User login

These Patients Knee’d Your Help

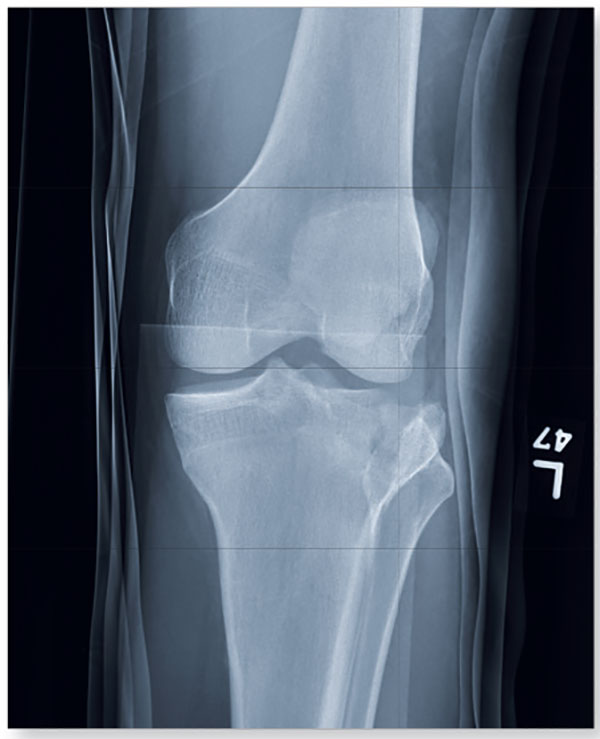

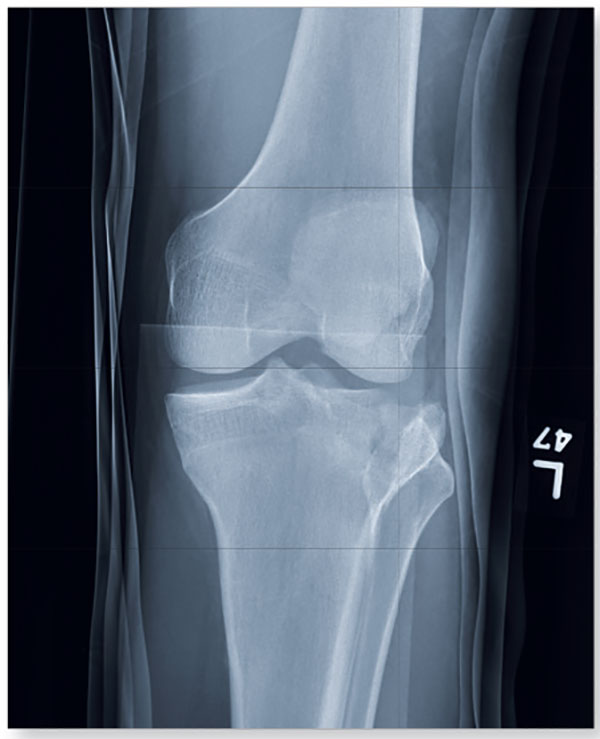

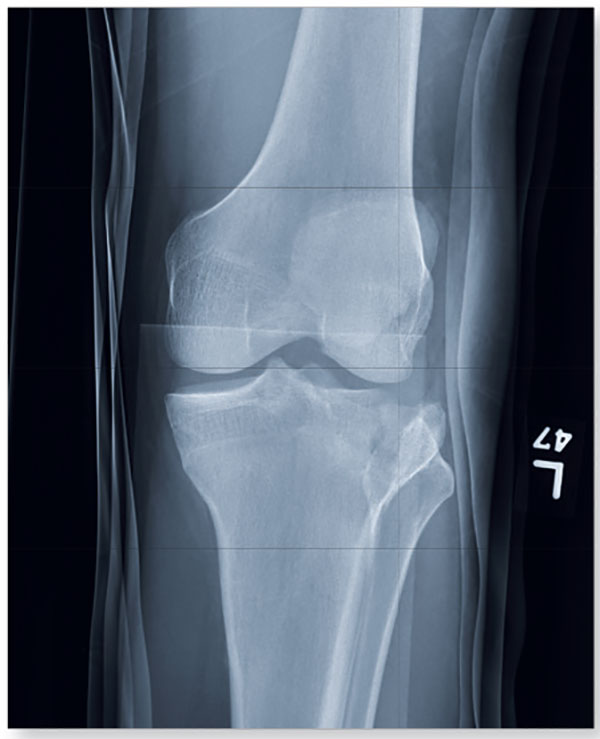

1. A 23-year-old man is brought in after being hit by a car. There is a moderate amount of soft tissue swelling around the knee, with limited flexion and extension due to pain. He can wiggle his toes, and there appears to be no neurovascular compromise.

Diagnosis: The image shows a comminuted and depressed fracture of the lateral tibial plateau. It is depressed approximately 6 to 7 mm. The patient was admitted, and orthopedic consultation was obtained. The patient subsequently underwent an open reduction and internal fixation of the fracture.

For more information, see “Clipped by an Oncoming Car.” Clinician Reviews. 2014;24(6):23,36.

2. A 20-year-old man presents after his car was broadsided by another vehicle. His air bag deployed, and the patient now complains of right-sided chest wall pain and right knee pain. Inspection of his right knee shows some joint deformity, with mild swelling and moderate tenderness. The patient is unable to perform flexion with his right knee. Good distal pulses are present, and sensation is intact.

Diagnosis: The radiograph demonstrates lateral dislocation of the patella, with no evidence of an acute fracture in any surrounding bones. The patella was easily reduced in the emergency department, and the patient was placed in a knee immobilizer. Orthopedic consultation was obtained.

For more information, see “Chest Wall and Knee Pain Following Motor Vehicle Collision.” Clinician Reviews. 2013;23(1):8.

3. A 70-year-old woman presents for evaluation of right knee pain secondary to a fall. When she tripped and fell, all her weight landed on her right knee; she says it is now “extremely painful” to bear weight on that leg. Inspection of her right knee shows no obvious deformity, but a moderate amount of swelling and limited range of motion. She also has moderate tenderness circumferentially around the knee. There is additional swelling and mild bruising on both the medial and lateral aspects of the right ankle.

Diagnosis: The radiograph has several findings, one of which is a nondisplaced proximal fibula fracture. In addition, there is a moderate suprapatellar joint effusion. The patient also has fairly advanced tricompartment degenerative arthrosis. (To review, the tricompartment comprises all three anatomic areas of the knee: the patellofemoral, lateral tibiofemoral, and medial tibiofemoral joints.) The patient was placed in a knee immobilizer, and orthopedic evaluation was coordinated.

For more information, see “In Middle of Trip, Woman Falls.” Clinician Reviews. 2016;26(6):20,53.

4. A 28-year-old man is brought to you by EMS for evaluation after a motor vehicle accident. The patient was an unrestrained driver in a truck that went off the road into a ditch. The paramedics state that he was partially ejected, with his left leg caught in the window. He complains of back and left leg pain. Primary survey shows no obvious injury. Secondary survey reveals moderate swelling and decreased range of motion in the left knee. Good distal pulses are present.

Diagnosis: The radiograph shows that the distal femur is medially dislocated relative to the tibial plateau. In addition, the patella is laterally dislocated. No obvious fractures are evident. Such injuries are typically associated with significant ligament injuries, especially of the medial collateral ligament (MCL), lateral collateral ligament (LCL), and anterior cruciate ligament (ACL). Orthopedics was consulted for reduction of the dislocation and further workup (including MRI of the knee).

For more information, see “Driver Partially Ejected From Vehicle.” Clinician Reviews. 2015;25(7):20,27.

1. A 23-year-old man is brought in after being hit by a car. There is a moderate amount of soft tissue swelling around the knee, with limited flexion and extension due to pain. He can wiggle his toes, and there appears to be no neurovascular compromise.

Diagnosis: The image shows a comminuted and depressed fracture of the lateral tibial plateau. It is depressed approximately 6 to 7 mm. The patient was admitted, and orthopedic consultation was obtained. The patient subsequently underwent an open reduction and internal fixation of the fracture.

For more information, see “Clipped by an Oncoming Car.” Clinician Reviews. 2014;24(6):23,36.

2. A 20-year-old man presents after his car was broadsided by another vehicle. His air bag deployed, and the patient now complains of right-sided chest wall pain and right knee pain. Inspection of his right knee shows some joint deformity, with mild swelling and moderate tenderness. The patient is unable to perform flexion with his right knee. Good distal pulses are present, and sensation is intact.

Diagnosis: The radiograph demonstrates lateral dislocation of the patella, with no evidence of an acute fracture in any surrounding bones. The patella was easily reduced in the emergency department, and the patient was placed in a knee immobilizer. Orthopedic consultation was obtained.

For more information, see “Chest Wall and Knee Pain Following Motor Vehicle Collision.” Clinician Reviews. 2013;23(1):8.

3. A 70-year-old woman presents for evaluation of right knee pain secondary to a fall. When she tripped and fell, all her weight landed on her right knee; she says it is now “extremely painful” to bear weight on that leg. Inspection of her right knee shows no obvious deformity, but a moderate amount of swelling and limited range of motion. She also has moderate tenderness circumferentially around the knee. There is additional swelling and mild bruising on both the medial and lateral aspects of the right ankle.

Diagnosis: The radiograph has several findings, one of which is a nondisplaced proximal fibula fracture. In addition, there is a moderate suprapatellar joint effusion. The patient also has fairly advanced tricompartment degenerative arthrosis. (To review, the tricompartment comprises all three anatomic areas of the knee: the patellofemoral, lateral tibiofemoral, and medial tibiofemoral joints.) The patient was placed in a knee immobilizer, and orthopedic evaluation was coordinated.

For more information, see “In Middle of Trip, Woman Falls.” Clinician Reviews. 2016;26(6):20,53.

4. A 28-year-old man is brought to you by EMS for evaluation after a motor vehicle accident. The patient was an unrestrained driver in a truck that went off the road into a ditch. The paramedics state that he was partially ejected, with his left leg caught in the window. He complains of back and left leg pain. Primary survey shows no obvious injury. Secondary survey reveals moderate swelling and decreased range of motion in the left knee. Good distal pulses are present.

Diagnosis: The radiograph shows that the distal femur is medially dislocated relative to the tibial plateau. In addition, the patella is laterally dislocated. No obvious fractures are evident. Such injuries are typically associated with significant ligament injuries, especially of the medial collateral ligament (MCL), lateral collateral ligament (LCL), and anterior cruciate ligament (ACL). Orthopedics was consulted for reduction of the dislocation and further workup (including MRI of the knee).

For more information, see “Driver Partially Ejected From Vehicle.” Clinician Reviews. 2015;25(7):20,27.

1. A 23-year-old man is brought in after being hit by a car. There is a moderate amount of soft tissue swelling around the knee, with limited flexion and extension due to pain. He can wiggle his toes, and there appears to be no neurovascular compromise.

Diagnosis: The image shows a comminuted and depressed fracture of the lateral tibial plateau. It is depressed approximately 6 to 7 mm. The patient was admitted, and orthopedic consultation was obtained. The patient subsequently underwent an open reduction and internal fixation of the fracture.

For more information, see “Clipped by an Oncoming Car.” Clinician Reviews. 2014;24(6):23,36.

2. A 20-year-old man presents after his car was broadsided by another vehicle. His air bag deployed, and the patient now complains of right-sided chest wall pain and right knee pain. Inspection of his right knee shows some joint deformity, with mild swelling and moderate tenderness. The patient is unable to perform flexion with his right knee. Good distal pulses are present, and sensation is intact.

Diagnosis: The radiograph demonstrates lateral dislocation of the patella, with no evidence of an acute fracture in any surrounding bones. The patella was easily reduced in the emergency department, and the patient was placed in a knee immobilizer. Orthopedic consultation was obtained.

For more information, see “Chest Wall and Knee Pain Following Motor Vehicle Collision.” Clinician Reviews. 2013;23(1):8.

3. A 70-year-old woman presents for evaluation of right knee pain secondary to a fall. When she tripped and fell, all her weight landed on her right knee; she says it is now “extremely painful” to bear weight on that leg. Inspection of her right knee shows no obvious deformity, but a moderate amount of swelling and limited range of motion. She also has moderate tenderness circumferentially around the knee. There is additional swelling and mild bruising on both the medial and lateral aspects of the right ankle.

Diagnosis: The radiograph has several findings, one of which is a nondisplaced proximal fibula fracture. In addition, there is a moderate suprapatellar joint effusion. The patient also has fairly advanced tricompartment degenerative arthrosis. (To review, the tricompartment comprises all three anatomic areas of the knee: the patellofemoral, lateral tibiofemoral, and medial tibiofemoral joints.) The patient was placed in a knee immobilizer, and orthopedic evaluation was coordinated.

For more information, see “In Middle of Trip, Woman Falls.” Clinician Reviews. 2016;26(6):20,53.

4. A 28-year-old man is brought to you by EMS for evaluation after a motor vehicle accident. The patient was an unrestrained driver in a truck that went off the road into a ditch. The paramedics state that he was partially ejected, with his left leg caught in the window. He complains of back and left leg pain. Primary survey shows no obvious injury. Secondary survey reveals moderate swelling and decreased range of motion in the left knee. Good distal pulses are present.

Diagnosis: The radiograph shows that the distal femur is medially dislocated relative to the tibial plateau. In addition, the patella is laterally dislocated. No obvious fractures are evident. Such injuries are typically associated with significant ligament injuries, especially of the medial collateral ligament (MCL), lateral collateral ligament (LCL), and anterior cruciate ligament (ACL). Orthopedics was consulted for reduction of the dislocation and further workup (including MRI of the knee).

For more information, see “Driver Partially Ejected From Vehicle.” Clinician Reviews. 2015;25(7):20,27.

Management of Relapsed and Refractory Multiple Myeloma

From the Division of Hematology and Oncology, University of North Carolina – Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC (Dr. Reeves), and the Division of Cellular Therapy and Hematological Malignancies, Duke Cancer Institute, Durham, NC (Dr. Tuchman).

Abstract

- Objective: To review the management considerations in patients with relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma (RRMM).

- Methods: Review of the literature.

- Results: RRMM is a heterogeneous disease and numerous treatment regimens have been studied. Despite improvement in progression-free and overall survival in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma with current therapies, myeloma remains incurable and repeated relapses are inevitable. Relapses are often characterized by diminished response to chemotherapy (refractoriness) and duration of response.

- Conclusion: Management of RRMM should be individualized using both patient- and disease-related factors, given substantial heterogeneity in both. Further research regarding the optimal timing, regimen, and duration of treatment is warranted.

Although advancements in treating multiple myeloma (MM) have resulted in improved median survival from approximately 2 years in the 1990s to more recent estimates of over 6 years, the disease remains incurable [1–3]. Its overall course is generally defined by a series of increasingly short remissions and treatment-refractory relapses until eventual death due to MM occurs. Objective criteria for defining both relapsed and refractory MM have been published [4]. Briefly, relapsed myeloma is that which has been previously treated with some form of systemic therapy and which has recurred. That recurrence can be clinical (ie, the development of new or worsening signs or symptoms of active MM) and/or biochemical (ie, rising monoclonal MM proteins in the serum or urine). Refractory MM on the other hand refers to MM that is resistant to particular drugs, defined as MM that is nonresponsive to primary or salvage therapy, or MM that progresses within 60 days of the last therapy [4]. At any juncture during the course of relapsed MM, patients will have disease that is either sensitive or refractory to specific myeloma drugs. In this article, we discuss management of these often concurrent entities together as relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma (RRMM).

There are numerous treatment options for patients with RRMM—3 new drugs were approved in November 2015 alone. The abundance of available drugs leaves treating clinicians with a daunting task of sequencing therapies among several choices. The durability of response to treatment typically lessens with each disease relapse, such that the clinician needs to think of sequencing not just second-line therapy, but third- and fourth-line as well, further complicating the decision. In this review, we aim to help clinicians individualize treatment plans for patients with RRMM.

Case Studies

Patient A

A 62-year-old man with IgG-kappa MM was diagnosed 4 years ago during evaluation of a pathologic humeral fracture. The disease was prognostically standard risk, with revised International Staging System (RISS) stage I disease (beta-2 microglobulin 3.4 mcg/mL, albumin 4.1 g/dL, normal cytogenetics with 46,XY in 20 cells analyzed, and myeloma fluorescent in situ hybridization [FISH] panel showing t(11;14) but no del17p, t(14;16), t(14;20), or t(4;14)) [5], and normal blood counts, organ function, and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) at diagnosis. He was treated with 5 cycles of standard lenalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone followed by high-dose melphalan with autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) and then lenalidomide continuous maintenance. He achieved a stringent complete response (ie, complete disappearance of myeloma-derived monoclonal proteins in the serum and urine, a normal serum free light chain ratio, and undetectable monoclonal plasma cells on a bone marrow aspirate and biopsy) [4]. His MM was monitored every 2 to 3 months for disease progression and medication toxicity. At month 38, a monoclonal protein spike (M-spike) on serum protein electrophoresis (SPEP) remained undetectable, but serum kappa free light chain levels increased from 1.98 mg/dL to 8 mg/dL with stable lambda serum free light chains and a ratio that rose to 16, consistent with low-level biochemical recurrence. He had no evidence of end-organ damage and therefore was maintained on lenalidomide maintenance for the time being. Over the next 12 months, his kappa serum free light chain level continued to slowly rise, reaching 24 mg/dL, while the ratio rose to 50. There was still no detectable M-spike. He developed mild anemia during this time, with his hemoglobin dropping from a prior value of approximately 11 g/dL to 9.8 g/dL, though kidney function remained normal. A repeat bone marrow aspirate and biopsy revealed 20% kappa-restricted plasma cells.

Patient B

A 75-year-old woman with IgA-kappa MM was diagnosed after laboratory testing by her primary care physician incidentally showed an elevated serum total protein level. The MM was intermediate risk, with RISS stage II disease, and with mild renal impairment resulting in an estimated creatinine clearance of 45 mL/min that was felt to be due to MM. She was initially treated with bortezomib and dexamethasone but received only 2 cycles because she developed painful peripheral neuropathy secondary to bortezomib. Bortezomib was stopped and she was then treated with lenalidomide and dexamethasone for 4 cycles. She achieved a complete response and elected to stop treatment due to fatigue. Her fatigue did not improve off treatment. Six months after stopping therapy, an M-spike was detectable at 0.1 g/dL and she developed a new painful lytic lesion in the left humerus.

Patient C

A 59-year-old man with lambda free light chain MM was diagnosed when he presented with acute renal failure requiring dialysis. The disease was RISS-III at diagnosis (high risk), with the t(4;14) genetic abnormality in his MM cells detected on bone marrow aspirate, an abnormality that has been associated with poor prognosis MM [6–8]. The patient was treated with cyclophosphamide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone [9] for 6 cycles, at which point his disease was in a very good partial response (>90% reduction in M-spike) [4], and his renal function had recovered to a new baseline creatinine clearance of 45 mL/min. He then underwent ASCT after melphalan conditioning followed by bortezomib maintenance therapy every 2 weeks. Eight months after ASCT, his lambda free light chain level increased from 1.25 mg/dL to 45 mg/dL and the ratio increased from 4 to 22. Renal function was unchanged and there was stable anemia, with hemoglobin of 10.1 g/dL.

When should treatment for RRMM commence?

Patients with MM in remission are closely monitored, with clinical and laboratory examinations generally conducted every 1 to 3 months. The history is focused on MM-related symptoms such as increasing bone pain or weight loss, and symptoms of therapy-related toxicity such as fatigue, gastrointestinal distress, or peripheral neuropathy. Laboratory assessment typically includes blood counts and chemistry measurements, as well as measurements of MM-derived monoclonal proteins: SPEP, serum immunofixation (IFE), serum immunoglobulin free light chain measurements, and urine protein electrophoresis and immunofixation (UPEP/urine IFE) [10]. Progressive disease biochemically is defined as a 25% increase in M-spike (at least 0.5 g/dL if the M-spike is in serum or > 200 mg/24 hours if in urine), and/or a rise of greater than 10 mg/dL difference between the involved and uninvolved serum free light chains. Clinically progressive disease is denoted as new evidence of end-organ damage such as a new plasma-cytoma, unexplained hypercalcemia, or worsening anemia due to MM [4]. Many, if not most, patients will have biochemical recurrence identified by laboratory measurements ofmonoclonal proteins before clinical recurrence transpires.

The velocity of relapse can help guide decisions about when to reinitiate therapy. High-velocity disease relapse, meaning rapid rise in monoclonal proteins, is an indicator of more aggressive disease, and treatment should be initiated promptly before development of symptoms [11]. Conversely, low-level, indolent recurrence can often be followed with a “watch and wait” approach to determine how the myeloma will progress over time. Expert guidelines suggest that a monoclonal protein doubling time of 2 months may be an appropriate cutoff for determining high versus low velocity [12], although 2 months is not a firm rule and the decision of when to restart treatment for any given patient with asymptomatic biochemical recurrence should be individualized. Importantly, it is not clear that changing therapy at the time of biochemical recurrence, prior to clinical disease progression, improves outcomes, but clinicians are often nonetheless hesitant to hold therapy in the face of biochemically recurrent MM given the potential for complications, such as a pathologic fracture. In patients with biochemically recurrent MM for whom re-initiation of systemic anti-myeloma therapy is being deferred, one can consider re-initiation of zoledronic acid therapy, since in a randomized controlled trial, zoledronic acid commenced at the time of biochemical relapse resulted in fewer skeletal events as compared to placebo [13].

What disease factors should be considered in choosing treatment for RRMM?

MM exhibits genetic complexity, and prior treatments may result in clonal evolution of and selection for an initially nondominant, treatment-resistant clone [14,15]. This heterogeneity and selection pressure may explain why 3-drug regimens often outperform 1- or 2-drug regimens, why each remission is generally shorter than the last, and why patients who have enjoyed a long duration of response to one therapy and been off it for some length of time may again have a good response when re-treated with the same therapy at time of MM relapse. So how does one know if a new clone has emerged? While there is no standard for monitoring intra-clonal heterogeneity presently, changes in clinical phenotype likely correlate with evolving clones. Some such changes include free light chain escape (ie, MM that initially secreted an intact M-spike and then only secretes free light chain at relapse), new development of extramedullary disease (plasmacytomas outside of bone) in patients who previously had MM only in the bone marrow, and resistance of some sites to treatment while others respond (a mixed response). The former 2 phenotypes in particular portend poor prognosis and unsurprisingly they can be seen together [16–19]. Restaging, meaning a complete reassessment of MM disease status at the time of relapse, including bone marrow aspirate and biopsy, is beneficial to help guide therapy, as those with high-risk features including high ISS stage [20], high-risk cytogenetics, increased LDH, and extramedullary disease should be treated with triplet therapy when possible [11]. Repeat imaging should also be considered as a new baseline comparator. This can be done with standard x-rays, positron-emission tomography/computed tomography (PET-CT), or magnetic resonance imaging. PET-CT offers the advantage of showing active disease sites and the presence of extramedullary disease, although it exposes the patient to more radiation than the other methods.

In terms of using genetics to guide therapy decisions in RRMM, the presence of the del(17p) abnormality either by karyotyping or FISH portends high risk and pomalidomide in one study was shown to mitigate that risk [21]. How genetics and prognostic markers should dictate therapy selection in RRMM otherwise, however, is unclear and an area of active research efforts.

What patient factors should be considered in choosing treatment?

Given the relatively large selection of possible regimens for the treatment of RRMM, patient preference can be incorporated into regimen selection. Patients who have long commutes or who are trying to work may not be ideal candidates to receive carfilzomib-based regimens given the twice-per-week infusion schedule (though a once-a-week dosing schedule is being tested) [22]. Patients who have poor venous access may be good candidates for all-oral regimens. Prior treatment tolerability and side effects should also be considered. Patients who experienced significant peripheral neuropathy with bortezomib may have less neuropathy with carfilzomib. Those with renal failure may tolerate pomalidomide better than lenalidomide [23].

Patient age and functional status are important considerations in choosing a treatment regimen for RRMM. Very old patients (a subjective categorization to include patients > 80 years by chronologic or physiologic age), those with functional dependence, or patients harboring substantial medical comorbidities are at risk for therapy toxicity and so often warrant less intensive approaches [24]. Deciding which patients empirically warrant less dose-intensive approaches can be challenging, especially with the growing recognition that fit seniors can often tolerate and enjoy the benefits of full-dose approaches, including sometimes even ASCT. Geriatric assessment instruments that interrogate a variety of geriatric-relevant domains, such as number of falls, independence in activities of daily living, and polypharmacy, are being investigated as toxicity predictors and may help make those decisions in the future. Such instruments have been shown to predict chemotherapy toxicity in solid tumors [25,26] and preliminarily in MM [27], but they remain investigational. While no validated geriatric assessment instruments are currently available for routine clinical employment in MM, clinicians should consider the geriatric domains that these instruments assess when choosing among treatment options. Clinically, that often translates to choosing gentler regimens with likely better tolerability, albeit perhaps with less efficacy, for patients judged to be vulnerable to toxicity.

As part of therapy selection in RRMM, the clinician needs to consider if the patient is a candidate for ASCT. For patients who did not undergo ASCT as part of initial treatment, ASCT can be considered at the time of relapse. Ideally, all patients who could eventually undergo ASCT should have hematopoietic stem cells collected and stored at the time of first induction; however, collection after re-induction chemotherapy has been shown to be feasible [28,29]. ASCT for RRMM appears to be effective, although rigorous randomized comparisons of ASCT versus treatment purely with novel drugs are lacking [30–32]. For patients who did receive ASCT consolidation in the frontline, if a response is sustained for 18 months or greater, existing guidelines suggest that a second ASCT is likely worthwhile [29]. Whether the routine usage of maintenance therapies (low-dose, usually single drugs used to prolong duration of remission once remission is achieved) should change that 18-month cutoff is unclear, however, since maintenance “artificially” makes ASCT appear more effective by prolonging post-ASCT duration of remission. The “is it worth it” discussion is also largely subjective and hinges heavily on the patient’s experience with the first ASCT. In our practice, we often use 3 years as the cutoff for considering repeat ASCT in patients on maintenance therapy, meaning that if a patient underwent ASCT and received maintenance, a remission lasting more than 3 years means we consider ASCT as part of therapy for relapse.

Allogeneic stem cell transplantation (allo-SCT) is a treatment option for RRMM generally reserved for fit patients younger than 65 years [22,33]. The timing of allo-SCT is also controversial, with some reserving it as a last option given a historically high transplant-related mortality and improved progression-free survival but not necessarily overall survival benefit. A recent consensus statement has suggested allo-SCT be considered (preferentially in a clinical trial) for eligible patients with high-risk disease who relapse after primary treatment that included ASCT [29]. With the abundance of new treatment options in RRMM with reasonable toxicity profiles, it is not clear for whom and when allo-SCT is best considered.

Which regimen should be used to treat a first relapse?

Entry into a well-designed clinical trial for patients with RRMM should be considered for every patient since there is a lack of evidence to guide the best sequencing of chemotherapies [11]. Beyond that, the choice of therapy is based upon 2 main factors: the disease itself (eg, indolent, asymptomatic biochemical recurrence versus aggressive clinical recurrence with new fractures or extramedullary plasmacytomas), and the patient’s preferences and characteristics, such as age, performance status, comorbidities, and toxicities from prior therapies. In looking for the “best” re-induction regimen, it is tempting to compare the efficacy of regimens across trials, but such efforts are fraught given the significant heterogeneity of the patient populations between trials. As an example, comparing daratumumab + pomalidomide + dexamethasone (DPd) to daratumumab + lenalidomide + dexamethasone (DRd), one may conclude that DRd is superior, given an overall response rate of 88% in DRd versus 58% in DPd. However, the DPd trial included patients who were refractory to lenalidomide and bortezomib, while the DRd study required only treatment with one prior therapy [34,35].

For patients who enjoyed a long remission after any particular chemotherapy regimen with good tolerability and with indolent features at the time of relapse, re-treating with the same regimen can be considered, although nowadays with so many new and highly potent agents available such “backtracking” is less common and some studies suggest that employing new agents may be beneficial. As an example, in the randomized ENDEAVOR study of bortezomib + dexamethasone versus carfilzomib + dexamethasone in RRMM, 54% of patients had been exposed to bortezomib whereas virtually none had received carfilzomib prior to study enroll-ment. Among those patients with prior bortezomib exposure, median progression-free survival was 15.6 versus 8.1 months (hazard ratio 0.56, [95% confidence interval 0.44 to 0.73]) for carfilzomib versus bortezomib, respectively. Follow-up was too immature for definitive conclusions to be drawn about overall survival, but the substantial difference in progression-free survival provides a compelling argument for using carfilzomib instead of going back to bortezomib for patients with prior bortezomib exposure [36].

For patients who are fit and not very old, we generally employ triplet re-induction. For the large number of these patients who were previously exposed to both lenalidomide and bortezomib, including as part of a maintenance strategy, outside of clinical trials we routinely use carfilzomib + pomalidomide + dexamethasone [41]. For patients who are lenalidomide-naïve but bortezomib-exposed, we often employ carfilzomib + lenalidomide + dexamethasone based on the phase 3 ASPIRE trial, which showed a significantly improved progression-free survival with carfilzomib + lenalidomide + dexamethasone versus lenalidomide + dexamethasone [47]. For patients who have previously received lenalidomide but not bortezomib, we consider pomalidomide + bortezomib + dexamethasone [52]. These regimens take advantage of the arguably most potent, most proven drugs in treating RRMM, namely proteasome inhibitors (bortezomib and carfilzomib) and immunomodulatory agents (lenalidomide and pomalidomide).

For patients who are more vulnerable to toxicity due to advanced age or comorbidities, we consider less intensive regimens, including dose-reduced triplets or doublets. Patients who had received lenalidomide-based combinations but not bortezomib are considered for a bortezomib-based re-induction, including bortezomib + dexamethasone alone. In the case of someone who had initially received a bortezomib-based combination but no lenalidomide, the new drugs are viable options: ixazomib [53] or elotuzumab [43] can both be added to standard lenalidomide + dexamethasone, with expectations of increasing response rates and progression-free survival and an acceptably low increased risk of severe toxicity. Ixazomib + lenalidomide + dexamethasone also has the benefit of being all-oral. For patients with bortezomib- and lenalidomide-exposed RRMM, using carfilzomib [54] or pomalidomide [55] with dexamethasone is reasonable.

Once MM has progressed beyond the arguable “core drugs” of early-stage MM, namely lenalidomide, bortezomib, carfilzomib, and pomalidomide, off protocol we favor daratumumab monotherapy [56,57]. Other options include panobinostat (given usually with bortezomib) [58] and bendamustine [59], among others.

Can agents to which the MM was previously refractory be reused?

With the understanding that MM is not a disease defined by a single molecular mutation, but rather clones and subclones, it is reasonable to think that even treatments that have previously failed may be beneficial to patients if they have been off those treatments for some length of time and sensitive subclones reemerge. Additionally, combining the “failed” agent with a new drug may overcome the previously seen refractoriness, as in the case of panobinostat + bortezomib [48]. That said, given the multitude of new treatment options for RRMM and data from such trials as ENDEAVOR as mentioned, revisiting previously used drugs is probably best reserved for second or greater relapses.

What should be the duration of therapy for RRMM?

There is no evidence to guide duration of therapy in RRMM. Most patients with relapsed disease will be considered for continuous treatment until disease progression, which usually means treatment for 6 to 12 months with full-dose induction, often to maximal response, followed by transition to some form of lower-dose maintenance in which parts of a multi-drug regimen may be eliminated and/or the doses for the remaining drugs may be reduced. Patients with a slow-velocity relapse and no markers of high-risk disease may be suitable candidates for a defined course of treatment without maintenance therapy [11], but most patients nowadays remain on some form of maintenance for RRMM after achieving remission.

What supportive care is needed in RRMM?

Bone Health

Skeletal-related events, namely fractures, can be devastating in MM. Bisphosphonates have been shown to decrease such events in MM and zoledronic acid has shown a trend toward improved survival, perhaps related to its impact on the bone marrow microenvironment or direct toxicity to myeloma cells [60,61]. It is unclear whether bisphosphonates improve overall survival in the relapsed setting, although zoledronic acid has shown decreased skeletal-related events in the setting of biochemical-only disease progression [13,62]. In active RRMM, our general practice is to resume parenteral bisphosphonate therapy (either zoledronic acid or pamidronate in our U.S. practices) usually every 3 to 4 weeks, depending on the length of the chemotherapy cycle.

Supportive Care

RRMM is a complex disease in which patients often experience a multitude of symptoms and other complications as a result of the disease itself as well as therapy. Aggressive supportive care is of paramount importance. As examples, zoster prophylaxis is required for virtually all patients on proteasome inhibitors, anticoagulation/antiplatelet therapies should be considered for venous thrombotic event prophylaxis, and proton pump inhibitors may be appropriate for these patients who often have a real risk of peptic ulcer disease due to the use of corticosteroids, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and/or aspirin prophylaxis. Attention to dental health is important for patients on bisphosphonates to minimize the risk of osteonecrosis of the jaw. Nutritional problems should be monitored and can arise due to anorexia, dysgeusia, diarrhea, or constipation. Peripheral neuropathy is extremely common and support should be offered in the form of adjusting therapy to minimize risk of worsening it, analgesics if needed, assistive devices to aid in ambulation, and/or physical therapy. Depression and anxiety are understandably prevalent in patients with RRMM, who face an incurable disease that provides constant reminders of its presence due to symptoms, the need for daily pills, or frequent clinic visits for treatment and/or blood product transfusions [63]. Supporting a patient’s emotional health is a vital component of enhancing quality of life in RRMM.

Case Studies Continued

Patient A was noted to have biochemical progression initially, with relapse detectable only in serum free light chains. Treatment commenced at the time of worsening anemia. Notably, his disease originally secreted IgG-kappa and at relapse secreted kappa free light chain only; that is, he developed “light chain escape,” which signifies a high-risk disease and likely heralds clonal evolution [64]. He had excellent caregiver support and lived within 20 minutes of a treatment center. His performance status remained good at the time of relapse and he had normal organ function. He was treated with carfilzomib + pomalidomide + dexamethasone for 4 cycles, achieving a very good partial response. He then received a second ASCT with melphalan conditioning and again achieved stringent complete response. Indefinite maintenance therapy commenced with pomalidomide, and at 16 months post-ASCT he was doing well and still in remission.

Patient B was symptomatic at the time of disease progression. As her primary complaint was that of a painful humeral lytic lesion, she first underwent a course of palliative radiation, which alleviated her pain. She did not wish to restart systemic treatment and instead elected to watch her MM closely with her oncologist on a monthly basis. By 3 months, her M-spike had reached 0.6 g/dL and her serum creatinine had increased slightly, resulting in a creatinine clearance of 34 mL/min. She lived approximately 90 minutes from the closest treatment facility and found it difficult to come for visits more than once monthly. Her Eastern College Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status was 2. With her advanced age and frailty, she was not considered to be a good candidate for ASCT. She requested to go back on lenalidomide and decided with her oncologist to try ixazomib + lenalidomide + dexamethasone, with which she achieved a very good partial response. She had difficulty with myelosuppression with lenalidomide, which was dropped after 4 cycles, and she is planned for ixazomib maintenance until disease progression or drug intolerance. She receives monthly zoledronic acid to reduce the risk of fractures.

Patient C has high-risk disease as indicated by R-ISS III stage disease at diagnosis and progression only 8 months after ASCT and while on bortezomib maintenance therapy. Although he currently only has evidence of biochemical relapse, prompt initiation of treatment was warranted to prevent further renal compromise such as during his initial presentation [65]. Further, PET-CT showed the presence of extramedullary soft tissue disease, another high-risk feature. He was a robust patient with good social support and received carfilzomib + pomalidomide + dexamethasone re-induction. He was not considered for a second ASCT given his short duration of response. With his high-risk features of early relapse after ASCT, R-ISS III, and extramedullary disease, it was recommended that he continue triplet drug therapy until disease relapse or drug intolerance.

Ongoing and Future Trials

The management of RRMM will continue to evolve as paradigms for treating MM change and new treatment options become available. In particular, immunotherapies (ie, approaches that harness the immune system’s ability to fight cancer) are under exploration and some such drugs that are already FDA-approved in other diseases are being tested in MM. Chimeric antigen receptor-T cells (CAR-T), a form of cell-based immunotherapy, have generated tremendous excitement in acute lymphocytic leukemia [66] and are being tested in MM [67]. New analogs of old drugs may offer more effective, less toxic ways to control MM. The role of ASCT is being explored in randomized trials investigating whether ASCT should be pursued early or late in a patient’s MM course. These studies will no doubt further augment the armamentarium of anti-myeloma drugs that have already resulted in the increasingly longer survival we see today in this disease [3,68]. That said, MM remains incurable, and almost all patients who live long enough eventually relapse and die of MM. Hence, further research and progress are critical.

Summary

A well-designed clinical trial should be considered for all patients with RRMM, and in lieu of an available trial, regimen selection should be tailored upon disease and patient characteristics. Carfilzomib-based regimens are among the most popular at the time of first relapse currently based upon their efficacy in bortezomib-refractory cases and tolerability. Pomalidomide shows activity in lenalidomide-refractory patients. Due to intra-clonal heterogeneity, triplet regimens are preferred for fit patients, reserving doublet or monotherapy for those patients who are frail or who have an indolent disease relapse. Ongoing research will undoubtedly improve outcomes for RRMM, a disease for which the prognosis is far better than it formerly was, but which still has quite a bit of room for improvement.

Corresponding author: Brandi Reeves, MD, University of North Carolina – Chapel Hill, 170 Manning Dr., Physicians’ Office Building, CB 7305, Chapel Hill, NC 27599, [email protected].

Financial disclosures: Dr. Tuchman reports the following: speakers’ bureau: Celgene, Takeda; consulting: Celgene, Takeda; research support: Celgene, Takeda, Novartis, Onyx.

1. Pulte D, Redaniel MT, Brenner H, et al. Recent improvement in survival of patients with multiple myeloma: variation by ethnicity. Leuk Lymphoma 2014;55:1083–9.

2. Kumar SK, Dispenzieri A, Lacy MQ, et al. Continued improvement in survival in multiple myeloma: changes in early mortality and outcomes in older patients. Leukemia 2014;28:1122–8.

3. Kumar SK, Rajkumar SV, Dispenzieri A, et al. Improved survival in multiple myeloma and the impact of novel therapies. Blood 2008;111:2516–20.

4. Rajkumar SV, Harousseau J-L, Durie B, et al. Consensus recommendations for the uniform reporting of clinical trials: report of the International Myeloma Workshop Consensus Panel 1. Blood 2011;117:4691–5.

5. Palumbo A, Avet-Loiseau H, Oliva S, et al. Revised International Staging System for Multiple Myeloma: A Report From International Myeloma Working Group. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:2863–9.

6. Hebraud B, Magrangeas F, Cleynen A, et al. Role of additional chromosomal changes in the prognostic value of t(4;14) and del(17p) in multiple myeloma: the IFM experience. Blood 2015;125:2095–100.

7. Karlin L, Soulier J, Chandesris O, et al. Clinical and biological features of t(4;14) multiple myeloma: a prospective study. Leuk Lymphoma 2011;52:238–46.

8. Moreau P, Cavo M, Sonneveld P, et al. Combination of international scoring system 3, high lactate dehydrogenase, and t(4;14) and/or del(17p) Identifies patients with multiple myeloma (MM) treated with front-line autologous stem-cell transplantation at high risk of early MM progression–related dDeath. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:2173–80.

9. Reeder CB, Reece DE, Kukreti V, et al. Long-term survival with cyclophosphamide, bortezomib and dexamethasone induction therapy in patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Br J Haematol 2014;167:563–5.

10. Kumar S, Paiva B, Anderson KC, et al. International Myeloma Working Group consensus criteria for response and minimal residual disease assessment in multiple myeloma. Lancet Oncol 2016;17:e328–46.

11. Laubach J, Garderet L, Mahindra A, et al. Management of relapsed multiple myeloma: recommendations of the International Myeloma Working Group. Leukemia 2016;30:1005–17.

12. Palumbo A, Rajkumar SV, San Miguel JF, et al. International Myeloma Working Group consensus statement for the management, treatment, and supportive care of patients with myeloma not Eligible for standard autologous stem-cell transplantation. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:587–600.

13. Garcia-Sanz R, Oriol A, Moreno MJ, et al. Zoledronic acid as compared with observation in multiple myeloma patients at biochemical relapse: results of the randomized AZABACHE Spanish trial. Haematologica 2015;100:1207–13.

14. Bahlis NJ. Darwinian evolution and tiding clones in multiple myeloma. Blood 2012;120:927–8.

15. Keats JJ, Chesi M, Egan JB, et al. Clonal competition with alternating dominance in multiple myeloma. Blood 2012;120:1067–76.

16. Brioli A, Giles H, Pawlyn C, et al. Serum free immunoglobulin light chain evaluation as a marker of impact from intraclonal heterogeneity on myeloma outcome. Blood 2014;123:3414–9.

17. Dawson MA, Patil S, Spencer A. Extramedullary relapse of multiple myeloma associated with a shift in secretion from intact immunoglobulin to light chains. Haematologica 2007;92:143–4.

18. Usmani SZ, Heuck C, Mitchell A, et al. Extramedullary disease portends poor prognosis in multiple myeloma and is over-represented in high-risk disease even in the era of novel agents. Haematologica 2012;97:1761–7.

19. Varettoni M, Corso A, Pica G, et al. Incidence, presenting features and outcome of extramedullary disease in multiple myeloma: a longitudinal study on 1003 consecutive patients. Ann Oncol 2010;21:325–30.

20. Greipp PR, San Miguel J, Durie BG, et al. International staging system for multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:3412–20.

21. Leleu X, Karlin L, Macro M, et al. Pomalidomide plus low-dose dexamethasone in multiple myeloma with deletion 17p and/or translocation (4;14): IFM 2010-02 trial results. Blood 2015;125:1411–7.

22. Berenson JR, Cartmell A, Bessudo A, et al. CHAMPION-1: a phase 1/2 study of once-weekly carfilzomib and dexamethasone for relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. Blood 2016 Jun 30;127:3360–8.

23. Richter J, Biran N, Duma N, et al. Safety and tolerability of pomalidomide-based regimens (pomalidomide-carfilzomib-dexamethasone with or without cyclophosphamide) in relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma and severe renal dysfunction: a case series. Hematol Oncol 2016 Mar 27. doi: 10.1002/hon.2290.

24. Wildes TM, Rosko A, Tuchman SA. Multiple myeloma in the older adult: better prospects, more challenges. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:2531–40.

25. Extermann M, Boler I, Reich RR, et al. Predicting the risk of chemotherapy toxicity in older patients: the Chemotherapy Risk Assessment Scale for High-Age Patients (CRASH) score. Cancer 2012;118(13):3377-86.

26. Hurria A, Togawa K, Mohile SG, et al. Predicting chemotherapy toxicity in older adults with cancer: a prospective multicenter study. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:3457–65.

27. Palumbo A, Bringhen S, Mateos M-V, et al. Geriatric assessment predicts survival and toxicities in elderly myeloma patients: an International Myeloma Working Group report. Blood 2015;125:2068–74.

28. Lemieux E, Hulin C, Caillot D, et al. Autologous stem cell transplantation: an effective salvage therapy in multiple myeloma. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2013;19:445–9.

29. Giralt S, Garderet L, Durie B, et al. American Society of Blood and Marrow Transplantation, European Society of Blood and Marrow Transplantation, Blood and Marrow Transplant Clinical Trials Network, and International Myeloma Working Group Consensus Conference on Salvage Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation in Patients with Relapsed Multiple Myeloma. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2015;21:2039–51.

30. Cook G, Williams C, Brown JM, et al. High-dose chemotherapy plus autologous stem-cell transplantation as consolidation therapy in patients with relapsed multiple myeloma after previous autologous stem-cell transplantation (NCRI Myeloma X Relapse [Intensive trial]): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2014;15:874–85.

31. Grövdal M, Nahi H, Gahrton G, et al. Autologous stem cell transplantation versus novel drugs or conventional chemotherapy for patients with relapsed multiple myeloma after previous ASCT. Bone Marrow Transplant 2015;50:808–12.

32. Singh Abbi KK, Zheng J, Devlin SM, et al. Second autologous stem cell transplant: an effective therapy for relapsed multiple myeloma. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2015;21:468–72.

33. Franssen LE, Raymakers RA, Buijs A, et al. Outcome of allogeneic transplantation in newly diagnosed and relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma: long-term follow-up in a single institution. European J Haematol 2016 Mar 29.

34. Chari AL, Sagar SA, Fay JW, et al. Open-label, multicenter, phase 1b study of daratumumab in combination with pomalidomide and dexamethasone in patients with at least 2 lines of prior therapy and relapsed or relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma. Blood 2015;126:508.

35. Plesner T, Gimsing P, Krejcik J, et al. Daratumumab in combination with lenalidomide and dexamethasone in patients with relapsed or relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma: Updated results of a phase 1/2 study (GEN503). Blood 2015;126:507.

36. Dimopoulos MA, Moreau P, Palumbo A, et al. Carfilzomib and dexamethasone versus bortezomib and dexamethasone for patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma (ENDEAVOR): a randomised, phase 3, open-label, multicentre study. Lancet Oncol 2016;17:27–38.

37. Richardson PG, Siegel D, Baz R, et al. Phase 1 study of pomalidomide MTD, safety, and efficacy in patients with refractory multiple myeloma who have received lenalidomide and bortezomib. Blood 2013;121:1961–7.

38. Richardson PG, Siegel DS, Vij R, et al. Pomalidomide alone or in combination with low-dose dexamethasone in relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma: a randomized phase 2 study. Blood 2014;123:1826–32.

39. Moreau P, Masszi T, Grzasko N, et al. Oral ixazomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone for multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med 2016;374:1621–34.

40. Reu FJ, Valent J, Malek E, et al. A phase I study of ixazomib in combination with panobinostat and dexamethasone in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. Blood 2015;126:4221.

41. Shah JJ, Stadtmauer EA, Abonour R, et al. Carfilzomib, pomalidomide, and dexamethasone for relapsed or refractory myeloma. Blood 2015;126:2284–90.

42. Palumbo A, Chanan-Khan AA, Weisel K, et al. Phase III randomized controlled study of daratumumab, bortezomib, and dexamethasone (DVd) versus bortezomib and dexamethasone (Vd) in patients (pts) with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma (RRMM): CASTOR study. J Clin Oncol 2016;34(suppl):abstr LBA4.

43. Lonial S, Dimopoulos M, Palumbo A, et al. Elotuzumab therapy for relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med 2015;373:621–31.

44. Lentzsch S, O’Sullivan A, Kennedy RC, et al. Combination of bendamustine, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone (BLD) in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma is feasible and highly effective: results of phase 1/2 open-label, dose escalation study. Blood 2012;119:4608–13.

45. Kumar SK, Krishnan A, LaPlant B, et al. Bendamustine, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone (BRD) is highly effective with durable responses in relapsed multiple myeloma. Am J Hematol 2015;90:1106–10.

46. Siegel DS, Martin T, Wang M, et al. A phase 2 study of single-agent carfilzomib (PX-171-003-A1) in patients with relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma. Blood 2012;120:2817–25.

47. Stewart AK, Rajkumar SV, Dimopoulos MA, et al. Carfilzomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone for relapsed multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med 2015;372:142–52.

48. San-Miguel JF, Hungria VT, Yoon SS, et al. Panobinostat plus bortezomib and dexamethasone versus placebo plus bortezomib and dexamethasone in patients with relapsed or relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma: a multicentre, randomised, double-blind phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncology 2014;15:1195–206.

49. Berdeja JG, Hart LL, Mace JR, et al. Phase I/II study of the combination of panobinostat and carfilzomib in patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma. Haematologica 2015;100:670–6.

50. Buda G, Orciuolo E, Galimberti S, Ghio F, Petrini M. VTDPACE as salvage therapy for heavily pretreated MM patients. Blood 2013;122:5377.

51. Voorhees PM, Mulkey F, Hassoun H, et al. Alliance A061202. A phase I/II study of pomalidomide, dexamethasone and ixazomib versus pomalidomide and dexamethasone for patients with multiple myeloma refractory to lenalidomide and proteasome inhibitor based therapy: phase I results. Blood 2015;126:375.

52. Lacy MQ, LaPlant BR, Laumann KM, et al. Pomalidomide, bortezomib and dexamethasone (PVD) for patients with relapsed lenalidomide refractory multiple myeloma (MM). Blood 2014;124:304.

53. Moreau P, Masszi T, Grzasko N, et al. Oral ixazomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone for multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med 2016;374:1621–34.

54. Vij R, Siegel DS, Jagannath S, et al. An open-label, single-arm, phase 2 study of single-agent carfilzomib in patients with relapsed and/or refractory multiple myeloma who have been previously treated with bortezomib. Br J Haematol 2012;158:739–48.

55. Leleu X, Attal M, Arnulf B, et al. Pomalidomide plus low-dose dexamethasone is active and well tolerated in bortezomib and lenalidomide-refractory multiple myeloma: Intergroupe Francophone du Myelome 2009-02. Blood 2013;121:1968–75.

56. Lonial S, Weiss BM, Usmani SZ, et al. Daratumumab monotherapy in patients with treatment-refractory multiple myeloma (SIRIUS): an open-label, randomised, phase 2 trial. Lancet 2016;387(10027):1551–60.

57. Lokhorst HM, Plesner T, Laubach JP, et al. Targeting CD38 with daratumumab monotherapy in multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med 2015;373:1207–19.

58. Richardson PG, Schlossman RL, Alsina M, et al. PANORAMA 2: panobinostat in combination with bortezomib and dexamethasone in patients with relapsed and bortezomib-refractory myeloma. Blood 2013;122:2331–7.

59. Stöhr E, Schmeel FC, Schmeel LC, et al. Bendamustine in heavily pre-treated patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2015;141:2205–12.

60. Mhaskar R, Redzepovic J, Wheatley K, et al. Bisphosphonates in multiple myeloma: a network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012(5):CD003188.

61. Dhodapkar MV, Singh J, Mehta J, et al. Anti-myeloma activity of pamidronate in vivo. Br J Haematol 1998;103:530–2.

62. Terpos E, Morgan G, Dimopoulos MA, et al. International Myeloma Working Group recommendations for the treatment of multiple myeloma-related bone disease. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:2347–57.

63. Kiely F, Cran A, Finnerty D, O’Brien T. Self-reported quality of life and symptom burden in ambulatory patients with multiple myeloma on disease-modifying treatment. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2016 May 2.

64. Brioli A, Giles H, Pawlyn C, et al. Serum free immunoglobulin light chain evaluation as a marker of impact from intraclonal heterogeneity on myeloma outcome. Blood 2014;123:3414–9.

65. Ludwig H, Sonneveld P, Davies F, et al. European perspective on multiple myeloma treatment strategies in 2014. Oncologist 2014;19:829–44.

66. Maude SL, Frey N, Shaw PA, et al. Chimeric antigen receptor T cells for sustained remissions in leukemia. N Engl J Med 2014;371:1507–17.

67. Garfall AL, Maus MV, Hwang W-T, et al. Chimeric antigen receptor T cells against CD19 for multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med 2015;373:1040–7.

68. Kumar SK, Dispenzieri A, Gertz MA, et al. Continued improvement in survival in multiple myeloma and the impact of novel agents. 54th ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts. Blood 2012;120(21):3972.

From the Division of Hematology and Oncology, University of North Carolina – Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC (Dr. Reeves), and the Division of Cellular Therapy and Hematological Malignancies, Duke Cancer Institute, Durham, NC (Dr. Tuchman).

Abstract

- Objective: To review the management considerations in patients with relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma (RRMM).

- Methods: Review of the literature.

- Results: RRMM is a heterogeneous disease and numerous treatment regimens have been studied. Despite improvement in progression-free and overall survival in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma with current therapies, myeloma remains incurable and repeated relapses are inevitable. Relapses are often characterized by diminished response to chemotherapy (refractoriness) and duration of response.

- Conclusion: Management of RRMM should be individualized using both patient- and disease-related factors, given substantial heterogeneity in both. Further research regarding the optimal timing, regimen, and duration of treatment is warranted.

Although advancements in treating multiple myeloma (MM) have resulted in improved median survival from approximately 2 years in the 1990s to more recent estimates of over 6 years, the disease remains incurable [1–3]. Its overall course is generally defined by a series of increasingly short remissions and treatment-refractory relapses until eventual death due to MM occurs. Objective criteria for defining both relapsed and refractory MM have been published [4]. Briefly, relapsed myeloma is that which has been previously treated with some form of systemic therapy and which has recurred. That recurrence can be clinical (ie, the development of new or worsening signs or symptoms of active MM) and/or biochemical (ie, rising monoclonal MM proteins in the serum or urine). Refractory MM on the other hand refers to MM that is resistant to particular drugs, defined as MM that is nonresponsive to primary or salvage therapy, or MM that progresses within 60 days of the last therapy [4]. At any juncture during the course of relapsed MM, patients will have disease that is either sensitive or refractory to specific myeloma drugs. In this article, we discuss management of these often concurrent entities together as relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma (RRMM).

There are numerous treatment options for patients with RRMM—3 new drugs were approved in November 2015 alone. The abundance of available drugs leaves treating clinicians with a daunting task of sequencing therapies among several choices. The durability of response to treatment typically lessens with each disease relapse, such that the clinician needs to think of sequencing not just second-line therapy, but third- and fourth-line as well, further complicating the decision. In this review, we aim to help clinicians individualize treatment plans for patients with RRMM.

Case Studies

Patient A

A 62-year-old man with IgG-kappa MM was diagnosed 4 years ago during evaluation of a pathologic humeral fracture. The disease was prognostically standard risk, with revised International Staging System (RISS) stage I disease (beta-2 microglobulin 3.4 mcg/mL, albumin 4.1 g/dL, normal cytogenetics with 46,XY in 20 cells analyzed, and myeloma fluorescent in situ hybridization [FISH] panel showing t(11;14) but no del17p, t(14;16), t(14;20), or t(4;14)) [5], and normal blood counts, organ function, and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) at diagnosis. He was treated with 5 cycles of standard lenalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone followed by high-dose melphalan with autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) and then lenalidomide continuous maintenance. He achieved a stringent complete response (ie, complete disappearance of myeloma-derived monoclonal proteins in the serum and urine, a normal serum free light chain ratio, and undetectable monoclonal plasma cells on a bone marrow aspirate and biopsy) [4]. His MM was monitored every 2 to 3 months for disease progression and medication toxicity. At month 38, a monoclonal protein spike (M-spike) on serum protein electrophoresis (SPEP) remained undetectable, but serum kappa free light chain levels increased from 1.98 mg/dL to 8 mg/dL with stable lambda serum free light chains and a ratio that rose to 16, consistent with low-level biochemical recurrence. He had no evidence of end-organ damage and therefore was maintained on lenalidomide maintenance for the time being. Over the next 12 months, his kappa serum free light chain level continued to slowly rise, reaching 24 mg/dL, while the ratio rose to 50. There was still no detectable M-spike. He developed mild anemia during this time, with his hemoglobin dropping from a prior value of approximately 11 g/dL to 9.8 g/dL, though kidney function remained normal. A repeat bone marrow aspirate and biopsy revealed 20% kappa-restricted plasma cells.

Patient B

A 75-year-old woman with IgA-kappa MM was diagnosed after laboratory testing by her primary care physician incidentally showed an elevated serum total protein level. The MM was intermediate risk, with RISS stage II disease, and with mild renal impairment resulting in an estimated creatinine clearance of 45 mL/min that was felt to be due to MM. She was initially treated with bortezomib and dexamethasone but received only 2 cycles because she developed painful peripheral neuropathy secondary to bortezomib. Bortezomib was stopped and she was then treated with lenalidomide and dexamethasone for 4 cycles. She achieved a complete response and elected to stop treatment due to fatigue. Her fatigue did not improve off treatment. Six months after stopping therapy, an M-spike was detectable at 0.1 g/dL and she developed a new painful lytic lesion in the left humerus.

Patient C

A 59-year-old man with lambda free light chain MM was diagnosed when he presented with acute renal failure requiring dialysis. The disease was RISS-III at diagnosis (high risk), with the t(4;14) genetic abnormality in his MM cells detected on bone marrow aspirate, an abnormality that has been associated with poor prognosis MM [6–8]. The patient was treated with cyclophosphamide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone [9] for 6 cycles, at which point his disease was in a very good partial response (>90% reduction in M-spike) [4], and his renal function had recovered to a new baseline creatinine clearance of 45 mL/min. He then underwent ASCT after melphalan conditioning followed by bortezomib maintenance therapy every 2 weeks. Eight months after ASCT, his lambda free light chain level increased from 1.25 mg/dL to 45 mg/dL and the ratio increased from 4 to 22. Renal function was unchanged and there was stable anemia, with hemoglobin of 10.1 g/dL.

When should treatment for RRMM commence?

Patients with MM in remission are closely monitored, with clinical and laboratory examinations generally conducted every 1 to 3 months. The history is focused on MM-related symptoms such as increasing bone pain or weight loss, and symptoms of therapy-related toxicity such as fatigue, gastrointestinal distress, or peripheral neuropathy. Laboratory assessment typically includes blood counts and chemistry measurements, as well as measurements of MM-derived monoclonal proteins: SPEP, serum immunofixation (IFE), serum immunoglobulin free light chain measurements, and urine protein electrophoresis and immunofixation (UPEP/urine IFE) [10]. Progressive disease biochemically is defined as a 25% increase in M-spike (at least 0.5 g/dL if the M-spike is in serum or > 200 mg/24 hours if in urine), and/or a rise of greater than 10 mg/dL difference between the involved and uninvolved serum free light chains. Clinically progressive disease is denoted as new evidence of end-organ damage such as a new plasma-cytoma, unexplained hypercalcemia, or worsening anemia due to MM [4]. Many, if not most, patients will have biochemical recurrence identified by laboratory measurements ofmonoclonal proteins before clinical recurrence transpires.

The velocity of relapse can help guide decisions about when to reinitiate therapy. High-velocity disease relapse, meaning rapid rise in monoclonal proteins, is an indicator of more aggressive disease, and treatment should be initiated promptly before development of symptoms [11]. Conversely, low-level, indolent recurrence can often be followed with a “watch and wait” approach to determine how the myeloma will progress over time. Expert guidelines suggest that a monoclonal protein doubling time of 2 months may be an appropriate cutoff for determining high versus low velocity [12], although 2 months is not a firm rule and the decision of when to restart treatment for any given patient with asymptomatic biochemical recurrence should be individualized. Importantly, it is not clear that changing therapy at the time of biochemical recurrence, prior to clinical disease progression, improves outcomes, but clinicians are often nonetheless hesitant to hold therapy in the face of biochemically recurrent MM given the potential for complications, such as a pathologic fracture. In patients with biochemically recurrent MM for whom re-initiation of systemic anti-myeloma therapy is being deferred, one can consider re-initiation of zoledronic acid therapy, since in a randomized controlled trial, zoledronic acid commenced at the time of biochemical relapse resulted in fewer skeletal events as compared to placebo [13].

What disease factors should be considered in choosing treatment for RRMM?

MM exhibits genetic complexity, and prior treatments may result in clonal evolution of and selection for an initially nondominant, treatment-resistant clone [14,15]. This heterogeneity and selection pressure may explain why 3-drug regimens often outperform 1- or 2-drug regimens, why each remission is generally shorter than the last, and why patients who have enjoyed a long duration of response to one therapy and been off it for some length of time may again have a good response when re-treated with the same therapy at time of MM relapse. So how does one know if a new clone has emerged? While there is no standard for monitoring intra-clonal heterogeneity presently, changes in clinical phenotype likely correlate with evolving clones. Some such changes include free light chain escape (ie, MM that initially secreted an intact M-spike and then only secretes free light chain at relapse), new development of extramedullary disease (plasmacytomas outside of bone) in patients who previously had MM only in the bone marrow, and resistance of some sites to treatment while others respond (a mixed response). The former 2 phenotypes in particular portend poor prognosis and unsurprisingly they can be seen together [16–19]. Restaging, meaning a complete reassessment of MM disease status at the time of relapse, including bone marrow aspirate and biopsy, is beneficial to help guide therapy, as those with high-risk features including high ISS stage [20], high-risk cytogenetics, increased LDH, and extramedullary disease should be treated with triplet therapy when possible [11]. Repeat imaging should also be considered as a new baseline comparator. This can be done with standard x-rays, positron-emission tomography/computed tomography (PET-CT), or magnetic resonance imaging. PET-CT offers the advantage of showing active disease sites and the presence of extramedullary disease, although it exposes the patient to more radiation than the other methods.

In terms of using genetics to guide therapy decisions in RRMM, the presence of the del(17p) abnormality either by karyotyping or FISH portends high risk and pomalidomide in one study was shown to mitigate that risk [21]. How genetics and prognostic markers should dictate therapy selection in RRMM otherwise, however, is unclear and an area of active research efforts.

What patient factors should be considered in choosing treatment?

Given the relatively large selection of possible regimens for the treatment of RRMM, patient preference can be incorporated into regimen selection. Patients who have long commutes or who are trying to work may not be ideal candidates to receive carfilzomib-based regimens given the twice-per-week infusion schedule (though a once-a-week dosing schedule is being tested) [22]. Patients who have poor venous access may be good candidates for all-oral regimens. Prior treatment tolerability and side effects should also be considered. Patients who experienced significant peripheral neuropathy with bortezomib may have less neuropathy with carfilzomib. Those with renal failure may tolerate pomalidomide better than lenalidomide [23].

Patient age and functional status are important considerations in choosing a treatment regimen for RRMM. Very old patients (a subjective categorization to include patients > 80 years by chronologic or physiologic age), those with functional dependence, or patients harboring substantial medical comorbidities are at risk for therapy toxicity and so often warrant less intensive approaches [24]. Deciding which patients empirically warrant less dose-intensive approaches can be challenging, especially with the growing recognition that fit seniors can often tolerate and enjoy the benefits of full-dose approaches, including sometimes even ASCT. Geriatric assessment instruments that interrogate a variety of geriatric-relevant domains, such as number of falls, independence in activities of daily living, and polypharmacy, are being investigated as toxicity predictors and may help make those decisions in the future. Such instruments have been shown to predict chemotherapy toxicity in solid tumors [25,26] and preliminarily in MM [27], but they remain investigational. While no validated geriatric assessment instruments are currently available for routine clinical employment in MM, clinicians should consider the geriatric domains that these instruments assess when choosing among treatment options. Clinically, that often translates to choosing gentler regimens with likely better tolerability, albeit perhaps with less efficacy, for patients judged to be vulnerable to toxicity.

As part of therapy selection in RRMM, the clinician needs to consider if the patient is a candidate for ASCT. For patients who did not undergo ASCT as part of initial treatment, ASCT can be considered at the time of relapse. Ideally, all patients who could eventually undergo ASCT should have hematopoietic stem cells collected and stored at the time of first induction; however, collection after re-induction chemotherapy has been shown to be feasible [28,29]. ASCT for RRMM appears to be effective, although rigorous randomized comparisons of ASCT versus treatment purely with novel drugs are lacking [30–32]. For patients who did receive ASCT consolidation in the frontline, if a response is sustained for 18 months or greater, existing guidelines suggest that a second ASCT is likely worthwhile [29]. Whether the routine usage of maintenance therapies (low-dose, usually single drugs used to prolong duration of remission once remission is achieved) should change that 18-month cutoff is unclear, however, since maintenance “artificially” makes ASCT appear more effective by prolonging post-ASCT duration of remission. The “is it worth it” discussion is also largely subjective and hinges heavily on the patient’s experience with the first ASCT. In our practice, we often use 3 years as the cutoff for considering repeat ASCT in patients on maintenance therapy, meaning that if a patient underwent ASCT and received maintenance, a remission lasting more than 3 years means we consider ASCT as part of therapy for relapse.

Allogeneic stem cell transplantation (allo-SCT) is a treatment option for RRMM generally reserved for fit patients younger than 65 years [22,33]. The timing of allo-SCT is also controversial, with some reserving it as a last option given a historically high transplant-related mortality and improved progression-free survival but not necessarily overall survival benefit. A recent consensus statement has suggested allo-SCT be considered (preferentially in a clinical trial) for eligible patients with high-risk disease who relapse after primary treatment that included ASCT [29]. With the abundance of new treatment options in RRMM with reasonable toxicity profiles, it is not clear for whom and when allo-SCT is best considered.

Which regimen should be used to treat a first relapse?

Entry into a well-designed clinical trial for patients with RRMM should be considered for every patient since there is a lack of evidence to guide the best sequencing of chemotherapies [11]. Beyond that, the choice of therapy is based upon 2 main factors: the disease itself (eg, indolent, asymptomatic biochemical recurrence versus aggressive clinical recurrence with new fractures or extramedullary plasmacytomas), and the patient’s preferences and characteristics, such as age, performance status, comorbidities, and toxicities from prior therapies. In looking for the “best” re-induction regimen, it is tempting to compare the efficacy of regimens across trials, but such efforts are fraught given the significant heterogeneity of the patient populations between trials. As an example, comparing daratumumab + pomalidomide + dexamethasone (DPd) to daratumumab + lenalidomide + dexamethasone (DRd), one may conclude that DRd is superior, given an overall response rate of 88% in DRd versus 58% in DPd. However, the DPd trial included patients who were refractory to lenalidomide and bortezomib, while the DRd study required only treatment with one prior therapy [34,35].

For patients who enjoyed a long remission after any particular chemotherapy regimen with good tolerability and with indolent features at the time of relapse, re-treating with the same regimen can be considered, although nowadays with so many new and highly potent agents available such “backtracking” is less common and some studies suggest that employing new agents may be beneficial. As an example, in the randomized ENDEAVOR study of bortezomib + dexamethasone versus carfilzomib + dexamethasone in RRMM, 54% of patients had been exposed to bortezomib whereas virtually none had received carfilzomib prior to study enroll-ment. Among those patients with prior bortezomib exposure, median progression-free survival was 15.6 versus 8.1 months (hazard ratio 0.56, [95% confidence interval 0.44 to 0.73]) for carfilzomib versus bortezomib, respectively. Follow-up was too immature for definitive conclusions to be drawn about overall survival, but the substantial difference in progression-free survival provides a compelling argument for using carfilzomib instead of going back to bortezomib for patients with prior bortezomib exposure [36].

For patients who are fit and not very old, we generally employ triplet re-induction. For the large number of these patients who were previously exposed to both lenalidomide and bortezomib, including as part of a maintenance strategy, outside of clinical trials we routinely use carfilzomib + pomalidomide + dexamethasone [41]. For patients who are lenalidomide-naïve but bortezomib-exposed, we often employ carfilzomib + lenalidomide + dexamethasone based on the phase 3 ASPIRE trial, which showed a significantly improved progression-free survival with carfilzomib + lenalidomide + dexamethasone versus lenalidomide + dexamethasone [47]. For patients who have previously received lenalidomide but not bortezomib, we consider pomalidomide + bortezomib + dexamethasone [52]. These regimens take advantage of the arguably most potent, most proven drugs in treating RRMM, namely proteasome inhibitors (bortezomib and carfilzomib) and immunomodulatory agents (lenalidomide and pomalidomide).

For patients who are more vulnerable to toxicity due to advanced age or comorbidities, we consider less intensive regimens, including dose-reduced triplets or doublets. Patients who had received lenalidomide-based combinations but not bortezomib are considered for a bortezomib-based re-induction, including bortezomib + dexamethasone alone. In the case of someone who had initially received a bortezomib-based combination but no lenalidomide, the new drugs are viable options: ixazomib [53] or elotuzumab [43] can both be added to standard lenalidomide + dexamethasone, with expectations of increasing response rates and progression-free survival and an acceptably low increased risk of severe toxicity. Ixazomib + lenalidomide + dexamethasone also has the benefit of being all-oral. For patients with bortezomib- and lenalidomide-exposed RRMM, using carfilzomib [54] or pomalidomide [55] with dexamethasone is reasonable.

Once MM has progressed beyond the arguable “core drugs” of early-stage MM, namely lenalidomide, bortezomib, carfilzomib, and pomalidomide, off protocol we favor daratumumab monotherapy [56,57]. Other options include panobinostat (given usually with bortezomib) [58] and bendamustine [59], among others.

Can agents to which the MM was previously refractory be reused?

With the understanding that MM is not a disease defined by a single molecular mutation, but rather clones and subclones, it is reasonable to think that even treatments that have previously failed may be beneficial to patients if they have been off those treatments for some length of time and sensitive subclones reemerge. Additionally, combining the “failed” agent with a new drug may overcome the previously seen refractoriness, as in the case of panobinostat + bortezomib [48]. That said, given the multitude of new treatment options for RRMM and data from such trials as ENDEAVOR as mentioned, revisiting previously used drugs is probably best reserved for second or greater relapses.

What should be the duration of therapy for RRMM?

There is no evidence to guide duration of therapy in RRMM. Most patients with relapsed disease will be considered for continuous treatment until disease progression, which usually means treatment for 6 to 12 months with full-dose induction, often to maximal response, followed by transition to some form of lower-dose maintenance in which parts of a multi-drug regimen may be eliminated and/or the doses for the remaining drugs may be reduced. Patients with a slow-velocity relapse and no markers of high-risk disease may be suitable candidates for a defined course of treatment without maintenance therapy [11], but most patients nowadays remain on some form of maintenance for RRMM after achieving remission.

What supportive care is needed in RRMM?

Bone Health

Skeletal-related events, namely fractures, can be devastating in MM. Bisphosphonates have been shown to decrease such events in MM and zoledronic acid has shown a trend toward improved survival, perhaps related to its impact on the bone marrow microenvironment or direct toxicity to myeloma cells [60,61]. It is unclear whether bisphosphonates improve overall survival in the relapsed setting, although zoledronic acid has shown decreased skeletal-related events in the setting of biochemical-only disease progression [13,62]. In active RRMM, our general practice is to resume parenteral bisphosphonate therapy (either zoledronic acid or pamidronate in our U.S. practices) usually every 3 to 4 weeks, depending on the length of the chemotherapy cycle.

Supportive Care