User login

FDA investigating risk of gadolinium contrast agent brain deposits

The Food and Drug Administration is investigating the risk of brain deposits after recurring use of gadolinium-based contrast agents for MRI, the agency announced in a statement.

Studies suggest that gadolinium-based contrast agent (GBCA) deposits may stay in the brains of patients who have four or more contrast MRI scans, though it is unknown whether these deposits cause adverse effects, the FDA said.

GBCAs are usually expelled through the kidneys, but may remain in the brain after repeated exposure. FDA’s National Center for Toxicological

Research will further investigate safety risks in consultation with researchers and industry, the statement said.

The FDA is not requiring manufacturers to change the labels of GBCA products until more information is known. The agency is, however, recommending that clinicians limit GBCA use to situations in which it would be necessary for patient care.

“Health care professionals are also urged to reassess the necessity of repetitive GBCA MRIs in established treatment protocols,” the FDA said.

Patients may report side effects and adverse events to the FDA’s MedWatch Safety Information and Adverse Event Reporting Program.

The Food and Drug Administration is investigating the risk of brain deposits after recurring use of gadolinium-based contrast agents for MRI, the agency announced in a statement.

Studies suggest that gadolinium-based contrast agent (GBCA) deposits may stay in the brains of patients who have four or more contrast MRI scans, though it is unknown whether these deposits cause adverse effects, the FDA said.

GBCAs are usually expelled through the kidneys, but may remain in the brain after repeated exposure. FDA’s National Center for Toxicological

Research will further investigate safety risks in consultation with researchers and industry, the statement said.

The FDA is not requiring manufacturers to change the labels of GBCA products until more information is known. The agency is, however, recommending that clinicians limit GBCA use to situations in which it would be necessary for patient care.

“Health care professionals are also urged to reassess the necessity of repetitive GBCA MRIs in established treatment protocols,” the FDA said.

Patients may report side effects and adverse events to the FDA’s MedWatch Safety Information and Adverse Event Reporting Program.

The Food and Drug Administration is investigating the risk of brain deposits after recurring use of gadolinium-based contrast agents for MRI, the agency announced in a statement.

Studies suggest that gadolinium-based contrast agent (GBCA) deposits may stay in the brains of patients who have four or more contrast MRI scans, though it is unknown whether these deposits cause adverse effects, the FDA said.

GBCAs are usually expelled through the kidneys, but may remain in the brain after repeated exposure. FDA’s National Center for Toxicological

Research will further investigate safety risks in consultation with researchers and industry, the statement said.

The FDA is not requiring manufacturers to change the labels of GBCA products until more information is known. The agency is, however, recommending that clinicians limit GBCA use to situations in which it would be necessary for patient care.

“Health care professionals are also urged to reassess the necessity of repetitive GBCA MRIs in established treatment protocols,” the FDA said.

Patients may report side effects and adverse events to the FDA’s MedWatch Safety Information and Adverse Event Reporting Program.

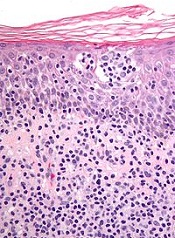

Cosmetic Corner: Dermatologists Weigh in on Products for Sensitive Skin

To improve patient care and outcomes, leading dermatologists offered their recommendations on top products for sensitive skin. Consideration must be given to:

- Aveeno Eczema Therapy Moisturizing Cream

- Cetaphil Restoraderm

- PRESCRIBEDsolutions Don’t Be So Sensitive Post-Procedure Cleanser

- Rosaliac AR Intense

- Vanicream

Cutis invites readers to send us their recommendations. Skin care products for babies, men’s shaving products, eye creams, and OTC dandruff treatments will be featured in upcoming editions of Cosmetic Corner. Please e-mail your recommendation(s) to the Editorial Office.

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect those of Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. and shall not be used for product endorsement purposes. Any reference made to a specific commercial product does not indicate or imply that Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. endorses, recommends, or favors the product mentioned. No guarantee is given to the effects of recommended products.

To improve patient care and outcomes, leading dermatologists offered their recommendations on top products for sensitive skin. Consideration must be given to:

- Aveeno Eczema Therapy Moisturizing Cream

- Cetaphil Restoraderm

- PRESCRIBEDsolutions Don’t Be So Sensitive Post-Procedure Cleanser

- Rosaliac AR Intense

- Vanicream

Cutis invites readers to send us their recommendations. Skin care products for babies, men’s shaving products, eye creams, and OTC dandruff treatments will be featured in upcoming editions of Cosmetic Corner. Please e-mail your recommendation(s) to the Editorial Office.

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect those of Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. and shall not be used for product endorsement purposes. Any reference made to a specific commercial product does not indicate or imply that Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. endorses, recommends, or favors the product mentioned. No guarantee is given to the effects of recommended products.

To improve patient care and outcomes, leading dermatologists offered their recommendations on top products for sensitive skin. Consideration must be given to:

- Aveeno Eczema Therapy Moisturizing Cream

- Cetaphil Restoraderm

- PRESCRIBEDsolutions Don’t Be So Sensitive Post-Procedure Cleanser

- Rosaliac AR Intense

- Vanicream

Cutis invites readers to send us their recommendations. Skin care products for babies, men’s shaving products, eye creams, and OTC dandruff treatments will be featured in upcoming editions of Cosmetic Corner. Please e-mail your recommendation(s) to the Editorial Office.

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect those of Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. and shall not be used for product endorsement purposes. Any reference made to a specific commercial product does not indicate or imply that Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. endorses, recommends, or favors the product mentioned. No guarantee is given to the effects of recommended products.

Some Public Hospitals Win, Others Lose with Obamacare

SAN FRANCISCO (Reuters) - A year and a half after the Affordable Care Act brought widespread reforms to the U.S. healthcare system, Chicago's Cook County Health & Hospitals System has made its first profit in 180 years.

Seven hundred miles south, the fortunes of Atlanta's primary public hospital, Grady Health System, haven't improved, and it remains as dependent as ever on philanthropy and county funding to stay afloat.

The disparity between the two "safety net" hospitals, both of which serve a disproportionate share of their communities' poorest patients, illustrates a growing divide nationwide.

In states like Illinois that have opted to accept federal money to expand Medicaid, some large, public hospitals are finding themselves on solid financial footing for the first time in decades, and formerly uninsured patients are now getting regular care.

But in states that did not expand the government medical program for the poor, primarily ones with conservative electorates opposed to Obamacare, including Georgia, the impact of the Affordable Care Act on public hospitals has been negligible.

While the public exchanges established by the federal government and 14 states have brought coverage to many previously uninsured people in all parts of the country, the effect on the poorest Americans varies drastically from state to state.

Nearly four million low-income, uninsured Americans living in states that didn't expand Medicaid would have qualified for coverage had their states chosen to expand it, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation. And public hospitals in those states, many of which rely on bond markets for funding, are likely to feel the pinch even more acutely over time, experts said.

"Providers in these states are going to be at a disadvantage," said Jim LeBuhn, senior director at Fitch Ratings. "It's going to make it that much more challenging for these providers to maintain their financial profiles."

Since the Affordable Care Act's first open enrollment in 2013, the number of Americans covered under Medicaid has risen by 21 percent, to 71.1 million.

Nonprofit hospitals in the 30 states that expanded Medicaid reported on average 13 percent less bad debt from unpaid bills last year, according to Moody's Investors Service. In contrast, according to Moody's, such "hospitals in non-expansion states saw bad debt increase through much of the year."

Hospitals in Medicaid expansion states, according to Kaiser, reported an average 32 percent decrease in uninsured patients and a 40 percent cut in unreimbursed costs of care for patients without the ability to pay, known in the industry as charity care costs. In non-expansion states, the number of uninsured patients declined by 4.4 percent and charity care costs dropped by 6.2 percent.

New recipients of Medicaid benefited, too. After one year, adults who gained the coverage were 55 percent more likely to have their own doctor than those who did not, Kaiser found. Medicaid also increased the likelihood of receiving preventive care, such as mammograms and cholesterol checks.

A TALE OF TWO HOSPITALS

Both Cook County and Grady are safety-net hospitals based in urban counties where the poverty level is slightly higher than the national average, and both have handled high numbers of uninsured clients in recent years: about half of the patients at Cook and nearly a third at Grady.

Since Obamacare took effect, the numbers at the Georgia hospital have remained about the same. But things have changed dramatically at the Illinois hospital, in large part due to the area's enrollment of about 170,000 of an estimated 330,000 eligible for the expanded Medicaid.

"This has been a sea change for us," said Dr. John Jay Shannon, Cook County Health's chief executive.

Within two years, the percent of uninsured patients at the hospital had dropped from more than a half to about a third, almost entirely driven by increased Medicaid coverage, hospital data show. And for the first time in the hospital's history, a majority of the patients it treated had coverage.

A third of the new Medicaid enrollees treated at Cook County were patients new to the system. And, hospital administrators say, those with chronic diseases such as diabetes, who used to be frequent emergency room visitors, now have personal physicians to help them manage their conditions.

In the fiscal year ending in November 2014, uncompensated charity care dropped to $342 million from $500 million the year before. Funding from Medicaid nearly doubled the health system's operating revenues, a major reason that, after ending 2013 with a net loss of $67.6 million, Cook County Health finished its most recent fiscal year in the black.

Now, the provider, like other safety-net hospitals, has a new challenge: holding onto old clients.

"For the first time in our history, we need to compete for our patients," said Shannon. "A world of improved access is also a world of choice."

At Grady Health System in Atlanta, meanwhile, the number of patients covered by insurance increased by less than 2 percent last year. Bad debt from unpaid bills has continued to climb, to $396 million from $269 million in 2013. And the percentage of patients covered by Medicaid didn't change.

"We've seen no difference from the Affordable Care Act," said John Haupert, Grady's chief executive. Many patients "are still coming to us as a safety-net provider and falling under our charity care."

Georgia is one of 20 states, disproportionately clustered in the South, that didn't expand Medicaid. About 89 percent of those left out of the new Medicaid coverage, because their states chose not to expand the program, live in the South, Kaiser Family Foundation found.

Grady has a better financial outlook than many hospitals in states that didn't expand Medicaid, thanks to a philanthropic campaign that has raised $350 million since 2008 to fund new infrastructure and expand clinical services. But, unlike Cook County, which has reduced some dependence on local government support with the help of Medicaid expansion dollars, Grady remains reliant on $57 million in tax support from two local counties. Without the local funding, Grady would be running a deficit.

"From a global perspective, it seems like the ACA is working," said Kevin Holloran, senior director at Standard & Poor's. But in non-expansion states, like Georgia, "it's really a neutral. It's just the status quo."

SAN FRANCISCO (Reuters) - A year and a half after the Affordable Care Act brought widespread reforms to the U.S. healthcare system, Chicago's Cook County Health & Hospitals System has made its first profit in 180 years.

Seven hundred miles south, the fortunes of Atlanta's primary public hospital, Grady Health System, haven't improved, and it remains as dependent as ever on philanthropy and county funding to stay afloat.

The disparity between the two "safety net" hospitals, both of which serve a disproportionate share of their communities' poorest patients, illustrates a growing divide nationwide.

In states like Illinois that have opted to accept federal money to expand Medicaid, some large, public hospitals are finding themselves on solid financial footing for the first time in decades, and formerly uninsured patients are now getting regular care.

But in states that did not expand the government medical program for the poor, primarily ones with conservative electorates opposed to Obamacare, including Georgia, the impact of the Affordable Care Act on public hospitals has been negligible.

While the public exchanges established by the federal government and 14 states have brought coverage to many previously uninsured people in all parts of the country, the effect on the poorest Americans varies drastically from state to state.

Nearly four million low-income, uninsured Americans living in states that didn't expand Medicaid would have qualified for coverage had their states chosen to expand it, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation. And public hospitals in those states, many of which rely on bond markets for funding, are likely to feel the pinch even more acutely over time, experts said.

"Providers in these states are going to be at a disadvantage," said Jim LeBuhn, senior director at Fitch Ratings. "It's going to make it that much more challenging for these providers to maintain their financial profiles."

Since the Affordable Care Act's first open enrollment in 2013, the number of Americans covered under Medicaid has risen by 21 percent, to 71.1 million.

Nonprofit hospitals in the 30 states that expanded Medicaid reported on average 13 percent less bad debt from unpaid bills last year, according to Moody's Investors Service. In contrast, according to Moody's, such "hospitals in non-expansion states saw bad debt increase through much of the year."

Hospitals in Medicaid expansion states, according to Kaiser, reported an average 32 percent decrease in uninsured patients and a 40 percent cut in unreimbursed costs of care for patients without the ability to pay, known in the industry as charity care costs. In non-expansion states, the number of uninsured patients declined by 4.4 percent and charity care costs dropped by 6.2 percent.

New recipients of Medicaid benefited, too. After one year, adults who gained the coverage were 55 percent more likely to have their own doctor than those who did not, Kaiser found. Medicaid also increased the likelihood of receiving preventive care, such as mammograms and cholesterol checks.

A TALE OF TWO HOSPITALS

Both Cook County and Grady are safety-net hospitals based in urban counties where the poverty level is slightly higher than the national average, and both have handled high numbers of uninsured clients in recent years: about half of the patients at Cook and nearly a third at Grady.

Since Obamacare took effect, the numbers at the Georgia hospital have remained about the same. But things have changed dramatically at the Illinois hospital, in large part due to the area's enrollment of about 170,000 of an estimated 330,000 eligible for the expanded Medicaid.

"This has been a sea change for us," said Dr. John Jay Shannon, Cook County Health's chief executive.

Within two years, the percent of uninsured patients at the hospital had dropped from more than a half to about a third, almost entirely driven by increased Medicaid coverage, hospital data show. And for the first time in the hospital's history, a majority of the patients it treated had coverage.

A third of the new Medicaid enrollees treated at Cook County were patients new to the system. And, hospital administrators say, those with chronic diseases such as diabetes, who used to be frequent emergency room visitors, now have personal physicians to help them manage their conditions.

In the fiscal year ending in November 2014, uncompensated charity care dropped to $342 million from $500 million the year before. Funding from Medicaid nearly doubled the health system's operating revenues, a major reason that, after ending 2013 with a net loss of $67.6 million, Cook County Health finished its most recent fiscal year in the black.

Now, the provider, like other safety-net hospitals, has a new challenge: holding onto old clients.

"For the first time in our history, we need to compete for our patients," said Shannon. "A world of improved access is also a world of choice."

At Grady Health System in Atlanta, meanwhile, the number of patients covered by insurance increased by less than 2 percent last year. Bad debt from unpaid bills has continued to climb, to $396 million from $269 million in 2013. And the percentage of patients covered by Medicaid didn't change.

"We've seen no difference from the Affordable Care Act," said John Haupert, Grady's chief executive. Many patients "are still coming to us as a safety-net provider and falling under our charity care."

Georgia is one of 20 states, disproportionately clustered in the South, that didn't expand Medicaid. About 89 percent of those left out of the new Medicaid coverage, because their states chose not to expand the program, live in the South, Kaiser Family Foundation found.

Grady has a better financial outlook than many hospitals in states that didn't expand Medicaid, thanks to a philanthropic campaign that has raised $350 million since 2008 to fund new infrastructure and expand clinical services. But, unlike Cook County, which has reduced some dependence on local government support with the help of Medicaid expansion dollars, Grady remains reliant on $57 million in tax support from two local counties. Without the local funding, Grady would be running a deficit.

"From a global perspective, it seems like the ACA is working," said Kevin Holloran, senior director at Standard & Poor's. But in non-expansion states, like Georgia, "it's really a neutral. It's just the status quo."

SAN FRANCISCO (Reuters) - A year and a half after the Affordable Care Act brought widespread reforms to the U.S. healthcare system, Chicago's Cook County Health & Hospitals System has made its first profit in 180 years.

Seven hundred miles south, the fortunes of Atlanta's primary public hospital, Grady Health System, haven't improved, and it remains as dependent as ever on philanthropy and county funding to stay afloat.

The disparity between the two "safety net" hospitals, both of which serve a disproportionate share of their communities' poorest patients, illustrates a growing divide nationwide.

In states like Illinois that have opted to accept federal money to expand Medicaid, some large, public hospitals are finding themselves on solid financial footing for the first time in decades, and formerly uninsured patients are now getting regular care.

But in states that did not expand the government medical program for the poor, primarily ones with conservative electorates opposed to Obamacare, including Georgia, the impact of the Affordable Care Act on public hospitals has been negligible.

While the public exchanges established by the federal government and 14 states have brought coverage to many previously uninsured people in all parts of the country, the effect on the poorest Americans varies drastically from state to state.

Nearly four million low-income, uninsured Americans living in states that didn't expand Medicaid would have qualified for coverage had their states chosen to expand it, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation. And public hospitals in those states, many of which rely on bond markets for funding, are likely to feel the pinch even more acutely over time, experts said.

"Providers in these states are going to be at a disadvantage," said Jim LeBuhn, senior director at Fitch Ratings. "It's going to make it that much more challenging for these providers to maintain their financial profiles."

Since the Affordable Care Act's first open enrollment in 2013, the number of Americans covered under Medicaid has risen by 21 percent, to 71.1 million.

Nonprofit hospitals in the 30 states that expanded Medicaid reported on average 13 percent less bad debt from unpaid bills last year, according to Moody's Investors Service. In contrast, according to Moody's, such "hospitals in non-expansion states saw bad debt increase through much of the year."

Hospitals in Medicaid expansion states, according to Kaiser, reported an average 32 percent decrease in uninsured patients and a 40 percent cut in unreimbursed costs of care for patients without the ability to pay, known in the industry as charity care costs. In non-expansion states, the number of uninsured patients declined by 4.4 percent and charity care costs dropped by 6.2 percent.

New recipients of Medicaid benefited, too. After one year, adults who gained the coverage were 55 percent more likely to have their own doctor than those who did not, Kaiser found. Medicaid also increased the likelihood of receiving preventive care, such as mammograms and cholesterol checks.

A TALE OF TWO HOSPITALS

Both Cook County and Grady are safety-net hospitals based in urban counties where the poverty level is slightly higher than the national average, and both have handled high numbers of uninsured clients in recent years: about half of the patients at Cook and nearly a third at Grady.

Since Obamacare took effect, the numbers at the Georgia hospital have remained about the same. But things have changed dramatically at the Illinois hospital, in large part due to the area's enrollment of about 170,000 of an estimated 330,000 eligible for the expanded Medicaid.

"This has been a sea change for us," said Dr. John Jay Shannon, Cook County Health's chief executive.

Within two years, the percent of uninsured patients at the hospital had dropped from more than a half to about a third, almost entirely driven by increased Medicaid coverage, hospital data show. And for the first time in the hospital's history, a majority of the patients it treated had coverage.

A third of the new Medicaid enrollees treated at Cook County were patients new to the system. And, hospital administrators say, those with chronic diseases such as diabetes, who used to be frequent emergency room visitors, now have personal physicians to help them manage their conditions.

In the fiscal year ending in November 2014, uncompensated charity care dropped to $342 million from $500 million the year before. Funding from Medicaid nearly doubled the health system's operating revenues, a major reason that, after ending 2013 with a net loss of $67.6 million, Cook County Health finished its most recent fiscal year in the black.

Now, the provider, like other safety-net hospitals, has a new challenge: holding onto old clients.

"For the first time in our history, we need to compete for our patients," said Shannon. "A world of improved access is also a world of choice."

At Grady Health System in Atlanta, meanwhile, the number of patients covered by insurance increased by less than 2 percent last year. Bad debt from unpaid bills has continued to climb, to $396 million from $269 million in 2013. And the percentage of patients covered by Medicaid didn't change.

"We've seen no difference from the Affordable Care Act," said John Haupert, Grady's chief executive. Many patients "are still coming to us as a safety-net provider and falling under our charity care."

Georgia is one of 20 states, disproportionately clustered in the South, that didn't expand Medicaid. About 89 percent of those left out of the new Medicaid coverage, because their states chose not to expand the program, live in the South, Kaiser Family Foundation found.

Grady has a better financial outlook than many hospitals in states that didn't expand Medicaid, thanks to a philanthropic campaign that has raised $350 million since 2008 to fund new infrastructure and expand clinical services. But, unlike Cook County, which has reduced some dependence on local government support with the help of Medicaid expansion dollars, Grady remains reliant on $57 million in tax support from two local counties. Without the local funding, Grady would be running a deficit.

"From a global perspective, it seems like the ACA is working," said Kevin Holloran, senior director at Standard & Poor's. But in non-expansion states, like Georgia, "it's really a neutral. It's just the status quo."

Nanocapsules exploit biology to destroy blood clots

Image by Andre E.X. Brown

Scientists say they have created drug-loaded nanocapsules that can target and destroy blood clots by exploiting the intrinsic properties of thrombosis.

These polymer capsules are “inherently responsive” to thrombus microenvironments.

They home to activated platelets, where exposure to thrombin prompts the capsules to degrade and release a thrombolytic drug—urokinase plasminogen activator—at the site of thrombosis.

Christoph Hagemeyer, PhD, of Baker IDI Heart and Diabetes Institute in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, and his colleagues described the creation and testing of these capsules in Advanced Materials.

“We’ve created a nanocapsule that contains a clot-busting drug,” Dr Hagemeyer explained. “The drug-loaded nanocapsule is coated with an antibody that specifically targets activated platelets . . . .”

“Once located at the site of the blood clot, thrombin (a molecule at the center of the clotting process) breaks open the outer layer of the nanocapsule, releasing the clot-busting drug. We are effectively hijacking the blood-clotting system to initiate the removal of the blockage in the blood vessel.”

Specifically, Dr Hagemeyer and his colleagues created the capsules via layer-by-layer assembly of brushlike poly(2-ethyl-2-oxazoline) with alkyne functional groups on mesoporous silica particle templates.

The team loaded the capsules with the thrombolytic agent urokinase plasminogen activator and incorporated a thrombin-sensitive cross-linker to activate capsule degradation and drug release at the site of thrombosis.

So the capsules would target activated platelets, the researchers attached an antibody to the capsules’ surface. The team used a phage-display-derived single-chain antibody that is specific for the fibrinogen receptor GPIIb/IIIa in its activated form.

Flow chamber experiments showed that the capsules do target surface-bound GPIIb/IIIa receptors expressed on activated platelets.

And exposing the capsules to thrombin revealed concentration-dependent degradation and drug release. The researchers exposed loaded capsules to simulated thrombotic conditions with a range of thrombin concentrations.

In the presence of 1 unit mL−1, capsules degraded/released their cargo after 4 hours. With higher thrombin concentrations—5 or 10 units mL−1—capsules released their cargo within 15 minutes. ![]()

Image by Andre E.X. Brown

Scientists say they have created drug-loaded nanocapsules that can target and destroy blood clots by exploiting the intrinsic properties of thrombosis.

These polymer capsules are “inherently responsive” to thrombus microenvironments.

They home to activated platelets, where exposure to thrombin prompts the capsules to degrade and release a thrombolytic drug—urokinase plasminogen activator—at the site of thrombosis.

Christoph Hagemeyer, PhD, of Baker IDI Heart and Diabetes Institute in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, and his colleagues described the creation and testing of these capsules in Advanced Materials.

“We’ve created a nanocapsule that contains a clot-busting drug,” Dr Hagemeyer explained. “The drug-loaded nanocapsule is coated with an antibody that specifically targets activated platelets . . . .”

“Once located at the site of the blood clot, thrombin (a molecule at the center of the clotting process) breaks open the outer layer of the nanocapsule, releasing the clot-busting drug. We are effectively hijacking the blood-clotting system to initiate the removal of the blockage in the blood vessel.”

Specifically, Dr Hagemeyer and his colleagues created the capsules via layer-by-layer assembly of brushlike poly(2-ethyl-2-oxazoline) with alkyne functional groups on mesoporous silica particle templates.

The team loaded the capsules with the thrombolytic agent urokinase plasminogen activator and incorporated a thrombin-sensitive cross-linker to activate capsule degradation and drug release at the site of thrombosis.

So the capsules would target activated platelets, the researchers attached an antibody to the capsules’ surface. The team used a phage-display-derived single-chain antibody that is specific for the fibrinogen receptor GPIIb/IIIa in its activated form.

Flow chamber experiments showed that the capsules do target surface-bound GPIIb/IIIa receptors expressed on activated platelets.

And exposing the capsules to thrombin revealed concentration-dependent degradation and drug release. The researchers exposed loaded capsules to simulated thrombotic conditions with a range of thrombin concentrations.

In the presence of 1 unit mL−1, capsules degraded/released their cargo after 4 hours. With higher thrombin concentrations—5 or 10 units mL−1—capsules released their cargo within 15 minutes. ![]()

Image by Andre E.X. Brown

Scientists say they have created drug-loaded nanocapsules that can target and destroy blood clots by exploiting the intrinsic properties of thrombosis.

These polymer capsules are “inherently responsive” to thrombus microenvironments.

They home to activated platelets, where exposure to thrombin prompts the capsules to degrade and release a thrombolytic drug—urokinase plasminogen activator—at the site of thrombosis.

Christoph Hagemeyer, PhD, of Baker IDI Heart and Diabetes Institute in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, and his colleagues described the creation and testing of these capsules in Advanced Materials.

“We’ve created a nanocapsule that contains a clot-busting drug,” Dr Hagemeyer explained. “The drug-loaded nanocapsule is coated with an antibody that specifically targets activated platelets . . . .”

“Once located at the site of the blood clot, thrombin (a molecule at the center of the clotting process) breaks open the outer layer of the nanocapsule, releasing the clot-busting drug. We are effectively hijacking the blood-clotting system to initiate the removal of the blockage in the blood vessel.”

Specifically, Dr Hagemeyer and his colleagues created the capsules via layer-by-layer assembly of brushlike poly(2-ethyl-2-oxazoline) with alkyne functional groups on mesoporous silica particle templates.

The team loaded the capsules with the thrombolytic agent urokinase plasminogen activator and incorporated a thrombin-sensitive cross-linker to activate capsule degradation and drug release at the site of thrombosis.

So the capsules would target activated platelets, the researchers attached an antibody to the capsules’ surface. The team used a phage-display-derived single-chain antibody that is specific for the fibrinogen receptor GPIIb/IIIa in its activated form.

Flow chamber experiments showed that the capsules do target surface-bound GPIIb/IIIa receptors expressed on activated platelets.

And exposing the capsules to thrombin revealed concentration-dependent degradation and drug release. The researchers exposed loaded capsules to simulated thrombotic conditions with a range of thrombin concentrations.

In the presence of 1 unit mL−1, capsules degraded/released their cargo after 4 hours. With higher thrombin concentrations—5 or 10 units mL−1—capsules released their cargo within 15 minutes. ![]()

Drug gets orphan designation for CTCL

The European Commission has granted orphan drug designation to synthetic hypericin, the active pharmaceutical ingredient in SGX301, for the treatment of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL).

SGX301 is a first-in-class, photodynamic therapy utilizing safe, visible light for activation. Synthetic hypericin is a potent photosensitizer that is topically applied to skin lesions and activated by visible fluorescent light 16 to 24 hours later.

This treatment approach is intended to prevent the secondary malignancies that may occur following chemotherapy or photodynamic therapies that are dependent on ultraviolet exposure.

Combined with photoactivation, hypericin has demonstrated significant antiproliferative effects on activated, normal human lymphoid cells and inhibited the growth of malignant T cells isolated from CTCL patients.

Topical hypericin has also proven safe in a phase 1 study of healthy volunteers.

In a phase 2 trial of patients with CTCL (mycosis fungoides only) or psoriasis, topical hypericin conferred a significant improvement over placebo. Among CTCL patients, the treatment prompted a response rate of 58.3%, compared to an 8.3% response rate for placebo (P≤0.04).

Topical hypericin was also well tolerated in this trial. There were no deaths or serious adverse events related to the treatment. However, there were reports of mild to moderate burning, itching, erythema, and pruritus at the application site.

Soligenix, Inc., the company developing SGX301, is currently working with CTCL centers, the National Organization for Rare Disorders, and the Cutaneous Lymphoma Foundation to begin a 120-subject phase 3 trial of SGX301.

About orphan designation

The European Commission grants orphan designation to medicines designed to treat a life-threatening or chronically debilitating condition that affects no more than 5 in 10,000 persons in the European Union and has no satisfactory treatment available.

In addition to a 10-year period of marketing exclusivity after product approval, orphan drug designation provides incentives for companies seeking protocol assistance from the European Medicines Agency during the product development phase, as well as direct access to the centralized authorization procedure.

SGX301 has both orphan designation and fast track designation from the US Food and Drug Administration for the first-line treatment of CTCL. ![]()

The European Commission has granted orphan drug designation to synthetic hypericin, the active pharmaceutical ingredient in SGX301, for the treatment of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL).

SGX301 is a first-in-class, photodynamic therapy utilizing safe, visible light for activation. Synthetic hypericin is a potent photosensitizer that is topically applied to skin lesions and activated by visible fluorescent light 16 to 24 hours later.

This treatment approach is intended to prevent the secondary malignancies that may occur following chemotherapy or photodynamic therapies that are dependent on ultraviolet exposure.

Combined with photoactivation, hypericin has demonstrated significant antiproliferative effects on activated, normal human lymphoid cells and inhibited the growth of malignant T cells isolated from CTCL patients.

Topical hypericin has also proven safe in a phase 1 study of healthy volunteers.

In a phase 2 trial of patients with CTCL (mycosis fungoides only) or psoriasis, topical hypericin conferred a significant improvement over placebo. Among CTCL patients, the treatment prompted a response rate of 58.3%, compared to an 8.3% response rate for placebo (P≤0.04).

Topical hypericin was also well tolerated in this trial. There were no deaths or serious adverse events related to the treatment. However, there were reports of mild to moderate burning, itching, erythema, and pruritus at the application site.

Soligenix, Inc., the company developing SGX301, is currently working with CTCL centers, the National Organization for Rare Disorders, and the Cutaneous Lymphoma Foundation to begin a 120-subject phase 3 trial of SGX301.

About orphan designation

The European Commission grants orphan designation to medicines designed to treat a life-threatening or chronically debilitating condition that affects no more than 5 in 10,000 persons in the European Union and has no satisfactory treatment available.

In addition to a 10-year period of marketing exclusivity after product approval, orphan drug designation provides incentives for companies seeking protocol assistance from the European Medicines Agency during the product development phase, as well as direct access to the centralized authorization procedure.

SGX301 has both orphan designation and fast track designation from the US Food and Drug Administration for the first-line treatment of CTCL. ![]()

The European Commission has granted orphan drug designation to synthetic hypericin, the active pharmaceutical ingredient in SGX301, for the treatment of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL).

SGX301 is a first-in-class, photodynamic therapy utilizing safe, visible light for activation. Synthetic hypericin is a potent photosensitizer that is topically applied to skin lesions and activated by visible fluorescent light 16 to 24 hours later.

This treatment approach is intended to prevent the secondary malignancies that may occur following chemotherapy or photodynamic therapies that are dependent on ultraviolet exposure.

Combined with photoactivation, hypericin has demonstrated significant antiproliferative effects on activated, normal human lymphoid cells and inhibited the growth of malignant T cells isolated from CTCL patients.

Topical hypericin has also proven safe in a phase 1 study of healthy volunteers.

In a phase 2 trial of patients with CTCL (mycosis fungoides only) or psoriasis, topical hypericin conferred a significant improvement over placebo. Among CTCL patients, the treatment prompted a response rate of 58.3%, compared to an 8.3% response rate for placebo (P≤0.04).

Topical hypericin was also well tolerated in this trial. There were no deaths or serious adverse events related to the treatment. However, there were reports of mild to moderate burning, itching, erythema, and pruritus at the application site.

Soligenix, Inc., the company developing SGX301, is currently working with CTCL centers, the National Organization for Rare Disorders, and the Cutaneous Lymphoma Foundation to begin a 120-subject phase 3 trial of SGX301.

About orphan designation

The European Commission grants orphan designation to medicines designed to treat a life-threatening or chronically debilitating condition that affects no more than 5 in 10,000 persons in the European Union and has no satisfactory treatment available.

In addition to a 10-year period of marketing exclusivity after product approval, orphan drug designation provides incentives for companies seeking protocol assistance from the European Medicines Agency during the product development phase, as well as direct access to the centralized authorization procedure.

SGX301 has both orphan designation and fast track designation from the US Food and Drug Administration for the first-line treatment of CTCL. ![]()

DAPT may be better for older patients after PCI

Photo courtesy of the CDC

A new study suggests less is more when it comes to antithrombotic therapy for higher-risk older patients with atrial fibrillation who have a heart attack and undergo percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).

At 2 years of follow-up, patients who had received triple therapy—warfarin, aspirin, and P2Y12 inhibitor—after PCI had similar rates of major adverse cardiac events (MACE) as patients who received dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT)—aspirin and P2Y12 inhibitor.

But patients on triple therapy had a higher incidence of intracranial hemorrhage and bleeding that required hospitalization.

These results appear in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology alongside a related editorial.

Researchers examined data from the National Cardiovascular Data Registry ACTION Registry-GWTG linked with Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services data, looking at records from January 2007 through December 2010.

They identified 4959 patients aged 65 and older with a history of atrial fibrillation who presented with acute myocardial infarction (MI) and underwent PCI. Most patients (72.4%, n=3589) were discharged on DAPT, but 27.6% (n=1370) were discharged on triple therapy.

In the DAPT arm, 97.2% of patients (n=3490) received clopidogrel, 2.5% (n=89) received prasugrel, and 0.3% (n=10) received ticlopidine. In the triple therapy arm, 98.2% of patients (n=1346) received clopidogrel, 1.4% (n=19) received prasugrel, and 0.4% (n=5) received ticlopidine.

Patients receiving triple therapy were more likely to be male, have a history of either angioplasty or coronary artery bypass surgery, and have a history of stroke. These patients were frequently already on warfarin before they were admitted to the hospital.

Patients who were released on DAPT were more likely to have had an in-hospital major bleeding event.

Incidence of MACE

Two years after discharge, the risk of MACE—death, hospital readmission for MI, or stroke readmission—was similar between the DAPT and triple therapy arms. The unadjusted cumulative incidence rate of MACE was 32.6% in the triple therapy arm and 32.7% in the DAPT arm (P=0.99).

The unadjusted cumulative incidence rates of the individual MACE components were also similar between the triple therapy and DAPT arms. All-cause mortality occurred in 23.8% and 24.8%, respectively (P=0.70), MI readmission occurred in 8.5% and 8.1%, respectively (P=0.54), and stroke readmission occurred in 4.7% and 5.3%, respectively (P=0.23).

After the researchers adjusted for patient, treatment, and hospital characteristics, there was still no significant difference between the arms with regard to the incidence of MACE or MACE components.

The adjusted hazard ratio (HR) was 0.99 for MACE (P=0.94), 0.98 for all-cause mortality (P=0.82), 1.03 for MI readmission (P=0.83), and 0.85 for stroke readmission (P=0.38).

Bleeding incidence

The cumulative incidence of bleeding requiring hospitalization within 2 years of discharge after PCI was significantly higher for the triple therapy arm than the DAPT arm—17.6% and 11.0%, respectively (P<0.0001).

The difference remained significant after the researchers adjusted for patient, treatment, and hospital characteristics. The adjusted HR was 1.61 (P<0.0001).

Similarly, the unadjusted cumulative incidence of intracranial hemorrhage was significantly higher for the triple therapy arm than the DAPT arm—3.4% and 1.5%, respectively (P<0.001).

This difference remained significant after adjustment. The adjusted HR was 2.04 (P<0.01).

“The increased risk of bleeding without apparent benefit of triple therapy observed in this study suggests that clinicians should carefully consider the risk-to-benefit ratio of triple therapy use in older atrial fibrillation patients who have had a heart attack treated with angioplasty,” said Connie N. Hess, MD, of the Duke University School of Medicine in Durham, North Carolina.

“Further prospective studies of different combinations of anticlotting agents are needed to define the optimal treatment regimen for this population.” ![]()

Photo courtesy of the CDC

A new study suggests less is more when it comes to antithrombotic therapy for higher-risk older patients with atrial fibrillation who have a heart attack and undergo percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).

At 2 years of follow-up, patients who had received triple therapy—warfarin, aspirin, and P2Y12 inhibitor—after PCI had similar rates of major adverse cardiac events (MACE) as patients who received dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT)—aspirin and P2Y12 inhibitor.

But patients on triple therapy had a higher incidence of intracranial hemorrhage and bleeding that required hospitalization.

These results appear in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology alongside a related editorial.

Researchers examined data from the National Cardiovascular Data Registry ACTION Registry-GWTG linked with Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services data, looking at records from January 2007 through December 2010.

They identified 4959 patients aged 65 and older with a history of atrial fibrillation who presented with acute myocardial infarction (MI) and underwent PCI. Most patients (72.4%, n=3589) were discharged on DAPT, but 27.6% (n=1370) were discharged on triple therapy.

In the DAPT arm, 97.2% of patients (n=3490) received clopidogrel, 2.5% (n=89) received prasugrel, and 0.3% (n=10) received ticlopidine. In the triple therapy arm, 98.2% of patients (n=1346) received clopidogrel, 1.4% (n=19) received prasugrel, and 0.4% (n=5) received ticlopidine.

Patients receiving triple therapy were more likely to be male, have a history of either angioplasty or coronary artery bypass surgery, and have a history of stroke. These patients were frequently already on warfarin before they were admitted to the hospital.

Patients who were released on DAPT were more likely to have had an in-hospital major bleeding event.

Incidence of MACE

Two years after discharge, the risk of MACE—death, hospital readmission for MI, or stroke readmission—was similar between the DAPT and triple therapy arms. The unadjusted cumulative incidence rate of MACE was 32.6% in the triple therapy arm and 32.7% in the DAPT arm (P=0.99).

The unadjusted cumulative incidence rates of the individual MACE components were also similar between the triple therapy and DAPT arms. All-cause mortality occurred in 23.8% and 24.8%, respectively (P=0.70), MI readmission occurred in 8.5% and 8.1%, respectively (P=0.54), and stroke readmission occurred in 4.7% and 5.3%, respectively (P=0.23).

After the researchers adjusted for patient, treatment, and hospital characteristics, there was still no significant difference between the arms with regard to the incidence of MACE or MACE components.

The adjusted hazard ratio (HR) was 0.99 for MACE (P=0.94), 0.98 for all-cause mortality (P=0.82), 1.03 for MI readmission (P=0.83), and 0.85 for stroke readmission (P=0.38).

Bleeding incidence

The cumulative incidence of bleeding requiring hospitalization within 2 years of discharge after PCI was significantly higher for the triple therapy arm than the DAPT arm—17.6% and 11.0%, respectively (P<0.0001).

The difference remained significant after the researchers adjusted for patient, treatment, and hospital characteristics. The adjusted HR was 1.61 (P<0.0001).

Similarly, the unadjusted cumulative incidence of intracranial hemorrhage was significantly higher for the triple therapy arm than the DAPT arm—3.4% and 1.5%, respectively (P<0.001).

This difference remained significant after adjustment. The adjusted HR was 2.04 (P<0.01).

“The increased risk of bleeding without apparent benefit of triple therapy observed in this study suggests that clinicians should carefully consider the risk-to-benefit ratio of triple therapy use in older atrial fibrillation patients who have had a heart attack treated with angioplasty,” said Connie N. Hess, MD, of the Duke University School of Medicine in Durham, North Carolina.

“Further prospective studies of different combinations of anticlotting agents are needed to define the optimal treatment regimen for this population.” ![]()

Photo courtesy of the CDC

A new study suggests less is more when it comes to antithrombotic therapy for higher-risk older patients with atrial fibrillation who have a heart attack and undergo percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).

At 2 years of follow-up, patients who had received triple therapy—warfarin, aspirin, and P2Y12 inhibitor—after PCI had similar rates of major adverse cardiac events (MACE) as patients who received dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT)—aspirin and P2Y12 inhibitor.

But patients on triple therapy had a higher incidence of intracranial hemorrhage and bleeding that required hospitalization.

These results appear in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology alongside a related editorial.

Researchers examined data from the National Cardiovascular Data Registry ACTION Registry-GWTG linked with Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services data, looking at records from January 2007 through December 2010.

They identified 4959 patients aged 65 and older with a history of atrial fibrillation who presented with acute myocardial infarction (MI) and underwent PCI. Most patients (72.4%, n=3589) were discharged on DAPT, but 27.6% (n=1370) were discharged on triple therapy.

In the DAPT arm, 97.2% of patients (n=3490) received clopidogrel, 2.5% (n=89) received prasugrel, and 0.3% (n=10) received ticlopidine. In the triple therapy arm, 98.2% of patients (n=1346) received clopidogrel, 1.4% (n=19) received prasugrel, and 0.4% (n=5) received ticlopidine.

Patients receiving triple therapy were more likely to be male, have a history of either angioplasty or coronary artery bypass surgery, and have a history of stroke. These patients were frequently already on warfarin before they were admitted to the hospital.

Patients who were released on DAPT were more likely to have had an in-hospital major bleeding event.

Incidence of MACE

Two years after discharge, the risk of MACE—death, hospital readmission for MI, or stroke readmission—was similar between the DAPT and triple therapy arms. The unadjusted cumulative incidence rate of MACE was 32.6% in the triple therapy arm and 32.7% in the DAPT arm (P=0.99).

The unadjusted cumulative incidence rates of the individual MACE components were also similar between the triple therapy and DAPT arms. All-cause mortality occurred in 23.8% and 24.8%, respectively (P=0.70), MI readmission occurred in 8.5% and 8.1%, respectively (P=0.54), and stroke readmission occurred in 4.7% and 5.3%, respectively (P=0.23).

After the researchers adjusted for patient, treatment, and hospital characteristics, there was still no significant difference between the arms with regard to the incidence of MACE or MACE components.

The adjusted hazard ratio (HR) was 0.99 for MACE (P=0.94), 0.98 for all-cause mortality (P=0.82), 1.03 for MI readmission (P=0.83), and 0.85 for stroke readmission (P=0.38).

Bleeding incidence

The cumulative incidence of bleeding requiring hospitalization within 2 years of discharge after PCI was significantly higher for the triple therapy arm than the DAPT arm—17.6% and 11.0%, respectively (P<0.0001).

The difference remained significant after the researchers adjusted for patient, treatment, and hospital characteristics. The adjusted HR was 1.61 (P<0.0001).

Similarly, the unadjusted cumulative incidence of intracranial hemorrhage was significantly higher for the triple therapy arm than the DAPT arm—3.4% and 1.5%, respectively (P<0.001).

This difference remained significant after adjustment. The adjusted HR was 2.04 (P<0.01).

“The increased risk of bleeding without apparent benefit of triple therapy observed in this study suggests that clinicians should carefully consider the risk-to-benefit ratio of triple therapy use in older atrial fibrillation patients who have had a heart attack treated with angioplasty,” said Connie N. Hess, MD, of the Duke University School of Medicine in Durham, North Carolina.

“Further prospective studies of different combinations of anticlotting agents are needed to define the optimal treatment regimen for this population.” ![]()

Physical activity can benefit kids with cancer

Photo by Bill Branson

Children with cancer can benefit from “adapted” physical activities, according to a pilot study published in ecancermedicalscience.

Investigators followed 11 cancer patients, ages 10 to 18, on a dog sledding expedition, which involved adapted training activities.

All of the patients completed the training and the expedition, and they exhibited significant improvements in physical and psychological health after completing the program.

“What I learned from this study is that we doctors have the false belief that kids with cancer cannot practice sport because they are too tired or weak from their treatments,” said study author Nicolas André, MD, PhD, of Hôpital d'Enfants de la Timone in Marseille, France.

“These perceptions are at least partly wrong. Adapted physical activities can be performed by most children with cancer, even during their treatment, and can bring a lot to children.”

To arrive at these conclusions, Dr André and his colleagues measured the effects of a 6-week long adapted physical activity program on children and adolescents with cancer.

The study included 11 patients—4 girls and 7 boys—with a mean age of 14.3 ± 2.9 years. Seven of the patients were still receiving treatment.

About the program

The patients first completed a physical preparation program consisting of general conditioning to improve their strength, speed, endurance, flexibility, skill, and ability to handle greater workloads.

Typically, these activities lasted from 60 to 120 minutes and took place 1 to 5 times a week. The intensity of physical activity was adjusted to each subject.

After completing the preparation, the patients began a 5-day long expedition in Quebec, Canada. They completed a session of physical training in the snow and had their first contact with the pack of dogs and the sleds the day before departure.

Overall, the subjects engaged in physical activity 4 to 5 hours per day during the expedition.

Results

The patients performed a series of physical tests and completed psychological questionnaires before and after the program. The results showed improvements in all physical and psychological parameters.

After completing the program, the subjects reported significant improvements in global self-esteem (P=0.02), perceived sport competence (P=0.02), and perceived physical strength (P=0.001).

They also demonstrated significant improvements in their ability to do sit-ups (P=0.01), their muscle tone (P=0.01), and their resting heart rate (P=0.03).

“Based on our work over the last 8 years, we all are convinced that practicing adapted physical activity is very positive for children with cancer,” said study author Laurent Grélot, PhD, of Aix Marseille University in France.

“It avoids cardiovascular and muscular deconditioning, can decrease treatment-induced fatigue, and can help maintaining social integration.”

Based on the success of this pilot study, the investigators are conducting a randomized trial to evaluate the benefits of adapted physical activities for children with cancer. ![]()

Photo by Bill Branson

Children with cancer can benefit from “adapted” physical activities, according to a pilot study published in ecancermedicalscience.

Investigators followed 11 cancer patients, ages 10 to 18, on a dog sledding expedition, which involved adapted training activities.

All of the patients completed the training and the expedition, and they exhibited significant improvements in physical and psychological health after completing the program.

“What I learned from this study is that we doctors have the false belief that kids with cancer cannot practice sport because they are too tired or weak from their treatments,” said study author Nicolas André, MD, PhD, of Hôpital d'Enfants de la Timone in Marseille, France.

“These perceptions are at least partly wrong. Adapted physical activities can be performed by most children with cancer, even during their treatment, and can bring a lot to children.”

To arrive at these conclusions, Dr André and his colleagues measured the effects of a 6-week long adapted physical activity program on children and adolescents with cancer.

The study included 11 patients—4 girls and 7 boys—with a mean age of 14.3 ± 2.9 years. Seven of the patients were still receiving treatment.

About the program

The patients first completed a physical preparation program consisting of general conditioning to improve their strength, speed, endurance, flexibility, skill, and ability to handle greater workloads.

Typically, these activities lasted from 60 to 120 minutes and took place 1 to 5 times a week. The intensity of physical activity was adjusted to each subject.

After completing the preparation, the patients began a 5-day long expedition in Quebec, Canada. They completed a session of physical training in the snow and had their first contact with the pack of dogs and the sleds the day before departure.

Overall, the subjects engaged in physical activity 4 to 5 hours per day during the expedition.

Results

The patients performed a series of physical tests and completed psychological questionnaires before and after the program. The results showed improvements in all physical and psychological parameters.

After completing the program, the subjects reported significant improvements in global self-esteem (P=0.02), perceived sport competence (P=0.02), and perceived physical strength (P=0.001).

They also demonstrated significant improvements in their ability to do sit-ups (P=0.01), their muscle tone (P=0.01), and their resting heart rate (P=0.03).

“Based on our work over the last 8 years, we all are convinced that practicing adapted physical activity is very positive for children with cancer,” said study author Laurent Grélot, PhD, of Aix Marseille University in France.

“It avoids cardiovascular and muscular deconditioning, can decrease treatment-induced fatigue, and can help maintaining social integration.”

Based on the success of this pilot study, the investigators are conducting a randomized trial to evaluate the benefits of adapted physical activities for children with cancer. ![]()

Photo by Bill Branson

Children with cancer can benefit from “adapted” physical activities, according to a pilot study published in ecancermedicalscience.

Investigators followed 11 cancer patients, ages 10 to 18, on a dog sledding expedition, which involved adapted training activities.

All of the patients completed the training and the expedition, and they exhibited significant improvements in physical and psychological health after completing the program.

“What I learned from this study is that we doctors have the false belief that kids with cancer cannot practice sport because they are too tired or weak from their treatments,” said study author Nicolas André, MD, PhD, of Hôpital d'Enfants de la Timone in Marseille, France.

“These perceptions are at least partly wrong. Adapted physical activities can be performed by most children with cancer, even during their treatment, and can bring a lot to children.”

To arrive at these conclusions, Dr André and his colleagues measured the effects of a 6-week long adapted physical activity program on children and adolescents with cancer.

The study included 11 patients—4 girls and 7 boys—with a mean age of 14.3 ± 2.9 years. Seven of the patients were still receiving treatment.

About the program

The patients first completed a physical preparation program consisting of general conditioning to improve their strength, speed, endurance, flexibility, skill, and ability to handle greater workloads.

Typically, these activities lasted from 60 to 120 minutes and took place 1 to 5 times a week. The intensity of physical activity was adjusted to each subject.

After completing the preparation, the patients began a 5-day long expedition in Quebec, Canada. They completed a session of physical training in the snow and had their first contact with the pack of dogs and the sleds the day before departure.

Overall, the subjects engaged in physical activity 4 to 5 hours per day during the expedition.

Results

The patients performed a series of physical tests and completed psychological questionnaires before and after the program. The results showed improvements in all physical and psychological parameters.

After completing the program, the subjects reported significant improvements in global self-esteem (P=0.02), perceived sport competence (P=0.02), and perceived physical strength (P=0.001).

They also demonstrated significant improvements in their ability to do sit-ups (P=0.01), their muscle tone (P=0.01), and their resting heart rate (P=0.03).

“Based on our work over the last 8 years, we all are convinced that practicing adapted physical activity is very positive for children with cancer,” said study author Laurent Grélot, PhD, of Aix Marseille University in France.

“It avoids cardiovascular and muscular deconditioning, can decrease treatment-induced fatigue, and can help maintaining social integration.”

Based on the success of this pilot study, the investigators are conducting a randomized trial to evaluate the benefits of adapted physical activities for children with cancer. ![]()

Product Update: Premama, SynDaver, ScribeAmerica, Xoft eBX System

SUPPLEMENTS FOR EXPECTANT/NEW MOMS

Premama®, a line of natural powdered drink mixes formulated to support the nutritional needs of expectant and new mothers, has introduced 2 products for preconception and postpartum health.

Fertility delivers a supplement formulation that includes myo-Inositol, which is clinically shown to help improve ovulatory function and healthy egg production, and folic acid to support prenatal health, according to Premama. Fertility is an unflavored drink mix that comes in packets of 2.2 g to be mixed with at least 12 oz of water or other noncarbonated flavored liquids such as juices or smoothies and taken daily.

Lactation is a berry-flavored drink mix daily supplement that is formulated with fenugreek, fennel seed, and blessed thistle to help support healthy milk production, according to Premama. Also included in Lactation are folic acid, Vitamin D3, calcium, and other essential nutrients for both mother and baby. A Lactation 2.5-mg packet mixes with at least 12 oz of water until blended well, or with noncarbonated, flavored liquids such as juices or smoothies.

All Premama products are physician approved, vegetarian, gluten free, and made in the United States. Premama products are available at retailers nationwide or online.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT www.drinkpremama.com

FREE EKG TRAINING APP FROM SYNDAVER

SynDaver™ Labs has released a free medical training electrocardiogram (EKG)simulator app for android devices on Google Play. The SynDaver EKG Simulator is a digital platform that can function with any medical training manikin, according to SynDaver. Currently available variables include heartbeats per minute, systolic pressure, diastolic pressure, respiration rate, SpO2, and temperature. Values are displayed both numerically and by color coordinated dynamic waveform with mutable audio indicators for heart rate.

The EKG Simulator app allows for 2 android devices to be paired using Bluetooth, which, says the manufacturer, is ideal for a classroom setting because it allows the instructor to update the display remotely to modify the training scenario. Download the free EKG Simulator at http://syndaver.com/shop/new/ekg-simulator/.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT www.syndaver.com

MEDICAL SCRIBES AND CODING TOOLS

ScribeAmerica was established in 2004 as a clinical documentation solution for providers transitioning to electronic health records (EHRs). ScribeAmerica says its focus on improving the accuracy and quality of patient documentation has resulted in higher patient satisfaction scores, improved revenue cycle, and better continuity of care.

ScribeAmerica recruits, trains, and manages over 7,300 scribes in nearly 900 locations nationwide. Certified Medical Scribes, current with all American College of Medical Scribe Specialists guidelines and testing, specialize in collecting medical data and entering it into a clinician’s EHR, resulting in improved operational workflow, claims ScribeAmerica. ScribeAmerica’s medical scribe programs are found in rural and urban hospitals, teaching facilities, private practices, and political organizations.

LiveCode Point of Service Coding is a real-time coding solution that reduces the latency in feedback and improves overall efficacy of the revenue cycle.

The Individualized Clinical Documentation Advisor (ICD-Advisor) provides custom reports tailored to the codes used most often in a specific practice. ScribeAmerica says its ICD-Advisor is fast, individualized to a practice’s needs, and affordable.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT www.scribeamerica.com

XOFT CERVICAL APPLICATOR FOR EBX

iCAD, Inc. has added a cervical applicator to the Xoft® Axxent® Electronic Brachytherapy (eBX) System® for intracavitary treatment of multiple gynecologic cancers in a minimally shielded setting. The cervical applicator is used to deliver a precise dose of radiation to larger target areas of the cervix while minimizing exposure to healthy tissue, according to iCAD.

Using proprietary miniaturized x-ray as the radiation source, the Xoft eBX System delivers isotope-free radiation treatment in a targeted prescribed dose directly to the site where cancer recurrence is most likely, designed to minimize exposure to healthy tissue such as the bladder and rectum. The system requires minimal shielding and therefore does not require room redesign or construction investment and also allows medical personnel to remain in the room with the patient during treatment, says iCAD.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT www.xoftinc.com

SUPPLEMENTS FOR EXPECTANT/NEW MOMS

Premama®, a line of natural powdered drink mixes formulated to support the nutritional needs of expectant and new mothers, has introduced 2 products for preconception and postpartum health.

Fertility delivers a supplement formulation that includes myo-Inositol, which is clinically shown to help improve ovulatory function and healthy egg production, and folic acid to support prenatal health, according to Premama. Fertility is an unflavored drink mix that comes in packets of 2.2 g to be mixed with at least 12 oz of water or other noncarbonated flavored liquids such as juices or smoothies and taken daily.

Lactation is a berry-flavored drink mix daily supplement that is formulated with fenugreek, fennel seed, and blessed thistle to help support healthy milk production, according to Premama. Also included in Lactation are folic acid, Vitamin D3, calcium, and other essential nutrients for both mother and baby. A Lactation 2.5-mg packet mixes with at least 12 oz of water until blended well, or with noncarbonated, flavored liquids such as juices or smoothies.

All Premama products are physician approved, vegetarian, gluten free, and made in the United States. Premama products are available at retailers nationwide or online.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT www.drinkpremama.com

FREE EKG TRAINING APP FROM SYNDAVER

SynDaver™ Labs has released a free medical training electrocardiogram (EKG)simulator app for android devices on Google Play. The SynDaver EKG Simulator is a digital platform that can function with any medical training manikin, according to SynDaver. Currently available variables include heartbeats per minute, systolic pressure, diastolic pressure, respiration rate, SpO2, and temperature. Values are displayed both numerically and by color coordinated dynamic waveform with mutable audio indicators for heart rate.

The EKG Simulator app allows for 2 android devices to be paired using Bluetooth, which, says the manufacturer, is ideal for a classroom setting because it allows the instructor to update the display remotely to modify the training scenario. Download the free EKG Simulator at http://syndaver.com/shop/new/ekg-simulator/.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT www.syndaver.com

MEDICAL SCRIBES AND CODING TOOLS

ScribeAmerica was established in 2004 as a clinical documentation solution for providers transitioning to electronic health records (EHRs). ScribeAmerica says its focus on improving the accuracy and quality of patient documentation has resulted in higher patient satisfaction scores, improved revenue cycle, and better continuity of care.

ScribeAmerica recruits, trains, and manages over 7,300 scribes in nearly 900 locations nationwide. Certified Medical Scribes, current with all American College of Medical Scribe Specialists guidelines and testing, specialize in collecting medical data and entering it into a clinician’s EHR, resulting in improved operational workflow, claims ScribeAmerica. ScribeAmerica’s medical scribe programs are found in rural and urban hospitals, teaching facilities, private practices, and political organizations.

LiveCode Point of Service Coding is a real-time coding solution that reduces the latency in feedback and improves overall efficacy of the revenue cycle.

The Individualized Clinical Documentation Advisor (ICD-Advisor) provides custom reports tailored to the codes used most often in a specific practice. ScribeAmerica says its ICD-Advisor is fast, individualized to a practice’s needs, and affordable.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT www.scribeamerica.com

XOFT CERVICAL APPLICATOR FOR EBX

iCAD, Inc. has added a cervical applicator to the Xoft® Axxent® Electronic Brachytherapy (eBX) System® for intracavitary treatment of multiple gynecologic cancers in a minimally shielded setting. The cervical applicator is used to deliver a precise dose of radiation to larger target areas of the cervix while minimizing exposure to healthy tissue, according to iCAD.

Using proprietary miniaturized x-ray as the radiation source, the Xoft eBX System delivers isotope-free radiation treatment in a targeted prescribed dose directly to the site where cancer recurrence is most likely, designed to minimize exposure to healthy tissue such as the bladder and rectum. The system requires minimal shielding and therefore does not require room redesign or construction investment and also allows medical personnel to remain in the room with the patient during treatment, says iCAD.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT www.xoftinc.com

SUPPLEMENTS FOR EXPECTANT/NEW MOMS

Premama®, a line of natural powdered drink mixes formulated to support the nutritional needs of expectant and new mothers, has introduced 2 products for preconception and postpartum health.

Fertility delivers a supplement formulation that includes myo-Inositol, which is clinically shown to help improve ovulatory function and healthy egg production, and folic acid to support prenatal health, according to Premama. Fertility is an unflavored drink mix that comes in packets of 2.2 g to be mixed with at least 12 oz of water or other noncarbonated flavored liquids such as juices or smoothies and taken daily.

Lactation is a berry-flavored drink mix daily supplement that is formulated with fenugreek, fennel seed, and blessed thistle to help support healthy milk production, according to Premama. Also included in Lactation are folic acid, Vitamin D3, calcium, and other essential nutrients for both mother and baby. A Lactation 2.5-mg packet mixes with at least 12 oz of water until blended well, or with noncarbonated, flavored liquids such as juices or smoothies.

All Premama products are physician approved, vegetarian, gluten free, and made in the United States. Premama products are available at retailers nationwide or online.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT www.drinkpremama.com

FREE EKG TRAINING APP FROM SYNDAVER

SynDaver™ Labs has released a free medical training electrocardiogram (EKG)simulator app for android devices on Google Play. The SynDaver EKG Simulator is a digital platform that can function with any medical training manikin, according to SynDaver. Currently available variables include heartbeats per minute, systolic pressure, diastolic pressure, respiration rate, SpO2, and temperature. Values are displayed both numerically and by color coordinated dynamic waveform with mutable audio indicators for heart rate.

The EKG Simulator app allows for 2 android devices to be paired using Bluetooth, which, says the manufacturer, is ideal for a classroom setting because it allows the instructor to update the display remotely to modify the training scenario. Download the free EKG Simulator at http://syndaver.com/shop/new/ekg-simulator/.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT www.syndaver.com

MEDICAL SCRIBES AND CODING TOOLS

ScribeAmerica was established in 2004 as a clinical documentation solution for providers transitioning to electronic health records (EHRs). ScribeAmerica says its focus on improving the accuracy and quality of patient documentation has resulted in higher patient satisfaction scores, improved revenue cycle, and better continuity of care.

ScribeAmerica recruits, trains, and manages over 7,300 scribes in nearly 900 locations nationwide. Certified Medical Scribes, current with all American College of Medical Scribe Specialists guidelines and testing, specialize in collecting medical data and entering it into a clinician’s EHR, resulting in improved operational workflow, claims ScribeAmerica. ScribeAmerica’s medical scribe programs are found in rural and urban hospitals, teaching facilities, private practices, and political organizations.

LiveCode Point of Service Coding is a real-time coding solution that reduces the latency in feedback and improves overall efficacy of the revenue cycle.

The Individualized Clinical Documentation Advisor (ICD-Advisor) provides custom reports tailored to the codes used most often in a specific practice. ScribeAmerica says its ICD-Advisor is fast, individualized to a practice’s needs, and affordable.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT www.scribeamerica.com

XOFT CERVICAL APPLICATOR FOR EBX

iCAD, Inc. has added a cervical applicator to the Xoft® Axxent® Electronic Brachytherapy (eBX) System® for intracavitary treatment of multiple gynecologic cancers in a minimally shielded setting. The cervical applicator is used to deliver a precise dose of radiation to larger target areas of the cervix while minimizing exposure to healthy tissue, according to iCAD.

Using proprietary miniaturized x-ray as the radiation source, the Xoft eBX System delivers isotope-free radiation treatment in a targeted prescribed dose directly to the site where cancer recurrence is most likely, designed to minimize exposure to healthy tissue such as the bladder and rectum. The system requires minimal shielding and therefore does not require room redesign or construction investment and also allows medical personnel to remain in the room with the patient during treatment, says iCAD.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT www.xoftinc.com

HIPAA – the home version

“Dad, Jason said that you saw him in the office today.”

“Gee, Nick, it was very busy. I don’t remember anything about his visit.”

My response to my son was a lie, but I have always been willing to feign ignorance to protect my patients’ privacy. When our kids were home and within earshot I never mentioned that I had seen one of their friends or schoolmates in the office. In fact, I pretty much never talked about my professional life when they were around. They knew my work took a big chunk of my time and, in the remaining few hours, we had other things to talk about. Unfortunately, all three of my children may have mistaken my silence as an indicator that I didn’t like my job, which was far from the truth.

After hearing enough evasive answers, they realized that I had no intention of sharing anything about their peers’ medical history, regardless of how trivial the incident may have been. Even before HIPAA, I knew that my children shouldn’t be trusted to keep even the most innocent-sounding tidbit within the boundaries of our home. After all they were just children.

I suspect that most of you are equally cautious about sharing patient information with your children, even your adult children. But what about your spouse? Let’s be honest here: How HIPAA-compliant is your home? Does pillow talk sometimes drift over the line and compromise doctor-patient confidentiality? I suspect that we all share stories about interesting cases with our spouses hoping that we haven’t revealed enough information for them to figure out who were are talking about.

Of course, “interesting” is a relative term. If your spouse’s postgraduate degree is in computer science and not in medicine, he or she may not find your story about “the highest creatinine I have ever seen” very titillating. But, the story that begins, “You won’t believe what this mother was feeding her 6-month-old” might get his or her attention.