User login

Caring for refugees requires flexibility, cultural humility

When the recent photo of a drowned Syrian toddler woke up the world to the Syrian refugee crisis more viscerally than ever before, multiple nations announced plans to take in more refugees. According to the U.S. State Department, approximately 10,000 Syrian refugees are already in processing, eventually headed to cities that may include Atlanta, San Diego, Houston, Dallas, Chicago, Boston, Boise, Nashville, Tucson, Buffalo, and Erie.

To pediatricians, that boy on the beach represents a child who might have ended up in their practice with diverse, complex needs greatly exceeding the typical needs of a U.S. child coming in for a well-child visit.

“Families are coming from a country that has been ravaged by civil war for over 4 years,” Dr. Susan S. Reines, a pediatrician with the Southeast Kaiser Permanente Medical Group and lead pediatrician for the Refugee Pediatric Clinic at DeKalb County Board of Health in Decatur, Georgia, said in an interview. “Cities have been destroyed, and millions have been forced to leave their homes and are displaced either within Syria or in neighboring countries.”

About a third of the more than 58,000 refugees admitted to the United States in 2012 were under 18 years old. Although the majority that year hailed from Bhutan, Burma, and Iraq, an increasing number of children have been coming from war-torn Syria since June 2014. The proposed ceiling for all refugees in the United States 2015 fiscal year is 70,000, a “significant number” of whom will be children with their families, according to a State Department spokesperson.

These children come with “unique medical, developmental and psychosocial needs,” noted Dr. Thomas J. Seery and fellow authors of “Caring for Refugee Children,” a Pediatrics in Review article recommended by Dr. Reines for pediatricians who may be caring for refugee children.

“The health care infrastructure of Syria is broken and many hospitals have closed, medications are difficult to obtain, and numerous doctors have fled the violence,” Dr. Reines said. She compared the anticipated health care problems of these children with those seen among Iraqi refugee children:

• Undernutrition and micronutrient deficiencies.

• Infectious diseases such as vaccine-preventable diseases like measles, but also typhoid, tuberculosis, and parasitic infections.

• Dental disease.

• Surgically amenable congenital anomalies such as congenital heart disease, myelomeningocele, and others that have not been repaired.

• Neurologic problems, such as cerebral palsy, intellectual disability, and autism.

• Hearing loss.

• Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD),depression, and anxiety.

• Trauma such as gunshot wounds, shrapnel injuries, and genital trauma secondary to sexual violence.

• Sequelae from illnesses that previously were easily treated, such as hearing loss and ear complications from otitis media, and rheumatic fever from inadequately treated strep throat.

• Underimmunization.

Various resources listed below, including Dr. Seery’s paper, can help guide providers in assessing and meeting these needs, and navigating paperwork and the U.S. refugee system. These resources also can help practitioners address the mental health concerns these patients and their families may face.

Mental health needs

Even children in the best physical shape will have experienced significant upheaval that could lead to depression, anxiety, and PTSD – conditions more common among refugee children than in the general population, research has shown.

“Mental health conditions will be especially present in these children uprooted from their homes and families, and exposed to the violence of war,” Dr. Francis E. Rushton Jr. of the department of pediatrics at the University of South Carolina, Columbia, and a member of the American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Community Health Services, said in an interview. Of the four major areas of health care need he described for these children, two relate to mental health: toxic mental stress and fractured families and the lack of nurture.

One challenge pediatricians face, however, is recognizing these conditions despite cultural differences that could obscure them.

“It is not uncommon for teens and adults to deny symptoms of depression, stress, and anxiety in early encounters,” Dr. Reines said. “Many cultures stigmatize psychiatric or mental health problems, and refugees may be reluctant to admit they are having difficulties.”

One way around this obstacle is to ask patients and their parents about sleep, energy level, appetite, weight changes, and thoughts of harming one’s self, she said. Mental stress also manifests as somatic symptoms, such as headaches, stomach aches, and back pain, particularly in teens.

“Infants and toddlers are generally most adaptable as long as parents are coping well, and can provide a buffer for stress with a safe and nurturing environment,” Dr. Reines said. Children of parents with depression or PTSD, or who have lost a parent, may feel abandoned and experience depression or developmental delays.

Although school-age children may have nightmares, show anxiety, and cling to their parents, they usually transition well to their new homes. Adolescents face the biggest difficulties, especially if they have lost a parent, must care for their siblings, or have experienced sexual trauma. “They may have more vivid memories of disturbing events and a greater understanding of what their family has endured,” Dr. Reines said. Further, language and educational deficits can lead to alienation and embarrassment, yet families may rebuff behavioral health referrals.

“In these cases, it’s best to keep communication open, encourage dialogue with family, and try to find an activity or sport the refugee can participate in to improve self-esteem,” Dr. Reines said.

Avoiding cultural confusion

While cultural challenges are obvious – language barriers may necessitate translators or bicultural caseworkers – others may be more subtle. Developmental screening questions that rely on blocks, certain pictures, or other culturally specific bases, for example, may not adequately capture a child’s development.

Dr. Reines stresses a strategy for managing cultural differences that is recommended in Dr. Seery’s article: striving for cultural humility rather than cultural competence.

“It is impossible for U.S. physicians who have never practiced outside of our culture and are not bicultural or bilingual to become truly culturally competent in health care delivery for so many refugee populations,” Dr. Reines said. Instead then, cultural humility emphasizes showing respect, interest, and a willingness to learn from patients, she explained.

Cultural humility is a “lifelong process” that also demands flexibility and “allows the practitioner to release the false sense of security associated with stereotyping,” Dr. Seery and his colleagues wrote.

At the same time, pediatricians are guarding against inadvertent stereotyping; however, they can be aware of some cultural generalities that may apply to their Syrian refugee patients.

“Arab communities stress the importance of family rather than the individual and are often more modest than Westerners,” Dr. Rushton said. Further, “Arab families frequently experience discrimination on the basis of their religion in the United States, and pediatricians should be aware of ongoing traumatization even after arrival in America,” he said.

Teens may become embarrassed with discussions about sex or alcohol because few teens from the Middle East drink or become sexually active before marriage, Dr. Reines added. She noted that a Muslim male may not shake hands with females outside his family – a practice providers should respect – and that important religious holidays such as Ramadan may influence a family’s compliance with a treatment plan.

Perhaps the most important commonality, however, is one universal to most refugee families, regardless of their home country.

“The vast majority of families that we meet show incredible courage and resilience, and caring for their children is their highest priority,” Dr. Reines said. “We can learn a great deal from these families, and caring for their children is a tremendously rewarding experience.”

Other cultural resources:

Bridging Refugee Youth and Children’s Services

“The Middle of Everywhere: Helping Refugees Enter the American Community,” by Mary Pipher (Orlando: Mariner Books, 2003)

“Immigrant Medicine,” a textbook by Patricia Walker, M.D., and Elizabeth Barnett, M.D. (New York, N.Y.: Elsevier, 2007)

“Opening cultural doors: Providing culturally sensitive healthcare to Arab American and American Muslim patients” (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005 Oct;193]:1307-11).

When the recent photo of a drowned Syrian toddler woke up the world to the Syrian refugee crisis more viscerally than ever before, multiple nations announced plans to take in more refugees. According to the U.S. State Department, approximately 10,000 Syrian refugees are already in processing, eventually headed to cities that may include Atlanta, San Diego, Houston, Dallas, Chicago, Boston, Boise, Nashville, Tucson, Buffalo, and Erie.

To pediatricians, that boy on the beach represents a child who might have ended up in their practice with diverse, complex needs greatly exceeding the typical needs of a U.S. child coming in for a well-child visit.

“Families are coming from a country that has been ravaged by civil war for over 4 years,” Dr. Susan S. Reines, a pediatrician with the Southeast Kaiser Permanente Medical Group and lead pediatrician for the Refugee Pediatric Clinic at DeKalb County Board of Health in Decatur, Georgia, said in an interview. “Cities have been destroyed, and millions have been forced to leave their homes and are displaced either within Syria or in neighboring countries.”

About a third of the more than 58,000 refugees admitted to the United States in 2012 were under 18 years old. Although the majority that year hailed from Bhutan, Burma, and Iraq, an increasing number of children have been coming from war-torn Syria since June 2014. The proposed ceiling for all refugees in the United States 2015 fiscal year is 70,000, a “significant number” of whom will be children with their families, according to a State Department spokesperson.

These children come with “unique medical, developmental and psychosocial needs,” noted Dr. Thomas J. Seery and fellow authors of “Caring for Refugee Children,” a Pediatrics in Review article recommended by Dr. Reines for pediatricians who may be caring for refugee children.

“The health care infrastructure of Syria is broken and many hospitals have closed, medications are difficult to obtain, and numerous doctors have fled the violence,” Dr. Reines said. She compared the anticipated health care problems of these children with those seen among Iraqi refugee children:

• Undernutrition and micronutrient deficiencies.

• Infectious diseases such as vaccine-preventable diseases like measles, but also typhoid, tuberculosis, and parasitic infections.

• Dental disease.

• Surgically amenable congenital anomalies such as congenital heart disease, myelomeningocele, and others that have not been repaired.

• Neurologic problems, such as cerebral palsy, intellectual disability, and autism.

• Hearing loss.

• Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD),depression, and anxiety.

• Trauma such as gunshot wounds, shrapnel injuries, and genital trauma secondary to sexual violence.

• Sequelae from illnesses that previously were easily treated, such as hearing loss and ear complications from otitis media, and rheumatic fever from inadequately treated strep throat.

• Underimmunization.

Various resources listed below, including Dr. Seery’s paper, can help guide providers in assessing and meeting these needs, and navigating paperwork and the U.S. refugee system. These resources also can help practitioners address the mental health concerns these patients and their families may face.

Mental health needs

Even children in the best physical shape will have experienced significant upheaval that could lead to depression, anxiety, and PTSD – conditions more common among refugee children than in the general population, research has shown.

“Mental health conditions will be especially present in these children uprooted from their homes and families, and exposed to the violence of war,” Dr. Francis E. Rushton Jr. of the department of pediatrics at the University of South Carolina, Columbia, and a member of the American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Community Health Services, said in an interview. Of the four major areas of health care need he described for these children, two relate to mental health: toxic mental stress and fractured families and the lack of nurture.

One challenge pediatricians face, however, is recognizing these conditions despite cultural differences that could obscure them.

“It is not uncommon for teens and adults to deny symptoms of depression, stress, and anxiety in early encounters,” Dr. Reines said. “Many cultures stigmatize psychiatric or mental health problems, and refugees may be reluctant to admit they are having difficulties.”

One way around this obstacle is to ask patients and their parents about sleep, energy level, appetite, weight changes, and thoughts of harming one’s self, she said. Mental stress also manifests as somatic symptoms, such as headaches, stomach aches, and back pain, particularly in teens.

“Infants and toddlers are generally most adaptable as long as parents are coping well, and can provide a buffer for stress with a safe and nurturing environment,” Dr. Reines said. Children of parents with depression or PTSD, or who have lost a parent, may feel abandoned and experience depression or developmental delays.

Although school-age children may have nightmares, show anxiety, and cling to their parents, they usually transition well to their new homes. Adolescents face the biggest difficulties, especially if they have lost a parent, must care for their siblings, or have experienced sexual trauma. “They may have more vivid memories of disturbing events and a greater understanding of what their family has endured,” Dr. Reines said. Further, language and educational deficits can lead to alienation and embarrassment, yet families may rebuff behavioral health referrals.

“In these cases, it’s best to keep communication open, encourage dialogue with family, and try to find an activity or sport the refugee can participate in to improve self-esteem,” Dr. Reines said.

Avoiding cultural confusion

While cultural challenges are obvious – language barriers may necessitate translators or bicultural caseworkers – others may be more subtle. Developmental screening questions that rely on blocks, certain pictures, or other culturally specific bases, for example, may not adequately capture a child’s development.

Dr. Reines stresses a strategy for managing cultural differences that is recommended in Dr. Seery’s article: striving for cultural humility rather than cultural competence.

“It is impossible for U.S. physicians who have never practiced outside of our culture and are not bicultural or bilingual to become truly culturally competent in health care delivery for so many refugee populations,” Dr. Reines said. Instead then, cultural humility emphasizes showing respect, interest, and a willingness to learn from patients, she explained.

Cultural humility is a “lifelong process” that also demands flexibility and “allows the practitioner to release the false sense of security associated with stereotyping,” Dr. Seery and his colleagues wrote.

At the same time, pediatricians are guarding against inadvertent stereotyping; however, they can be aware of some cultural generalities that may apply to their Syrian refugee patients.

“Arab communities stress the importance of family rather than the individual and are often more modest than Westerners,” Dr. Rushton said. Further, “Arab families frequently experience discrimination on the basis of their religion in the United States, and pediatricians should be aware of ongoing traumatization even after arrival in America,” he said.

Teens may become embarrassed with discussions about sex or alcohol because few teens from the Middle East drink or become sexually active before marriage, Dr. Reines added. She noted that a Muslim male may not shake hands with females outside his family – a practice providers should respect – and that important religious holidays such as Ramadan may influence a family’s compliance with a treatment plan.

Perhaps the most important commonality, however, is one universal to most refugee families, regardless of their home country.

“The vast majority of families that we meet show incredible courage and resilience, and caring for their children is their highest priority,” Dr. Reines said. “We can learn a great deal from these families, and caring for their children is a tremendously rewarding experience.”

Other cultural resources:

Bridging Refugee Youth and Children’s Services

“The Middle of Everywhere: Helping Refugees Enter the American Community,” by Mary Pipher (Orlando: Mariner Books, 2003)

“Immigrant Medicine,” a textbook by Patricia Walker, M.D., and Elizabeth Barnett, M.D. (New York, N.Y.: Elsevier, 2007)

“Opening cultural doors: Providing culturally sensitive healthcare to Arab American and American Muslim patients” (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005 Oct;193]:1307-11).

When the recent photo of a drowned Syrian toddler woke up the world to the Syrian refugee crisis more viscerally than ever before, multiple nations announced plans to take in more refugees. According to the U.S. State Department, approximately 10,000 Syrian refugees are already in processing, eventually headed to cities that may include Atlanta, San Diego, Houston, Dallas, Chicago, Boston, Boise, Nashville, Tucson, Buffalo, and Erie.

To pediatricians, that boy on the beach represents a child who might have ended up in their practice with diverse, complex needs greatly exceeding the typical needs of a U.S. child coming in for a well-child visit.

“Families are coming from a country that has been ravaged by civil war for over 4 years,” Dr. Susan S. Reines, a pediatrician with the Southeast Kaiser Permanente Medical Group and lead pediatrician for the Refugee Pediatric Clinic at DeKalb County Board of Health in Decatur, Georgia, said in an interview. “Cities have been destroyed, and millions have been forced to leave their homes and are displaced either within Syria or in neighboring countries.”

About a third of the more than 58,000 refugees admitted to the United States in 2012 were under 18 years old. Although the majority that year hailed from Bhutan, Burma, and Iraq, an increasing number of children have been coming from war-torn Syria since June 2014. The proposed ceiling for all refugees in the United States 2015 fiscal year is 70,000, a “significant number” of whom will be children with their families, according to a State Department spokesperson.

These children come with “unique medical, developmental and psychosocial needs,” noted Dr. Thomas J. Seery and fellow authors of “Caring for Refugee Children,” a Pediatrics in Review article recommended by Dr. Reines for pediatricians who may be caring for refugee children.

“The health care infrastructure of Syria is broken and many hospitals have closed, medications are difficult to obtain, and numerous doctors have fled the violence,” Dr. Reines said. She compared the anticipated health care problems of these children with those seen among Iraqi refugee children:

• Undernutrition and micronutrient deficiencies.

• Infectious diseases such as vaccine-preventable diseases like measles, but also typhoid, tuberculosis, and parasitic infections.

• Dental disease.

• Surgically amenable congenital anomalies such as congenital heart disease, myelomeningocele, and others that have not been repaired.

• Neurologic problems, such as cerebral palsy, intellectual disability, and autism.

• Hearing loss.

• Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD),depression, and anxiety.

• Trauma such as gunshot wounds, shrapnel injuries, and genital trauma secondary to sexual violence.

• Sequelae from illnesses that previously were easily treated, such as hearing loss and ear complications from otitis media, and rheumatic fever from inadequately treated strep throat.

• Underimmunization.

Various resources listed below, including Dr. Seery’s paper, can help guide providers in assessing and meeting these needs, and navigating paperwork and the U.S. refugee system. These resources also can help practitioners address the mental health concerns these patients and their families may face.

Mental health needs

Even children in the best physical shape will have experienced significant upheaval that could lead to depression, anxiety, and PTSD – conditions more common among refugee children than in the general population, research has shown.

“Mental health conditions will be especially present in these children uprooted from their homes and families, and exposed to the violence of war,” Dr. Francis E. Rushton Jr. of the department of pediatrics at the University of South Carolina, Columbia, and a member of the American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Community Health Services, said in an interview. Of the four major areas of health care need he described for these children, two relate to mental health: toxic mental stress and fractured families and the lack of nurture.

One challenge pediatricians face, however, is recognizing these conditions despite cultural differences that could obscure them.

“It is not uncommon for teens and adults to deny symptoms of depression, stress, and anxiety in early encounters,” Dr. Reines said. “Many cultures stigmatize psychiatric or mental health problems, and refugees may be reluctant to admit they are having difficulties.”

One way around this obstacle is to ask patients and their parents about sleep, energy level, appetite, weight changes, and thoughts of harming one’s self, she said. Mental stress also manifests as somatic symptoms, such as headaches, stomach aches, and back pain, particularly in teens.

“Infants and toddlers are generally most adaptable as long as parents are coping well, and can provide a buffer for stress with a safe and nurturing environment,” Dr. Reines said. Children of parents with depression or PTSD, or who have lost a parent, may feel abandoned and experience depression or developmental delays.

Although school-age children may have nightmares, show anxiety, and cling to their parents, they usually transition well to their new homes. Adolescents face the biggest difficulties, especially if they have lost a parent, must care for their siblings, or have experienced sexual trauma. “They may have more vivid memories of disturbing events and a greater understanding of what their family has endured,” Dr. Reines said. Further, language and educational deficits can lead to alienation and embarrassment, yet families may rebuff behavioral health referrals.

“In these cases, it’s best to keep communication open, encourage dialogue with family, and try to find an activity or sport the refugee can participate in to improve self-esteem,” Dr. Reines said.

Avoiding cultural confusion

While cultural challenges are obvious – language barriers may necessitate translators or bicultural caseworkers – others may be more subtle. Developmental screening questions that rely on blocks, certain pictures, or other culturally specific bases, for example, may not adequately capture a child’s development.

Dr. Reines stresses a strategy for managing cultural differences that is recommended in Dr. Seery’s article: striving for cultural humility rather than cultural competence.

“It is impossible for U.S. physicians who have never practiced outside of our culture and are not bicultural or bilingual to become truly culturally competent in health care delivery for so many refugee populations,” Dr. Reines said. Instead then, cultural humility emphasizes showing respect, interest, and a willingness to learn from patients, she explained.

Cultural humility is a “lifelong process” that also demands flexibility and “allows the practitioner to release the false sense of security associated with stereotyping,” Dr. Seery and his colleagues wrote.

At the same time, pediatricians are guarding against inadvertent stereotyping; however, they can be aware of some cultural generalities that may apply to their Syrian refugee patients.

“Arab communities stress the importance of family rather than the individual and are often more modest than Westerners,” Dr. Rushton said. Further, “Arab families frequently experience discrimination on the basis of their religion in the United States, and pediatricians should be aware of ongoing traumatization even after arrival in America,” he said.

Teens may become embarrassed with discussions about sex or alcohol because few teens from the Middle East drink or become sexually active before marriage, Dr. Reines added. She noted that a Muslim male may not shake hands with females outside his family – a practice providers should respect – and that important religious holidays such as Ramadan may influence a family’s compliance with a treatment plan.

Perhaps the most important commonality, however, is one universal to most refugee families, regardless of their home country.

“The vast majority of families that we meet show incredible courage and resilience, and caring for their children is their highest priority,” Dr. Reines said. “We can learn a great deal from these families, and caring for their children is a tremendously rewarding experience.”

Other cultural resources:

Bridging Refugee Youth and Children’s Services

“The Middle of Everywhere: Helping Refugees Enter the American Community,” by Mary Pipher (Orlando: Mariner Books, 2003)

“Immigrant Medicine,” a textbook by Patricia Walker, M.D., and Elizabeth Barnett, M.D. (New York, N.Y.: Elsevier, 2007)

“Opening cultural doors: Providing culturally sensitive healthcare to Arab American and American Muslim patients” (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005 Oct;193]:1307-11).

Characteristics Associated With Active Defects in Juvenile Spondylolysis

Spondylolysis, a defect in the pars interarticularis, is the single most common identifiable source of persistent low back pain in adolescent athletes.1,2 The diagnosis of spondylolysis is confirmed by radiographic imaging.3 However, there is controversy regarding which imaging modality is preferred—specifically, which to use for first-line advanced imaging after plain radiographs are obtained.3 Single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) consistently has been shown to be the most sensitive modality, and it is considered the gold standard.4-7 Patients with a positive SPECT scan are then routinely imaged with computed tomography (CT) for bone detail and staging of the pars defect.8 This imaging or diagnostic sequence yields organ-specific radiation doses (15-30 mSv) as much as 50-fold higher than those of plain radiography.9 Recent epidemiologic studies have shown that this organ dose results in an increased risk of cancer, especially in children.10

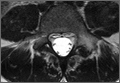

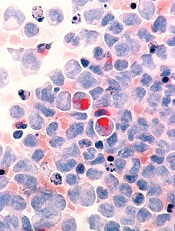

Diagnosis is crucial in early-stage lumbar spondylolysis, as osseous healing can occur with conservative treatment.11,12 High signal change (HSC) in the pedicle or pars interarticularis (Figure 1) on fluid-specific (T2) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) sequences has been shown to be important in the diagnosis of early spondylolysis and, subsequently, a good predictor of bony healing.13,14 We conducted a study to determine the clinical and radiographic characteristics associated with the diagnosis of early or active spondylolysis.

Materials and Methods

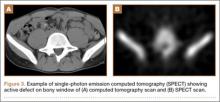

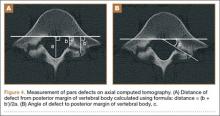

The study was reviewed and approved by the local institutional review board. Using the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) diagnosis code for spondylolysis (756.11), we retrospectively identified patients (age, 12-21 years) from 2002–2011 billing data from a single specialty spine practice. Baseline data—including height, weight, sex, age, symptom duration, sporting activities, defect location, pain score, and previous treatments—were collected from a standardized patient intake questionnaire and office medical records. We also determined radiographic data, including level, laterality (right vs left, unilateral vs bilateral), presence of listhesis, and slip grade and percentage. CT scans were reviewed to confirm the spondylolysis diagnosis and to measure parameters described by Fujii and colleagues.15 These parameters include spondylolysis chronicity (early, progressive, terminal) (Figure 2), distance from defect to posterior margin of vertebral body, and defect angle relative to posterior margin of vertebral body. We also measured sagittal radiographic parameters, including pelvic incidence and lumbar lordosis.

Pars lesions were divided into active and inactive defects16 based on signal characteristics on either MRI or SPECT (Figure 3). Defects with a positive SPECT or HSC on T2 MRI were classified as active; all other defects were classified as inactive. All MRIs were reviewed by a radiologist, and any mention of HSC in the pedicle or pars of the corresponding level was considered positive. For the sake of accuracy, all MRIs were also reviewed by a spine surgeon. All CT measurements were done by 1 of 2 authors. Demographic, clinical, and radiographic characteristics were compared between patients with active defects and patients with inactive defects. Independent t tests and Fisher exact tests were used to compare continuous and categorical variables, respectively. Threshold P was set at .01 to account for the small sample size and multiple concurrent comparisons.

Results

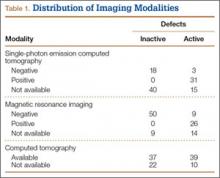

Fifty-seven patients (29 males, 28 females) with a total of 108 pars defects (6 unilateral, 102 bilateral) were identified. Mean age was 14.64 years. Of the 108 defects, 49 were classified as active and 59 as inactive. SPECT results were available for 52 defects, MRI results for 85, and CT results for 76 (Table 1). There was no difference between the active and inactive groups in age (14.7 vs 14.6 years; P = .083), body mass index (24.2 vs 21.7 kg/m2; P = .034), symptom duration (236.3 vs 397.4 days; P = .016), lumbar lordosis (27.4° vs 32.1°; P = .097), pelvic incidence (59.0° vs 61.2°; P = .488), slip percentage (9.5% vs 14.2%; P = .034), and laterality (right vs left, P = .847; unilateral vs bilateral, P = .281) (Table 2). There was a significant difference between the active and inactive groups in sex (35 vs 19 males; P < .0001) and presence of listhesis (16 vs 35; P = .006) (Table 2).

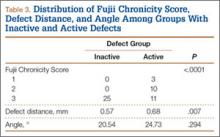

Of the 49 active defects, 3 were graded as early, 10 as progressive, and 11 as terminal (Table 3). There was a statistically significant (P < .0001) difference between active and inactive lesions for each stage. Mean distance from posterior margin of the vertebral body was 0.57 mm and 0.68 mm for inactive and active lesions, respectively (P = .007). There was no significant difference (P = .294) in the posterior angle of the vertebral body and the defect between inactive (20.54°) and active (24.73°) lesions (Table 3).

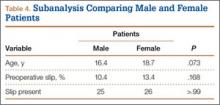

Subanalysis by sex showed no difference in age (males, 16.4 years vs females, 18.7 years; P = .073), slip percentage (10.4% vs 13.4%; P = .168), or presence or absence of slip (25 vs 26; P > .99) (Table 4).

Discussion

Increasing MRI resolution combined with increasing concern about unnecessary radiation exposure has added to the attractiveness of MRI in the diagnosis of spondylolysis. Spondylolysis progresses on a continuum, starting with a stress reaction (early or active defect) and ending with either healing or nonunion of the pars defect (terminal defect) (Figure 4). Although risk factors for progression are not clearly defined, Fujii and colleagues15 showed that the reaction around the defect is the most important factor for osseous union. It would then make sense that the earlier the spondylolytic defect is identified, the higher the likelihood for union, especially with nonoperative treatment such as rest, activity restriction, and bracing.12,17

There is a lack of consensus regarding MRI use in the diagnosis of spondylolysis. Masci and colleagues18 prospectively evaluated 50 defects in 39 patients using a 1.5-Tesla MRI scanner, concluded MRI is inferior to SPECT/CT, and recommended that SPECT remain the first-line advanced imaging modality. Conversely, Campbell and colleagues4 prospectively evaluated 40 defects in 22 patients using a 1.0-Tesla magnet and concluded that MRI can be used as an effective and reliable first-line advanced imaging modality. These are the only 2 prospective studies conducted within the past decade. Both were underpowered and used outdated technology (newer MRI scanners use 3.0-Tesla magnets). In addition, specific imaging characteristics (eg, edema in pars or pedicle on fluid-specific sequences) that suggest a positive finding—versus overt fracture on T1 MRI—have been recently emphasized. Neither Masci and colleagues18 nor Campbell and colleagues4 detailed what constituted a positive MRI finding. Although an adequately powered prospective study will provide a better analysis of the utility of MRI versus SPECT, such a study is costly and time-consuming. It is important to identify patient and lesion characteristics to help optimize the usefulness of MRI. It is also important to identify the subset of patients most likely to experience osseous healing of active defects,16 as this is the same subset of patients most likely to respond to nonoperative treatment.

We conducted the present study to identify any clinical or radiographic characteristics associated with the diagnosis of early or active spondylolysis. Almost equal numbers of active and inactive defects (49, 59) were identified. There were no differences in patient characteristics, including age, body mass index, and symptom duration. However, there was a significant sex difference—a relatively high proportion of males with active spondylolysis. This finding, which had been reported before,16,19,20 is probably the result of several factors, including males’ lower lumbar spine bone mineral density21; their relatively less spinal flexibility, which affects the distribution of torsional loads on the spine22; and their relatively greater participation in sports, especially sports involving high-velocity, torsional loading of the lumbar spine.23 Studies are needed to delineate the extent to which sex influences the development and persistence of active spondylolytic lesions. Alternatively, a subanalysis revealed an age difference, between our female and male cohorts (18.7 vs 16.4 years), that may have contributed to the high proportion of males with active spondylolysis.

Although the groups’ difference in symptom duration was not significant, it was trending toward significance. As discussed, it could be explained that, along the continuum of disease, earlier defects are more active and either achieve fibrous or osseous union or become chronic and “burn out” to inactive lesions, potentially leading to a listhesis.24 The listhesis association was higher in the inactive group than in the active group (P = .006). The difference in numbers of active and inactive defects at each stage (early, progressive, late) confirms this finding, with no inactive lesions in the early and progressive stages and many fewer active lesions in the terminal stage. Overall, presence of a spondylolisthesis on plain radiographs may obviate the need for SPECT or MRI, as it indicates an inactive chronic lesion—unless new symptoms are suspicious for reactivation or development of previously described adjacent-level pars defects.

No other radiographic parameters were found to be significant—consistent with findings of other studies.2,5,16 Pelvic incidence has been shown to predict progression of spondylisthesis, but under our study parameters it appears not to be associated with development of a slip.

This study had several weaknesses. First, it was retrospective, and imaging parameters were inconsistent, as we included patients who underwent imaging at other facilities. Second, the timing of imaging was inconsistent. Ideally, the same sequence protocol would be used, and all imaging studies (MRI, SPECT, CT) would be performed within a specific period after the initial concern for a spondylolysis was raised. Last, not all patients underwent all 3 advanced imaging modalities; having all 3 would have allowed for a retrospective comparison of MRI and SPECT sensitivity in detecting spondylolysis. Such a comparison would have been interesting, though it was not the goal of this study.

With its technological improvements and lack of radiation exposure, MRI is becoming more attractive as a first-line advanced imaging modality. Although the superiority of MRI over SPECT is yet to be confirmed, clinical use of MRI in the evaluation of spondylolysis seems to be increasing. It is therefore important to characterize the spondylolytic defects that are readily detected with MRI.

Active or early juvenile spondylolysis appears to be associated with males and absence of an associated listhesis. These clinical and radiographic characteristics may be important in the identification of patients with higher potential for osseous healing after nonoperative treatment.

1. Micheli LJ, Wood R. Back pain in young athletes. Significant differences from adults in causes and patterns. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1995;149(1):15-18.

2. Sakai T, Sairyo K, Suzue N, Kosaka H, Yasui N. Incidence and etiology of lumbar spondylolysis: review of the literature. J Orthop Sci. 2010;15(3):281-288.

3. Standaert CJ, Herring SA. Expert opinion and controversies in sports and musculoskeletal medicine: the diagnosis and treatment of spondylolysis in adolescent athletes. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;88(4):537-540.

4. Campbell RS, Grainger AJ, Hide IG, Papastefanou S, Greenough CG. Juvenile spondylolysis: a comparative analysis of CT, SPECT and MRI. Skeletal Radiol. 2005;34(2):63-73.

5. Kalichman L, Kim DH, Li L, Guermazi A, Berkin V, Hunter DJ. Spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis: prevalence and association with low back pain in the adult community-based population. Spine. 2009;34(2):199-205.

6. Zukotynski K, Curtis C, Grant FD, Micheli L, Treves ST. The value of SPECT in the detection of stress injury to the pars interarticularis in patients with low back pain. J Orthop Surg Res. 2010;5:13.

7. Leone A, Cianfoni A, Cerase A, Magarelli N, Bonomo L. Lumbar spondylolysis: a review. Skeletal Radiol. 2011;40(6):683-700.

8. Gregory PL, Batt ME, Kerslake RW, Scammell BE, Webb JF. The value of combining single photon emission computerised tomography and computerised tomography in the investigation of spondylolysis. Eur Spine J. 2004;13(6):503-509.

9. Brenner DJ, Hall EJ. Computed tomography—an increasing source of radiation exposure. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(22):2277-2284.

10. Brenner DJ, Shuryak I, Einstein AJ. Impact of reduced patient life expectancy on potential cancer risks from radiologic imaging. Radiology. 2011;261(1):193-198.

11. Sairyo K, Sakai T, Yasui N, Dezawa A. Conservative treatment for pediatric lumbar spondylolysis to achieve bone healing using a hard brace: what type and how long?: Clinical article. J Neurosurg Spine. 2012;16(6):610-614.

12. Steiner ME, Micheli LJ. Treatment of symptomatic spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis with the modified Boston brace. Spine. 1985;10(10):937-943.

13. Sairyo K, Katoh S, Takata Y, et al. MRI signal changes of the pedicle as an indicator for early diagnosis of spondylolysis in children and adolescents: a clinical and biomechanical study. Spine. 2006;31(2):206-211.

14. Sakai T, Sairyo K, Mima S, Yasui N. Significance of magnetic resonance imaging signal change in the pedicle in the management of pediatric lumbar spondylolysis. Spine. 2010;35(14):E641-E645.

15. Fujii K, Katoh S, Sairyo K, Ikata T, Yasui N. Union of defects in the pars interarticularis of the lumbar spine in children and adolescents. The radiological outcome after conservative treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2004;86(2):225-231.

16. Gregg CD, Dean S, Schneiders AG. Variables associated with active spondylolysis. Phys Ther Sport. 2009;10(4):121-124.

17. Kobayashi A, Kobayashi T, Kato K, Higuchi H, Takagishi K. Diagnosis of radiographically occult lumbar spondylolysis in young athletes by magnetic resonance imaging. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(1):169-176.

18. Masci L, Pike J, Malara F, Phillips B, Bennell K, Brukner P. Use of the one-legged hyperextension test and magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of active spondylolysis. Br J Sports Med. 2006;40(11):940-946.

19. Beutler WJ, Fredrickson BE, Murtland A, Sweeney CA, Grant WD, Baker D. The natural history of spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis: 45-year follow-up evaluation. Spine. 2003;28(10):1027-1035.

20. Miller SF, Congeni J, Swanson K. Long-term functional and anatomical follow-up of early detected spondylolysis in young athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32(4):928-933.

21. Zanchetta JR, Plotkin H, Alvarez Filgueira ML. Bone mass in children: normative values for the 2-20-year-old population. Bone. 1995;16(4 suppl):393S-399S.

22. Kondratek M, Krauss J, Stiller C, Olson R. Normative values for active lumbar range of motion in children. Pediatr Phys Ther. 2007;19(3):236-244.

23. Hardcastle P, Annear P, Foster DH, et al. Spinal abnormalities in young fast bowlers. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1992;74(3):421-425.

24. Fredrickson BE, Baker D, McHolick WJ, Yuan HA, Lubicky JP. The natural history of spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1984;66(5):699-707.

Spondylolysis, a defect in the pars interarticularis, is the single most common identifiable source of persistent low back pain in adolescent athletes.1,2 The diagnosis of spondylolysis is confirmed by radiographic imaging.3 However, there is controversy regarding which imaging modality is preferred—specifically, which to use for first-line advanced imaging after plain radiographs are obtained.3 Single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) consistently has been shown to be the most sensitive modality, and it is considered the gold standard.4-7 Patients with a positive SPECT scan are then routinely imaged with computed tomography (CT) for bone detail and staging of the pars defect.8 This imaging or diagnostic sequence yields organ-specific radiation doses (15-30 mSv) as much as 50-fold higher than those of plain radiography.9 Recent epidemiologic studies have shown that this organ dose results in an increased risk of cancer, especially in children.10

Diagnosis is crucial in early-stage lumbar spondylolysis, as osseous healing can occur with conservative treatment.11,12 High signal change (HSC) in the pedicle or pars interarticularis (Figure 1) on fluid-specific (T2) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) sequences has been shown to be important in the diagnosis of early spondylolysis and, subsequently, a good predictor of bony healing.13,14 We conducted a study to determine the clinical and radiographic characteristics associated with the diagnosis of early or active spondylolysis.

Materials and Methods

The study was reviewed and approved by the local institutional review board. Using the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) diagnosis code for spondylolysis (756.11), we retrospectively identified patients (age, 12-21 years) from 2002–2011 billing data from a single specialty spine practice. Baseline data—including height, weight, sex, age, symptom duration, sporting activities, defect location, pain score, and previous treatments—were collected from a standardized patient intake questionnaire and office medical records. We also determined radiographic data, including level, laterality (right vs left, unilateral vs bilateral), presence of listhesis, and slip grade and percentage. CT scans were reviewed to confirm the spondylolysis diagnosis and to measure parameters described by Fujii and colleagues.15 These parameters include spondylolysis chronicity (early, progressive, terminal) (Figure 2), distance from defect to posterior margin of vertebral body, and defect angle relative to posterior margin of vertebral body. We also measured sagittal radiographic parameters, including pelvic incidence and lumbar lordosis.

Pars lesions were divided into active and inactive defects16 based on signal characteristics on either MRI or SPECT (Figure 3). Defects with a positive SPECT or HSC on T2 MRI were classified as active; all other defects were classified as inactive. All MRIs were reviewed by a radiologist, and any mention of HSC in the pedicle or pars of the corresponding level was considered positive. For the sake of accuracy, all MRIs were also reviewed by a spine surgeon. All CT measurements were done by 1 of 2 authors. Demographic, clinical, and radiographic characteristics were compared between patients with active defects and patients with inactive defects. Independent t tests and Fisher exact tests were used to compare continuous and categorical variables, respectively. Threshold P was set at .01 to account for the small sample size and multiple concurrent comparisons.

Results

Fifty-seven patients (29 males, 28 females) with a total of 108 pars defects (6 unilateral, 102 bilateral) were identified. Mean age was 14.64 years. Of the 108 defects, 49 were classified as active and 59 as inactive. SPECT results were available for 52 defects, MRI results for 85, and CT results for 76 (Table 1). There was no difference between the active and inactive groups in age (14.7 vs 14.6 years; P = .083), body mass index (24.2 vs 21.7 kg/m2; P = .034), symptom duration (236.3 vs 397.4 days; P = .016), lumbar lordosis (27.4° vs 32.1°; P = .097), pelvic incidence (59.0° vs 61.2°; P = .488), slip percentage (9.5% vs 14.2%; P = .034), and laterality (right vs left, P = .847; unilateral vs bilateral, P = .281) (Table 2). There was a significant difference between the active and inactive groups in sex (35 vs 19 males; P < .0001) and presence of listhesis (16 vs 35; P = .006) (Table 2).

Of the 49 active defects, 3 were graded as early, 10 as progressive, and 11 as terminal (Table 3). There was a statistically significant (P < .0001) difference between active and inactive lesions for each stage. Mean distance from posterior margin of the vertebral body was 0.57 mm and 0.68 mm for inactive and active lesions, respectively (P = .007). There was no significant difference (P = .294) in the posterior angle of the vertebral body and the defect between inactive (20.54°) and active (24.73°) lesions (Table 3).

Subanalysis by sex showed no difference in age (males, 16.4 years vs females, 18.7 years; P = .073), slip percentage (10.4% vs 13.4%; P = .168), or presence or absence of slip (25 vs 26; P > .99) (Table 4).

Discussion

Increasing MRI resolution combined with increasing concern about unnecessary radiation exposure has added to the attractiveness of MRI in the diagnosis of spondylolysis. Spondylolysis progresses on a continuum, starting with a stress reaction (early or active defect) and ending with either healing or nonunion of the pars defect (terminal defect) (Figure 4). Although risk factors for progression are not clearly defined, Fujii and colleagues15 showed that the reaction around the defect is the most important factor for osseous union. It would then make sense that the earlier the spondylolytic defect is identified, the higher the likelihood for union, especially with nonoperative treatment such as rest, activity restriction, and bracing.12,17

There is a lack of consensus regarding MRI use in the diagnosis of spondylolysis. Masci and colleagues18 prospectively evaluated 50 defects in 39 patients using a 1.5-Tesla MRI scanner, concluded MRI is inferior to SPECT/CT, and recommended that SPECT remain the first-line advanced imaging modality. Conversely, Campbell and colleagues4 prospectively evaluated 40 defects in 22 patients using a 1.0-Tesla magnet and concluded that MRI can be used as an effective and reliable first-line advanced imaging modality. These are the only 2 prospective studies conducted within the past decade. Both were underpowered and used outdated technology (newer MRI scanners use 3.0-Tesla magnets). In addition, specific imaging characteristics (eg, edema in pars or pedicle on fluid-specific sequences) that suggest a positive finding—versus overt fracture on T1 MRI—have been recently emphasized. Neither Masci and colleagues18 nor Campbell and colleagues4 detailed what constituted a positive MRI finding. Although an adequately powered prospective study will provide a better analysis of the utility of MRI versus SPECT, such a study is costly and time-consuming. It is important to identify patient and lesion characteristics to help optimize the usefulness of MRI. It is also important to identify the subset of patients most likely to experience osseous healing of active defects,16 as this is the same subset of patients most likely to respond to nonoperative treatment.

We conducted the present study to identify any clinical or radiographic characteristics associated with the diagnosis of early or active spondylolysis. Almost equal numbers of active and inactive defects (49, 59) were identified. There were no differences in patient characteristics, including age, body mass index, and symptom duration. However, there was a significant sex difference—a relatively high proportion of males with active spondylolysis. This finding, which had been reported before,16,19,20 is probably the result of several factors, including males’ lower lumbar spine bone mineral density21; their relatively less spinal flexibility, which affects the distribution of torsional loads on the spine22; and their relatively greater participation in sports, especially sports involving high-velocity, torsional loading of the lumbar spine.23 Studies are needed to delineate the extent to which sex influences the development and persistence of active spondylolytic lesions. Alternatively, a subanalysis revealed an age difference, between our female and male cohorts (18.7 vs 16.4 years), that may have contributed to the high proportion of males with active spondylolysis.

Although the groups’ difference in symptom duration was not significant, it was trending toward significance. As discussed, it could be explained that, along the continuum of disease, earlier defects are more active and either achieve fibrous or osseous union or become chronic and “burn out” to inactive lesions, potentially leading to a listhesis.24 The listhesis association was higher in the inactive group than in the active group (P = .006). The difference in numbers of active and inactive defects at each stage (early, progressive, late) confirms this finding, with no inactive lesions in the early and progressive stages and many fewer active lesions in the terminal stage. Overall, presence of a spondylolisthesis on plain radiographs may obviate the need for SPECT or MRI, as it indicates an inactive chronic lesion—unless new symptoms are suspicious for reactivation or development of previously described adjacent-level pars defects.

No other radiographic parameters were found to be significant—consistent with findings of other studies.2,5,16 Pelvic incidence has been shown to predict progression of spondylisthesis, but under our study parameters it appears not to be associated with development of a slip.

This study had several weaknesses. First, it was retrospective, and imaging parameters were inconsistent, as we included patients who underwent imaging at other facilities. Second, the timing of imaging was inconsistent. Ideally, the same sequence protocol would be used, and all imaging studies (MRI, SPECT, CT) would be performed within a specific period after the initial concern for a spondylolysis was raised. Last, not all patients underwent all 3 advanced imaging modalities; having all 3 would have allowed for a retrospective comparison of MRI and SPECT sensitivity in detecting spondylolysis. Such a comparison would have been interesting, though it was not the goal of this study.

With its technological improvements and lack of radiation exposure, MRI is becoming more attractive as a first-line advanced imaging modality. Although the superiority of MRI over SPECT is yet to be confirmed, clinical use of MRI in the evaluation of spondylolysis seems to be increasing. It is therefore important to characterize the spondylolytic defects that are readily detected with MRI.

Active or early juvenile spondylolysis appears to be associated with males and absence of an associated listhesis. These clinical and radiographic characteristics may be important in the identification of patients with higher potential for osseous healing after nonoperative treatment.

Spondylolysis, a defect in the pars interarticularis, is the single most common identifiable source of persistent low back pain in adolescent athletes.1,2 The diagnosis of spondylolysis is confirmed by radiographic imaging.3 However, there is controversy regarding which imaging modality is preferred—specifically, which to use for first-line advanced imaging after plain radiographs are obtained.3 Single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) consistently has been shown to be the most sensitive modality, and it is considered the gold standard.4-7 Patients with a positive SPECT scan are then routinely imaged with computed tomography (CT) for bone detail and staging of the pars defect.8 This imaging or diagnostic sequence yields organ-specific radiation doses (15-30 mSv) as much as 50-fold higher than those of plain radiography.9 Recent epidemiologic studies have shown that this organ dose results in an increased risk of cancer, especially in children.10

Diagnosis is crucial in early-stage lumbar spondylolysis, as osseous healing can occur with conservative treatment.11,12 High signal change (HSC) in the pedicle or pars interarticularis (Figure 1) on fluid-specific (T2) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) sequences has been shown to be important in the diagnosis of early spondylolysis and, subsequently, a good predictor of bony healing.13,14 We conducted a study to determine the clinical and radiographic characteristics associated with the diagnosis of early or active spondylolysis.

Materials and Methods

The study was reviewed and approved by the local institutional review board. Using the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) diagnosis code for spondylolysis (756.11), we retrospectively identified patients (age, 12-21 years) from 2002–2011 billing data from a single specialty spine practice. Baseline data—including height, weight, sex, age, symptom duration, sporting activities, defect location, pain score, and previous treatments—were collected from a standardized patient intake questionnaire and office medical records. We also determined radiographic data, including level, laterality (right vs left, unilateral vs bilateral), presence of listhesis, and slip grade and percentage. CT scans were reviewed to confirm the spondylolysis diagnosis and to measure parameters described by Fujii and colleagues.15 These parameters include spondylolysis chronicity (early, progressive, terminal) (Figure 2), distance from defect to posterior margin of vertebral body, and defect angle relative to posterior margin of vertebral body. We also measured sagittal radiographic parameters, including pelvic incidence and lumbar lordosis.

Pars lesions were divided into active and inactive defects16 based on signal characteristics on either MRI or SPECT (Figure 3). Defects with a positive SPECT or HSC on T2 MRI were classified as active; all other defects were classified as inactive. All MRIs were reviewed by a radiologist, and any mention of HSC in the pedicle or pars of the corresponding level was considered positive. For the sake of accuracy, all MRIs were also reviewed by a spine surgeon. All CT measurements were done by 1 of 2 authors. Demographic, clinical, and radiographic characteristics were compared between patients with active defects and patients with inactive defects. Independent t tests and Fisher exact tests were used to compare continuous and categorical variables, respectively. Threshold P was set at .01 to account for the small sample size and multiple concurrent comparisons.

Results

Fifty-seven patients (29 males, 28 females) with a total of 108 pars defects (6 unilateral, 102 bilateral) were identified. Mean age was 14.64 years. Of the 108 defects, 49 were classified as active and 59 as inactive. SPECT results were available for 52 defects, MRI results for 85, and CT results for 76 (Table 1). There was no difference between the active and inactive groups in age (14.7 vs 14.6 years; P = .083), body mass index (24.2 vs 21.7 kg/m2; P = .034), symptom duration (236.3 vs 397.4 days; P = .016), lumbar lordosis (27.4° vs 32.1°; P = .097), pelvic incidence (59.0° vs 61.2°; P = .488), slip percentage (9.5% vs 14.2%; P = .034), and laterality (right vs left, P = .847; unilateral vs bilateral, P = .281) (Table 2). There was a significant difference between the active and inactive groups in sex (35 vs 19 males; P < .0001) and presence of listhesis (16 vs 35; P = .006) (Table 2).

Of the 49 active defects, 3 were graded as early, 10 as progressive, and 11 as terminal (Table 3). There was a statistically significant (P < .0001) difference between active and inactive lesions for each stage. Mean distance from posterior margin of the vertebral body was 0.57 mm and 0.68 mm for inactive and active lesions, respectively (P = .007). There was no significant difference (P = .294) in the posterior angle of the vertebral body and the defect between inactive (20.54°) and active (24.73°) lesions (Table 3).

Subanalysis by sex showed no difference in age (males, 16.4 years vs females, 18.7 years; P = .073), slip percentage (10.4% vs 13.4%; P = .168), or presence or absence of slip (25 vs 26; P > .99) (Table 4).

Discussion

Increasing MRI resolution combined with increasing concern about unnecessary radiation exposure has added to the attractiveness of MRI in the diagnosis of spondylolysis. Spondylolysis progresses on a continuum, starting with a stress reaction (early or active defect) and ending with either healing or nonunion of the pars defect (terminal defect) (Figure 4). Although risk factors for progression are not clearly defined, Fujii and colleagues15 showed that the reaction around the defect is the most important factor for osseous union. It would then make sense that the earlier the spondylolytic defect is identified, the higher the likelihood for union, especially with nonoperative treatment such as rest, activity restriction, and bracing.12,17

There is a lack of consensus regarding MRI use in the diagnosis of spondylolysis. Masci and colleagues18 prospectively evaluated 50 defects in 39 patients using a 1.5-Tesla MRI scanner, concluded MRI is inferior to SPECT/CT, and recommended that SPECT remain the first-line advanced imaging modality. Conversely, Campbell and colleagues4 prospectively evaluated 40 defects in 22 patients using a 1.0-Tesla magnet and concluded that MRI can be used as an effective and reliable first-line advanced imaging modality. These are the only 2 prospective studies conducted within the past decade. Both were underpowered and used outdated technology (newer MRI scanners use 3.0-Tesla magnets). In addition, specific imaging characteristics (eg, edema in pars or pedicle on fluid-specific sequences) that suggest a positive finding—versus overt fracture on T1 MRI—have been recently emphasized. Neither Masci and colleagues18 nor Campbell and colleagues4 detailed what constituted a positive MRI finding. Although an adequately powered prospective study will provide a better analysis of the utility of MRI versus SPECT, such a study is costly and time-consuming. It is important to identify patient and lesion characteristics to help optimize the usefulness of MRI. It is also important to identify the subset of patients most likely to experience osseous healing of active defects,16 as this is the same subset of patients most likely to respond to nonoperative treatment.

We conducted the present study to identify any clinical or radiographic characteristics associated with the diagnosis of early or active spondylolysis. Almost equal numbers of active and inactive defects (49, 59) were identified. There were no differences in patient characteristics, including age, body mass index, and symptom duration. However, there was a significant sex difference—a relatively high proportion of males with active spondylolysis. This finding, which had been reported before,16,19,20 is probably the result of several factors, including males’ lower lumbar spine bone mineral density21; their relatively less spinal flexibility, which affects the distribution of torsional loads on the spine22; and their relatively greater participation in sports, especially sports involving high-velocity, torsional loading of the lumbar spine.23 Studies are needed to delineate the extent to which sex influences the development and persistence of active spondylolytic lesions. Alternatively, a subanalysis revealed an age difference, between our female and male cohorts (18.7 vs 16.4 years), that may have contributed to the high proportion of males with active spondylolysis.

Although the groups’ difference in symptom duration was not significant, it was trending toward significance. As discussed, it could be explained that, along the continuum of disease, earlier defects are more active and either achieve fibrous or osseous union or become chronic and “burn out” to inactive lesions, potentially leading to a listhesis.24 The listhesis association was higher in the inactive group than in the active group (P = .006). The difference in numbers of active and inactive defects at each stage (early, progressive, late) confirms this finding, with no inactive lesions in the early and progressive stages and many fewer active lesions in the terminal stage. Overall, presence of a spondylolisthesis on plain radiographs may obviate the need for SPECT or MRI, as it indicates an inactive chronic lesion—unless new symptoms are suspicious for reactivation or development of previously described adjacent-level pars defects.

No other radiographic parameters were found to be significant—consistent with findings of other studies.2,5,16 Pelvic incidence has been shown to predict progression of spondylisthesis, but under our study parameters it appears not to be associated with development of a slip.

This study had several weaknesses. First, it was retrospective, and imaging parameters were inconsistent, as we included patients who underwent imaging at other facilities. Second, the timing of imaging was inconsistent. Ideally, the same sequence protocol would be used, and all imaging studies (MRI, SPECT, CT) would be performed within a specific period after the initial concern for a spondylolysis was raised. Last, not all patients underwent all 3 advanced imaging modalities; having all 3 would have allowed for a retrospective comparison of MRI and SPECT sensitivity in detecting spondylolysis. Such a comparison would have been interesting, though it was not the goal of this study.

With its technological improvements and lack of radiation exposure, MRI is becoming more attractive as a first-line advanced imaging modality. Although the superiority of MRI over SPECT is yet to be confirmed, clinical use of MRI in the evaluation of spondylolysis seems to be increasing. It is therefore important to characterize the spondylolytic defects that are readily detected with MRI.

Active or early juvenile spondylolysis appears to be associated with males and absence of an associated listhesis. These clinical and radiographic characteristics may be important in the identification of patients with higher potential for osseous healing after nonoperative treatment.

1. Micheli LJ, Wood R. Back pain in young athletes. Significant differences from adults in causes and patterns. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1995;149(1):15-18.

2. Sakai T, Sairyo K, Suzue N, Kosaka H, Yasui N. Incidence and etiology of lumbar spondylolysis: review of the literature. J Orthop Sci. 2010;15(3):281-288.

3. Standaert CJ, Herring SA. Expert opinion and controversies in sports and musculoskeletal medicine: the diagnosis and treatment of spondylolysis in adolescent athletes. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;88(4):537-540.

4. Campbell RS, Grainger AJ, Hide IG, Papastefanou S, Greenough CG. Juvenile spondylolysis: a comparative analysis of CT, SPECT and MRI. Skeletal Radiol. 2005;34(2):63-73.

5. Kalichman L, Kim DH, Li L, Guermazi A, Berkin V, Hunter DJ. Spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis: prevalence and association with low back pain in the adult community-based population. Spine. 2009;34(2):199-205.

6. Zukotynski K, Curtis C, Grant FD, Micheli L, Treves ST. The value of SPECT in the detection of stress injury to the pars interarticularis in patients with low back pain. J Orthop Surg Res. 2010;5:13.

7. Leone A, Cianfoni A, Cerase A, Magarelli N, Bonomo L. Lumbar spondylolysis: a review. Skeletal Radiol. 2011;40(6):683-700.

8. Gregory PL, Batt ME, Kerslake RW, Scammell BE, Webb JF. The value of combining single photon emission computerised tomography and computerised tomography in the investigation of spondylolysis. Eur Spine J. 2004;13(6):503-509.

9. Brenner DJ, Hall EJ. Computed tomography—an increasing source of radiation exposure. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(22):2277-2284.

10. Brenner DJ, Shuryak I, Einstein AJ. Impact of reduced patient life expectancy on potential cancer risks from radiologic imaging. Radiology. 2011;261(1):193-198.

11. Sairyo K, Sakai T, Yasui N, Dezawa A. Conservative treatment for pediatric lumbar spondylolysis to achieve bone healing using a hard brace: what type and how long?: Clinical article. J Neurosurg Spine. 2012;16(6):610-614.

12. Steiner ME, Micheli LJ. Treatment of symptomatic spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis with the modified Boston brace. Spine. 1985;10(10):937-943.

13. Sairyo K, Katoh S, Takata Y, et al. MRI signal changes of the pedicle as an indicator for early diagnosis of spondylolysis in children and adolescents: a clinical and biomechanical study. Spine. 2006;31(2):206-211.

14. Sakai T, Sairyo K, Mima S, Yasui N. Significance of magnetic resonance imaging signal change in the pedicle in the management of pediatric lumbar spondylolysis. Spine. 2010;35(14):E641-E645.

15. Fujii K, Katoh S, Sairyo K, Ikata T, Yasui N. Union of defects in the pars interarticularis of the lumbar spine in children and adolescents. The radiological outcome after conservative treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2004;86(2):225-231.

16. Gregg CD, Dean S, Schneiders AG. Variables associated with active spondylolysis. Phys Ther Sport. 2009;10(4):121-124.

17. Kobayashi A, Kobayashi T, Kato K, Higuchi H, Takagishi K. Diagnosis of radiographically occult lumbar spondylolysis in young athletes by magnetic resonance imaging. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(1):169-176.

18. Masci L, Pike J, Malara F, Phillips B, Bennell K, Brukner P. Use of the one-legged hyperextension test and magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of active spondylolysis. Br J Sports Med. 2006;40(11):940-946.

19. Beutler WJ, Fredrickson BE, Murtland A, Sweeney CA, Grant WD, Baker D. The natural history of spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis: 45-year follow-up evaluation. Spine. 2003;28(10):1027-1035.

20. Miller SF, Congeni J, Swanson K. Long-term functional and anatomical follow-up of early detected spondylolysis in young athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32(4):928-933.

21. Zanchetta JR, Plotkin H, Alvarez Filgueira ML. Bone mass in children: normative values for the 2-20-year-old population. Bone. 1995;16(4 suppl):393S-399S.

22. Kondratek M, Krauss J, Stiller C, Olson R. Normative values for active lumbar range of motion in children. Pediatr Phys Ther. 2007;19(3):236-244.

23. Hardcastle P, Annear P, Foster DH, et al. Spinal abnormalities in young fast bowlers. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1992;74(3):421-425.

24. Fredrickson BE, Baker D, McHolick WJ, Yuan HA, Lubicky JP. The natural history of spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1984;66(5):699-707.

1. Micheli LJ, Wood R. Back pain in young athletes. Significant differences from adults in causes and patterns. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1995;149(1):15-18.

2. Sakai T, Sairyo K, Suzue N, Kosaka H, Yasui N. Incidence and etiology of lumbar spondylolysis: review of the literature. J Orthop Sci. 2010;15(3):281-288.

3. Standaert CJ, Herring SA. Expert opinion and controversies in sports and musculoskeletal medicine: the diagnosis and treatment of spondylolysis in adolescent athletes. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;88(4):537-540.

4. Campbell RS, Grainger AJ, Hide IG, Papastefanou S, Greenough CG. Juvenile spondylolysis: a comparative analysis of CT, SPECT and MRI. Skeletal Radiol. 2005;34(2):63-73.

5. Kalichman L, Kim DH, Li L, Guermazi A, Berkin V, Hunter DJ. Spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis: prevalence and association with low back pain in the adult community-based population. Spine. 2009;34(2):199-205.

6. Zukotynski K, Curtis C, Grant FD, Micheli L, Treves ST. The value of SPECT in the detection of stress injury to the pars interarticularis in patients with low back pain. J Orthop Surg Res. 2010;5:13.

7. Leone A, Cianfoni A, Cerase A, Magarelli N, Bonomo L. Lumbar spondylolysis: a review. Skeletal Radiol. 2011;40(6):683-700.

8. Gregory PL, Batt ME, Kerslake RW, Scammell BE, Webb JF. The value of combining single photon emission computerised tomography and computerised tomography in the investigation of spondylolysis. Eur Spine J. 2004;13(6):503-509.

9. Brenner DJ, Hall EJ. Computed tomography—an increasing source of radiation exposure. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(22):2277-2284.

10. Brenner DJ, Shuryak I, Einstein AJ. Impact of reduced patient life expectancy on potential cancer risks from radiologic imaging. Radiology. 2011;261(1):193-198.

11. Sairyo K, Sakai T, Yasui N, Dezawa A. Conservative treatment for pediatric lumbar spondylolysis to achieve bone healing using a hard brace: what type and how long?: Clinical article. J Neurosurg Spine. 2012;16(6):610-614.

12. Steiner ME, Micheli LJ. Treatment of symptomatic spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis with the modified Boston brace. Spine. 1985;10(10):937-943.

13. Sairyo K, Katoh S, Takata Y, et al. MRI signal changes of the pedicle as an indicator for early diagnosis of spondylolysis in children and adolescents: a clinical and biomechanical study. Spine. 2006;31(2):206-211.

14. Sakai T, Sairyo K, Mima S, Yasui N. Significance of magnetic resonance imaging signal change in the pedicle in the management of pediatric lumbar spondylolysis. Spine. 2010;35(14):E641-E645.

15. Fujii K, Katoh S, Sairyo K, Ikata T, Yasui N. Union of defects in the pars interarticularis of the lumbar spine in children and adolescents. The radiological outcome after conservative treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2004;86(2):225-231.

16. Gregg CD, Dean S, Schneiders AG. Variables associated with active spondylolysis. Phys Ther Sport. 2009;10(4):121-124.

17. Kobayashi A, Kobayashi T, Kato K, Higuchi H, Takagishi K. Diagnosis of radiographically occult lumbar spondylolysis in young athletes by magnetic resonance imaging. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(1):169-176.

18. Masci L, Pike J, Malara F, Phillips B, Bennell K, Brukner P. Use of the one-legged hyperextension test and magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of active spondylolysis. Br J Sports Med. 2006;40(11):940-946.

19. Beutler WJ, Fredrickson BE, Murtland A, Sweeney CA, Grant WD, Baker D. The natural history of spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis: 45-year follow-up evaluation. Spine. 2003;28(10):1027-1035.

20. Miller SF, Congeni J, Swanson K. Long-term functional and anatomical follow-up of early detected spondylolysis in young athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32(4):928-933.

21. Zanchetta JR, Plotkin H, Alvarez Filgueira ML. Bone mass in children: normative values for the 2-20-year-old population. Bone. 1995;16(4 suppl):393S-399S.

22. Kondratek M, Krauss J, Stiller C, Olson R. Normative values for active lumbar range of motion in children. Pediatr Phys Ther. 2007;19(3):236-244.

23. Hardcastle P, Annear P, Foster DH, et al. Spinal abnormalities in young fast bowlers. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1992;74(3):421-425.

24. Fredrickson BE, Baker D, McHolick WJ, Yuan HA, Lubicky JP. The natural history of spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1984;66(5):699-707.

Current Evidence Does Not Support Medicare’s 3-Day Rule in Primary Total Joint Arthroplasty

Medicare beneficiaries’ demand for total hip arthroplasty (THA) and total knee arthroplasty (TKA) has increased significantly over the past several years, with recent studies reporting 209,945 primary THAs and 243,802 primary TKAs performed annually.1,2 With this demand has come an increase in the percentage of patients discharged to an extended-care facility (ECF) for skilled nursing care or acute rehabilitation—an estimated 49.3% for THA and 41.5% for TKA.1,2 To qualify for discharge to an ECF, Medicare beneficiaries are required to have an inpatient stay of at least 3 consecutive days.3 Although the basis of this rule is unclear, it is thought to prevent hasty discharge of unstable patients.

We conducted a study to explore the effect of this policy on length of stay (LOS) in a population of patients who underwent primary total joint arthroplasty (TJA). Based on a pilot study by our group, we hypothesized that such a statuary requirement would be associated with increased LOS and would not prevent discharge of potentially unstable patients. Specifically, we explored whether patients who could have been discharged earlier experienced any later inpatient complications or 30-day readmission to justify staying past their discharge readiness.

Materials and Methods

Institutional review board approval was obtained for this study. Between 2011 and 2012, the senior authors (Dr. Wellman, Dr. Attarian, Dr. Bolognesi) treated 985 patients with Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes 27130 (THA) and 27447 (TKA). Of the 985 patients, 287 (29.13%) were discharged to an ECF and were included in the study. Three of the 287 were excluded: 2 for requiring preadmission for medical optimization and 1 for having another procedure with plastic surgery. All patients were admitted from home on day of surgery and had a standardized clinical pathway with respect to pain control, mobilization, and anticoagulation. Physical therapy and occupational therapy (PT/OT) were initiated on day of surgery and were continued daily until discharge.

The primary outcome was discharge readiness, defined as meeting the criteria of stable blood pressure, pulse, and breathing; no fever over 101.5°F for 24 hours before discharge; wound healing with no concerns; pain controlled with oral medications; and ambulation or the potential for rehabilitation at the receiving facility. Secondary outcomes were changes in PT/OT progress, medical interventions, and 30-day readmission rate. PT/OT progress was categorized as either slow or steady by the therapist assigned to each patient at time of hospitalization. Steady progress indicated overall improvement on several measures, including transfers, ambulation distance, and ability to adhere to postoperative precautions; slow progress indicated no improvement on these measures.

Results for continuous variables were summarized with means, standard deviations, and ranges, and results for categorical variables were summarized with counts and percentages. Student t test was used to evaluate increase in LOS, and the McNemar test for paired data was used to analyze rehabilitation gains from readiness-for-discharge day to the next postoperative day (POD). SAS Version 9.2 software (SAS Institute) was used for all analyses.

Results

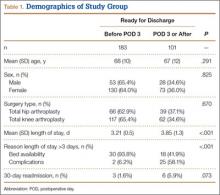

Of the 284 patients included in the study, 203 were female (71.5%), 81 male (28.5%). Mean (SD) age was 68 (11) years (range, 21-92 years). One hundred seventy-nine patients (63.0%) underwent TKA, and 105 (37.0%) underwent THA. Two hundred twenty-seven patients (80.0%) were discharged to skilled nursing care, and 57 (20.1%) to inpatient rehabilitation. Mean (SD) LOS was 3.44 (0.92) days (range, 3-9 days). One hundred eighty-three patients (64.4%) were ready for discharge on POD 2, 76 (26.8%) on POD 3, and 25 (8.8%) after POD 3. Delaying discharge until POD 3 increased LOS by 1.08 days (P < .001). Two hundred nine patients (73.6%) were discharged on POD 3, and 75 (26.4%) after POD 3. Reasons for being discharged after POD 3 were lack of ECF bed availability (48 patients, 64.0%) and postoperative complications (27 patients, 36.0%). Patients ready for discharge on POD 2 had fewer complications than patients ready after POD 2 (P < .001).

Analysis of the 183 patients who were ready for discharge on POD 2 demonstrated a statistically significant (P = .038) change in rehabilitation progress by staying an additional hospital day. However, this difference was not clinically significant: Only 17.5% of patients improved, while 82.5% remained unchanged or declined in progress. Most important, among patients who demonstrated rehabilitation gains, the improvement was not sufficient to change the decision regarding discharge destination. Three patients (1.6%) ready for discharge on POD 2 were readmitted within 30 days of discharge (2 for wound infection, 1 for syncope). Risk for 30-day readmission or development of an inpatient complication in patients ready for discharge on POD 2 was not significant (P = .073). Table 1 summarizes the statistical results.

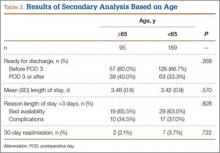

As age 65 years or older is one of the major criteria for Medicare eligibility, a secondary analysis was performed to explore whether there were age-related differences in the study outcomes. We found no significant differences between patients 65 years or older and patients younger than 65 years with respect to discharge readiness, LOS, postoperative complications, or 30-day readmission. Table 2 summarizes the statistical results based on age.

Discussion