User login

Unassigned, Undocumented Inpatients Present Challenges; Some Hospitalists Have Solutions

Hospitalists are charged with giving the best of care and treatment, regardless of whether or not a patient is insured or has a PCP to transition to after discharge. But patients who do not have insurance or a PCP pose many challenges to hospitalists, as well as the healthcare systems they work in. Although some hospitals and health systems have found ways to address these challenges, issues persist, with high costs to care for these patients topping the list. In 2013, the cost of community hospitals’ uncompensated care climbed to $46.4 billion.1

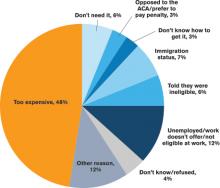

Typically, undocumented and unassigned patients face many social and economic challenges. Many of these patients are unemployed or work as independent contractors without employer-offered health insurance. Some have multiple jobs, can’t take time off from work for doctor appointments, or are undocumented workers.

More patients have acquired health insurance in recent years as a result of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and Medicaid expansion; however, some eligible people never complete the necessary forms.

With or without insurance, some patients don’t establish primary care because they have been healthy, have difficulty navigating the healthcare system, lack transportation, or desire more culturally tailored care. Some Medicare and Medicaid patients don’t have a PCP in their community who accepts these programs.

Treatment Challenges

Uninsured patients often are sicker and have more complex conditions than those with insurance, according to Beth Feldpush, DrPH, senior vice president of policy and advocacy at the nonprofit trade group America’s Essential Hospitals, which is based in Washington, D.C., and represents 250 safety net hospitals throughout the U.S.

“Because they can’t afford regular preventive and primary care, they forgo needed healthcare services until their conditions worsen and they require costly hospital care,” says Dr. Feldpush. Uninsured patients often lack the resources for follow-up care to help them recover and stay well. She says more than half of all inpatient discharges and outpatient visits at her groups’ hospitals are for uninsured or Medicaid patients.

When an uninsured patient is discharged from the hospital, finding follow-up care can be difficult.

“Their ability to get an appointment to see a PCP is extremely limited, because many providers don’t see patients without health insurance,” says Scott Sears, MD, MBA, chief clinical officer of Tacoma, Wash.-based Sound Physicians. Dr. Sears notes that in some hospitalist programs, as many as 40% of hospitalized patients lack insurance. “But without secured follow-up care, hospitalists are hesitant to send patients home, because they could relapse.”

Typically, these patients are not completely well and should be transferred to a skilled nursing or hospice facility; however, many facilities won’t accept them without insurance. Often, these patients need a PCP to monitor them with laboratory tests and other follow-up tests, to prescribe and monitor medications, and to ensure that they are following their plan of care.

At some medical facilities, subspecialists who consult on patients may screen them and refuse to see anyone without health insurance.

“So even though some patients may need subspecialty support, they may not have access to it,” Dr. Sears says. “While some patients without insurance qualify for Medicaid or other programs, due to the amount of paperwork and time to enroll, they end up staying in the hospital even though they are ready for discharge.”

Transitional Challenges

Most patients admitted to the hospital either have exacerbations of chronic conditions or a new diagnosis. “It’s rare to hospitalize a patient with a discrete illness that wouldn’t need care after discharge, so having a robust PCP partner is critical to a patient’s health,” says Honora Englander, MD, medical director of the Care Transitions Innovation (C-TRAIN) program at Oregon Health and Science University (OHSU) in Portland. For many patients, psychosocial complexity complicates their transition out of the hospital. An effective system needs to address a patient’s mental health, housing, and other social needs.

It may take four to six weeks for a patient without an established PCP to get a new patient appointment. “This is a huge impediment, as the patient won’t have anyone to ensure that he or she continues along the proper care path,” Dr. Sears says.

“Studies estimate that more than half of medication errors that patients experience occur during transitions and after discharge,” Dr. Sears says.2 “Intervention with a healthcare provider who can review proper use after discharge can dramatically reduce errors and [improve] patient outcomes.”

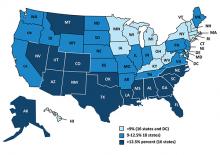

Rates of patients without a PCP vary by region for Sound Physicians. In the northwest region, about 25% of admitted patients lack a PCP; in the gulf region, the figure can be as high as 60%.

“In Texas, there is a large number of patients and not as many PCPs,” he adds. “There is also a larger percentage of patients without health insurance. Sometimes patients have coverage but have never established care with a PCP.”

As a result of not having a PCP to transition to, some patients return to the hospital soon after discharge, Dr. Feldpush notes.

Tips for Treating Uninsured Patients

Some facilities have found successful ways to help hospitalized patients without health insurance. Dr. Sears says that hospitalists can investigate which clinics accept uninsured patients or which local physician groups are willing to see them after discharge, in exchange for hospitalists taking care of them in the hospital. They also can investigate the community-based insurance programs that are available.

Teresa Coker, MSN, ARNP, FNP-BC, a Sound Physicians program manager at Mercy Medical Center in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, says that when patients lack insurance at her hospital, an organization will review the patient’s case, determine insurance eligibility, and assist the patient in completing the appropriate paperwork. When patients are not eligible, they are instructed to inquire about the hospital’s charity care program if they receive a bill they are unable to pay.

In addition, the community has a free health clinic that serves those without insurance. “Patients are given the address and hours prior to discharge, because it is walk-in only,” Coker says. “All patients are recommended to follow up within one week, or sooner if medications are needed.”

Dr. Englander advocates that physicians take into account medication costs, transportation, and other social considerations when planning care after hospitalization. The team at OHSU developed a low-cost formulary (based in part on widely available $4 plans from national pharmacy chains), and OHSU provides medications for uninsured patients in the program for up to 30 days following discharge.

For patients who can’t afford the $4 drug plan, case managers offer coupons for $4 prescriptions, says Malik Merchant, MD, area medical officer for the Schumachergroup in Harker Heights, Texas. He says that as many as 30% of the patients in his area are undocumented or unassigned. For more expensive medications, a social worker offers pharmaceutical company coupons when they are available. The institution also has a small budget to pay for drugs.

Dr. Merchant has found the biggest challenge to be the transition of care from inpatient to outpatient.

“Case managers and social workers prepare a financial worksheet that provides the possibility of overall cost savings for the institution, if patients are willing to participate in some upfront cost,” he says. “When our parent institution came on board, we developed contracts with local pharmacies, [a] skilled nursing facility, and PCPs to take these patients until they recovered from an acute illness. Our institution paid for these services at a reduced rate but saved money by reducing the length of their hospital stay.”

Dr. Feldpush says her group’s hospitals work hard to reach the uninsured. South Florida’s Memorial Healthcare System (MHS) created the Health Intervention with Targeted Services (HITS) Program, an outreach initiative that links patients with insurance programs or medical homes.3 The HITS team used a geographic information system map to target 15 neighborhoods with the highest rates of hospitalized, uninsured patients. Over a six-month period, the team approached these neighborhoods using various outreach strategies, such as health fairs, educational workshops, and door-to-door visits.3

Approximately 6,910 HITS participants have been enrolled in Medicaid, Florida’s children’s health insurance program, or an MHS community health center. Over a three-year study period, MHS saved $284,856 in the ED, about $2.8 million in inpatient costs, and roughly $4 million overall.3

Barriers to Follow-Up Care

Whether you are looking to help uninsured patients, those without a PCP, or both, the key is to try to fill in the gaps.

“As hospitalists, we need to work with pharmacists, case managers and social workers, and others to identify affordable and effective ways to provide care,” Dr. Englander says. “Interprofessional team members, community partners, and family members can help hospitalists understand patient and population health needs and available resources.”

In an effort to close transitional care gaps, OHSU developed the C-TRAIN program, a multi-component transitional care intervention that includes four main elements:

- Transitional care nurse who sees patients in the hospital, makes home visits, and helps coordinate care 30 days post-discharge;

- Inpatient pharmacy consultation and prescription medications at discharge from a low-cost, value-based formulary;

- Medical home linkages, whereby OHSU partners with and provides payment to three community clinics to provide primary care for uninsured patients; and

- Monthly implementation team meetings that convene diverse healthcare stakeholders to integrate elements of the healthcare system and engage in ongoing quality improvement.

The Schumachergroup has also found an effective solution.

“The department head of our case managers and social workers made an agreement with a local multispecialty group,” Dr. Merchant says. “The group agreed to take all discharged patients and be their PCP for 30 days, even if the patient couldn’t pay, in exchange for receiving all patients who had good insurance but did not have an established PCP.

“This has worked well. Every patient discharged from our facility has a PCP listed at discharge, and the unit clerk makes an appointment and documents it in the electronic medical record.”

Sound Physicians has set up a service line, called transitional care services, to smooth transitions of care after discharge for up to 90 days, depending on their clinical needs. It hires providers who work in post-acute facilities and who can also visit patients at home. After discharge, a nurse practitioner will visit the patient, connect him or her with a PCP, and get the patient access to care.

“Smaller hospitalist groups could set up post-discharge clinics,” Dr. Sears suggests, “so when they discharge a patient without a PCP, [the patient] could return to see one of the hospitalists there.”

Mount Carmel East Hospital, a Sound Physicians’ hospital in Columbus, Ohio, has a financial assistance program.

“The case management department provides community health resources to patients who are insured but have no PCP,” says Shelli Morris, RN. “We also have a hotline that patients can call for a list of PCPs that are accepting new patients.”

When a patient lacks insurance or a PCP, Morris is contacted by the physician or case management to provide a referral to a neighborhood health clinic. “Then, as a courtesy, we set up a post-hospital follow-up appointment,” she says.

By working with other care team members at facilities such as outpatient clinics and pharmacies, hospitalists and other staff have been able to improve care for patients without insurance or a PCP after discharge. Knowing the funding that is available, as well as programs to help these patients, is also integral.

Karen Appold is a medical writer in Pennsylvania.

References

- American Hospital Association. American Hospital Association Uncompensated Hospital Care Cost Fact Sheet. Accessed October 8, 2015.

- The Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. Health IT in long-term and post acute care: issue brief. March 15, 2013. Accessed October 8, 2015.

- Addison E. Gage award winner HITS the streets to connect with the uninsured. America’s Essential Hospitals. July 22, 2014. Accessed October 8, 2015.

- DeNavas C, Proctor BD, Smith JC. Income, poverty, and health insurance coverage in the United States: 2010. United States Census Bureau. September 2011. Accessed October 8, 2015.

- United States Census Bureau. People without health insurance coverage by selected characteristics: 2010 and 2011. Accessed October 8, 2015.

- Coughlin TA, Holahan J, Caswell K, McGrath M. Uncompensated care for the uninsured in 2013: a detailed examination. The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. May 30, 2014. Accessed October 8, 2015.

Hospitalists are charged with giving the best of care and treatment, regardless of whether or not a patient is insured or has a PCP to transition to after discharge. But patients who do not have insurance or a PCP pose many challenges to hospitalists, as well as the healthcare systems they work in. Although some hospitals and health systems have found ways to address these challenges, issues persist, with high costs to care for these patients topping the list. In 2013, the cost of community hospitals’ uncompensated care climbed to $46.4 billion.1

Typically, undocumented and unassigned patients face many social and economic challenges. Many of these patients are unemployed or work as independent contractors without employer-offered health insurance. Some have multiple jobs, can’t take time off from work for doctor appointments, or are undocumented workers.

More patients have acquired health insurance in recent years as a result of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and Medicaid expansion; however, some eligible people never complete the necessary forms.

With or without insurance, some patients don’t establish primary care because they have been healthy, have difficulty navigating the healthcare system, lack transportation, or desire more culturally tailored care. Some Medicare and Medicaid patients don’t have a PCP in their community who accepts these programs.

Treatment Challenges

Uninsured patients often are sicker and have more complex conditions than those with insurance, according to Beth Feldpush, DrPH, senior vice president of policy and advocacy at the nonprofit trade group America’s Essential Hospitals, which is based in Washington, D.C., and represents 250 safety net hospitals throughout the U.S.

“Because they can’t afford regular preventive and primary care, they forgo needed healthcare services until their conditions worsen and they require costly hospital care,” says Dr. Feldpush. Uninsured patients often lack the resources for follow-up care to help them recover and stay well. She says more than half of all inpatient discharges and outpatient visits at her groups’ hospitals are for uninsured or Medicaid patients.

When an uninsured patient is discharged from the hospital, finding follow-up care can be difficult.

“Their ability to get an appointment to see a PCP is extremely limited, because many providers don’t see patients without health insurance,” says Scott Sears, MD, MBA, chief clinical officer of Tacoma, Wash.-based Sound Physicians. Dr. Sears notes that in some hospitalist programs, as many as 40% of hospitalized patients lack insurance. “But without secured follow-up care, hospitalists are hesitant to send patients home, because they could relapse.”

Typically, these patients are not completely well and should be transferred to a skilled nursing or hospice facility; however, many facilities won’t accept them without insurance. Often, these patients need a PCP to monitor them with laboratory tests and other follow-up tests, to prescribe and monitor medications, and to ensure that they are following their plan of care.

At some medical facilities, subspecialists who consult on patients may screen them and refuse to see anyone without health insurance.

“So even though some patients may need subspecialty support, they may not have access to it,” Dr. Sears says. “While some patients without insurance qualify for Medicaid or other programs, due to the amount of paperwork and time to enroll, they end up staying in the hospital even though they are ready for discharge.”

Transitional Challenges

Most patients admitted to the hospital either have exacerbations of chronic conditions or a new diagnosis. “It’s rare to hospitalize a patient with a discrete illness that wouldn’t need care after discharge, so having a robust PCP partner is critical to a patient’s health,” says Honora Englander, MD, medical director of the Care Transitions Innovation (C-TRAIN) program at Oregon Health and Science University (OHSU) in Portland. For many patients, psychosocial complexity complicates their transition out of the hospital. An effective system needs to address a patient’s mental health, housing, and other social needs.

It may take four to six weeks for a patient without an established PCP to get a new patient appointment. “This is a huge impediment, as the patient won’t have anyone to ensure that he or she continues along the proper care path,” Dr. Sears says.

“Studies estimate that more than half of medication errors that patients experience occur during transitions and after discharge,” Dr. Sears says.2 “Intervention with a healthcare provider who can review proper use after discharge can dramatically reduce errors and [improve] patient outcomes.”

Rates of patients without a PCP vary by region for Sound Physicians. In the northwest region, about 25% of admitted patients lack a PCP; in the gulf region, the figure can be as high as 60%.

“In Texas, there is a large number of patients and not as many PCPs,” he adds. “There is also a larger percentage of patients without health insurance. Sometimes patients have coverage but have never established care with a PCP.”

As a result of not having a PCP to transition to, some patients return to the hospital soon after discharge, Dr. Feldpush notes.

Tips for Treating Uninsured Patients

Some facilities have found successful ways to help hospitalized patients without health insurance. Dr. Sears says that hospitalists can investigate which clinics accept uninsured patients or which local physician groups are willing to see them after discharge, in exchange for hospitalists taking care of them in the hospital. They also can investigate the community-based insurance programs that are available.

Teresa Coker, MSN, ARNP, FNP-BC, a Sound Physicians program manager at Mercy Medical Center in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, says that when patients lack insurance at her hospital, an organization will review the patient’s case, determine insurance eligibility, and assist the patient in completing the appropriate paperwork. When patients are not eligible, they are instructed to inquire about the hospital’s charity care program if they receive a bill they are unable to pay.

In addition, the community has a free health clinic that serves those without insurance. “Patients are given the address and hours prior to discharge, because it is walk-in only,” Coker says. “All patients are recommended to follow up within one week, or sooner if medications are needed.”

Dr. Englander advocates that physicians take into account medication costs, transportation, and other social considerations when planning care after hospitalization. The team at OHSU developed a low-cost formulary (based in part on widely available $4 plans from national pharmacy chains), and OHSU provides medications for uninsured patients in the program for up to 30 days following discharge.

For patients who can’t afford the $4 drug plan, case managers offer coupons for $4 prescriptions, says Malik Merchant, MD, area medical officer for the Schumachergroup in Harker Heights, Texas. He says that as many as 30% of the patients in his area are undocumented or unassigned. For more expensive medications, a social worker offers pharmaceutical company coupons when they are available. The institution also has a small budget to pay for drugs.

Dr. Merchant has found the biggest challenge to be the transition of care from inpatient to outpatient.

“Case managers and social workers prepare a financial worksheet that provides the possibility of overall cost savings for the institution, if patients are willing to participate in some upfront cost,” he says. “When our parent institution came on board, we developed contracts with local pharmacies, [a] skilled nursing facility, and PCPs to take these patients until they recovered from an acute illness. Our institution paid for these services at a reduced rate but saved money by reducing the length of their hospital stay.”

Dr. Feldpush says her group’s hospitals work hard to reach the uninsured. South Florida’s Memorial Healthcare System (MHS) created the Health Intervention with Targeted Services (HITS) Program, an outreach initiative that links patients with insurance programs or medical homes.3 The HITS team used a geographic information system map to target 15 neighborhoods with the highest rates of hospitalized, uninsured patients. Over a six-month period, the team approached these neighborhoods using various outreach strategies, such as health fairs, educational workshops, and door-to-door visits.3

Approximately 6,910 HITS participants have been enrolled in Medicaid, Florida’s children’s health insurance program, or an MHS community health center. Over a three-year study period, MHS saved $284,856 in the ED, about $2.8 million in inpatient costs, and roughly $4 million overall.3

Barriers to Follow-Up Care

Whether you are looking to help uninsured patients, those without a PCP, or both, the key is to try to fill in the gaps.

“As hospitalists, we need to work with pharmacists, case managers and social workers, and others to identify affordable and effective ways to provide care,” Dr. Englander says. “Interprofessional team members, community partners, and family members can help hospitalists understand patient and population health needs and available resources.”

In an effort to close transitional care gaps, OHSU developed the C-TRAIN program, a multi-component transitional care intervention that includes four main elements:

- Transitional care nurse who sees patients in the hospital, makes home visits, and helps coordinate care 30 days post-discharge;

- Inpatient pharmacy consultation and prescription medications at discharge from a low-cost, value-based formulary;

- Medical home linkages, whereby OHSU partners with and provides payment to three community clinics to provide primary care for uninsured patients; and

- Monthly implementation team meetings that convene diverse healthcare stakeholders to integrate elements of the healthcare system and engage in ongoing quality improvement.

The Schumachergroup has also found an effective solution.

“The department head of our case managers and social workers made an agreement with a local multispecialty group,” Dr. Merchant says. “The group agreed to take all discharged patients and be their PCP for 30 days, even if the patient couldn’t pay, in exchange for receiving all patients who had good insurance but did not have an established PCP.

“This has worked well. Every patient discharged from our facility has a PCP listed at discharge, and the unit clerk makes an appointment and documents it in the electronic medical record.”

Sound Physicians has set up a service line, called transitional care services, to smooth transitions of care after discharge for up to 90 days, depending on their clinical needs. It hires providers who work in post-acute facilities and who can also visit patients at home. After discharge, a nurse practitioner will visit the patient, connect him or her with a PCP, and get the patient access to care.

“Smaller hospitalist groups could set up post-discharge clinics,” Dr. Sears suggests, “so when they discharge a patient without a PCP, [the patient] could return to see one of the hospitalists there.”

Mount Carmel East Hospital, a Sound Physicians’ hospital in Columbus, Ohio, has a financial assistance program.

“The case management department provides community health resources to patients who are insured but have no PCP,” says Shelli Morris, RN. “We also have a hotline that patients can call for a list of PCPs that are accepting new patients.”

When a patient lacks insurance or a PCP, Morris is contacted by the physician or case management to provide a referral to a neighborhood health clinic. “Then, as a courtesy, we set up a post-hospital follow-up appointment,” she says.

By working with other care team members at facilities such as outpatient clinics and pharmacies, hospitalists and other staff have been able to improve care for patients without insurance or a PCP after discharge. Knowing the funding that is available, as well as programs to help these patients, is also integral.

Karen Appold is a medical writer in Pennsylvania.

References

- American Hospital Association. American Hospital Association Uncompensated Hospital Care Cost Fact Sheet. Accessed October 8, 2015.

- The Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. Health IT in long-term and post acute care: issue brief. March 15, 2013. Accessed October 8, 2015.

- Addison E. Gage award winner HITS the streets to connect with the uninsured. America’s Essential Hospitals. July 22, 2014. Accessed October 8, 2015.

- DeNavas C, Proctor BD, Smith JC. Income, poverty, and health insurance coverage in the United States: 2010. United States Census Bureau. September 2011. Accessed October 8, 2015.

- United States Census Bureau. People without health insurance coverage by selected characteristics: 2010 and 2011. Accessed October 8, 2015.

- Coughlin TA, Holahan J, Caswell K, McGrath M. Uncompensated care for the uninsured in 2013: a detailed examination. The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. May 30, 2014. Accessed October 8, 2015.

Hospitalists are charged with giving the best of care and treatment, regardless of whether or not a patient is insured or has a PCP to transition to after discharge. But patients who do not have insurance or a PCP pose many challenges to hospitalists, as well as the healthcare systems they work in. Although some hospitals and health systems have found ways to address these challenges, issues persist, with high costs to care for these patients topping the list. In 2013, the cost of community hospitals’ uncompensated care climbed to $46.4 billion.1

Typically, undocumented and unassigned patients face many social and economic challenges. Many of these patients are unemployed or work as independent contractors without employer-offered health insurance. Some have multiple jobs, can’t take time off from work for doctor appointments, or are undocumented workers.

More patients have acquired health insurance in recent years as a result of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and Medicaid expansion; however, some eligible people never complete the necessary forms.

With or without insurance, some patients don’t establish primary care because they have been healthy, have difficulty navigating the healthcare system, lack transportation, or desire more culturally tailored care. Some Medicare and Medicaid patients don’t have a PCP in their community who accepts these programs.

Treatment Challenges

Uninsured patients often are sicker and have more complex conditions than those with insurance, according to Beth Feldpush, DrPH, senior vice president of policy and advocacy at the nonprofit trade group America’s Essential Hospitals, which is based in Washington, D.C., and represents 250 safety net hospitals throughout the U.S.

“Because they can’t afford regular preventive and primary care, they forgo needed healthcare services until their conditions worsen and they require costly hospital care,” says Dr. Feldpush. Uninsured patients often lack the resources for follow-up care to help them recover and stay well. She says more than half of all inpatient discharges and outpatient visits at her groups’ hospitals are for uninsured or Medicaid patients.

When an uninsured patient is discharged from the hospital, finding follow-up care can be difficult.

“Their ability to get an appointment to see a PCP is extremely limited, because many providers don’t see patients without health insurance,” says Scott Sears, MD, MBA, chief clinical officer of Tacoma, Wash.-based Sound Physicians. Dr. Sears notes that in some hospitalist programs, as many as 40% of hospitalized patients lack insurance. “But without secured follow-up care, hospitalists are hesitant to send patients home, because they could relapse.”

Typically, these patients are not completely well and should be transferred to a skilled nursing or hospice facility; however, many facilities won’t accept them without insurance. Often, these patients need a PCP to monitor them with laboratory tests and other follow-up tests, to prescribe and monitor medications, and to ensure that they are following their plan of care.

At some medical facilities, subspecialists who consult on patients may screen them and refuse to see anyone without health insurance.

“So even though some patients may need subspecialty support, they may not have access to it,” Dr. Sears says. “While some patients without insurance qualify for Medicaid or other programs, due to the amount of paperwork and time to enroll, they end up staying in the hospital even though they are ready for discharge.”

Transitional Challenges

Most patients admitted to the hospital either have exacerbations of chronic conditions or a new diagnosis. “It’s rare to hospitalize a patient with a discrete illness that wouldn’t need care after discharge, so having a robust PCP partner is critical to a patient’s health,” says Honora Englander, MD, medical director of the Care Transitions Innovation (C-TRAIN) program at Oregon Health and Science University (OHSU) in Portland. For many patients, psychosocial complexity complicates their transition out of the hospital. An effective system needs to address a patient’s mental health, housing, and other social needs.

It may take four to six weeks for a patient without an established PCP to get a new patient appointment. “This is a huge impediment, as the patient won’t have anyone to ensure that he or she continues along the proper care path,” Dr. Sears says.

“Studies estimate that more than half of medication errors that patients experience occur during transitions and after discharge,” Dr. Sears says.2 “Intervention with a healthcare provider who can review proper use after discharge can dramatically reduce errors and [improve] patient outcomes.”

Rates of patients without a PCP vary by region for Sound Physicians. In the northwest region, about 25% of admitted patients lack a PCP; in the gulf region, the figure can be as high as 60%.

“In Texas, there is a large number of patients and not as many PCPs,” he adds. “There is also a larger percentage of patients without health insurance. Sometimes patients have coverage but have never established care with a PCP.”

As a result of not having a PCP to transition to, some patients return to the hospital soon after discharge, Dr. Feldpush notes.

Tips for Treating Uninsured Patients

Some facilities have found successful ways to help hospitalized patients without health insurance. Dr. Sears says that hospitalists can investigate which clinics accept uninsured patients or which local physician groups are willing to see them after discharge, in exchange for hospitalists taking care of them in the hospital. They also can investigate the community-based insurance programs that are available.

Teresa Coker, MSN, ARNP, FNP-BC, a Sound Physicians program manager at Mercy Medical Center in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, says that when patients lack insurance at her hospital, an organization will review the patient’s case, determine insurance eligibility, and assist the patient in completing the appropriate paperwork. When patients are not eligible, they are instructed to inquire about the hospital’s charity care program if they receive a bill they are unable to pay.

In addition, the community has a free health clinic that serves those without insurance. “Patients are given the address and hours prior to discharge, because it is walk-in only,” Coker says. “All patients are recommended to follow up within one week, or sooner if medications are needed.”

Dr. Englander advocates that physicians take into account medication costs, transportation, and other social considerations when planning care after hospitalization. The team at OHSU developed a low-cost formulary (based in part on widely available $4 plans from national pharmacy chains), and OHSU provides medications for uninsured patients in the program for up to 30 days following discharge.

For patients who can’t afford the $4 drug plan, case managers offer coupons for $4 prescriptions, says Malik Merchant, MD, area medical officer for the Schumachergroup in Harker Heights, Texas. He says that as many as 30% of the patients in his area are undocumented or unassigned. For more expensive medications, a social worker offers pharmaceutical company coupons when they are available. The institution also has a small budget to pay for drugs.

Dr. Merchant has found the biggest challenge to be the transition of care from inpatient to outpatient.

“Case managers and social workers prepare a financial worksheet that provides the possibility of overall cost savings for the institution, if patients are willing to participate in some upfront cost,” he says. “When our parent institution came on board, we developed contracts with local pharmacies, [a] skilled nursing facility, and PCPs to take these patients until they recovered from an acute illness. Our institution paid for these services at a reduced rate but saved money by reducing the length of their hospital stay.”

Dr. Feldpush says her group’s hospitals work hard to reach the uninsured. South Florida’s Memorial Healthcare System (MHS) created the Health Intervention with Targeted Services (HITS) Program, an outreach initiative that links patients with insurance programs or medical homes.3 The HITS team used a geographic information system map to target 15 neighborhoods with the highest rates of hospitalized, uninsured patients. Over a six-month period, the team approached these neighborhoods using various outreach strategies, such as health fairs, educational workshops, and door-to-door visits.3

Approximately 6,910 HITS participants have been enrolled in Medicaid, Florida’s children’s health insurance program, or an MHS community health center. Over a three-year study period, MHS saved $284,856 in the ED, about $2.8 million in inpatient costs, and roughly $4 million overall.3

Barriers to Follow-Up Care

Whether you are looking to help uninsured patients, those without a PCP, or both, the key is to try to fill in the gaps.

“As hospitalists, we need to work with pharmacists, case managers and social workers, and others to identify affordable and effective ways to provide care,” Dr. Englander says. “Interprofessional team members, community partners, and family members can help hospitalists understand patient and population health needs and available resources.”

In an effort to close transitional care gaps, OHSU developed the C-TRAIN program, a multi-component transitional care intervention that includes four main elements:

- Transitional care nurse who sees patients in the hospital, makes home visits, and helps coordinate care 30 days post-discharge;

- Inpatient pharmacy consultation and prescription medications at discharge from a low-cost, value-based formulary;

- Medical home linkages, whereby OHSU partners with and provides payment to three community clinics to provide primary care for uninsured patients; and

- Monthly implementation team meetings that convene diverse healthcare stakeholders to integrate elements of the healthcare system and engage in ongoing quality improvement.

The Schumachergroup has also found an effective solution.

“The department head of our case managers and social workers made an agreement with a local multispecialty group,” Dr. Merchant says. “The group agreed to take all discharged patients and be their PCP for 30 days, even if the patient couldn’t pay, in exchange for receiving all patients who had good insurance but did not have an established PCP.

“This has worked well. Every patient discharged from our facility has a PCP listed at discharge, and the unit clerk makes an appointment and documents it in the electronic medical record.”

Sound Physicians has set up a service line, called transitional care services, to smooth transitions of care after discharge for up to 90 days, depending on their clinical needs. It hires providers who work in post-acute facilities and who can also visit patients at home. After discharge, a nurse practitioner will visit the patient, connect him or her with a PCP, and get the patient access to care.

“Smaller hospitalist groups could set up post-discharge clinics,” Dr. Sears suggests, “so when they discharge a patient without a PCP, [the patient] could return to see one of the hospitalists there.”

Mount Carmel East Hospital, a Sound Physicians’ hospital in Columbus, Ohio, has a financial assistance program.

“The case management department provides community health resources to patients who are insured but have no PCP,” says Shelli Morris, RN. “We also have a hotline that patients can call for a list of PCPs that are accepting new patients.”

When a patient lacks insurance or a PCP, Morris is contacted by the physician or case management to provide a referral to a neighborhood health clinic. “Then, as a courtesy, we set up a post-hospital follow-up appointment,” she says.

By working with other care team members at facilities such as outpatient clinics and pharmacies, hospitalists and other staff have been able to improve care for patients without insurance or a PCP after discharge. Knowing the funding that is available, as well as programs to help these patients, is also integral.

Karen Appold is a medical writer in Pennsylvania.

References

- American Hospital Association. American Hospital Association Uncompensated Hospital Care Cost Fact Sheet. Accessed October 8, 2015.

- The Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. Health IT in long-term and post acute care: issue brief. March 15, 2013. Accessed October 8, 2015.

- Addison E. Gage award winner HITS the streets to connect with the uninsured. America’s Essential Hospitals. July 22, 2014. Accessed October 8, 2015.

- DeNavas C, Proctor BD, Smith JC. Income, poverty, and health insurance coverage in the United States: 2010. United States Census Bureau. September 2011. Accessed October 8, 2015.

- United States Census Bureau. People without health insurance coverage by selected characteristics: 2010 and 2011. Accessed October 8, 2015.

- Coughlin TA, Holahan J, Caswell K, McGrath M. Uncompensated care for the uninsured in 2013: a detailed examination. The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. May 30, 2014. Accessed October 8, 2015.

Expert panel issues guidelines for treatment of hematologic cancers in pregnancy

Consensus guidelines for the perinatal management of hematologic malignancies detected during pregnancy have been issued by a panel of international experts.

The guidelines, published online in the Journal of Clinical Oncology, aim to ensure that timely treatment of the cancers is not delayed in pregnant women (doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.62.4445).

While rare, hematologic malignancies in pregnancy introduce clinical, social, ethical, and moral dilemmas. Evidence-based data are scarce, according to the researchers, who note the International Network on Cancer, Infertility and Pregnancy registers all cancers occurring during gestation.

“Patient accrual is ongoing and essential, because registration of new cases and long-term follow-up will improve clinical knowledge and increase the level of evidence,” Dr. Michael Lishner of Tel Aviv University and Meir Medical Center, Kfar Saba, Israel, and his fellow panelists wrote.

Hodgkin lymphoma

The researchers note that Hodgkin lymphoma is the most common hematologic cancer in pregnancy, and the prognosis for these patients is excellent. When diagnosed during the first trimester, a regimen based on vinblastine monotherapy has been used. ABVD (doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, dacarbazine) therapy can be used postpartum and has been used in cases of progression during pregnancy, the panelists wrote.

“The limited data available suggest that ABVD may be administered safely and effectively during the latter phases of pregnancy,” the panel wrote. “Although it may be associated with prematurity and lower birth weights, studies have not reported significant disadvantages.”

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma

The second most common cancer in pregnancy is non-Hodgkin lymphoma. In the case of indolent disease, watchful waiting is possible, with the intent to treat with monoclonal antibodies – with or without chemotherapy – if symptoms or evidence of disease progression are noted. Steroids can be administered during the first trimester as a bridge to the second trimester, when chemotherapy can be used with relatively greater safety, the panelists noted.

Aggressive lymphomas diagnosed before 20 weeks’ gestation warrant pregnancy termination and treatment, they recommend. When diagnosed after 20 weeks, therapy should be comparable to that given a nonpregnant woman, including monoclonal antibodies (R-CHOP).

Chronic myeloid leukemia

Chronic myeloid leukemia occurs in approximately 1 in 100,000 pregnancies and is typically diagnosed during routine blood testing in an asymptomatic patient. As a result, treatment may not be needed until the patient’s white count or platelet count have risen to levels associated with the onset of symptoms. An approximate guideline is a white cell count greater than 100 X 109/L and a platelet count greater than 500 X 109/L.

Therapeutic approaches in pregnancy include interferon-a (INF-a), which does not inhibit DNA synthesis or readily cross the placenta, and leukapheresis, which is frequently required two to three times per week during the first and second trimesters. Counts tend to drop during the third trimester, allowing less frequent intervention.

Consideration should be given to adding aspirin or low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) when the platelet count exceeds 1,000 X 109/L.

Myeloproliferative neoplasms

The most common myeloproliferative neoplasm seen in women of childbearing age is essential thrombocytosis.

“A large meta-analysis of pregnant women with essential thrombocytosis reported a live birth rate of 50%-70%, first trimester loss in 25%-40%, late pregnancy loss in 10%, placental abruption in 3.6%, and intrauterine growth restriction in 4.5%. Maternal morbidity is rare, but stroke has been reported,” according to the panelists.

Limited literature suggests similar outcomes for pregnant women with polycythemia vera and primary myelofibrosis.

In low-risk pregnancies, aspirin (75 mg/day) should be offered unless clearly contraindicated. For women with polycythemia vera, venesection may be continued when tolerated to maintain the hematocrit within the gestation-appropriate range.

Fetal ultrasound scans should be performed at 20, 26, and 34 weeks of gestation and uterine artery Doppler should be performed at 20 weeks’ gestation. If the mean pulsatility index exceeds 1.4, the pregnancy may be considered high risk, and treatment and monitoring should be increased.

In high-risk pregnancies, additional treatment includes cytoreductive therapy with or without LMWH. If cytoreductive therapy is required, INF-a should be titrated to maintain a platelet count of less than 400 X 109/L and hematocrit within appropriate range.

Local protocols regarding interruption of LMWH should be adhered to during labor, and dehydration should be avoided. Platelet count and hematocrit may increase postpartum, requiring cytoreductive therapy. Thromboprophylaxis should be considered at 6 weeks’ postpartum because of the increased risk of thrombosis, the guidelines note.

Acute leukemia

“The remarkable anemia, thrombocytopenia, and neutropenia that characterize acute myeloid and lymphoblastic leukemia” require prompt treatment. Leukapheresis in the presence of clinically significant evidence of leukostasis can be considered, regardless of gestational stage. When patients are diagnosed with acute myeloid leukemia during the first trimester, pregnancy termination followed by conventional induction therapy (cytarabine/anthracycline) is recommended.

Those diagnosed later in pregnancy can receive conventional induction therapy, although this seems to be associated with increased risk of fetal growth restriction and even fetal loss. “Notably, neonates rarely experience neutropenia and cardiac impairment unless exposed to lipophilic idarubicin, which should not be used,” the panelists wrote.

When acute promyelocytic leukemia is diagnosed in the first trimester, pregnancy termination is recommended before initiating conventional ATRA-anthracycline therapy. Later in pregnancy, the regimen demonstrates low teratogenicity and can be used in women diagnosed after that stage. Arsenic treatment is highly teratogenic and is prohibited throughout gestation.

Acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL) requires prophylactic CNS therapy, including methotrexate and L-asparaginase, which are fetotoxic. Methotrexate interferes with organogenesis and is prohibited before week 20 of gestation. L-asparaginase may increase the high risk for thromboembolic events attributed to the combination of pregnancy and malignancy.

Notably, tyrosine kinase inhibitors, essential for patients with Philadelphia chromosome–positive ALL, are teratogenic. Given these limitations, women diagnosed with ALL before 20 weeks’ gestation should undergo termination of the pregnancy and start conventional treatment. After week 20, conventional chemotherapy can be administered during pregnancy. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors can be initiated postpartum.

The guidelines also contain recommendations on diagnostic testing and radiotherapy, maternal supportive care, and perinatal and pediatric aspects of hematologic malignancies in pregnancy. An online appendix offers recommendations on the treatment of rare hematologic malignancies, including hairy cell leukemia, multiple myeloma, and myelodysplastic syndromes.

Dr. Lishner and nine of his coauthors had no financial relationships to disclose. Three coauthors received honoraria and research funding or are consultants to a wide variety of drug makers.

On Twitter @maryjodales

Consensus guidelines for the perinatal management of hematologic malignancies detected during pregnancy have been issued by a panel of international experts.

The guidelines, published online in the Journal of Clinical Oncology, aim to ensure that timely treatment of the cancers is not delayed in pregnant women (doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.62.4445).

While rare, hematologic malignancies in pregnancy introduce clinical, social, ethical, and moral dilemmas. Evidence-based data are scarce, according to the researchers, who note the International Network on Cancer, Infertility and Pregnancy registers all cancers occurring during gestation.

“Patient accrual is ongoing and essential, because registration of new cases and long-term follow-up will improve clinical knowledge and increase the level of evidence,” Dr. Michael Lishner of Tel Aviv University and Meir Medical Center, Kfar Saba, Israel, and his fellow panelists wrote.

Hodgkin lymphoma

The researchers note that Hodgkin lymphoma is the most common hematologic cancer in pregnancy, and the prognosis for these patients is excellent. When diagnosed during the first trimester, a regimen based on vinblastine monotherapy has been used. ABVD (doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, dacarbazine) therapy can be used postpartum and has been used in cases of progression during pregnancy, the panelists wrote.

“The limited data available suggest that ABVD may be administered safely and effectively during the latter phases of pregnancy,” the panel wrote. “Although it may be associated with prematurity and lower birth weights, studies have not reported significant disadvantages.”

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma

The second most common cancer in pregnancy is non-Hodgkin lymphoma. In the case of indolent disease, watchful waiting is possible, with the intent to treat with monoclonal antibodies – with or without chemotherapy – if symptoms or evidence of disease progression are noted. Steroids can be administered during the first trimester as a bridge to the second trimester, when chemotherapy can be used with relatively greater safety, the panelists noted.

Aggressive lymphomas diagnosed before 20 weeks’ gestation warrant pregnancy termination and treatment, they recommend. When diagnosed after 20 weeks, therapy should be comparable to that given a nonpregnant woman, including monoclonal antibodies (R-CHOP).

Chronic myeloid leukemia

Chronic myeloid leukemia occurs in approximately 1 in 100,000 pregnancies and is typically diagnosed during routine blood testing in an asymptomatic patient. As a result, treatment may not be needed until the patient’s white count or platelet count have risen to levels associated with the onset of symptoms. An approximate guideline is a white cell count greater than 100 X 109/L and a platelet count greater than 500 X 109/L.

Therapeutic approaches in pregnancy include interferon-a (INF-a), which does not inhibit DNA synthesis or readily cross the placenta, and leukapheresis, which is frequently required two to three times per week during the first and second trimesters. Counts tend to drop during the third trimester, allowing less frequent intervention.

Consideration should be given to adding aspirin or low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) when the platelet count exceeds 1,000 X 109/L.

Myeloproliferative neoplasms

The most common myeloproliferative neoplasm seen in women of childbearing age is essential thrombocytosis.

“A large meta-analysis of pregnant women with essential thrombocytosis reported a live birth rate of 50%-70%, first trimester loss in 25%-40%, late pregnancy loss in 10%, placental abruption in 3.6%, and intrauterine growth restriction in 4.5%. Maternal morbidity is rare, but stroke has been reported,” according to the panelists.

Limited literature suggests similar outcomes for pregnant women with polycythemia vera and primary myelofibrosis.

In low-risk pregnancies, aspirin (75 mg/day) should be offered unless clearly contraindicated. For women with polycythemia vera, venesection may be continued when tolerated to maintain the hematocrit within the gestation-appropriate range.

Fetal ultrasound scans should be performed at 20, 26, and 34 weeks of gestation and uterine artery Doppler should be performed at 20 weeks’ gestation. If the mean pulsatility index exceeds 1.4, the pregnancy may be considered high risk, and treatment and monitoring should be increased.

In high-risk pregnancies, additional treatment includes cytoreductive therapy with or without LMWH. If cytoreductive therapy is required, INF-a should be titrated to maintain a platelet count of less than 400 X 109/L and hematocrit within appropriate range.

Local protocols regarding interruption of LMWH should be adhered to during labor, and dehydration should be avoided. Platelet count and hematocrit may increase postpartum, requiring cytoreductive therapy. Thromboprophylaxis should be considered at 6 weeks’ postpartum because of the increased risk of thrombosis, the guidelines note.

Acute leukemia

“The remarkable anemia, thrombocytopenia, and neutropenia that characterize acute myeloid and lymphoblastic leukemia” require prompt treatment. Leukapheresis in the presence of clinically significant evidence of leukostasis can be considered, regardless of gestational stage. When patients are diagnosed with acute myeloid leukemia during the first trimester, pregnancy termination followed by conventional induction therapy (cytarabine/anthracycline) is recommended.

Those diagnosed later in pregnancy can receive conventional induction therapy, although this seems to be associated with increased risk of fetal growth restriction and even fetal loss. “Notably, neonates rarely experience neutropenia and cardiac impairment unless exposed to lipophilic idarubicin, which should not be used,” the panelists wrote.

When acute promyelocytic leukemia is diagnosed in the first trimester, pregnancy termination is recommended before initiating conventional ATRA-anthracycline therapy. Later in pregnancy, the regimen demonstrates low teratogenicity and can be used in women diagnosed after that stage. Arsenic treatment is highly teratogenic and is prohibited throughout gestation.

Acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL) requires prophylactic CNS therapy, including methotrexate and L-asparaginase, which are fetotoxic. Methotrexate interferes with organogenesis and is prohibited before week 20 of gestation. L-asparaginase may increase the high risk for thromboembolic events attributed to the combination of pregnancy and malignancy.

Notably, tyrosine kinase inhibitors, essential for patients with Philadelphia chromosome–positive ALL, are teratogenic. Given these limitations, women diagnosed with ALL before 20 weeks’ gestation should undergo termination of the pregnancy and start conventional treatment. After week 20, conventional chemotherapy can be administered during pregnancy. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors can be initiated postpartum.

The guidelines also contain recommendations on diagnostic testing and radiotherapy, maternal supportive care, and perinatal and pediatric aspects of hematologic malignancies in pregnancy. An online appendix offers recommendations on the treatment of rare hematologic malignancies, including hairy cell leukemia, multiple myeloma, and myelodysplastic syndromes.

Dr. Lishner and nine of his coauthors had no financial relationships to disclose. Three coauthors received honoraria and research funding or are consultants to a wide variety of drug makers.

On Twitter @maryjodales

Consensus guidelines for the perinatal management of hematologic malignancies detected during pregnancy have been issued by a panel of international experts.

The guidelines, published online in the Journal of Clinical Oncology, aim to ensure that timely treatment of the cancers is not delayed in pregnant women (doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.62.4445).

While rare, hematologic malignancies in pregnancy introduce clinical, social, ethical, and moral dilemmas. Evidence-based data are scarce, according to the researchers, who note the International Network on Cancer, Infertility and Pregnancy registers all cancers occurring during gestation.

“Patient accrual is ongoing and essential, because registration of new cases and long-term follow-up will improve clinical knowledge and increase the level of evidence,” Dr. Michael Lishner of Tel Aviv University and Meir Medical Center, Kfar Saba, Israel, and his fellow panelists wrote.

Hodgkin lymphoma

The researchers note that Hodgkin lymphoma is the most common hematologic cancer in pregnancy, and the prognosis for these patients is excellent. When diagnosed during the first trimester, a regimen based on vinblastine monotherapy has been used. ABVD (doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, dacarbazine) therapy can be used postpartum and has been used in cases of progression during pregnancy, the panelists wrote.

“The limited data available suggest that ABVD may be administered safely and effectively during the latter phases of pregnancy,” the panel wrote. “Although it may be associated with prematurity and lower birth weights, studies have not reported significant disadvantages.”

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma

The second most common cancer in pregnancy is non-Hodgkin lymphoma. In the case of indolent disease, watchful waiting is possible, with the intent to treat with monoclonal antibodies – with or without chemotherapy – if symptoms or evidence of disease progression are noted. Steroids can be administered during the first trimester as a bridge to the second trimester, when chemotherapy can be used with relatively greater safety, the panelists noted.

Aggressive lymphomas diagnosed before 20 weeks’ gestation warrant pregnancy termination and treatment, they recommend. When diagnosed after 20 weeks, therapy should be comparable to that given a nonpregnant woman, including monoclonal antibodies (R-CHOP).

Chronic myeloid leukemia

Chronic myeloid leukemia occurs in approximately 1 in 100,000 pregnancies and is typically diagnosed during routine blood testing in an asymptomatic patient. As a result, treatment may not be needed until the patient’s white count or platelet count have risen to levels associated with the onset of symptoms. An approximate guideline is a white cell count greater than 100 X 109/L and a platelet count greater than 500 X 109/L.

Therapeutic approaches in pregnancy include interferon-a (INF-a), which does not inhibit DNA synthesis or readily cross the placenta, and leukapheresis, which is frequently required two to three times per week during the first and second trimesters. Counts tend to drop during the third trimester, allowing less frequent intervention.

Consideration should be given to adding aspirin or low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) when the platelet count exceeds 1,000 X 109/L.

Myeloproliferative neoplasms

The most common myeloproliferative neoplasm seen in women of childbearing age is essential thrombocytosis.

“A large meta-analysis of pregnant women with essential thrombocytosis reported a live birth rate of 50%-70%, first trimester loss in 25%-40%, late pregnancy loss in 10%, placental abruption in 3.6%, and intrauterine growth restriction in 4.5%. Maternal morbidity is rare, but stroke has been reported,” according to the panelists.

Limited literature suggests similar outcomes for pregnant women with polycythemia vera and primary myelofibrosis.

In low-risk pregnancies, aspirin (75 mg/day) should be offered unless clearly contraindicated. For women with polycythemia vera, venesection may be continued when tolerated to maintain the hematocrit within the gestation-appropriate range.

Fetal ultrasound scans should be performed at 20, 26, and 34 weeks of gestation and uterine artery Doppler should be performed at 20 weeks’ gestation. If the mean pulsatility index exceeds 1.4, the pregnancy may be considered high risk, and treatment and monitoring should be increased.

In high-risk pregnancies, additional treatment includes cytoreductive therapy with or without LMWH. If cytoreductive therapy is required, INF-a should be titrated to maintain a platelet count of less than 400 X 109/L and hematocrit within appropriate range.

Local protocols regarding interruption of LMWH should be adhered to during labor, and dehydration should be avoided. Platelet count and hematocrit may increase postpartum, requiring cytoreductive therapy. Thromboprophylaxis should be considered at 6 weeks’ postpartum because of the increased risk of thrombosis, the guidelines note.

Acute leukemia

“The remarkable anemia, thrombocytopenia, and neutropenia that characterize acute myeloid and lymphoblastic leukemia” require prompt treatment. Leukapheresis in the presence of clinically significant evidence of leukostasis can be considered, regardless of gestational stage. When patients are diagnosed with acute myeloid leukemia during the first trimester, pregnancy termination followed by conventional induction therapy (cytarabine/anthracycline) is recommended.

Those diagnosed later in pregnancy can receive conventional induction therapy, although this seems to be associated with increased risk of fetal growth restriction and even fetal loss. “Notably, neonates rarely experience neutropenia and cardiac impairment unless exposed to lipophilic idarubicin, which should not be used,” the panelists wrote.

When acute promyelocytic leukemia is diagnosed in the first trimester, pregnancy termination is recommended before initiating conventional ATRA-anthracycline therapy. Later in pregnancy, the regimen demonstrates low teratogenicity and can be used in women diagnosed after that stage. Arsenic treatment is highly teratogenic and is prohibited throughout gestation.

Acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL) requires prophylactic CNS therapy, including methotrexate and L-asparaginase, which are fetotoxic. Methotrexate interferes with organogenesis and is prohibited before week 20 of gestation. L-asparaginase may increase the high risk for thromboembolic events attributed to the combination of pregnancy and malignancy.

Notably, tyrosine kinase inhibitors, essential for patients with Philadelphia chromosome–positive ALL, are teratogenic. Given these limitations, women diagnosed with ALL before 20 weeks’ gestation should undergo termination of the pregnancy and start conventional treatment. After week 20, conventional chemotherapy can be administered during pregnancy. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors can be initiated postpartum.

The guidelines also contain recommendations on diagnostic testing and radiotherapy, maternal supportive care, and perinatal and pediatric aspects of hematologic malignancies in pregnancy. An online appendix offers recommendations on the treatment of rare hematologic malignancies, including hairy cell leukemia, multiple myeloma, and myelodysplastic syndromes.

Dr. Lishner and nine of his coauthors had no financial relationships to disclose. Three coauthors received honoraria and research funding or are consultants to a wide variety of drug makers.

On Twitter @maryjodales

FROM JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY

Pediatric heart transplant results not improving

A 25-year study of heart transplants in children with congenital heart disease (CHD) at one institution has found that results haven’t improved over time despite advances in technology and techniques. To improve outcomes, transplant surgeons may need to do a better job of selecting patients and matching patients and donors, according to study in the December issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;150:1455-62).

“Strategies to improve outcomes in CHD patients might need to address selection criteria, transplantation timing, pretransplant and posttransplant care,” noted Dr. Bahaaldin Alsoufi, of the division of cardiothoracic surgery, Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, Emory University. “The effect of donor/recipient race mismatch warrants further investigation and might impact organ allocation algorithms or immunosuppression management,” wrote Dr. Alsoufi and his colleagues.

The researchers analyzed results of 124 children with CHD who had heart transplants from 1988 to 2013 at Emory University and Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta. Median age was 3.8 years; 61% were boys. Ten years after heart transplantation, 44% (54) of patients were alive without a second transplant, 13% (17) had a second transplant and 43% (53) died without a second transplant. After the second transplant, 9 of the 17 patients were alive, but 3 of them had gone onto a third transplant. Overall 15-year survival following the first transplant was 41% (51).

The study cited data from the Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation that reported more than 11,000 pediatric heart transplants worldwide in 2013, and CHD represents about 54% of all heart transplants in infants.

A multivariate analysis identified the following risk factors for early mortality after transplant: age younger than 12 months (hazard ration [HR] 7.2) and prolonged cardiopulmonary bypass (HR 5). Late-phase mortality risk factors were age younger than 12 months (HR 3) and donor/recipient race mismatch (HR 2.2).

“Survival was not affected by era, underlying anomaly, prior Fontan, sensitization or pulmonary artery augmentation,” wrote Dr. Alsoufi and his colleagues.

Among the risk factors, longer bypass times may be a surrogate for a more complicated operation, the authors said. But where prior sternotomy is a risk factor following a heart transplant in adults, the study found no such risk in children. Another risk factor previous reports identified is pulmonary artery augmentation, but, again, this study found no risk in the pediatric group.

The researchers looked at days on the waiting list, with a median wait of 39 days in the study group. In all, 175 children were listed for transplants, but 51 did not go through for various reasons. Most of the children with CHD who had a heart transplant had previous surgery; only 13% had a primary heart transplant, mostly in the earlier phase of the study.

Dr. Alsoufi and coauthors also identified African American race as a risk factor for lower survival, which is consistent with other reports. But this study agreed with a previous report that donor/recipient race mismatch was a significant risk factor in white and African American patients (Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;87:204-9). “While our finding might be anecdotal and specific to our geographic population, this warrants some investigation and might have some impact on future organ allocation algorithms and immunosuppression management,” the researchers wrote.

The authors had no relevant disclosures. Emory University School of Medicine, Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta provided study funding.

In his invited commentary, Dr. Robert D.B. Jaquiss of Duke University, Durham, N.C., took issue with the study authors’ “distress” at the lack of improvement in survival over the 25-year term of the study (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;150:1463-4) . Using the year 2000 as a demarcation line for early and late-phase results, Dr. Jaquiss said, “It must be pointed out that in the latter period recipients were much more ill.” He noted that 89% of post-2000 heart transplant patients had UNOS status 1 vs. 49% in the pre-2000 period.

|

Dr. Robert Jaquiss |

“Considering these between-era differences, an alternative, less ‘discouraging’ interpretation is that excellent outcomes were maintained despite the trend toward transplantation in sicker patients, undergoing more complex transplants, with longer ischemic times,” he said.

Dr. Jaquiss also cited “remarkably outstanding outcomes” in Fontan patients, reporting only one operative death in 33 patients. He found the lower survival for African-American patients in the study group “more sobering,” but also controversial because, among other reasons, “a complete mechanistic explanation remains elusive.” How these findings influence pediatric heart transplant practice “requires thoughtful and extensive investigation and discussion,” he said.

Wait-list mortality and mechanical bridge to transplant also deserve mention, he noted. “Though they are only briefly mentioned, the patients who died prior to transplant provide mute testimony to the lack of timely access to suitable donors,” Dr. Jaquiss said. Durable mechanical circulatory support can provide a bridge for these patients, but was not available through the majority of the study period.

“It is striking that no patient in this report was supported by a ventricular assist device (VAD), and only a small number (5%) had been on [extracorporeal membrane oxygenation] support,” Dr. Jaquiss said. “This is an unfortunate and unavoidable weakness of this report, given the recent introduction of VADs for pediatric heart transplant candidates.” The use of VAD in patients with CHD is “increasing rapidly,” he said.

Dr. Jaquiss had no disclosures.

In his invited commentary, Dr. Robert D.B. Jaquiss of Duke University, Durham, N.C., took issue with the study authors’ “distress” at the lack of improvement in survival over the 25-year term of the study (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;150:1463-4) . Using the year 2000 as a demarcation line for early and late-phase results, Dr. Jaquiss said, “It must be pointed out that in the latter period recipients were much more ill.” He noted that 89% of post-2000 heart transplant patients had UNOS status 1 vs. 49% in the pre-2000 period.

|

Dr. Robert Jaquiss |

“Considering these between-era differences, an alternative, less ‘discouraging’ interpretation is that excellent outcomes were maintained despite the trend toward transplantation in sicker patients, undergoing more complex transplants, with longer ischemic times,” he said.

Dr. Jaquiss also cited “remarkably outstanding outcomes” in Fontan patients, reporting only one operative death in 33 patients. He found the lower survival for African-American patients in the study group “more sobering,” but also controversial because, among other reasons, “a complete mechanistic explanation remains elusive.” How these findings influence pediatric heart transplant practice “requires thoughtful and extensive investigation and discussion,” he said.

Wait-list mortality and mechanical bridge to transplant also deserve mention, he noted. “Though they are only briefly mentioned, the patients who died prior to transplant provide mute testimony to the lack of timely access to suitable donors,” Dr. Jaquiss said. Durable mechanical circulatory support can provide a bridge for these patients, but was not available through the majority of the study period.

“It is striking that no patient in this report was supported by a ventricular assist device (VAD), and only a small number (5%) had been on [extracorporeal membrane oxygenation] support,” Dr. Jaquiss said. “This is an unfortunate and unavoidable weakness of this report, given the recent introduction of VADs for pediatric heart transplant candidates.” The use of VAD in patients with CHD is “increasing rapidly,” he said.

Dr. Jaquiss had no disclosures.

In his invited commentary, Dr. Robert D.B. Jaquiss of Duke University, Durham, N.C., took issue with the study authors’ “distress” at the lack of improvement in survival over the 25-year term of the study (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;150:1463-4) . Using the year 2000 as a demarcation line for early and late-phase results, Dr. Jaquiss said, “It must be pointed out that in the latter period recipients were much more ill.” He noted that 89% of post-2000 heart transplant patients had UNOS status 1 vs. 49% in the pre-2000 period.

|

Dr. Robert Jaquiss |

“Considering these between-era differences, an alternative, less ‘discouraging’ interpretation is that excellent outcomes were maintained despite the trend toward transplantation in sicker patients, undergoing more complex transplants, with longer ischemic times,” he said.

Dr. Jaquiss also cited “remarkably outstanding outcomes” in Fontan patients, reporting only one operative death in 33 patients. He found the lower survival for African-American patients in the study group “more sobering,” but also controversial because, among other reasons, “a complete mechanistic explanation remains elusive.” How these findings influence pediatric heart transplant practice “requires thoughtful and extensive investigation and discussion,” he said.

Wait-list mortality and mechanical bridge to transplant also deserve mention, he noted. “Though they are only briefly mentioned, the patients who died prior to transplant provide mute testimony to the lack of timely access to suitable donors,” Dr. Jaquiss said. Durable mechanical circulatory support can provide a bridge for these patients, but was not available through the majority of the study period.

“It is striking that no patient in this report was supported by a ventricular assist device (VAD), and only a small number (5%) had been on [extracorporeal membrane oxygenation] support,” Dr. Jaquiss said. “This is an unfortunate and unavoidable weakness of this report, given the recent introduction of VADs for pediatric heart transplant candidates.” The use of VAD in patients with CHD is “increasing rapidly,” he said.

Dr. Jaquiss had no disclosures.

A 25-year study of heart transplants in children with congenital heart disease (CHD) at one institution has found that results haven’t improved over time despite advances in technology and techniques. To improve outcomes, transplant surgeons may need to do a better job of selecting patients and matching patients and donors, according to study in the December issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;150:1455-62).

“Strategies to improve outcomes in CHD patients might need to address selection criteria, transplantation timing, pretransplant and posttransplant care,” noted Dr. Bahaaldin Alsoufi, of the division of cardiothoracic surgery, Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, Emory University. “The effect of donor/recipient race mismatch warrants further investigation and might impact organ allocation algorithms or immunosuppression management,” wrote Dr. Alsoufi and his colleagues.

The researchers analyzed results of 124 children with CHD who had heart transplants from 1988 to 2013 at Emory University and Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta. Median age was 3.8 years; 61% were boys. Ten years after heart transplantation, 44% (54) of patients were alive without a second transplant, 13% (17) had a second transplant and 43% (53) died without a second transplant. After the second transplant, 9 of the 17 patients were alive, but 3 of them had gone onto a third transplant. Overall 15-year survival following the first transplant was 41% (51).

The study cited data from the Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation that reported more than 11,000 pediatric heart transplants worldwide in 2013, and CHD represents about 54% of all heart transplants in infants.

A multivariate analysis identified the following risk factors for early mortality after transplant: age younger than 12 months (hazard ration [HR] 7.2) and prolonged cardiopulmonary bypass (HR 5). Late-phase mortality risk factors were age younger than 12 months (HR 3) and donor/recipient race mismatch (HR 2.2).

“Survival was not affected by era, underlying anomaly, prior Fontan, sensitization or pulmonary artery augmentation,” wrote Dr. Alsoufi and his colleagues.

Among the risk factors, longer bypass times may be a surrogate for a more complicated operation, the authors said. But where prior sternotomy is a risk factor following a heart transplant in adults, the study found no such risk in children. Another risk factor previous reports identified is pulmonary artery augmentation, but, again, this study found no risk in the pediatric group.

The researchers looked at days on the waiting list, with a median wait of 39 days in the study group. In all, 175 children were listed for transplants, but 51 did not go through for various reasons. Most of the children with CHD who had a heart transplant had previous surgery; only 13% had a primary heart transplant, mostly in the earlier phase of the study.

Dr. Alsoufi and coauthors also identified African American race as a risk factor for lower survival, which is consistent with other reports. But this study agreed with a previous report that donor/recipient race mismatch was a significant risk factor in white and African American patients (Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;87:204-9). “While our finding might be anecdotal and specific to our geographic population, this warrants some investigation and might have some impact on future organ allocation algorithms and immunosuppression management,” the researchers wrote.

The authors had no relevant disclosures. Emory University School of Medicine, Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta provided study funding.

A 25-year study of heart transplants in children with congenital heart disease (CHD) at one institution has found that results haven’t improved over time despite advances in technology and techniques. To improve outcomes, transplant surgeons may need to do a better job of selecting patients and matching patients and donors, according to study in the December issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;150:1455-62).

“Strategies to improve outcomes in CHD patients might need to address selection criteria, transplantation timing, pretransplant and posttransplant care,” noted Dr. Bahaaldin Alsoufi, of the division of cardiothoracic surgery, Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, Emory University. “The effect of donor/recipient race mismatch warrants further investigation and might impact organ allocation algorithms or immunosuppression management,” wrote Dr. Alsoufi and his colleagues.

The researchers analyzed results of 124 children with CHD who had heart transplants from 1988 to 2013 at Emory University and Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta. Median age was 3.8 years; 61% were boys. Ten years after heart transplantation, 44% (54) of patients were alive without a second transplant, 13% (17) had a second transplant and 43% (53) died without a second transplant. After the second transplant, 9 of the 17 patients were alive, but 3 of them had gone onto a third transplant. Overall 15-year survival following the first transplant was 41% (51).

The study cited data from the Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation that reported more than 11,000 pediatric heart transplants worldwide in 2013, and CHD represents about 54% of all heart transplants in infants.