User login

Dual bronchodilator combination shines in patients with high-risk COPD

It may be time to revise guidelines when it comes to initial treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) complicated by exacerbations, based on data from a phase III trial reported at an international conference of the American Thoracic Society. The trial, known as FLAME, undertook a head-to-head comparison of 2 inhaled drug combinations (indacaterol and glycopyrronium vs salmeterol and fluticasone) among more than 3300 patients from 43 countries. After a year, the annual rate of exacerbations was 11% lower with indacaterol-glycopyrronium than with salmeterol-fluticasone. More on the results of the trial is available at Family Practice News: http://www.familypracticenews.com/specialty-focus/pulmonary-sleep-medicine/single-article-page/dual-bronchodilator-combination-shines-in-patients-with-high-risk-copd/60032e8e9b0393af639f41566f165d80.html.

It may be time to revise guidelines when it comes to initial treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) complicated by exacerbations, based on data from a phase III trial reported at an international conference of the American Thoracic Society. The trial, known as FLAME, undertook a head-to-head comparison of 2 inhaled drug combinations (indacaterol and glycopyrronium vs salmeterol and fluticasone) among more than 3300 patients from 43 countries. After a year, the annual rate of exacerbations was 11% lower with indacaterol-glycopyrronium than with salmeterol-fluticasone. More on the results of the trial is available at Family Practice News: http://www.familypracticenews.com/specialty-focus/pulmonary-sleep-medicine/single-article-page/dual-bronchodilator-combination-shines-in-patients-with-high-risk-copd/60032e8e9b0393af639f41566f165d80.html.

It may be time to revise guidelines when it comes to initial treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) complicated by exacerbations, based on data from a phase III trial reported at an international conference of the American Thoracic Society. The trial, known as FLAME, undertook a head-to-head comparison of 2 inhaled drug combinations (indacaterol and glycopyrronium vs salmeterol and fluticasone) among more than 3300 patients from 43 countries. After a year, the annual rate of exacerbations was 11% lower with indacaterol-glycopyrronium than with salmeterol-fluticasone. More on the results of the trial is available at Family Practice News: http://www.familypracticenews.com/specialty-focus/pulmonary-sleep-medicine/single-article-page/dual-bronchodilator-combination-shines-in-patients-with-high-risk-copd/60032e8e9b0393af639f41566f165d80.html.

How can I predict bleeding in my elderly patient taking anticoagulants?

Advanced age, as well as coexisting medical conditions, medications, and the timing and intensity of therapy are all factors that increase the risk of bleeding in patients taking anticoagulants. This article from the Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine lists scoring tools that can help identify patients at heightened risk and describes considerations that come into play when determining whether the risk of bleeding outweighs the benefits of anticoagulation. Read more at http://www.ccjm.org/current-issue/issue-single-view/how-can-i-predict-bleeding-in-my-elderly-patient-taking-anticoagulants/f0c1ece959ee916bee40669ae636c38a.html.

Advanced age, as well as coexisting medical conditions, medications, and the timing and intensity of therapy are all factors that increase the risk of bleeding in patients taking anticoagulants. This article from the Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine lists scoring tools that can help identify patients at heightened risk and describes considerations that come into play when determining whether the risk of bleeding outweighs the benefits of anticoagulation. Read more at http://www.ccjm.org/current-issue/issue-single-view/how-can-i-predict-bleeding-in-my-elderly-patient-taking-anticoagulants/f0c1ece959ee916bee40669ae636c38a.html.

Advanced age, as well as coexisting medical conditions, medications, and the timing and intensity of therapy are all factors that increase the risk of bleeding in patients taking anticoagulants. This article from the Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine lists scoring tools that can help identify patients at heightened risk and describes considerations that come into play when determining whether the risk of bleeding outweighs the benefits of anticoagulation. Read more at http://www.ccjm.org/current-issue/issue-single-view/how-can-i-predict-bleeding-in-my-elderly-patient-taking-anticoagulants/f0c1ece959ee916bee40669ae636c38a.html.

Was Anything Learned at Tomah?

On Tuesday The Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Government Affairs issued 2 reports on its investigations into the oversight of the Tomah VAMC, which found that the VA and VA Office of Inspector General (OIG) both failed to adequately address the facility’s problems despite ample warnings of dangerous conditions. It was not until after the death of Marine Jason Simcakoski from an opioid overdose in March 2014 and a 2015 report from the Center for Investigative Reporting that Tomah leadership and opioid prescribing practices came under close scrutiny.

Although numerous complaints surfaced in the past, according to the Senate committee reports, little if anything was done to fix the problems. According to a staff report from committee Chairman Ron Johnson (R-Wisc.), “Despite receiving various complaints over the course of several years, federal law enforcement agencies and other executive branch entities failed to identify or address the root causes.”

In his opening statement, Senator Johnson laid much of the blame on OIG. “The failure of the Office of the Inspector General to live up to its mission is really the root cause of why these problems continue to go on,” said Johnson.

The majority staff report also asserted that a “culture of fear and whistleblower retaliation at the Tomah VAMC allowed overprescription and other abuses to continue unaddressed. The belief among Tomah VAMC staff that they could not report wrongdoing compromised patient care.”

The staff of minority staff member Thomas Carper (D-Del.) also noted in a report that the efforts to address the problems at the Tomah VAMC “were not effective.” Still, according to the minority report recommendations were made, but “Tomah VAMC senior leadership declined to implement both VISN 12 recommendations (such as conducting an administrative investigative board review for Dr. Houlihan) and VA OIG suggestions aimed at addressing problems at the facility.”

According to Senator Carper, chronic understaffing, a shortage of qualified mental health care professionals, and a lack of adequate oversight may have contributed to Tomah’s problems. Nevertheless, Carper pointed out ,“our staff found that the VA OIG’s decision to administratively close an investigation it conducted at Tomah without publicly releasing a report made it more difficult for the VA and the public to identify and correct what was going wrong.”

In addressing the hearing, VA Deputy Secretary Sloan Gibson pledged to change the culture of the facility. “In order to create a more transparent culture and improve communication with Tomah VAMC employees,” Sloan told the committee, “leadership has taken a number of actions, including town hall meetings, supervisory forums, and expanded all-employee communications.”

Deputy Secretary Gibson also touted the VA’s efforts to address overprescription of opioids. According to Gibson, since 2012:

- 151,982 fewer patients are receiving opioids (22% reduction);

- 51,916 fewer patients are receiving opioids and benzodiazepines together (42% reduction);

- 94,045 more patients on opioids have had a urine drug screen to help guide treatment decisions (37% increase); and

- 122,065 fewer patients are on long-term opioid therapy (28% reduction).

Newly confirmed Inspector General of the VA Michael Missal also tried to focus on the future. “My office has learned important lessons from the Tomah health care inspections that should help us better meet our mission going forward,” he told the committee. “The changes that we have made should increase the confidence that veterans, veterans service organizations, Congress, and the American public have in the OIG.”

On Tuesday The Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Government Affairs issued 2 reports on its investigations into the oversight of the Tomah VAMC, which found that the VA and VA Office of Inspector General (OIG) both failed to adequately address the facility’s problems despite ample warnings of dangerous conditions. It was not until after the death of Marine Jason Simcakoski from an opioid overdose in March 2014 and a 2015 report from the Center for Investigative Reporting that Tomah leadership and opioid prescribing practices came under close scrutiny.

Although numerous complaints surfaced in the past, according to the Senate committee reports, little if anything was done to fix the problems. According to a staff report from committee Chairman Ron Johnson (R-Wisc.), “Despite receiving various complaints over the course of several years, federal law enforcement agencies and other executive branch entities failed to identify or address the root causes.”

In his opening statement, Senator Johnson laid much of the blame on OIG. “The failure of the Office of the Inspector General to live up to its mission is really the root cause of why these problems continue to go on,” said Johnson.

The majority staff report also asserted that a “culture of fear and whistleblower retaliation at the Tomah VAMC allowed overprescription and other abuses to continue unaddressed. The belief among Tomah VAMC staff that they could not report wrongdoing compromised patient care.”

The staff of minority staff member Thomas Carper (D-Del.) also noted in a report that the efforts to address the problems at the Tomah VAMC “were not effective.” Still, according to the minority report recommendations were made, but “Tomah VAMC senior leadership declined to implement both VISN 12 recommendations (such as conducting an administrative investigative board review for Dr. Houlihan) and VA OIG suggestions aimed at addressing problems at the facility.”

According to Senator Carper, chronic understaffing, a shortage of qualified mental health care professionals, and a lack of adequate oversight may have contributed to Tomah’s problems. Nevertheless, Carper pointed out ,“our staff found that the VA OIG’s decision to administratively close an investigation it conducted at Tomah without publicly releasing a report made it more difficult for the VA and the public to identify and correct what was going wrong.”

In addressing the hearing, VA Deputy Secretary Sloan Gibson pledged to change the culture of the facility. “In order to create a more transparent culture and improve communication with Tomah VAMC employees,” Sloan told the committee, “leadership has taken a number of actions, including town hall meetings, supervisory forums, and expanded all-employee communications.”

Deputy Secretary Gibson also touted the VA’s efforts to address overprescription of opioids. According to Gibson, since 2012:

- 151,982 fewer patients are receiving opioids (22% reduction);

- 51,916 fewer patients are receiving opioids and benzodiazepines together (42% reduction);

- 94,045 more patients on opioids have had a urine drug screen to help guide treatment decisions (37% increase); and

- 122,065 fewer patients are on long-term opioid therapy (28% reduction).

Newly confirmed Inspector General of the VA Michael Missal also tried to focus on the future. “My office has learned important lessons from the Tomah health care inspections that should help us better meet our mission going forward,” he told the committee. “The changes that we have made should increase the confidence that veterans, veterans service organizations, Congress, and the American public have in the OIG.”

On Tuesday The Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Government Affairs issued 2 reports on its investigations into the oversight of the Tomah VAMC, which found that the VA and VA Office of Inspector General (OIG) both failed to adequately address the facility’s problems despite ample warnings of dangerous conditions. It was not until after the death of Marine Jason Simcakoski from an opioid overdose in March 2014 and a 2015 report from the Center for Investigative Reporting that Tomah leadership and opioid prescribing practices came under close scrutiny.

Although numerous complaints surfaced in the past, according to the Senate committee reports, little if anything was done to fix the problems. According to a staff report from committee Chairman Ron Johnson (R-Wisc.), “Despite receiving various complaints over the course of several years, federal law enforcement agencies and other executive branch entities failed to identify or address the root causes.”

In his opening statement, Senator Johnson laid much of the blame on OIG. “The failure of the Office of the Inspector General to live up to its mission is really the root cause of why these problems continue to go on,” said Johnson.

The majority staff report also asserted that a “culture of fear and whistleblower retaliation at the Tomah VAMC allowed overprescription and other abuses to continue unaddressed. The belief among Tomah VAMC staff that they could not report wrongdoing compromised patient care.”

The staff of minority staff member Thomas Carper (D-Del.) also noted in a report that the efforts to address the problems at the Tomah VAMC “were not effective.” Still, according to the minority report recommendations were made, but “Tomah VAMC senior leadership declined to implement both VISN 12 recommendations (such as conducting an administrative investigative board review for Dr. Houlihan) and VA OIG suggestions aimed at addressing problems at the facility.”

According to Senator Carper, chronic understaffing, a shortage of qualified mental health care professionals, and a lack of adequate oversight may have contributed to Tomah’s problems. Nevertheless, Carper pointed out ,“our staff found that the VA OIG’s decision to administratively close an investigation it conducted at Tomah without publicly releasing a report made it more difficult for the VA and the public to identify and correct what was going wrong.”

In addressing the hearing, VA Deputy Secretary Sloan Gibson pledged to change the culture of the facility. “In order to create a more transparent culture and improve communication with Tomah VAMC employees,” Sloan told the committee, “leadership has taken a number of actions, including town hall meetings, supervisory forums, and expanded all-employee communications.”

Deputy Secretary Gibson also touted the VA’s efforts to address overprescription of opioids. According to Gibson, since 2012:

- 151,982 fewer patients are receiving opioids (22% reduction);

- 51,916 fewer patients are receiving opioids and benzodiazepines together (42% reduction);

- 94,045 more patients on opioids have had a urine drug screen to help guide treatment decisions (37% increase); and

- 122,065 fewer patients are on long-term opioid therapy (28% reduction).

Newly confirmed Inspector General of the VA Michael Missal also tried to focus on the future. “My office has learned important lessons from the Tomah health care inspections that should help us better meet our mission going forward,” he told the committee. “The changes that we have made should increase the confidence that veterans, veterans service organizations, Congress, and the American public have in the OIG.”

Editor’s Note

With great pleasure I announce a partnership with the Association of Military Dermatologists (AMD) whereby Cutis® is the official journal of the organization. We welcome the AMD President Nicholas Logemann, DO, and the active members of the AMD—dermatologists in the Army, Navy, Air Force, and US Public Health Service—who provide laudable care to their charges in the United States and around the world.

The AMD strives to “[k]eep our troops fit to fight, take care of our wounded warriors on the field and back home, and provide quality Dermatologic care to their dependents, our retirees, and others in need of humanitarian assistance throughout the world when duty calls.” In addition to their clinical mission, members of the AMD have an educational mission by which they, at any one time, are training approximately 50 young active-duty physicians in dermatology residency training programs at their 3 sites in Bethesda, Maryland; San Antonio, Texas; and San Diego, California.

The value of this collaboration for the readers of Cutis is illustrated by the inaugural Military Dermatology column, “Managing Residual Limb Hyperhidrosis in Wounded Warriors: What Have We Learned?” This topic and others that will be featured in this new column, which will be published quarterly, will focus on an important area of skin disease that we may all see in our practices but an area in which AMD physicians have extensive expertise that they will share with us.

On a personal note, my dermatology training was in the US Public Health Service and I am an (inactive) member of the organization. I would urge all of our readers to consider supporting the mission of the AMD by visiting their website (http://www.militaryderm.org) and consider joining the organization, which accepts civilian members.

Vincent A. DeLeo, MD

Editor-in-Chief, Cutis

With great pleasure I announce a partnership with the Association of Military Dermatologists (AMD) whereby Cutis® is the official journal of the organization. We welcome the AMD President Nicholas Logemann, DO, and the active members of the AMD—dermatologists in the Army, Navy, Air Force, and US Public Health Service—who provide laudable care to their charges in the United States and around the world.

The AMD strives to “[k]eep our troops fit to fight, take care of our wounded warriors on the field and back home, and provide quality Dermatologic care to their dependents, our retirees, and others in need of humanitarian assistance throughout the world when duty calls.” In addition to their clinical mission, members of the AMD have an educational mission by which they, at any one time, are training approximately 50 young active-duty physicians in dermatology residency training programs at their 3 sites in Bethesda, Maryland; San Antonio, Texas; and San Diego, California.

The value of this collaboration for the readers of Cutis is illustrated by the inaugural Military Dermatology column, “Managing Residual Limb Hyperhidrosis in Wounded Warriors: What Have We Learned?” This topic and others that will be featured in this new column, which will be published quarterly, will focus on an important area of skin disease that we may all see in our practices but an area in which AMD physicians have extensive expertise that they will share with us.

On a personal note, my dermatology training was in the US Public Health Service and I am an (inactive) member of the organization. I would urge all of our readers to consider supporting the mission of the AMD by visiting their website (http://www.militaryderm.org) and consider joining the organization, which accepts civilian members.

Vincent A. DeLeo, MD

Editor-in-Chief, Cutis

With great pleasure I announce a partnership with the Association of Military Dermatologists (AMD) whereby Cutis® is the official journal of the organization. We welcome the AMD President Nicholas Logemann, DO, and the active members of the AMD—dermatologists in the Army, Navy, Air Force, and US Public Health Service—who provide laudable care to their charges in the United States and around the world.

The AMD strives to “[k]eep our troops fit to fight, take care of our wounded warriors on the field and back home, and provide quality Dermatologic care to their dependents, our retirees, and others in need of humanitarian assistance throughout the world when duty calls.” In addition to their clinical mission, members of the AMD have an educational mission by which they, at any one time, are training approximately 50 young active-duty physicians in dermatology residency training programs at their 3 sites in Bethesda, Maryland; San Antonio, Texas; and San Diego, California.

The value of this collaboration for the readers of Cutis is illustrated by the inaugural Military Dermatology column, “Managing Residual Limb Hyperhidrosis in Wounded Warriors: What Have We Learned?” This topic and others that will be featured in this new column, which will be published quarterly, will focus on an important area of skin disease that we may all see in our practices but an area in which AMD physicians have extensive expertise that they will share with us.

On a personal note, my dermatology training was in the US Public Health Service and I am an (inactive) member of the organization. I would urge all of our readers to consider supporting the mission of the AMD by visiting their website (http://www.militaryderm.org) and consider joining the organization, which accepts civilian members.

Vincent A. DeLeo, MD

Editor-in-Chief, Cutis

When should we stop aspirin during pregnancy?

When should we stop aspirin during pregnancy?

In his Editorial, Dr. Barbieri discusses the ideal time to start aspirin in women at high risk for preeclampsia, but does not identify when to stop this medication. At our community health center, we have been stopping oral aspirin 81 mg at 36 weeks’ gestation because of the “potential” for postpartum hemorrhage or intrapartum hemorrhage after this time. Is there any literature regarding the evidence behind this date?

Tammy R. Gruenberg, MD, MPH

Bronx, New York

Dr. Barbieri responds

I appreciate Dr. Gruenberg’s important advice for our readers. Although low-dose aspirin is not known to be a major risk factor for adverse maternal or fetal outcomes, it is wise to stop the therapy a week prior to delivery, to reduce the theoretical risk of postpartum hemorrhage. Stopping aspirin at 36 or 37 weeks’ gestation will ensure that the majority of women are not taking aspirin at delivery.

Another shoulder dystocia maneuver?

An additional technique that I use for managing shoulder dystocia is to simply track upward with the baby’s head, delivering the posterior shoulder without injury to the arm. Once the posterior shoulder clears the plane of the pubis and the anterior shoulder is mobilized, the posterior shoulder is rotated anterior in front of the pubic plane and the body unscrews itself from the pelvis. I also described this technique in a published letter to the editor in August 2013.

Dr. Barbieri’s suggestions in his April 2016 article are complicated for the less experienced ObGyn and could be dangerous for the baby (with potential fractures, nerve, and vascular injuries). Think about the described Gaskin maneuver: you flip the patient over on all fours, pull the baby’s head down, and deliver the superior shoulder (formerly the posterior shoulder).

Many obese and exhausted patients with epidurals will not be able to flip over for the Gaskin maneuver. The beauty of what I suggest is that this repositioning is not needed, and pulling on arms and axillae can endanger the baby.

Robert Graebe, MD

Long Branch, New Jersey

Dr. Barbieri responds

I thank Dr. Graebe for describing his approach to resolving an intractable shoulder dystocia. Personally, I try to avoid applying force to the fetal head once a shoulder dystocia has been diagnosed.

QUICK POLL RESULTS

Preferred approaches to resolving the difficult shoulder dystocia

In his article, "Intractable shoulder dystocia: A posterior axilla maneuver may save the day," which appeared in the April 2016 issue of OBG Management, Editor in Chief Robert L. Barbieri, MD, offered several posterior axilla maneuvers to use when initial shoulder dystocia management steps are not enough.

He indicated his preferred maneuver as the Menticoglou, and asked readers: "What is your preferred approach to resolving the difficult shoulder dystocia?"

More than 100 readers weighed in:

- 33.6% (38 readers) prefer the Menicoglou maneuver

- 21.2% (24 readers) prefer the Schramm maneuver

- 19.5% (22 readers) prefer the Holman maneuver

- 15% (17 readers) prefer the Willughby maneuver

- 10.6% (12 readers) prefer the Hofmeyr-Cluver maneuver.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

When should we stop aspirin during pregnancy?

In his Editorial, Dr. Barbieri discusses the ideal time to start aspirin in women at high risk for preeclampsia, but does not identify when to stop this medication. At our community health center, we have been stopping oral aspirin 81 mg at 36 weeks’ gestation because of the “potential” for postpartum hemorrhage or intrapartum hemorrhage after this time. Is there any literature regarding the evidence behind this date?

Tammy R. Gruenberg, MD, MPH

Bronx, New York

Dr. Barbieri responds

I appreciate Dr. Gruenberg’s important advice for our readers. Although low-dose aspirin is not known to be a major risk factor for adverse maternal or fetal outcomes, it is wise to stop the therapy a week prior to delivery, to reduce the theoretical risk of postpartum hemorrhage. Stopping aspirin at 36 or 37 weeks’ gestation will ensure that the majority of women are not taking aspirin at delivery.

Another shoulder dystocia maneuver?

An additional technique that I use for managing shoulder dystocia is to simply track upward with the baby’s head, delivering the posterior shoulder without injury to the arm. Once the posterior shoulder clears the plane of the pubis and the anterior shoulder is mobilized, the posterior shoulder is rotated anterior in front of the pubic plane and the body unscrews itself from the pelvis. I also described this technique in a published letter to the editor in August 2013.

Dr. Barbieri’s suggestions in his April 2016 article are complicated for the less experienced ObGyn and could be dangerous for the baby (with potential fractures, nerve, and vascular injuries). Think about the described Gaskin maneuver: you flip the patient over on all fours, pull the baby’s head down, and deliver the superior shoulder (formerly the posterior shoulder).

Many obese and exhausted patients with epidurals will not be able to flip over for the Gaskin maneuver. The beauty of what I suggest is that this repositioning is not needed, and pulling on arms and axillae can endanger the baby.

Robert Graebe, MD

Long Branch, New Jersey

Dr. Barbieri responds

I thank Dr. Graebe for describing his approach to resolving an intractable shoulder dystocia. Personally, I try to avoid applying force to the fetal head once a shoulder dystocia has been diagnosed.

QUICK POLL RESULTS

Preferred approaches to resolving the difficult shoulder dystocia

In his article, "Intractable shoulder dystocia: A posterior axilla maneuver may save the day," which appeared in the April 2016 issue of OBG Management, Editor in Chief Robert L. Barbieri, MD, offered several posterior axilla maneuvers to use when initial shoulder dystocia management steps are not enough.

He indicated his preferred maneuver as the Menticoglou, and asked readers: "What is your preferred approach to resolving the difficult shoulder dystocia?"

More than 100 readers weighed in:

- 33.6% (38 readers) prefer the Menicoglou maneuver

- 21.2% (24 readers) prefer the Schramm maneuver

- 19.5% (22 readers) prefer the Holman maneuver

- 15% (17 readers) prefer the Willughby maneuver

- 10.6% (12 readers) prefer the Hofmeyr-Cluver maneuver.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

When should we stop aspirin during pregnancy?

In his Editorial, Dr. Barbieri discusses the ideal time to start aspirin in women at high risk for preeclampsia, but does not identify when to stop this medication. At our community health center, we have been stopping oral aspirin 81 mg at 36 weeks’ gestation because of the “potential” for postpartum hemorrhage or intrapartum hemorrhage after this time. Is there any literature regarding the evidence behind this date?

Tammy R. Gruenberg, MD, MPH

Bronx, New York

Dr. Barbieri responds

I appreciate Dr. Gruenberg’s important advice for our readers. Although low-dose aspirin is not known to be a major risk factor for adverse maternal or fetal outcomes, it is wise to stop the therapy a week prior to delivery, to reduce the theoretical risk of postpartum hemorrhage. Stopping aspirin at 36 or 37 weeks’ gestation will ensure that the majority of women are not taking aspirin at delivery.

Another shoulder dystocia maneuver?

An additional technique that I use for managing shoulder dystocia is to simply track upward with the baby’s head, delivering the posterior shoulder without injury to the arm. Once the posterior shoulder clears the plane of the pubis and the anterior shoulder is mobilized, the posterior shoulder is rotated anterior in front of the pubic plane and the body unscrews itself from the pelvis. I also described this technique in a published letter to the editor in August 2013.

Dr. Barbieri’s suggestions in his April 2016 article are complicated for the less experienced ObGyn and could be dangerous for the baby (with potential fractures, nerve, and vascular injuries). Think about the described Gaskin maneuver: you flip the patient over on all fours, pull the baby’s head down, and deliver the superior shoulder (formerly the posterior shoulder).

Many obese and exhausted patients with epidurals will not be able to flip over for the Gaskin maneuver. The beauty of what I suggest is that this repositioning is not needed, and pulling on arms and axillae can endanger the baby.

Robert Graebe, MD

Long Branch, New Jersey

Dr. Barbieri responds

I thank Dr. Graebe for describing his approach to resolving an intractable shoulder dystocia. Personally, I try to avoid applying force to the fetal head once a shoulder dystocia has been diagnosed.

QUICK POLL RESULTS

Preferred approaches to resolving the difficult shoulder dystocia

In his article, "Intractable shoulder dystocia: A posterior axilla maneuver may save the day," which appeared in the April 2016 issue of OBG Management, Editor in Chief Robert L. Barbieri, MD, offered several posterior axilla maneuvers to use when initial shoulder dystocia management steps are not enough.

He indicated his preferred maneuver as the Menticoglou, and asked readers: "What is your preferred approach to resolving the difficult shoulder dystocia?"

More than 100 readers weighed in:

- 33.6% (38 readers) prefer the Menicoglou maneuver

- 21.2% (24 readers) prefer the Schramm maneuver

- 19.5% (22 readers) prefer the Holman maneuver

- 15% (17 readers) prefer the Willughby maneuver

- 10.6% (12 readers) prefer the Hofmeyr-Cluver maneuver.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Choosing a Graft for Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction: Surgeon Influence Reigns Supreme

Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries affect >175,000 people each year,1 with >100,000 Americans undergoing ACL reconstruction annually.2 Due to the high impact this injury has on the general population, and especially on athletes, it is important to determine the factors that influence a patient’s selection of a particular graft type. With increasing access to information and other outside influences, surgeons should attempt to provide as much objective information as possible in order to allow patients to make appropriate informed decisions regarding their graft choice for ACL surgery.

While autografts are used in >60% of primary ACL reconstructions, allografts are used in >80% of revision procedures.3 Both autografts and allografts offer advantages and disadvantages, and the advantages of each may depend on patient age, activity level, and occupation.4 For example, graft rerupture rates have been shown to be higher in patients with ACL allografts4, while kneeling pain has been shown to be worse in patients with bone-patellar tendon-bone (BPTB) autografts compared to hamstring autografts5 as well as BPTB allografts.4

Patient satisfaction rates are high for ACL autografts and allografts. Boonriong and Kietsiriroje6 have shown visual analog scale (VAS) patient satisfaction score averages to be 88 out of 100 for BPTB autografts and 93 out of 100 for hamstring tendon autografts. Fox and colleagues7 showed that 87% of patients were completely or mostly satisfied following revision ACL reconstruction with patellar tendon allograft. Cohen and colleagues8 evaluated 240 patients undergoing primary ACL reconstruction; 63.3% underwent ACL reconstruction with an allograft and 35.4% with an autograft. Of all patients enrolled in the study, 93% were satisfied with their graft choice, with 12.7% of patients opting to choose another graft if in the same situation again. Of those patients, 63.3% would have switched from an autograft to allograft. Although these numbers represent high patient satisfaction following a variety of ACL graft types, it is important to continue to identify graft selection factors in order to maximize patient outcomes.

The purposes of this prospective study were to assess patients’ knowledge of their graft type used for ACL reconstruction, to determine the most influential factors involved in graft selection, and to determine the level of satisfaction with the graft of choice at a minimum of 1-year follow-up. Based on a previous retrospective study,8 we hypothesized that physician recommendation would be the most influential factor in ACL graft selection. We also hypothesized that patients receiving an autograft would be more accurate in stating their graft harvest location compared to allograft patients.

Materials and Methods

We prospectively enrolled 304 patients who underwent primary ACL reconstruction from January 2008 to September 2013. Surgery was performed by 9 different surgeons within the same practice. All patients undergoing primary ACL reconstruction were eligible for the study.

All surgeons explained to each patient the pros and cons of each graft choice based upon peer-reviewed literature. Each patient was allowed to choose autograft or allograft, although most of the surgeons strongly encourage patients under age 25 years to choose autograft. One of the surgeons specifically encourages a patellar tendon autograft in patients under age 30 to 35 years, except for those patients with a narrow patellar tendon on magnetic resonance imaging, in which case he recommends a hamstring autograft. Another surgeon also specifically encourages patellar tendon autograft in patients under 35 years, except in skeletally immature patients, for whom he encourages hamstring autograft. However, none of the surgeons prohibited patients from choosing autograft or allograft, regardless of age.

The Institutional Review Board at our institution provided approval for this study. At the first postoperative follow-up appointment, each patient completed a questionnaire asking to select from a list the type (“your own” or “a cadaver”) and harvest site of the graft that was used for the surgery. Patients were also asked how they decided upon that graft type by ranking a list of 4 factors from 1 to 4. These included (1) physician recommendation, (2) family/friend’s recommendation, (3) coach’s recommendation, and (4) the media. Patients had the option of ranking more than one factor as most important in their decision. In addition, patients were asked to list any other factors that influenced their decision regarding graft type.

At a minimum of 1 year following surgery, patients completed the same questionnaire described above. In addition, patients were asked if they were satisfied with their graft and whether they would choose the same graft type if undergoing ACL reconstruction again. Patients who would have chosen a different graft were asked which graft they would have chosen and why. Any patient who experienced graft rupture prior to follow-up was included in the analysis.

Statistical Analysis

Chi square tests were used to compare dichotomous outcomes. A type I error of less than 5% (P < .05) was considered statistically significant.

Results

At least 1 year following ACL reconstruction, 213 of 304 patients (70%) successfully completed the same questionnaire as they did at their first postoperative follow-up appointment. The mean age of these patients at the time of surgery was 31.9 ± 11.0 years (range, 13.9 to 58.0 years). The mean follow-up time was 1.4 ± 0.4 years (range, 1.0 to 2.6 years), and 59% of these patients were male.

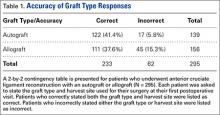

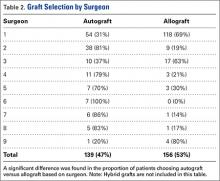

Autografts were used for 139 patients (139/304, 46%), allografts for 156 patients (156/304, 51%), and hybrid grafts for 9 patients (9/304, 3%). Overall, 77% of patients were accurate in stating the type of graft used for their ACL reconstruction, including 88% of autograft patients, 71% of allograft patients, and 11% of hybrid graft patients (Table 1). Patients who underwent reconstruction with an autograft were significantly more accurate in stating their graft type compared to patients with an allograft (P < .001). Graft type by surgeon is shown in Table 2. A statistically significant difference was found in the proportion of patients choosing autograft versus allograft based on surgeon (P < .0001).

When asked which type of graft was used for their surgery, 12 of 304 patients (4%) did not know their graft type or harvest location. Twenty-nine patients stated that their graft was an allograft but did not know the harvest location. Five patients stated that their graft was an autograft but did not know the harvest location. The 34 patients who classified their choice of graft but did not know the harvest site (11%) stated their surgeon never told them where their graft was from or they did not remember. A complete list of graft type responses is shown in Table 3.

Of the 29 patients who stated that their graft was an allograft but did not know the harvest location, 19 (66%) had a tibialis anterior allograft, 7 (24%) had a BPTB allograft, 2 (7%) had an Achilles tendon allograft, and 1 (3%) had a tibialis anterior autograft.

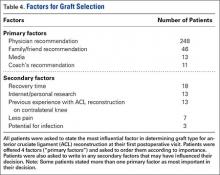

Physician recommendation was the most important decision-making factor listed for 82% of patients at their first postoperative appointment (Table 4). In addition to the 4 factors listed on our survey, patients were allowed to write in other factors involved in their decision. The most popular answers included recovery time, personal research on graft types, and prior personal experience with ACL reconstruction on the contralateral knee.

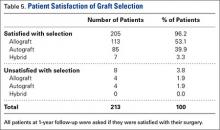

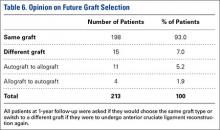

At the time of 1-year follow-up, 205 of 213 patients (96%) said they were satisfied with their graft choice (Table 5). All 4 unsatisfied autograft patients received a hamstring autograft, 3 of which were performed by the same surgeon. No significant difference was found in satisfaction rates between patients with autograft vs allograft (P = .87). There was a higher satisfaction rate among patients with a BPTB autograft compared to those with a hamstring autograft (P = .043). Of the unsatisfied patients, 3 patients stated that their graft had failed in the time prior to follow-up and 2 patients stated that they were having donor site pain following surgery with hamstring autograft and would consider an allograft if the reconstruction were repeated (Table 6). Two patients stated that they were unsatisfied with their graft but would need to do more research before deciding on a different graft type.

As shown in Tables 5 and 6, there is a discrepancy between the number of patients who were unsatisfied with their graft and the number of patients who stated that they would switch to a different graft type if they were to have ACL reconstruction again. A number of patients stated that they were satisfied with their graft, yet they would switch to a different graft. The main reasons for this related to issues from a hamstring autograft harvest site. One patient noted that although she was satisfied with her graft, she would switch after doing further research.

Discussion

Determining the decision-making factors for patients choosing between graft types for ACL reconstruction is important to ensure that patients can make a decision based on objective information. Several previous studies have evaluated patient selection of ACL grafts.8-10 All 3 of these studies showed that surgeon recommendation is the primary factor in a patient’s decision. Similar to previous studies, we also found that physician recommendation is the most influential factor involved in this decision.

At an average follow-up of 41 months, Cohen and colleagues8 found that 1.3% of patients did not know whether they received an autograft or allograft for their ACL reconstruction. Furthermore, 50.7% of patients stating they received an allograft in Cohen’s study8 were unsure of the harvest location. In our study, 4% of patients at their first postoperative visit did not know whether they had received an autograft or allograft and 10% of patients stating they received an allograft selected an unknown harvest site. In contrast, only 2% of autograft patients in our study were unsure of the harvest location at their first postoperative appointment. It is likely that, over time, patients with an allograft forget the harvest location, whereas autograft patients are more likely to remember the location of harvest. This is especially true in patients with anterior knee pain or hamstring pain following ACL reconstruction with a BPTB or hamstring tendon autograft, respectively.

In terms of patients’ knowledge of their graft type, we found an overall accuracy of 77%, with 88% of autograft patients, 71% of allograft patients, and 11% of hybrid graft patients remembering their graft type and harvest location. Although we do not believe it to be critical for patients to remember these details, we do believe that patients who do not know their graft type likely relied on the recommendation of their physician.

We found a significant difference in the proportion of patients choosing autograft vs allograft based on surgeon, despite these surgeons citing available data in the literature to each patient and ultimately allowing each patient to make his or her own decision. This is partly due to the low sample size of most of the surgeons involved. However, the main reason for this distortion is likely that different surgeons may highlight different aspects of the literature to “spin” patients towards one graft or another in certain cases.

Currently, there remains a lack of clarity in the literature on appropriate ACL graft choices for patients. With constant new findings being published on different aspects of various grafts, it is important for surgeons to remain up to date with the literature. Nevertheless, we believe that certain biases are inevitable among surgeons due to unique training experiences as well as experience with their own patients.

Cohen and colleagues8 found that only 7% of patients reported that their own personal research influenced their decision, and only 6.4% of patients reported the media as their primary decision-making factor. Cheung and colleagues9 conducted a retrospective study and found that more than half of patients did significant personal research prior to making a decision regarding their graft type. Most of this research was done using medical websites and literature. Koh and colleagues10 noted that >80% of patients consulted the internet for graft information before making a decision. Koh’s study10 was performed in Korea and therefore the high prevalence of internet use may be culturally-related.

Overall, quality of information for patients undergoing ACL reconstruction is mixed across the internet, with only 22.5% of top websites being affiliated with an academic institution and 35.5% of websites authored by private physicians or physician groups.11 Although a majority of internet websites offer discussion into the condition and surgical procedure of ACL reconstruction, less than half of these websites share the equally important information on the eligibility for surgery and concomitant complications following surgery.11In our study, only 39 patients (13%) listed the media as either the first (13, 4%) or second (26, 9%) most important factor in their graft decision. Clearly there is some discrepancy between studies regarding the influence of personal research and media. There are a few potential reasons for this. First, we did not explicitly ask patients if their own personal research had any influence on their graft decision. Rather, we asked patients to rank their decision-making factors, and few patients ranked the media as their first or second greatest influence. Second, the word “media” was used in our questionnaire rather than “online research” or “internet.” It may seem somewhat vague to patients what the word “media” really means in terms of their own research, whereas listing “online research” or “internet” as selection options may have influenced patient responses.

In our study, we asked patients for any additional factors that influenced their graft choice. Thirteen patients (4%) noted that “personal research” through internet, orthopaedic literature, and the media influenced their graft decision. This corroborates the idea that “media” may have seemed vague to some patients. Of these patients, 9 chose an autograft and 4 chose an allograft. The relative ease in accessing information regarding graft choice in ACL reconstruction should be noted. Numerous websites offer advice, graft options, and commentary from group practices and orthopaedic surgeons. Whether or not these sources provide reasonable support for one graft vs another graft remains to be answered. The physician should be responsible for providing the patient with this collected objective information.

In our study, 205 patients (96%) were satisfied with their graft choice at the time of follow-up, with 15 patients (7%) stating that they would have chosen a different graft type if they could redo the operation. Cheung and colleagues9 found a satisfaction rate of 87.4% at an average follow-up time of 19 months, with 4.6% stating they would have chosen a different graft type. Many factors can contribute to patient satisfaction after ACL reconstruction. Looking at patient variables such as age, demographics, occupation, activity level, surgical technique including tunnel placement and fixation, postoperative rehabilitation, and graft type may influence the success of the patient after ACL reconstruction.

The strengths of this study include the patient population size with 1-year follow-up as well as the prospective study design. In comparison to a previous retrospective study in 2009 by Cohen and colleagues8with a sample size of 240 patients, our study collected 213 patients with 70% follow-up at minimum 1 year. Collecting data prospectively ensures accurate representation of the factors influencing each patient’s graft selection, while follow-up data was useful for patient satisfaction.

The limitations of this study include the percentage of patients lost from follow-up as well as any bias generated from the organization of the questionnaire. Unfortunately, with a younger, transient population of patients undergoing ACL reconstruction in a major metropolitan area, a percentage of patients are lost to follow-up. Many attempts were made to locate these patients. Another potential limitation was the order of decision factors listed on the questionnaire. These factors were not ordered randomly on each survey, but were listed in the following order: (1) physician recommendation (2) family/friend’s recommendation (3) coach’s recommendation and (4) the media. This may have influenced patient responses. The organization of these factors in the questionnaire started with physician recommendation, which may have influenced the patient’s initial thought process of which factor had the greatest influence in their graft decision. In addition, for the surveys completed at least 1 year following surgery, some patients were contacted via e-mail and others via telephone. Thus, some patients may have changed their answers if they were able to see the questions rather than hearing the questions. We believe this is particularly true of the question regarding graft harvest site.

Our study indicates that the majority of patients undergoing ACL reconstruction are primarily influenced by the physician’s recommendation.

1. Madick S. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction of the knee. AORN J. 2011;93(2):210-222.

2. Baer GS, Harner CD. Clinical outcomes of allograft versus autograft in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Clin Sports Med. 2007;26(4):661-681.

3. Paxton EW, Namba RS, Maletis GB, et al. A prospective study of 80,000 total joint and 5000 anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction procedures in a community-based registry in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(suppl 2):117-132.

4. Kraeutler MJ, Bravman JT, McCarty EC. Bone-patellar tendon-bone autograft versus allograft in outcomes of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: A meta-analysis of 5182 patients. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(10):2439-2448.

5. Spindler KP, Kuhn JE, Freedman KB, Matthews CE, Dittus RS, Harrell FE Jr. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction autograft choice: bone-tendon-bone versus hamstring: does it really matter? A systematic review. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32(8):1986-1995.

6. Boonriong T, Kietsiriroje N. Arthroscopically assisted anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: comparison of bone-patellar tendon-bone versus hamstring tendon autograft. J Med Assoc Thai. 2004;87(9):1100-1107.

7. Fox JA, Pierce M, Bojchuk J, Hayden J, Bush-Joseph CA, Bach BR Jr. Revision anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with nonirradiated fresh-frozen patellar tendon allograft. Arthroscopy. 2004;20(8):787-794.

8. Cohen SB, Yucha DT, Ciccotti MC, Goldstein DT, Ciccotti MA, Ciccotti MG. Factors affecting patient selection of graft type in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Arthroscopy. 2009;25(9):1006-1010.

9. Cheung SC, Allen CR, Gallo RA, Ma CB, Feeley BT. Patients’ attitudes and factors in their selection of grafts for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee. 2012;19(1):49-54.

10. Koh HS, In Y, Kong CG, Won HY, Kim KH, Lee JH. Factors affecting patients’ graft choice in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Clin Orthop Surg. 2010;2(2):69-75.

11. Duncan IC, Kane PW, Lawson KA, Cohen SB, Ciccotti MG, Dodson CC. Evaluation of information available on the internet regarding anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(6):1101-1107.

Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries affect >175,000 people each year,1 with >100,000 Americans undergoing ACL reconstruction annually.2 Due to the high impact this injury has on the general population, and especially on athletes, it is important to determine the factors that influence a patient’s selection of a particular graft type. With increasing access to information and other outside influences, surgeons should attempt to provide as much objective information as possible in order to allow patients to make appropriate informed decisions regarding their graft choice for ACL surgery.

While autografts are used in >60% of primary ACL reconstructions, allografts are used in >80% of revision procedures.3 Both autografts and allografts offer advantages and disadvantages, and the advantages of each may depend on patient age, activity level, and occupation.4 For example, graft rerupture rates have been shown to be higher in patients with ACL allografts4, while kneeling pain has been shown to be worse in patients with bone-patellar tendon-bone (BPTB) autografts compared to hamstring autografts5 as well as BPTB allografts.4

Patient satisfaction rates are high for ACL autografts and allografts. Boonriong and Kietsiriroje6 have shown visual analog scale (VAS) patient satisfaction score averages to be 88 out of 100 for BPTB autografts and 93 out of 100 for hamstring tendon autografts. Fox and colleagues7 showed that 87% of patients were completely or mostly satisfied following revision ACL reconstruction with patellar tendon allograft. Cohen and colleagues8 evaluated 240 patients undergoing primary ACL reconstruction; 63.3% underwent ACL reconstruction with an allograft and 35.4% with an autograft. Of all patients enrolled in the study, 93% were satisfied with their graft choice, with 12.7% of patients opting to choose another graft if in the same situation again. Of those patients, 63.3% would have switched from an autograft to allograft. Although these numbers represent high patient satisfaction following a variety of ACL graft types, it is important to continue to identify graft selection factors in order to maximize patient outcomes.

The purposes of this prospective study were to assess patients’ knowledge of their graft type used for ACL reconstruction, to determine the most influential factors involved in graft selection, and to determine the level of satisfaction with the graft of choice at a minimum of 1-year follow-up. Based on a previous retrospective study,8 we hypothesized that physician recommendation would be the most influential factor in ACL graft selection. We also hypothesized that patients receiving an autograft would be more accurate in stating their graft harvest location compared to allograft patients.

Materials and Methods

We prospectively enrolled 304 patients who underwent primary ACL reconstruction from January 2008 to September 2013. Surgery was performed by 9 different surgeons within the same practice. All patients undergoing primary ACL reconstruction were eligible for the study.

All surgeons explained to each patient the pros and cons of each graft choice based upon peer-reviewed literature. Each patient was allowed to choose autograft or allograft, although most of the surgeons strongly encourage patients under age 25 years to choose autograft. One of the surgeons specifically encourages a patellar tendon autograft in patients under age 30 to 35 years, except for those patients with a narrow patellar tendon on magnetic resonance imaging, in which case he recommends a hamstring autograft. Another surgeon also specifically encourages patellar tendon autograft in patients under 35 years, except in skeletally immature patients, for whom he encourages hamstring autograft. However, none of the surgeons prohibited patients from choosing autograft or allograft, regardless of age.

The Institutional Review Board at our institution provided approval for this study. At the first postoperative follow-up appointment, each patient completed a questionnaire asking to select from a list the type (“your own” or “a cadaver”) and harvest site of the graft that was used for the surgery. Patients were also asked how they decided upon that graft type by ranking a list of 4 factors from 1 to 4. These included (1) physician recommendation, (2) family/friend’s recommendation, (3) coach’s recommendation, and (4) the media. Patients had the option of ranking more than one factor as most important in their decision. In addition, patients were asked to list any other factors that influenced their decision regarding graft type.

At a minimum of 1 year following surgery, patients completed the same questionnaire described above. In addition, patients were asked if they were satisfied with their graft and whether they would choose the same graft type if undergoing ACL reconstruction again. Patients who would have chosen a different graft were asked which graft they would have chosen and why. Any patient who experienced graft rupture prior to follow-up was included in the analysis.

Statistical Analysis

Chi square tests were used to compare dichotomous outcomes. A type I error of less than 5% (P < .05) was considered statistically significant.

Results

At least 1 year following ACL reconstruction, 213 of 304 patients (70%) successfully completed the same questionnaire as they did at their first postoperative follow-up appointment. The mean age of these patients at the time of surgery was 31.9 ± 11.0 years (range, 13.9 to 58.0 years). The mean follow-up time was 1.4 ± 0.4 years (range, 1.0 to 2.6 years), and 59% of these patients were male.

Autografts were used for 139 patients (139/304, 46%), allografts for 156 patients (156/304, 51%), and hybrid grafts for 9 patients (9/304, 3%). Overall, 77% of patients were accurate in stating the type of graft used for their ACL reconstruction, including 88% of autograft patients, 71% of allograft patients, and 11% of hybrid graft patients (Table 1). Patients who underwent reconstruction with an autograft were significantly more accurate in stating their graft type compared to patients with an allograft (P < .001). Graft type by surgeon is shown in Table 2. A statistically significant difference was found in the proportion of patients choosing autograft versus allograft based on surgeon (P < .0001).

When asked which type of graft was used for their surgery, 12 of 304 patients (4%) did not know their graft type or harvest location. Twenty-nine patients stated that their graft was an allograft but did not know the harvest location. Five patients stated that their graft was an autograft but did not know the harvest location. The 34 patients who classified their choice of graft but did not know the harvest site (11%) stated their surgeon never told them where their graft was from or they did not remember. A complete list of graft type responses is shown in Table 3.

Of the 29 patients who stated that their graft was an allograft but did not know the harvest location, 19 (66%) had a tibialis anterior allograft, 7 (24%) had a BPTB allograft, 2 (7%) had an Achilles tendon allograft, and 1 (3%) had a tibialis anterior autograft.

Physician recommendation was the most important decision-making factor listed for 82% of patients at their first postoperative appointment (Table 4). In addition to the 4 factors listed on our survey, patients were allowed to write in other factors involved in their decision. The most popular answers included recovery time, personal research on graft types, and prior personal experience with ACL reconstruction on the contralateral knee.

At the time of 1-year follow-up, 205 of 213 patients (96%) said they were satisfied with their graft choice (Table 5). All 4 unsatisfied autograft patients received a hamstring autograft, 3 of which were performed by the same surgeon. No significant difference was found in satisfaction rates between patients with autograft vs allograft (P = .87). There was a higher satisfaction rate among patients with a BPTB autograft compared to those with a hamstring autograft (P = .043). Of the unsatisfied patients, 3 patients stated that their graft had failed in the time prior to follow-up and 2 patients stated that they were having donor site pain following surgery with hamstring autograft and would consider an allograft if the reconstruction were repeated (Table 6). Two patients stated that they were unsatisfied with their graft but would need to do more research before deciding on a different graft type.

As shown in Tables 5 and 6, there is a discrepancy between the number of patients who were unsatisfied with their graft and the number of patients who stated that they would switch to a different graft type if they were to have ACL reconstruction again. A number of patients stated that they were satisfied with their graft, yet they would switch to a different graft. The main reasons for this related to issues from a hamstring autograft harvest site. One patient noted that although she was satisfied with her graft, she would switch after doing further research.

Discussion

Determining the decision-making factors for patients choosing between graft types for ACL reconstruction is important to ensure that patients can make a decision based on objective information. Several previous studies have evaluated patient selection of ACL grafts.8-10 All 3 of these studies showed that surgeon recommendation is the primary factor in a patient’s decision. Similar to previous studies, we also found that physician recommendation is the most influential factor involved in this decision.

At an average follow-up of 41 months, Cohen and colleagues8 found that 1.3% of patients did not know whether they received an autograft or allograft for their ACL reconstruction. Furthermore, 50.7% of patients stating they received an allograft in Cohen’s study8 were unsure of the harvest location. In our study, 4% of patients at their first postoperative visit did not know whether they had received an autograft or allograft and 10% of patients stating they received an allograft selected an unknown harvest site. In contrast, only 2% of autograft patients in our study were unsure of the harvest location at their first postoperative appointment. It is likely that, over time, patients with an allograft forget the harvest location, whereas autograft patients are more likely to remember the location of harvest. This is especially true in patients with anterior knee pain or hamstring pain following ACL reconstruction with a BPTB or hamstring tendon autograft, respectively.

In terms of patients’ knowledge of their graft type, we found an overall accuracy of 77%, with 88% of autograft patients, 71% of allograft patients, and 11% of hybrid graft patients remembering their graft type and harvest location. Although we do not believe it to be critical for patients to remember these details, we do believe that patients who do not know their graft type likely relied on the recommendation of their physician.

We found a significant difference in the proportion of patients choosing autograft vs allograft based on surgeon, despite these surgeons citing available data in the literature to each patient and ultimately allowing each patient to make his or her own decision. This is partly due to the low sample size of most of the surgeons involved. However, the main reason for this distortion is likely that different surgeons may highlight different aspects of the literature to “spin” patients towards one graft or another in certain cases.

Currently, there remains a lack of clarity in the literature on appropriate ACL graft choices for patients. With constant new findings being published on different aspects of various grafts, it is important for surgeons to remain up to date with the literature. Nevertheless, we believe that certain biases are inevitable among surgeons due to unique training experiences as well as experience with their own patients.

Cohen and colleagues8 found that only 7% of patients reported that their own personal research influenced their decision, and only 6.4% of patients reported the media as their primary decision-making factor. Cheung and colleagues9 conducted a retrospective study and found that more than half of patients did significant personal research prior to making a decision regarding their graft type. Most of this research was done using medical websites and literature. Koh and colleagues10 noted that >80% of patients consulted the internet for graft information before making a decision. Koh’s study10 was performed in Korea and therefore the high prevalence of internet use may be culturally-related.

Overall, quality of information for patients undergoing ACL reconstruction is mixed across the internet, with only 22.5% of top websites being affiliated with an academic institution and 35.5% of websites authored by private physicians or physician groups.11 Although a majority of internet websites offer discussion into the condition and surgical procedure of ACL reconstruction, less than half of these websites share the equally important information on the eligibility for surgery and concomitant complications following surgery.11In our study, only 39 patients (13%) listed the media as either the first (13, 4%) or second (26, 9%) most important factor in their graft decision. Clearly there is some discrepancy between studies regarding the influence of personal research and media. There are a few potential reasons for this. First, we did not explicitly ask patients if their own personal research had any influence on their graft decision. Rather, we asked patients to rank their decision-making factors, and few patients ranked the media as their first or second greatest influence. Second, the word “media” was used in our questionnaire rather than “online research” or “internet.” It may seem somewhat vague to patients what the word “media” really means in terms of their own research, whereas listing “online research” or “internet” as selection options may have influenced patient responses.

In our study, we asked patients for any additional factors that influenced their graft choice. Thirteen patients (4%) noted that “personal research” through internet, orthopaedic literature, and the media influenced their graft decision. This corroborates the idea that “media” may have seemed vague to some patients. Of these patients, 9 chose an autograft and 4 chose an allograft. The relative ease in accessing information regarding graft choice in ACL reconstruction should be noted. Numerous websites offer advice, graft options, and commentary from group practices and orthopaedic surgeons. Whether or not these sources provide reasonable support for one graft vs another graft remains to be answered. The physician should be responsible for providing the patient with this collected objective information.

In our study, 205 patients (96%) were satisfied with their graft choice at the time of follow-up, with 15 patients (7%) stating that they would have chosen a different graft type if they could redo the operation. Cheung and colleagues9 found a satisfaction rate of 87.4% at an average follow-up time of 19 months, with 4.6% stating they would have chosen a different graft type. Many factors can contribute to patient satisfaction after ACL reconstruction. Looking at patient variables such as age, demographics, occupation, activity level, surgical technique including tunnel placement and fixation, postoperative rehabilitation, and graft type may influence the success of the patient after ACL reconstruction.

The strengths of this study include the patient population size with 1-year follow-up as well as the prospective study design. In comparison to a previous retrospective study in 2009 by Cohen and colleagues8with a sample size of 240 patients, our study collected 213 patients with 70% follow-up at minimum 1 year. Collecting data prospectively ensures accurate representation of the factors influencing each patient’s graft selection, while follow-up data was useful for patient satisfaction.

The limitations of this study include the percentage of patients lost from follow-up as well as any bias generated from the organization of the questionnaire. Unfortunately, with a younger, transient population of patients undergoing ACL reconstruction in a major metropolitan area, a percentage of patients are lost to follow-up. Many attempts were made to locate these patients. Another potential limitation was the order of decision factors listed on the questionnaire. These factors were not ordered randomly on each survey, but were listed in the following order: (1) physician recommendation (2) family/friend’s recommendation (3) coach’s recommendation and (4) the media. This may have influenced patient responses. The organization of these factors in the questionnaire started with physician recommendation, which may have influenced the patient’s initial thought process of which factor had the greatest influence in their graft decision. In addition, for the surveys completed at least 1 year following surgery, some patients were contacted via e-mail and others via telephone. Thus, some patients may have changed their answers if they were able to see the questions rather than hearing the questions. We believe this is particularly true of the question regarding graft harvest site.

Our study indicates that the majority of patients undergoing ACL reconstruction are primarily influenced by the physician’s recommendation.

Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries affect >175,000 people each year,1 with >100,000 Americans undergoing ACL reconstruction annually.2 Due to the high impact this injury has on the general population, and especially on athletes, it is important to determine the factors that influence a patient’s selection of a particular graft type. With increasing access to information and other outside influences, surgeons should attempt to provide as much objective information as possible in order to allow patients to make appropriate informed decisions regarding their graft choice for ACL surgery.

While autografts are used in >60% of primary ACL reconstructions, allografts are used in >80% of revision procedures.3 Both autografts and allografts offer advantages and disadvantages, and the advantages of each may depend on patient age, activity level, and occupation.4 For example, graft rerupture rates have been shown to be higher in patients with ACL allografts4, while kneeling pain has been shown to be worse in patients with bone-patellar tendon-bone (BPTB) autografts compared to hamstring autografts5 as well as BPTB allografts.4

Patient satisfaction rates are high for ACL autografts and allografts. Boonriong and Kietsiriroje6 have shown visual analog scale (VAS) patient satisfaction score averages to be 88 out of 100 for BPTB autografts and 93 out of 100 for hamstring tendon autografts. Fox and colleagues7 showed that 87% of patients were completely or mostly satisfied following revision ACL reconstruction with patellar tendon allograft. Cohen and colleagues8 evaluated 240 patients undergoing primary ACL reconstruction; 63.3% underwent ACL reconstruction with an allograft and 35.4% with an autograft. Of all patients enrolled in the study, 93% were satisfied with their graft choice, with 12.7% of patients opting to choose another graft if in the same situation again. Of those patients, 63.3% would have switched from an autograft to allograft. Although these numbers represent high patient satisfaction following a variety of ACL graft types, it is important to continue to identify graft selection factors in order to maximize patient outcomes.

The purposes of this prospective study were to assess patients’ knowledge of their graft type used for ACL reconstruction, to determine the most influential factors involved in graft selection, and to determine the level of satisfaction with the graft of choice at a minimum of 1-year follow-up. Based on a previous retrospective study,8 we hypothesized that physician recommendation would be the most influential factor in ACL graft selection. We also hypothesized that patients receiving an autograft would be more accurate in stating their graft harvest location compared to allograft patients.

Materials and Methods

We prospectively enrolled 304 patients who underwent primary ACL reconstruction from January 2008 to September 2013. Surgery was performed by 9 different surgeons within the same practice. All patients undergoing primary ACL reconstruction were eligible for the study.

All surgeons explained to each patient the pros and cons of each graft choice based upon peer-reviewed literature. Each patient was allowed to choose autograft or allograft, although most of the surgeons strongly encourage patients under age 25 years to choose autograft. One of the surgeons specifically encourages a patellar tendon autograft in patients under age 30 to 35 years, except for those patients with a narrow patellar tendon on magnetic resonance imaging, in which case he recommends a hamstring autograft. Another surgeon also specifically encourages patellar tendon autograft in patients under 35 years, except in skeletally immature patients, for whom he encourages hamstring autograft. However, none of the surgeons prohibited patients from choosing autograft or allograft, regardless of age.

The Institutional Review Board at our institution provided approval for this study. At the first postoperative follow-up appointment, each patient completed a questionnaire asking to select from a list the type (“your own” or “a cadaver”) and harvest site of the graft that was used for the surgery. Patients were also asked how they decided upon that graft type by ranking a list of 4 factors from 1 to 4. These included (1) physician recommendation, (2) family/friend’s recommendation, (3) coach’s recommendation, and (4) the media. Patients had the option of ranking more than one factor as most important in their decision. In addition, patients were asked to list any other factors that influenced their decision regarding graft type.

At a minimum of 1 year following surgery, patients completed the same questionnaire described above. In addition, patients were asked if they were satisfied with their graft and whether they would choose the same graft type if undergoing ACL reconstruction again. Patients who would have chosen a different graft were asked which graft they would have chosen and why. Any patient who experienced graft rupture prior to follow-up was included in the analysis.

Statistical Analysis

Chi square tests were used to compare dichotomous outcomes. A type I error of less than 5% (P < .05) was considered statistically significant.

Results

At least 1 year following ACL reconstruction, 213 of 304 patients (70%) successfully completed the same questionnaire as they did at their first postoperative follow-up appointment. The mean age of these patients at the time of surgery was 31.9 ± 11.0 years (range, 13.9 to 58.0 years). The mean follow-up time was 1.4 ± 0.4 years (range, 1.0 to 2.6 years), and 59% of these patients were male.

Autografts were used for 139 patients (139/304, 46%), allografts for 156 patients (156/304, 51%), and hybrid grafts for 9 patients (9/304, 3%). Overall, 77% of patients were accurate in stating the type of graft used for their ACL reconstruction, including 88% of autograft patients, 71% of allograft patients, and 11% of hybrid graft patients (Table 1). Patients who underwent reconstruction with an autograft were significantly more accurate in stating their graft type compared to patients with an allograft (P < .001). Graft type by surgeon is shown in Table 2. A statistically significant difference was found in the proportion of patients choosing autograft versus allograft based on surgeon (P < .0001).

When asked which type of graft was used for their surgery, 12 of 304 patients (4%) did not know their graft type or harvest location. Twenty-nine patients stated that their graft was an allograft but did not know the harvest location. Five patients stated that their graft was an autograft but did not know the harvest location. The 34 patients who classified their choice of graft but did not know the harvest site (11%) stated their surgeon never told them where their graft was from or they did not remember. A complete list of graft type responses is shown in Table 3.

Of the 29 patients who stated that their graft was an allograft but did not know the harvest location, 19 (66%) had a tibialis anterior allograft, 7 (24%) had a BPTB allograft, 2 (7%) had an Achilles tendon allograft, and 1 (3%) had a tibialis anterior autograft.

Physician recommendation was the most important decision-making factor listed for 82% of patients at their first postoperative appointment (Table 4). In addition to the 4 factors listed on our survey, patients were allowed to write in other factors involved in their decision. The most popular answers included recovery time, personal research on graft types, and prior personal experience with ACL reconstruction on the contralateral knee.

At the time of 1-year follow-up, 205 of 213 patients (96%) said they were satisfied with their graft choice (Table 5). All 4 unsatisfied autograft patients received a hamstring autograft, 3 of which were performed by the same surgeon. No significant difference was found in satisfaction rates between patients with autograft vs allograft (P = .87). There was a higher satisfaction rate among patients with a BPTB autograft compared to those with a hamstring autograft (P = .043). Of the unsatisfied patients, 3 patients stated that their graft had failed in the time prior to follow-up and 2 patients stated that they were having donor site pain following surgery with hamstring autograft and would consider an allograft if the reconstruction were repeated (Table 6). Two patients stated that they were unsatisfied with their graft but would need to do more research before deciding on a different graft type.

As shown in Tables 5 and 6, there is a discrepancy between the number of patients who were unsatisfied with their graft and the number of patients who stated that they would switch to a different graft type if they were to have ACL reconstruction again. A number of patients stated that they were satisfied with their graft, yet they would switch to a different graft. The main reasons for this related to issues from a hamstring autograft harvest site. One patient noted that although she was satisfied with her graft, she would switch after doing further research.

Discussion

Determining the decision-making factors for patients choosing between graft types for ACL reconstruction is important to ensure that patients can make a decision based on objective information. Several previous studies have evaluated patient selection of ACL grafts.8-10 All 3 of these studies showed that surgeon recommendation is the primary factor in a patient’s decision. Similar to previous studies, we also found that physician recommendation is the most influential factor involved in this decision.