User login

Really? Cancer screening doesn’t save lives?

This transcript from Impact Factor has been edited for clarity.

If you are my age or older, and like me, you are something of a rule follower, then you’re getting screened for various cancers.

Colonoscopies, mammograms, cervical cancer screening, chest CTs for people with a significant smoking history. The tests are done and usually, but not always, they are negative. And if positive, usually, but not always, follow-up tests are negative, and if they aren’t and a new cancer is diagnosed you tell yourself, Well, at least we caught it early. Isn’t it good that I’m a rule follower? My life was just saved.

But it turns out, proving that cancer screening actually saves lives is quite difficult. Is it possible that all this screening is for nothing?

The benefits, risks, or perhaps futility of cancer screening is in the news this week because of this article, appearing in JAMA Internal Medicine.

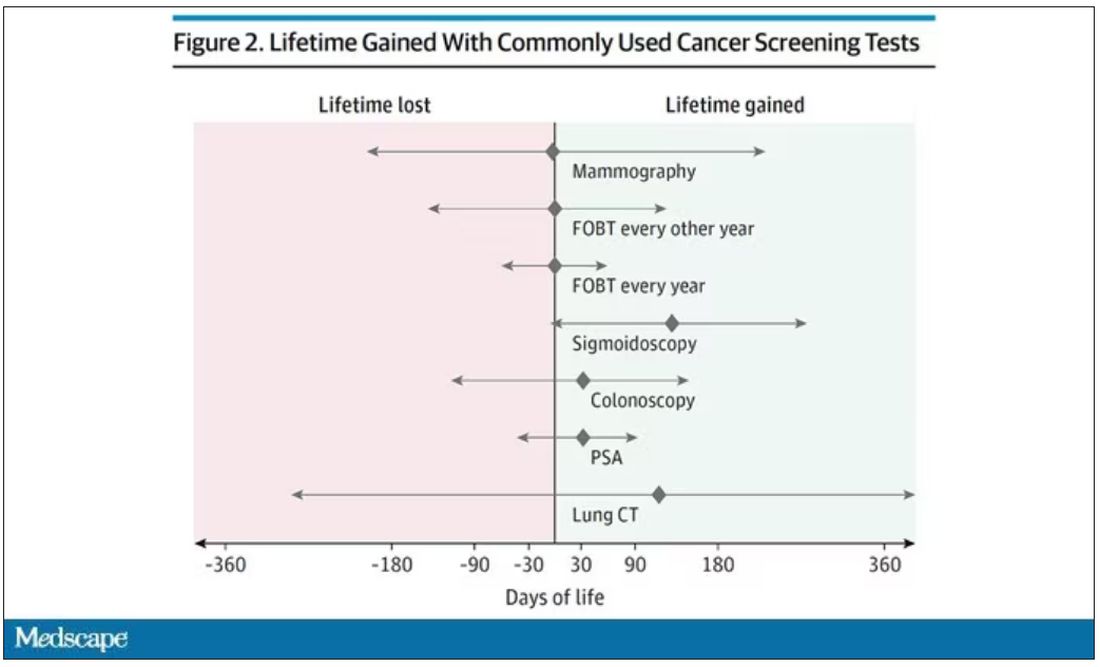

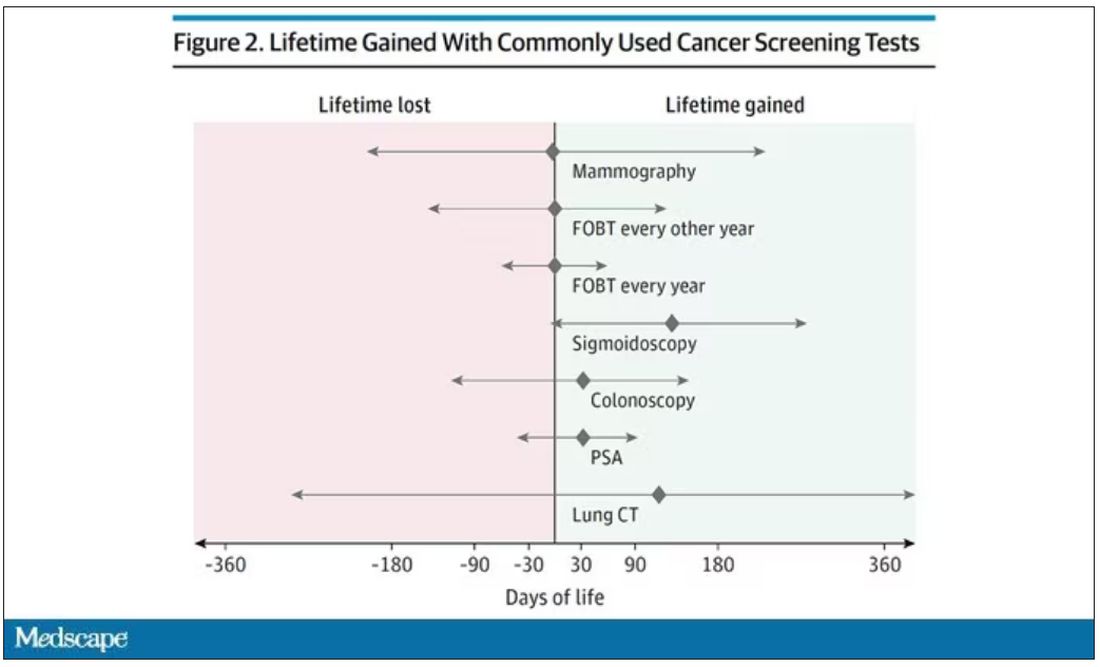

It’s a meta-analysis of very specific randomized trials of cancer screening modalities and concludes that, with the exception of sigmoidoscopy for colon cancer screening, none of them meaningfully change life expectancy.

Now – a bit of inside baseball here – I almost never choose to discuss meta-analyses on Impact Factor. It’s hard enough to dig deep into the methodology of a single study, but with a meta-analysis, you’re sort of obligated to review all the included studies, and, what’s worse, the studies that were not included but might bear on the central question.

In this case, though, the topic is important enough to think about a bit more, and the conclusions have large enough implications for public health that we should question them a bit.

First, let’s run down the study as presented.

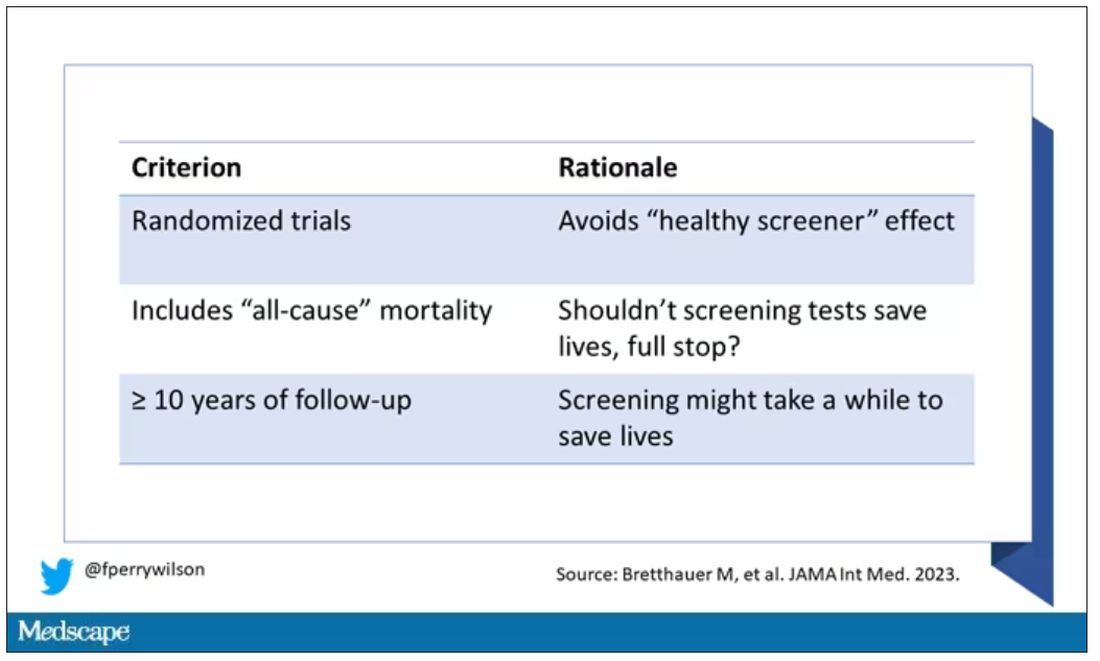

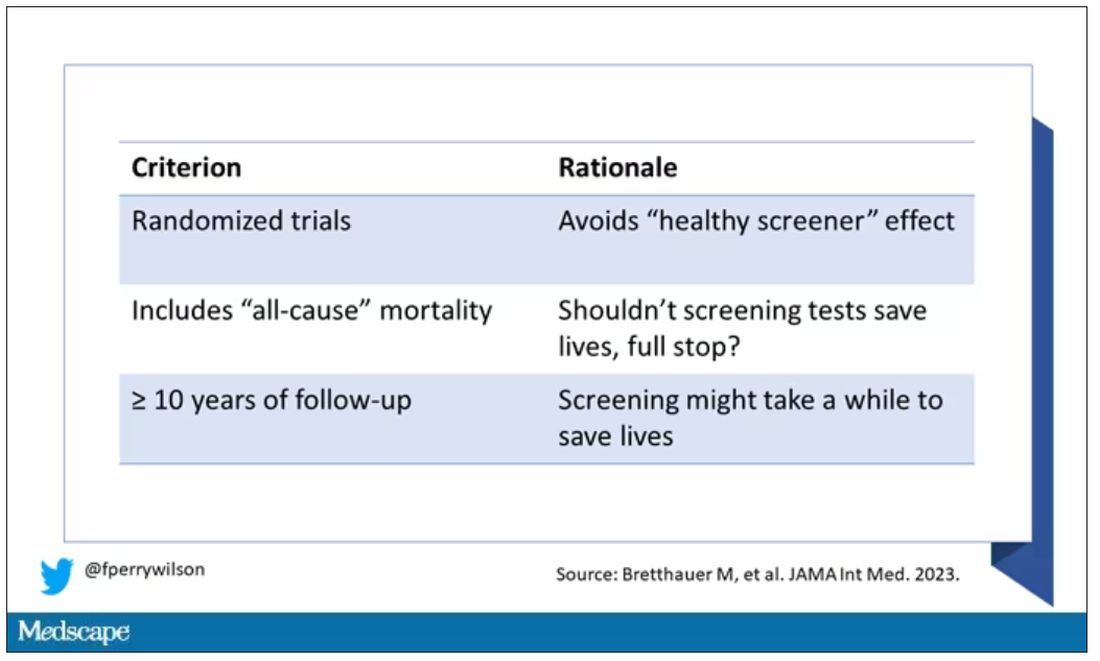

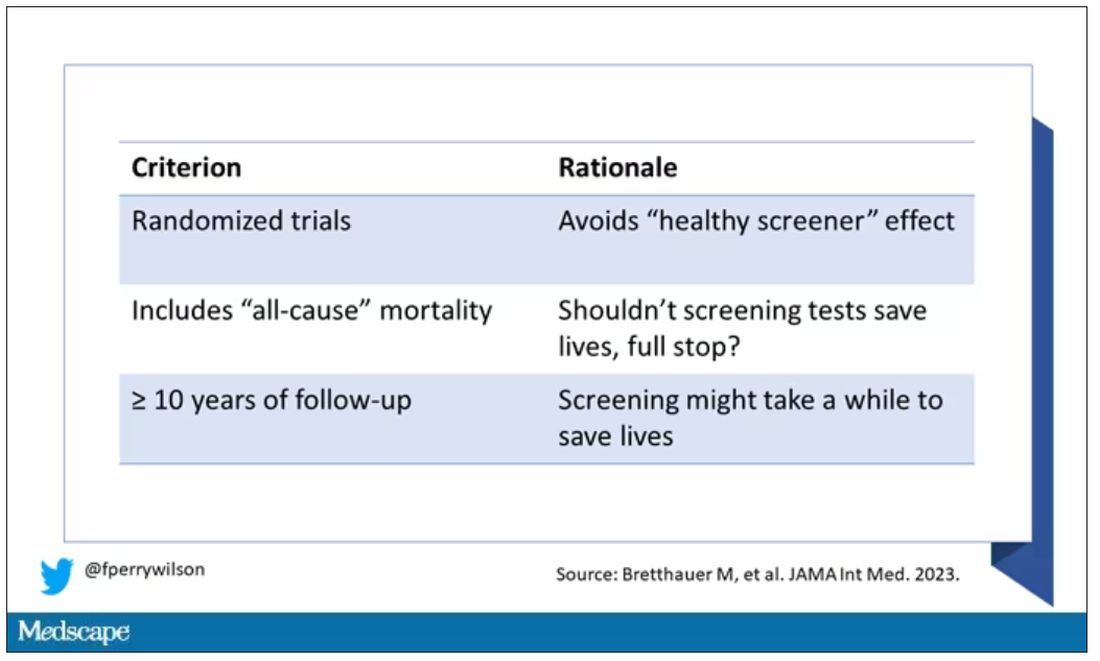

The authors searched for randomized trials of cancer screening modalities. This is important, and I think appropriate. They wanted studies that took some people and assigned them to screening, and some people to no screening – avoiding the confounding that would come from observational data (rule followers like me tend to live longer owing to a variety of healthful behaviors, not just cancer screening).

They didn’t stop at just randomized trials, though. They wanted trials that reported on all-cause, not cancer-specific, mortality. We’ll dig into the distinction in a sec. Finally, they wanted trials with at least 10 years of follow-up time.

These are pretty strict criteria – and after applying that filter, we are left with a grand total of 18 studies to analyze. Most were in the colon cancer space; only two studies met criteria for mammography screening.

Right off the bat, this raises concerns to me. In the universe of high-quality studies of cancer screening modalities, this is just the tip of the iceberg. And the results of meta-analyses are always dependent on the included studies – definitionally.

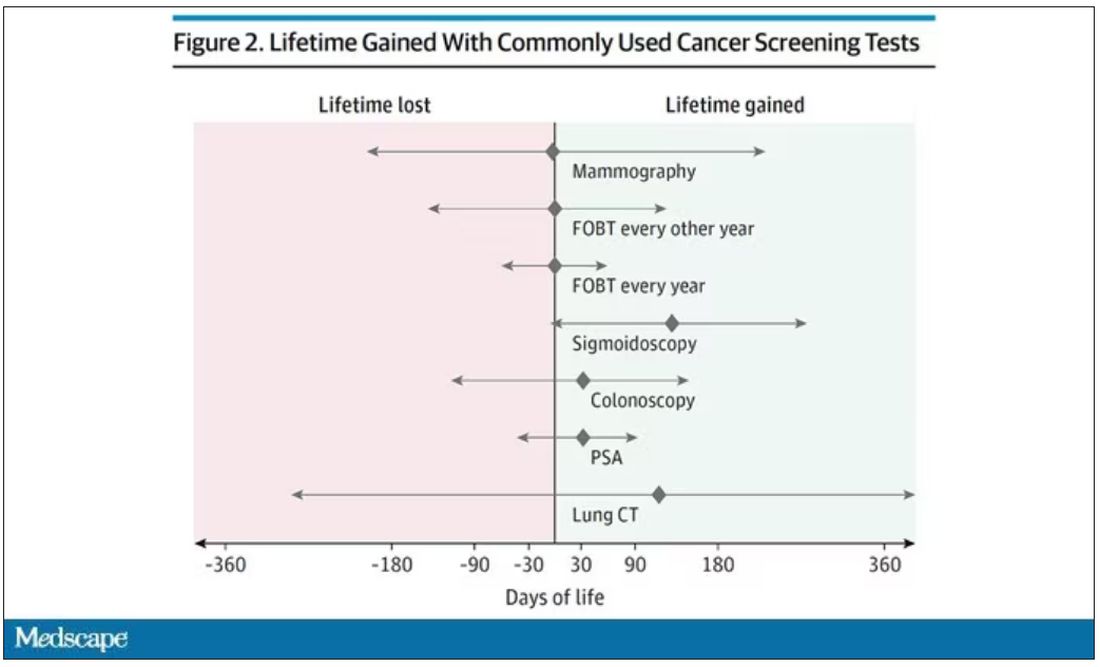

The results as presented are compelling.

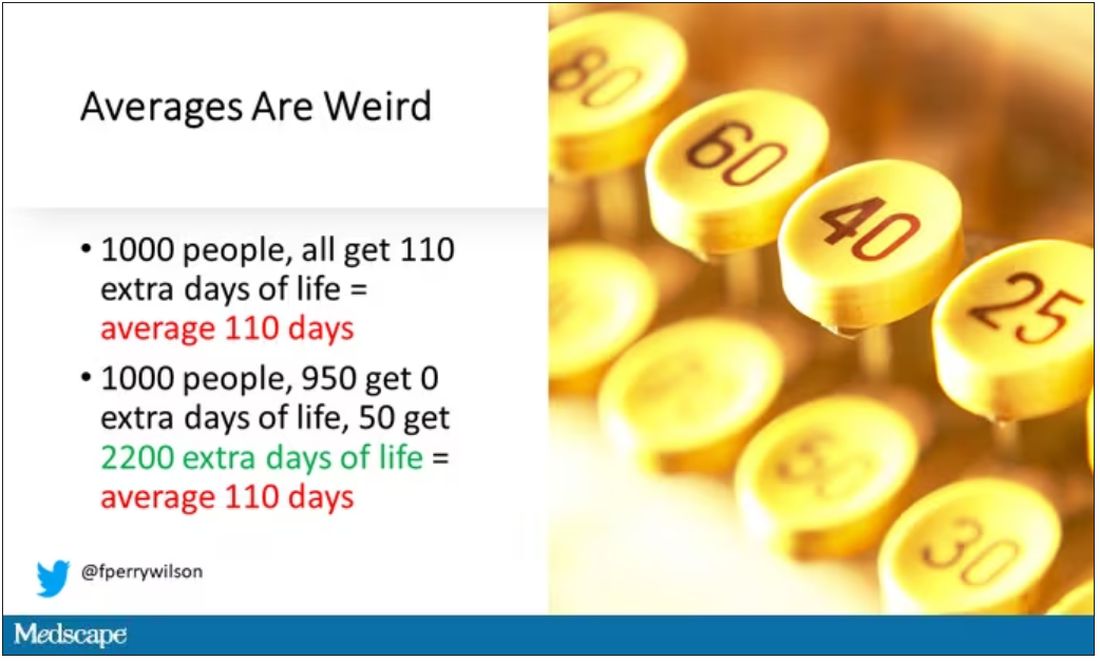

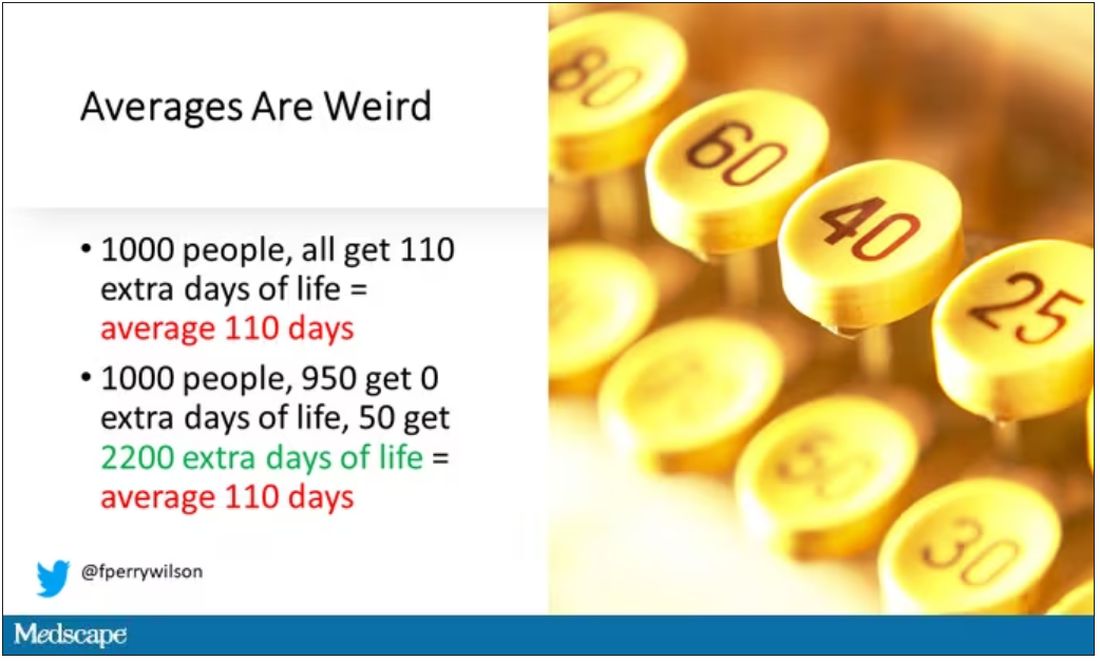

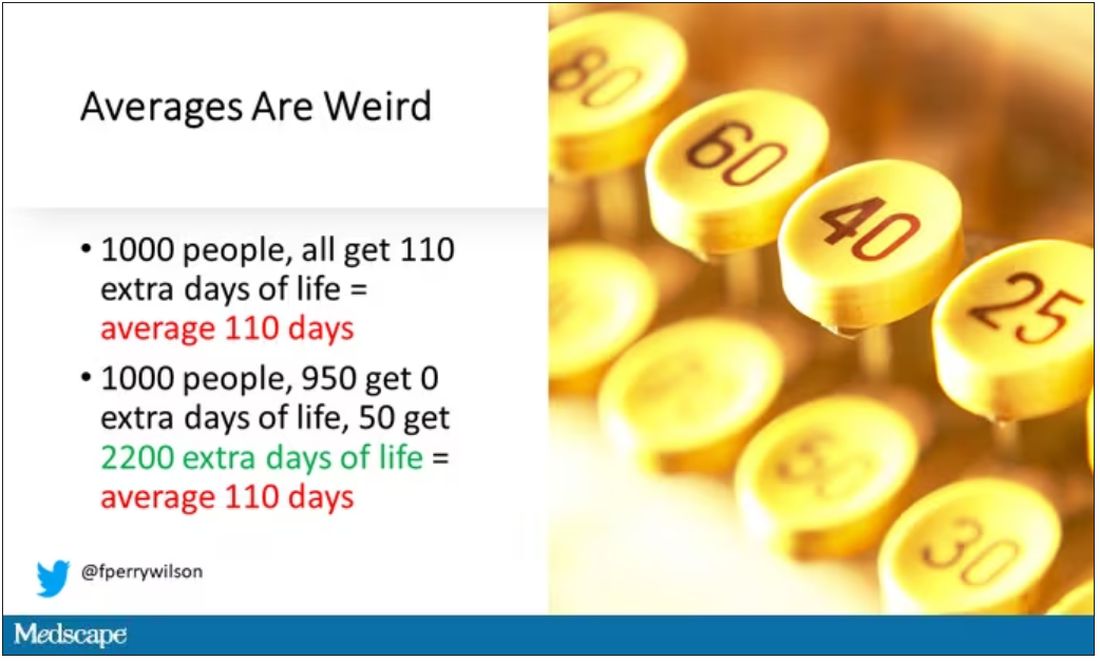

(Side note: Averages are tricky here. It’s not like everyone who gets screened gets 110 extra days. Most people get nothing, and some people – those whose colon cancer was detected early – get a bunch of extra days.)

And a thing about meta-analysis: Meeting the criteria to be included in a meta-analysis does not necessarily mean the study was a good one. For example, one of the two mammography screening studies included is this one, from Miller and colleagues.

On the surface, it looks good – a large randomized trial of mammography screening in Canada, with long-term follow-up including all-cause mortality. Showing, by the way, no effect of screening on either breast cancer–specific or all-cause mortality.

But that study came under a lot of criticism owing to allegations that randomization was broken and women with palpable breast masses were preferentially put into the mammography group, making those outcomes worse.

The authors of the current meta-analysis don’t mention this. Indeed, they state that they don’t perform any assessments of the quality of the included studies.

But I don’t want to criticize all the included studies. Let’s think bigger picture.

Randomized trials of screening for cancers like colon, breast, and lung cancer in smokers have generally shown that those randomized to screening had lower target-cancer–specific mortality. Across all the randomized mammography studies, for example, women randomized to mammography were about 20% less likely to die of breast cancer than were those who were randomized to not be screened – particularly among those above age 50.

But it’s true that all-cause mortality, on the whole, has not differed statistically between those randomized to mammography vs. no mammography. What’s the deal?

Well, the authors of the meta-analysis engage in some zero-sum thinking here. They say that if it is true that screening tests reduce cancer-specific deaths, but all-cause mortality is not different, screening tests must increase mortality due to other causes. How? They cite colonic perforation during colonoscopy as an example of a harm that could lead to earlier death, which makes some sense. For mammogram and other less invasive screening modalities, they suggest that the stress and anxiety associated with screening might increase the risk for death – this is a bit harder for me to defend.

The thing is, statistics really isn’t a zero-sum game. It’s a question of signal vs. noise. Take breast cancer, for example. Without screening, about 3.2% of women in this country would die of breast cancer. With screening, 2.8% would die (that’s a 20% reduction on the relative scale). The truth is, most women don’t die of breast cancer. Most people don’t die of colon cancer. Even most smokers don’t die of lung cancer. Most people die of heart disease. And then cancer – but there are a lot of cancers out there, and only a handful have decent screening tests.

In other words, the screening tests are unlikely to help most people because most people will not die of the particular type of cancer being screened for. But it will help some small number of those people being screened a lot, potentially saving their lives. If we knew who those people were in advance, it would be great, but then I suppose we wouldn’t need the screening test in the first place.

It’s not fair, then, to say that mammography increases non–breast cancer causes of death. In reality, it’s just that the impact of mammography on all-cause mortality is washed out by the random noise inherent to studying a sample of individuals rather than the entire population.

I’m reminded of that old story about the girl on the beach after a storm, throwing beached starfish back into the water. Someone comes by and says, “Why are you doing that? There are millions of starfish here – it doesn’t matter if you throw a few back.” And she says, “It matters for this one.”

There are other issues with aggregating data like these and concluding that there is no effect on all-cause mortality. For one, it assumes the people randomized to no screening never got screening. Most of these studies lasted 5-10 years, some with longer follow-up, but many people in the no-screening arm may have been screened as recommendations have changed. That would tend to bias the results against screening because the so-called control group, well, isn’t.

It also fails to acknowledge the reality that screening for disease can be thought of as a package deal. Instead of asking whether screening for breast cancer, and colon cancer, and lung cancer individually saves lives, the real relevant question is whether a policy of screening for cancer in general saves lives. And that hasn’t been studied very broadly, except in one trial looking at screening for four cancers. That study is in this meta-analysis and, interestingly, seems to suggest that the policy does extend life – by 123 days. Again, be careful how you think about that average.

I don’t want to be an absolutist here. Whether these screening tests are a good idea or not is actually a moving target. As treatment for cancer gets better, detecting cancer early may not be as important. As new screening modalities emerge, older ones may not be preferable any longer. Better testing, genetic or otherwise, might allow us to tailor screening more narrowly than the population-based approach we have now.

But I worry that a meta-analysis like this, which concludes that screening doesn’t help on the basis of a handful of studies – without acknowledgment of the signal-to-noise problem, without accounting for screening in the control group, without acknowledging that screening should be thought of as a package – will lead some people to make the decision to forgo screening. for, say, 49 out of 50 of them, that may be fine. But for 1 out of 50 or so, well, it matters for that one.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. His science communication work can be found in the Huffington Post, on NPR, and on Medscape. He tweets @fperrywilson and his new book, How Medicine Works and When It Doesn’t, is available now. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript from Impact Factor has been edited for clarity.

If you are my age or older, and like me, you are something of a rule follower, then you’re getting screened for various cancers.

Colonoscopies, mammograms, cervical cancer screening, chest CTs for people with a significant smoking history. The tests are done and usually, but not always, they are negative. And if positive, usually, but not always, follow-up tests are negative, and if they aren’t and a new cancer is diagnosed you tell yourself, Well, at least we caught it early. Isn’t it good that I’m a rule follower? My life was just saved.

But it turns out, proving that cancer screening actually saves lives is quite difficult. Is it possible that all this screening is for nothing?

The benefits, risks, or perhaps futility of cancer screening is in the news this week because of this article, appearing in JAMA Internal Medicine.

It’s a meta-analysis of very specific randomized trials of cancer screening modalities and concludes that, with the exception of sigmoidoscopy for colon cancer screening, none of them meaningfully change life expectancy.

Now – a bit of inside baseball here – I almost never choose to discuss meta-analyses on Impact Factor. It’s hard enough to dig deep into the methodology of a single study, but with a meta-analysis, you’re sort of obligated to review all the included studies, and, what’s worse, the studies that were not included but might bear on the central question.

In this case, though, the topic is important enough to think about a bit more, and the conclusions have large enough implications for public health that we should question them a bit.

First, let’s run down the study as presented.

The authors searched for randomized trials of cancer screening modalities. This is important, and I think appropriate. They wanted studies that took some people and assigned them to screening, and some people to no screening – avoiding the confounding that would come from observational data (rule followers like me tend to live longer owing to a variety of healthful behaviors, not just cancer screening).

They didn’t stop at just randomized trials, though. They wanted trials that reported on all-cause, not cancer-specific, mortality. We’ll dig into the distinction in a sec. Finally, they wanted trials with at least 10 years of follow-up time.

These are pretty strict criteria – and after applying that filter, we are left with a grand total of 18 studies to analyze. Most were in the colon cancer space; only two studies met criteria for mammography screening.

Right off the bat, this raises concerns to me. In the universe of high-quality studies of cancer screening modalities, this is just the tip of the iceberg. And the results of meta-analyses are always dependent on the included studies – definitionally.

The results as presented are compelling.

(Side note: Averages are tricky here. It’s not like everyone who gets screened gets 110 extra days. Most people get nothing, and some people – those whose colon cancer was detected early – get a bunch of extra days.)

And a thing about meta-analysis: Meeting the criteria to be included in a meta-analysis does not necessarily mean the study was a good one. For example, one of the two mammography screening studies included is this one, from Miller and colleagues.

On the surface, it looks good – a large randomized trial of mammography screening in Canada, with long-term follow-up including all-cause mortality. Showing, by the way, no effect of screening on either breast cancer–specific or all-cause mortality.

But that study came under a lot of criticism owing to allegations that randomization was broken and women with palpable breast masses were preferentially put into the mammography group, making those outcomes worse.

The authors of the current meta-analysis don’t mention this. Indeed, they state that they don’t perform any assessments of the quality of the included studies.

But I don’t want to criticize all the included studies. Let’s think bigger picture.

Randomized trials of screening for cancers like colon, breast, and lung cancer in smokers have generally shown that those randomized to screening had lower target-cancer–specific mortality. Across all the randomized mammography studies, for example, women randomized to mammography were about 20% less likely to die of breast cancer than were those who were randomized to not be screened – particularly among those above age 50.

But it’s true that all-cause mortality, on the whole, has not differed statistically between those randomized to mammography vs. no mammography. What’s the deal?

Well, the authors of the meta-analysis engage in some zero-sum thinking here. They say that if it is true that screening tests reduce cancer-specific deaths, but all-cause mortality is not different, screening tests must increase mortality due to other causes. How? They cite colonic perforation during colonoscopy as an example of a harm that could lead to earlier death, which makes some sense. For mammogram and other less invasive screening modalities, they suggest that the stress and anxiety associated with screening might increase the risk for death – this is a bit harder for me to defend.

The thing is, statistics really isn’t a zero-sum game. It’s a question of signal vs. noise. Take breast cancer, for example. Without screening, about 3.2% of women in this country would die of breast cancer. With screening, 2.8% would die (that’s a 20% reduction on the relative scale). The truth is, most women don’t die of breast cancer. Most people don’t die of colon cancer. Even most smokers don’t die of lung cancer. Most people die of heart disease. And then cancer – but there are a lot of cancers out there, and only a handful have decent screening tests.

In other words, the screening tests are unlikely to help most people because most people will not die of the particular type of cancer being screened for. But it will help some small number of those people being screened a lot, potentially saving their lives. If we knew who those people were in advance, it would be great, but then I suppose we wouldn’t need the screening test in the first place.

It’s not fair, then, to say that mammography increases non–breast cancer causes of death. In reality, it’s just that the impact of mammography on all-cause mortality is washed out by the random noise inherent to studying a sample of individuals rather than the entire population.

I’m reminded of that old story about the girl on the beach after a storm, throwing beached starfish back into the water. Someone comes by and says, “Why are you doing that? There are millions of starfish here – it doesn’t matter if you throw a few back.” And she says, “It matters for this one.”

There are other issues with aggregating data like these and concluding that there is no effect on all-cause mortality. For one, it assumes the people randomized to no screening never got screening. Most of these studies lasted 5-10 years, some with longer follow-up, but many people in the no-screening arm may have been screened as recommendations have changed. That would tend to bias the results against screening because the so-called control group, well, isn’t.

It also fails to acknowledge the reality that screening for disease can be thought of as a package deal. Instead of asking whether screening for breast cancer, and colon cancer, and lung cancer individually saves lives, the real relevant question is whether a policy of screening for cancer in general saves lives. And that hasn’t been studied very broadly, except in one trial looking at screening for four cancers. That study is in this meta-analysis and, interestingly, seems to suggest that the policy does extend life – by 123 days. Again, be careful how you think about that average.

I don’t want to be an absolutist here. Whether these screening tests are a good idea or not is actually a moving target. As treatment for cancer gets better, detecting cancer early may not be as important. As new screening modalities emerge, older ones may not be preferable any longer. Better testing, genetic or otherwise, might allow us to tailor screening more narrowly than the population-based approach we have now.

But I worry that a meta-analysis like this, which concludes that screening doesn’t help on the basis of a handful of studies – without acknowledgment of the signal-to-noise problem, without accounting for screening in the control group, without acknowledging that screening should be thought of as a package – will lead some people to make the decision to forgo screening. for, say, 49 out of 50 of them, that may be fine. But for 1 out of 50 or so, well, it matters for that one.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. His science communication work can be found in the Huffington Post, on NPR, and on Medscape. He tweets @fperrywilson and his new book, How Medicine Works and When It Doesn’t, is available now. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript from Impact Factor has been edited for clarity.

If you are my age or older, and like me, you are something of a rule follower, then you’re getting screened for various cancers.

Colonoscopies, mammograms, cervical cancer screening, chest CTs for people with a significant smoking history. The tests are done and usually, but not always, they are negative. And if positive, usually, but not always, follow-up tests are negative, and if they aren’t and a new cancer is diagnosed you tell yourself, Well, at least we caught it early. Isn’t it good that I’m a rule follower? My life was just saved.

But it turns out, proving that cancer screening actually saves lives is quite difficult. Is it possible that all this screening is for nothing?

The benefits, risks, or perhaps futility of cancer screening is in the news this week because of this article, appearing in JAMA Internal Medicine.

It’s a meta-analysis of very specific randomized trials of cancer screening modalities and concludes that, with the exception of sigmoidoscopy for colon cancer screening, none of them meaningfully change life expectancy.

Now – a bit of inside baseball here – I almost never choose to discuss meta-analyses on Impact Factor. It’s hard enough to dig deep into the methodology of a single study, but with a meta-analysis, you’re sort of obligated to review all the included studies, and, what’s worse, the studies that were not included but might bear on the central question.

In this case, though, the topic is important enough to think about a bit more, and the conclusions have large enough implications for public health that we should question them a bit.

First, let’s run down the study as presented.

The authors searched for randomized trials of cancer screening modalities. This is important, and I think appropriate. They wanted studies that took some people and assigned them to screening, and some people to no screening – avoiding the confounding that would come from observational data (rule followers like me tend to live longer owing to a variety of healthful behaviors, not just cancer screening).

They didn’t stop at just randomized trials, though. They wanted trials that reported on all-cause, not cancer-specific, mortality. We’ll dig into the distinction in a sec. Finally, they wanted trials with at least 10 years of follow-up time.

These are pretty strict criteria – and after applying that filter, we are left with a grand total of 18 studies to analyze. Most were in the colon cancer space; only two studies met criteria for mammography screening.

Right off the bat, this raises concerns to me. In the universe of high-quality studies of cancer screening modalities, this is just the tip of the iceberg. And the results of meta-analyses are always dependent on the included studies – definitionally.

The results as presented are compelling.

(Side note: Averages are tricky here. It’s not like everyone who gets screened gets 110 extra days. Most people get nothing, and some people – those whose colon cancer was detected early – get a bunch of extra days.)

And a thing about meta-analysis: Meeting the criteria to be included in a meta-analysis does not necessarily mean the study was a good one. For example, one of the two mammography screening studies included is this one, from Miller and colleagues.

On the surface, it looks good – a large randomized trial of mammography screening in Canada, with long-term follow-up including all-cause mortality. Showing, by the way, no effect of screening on either breast cancer–specific or all-cause mortality.

But that study came under a lot of criticism owing to allegations that randomization was broken and women with palpable breast masses were preferentially put into the mammography group, making those outcomes worse.

The authors of the current meta-analysis don’t mention this. Indeed, they state that they don’t perform any assessments of the quality of the included studies.

But I don’t want to criticize all the included studies. Let’s think bigger picture.

Randomized trials of screening for cancers like colon, breast, and lung cancer in smokers have generally shown that those randomized to screening had lower target-cancer–specific mortality. Across all the randomized mammography studies, for example, women randomized to mammography were about 20% less likely to die of breast cancer than were those who were randomized to not be screened – particularly among those above age 50.

But it’s true that all-cause mortality, on the whole, has not differed statistically between those randomized to mammography vs. no mammography. What’s the deal?

Well, the authors of the meta-analysis engage in some zero-sum thinking here. They say that if it is true that screening tests reduce cancer-specific deaths, but all-cause mortality is not different, screening tests must increase mortality due to other causes. How? They cite colonic perforation during colonoscopy as an example of a harm that could lead to earlier death, which makes some sense. For mammogram and other less invasive screening modalities, they suggest that the stress and anxiety associated with screening might increase the risk for death – this is a bit harder for me to defend.

The thing is, statistics really isn’t a zero-sum game. It’s a question of signal vs. noise. Take breast cancer, for example. Without screening, about 3.2% of women in this country would die of breast cancer. With screening, 2.8% would die (that’s a 20% reduction on the relative scale). The truth is, most women don’t die of breast cancer. Most people don’t die of colon cancer. Even most smokers don’t die of lung cancer. Most people die of heart disease. And then cancer – but there are a lot of cancers out there, and only a handful have decent screening tests.

In other words, the screening tests are unlikely to help most people because most people will not die of the particular type of cancer being screened for. But it will help some small number of those people being screened a lot, potentially saving their lives. If we knew who those people were in advance, it would be great, but then I suppose we wouldn’t need the screening test in the first place.

It’s not fair, then, to say that mammography increases non–breast cancer causes of death. In reality, it’s just that the impact of mammography on all-cause mortality is washed out by the random noise inherent to studying a sample of individuals rather than the entire population.

I’m reminded of that old story about the girl on the beach after a storm, throwing beached starfish back into the water. Someone comes by and says, “Why are you doing that? There are millions of starfish here – it doesn’t matter if you throw a few back.” And she says, “It matters for this one.”

There are other issues with aggregating data like these and concluding that there is no effect on all-cause mortality. For one, it assumes the people randomized to no screening never got screening. Most of these studies lasted 5-10 years, some with longer follow-up, but many people in the no-screening arm may have been screened as recommendations have changed. That would tend to bias the results against screening because the so-called control group, well, isn’t.

It also fails to acknowledge the reality that screening for disease can be thought of as a package deal. Instead of asking whether screening for breast cancer, and colon cancer, and lung cancer individually saves lives, the real relevant question is whether a policy of screening for cancer in general saves lives. And that hasn’t been studied very broadly, except in one trial looking at screening for four cancers. That study is in this meta-analysis and, interestingly, seems to suggest that the policy does extend life – by 123 days. Again, be careful how you think about that average.

I don’t want to be an absolutist here. Whether these screening tests are a good idea or not is actually a moving target. As treatment for cancer gets better, detecting cancer early may not be as important. As new screening modalities emerge, older ones may not be preferable any longer. Better testing, genetic or otherwise, might allow us to tailor screening more narrowly than the population-based approach we have now.

But I worry that a meta-analysis like this, which concludes that screening doesn’t help on the basis of a handful of studies – without acknowledgment of the signal-to-noise problem, without accounting for screening in the control group, without acknowledging that screening should be thought of as a package – will lead some people to make the decision to forgo screening. for, say, 49 out of 50 of them, that may be fine. But for 1 out of 50 or so, well, it matters for that one.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. His science communication work can be found in the Huffington Post, on NPR, and on Medscape. He tweets @fperrywilson and his new book, How Medicine Works and When It Doesn’t, is available now. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Medicare announces 10 drugs targeted for price cuts in 2026

People on Medicare may in 2026 see prices drop for 10 medicines, including pricey diabetes, cancer, blood clot, and arthritis treatments, if advocates for federal drug-price negotiations can implement their plans amid tough opposition.

It’s unclear at this time, though, how these negotiations will play out. The Chamber of Commerce has sided with pharmaceutical companies in bids to block direct Medicare negotiation of drug prices. Many influential Republicans in Congress oppose this plan, which has deep support from both Democrats and AARP.

While facing strong opposition to negotiations, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services sought in its announcement to illustrate the high costs of the selected medicines.

CMS provided data on total Part D costs for selected medicines for the period from June 2022 to May 2023, along with tallies of the number of people taking these drugs. The 10 selected medicines are as follows:

- Eliquis (generic name: apixaban), used to prevent and treat serious blood clots. It is taken by about 3.7 million people through Part D plans. The estimated cost is $16.4 billion.

- Jardiance (generic name: empagliflozin), used for diabetes and heart failure. It is taken by almost 1.6 million people through Part D plans. The estimated cost is $7.06 billion.

- Xarelto (generic name: rivaroxaban), used for blood clots. It is taken by about 1.3 million people through Part D plans. The estimated cost is $6 billion.

- Januvia (generic name: sitagliptin), used for diabetes. It is taken by about 869,00 people through Part D plans. The estimated cost is $4.1 billion.

- Farxiga (generic name: dapagliflozin), used for diabetes, heart failure, and chronic kidney disease. It is taken by about 799,000 people through Part D plans. The estimated cost is almost $3.3 billion.

- Entresto (generic name: sacubitril/valsartan), used to treat heart failure. It is taken by 587,000 people through Part D plans. The estimated cost is $2.9 billion.

- Enbrel( generic name: etanercept), used for rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, and psoriatic arthritis. It is taken by 48,000 people through Part D plans. The estimated cost is $2.8 billion.

- Imbruvica (generic name: ibrutinib), used to treat some blood cancers. It is taken by about 20,000 people in Part D plans. The estimated cost is $2.7 billion.

- Stelara (generic name: ustekinumab), used to treat plaque psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, or certain bowel conditions (Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis). It is used by about 22,000 people through Part D plans. The estimated cost is $2.6 billion.

- Fiasp; Fiasp FlexTouch; Fiasp PenFill; NovoLog; NovoLog FlexPen; NovoLog PenFill. These are forms of insulin used to treat diabetes. They are used by about 777,000 people through Part D plans. The estimated cost is $2.6 billion.

A vocal critic of Medicare drug negotiations, Joel White, president of the Council for Affordable Health Coverage, called the announcement of the 10 drugs selected for negotiation “a hollow victory lap.” A former Republican staffer on the House Ways and Means Committee, Mr. White aided with the development of the Medicare Part D plans and has kept tabs on the pharmacy programs since its launch in 2006.

“No one’s costs will go down now or for years because of this announcement” about Part D negotiations, Mr. White said in a statement.

According to its website, CAHC includes among its members the American Academy of Ophthalmology as well as some patient groups, drugmakers, such as Johnson & Johnson, and insurers and industry groups, such as the National Association of Manufacturers.

Separately, the influential Chamber of Commerce is making a strong push to at least delay the implementation of the Medicare Part D drug negotiations. On Aug. 28, the chamber released a letter sent to the Biden administration, raising concerns about a “rush” to implement the provisions of the Inflation Reduction Act.

The chamber also has filed suit to challenge the drug negotiation provisions of the Inflation Reduction Act, requesting that the court issue a preliminary injunction by Oct. 1, 2023.

Other pending legal challenges to direct Medicare drug negotiations include suits filed by Merck, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Johnson & Johnson, Boehringer Ingelheim, and AstraZeneca, according to an email from Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America. PhRMA also said it is a party to a case.

In addition, the three congressional Republicans with most direct influence over Medicare policy issued on Aug. 29 a joint statement outlining their objections to the planned negotiations on drug prices.

This drug-negotiation proposal is “an unworkable, legally dubious scheme that will lead to higher prices for new drugs coming to market, stifle the development of new cures, and destroy jobs,” said House Energy and Commerce Committee Chair Cathy McMorris Rodgers (R-Wash.), House Ways and Means Committee Chair Jason Smith (R-Mo.), and Senate Finance Committee Ranking Member Mike Crapo (R-Idaho).

Democrats were equally firm and vocal in their support of the negotiations. Senate Finance Chairman Ron Wyden (D-Ore.) issued a statement on Aug. 29 that said the release of the list of the 10 drugs selected for Medicare drug negotiations is part of a “seismic shift in the relationship between Big Pharma, the federal government, and seniors who are counting on lower prices.

“I will be following the negotiation process closely and will fight any attempt by Big Pharma to undo or undermine the progress that’s been made,” Mr. Wyden said.

In addition, AARP issued a statement of its continued support for Medicare drug negotiations.

“The No. 1 reason seniors skip or ration their prescriptions is because they can’t afford them. This must stop,” said AARP executive vice president and chief advocacy and engagement officer Nancy LeaMond in the statement. “The big drug companies and their allies continue suing to overturn the Medicare drug price negotiation program to keep up their price gouging. We can’t allow seniors to be Big Pharma’s cash machine anymore.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

People on Medicare may in 2026 see prices drop for 10 medicines, including pricey diabetes, cancer, blood clot, and arthritis treatments, if advocates for federal drug-price negotiations can implement their plans amid tough opposition.

It’s unclear at this time, though, how these negotiations will play out. The Chamber of Commerce has sided with pharmaceutical companies in bids to block direct Medicare negotiation of drug prices. Many influential Republicans in Congress oppose this plan, which has deep support from both Democrats and AARP.

While facing strong opposition to negotiations, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services sought in its announcement to illustrate the high costs of the selected medicines.

CMS provided data on total Part D costs for selected medicines for the period from June 2022 to May 2023, along with tallies of the number of people taking these drugs. The 10 selected medicines are as follows:

- Eliquis (generic name: apixaban), used to prevent and treat serious blood clots. It is taken by about 3.7 million people through Part D plans. The estimated cost is $16.4 billion.

- Jardiance (generic name: empagliflozin), used for diabetes and heart failure. It is taken by almost 1.6 million people through Part D plans. The estimated cost is $7.06 billion.

- Xarelto (generic name: rivaroxaban), used for blood clots. It is taken by about 1.3 million people through Part D plans. The estimated cost is $6 billion.

- Januvia (generic name: sitagliptin), used for diabetes. It is taken by about 869,00 people through Part D plans. The estimated cost is $4.1 billion.

- Farxiga (generic name: dapagliflozin), used for diabetes, heart failure, and chronic kidney disease. It is taken by about 799,000 people through Part D plans. The estimated cost is almost $3.3 billion.

- Entresto (generic name: sacubitril/valsartan), used to treat heart failure. It is taken by 587,000 people through Part D plans. The estimated cost is $2.9 billion.

- Enbrel( generic name: etanercept), used for rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, and psoriatic arthritis. It is taken by 48,000 people through Part D plans. The estimated cost is $2.8 billion.

- Imbruvica (generic name: ibrutinib), used to treat some blood cancers. It is taken by about 20,000 people in Part D plans. The estimated cost is $2.7 billion.

- Stelara (generic name: ustekinumab), used to treat plaque psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, or certain bowel conditions (Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis). It is used by about 22,000 people through Part D plans. The estimated cost is $2.6 billion.

- Fiasp; Fiasp FlexTouch; Fiasp PenFill; NovoLog; NovoLog FlexPen; NovoLog PenFill. These are forms of insulin used to treat diabetes. They are used by about 777,000 people through Part D plans. The estimated cost is $2.6 billion.

A vocal critic of Medicare drug negotiations, Joel White, president of the Council for Affordable Health Coverage, called the announcement of the 10 drugs selected for negotiation “a hollow victory lap.” A former Republican staffer on the House Ways and Means Committee, Mr. White aided with the development of the Medicare Part D plans and has kept tabs on the pharmacy programs since its launch in 2006.

“No one’s costs will go down now or for years because of this announcement” about Part D negotiations, Mr. White said in a statement.

According to its website, CAHC includes among its members the American Academy of Ophthalmology as well as some patient groups, drugmakers, such as Johnson & Johnson, and insurers and industry groups, such as the National Association of Manufacturers.

Separately, the influential Chamber of Commerce is making a strong push to at least delay the implementation of the Medicare Part D drug negotiations. On Aug. 28, the chamber released a letter sent to the Biden administration, raising concerns about a “rush” to implement the provisions of the Inflation Reduction Act.

The chamber also has filed suit to challenge the drug negotiation provisions of the Inflation Reduction Act, requesting that the court issue a preliminary injunction by Oct. 1, 2023.

Other pending legal challenges to direct Medicare drug negotiations include suits filed by Merck, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Johnson & Johnson, Boehringer Ingelheim, and AstraZeneca, according to an email from Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America. PhRMA also said it is a party to a case.

In addition, the three congressional Republicans with most direct influence over Medicare policy issued on Aug. 29 a joint statement outlining their objections to the planned negotiations on drug prices.

This drug-negotiation proposal is “an unworkable, legally dubious scheme that will lead to higher prices for new drugs coming to market, stifle the development of new cures, and destroy jobs,” said House Energy and Commerce Committee Chair Cathy McMorris Rodgers (R-Wash.), House Ways and Means Committee Chair Jason Smith (R-Mo.), and Senate Finance Committee Ranking Member Mike Crapo (R-Idaho).

Democrats were equally firm and vocal in their support of the negotiations. Senate Finance Chairman Ron Wyden (D-Ore.) issued a statement on Aug. 29 that said the release of the list of the 10 drugs selected for Medicare drug negotiations is part of a “seismic shift in the relationship between Big Pharma, the federal government, and seniors who are counting on lower prices.

“I will be following the negotiation process closely and will fight any attempt by Big Pharma to undo or undermine the progress that’s been made,” Mr. Wyden said.

In addition, AARP issued a statement of its continued support for Medicare drug negotiations.

“The No. 1 reason seniors skip or ration their prescriptions is because they can’t afford them. This must stop,” said AARP executive vice president and chief advocacy and engagement officer Nancy LeaMond in the statement. “The big drug companies and their allies continue suing to overturn the Medicare drug price negotiation program to keep up their price gouging. We can’t allow seniors to be Big Pharma’s cash machine anymore.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

People on Medicare may in 2026 see prices drop for 10 medicines, including pricey diabetes, cancer, blood clot, and arthritis treatments, if advocates for federal drug-price negotiations can implement their plans amid tough opposition.

It’s unclear at this time, though, how these negotiations will play out. The Chamber of Commerce has sided with pharmaceutical companies in bids to block direct Medicare negotiation of drug prices. Many influential Republicans in Congress oppose this plan, which has deep support from both Democrats and AARP.

While facing strong opposition to negotiations, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services sought in its announcement to illustrate the high costs of the selected medicines.

CMS provided data on total Part D costs for selected medicines for the period from June 2022 to May 2023, along with tallies of the number of people taking these drugs. The 10 selected medicines are as follows:

- Eliquis (generic name: apixaban), used to prevent and treat serious blood clots. It is taken by about 3.7 million people through Part D plans. The estimated cost is $16.4 billion.

- Jardiance (generic name: empagliflozin), used for diabetes and heart failure. It is taken by almost 1.6 million people through Part D plans. The estimated cost is $7.06 billion.

- Xarelto (generic name: rivaroxaban), used for blood clots. It is taken by about 1.3 million people through Part D plans. The estimated cost is $6 billion.

- Januvia (generic name: sitagliptin), used for diabetes. It is taken by about 869,00 people through Part D plans. The estimated cost is $4.1 billion.

- Farxiga (generic name: dapagliflozin), used for diabetes, heart failure, and chronic kidney disease. It is taken by about 799,000 people through Part D plans. The estimated cost is almost $3.3 billion.

- Entresto (generic name: sacubitril/valsartan), used to treat heart failure. It is taken by 587,000 people through Part D plans. The estimated cost is $2.9 billion.

- Enbrel( generic name: etanercept), used for rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, and psoriatic arthritis. It is taken by 48,000 people through Part D plans. The estimated cost is $2.8 billion.

- Imbruvica (generic name: ibrutinib), used to treat some blood cancers. It is taken by about 20,000 people in Part D plans. The estimated cost is $2.7 billion.

- Stelara (generic name: ustekinumab), used to treat plaque psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, or certain bowel conditions (Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis). It is used by about 22,000 people through Part D plans. The estimated cost is $2.6 billion.

- Fiasp; Fiasp FlexTouch; Fiasp PenFill; NovoLog; NovoLog FlexPen; NovoLog PenFill. These are forms of insulin used to treat diabetes. They are used by about 777,000 people through Part D plans. The estimated cost is $2.6 billion.

A vocal critic of Medicare drug negotiations, Joel White, president of the Council for Affordable Health Coverage, called the announcement of the 10 drugs selected for negotiation “a hollow victory lap.” A former Republican staffer on the House Ways and Means Committee, Mr. White aided with the development of the Medicare Part D plans and has kept tabs on the pharmacy programs since its launch in 2006.

“No one’s costs will go down now or for years because of this announcement” about Part D negotiations, Mr. White said in a statement.

According to its website, CAHC includes among its members the American Academy of Ophthalmology as well as some patient groups, drugmakers, such as Johnson & Johnson, and insurers and industry groups, such as the National Association of Manufacturers.

Separately, the influential Chamber of Commerce is making a strong push to at least delay the implementation of the Medicare Part D drug negotiations. On Aug. 28, the chamber released a letter sent to the Biden administration, raising concerns about a “rush” to implement the provisions of the Inflation Reduction Act.

The chamber also has filed suit to challenge the drug negotiation provisions of the Inflation Reduction Act, requesting that the court issue a preliminary injunction by Oct. 1, 2023.

Other pending legal challenges to direct Medicare drug negotiations include suits filed by Merck, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Johnson & Johnson, Boehringer Ingelheim, and AstraZeneca, according to an email from Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America. PhRMA also said it is a party to a case.

In addition, the three congressional Republicans with most direct influence over Medicare policy issued on Aug. 29 a joint statement outlining their objections to the planned negotiations on drug prices.

This drug-negotiation proposal is “an unworkable, legally dubious scheme that will lead to higher prices for new drugs coming to market, stifle the development of new cures, and destroy jobs,” said House Energy and Commerce Committee Chair Cathy McMorris Rodgers (R-Wash.), House Ways and Means Committee Chair Jason Smith (R-Mo.), and Senate Finance Committee Ranking Member Mike Crapo (R-Idaho).

Democrats were equally firm and vocal in their support of the negotiations. Senate Finance Chairman Ron Wyden (D-Ore.) issued a statement on Aug. 29 that said the release of the list of the 10 drugs selected for Medicare drug negotiations is part of a “seismic shift in the relationship between Big Pharma, the federal government, and seniors who are counting on lower prices.

“I will be following the negotiation process closely and will fight any attempt by Big Pharma to undo or undermine the progress that’s been made,” Mr. Wyden said.

In addition, AARP issued a statement of its continued support for Medicare drug negotiations.

“The No. 1 reason seniors skip or ration their prescriptions is because they can’t afford them. This must stop,” said AARP executive vice president and chief advocacy and engagement officer Nancy LeaMond in the statement. “The big drug companies and their allies continue suing to overturn the Medicare drug price negotiation program to keep up their price gouging. We can’t allow seniors to be Big Pharma’s cash machine anymore.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

No link between most cancers and depression/anxiety: Study

from a large, individual participant data meta-analysis.

An exception was for lung and smoking-related cancers, but key covariates appeared to explain the relationship between depression, anxiety, and these cancer types, the investigators reported.

The findings challenge a common theory that depression and anxiety increase cancer risk and should “change current thinking,” they argue.

“Our results may come as a relief to many patients with cancer who believe their diagnosis is attributed to previous anxiety or depression,” first author Lonneke A. van Tuijl, PhD, of the University of Groningen and Utrecht University, the Netherlands, noted in a press release.

Analyses included data from up to nearly 320,000 individuals from the 18 prospective cohorts included in the international Psychosocial Factors and Cancer Incidence (PSY-CA) consortium. The cohorts are from studies conducted in the Netherlands, United Kingdom, Norway, and Canada, and included 25,803 patients with cancer. During follow-up of up to 26 years and more than 3.2 million person-years, depression and anxiety symptoms and diagnoses showed no association with overall breast, prostate, colorectal, and alcohol-related cancers (hazard ratios, 0.98-1.05).

For the specific cancer types, the investigators “found no evidence for an association between depression or anxiety and the incidence of colorectal cancer (HRs, 0.88-1.13), prostate cancer (HRs, 0.97-1.17), or alcohol-related cancers (HRs, 0.97-1.06).”

“For breast cancer, all pooled HRs were consistently negative but mean pooled HRs were close to 1 (HRs, 0.92-0.98) and the upper limit of the 95% confidence intervals all exceeded 1 (with the exception of anxiety symptoms),” they noted.

An increase in risk observed between depression and anxiety symptoms and diagnoses and lung cancer (HRs, 1.12-1.60) and smoking-related cancers (HRs, 1.06-1.60), in minimally adjusted models, was substantially attenuated after adjusting for known risk factors such as smoking, alcohol use, and body mass index (HRs, 1.04-1.08), the investigators reported.

The findings were published online in Cancer.

“Depression and anxiety have long been hypothesized to increase the risk for cancer. It is thought that the increased cancer risk can occur via several pathways, including health behaviors, or by influencing mutation, viral oncogenes, cell proliferation, or DNA repair,” the authors explained, noting that “[c]onclusions drawn in meta-analyses vary greatly, with some supporting an association between depression, anxiety, and cancer incidence and others finding no or a negligible association.”

The current findings “may help health professionals to alleviate feelings of guilt and self-blame in patients with cancer who attribute their diagnosis to previous depression or anxiety,” they said, noting that the findings “also underscore the importance of addressing tobacco smoking and other unhealthy behaviors – including those that may develop as a result of anxiety or depression.”

“However, further research is needed to understand exactly how depression, anxiety, health behaviors, and lung cancer are related,” said Dr. Tuijl.

Dr. Tuijl has received grants and travel support from the Dutch Cancer Society (KWF).

from a large, individual participant data meta-analysis.

An exception was for lung and smoking-related cancers, but key covariates appeared to explain the relationship between depression, anxiety, and these cancer types, the investigators reported.

The findings challenge a common theory that depression and anxiety increase cancer risk and should “change current thinking,” they argue.

“Our results may come as a relief to many patients with cancer who believe their diagnosis is attributed to previous anxiety or depression,” first author Lonneke A. van Tuijl, PhD, of the University of Groningen and Utrecht University, the Netherlands, noted in a press release.

Analyses included data from up to nearly 320,000 individuals from the 18 prospective cohorts included in the international Psychosocial Factors and Cancer Incidence (PSY-CA) consortium. The cohorts are from studies conducted in the Netherlands, United Kingdom, Norway, and Canada, and included 25,803 patients with cancer. During follow-up of up to 26 years and more than 3.2 million person-years, depression and anxiety symptoms and diagnoses showed no association with overall breast, prostate, colorectal, and alcohol-related cancers (hazard ratios, 0.98-1.05).

For the specific cancer types, the investigators “found no evidence for an association between depression or anxiety and the incidence of colorectal cancer (HRs, 0.88-1.13), prostate cancer (HRs, 0.97-1.17), or alcohol-related cancers (HRs, 0.97-1.06).”

“For breast cancer, all pooled HRs were consistently negative but mean pooled HRs were close to 1 (HRs, 0.92-0.98) and the upper limit of the 95% confidence intervals all exceeded 1 (with the exception of anxiety symptoms),” they noted.

An increase in risk observed between depression and anxiety symptoms and diagnoses and lung cancer (HRs, 1.12-1.60) and smoking-related cancers (HRs, 1.06-1.60), in minimally adjusted models, was substantially attenuated after adjusting for known risk factors such as smoking, alcohol use, and body mass index (HRs, 1.04-1.08), the investigators reported.

The findings were published online in Cancer.

“Depression and anxiety have long been hypothesized to increase the risk for cancer. It is thought that the increased cancer risk can occur via several pathways, including health behaviors, or by influencing mutation, viral oncogenes, cell proliferation, or DNA repair,” the authors explained, noting that “[c]onclusions drawn in meta-analyses vary greatly, with some supporting an association between depression, anxiety, and cancer incidence and others finding no or a negligible association.”

The current findings “may help health professionals to alleviate feelings of guilt and self-blame in patients with cancer who attribute their diagnosis to previous depression or anxiety,” they said, noting that the findings “also underscore the importance of addressing tobacco smoking and other unhealthy behaviors – including those that may develop as a result of anxiety or depression.”

“However, further research is needed to understand exactly how depression, anxiety, health behaviors, and lung cancer are related,” said Dr. Tuijl.

Dr. Tuijl has received grants and travel support from the Dutch Cancer Society (KWF).

from a large, individual participant data meta-analysis.

An exception was for lung and smoking-related cancers, but key covariates appeared to explain the relationship between depression, anxiety, and these cancer types, the investigators reported.

The findings challenge a common theory that depression and anxiety increase cancer risk and should “change current thinking,” they argue.

“Our results may come as a relief to many patients with cancer who believe their diagnosis is attributed to previous anxiety or depression,” first author Lonneke A. van Tuijl, PhD, of the University of Groningen and Utrecht University, the Netherlands, noted in a press release.

Analyses included data from up to nearly 320,000 individuals from the 18 prospective cohorts included in the international Psychosocial Factors and Cancer Incidence (PSY-CA) consortium. The cohorts are from studies conducted in the Netherlands, United Kingdom, Norway, and Canada, and included 25,803 patients with cancer. During follow-up of up to 26 years and more than 3.2 million person-years, depression and anxiety symptoms and diagnoses showed no association with overall breast, prostate, colorectal, and alcohol-related cancers (hazard ratios, 0.98-1.05).

For the specific cancer types, the investigators “found no evidence for an association between depression or anxiety and the incidence of colorectal cancer (HRs, 0.88-1.13), prostate cancer (HRs, 0.97-1.17), or alcohol-related cancers (HRs, 0.97-1.06).”

“For breast cancer, all pooled HRs were consistently negative but mean pooled HRs were close to 1 (HRs, 0.92-0.98) and the upper limit of the 95% confidence intervals all exceeded 1 (with the exception of anxiety symptoms),” they noted.

An increase in risk observed between depression and anxiety symptoms and diagnoses and lung cancer (HRs, 1.12-1.60) and smoking-related cancers (HRs, 1.06-1.60), in minimally adjusted models, was substantially attenuated after adjusting for known risk factors such as smoking, alcohol use, and body mass index (HRs, 1.04-1.08), the investigators reported.

The findings were published online in Cancer.

“Depression and anxiety have long been hypothesized to increase the risk for cancer. It is thought that the increased cancer risk can occur via several pathways, including health behaviors, or by influencing mutation, viral oncogenes, cell proliferation, or DNA repair,” the authors explained, noting that “[c]onclusions drawn in meta-analyses vary greatly, with some supporting an association between depression, anxiety, and cancer incidence and others finding no or a negligible association.”

The current findings “may help health professionals to alleviate feelings of guilt and self-blame in patients with cancer who attribute their diagnosis to previous depression or anxiety,” they said, noting that the findings “also underscore the importance of addressing tobacco smoking and other unhealthy behaviors – including those that may develop as a result of anxiety or depression.”

“However, further research is needed to understand exactly how depression, anxiety, health behaviors, and lung cancer are related,” said Dr. Tuijl.

Dr. Tuijl has received grants and travel support from the Dutch Cancer Society (KWF).

FROM CANCER

Even an hour’s walk a week lowers risk in type 2 diabetes

although the impact on retinopathy is weaker, reveals a cohort study of U.K. individuals.

The research, based on data from more than 18,000 participants in the U.K. Biobank, suggests that the minimal level of self-reported activity to reduce the risk for both neuropathy and nephropathy may be the equivalent of less than 1.5 hours of walking per week.

The results are “encouraging and reassuring for both physicians and patients,” lead author Frederik P.B. Kristensen, MSc, PhD student, department of clinical epidemiology, Aarhus (Denmark) University, said in an interview.

“Our findings are particularly promising for neuropathy since, currently, no disease-modifying treatment exists, and there are limited preventive strategies available.”

Mr. Kristensen highlighted that “most diabetes research has focused on all-cause mortality and macrovascular complications. In the current study, we also found the same pattern for microvascular complications: Even small amounts of physical activity will benefit your health status.”

The minimal level of activity they identified, he said, is also an “achievable [goal] for most type 2 diabetes patients.”

Mr. Kristensen added, however, that the study was limited by excluding individuals with limited mobility and those living in temporary accommodation or care homes.

And prospective studies are required to determine the dose-response relationship between total, not just leisure-time, activity – ideally measured objectively – and risk for microvascular complications, he observed.

The research was published recently in Diabetes Care.

Impact of exercise on microvascular complications in T2D has been uncertain

The authors point out that microvascular complications – such as nerve damage (neuropathy), kidney problems (nephropathy), and eye complications (retinopathy) – occur in more than 50% of individuals with type 2 diabetes and have a “substantial impact” on quality of life, on top of the impact of macrovascular complications (such as cardiovascular disease), disability, and mortality.

Although physical activity is seen as a “cornerstone in the multifactorial management of type 2 diabetes because of its beneficial effects on metabolic risk factors,” the impact on microvascular complications is “uncertain” and the evidence is limited and “conflicting.”

The researchers therefore sought to examine the dose-response association, including the minimal effective level, between leisure-time physical activity and neuropathy, nephropathy, and retinopathy.

They conducted a cohort study of individuals aged 37-82 years from the U.K. Biobank who had type 2 diabetes, which was identified using the Eastwood algorithm and/or an A1c greater than or equal to 48 mmol/mol (6.5%).

Individuals with type 1 diabetes or gestational diabetes were excluded, as were those with major disabling somatic disorders, neurodegenerative diseases, and mental disorders, among others.

Leisure-time physical activity was based on the self-reported frequency, duration, and types of physical activities and was combined to calculate the total leisure time activity in MET-hours per week.

Using the American Diabetes Association/World Health Organization recommendations of 150-300 minutes of moderate to vigorous leisure-time physical activity per week, the researchers determined the recommended moderate activity level to be 150 minutes, (equivalent to 2.5 hours, or 7.5 MET-hours per week).

In all, 18,092 individuals with type 2 diabetes were included in the analysis, of whom 37% were women. The mean age was 60 years.

Ten percent of participants performed no leisure-time physical activity, 38% performed activity below the threshold for moderate activity, 20% performed at the recommended level, and 32% were more active.

Those performing no physical activity were more likely to be women, to be younger, to have a higher body mass index, and to have a greater average A1c, as well as have a more unfavorable sociodemographic and behavioral profile.

Over a median follow-up of 12.1 years, 3.7% of the participants were diagnosed with neuropathy, 10.2% with nephropathy, and 11.7% with retinopathy, equating to an incidence per 1,000 person-years of 3.5, 9,8, and 11.4, respectively.

The researchers found that any level of physical activity was associated with an approximate reduction in the risk for neuropathy and nephropathy.

Multivariate analysis indicated that, compared with no physical activity, activity below the recommended level was associated with an adjusted hazard ratio (aHR) for neuropathy of 0.71, whereas the aHR for activity at the recommended level was 0.73 and that for activity above the recommended level was 0.67.

The aHR for nephropathy, compared with no physical activity, was 0.79 for activity below the recommended level, 0.80 for activity at the recommended level, and 0.80 for activity above the recommended level.

The association between physical activity and retinopathy was weaker, however, at aHRs of 0.91, 0.91, and 0.98 for activity below, at, and above the recommended level, respectively.

The researchers suggest that this lower association could be due to differences in the etiology of the different forms of microvascular complications.

Hyperglycemia is the key driver in the development of retinopathy, they note, whereas other metabolic risk factors, such as obesity, insulin resistance, inflammation, dyslipidemia, and hypertension, play a role in neuropathy and nephropathy.

The associations were also less pronounced in women.

Mr. Kristensen said that this is “an important area that needs to be addressed.”

“While different rates between men and women regarding incidence of type 2 diabetes, metabolic risk factors, complications, and the initiation of, and adherence to, therapy have been found,” he continued, “the exact mechanisms remain unclear. We need a further understanding of sex-differences in metabolic regulation, as well as in material living conditions, social and psychological factors, and access to health care, which may influence the risk of complications.”

Mr. Kristensen added, “Sex differences may be present in more areas than we are aware.”

Mr. Kristensen is supported by a PhD grant from Aarhus University. Other authors received funding from the Danish Diabetes Association, the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council, the New South Wales Government, the Spanish Ministry of Universities, the European Union NextGenerationEU/PRTR (Plan de Recuperación) through a Margarita Salas contract of the University of Vigo, and the Government of Andalusia, Research Talent Recruitment Programme. No relevant financial relationships were declared.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

although the impact on retinopathy is weaker, reveals a cohort study of U.K. individuals.

The research, based on data from more than 18,000 participants in the U.K. Biobank, suggests that the minimal level of self-reported activity to reduce the risk for both neuropathy and nephropathy may be the equivalent of less than 1.5 hours of walking per week.

The results are “encouraging and reassuring for both physicians and patients,” lead author Frederik P.B. Kristensen, MSc, PhD student, department of clinical epidemiology, Aarhus (Denmark) University, said in an interview.

“Our findings are particularly promising for neuropathy since, currently, no disease-modifying treatment exists, and there are limited preventive strategies available.”

Mr. Kristensen highlighted that “most diabetes research has focused on all-cause mortality and macrovascular complications. In the current study, we also found the same pattern for microvascular complications: Even small amounts of physical activity will benefit your health status.”

The minimal level of activity they identified, he said, is also an “achievable [goal] for most type 2 diabetes patients.”

Mr. Kristensen added, however, that the study was limited by excluding individuals with limited mobility and those living in temporary accommodation or care homes.

And prospective studies are required to determine the dose-response relationship between total, not just leisure-time, activity – ideally measured objectively – and risk for microvascular complications, he observed.

The research was published recently in Diabetes Care.

Impact of exercise on microvascular complications in T2D has been uncertain

The authors point out that microvascular complications – such as nerve damage (neuropathy), kidney problems (nephropathy), and eye complications (retinopathy) – occur in more than 50% of individuals with type 2 diabetes and have a “substantial impact” on quality of life, on top of the impact of macrovascular complications (such as cardiovascular disease), disability, and mortality.

Although physical activity is seen as a “cornerstone in the multifactorial management of type 2 diabetes because of its beneficial effects on metabolic risk factors,” the impact on microvascular complications is “uncertain” and the evidence is limited and “conflicting.”

The researchers therefore sought to examine the dose-response association, including the minimal effective level, between leisure-time physical activity and neuropathy, nephropathy, and retinopathy.

They conducted a cohort study of individuals aged 37-82 years from the U.K. Biobank who had type 2 diabetes, which was identified using the Eastwood algorithm and/or an A1c greater than or equal to 48 mmol/mol (6.5%).

Individuals with type 1 diabetes or gestational diabetes were excluded, as were those with major disabling somatic disorders, neurodegenerative diseases, and mental disorders, among others.

Leisure-time physical activity was based on the self-reported frequency, duration, and types of physical activities and was combined to calculate the total leisure time activity in MET-hours per week.

Using the American Diabetes Association/World Health Organization recommendations of 150-300 minutes of moderate to vigorous leisure-time physical activity per week, the researchers determined the recommended moderate activity level to be 150 minutes, (equivalent to 2.5 hours, or 7.5 MET-hours per week).

In all, 18,092 individuals with type 2 diabetes were included in the analysis, of whom 37% were women. The mean age was 60 years.

Ten percent of participants performed no leisure-time physical activity, 38% performed activity below the threshold for moderate activity, 20% performed at the recommended level, and 32% were more active.

Those performing no physical activity were more likely to be women, to be younger, to have a higher body mass index, and to have a greater average A1c, as well as have a more unfavorable sociodemographic and behavioral profile.

Over a median follow-up of 12.1 years, 3.7% of the participants were diagnosed with neuropathy, 10.2% with nephropathy, and 11.7% with retinopathy, equating to an incidence per 1,000 person-years of 3.5, 9,8, and 11.4, respectively.

The researchers found that any level of physical activity was associated with an approximate reduction in the risk for neuropathy and nephropathy.

Multivariate analysis indicated that, compared with no physical activity, activity below the recommended level was associated with an adjusted hazard ratio (aHR) for neuropathy of 0.71, whereas the aHR for activity at the recommended level was 0.73 and that for activity above the recommended level was 0.67.

The aHR for nephropathy, compared with no physical activity, was 0.79 for activity below the recommended level, 0.80 for activity at the recommended level, and 0.80 for activity above the recommended level.

The association between physical activity and retinopathy was weaker, however, at aHRs of 0.91, 0.91, and 0.98 for activity below, at, and above the recommended level, respectively.

The researchers suggest that this lower association could be due to differences in the etiology of the different forms of microvascular complications.

Hyperglycemia is the key driver in the development of retinopathy, they note, whereas other metabolic risk factors, such as obesity, insulin resistance, inflammation, dyslipidemia, and hypertension, play a role in neuropathy and nephropathy.

The associations were also less pronounced in women.

Mr. Kristensen said that this is “an important area that needs to be addressed.”

“While different rates between men and women regarding incidence of type 2 diabetes, metabolic risk factors, complications, and the initiation of, and adherence to, therapy have been found,” he continued, “the exact mechanisms remain unclear. We need a further understanding of sex-differences in metabolic regulation, as well as in material living conditions, social and psychological factors, and access to health care, which may influence the risk of complications.”

Mr. Kristensen added, “Sex differences may be present in more areas than we are aware.”

Mr. Kristensen is supported by a PhD grant from Aarhus University. Other authors received funding from the Danish Diabetes Association, the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council, the New South Wales Government, the Spanish Ministry of Universities, the European Union NextGenerationEU/PRTR (Plan de Recuperación) through a Margarita Salas contract of the University of Vigo, and the Government of Andalusia, Research Talent Recruitment Programme. No relevant financial relationships were declared.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

although the impact on retinopathy is weaker, reveals a cohort study of U.K. individuals.

The research, based on data from more than 18,000 participants in the U.K. Biobank, suggests that the minimal level of self-reported activity to reduce the risk for both neuropathy and nephropathy may be the equivalent of less than 1.5 hours of walking per week.

The results are “encouraging and reassuring for both physicians and patients,” lead author Frederik P.B. Kristensen, MSc, PhD student, department of clinical epidemiology, Aarhus (Denmark) University, said in an interview.

“Our findings are particularly promising for neuropathy since, currently, no disease-modifying treatment exists, and there are limited preventive strategies available.”

Mr. Kristensen highlighted that “most diabetes research has focused on all-cause mortality and macrovascular complications. In the current study, we also found the same pattern for microvascular complications: Even small amounts of physical activity will benefit your health status.”

The minimal level of activity they identified, he said, is also an “achievable [goal] for most type 2 diabetes patients.”

Mr. Kristensen added, however, that the study was limited by excluding individuals with limited mobility and those living in temporary accommodation or care homes.

And prospective studies are required to determine the dose-response relationship between total, not just leisure-time, activity – ideally measured objectively – and risk for microvascular complications, he observed.

The research was published recently in Diabetes Care.

Impact of exercise on microvascular complications in T2D has been uncertain

The authors point out that microvascular complications – such as nerve damage (neuropathy), kidney problems (nephropathy), and eye complications (retinopathy) – occur in more than 50% of individuals with type 2 diabetes and have a “substantial impact” on quality of life, on top of the impact of macrovascular complications (such as cardiovascular disease), disability, and mortality.

Although physical activity is seen as a “cornerstone in the multifactorial management of type 2 diabetes because of its beneficial effects on metabolic risk factors,” the impact on microvascular complications is “uncertain” and the evidence is limited and “conflicting.”

The researchers therefore sought to examine the dose-response association, including the minimal effective level, between leisure-time physical activity and neuropathy, nephropathy, and retinopathy.

They conducted a cohort study of individuals aged 37-82 years from the U.K. Biobank who had type 2 diabetes, which was identified using the Eastwood algorithm and/or an A1c greater than or equal to 48 mmol/mol (6.5%).

Individuals with type 1 diabetes or gestational diabetes were excluded, as were those with major disabling somatic disorders, neurodegenerative diseases, and mental disorders, among others.

Leisure-time physical activity was based on the self-reported frequency, duration, and types of physical activities and was combined to calculate the total leisure time activity in MET-hours per week.

Using the American Diabetes Association/World Health Organization recommendations of 150-300 minutes of moderate to vigorous leisure-time physical activity per week, the researchers determined the recommended moderate activity level to be 150 minutes, (equivalent to 2.5 hours, or 7.5 MET-hours per week).

In all, 18,092 individuals with type 2 diabetes were included in the analysis, of whom 37% were women. The mean age was 60 years.

Ten percent of participants performed no leisure-time physical activity, 38% performed activity below the threshold for moderate activity, 20% performed at the recommended level, and 32% were more active.

Those performing no physical activity were more likely to be women, to be younger, to have a higher body mass index, and to have a greater average A1c, as well as have a more unfavorable sociodemographic and behavioral profile.

Over a median follow-up of 12.1 years, 3.7% of the participants were diagnosed with neuropathy, 10.2% with nephropathy, and 11.7% with retinopathy, equating to an incidence per 1,000 person-years of 3.5, 9,8, and 11.4, respectively.

The researchers found that any level of physical activity was associated with an approximate reduction in the risk for neuropathy and nephropathy.

Multivariate analysis indicated that, compared with no physical activity, activity below the recommended level was associated with an adjusted hazard ratio (aHR) for neuropathy of 0.71, whereas the aHR for activity at the recommended level was 0.73 and that for activity above the recommended level was 0.67.

The aHR for nephropathy, compared with no physical activity, was 0.79 for activity below the recommended level, 0.80 for activity at the recommended level, and 0.80 for activity above the recommended level.

The association between physical activity and retinopathy was weaker, however, at aHRs of 0.91, 0.91, and 0.98 for activity below, at, and above the recommended level, respectively.

The researchers suggest that this lower association could be due to differences in the etiology of the different forms of microvascular complications.

Hyperglycemia is the key driver in the development of retinopathy, they note, whereas other metabolic risk factors, such as obesity, insulin resistance, inflammation, dyslipidemia, and hypertension, play a role in neuropathy and nephropathy.

The associations were also less pronounced in women.

Mr. Kristensen said that this is “an important area that needs to be addressed.”

“While different rates between men and women regarding incidence of type 2 diabetes, metabolic risk factors, complications, and the initiation of, and adherence to, therapy have been found,” he continued, “the exact mechanisms remain unclear. We need a further understanding of sex-differences in metabolic regulation, as well as in material living conditions, social and psychological factors, and access to health care, which may influence the risk of complications.”

Mr. Kristensen added, “Sex differences may be present in more areas than we are aware.”

Mr. Kristensen is supported by a PhD grant from Aarhus University. Other authors received funding from the Danish Diabetes Association, the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council, the New South Wales Government, the Spanish Ministry of Universities, the European Union NextGenerationEU/PRTR (Plan de Recuperación) through a Margarita Salas contract of the University of Vigo, and the Government of Andalusia, Research Talent Recruitment Programme. No relevant financial relationships were declared.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM DIABETES CARE

When is antibiotic prophylaxis required for dermatologic surgery?

SAN DIEGO – The need for antibiotic prophylaxis in dermatologic surgery depends on the type of procedure, the patient, what infection you’re trying to keep at bay, and the type of wound, according to Tissa Hata, MD, professor of dermatology at the University of California, San Diego.

Among the many studies in the medical literature that have examined the use of antibiotics to prevent surgical site infections, one study published in 2006 has the largest number of patients to date, Dr. Hata said at a conference on superficial anatomy and cutaneous surgery sponsored by UCSD and Scripps Clinic. In the prospective study of wound infections in patients undergoing dermatologic surgery without prophylactic antibiotics, researchers in Australia prospectively examined 5,091 lesions, mostly nonmelanoma skin cancers, in 2,424 patients over the course of 3 years.

By procedure, the infection rate was highest for skin grafts (8.70%) and wedge excision of the lip or ear (8.57%), followed by skin flap repairs (2.94%), curettage (0.73%), and simple excision and closure (0.54%). By anatomic site, groin excisional surgery had the highest infection rate (10%), followed by surgical procedures below the knee (6.92%), while those performed on the face had a low rate (0.81%). “Based on their analysis, they suggest antibiotic prophylaxis for all procedures below the knee and groin, wedge excisions of the lip and ear, and all skin grafts,” Dr. Hata said.