User login

Complete excision most effective for BI-ALCL

![]()

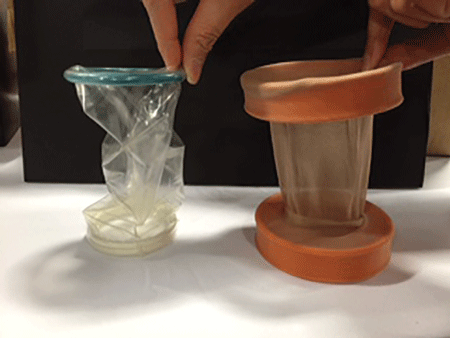

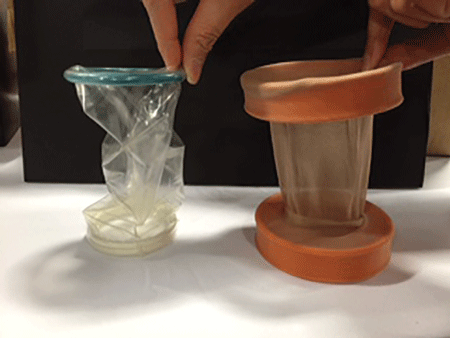

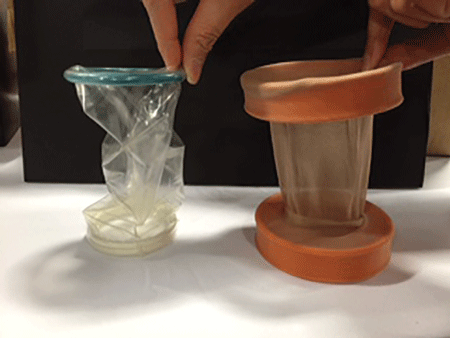

Photo courtesy of the FDA

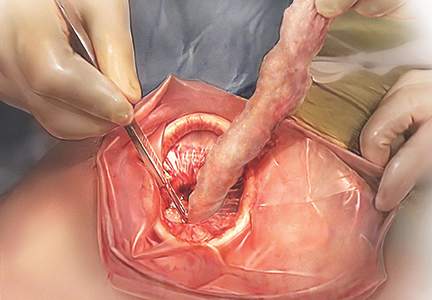

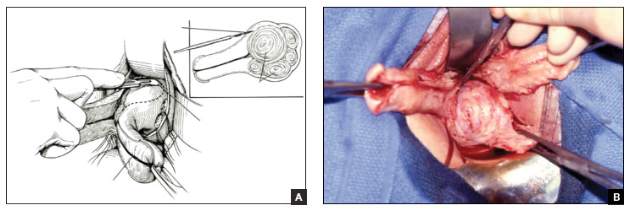

The optimal treatment approach for most women with breast implant-associated anaplastic large-cell lymphoma (BI-ALCL) is complete surgical excision of the implant and surrounding capsule, a new study suggests.

The study, published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology, represents the most comprehensive study of BI-ALCL to date, including 87 patients and 30 investigators from 14 institutions across 5 continents.

BI-ALCL is a rare T-cell lymphoma that forms in the scar tissue or in the fluid surrounding a breast implant. The disease manifests as a large fluid collection around the implant over a year after implantation, usually taking an average of 8 years to develop.

An estimated 10 million women worldwide have breast implants, and the annual incidence of BI-ALCL is estimated to be 0.1 to 0.3 per 100,000 women with breast implants.

“Although this disease is rare, it appears to be amenable to treatment, and, in the vast majority of patients, the outcome is very good,” said Mark Clemens, MD, of The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

“The disease can be reliably diagnosed, and, when treated appropriately, it has a good prognosis.”

Still, the optimal management for BI-ALCL hasn’t been clear. So with this study, Dr Clemens and his colleagues sought to evaluate treatment efficacy on disease outcomes and determine the best treatment approach. The study expands on previous research published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology in 2014.

The researchers gathered detailed treatment and outcome information from a total of 87 BI-ALCL patients, including 37 whose information had not previously been published. A review of treatment approaches in relation to event-free survival and overall survival revealed that surgery was the optimal frontline therapy for BI-ALCL.

“We determined that complete surgical excision was essential for the management of this disease,” Dr Clemens said. “Patients did not do as well unless they were treated with full removal of the breast implant and complete excision of the capsule around the implant.”

Patients with complete surgical excision had a recurrence rate of 4% at 5 years, compared to 28% for patients who received radiation therapy and 32% for chemotherapy.

In addition, patients who underwent a complete surgical excision had better overall survival (P=0.022) and event-free survival (P=0.014) than patients who received a partial capsulectomy, systemic chemotherapy, or radiation.

“This lymphoma represents a different paradigm from systemic anaplastic large-cell lymphoma, in particular because of its strong association with breast implants,” said Roberto N. Miranda, MD, of The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center.

“We have demonstrated that this is a predominantly localized disease where surgical excision has a primary role.”

The researchers emphasized that, despite the overall good prognosis, some rare cases of BI-ALCL exhibit more aggressive behavior with systemic dissemination. As a part of this study, the team is gathering tissue from these patients to assess underlying mechanisms for progression of disease.

Additional research is ongoing to optimize therapy for these cases through genetic profiling and defining the role of chemotherapy and radiation. The researchers are also studying animal models to further assess the role of breast implants in the pathogenesis of this lymphoma. ![]()

![]()

Photo courtesy of the FDA

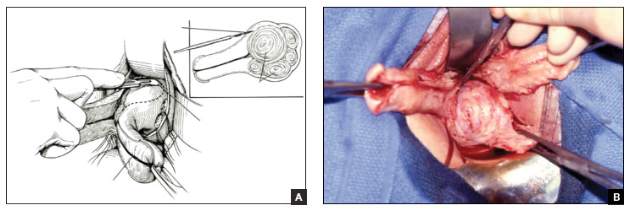

The optimal treatment approach for most women with breast implant-associated anaplastic large-cell lymphoma (BI-ALCL) is complete surgical excision of the implant and surrounding capsule, a new study suggests.

The study, published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology, represents the most comprehensive study of BI-ALCL to date, including 87 patients and 30 investigators from 14 institutions across 5 continents.

BI-ALCL is a rare T-cell lymphoma that forms in the scar tissue or in the fluid surrounding a breast implant. The disease manifests as a large fluid collection around the implant over a year after implantation, usually taking an average of 8 years to develop.

An estimated 10 million women worldwide have breast implants, and the annual incidence of BI-ALCL is estimated to be 0.1 to 0.3 per 100,000 women with breast implants.

“Although this disease is rare, it appears to be amenable to treatment, and, in the vast majority of patients, the outcome is very good,” said Mark Clemens, MD, of The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

“The disease can be reliably diagnosed, and, when treated appropriately, it has a good prognosis.”

Still, the optimal management for BI-ALCL hasn’t been clear. So with this study, Dr Clemens and his colleagues sought to evaluate treatment efficacy on disease outcomes and determine the best treatment approach. The study expands on previous research published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology in 2014.

The researchers gathered detailed treatment and outcome information from a total of 87 BI-ALCL patients, including 37 whose information had not previously been published. A review of treatment approaches in relation to event-free survival and overall survival revealed that surgery was the optimal frontline therapy for BI-ALCL.

“We determined that complete surgical excision was essential for the management of this disease,” Dr Clemens said. “Patients did not do as well unless they were treated with full removal of the breast implant and complete excision of the capsule around the implant.”

Patients with complete surgical excision had a recurrence rate of 4% at 5 years, compared to 28% for patients who received radiation therapy and 32% for chemotherapy.

In addition, patients who underwent a complete surgical excision had better overall survival (P=0.022) and event-free survival (P=0.014) than patients who received a partial capsulectomy, systemic chemotherapy, or radiation.

“This lymphoma represents a different paradigm from systemic anaplastic large-cell lymphoma, in particular because of its strong association with breast implants,” said Roberto N. Miranda, MD, of The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center.

“We have demonstrated that this is a predominantly localized disease where surgical excision has a primary role.”

The researchers emphasized that, despite the overall good prognosis, some rare cases of BI-ALCL exhibit more aggressive behavior with systemic dissemination. As a part of this study, the team is gathering tissue from these patients to assess underlying mechanisms for progression of disease.

Additional research is ongoing to optimize therapy for these cases through genetic profiling and defining the role of chemotherapy and radiation. The researchers are also studying animal models to further assess the role of breast implants in the pathogenesis of this lymphoma. ![]()

![]()

Photo courtesy of the FDA

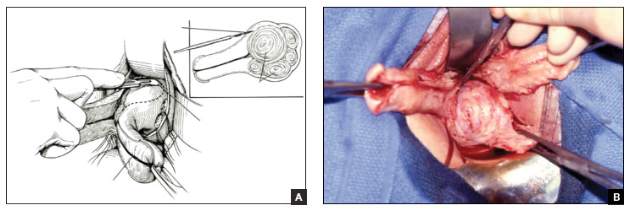

The optimal treatment approach for most women with breast implant-associated anaplastic large-cell lymphoma (BI-ALCL) is complete surgical excision of the implant and surrounding capsule, a new study suggests.

The study, published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology, represents the most comprehensive study of BI-ALCL to date, including 87 patients and 30 investigators from 14 institutions across 5 continents.

BI-ALCL is a rare T-cell lymphoma that forms in the scar tissue or in the fluid surrounding a breast implant. The disease manifests as a large fluid collection around the implant over a year after implantation, usually taking an average of 8 years to develop.

An estimated 10 million women worldwide have breast implants, and the annual incidence of BI-ALCL is estimated to be 0.1 to 0.3 per 100,000 women with breast implants.

“Although this disease is rare, it appears to be amenable to treatment, and, in the vast majority of patients, the outcome is very good,” said Mark Clemens, MD, of The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

“The disease can be reliably diagnosed, and, when treated appropriately, it has a good prognosis.”

Still, the optimal management for BI-ALCL hasn’t been clear. So with this study, Dr Clemens and his colleagues sought to evaluate treatment efficacy on disease outcomes and determine the best treatment approach. The study expands on previous research published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology in 2014.

The researchers gathered detailed treatment and outcome information from a total of 87 BI-ALCL patients, including 37 whose information had not previously been published. A review of treatment approaches in relation to event-free survival and overall survival revealed that surgery was the optimal frontline therapy for BI-ALCL.

“We determined that complete surgical excision was essential for the management of this disease,” Dr Clemens said. “Patients did not do as well unless they were treated with full removal of the breast implant and complete excision of the capsule around the implant.”

Patients with complete surgical excision had a recurrence rate of 4% at 5 years, compared to 28% for patients who received radiation therapy and 32% for chemotherapy.

In addition, patients who underwent a complete surgical excision had better overall survival (P=0.022) and event-free survival (P=0.014) than patients who received a partial capsulectomy, systemic chemotherapy, or radiation.

“This lymphoma represents a different paradigm from systemic anaplastic large-cell lymphoma, in particular because of its strong association with breast implants,” said Roberto N. Miranda, MD, of The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center.

“We have demonstrated that this is a predominantly localized disease where surgical excision has a primary role.”

The researchers emphasized that, despite the overall good prognosis, some rare cases of BI-ALCL exhibit more aggressive behavior with systemic dissemination. As a part of this study, the team is gathering tissue from these patients to assess underlying mechanisms for progression of disease.

Additional research is ongoing to optimize therapy for these cases through genetic profiling and defining the role of chemotherapy and radiation. The researchers are also studying animal models to further assess the role of breast implants in the pathogenesis of this lymphoma. ![]()

Team identifies potential biomarkers for AML therapy

Photo by Kristin Gladney

New research published in Cell Reports has revealed biomarkers that may help predict which acute myeloid leukemia (AML) patients will respond to treatment with PU-H71.

This drug targets a tumor-enriched form of the protein Hsp90 called teHSP90, which is critical to the growth of cancer cells.

However, previous preclinical experiments showed that PU-H71 only kills some AML cells.

“We observed that only a subset of leukemia patient samples were sensitive to the drug,” said study author Monica Guzman, PhD, of Weill Cornell Medical College in New York, New York.

“We wanted to be able to identify which patients with leukemia would respond to this drug.”

So Dr Guzman and her colleagues focused on groups of proteins that function within signaling networks in leukemia cells.

The researchers found that 2 of these networks, JAK-STAT and PI3K-AKT, were important for leukemia cells to function. These signaling pathways are critical for the survival of AML cells, and they, in turn, are dependent on teHsp90.

The team treated AML cells with PU-H71 and found that cells with greater JAK-STAT and PI3K-AKT activity were killed by the drug. Cells with less active signaling networks did not respond to PU-H71.

“Higher activation of these networks makes the leukemia cells more dependent on Hsp90,” Dr Guzman said. “Since PU-H71 targets teHsp90, leukemia samples with these features are good targets for treatment with the drug.”

The next step for Dr Guzman’s team is to test their findings in patients. Ideally, the JAK-STAT and PI3K-AKT signaling pathways will serve as biomarkers for identifying patients whose leukemias will be sensitive to PU-H71.

“We are working on a tool that will quickly and easily identify patients whose cancers will respond to PU-H71,” Dr Guzman said. “We are really looking forward to seeing this in leukemic patients and being able to offer them a new treatment.” ![]()

Photo by Kristin Gladney

New research published in Cell Reports has revealed biomarkers that may help predict which acute myeloid leukemia (AML) patients will respond to treatment with PU-H71.

This drug targets a tumor-enriched form of the protein Hsp90 called teHSP90, which is critical to the growth of cancer cells.

However, previous preclinical experiments showed that PU-H71 only kills some AML cells.

“We observed that only a subset of leukemia patient samples were sensitive to the drug,” said study author Monica Guzman, PhD, of Weill Cornell Medical College in New York, New York.

“We wanted to be able to identify which patients with leukemia would respond to this drug.”

So Dr Guzman and her colleagues focused on groups of proteins that function within signaling networks in leukemia cells.

The researchers found that 2 of these networks, JAK-STAT and PI3K-AKT, were important for leukemia cells to function. These signaling pathways are critical for the survival of AML cells, and they, in turn, are dependent on teHsp90.

The team treated AML cells with PU-H71 and found that cells with greater JAK-STAT and PI3K-AKT activity were killed by the drug. Cells with less active signaling networks did not respond to PU-H71.

“Higher activation of these networks makes the leukemia cells more dependent on Hsp90,” Dr Guzman said. “Since PU-H71 targets teHsp90, leukemia samples with these features are good targets for treatment with the drug.”

The next step for Dr Guzman’s team is to test their findings in patients. Ideally, the JAK-STAT and PI3K-AKT signaling pathways will serve as biomarkers for identifying patients whose leukemias will be sensitive to PU-H71.

“We are working on a tool that will quickly and easily identify patients whose cancers will respond to PU-H71,” Dr Guzman said. “We are really looking forward to seeing this in leukemic patients and being able to offer them a new treatment.” ![]()

Photo by Kristin Gladney

New research published in Cell Reports has revealed biomarkers that may help predict which acute myeloid leukemia (AML) patients will respond to treatment with PU-H71.

This drug targets a tumor-enriched form of the protein Hsp90 called teHSP90, which is critical to the growth of cancer cells.

However, previous preclinical experiments showed that PU-H71 only kills some AML cells.

“We observed that only a subset of leukemia patient samples were sensitive to the drug,” said study author Monica Guzman, PhD, of Weill Cornell Medical College in New York, New York.

“We wanted to be able to identify which patients with leukemia would respond to this drug.”

So Dr Guzman and her colleagues focused on groups of proteins that function within signaling networks in leukemia cells.

The researchers found that 2 of these networks, JAK-STAT and PI3K-AKT, were important for leukemia cells to function. These signaling pathways are critical for the survival of AML cells, and they, in turn, are dependent on teHsp90.

The team treated AML cells with PU-H71 and found that cells with greater JAK-STAT and PI3K-AKT activity were killed by the drug. Cells with less active signaling networks did not respond to PU-H71.

“Higher activation of these networks makes the leukemia cells more dependent on Hsp90,” Dr Guzman said. “Since PU-H71 targets teHsp90, leukemia samples with these features are good targets for treatment with the drug.”

The next step for Dr Guzman’s team is to test their findings in patients. Ideally, the JAK-STAT and PI3K-AKT signaling pathways will serve as biomarkers for identifying patients whose leukemias will be sensitive to PU-H71.

“We are working on a tool that will quickly and easily identify patients whose cancers will respond to PU-H71,” Dr Guzman said. “We are really looking forward to seeing this in leukemic patients and being able to offer them a new treatment.” ![]()

Catheter approved to treat DVT

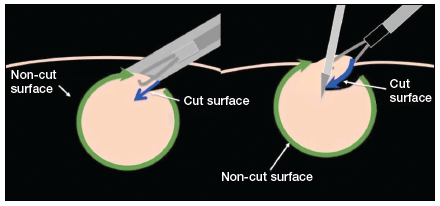

thrombectomy catheter

Image courtesy of

Boston Scientific

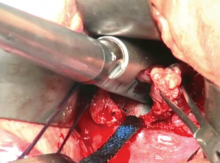

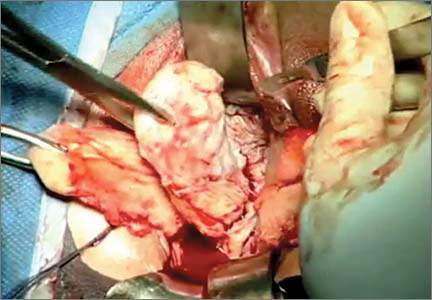

The AngioJet ZelanteDVT thrombectomy catheter has been approved for commercialization in the US and Europe.

The device received the CE mark and approval from the US Food and Drug Administration to treat deep vein thrombosis (DVT) in large-diameter

upper and lower limb peripheral veins.

The ZelanteDVT catheter was designed to remove large venous clot burdens and facilitate rapid restoration of blood flow, potentially decreasing procedural time, relieving symptoms, and reducing late complications.

The ZelanteDVT Thrombectomy Set is intended for use with the AngioJet Ultra Console to break apart and remove thrombi, including DVT, from iliofemoral and lower extremity veins greater than or equal to 6.0 mm in diameter and upper extremity peripheral veins greater than or equal to 6.0 mm in diameter.

The set is also intended for use with the AngioJet Power Pulse technique for the controlled and selective infusion of physician-specified fluids, including thrombolytic agents, into the peripheral vascular system.

The ZelanteDVT catheter is a product of Boston Scientific. For more information on the device, visit the company’s website. ![]()

thrombectomy catheter

Image courtesy of

Boston Scientific

The AngioJet ZelanteDVT thrombectomy catheter has been approved for commercialization in the US and Europe.

The device received the CE mark and approval from the US Food and Drug Administration to treat deep vein thrombosis (DVT) in large-diameter

upper and lower limb peripheral veins.

The ZelanteDVT catheter was designed to remove large venous clot burdens and facilitate rapid restoration of blood flow, potentially decreasing procedural time, relieving symptoms, and reducing late complications.

The ZelanteDVT Thrombectomy Set is intended for use with the AngioJet Ultra Console to break apart and remove thrombi, including DVT, from iliofemoral and lower extremity veins greater than or equal to 6.0 mm in diameter and upper extremity peripheral veins greater than or equal to 6.0 mm in diameter.

The set is also intended for use with the AngioJet Power Pulse technique for the controlled and selective infusion of physician-specified fluids, including thrombolytic agents, into the peripheral vascular system.

The ZelanteDVT catheter is a product of Boston Scientific. For more information on the device, visit the company’s website. ![]()

thrombectomy catheter

Image courtesy of

Boston Scientific

The AngioJet ZelanteDVT thrombectomy catheter has been approved for commercialization in the US and Europe.

The device received the CE mark and approval from the US Food and Drug Administration to treat deep vein thrombosis (DVT) in large-diameter

upper and lower limb peripheral veins.

The ZelanteDVT catheter was designed to remove large venous clot burdens and facilitate rapid restoration of blood flow, potentially decreasing procedural time, relieving symptoms, and reducing late complications.

The ZelanteDVT Thrombectomy Set is intended for use with the AngioJet Ultra Console to break apart and remove thrombi, including DVT, from iliofemoral and lower extremity veins greater than or equal to 6.0 mm in diameter and upper extremity peripheral veins greater than or equal to 6.0 mm in diameter.

The set is also intended for use with the AngioJet Power Pulse technique for the controlled and selective infusion of physician-specified fluids, including thrombolytic agents, into the peripheral vascular system.

The ZelanteDVT catheter is a product of Boston Scientific. For more information on the device, visit the company’s website. ![]()

AHA: New spotlight on peripheral artery disease

ORLANDO – Peripheral artery disease constitutes “a health crisis that is largely unnoticed” by the public and all too often by physicians as well – but that’s all about to change, Dr. Mark A. Creager said in his presidential address at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

In the coming months, look for rollout of major AHA initiatives on peripheral vascular disease. These programs grew out of a summit meeting of thought leaders in the field of vascular disease convened recently by the AHA in order to find ways to boost public awareness and improve the quality of care for patients with peripheral artery disease (PAD), venous thromboembolism, and aortic aneurysm.

PAD is all too often thought of as a disease of the legs, when in fact it is a clinical manifestation of systemic atherosclerosis, Dr. Creager noted. PAD affects on estimated 200 million people worldwide. In the United States alone, it accounts for $20 billion per year in health care costs. The mortality risk in affected patients is two- to fourfold greater than in individuals without PAD. Moreover, the risk of acute MI, stroke, or cardiovascular death among patients with PAD exceeds that of patients with established cerebrovascular disease.

“Clearly the unrecognized epidemic of vascular disease requires our attention,” observed Dr. Creager, professor of medicine and director of the Heart and Vascular Center at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center in Lebanon, N.H.

Indeed, he made it clear that improved diagnosis and treatment of PAD will be a major AHA priority during his term as president. Noting that the annual rate of deaths due to cardiovascular disease and stroke has already dropped by 13.7% in the 5 years since the AHA set the ambitious goal of a 20% reduction by the year 2020, he emphasized that a critical element in getting the rest of the way there involves addressing peripheral vascular diseases more effectively.

Improved public awareness about PAD has to be a priority. One survey found that 75% of the public is unaware of PAD. It’s a condition which Dr. Creager and others have shown has its highest prevalence in Americans in the lowest income and educational strata, largely independent of traditional cardiovascular risk factors.

“Even physicians often fail to consider PAD, chalking up leg pain to age or arthritis. In one study, physicians missed the diagnosis of PAD half the time. And even when physicians diagnose PAD, they often don’t treat it adequately,” according to Dr. Creager.

The use of statins and antiplatelet therapy in patients with PAD each reduces the risk of MI, stroke, or cardiovascular death by about 25%. Yet when Dr. Creager and coworkers analyzed National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data, they found only 19% of patients with PAD who didn’t have previously established coronary or cerebrovascular disease were on a statin, just 21% were on an ACE inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker, and 27% were on antiplatelet therapy (Circulation. 2011 Jul 5;124[1]:17-23).

Among patients with symptomatic PAD, studies have shown that supervised exercise training can double walking distance. That’s a major quality of life benefit, yet one that goes unconsidered if the diagnosis is missed. “It’s rarely instituted even with the diagnosis, largely because of the lack of reimbursement,” according to Dr. Creager.

He painted a picture of PAD as a field ripe with opportunities for improved outcomes.

“Our ability to diagnose and treat vascular diseases has never been greater. The field of vascular biology has virtually exploded in recent years,” he said. “I’d like to focus not only on the extent of this crisis, but also on the importance of using what we know to treat it and prevent it, and on the urgency of intensifying our research efforts to better understand it.”

In the diagnostic arena, optical coherence tomography, intravascular ultrasound, PET-CT, and contrast-enhanced MRI provide an unprecedented ability to image plaques and assess their vulnerability to rupture.

On the interventional front, innovative bioengineering has led to the development of drug-coated balloons and bioabsorbable vascular scaffolds with the potential to curb restenosis and preserve patency following endovascular treatment of critical lesions.

In terms of medical management, the novel, super-potent LDL cholesterol–lowering inhibitors of PCSK9 (proprotein convertase subtilisin-kexin type 9) will need to be studied in order to see if they have a special role in the treatment and/or prevention of PAD.

Roughly 2 decades ago, Dr. Creager and coinvestigators showed that endothelial function typically drops by 30% in our twenties and then in our thirties, and by 50% once we’re in our forties. A high research priority in PAD will be to learn how to more effectively prolong endothelial health and prevent vascular stiffness, he said.

He reported having no financial conflicts regarding his presentation.

ORLANDO – Peripheral artery disease constitutes “a health crisis that is largely unnoticed” by the public and all too often by physicians as well – but that’s all about to change, Dr. Mark A. Creager said in his presidential address at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

In the coming months, look for rollout of major AHA initiatives on peripheral vascular disease. These programs grew out of a summit meeting of thought leaders in the field of vascular disease convened recently by the AHA in order to find ways to boost public awareness and improve the quality of care for patients with peripheral artery disease (PAD), venous thromboembolism, and aortic aneurysm.

PAD is all too often thought of as a disease of the legs, when in fact it is a clinical manifestation of systemic atherosclerosis, Dr. Creager noted. PAD affects on estimated 200 million people worldwide. In the United States alone, it accounts for $20 billion per year in health care costs. The mortality risk in affected patients is two- to fourfold greater than in individuals without PAD. Moreover, the risk of acute MI, stroke, or cardiovascular death among patients with PAD exceeds that of patients with established cerebrovascular disease.

“Clearly the unrecognized epidemic of vascular disease requires our attention,” observed Dr. Creager, professor of medicine and director of the Heart and Vascular Center at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center in Lebanon, N.H.

Indeed, he made it clear that improved diagnosis and treatment of PAD will be a major AHA priority during his term as president. Noting that the annual rate of deaths due to cardiovascular disease and stroke has already dropped by 13.7% in the 5 years since the AHA set the ambitious goal of a 20% reduction by the year 2020, he emphasized that a critical element in getting the rest of the way there involves addressing peripheral vascular diseases more effectively.

Improved public awareness about PAD has to be a priority. One survey found that 75% of the public is unaware of PAD. It’s a condition which Dr. Creager and others have shown has its highest prevalence in Americans in the lowest income and educational strata, largely independent of traditional cardiovascular risk factors.

“Even physicians often fail to consider PAD, chalking up leg pain to age or arthritis. In one study, physicians missed the diagnosis of PAD half the time. And even when physicians diagnose PAD, they often don’t treat it adequately,” according to Dr. Creager.

The use of statins and antiplatelet therapy in patients with PAD each reduces the risk of MI, stroke, or cardiovascular death by about 25%. Yet when Dr. Creager and coworkers analyzed National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data, they found only 19% of patients with PAD who didn’t have previously established coronary or cerebrovascular disease were on a statin, just 21% were on an ACE inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker, and 27% were on antiplatelet therapy (Circulation. 2011 Jul 5;124[1]:17-23).

Among patients with symptomatic PAD, studies have shown that supervised exercise training can double walking distance. That’s a major quality of life benefit, yet one that goes unconsidered if the diagnosis is missed. “It’s rarely instituted even with the diagnosis, largely because of the lack of reimbursement,” according to Dr. Creager.

He painted a picture of PAD as a field ripe with opportunities for improved outcomes.

“Our ability to diagnose and treat vascular diseases has never been greater. The field of vascular biology has virtually exploded in recent years,” he said. “I’d like to focus not only on the extent of this crisis, but also on the importance of using what we know to treat it and prevent it, and on the urgency of intensifying our research efforts to better understand it.”

In the diagnostic arena, optical coherence tomography, intravascular ultrasound, PET-CT, and contrast-enhanced MRI provide an unprecedented ability to image plaques and assess their vulnerability to rupture.

On the interventional front, innovative bioengineering has led to the development of drug-coated balloons and bioabsorbable vascular scaffolds with the potential to curb restenosis and preserve patency following endovascular treatment of critical lesions.

In terms of medical management, the novel, super-potent LDL cholesterol–lowering inhibitors of PCSK9 (proprotein convertase subtilisin-kexin type 9) will need to be studied in order to see if they have a special role in the treatment and/or prevention of PAD.

Roughly 2 decades ago, Dr. Creager and coinvestigators showed that endothelial function typically drops by 30% in our twenties and then in our thirties, and by 50% once we’re in our forties. A high research priority in PAD will be to learn how to more effectively prolong endothelial health and prevent vascular stiffness, he said.

He reported having no financial conflicts regarding his presentation.

ORLANDO – Peripheral artery disease constitutes “a health crisis that is largely unnoticed” by the public and all too often by physicians as well – but that’s all about to change, Dr. Mark A. Creager said in his presidential address at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

In the coming months, look for rollout of major AHA initiatives on peripheral vascular disease. These programs grew out of a summit meeting of thought leaders in the field of vascular disease convened recently by the AHA in order to find ways to boost public awareness and improve the quality of care for patients with peripheral artery disease (PAD), venous thromboembolism, and aortic aneurysm.

PAD is all too often thought of as a disease of the legs, when in fact it is a clinical manifestation of systemic atherosclerosis, Dr. Creager noted. PAD affects on estimated 200 million people worldwide. In the United States alone, it accounts for $20 billion per year in health care costs. The mortality risk in affected patients is two- to fourfold greater than in individuals without PAD. Moreover, the risk of acute MI, stroke, or cardiovascular death among patients with PAD exceeds that of patients with established cerebrovascular disease.

“Clearly the unrecognized epidemic of vascular disease requires our attention,” observed Dr. Creager, professor of medicine and director of the Heart and Vascular Center at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center in Lebanon, N.H.

Indeed, he made it clear that improved diagnosis and treatment of PAD will be a major AHA priority during his term as president. Noting that the annual rate of deaths due to cardiovascular disease and stroke has already dropped by 13.7% in the 5 years since the AHA set the ambitious goal of a 20% reduction by the year 2020, he emphasized that a critical element in getting the rest of the way there involves addressing peripheral vascular diseases more effectively.

Improved public awareness about PAD has to be a priority. One survey found that 75% of the public is unaware of PAD. It’s a condition which Dr. Creager and others have shown has its highest prevalence in Americans in the lowest income and educational strata, largely independent of traditional cardiovascular risk factors.

“Even physicians often fail to consider PAD, chalking up leg pain to age or arthritis. In one study, physicians missed the diagnosis of PAD half the time. And even when physicians diagnose PAD, they often don’t treat it adequately,” according to Dr. Creager.

The use of statins and antiplatelet therapy in patients with PAD each reduces the risk of MI, stroke, or cardiovascular death by about 25%. Yet when Dr. Creager and coworkers analyzed National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data, they found only 19% of patients with PAD who didn’t have previously established coronary or cerebrovascular disease were on a statin, just 21% were on an ACE inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker, and 27% were on antiplatelet therapy (Circulation. 2011 Jul 5;124[1]:17-23).

Among patients with symptomatic PAD, studies have shown that supervised exercise training can double walking distance. That’s a major quality of life benefit, yet one that goes unconsidered if the diagnosis is missed. “It’s rarely instituted even with the diagnosis, largely because of the lack of reimbursement,” according to Dr. Creager.

He painted a picture of PAD as a field ripe with opportunities for improved outcomes.

“Our ability to diagnose and treat vascular diseases has never been greater. The field of vascular biology has virtually exploded in recent years,” he said. “I’d like to focus not only on the extent of this crisis, but also on the importance of using what we know to treat it and prevent it, and on the urgency of intensifying our research efforts to better understand it.”

In the diagnostic arena, optical coherence tomography, intravascular ultrasound, PET-CT, and contrast-enhanced MRI provide an unprecedented ability to image plaques and assess their vulnerability to rupture.

On the interventional front, innovative bioengineering has led to the development of drug-coated balloons and bioabsorbable vascular scaffolds with the potential to curb restenosis and preserve patency following endovascular treatment of critical lesions.

In terms of medical management, the novel, super-potent LDL cholesterol–lowering inhibitors of PCSK9 (proprotein convertase subtilisin-kexin type 9) will need to be studied in order to see if they have a special role in the treatment and/or prevention of PAD.

Roughly 2 decades ago, Dr. Creager and coinvestigators showed that endothelial function typically drops by 30% in our twenties and then in our thirties, and by 50% once we’re in our forties. A high research priority in PAD will be to learn how to more effectively prolong endothelial health and prevent vascular stiffness, he said.

He reported having no financial conflicts regarding his presentation.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Décolletage Rejuvenation With Cosmetic Injectables and Beyond

As more patients undergo facial rejuvenation procedures for a more youthful look, there is a growing demand for rejuvenation of the décolletage (neck and chest) to achieve a more natural and seamless transition from the skin of the face to the chest. The same modalities that are used on the face to treat skin rhytides, texture, and discoloration have been used successfully in the décolletage area.

Vanaman and Fabi (Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;136[suppl 5]:276S-281S) recently reviewed the chest anatomy and discussed the safe and effective use of cosmetic injectables alone or in combination with other modalities to address rhytides of the décolletage. The relatively low density of skin pilosebaceous units on the chest allows for slower healing and thus makes the area more vulnerable to scarring with the use of more invasive resurfacing modalities (eg, deeper chemical peels, ablative lasers). The use of cosmetic injectables offers a safer treatment option of chest rhytides. Furthermore, proper candidate selection excludes patients with known sensitivity to cosmetic injectables or their components, history of keloid or hypertrophic scar formation, and active inflammation in the treatment area.

Poly-L-lactic acid (PLLA) is a biodegradable, biocompatible, semipermanent, synthetic soft tissue biostimulator that promotes neocollagenesis by fibroblasts over time (3–6 months). The manufacturer’s recommendation for PLLA reconstitution is at least 2 hours prior to injection with sterile water of no less than 5 mL dilution. Vanaman and Fabi reported usually diluting the day prior to injection with 16 mL total volume. This technique showed the greatest improvement in chest rhytides with no adverse events reported in a retrospective analysis. Poly-L-lactic acid should be injected in a retrograde linear fashion in the plane of the subcutaneous fat, with injection boundaries on the suprasternal notch superiorly, the midclavicular line laterally, and the fourth rib inferolaterally for rejuvenation of the décolletage.

Nodule formation is a well-known complication of PLLA injection, although pain, bruising, edema, pruritus, and hematomas are more commonly seen. The risk of nodule formation can be decreased using several techniques, including avoiding overcorrection and excessive use of product in each individual session, avoiding intradermal injection, diluting to more than 5 mL with reconstitution at least overnight, massaging the area posttreatment (in office by the clinician and at home by the patient), and scheduling treatment sessions at least 4 weeks apart. Usually, 3 to 4 treatments are required and the results can last 2 years or longer without touch-ups.

Nonanimal stabilized hyaluronic acid (NASHA) fillers also can be used to correct chest rhytides; however, using NASHA fillers requires more syringes and results typically last only 6 to 8 months, making it more cost effective to use 2 to 3 vials of PLLA. Moreover, in Vanaman and Fabi’s experience, PLLA is associated with fewer nodules, possibly due to the depth of injection of PLLA into the subcutaneous fat versus injection into the deep dermis with NASHA fillers. Vanaman and Fabi currently are investigating the use of calcium hydroxylapatite fillers alone or in combination with an energy-based modality (microfocused ultrasound) with visualization in the treatment of rhytides in the décolletage.

What’s the Issue?

The availability of many modalities to keep facial skin looking fresh and rejuvenated has led to an increased demand for products and procedures to rejuvenate the décolletage. It is important for dermatologists to acknowledge the more delicate nature of the décolletage versus the face. Less invasive modalities such as cosmetic injectables can be employed in a safe and effective manner to correct rhytides of the chest with proper techniques, products, and patient selection. For a more natural transition from the skin of the face to the décolletage, it also may be necessary to adopt a multimodal approach by using botulinum toxin and fillers, as well as going beyond correction of rhytides to address skin texture and discoloration with chemical peels and lasers. Have you seen an increased demand for procedures to rejuvenate the décolletage in your practice?

As more patients undergo facial rejuvenation procedures for a more youthful look, there is a growing demand for rejuvenation of the décolletage (neck and chest) to achieve a more natural and seamless transition from the skin of the face to the chest. The same modalities that are used on the face to treat skin rhytides, texture, and discoloration have been used successfully in the décolletage area.

Vanaman and Fabi (Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;136[suppl 5]:276S-281S) recently reviewed the chest anatomy and discussed the safe and effective use of cosmetic injectables alone or in combination with other modalities to address rhytides of the décolletage. The relatively low density of skin pilosebaceous units on the chest allows for slower healing and thus makes the area more vulnerable to scarring with the use of more invasive resurfacing modalities (eg, deeper chemical peels, ablative lasers). The use of cosmetic injectables offers a safer treatment option of chest rhytides. Furthermore, proper candidate selection excludes patients with known sensitivity to cosmetic injectables or their components, history of keloid or hypertrophic scar formation, and active inflammation in the treatment area.

Poly-L-lactic acid (PLLA) is a biodegradable, biocompatible, semipermanent, synthetic soft tissue biostimulator that promotes neocollagenesis by fibroblasts over time (3–6 months). The manufacturer’s recommendation for PLLA reconstitution is at least 2 hours prior to injection with sterile water of no less than 5 mL dilution. Vanaman and Fabi reported usually diluting the day prior to injection with 16 mL total volume. This technique showed the greatest improvement in chest rhytides with no adverse events reported in a retrospective analysis. Poly-L-lactic acid should be injected in a retrograde linear fashion in the plane of the subcutaneous fat, with injection boundaries on the suprasternal notch superiorly, the midclavicular line laterally, and the fourth rib inferolaterally for rejuvenation of the décolletage.

Nodule formation is a well-known complication of PLLA injection, although pain, bruising, edema, pruritus, and hematomas are more commonly seen. The risk of nodule formation can be decreased using several techniques, including avoiding overcorrection and excessive use of product in each individual session, avoiding intradermal injection, diluting to more than 5 mL with reconstitution at least overnight, massaging the area posttreatment (in office by the clinician and at home by the patient), and scheduling treatment sessions at least 4 weeks apart. Usually, 3 to 4 treatments are required and the results can last 2 years or longer without touch-ups.

Nonanimal stabilized hyaluronic acid (NASHA) fillers also can be used to correct chest rhytides; however, using NASHA fillers requires more syringes and results typically last only 6 to 8 months, making it more cost effective to use 2 to 3 vials of PLLA. Moreover, in Vanaman and Fabi’s experience, PLLA is associated with fewer nodules, possibly due to the depth of injection of PLLA into the subcutaneous fat versus injection into the deep dermis with NASHA fillers. Vanaman and Fabi currently are investigating the use of calcium hydroxylapatite fillers alone or in combination with an energy-based modality (microfocused ultrasound) with visualization in the treatment of rhytides in the décolletage.

What’s the Issue?

The availability of many modalities to keep facial skin looking fresh and rejuvenated has led to an increased demand for products and procedures to rejuvenate the décolletage. It is important for dermatologists to acknowledge the more delicate nature of the décolletage versus the face. Less invasive modalities such as cosmetic injectables can be employed in a safe and effective manner to correct rhytides of the chest with proper techniques, products, and patient selection. For a more natural transition from the skin of the face to the décolletage, it also may be necessary to adopt a multimodal approach by using botulinum toxin and fillers, as well as going beyond correction of rhytides to address skin texture and discoloration with chemical peels and lasers. Have you seen an increased demand for procedures to rejuvenate the décolletage in your practice?

As more patients undergo facial rejuvenation procedures for a more youthful look, there is a growing demand for rejuvenation of the décolletage (neck and chest) to achieve a more natural and seamless transition from the skin of the face to the chest. The same modalities that are used on the face to treat skin rhytides, texture, and discoloration have been used successfully in the décolletage area.

Vanaman and Fabi (Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;136[suppl 5]:276S-281S) recently reviewed the chest anatomy and discussed the safe and effective use of cosmetic injectables alone or in combination with other modalities to address rhytides of the décolletage. The relatively low density of skin pilosebaceous units on the chest allows for slower healing and thus makes the area more vulnerable to scarring with the use of more invasive resurfacing modalities (eg, deeper chemical peels, ablative lasers). The use of cosmetic injectables offers a safer treatment option of chest rhytides. Furthermore, proper candidate selection excludes patients with known sensitivity to cosmetic injectables or their components, history of keloid or hypertrophic scar formation, and active inflammation in the treatment area.

Poly-L-lactic acid (PLLA) is a biodegradable, biocompatible, semipermanent, synthetic soft tissue biostimulator that promotes neocollagenesis by fibroblasts over time (3–6 months). The manufacturer’s recommendation for PLLA reconstitution is at least 2 hours prior to injection with sterile water of no less than 5 mL dilution. Vanaman and Fabi reported usually diluting the day prior to injection with 16 mL total volume. This technique showed the greatest improvement in chest rhytides with no adverse events reported in a retrospective analysis. Poly-L-lactic acid should be injected in a retrograde linear fashion in the plane of the subcutaneous fat, with injection boundaries on the suprasternal notch superiorly, the midclavicular line laterally, and the fourth rib inferolaterally for rejuvenation of the décolletage.

Nodule formation is a well-known complication of PLLA injection, although pain, bruising, edema, pruritus, and hematomas are more commonly seen. The risk of nodule formation can be decreased using several techniques, including avoiding overcorrection and excessive use of product in each individual session, avoiding intradermal injection, diluting to more than 5 mL with reconstitution at least overnight, massaging the area posttreatment (in office by the clinician and at home by the patient), and scheduling treatment sessions at least 4 weeks apart. Usually, 3 to 4 treatments are required and the results can last 2 years or longer without touch-ups.

Nonanimal stabilized hyaluronic acid (NASHA) fillers also can be used to correct chest rhytides; however, using NASHA fillers requires more syringes and results typically last only 6 to 8 months, making it more cost effective to use 2 to 3 vials of PLLA. Moreover, in Vanaman and Fabi’s experience, PLLA is associated with fewer nodules, possibly due to the depth of injection of PLLA into the subcutaneous fat versus injection into the deep dermis with NASHA fillers. Vanaman and Fabi currently are investigating the use of calcium hydroxylapatite fillers alone or in combination with an energy-based modality (microfocused ultrasound) with visualization in the treatment of rhytides in the décolletage.

What’s the Issue?

The availability of many modalities to keep facial skin looking fresh and rejuvenated has led to an increased demand for products and procedures to rejuvenate the décolletage. It is important for dermatologists to acknowledge the more delicate nature of the décolletage versus the face. Less invasive modalities such as cosmetic injectables can be employed in a safe and effective manner to correct rhytides of the chest with proper techniques, products, and patient selection. For a more natural transition from the skin of the face to the décolletage, it also may be necessary to adopt a multimodal approach by using botulinum toxin and fillers, as well as going beyond correction of rhytides to address skin texture and discoloration with chemical peels and lasers. Have you seen an increased demand for procedures to rejuvenate the décolletage in your practice?

Lixisenatide not cardioprotective in type 2 diabetes

Adding lixisenatide to usual care failed to prevent major cardiovascular events in an industry-sponsored clinical trial involving patients with type 2 diabetes who had a recent acute coronary syndrome, according to a report published online Dec. 3 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Lixisenatide, a GLP-1-receptor agonist, is a glucose-lowering agent that inhibits glucagon secretion, prompts insulin production in response to hyperglycemia, and slows gastric emptying. In preliminary studies, lixisenatide showed some cardioprotective effects in myocardial ischemia and heart failure. To assess whether the drug would benefit diabetes patients at high CV risk, investigators conducted a randomized double-blind trial comparing lixisenatide with placebo in 6,068 patients who had type 2 diabetes and who had experienced acute coronary syndrome (ACS) during the preceding 6 months.

In addition to receiving usual diabetes care provided by their treating physicians, these patients (mean age, 60 years) were randomly assigned to self-administer once-daily subcutaneous injections of lixisenatide (n = 3,034) or a matching placebo (n = 3,034) and were followed for a mean of 25 months at 49 medical centers worldwide, said Dr. Marc A. Pfeffer of the cardiovascular division, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and Dzau Professor of Medicine a Harvard Medical School, Boston.

The primary endpoint of the study – a composite of death from CV causes, nonfatal MI, nonfatal stroke, or hospitalization for unstable angina – occurred in 13.4% of patients receiving lixisenatide and 13.2% of those receiving placebo, a nonsignificant difference. There were no differences between the two study groups in any of the individual components of this composite endpoint (N Engl J Med. 2015 Dec. 3. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1509225).

Sensitivity analyses and post hoc analyses of several subgroups of patients yielded similar results. When hospitalization for heart failure and coronary revascularization procedures were added to the primary endpoint, lixisenatide still provided no cardioprotective effect compared with placebo. Mortality from any cause was not significantly different between the two study groups, at 7.0% with lixisenatide and 7.4% with placebo.

Adverse effects leading to withdrawal from the study were more common with lixisenatide (11.4%) than placebo (7.2%). In particular, treatment discontinuation due to nausea and vomiting occurred in 3.0% of patients taking active treatment, compared with 0.4% of those taking placebo.

Sanofi, maker of lixisenatide, funded the study. Dr. Pfeffer reported receiving grants and personal fees from Sanofi and 20 other drug companies; his associates reported ties to numerous industry sources.

Adding lixisenatide to usual care failed to prevent major cardiovascular events in an industry-sponsored clinical trial involving patients with type 2 diabetes who had a recent acute coronary syndrome, according to a report published online Dec. 3 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Lixisenatide, a GLP-1-receptor agonist, is a glucose-lowering agent that inhibits glucagon secretion, prompts insulin production in response to hyperglycemia, and slows gastric emptying. In preliminary studies, lixisenatide showed some cardioprotective effects in myocardial ischemia and heart failure. To assess whether the drug would benefit diabetes patients at high CV risk, investigators conducted a randomized double-blind trial comparing lixisenatide with placebo in 6,068 patients who had type 2 diabetes and who had experienced acute coronary syndrome (ACS) during the preceding 6 months.

In addition to receiving usual diabetes care provided by their treating physicians, these patients (mean age, 60 years) were randomly assigned to self-administer once-daily subcutaneous injections of lixisenatide (n = 3,034) or a matching placebo (n = 3,034) and were followed for a mean of 25 months at 49 medical centers worldwide, said Dr. Marc A. Pfeffer of the cardiovascular division, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and Dzau Professor of Medicine a Harvard Medical School, Boston.

The primary endpoint of the study – a composite of death from CV causes, nonfatal MI, nonfatal stroke, or hospitalization for unstable angina – occurred in 13.4% of patients receiving lixisenatide and 13.2% of those receiving placebo, a nonsignificant difference. There were no differences between the two study groups in any of the individual components of this composite endpoint (N Engl J Med. 2015 Dec. 3. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1509225).

Sensitivity analyses and post hoc analyses of several subgroups of patients yielded similar results. When hospitalization for heart failure and coronary revascularization procedures were added to the primary endpoint, lixisenatide still provided no cardioprotective effect compared with placebo. Mortality from any cause was not significantly different between the two study groups, at 7.0% with lixisenatide and 7.4% with placebo.

Adverse effects leading to withdrawal from the study were more common with lixisenatide (11.4%) than placebo (7.2%). In particular, treatment discontinuation due to nausea and vomiting occurred in 3.0% of patients taking active treatment, compared with 0.4% of those taking placebo.

Sanofi, maker of lixisenatide, funded the study. Dr. Pfeffer reported receiving grants and personal fees from Sanofi and 20 other drug companies; his associates reported ties to numerous industry sources.

Adding lixisenatide to usual care failed to prevent major cardiovascular events in an industry-sponsored clinical trial involving patients with type 2 diabetes who had a recent acute coronary syndrome, according to a report published online Dec. 3 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Lixisenatide, a GLP-1-receptor agonist, is a glucose-lowering agent that inhibits glucagon secretion, prompts insulin production in response to hyperglycemia, and slows gastric emptying. In preliminary studies, lixisenatide showed some cardioprotective effects in myocardial ischemia and heart failure. To assess whether the drug would benefit diabetes patients at high CV risk, investigators conducted a randomized double-blind trial comparing lixisenatide with placebo in 6,068 patients who had type 2 diabetes and who had experienced acute coronary syndrome (ACS) during the preceding 6 months.

In addition to receiving usual diabetes care provided by their treating physicians, these patients (mean age, 60 years) were randomly assigned to self-administer once-daily subcutaneous injections of lixisenatide (n = 3,034) or a matching placebo (n = 3,034) and were followed for a mean of 25 months at 49 medical centers worldwide, said Dr. Marc A. Pfeffer of the cardiovascular division, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and Dzau Professor of Medicine a Harvard Medical School, Boston.

The primary endpoint of the study – a composite of death from CV causes, nonfatal MI, nonfatal stroke, or hospitalization for unstable angina – occurred in 13.4% of patients receiving lixisenatide and 13.2% of those receiving placebo, a nonsignificant difference. There were no differences between the two study groups in any of the individual components of this composite endpoint (N Engl J Med. 2015 Dec. 3. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1509225).

Sensitivity analyses and post hoc analyses of several subgroups of patients yielded similar results. When hospitalization for heart failure and coronary revascularization procedures were added to the primary endpoint, lixisenatide still provided no cardioprotective effect compared with placebo. Mortality from any cause was not significantly different between the two study groups, at 7.0% with lixisenatide and 7.4% with placebo.

Adverse effects leading to withdrawal from the study were more common with lixisenatide (11.4%) than placebo (7.2%). In particular, treatment discontinuation due to nausea and vomiting occurred in 3.0% of patients taking active treatment, compared with 0.4% of those taking placebo.

Sanofi, maker of lixisenatide, funded the study. Dr. Pfeffer reported receiving grants and personal fees from Sanofi and 20 other drug companies; his associates reported ties to numerous industry sources.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Adding lixisenatide to usual care failed to prevent major cardiovascular events in patients with type 2 diabetes who had a recent ACS.

Major finding: Death from CV causes, nonfatal MI, nonfatal stroke, or hospitalization for unstable angina occurred in 13.4% of participants receiving lixisenatide and 13.2% of those receiving placebo.

Data source: An international randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial involving 6,068 patients followed for a median of 2 years.

Disclosures: Sanofi, maker of lixisenatide, funded the study. Dr. Pfeffer reported receiving grants and personal fees from Sanofi and 20 other drug companies; his associates reported ties to numerous industry sources.

Pediatric Dermatology Consult - November 2015

Tinea versicolor

Tinea versicolor – also called pityriasis versicolor – is a benign superficial fungal skin infection caused by Malassezia. It presents as well-demarcated, oval, finely scaling macules, patches, or thin plaques, which can be hypopigmented, hyperpigmented, or erythematous.1,2,3 . The name, tinea versicolor, highlights the variability in the color of lesions.4

Scale may be minimal, but becomes more noticeable when lesions are scraped, which is called the “evoked scale sign.”5 The lesions may be asymptomatic or slightly pruritic.1 Lesions range in size from several millimeters to several centimeters and may coalesce.6 They are most commonly found on the chest, back, upper arms, and neck,2,7 but in children the face may be affected.1,3,8 Hypopigmented lesions may be most noticeable during the summer when the surrounding uninvolved skin darkens with sun exposure.9 Tinea versicolor is not contagious, but pigmentary changes may cause cosmetic concerns, and the condition may persist for years if not treated.2,4

Malassezia is a dimorphic fungus that is part of the normal skin flora in its yeast form, but if Malassezia converts to its hyphal form, it is able penetrate the stratum corneum and cause the tinea versicolor rash.1,10 The reason for the conversion from yeast to hyphal form is not fully understood.11Malassezia is lipophilic, so it thrives when sebum production is high, which is why tinea versicolor most commonly develops in adolescence or young adulthood, although it may be seen in younger children and older adults.12 Genetic predisposition, warm and humid environments, oily skin, use of oily creams, use of corticosteroids, hyperhidrosis, physical activity, malnutrition, immunosuppression, and exposure to sunlight increase susceptibility.1,13,14

Tinea versicolor is most commonly caused by Malassezia globosa and Malassezia furfur.13,15,16 Hypopigmentation may be caused by Malassezia’s production of azelaic acid, which inhibits the dopa-tyrosinase reaction that is part of melanin synthesis.15,17,18 Hyperpigmentation may result from inflammation.15,18 The evoked scale sign results from the production of keratinase, which disrupts the stratum corneum.5

Tinea versicolor often can be diagnosed by its characteristic clinical appearance and may fluoresce golden under a Wood’s ultraviolet lamp.19 Diagnosis can be confirmed by microscopic examination of skin scrapings treated with potassium hydroxide (KOH), which will have a “spaghetti and meatball” appearance, with the hyphae resembling spaghetti and spores resembling meatballs.1 For young children, removing scale with transparent tape can be a good alternative to scraping skin with a blade.2,19

Differential diagnosis

Postinflammatory pigment changes, both hypo and hyper, usually lack scale, may be anywhere on the body, and should have the same distribution as some original inflammation.

Pityriasis alba presents with hypopigmented patches, typically on the face, and has a more subtle “blotchy” appearance, without discrete oval patches. Pityriasis rosea may appear similar to tinea versicolor with erythema and scale, but it typically begins with a single, large herald patch, and scale is primarily at the outer border of the lesions.1

Tinea corporis (“ringworm”), which is caused by a dermatophyte, is more distinctly ring shaped with a scaly, vesicular, papular, or pustular border and there is often a clear center that may not scale when scraped.5,9 It is much more commonly localized, except in immunosuppressed patients or if mistreated with topical corticosteroids. Vitiligo lesions are completely depigmented, rather than just hypopigmented, and lack scale.1 Psoriasis scale is thicker and is visible without any provocation.

Treatment

First-line treatments for tinea versicolor include ketoconazole shampoo, selenium sulfide lotion or shampoo, and zinc pyrithione shampoo, which are left on for 5-10 minutes before rinsing.1,20 Any of these treatments is a fine first choice, as all are effective, and there are no robust data establishing the superiority of any single treatment.20 The typical treatment duration is 1-4 weeks.1 Longer treatment durations yield better cure rates.20 Ketoconazole and selenium sulfide also are available in foam formulations.11 Shampoo and foam formulations have the benefit of easily covering a large affected area.

Alternatively, terbinafine cream can be applied twice daily for a week or ketoconazole cream can be applied twice daily for 1-4 weeks.1,21 It is advisable to treat the whole trunk, neck, arms, and legs down to the knees, even if only a small area is involved.14,22 Antifungal treatments are well tolerated, with skin irritation and contact allergy being the most common adverse effects.1 Selenium sulfide has a strong odor.1

Hypopigmentation and hyperpigmentation can persist for months after the active infection has resolved and do not necessarily indicate a treatment failure.2,20 However, because Malassezia is a part of the normal skin flora, recurrence is common, occurring in 60%-80% of patients within 2 years.14 Recurrence or persistence of an active infection can be proven by a positive KOH scrape test. If a first treatment fails, a different first-line topical medication should be tried.1 Referral to a dermatologist is recommended if the eruption is unresponsive to two treatments.1

Oral antifungals such as itraconazole, fluconazole, and pramiconazole are effective for tinea versicolor, but have more adverse effects than topicals and interact with other medications because of their inhibition of the cytochrome P450 system, so they are used only for refractory or widespread disease.1,11 In 2013, the Food and Drug Administration issued a black box warning against oral ketoconazole due its ability to cause life-threatening hepatotoxicity and adrenal insufficiency1,23,24; it should not be used to treat tinea versicolor. Topical ketoconazole is safe and remains a first-line treatment for tinea versicolor, as discussed above.24 Oral terbinafine is not effective for tinea versicolor despite its efficacy as a topical treatment.11

Patients with recurrent tinea versicolor can try preventive therapy with ketoconazole shampoo, zinc pyrithione shampoo, or selenium sulfide lotion or shampoo one to four times per month.1 Oral antifungals also are effective for prevention of recurrence, but should be used only if the condition is refractory to topical prophylaxis.20,25 It is important to remember that hypopigmentation and hyperpigmentation may persist for months after resolution of active infection; absence of hyphae on skin scraping prepared with KOH confirms absence of active disease.15,16

References

- BMJ. 2015;350:h1394. doi:10.1136/bmj.h1394.

- Lancet. 2004 Sep 25-Oct 1;364(9440):1173-82.

- Pediatr Dermatol. 1991;8(1):9-12.

- J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2002;16(1):19-33.

- Arch Dermatol. 2009;145(9):1078.

- Vitiligo and other disorders of pigmentation, in: “Dermatology,” Vol 1. 3rd ed. (Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders, 2012, pp.1041-2.)

- Am J Clin Dermatol. 2000 Mar-Apr;1(2):75-80.

- Mycoses. 1995;38(5-6):227-8.

- “Skin Disorders Due to Fungi,” in: Hurwitz Clinical Pediatric Dermatology 4th ed. (Philadelphia: Saunders, 2011, pp. 396-403).

- Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2002 Apr;23(4):212-6.

- Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2014 Aug;15(12):1707-13.

- Clin Microbiol Rev. 2002 Jan;15(1):21-57.

- Clin Dermatol. 2010 Mar 4;28(2):185-9.

- J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994 Sep;31(3 Pt 2):S18-20.

- Int J Dermatol. 2014 Feb;53(2):137-41

- Mycopathologia. 2006 Dec;162(6):373-6.

- J Invest Dermatol. 1978 Sep;71(3):205-8.

- Int J Dermatol. 1992 Apr;31(4):253-6.

- Pediatr Dermatol. 2000 Jan-Feb;17(1):68-9.

- Arch Dermatol. 2010 Oct;146(10):1132-40.

- Dermatology (Basel). 1997;194(1):22-4. doi:10.1159/000246179.

- Red Book Plus: 2009 Report of the Committee on Infectious Disease.

- http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm362415.htm

- J Cutan Med Surg. 2015 Jul-Aug;19(4):352-7.

- Arch Dermatol. 2002 Jan;138(1):69-73.

Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital-San Diego and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. Ms. Haddock is a medical student at the University of California, San Diego, and a research associate at the hospital. Dr. Eichenfield and Ms. Haddock said they have no relevant financial disclosures.

Email to [email protected].

Tinea versicolor

Tinea versicolor – also called pityriasis versicolor – is a benign superficial fungal skin infection caused by Malassezia. It presents as well-demarcated, oval, finely scaling macules, patches, or thin plaques, which can be hypopigmented, hyperpigmented, or erythematous.1,2,3 . The name, tinea versicolor, highlights the variability in the color of lesions.4

Scale may be minimal, but becomes more noticeable when lesions are scraped, which is called the “evoked scale sign.”5 The lesions may be asymptomatic or slightly pruritic.1 Lesions range in size from several millimeters to several centimeters and may coalesce.6 They are most commonly found on the chest, back, upper arms, and neck,2,7 but in children the face may be affected.1,3,8 Hypopigmented lesions may be most noticeable during the summer when the surrounding uninvolved skin darkens with sun exposure.9 Tinea versicolor is not contagious, but pigmentary changes may cause cosmetic concerns, and the condition may persist for years if not treated.2,4

Malassezia is a dimorphic fungus that is part of the normal skin flora in its yeast form, but if Malassezia converts to its hyphal form, it is able penetrate the stratum corneum and cause the tinea versicolor rash.1,10 The reason for the conversion from yeast to hyphal form is not fully understood.11Malassezia is lipophilic, so it thrives when sebum production is high, which is why tinea versicolor most commonly develops in adolescence or young adulthood, although it may be seen in younger children and older adults.12 Genetic predisposition, warm and humid environments, oily skin, use of oily creams, use of corticosteroids, hyperhidrosis, physical activity, malnutrition, immunosuppression, and exposure to sunlight increase susceptibility.1,13,14

Tinea versicolor is most commonly caused by Malassezia globosa and Malassezia furfur.13,15,16 Hypopigmentation may be caused by Malassezia’s production of azelaic acid, which inhibits the dopa-tyrosinase reaction that is part of melanin synthesis.15,17,18 Hyperpigmentation may result from inflammation.15,18 The evoked scale sign results from the production of keratinase, which disrupts the stratum corneum.5

Tinea versicolor often can be diagnosed by its characteristic clinical appearance and may fluoresce golden under a Wood’s ultraviolet lamp.19 Diagnosis can be confirmed by microscopic examination of skin scrapings treated with potassium hydroxide (KOH), which will have a “spaghetti and meatball” appearance, with the hyphae resembling spaghetti and spores resembling meatballs.1 For young children, removing scale with transparent tape can be a good alternative to scraping skin with a blade.2,19

Differential diagnosis

Postinflammatory pigment changes, both hypo and hyper, usually lack scale, may be anywhere on the body, and should have the same distribution as some original inflammation.

Pityriasis alba presents with hypopigmented patches, typically on the face, and has a more subtle “blotchy” appearance, without discrete oval patches. Pityriasis rosea may appear similar to tinea versicolor with erythema and scale, but it typically begins with a single, large herald patch, and scale is primarily at the outer border of the lesions.1

Tinea corporis (“ringworm”), which is caused by a dermatophyte, is more distinctly ring shaped with a scaly, vesicular, papular, or pustular border and there is often a clear center that may not scale when scraped.5,9 It is much more commonly localized, except in immunosuppressed patients or if mistreated with topical corticosteroids. Vitiligo lesions are completely depigmented, rather than just hypopigmented, and lack scale.1 Psoriasis scale is thicker and is visible without any provocation.

Treatment

First-line treatments for tinea versicolor include ketoconazole shampoo, selenium sulfide lotion or shampoo, and zinc pyrithione shampoo, which are left on for 5-10 minutes before rinsing.1,20 Any of these treatments is a fine first choice, as all are effective, and there are no robust data establishing the superiority of any single treatment.20 The typical treatment duration is 1-4 weeks.1 Longer treatment durations yield better cure rates.20 Ketoconazole and selenium sulfide also are available in foam formulations.11 Shampoo and foam formulations have the benefit of easily covering a large affected area.

Alternatively, terbinafine cream can be applied twice daily for a week or ketoconazole cream can be applied twice daily for 1-4 weeks.1,21 It is advisable to treat the whole trunk, neck, arms, and legs down to the knees, even if only a small area is involved.14,22 Antifungal treatments are well tolerated, with skin irritation and contact allergy being the most common adverse effects.1 Selenium sulfide has a strong odor.1

Hypopigmentation and hyperpigmentation can persist for months after the active infection has resolved and do not necessarily indicate a treatment failure.2,20 However, because Malassezia is a part of the normal skin flora, recurrence is common, occurring in 60%-80% of patients within 2 years.14 Recurrence or persistence of an active infection can be proven by a positive KOH scrape test. If a first treatment fails, a different first-line topical medication should be tried.1 Referral to a dermatologist is recommended if the eruption is unresponsive to two treatments.1

Oral antifungals such as itraconazole, fluconazole, and pramiconazole are effective for tinea versicolor, but have more adverse effects than topicals and interact with other medications because of their inhibition of the cytochrome P450 system, so they are used only for refractory or widespread disease.1,11 In 2013, the Food and Drug Administration issued a black box warning against oral ketoconazole due its ability to cause life-threatening hepatotoxicity and adrenal insufficiency1,23,24; it should not be used to treat tinea versicolor. Topical ketoconazole is safe and remains a first-line treatment for tinea versicolor, as discussed above.24 Oral terbinafine is not effective for tinea versicolor despite its efficacy as a topical treatment.11

Patients with recurrent tinea versicolor can try preventive therapy with ketoconazole shampoo, zinc pyrithione shampoo, or selenium sulfide lotion or shampoo one to four times per month.1 Oral antifungals also are effective for prevention of recurrence, but should be used only if the condition is refractory to topical prophylaxis.20,25 It is important to remember that hypopigmentation and hyperpigmentation may persist for months after resolution of active infection; absence of hyphae on skin scraping prepared with KOH confirms absence of active disease.15,16

References

- BMJ. 2015;350:h1394. doi:10.1136/bmj.h1394.

- Lancet. 2004 Sep 25-Oct 1;364(9440):1173-82.

- Pediatr Dermatol. 1991;8(1):9-12.

- J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2002;16(1):19-33.

- Arch Dermatol. 2009;145(9):1078.

- Vitiligo and other disorders of pigmentation, in: “Dermatology,” Vol 1. 3rd ed. (Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders, 2012, pp.1041-2.)

- Am J Clin Dermatol. 2000 Mar-Apr;1(2):75-80.

- Mycoses. 1995;38(5-6):227-8.

- “Skin Disorders Due to Fungi,” in: Hurwitz Clinical Pediatric Dermatology 4th ed. (Philadelphia: Saunders, 2011, pp. 396-403).

- Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2002 Apr;23(4):212-6.

- Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2014 Aug;15(12):1707-13.

- Clin Microbiol Rev. 2002 Jan;15(1):21-57.

- Clin Dermatol. 2010 Mar 4;28(2):185-9.

- J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994 Sep;31(3 Pt 2):S18-20.

- Int J Dermatol. 2014 Feb;53(2):137-41

- Mycopathologia. 2006 Dec;162(6):373-6.

- J Invest Dermatol. 1978 Sep;71(3):205-8.

- Int J Dermatol. 1992 Apr;31(4):253-6.

- Pediatr Dermatol. 2000 Jan-Feb;17(1):68-9.

- Arch Dermatol. 2010 Oct;146(10):1132-40.

- Dermatology (Basel). 1997;194(1):22-4. doi:10.1159/000246179.

- Red Book Plus: 2009 Report of the Committee on Infectious Disease.

- http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm362415.htm

- J Cutan Med Surg. 2015 Jul-Aug;19(4):352-7.

- Arch Dermatol. 2002 Jan;138(1):69-73.

Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital-San Diego and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. Ms. Haddock is a medical student at the University of California, San Diego, and a research associate at the hospital. Dr. Eichenfield and Ms. Haddock said they have no relevant financial disclosures.

Email to [email protected].

Tinea versicolor

Tinea versicolor – also called pityriasis versicolor – is a benign superficial fungal skin infection caused by Malassezia. It presents as well-demarcated, oval, finely scaling macules, patches, or thin plaques, which can be hypopigmented, hyperpigmented, or erythematous.1,2,3 . The name, tinea versicolor, highlights the variability in the color of lesions.4

Scale may be minimal, but becomes more noticeable when lesions are scraped, which is called the “evoked scale sign.”5 The lesions may be asymptomatic or slightly pruritic.1 Lesions range in size from several millimeters to several centimeters and may coalesce.6 They are most commonly found on the chest, back, upper arms, and neck,2,7 but in children the face may be affected.1,3,8 Hypopigmented lesions may be most noticeable during the summer when the surrounding uninvolved skin darkens with sun exposure.9 Tinea versicolor is not contagious, but pigmentary changes may cause cosmetic concerns, and the condition may persist for years if not treated.2,4

Malassezia is a dimorphic fungus that is part of the normal skin flora in its yeast form, but if Malassezia converts to its hyphal form, it is able penetrate the stratum corneum and cause the tinea versicolor rash.1,10 The reason for the conversion from yeast to hyphal form is not fully understood.11Malassezia is lipophilic, so it thrives when sebum production is high, which is why tinea versicolor most commonly develops in adolescence or young adulthood, although it may be seen in younger children and older adults.12 Genetic predisposition, warm and humid environments, oily skin, use of oily creams, use of corticosteroids, hyperhidrosis, physical activity, malnutrition, immunosuppression, and exposure to sunlight increase susceptibility.1,13,14

Tinea versicolor is most commonly caused by Malassezia globosa and Malassezia furfur.13,15,16 Hypopigmentation may be caused by Malassezia’s production of azelaic acid, which inhibits the dopa-tyrosinase reaction that is part of melanin synthesis.15,17,18 Hyperpigmentation may result from inflammation.15,18 The evoked scale sign results from the production of keratinase, which disrupts the stratum corneum.5

Tinea versicolor often can be diagnosed by its characteristic clinical appearance and may fluoresce golden under a Wood’s ultraviolet lamp.19 Diagnosis can be confirmed by microscopic examination of skin scrapings treated with potassium hydroxide (KOH), which will have a “spaghetti and meatball” appearance, with the hyphae resembling spaghetti and spores resembling meatballs.1 For young children, removing scale with transparent tape can be a good alternative to scraping skin with a blade.2,19

Differential diagnosis

Postinflammatory pigment changes, both hypo and hyper, usually lack scale, may be anywhere on the body, and should have the same distribution as some original inflammation.

Pityriasis alba presents with hypopigmented patches, typically on the face, and has a more subtle “blotchy” appearance, without discrete oval patches. Pityriasis rosea may appear similar to tinea versicolor with erythema and scale, but it typically begins with a single, large herald patch, and scale is primarily at the outer border of the lesions.1

Tinea corporis (“ringworm”), which is caused by a dermatophyte, is more distinctly ring shaped with a scaly, vesicular, papular, or pustular border and there is often a clear center that may not scale when scraped.5,9 It is much more commonly localized, except in immunosuppressed patients or if mistreated with topical corticosteroids. Vitiligo lesions are completely depigmented, rather than just hypopigmented, and lack scale.1 Psoriasis scale is thicker and is visible without any provocation.

Treatment

First-line treatments for tinea versicolor include ketoconazole shampoo, selenium sulfide lotion or shampoo, and zinc pyrithione shampoo, which are left on for 5-10 minutes before rinsing.1,20 Any of these treatments is a fine first choice, as all are effective, and there are no robust data establishing the superiority of any single treatment.20 The typical treatment duration is 1-4 weeks.1 Longer treatment durations yield better cure rates.20 Ketoconazole and selenium sulfide also are available in foam formulations.11 Shampoo and foam formulations have the benefit of easily covering a large affected area.