User login

Estrogen therapy linked to brain atrophy in women with diabetes

WASHINGTON – Women with type 2 diabetes who take estrogen therapy showed lower total gray matter volume, with atrophy particularly evident in the hippocampus.

A new analysis of the Women’s Health Initiative Memory study suggested that these hormone therapy–related decrements in brain volume seem to stabilize in the years after treatment ends. However, said Christina E. Hugenschmidt, Ph.D., the findings also suggested caution when considering a prescription for estrogen therapy for a woman with emerging or frank diabetes.

“The concern is that prescribing estrogen to a woman with diabetes could increase her risk of brain atrophy,” she said at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference 2015.

Dr. Hugenschmidt of Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, N.C., reviewed data from the Women’s Health Initiate Memory Study–MRI (WHIMS-MRI).

The parallel placebo-controlled trial randomized women aged 65 years and older to placebo, or 0.625 mg conjugated equine estrogen with or without 2.5 mg progesterone. They were all free of cognitive decline at baseline.

Dr. Hugenschmidt focused on 1,400 women who underwent two magnetic resonance imaging brain scans: one 2.5 years after beginning the study and another about 5 years after that. The primary outcomes were total brain volume, including any ischemic lesions, total gray matter, total white matter, frontal lobe and hippocampal volume, and ischemic white matter lesion load.

At enrollment, the women were a mean age of 70 years old; 124 had type 2 diabetes. About 42% had long-standing disease of 10 years or longer. Not surprisingly, there were some significant differences between the diabetic and nondiabetic groups: Body mass index, waist girth, and waist/hip ratio were all significantly larger in the women with diabetes.

At the first scan, women with diabetes who had been randomized to estrogen therapy had about 18 cc less total brain volume than those without diabetes. The brain volumes of women with diabetes who were taking placebo were nearly identical to those of the nondiabetic women, regardless of what treatment they were taking.

The difference seemed to be driven by a loss of gray matter, Dr. Hugenschmidt said. There was no significant effect on white matter. The hippocampus appeared to have a similar amount of shrinkage. However, she added, there were no differences in cognitive scores on the Mini Mental State Exam.

Insulin use didn’t appear to ameliorate the findings of smaller brain volume among those with diabetes. Atrophy didn’t progress, however; findings at the same scan were similar.

The findings may be linked to the suppression of a natural process that occurs during the perimenopausal transition, Dr. Hugenschmidt said. Estrogen is crucial in maintaining the brain’s energy metabolism. It works by increasing glucose transport and aerobic glycolysis. But during this time of life, as estrogen wanes, it becomes uncoupled from the glucose metabolism pathway. The female brain then begins to use ketone bodies as its primary source of energy. Intact estrogen levels normally downregulate the use of alternative energy sources before menopause; supplementing them seems to prevent this transition from occurring.

“Among older women with diabetes for whom the glucose-based energy metabolism promoted by estrogen is already compromised, this downregulation of alternative energy sources may lead to increased atrophy of gray matter, which has a greater metabolic demand relative to white matter,” Dr. Hugenschmidt and her colleagues wrote in a paper published in Neurology (2015 July 10 [doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000001816]).

Dr. Hugenschmidt reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

WASHINGTON – Women with type 2 diabetes who take estrogen therapy showed lower total gray matter volume, with atrophy particularly evident in the hippocampus.

A new analysis of the Women’s Health Initiative Memory study suggested that these hormone therapy–related decrements in brain volume seem to stabilize in the years after treatment ends. However, said Christina E. Hugenschmidt, Ph.D., the findings also suggested caution when considering a prescription for estrogen therapy for a woman with emerging or frank diabetes.

“The concern is that prescribing estrogen to a woman with diabetes could increase her risk of brain atrophy,” she said at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference 2015.

Dr. Hugenschmidt of Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, N.C., reviewed data from the Women’s Health Initiate Memory Study–MRI (WHIMS-MRI).

The parallel placebo-controlled trial randomized women aged 65 years and older to placebo, or 0.625 mg conjugated equine estrogen with or without 2.5 mg progesterone. They were all free of cognitive decline at baseline.

Dr. Hugenschmidt focused on 1,400 women who underwent two magnetic resonance imaging brain scans: one 2.5 years after beginning the study and another about 5 years after that. The primary outcomes were total brain volume, including any ischemic lesions, total gray matter, total white matter, frontal lobe and hippocampal volume, and ischemic white matter lesion load.

At enrollment, the women were a mean age of 70 years old; 124 had type 2 diabetes. About 42% had long-standing disease of 10 years or longer. Not surprisingly, there were some significant differences between the diabetic and nondiabetic groups: Body mass index, waist girth, and waist/hip ratio were all significantly larger in the women with diabetes.

At the first scan, women with diabetes who had been randomized to estrogen therapy had about 18 cc less total brain volume than those without diabetes. The brain volumes of women with diabetes who were taking placebo were nearly identical to those of the nondiabetic women, regardless of what treatment they were taking.

The difference seemed to be driven by a loss of gray matter, Dr. Hugenschmidt said. There was no significant effect on white matter. The hippocampus appeared to have a similar amount of shrinkage. However, she added, there were no differences in cognitive scores on the Mini Mental State Exam.

Insulin use didn’t appear to ameliorate the findings of smaller brain volume among those with diabetes. Atrophy didn’t progress, however; findings at the same scan were similar.

The findings may be linked to the suppression of a natural process that occurs during the perimenopausal transition, Dr. Hugenschmidt said. Estrogen is crucial in maintaining the brain’s energy metabolism. It works by increasing glucose transport and aerobic glycolysis. But during this time of life, as estrogen wanes, it becomes uncoupled from the glucose metabolism pathway. The female brain then begins to use ketone bodies as its primary source of energy. Intact estrogen levels normally downregulate the use of alternative energy sources before menopause; supplementing them seems to prevent this transition from occurring.

“Among older women with diabetes for whom the glucose-based energy metabolism promoted by estrogen is already compromised, this downregulation of alternative energy sources may lead to increased atrophy of gray matter, which has a greater metabolic demand relative to white matter,” Dr. Hugenschmidt and her colleagues wrote in a paper published in Neurology (2015 July 10 [doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000001816]).

Dr. Hugenschmidt reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

WASHINGTON – Women with type 2 diabetes who take estrogen therapy showed lower total gray matter volume, with atrophy particularly evident in the hippocampus.

A new analysis of the Women’s Health Initiative Memory study suggested that these hormone therapy–related decrements in brain volume seem to stabilize in the years after treatment ends. However, said Christina E. Hugenschmidt, Ph.D., the findings also suggested caution when considering a prescription for estrogen therapy for a woman with emerging or frank diabetes.

“The concern is that prescribing estrogen to a woman with diabetes could increase her risk of brain atrophy,” she said at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference 2015.

Dr. Hugenschmidt of Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, N.C., reviewed data from the Women’s Health Initiate Memory Study–MRI (WHIMS-MRI).

The parallel placebo-controlled trial randomized women aged 65 years and older to placebo, or 0.625 mg conjugated equine estrogen with or without 2.5 mg progesterone. They were all free of cognitive decline at baseline.

Dr. Hugenschmidt focused on 1,400 women who underwent two magnetic resonance imaging brain scans: one 2.5 years after beginning the study and another about 5 years after that. The primary outcomes were total brain volume, including any ischemic lesions, total gray matter, total white matter, frontal lobe and hippocampal volume, and ischemic white matter lesion load.

At enrollment, the women were a mean age of 70 years old; 124 had type 2 diabetes. About 42% had long-standing disease of 10 years or longer. Not surprisingly, there were some significant differences between the diabetic and nondiabetic groups: Body mass index, waist girth, and waist/hip ratio were all significantly larger in the women with diabetes.

At the first scan, women with diabetes who had been randomized to estrogen therapy had about 18 cc less total brain volume than those without diabetes. The brain volumes of women with diabetes who were taking placebo were nearly identical to those of the nondiabetic women, regardless of what treatment they were taking.

The difference seemed to be driven by a loss of gray matter, Dr. Hugenschmidt said. There was no significant effect on white matter. The hippocampus appeared to have a similar amount of shrinkage. However, she added, there were no differences in cognitive scores on the Mini Mental State Exam.

Insulin use didn’t appear to ameliorate the findings of smaller brain volume among those with diabetes. Atrophy didn’t progress, however; findings at the same scan were similar.

The findings may be linked to the suppression of a natural process that occurs during the perimenopausal transition, Dr. Hugenschmidt said. Estrogen is crucial in maintaining the brain’s energy metabolism. It works by increasing glucose transport and aerobic glycolysis. But during this time of life, as estrogen wanes, it becomes uncoupled from the glucose metabolism pathway. The female brain then begins to use ketone bodies as its primary source of energy. Intact estrogen levels normally downregulate the use of alternative energy sources before menopause; supplementing them seems to prevent this transition from occurring.

“Among older women with diabetes for whom the glucose-based energy metabolism promoted by estrogen is already compromised, this downregulation of alternative energy sources may lead to increased atrophy of gray matter, which has a greater metabolic demand relative to white matter,” Dr. Hugenschmidt and her colleagues wrote in a paper published in Neurology (2015 July 10 [doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000001816]).

Dr. Hugenschmidt reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

On Twitter @Alz_Gal

AT AAIC 2015

Key clinical point: Prescribing estrogen therapy for older women with type 2 diabetes could increase the risk of brain atrophy.

Major finding: Older women with type 2 diabetes who took estrogen therapy had about an 18-cc lower total brain volume than women with diabetes who took placebo and than women without the disease.

Data source: WHIMS-MRI was a large parallel-group study that examined the effect of hormone therapy on the brain and cognition in postmenopausal women.

Disclosures: Dr. Hugenschmidt reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

A weekly speech and language therapy service for head and neck radiotherapy patients during treatment: maximizing accessibility and efficiency

Background Our hospital did not provide a weekly speech and language therapy (SLT) service for head and neck cancer patients during radiotherapy treatment. SLT is recommended in the international guidelines, but many centers do not offer this service. In the case of our hospital, SLT was not provided because there were no funds to cover the costs of additional staff.

Objectives To create a new service model within a multidisciplinary setting to comply with the international SLT guidelines and without increasing staff. We aimed to measure the accessibility and efficiency of a new model of service delivery at our center both for patients and for the service.

Methods 79 patients were recruited for the study. We followed 1 group of patients (n = 29; observation group) throughout their treatment for 6 weeks to establish if there was a clinical need to offer SLT at the treatment center. A second group of patients (n = 50; intervention group) received a weekly SLT review at the treatment center throughout their radiotherapy. Data collected at the tertiary cancer center for 6 months included: age, gender, tumor site and size, treatment modality, swallowing outcomes, communication outcomes, patient satisfaction, multidisciplinary team feedback, and time efficiency. The observation group did not participate in the intervention group because the data was collected between 2 different groups of participants. However, all participants were referred to their local SLT service at the end of their treatment if that was clinically indicated, regardless of the group they had been in.

Results The proportion of patients accessing SLT services during treatment and the time efficiency of the service were both improved with this model of delivery. The service’s compliance with international guidelines was met. More patients continued with oral intake during their treatment at our center with the new service. Improvements were also reported in communication clarity and communication confidence in the same group.

Conclusion Offering head and neck cancer patients SLT at the same time and place as their radiotherapy treatment improves patient outcomes and increases SLT efficiencies. As this was not a treatment study, further clinical trials are required with regards to functional outcomes.

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Background Our hospital did not provide a weekly speech and language therapy (SLT) service for head and neck cancer patients during radiotherapy treatment. SLT is recommended in the international guidelines, but many centers do not offer this service. In the case of our hospital, SLT was not provided because there were no funds to cover the costs of additional staff.

Objectives To create a new service model within a multidisciplinary setting to comply with the international SLT guidelines and without increasing staff. We aimed to measure the accessibility and efficiency of a new model of service delivery at our center both for patients and for the service.

Methods 79 patients were recruited for the study. We followed 1 group of patients (n = 29; observation group) throughout their treatment for 6 weeks to establish if there was a clinical need to offer SLT at the treatment center. A second group of patients (n = 50; intervention group) received a weekly SLT review at the treatment center throughout their radiotherapy. Data collected at the tertiary cancer center for 6 months included: age, gender, tumor site and size, treatment modality, swallowing outcomes, communication outcomes, patient satisfaction, multidisciplinary team feedback, and time efficiency. The observation group did not participate in the intervention group because the data was collected between 2 different groups of participants. However, all participants were referred to their local SLT service at the end of their treatment if that was clinically indicated, regardless of the group they had been in.

Results The proportion of patients accessing SLT services during treatment and the time efficiency of the service were both improved with this model of delivery. The service’s compliance with international guidelines was met. More patients continued with oral intake during their treatment at our center with the new service. Improvements were also reported in communication clarity and communication confidence in the same group.

Conclusion Offering head and neck cancer patients SLT at the same time and place as their radiotherapy treatment improves patient outcomes and increases SLT efficiencies. As this was not a treatment study, further clinical trials are required with regards to functional outcomes.

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Background Our hospital did not provide a weekly speech and language therapy (SLT) service for head and neck cancer patients during radiotherapy treatment. SLT is recommended in the international guidelines, but many centers do not offer this service. In the case of our hospital, SLT was not provided because there were no funds to cover the costs of additional staff.

Objectives To create a new service model within a multidisciplinary setting to comply with the international SLT guidelines and without increasing staff. We aimed to measure the accessibility and efficiency of a new model of service delivery at our center both for patients and for the service.

Methods 79 patients were recruited for the study. We followed 1 group of patients (n = 29; observation group) throughout their treatment for 6 weeks to establish if there was a clinical need to offer SLT at the treatment center. A second group of patients (n = 50; intervention group) received a weekly SLT review at the treatment center throughout their radiotherapy. Data collected at the tertiary cancer center for 6 months included: age, gender, tumor site and size, treatment modality, swallowing outcomes, communication outcomes, patient satisfaction, multidisciplinary team feedback, and time efficiency. The observation group did not participate in the intervention group because the data was collected between 2 different groups of participants. However, all participants were referred to their local SLT service at the end of their treatment if that was clinically indicated, regardless of the group they had been in.

Results The proportion of patients accessing SLT services during treatment and the time efficiency of the service were both improved with this model of delivery. The service’s compliance with international guidelines was met. More patients continued with oral intake during their treatment at our center with the new service. Improvements were also reported in communication clarity and communication confidence in the same group.

Conclusion Offering head and neck cancer patients SLT at the same time and place as their radiotherapy treatment improves patient outcomes and increases SLT efficiencies. As this was not a treatment study, further clinical trials are required with regards to functional outcomes.

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Health care expenditures associated with depression in adults with cancer

Background The rates of depression in adults with cancer have been reported as high as 38%-58%. How depression affects overall health care expenditures in individuals with cancer is an under-researched area.

Objective To estimate excess average total health care expenditures associated with depression in adults with cancer by comparing those with and without depression after controlling for demographic, socioeconomic, access to care, and other health status variables.

Methods Cross-sectional data on 4,766 adult survivors of cancer from 2006-2009 of the nationally representative household survey, Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS), were used. The patients were older than 21 years. Cancer and depression were identified from the patients’ medical conditions files. Dependent variables consisted of total, inpatient, outpatient, emergency department, prescription drugs, and other expenditures. Ordinary least square (OLS) on logged dollars and generalized linear models with log-link function were performed. All analyses (SAS 9.3 and STATA12) accounted for the complex survey design of the MEPS.

Results Overall, 14% of individuals with cancer reported having depression. In those with cancer and depression, the average annual health care expenditures were $18,401 compared with $12,091 in those without depression. After adjusting for demographic, socioeconomic, access to care, and other health status variables, those with depression had about 31.7% greater total expenditures compared with those without depression. Total, outpatient, and prescription expenditures were higher in individuals with depression than in those without depression. Individuals with cancer and depression were significantly more likely to use emergency departments (adjusted odds ratio, 1.46) compared with their counterparts without depression.

Limitations Cancer patients who died during the reporting year were excluded. The financial burden of depression may have been underestimated because the costs of end-of-life care are high. The burden for each cancer type was not analyzed because of the small sample size.

Conclusion In adults with cancer, those with depression had higher health care utilization and expenditures compared with those without depression.

Funding/sponsorship One author partially supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, U54GM104942.

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Background The rates of depression in adults with cancer have been reported as high as 38%-58%. How depression affects overall health care expenditures in individuals with cancer is an under-researched area.

Objective To estimate excess average total health care expenditures associated with depression in adults with cancer by comparing those with and without depression after controlling for demographic, socioeconomic, access to care, and other health status variables.

Methods Cross-sectional data on 4,766 adult survivors of cancer from 2006-2009 of the nationally representative household survey, Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS), were used. The patients were older than 21 years. Cancer and depression were identified from the patients’ medical conditions files. Dependent variables consisted of total, inpatient, outpatient, emergency department, prescription drugs, and other expenditures. Ordinary least square (OLS) on logged dollars and generalized linear models with log-link function were performed. All analyses (SAS 9.3 and STATA12) accounted for the complex survey design of the MEPS.

Results Overall, 14% of individuals with cancer reported having depression. In those with cancer and depression, the average annual health care expenditures were $18,401 compared with $12,091 in those without depression. After adjusting for demographic, socioeconomic, access to care, and other health status variables, those with depression had about 31.7% greater total expenditures compared with those without depression. Total, outpatient, and prescription expenditures were higher in individuals with depression than in those without depression. Individuals with cancer and depression were significantly more likely to use emergency departments (adjusted odds ratio, 1.46) compared with their counterparts without depression.

Limitations Cancer patients who died during the reporting year were excluded. The financial burden of depression may have been underestimated because the costs of end-of-life care are high. The burden for each cancer type was not analyzed because of the small sample size.

Conclusion In adults with cancer, those with depression had higher health care utilization and expenditures compared with those without depression.

Funding/sponsorship One author partially supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, U54GM104942.

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Background The rates of depression in adults with cancer have been reported as high as 38%-58%. How depression affects overall health care expenditures in individuals with cancer is an under-researched area.

Objective To estimate excess average total health care expenditures associated with depression in adults with cancer by comparing those with and without depression after controlling for demographic, socioeconomic, access to care, and other health status variables.

Methods Cross-sectional data on 4,766 adult survivors of cancer from 2006-2009 of the nationally representative household survey, Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS), were used. The patients were older than 21 years. Cancer and depression were identified from the patients’ medical conditions files. Dependent variables consisted of total, inpatient, outpatient, emergency department, prescription drugs, and other expenditures. Ordinary least square (OLS) on logged dollars and generalized linear models with log-link function were performed. All analyses (SAS 9.3 and STATA12) accounted for the complex survey design of the MEPS.

Results Overall, 14% of individuals with cancer reported having depression. In those with cancer and depression, the average annual health care expenditures were $18,401 compared with $12,091 in those without depression. After adjusting for demographic, socioeconomic, access to care, and other health status variables, those with depression had about 31.7% greater total expenditures compared with those without depression. Total, outpatient, and prescription expenditures were higher in individuals with depression than in those without depression. Individuals with cancer and depression were significantly more likely to use emergency departments (adjusted odds ratio, 1.46) compared with their counterparts without depression.

Limitations Cancer patients who died during the reporting year were excluded. The financial burden of depression may have been underestimated because the costs of end-of-life care are high. The burden for each cancer type was not analyzed because of the small sample size.

Conclusion In adults with cancer, those with depression had higher health care utilization and expenditures compared with those without depression.

Funding/sponsorship One author partially supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, U54GM104942.

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Pain, quality of life measures improve more in OA than RA after knee arthroplasty

Total knee arthroplasty provides osteoarthritis patients with greater improvement in pain and health-related quality of life than it does for rheumatoid arthritis patients, possibly relating to the lower pain and younger age of RA patients at the time of surgery, according to a study based on patients’ responses to semiannual questionnaires.

The study included 834 patients diagnosed with RA and 315 patients diagnosed with osteoarthritis (OA), who had a primary total knee arthroplasty (TKA) between Jan. 1, 1999, and June 30, 2012. The patients were probed on their demographic characteristics, disease duration, mental health, functional status, health-related quality of life (HRQoL), pain, and usage of pain medication. All study participants participated in at least three consecutive sampling intervals: a 6-month preoperative period, a 6-month immediate postoperative period, and a subsequent 6-month “recovery” period. Of the patients who underwent a TKA, 144 (11%) did not complete all three sampling intervals.

At baseline, compared with OA patients, RA patients had significantly less severe scores for measures of pain, lesser usage of pain medications, and significantly more severe scores for measures of disease activity.

After recovering from a TKA, the RA and OA patients improved in almost all outcome measures of pain, function, and HRQoL. The surgery had a larger beneficial effect in OA patients than in RA patients for all measures of pain and HRQoL indices, except for the RA disease activity index (RADAI)/total joint count. In contrast to the OA patients, RA patients showed greater improvements in joint involvement.

For both groups, all outcome measures of pain and function worsened a year before TKA and improved immediately after the surgery; however, the improvement leveled off in the 6-12 months after the procedure.

“After adjusting for preoperative variables, post TKA, a diagnosis of RA (vs. OA) (P = .03), income (P < .01), and anxiety (P = .03) were most useful in predicting the reduction in [visual analog scale] pain scores,” noted Dr. Anand Dusad of the Veterans Affairs Nebraska–Western Iowa Health Care System, Omaha, and his colleagues.

“In summary, using a large cohort of arthritis patients, we have shown that TKA is performed in patients with severe disease and leads to marked improvements in pain function and HRQoL,” according to the researchers.

Read the full study published online July 20 in Arthritis & Rheumatology (doi:10.1002/art.39221).

Total knee arthroplasty provides osteoarthritis patients with greater improvement in pain and health-related quality of life than it does for rheumatoid arthritis patients, possibly relating to the lower pain and younger age of RA patients at the time of surgery, according to a study based on patients’ responses to semiannual questionnaires.

The study included 834 patients diagnosed with RA and 315 patients diagnosed with osteoarthritis (OA), who had a primary total knee arthroplasty (TKA) between Jan. 1, 1999, and June 30, 2012. The patients were probed on their demographic characteristics, disease duration, mental health, functional status, health-related quality of life (HRQoL), pain, and usage of pain medication. All study participants participated in at least three consecutive sampling intervals: a 6-month preoperative period, a 6-month immediate postoperative period, and a subsequent 6-month “recovery” period. Of the patients who underwent a TKA, 144 (11%) did not complete all three sampling intervals.

At baseline, compared with OA patients, RA patients had significantly less severe scores for measures of pain, lesser usage of pain medications, and significantly more severe scores for measures of disease activity.

After recovering from a TKA, the RA and OA patients improved in almost all outcome measures of pain, function, and HRQoL. The surgery had a larger beneficial effect in OA patients than in RA patients for all measures of pain and HRQoL indices, except for the RA disease activity index (RADAI)/total joint count. In contrast to the OA patients, RA patients showed greater improvements in joint involvement.

For both groups, all outcome measures of pain and function worsened a year before TKA and improved immediately after the surgery; however, the improvement leveled off in the 6-12 months after the procedure.

“After adjusting for preoperative variables, post TKA, a diagnosis of RA (vs. OA) (P = .03), income (P < .01), and anxiety (P = .03) were most useful in predicting the reduction in [visual analog scale] pain scores,” noted Dr. Anand Dusad of the Veterans Affairs Nebraska–Western Iowa Health Care System, Omaha, and his colleagues.

“In summary, using a large cohort of arthritis patients, we have shown that TKA is performed in patients with severe disease and leads to marked improvements in pain function and HRQoL,” according to the researchers.

Read the full study published online July 20 in Arthritis & Rheumatology (doi:10.1002/art.39221).

Total knee arthroplasty provides osteoarthritis patients with greater improvement in pain and health-related quality of life than it does for rheumatoid arthritis patients, possibly relating to the lower pain and younger age of RA patients at the time of surgery, according to a study based on patients’ responses to semiannual questionnaires.

The study included 834 patients diagnosed with RA and 315 patients diagnosed with osteoarthritis (OA), who had a primary total knee arthroplasty (TKA) between Jan. 1, 1999, and June 30, 2012. The patients were probed on their demographic characteristics, disease duration, mental health, functional status, health-related quality of life (HRQoL), pain, and usage of pain medication. All study participants participated in at least three consecutive sampling intervals: a 6-month preoperative period, a 6-month immediate postoperative period, and a subsequent 6-month “recovery” period. Of the patients who underwent a TKA, 144 (11%) did not complete all three sampling intervals.

At baseline, compared with OA patients, RA patients had significantly less severe scores for measures of pain, lesser usage of pain medications, and significantly more severe scores for measures of disease activity.

After recovering from a TKA, the RA and OA patients improved in almost all outcome measures of pain, function, and HRQoL. The surgery had a larger beneficial effect in OA patients than in RA patients for all measures of pain and HRQoL indices, except for the RA disease activity index (RADAI)/total joint count. In contrast to the OA patients, RA patients showed greater improvements in joint involvement.

For both groups, all outcome measures of pain and function worsened a year before TKA and improved immediately after the surgery; however, the improvement leveled off in the 6-12 months after the procedure.

“After adjusting for preoperative variables, post TKA, a diagnosis of RA (vs. OA) (P = .03), income (P < .01), and anxiety (P = .03) were most useful in predicting the reduction in [visual analog scale] pain scores,” noted Dr. Anand Dusad of the Veterans Affairs Nebraska–Western Iowa Health Care System, Omaha, and his colleagues.

“In summary, using a large cohort of arthritis patients, we have shown that TKA is performed in patients with severe disease and leads to marked improvements in pain function and HRQoL,” according to the researchers.

Read the full study published online July 20 in Arthritis & Rheumatology (doi:10.1002/art.39221).

FROM ARTHRITIS & RHEUMATOLOGY

Database may help predict cancer patients’ survival

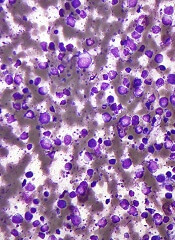

Photo by Darren Baker

A newly developed database may help physicians predict survival outcomes in patients with hematologic and solid tumor malignancies, according to a paper published in Nature Medicine.

The database, known as PRECOG, integrates gene expression patterns of 39 types of cancer from nearly 18,000 patients with data about how long those patients lived.

By combining these data, researchers were able to see broad patterns that correlate with survival. They also believe this information could help them pinpoint potential therapeutic targets for a range of cancers.

“We were able to identify key pathways that can dramatically stratify survival across diverse cancer types,” said Ash Alizadeh, MD, PhD, of Stanford University in California.

“The patterns were very striking, especially because few such examples are currently available for the use of genes or immune cells for cancer prognosis.”

In addition to identifying potentially useful gene expression patterns, the researchers used an analytical tool called CIBERSORT to determine the composition of leukocytes that flock to a tumor.

“We were able to infer which immune cells are present or absent in individual solid tumors, to estimate their prevalence, and to correlate that information with patient survival,” said Aaron Newman, PhD, of Stanford University.

“We found you can even broadly distinguish cancer types just based on what kind of immune cells have infiltrated the tumor.”

Compiling the data

Researchers have tried for years to identify specific patterns of gene expression in cancerous tumors that differ from those in normal tissue. But the extreme variability among individual patients and tumors has made the process difficult, even when focused on particular cancer types.

“There are many more genes in a cell than there are patients with any one type of cancer, and this makes discovering the important genes for cancer outcomes a tough problem,” said Andrew Gentles, PhD, of Stanford University.

“Because it’s easy to find spurious associations that don’t hold up in follow-up studies, we combined information from a vast array of cancer types to better see meaningful correlations.”

The researchers first collected publicly available data on gene expression patterns of many types of cancers.

They then matched the gene expression profiles with clinical information about the patients, including their age, disease status, and how long they survived after diagnosis. Finally, the team combined the studies in a database.

“We wanted to be able to connect gene expression data with patient outcome for thousands of people at once,” Dr Alizadeh said. “Then, we could ask what we could learn more broadly.”

Surprising findings

The researchers were surprised to find that prognostic genes were often shared among distinct cancer types, suggesting that similar biological programs impact survival across cancers.

They were able to identify the top 10 genes that seemed to confer adverse outcomes—FOXM1, BIRC5, TOP2A, TPX2, NME1, CCNB1, CEP55, TYMS, CENPF, and CDKN3—and the top 10 genes associated with more positive outcomes—KLRB1, ITM2B, CBX7, CD2, CREBL2, SATB1, NR3C1, TMEM66, KLRK1, and FUCA1.

Many of these genes are involved in aspects of cell division or are associated with distinct leukocytes that flood a tumor.

The researchers were also able to identify combinations of leukocytes that appear to be correlated with outcomes.

In particular, elevated numbers of plasma cells and certain types of T cells correlated with better patient survival rates across many different solid tumors. But a high proportion of granulocytes was associated with adverse outcomes.

The researchers hope that PRECOG and CIBERSORT will increase our understanding of cancer biology and aid the development of new therapies for cancer patients. The team is applying these tools to better predict which patients will respond to new and emerging anticancer therapies.

Dr Alizadeh said this is especially important given recent advances in the development of drugs that engage immune responses but work well only for a subset of cancer patients. ![]()

Photo by Darren Baker

A newly developed database may help physicians predict survival outcomes in patients with hematologic and solid tumor malignancies, according to a paper published in Nature Medicine.

The database, known as PRECOG, integrates gene expression patterns of 39 types of cancer from nearly 18,000 patients with data about how long those patients lived.

By combining these data, researchers were able to see broad patterns that correlate with survival. They also believe this information could help them pinpoint potential therapeutic targets for a range of cancers.

“We were able to identify key pathways that can dramatically stratify survival across diverse cancer types,” said Ash Alizadeh, MD, PhD, of Stanford University in California.

“The patterns were very striking, especially because few such examples are currently available for the use of genes or immune cells for cancer prognosis.”

In addition to identifying potentially useful gene expression patterns, the researchers used an analytical tool called CIBERSORT to determine the composition of leukocytes that flock to a tumor.

“We were able to infer which immune cells are present or absent in individual solid tumors, to estimate their prevalence, and to correlate that information with patient survival,” said Aaron Newman, PhD, of Stanford University.

“We found you can even broadly distinguish cancer types just based on what kind of immune cells have infiltrated the tumor.”

Compiling the data

Researchers have tried for years to identify specific patterns of gene expression in cancerous tumors that differ from those in normal tissue. But the extreme variability among individual patients and tumors has made the process difficult, even when focused on particular cancer types.

“There are many more genes in a cell than there are patients with any one type of cancer, and this makes discovering the important genes for cancer outcomes a tough problem,” said Andrew Gentles, PhD, of Stanford University.

“Because it’s easy to find spurious associations that don’t hold up in follow-up studies, we combined information from a vast array of cancer types to better see meaningful correlations.”

The researchers first collected publicly available data on gene expression patterns of many types of cancers.

They then matched the gene expression profiles with clinical information about the patients, including their age, disease status, and how long they survived after diagnosis. Finally, the team combined the studies in a database.

“We wanted to be able to connect gene expression data with patient outcome for thousands of people at once,” Dr Alizadeh said. “Then, we could ask what we could learn more broadly.”

Surprising findings

The researchers were surprised to find that prognostic genes were often shared among distinct cancer types, suggesting that similar biological programs impact survival across cancers.

They were able to identify the top 10 genes that seemed to confer adverse outcomes—FOXM1, BIRC5, TOP2A, TPX2, NME1, CCNB1, CEP55, TYMS, CENPF, and CDKN3—and the top 10 genes associated with more positive outcomes—KLRB1, ITM2B, CBX7, CD2, CREBL2, SATB1, NR3C1, TMEM66, KLRK1, and FUCA1.

Many of these genes are involved in aspects of cell division or are associated with distinct leukocytes that flood a tumor.

The researchers were also able to identify combinations of leukocytes that appear to be correlated with outcomes.

In particular, elevated numbers of plasma cells and certain types of T cells correlated with better patient survival rates across many different solid tumors. But a high proportion of granulocytes was associated with adverse outcomes.

The researchers hope that PRECOG and CIBERSORT will increase our understanding of cancer biology and aid the development of new therapies for cancer patients. The team is applying these tools to better predict which patients will respond to new and emerging anticancer therapies.

Dr Alizadeh said this is especially important given recent advances in the development of drugs that engage immune responses but work well only for a subset of cancer patients. ![]()

Photo by Darren Baker

A newly developed database may help physicians predict survival outcomes in patients with hematologic and solid tumor malignancies, according to a paper published in Nature Medicine.

The database, known as PRECOG, integrates gene expression patterns of 39 types of cancer from nearly 18,000 patients with data about how long those patients lived.

By combining these data, researchers were able to see broad patterns that correlate with survival. They also believe this information could help them pinpoint potential therapeutic targets for a range of cancers.

“We were able to identify key pathways that can dramatically stratify survival across diverse cancer types,” said Ash Alizadeh, MD, PhD, of Stanford University in California.

“The patterns were very striking, especially because few such examples are currently available for the use of genes or immune cells for cancer prognosis.”

In addition to identifying potentially useful gene expression patterns, the researchers used an analytical tool called CIBERSORT to determine the composition of leukocytes that flock to a tumor.

“We were able to infer which immune cells are present or absent in individual solid tumors, to estimate their prevalence, and to correlate that information with patient survival,” said Aaron Newman, PhD, of Stanford University.

“We found you can even broadly distinguish cancer types just based on what kind of immune cells have infiltrated the tumor.”

Compiling the data

Researchers have tried for years to identify specific patterns of gene expression in cancerous tumors that differ from those in normal tissue. But the extreme variability among individual patients and tumors has made the process difficult, even when focused on particular cancer types.

“There are many more genes in a cell than there are patients with any one type of cancer, and this makes discovering the important genes for cancer outcomes a tough problem,” said Andrew Gentles, PhD, of Stanford University.

“Because it’s easy to find spurious associations that don’t hold up in follow-up studies, we combined information from a vast array of cancer types to better see meaningful correlations.”

The researchers first collected publicly available data on gene expression patterns of many types of cancers.

They then matched the gene expression profiles with clinical information about the patients, including their age, disease status, and how long they survived after diagnosis. Finally, the team combined the studies in a database.

“We wanted to be able to connect gene expression data with patient outcome for thousands of people at once,” Dr Alizadeh said. “Then, we could ask what we could learn more broadly.”

Surprising findings

The researchers were surprised to find that prognostic genes were often shared among distinct cancer types, suggesting that similar biological programs impact survival across cancers.

They were able to identify the top 10 genes that seemed to confer adverse outcomes—FOXM1, BIRC5, TOP2A, TPX2, NME1, CCNB1, CEP55, TYMS, CENPF, and CDKN3—and the top 10 genes associated with more positive outcomes—KLRB1, ITM2B, CBX7, CD2, CREBL2, SATB1, NR3C1, TMEM66, KLRK1, and FUCA1.

Many of these genes are involved in aspects of cell division or are associated with distinct leukocytes that flood a tumor.

The researchers were also able to identify combinations of leukocytes that appear to be correlated with outcomes.

In particular, elevated numbers of plasma cells and certain types of T cells correlated with better patient survival rates across many different solid tumors. But a high proportion of granulocytes was associated with adverse outcomes.

The researchers hope that PRECOG and CIBERSORT will increase our understanding of cancer biology and aid the development of new therapies for cancer patients. The team is applying these tools to better predict which patients will respond to new and emerging anticancer therapies.

Dr Alizadeh said this is especially important given recent advances in the development of drugs that engage immune responses but work well only for a subset of cancer patients. ![]()

Antibiotic can affect INR levels

Treatment with the antibiotic dicloxacillin may cause a significant decrease in international normalized ratio (INR) levels among patients taking vitamin K antagonists (VKAs), according to research published in JAMA.

Researchers studied 7400 patients on VKA therapy and found that 61% of patients taking warfarin and dicloxacillin experienced a decrease in INR after dicloxacillin exposure.

Forty-one percent of patients taking phenprocoumon had a decrease in INR after exposure to the antibiotic.

Anton Pottegard, PhD, of the University of Southern Denmark, Odense, and his colleagues conducted this research using Thrombobase, a clinical database of all VKA-treated patients followed up by 3 outpatient clinics and 50 general practitioners in Funen, Denmark.

The researchers included all patients who filled a prescription for dicloxacillin while receiving warfarin or phenprocoumon between March 1998 and November 2012.

INR results were grouped by the week relative to dicloxacillin exposure. The last INR measurement before dicloxacillin exposure was compared with the first measurement within weeks 2 to 4 after dicloxacillin exposure.

Of the 519 patients taking warfarin and initiating treatment with dicloxacillin, 236 met inclusion criteria. The average INR level was 2.6 prior to dicloxacillin exposure and 2 at two to four weeks after dicloxacillin exposure.

In total, 61% of patients (n=144) experienced sub-therapeutic INR levels (<2.0) within 2 to 4 weeks of dicloxacillin exposure.

Among patients taking phenprocoumon (n=64), average INR levels were 2.6 before exposure to dicloxacillin and 2.3 at two to four weeks after exposure. The proportion of patients with sub-therapeutic INR levels after dicloxacillin exposure was 41% (n=26).

The researchers said these results suggest treatment with dicloxacillin can cause a significant decrease in INR levels among patients taking VKAs. ![]()

Treatment with the antibiotic dicloxacillin may cause a significant decrease in international normalized ratio (INR) levels among patients taking vitamin K antagonists (VKAs), according to research published in JAMA.

Researchers studied 7400 patients on VKA therapy and found that 61% of patients taking warfarin and dicloxacillin experienced a decrease in INR after dicloxacillin exposure.

Forty-one percent of patients taking phenprocoumon had a decrease in INR after exposure to the antibiotic.

Anton Pottegard, PhD, of the University of Southern Denmark, Odense, and his colleagues conducted this research using Thrombobase, a clinical database of all VKA-treated patients followed up by 3 outpatient clinics and 50 general practitioners in Funen, Denmark.

The researchers included all patients who filled a prescription for dicloxacillin while receiving warfarin or phenprocoumon between March 1998 and November 2012.

INR results were grouped by the week relative to dicloxacillin exposure. The last INR measurement before dicloxacillin exposure was compared with the first measurement within weeks 2 to 4 after dicloxacillin exposure.

Of the 519 patients taking warfarin and initiating treatment with dicloxacillin, 236 met inclusion criteria. The average INR level was 2.6 prior to dicloxacillin exposure and 2 at two to four weeks after dicloxacillin exposure.

In total, 61% of patients (n=144) experienced sub-therapeutic INR levels (<2.0) within 2 to 4 weeks of dicloxacillin exposure.

Among patients taking phenprocoumon (n=64), average INR levels were 2.6 before exposure to dicloxacillin and 2.3 at two to four weeks after exposure. The proportion of patients with sub-therapeutic INR levels after dicloxacillin exposure was 41% (n=26).

The researchers said these results suggest treatment with dicloxacillin can cause a significant decrease in INR levels among patients taking VKAs. ![]()

Treatment with the antibiotic dicloxacillin may cause a significant decrease in international normalized ratio (INR) levels among patients taking vitamin K antagonists (VKAs), according to research published in JAMA.

Researchers studied 7400 patients on VKA therapy and found that 61% of patients taking warfarin and dicloxacillin experienced a decrease in INR after dicloxacillin exposure.

Forty-one percent of patients taking phenprocoumon had a decrease in INR after exposure to the antibiotic.

Anton Pottegard, PhD, of the University of Southern Denmark, Odense, and his colleagues conducted this research using Thrombobase, a clinical database of all VKA-treated patients followed up by 3 outpatient clinics and 50 general practitioners in Funen, Denmark.

The researchers included all patients who filled a prescription for dicloxacillin while receiving warfarin or phenprocoumon between March 1998 and November 2012.

INR results were grouped by the week relative to dicloxacillin exposure. The last INR measurement before dicloxacillin exposure was compared with the first measurement within weeks 2 to 4 after dicloxacillin exposure.

Of the 519 patients taking warfarin and initiating treatment with dicloxacillin, 236 met inclusion criteria. The average INR level was 2.6 prior to dicloxacillin exposure and 2 at two to four weeks after dicloxacillin exposure.

In total, 61% of patients (n=144) experienced sub-therapeutic INR levels (<2.0) within 2 to 4 weeks of dicloxacillin exposure.

Among patients taking phenprocoumon (n=64), average INR levels were 2.6 before exposure to dicloxacillin and 2.3 at two to four weeks after exposure. The proportion of patients with sub-therapeutic INR levels after dicloxacillin exposure was 41% (n=26).

The researchers said these results suggest treatment with dicloxacillin can cause a significant decrease in INR levels among patients taking VKAs. ![]()

Common chemicals may increase cancer risk

Common environmental chemicals assumed to be safe at low doses may act separately or together to induce cancer development, according to research published in Carcinogenesis.

Investigators studied low-dose effects of 85 common chemicals not considered to be carcinogenic to humans, reviewing the actions of these chemicals against a long list of mechanisms that are important for cancer development.

The team compared the chemicals’ biological activity patterns to 11 known hallmarks of cancer—distinctive patterns of cellular and genetic disruption associated with early cancer development.

The chemicals included the pain reliever acetaminophen; bisphenol A (BPA), which is used in plastic food and beverage containers; rotenone, a broad-spectrum insecticide; paraquat, an agricultural herbicide; and triclosan, an antibacterial agent used in soaps and cosmetics.

The investigators learned that 50 of the 85 chemicals they analyzed can disrupt cell function in ways that correlate with known early patterns of cancer, even at the low, presumably benign levels at which most people are exposed.

For 13 of the chemicals, the team found evidence of a dose-response threshold—a level of exposure at which a chemical is considered toxic by regulators. For 22 chemicals, there was no toxicity information at all.

“Our findings also suggest these molecules may be acting in synergy to increase cancer activity,” said William Bisson, PhD, of Oregon State University in Corvallis.

“For example, EDTA, a metal-ion-binding compound used in manufacturing and medicine, interferes with the body’s repair of damaged genes. EDTA doesn’t cause genetic mutations itself, but if you’re exposed to it along with some substance that is mutagenic, it enhances the effect because it disrupts DNA repair, a key layer of cancer defense.”

Dr Bisson said the main purpose of this study was to highlight gaps in knowledge of environmentally influenced cancers and to set forth a research agenda for the next few years. He added that more research is still necessary to assess early exposure and to understand early stages of cancer development.

Traditional risk assessment, Dr Bisson said, has historically focused on a quest for single chemicals and single modes of action—approaches that may underestimate cancer risk. With this study, investigators took a different tack, examining the interplay over time of independent molecular processes triggered by low-dose exposures to chemicals.

“Cancer is a disease of diseases,” Dr Bisson said. “It follows multi-step development patterns, and, in most cases, it has a long latency period. It has to be tackled from an angle that considers the complexity of these patterns. A better understanding of what’s driving things to the point where they get uncontrollable will be key for the development of effective strategies for prevention and early detection.” ![]()

Common environmental chemicals assumed to be safe at low doses may act separately or together to induce cancer development, according to research published in Carcinogenesis.

Investigators studied low-dose effects of 85 common chemicals not considered to be carcinogenic to humans, reviewing the actions of these chemicals against a long list of mechanisms that are important for cancer development.

The team compared the chemicals’ biological activity patterns to 11 known hallmarks of cancer—distinctive patterns of cellular and genetic disruption associated with early cancer development.

The chemicals included the pain reliever acetaminophen; bisphenol A (BPA), which is used in plastic food and beverage containers; rotenone, a broad-spectrum insecticide; paraquat, an agricultural herbicide; and triclosan, an antibacterial agent used in soaps and cosmetics.

The investigators learned that 50 of the 85 chemicals they analyzed can disrupt cell function in ways that correlate with known early patterns of cancer, even at the low, presumably benign levels at which most people are exposed.

For 13 of the chemicals, the team found evidence of a dose-response threshold—a level of exposure at which a chemical is considered toxic by regulators. For 22 chemicals, there was no toxicity information at all.

“Our findings also suggest these molecules may be acting in synergy to increase cancer activity,” said William Bisson, PhD, of Oregon State University in Corvallis.

“For example, EDTA, a metal-ion-binding compound used in manufacturing and medicine, interferes with the body’s repair of damaged genes. EDTA doesn’t cause genetic mutations itself, but if you’re exposed to it along with some substance that is mutagenic, it enhances the effect because it disrupts DNA repair, a key layer of cancer defense.”

Dr Bisson said the main purpose of this study was to highlight gaps in knowledge of environmentally influenced cancers and to set forth a research agenda for the next few years. He added that more research is still necessary to assess early exposure and to understand early stages of cancer development.

Traditional risk assessment, Dr Bisson said, has historically focused on a quest for single chemicals and single modes of action—approaches that may underestimate cancer risk. With this study, investigators took a different tack, examining the interplay over time of independent molecular processes triggered by low-dose exposures to chemicals.

“Cancer is a disease of diseases,” Dr Bisson said. “It follows multi-step development patterns, and, in most cases, it has a long latency period. It has to be tackled from an angle that considers the complexity of these patterns. A better understanding of what’s driving things to the point where they get uncontrollable will be key for the development of effective strategies for prevention and early detection.” ![]()

Common environmental chemicals assumed to be safe at low doses may act separately or together to induce cancer development, according to research published in Carcinogenesis.

Investigators studied low-dose effects of 85 common chemicals not considered to be carcinogenic to humans, reviewing the actions of these chemicals against a long list of mechanisms that are important for cancer development.

The team compared the chemicals’ biological activity patterns to 11 known hallmarks of cancer—distinctive patterns of cellular and genetic disruption associated with early cancer development.

The chemicals included the pain reliever acetaminophen; bisphenol A (BPA), which is used in plastic food and beverage containers; rotenone, a broad-spectrum insecticide; paraquat, an agricultural herbicide; and triclosan, an antibacterial agent used in soaps and cosmetics.

The investigators learned that 50 of the 85 chemicals they analyzed can disrupt cell function in ways that correlate with known early patterns of cancer, even at the low, presumably benign levels at which most people are exposed.

For 13 of the chemicals, the team found evidence of a dose-response threshold—a level of exposure at which a chemical is considered toxic by regulators. For 22 chemicals, there was no toxicity information at all.

“Our findings also suggest these molecules may be acting in synergy to increase cancer activity,” said William Bisson, PhD, of Oregon State University in Corvallis.

“For example, EDTA, a metal-ion-binding compound used in manufacturing and medicine, interferes with the body’s repair of damaged genes. EDTA doesn’t cause genetic mutations itself, but if you’re exposed to it along with some substance that is mutagenic, it enhances the effect because it disrupts DNA repair, a key layer of cancer defense.”

Dr Bisson said the main purpose of this study was to highlight gaps in knowledge of environmentally influenced cancers and to set forth a research agenda for the next few years. He added that more research is still necessary to assess early exposure and to understand early stages of cancer development.

Traditional risk assessment, Dr Bisson said, has historically focused on a quest for single chemicals and single modes of action—approaches that may underestimate cancer risk. With this study, investigators took a different tack, examining the interplay over time of independent molecular processes triggered by low-dose exposures to chemicals.

“Cancer is a disease of diseases,” Dr Bisson said. “It follows multi-step development patterns, and, in most cases, it has a long latency period. It has to be tackled from an angle that considers the complexity of these patterns. A better understanding of what’s driving things to the point where they get uncontrollable will be key for the development of effective strategies for prevention and early detection.” ![]()

DLBCL tied to metabolic disruption

Researchers say they have found evidence linking disrupted metabolism and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL).

“The link between metabolism and cancer has been proposed or inferred to exist for a long time, but what is more scarce is evidence for a direct connection—genetic mutations in metabolic enzymes,” said Ricardo C.T. Aguiar, MD, PhD, of the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio.

“We have discovered a metabolic imbalance that is oncogenic or pro-cancer.”

Dr Aguiar and his colleagues described this discovery in Nature Communications.

The team found that the gene encoding the enzyme D2-hydroxyglutarate dehydrogenase (D2HGDH) is mutated in DLBCL.

The mutated lymphoma cell displays a deficiency of a metabolite called alpha-ketoglutarate (α-KG), which is needed in steady levels for cells to be healthy.

“When the levels of α-KG are abnormally low, another class of enzymes called dioxygenases don‘t function properly, resulting in a host of additional disturbances,” Dr Aguiar said.

He added that α-KG has been identified as a critical regulator of aging and stem cell maintenance. So the implications of his group’s findings are not limited to cancer biology. ![]()

Researchers say they have found evidence linking disrupted metabolism and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL).

“The link between metabolism and cancer has been proposed or inferred to exist for a long time, but what is more scarce is evidence for a direct connection—genetic mutations in metabolic enzymes,” said Ricardo C.T. Aguiar, MD, PhD, of the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio.

“We have discovered a metabolic imbalance that is oncogenic or pro-cancer.”

Dr Aguiar and his colleagues described this discovery in Nature Communications.

The team found that the gene encoding the enzyme D2-hydroxyglutarate dehydrogenase (D2HGDH) is mutated in DLBCL.

The mutated lymphoma cell displays a deficiency of a metabolite called alpha-ketoglutarate (α-KG), which is needed in steady levels for cells to be healthy.

“When the levels of α-KG are abnormally low, another class of enzymes called dioxygenases don‘t function properly, resulting in a host of additional disturbances,” Dr Aguiar said.

He added that α-KG has been identified as a critical regulator of aging and stem cell maintenance. So the implications of his group’s findings are not limited to cancer biology. ![]()

Researchers say they have found evidence linking disrupted metabolism and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL).

“The link between metabolism and cancer has been proposed or inferred to exist for a long time, but what is more scarce is evidence for a direct connection—genetic mutations in metabolic enzymes,” said Ricardo C.T. Aguiar, MD, PhD, of the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio.

“We have discovered a metabolic imbalance that is oncogenic or pro-cancer.”

Dr Aguiar and his colleagues described this discovery in Nature Communications.

The team found that the gene encoding the enzyme D2-hydroxyglutarate dehydrogenase (D2HGDH) is mutated in DLBCL.

The mutated lymphoma cell displays a deficiency of a metabolite called alpha-ketoglutarate (α-KG), which is needed in steady levels for cells to be healthy.

“When the levels of α-KG are abnormally low, another class of enzymes called dioxygenases don‘t function properly, resulting in a host of additional disturbances,” Dr Aguiar said.

He added that α-KG has been identified as a critical regulator of aging and stem cell maintenance. So the implications of his group’s findings are not limited to cancer biology. ![]()

Of Mice and Men

Fever in an elderly man is a nonspecific finding, occurring most commonly with infections but also with certain malignancies, rheumatologic disorders, and drug exposures. The complaint of rigors with diaphoresis makes an infection most likely. The acuity of his illness makes infections with more chronic presentations such as tuberculosis or actinomycosis less likely. The presence of frontal headache might suggest a sinus or brain source, but headache also occurs in generalized infections such as pneumonia, bacteremia from any cause, malaria, rickettsial infections, viral illnesses, and others. Additional history should include detailed inquiry into travel, vocational, and avocational exposures.

The patient's difficulty standing implies the development of lower extremity weakness and infections associated with neurological syndromes. His leg weakness may be related to early Guillain‐Barre syndrome, which is associated most commonly with Campylobacter jejuni, but also other bacteria and viruses such as Haemophilus influenza, Mycoplasma pneumonia, Influenza virus, Cytomegalovirus and hepatitis E. Other viral infections associated with pure motor deficits include echovirus, coxsackie virus, enterovirus, and West Nile virus (WNV). The paralytic syndrome associated with enteroviruses is more common in children, whereas the neuroinvasive variant of WNV more often affects the elderly and can be associated with encephalitis as well as a flaccid paralysis. Although acute paralytic shellfish poisoning could account for both his weakness and his acute gastrointestinal syndrome, this diagnosis is unlikely because the symptoms often have a prominent sensory component, and there is usually the history of recent ingestion of the suspect bivalves. Like all adults presenting for medical care, he should be screened for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection; if testing is positive, the differential diagnosis for his current illness broadens significantly. Finally, he may have a spinal cord disorder or infection such as an epidural abscess, or transverse myelitis, which would present with lower extremity weakness and fever. It would be helpful to know the time of year of his illness, exposure to mosquito bites, his neurological exam findings, and results of blood and stool cultures. If the patient had signs of meningitis or encephalitis, cerebral spinal fluid analysis would be helpful. If his neurological exam was suggestive of cord involvement, it would be helpful to know the results of magnetic resonance imaging of the spinal cord.

The patient's past medical history includes relatively common problems for a 73‐year‐old man and does not substantially influence the differential diagnosis of his current illness. His travel history to Uganda a year previously may be relevant, because malaria (Plasmodium vivax) could present with fever and weakness. Less commonly, African trypanosomiasis (Trypanosoma brucei gambiense) can, in the late phase, present with fever and malaise, but also typically includes symptoms of encephalitis, including depressed mental status, confusion, ataxia, and possibly personality changes. His travel to Zurich should not impose any particular infection risk, unless he was hiking in the mountains around Zurich, where he could have contracted tick‐borne encephalitis; however, his travel more than 6 months prior to presentation makes this unlikely. Lyme disease due to Borrelia burgdorferi is also a potential exposure in the Swiss mountains, and can present with fever in the acute phase, as well as arthritis with chronic disease, but should not cause fever, rigor, diaphoresis, and headache many months later. Summering in Cape Cod puts him at risk for babesiosis, but an incubation period of 5 months is too long. Keeping chickens places him at risk for Salmonella exposure and typhoid fever. Ingesting raw oysters carries a risk for shellfish poisoning and Vibrio infections, but the incubation period (1 month) again seems too long to cause his current symptoms.

Notable physical findings are an ill‐appearing man with injected sclera and a high fever but normal blood pressure and heart rate. He also demonstrates proximal lower extremity weakness manifested by difficulty rising from a chair and a slow gait with short strides and deliberate (possibly on‐block) turning. His neurological exam is most consistent with Parkinsonian symptoms that have been described in patients with severe influenza A, which would explain all of his other symptoms as well. Pulse‐temperature dissociation is classically described with typhoid fever but usually occurs later in the disease course, and could be masked by the patient's metoprolol. Typhoid fever can also be associated with neurological symptoms including meningitis and movement disorders.

The patient has a remarkable bandemia, suggesting a bacterial infection, as well as a slight reduction in hematocrit and platelet count. Additionally, his labs revealed a mild transaminitis, but with significantly elevated alkaline phosphatase and GGT, and microscopic hematuria. His ferritin is significantly elevated, which may simply represent an acute phase reactant. Infections associated with hepatitis, cytopenias, and hematuria include sepsis with disseminated intravascular coagulation, previously mentioned malaria, leptospirosis, dengue, ehrlichiosis, and rickettsial diseases, but he has no special risks for these infections, and other aspects of his illness (Parkinsonian features, bandemia) do not fit. His lung findings with hematuria might suggest a pulmonary/renal syndrome, but, once again, other features of his illness are not typical of these syndromes. Salmonella (typhoid fever) or influenza, now complicated by an early bacterial pneumonia, are viable possibilities.

The patient's ongoing clinical course is notable for a nontoxic (non‐SIRS) appearance but continued high‐grade fever with blood and urine cultures that are sterile. This argues against a common bacteremia with sepsis, and for either relapsing malaria (P vivax), influenza with a Parkinsonian‐like illness, typhoid fever, leptospirosis, dengue, or a rickettsial infection. Mycoplasma pneumonia is also possible given the atypical chest x‐ray appearance, slightly low hematocrit with elevated bilirubin, and neurological symptoms that may represent ataxia.

The subsequent negative laboratory tests listed are helpful in likely excluding many of the diagnoses suggested such as malaria, Babesia, common bacteremias, viral hepatitis, HIV, and WNV. Furthermore, the new history of mouse exposure brings to the forefront rodent‐associated infections, specifically exposure to mouse urine, a vehicle for leptospirosis. The patient's hepatitis, anemia, thrombocytopenia, scleral injection, along with the rest of his symptoms in the context of exposure to mouse urine makes leptospirosis the likely diagnosis. A negative Leptospira antibody early in his illness does not rule out the disease, and a convalescent titer should be obtained to confirm the diagnosis.

COMMENTARY

This case describes an elderly man who presented with a fever of unknown origin (FUO), and was eventually diagnosed with leptospirosis. FUO presents slightly differently in elderly patients, as elderly patients are less likely to mount a high fever, and when they do, the etiology is more likely to indicate a serious bacterial or viral infection. Additionally, an etiology for FUO in the elderly is found in over 70% of presenting cases, compared to 51% in patients under the age of 65 years.[1] A detailed, comprehensive social, travel, and exposure history and physical examination remains the cornerstone of elucidating the diagnosis for FUO. The exposure to mouse urine in this case was an unusual and a helpful piece of the history to further focus the differential diagnosis.

Leptospirosis is an emerging bacterial zoonosis, and causes both endemic and epidemic severe multisystem disease. The Leptospira spirochete is maintained in nature through a chronic renal infection in mammalian reservoir hosts, such as mice,[2, 4] and is transmitted through direct or aerosolized contact with infected urine or tissue. After a mean incubation period of 10 days, a variety of clinical manifestations may be seen. In this case, the patient's clinical presentation revealed many classic symptoms of leptospirosis, including fevers, rigors, headache, lower extremity myalgias, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea; however, these symptoms are nonspecific. The presence of a conjunctival suffusion in leptospirosis infection had a specificity of 98% in a high‐incidence cohort of febrile patients in Sri Lanka,[3] and was an important diagnostic clue in this case. Leptospirosis is a self‐limited illness in most patients, with an initial septicemic, febrile phase followed by an immune phase. A more severe presentation may be seen in the immune phase of the illness, which includes renal and hepatic dysfunction (known as Weil's disease), as well as cardiac, pulmonary, and central nervous system abnormalities. With a 14% case fatality rate, the risk of death has been shown to be higher in patients over 40 years old, with altered mental status and multiorgan failure.[4]

The early diagnosis of leptospirosis relies heavily on physical exam findings and epidemiologic history. In this case, the patient's laboratory abnormalities, including immature granulocytes, thrombocytopenia, hyponatremia, hypokalemia, mild hepatitis, and pyuria with granular casts are all reported with leptospirosis infection2; however, independently, these laboratory findings are nonspecific. Patients may not have a detectable antibody levels in the acute phase of the disease. In this case, given the strong clinical suspicion based on the findings of conjunctival suffusion and exposure to mouse urine history, the lack of a more plausible alternate diagnosis, and known delay in antibody positivity, the patient was treated empirically with doxycycline for presumed leptospirosis.[5] Forthcoming novel diagnostic strategies such as next‐generation DNA sequencing techniques may provide real‐time diagnosis of this zoonotic infection, thus decreasing the window period between empirical antimicrobial coverage and diagnostic confirmation.[6]

Leptospirosis is prevalent in tropical climates and has been associated with impoverished communities.[7] Urban slums, with poor sanitation and high rodent density, are an ideal environment for leptospirosis. The reported risk of infection in a Brazilian slum was as high as 3% per year.[8] Additionally, rodent sightings, as well as the presence of chickens, were risk factors for leptospirosis transmission in urban slums.[9] Correspondingly in this case, we hypothesize that the patient's interest in urban farming, specifically the chickens he kept, likely attracted the mice infected with leptospirosis. Urban chicken farming is becoming increasingly popular in the United States,[10] and may be a developing risk factor for human leptospirosis infection. Leptospirosis is one of many emerging zoonoses, such as avian influenza, tick‐borne illness, and ebola, resulting from changing human ecology. Thus, when considering infectious etiologies, clinicians should ask patients about vocational and avocational exposures, including new trends such as urban farming, which may expose them to previously underappreciated illnesses.

TEACHING POINTS

- Elderly patients with a FUO are more likely to be diagnosed with an underlying serious bacterial or viral infection when compared to a younger cohort of FUO patients.

- The diagnosis of leptospirosis may initially be based on clinical suspicion in patients with classic features and exposures, noting the high specificity of conjunctival suffusion, and initial titers may be nondiagnostic; therefore, empiric treatment should be considered when clinical suspicion is high.

- Increased interest in urban chicken farming in the United States, with associated higher rodent density, may represent a newly recognized risk factor for human leptospirosis infection.

Disclosures

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

- , , . Fever of unknown origin in older persons. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2007;21(4):937–945.

- . Leptospirosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2011;14(2):296–326.

- , , , et al. Leptospirosis as frequent cause of acute febrile illness in southern Sri Lanka. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17(9):1678–1684.

- , , , et al. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2010.

- , . Antibiotics for leptospirosis. The Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;2:CD008264.

- , , , et al. Actionable diagnosis of neuroleptospirosis by next‐generation sequencing. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(25):2408–2417.

- , , , . Cases distribution of leptospirosis in City of Manaus, State of Amazonas, Brazil, 2000–2010. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2012;45(6):713–716.

- , , , et al. Prospective study of leptospirosis transmission in an urban slum community: role of poor environment in repeated exposures to the leptospira agent. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8(5):e2927.

- , , , et al. Impact of environment and social gradient on leptospira infection in urban slums. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2008;2(4):e228.

- Urban chicken ownership in four U.S. cities. United States Department of Agriculture website. Available at: http://www.aphis.usda.gov/animal_health/nahms/poultry/downloads/poultry10/Poultry10_dr_Urban_Chicken_Four.pdf. Published April 2013. Accessed June 9, 2015.