User login

Should newborns at 22 or 23 weeks’ gestational age be aggressively resuscitated?

For many decades the limit of viability was believed to be approximately 24 weeks of gestation. In many medical centers, newborns delivered at less than 25 weeks are evaluated in the delivery room and the decision to resuscitate is based on the infant’s clinical response. In the past, aggressive and extended resuscitation of newborns at 22 and 23 weeks was not common because the prognosis was bleak and clinicians did not want to inflict unnecessary pain when the chances for survival were limited. Recent advances in obstetric and pediatric care, however, have resulted in the survival of some infants born at 22 weeks’ gestation, calling into question long-held beliefs about the limits of viability.

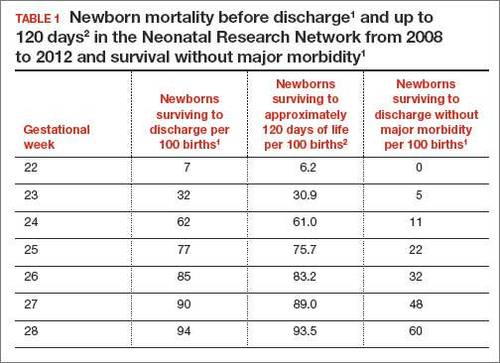

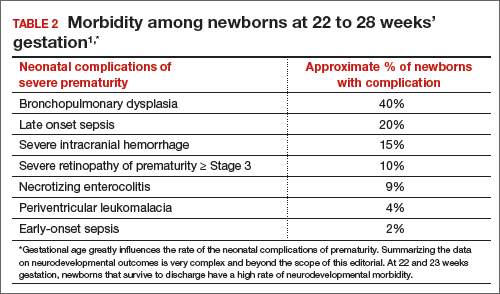

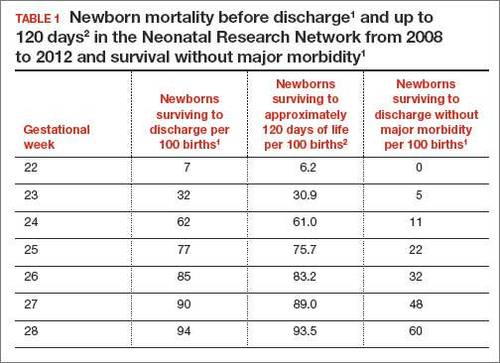

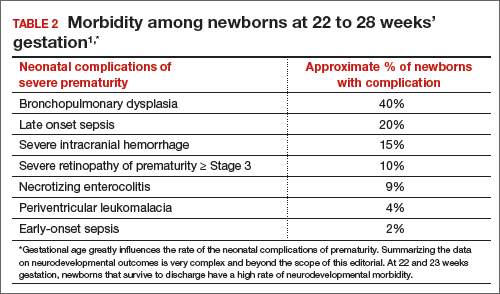

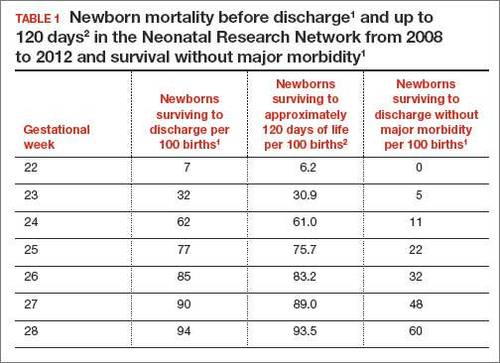

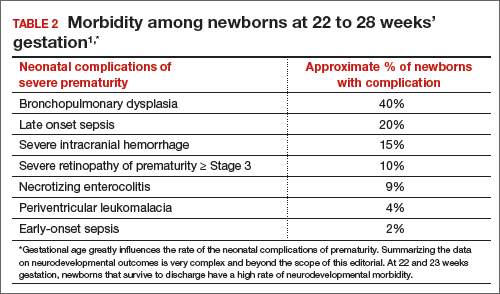

In 2 recent reports, investigators used data from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) Neonatal Research Network to acquire detailed information about newborn survival and morbidity at 22 through 28 weeks’ gestation (TABLES 1 and 2).1,2 These data show that the survival of newborns at 23 through 27 weeks’ gestation is increasing, albeit slowly. Survival, without major morbidity, is gradually improving for newborns at 25 through 28 weeks.1,2 But what is the prognosis for a fetus born at 22 or 23 weeks?

There are several aspects of this issue to consider, including accurate dating of the gestational age and current viability outcomes data.

Determining the limit of viability: Accurate dating is essentialThe limit of viability is the milestone in gestation when there is a high probability of extrauterine survival. A major challenge in studies of the limit of viability for newborns is that accurate gestational dating is not always available. For example, in recent reports from the NICHD Neonatal Research Network the gestational age was determined by the best obstetric estimate, or the Ballard or Dubowitz examination, of the newborn.1,2

It is well known that ultrasound dating early in gestation is a better estimate of gestational age than last menstrual period, uterine sizing, or pediatric examination of the newborn. Hence, the available data are limited by the absence of precise gestational dating with early ultrasound. Data on the limit of viability with large numbers of births between 22 and 24 weeks with early ultrasound dating would help to refine our understanding of the limit of viability.

At 23 weeks, each day of in utero development is criticalThe importance of each additional day spent in utero during the 23rd week of gestation was demonstrated in a small cohort in 2001.4 Overall, during the 23rd week of gestation the survival of newborns to discharge was 33%.4 This finding is similar to the survival rate reported by the NICHD Neonatal Research Network in 2012.1 However, survival was vastly different early, compared with later, in the 23rd week4:

- from 23 weeks 0 days to 23 weeks 2 days: no newborn survived

- at 23 weeks 3 days and 23 weeks 4 days: 40% of newborns survived

- at 23 weeks 5 days and 23 weeks 6 days: 63% of newborns survived (a similar survival rate of 24-week gestations was reported by the NICHD Neonatal Research Network1).

The development of the fetus across the 23rd week of gestation appears to be critical to newborn survival. Hence, every day of in utero development during the 23rd week is critically important. A great challenge for obstetricians is how to approach the woman with threatened preterm birth at 22 weeks 0 days’ gestation. If the woman delivers within a few days, the likelihood of survival is minimal. However, if the pregnancy can be extended to 23 weeks and 5 days, survival rates increase significantly.

Aligning the actions of birth team, mother, and familyFactors that influence the limit of viability include:

- gestational age

- gender of the fetus (Females are more likely than males to survive.)

- treatment of the mother with glucocorticoids prior to birth

- newborn weight.

To increase the likelihood of newborn survival, obstetricians need to treat women at risk for preterm birth with antenatal glucocorticoids and antibiotics for rupture of membranes and to limit fetal stress during the birth process. Guidelines have evolved to encourage clinicians to treat women at preterm birth risk with glucocorticoids either at:

- 23 weeks’ gestation or

- 22 weeks’ gestation, if birth is anticipated to occur at 23 weeks or later.5

At birth, pediatricians are then faced with the very difficult decision of whether or not to aggressively resuscitate the severely preterm infant. Complex medical, social, and ethical issues ultimately guide pediatricians’ actions in this challenging situation. It is important for their actions to be in consensus with the obstetrician, the mother, and the mother’s family and for a consensus to be reached. Dissonant plans may increase adverse outcomes for the newborn. In one study when pediatricians and obstetricians were not aligned in their actions, the risk of death of an extremely preterm newborn significantly increased.6

Prior to birth, team meetings that include the obstetricians, pediatricians, mother, and family will help to set expectations about the course of care and, in turn, improve perceived outcomes.5 If feasible, obstetricians and pediatricians should develop joint institutional guidelines about the general approach to pregnant women when birth may occur at 22 or 23 weeks’ gestation.5

A neonatal outcomes predictor

The National Institute of Child Health and Human Development provides a Web-based tool for estimating newborn outcomes based on gestational age (22 to 25 weeks), birth weight, gender, singleton or multiple gestation, and exposure to antenatal glucocorticoid treatment. The outcomes tool provides estimates for survival and survival with severe morbidity. It uses data collected by the Neonatal Research Network to predict outcomes. To access the outcomes data assessment, visit https://www.nichd.nih.gov/about/org/der/branches/ppb/programs/epbo/Pages/epbo_case.aspx.

Is aggressive management of preterm birth and neonatal resuscitation a self-fulfilling prophecy?The beliefs and training of clinicians may influence the outcome of extremely preterm newborns. For example, if obstetricians and pediatricians focus on the fact that birth at 23 weeks is not likely to result in survival without severe morbidity, they may withhold key interventions such as antenatal glucocorticoids, antibiotics for rupture of the membranes, and aggressive newborn resuscitation.7 Consequently the likelihood of survival may be reduced.

If clinicians believe in maximal interventions for all newborns at 22 and 23 weeks’ gestation, their actions may result in a small increase in newborn survival—but at the cost of painful and unnecessary interventions in many newborns who are destined to die. Finding the right balance along the broad spectrum from expectant management to aggressive and extended resuscitation is challenging. Clearly there is no “right answer” with these extremely difficult decisions.

Future trends in the limit of viabilityIn 1963, Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy, at 34 weeks’ gestation, went into preterm labor and delivered her son Patrick at a community hospital. Patrick developed respiratory distress syndrome and was transferred to the Boston Children’s Hospital. He died shortly thereafter.8 Would Patrick have survived if he had been delivered at an institution capable of providing high-risk obstetric and newborn services? Would such modern interventions as antenatal glucocorticoids, antibiotics for ruptured membranes, liberal use of cesarean delivery, and aggressive neonatal resuscitation have improved his chances for survival?

From our current perspective, it is surprising that a 34-week newborn died shortly after birth. With modern obstetric and pediatric care that scenario is unusual. It is possible that future advances in medical care will push the limit of viability to 22 weeks’ gestation. Future generations of clinicians may be surprised that the medicine we practice today is so limited.

However, given our current resources, it is unlikely that newborns at 22 weeks’ gestation will survive, or survive without severe morbidity. Consequently, routine aggressive resuscitation of newborns at 22 weeks should be approached with caution. At 23 weeks and later, many newborns will survive and a few will survive without severe morbidity. Given the complexity of the issues, the approach to resuscitation of infants at 22 and 23 weeks must account for the perspectives of the birth mother and her family, obstetricians, and pediatricians. Managing threatened preterm birth at 22 and 23 weeks is one of our greatest challenges as obstetricians, and we need to meet this challenge with grace and skill.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Stoll BJ, Hansen NI, Bell EF, et al; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network. Trends in care practices, morbidity and mortality of extremely preterm neonates, 1993-2012. JAMA. 2015;314(10):1039–1051.

- Patel RM, Kandefer S, Walsh MC, et al; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network. Causes and timing of death in extremely premature infants from 2000 through 2011. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(4):331–340.

- Donovan EF, Tyson JE, Ehrenkranz RA, et al. Inaccuracy of Ballard scores before 28 weeks’ gestation. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network. J Pediatr. 1999;135(2 pt 1):147–152.

- McElrath TF, Robinson JN, Ecker JL, Ringer SA, Norwitz ER. Neonatal outcome of infants born at 23 weeks’ gestation. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;97(1):49–52.

- Raju TN, Mercer BM, Burchfield DJ, Joseph GF Jr. Periviable birth: executive summary of a joint workshop by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, American Academy of Pediatrics, and American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(5):1083–1096.

- Guinsburg R, Branco de Almeida MF, dos Santos Rodrigues Sadeck L, et al; Brazilian Network on Neonatal Research. Proactive management of extreme prematurity: disagreement between obstetricians and neonatologists. J Perinatol. 2012;32(12):913-919.

- Tucker Emonds B, McKenzie F, Farrow V, Raglan G, Schulkin J. A national survey of obstetricians’ attitudes toward and practice of periviable interventions. J Perinatol. 2015;35(5):338–343.

- Altman LK. A Kennedy baby’s life and death. New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2013/07/30/health/a-kennedy-babys-life-and-death.html?_r=0. Published July 29, 2013. Accessed November 19, 2015.

For many decades the limit of viability was believed to be approximately 24 weeks of gestation. In many medical centers, newborns delivered at less than 25 weeks are evaluated in the delivery room and the decision to resuscitate is based on the infant’s clinical response. In the past, aggressive and extended resuscitation of newborns at 22 and 23 weeks was not common because the prognosis was bleak and clinicians did not want to inflict unnecessary pain when the chances for survival were limited. Recent advances in obstetric and pediatric care, however, have resulted in the survival of some infants born at 22 weeks’ gestation, calling into question long-held beliefs about the limits of viability.

In 2 recent reports, investigators used data from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) Neonatal Research Network to acquire detailed information about newborn survival and morbidity at 22 through 28 weeks’ gestation (TABLES 1 and 2).1,2 These data show that the survival of newborns at 23 through 27 weeks’ gestation is increasing, albeit slowly. Survival, without major morbidity, is gradually improving for newborns at 25 through 28 weeks.1,2 But what is the prognosis for a fetus born at 22 or 23 weeks?

There are several aspects of this issue to consider, including accurate dating of the gestational age and current viability outcomes data.

Determining the limit of viability: Accurate dating is essentialThe limit of viability is the milestone in gestation when there is a high probability of extrauterine survival. A major challenge in studies of the limit of viability for newborns is that accurate gestational dating is not always available. For example, in recent reports from the NICHD Neonatal Research Network the gestational age was determined by the best obstetric estimate, or the Ballard or Dubowitz examination, of the newborn.1,2

It is well known that ultrasound dating early in gestation is a better estimate of gestational age than last menstrual period, uterine sizing, or pediatric examination of the newborn. Hence, the available data are limited by the absence of precise gestational dating with early ultrasound. Data on the limit of viability with large numbers of births between 22 and 24 weeks with early ultrasound dating would help to refine our understanding of the limit of viability.

At 23 weeks, each day of in utero development is criticalThe importance of each additional day spent in utero during the 23rd week of gestation was demonstrated in a small cohort in 2001.4 Overall, during the 23rd week of gestation the survival of newborns to discharge was 33%.4 This finding is similar to the survival rate reported by the NICHD Neonatal Research Network in 2012.1 However, survival was vastly different early, compared with later, in the 23rd week4:

- from 23 weeks 0 days to 23 weeks 2 days: no newborn survived

- at 23 weeks 3 days and 23 weeks 4 days: 40% of newborns survived

- at 23 weeks 5 days and 23 weeks 6 days: 63% of newborns survived (a similar survival rate of 24-week gestations was reported by the NICHD Neonatal Research Network1).

The development of the fetus across the 23rd week of gestation appears to be critical to newborn survival. Hence, every day of in utero development during the 23rd week is critically important. A great challenge for obstetricians is how to approach the woman with threatened preterm birth at 22 weeks 0 days’ gestation. If the woman delivers within a few days, the likelihood of survival is minimal. However, if the pregnancy can be extended to 23 weeks and 5 days, survival rates increase significantly.

Aligning the actions of birth team, mother, and familyFactors that influence the limit of viability include:

- gestational age

- gender of the fetus (Females are more likely than males to survive.)

- treatment of the mother with glucocorticoids prior to birth

- newborn weight.

To increase the likelihood of newborn survival, obstetricians need to treat women at risk for preterm birth with antenatal glucocorticoids and antibiotics for rupture of membranes and to limit fetal stress during the birth process. Guidelines have evolved to encourage clinicians to treat women at preterm birth risk with glucocorticoids either at:

- 23 weeks’ gestation or

- 22 weeks’ gestation, if birth is anticipated to occur at 23 weeks or later.5

At birth, pediatricians are then faced with the very difficult decision of whether or not to aggressively resuscitate the severely preterm infant. Complex medical, social, and ethical issues ultimately guide pediatricians’ actions in this challenging situation. It is important for their actions to be in consensus with the obstetrician, the mother, and the mother’s family and for a consensus to be reached. Dissonant plans may increase adverse outcomes for the newborn. In one study when pediatricians and obstetricians were not aligned in their actions, the risk of death of an extremely preterm newborn significantly increased.6

Prior to birth, team meetings that include the obstetricians, pediatricians, mother, and family will help to set expectations about the course of care and, in turn, improve perceived outcomes.5 If feasible, obstetricians and pediatricians should develop joint institutional guidelines about the general approach to pregnant women when birth may occur at 22 or 23 weeks’ gestation.5

A neonatal outcomes predictor

The National Institute of Child Health and Human Development provides a Web-based tool for estimating newborn outcomes based on gestational age (22 to 25 weeks), birth weight, gender, singleton or multiple gestation, and exposure to antenatal glucocorticoid treatment. The outcomes tool provides estimates for survival and survival with severe morbidity. It uses data collected by the Neonatal Research Network to predict outcomes. To access the outcomes data assessment, visit https://www.nichd.nih.gov/about/org/der/branches/ppb/programs/epbo/Pages/epbo_case.aspx.

Is aggressive management of preterm birth and neonatal resuscitation a self-fulfilling prophecy?The beliefs and training of clinicians may influence the outcome of extremely preterm newborns. For example, if obstetricians and pediatricians focus on the fact that birth at 23 weeks is not likely to result in survival without severe morbidity, they may withhold key interventions such as antenatal glucocorticoids, antibiotics for rupture of the membranes, and aggressive newborn resuscitation.7 Consequently the likelihood of survival may be reduced.

If clinicians believe in maximal interventions for all newborns at 22 and 23 weeks’ gestation, their actions may result in a small increase in newborn survival—but at the cost of painful and unnecessary interventions in many newborns who are destined to die. Finding the right balance along the broad spectrum from expectant management to aggressive and extended resuscitation is challenging. Clearly there is no “right answer” with these extremely difficult decisions.

Future trends in the limit of viabilityIn 1963, Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy, at 34 weeks’ gestation, went into preterm labor and delivered her son Patrick at a community hospital. Patrick developed respiratory distress syndrome and was transferred to the Boston Children’s Hospital. He died shortly thereafter.8 Would Patrick have survived if he had been delivered at an institution capable of providing high-risk obstetric and newborn services? Would such modern interventions as antenatal glucocorticoids, antibiotics for ruptured membranes, liberal use of cesarean delivery, and aggressive neonatal resuscitation have improved his chances for survival?

From our current perspective, it is surprising that a 34-week newborn died shortly after birth. With modern obstetric and pediatric care that scenario is unusual. It is possible that future advances in medical care will push the limit of viability to 22 weeks’ gestation. Future generations of clinicians may be surprised that the medicine we practice today is so limited.

However, given our current resources, it is unlikely that newborns at 22 weeks’ gestation will survive, or survive without severe morbidity. Consequently, routine aggressive resuscitation of newborns at 22 weeks should be approached with caution. At 23 weeks and later, many newborns will survive and a few will survive without severe morbidity. Given the complexity of the issues, the approach to resuscitation of infants at 22 and 23 weeks must account for the perspectives of the birth mother and her family, obstetricians, and pediatricians. Managing threatened preterm birth at 22 and 23 weeks is one of our greatest challenges as obstetricians, and we need to meet this challenge with grace and skill.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

For many decades the limit of viability was believed to be approximately 24 weeks of gestation. In many medical centers, newborns delivered at less than 25 weeks are evaluated in the delivery room and the decision to resuscitate is based on the infant’s clinical response. In the past, aggressive and extended resuscitation of newborns at 22 and 23 weeks was not common because the prognosis was bleak and clinicians did not want to inflict unnecessary pain when the chances for survival were limited. Recent advances in obstetric and pediatric care, however, have resulted in the survival of some infants born at 22 weeks’ gestation, calling into question long-held beliefs about the limits of viability.

In 2 recent reports, investigators used data from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) Neonatal Research Network to acquire detailed information about newborn survival and morbidity at 22 through 28 weeks’ gestation (TABLES 1 and 2).1,2 These data show that the survival of newborns at 23 through 27 weeks’ gestation is increasing, albeit slowly. Survival, without major morbidity, is gradually improving for newborns at 25 through 28 weeks.1,2 But what is the prognosis for a fetus born at 22 or 23 weeks?

There are several aspects of this issue to consider, including accurate dating of the gestational age and current viability outcomes data.

Determining the limit of viability: Accurate dating is essentialThe limit of viability is the milestone in gestation when there is a high probability of extrauterine survival. A major challenge in studies of the limit of viability for newborns is that accurate gestational dating is not always available. For example, in recent reports from the NICHD Neonatal Research Network the gestational age was determined by the best obstetric estimate, or the Ballard or Dubowitz examination, of the newborn.1,2

It is well known that ultrasound dating early in gestation is a better estimate of gestational age than last menstrual period, uterine sizing, or pediatric examination of the newborn. Hence, the available data are limited by the absence of precise gestational dating with early ultrasound. Data on the limit of viability with large numbers of births between 22 and 24 weeks with early ultrasound dating would help to refine our understanding of the limit of viability.

At 23 weeks, each day of in utero development is criticalThe importance of each additional day spent in utero during the 23rd week of gestation was demonstrated in a small cohort in 2001.4 Overall, during the 23rd week of gestation the survival of newborns to discharge was 33%.4 This finding is similar to the survival rate reported by the NICHD Neonatal Research Network in 2012.1 However, survival was vastly different early, compared with later, in the 23rd week4:

- from 23 weeks 0 days to 23 weeks 2 days: no newborn survived

- at 23 weeks 3 days and 23 weeks 4 days: 40% of newborns survived

- at 23 weeks 5 days and 23 weeks 6 days: 63% of newborns survived (a similar survival rate of 24-week gestations was reported by the NICHD Neonatal Research Network1).

The development of the fetus across the 23rd week of gestation appears to be critical to newborn survival. Hence, every day of in utero development during the 23rd week is critically important. A great challenge for obstetricians is how to approach the woman with threatened preterm birth at 22 weeks 0 days’ gestation. If the woman delivers within a few days, the likelihood of survival is minimal. However, if the pregnancy can be extended to 23 weeks and 5 days, survival rates increase significantly.

Aligning the actions of birth team, mother, and familyFactors that influence the limit of viability include:

- gestational age

- gender of the fetus (Females are more likely than males to survive.)

- treatment of the mother with glucocorticoids prior to birth

- newborn weight.

To increase the likelihood of newborn survival, obstetricians need to treat women at risk for preterm birth with antenatal glucocorticoids and antibiotics for rupture of membranes and to limit fetal stress during the birth process. Guidelines have evolved to encourage clinicians to treat women at preterm birth risk with glucocorticoids either at:

- 23 weeks’ gestation or

- 22 weeks’ gestation, if birth is anticipated to occur at 23 weeks or later.5

At birth, pediatricians are then faced with the very difficult decision of whether or not to aggressively resuscitate the severely preterm infant. Complex medical, social, and ethical issues ultimately guide pediatricians’ actions in this challenging situation. It is important for their actions to be in consensus with the obstetrician, the mother, and the mother’s family and for a consensus to be reached. Dissonant plans may increase adverse outcomes for the newborn. In one study when pediatricians and obstetricians were not aligned in their actions, the risk of death of an extremely preterm newborn significantly increased.6

Prior to birth, team meetings that include the obstetricians, pediatricians, mother, and family will help to set expectations about the course of care and, in turn, improve perceived outcomes.5 If feasible, obstetricians and pediatricians should develop joint institutional guidelines about the general approach to pregnant women when birth may occur at 22 or 23 weeks’ gestation.5

A neonatal outcomes predictor

The National Institute of Child Health and Human Development provides a Web-based tool for estimating newborn outcomes based on gestational age (22 to 25 weeks), birth weight, gender, singleton or multiple gestation, and exposure to antenatal glucocorticoid treatment. The outcomes tool provides estimates for survival and survival with severe morbidity. It uses data collected by the Neonatal Research Network to predict outcomes. To access the outcomes data assessment, visit https://www.nichd.nih.gov/about/org/der/branches/ppb/programs/epbo/Pages/epbo_case.aspx.

Is aggressive management of preterm birth and neonatal resuscitation a self-fulfilling prophecy?The beliefs and training of clinicians may influence the outcome of extremely preterm newborns. For example, if obstetricians and pediatricians focus on the fact that birth at 23 weeks is not likely to result in survival without severe morbidity, they may withhold key interventions such as antenatal glucocorticoids, antibiotics for rupture of the membranes, and aggressive newborn resuscitation.7 Consequently the likelihood of survival may be reduced.

If clinicians believe in maximal interventions for all newborns at 22 and 23 weeks’ gestation, their actions may result in a small increase in newborn survival—but at the cost of painful and unnecessary interventions in many newborns who are destined to die. Finding the right balance along the broad spectrum from expectant management to aggressive and extended resuscitation is challenging. Clearly there is no “right answer” with these extremely difficult decisions.

Future trends in the limit of viabilityIn 1963, Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy, at 34 weeks’ gestation, went into preterm labor and delivered her son Patrick at a community hospital. Patrick developed respiratory distress syndrome and was transferred to the Boston Children’s Hospital. He died shortly thereafter.8 Would Patrick have survived if he had been delivered at an institution capable of providing high-risk obstetric and newborn services? Would such modern interventions as antenatal glucocorticoids, antibiotics for ruptured membranes, liberal use of cesarean delivery, and aggressive neonatal resuscitation have improved his chances for survival?

From our current perspective, it is surprising that a 34-week newborn died shortly after birth. With modern obstetric and pediatric care that scenario is unusual. It is possible that future advances in medical care will push the limit of viability to 22 weeks’ gestation. Future generations of clinicians may be surprised that the medicine we practice today is so limited.

However, given our current resources, it is unlikely that newborns at 22 weeks’ gestation will survive, or survive without severe morbidity. Consequently, routine aggressive resuscitation of newborns at 22 weeks should be approached with caution. At 23 weeks and later, many newborns will survive and a few will survive without severe morbidity. Given the complexity of the issues, the approach to resuscitation of infants at 22 and 23 weeks must account for the perspectives of the birth mother and her family, obstetricians, and pediatricians. Managing threatened preterm birth at 22 and 23 weeks is one of our greatest challenges as obstetricians, and we need to meet this challenge with grace and skill.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Stoll BJ, Hansen NI, Bell EF, et al; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network. Trends in care practices, morbidity and mortality of extremely preterm neonates, 1993-2012. JAMA. 2015;314(10):1039–1051.

- Patel RM, Kandefer S, Walsh MC, et al; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network. Causes and timing of death in extremely premature infants from 2000 through 2011. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(4):331–340.

- Donovan EF, Tyson JE, Ehrenkranz RA, et al. Inaccuracy of Ballard scores before 28 weeks’ gestation. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network. J Pediatr. 1999;135(2 pt 1):147–152.

- McElrath TF, Robinson JN, Ecker JL, Ringer SA, Norwitz ER. Neonatal outcome of infants born at 23 weeks’ gestation. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;97(1):49–52.

- Raju TN, Mercer BM, Burchfield DJ, Joseph GF Jr. Periviable birth: executive summary of a joint workshop by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, American Academy of Pediatrics, and American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(5):1083–1096.

- Guinsburg R, Branco de Almeida MF, dos Santos Rodrigues Sadeck L, et al; Brazilian Network on Neonatal Research. Proactive management of extreme prematurity: disagreement between obstetricians and neonatologists. J Perinatol. 2012;32(12):913-919.

- Tucker Emonds B, McKenzie F, Farrow V, Raglan G, Schulkin J. A national survey of obstetricians’ attitudes toward and practice of periviable interventions. J Perinatol. 2015;35(5):338–343.

- Altman LK. A Kennedy baby’s life and death. New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2013/07/30/health/a-kennedy-babys-life-and-death.html?_r=0. Published July 29, 2013. Accessed November 19, 2015.

- Stoll BJ, Hansen NI, Bell EF, et al; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network. Trends in care practices, morbidity and mortality of extremely preterm neonates, 1993-2012. JAMA. 2015;314(10):1039–1051.

- Patel RM, Kandefer S, Walsh MC, et al; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network. Causes and timing of death in extremely premature infants from 2000 through 2011. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(4):331–340.

- Donovan EF, Tyson JE, Ehrenkranz RA, et al. Inaccuracy of Ballard scores before 28 weeks’ gestation. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network. J Pediatr. 1999;135(2 pt 1):147–152.

- McElrath TF, Robinson JN, Ecker JL, Ringer SA, Norwitz ER. Neonatal outcome of infants born at 23 weeks’ gestation. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;97(1):49–52.

- Raju TN, Mercer BM, Burchfield DJ, Joseph GF Jr. Periviable birth: executive summary of a joint workshop by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, American Academy of Pediatrics, and American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(5):1083–1096.

- Guinsburg R, Branco de Almeida MF, dos Santos Rodrigues Sadeck L, et al; Brazilian Network on Neonatal Research. Proactive management of extreme prematurity: disagreement between obstetricians and neonatologists. J Perinatol. 2012;32(12):913-919.

- Tucker Emonds B, McKenzie F, Farrow V, Raglan G, Schulkin J. A national survey of obstetricians’ attitudes toward and practice of periviable interventions. J Perinatol. 2015;35(5):338–343.

- Altman LK. A Kennedy baby’s life and death. New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2013/07/30/health/a-kennedy-babys-life-and-death.html?_r=0. Published July 29, 2013. Accessed November 19, 2015.

Does the discontinuation of menopausal hormone therapy affect a woman’s cardiovascular risk?

This recently published study from Finland generated headlines when its authors concluded that stopping HT elevates the risk of mortality from cardiovascular disease (CVD), including cardiac and cerebrovascular events. Using nationwide data, investigators compared the CVD mortality rate among women who discontinued HT during the years 1994 through 2009 (n = 332,202) with expected (not actual) CVD mortality rates in the background population.

Within the first year after HT discontinuation, elevations in death rates from cardiac events and stroke were noted (standardized mortality ratio, 1.26 and 1.63, respectively), while in the subsequent year, reductions in such mortality were observed (P<.05 for all comparisons).

The absolute increased risk of death from cardiac events reported within the first year after discontinuation of HT was 4 deaths per 10,000 woman-years of exposure. The absolute risk of death from stroke was 5 additional events per 10,000 woman-years. This level of risk is considered to be rare.

How these data compare to those of other studiesIn contrast with these Finnish data, findings from the Women’s Health Initiative—the largest randomized trial of menopausal HT—do not indicate an increase in mortality or an increase in coronary heart or stroke events among women stopping HT.1,2

It seems likely that limitations associated with the Finnish observational data account for this discordance. For example, Mikkola and colleagues did not know why women discontinued HT, raising the possibility that women with symptoms suggestive of CVD or development of new risk factors preferentially stopped HT, potentially introducing important bias into the Finnish analysis.

What this evidence means for practiceWomen and their clinicians should make decisions regarding whether to continue, reduce the dose, or discontinue HT through shared decision making, focusing on individual patient quality of life parameters as well as changing risk concerns related to such entities as cancer, CVD, and osteoporosis.3 Dramatic as they are, findings from this Finnish report should not impact how we counsel women regarding use or discontinuation of HT.

—Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD; JoAnn E. Manson, MD, DrPH; and Cynthia A. Stuenkel, MD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Heiss G, Wallace R, Anderson GL, et al; WHI investigators. Health risks and benefits 3 years after stopping randomized treatment with estrogen and progestin. JAMA. 2008;299(9):1036–1045.

- LaCroix AZ, Chlebowski RT, Manson JE, et al; WHI investigators. Health outcomes after stopping conjugated equine estrogens among postmenopausal women with prior hysterectomy. JAMA. 2011;305(13):1305–1314.

- Kaunitz AM. Extended duration use of menopausal hormone therapy. Menopause. 2014;21(6):679–68.

This recently published study from Finland generated headlines when its authors concluded that stopping HT elevates the risk of mortality from cardiovascular disease (CVD), including cardiac and cerebrovascular events. Using nationwide data, investigators compared the CVD mortality rate among women who discontinued HT during the years 1994 through 2009 (n = 332,202) with expected (not actual) CVD mortality rates in the background population.

Within the first year after HT discontinuation, elevations in death rates from cardiac events and stroke were noted (standardized mortality ratio, 1.26 and 1.63, respectively), while in the subsequent year, reductions in such mortality were observed (P<.05 for all comparisons).

The absolute increased risk of death from cardiac events reported within the first year after discontinuation of HT was 4 deaths per 10,000 woman-years of exposure. The absolute risk of death from stroke was 5 additional events per 10,000 woman-years. This level of risk is considered to be rare.

How these data compare to those of other studiesIn contrast with these Finnish data, findings from the Women’s Health Initiative—the largest randomized trial of menopausal HT—do not indicate an increase in mortality or an increase in coronary heart or stroke events among women stopping HT.1,2

It seems likely that limitations associated with the Finnish observational data account for this discordance. For example, Mikkola and colleagues did not know why women discontinued HT, raising the possibility that women with symptoms suggestive of CVD or development of new risk factors preferentially stopped HT, potentially introducing important bias into the Finnish analysis.

What this evidence means for practiceWomen and their clinicians should make decisions regarding whether to continue, reduce the dose, or discontinue HT through shared decision making, focusing on individual patient quality of life parameters as well as changing risk concerns related to such entities as cancer, CVD, and osteoporosis.3 Dramatic as they are, findings from this Finnish report should not impact how we counsel women regarding use or discontinuation of HT.

—Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD; JoAnn E. Manson, MD, DrPH; and Cynthia A. Stuenkel, MD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

This recently published study from Finland generated headlines when its authors concluded that stopping HT elevates the risk of mortality from cardiovascular disease (CVD), including cardiac and cerebrovascular events. Using nationwide data, investigators compared the CVD mortality rate among women who discontinued HT during the years 1994 through 2009 (n = 332,202) with expected (not actual) CVD mortality rates in the background population.

Within the first year after HT discontinuation, elevations in death rates from cardiac events and stroke were noted (standardized mortality ratio, 1.26 and 1.63, respectively), while in the subsequent year, reductions in such mortality were observed (P<.05 for all comparisons).

The absolute increased risk of death from cardiac events reported within the first year after discontinuation of HT was 4 deaths per 10,000 woman-years of exposure. The absolute risk of death from stroke was 5 additional events per 10,000 woman-years. This level of risk is considered to be rare.

How these data compare to those of other studiesIn contrast with these Finnish data, findings from the Women’s Health Initiative—the largest randomized trial of menopausal HT—do not indicate an increase in mortality or an increase in coronary heart or stroke events among women stopping HT.1,2

It seems likely that limitations associated with the Finnish observational data account for this discordance. For example, Mikkola and colleagues did not know why women discontinued HT, raising the possibility that women with symptoms suggestive of CVD or development of new risk factors preferentially stopped HT, potentially introducing important bias into the Finnish analysis.

What this evidence means for practiceWomen and their clinicians should make decisions regarding whether to continue, reduce the dose, or discontinue HT through shared decision making, focusing on individual patient quality of life parameters as well as changing risk concerns related to such entities as cancer, CVD, and osteoporosis.3 Dramatic as they are, findings from this Finnish report should not impact how we counsel women regarding use or discontinuation of HT.

—Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD; JoAnn E. Manson, MD, DrPH; and Cynthia A. Stuenkel, MD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Heiss G, Wallace R, Anderson GL, et al; WHI investigators. Health risks and benefits 3 years after stopping randomized treatment with estrogen and progestin. JAMA. 2008;299(9):1036–1045.

- LaCroix AZ, Chlebowski RT, Manson JE, et al; WHI investigators. Health outcomes after stopping conjugated equine estrogens among postmenopausal women with prior hysterectomy. JAMA. 2011;305(13):1305–1314.

- Kaunitz AM. Extended duration use of menopausal hormone therapy. Menopause. 2014;21(6):679–68.

- Heiss G, Wallace R, Anderson GL, et al; WHI investigators. Health risks and benefits 3 years after stopping randomized treatment with estrogen and progestin. JAMA. 2008;299(9):1036–1045.

- LaCroix AZ, Chlebowski RT, Manson JE, et al; WHI investigators. Health outcomes after stopping conjugated equine estrogens among postmenopausal women with prior hysterectomy. JAMA. 2011;305(13):1305–1314.

- Kaunitz AM. Extended duration use of menopausal hormone therapy. Menopause. 2014;21(6):679–68.

Patient denies consent to endometriosis treatment

Patient denies consent to endometriosis treatment

A woman underwent laparoscopic surgery to remove an ovarian cyst. During surgery, the gynecologist found endometriosis and used electrosurgery to destroy the implants. Following extensive electrosurgery, a hemorrhage occurred. The gynecologist placed 5 large clips to control bleeding. The patient was discharged. When she returned to the hospital in pain, she was sent home again. She visited another emergency department (ED), where a clip was found to have blocked a ureter. She underwent ureteroneocystostomy to repair the damage. The patient now reports incontinence, a ligated ureter, and extensive scar tissue, which may keep her from being able to become pregnant.

Patient’s claim She only consented to ovarian cyst removal, not to any other procedures. The gynecologist was negligent in performing electrosurgery and placing the clips. A urologist should have checked for injury.

Physician’s defense When a patient agrees to laparoscopic surgery, she also agrees to exploratory abdominal surgery. The gynecologist performs electrosurgery to treat endometriosis in 30% to 60% of her surgical cases. Electrosurgery was essential to stop the patient’s pain. The clips were carefully placed when treating the hemorrhage.

Verdict A $206,886 California verdict was returned against the gynecologist.

Eclampsia, death: $6.9M settlement

A mother delivered a healthy baby on May 21. Twice in the week following delivery, she returned to the ED reporting shortness of breath, swollen legs, and elevated blood pressure. Pulmonary embolism was excluded both times. After the second visit, she was discharged with a diagnosis of shortness of breath of unknown etiology. The patient’s ObGyn was not contacted nor was urinalysis performed. On June 1, she suffered seizures and brain injury; she died on June 10.

Estate’s claim The ED physicians failed to diagnose and treat eclampsia.

Defendant’s defense The case was settled early in the trial.

Verdict A $6.9 million Illinois settlement was reached with the hospital.

Child has CP: $8M settlement

At 40 1/7 weeks’ gestation, labor was induced in an obese woman who had a heart condition. Over the next 36 hours, dinoprostone and oxytocin were administered, but her cervix only dilated to 2 cm. Two days later, the fetal heart rate reached 160 bpm. The ObGyn ordered terbutaline in anticipation of cesarean delivery, but he did not come to the hospital. The fetal heart rate continued to rise and then bradycardia occurred. When notified, the ObGyn came to the hospital for an emergency cesarean delivery. The child was severely depressed at birth with Apgar scores of 0, 1, and 2 at 1, 5, and 10 minutes, respectively. Magnetic resonance imaging at 23 days showed distinct hypoxic ischemic injury in the infant. Cerebral palsy was later diagnosed. The child is nonambulatory with significant cognitive impairment.

Parents’ claim Failure to perform cesarean delivery in a timely manner caused injury to the child.

Defendant’s defense The case was settled during the trial.

Verdict An $8 million Wisconsin settlement was reached with the medical center and physician group.

Infant has a stroke: $3M settlement

A 26-year-old diabetic woman was referred to a maternal-fetal medicine (MFM) specialist. She had been hospitalized for nausea and dehydration several times during her pregnancy, but it appeared that fetal development was normal.

As labor progressed, fetal distress was diagnosed in the setting of low blood pressure. When notified, the MFM immediately ordered an emergency cesarean delivery. A few days after birth, it was determined that the child had a stroke in utero.

Parents’ claim Emergency cesarean delivery should have been performed earlier. Hospital staff did not communicate fetal distress to the MFM in a timely manner.

Defendant’s defense The case was settled at trial.

Verdict A $3 million Connecticut settlement was reached with the hospital.

Patient denies consent to endometriosis treatment

A woman underwent laparoscopic surgery to remove an ovarian cyst. During surgery, the gynecologist found endometriosis and used electrosurgery to destroy the implants. Following extensive electrosurgery, a hemorrhage occurred. The gynecologist placed 5 large clips to control bleeding. The patient was discharged. When she returned to the hospital in pain, she was sent home again. She visited another emergency department (ED), where a clip was found to have blocked a ureter. She underwent ureteroneocystostomy to repair the damage. The patient now reports incontinence, a ligated ureter, and extensive scar tissue, which may keep her from being able to become pregnant.

Patient’s claim She only consented to ovarian cyst removal, not to any other procedures. The gynecologist was negligent in performing electrosurgery and placing the clips. A urologist should have checked for injury.

Physician’s defense When a patient agrees to laparoscopic surgery, she also agrees to exploratory abdominal surgery. The gynecologist performs electrosurgery to treat endometriosis in 30% to 60% of her surgical cases. Electrosurgery was essential to stop the patient’s pain. The clips were carefully placed when treating the hemorrhage.

Verdict A $206,886 California verdict was returned against the gynecologist.

Eclampsia, death: $6.9M settlement

A mother delivered a healthy baby on May 21. Twice in the week following delivery, she returned to the ED reporting shortness of breath, swollen legs, and elevated blood pressure. Pulmonary embolism was excluded both times. After the second visit, she was discharged with a diagnosis of shortness of breath of unknown etiology. The patient’s ObGyn was not contacted nor was urinalysis performed. On June 1, she suffered seizures and brain injury; she died on June 10.

Estate’s claim The ED physicians failed to diagnose and treat eclampsia.

Defendant’s defense The case was settled early in the trial.

Verdict A $6.9 million Illinois settlement was reached with the hospital.

Child has CP: $8M settlement

At 40 1/7 weeks’ gestation, labor was induced in an obese woman who had a heart condition. Over the next 36 hours, dinoprostone and oxytocin were administered, but her cervix only dilated to 2 cm. Two days later, the fetal heart rate reached 160 bpm. The ObGyn ordered terbutaline in anticipation of cesarean delivery, but he did not come to the hospital. The fetal heart rate continued to rise and then bradycardia occurred. When notified, the ObGyn came to the hospital for an emergency cesarean delivery. The child was severely depressed at birth with Apgar scores of 0, 1, and 2 at 1, 5, and 10 minutes, respectively. Magnetic resonance imaging at 23 days showed distinct hypoxic ischemic injury in the infant. Cerebral palsy was later diagnosed. The child is nonambulatory with significant cognitive impairment.

Parents’ claim Failure to perform cesarean delivery in a timely manner caused injury to the child.

Defendant’s defense The case was settled during the trial.

Verdict An $8 million Wisconsin settlement was reached with the medical center and physician group.

Infant has a stroke: $3M settlement

A 26-year-old diabetic woman was referred to a maternal-fetal medicine (MFM) specialist. She had been hospitalized for nausea and dehydration several times during her pregnancy, but it appeared that fetal development was normal.

As labor progressed, fetal distress was diagnosed in the setting of low blood pressure. When notified, the MFM immediately ordered an emergency cesarean delivery. A few days after birth, it was determined that the child had a stroke in utero.

Parents’ claim Emergency cesarean delivery should have been performed earlier. Hospital staff did not communicate fetal distress to the MFM in a timely manner.

Defendant’s defense The case was settled at trial.

Verdict A $3 million Connecticut settlement was reached with the hospital.

Patient denies consent to endometriosis treatment

A woman underwent laparoscopic surgery to remove an ovarian cyst. During surgery, the gynecologist found endometriosis and used electrosurgery to destroy the implants. Following extensive electrosurgery, a hemorrhage occurred. The gynecologist placed 5 large clips to control bleeding. The patient was discharged. When she returned to the hospital in pain, she was sent home again. She visited another emergency department (ED), where a clip was found to have blocked a ureter. She underwent ureteroneocystostomy to repair the damage. The patient now reports incontinence, a ligated ureter, and extensive scar tissue, which may keep her from being able to become pregnant.

Patient’s claim She only consented to ovarian cyst removal, not to any other procedures. The gynecologist was negligent in performing electrosurgery and placing the clips. A urologist should have checked for injury.

Physician’s defense When a patient agrees to laparoscopic surgery, she also agrees to exploratory abdominal surgery. The gynecologist performs electrosurgery to treat endometriosis in 30% to 60% of her surgical cases. Electrosurgery was essential to stop the patient’s pain. The clips were carefully placed when treating the hemorrhage.

Verdict A $206,886 California verdict was returned against the gynecologist.

Eclampsia, death: $6.9M settlement

A mother delivered a healthy baby on May 21. Twice in the week following delivery, she returned to the ED reporting shortness of breath, swollen legs, and elevated blood pressure. Pulmonary embolism was excluded both times. After the second visit, she was discharged with a diagnosis of shortness of breath of unknown etiology. The patient’s ObGyn was not contacted nor was urinalysis performed. On June 1, she suffered seizures and brain injury; she died on June 10.

Estate’s claim The ED physicians failed to diagnose and treat eclampsia.

Defendant’s defense The case was settled early in the trial.

Verdict A $6.9 million Illinois settlement was reached with the hospital.

Child has CP: $8M settlement

At 40 1/7 weeks’ gestation, labor was induced in an obese woman who had a heart condition. Over the next 36 hours, dinoprostone and oxytocin were administered, but her cervix only dilated to 2 cm. Two days later, the fetal heart rate reached 160 bpm. The ObGyn ordered terbutaline in anticipation of cesarean delivery, but he did not come to the hospital. The fetal heart rate continued to rise and then bradycardia occurred. When notified, the ObGyn came to the hospital for an emergency cesarean delivery. The child was severely depressed at birth with Apgar scores of 0, 1, and 2 at 1, 5, and 10 minutes, respectively. Magnetic resonance imaging at 23 days showed distinct hypoxic ischemic injury in the infant. Cerebral palsy was later diagnosed. The child is nonambulatory with significant cognitive impairment.

Parents’ claim Failure to perform cesarean delivery in a timely manner caused injury to the child.

Defendant’s defense The case was settled during the trial.

Verdict An $8 million Wisconsin settlement was reached with the medical center and physician group.

Infant has a stroke: $3M settlement

A 26-year-old diabetic woman was referred to a maternal-fetal medicine (MFM) specialist. She had been hospitalized for nausea and dehydration several times during her pregnancy, but it appeared that fetal development was normal.

As labor progressed, fetal distress was diagnosed in the setting of low blood pressure. When notified, the MFM immediately ordered an emergency cesarean delivery. A few days after birth, it was determined that the child had a stroke in utero.

Parents’ claim Emergency cesarean delivery should have been performed earlier. Hospital staff did not communicate fetal distress to the MFM in a timely manner.

Defendant’s defense The case was settled at trial.

Verdict A $3 million Connecticut settlement was reached with the hospital.

In this Article

- Eclampsia, death: $6.9M settlement

- Child has CP: $8M settlement

- Infant has a stroke: $3M settlement

Pediatric cancer deaths on the decline in UK

Photo by Bill Branson

The rate of pediatric cancer deaths in the UK has dropped by 24% in the last decade, according to new figures published by Cancer Research UK.

The latest figures suggest the number of children age 14 and younger dying from cancer each year in the UK has dropped from around 330 in the early 2000s (2001-2003) to around 260 in more recent years (2011-2013).

But this still means that about 5 children die from cancer every week in the UK.

The data suggest that around 1500 children are diagnosed with cancer every year in the UK. This is the annual average number of new cases for all children’s cancers (ages 0-14), excluding non-melanoma skin cancer, in the UK from 2010 to 2012.

The figures also indicate that overall survival for children’s cancers has tripled since the 1960s, and three quarters of children with cancer are cured.

“Although we’re losing fewer young lives to cancer, a lot more needs to be done,” said Pam Kearns, director of the Cancer Research UK Clinical Trials Unit in Birmingham.

The data on mortality according to cancer type spans the period from 1996 to 2005 and includes children ages 0 to 14 living in Great Britain (not the whole UK).

These data indicate that the average number of annual deaths for pediatric leukemias was 59.7 for males and 45.6 for females during the period analyzed. These deaths made up 30.3% and 29.6%, respectively, of all childhood cancer deaths.

The average number of annual deaths for pediatric lymphomas was 12 for males and 5.5 for females. These deaths made up 6.1% and 3.6%, respectively, of all childhood cancer deaths.

Cancer Research UK compiles UK-wide incidence data produced by the regional cancer registries in England and the 3 national registries in Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland for the UK statistics.

The organization must wait until all of the data has been published by each country before publishing the figures on the Cancer Research UK website. ![]()

Photo by Bill Branson

The rate of pediatric cancer deaths in the UK has dropped by 24% in the last decade, according to new figures published by Cancer Research UK.

The latest figures suggest the number of children age 14 and younger dying from cancer each year in the UK has dropped from around 330 in the early 2000s (2001-2003) to around 260 in more recent years (2011-2013).

But this still means that about 5 children die from cancer every week in the UK.

The data suggest that around 1500 children are diagnosed with cancer every year in the UK. This is the annual average number of new cases for all children’s cancers (ages 0-14), excluding non-melanoma skin cancer, in the UK from 2010 to 2012.

The figures also indicate that overall survival for children’s cancers has tripled since the 1960s, and three quarters of children with cancer are cured.

“Although we’re losing fewer young lives to cancer, a lot more needs to be done,” said Pam Kearns, director of the Cancer Research UK Clinical Trials Unit in Birmingham.

The data on mortality according to cancer type spans the period from 1996 to 2005 and includes children ages 0 to 14 living in Great Britain (not the whole UK).

These data indicate that the average number of annual deaths for pediatric leukemias was 59.7 for males and 45.6 for females during the period analyzed. These deaths made up 30.3% and 29.6%, respectively, of all childhood cancer deaths.

The average number of annual deaths for pediatric lymphomas was 12 for males and 5.5 for females. These deaths made up 6.1% and 3.6%, respectively, of all childhood cancer deaths.

Cancer Research UK compiles UK-wide incidence data produced by the regional cancer registries in England and the 3 national registries in Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland for the UK statistics.

The organization must wait until all of the data has been published by each country before publishing the figures on the Cancer Research UK website. ![]()

Photo by Bill Branson

The rate of pediatric cancer deaths in the UK has dropped by 24% in the last decade, according to new figures published by Cancer Research UK.

The latest figures suggest the number of children age 14 and younger dying from cancer each year in the UK has dropped from around 330 in the early 2000s (2001-2003) to around 260 in more recent years (2011-2013).

But this still means that about 5 children die from cancer every week in the UK.

The data suggest that around 1500 children are diagnosed with cancer every year in the UK. This is the annual average number of new cases for all children’s cancers (ages 0-14), excluding non-melanoma skin cancer, in the UK from 2010 to 2012.

The figures also indicate that overall survival for children’s cancers has tripled since the 1960s, and three quarters of children with cancer are cured.

“Although we’re losing fewer young lives to cancer, a lot more needs to be done,” said Pam Kearns, director of the Cancer Research UK Clinical Trials Unit in Birmingham.

The data on mortality according to cancer type spans the period from 1996 to 2005 and includes children ages 0 to 14 living in Great Britain (not the whole UK).

These data indicate that the average number of annual deaths for pediatric leukemias was 59.7 for males and 45.6 for females during the period analyzed. These deaths made up 30.3% and 29.6%, respectively, of all childhood cancer deaths.

The average number of annual deaths for pediatric lymphomas was 12 for males and 5.5 for females. These deaths made up 6.1% and 3.6%, respectively, of all childhood cancer deaths.

Cancer Research UK compiles UK-wide incidence data produced by the regional cancer registries in England and the 3 national registries in Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland for the UK statistics.

The organization must wait until all of the data has been published by each country before publishing the figures on the Cancer Research UK website. ![]()

Improving hospital-to-home transitions

Photo by Logan Tuttle

Bringing acutely ill children home from the hospital can overwhelm family caregivers and affect a child’s recovery and long-term health, according to a study published in Pediatrics.

Investigators interviewed family caregivers to determine how the hospital-to-home transition affects patients and their families.

The results provided investigators with “family-centered” input that has allowed them to design and test interventions for improving the transition.

The families suggested a need for in-home follow up visits, telephone calls from nurses, enhanced care plans, and other measures.

“Our study finds that transitions from hospital to home affect the lives of families in ways that may impact patient outcomes at discharge,” explained Andrew Beck, MD, of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital in Ohio.

“Many family caregivers expressed mental exhaustion, being in a fog, the emotional toll of having an ill child, and uncertainty on how to care for their child after hospitalization.”

To gain these insights, Dr Beck and his colleagues conducted focus groups and individual interviews with 61 family caregivers.

These individuals were caring for children who had been discharged from the hospital in the preceding 30 days. Eighty-seven percent of participants were female, 46% were nonwhite, 38% were the only adult in the household, and 56% resided in areas with high rates of poverty.

All of the children under care had been discharged from Cincinnati Children’s, a large urban medical center with a diverse patient population.

The investigators conducted a detailed analysis of transcripts from the focus groups and interviews, which revealed 12 different themes of caregiver concerns that fell into 4 overarching concepts:

- “In a fog”—barriers to processing and acting on information

a. mental exhaustion (this is too much)

b. handling uncertainty

c. information overload

d. usability of information

- “What I wish I had”

a. information desired

b. suggested improvements in the discharge process

- “Am I ready to go home?”

a. emotional discharge readiness

b. clinical discharge readiness

- “I’m home, now what?”—having confidence about post-discharge care

a. knowing who to call

b. bridging the gap (desiring a call or nurse home visit)

c. caring for a sick child

d. confidence in caring for a sick child.

“Participants in our study expressed a desire for specific details about worrisome clinical signs or symptoms,” said Lauren Solan, MD, a fellow at Cincinnati Children’s during the study and now a physician at the University of Rochester Medical Center in New York.

“Interventions designed to address informational needs and gaps identified by caregivers may improve feelings of readiness or preparation for transition to the home.”

The current study is part of a multi-stage research project led by Cincinnati Children’s called the Hospital-to-Home Outcomes (H2O) Study, which is focused on improving hospital-to-home transitions for children. This paper zeroed in on obtaining detailed qualitative input from caregivers that would help develop and refine “family-centered” solutions.

In a follow-up study already underway, investigators are testing the effectiveness of nurse follow-up visits in patient homes. The content and structure of these visits have been enhanced based on family input. The investigators are enrolling up to 1500 participants to measure the impact of these visits on hospital readmission rates and outcomes found to be meaningful to families. ![]()

Photo by Logan Tuttle

Bringing acutely ill children home from the hospital can overwhelm family caregivers and affect a child’s recovery and long-term health, according to a study published in Pediatrics.

Investigators interviewed family caregivers to determine how the hospital-to-home transition affects patients and their families.

The results provided investigators with “family-centered” input that has allowed them to design and test interventions for improving the transition.

The families suggested a need for in-home follow up visits, telephone calls from nurses, enhanced care plans, and other measures.

“Our study finds that transitions from hospital to home affect the lives of families in ways that may impact patient outcomes at discharge,” explained Andrew Beck, MD, of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital in Ohio.

“Many family caregivers expressed mental exhaustion, being in a fog, the emotional toll of having an ill child, and uncertainty on how to care for their child after hospitalization.”

To gain these insights, Dr Beck and his colleagues conducted focus groups and individual interviews with 61 family caregivers.

These individuals were caring for children who had been discharged from the hospital in the preceding 30 days. Eighty-seven percent of participants were female, 46% were nonwhite, 38% were the only adult in the household, and 56% resided in areas with high rates of poverty.

All of the children under care had been discharged from Cincinnati Children’s, a large urban medical center with a diverse patient population.

The investigators conducted a detailed analysis of transcripts from the focus groups and interviews, which revealed 12 different themes of caregiver concerns that fell into 4 overarching concepts:

- “In a fog”—barriers to processing and acting on information

a. mental exhaustion (this is too much)

b. handling uncertainty

c. information overload

d. usability of information

- “What I wish I had”

a. information desired

b. suggested improvements in the discharge process

- “Am I ready to go home?”

a. emotional discharge readiness

b. clinical discharge readiness

- “I’m home, now what?”—having confidence about post-discharge care

a. knowing who to call

b. bridging the gap (desiring a call or nurse home visit)

c. caring for a sick child

d. confidence in caring for a sick child.

“Participants in our study expressed a desire for specific details about worrisome clinical signs or symptoms,” said Lauren Solan, MD, a fellow at Cincinnati Children’s during the study and now a physician at the University of Rochester Medical Center in New York.

“Interventions designed to address informational needs and gaps identified by caregivers may improve feelings of readiness or preparation for transition to the home.”

The current study is part of a multi-stage research project led by Cincinnati Children’s called the Hospital-to-Home Outcomes (H2O) Study, which is focused on improving hospital-to-home transitions for children. This paper zeroed in on obtaining detailed qualitative input from caregivers that would help develop and refine “family-centered” solutions.

In a follow-up study already underway, investigators are testing the effectiveness of nurse follow-up visits in patient homes. The content and structure of these visits have been enhanced based on family input. The investigators are enrolling up to 1500 participants to measure the impact of these visits on hospital readmission rates and outcomes found to be meaningful to families. ![]()

Photo by Logan Tuttle

Bringing acutely ill children home from the hospital can overwhelm family caregivers and affect a child’s recovery and long-term health, according to a study published in Pediatrics.

Investigators interviewed family caregivers to determine how the hospital-to-home transition affects patients and their families.

The results provided investigators with “family-centered” input that has allowed them to design and test interventions for improving the transition.

The families suggested a need for in-home follow up visits, telephone calls from nurses, enhanced care plans, and other measures.

“Our study finds that transitions from hospital to home affect the lives of families in ways that may impact patient outcomes at discharge,” explained Andrew Beck, MD, of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital in Ohio.

“Many family caregivers expressed mental exhaustion, being in a fog, the emotional toll of having an ill child, and uncertainty on how to care for their child after hospitalization.”

To gain these insights, Dr Beck and his colleagues conducted focus groups and individual interviews with 61 family caregivers.

These individuals were caring for children who had been discharged from the hospital in the preceding 30 days. Eighty-seven percent of participants were female, 46% were nonwhite, 38% were the only adult in the household, and 56% resided in areas with high rates of poverty.

All of the children under care had been discharged from Cincinnati Children’s, a large urban medical center with a diverse patient population.

The investigators conducted a detailed analysis of transcripts from the focus groups and interviews, which revealed 12 different themes of caregiver concerns that fell into 4 overarching concepts:

- “In a fog”—barriers to processing and acting on information

a. mental exhaustion (this is too much)

b. handling uncertainty

c. information overload

d. usability of information

- “What I wish I had”

a. information desired

b. suggested improvements in the discharge process

- “Am I ready to go home?”

a. emotional discharge readiness

b. clinical discharge readiness

- “I’m home, now what?”—having confidence about post-discharge care

a. knowing who to call

b. bridging the gap (desiring a call or nurse home visit)

c. caring for a sick child

d. confidence in caring for a sick child.

“Participants in our study expressed a desire for specific details about worrisome clinical signs or symptoms,” said Lauren Solan, MD, a fellow at Cincinnati Children’s during the study and now a physician at the University of Rochester Medical Center in New York.

“Interventions designed to address informational needs and gaps identified by caregivers may improve feelings of readiness or preparation for transition to the home.”

The current study is part of a multi-stage research project led by Cincinnati Children’s called the Hospital-to-Home Outcomes (H2O) Study, which is focused on improving hospital-to-home transitions for children. This paper zeroed in on obtaining detailed qualitative input from caregivers that would help develop and refine “family-centered” solutions.

In a follow-up study already underway, investigators are testing the effectiveness of nurse follow-up visits in patient homes. The content and structure of these visits have been enhanced based on family input. The investigators are enrolling up to 1500 participants to measure the impact of these visits on hospital readmission rates and outcomes found to be meaningful to families. ![]()

Activity trackers can monitor HSCT recipients

Activity trackers like the Fitbit can count steps and measure sleep, but a new study suggests they can also be used to gauge patients’ symptoms and overall functional status after hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT).

Researchers used Fitbits to track the physical activity of 32 HSCT recipients and found that decreases in average daily steps were associated with increases in pain, fatigue, and other symptoms, as well as a reduction in self-reported activities.

The researchers say the findings, published in Quality of Life Research, indicate that activity trackers could be a useful tool for tracking symptoms and physical function systematically, especially for patients who may not be able to self-report their symptoms using questionnaires because of language barriers, literacy, or cognitive or health status.

“We found that changes in daily steps are highly correlated with pain and fatigue,” said Antonia Bennett, PhD, of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

“These wearables provide a way to monitor how patients are doing, and they provide continuous data with very little patient burden.”

For this study, Dr Bennett and her colleagues evaluated daily steps, as measured by Fitbit Flex activity trackers, and symptoms in 32 adults who underwent autologous or allogeneic HSCT to treat leukemia, lymphoma, myeloma, myelodysplastic syndromes, aplastic anemia, or solid tumor malignancy.

The patients wore the activity trackers and completed assessments about their symptoms and quality of life for 4 weeks during transplant hospitalization and 4 weeks after discharge.

Each week, the patients reported symptomatic treatment toxicities using single items from PROCTCAE and symptoms, physical health, mental health, and quality of life using PROMIS_ Global-10. The researchers compared these answers with pedometry data, summarized as average daily steps per week, using linear mixed models.

These analyses showed that decreases in a patient’s average daily steps were associated with increases in the following:

- Pain (852 fewer steps per unit increase in pain score, P<0.001)

- Fatigue (886 fewer steps, P<0.001)

- Vomiting (518 fewer steps, P<0.01)

- Shaking/chills (587 fewer steps, P<0.01)

- Diarrhea (719 fewer steps, P<0.001)

- Shortness of breath (1018 fewer steps, P<0.05)

- Reduction in carrying out social activities (705 fewer steps, P<0.01)

- Reduction in carrying out physical activities (618 fewer steps, P<0.01)

- Global physical health (101 fewer steps, P<0.001).

However, decreases in daily steps were not linked to global mental health or quality of life.

“Studies like this demonstrate that wearable devices can measure an aspect of physical function that is directly related to symptomatic toxicities following treatment,” said William Wood, MD, of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

“As clinicians, we often want to know–overall, how well are our patients doing with treatment? Are they better, worse, or about the same? Data from wearable devices may allow us to answer these questions with much more precision than we’ve had in the past.” ![]()

Activity trackers like the Fitbit can count steps and measure sleep, but a new study suggests they can also be used to gauge patients’ symptoms and overall functional status after hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT).

Researchers used Fitbits to track the physical activity of 32 HSCT recipients and found that decreases in average daily steps were associated with increases in pain, fatigue, and other symptoms, as well as a reduction in self-reported activities.

The researchers say the findings, published in Quality of Life Research, indicate that activity trackers could be a useful tool for tracking symptoms and physical function systematically, especially for patients who may not be able to self-report their symptoms using questionnaires because of language barriers, literacy, or cognitive or health status.

“We found that changes in daily steps are highly correlated with pain and fatigue,” said Antonia Bennett, PhD, of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

“These wearables provide a way to monitor how patients are doing, and they provide continuous data with very little patient burden.”

For this study, Dr Bennett and her colleagues evaluated daily steps, as measured by Fitbit Flex activity trackers, and symptoms in 32 adults who underwent autologous or allogeneic HSCT to treat leukemia, lymphoma, myeloma, myelodysplastic syndromes, aplastic anemia, or solid tumor malignancy.

The patients wore the activity trackers and completed assessments about their symptoms and quality of life for 4 weeks during transplant hospitalization and 4 weeks after discharge.

Each week, the patients reported symptomatic treatment toxicities using single items from PROCTCAE and symptoms, physical health, mental health, and quality of life using PROMIS_ Global-10. The researchers compared these answers with pedometry data, summarized as average daily steps per week, using linear mixed models.

These analyses showed that decreases in a patient’s average daily steps were associated with increases in the following:

- Pain (852 fewer steps per unit increase in pain score, P<0.001)

- Fatigue (886 fewer steps, P<0.001)

- Vomiting (518 fewer steps, P<0.01)

- Shaking/chills (587 fewer steps, P<0.01)

- Diarrhea (719 fewer steps, P<0.001)

- Shortness of breath (1018 fewer steps, P<0.05)

- Reduction in carrying out social activities (705 fewer steps, P<0.01)

- Reduction in carrying out physical activities (618 fewer steps, P<0.01)

- Global physical health (101 fewer steps, P<0.001).

However, decreases in daily steps were not linked to global mental health or quality of life.

“Studies like this demonstrate that wearable devices can measure an aspect of physical function that is directly related to symptomatic toxicities following treatment,” said William Wood, MD, of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

“As clinicians, we often want to know–overall, how well are our patients doing with treatment? Are they better, worse, or about the same? Data from wearable devices may allow us to answer these questions with much more precision than we’ve had in the past.” ![]()

Activity trackers like the Fitbit can count steps and measure sleep, but a new study suggests they can also be used to gauge patients’ symptoms and overall functional status after hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT).

Researchers used Fitbits to track the physical activity of 32 HSCT recipients and found that decreases in average daily steps were associated with increases in pain, fatigue, and other symptoms, as well as a reduction in self-reported activities.

The researchers say the findings, published in Quality of Life Research, indicate that activity trackers could be a useful tool for tracking symptoms and physical function systematically, especially for patients who may not be able to self-report their symptoms using questionnaires because of language barriers, literacy, or cognitive or health status.

“We found that changes in daily steps are highly correlated with pain and fatigue,” said Antonia Bennett, PhD, of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

“These wearables provide a way to monitor how patients are doing, and they provide continuous data with very little patient burden.”

For this study, Dr Bennett and her colleagues evaluated daily steps, as measured by Fitbit Flex activity trackers, and symptoms in 32 adults who underwent autologous or allogeneic HSCT to treat leukemia, lymphoma, myeloma, myelodysplastic syndromes, aplastic anemia, or solid tumor malignancy.

The patients wore the activity trackers and completed assessments about their symptoms and quality of life for 4 weeks during transplant hospitalization and 4 weeks after discharge.