User login

Fast Track to Abdominal Pain

ANSWER

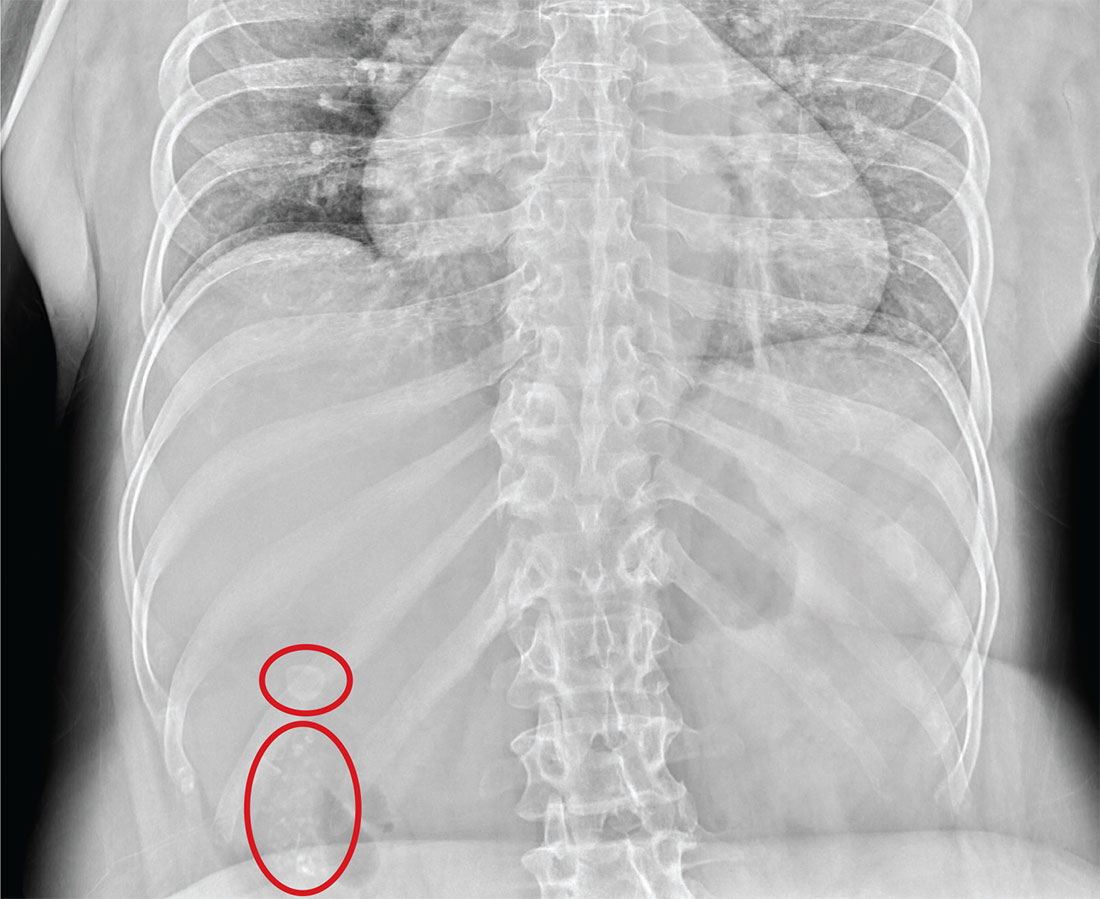

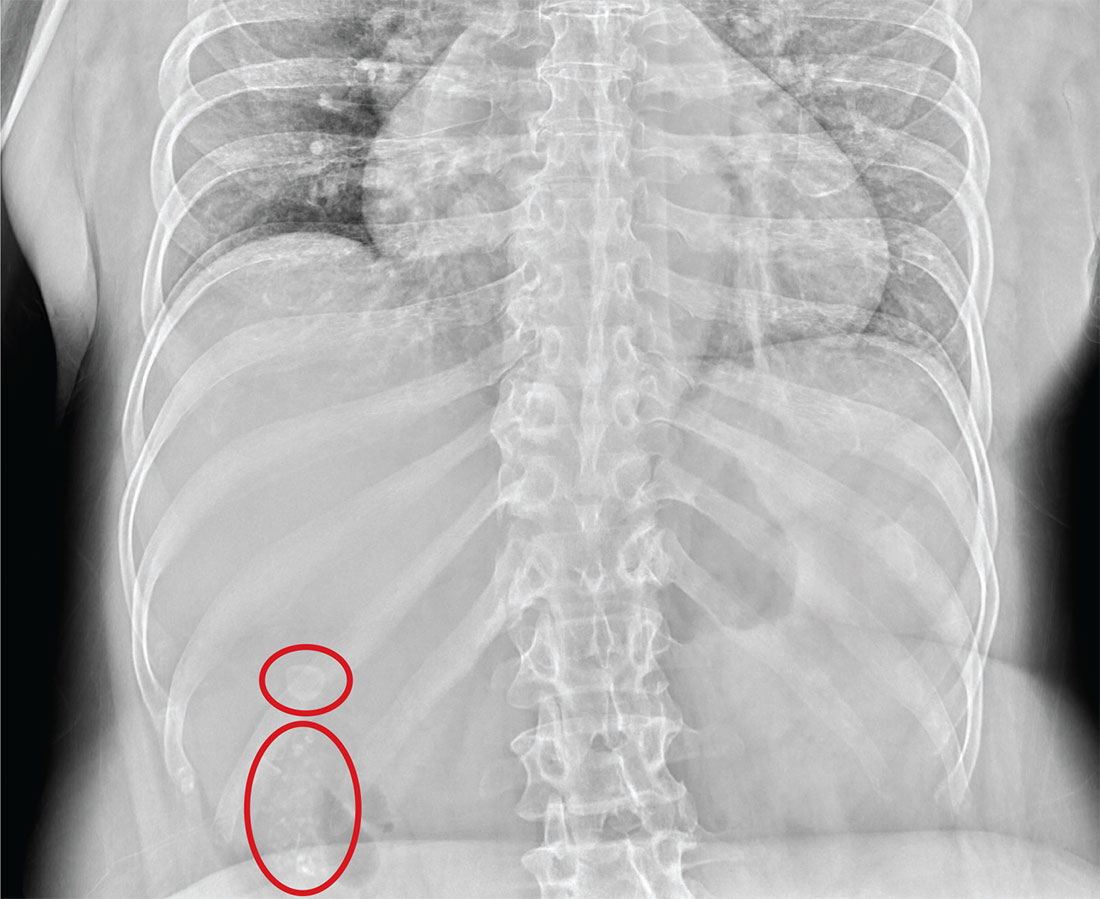

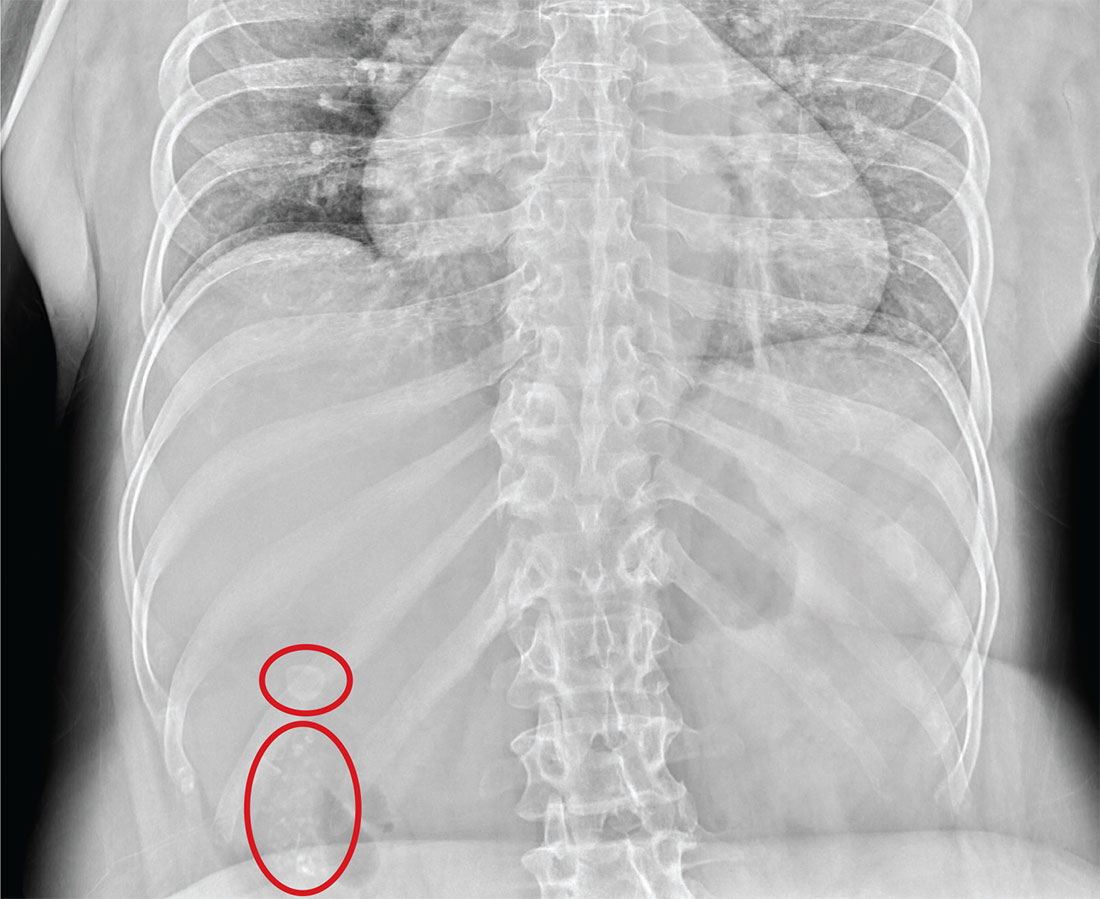

The radiograph illustrates a large calcification within the right upper quadrant—most likely a gallstone. Several smaller calcifications are clustered together in the same area, making the diagnosis cholelithiasis. The patient was referred to the general surgery clinic for further

evaluation.

For recent findings on gallstone disease and heart risk, see here.

ANSWER

The radiograph illustrates a large calcification within the right upper quadrant—most likely a gallstone. Several smaller calcifications are clustered together in the same area, making the diagnosis cholelithiasis. The patient was referred to the general surgery clinic for further

evaluation.

For recent findings on gallstone disease and heart risk, see here.

ANSWER

The radiograph illustrates a large calcification within the right upper quadrant—most likely a gallstone. Several smaller calcifications are clustered together in the same area, making the diagnosis cholelithiasis. The patient was referred to the general surgery clinic for further

evaluation.

For recent findings on gallstone disease and heart risk, see here.

An NP student you are precepting in the emergency department fast track area presents her patient to you: a 60-year-old woman with abdominal pain. The pain is chronic but has worsened slightly, prompting the patient, who does not have a primary care provider, to present today. She experiences occasional nausea but no fever, and she denies any bowel or bladder complaints other than constipation. Her medical history is significant for mild hypertension.

On exam, your student notes an obese female who is in no obvious distress. The patient’s vital signs are all within normal limits. The abdominal exam is unimpressive, revealing a soft abdomen with good bowel sounds. Although she does have mild diffuse tenderness, she has no rebound or guarding.

Although your student suspects the patient is just constipated, she orders blood work and urinalysis. An abdominal survey is obtained as well. What is your impression?

In favorable intermediate-risk prostate cancer, brachytherapy alone suffices

BOSTON – In a finding hailed as “paradigm changing,” men with favorable intermediate-risk prostate cancer may have good disease control with brachytherapy alone, with fewer late-term toxicities than with brachytherapy combined with external-beam radiation, investigators reported.

After 5 years of follow-up, there were no significant differences in rates of freedom from disease progression among patients assigned to receive combined external-beam radiation (EBRT) and transperineal interstitial permanent brachytherapy (PB) or PB alone in selected patients with intermediate-risk prostatic carcinoma.

“I think you’re underselling your results – I’m pretty excited about these results,” Colleen Lawton, MD, professor and vice chair of radiation oncology at the Medical College of Wisconsin in Milwaukee, told Dr. Prestidge at the annual meeting of the American Society of Radiation Oncology.

The results show that, “for the intermediate-risk group, not the worst of intermediate [risk] but the vast majority, they don’t need the toxicity of that external beam, and they don’t need the cost of it,” she said at a briefing following his presentation of the data in a plenary session.

Dr. Lawton said that, when the NRG Oncology/RTOG 0232study was initiated (the first patients were enrolled in 2003), “there were factions that believed you could not treat intermediate-risk prostate cancer – which isn’t the best, isn’t the worse, but is somewhere in the middle – with anything but the combination, and this shows that’s not true.”

The trial was designed to test the hypothesis that patients with intermediate-risk prostate cancer treated with combined EBRT and PB would have a 10% improvement in freedom from progression (FFP), compared with men treated with PB alone.

A total of 579 patients with histologically confirmed prostate cancer, stages T1c-2b and Zubrod performance score 0 or 1 were enrolled. The patients also had Gleason score 2-6 and prostate-specific antigen (PSA) from 10 to less than 20 ng/mL; Gleason score and PSA less than 10 ng/mL; or prostate volume less than 60 cc.

In addition, androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) was not allowed on the study, and patients could not have distant metastases or radiographically suspicious nodes at the time of enrollment.

Patients were stratified by stage, Gleason score, PSA and history of ADT, and then randomized to the combined therapy, consisting of 45 Gy in a partial pelvis dose delivered in 1.8 Gy fractions for 5 weeks, followed 2-4 weeks later with brachytherapy using either a radioactive iodine (I-125) source prescribed as a 110-Gy boost dose, or palladium 103 in a 100 Gy boost dose; or brachytherapy alone (145-Gy dose with I-I25, 125-Gy dose with palladium 103). EBRT was delivered by either intensity-modulated radiation (43%) or 3D conformal radiation.

Five years after randomization, there were a total of 66 cases of treatment failure (measured as either biochemical failure according to ASTRO criteria, local progression, distant metastases, or death from any cause), 34 occurring in men treated with the combination, and 32 in men treated with brachytherapy alone. Biochemical failures accounted for 68% of events among patients on the combined modalities and 53% of those on brachytherapy alone. There were 9 deaths in the combined arm and 14 deaths in the brachytherapy-only arm, but none were prostate cancer related, Dr. Prestidge said.

In multivariate analysis adjusted for treatment type, age, race, prior hormonal therapy, Gleason/PSA, and tumor stage, the only significant predictor of FFP was Gleason 7/PSA less than 10 ng/mL, which was associated with better outcomes, compared with Gleason score less than 7/PSA 10-20 ng/mL (odds ratio, 0.5; P = .046).

There was no difference in 5-year overall survival between the groups.

As noted before, there were no significant differences in acute toxicities, but there were significantly more late grade 2 or greater toxicities among patients who underwent EBRT and PB (53% vs. 37%; P less than .0001), and more late grade 3 or greater toxicities (12% vs. 7%; P = .039).

Michael J Zelefsky, MD, professor of radiation oncology and chief of the brachytherapy service at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York, the invited discussant, said that the study suggests that “combining EBRT with brachytherapy for favorable intermediate-risk disease may constitute unnecessary overkill.”

He asserted, however, that favorable intermediate-risk disease behaves clinically more like low-risk disease, whereas unfavorable intermediate-risk disease is closer to high-risk disease in its clinical behavior.

It is plausible that, for patients with unfavorable intermediate-risk disease, added dose intensification associated with combined modality therapy could result in improved FFP and local tumor control, he said.

The study was funded by the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Prestidge disclosed consulting for Varian, Elekta, and IsoRay. Dr. Zelefsky disclosed receiving honoraria from Bebig Brachytherapy, Augmenix, and as editor-in-chief of Brachytherapy. Dr. Lawton reported no relevant disclosures.

BOSTON – In a finding hailed as “paradigm changing,” men with favorable intermediate-risk prostate cancer may have good disease control with brachytherapy alone, with fewer late-term toxicities than with brachytherapy combined with external-beam radiation, investigators reported.

After 5 years of follow-up, there were no significant differences in rates of freedom from disease progression among patients assigned to receive combined external-beam radiation (EBRT) and transperineal interstitial permanent brachytherapy (PB) or PB alone in selected patients with intermediate-risk prostatic carcinoma.

“I think you’re underselling your results – I’m pretty excited about these results,” Colleen Lawton, MD, professor and vice chair of radiation oncology at the Medical College of Wisconsin in Milwaukee, told Dr. Prestidge at the annual meeting of the American Society of Radiation Oncology.

The results show that, “for the intermediate-risk group, not the worst of intermediate [risk] but the vast majority, they don’t need the toxicity of that external beam, and they don’t need the cost of it,” she said at a briefing following his presentation of the data in a plenary session.

Dr. Lawton said that, when the NRG Oncology/RTOG 0232study was initiated (the first patients were enrolled in 2003), “there were factions that believed you could not treat intermediate-risk prostate cancer – which isn’t the best, isn’t the worse, but is somewhere in the middle – with anything but the combination, and this shows that’s not true.”

The trial was designed to test the hypothesis that patients with intermediate-risk prostate cancer treated with combined EBRT and PB would have a 10% improvement in freedom from progression (FFP), compared with men treated with PB alone.

A total of 579 patients with histologically confirmed prostate cancer, stages T1c-2b and Zubrod performance score 0 or 1 were enrolled. The patients also had Gleason score 2-6 and prostate-specific antigen (PSA) from 10 to less than 20 ng/mL; Gleason score and PSA less than 10 ng/mL; or prostate volume less than 60 cc.

In addition, androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) was not allowed on the study, and patients could not have distant metastases or radiographically suspicious nodes at the time of enrollment.

Patients were stratified by stage, Gleason score, PSA and history of ADT, and then randomized to the combined therapy, consisting of 45 Gy in a partial pelvis dose delivered in 1.8 Gy fractions for 5 weeks, followed 2-4 weeks later with brachytherapy using either a radioactive iodine (I-125) source prescribed as a 110-Gy boost dose, or palladium 103 in a 100 Gy boost dose; or brachytherapy alone (145-Gy dose with I-I25, 125-Gy dose with palladium 103). EBRT was delivered by either intensity-modulated radiation (43%) or 3D conformal radiation.

Five years after randomization, there were a total of 66 cases of treatment failure (measured as either biochemical failure according to ASTRO criteria, local progression, distant metastases, or death from any cause), 34 occurring in men treated with the combination, and 32 in men treated with brachytherapy alone. Biochemical failures accounted for 68% of events among patients on the combined modalities and 53% of those on brachytherapy alone. There were 9 deaths in the combined arm and 14 deaths in the brachytherapy-only arm, but none were prostate cancer related, Dr. Prestidge said.

In multivariate analysis adjusted for treatment type, age, race, prior hormonal therapy, Gleason/PSA, and tumor stage, the only significant predictor of FFP was Gleason 7/PSA less than 10 ng/mL, which was associated with better outcomes, compared with Gleason score less than 7/PSA 10-20 ng/mL (odds ratio, 0.5; P = .046).

There was no difference in 5-year overall survival between the groups.

As noted before, there were no significant differences in acute toxicities, but there were significantly more late grade 2 or greater toxicities among patients who underwent EBRT and PB (53% vs. 37%; P less than .0001), and more late grade 3 or greater toxicities (12% vs. 7%; P = .039).

Michael J Zelefsky, MD, professor of radiation oncology and chief of the brachytherapy service at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York, the invited discussant, said that the study suggests that “combining EBRT with brachytherapy for favorable intermediate-risk disease may constitute unnecessary overkill.”

He asserted, however, that favorable intermediate-risk disease behaves clinically more like low-risk disease, whereas unfavorable intermediate-risk disease is closer to high-risk disease in its clinical behavior.

It is plausible that, for patients with unfavorable intermediate-risk disease, added dose intensification associated with combined modality therapy could result in improved FFP and local tumor control, he said.

The study was funded by the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Prestidge disclosed consulting for Varian, Elekta, and IsoRay. Dr. Zelefsky disclosed receiving honoraria from Bebig Brachytherapy, Augmenix, and as editor-in-chief of Brachytherapy. Dr. Lawton reported no relevant disclosures.

BOSTON – In a finding hailed as “paradigm changing,” men with favorable intermediate-risk prostate cancer may have good disease control with brachytherapy alone, with fewer late-term toxicities than with brachytherapy combined with external-beam radiation, investigators reported.

After 5 years of follow-up, there were no significant differences in rates of freedom from disease progression among patients assigned to receive combined external-beam radiation (EBRT) and transperineal interstitial permanent brachytherapy (PB) or PB alone in selected patients with intermediate-risk prostatic carcinoma.

“I think you’re underselling your results – I’m pretty excited about these results,” Colleen Lawton, MD, professor and vice chair of radiation oncology at the Medical College of Wisconsin in Milwaukee, told Dr. Prestidge at the annual meeting of the American Society of Radiation Oncology.

The results show that, “for the intermediate-risk group, not the worst of intermediate [risk] but the vast majority, they don’t need the toxicity of that external beam, and they don’t need the cost of it,” she said at a briefing following his presentation of the data in a plenary session.

Dr. Lawton said that, when the NRG Oncology/RTOG 0232study was initiated (the first patients were enrolled in 2003), “there were factions that believed you could not treat intermediate-risk prostate cancer – which isn’t the best, isn’t the worse, but is somewhere in the middle – with anything but the combination, and this shows that’s not true.”

The trial was designed to test the hypothesis that patients with intermediate-risk prostate cancer treated with combined EBRT and PB would have a 10% improvement in freedom from progression (FFP), compared with men treated with PB alone.

A total of 579 patients with histologically confirmed prostate cancer, stages T1c-2b and Zubrod performance score 0 or 1 were enrolled. The patients also had Gleason score 2-6 and prostate-specific antigen (PSA) from 10 to less than 20 ng/mL; Gleason score and PSA less than 10 ng/mL; or prostate volume less than 60 cc.

In addition, androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) was not allowed on the study, and patients could not have distant metastases or radiographically suspicious nodes at the time of enrollment.

Patients were stratified by stage, Gleason score, PSA and history of ADT, and then randomized to the combined therapy, consisting of 45 Gy in a partial pelvis dose delivered in 1.8 Gy fractions for 5 weeks, followed 2-4 weeks later with brachytherapy using either a radioactive iodine (I-125) source prescribed as a 110-Gy boost dose, or palladium 103 in a 100 Gy boost dose; or brachytherapy alone (145-Gy dose with I-I25, 125-Gy dose with palladium 103). EBRT was delivered by either intensity-modulated radiation (43%) or 3D conformal radiation.

Five years after randomization, there were a total of 66 cases of treatment failure (measured as either biochemical failure according to ASTRO criteria, local progression, distant metastases, or death from any cause), 34 occurring in men treated with the combination, and 32 in men treated with brachytherapy alone. Biochemical failures accounted for 68% of events among patients on the combined modalities and 53% of those on brachytherapy alone. There were 9 deaths in the combined arm and 14 deaths in the brachytherapy-only arm, but none were prostate cancer related, Dr. Prestidge said.

In multivariate analysis adjusted for treatment type, age, race, prior hormonal therapy, Gleason/PSA, and tumor stage, the only significant predictor of FFP was Gleason 7/PSA less than 10 ng/mL, which was associated with better outcomes, compared with Gleason score less than 7/PSA 10-20 ng/mL (odds ratio, 0.5; P = .046).

There was no difference in 5-year overall survival between the groups.

As noted before, there were no significant differences in acute toxicities, but there were significantly more late grade 2 or greater toxicities among patients who underwent EBRT and PB (53% vs. 37%; P less than .0001), and more late grade 3 or greater toxicities (12% vs. 7%; P = .039).

Michael J Zelefsky, MD, professor of radiation oncology and chief of the brachytherapy service at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York, the invited discussant, said that the study suggests that “combining EBRT with brachytherapy for favorable intermediate-risk disease may constitute unnecessary overkill.”

He asserted, however, that favorable intermediate-risk disease behaves clinically more like low-risk disease, whereas unfavorable intermediate-risk disease is closer to high-risk disease in its clinical behavior.

It is plausible that, for patients with unfavorable intermediate-risk disease, added dose intensification associated with combined modality therapy could result in improved FFP and local tumor control, he said.

The study was funded by the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Prestidge disclosed consulting for Varian, Elekta, and IsoRay. Dr. Zelefsky disclosed receiving honoraria from Bebig Brachytherapy, Augmenix, and as editor-in-chief of Brachytherapy. Dr. Lawton reported no relevant disclosures.

AT ASTRO 2016

Key clinical point: It may be clinically unnecessary to add external-beam radiation to brachytherapy in men with favorable intermediate-risk prostate cancer.

Major finding: Outcomes were comparable for men with favorable intermediate-risk prostate cancer treated with external-beam radiation plus brachytherapy or brachytherapy alone.

Data source: Randomized, controlled trial in 579 men with intermediate-risk prostate cancer.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Prestidge disclosed consulting for Varian, Elekta, and IsoRay. Dr. Zelefsky disclosed receiving honoraria from Bebig Brachytherapy, Augmenix, and as editor-in-chief of Brachytherapy. Dr. Lawton reported no relevant disclosures.

Ear-worn device helps Parkinson’s patients to improve their voice

PORTLAND, ORE. – A new device worn on one ear may help individuals with Parkinson’s disease to overcome speech deficits associated with the disease. When triggered by the wearer’s voice, the device, SpeechVive, provides a simulated room crowd noise or “babble” only when they are talking. Because it capitalizes on natural reflexes to this simulated background noise, improvement can occur independent of speech training.

Researchers led by Jessica Huber, PhD, a professor of speech, language, and hearing sciences at Purdue University in West Lafayette, Ind., investigated changes to speech after 3 months of daily use of the SpeechVive device by 16 individuals. The cohort had a mean age of 64.5 years (range: 56-78 years) and a mean disease duration of 8.1 years (range: 2-17 years). Six participants had previously had speech therapy (five with LSVT [Lee Silverman Voice Treatment] LOUD speech training exercises), and two had deep brain stimulation implants.

Similar to an earlier study of 39 participants, “We found a nice increase in loudness, that they just can wear the device, and they’re louder in their everyday communication,” Dr. Huber said in an interview during a poster session at the World Parkinson Congress. New to this study was a finding that the melody of speech was a little better, “so their questions are more like questions, and their statements are more like statements, so are the rising intonation on questions and the falling intonation on a statement.” Participants were also able to say more on one breath and to sound more natural with appropriate pauses because of the longer utterances.

After 3 months of use, participants as a group increased their sound pressure level (loudness) from 76.6 dB to 78.8 dB (a gain of 2.2 dB) from having the device OFF to ON. When it was then turned off, they had an intermediate sound pressure level of 77.7 dB (both P less than .0001 vs. pretest OFF). Intonation variability and intonation range also showed significant improvements for both statements and questions with the use of the device (all P less than or equal to .01). There were also improvements in a correct statement or question being produced, pausing patterns, and utterance length. No adverse events occurred in the study.

Dr. Huber said patients in the study were quite variable in their responses to SpeechVive for the different measures of speech. In general, she has found that about 75% of users get louder with the device, and some have clearer articulation or slower speech. Another 10%-15% have slower speech or better articulation without an increase in loudness.

A total of 50% of the users have a “carry-over” effect after using the device when they are not wearing it. “After about 8 weeks, they don’t need to keep wearing the device every day,” Dr. Huber noted. Others may wear it in the morning and have a lasting effect for the rest of the day, and some lose any benefit as soon as taking the device off. Not all patients reach a normal speech loudness, “but they’re going to get way better” than where they started, she said.

Available speech therapies

People with Parkinson’s disease (PD) often have reduced vocal loudness, increased speech rate, and slurred articulation. Available speech therapies have included adduction exercises, vocal function exercises, and LSVT LOUD speech training exercises. For some individuals with PD, these behavioral treatments may not carry over into daily life.

The SpeechVive consists of a piece placed into the ear canal and a piece that sits behind the ear, similar to a slightly larger version of a modern hearing aid. It is designed large enough that many patients, who have motor deficits, can don it themselves. Because it is on just one ear, users can hear other people talking and what is going on around them.

Dr. Huber noted several strengths of the device. First, it does not impose any cognitive load on the user because its effect is based on an automatic reflex. Second, little training is necessary. It is easy for the user to put on the device, and many of its beneficial effects occur as soon as it is activated. Third, compliance can be tracked using data stored by the device itself.

In a previous study, she saw that after using the device for 8 weeks, participants used more effective patterns with their respiratory and laryngeal mechanisms to produce louder speech. “It’s not like they’re working super hard after 8 weeks.” She thinks they are just not usually using their speech apparatus in the most efficient manner, and they become more efficient after using the device. They may also not sense how loud they are without it, so it helps patients “recalibrate” a sense of their own voices, something the LSVT LOUD training also does.

Jori Fleisher, MD, a movement disorders neurologist at the New York University Langone Medical Center, commented that the study shows an interesting approach to the common and difficult problem of hypophonia and dysphonia in people with Parkinson’s disease. “It can be very difficult to speak loud enough to be heard, and it often leads to people withdrawing socially and not speaking as much in conversation as they normally would,” she said. “LSVT LOUD works in practice when you’re actually doing the exercises, but often when people stop doing the exercises, their voice goes back toward their normal. So this is something that you can keep with you and sort of have constant prompting to overcome that tendency toward quieter voice. It has a lot of promise.”

She said she would like to see the data on compliance or adherence with using the device “because it seems like a great idea, but how much are people actually using it? ... Having more long-term follow-up to see whether this is something that people want to put into practice in their daily life would be very useful.” She also said she would like to see how long the carry-over effect lasts once people take off the device to be able to compare it with sessions of speech therapy or doing speech exercises.

SpeechVive is $2,495, which includes the device, a charger, and earpiece fittings. It is available only in the United States, but the company now has clearance to market it in Canada.

The research was funded by a grant from SpeechVive. Dr. Huber is the inventor of SpeechVive, has a patent on it, has a financial interest in the SpeechVive company, and sits on its board of directors. Dr. Fleisher reported having no financial conflicts.

PORTLAND, ORE. – A new device worn on one ear may help individuals with Parkinson’s disease to overcome speech deficits associated with the disease. When triggered by the wearer’s voice, the device, SpeechVive, provides a simulated room crowd noise or “babble” only when they are talking. Because it capitalizes on natural reflexes to this simulated background noise, improvement can occur independent of speech training.

Researchers led by Jessica Huber, PhD, a professor of speech, language, and hearing sciences at Purdue University in West Lafayette, Ind., investigated changes to speech after 3 months of daily use of the SpeechVive device by 16 individuals. The cohort had a mean age of 64.5 years (range: 56-78 years) and a mean disease duration of 8.1 years (range: 2-17 years). Six participants had previously had speech therapy (five with LSVT [Lee Silverman Voice Treatment] LOUD speech training exercises), and two had deep brain stimulation implants.

Similar to an earlier study of 39 participants, “We found a nice increase in loudness, that they just can wear the device, and they’re louder in their everyday communication,” Dr. Huber said in an interview during a poster session at the World Parkinson Congress. New to this study was a finding that the melody of speech was a little better, “so their questions are more like questions, and their statements are more like statements, so are the rising intonation on questions and the falling intonation on a statement.” Participants were also able to say more on one breath and to sound more natural with appropriate pauses because of the longer utterances.

After 3 months of use, participants as a group increased their sound pressure level (loudness) from 76.6 dB to 78.8 dB (a gain of 2.2 dB) from having the device OFF to ON. When it was then turned off, they had an intermediate sound pressure level of 77.7 dB (both P less than .0001 vs. pretest OFF). Intonation variability and intonation range also showed significant improvements for both statements and questions with the use of the device (all P less than or equal to .01). There were also improvements in a correct statement or question being produced, pausing patterns, and utterance length. No adverse events occurred in the study.

Dr. Huber said patients in the study were quite variable in their responses to SpeechVive for the different measures of speech. In general, she has found that about 75% of users get louder with the device, and some have clearer articulation or slower speech. Another 10%-15% have slower speech or better articulation without an increase in loudness.

A total of 50% of the users have a “carry-over” effect after using the device when they are not wearing it. “After about 8 weeks, they don’t need to keep wearing the device every day,” Dr. Huber noted. Others may wear it in the morning and have a lasting effect for the rest of the day, and some lose any benefit as soon as taking the device off. Not all patients reach a normal speech loudness, “but they’re going to get way better” than where they started, she said.

Available speech therapies

People with Parkinson’s disease (PD) often have reduced vocal loudness, increased speech rate, and slurred articulation. Available speech therapies have included adduction exercises, vocal function exercises, and LSVT LOUD speech training exercises. For some individuals with PD, these behavioral treatments may not carry over into daily life.

The SpeechVive consists of a piece placed into the ear canal and a piece that sits behind the ear, similar to a slightly larger version of a modern hearing aid. It is designed large enough that many patients, who have motor deficits, can don it themselves. Because it is on just one ear, users can hear other people talking and what is going on around them.

Dr. Huber noted several strengths of the device. First, it does not impose any cognitive load on the user because its effect is based on an automatic reflex. Second, little training is necessary. It is easy for the user to put on the device, and many of its beneficial effects occur as soon as it is activated. Third, compliance can be tracked using data stored by the device itself.

In a previous study, she saw that after using the device for 8 weeks, participants used more effective patterns with their respiratory and laryngeal mechanisms to produce louder speech. “It’s not like they’re working super hard after 8 weeks.” She thinks they are just not usually using their speech apparatus in the most efficient manner, and they become more efficient after using the device. They may also not sense how loud they are without it, so it helps patients “recalibrate” a sense of their own voices, something the LSVT LOUD training also does.

Jori Fleisher, MD, a movement disorders neurologist at the New York University Langone Medical Center, commented that the study shows an interesting approach to the common and difficult problem of hypophonia and dysphonia in people with Parkinson’s disease. “It can be very difficult to speak loud enough to be heard, and it often leads to people withdrawing socially and not speaking as much in conversation as they normally would,” she said. “LSVT LOUD works in practice when you’re actually doing the exercises, but often when people stop doing the exercises, their voice goes back toward their normal. So this is something that you can keep with you and sort of have constant prompting to overcome that tendency toward quieter voice. It has a lot of promise.”

She said she would like to see the data on compliance or adherence with using the device “because it seems like a great idea, but how much are people actually using it? ... Having more long-term follow-up to see whether this is something that people want to put into practice in their daily life would be very useful.” She also said she would like to see how long the carry-over effect lasts once people take off the device to be able to compare it with sessions of speech therapy or doing speech exercises.

SpeechVive is $2,495, which includes the device, a charger, and earpiece fittings. It is available only in the United States, but the company now has clearance to market it in Canada.

The research was funded by a grant from SpeechVive. Dr. Huber is the inventor of SpeechVive, has a patent on it, has a financial interest in the SpeechVive company, and sits on its board of directors. Dr. Fleisher reported having no financial conflicts.

PORTLAND, ORE. – A new device worn on one ear may help individuals with Parkinson’s disease to overcome speech deficits associated with the disease. When triggered by the wearer’s voice, the device, SpeechVive, provides a simulated room crowd noise or “babble” only when they are talking. Because it capitalizes on natural reflexes to this simulated background noise, improvement can occur independent of speech training.

Researchers led by Jessica Huber, PhD, a professor of speech, language, and hearing sciences at Purdue University in West Lafayette, Ind., investigated changes to speech after 3 months of daily use of the SpeechVive device by 16 individuals. The cohort had a mean age of 64.5 years (range: 56-78 years) and a mean disease duration of 8.1 years (range: 2-17 years). Six participants had previously had speech therapy (five with LSVT [Lee Silverman Voice Treatment] LOUD speech training exercises), and two had deep brain stimulation implants.

Similar to an earlier study of 39 participants, “We found a nice increase in loudness, that they just can wear the device, and they’re louder in their everyday communication,” Dr. Huber said in an interview during a poster session at the World Parkinson Congress. New to this study was a finding that the melody of speech was a little better, “so their questions are more like questions, and their statements are more like statements, so are the rising intonation on questions and the falling intonation on a statement.” Participants were also able to say more on one breath and to sound more natural with appropriate pauses because of the longer utterances.

After 3 months of use, participants as a group increased their sound pressure level (loudness) from 76.6 dB to 78.8 dB (a gain of 2.2 dB) from having the device OFF to ON. When it was then turned off, they had an intermediate sound pressure level of 77.7 dB (both P less than .0001 vs. pretest OFF). Intonation variability and intonation range also showed significant improvements for both statements and questions with the use of the device (all P less than or equal to .01). There were also improvements in a correct statement or question being produced, pausing patterns, and utterance length. No adverse events occurred in the study.

Dr. Huber said patients in the study were quite variable in their responses to SpeechVive for the different measures of speech. In general, she has found that about 75% of users get louder with the device, and some have clearer articulation or slower speech. Another 10%-15% have slower speech or better articulation without an increase in loudness.

A total of 50% of the users have a “carry-over” effect after using the device when they are not wearing it. “After about 8 weeks, they don’t need to keep wearing the device every day,” Dr. Huber noted. Others may wear it in the morning and have a lasting effect for the rest of the day, and some lose any benefit as soon as taking the device off. Not all patients reach a normal speech loudness, “but they’re going to get way better” than where they started, she said.

Available speech therapies

People with Parkinson’s disease (PD) often have reduced vocal loudness, increased speech rate, and slurred articulation. Available speech therapies have included adduction exercises, vocal function exercises, and LSVT LOUD speech training exercises. For some individuals with PD, these behavioral treatments may not carry over into daily life.

The SpeechVive consists of a piece placed into the ear canal and a piece that sits behind the ear, similar to a slightly larger version of a modern hearing aid. It is designed large enough that many patients, who have motor deficits, can don it themselves. Because it is on just one ear, users can hear other people talking and what is going on around them.

Dr. Huber noted several strengths of the device. First, it does not impose any cognitive load on the user because its effect is based on an automatic reflex. Second, little training is necessary. It is easy for the user to put on the device, and many of its beneficial effects occur as soon as it is activated. Third, compliance can be tracked using data stored by the device itself.

In a previous study, she saw that after using the device for 8 weeks, participants used more effective patterns with their respiratory and laryngeal mechanisms to produce louder speech. “It’s not like they’re working super hard after 8 weeks.” She thinks they are just not usually using their speech apparatus in the most efficient manner, and they become more efficient after using the device. They may also not sense how loud they are without it, so it helps patients “recalibrate” a sense of their own voices, something the LSVT LOUD training also does.

Jori Fleisher, MD, a movement disorders neurologist at the New York University Langone Medical Center, commented that the study shows an interesting approach to the common and difficult problem of hypophonia and dysphonia in people with Parkinson’s disease. “It can be very difficult to speak loud enough to be heard, and it often leads to people withdrawing socially and not speaking as much in conversation as they normally would,” she said. “LSVT LOUD works in practice when you’re actually doing the exercises, but often when people stop doing the exercises, their voice goes back toward their normal. So this is something that you can keep with you and sort of have constant prompting to overcome that tendency toward quieter voice. It has a lot of promise.”

She said she would like to see the data on compliance or adherence with using the device “because it seems like a great idea, but how much are people actually using it? ... Having more long-term follow-up to see whether this is something that people want to put into practice in their daily life would be very useful.” She also said she would like to see how long the carry-over effect lasts once people take off the device to be able to compare it with sessions of speech therapy or doing speech exercises.

SpeechVive is $2,495, which includes the device, a charger, and earpiece fittings. It is available only in the United States, but the company now has clearance to market it in Canada.

The research was funded by a grant from SpeechVive. Dr. Huber is the inventor of SpeechVive, has a patent on it, has a financial interest in the SpeechVive company, and sits on its board of directors. Dr. Fleisher reported having no financial conflicts.

AT WPC 2016

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Loudness increased 2.2 dB from 76.6 dB to 78.8 dB after 3 months of use. Intonation also improved.

Data source: A prospective study of 16 participants with hypophonia comparing speech parameters with and without the device after 3 months of use.

Disclosures: The research was funded by a grant from SpeechVive. Dr. Huber is the inventor of SpeechVive, has a patent on it, has a financial interest in the SpeechVive company, and sits on its board of directors. Dr. Fleisher reported having no financial conflicts.

Calcium channel blocker reduces cardiac iron loading in thalassemia major

The calcium channel blocker amlodipine, added to iron chelation therapy, significantly reduced excess myocardial iron concentration in patients with thalassemia major, compared with chelation alone, according to results from a randomized trial.

The findings (Blood. 2016;128[12]:1555-61) suggest that amlodipine, a cheap, widely available drug with a well-established safety profile, may serve as an adjunct to standard treatment for people with thalassemia major and cardiac siderosis. Cardiovascular disease caused by excess myocardial iron remains a major cause of morbidity and mortality in thalassemia major.

Juliano L. Fernandes, MD, PhD, of the Jose Michel Kalaf Research Institute in Campinas, Brazil, led the study, which randomized 62 patients already receiving chelation treatment for thalassemia major to 1 year of chelation plus placebo (n = 31) or chelation plus 5 mg daily amlodipine (n = 31).

Patients in each arm were subdivided into two subgroups: those whose baseline myocardial iron concentration was within normal thresholds, and those with excess myocardial iron concentration as measured by magnetic resonance imaging (above 0.59 mg/g dry weight or with a cardiac T2* below 35 milliseconds).

In the amlodipine arm, patients with excess cardiac iron at baseline (n = 15) saw significant reductions in myocardial iron concentrations at 1 year, compared with those randomized to placebo (n = 15). The former had a median reduction of –0.26 mg/g (95% confidence interval, –1.02 to –0.01) while the placebo group saw an increase of 0.01 mg/g (95% CI, 20.13 to 20.23; P = .02).

The investigators acknowledged that some of the findings were limited by the study’s short observation period.

Patients without excess myocardial iron concentration at baseline did not see significant changes associated with amlodipine. While Dr. Fernandes and his colleagues could not conclude that the drug prevented excess cardiac iron from accumulating, “our data cannot rule out the possibility that extended use of amlodipine might prevent myocardial iron accumulation with a longer observation period.”

Secondary endpoints of the study included measurements of iron storage in the liver and of serum ferritin, neither of which appeared to be affected by amlodipine treatment, which the investigators said was consistent with the drug’s known mechanism of action. No serious adverse effects were reported related to amlodipine treatment.

Dr. Fernandes and his colleagues also did not find improvements in left ventricular ejection fraction associated with amlodipine use at 12 months. This may be due, they wrote in their analysis, to a “relatively low prevalence of reduced ejection fraction or severe myocardial siderosis upon trial enrollment, limiting the power of the study to assess these outcomes.”

The government of Brazil and the Sultan Bin Khalifa Translational Research Scholarship sponsored the study. Dr. Fernandes reported receiving fees from Novartis and Sanofi. The remaining 12 authors disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Why is this small clinical trial of such pivotal importance in this day and age of massive multicenter prospective randomized studies? The answer is that it tells us that iron entry into the heart through L-type calcium channels, a mechanism that has been clearly demonstrated in vitro, seems to be actually occurring in humans. As an added bonus, we have a possible new adjunctive treatment of iron cardiomyopathy. More clinical studies are needed, and certainly biochemical studies need to continue because all calcium channel blockers do not have the same effect in vitro, but at least the “channels” for more progress on both clinical and biochemical fronts are now open.

Thomas D. Coates, MD, is with Children’s Hospital of Los Angeles and University of Southern California, Los Angeles. He made his remarks in an editorial that accompanied the published study.

Why is this small clinical trial of such pivotal importance in this day and age of massive multicenter prospective randomized studies? The answer is that it tells us that iron entry into the heart through L-type calcium channels, a mechanism that has been clearly demonstrated in vitro, seems to be actually occurring in humans. As an added bonus, we have a possible new adjunctive treatment of iron cardiomyopathy. More clinical studies are needed, and certainly biochemical studies need to continue because all calcium channel blockers do not have the same effect in vitro, but at least the “channels” for more progress on both clinical and biochemical fronts are now open.

Thomas D. Coates, MD, is with Children’s Hospital of Los Angeles and University of Southern California, Los Angeles. He made his remarks in an editorial that accompanied the published study.

Why is this small clinical trial of such pivotal importance in this day and age of massive multicenter prospective randomized studies? The answer is that it tells us that iron entry into the heart through L-type calcium channels, a mechanism that has been clearly demonstrated in vitro, seems to be actually occurring in humans. As an added bonus, we have a possible new adjunctive treatment of iron cardiomyopathy. More clinical studies are needed, and certainly biochemical studies need to continue because all calcium channel blockers do not have the same effect in vitro, but at least the “channels” for more progress on both clinical and biochemical fronts are now open.

Thomas D. Coates, MD, is with Children’s Hospital of Los Angeles and University of Southern California, Los Angeles. He made his remarks in an editorial that accompanied the published study.

The calcium channel blocker amlodipine, added to iron chelation therapy, significantly reduced excess myocardial iron concentration in patients with thalassemia major, compared with chelation alone, according to results from a randomized trial.

The findings (Blood. 2016;128[12]:1555-61) suggest that amlodipine, a cheap, widely available drug with a well-established safety profile, may serve as an adjunct to standard treatment for people with thalassemia major and cardiac siderosis. Cardiovascular disease caused by excess myocardial iron remains a major cause of morbidity and mortality in thalassemia major.

Juliano L. Fernandes, MD, PhD, of the Jose Michel Kalaf Research Institute in Campinas, Brazil, led the study, which randomized 62 patients already receiving chelation treatment for thalassemia major to 1 year of chelation plus placebo (n = 31) or chelation plus 5 mg daily amlodipine (n = 31).

Patients in each arm were subdivided into two subgroups: those whose baseline myocardial iron concentration was within normal thresholds, and those with excess myocardial iron concentration as measured by magnetic resonance imaging (above 0.59 mg/g dry weight or with a cardiac T2* below 35 milliseconds).

In the amlodipine arm, patients with excess cardiac iron at baseline (n = 15) saw significant reductions in myocardial iron concentrations at 1 year, compared with those randomized to placebo (n = 15). The former had a median reduction of –0.26 mg/g (95% confidence interval, –1.02 to –0.01) while the placebo group saw an increase of 0.01 mg/g (95% CI, 20.13 to 20.23; P = .02).

The investigators acknowledged that some of the findings were limited by the study’s short observation period.

Patients without excess myocardial iron concentration at baseline did not see significant changes associated with amlodipine. While Dr. Fernandes and his colleagues could not conclude that the drug prevented excess cardiac iron from accumulating, “our data cannot rule out the possibility that extended use of amlodipine might prevent myocardial iron accumulation with a longer observation period.”

Secondary endpoints of the study included measurements of iron storage in the liver and of serum ferritin, neither of which appeared to be affected by amlodipine treatment, which the investigators said was consistent with the drug’s known mechanism of action. No serious adverse effects were reported related to amlodipine treatment.

Dr. Fernandes and his colleagues also did not find improvements in left ventricular ejection fraction associated with amlodipine use at 12 months. This may be due, they wrote in their analysis, to a “relatively low prevalence of reduced ejection fraction or severe myocardial siderosis upon trial enrollment, limiting the power of the study to assess these outcomes.”

The government of Brazil and the Sultan Bin Khalifa Translational Research Scholarship sponsored the study. Dr. Fernandes reported receiving fees from Novartis and Sanofi. The remaining 12 authors disclosed no conflicts of interest.

The calcium channel blocker amlodipine, added to iron chelation therapy, significantly reduced excess myocardial iron concentration in patients with thalassemia major, compared with chelation alone, according to results from a randomized trial.

The findings (Blood. 2016;128[12]:1555-61) suggest that amlodipine, a cheap, widely available drug with a well-established safety profile, may serve as an adjunct to standard treatment for people with thalassemia major and cardiac siderosis. Cardiovascular disease caused by excess myocardial iron remains a major cause of morbidity and mortality in thalassemia major.

Juliano L. Fernandes, MD, PhD, of the Jose Michel Kalaf Research Institute in Campinas, Brazil, led the study, which randomized 62 patients already receiving chelation treatment for thalassemia major to 1 year of chelation plus placebo (n = 31) or chelation plus 5 mg daily amlodipine (n = 31).

Patients in each arm were subdivided into two subgroups: those whose baseline myocardial iron concentration was within normal thresholds, and those with excess myocardial iron concentration as measured by magnetic resonance imaging (above 0.59 mg/g dry weight or with a cardiac T2* below 35 milliseconds).

In the amlodipine arm, patients with excess cardiac iron at baseline (n = 15) saw significant reductions in myocardial iron concentrations at 1 year, compared with those randomized to placebo (n = 15). The former had a median reduction of –0.26 mg/g (95% confidence interval, –1.02 to –0.01) while the placebo group saw an increase of 0.01 mg/g (95% CI, 20.13 to 20.23; P = .02).

The investigators acknowledged that some of the findings were limited by the study’s short observation period.

Patients without excess myocardial iron concentration at baseline did not see significant changes associated with amlodipine. While Dr. Fernandes and his colleagues could not conclude that the drug prevented excess cardiac iron from accumulating, “our data cannot rule out the possibility that extended use of amlodipine might prevent myocardial iron accumulation with a longer observation period.”

Secondary endpoints of the study included measurements of iron storage in the liver and of serum ferritin, neither of which appeared to be affected by amlodipine treatment, which the investigators said was consistent with the drug’s known mechanism of action. No serious adverse effects were reported related to amlodipine treatment.

Dr. Fernandes and his colleagues also did not find improvements in left ventricular ejection fraction associated with amlodipine use at 12 months. This may be due, they wrote in their analysis, to a “relatively low prevalence of reduced ejection fraction or severe myocardial siderosis upon trial enrollment, limiting the power of the study to assess these outcomes.”

The government of Brazil and the Sultan Bin Khalifa Translational Research Scholarship sponsored the study. Dr. Fernandes reported receiving fees from Novartis and Sanofi. The remaining 12 authors disclosed no conflicts of interest.

FROM BLOOD

Key clinical point: Amlodipine added to standard chelation therapy significantly reduced cardiac iron in thalassemia major patients with cardiac siderosis.

Major finding: At 12 months, cardiac iron was a median 0.26 mg/g lower in subjects with myocardial iron overload treated with 5 mg daily amlodipine plus chelation, while patients treated with chelation alone saw a 0.01 mg/g increase (P = .02).

Data source: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial enrolling from 62 patients with TM from six centers in Brazil, about half with cardiac siderosis at baseline.

Disclosures: The Brazil government and the Sultan Bin Khalifa Translational Research Scholarship sponsored the investigation. Its lead author reported receiving fees from Novartis and Sanofi. Other study investigators and the author of a linked editorial declared no conflicts of interest.

Periostin level may indicate upper-airway disease in asthmatics

LONDON – Measuring serum levels of the extracellular protein periostin could help identify patients with asthma who have comorbid upper-airway disease, according to research from a late-breaking oral abstract presented at the annual congress of the European Respiratory Society.

Periostin is known to be involved in the pathophysiology of upper-airway disease, linked to both airway remodeling and inflammation. Levels of periostin have been shown to be higher in patients with asthma, allergic rhinitis, and chronic rhinosinusitis than in healthy individuals, and there are data suggesting that it could be linked to severity. However, little is known about whether serum periostin can be used to detect and perhaps monitor upper-airway disease in patients with asthma.

Serum periostin levels were found to be higher in asthma patients with comorbid chronic rhinosinusitis, compared with those with no comorbid upper-airway disease (119.8 vs. 86.3 ng/mL; P = .04).

Levels of periostin in the serum were also significantly higher in asthma patients with chronic rhinosinusitis who also had nasal polyps than in those who did not have nasal polyps (143.3 vs. 94.0 ng/mL; P = .01).

“Serum periostin is a sensitive biomarker for detecting comorbid chronic rhinosinusitis, especially in patients with chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps,” said Dr. Takamitsu Asano, who reported the findings at the meeting. Dr. Asano of Nagoya (Japan) City University Graduate School of Medical Sciences noted that the serum periostin could also reflect the severity of chronic rhinosinusitis in patients with asthma.

“Upper-airway diseases are considered risk factors for the exacerbation and poor control of asthma,” Dr. Asano explained. It is thought, he said, that 40%-50% of patients with asthma have comorbid chronic rhinosinusitis, and 57%-70% have comorbid allergic rhinitis.

Dr. Asano and colleagues at Nagoya City University and Saga (Japan) Medical School recruited 65 patients with stable asthma, with or without comorbid upper-airway disease, between July 2014 and December 2015. Of these patients, 20 had no comorbid upper-airway disease, 22 had rhinitis, 21 had chronic rhinosinusitis, and two had confirmed nasal polyps. Of the 21 patients with chronic rhinosinusitis, 10 had and 11 did not have nasal polyps. Patients’ diagnoses were checked by otorhinolaryngology specialists.

The recruited patients, who were a mean age of 56 years, with an asthma disease duration of 9 years, underwent the following tests: fractional exhaled nitric oxide testing, spirometry, sputum induction, and sinus computed tomography scanning. They also had their blood tested for serum periostin, eosinophils, eotaxin, and immunoglobulin E levels.

Serum periostin levels were found to correlate with the results of fractional exhaled nitric oxide testing, and with blood and sputum eosinophil counts, with respective correlation coefficients of 0.36 (P = .003), 0.35 (P = .005), and 0.44 (P = .004).

In a separate study presented by Dr. Cecile Holweg of Genentech, several patient factors were found to influence the level of serum periostin. Using data from trials of the experimental asthma therapy lebrikizumab and the asthma therapy omalizumab (Xolair), the biologic variability in serum periostin and blood eosinophils was characterized according to patient demographics, asthma severity, concomitant medication use, and comorbidities, including upper-airway diseases.

Multivariate analysis showed that serum periostin levels were higher in patients with nasal polyps and in patients from South America and Asia. Conversely, serum periostin levels were lower in patients with high body mass index and in patients who were current smokers.

Raised eosinophil counts were also seen in patients with nasal polyps and lower eosinophil counts were observed in current smokers.

“These factors should be taken into account when making treatment decisions based on these biomarkers,” Dr. Holweg concluded.

Dr. Asano has received financial support from Novartis, AstraZeneca, Merck Sharp & Dohme, and Eisai Co. Dr. Holweg is an employee of Genentech.

LONDON – Measuring serum levels of the extracellular protein periostin could help identify patients with asthma who have comorbid upper-airway disease, according to research from a late-breaking oral abstract presented at the annual congress of the European Respiratory Society.

Periostin is known to be involved in the pathophysiology of upper-airway disease, linked to both airway remodeling and inflammation. Levels of periostin have been shown to be higher in patients with asthma, allergic rhinitis, and chronic rhinosinusitis than in healthy individuals, and there are data suggesting that it could be linked to severity. However, little is known about whether serum periostin can be used to detect and perhaps monitor upper-airway disease in patients with asthma.

Serum periostin levels were found to be higher in asthma patients with comorbid chronic rhinosinusitis, compared with those with no comorbid upper-airway disease (119.8 vs. 86.3 ng/mL; P = .04).

Levels of periostin in the serum were also significantly higher in asthma patients with chronic rhinosinusitis who also had nasal polyps than in those who did not have nasal polyps (143.3 vs. 94.0 ng/mL; P = .01).

“Serum periostin is a sensitive biomarker for detecting comorbid chronic rhinosinusitis, especially in patients with chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps,” said Dr. Takamitsu Asano, who reported the findings at the meeting. Dr. Asano of Nagoya (Japan) City University Graduate School of Medical Sciences noted that the serum periostin could also reflect the severity of chronic rhinosinusitis in patients with asthma.

“Upper-airway diseases are considered risk factors for the exacerbation and poor control of asthma,” Dr. Asano explained. It is thought, he said, that 40%-50% of patients with asthma have comorbid chronic rhinosinusitis, and 57%-70% have comorbid allergic rhinitis.

Dr. Asano and colleagues at Nagoya City University and Saga (Japan) Medical School recruited 65 patients with stable asthma, with or without comorbid upper-airway disease, between July 2014 and December 2015. Of these patients, 20 had no comorbid upper-airway disease, 22 had rhinitis, 21 had chronic rhinosinusitis, and two had confirmed nasal polyps. Of the 21 patients with chronic rhinosinusitis, 10 had and 11 did not have nasal polyps. Patients’ diagnoses were checked by otorhinolaryngology specialists.

The recruited patients, who were a mean age of 56 years, with an asthma disease duration of 9 years, underwent the following tests: fractional exhaled nitric oxide testing, spirometry, sputum induction, and sinus computed tomography scanning. They also had their blood tested for serum periostin, eosinophils, eotaxin, and immunoglobulin E levels.

Serum periostin levels were found to correlate with the results of fractional exhaled nitric oxide testing, and with blood and sputum eosinophil counts, with respective correlation coefficients of 0.36 (P = .003), 0.35 (P = .005), and 0.44 (P = .004).

In a separate study presented by Dr. Cecile Holweg of Genentech, several patient factors were found to influence the level of serum periostin. Using data from trials of the experimental asthma therapy lebrikizumab and the asthma therapy omalizumab (Xolair), the biologic variability in serum periostin and blood eosinophils was characterized according to patient demographics, asthma severity, concomitant medication use, and comorbidities, including upper-airway diseases.

Multivariate analysis showed that serum periostin levels were higher in patients with nasal polyps and in patients from South America and Asia. Conversely, serum periostin levels were lower in patients with high body mass index and in patients who were current smokers.

Raised eosinophil counts were also seen in patients with nasal polyps and lower eosinophil counts were observed in current smokers.

“These factors should be taken into account when making treatment decisions based on these biomarkers,” Dr. Holweg concluded.

Dr. Asano has received financial support from Novartis, AstraZeneca, Merck Sharp & Dohme, and Eisai Co. Dr. Holweg is an employee of Genentech.

LONDON – Measuring serum levels of the extracellular protein periostin could help identify patients with asthma who have comorbid upper-airway disease, according to research from a late-breaking oral abstract presented at the annual congress of the European Respiratory Society.

Periostin is known to be involved in the pathophysiology of upper-airway disease, linked to both airway remodeling and inflammation. Levels of periostin have been shown to be higher in patients with asthma, allergic rhinitis, and chronic rhinosinusitis than in healthy individuals, and there are data suggesting that it could be linked to severity. However, little is known about whether serum periostin can be used to detect and perhaps monitor upper-airway disease in patients with asthma.

Serum periostin levels were found to be higher in asthma patients with comorbid chronic rhinosinusitis, compared with those with no comorbid upper-airway disease (119.8 vs. 86.3 ng/mL; P = .04).

Levels of periostin in the serum were also significantly higher in asthma patients with chronic rhinosinusitis who also had nasal polyps than in those who did not have nasal polyps (143.3 vs. 94.0 ng/mL; P = .01).

“Serum periostin is a sensitive biomarker for detecting comorbid chronic rhinosinusitis, especially in patients with chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps,” said Dr. Takamitsu Asano, who reported the findings at the meeting. Dr. Asano of Nagoya (Japan) City University Graduate School of Medical Sciences noted that the serum periostin could also reflect the severity of chronic rhinosinusitis in patients with asthma.

“Upper-airway diseases are considered risk factors for the exacerbation and poor control of asthma,” Dr. Asano explained. It is thought, he said, that 40%-50% of patients with asthma have comorbid chronic rhinosinusitis, and 57%-70% have comorbid allergic rhinitis.

Dr. Asano and colleagues at Nagoya City University and Saga (Japan) Medical School recruited 65 patients with stable asthma, with or without comorbid upper-airway disease, between July 2014 and December 2015. Of these patients, 20 had no comorbid upper-airway disease, 22 had rhinitis, 21 had chronic rhinosinusitis, and two had confirmed nasal polyps. Of the 21 patients with chronic rhinosinusitis, 10 had and 11 did not have nasal polyps. Patients’ diagnoses were checked by otorhinolaryngology specialists.

The recruited patients, who were a mean age of 56 years, with an asthma disease duration of 9 years, underwent the following tests: fractional exhaled nitric oxide testing, spirometry, sputum induction, and sinus computed tomography scanning. They also had their blood tested for serum periostin, eosinophils, eotaxin, and immunoglobulin E levels.

Serum periostin levels were found to correlate with the results of fractional exhaled nitric oxide testing, and with blood and sputum eosinophil counts, with respective correlation coefficients of 0.36 (P = .003), 0.35 (P = .005), and 0.44 (P = .004).

In a separate study presented by Dr. Cecile Holweg of Genentech, several patient factors were found to influence the level of serum periostin. Using data from trials of the experimental asthma therapy lebrikizumab and the asthma therapy omalizumab (Xolair), the biologic variability in serum periostin and blood eosinophils was characterized according to patient demographics, asthma severity, concomitant medication use, and comorbidities, including upper-airway diseases.

Multivariate analysis showed that serum periostin levels were higher in patients with nasal polyps and in patients from South America and Asia. Conversely, serum periostin levels were lower in patients with high body mass index and in patients who were current smokers.

Raised eosinophil counts were also seen in patients with nasal polyps and lower eosinophil counts were observed in current smokers.

“These factors should be taken into account when making treatment decisions based on these biomarkers,” Dr. Holweg concluded.

Dr. Asano has received financial support from Novartis, AstraZeneca, Merck Sharp & Dohme, and Eisai Co. Dr. Holweg is an employee of Genentech.

AT THE ERS CONGRESS 2016

Key clinical point: Measuring serum periostin could be useful for chronic rhinosinusitis detection in asthma patients.

Major finding: Serum periostin levels were higher in patients with comorbid chronic rhinosinusitis, compared with those with no comorbid upper-airway disease (119.8 vs. 86.3 ng/mL, P = .04).

Data source: Prospective study of comorbid upper-airway disease, rhinitis, and chronic rhinosinusitis in 65 patients with asthma.

Disclosures: Dr. Asano has received financial support from Novartis, AstraZeneca, Merck Sharp & Dohme, and Eisai Co.

Elevated troponins are serious business, even without an MI

Sometimes it seems like cardiac troponin testing has become nearly as ubiquitous as the CBC and the BMP. Concern over atypical presentations of MI has contributed to widespread use in emergency departments and hospitalized patients. But once the test comes back elevated, what do you do with that information?

Typically, the next step is to consult Cardiology, which is a reasonable request with or without a suspicion of MI. Frequently, invasive management is not an option; or perhaps the diagnosis is “type 2 MI.”1

A growing body of evidence is making it clear that any elevation in cardiac troponin is a serious predictor of risk and that the risk is highest if the patient is not having an MI.2 My colleagues and I recently conducted a cohort study of more than 700 veterans at our VA Medical Center addressing this question. We evaluated long-term mortality (6 years) comparing veterans who were diagnosed with MI with those who had troponin elevation and no clinical MI. The diagnostic determination was made for all subjects prospectively as part of a quality improvement project that sought to better care for MI patients at our facility. (In some cases, only single troponin values were measured so we cannot say that all patients in our investigation had a true type 2 MI.)

We found that veterans with an elevation in troponin that was not caused by MI had higher risk of mortality risk than did MI patients.3 The risk started to diverge at 30 days and was 42.0% at 1 year, compared with 29.0% for those with MI (odds ratio, 0.56; 95% confidence interval, 0.41-0.78). This risk continued to separate and, at 6 years, was 77.7% vs. 58.7% (OR, 0.41; 95% CI 0.30-0.56). Our observations agree with other recent publications; what we tried to do in advancing the literature was to construct a robust Cox proportional hazard model to try to better understand if the risk seen in these patients is just because of their being “sicker.”

We tried to capture a number of other acute illness states with variables including TIMI score, being in hospice care, having a “do not resuscitate” order, being in the ICU, receiving CPR, and having a fever or leukocytosis, etc. Despite this modeling, elevated troponin remained a significant predictor of risk. While several variables we modeled remained significant predictors of mortality, their distribution between our two cohorts did not explain the excess mortality risk associated with non-MI troponin.

Unfortunately, there are no viable treatment options specific for patients with non-MI troponin elevation and type 2 MI. Given that the causes are multiple and heterogeneous, there may not be a common pathway to target for reducing cardiovascular risk. Regardless, the observation of non-MI troponin or type 2 MI should be taken seriously and not be ignored.

In selected patients, particularly those without known coronary artery disease, it may be appropriate to perform diagnostic testing or risk assessment with noninvasive imaging prior to discharge. Those with coronary artery disease should be treated aggressively for prevention of future cardiovascular events with both medical therapy and risk factor reduction.

1. Thygesen K, Alpert JS, et al. Third universal definition of myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:1581-98.

2. Alcalai R, Planer D, Culhaoglu A, Osman A, Pollak A and Lotan C. Acute coronary syndrome vs nonspecific troponin elevation: clinical predictors and survival analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:276-81.

3. Winchester DE, Burke L, Agarwal N, Schmalfuss C and Pepine CJ. Predictors of short- and long-term mortality in hospitalized veterans with elevated troponin. J Hosp Med. 2016 Jun 3. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2619.

David Winchester, MD, is assistant professor in the division of cardiovascular medicine at the University of Florida (Gainesville), and practices general cardiology at the Malcom Randall VA Medical Center, Gainesville.

Sometimes it seems like cardiac troponin testing has become nearly as ubiquitous as the CBC and the BMP. Concern over atypical presentations of MI has contributed to widespread use in emergency departments and hospitalized patients. But once the test comes back elevated, what do you do with that information?

Typically, the next step is to consult Cardiology, which is a reasonable request with or without a suspicion of MI. Frequently, invasive management is not an option; or perhaps the diagnosis is “type 2 MI.”1

A growing body of evidence is making it clear that any elevation in cardiac troponin is a serious predictor of risk and that the risk is highest if the patient is not having an MI.2 My colleagues and I recently conducted a cohort study of more than 700 veterans at our VA Medical Center addressing this question. We evaluated long-term mortality (6 years) comparing veterans who were diagnosed with MI with those who had troponin elevation and no clinical MI. The diagnostic determination was made for all subjects prospectively as part of a quality improvement project that sought to better care for MI patients at our facility. (In some cases, only single troponin values were measured so we cannot say that all patients in our investigation had a true type 2 MI.)

We found that veterans with an elevation in troponin that was not caused by MI had higher risk of mortality risk than did MI patients.3 The risk started to diverge at 30 days and was 42.0% at 1 year, compared with 29.0% for those with MI (odds ratio, 0.56; 95% confidence interval, 0.41-0.78). This risk continued to separate and, at 6 years, was 77.7% vs. 58.7% (OR, 0.41; 95% CI 0.30-0.56). Our observations agree with other recent publications; what we tried to do in advancing the literature was to construct a robust Cox proportional hazard model to try to better understand if the risk seen in these patients is just because of their being “sicker.”

We tried to capture a number of other acute illness states with variables including TIMI score, being in hospice care, having a “do not resuscitate” order, being in the ICU, receiving CPR, and having a fever or leukocytosis, etc. Despite this modeling, elevated troponin remained a significant predictor of risk. While several variables we modeled remained significant predictors of mortality, their distribution between our two cohorts did not explain the excess mortality risk associated with non-MI troponin.

Unfortunately, there are no viable treatment options specific for patients with non-MI troponin elevation and type 2 MI. Given that the causes are multiple and heterogeneous, there may not be a common pathway to target for reducing cardiovascular risk. Regardless, the observation of non-MI troponin or type 2 MI should be taken seriously and not be ignored.

In selected patients, particularly those without known coronary artery disease, it may be appropriate to perform diagnostic testing or risk assessment with noninvasive imaging prior to discharge. Those with coronary artery disease should be treated aggressively for prevention of future cardiovascular events with both medical therapy and risk factor reduction.

1. Thygesen K, Alpert JS, et al. Third universal definition of myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:1581-98.

2. Alcalai R, Planer D, Culhaoglu A, Osman A, Pollak A and Lotan C. Acute coronary syndrome vs nonspecific troponin elevation: clinical predictors and survival analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:276-81.

3. Winchester DE, Burke L, Agarwal N, Schmalfuss C and Pepine CJ. Predictors of short- and long-term mortality in hospitalized veterans with elevated troponin. J Hosp Med. 2016 Jun 3. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2619.

David Winchester, MD, is assistant professor in the division of cardiovascular medicine at the University of Florida (Gainesville), and practices general cardiology at the Malcom Randall VA Medical Center, Gainesville.

Sometimes it seems like cardiac troponin testing has become nearly as ubiquitous as the CBC and the BMP. Concern over atypical presentations of MI has contributed to widespread use in emergency departments and hospitalized patients. But once the test comes back elevated, what do you do with that information?

Typically, the next step is to consult Cardiology, which is a reasonable request with or without a suspicion of MI. Frequently, invasive management is not an option; or perhaps the diagnosis is “type 2 MI.”1

A growing body of evidence is making it clear that any elevation in cardiac troponin is a serious predictor of risk and that the risk is highest if the patient is not having an MI.2 My colleagues and I recently conducted a cohort study of more than 700 veterans at our VA Medical Center addressing this question. We evaluated long-term mortality (6 years) comparing veterans who were diagnosed with MI with those who had troponin elevation and no clinical MI. The diagnostic determination was made for all subjects prospectively as part of a quality improvement project that sought to better care for MI patients at our facility. (In some cases, only single troponin values were measured so we cannot say that all patients in our investigation had a true type 2 MI.)

We found that veterans with an elevation in troponin that was not caused by MI had higher risk of mortality risk than did MI patients.3 The risk started to diverge at 30 days and was 42.0% at 1 year, compared with 29.0% for those with MI (odds ratio, 0.56; 95% confidence interval, 0.41-0.78). This risk continued to separate and, at 6 years, was 77.7% vs. 58.7% (OR, 0.41; 95% CI 0.30-0.56). Our observations agree with other recent publications; what we tried to do in advancing the literature was to construct a robust Cox proportional hazard model to try to better understand if the risk seen in these patients is just because of their being “sicker.”

We tried to capture a number of other acute illness states with variables including TIMI score, being in hospice care, having a “do not resuscitate” order, being in the ICU, receiving CPR, and having a fever or leukocytosis, etc. Despite this modeling, elevated troponin remained a significant predictor of risk. While several variables we modeled remained significant predictors of mortality, their distribution between our two cohorts did not explain the excess mortality risk associated with non-MI troponin.

Unfortunately, there are no viable treatment options specific for patients with non-MI troponin elevation and type 2 MI. Given that the causes are multiple and heterogeneous, there may not be a common pathway to target for reducing cardiovascular risk. Regardless, the observation of non-MI troponin or type 2 MI should be taken seriously and not be ignored.

In selected patients, particularly those without known coronary artery disease, it may be appropriate to perform diagnostic testing or risk assessment with noninvasive imaging prior to discharge. Those with coronary artery disease should be treated aggressively for prevention of future cardiovascular events with both medical therapy and risk factor reduction.

1. Thygesen K, Alpert JS, et al. Third universal definition of myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:1581-98.

2. Alcalai R, Planer D, Culhaoglu A, Osman A, Pollak A and Lotan C. Acute coronary syndrome vs nonspecific troponin elevation: clinical predictors and survival analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:276-81.

3. Winchester DE, Burke L, Agarwal N, Schmalfuss C and Pepine CJ. Predictors of short- and long-term mortality in hospitalized veterans with elevated troponin. J Hosp Med. 2016 Jun 3. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2619.

David Winchester, MD, is assistant professor in the division of cardiovascular medicine at the University of Florida (Gainesville), and practices general cardiology at the Malcom Randall VA Medical Center, Gainesville.

Lung cryobiopsies could reduce need for surgical biopsy

LONDON – The vast majority of surgical lung biopsies currently used to diagnose interstitial lung diseases (ILDs) could be avoided, suggests research presented at the annual congress of the European Respiratory Society.

During an oral presentation, Benjamin Bondue, MD, of Hopital Erasme, Brussels, presented the preliminary results of a Belgian prospective study evaluating the role of transbronchial lung cryobiopsies in 24 patients with undefined ILD treated at three participating centers.

Cryobiopsies were found to have a diagnostic yield of 79%, meaning that patients might be able to avoid undergoing a more invasive surgical removal of tissue in many cases. Compared with surgical biopsy, cryobiopsies offered the potential advantage of lower morbidity and shorter hospitalization time, Dr. Bondue said. He reported that patients needed to stay in hospital just 1.2 days after the procedure in the study.

“Our data also show that there is some benefit of surgical lung biopsy after cryobiopsy if we identify an NSIP [nonspecific interstitial pneumonia] pattern or idiopathic conditions, or if we cannot obtain a clear pathological diagnosis,” he reported. Acknowledging the study was small and conducted in a single center, he said the use of cryobiopsies following surgical biopsy might be worth further study.

Transbronchial lung cryobiopsy is a relatively new technique that uses a cryoprobe inserted down through a bronchoscope about 1-2 cm from the thoracic wall. Once in place, the probe is cooled for between 3 and 6 seconds, lung tissue freezes to the probe, and the probe and bronchoscope are removed together. This method allows for larger samples of tissue to be taken than does traditional transbronchial biopsy, which involves using large forceps to obtain tissue samples (Respirology. 2014;19:645-54).

In the Belgian study, Dr. Bondue noted that a Fogarty balloon was used to control any bleeding and that four transbronchial lung cryobiopsies were obtained from two different segments of the same lobe of a patient’s lungs. All biopsies were then analyzed by an expert pathologist in ILDs, and reviewed by two other expert pathologists when needed. The mean sample size obtained was 16 mm2.

The patients included in the study had undergone chest X-ray and had inconclusive findings in the majority (84%) of cases. They then had the option to undergo cryobiopsy or surgical lung biopsy, with the latter performed following discussion among a multidisciplinary team’s members.