User login

Limit primary site radiation, but not craniospinal dose in medulloblastoma

BOSTON – For children with average-risk medulloblastoma, it is safe to limit the radiation boost to the posterior fossa, but reducing doses to the craniospinal axis results in worse outcomes among younger children, and is not advisable, according to results from the largest trial conducted in this population.

There were no significant differences in either 5-year event-free survival (EFS) or overall survival (OS) between children who received an involved field radiation therapy boost (boost to the tumor bed only) or a standard volume boost (to the whole posterior fossa) in a phase III randomized trial, reported lead author Jeff M. Michalski, MD, MBA, FASTRO, professor of radiation oncology at Washington University, St. Louis.

“We conclude that the survival rates and event-free survival rates following reduced boost volumes were comparable to standard radiation treatment volumes for the primary tumor site. This is the first trial to state definitively that there is no survival difference between these two approaches,” he said at a briefing following his presentation of the data in an oral abstract session at the annual meeting of the American Society for Radiation Oncology.

“However, the reduced craniospinal axis irradiation was associated with a higher event rate and worse survival. We believe that physicians can adopt smaller boost volumes to the posterior fossa in children with average-risk medulloblastoma, average risk being no evidence of spread at the time of diagnosis and near-complete or complete resection. But for all children, the standard of 23.4 Gy remains necessary to retain high-level tumor control,” he added.

Aggressive malignancy

Medulloblastoma, an aggressive tumor with the propensity to spread from the lower brain to the upper brain and spine, is the most common brain malignancy in children. The current standard of care for children with average-risk disease is surgical resection followed by systemic chemotherapy followed by irradiation to both the posterior fossa and to the craniospinal axis.

“Unfortunately, this strategy has significant negative consequences for the patients’ neurocognitive abilities, endocrine function, and hearing,” Dr. Michalski said.

The Children’s Oncology Group ACNS0331 trial was designed to determine whether reducing the volume of the boost from the whole posterior to the tumor bed only would compromise EFS and OS, and whether reducing the dose to the craniospinal axis from the current 23.4 Gy to 18 Gy in children aged 3-7 years would compromise survival measures.

The trial had two randomizations, both at the time of study enrollment. In the first, children from the ages of 3 to 7 years were randomly assigned to either low-dose craniospinal irradiation (18 Gy, 116 children) or to the standard dose (23.4 Gy, 110 children). All children aged 8 and older were assigned to receive the standard dose.

For the second randomization, all children were randomly allocated to either involved field RT boost or to standard volume boost to the whole posterior fossa.

Following radiation, all children were assigned to nine cycles of maintenance chemotherapy.

At a median follow-up of 6.6 years, 5-year EFS estimates for the primary site irradiation endpoint were 82.2% for 227 patients who received the involved-field radiation, compared with 80.8% for 237 patients who received whole posterior fossa irradiation.

Respective 5-year OS estimates were 84.1% and 85.2%. The upper limit of the hazard ratio confidence interval (CI) for the involved field therapy was lower than the prespecified limit, indicating that involved-field radiation was noninferior.

For the endpoint of low- vs. standard-dose craniospinal irradiation, the 5-year EFS estimates were 72.1% and 82.6%, respectively. The upper limit of the hazard ratio CI exceeded the prespecified limit, indicating that EFS was worse with the low-dose strategy.

Similarly, respective 5-year OS estimates were 78.1% and 85.9%, with the upper limit of the CI also higher than the prespecified upper limit.

When the investigators looked at the patterns of failure among the children in the two randomizations, they saw that there was no significant difference in the rate of isolated local failure between the involved-field or whole posterior fossa groups, or between the low-dose or high-dose craniospinal irradiation groups.

The finding that radiation volume to the primary site can be reduced is likely to be practice changing, said Geraldine Jacobson, MD, MPH, professor and chair of radiation oncology at West Virginia University, Morgantown. Dr. Jacobson moderated the briefing.

However, the worse survival with the low-dose craniospinal radiation “leaves the COG investigators with the challenge to explore other avenues for reducing toxicity of craniospinal irradiation,” she said.

BOSTON – For children with average-risk medulloblastoma, it is safe to limit the radiation boost to the posterior fossa, but reducing doses to the craniospinal axis results in worse outcomes among younger children, and is not advisable, according to results from the largest trial conducted in this population.

There were no significant differences in either 5-year event-free survival (EFS) or overall survival (OS) between children who received an involved field radiation therapy boost (boost to the tumor bed only) or a standard volume boost (to the whole posterior fossa) in a phase III randomized trial, reported lead author Jeff M. Michalski, MD, MBA, FASTRO, professor of radiation oncology at Washington University, St. Louis.

“We conclude that the survival rates and event-free survival rates following reduced boost volumes were comparable to standard radiation treatment volumes for the primary tumor site. This is the first trial to state definitively that there is no survival difference between these two approaches,” he said at a briefing following his presentation of the data in an oral abstract session at the annual meeting of the American Society for Radiation Oncology.

“However, the reduced craniospinal axis irradiation was associated with a higher event rate and worse survival. We believe that physicians can adopt smaller boost volumes to the posterior fossa in children with average-risk medulloblastoma, average risk being no evidence of spread at the time of diagnosis and near-complete or complete resection. But for all children, the standard of 23.4 Gy remains necessary to retain high-level tumor control,” he added.

Aggressive malignancy

Medulloblastoma, an aggressive tumor with the propensity to spread from the lower brain to the upper brain and spine, is the most common brain malignancy in children. The current standard of care for children with average-risk disease is surgical resection followed by systemic chemotherapy followed by irradiation to both the posterior fossa and to the craniospinal axis.

“Unfortunately, this strategy has significant negative consequences for the patients’ neurocognitive abilities, endocrine function, and hearing,” Dr. Michalski said.

The Children’s Oncology Group ACNS0331 trial was designed to determine whether reducing the volume of the boost from the whole posterior to the tumor bed only would compromise EFS and OS, and whether reducing the dose to the craniospinal axis from the current 23.4 Gy to 18 Gy in children aged 3-7 years would compromise survival measures.

The trial had two randomizations, both at the time of study enrollment. In the first, children from the ages of 3 to 7 years were randomly assigned to either low-dose craniospinal irradiation (18 Gy, 116 children) or to the standard dose (23.4 Gy, 110 children). All children aged 8 and older were assigned to receive the standard dose.

For the second randomization, all children were randomly allocated to either involved field RT boost or to standard volume boost to the whole posterior fossa.

Following radiation, all children were assigned to nine cycles of maintenance chemotherapy.

At a median follow-up of 6.6 years, 5-year EFS estimates for the primary site irradiation endpoint were 82.2% for 227 patients who received the involved-field radiation, compared with 80.8% for 237 patients who received whole posterior fossa irradiation.

Respective 5-year OS estimates were 84.1% and 85.2%. The upper limit of the hazard ratio confidence interval (CI) for the involved field therapy was lower than the prespecified limit, indicating that involved-field radiation was noninferior.

For the endpoint of low- vs. standard-dose craniospinal irradiation, the 5-year EFS estimates were 72.1% and 82.6%, respectively. The upper limit of the hazard ratio CI exceeded the prespecified limit, indicating that EFS was worse with the low-dose strategy.

Similarly, respective 5-year OS estimates were 78.1% and 85.9%, with the upper limit of the CI also higher than the prespecified upper limit.

When the investigators looked at the patterns of failure among the children in the two randomizations, they saw that there was no significant difference in the rate of isolated local failure between the involved-field or whole posterior fossa groups, or between the low-dose or high-dose craniospinal irradiation groups.

The finding that radiation volume to the primary site can be reduced is likely to be practice changing, said Geraldine Jacobson, MD, MPH, professor and chair of radiation oncology at West Virginia University, Morgantown. Dr. Jacobson moderated the briefing.

However, the worse survival with the low-dose craniospinal radiation “leaves the COG investigators with the challenge to explore other avenues for reducing toxicity of craniospinal irradiation,” she said.

BOSTON – For children with average-risk medulloblastoma, it is safe to limit the radiation boost to the posterior fossa, but reducing doses to the craniospinal axis results in worse outcomes among younger children, and is not advisable, according to results from the largest trial conducted in this population.

There were no significant differences in either 5-year event-free survival (EFS) or overall survival (OS) between children who received an involved field radiation therapy boost (boost to the tumor bed only) or a standard volume boost (to the whole posterior fossa) in a phase III randomized trial, reported lead author Jeff M. Michalski, MD, MBA, FASTRO, professor of radiation oncology at Washington University, St. Louis.

“We conclude that the survival rates and event-free survival rates following reduced boost volumes were comparable to standard radiation treatment volumes for the primary tumor site. This is the first trial to state definitively that there is no survival difference between these two approaches,” he said at a briefing following his presentation of the data in an oral abstract session at the annual meeting of the American Society for Radiation Oncology.

“However, the reduced craniospinal axis irradiation was associated with a higher event rate and worse survival. We believe that physicians can adopt smaller boost volumes to the posterior fossa in children with average-risk medulloblastoma, average risk being no evidence of spread at the time of diagnosis and near-complete or complete resection. But for all children, the standard of 23.4 Gy remains necessary to retain high-level tumor control,” he added.

Aggressive malignancy

Medulloblastoma, an aggressive tumor with the propensity to spread from the lower brain to the upper brain and spine, is the most common brain malignancy in children. The current standard of care for children with average-risk disease is surgical resection followed by systemic chemotherapy followed by irradiation to both the posterior fossa and to the craniospinal axis.

“Unfortunately, this strategy has significant negative consequences for the patients’ neurocognitive abilities, endocrine function, and hearing,” Dr. Michalski said.

The Children’s Oncology Group ACNS0331 trial was designed to determine whether reducing the volume of the boost from the whole posterior to the tumor bed only would compromise EFS and OS, and whether reducing the dose to the craniospinal axis from the current 23.4 Gy to 18 Gy in children aged 3-7 years would compromise survival measures.

The trial had two randomizations, both at the time of study enrollment. In the first, children from the ages of 3 to 7 years were randomly assigned to either low-dose craniospinal irradiation (18 Gy, 116 children) or to the standard dose (23.4 Gy, 110 children). All children aged 8 and older were assigned to receive the standard dose.

For the second randomization, all children were randomly allocated to either involved field RT boost or to standard volume boost to the whole posterior fossa.

Following radiation, all children were assigned to nine cycles of maintenance chemotherapy.

At a median follow-up of 6.6 years, 5-year EFS estimates for the primary site irradiation endpoint were 82.2% for 227 patients who received the involved-field radiation, compared with 80.8% for 237 patients who received whole posterior fossa irradiation.

Respective 5-year OS estimates were 84.1% and 85.2%. The upper limit of the hazard ratio confidence interval (CI) for the involved field therapy was lower than the prespecified limit, indicating that involved-field radiation was noninferior.

For the endpoint of low- vs. standard-dose craniospinal irradiation, the 5-year EFS estimates were 72.1% and 82.6%, respectively. The upper limit of the hazard ratio CI exceeded the prespecified limit, indicating that EFS was worse with the low-dose strategy.

Similarly, respective 5-year OS estimates were 78.1% and 85.9%, with the upper limit of the CI also higher than the prespecified upper limit.

When the investigators looked at the patterns of failure among the children in the two randomizations, they saw that there was no significant difference in the rate of isolated local failure between the involved-field or whole posterior fossa groups, or between the low-dose or high-dose craniospinal irradiation groups.

The finding that radiation volume to the primary site can be reduced is likely to be practice changing, said Geraldine Jacobson, MD, MPH, professor and chair of radiation oncology at West Virginia University, Morgantown. Dr. Jacobson moderated the briefing.

However, the worse survival with the low-dose craniospinal radiation “leaves the COG investigators with the challenge to explore other avenues for reducing toxicity of craniospinal irradiation,” she said.

Key clinical point: Primary site irradiation in children with medulloblastoma can be limited to the tumor bed rather than the whole posterior fossa.

Major finding: There were no differences in EFS or OS when radiation was limited to the tumor bed, but reduced dose to the craniospinal axis was associated with worse survival.

Data source: Randomized phase III trial of 690 children with average-risk medulloblastoma.

Disclosures: The National Cancer Institute funded the study. Dr. Michalski and Dr. Jacobson reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

Martina Mancini, PhD, and Graham Harker

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Boost dose pays off long term after surgery, WBRT for DCIS

BOSTON – Adding a boost dose after surgery and whole-breast radiation therapy (WBRT) for ductal carcinoma in situ offers a small but significant reduction in long-term risk of same-breast recurrence, according to results of a multicenter study.

An analysis of pooled data from 10 institutions showed that after 15 years of follow-up, 91.6% of women who had been treated with breast-conserving surgery, WBRT, and a boost dose remained free of ipsilateral breast tumor recurrence (IBTR), compared with 88% of women who received WBRT alone, reported Meena Savur Moran, MD, director of the breast cancer radiotherapy program at Smilow Cancer Hospital, Yale New Haven, Connecticut.

The absolute differences between the groups – 3% at 10 years, and 4% at 15 years – “don’t seem like a lot, but it is clinically important for patients, because what we’ve learned from the invasive cancer data is that this small, incremental decrease results in about a 40% less mastectomy rate for salvage mastectomies for recurrences,” she said.

It is common practice in many centers to give a radiation boost to the tumor bed of 8-16 Gy in 4-8 additional fractions following breast-conserving surgery and WBRT. This has been shown in invasive cancers to be associated with a statistically significant decrease in risk for IBTR in all age groups of about 4% at 20 years.

Yet because DCIS generally has an excellent prognosis with very few recurrences after whole-breast irradiation, it has been harder to determine whether radiation boosting would offer similar benefit to that seen in invasive cancers,

In an attempt to answer this question, investigators from 10 centers collaborated to create a DCIS database of patients treated with WBRT either with or without boost, and then analyzed the results.

The final cohort included 4,131 patients, far exceeding the minimum sample size the statisticians calculated would be needed to detect a benefit.

The median age of patients at the time of therapy was 56.1 years, median follow-up was 9 years, and the median boost dose was 14 Gy. In all, 4% of patients had positive tumor margins after surgery.

Rates of IBTR-free survival with boost vs. no boost were 97.1% vs. 96.3% at 5 years, 94.1% vs. 92.5% at 10 years, and, as noted before, 91.6% vs. 88% at 15 years (P = .0389).

In both univariate and in multivariate analysis controlling for tumor grade, comedo carcinoma, tamoxifen use, margin status, and age, IBTR was significantly associated with lower risk for recurrence.

The investigators also conducted a boost/no boost analysis stratified by margin status using both the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP) definition of negative margins as no ink on tumor, and the joint Society of Surgical Oncology, ASTRO, and American Society of Clinical Oncology guideline definition as less than 2 mm, and in each case found that among patients with negative margins, boosting offered a significant recurrence-free advantage.

Finally, they found that boosting offered a significant advantage both for patients 50 and older (P = .0073) and those 49 and younger (P = .0166).

“For DCIS, most of who treat breast cancer have used a boost, but we really extrapolated from the treatment from invasive breast cancer. Evidence for this practice until now in specific for DCIS has been lacking,” said Geraldine Jacobson, MD, MPH, professor and chair of radiation oncology at West Virginia University, Morgantown. Dr. Jacobson moderated the briefing.

She noted that the large sample size and long follow-up of the study was necessary for the treatment benefit to emerge.

BOSTON – Adding a boost dose after surgery and whole-breast radiation therapy (WBRT) for ductal carcinoma in situ offers a small but significant reduction in long-term risk of same-breast recurrence, according to results of a multicenter study.

An analysis of pooled data from 10 institutions showed that after 15 years of follow-up, 91.6% of women who had been treated with breast-conserving surgery, WBRT, and a boost dose remained free of ipsilateral breast tumor recurrence (IBTR), compared with 88% of women who received WBRT alone, reported Meena Savur Moran, MD, director of the breast cancer radiotherapy program at Smilow Cancer Hospital, Yale New Haven, Connecticut.

The absolute differences between the groups – 3% at 10 years, and 4% at 15 years – “don’t seem like a lot, but it is clinically important for patients, because what we’ve learned from the invasive cancer data is that this small, incremental decrease results in about a 40% less mastectomy rate for salvage mastectomies for recurrences,” she said.

It is common practice in many centers to give a radiation boost to the tumor bed of 8-16 Gy in 4-8 additional fractions following breast-conserving surgery and WBRT. This has been shown in invasive cancers to be associated with a statistically significant decrease in risk for IBTR in all age groups of about 4% at 20 years.

Yet because DCIS generally has an excellent prognosis with very few recurrences after whole-breast irradiation, it has been harder to determine whether radiation boosting would offer similar benefit to that seen in invasive cancers,

In an attempt to answer this question, investigators from 10 centers collaborated to create a DCIS database of patients treated with WBRT either with or without boost, and then analyzed the results.

The final cohort included 4,131 patients, far exceeding the minimum sample size the statisticians calculated would be needed to detect a benefit.

The median age of patients at the time of therapy was 56.1 years, median follow-up was 9 years, and the median boost dose was 14 Gy. In all, 4% of patients had positive tumor margins after surgery.

Rates of IBTR-free survival with boost vs. no boost were 97.1% vs. 96.3% at 5 years, 94.1% vs. 92.5% at 10 years, and, as noted before, 91.6% vs. 88% at 15 years (P = .0389).

In both univariate and in multivariate analysis controlling for tumor grade, comedo carcinoma, tamoxifen use, margin status, and age, IBTR was significantly associated with lower risk for recurrence.

The investigators also conducted a boost/no boost analysis stratified by margin status using both the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP) definition of negative margins as no ink on tumor, and the joint Society of Surgical Oncology, ASTRO, and American Society of Clinical Oncology guideline definition as less than 2 mm, and in each case found that among patients with negative margins, boosting offered a significant recurrence-free advantage.

Finally, they found that boosting offered a significant advantage both for patients 50 and older (P = .0073) and those 49 and younger (P = .0166).

“For DCIS, most of who treat breast cancer have used a boost, but we really extrapolated from the treatment from invasive breast cancer. Evidence for this practice until now in specific for DCIS has been lacking,” said Geraldine Jacobson, MD, MPH, professor and chair of radiation oncology at West Virginia University, Morgantown. Dr. Jacobson moderated the briefing.

She noted that the large sample size and long follow-up of the study was necessary for the treatment benefit to emerge.

BOSTON – Adding a boost dose after surgery and whole-breast radiation therapy (WBRT) for ductal carcinoma in situ offers a small but significant reduction in long-term risk of same-breast recurrence, according to results of a multicenter study.

An analysis of pooled data from 10 institutions showed that after 15 years of follow-up, 91.6% of women who had been treated with breast-conserving surgery, WBRT, and a boost dose remained free of ipsilateral breast tumor recurrence (IBTR), compared with 88% of women who received WBRT alone, reported Meena Savur Moran, MD, director of the breast cancer radiotherapy program at Smilow Cancer Hospital, Yale New Haven, Connecticut.

The absolute differences between the groups – 3% at 10 years, and 4% at 15 years – “don’t seem like a lot, but it is clinically important for patients, because what we’ve learned from the invasive cancer data is that this small, incremental decrease results in about a 40% less mastectomy rate for salvage mastectomies for recurrences,” she said.

It is common practice in many centers to give a radiation boost to the tumor bed of 8-16 Gy in 4-8 additional fractions following breast-conserving surgery and WBRT. This has been shown in invasive cancers to be associated with a statistically significant decrease in risk for IBTR in all age groups of about 4% at 20 years.

Yet because DCIS generally has an excellent prognosis with very few recurrences after whole-breast irradiation, it has been harder to determine whether radiation boosting would offer similar benefit to that seen in invasive cancers,

In an attempt to answer this question, investigators from 10 centers collaborated to create a DCIS database of patients treated with WBRT either with or without boost, and then analyzed the results.

The final cohort included 4,131 patients, far exceeding the minimum sample size the statisticians calculated would be needed to detect a benefit.

The median age of patients at the time of therapy was 56.1 years, median follow-up was 9 years, and the median boost dose was 14 Gy. In all, 4% of patients had positive tumor margins after surgery.

Rates of IBTR-free survival with boost vs. no boost were 97.1% vs. 96.3% at 5 years, 94.1% vs. 92.5% at 10 years, and, as noted before, 91.6% vs. 88% at 15 years (P = .0389).

In both univariate and in multivariate analysis controlling for tumor grade, comedo carcinoma, tamoxifen use, margin status, and age, IBTR was significantly associated with lower risk for recurrence.

The investigators also conducted a boost/no boost analysis stratified by margin status using both the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP) definition of negative margins as no ink on tumor, and the joint Society of Surgical Oncology, ASTRO, and American Society of Clinical Oncology guideline definition as less than 2 mm, and in each case found that among patients with negative margins, boosting offered a significant recurrence-free advantage.

Finally, they found that boosting offered a significant advantage both for patients 50 and older (P = .0073) and those 49 and younger (P = .0166).

“For DCIS, most of who treat breast cancer have used a boost, but we really extrapolated from the treatment from invasive breast cancer. Evidence for this practice until now in specific for DCIS has been lacking,” said Geraldine Jacobson, MD, MPH, professor and chair of radiation oncology at West Virginia University, Morgantown. Dr. Jacobson moderated the briefing.

She noted that the large sample size and long follow-up of the study was necessary for the treatment benefit to emerge.

AT THE ASTRO ANNUAL MEETING 2016

Key clinical point: This study shows a significant benefit for adding a boost radiation dose following breast-conserving surgery and whole-breast radiation for ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS).

Major finding: After 15 years of follow-up, 91.6% of women who had received a boost dose were free of ipsilateral breast recurrence, compared with 88% of women who did not have a boost.

Data source: Analysis of pooled data on 4,131 patients with DCIS treated at 10 academic medical centers.

Disclosures: The study was supported by participating institutions. Dr. Moran and Dr. Jacobson reported no conflicts of interest.

Patient-specific model takes variability out of blood glucose average

Researchers have identified a patient-specific correction factor based on the age of a patient’s red blood cells that can improve the accuracy of average blood glucose estimations from hemoglobin A1c measures in patients with diabetes.

“The true average glucose concentration of a nondiabetic and a poorly controlled diabetic may differ by less than 15 mg/dL, but patients with identical HbA1c values may have true average glucose concentrations that differ by more than 60 mg/dL,” wrote Roy Malka, PhD, a mathematician and research fellow at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and his associates.

In an article published in the Oct. 5 online edition of Science Translational Medicine, the researchers reported the development of a mathematical model for HbA1c formation inside the red blood cell, based on the chemical contributions of glycemic and nonglycemic factors, as well as the average age of a patient’s red blood cells.

Using existing continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) data from four different groups – totaling more than 200 diabetes patients – the researchers then personalized the parameters of the model to each patient to see the impact of patient-specific variation in the relationship between average concentration of glucose in the blood and HbA1c.

Finally, they applied the personalized model to data from each patient to determine its accuracy in estimating future blood glucose from future HbA1c measurements, and compared the blood glucose estimates with those made using the current standard method (Sci Transl Med. 2016, Oct 5. http://stm.sciencemag.org/lookup/doi/10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf9304).

This showed that their patient-specific model reduced the median absolute error in estimated average blood glucose from more than 15 mg/dL to less than 5 mg/dL, representing an error reduction of more than 66%.

“The model would require one pair of CGM-measured AG [average blood glucose] and an HbA1c measurement that would be used to determine the patient’s [mean red blood cell count (MRBC)],” the researchers wrote. “MRBC would then be used going forward to refine the future [average glucose (AG)] calculated on the basis of HbA1c.”

The researchers pointed out that work was still needed to calculate the duration of CGM that would allow sufficient calibration of MRBC. However, their analysis suggested that no more than 30 days would be needed, and significant improvements could be achieved within just 21 days.

In patients with stable monthly glucose averages, the prior month would be enough for calibration, and even a single week of stable weekly glucose averages might be sufficient.

“The improvement in AG calculation afforded by our model should improve medical care and provide for a personalized approach to determining AG from HbA1c.”

The ADAG study was supported by the American Diabetes Association, the European Association for the Study of Diabetes, Abbott Diabetes Care, Bayer Healthcare, GlaxoSmithKline, Sanofi-Aventis Netherlands, Merck, LifeScan, Medtronic MiniMed, and HemoCue. Two authors were supported by the National Institutes of Health, and Abbott Diagnostics. The authors are also listed as inventors on a patent application related to this work submitted by Partners HealthCare.

Researchers have identified a patient-specific correction factor based on the age of a patient’s red blood cells that can improve the accuracy of average blood glucose estimations from hemoglobin A1c measures in patients with diabetes.

“The true average glucose concentration of a nondiabetic and a poorly controlled diabetic may differ by less than 15 mg/dL, but patients with identical HbA1c values may have true average glucose concentrations that differ by more than 60 mg/dL,” wrote Roy Malka, PhD, a mathematician and research fellow at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and his associates.

In an article published in the Oct. 5 online edition of Science Translational Medicine, the researchers reported the development of a mathematical model for HbA1c formation inside the red blood cell, based on the chemical contributions of glycemic and nonglycemic factors, as well as the average age of a patient’s red blood cells.

Using existing continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) data from four different groups – totaling more than 200 diabetes patients – the researchers then personalized the parameters of the model to each patient to see the impact of patient-specific variation in the relationship between average concentration of glucose in the blood and HbA1c.

Finally, they applied the personalized model to data from each patient to determine its accuracy in estimating future blood glucose from future HbA1c measurements, and compared the blood glucose estimates with those made using the current standard method (Sci Transl Med. 2016, Oct 5. http://stm.sciencemag.org/lookup/doi/10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf9304).

This showed that their patient-specific model reduced the median absolute error in estimated average blood glucose from more than 15 mg/dL to less than 5 mg/dL, representing an error reduction of more than 66%.

“The model would require one pair of CGM-measured AG [average blood glucose] and an HbA1c measurement that would be used to determine the patient’s [mean red blood cell count (MRBC)],” the researchers wrote. “MRBC would then be used going forward to refine the future [average glucose (AG)] calculated on the basis of HbA1c.”

The researchers pointed out that work was still needed to calculate the duration of CGM that would allow sufficient calibration of MRBC. However, their analysis suggested that no more than 30 days would be needed, and significant improvements could be achieved within just 21 days.

In patients with stable monthly glucose averages, the prior month would be enough for calibration, and even a single week of stable weekly glucose averages might be sufficient.

“The improvement in AG calculation afforded by our model should improve medical care and provide for a personalized approach to determining AG from HbA1c.”

The ADAG study was supported by the American Diabetes Association, the European Association for the Study of Diabetes, Abbott Diabetes Care, Bayer Healthcare, GlaxoSmithKline, Sanofi-Aventis Netherlands, Merck, LifeScan, Medtronic MiniMed, and HemoCue. Two authors were supported by the National Institutes of Health, and Abbott Diagnostics. The authors are also listed as inventors on a patent application related to this work submitted by Partners HealthCare.

Researchers have identified a patient-specific correction factor based on the age of a patient’s red blood cells that can improve the accuracy of average blood glucose estimations from hemoglobin A1c measures in patients with diabetes.

“The true average glucose concentration of a nondiabetic and a poorly controlled diabetic may differ by less than 15 mg/dL, but patients with identical HbA1c values may have true average glucose concentrations that differ by more than 60 mg/dL,” wrote Roy Malka, PhD, a mathematician and research fellow at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and his associates.

In an article published in the Oct. 5 online edition of Science Translational Medicine, the researchers reported the development of a mathematical model for HbA1c formation inside the red blood cell, based on the chemical contributions of glycemic and nonglycemic factors, as well as the average age of a patient’s red blood cells.

Using existing continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) data from four different groups – totaling more than 200 diabetes patients – the researchers then personalized the parameters of the model to each patient to see the impact of patient-specific variation in the relationship between average concentration of glucose in the blood and HbA1c.

Finally, they applied the personalized model to data from each patient to determine its accuracy in estimating future blood glucose from future HbA1c measurements, and compared the blood glucose estimates with those made using the current standard method (Sci Transl Med. 2016, Oct 5. http://stm.sciencemag.org/lookup/doi/10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf9304).

This showed that their patient-specific model reduced the median absolute error in estimated average blood glucose from more than 15 mg/dL to less than 5 mg/dL, representing an error reduction of more than 66%.

“The model would require one pair of CGM-measured AG [average blood glucose] and an HbA1c measurement that would be used to determine the patient’s [mean red blood cell count (MRBC)],” the researchers wrote. “MRBC would then be used going forward to refine the future [average glucose (AG)] calculated on the basis of HbA1c.”

The researchers pointed out that work was still needed to calculate the duration of CGM that would allow sufficient calibration of MRBC. However, their analysis suggested that no more than 30 days would be needed, and significant improvements could be achieved within just 21 days.

In patients with stable monthly glucose averages, the prior month would be enough for calibration, and even a single week of stable weekly glucose averages might be sufficient.

“The improvement in AG calculation afforded by our model should improve medical care and provide for a personalized approach to determining AG from HbA1c.”

The ADAG study was supported by the American Diabetes Association, the European Association for the Study of Diabetes, Abbott Diabetes Care, Bayer Healthcare, GlaxoSmithKline, Sanofi-Aventis Netherlands, Merck, LifeScan, Medtronic MiniMed, and HemoCue. Two authors were supported by the National Institutes of Health, and Abbott Diagnostics. The authors are also listed as inventors on a patent application related to this work submitted by Partners HealthCare.

Key clinical point:

Major finding: A patient-specific model of the relationship between HbA1c and average blood sugar reduced the median absolute error in estimated average blood glucose from more than 15 mg/dL to less than 5 mg/dL, representing an error reduction of more than 66%.

Data source: Mathematical modeling validated via four sets of patient continuous glucose monitoring data.

Disclosures: The ADAG study was supported by the American Diabetes Association, the European Association for the Study of Diabetes, Abbott Diabetes Care, Bayer Healthcare, GlaxoSmithKline, Sanofi-Aventis Netherlands, Merck, LifeScan, Medtronic MiniMed, and HemoCue. Two authors were supported by the National Institutes of Health, and Abbott Diagnostics. The authors are also listed as inventors on a patent application related to this work submitted by Partners HealthCare.

In lupus, optimize non-immunosuppressives to dial back prednisone

LAS VEGAS – For patients with mild to moderate systemic lupus erythematosus, don’t go above six milligrams of prednisone daily, because the treatment is likely to be worse than the disease in the long run, said Michelle Petri, MD.

Speaking at the annual Perspectives in Rheumatic Diseases presented by Global Academy for Medical Education, Dr. Petri shared evidence-backed clinical pearls to help rheumatologists dial in good disease control for their systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) patients without turning to too much prednisone.

Prednisone is also an independent risk factor for cardiovascular events, with dose-dependent effects, she said. She referred to a 2012 study she coauthored (Am J Epidemiol. 2012 Oct;176[8]:708-19) that found an age-adjusted cardiovascular event rate ratio of 2.4 when patients took 10-19 mg of prednisone daily (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.5-3.8; P = .0002). When the daily prednisone dose was over 20 mg, the rate ratio was 5.1 (95% CI, 3.1-8.4; P less than .0001).

Since it’s so important to minimize prednisone exposure, rheumatologists should be familiar with the full toolkit of non-immunosuppressive immunomodulators, and understand how to help patients assess risks and benefits of various treatments.“Non-immunosuppressive immunomodulators can control mild to moderate systemic lupus, helping to avoid steroids,” Dr. Petri said.

Hydroxychloroquine, when used as background therapy, has proved to have multiple benefits. Not only are flares reduced, but organ damage is reduced, lipids improve, fewer clots occur, and seizures are prevented, she said. There’s also an overall improvement in survival with hydroxychloroquine. In lupus nephritis, “continuing hydroxychloroquine improves complete response rates with mycophenolate mofetil,” Dr. Petri said.

Concerns about hydroxychloroquine-related retinopathy sometimes stand in the way of its use as background therapy, so Dr. Petri encouraged rheumatologists to have a realistic risk-benefit assessment. Higher risk for retinopathy is associated with higher dosing (greater than 6.5 mg/kg of hydroxychloroquine or 3 mg/kg of chloroquine); a higher fat body habitus, unless dosing is appropriately adjusted; the presence of renal disease or concomitant retinal disease; and age over 60.

Newer imaging techniques may sacrifice specificity for very high sensitivity in detecting hydroxychloroquine-related retinopathy, Dr. Petri said. High-speed ultra-high resolution optical coherence tomography (hsUHR-OCT) and multifocal electroretinography (mfERG) are imaging techniques that can detect hydroxychloroquine-related retinopathy, but should be reserved for patients with SLE who actually have visual symptoms, she said. Dr. Petri cited a study of 15 patients who were taking hydroxychloroquine, and 6 age-matched controls with normal visual function. All underwent visual field testing, mfERG, and hsUHR-OCT. The study “was unable to find an asymptomatic patient with evidence of definite damage on hsUHR-OCT” as well as mfERG, she said (Arch Ophthalmol. 2007 Jun;125[6]:775-80).

Vitamin D supplementation gives a modest boost to overall disease control and also affords some renal protection, Dr. Petri said. She was the lead author on a 2013 study that showed that a 20-unit increase in 25-hydroxy vitamin D was associated with reduced global disease severity scores, as well as a 21% reduction in the odds of having a SLEDAI (Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index) score of 5 or more, and a 15% decrease in the odds of having a urine protein to creatinine ratio greater than 0.5 (Arthritis Rheum. 2013 Jul;65[7]:1865-71).

When it comes to vitamin D, more matters, Dr. Petri said. “Go above 40 [ng/mL] on vitamin D,” she said, noting that there may be pleiotropic cardiovascular and hematologic benefits as well.

Though dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) is not approved by the Food and Drug Administration to treat SLE, 200 mg of DHEA daily helped women with active SLE improve or stabilize disease activity, and also helped 51% of women in one study reduce prednisone to less than 7.5 mg daily, compared with 29% of women taking placebo (P = .03) (Arthritis Rheum. 2002 Jul;46[7]:1820-9). There’s also “mild protection against bone loss,” Dr. Petri said.

Dr. Petri reported receiving research grants and serving as a consultant to several pharmaceutical companies. Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

LAS VEGAS – For patients with mild to moderate systemic lupus erythematosus, don’t go above six milligrams of prednisone daily, because the treatment is likely to be worse than the disease in the long run, said Michelle Petri, MD.

Speaking at the annual Perspectives in Rheumatic Diseases presented by Global Academy for Medical Education, Dr. Petri shared evidence-backed clinical pearls to help rheumatologists dial in good disease control for their systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) patients without turning to too much prednisone.

Prednisone is also an independent risk factor for cardiovascular events, with dose-dependent effects, she said. She referred to a 2012 study she coauthored (Am J Epidemiol. 2012 Oct;176[8]:708-19) that found an age-adjusted cardiovascular event rate ratio of 2.4 when patients took 10-19 mg of prednisone daily (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.5-3.8; P = .0002). When the daily prednisone dose was over 20 mg, the rate ratio was 5.1 (95% CI, 3.1-8.4; P less than .0001).

Since it’s so important to minimize prednisone exposure, rheumatologists should be familiar with the full toolkit of non-immunosuppressive immunomodulators, and understand how to help patients assess risks and benefits of various treatments.“Non-immunosuppressive immunomodulators can control mild to moderate systemic lupus, helping to avoid steroids,” Dr. Petri said.

Hydroxychloroquine, when used as background therapy, has proved to have multiple benefits. Not only are flares reduced, but organ damage is reduced, lipids improve, fewer clots occur, and seizures are prevented, she said. There’s also an overall improvement in survival with hydroxychloroquine. In lupus nephritis, “continuing hydroxychloroquine improves complete response rates with mycophenolate mofetil,” Dr. Petri said.

Concerns about hydroxychloroquine-related retinopathy sometimes stand in the way of its use as background therapy, so Dr. Petri encouraged rheumatologists to have a realistic risk-benefit assessment. Higher risk for retinopathy is associated with higher dosing (greater than 6.5 mg/kg of hydroxychloroquine or 3 mg/kg of chloroquine); a higher fat body habitus, unless dosing is appropriately adjusted; the presence of renal disease or concomitant retinal disease; and age over 60.

Newer imaging techniques may sacrifice specificity for very high sensitivity in detecting hydroxychloroquine-related retinopathy, Dr. Petri said. High-speed ultra-high resolution optical coherence tomography (hsUHR-OCT) and multifocal electroretinography (mfERG) are imaging techniques that can detect hydroxychloroquine-related retinopathy, but should be reserved for patients with SLE who actually have visual symptoms, she said. Dr. Petri cited a study of 15 patients who were taking hydroxychloroquine, and 6 age-matched controls with normal visual function. All underwent visual field testing, mfERG, and hsUHR-OCT. The study “was unable to find an asymptomatic patient with evidence of definite damage on hsUHR-OCT” as well as mfERG, she said (Arch Ophthalmol. 2007 Jun;125[6]:775-80).

Vitamin D supplementation gives a modest boost to overall disease control and also affords some renal protection, Dr. Petri said. She was the lead author on a 2013 study that showed that a 20-unit increase in 25-hydroxy vitamin D was associated with reduced global disease severity scores, as well as a 21% reduction in the odds of having a SLEDAI (Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index) score of 5 or more, and a 15% decrease in the odds of having a urine protein to creatinine ratio greater than 0.5 (Arthritis Rheum. 2013 Jul;65[7]:1865-71).

When it comes to vitamin D, more matters, Dr. Petri said. “Go above 40 [ng/mL] on vitamin D,” she said, noting that there may be pleiotropic cardiovascular and hematologic benefits as well.

Though dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) is not approved by the Food and Drug Administration to treat SLE, 200 mg of DHEA daily helped women with active SLE improve or stabilize disease activity, and also helped 51% of women in one study reduce prednisone to less than 7.5 mg daily, compared with 29% of women taking placebo (P = .03) (Arthritis Rheum. 2002 Jul;46[7]:1820-9). There’s also “mild protection against bone loss,” Dr. Petri said.

Dr. Petri reported receiving research grants and serving as a consultant to several pharmaceutical companies. Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

LAS VEGAS – For patients with mild to moderate systemic lupus erythematosus, don’t go above six milligrams of prednisone daily, because the treatment is likely to be worse than the disease in the long run, said Michelle Petri, MD.

Speaking at the annual Perspectives in Rheumatic Diseases presented by Global Academy for Medical Education, Dr. Petri shared evidence-backed clinical pearls to help rheumatologists dial in good disease control for their systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) patients without turning to too much prednisone.

Prednisone is also an independent risk factor for cardiovascular events, with dose-dependent effects, she said. She referred to a 2012 study she coauthored (Am J Epidemiol. 2012 Oct;176[8]:708-19) that found an age-adjusted cardiovascular event rate ratio of 2.4 when patients took 10-19 mg of prednisone daily (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.5-3.8; P = .0002). When the daily prednisone dose was over 20 mg, the rate ratio was 5.1 (95% CI, 3.1-8.4; P less than .0001).

Since it’s so important to minimize prednisone exposure, rheumatologists should be familiar with the full toolkit of non-immunosuppressive immunomodulators, and understand how to help patients assess risks and benefits of various treatments.“Non-immunosuppressive immunomodulators can control mild to moderate systemic lupus, helping to avoid steroids,” Dr. Petri said.

Hydroxychloroquine, when used as background therapy, has proved to have multiple benefits. Not only are flares reduced, but organ damage is reduced, lipids improve, fewer clots occur, and seizures are prevented, she said. There’s also an overall improvement in survival with hydroxychloroquine. In lupus nephritis, “continuing hydroxychloroquine improves complete response rates with mycophenolate mofetil,” Dr. Petri said.

Concerns about hydroxychloroquine-related retinopathy sometimes stand in the way of its use as background therapy, so Dr. Petri encouraged rheumatologists to have a realistic risk-benefit assessment. Higher risk for retinopathy is associated with higher dosing (greater than 6.5 mg/kg of hydroxychloroquine or 3 mg/kg of chloroquine); a higher fat body habitus, unless dosing is appropriately adjusted; the presence of renal disease or concomitant retinal disease; and age over 60.

Newer imaging techniques may sacrifice specificity for very high sensitivity in detecting hydroxychloroquine-related retinopathy, Dr. Petri said. High-speed ultra-high resolution optical coherence tomography (hsUHR-OCT) and multifocal electroretinography (mfERG) are imaging techniques that can detect hydroxychloroquine-related retinopathy, but should be reserved for patients with SLE who actually have visual symptoms, she said. Dr. Petri cited a study of 15 patients who were taking hydroxychloroquine, and 6 age-matched controls with normal visual function. All underwent visual field testing, mfERG, and hsUHR-OCT. The study “was unable to find an asymptomatic patient with evidence of definite damage on hsUHR-OCT” as well as mfERG, she said (Arch Ophthalmol. 2007 Jun;125[6]:775-80).

Vitamin D supplementation gives a modest boost to overall disease control and also affords some renal protection, Dr. Petri said. She was the lead author on a 2013 study that showed that a 20-unit increase in 25-hydroxy vitamin D was associated with reduced global disease severity scores, as well as a 21% reduction in the odds of having a SLEDAI (Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index) score of 5 or more, and a 15% decrease in the odds of having a urine protein to creatinine ratio greater than 0.5 (Arthritis Rheum. 2013 Jul;65[7]:1865-71).

When it comes to vitamin D, more matters, Dr. Petri said. “Go above 40 [ng/mL] on vitamin D,” she said, noting that there may be pleiotropic cardiovascular and hematologic benefits as well.

Though dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) is not approved by the Food and Drug Administration to treat SLE, 200 mg of DHEA daily helped women with active SLE improve or stabilize disease activity, and also helped 51% of women in one study reduce prednisone to less than 7.5 mg daily, compared with 29% of women taking placebo (P = .03) (Arthritis Rheum. 2002 Jul;46[7]:1820-9). There’s also “mild protection against bone loss,” Dr. Petri said.

Dr. Petri reported receiving research grants and serving as a consultant to several pharmaceutical companies. Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE ANNUAL PERSPECTIVES IN RHEUMATIC DISEASES

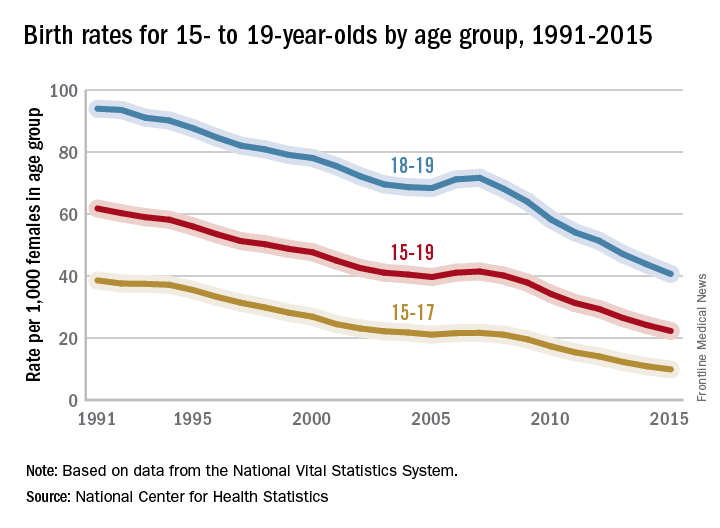

Teen birth rates continue to decline in the United States

The teen birth rate of 22.3/1,000 females aged 15-19 years for 2015 was down by almost 8% from the year before and marks the seventh consecutive year of historic lows. Since 1991, when 61.8/1,000 teens aged 15-19 gave birth, the rate has fallen 64%, the NCHS reported.

For teens aged 15-19 years, the birth rate declined for each race/ethnicity: dropping 8% for non-Hispanic whites and Hispanics, 9% for non-Hispanic blacks, 10% for Asians or Pacific Islanders, and 6% for American Indians or Alaska Natives. All rates for 2015 were historically low.

The teen birth rate of 22.3/1,000 females aged 15-19 years for 2015 was down by almost 8% from the year before and marks the seventh consecutive year of historic lows. Since 1991, when 61.8/1,000 teens aged 15-19 gave birth, the rate has fallen 64%, the NCHS reported.

For teens aged 15-19 years, the birth rate declined for each race/ethnicity: dropping 8% for non-Hispanic whites and Hispanics, 9% for non-Hispanic blacks, 10% for Asians or Pacific Islanders, and 6% for American Indians or Alaska Natives. All rates for 2015 were historically low.

The teen birth rate of 22.3/1,000 females aged 15-19 years for 2015 was down by almost 8% from the year before and marks the seventh consecutive year of historic lows. Since 1991, when 61.8/1,000 teens aged 15-19 gave birth, the rate has fallen 64%, the NCHS reported.

For teens aged 15-19 years, the birth rate declined for each race/ethnicity: dropping 8% for non-Hispanic whites and Hispanics, 9% for non-Hispanic blacks, 10% for Asians or Pacific Islanders, and 6% for American Indians or Alaska Natives. All rates for 2015 were historically low.

Vitamin D deficiency linked to hepatitis B infection

More than half of hepatitis B patients were vitamin D deficient, and deficiency was associated with worse outcomes, in a Vietnamese study published in BMC Infectious Diseases.

A total of 48% of 165 chronic hepatitis B patients, 54% of 127 hepatitis B virus (HBV)-associated cirrhosis patients, and 55% of 108 virus-associated hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) patients had levels below 20 ng/mL, compared with 33% of 122 healthy controls.

Vitamin D levels inversely correlated with viral DNA loads, and lower levels were associated with more severe cirrhosis. On multivariate analyses adjusted for age and sex, HBV infection was an independent risk factor for vitamin D inadequacy (BMC Infect Dis. 2016 Sep 23;16[1]:507).

“These findings suggest that serum vitamin D levels contribute significantly to the clinical courses of HBV infection, including the severe consequences of” cirrhosis and HCC. “Our findings allow speculating that vitamin D and its analogs might provide a potential therapeutic addendum in the treatment of chronic liver diseases,” concluded investigators led by Nghiem Xuan Hoan, MD, of the Vietnamese-German Center for Medical Research in Hanoi.

Total vitamin D (25[OH] D2 and D3) levels were measured only once in the study; the cross-sectional design meant that “we could not determine the fluctuation of vitamin D levels over the course of HBV infection as well as the causative association of vitamin D levels and HBV-related liver diseases,” the researchers explained.

Low levels could be caused by impaired hepatic function, because the liver is key to vitamin D metabolism. HBV patients also tended to be older than the healthy controls were, which also might have contributed to the greater likelihood of deficiency.

Even so, a case seems to be building that vitamin D has an active role in HBV liver disease. Other investigations also have found an inverse relationship between viral loads and vitamin D status, and low levels previously have been associated with HCC.

Vitamin D is involved in adaptive and innate immune responses that clear the virus and other infections from the body, or at least keep them in check. Deficiency has been associated with susceptibility to various infections and inflammatory diseases, as well as carcinogenesis.

There was no industry funding for the work, and the authors had no disclosures.

More than half of hepatitis B patients were vitamin D deficient, and deficiency was associated with worse outcomes, in a Vietnamese study published in BMC Infectious Diseases.

A total of 48% of 165 chronic hepatitis B patients, 54% of 127 hepatitis B virus (HBV)-associated cirrhosis patients, and 55% of 108 virus-associated hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) patients had levels below 20 ng/mL, compared with 33% of 122 healthy controls.

Vitamin D levels inversely correlated with viral DNA loads, and lower levels were associated with more severe cirrhosis. On multivariate analyses adjusted for age and sex, HBV infection was an independent risk factor for vitamin D inadequacy (BMC Infect Dis. 2016 Sep 23;16[1]:507).

“These findings suggest that serum vitamin D levels contribute significantly to the clinical courses of HBV infection, including the severe consequences of” cirrhosis and HCC. “Our findings allow speculating that vitamin D and its analogs might provide a potential therapeutic addendum in the treatment of chronic liver diseases,” concluded investigators led by Nghiem Xuan Hoan, MD, of the Vietnamese-German Center for Medical Research in Hanoi.

Total vitamin D (25[OH] D2 and D3) levels were measured only once in the study; the cross-sectional design meant that “we could not determine the fluctuation of vitamin D levels over the course of HBV infection as well as the causative association of vitamin D levels and HBV-related liver diseases,” the researchers explained.

Low levels could be caused by impaired hepatic function, because the liver is key to vitamin D metabolism. HBV patients also tended to be older than the healthy controls were, which also might have contributed to the greater likelihood of deficiency.

Even so, a case seems to be building that vitamin D has an active role in HBV liver disease. Other investigations also have found an inverse relationship between viral loads and vitamin D status, and low levels previously have been associated with HCC.

Vitamin D is involved in adaptive and innate immune responses that clear the virus and other infections from the body, or at least keep them in check. Deficiency has been associated with susceptibility to various infections and inflammatory diseases, as well as carcinogenesis.

There was no industry funding for the work, and the authors had no disclosures.

More than half of hepatitis B patients were vitamin D deficient, and deficiency was associated with worse outcomes, in a Vietnamese study published in BMC Infectious Diseases.

A total of 48% of 165 chronic hepatitis B patients, 54% of 127 hepatitis B virus (HBV)-associated cirrhosis patients, and 55% of 108 virus-associated hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) patients had levels below 20 ng/mL, compared with 33% of 122 healthy controls.

Vitamin D levels inversely correlated with viral DNA loads, and lower levels were associated with more severe cirrhosis. On multivariate analyses adjusted for age and sex, HBV infection was an independent risk factor for vitamin D inadequacy (BMC Infect Dis. 2016 Sep 23;16[1]:507).

“These findings suggest that serum vitamin D levels contribute significantly to the clinical courses of HBV infection, including the severe consequences of” cirrhosis and HCC. “Our findings allow speculating that vitamin D and its analogs might provide a potential therapeutic addendum in the treatment of chronic liver diseases,” concluded investigators led by Nghiem Xuan Hoan, MD, of the Vietnamese-German Center for Medical Research in Hanoi.

Total vitamin D (25[OH] D2 and D3) levels were measured only once in the study; the cross-sectional design meant that “we could not determine the fluctuation of vitamin D levels over the course of HBV infection as well as the causative association of vitamin D levels and HBV-related liver diseases,” the researchers explained.

Low levels could be caused by impaired hepatic function, because the liver is key to vitamin D metabolism. HBV patients also tended to be older than the healthy controls were, which also might have contributed to the greater likelihood of deficiency.

Even so, a case seems to be building that vitamin D has an active role in HBV liver disease. Other investigations also have found an inverse relationship between viral loads and vitamin D status, and low levels previously have been associated with HCC.

Vitamin D is involved in adaptive and innate immune responses that clear the virus and other infections from the body, or at least keep them in check. Deficiency has been associated with susceptibility to various infections and inflammatory diseases, as well as carcinogenesis.

There was no industry funding for the work, and the authors had no disclosures.

FROM BMC INFECTIOUS DISEASES

Asleep deep brain stimulation placement offers advantages in Parkinson’s

PORTLAND, ORE. – Performing deep brain stimulation surgery for Parkinson’s disease using intraoperative CT imaging while the patient is under general anesthesia had clinical advantages and no disadvantages over surgery using microelectrode recording for lead placement with the patient awake, in a prospective, open-label study of 64 patients.

Regarding motor outcomes after asleep surgery, “We found that it was noninferior, so in other words, the change in scores following surgery were the same for asleep and awake patients,” physician assistant and study coauthor Shannon Anderson said during a poster session at the World Parkinson Congress. “What was surprising to us was that verbal fluency ... the ability to come up with the right word, actually improved in our asleep DBS [deep brain stimulation] group, which is a huge complication for patients [and] has a really negative impact on their life.”

Patients with Parkinson’s disease and motor complications (n = 64) were enrolled prospectively at the Oregon Health & Science University in Portland. Thirty received asleep procedures under general anesthesia with ICT guidance for lead targeting to the globus pallidus pars interna (GPi; n = 21) or to the subthalamic nucleus (STN; n = 9). Thirty-four patients received DBS devices with MER guidance (15 STN; 19 GPi). At baseline, the two groups were similar in age (mean 61.1-62.7 years) and off-medication motor subscale scores of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (mUPDRS; mean 43.0-43.5). The university investigators optimized the DBS parameters at 1, 2, 3, and 6 months after implantation. The same surgeon performed all the procedures at the same medical center.

Motor improvements were similar between the asleep and awake cohorts. At 6 months, the ICT (asleep) group experienced a mean improvement in motor abilities of 14.3 (plus or minus 10.88) on the mUPDRS off-medication and on DBS, compared with an improvement of 17.6 (plus or minus 12.26) for the MER (awake) group (P = .25).

Better language measures with asleep DBS

Asleep DBS with ICT resulted in improvements in aspects of language, whereas awake patients lost language abilities. The asleep group showed a 0.8-point increase in phonemic fluency and a 1.0-point increase in semantic fluency at 6 months versus a worsening on both language measures (–3.5 points and –4.7 points, respectively; both P less than .001) if DBS was performed via MER on awake patients.

Although both cohorts showed significant improvements on the 39-item Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire at 6 months, the cohorts did not differ in their degrees of improvement. Similarly, both had improvements on scores of activities of daily living, and both cohorts had a 4-4.5 hours/day increase in “on” time without dyskinesia and a 2.6-3.5 hours/day decrease in “on” time with dyskinesia.

Patients tolerated asleep DBS well, and there were no serious complications.

The sleep surgery is much shorter, “so it’s about 2 hours long as opposed to 4, 5, sometimes 8, 10 hours with the awake. There [are fewer] complications, so less risk of hemorrhage or seizures or things like that,” Ms. Anderson said. “In a separate study, we found that it’s a much more accurate placement of the electrodes so the target is much more accurate. So, all of those things considered, we feel the asleep version is definitely the superior choice between the two.”

Being asleep is much more comfortable for the patient, added study leader Matthew Brodsky, MD. “But the biggest advantage is that it’s a single pass into the brain as opposed to multiple passes.” The average number of passes using MER is two to three per side of the brain, and in some centers, four or more. “Problems such as speech prosody are related to pokes in the brain, if you will, rather than stimulation,” he said.

Ms. Anderson said MER “is a fantastic research tool, and it gives us a lot of information on the electrophysiology, but really, there’s no need for it in the clinical application of DBS.”

Based on the asleep procedure’s accuracy, lower rate of complications, shorter operating room time, and noninferiority in terms of motor outcomes, she said, “Our recommendation is that more centers, more neurosurgeons be trained in this technique ... We’d like to see the clinical field move toward that area and really reserve microelectrode recording for the research side of things.”

“If you talk to folks who are considering brain surgery for their Parkinson’s, for some of them, the idea of being awake in the operating room and undergoing this is a barrier that they can’t quite overcome,” Dr. Brodsky said. “So, having this as an option makes it easier for them to sign up for the process.”

Richard Smeyne, PhD, director of the Jefferson Comprehensive Parkinson’s Center at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia, said that the asleep procedure is the newer one and can target either the GPi or the STN. “The asleep DBS seems to have a little bit better improvement on speech afterwards than the awake DBS, and there could be several causes of this,” he said. “Some might be operative in that you can make smaller holes, you can get really nice guidance, you don’t have to sort of move around as in the awake DBS.”

In addition, CT scanning with the patients asleep in the operating room allows more time in the scanner and greater precision in anatomical placement of the DBS leads.

“If I had to choose, looking at this particular study, it would suggest that the asleep DBS is actually a better overall way to go,” Dr. Smeyne said. However, he had no objection to awake procedures “if the neurosurgeon has a record of good results with it ... But if you have the option ... that becomes an individual choice that you should discuss with the neurosurgeon.”

Some of the work presented in the study was supported by a research grant from Medtronic. Ms. Anderson and Dr. Brodsky reported having no other financial disclosures. Dr. Smeyne reported having no financial disclosures.

PORTLAND, ORE. – Performing deep brain stimulation surgery for Parkinson’s disease using intraoperative CT imaging while the patient is under general anesthesia had clinical advantages and no disadvantages over surgery using microelectrode recording for lead placement with the patient awake, in a prospective, open-label study of 64 patients.

Regarding motor outcomes after asleep surgery, “We found that it was noninferior, so in other words, the change in scores following surgery were the same for asleep and awake patients,” physician assistant and study coauthor Shannon Anderson said during a poster session at the World Parkinson Congress. “What was surprising to us was that verbal fluency ... the ability to come up with the right word, actually improved in our asleep DBS [deep brain stimulation] group, which is a huge complication for patients [and] has a really negative impact on their life.”

Patients with Parkinson’s disease and motor complications (n = 64) were enrolled prospectively at the Oregon Health & Science University in Portland. Thirty received asleep procedures under general anesthesia with ICT guidance for lead targeting to the globus pallidus pars interna (GPi; n = 21) or to the subthalamic nucleus (STN; n = 9). Thirty-four patients received DBS devices with MER guidance (15 STN; 19 GPi). At baseline, the two groups were similar in age (mean 61.1-62.7 years) and off-medication motor subscale scores of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (mUPDRS; mean 43.0-43.5). The university investigators optimized the DBS parameters at 1, 2, 3, and 6 months after implantation. The same surgeon performed all the procedures at the same medical center.

Motor improvements were similar between the asleep and awake cohorts. At 6 months, the ICT (asleep) group experienced a mean improvement in motor abilities of 14.3 (plus or minus 10.88) on the mUPDRS off-medication and on DBS, compared with an improvement of 17.6 (plus or minus 12.26) for the MER (awake) group (P = .25).

Better language measures with asleep DBS

Asleep DBS with ICT resulted in improvements in aspects of language, whereas awake patients lost language abilities. The asleep group showed a 0.8-point increase in phonemic fluency and a 1.0-point increase in semantic fluency at 6 months versus a worsening on both language measures (–3.5 points and –4.7 points, respectively; both P less than .001) if DBS was performed via MER on awake patients.

Although both cohorts showed significant improvements on the 39-item Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire at 6 months, the cohorts did not differ in their degrees of improvement. Similarly, both had improvements on scores of activities of daily living, and both cohorts had a 4-4.5 hours/day increase in “on” time without dyskinesia and a 2.6-3.5 hours/day decrease in “on” time with dyskinesia.

Patients tolerated asleep DBS well, and there were no serious complications.

The sleep surgery is much shorter, “so it’s about 2 hours long as opposed to 4, 5, sometimes 8, 10 hours with the awake. There [are fewer] complications, so less risk of hemorrhage or seizures or things like that,” Ms. Anderson said. “In a separate study, we found that it’s a much more accurate placement of the electrodes so the target is much more accurate. So, all of those things considered, we feel the asleep version is definitely the superior choice between the two.”

Being asleep is much more comfortable for the patient, added study leader Matthew Brodsky, MD. “But the biggest advantage is that it’s a single pass into the brain as opposed to multiple passes.” The average number of passes using MER is two to three per side of the brain, and in some centers, four or more. “Problems such as speech prosody are related to pokes in the brain, if you will, rather than stimulation,” he said.

Ms. Anderson said MER “is a fantastic research tool, and it gives us a lot of information on the electrophysiology, but really, there’s no need for it in the clinical application of DBS.”

Based on the asleep procedure’s accuracy, lower rate of complications, shorter operating room time, and noninferiority in terms of motor outcomes, she said, “Our recommendation is that more centers, more neurosurgeons be trained in this technique ... We’d like to see the clinical field move toward that area and really reserve microelectrode recording for the research side of things.”

“If you talk to folks who are considering brain surgery for their Parkinson’s, for some of them, the idea of being awake in the operating room and undergoing this is a barrier that they can’t quite overcome,” Dr. Brodsky said. “So, having this as an option makes it easier for them to sign up for the process.”

Richard Smeyne, PhD, director of the Jefferson Comprehensive Parkinson’s Center at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia, said that the asleep procedure is the newer one and can target either the GPi or the STN. “The asleep DBS seems to have a little bit better improvement on speech afterwards than the awake DBS, and there could be several causes of this,” he said. “Some might be operative in that you can make smaller holes, you can get really nice guidance, you don’t have to sort of move around as in the awake DBS.”

In addition, CT scanning with the patients asleep in the operating room allows more time in the scanner and greater precision in anatomical placement of the DBS leads.

“If I had to choose, looking at this particular study, it would suggest that the asleep DBS is actually a better overall way to go,” Dr. Smeyne said. However, he had no objection to awake procedures “if the neurosurgeon has a record of good results with it ... But if you have the option ... that becomes an individual choice that you should discuss with the neurosurgeon.”

Some of the work presented in the study was supported by a research grant from Medtronic. Ms. Anderson and Dr. Brodsky reported having no other financial disclosures. Dr. Smeyne reported having no financial disclosures.

PORTLAND, ORE. – Performing deep brain stimulation surgery for Parkinson’s disease using intraoperative CT imaging while the patient is under general anesthesia had clinical advantages and no disadvantages over surgery using microelectrode recording for lead placement with the patient awake, in a prospective, open-label study of 64 patients.

Regarding motor outcomes after asleep surgery, “We found that it was noninferior, so in other words, the change in scores following surgery were the same for asleep and awake patients,” physician assistant and study coauthor Shannon Anderson said during a poster session at the World Parkinson Congress. “What was surprising to us was that verbal fluency ... the ability to come up with the right word, actually improved in our asleep DBS [deep brain stimulation] group, which is a huge complication for patients [and] has a really negative impact on their life.”

Patients with Parkinson’s disease and motor complications (n = 64) were enrolled prospectively at the Oregon Health & Science University in Portland. Thirty received asleep procedures under general anesthesia with ICT guidance for lead targeting to the globus pallidus pars interna (GPi; n = 21) or to the subthalamic nucleus (STN; n = 9). Thirty-four patients received DBS devices with MER guidance (15 STN; 19 GPi). At baseline, the two groups were similar in age (mean 61.1-62.7 years) and off-medication motor subscale scores of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (mUPDRS; mean 43.0-43.5). The university investigators optimized the DBS parameters at 1, 2, 3, and 6 months after implantation. The same surgeon performed all the procedures at the same medical center.

Motor improvements were similar between the asleep and awake cohorts. At 6 months, the ICT (asleep) group experienced a mean improvement in motor abilities of 14.3 (plus or minus 10.88) on the mUPDRS off-medication and on DBS, compared with an improvement of 17.6 (plus or minus 12.26) for the MER (awake) group (P = .25).

Better language measures with asleep DBS

Asleep DBS with ICT resulted in improvements in aspects of language, whereas awake patients lost language abilities. The asleep group showed a 0.8-point increase in phonemic fluency and a 1.0-point increase in semantic fluency at 6 months versus a worsening on both language measures (–3.5 points and –4.7 points, respectively; both P less than .001) if DBS was performed via MER on awake patients.

Although both cohorts showed significant improvements on the 39-item Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire at 6 months, the cohorts did not differ in their degrees of improvement. Similarly, both had improvements on scores of activities of daily living, and both cohorts had a 4-4.5 hours/day increase in “on” time without dyskinesia and a 2.6-3.5 hours/day decrease in “on” time with dyskinesia.

Patients tolerated asleep DBS well, and there were no serious complications.

The sleep surgery is much shorter, “so it’s about 2 hours long as opposed to 4, 5, sometimes 8, 10 hours with the awake. There [are fewer] complications, so less risk of hemorrhage or seizures or things like that,” Ms. Anderson said. “In a separate study, we found that it’s a much more accurate placement of the electrodes so the target is much more accurate. So, all of those things considered, we feel the asleep version is definitely the superior choice between the two.”

Being asleep is much more comfortable for the patient, added study leader Matthew Brodsky, MD. “But the biggest advantage is that it’s a single pass into the brain as opposed to multiple passes.” The average number of passes using MER is two to three per side of the brain, and in some centers, four or more. “Problems such as speech prosody are related to pokes in the brain, if you will, rather than stimulation,” he said.

Ms. Anderson said MER “is a fantastic research tool, and it gives us a lot of information on the electrophysiology, but really, there’s no need for it in the clinical application of DBS.”

Based on the asleep procedure’s accuracy, lower rate of complications, shorter operating room time, and noninferiority in terms of motor outcomes, she said, “Our recommendation is that more centers, more neurosurgeons be trained in this technique ... We’d like to see the clinical field move toward that area and really reserve microelectrode recording for the research side of things.”

“If you talk to folks who are considering brain surgery for their Parkinson’s, for some of them, the idea of being awake in the operating room and undergoing this is a barrier that they can’t quite overcome,” Dr. Brodsky said. “So, having this as an option makes it easier for them to sign up for the process.”

Richard Smeyne, PhD, director of the Jefferson Comprehensive Parkinson’s Center at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia, said that the asleep procedure is the newer one and can target either the GPi or the STN. “The asleep DBS seems to have a little bit better improvement on speech afterwards than the awake DBS, and there could be several causes of this,” he said. “Some might be operative in that you can make smaller holes, you can get really nice guidance, you don’t have to sort of move around as in the awake DBS.”

In addition, CT scanning with the patients asleep in the operating room allows more time in the scanner and greater precision in anatomical placement of the DBS leads.

“If I had to choose, looking at this particular study, it would suggest that the asleep DBS is actually a better overall way to go,” Dr. Smeyne said. However, he had no objection to awake procedures “if the neurosurgeon has a record of good results with it ... But if you have the option ... that becomes an individual choice that you should discuss with the neurosurgeon.”

Some of the work presented in the study was supported by a research grant from Medtronic. Ms. Anderson and Dr. Brodsky reported having no other financial disclosures. Dr. Smeyne reported having no financial disclosures.

AT WPC 2016

Key clinical point: