User login

AATS Mitral Conclave Call for Abstracts & Videos

AATS invites you to submit your abstracts and videos to the 2017 Mitral Conclave.

AATS Mitral Conclave

April 27-28, 2017

New York, NY

Submission Deadline:

Sunday, January 8, 2017 @ 11.59 pm EST

Share:

AATS invites you to submit your abstracts and videos to the 2017 Mitral Conclave.

AATS Mitral Conclave

April 27-28, 2017

New York, NY

Submission Deadline:

Sunday, January 8, 2017 @ 11.59 pm EST

Share:

AATS invites you to submit your abstracts and videos to the 2017 Mitral Conclave.

AATS Mitral Conclave

April 27-28, 2017

New York, NY

Submission Deadline:

Sunday, January 8, 2017 @ 11.59 pm EST

Share:

Hinged-Knee External Fixator Used to Reduce and Maintain Subacute Tibiofemoral Coronal Subluxation

Dislocation of the knee is a severe injury that usually results from high-energy blunt trauma.1 Recognition of knee dislocations has increased with expansion of the definition beyond radiographically confirmed loss of tibiofemoral articulation to include injury of multiple knee ligaments with multidirectional joint instability, or the rupture of the anterior and posterior cruciate ligaments (ACL, PCL) when no gross dislocation can be identified2 (though knee dislocations without rupture of either ligament have been reported3,4). Knee dislocations account for 0.02% to 0.2% of orthopedic injuries.5 These multiligamentous injuries are rare, but their clinical outcomes are often complicated by arthrofibrosis, pain, and instability, as surgeons contend with the competing interests of long-term joint stability and range of motion (ROM).6-9

Whereas treatment standards for acute knee dislocations are becoming clearer, treatment of subacute and chronic tibiofemoral dislocations and subluxations is less defined.5 Success with articulated external fixation originally across the ankle and elbow inspired interest in its use for the knee.10-12 Richter and Lobenhoffer13 and Simonian and colleagues14 were the first to report on the postoperative use of a hinged external fixation device to help maintain the reduction of chronic fixed posterior knee dislocations. The literature has even supported nonoperative reduction of small fixed anterior or posterior (sagittal) subluxations with knee bracing alone.15,16 However, there are no reports on treatment of chronic tibial subluxation in the coronal plane.

We report a case of a hinged-knee external fixator (HEF) used alone to reduce a chronic medial tibia subluxation that presented after initial repair of a knee dislocation sustained in a motor vehicle accident. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

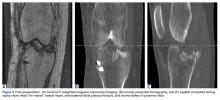

A 51-year-old healthy woman who was traveling out of state sustained multiple orthopedic injuries in a motor vehicle accident. She had a pelvic fracture, a contralateral femoral shaft fracture, significant multiligamentous damage to the right knee, and a cavitary impaction fracture of the tibial eminence with resultant coronal tibial subluxation. Initial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed the tibia injury likely was the result of varus translation, as the medial femoral condyle impacted the tibial spine, disrupting the ACL (Figures 1A, 1B).

On initial presentation to our clinic 5 weeks after injury, x-rays showed progressive medial subluxation of the tibia in relation to the femur with translation of about a third of the tibial width medially (Figures 2A, 2B).

Given the worsening tibial subluxation and resultant instability, the patient was taken to the operating room for examination under anesthesia, and planned closed reduction and spanning external fixation. Fluoroscopy of the lateral translation and external rotation of the tibia allowed us to reduce the joint, with the lateral tibial plateau and lateral femoral condyle relatively but not completely concentric. A rigid spanning multiplanar external fixator was then placed to maintain the knee joint in a more reduced position.

A week later, the patient was taken back to the operating room for arthroscopic evaluation of the knee joint. At the time of her index operation at the outside institution, she had undergone arthroscopic débridement of intra-articular loose bodies and lateral meniscus repair. Now it was found that the meniscus was not healed but had displaced. A bucket-handle lateral meniscus tear appeared to be blocking lateral translation of the tibia, thus impeding complete reduction.

Given the meniscus deformity that resulted from the chronicity of the injury and the resultant subluxation, a sub-total lateral meniscectomy was performed. As the patient was now noted to have an intact medial collateral ligament and an intact en masse lateral repair, we converted the spanning external fixator to a Compass Universal Hinge (Smith & Nephew) to maintain reduction without further ligamentous reconstruction (Figure 4).

After HEF placement, the patient spent a short time recovering at an inpatient rehabilitation facility before starting aggressive twice-a-week outpatient physical therapy. Initially after HEF placement, she could not actively flex the knee to about 40° or fully extend it concentrically. Given these limitations and concern about interval development of arthrofibrosis, manipulation under anesthesia was performed, 3 weeks after surgery, and 90° of flexion was obtained.

Six weeks after HEF removal, the patient was ambulating well with a cane, pain was minimal, and knee ROM was up to 110° of flexion. Tibiofemoral stability remained constant—no change in medial or lateral joint space opening. Full-extension radiographs showed medial translation of about 5 mm, which decreased to 1 mm on Rosenberg view. This represents marked improvement over the severe subluxation on initial presentation.

Follow-up over the next months revealed continued improvement in the right lower extremity strength, increased tolerance for physical activity, and stable right medial tibial translation.

At 5-year follow-up, the patient was asymptomatic, had continued coronal and sagittal stability, and was tolerating regular aerobic exercise, including hiking, weight training, and cycling. Physical examination revealed grade 1B Lachman, grade 0 pivot shift, and grade 0 posterior drawer. There was 3 mm increased lateral compartment opening in full extension, which increased to about 6 mm at 30° with endpoint.

Discussion

Although knee dislocations with multiligamentous involvement are rare, their outcomes can be poor. Fortunately, the principles of managing these complex injuries in the acute stage are becoming clearer. In a systematic review, Levy and colleagues18 found that operative treatment of a dislocated knee within 3 weeks after injury, compared with nonoperative or delayed treatment, resulted in improved functional outcomes. Ligament repair and reconstruction yielded similar outcomes, though repair of the posterolateral corner had a comparatively higher rate of failure. For associated lateral injuries, Shelbourne and colleagues17 advocated en masse repair in which the healing tissue complex is reattached to the tibia nonanatomically, without dissecting individual structures—a technique used in the original repair of our patient’s injuries.

Originally designed for other joints, hinged external fixators are now occasionally used for rehabilitation after traumatic knee injury. Stannard and colleagues9 recently confirmed the utility of the HEF as a supplement to ligament reconstruction for recovery from acute knee dislocation.9 Compared with postoperative use of a hinged-knee brace, HEF use resulted in fewer failed ligament reconstructions as well as equivalent joint ROM and Lysholm and IKDC scores at final follow-up. This clinical outcome is supported by results of kinematic studies of these hinged devices, which are capable of rigid fixation in all planes except sagittal and can reduce stress on intra-articular and periarticular ligaments when placed on the appropriate flexion-extension axis of the knee.19,20Unfortunately, the situation is more complicated for subacute or chronic tibial subluxation than for acute subluxation. Maak and colleagues16 described 3 operative steps that are crucial in obtaining desired outcomes in this setting: complete release of scar tissue, re-creation of knee axis through ACL and PCL reconstruction, and postoperative application of a HEF or knee brace. These recommendations mimic the management course described by Richter and Lobenhoffer13 and Simonian and colleagues,14 who treated chronic fixed posterior tibial subluxations with arthrolysis, ligament reconstruction, and use of HEFs for 6 weeks, supporting postoperative rehabilitation. All cases maintained reduction at follow-up after fixator removal.

It is also possible for small fixed anterior or posterior tibial subluxations to be managed nonoperatively. Strobel and colleagues15 described a series of 109 patients with fixed posterior subluxations treated at night with posterior tibial support braces. Mean subluxation was reduced from 6.93 mm to 2.58 mm after an average treatment period of 180 days. Although 60% of all subluxations were completely reduced, reductions were significantly more successful for those displaced <10 mm.

Management of subacute or chronic fixed coronal tibial subluxations is yet to be described. In this article, we have reported on acceptable reduction of a subacute medial tibial subluxation with use of a HEF for 6 weeks after arthroscopic débridement of a deformed subacute bucket-handle lateral meniscus tear. Our case report is unique in that it describes use of a HEF alone for the reduction of a subacute tibial subluxation in any plane without the need for more extensive ligament reconstruction.

The injury here was primarily a lateral ligamentous injury. In the nonanatomical repair that was performed, the LCL and the iliotibial band were reattached to the proximal-lateral tibia. Had we started treating this injury from the time of the patient’s accident, then, depending on repair integrity, we might have considered acute augmentation of the anatomical repair of LCL with Larson-type reconstruction of the LCL and the popliteofibular ligament. Alternatively, acute reconstruction of the LCL and popliteus would be considered if the lateral structures were either irreparable or of very poor quality. In addition, had we initially seen the coronal instability/translation, we might have acutely considered either a staged procedure of a multiplanar external fixator or a HEF.

Given the narrowed lateral joint space, the débridement of the lateral meniscus, and the risk of developing posttraumatic arthritis, our patient will probably need total knee arthroplasty (TKA) at some point. We informed her that she had advanced lateral compartment joint space narrowing and arthritic progression and that she would eventually need TKA based on pain or dysfunction. We think the longevity of that TKA will be predictable and good, as she now had improved tibiofemoral alignment and stability of the collateral ligamentous structures. If she had been allowed to maintain the coronally subluxed position, it would have led to medial ligamentous attenuation and would have compromised the success and longevity of the TKA. In essence, a crucial part of the utility of the HEF was improved coronal tibiofemoral alignment and, therefore, decreased abnormal forces on both the repaired lateral ligaments and the native medial ligamentous structures. Although temporary external fixation issues related to infection risk and patient discomfort are recognized,21-23 use of HEF alone can be part of the treatment considerations for fixed tibial subluxations in any plane when they present after treatment for multiligamentous injury.

Am J Orthop. 2016;45(7):E497-E502. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2016. All rights reserved.

1. Stannard JP, Sheils TM, McGwin G, Volgas DA, Alonso JE. Use of a hinged external knee fixator after surgery for knee dislocation. Arthroscopy. 2003;19(6):626-631.

2. Yeh WL, Tu YK, Su JY, Hsu RW. Knee dislocation: treatment of high-velocity knee dislocation. J Trauma. 1999;46(4):693-701.

3. Bellabarba C, Bush-Joseph CA, Bach BR Jr. Knee dislocation without anterior cruciate ligament disruption. A report of three cases. Am J Knee Surg. 1996;9(4):167-170.

4. Cooper DE, Speer KP, Wickiewicz TL, Warren RF. Complete knee dislocation without posterior cruciate ligament disruption. A report of four cases and review of the literature. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1992;(284):228-233.

5. Howells NR, Brunton LR, Robinson J, Porteus AJ, Eldridge JD, Murray JR. Acute knee dislocation: an evidence based approach to the management of the multiligament injured knee. Injury. 2011;42(11):1198-1204.

6. Magit D, Wolff A, Sutton K, Medvecky MJ. Arthrofibrosis of the knee. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2007;15(11):682-694.

7. Medvecky MJ, Zazulak BT, Hewett TE. A multidisciplinary approach to the evaluation, reconstruction and rehabilitation of the multi-ligament injured athlete. Sports Med. 2007;37(2):169-187.

8. Noyes FR, Barber-Westin SD. Reconstruction of the anterior and posterior cruciate ligaments after knee dislocation. Use of early protected postoperative motion to decrease arthrofibrosis. Am J Sports Med. 1997;25(6):769-778.

9. Stannard JP, Nuelle CW, McGwin G, Volgas DA. Hinged external fixation in the treatment of knee dislocations: a prospective randomized study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(3):184-191.

10. Bottlang M, Marsh JL, Brown TD. Articulated external fixation of the ankle: minimizing motion resistance by accurate axis alignment. J Biomech. 1999;32(1):63-70.

11. Madey SM, Bottlang M, Steyers CM, Marsh JL, Brown TD. Hinged external fixation of the elbow: optimal axis alignment to minimize motion resistance. J Orthop Trauma. 2000;14(1):41-47.

12. Jupiter JB, Ring D. Treatment of unreduced elbow dislocations with hinged external fixation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84(9):1630-1635.

13. Richter M, Lobenhoffer P. Chronic posterior knee dislocation: treatment with arthrolysis, posterior cruciate ligament reconstruction and hinged external fixation device. Injury. 1998;29(7):546-549.

14. Simonian PT, Wickiewicz TL, Hotchkiss RN, Warren RF. Chronic knee dislocation: reduction, reconstruction, and application of a skeletally fixed knee hinge. A report of two cases. Am J Sports Med. 1998;26(4):591-596.

15. Strobel MJ, Weiler A, Schulz MS, Russe K, Eichhorn HJ. Fixed posterior subluxation in posterior cruciate ligament-deficient knees: diagnosis and treatment of a new clinical sign. Am J Sports Med. 2002;30(1):32-38.

16. Maak TG, Marx RG, Wickiewicz TL. Management of chronic tibial subluxation in the multiple-ligament injured knee. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev. 2011;19(2):147-152.

17. Shelbourne KD, Haro MS, Gray T. Knee dislocation with lateral side injury: results of an en masse surgical repair technique of the lateral side. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(7):1105-1116.

18. Levy BA, Fanelli GC, Whelan DB, et al. Controversies in the treatment of knee dislocations and multiligament reconstruction. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2009;17(4):197-206.

19. Fitzpatrick DC, Sommers MB, Kam BC, Marsh JL, Bottlang M. Knee stability after articulated external fixation. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33(11):1735-1741.

20. Sommers MB, Fitzpatrick DC, Kahn KM, Marsh JL, Bottlang M. Hinged external fixation of the knee: intrinsic factors influencing passive joint motion. J Orthop Trauma. 2004;18(3):163-169.

21. Anglen JO, Aleto T. Temporary transarticular external fixation of the knee and ankle. J Orthop Trauma. 1998;12(6):431-434.

22. Behrens F. General theory and principles of external fixation. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1989;(241):15-23.

23. Haidukewych GJ. Temporary external fixation for the management of complex intra- and periarticular fractures of the lower extremity. J Orthop Trauma. 2002;16(9):678-685.

Dislocation of the knee is a severe injury that usually results from high-energy blunt trauma.1 Recognition of knee dislocations has increased with expansion of the definition beyond radiographically confirmed loss of tibiofemoral articulation to include injury of multiple knee ligaments with multidirectional joint instability, or the rupture of the anterior and posterior cruciate ligaments (ACL, PCL) when no gross dislocation can be identified2 (though knee dislocations without rupture of either ligament have been reported3,4). Knee dislocations account for 0.02% to 0.2% of orthopedic injuries.5 These multiligamentous injuries are rare, but their clinical outcomes are often complicated by arthrofibrosis, pain, and instability, as surgeons contend with the competing interests of long-term joint stability and range of motion (ROM).6-9

Whereas treatment standards for acute knee dislocations are becoming clearer, treatment of subacute and chronic tibiofemoral dislocations and subluxations is less defined.5 Success with articulated external fixation originally across the ankle and elbow inspired interest in its use for the knee.10-12 Richter and Lobenhoffer13 and Simonian and colleagues14 were the first to report on the postoperative use of a hinged external fixation device to help maintain the reduction of chronic fixed posterior knee dislocations. The literature has even supported nonoperative reduction of small fixed anterior or posterior (sagittal) subluxations with knee bracing alone.15,16 However, there are no reports on treatment of chronic tibial subluxation in the coronal plane.

We report a case of a hinged-knee external fixator (HEF) used alone to reduce a chronic medial tibia subluxation that presented after initial repair of a knee dislocation sustained in a motor vehicle accident. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 51-year-old healthy woman who was traveling out of state sustained multiple orthopedic injuries in a motor vehicle accident. She had a pelvic fracture, a contralateral femoral shaft fracture, significant multiligamentous damage to the right knee, and a cavitary impaction fracture of the tibial eminence with resultant coronal tibial subluxation. Initial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed the tibia injury likely was the result of varus translation, as the medial femoral condyle impacted the tibial spine, disrupting the ACL (Figures 1A, 1B).

On initial presentation to our clinic 5 weeks after injury, x-rays showed progressive medial subluxation of the tibia in relation to the femur with translation of about a third of the tibial width medially (Figures 2A, 2B).

Given the worsening tibial subluxation and resultant instability, the patient was taken to the operating room for examination under anesthesia, and planned closed reduction and spanning external fixation. Fluoroscopy of the lateral translation and external rotation of the tibia allowed us to reduce the joint, with the lateral tibial plateau and lateral femoral condyle relatively but not completely concentric. A rigid spanning multiplanar external fixator was then placed to maintain the knee joint in a more reduced position.

A week later, the patient was taken back to the operating room for arthroscopic evaluation of the knee joint. At the time of her index operation at the outside institution, she had undergone arthroscopic débridement of intra-articular loose bodies and lateral meniscus repair. Now it was found that the meniscus was not healed but had displaced. A bucket-handle lateral meniscus tear appeared to be blocking lateral translation of the tibia, thus impeding complete reduction.

Given the meniscus deformity that resulted from the chronicity of the injury and the resultant subluxation, a sub-total lateral meniscectomy was performed. As the patient was now noted to have an intact medial collateral ligament and an intact en masse lateral repair, we converted the spanning external fixator to a Compass Universal Hinge (Smith & Nephew) to maintain reduction without further ligamentous reconstruction (Figure 4).

After HEF placement, the patient spent a short time recovering at an inpatient rehabilitation facility before starting aggressive twice-a-week outpatient physical therapy. Initially after HEF placement, she could not actively flex the knee to about 40° or fully extend it concentrically. Given these limitations and concern about interval development of arthrofibrosis, manipulation under anesthesia was performed, 3 weeks after surgery, and 90° of flexion was obtained.

Six weeks after HEF removal, the patient was ambulating well with a cane, pain was minimal, and knee ROM was up to 110° of flexion. Tibiofemoral stability remained constant—no change in medial or lateral joint space opening. Full-extension radiographs showed medial translation of about 5 mm, which decreased to 1 mm on Rosenberg view. This represents marked improvement over the severe subluxation on initial presentation.

Follow-up over the next months revealed continued improvement in the right lower extremity strength, increased tolerance for physical activity, and stable right medial tibial translation.

At 5-year follow-up, the patient was asymptomatic, had continued coronal and sagittal stability, and was tolerating regular aerobic exercise, including hiking, weight training, and cycling. Physical examination revealed grade 1B Lachman, grade 0 pivot shift, and grade 0 posterior drawer. There was 3 mm increased lateral compartment opening in full extension, which increased to about 6 mm at 30° with endpoint.

Discussion

Although knee dislocations with multiligamentous involvement are rare, their outcomes can be poor. Fortunately, the principles of managing these complex injuries in the acute stage are becoming clearer. In a systematic review, Levy and colleagues18 found that operative treatment of a dislocated knee within 3 weeks after injury, compared with nonoperative or delayed treatment, resulted in improved functional outcomes. Ligament repair and reconstruction yielded similar outcomes, though repair of the posterolateral corner had a comparatively higher rate of failure. For associated lateral injuries, Shelbourne and colleagues17 advocated en masse repair in which the healing tissue complex is reattached to the tibia nonanatomically, without dissecting individual structures—a technique used in the original repair of our patient’s injuries.

Originally designed for other joints, hinged external fixators are now occasionally used for rehabilitation after traumatic knee injury. Stannard and colleagues9 recently confirmed the utility of the HEF as a supplement to ligament reconstruction for recovery from acute knee dislocation.9 Compared with postoperative use of a hinged-knee brace, HEF use resulted in fewer failed ligament reconstructions as well as equivalent joint ROM and Lysholm and IKDC scores at final follow-up. This clinical outcome is supported by results of kinematic studies of these hinged devices, which are capable of rigid fixation in all planes except sagittal and can reduce stress on intra-articular and periarticular ligaments when placed on the appropriate flexion-extension axis of the knee.19,20Unfortunately, the situation is more complicated for subacute or chronic tibial subluxation than for acute subluxation. Maak and colleagues16 described 3 operative steps that are crucial in obtaining desired outcomes in this setting: complete release of scar tissue, re-creation of knee axis through ACL and PCL reconstruction, and postoperative application of a HEF or knee brace. These recommendations mimic the management course described by Richter and Lobenhoffer13 and Simonian and colleagues,14 who treated chronic fixed posterior tibial subluxations with arthrolysis, ligament reconstruction, and use of HEFs for 6 weeks, supporting postoperative rehabilitation. All cases maintained reduction at follow-up after fixator removal.

It is also possible for small fixed anterior or posterior tibial subluxations to be managed nonoperatively. Strobel and colleagues15 described a series of 109 patients with fixed posterior subluxations treated at night with posterior tibial support braces. Mean subluxation was reduced from 6.93 mm to 2.58 mm after an average treatment period of 180 days. Although 60% of all subluxations were completely reduced, reductions were significantly more successful for those displaced <10 mm.

Management of subacute or chronic fixed coronal tibial subluxations is yet to be described. In this article, we have reported on acceptable reduction of a subacute medial tibial subluxation with use of a HEF for 6 weeks after arthroscopic débridement of a deformed subacute bucket-handle lateral meniscus tear. Our case report is unique in that it describes use of a HEF alone for the reduction of a subacute tibial subluxation in any plane without the need for more extensive ligament reconstruction.

The injury here was primarily a lateral ligamentous injury. In the nonanatomical repair that was performed, the LCL and the iliotibial band were reattached to the proximal-lateral tibia. Had we started treating this injury from the time of the patient’s accident, then, depending on repair integrity, we might have considered acute augmentation of the anatomical repair of LCL with Larson-type reconstruction of the LCL and the popliteofibular ligament. Alternatively, acute reconstruction of the LCL and popliteus would be considered if the lateral structures were either irreparable or of very poor quality. In addition, had we initially seen the coronal instability/translation, we might have acutely considered either a staged procedure of a multiplanar external fixator or a HEF.

Given the narrowed lateral joint space, the débridement of the lateral meniscus, and the risk of developing posttraumatic arthritis, our patient will probably need total knee arthroplasty (TKA) at some point. We informed her that she had advanced lateral compartment joint space narrowing and arthritic progression and that she would eventually need TKA based on pain or dysfunction. We think the longevity of that TKA will be predictable and good, as she now had improved tibiofemoral alignment and stability of the collateral ligamentous structures. If she had been allowed to maintain the coronally subluxed position, it would have led to medial ligamentous attenuation and would have compromised the success and longevity of the TKA. In essence, a crucial part of the utility of the HEF was improved coronal tibiofemoral alignment and, therefore, decreased abnormal forces on both the repaired lateral ligaments and the native medial ligamentous structures. Although temporary external fixation issues related to infection risk and patient discomfort are recognized,21-23 use of HEF alone can be part of the treatment considerations for fixed tibial subluxations in any plane when they present after treatment for multiligamentous injury.

Am J Orthop. 2016;45(7):E497-E502. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2016. All rights reserved.

Dislocation of the knee is a severe injury that usually results from high-energy blunt trauma.1 Recognition of knee dislocations has increased with expansion of the definition beyond radiographically confirmed loss of tibiofemoral articulation to include injury of multiple knee ligaments with multidirectional joint instability, or the rupture of the anterior and posterior cruciate ligaments (ACL, PCL) when no gross dislocation can be identified2 (though knee dislocations without rupture of either ligament have been reported3,4). Knee dislocations account for 0.02% to 0.2% of orthopedic injuries.5 These multiligamentous injuries are rare, but their clinical outcomes are often complicated by arthrofibrosis, pain, and instability, as surgeons contend with the competing interests of long-term joint stability and range of motion (ROM).6-9

Whereas treatment standards for acute knee dislocations are becoming clearer, treatment of subacute and chronic tibiofemoral dislocations and subluxations is less defined.5 Success with articulated external fixation originally across the ankle and elbow inspired interest in its use for the knee.10-12 Richter and Lobenhoffer13 and Simonian and colleagues14 were the first to report on the postoperative use of a hinged external fixation device to help maintain the reduction of chronic fixed posterior knee dislocations. The literature has even supported nonoperative reduction of small fixed anterior or posterior (sagittal) subluxations with knee bracing alone.15,16 However, there are no reports on treatment of chronic tibial subluxation in the coronal plane.

We report a case of a hinged-knee external fixator (HEF) used alone to reduce a chronic medial tibia subluxation that presented after initial repair of a knee dislocation sustained in a motor vehicle accident. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 51-year-old healthy woman who was traveling out of state sustained multiple orthopedic injuries in a motor vehicle accident. She had a pelvic fracture, a contralateral femoral shaft fracture, significant multiligamentous damage to the right knee, and a cavitary impaction fracture of the tibial eminence with resultant coronal tibial subluxation. Initial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed the tibia injury likely was the result of varus translation, as the medial femoral condyle impacted the tibial spine, disrupting the ACL (Figures 1A, 1B).

On initial presentation to our clinic 5 weeks after injury, x-rays showed progressive medial subluxation of the tibia in relation to the femur with translation of about a third of the tibial width medially (Figures 2A, 2B).

Given the worsening tibial subluxation and resultant instability, the patient was taken to the operating room for examination under anesthesia, and planned closed reduction and spanning external fixation. Fluoroscopy of the lateral translation and external rotation of the tibia allowed us to reduce the joint, with the lateral tibial plateau and lateral femoral condyle relatively but not completely concentric. A rigid spanning multiplanar external fixator was then placed to maintain the knee joint in a more reduced position.

A week later, the patient was taken back to the operating room for arthroscopic evaluation of the knee joint. At the time of her index operation at the outside institution, she had undergone arthroscopic débridement of intra-articular loose bodies and lateral meniscus repair. Now it was found that the meniscus was not healed but had displaced. A bucket-handle lateral meniscus tear appeared to be blocking lateral translation of the tibia, thus impeding complete reduction.

Given the meniscus deformity that resulted from the chronicity of the injury and the resultant subluxation, a sub-total lateral meniscectomy was performed. As the patient was now noted to have an intact medial collateral ligament and an intact en masse lateral repair, we converted the spanning external fixator to a Compass Universal Hinge (Smith & Nephew) to maintain reduction without further ligamentous reconstruction (Figure 4).

After HEF placement, the patient spent a short time recovering at an inpatient rehabilitation facility before starting aggressive twice-a-week outpatient physical therapy. Initially after HEF placement, she could not actively flex the knee to about 40° or fully extend it concentrically. Given these limitations and concern about interval development of arthrofibrosis, manipulation under anesthesia was performed, 3 weeks after surgery, and 90° of flexion was obtained.

Six weeks after HEF removal, the patient was ambulating well with a cane, pain was minimal, and knee ROM was up to 110° of flexion. Tibiofemoral stability remained constant—no change in medial or lateral joint space opening. Full-extension radiographs showed medial translation of about 5 mm, which decreased to 1 mm on Rosenberg view. This represents marked improvement over the severe subluxation on initial presentation.

Follow-up over the next months revealed continued improvement in the right lower extremity strength, increased tolerance for physical activity, and stable right medial tibial translation.

At 5-year follow-up, the patient was asymptomatic, had continued coronal and sagittal stability, and was tolerating regular aerobic exercise, including hiking, weight training, and cycling. Physical examination revealed grade 1B Lachman, grade 0 pivot shift, and grade 0 posterior drawer. There was 3 mm increased lateral compartment opening in full extension, which increased to about 6 mm at 30° with endpoint.

Discussion

Although knee dislocations with multiligamentous involvement are rare, their outcomes can be poor. Fortunately, the principles of managing these complex injuries in the acute stage are becoming clearer. In a systematic review, Levy and colleagues18 found that operative treatment of a dislocated knee within 3 weeks after injury, compared with nonoperative or delayed treatment, resulted in improved functional outcomes. Ligament repair and reconstruction yielded similar outcomes, though repair of the posterolateral corner had a comparatively higher rate of failure. For associated lateral injuries, Shelbourne and colleagues17 advocated en masse repair in which the healing tissue complex is reattached to the tibia nonanatomically, without dissecting individual structures—a technique used in the original repair of our patient’s injuries.

Originally designed for other joints, hinged external fixators are now occasionally used for rehabilitation after traumatic knee injury. Stannard and colleagues9 recently confirmed the utility of the HEF as a supplement to ligament reconstruction for recovery from acute knee dislocation.9 Compared with postoperative use of a hinged-knee brace, HEF use resulted in fewer failed ligament reconstructions as well as equivalent joint ROM and Lysholm and IKDC scores at final follow-up. This clinical outcome is supported by results of kinematic studies of these hinged devices, which are capable of rigid fixation in all planes except sagittal and can reduce stress on intra-articular and periarticular ligaments when placed on the appropriate flexion-extension axis of the knee.19,20Unfortunately, the situation is more complicated for subacute or chronic tibial subluxation than for acute subluxation. Maak and colleagues16 described 3 operative steps that are crucial in obtaining desired outcomes in this setting: complete release of scar tissue, re-creation of knee axis through ACL and PCL reconstruction, and postoperative application of a HEF or knee brace. These recommendations mimic the management course described by Richter and Lobenhoffer13 and Simonian and colleagues,14 who treated chronic fixed posterior tibial subluxations with arthrolysis, ligament reconstruction, and use of HEFs for 6 weeks, supporting postoperative rehabilitation. All cases maintained reduction at follow-up after fixator removal.

It is also possible for small fixed anterior or posterior tibial subluxations to be managed nonoperatively. Strobel and colleagues15 described a series of 109 patients with fixed posterior subluxations treated at night with posterior tibial support braces. Mean subluxation was reduced from 6.93 mm to 2.58 mm after an average treatment period of 180 days. Although 60% of all subluxations were completely reduced, reductions were significantly more successful for those displaced <10 mm.

Management of subacute or chronic fixed coronal tibial subluxations is yet to be described. In this article, we have reported on acceptable reduction of a subacute medial tibial subluxation with use of a HEF for 6 weeks after arthroscopic débridement of a deformed subacute bucket-handle lateral meniscus tear. Our case report is unique in that it describes use of a HEF alone for the reduction of a subacute tibial subluxation in any plane without the need for more extensive ligament reconstruction.

The injury here was primarily a lateral ligamentous injury. In the nonanatomical repair that was performed, the LCL and the iliotibial band were reattached to the proximal-lateral tibia. Had we started treating this injury from the time of the patient’s accident, then, depending on repair integrity, we might have considered acute augmentation of the anatomical repair of LCL with Larson-type reconstruction of the LCL and the popliteofibular ligament. Alternatively, acute reconstruction of the LCL and popliteus would be considered if the lateral structures were either irreparable or of very poor quality. In addition, had we initially seen the coronal instability/translation, we might have acutely considered either a staged procedure of a multiplanar external fixator or a HEF.

Given the narrowed lateral joint space, the débridement of the lateral meniscus, and the risk of developing posttraumatic arthritis, our patient will probably need total knee arthroplasty (TKA) at some point. We informed her that she had advanced lateral compartment joint space narrowing and arthritic progression and that she would eventually need TKA based on pain or dysfunction. We think the longevity of that TKA will be predictable and good, as she now had improved tibiofemoral alignment and stability of the collateral ligamentous structures. If she had been allowed to maintain the coronally subluxed position, it would have led to medial ligamentous attenuation and would have compromised the success and longevity of the TKA. In essence, a crucial part of the utility of the HEF was improved coronal tibiofemoral alignment and, therefore, decreased abnormal forces on both the repaired lateral ligaments and the native medial ligamentous structures. Although temporary external fixation issues related to infection risk and patient discomfort are recognized,21-23 use of HEF alone can be part of the treatment considerations for fixed tibial subluxations in any plane when they present after treatment for multiligamentous injury.

Am J Orthop. 2016;45(7):E497-E502. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2016. All rights reserved.

1. Stannard JP, Sheils TM, McGwin G, Volgas DA, Alonso JE. Use of a hinged external knee fixator after surgery for knee dislocation. Arthroscopy. 2003;19(6):626-631.

2. Yeh WL, Tu YK, Su JY, Hsu RW. Knee dislocation: treatment of high-velocity knee dislocation. J Trauma. 1999;46(4):693-701.

3. Bellabarba C, Bush-Joseph CA, Bach BR Jr. Knee dislocation without anterior cruciate ligament disruption. A report of three cases. Am J Knee Surg. 1996;9(4):167-170.

4. Cooper DE, Speer KP, Wickiewicz TL, Warren RF. Complete knee dislocation without posterior cruciate ligament disruption. A report of four cases and review of the literature. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1992;(284):228-233.

5. Howells NR, Brunton LR, Robinson J, Porteus AJ, Eldridge JD, Murray JR. Acute knee dislocation: an evidence based approach to the management of the multiligament injured knee. Injury. 2011;42(11):1198-1204.

6. Magit D, Wolff A, Sutton K, Medvecky MJ. Arthrofibrosis of the knee. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2007;15(11):682-694.

7. Medvecky MJ, Zazulak BT, Hewett TE. A multidisciplinary approach to the evaluation, reconstruction and rehabilitation of the multi-ligament injured athlete. Sports Med. 2007;37(2):169-187.

8. Noyes FR, Barber-Westin SD. Reconstruction of the anterior and posterior cruciate ligaments after knee dislocation. Use of early protected postoperative motion to decrease arthrofibrosis. Am J Sports Med. 1997;25(6):769-778.

9. Stannard JP, Nuelle CW, McGwin G, Volgas DA. Hinged external fixation in the treatment of knee dislocations: a prospective randomized study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(3):184-191.

10. Bottlang M, Marsh JL, Brown TD. Articulated external fixation of the ankle: minimizing motion resistance by accurate axis alignment. J Biomech. 1999;32(1):63-70.

11. Madey SM, Bottlang M, Steyers CM, Marsh JL, Brown TD. Hinged external fixation of the elbow: optimal axis alignment to minimize motion resistance. J Orthop Trauma. 2000;14(1):41-47.

12. Jupiter JB, Ring D. Treatment of unreduced elbow dislocations with hinged external fixation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84(9):1630-1635.

13. Richter M, Lobenhoffer P. Chronic posterior knee dislocation: treatment with arthrolysis, posterior cruciate ligament reconstruction and hinged external fixation device. Injury. 1998;29(7):546-549.

14. Simonian PT, Wickiewicz TL, Hotchkiss RN, Warren RF. Chronic knee dislocation: reduction, reconstruction, and application of a skeletally fixed knee hinge. A report of two cases. Am J Sports Med. 1998;26(4):591-596.

15. Strobel MJ, Weiler A, Schulz MS, Russe K, Eichhorn HJ. Fixed posterior subluxation in posterior cruciate ligament-deficient knees: diagnosis and treatment of a new clinical sign. Am J Sports Med. 2002;30(1):32-38.

16. Maak TG, Marx RG, Wickiewicz TL. Management of chronic tibial subluxation in the multiple-ligament injured knee. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev. 2011;19(2):147-152.

17. Shelbourne KD, Haro MS, Gray T. Knee dislocation with lateral side injury: results of an en masse surgical repair technique of the lateral side. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(7):1105-1116.

18. Levy BA, Fanelli GC, Whelan DB, et al. Controversies in the treatment of knee dislocations and multiligament reconstruction. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2009;17(4):197-206.

19. Fitzpatrick DC, Sommers MB, Kam BC, Marsh JL, Bottlang M. Knee stability after articulated external fixation. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33(11):1735-1741.

20. Sommers MB, Fitzpatrick DC, Kahn KM, Marsh JL, Bottlang M. Hinged external fixation of the knee: intrinsic factors influencing passive joint motion. J Orthop Trauma. 2004;18(3):163-169.

21. Anglen JO, Aleto T. Temporary transarticular external fixation of the knee and ankle. J Orthop Trauma. 1998;12(6):431-434.

22. Behrens F. General theory and principles of external fixation. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1989;(241):15-23.

23. Haidukewych GJ. Temporary external fixation for the management of complex intra- and periarticular fractures of the lower extremity. J Orthop Trauma. 2002;16(9):678-685.

1. Stannard JP, Sheils TM, McGwin G, Volgas DA, Alonso JE. Use of a hinged external knee fixator after surgery for knee dislocation. Arthroscopy. 2003;19(6):626-631.

2. Yeh WL, Tu YK, Su JY, Hsu RW. Knee dislocation: treatment of high-velocity knee dislocation. J Trauma. 1999;46(4):693-701.

3. Bellabarba C, Bush-Joseph CA, Bach BR Jr. Knee dislocation without anterior cruciate ligament disruption. A report of three cases. Am J Knee Surg. 1996;9(4):167-170.

4. Cooper DE, Speer KP, Wickiewicz TL, Warren RF. Complete knee dislocation without posterior cruciate ligament disruption. A report of four cases and review of the literature. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1992;(284):228-233.

5. Howells NR, Brunton LR, Robinson J, Porteus AJ, Eldridge JD, Murray JR. Acute knee dislocation: an evidence based approach to the management of the multiligament injured knee. Injury. 2011;42(11):1198-1204.

6. Magit D, Wolff A, Sutton K, Medvecky MJ. Arthrofibrosis of the knee. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2007;15(11):682-694.

7. Medvecky MJ, Zazulak BT, Hewett TE. A multidisciplinary approach to the evaluation, reconstruction and rehabilitation of the multi-ligament injured athlete. Sports Med. 2007;37(2):169-187.

8. Noyes FR, Barber-Westin SD. Reconstruction of the anterior and posterior cruciate ligaments after knee dislocation. Use of early protected postoperative motion to decrease arthrofibrosis. Am J Sports Med. 1997;25(6):769-778.

9. Stannard JP, Nuelle CW, McGwin G, Volgas DA. Hinged external fixation in the treatment of knee dislocations: a prospective randomized study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(3):184-191.

10. Bottlang M, Marsh JL, Brown TD. Articulated external fixation of the ankle: minimizing motion resistance by accurate axis alignment. J Biomech. 1999;32(1):63-70.

11. Madey SM, Bottlang M, Steyers CM, Marsh JL, Brown TD. Hinged external fixation of the elbow: optimal axis alignment to minimize motion resistance. J Orthop Trauma. 2000;14(1):41-47.

12. Jupiter JB, Ring D. Treatment of unreduced elbow dislocations with hinged external fixation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84(9):1630-1635.

13. Richter M, Lobenhoffer P. Chronic posterior knee dislocation: treatment with arthrolysis, posterior cruciate ligament reconstruction and hinged external fixation device. Injury. 1998;29(7):546-549.

14. Simonian PT, Wickiewicz TL, Hotchkiss RN, Warren RF. Chronic knee dislocation: reduction, reconstruction, and application of a skeletally fixed knee hinge. A report of two cases. Am J Sports Med. 1998;26(4):591-596.

15. Strobel MJ, Weiler A, Schulz MS, Russe K, Eichhorn HJ. Fixed posterior subluxation in posterior cruciate ligament-deficient knees: diagnosis and treatment of a new clinical sign. Am J Sports Med. 2002;30(1):32-38.

16. Maak TG, Marx RG, Wickiewicz TL. Management of chronic tibial subluxation in the multiple-ligament injured knee. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev. 2011;19(2):147-152.

17. Shelbourne KD, Haro MS, Gray T. Knee dislocation with lateral side injury: results of an en masse surgical repair technique of the lateral side. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(7):1105-1116.

18. Levy BA, Fanelli GC, Whelan DB, et al. Controversies in the treatment of knee dislocations and multiligament reconstruction. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2009;17(4):197-206.

19. Fitzpatrick DC, Sommers MB, Kam BC, Marsh JL, Bottlang M. Knee stability after articulated external fixation. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33(11):1735-1741.

20. Sommers MB, Fitzpatrick DC, Kahn KM, Marsh JL, Bottlang M. Hinged external fixation of the knee: intrinsic factors influencing passive joint motion. J Orthop Trauma. 2004;18(3):163-169.

21. Anglen JO, Aleto T. Temporary transarticular external fixation of the knee and ankle. J Orthop Trauma. 1998;12(6):431-434.

22. Behrens F. General theory and principles of external fixation. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1989;(241):15-23.

23. Haidukewych GJ. Temporary external fixation for the management of complex intra- and periarticular fractures of the lower extremity. J Orthop Trauma. 2002;16(9):678-685.

IV brivaracetam similarly well tolerated as oral formulation

HOUSTON – Pooled data for a recently approved antiepileptic drug show good safety and tolerability when it’s administered intravenously.

Intravenous brivaracetam, when given to 104 patients with epilepsy and 49 healthy volunteers, was generally well tolerated, though about one in three patients experienced somnolence, and one in four had some dizziness and fatigue. This adverse event profile was similar to that seen in clinical trials of the oral formulation of brivaracetam, Pavel Klein, MD, said in an interview during a poster session at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society, though euphoria and dysgeusia were more common among healthy volunteers receiving intravenous brivaracetam.

“Looking at the side effects, the medication was well tolerated. … The main side effects were dizziness, somnolence, and fatigue, and by and large, these were mild or moderate. Nobody discontinued the medication because of side effects in the patient population,” said Dr. Klein, director of the Mid-Atlantic Epilepsy and Sleep Center, Bethesda, Md.

In the overall group of participants in all three studies, somnolence was seen in 30.1% of participants, dizziness in 15.7%, and fatigue in 15.0%. However, when compared with patients with epilepsy, healthy volunteers given brivaracetam 100 mg IV had a higher overall adverse event incidence, and notably more dizziness (35.5% versus 7.7%) and fatigue (29.0% versus 4.8%). One epilepsy patient in the phase III study (1/104; 1%) discontinued the study because of an adverse event.

Also, healthy volunteers, rather than patients, were more likely to experience euphoric mood and dysgeusia with intravenous as compared with oral brivaracetam.

The reason for these differences between the epilepsy and nonepilepsy groups is not known; however, wrote Dr. Klein and his coauthors, part of the difference might be “due to heterogeneous medical histories and concomitant medication use.”

Otherwise, intravenous brivaracetam administration was associated with about the same number of adverse events as when the drug was taken orally.

Brivaracetam, approved earlier in 2016, like levetiracetam, is a ligand for the synaptic vesicle protein 2a, the mechanism that’s thought to be responsible for the antiepileptic effect of this drug class. However, brivaracetam has a 15- to 30-fold higher affinity for its target than its older cousin. It’s approved in the United States as adjunctive therapy for focal seizures in individuals aged 16 and older with epilepsy. When administered intravenously, brivaracetam may be given as a bolus or an infusion over 15 minutes.

Dr. Klein serves on the speakers bureau of UCB Pharma, and has received research support from the company, which funded the study and assisted with poster preparation.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

HOUSTON – Pooled data for a recently approved antiepileptic drug show good safety and tolerability when it’s administered intravenously.

Intravenous brivaracetam, when given to 104 patients with epilepsy and 49 healthy volunteers, was generally well tolerated, though about one in three patients experienced somnolence, and one in four had some dizziness and fatigue. This adverse event profile was similar to that seen in clinical trials of the oral formulation of brivaracetam, Pavel Klein, MD, said in an interview during a poster session at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society, though euphoria and dysgeusia were more common among healthy volunteers receiving intravenous brivaracetam.

“Looking at the side effects, the medication was well tolerated. … The main side effects were dizziness, somnolence, and fatigue, and by and large, these were mild or moderate. Nobody discontinued the medication because of side effects in the patient population,” said Dr. Klein, director of the Mid-Atlantic Epilepsy and Sleep Center, Bethesda, Md.

In the overall group of participants in all three studies, somnolence was seen in 30.1% of participants, dizziness in 15.7%, and fatigue in 15.0%. However, when compared with patients with epilepsy, healthy volunteers given brivaracetam 100 mg IV had a higher overall adverse event incidence, and notably more dizziness (35.5% versus 7.7%) and fatigue (29.0% versus 4.8%). One epilepsy patient in the phase III study (1/104; 1%) discontinued the study because of an adverse event.

Also, healthy volunteers, rather than patients, were more likely to experience euphoric mood and dysgeusia with intravenous as compared with oral brivaracetam.

The reason for these differences between the epilepsy and nonepilepsy groups is not known; however, wrote Dr. Klein and his coauthors, part of the difference might be “due to heterogeneous medical histories and concomitant medication use.”

Otherwise, intravenous brivaracetam administration was associated with about the same number of adverse events as when the drug was taken orally.

Brivaracetam, approved earlier in 2016, like levetiracetam, is a ligand for the synaptic vesicle protein 2a, the mechanism that’s thought to be responsible for the antiepileptic effect of this drug class. However, brivaracetam has a 15- to 30-fold higher affinity for its target than its older cousin. It’s approved in the United States as adjunctive therapy for focal seizures in individuals aged 16 and older with epilepsy. When administered intravenously, brivaracetam may be given as a bolus or an infusion over 15 minutes.

Dr. Klein serves on the speakers bureau of UCB Pharma, and has received research support from the company, which funded the study and assisted with poster preparation.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

HOUSTON – Pooled data for a recently approved antiepileptic drug show good safety and tolerability when it’s administered intravenously.

Intravenous brivaracetam, when given to 104 patients with epilepsy and 49 healthy volunteers, was generally well tolerated, though about one in three patients experienced somnolence, and one in four had some dizziness and fatigue. This adverse event profile was similar to that seen in clinical trials of the oral formulation of brivaracetam, Pavel Klein, MD, said in an interview during a poster session at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society, though euphoria and dysgeusia were more common among healthy volunteers receiving intravenous brivaracetam.

“Looking at the side effects, the medication was well tolerated. … The main side effects were dizziness, somnolence, and fatigue, and by and large, these were mild or moderate. Nobody discontinued the medication because of side effects in the patient population,” said Dr. Klein, director of the Mid-Atlantic Epilepsy and Sleep Center, Bethesda, Md.

In the overall group of participants in all three studies, somnolence was seen in 30.1% of participants, dizziness in 15.7%, and fatigue in 15.0%. However, when compared with patients with epilepsy, healthy volunteers given brivaracetam 100 mg IV had a higher overall adverse event incidence, and notably more dizziness (35.5% versus 7.7%) and fatigue (29.0% versus 4.8%). One epilepsy patient in the phase III study (1/104; 1%) discontinued the study because of an adverse event.

Also, healthy volunteers, rather than patients, were more likely to experience euphoric mood and dysgeusia with intravenous as compared with oral brivaracetam.

The reason for these differences between the epilepsy and nonepilepsy groups is not known; however, wrote Dr. Klein and his coauthors, part of the difference might be “due to heterogeneous medical histories and concomitant medication use.”

Otherwise, intravenous brivaracetam administration was associated with about the same number of adverse events as when the drug was taken orally.

Brivaracetam, approved earlier in 2016, like levetiracetam, is a ligand for the synaptic vesicle protein 2a, the mechanism that’s thought to be responsible for the antiepileptic effect of this drug class. However, brivaracetam has a 15- to 30-fold higher affinity for its target than its older cousin. It’s approved in the United States as adjunctive therapy for focal seizures in individuals aged 16 and older with epilepsy. When administered intravenously, brivaracetam may be given as a bolus or an infusion over 15 minutes.

Dr. Klein serves on the speakers bureau of UCB Pharma, and has received research support from the company, which funded the study and assisted with poster preparation.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

AT AES 2016

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Somnolence was the most frequent adverse event with intravenous brivaracetam, reported by 30.1% of all study participants.

Data source: Pooled data from clinical trials in 104 patients with focal or generalized seizures and 49 healthy controls.

Disclosures: Dr. Klein serves on the speakers bureau of UCB Pharma, and has received research support from the company, which funded the study and assisted with poster preparation.

Echocardiogram, exercise testing improve PAH prognostic accuracy

Adding echocardiography and cardiopulmonary exercise testing to baseline right heart catheterization improves prognostic accuracy in idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension, according to a prospective Italian study of 102 newly diagnosed patients.

A combination of low right ventricular fractional area change (RVFAC) on echocardiography and low oxygen pulse on cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET) “identifies patients at a particularly high risk of clinical deterioration.” Both are markers of right ventricular (RV) function, which is a major determinant of outcome in idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension [iPAH], said investigators led by Roberto Badagliacca, MD, of the Sapienza University of Rome (Chest. 2016 Aug 20. pii: S0012-3692(16)56052-8. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2016.07.036).

PAH diagnosis requires right heart catheterization, and findings have long been known to predict PAH outcome. However, catheterization allows only “an indirect description of RV function,” the investigators said. Recent studies have shown that RV echocardiography and CPET improve the accuracy of heart failure prognosis, so the investigators wanted to see if they’d do the same for PAH.

Their results “strongly suggest that noninvasive measurements related to RV function obtained by combining resting echocardiography and CPET are of added value to right heart catheterization in the assessment of severity and prognostication of PAH,” they said.

During a mean follow-up of 528 days, 54 patients (53%) had clinical worsening, defined as a 15% reduction in 6-minute walk distance from baseline plus a worsening of functional class, nonelective PAH hospitalization, or death.

Baseline functional class and cardiac index proved to be independent predictors of clinical worsening. Adding echocardiographic and CPET variables independently improved prognostic power (area under the curve, 0.81 vs. 0.66; P = .005).

Compared with patients with high RVFAC and high oxygen pulse at baseline, patients with low RVFAC and low oxygen pulse had a 99.8 increase in the hazard ratio for clinical worsening, and those with high RVFAC and low oxygen had a 29.4 increase (P = .0001).

Several echocardiographic variables for RV function have previously been reported as independent predictors of PAH outcome. “The new finding here is that RVFAC outperformed other echocardiographic indices of systolic function,” the investigators wrote.

“As for peak oxygen pulse, this variable is thought to assess maximum [stroke volume],” assumed to be determined by RV function; MRI-determined stroke volume has been previously shown to be an important predictor of survival in PAH,” they said.

The mean age in the study was 52 years, mean functional class was 2.7, and mean 6-minute walk distance was 430 m; 62 subjects were women. The most relevant comorbidities were diabetes in 5 patients, hypercholesterolemia in 10, thyroid diseases in 6, and clinical depression in 7. Patients with severe tricuspid regurgitation or exercise-induced opening of the foramen ovale were excluded. However, a reanalysis including patients with exercise-induced right to left shunting showed the same independent predictors of PAH outcome.

After diagnosis, patients were treated with endothelin receptor antagonists, phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors, and prostanoids.

Dr. Badagliacca reported speaker and adviser fees from United Therapeutics, Dompe, GSK, and Bayer. His colleagues reported no conflicts of interest.

Adding echocardiography and cardiopulmonary exercise testing to baseline right heart catheterization improves prognostic accuracy in idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension, according to a prospective Italian study of 102 newly diagnosed patients.

A combination of low right ventricular fractional area change (RVFAC) on echocardiography and low oxygen pulse on cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET) “identifies patients at a particularly high risk of clinical deterioration.” Both are markers of right ventricular (RV) function, which is a major determinant of outcome in idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension [iPAH], said investigators led by Roberto Badagliacca, MD, of the Sapienza University of Rome (Chest. 2016 Aug 20. pii: S0012-3692(16)56052-8. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2016.07.036).

PAH diagnosis requires right heart catheterization, and findings have long been known to predict PAH outcome. However, catheterization allows only “an indirect description of RV function,” the investigators said. Recent studies have shown that RV echocardiography and CPET improve the accuracy of heart failure prognosis, so the investigators wanted to see if they’d do the same for PAH.

Their results “strongly suggest that noninvasive measurements related to RV function obtained by combining resting echocardiography and CPET are of added value to right heart catheterization in the assessment of severity and prognostication of PAH,” they said.

During a mean follow-up of 528 days, 54 patients (53%) had clinical worsening, defined as a 15% reduction in 6-minute walk distance from baseline plus a worsening of functional class, nonelective PAH hospitalization, or death.

Baseline functional class and cardiac index proved to be independent predictors of clinical worsening. Adding echocardiographic and CPET variables independently improved prognostic power (area under the curve, 0.81 vs. 0.66; P = .005).

Compared with patients with high RVFAC and high oxygen pulse at baseline, patients with low RVFAC and low oxygen pulse had a 99.8 increase in the hazard ratio for clinical worsening, and those with high RVFAC and low oxygen had a 29.4 increase (P = .0001).

Several echocardiographic variables for RV function have previously been reported as independent predictors of PAH outcome. “The new finding here is that RVFAC outperformed other echocardiographic indices of systolic function,” the investigators wrote.

“As for peak oxygen pulse, this variable is thought to assess maximum [stroke volume],” assumed to be determined by RV function; MRI-determined stroke volume has been previously shown to be an important predictor of survival in PAH,” they said.

The mean age in the study was 52 years, mean functional class was 2.7, and mean 6-minute walk distance was 430 m; 62 subjects were women. The most relevant comorbidities were diabetes in 5 patients, hypercholesterolemia in 10, thyroid diseases in 6, and clinical depression in 7. Patients with severe tricuspid regurgitation or exercise-induced opening of the foramen ovale were excluded. However, a reanalysis including patients with exercise-induced right to left shunting showed the same independent predictors of PAH outcome.

After diagnosis, patients were treated with endothelin receptor antagonists, phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors, and prostanoids.

Dr. Badagliacca reported speaker and adviser fees from United Therapeutics, Dompe, GSK, and Bayer. His colleagues reported no conflicts of interest.

Adding echocardiography and cardiopulmonary exercise testing to baseline right heart catheterization improves prognostic accuracy in idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension, according to a prospective Italian study of 102 newly diagnosed patients.

A combination of low right ventricular fractional area change (RVFAC) on echocardiography and low oxygen pulse on cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET) “identifies patients at a particularly high risk of clinical deterioration.” Both are markers of right ventricular (RV) function, which is a major determinant of outcome in idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension [iPAH], said investigators led by Roberto Badagliacca, MD, of the Sapienza University of Rome (Chest. 2016 Aug 20. pii: S0012-3692(16)56052-8. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2016.07.036).

PAH diagnosis requires right heart catheterization, and findings have long been known to predict PAH outcome. However, catheterization allows only “an indirect description of RV function,” the investigators said. Recent studies have shown that RV echocardiography and CPET improve the accuracy of heart failure prognosis, so the investigators wanted to see if they’d do the same for PAH.

Their results “strongly suggest that noninvasive measurements related to RV function obtained by combining resting echocardiography and CPET are of added value to right heart catheterization in the assessment of severity and prognostication of PAH,” they said.

During a mean follow-up of 528 days, 54 patients (53%) had clinical worsening, defined as a 15% reduction in 6-minute walk distance from baseline plus a worsening of functional class, nonelective PAH hospitalization, or death.

Baseline functional class and cardiac index proved to be independent predictors of clinical worsening. Adding echocardiographic and CPET variables independently improved prognostic power (area under the curve, 0.81 vs. 0.66; P = .005).

Compared with patients with high RVFAC and high oxygen pulse at baseline, patients with low RVFAC and low oxygen pulse had a 99.8 increase in the hazard ratio for clinical worsening, and those with high RVFAC and low oxygen had a 29.4 increase (P = .0001).

Several echocardiographic variables for RV function have previously been reported as independent predictors of PAH outcome. “The new finding here is that RVFAC outperformed other echocardiographic indices of systolic function,” the investigators wrote.

“As for peak oxygen pulse, this variable is thought to assess maximum [stroke volume],” assumed to be determined by RV function; MRI-determined stroke volume has been previously shown to be an important predictor of survival in PAH,” they said.

The mean age in the study was 52 years, mean functional class was 2.7, and mean 6-minute walk distance was 430 m; 62 subjects were women. The most relevant comorbidities were diabetes in 5 patients, hypercholesterolemia in 10, thyroid diseases in 6, and clinical depression in 7. Patients with severe tricuspid regurgitation or exercise-induced opening of the foramen ovale were excluded. However, a reanalysis including patients with exercise-induced right to left shunting showed the same independent predictors of PAH outcome.

After diagnosis, patients were treated with endothelin receptor antagonists, phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors, and prostanoids.

Dr. Badagliacca reported speaker and adviser fees from United Therapeutics, Dompe, GSK, and Bayer. His colleagues reported no conflicts of interest.

FROM CHEST

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Baseline functional class and cardiac index proved to be independent predictors of clinical worsening. Adding echocardiographic and CPET variables independently improved prognostic power (area under the curve, 0.81 vs. 0.66; P = .005).

Data source: A prospective Italian study of 102 newly diagnosed patients.

Disclosures: The lead investigator reported speaker and adviser fees from United Therapeutics, Dompe, GSK, and Bayer.

Strength of fibromyalgia as marker for seizures questioned

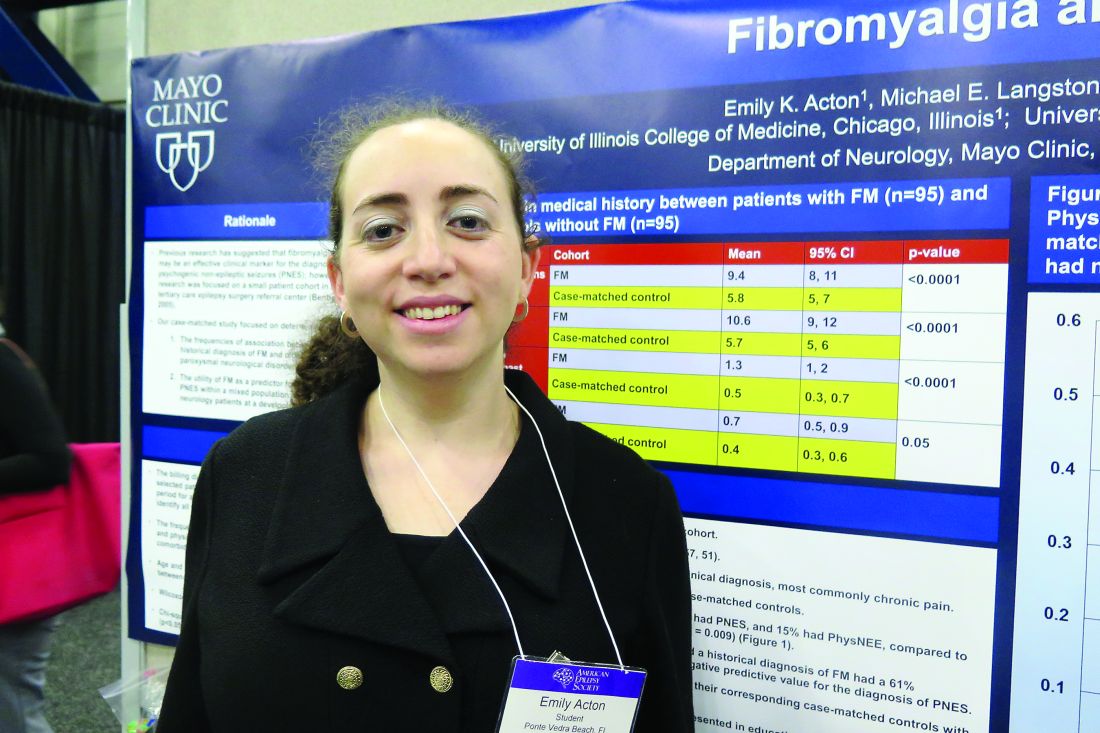

HOUSTON – The specificity of fibromyalgia as a marker for psychogenic nonepileptic seizures is less reliable than previously described, results from a large analysis showed.

“Fibromyalgia has been referred to as a reliable clinical indicator for differentiating psychogenic nonepileptic seizures from epilepsy, but there hasn’t been a lot of research looking into this idea,” Emily K. Acton said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. In fact, the most recent study to investigate the association focused on a small patient cohort in a tertiary care epilepsy referral center and found that a diagnosis of fibromyalgia had a predictive value of 75% and a specificity of 99% for the diagnosis of psychogenic nonepileptic seizures (Epilepsy Behav. 2005; 6[2]:264-5).

Ms. Acton reported that of the 1,730 patients studied, 95 (5.5%) had a medical history of fibromyalgia. A majority of the 95 patients (95%) were female, and the mean age was 53 years. In addition, 43% of fibromyalgia patients had a nonparoxysmal, neurologic primary clinical diagnosis, most commonly chronic pain. She said that no differences were seen between fibromyalgia patients and case-matched controls in terms of age, race, marital status, or reason for referral. However, compared with case-matched controls, fibromyalgia patients were underrepresented in education (P = .02) and employment (P = .009).

Paroxysmal events were present in 57% of fibromyalgia patients and in 54% of case-matched controls. Among fibromyalgia patients with paroxysmal disorders, 11% had epileptic seizures, 74% had PNES, and 15% had physiologic nonepileptic events. Among matched controls, 37% had epileptic seizures, 51% had PNES, and 12% had physiologic nonepileptic events (P = .009).

After comparing the two groups of patients, the researchers determined that a historical diagnosis of fibromyalgia had a 61% sensitivity, 64% specificity, 74% positive predictive value, and 49% negative predictive value for the diagnosis of PNES. “Another interesting finding was that quite a few of our fibromyalgia patients felt they didn’t have fibromyalgia,” Ms. Action said. “Unprompted, during the course of their first visit, about 10% of this cohort mentioned to a physician that they were diagnosed with fibromyalgia, but they didn’t believe it.”

In their abstract, the researchers wrote that the study design “and a larger sample size involving mixed general neurology patients may account for the lesser association seen between fibromyalgia and PNES in this study.” They reported having no financial disclosures.

HOUSTON – The specificity of fibromyalgia as a marker for psychogenic nonepileptic seizures is less reliable than previously described, results from a large analysis showed.

“Fibromyalgia has been referred to as a reliable clinical indicator for differentiating psychogenic nonepileptic seizures from epilepsy, but there hasn’t been a lot of research looking into this idea,” Emily K. Acton said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. In fact, the most recent study to investigate the association focused on a small patient cohort in a tertiary care epilepsy referral center and found that a diagnosis of fibromyalgia had a predictive value of 75% and a specificity of 99% for the diagnosis of psychogenic nonepileptic seizures (Epilepsy Behav. 2005; 6[2]:264-5).

Ms. Acton reported that of the 1,730 patients studied, 95 (5.5%) had a medical history of fibromyalgia. A majority of the 95 patients (95%) were female, and the mean age was 53 years. In addition, 43% of fibromyalgia patients had a nonparoxysmal, neurologic primary clinical diagnosis, most commonly chronic pain. She said that no differences were seen between fibromyalgia patients and case-matched controls in terms of age, race, marital status, or reason for referral. However, compared with case-matched controls, fibromyalgia patients were underrepresented in education (P = .02) and employment (P = .009).

Paroxysmal events were present in 57% of fibromyalgia patients and in 54% of case-matched controls. Among fibromyalgia patients with paroxysmal disorders, 11% had epileptic seizures, 74% had PNES, and 15% had physiologic nonepileptic events. Among matched controls, 37% had epileptic seizures, 51% had PNES, and 12% had physiologic nonepileptic events (P = .009).

After comparing the two groups of patients, the researchers determined that a historical diagnosis of fibromyalgia had a 61% sensitivity, 64% specificity, 74% positive predictive value, and 49% negative predictive value for the diagnosis of PNES. “Another interesting finding was that quite a few of our fibromyalgia patients felt they didn’t have fibromyalgia,” Ms. Action said. “Unprompted, during the course of their first visit, about 10% of this cohort mentioned to a physician that they were diagnosed with fibromyalgia, but they didn’t believe it.”

In their abstract, the researchers wrote that the study design “and a larger sample size involving mixed general neurology patients may account for the lesser association seen between fibromyalgia and PNES in this study.” They reported having no financial disclosures.

HOUSTON – The specificity of fibromyalgia as a marker for psychogenic nonepileptic seizures is less reliable than previously described, results from a large analysis showed.

“Fibromyalgia has been referred to as a reliable clinical indicator for differentiating psychogenic nonepileptic seizures from epilepsy, but there hasn’t been a lot of research looking into this idea,” Emily K. Acton said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. In fact, the most recent study to investigate the association focused on a small patient cohort in a tertiary care epilepsy referral center and found that a diagnosis of fibromyalgia had a predictive value of 75% and a specificity of 99% for the diagnosis of psychogenic nonepileptic seizures (Epilepsy Behav. 2005; 6[2]:264-5).

Ms. Acton reported that of the 1,730 patients studied, 95 (5.5%) had a medical history of fibromyalgia. A majority of the 95 patients (95%) were female, and the mean age was 53 years. In addition, 43% of fibromyalgia patients had a nonparoxysmal, neurologic primary clinical diagnosis, most commonly chronic pain. She said that no differences were seen between fibromyalgia patients and case-matched controls in terms of age, race, marital status, or reason for referral. However, compared with case-matched controls, fibromyalgia patients were underrepresented in education (P = .02) and employment (P = .009).

Paroxysmal events were present in 57% of fibromyalgia patients and in 54% of case-matched controls. Among fibromyalgia patients with paroxysmal disorders, 11% had epileptic seizures, 74% had PNES, and 15% had physiologic nonepileptic events. Among matched controls, 37% had epileptic seizures, 51% had PNES, and 12% had physiologic nonepileptic events (P = .009).

After comparing the two groups of patients, the researchers determined that a historical diagnosis of fibromyalgia had a 61% sensitivity, 64% specificity, 74% positive predictive value, and 49% negative predictive value for the diagnosis of PNES. “Another interesting finding was that quite a few of our fibromyalgia patients felt they didn’t have fibromyalgia,” Ms. Action said. “Unprompted, during the course of their first visit, about 10% of this cohort mentioned to a physician that they were diagnosed with fibromyalgia, but they didn’t believe it.”

In their abstract, the researchers wrote that the study design “and a larger sample size involving mixed general neurology patients may account for the lesser association seen between fibromyalgia and PNES in this study.” They reported having no financial disclosures.

AT AES 2016

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The diagnosis of fibromyalgia had a 61% sensitivity, 64% specificity, and a 74% positive predictive value for the diagnosis of PNES.

Data source: A retrospective review of 1,730 consecutive patients seen by a single epileptologist at a neurology clinic over a 3-year period.

Disclosures: The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

Increasing maternal vaccine uptake requires paradigm shift

ATLANTA – Both the influenza and the tetanus-diphtheria-acellular pertussis (Tdap) vaccines have been recommended during pregnancy for years, but uptake remains low.

The most recent national data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show that the Tdap vaccination rate is about 14% before pregnancy and 10% during pregnancy. For influenza, the vaccination rate among pregnant women is about 50%, with 14% of women being vaccinated in the 6 months before pregnancy and 36% during pregnancy.

To get a handle on how ob.gyn. practices approach vaccination, Dr. O’Leary and his colleagues sent out a mail and Internet survey to 482 physicians from June through September 2015 and analyzed 353 responses.

Among the responders, 92% routinely assessed whether their pregnant patients had received the Tdap vaccine, and 98% routinely assessed whether pregnant patients had received the influenza vaccine. But only about half of the physicians (51%) assessed Tdap vaccination in nonpregnant patients, and 82% assessed influenza vaccine status in nonpregnant patients.

For the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine, ob.gyns. were more likely to ask their nonpregnant patients about the vaccine. A total of 46% of providers routinely assessed whether their pregnant patients had received it, while 92% assessed whether their nonpregnant patients needed or had received the HPV vaccine.

The numbers were lower when it came to actually administering the vaccines. Just over three-quarters of providers routinely administered the Tdap vaccine, and 85% routinely administered the influenza vaccine to their pregnant patients.

For their nonpregnant patients, 55% routinely administered Tdap, 70% routinely administered the flu vaccine, and 82% routinely administered the HPV vaccine.

Ob.gyns. were most likely to have standing orders in place for influenza vaccine for their pregnant patients, with 66% of providers reporting that they had these orders in place, compared with 51% for nonpregnant patients. Standing orders were less likely for Tdap vaccine administration (39% for pregnant patients and 37% for nonpregnant patients).

Barriers

Reimbursement-related issues topped the reasons that ob.gyns. found it burdensome to stock and administer vaccines. The most commonly reported barrier – cited by 54% of the respondents – was lack of adequate reimbursement for purchasing vaccines, and 30% of physicians cited this as a major barrier. Similarly, lack of adequate reimbursement for administration of the vaccine was listed as a major barrier for a quarter of the respondents and a moderate barrier by 21% of the respondents.

A quarter of physicians also cited difficulty determining if a patient’s insurance would reimburse for a vaccine as a major barrier.

Other barriers included having too little time for vaccination during visits when other preventive services took precedence, having patients who refused vaccines because of safety concerns, the burden of storing, ordering, and tracking vaccines, and difficulty determining whether a patient had already received a particular vaccine.

Fewer than 2% of ob.gyns., however, reported uncertainty about a particular vaccine’s effectiveness or safety in pregnant women as a barrier.

“Physician attitudinal barriers are nonexistent,” Dr. O’Leary said. “The perceived barriers were primarily financial, but logistical and patient attitudinal barriers were also important.”

Testing interventions

While the barriers to routine vaccine administration are clear, the solutions are less obvious. A recently reported intensive intervention to increase the uptake of maternal vaccines in ob.gyn. practices had only modest success in increasing Tdap vaccination and no significant impact on administration of the influenza vaccine.