User login

Ocaliva approved for primary biliary cholangitis

Obeticholic acid (Ocaliva) has been granted accelerated approval for use in combination with ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) for the treatment of primary biliary cholangitis in adults with an inadequate response to UDCA, and for use as a single therapy in adults unable to tolerate UDCA, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration announced.

Obeticholic acid should not be used in patients with complete biliary obstruction.

Given orally, obeticholic acid binds to the farnesoid X receptor (FXR), a receptor found in cells of the liver and intestine. FXR is a key regulator of bile acid metabolic pathways. Obeticholic acid increases bile flow from the liver and suppresses bile acid production in the liver, thus reducing exposure to toxic levels of bile acids.

Obeticholic acid was shown to reduce levels of alkaline phosphatase, which was used as a surrogate endpoint to predict clinical benefit, including an improvement in transplant-free survival. The FDA’s accelerated approval program allows approval based on a surrogate endpoint that is reasonably likely to predict clinical benefit. The manufacturer will conduct confirmatory clinical trials to examine any improvements in survival, progression to cirrhosis, or other disease-related symptoms.

After 12 months, in a controlled clinical trial with 216 participants, the proportion of participants achieving reductions in levels of alkaline phosphatase was higher among treated participants than in participants given placebo. Pruritus, fatigue, abdominal pain and discomfort, arthralgia, oropharyngeal pain, dizziness, and constipation were the drug’s most common side effects in the study.

Obeticholic acid is manufactured by Intercept Pharmaceuticals.

Obeticholic acid (Ocaliva) has been granted accelerated approval for use in combination with ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) for the treatment of primary biliary cholangitis in adults with an inadequate response to UDCA, and for use as a single therapy in adults unable to tolerate UDCA, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration announced.

Obeticholic acid should not be used in patients with complete biliary obstruction.

Given orally, obeticholic acid binds to the farnesoid X receptor (FXR), a receptor found in cells of the liver and intestine. FXR is a key regulator of bile acid metabolic pathways. Obeticholic acid increases bile flow from the liver and suppresses bile acid production in the liver, thus reducing exposure to toxic levels of bile acids.

Obeticholic acid was shown to reduce levels of alkaline phosphatase, which was used as a surrogate endpoint to predict clinical benefit, including an improvement in transplant-free survival. The FDA’s accelerated approval program allows approval based on a surrogate endpoint that is reasonably likely to predict clinical benefit. The manufacturer will conduct confirmatory clinical trials to examine any improvements in survival, progression to cirrhosis, or other disease-related symptoms.

After 12 months, in a controlled clinical trial with 216 participants, the proportion of participants achieving reductions in levels of alkaline phosphatase was higher among treated participants than in participants given placebo. Pruritus, fatigue, abdominal pain and discomfort, arthralgia, oropharyngeal pain, dizziness, and constipation were the drug’s most common side effects in the study.

Obeticholic acid is manufactured by Intercept Pharmaceuticals.

Obeticholic acid (Ocaliva) has been granted accelerated approval for use in combination with ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) for the treatment of primary biliary cholangitis in adults with an inadequate response to UDCA, and for use as a single therapy in adults unable to tolerate UDCA, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration announced.

Obeticholic acid should not be used in patients with complete biliary obstruction.

Given orally, obeticholic acid binds to the farnesoid X receptor (FXR), a receptor found in cells of the liver and intestine. FXR is a key regulator of bile acid metabolic pathways. Obeticholic acid increases bile flow from the liver and suppresses bile acid production in the liver, thus reducing exposure to toxic levels of bile acids.

Obeticholic acid was shown to reduce levels of alkaline phosphatase, which was used as a surrogate endpoint to predict clinical benefit, including an improvement in transplant-free survival. The FDA’s accelerated approval program allows approval based on a surrogate endpoint that is reasonably likely to predict clinical benefit. The manufacturer will conduct confirmatory clinical trials to examine any improvements in survival, progression to cirrhosis, or other disease-related symptoms.

After 12 months, in a controlled clinical trial with 216 participants, the proportion of participants achieving reductions in levels of alkaline phosphatase was higher among treated participants than in participants given placebo. Pruritus, fatigue, abdominal pain and discomfort, arthralgia, oropharyngeal pain, dizziness, and constipation were the drug’s most common side effects in the study.

Obeticholic acid is manufactured by Intercept Pharmaceuticals.

TAVR degeneration estimated at 50% after 8 years

PARIS – The first-ever study of the long-term durability of transcatheter bioprosthetic aortic valves has documented a disturbing rise in the valve degeneration rate occurring 5-7 years post implant.

Prior consistently reassuring follow-up studies have been intermediate in length, with a maximum of 5 years. The PARTNER 2A trial, which generated enormous enthusiasm for moving TAVR to intermediate-risk patients on the basis of positive results presented at the 2016 meeting of the American College of Cardiology, reported 2-year results.

“We found, as have others, that there’s very little degeneration in the first 4 years: 94% freedom from degeneration. But at 6 years, it’s 82%, and we estimate that by 8 years, it’s about 50%,” Dr. Danny Dvir reported at the annual congress of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions.

“We need to be cautious: This is our first look at the data. But we have a signal for a problem,” said Dr. Dvir of St. Paul’s Hospital in Vancouver.

He presented a retrospective study of 378 patients who underwent TAVR 5-14 years ago at two pioneering centers for the procedure: St. Paul’s and Charles Nicolle Hospital in Rouen, France. Patients’ average age at the time of TAVR was 82.3 years, with an STS score of 8.3%. The study featured serial echocardiography conducted during house calls in this frail elderly population.

Thirty-five patients developed prosthetic valve degeneration, defined by at least moderate regurgitation and/or a mean gradient of at least 20 mm Hg in 23 cases and stenosis in 12. The risk of degeneration was unrelated to the use of warfarin, a finding that suggests the valve deterioration issue is unrelated to clotting. The strongest risk factor for transcatheter valve degeneration in this study was baseline renal failure at the time of TAVR.

Dr. Dvir’s presentation was the talk of the meeting, and it cast a pall over the proceedings. The red flag raised by the study regarding valve durability has major implications regarding the current enthusiasm among many interventional cardiologists to routinely extend TAVR to intermediate and even lower-risk patients. As one audience member later confessed, “I have felt sick since hearing that presentation.”

Discussant Dr. A. Pieter Kappetein observed that transcatheter heart valve durability was a hot topic of discussion about 4 years ago but subsequently faded below the radar as a concern – until Dr. Dvir’s study.

“This is a very important study that puts transcatheter heart valve implantation in a little bit different light,” said Dr. Kappetein, professor of cardiothoracic surgery at Erasmus University in Rotterdam, the Netherlands.

He noted that the surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) literature shows that the rate of structural valve deterioration is age related. It’s higher in 75-year-olds than in 85-year-olds, and higher still in 65-year-olds.

“Valve degeneration didn’t play a major role when we were doing TAVR in 80- and 85-year-olds because of their limited life expectancy, but it will play a role in younger patients. So I think we have to be careful before we move toward lower-risk patients,” the surgeon continued.

Dr. Jean-Francois Obadia, who performs both SAVR and TAVR, noted that the median duration of freedom from valve degeneration for Edwards Lifescience’s Carpentier surgical aortic valve is a hefty 17.9 years.

“This should be the gold standard,” declared Dr. Obadia, head of the department of adult cardiovascular surgery and heart transplantation at the Louis Pradel Cardiothoracic Hospital of Claude Bernard University in Lyon, France.

“Dr. Dvir’s study is one of the key messages we all should take back home: a 50% rate of valve deterioration at 8 years. Valve deterioration is the Achilles’ heel of bioprostheses. There is a lot of improvement left to do for the TAVR,” he said.

Dr. Dvir and others were quick to note that his long-term study was of necessity restricted to early-generation, balloon-expandable devices: the Cribier Edwards, Edwards Sapien, and Sapien XT valves. Contemporary valves, patient selection methods, and procedural techniques are far advanced in comparison.

“The Sapien 3 has much less paravalvular leakage than earlier-generation valves. Maybe with less paravalvular leakage and better hemodynamics there will be a decreased rate of degeneration. It could be. We need to see. We have to wait a few more years to see if later-generation transcatheter heart valves are more durable,” Dr. Dvir said.

To gain a better understanding of the full dimensions of the valve degeneration issue, he and his coinvestigators have formed the VALID (VAlve Long-term Durability International Data) registry. Operators interested in contributing patients to what is hoped will be a very large and informative data base are encouraged to contact Dr. Dvir ([email protected]).

In the meantime, he has reservations about extending TAVR to intermediate-risk patients outside of the rigorous clinical trial setting. He added that he’d feel far more comfortable in performing TAVR in intermediate-risk 70- to 75-year-olds if there was a tried and true valve-in-valve replacement method, something that doesn’t yet exist. The major limitation of current attempts at valve-in-valve replacement is underexpansion because the former valve doesn’t allow sufficient room for the new one to expand fully, resulting in residual stenosis.

“If you tell me that you can implant a platform that will enable a safe valve-in-valve procedure in 5, 7, 10 years – a less invasive bailout for a failed prosthetic valve – if you can do that safely and effectively I would be more keen to do TAVR even in a young patient,” the interventional cardiologist said.

He and others are working on this unmet need. Dr. Dvir’s novel valve, being developed with Edwards Lifesciences, has performed well in valve-in-valve procedures in cadavers and animals. The first clinical trials are being planned.

“We need to think always that a bioprosthetic valve is not a cure, it’s a palliation. We treat the patients, they feel better, but we leave them with some kind of a chronic disease that’s prone to thrombosis, prone to degeneration and failure, prone to many different things,” he reflected.

The study was conducted without commercial support. Dr. Dvir reported serving as a consultant to Edwards Lifesciences, Medtronic, and St. Jude Medical.

PARIS – The first-ever study of the long-term durability of transcatheter bioprosthetic aortic valves has documented a disturbing rise in the valve degeneration rate occurring 5-7 years post implant.

Prior consistently reassuring follow-up studies have been intermediate in length, with a maximum of 5 years. The PARTNER 2A trial, which generated enormous enthusiasm for moving TAVR to intermediate-risk patients on the basis of positive results presented at the 2016 meeting of the American College of Cardiology, reported 2-year results.

“We found, as have others, that there’s very little degeneration in the first 4 years: 94% freedom from degeneration. But at 6 years, it’s 82%, and we estimate that by 8 years, it’s about 50%,” Dr. Danny Dvir reported at the annual congress of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions.

“We need to be cautious: This is our first look at the data. But we have a signal for a problem,” said Dr. Dvir of St. Paul’s Hospital in Vancouver.

He presented a retrospective study of 378 patients who underwent TAVR 5-14 years ago at two pioneering centers for the procedure: St. Paul’s and Charles Nicolle Hospital in Rouen, France. Patients’ average age at the time of TAVR was 82.3 years, with an STS score of 8.3%. The study featured serial echocardiography conducted during house calls in this frail elderly population.

Thirty-five patients developed prosthetic valve degeneration, defined by at least moderate regurgitation and/or a mean gradient of at least 20 mm Hg in 23 cases and stenosis in 12. The risk of degeneration was unrelated to the use of warfarin, a finding that suggests the valve deterioration issue is unrelated to clotting. The strongest risk factor for transcatheter valve degeneration in this study was baseline renal failure at the time of TAVR.

Dr. Dvir’s presentation was the talk of the meeting, and it cast a pall over the proceedings. The red flag raised by the study regarding valve durability has major implications regarding the current enthusiasm among many interventional cardiologists to routinely extend TAVR to intermediate and even lower-risk patients. As one audience member later confessed, “I have felt sick since hearing that presentation.”

Discussant Dr. A. Pieter Kappetein observed that transcatheter heart valve durability was a hot topic of discussion about 4 years ago but subsequently faded below the radar as a concern – until Dr. Dvir’s study.

“This is a very important study that puts transcatheter heart valve implantation in a little bit different light,” said Dr. Kappetein, professor of cardiothoracic surgery at Erasmus University in Rotterdam, the Netherlands.

He noted that the surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) literature shows that the rate of structural valve deterioration is age related. It’s higher in 75-year-olds than in 85-year-olds, and higher still in 65-year-olds.

“Valve degeneration didn’t play a major role when we were doing TAVR in 80- and 85-year-olds because of their limited life expectancy, but it will play a role in younger patients. So I think we have to be careful before we move toward lower-risk patients,” the surgeon continued.

Dr. Jean-Francois Obadia, who performs both SAVR and TAVR, noted that the median duration of freedom from valve degeneration for Edwards Lifescience’s Carpentier surgical aortic valve is a hefty 17.9 years.

“This should be the gold standard,” declared Dr. Obadia, head of the department of adult cardiovascular surgery and heart transplantation at the Louis Pradel Cardiothoracic Hospital of Claude Bernard University in Lyon, France.

“Dr. Dvir’s study is one of the key messages we all should take back home: a 50% rate of valve deterioration at 8 years. Valve deterioration is the Achilles’ heel of bioprostheses. There is a lot of improvement left to do for the TAVR,” he said.

Dr. Dvir and others were quick to note that his long-term study was of necessity restricted to early-generation, balloon-expandable devices: the Cribier Edwards, Edwards Sapien, and Sapien XT valves. Contemporary valves, patient selection methods, and procedural techniques are far advanced in comparison.

“The Sapien 3 has much less paravalvular leakage than earlier-generation valves. Maybe with less paravalvular leakage and better hemodynamics there will be a decreased rate of degeneration. It could be. We need to see. We have to wait a few more years to see if later-generation transcatheter heart valves are more durable,” Dr. Dvir said.

To gain a better understanding of the full dimensions of the valve degeneration issue, he and his coinvestigators have formed the VALID (VAlve Long-term Durability International Data) registry. Operators interested in contributing patients to what is hoped will be a very large and informative data base are encouraged to contact Dr. Dvir ([email protected]).

In the meantime, he has reservations about extending TAVR to intermediate-risk patients outside of the rigorous clinical trial setting. He added that he’d feel far more comfortable in performing TAVR in intermediate-risk 70- to 75-year-olds if there was a tried and true valve-in-valve replacement method, something that doesn’t yet exist. The major limitation of current attempts at valve-in-valve replacement is underexpansion because the former valve doesn’t allow sufficient room for the new one to expand fully, resulting in residual stenosis.

“If you tell me that you can implant a platform that will enable a safe valve-in-valve procedure in 5, 7, 10 years – a less invasive bailout for a failed prosthetic valve – if you can do that safely and effectively I would be more keen to do TAVR even in a young patient,” the interventional cardiologist said.

He and others are working on this unmet need. Dr. Dvir’s novel valve, being developed with Edwards Lifesciences, has performed well in valve-in-valve procedures in cadavers and animals. The first clinical trials are being planned.

“We need to think always that a bioprosthetic valve is not a cure, it’s a palliation. We treat the patients, they feel better, but we leave them with some kind of a chronic disease that’s prone to thrombosis, prone to degeneration and failure, prone to many different things,” he reflected.

The study was conducted without commercial support. Dr. Dvir reported serving as a consultant to Edwards Lifesciences, Medtronic, and St. Jude Medical.

PARIS – The first-ever study of the long-term durability of transcatheter bioprosthetic aortic valves has documented a disturbing rise in the valve degeneration rate occurring 5-7 years post implant.

Prior consistently reassuring follow-up studies have been intermediate in length, with a maximum of 5 years. The PARTNER 2A trial, which generated enormous enthusiasm for moving TAVR to intermediate-risk patients on the basis of positive results presented at the 2016 meeting of the American College of Cardiology, reported 2-year results.

“We found, as have others, that there’s very little degeneration in the first 4 years: 94% freedom from degeneration. But at 6 years, it’s 82%, and we estimate that by 8 years, it’s about 50%,” Dr. Danny Dvir reported at the annual congress of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions.

“We need to be cautious: This is our first look at the data. But we have a signal for a problem,” said Dr. Dvir of St. Paul’s Hospital in Vancouver.

He presented a retrospective study of 378 patients who underwent TAVR 5-14 years ago at two pioneering centers for the procedure: St. Paul’s and Charles Nicolle Hospital in Rouen, France. Patients’ average age at the time of TAVR was 82.3 years, with an STS score of 8.3%. The study featured serial echocardiography conducted during house calls in this frail elderly population.

Thirty-five patients developed prosthetic valve degeneration, defined by at least moderate regurgitation and/or a mean gradient of at least 20 mm Hg in 23 cases and stenosis in 12. The risk of degeneration was unrelated to the use of warfarin, a finding that suggests the valve deterioration issue is unrelated to clotting. The strongest risk factor for transcatheter valve degeneration in this study was baseline renal failure at the time of TAVR.

Dr. Dvir’s presentation was the talk of the meeting, and it cast a pall over the proceedings. The red flag raised by the study regarding valve durability has major implications regarding the current enthusiasm among many interventional cardiologists to routinely extend TAVR to intermediate and even lower-risk patients. As one audience member later confessed, “I have felt sick since hearing that presentation.”

Discussant Dr. A. Pieter Kappetein observed that transcatheter heart valve durability was a hot topic of discussion about 4 years ago but subsequently faded below the radar as a concern – until Dr. Dvir’s study.

“This is a very important study that puts transcatheter heart valve implantation in a little bit different light,” said Dr. Kappetein, professor of cardiothoracic surgery at Erasmus University in Rotterdam, the Netherlands.

He noted that the surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) literature shows that the rate of structural valve deterioration is age related. It’s higher in 75-year-olds than in 85-year-olds, and higher still in 65-year-olds.

“Valve degeneration didn’t play a major role when we were doing TAVR in 80- and 85-year-olds because of their limited life expectancy, but it will play a role in younger patients. So I think we have to be careful before we move toward lower-risk patients,” the surgeon continued.

Dr. Jean-Francois Obadia, who performs both SAVR and TAVR, noted that the median duration of freedom from valve degeneration for Edwards Lifescience’s Carpentier surgical aortic valve is a hefty 17.9 years.

“This should be the gold standard,” declared Dr. Obadia, head of the department of adult cardiovascular surgery and heart transplantation at the Louis Pradel Cardiothoracic Hospital of Claude Bernard University in Lyon, France.

“Dr. Dvir’s study is one of the key messages we all should take back home: a 50% rate of valve deterioration at 8 years. Valve deterioration is the Achilles’ heel of bioprostheses. There is a lot of improvement left to do for the TAVR,” he said.

Dr. Dvir and others were quick to note that his long-term study was of necessity restricted to early-generation, balloon-expandable devices: the Cribier Edwards, Edwards Sapien, and Sapien XT valves. Contemporary valves, patient selection methods, and procedural techniques are far advanced in comparison.

“The Sapien 3 has much less paravalvular leakage than earlier-generation valves. Maybe with less paravalvular leakage and better hemodynamics there will be a decreased rate of degeneration. It could be. We need to see. We have to wait a few more years to see if later-generation transcatheter heart valves are more durable,” Dr. Dvir said.

To gain a better understanding of the full dimensions of the valve degeneration issue, he and his coinvestigators have formed the VALID (VAlve Long-term Durability International Data) registry. Operators interested in contributing patients to what is hoped will be a very large and informative data base are encouraged to contact Dr. Dvir ([email protected]).

In the meantime, he has reservations about extending TAVR to intermediate-risk patients outside of the rigorous clinical trial setting. He added that he’d feel far more comfortable in performing TAVR in intermediate-risk 70- to 75-year-olds if there was a tried and true valve-in-valve replacement method, something that doesn’t yet exist. The major limitation of current attempts at valve-in-valve replacement is underexpansion because the former valve doesn’t allow sufficient room for the new one to expand fully, resulting in residual stenosis.

“If you tell me that you can implant a platform that will enable a safe valve-in-valve procedure in 5, 7, 10 years – a less invasive bailout for a failed prosthetic valve – if you can do that safely and effectively I would be more keen to do TAVR even in a young patient,” the interventional cardiologist said.

He and others are working on this unmet need. Dr. Dvir’s novel valve, being developed with Edwards Lifesciences, has performed well in valve-in-valve procedures in cadavers and animals. The first clinical trials are being planned.

“We need to think always that a bioprosthetic valve is not a cure, it’s a palliation. We treat the patients, they feel better, but we leave them with some kind of a chronic disease that’s prone to thrombosis, prone to degeneration and failure, prone to many different things,” he reflected.

The study was conducted without commercial support. Dr. Dvir reported serving as a consultant to Edwards Lifesciences, Medtronic, and St. Jude Medical.

AT EUROPCR 2016

Key clinical point: The first study to examine transcatheter aortic bioprosthetic valve performance beyond 5 years has found a 50% rate of valve degeneration 8 years post TAVR.

Major finding: A sharp increase in the incidence of degeneration of these early-generation valves occurred 5-7 years post TAVR.

Data source: This retrospective study featured serial home echocardiography in 378 patients who underwent TAVR 5-14 years ago at two pioneering centers for the procedure.

Disclosures: The presenter of this study, conducted without commercial support, serves as a consultant to Edwards Lifesciences, Medtronic, and St. Jude Medical.

Zinbryta approved by FDA for relapsing forms of multiple sclerosis

Daclizumab (Zinbryta) has been approved as a patient-injected, once-monthly treatment for adults with relapsing forms of multiple sclerosis (MS), according to the Food and Drug Administration.

Daclizumab has serious safety risks, including severe and potentially life-threatening liver injury and immune disorders, and should generally be used only when patients have an inadequate response to two or more MS drugs, the FDA said in a press release. The drug has a boxed warning and is available only through a restricted distribution program under a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy.

Liver function tests should be performed before starting daclizumab, and liver function should be monitored monthly before each dose, and for up to 6 months after the last dose. Immune disorders associated with use of daclizumab include noninfectious colitis, skin reactions, and lymphadenopathy. Other highlighted warnings include anaphylaxis and angioedema, increased risk of infections, and symptoms of depression and suicidal ideation.

Daclizumab was associated with a reduction in clinical relapses in a comparator trial of 1,841 participants who received either daclizumab or interferon beta-1a (Avonex) and were studied for 144 weeks. Fewer relapses also were seen with daclizumab than with placebo in a second 52-week study of 412 participants.

The most common adverse reactions reported by patients receiving daclizumab in the comparator trial included nasopharyngitis, upper respiratory tract infection, rash, influenza, dermatitis, oropharyngeal pain, eczema, and enlargement of lymph nodes. The most common adverse reactions reported in the placebo trial were depression, rash, and increased levels of alanine aminotransferase.

Daclizumab will be marketed as Zinbryta by Biogen.

Read the FDA’s full statement on the FDA website.

Daclizumab (Zinbryta) has been approved as a patient-injected, once-monthly treatment for adults with relapsing forms of multiple sclerosis (MS), according to the Food and Drug Administration.

Daclizumab has serious safety risks, including severe and potentially life-threatening liver injury and immune disorders, and should generally be used only when patients have an inadequate response to two or more MS drugs, the FDA said in a press release. The drug has a boxed warning and is available only through a restricted distribution program under a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy.

Liver function tests should be performed before starting daclizumab, and liver function should be monitored monthly before each dose, and for up to 6 months after the last dose. Immune disorders associated with use of daclizumab include noninfectious colitis, skin reactions, and lymphadenopathy. Other highlighted warnings include anaphylaxis and angioedema, increased risk of infections, and symptoms of depression and suicidal ideation.

Daclizumab was associated with a reduction in clinical relapses in a comparator trial of 1,841 participants who received either daclizumab or interferon beta-1a (Avonex) and were studied for 144 weeks. Fewer relapses also were seen with daclizumab than with placebo in a second 52-week study of 412 participants.

The most common adverse reactions reported by patients receiving daclizumab in the comparator trial included nasopharyngitis, upper respiratory tract infection, rash, influenza, dermatitis, oropharyngeal pain, eczema, and enlargement of lymph nodes. The most common adverse reactions reported in the placebo trial were depression, rash, and increased levels of alanine aminotransferase.

Daclizumab will be marketed as Zinbryta by Biogen.

Read the FDA’s full statement on the FDA website.

Daclizumab (Zinbryta) has been approved as a patient-injected, once-monthly treatment for adults with relapsing forms of multiple sclerosis (MS), according to the Food and Drug Administration.

Daclizumab has serious safety risks, including severe and potentially life-threatening liver injury and immune disorders, and should generally be used only when patients have an inadequate response to two or more MS drugs, the FDA said in a press release. The drug has a boxed warning and is available only through a restricted distribution program under a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy.

Liver function tests should be performed before starting daclizumab, and liver function should be monitored monthly before each dose, and for up to 6 months after the last dose. Immune disorders associated with use of daclizumab include noninfectious colitis, skin reactions, and lymphadenopathy. Other highlighted warnings include anaphylaxis and angioedema, increased risk of infections, and symptoms of depression and suicidal ideation.

Daclizumab was associated with a reduction in clinical relapses in a comparator trial of 1,841 participants who received either daclizumab or interferon beta-1a (Avonex) and were studied for 144 weeks. Fewer relapses also were seen with daclizumab than with placebo in a second 52-week study of 412 participants.

The most common adverse reactions reported by patients receiving daclizumab in the comparator trial included nasopharyngitis, upper respiratory tract infection, rash, influenza, dermatitis, oropharyngeal pain, eczema, and enlargement of lymph nodes. The most common adverse reactions reported in the placebo trial were depression, rash, and increased levels of alanine aminotransferase.

Daclizumab will be marketed as Zinbryta by Biogen.

Read the FDA’s full statement on the FDA website.

Consider patient-centered outcomes in ventral hernia repair decision

CHICAGO – Elective ventral hernia repair improves hernia-related quality of life for low- to moderate-risk patients, according to findings from a prospective patient-centered study.

The findings suggest that the risks and benefits of a conservative operative strategy should be reassessed, and that patient-centered outcomes should be considered, Dr. Julie Holihan reported at the annual meeting of the American Surgical Association.

Of 152 patients with a ventral hernia from a single hernia clinic, 97 were managed non-operatively, and 55 were managed operatively. In a propensity-matched cohort of 90 patients with similar demographics, baseline comorbidities, and quality of life scores, only operatively managed patients had improved quality of life scores at 6 months (improvement from 34.7 to 56.9 vs. from 35.6 to 36.6), according to Dr. Holihan of the University of Texas, Houston.

Further, satisfaction scores increased significantly more in the operative than in the non-operative group at follow-up (from a median score of 2 at baseline in both groups to scores of 9 and 3, respectively), and pain scores decreased significantly more in the operative group than in the non-operative group (from a baseline score of 5 down to 3 in the operative group, with no change [score of 6] in the non-operative group).

Two surgical site infections and one hernia recurrence occurred in the operative group.

Notably, the predicted risk of surgery in the cohort was much greater than the observed risk.

“We may be overestimating surgical risk in these patients,” she said.

Based on a multivariable analysis in the overall cohort, non-operative management was strongly associated with lower quality of life score (coefficient, -26.5), Dr. Holihan said.

Nonoperative management of ventral hernias is often recommended for patients, particularly in those with increased risk of surgical complications due to factors such as obesity, poorly controlled diabetes, smoking, or significant comorbidities like coronary artery disease, but this approach to management has not been well studied with respect to patient-centered outcomes such as quality of life and function, she explained.

Traditional outcomes that have been studied, including infection and hernia recurrence, may not be the outcomes that are most important to patients, she added.

For the current study, patients with ventral hernias were prospectively enrolled between June 2014 and June 2015. Non-operative management was recommended for smokers, those with a body mass index greater than 33 kg/m2, and those with poorly controlled diabetes. Measured outcomes included surgical site infection, hernia recurrence, and quality of life using a validated quality of life measure.

This is the first prospective study comparing management strategies in ventral hernia patients with comorbidities, Dr. Holihan said.

She concluded that “the elective repair of ventral hernia, compared with non-operative management, improves patient-centered outcomes in similar-risk patients.”

“Furthermore, the low occurrence of complications suggests that we may be overestimating surgical risk and that we may be too conservative in our patient selection for elective ventral hernia repair. It may be time to reevaluate patient selection criteria in order to better incorporate patient-centered outcomes,” she said.

In response to a question about managing patients with higher risk and/or higher BMI, Dr. Holihan’s coauthor, Dr. Mike K. Liang, also of the University of Texas, Houston, noted that the findings of the study provide estimates for potential future randomized trials. He also noted that the moderate-risk patients at the center often undergo “prehabilitation,” or a preoperative exercise and diet program designed to help optimize outcomes. Currently, patients with BMI of 30-40 kg/m2 are randomized to preoperative rehabilitation vs. current care.

“BMI is a very important decision making factor. We were not able to pick a standardized point [with respect to BMI] for when to operate vs. non-operate. Because of that, we used BMI as a factor in developing our propensity score,” he said, explaining that this is why the propensity-matched groups had similar BMI, while the non-operative group in the overall cohort had substantially higher BMI.

A randomized trial on prehabilitation may be able to provide some insight into the effects of rapid changes in weight and how they affect outcomes in order to make the best choices regarding surgery.

“We do hypothesize that significant weight loss prior to surgery may improve outcomes, and may make the abdominal wall more compliant and enable us to tackle more challenging hernias. We also hypothesize that patients who have a sudden increase in weight after having their ventral hernia repaired may end up having worse outcomes. Hopefully in the next year we will be able to shed more light on these very important questions.”

The authors reported having no disclosures.

The complete manuscript of this presentation is anticipated to be published in the Annals of Surgery pending editorial review.

CHICAGO – Elective ventral hernia repair improves hernia-related quality of life for low- to moderate-risk patients, according to findings from a prospective patient-centered study.

The findings suggest that the risks and benefits of a conservative operative strategy should be reassessed, and that patient-centered outcomes should be considered, Dr. Julie Holihan reported at the annual meeting of the American Surgical Association.

Of 152 patients with a ventral hernia from a single hernia clinic, 97 were managed non-operatively, and 55 were managed operatively. In a propensity-matched cohort of 90 patients with similar demographics, baseline comorbidities, and quality of life scores, only operatively managed patients had improved quality of life scores at 6 months (improvement from 34.7 to 56.9 vs. from 35.6 to 36.6), according to Dr. Holihan of the University of Texas, Houston.

Further, satisfaction scores increased significantly more in the operative than in the non-operative group at follow-up (from a median score of 2 at baseline in both groups to scores of 9 and 3, respectively), and pain scores decreased significantly more in the operative group than in the non-operative group (from a baseline score of 5 down to 3 in the operative group, with no change [score of 6] in the non-operative group).

Two surgical site infections and one hernia recurrence occurred in the operative group.

Notably, the predicted risk of surgery in the cohort was much greater than the observed risk.

“We may be overestimating surgical risk in these patients,” she said.

Based on a multivariable analysis in the overall cohort, non-operative management was strongly associated with lower quality of life score (coefficient, -26.5), Dr. Holihan said.

Nonoperative management of ventral hernias is often recommended for patients, particularly in those with increased risk of surgical complications due to factors such as obesity, poorly controlled diabetes, smoking, or significant comorbidities like coronary artery disease, but this approach to management has not been well studied with respect to patient-centered outcomes such as quality of life and function, she explained.

Traditional outcomes that have been studied, including infection and hernia recurrence, may not be the outcomes that are most important to patients, she added.

For the current study, patients with ventral hernias were prospectively enrolled between June 2014 and June 2015. Non-operative management was recommended for smokers, those with a body mass index greater than 33 kg/m2, and those with poorly controlled diabetes. Measured outcomes included surgical site infection, hernia recurrence, and quality of life using a validated quality of life measure.

This is the first prospective study comparing management strategies in ventral hernia patients with comorbidities, Dr. Holihan said.

She concluded that “the elective repair of ventral hernia, compared with non-operative management, improves patient-centered outcomes in similar-risk patients.”

“Furthermore, the low occurrence of complications suggests that we may be overestimating surgical risk and that we may be too conservative in our patient selection for elective ventral hernia repair. It may be time to reevaluate patient selection criteria in order to better incorporate patient-centered outcomes,” she said.

In response to a question about managing patients with higher risk and/or higher BMI, Dr. Holihan’s coauthor, Dr. Mike K. Liang, also of the University of Texas, Houston, noted that the findings of the study provide estimates for potential future randomized trials. He also noted that the moderate-risk patients at the center often undergo “prehabilitation,” or a preoperative exercise and diet program designed to help optimize outcomes. Currently, patients with BMI of 30-40 kg/m2 are randomized to preoperative rehabilitation vs. current care.

“BMI is a very important decision making factor. We were not able to pick a standardized point [with respect to BMI] for when to operate vs. non-operate. Because of that, we used BMI as a factor in developing our propensity score,” he said, explaining that this is why the propensity-matched groups had similar BMI, while the non-operative group in the overall cohort had substantially higher BMI.

A randomized trial on prehabilitation may be able to provide some insight into the effects of rapid changes in weight and how they affect outcomes in order to make the best choices regarding surgery.

“We do hypothesize that significant weight loss prior to surgery may improve outcomes, and may make the abdominal wall more compliant and enable us to tackle more challenging hernias. We also hypothesize that patients who have a sudden increase in weight after having their ventral hernia repaired may end up having worse outcomes. Hopefully in the next year we will be able to shed more light on these very important questions.”

The authors reported having no disclosures.

The complete manuscript of this presentation is anticipated to be published in the Annals of Surgery pending editorial review.

CHICAGO – Elective ventral hernia repair improves hernia-related quality of life for low- to moderate-risk patients, according to findings from a prospective patient-centered study.

The findings suggest that the risks and benefits of a conservative operative strategy should be reassessed, and that patient-centered outcomes should be considered, Dr. Julie Holihan reported at the annual meeting of the American Surgical Association.

Of 152 patients with a ventral hernia from a single hernia clinic, 97 were managed non-operatively, and 55 were managed operatively. In a propensity-matched cohort of 90 patients with similar demographics, baseline comorbidities, and quality of life scores, only operatively managed patients had improved quality of life scores at 6 months (improvement from 34.7 to 56.9 vs. from 35.6 to 36.6), according to Dr. Holihan of the University of Texas, Houston.

Further, satisfaction scores increased significantly more in the operative than in the non-operative group at follow-up (from a median score of 2 at baseline in both groups to scores of 9 and 3, respectively), and pain scores decreased significantly more in the operative group than in the non-operative group (from a baseline score of 5 down to 3 in the operative group, with no change [score of 6] in the non-operative group).

Two surgical site infections and one hernia recurrence occurred in the operative group.

Notably, the predicted risk of surgery in the cohort was much greater than the observed risk.

“We may be overestimating surgical risk in these patients,” she said.

Based on a multivariable analysis in the overall cohort, non-operative management was strongly associated with lower quality of life score (coefficient, -26.5), Dr. Holihan said.

Nonoperative management of ventral hernias is often recommended for patients, particularly in those with increased risk of surgical complications due to factors such as obesity, poorly controlled diabetes, smoking, or significant comorbidities like coronary artery disease, but this approach to management has not been well studied with respect to patient-centered outcomes such as quality of life and function, she explained.

Traditional outcomes that have been studied, including infection and hernia recurrence, may not be the outcomes that are most important to patients, she added.

For the current study, patients with ventral hernias were prospectively enrolled between June 2014 and June 2015. Non-operative management was recommended for smokers, those with a body mass index greater than 33 kg/m2, and those with poorly controlled diabetes. Measured outcomes included surgical site infection, hernia recurrence, and quality of life using a validated quality of life measure.

This is the first prospective study comparing management strategies in ventral hernia patients with comorbidities, Dr. Holihan said.

She concluded that “the elective repair of ventral hernia, compared with non-operative management, improves patient-centered outcomes in similar-risk patients.”

“Furthermore, the low occurrence of complications suggests that we may be overestimating surgical risk and that we may be too conservative in our patient selection for elective ventral hernia repair. It may be time to reevaluate patient selection criteria in order to better incorporate patient-centered outcomes,” she said.

In response to a question about managing patients with higher risk and/or higher BMI, Dr. Holihan’s coauthor, Dr. Mike K. Liang, also of the University of Texas, Houston, noted that the findings of the study provide estimates for potential future randomized trials. He also noted that the moderate-risk patients at the center often undergo “prehabilitation,” or a preoperative exercise and diet program designed to help optimize outcomes. Currently, patients with BMI of 30-40 kg/m2 are randomized to preoperative rehabilitation vs. current care.

“BMI is a very important decision making factor. We were not able to pick a standardized point [with respect to BMI] for when to operate vs. non-operate. Because of that, we used BMI as a factor in developing our propensity score,” he said, explaining that this is why the propensity-matched groups had similar BMI, while the non-operative group in the overall cohort had substantially higher BMI.

A randomized trial on prehabilitation may be able to provide some insight into the effects of rapid changes in weight and how they affect outcomes in order to make the best choices regarding surgery.

“We do hypothesize that significant weight loss prior to surgery may improve outcomes, and may make the abdominal wall more compliant and enable us to tackle more challenging hernias. We also hypothesize that patients who have a sudden increase in weight after having their ventral hernia repaired may end up having worse outcomes. Hopefully in the next year we will be able to shed more light on these very important questions.”

The authors reported having no disclosures.

The complete manuscript of this presentation is anticipated to be published in the Annals of Surgery pending editorial review.

AT THE ASA ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: Elective ventral hernia repair improves hernia-related quality of life for low- to moderate-risk patients, according to findings from a prospective patient-centered study.

Major finding: In a propensity-matched cohort, only operatively managed patients had improved quality of life scores at 6 months (improvement from 34.7 to 56.9 vs. from 35.6 to 36.6 for nonoperative patients).

Data source: A prospective patient-centered study of 152 patients.

Disclosures: The authors reported having no disclosures.

Persistent Cough, Peculiar Heart Sound

ANSWER

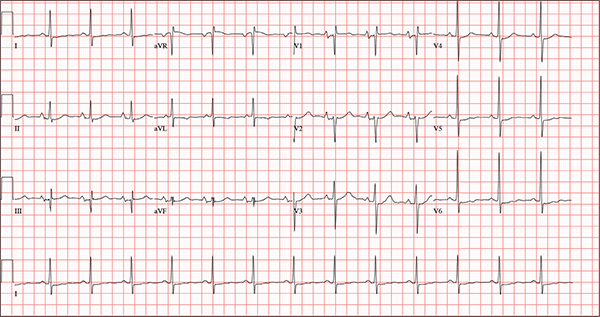

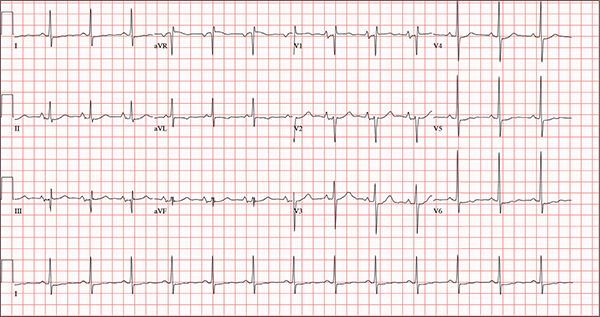

The correct interpretation of this ECG includes normal sinus rhythm, biatrial enlargement, nonspecific ST-T wave abnormality, and an RSR’ or QR pattern in V1, suggestive of right ventricular conduction delay.

Biatrial enlargement by definition encompasses right atrial enlargement (criteria include P waves in leads II, III, and aVF measuring 2.5 mm or more) and left atrial enlargement (evidenced by P waves in lead I ≥ 110 ms, and a biphasic, or “notched,” P wave with terminal negativity in lead V1).

Lead V1 may be interpreted as either an RSR’ or a QR pattern. However, the QRS duration of < 120 ms precludes this from meeting criteria for a right bundle branch block.

Finally, nonspecific ST-T wave changes were present in the precordial leads. These may be consistent with pulmonary disease.

ANSWER

The correct interpretation of this ECG includes normal sinus rhythm, biatrial enlargement, nonspecific ST-T wave abnormality, and an RSR’ or QR pattern in V1, suggestive of right ventricular conduction delay.

Biatrial enlargement by definition encompasses right atrial enlargement (criteria include P waves in leads II, III, and aVF measuring 2.5 mm or more) and left atrial enlargement (evidenced by P waves in lead I ≥ 110 ms, and a biphasic, or “notched,” P wave with terminal negativity in lead V1).

Lead V1 may be interpreted as either an RSR’ or a QR pattern. However, the QRS duration of < 120 ms precludes this from meeting criteria for a right bundle branch block.

Finally, nonspecific ST-T wave changes were present in the precordial leads. These may be consistent with pulmonary disease.

ANSWER

The correct interpretation of this ECG includes normal sinus rhythm, biatrial enlargement, nonspecific ST-T wave abnormality, and an RSR’ or QR pattern in V1, suggestive of right ventricular conduction delay.

Biatrial enlargement by definition encompasses right atrial enlargement (criteria include P waves in leads II, III, and aVF measuring 2.5 mm or more) and left atrial enlargement (evidenced by P waves in lead I ≥ 110 ms, and a biphasic, or “notched,” P wave with terminal negativity in lead V1).

Lead V1 may be interpreted as either an RSR’ or a QR pattern. However, the QRS duration of < 120 ms precludes this from meeting criteria for a right bundle branch block.

Finally, nonspecific ST-T wave changes were present in the precordial leads. These may be consistent with pulmonary disease.

A 54-year-old man presents with a four-day history of productive cough, low-grade fever, and malaise. The patient, a long-haul trucker, has been on the road for the past 30 days, traveling from Florida to California, and then to New Jersey. He first noticed a change in his cough after leaving Chicago. He says he’s tried OTC cough syrups to no avail, and he wants you to prescribe antibiotics so he can get back to work. He denies blood in his sputum; the specimen he provides on request is yellow, mucoid, and malodorous. You know this patient well: He has been in your patient panel for the past five years. His active problem list includes chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hypertension, type 2 diabetes, obesity, and heavy tobacco use. He is rarely compliant with any of the treatment regimens you prescribe, and he frequently misses scheduled appointments due to his job. The patient is divorced, with no children, and spends most of his time on the road. His family history is remarkable for diabetes and hypertension in both parents. He had a history of binge drinking in his early 20s but has never had a citation for driving under the influence. He denies current recreational drug use, but he admits to using amphetamines prior to his employer’s mandatory drug monitoring. He smokes 2 to 2.5 packs of cigarettes per day and always has one in his mouth. His surgical history includes appendectomy and cholecystectomy, as well as two laparoscopic procedures for abdominal adhesions. His current medication list includes an albuterol inhaler, hydrochlorothiazide, metoprolol, and metformin; however, he states he rarely takes any of them on a daily basis. He is allergic to tetracycline, which produces urticaria and a rash. Vital signs include a blood pressure of 168/114 mm Hg; pulse, 80 beats/min; respiratory rate, 14 breaths/min-1; O2 saturation, 92% on room air; and temperature, 101°F. The review of systems is positive for headaches, toothache in numbers 13 and 14, and bleeding hemorrhoids. The remainder of the review is noncontributory. The physical exam reveals a disheveled male who appears uncomfortable and diaphoretic. His weight is 314 lb and his height, 70 in. Pertinent physical findings include consolidation in the right lower chest that does not change with coughing. He has coarse respiratory sounds in all other lung fields. There are no murmurs or rubs; however, there is a fixed, split-second heart sound that you haven’t heard in previous exams. The patient’s abdomen is rotund and nontender, with wellhealed surgical scars. Two large, inflamed hemorrhoids are present, and a stool guaiac test is positive for blood. The peripheral exam reveals 2+ bilateral pitting edema. All pulses are full, and there are no focal neurologic abnormalities. Given your concern about the unfamiliar heart sound, you order an ECG in addition to laboratory bloodwork and chest x-ray. The white blood cell count measures 12.4 x 1,000 μL, and the chest xray is consistent with right lower lobe pneumonia. The ECG reveals a ventricular rate of 82 beats/min; PR interval, 148 ms; QRS duration, 82 ms; QT/QTc interval, 378/441 ms; P axis, 42°; R wave axis, 20°; and T axis, 96°. What is your interpretation of this ECG?

Case of colistin-resistant E. coli identified in the United States

In what is believed to be the first case of its kind in the United States, researchers identified a female patient with colistin-resistant Escherichia coli. The patient harbored mcr-1, a gene resistant to colistin, an antibiotic used as a last resort for infections that are resistant to carbapenems.

The finding comes at a time when a search for colistin-resistant bacteria by officials from the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services revealed colistin-resistant E. coli in a single sample from a pig intestine. Combined, “these discoveries are of concern because colistin is used as a last-resort drug to treat patients with multidrug resistant infections,” according to a communication from the HHS dated May 26. “Finding colistin-resistant bacteria in the United States is important, as it was only last November that scientists in China first reported that the mcr-1 gene in bacteria confers colistin resistance.”

Researchers led by Patrick McGann, Ph.D., who reported the human case in an article published online May 26 in Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, wrote that the recent discovery of a plasmid-borne colistin resistance gene, mcr-1, “heralds the emergence of truly pan-drug resistant bacteria. The gene has been found primarily in Escherichia coli, but has also been identified in other members of the Enterobacteriaceae from human, animal, food and environmental samples on every continent” (Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2016 May 26. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01103-16).

As a result of this threat, in May, Dr. McGann, of the Department of Defense’s Multidrug-resistant Organism Repository and Surveillance Network at Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, Silver Spring, Md., and his associates began analyzing all extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)–producing E. coli clinical isolates submitted to Walter Reed National Military Medical Center for analysis for resistance to colistin by E-test.

The case of interest was the presence of mcr-1 in an E. coli isolate cultured from a 49-year-old woman who presented to a military clinic in Pennsylvania with symptoms suggestive of a urinary tract infection, and who reported no travel history within the prior 5 months. Susceptibility testing at Walter Reed indicated an ESBL phenotype.

“The isolate was included in the first 6 ESBL-producing E. coli selected for colistin susceptibility testing, and it was the only isolate to have a MIC of colistin of 4 mcg/mL [all others had MICs of 0.25 mcg/mL or less]. Colistin MIC was confirmed by microbroth dilution and mcr-1 detected by real-time PCR.”

Since mcr-1 testing at Walter Reed has been underway for a short time, “it remains unclear what the true prevalence of mcr-1 is in the population,” the researchers noted. “The association between mcr-1 and IncF plasmids is concerning as these plasmids are vehicles for the dissemination of antibiotic resistance and virulence genes against Enterobacteriaceae. Continued surveillance to determine the true frequency for this gene in the USA is critical.”

The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

In what is believed to be the first case of its kind in the United States, researchers identified a female patient with colistin-resistant Escherichia coli. The patient harbored mcr-1, a gene resistant to colistin, an antibiotic used as a last resort for infections that are resistant to carbapenems.

The finding comes at a time when a search for colistin-resistant bacteria by officials from the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services revealed colistin-resistant E. coli in a single sample from a pig intestine. Combined, “these discoveries are of concern because colistin is used as a last-resort drug to treat patients with multidrug resistant infections,” according to a communication from the HHS dated May 26. “Finding colistin-resistant bacteria in the United States is important, as it was only last November that scientists in China first reported that the mcr-1 gene in bacteria confers colistin resistance.”

Researchers led by Patrick McGann, Ph.D., who reported the human case in an article published online May 26 in Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, wrote that the recent discovery of a plasmid-borne colistin resistance gene, mcr-1, “heralds the emergence of truly pan-drug resistant bacteria. The gene has been found primarily in Escherichia coli, but has also been identified in other members of the Enterobacteriaceae from human, animal, food and environmental samples on every continent” (Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2016 May 26. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01103-16).

As a result of this threat, in May, Dr. McGann, of the Department of Defense’s Multidrug-resistant Organism Repository and Surveillance Network at Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, Silver Spring, Md., and his associates began analyzing all extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)–producing E. coli clinical isolates submitted to Walter Reed National Military Medical Center for analysis for resistance to colistin by E-test.

The case of interest was the presence of mcr-1 in an E. coli isolate cultured from a 49-year-old woman who presented to a military clinic in Pennsylvania with symptoms suggestive of a urinary tract infection, and who reported no travel history within the prior 5 months. Susceptibility testing at Walter Reed indicated an ESBL phenotype.

“The isolate was included in the first 6 ESBL-producing E. coli selected for colistin susceptibility testing, and it was the only isolate to have a MIC of colistin of 4 mcg/mL [all others had MICs of 0.25 mcg/mL or less]. Colistin MIC was confirmed by microbroth dilution and mcr-1 detected by real-time PCR.”

Since mcr-1 testing at Walter Reed has been underway for a short time, “it remains unclear what the true prevalence of mcr-1 is in the population,” the researchers noted. “The association between mcr-1 and IncF plasmids is concerning as these plasmids are vehicles for the dissemination of antibiotic resistance and virulence genes against Enterobacteriaceae. Continued surveillance to determine the true frequency for this gene in the USA is critical.”

The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

In what is believed to be the first case of its kind in the United States, researchers identified a female patient with colistin-resistant Escherichia coli. The patient harbored mcr-1, a gene resistant to colistin, an antibiotic used as a last resort for infections that are resistant to carbapenems.

The finding comes at a time when a search for colistin-resistant bacteria by officials from the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services revealed colistin-resistant E. coli in a single sample from a pig intestine. Combined, “these discoveries are of concern because colistin is used as a last-resort drug to treat patients with multidrug resistant infections,” according to a communication from the HHS dated May 26. “Finding colistin-resistant bacteria in the United States is important, as it was only last November that scientists in China first reported that the mcr-1 gene in bacteria confers colistin resistance.”

Researchers led by Patrick McGann, Ph.D., who reported the human case in an article published online May 26 in Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, wrote that the recent discovery of a plasmid-borne colistin resistance gene, mcr-1, “heralds the emergence of truly pan-drug resistant bacteria. The gene has been found primarily in Escherichia coli, but has also been identified in other members of the Enterobacteriaceae from human, animal, food and environmental samples on every continent” (Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2016 May 26. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01103-16).

As a result of this threat, in May, Dr. McGann, of the Department of Defense’s Multidrug-resistant Organism Repository and Surveillance Network at Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, Silver Spring, Md., and his associates began analyzing all extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)–producing E. coli clinical isolates submitted to Walter Reed National Military Medical Center for analysis for resistance to colistin by E-test.

The case of interest was the presence of mcr-1 in an E. coli isolate cultured from a 49-year-old woman who presented to a military clinic in Pennsylvania with symptoms suggestive of a urinary tract infection, and who reported no travel history within the prior 5 months. Susceptibility testing at Walter Reed indicated an ESBL phenotype.

“The isolate was included in the first 6 ESBL-producing E. coli selected for colistin susceptibility testing, and it was the only isolate to have a MIC of colistin of 4 mcg/mL [all others had MICs of 0.25 mcg/mL or less]. Colistin MIC was confirmed by microbroth dilution and mcr-1 detected by real-time PCR.”

Since mcr-1 testing at Walter Reed has been underway for a short time, “it remains unclear what the true prevalence of mcr-1 is in the population,” the researchers noted. “The association between mcr-1 and IncF plasmids is concerning as these plasmids are vehicles for the dissemination of antibiotic resistance and virulence genes against Enterobacteriaceae. Continued surveillance to determine the true frequency for this gene in the USA is critical.”

The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

FROM ANTIMICROBIAL AGENTS AND CHEMOTHERAPY

Key clinical point: Researchers have identified the first case of colistin-resistant E. coli in the United States.

Major finding: Mcr-1 was present in an E. coli sampled from a patient with a urinary tract infection in the United States.

Data source: A case report of a 49-year-old woman who presented to a military clinic in Pennsylvania with symptoms suggestive of a urinary tract infection.

Disclosures: The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

Family psychiatry considers key issues

These are exciting times for family psychiatry. In this column, I would like to sum up some of the key themes from the recent American Psychiatric Association meeting in Atlanta and how family fits in.

The Association of Family Psychiatrists (AFP), which has been in existence for about 40 years as an APA Allied organization, met last month during the APA annual meeting. Dr. Greg Miller is our representative on the Assembly Committee of Representatives of Subspecialties and Sections (ACROSS). This representation gives us an opportunity to ensure that family is considered in APA initiatives.

Who are we?

AFP psychiatrists are chairs of departments, residency directors, medical directors of general and psychiatric hospitals, child psychiatrists, and psychiatrists in private practice. Our members also are residents and allied members, such as psychologists, and directors of family and consumer organizations. One such organization is Families for Depression Awareness (familyaware.org). Its current executive director, Marlin W. Collingwood II and director of development, Valerie Cordero, attended our meeting, and encouraged us to include patient and family advocates in our presentations and activities.

Our meeting was sponsored by the Family Process Institute (FPI), most widely known for its journal, Family Process, the preeminent family therapy journal worldwide. We were pleased that Nadine J. Kaslow, Ph.D., attended. Not only is she a former director of FPI, but also she is the former editor of the Journal of Family Psychology. Dr. Kaslow, professor and vice chair for faculty development in the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Emory University, Atlanta, also is the 2014 president of the American Psychological Association.

What do we do?

We discussed the changes in our specialty, mainly the broadening of family psychiatry to include family inclusion and family psychoeducation, and community involvement of families. We identified many opportunities to include in global health, integrated care in primary care, and specialty care. We announced a new book that I wrote with three other AFP members: Dr. Ira D. Glick; Douglas S. Rait, Ph.D.; and Dr. Michael S. Ascher. The book is called “Couples & Family Therapy in Clinical Practice,” 5th Edition (see www.wiley.com).

Also, at this meeting, we presented the 2016 winners for the Residency Recognition Award for Excellence in Family-Oriented Care:

• Dr. Jessica Abellard, Cooper Medical School of Rowan University, Camden, N.J.

• Dr. Aislinn Bird, Stanford (Calif.) University.

• Dr. Oliver Harper, NYU Langone Medical Center.

• Dr. Randi Libbon, University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora.

• Dr. Richa Maheshwari, NYC Langone Medical Center.

• Dr. Josh Nelson, University of Rochester, New York

• Dr. Mitali Patnaik, Drexel University, Philadelphia.

• Dr. Puneet Sahota, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

AFP’s presence at the APA

Many members of AFP and other psychiatrists interested in family care presented at the APA.

Dr. Sarah A. Nguyen and her colleagues, Dr. Daniel Patterson, social worker Madeleine S. Abrams, and Dr. Andrea Weiss, from Montefiore Medical Center, New York, presented a poster: “Importance and Utilization of Family Therapy in Training: Resident Perspectives.” Dr. Nguyen and her colleagues noted that only eight residency programs nationwide provide in-depth training in family skills and therapy. Their poster provided a PGY-4 resident perspective on the significance that family therapy training has in understanding the ways in which the context of family and larger systems has an impact on the individual.

An understanding of the resident’s own family, cultural, and social context also serves as the springboard to broaden the individual biopsychosocial conceptualization. This personal development was an essential turning point for continued professional development, as the progression of each year of training allowed for a greater appreciation of the complexity of the individual within the family and larger systems context.

Working with cultural psychiatrists

Several cultural psychiatrists are members of AFP and the Society for the Study of Psychiatry and Culture (SSPC). Psychiatry has evolved from the study of the individual to the study of culture, with minimal discussion of the family that mediates between the individual and the culture. Two APA workshops addressed this gap in theory and practice: “Contextualizing the patient interview” (which I conducted this with Dr. Ellen M. Berman) and “Cultural Family Therapy” (Dr. Vincenzo Di Nicola and Dr. Berman). The theme of SSPC’s 38th annual meeting, which will run from April 27-29, 2017, in Philadelphia, will focus on the role of family in culture (See psychiatryandculture.org) for details.

Dr. Francis G. Lu, presenting at his 32nd consecutive APA, gave the APA Distinguished Psychiatrist Lecture on Cultural Psychiatry. He also held a media session called “The Resilience of Family in Film: Aparajito.” This movie by Indian director Satyajit Ray depicts love, loss, tragedy, and resilience in the family of Apu. Dr. Lu led the audience through a nuanced discussion about the power of film to enhance our understanding of “other” and culture, and its impact on our practice.

“Liminal” or “threshold” people are terms that Dr. Di Nicola uses to describe people at the margins of society. These are people who are most at risk for illness. Immigrants, one type of threshold people, tend to congregate in close family communities. Addressing the family as a unit acknowledges the family’s role as the bearer of culture, and as the bearer and interpreter of illness and health. Dr. Di Nicola states: “I believe that each family is the bearer of the culture within which it is embedded and the vehicle for intergenerational transmission, for maintaining culture, and for generating its own small scale cultural adaptations, yielding three yoked family functions: cultural transmissions, cultural maintenance/coherence, and cultural adaptation” (For details, see http://www.slideshare.net/PhiloShrink/cultural-family-therapy-integrating-family-therapy-with-cultural-psychiatry).

Working in global mental health

Once again, psychiatry is beginning to recognize the importance of the social determinants of health. Severe stress tied to rapid and massive culture change, social trauma that occurs with immigration, and the experience of refugees, war, incarceration, all affect the health of the family and individuals.

Dr. James Griffith, chair of the department of psychiatry at George Washington University, Washington, promotes the inclusion of families in global mental health. Few mental health providers are on the global stage, and so families essentially act as health care extenders. Prior to current hospital practice, families would stay in hospital waiting rooms and sleep by the patient’s bedside. Families took care of patients, feeding and changing them, and assisting the nurses. Families provided reassurance, support and comfort to their sick relatives and acted as their advocates. In China, in American mission-run hospitals, families were indispensable (“Family-Centred Care in American Hospitals in Late-Qing China,” Clio Medica, 2009;86:55). In the 19th century, fear of infectious diseases prompted hospitals to discourage this practice.

Today, in developing countries, families are still indispensable – both for medical and psychiatric care. Families can be educated and welcomed as members of the treatment team.

Understanding the patient’s family system and its relationship to the culture at large is indispensable when developing effective interventions. Providers who can initiate discussions with families about the stigma of mental illness, etiology, and relapse prevention, and set the stage for better patient outcomes. Families with cell phones can be given access to Internet educational and patient care programs.

Integrating families into health care

Dr. Eliot Sorel, an internationally recognized global health leader, educator, and health systems policy expert, advocates for moving mental health into public health. The fragmentation of the health care system makes it imperative that families understand the challenges of navigating the health care system. APA public health position papers can be amended to include the wording “patient- and family-centered care.” The integration of physical and mental health in the delivery of general health care allows for many opportunities for family involvement. Dr. Atul Gawande, the foremost physician spokesperson for health care reform, focuses on the need for team-based health care reform, from the bedside to population management. Family members are key people on the health care team.

Relational psychiatry and the DSM

Family psychiatry is sometimes referred to as relational psychiatry. The study of relationships range from courting behaviors, attraction, marriage, child rearing, interpersonal violence, and grieving. Attachment theory helps us understand the strong bonds between family members, and the formation of individual and family identity. At a social level, the bonds between the family and society/culture/community are looser but still strong and contribute to a sense of belonging.

There has been a strong push for including relational diagnoses in the DSM. The rationale for inclusion is twofold: to bring attention to relational difficulties and to bring validation to those diagnoses tied to insurance coverage and payment. For a debate with Dr. Marianne Z. Wamboldt about the pros and cons of the inclusion of relational diagnoses in the DSM see “Relational Diagnoses and the DSM,” Clinical Psychiatry News, Families in Psychiatry, Oct. 19, 2012).

Currently as psychiatrists, we bill family meetings and consultations using codes 90846 and 90847. Meeting families occurs as part of the initial assessment of the patient. This interview assesses for strengths and stressors in the family system, and can be billed as part of the initial assessment. With the move to population health care, we will begin to see changes in physician reimbursement and increased recognition of the role of families in contextualizing the patient’s experience.

Families and advocacy

The Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act of 2008, or the Parity Act, requires health insurance carriers to achieve coverage parity between Mental Health/Substance Use Disorders (MH/SUD) and medical/surgical benefits. The MHPAEA originally applied to group health plans and group health insurance coverage, and was amended by the Affordable Care Act to apply also to individual health insurance coverage. The Parity Act was the signature achievement of former Rep. Patrick J. Kennedy’s 16 years in Congress. At the APA, Mr. Kennedy said: “The brain is an organ – a part of the body – and needs to be covered like all other organs.” He encouraged us to continue to advocate for the rights of people with mental illness. In his writing and advocacy work, he frequently references his own family. His is one of the many ways of doing family work.

Looking for allies

AFP has allies in all areas of psychiatry. Family psychiatrists think family in all subspecialties, from child psychiatry, psychosomatic medicine, global health to geriatric psychiatry. Where ever we work, we emphasize the importance of including families in patient care, and educating and supporting families, and when needed, providing family therapy or access to family therapy. Our activities are described on our website, www.familypsychiatrists.org. We welcome any psychiatrists interested in integrating family care into their specialty area. Those interested in joining us should contact our president, Dr. Berman, at [email protected].

Providers who can initiate discussions with families about the stigma of mental illness, etiology, and relapse prevention, set the stage for better patient outcomes. Families with cell phones can be given access to Internet educational and patient care programs.

As psychiatry continues to evolve and become more evidence-based, let us research how to use the strengths that lie within the family system, acknowledging the support that patients find among their families and communities. As former Rep. Kennedy states: “Our country is a young country, and we are still finding out who we are.” In a similar way, psychiatry is a young medical specialty. Let us become a specialty that truly honors families.

The Family Process Institute offers a writing workshop to emerging writers in family therapy that is open to all residents and early career psychiatrists. See www.familyprocess.org/newwriters for details.

Dr. Heru is professor of psychiatry at the University of Colorado, Denver. She is the author of several books, including “Working With Families in Medical Settings: A Multidisciplinary Guide for Psychiatrists and Other Health Professionals” (Routledge, 2013).

These are exciting times for family psychiatry. In this column, I would like to sum up some of the key themes from the recent American Psychiatric Association meeting in Atlanta and how family fits in.

The Association of Family Psychiatrists (AFP), which has been in existence for about 40 years as an APA Allied organization, met last month during the APA annual meeting. Dr. Greg Miller is our representative on the Assembly Committee of Representatives of Subspecialties and Sections (ACROSS). This representation gives us an opportunity to ensure that family is considered in APA initiatives.

Who are we?

AFP psychiatrists are chairs of departments, residency directors, medical directors of general and psychiatric hospitals, child psychiatrists, and psychiatrists in private practice. Our members also are residents and allied members, such as psychologists, and directors of family and consumer organizations. One such organization is Families for Depression Awareness (familyaware.org). Its current executive director, Marlin W. Collingwood II and director of development, Valerie Cordero, attended our meeting, and encouraged us to include patient and family advocates in our presentations and activities.

Our meeting was sponsored by the Family Process Institute (FPI), most widely known for its journal, Family Process, the preeminent family therapy journal worldwide. We were pleased that Nadine J. Kaslow, Ph.D., attended. Not only is she a former director of FPI, but also she is the former editor of the Journal of Family Psychology. Dr. Kaslow, professor and vice chair for faculty development in the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Emory University, Atlanta, also is the 2014 president of the American Psychological Association.

What do we do?

We discussed the changes in our specialty, mainly the broadening of family psychiatry to include family inclusion and family psychoeducation, and community involvement of families. We identified many opportunities to include in global health, integrated care in primary care, and specialty care. We announced a new book that I wrote with three other AFP members: Dr. Ira D. Glick; Douglas S. Rait, Ph.D.; and Dr. Michael S. Ascher. The book is called “Couples & Family Therapy in Clinical Practice,” 5th Edition (see www.wiley.com).

Also, at this meeting, we presented the 2016 winners for the Residency Recognition Award for Excellence in Family-Oriented Care:

• Dr. Jessica Abellard, Cooper Medical School of Rowan University, Camden, N.J.

• Dr. Aislinn Bird, Stanford (Calif.) University.

• Dr. Oliver Harper, NYU Langone Medical Center.

• Dr. Randi Libbon, University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora.

• Dr. Richa Maheshwari, NYC Langone Medical Center.

• Dr. Josh Nelson, University of Rochester, New York

• Dr. Mitali Patnaik, Drexel University, Philadelphia.

• Dr. Puneet Sahota, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

AFP’s presence at the APA

Many members of AFP and other psychiatrists interested in family care presented at the APA.