User login

Industry funding falls for rheumatology research

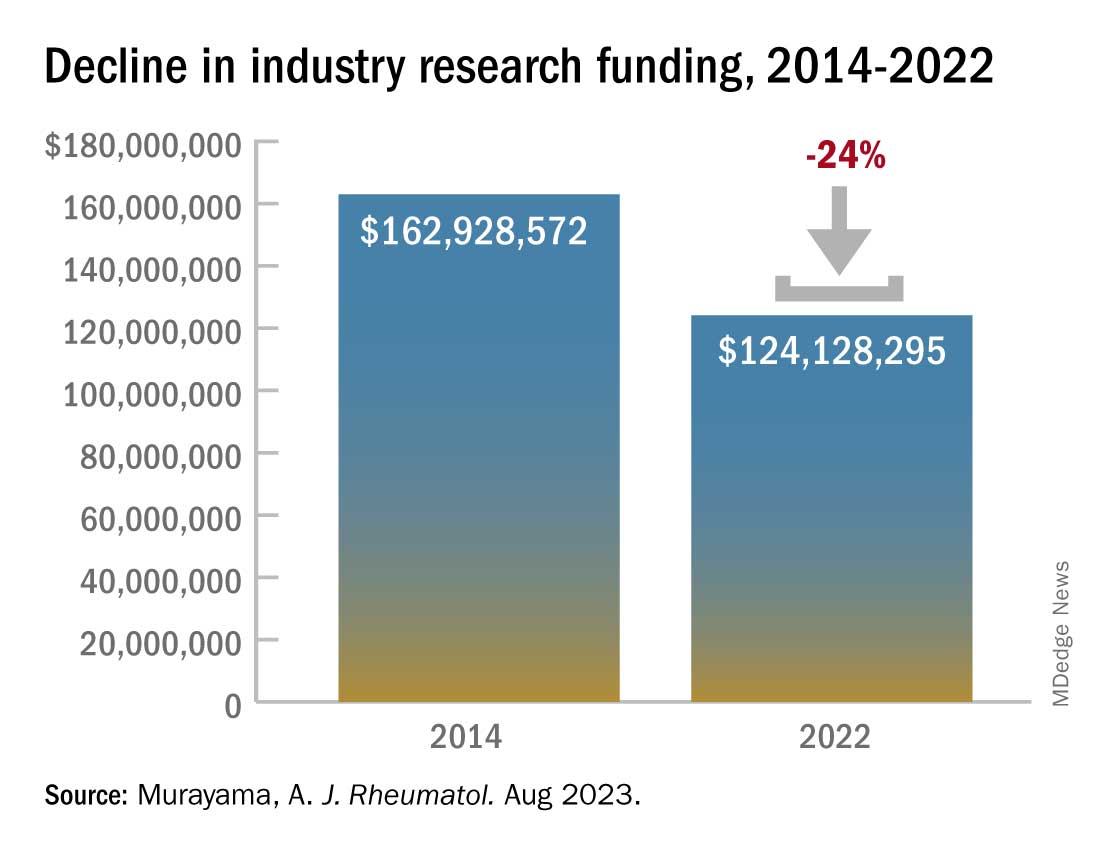

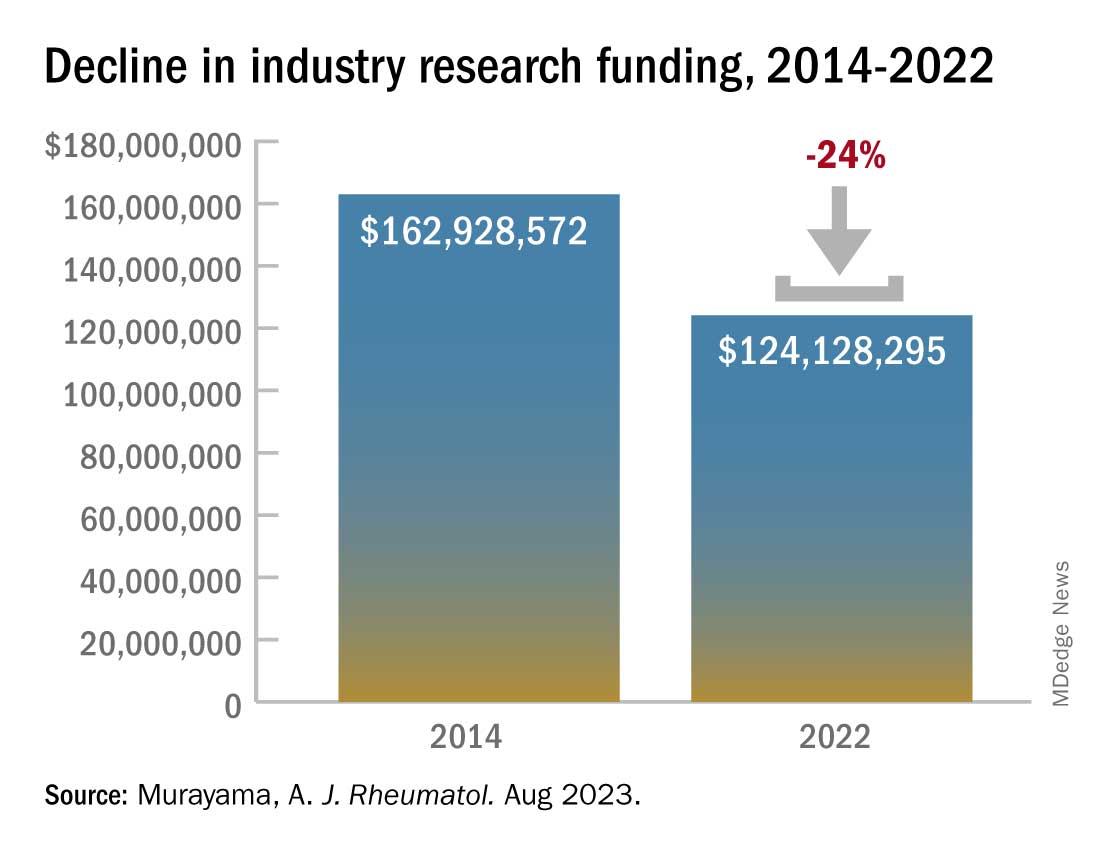

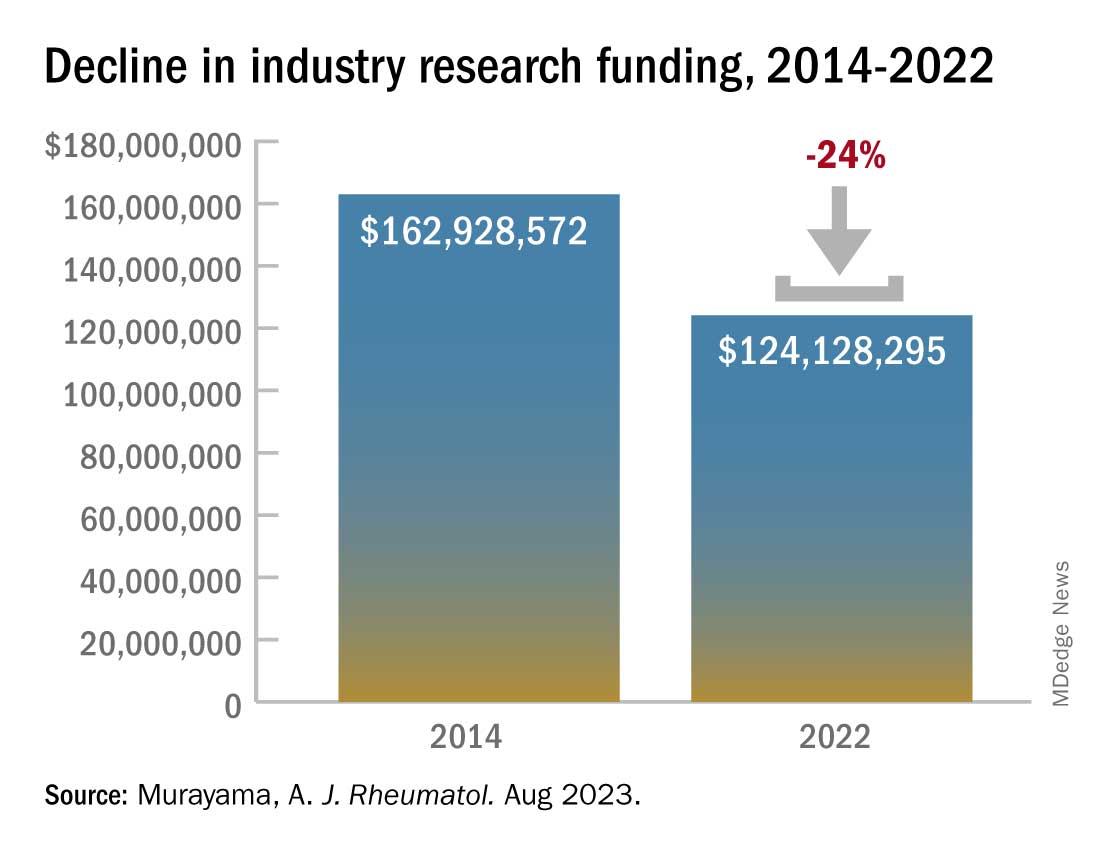

Industry-sponsored research funding has fallen by more than 20% from 2014 to 2022, according to a new analysis.

“Despite the growing partnerships and networks between rheumatologists, the public sector, and the health care industry to optimize research funding allocations, the declining trend in industry-sponsored research payments is a concerning sign for all rheumatologists,” writes study author Anju Murayama, an undergraduate medical student at the Tohoku University School of Medicine in Sendai City, Japan. The data suggest that “more and more rheumatologists are facing difficulties in obtaining research funding from the health care industry.”

Dr. Murayama used the Open Payments Database, which contains records of payments made by drug and pharmaceutical companies to health care providers. The analysis included research payments provided directly to rheumatologists (direct-research payments) and payments given to clinicians or health care organizations related to research whose principal investigator was a rheumatologist (associated-research payments). These associated payments included costs for study enrollment and screening, safety monitoring committees, research publication, and more.

The research was published August 15 in The Journal of Rheumatology .

In 2014, the total direct payments to rheumatologists from industry were $1.4 million. These payments jumped to nearly $4.6 million in 2016 but have declined since. In 2022, there were $976,481 in total payments, a 31% drop from 9 years before.

This decline comes after an observed drop in research funding from the public sector. From 2014 to 2017, public-sector research funding to members of the American College of Rheumatology fell by 7.5%. Timothy Niewold, MD, a rheumatologist and vice chair for research in the department of medicine at Hospital for Special Surgery, New York, said that he and colleagues have felt the funding squeeze from both public and industry sectors. “The budgets for trials have seemed tight,” he told this news organization. With the overhead and cost of doing a trial at an academic institution like HSS, “sometimes you can’t make the budget work,” and researchers must pass on industry-funded trials.

The analysis also found a larger discrepancy between average and median associated-research payments. Of the $1.4 billion in associated-research payments combined over the 9-year period, the median payments per physician ($173,022) were much smaller than the mean payments ($989,753), which indicates that “only a very small number of rheumatologists received substantial amounts of research funding from the industry,” Dr. Murayama wrote in an email to this news organization. “This finding might support statements published by Scher and Schett in Nature Review Rheumatology suggesting that many industry-initiated clinical trials are conducted and authored by a small number of influential rheumatologists, often referred to as key opinion leaders.”

The analysis also found that of all associated payments, less than 3% ($39.2 million) went to funding preclinical research, which is “more disappointing than surprising,” Dr. Niewold said. Though clinical trials are expensive and require larger amounts of investment, industry partnerships at preclinical phases of research are important for devising novel solutions for these complex rheumatic diseases, he noted. “The clinical trials are one piece,” he added, “but you need the whole [research] continuum.”

Dr. Niewold reports receiving research grants from EMD Serono and Zenas Biopharma and consulting for Thermo Fisher Scientific, Progentec Diagnostics, Roivant Sciences, Ventus, S3 Connected Health, AstraZeneca, and Inova. Dr. Murayama reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Industry-sponsored research funding has fallen by more than 20% from 2014 to 2022, according to a new analysis.

“Despite the growing partnerships and networks between rheumatologists, the public sector, and the health care industry to optimize research funding allocations, the declining trend in industry-sponsored research payments is a concerning sign for all rheumatologists,” writes study author Anju Murayama, an undergraduate medical student at the Tohoku University School of Medicine in Sendai City, Japan. The data suggest that “more and more rheumatologists are facing difficulties in obtaining research funding from the health care industry.”

Dr. Murayama used the Open Payments Database, which contains records of payments made by drug and pharmaceutical companies to health care providers. The analysis included research payments provided directly to rheumatologists (direct-research payments) and payments given to clinicians or health care organizations related to research whose principal investigator was a rheumatologist (associated-research payments). These associated payments included costs for study enrollment and screening, safety monitoring committees, research publication, and more.

The research was published August 15 in The Journal of Rheumatology .

In 2014, the total direct payments to rheumatologists from industry were $1.4 million. These payments jumped to nearly $4.6 million in 2016 but have declined since. In 2022, there were $976,481 in total payments, a 31% drop from 9 years before.

This decline comes after an observed drop in research funding from the public sector. From 2014 to 2017, public-sector research funding to members of the American College of Rheumatology fell by 7.5%. Timothy Niewold, MD, a rheumatologist and vice chair for research in the department of medicine at Hospital for Special Surgery, New York, said that he and colleagues have felt the funding squeeze from both public and industry sectors. “The budgets for trials have seemed tight,” he told this news organization. With the overhead and cost of doing a trial at an academic institution like HSS, “sometimes you can’t make the budget work,” and researchers must pass on industry-funded trials.

The analysis also found a larger discrepancy between average and median associated-research payments. Of the $1.4 billion in associated-research payments combined over the 9-year period, the median payments per physician ($173,022) were much smaller than the mean payments ($989,753), which indicates that “only a very small number of rheumatologists received substantial amounts of research funding from the industry,” Dr. Murayama wrote in an email to this news organization. “This finding might support statements published by Scher and Schett in Nature Review Rheumatology suggesting that many industry-initiated clinical trials are conducted and authored by a small number of influential rheumatologists, often referred to as key opinion leaders.”

The analysis also found that of all associated payments, less than 3% ($39.2 million) went to funding preclinical research, which is “more disappointing than surprising,” Dr. Niewold said. Though clinical trials are expensive and require larger amounts of investment, industry partnerships at preclinical phases of research are important for devising novel solutions for these complex rheumatic diseases, he noted. “The clinical trials are one piece,” he added, “but you need the whole [research] continuum.”

Dr. Niewold reports receiving research grants from EMD Serono and Zenas Biopharma and consulting for Thermo Fisher Scientific, Progentec Diagnostics, Roivant Sciences, Ventus, S3 Connected Health, AstraZeneca, and Inova. Dr. Murayama reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Industry-sponsored research funding has fallen by more than 20% from 2014 to 2022, according to a new analysis.

“Despite the growing partnerships and networks between rheumatologists, the public sector, and the health care industry to optimize research funding allocations, the declining trend in industry-sponsored research payments is a concerning sign for all rheumatologists,” writes study author Anju Murayama, an undergraduate medical student at the Tohoku University School of Medicine in Sendai City, Japan. The data suggest that “more and more rheumatologists are facing difficulties in obtaining research funding from the health care industry.”

Dr. Murayama used the Open Payments Database, which contains records of payments made by drug and pharmaceutical companies to health care providers. The analysis included research payments provided directly to rheumatologists (direct-research payments) and payments given to clinicians or health care organizations related to research whose principal investigator was a rheumatologist (associated-research payments). These associated payments included costs for study enrollment and screening, safety monitoring committees, research publication, and more.

The research was published August 15 in The Journal of Rheumatology .

In 2014, the total direct payments to rheumatologists from industry were $1.4 million. These payments jumped to nearly $4.6 million in 2016 but have declined since. In 2022, there were $976,481 in total payments, a 31% drop from 9 years before.

This decline comes after an observed drop in research funding from the public sector. From 2014 to 2017, public-sector research funding to members of the American College of Rheumatology fell by 7.5%. Timothy Niewold, MD, a rheumatologist and vice chair for research in the department of medicine at Hospital for Special Surgery, New York, said that he and colleagues have felt the funding squeeze from both public and industry sectors. “The budgets for trials have seemed tight,” he told this news organization. With the overhead and cost of doing a trial at an academic institution like HSS, “sometimes you can’t make the budget work,” and researchers must pass on industry-funded trials.

The analysis also found a larger discrepancy between average and median associated-research payments. Of the $1.4 billion in associated-research payments combined over the 9-year period, the median payments per physician ($173,022) were much smaller than the mean payments ($989,753), which indicates that “only a very small number of rheumatologists received substantial amounts of research funding from the industry,” Dr. Murayama wrote in an email to this news organization. “This finding might support statements published by Scher and Schett in Nature Review Rheumatology suggesting that many industry-initiated clinical trials are conducted and authored by a small number of influential rheumatologists, often referred to as key opinion leaders.”

The analysis also found that of all associated payments, less than 3% ($39.2 million) went to funding preclinical research, which is “more disappointing than surprising,” Dr. Niewold said. Though clinical trials are expensive and require larger amounts of investment, industry partnerships at preclinical phases of research are important for devising novel solutions for these complex rheumatic diseases, he noted. “The clinical trials are one piece,” he added, “but you need the whole [research] continuum.”

Dr. Niewold reports receiving research grants from EMD Serono and Zenas Biopharma and consulting for Thermo Fisher Scientific, Progentec Diagnostics, Roivant Sciences, Ventus, S3 Connected Health, AstraZeneca, and Inova. Dr. Murayama reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF RHEUMATOLOGY

FDA approves canakinumab for gout flares

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved canakinumab (Ilaris) for the treatment of gout flares in adults who cannot be treated with NSAIDs, colchicine, or repeated courses of corticosteroids. The drug is also indicated for people who could not tolerate or had an inadequate response to NSAIDs or colchicine.

The drug, a humanized anti–interleukin-1 beta monoclonal antibody, is the first and only biologic approved in the United States for the treatment of gout flares, according to Novartis. It is administered in a single, subcutaneous injection of 150 mg.

“At Novartis, we are committed to bringing medicines that address high unmet needs to patients. We are proud to receive approval on our eighth indication for Ilaris in the U.S. and provide the first biologic medicine option for people with gout flares to help treat this painful and debilitating condition,” the company said in a statement to this news organization.

Canakinumab was first approved in the United States in 2009 for the treatment of children and adults with cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome (CAPS). Since then, it has been approved for the treatment of several other autoinflammatory diseases, including Still’s disease and recurrent fever syndromes.

In 2011, an FDA advisory panel voted against the approval of canakinumab to treat acute gout flares refractory to NSAIDs, colchicine, or repeated courses of corticosteroids, while in 2013, the European Medicine Agency approved the drug for this treatment indication.

Since that FDA advisory committee meeting and the FDA’s subsequent rejection letter, “[Novartis] has conducted additional studies in patients with gout flares and other related populations to further characterize the short- and long-term safety of canakinumab supporting the current application. To further support the benefit-risk [profile of the drug], the indication is for a more restricted population than initially proposed in 2011,” the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research said in a statement to this news organization. “Given these considerations and the available safety information, the Agency determined that canakinumab, at the recommended dosage, has a favorable risk-benefit profile” in the specified patient population.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved canakinumab (Ilaris) for the treatment of gout flares in adults who cannot be treated with NSAIDs, colchicine, or repeated courses of corticosteroids. The drug is also indicated for people who could not tolerate or had an inadequate response to NSAIDs or colchicine.

The drug, a humanized anti–interleukin-1 beta monoclonal antibody, is the first and only biologic approved in the United States for the treatment of gout flares, according to Novartis. It is administered in a single, subcutaneous injection of 150 mg.

“At Novartis, we are committed to bringing medicines that address high unmet needs to patients. We are proud to receive approval on our eighth indication for Ilaris in the U.S. and provide the first biologic medicine option for people with gout flares to help treat this painful and debilitating condition,” the company said in a statement to this news organization.

Canakinumab was first approved in the United States in 2009 for the treatment of children and adults with cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome (CAPS). Since then, it has been approved for the treatment of several other autoinflammatory diseases, including Still’s disease and recurrent fever syndromes.

In 2011, an FDA advisory panel voted against the approval of canakinumab to treat acute gout flares refractory to NSAIDs, colchicine, or repeated courses of corticosteroids, while in 2013, the European Medicine Agency approved the drug for this treatment indication.

Since that FDA advisory committee meeting and the FDA’s subsequent rejection letter, “[Novartis] has conducted additional studies in patients with gout flares and other related populations to further characterize the short- and long-term safety of canakinumab supporting the current application. To further support the benefit-risk [profile of the drug], the indication is for a more restricted population than initially proposed in 2011,” the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research said in a statement to this news organization. “Given these considerations and the available safety information, the Agency determined that canakinumab, at the recommended dosage, has a favorable risk-benefit profile” in the specified patient population.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved canakinumab (Ilaris) for the treatment of gout flares in adults who cannot be treated with NSAIDs, colchicine, or repeated courses of corticosteroids. The drug is also indicated for people who could not tolerate or had an inadequate response to NSAIDs or colchicine.

The drug, a humanized anti–interleukin-1 beta monoclonal antibody, is the first and only biologic approved in the United States for the treatment of gout flares, according to Novartis. It is administered in a single, subcutaneous injection of 150 mg.

“At Novartis, we are committed to bringing medicines that address high unmet needs to patients. We are proud to receive approval on our eighth indication for Ilaris in the U.S. and provide the first biologic medicine option for people with gout flares to help treat this painful and debilitating condition,” the company said in a statement to this news organization.

Canakinumab was first approved in the United States in 2009 for the treatment of children and adults with cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome (CAPS). Since then, it has been approved for the treatment of several other autoinflammatory diseases, including Still’s disease and recurrent fever syndromes.

In 2011, an FDA advisory panel voted against the approval of canakinumab to treat acute gout flares refractory to NSAIDs, colchicine, or repeated courses of corticosteroids, while in 2013, the European Medicine Agency approved the drug for this treatment indication.

Since that FDA advisory committee meeting and the FDA’s subsequent rejection letter, “[Novartis] has conducted additional studies in patients with gout flares and other related populations to further characterize the short- and long-term safety of canakinumab supporting the current application. To further support the benefit-risk [profile of the drug], the indication is for a more restricted population than initially proposed in 2011,” the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research said in a statement to this news organization. “Given these considerations and the available safety information, the Agency determined that canakinumab, at the recommended dosage, has a favorable risk-benefit profile” in the specified patient population.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Raised Linear Plaques on the Back

The Diagnosis: Flagellate Dermatitis

Upon further questioning by dermatology, the patient noted recent ingestion of shiitake mushrooms, which were not a part of his typical diet. Based on the appearance of the rash in the context of ingesting shiitake mushrooms, our patient was diagnosed with flagellate dermatitis. At 6-week followup, the patient’s rash had resolved spontaneously without further intervention.

Flagellate dermatitis usually appears on the torso as linear whiplike streaks.1 The eruption often is pruritic and may be preceded by severe pruritus. Flagellate dermatitis also is a well-documented complication of bleomycin sulfate therapy with an incidence rate of 8% to 66%.2

Other chemotherapeutic causes include peplomycin, bendamustine, docetaxel, cisplatin, and trastuzumab.3 Flagellate dermatitis also is seen in some patients with dermatomyositis.4 A thorough patient history, including medications and dietary habits, is necessary to differentiate flagellate dermatitis from dermatomyositis.

Flagellate dermatitis, also known as shiitake dermatitis, is observed as erythematous flagellate eruptions involving the trunk or extremities that present within 2 hours to 5 days of handling or consuming undercooked or raw shiitake mushrooms (Lentinula edodes),5,6 as was observed in our patient. Lentinan is the polysaccharide component of the shiitake species and is destabilized by heat.6 Ingestion of polysaccharide is associated with dermatitis, particularly in Japan, China, and Korea; however, the consumption of shiitake mushrooms has increased worldwide, and cases increasingly are reported outside of these typical regions. The rash typically resolves spontaneously; therefore, treatment is supportive. However, more severe symptomatic cases may require courses of topical corticosteroids and antihistamines.6

In our case, the differential diagnosis consisted of acute urticaria, cutaneous dermatomyositis, dermatographism, and maculopapular cutaneous mastocytosis. Acute urticaria displays well-circumscribed edematous papules or plaques, and individual lesions last less than 24 hours. Cutaneous dermatomyositis includes additional systemic manifestations such as fatigue, malaise, and myalgia, as well as involvement of the gastrointestinal, respiratory, or cardiac organs. Dermatographism is evoked by stroking or rubbing of the skin, which results in asymptomatic lesions that persist for 15 to 30 minutes. Cases of maculopapular cutaneous mastocytosis more often are seen in children, and the histamine release most often causes gastrointestinal tract symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea, as well as flushing, blushing, pruritus, respiratory difficulty, and malaise.

- Biswas A, Chaudhari PB, Sharma P, et al. Bleomycin induced flagellate erythema: revisiting a unique complication. J Cancer Res Ther. 2013;9:500-503.

- Yagoda A, Mukherji B, Young C, et al. Bleomycin, an anti-tumor antibiotic: clinical experience in 274 patients. Ann Intern Med. 1972;77:861-870.

- Cohen PR. Trastuzumab-associated flagellate erythema: report in a woman with metastatic breast cancer and review of antineoplastic therapy-induced flagellate dermatoses. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2015;5:253-264. doi:10.1007/s13555-015-0085-2

- Grynszpan R, Niemeyer-Corbellini JP, Lopes MS, et al. Bleomycininduced flagellate dermatitis. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013:bcr2013009764. doi:10.1136/bcr-2013-009764

- Stephany MP, Chung S, Handler MZ, et al. Shiitake mushroom dermatitis: a review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2016;17:485-489.

- Boels D, Landreau A, Bruneau C, et al. Shiitake dermatitis recorded by French Poison Control Centers—new case series with clinical observations. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2014;52:625-628.

The Diagnosis: Flagellate Dermatitis

Upon further questioning by dermatology, the patient noted recent ingestion of shiitake mushrooms, which were not a part of his typical diet. Based on the appearance of the rash in the context of ingesting shiitake mushrooms, our patient was diagnosed with flagellate dermatitis. At 6-week followup, the patient’s rash had resolved spontaneously without further intervention.

Flagellate dermatitis usually appears on the torso as linear whiplike streaks.1 The eruption often is pruritic and may be preceded by severe pruritus. Flagellate dermatitis also is a well-documented complication of bleomycin sulfate therapy with an incidence rate of 8% to 66%.2

Other chemotherapeutic causes include peplomycin, bendamustine, docetaxel, cisplatin, and trastuzumab.3 Flagellate dermatitis also is seen in some patients with dermatomyositis.4 A thorough patient history, including medications and dietary habits, is necessary to differentiate flagellate dermatitis from dermatomyositis.

Flagellate dermatitis, also known as shiitake dermatitis, is observed as erythematous flagellate eruptions involving the trunk or extremities that present within 2 hours to 5 days of handling or consuming undercooked or raw shiitake mushrooms (Lentinula edodes),5,6 as was observed in our patient. Lentinan is the polysaccharide component of the shiitake species and is destabilized by heat.6 Ingestion of polysaccharide is associated with dermatitis, particularly in Japan, China, and Korea; however, the consumption of shiitake mushrooms has increased worldwide, and cases increasingly are reported outside of these typical regions. The rash typically resolves spontaneously; therefore, treatment is supportive. However, more severe symptomatic cases may require courses of topical corticosteroids and antihistamines.6

In our case, the differential diagnosis consisted of acute urticaria, cutaneous dermatomyositis, dermatographism, and maculopapular cutaneous mastocytosis. Acute urticaria displays well-circumscribed edematous papules or plaques, and individual lesions last less than 24 hours. Cutaneous dermatomyositis includes additional systemic manifestations such as fatigue, malaise, and myalgia, as well as involvement of the gastrointestinal, respiratory, or cardiac organs. Dermatographism is evoked by stroking or rubbing of the skin, which results in asymptomatic lesions that persist for 15 to 30 minutes. Cases of maculopapular cutaneous mastocytosis more often are seen in children, and the histamine release most often causes gastrointestinal tract symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea, as well as flushing, blushing, pruritus, respiratory difficulty, and malaise.

The Diagnosis: Flagellate Dermatitis

Upon further questioning by dermatology, the patient noted recent ingestion of shiitake mushrooms, which were not a part of his typical diet. Based on the appearance of the rash in the context of ingesting shiitake mushrooms, our patient was diagnosed with flagellate dermatitis. At 6-week followup, the patient’s rash had resolved spontaneously without further intervention.

Flagellate dermatitis usually appears on the torso as linear whiplike streaks.1 The eruption often is pruritic and may be preceded by severe pruritus. Flagellate dermatitis also is a well-documented complication of bleomycin sulfate therapy with an incidence rate of 8% to 66%.2

Other chemotherapeutic causes include peplomycin, bendamustine, docetaxel, cisplatin, and trastuzumab.3 Flagellate dermatitis also is seen in some patients with dermatomyositis.4 A thorough patient history, including medications and dietary habits, is necessary to differentiate flagellate dermatitis from dermatomyositis.

Flagellate dermatitis, also known as shiitake dermatitis, is observed as erythematous flagellate eruptions involving the trunk or extremities that present within 2 hours to 5 days of handling or consuming undercooked or raw shiitake mushrooms (Lentinula edodes),5,6 as was observed in our patient. Lentinan is the polysaccharide component of the shiitake species and is destabilized by heat.6 Ingestion of polysaccharide is associated with dermatitis, particularly in Japan, China, and Korea; however, the consumption of shiitake mushrooms has increased worldwide, and cases increasingly are reported outside of these typical regions. The rash typically resolves spontaneously; therefore, treatment is supportive. However, more severe symptomatic cases may require courses of topical corticosteroids and antihistamines.6

In our case, the differential diagnosis consisted of acute urticaria, cutaneous dermatomyositis, dermatographism, and maculopapular cutaneous mastocytosis. Acute urticaria displays well-circumscribed edematous papules or plaques, and individual lesions last less than 24 hours. Cutaneous dermatomyositis includes additional systemic manifestations such as fatigue, malaise, and myalgia, as well as involvement of the gastrointestinal, respiratory, or cardiac organs. Dermatographism is evoked by stroking or rubbing of the skin, which results in asymptomatic lesions that persist for 15 to 30 minutes. Cases of maculopapular cutaneous mastocytosis more often are seen in children, and the histamine release most often causes gastrointestinal tract symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea, as well as flushing, blushing, pruritus, respiratory difficulty, and malaise.

- Biswas A, Chaudhari PB, Sharma P, et al. Bleomycin induced flagellate erythema: revisiting a unique complication. J Cancer Res Ther. 2013;9:500-503.

- Yagoda A, Mukherji B, Young C, et al. Bleomycin, an anti-tumor antibiotic: clinical experience in 274 patients. Ann Intern Med. 1972;77:861-870.

- Cohen PR. Trastuzumab-associated flagellate erythema: report in a woman with metastatic breast cancer and review of antineoplastic therapy-induced flagellate dermatoses. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2015;5:253-264. doi:10.1007/s13555-015-0085-2

- Grynszpan R, Niemeyer-Corbellini JP, Lopes MS, et al. Bleomycininduced flagellate dermatitis. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013:bcr2013009764. doi:10.1136/bcr-2013-009764

- Stephany MP, Chung S, Handler MZ, et al. Shiitake mushroom dermatitis: a review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2016;17:485-489.

- Boels D, Landreau A, Bruneau C, et al. Shiitake dermatitis recorded by French Poison Control Centers—new case series with clinical observations. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2014;52:625-628.

- Biswas A, Chaudhari PB, Sharma P, et al. Bleomycin induced flagellate erythema: revisiting a unique complication. J Cancer Res Ther. 2013;9:500-503.

- Yagoda A, Mukherji B, Young C, et al. Bleomycin, an anti-tumor antibiotic: clinical experience in 274 patients. Ann Intern Med. 1972;77:861-870.

- Cohen PR. Trastuzumab-associated flagellate erythema: report in a woman with metastatic breast cancer and review of antineoplastic therapy-induced flagellate dermatoses. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2015;5:253-264. doi:10.1007/s13555-015-0085-2

- Grynszpan R, Niemeyer-Corbellini JP, Lopes MS, et al. Bleomycininduced flagellate dermatitis. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013:bcr2013009764. doi:10.1136/bcr-2013-009764

- Stephany MP, Chung S, Handler MZ, et al. Shiitake mushroom dermatitis: a review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2016;17:485-489.

- Boels D, Landreau A, Bruneau C, et al. Shiitake dermatitis recorded by French Poison Control Centers—new case series with clinical observations. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2014;52:625-628.

A 77-year-old man with a history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and nonmelanoma skin cancer presented to the dermatology clinic for evaluation of a new rash of 2 days’ duration. He trialed a previously prescribed triamcinolone cream 0.1% without improvement. The patient denied any recent travel, as well as fever, nausea, vomiting, or changes in bowel habits. Physical examination revealed diffuse, erythematous, raised, linear plaques on the mid to lower back.

Parity for prompt and staged STEMI complete revascularization: MULTISTARS-AMI

The conclusion comes from a randomized outcomes trial of 840 patients that compared prompt same-session CR with a staged procedure carried out weeks later.

That CR is a worthy goal in such cases is largely settled, unlike the question of when to pursue revascularization of nonculprit lesions for best results. So the timing varies in practice, often depending on the patient’s clinical stability, risk status, or practical issues like cath lab resources or personnel.

The new trial, MULTISTARS-AMI, supports that kind of flexibility as safe in practice. Immediate, same-session CR led to a 48% drop in risk for a broad composite primary endpoint at 1 year, compared with staged CR an average of 37 days later. The finding was significant for noninferiority in the study’s primary analysis and secondarily, was significant for superiority (P < .001 in both cases).

The composite endpoint included death from any cause, MI, stroke, unplanned ischemia-driven revascularization, or heart failure (HF) hospitalization.

CR’s immediate effect on outcomes was numerically pronounced, but because it was prespecified as a noninferiority trial, MULTISTARS-AMI could show only that the strategy is comparable to staged CR, emphasized Barbara E. Stähli, MD, MPH, MBA, at a press conference.

Still, it appears to be the first trial of its kind to show that operators and patients can safely choose either percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) approach and attain similar outcomes, said Dr. Stähli, University Hospital Zurich, MULTISTARS-AMI’s principal investigator.

Not only were the two approaches similar with respect to safety, she noted, but immediate CR seemed to require less use of contrast agent and fluoroscopy. “And you have only one procedure, so there’s only one arterial puncture.”

Dr. Stähli formally presented MULTISTARS-AMI at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology, held in Amsterdam. She is also lead author on its publication in the New England Journal of Medicine.

After her presentation, invited discussant Robert A. Byrne, PhD, MD, MB, BCh, said that the trial’s central message is that STEMI patients with MVD having primary PCI “should undergo complete revascularization within the first 45 days, with the timing of the non–infarct-related artery procedure individualized according to clinical risk and logistical considerations.”

Still, the trial “provides evidence, but not strong evidence, of benefits with routine immediate PCI during the index procedure as compared with staged outpatient PCI,” said Dr. Byrne, Mater Private Hospital and RCSI University of Medicine and Health Sciences, Dublin.

MULTISTARS-AMI randomly assigned patients at 37 European sites to undergo same-session CR (418 patients) or CR staged 19-45 days later (422 patients).

Rates for the primary endpoint at 1 year were 8.5% and 16.3%, respectively, for a risk ratio of 0.52 (95% confidence interval, 0.38-0.72). The difference was driven by fewer instances of nonfatal MI, 0.36 (95% CI, 0.16-0.80), and unplanned ischemia-driven revascularization, 0.42 (95% CI, 0.24-0.74), in the immediate-CR group.

The wee hours

Sunil V. Rao, MD, director of interventional cardiology at NYU Langone Health System, New York, said that, in general at his center, patients who are stable with a good primary PCI outcome and whose lesions aren’t very high risk are often discharged to return later for the staged CR procedure.

But after the new insights from MULTISTARS-AMI, Dr. Rao, who is not connected to the study, said in an interview that immediate same-session CR is indeed likely preferable to staged CR performed weeks later.

Same-session CR, however, may not always be practical or wise, he observed. For example, some patients with STEMI can be pretty sick with MVD that involves very complex lesions that might be better handled later.

“The wee hours of the night may not be the best time to tackle such complex lesions,” Dr. Rao observed. If confronted with, for example, a bifurcation that requires a complex procedure, “2 o’clock in the morning is probably not the best time to address something like that.”

So the trial’s more realistic translational message, he proposed, may be to perform CR after the primary PCI but during the same hospitalization, “unless there are some real mitigating circumstances.”

The trial was supported by Boston Scientific. Dr. Stähli had no disclosures. Dr. Byrne discloses research funding to his institution from Abbott Vascular, Translumina, Biosensors, and Boston Scientific. Dr. Rao had no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The conclusion comes from a randomized outcomes trial of 840 patients that compared prompt same-session CR with a staged procedure carried out weeks later.

That CR is a worthy goal in such cases is largely settled, unlike the question of when to pursue revascularization of nonculprit lesions for best results. So the timing varies in practice, often depending on the patient’s clinical stability, risk status, or practical issues like cath lab resources or personnel.

The new trial, MULTISTARS-AMI, supports that kind of flexibility as safe in practice. Immediate, same-session CR led to a 48% drop in risk for a broad composite primary endpoint at 1 year, compared with staged CR an average of 37 days later. The finding was significant for noninferiority in the study’s primary analysis and secondarily, was significant for superiority (P < .001 in both cases).

The composite endpoint included death from any cause, MI, stroke, unplanned ischemia-driven revascularization, or heart failure (HF) hospitalization.

CR’s immediate effect on outcomes was numerically pronounced, but because it was prespecified as a noninferiority trial, MULTISTARS-AMI could show only that the strategy is comparable to staged CR, emphasized Barbara E. Stähli, MD, MPH, MBA, at a press conference.

Still, it appears to be the first trial of its kind to show that operators and patients can safely choose either percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) approach and attain similar outcomes, said Dr. Stähli, University Hospital Zurich, MULTISTARS-AMI’s principal investigator.

Not only were the two approaches similar with respect to safety, she noted, but immediate CR seemed to require less use of contrast agent and fluoroscopy. “And you have only one procedure, so there’s only one arterial puncture.”

Dr. Stähli formally presented MULTISTARS-AMI at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology, held in Amsterdam. She is also lead author on its publication in the New England Journal of Medicine.

After her presentation, invited discussant Robert A. Byrne, PhD, MD, MB, BCh, said that the trial’s central message is that STEMI patients with MVD having primary PCI “should undergo complete revascularization within the first 45 days, with the timing of the non–infarct-related artery procedure individualized according to clinical risk and logistical considerations.”

Still, the trial “provides evidence, but not strong evidence, of benefits with routine immediate PCI during the index procedure as compared with staged outpatient PCI,” said Dr. Byrne, Mater Private Hospital and RCSI University of Medicine and Health Sciences, Dublin.

MULTISTARS-AMI randomly assigned patients at 37 European sites to undergo same-session CR (418 patients) or CR staged 19-45 days later (422 patients).

Rates for the primary endpoint at 1 year were 8.5% and 16.3%, respectively, for a risk ratio of 0.52 (95% confidence interval, 0.38-0.72). The difference was driven by fewer instances of nonfatal MI, 0.36 (95% CI, 0.16-0.80), and unplanned ischemia-driven revascularization, 0.42 (95% CI, 0.24-0.74), in the immediate-CR group.

The wee hours

Sunil V. Rao, MD, director of interventional cardiology at NYU Langone Health System, New York, said that, in general at his center, patients who are stable with a good primary PCI outcome and whose lesions aren’t very high risk are often discharged to return later for the staged CR procedure.

But after the new insights from MULTISTARS-AMI, Dr. Rao, who is not connected to the study, said in an interview that immediate same-session CR is indeed likely preferable to staged CR performed weeks later.

Same-session CR, however, may not always be practical or wise, he observed. For example, some patients with STEMI can be pretty sick with MVD that involves very complex lesions that might be better handled later.

“The wee hours of the night may not be the best time to tackle such complex lesions,” Dr. Rao observed. If confronted with, for example, a bifurcation that requires a complex procedure, “2 o’clock in the morning is probably not the best time to address something like that.”

So the trial’s more realistic translational message, he proposed, may be to perform CR after the primary PCI but during the same hospitalization, “unless there are some real mitigating circumstances.”

The trial was supported by Boston Scientific. Dr. Stähli had no disclosures. Dr. Byrne discloses research funding to his institution from Abbott Vascular, Translumina, Biosensors, and Boston Scientific. Dr. Rao had no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The conclusion comes from a randomized outcomes trial of 840 patients that compared prompt same-session CR with a staged procedure carried out weeks later.

That CR is a worthy goal in such cases is largely settled, unlike the question of when to pursue revascularization of nonculprit lesions for best results. So the timing varies in practice, often depending on the patient’s clinical stability, risk status, or practical issues like cath lab resources or personnel.

The new trial, MULTISTARS-AMI, supports that kind of flexibility as safe in practice. Immediate, same-session CR led to a 48% drop in risk for a broad composite primary endpoint at 1 year, compared with staged CR an average of 37 days later. The finding was significant for noninferiority in the study’s primary analysis and secondarily, was significant for superiority (P < .001 in both cases).

The composite endpoint included death from any cause, MI, stroke, unplanned ischemia-driven revascularization, or heart failure (HF) hospitalization.

CR’s immediate effect on outcomes was numerically pronounced, but because it was prespecified as a noninferiority trial, MULTISTARS-AMI could show only that the strategy is comparable to staged CR, emphasized Barbara E. Stähli, MD, MPH, MBA, at a press conference.

Still, it appears to be the first trial of its kind to show that operators and patients can safely choose either percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) approach and attain similar outcomes, said Dr. Stähli, University Hospital Zurich, MULTISTARS-AMI’s principal investigator.

Not only were the two approaches similar with respect to safety, she noted, but immediate CR seemed to require less use of contrast agent and fluoroscopy. “And you have only one procedure, so there’s only one arterial puncture.”

Dr. Stähli formally presented MULTISTARS-AMI at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology, held in Amsterdam. She is also lead author on its publication in the New England Journal of Medicine.

After her presentation, invited discussant Robert A. Byrne, PhD, MD, MB, BCh, said that the trial’s central message is that STEMI patients with MVD having primary PCI “should undergo complete revascularization within the first 45 days, with the timing of the non–infarct-related artery procedure individualized according to clinical risk and logistical considerations.”

Still, the trial “provides evidence, but not strong evidence, of benefits with routine immediate PCI during the index procedure as compared with staged outpatient PCI,” said Dr. Byrne, Mater Private Hospital and RCSI University of Medicine and Health Sciences, Dublin.

MULTISTARS-AMI randomly assigned patients at 37 European sites to undergo same-session CR (418 patients) or CR staged 19-45 days later (422 patients).

Rates for the primary endpoint at 1 year were 8.5% and 16.3%, respectively, for a risk ratio of 0.52 (95% confidence interval, 0.38-0.72). The difference was driven by fewer instances of nonfatal MI, 0.36 (95% CI, 0.16-0.80), and unplanned ischemia-driven revascularization, 0.42 (95% CI, 0.24-0.74), in the immediate-CR group.

The wee hours

Sunil V. Rao, MD, director of interventional cardiology at NYU Langone Health System, New York, said that, in general at his center, patients who are stable with a good primary PCI outcome and whose lesions aren’t very high risk are often discharged to return later for the staged CR procedure.

But after the new insights from MULTISTARS-AMI, Dr. Rao, who is not connected to the study, said in an interview that immediate same-session CR is indeed likely preferable to staged CR performed weeks later.

Same-session CR, however, may not always be practical or wise, he observed. For example, some patients with STEMI can be pretty sick with MVD that involves very complex lesions that might be better handled later.

“The wee hours of the night may not be the best time to tackle such complex lesions,” Dr. Rao observed. If confronted with, for example, a bifurcation that requires a complex procedure, “2 o’clock in the morning is probably not the best time to address something like that.”

So the trial’s more realistic translational message, he proposed, may be to perform CR after the primary PCI but during the same hospitalization, “unless there are some real mitigating circumstances.”

The trial was supported by Boston Scientific. Dr. Stähli had no disclosures. Dr. Byrne discloses research funding to his institution from Abbott Vascular, Translumina, Biosensors, and Boston Scientific. Dr. Rao had no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ESC CONGRESS 2023

Dietary nitrates reduce contrast-induced nephropathy in ACS

AMSTERDAM –

In the NITRATE-CIN Study, non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction acute coronary syndrome (ACS) patients at risk of renal injury from coronary angiography who received dietary inorganic nitrates had a 70% reduction in CIN compared with those given placebo.

The nitrate group also showed an impressive reduction in periprocedural myocardial infarction (MI) and improved renal function at 3 months, as well as a halving of major adverse cardiovascular events and major adverse kidney events at 1 year.

The trial was presented by Dan Jones, MD, Barts Health NHS Trust, London, at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

“Currently, aside from intravenous hydration, there is no proven treatment that reduces contrast-induced nephropathy. We feel that dietary inorganic nitrate shows huge promise in this study, and these findings could have important implications in reducing this serious complication of coronary angiography,” Dr. Jones concluded.

He explained that the product used was a formulation of dietary inorganic nitrates given as potassium nitrate capsules, which the study investigators produced specifically for this trial.

At this point, “the only way to get inorganic nitrate is in the diet – specifically by consuming beetroot juice or green leafy vegetables such as spinach and rocket. From a clinician perspective, while these results suggest this is an effective therapy and has great potential, it is not currently possible to prescribe the medication we used in our study, although we are working on producing a commercial product,” he said in an interview.

However, Dr. Jones noted that it is possible to buy beetroot shots, which contain 7 mmol of potassium nitrate in each shot, from health food shops and websites, and two such shots per day for 5 days would give a dose similar to that used in this study, starting the day before angiography.

“While we need a larger multicenter study to confirm these results, studies so far suggest no signal at all that there is any harm in this approach, and there could be a great deal of benefit in taking a couple of beetroot shots prior to and for a few days after an angiogram,” he said.

Dietary nitrates “make sense”

Designated discussant of the NITRATE-CIN trial at the ESC Hotline session, Roxanna Mehran, MD, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, said the study was well designed, and the “interesting and plausible” hypothesis to raise nitric oxide levels by dietary nitrates “makes sense.”

On the main findings of a major significant 50% reduction in acute kidney injury, Dr. Mehran said, “It is difficult to imagine such a reduction is possible.”

She pointed out that the large reduction in major adverse cardiac events and major adverse kidney events at 1 year also suggests that there is a sustained benefit in protecting the kidney.

“We’re all going to get on beet juice after this,” she quipped.

Still, Dr. Mehran questioned whether the results were “too good to be true,” adding that a larger trial actually powered for longer term outcome events is needed, as well as a better understanding of whether CIN has a causative role in mortality.

Responding to questions about whether such a large effect could actually be achieved with dietary nitrates, Dr. Jones said he thought there would definitely be some benefits, but maybe not quite as large as those seen in this study.

“From our pilot data we thought nitrate may be effective in preventing CIN,” he said in an interview. “We recruited a higher risk group than we thought, which is why the control event rates were higher than we expected, but the acute kidney injury reduction is roughly what we had estimated, and makes sense biologically.”

Dr. Jones acknowledged that the large reductions in long-term major adverse cardiovascular and kidney events were unexpected.

“The trial was not powered to see reductions in these outcomes, so we need to see if those event reductions can be replicated in larger multicenter trials,” he said. “But this was a double-blind placebo-controlled trial so in this trial the effects are real, and I think the effect size in this trial is too large for there not to be a beneficial effect.

“But I’m not so sure that we would see the same magnitude of effect when we have a larger study with tighter confidence intervals but perhaps a 20%-25% reduction in cardiovascular and kidney may be more realistic, which would still be amazing for such an easy and cost-effective intervention,” Dr. Jones added.

A larger trial is now being planned.

The researchers are also working on the development of a commercial form of dietary inorganic nitrate that would be needed for larger multicenter studies and would then be generally available. “We want this to be a low-cost product that would be available to all,” Dr. Jones said.

He noted that other studies have shown that dietary inorganic nitrates in the form of beetroot juice lower blood pressure; there are suggestions it may also lower cholesterol and prevent stent restenosis, and athletes sometimes take it to increase their aerobic capacity.

“There appears to be many benefits of dietary nitrates, and the one thing we can do at this time is to encourage people to increase their dietary nitrate consumption by eating large quantities of green leafy vegetables and beetroot,” Dr. Jones said.

Replacing lost nitric oxide

In his presentation, Dr. Jones noted that CIN is a serious complication after coronary angiography and is associated with longer hospital stays, worse long-term kidney function, and increased risk of MI and death.

The incidence varies depending on patient risk and definitions used, but it can affect up to 50% of high-risk ACS patients – older patients and/or those with heart failure, chronic kidney disease, or diabetes.

“We don’t really understand the mechanisms that cause CIN, but multiple proposed mechanisms exist, and we know from previous studies that a deficiency of nitric oxide is crucial to the development of CIN,” he explained. “We also know that [nitric oxide] is crucial for normal renal hemostasis. Therefore, a potential therapeutic target to prevent CIN would be to replace this lost nitric oxide.”

The inorganic nitrate evaluated in this trial is found in the diet, is produced endogenously, and is different from medicinally synthesized organic nitrates such as isosorbide mononitrate, he said.

“Isosorbide mononitrate/dinitrate tablets contain organic nitrates and while they are good for angina, we know that they do not have the same beneficial effects on the sustained generation of nitric oxide as inorganic nitrates,” Dr. Jones added.

NITRATE-CIN study

NITRATE-CIN was a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial conducted at Queen Mary University of London and St. Bartholomew’s Hospital in London, which tested the effectiveness of inorganic nitrate in preventing contrast-induced nephropathy in 640 patients with non-ST elevation ACS referred for invasive coronary angiography.

To be eligible for the trial, patients had to be at risk of contrast-induced nephropathy with an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) less than 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2 or have two of the following significant risk factors: diabetes, liver failure, over 70 years of age, exposure to contrast within 7 days, heart failure, or on concomitant renally acting drugs.

Patients were randomly assigned to a formulation of potassium nitrate (12 mmol/744 mg nitrate) per day given as capsules for a 5-day course with the first dose administered prior to angiography or to a control group that received potassium chloride with a matched potassium concentration.

The patient population had a mean age of 71 years, 73% were male, 75% were White, 46% had diabetes, and 56% had chronic kidney disease. There was a 13% loss to follow-up, which was attributed to the COVID pandemic.

The amount of contrast administration was 180 mL in the placebo and 170 mL in the nitrate arm, with 50% of patients undergoing some sort of revascularization.

The primary endpoint was the incidence of CIN as defined by KDIGO criteria – a series of stages of acute kidney injury defined by changes in serum creatinine within 72 hours and up to 1 week.

Results showed that this primary CIN endpoint was reduced significantly from 30% in the placebo arm to 9.1% in the nitrate group, a 70% relative risk reduction (P < .0001). The majority (90%) of this CIN was stage 1, but 10% was stage 2.

Consistent results were seen when an alternative definition of CIN (Mehran) was used, although the rates in both arms were lower than when the KDIGO definition was used.

The benefit was seen across prespecified subgroups including diabetes status, troponin positivity, and Mehran risk. But the benefit seemed to be attenuated in patients on preexisting organic nitrate therapy, although the numbers in these groups were too small to draw definitive conclusions.

As would be expected, there were significant elevations in both systemic nitrate and nitrite levels both up to 72 hours after the procedure, which was consistent with the 5-day course. This was associated with reductions in systolic and diastolic blood pressure, but not associated with any adverse events, Dr. Jones reported.

Rates of procedural MI, a prespecified secondary endpoint, were reduced from 12.5% to 4.1% in those on inorganic nitrates (P = .003).

Looking at longer term outcomes, kidney function was improved at 3 months as measured by change in eGFR, which showed a 10% relative improvement of 5.2 mL/min per 1.73 m2 (10%) in the nitrate group vs. the placebo group. Serum creatinine levels were also significantly increased in the nitrate group.

At 12 months, there was a significant 50% relative reduction in major adverse cardiovascular events – including all-cause mortality, recurrent MI, and recurrent revascularization – which were reduced from 18.1% in the placebo group to 9.1% in the nitrate group, with a reduction in all three of the constituent components of the composite endpoint including all-cause mortality.

Major adverse kidney events (all-cause mortality, renal replacement therapy, or persistent renal dysfunction) were also reduced at 12 months from 28.4% in the placebo group to 10.7% in the nitrate group (P < .0001), a 60% relative reduction. This was driven by lower rates of all-cause mortality and persistent renal dysfunction.

While Dr. Jones said these results on major cardiovascular and kidney outcomes should be viewed as hypothesis-generating at the present time, he said there were biological mechanisms that could explain these benefits.

“We saw a reduction in procedural MI, and we know there is a lot of similar biology in preventing procedural MI and subsequent cardiac events in the acute phase. This, in combination with the large reduction in acute kidney injury, could explain why there’s improved outcomes out to 12 months.”

In her comments, Dr. Mehran congratulated the investigators on having conducted the first study to have shown benefit in the prevention of contrast-associated acute kidney injury as well as major adverse cardiovascular and kidney events associated with the condition.

She used the term “contrast-associated acute kidney injury” rather than “contrast-induced nephropathy” because, she said, it has not been proven that the acute kidney injury seen after angiography is actually caused by the contrast and “so many other things are occurring during procedures when these patients are presenting with different syndromes.”

Dr. Mehran pointed out some weaknesses in the NITRATE-CIN study including the single-center design, the large volume of contrast administered, 13% of patients missing the primary endpoint blood draw, and an imbalance in relevant baseline characteristics despite randomization.

The NITRATE-CIN study was funded by Heart Research UK. Dr. Jones has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

AMSTERDAM –

In the NITRATE-CIN Study, non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction acute coronary syndrome (ACS) patients at risk of renal injury from coronary angiography who received dietary inorganic nitrates had a 70% reduction in CIN compared with those given placebo.

The nitrate group also showed an impressive reduction in periprocedural myocardial infarction (MI) and improved renal function at 3 months, as well as a halving of major adverse cardiovascular events and major adverse kidney events at 1 year.

The trial was presented by Dan Jones, MD, Barts Health NHS Trust, London, at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

“Currently, aside from intravenous hydration, there is no proven treatment that reduces contrast-induced nephropathy. We feel that dietary inorganic nitrate shows huge promise in this study, and these findings could have important implications in reducing this serious complication of coronary angiography,” Dr. Jones concluded.

He explained that the product used was a formulation of dietary inorganic nitrates given as potassium nitrate capsules, which the study investigators produced specifically for this trial.

At this point, “the only way to get inorganic nitrate is in the diet – specifically by consuming beetroot juice or green leafy vegetables such as spinach and rocket. From a clinician perspective, while these results suggest this is an effective therapy and has great potential, it is not currently possible to prescribe the medication we used in our study, although we are working on producing a commercial product,” he said in an interview.

However, Dr. Jones noted that it is possible to buy beetroot shots, which contain 7 mmol of potassium nitrate in each shot, from health food shops and websites, and two such shots per day for 5 days would give a dose similar to that used in this study, starting the day before angiography.

“While we need a larger multicenter study to confirm these results, studies so far suggest no signal at all that there is any harm in this approach, and there could be a great deal of benefit in taking a couple of beetroot shots prior to and for a few days after an angiogram,” he said.

Dietary nitrates “make sense”

Designated discussant of the NITRATE-CIN trial at the ESC Hotline session, Roxanna Mehran, MD, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, said the study was well designed, and the “interesting and plausible” hypothesis to raise nitric oxide levels by dietary nitrates “makes sense.”

On the main findings of a major significant 50% reduction in acute kidney injury, Dr. Mehran said, “It is difficult to imagine such a reduction is possible.”

She pointed out that the large reduction in major adverse cardiac events and major adverse kidney events at 1 year also suggests that there is a sustained benefit in protecting the kidney.

“We’re all going to get on beet juice after this,” she quipped.

Still, Dr. Mehran questioned whether the results were “too good to be true,” adding that a larger trial actually powered for longer term outcome events is needed, as well as a better understanding of whether CIN has a causative role in mortality.

Responding to questions about whether such a large effect could actually be achieved with dietary nitrates, Dr. Jones said he thought there would definitely be some benefits, but maybe not quite as large as those seen in this study.

“From our pilot data we thought nitrate may be effective in preventing CIN,” he said in an interview. “We recruited a higher risk group than we thought, which is why the control event rates were higher than we expected, but the acute kidney injury reduction is roughly what we had estimated, and makes sense biologically.”

Dr. Jones acknowledged that the large reductions in long-term major adverse cardiovascular and kidney events were unexpected.

“The trial was not powered to see reductions in these outcomes, so we need to see if those event reductions can be replicated in larger multicenter trials,” he said. “But this was a double-blind placebo-controlled trial so in this trial the effects are real, and I think the effect size in this trial is too large for there not to be a beneficial effect.

“But I’m not so sure that we would see the same magnitude of effect when we have a larger study with tighter confidence intervals but perhaps a 20%-25% reduction in cardiovascular and kidney may be more realistic, which would still be amazing for such an easy and cost-effective intervention,” Dr. Jones added.

A larger trial is now being planned.

The researchers are also working on the development of a commercial form of dietary inorganic nitrate that would be needed for larger multicenter studies and would then be generally available. “We want this to be a low-cost product that would be available to all,” Dr. Jones said.

He noted that other studies have shown that dietary inorganic nitrates in the form of beetroot juice lower blood pressure; there are suggestions it may also lower cholesterol and prevent stent restenosis, and athletes sometimes take it to increase their aerobic capacity.

“There appears to be many benefits of dietary nitrates, and the one thing we can do at this time is to encourage people to increase their dietary nitrate consumption by eating large quantities of green leafy vegetables and beetroot,” Dr. Jones said.

Replacing lost nitric oxide

In his presentation, Dr. Jones noted that CIN is a serious complication after coronary angiography and is associated with longer hospital stays, worse long-term kidney function, and increased risk of MI and death.

The incidence varies depending on patient risk and definitions used, but it can affect up to 50% of high-risk ACS patients – older patients and/or those with heart failure, chronic kidney disease, or diabetes.

“We don’t really understand the mechanisms that cause CIN, but multiple proposed mechanisms exist, and we know from previous studies that a deficiency of nitric oxide is crucial to the development of CIN,” he explained. “We also know that [nitric oxide] is crucial for normal renal hemostasis. Therefore, a potential therapeutic target to prevent CIN would be to replace this lost nitric oxide.”

The inorganic nitrate evaluated in this trial is found in the diet, is produced endogenously, and is different from medicinally synthesized organic nitrates such as isosorbide mononitrate, he said.

“Isosorbide mononitrate/dinitrate tablets contain organic nitrates and while they are good for angina, we know that they do not have the same beneficial effects on the sustained generation of nitric oxide as inorganic nitrates,” Dr. Jones added.

NITRATE-CIN study

NITRATE-CIN was a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial conducted at Queen Mary University of London and St. Bartholomew’s Hospital in London, which tested the effectiveness of inorganic nitrate in preventing contrast-induced nephropathy in 640 patients with non-ST elevation ACS referred for invasive coronary angiography.

To be eligible for the trial, patients had to be at risk of contrast-induced nephropathy with an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) less than 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2 or have two of the following significant risk factors: diabetes, liver failure, over 70 years of age, exposure to contrast within 7 days, heart failure, or on concomitant renally acting drugs.

Patients were randomly assigned to a formulation of potassium nitrate (12 mmol/744 mg nitrate) per day given as capsules for a 5-day course with the first dose administered prior to angiography or to a control group that received potassium chloride with a matched potassium concentration.

The patient population had a mean age of 71 years, 73% were male, 75% were White, 46% had diabetes, and 56% had chronic kidney disease. There was a 13% loss to follow-up, which was attributed to the COVID pandemic.

The amount of contrast administration was 180 mL in the placebo and 170 mL in the nitrate arm, with 50% of patients undergoing some sort of revascularization.

The primary endpoint was the incidence of CIN as defined by KDIGO criteria – a series of stages of acute kidney injury defined by changes in serum creatinine within 72 hours and up to 1 week.

Results showed that this primary CIN endpoint was reduced significantly from 30% in the placebo arm to 9.1% in the nitrate group, a 70% relative risk reduction (P < .0001). The majority (90%) of this CIN was stage 1, but 10% was stage 2.

Consistent results were seen when an alternative definition of CIN (Mehran) was used, although the rates in both arms were lower than when the KDIGO definition was used.

The benefit was seen across prespecified subgroups including diabetes status, troponin positivity, and Mehran risk. But the benefit seemed to be attenuated in patients on preexisting organic nitrate therapy, although the numbers in these groups were too small to draw definitive conclusions.

As would be expected, there were significant elevations in both systemic nitrate and nitrite levels both up to 72 hours after the procedure, which was consistent with the 5-day course. This was associated with reductions in systolic and diastolic blood pressure, but not associated with any adverse events, Dr. Jones reported.

Rates of procedural MI, a prespecified secondary endpoint, were reduced from 12.5% to 4.1% in those on inorganic nitrates (P = .003).

Looking at longer term outcomes, kidney function was improved at 3 months as measured by change in eGFR, which showed a 10% relative improvement of 5.2 mL/min per 1.73 m2 (10%) in the nitrate group vs. the placebo group. Serum creatinine levels were also significantly increased in the nitrate group.

At 12 months, there was a significant 50% relative reduction in major adverse cardiovascular events – including all-cause mortality, recurrent MI, and recurrent revascularization – which were reduced from 18.1% in the placebo group to 9.1% in the nitrate group, with a reduction in all three of the constituent components of the composite endpoint including all-cause mortality.

Major adverse kidney events (all-cause mortality, renal replacement therapy, or persistent renal dysfunction) were also reduced at 12 months from 28.4% in the placebo group to 10.7% in the nitrate group (P < .0001), a 60% relative reduction. This was driven by lower rates of all-cause mortality and persistent renal dysfunction.

While Dr. Jones said these results on major cardiovascular and kidney outcomes should be viewed as hypothesis-generating at the present time, he said there were biological mechanisms that could explain these benefits.

“We saw a reduction in procedural MI, and we know there is a lot of similar biology in preventing procedural MI and subsequent cardiac events in the acute phase. This, in combination with the large reduction in acute kidney injury, could explain why there’s improved outcomes out to 12 months.”

In her comments, Dr. Mehran congratulated the investigators on having conducted the first study to have shown benefit in the prevention of contrast-associated acute kidney injury as well as major adverse cardiovascular and kidney events associated with the condition.

She used the term “contrast-associated acute kidney injury” rather than “contrast-induced nephropathy” because, she said, it has not been proven that the acute kidney injury seen after angiography is actually caused by the contrast and “so many other things are occurring during procedures when these patients are presenting with different syndromes.”

Dr. Mehran pointed out some weaknesses in the NITRATE-CIN study including the single-center design, the large volume of contrast administered, 13% of patients missing the primary endpoint blood draw, and an imbalance in relevant baseline characteristics despite randomization.

The NITRATE-CIN study was funded by Heart Research UK. Dr. Jones has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

AMSTERDAM –

In the NITRATE-CIN Study, non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction acute coronary syndrome (ACS) patients at risk of renal injury from coronary angiography who received dietary inorganic nitrates had a 70% reduction in CIN compared with those given placebo.

The nitrate group also showed an impressive reduction in periprocedural myocardial infarction (MI) and improved renal function at 3 months, as well as a halving of major adverse cardiovascular events and major adverse kidney events at 1 year.

The trial was presented by Dan Jones, MD, Barts Health NHS Trust, London, at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

“Currently, aside from intravenous hydration, there is no proven treatment that reduces contrast-induced nephropathy. We feel that dietary inorganic nitrate shows huge promise in this study, and these findings could have important implications in reducing this serious complication of coronary angiography,” Dr. Jones concluded.

He explained that the product used was a formulation of dietary inorganic nitrates given as potassium nitrate capsules, which the study investigators produced specifically for this trial.

At this point, “the only way to get inorganic nitrate is in the diet – specifically by consuming beetroot juice or green leafy vegetables such as spinach and rocket. From a clinician perspective, while these results suggest this is an effective therapy and has great potential, it is not currently possible to prescribe the medication we used in our study, although we are working on producing a commercial product,” he said in an interview.

However, Dr. Jones noted that it is possible to buy beetroot shots, which contain 7 mmol of potassium nitrate in each shot, from health food shops and websites, and two such shots per day for 5 days would give a dose similar to that used in this study, starting the day before angiography.

“While we need a larger multicenter study to confirm these results, studies so far suggest no signal at all that there is any harm in this approach, and there could be a great deal of benefit in taking a couple of beetroot shots prior to and for a few days after an angiogram,” he said.

Dietary nitrates “make sense”

Designated discussant of the NITRATE-CIN trial at the ESC Hotline session, Roxanna Mehran, MD, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, said the study was well designed, and the “interesting and plausible” hypothesis to raise nitric oxide levels by dietary nitrates “makes sense.”

On the main findings of a major significant 50% reduction in acute kidney injury, Dr. Mehran said, “It is difficult to imagine such a reduction is possible.”

She pointed out that the large reduction in major adverse cardiac events and major adverse kidney events at 1 year also suggests that there is a sustained benefit in protecting the kidney.

“We’re all going to get on beet juice after this,” she quipped.

Still, Dr. Mehran questioned whether the results were “too good to be true,” adding that a larger trial actually powered for longer term outcome events is needed, as well as a better understanding of whether CIN has a causative role in mortality.

Responding to questions about whether such a large effect could actually be achieved with dietary nitrates, Dr. Jones said he thought there would definitely be some benefits, but maybe not quite as large as those seen in this study.

“From our pilot data we thought nitrate may be effective in preventing CIN,” he said in an interview. “We recruited a higher risk group than we thought, which is why the control event rates were higher than we expected, but the acute kidney injury reduction is roughly what we had estimated, and makes sense biologically.”

Dr. Jones acknowledged that the large reductions in long-term major adverse cardiovascular and kidney events were unexpected.

“The trial was not powered to see reductions in these outcomes, so we need to see if those event reductions can be replicated in larger multicenter trials,” he said. “But this was a double-blind placebo-controlled trial so in this trial the effects are real, and I think the effect size in this trial is too large for there not to be a beneficial effect.

“But I’m not so sure that we would see the same magnitude of effect when we have a larger study with tighter confidence intervals but perhaps a 20%-25% reduction in cardiovascular and kidney may be more realistic, which would still be amazing for such an easy and cost-effective intervention,” Dr. Jones added.

A larger trial is now being planned.

The researchers are also working on the development of a commercial form of dietary inorganic nitrate that would be needed for larger multicenter studies and would then be generally available. “We want this to be a low-cost product that would be available to all,” Dr. Jones said.

He noted that other studies have shown that dietary inorganic nitrates in the form of beetroot juice lower blood pressure; there are suggestions it may also lower cholesterol and prevent stent restenosis, and athletes sometimes take it to increase their aerobic capacity.

“There appears to be many benefits of dietary nitrates, and the one thing we can do at this time is to encourage people to increase their dietary nitrate consumption by eating large quantities of green leafy vegetables and beetroot,” Dr. Jones said.

Replacing lost nitric oxide

In his presentation, Dr. Jones noted that CIN is a serious complication after coronary angiography and is associated with longer hospital stays, worse long-term kidney function, and increased risk of MI and death.

The incidence varies depending on patient risk and definitions used, but it can affect up to 50% of high-risk ACS patients – older patients and/or those with heart failure, chronic kidney disease, or diabetes.

“We don’t really understand the mechanisms that cause CIN, but multiple proposed mechanisms exist, and we know from previous studies that a deficiency of nitric oxide is crucial to the development of CIN,” he explained. “We also know that [nitric oxide] is crucial for normal renal hemostasis. Therefore, a potential therapeutic target to prevent CIN would be to replace this lost nitric oxide.”

The inorganic nitrate evaluated in this trial is found in the diet, is produced endogenously, and is different from medicinally synthesized organic nitrates such as isosorbide mononitrate, he said.

“Isosorbide mononitrate/dinitrate tablets contain organic nitrates and while they are good for angina, we know that they do not have the same beneficial effects on the sustained generation of nitric oxide as inorganic nitrates,” Dr. Jones added.

NITRATE-CIN study

NITRATE-CIN was a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial conducted at Queen Mary University of London and St. Bartholomew’s Hospital in London, which tested the effectiveness of inorganic nitrate in preventing contrast-induced nephropathy in 640 patients with non-ST elevation ACS referred for invasive coronary angiography.

To be eligible for the trial, patients had to be at risk of contrast-induced nephropathy with an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) less than 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2 or have two of the following significant risk factors: diabetes, liver failure, over 70 years of age, exposure to contrast within 7 days, heart failure, or on concomitant renally acting drugs.

Patients were randomly assigned to a formulation of potassium nitrate (12 mmol/744 mg nitrate) per day given as capsules for a 5-day course with the first dose administered prior to angiography or to a control group that received potassium chloride with a matched potassium concentration.

The patient population had a mean age of 71 years, 73% were male, 75% were White, 46% had diabetes, and 56% had chronic kidney disease. There was a 13% loss to follow-up, which was attributed to the COVID pandemic.

The amount of contrast administration was 180 mL in the placebo and 170 mL in the nitrate arm, with 50% of patients undergoing some sort of revascularization.

The primary endpoint was the incidence of CIN as defined by KDIGO criteria – a series of stages of acute kidney injury defined by changes in serum creatinine within 72 hours and up to 1 week.

Results showed that this primary CIN endpoint was reduced significantly from 30% in the placebo arm to 9.1% in the nitrate group, a 70% relative risk reduction (P < .0001). The majority (90%) of this CIN was stage 1, but 10% was stage 2.

Consistent results were seen when an alternative definition of CIN (Mehran) was used, although the rates in both arms were lower than when the KDIGO definition was used.

The benefit was seen across prespecified subgroups including diabetes status, troponin positivity, and Mehran risk. But the benefit seemed to be attenuated in patients on preexisting organic nitrate therapy, although the numbers in these groups were too small to draw definitive conclusions.

As would be expected, there were significant elevations in both systemic nitrate and nitrite levels both up to 72 hours after the procedure, which was consistent with the 5-day course. This was associated with reductions in systolic and diastolic blood pressure, but not associated with any adverse events, Dr. Jones reported.

Rates of procedural MI, a prespecified secondary endpoint, were reduced from 12.5% to 4.1% in those on inorganic nitrates (P = .003).

Looking at longer term outcomes, kidney function was improved at 3 months as measured by change in eGFR, which showed a 10% relative improvement of 5.2 mL/min per 1.73 m2 (10%) in the nitrate group vs. the placebo group. Serum creatinine levels were also significantly increased in the nitrate group.

At 12 months, there was a significant 50% relative reduction in major adverse cardiovascular events – including all-cause mortality, recurrent MI, and recurrent revascularization – which were reduced from 18.1% in the placebo group to 9.1% in the nitrate group, with a reduction in all three of the constituent components of the composite endpoint including all-cause mortality.