PDF. Published 2014. Accessed November 23, 2016.

13. Rosendaal FR, Cannegieter SC, van der Meer FJ, Briët E. A method to determine the optimal intensity of oral anticoagulant therapy. Thromb Haemost. 1993;69(3):236-239.

14. Guyatt GH, Akl EA, Crowther M, Gutterman DD, Schuünemann HJ; American College of Chest Physicians Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis Panel. Executive summary: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(suppl 2):7S-47S.

Sprint to find Zika vaccine could hinge on summer outbreaks

As warmer temperatures herald the arrival of pesky mosquitoes, researchers are feverishly working on several promising vaccines against Zika, a virus notorious for infecting humans through this insect’s bite.

The speed and debilitating effects of last year’s Zika outbreak in the Western Hemisphere prompted a sprint to develop a vaccine. Just a little more than a year after the pandemic was declared a global health emergency, a handful of candidates are undergoing preliminary testing in humans.

“On one hand, you don’t want to see outbreaks of infection,” said Anthony Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. “But on the other hand, [without that testing] you might have to wait a long time to make sure that the vaccine works.”

All the vaccines currently being tested are in phase I clinical trials, which means they are being tested for safety in a small number of people. According to a review paper published Tuesday in the journal Immunity, the vaccines represent a variety of scientific techniques to thwart the disease, ranging from inactivating the virus to manipulating its DNA.

The NIAID announced Tuesday it is launching yet another phase I trial for a vaccine made out of proteins found in mosquito saliva. The product is intended to trigger a human immune system response to the mosquito’s saliva and any viruses mixed with it. If successful, the product could protect humans against a spectrum of mosquito-transmitted diseases, including Zika.

Col. Nelson Michael, MD, PhD, director of the U.S. Military HIV Research Program at the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research in Silver Spring, Md., and coauthor of the paper, said he expects preliminary reports on the safety of some of the older vaccines in April. As of now, he said, it is impossible to guess which vaccine will prove most effective in providing immunity.

“Sometimes it’s difficult to predict which horse will win the race,” Michael said.

Zika – which is spread from infected people to others by mosquito bites or sexual contact, often infects people without showing symptoms. In some cases, it causes flu-like symptoms, such as fever, muscle aches and joint pain in adults – and, in rare cases, Guillain-Barré syndrome, which can cause temporary paralysis. But it is most notorious for causing some children to be born with microcephaly – a birth defect in which a child’s head is smaller than the average size – if their mothers were exposed to Zika.

The virus garnered international attention after hundreds of cases of disabled babies surfaced in Brazil. It quickly swept through South America and the Caribbean before stopping on the southern coast of the U.S.

The World Health Organization declared the outbreak a “public health emergency of international concern” on Feb. 1, 2016, then ended the alert on Nov. 18.