User login

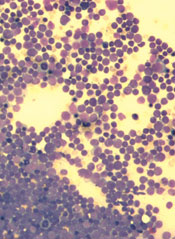

CHMP recommends blinatumomab for ALL

The European Medicines Agency’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) has recommended conditional marketing authorization for blinatumomab (Blincyto) to treat adults with relapsed or refractory Philadelphia chromosome-negative (Ph-) B-precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).

Blinatumomab is a bispecific T-cell engager (BiTE®) antibody construct that binds to CD19 on the surface of B cells and CD3 on the surface of T cells.

The product already has conditional approval in the US to treat patients with relapsed or refractory Ph- B-precursor ALL.

The CHMP’s positive opinion of blinatumomab will be reviewed by the European Commission (EC).

The EC usually follows the CHMP’s recommendations and is expected to deliver its final decision within 3 months. The EC’s decision will apply to the 28 member countries of the European Union, as well as Iceland, Lichtenstein, and Norway.

Conditional marketing authorizations are valid for 1 year, on a renewable basis. The holder is required to complete ongoing studies or conduct new studies with the goal of confirming that a drug’s benefit-risk balance is positive.

Conditional marketing authorization is converted to a full authorization once these commitments have been fulfilled.

The conditional marketing authorization application for blinatumomab is based on a pair of phase 2 trials—Study ‘211 and Study ‘206.

Study ‘211

Results of Study ‘211 were presented at EHA 2014. The trial included 189 patients with Ph- relapsed or refractory B-precursor ALL.

The primary endpoint was complete remission or complete remission with partial hematologic recovery (CR/CRh). About 43% of patients achieved this endpoint within 2 cycles of therapy.

According to researchers, the most serious adverse events in this study were infection (31.7%), neurologic events (16.4%), neutropenia/febrile neutropenia (15.3%), cytokine release syndrome (CRS, 0.5%), and tumor lysis syndrome (0.5%).

Study ‘206

Results of Study ‘206 were presented at ASCO 2012. The trial included 36 patients with relapsed or refractory B-precursor ALL.

In this trial, the CR/CRh rate was 69.4% (25/36), with 15 patients achieving a CR (41.7%), and 10 patients achieving CRh (27.8%).

The “medically important” adverse events in this study, according to researchers, were CRS (n=3), central nervous system (CNS) events (3 seizures and 3 cases of encephalopathy), and fungal infection resulting in death (n=1).

However, the researchers found they could prevent CRS with dexamethasone. In addition, the CNS events were reversible, and blinatumomab could be reintroduced in 4 of the 6 patients with CNS events.

Blinatumomab is under development by Amgen. For more details on the drug, visit www.blincyto.com. ![]()

The European Medicines Agency’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) has recommended conditional marketing authorization for blinatumomab (Blincyto) to treat adults with relapsed or refractory Philadelphia chromosome-negative (Ph-) B-precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).

Blinatumomab is a bispecific T-cell engager (BiTE®) antibody construct that binds to CD19 on the surface of B cells and CD3 on the surface of T cells.

The product already has conditional approval in the US to treat patients with relapsed or refractory Ph- B-precursor ALL.

The CHMP’s positive opinion of blinatumomab will be reviewed by the European Commission (EC).

The EC usually follows the CHMP’s recommendations and is expected to deliver its final decision within 3 months. The EC’s decision will apply to the 28 member countries of the European Union, as well as Iceland, Lichtenstein, and Norway.

Conditional marketing authorizations are valid for 1 year, on a renewable basis. The holder is required to complete ongoing studies or conduct new studies with the goal of confirming that a drug’s benefit-risk balance is positive.

Conditional marketing authorization is converted to a full authorization once these commitments have been fulfilled.

The conditional marketing authorization application for blinatumomab is based on a pair of phase 2 trials—Study ‘211 and Study ‘206.

Study ‘211

Results of Study ‘211 were presented at EHA 2014. The trial included 189 patients with Ph- relapsed or refractory B-precursor ALL.

The primary endpoint was complete remission or complete remission with partial hematologic recovery (CR/CRh). About 43% of patients achieved this endpoint within 2 cycles of therapy.

According to researchers, the most serious adverse events in this study were infection (31.7%), neurologic events (16.4%), neutropenia/febrile neutropenia (15.3%), cytokine release syndrome (CRS, 0.5%), and tumor lysis syndrome (0.5%).

Study ‘206

Results of Study ‘206 were presented at ASCO 2012. The trial included 36 patients with relapsed or refractory B-precursor ALL.

In this trial, the CR/CRh rate was 69.4% (25/36), with 15 patients achieving a CR (41.7%), and 10 patients achieving CRh (27.8%).

The “medically important” adverse events in this study, according to researchers, were CRS (n=3), central nervous system (CNS) events (3 seizures and 3 cases of encephalopathy), and fungal infection resulting in death (n=1).

However, the researchers found they could prevent CRS with dexamethasone. In addition, the CNS events were reversible, and blinatumomab could be reintroduced in 4 of the 6 patients with CNS events.

Blinatumomab is under development by Amgen. For more details on the drug, visit www.blincyto.com. ![]()

The European Medicines Agency’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) has recommended conditional marketing authorization for blinatumomab (Blincyto) to treat adults with relapsed or refractory Philadelphia chromosome-negative (Ph-) B-precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).

Blinatumomab is a bispecific T-cell engager (BiTE®) antibody construct that binds to CD19 on the surface of B cells and CD3 on the surface of T cells.

The product already has conditional approval in the US to treat patients with relapsed or refractory Ph- B-precursor ALL.

The CHMP’s positive opinion of blinatumomab will be reviewed by the European Commission (EC).

The EC usually follows the CHMP’s recommendations and is expected to deliver its final decision within 3 months. The EC’s decision will apply to the 28 member countries of the European Union, as well as Iceland, Lichtenstein, and Norway.

Conditional marketing authorizations are valid for 1 year, on a renewable basis. The holder is required to complete ongoing studies or conduct new studies with the goal of confirming that a drug’s benefit-risk balance is positive.

Conditional marketing authorization is converted to a full authorization once these commitments have been fulfilled.

The conditional marketing authorization application for blinatumomab is based on a pair of phase 2 trials—Study ‘211 and Study ‘206.

Study ‘211

Results of Study ‘211 were presented at EHA 2014. The trial included 189 patients with Ph- relapsed or refractory B-precursor ALL.

The primary endpoint was complete remission or complete remission with partial hematologic recovery (CR/CRh). About 43% of patients achieved this endpoint within 2 cycles of therapy.

According to researchers, the most serious adverse events in this study were infection (31.7%), neurologic events (16.4%), neutropenia/febrile neutropenia (15.3%), cytokine release syndrome (CRS, 0.5%), and tumor lysis syndrome (0.5%).

Study ‘206

Results of Study ‘206 were presented at ASCO 2012. The trial included 36 patients with relapsed or refractory B-precursor ALL.

In this trial, the CR/CRh rate was 69.4% (25/36), with 15 patients achieving a CR (41.7%), and 10 patients achieving CRh (27.8%).

The “medically important” adverse events in this study, according to researchers, were CRS (n=3), central nervous system (CNS) events (3 seizures and 3 cases of encephalopathy), and fungal infection resulting in death (n=1).

However, the researchers found they could prevent CRS with dexamethasone. In addition, the CNS events were reversible, and blinatumomab could be reintroduced in 4 of the 6 patients with CNS events.

Blinatumomab is under development by Amgen. For more details on the drug, visit www.blincyto.com. ![]()

CHMP recommends authorization for idarucizumab

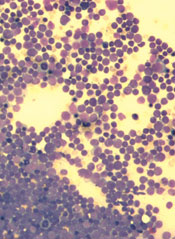

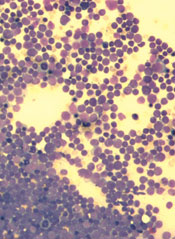

Image by Andre E.X. Brown

The European Medicines Agency’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) is recommending that idarucizumab receive marketing authorization in the European Union.

Idarucizumab (to be marketed as Praxbind) is a humanized antibody fragment designed to reverse the anticoagulant effects of dabigatran etexilate (Pradaxa).

Idarucizumab is intended for patients who must undergo emergency surgery/urgent procedures and those who experience uncontrolled or life-threatening bleeding while on dabigatran.

The CHMP’s positive opinion of idarucizumab will be reviewed by the European Commission (EC).

The EC usually follows the CHMP’s recommendations and is expected to deliver its final decision within 3 months. The EC’s decision will apply to the 28 member countries of the European Union, as well as Iceland, Lichtenstein, and Norway.

The CHMP’s positive opinion was based on results with idarucizumab in healthy volunteers and an interim analysis of the phase 3 RE-VERSE AD trial.

In the study of healthy volunteers, the pharmacokinetic profile of idarucizumab met the requirement for rapid peak exposure and rapid elimination, with no effect on pharmacodynamic parameters. And researchers said the drug was well tolerated.

In RE-VERSE AD, researchers evaluated idarucizumab in emergency settings. The drug normalized diluted thrombin time and ecarin clotting time in a majority of dabigatran-treated patients with uncontrolled or life-threatening bleeding complications and most patients who required emergency surgery or an invasive procedure.

The researchers said there were no safety concerns related to idarucizumab. However, 23% of patients in this trial experienced serious adverse events, 20% of patients died, and several patients had thrombotic or bleeding events.

Idarucizumab is being developed by Boehringer Ingelheim, the company that makes dabigatran.

Idarucizumab is currently under review by regulatory authorities worldwide, including the US Food and Drug Administration. Boehringer Ingelheim plans to submit idarucizumab in all countries where dabigatran is licensed. ![]()

Image by Andre E.X. Brown

The European Medicines Agency’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) is recommending that idarucizumab receive marketing authorization in the European Union.

Idarucizumab (to be marketed as Praxbind) is a humanized antibody fragment designed to reverse the anticoagulant effects of dabigatran etexilate (Pradaxa).

Idarucizumab is intended for patients who must undergo emergency surgery/urgent procedures and those who experience uncontrolled or life-threatening bleeding while on dabigatran.

The CHMP’s positive opinion of idarucizumab will be reviewed by the European Commission (EC).

The EC usually follows the CHMP’s recommendations and is expected to deliver its final decision within 3 months. The EC’s decision will apply to the 28 member countries of the European Union, as well as Iceland, Lichtenstein, and Norway.

The CHMP’s positive opinion was based on results with idarucizumab in healthy volunteers and an interim analysis of the phase 3 RE-VERSE AD trial.

In the study of healthy volunteers, the pharmacokinetic profile of idarucizumab met the requirement for rapid peak exposure and rapid elimination, with no effect on pharmacodynamic parameters. And researchers said the drug was well tolerated.

In RE-VERSE AD, researchers evaluated idarucizumab in emergency settings. The drug normalized diluted thrombin time and ecarin clotting time in a majority of dabigatran-treated patients with uncontrolled or life-threatening bleeding complications and most patients who required emergency surgery or an invasive procedure.

The researchers said there were no safety concerns related to idarucizumab. However, 23% of patients in this trial experienced serious adverse events, 20% of patients died, and several patients had thrombotic or bleeding events.

Idarucizumab is being developed by Boehringer Ingelheim, the company that makes dabigatran.

Idarucizumab is currently under review by regulatory authorities worldwide, including the US Food and Drug Administration. Boehringer Ingelheim plans to submit idarucizumab in all countries where dabigatran is licensed. ![]()

Image by Andre E.X. Brown

The European Medicines Agency’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) is recommending that idarucizumab receive marketing authorization in the European Union.

Idarucizumab (to be marketed as Praxbind) is a humanized antibody fragment designed to reverse the anticoagulant effects of dabigatran etexilate (Pradaxa).

Idarucizumab is intended for patients who must undergo emergency surgery/urgent procedures and those who experience uncontrolled or life-threatening bleeding while on dabigatran.

The CHMP’s positive opinion of idarucizumab will be reviewed by the European Commission (EC).

The EC usually follows the CHMP’s recommendations and is expected to deliver its final decision within 3 months. The EC’s decision will apply to the 28 member countries of the European Union, as well as Iceland, Lichtenstein, and Norway.

The CHMP’s positive opinion was based on results with idarucizumab in healthy volunteers and an interim analysis of the phase 3 RE-VERSE AD trial.

In the study of healthy volunteers, the pharmacokinetic profile of idarucizumab met the requirement for rapid peak exposure and rapid elimination, with no effect on pharmacodynamic parameters. And researchers said the drug was well tolerated.

In RE-VERSE AD, researchers evaluated idarucizumab in emergency settings. The drug normalized diluted thrombin time and ecarin clotting time in a majority of dabigatran-treated patients with uncontrolled or life-threatening bleeding complications and most patients who required emergency surgery or an invasive procedure.

The researchers said there were no safety concerns related to idarucizumab. However, 23% of patients in this trial experienced serious adverse events, 20% of patients died, and several patients had thrombotic or bleeding events.

Idarucizumab is being developed by Boehringer Ingelheim, the company that makes dabigatran.

Idarucizumab is currently under review by regulatory authorities worldwide, including the US Food and Drug Administration. Boehringer Ingelheim plans to submit idarucizumab in all countries where dabigatran is licensed. ![]()

Cardiac biomarkers predict cancer mortality

High circulating levels of six cardiovascular biomarkers predicted cancer mortality even before the start of treatment and regardless of tumor type or stage, according to a study published online Sept. 28 in Heart.

Cancer patients had high levels of these biomarkers even though they had no clinical signs of heart disease or concurrent infections, wrote Noemi Pavo of Medical University of Vienna. The findings suggest that these patients could benefit from enhanced heart failure therapies that go beyond the current focus on preventing cardiotoxic side effects of chemotherapy and radiotherapy, noted Dr. Pavo and her associates.

Cardiovascular hormone and peptide levels can rise during cancer treatment, but whether cancer itself affects these biomarkers has been unclear, the investigators said. Therefore, they prospectively measured levels of five cardiovascular hormones – NT-proBNP, MR-proANP, MR-proADM, CT-pro-ET, and copeptin – in addition to high-sensitive troponin, the proinflammatory markers interleukin 6 and C-reactive protein, and cytokines serum amyloid A, haptoglobin, and fibronectin, in 555 patients with newly diagnosed, as-yet-untreated cancer (Heart 2015 Sep 28. doi:10.1136/heartjnl-2015-307848).

A total of 186 patients (34%) died after an average of 25 months of follow-up, the researchers reported. Levels of all cardiovascular hormones and hsTnT increased with tumor stage progression. After the researchers controlled for age, tumor type, tumor stage, glomerular filtration rate, and cardiac status, rising levels of all five cardiac hormones and hsTnT independently predicted mortality, with adjusted hazard ratios ranging from 1.21 for CT-proET-1 and hsTnT to 1.54 for the natural logarithm of NT-proBNP, and P values ranging from .014 to less than.001.

“All of these markers are strongly related to mortality, implying a direct association with disease progression,” the researchers said. “While our endpoint [was] all-cause mortality, precise information about the percentage of cardiovascular-related death would certainly be of important clinical interest. Since post hoc interpretations of certifications of death are not reliable, the development of a cardiac disease during cancer progression should be documented in longitudinal studies in the future.”

An unrestricted grant from Thermo Fisher funded the study. The researchers declared no competing interests.

This study opens the potential for new management strategies integrating cardiology and oncology. Treating overt and perhaps subclinical cardiac dysfunction may improve outcomes in patients with cancer, and may possibly improve progression-free cancer survival based on optimizing cancer treatment and preventing interruptions. These biomarkers could serve as a surveillance strategy for both cardiologists and oncologists. It would be equally tantalizing to know whether treating the cancer effectively improves cardiac outcomes, but this will be more challenging to unravel if the cancer treatment imparts potential cardiotoxicity.

The key next stage will be to reproduce these findings in a prospectively designed multicenter study with larger numbers to validate the conclusion, collect the mode of death, and also to consider whether serial biomarker assessment adds further predictive power. Pavo et al. should be congratulated on bringing to our attention the widening complexity of biomarker biology and the potential to identify single biomarkers with the unique properties to predict both cardiovascular and oncology outcomes.

Dr. Alexander Lyon is at Imperial College and Royal Brompton Hospital in London. He reported receiving research funding and having consulting and advisory relationships with Pfizer, Onyx Pharmaceuticals, Ferring Pharmaceuticals, and Clinigen Group. These remarks are from his editorial (Heart 2015 Sep. 28. doi:10.1136/heartjnl-2015-308208).

This study opens the potential for new management strategies integrating cardiology and oncology. Treating overt and perhaps subclinical cardiac dysfunction may improve outcomes in patients with cancer, and may possibly improve progression-free cancer survival based on optimizing cancer treatment and preventing interruptions. These biomarkers could serve as a surveillance strategy for both cardiologists and oncologists. It would be equally tantalizing to know whether treating the cancer effectively improves cardiac outcomes, but this will be more challenging to unravel if the cancer treatment imparts potential cardiotoxicity.

The key next stage will be to reproduce these findings in a prospectively designed multicenter study with larger numbers to validate the conclusion, collect the mode of death, and also to consider whether serial biomarker assessment adds further predictive power. Pavo et al. should be congratulated on bringing to our attention the widening complexity of biomarker biology and the potential to identify single biomarkers with the unique properties to predict both cardiovascular and oncology outcomes.

Dr. Alexander Lyon is at Imperial College and Royal Brompton Hospital in London. He reported receiving research funding and having consulting and advisory relationships with Pfizer, Onyx Pharmaceuticals, Ferring Pharmaceuticals, and Clinigen Group. These remarks are from his editorial (Heart 2015 Sep. 28. doi:10.1136/heartjnl-2015-308208).

This study opens the potential for new management strategies integrating cardiology and oncology. Treating overt and perhaps subclinical cardiac dysfunction may improve outcomes in patients with cancer, and may possibly improve progression-free cancer survival based on optimizing cancer treatment and preventing interruptions. These biomarkers could serve as a surveillance strategy for both cardiologists and oncologists. It would be equally tantalizing to know whether treating the cancer effectively improves cardiac outcomes, but this will be more challenging to unravel if the cancer treatment imparts potential cardiotoxicity.

The key next stage will be to reproduce these findings in a prospectively designed multicenter study with larger numbers to validate the conclusion, collect the mode of death, and also to consider whether serial biomarker assessment adds further predictive power. Pavo et al. should be congratulated on bringing to our attention the widening complexity of biomarker biology and the potential to identify single biomarkers with the unique properties to predict both cardiovascular and oncology outcomes.

Dr. Alexander Lyon is at Imperial College and Royal Brompton Hospital in London. He reported receiving research funding and having consulting and advisory relationships with Pfizer, Onyx Pharmaceuticals, Ferring Pharmaceuticals, and Clinigen Group. These remarks are from his editorial (Heart 2015 Sep. 28. doi:10.1136/heartjnl-2015-308208).

High circulating levels of six cardiovascular biomarkers predicted cancer mortality even before the start of treatment and regardless of tumor type or stage, according to a study published online Sept. 28 in Heart.

Cancer patients had high levels of these biomarkers even though they had no clinical signs of heart disease or concurrent infections, wrote Noemi Pavo of Medical University of Vienna. The findings suggest that these patients could benefit from enhanced heart failure therapies that go beyond the current focus on preventing cardiotoxic side effects of chemotherapy and radiotherapy, noted Dr. Pavo and her associates.

Cardiovascular hormone and peptide levels can rise during cancer treatment, but whether cancer itself affects these biomarkers has been unclear, the investigators said. Therefore, they prospectively measured levels of five cardiovascular hormones – NT-proBNP, MR-proANP, MR-proADM, CT-pro-ET, and copeptin – in addition to high-sensitive troponin, the proinflammatory markers interleukin 6 and C-reactive protein, and cytokines serum amyloid A, haptoglobin, and fibronectin, in 555 patients with newly diagnosed, as-yet-untreated cancer (Heart 2015 Sep 28. doi:10.1136/heartjnl-2015-307848).

A total of 186 patients (34%) died after an average of 25 months of follow-up, the researchers reported. Levels of all cardiovascular hormones and hsTnT increased with tumor stage progression. After the researchers controlled for age, tumor type, tumor stage, glomerular filtration rate, and cardiac status, rising levels of all five cardiac hormones and hsTnT independently predicted mortality, with adjusted hazard ratios ranging from 1.21 for CT-proET-1 and hsTnT to 1.54 for the natural logarithm of NT-proBNP, and P values ranging from .014 to less than.001.

“All of these markers are strongly related to mortality, implying a direct association with disease progression,” the researchers said. “While our endpoint [was] all-cause mortality, precise information about the percentage of cardiovascular-related death would certainly be of important clinical interest. Since post hoc interpretations of certifications of death are not reliable, the development of a cardiac disease during cancer progression should be documented in longitudinal studies in the future.”

An unrestricted grant from Thermo Fisher funded the study. The researchers declared no competing interests.

High circulating levels of six cardiovascular biomarkers predicted cancer mortality even before the start of treatment and regardless of tumor type or stage, according to a study published online Sept. 28 in Heart.

Cancer patients had high levels of these biomarkers even though they had no clinical signs of heart disease or concurrent infections, wrote Noemi Pavo of Medical University of Vienna. The findings suggest that these patients could benefit from enhanced heart failure therapies that go beyond the current focus on preventing cardiotoxic side effects of chemotherapy and radiotherapy, noted Dr. Pavo and her associates.

Cardiovascular hormone and peptide levels can rise during cancer treatment, but whether cancer itself affects these biomarkers has been unclear, the investigators said. Therefore, they prospectively measured levels of five cardiovascular hormones – NT-proBNP, MR-proANP, MR-proADM, CT-pro-ET, and copeptin – in addition to high-sensitive troponin, the proinflammatory markers interleukin 6 and C-reactive protein, and cytokines serum amyloid A, haptoglobin, and fibronectin, in 555 patients with newly diagnosed, as-yet-untreated cancer (Heart 2015 Sep 28. doi:10.1136/heartjnl-2015-307848).

A total of 186 patients (34%) died after an average of 25 months of follow-up, the researchers reported. Levels of all cardiovascular hormones and hsTnT increased with tumor stage progression. After the researchers controlled for age, tumor type, tumor stage, glomerular filtration rate, and cardiac status, rising levels of all five cardiac hormones and hsTnT independently predicted mortality, with adjusted hazard ratios ranging from 1.21 for CT-proET-1 and hsTnT to 1.54 for the natural logarithm of NT-proBNP, and P values ranging from .014 to less than.001.

“All of these markers are strongly related to mortality, implying a direct association with disease progression,” the researchers said. “While our endpoint [was] all-cause mortality, precise information about the percentage of cardiovascular-related death would certainly be of important clinical interest. Since post hoc interpretations of certifications of death are not reliable, the development of a cardiac disease during cancer progression should be documented in longitudinal studies in the future.”

An unrestricted grant from Thermo Fisher funded the study. The researchers declared no competing interests.

FROM HEART

Key clinical point: High levels of cardiac hormones and peptides predicted mortality in patients with first-time, as-yet-untreated cancer.

Major finding: Rising levels of all biomarkers significantly predicted mortality, with adjusted hazard ratios ranging from 1.21 to 1.54.

Data source: Prospective observational study of 555 cancer patients.

Disclosures: An unrestricted grant from Thermo Fisher funded the study. The researchers declared no competing interests.

S. lugdunensis osteoarticular infection often linked to orthopedic devices

SAN DIEGO – Bone and joint infections caused by Staphylococcus lugdunensis are an underestimated hospital-acquired infection often associated with orthopedic devices, according to a multicenter study.

“Consider potential relapse even after 1 year of the end of antibiotic treatment and follow patients with bone and joint infections caused by S. lugdunensis for a minimum 2 years after the end of treatment,” lead study author Dr. Piseth Seng said in an interview at the annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy.

S. lugdunensis is a virulent coagulase-negative staphylococcus which behaves like S. aureus. Prior to the current study, only 47 cases are believed to be published in the medical literature, according to Dr. Seng of the department of internal medicine at Assistance Publique des Hôpitaux de Marseille (France). The purpose of the current study was to report a series of 138 cases of S. lugdunensis osteoarticular infection managed in nine hospital centers and three private clinics in France from January 1995 to December 2014.

The mean age of patients was 61 years, and 68% were male. Of the 138 cases, 113 (82%) were associated with an orthopedic device, including 2 cases of infection after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction, 66 cases of prosthetic joint infection, and 3 cases of vertebral orthopedic device infection. The majority of orthopedic device infections (88%) occurred more than 1 month after implantation, while the remaining 12% occurred within the first month of implantation.

The researchers identified 30 cases (22%) of bone and joint infection that occurred in the absence of an orthopedic device, including 7 cases of arthritis, 21 cases of osteitis, and 2 cases of vertebral osteomyelitis.

The majority of patients (91%) received a combination of antibiotic and surgical treatment, including amputation (6%), orthopedic prosthesis removal (14%), internal orthopedic device removal (23%), and surgical debridement and retention of the orthopedic device (41%). The proportion of S. lugdunensis strains with reduced susceptibility to antistaphylococcal agents was low. Resistant strains included five to oxacillin, four to fosfomycin, two to fusidic acid, two to co-trimoxazole, one to rifampicin, and one to clindamycin.

To date, relapses have occurred in 19% of the 123 patients in whom researchers have complete follow-up data. The readmission rate among these patients was 76%, and four (3%) died of their infection. “These relapses were not associated with risk factor or comorbidity or polymicrobial infection,” noted Dr. Seng, who characterized the incidence of bone and joint infections caused by S. lugdunensis as being under reported. “S. lugdunensis is known as an organism forming biofilms, but treatment options (surgical debridement or prosthesis removal) did not influence clinical outcomes.”

The mean time to relapse was 305 days and no risk factor or comorbidity was associated with relapse.

Dr. Seng acknowledged that the study was limited by its retrospective design. He and his associates reported having no financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Bone and joint infections caused by Staphylococcus lugdunensis are an underestimated hospital-acquired infection often associated with orthopedic devices, according to a multicenter study.

“Consider potential relapse even after 1 year of the end of antibiotic treatment and follow patients with bone and joint infections caused by S. lugdunensis for a minimum 2 years after the end of treatment,” lead study author Dr. Piseth Seng said in an interview at the annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy.

S. lugdunensis is a virulent coagulase-negative staphylococcus which behaves like S. aureus. Prior to the current study, only 47 cases are believed to be published in the medical literature, according to Dr. Seng of the department of internal medicine at Assistance Publique des Hôpitaux de Marseille (France). The purpose of the current study was to report a series of 138 cases of S. lugdunensis osteoarticular infection managed in nine hospital centers and three private clinics in France from January 1995 to December 2014.

The mean age of patients was 61 years, and 68% were male. Of the 138 cases, 113 (82%) were associated with an orthopedic device, including 2 cases of infection after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction, 66 cases of prosthetic joint infection, and 3 cases of vertebral orthopedic device infection. The majority of orthopedic device infections (88%) occurred more than 1 month after implantation, while the remaining 12% occurred within the first month of implantation.

The researchers identified 30 cases (22%) of bone and joint infection that occurred in the absence of an orthopedic device, including 7 cases of arthritis, 21 cases of osteitis, and 2 cases of vertebral osteomyelitis.

The majority of patients (91%) received a combination of antibiotic and surgical treatment, including amputation (6%), orthopedic prosthesis removal (14%), internal orthopedic device removal (23%), and surgical debridement and retention of the orthopedic device (41%). The proportion of S. lugdunensis strains with reduced susceptibility to antistaphylococcal agents was low. Resistant strains included five to oxacillin, four to fosfomycin, two to fusidic acid, two to co-trimoxazole, one to rifampicin, and one to clindamycin.

To date, relapses have occurred in 19% of the 123 patients in whom researchers have complete follow-up data. The readmission rate among these patients was 76%, and four (3%) died of their infection. “These relapses were not associated with risk factor or comorbidity or polymicrobial infection,” noted Dr. Seng, who characterized the incidence of bone and joint infections caused by S. lugdunensis as being under reported. “S. lugdunensis is known as an organism forming biofilms, but treatment options (surgical debridement or prosthesis removal) did not influence clinical outcomes.”

The mean time to relapse was 305 days and no risk factor or comorbidity was associated with relapse.

Dr. Seng acknowledged that the study was limited by its retrospective design. He and his associates reported having no financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Bone and joint infections caused by Staphylococcus lugdunensis are an underestimated hospital-acquired infection often associated with orthopedic devices, according to a multicenter study.

“Consider potential relapse even after 1 year of the end of antibiotic treatment and follow patients with bone and joint infections caused by S. lugdunensis for a minimum 2 years after the end of treatment,” lead study author Dr. Piseth Seng said in an interview at the annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy.

S. lugdunensis is a virulent coagulase-negative staphylococcus which behaves like S. aureus. Prior to the current study, only 47 cases are believed to be published in the medical literature, according to Dr. Seng of the department of internal medicine at Assistance Publique des Hôpitaux de Marseille (France). The purpose of the current study was to report a series of 138 cases of S. lugdunensis osteoarticular infection managed in nine hospital centers and three private clinics in France from January 1995 to December 2014.

The mean age of patients was 61 years, and 68% were male. Of the 138 cases, 113 (82%) were associated with an orthopedic device, including 2 cases of infection after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction, 66 cases of prosthetic joint infection, and 3 cases of vertebral orthopedic device infection. The majority of orthopedic device infections (88%) occurred more than 1 month after implantation, while the remaining 12% occurred within the first month of implantation.

The researchers identified 30 cases (22%) of bone and joint infection that occurred in the absence of an orthopedic device, including 7 cases of arthritis, 21 cases of osteitis, and 2 cases of vertebral osteomyelitis.

The majority of patients (91%) received a combination of antibiotic and surgical treatment, including amputation (6%), orthopedic prosthesis removal (14%), internal orthopedic device removal (23%), and surgical debridement and retention of the orthopedic device (41%). The proportion of S. lugdunensis strains with reduced susceptibility to antistaphylococcal agents was low. Resistant strains included five to oxacillin, four to fosfomycin, two to fusidic acid, two to co-trimoxazole, one to rifampicin, and one to clindamycin.

To date, relapses have occurred in 19% of the 123 patients in whom researchers have complete follow-up data. The readmission rate among these patients was 76%, and four (3%) died of their infection. “These relapses were not associated with risk factor or comorbidity or polymicrobial infection,” noted Dr. Seng, who characterized the incidence of bone and joint infections caused by S. lugdunensis as being under reported. “S. lugdunensis is known as an organism forming biofilms, but treatment options (surgical debridement or prosthesis removal) did not influence clinical outcomes.”

The mean time to relapse was 305 days and no risk factor or comorbidity was associated with relapse.

Dr. Seng acknowledged that the study was limited by its retrospective design. He and his associates reported having no financial disclosures.

AT ICAAC 2015

Key clinical point: S. lugdunensis infections are often associated with orthopedic devices.

Major finding: Of 138 cases of S. lugdunensis osteoarticular infection, 113 (82%) were associated with an orthopedic device.

Data source: A retrospective study of 138 cases of S. lugdunensis osteoarticular infection managed in nine hospitals and three private clinics in France.

Disclosures: The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

Planned Parenthood videos explain sexual consent to young adults

Planned Parenthood Federation of America has released a series of videos geared to teens and young adults that explains and provides examples of giving, hearing, and asking for consent; addressing both verbal and nonverbal cues; and fostering healthy communication around sex and relationships.

The videos are intended to inform and ultimately reduce sexual assault by ensuring that sex is safe and mutually consensual, Dr. Leslie Kantor, vice president of education at Planned Parenthood Federation of America, said in a statement. They can be a valuable resource for teens because consent is often hard to demonstrate; even though there has been emphasis on telling people that they must obtain consent in a sexual encounter, there are few examples illustrating what it looks like, said Dr. Kantor.

“To address sexual assault in this country and move us toward a healthy culture of consent, young people must understand consent and have the skills to engage in healthy communication around sex and relationships. Open, honest communication between partners is necessary to ensure that sex is safe and mutually consensual, which is a skill that can be learned. Education about consent is sexual assault prevention,” Dr. Kantor wrote.

The four-part video series can be viewed in its entirety on Planned Parenthood’s YouTube channel, and lesson plans that accompany the videos can be obtained by emailing [email protected]. Young people can find more information about consent on PlannedParenthood.org’s Info for Teens page and submit questions to Planned Parenthood’s Tumblr, Facebook, and Twitter pages.

Planned Parenthood Federation of America has released a series of videos geared to teens and young adults that explains and provides examples of giving, hearing, and asking for consent; addressing both verbal and nonverbal cues; and fostering healthy communication around sex and relationships.

The videos are intended to inform and ultimately reduce sexual assault by ensuring that sex is safe and mutually consensual, Dr. Leslie Kantor, vice president of education at Planned Parenthood Federation of America, said in a statement. They can be a valuable resource for teens because consent is often hard to demonstrate; even though there has been emphasis on telling people that they must obtain consent in a sexual encounter, there are few examples illustrating what it looks like, said Dr. Kantor.

“To address sexual assault in this country and move us toward a healthy culture of consent, young people must understand consent and have the skills to engage in healthy communication around sex and relationships. Open, honest communication between partners is necessary to ensure that sex is safe and mutually consensual, which is a skill that can be learned. Education about consent is sexual assault prevention,” Dr. Kantor wrote.

The four-part video series can be viewed in its entirety on Planned Parenthood’s YouTube channel, and lesson plans that accompany the videos can be obtained by emailing [email protected]. Young people can find more information about consent on PlannedParenthood.org’s Info for Teens page and submit questions to Planned Parenthood’s Tumblr, Facebook, and Twitter pages.

Planned Parenthood Federation of America has released a series of videos geared to teens and young adults that explains and provides examples of giving, hearing, and asking for consent; addressing both verbal and nonverbal cues; and fostering healthy communication around sex and relationships.

The videos are intended to inform and ultimately reduce sexual assault by ensuring that sex is safe and mutually consensual, Dr. Leslie Kantor, vice president of education at Planned Parenthood Federation of America, said in a statement. They can be a valuable resource for teens because consent is often hard to demonstrate; even though there has been emphasis on telling people that they must obtain consent in a sexual encounter, there are few examples illustrating what it looks like, said Dr. Kantor.

“To address sexual assault in this country and move us toward a healthy culture of consent, young people must understand consent and have the skills to engage in healthy communication around sex and relationships. Open, honest communication between partners is necessary to ensure that sex is safe and mutually consensual, which is a skill that can be learned. Education about consent is sexual assault prevention,” Dr. Kantor wrote.

The four-part video series can be viewed in its entirety on Planned Parenthood’s YouTube channel, and lesson plans that accompany the videos can be obtained by emailing [email protected]. Young people can find more information about consent on PlannedParenthood.org’s Info for Teens page and submit questions to Planned Parenthood’s Tumblr, Facebook, and Twitter pages.

Billing audits: The bane of a small practice

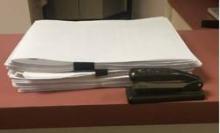

The photo you see below is a reasonably thick pile of paper, roughly 2 inches high. It’s certainly not as bad as some charts I’ve seen, especially at the VA, but still a lot of pages.

What is it?

This is, believe it or not, the stacked copies of charts we had to print in the last 30 days to fax to insurance companies for billing audits. Yeah – just the last 30 days.

Mind you, to date I don’t have any sort of actual complaints or charges against me for fraudulent billing. If anything, I tend to underbill for fear of risking the ire of insurance companies.

On one level, I understand it. The news is replete with stories of physicians who made fraudulent insurance claims, and the insurance companies want to make sure others are playing fair. Just like security cameras and magnetic tags at retailers, they’re doing what they can to avoid losses. I get that.

On the other hand, this irritates me, and it is a pain in the butt. Someone here has to print up the requested notes, organize them, fill out the accompanying forms, and fax them back. I also have to sign each note in the pile. For the number of charts they typically want, this process takes about 30-45 minutes. Then we fax them, and a 100-plus-page document ties up your office fax for a while. Incoming and outgoing faxes, such as medication refills, get put on hold. Overall, it takes maybe an hour of staff time to do this, not to mention the cost of paper and ink used.

About 25% of the time the company calls us after a few days to say they never got them (even though we have a confirmation). For this reason, we always hold onto the print-out for a month so we don’t have to start over again. Then it all has to be shredded.

In a large practice, I’m sure there are dedicated medical records staff members for this. But in my small solo world it means that someone has to let phones go to voicemail, dictations get delayed, and other work piles up, just so the insurance red tape gets done. Then we have to catch up on the more routine issues of patient care.

I can’t really refuse to send them, either. Doing so, in the insurance company’s mind, would be an admission of guilt that I never saw the patient and my claim is bogus. Then they’ll withhold payment, or ask for a refund.

This is, regrettably, a case where a few bad apples – docs filing bogus claims – have spoiled the entire barrel. Now we’re all guilty of fraud until proven innocent by sending these records. Isn’t that the reverse of the American justice system’s ideal?

I also wonder if there’s an intentional drudgery factor here. By making me do something that’s irritatingly time-wasting, is an insurance plan hoping I’ll drop them because I’m sick of this process? Does having fewer contracted neurologists work out to their benefit? It certainly isn’t to the patient’s advantage.

I don’t have an easy answer. I don’t like the wrench these requests throw into the office routine, but I also know that fraud surveillance is a necessary evil. I just wish there was a less time-consuming way of doing it.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

The photo you see below is a reasonably thick pile of paper, roughly 2 inches high. It’s certainly not as bad as some charts I’ve seen, especially at the VA, but still a lot of pages.

What is it?

This is, believe it or not, the stacked copies of charts we had to print in the last 30 days to fax to insurance companies for billing audits. Yeah – just the last 30 days.

Mind you, to date I don’t have any sort of actual complaints or charges against me for fraudulent billing. If anything, I tend to underbill for fear of risking the ire of insurance companies.

On one level, I understand it. The news is replete with stories of physicians who made fraudulent insurance claims, and the insurance companies want to make sure others are playing fair. Just like security cameras and magnetic tags at retailers, they’re doing what they can to avoid losses. I get that.

On the other hand, this irritates me, and it is a pain in the butt. Someone here has to print up the requested notes, organize them, fill out the accompanying forms, and fax them back. I also have to sign each note in the pile. For the number of charts they typically want, this process takes about 30-45 minutes. Then we fax them, and a 100-plus-page document ties up your office fax for a while. Incoming and outgoing faxes, such as medication refills, get put on hold. Overall, it takes maybe an hour of staff time to do this, not to mention the cost of paper and ink used.

About 25% of the time the company calls us after a few days to say they never got them (even though we have a confirmation). For this reason, we always hold onto the print-out for a month so we don’t have to start over again. Then it all has to be shredded.

In a large practice, I’m sure there are dedicated medical records staff members for this. But in my small solo world it means that someone has to let phones go to voicemail, dictations get delayed, and other work piles up, just so the insurance red tape gets done. Then we have to catch up on the more routine issues of patient care.

I can’t really refuse to send them, either. Doing so, in the insurance company’s mind, would be an admission of guilt that I never saw the patient and my claim is bogus. Then they’ll withhold payment, or ask for a refund.

This is, regrettably, a case where a few bad apples – docs filing bogus claims – have spoiled the entire barrel. Now we’re all guilty of fraud until proven innocent by sending these records. Isn’t that the reverse of the American justice system’s ideal?

I also wonder if there’s an intentional drudgery factor here. By making me do something that’s irritatingly time-wasting, is an insurance plan hoping I’ll drop them because I’m sick of this process? Does having fewer contracted neurologists work out to their benefit? It certainly isn’t to the patient’s advantage.

I don’t have an easy answer. I don’t like the wrench these requests throw into the office routine, but I also know that fraud surveillance is a necessary evil. I just wish there was a less time-consuming way of doing it.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

The photo you see below is a reasonably thick pile of paper, roughly 2 inches high. It’s certainly not as bad as some charts I’ve seen, especially at the VA, but still a lot of pages.

What is it?

This is, believe it or not, the stacked copies of charts we had to print in the last 30 days to fax to insurance companies for billing audits. Yeah – just the last 30 days.

Mind you, to date I don’t have any sort of actual complaints or charges against me for fraudulent billing. If anything, I tend to underbill for fear of risking the ire of insurance companies.

On one level, I understand it. The news is replete with stories of physicians who made fraudulent insurance claims, and the insurance companies want to make sure others are playing fair. Just like security cameras and magnetic tags at retailers, they’re doing what they can to avoid losses. I get that.

On the other hand, this irritates me, and it is a pain in the butt. Someone here has to print up the requested notes, organize them, fill out the accompanying forms, and fax them back. I also have to sign each note in the pile. For the number of charts they typically want, this process takes about 30-45 minutes. Then we fax them, and a 100-plus-page document ties up your office fax for a while. Incoming and outgoing faxes, such as medication refills, get put on hold. Overall, it takes maybe an hour of staff time to do this, not to mention the cost of paper and ink used.

About 25% of the time the company calls us after a few days to say they never got them (even though we have a confirmation). For this reason, we always hold onto the print-out for a month so we don’t have to start over again. Then it all has to be shredded.

In a large practice, I’m sure there are dedicated medical records staff members for this. But in my small solo world it means that someone has to let phones go to voicemail, dictations get delayed, and other work piles up, just so the insurance red tape gets done. Then we have to catch up on the more routine issues of patient care.

I can’t really refuse to send them, either. Doing so, in the insurance company’s mind, would be an admission of guilt that I never saw the patient and my claim is bogus. Then they’ll withhold payment, or ask for a refund.

This is, regrettably, a case where a few bad apples – docs filing bogus claims – have spoiled the entire barrel. Now we’re all guilty of fraud until proven innocent by sending these records. Isn’t that the reverse of the American justice system’s ideal?

I also wonder if there’s an intentional drudgery factor here. By making me do something that’s irritatingly time-wasting, is an insurance plan hoping I’ll drop them because I’m sick of this process? Does having fewer contracted neurologists work out to their benefit? It certainly isn’t to the patient’s advantage.

I don’t have an easy answer. I don’t like the wrench these requests throw into the office routine, but I also know that fraud surveillance is a necessary evil. I just wish there was a less time-consuming way of doing it.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Racial, Economic Disparities in Life Expectancy after Heart Attack

After a heart attack, black patients typically don't live as long as whites - a racial difference that is starkest among the affluent - according to a new U.S. study.

Researchers evaluated data on more than 132,000 white heart attack patients and almost 9,000 black patients covered by Medicare, the government health program for the elderly and disabled. They used postal codes to assess income levels in patients' communities.

After 17 years of follow-up, the overall survival rate was 7.4 percent for white patients and 5.7 percent for black patients, according to the results published in Circulation, the journal of the American Heart Association.

On average, across all ages, white patients in low-income areas lived longer after a heart attack - about 5.6 years compared with 5.4 years for black patients. But in high-income communities, the gap widened to a life expectancy of seven years for white people and 6.3 years for black individuals.

"We found that socioeconomic status did not explain the racial disparities in life expectancy after a heart attack," lead study author Dr. Emily Bucholz of Boston Children's Hospital said by email.

"Contrary to common belief, this suggests that improving socioeconomic standing may improve outcomes for black and white patients globally but is unlikely to eliminate racial disparities in health," Bucholz added.

To see how race and class impact heart attack outcomes, Bucholz and colleagues reviewed health records collected from 1994 to 1996 for patients aged 65 to 90 years.

Just 6.3 percent of the patients were black, and only 6.8 percent lived in low-income communities, based on the typical household income in their postal codes.

Among white patients under 80, life expectancy was longest for patients in the most affluent neighborhoods and it got progressively shorter for middle-income and poor communities, the study found.

By contrast, life expectancy was similar for black patients residing in poor and middle-income communities across all ages. Only black patients under age 75 living in affluent areas had a survival advantage compared with their peers in less wealthy neighborhoods.

One shortcoming of the study is that it included a small proportion of black and poor patients, the authors acknowledge. It's also possible that using postal codes to assess income may have led to some instances where income levels were inflated or underestimated, the authors note.

It's possible that black patients living in affluent areas don't fare as well as white patients because they don't have the same amount of social support from their peers, said Dr. Joaquin Cigarroa, a cardiovascular medicine researcher at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland.

In poor neighborhoods, black patients may face additional challenges to surviving a heart attack, added Cigarroa, who wasn't involved in the study.

"They more often live in low socioeconomic segments of our community that often have less access to health care resources and less access to stores with good nutrition," Cigarroa said by email. "In addition, these segments of our community are often not ideally configured for promoting physical activity with parks, sidewalks, bike lanes, etc."

The study findings highlight a need to improve outcomes among poor and black patients and suggest some differences in heart attack survival may come down to disparities in quality of care, said senior study author Dr. Harlan Krumholz of Yale University School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut.

Because black patients have a greater burden of heart disease than white people, doctors may also need to focus more on prevention in this community, Krumholz said by email.

"Healthy heart habits may be even more important for African-Americans, for whom avoiding a heart attack is even more important given their worse outcomes after the event," Krumholz said.

After a heart attack, black patients typically don't live as long as whites - a racial difference that is starkest among the affluent - according to a new U.S. study.

Researchers evaluated data on more than 132,000 white heart attack patients and almost 9,000 black patients covered by Medicare, the government health program for the elderly and disabled. They used postal codes to assess income levels in patients' communities.

After 17 years of follow-up, the overall survival rate was 7.4 percent for white patients and 5.7 percent for black patients, according to the results published in Circulation, the journal of the American Heart Association.

On average, across all ages, white patients in low-income areas lived longer after a heart attack - about 5.6 years compared with 5.4 years for black patients. But in high-income communities, the gap widened to a life expectancy of seven years for white people and 6.3 years for black individuals.

"We found that socioeconomic status did not explain the racial disparities in life expectancy after a heart attack," lead study author Dr. Emily Bucholz of Boston Children's Hospital said by email.

"Contrary to common belief, this suggests that improving socioeconomic standing may improve outcomes for black and white patients globally but is unlikely to eliminate racial disparities in health," Bucholz added.

To see how race and class impact heart attack outcomes, Bucholz and colleagues reviewed health records collected from 1994 to 1996 for patients aged 65 to 90 years.

Just 6.3 percent of the patients were black, and only 6.8 percent lived in low-income communities, based on the typical household income in their postal codes.

Among white patients under 80, life expectancy was longest for patients in the most affluent neighborhoods and it got progressively shorter for middle-income and poor communities, the study found.

By contrast, life expectancy was similar for black patients residing in poor and middle-income communities across all ages. Only black patients under age 75 living in affluent areas had a survival advantage compared with their peers in less wealthy neighborhoods.

One shortcoming of the study is that it included a small proportion of black and poor patients, the authors acknowledge. It's also possible that using postal codes to assess income may have led to some instances where income levels were inflated or underestimated, the authors note.

It's possible that black patients living in affluent areas don't fare as well as white patients because they don't have the same amount of social support from their peers, said Dr. Joaquin Cigarroa, a cardiovascular medicine researcher at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland.

In poor neighborhoods, black patients may face additional challenges to surviving a heart attack, added Cigarroa, who wasn't involved in the study.

"They more often live in low socioeconomic segments of our community that often have less access to health care resources and less access to stores with good nutrition," Cigarroa said by email. "In addition, these segments of our community are often not ideally configured for promoting physical activity with parks, sidewalks, bike lanes, etc."

The study findings highlight a need to improve outcomes among poor and black patients and suggest some differences in heart attack survival may come down to disparities in quality of care, said senior study author Dr. Harlan Krumholz of Yale University School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut.

Because black patients have a greater burden of heart disease than white people, doctors may also need to focus more on prevention in this community, Krumholz said by email.

"Healthy heart habits may be even more important for African-Americans, for whom avoiding a heart attack is even more important given their worse outcomes after the event," Krumholz said.

After a heart attack, black patients typically don't live as long as whites - a racial difference that is starkest among the affluent - according to a new U.S. study.

Researchers evaluated data on more than 132,000 white heart attack patients and almost 9,000 black patients covered by Medicare, the government health program for the elderly and disabled. They used postal codes to assess income levels in patients' communities.

After 17 years of follow-up, the overall survival rate was 7.4 percent for white patients and 5.7 percent for black patients, according to the results published in Circulation, the journal of the American Heart Association.

On average, across all ages, white patients in low-income areas lived longer after a heart attack - about 5.6 years compared with 5.4 years for black patients. But in high-income communities, the gap widened to a life expectancy of seven years for white people and 6.3 years for black individuals.

"We found that socioeconomic status did not explain the racial disparities in life expectancy after a heart attack," lead study author Dr. Emily Bucholz of Boston Children's Hospital said by email.

"Contrary to common belief, this suggests that improving socioeconomic standing may improve outcomes for black and white patients globally but is unlikely to eliminate racial disparities in health," Bucholz added.

To see how race and class impact heart attack outcomes, Bucholz and colleagues reviewed health records collected from 1994 to 1996 for patients aged 65 to 90 years.

Just 6.3 percent of the patients were black, and only 6.8 percent lived in low-income communities, based on the typical household income in their postal codes.

Among white patients under 80, life expectancy was longest for patients in the most affluent neighborhoods and it got progressively shorter for middle-income and poor communities, the study found.

By contrast, life expectancy was similar for black patients residing in poor and middle-income communities across all ages. Only black patients under age 75 living in affluent areas had a survival advantage compared with their peers in less wealthy neighborhoods.

One shortcoming of the study is that it included a small proportion of black and poor patients, the authors acknowledge. It's also possible that using postal codes to assess income may have led to some instances where income levels were inflated or underestimated, the authors note.

It's possible that black patients living in affluent areas don't fare as well as white patients because they don't have the same amount of social support from their peers, said Dr. Joaquin Cigarroa, a cardiovascular medicine researcher at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland.

In poor neighborhoods, black patients may face additional challenges to surviving a heart attack, added Cigarroa, who wasn't involved in the study.

"They more often live in low socioeconomic segments of our community that often have less access to health care resources and less access to stores with good nutrition," Cigarroa said by email. "In addition, these segments of our community are often not ideally configured for promoting physical activity with parks, sidewalks, bike lanes, etc."

The study findings highlight a need to improve outcomes among poor and black patients and suggest some differences in heart attack survival may come down to disparities in quality of care, said senior study author Dr. Harlan Krumholz of Yale University School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut.

Because black patients have a greater burden of heart disease than white people, doctors may also need to focus more on prevention in this community, Krumholz said by email.

"Healthy heart habits may be even more important for African-Americans, for whom avoiding a heart attack is even more important given their worse outcomes after the event," Krumholz said.

Bipolar phenotype affects present, future self-image

Higher positivity ratings for current self-images were associated with lower depression and anxiety scores among young adults with Bipolar Spectrum Disorder (BPSD), suggesting that BPSD phenotype can shape the relationship between affect and current and future self-images.

As reported in the Journal of Affective Disorders, lead author Dr. Martina Di Simplicio of MRC Cognition and Brain Sciences Unit, Cambridge, England, and her associates assessed a nonclinical sample of 47 participants (66% female; mean age, 23) for hypomanic experiences and BPSD vulnerability, split into two groups based on their Mood Disorders Questionnaire (MDQ) score. Seventy-five percent of the participants in the high MDQ group generated at least one negative current self-image, compared with 48% of participants in the low MDQ group (P = .055).

The investigators noted that, for those with high MDQ scores, the relationship between affect and perception of the stability of negative self-images is different compared with those with low MDQ scores. And while 75% participants in the BPSD phenotype group were likely to endorse negative images of the current self (compared with less than 50% of the group without hypomanic experiences, almost none of the patients from either group had negative images of the future self).

“BPSD phenotype presents with both alterations and resilience in how self-images and mood shape each other. Further investigations could elucidate how this relationship is affected by illness progression and offer targets for early interventions based on experimental cognitive models,” the investigators wrote.

Read the article in Journal of Affective Disorders (doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.08.042).

Higher positivity ratings for current self-images were associated with lower depression and anxiety scores among young adults with Bipolar Spectrum Disorder (BPSD), suggesting that BPSD phenotype can shape the relationship between affect and current and future self-images.

As reported in the Journal of Affective Disorders, lead author Dr. Martina Di Simplicio of MRC Cognition and Brain Sciences Unit, Cambridge, England, and her associates assessed a nonclinical sample of 47 participants (66% female; mean age, 23) for hypomanic experiences and BPSD vulnerability, split into two groups based on their Mood Disorders Questionnaire (MDQ) score. Seventy-five percent of the participants in the high MDQ group generated at least one negative current self-image, compared with 48% of participants in the low MDQ group (P = .055).

The investigators noted that, for those with high MDQ scores, the relationship between affect and perception of the stability of negative self-images is different compared with those with low MDQ scores. And while 75% participants in the BPSD phenotype group were likely to endorse negative images of the current self (compared with less than 50% of the group without hypomanic experiences, almost none of the patients from either group had negative images of the future self).

“BPSD phenotype presents with both alterations and resilience in how self-images and mood shape each other. Further investigations could elucidate how this relationship is affected by illness progression and offer targets for early interventions based on experimental cognitive models,” the investigators wrote.

Read the article in Journal of Affective Disorders (doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.08.042).

Higher positivity ratings for current self-images were associated with lower depression and anxiety scores among young adults with Bipolar Spectrum Disorder (BPSD), suggesting that BPSD phenotype can shape the relationship between affect and current and future self-images.

As reported in the Journal of Affective Disorders, lead author Dr. Martina Di Simplicio of MRC Cognition and Brain Sciences Unit, Cambridge, England, and her associates assessed a nonclinical sample of 47 participants (66% female; mean age, 23) for hypomanic experiences and BPSD vulnerability, split into two groups based on their Mood Disorders Questionnaire (MDQ) score. Seventy-five percent of the participants in the high MDQ group generated at least one negative current self-image, compared with 48% of participants in the low MDQ group (P = .055).

The investigators noted that, for those with high MDQ scores, the relationship between affect and perception of the stability of negative self-images is different compared with those with low MDQ scores. And while 75% participants in the BPSD phenotype group were likely to endorse negative images of the current self (compared with less than 50% of the group without hypomanic experiences, almost none of the patients from either group had negative images of the future self).

“BPSD phenotype presents with both alterations and resilience in how self-images and mood shape each other. Further investigations could elucidate how this relationship is affected by illness progression and offer targets for early interventions based on experimental cognitive models,” the investigators wrote.

Read the article in Journal of Affective Disorders (doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.08.042).

FROM THE JOURNAL OF AFFECTIVE DISORDERS

CBT improves depression but not self-care in heart failure patients

Cognitive behavioral therapy significantly improved major depression but did not improve self-care by heart failure patients, investigators reported online in JAMA Internal Medicine.

“The results suggest that CBT is superior to usual care for depression in patients with heart failure,” said Dr. Kenneth Freedland and his associates at Washington University in St. Louis. They called the findings “especially encouraging” in light of recent negative results from the SADHART-CHF and MOOD-HF trials of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in this population.Patients in heart failure often have major depression, which increases their chances of poor self-care, hospitalization, and mortality, the researchers noted. Their single-blind, randomized trial included 158 patients who were in New York Heart Association class I, II, or III heart failure and met criteria for major depression. Patients in the intervention group received standard medical care, plus up to 6 months of CBT designed for cardiac patients.Patients received CBT weekly, then biweekly, and then monthly as they reached their treatment goals, but they also received telephone follow-up to help prevent relapse. The control group received standard medical care plus consultation with a cardiac nurse, written materials on heart failure self-care, and three follow-up phone calls with the nurse (JAMA Intern Med. 2015 Sept. 28. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.5220). At 6 months, the CBT group scored significantly lower on the BDI-II than did controls (mean score, 12.8 [standard deviation, 10.6] vs. 17.3 [10.7]; P = .008), the researchers said. Remission rates with CBT were 46% based on the BDI-II and 51% based on the Hamilton Depression Scale, both of which significantly exceeded remission rates of 19-20% for controls. The CBT group also improved significantly more than did controls on standard measures for anxiety, heart failure-related quality of life, mental health–related quality of life, fatigue, and social functioning, but not on measures of physical functioning, the researchers reported.

The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute partially funded the study. The researchers declared no competing interests.

When depression occurs in patients with heart failure, which is often, the illness burden and management complexity increase multifold. Freedland et al. tested the hypothesis that the effective treatment of comorbid depression with cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) would also lead to improvements in heart failure self-care and physical functioning and found that it did not. The good news is that CBT did significantly improve emotional health and overall quality of life, and the improvement in depressive symptoms associated with CBT was larger than observed in pharmacotherapy trials for depression in patients with heart disease. This supports evidence for a shift in practice away from so much pharmacotherapy and more use of psychotherapy to achieve better mental health and overall quality of life outcomes in patients with heart failure. In reframing how we think about the management of depression in patients with heart failure, we should be talking more and prescribing less.

Dr. Patrick G. O’Malley is deputy editor of JAMA Internal Medicine. He declared no competing interests. These comments were taken from his accompanying editorial (JAMA Intern Med. 2015 Sept. 28).

When depression occurs in patients with heart failure, which is often, the illness burden and management complexity increase multifold. Freedland et al. tested the hypothesis that the effective treatment of comorbid depression with cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) would also lead to improvements in heart failure self-care and physical functioning and found that it did not. The good news is that CBT did significantly improve emotional health and overall quality of life, and the improvement in depressive symptoms associated with CBT was larger than observed in pharmacotherapy trials for depression in patients with heart disease. This supports evidence for a shift in practice away from so much pharmacotherapy and more use of psychotherapy to achieve better mental health and overall quality of life outcomes in patients with heart failure. In reframing how we think about the management of depression in patients with heart failure, we should be talking more and prescribing less.

Dr. Patrick G. O’Malley is deputy editor of JAMA Internal Medicine. He declared no competing interests. These comments were taken from his accompanying editorial (JAMA Intern Med. 2015 Sept. 28).

When depression occurs in patients with heart failure, which is often, the illness burden and management complexity increase multifold. Freedland et al. tested the hypothesis that the effective treatment of comorbid depression with cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) would also lead to improvements in heart failure self-care and physical functioning and found that it did not. The good news is that CBT did significantly improve emotional health and overall quality of life, and the improvement in depressive symptoms associated with CBT was larger than observed in pharmacotherapy trials for depression in patients with heart disease. This supports evidence for a shift in practice away from so much pharmacotherapy and more use of psychotherapy to achieve better mental health and overall quality of life outcomes in patients with heart failure. In reframing how we think about the management of depression in patients with heart failure, we should be talking more and prescribing less.

Dr. Patrick G. O’Malley is deputy editor of JAMA Internal Medicine. He declared no competing interests. These comments were taken from his accompanying editorial (JAMA Intern Med. 2015 Sept. 28).

Cognitive behavioral therapy significantly improved major depression but did not improve self-care by heart failure patients, investigators reported online in JAMA Internal Medicine.

“The results suggest that CBT is superior to usual care for depression in patients with heart failure,” said Dr. Kenneth Freedland and his associates at Washington University in St. Louis. They called the findings “especially encouraging” in light of recent negative results from the SADHART-CHF and MOOD-HF trials of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in this population.Patients in heart failure often have major depression, which increases their chances of poor self-care, hospitalization, and mortality, the researchers noted. Their single-blind, randomized trial included 158 patients who were in New York Heart Association class I, II, or III heart failure and met criteria for major depression. Patients in the intervention group received standard medical care, plus up to 6 months of CBT designed for cardiac patients.Patients received CBT weekly, then biweekly, and then monthly as they reached their treatment goals, but they also received telephone follow-up to help prevent relapse. The control group received standard medical care plus consultation with a cardiac nurse, written materials on heart failure self-care, and three follow-up phone calls with the nurse (JAMA Intern Med. 2015 Sept. 28. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.5220). At 6 months, the CBT group scored significantly lower on the BDI-II than did controls (mean score, 12.8 [standard deviation, 10.6] vs. 17.3 [10.7]; P = .008), the researchers said. Remission rates with CBT were 46% based on the BDI-II and 51% based on the Hamilton Depression Scale, both of which significantly exceeded remission rates of 19-20% for controls. The CBT group also improved significantly more than did controls on standard measures for anxiety, heart failure-related quality of life, mental health–related quality of life, fatigue, and social functioning, but not on measures of physical functioning, the researchers reported.

The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute partially funded the study. The researchers declared no competing interests.

Cognitive behavioral therapy significantly improved major depression but did not improve self-care by heart failure patients, investigators reported online in JAMA Internal Medicine.

“The results suggest that CBT is superior to usual care for depression in patients with heart failure,” said Dr. Kenneth Freedland and his associates at Washington University in St. Louis. They called the findings “especially encouraging” in light of recent negative results from the SADHART-CHF and MOOD-HF trials of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in this population.Patients in heart failure often have major depression, which increases their chances of poor self-care, hospitalization, and mortality, the researchers noted. Their single-blind, randomized trial included 158 patients who were in New York Heart Association class I, II, or III heart failure and met criteria for major depression. Patients in the intervention group received standard medical care, plus up to 6 months of CBT designed for cardiac patients.Patients received CBT weekly, then biweekly, and then monthly as they reached their treatment goals, but they also received telephone follow-up to help prevent relapse. The control group received standard medical care plus consultation with a cardiac nurse, written materials on heart failure self-care, and three follow-up phone calls with the nurse (JAMA Intern Med. 2015 Sept. 28. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.5220). At 6 months, the CBT group scored significantly lower on the BDI-II than did controls (mean score, 12.8 [standard deviation, 10.6] vs. 17.3 [10.7]; P = .008), the researchers said. Remission rates with CBT were 46% based on the BDI-II and 51% based on the Hamilton Depression Scale, both of which significantly exceeded remission rates of 19-20% for controls. The CBT group also improved significantly more than did controls on standard measures for anxiety, heart failure-related quality of life, mental health–related quality of life, fatigue, and social functioning, but not on measures of physical functioning, the researchers reported.

The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute partially funded the study. The researchers declared no competing interests.

FROM JAMA INTERNAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Cognitive behavior therapy significantly improved major depression but not self-care among patients with heart failure.