User login

Trends in Thumb Carpometacarpal Interposition Arthroplasty in the United States, 2005–2011

A common entity, osteoarthritis (OA) at the base of the thumb is largely caused by the unique anatomy and biomechanics of the thumb carpometacarpal (CMC) joint.1 Radiographically evident CMC degeneration occurs in 40% of women and 25% of men over age 75 years, making the thumb CMC joint the most common site of surgical reconstruction for upper extremity OA.2,3

Over the past 40 years, numerous surgical techniques for managing thumb CMC-OA have been described. These include volar ligament reconstruction, first metacarpal osteotomy, CMC arthrodesis, CMC joint replacement, and trapeziectomy. Trapeziectomy can be performed in isolation or in combination with tendon interposition, ligament reconstruction, or ligament reconstruction and tendon interposition (LRTI).4-20 The authors of a recent systematic review concluded there is no evidence that any one surgical procedure for CMC-OA is superior to another in terms of pain, function, satisfaction, range of motion, or strength.4 Nevertheless, a recent survey found that 719 (62%) of 1156 US hand surgeons used LRTI as the treatment of choice for advanced CMC-OA.21

Our detailed literature search yielded no other database studies characterizing current trends in the practice patterns of US orthopedic surgeons who perform interposition arthroplasty for CMC arthritis. Analysis of these trends is important not only to patients but also to the broader orthopedic and health care community.22

We conducted a study to investigate current trends in CMC interposition arthroplasty across time, sex, age, and region of the United States; per-patient charges and reimbursements; and the association between this procedure and concomitantly performed carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) and carpal tunnel release (CTR). In addition, we compared incidence of CMC interposition arthroplasty with that of CMC arthrodesis.

Patients and Methods

All data were derived from the PearlDiver Patient Records Database (PearlDiver Technologies), a publicly available database of patients. The database stores procedure volumes, demographics, and average charge information for patients with International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) diagnoses and procedures or Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes. Data for the present study were drawn from the Medicare database within the PearlDiver records, which has a total of 179,094,296 patient records covering the period 2005–2011. This study did not require institutional review board approval, as it used existing, publicly available data without identifiers linked to subjects.

PearlDiver Technologies granted us database access for academic research. The database was stored on a password-protected server maintained by PearlDiver. ICD-9 and CPT codes can be searched in isolation or in combination. Search results yield number of patients with a searched code (or combination of codes) in each year, age group, or region of the United States, as well as mean charge and mean reimbursement for the code or combination of codes.

We used CPT code 25447 (arthroplasty, interposition, intercarpal, or CMC joints) to search the database for patients who underwent thumb CMC interposition arthroplasty. Although this code does not specify thumb, we are unaware of any procedure (other than thumb CMC interposition arthroplasty) typically given this code. Our search yielded procedure volumes, sex distribution, age distribution, region volumes, and mean per-patient charges and reimbursements for each CPT code. We then searched the resulting cohort for CTS (ICD-9 code 354.0), endoscopic CTR (CPT code 29848), and open CTR (CPT code 64721) to find CTR performed concomitantly with CMC interposition arthroplasty. Last, patients were tracked in the database past their surgery date to evaluate for postoperative physical or occupational therapy evaluations within 6 months (using CPT codes appearing in at least 1% of the cohort: 97001, 97003, 97004, 97110, 97112, 97124, 97140, 97150, 97350, 97535) and postoperative thumb, hand, or wrist radiographs within 6 months (using CPT codes appearing in at least 1% of the cohort: 73140, 73130, 73110). To ensure adequacy of 6-month postoperative data, we included in this portion of the study only those patients with surgery dates between 2005 and 2010.

For comparative purposes, we also searched the database for patients who underwent thumb CMC arthrodesis within the same period—using CPT codes 26841 and 26842 (arthrodesis CMC joint thumb, with or without internal fixation; with or without autograft) and CPT code 26820 (fusion in opposition, thumb, with autogenous graft).

Overall procedure volume data are reported as number of patients with the given CPT code in the database output in a given year. Age-group and sex analyses are reported as number of patients reported in the database output and as percentage of patients who underwent the CPT code of interest that year. Mean charges and reimbursements are reported as results by the database for the code of interest (CPT 25447). Data for the region analysis are presented as an incidence, as there is an uneven distribution of patient volumes among regions. This incidence is calculated as number of patients in a particular region and year normalized to total number of patients in the database for that particular region or year. Regions are defined as Midwest (IA, IL, IN, KS, MI, MN, MO, ND, NE, OH, SD, WI), Northeast (CT, MA, ME, NH, NJ, NY, PA, RI, VT), South (AL, AR, DC, DE, FL, GA, KY, LA, MD, MS, NC, OK, SC, TN, TX, VA, WV), and West (AK, AZ, CA, CO, HI, ID, MT, NM, NV, OR, UT, WA, WY).

Chi-squared linear-by-linear association analysis was used to determine statistical significance with regard to trends over time in procedure volumes, sex, age group, and region. For all statistical comparisons, P < .05 was considered significant.

Results

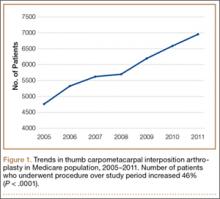

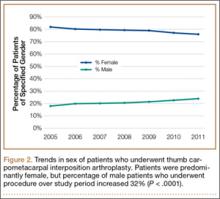

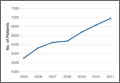

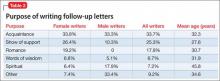

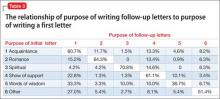

In the database, we identified 41,171 unique patients who underwent CMC interposition arthroplasty between 2005 and 2011. Over the 7-year study period, number of patients who had CMC interposition arthroplasty increased 46.2%, from 4761 in 2005 to 6960 in 2011 (P < .0001) (Table 1, Figure 1). Throughout this period, females underwent CMC interposition arthroplasty more frequently than males at all time points (P < .0001). Overall ratio of female to male patients, however, changed significantly. In 2005, 18.1% of all CMC interposition arthroplasties were performed on male patients; this increased to 23.9% of all procedures by 2011 (P < .0001) (Figure 2). Table 1 presents an age-group analysis. There were no significant differences in relative percentage of patients in any given age group who underwent CMC interposition arthroplasty over the study period.

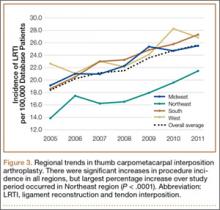

Analysis of overall procedure incidence by region revealed significant increases in all regions (P < .0001), ranging from 18.5% (West) to 54.5% (Northeast) (Figure 3). At all time points, the incidence of CMC interposition arthroplasty was significantly lower in the Northeast than in any other region and compared with the overall average.

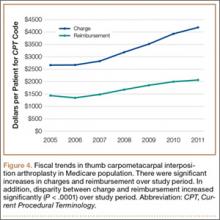

Between 2005 and 2011, there were significant increases in both per-patient charges and reimbursements for CMC interposition arthroplasty (Figure 4). Mean per-patient charge increased from $2676 in 2005 to $4181 in 2011 (P < .0001), and mean per-patient reimbursement increased from $1445 in 2005 to $2061 in 2011 (P < .0001). The discrepancy between charge and reimbursement increased throughout the study period: Reimbursement in 2005 was 54.0% of the charge; this decreased to 49.3% by 2011 but was not statistically significant (P = .08).

Overall, 40.9% of patients who underwent CMC interposition arthroplasty also had a CTS diagnosis. Between 15.5% and 17.3% of these patients had concomitant open or endoscopic CTR at time of CMC interposition arthroplasty (Table 2). Percentage of patients who underwent concomitant CTR did not change significantly from 2005 to 2011 (P = .139). Use of postoperative occupational and/or physical therapy increased significantly over the study period, from 33.5% of patients in 2005 to 50.7% of patients in 2010 (P < .0001). Use of postoperative thumb, hand, and/or wrist radiography also increased throughout the study period, from 7.4% of patients in 2005 to 18.7% of patients in 2010 (P < .0001).

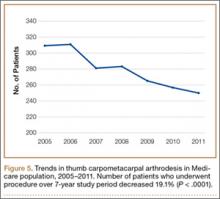

We identified 1916 unique patients who underwent thumb CMC arthrodesis between 2005 and 2011. Over the 7-year study period, there was a 19.1% decrease in number of patients who underwent CMC arthrodesis, from 309 in 2005 to 250 in 2011 (P < .0001) (Figure 5). Significantly fewer patients had CMC arthrodesis compared with CMC interposition arthroplasty at all time points, ranging from 6.5% (thumb CMC arthrodesis:CMC interposition arthroplasty) in 2005 to 3.6% in 2011 (P < .0001).

Discussion

Our results demonstrated a significant increase in use of thumb CMC interposition arthroplasty in a US Medicare population, with an increase of more than 46% from 2005 to 2011. This finding supports the findings of a recent cross-sectional survey-based study in which 719 (62%) of 1156 surveyed US hand surgeons reported performing trapeziectomy with LRTI for advanced thumb CMC-OA.21 A prior study had similar findings, with 692 (68%) of 1024 American Society for Surgery of the Hand (ASSH) members performing LRTI and 766 (75%) of 1024 performing some type of CMC interposition with trapeziectomy for advanced CMC-OA.23 This preference for CMC interposition arthroplasty prevails despite the fact that numerous studies have shown no superiority of any surgical procedure to another for CMC-OA in terms of pain, function, satisfaction, range of motion, and strength.7,15,18,19,24-34 Our data demonstrated that, not only does CMC interposition arthroplasty remain the most frequently used procedure for thumb CMC-OA, the incidence of CMC interposition arthroplasty continues to increase yearly.

The incidence of thumb CMC-OA is higher in women than in men, with more joint laxity a known contributor and subtle sex differences in trapezium geometry and congruence postulated as additional factors.3,35,36 This trend was confirmed in the present study, as females underwent significantly more CMC interposition arthroplasties at all time points. It is interesting that the overall ratio of female to male patients changed significantly over the study period, with the percentage of patients who were male increasing from 18.1% in 2005 to 23.9% in 2011. No previous studies have captured such a large cross section of the population to establish this trend. Although this trend is not necessarily intuitive, potential theories include increased acceptance of CMC interposition arthroplasty as a surgical option for male patients, and potentially a larger number of male patients seeking medical care for thumb CMC-OA in recent years.

Increases in procedure incidence were noted in all regions of the United States, but the largest percentage increase occurred in the Northeast. Despite this increase, the Northeast also had significantly lower CMC interposition arthroplasty incidence compared with all other regions and with the average procedure incidence throughout the study period—demonstrating some regional bias as to treatment of thumb CMC-OA. Unfortunately, because of database limitations and lack of specific CPT codes for other treatment options for thumb CMC-OA, we cannot ascertain if other types of surgery are more frequently used in the Northeast.

CTS and thumb CMC-OA often coexist.37 The estimated incidence of concomitant CTS in patients with CMC-OA is between 4% and 43%, but the rate of concomitant CTR and CMC interposition arthroplasty was not previously characterized in the literature.38,39 Results of the present study supported these findings; 41% of patients who underwent CMC interposition arthroplasty in our study also had a CTS diagnosis, compared with 43% in the 246-patient study by Florack and colleagues.38 We also found that 16% to 17% of patients who underwent CMC interposition arthroplasty underwent concomitant CTR; this rate remained consistent throughout the study period.

Our study demonstrated that, compared with CMC interposition arthroplasties, significantly fewer thumb CMC arthrodesis procedures were performed in the same Medicare population during the same period. Furthermore, the number of thumb CMC arthrodesis procedures declined yearly, with an overall decrease of 19% from 2005 to 2011. In a recent single-blinded, randomized trial, Vermeulen and colleagues40 compared thumb CMC arthrodesis and trapeziectomy with LRTI. They found superior patient satisfaction and significantly lower complication rates in women who underwent LRTI versus arthrodesis. The study was terminated prematurely because of these complications and thus was underpowered to determine differences in specific outcome measures. Previous studies comparing arthrodesis and interposition arthroplasties reported inconsistent outcomes. Hart and colleagues41 found no significant differences in pain or function between CMC arthrodesis and LRTI at a mean 7-year follow-up in a level II randomized controlled trial. Hartigan and colleagues15 reached similar conclusions in their retrospective comparison of the procedures. Without clear evidence supporting arthrodesis over interposition arthroplasty, the majority of surgeons favor interposition arthroplasty for thumb CMC-OA. Among Medicare patients, use of thumb CMC arthrodesis continues to fall.

This national database study had several limitations, which are common to all studies using the PearlDiver database22,42-47:

1. The power of the analysis depended on the quality of available data. Potential sources of error included accuracy of billing codes, and miscoding or noncoding by physicians.46

2. Although we used this database to try to accurately represent a large population of interest, we cannot guarantee the database represented a true cross section of the United States.

3. For the Medicare population, the PearlDiver database indexes data only in 7-year increments. Although the study period was long enough to detect significant trends, some data may not be accurately captured over a 7-year period.

4. Patients were not randomized to a treatment group.

5. The PearlDiver database does not include any clinical outcome data. Therefore, we cannot comment on the efficacy of the reported evaluations and interventions.

6. There is no specific CPT code for thumb CMC interposition arthroplasty. However, we are unaware of a CMC interposition arthroplasty performed for any area besides the thumb. Theoretically, the study population can include a negligible percentage of patients who had interposition arthroplasty of a CMC joint other than the thumb.

7. The database cannot be searched for use of thumb CMC-OA surgical techniques other than CMC interposition arthroplasty or arthrodesis, as isolated trapeziectomy, volar ligament reconstruction, implant arthroplasty, and metacarpal osteotomy lack specific CPT codes.

Conclusion

Thumb CMC-OA is a common entity among Medicare patients. There are numerous surgical options for cases that have failed conservative treatment. Despite the lack of evidence that thumb CMC interposition arthroplasty is superior to other surgical options, the number of patients who had this procedure increased 46% during the 2005–2011 study period. Although the majority of patients who undergo CMC interposition arthroplasty are female, the percentage of male patients has increased significantly. More than 40% of patients who have CMC interposition arthroplasty are also diagnosed with CTS, and 16% to 17% of patients who have CMC interposition arthroplasty will have a concomitant CTR. CMC arthrodesis is used in significantly fewer patients of Medicare age, and its use has been declining.

1. Hentz VR. Surgical treatment of trapeziometacarpal joint arthritis: a historical perspective. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(4):1184-1189.

2. Armstrong AL, Hunter JB, Davis TR. The prevalence of degenerative arthritis of the base of the thumb in post-menopausal women. J Hand Surg Br. 1994;19(3):340-341.

3. Van Heest AE, Kallemeier P. Thumb carpal metacarpal arthritis. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2008;16(3):140-151.

4. Vermeulen GM, Slijper H, Feitz R, Hovius SE, Moojen TM, Selles RW. Surgical management of primary thumb carpometacarpal osteoarthritis: a systematic review. J Hand Surg Am. 2011;36(1):157-169.

5. Bodin ND, Spangler R, Thoder JJ. Interposition arthroplasty options for carpometacarpal arthritis of the thumb. Hand Clin. 2010;26(3):339-350, v-vi.

6. Cooney WP, Linscheid RL, Askew LJ. Total arthroplasty of the thumb trapeziometacarpal joint. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1987;(220):35-45.

7. De Smet L, Vandenberghe L, Degreef I. Long-term outcome of trapeziectomy with ligament reconstruction and tendon interposition (LRTI) versus prosthesis arthroplasty for basal joint osteoarthritis of the thumb. Acta Orthop Belg. 2013;79(2):146-149.

8. Dell PC, Muniz RB. Interposition arthroplasty of the trapeziometacarpal joint for osteoarthritis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1987;(220):27-34.

9. Dhar S, Gray IC, Jones WA, Beddow FH. Simple excision of the trapezium for osteoarthritis of the carpometacarpal joint of the thumb. J Hand Surg Br. 1994;19(4):485-488.

10. Eaton RG, Littler JW. Ligament reconstruction for the painful thumb carpometacarpal joint. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1973;55(8):1655-1666.

11. Eaton RG, Lane LB, Littler JW, Keyser JJ. Ligament reconstruction for the painful thumb carpometacarpal joint: a long-term assessment. J Hand Surg Am. 1984;9(5):692-699.

12. Eaton RG, Glickel SZ, Littler JW. Tendon interposition arthroplasty for degenerative arthritis of the trapeziometacarpal joint of the thumb. J Hand Surg Am. 1985;10(5):645-654.

13. Elfar JC, Burton RI. Ligament reconstruction and tendon interposition for thumb basal arthritis. Hand Clin. 2013;29(1):15-25.

14. Froimson AI. Tendon arthroplasty of the trapeziometacarpal joint. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1970;70:191-199.

15. Hartigan BJ, Stern PJ, Kiefhaber TR. Thumb carpometacarpal osteoarthritis: arthrodesis compared with ligament reconstruction and tendon interposition. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83(10):1470-1478.

16. Kenniston JA, Bozentka DJ. Treatment of advanced carpometacarpal joint disease: arthrodesis. Hand Clin. 2008;24(3):285-294, vi-vii.

17. Kokkalis ZT, Zanaros G, Weiser RW, Sotereanos DG. Trapezium resection with suspension and interposition arthroplasty using acellular dermal allograft for thumb carpometacarpal arthritis. J Hand Surg Am. 2009;34(6):1029-1036.

18. Kriegs-Au G, Petje G, Fojtl E, Ganger R, Zachs I. Ligament reconstruction with or without tendon interposition to treat primary thumb carpometacarpal osteoarthritis. Surgical technique. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87 suppl 1(Pt 1):78-85.

19. Park MJ, Lichtman G, Christian JB, et al. Surgical treatment of thumb carpometacarpal joint arthritis: a single institution experience from 1995–2005. Hand. 2008;3(4):304-310.

20. Park MJ, Lee AT, Yao J. Treatment of thumb carpometacarpal arthritis with arthroscopic hemitrapeziectomy and interposition arthroplasty. Orthopedics. 2012;35(12):e1759-e1764.

21. Wolf JM, Delaronde S. Current trends in nonoperative and operative treatment of trapeziometacarpal osteoarthritis: a survey of US hand surgeons. J Hand Surg Am. 2012;37(1):77-82.

22. Zhang AL, Kreulen C, Ngo SS, Hame SL, Wang JC, Gamradt SC. Demographic trends in arthroscopic SLAP repair in the United States. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(5):1144-1147.

23. Brunton LM, Wilgis EF. A survey to determine current practice patterns in the surgical treatment of advanced thumb carpometacarpal osteoarthrosis. Hand. 2010;5(4):415-422.

24. Belcher HJ, Nicholl JE. A comparison of trapeziectomy with and without ligament reconstruction and tendon interposition. J Hand Surg Br. 2000;25(4):350-356.

25. Davis TR, Pace A. Trapeziectomy for trapeziometacarpal joint osteoarthritis: is ligament reconstruction and temporary stabilisation of the pseudarthrosis with a Kirschner wire important? J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2009;34(3):312-321.

26. Davis TR, Brady O, Dias JJ. Excision of the trapezium for osteoarthritis of the trapeziometacarpal joint: a study of the benefit of ligament reconstruction or tendon interposition. J Hand Surg Am. 2004;29(6):1069-1077.

27. De Smet L, Sioen W, Spaepen D, van Ransbeeck H. Treatment of basal joint arthritis of the thumb: trapeziectomy with or without tendon interposition/ligament reconstruction. Hand Surg. 2004;9(1):5-9.

28. Field J, Buchanan D. To suspend or not to suspend: a randomised single blind trial of simple trapeziectomy versus trapeziectomy and flexor carpi radialis suspension. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2007;32(4):462-466.

29. Gerwin M, Griffith A, Weiland AJ, Hotchkiss RN, McCormack RR. Ligament reconstruction basal joint arthroplasty without tendon interposition. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1997;(342):42-45.

30. Jorheim M, Isaxon I, Flondell M, Kalen P, Atroshi I. Short-term outcomes of trapeziometacarpal Artelon implant compared with tendon suspension interposition arthroplasty for osteoarthritis: a matched cohort study. J Hand Surg Am. 2009;34(8):1381-1387.

31. Lehmann O, Herren DB, Simmen BR. Comparison of tendon suspension-interposition and silicon spacers in the treatment of degenerative osteoarthritis of the base of the thumb. Ann Chir Main Memb Super. 1998;17(1):25-30.

32. Nilsson A, Liljensten E, Bergstrom C, Sollerman C. Results from a degradable TMC joint spacer (Artelon) compared with tendon arthroplasty. J Hand Surg Am. 2005;30(2):380-389.

33. Schroder J, Kerkhoffs GM, Voerman HJ, Marti RK. Surgical treatment of basal joint disease of the thumb: comparison between resection-interposition arthroplasty and trapezio-metacarpal arthrodesis. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2002;122(1):35-38.

34. Tagil M, Kopylov P. Swanson versus APL arthroplasty in the treatment of osteoarthritis of the trapeziometacarpal joint: a prospective and randomized study in 26 patients. J Hand Surg Br. 2002;27(5):452-456.

35. North ER, Rutledge WM. The trapezium-thumb metacarpal joint: the relationship of joint shape and degenerative joint disease. Hand. 1983;15(2):201-206.

36. Ateshian GA, Rosenwasser MP, Mow VC. Curvature characteristics and congruence of the thumb carpometacarpal joint: differences between female and male joints. J Biomech. 1992;25(6):591-607.

37. Sless Y, Sampson SP. Experience with transtrapezium approach for transverse carpal ligament release in patients with coexisted trapeziometacarpal joint osteoarthritis and carpal tunnel syndrome. Hand. 2007;2(3):151-154.

38. Florack TM, Miller RJ, Pellegrini VD, Burton RI, Dunn MG. The prevalence of carpal tunnel syndrome in patients with basal joint arthritis of the thumb. J Hand Surg Am. 1992;17(4):624-630.

39. Tsai TM, Laurentin-Perez LA, Wong MS, Tamai M. Ideas and innovations: radial approach to carpal tunnel release in conjunction with thumb carpometacarpal arthroplasty. Hand Surg. 2005;10(1):61-66.

40. Vermeulen GM, Brink SM, Slijper H, et al. Trapeziometacarpal arthrodesis or trapeziectomy with ligament reconstruction in primary trapeziometacarpal osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(9):726-733.

41. Hart R, Janecek M, Siska V, Kucera B, Stipcak V. Interposition suspension arthroplasty according to Epping versus arthrodesis for trapeziometacarpal osteoarthritis. Eur Surg. 2006;38(6):433-438.

42. Abrams GD, Frank RM, Gupta AK, Harris JD, McCormick FM, Cole BJ. Trends in meniscus repair and meniscectomy in the United States, 2005–2011. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(10):2333-2339.

43. Montgomery SR, Ngo SS, Hobson T, et al. Trends and demographics in hip arthroscopy in the United States. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(4):661-665.

44. Zhang AL, Montgomery SR, Ngo SS, Hame SL, Wang JC, Gamradt SC. Arthroscopic versus open shoulder stabilization: current practice patterns in the United States. Arthroscopy. 2014;30(4):436-443.

45. Yeranosian MG, Arshi A, Terrell RD, Wang JC, McAllister DR, Petrigliano FA. Incidence of acute postoperative infections requiring reoperation after arthroscopic shoulder surgery. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(2):437-441.

46. Yeranosian MG, Terrell RD, Wang JC, McAllister DR, Petrigliano FA. The costs associated with the evaluation of rotator cuff tears before surgical repair. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(12):1662-1666.

47. Daffner SD, Hymanson HJ, Wang JC. Cost and use of conservative management of lumbar disc herniation before surgical discectomy. Spine J. 2010;10(6):463-468.

A common entity, osteoarthritis (OA) at the base of the thumb is largely caused by the unique anatomy and biomechanics of the thumb carpometacarpal (CMC) joint.1 Radiographically evident CMC degeneration occurs in 40% of women and 25% of men over age 75 years, making the thumb CMC joint the most common site of surgical reconstruction for upper extremity OA.2,3

Over the past 40 years, numerous surgical techniques for managing thumb CMC-OA have been described. These include volar ligament reconstruction, first metacarpal osteotomy, CMC arthrodesis, CMC joint replacement, and trapeziectomy. Trapeziectomy can be performed in isolation or in combination with tendon interposition, ligament reconstruction, or ligament reconstruction and tendon interposition (LRTI).4-20 The authors of a recent systematic review concluded there is no evidence that any one surgical procedure for CMC-OA is superior to another in terms of pain, function, satisfaction, range of motion, or strength.4 Nevertheless, a recent survey found that 719 (62%) of 1156 US hand surgeons used LRTI as the treatment of choice for advanced CMC-OA.21

Our detailed literature search yielded no other database studies characterizing current trends in the practice patterns of US orthopedic surgeons who perform interposition arthroplasty for CMC arthritis. Analysis of these trends is important not only to patients but also to the broader orthopedic and health care community.22

We conducted a study to investigate current trends in CMC interposition arthroplasty across time, sex, age, and region of the United States; per-patient charges and reimbursements; and the association between this procedure and concomitantly performed carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) and carpal tunnel release (CTR). In addition, we compared incidence of CMC interposition arthroplasty with that of CMC arthrodesis.

Patients and Methods

All data were derived from the PearlDiver Patient Records Database (PearlDiver Technologies), a publicly available database of patients. The database stores procedure volumes, demographics, and average charge information for patients with International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) diagnoses and procedures or Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes. Data for the present study were drawn from the Medicare database within the PearlDiver records, which has a total of 179,094,296 patient records covering the period 2005–2011. This study did not require institutional review board approval, as it used existing, publicly available data without identifiers linked to subjects.

PearlDiver Technologies granted us database access for academic research. The database was stored on a password-protected server maintained by PearlDiver. ICD-9 and CPT codes can be searched in isolation or in combination. Search results yield number of patients with a searched code (or combination of codes) in each year, age group, or region of the United States, as well as mean charge and mean reimbursement for the code or combination of codes.

We used CPT code 25447 (arthroplasty, interposition, intercarpal, or CMC joints) to search the database for patients who underwent thumb CMC interposition arthroplasty. Although this code does not specify thumb, we are unaware of any procedure (other than thumb CMC interposition arthroplasty) typically given this code. Our search yielded procedure volumes, sex distribution, age distribution, region volumes, and mean per-patient charges and reimbursements for each CPT code. We then searched the resulting cohort for CTS (ICD-9 code 354.0), endoscopic CTR (CPT code 29848), and open CTR (CPT code 64721) to find CTR performed concomitantly with CMC interposition arthroplasty. Last, patients were tracked in the database past their surgery date to evaluate for postoperative physical or occupational therapy evaluations within 6 months (using CPT codes appearing in at least 1% of the cohort: 97001, 97003, 97004, 97110, 97112, 97124, 97140, 97150, 97350, 97535) and postoperative thumb, hand, or wrist radiographs within 6 months (using CPT codes appearing in at least 1% of the cohort: 73140, 73130, 73110). To ensure adequacy of 6-month postoperative data, we included in this portion of the study only those patients with surgery dates between 2005 and 2010.

For comparative purposes, we also searched the database for patients who underwent thumb CMC arthrodesis within the same period—using CPT codes 26841 and 26842 (arthrodesis CMC joint thumb, with or without internal fixation; with or without autograft) and CPT code 26820 (fusion in opposition, thumb, with autogenous graft).

Overall procedure volume data are reported as number of patients with the given CPT code in the database output in a given year. Age-group and sex analyses are reported as number of patients reported in the database output and as percentage of patients who underwent the CPT code of interest that year. Mean charges and reimbursements are reported as results by the database for the code of interest (CPT 25447). Data for the region analysis are presented as an incidence, as there is an uneven distribution of patient volumes among regions. This incidence is calculated as number of patients in a particular region and year normalized to total number of patients in the database for that particular region or year. Regions are defined as Midwest (IA, IL, IN, KS, MI, MN, MO, ND, NE, OH, SD, WI), Northeast (CT, MA, ME, NH, NJ, NY, PA, RI, VT), South (AL, AR, DC, DE, FL, GA, KY, LA, MD, MS, NC, OK, SC, TN, TX, VA, WV), and West (AK, AZ, CA, CO, HI, ID, MT, NM, NV, OR, UT, WA, WY).

Chi-squared linear-by-linear association analysis was used to determine statistical significance with regard to trends over time in procedure volumes, sex, age group, and region. For all statistical comparisons, P < .05 was considered significant.

Results

In the database, we identified 41,171 unique patients who underwent CMC interposition arthroplasty between 2005 and 2011. Over the 7-year study period, number of patients who had CMC interposition arthroplasty increased 46.2%, from 4761 in 2005 to 6960 in 2011 (P < .0001) (Table 1, Figure 1). Throughout this period, females underwent CMC interposition arthroplasty more frequently than males at all time points (P < .0001). Overall ratio of female to male patients, however, changed significantly. In 2005, 18.1% of all CMC interposition arthroplasties were performed on male patients; this increased to 23.9% of all procedures by 2011 (P < .0001) (Figure 2). Table 1 presents an age-group analysis. There were no significant differences in relative percentage of patients in any given age group who underwent CMC interposition arthroplasty over the study period.

Analysis of overall procedure incidence by region revealed significant increases in all regions (P < .0001), ranging from 18.5% (West) to 54.5% (Northeast) (Figure 3). At all time points, the incidence of CMC interposition arthroplasty was significantly lower in the Northeast than in any other region and compared with the overall average.

Between 2005 and 2011, there were significant increases in both per-patient charges and reimbursements for CMC interposition arthroplasty (Figure 4). Mean per-patient charge increased from $2676 in 2005 to $4181 in 2011 (P < .0001), and mean per-patient reimbursement increased from $1445 in 2005 to $2061 in 2011 (P < .0001). The discrepancy between charge and reimbursement increased throughout the study period: Reimbursement in 2005 was 54.0% of the charge; this decreased to 49.3% by 2011 but was not statistically significant (P = .08).

Overall, 40.9% of patients who underwent CMC interposition arthroplasty also had a CTS diagnosis. Between 15.5% and 17.3% of these patients had concomitant open or endoscopic CTR at time of CMC interposition arthroplasty (Table 2). Percentage of patients who underwent concomitant CTR did not change significantly from 2005 to 2011 (P = .139). Use of postoperative occupational and/or physical therapy increased significantly over the study period, from 33.5% of patients in 2005 to 50.7% of patients in 2010 (P < .0001). Use of postoperative thumb, hand, and/or wrist radiography also increased throughout the study period, from 7.4% of patients in 2005 to 18.7% of patients in 2010 (P < .0001).

We identified 1916 unique patients who underwent thumb CMC arthrodesis between 2005 and 2011. Over the 7-year study period, there was a 19.1% decrease in number of patients who underwent CMC arthrodesis, from 309 in 2005 to 250 in 2011 (P < .0001) (Figure 5). Significantly fewer patients had CMC arthrodesis compared with CMC interposition arthroplasty at all time points, ranging from 6.5% (thumb CMC arthrodesis:CMC interposition arthroplasty) in 2005 to 3.6% in 2011 (P < .0001).

Discussion

Our results demonstrated a significant increase in use of thumb CMC interposition arthroplasty in a US Medicare population, with an increase of more than 46% from 2005 to 2011. This finding supports the findings of a recent cross-sectional survey-based study in which 719 (62%) of 1156 surveyed US hand surgeons reported performing trapeziectomy with LRTI for advanced thumb CMC-OA.21 A prior study had similar findings, with 692 (68%) of 1024 American Society for Surgery of the Hand (ASSH) members performing LRTI and 766 (75%) of 1024 performing some type of CMC interposition with trapeziectomy for advanced CMC-OA.23 This preference for CMC interposition arthroplasty prevails despite the fact that numerous studies have shown no superiority of any surgical procedure to another for CMC-OA in terms of pain, function, satisfaction, range of motion, and strength.7,15,18,19,24-34 Our data demonstrated that, not only does CMC interposition arthroplasty remain the most frequently used procedure for thumb CMC-OA, the incidence of CMC interposition arthroplasty continues to increase yearly.

The incidence of thumb CMC-OA is higher in women than in men, with more joint laxity a known contributor and subtle sex differences in trapezium geometry and congruence postulated as additional factors.3,35,36 This trend was confirmed in the present study, as females underwent significantly more CMC interposition arthroplasties at all time points. It is interesting that the overall ratio of female to male patients changed significantly over the study period, with the percentage of patients who were male increasing from 18.1% in 2005 to 23.9% in 2011. No previous studies have captured such a large cross section of the population to establish this trend. Although this trend is not necessarily intuitive, potential theories include increased acceptance of CMC interposition arthroplasty as a surgical option for male patients, and potentially a larger number of male patients seeking medical care for thumb CMC-OA in recent years.

Increases in procedure incidence were noted in all regions of the United States, but the largest percentage increase occurred in the Northeast. Despite this increase, the Northeast also had significantly lower CMC interposition arthroplasty incidence compared with all other regions and with the average procedure incidence throughout the study period—demonstrating some regional bias as to treatment of thumb CMC-OA. Unfortunately, because of database limitations and lack of specific CPT codes for other treatment options for thumb CMC-OA, we cannot ascertain if other types of surgery are more frequently used in the Northeast.

CTS and thumb CMC-OA often coexist.37 The estimated incidence of concomitant CTS in patients with CMC-OA is between 4% and 43%, but the rate of concomitant CTR and CMC interposition arthroplasty was not previously characterized in the literature.38,39 Results of the present study supported these findings; 41% of patients who underwent CMC interposition arthroplasty in our study also had a CTS diagnosis, compared with 43% in the 246-patient study by Florack and colleagues.38 We also found that 16% to 17% of patients who underwent CMC interposition arthroplasty underwent concomitant CTR; this rate remained consistent throughout the study period.

Our study demonstrated that, compared with CMC interposition arthroplasties, significantly fewer thumb CMC arthrodesis procedures were performed in the same Medicare population during the same period. Furthermore, the number of thumb CMC arthrodesis procedures declined yearly, with an overall decrease of 19% from 2005 to 2011. In a recent single-blinded, randomized trial, Vermeulen and colleagues40 compared thumb CMC arthrodesis and trapeziectomy with LRTI. They found superior patient satisfaction and significantly lower complication rates in women who underwent LRTI versus arthrodesis. The study was terminated prematurely because of these complications and thus was underpowered to determine differences in specific outcome measures. Previous studies comparing arthrodesis and interposition arthroplasties reported inconsistent outcomes. Hart and colleagues41 found no significant differences in pain or function between CMC arthrodesis and LRTI at a mean 7-year follow-up in a level II randomized controlled trial. Hartigan and colleagues15 reached similar conclusions in their retrospective comparison of the procedures. Without clear evidence supporting arthrodesis over interposition arthroplasty, the majority of surgeons favor interposition arthroplasty for thumb CMC-OA. Among Medicare patients, use of thumb CMC arthrodesis continues to fall.

This national database study had several limitations, which are common to all studies using the PearlDiver database22,42-47:

1. The power of the analysis depended on the quality of available data. Potential sources of error included accuracy of billing codes, and miscoding or noncoding by physicians.46

2. Although we used this database to try to accurately represent a large population of interest, we cannot guarantee the database represented a true cross section of the United States.

3. For the Medicare population, the PearlDiver database indexes data only in 7-year increments. Although the study period was long enough to detect significant trends, some data may not be accurately captured over a 7-year period.

4. Patients were not randomized to a treatment group.

5. The PearlDiver database does not include any clinical outcome data. Therefore, we cannot comment on the efficacy of the reported evaluations and interventions.

6. There is no specific CPT code for thumb CMC interposition arthroplasty. However, we are unaware of a CMC interposition arthroplasty performed for any area besides the thumb. Theoretically, the study population can include a negligible percentage of patients who had interposition arthroplasty of a CMC joint other than the thumb.

7. The database cannot be searched for use of thumb CMC-OA surgical techniques other than CMC interposition arthroplasty or arthrodesis, as isolated trapeziectomy, volar ligament reconstruction, implant arthroplasty, and metacarpal osteotomy lack specific CPT codes.

Conclusion

Thumb CMC-OA is a common entity among Medicare patients. There are numerous surgical options for cases that have failed conservative treatment. Despite the lack of evidence that thumb CMC interposition arthroplasty is superior to other surgical options, the number of patients who had this procedure increased 46% during the 2005–2011 study period. Although the majority of patients who undergo CMC interposition arthroplasty are female, the percentage of male patients has increased significantly. More than 40% of patients who have CMC interposition arthroplasty are also diagnosed with CTS, and 16% to 17% of patients who have CMC interposition arthroplasty will have a concomitant CTR. CMC arthrodesis is used in significantly fewer patients of Medicare age, and its use has been declining.

A common entity, osteoarthritis (OA) at the base of the thumb is largely caused by the unique anatomy and biomechanics of the thumb carpometacarpal (CMC) joint.1 Radiographically evident CMC degeneration occurs in 40% of women and 25% of men over age 75 years, making the thumb CMC joint the most common site of surgical reconstruction for upper extremity OA.2,3

Over the past 40 years, numerous surgical techniques for managing thumb CMC-OA have been described. These include volar ligament reconstruction, first metacarpal osteotomy, CMC arthrodesis, CMC joint replacement, and trapeziectomy. Trapeziectomy can be performed in isolation or in combination with tendon interposition, ligament reconstruction, or ligament reconstruction and tendon interposition (LRTI).4-20 The authors of a recent systematic review concluded there is no evidence that any one surgical procedure for CMC-OA is superior to another in terms of pain, function, satisfaction, range of motion, or strength.4 Nevertheless, a recent survey found that 719 (62%) of 1156 US hand surgeons used LRTI as the treatment of choice for advanced CMC-OA.21

Our detailed literature search yielded no other database studies characterizing current trends in the practice patterns of US orthopedic surgeons who perform interposition arthroplasty for CMC arthritis. Analysis of these trends is important not only to patients but also to the broader orthopedic and health care community.22

We conducted a study to investigate current trends in CMC interposition arthroplasty across time, sex, age, and region of the United States; per-patient charges and reimbursements; and the association between this procedure and concomitantly performed carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) and carpal tunnel release (CTR). In addition, we compared incidence of CMC interposition arthroplasty with that of CMC arthrodesis.

Patients and Methods

All data were derived from the PearlDiver Patient Records Database (PearlDiver Technologies), a publicly available database of patients. The database stores procedure volumes, demographics, and average charge information for patients with International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) diagnoses and procedures or Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes. Data for the present study were drawn from the Medicare database within the PearlDiver records, which has a total of 179,094,296 patient records covering the period 2005–2011. This study did not require institutional review board approval, as it used existing, publicly available data without identifiers linked to subjects.

PearlDiver Technologies granted us database access for academic research. The database was stored on a password-protected server maintained by PearlDiver. ICD-9 and CPT codes can be searched in isolation or in combination. Search results yield number of patients with a searched code (or combination of codes) in each year, age group, or region of the United States, as well as mean charge and mean reimbursement for the code or combination of codes.

We used CPT code 25447 (arthroplasty, interposition, intercarpal, or CMC joints) to search the database for patients who underwent thumb CMC interposition arthroplasty. Although this code does not specify thumb, we are unaware of any procedure (other than thumb CMC interposition arthroplasty) typically given this code. Our search yielded procedure volumes, sex distribution, age distribution, region volumes, and mean per-patient charges and reimbursements for each CPT code. We then searched the resulting cohort for CTS (ICD-9 code 354.0), endoscopic CTR (CPT code 29848), and open CTR (CPT code 64721) to find CTR performed concomitantly with CMC interposition arthroplasty. Last, patients were tracked in the database past their surgery date to evaluate for postoperative physical or occupational therapy evaluations within 6 months (using CPT codes appearing in at least 1% of the cohort: 97001, 97003, 97004, 97110, 97112, 97124, 97140, 97150, 97350, 97535) and postoperative thumb, hand, or wrist radiographs within 6 months (using CPT codes appearing in at least 1% of the cohort: 73140, 73130, 73110). To ensure adequacy of 6-month postoperative data, we included in this portion of the study only those patients with surgery dates between 2005 and 2010.

For comparative purposes, we also searched the database for patients who underwent thumb CMC arthrodesis within the same period—using CPT codes 26841 and 26842 (arthrodesis CMC joint thumb, with or without internal fixation; with or without autograft) and CPT code 26820 (fusion in opposition, thumb, with autogenous graft).

Overall procedure volume data are reported as number of patients with the given CPT code in the database output in a given year. Age-group and sex analyses are reported as number of patients reported in the database output and as percentage of patients who underwent the CPT code of interest that year. Mean charges and reimbursements are reported as results by the database for the code of interest (CPT 25447). Data for the region analysis are presented as an incidence, as there is an uneven distribution of patient volumes among regions. This incidence is calculated as number of patients in a particular region and year normalized to total number of patients in the database for that particular region or year. Regions are defined as Midwest (IA, IL, IN, KS, MI, MN, MO, ND, NE, OH, SD, WI), Northeast (CT, MA, ME, NH, NJ, NY, PA, RI, VT), South (AL, AR, DC, DE, FL, GA, KY, LA, MD, MS, NC, OK, SC, TN, TX, VA, WV), and West (AK, AZ, CA, CO, HI, ID, MT, NM, NV, OR, UT, WA, WY).

Chi-squared linear-by-linear association analysis was used to determine statistical significance with regard to trends over time in procedure volumes, sex, age group, and region. For all statistical comparisons, P < .05 was considered significant.

Results

In the database, we identified 41,171 unique patients who underwent CMC interposition arthroplasty between 2005 and 2011. Over the 7-year study period, number of patients who had CMC interposition arthroplasty increased 46.2%, from 4761 in 2005 to 6960 in 2011 (P < .0001) (Table 1, Figure 1). Throughout this period, females underwent CMC interposition arthroplasty more frequently than males at all time points (P < .0001). Overall ratio of female to male patients, however, changed significantly. In 2005, 18.1% of all CMC interposition arthroplasties were performed on male patients; this increased to 23.9% of all procedures by 2011 (P < .0001) (Figure 2). Table 1 presents an age-group analysis. There were no significant differences in relative percentage of patients in any given age group who underwent CMC interposition arthroplasty over the study period.

Analysis of overall procedure incidence by region revealed significant increases in all regions (P < .0001), ranging from 18.5% (West) to 54.5% (Northeast) (Figure 3). At all time points, the incidence of CMC interposition arthroplasty was significantly lower in the Northeast than in any other region and compared with the overall average.

Between 2005 and 2011, there were significant increases in both per-patient charges and reimbursements for CMC interposition arthroplasty (Figure 4). Mean per-patient charge increased from $2676 in 2005 to $4181 in 2011 (P < .0001), and mean per-patient reimbursement increased from $1445 in 2005 to $2061 in 2011 (P < .0001). The discrepancy between charge and reimbursement increased throughout the study period: Reimbursement in 2005 was 54.0% of the charge; this decreased to 49.3% by 2011 but was not statistically significant (P = .08).

Overall, 40.9% of patients who underwent CMC interposition arthroplasty also had a CTS diagnosis. Between 15.5% and 17.3% of these patients had concomitant open or endoscopic CTR at time of CMC interposition arthroplasty (Table 2). Percentage of patients who underwent concomitant CTR did not change significantly from 2005 to 2011 (P = .139). Use of postoperative occupational and/or physical therapy increased significantly over the study period, from 33.5% of patients in 2005 to 50.7% of patients in 2010 (P < .0001). Use of postoperative thumb, hand, and/or wrist radiography also increased throughout the study period, from 7.4% of patients in 2005 to 18.7% of patients in 2010 (P < .0001).

We identified 1916 unique patients who underwent thumb CMC arthrodesis between 2005 and 2011. Over the 7-year study period, there was a 19.1% decrease in number of patients who underwent CMC arthrodesis, from 309 in 2005 to 250 in 2011 (P < .0001) (Figure 5). Significantly fewer patients had CMC arthrodesis compared with CMC interposition arthroplasty at all time points, ranging from 6.5% (thumb CMC arthrodesis:CMC interposition arthroplasty) in 2005 to 3.6% in 2011 (P < .0001).

Discussion

Our results demonstrated a significant increase in use of thumb CMC interposition arthroplasty in a US Medicare population, with an increase of more than 46% from 2005 to 2011. This finding supports the findings of a recent cross-sectional survey-based study in which 719 (62%) of 1156 surveyed US hand surgeons reported performing trapeziectomy with LRTI for advanced thumb CMC-OA.21 A prior study had similar findings, with 692 (68%) of 1024 American Society for Surgery of the Hand (ASSH) members performing LRTI and 766 (75%) of 1024 performing some type of CMC interposition with trapeziectomy for advanced CMC-OA.23 This preference for CMC interposition arthroplasty prevails despite the fact that numerous studies have shown no superiority of any surgical procedure to another for CMC-OA in terms of pain, function, satisfaction, range of motion, and strength.7,15,18,19,24-34 Our data demonstrated that, not only does CMC interposition arthroplasty remain the most frequently used procedure for thumb CMC-OA, the incidence of CMC interposition arthroplasty continues to increase yearly.

The incidence of thumb CMC-OA is higher in women than in men, with more joint laxity a known contributor and subtle sex differences in trapezium geometry and congruence postulated as additional factors.3,35,36 This trend was confirmed in the present study, as females underwent significantly more CMC interposition arthroplasties at all time points. It is interesting that the overall ratio of female to male patients changed significantly over the study period, with the percentage of patients who were male increasing from 18.1% in 2005 to 23.9% in 2011. No previous studies have captured such a large cross section of the population to establish this trend. Although this trend is not necessarily intuitive, potential theories include increased acceptance of CMC interposition arthroplasty as a surgical option for male patients, and potentially a larger number of male patients seeking medical care for thumb CMC-OA in recent years.

Increases in procedure incidence were noted in all regions of the United States, but the largest percentage increase occurred in the Northeast. Despite this increase, the Northeast also had significantly lower CMC interposition arthroplasty incidence compared with all other regions and with the average procedure incidence throughout the study period—demonstrating some regional bias as to treatment of thumb CMC-OA. Unfortunately, because of database limitations and lack of specific CPT codes for other treatment options for thumb CMC-OA, we cannot ascertain if other types of surgery are more frequently used in the Northeast.

CTS and thumb CMC-OA often coexist.37 The estimated incidence of concomitant CTS in patients with CMC-OA is between 4% and 43%, but the rate of concomitant CTR and CMC interposition arthroplasty was not previously characterized in the literature.38,39 Results of the present study supported these findings; 41% of patients who underwent CMC interposition arthroplasty in our study also had a CTS diagnosis, compared with 43% in the 246-patient study by Florack and colleagues.38 We also found that 16% to 17% of patients who underwent CMC interposition arthroplasty underwent concomitant CTR; this rate remained consistent throughout the study period.

Our study demonstrated that, compared with CMC interposition arthroplasties, significantly fewer thumb CMC arthrodesis procedures were performed in the same Medicare population during the same period. Furthermore, the number of thumb CMC arthrodesis procedures declined yearly, with an overall decrease of 19% from 2005 to 2011. In a recent single-blinded, randomized trial, Vermeulen and colleagues40 compared thumb CMC arthrodesis and trapeziectomy with LRTI. They found superior patient satisfaction and significantly lower complication rates in women who underwent LRTI versus arthrodesis. The study was terminated prematurely because of these complications and thus was underpowered to determine differences in specific outcome measures. Previous studies comparing arthrodesis and interposition arthroplasties reported inconsistent outcomes. Hart and colleagues41 found no significant differences in pain or function between CMC arthrodesis and LRTI at a mean 7-year follow-up in a level II randomized controlled trial. Hartigan and colleagues15 reached similar conclusions in their retrospective comparison of the procedures. Without clear evidence supporting arthrodesis over interposition arthroplasty, the majority of surgeons favor interposition arthroplasty for thumb CMC-OA. Among Medicare patients, use of thumb CMC arthrodesis continues to fall.

This national database study had several limitations, which are common to all studies using the PearlDiver database22,42-47:

1. The power of the analysis depended on the quality of available data. Potential sources of error included accuracy of billing codes, and miscoding or noncoding by physicians.46

2. Although we used this database to try to accurately represent a large population of interest, we cannot guarantee the database represented a true cross section of the United States.

3. For the Medicare population, the PearlDiver database indexes data only in 7-year increments. Although the study period was long enough to detect significant trends, some data may not be accurately captured over a 7-year period.

4. Patients were not randomized to a treatment group.

5. The PearlDiver database does not include any clinical outcome data. Therefore, we cannot comment on the efficacy of the reported evaluations and interventions.

6. There is no specific CPT code for thumb CMC interposition arthroplasty. However, we are unaware of a CMC interposition arthroplasty performed for any area besides the thumb. Theoretically, the study population can include a negligible percentage of patients who had interposition arthroplasty of a CMC joint other than the thumb.

7. The database cannot be searched for use of thumb CMC-OA surgical techniques other than CMC interposition arthroplasty or arthrodesis, as isolated trapeziectomy, volar ligament reconstruction, implant arthroplasty, and metacarpal osteotomy lack specific CPT codes.

Conclusion

Thumb CMC-OA is a common entity among Medicare patients. There are numerous surgical options for cases that have failed conservative treatment. Despite the lack of evidence that thumb CMC interposition arthroplasty is superior to other surgical options, the number of patients who had this procedure increased 46% during the 2005–2011 study period. Although the majority of patients who undergo CMC interposition arthroplasty are female, the percentage of male patients has increased significantly. More than 40% of patients who have CMC interposition arthroplasty are also diagnosed with CTS, and 16% to 17% of patients who have CMC interposition arthroplasty will have a concomitant CTR. CMC arthrodesis is used in significantly fewer patients of Medicare age, and its use has been declining.

1. Hentz VR. Surgical treatment of trapeziometacarpal joint arthritis: a historical perspective. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(4):1184-1189.

2. Armstrong AL, Hunter JB, Davis TR. The prevalence of degenerative arthritis of the base of the thumb in post-menopausal women. J Hand Surg Br. 1994;19(3):340-341.

3. Van Heest AE, Kallemeier P. Thumb carpal metacarpal arthritis. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2008;16(3):140-151.

4. Vermeulen GM, Slijper H, Feitz R, Hovius SE, Moojen TM, Selles RW. Surgical management of primary thumb carpometacarpal osteoarthritis: a systematic review. J Hand Surg Am. 2011;36(1):157-169.

5. Bodin ND, Spangler R, Thoder JJ. Interposition arthroplasty options for carpometacarpal arthritis of the thumb. Hand Clin. 2010;26(3):339-350, v-vi.

6. Cooney WP, Linscheid RL, Askew LJ. Total arthroplasty of the thumb trapeziometacarpal joint. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1987;(220):35-45.

7. De Smet L, Vandenberghe L, Degreef I. Long-term outcome of trapeziectomy with ligament reconstruction and tendon interposition (LRTI) versus prosthesis arthroplasty for basal joint osteoarthritis of the thumb. Acta Orthop Belg. 2013;79(2):146-149.

8. Dell PC, Muniz RB. Interposition arthroplasty of the trapeziometacarpal joint for osteoarthritis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1987;(220):27-34.

9. Dhar S, Gray IC, Jones WA, Beddow FH. Simple excision of the trapezium for osteoarthritis of the carpometacarpal joint of the thumb. J Hand Surg Br. 1994;19(4):485-488.

10. Eaton RG, Littler JW. Ligament reconstruction for the painful thumb carpometacarpal joint. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1973;55(8):1655-1666.

11. Eaton RG, Lane LB, Littler JW, Keyser JJ. Ligament reconstruction for the painful thumb carpometacarpal joint: a long-term assessment. J Hand Surg Am. 1984;9(5):692-699.

12. Eaton RG, Glickel SZ, Littler JW. Tendon interposition arthroplasty for degenerative arthritis of the trapeziometacarpal joint of the thumb. J Hand Surg Am. 1985;10(5):645-654.

13. Elfar JC, Burton RI. Ligament reconstruction and tendon interposition for thumb basal arthritis. Hand Clin. 2013;29(1):15-25.

14. Froimson AI. Tendon arthroplasty of the trapeziometacarpal joint. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1970;70:191-199.

15. Hartigan BJ, Stern PJ, Kiefhaber TR. Thumb carpometacarpal osteoarthritis: arthrodesis compared with ligament reconstruction and tendon interposition. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83(10):1470-1478.

16. Kenniston JA, Bozentka DJ. Treatment of advanced carpometacarpal joint disease: arthrodesis. Hand Clin. 2008;24(3):285-294, vi-vii.

17. Kokkalis ZT, Zanaros G, Weiser RW, Sotereanos DG. Trapezium resection with suspension and interposition arthroplasty using acellular dermal allograft for thumb carpometacarpal arthritis. J Hand Surg Am. 2009;34(6):1029-1036.

18. Kriegs-Au G, Petje G, Fojtl E, Ganger R, Zachs I. Ligament reconstruction with or without tendon interposition to treat primary thumb carpometacarpal osteoarthritis. Surgical technique. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87 suppl 1(Pt 1):78-85.

19. Park MJ, Lichtman G, Christian JB, et al. Surgical treatment of thumb carpometacarpal joint arthritis: a single institution experience from 1995–2005. Hand. 2008;3(4):304-310.

20. Park MJ, Lee AT, Yao J. Treatment of thumb carpometacarpal arthritis with arthroscopic hemitrapeziectomy and interposition arthroplasty. Orthopedics. 2012;35(12):e1759-e1764.

21. Wolf JM, Delaronde S. Current trends in nonoperative and operative treatment of trapeziometacarpal osteoarthritis: a survey of US hand surgeons. J Hand Surg Am. 2012;37(1):77-82.

22. Zhang AL, Kreulen C, Ngo SS, Hame SL, Wang JC, Gamradt SC. Demographic trends in arthroscopic SLAP repair in the United States. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(5):1144-1147.

23. Brunton LM, Wilgis EF. A survey to determine current practice patterns in the surgical treatment of advanced thumb carpometacarpal osteoarthrosis. Hand. 2010;5(4):415-422.

24. Belcher HJ, Nicholl JE. A comparison of trapeziectomy with and without ligament reconstruction and tendon interposition. J Hand Surg Br. 2000;25(4):350-356.

25. Davis TR, Pace A. Trapeziectomy for trapeziometacarpal joint osteoarthritis: is ligament reconstruction and temporary stabilisation of the pseudarthrosis with a Kirschner wire important? J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2009;34(3):312-321.

26. Davis TR, Brady O, Dias JJ. Excision of the trapezium for osteoarthritis of the trapeziometacarpal joint: a study of the benefit of ligament reconstruction or tendon interposition. J Hand Surg Am. 2004;29(6):1069-1077.

27. De Smet L, Sioen W, Spaepen D, van Ransbeeck H. Treatment of basal joint arthritis of the thumb: trapeziectomy with or without tendon interposition/ligament reconstruction. Hand Surg. 2004;9(1):5-9.

28. Field J, Buchanan D. To suspend or not to suspend: a randomised single blind trial of simple trapeziectomy versus trapeziectomy and flexor carpi radialis suspension. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2007;32(4):462-466.

29. Gerwin M, Griffith A, Weiland AJ, Hotchkiss RN, McCormack RR. Ligament reconstruction basal joint arthroplasty without tendon interposition. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1997;(342):42-45.

30. Jorheim M, Isaxon I, Flondell M, Kalen P, Atroshi I. Short-term outcomes of trapeziometacarpal Artelon implant compared with tendon suspension interposition arthroplasty for osteoarthritis: a matched cohort study. J Hand Surg Am. 2009;34(8):1381-1387.

31. Lehmann O, Herren DB, Simmen BR. Comparison of tendon suspension-interposition and silicon spacers in the treatment of degenerative osteoarthritis of the base of the thumb. Ann Chir Main Memb Super. 1998;17(1):25-30.

32. Nilsson A, Liljensten E, Bergstrom C, Sollerman C. Results from a degradable TMC joint spacer (Artelon) compared with tendon arthroplasty. J Hand Surg Am. 2005;30(2):380-389.

33. Schroder J, Kerkhoffs GM, Voerman HJ, Marti RK. Surgical treatment of basal joint disease of the thumb: comparison between resection-interposition arthroplasty and trapezio-metacarpal arthrodesis. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2002;122(1):35-38.

34. Tagil M, Kopylov P. Swanson versus APL arthroplasty in the treatment of osteoarthritis of the trapeziometacarpal joint: a prospective and randomized study in 26 patients. J Hand Surg Br. 2002;27(5):452-456.

35. North ER, Rutledge WM. The trapezium-thumb metacarpal joint: the relationship of joint shape and degenerative joint disease. Hand. 1983;15(2):201-206.

36. Ateshian GA, Rosenwasser MP, Mow VC. Curvature characteristics and congruence of the thumb carpometacarpal joint: differences between female and male joints. J Biomech. 1992;25(6):591-607.

37. Sless Y, Sampson SP. Experience with transtrapezium approach for transverse carpal ligament release in patients with coexisted trapeziometacarpal joint osteoarthritis and carpal tunnel syndrome. Hand. 2007;2(3):151-154.

38. Florack TM, Miller RJ, Pellegrini VD, Burton RI, Dunn MG. The prevalence of carpal tunnel syndrome in patients with basal joint arthritis of the thumb. J Hand Surg Am. 1992;17(4):624-630.

39. Tsai TM, Laurentin-Perez LA, Wong MS, Tamai M. Ideas and innovations: radial approach to carpal tunnel release in conjunction with thumb carpometacarpal arthroplasty. Hand Surg. 2005;10(1):61-66.

40. Vermeulen GM, Brink SM, Slijper H, et al. Trapeziometacarpal arthrodesis or trapeziectomy with ligament reconstruction in primary trapeziometacarpal osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(9):726-733.

41. Hart R, Janecek M, Siska V, Kucera B, Stipcak V. Interposition suspension arthroplasty according to Epping versus arthrodesis for trapeziometacarpal osteoarthritis. Eur Surg. 2006;38(6):433-438.

42. Abrams GD, Frank RM, Gupta AK, Harris JD, McCormick FM, Cole BJ. Trends in meniscus repair and meniscectomy in the United States, 2005–2011. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(10):2333-2339.

43. Montgomery SR, Ngo SS, Hobson T, et al. Trends and demographics in hip arthroscopy in the United States. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(4):661-665.

44. Zhang AL, Montgomery SR, Ngo SS, Hame SL, Wang JC, Gamradt SC. Arthroscopic versus open shoulder stabilization: current practice patterns in the United States. Arthroscopy. 2014;30(4):436-443.

45. Yeranosian MG, Arshi A, Terrell RD, Wang JC, McAllister DR, Petrigliano FA. Incidence of acute postoperative infections requiring reoperation after arthroscopic shoulder surgery. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(2):437-441.

46. Yeranosian MG, Terrell RD, Wang JC, McAllister DR, Petrigliano FA. The costs associated with the evaluation of rotator cuff tears before surgical repair. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(12):1662-1666.

47. Daffner SD, Hymanson HJ, Wang JC. Cost and use of conservative management of lumbar disc herniation before surgical discectomy. Spine J. 2010;10(6):463-468.

1. Hentz VR. Surgical treatment of trapeziometacarpal joint arthritis: a historical perspective. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(4):1184-1189.

2. Armstrong AL, Hunter JB, Davis TR. The prevalence of degenerative arthritis of the base of the thumb in post-menopausal women. J Hand Surg Br. 1994;19(3):340-341.

3. Van Heest AE, Kallemeier P. Thumb carpal metacarpal arthritis. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2008;16(3):140-151.

4. Vermeulen GM, Slijper H, Feitz R, Hovius SE, Moojen TM, Selles RW. Surgical management of primary thumb carpometacarpal osteoarthritis: a systematic review. J Hand Surg Am. 2011;36(1):157-169.

5. Bodin ND, Spangler R, Thoder JJ. Interposition arthroplasty options for carpometacarpal arthritis of the thumb. Hand Clin. 2010;26(3):339-350, v-vi.

6. Cooney WP, Linscheid RL, Askew LJ. Total arthroplasty of the thumb trapeziometacarpal joint. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1987;(220):35-45.

7. De Smet L, Vandenberghe L, Degreef I. Long-term outcome of trapeziectomy with ligament reconstruction and tendon interposition (LRTI) versus prosthesis arthroplasty for basal joint osteoarthritis of the thumb. Acta Orthop Belg. 2013;79(2):146-149.

8. Dell PC, Muniz RB. Interposition arthroplasty of the trapeziometacarpal joint for osteoarthritis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1987;(220):27-34.

9. Dhar S, Gray IC, Jones WA, Beddow FH. Simple excision of the trapezium for osteoarthritis of the carpometacarpal joint of the thumb. J Hand Surg Br. 1994;19(4):485-488.

10. Eaton RG, Littler JW. Ligament reconstruction for the painful thumb carpometacarpal joint. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1973;55(8):1655-1666.

11. Eaton RG, Lane LB, Littler JW, Keyser JJ. Ligament reconstruction for the painful thumb carpometacarpal joint: a long-term assessment. J Hand Surg Am. 1984;9(5):692-699.

12. Eaton RG, Glickel SZ, Littler JW. Tendon interposition arthroplasty for degenerative arthritis of the trapeziometacarpal joint of the thumb. J Hand Surg Am. 1985;10(5):645-654.

13. Elfar JC, Burton RI. Ligament reconstruction and tendon interposition for thumb basal arthritis. Hand Clin. 2013;29(1):15-25.

14. Froimson AI. Tendon arthroplasty of the trapeziometacarpal joint. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1970;70:191-199.

15. Hartigan BJ, Stern PJ, Kiefhaber TR. Thumb carpometacarpal osteoarthritis: arthrodesis compared with ligament reconstruction and tendon interposition. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83(10):1470-1478.

16. Kenniston JA, Bozentka DJ. Treatment of advanced carpometacarpal joint disease: arthrodesis. Hand Clin. 2008;24(3):285-294, vi-vii.

17. Kokkalis ZT, Zanaros G, Weiser RW, Sotereanos DG. Trapezium resection with suspension and interposition arthroplasty using acellular dermal allograft for thumb carpometacarpal arthritis. J Hand Surg Am. 2009;34(6):1029-1036.

18. Kriegs-Au G, Petje G, Fojtl E, Ganger R, Zachs I. Ligament reconstruction with or without tendon interposition to treat primary thumb carpometacarpal osteoarthritis. Surgical technique. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87 suppl 1(Pt 1):78-85.

19. Park MJ, Lichtman G, Christian JB, et al. Surgical treatment of thumb carpometacarpal joint arthritis: a single institution experience from 1995–2005. Hand. 2008;3(4):304-310.

20. Park MJ, Lee AT, Yao J. Treatment of thumb carpometacarpal arthritis with arthroscopic hemitrapeziectomy and interposition arthroplasty. Orthopedics. 2012;35(12):e1759-e1764.

21. Wolf JM, Delaronde S. Current trends in nonoperative and operative treatment of trapeziometacarpal osteoarthritis: a survey of US hand surgeons. J Hand Surg Am. 2012;37(1):77-82.

22. Zhang AL, Kreulen C, Ngo SS, Hame SL, Wang JC, Gamradt SC. Demographic trends in arthroscopic SLAP repair in the United States. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(5):1144-1147.

23. Brunton LM, Wilgis EF. A survey to determine current practice patterns in the surgical treatment of advanced thumb carpometacarpal osteoarthrosis. Hand. 2010;5(4):415-422.

24. Belcher HJ, Nicholl JE. A comparison of trapeziectomy with and without ligament reconstruction and tendon interposition. J Hand Surg Br. 2000;25(4):350-356.

25. Davis TR, Pace A. Trapeziectomy for trapeziometacarpal joint osteoarthritis: is ligament reconstruction and temporary stabilisation of the pseudarthrosis with a Kirschner wire important? J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2009;34(3):312-321.

26. Davis TR, Brady O, Dias JJ. Excision of the trapezium for osteoarthritis of the trapeziometacarpal joint: a study of the benefit of ligament reconstruction or tendon interposition. J Hand Surg Am. 2004;29(6):1069-1077.

27. De Smet L, Sioen W, Spaepen D, van Ransbeeck H. Treatment of basal joint arthritis of the thumb: trapeziectomy with or without tendon interposition/ligament reconstruction. Hand Surg. 2004;9(1):5-9.

28. Field J, Buchanan D. To suspend or not to suspend: a randomised single blind trial of simple trapeziectomy versus trapeziectomy and flexor carpi radialis suspension. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2007;32(4):462-466.

29. Gerwin M, Griffith A, Weiland AJ, Hotchkiss RN, McCormack RR. Ligament reconstruction basal joint arthroplasty without tendon interposition. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1997;(342):42-45.

30. Jorheim M, Isaxon I, Flondell M, Kalen P, Atroshi I. Short-term outcomes of trapeziometacarpal Artelon implant compared with tendon suspension interposition arthroplasty for osteoarthritis: a matched cohort study. J Hand Surg Am. 2009;34(8):1381-1387.

31. Lehmann O, Herren DB, Simmen BR. Comparison of tendon suspension-interposition and silicon spacers in the treatment of degenerative osteoarthritis of the base of the thumb. Ann Chir Main Memb Super. 1998;17(1):25-30.

32. Nilsson A, Liljensten E, Bergstrom C, Sollerman C. Results from a degradable TMC joint spacer (Artelon) compared with tendon arthroplasty. J Hand Surg Am. 2005;30(2):380-389.

33. Schroder J, Kerkhoffs GM, Voerman HJ, Marti RK. Surgical treatment of basal joint disease of the thumb: comparison between resection-interposition arthroplasty and trapezio-metacarpal arthrodesis. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2002;122(1):35-38.

34. Tagil M, Kopylov P. Swanson versus APL arthroplasty in the treatment of osteoarthritis of the trapeziometacarpal joint: a prospective and randomized study in 26 patients. J Hand Surg Br. 2002;27(5):452-456.

35. North ER, Rutledge WM. The trapezium-thumb metacarpal joint: the relationship of joint shape and degenerative joint disease. Hand. 1983;15(2):201-206.

36. Ateshian GA, Rosenwasser MP, Mow VC. Curvature characteristics and congruence of the thumb carpometacarpal joint: differences between female and male joints. J Biomech. 1992;25(6):591-607.

37. Sless Y, Sampson SP. Experience with transtrapezium approach for transverse carpal ligament release in patients with coexisted trapeziometacarpal joint osteoarthritis and carpal tunnel syndrome. Hand. 2007;2(3):151-154.

38. Florack TM, Miller RJ, Pellegrini VD, Burton RI, Dunn MG. The prevalence of carpal tunnel syndrome in patients with basal joint arthritis of the thumb. J Hand Surg Am. 1992;17(4):624-630.

39. Tsai TM, Laurentin-Perez LA, Wong MS, Tamai M. Ideas and innovations: radial approach to carpal tunnel release in conjunction with thumb carpometacarpal arthroplasty. Hand Surg. 2005;10(1):61-66.

40. Vermeulen GM, Brink SM, Slijper H, et al. Trapeziometacarpal arthrodesis or trapeziectomy with ligament reconstruction in primary trapeziometacarpal osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(9):726-733.

41. Hart R, Janecek M, Siska V, Kucera B, Stipcak V. Interposition suspension arthroplasty according to Epping versus arthrodesis for trapeziometacarpal osteoarthritis. Eur Surg. 2006;38(6):433-438.

42. Abrams GD, Frank RM, Gupta AK, Harris JD, McCormick FM, Cole BJ. Trends in meniscus repair and meniscectomy in the United States, 2005–2011. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(10):2333-2339.

43. Montgomery SR, Ngo SS, Hobson T, et al. Trends and demographics in hip arthroscopy in the United States. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(4):661-665.

44. Zhang AL, Montgomery SR, Ngo SS, Hame SL, Wang JC, Gamradt SC. Arthroscopic versus open shoulder stabilization: current practice patterns in the United States. Arthroscopy. 2014;30(4):436-443.

45. Yeranosian MG, Arshi A, Terrell RD, Wang JC, McAllister DR, Petrigliano FA. Incidence of acute postoperative infections requiring reoperation after arthroscopic shoulder surgery. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(2):437-441.

46. Yeranosian MG, Terrell RD, Wang JC, McAllister DR, Petrigliano FA. The costs associated with the evaluation of rotator cuff tears before surgical repair. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(12):1662-1666.

47. Daffner SD, Hymanson HJ, Wang JC. Cost and use of conservative management of lumbar disc herniation before surgical discectomy. Spine J. 2010;10(6):463-468.

Simultaneous Bilateral Functional Radiography in Ulnar Collateral Ligament Lesion of the Thumb: An Original Technique

Gamekeeper’s or skier’s thumb is caused by an injury to the ulnar collateral ligament (UCL) of the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joint of the thumb. The mechanism of injury is forced radial and palmar abduction and hyperextension.

This lesion was initially described in 1955 by Campbell.1 It occurred in gamekeepers who worked in preserves in Scotland. The UCL was injured because of the way they killed rabbits—hence, gamekeeper’s thumb. Now these injuries are more common in skiers—skier’s thumb. In skiers, the mechanism of injury is the force exerted by the ski pole strap on the thumb during a fall. This injury is also seen in breakdancers.1,2

Different lesions can result, the most common being that of the UCL. The UCL lesion may be partial, with no joint instability,3,4 or total, with instability and subdislocation of the proximal phalanx.5-9 Rupture of the thumb adductor aponeurosis and displacement of the long extensor have been described as the cause of thumb instability.6-8

UCL rupture can occur in its extension or can cause a fracture-tearing in the proximal phalanx.9-12 Intra-articular fractures are sometimes found. The essential problem in UCL injuries is the impossibility of spontaneous healing once the rupture is complete, because of the Stener effect. (When the UCL ruptures, its proximal part retracts and runs above the fibrous expansion of the adductor muscle, which is interposed between the 2 parts of the ruptured UCL and prevents healing, even if the thumb is immobilized.) In these cases, only surgery can repair the lesion.2

In any thumb injury, particularly one caused by hyperabduction, a UCL lesion should be considered. The main problem is diagnosing sprain severity, which is evidenced by the degree of joint hypermobility. Radiologic examination should be performed in all cases to rule out fracture with tear, posterior capsular tear, palmar plate tear, and palmar subdislocation of the proximal phalanx, all of which are associated with UCL tearing.7-9

If the diagnosis is suspected, and radiographs show no fracture, comparative radiographs should be obtained in forced valgus.

Technique

We report on a simple, reliable, reproducible method that allows the patient’s thumbs to be compared, under the same force application conditions, on a single radiograph. This technique reduces the patient’s and examiner’s exposure to x-rays and is well tolerated by the patient. Anesthesia for the thumb is usually not necessary.

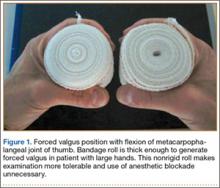

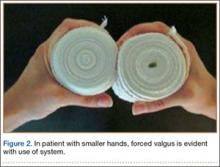

In each hand, the patient holds a cylindrical object, such as a drinking glass (standard diameter, 7.5-8.5 cm). We use an elastic crepe bandage roll (diameter, 7.5 cm; width, 10 cm). This roll is common in emergency departments (EDs) and easily accessible. The patient holds the rolls in his or her hands with the thumbs in the posteroanterior position (Figures 1–3) and places himself or herself on a 18×24-cm frame or directly on the radiography table.

Both thumbs are captured on a single functional radiograph for comparison of forced valgus of the MCP joints, as in our example cases. The patients provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of these case reports.

Case Reports

Control Case

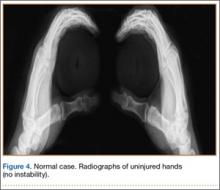

The single functional radiograph of both thumbs showed no evidence of joint laxity on the valgus stress test (Figure 4).

Case 1

A 72-year-old woman landed on her left hand when she fell backward while supporting the hand on a piece of furniture. She presented to the ED with pain in the region of the thumb and thenar eminence. Posteroanterior and lateral radiograph projections showed no significant bone injury (Figure 5). Given the patient’s persistent pain, the traumatologist suspected damage to the thumb UCL, so a simultaneous bilateral functional radiographic projection was obtained. The projection showed joint laxity, implying damage to the thumb UCL. Repair and reinsertion of the UCL were performed using a bone harpoon suture.

Case 2

A 58-year-old man sustained a left hand injury when, using both hands, he tried to catch hold of a falling wooden plank. When he presented to the ED the following week, he was given a diagnosis of thumb contusion and forced hyperabduction and was wearing a metal strap for immobilization. Radiographs showed no bone damage (Figure 6). Thumb UCL injury was suspected on the basis of the physical examination findings and the mechanism of injury. A bilateral simultaneous functional radiographic projection showed significant joint laxity. Surgical treatment with the pull-out technique was performed.

Case 3